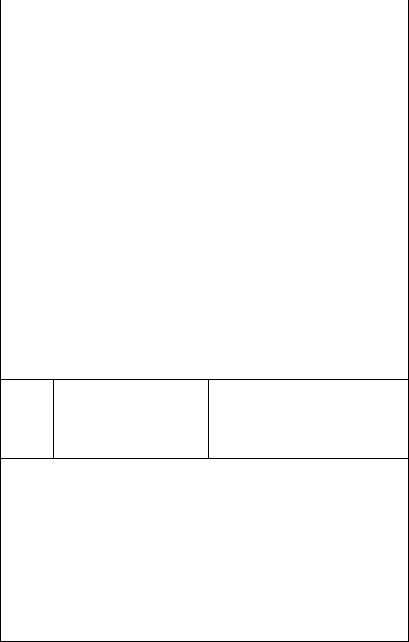

1. сокр. к детский церебральный паралич

Все значения слова «ДЦП»

-

ДЦП может быть выявлен сразу после рождения ребёнка, а может проявляться постепенно в грудном возрасте.

-

Нарушения мелкой моторики могут проявляться в виде нарушений приёма или передачи сигнала при органических поражениях головного мозга, травмах головы, ДЦП, травмах конечностей и других заболеваниях.

-

Для медицинского работника – это последствия пре-, пери- или постнатального поражения мозга: от лёгких, типа минимальной мозговой дисфункции (ММД), до самых тяжёлых, типа детского церебрального паралича (ДЦП) или генетической патологии.

- (все предложения)

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

ДЦП, [дэцепэ́], нескл., м. (сокр.: детский церебральный паралич)

Рядом по алфавиту:

дуэ́ль , -и

дуэ́льный

дуэля́нт , -а

дуэ́нья , -и, р. мн. -ний

дуэ́т , -а

дуэ́тец , -тца, тв. -тцем, р. мн. -тцев

дуэ́тик , -а

дуэ́тный

дуэтти́но , нескл., м. и с.

ду́ющий(ся)

дха́рма , -ы

дхарми́ческий

дхол , -а и доо́л, -а (муз. инструмент)

дхо́ти , нескл., с.

дхья́на , -ы

ДЦП , [дэцепэ́], нескл., м. (сокр.: детский церебральный паралич)

дщерь , -и

ды́ба , -ы

ды́бить(ся) , ды́блю, ды́бит(ся)

дыбки́ , : на дыбки́

ды́бом , нареч.

дыбы́ , : на дыбы́

ды́бящий(ся)

ды́лда , -ы, м. и ж. (сниж.)

ды́лдистый

ды́лдушка , -и, р. мн. -шек, м. и ж.

дым , -а и -у, предл. в дыму́, мн. -ы́, -о́в

дымаппарату́ра , -ы

дыма́рь , -аря́

дымзаве́са , -ы

дыми́на , -ы, м. (густой дым)

Взрослому человеку при ДЦП тяжело двигаться из-за веса. В результате взрослому человеку приходится перемещаться в инвалидном кресле. При ДЦП у взрослого (в МКБ-10 под кодом G80) нарушается моторика конечностей. Из-за этого тяжело двигаться и совершать резкие движения, поэтому трудно о себе заботиться. Даже приготовление пищи вызывает много сложностей.

Особенности

Таким людям невозможно работать, тем более физическим трудом. У взрослых людей с ДЦП присутствует отсталость в развитии или отклонения в психике из-за поврежденных структур мозга, отвечающих за рассудок. Таким людям тяжело разговаривать, так как нарушается работа мышц. В результате, возникают сложности с приемом еды и появляется на лице неестественная мимика.

У взрослого больного чаще начинает развиваться эпилепсия. Наблюдается ненормальное восприятие окружающего мира, опять же, связанное с повреждением мозга больного. К тому же, часто у человека с этим диагнозом начинает быстро снижаться зрение и слух.

Помимо физических последствий, у взрослого пациента появляются психологические последствия. У больного начинает развиваться психическое расстройство. Это невроз или депрессия. Также меняется в худшую сторону сознание.

При ДЦП во взрослом возрасте у женщин не возникает сложностей с беременностью и родами. Больные беременные женщины вынашивают ребенка, без каких-либо затруднений. Беременным с ДЦП врачи часто советуют делать кесарево сечение, но так делается только при тяжелой форме. Больным беременным требуется пристальное наблюдение у гинеколога. Женщины с ДЦП могут родить двойню или тройню без осложнений. ДЦП от взрослых родителей не передается детям. У взрослых людей почти всегда рождаются здоровые малыши.

Симптомы

Характерно плавное течение ДЦП у взрослых людей. С годами детское заболевание перерастает, врожденные или приобретенные патологии сопровождают больного на протяжении жизни. При незначительных повреждениях головного мозга и своевременном диагностировании с последующим симптоматическим лечением, возможно снижение когнитивных и двигательных нарушений. Симптомы ДЦП у взрослых:

- Общая мышечная слабость. Зачастую встречается у больных, сопровождается болью, вызываемой деформацией костей.

- Артроз и артрит. Возникающие еще в детском возрасте, нарушения двигательной системы, сопровождающиеся неправильным взаимодействием суставов, начинают доставлять неудобства с течением времени.

- Болевые ощущения. Внезапно возникающая, боль острого или хронического характера беспокоит больного. Чаще всего, поражаемыми областями становятся колени, верх или низ спины. Страдающий от этих болей, человек не может самостоятельно определить их силу и очаг распространения.

- Преждевременное старение. Признаки, сопутствующие этому симптому, начинают проявляться при достижении больным возраста 40 лет. Причиной этому служит вынужденная работа ослабленных, плохо развитых органов в полную силу наравне с полностью здоровыми для поддержания организма больного. В связи с чем наступает ранний износ некоторых систем (сердечно-сосудистой, дыхательной).

Последствия

Последствия ДЦП у взрослых:

- В основном, при ДЦП пациент не в состоянии нормально передвигаться на своих ногах. Из-за нарушения координации ему, помимо трудностей при ходьбе, еще сложнее сохранять равновесие, поэтому пациенту нужна постоянная помощь близких людей.

- У больного пропадает способность осуществлять некоторые виды моторики, из-за этого он не в силах сам о себе позаботиться, а о работе, тем более физической, и речи идти не может.

- У многих пациентов повреждается структура, отвечающая за умственное состояние, поэтому они отстают в развитии или имеют психологические отклонения.

- У больного ухудшается речь, так как возникает нарушение в сокращениях лицевых мышц. Также появляются сложности с приемом пищи и неестественная мимика.

- Часто у пациента начинает развиваться эпилепсия.

- Иногда возникает ненормальное восприятие окружающего мира из-за повреждения мозга.

- У пациента начинает быстро снижаться слух и зрение.

- Появляются психологические расстройства. Это выражается, в свою очередь, в фобиях или депрессии.

- Пациенту тяжело общаться с другими людьми из-за замкнутого образа жизни.

Хирургия

Хирургическое лечение ДЦП непременно предусматривает проведение комплексной медицинской диагностики состояния здоровья пациента. В комплекс входят:

- электромиография;

- ЭНГ и др.

Помимо перечисленного комплекса диагностики, пациент проходит консультации у офтальмолога, ортопеда, эпилептолога, психиатра, в исключительных случаях даже логопеда, а также других специалистов, каждый из которых должен предоставить свое медицинское разрешение на хирургическое лечение патологии пациента в анатомической области, касающейся своей специализации.

Нейрохирургия при лечении взрослых- инвалидов с ДЦП является серьезным и радикальным методом терапии. Поэтому использовать его необходимо, все тщательно взвесив, и получить консультации у разных специалистов. Когда адаптивное лечение не дает ожидаемых и видимых улучшений лечения, при этом переходит в судороги или гиперкинезы, которые все сильнее сковывают человека, а движения вызывают боль — поможет нейрохирургия. Иначе ухудшение здоровья неизбежно.

Развитие обширного паралича мускулатуры постепенно переходит в воспаление эпидуральной клетчатки, которая, в свою очередь, влияет на кровообращение и метаболические процессы в организме. Эти нарушения неизбежно приводят к сбою оттока венозной крови из шейного отдела позвоночника, что может привести к нарушению работы спинного мозга.

Как возможность решения проблемы, можно использовать не менее 2 блокад ботулотоксина, а когда и они не дадут эффекта, то вариантов больше не существует.

Занятия ЛФК

Общее предписание для всех упражнений ЛФК:

- Систематичность.

- Регулярность.

- Целеустремленность.

- Индивидуальность (прямолинейно зависящие от возраста, диагноза, состояния и психики реабилитируемого пациента).

- Постепенное увеличение физической нагрузки.

Виды упражнений

Основные виды упражнения лфк при ДЦП:

- Занятия на растяжку, направленные на снижение и снятие чрезмерного мышечного тонуса.

- Упражнения на развитие чувствительности и силы мускулатуры, в том числе позволяющие скорректировать отдельную группу мышц.

- Занятия, направленные на восстановление функционального состояния мышечной ткани методом восстановления и развития восприимчивости нервных окончаний.

- Упражнения, направленные на развитие ведущей и антагонистической мускулатуры.

- Нагрузки на выносливость для улучшения работы органов.

- Упражнения, снимающие судороги и спазмы мускулатуры.

- Ходьба, направленная на развитие походки и осанки.

- Упражнения на развитие органов восприятия окружающего мира (визуальных и тактильных).

- Упражнения, развивающие вестибулярный аппарат.

