Coordinates: 24°N 54°E / 24°N 54°E

|

United Arab Emirates الْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة (Arabic) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem |

|

| Motto: الله الوطن الرئيس

God, Nation, President |

|

| Anthem: عيشي بلادي «Īšiy Bilādī« «Long Live My Country» |

|

Location of United Arab Emirates (green) in the Arabian Peninsula |

|

|

United Arab Emirates |

|

| Capital | Abu Dhabi 24°28′N 54°22′E / 24.467°N 54.367°E |

| Largest city | Dubai 25°15′N 55°18′E / 25.250°N 55.300°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Common languages | Gulf Arabic, English[2] |

| Ethnic groups

(2015)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Emirati[4] |

| Government | Federal Islamic parliamentary elective semi-constitutional monarchy[5][6][7] |

|

• President |

Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan[8] |

|

• Vice President and |

Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum |

| Legislature |

|

| Establishment | |

|

• Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah |

1708 |

|

• Sharjah |

1727 |

|

• Abu Dhabi |

1761 |

|

• Umm Al Quwain |

1768 |

|

• Ajman |

1816 |

|

• Dubai |

1833 |

|

• Fujairah |

1879 |

|

• Independence from the United Kingdom and the Trucial States |

2 December 1971 |

|

• Admitted to the United Nations |

9 December 1971 |

|

• Admission of Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah to the UAE |

10 February 1972 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

83,600 km2 (32,300 sq mi) (114th) |

|

• Water (%) |

negligible |

| Population | |

|

• 2020 estimate |

9,282,410[9] (92nd) |

|

• 2005 census |

4,106,427 |

|

• Density |

121/km2 (313.4/sq mi) (110th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) | 26.0[11] low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 26th |

| Currency | UAE dirham (AED) |

| Time zone | UTC+04:00 (GST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +971 |

| ISO 3166 code | AE |

| Internet TLD |

|

|

United Arab Emirates portal |

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; Arabic: اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة al-ʾImārāt al-ʿArabīyah al-Muttaḥidah), or simply the Emirates (Arabic: الِْإمَارَات al-ʾImārāt), is a country in Western Asia (The Middle East). It is located at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula and shares borders with Oman and Saudi Arabia, while having maritime borders in the Persian Gulf with Qatar and Iran. Abu Dhabi is the nation’s capital, while Dubai, the most populated city, is an international hub.

The United Arab Emirates is an elective monarchy formed from a federation of seven emirates, consisting of Abu Dhabi (the capital), Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah and Umm Al Quwain.[13] Each emirate is governed by an emir and together the emirs form the Federal Supreme Council. The members of the Federal Supreme Council elect a president (as of 14th May 2022, His Highness Sheikh Mohamed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan)[14] and vice president (His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum) from among their members. In practice, the emir of Abu Dhabi serves as president while the ruler of Dubai is vice president and also prime minister.[15] In 2013, the country had a population of 9.2 million, of which 1.4 million were Emirati citizens and 7.8 million were expatriates.[16][17][18] As of 2020, the United Arab Emirates has an estimated population of roughly 9.9 million.[19]

The area which is today the United Arab Emirates has been inhabited for over 125,000 years. It has been the crossroads of trading for many civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Persia, and India.[20]

Islam is the official religion and Arabic the official language. The United Arab Emirates’ oil and natural gas reserves are the world’s sixth and seventh-largest, respectively.[21][22] Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, ruler of Abu Dhabi and the country’s first president, oversaw the development of the Emirates by investing oil revenues into healthcare, education, and infrastructure.[23] The United Arab Emirates has the most diversified economy among the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council.[24] In the 21st century, the country has become less reliant on oil and gas and is economically focusing on tourism and business. The government does not levy income tax, although there is a corporate tax in place and a 5% value-added tax was established in 2018.[25]

Human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, Freedom House and Human Rights Watch, regard UAE as generally substandard on human rights, with citizens criticising the regime imprisoned and tortured, families harassed by the state security apparatus, and cases of forced disappearances.[26][27] Individual rights such as the freedoms of assembly, association, the press, expression, and religion are also severely repressed.[28]

The UAE is considered a middle power. It is a member of the United Nations, Arab League, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, OPEC, Non-Aligned Movement, and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

History[edit]

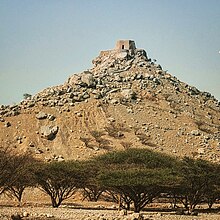

Human occupation in the region has been traced back to the emergence of anatomically modern humans from Africa circa 124,000 BCE through finds at the Faya-2 site in Mleiha, Sharjah. Burial sites dating back to the Neolithic Age and the Bronze Age include the oldest known such inland site at Jebel Buhais. Known as Magan to the Sumerians, the area was home to a prosperous Bronze Age trading culture during the Umm Al Nar period which traded between the Indus Valley, Bahrain and Mesopotamia as well as Iran, Bactria and the Levant. The ensuing Wadi Suq period and three Iron Ages saw the emergence of nomadism as well as the development of water management and irrigation systems supporting human settlement in both the coast and interior. The Islamic Age began with the expulsion of the Sasanians and the subsequent Battle of Dibba.[29] The region’s history of trade led to the emergence of Julfar, in the present-day emirate of Ras Al Khaimah, as a regional trading and maritime hub in the area. The maritime dominance of the Persian Gulf by Arab traders led to conflicts with European powers, including the Portuguese Empire and the British Empire.[20]

Following decades of maritime conflict, the coastal emirates became known as the Trucial States with the signing of the General Maritime Treaty with the British in 1820 (ratified in 1853 and again in 1892), which established the Trucial States as a British protectorate. This arrangement ended with independence and the establishment of the United Arab Emirates on 2 December 1971 following the British withdrawal from its treaty obligations. Six emirates joined the UAE in 1971; the seventh, Ras Al Khaimah, joined the federation on 10 February 1972.[30]

Antiquity[edit]

Stone tools recovered reveal a settlement of people from Africa some 127,000 years ago and a stone tool used for butchering animals discovered on the Arabian coast suggests an even older habitation from 130,000 years ago.[31] There is no proof of contact with the outside world at that stage, although in time lively trading links developed with civilisations in Mesopotamia, Iran and the Harappan culture of the Indus Valley. This contact persisted and became wider, probably motivated by the trade in copper from the Hajar Mountains, which commenced around 3,000 BCE.[32] Sumerian sources talk of the Magan civilisation, which has been identified as encompassing the modern UAE and Oman.[33]

There are six periods of human settlement with distinctive behaviours in the region before Islam, which include the Hafit period from 3,200 to 2,600 BCE, the Umm Al Nar culture from 2,600 to 2,000 BCE, and the Wadi Suq culture from 2,000 to 1,300 BCE. From 1,200 BCE to the advent of Islam in Eastern Arabia, through three distinctive Iron Ages and the Mleiha period, the area was variously occupied by the Achaemenids and other forces, and saw the construction of fortified settlements and extensive husbandry thanks to the development of the falaj irrigation system.

In ancient times, Al Hasa (today’s Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia) was part of Al Bahreyn and adjoined Greater Oman (today’s UAE and Oman). From the second century CE, there was a movement of tribes from Al Bahreyn towards the lower Gulf, together with a migration among the Azdite Qahtani (or Yamani) and Quda’ah tribal groups from south-west Arabia towards central Oman.

Islam[edit]

The spread of Islam to the northeastern tip of the Arabian Peninsula is thought to have followed directly from a letter sent by the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, to the rulers of Oman in 630 CE, nine years after the hijrah. This led to a group of rulers travelling to Medina, converting to Islam and subsequently driving a successful uprising against the unpopular Sassanids, who dominated the coast at the time.[34] Following the death of Muhammad, the new Islamic communities south of the Persian Gulf threatened to disintegrate, with insurrections against the Muslim leaders. Caliph Abu Bakr sent an army from the capital Medina which completed its reconquest of the territory (the Ridda Wars) with the Battle of Dibba in which 10,000 lives are thought to have been lost.[35] This assured the integrity of the Caliphate and the unification of the Arabian Peninsula under the newly emerging Rashidun Caliphate.

