- Пол Мужской

- Происхождение имени

Русское

- Планета покровитель имени Венера

- Знак зодиака имени Козерог, Овен

- Цвет имени Синий Бордовый Индиго

- Значение имени в нумералогии 6

- Камни-талисманы для имени Гранат, Изумруд, Аметист, Агат, Александрит, Сердолик, Дымчатый Кварц.

Значение имени Детройт для человека, происхождение имени, судьба и характер человека с именем Детройт.

Национальность, перевод и правильное написание имени Детройт. Какие цвета, обереги, планеты покровители и знаки зодиака подходят имени Детройт?

Подробный анализ и описание имени Детройт вы сможете прочесть в данной статье абсолютно бесплатно.

Полный анализ имени Детройт, значение, и расшифровка по буквам

В имени Детройт 7 буквы. Это люди, которые придерживаются канонов. Они живут с внушенными при воспитании правилами, стараются никогда их не нарушать, для них это единственный путь, который ведет к счастью. Из-за этого они зачастую упрямы и нетерпимы, даже тогда, когда это совершенно неуместно. Скрытое значение и смысл имени Детройт можно узнать после анализа каждой буквы.

Формула для вычисления числа имени: Детройт

- Детройт. Д + Е + Т + Р + О + Й + Т

- 5 + 6 + 2 + 9 + 7 + 2 + 2

- Сумма — 33 Далее 3 + 3 = 6.

- Д — обдумывают последовательность действий, приступая к любой работе. Основным ориентиром является семья. Достаточно капризны, находят себя в благотворительности. Обладают скрытыми экстрасенсорными способностями, не желают развиваться внутренне, основной акцент люди с данной буквой делают на кратковременных положительных впечатлениях со стороны окружающих или близких людей.

- Е — любят самовыражаться, обмениваться опытом с окружающими людьми. Часто в конфликте это посредники. Достаточно болтливые личности, проницательны, имеют понимание о таинственном мире. Очень любят путешествовать и узнавать что-то новое, не задерживаются на одном месте надолго.

- Т — данные личности очень чувствительны к раздражителям и креативны. Наделены высоким уровнем интуиции, постоянно ищут истину, не умеют сопоставлять собственные возможности с желаниями. Им свойственно завершать поставленные задачи, не откладывая на другой день. Проявляют требовательность к себе и окружающим их людям. Находятся в поиске истины, но часто переоценивают свои возможности.

- Р — наделены уверенностью в себе, храбростью, могут противостоять внешнему воздействию, очень увлеченные особи. Склонны на неоправданный риск, это авантюрные личности, которые склоны к не опровергаемым высказываниям. Часто рискуют ради достижения цели, имеют потенциал и желание для становления лидерами.

- О — личности, связанные с данной буквой, могут испытывать сильнейшие чувства, стремятся узнать самого себя как можно лучше. Всегда в поиске своего истинного предназначения, совершенствуются сами и хотят усовершенствовать окружающий мир. Обладают достаточно хорошей интуицией, умеют грамотно распорядится финансами. Им свойственно переменчивое настроение от уныния к восторгу.

- Й — замкнутые люди, которым достаточно сложно найти общий язык с посторонними личностями. Мелочность – одна из черт их характера. Часто такие люди думают, что они уникальны и стараются везде себя проявить, данная идея живет в них до последнего дня.

- Т — данные личности очень чувствительны к раздражителям и креативны. Наделены высоким уровнем интуиции, постоянно ищут истину, не умеют сопоставлять собственные возможности с желаниями. Им свойственно завершать поставленные задачи, не откладывая на другой день. Проявляют требовательность к себе и окружающим их людям. Находятся в поиске истины, но часто переоценивают свои возможности.

Происхождение имени Детройт

История русского имени Детройт. Откуда произошло имя Детройт, и откуда вообще произошли большинство русских имен. В истории России и в её разные периоды будь то в средневековой Руси или Советского Союза, то и дело, появлялись новые имена, в дохристианское время были популярны имена Олег, Святослав, Мстислав, беляна, Млада, Забава, Велеслава, Болеслава, Добродея.

После того, как Русь крестили, вместе с религией вошли в обиход и новые имена, во множестве взятые из Византии (тогдашней Греции), которая была центром православия. После принятия православия в обиход активно вошли такие имена как: Антонина, Максимилиан, Василий, Варвара, Ангелина, Владислав и прочие.

На этой странице мы раскроем значение и смысл имени Детройт, а также выясним возможные перспективы и советы относительно развития человека в личной жизни и в его профессиональной деятельности.

Знаки зодиака для имени Детройт

Козерог – знак зодиака. Данный знак наделен умением пользоваться всеми прелестями жизни, склонны быть лидером, любят учиться чему-то новому и развиваться, твердо стоят на земле и идут на пролом к своей цели. Рисковать Козерог лишний раз не будет, может быть убежденным пессимистом и закрытой личностью из-за собственной неуверенности. Отдыхать и расслабляться полноценно такие люди не могут и считают это потраченным впустую временем. Советовать что-то Козерогу это плохая идея, он этого точно не оценит. Они всегда сами знают, как правильно поступить в какой-либо ситуации, при этом успевают учить окружающих и указывать на их ошибки. Отдаются работе по полной, так как тратить время впустую и стоять на месте попросту не умеют. А если все же посидеть без дела приходится Козерог начинает чахнуть. Вторую половинку выбирают прежде всего головой, поэтому обеспечивают себе долгую и счастливую семейную жизнь.

Овен – знак зодиака. Хотите увидеть настоящего безумца? Овен обладает огромнейшим запасом энергии, с желанием идти к победе, готов на подвиги и импульсивные решения. Проще говоря – баран. Эти люди самые упертые в мире. Даже если Ваша правота была доказана, и овен в нее поверил, собеседника все равно будут уверять в том, что он ошибается. Выиграть в споре просто невозможно, лучше не старайтесь, поберегите собственные нервные клетки, выслушайте, покивайте головой и больше не ввязывайтесь в подобный разговор. Овны не переносят конкуренцию, если кто-то из окружающих будет в каком-то аспекте превосходить Овна, он сделает все чтобы быть лучше оппонента.

Нумерология имени Детройт и его значение

Нумерология имени Детройт поможет Вам узнать характер и отличительные качества человека с таким именем.

Также можно узнать о судьбе, успехе в личной жизни и карьере, расшифровывать знаки судьбы и пробовать предсказывать будущее.

В нумерологии имени Детройт присвоено число – 6.

Девиз шестерок и этого имени в жизни: «Борьба за равенство и справедливость!».

Влияние имени Детройт на профессию

Влияние на карьеру и профессию. Какую роль шестерка играет при выборе дела всей жизни? Чтобы реализовать себя в профессии у таких людей есть много возможностей. Подойдет работа, которая будет близко связана с законом, судебной системой или благотворительностью.

Влияние имени Детройт на личную жизнь

Роль имени Детройт в личной жизни. Данное число говорит о том, что человек готов к долгим и стабильным отношениям с браке. Но это не значит, что личная жизнь сложится удачно. Первый опыт взаимоотношений с противоположным полом в четырех случаях из пяти будет неудачным и болезненным. Это происходит из-за того, что многие люди видят выгоду и не прочь воспользоваться добрым и наивным человеком. Шестерки ценят гармонию, спокойствие, умеют поддержать ближних, это и помогает им сойтись с практически любым характером. Таким людям идеально подойдут те же шестерки (данный союз получится действительно крепким), тройки, единицы, девятки и четверки.

Планета-покровитель для имени Детройт

Планета-покровитель имени Детройт – Венера. Представителям данного типа присуща чувственность и любвеобильность, так как их планете-покровителю также приписываются подобные качества. Их очаровательность помогает им в сложных ситуациях, где нужно показать изворотливость ума и твердость характера (данные качества не относятся к людям данного типа). Они трепетно относятся ко всему возвышенному и прекрасному, часто находят себя в творческих сферах или искусстве. Они не нуждаются в финансах, так как часто состоят в браке с состоятельным партнером, обладают привлекательностью и изысканным вкусом, любят все красивое, но бывают высокомерны. Стараются успевать за временем, познавать новое и учится, проявляют трудолюбие если нужно достичь поставленной цели. Их слабость – отдых душой и телом, характер уживчивый и миролюбивый. Найдут общий язык с человеком любого типа.

