Coordinates: 16°42′43″S 64°39′58″W / 16.712°S 64.666°W

|

Plurinational State of Bolivia Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia (Spanish) Co-official names[a]

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

||||||

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Bolivia (Spanish) «National Anthem of Bolivia» |

||||||

| Dual flag: Wiphala[1][2][3]

|

||||||

Location of Bolivia (dark green) in South America (gray) |

||||||

| Capital | La Paz (executive and legislative) Sucre (constitutional and judicial) |

|||||

| Largest city | Santa Cruz de la Sierra 17°48′S 63°10′W / 17.800°S 63.167°W |

|||||

| Official languages | Spanish | |||||

| Co-official languages |

|

|||||

| Ethnic groups

(2009[4][better source needed]) |

|

|||||

| Religion

(2018)[5] |

|

|||||

| Demonym(s) | Bolivian | |||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | |||||

|

• President |

Luis Arce | |||||

|

• Vice President |

David Choquehuanca | |||||

|

• President of the Senate |

Andrónico Rodríguez | |||||

|

• President of the Chamber of Deputies |

Jerges Mercado Suárez | |||||

| Legislature | Plurinational Legislative Assembly | |||||

|

• Upper house |

Chamber of Senators | |||||

|

• Lower house |

Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| Independence

from Spain |

||||||

|

• Declared |

6 August 1825 | |||||

|

• Recognized |

21 July 1847 | |||||

|

• Current constitution |

7 February 2009 | |||||

| Area | ||||||

|

• Total |

1,098,581 km2 (424,164 sq mi) (27th) | |||||

|

• Water (%) |

1.29 | |||||

| Population | ||||||

|

• 2022 estimate |

12,054,379[6] (79th) | |||||

|

• Density |

10.4/km2 (26.9/sq mi) (224th) | |||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | |||||

|

• Total |

||||||

|

• Per capita |

||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | |||||

|

• Total |

||||||

|

• Per capita |

||||||

| Gini (2019) | medium |

|||||

| HDI (2021) | medium · 118th |

|||||

| Currency | Boliviano (BOB) | |||||

| Time zone | UTC−4 (BOT) | |||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | |||||

| Driving side | right | |||||

| Calling code | +591 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | BO | |||||

| Internet TLD | .bo | |||||

|

Bolivia,[b] officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia,[c][11][12] is a landlocked country located in western-central South America. It is bordered by Brazil to the north and east, Paraguay to the southeast, Argentina to the south, Chile to the southwest and Peru to the west. The seat of government and executive capital is La Paz, while the constitutional capital is Sucre. The largest city and principal industrial center is Santa Cruz de la Sierra, located on the Llanos Orientales (tropical lowlands), a mostly flat region in the east of the country.

The sovereign state of Bolivia is a constitutionally unitary state, divided into nine departments. Its geography varies from the peaks of the Andes in the West, to the Eastern Lowlands, situated within the Amazon basin. One-third of the country is within the Andean mountain range. With 1,098,581 km2 (424,164 sq mi) of area, Bolivia is the fifth largest country in South America, after Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Colombia (and alongside Paraguay, one of the only two landlocked countries in the Americas), the 27th largest in the world, the largest landlocked country in the Southern Hemisphere, and the world’s seventh largest landlocked country, after Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Chad, Niger, Mali, and Ethiopia.

The country’s population, estimated at 12 million,[6] is multiethnic, including Amerindians, Mestizos, Europeans, Asians, and Africans. Spanish is the official and predominant language, although 36 indigenous languages also have official status, of which the most commonly spoken are Guarani, Aymara, and Quechua languages.

Before Spanish colonization, the Andean region of Bolivia was part of the Inca Empire, while the northern and eastern lowlands were inhabited by independent tribes. Spanish conquistadors arriving from Cusco and Asunción took control of the region in the 16th century. During the Spanish colonial period Bolivia was administered by the Real Audiencia of Charcas. Spain built its empire in large part upon the silver that was extracted from Bolivia’s mines.

After the first call for independence in 1809, 16 years of war followed before the establishment of the Republic, named for Simón Bolívar.[13] Over the course of the 19th and early 20th century Bolivia lost control of several peripheral territories to neighboring countries including the seizure of its coastline by Chile in 1879. Bolivia remained relatively politically stable until 1971, when Hugo Banzer led a CIA-supported coup d’état which replaced the socialist government of Juan José Torres with a military dictatorship headed by Banzer. Banzer’s regime cracked down on left-wing and socialist opposition and other forms of dissent, resulting in the torture and deaths of a number of Bolivian citizens. Banzer was ousted in 1978 and later returned as the democratically elected president of Bolivia from 1997 to 2001. Under the 2006–2019 presidency of Evo Morales the country saw significant economic growth and political stability.

Modern Bolivia is a charter member of the UN, IMF, NAM,[14] OAS, ACTO, Bank of the South, ALBA, and USAN. Bolivia remains the second poorest country in South America, though it has slashed poverty rates and has the fastest growing economy in South America (in terms of GDP). It is a developing country. Its main economic activities include agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, and manufacturing goods such as textiles, clothing, refined metals, and refined petroleum. Bolivia is very rich in minerals, including tin, silver, lithium, and copper.

Etymology[edit]

Bolivia is named after Simón Bolívar, a Venezuelan leader in the Spanish American wars of independence.[15] The leader of Venezuela, Antonio José de Sucre, had been given the option by Bolívar to either unite Charcas (present-day Bolivia) with the newly formed Republic of Peru, to unite with the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, or to formally declare its independence from Spain as a wholly independent state. Sucre opted to create a brand new state and on 6 August 1825, with local support, named it in honor of Simón Bolívar.[16]

The original name was Republic of Bolívar. Some days later, congressman Manuel Martín Cruz proposed: «If from Romulus, Rome, then from Bolívar, Bolivia» (Spanish: Si de Rómulo, Roma; de Bolívar, Bolivia). The name was approved by the Republic on 3 October 1825. In 2009, a new constitution changed the country’s official name to «Plurinational State of Bolivia» to reflect the multi-ethnic nature of the country and the strengthened rights of Bolivia’s indigenous peoples under the new constitution.[17][18]

History[edit]

Pre-colonial[edit]

Tiwanaku at its largest territorial extent, AD 950 (present-day boundaries shown).

The region now known as Bolivia had been occupied for over 2,500 years when the Aymara arrived. However, present-day Aymara associate themselves with the ancient civilization of the Tiwanaku Empire which had its capital at Tiwanaku, in Western Bolivia. The capital city of Tiwanaku dates from as early as 1500 BC when it was a small, agriculturally-based village.[19]

The Aymara community grew to urban proportions between AD 600 and AD 800, becoming an important regional power in the southern Andes. According to early estimates,[when?] the city covered approximately 6.5 square kilometers (2.5 square miles) at its maximum extent and had between 15,000 and 30,000 inhabitants.[20] In 1996 satellite imaging was used to map the extent of fossilized suka kollus (flooded raised fields) across the three primary valleys of Tiwanaku, arriving at population-carrying capacity estimates of anywhere between 285,000 and 1,482,000 people.[21]

Around AD 400, Tiwanaku went from being a locally dominant force to a predatory state. Tiwanaku expanded its reaches into the Yungas and brought its culture and way of life to many other cultures in Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. Tiwanaku was not a violent culture in many respects. In order to expand its reach, Tiwanaku exercised great political astuteness, creating colonies, fostering trade agreements (which made the other cultures rather dependent), and instituting state cults.[22]

The empire continued to grow with no end in sight. William H. Isbell states «Tiahuanaco underwent a dramatic transformation between AD 600 and 700 that established new monumental standards for civic architecture and greatly increased the resident population.»[23] Tiwanaku continued to absorb cultures rather than eradicate them. Archaeologists note a dramatic adoption of Tiwanaku ceramics into the cultures which became part of the Tiwanaku empire. Tiwanaku’s power was further solidified through the trade it implemented among the cities within its empire.[22]

Tiwanaku’s elites gained their status through the surplus food they controlled, collected from outlying regions, and then redistributed to the general populace. Further, this elite’s control of llama herds became a powerful control mechanism, as llamas were essential for carrying goods between the civic center and the periphery. These herds also came to symbolize class distinctions between the commoners and the elites. Through this control and manipulation of surplus resources, the elite’s power continued to grow until about AD 950. At this time, a dramatic shift in climate occurred,[24] causing a significant drop in precipitation in the Titicaca Basin, believed by archaeologists to have been on the scale of a major drought.