Зачастую пациентам с заболеванием ДЦП предписывают развитие мускулатуры тела, выполняя ряд упражнений с постепенно нарастающей интенсивностью и нагрузкой. В случае, если не будет применяться то через определенный временной промежуток опорно-двигательные функции могут быть не реализованы и угнетены. В связи с чем для взрослых людей, страдающих последствиями ДЦП, немаловажным является занятие лфк при том, что с возрастом для приведения мускулатуры в желаемый тонус необходимо гораздо больше времени, чем детям.

Массаж

Поглаживания при массаже обладают расслабляющим эффектом. Движения рук массажиста должны быть медленными и мягкими. При растирании и разминании специалист помогает расслабиться, эти приемы лучше делать нежно, мягко и медленнее, чем обычно.

Потряхивание — специальный и эффективный прием, который можно использовать для снижения тонуса мышц конечностей.

Разминка

В первую очередь, разминаются мышцы спины:

- Движения рук следуют от поясничной области к шее (паравертебральные области тщательно массируют с помощью сегментарного и точечного массажа).

- Подготовительный массаж (растирания, поглаживание, неглубокое массирование проблемных областей мускулатуры).

- Массаж, проецирующий слабые болевые ощущения на удаленные от очага боли области тела.

- Поглаживания завершают процедуру массажа мышц спины. Затем следует обработка мускулатуры ног и ягодиц.

Массаж верхнего плечевого пояса

Следующий этап. Массаж верхнего плечевого пояса, мускулатуры грудного и брюшного отдела. При массировании мышц грудной клетки помогают приемы для активизации дыхания. В процессе следует применить комплекс упражнений на растяжение мышц.

При ДЦП категорически запрещено использовать приемы выжимания, рубления, поколачивания. Длительность сеанса должна составлять не более 20 минут. Среднее количество процедур массажа при ДЦП составляет примерно 2-3 раза каждые полгода.

Медикаментозное лечение

Медикаментозное лечение ДЦП у взрослых позволяет поддержать и восстановить моторные и сенсорные функции. Лекарствами полностью победить болезнь невозможно, но можно сделать жизнь больного нормальной и радостной для него. Применяется медикаментозное лечение часто при сильном поражении структуры мозга.

Для лечения судорожных припадков взрослым, больным ДЦП, применяют два вида препарата. Различные антиконвульсанты используются для борьбы с судорогами. Они отличаются механизмом воздействия на человеческий организм.

Бензодиазепины применяют только в крайних случаях для остановки частых припадков у больного. Они действуют на внутриклеточные процессы в человеческом мозге.

Что врачи назначают?

«Диазепам». Этот препарат применяется против частых судорог. Дозировку назначает лечащий врач, исходя из результата ЭЭГ и типа судорог. Нет общего препарата для всех видов припадков. Иногда врачам приходится назначать комплексную лекарственную терапию.

Для релаксанта используется «Лиорезал» и «Диазепам». Они вместе способны заблокировать сигналы от мозга, направленные на сокращение мышц.

Препарат «Дантролен» применяется для улучшения контроля над сокращениями мышц. Эти средства позволяют снизить мышечный тонус на период лечения.

Для длительного закрепления результата нужно применять физиотерапию. У препаратов есть и побочные действия. Они могут вызывать у взрослого человека сонливость и аллергическую сыпь.

Также больным взрослым людям врачи выписывают дегидратирующий лекарственный препарат. Он направлен на усиление диуреза и снижения продуктов ликвора. Больным ДЦП необходимо принимать и препараты, направленные на улучшение циркуляции крови в мозгу. Такие лекарства позволяют улучшить свойство крови. К таким препаратам относится «Эмоксипин».

С диагнозом ДЦП (детский церебральный паралич) я живу с рождения. Точнее — с годовалого возраста (примерно тогда врачи наконец-то определили, как называется то, что со мной происходит). Я окончила спецшколу для детей с ДЦП, а через 11 лет пришла туда работать. С тех пор прошло уже 20 лет… По самым скромным подсчетам, я знаю, более или менее близко, больше полутысячи ДЦПшников. Думаю, этого достаточно для того, чтобы развеять мифы, которым склонны верить те, кто столкнулся с этим диагнозом впервые.

Миф первый: ДЦП — тяжелое заболевание

Не секрет, что многие родители, услышав от врача этот диагноз, испытывают шок. Особенно в последние годы, когда СМИ все чаще и чаще рассказывают о людях с тяжелой формой ДЦП — о колясочниках с поражением рук и ног, невнятной речью и постоянными насильственными движениями (гиперкинезами). Им и невдомек, что многие люди с ДЦП нормально говорят и уверенно ходят, а при легких формах вообще не выделяются среди здоровых. Откуда же берется этот миф?

Как и многие другие заболевания, ДЦП варьируется от легкой до тяжелой степени. По сути, это даже не болезнь, а общая причина целого ряда расстройств. Ее суть — в том, что во время беременности или родов у младенца оказываются поражены отдельные участки коры головного мозга, в основном те, которые отвечают за двигательные функции и координацию движений. Это и вызывает ДЦП – нарушение правильной работы отдельных мышц вплоть до полной невозможности управлять ими. Медики насчитывают более 1000 факторов, которые могут запустить этот процесс. Очевидно, что разные факторы вызывают разные последствия.

Традиционно выделяются 5 основных форм ДЦП, плюс смешанные формы:

Спастическая тетраплегия

– самая тяжелая форма, когда больной из-за чрезмерного напряжения мышц не в состоянии управлять ни руками, ни ногами и нередко испытывает сильные боли. Ею страдает только 2% людей с ДЦП (здесь и далее статистика взята из Интернета), но именно о них чаще всего рассказывают в СМИ.

Спастическая диплегия

– форма, при которой сильно поражены либо верхние, либо нижние конечности. Чаще страдают ноги – человек ходит с полусогнутыми коленями. Для болезни Литтля, наоборот, характерно сильное поражение рук и речи при относительно здоровых ногах. Последствия спастической диплегии имеют 40% ДЦПшников.

При гемиплегической форме

поражены двигательные функции руки и ноги с одной стороны тела. Ее признаки есть у 32%.

У 10 % людей с ДЦП основная форма – дискинетическая или гиперкинетическая

. Для нее характерны сильные непроизвольные движения – гиперкинезы – во всех конечностях, а также в мышцах лица и шеи. Гиперкинезы часто встречаются и при других формах ДЦП.

Для атаксической формы

характерен пониженный тонус мышц, вялые замедленные движения, сильное нарушение равновесия. Она наблюдается у 15% больных.

Итак, малыш родился с одной из форм ДЦП. А дальше включаются другие факторы — факторы жизни, которая, как известно, у каждого — своя. Поэтому то, что происходит с ним после года, правильнее называть последствиями ДЦП. Они могут быть совершенно разными даже в рамках одной формы. Знаю человека со спастической диплегией ног и довольно сильными гиперкинезами, который окончил мехмат МГУ, преподает в институте и ходит в турпоходы со здоровыми людьми.

С ДЦП рождается, по разным данным, 3-8 младенцев из 1000. Большинство (до 85 %) имеет легкую и среднюю тяжесть заболевания. Это значит, что многие люди просто не связывают особенности их походки или речи со «страшным» диагнозом и считают, что в их окружении ДЦПшников нет. Поэтому единственный источник сведений для них — публикации в СМИ, которые отнюдь не стремятся к объективности…

Миф второй: ДЦП излечим

Для большинства родителей детей с ДЦП этот миф крайне привлекателен. Не задумываясь о том, что нарушения в работе мозга сегодня не исправляются никакими средствами, они пренебрегают «неэффективными» советами рядовых врачей, тратя все сбережения и собирая огромные суммы с помощью благотворительных фондов, чтобы оплатить дорогостоящий курс в очередном популярном центре. Между тем, секрет облегчения последствий ДЦП отнюдь не столько в модных процедурах, сколько в постоянной работе с малышом начиная с первых недель жизни. Ванны, обычные массажи, игры с распрямлением ножек и ручек, поворотами головы и выработкой точности движений, общение — вот та база, которая в большинстве случаев помогает организму ребенка частично компенсировать нарушения. Ведь главная задача раннего лечения последствий ДЦП — не исправление самого дефекта, а предупреждение неправильного развития мышц и суставов. А этого можно достичь только ежедневным трудом.

Миф третий: ДЦП не прогрессирует

Так утешают себя те, кто столкнулся с нетяжелыми последствиями заболевания. Формально это верно – состояние мозга действительно не меняется. Однако даже легкая форма гемиплегии, практически не заметная окружающим, уже к 18 годам неизбежно вызывает искривление позвоночника, которое, если им не заниматься, — прямой путь к раннему остеохондрозу или межпозвонковым грыжам. А это – сильные боли и ограничение подвижности вплоть до невозможности ходить. Подобные типичные последствия есть у каждой формы ДЦП. Беда лишь в том, что в России эти данные практически не обобщаются, а потому растущих ДЦПшников и их родных никто не предупреждает об опасностях, подстерегающих в будущем.

Гораздо лучше известно родителям, что пораженные участки мозга становятся чувствительными к общему состоянию организма. Временное усиление спастики или гиперкинезов могут вызвать даже банальный грипп или скачок давления. В редких случаях нервное потрясение или серьезное заболевание вызывают резкое длительное усиление всех последствий ДЦП и даже появление новых.

Разумеется, это не значит, что людей с ДЦП надо содержать в тепличных условиях. Наоборот: чем крепче организм человека, тем легче он адаптируется к неблагоприятным факторам. Однако если процедура или физическое упражнение регулярно вызывают, к примеру, усиление спастики, от них нужно отказаться. Ни в коем случае нельзя делать что-либо через «не могу»!

