| Bugs Bunny | |

|---|---|

| Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies character | |

|

|

| First appearance | Porky’s Hare Hunt (preliminary version)[1] April 30, 1938 A Wild Hare (official)[1] July 27, 1940 |

| Created by | Ben Hardaway Cal Dalton Charles Thorson Official Tex Avery Chuck Jones Bob Givens Robert McKimson |

| Designed by | Cal Dalton Charles Thorson (1939–1940) Official Bob Givens (1940–1943) Robert McKimson (1943–) |

| Voiced by | Mel Blanc (1938–1989) Jeff Bergman (1990–1993, 1997–1998, 2002–2004, 2007, 2011–present) Greg Burson (1990–2000) Billy West (1996–2006) Joe Alaskey (1997–2011) Sam Vincent (Baby Looney Tunes; 2001–2006) Eric Bauza (2018–present) (see below) |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Bun-Bun Rabbit |

| Species | Hare/Rabbit[2][3] |

| Gender | Male |

| Significant other | Lola Bunny (girlfriend) |

| Relatives | Clyde Bunny (nephew) |

Bugs Bunny is an animated cartoon character created in the late 1930s at Warner Bros. Cartoons (originally Leon Schlesinger Productions) and voiced originally by Mel Blanc.[4] Bugs is best known for his featured roles in the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of animated short films, produced by Warner Bros. Earlier iterations of the character first appeared in Ben Hardaway’s Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938) and subsequent shorts before Bugs’s definitive characterization debuted in Tex Avery’s A Wild Hare (1940).[1] Bob Givens and Robert McKimson are credited for defining Bugs’s design.[1]

Bugs is an anthropomorphic gray and white rabbit or hare who is characterized by his flippant, insouciant personality. He is also characterized by a Brooklyn accent, his portrayal as a trickster, and his catch phrase «Eh…What’s up, doc?». Through his popularity during the golden age of American animation, Bugs became an American cultural icon and Warner Bros.’ official mascot.[5]

Bugs starred in more than 160 short films produced between 1940 and 1964.[6] He has since appeared in feature films, television shows, comics, and other media. He has appeared in more films than any other cartoon character, is the ninth most-portrayed film personality in the world[7] and has his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[8]

Development

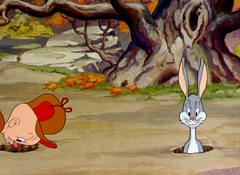

Bugs’ preliminary debut (as an unnamed little white rabbit) in Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938).

According to Chase Craig, who wrote and drew the first Bugs Bunny comic Sunday pages and the first Bugs comic book, «Bugs was not the creation of any one man; however, he rather represented the creative talents of perhaps five or six directors and many cartoon writers including Charlie Thorson.[9] In those days, the stories were often the work of a group who suggested various gags, bounced them around and finalized them in a joint story conference.»[10] A Bugs-like rabbit with some of the personality of a finalized Bugs, though looking very different, was originally featured in the film Porky’s Hare Hunt, released on April 30, 1938. It was co-directed by Ben «Bugs» Hardaway and an uncredited director Cal Dalton (who was responsible for the initial design of the rabbit). This cartoon has an almost identical plot to Avery’s Porky’s Duck Hunt (1937), which had introduced Daffy Duck. Porky Pig is again cast as a hunter tracking a silly prey who is more interested in driving his pursuer insane and less interested in escaping. Hare Hunt replaces the little black duck with a small white rabbit. According to Friz Freleng, Hardaway and Dalton had decided to «dress the duck in a rabbit suit».[11] The white rabbit had an oval head and a shapeless body. In characterization, he was «a rural buffoon». Mel Blanc gave the character a voice and laugh much like those he later used for Woody Woodpecker. He was loud, zany with a goofy, guttural laugh.[12] The rabbit character was popular enough with audiences that the Termite Terrace staff decided to use it again.[13]

The rabbit comes back in Prest-O Change-O (1939), directed by Chuck Jones, where he is the pet rabbit of unseen character Sham-Fu the Magician. Two dogs, fleeing the local dogcatcher, enter the rabbit’s absent master’s house. The rabbit harasses them but is ultimately bested by the bigger of the two dogs. This version of the rabbit was cool, graceful, and controlled. He retained the guttural laugh but was otherwise silent.[12]

The rabbit’s third appearance comes in Hare-um Scare-um (1939), directed again by Dalton and Hardaway. This cartoon—the first in which he is depicted as a gray bunny instead of a white one—is also notable as the rabbit’s first singing role. Charlie Thorson, lead animator on the film, gave the character a name. He had written «Bug’s Bunny» on the model sheet that he drew for Hardaway.[13][14] In promotional material for the cartoon, including a surviving 1939 presskit, the name on the model sheet was altered to become the rabbit’s own name: «Bugs» Bunny (quotation marks only used, on and off, until 1944).[15]

In his autobiography, Blanc claimed that another proposed name for the character was «Happy Rabbit.»[16] In the actual cartoons and publicity, however, the name «Happy» only seems to have been used in reference to Bugs Hardaway. In Hare-um Scare-um, a newspaper headline reads, «Happy Hardaway.»[17] Animation historian David Gerstein disputes that «Happy Rabbit» was ever used as an official name, arguing that the only usage of the term came from Mel Blanc himself in humorous and fanciful tales he told about the character’s development in the 1970s and 1980s; the name «Bugs Bunny» was used as early as August 1939, in the Motion Picture Herald, in a review for the short Hare-um Scare-um.[18]

Thorson had been approached by Tedd Pierce, head of the story department, and asked to design a better rabbit. The decision was influenced by Thorson’s experience in designing hares. He had designed Max Hare in Toby Tortoise Returns (Disney, 1936). For Hardaway, Thorson created the model sheet previously mentioned, with six different rabbit poses. Thorson’s model sheet is «a comic rendition of the stereotypical fuzzy bunny». He had a pear-shaped body with a protruding rear end. His face was flat and had large expressive eyes. He had an exaggerated long neck, gloved hands with three fingers, oversized feet, and a «smart aleck» grin. The result was influenced by Walt Disney Animation Studios’ tendency to draw animals in the style of cute infants.[11] He had an obvious Disney influence, but looked like an awkward merger of the lean and streamlined Max Hare from The Tortoise and the Hare (1935) and the round, soft bunnies from Little Hiawatha (1937).[12]

In Jones’ Elmer’s Candid Camera (1940), the rabbit first meets Elmer Fudd. This time the rabbit looks more like the present-day Bugs, taller and with a similar face—but retaining the more primitive voice. Candid Camera’s Elmer character design is also different: taller and chubbier in the face than the modern model, though Arthur Q. Bryan’s character voice is already established.

Official debut

While Porky’s Hare Hunt was the first Warner Bros. cartoon to feature what would become Bugs Bunny, A Wild Hare, directed by Tex Avery and released on July 27, 1940, is widely considered to be the first official Bugs Bunny cartoon.[1][19] It is the first film where both Elmer Fudd and Bugs, both redesigned by Bob Givens, are shown in their fully developed forms as hunter and tormentor, respectively; the first in which Mel Blanc uses what became Bugs’ standard voice; and the first in which Bugs uses his catchphrase, «What’s up, Doc?»[20] A Wild Hare was a huge success in theaters and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Cartoon Short Subject.[21]

For the film, Avery asked Givens to remodel the rabbit. The result had a closer resemblance to Max Hare. He had a more elongated body, stood more erect, and looked more poised. If Thorson’s rabbit looked like an infant, Givens’ version looked like an adolescent.[11] Blanc gave Bugs the voice of a city slicker. The rabbit was as audacious as he had been in Hare-um Scare-um and as cool and collected as in Prest-O Change-O.[12]

Immediately following on A Wild Hare, Bob Clampett’s Patient Porky (1940) features a cameo appearance by Bugs, announcing to the audience that 750 rabbits have been born. The gag uses Bugs’ Wild Hare visual design, but his goofier pre-Wild Hare voice characterization.

The second full-fledged role for the mature Bugs, Chuck Jones’ Elmer’s Pet Rabbit (1941), is the first to use Bugs’ name on-screen: it appears in a title card, «featuring Bugs Bunny,» at the start of the film (which was edited in following the success of A Wild Hare). However, Bugs’ voice and personality in this cartoon is noticeably different, and his design was slightly altered as well; Bugs’ visual design is based on the earlier version in Candid Camera, but with yellow gloves and no buck teeth, has a lower-pitched voice and a more aggressive, arrogant and thuggish personality instead of a fun-loving personality. After Pet Rabbit, however, subsequent Bugs appearances returned to normal: the Wild Hare visual design and personality returned, and Blanc re-used the Wild Hare voice characterization.

Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941), directed by Friz Freleng, became the second Bugs Bunny cartoon to receive an Academy Award nomination.[22] The fact that it did not win the award was later spoofed somewhat in What’s Cookin’ Doc? (1944), in which Bugs demands a recount (claiming to be a victim of «sa-bo-TAH-gee») after losing the Oscar to James Cagney and presents a clip from Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt to prove his point.[23]

World War II

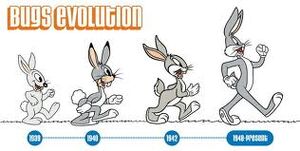

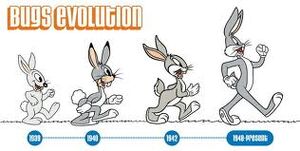

Evolution of Bugs’ design over the years.

By 1942, Bugs had become the number one star of Merrie Melodies. The series was originally intended only for one-shot characters in films after several early attempts to introduce characters (Foxy, Goopy Geer, and Piggy) failed under Harman–Ising. By the mid-1930s, under Leon Schlesinger, Merrie Melodies started introducing newer characters. Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid (1942) shows a slight redesign of Bugs, with less-prominent front teeth and a rounder head. The character was reworked by Robert McKimson, then an animator in Clampett’s unit. The redesign at first was only used in the films created by Clampett’s unit, but in time it was taken up by the other directors, with Freleng and Frank Tashlin the first. For Tortoise Wins by a Hare (1943), he created yet another version, with more slanted eyes, longer teeth and a much larger mouth. He used this version until 1949 (as did Art Davis for the one Bugs Bunny film he directed, Bowery Bugs) when he started using the version he had designed for Clampett. Jones came up with his own slight modification, and the voice had slight variations between the units.[14] Bugs also made cameos in Avery’s final Warner Bros. cartoon, Crazy Cruise.[24]

Since Bugs’ debut in A Wild Hare, he appeared only in color Merrie Melodies films (making him one of the few recurring characters created for that series in the Schlesinger era prior to the full conversion to color), alongside Egghead, Inki, Sniffles, and Elmer Fudd (who actually co-existed in 1937 along with Egghead as a separate character). While Bugs made a cameo in Porky Pig’s Feat (1943), this was his only appearance in a black-and-white Looney Tunes film. He did not star in a Looney Tunes film until that series made its complete conversion to only color cartoons beginning in 1944. Buckaroo Bugs was Bugs’ first film in the Looney Tunes series and was also the last Warner Bros. cartoon to credit Schlesinger (as he had retired and sold his studio to Warner Bros. that year).[23]

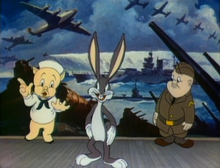

Bugs’ popularity soared during World War II because of his free and easy attitude, and he began receiving special star billing in his cartoons by 1943. By that time, Warner Bros. had become the most profitable cartoon studio in the United States.[25] In company with cartoon studios such as Disney and Famous Studios, Warners pitted its characters against Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, and the Japanese. Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips (1944) features Bugs at odds with a group of Japanese soldiers. This cartoon has since been pulled from distribution due to its depiction of Japanese people.[26] One US Navy propaganda film saved from destruction features the voice of Mel Blanc in «Tokyo Woes»[27] (1945) about the propaganda radio host Tokyo Rose. He also faces off against Hermann Göring and Hitler in Herr Meets Hare (1945), which introduced his well-known reference to Albuquerque as he mistakenly winds up in the Black Forest of ‘Joimany’ instead of Las Vegas, Nevada.[28] Bugs also appeared in the 1942 two-minute U.S. war bonds commercial film Any Bonds Today?, along with Porky and Elmer.

At the end of Super-Rabbit (1943), Bugs appears wearing a United States Marine Corps dress blue uniform. As a result, the Marine Corps made Bugs an honorary Marine master sergeant.[29] From 1943 to 1946, Bugs was the official mascot of Kingman Army Airfield, Kingman, Arizona, where thousands of aerial gunners were trained during World War II. Some notable trainees included Clark Gable and Charles Bronson. Bugs also served as the mascot for 530 Squadron of the 380th Bombardment Group, 5th Air Force, U.S. Air Force, which was attached to the Royal Australian Air Force and operated out of Australia’s Northern Territory from 1943 to 1945, flying B-24 Liberator bombers.[30] Bugs riding an air delivered torpedo served as the squadron logo for Marine Torpedo/Bomber Squadron 242 in the Second World War. Additionally, Bugs appeared on the nose of B-24J #42-110157, in both the 855th Bomb Squadron of the 491st Bombardment Group (Heavy) and later in the 786th BS of the 466th BG(H), both being part of the 8th Air Force operating out of England.

In 1944, Bugs Bunny made a cameo appearance in Jasper Goes Hunting, a Puppetoons film produced by rival studio Paramount Pictures. In this cameo (animated by McKimson, with Blanc providing the usual voice), Bugs (after being threatened at gunpoint) pops out of a rabbit hole, saying his usual catchphrase; after hearing the orchestra play the wrong theme song, he realizes «Hey, I’m in the wrong picture!» and then goes back in the hole.[31] Bugs also made a cameo in the Private Snafu short Gas, in which he is found stowed away in the titular private’s belongings; his only spoken line is his usual catchphrase.

Although it was usually Porky Pig who brought the Looney Tunes films to a close with his stuttering, «That’s all, folks!», Bugs replaced him at the end of Hare Tonic and Baseball Bugs, bursting through a drum just as Porky did, but munching on a carrot and saying, in his Bronx/Brooklyn accent, «And that’s the end!»

Post-World War II era

After World War II, Bugs continued to appear in numerous Warner Bros. cartoons, making his last «Golden Age» appearance in False Hare (1964). He starred in over 167 theatrical short films, most of which were directed by Friz Freleng, Robert McKimson, and Chuck Jones. Freleng’s Knighty Knight Bugs (1958), in which a medieval Bugs trades blows with Yosemite Sam and his fire-breathing dragon (which has a cold), won an Academy Award for Best Cartoon Short Subject (becoming the first and only Bugs Bunny cartoon to win said award).[32] Three of Jones’ films—Rabbit Fire, Rabbit Seasoning and Duck! Rabbit, Duck!—compose what is often referred to as the «Rabbit Season/Duck Season» trilogy and were the origins of the rivalry between Bugs and Daffy Duck.[33] Jones’ classic What’s Opera, Doc? (1957), casts Bugs and Elmer Fudd in a parody of Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. It was deemed «culturally significant» by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1992, becoming the first cartoon short to receive this honor.[34]

In the fall of 1960, ABC debuted the prime-time television program The Bugs Bunny Show. This show packaged many of the post-1948 Warners cartoons with newly animated wraparounds. Throughout its run, the series was highly successful, and helped cement Warner Bros. Animation as a mainstay of Saturday-morning cartoons. After two seasons, it was moved from its evening slot to reruns on Saturday mornings. The Bugs Bunny Show changed format and exact title frequently but remained on network television for 40 years. The packaging was later completely different, with each cartoon simply presented on its own, title and all, though some clips from the new bridging material were sometimes used as filler.[35]

Later years

Bugs did not appear in any of the post-1964 Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies films produced by DePatie-Freleng Enterprises or Seven Arts Productions, nor did he appear in Filmation’s Daffy Duck and Porky Pig Meet the Groovie Goolies. He did, however, have two cameo appearances in the 1974 Joe Adamson short A Political Cartoon; one at the beginning of the short, and another in which he is interviewed at a pet store. Bugs was animated in this short by Mark Kausler.[36] He did not appear in new material on-screen again until Bugs and Daffy’s Carnival of the Animals aired in 1976.

From the late 1970s through the early 1990s, Bugs was featured in various animated specials for network television, such as Bugs Bunny’s Thanksgiving Diet, Bugs Bunny’s Easter Special, Bugs Bunny’s Looney Christmas Tales, and Bugs Bunny’s Bustin’ Out All Over. Bugs also starred in several theatrical compilation features during this time, including the United Artists distributed documentary Bugs Bunny: Superstar (1975)[37][38] and Warner Bros.’ own releases: The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie (1979), The Looney Looney Looney Bugs Bunny Movie (1981), Bugs Bunny’s 3rd Movie: 1001 Rabbit Tales (1982), and Daffy Duck’s Quackbusters (1988).

In the 1988 live-action/animated comedy Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Bugs appeared as one of the inhabitants of Toontown. However, since the film was being produced by Disney, Warner Bros. would only allow the use of their biggest star if he got an equal amount of screen time as Disney’s biggest star, Mickey Mouse. Because of this, both characters are always together in frame when onscreen. Roger Rabbit was also one of the final productions in which Mel Blanc voiced Bugs (as well as the other Looney Tunes characters) before his death in 1989.

Bugs later appeared in another animated production featuring numerous characters from rival studios: the 1990 drug prevention TV special Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue.[39][40][41] This special is notable for being the first time that someone other than Blanc voiced Bugs and Daffy (both characters were voiced by Jeff Bergman for this). Bugs also made guest appearances in the early 1990s television series Tiny Toon Adventures, as the principal of Acme Looniversity and the mentor of Babs and Buster Bunny. He made further cameos in Warner Bros.’ subsequent animated TV shows Taz-Mania, Animaniacs, and Histeria!