Правильное написание имени Детройт, на латинице и на кирилице

В русском языке, данное имя правильно писать так: Детройт

Если мы попробуем перевести данное имя на английский язык (транслитерация), у нас получится — detrojt

Правильное склонение имени Детройт по падежам

| Падеж | Падежный вопрос | Имя |

|---|---|---|

| Именительный | Кто? | Детройт |

| Родительный | Нет Кого? | Детройт |

| Дательный | Рад Кому? | Детройт |

| Винительный | Вижу Кого? | Детройт |

| Творительный | Доволен Кем? | Детройт |

| Предложный | О ком думаю? | Детройт |

Уважаемые гости нашего сайта!

Делитесь своим мнением относительно значения данного имени, если у вас есть какая-то информация об имени, которая не указана в статье — напишите о ней в комментариях ниже, и мы вместе с вами дополним историю этого замечального имени,

благодарим за ваш вклад в развитие нашего проекта!

Если Вам понравилось значение и описание имени Детройт? или у Вас есть знакомые с таким именем, опишите в комментариях — какая у них судьба, национальность и характер. Нам очень интересно ваше мнение!

Знаете ли Вы успешных или известных личностей по имени Детройт? Нам будет интересно обсудить с Вами значение имени Детройт в комментариях под этой статьей.

|

Detroit Détroit (French) |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

From top, left to right: skyline of Detroit; Book Tower; Renaissance Center; Fisher Building; Comerica Park; Ambassador Bridge; and Belle Isle Park |

|

|

Flag Seal Logo |

|

| Etymology: French: détroit (strait) | |

| Nicknames:

The Motor City, Motown, The D, 313, D-Town, Renaissance City, The Town That Put The World on Wheels |

|

| Motto(s):

Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus |

|

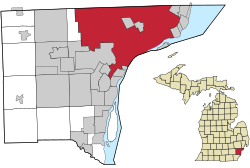

Interactive map of Detroit |

|

| Coordinates: 42°19′53″N 83°02′45″W / 42.33139°N 83.04583°WCoordinates: 42°19′53″N 83°02′45″W / 42.33139°N 83.04583°W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | Michigan |

| County | Wayne |

| Founded | July 24, 1701 |

| Incorporated | September 13, 1806 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Detroit City Council |

| • Mayor | Mike Duggan (D) |

| • Clerk | Janice Winfrey |

| • City council |

Members

|

| Area

[2] |

|

| • City | 142.89 sq mi (370.09 km2) |

| • Land | 138.73 sq mi (359.31 km2) |

| • Water | 4.16 sq mi (10.78 km2) |

| • Urban | 1,284.8 sq mi (3,327.7 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,888.4 sq mi (10,071 km2) |

| Elevation

[1] |

656 ft (200 m) |

| Population

(2020)[3] |

|

| • City | 639,111 |

| • Estimate

(2021)[3] |

632,464 |

| • Rank | 27th in the United States 1st in Michigan |

| • Density | 4,606.84/sq mi (1,778.71/km2) |

| • Urban

[4] |

3,776,890 (US: 12th) |

| • Urban density | 2,939.6/sq mi (1,135.0/km2) |

| • Metro

[5] |

4,365,205 (US: 14th) |

| Demonym | Detroiter |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

482XX |

| Area code | 313 |

| FIPS code | 26-22000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1617959[1] |

| Major airports | Detroit Metropolitan Airport, Coleman A. Young International Airport |

| Mass transit | Detroit Department of Transportation, Detroit People Mover, QLine |

| Website | www.detroitmi.gov |

Detroit ( də-TROYT, locally also DEE-troyt; French: Détroit, lit. ‘strait’) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 census,[6] making it the 27th-most populous city in the United States. The metropolitan area, known as Metro Detroit, is home to 4.3 million people, making it the second-largest in the Midwest after the Chicago metropolitan area, and the 14th-largest in the United States. Regarded as a major cultural center,[7][8] Detroit is known for its contributions to music, art, architecture and design, in addition to its historical automotive background.[9] Time named Detroit as one of the fifty World’s Greatest Places of 2022 to explore.[10]

Detroit is a major port on the Detroit River, one of the four major straits that connect the Great Lakes system to the Saint Lawrence Seaway. The City of Detroit anchors the third-largest regional economy in the Midwest, behind Chicago and Minneapolis–Saint Paul, and the 16th-largest in the United States.[11] Detroit is best known as the center of the U.S. automobile industry, and the «Big Three» auto manufacturers General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis North America (Chrysler) are all headquartered in Metro Detroit.[12] As of 2007, the Detroit metropolitan area is the number one exporting region among 310 defined metropolitan areas in the United States.[13] The Detroit Metropolitan Airport is among the most important hub airports in the United States. Detroit and its neighboring Canadian city Windsor are connected through a highway tunnel, railway tunnel, and the Ambassador Bridge, which is the second-busiest international crossing in North America, after San Diego–Tijuana.[14] Both cities will soon be connected by a new bridge currently under construction, the Gordie Howe International Bridge, which will provide a complete freeway-to-freeway link. The new bridge is expected to be open by 2024.[15]

In 1701, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and Alphonse de Tonty founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, the future city of Detroit. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, it became an important industrial hub at the center of the Great Lakes region. The city’s population became the fourth-largest in the nation in 1920, after only New York City, Chicago and Philadelphia, with the expansion of the auto industry in the early 20th century.[16] As Detroit’s industrialization took off, the Detroit River became the busiest commercial hub in the world. The strait carried over 65 million tons of shipping commerce through Detroit to locations all over the world each year; the freight throughput was more than three times that of New York and about four times that of London. By the 1940s, the city’s population remained the fourth-largest in the country. However, due to industrial restructuring, the loss of jobs in the auto industry, and rapid suburbanization, among other reasons, Detroit entered a state of urban decay and lost considerable population from the late 20th century to the present. Since reaching a peak of 1.85 million at the 1950 census, Detroit’s population has declined by more than 65 percent.[6] In 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy, which it successfully exited in December 2014, when the city government regained control of Detroit’s finances.[17]

Detroit’s diverse culture has had both local and international influence, particularly in music, with the city giving rise to the genres of Motown and techno, and playing an important role in the development of jazz, hip-hop, rock, and punk. The rapid growth of Detroit in its boom years resulted in a globally unique stock of architectural monuments and historic places. Since the 2000s, conservation efforts have managed to save many architectural pieces and achieved several large-scale revitalizations, including the restoration of several historic theatres and entertainment venues, high-rise renovations, new sports stadiums, and a riverfront revitalization project. More recently, the population of Downtown Detroit, Midtown Detroit, and various other neighborhoods have increased.[citation needed] An increasingly popular tourist destination, Detroit receives 16 million visitors per year.[18] In 2015, Detroit was named a «City of Design» by UNESCO, the first U.S. city to receive that designation.[19]

Toponymy[edit]

Detroit is named after the Detroit River, connecting Lake Huron with Lake Erie. The city’s name comes from the French word ‘détroit‘ meaning «strait» as the city was situated on a narrow passage of water linking two lakes. The river was known as “le détroit du Lac Érié,» among the French, which meant «the strait of Lake Erie».[20][21]

History[edit]

Early settlement[edit]

Paleo-Indian people inhabited areas near Detroit as early as 11,000 years ago including the culture referred to as the Mound-builders.[22] By the 17th century, the region was inhabited by Huron, Odawa, Potawatomi and Iroquois peoples.[23] The area is known by the Anishinaabe people as Waawiiyaataanong, translating to ‘where the water curves around’.[24]