Особое внимание должны проявлять родители к состоянию ребенка с 12 до 18 лет. В это время даже здоровые дети испытывают серьезные перегрузки из-за особенностей перестройки организма. (Одна из проблем этого возраста – рост скелета, опережающий развитие мышечных тканей.) Знаю несколько случаев, когда ходячие дети из-за проблем с коленными и тазобедренными суставами в этом возрасте садились на коляску, причем навсегда. Именно поэтому западные врачи не рекомендуют ставить на ноги ДЦПшников 12-18 лет, если до этого они не ходили.

Миф четвертый: всё от ДЦП

Последствия ДЦП бывают самые разные, и все же их перечень ограничен. Однако близкие людей с этим диагнозом порой считают ДЦП причиной не только нарушения двигательных функций, а также зрения и слуха, но и таких явлений как аутизм или синдром гиперактивности. А главное – считают: стоит вылечить ДЦП – и все остальные проблемы решатся сами собой. Между тем, даже если причиной болезни действительно стал ДЦП, лечить надо не только его, но и конкретное заболевание.

В процессе родов у СильвестраСталлоне были частично повреждены нервные окончания лица — часть щеки, губ и языка актера так и остались парализованными, впрочем невнятная речь, ухмылка и большие грустные глаза стали в дальнейшем визитной карточкой.

Особенно забавно фраза «У вас же ДЦП, чего вы хотите!» звучит в устах врачей. Не раз и не два я слышала ее от докторов разных специальностей. В этом случае приходится терпеливо и настойчиво объяснять, что хочу я того же, что и любой другой человек, – облегчения собственного состояния. Как правило, врач сдается и назначает те процедуры, которые мне необходимы. В крайнем случае, помогает поход к заведующему. Но в любом случае, сталкиваясь с тем или иным заболеванием, человеку с ДЦП приходится быть особенно внимательным к себе и порой подсказывать врачам нужное лечение, чтобы свести к минимуму негативное воздействие процедур.

Миф пятый: с ДЦП никуда не берут

Здесь утверждать что-либо с опорой на статистику крайне сложно, ибо надежных данных попросту нет. Однако, если судить по выпускникам массовых классов спецшколы-интерната № 17 г. Москвы, где я работаю, лишь единицы после школы остаются сидеть дома. Примерно половина поступает в специализированные колледжи или отделения вузов, треть — в обычные вузы и колледжи, кое-кто сразу идет работать. В дальнейшем трудоустраивается не менее половины выпускников. Иногда девушки после окончания школы быстро выходят замуж и начинают «работать» мамой. С выпускниками классов для детей с умственной отсталостью ситуация сложнее, однако и там около половины выпускников продолжает учебу в специализированных колледжах.

Этот миф распространяют в основном те, кто не в состоянии трезво оценить свои способности и хочет учиться или работать там, где ему вряд ли удастся соответствовать предъявляемым требованиям. Получая отказ, такие люди и их родители нередко обращаются в СМИ, стремясь силой добиться своего. Если же человек умеет соизмерять желания с возможностями, он находит свой путь без разборок и скандалов.

Показательный пример – наша выпускница Екатерина К., девушка с тяжелой формой болезни Литтля. Катя ходит, но может работать на компьютере всего одним пальцем левой руки, а ее речь понимают только очень близкие люди. Первая попытка поступить в вуз на психолога не удалась – посмотрев на необычную абитуриентку, несколько преподавателей заявили, что отказываются ее учить. Через год девушка поступила в Академию печати на редакторский факультет, где была дистанционная форма обучения. Учеба пошла настолько успешно, что Катя стала подрабатывать сдачей тестов за своих однокашников. Устроиться после окончания вуза на постоянную работу ей не удалось (одна из причин – отсутствие трудовой рекомендации МСЭ). Однако время от времени она работает модератором учебных сайтов в ряде вузов столицы (трудовой договор оформляется на другого человека). А в свободное время пишет стихи и прозу, выкладывая произведения на собственный сайт.

Сухой остаток

Что же я могу посоветовать родителям, которые узнали, что у их малыша ДЦП?

Прежде всего – успокоиться и постараться уделять ему как можно больше внимания, окружая его (особенно в раннем возрасте!) только положительными эмоциями. При этом постарайтесь жить так, будто в вашей семье растет обычный ребенок – гуляйте с ним во дворе, копайтесь в песочнице, помогая своему малышу наладить контакт со сверстниками. Не нужно лишний раз напоминать ему о болезни – ребенок должен сам прийти к пониманию своих особенностей.

Второе – не уповайте на то, что рано или поздно ваш ребенок будет здоровым. Примите его таким, какой он есть. Не следует думать, что в первые годы жизни все силы надо бросить на лечение, оставив развитие интеллекта «на потом». Развитие ума, души и тела взаимосвязаны. Очень многое в преодолении последствий ДЦП зависит от желания ребенка их преодолеть, а без развития интеллекта оно просто не возникнет. Если же малыш не понимает, зачем нужно терпеть дискомфорт и трудности, связанные с лечением, пользы от таких процедур будет немного.

Третье – будьте снисходительны к тем, кто задает нетактичные вопросы и дает «глупые» советы. Помните: недавно вы сами знали о ДЦП не больше, чем они. Постарайтесь спокойно вести такие разговоры, ведь от того, как вы будете общаться с окружающими, зависит их отношение к вашему ребенку.

А главное – верьте: у вашего ребенка всё будет хорошо, если он вырастет открытым и доброжелательным человеком.

код для сайта или блога

No related articles yet.

Анастасия

Прочитала статью. Моя тема:)

32 года, правосторонний гемипарез (лёгкая форма ДЦП). Обычный детский сад, обычная школа, ВУЗ, самостоятельные поиски работы (на ней, собственно, сейчас и нахожусь), путешествия, друзья,обычная жизнь….

И через «хромоногую» прошла, и через «косолапую», и через бог весть что. И многое ещё будет, я уверенна!

НО! Главное это позитивный настрой и сила характера, оптимизм!!

Нана

А действительно с возрастом следует ждать ухудшений? У меня легкая степень, спастика в ногах

Анжела

А меня отношение людей, не благоприятные условия жизни сломали. В 36 лет у меня не ни образования, ни работы, ни семьи хотя легкая форма (правосторонний гемипарез).

Наташа

После прививок появилось много «дцп». Хотя детки и вовсе и не дцп. Там ничего врожденного и внутриутробного нет. Но приписывают к дцп и соответственно неправильно «залечивают». В результате — действительно разновидность паралича получают.

Часто причина «врожденного» дцп вовсе и не травма, а внутриутробная инфекция.

Елена

Замечательная статья, поднимающая огромную проблему — как «с этим» жить. Хорошо показано, что одинаково плохо и не учитывать наличие связанных с заболеванием ограничений и придавать им избыточное значение. Не стоит фокусировать внимание на том, чего ты не можешь, а нужно сосредоточиться на том, что доступно.

И действительно очень важно уделять внимание интеллектуальному развитию. Мы даже Цереброкурин кололи, он нам дал огромный толчок в развитии, всё-таки эмбриональные нейропептиды действительно помогают использовать имеющиеся возможности мозга. Моё мнение, что не нужно ждать чуда, но и опускать руки тоже нельзя.

Автор прав: «этого можно достичь только ежедневным трудом» самих родителей и чем раньше они эти займутся, тем продуктивнее. Начинать «предупреждение неправильного развития мышц и суставов» после полуторагодовалого возраста поздно — «паровоз ушел». Знаю на личном опыте и на опыте других родителей.

Екатерина, всего Вам хорошего.

* Кинесте́зия (др.-греч. κινέω — «двигаю, прикасаюсь» + αἴσθησις — «чувство, ощущение») — так называемое «мышечное чувство», чувство положения и перемещения как отдельных членов, так и всего человеческого тела. (Википедиия)

Ольга

не согласна абсолютно с автором. во-первых, почему при рассмотрении форм дцп ничего не сказали про двойную гемиплегию? она отличается от обычной гемиплегии и от спастического тетрапареза. во-вторых, дцп действительно излечим. если подразумевать развитие компенсаторных возможностей мозга и улучшение состояния пациента. в-третьих, автор в глаза тяжелых детей видела??? таких, о которых и речи нет вынести поиграться в песочницу. когда чуть не так посмотри на ребенка и его трясет от судорог. и крик не прекращается. и он выгибается дугой так, что синяки на руках у мамы, когда она пытается его держать. когда не только сидеть — лежать ребенок не может. в-четвертых. форма дцп — это вообще ни о чем. главное — тяжесть заболевания. я видела спастическую диплегию у двоих детей — один почти не отличается от сверстников, другой — весь скрюченный и с судорогами, разумеется, даже ровно сидеть в коляске не может. а диагноз один.

Елена

не совсем согласна со статьей как мама ребенка с ДЦП-спастическая диплегия, средней степени тяжести. Как маме мне легче жить и бороться думая, что это если и неизлечимо, то поправимо-возможно максимально приблизить ребенка к «норм.» социальной жизни. за 5 лет успели наслушаться что сына лучше в интернат сдать, а самим родить здорового…и это-от двух разных врачей-ортопедов! сказано было при ребенке, у которого сохраненный интеллект и он все слышал…конечно замкнулся, стал сторониться чужих….но у нас огромный скачок-сын ходит сам, правда плохо с равновесием и колени согнуты…но мы боремся.начали довольно поздно-с 10мес, до этого лечили другие последствия преждевременных родов и пофигизма врачей…

Детский церебральный паралич (ДЦП) – общий медицинский термин, который используют для обозначения группы двигательных нарушений, прогрессирующих у грудничка вследствие травматизации различных зон мозга в околородовом периоде. Первые симптомы ДЦП иногда можно выявить уже после рождения ребёнка. Но обычно признаки недуга проявляются у младенцев в грудном возрасте (до 1 года).