As the rainfall decreased, many of the cities farther away from Lake Titicaca began to tender fewer foodstuffs to the elites. As the surplus of food decreased, and thus the amount available to underpin their power, the control of the elites began to falter. The capital city became the last place viable for food production due to the resiliency of the raised field method of agriculture. Tiwanaku disappeared around AD 1000 because food production, the main source of the elites’ power, dried up. The area remained uninhabited for centuries thereafter.[24]

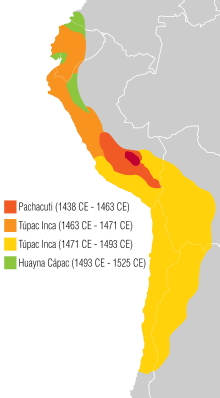

Between 1438 and 1527, the Inca empire expanded from its capital at Cusco, Peru. It gained control over much of what is now Andean Bolivia and extended its control into the fringes of the Amazon basin.

Colonial period[edit]

Casa de La Moneda, Potosí

The Spanish conquest of the Inca empire began in 1524 and was mostly completed by 1533. The territory now called Bolivia was known as Charcas, and was under the authority of the Viceroy of Peru in Lima. Local government came from the Audiencia de Charcas located in Chuquisaca (La Plata—modern Sucre). Founded in 1545 as a mining town, Potosí soon produced fabulous wealth, becoming the largest city in the New World with a population exceeding 150,000 people.[25]

By the late 16th century, Bolivian silver was an important source of revenue for the Spanish Empire.[26] A steady stream of natives served as labor force under the brutal, slave conditions of the Spanish version of the pre-Columbian draft system called the mita.[27] Charcas was transferred to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776 and the people from Buenos Aires, the capital of the Viceroyalty, coined the term «Upper Peru» (Spanish: Alto Perú) as a popular reference to the Royal Audiencia of Charcas. Túpac Katari led the indigenous rebellion that laid siege to La Paz in March 1781,[28] during which 20,000 people died.[29] As Spanish royal authority weakened during the Napoleonic wars, sentiment against colonial rule grew.

Independence and subsequent wars[edit]

Casa de La Libertad, Sucre

Banco Central de Bolivia, Sucre

The struggle for independence started in the city of Sucre on 25 May 1809 and the Chuquisaca Revolution (Chuquisaca was then the name of the city) is known as the first cry of Freedom in Latin America. That revolution was followed by the La Paz revolution on 16 July 1809. The La Paz revolution marked a complete split with the Spanish government, while the Chuquisaca Revolution established a local independent junta in the name of the Spanish King deposed by Napoleon Bonaparte. Both revolutions were short-lived and defeated by the Spanish authorities in the Viceroyalty of the Rio de La Plata, but the following year the Spanish American wars of independence raged across the continent.

Bolivia was captured and recaptured many times during the war by the royalists and patriots. Buenos Aires sent three military campaigns, all of which were defeated, and eventually limited itself to protecting the national borders at Salta. Bolivia was finally freed of Royalist dominion by Marshal Antonio José de Sucre, with a military campaign coming from the North in support of the campaign of Simón Bolívar. After 16 years of war the Republic was proclaimed on 6 August 1825.

The first coat of arms of Bolivia, formerly named the Republic of Bolívar in honor of Simón Bolívar

In 1836, Bolivia, under the rule of Marshal Andrés de Santa Cruz, invaded Peru to reinstall the deposed president, General Luis José de Orbegoso. Peru and Bolivia formed the Peru-Bolivian Confederation, with de Santa Cruz as the Supreme Protector. Following tension between the Confederation and Chile, Chile declared war on 28 December 1836. Argentina separately declared war on the Confederation on 9 May 1837. The Peruvian-Bolivian forces achieved several major victories during the War of the Confederation: the defeat of the Argentine expedition and the defeat of the first Chilean expedition on the fields of Paucarpata near the city of Arequipa. The Chilean army and its Peruvian rebel allies surrendered unconditionally and signed the Paucarpata Treaty. The treaty stipulated that Chile would withdraw from Peru-Bolivia, Chile would return captured Confederate ships, economic relations would be normalized, and the Confederation would pay Peruvian debt to Chile. However, the Chilean government and public rejected the peace treaty. Chile organized a second attack on the Confederation and defeated it in the Battle of Yungay. After this defeat, Santa Cruz resigned and went to exile in Ecuador and then Paris, and the Peruvian-Bolivian Confederation was dissolved.

Following the renewed independence of Peru, Peruvian president General Agustín Gamarra invaded Bolivia. On 18 November 1841, the battle de Ingavi took place, in which the Bolivian Army defeated the Peruvian troops of Gamarra (killed in the battle). After the victory, Bolivia invaded Perú on several fronts. The eviction of the Bolivian troops from the south of Peru would be achieved by the greater availability of material and human resources of Peru; the Bolivian Army did not have enough troops to maintain an occupation. In the district of Locumba – Tacna, a column of Peruvian soldiers and peasants defeated a Bolivian regiment in the so-called Battle of Los Altos de Chipe (Locumba). In the district of Sama and in Arica, the Peruvian colonel José María Lavayén organized a troop that managed to defeat the Bolivian forces of Colonel Rodríguez Magariños and threaten the port of Arica. In the battle of Tarapacá on 7 January 1842, Peruvian militias formed by the commander Juan Buendía defeated a detachment led by Bolivian colonel José María García, who died in the confrontation. Bolivian troops left Tacna, Arica and Tarapacá in February 1842, retreating towards Moquegua and Puno.[30] The battles of Motoni and Orurillo forced the withdrawal of Bolivian forces occupying Peruvian territory and exposed Bolivia to the threat of counter-invasion. The Treaty of Puno was signed on 7 June 1842, ending the war. However, the climate of tension between Lima and La Paz would continue until 1847, when the signing of a Peace and Trade Treaty became effective.

The estimated population of the main three cities in 1843 was La Paz 300,000, Cochabamba 250,000 and Potosi 200,000.[31]

A period of political and economic instability in the early-to-mid-19th century weakened Bolivia. In addition, during the War of the Pacific (1879–83), Chile occupied vast territories rich in natural resources south west of Bolivia, including the Bolivian coast. Chile took control of today’s Chuquicamata area, the adjoining rich salitre (saltpeter) fields, and the port of Antofagasta among other Bolivian territories.

Since independence, Bolivia has lost over half of its territory to neighboring countries.[32] Through diplomatic channels in 1909, it lost the basin of the Madre de Dios River and the territory of the Purus in the Amazon, yielding 250,000 km2 to Peru.[33] It also lost the state of Acre, in the Acre War, important because this region was known for its production of rubber. Peasants and the Bolivian army fought briefly but after a few victories, and facing the prospect of a total war against Brazil, it was forced to sign the Treaty of Petrópolis in 1903, in which Bolivia lost this rich territory. Popular myth has it that Bolivian president Mariano Melgarejo (1864–71) traded the land for what he called «a magnificent white horse» and Acre was subsequently flooded by Brazilians, which ultimately led to confrontation and fear of war with Brazil.[34]

In the late 19th century, an increase in the world price of silver brought Bolivia relative prosperity and political stability.

Early 20th century[edit]

Bolivia’s territorial losses (1867–1938)

During the early 20th century, tin replaced silver as the country’s most important source of wealth. A succession of governments controlled by the economic and social elite followed laissez-faire capitalist policies through the first 30 years of the 20th century.[35]

Living conditions of the native people, who constitute most of the population, remained deplorable. With work opportunities limited to primitive conditions in the mines and in large estates having nearly feudal status, they had no access to education, economic opportunity, and political participation. Bolivia’s defeat by Paraguay in the Chaco War (1932–1935), where Bolivia lost a great part of the Gran Chaco region in dispute, marked a turning-point.[36][37][38]

On 7 April 1943, Bolivia entered World War II, joining part of the Allies, which caused president Enrique Peñaranda to declare war on the Axis powers of Germany, Italy and Japan.

The Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR), the most historic political party, emerged as a broad-based party. Denied its victory in the 1951 presidential elections, the MNR led a successful revolution in 1952. Under President Víctor Paz Estenssoro, the MNR, having strong popular pressure, introduced universal suffrage into his political platform and carried out a sweeping land-reform promoting rural education and nationalization of the country’s largest tin mines.