Bugs returned to the silver screen in Box-Office Bunny (1991). This was the first Bugs Bunny cartoon since 1964 to be released in theaters and it was created for Bugs’ 50th anniversary celebration. It was followed by (Blooper) Bunny, a cartoon that was shelved from theaters,[42] but later premiered on Cartoon Network in 1997 and has since gained a cult following among animation fans for its edgy humor.[43][44][45]

In 1996, Bugs and the other Looney Tunes characters appeared in the live-action/animated film, Space Jam, directed by Joe Pytka and starring NBA superstar Michael Jordan. The film also introduced the character Lola Bunny, who becomes Bugs’ new love interest. Space Jam received mixed reviews from critics,[46][47] but was a box office success (grossing over $230 million worldwide).[48] The success of Space Jam led to the development of another live-action/animated film, Looney Tunes: Back in Action, released in 2003 and directed by Joe Dante. Unlike Space Jam, Back in Action was a box-office bomb,[49] though it did receive more positive reviews from critics.[50][51][52]

In 1997, Bugs appeared on a U.S. postage stamp, the first cartoon to be so honored, beating the iconic Mickey Mouse. The stamp is number seven on the list of the ten most popular U.S. stamps, as calculated by the number of stamps purchased but not used. The introduction of Bugs onto a stamp was controversial at the time, as it was seen as a step toward the ‘commercialization’ of stamp art. The postal service rejected many designs and went with a postal-themed drawing. Avery Dennison printed the Bugs Bunny stamp sheet, which featured «a special ten-stamp design and was the first self-adhesive souvenir sheet issued by the U.S. Postal Service.»[53]

More recent years

A younger version of Bugs is the main character of Baby Looney Tunes, which debuted on Kids’ WB in 2001. In the action-comedy Loonatics Unleashed, his definite descendant Ace Bunny is the leader of the Loonatics team and seems to have inherited his ancestor’s Brooklyn accent and rapier wit.[54]

In 2011, Bugs Bunny and the rest of the Looney Tunes gang returned to television in the Cartoon Network sitcom, The Looney Tunes Show. The characters feature new designs by artist Jessica Borutski. Among the changes to Bugs’ appearance were the simplification and enlargement of his feet, as well as a change to his fur from gray to a shade of mauve (though in the second season, his fur was changed back to gray).[55] In the series, Bugs and Daffy Duck are portrayed as best friends as opposed to their usual pairing as friendly rivals. At the same time, Bugs is more vocally exasperated by Daffy’s antics in the series (sometimes to the point of anger), compared to his usual level-headed personality from the original cartoons. Bugs and Daffy are friends with Porky Pig in the series, although Bugs tends to be a better friend to Porky than Daffy is. Bugs also dates Lola Bunny in the show despite the fact that he finds her to be «crazy» and a bit too talkative at first (he later learns to accept her personality quirks, similar to his tolerance for Daffy). Unlike the original cartoons, Bugs lives in a regular home which he shares with Daffy, Taz (whom he treats as a pet dog) and Speedy Gonzales, in the middle of a cul-de-sac with their neighbors Yosemite Sam, Granny, and Witch Hazel.

In 2015, Bugs starred in the direct-to-video film Looney Tunes: Rabbits Run,[56] and later returned to television yet again as the star of Cartoon Network and Boomerang’s comedy series New Looney Tunes (formerly Wabbit).[57][58]

In 2020, Bugs began appearing on the HBO Max streaming series Looney Tunes Cartoons. His design for this series primarily resembles his Bob Clampett days, complete with yellow gloves and his signature carrot. His personality is a combination of Freleng’s trickery, Clampett’s defiance, and Jones’ resilience, while also maintaining his confident, insolent, smooth-talking demeanor. Bugs is voiced by Eric Bauza, who is also the current voice of Daffy Duck and Tweety, among others.[59] Bugs made his return to movie theaters in the 2021 Space Jam sequel Space Jam: A New Legacy, this time starring NBA superstar LeBron James.[60] In 2022, a new pre-school animated series titled Bugs Bunny Builders aired on HBO Max and Cartoonito.[61]

Bugs has also appeared in numerous video games, including the Bugs Bunny’s Crazy Castle series, Bugs Bunny Birthday Blowout, Bugs Bunny: Rabbit Rampage, Bugs Bunny in Double Trouble, Looney Tunes B-Ball, Looney Tunes Racing, Looney Tunes: Space Race, Bugs Bunny Lost in Time, Bugs Bunny and Taz Time Busters, Loons: The Fight for Fame, Looney Tunes: Acme Arsenal, Scooby Doo and Looney Tunes: Cartoon Universe, Looney Tunes Dash, Looney Tunes World of Mayhem and MultiVersus.

Personality and catchphrases

«Some people call me cocky and brash, but actually I am just self-assured. I’m nonchalant, imperturbable, contemplative. I play it cool, but I can get hot under the collar. And above all I’m a very ‘aware’ character. I’m well aware that I am appearing in an animated cartoon….And sometimes I chomp on my carrot for the same reason that a stand-up comic chomps on his cigar. It saves me from rushing from the last joke to the next one too fast. And I sometimes don’t act, I react. And I always treat the contest with my pursuers as ‘fun and games.’ When momentarily I appear to be cornered or in dire danger and I scream, don’t be consoined – it’s actually a big put-on. Let’s face it, Doc. I’ve read the script and I already know how it turns out.»

—Bob Clampett on Bugs Bunny, written in first person.[62]

Bugs Bunny is characterized as being clever and capable of outsmarting almost anyone who antagonizes him, including Elmer Fudd, Yosemite Sam, Tasmanian Devil, Marvin the Martian, Wile E. Coyote, Gossamer, Witch Hazel, Rocky and Mugsy, The Crusher, Beaky Buzzard, Willoughby, Count Bloodcount, Daffy Duck and a host of others. The only one to consistently beat Bugs is Cecil Turtle, who defeats Bugs in three consecutive shorts based on the premise of the Aesop fable The Tortoise and the Hare. In a rare villain turn, Bugs turns to a life of crime in 1949’s Rebel Rabbit, taking on the entire United States government by vandalizing monuments in an effort to prove he is worth more than the two-cent bounty on his head; while he succeeds in raising the bounty to $1,000,000, the full force of the military ends up capturing Bugs and sending him to Alcatraz.

Bugs almost always wins these conflicts, a plot pattern which recurs in Looney Tunes films directed by Chuck Jones. Concerned that viewers would lose sympathy for an aggressive protagonist who always won, Jones arranged for Bugs to be bullied, cheated, or threatened by the antagonists while minding his own business, justifying his subsequent antics as retaliation or self-defense. He has also been known to break the fourth wall by «communicating» with the audience, either by explaining the situation (e.g. «Be with you in a minute, folks!»), describing someone to the audience (e.g. «Feisty, ain’t they?»), clueing in on the story (e.g. «That happens to him all during the picture, folks.»), explaining that one of his antagonists’ actions have pushed him to the breaking point («Of course you realize, this means war.» — a line borrowed from Groucho Marx in Duck Soup and used again in the next Marx Brothers film A Night at the Opera (1935)[63] ), admitting his own deviousness toward his antagonists («Ain’t I a stinker?» — a line borrowed from Lou Costello[64][65][63]), etc. This style was used and established by Tex Avery.

Bugs usually tries to placate his antagonist and avoid conflict but, when an antagonist pushes him too far, Bugs may address the audience and invoke his catchphrase «Of course you realize this means war!» before he retaliates in a devastating manner. As mentioned earlier, this line was taken from Groucho Marx. Bugs paid homage to Groucho in other ways, such as occasionally adopting his stooped walk or leering eyebrow-raising (in Hair-Raising Hare, for example) or sometimes with a direct impersonation (as in Slick Hare). Other directors, such as Friz Freleng, characterized Bugs as altruistic. When Bugs meets other successful characters (such as Cecil Turtle in Tortoise Beats Hare, the Gremlin in Falling Hare, and the unnamed mouse in Rhapsody Rabbit), his overconfidence becomes a disadvantage and sometimes even leads to his undoing.

Bugs’ nonchalant carrot-chewing standing position, as explained by Freleng, Jones and Bob Clampett, originated in a scene from the film It Happened One Night (1934), in which Clark Gable’s character Peter Warne leans against a fence, eating carrots rapidly and talking with his mouth full to Claudette Colbert’s character. This scene was well known while the film was popular, and viewers at the time likely recognized Bugs Bunny’s behavior as satire. Coincidentally, the film also features a minor character, Oscar Shapely, who addresses Peter Warne as «Doc», and Warne mentions an imaginary person named «Bugs Dooley» to frighten Shapely.[66]

«‘What’s up Doc?’ is a very simple thing. It’s only funny because it’s in a situation. It was an all Bugs Bunny line. It wasn’t funny. If you put it in human terms; you come home late one night from work, you walk up to the gate in the yard, you walk through the gate and up into the front room, the door is partly open and there’s some guy shooting under your living room. So what do you do? You run if you have any sense, the least you can do is call the cops. But what if you come up and tap him on the shoulder and look over and say ‘What’s up Doc?’ You’re interested in what he’s doing. That’s ridiculous. That’s not what you say at a time like that. So that’s why it’s funny, I think. In other words it’s asking a perfectly legitimate question in a perfectly illogical situation.»