In 637, Julfar (in the area of today’s Ras Al Khaimah) was an important port that was used as a staging post for the Islamic invasion of the Sasanian Empire.[36] The area of the Al Ain/Buraimi Oasis was known as Tu’am and was an important trading post for camel routes between the coast and the Arabian interior.[37]

The earliest Christian site in the UAE was first discovered in the 1990s, an extensive monastic complex on what is now known as Sir Bani Yas Island and which dates back to the seventh century. Thought to be Nestorian and built in 600 CE, the church appears to have been abandoned peacefully in 750 CE.[38] It forms a rare physical link to a legacy of Christianity, which is thought to have spread across the peninsula from 50 to 350 CE following trade routes. Certainly, by the fifth century, Oman had a bishop named John – the last bishop of Oman being Etienne, in 676 CE.[39]

Portuguese era[edit]

The harsh desert environment led to the emergence of the «versatile tribesman», nomadic groups who subsisted due to a variety of economic activities, including animal husbandry, agriculture and hunting. The seasonal movements of these groups led not only to frequent clashes between groups but also to the establishment of seasonal and semi-seasonal settlements and centres. These formed tribal groupings whose names are still carried by modern Emiratis, including the Bani Yas and Al Bu Falah of Abu Dhabi, Al Ain, Liwa and the west coast, the Dhawahir, Awamir, Al Ali and Manasir of the interior, the Sharqiyin of the east coast and the Qawasim to the North.[40]

With the expansion of European colonial empires, Portuguese, English and Dutch forces appeared in the Persian Gulf region. By the 18th century, the Bani Yas confederation was the dominant force in most of the area now known as Abu Dhabi,[41][42][43] while the Northern Al Qawasim (Al Qasimi) dominated maritime commerce. The Portuguese maintained an influence over the coastal settlements, building forts in the wake of the bloody 16th-century conquests of coastal communities by Albuquerque and the Portuguese commanders who followed him – particularly on the east coast at Muscat, Sohar and Khor Fakkan.[44]

The southern coast of the Persian Gulf was known to the British as the «Pirate Coast»,[45][46] as boats of the Al Qawasim federation harassed British-flagged shipping from the 17th century into the 19th.[47] The charge of piracy is disputed by modern Emirati historians, including the current Ruler of Sharjah, Sheikh Sultan Al Qasimi, in his 1986 book The Myth of Arab Piracy in the Gulf.[48]

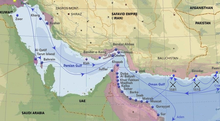

Purple – Portuguese in the Persian Gulf in the 16th and 17th century. Main cities, ports and routes.

British expeditions to protect their Indian trade routes led to campaigns against Ras Al Khaimah and other harbours along the coast, including the Persian Gulf campaign of 1809 and the more successful campaign of 1819. The following year, Britain and a number of local rulers signed a maritime truce, giving rise to the term Trucial States, which came to define the status of the coastal emirates. A further treaty was signed in 1843 and, in 1853 the Perpetual Maritime Truce was agreed. To this was added the ‘Exclusive Agreements’, signed in 1892, which made the Trucial States a British protectorate.[49]

Under the 1892 treaty, the trucial sheikhs agreed not to dispose of any territory except to the British and not to enter into relationships with any foreign government other than the British without their consent. In return, the British promised to protect the Trucial Coast from all aggression by sea and to help in case of land attack. The Exclusive Agreement was signed by the Rulers of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Ras Al Khaimah and Umm Al Quwain between 6 and 8 March 1892. It was subsequently ratified by the Governor-General of India and the British Government in London.[citation needed] British maritime policing meant that pearling fleets could operate in relative security. However, the British prohibition of the slave trade meant an important source of income was lost to some sheikhs and merchants.[50]

In 1869, the Qubaisat tribe settled at Khawr al Udayd and tried to enlist the support of the Ottomans, whose flag was occasionally seen flying there. Khawr al Udayd was claimed by Abu Dhabi at that time, a claim supported by the British. In 1906, the British Political Resident, Percy Cox, confirmed in writing to the ruler of Abu Dhabi, Zayed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan (‘Zayed the Great’) that Khawr al Udayd belonged to his sheikhdom.[51]

British era and discovery of oil[edit]

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the pearling industry thrived, providing both income and employment to the people of the Persian Gulf.[52] The First World War had a severe impact on the industry, but it was the economic depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s, coupled with the invention of the cultured pearl, that wiped out the trade. The remnants of the trade eventually faded away shortly after the Second World War, when the newly independent Government of India imposed heavy taxation on pearls imported from the Arab states of the Persian Gulf. The decline of pearling resulted in extreme economic hardship in the Trucial States.[53]

In 1922, the British government secured undertakings from the rulers of the Trucial States not to sign concessions with foreign companies without their consent. Aware of the potential for the development of natural resources such as oil, following finds in Persia (from 1908) and Mesopotamia (from 1927), a British-led oil company, the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), showed an interest in the region. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC, later to become British Petroleum, or BP) had a 23.75% share in IPC. From 1935, onshore concessions to explore for oil were granted by local rulers, with APOC signing the first one on behalf of Petroleum Concessions Ltd (PCL), an associate company of IPC.[54] APOC was prevented from developing the region alone because of the restrictions of the Red Line Agreement, which required it to operate through IPC. A number of options between PCL and the trucial rulers were signed, providing useful revenue for communities experiencing poverty following the collapse of the pearl trade. However, the wealth of oil which the rulers could see from the revenues accruing to surrounding countries such as Iran, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia remained elusive. The first bore holes in Abu Dhabi were drilled by IPC’s operating company, Petroleum Development (Trucial Coast) Ltd (PDTC) at Ras Sadr in 1950, with a 13,000-foot-deep (4,000-metre) bore hole taking a year to drill and turning out dry, at the tremendous cost at the time of £1 million.

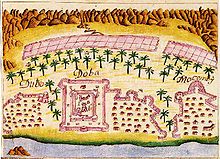

Dubai in 1950; the area in this photo shows Bur Dubai in the foreground (centered on Al-Fahidi Fort); Deira in middle-right on the other side of the creek; and Al Shindagha (left) and Al Ras (right) in the background across the creek again from Deira

The British set up a development office that helped in some small developments in the emirates. The seven sheikhs of the emirates then decided to form a council to coordinate matters between them and took over the development office. In 1952, they formed the Trucial States Council,[55] and appointed Adi Bitar, Dubai’s Sheikh Rashid’s legal advisor, as Secretary General and Legal Advisor to the council. The council was terminated once the United Arab Emirates was formed.[56] The tribal nature of society and the lack of definition of borders between emirates frequently led to disputes, settled either through mediation or, more rarely, force. The Trucial Oman Scouts was a small military force used by the British to keep the peace.

In 1953, a subsidiary of BP, D’Arcy Exploration Ltd, obtained an offshore concession from the ruler of Abu Dhabi. BP joined with Compagnie Française des Pétroles (later Total) to form operating companies, Abu Dhabi Marine Areas Ltd (ADMA) and Dubai Marine Areas Ltd (DUMA). A number of undersea oil surveys were carried out, including one led by the famous marine explorer Jacques Cousteau.[57][58] In 1958, a floating platform rig was towed from Hamburg, Germany, and positioned over the Umm Shaif pearl bed, in Abu Dhabi waters, where drilling began. In March, it struck oil in the Upper Thamama, a rock formation that would provide many valuable oil finds. This was the first commercial discovery of the Trucial Coast, leading to the first exports of oil in 1962. ADMA made further offshore discoveries at Zakum and elsewhere, and other companies made commercial finds such as the Fateh oilfield off Dubai and the Mubarak field off Sharjah (shared with Iran).[59]

Meanwhile, onshore exploration was hindered by territorial disputes. In 1955, the United Kingdom represented Abu Dhabi and Oman in their dispute with Saudi Arabia over the Buraimi Oasis.[60] A 1974 agreement between Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia seemed to have settled the Abu Dhabi-Saudi border dispute, but this has not been ratified.[61] The UAE’s border with Oman was ratified in 2008.[62]

PDTC continued its onshore exploration away from the disputed area, drilling five more bore holes that were also dry. However, on 27 October 1960, the company discovered oil in commercial quantities at the Murban No. 3 well on the coast near Tarif.[63] In 1962, PDTC became the Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company. As oil revenues increased, the ruler of Abu Dhabi, Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, undertook a massive construction program, building schools, housing, hospitals and roads. When Dubai’s oil exports commenced in 1969, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai, was able to invest the revenues from the limited reserves found to spark the diversification drive that would create the modern global city of Dubai.[64]