Late 20th century[edit]

Twelve years of tumultuous rule left the MNR divided. In 1964, a military junta overthrew President Estenssoro at the outset of his third term. The 1969 death of President René Barrientos Ortuño, a former member of the junta who was elected president in 1966, led to a succession of weak governments. Alarmed by the rising Popular Assembly and the increase in the popularity of President Juan José Torres, the military, the MNR, and others installed Colonel (later General) Hugo Banzer Suárez as president in 1971. He returned to the presidency in 1997 through 2001. Juan José Torres, who had fled Bolivia, was kidnapped and assassinated in 1976 as part of Operation Condor, the U.S.-supported campaign of political repression by South American right-wing dictators.[39]

The United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) financed and trained the Bolivian military dictatorship in the 1960s. The revolutionary leader Che Guevara was killed by a team of CIA officers and members of the Bolivian Army on 9 October 1967, in Bolivia. Félix Rodríguez was a CIA officer on the team with the Bolivian Army that captured and shot Guevara.[40] Rodriguez said that after he received a Bolivian presidential execution order, he told «the soldier who pulled the trigger to aim carefully, to remain consistent with the Bolivian government’s story that Che had been killed in action during a clash with the Bolivian army.» Rodriguez said the US government had wanted Che in Panama, and «I could have tried to falsify the command to the troops, and got Che to Panama as the US government said they had wanted», but that he had chosen to «let history run its course» as desired by Bolivia.[41]

Elections in 1979 and 1981 were inconclusive and marked by fraud. There were coups d’état, counter-coups, and caretaker governments. In 1980, General Luis García Meza Tejada carried out a ruthless and violent coup d’état that did not have popular support. The Bolivian Workers’ Center, which tried to resist the putsch, was violently repressed. More than a thousand people were killed in less than a year. Cousin of one of the most important narco-trafficker of the country, Luis García Meza Tejada favors the production of cocaine.[42] He pacified the people by promising to remain in power only for one year. At the end of the year, he staged a televised rally to claim popular support and announced, «Bueno, me quedo«, or, «All right; I’ll stay [in office]».[43] After a military rebellion forced out Meza in 1981, three other military governments in 14 months struggled with Bolivia’s growing problems. Unrest forced the military to convoke the Congress, elected in 1980, and allow it to choose a new chief executive. In October 1982, Hernán Siles Zuazo again became president, 22 years after the end of his first term of office (1956–1960).

Democratic transition[edit]

In 1993, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada was elected president in alliance with the Tupac Katari Revolutionary Liberation Movement, which inspired indigenous-sensitive and multicultural-aware policies.[44] Sánchez de Lozada pursued an aggressive economic and social reform agenda. The most dramatic reform was privatization under the «capitalization» program, under which investors, typically foreign, acquired 50% ownership and management control of public enterprises in return for agreed upon capital investments.[45][46] In 1993, Sanchez de Lozada introduced the Plan de Todos, which led to the decentralization of government, introduction of intercultural bilingual education, implementation of agrarian legislation, and privatization of state owned businesses. The plan explicitly stated that Bolivian citizens would own a minimum of 51% of enterprises; under the plan, most state-owned enterprises (SOEs), though not mines, were sold.[47] This privatization of SOEs led to a neoliberal structuring.[48]

The reforms and economic restructuring were strongly opposed by certain segments of society, which instigated frequent and sometimes violent protests, particularly in La Paz and the Chapare coca-growing region, from 1994 through 1996. The indigenous population of the Andean region was not able to benefit from government reforms.[49] During this time, the umbrella labor-organization of Bolivia, the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB), became increasingly unable to effectively challenge government policy. A teachers’ strike in 1995 was defeated because the COB could not marshal the support of many of its members, including construction and factory workers.

1997–2002 General Banzer Presidency[edit]

In the 1997 elections, General Hugo Banzer, leader of the Nationalist Democratic Action party (ADN) and former dictator (1971–1978), won 22% of the vote, while the MNR candidate won 18%. At the outset of his government, President Banzer launched a policy of using special police-units to eradicate physically the illegal coca of the Chapare region. The MIR of Jaime Paz Zamora remained a coalition-partner throughout the Banzer government, supporting this policy (called the Dignity Plan).[50] The Banzer government basically continued the free-market and privatization-policies of its predecessor. The relatively robust economic growth of the mid-1990s continued until about the third year of its term in office. After that, regional, global and domestic factors contributed to a decline in economic growth. Financial crises in Argentina and Brazil, lower world prices for export commodities, and reduced employment in the coca sector depressed the Bolivian economy. The public also perceived a significant amount of public sector corruption. These factors contributed to increasing social protests during the second half of Banzer’s term.

Between January 1999 and April 2000, large-scale protests erupted in Cochabamba, Bolivia’s third largest city at the time, in response to the privatization of water resources by foreign companies and a subsequent doubling of water prices. On 6 August 2001, Banzer resigned from office after being diagnosed with cancer. He died less than a year later. Vice President Jorge Fernando Quiroga Ramírez completed the final year of his term.

2002–2005 Sánchez de Lozada / Mesa presidency[edit]

In the June 2002 national elections, former President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (MNR) placed first with 22.5% of the vote, followed by coca-advocate and native peasant-leader Evo Morales (Movement Toward Socialism, MAS) with 20.9%. A July agreement between the MNR and the fourth-place MIR, which had again been led in the election by former President Jaime Paz Zamora, virtually ensured the election of Sánchez de Lozada in the congressional run-off, and on 6 August he was sworn in for the second time. The MNR platform featured three overarching objectives: economic reactivation (and job creation), anti-corruption, and social inclusion.

In 2003 the Bolivian gas conflict broke out. On 12 October 2003, the government imposed martial law in El Alto after 16 people were shot by the police and several dozen wounded in violent clashes. Faced with the option of resigning or more bloodshed, Sánchez de Lozada offered his resignation in a letter to an emergency session of Congress. After his resignation was accepted and his vice president, Carlos Mesa, invested, he left on a commercially scheduled flight for the United States.

The country’s internal situation became unfavorable for such political action on the international stage. After a resurgence of gas protests in 2005, Carlos Mesa attempted to resign in January 2005, but his offer was refused by Congress. On 22 March 2005, after weeks of new street protests from organizations accusing Mesa of bowing to U.S. corporate interests, Mesa again offered his resignation to Congress, which was accepted on 10 June. The chief justice of the Supreme Court, Eduardo Rodríguez, was sworn as interim president to succeed the outgoing Carlos Mesa.

2005–2019 Morales Presidency[edit]

Evo Morales won the 2005 presidential election with 53.7% of the votes in Bolivian elections.[51] On 1 May 2006, Morales announced his intent to re-nationalize Bolivian hydrocarbon assets following protests which demanded this action.[52] Fulfilling a campaign promise, on 6 August 2006, Morales opened the Bolivian Constituent Assembly to begin writing a new constitution aimed at giving more power to the indigenous majority.[53]

In August 2007, a conflict which came to be known as The Calancha Case arose in Sucre.[undue weight? – discuss] Local citizens demanded that an official discussion of the seat of government be included in the agenda of the full body of the Bolivian Constituent Assembly. The people of Sucre wanted to make Sucre the full capital of the country, including returning the executive and legislative branches to the city, but the government rejected the demand as impractical. Three people died in the conflict and as many as 500 were wounded.[54] The result of the conflict was to include text in the constitution stating that the capital of Bolivia is officially Sucre, while leaving the executive and legislative branches in La Paz. In May 2008, Evo Morales was a signatory to the UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations.