The first Europeans did not penetrate into the region and reach the straits of Detroit until French missionaries and traders worked their way around the League of the Iroquois, with whom they were at war and other Iroquoian tribes in the 1630s.[25] The Huron and Neutral peoples held the north side of Lake Erie until the 1650s, when the Iroquois pushed both and the Erie people away from the lake and its beaver-rich feeder streams in the Beaver Wars of 1649–1655.[25] By the 1670s, the war-weakened Iroquois laid claim to as far south as the Ohio River valley in northern Kentucky as hunting grounds,[25] and had absorbed many other Iroquoian peoples after defeating them in war.[25] For the next hundred years, virtually no British or French action was contemplated without consultation with the Iroquois or consideration of their likely response.[25] When the French and Indian War evicted the Kingdom of France from Canada, it removed one barrier to American colonists migrating west.[26]

British negotiations with the Iroquois would both prove critical and lead to a Crown policy limiting settlements below the Great Lakes and west of the Alleghenies. Many colonial American would-be migrants resented this restraint and became supporters of the American Revolution. The 1778 raids and resultant 1779 decisive Sullivan Expedition reopened the Ohio Country to westward emigration, which began almost immediately. By 1800 white settlers were pouring westwards.[27]

Later settlement[edit]

Topographical plan of the Town of Detroit and Fort Lernoult showing major streets, gardens, fortifications, military complexes, and public buildings (John Jacob Ulrich Rivardi, ca. 1800)

The city was named by French colonists, referring to the Detroit River (French: le détroit du lac Érié, meaning the strait of Lake Erie), linking Lake Huron and Lake Erie; in the historical context, the strait included the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River.[28][29]

On July 24, 1701, the French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, with his lieutenant Alphonse de Tonty and along with more than a hundred other settlers, began constructing a small fort on the north bank of the Detroit River. Cadillac would later name the settlement Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit,[30] after Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain, Minister of Marine under Louis XIV.[31] A church was soon founded here, and the parish was known as Sainte Anne de Détroit. France offered free land to colonists to attract families to Detroit; when it reached a population of 800 in 1765, this was the largest European settlement between Montreal and New Orleans, both also French settlements, in the former colonies of New France and La Louisiane, respectively.[32]

By 1773, after the addition of Anglo-American settlers, the population of Detroit was 1,400. By 1778, its population reached 2,144 and it was the third-largest city in what was known as the Province of Quebec since the British takeover of French colonies following their victory in the Seven Years’ War.[33]

The region’s economy was based on the lucrative fur trade, in which numerous Native American people had important roles as trappers and traders. Today the flag of Detroit reflects its French colonial heritage. Descendants of the earliest French and French-Canadian settlers formed a cohesive community, who gradually were superseded as the dominant population after more Anglo-American settlers arrived in the early 19th century with American westward migration. Living along the shores of Lake St. Clair and south to Monroe and downriver suburbs, the ethnic French Canadians of Detroit, also known as Muskrat French in reference to the fur trade, remain a subculture in the region in the 21st century.[34][35]

During the French and Indian War (1754–63), the North American front of the Seven Years’ War between Britain and France, British troops gained control of the settlement in 1760 and shortened its name to Detroit. Several regional Native American tribes, such as the Potowatomi, Ojibwe and Huron, launched Pontiac’s War in 1763, and laid siege to Fort Detroit, but failed to capture it. In defeat, France ceded its territory in North America east of the Mississippi to Britain following the war.[36]

Following the American Revolutionary War and the establishment of the United States as an independent country, Britain ceded Detroit along with other territories in the area under the Jay Treaty (1796), which established the northern border with its colony of Canada.[37] The Great Fire of 1805 destroyed most of the Detroit settlement, which had primarily buildings made of wood. One stone fort, a river warehouse, and brick chimneys of former wooden homes were the sole structures to survive.[38] Of the 600 Detroit residents in this area, none died in the fire.[39]

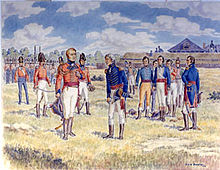

19th century[edit]

From 1805 to 1847, Detroit was the capital of Michigan as a territory and as a state. William Hull, the United States commander at Detroit surrendered without a fight to British troops and their Native American allies during the War of 1812 in the siege of Detroit, believing his forces were vastly outnumbered. The Battle of Frenchtown (January 18–23, 1813) was part of a U.S. effort to retake the city, and U.S. troops suffered their highest fatalities of any battle in the war. This battle is commemorated at River Raisin National Battlefield Park south of Detroit in Monroe County. Detroit was recaptured by the United States later that year.[40]

The settlement was incorporated as a city in 1815.[41] As the city expanded, a geometric street plan developed by Augustus B. Woodward was followed, featuring grand boulevards as in Paris.[42]

Prior to the American Civil War, the city’s access to the Canada–US border made it a key stop for refugee slaves gaining freedom in the North along the Underground Railroad. Many went across the Detroit River to Canada to escape pursuit by slave catchers.[43][41] An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 African-American refugees settled in Canada.[44] George DeBaptiste was considered to be the «president» of the Detroit Underground Railroad, William Lambert the «vice president» or «secretary», and Laura Haviland the «superintendent».[45]

Numerous men from Detroit volunteered to fight for the Union during the American Civil War, including the 24th Michigan Infantry Regiment. It was part of the legendary Iron Brigade, which fought with distinction and suffered 82% casualties at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. When the First Volunteer Infantry Regiment arrived to fortify Washington, D.C., President Abraham Lincoln is quoted as saying, «Thank God for Michigan!» George Armstrong Custer led the Michigan Brigade during the Civil War and called them the «Wolverines».[46]

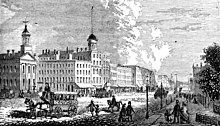

During the late 19th century, wealthy industry and shipping magnates commissioned the design and construction of several Gilded Age mansions east and west of the current downtown, along the major avenues of the Woodward plan. Most notable among them was the David Whitney House at 4421 Woodward Avenue, and the grand avenue became a favored address for mansions. During this period, some referred to Detroit as the «Paris of the West» for its architecture, grand avenues in the Paris style, and for Washington Boulevard, recently electrified by Thomas Edison.[41] The city had grown steadily from the 1830s with the rise of shipping, shipbuilding, and manufacturing industries. Strategically located along the Great Lakes waterway, Detroit emerged as a major port and transportation hub.[citation needed]

In 1896, a thriving carriage trade prompted Henry Ford to build his first automobile in a rented workshop on Mack Avenue. During this growth period, Detroit expanded its borders by annexing all or part of several surrounding villages and townships.[47]

20th century[edit]

In 1903, Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company. Ford’s manufacturing—and those of automotive pioneers William C. Durant, the Dodge Brothers, Packard, and Walter Chrysler—established Detroit’s status in the early 20th century as the world’s automotive capital.[41] The growth of the auto industry was reflected by changes in businesses throughout the Midwest and nation, with the development of garages to service vehicles and gas stations, as well as factories for parts and tires.[citation needed]

In 1907, the Detroit River carried 67,292,504 tons of shipping commerce through Detroit to locations all over the world. For comparison, London shipped 18,727,230 tons, and New York shipped 20,390,953 tons. The river was dubbed «the Greatest Commercial Artery on Earth» by The Detroit News in 1908.