Independence[edit]

Historic photo depicting the first hoisting of the United Arab Emirates flag by the rulers of the emirates at The Union House, Dubai on 2 December 1971

By 1966, it had become clear the British government could no longer afford to administer and protect the Trucial States, what is now the United Arab Emirates. British Members of Parliament (MPs) debated the preparedness of the Royal Navy to defend the sheikhdoms. Secretary of State for Defence Denis Healey reported that the British Armed Forces were seriously overstretched and in some respects dangerously under-equipped to defend the sheikhdoms. On 24 January 1968, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced the government’s decision, reaffirmed in March 1971 by Prime Minister Edward Heath, to end the treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Sheikhdoms, that had been, together with Bahrain and Qatar, under British protection. Days after the announcement, the ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, fearing vulnerability, tried to persuade the British to honour the protection treaties by offering to pay the full costs of keeping the British Armed Forces in the Emirates. The British Labour government rejected the offer.[65] After Labour MP Goronwy Roberts informed Sheikh Zayed of the news of British withdrawal, the nine Persian Gulf sheikhdoms attempted to form a union of Arab emirates, but by mid-1971 they were still unable to agree on terms of union even though the British treaty relationship was to expire in December of that year.[66]

Fears of vulnerability were realised the day before independence. An Iranian destroyer group broke formation from an exercise in the lower Gulf, sailing to the Tunb islands. The islands were taken by force, civilians and Arab defenders alike allowed to flee. A British warship stood idle during the course of the invasion.[67] A destroyer group approached the island Abu Musa as well. But there, Sheikh Khalid bin Mohammed Al Qasimi had already negotiated with the Iranian Shah, and the island was quickly leased to Iran for $3 million a year. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia laid claim to swathes of Abu Dhabi.[68]

Originally intended to be part of the proposed Federation of Arab Emirates, Bahrain became independent in August, and Qatar in September 1971. When the British-Trucial Sheikhdoms treaty expired on 1 December 1971, both emirates became fully independent.[69] On 2 December 1971, at the Dubai Guesthouse (now known as Union House) six of the emirates (Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Sharjah and Umm Al Quwain) agreed to enter into a union called the United Arab Emirates. Ras al-Khaimah joined it later, on 10 January 1972.[70][71] In February 1972, the Federal National Council (FNC) was created; it was a 40-member consultative body appointed by the seven rulers. The UAE joined the Arab League on 6 December 1971 and the United Nations on 9 December.[72] It was a founding member of the Gulf Cooperation Council in May 1981, with Abu Dhabi hosting the first GCC summit.

A 19-year-old Emirati from Abu Dhabi, Abdullah Mohammed Al Maainah, designed the UAE flag in 1971. The four colours of the flag are the Pan-Arab colours of red, green, white, and black, and represent the unity of the Arab nations. It was adopted on 2 December 1971. Al Maainah went on to serve as the UAE ambassador to Chile and currently serves as the UAE ambassador to the Czech Republic.[73]

Post-Independence period[edit]

The UAE supported military operations by the US and other coalition nations engaged in the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan (2001) and Saddam Hussein in Ba’athist Iraq (2003) as well as operations supporting the Global War on Terror for the Horn of Africa at Al Dhafra Air Base located outside of Abu Dhabi. The air base also supported Allied operations during the 1991 Persian Gulf War and Operation Northern Watch. The country had already signed a military defence agreement with the U.S. in 1994 and one with France in 1995.[74][75] In January 2008, France and the UAE signed a deal allowing France to set up a permanent military base in the emirate of Abu Dhabi.[76] The UAE joined international military operations in Libya in March 2011.

On 2 November 2004, the UAE’s first president, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, died. Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan was elected as the President of the UAE. In accordance with the constitution, the UAE’s Supreme Council of Rulers elected Khalifa as president. Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan succeeded Khalifa as Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi.[77] In January 2006, Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the prime minister of the UAE and the ruler of Dubai, died, and Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum assumed both roles.

The first ever national elections were held in the UAE on 16 December 2006. A number of voters chose half of the members of the Federal National Council. The UAE has largely escaped the Arab Spring, which other countries have experienced; however, 60 Emirati activists from Al Islah were apprehended for an alleged coup attempt and the attempt of the establishment of an Islamist state in the UAE.[78][79][80] Mindful of the protests in nearby Bahrain, in November 2012 the UAE outlawed online mockery of its own government or attempts to organise public protests through social media.[23]

On 29 January 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached the UAE, as a 73-year-old Chinese woman had tested positive for the disease.[81] Two months later, in March, the government announced the closure of shopping malls, schools, and places of worship, in addition to imposing a 24-hour curfew, and suspending all Emirates passenger flights.[82][83][84][85][86] This resulted in a major economic downturn, which eventually led to the merger of more than 50% of the UAE’s federal agencies.[87]

On 29 August 2020, the UAE established normal diplomatic relations with Israel and with the help of the United States, they signed the Abraham Accords with Bahrain.[88]

On 9 February 2021, the UAE achieved a historic milestone when its probe, named Hope, successfully reached Mars’ orbit. The UAE became the first country in the Arab world to reach Mars, the fifth country to successfully reach Mars, and the second country, after an Indian probe, to orbit Mars on its maiden attempt.

On 14 May 2022, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan was elected as the UAE’s new president after the death of Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan.[89]

On 27 February 2023, Emirati astronaut Sultan Al Neyadi, along with three fellow SpaceX Crew-6 members, became the first Arab to embark on a month-long space mission to the International Space Station.

Geography[edit]

Satellite image of United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates is situated in the Middle East, bordering the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf, between Oman and Saudi Arabia; it is in a strategic location slightly south of the Strait of Hormuz, a vital transit point for world crude oil.[90]

The UAE lies between 22°30′ and 26°10′ north latitude and between 51° and 56°25′ east longitude. It shares a 530-kilometre (330 mi) border with Saudi Arabia on the west, south, and southeast, and a 450-kilometre (280 mi) border with Oman on the southeast and northeast. The land border with Qatar in the Khawr al Udayd area is about nineteen kilometres (12 miles) in the northwest; however, it is a source of ongoing dispute.[91] Following Britain’s military departure from the UAE in 1971, and its establishment as a new state, the UAE laid claim to islands resulting in disputes with Iran that remain unresolved.[92] The UAE also disputes claim on other islands against the neighboring state of Qatar.[93] The largest emirate, Abu Dhabi, accounts for 87% of the UAE’s total area[94] (67,340 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi)).[95] The smallest emirate, Ajman, encompasses only 259 km2 (100 sq mi) (see figure).[96]

The UAE coast stretches for nearly 650 km (404 mi) along the southern shore of the Persian Gulf, briefly interrupted by an isolated outcrop of the Sultanate of Oman. Six of the emirates are situated along the Persian Gulf, and the seventh, Fujairah is on the eastern coast of the peninsula with direct access to the Gulf of Oman.[97] Most of the coast consists of salt pans that extend 8–10 km inland.[98] The largest natural harbor is at Dubai, although other ports have been dredged at Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, and elsewhere.[99] Numerous islands are found in the Persian Gulf, and the ownership of some of them has been the subject of international disputes with both Iran and Qatar. The smaller islands, as well as many coral reefs and shifting sandbars, are a menace to navigation. Strong tides and occasional windstorms further complicate ship movements near the shore. The UAE also has a stretch of the Al Bāţinah coast of the Gulf of Oman. The Musandam Peninsula, the very tip of Arabia by the Strait of Hormuz, and Madha are exclaves of Oman separated by the UAE.[100]

South and west of Abu Dhabi, vast, rolling sand dunes merge into the Rub al-Khali (Empty Quarter) of Saudi Arabia.[101] The desert area of Abu Dhabi includes two important oases with adequate underground water for permanent settlements and cultivation. The extensive Liwa Oasis is in the south near the undefined border with Saudi Arabia. About 100 km (62 mi) to the northeast of Liwa is the Al-Buraimi oasis, which extends on both sides of the Abu Dhabi-Oman border. Lake Zakher in Al Ain is a human-made lake near the border with Oman that was created from treated waste water.[102]

Prior to withdrawing from the area in 1971, Britain delineated the internal borders among the seven emirates in order to preempt territorial disputes that might hamper formation of the federation. In general, the rulers of the emirates accepted the British interventions, but in the case of boundary disputes between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, and also between Dubai and Sharjah, conflicting claims were not resolved until after the UAE became independent. The most complicated borders were in the Al-Hajar al-Gharbi Mountains, where five of the emirates contested jurisdiction over more than a dozen enclaves.