—Chuck Jones on Bugs Bunny’s catchphrase «What’s up Doc?»[67]

The carrot-chewing scenes are generally followed by Bugs’ most well-known catchphrase, «What’s up, Doc?», which was written by director Tex Avery for his first Bugs Bunny film, A Wild Hare (1940). Avery explained later that it was a common expression in his native Texas and that he did not think much of the phrase. Back then «doc» meant the same as «dude» does today. When the cartoon was first screened in theaters, the «What’s up, Doc?» scene generated a tremendously positive audience reaction.[20][68] As a result, the scene became a recurring element in subsequent cartoons. The phrase was sometimes modified for a situation. For example, Bugs says «What’s up, dogs?» to the antagonists in A Hare Grows in Manhattan, «What’s up, Duke?» to the knight in Knight-mare Hare, and «What’s up, prune-face?» to the aged Elmer in The Old Grey Hare. He might also greet Daffy with «What’s up, Duck?» He used one variation, «What’s all the hub-bub, bub?» only once, in Falling Hare. Another variation is used in Looney Tunes: Back in Action when he greets a blaster-wielding Marvin the Martian saying «What’s up, Darth?»

Several Chuck Jones films in the late 1940s and 1950s depict Bugs travelling via cross-country (and, in some cases, intercontinental) tunnel-digging, ending up in places as varied as Barcelona, Spain (Bully for Bugs), the Himalayas (The Abominable Snow Rabbit), and Antarctica (Frigid Hare) all because he «knew (he) shoulda taken that left toin at Albukoikee.» He first utters that phrase in Herr Meets Hare (1945), when he emerges in the Black Forest, a cartoon seldom seen today due to its blatantly topical subject matter. When Hermann Göring says to Bugs, «There is no Las Vegas in ‘Chermany'» and takes a potshot at Bugs, Bugs dives into his hole and says, «Joimany! Yipe!», as Bugs realizes he is behind enemy lines. The confused response to his «left toin» comment also followed a pattern. For example, when he tunnels into Scotland in My Bunny Lies over the Sea (1948), while thinking he is heading for the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California, it provides another chance for an ethnic joke: «Therrre arrre no La Brrrea Tarrr Pits in Scotland!» (to which Bugs responds, «Scotland!? Eh…what’s up, Mac-doc?»). A couple of late-1950s/early-1960s cartoons of this ilk also featured Daffy Duck travelling with Bugs («Hey, wait a minute! Since when is Pismo Beach inside a cave?»).

Voice actors

The following are the various vocal artists who have voiced Bugs Bunny over the last 80-plus years for both Warner Bros. official productions and others:

Mel Blanc

Mel Blanc was the original voice of Bugs and voiced the character for nearly five decades.

Mel Blanc voiced the character for almost 50 years, from Bugs’ debut in the 1940 short A Wild Hare until Blanc’s death in 1989. Blanc described the voice as a combination of Bronx and Brooklyn accents; however, Tex Avery claimed that he asked Blanc to give the character not a New York accent per se, but a voice like that of actor Frank McHugh, who frequently appeared in supporting roles in the 1930s and whose voice might be described as New York Irish.[14] In Bugs’ second cartoon Elmer’s Pet Rabbit, Blanc created a completely new voice for Bugs, which sounded like a Jimmy Stewart impression, but the directors decided the previous voice was better. Though Blanc’s best known character was the carrot-chomping rabbit, munching on the carrots interrupted the dialogue. Various substitutes, such as celery, were tried, but none of them sounded like a carrot. So, for the sake of expedience, Blanc munched and then spit the carrot bits into a spittoon, rather than swallowing them, and continued with the dialogue. One often-repeated story, which dates back to the 1940s,[69] is that Blanc was allergic to carrots and had to spit them out to minimize any allergic reaction — but his autobiography makes no such claim.[16] In fact, in a 1984 interview with Tim Lawson, co-author of The Magic Behind The Voices: A Who’s Who of Voice Actors, Blanc emphatically denied being allergic to carrots.

Others

- Ben Hardaway (as an early iteration of Bugs; one line in Porky’s Hare Hunt)[70]

- Bob Clampett (vocal effects and additional lines in A Corny Concerto and Falling Hare)[71]

- Gilbert Mack (Golden Records records, Bugs Bunny Songfest)[72][73]

- Dave Barry (Golden Records records, Bugs Bunny Easter Song and Mr. Easter Rabbit, Bugs Bunny Songfest)[72][73][74]

- Daws Butler (imitating Groucho Marx and Ed Norton in Wideo Wabbit)

- Ricky Nelson (singing «Gee Whiz, Whilikins, Golly Gee» in an episode of The Bugs Bunny Show)[75]

- Jerry Hausner (additional lines in Devil’s Feud Cake, The Bugs Bunny Show and some commercials)[72][71]

- Larry Storch (1973 ABC Saturday Mornings promotion)[76]

- Mike Sammes (Bugs Bunny Comes to London)[77]

- Richard Andrews (Bugs Bunny Exercise and Adventure Album)[78]

- Bob Bergen (ABC Family Fun Fair)[79][80]

- Darrell Hammond («Wappin'»)

- Jeff Bergman (62nd Academy Awards, Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue, The Earth Day Special, Gremlins 2: The New Batch, Tiny Toon Adventures, Box Office Bunny, Bugs Bunny’s Overtures to Disaster, (Blooper) Bunny, Bugs Bunny’s Lunar Tunes, Invasion of the Bunny Snatchers, Bugs Bunny’s Creature Features, Special Delivery Symphony,[81] Pride of the Martians, The Looney Tunes Show, Scooby Doo & Looney Tunes Cartoon Universe: Adventure, Looney Tunes Dash, Looney Tunes: Rabbits Run, Wun Wabbit Wun,[82] New Looney Tunes, Daffy Duck Dance Off,[83] Ani-Mayhem,[84] Meet Bugs (and Daffy),[85] Space Jam: A New Legacy,[86] Tiny Toons Looniversity,[87] various commercials)[88][89][90][91]

- Noel Blanc (You Rang? answering machine messages,[92] Chevrolet Monte Carlo 400 with the Looney Tunes)

- Keith Scott (Bugs Bunny’s 50th Anniversary bumper,[93] Bugs Bunny demonstration animatronic,[94][95] Looney Tunes Musical Revue,[96][97] Spectacular Light and Sound Show Illuminanza,[98][99] Looney Tunes: We Got the Beat!,[100][101] Looney Tunes on Ice, Looney Tunes LIVE! Classroom Capers,[102] Christmas Moments with Looney Tunes, The Looney Tunes Radio Show,[103][104] Looney Rock, Looney Tunes Christmas Carols,[105][106][107] various commercials)[88][108][109][110]

- Greg Burson (1990 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, Bugs Bunny’s Birthday Ball, Yakety Yak, Take It Back, Looney Tunes River Ride, Tiny Toon Adventures, Yosemite Sam and the Gold River Adventure!, The Toonite Show Starring Bugs Bunny,[111] Taz-Mania, Bugs Bunny: Rabbit Rampage,[112] Animaniacs, The Bugs Bunny Wacky World Games,[113] Acme Animation Factory,[114] Have Yourself a Looney Tunes Christmas, Looney Tunes B-Ball,[115] 67th Academy Awards, Carrotblanca, Bugs ‘n’ Daffy intro, From Hare to Eternity, Warner Bros. Kids Club,[116] Bugs Bunny’s Learning Adventures, Looney Tunes: What’s Up Rock?!,[100] Looney Tunes: Back in Action animation test,[117] various commercials)[88]

- John Blackman (Hey Hey It’s Saturday)[118]

- John Willyard (1992 Six Flags Great Adventure commercial)[119]

- Mendi Segal (Bugs & Friends Sing the Beatles, The Looney West)[120][121]

- Billy West (Space Jam, Bugs & Friends Sing Elvis,[122] Histeria!, Warner Bros. Sing-Along: Quest for Camelot, Warner Bros. Sing-Along: Looney Tunes, The Looney Tunes Rockin’ Road Show,[123] The Looney Tunes Kwazy Christmas,[124][125] Bah, Humduck! A Looney Tunes Christmas, A Looney Tunes Sing-A-Long Christmas,[126] various video games, webtoons, and commercials)[88]

- Joe Alaskey (Chasers Anonymous, Gatorade commercial, Tweety’s High-Flying Adventure, Looney Tunes: Back in Action, Looney Tunes: Back in Action (video game), Hare and Loathing in Las Vegas, Looney Tunes webtoons, Daffy Duck for President, Aflac commercial, Looney Tunes: Acme Arsenal, Justice League: The New Frontier, Looney Tunes: Cartoon Conductor, Looney Tunes: Laff Riot pilot,[127] Looney Tunes Dance Off,[128] TomTom Looney Tunes GPS,[129] Looney Tunes ClickN READ Phonics)[88]