With the rapid growth of industrial workers in the auto factories, labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor and the United Auto Workers fought to organize workers to gain them better working conditions and wages. They initiated strikes and other tactics in support of improvements such as the 8-hour day/40-hour work week, increased wages, greater benefits, and improved working conditions. The labor activism during those years increased the influence of union leaders in the city such as Jimmy Hoffa of the Teamsters and Walter Reuther of the Autoworkers.[48]

Due to the booming auto industry, Detroit became the fourth-largest city in the nation in 1920, following New York City, Chicago and Philadelphia.[49]

The prohibition of alcohol from 1920 to 1933 resulted in the Detroit River becoming a major conduit for smuggling of illegal Canadian spirits.[16]

Detroit, like many places in the United States, developed racial conflict and discrimination in the 20th century following the rapid demographic changes as hundreds of thousands of new workers were attracted to the industrial city; in a short period, it became the fourth-largest city in the nation. The Great Migration brought rural blacks from the South; they were outnumbered by southern whites who also migrated to the city. Immigration brought southern and eastern Europeans of Catholic and Jewish faith; these new groups competed with native-born whites for jobs and housing in the booming city.[citation needed]

Detroit was one of the major Midwest cities that was a site for the dramatic urban revival of the Ku Klux Klan beginning in 1915. «By the 1920s the city had become a stronghold of the KKK», whose members primarily opposed Catholic and Jewish immigrants, but also practiced discrimination against Black Americans.[50] Even after the decline of the KKK in the late 1920s, the Black Legion, a secret vigilante group, was active in the Detroit area in the 1930s. One-third of its estimated 20,000 to 30,000 members in Michigan were based in the city. It was defeated after numerous prosecutions following the kidnapping and murder in 1936 of Charles Poole, a Catholic organizer with the federal Works Progress Administration. Some 49 men of the Black Legion were convicted of numerous crimes, with many sentenced to life in prison for murder.[51]

In the 1940s the world’s «first urban depressed freeway» ever built, the Davison,[52] was constructed in Detroit. During World War II, the government encouraged retooling of the American automobile industry in support of the Allied powers, leading to Detroit’s key role in the American Arsenal of Democracy.[53]

Jobs expanded so rapidly due to the defense buildup in World War II that 400,000 people migrated to the city from 1941 to 1943, including 50,000 blacks in the second wave of the Great Migration, and 350,000 whites, many of them from the South. Whites, including ethnic Europeans, feared black competition for jobs and scarce housing. The federal government prohibited discrimination in defense work, but when in June 1943 Packard promoted three black people to work next to whites on its assembly lines, 25,000 white workers walked off the job.[54]

The Detroit race riot of 1943 took place in June, three weeks after the Packard plant protest, beginning with an altercation at Belle Isle. Blacks suffered 25 deaths (of a total of 34), three-quarters of 600 wounded, and most of the losses due to property damage. Rioters moved through the city, and young whites traveled across town to attack more settled blacks in their neighborhood of Paradise Valley.[55][56]

The skyline of Detroit on June 6, 1929

Postwar era[edit]

Industrial mergers in the 1950s, especially in the automobile sector, increased oligopoly in the American auto industry. Detroit manufacturers such as Packard and Hudson merged into other companies and eventually disappeared. At its peak population of 1,849,568, in the 1950 Census, the city was the fifth-largest in the United States, after New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles.[57]

From top: Aerial photo of Detroit (1932); Detroit at its population peak in the mid-20th century. Looking south down Woodward Avenue from the Maccabees Building with the city’s skyline in the distance.

In this postwar era, the auto industry continued to create opportunities for many African Americans from the South, who continued with their Great Migration to Detroit and other northern and western cities to escape the strict Jim Crow laws and racial discrimination policies of the South. Postwar Detroit was a prosperous industrial center of mass production. The auto industry comprised about 60% of all industry in the city, allowing space for a plethora of separate booming businesses including stove making, brewing, furniture building, oil refineries, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and more. The expansion of jobs created unique opportunities for black Americans, who saw novel high employment rates: there was a 103% increase in the number of blacks employed in postwar Detroit. Black Americans who immigrated to northern industrial cities from the south still faced intense racial discrimination in the employment sector. Racial discrimination kept the workforce and better jobs predominantly white, while many black Detroiters held lower-paying factory jobs. Despite changes in demographics as the city’s black population expanded, Detroit’s police force, fire department, and other city jobs continued to be held by predominantly white residents. This created an unbalanced racial power dynamic.[58]

Unequal opportunities in employment resulted in unequal housing opportunities for the majority of the black community: with overall lower incomes and facing the backlash of discriminatory housing policies, the black community was limited to lower cost, lower quality housing in the city. The surge in Detroit’s black population with the Great Migration augmented the strain on housing scarcity. The liveable areas available to the black community were limited, and as a result, families often crowded together in unsanitary, unsafe, and illegal quarters. Such discrimination became increasingly evident in the policies of redlining implemented by banks and federal housing groups, which almost completely restricted the ability of blacks to improve their housing and encouraged white people to guard the racial divide that defined their neighborhoods. As a result, black people were often denied bank loans to obtain better housing, and interest rates and rents were unfairly inflated to prevent their moving into white neighborhoods. White residents and political leaders largely opposed the influx of black Detroiters to white neighborhoods, believing that their presence would lead to neighborhood deterioration (most predominantly black neighborhoods deteriorated due to local and federal governmental neglect). This perpetuated a cyclical exclusionary process that marginalized the agency of black Detroiters by trapping them in the unhealthiest, least safe areas of the city.[58]

As in other major American cities in the postwar era, construction of a federally subsidized, extensive highway and freeway system around Detroit, and pent-up demand for new housing stimulated suburbanization; highways made commuting by car for higher-income residents easier. However, this construction had negative implications for many lower-income urban residents. Highways were constructed through and completely demolished neighborhoods of poor residents and black communities who had less political power to oppose them. The neighborhoods were mostly low income, considered blighted, or made up of older housing where investment had been lacking due to racial redlining, so the highways were presented as a kind of urban renewal. These neighborhoods (such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley) were extremely important to the black communities of Detroit, providing spaces for independent black businesses and social/cultural organizations. Their destruction displaced residents with little consideration of the effects of breaking up functioning neighborhoods and businesses.[58]

In 1956, Detroit’s last heavily used electric streetcar line, which traveled along the length of Woodward Avenue, was removed and replaced with gas-powered buses. It was the last line of what had once been a 534-mile network of electric streetcars. In 1941, at peak times, a streetcar ran on Woodward Avenue every 60 seconds.[59][60]

All of these changes in the area’s transportation system favored low-density, auto-oriented development rather than high-density urban development. Industry also moved to the suburbs, seeking large plots of land for single-story factories. By the 21st century, the metro Detroit area had developed as one of the most sprawling job markets in the United States; combined with poor public transport, this resulted in many new jobs being beyond the reach of urban low-income workers.[61]

In 1950, the city held about one-third of the state’s population, anchored by its industries and workers. Over the next sixty years, the city’s population declined to less than 10 percent of the state’s population. During the same time period, the sprawling Detroit metropolitan area, which surrounds and includes the city, grew to contain more than half of Michigan’s population.[41] The shift of population and jobs eroded Detroit’s tax base.[citation needed]

I have a dream this afternoon that my four little children, that my four little children will not come up in the same young days that I came up within, but they will be judged on the basis of the content of their character, not the color of their skin … I have a dream this evening that one day we will recognize the words of Jefferson that «all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.» I have a dream …

—Martin Luther King Jr. (June 1963 Speech at the Great March on Detroit)[62]

In June 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a major speech as part of a civil rights march in Detroit that foreshadowed his «I Have a Dream» speech in Washington, D.C., two months later. While the civil rights movement gained significant federal civil rights laws in 1964 and 1965, longstanding inequities resulted in confrontations between the police and inner-city black youth who wanted change.[63]

Longstanding tensions in Detroit culminated in the Twelfth Street riot in July 1967. Governor George W. Romney ordered the Michigan National Guard into Detroit, and President Johnson sent in U.S. Army troops. The result was 43 dead, 467 injured, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed, mostly in black residential and business areas. Thousands of small businesses closed permanently or relocated to safer neighborhoods. The affected district lay in ruins for decades.[64] According to the Chicago Tribune, it was the 3rd most costly riot in the United States.[65]

On August 18, 1970, the NAACP filed suit against Michigan state officials, including Governor William Milliken, charging de facto public school segregation. The NAACP argued that although schools were not legally segregated, the city of Detroit and its surrounding counties had enacted policies to maintain racial segregation in public schools. The NAACP also suggested a direct relationship between unfair housing practices and educational segregation, as the composition of students in the schools followed segregated neighborhoods.[66] The District Court held all levels of government accountable for the segregation in its ruling. The Sixth Circuit Court affirmed some of the decision, holding that it was the state’s responsibility to integrate across the segregated metropolitan area.[67] The U.S. Supreme Court took up the case February 27, 1974.[66] The subsequent Milliken v. Bradley decision had nationwide influence. In a narrow decision, the US Supreme Court found schools were a subject of local control, and suburbs could not be forced to aid with the desegregation of the city’s school district.[68]

«Milliken was perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of that period», said Myron Orfield, professor of law at the University of Minnesota. «Had that gone the other way, it would have opened the door to fixing nearly all of Detroit’s current problems.»[69] John Mogk, a professor of law and an expert in urban planning at Wayne State University in Detroit, says,

Everybody thinks that it was the riots [in 1967] that caused the white families to leave. Some people were leaving at that time but, really, it was after Milliken that you saw mass flight to the suburbs. If the case had gone the other way, it is likely that Detroit would not have experienced the steep decline in its tax base that has occurred since then.[69]

1970s and decline[edit]

First Williams Block in 1915 (left) and 1989 (right).