2009 marked the creation of a new constitution and the renaming of the country to the Plurinational State of Bolivia. The previous constitution did not allow a consecutive reelection of a president, but the new constitution allowed for just one reelection, starting the dispute if Evo Morales was enabled to run for a second term arguing he was elected under the last constitution. This also triggered a new general election in which Evo Morales was re-elected with 61.36% of the vote. His party, Movement for Socialism, also won a two-thirds majority in both houses of the National Congress.[55] By 2013, after being reelected under the new constitution, Evo Morales and his party attempted a third term as President of Bolivia. The opposition argued that a third term would be unconstitutional but the Bolivian Constitutional Court ruled that Morales’ first term under the previous constitution, did not count towards his term limit.[56] This allowed Evo Morales to run for a third term in 2014, and he was re-elected with 64.22% of the vote.[57] On 17 October 2015, Morales surpassed Andrés de Santa Cruz’s nine years, eight months, and twenty-four days in office and became Bolivia’s longest serving president.[58] During his third term, Evo Morales began to plan for a fourth, and the 2016 Bolivian constitutional referendum asked voters to override the constitution and allow Evo Morales to run for an additional term in office. Morales narrowly lost the referendum,[59] however in 2017 his party then petitioned the Bolivian Constitutional Court to override the constitution on the basis that the American Convention on Human Rights made term limits a human rights violation.[60] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights determined that term limits are not a human rights violation in 2018,[61][62] however, once again the Bolivian Constitutional Court ruled that Morales has permission to run for a fourth term in the 2019 elections, and this permission was not retracted. «[T]he country’s highest court overruled the constitution, scrapping term limits altogether for every office. Morales can now run for a fourth term in 2019 – and for every election thereafter.»[63]

The revenues generated by the partial nationalization of hydrocarbons made it possible to finance several social measures: the Renta Dignidad (or old age minimum) for people over 60 years old; the Juana Azurduy voucher (named after the revolutionary Juana Azurduy de Padilla, 1780–1862), which ensures the complete coverage of medical expenses for pregnant women and their children in order to fight infant mortality; the Juancito Pinto voucher (named after a child hero of the Pacific War, 1879–1884), an aid paid until the end of secondary school to parents whose children are in school in order to combat school dropout, and the Single Health System, which since 2018 has offered all Bolivians free medical care.[64]

The reforms adopted have made the Bolivian economic system the most successful and stable in the region. Between 2006 and 2019, GDP has grown from $9 billion to over $40 billion, real wages have increased, GDP per capita has tripled, foreign exchange reserves are on the rise, inflation has been essentially eliminated, and extreme poverty has fallen from 38% to 15%, a 23-point drop.[65]

Interim government 2019–2020[edit]

During the 2019 elections, the transmission of the unofficial quick counting process was interrupted; at the time, Morales had a lead of 46.86 percent to Mesa’s 36.72, after 95.63 percent of tally sheets were counted.[66] The Transmisión de Resultados Electorales Preliminares (TREP) is a quick count process used in Latin America as a transparency measure in electoral processes that is meant to provide a preliminary results on election day, and its shutdown without further explanation[citation needed] raised consternation among opposition politicians and certain election monitors.[67][68] Two days after the interruption, the official count showed Morales fractionally clearing the 10-point margin he needed to avoid a runoff election, with the final official tally counted as 47.08 percent to Mesa’s 36.51 percent, starting a wave of protests and tension in the country.

Amidst allegations of fraud perpetrated by the Morales government, widespread protests were organized to dispute the election. On 10 November, the Organization of American States (OAS) released a preliminary report concluding several irregularities in the election,[69][70][71] though these findings were heavily disputed.[72] The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) concluded that «it is very likely that Morales won the required 10 percentage point margin to win in the first round of the election on 20 October 2019.»[73] David Rosnick, an economist for CEPR, showed that «a basic coding error» was discovered in the OAS’s data, which explained that the OAS had misused its own data when it ordered the time stamps on the tally sheets alphabetically rather than chronologically.[74] However, the OAS stood by its findings arguing that the «researchers’ work did not address many of the allegations mentioned in the OAS report, including the accusation that Bolivian officials maintained hidden servers that could have permitted the alteration of results».[75] Additionally, observers from the European Union released a report with similar findings and conclusions as the OAS.[76][77] The tech security company hired by the TSE (under the Morales administration) to audit the elections, also stated that there were multiple irregularities and violations of procedure and that «our function as an auditor security company is to declare everything that was found, and much of what was found supports the conclusion that the electoral process should be declared null and void».[78] The New York Times reported on 7 June 2020 that the OAS analysis immediately after the 20 October election was flawed yet fuelled «a chain of events that changed the South American nation’s history».[79][80][81]

After weeks of protests, Morales resigned on national television shortly after the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces General Williams Kaliman had urged that he do so in order to restore «peace and stability».[82][83] Morales flew to Mexico and was granted asylum there, along with his vice president and several other members of his government.[84][85] Opposition Senator Jeanine Áñez’s declared herself interim president, claiming constitutional succession after the president, vice president and both head of the legislature chambers. She was confirmed as interim president by the constitutional court who declared her succession to be constitutional and automatic.[86][87] Morales, his supporters, the Governments of Mexico and Nicaragua, and other personalities argued the event was a coup d’état. However, local investigators and analysts pointed out that even after Morales’ resignation and during all of Añez’s term in office, the Chambers of Senators and Deputies were ruled by Morales’ political party MAS, making it impossible to be a coup d’état, as such an event would not allow the original government to maintain legislative power.[88][89] International politicians, scholars and journalists are divided between describing the event as a coup or a spontaneous social uprising against an unconstitutional fourth term.[90][91][92][93][94][95][96][excessive citations] Protests to reinstate Morales as president continued becoming highly violent: burning public buses and private houses, destroying public infrastructure and harming pedestrians.[97][98][99][100][101] The protests were met with more violence by security forces against Morales supporters after Áñez exempted police and military from criminal responsibility in operations for «the restoration of order and public stability».[102][103]

In April 2020, the interim government took out a loan of more than $327 million from the International Monetary Fund in order to meet the country’s needs during the COVID-19 pandemic.[104]

.

New elections were scheduled for 3 May 2020. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the Bolivian electoral body, the TSE, made an announcement postponing the election. MAS reluctantly agreed with the first delay only. A date for the new election was delayed twice more, in the face of massive protests and violence.[105][106][107] The final proposed date for the elections was 18 October 2020.[108] Observers from the OAS, UNIORE, and the UN all reported that they found no fraudulent actions in the 2020 elections.[109]

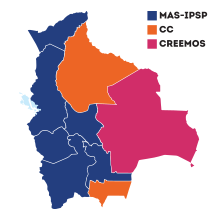

The general election had a record voter turnout of 88.4% and ended in a landslide win for MAS which took 55.1% of the votes compared to 28.8% for centrist former president Carlos Mesa. Both Mesa and Áñez conceded defeat. «I congratulate the winners and I ask them to govern with Bolivia and democracy in mind», Áñez said on Twitter.[110][111]

Government of Luis Arce: 2020–present[edit]

On 8 November 2020, Luis Arce was sworn in as President of Bolivia alongside his Vice President David Choquehuanca.[112] In February 2021, the Arce government returned an amount of around $351 million to the IMF. This comprised a loan of $327 million taken out by the interim government in April 2020 and interest of around $24 million. The government said it returned the loan to protect Bolivia’s economic sovereignty and because the conditions attached to the loan were unacceptable.[104]

According to the Bolivian Institute of Foreign Trade, Bolivia had the lowest accumulated inflation of Latin America by October 2021.[113][114][115]

Geography[edit]

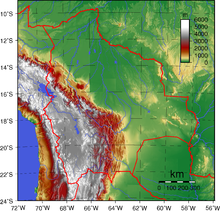

Topographical map of Bolivia

Bolivia is located in the central zone of South America, between 57°26’–69°38’W and 9°38’–22°53’S. With an area of 1,098,581 square kilometers (424,164 sq mi), Bolivia is the world’s 28th-largest country, and the fifth largest country in South America,[116] extending from the Central Andes through part of the Gran Chaco, Pantanal and as far as the Amazon. The geographic center of the country is the so-called Puerto Estrella («Star Port») on the Río Grande, in Ñuflo de Chávez Province, Santa Cruz Department.

The geography of the country exhibits a great variety of terrain and climates. Bolivia has a high level of biodiversity,[117] considered one of the greatest in the world, as well as several ecoregions with ecological sub-units such as the Altiplano, tropical rainforests (including Amazon rainforest), dry valleys, and the Chiquitania, which is a tropical savanna.[citation needed] These areas feature enormous variations in altitude, from an elevation of 6,542 meters (21,463 ft) above sea level in Nevado Sajama to nearly 70 meters (230 ft) along the Paraguay River. Although a country of great geographic diversity, Bolivia has remained a landlocked country since the War of the Pacific. Puerto Suárez, San Matías and Puerto Quijarro are located in the Bolivian Pantanal.