- Samuel Vincent (Baby Looney Tunes, Baby Looney Tunes’ Eggs-traordinary Adventure)[88]

- Robert Smigel (Saturday Night Live Season 28, Ep. 14)[130]

- Eric Goldberg (additional lines in Looney Tunes: Back in Action, Looney Tunes: Back in Action interview)[131][132]

- Seth MacFarlane (Stewie Griffin: The Untold Story, Family Guy)[133]

- Bill Farmer (Robot Chicken)[134]

- James Arnold Taylor (Drawn Together)

- Kevin Shinick (Mad)[135]

- Gary Martin (Looney Tunes All-Stars promotions, Looney Tunes Take-Over Weekend promotion, Looney Tunes Marathon promotion)[90]

- Eric Bauza (Looney Tunes World of Mayhem,[136] Looney Tunes Cartoons, Bugs Bunny in The Golden Carrot, Space Jam: A New Legacy (as Big Chungus),[137] Space Jam: A New Legacy live show, Bugs and Daffy’s Thanksgiving Road Trip,[138][139] MultiVersus,[140] Bugs Bunny Builders[141])[88]

Comics

Comic books

Bugs Bunny was continuously featured in comic books for more than 40 years, from 1941 to 1983, and has appeared sporadically since then. Bugs first appeared in comic books in 1941, in Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics #1, published by Dell Comics. Bugs was a recurring star in that book all through its 153-issue run, which lasted until July 1954. Western Publishing (and its Dell imprint) published 245 issues of a Bugs Bunny comic book from Dec. 1952/Jan. 1953 to 1983. The company also published 81 issues of the joint title Yosemite Sam and Bugs Bunny from December 1970 to 1983. During the 1950s Dell also published a number of Bugs Bunny spinoff titles.

Creators on those series included Chase Craig, Helen Houghton,[142] Eleanor Packer,[143] Lloyd Turner,[144] Michael Maltese, John Liggera,[145] Tony Strobl, Veve Risto, Cecil Beard, Pete Alvorado, Carl Fallberg, Cal Howard, Vic Lockman, Lynn Karp, Pete Llanuza, Pete Hansen, Jack Carey, Del Connell, Kellog Adams, Jack Manning, Mark Evanier, Tom McKimson, Joe Messerli, Carlos Garzon, Donald F. Glut, Sealtiel Alatriste, Sandro Costa, and Massimo Fechi.

The German publisher Condor published a 76-issues Bugs Bunny series (translated and reprinted from the American comics) in the mid-1970s. The Danish publisher Egmont Ehapa produced a weekly reprint series in the mid-1990s.

Comic strip

The Bugs Bunny comic strip ran for almost 50 years, from January 10, 1943, to December 30, 1990, syndicated by the Newspaper Enterprise Association. It started out as a Sunday page and added a daily strip on November 1, 1948.[146]

The strip originated with Chase Craig, who did the first five weeks before leaving for military service in World War II.[147] Roger Armstrong illustrated the strip from 1942 to 1944.[148] The creators most associated with the strip are writers Albert Stoffel (1947–1979)[149] & Carl Fallberg (1950–1969),[150] and artist Ralph Heimdahl, who worked on it from 1947 to 1979.[151] Other creators associated with the Bugs Bunny strip include Jack Hamm, Carl Buettner, Phil Evans, Carl Barks (1952), Tom McKimson, Arnold Drake, Frank Hill, Brett Koth, and Shawn Keller.[152][153]

Reception and legacy

Statue evoking Bugs Bunny at Butterfly Park Bangladesh.

Like Mickey Mouse for Disney, Bugs Bunny has served as the mascot for Warner Bros. and its various divisions. According to Guinness World Records, Bugs has appeared in more films (both short and feature-length) than any other cartoon character, and is the ninth most portrayed film personality in the world.[7] On December 10, 1985, Bugs became the second cartoon character (after Mickey) to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[8]

He also has been a pitchman for companies including Kool-Aid and Nike. His Nike commercials with Michael Jordan as «Hare Jordan» for the Air Jordan VII and VIII became precursors to Space Jam. As a result, he has spent time as an honorary member of Jordan Brand, including having Jordan’s Jumpman logo done in his image. In 2015, as part of the 30th anniversary of Jordan Brand, Nike released a mid-top Bugs Bunny version of the Air Jordan I, named the «Air Jordan Mid 1 Hare», along with a women’s equivalent inspired by Lola Bunny called the «Air Jordan Mid 1 Lola», along with a commercial featuring Bugs and Ahmad Rashad.[154]

In 2002, TV Guide compiled a list of the 50 greatest cartoon characters of all time as part of the magazine’s 50th anniversary. Bugs Bunny was given the honor of number 1.[155][156] In a CNN broadcast on July 31, 2002, a TV Guide editor talked about the group that created the list. The editor also explained why Bugs pulled top billing: «His stock…has never gone down…Bugs is the best example…of the smart-aleck American comic. He not only is a great cartoon character, he’s a great comedian. He was written well. He was drawn beautifully. He has thrilled and made many generations laugh. He is tops.»[157] Some have noted that comedian Eric Andre is the nearest contemporary comedic equivalent to Bugs. They attribute this to, «their ability to constantly flip the script on their unwitting counterparts.»[158]

Notable films

- Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938) – debut of Bugs-like character

- A Wild Hare (1940) – official debut; Oscar nominee

- Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941) – Oscar nominee

- What’s Opera, Doc? (1957) – voted #1 of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time and inducted into the National Film Registry

- Knighty Knight Bugs (1958) – Oscar winner

- False Hare (1964) – final regular cartoon

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) – first, and so far, only appearance in a Disney film; appeared alongside Disney’s mascot, Mickey Mouse, for the first time – Oscar winner

- Box-Office Bunny (1990) – first theatrically released short since 1964

- Space Jam (1996) – appeared alongside NBA superstar, Michael Jordan

- Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003) – appeared alongside Brendan Fraser, Jenna Elfman and Steve Martin

- Space Jam: A New Legacy (2021) – appeared alongside NBA superstar, LeBron James

Language

The American use of Nimrod to mean «idiot» is often said to have originated from Bugs’s exclamation «What a Nimrod!» to describe the inept hunter Elmer Fudd.[159] However, it is Daffy Duck who refers to Fudd as «my little Nimrod» in the 1948 short «What Makes Daffy Duck»,[160] and the Oxford English Dictionary records earlier negative uses of the term «nimrod».[161]

See also

- Looney Tunes

- Merrie Melodies

- Golden age of American animation

References

- ^ a b c d e Adamson, Joe (1990). Bugs Bunny: 50 Years and Only One Grey Hare. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-1855-7.

- ^ «Is Bugs Bunny a Rabbit or a Hare?». November 30, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ «What’s the Difference Between Rabbits and Hares?». Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ «Mel Blanc». Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ «Bugs Bunny: The Trickster, American Style». Weekend Edition Sunday. NPR. January 6, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 58–62. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ a b «Most Portrayed Character in Film». Guinness World Records. May 2011. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012.

- ^ a b «Bugs Bunny». Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ Walz, Eugene (1998). Cartoon Charlie: The Life and Art of Animation Pioneer Charles Thorson. Great Plains Publications. pp. 26. ISBN 0-9697804-9-4.

- ^ Chase Craig recollections of «Michael Maltese,» Chase Craig Collection, CSUN

- ^ a b c Walz (1998), p. 49-67

- ^ a b c d Barrier (2003), p. 359-362

- ^ a b «‘Bugs Bunny’'″. Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica.com. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c Barrier, Michael (November 6, 2003). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. United States: Oxford University Press. p. 672. ISBN 978-0-19-516729-0.

- ^ «Leading the Animation Conversation » Rare 1939 Looney Tunes Book found!». Cartoon Brew. April 3, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Blanc, Mel; Bashe, Philip (1989). That’s Not All, Folks!. Clayton South, VIC, Australia: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-51244-3.

- ^ «Looney Tunes Hidden Gags». Gregbrian.tripod.com. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Motion Picture Herald: August 12, 1939[permanent dead link] «…With gun and determination, he takes to the field and tracks his prey in the zany person of «Bugs» Bunny, a true lineal descendant of the original Mad Hatter if there ever was one…»

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2003), Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516729-0

- ^ a b Adamson, Joe (1975). Tex Avery: King of Cartoons. New York City: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80248-1.

- ^ «1940 academy awards». Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ «1941 academy awards». Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ a b «Globat Login». Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Lehman, Christopher P. (2008). The Colored Cartoon: Black Representation in American Animated Short Films, 1907–1954. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-55849-613-2. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ «Warner Bros. Studio biography Archived May 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine». AnimationUSA.com. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ Bugs Bunny Nips The Nips at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- ^ Leon Schlessinger, Tokyo Woes, retrieved May 22, 2017

- ^ «Herr Meets Hare». BCDB. January 10, 2013. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013.

- ^ Audio commentary by Paul Dini for Super-Rabbit on the Looney Tunes Golden Collection: Volume 3 (2005).