In November 1973, the city elected Coleman Young as its first black mayor. After taking office, Young emphasized increasing racial diversity in the police department, which was predominantly white.[70] Young also worked to improve Detroit’s transportation system, but the tension between Young and his suburban counterparts over regional matters was problematic throughout his mayoral term. In 1976, the federal government offered $600 million for building a regional rapid transit system, under a single regional authority.[71] But the inability of Detroit and its suburban neighbors to solve conflicts over transit planning resulted in the region losing the majority of funding for rapid transit.[citation needed]

Following the failure to reach a regional agreement over the larger system, the city moved forward with construction of the elevated downtown circulator portion of the system, which became known as the Detroit People Mover.[72]

The gasoline crises of 1973 and 1979 also affected Detroit and the U.S. auto industry. Buyers chose smaller, more fuel-efficient cars made by foreign makers as the price of gas rose. Efforts to revive the city were stymied by the struggles of the auto industry, as their sales and market share declined. Automakers laid off thousands of employees and closed plants in the city, further eroding the tax base. To counteract this, the city used eminent domain to build two large new auto assembly plants in the city.[73]

As mayor, Young sought to revive the city by seeking to increase investment in the city’s declining downtown. The Renaissance Center, a mixed-use office and retail complex, opened in 1977. This group of skyscrapers was an attempt to keep businesses in downtown.[41][74][75] Young also gave city support to other large developments to attract middle and upper-class residents back to the city. Despite the Renaissance Center and other projects, the downtown area continued to lose businesses to the automobile-dependent suburbs. Major stores and hotels closed, and many large office buildings went vacant. Young was criticized for being too focused on downtown development and not doing enough to lower the city’s high crime rate and improve city services to residents.[citation needed]

High unemployment was compounded by middle-class flight to the suburbs, and some residents leaving the state to find work. The result for the city was a higher proportion of poor in its population, reduced tax base, depressed property values, abandoned buildings, abandoned neighborhoods, high crime rates, and a pronounced demographic imbalance.[citation needed]

1980s[edit]

On August 16, 1987, Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashed near Detroit Metro airport, killing all but one of the 155 people on board, as well as two people on the ground.[76]

1990s & 2000s[edit]

In 1993, Young retired as Detroit’s longest-serving mayor, deciding not to seek a sixth term. That year the city elected Dennis Archer, a former Michigan Supreme Court justice. Archer prioritized downtown development and easing tensions with Detroit’s suburban neighbors. A referendum to allow casino gambling in the city passed in 1996; several temporary casino facilities opened in 1999, and permanent downtown casinos with hotels opened in 2007–08.[77]

Campus Martius, a reconfiguration of downtown’s main intersection as a new park, was opened in 2004. The park has been cited as one of the best public spaces in the United States.[78][79][80] The city’s riverfront on the Detroit River has been the focus of redevelopment, following successful examples of other older industrial cities. In 2001, the first portion of the International Riverfront was completed as a part of the city’s 300th-anniversary celebration.

2010s[edit]

In September 2008, Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick (who had served for six years) resigned following felony convictions. In 2013, Kilpatrick was convicted on 24 federal felony counts, including mail fraud, wire fraud, and racketeering,[81] and was sentenced to 28 years in federal prison.[82] The former mayor’s activities cost the city an estimated $20 million.[83]

The city’s financial crisis resulted in Michigan taking over administrative control of its government.[84] The state governor declared a financial emergency in March 2013, appointing Kevyn Orr as emergency manager. On July 18, 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy.[85] It was declared bankrupt by U.S. District Court on December 3, 2013, in light of the city’s $18.5 billion debt and its inability to fully repay its thousands of creditors.[86] On November 7, 2014, the city’s plan for exiting bankruptcy was approved. The following month, on December 11, the city officially exited bankruptcy. The plan allowed the city to eliminate $7 billion in debt and invest $1.7 billion into improved city services.[87]

One way the city obtained this money was through the Detroit Institute of Arts. Holding over 60,000 pieces of art worth billions of dollars, some saw it as the key to funding this investment. The city came up with a plan to monetize the art and sell it leading to the DIA becoming a private organization. After months of legal battles, the city finally got hundreds of millions of dollars towards funding a new Detroit.[88]

One of the largest post-bankruptcy efforts to improve city services has been to work to fix the city’s broken street lighting system. At one time it was estimated that 40% of lights were not working, which resulted in public safety issues and abandonment of housing. The plan called for replacing outdated high-pressure sodium lights with 65,000 LED lights. Construction began in late 2014 and finished in December 2016; Detroit is the largest U.S. city with all LED street lighting.[89]

In the 2010s, several initiatives were taken by Detroit’s citizens and new residents to improve the cityscape by renovating and revitalizing neighborhoods. Such projects include volunteer renovation groups[90] and various urban gardening movements.[91] Miles of associated parks and landscaping have been completed in recent years. In 2011, the Port Authority Passenger Terminal opened, with the riverwalk connecting Hart Plaza to the Renaissance Center.[75]

One symbol of the city’s decades-long decline, the Michigan Central Station, was long vacant. The city renovated it with new windows, elevators and facilities, completing the work in December 2015.[92] In 2018, Ford Motor Company purchased the building and plans to use it for mobility testing with a potential return of train service.[93] Several other landmark buildings have been privately renovated and adapted as condominiums, hotels, offices, or for cultural uses. Detroit is mentioned as a city of renaissance and has reversed many of the trends of the prior decades.[citation needed][94][95]

The city has also seen a rise in gentrification.[citation needed] In downtown, for example, the construction of Little Caesars Arena brought with it new, high class shops and restaurants up and down Woodward Ave. Office tower and condominium construction has led to an influx of wealthy families, but also a displacement of long-time residents and culture.[96][97]

Areas outside of downtown and other recently revived areas have an average household income of about 25% less than the gentrified areas, a gap that is continuing to grow.[98] Rents and cost of living in these gentrified areas rise every year,[citation needed] pushing minorities and the poor out, causing more and more racial disparity and separation in the city. In 2019, the cost of a one-bedroom loft in Rivertown reached $300,000, with a five-year sale price change of over 500% and average income rising by 18%.[99]

Geography[edit]

A Satellite image from Sentinel-2 taken in September 2021 of Detroit and its surrounding metropolitan area with Windsor across the river.