Bolivia can be divided into three physiographic regions:

Sol de Mañana (Morning Sun in Spanish), a geothermal field in Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve, southwestern Bolivia. The area, characterized by intense volcanic activity, with sulfur spring fields and mud lakes, has indeed no geysers but rather holes that emit pressurized steam up to 50 meters high.

- The Andean region in the southwest spans 28% of the national territory, extending over 307,603 square kilometers (118,766 sq mi). This area is located above 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) altitude and is located between two big Andean chains, the Cordillera Occidental («Western Range») and the Cordillera Central («Central Range»), with some of the highest spots in the Americas such as the Nevado Sajama, with an altitude of 6,542 meters (21,463 ft), and the Illimani, at 6,462 meters (21,201 ft). Also located in the Cordillera Central is Lake Titicaca, the highest commercially navigable lake in the world and the largest lake in South America;[118] the lake is shared with Peru. Also in this region are the Altiplano and the Salar de Uyuni, which is the largest salt flat in the world and an important source of lithium.

- The Sub-Andean region in the center and south of the country is an intermediate region between the Altiplano and the eastern llanos (plain); this region comprises 13% of the territory of Bolivia, extending over 142,815 km2 (55,141 sq mi), and encompassing the Bolivian valleys and the Yungas region. It is distinguished by its farming activities and its temperate climate.

- The Llanos region in the northeast comprises 59% of the territory, with 648,163 km2 (250,257 sq mi). It is located to the north of the Cordillera Central and extends from the Andean foothills to the Paraguay River. It is a region of flat land and small plateaus, all covered by extensive rain forests containing enormous biodiversity. The region is below 400 meters (1,300 ft) above sea level.

Bolivia has three drainage basins:

- The first is the Amazon Basin, also called the North Basin (724,000 km2 (280,000 sq mi)/66% of the territory). The rivers of this basin generally have big meanders which form lakes such as Murillo Lake in Pando Department. The main Bolivian tributary to the Amazon basin is the Mamoré River, with a length of 2,000 km (1,200 mi) running north to the confluence with the Beni River, 1,113 km (692 mi) in length and the second most important river of the country. The Beni River, along with the Madeira River, forms the main tributary of the Amazon River. From east to west, the basin is formed by other important rivers, such as the Madre de Dios River, the Orthon River, the Abuna River, the Yata River, and the Guaporé River. The most important lakes are Rogaguado Lake, Rogagua Lake, and Jara Lake.

- The second is the Río de la Plata Basin, also called the South Basin (229,500 km2 (88,600 sq mi)/21% of the territory). The tributaries in this basin are in general less abundant than the ones forming the Amazon Basin. The Rio de la Plata Basin is mainly formed by the Paraguay River, Pilcomayo River, and Bermejo River. The most important lakes are Uberaba Lake and Mandioré Lake, both located in the Bolivian marshland.

- The third basin is the Central Basin, which is an endorheic basin (145,081 square kilometers (56,016 sq mi)/13% of the territory). The Altiplano has large numbers of lakes and rivers that do not run into any ocean because they are enclosed by the Andean mountains. The most important river is the Desaguadero River, with a length of 436 km (271 mi), the longest river of the Altiplano; it begins in Lake Titicaca and then runs in a southeast direction to Poopó Lake. The basin is then formed by Lake Titicaca, Lake Poopó, the Desaguadero River, and great salt flats, including the Salar de Uyuni and Coipasa Lake.

Geology[edit]

Bolivia map of Köppen climate classification.[119]

The geology of Bolivia comprises a variety of different lithologies as well as tectonic and sedimentary environments. On a synoptic scale, geological units coincide with topographical units. Most elementally, the country is divided into a mountainous western area affected by the subduction processes in the Pacific and an eastern lowlands of stable platforms and shields.

Climate[edit]

The climate of Bolivia varies drastically from one eco-region to the other, from the tropics in the eastern llanos to a polar climate in the western Andes. The summers are warm, humid in the east and dry in the west, with rains that often modify temperatures, humidity, winds, atmospheric pressure and evaporation, yielding very different climates in different areas. When the climatological phenomenon known as El Niño[120][121] takes place, it causes great alterations in the weather. Winters are very cold in the west, and it snows in the mountain ranges, while in the western regions, windy days are more common. The autumn is dry in the non-tropical regions.

- Llanos. A humid tropical climate with an average temperature of 25 °C (77 °F). The wind coming from the Amazon rainforest causes significant rainfall. In May, there is low precipitation because of dry winds, and most days have clear skies. Even so, winds from the south, called surazos, can bring cooler temperatures lasting several days.

- Altiplano. Desert-Polar climates, with strong and cold winds. The average temperature ranges from 15 to 20 °C. At night, temperatures descend drastically to slightly above 0 °C, while during the day, the weather is dry and solar radiation is high. Ground frosts occur every month, and snow is frequent.

- Valleys and Yungas. Temperate climate. The humid northeastern winds are pushed to the mountains, making this region very humid and rainy. Temperatures are cooler at higher elevations. Snow occurs at altitudes of 2,000 meters (6,600 ft).

- Chaco. Subtropical semi-arid climate. Rainy and humid in January and the rest of the year, with warm days and cold nights.

Issues with climate change[edit]

Bolivia is especially vulnerable to the negative consequences of climate change. Twenty percent of the world’s tropical glaciers are located within the country,[122] and are more sensitive to change in temperature due to the tropical climate they are located in. Temperatures in the Andes increased by 0.1 °C per decade from 1939 to 1998, and more recently the rate of increase has tripled (to 0.33 °C per decade from 1980 to 2005),[123] causing glaciers to recede at an accelerated pace and create unforeseen water shortages in Andean agricultural towns. Farmers have taken to temporary city jobs when there is poor yield for their crops, while others have started permanently leaving the agricultural sector and are migrating to nearby towns for other forms of work;[124] some view these migrants as the first generation of climate refugees.[125] Cities that are neighbouring agricultural land, like El Alto, face the challenge of providing services to the influx of new migrants; because there is no alternative water source, the city’s water source is now being constricted.

Bolivia’s government and other agencies have acknowledged the need to instill new policies battling the effects of climate change. The World Bank has provided funding through the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and are using the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR II) to construct new irrigation systems, protect riverbanks and basins, and work on building water resources with the help of indigenous communities.[126] Bolivia has also implemented the Bolivian Strategy on Climate Change, which is based on taking action in these four areas:

- Promoting clean development in Bolivia by introducing technological changes in the agriculture, forestry, and industrial sectors, aimed to reduce GHG emissions with a positive impact on development.

- Contributing to carbon management in forests, wetlands and other managed natural ecosystems.

- Increasing effectiveness in energy supply and use to mitigate effects of GHG emissions and risk of contingencies.

- Focus on increased and efficient observations, and understanding of environmental changes in Bolivia to develop effective and timely responses.[127]

Bolivia comprises about 20% of the world’s tropical glaciers, along with the Andes Mountains. However, they are vulnerable to global warming and have lost 43% of their surface area between 1986 and 2014. Some Bolivian glaciers have lost more than two-thirds of their mass since the 1980s points out Unesco in 2018. While the temperature in the tropical Andes is expected to rise by two to five degrees by the end of the 21st century, glaciers would still lose between 78% and 97% of their mass. Glaciers account for between 60% and 85% of La Paz’s water supply, depending on the year.[128]

Biodiversity[edit]

Bolivia, with an enormous variety of organisms and ecosystems, is part of the «Like-Minded Megadiverse Countries».[129]

Bolivia’s variable altitudes, ranging from 90–6,542 meters (295–21,463 ft) above sea level, allow for a vast biologic diversity. The territory of Bolivia comprises four types of biomes, 32 ecological regions, and 199 ecosystems. Within this geographic area there are several natural parks and reserves such as the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, the Madidi National Park, the Tunari National Park, the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve, and the Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area, among others.