- ^ «History of the 380th Bomb Group». 380th.org. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ «Jasper Goes Hunting information». Bcdb.com. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ «1958 academy awards». Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ Michael Barrier’s audio commentary for Disc One of Looney Tunes Golden Collection: Volume 1 (2005).

- ^ «Complete National Film Registry Listing — National Film Preservation Board». Library of Congress.

- ^ ««Archived copy». Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)«. Looney Tunes on Television. Retrieved November 7, 2010. - ^ «Animation Anecdotes #258». Cartoon Research. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ You Must Remember This: The Warner Bros. Story (2008), p. 255.

- ^ WB retained a pair of features from 1949 that they merely distributed, and all short subjects released on or after September 1, 1948; in addition to all cartoons released in August 1948.

- ^ «Cartoon special: Congressmen treated to preview of program to air on network, independent and cable outlets». The Los Angeles Times. April 19, 1990. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Bernstein, Sharon (April 20, 1990). «Children’s TV: On Saturday, networks will simulcast ‘Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue,’ an animated feature on drug abuse». The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ «Hollywood and Networks Fight Drugs With Cartoon». New York Times. April 21, 1990. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ «Karmatoons — What I have Done».

- ^ Knight, Richard. «Consider the Source». Chicagoreader.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ «(Blooper) Bunny!». August 2, 1991 – via IMDb.

- ^ Ford, Greg. Audio commentary for (Blooper) Bunny on Disc One of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection: Volume 1.

- ^ «Space Jam». Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 17, 1996). «Space Jam». Variety. Reed Business Information. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ «Space Jam (1996)». Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide.

- ^ «Looney Tunes: Back in Action». Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ «Looney Tunes: Back in Action Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More». Metacritic. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ «Looney Tunes: Back in Action :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews». Rogerebert.suntimes.com. November 14, 2003. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Looney Tunes: Bugs Bunny stamp. Archived June 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine National Postal Museum Smithsonian.

- ^ George Gene Gustines (June 6, 2005). «It’s 2772. Who Loves Ya, Tech E. Coyote?». The New York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ Yes!! I can finally Blog about my Redesign of «The Looney Tunes Show» — Jessica Borutski

- ^ King, Darryn (May 5, 2015). «Bugs Bunny to Return in Direct-to-Video ‘Rabbits Run’«. Cartoon Brew. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Steinberg, Brian (March 10, 2014). «Cartoon Network To Launch First Mini-Series, New Takes on Tom & Jerry, Bugs Bunny». Variety.com. Variety Media, LLC. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ Steinberg, Brian (June 29, 2015). «Bugs Bunny, Scooby-Doo Return in New Shows to Boost Boomerang».

- ^ Porter, Rick (October 29, 2019). «‘Looney Tunes’ Update, Hanna-Barbera Series Set at HBO Max». The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ «SpringHill Ent. Twitter ನಲ್ಲಿ: «July 16, 2021 🎥🏀🥕 #SaveTheDate… ««. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- ^ ««Bugs Bunny Builders» Join Looney Tunes Mania». KOIN.com. August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ «Chapter 11: What’s Up Doc?». Draw the Looney Tunes: The Warner Bros. Character Design Manual. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. 2005. p. 166. ISBN 0-8118-5016-1.

- ^ a b «Tex Avery».

- ^ «The Warner Brothers Cartoon Companion: A».

- ^ «Other Abbott and Costello horror comedies are: Hold That Ghost (1941), Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), Jack and». www.vaiden.net.

- ^ «It Happened One Night film review by Tim Dirks». Filmsite.org. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Sito, Tom (June 17, 1998). «Chuck Jones Interview». Archive of American Television. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ «What’s Up, Doc? A Look at the Texas Roots of Tex Avery and Bugs Bunny». December 18, 2020.

- ^ «Warner Club News (1944)». Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ «Point of View: Moose and Squirrel». News From ME. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

Blanc did Bugs from the start, all through the various prototype versions. One brief exception is Bugs’ line, «Of course you know, this means war» in Porky’s Hare Hunt. That one line was done by director-storyman Ben «Bugs» Hardaway.

- ^ a b Scott, Keith (October 3, 2022). Cartoon Voices of the Golden Age, Vol. 2. BearManor Media.

- ^ a b c «Bugs Bunny on Record». News From ME. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b «Golden Records’ «Bugs Bunny Songfest» (1961)». cartoonresearch.com. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «78 RPM — Golden Records — USA — R191». 45worlds. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Celebrities that you’re surprised were never caricatured in a classic cartoon». Anime Superhero News. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ «Voice(s) of Bugs Bunny in ABC». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ «Bugs Bunny’s «British Invasion» on Records». cartoonresearch.com. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Bugs Bunny Breaks a Sweat». cartoonresearch.com. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «ABC Family Fun Fair». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ «ABC Family Fun Fair planned at city mall». The Oklahoman. August 23, 1987. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Special Delivery Symphony (Looney Tunes Discover Music) Paperback – 31 Dec. 1993. ASIN 0943351588.

- ^ «Wun Wabbit Wun». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ «Daffy Duck Dance Off». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ «Voice(s) of Bugs Bunny in Ani-Mayhem». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ «Meet Bugs (And Daffy)». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Weiss, Josh (November 19, 2018). «Development: Space Jam 2 to film on West Coast; Mr. Mercedes driving toward Season 3; more». SYFY WIRE. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Weiss, Josh (July 15, 2021). «‘TINY TOONS’ REBOOT ON HBO MAX WILL FEATURE A ‘DUMBLEDORE’-ESQUE BUGS BUNNY, RETURN TO LOONIVERSITY». SYFY WIRE. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Bugs Bunny Voices (Looney Tunes)». Behind The Voice Actors.

- ^ «Voice(s) of Bugs Bunny in Cartoon Network». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ a b «Voice(s) of Bugs Bunny in Boomerang». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Ad Council». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ «You Rang? Answering Machine Messages Bugs Bunny». YouTube. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ «Porky Pig (1990)». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ «Flashback: Movie World Turns 25». Gold Coast Bulletin. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ «Australian Theme Park Exhibit/Mall Interactive Animatronics 1980s onwards». Vimeo. November 30, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ «Looney Tunes Musical Revue». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ «06 Looney Tunes Stage Show_0001». Flickr. March 29, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ «Spectacular Light and Sound Show Illuminanza». Facebook. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ «Warner Bros. Movie World Illuminanza». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ a b «Looney Tunes: What’s Up Rock?». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ «New Looney Tunes show unveiled at Movie World». Leisure Management. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ «‘CLASSROOM CAPERS’«. Alastair Fleming Associates. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ «That Wascally Wabbit». Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ «The Day I Met Bugs Bunny». Ian Heydon. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ «Looney Tunes featuring Santa Claus, Lauren & Andrew — Carols by Candlelight 2013». YouTube. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ «Looney Tunes Christmas Carols». K-Zone. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ «Carols by Candlelight». National Boys Choir of Australia. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ «Keith Scott: Down Under’s Voice Over Marvel». Animation World Network. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ «Keith Scott». Grace Gibson Shop. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ «Keith Scott-«The One-Man Crowd»». Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ «The Toonite Show Starring Bugs Bunny». Behind The Voice Actors.

- ^ «Bugs Bunny: Rabbit Rampage». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ «Bugs Bunny Wacky World Games». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ «Acme Animation Factory». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ «Looney Tunes B-Ball». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ «Warner Bros. Kids Club». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ «Zac Vega on Twitter: «Here’s what appears to be an animation test by THE Eric Goldberg himself for «Looney Tunes: Back in Action.» Voices by Greg Burson.»«. Twitter. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ «Hey Hey It’s Saturday». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ «Voice(s) of Bugs Bunny in Six Flags Parks». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ «Joe Alaskey and Looney Tunes on Records». cartoonresearch.com. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ The Looney West. (Musical CD, 1996). WorldCat. OCLC 670529500. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ «Bugs & Friends Sing Elvis». VGMdb. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ «The Looney Tunes Rockin’ Road Show». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ «THE LOONEY TUNES KWAZY CHRISTMAS». VGMdb. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ «A Looney Tunes Kwazy Christmas». YouTube Music. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Monger, James. «A Looney Tunes Sing-A-Long Christmas». AllMusic. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ «Laff Riot (full Unaired Pilot)». November 4, 2009.

- ^ «Looney Tunes Dance Off». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Eh, what’s up, Doc? TomTom offers Looney Tunes voices for GPS navigators

Consumer Reports. September 27, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2016. - ^ «Voice of Bugs Bunny in Saturday Night Live». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ «Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003) — Trivia». IMDb. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «‘Looney Tunes: Back in Action’ Interview». YouTube. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Voice of Bugs Bunny in Family Guy Presents Stewie Griffin: The Untold Story». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Voice of Bugs Bunny in Robot Chicken». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Voice of Bugs Bunny in Mad». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ «Bugs Bunny». Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ «Sebastián Ortiz Ramírez on Twitter: «You know, I never knew, noticed or realized until now that Eric Bauza did Bugs’s Voice when he turned into Big Chungus on Bugs’s Introduction scene in «Space Jam: A New Legacy».»«. Twitter. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (November 22, 2021). «Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck Star in First Looney Tunes Scripted Podcast Series (Podcast News Roundup)». Variety.