Этиология

Детский церебральный паралич у ребёнка прогрессирует из-за того, что определённые участки его ЦНС были повреждены непосредственно во внутриутробном периоде развития, во время процесса рождения либо же в первые месяцы его жизни (обычно до 1 года). На самом деле причины ДЦП довольно разнообразны. Но все они приводят к одному – некоторые зоны мозга начинают неполноценно функционировать или же полностью погибают.

Причины возникновения ДЦП у ребёнка во внутриутробном периоде:

- токсикоз;

- несвоевременная отслойка «детского места» (плаценты);

- угроза выкидыша;

- нефропатия беременных;

- травматизация во время вынашивания ребёнка;

- гипоксия плода;

- фетоплацентарная недостаточность;

- наличие соматических недугов у матери ребёнка;

- резус-конфликт. Данное патологическое состояние развивается из-за того, что у матери и ребёнка различные резус-факторы, поэтому её организм отторгает плод;

- недуги инфекционной природы, которые перенесла будущая мать во время вынашивания плода. К самым потенциально опасным патологиям относят , ;

- гипоксия плода.

Причины, провоцирующие ДЦП в процессе родовой деятельности:

- узкий таз (травма головы ребёнка во время прохождения его по родовым путям матери);

- родовая травма;

- нарушение родовой активности;

- роды ранее установленного срока;

- большой вес новорождённого;

- стремительные роды – представляют наибольшую опасность для младенца;

- ягодичное предлежание ребёнка.

Причины прогрессирования недуга в первые месяцы жизни новорождённого:

- дефекты развития элементов дыхательной системы;

- асфиксия новорождённых;

- аспирация околоплодными водами;

- гемолитическая болезнь.

Разновидности

Выделяют 5 форм ДЦП, которые различаются между собой зоной поражения мозга:

- спастическая диплегия.

Эта форма ДЦП диагностируется у новорождённых чаще остальных. Основная причина её прогрессирования – травматизация зон мозга, которые являются «ответственными» за двигательную активность конечностей. Характерный признак развития недуга у ребёнка до года – частичный или полный паралич ног и рук; - атонически-астатическая форма ДЦП.

В этом случае наблюдается поражение мозжечка. Признаки ДЦП этого типа – больной не может держать равновесие, координация нарушена, мышечная атония. Все эти симптомы проявляются у малыша в возрасте до года; - гемипаретическая форма.

Участки-«мишени» мозга – подкорковые и корковые структуры одного из полушарий, отвечающие за двигательную активность; - двойная гемиплегия.

В этом случае поражаются сразу два полушария. Данная форма церебрального паралича является самой тяжёлой; - гиперкинетическая форма ДЦП.

В большей части клинических ситуаций она сочетается со спастической диплегией. Развивается из-за поражения подкорковых центров. Характерный симптом гиперкинетической формы ДЦП – совершение непроизвольных и неконтролируемых движений. Примечательно то, что такая патологическая активность может возрастать, если ребёнок до года или старше волнуется или устал.

Классификация, основывающаяся на возрасте ребёнка:

- ранняя форма.

В этом случае симптомы ДЦП отмечаются у новорождённого в период от рождения до полугода; - начальная остаточная форма.

Период её проявления – от 6 месяцев и до 2 лет; - поздняя остаточная

– от 24 месяцев.

Симптоматика

Детский церебральный паралич имеет множество проявлений. Симптомы недуга напрямую зависят от степени поражения структур мозга, а также от места локализации очага в данном органе. Заметить прогрессирование церебрального паралича можно заметить уже после рождения, но чаще его выявляют через пару месяцев, когда становится явно видно, что новорождённый отстаёт в развитии.

Признаки детского церебрального паралича у новорождённого:

- малыша совершенно не интересуют игрушки;

- новорождённый долгое время не переворачивается самостоятельно и не держит голову;

- если попробовать поставить малыша, то он будет становиться не на стопу, а только на носочки;

- движения конечностями носят хаотичный характер.

Симптомы ДЦП:

- парезы. Обычно только половина тела, но иногда они распространяются на ноги и руки. Поражённые конечности изменяются – они укорачиваются и становятся тоньше. Характерные деформации скелета при детском церебральном параличе – , деформация грудины;

- нарушение тонуса мышечных структур. У больного ребёнка наблюдается либо спастическое напряжение, либо же полная гипотония. Если имеет место гипертонус, то конечности принимают неестественное для них положение. При гипотонии ребёнок слабый, наблюдается тремор, он может часто падать, так как мышечные структуры ног не поддерживают его тело;

- выраженный болевой синдром. При детском церебральном параличе он развивается вследствие различных деформаций костей. Боль имеет чёткую локализацию. Чаще он возникает в плечах, спине и шее;

- нарушение физиологического процесса глотания еды. Этот признак детского церебрального паралича можно выявить сразу после рождения. Младенцы не могут полноценно сосать материнскую грудь, а груднички не пьют из бутылочки. Этот симптом возникает из-за пареза мышечных структур глотки. Также из-за этого возникает слюнотечение;

- нарушение речевой функции. Возникает из-за пареза голосовых связок, горла, губ. Иногда эти элементы поражаются одновременно;

- судорожный синдром. Судороги проявляются в любое время и в любом возрасте;

- хаотичные патологически движения. Ребёнок совершает резкие движения, может гримасничать, принимать определённые позы и прочее;

- контрактуры суставных сочленений;

- значительное или умеренное снижение слуховой функции;

- задержка развития. Данный симптом детского церебрального паралича встречается не у всех больных детей;

- снижение зрительной функции. Чаще возникает и косоглазие;

- сбой работы органов ЖКТ;

- больной непроизвольно выделяет экскременты и урину;

- прогрессирование эндокринных недугов. У детей с таким диагнозом часто диагностируют , дистрофию, задержку роста, .

Осложнения

ДЦП является хроническим недугом, но со временем он не прогрессирует. Состояние пациента может усугубиться, если возникнут вторичные патологии, такие как , кровоизлияния, соматические недуги.

Осложнения ДЦП:

- инвалидизация;

- нарушение адаптации в социуме;

- возникновение мышечных контрактур;

- нарушение потребления еды, так как парез поразил мышцы глотки.

Диагностические мероприятия

Диагностикой недуга занимается невролог. Стандартный план диагностики включает в себя такие методы обследования:

- тщательный осмотр. Медицинский специалист оценивает рефлексы, остроту зрения и слуха, мышечные функции;

- электроэнцефалография;

- электронейрография;

- электромиография;

Дополнительно больного могут направить на консультации к узким специалистам:

- логопед;

- офтальмолог;

- психиатр;

- эпилептолог.

Лечебные мероприятия

Сразу стоит сказать, что такую патологию полностью излечить невозможно. Поэтому лечение ДЦП в первую очередь направлено на уменьшение проявления симптомов. Специальные реабилитационные комплексы дают возможность постепенно развить речь, интеллектуальные и двигательные навыки.

Реабилитационная терапия состоит из таких мероприятий:

- занятия с логопедом. Необходимы, чтобы у больного ребёнка нормализовалась речевая функция;

- ЛФК. Комплекс упражнений разрабатывает только специалист строго индивидуально для каждого пациента. Их необходимо выполнять ежедневно, чтобы они оказали необходимый эффект;

- массаж при ДЦП является очень эффективным методом реабилитации. Врачи прибегают к сегментарному, точечному и классическому видам. Массаж при ДЦП должен проводить только высококвалифицированный специалист;

- использование технических средств. К таковым относят костыли, специальные вставки, помещаемые в обувь, ходунки и прочее.

Физиотерапевтические методы и анималотерапию также активно применяют в лечении ДЦП:

- водолечение;

- оксигенобаротерапия;

- лечение грязями;

- электростимуляция;

- прогревание тела;

- электрофорез с фармацевтическими препаратами;

- дельфинотерапия;

- иппотерапия. Это современный метод лечения, основанный на общении больного с лошадьми.

Медикаментозная терапия:

- если у ребёнка отмечаются эпилептические припадки различной степени интенсивности, то ему обязательно назначают противосудорожные препараты, чтобы купировать приступы;

- ноотропные фармацевтические средства. Основная цель их назначения – нормализация обращения крови в мозге;

- миорелаксанты. Данные фармацевтические средства пациентам назначают, если у них наблюдается гипертонус мышечных структур;

- метаболические средства;

- противопаркинсонические лекарственные средства;

- антидепрессанты;

- нейролептики;

- спазмолитики. Эти препараты больному назначают при сильном болевом синдроме;

- анальгетики;

- транквилизаторы.

К операбельному лечению детского церебрального паралича медицинские специалисты прибегают только в тяжёлых клинических ситуациях, когда консервативная терапия не оказывает желаемого эффекта. Прибегают к таким видам вмешательств:

- операции на мозге. Врачи осуществляют деструкцию структур, которые являются причиной прогрессирования неврологических нарушений;

- спинальная ризотомия. К данному операбельному вмешательству врачи прибегают в случае сильного мышечного гипертонуса и выраженного болевого синдрома. Её суть заключается в прерывании патологической импульсации, которая исходит из спинного мозга;

- тенотомия. Суть операции состоит в создании опорного положения поражённой конечности. Её назначают, если у пациента формируются контрактуры;

- иногда специалисты осуществляют пересадку сухожилий или костей, чтобы хоть немного стабилизовать скелет.