Bolivia boasts over 17,000 species of seed plants, including over 1,200 species of fern, 1,500 species of marchantiophyta and moss, and at least 800 species of fungus. In addition, there are more than 3,000 species of medicinal plants. Bolivia is considered the place of origin for such species as peppers and chili peppers, peanuts, the common beans, yucca, and several species of palm. Bolivia also naturally produces over 4,000 kinds of potatoes. The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.47/10, ranking it 21st globally out of 172 countries.[130]

Bolivia has more than 2,900 animal species, including 398 mammals, over 1,400 birds (about 14% of birds known in the world, being the sixth most diverse country in terms of bird species)[131][unreliable source?], 204 amphibians, 277 reptiles, and 635 fish, all fresh water fish as Bolivia is a landlocked country. In addition, there are more than 3,000 types of butterfly, and more than 60 domestic animals.

In 2020 a new species of snake, the Mountain Fer-De-Lance Viper, was discovered in Bolivia.[132]

Environmental policy[edit]

A Ministry of Environment and Water was created in 2006 after the election of Evo Morales, who reversed the privatization of the water distribution sector in the 1990s by President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. The new Constitution, approved by referendum in 2009, makes access to water a fundamental right. In July 2010, at the initiative of Bolivia, the United Nations passed a resolution recognizing as «fundamental» the «right to safe and clean drinking water.[128]

Bolivia has gained global attention for its ‘Law of the Rights of Mother Earth’, which accords nature the same rights as humans.[133]

Scientists began alerting the Bolivian government to the problem of melting glaciers in the 1990s, but it was not until 2012 that the authorities responded with real protection policies. A Project for Adaptation to the Impact of Accelerated Glacier Recession in the Tropical Andes (PRAA) was then set up, with the mission to «strengthen the monitoring network» and «generate information useful for decision-making.» The glaciers have since been monitored by cameras, probes, drones and satellite. Authorities have also developed programs to educate the population about the consequences of global warming to push back on certain harmful agricultural practices.[128]

In February 2017, the government mobilized $200 million to combat drought and global warming.[128]

Government and politics[edit]

Bolivia has been governed by democratically elected governments since 1982; prior to that, it was governed by various dictatorships. Presidents Hernán Siles Zuazo (1982–85) and Víctor Paz Estenssoro (1985–89) began a tradition of ceding power peacefully which has continued, although three presidents have stepped down in the face of extraordinary circumstances: Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada in 2003, Carlos Mesa in 2005, and Evo Morales in 2019.

Bolivia’s multiparty democracy has seen a wide variety of parties in the presidency and parliament, although the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement, Nationalist Democratic Action, and the Revolutionary Left Movement predominated from 1985 to 2005. On 11 November 2019, all senior governmental positions were vacated following the resignation of Evo Morales and his government. On 13 November 2019, Jeanine Áñez, a former senator representing Beni, declared herself acting President of Bolivia. Luis Arce was elected on 23 October 2020; he took office as president on 8 November 2020.

The constitution, drafted in 2006–07 and approved in 2009, provides for balanced executive, legislative, judicial, and electoral powers, as well as several levels of autonomy. The traditionally strong executive branch tends to overshadow the Congress, whose role is generally limited to debating and approving legislation initiated by the executive. The judiciary, consisting of the Supreme Court and departmental and lower courts, has long been riddled with corruption and inefficiency. Through revisions to the constitution in 1994, and subsequent laws, the government has initiated potentially far-reaching reforms in the judicial system as well as increasing decentralizing powers to departments, municipalities, and indigenous territories.

The executive branch is headed by a president and vice president, and consists of a variable number (currently, 20) of government ministries. The president is elected to a five-year term by popular vote, and governs from the Presidential Palace (popularly called the Burnt Palace, Palacio Quemado) in La Paz. In the case that no candidate receives an absolute majority of the popular vote or more than 40% of the vote with an advantage of more than 10% over the second-place finisher, a run-off is to be held among the two candidates most voted.[134]

The Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional (Plurinational Legislative Assembly or National Congress) has two chambers. The Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies) has 130 members elected to five-year terms, 63 from single-member districts (circunscripciones), 60 by proportional representation, and seven by the minority indigenous peoples of seven departments. The Cámara de Senadores (Chamber of Senators) has 36 members (four per department). Members of the Assembly are elected to five-year terms. The body has its headquarters on the Plaza Murillo in La Paz, but also holds honorary sessions elsewhere in Bolivia. The Vice President serves as titular head of the combined Assembly.

The Supreme Court Building in the capital of Bolivia, Sucre

The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court of Justice, the Plurinational Constitutional Court, the Judiciary Council, Agrarian and Environmental Court, and District (departmental) and lower courts. In October 2011, Bolivia held its first judicial elections to choose members of the national courts by popular vote, a reform brought about by Evo Morales.

The Plurinational Electoral Organ is an independent branch of government which replaced the National Electoral Court in 2010. The branch consists of the Supreme Electoral Courts, the nine Departmental Electoral Court, Electoral Judges, the anonymously selected Juries at Election Tables, and Electoral Notaries.[135] Wilfredo Ovando presides over the seven-member Supreme Electoral Court. Its operations are mandated by the Constitution and regulated by the Electoral Regime Law (Law 026, passed 2010). The Organ’s first elections were the country’s first judicial election in October 2011, and five municipal special elections held in 2011.

Capital[edit]

Government buildings in Bolivia’s judicial capital Sucre

Bolivia has its constitutionally recognized capital in Sucre, while La Paz is the seat of government. La Plata (now Sucre) was proclaimed the provisional capital of the newly independent Alto Perú (later, Bolivia) on 1 July 1826.[136] On 12 July 1839, President José Miguel de Velasco proclaimed a law naming the city as the capital of Bolivia, and renaming it in honor of the revolutionary leader Antonio José de Sucre.[136] The Bolivian seat of government moved to La Paz at the start of the twentieth century as a consequence of Sucre’s relative remoteness from economic activity after the decline of Potosí and its silver industry and of the Liberal Party in the War of 1899.

The 2009 Constitution assigns the role of national capital to Sucre, not referring to La Paz in the text.[134] In addition to being the constitutional capital, the Supreme Court of Bolivia is located in Sucre, making it the judicial capital. Nonetheless, the Palacio Quemado (the Presidential Palace and seat of Bolivian executive power) is located in La Paz, as are the National Congress and Plurinational Electoral Organ. La Paz thus continues to be the seat of government.

Foreign relations[edit]

Despite losing its maritime coast, the so-called Litoral Department, after the War of the Pacific, Bolivia has historically maintained, as a state policy, a maritime claim to that part of Chile; the claim asks for sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean and its maritime space. The issue has also been presented before the Organization of American States; in 1979, the OAS passed the 426 Resolution,[137] which declared that the Bolivian problem is a hemispheric problem. On 4 April 1884, a truce was signed with Chile, whereby Chile gave facilities of access to Bolivian products through Antofagasta, and freed the payment of export rights in the port of Arica. In October 1904, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship was signed, and Chile agreed to build a railway between Arica and La Paz, to improve access of Bolivian products to the ports.

The Special Economical Zone for Bolivia in Ilo (ZEEBI) is a special economic area of 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) of maritime coast, and a total extension of 358 hectares (880 acres), called Mar Bolivia («Sea Bolivia»), where Bolivia may maintain a free port near Ilo, Peru under its administration and operation[138][unreliable source?] for a period of 99 years starting in 1992; once that time has passed, all the construction and territory revert to the Peruvian government. Since 1964, Bolivia has had its own port facilities in the Bolivian Free Port in Rosario, Argentina. This port is located on the Paraná River, which is directly connected to the Atlantic Ocean.

In 2018, Bolivia signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[139][140]

The dispute with Chile was taken to the International Court of Justice. The court ruled in support of the Chilean position, and declared that although Chile may have held talks about a Bolivian corridor to the sea, the country was not required to negotiate one or to surrender its territory.[141]

Military[edit]

The Bolivian military comprises three branches: Ejército (Army), Naval (Navy) and Fuerza Aérea (Air Force).

The Bolivian army has around 31,500 men. There are six military regions (regiones militares—RMs) in the army. The army is organized into ten divisions. Although it is landlocked Bolivia keeps a navy. The Bolivian Naval Force (Fuerza Naval Boliviana in Spanish) is a naval force about 5,000 strong in 2008.[142] The Bolivian Air Force (‘Fuerza Aérea Boliviana’ or «FAB») has nine air bases, located at La Paz, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, Puerto Suárez, Tarija, Villamontes, Cobija, Riberalta, and Roboré.