Biodiversity[edit]

The UAE contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Al Hajar montane woodlands, Gulf of Oman desert and semi-desert, Al-Hajar foothill xeric woodlands and shrublands, and Al-Hajar montane woodlands and shrublands.[103]

The oases grow date palms, acacia and eucalyptus trees. In the desert, the flora is very sparse and consists of grasses and thorn bushes. The indigenous fauna had come close to extinction because of intensive hunting, which has led to a conservation program on Sir Bani Yas Island initiated by Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan in the 1970s, resulting in the survival of, for example, Arabian Oryx, Arabian camel and leopards. Coastal fish and mammals consist mainly of mackerel, perch, and tuna, as well as sharks and whales.

Climate[edit]

The climate of the UAE is subtropical-arid with hot summers and warm winters. The climate is categorized as desert climate. The hottest months are July and August, when average maximum temperatures reach above 45 °C (113 °F) on the coastal plain. In the Al Hajar Mountains, temperatures are considerably lower, a result of increased elevation.[104] Average minimum temperatures in January and February are between 10 and 14 °C (50 and 57 °F).[105] During the late summer months, a humid southeastern wind known as Sharqi (i.e. «Easterner») makes the coastal region especially unpleasant. The average annual rainfall in the coastal area is less than 120 mm (4.7 in), but in some mountainous areas annual rainfall often reaches 350 mm (13.8 in). Rain in the coastal region falls in short, torrential bursts during the winter months, sometimes resulting in floods in ordinarily dry wadi beds.[106] The region is prone to occasional, violent dust storms, which can severely reduce visibility.

On 28 December 2004, there was snow recorded in the UAE for the first time, in the Jebel Jais mountain cluster in Ras al-Khaimah.[107] A few years later, there were more sightings of snow and hail.[108][109] The Jebel Jais mountain cluster has experienced snow only twice since records began.[110]

Government and politics[edit]

The UAE is an authoritarian state.[111][112][113][114] According to The New York Times, the UAE is «an autocracy with the sheen of a progressive, modern state».[115] The UAE has been described as a «tribal autocracy» where the seven constituent monarchies are led by tribal rulers in an autocratic fashion.[116] There are no democratically elected institutions, and there is no formal commitment to free speech.[117] According to human rights organizations, there are systematic human rights violations, including the torture and forced disappearance of government critics.[117] The UAE ranks poorly in freedom indices measuring civil liberties and political rights. The UAE is annually ranked as «Not Free» in Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World report, which measures civil liberties and political rights.[118] The UAE also ranks poorly in the annual Reporters without Borders’ Press Freedom Index.

Government[edit]

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federal constitutional monarchy made up from a federation of seven hereditary tribal monarchy-styled political system called Sheikhdoms. It is governed by a Federal Supreme Council made up of the ruling Sheikhs of Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Fujairah, Sharjah, Dubai, Ras al-Khaimah and Umm al-Quwain. All responsibilities not granted to the national government are reserved to the individual emirate.[119] A percentage of revenues from each emirate is allocated to the UAE’s central budget.[120] The United Arab Emirates uses the title Sheikh instead of Emir to refer to the rulers of individual emirates. The title is used due to the sheikhdom styled governing system in adherence to the culture of tribes of Arabia, where Sheikh means leader, elder, or the tribal chief of the clan who partakes in shared decision making with his followers.

The President and Vice President are elected by the Federal Supreme Council. Usually, a sheikh from Abu Dhabi holds the presidency and a sheikh from Dubai the prime ministership. All prime ministers but one have served concurrently as vice president. Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan is the UAE founding father and widely credited for unifying the seven emirates into one country. He was the UAE’s first president from the nation’s founding until his death on 2 November 2004. On the following day the Federal Supreme Council elected his son, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, to the post.[121]

The federal government is composed of three branches:

- Legislative: A unicameral Federal Supreme Council and the advisory Federal National Council (FNC).

- Executive: The President, who is also commander-in-chief of the military, the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers.

- Judicial: The Supreme Court and lower federal courts.

The UAE e-Government is the extension of the UAE Federal Government in its electronic form.[122] The UAE’s Council of Ministers (Arabic: مجلس الوزراء) is the chief executive branch of the government presided over by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister, who is appointed by the Federal Supreme Council, appoints the ministers. The Council of Ministers is made up of 22 members and manages all internal and foreign affairs of the federation under its constitutional and federal law.[123] In December 2019,[124] the UAE became the only Arab country, and one of only five countries in the world, to attain gender parity in a national legislative body, with its lower house 50 per cent women.[125][126]

The UAE is the only country in the world that has a Ministry of Tolerance,[127] a Ministry of Happiness,[128] and a Ministry of Artificial Intelligence.[129] The UAE also has a virtual ministry called the Ministry of Possibilities, designed to find solutions to challenges and improve quality of life.[130][131] The UAE also has a National Youth Council, which is represented in the UAE cabinet by the Minister of Youth.[132][133]

The UAE legislative is the Federal National Council which convenes nationwide elections every 4 years. The FNC consists of 40 members drawn from all the emirates. Each emirate is allocated specific seats to ensure full representation. Half are appointed by the rulers of the constituent emirates, and the other half are elected. By law, the council members have to be equally divided between males and females. The FNC is restricted to a largely consultative role.[134][135][136]

Foreign relations[edit]

The UAE has broad diplomatic and commercial relations with most countries and members of the United Nations. It plays a significant role in OPEC, and is one of the founding members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The UAE is a member of the United Nations and several of its specialized agencies (ICAO, ILO, UPU, WHO, WIPO), as well as the World Bank, IMF, Arab League, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Non-Aligned Movement. Also, it is an observer in the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. Most countries have diplomatic missions in the capital Abu Dhabi with most consulates being in UAE’s largest city, Dubai.

Emirati foreign relations are motivated to a large extent by identity and relationship to the Arab world.[137] The United Arab Emirates has strong ties with Bahrain,[138] China,[139] Egypt,[140] France,[141] India,[142] Jordan,[143] Pakistan,[144] Russia,[145] Saudi Arabia[146] and the United States.[147]

Following the British withdrawal from the UAE in 1971 and the establishment of the UAE as a state, the UAE disputed rights to three islands in the Persian Gulf against Iran, namely Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb. The UAE tried to bring the matter to the International Court of Justice, but Iran dismissed the notion.[148] Pakistan was the first country to formally recognize the UAE upon its formation.[149] The UAE alongside multiple Middle Eastern and African countries cut diplomatic ties with Qatar in June 2017 due to allegations of Qatar being a state sponsor of terrorism, resulting in the Qatar diplomatic crisis. Ties were restored in January 2021.[150] The UAE recognized Israel in August 2020, reaching a historic Israel–United Arab Emirates peace agreement and leading towards full normalization of relations between the two countries.[151][152][153]

Military[edit]

The United Arab Emirates military force was formed in 1971 from the historical Trucial Oman Scouts, long a symbol of public order in Eastern Arabia and commanded by British officers. The Trucial Oman Scouts were turned over to the United Arab Emirates, as the nucleus of its defence forces in 1971, with the formation of the UAE, and was absorbed into the Union Defence Force.