О таком заболевании, как детский церебральный паралич, каждый слышал хотя бы раз, хотя, возможно, и не сталкивался. Что такое ДЦП в общем плане? Понятие объединяет группу хронических двигательных расстройств, которые возникают вследствие повреждения мозговых структур, и происходит это до появления на свет, в предродовой период. Нарушения, наблюдаемые при параличе, могут быть разные.

Болезнь ДЦП – что это такое?

Церебральный паралич – заболевание нервной системы, возникающее в результате поражения головного мозга: ствола, коры, подкорковых областей, капсул. Патология нервной системы ДЦП у новорожденных не является наследственной, но некоторые генетические факторы в ее развитии участвуют (максимум в 15% случаев). Зная, что такое ДЦП у детей, врачи умеют вовремя его диагностировать и предотвращать развитие болезни в перинатальный период.

Патология включает различные расстройства: параличи и парезы, гиперкинезы, изменения мышечного тонуса, нарушения речи и координации движений, отставание в моторном и психическом развитии. Традиционно принято разделять болезнь ДЦП на формы. Основных пять (плюс неутонченная и смешанная):

- Спастическая диплегия

– самый распространенный тип патологии (40% случаев), при котором нарушены функции мышц верхних или нижних конечностей, позвоночник и суставы деформированы. - Спастическая тетраплегия

, частичная или полная парализация конечностей – одна из самых тяжелых форм, выраженная в чрезмерном напряжении мышц. Человек не в состоянии управлять ногами и руками, страдает от болей. - Гемиплегическая форма

характеризуется ослаблением мышц лишь одной половины тела. Рука на пораженной стороне страдает больше, чем нога. Распространенность – 32%. - Дискинетическая (гиперкинетическая) форма

иногда встречается при других видах ДЦП. Выражается в появлении непроизвольных движений в руках и ногах, мышцах лица и шеи. - Атаксическая

– форма церебрального паралича, проявляющаяся в пониженном мышечном тонусе, атаксии (несогласованности действий). Движения заторможенные, равновесие сильно нарушено.

Детский церебральный паралич – причины возникновения

Если развивается одна из форм ДЦП, причины возникновения могут быть разными. Они оказывают влияние на развитие плода в период беременности и первый месяц жизни малыша. Серьезный фактор риска – . Но главную причину не всегда можно определить. Основные процессы, приводящие к тому, что такое заболевание, как ДЦП развивается:

- и ишемические поражения. От недостатка кислорода страдают те участки мозга, которые отвечают на обеспечение двигательных механизмов.

- Нарушение развития мозговых структур.

- с развитием гемолитической желтухи новорожденных.

- Патологии беременности ( , ). Иногда, если развивается ДЦП, причины кроются в перенесенных заболеваниях матери: сахарном диабете, пороках сердца, гипертензии и др.

- вирусные, например, герпес.

- Врачебная ошибка во время ведения родов.

- Инфекционные и токсические поражения мозга в младенчестве.

ДЦП – симптомы

Когда возникает вопрос: что такое ДЦП, сразу приходит на ум патология с нарушениями двигательной активности и речи. На самом деле почти у трети детей с данным диагнозом развиваются другие генетические заболевания, которые похожи на церебральный паралич лишь внешне. Первые признаки ДЦП можно выявить сразу после рождения. Основные симптомы, проявляющиеся в первые 30 дней:

- отсутствие поясничного изгиба и складок под ягодицами;

- видимая асимметрия туловища;

- тонус мышц или их ослабление;

- неестественные, замедленные движения малыша;

- подергивания мышц с частичной парализацией;

- потеря аппетита, тревожность.

Впоследствии, когда ребенок начинает активно развиваться, патология проявляет себя отсутствием необходимых рефлексов и реакций. Младенец не держит головку, остро реагирует на прикосновения и не реагирует на шум, совершает однотипные движения и принимает неестественные позы, с трудом сосет грудь, проявляет чрезмерную раздражительность или вялость. До трехмесячного возраста поставить диагноз реально, если внимательно следить за развитием малыша.

Стадии ДЦП

Чем раньше диагностируют патологию, тем больше шансов на полное излечение. Заболевание не прогрессирует, но все зависит от степени поражения мозга. Стадии ДЦП у детей делятся на:

- раннюю, симптомы которой проявляются у грудничков до 3 месяцев;

- начальную резидуальную (остаточную), соотносящуюся с возрастом от 4 месяцев до трех лет, когда складывается, но не зафиксированы патологически двигательный и речевой стереотипы;

- позднюю резидуальную, для которой характерен набор проявлений, не выявляемых в более раннем возрасте.

Не всегда диагноз ДЦП гарантирует инвалидность и несостоятельность, но комплексную терапию важно начать вовремя. У мозга грудничка больше возможностей для восстановления его функций. Основная задача лечения в детском возрасте – развитие по максимуму всех умений и навыков. На раннем этапе сюда входит коррекция двигательных расстройств, гимнастика и массаж, стимуляция рефлексов. Усилия врачей направлены на купирование патологий, могут назначаться:

- препараты для снижения ;

- стимулирующие лекарства для развития ЦСН;

- витаминотерапия;

- физиотерапия.

Можно ли вылечить ДЦП?

Главный вопрос, волнующий родителей больного малыша: можно ли вылечить ДЦП у ребенка полностью? Нельзя однозначно это заявить, особенно когда изменения произошли в структурах мозга, но болезнь поддается коррекции. В возрасте до 3-х лет в 60-70% случаев удается восстановить нормальную работу мозга и особенно двигательных функций. Со стороны родителей важно не пропустить первые симптомы, не игнорировать проявление отклонений во время беременности и родов.

Основная задача врачей, занимающихся ребенком с ДЦП – не столько излечить, сколько адаптировать пациента. Малыш должен реализовать свои возможности в полной мере. Лечение подразумевает медикаментозную и другие виды терапии, а также обучение: развитие эмоциональной сферы, совершенствование слуха и речи, социальную адаптацию. При диагнозе детский церебральный паралич лечение не может быть однозначным. Все зависит от сложности и локализации поражения.

Массаж при детском церебральном параличе

Понимая, что такое ДЦП и как важно своевременно начать реабилитацию, родители малыша должны регулярно проходить с ним курсы лечебного массажа и ЛФК. Ежедневные процедуры не только при посещении врача, но и на дому – залог успеха. Больные ДЦП получают от массажа огромную пользу: лимфоток и кровоток улучшаются, активируется обмен веществ, поврежденные мышцы расслабляются или стимулируются (в зависимости проблемы). Массаж должен проводиться на определенных группах мышц и сочетается с дыхательными движениями. Классическая техника для расслабления:

- Поверхностные и легкие движения массажиста, поглаживание кожи.

- Катание плечевых мышц и тазобедренного сустава.

- Валяние больших мышечных групп.

- Растирание, в том числе сильное, всего тела, спины, ягодиц.

Особенности детей с ДЦП

Родителям бывает трудно принять диагноз, который поставлен их ребенку, однако здесь важно не опускать руки и направить все силы на реабилитацию и адаптацию малыша. При получении должного ухода и лечения люди с ДЦП чувствуют себя полноценными членами общества. Но важно понимать, что у каждого патология проявляется в индивидуальном порядке, это и определяет характер терапии, ее длительность и прогноз (положительный или не очень). Особенности развития детей с параличом обусловлены возникающими при координировании движений трудностями. Это проявляется в следующем:

- Замедленность движений, которая формирует дисбаланс развития мышления.

Возникают проблемы с освоением математики, так как деткам трудно считать. - Эмоциональные нарушения

– повышенная ранимость, впечатлительность, привязанность к родителям. - Измененная работоспособность ума.

Даже в случаях, когда интеллект развивается нормально и страдают только мышцы, ребенок не может переварить всю поступающую информацию так же быстро, как сверстники.

Уход за ребенком с ДЦП

Что важно учитывать и как ухаживать за ребенком с ДЦП в психическом и физическом плане? Последнее подразумевает соблюдение всех рекомендаций врача, занятие физкультурой, обеспечение полноценного сна, регулярные прогулки, игры, купания, занятия. Важно, чтобы ежедневные рутинные действия ребенок воспринимал, как дополнительное упражнение для закрепления образцов движений. В эмоциональном плане от родителей зависит будущее ребенка. Если проявлять жалость и чрезмерную опеку, малыш может замкнуться в себе, стремясь к развитию.

Правила такие:

- Не делать акцентов на особенностях поведения, которые вызваны болезнью.

- Проявления активности, напротив, поощрять.

- Формировать правильную самооценку.

- Побуждать к новым шагам к развитию.

Если ДЦП у новорожденных может никак не проявлять себя, то в более позднем возрасте различия заметны. Малышу трудно сохранять устойчивую позу лежа, сидя, координация движений нарушена. Опору подвижную и нет он может получить с помощью специального приспособления. Реабилитация детей с ДЦП (в т. ч. младенцев) подразумевает использование таких устройств:

- Клин

– треугольник из плотного материала, который располагают под грудью малыша для удобства лежания. Верхняя часть туловища приподнимается, ребенку проще контролировать положение головы, двигать руками и ногами. - Угловая доска

подразумевает фиксирование положения тела на боку. Предназначена для детей с тяжелыми нарушениями. - Стендер

наклонный необходим для освоения позы стоя. Ребенок находится под определенным углом наклона (он регулируется). - Стояк

– похож на стендер, но предназначен для детей, которые умеют удерживать положение туловища, но не способны стоять без поддержки. - Подвесные гамаки

, с помощью которых младенец способен удерживать таз и плечи на одном уровне, голову на средней линии. Пресекает попытки выгибания спинки. - Приспособления для игры

– мягкие валики, мячи надувные.