Law and crime[edit]

There are 54 prisons in Bolivia, which incarcerate around 8,700 people as of 2010. The prisons are managed by the Penitentiary Regime Directorate (Spanish: Dirección de Régimen Penintenciario). There are 17 prisons in departmental capital cities and 36 provincial prisons.[143]

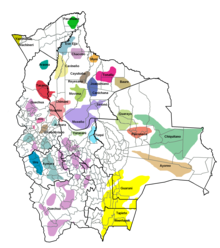

Administrative divisions[edit]

Bolivia has nine departments—Pando, La Paz, Beni, Oruro, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, Potosí, Chuquisaca, Tarija.

According to what is established by the Bolivian Political Constitution, the Law of Autonomies and Decentralization regulates the procedure for the elaboration of Statutes of Autonomy, the transfer and distribution of direct competences between the central government and the autonomous entities.[144]

There are four levels of decentralization: Departmental government, constituted by the Departmental Assembly, with rights over the legislation of the department. The governor is chosen by universal suffrage. Municipal government, constituted by a Municipal Council, with rights over the legislation of the municipality. The mayor is chosen by universal suffrage. Regional government, formed by several provinces or municipalities of geographical continuity within a department. It is constituted by a Regional Assembly. Original indigenous government, self-governance of original indigenous people on the ancient territories where they live.

| No. | Department | Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pando | Cobija |

Territorial division of Bolivia |

| 2 | La Paz | La Paz | |

| 3 | Beni | Trinidad | |

| 4 | Oruro | Oruro | |

| 5 | Cochabamba | Cochabamba | |

| 6 | Santa Cruz | Santa Cruz de la Sierra | |

| 7 | Potosí | Potosí | |

| 8 | Chuquisaca | Sucre | |

| 9 | Tarija | Tarija |

El Palmar Nature Preserve, in northern Chuquisaca

While Bolivia’s administrative divisions have similar status under governmental jurisprudence, each department varies in quantitative and qualitative factors. Generally speaking, Departments can be grouped either by geography or by political-cultural orientation. For example, Santa Cruz, Beni and Pando make up the low-lying «Camba» heartlands of the Amazon, Moxos and Chiquitanía. When considering political orientation, Beni, Pando, Santa Cruz, Tarija are generally grouped for regionalist autonomy movements; this region is known as the «Media Luna». Conversely, La Paz, Oruro, Potosí, Cochabamba have been traditionally associated with Andean politics and culture. Today, Chuquisaca vacillates between the Andean cultural bloc and the Camba bloc.

Economy[edit]

A proportional representation of Bolivia exports, 2019

In recent history, Bolivia has consistently led Latin America in measures of economic growth, fiscal stability and foreign reserves.[145] Bolivia’s estimated 2012 gross domestic product (GDP) totaled $27.43 billion at official exchange rate and $56.14 billion at purchasing power parity. Despite a series of mostly political setbacks, between 2006 and 2009 the Morales administration spurred growth higher than at any point in the preceding 30 years. The growth was accompanied by a moderate decrease in inequality.[146] Under Morales, per capita GDP doubled from US$1,182 in 2006 to US$2,238 in 2012. GDP growth under Morales averaged 5 percent a year, and in 2014 only Panama and the Dominican Republic performed better in all of Latin America.[147] Bolivia’s nominal GDP increased from 11.5 billion in 2006 to 41 billion in 2019.[148]

Bolivia in 2016 boasted the highest proportional rate of financial reserves of any nation in the world, with Bolivia’s rainy day fund totaling some US$15 billion or nearly two-thirds of total annual GDP, up from a fifth of GDP in 2005. Even the IMF was impressed by Morales’ fiscal prudence.[147]

Historical challenges[edit]

A major blow to the Bolivian economy came with a drastic fall in the price of tin during the early 1980s, which impacted one of Bolivia’s main sources of income and one of its major mining industries.[149] Since 1985, the government of Bolivia has implemented a far-reaching program of macroeconomic stabilization and structural reform aimed at maintaining price stability, creating conditions for sustained growth, and alleviating scarcity. A major reform of the customs service has significantly improved transparency in this area. Parallel legislative reforms have locked into place market-liberal policies, especially in the hydrocarbon and telecommunication sectors, that have encouraged private investment. Foreign investors are accorded national treatment.[150]

In April 2000, Hugo Banzer, the former president of Bolivia, signed a contract with Aguas del Tunari, a private consortium, to operate and improve the water supply in Bolivia’s third-largest city, Cochabamba. Shortly thereafter, the company tripled the water rates in that city, an action which resulted in protests and rioting among those who could no longer afford clean water.[151][152] Amidst Bolivia’s nationwide economic collapse and growing national unrest over the state of the economy, the Bolivian government was forced to withdraw the water contract.

Once Bolivia’s government depended heavily on foreign assistance to finance development projects and to pay the public staff. At the end of 2002, the government owed $4.5 billion to its foreign creditors, with $1.6 billion of this amount owed to other governments and most of the balance owed to multilateral development banks. Most payments to other governments have been rescheduled on several occasions since 1987 through the Paris Club mechanism. External creditors have been willing to do this because the Bolivian government has generally achieved the monetary and fiscal targets set by IMF programs since 1987, though economic crises have undercut Bolivia’s normally good record. However, by 2013 the foreign assistance is just a fraction of the government budget thanks to tax collection mainly from the profitable exports to Brazil and Argentina of natural gas.

Agriculture[edit]

Agriculture is less relevant in the country’s GDP compared to the rest of Latin America. The country produces close to 10 million tons of sugarcane per year and is the 10th largest producer of soybean in the world. It also has considerable yields of maize, potato, sorghum, banana, rice, and wheat. The country’s largest exports are based on soy (soybean meal and soybean oil).[153] The culture of soy was brought by Brazilians to the country: in 2006, almost 50% of soy producers in Bolivia were people from Brazil, or descendants of Brazilians. The first Brazilian producers began to arrive in the country in the 1990s. Before that, there was a lot of land in the country that was not used, or where only subsistence agriculture was practiced.[154]

Bolivia’s most lucrative agricultural product continues to be coca, of which Bolivia is currently the world’s third largest cultivator.[155][156]

Mineral resources[edit]

Bolivia, while historically renowned for its vast mineral wealth, is relatively under-explored in geological and mineralogical terms. The country is rich in various mineral and natural resources, sitting at the heart of South America in the Central Andes.

Mining is a major sector of the economy, with most of the country’s exports being dependent on it.[157] In 2019, the country was the eighth largest world producer of silver;[158] fifth largest world producer of tin[159] and antimony;[160] seventh largest producer of zinc,[161]

eighth largest producer of lead,[162] fourth largest world producer of boron;[163] and the sixth largest world producer of tungsten.[164] The country also has considerable gold production, which varies close to 25 tons/year, and also has amethyst extraction.[165]

Bolivia has the world’s largest lithium reserves, second largest antimony reserves, third largest iron ore reserves, sixth largest tin reserves, ninth largest lead, silver, and copper reserves, tenth largest zinc reserves, and undisclosed but productive reserves of gold and tungsten. Additionally, there is believed to be considerable reserves of uranium and nickel present in the country’s largely under-explored eastern regions. Diamond reserves may also be present in some formations of the Serranías Chiquitanas in Santa Cruz Department.

Bolivia has the second largest natural gas reserves in South America.[166] Its natural gas exports bring in millions of dollars per day, in royalties, rents, and taxes.[145] From 2007 to 2017, what is referred to as the «government take» on gas totaled approximately $22 billion.[145]

Most of Bolivia’s gas comes from megafields located in San Alberto, San Antonio, Margarita, and Incahuasi.[167] These areas are in the territory of the indigenous Guarani people, and the region is frequently viewed as a remote backwater by non-residents.[167]

The government held a binding referendum in 2005 on the Hydrocarbon Law. Among other provisions, the law requires that companies sell their production to the state hydrocarbons company Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) and for domestic demand to be met before exporting hydrocarbons and increased the state’s royalties from natural gas.[168] The passage of the Hydrocarbon law in opposition to then-President Carlos Mesa can be understood as part of the Bolivian gas conflict which ultimately resulted in election of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president.[169]

The US Geological Service estimates that Bolivia has 21 million tonnes of lithium, which represent at least 25% of world reserves — the largest in the world. However, to mine for it would involve disturbing the country’s salt flats (called Salar de Uyuni), an important natural feature which boosts tourism in the region. The government does not want to destroy this unique natural landscape to meet the rising world demand for lithium.[170] On the other hand, sustainable extraction of lithium is attempted by the government. This project is carried out by the public company «Recursos Evaporíticos» subsidiary of COMIBOL.