Although initially small in number, the UAE armed forces have grown significantly over the years and are presently equipped with some of the most modern weapon systems, purchased from a variety of western military advanced countries, mainly France, the US and the UK. Most officers are graduates of the United Kingdom’s Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, with others having attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, the Royal Military College, Duntroon in Australia, and St Cyr, the military academy of France. France and the United States have played the most strategically significant roles with defence cooperation agreements and military material provision.[154]

Some of the UAE military deployments include an infantry battalion to the United Nations UNOSOM II force in Somalia in 1993, the 35th Mechanised Infantry Battalion to Kosovo, a regiment to Kuwait during the Iraq War, demining operations in Lebanon, Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, American-led intervention in Libya, American-led intervention in Syria, and the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen. The active and effective military role, despite its small active personnel, has led the UAE military to be nicknamed as «Little Sparta» by United States Armed Forces Generals and former US defense secretary James Mattis.[155]

The UAE intervened in the Libyan Civil War in support of General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army in its conflict with the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA).[156][157][158]

Examples of the military assets deployed include the enforcement of the no-fly-zone over Libya by sending six UAEAF F-16 and six Mirage 2000 multi-role fighter aircraft,[159] ground troop deployment in Afghanistan,[160] 30 UAEAF F-16s and ground troops deployment in Southern Yemen,[161] and helping the US launch its first airstrikes against ISIL targets in Syria.[162]

The UAE has begun production of a greater amount of military equipment, in a bid to reduce foreign dependence and help with national industrialisation. Example of national military development include the Abu Dhabi Shipbuilding company (ADSB), which produces a range of ships and is a prime contractor in the Baynunah Programme, a programme to design, develop and produce corvettes customised for operation in the shallow waters of the Persian Gulf. The UAE is also producing weapons and ammunition through Caracal International, military transport vehicles through Nimr LLC and unmanned aerial vehicles collectively through Emirates Defence Industries Company. The UAE operates the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon F-16E Block 60 unique variant unofficially called «Desert Falcon», developed by General Dynamics with collaboration of the UAE and specifically for the United Arab Emirates Air Force.[163] The United Arab Emirates Army operates a customized Leclerc tank and is the only other operator of the tank aside from the French Army.[164] The largest defence exhibition and conference in the Middle East, International Defence Exhibition, takes place biennially in Abu Dhabi.

The UAE introduced a mandatory military service for adult males, since 2014, for 16 months to expand its reserve force.[165] The highest loss of life in the history of UAE military occurred on Friday 4 September 2015, in which 52 soldiers were killed in Marib area of central Yemen by a Tochka missile which targeted a weapons cache and caused a large explosion.[166]

Administrative divisions[edit]

The United Arab Emirates comprises seven emirates. Dubai is the most populous emirate with 35.6% of the UAE population. The Emirate of Abu Dhabi has 31.2%, meaning that over two-thirds of the UAE population lives in either Abu Dhabi or Dubai.

Abu Dhabi has an area of 67,340 square kilometres (26,000 square miles), which is 86.7% of the country’s total area, excluding the islands. It has a coastline extending for more than 400 km (250 mi) and is divided for administrative purposes into three major regions.

The Emirate of Dubai extends along the Persian Gulf coast of the UAE for approximately 72 km (45 mi). Dubai has an area of 3,885 square kilometres (1,500 square miles), which is equivalent to 5% of the country’s total area, excluding the islands. The Emirate of Sharjah extends along approximately 16 km (10 mi) of the UAE’s Persian Gulf coastline and for more than 80 km (50 mi) into the interior. The northern emirates which include Fujairah, Ajman, Ras al-Khaimah, and Umm al-Qaiwain all have a total area of 3,881 square kilometres (1,498 square miles). There are two areas under joint control. One is jointly controlled by Oman and Ajman, the other by Fujairah and Sharjah.

There is an Omani exclave surrounded by UAE territory, known as Wadi Madha. It is located halfway between the Musandam peninsula and the rest of Oman in the Emirate of Sharjah. It covers approximately 75 square kilometres (29 square miles) and the boundary was settled in 1969. The north-east corner of Madha is closest to the Khor Fakkan-Fujairah road, barely 10 metres (33 feet) away. Within the Omani exclave of Madha, is a UAE exclave called Nahwa, also belonging to the Emirate of Sharjah. It is about eight kilometres (5.0 miles) on a dirt track west of the town of New Madha. It consists of about forty houses with its own clinic and telephone exchange.

| Flag | Emirate | Capital | Population | Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | % | (km2) | (mi2) | % | |||

| Abu Dhabi | Abu Dhabi | 2,784,490 | 29.0% | 67,340 | 26,000 | 86.7% | |

| Ajman | Ajman | 372,922 | 3.9% | 259 | 100 | 0.3% | |

| Dubai | Dubai | 4,177,059 | 42.8% | 3,885 | 1,500 | 5.0% | |

| Fujairah | Fujairah | 152,000 | 1.6% | 1,165 | 450 | 1.5% | |

| Ras al-Khaimah | Ras al-Khaimah | 416,600 | 4.3% | 2,486 | 950 | 3.2% | |

| Sharjah | Sharjah | 2,374,132 | 24.7% | 2,590 | 1,000 | 3.3% | |

| Umm al-Quwain | Umm al-Quwain | 72,000 | 0.8% | 777 | 300 | 1% | |

| UAE | Abu Dhabi | 9,599,353 | 100% | 77,700 | 30,000 | 100% |

Law[edit]

The UAE has a federal court system. There are three main branches within the court structure: civil, criminal and Sharia law. The UAE’s judicial system is derived from the civil law system and Sharia law. The court system consists of civil courts and Sharia courts. UAE’s criminal and civil courts apply elements of Sharia law, codified into its criminal code and family law.

Corporal and capital punishment[edit]

Flogging is a punishment for criminal offences such as adultery, premarital sex and drug or alcohol use. It is often accompanied by brutal beatings by the police. [27][167] According to Sharia court rulings, flogging ranges from 80 to 200 lashes.[27][168][169] Verbal abuse pertaining to a person’s honour is illegal and punishable by 80 lashes.[170] Between 2007 and 2014, many people in the UAE were sentenced to 100 lashes.[171][172] More recently in 2015, two men were sentenced to 80 lashes for hitting and insulting a woman.[173] In 2014, an expatriate in Abu Dhabi was sentenced to 10 years in prison and 80 lashes after alcohol consumption and raping a toddler.[174] As of November 2020, alcohol consumption for Muslims and non Muslims is legal. In the past, many Muslims have been sentenced to 80 or 40 lashes for alcohol consumption.[175][176] Illicit sex is sometimes penalized by 60 lashes.[177] Eighty lashes is the standard number for anyone sentenced to flogging in several emirates.[178] Sharia courts have penalized domestic workers with floggings.[179] In October 2013, a Filipino housemaid was sentenced to 100 lashes for illegitimate pregnancy.[180] Drunk-driving is strictly illegal and punishable by 80 lashes; many expatriates have been sentenced to 80 lashes for drunk-driving.[181][182] Under UAE law, premarital sex is punishable by 100 lashes.[183]

Stoning is a legal punishment in the UAE. In May 2014, an Asian housemaid was sentenced to death by stoning in Abu Dhabi.[184][185] Other expatriates have been sentenced to death by stoning for committing adultery.[186] Between 2009 and 2013, several people were sentenced to death by stoning.[187][188] Abortion is illegal and punishable by a maximum penalty of 100 lashes and up to five years in prison.[189] In recent years, several people have retracted their guilty plea in illicit sex cases after being sentenced to stoning or 100 lashes.[190][191] The punishment for committing adultery is 100 lashes for unmarried people and stoning to death for married people.[192]

Amputation is a legal punishment in the UAE due to the Sharia courts.[193][194][195] Crucifixion is a legal punishment in the UAE.[196][197][198] Article 1 of the Federal Penal Code states that «provisions of the Islamic Law shall apply to the crimes of doctrinal punishment, punitive punishment and blood money.»[199] The Federal Penal Code repealed only those provisions within the penal codes of individual emirates which are contradictory to the Federal Penal Code. Hence, both are enforceable simultaneously.[200]

A man pictured with alcoholic beverages in Dubai. Alcoholic beverages were not widely available in the UAE before 2020

In recent history, the UAE has declared its intention to move towards a more tolerant legal code, and to phase out corporal punishment altogether in favor of private punishment.[201] With alcohol and cohabitation laws being loosened in advance of the 2020 World Expo, Emirati laws have become increasingly acceptable to visitors from non-Muslim countries.[202]

Sharia courts and family law[edit]

Sharia courts have exclusive jurisdiction over family law cases and also have jurisdiction over several criminal cases including adultery, premarital sex, robbery, alcohol consumption and related crimes. The Sharia-based personal status law regulates matters such as marriage, divorce and child custody. The Islamic personal status law is applied to Muslims and sometimes non-Muslims.[203] Non-Muslim expatriates can be liable to Sharia rulings on marriage, divorce and child custody.[203]