Metropolitan area[edit]

Detroit is the center of a three-county urban area (with a population of 3,734,090 within an area of 1,337 square miles (3,460 km2) according to the 2010 United States Census), six-county metropolitan statistical area (population of 4,296,250 in an area of 3,913 square miles [10,130 km2] as of the 2010 census), and a nine-county Combined Statistical Area (population of 5.3 million within 5,814 square miles [15,060 km2] as of 2010).[100][101][102]

Topography[edit]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 142.87 square miles (370.03 km2), of which 138.75 square miles (359.36 km2) is land and 4.12 square miles (10.67 km2) is water.[103] Detroit is the principal city in Metro Detroit and Southeast Michigan. It is situated in the Midwestern United States and the Great Lakes region.[104]

The Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge is the only international wildlife preserve in North America, and is uniquely located in the heart of a major metropolitan area. The Refuge includes islands, coastal wetlands, marshes, shoals, and waterfront lands along 48 miles (77 km) of the Detroit River and Western Lake Erie shoreline.[105]

The city slopes gently from the northwest to southeast on a till plain composed largely of glacial and lake clay. The most notable topographical feature in the city is the Detroit Moraine, a broad clay ridge on which the older portions of Detroit and Windsor are located, rising approximately 62 feet (19 m) above the river at its highest point.[106] The highest elevation in the city is directly north of Gorham Playground on the northwest side approximately three blocks south of 8 Mile Road, at a height of 675 to 680 feet (206 to 207 m).[107] Detroit’s lowest elevation is along the Detroit River, at a surface height of 572 feet (174 m).[108]

Belle Isle Park is a 982-acre (1.534 sq mi; 397 ha) island park in the Detroit River, between Detroit and Windsor, Ontario. It is connected to the mainland by the MacArthur Bridge in Detroit. Belle Isle Park contains such attractions as the James Scott Memorial Fountain, the Belle Isle Conservatory, the Detroit Yacht Club on an adjacent island, a half-mile (800 m) beach, a golf course, a nature center, monuments, and gardens. Both the Detroit and Windsor skylines can be viewed at the island’s Sunset Point.[109]

Three road systems cross the city: the original French template, with avenues radiating from the waterfront, and true north–south roads based on the Northwest Ordinance township system. The city is north of Windsor, Ontario. Detroit is the only major city along the Canada–U.S. border in which one travels south in order to cross into Canada.[110]

Detroit has four border crossings: the Ambassador Bridge and the Detroit–Windsor Tunnel provide motor vehicle thoroughfares, with the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel providing railroad access to and from Canada. The fourth border crossing is the Detroit–Windsor Truck Ferry, near the Windsor Salt Mine and Zug Island. Near Zug Island, the southwest part of the city was developed over a 1,500-acre (610 ha) salt mine that is 1,100 feet (340 m) below the surface. The Detroit salt mine run by the Detroit Salt Company has over 100 miles (160 km) of roads within.[111][112]

Climate[edit]

| Detroit, Michigan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Detroit and the rest of southeastern Michigan have a hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa) which is influenced by the Great Lakes like other places in the state;[113][114][115] the city and close-in suburbs are part of USDA Hardiness zone 6b, while the more distant northern and western suburbs generally are included in zone 6a.[116] Winters are cold, with moderate snowfall and temperatures not rising above freezing on an average 44 days annually, while dropping to or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on an average 4.4 days a year; summers are warm to hot with temperatures exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) on 12 days.[117] The warm season runs from May to September. The monthly daily mean temperature ranges from 25.6 °F (−3.6 °C) in January to 73.6 °F (23.1 °C) in July. Official temperature extremes range from 105 °F (41 °C) on July 24, 1934, down to −21 °F (−29 °C) on January 21, 1984; the record low maximum is −4 °F (−20 °C) on January 19, 1994, while, conversely the record high minimum is 80 °F (27 °C) on August 1, 2006, the most recent of five occurrences.[117] A decade or two may pass between readings of 100 °F (38 °C) or higher, which last occurred July 17, 2012. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 20 thru April 22, allowing a growing season of 180 days.[117]

Precipitation is moderate and somewhat evenly distributed throughout the year, although the warmer months such as May and June average more, averaging 33.5 inches (850 mm) annually, but historically ranging from 20.49 in (520 mm) in 1963 to 47.70 in (1,212 mm) in 2011.[117] Snowfall, which typically falls in measurable amounts between November 15 through April 4 (occasionally in October and very rarely in May),[117] averages 42.5 inches (108 cm) per season, although historically ranging from 11.5 in (29 cm) in 1881–82 to 94.9 in (241 cm) in 2013–14.[117] A thick snowpack is not often seen, with an average of only 27.5 days with 3 in (7.6 cm) or more of snow cover.[117] Thunderstorms are frequent in the Detroit area. These usually occur during spring and summer.[118]

| Climate data for Detroit (DTW), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1874–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

70 (21) |

86 (30) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

81 (27) |

69 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.0 (11.7) |

55.3 (12.9) |

69.3 (20.7) |

79.6 (26.4) |

87.2 (30.7) |

92.6 (33.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

92.1 (33.4) |

89.3 (31.8) |

80.6 (27.0) |

66.7 (19.3) |

56.1 (13.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.3 (0.2) |

35.2 (1.8) |

45.9 (7.7) |

58.7 (14.8) |

70.3 (21.3) |

79.7 (26.5) |

83.7 (28.7) |

81.4 (27.4) |

74.4 (23.6) |

62.0 (16.7) |

48.6 (9.2) |

37.2 (2.9) |

59.1 (15.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.8 (−3.4) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

37.2 (2.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

74.1 (23.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

64.9 (18.3) |

53.0 (11.7) |

41.2 (5.1) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

50.6 (10.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

39.1 (3.9) |

50.2 (10.1) |

60.2 (15.7) |

64.4 (18.0) |

63.2 (17.3) |

55.5 (13.1) |

44.0 (6.7) |

33.9 (1.1) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

42.0 (5.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 0.1 (−17.7) |

3.5 (−15.8) |

12.0 (−11.1) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

36.3 (2.4) |

47.3 (8.5) |

54.1 (12.3) |

53.4 (11.9) |

41.6 (5.3) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

8.8 (−12.9) |

−3.7 (−19.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−20 (−29) |

−4 (−20) |

8 (−13) |

25 (−4) |

36 (2) |

42 (6) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

17 (−8) |

0 (−18) |

−11 (−24) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.23 (57) |

2.08 (53) |

2.43 (62) |

3.26 (83) |

3.72 (94) |

3.26 (83) |

3.51 (89) |

3.26 (83) |

3.22 (82) |

2.53 (64) |

2.57 (65) |

2.25 (57) |

34.32 (872) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.0 (36) |

12.5 (32) |

6.2 (16) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.9 (4.8) |

8.9 (23) |

45.0 (114) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.4 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 13.1 | 136.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 10.7 | 9.2 | 5.3 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 8.0 | 37.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.7 | 72.5 | 70.0 | 66.0 | 65.3 | 67.3 | 68.5 | 71.5 | 73.4 | 71.6 | 74.6 | 76.7 | 71.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 16.2 (−8.8) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

35.1 (1.7) |

45.7 (7.6) |

55.6 (13.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

59.7 (15.4) |

53.2 (11.8) |

41.4 (5.2) |

32.4 (0.2) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

38.8 (3.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.9 | 138.3 | 184.9 | 217.0 | 275.9 | 301.8 | 317.0 | 283.5 | 227.6 | 176.0 | 106.3 | 87.7 | 2,435.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 47 | 50 | 54 | 61 | 66 | 69 | 66 | 61 | 51 | 36 | 31 | 55 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[117][119][120] |

See or edit raw graph data.

| Climate data for Detroit | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 33.6 (0.9) |

32.7 (0.4) |

33.4 (0.8) |

39.7 (4.3) |

48.9 (9.4) |

63.9 (17.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

75.4 (24.1) |

70.5 (21.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

48.6 (9.2) |

38.1 (3.4) |

51.7 (10.9) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [121] |

Cityscape[edit]

Architecture[edit]

Seen in panorama, Detroit’s waterfront shows a variety of architectural styles. The post modern Neo-Gothic spires of the One Detroit Center (1993) were designed to refer to the city’s Art Deco skyscrapers. Together with the Renaissance Center, these buildings form a distinctive and recognizable skyline. Examples of the Art Deco style include the Guardian Building and Penobscot Building downtown, as well as the Fisher Building and Cadillac Place in the New Center area near Wayne State University. Among the city’s prominent structures are United States’ largest Fox Theatre, the Detroit Opera House, and the Detroit Institute of Arts, all built in the early 20th century.[122][123]

While the Downtown and New Center areas contain high-rise buildings, the majority of the surrounding city consists of low-rise structures and single-family homes. Outside of the city’s core, residential high-rises are found in upper-class neighborhoods such as the East Riverfront, extending toward Grosse Pointe, and the Palmer Park neighborhood just west of Woodward. The University Commons-Palmer Park district in northwest Detroit, near the University of Detroit Mercy and Marygrove College, anchors historic neighborhoods including Palmer Woods, Sherwood Forest, and the University District.[citation needed]