Развитие детей с ДЦП

Чтобы улучшить прогноз, необходимо помимо прохождения терапии практиковать развивающие занятия с детьми, ДЦП требует ежедневных упражнений: логопедических, подвижных, водных и т.д. С малышами полезно играть в игры, совершенствуя тактильные, слуховые, зрительные ощущения, развивая концентрацию. Фигурки животных и мячи – самые доступные и полезные игрушки. Но не меньше покупных изделий ребенка привлекают простые предметы:

- пуговицы;

- обрезки ткани;

- бумага;

- посуда;

- песок;

- вода и т.д.

ДЦП – прогноз

Если поставлен диагноз ДЦП, прогноз для жизни, как правило, благоприятный. Больные могут стать нормальными родителями и доживают до глубокой старости, хотя продолжительность жизни может быть снижена из-за психического недоразвития, развитием вторичного недуга – эпилепсии, и отсутствии социальной адаптации в обществе. Если вовремя начать лечение, можно добиться почти полного выздоровления.

Что такое ДЦП? Неприятная, но не смертельная патология, с которой есть шанс жить полноценной жизнью. По статистике, 2-6 из 1000 новорожденных страдают церебральным параличом и вынуждены проходить пожизненную реабилитацию. Развитие осложнено, но большинство пациентов (до 85%) имеют легкую и среднюю форму недуга и ведут полноценный образ жизни. Гарантия успеха: поставленный в детском возрасте диагноз и прохождение полного комплекса мероприятий – медикаментозной и физиотерапии, регулярных занятий дома.

Диагноз, который пугает всех и каждого — детский церебральный паралич. Причины, формы ДЦП — эти вопросы волнуют любого современного родителя, если во время вынашивания ребенка доктор говорит о высокой вероятности такого отклонения либо если пришлось столкнуться с ним уже после рождения.

О чем идет речь?

ДЦП — термин собирательный, его применяют к нескольким типам и видам состояний, при которых страдают опорная система человека и возможности двигаться. Причина врожденного ДЦП — повреждение мозговых центров, ответственных за возможность совершения различных произвольных передвижений. Состояние больного неумолимо регрессирует, рано или поздно патология становится причиной мозговой дегенерации. Первичные нарушения происходят еще во время развития плода в материнском организме, несколько реже ДЦП объясняется особенностями родов. Есть риск, что причиной ДЦП окажутся некоторые события, произошедшие с ребенком вскоре после рождения и негативно повлиявшие на здоровье головного мозга. Оказать такое воздействие могут внешние факторы только в ранний период после рождения.

Уже сегодня докторам известно огромное количество факторов, способных спровоцировать ДЦП. Причины разнообразны, а защитить от них свое чадо не всегда легко. Впрочем, из медицинской статистики видно, что чаще всего диагноз ставят недоношенным детишкам. До половины всех случаев с ДЦП — малыши, рожденные раньше срока. Эта причина считается самой значимой.

Факторы и риски

Раньше из причин, почему дети рождаются с ДЦП, первой и самой главной считали травму, полученную в момент появления на свет. Спровоцировать ее могут:

- слишком быстрое рождение;

- технологии, методы, применяемые акушерами;

- зауженный материнский таз;

- неправильная тазовая анатомия матери.

В настоящее время врачам доподлинно известно, что родовые травмы приводят к ДЦП лишь в крайне малом проценте случаев. Преимущественная доля — это специфика развития ребенка во время нахождения в материнской утробе. Считавшаяся ранее основной причиной возникновения ДЦП проблема родов (к примеру, затяжных, очень тяжелых) сейчас классифицируется как последствие нарушений, произошедших во время вынашивания ребенка.

Рассмотрим это подробнее. Современные врачи, выясняя с ДЦП, проанализировали статистику влияния аутоиммунных механизмов. Как удалось выявить, некоторые факторы оказывают значимое воздействие на формирование тканей на этапе появления эмбриона. Современная медицина считает, что это — одна из причин, объясняющих немалый процент случаев отклонений здоровья. Аутоиммунные нарушения влияют не только во время нахождения в материнском организме, но и воздействуют на ребенка после родов.

Вскоре после рождения прежде здоровый ребенок может стать жертвой ДЦП в силу инфицирования, на фоне которого развился энцефалит. Спровоцировать беду могут:

- корь;

- ветряная оспа;

- грипп.

Известно, что к основным причинам ДЦП относится гемолитическая болезнь, проявляющаяся себя желтухой в силу недостаточности функционирования печени. Иногда у ребенка выявляется резус-конфликт, который также может спровоцировать ДЦП.

Далеко не всегда удается определить причину, почему дети рождаются с ДЦП. Отзывы врачей неутешительны: даже МРТ и КТ (самые эффективные и точные методы исследования) не всегда могут предоставить достаточно данных для формирования цельной картины.

Сложность вопроса

Если человек отличается от окружающих, он привлекает к себе внимание — этот факт ни у кого не вызывает сомнений. Дети, больные ДЦП — это всегда объект интереса окружающих, от обывателей до профессионалов. Особенная сложность заболевания — в его влиянии на весь организм. При ДЦП страдает возможность контролировать собственное тело, так как нарушается функциональность ЦНС. Конечности, мышцы лица не подчиняются больному, и это сразу бросается в глаза. При ДЦП у половины всех пациентов также отмечаются задержки развития:

- речи;

- интеллекта;

- эмоционального фона.

Нередко ДЦП сопровождается эпилепсией, судорожностью, тремором, неправильно сформированным телом, непропорциональными органами — пораженные участки растут и развиваются значительно медленнее здоровых элементов организма. У некоторых больных нарушается зрительная система, у других ДЦП — причина психических, слуховых, глотательных нарушений. Возможен неадекватный мышечный тонус или проблемы с мочеиспусканием, дефекацией. Сила проявлений определяется масштабностью нарушения мозговой функциональности.

Важные нюансы

Известны такие случаи, когда больные успешно адаптировались к социуму. Им доступна нормальная человеческая жизнь, полноценная, наполненная событиями, радостями. Возможен и другой вариант развития событий: если при ДЦП пострадали довольно большие участки головного мозга, это станет причиной присвоения статуса инвалида. Такие дети полностью зависят от окружающих, по мере взросления зависимость не становится слабее.

В некоторой степени будущее ребенка зависит от его родителей. Известны некоторые подходы, методы, технологии, позволяющие стабилизировать и улучшить состояние больного. В то же время не стоит рассчитывать на чудо: причина ДЦП — поражение ЦНС, то есть излечению болезнь не поддается.

Со временем у некоторых детей симптоматика ДЦП становится все шире. Врачи расходятся во мнении, можно ли считать это прогрессом болезни. С одной стороны, первопричина не меняется, но ребенок со временем пытается освоить новые умения, зачастую сталкиваясь с неудачей на этом пути. Встретившись с ребенком с ДЦП, не стоит его опасаться: болезнь не передается от человека к человеку, не наследуется, поэтому фактически единственная ее жертва — это сам пациент.

Как заметить? Основные симптомы ДЦП

Причина возникновения нарушения — сбой в работе ЦНС, приводящий к дисфункции двигательных мозговых центров. Впервые симптоматику можно заметить у малыша в трехмесячном возрасте. Такой ребенок:

- развивается с задержкой;

- ощутимо отстает от сверстников;

- страдает судорожностью;

- совершает странные, несвойственные малышам движения.

Отличительная особенность столь раннего возраста — повышенные мозговые компенсаторные возможности, поэтому терапевтический курс будет в большей степени эффективен, если получится поставить диагноз рано. Чем позднее выявят болезнь, тем хуже прогноз.

Причины и дискуссии

Причина возникновения основных симптомов ДЦП — нарушение в работе мозговых центров. Спровоцировать это могут разнообразные повреждения, сформировавшиеся под влиянием широкого спектра факторов. Некоторые появляются еще во время развития в материнском организме, другие — при рождении и вскоре после. Как правило, ДЦП развивается лишь на первом году жизни, но не позднее. В большинстве случаев выявляется дисфункция следующих мозговых участков:

- кора;

- область под корой;

- мозговой ствол;

- капсулы.

Есть мнение, что при ДЦП страдает функциональность спинного мозга, но подтверждения в настоящий момент нет. Травмы спинного мозга установлены лишь у 1 % больных, поэтому нет возможности провести достоверные исследования.

Дефекты и патологии

Одна из самых часто встречающихся причин диагноза ДЦП — дефекты, полученные в период внутриутробного развития. Современные врачи знают следующие ситуации, при которых высока вероятность отклонений:

- миелинизация медленнее нормы;

- неправильное деление клеток нервной системы;

- нарушение связей между нейронами;

- ошибки формирования сосудов;

- отравляющее воздействие непрямого билирубина, приведшее к повреждению тканей (наблюдается при конфликте резус-факторов);

- инфицирование;

- рубцы;

- новообразования.

В среднем у восьми детей из десяти больных причина возникновения ДЦП — одна из указанных.

Особенно опасными инфекциями считаются токсоплазмоз, грипп, краснуха.