Emirati women must receive permission from a male guardian to marry and remarry.[204] This requirement is derived from the UAE’s interpretation of Sharia, and has been federal law since 2005.[204] In all emirates, it is illegal for Muslim women to marry non-Muslims.[205] In the UAE, a marriage union between a Muslim woman and non-Muslim man is punishable by law, since it is considered a form of «fornication».[205] The UAE Marriage Fund reported in 2012 that a majority of women over 30 were unmarried; this had tripled from 1995, when only one-fifth of women over 30 were unmarried.[206]

Kissing in certain public places is illegal and could result in deportation.[207] Expats in Dubai have been deported for kissing in public.[208][209][210] In Abu Dhabi, people have been sentenced to 80 lashes for kissing in public.[211] A new federal law in the UAE prohibits swearing in WhatsApp and penalizes swearing by a 250,000 AED fine and imprisonment;[212] expatriates are penalized by deportation.[212][213][214] In July 2015, an Australian expatriate was deported for swearing on Facebook.[215][216][217][218][219]

Homosexuality is illegal and is a capital offence in the UAE.[220][221] In 2013, an Emirati man was on trial for being accused of a «gay handshake».[221] Article 80 of the Abu Dhabi Penal Code makes sodomy punishable with imprisonment of up to 14 years, while article 177 of the Penal Code of Dubai imposes imprisonment of up to 10 years on consensual sodomy.[222]

In November 2020, UAE announced that it decriminalised alcohol, lifted ban on unmarried couples living together and ended lenient punishment on honor killing. Foreigners living in the Emirates were allowed to follow their native country’s laws on divorce and inheritance.[223]

Blasphemy law[edit]

Apostasy is a capital crime in the UAE.[224][225] Blasphemy is illegal; expatriates involved in insulting Islam are liable for deportation.[226] UAE incorporates hudud crimes of Sharia (i.e., crimes against God) into its Penal Code – apostasy being one of them.[227] Article 1 and Article 66 of UAE’s Penal Code requires hudud crimes to be punished with the death penalty;[227][228] therefore, apostasy is punishable by death in the UAE.

Rape[edit]

In several cases, the courts of the UAE have jailed women who have reported rape.[229][230][78][231][232][233] For example, a British woman, after she reported being gang raped by three men, was charged with the crime of «alcohol consumption».[78][232] Another British woman was charged with «public intoxication and extramarital sex» after she reported being raped,[230] while an Australian woman was similarly sentenced to jail after she reported gang rape in the UAE.[230][78] In another recent case, an 18-year Emirati girl withdrew her complaint of gang rape by six men when the prosecution threatened her with a long jail term and flogging.[234] The woman still had to serve one year in jail.[235] In July 2013, a Norwegian woman, Marte Dalelv, reported rape to the police and received a prison sentence for «illicit sex and alcohol consumption».[230]

Human rights[edit]

Flogging and stoning are legal punishments in the UAE. The requirement is derived from Sharia law, and has been federal law since 2005.[236] Some domestic workers in the UAE are victims of the country’s interpretations of Sharia judicial punishments such as flogging and stoning.[179] The annual Freedom House report on Freedom in the World has listed the United Arab Emirates as «Not Free» every year since 1999, the first year for which records are available on their website.[118]

The UAE has escaped the Arab Spring; however, more than 100 Emirati activists were jailed and tortured because they sought reforms.[80][237][238] Since 2011, the UAE government has increasingly carried out forced disappearances.[239][240][241][242][243][244] Many foreign nationals and Emirati citizens have been arrested and abducted by the state. The UAE government denies these people are being held (to conceal their whereabouts), placing these people outside the protection of the law.[238][240][245] According to Human Rights Watch, the reports of forced disappearance and torture in the UAE are of grave concern.[241]

The Arab Organization for Human Rights has obtained testimonies from many defendants, for its report on «Forced Disappearance and Torture in the UAE», who reported that they had been kidnapped, tortured and abused in detention centres.[240][245] The report included 16 different methods of torture including severe beatings, threats with electrocution and denying access to medical care.[240][245]

In 2013, 94 Emirati activists were held in secret detention centres and put on trial for allegedly attempting to overthrow the government.[246] Human rights organizations have spoken out against the secrecy of the trial. An Emirati, whose father is among the defendants, was arrested for tweeting about the trial. In April 2013, he was sentenced to 10 months in jail.[247] The latest forced disappearance involves three sisters from Abu Dhabi.[248]

Repressive measures were also used against non-Emiratis in order to justify the UAE government’s claim that there is an «international plot» in which UAE citizens and foreigners were working together to destabilize the country.[245] Foreign nationals were also subjected to a campaign of deportations.[245] There are many documented cases of Egyptians and other foreign nationals who had spent years working in the UAE and were then given only a few days to leave the country.[245]

Foreign nationals subjected to forced disappearance include two Libyans[249] and two Qataris.[245][250] Amnesty International reported that the Qatari men have been abducted by the UAE government and the UAE government has withheld information about the men’s fate from their families.[245][250] Amongst the foreign nationals detained, imprisoned and expelled is Iyad El-Baghdadi, a popular blogger and Twitter personality.[245] He was arrested by UAE authorities, detained, imprisoned and then expelled from the country.[245] Despite his lifetime residence in the UAE, as a Palestinian citizen, El-Baghdadi had no recourse to contest this order.[245] He could not be deported back to the Palestinian territories, therefore he was deported to Malaysia.[245]

In recent years, many Shia Muslim expatriates have been deported from the UAE.[251][252][253] Lebanese Shia families in particular have been deported for their alleged sympathy for Hezbollah.[254][255][256][257][258][259] According to some organizations, more than 4,000 Shia expatriates have been deported from the UAE in recent years.[260][261]

The issue of sexual abuse among female domestic workers is another area of concern, particularly given that domestic servants are not covered by the UAE labour law of 1980 or the draft labour law of 2007.[262] Worker protests have been suppressed and protesters imprisoned without due process.[263] In its 2013 Annual Report, Amnesty International drew attention to the United Arab Emirates’ poor record on a number of human rights issues. They highlighted the government’s restrictive approach to freedom of speech and assembly, their use of arbitrary arrest and torture, and UAE’s use of the death penalty.[264]

The State Security Apparatus in the UAE has been accused of a series of atrocities and human rights abuses including enforced disappearance, arbitrary arrests and torture.[265]

Freedom of association is also severely curtailed. All associations and NGOs have to register through the Ministry of Social Affairs and are therefore under de facto State control. About twenty non-political groups operate on the territory without registration. All associations have to be submitted to censorship guidelines and all publications have first to be approved by the government.[266]

Migrant workers[edit]

Migrant workers in the UAE are not allowed to join trade unions or go on strike. Those who strike may risk prison and deportation,[267][268] as seen in 2014 when dozens of workers were deported for striking.[269] The International Trade Union Confederation has called on the United Nations to investigate evidence that thousands of migrant workers in the UAE are treated as slave labour.[270]

In 2019, an investigation performed by The Guardian revealed that thousands of migrant construction workers employed on infrastructure and building projects for the UAE’s Expo 2020 exhibition were working in an unsafe environment. Some were even exposed to potentially fatal situations due to cardiovascular issues. Long hours in the sun made them vulnerable to heat strokes.[271]

A report in January 2020 highlighted that the employers in the United Arab Emirates have been exploiting the Indian labor and hiring them on tourist visas, which is easier and cheaper than work permits. These migrant workers are left open to labor abuse, where they also fear reporting exploitation due to their illegal status. Besides, the issue remains unknown as the visit visa data is not maintained in both the UAE and Indian migration and employment records.[272]

Dubai construction workers having lunch break.