Forty-two significant structures or sites are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Neighborhoods constructed prior to World War II feature the architecture of the times, with wood-frame and brick houses in the working-class neighborhoods, larger brick homes in middle-class neighborhoods, and ornate mansions in upper-class neighborhoods such as Brush Park, Woodbridge, Indian Village, Palmer Woods, Boston-Edison, and others.[citation needed]

Some of the oldest neighborhoods are along the major Woodward and East Jefferson corridors, which formed spines of the city. Some newer residential construction may also be found along the Woodward corridor and in the far west and northeast. The oldest extant neighborhoods include West Canfield and Brush Park. There have been multi-million dollar restorations of existing homes and construction of new homes and condominiums here.[74][124]

The city has one of the United States’ largest surviving collections of late 19th- and early 20th-century buildings.[123] Architecturally significant churches and cathedrals in the city include St. Joseph’s, Old St. Mary’s, the Sweetest Heart of Mary, and the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament.[122]

The city has substantial activity in urban design, historic preservation, and architecture.[125] A number of downtown redevelopment projects—of which Campus Martius Park is one of the most notable—have revitalized parts of the city. Grand Circus Park and historic district is near the city’s theater district; Ford Field, home of the Detroit Lions, and Comerica Park, home of the Detroit Tigers.[122] Little Caesars Arena, a new home for the Detroit Red Wings and the Detroit Pistons, with attached residential, hotel, and retail use, opened on September 5, 2017.[126] The plans for the project call for mixed-use residential on the blocks surrounding the arena and the renovation of the vacant 14-story Eddystone Hotel. It will be a part of The District Detroit, a group of places owned by Olympia Entertainment Inc., including Comerica Park and the Detroit Opera House, among others.[citation needed]

The Detroit International Riverfront includes a partially completed three-and-one-half-mile riverfront promenade with a combination of parks, residential buildings, and commercial areas. It extends from Hart Plaza to the MacArthur Bridge, which connects to Belle Isle Park, the largest island park in a U.S. city. The riverfront includes Tri-Centennial State Park and Harbor, Michigan’s first urban state park. The second phase is a two-mile (3.2-kilometer) extension from Hart Plaza to the Ambassador Bridge for a total of five miles (8.0 kilometres) of parkway from bridge to bridge. Civic planners envision the pedestrian parks will stimulate residential redevelopment of riverfront properties condemned under eminent domain.[127]

Other major parks include River Rouge (in the southwest side), the largest park in Detroit; Palmer (north of Highland Park) and Chene Park (on the east river downtown).[128]

Neighborhoods[edit]

Detroit has a variety of neighborhood types. The revitalized Downtown, Midtown, Corktown, New Center areas feature many historic buildings and are high density, while further out, particularly in the northeast and on the fringes,[129] high vacancy levels are problematic, for which a number of solutions have been proposed. In 2007, Downtown Detroit was recognized as the best city neighborhood in which to retire among the United States’ largest metro areas by CNNMoney editors.[130]

Lafayette Park is a revitalized neighborhood on the city’s east side, part of the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe residential district.[131] The 78-acre (32 ha) development was originally called the Gratiot Park. Planned by Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Alfred Caldwell it includes a landscaped, 19-acre (7.7 ha) park with no through traffic, in which these and other low-rise apartment buildings are situated.[131] Immigrants have contributed to the city’s neighborhood revitalization, especially in southwest Detroit.[132] Southwest Detroit has experienced a thriving economy in recent years, as evidenced by new housing, increased business openings and the recently opened Mexicantown International Welcome Center.[133]

The city has numerous neighborhoods consisting of vacant properties resulting in low inhabited density in those areas, stretching city services and infrastructure. These neighborhoods are concentrated in the northeast and on the city’s fringes.[129] A 2009 parcel survey found about a quarter of residential lots in the city to be undeveloped or vacant, and about 10% of the city’s housing to be unoccupied.[129][134][135] The survey also reported that most (86%) of the city’s homes are in good condition with a minority (9%) in fair condition needing only minor repairs.[134][135][136][137]

To deal with vacancy issues, the city has begun demolishing the derelict houses, razing 3,000 of the total 10,000 in 2010,[138] but the resulting low density creates a strain on the city’s infrastructure. To remedy this, a number of solutions have been proposed including resident relocation from more sparsely populated neighborhoods and converting unused space to urban agricultural use, including Hantz Woodlands, though the city expects to be in the planning stages for up to another two years.[139][140]

Public funding and private investment have also been made with promises to rehabilitate neighborhoods. In April 2008, the city announced a $300-million stimulus plan to create jobs and revitalize neighborhoods, financed by city bonds and paid for by earmarking about 15% of the wagering tax.[139] The city’s working plans for neighborhood revitalizations include 7-Mile/Livernois, Brightmoor, East English Village, Grand River/Greenfield, North End, and Osborn.[139] Private organizations have pledged substantial funding to the efforts.[141][142] Additionally, the city has cleared a 1,200-acre (490 ha) section of land for large-scale neighborhood construction, which the city is calling the Far Eastside Plan.[143] In 2011, Mayor Dave Bing announced a plan to categorize neighborhoods by their needs and prioritize the most needed services for those neighborhoods.[144]

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 1,422 | — | |

| 1830 | 2,222 | 56.3% | |

| 1840 | 9,102 | 309.6% | |

| 1850 | 21,019 | 130.9% | |

| 1860 | 45,619 | 117.0% | |

| 1870 | 79,577 | 74.4% | |

| 1880 | 116,340 | 46.2% | |

| 1890 | 205,876 | 77.0% | |

| 1900 | 285,704 | 38.8% | |

| 1910 | 465,766 | 63.0% | |

| 1920 | 993,678 | 113.3% | |

| 1930 | 1,568,662 | 57.9% | |

| 1940 | 1,623,452 | 3.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,849,568 | 13.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,670,144 | −9.7% | |

| 1970 | 1,514,063 | −9.3% | |

| 1980 | 1,203,368 | −20.5% | |

| 1990 | 1,027,974 | −14.6% | |

| 2000 | 951,270 | −7.5% | |

| 2010 | 713,777 | −25.0% | |

| 2020 | 639,111 | −10.5% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 632,464 | [3] | −1.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[145] 2010–2020[6] |

In the 2020 United States Census, the city had 639,111 residents, ranking it the 27th most populous city in the United States.[146][147]

2020 census[edit]

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[148] | Pop 2020[149] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 55,604 | 60,770 | 7.79% | 9.51% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 586,573 | 493,212 | 82.18% | 77.17% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,927 | 1,399 | 0.27% | 0.22% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 7,436 | 10,085 | 1.04% | 1.58% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 82 | 111 | 0.01% | 0.02% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 994 | 3,066 | 0.14% | 0.48% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 12,482 | 19,199 | 1.75% | 3.00% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 48,679 | 51,269 | 6.82% | 8.02% |

| Total | 713,777 | 639,111 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Of the large shrinking cities in the United States, Detroit has had the most dramatic decline in the population of the past 70 years (down 1,210,457) and the second-largest percentage decline (down 65.4%). While the drop in Detroit’s population has been ongoing since 1950, the most dramatic period was the significant 25% decline between the 2000 and 2010 Census.[147]

Previously a major population center and site of worldwide automobile manufacturing, Detroit has suffered a long economic decline produced by numerous factors.[150][151][152] Like many industrial American cities, Detroit’s peak population was in 1950, before postwar suburbanization took effect. The peak population was 1.8 million people.[147]

Following suburbanization, industrial restructuring, and loss of jobs, by the 2010 census, the city had less than 40 percent of that number, with just over 700,000 residents. The city has declined in population in each census since 1950.[147][153] The population collapse has resulted in large numbers of abandoned homes and commercial buildings, and areas of the city hit hard by urban decay.[154][155][156][157][158]

Detroit’s 639,111 residents represent 269,445 households, and 162,924 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,144.3 people per square mile (1,895/km2). There were 349,170 housing units at an average density of 2,516.5 units per square mile (971.6/km2). Housing density has declined. The city has demolished thousands of Detroit’s abandoned houses, planting some areas and in others allowing the growth of urban prairie.