Известно, что ребенок с ДЦП может родиться у женщины, страдающей следующими болезнями:

- сахарный диабет;

- сифилис;

- патологии сердца;

- сосудистые заболевания.

И инфекционные, и хронические патологические процессы в материнском организме — возможные причины возникновения ДЦП у ребенка.

Материнский организм и плод могут обладать конфликтующими антигенами, резус-факторами: это приводит к тяжелым нарушениям здоровья ребенка, включая ДЦП.

Повышены риски, если во время беременности женщина принимает лекарства, способные отрицательно влиять на плод. Аналогичные опасности связаны с употреблением спиртного и куренем. Выясняя, что является причиной ДЦП, врачи установили, что чаще такие дети рождаются у женщин, если роды перенесены в возрасте до совершеннолетнего или старше сорокалетнего. В то же время нельзя говорить о том, что перечисленные причины гарантированно спровоцируют ДЦП. Все они лишь повышают риск отклонений, являются признанными закономерностями, учитывать которые нужно, планируя ребенка и вынашивая плод.

Нечем дышать!

Гипоксия — часто встречающаяся причина возникновения ДЦП у детей. Лечение патологии, если она спровоцирована именно нехваткой кислорода, ничем не отличается от прочих причин. Как такового выздоровления со временем не будет, но при раннем обнаружении признаков можно начать адекватный курс реабилитации пациента.

Гипоксия возможна и при вынашивании плода, и при родах. Если вес ребенка меньше нормы, есть все основания предполагать, что гипоксия сопровождала определенный этап беременности. Спровоцировать состояние могут болезни сердца, сосудов, эндокринных органов, заражение вирусом, почечные нарушения. Иногда гипоксия провоцируется токсикозом в тяжелой форме или на поздних сроках. Одна из причин ДЦП у детей — нарушение кровотока в малом тазу матери во время вынашивания чада.

Перечисленные факторы отрицательно влияют на снабжение плаценты кровью, из которой клетки эмбриона получают питательные компоненты и кислород, жизненно важные для правильного развития. При нарушении кровотока метаболизм ослабевает, эмбрион развивается медленно, есть вероятность малого веса или роста, нарушения функциональности разных систем и органов, включая ЦНС. Говорят о недостаточности веса, если новорожденный весит 2,5 кг и меньше. Существует классификация:

- рожденные до 37 недели гестации дети с адекватным для своего возраста весом;

- недоношенные детишки с маленькой массой;

- рожденные вовремя или позднее срока дети с малым весом.

О гипоксии, задержке развития говорят только применительно к двум последним группам. Первая считается нормой. Для недоношенных, рожденных вовремя и позднее срока детей с недостатком массы риск развития ДЦП оценивается достаточно высоким.

Здоровье ребенка зависит от матери

Преимущественно причины ДЦП у детей обусловлены периодом развития в материнском организме. Аномалии у плода возможны под влиянием разных факторов, но чаще всего причиной становятся:

- развитие диабета (нарушения в среднем — у трех детей из ста рожденных у матерей, страдавших гестационным диабетом);

- нарушения в работе сердца и сосудов (инфаркт, резкие изменения уровня давления);

- инфекционный агент;

- физическая травма;

- отравление в острой форме;

- стресс.

Один из факторов опасности — многоплодная беременность. Эта причина ДЦП у новорожденных имеет следующее объяснение: при вынашивании нескольких эмбрионов сразу материнский организм сталкивается с повышенными показателями нагрузки, а значит, существенно выше вероятность рождения детей раньше срока, с малым весом.

Появление на свет: не все так просто

Распространенная причина ДЦП у новорожденных — родовая травма. Несмотря на стереотипы, гласящие, что это возможно лишь в случае ошибки акушера, на практике травмы гораздо чаще объясняются особенностями материнского или детского организма. К примеру, у роженицы может быть очень узкий таз. Возможна и другая причина: ребенок очень крупный. Во время появления на свет организм чада может пострадать, нанесенный ему вред становится причиной разнообразных болезней. Нередко наблюдаются клинические проявления ДЦП у новорожденных детей по причинам:

- неправильное положение эмбриона в матке;

- помещение головы в таз по неправильной оси;

- слишком быстрые или очень продолжительные роды;

- использование неподходящих принадлежностей;

- ошибки акушера;

- асфиксия по разным причинам.

В настоящее время одним из наиболее безопасных вариантов рождения считается кесарево сечение, но даже такой подход не может гарантировать отсутствия родовой травмы. В частности, есть вероятность повреждения позвонков шеи или груди. Если при рождении прибегали к кесареву сечению, необходимо вскоре после родов показать младенца остеопату для проверки адекватности состояния позвоночника.

В среднем ДЦП встречается у двух девочек из тысячи, а для мальчиков частота немногим выше — три случая на тысячу младенцев. Бытует мнение, что такая разница объясняется большим размером тела мальчиков, а значит, риск получения травмы выше.

В настоящее время от ДЦП застраховаться невозможно, как нет стопроцентной гарантии его предусмотреть, предупредить. Во внушительном проценте случаев причины приобретенного ДЦП, врожденного удается установить уже постфактум, когда аномалии проявляют себя в развитии ребенка. В некоторых случаях уже во время беременности есть признаки, указывающие на вероятность ДЦП, но в своей основной массе они не поддаются коррекции либо устраняются лишь с большим трудом. И все же отчаиваться не стоит: с ДЦП можно жить, можно развиваться, быть счастливым. В современном обществе довольно активно продвигается реабилитационная программа для таких детишек, совершенствуется оборудование, а значит, отрицательное воздействие болезни смягчается.

Актуальность вопроса

Статистические исследования показывают, что в среднем в возрасте до года ДЦП диагностируют с частотой до 7 из тысячи детей. В нашей стране средние статистические показатели — до 6 на тысячу. Среди недоношенных частота встречаемости приблизительно в десять раз больше относительно средней по миру. Врачи считают, что ДЦП — первая беда среди хронических болезней, поражающих детишек. В некоторой степени болезнь связана с ухудшением экологии; определенным фактором признается неонатология, поскольку даже дети, чей вес — всего лишь 500 г, в больничных условиях могут выжить. Безусловно, это настоящий прогресс науки и техники, но вот частота ДЦП среди таких детей, к сожалению, существенно выше среднего, поэтому важно не просто научиться выхаживать весящих столь мало детей, но и разработать способы обеспечения им полноценной, здоровой жизни.

Особенности болезни

Выделяют пять типов ДЦП. Чаще всего встречается спастическая диплегия. Разные специалисты оценивают частоту таких случаев в 40-80% от общего количества диагнозов. Такой тип ДЦП устанавливают, если поражения мозговых центров становятся причиной парезов, от которых в первую очередь страдают нижние конечности.

Одна из форм ДЦП — поражение двигательных центров в одной половине мозга. Это позволяет установить гемипаретический тип. Парезы свойственны только одной половине тела, противоположной тому мозговому полушарию, которое пострадало от агрессивных факторов.

До четверти всех случаев — это гиперкинетический ДЦП, обусловленный нарушением деятельности подкорки головного мозга. Симптоматика болезни — непроизвольные движения, активизирующиеся, если больной устал или взволнован.

Если нарушения сконцентрированы в мозжечке, диагноз звучит как «атонически-астатический ДЦП». Болезнь выражена статическими нарушениями, атонией мышц, невозможностью координации движений. В среднем такой тип ДЦП выявляют у одного больного из десяти пациентов.

Самый сложный случай — двойная гемиплегия. ДЦП обусловлен абсолютным нарушением функциональности полушарий мозга, в силу чего мышцы ригидны. Такие дети не могут сидеть, стоять, держать головку.

В некоторых случаях ДЦП развивается по комбинированному сценарию, когда одновременно появляется симптоматика разных форм. Чаще всего сочетаются гиперкинетический тип и спастическая диплегия.

Все индивидуально

Степень выраженности отклонений при ДЦП различна, а клинические проявления зависят не только от локализации больных мозговых областей, но и от глубины нарушений. Известны такие случаи, когда уже в первые часы жизни видны проблемы здоровья малыша, но в большинстве случаев можно поставить диагноз лишь спустя несколько месяцев после рождения, когда заметно отставание в развитии.

Заподозрить ДЦП можно, если ребенок не успевает в двигательном развитии за сверстниками. Довольно долго малыш не может обучиться держать головку (в некоторых случаях этого так и не происходит). Ему неинтересны игрушки, он не пытается перевернуться, осознанно шевелить конечностями. При попытке дать ему игрушку ребенок не пытается ее удержать. Если поставить чадо на ноги, оно не сможет встать на стопу полностью, а попытается подняться на цыпочки.

Возможны парезы отдельной конечности или одной стороны, могут пострадать все конечности сразу. Органы, ответственные за речь, недостаточно качественно иннервированы, а значит, произношение дается с трудом. Иногда при ДЦП диагностируется дисфагия, то есть невозможность проглатывать пищу. Это возможно, если парезы локализованы в глотке, гортани.

При значительной мышечной спастичности пораженные конечности могут быть абсолютно неподвижными. Такие части тела отстают в развитии. Это приводит к видоизменению скелета — деформируется грудная клетка, искривляется позвоночник. При ДЦП в пораженных конечностях выявляют контрактуры суставов, а значит, нарушения, связанные с попытками движения, становятся еще более существенными. Большинство детей с ДЦП страдают достаточно сильными болями, объясняющимися нарушениями скелета. Наиболее выражен синдром в шее, плечах, ступнях, спине.