In a 22 July 2020 news piece, Reuters reported human rights groups as saying conditions had deteriorated because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many migrant workers racked up debt and depended on the help of charities. The report cited salary delays and layoffs as a major risk, in addition to overcrowded living conditions, lack of support and problems linked with healthcare and sick pay. Reuters reported at least 200,000 workers, mostly from India but also from Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Nepal, had been repatriated, according to their diplomatic missions.[273]

On 2 May 2020, the Consul General of India in Dubai, Vipul, confirmed that more than 150,000 Indians in the United Arab Emirates registered to be repatriated through the e-registration option provided by Indian consulates in the UAE. According to the figures, 25% applicants lost their jobs and nearly 15% were stranded in the country due to lockdown. Besides, 50% of the total applicants were from the state of Kerala, India.[274]

On 9 October 2020, The Telegraph reported that many migrant workers were left abandoned, as they lost their jobs amidst the tightening economy due to COVID-19. With no jobs and expired visas, many hived in parks under the city’s glistening skyscrapers, appealing for repatriation flights home. White collar job workers were also threatened by the pandemic in the Emirates, as many UK expats returned home since the beginning of coronavirus.[275]

Various human rights organisations have raised serious concerns about the alleged abuse of migrant workers by major contractors organising Expo 2020. UAE’s business solution provider German Pavilion is also held accountable for abusing migrant workers.[276]

Miscellaneous[edit]

Dancing in public is illegal in the UAE.[277][278][279]

Media[edit]

The UAE’s media is annually classified as «not free» in the Freedom of the Press report by Freedom House.[280] The UAE ranks poorly in the annual Press Freedom Index by Reporters without Borders. Dubai Media City and twofour54 are the UAE’s main media zones. The UAE is home to some pan-Arab broadcasters, including the Middle East Broadcasting Centre and Orbit Showtime Network. In 2007, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum decreed that journalists can no longer be prosecuted or imprisoned for reasons relating to their work.[281] At the same time, the UAE has made it illegal to disseminate online material that can threaten «public order»,[282] and hands down prison terms for those who «deride or damage» the reputation of the state and «display contempt» for religion. Journalists who are arrested for violating this law are often brutally beaten by the police. [283]

Print media[edit]

According to UAE Year Book 2013, there are seven Arabic newspapers and eight English language newspapers, as well as a Tagalog newspaper produced and published in the UAE.

[edit]

New media, such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram are used widely in the UAE by the government entities and by the public as well.[284] The UAE Government avails official social media accounts to communicate with public and hear their needs.[284]

Economy[edit]

The UAE has developed from a juxtaposition of Bedouin tribes to one of the world’s most wealthy states in only about 50 years. It is the 6th wealthiest country in the Middle East after Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey and Egypt. Economic growth has been impressive and steady throughout the history of this young confederation of emirates with brief periods of recessions only, e.g. in the global financial and economic crisis years 2008–09, and a couple of more mixed years starting in 2015 and persisting until 2019. Between 2000 and 2018, average real gross domestic product (GDP) growth was at close to 4%.[285] It is the second largest economy in the GCC (after Saudi Arabia),[286] with a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of US$414.2 billion, and a real GDP of 392.8 billion constant 2010 USD in 2018.[285] Since its independence in 1971, the UAE’s economy has grown by nearly 231 times to 1.45 trillion AED in 2013. The non-oil trade has grown to 1.2 trillion AED, a growth by around 28 times from 1981 to 2012.[286] Backed by the world’s seventh-largest oil deposits, and thanks to considerate investments combined with decided economic liberalism and firm Government control, the UAE has seen their real GDP more than triple in the last four decades. Nowadays the UAE is one of the world’s richest countries, with GDP per capita almost 80% higher than OECD average.[285]

As impressive as economic growth has been in the UAE, the total population has increased from just around 550,000 in 1975 to close to 10 million in 2018. This growth is mainly due to the influx of foreign workers into the country, making the national population a minority. The UAE features a unique labour market system, in which residence in the UAE is conditional on stringent visa rules. This system is a major advantage in terms of macroeconomic stability, as labour supply adjusts quickly to demand throughout economic business cycles. This allows the Government to keep unemployment in the country on a very low level of less than 3%, and it also gives the Government more leeway in terms of macroeconomic policies – where other governments often need to make trade-offs between fighting unemployment and fighting inflation.[285]

Between 2014 and 2018, the accommodation and food, education, information and communication, arts and recreation, and real estate sectors overperformed in terms of growth, whereas the construction, logistics, professional services, public, and oil and gas sectors underperformed.[285]

Business and finance[edit]

The UAE offers businesses a strong enabling environment: stable political and macroeconomic conditions, a future-oriented Government, good general infrastructure and ICT infrastructure. Moreover, the country has made continuous and convincing improvements to its regulatory environment[285] and is ranked as the 26th best nation in the world for doing business by the Doing Business 2017 Report published by the World Bank Group.[287] The UAE are in the top ranks of several other global indices, such as the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), the World Happiness Report (WHR) and 33rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.[288] The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), for example, assigns the UAE rank two regionally in terms of business environment and 22 worldwide. From the 2018 Arab Youth Survey the UAE emerges as the top Arab country in areas such as living, safety and security, economic opportunities, and starting a business, and as an example for other states to emulate.[285]

The weaker points remain the level of education across the UAE population, limitations in the financial and labour markets, barriers to trade and some regulations that hinder business dynamism. The major challenge for the country, though, remains translating investments and strong enabling conditions into knowledge, innovation and creative outputs.[285]

A proportional representation of United Arab Emirates exports, 2019

UAE law does not allow trade unions to exist.[289] The right to collective bargaining and the right to strike are not recognised, and the Ministry of Labour has the power to force workers to go back to work. Migrant workers who participate in a strike can have their work permits cancelled and be deported.[289] Consequently, there are very few anti-discrimination laws in relation to labour issues, with Emiratis – and other GCC Arabs – getting preference in public sector jobs despite lesser credentials than competitors and lower motivation. In fact, just over eighty percent of Emirati workers hold government posts, with many of the rest taking part in state-owned enterprises such as Emirates airlines and Dubai Properties.[290]

The UAE’s monetary policy stresses stability and predictability, as the Central Bank of the UAE (CBUAE) keeps a peg to the US Dollar (USD) and moves interest rates close to the Federal Funds Rate. This policy makes sense in the current situation of global and regional economic and geopolitical uncertainty. Also considering the fact that exports have become the main driver of the UAE’s economic growth (the contribution of international trade to GDP grew from 31% in 2017 to 33.5% in 2018, outpacing overall GDP growth for the period), and the fact that the AED is currently undervalued, a departure from this policy – and particularly the peg – would negatively affect this important part of the UAE economy in the short term. In the mid- to long term, however, the peg will become less important, as the UAE transitions to a knowledge-based economy – and becomes yet more independent from the oil and gas sector (oil is currently still being traded not in AED, but in USD). On the contrary, it will become more and more important for the Government to have monetary policy at its free disposal to target inflation, shun too heavy reliance on taxes, and avoid situations where decisions on exchange rates and interest rates contradict fiscal policy measures – as has been the case in recent years, where monetary policy has limited fiscal policy effects on economic expansion.[285]

According to Fitch Ratings, the decline in property sector follows risks of progressively worsening the quality of assets in possession with UAE banks, leading the economy to rougher times ahead. Even though as compared to retail and property, UAE banks fared well. The higher US interest rates followed since 2016 – which the UAE currency complies to – have boosted profitability. However, the likelihood of plunging interest rates and increasing provisioning costs on bad loans, point to difficult times ahead for the economy.[291]

Since 2015, economic growth has been more mixed due to a number of factors impacting both demand and supply. In 2017 and 2018 growth has been positive but on a low level of 0.8 and 1.4%, respectively. To support the economy the Government is currently following an expansionary fiscal policy. However, the effects of this policy are partially offset by monetary policy, which has been contractionary. If not for the fiscal stimulus in 2018, the UAE economy would probably have contracted in that year. One of the factors responsible for slower growth has been a credit crunch, which is due to, among other factors, higher interest rates. Government debt has remained on a low level, despite high deficits in a few recent years. Risks related to government debt remain low. Inflation has been picking up in 2017 and 18. Contributing factors were the introduction of a value added tax (VAT) of 5%[292] in 2018 as well as higher commodity prices. Despite the Government’s expansionary fiscal policy and a growing economy in 2018 and at the beginning of 2019, prices have been dropping in late 2018 and 2019 owing to oversupply in some sectors of importance to consumer prices.[285]

The UAE has an attractive tax system for companies and wealthy individuals, making it a preferred destination for companies seeking tax avoidance. The NGO Tax Justice Network places them in 2021 in the group of the ten largest tax havens.[293]

VAT[edit]

The UAE government implemented value added tax (VAT) in the country from January 1, 2018 at a standard rate of 5%.[294]

Oil and gas[edit]

Ruwais Refinery is the fourth-largest single-site oil refinery in the world and the biggest in the Middle East.