- ^ «Bugs & Daffy’s Thanksgiving Road Trip». Spotify. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Leane, Rob (November 18, 2021). «MultiVersus: Shaggy, Batman & Arya Stark join Warner Bros crossover game». Radio Times.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (June 14, 2022). «Trailer: ‘Bugs Bunny Builders’ Breaks Ground on Cartoonito July 25». Animation Magazine.

- ^ Houhgton entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Packer entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Turner entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Liggera entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ Craig entry, Lambiek’s Comiclopedia. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Armstrong entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Stoffel entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Fallberg entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Heimdahl entry, Who’s Who of American Comics Books, 1928–1999. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- ^ Ron Goulart, Encyclopedia of American Comics. New York, Facts on File, 1992. ISBN 9780816025824 pp. 33-4,37,57,73-74,106,262-263.

- ^ John Cawley. «Back to the Rabbit Hole: Koth and Krller, the Men Behind the New and Improved Bugs Bunny Comic Strip.» Animato no.20 (Summer 1990), pp.30-31.

- ^ Bugs Bunny Shares the Scoop on his Latest Partnership with Michael Jordan Nike

- ^ «Bugs Bunny tops greatest cartoon characters list». CNN.com. July 30, 2002. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ^ «List of All-time Cartoon Characters». CNN.com. CNN. July 30, 2002. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ «CNN LIVE TODAY: ‘TV Guide’ Tipping Hat to Cartoon Characters». CNN.com. CNN. July 31, 2002. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ Neilan, Dan. «Eric Andre’s nearest comedic equivalent may be Bugs Bunny». The A.V. Club. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (3rd Edition, 2009). Garner’s Modern American Usage, p. liii. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-538275-7.

- ^ Arthur Davis (director) (February 14, 1948). What Makes Daffy Duck (Animated short). Event occurs at 5:34.

Precisely what I was wondering, my little Nimrod.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 3rd edition, updated 2020, s.v.

Bibliography

- Adamson, Joe (1990). Bugs Bunny: 50 Years and Only One Grey Hare. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-1855-7.

- Beck, Jerry; Friedwald, Will (1989). Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-0894-2.

- Jones, Chuck (1989). Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-12348-9.

- Blanc, Mel; Bashe, Philip (1988). That’s Not All, Folks!. Clayton South, VIC, Australia: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-39089-5.

- Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons (Revised ed.). New York: Plume Book. ISBN 0-452-25993-2.

- Barrier, Michael (2003). «Warner Bros., 1933-1940». Hollywood Cartoons : American Animation in Its Golden Age: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198020790.

- Rubin, Rachel (2000). «A Gang of Little Yids». Jewish Gangsters of Modern Literature. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252025396.

- Sandler, Kevin S. (2001), «The Wabbit We-negatiotes: Looney Tunes in a Conglomerate Age», in Pomerance, Murray (ed.), Ladies and Gentlemen, Boys and Girls: Gender in Film at the End of the Twentieth Century, State University of New York Press, ISBN 9780791448854

- Walz, Gene (1998), «Charlie Thorson and the Temporary Disneyfication of Warner Bros. Cartoons», in Sandler, Kevin S. (ed.), Reading the Rabbit: Explorations in Warner Bros. Animation, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 9780813525389

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bugs Bunny.

- Bugs Bunny on IMDb

- Bugs Bunny at Toonopedia

| Bugs Bunny | |

|---|---|

| Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies character | |

|

|

| First appearance | Porky’s Hare Hunt (preliminary version)[1] April 30, 1938 A Wild Hare (official)[1] July 27, 1940 |

| Created by | Ben Hardaway Cal Dalton Charles Thorson Official Tex Avery Chuck Jones Bob Givens Robert McKimson |

| Designed by | Cal Dalton Charles Thorson (1939–1940) Official Bob Givens (1940–1943) Robert McKimson (1943–) |

| Voiced by | Mel Blanc (1938–1989) Jeff Bergman (1990–1993, 1997–1998, 2002–2004, 2007, 2011–present) Greg Burson (1990–2000) Billy West (1996–2006) Joe Alaskey (1997–2011) Sam Vincent (Baby Looney Tunes; 2001–2006) Eric Bauza (2018–present) (see below) |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Bun-Bun Rabbit |

| Species | Hare/Rabbit[2][3] |

| Gender | Male |

| Significant other | Lola Bunny (girlfriend) |

| Relatives | Clyde Bunny (nephew) |

Bugs Bunny is an animated cartoon character created in the late 1930s at Warner Bros. Cartoons (originally Leon Schlesinger Productions) and voiced originally by Mel Blanc.[4] Bugs is best known for his featured roles in the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of animated short films, produced by Warner Bros. Earlier iterations of the character first appeared in Ben Hardaway’s Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938) and subsequent shorts before Bugs’s definitive characterization debuted in Tex Avery’s A Wild Hare (1940).[1] Bob Givens and Robert McKimson are credited for defining Bugs’s design.[1]

Bugs is an anthropomorphic gray and white rabbit or hare who is characterized by his flippant, insouciant personality. He is also characterized by a Brooklyn accent, his portrayal as a trickster, and his catch phrase «Eh…What’s up, doc?». Through his popularity during the golden age of American animation, Bugs became an American cultural icon and Warner Bros.’ official mascot.[5]

Bugs starred in more than 160 short films produced between 1940 and 1964.[6] He has since appeared in feature films, television shows, comics, and other media. He has appeared in more films than any other cartoon character, is the ninth most-portrayed film personality in the world[7] and has his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[8]

Development

Bugs’ preliminary debut (as an unnamed little white rabbit) in Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938).

According to Chase Craig, who wrote and drew the first Bugs Bunny comic Sunday pages and the first Bugs comic book, «Bugs was not the creation of any one man; however, he rather represented the creative talents of perhaps five or six directors and many cartoon writers including Charlie Thorson.[9] In those days, the stories were often the work of a group who suggested various gags, bounced them around and finalized them in a joint story conference.»[10] A Bugs-like rabbit with some of the personality of a finalized Bugs, though looking very different, was originally featured in the film Porky’s Hare Hunt, released on April 30, 1938. It was co-directed by Ben «Bugs» Hardaway and an uncredited director Cal Dalton (who was responsible for the initial design of the rabbit). This cartoon has an almost identical plot to Avery’s Porky’s Duck Hunt (1937), which had introduced Daffy Duck. Porky Pig is again cast as a hunter tracking a silly prey who is more interested in driving his pursuer insane and less interested in escaping. Hare Hunt replaces the little black duck with a small white rabbit. According to Friz Freleng, Hardaway and Dalton had decided to «dress the duck in a rabbit suit».[11] The white rabbit had an oval head and a shapeless body. In characterization, he was «a rural buffoon». Mel Blanc gave the character a voice and laugh much like those he later used for Woody Woodpecker. He was loud, zany with a goofy, guttural laugh.[12] The rabbit character was popular enough with audiences that the Termite Terrace staff decided to use it again.[13]

The rabbit comes back in Prest-O Change-O (1939), directed by Chuck Jones, where he is the pet rabbit of unseen character Sham-Fu the Magician. Two dogs, fleeing the local dogcatcher, enter the rabbit’s absent master’s house. The rabbit harasses them but is ultimately bested by the bigger of the two dogs. This version of the rabbit was cool, graceful, and controlled. He retained the guttural laugh but was otherwise silent.[12]

The rabbit’s third appearance comes in Hare-um Scare-um (1939), directed again by Dalton and Hardaway. This cartoon—the first in which he is depicted as a gray bunny instead of a white one—is also notable as the rabbit’s first singing role. Charlie Thorson, lead animator on the film, gave the character a name. He had written «Bug’s Bunny» on the model sheet that he drew for Hardaway.[13][14] In promotional material for the cartoon, including a surviving 1939 presskit, the name on the model sheet was altered to become the rabbit’s own name: «Bugs» Bunny (quotation marks only used, on and off, until 1944).[15]

In his autobiography, Blanc claimed that another proposed name for the character was «Happy Rabbit.»[16] In the actual cartoons and publicity, however, the name «Happy» only seems to have been used in reference to Bugs Hardaway. In Hare-um Scare-um, a newspaper headline reads, «Happy Hardaway.»[17] Animation historian David Gerstein disputes that «Happy Rabbit» was ever used as an official name, arguing that the only usage of the term came from Mel Blanc himself in humorous and fanciful tales he told about the character’s development in the 1970s and 1980s; the name «Bugs Bunny» was used as early as August 1939, in the Motion Picture Herald, in a review for the short Hare-um Scare-um.[18]

Thorson had been approached by Tedd Pierce, head of the story department, and asked to design a better rabbit. The decision was influenced by Thorson’s experience in designing hares. He had designed Max Hare in Toby Tortoise Returns (Disney, 1936). For Hardaway, Thorson created the model sheet previously mentioned, with six different rabbit poses. Thorson’s model sheet is «a comic rendition of the stereotypical fuzzy bunny». He had a pear-shaped body with a protruding rear end. His face was flat and had large expressive eyes. He had an exaggerated long neck, gloved hands with three fingers, oversized feet, and a «smart aleck» grin. The result was influenced by Walt Disney Animation Studios’ tendency to draw animals in the style of cute infants.[11] He had an obvious Disney influence, but looked like an awkward merger of the lean and streamlined Max Hare from The Tortoise and the Hare (1935) and the round, soft bunnies from Little Hiawatha (1937).[12]

In Jones’ Elmer’s Candid Camera (1940), the rabbit first meets Elmer Fudd. This time the rabbit looks more like the present-day Bugs, taller and with a similar face—but retaining the more primitive voice. Candid Camera’s Elmer character design is also different: taller and chubbier in the face than the modern model, though Arthur Q. Bryan’s character voice is already established.