It is thought that due to the importance of lithium for batteries for electric vehicles and stabilization of electric grids with large proportions of intermittent renewables in the electricity mix, Bolivia could be strengthened geopolitically. However, this perspective has also been criticized for underestimating the power of economic incentives for expanded production in other parts of the world.[171]

Foreign-exchange reserves[edit]

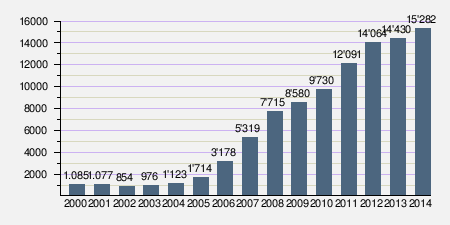

The amount in reserve currencies and gold held by Bolivia’s Central Bank advanced from 1.085 billion US dollars in 2000, under Hugo Banzer Suarez’s government, to 15.282 billion US dollars in 2014 under Evo Morales’ government.

| Foreign-exchange reserves 2000–2014 (MM US$) [172] |

|

|

| Fuente: Banco Central de Bolivia, Gráfica elaborada por: Wikipedia. |

Tourism[edit]

The income from tourism has become increasingly important. Bolivia’s tourist industry has placed an emphasis on attracting ethnic diversity.[174] The most visited places include Nevado Sajama, Torotoro National Park, Madidi National Park, Tiwanaku and the city of La Paz.

The best known of the various festivals found in the country is the «Carnaval de Oruro», which was among the first 19 «Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity», as proclaimed by UNESCO in May 2001.[175]

Transport[edit]

Roads[edit]

Bolivia’s Yungas Road was called the «world’s most dangerous road» by the Inter-American Development Bank, called (El Camino de la Muerte) in Spanish.[176] The northern portion of the road, much of it unpaved and without guardrails, was cut into the Cordillera Oriental Mountain in the 1930s. The fall from the narrow 12 feet (3.7 m) path is as much as 2,000 feet (610 m) in some places and due to the humid weather from the Amazon there are often poor conditions like mudslides and falling rocks.[177] Each year over 25,000 bikers cycle along the 40 miles (64 km) road. In 2018, an Israeli woman was killed by a falling rock while cycling on the road.[178]

The Apolo road goes deep into La Paz. Roads in this area were originally built to allow access to mines located near Charazani. Other noteworthy roads run to Coroico, Sorata, the Zongo Valley (Illimani mountain), and along the Cochabamba highway (carretera).[179] According to researchers with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bolivia’s road network was still underdeveloped as of 2014. In lowland areas of Bolivia there is less than 2,000 kilometers (2,000,000 m) of paved road. There have been some recent investments; animal husbandry has expanded in Guayaramerín, which might be due to a new road connecting Guayaramerín with Trinidad.[180] The country only opened its first duplicated highway in 2015: a 203 km stretch between the capital La Paz and Oruro.[181]

Air[edit]

The General Directorate of Civil Aeronautics (Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil—DGAC) formerly part of the FAB, administers a civil aeronautics school called the National Institute of Civil Aeronautics (Instituto Nacional de Aeronáutica Civil—INAC), and two commercial air transport services TAM and TAB.

TAM – Transporte Aéreo Militar (the Bolivian Military Airline) was an airline based in La Paz, Bolivia. It was the civilian wing of the ‘Fuerza Aérea Boliviana’ (the Bolivian Air Force), operating passenger services to remote towns and communities in the North and Northeast of Bolivia. TAM (a.k.a. TAM Group 71) has been a part of the FAB since 1945. The airline company has suspended its operations since 23 September 2019.[182]

Boliviana de Aviación, often referred to as simply BoA, is the flag carrier airline of Bolivia and is wholly owned by the country’s government.[183]

A private airline serving regional destinations is Línea Aérea Amaszonas,[184] with services including some international destinations.

Although a civil transport airline, TAB – Transportes Aéreos Bolivianos, was created as a subsidiary company of the FAB in 1977. It is subordinate to the Air Transport Management (Gerencia de Transportes Aéreos) and is headed by an FAB general. TAB, a charter heavy cargo airline, links Bolivia with most countries of the Western Hemisphere; its inventory includes a fleet of Hercules C130 aircraft. TAB is headquartered adjacent to El Alto International Airport. TAB flies to Miami and Houston, with a stop in Panama.

The three largest, and main international airports in Bolivia are El Alto International Airport in La Paz, Viru Viru International Airport in Santa Cruz, and Jorge Wilstermann International Airport in Cochabamba. There are regional airports in other cities that connect to these three hubs.[185]

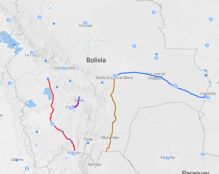

Rail[edit]

Railways in Bolivia (interactive map)

━━━ Routes with passenger traffic

━━━ Routes in usable state

·········· Unusable or dismantled routes

The Bolivian rail network has had a peculiar development throughout its history.

Technology[edit]

Bolivia owns a communications satellite which was offshored/outsourced and launched by China, named Túpac Katari 1.[186] In 2015, it was announced that electrical power advancements include a planned $300 million nuclear reactor developed by the Russian nuclear company Rosatom.[187] Bolivia was ranked 104th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, up from 110th in 2019.[188][189][190][191]

Water supply and sanitation[edit]

Bolivia’s drinking water and sanitation coverage has greatly improved since 1990 due to a considerable increase in sectoral investment. However, the country has the continent’s lowest coverage levels and services are of low quality. Political and institutional instability have contributed to the weakening of the sector’s institutions at the national and local levels.

Two concessions to foreign private companies in two of the three largest cities – Cochabamba and La Paz/El Alto – were prematurely ended in 2000 and 2006 respectively. The country’s second largest city, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, manages its own water and sanitation system relatively successfully by way of cooperatives. The government of Evo Morales intends to strengthen citizen participation within the sector. Increasing coverage requires a substantial increase of investment financing.

According to the government the main problems in the sector are low access to sanitation throughout the country; low access to water in rural areas; insufficient and ineffective investments; a low visibility of community service providers; a lack of respect of indigenous customs; «technical and institutional difficulties in the design and implementation of projects»; a lack of capacity to operate and maintain infrastructure; an institutional framework that is «not consistent with the political change in the country»; «ambiguities in the social participation schemes»; a reduction in the quantity and

quality of water due to climate change; pollution and a lack of integrated water resources management; and the lack of policies and programs for the reuse of wastewater.[192]

Only 27% of the population has access to improved sanitation, 80 to 88% has access to improved water sources. Coverage in urban areas is bigger than in rural ones.[193]

Some regions of Bolivia are largely under the power of the ganaderos, the large cattle and pig owners, and many small farmers are still reduced to peons. Nevertheless, the presence of the state has been clearly reinforced under the government of Evo Morales. The government tends to accommodate the interests of large landowners while trying to improve the living and working conditions of small farmers.[194]

Agriculture[edit]

The agrarian reform promised by Evo Morales — and approved in a referendum by nearly 80 per cent of the population — has never been implemented. Intended to abolish latifundism by reducing the maximum size of properties that do not have an «economic and social function» to 5,000 hectares, with the remainder to be distributed among small agricultural workers and landless indigenous people, it was strongly opposed by the Bolivian oligarchy. In 2009, the government gave in to the agribusiness sector, which in return committed to end the pressure it was exerting and jeopardizing until the new constitution was in place.[194]

However, a series of economic reforms and projects have improved the condition of modest peasant families. They received farm machinery, tractors, fertilizers, seeds and breeding stock, while the state built irrigation systems, roads and bridges to make it easier for them to sell their produce in the markets. The situation of many indigenous people and small farmers was regularized through the granting of land titles for the land they were using.[194]

In 2007, the government created a «Bank for Productive Development» through which small workers and agricultural producers can borrow easily, at low rates and with repayment terms adapted to agricultural cycles. As a result of improved banking supervision, borrowing rates have been reduced by a factor of three between 2014 and 2019 across all banking institutions for small and medium-sized agricultural producers. In addition, the law now requires banks to devote at least 60% of their resources to productive credits or to the construction of social housing.[194]