The UAE leadership has driven forward economic diversification efforts already before the oil price crash in the 1980s, and the UAE is nowadays the most diversified economy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Although the oil and gas sector does still play an important role in the UAE economy, these efforts have paid off in terms of great resilience during periods of oil price fluctuations and economic turbulence.

In 2018, the oil and gas sector contributed 26% to overall GDP. The introduction of the VAT has provided the Government with an additional source of income – approximately 6% of the total revenue in 2018, or 27 billion United Arab Emirates Dirham (AED) – affording its fiscal policy more independence from oil- and gas-related revenue, which constitutes about 36% of the total government revenue. While the government may still adjust the exact arrangement of the VAT, it is not likely that any new taxes will be introduced in the foreseeable future. Additional taxes would destroy one of the UAE’s main enticements for businesses to operate in the country and put a heavy burden on the economy.[285] The UAE emits a lot of carbon dioxide per person compared to other countries.[295] The Barakah nuclear power plant is the first on the Arabian peninsula and expected to reduce the carbon footprint of the country.[296]

Tourism[edit]

Tourism acts as a growth sector for the entire UAE economy. Dubai is the top tourism destination in the Middle East.[231] According to the annual MasterCard Global Destination Cities Index, Dubai is the fifth most popular tourism destination in the world.[297] Dubai holds up to 66% share of the UAE’s tourism economy, with Abu Dhabi having 16% and Sharjah 10%. Dubai welcomed 10 million tourists in 2013.

The UAE has the most advanced and developed infrastructure in the region.[298] Since the 1980s, the UAE has been spending billions of dollars on infrastructure. These developments are particularly evident in the larger emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The northern emirates are rapidly following suit, providing major incentives for developers of residential and commercial property.[299][300]

The inbound tourism expenditure in the UAE for 2019 accounted for 118.6 percent share of the outbound tourism expenditure.[300] Since 6 January 2020, tourist visas to the United Arab Emirates are valid for five years.[301] It has been projected that the travel and tourism industry will contribute about 280.6 billion United Arab Emirati dirham to the UAE’s GDP by 2028.[300]

Transport[edit]

Air[edit]

Dubai International Airport became the busiest airport in the world by international passenger traffic in 2014, overtaking London Heathrow.[302]

Highways[edit]

E 311, one of major roads in the UAE.

Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain, and Ras Al Khaimah are connected by the E11 highway, which is the longest road in the UAE. In Dubai, in addition to the Dubai Metro, The Dubai Tram and Palm Jumeirah Monorail also connect specific parts of the city. There is also a bus, taxi, abra and water taxi network run by RTA. T1, a double-decker tram system in Downtown Dubai, were operational from 2015 to 2019.

Salik, meaning «open» or «clear», is Dubai’s electronic toll collection system that was launched in July 2007 and is part of Dubai’s traffic congestion management system. Each time one passes through a Salik tolling point, a toll is deducted from the drivers’ prepaid toll account using advanced Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology. There are four Salik tolling points placed in strategic locations in Dubai: at Al Maktoum Bridge, Al Garhoud Bridge, and along Sheikh Zayed Road at Al Safa and Al Barsha.[303]

Eligibility to drive[edit]

Individual customers, citizens and residents, who are above the legal age and medically fit, are eligible to get a driving learning permit and apply for a new driving licence. The minimum age requirement to obtain a driving licence depends on the vehicle, for which you are obtaining the licence. The minimum age requirement is as follows:[304]

- 17 years for motorcycles and for vehicles for people with special needs

- 18 years for cars and light vehicles

- 20 years for heavy vehicles and tractors

- 21 years for buses.

Rail[edit]

A Dubai Metro train. Dubai Metro is the Arabian peninsula’s first rapid transit system and was the world’s longest driverless metro network until 2016.

A 1,200 km (750 mi) country-wide railway is under construction which will connect all the major cities and ports.[305] The Dubai Metro is the first urban train network in the Arabian Peninsula.[306]

Sea[edit]

The major ports of the United Arab Emirates are Khalifa Port, Zayed Port, Port Jebel Ali, Port Rashid, Port Khalid, Port Saeed, and Port Khor Fakkan.[307]

The Emirates are increasingly developing their logistics and ports in order to participate in trade between Europe and China or Africa. For this purpose, ports are being rapidly expanded and investments are being made in their technology.

The Emirates have historically been and currently still are part of the Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast to the south via the southern tip of India to Mombasa, from there through the Red Sea via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there to the Upper Adriatic region and the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its rail connections to Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the North Sea.[308][309]

Telecommunications[edit]

The UAE is served by two telecommunications operators, Etisalat and Emirates Integrated Telecommunications Company («du»). Etisalat operated a monopoly until du launched mobile services in February 2007.[310] Internet subscribers were expected to increase from 0.904 million in 2007 to 2.66 million in 2012.[311] The regulator, the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority, mandates filtering websites for religious, political and sexual content.[312]

5G wireless services were installed nationwide in 2019 through a partnership with Huawei.[313]

Culture[edit]

An Emirati folk dance, the women flip their hair sideways in brightly coloured traditional dress.

Emirati culture is based on Arabian culture and has been influenced by the cultures of Persia, India, and East Africa.[314] Arabian and Arabian inspired architecture is part of the expression of the local Emirati identity.[315] Arabian influence on Emirati culture is noticeably visible in traditional Emirati architecture and folk arts.[314] For example, the distinctive wind tower which tops traditional Emirati buildings, the barjeel has become an identifying mark of Emirati architecture and is attributed to Arabian influence.[314] This influence is derived both from traders who fled the tax regime in Persia in the early 19th century and from Emirati ownership of ports on the Arabian coast, for instance the Al Qassimi port of Lingeh.[316]

A band performs Yowlah in an Emirati wedding. Yowlah is a cultural dance derived from Arab tribes sword battles.

The United Arab Emirates has a diverse society.[317] Dubai’s economy depends more on international trade and tourism, and is more open to visitors, while Abu Dhabi society is more domestic as the city’s economy is focused on fossil fuel extraction.[318]

Major holidays in the United Arab Emirates include Eid al Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan, and National Day (2 December), which marks the formation of the United Arab Emirates.[319] Emirati males prefer to wear a kandura, an ankle-length white tunic woven from wool or cotton, and Emirati women wear an abaya, a black over-garment that covers most parts of the body.[320]

Ancient Emirati poetry was strongly influenced by the eighth-century Arab scholar Al Khalil bin Ahmed. The earliest known poet in the UAE is Ibn Majid, born between 1432 and 1437 in Ras Al-Khaimah. The most famous Emirati writers were Mubarak Al Oqaili (1880–1954), Salem bin Ali al Owais (1887–1959) and Ahmed bin Sulayem (1905–1976). Three other poets from Sharjah, known as the Hirah group, are observed to have been heavily influenced by the Apollo and Romantic poets.[321] The Sharjah International Book Fair is the oldest and largest in the country.

The list of museums in the United Arab Emirates includes some of regional repute, most famously Sharjah with its Heritage District containing 17 museums,[322] which in 1998 was the Cultural Capital of the Arab World.[323] In Dubai, the area of Al Quoz has attracted a number of art galleries as well as museums such as the Salsali Private Museum.[324] Abu Dhabi has established a culture district on Saadiyat Island. Six grand projects are planned, including the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and the Louvre Abu Dhabi.[325] Dubai also plans to build a Kunsthal museum and a district for galleries and artists.[326]

Emirati culture is a part of the culture of Eastern Arabia. Liwa is a type of music and dance performed locally, mainly in communities that contain descendants of Bantu peoples from the African Great Lakes region.[321] The Dubai Desert Rock Festival is also another major festival consisting of heavy metal and rock artists.[327] The cinema of the United Arab Emirates is minimal but expanding.

Cuisine[edit]

The traditional food of the Emirates has always been rice, fish and meat. The people of the United Arab Emirates have adopted most of their foods from other West and South Asian countries including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, India and Oman. Seafood has been the mainstay of the Emirati diet for centuries. Meat and rice are other staple foods, with lamb and mutton preferred to goat and beef. Popular beverages are coffee and tea, which can be complemented with cardamom, saffron, or mint to give them a distinctive flavour.[328]