Official debut

While Porky’s Hare Hunt was the first Warner Bros. cartoon to feature what would become Bugs Bunny, A Wild Hare, directed by Tex Avery and released on July 27, 1940, is widely considered to be the first official Bugs Bunny cartoon.[1][19] It is the first film where both Elmer Fudd and Bugs, both redesigned by Bob Givens, are shown in their fully developed forms as hunter and tormentor, respectively; the first in which Mel Blanc uses what became Bugs’ standard voice; and the first in which Bugs uses his catchphrase, «What’s up, Doc?»[20] A Wild Hare was a huge success in theaters and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Cartoon Short Subject.[21]

For the film, Avery asked Givens to remodel the rabbit. The result had a closer resemblance to Max Hare. He had a more elongated body, stood more erect, and looked more poised. If Thorson’s rabbit looked like an infant, Givens’ version looked like an adolescent.[11] Blanc gave Bugs the voice of a city slicker. The rabbit was as audacious as he had been in Hare-um Scare-um and as cool and collected as in Prest-O Change-O.[12]

Immediately following on A Wild Hare, Bob Clampett’s Patient Porky (1940) features a cameo appearance by Bugs, announcing to the audience that 750 rabbits have been born. The gag uses Bugs’ Wild Hare visual design, but his goofier pre-Wild Hare voice characterization.

The second full-fledged role for the mature Bugs, Chuck Jones’ Elmer’s Pet Rabbit (1941), is the first to use Bugs’ name on-screen: it appears in a title card, «featuring Bugs Bunny,» at the start of the film (which was edited in following the success of A Wild Hare). However, Bugs’ voice and personality in this cartoon is noticeably different, and his design was slightly altered as well; Bugs’ visual design is based on the earlier version in Candid Camera, but with yellow gloves and no buck teeth, has a lower-pitched voice and a more aggressive, arrogant and thuggish personality instead of a fun-loving personality. After Pet Rabbit, however, subsequent Bugs appearances returned to normal: the Wild Hare visual design and personality returned, and Blanc re-used the Wild Hare voice characterization.

Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941), directed by Friz Freleng, became the second Bugs Bunny cartoon to receive an Academy Award nomination.[22] The fact that it did not win the award was later spoofed somewhat in What’s Cookin’ Doc? (1944), in which Bugs demands a recount (claiming to be a victim of «sa-bo-TAH-gee») after losing the Oscar to James Cagney and presents a clip from Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt to prove his point.[23]

World War II

Evolution of Bugs’ design over the years.

By 1942, Bugs had become the number one star of Merrie Melodies. The series was originally intended only for one-shot characters in films after several early attempts to introduce characters (Foxy, Goopy Geer, and Piggy) failed under Harman–Ising. By the mid-1930s, under Leon Schlesinger, Merrie Melodies started introducing newer characters. Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid (1942) shows a slight redesign of Bugs, with less-prominent front teeth and a rounder head. The character was reworked by Robert McKimson, then an animator in Clampett’s unit. The redesign at first was only used in the films created by Clampett’s unit, but in time it was taken up by the other directors, with Freleng and Frank Tashlin the first. For Tortoise Wins by a Hare (1943), he created yet another version, with more slanted eyes, longer teeth and a much larger mouth. He used this version until 1949 (as did Art Davis for the one Bugs Bunny film he directed, Bowery Bugs) when he started using the version he had designed for Clampett. Jones came up with his own slight modification, and the voice had slight variations between the units.[14] Bugs also made cameos in Avery’s final Warner Bros. cartoon, Crazy Cruise.[24]

Since Bugs’ debut in A Wild Hare, he appeared only in color Merrie Melodies films (making him one of the few recurring characters created for that series in the Schlesinger era prior to the full conversion to color), alongside Egghead, Inki, Sniffles, and Elmer Fudd (who actually co-existed in 1937 along with Egghead as a separate character). While Bugs made a cameo in Porky Pig’s Feat (1943), this was his only appearance in a black-and-white Looney Tunes film. He did not star in a Looney Tunes film until that series made its complete conversion to only color cartoons beginning in 1944. Buckaroo Bugs was Bugs’ first film in the Looney Tunes series and was also the last Warner Bros. cartoon to credit Schlesinger (as he had retired and sold his studio to Warner Bros. that year).[23]

Bugs’ popularity soared during World War II because of his free and easy attitude, and he began receiving special star billing in his cartoons by 1943. By that time, Warner Bros. had become the most profitable cartoon studio in the United States.[25] In company with cartoon studios such as Disney and Famous Studios, Warners pitted its characters against Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, and the Japanese. Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips (1944) features Bugs at odds with a group of Japanese soldiers. This cartoon has since been pulled from distribution due to its depiction of Japanese people.[26] One US Navy propaganda film saved from destruction features the voice of Mel Blanc in «Tokyo Woes»[27] (1945) about the propaganda radio host Tokyo Rose. He also faces off against Hermann Göring and Hitler in Herr Meets Hare (1945), which introduced his well-known reference to Albuquerque as he mistakenly winds up in the Black Forest of ‘Joimany’ instead of Las Vegas, Nevada.[28] Bugs also appeared in the 1942 two-minute U.S. war bonds commercial film Any Bonds Today?, along with Porky and Elmer.

At the end of Super-Rabbit (1943), Bugs appears wearing a United States Marine Corps dress blue uniform. As a result, the Marine Corps made Bugs an honorary Marine master sergeant.[29] From 1943 to 1946, Bugs was the official mascot of Kingman Army Airfield, Kingman, Arizona, where thousands of aerial gunners were trained during World War II. Some notable trainees included Clark Gable and Charles Bronson. Bugs also served as the mascot for 530 Squadron of the 380th Bombardment Group, 5th Air Force, U.S. Air Force, which was attached to the Royal Australian Air Force and operated out of Australia’s Northern Territory from 1943 to 1945, flying B-24 Liberator bombers.[30] Bugs riding an air delivered torpedo served as the squadron logo for Marine Torpedo/Bomber Squadron 242 in the Second World War. Additionally, Bugs appeared on the nose of B-24J #42-110157, in both the 855th Bomb Squadron of the 491st Bombardment Group (Heavy) and later in the 786th BS of the 466th BG(H), both being part of the 8th Air Force operating out of England.

In 1944, Bugs Bunny made a cameo appearance in Jasper Goes Hunting, a Puppetoons film produced by rival studio Paramount Pictures. In this cameo (animated by McKimson, with Blanc providing the usual voice), Bugs (after being threatened at gunpoint) pops out of a rabbit hole, saying his usual catchphrase; after hearing the orchestra play the wrong theme song, he realizes «Hey, I’m in the wrong picture!» and then goes back in the hole.[31] Bugs also made a cameo in the Private Snafu short Gas, in which he is found stowed away in the titular private’s belongings; his only spoken line is his usual catchphrase.

Although it was usually Porky Pig who brought the Looney Tunes films to a close with his stuttering, «That’s all, folks!», Bugs replaced him at the end of Hare Tonic and Baseball Bugs, bursting through a drum just as Porky did, but munching on a carrot and saying, in his Bronx/Brooklyn accent, «And that’s the end!»

Post-World War II era

After World War II, Bugs continued to appear in numerous Warner Bros. cartoons, making his last «Golden Age» appearance in False Hare (1964). He starred in over 167 theatrical short films, most of which were directed by Friz Freleng, Robert McKimson, and Chuck Jones. Freleng’s Knighty Knight Bugs (1958), in which a medieval Bugs trades blows with Yosemite Sam and his fire-breathing dragon (which has a cold), won an Academy Award for Best Cartoon Short Subject (becoming the first and only Bugs Bunny cartoon to win said award).[32] Three of Jones’ films—Rabbit Fire, Rabbit Seasoning and Duck! Rabbit, Duck!—compose what is often referred to as the «Rabbit Season/Duck Season» trilogy and were the origins of the rivalry between Bugs and Daffy Duck.[33] Jones’ classic What’s Opera, Doc? (1957), casts Bugs and Elmer Fudd in a parody of Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. It was deemed «culturally significant» by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1992, becoming the first cartoon short to receive this honor.[34]