Проявления и симптомы

На гиперкинетическую форму указывают внезапные движения, которые пациент не может контролировать. Некоторые поворачивают голову, кивают, гримасничают или подергиваются, принимают вычурные позы, совершают странные движения.

При атонической астатической форме больной не может координировать движения, при попытке ходьбы неустойчив, часто падает, не может поддерживать равновесие стоя. Такие люди чаще страдают треморами, а мышцы очень слабые.

ДЦП часто сопровождается косоглазием, желудочно-кишечными нарушениями, дыхательной дисфункцией и недержанием мочи. До 40 % больных страдают эпилепсией, а у 60 % ослаблено зрение. Некоторые плохо слышат, другие вовсе не воспринимают звуки. До половины всех больных имеют нарушения в работе эндокринной системы, выраженные сбоем гормонального фона, излишками веса, задержкой роста. Нередко при ДЦП выявляют олигофрению, замедленное психическое развитие, снижение возможности обучаться. Для многих пациентов характерны поведенческие отклонения и расстройства восприятия. До 35% больных отличаются нормальным уровнем интеллекта, а у каждого третьего умственные нарушения оцениваются как легкая степень.

Болезнь хроническая, вне зависимости от формы. Когда больной становится взрослее, постепенно проявляются скрытые ранее патологические нарушения, что воспринимается ложным прогрессом. Нередко ухудшение состояния объясняется вторичными сложностями со здоровьем, поскольку при ДЦП часты:

- инсульты;

- соматические болезни;

- эпилепсия.

Нередко диагностируют кровоизлияния.

Как обнаружить?

Пока не удалось разработать таких тестов и программ, которые бы позволили доподлинно установить ДЦП. Некоторые типичные проявления болезни привлекают внимание врачей, благодаря чему болезнь удается выявить на раннем этапе жизни. Предположить ДЦП можно по низкому баллу по шкале Апгар, по нарушениям тонуса мышц и двигательной активности, отставанию, отсутствию контакта с ближайшим родственником — больные не реагируют на мать. Все эти проявления — повод для детального обследования.

Значения аббревиатуры

ИКСИ РАН

- Институт комплексных социальных исследований Российской академии наук

Значения аббревиатуры

медучасток

- медицинский участок

Значения аббревиатуры

КСИВ

- «Краткие сообщения Института востоковедения»

Значения аббревиатуры

ТТЭС

- Ташкентская тепловая электростанция

- технико-технологический экспертный совет

Значения аббревиатуры

КСМБ

- Коммунистический Союз Молодёжи Белоруссии

Значения аббревиатуры

СДПБ

- Объединённая социал-демократическая партия благосостояния

Значения аббревиатуры

ПМК-10

- «Передвижная механизированная колонна № 10»

Значения аббревиатуры

райпромсовет

- районный совет промысловой кооперации

Значения аббревиатуры

КЛЕН

- Кировский лицей естественных наук

- «клянусь любить его (её) навек»

- «кого люблю — ебать не стану»

- Лицей естественных наук города Кирова

Значения аббревиатуры

МОЛГН

- межобластная лаборатория государственного надзора за стандартами и измерительной техникой

Значения аббревиатуры

УФСС

- Украинская федерация спорта с собаками

Значения аббревиатуры

инстр.

- инструктор

- инструкция

- инструмент

- инструментальный

Значения аббревиатуры

ОУНТ

- однослойная углеродная нанотрубка

- одностенная углеродная нанотрубка

Значения аббревиатуры

МОУП

- международная организация уголовной полиции

- Международный открытый университет Поволжья

- минское областное унитарное предприятие

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры ОСКИ

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры идиот

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры ГИОХИН АН СССР

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры УНИА

Всего значений: 2

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры НИЧ МТУСИ

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры Инфотранс

Всего значений: 2

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры ЦГАОО

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры АПГНТМ

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры УП

Всего значений: 41

(показано 5)

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры УЗВС

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры ЗРАДн

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры МАВИАЛ

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры ширик

Всего значений: 1

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры КФ

Всего значений: 38

(показано 5)

Случайная аббревиатура

Значения аббревиатуры Главширпотреб

Всего значений: 1

Справочник по формулированию клинического диагноза болезней нервной системы (Шток, Левин, 2006)

Глава 20. Заболевания мышц и нервно-мышечной передачи

Примечание. В данной подрубрике может кодироваться рабдомиолиз, иди опатический или вторичный (осложнение полиомиелита, дерматомиозита, лекарственной миопатии, метаболических миопатии, полимиозита)

|

G73.7* |

Миопатия при других болез |

ОФД. Вторичная миопатия (мио- |

|

нях, классифицированных в |

патический синдром) с указанием |

|

|

других рубриках |

основного заболевания |

|

Примечание. В данной подрубрике может кодироваться миопатия при амилоидозе (Е85.- +), карциноидном синдроме (Е34.0+), алиментарной недо статочности (Е40-Е64+), остеомаляции (М83.- +), дефиците витамина D (Е55.- +), травме и ишемии (Т79.6+)

|

G72.9 |

Миопатия неуточненная |

Код для статистического учета не |

|

уточненных случаев миопатии |

||

(лава 21 Детский церебральный паралич

Детский церебральный паралич (ДЦП) — заболевание, характеризу ющееся непрогрессирующим поражением головного мозга, возни кающим до родов, во время родов либо сразу после них и преимуще ственно проявляющимся двигательными нарушениями (параличами, нарушением координации, непроизвольными движениями).

Д Ц П может возникать под влиянием различных экзогенных и эндогенных факторов, которые могут взаимодействовать между собой. Таким образом, Д Ц П можно рассматривать как мультифакториальное заболевание. Причиной Д Ц П могут быть внутриутробные инфекции, внутриутробная гипоксия (например, вследствие нару шения плацентарного кровообращения), несовместимость матери и плода по резус-фактору с развитием ядерной желтухи, преждевре менные роды и родовая травма, гипоксия и асфиксия во время удли ненных или осложненных родов, травмы, сосудистые повреждения, инфекции в послеродовом периоде. У большинства больных реша ющее значение имеет не родовая травма, а пренатальные факторы, действующие во внутриутробном периоде и нередко повышающие чувствительность плода к действию неблагоприятных факторов во

Глава 21. Детский церебральный паралич

время родов. У значительной части больных причина развития Д Ц П остается неизвестной.

Наряду с двигательными нарушениями (параличи, насильствен ные движения, нарушение координации движений, задержка мо торного развития с персистированием примитивных рефлексов и формированием патологических позных установок) часто отмеча ется задержка психического развития с формированием умственной отсталости, аутизм, эпилептические припадки, глазодвигательные нарушения (косоглазие, нистагм, паралич взора). Клинические про явления полиморфны и зависят от характера и степени нарушения развития и патологических изменений мозга.

Выделяют шесть основных форм Д Ц П :

1.Спастическая диплегия (болезнь Литтла).

2.Гемиплегическая форма.

3.Двойная гемиплегия.

4.Гиперкинетическая форма.

5.Атактическая форма.

6.Атонически-астатическая форма.

ДЦ П кодируется в рубрике G80. В подрубриках G80.0-G80.9 представлены разные клинические формы Д Ц П . В развернутом ди агнозе дополнительно указываются названия клинических форм, перечисленные в подрубриках. Помимо двигательных нарушений, при решении вопросов оценки инвалидизации, социальной адапта ции и перспектив реабилитации большое значение имеет состояние когнитивных функций и интеллекта. Поэтому при наличии таких расстройств их особенности должны быть отражены в диагнозе (на пример, задержка умственного развития, выраженные когнитивные нарушения с указанием степени обучаемости).

|

МКБ-10 |

Предлагаемые общая формулировка |

||

|

диагноза (ОФД) и примеры |

|||

|

Код |

|||

|

Название болезни |

развернутой формулировки диагноза |

||

|

рубрик |

(ПРФД) |

||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

G80.0 |

Спастический церебральный |

ОФД. Та же, что и в МКБ-10 |

|

|

паралич |

ПРФД. Детский церебральный па |

||

|

ралич выраженным спастическим |

|||

Справочник по формулированию диагноза болезней нервной системы

Врожденный спастический тетрапарезом (двойная гемиплегия) паралич (церебральный) с формированием сгибательной контрактуры нижних конечностей, глубокой умственной отсталостью, частыми вторично-генерализован ными эпилептическими припад

ками

Примечание. В данной подрубрике по определению кодируются все случаи ДЦП с преобладанием спастического паралича, за исключением диплегической и гемиплегической форм (см. ниже). Таким образом, чаще всего эта рубрика используется по отношению к двойной гемиплегии.

Двойная гемиплегия — одна из самых тяжелых форм ДЦП, обычно свя занная с обширным повреждением головного мозга (вследствие внутрутробной инфекции, тяжелой родовой асфиксии и т. д.). Руки и ноги при этой форме поражаются примерно в равной степени, хотя у части больных функция рук страдает в большей степени, чем функция ног. Сразу по сле рождения отмечается диффузная мышечная гипотония, но в течение первого года жизни происходит повышение тонуса в мышцах туловища и конечностей. У большинства этих больных не удается добиться развития двигательных навыков, интеллекта, речи

|

G80.1 |

Спастическая диплегия |

ОФД. ДЦП, диплегическая форма |

|

ПРФД. ДЦП, диплегическая форма |

||

|

с выраженным нарушением функ |

||

|

ции нижних конечностей и легким |

||

|

нарушением функции верхних ко |

||

|

нечностей, умеренная дизартрия, |

||

|

умеренная задержка психомотор |

||

|

ного развития |

||