Of the 269,445 households, 34.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 21.5% were married couples living together, 31.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 39.5% were non-families, 34.0% were made up of individuals, and 3.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59, and the average family size was 3.36.

There was a wide distribution of age in the city, with 31.1% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 19.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.4% 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.5 males.

Religion[edit]

According to a 2014 study, 67% of the population of the city identified themselves as Christians, with 49% professing attendance at Protestant churches, and 16% professing Roman Catholic beliefs,[159][160] while 24% claim no religious affiliation. Other religions collectively make up about 8% of the population.

Income and employment[edit]

The loss of industrial and working-class jobs in the city has resulted in high rates of poverty and associated problems.[161] From 2000 to 2009, the city’s estimated median household income fell from $29,526 to $26,098.[162] As of 2010, the mean income of Detroit is below the overall U.S. average by several thousand dollars. Of every three Detroit residents, one lives in poverty. Luke Bergmann, author of Getting Ghost: Two Young Lives and the Struggle for the Soul of an American City, said in 2010, «Detroit is now one of the poorest big cities in the country».[163]

In the 2018 American Community Survey, median household income in the city was $31,283, compared with the median for Michigan of $56,697.[164] The median income for a family was $36,842, well below the state median of $72,036.[165] 33.4% of families had income at or below the federally defined poverty level. Out of the total population, 47.3% of those under the age of 18 and 21.0% of those 65 and older had income at or below the federally defined poverty line.[166]

Oakland County in Metro Detroit, once rated amongst the wealthiest US counties per household, is no longer shown in the top 25 listing of Forbes magazine. But internal county statistical methods—based on measuring per capita income for counties with more than one million residents—show Oakland is still within the top 12[citation needed], slipping from the fourth-most affluent such county in the U.S. in 2004 to 11th-most affluent in 2009.[167][168][169] Detroit dominates Wayne County, which has an average household income of about $38,000, compared to Oakland County’s $62,000.[170][171]

| Area | Number of house- holds |

Median House- hold Income |

Per Capita Income |

Percent- age in poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit City | 263,688 | $30,894 ( |

$18,621 ( |

35.0% ( |

| Wayne County, MI | 682,282 | $47,301 | $27,282 | 19.8% |

| United States | 120,756,048 | $62,843 | $34,103 | 11.4% |

Race and ethnicity[edit]

| Self-identified race | 2020[173] | 2010[174] | 1990[175] | 1970[175] | 1950[175] | 1940[175] | 1930[175] | 1920[175] | 1910[175] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 14.7% | 10.6% | 21.6% | 55.5% | 83.6% | 90.7% | 92.2% | 95.8% | 98.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 11% | 7.8% | 20.7% | 54.0%[c] | — | 90.4% | — | — | — |

| Black or African American | 77.7% | 82.7% | 75.7% | 43.7% | 16.2% | 9.2% | 7.7% | 4.1% | 1.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 8.0% | 6.8% | 2.8% | 1.8%[c] | — | 0.3% | — | — | — |

| Asian | 1.6% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | — |

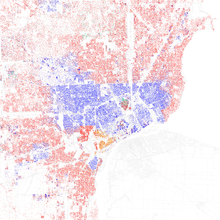

Map of racial distribution in Detroit, 2010 U.S. Census. Each dot is 25 people: ⬤ White

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Other

Beginning with the rise of the automobile industry, Detroit’s population increased more than sixfold during the first half of the 20th century as an influx of European, Middle Eastern (Lebanese, Assyrian/Chaldean), and Southern migrants brought their families to the city.[176] With this economic boom following World War I, the African American population grew from a mere 6,000 in 1910[177] to more than 120,000 by 1930.[178] This influx of thousands of African Americans in the 20th century became known as the Great Migration.[179] Perhaps one of the most overt examples of neighborhood discrimination occurred in 1925 when African American physician Ossian Sweet found his home surrounded by an angry mob of his hostile white neighbors violently protesting his new move into a traditionally white neighborhood. Sweet and ten of his family members and friends were put on trial for murder as one of the mob members throwing rocks at the newly purchased house was shot and killed by someone firing out of a second-floor window.[180] Many middle-class families experienced the same kind of hostility as they sought the security of homeownership and the potential for upward mobility.[citation needed]

Detroit has a relatively large Mexican-American population. In the early 20th century, thousands of Mexicans came to Detroit to work in agricultural, automotive, and steel jobs. During the Mexican Repatriation of the 1930s many Mexicans in Detroit were willingly repatriated or forced to repatriate. By the 1940s much of the Mexican community began to settle what is now Mexicantown.[181]

After World War II, many people from Appalachia also settled in Detroit. Appalachians formed communities and their children acquired southern accents.[182] Many Lithuanians also settled in Detroit during the World War II era, especially on the city’s Southwest side in the West Vernor area,[183] where the renovated Lithuanian Hall reopened in 2006.[184][185]

By 1940, 80% of Detroit deeds contained restrictive covenants prohibiting African Americans from buying houses they could afford. These discriminatory tactics were successful as a majority of black people in Detroit resorted to living in all-black neighborhoods such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. At this time, white people still made up about 90.4% of the city’s population.[175] From the 1940s to the 1970s a second wave of black people moved to Detroit in search of employment and with the desire to escape the Jim Crow laws enforcing segregation in the south.[186] However, they soon found themselves once again excluded from many opportunities in Detroit—through violence and policy perpetuating economic discrimination (e.g., redlining).[187] White residents attacked black homes: breaking windows, starting fires, and detonating bombs.[188][187] An especially grueling result of this increasing competition between black and white people was the Riot of 1943 that had violent ramifications.[189] This era of intolerance made it almost impossible for African Americans to be successful without access to proper housing or the economic stability to maintain their homes and the conditions of many neighborhoods began to decline. In 1948, the landmark Supreme Court case of Shelley v. Kraemer outlawed restrictive covenants and while racism in housing did not disappear, it allowed affluent black families to begin moving to traditionally white neighborhoods. Many white families with the financial ability moved to the suburbs of Detroit taking their jobs and tax dollars with them, as macrostructural processes such as «white flight» and «suburbanization» led to a complete population shift.

The Detroit riot of 1967 is considered to be one of the greatest racial turning points in the history of the city. The ramifications of the uprising were widespread as there were many allegations of white police brutality towards Black Americans and over $36 million of insured property was lost. Discrimination and deindustrialization in tandem with racial tensions that had been intensifying in the previous years boiled over and led to an event considered to be the most damaging in Detroit’s history.[190]

The population of Latinos significantly increased in the 1990s due to immigration from Jalisco. By 2010 Detroit had 48,679 Hispanics, including 36,452 Mexicans: a 70% increase from 1990.[191] While African Americans previously[when?] comprised only 13% of Michigan’s population, by 2010 they made up nearly 82% of Detroit’s population. The next largest population groups were white people, at 10%, and Hispanics, at 6%.[192] In 2001, 103,000 Jews, or about 1.9% of the population, were living in the Detroit area, in both Detroit and Ann Arbor.[193]

According to the 2010 census, segregation in Detroit has decreased in absolute and relative terms and in the first decade of the 21st century, about two-thirds of the total black population in the metropolitan area resided within the city limits of Detroit.[194][195] The number of integrated neighborhoods increased from 100 in 2000 to 204 in 2010. Detroit also moved down the ranking from number one most segregated city to number four.[196] A 2011 op-ed in The New York Times attributed the decreased segregation rating to the overall exodus from the city, cautioning that these areas may soon become more segregated. This pattern already happened in the 1970s, when apparent integration was a precursor to white flight and resegregation.[188] Over a 60-year period, white flight occurred in the city. According to an estimate of the Michigan Metropolitan Information Center, from 2008 to 2009 the percentage of non-Hispanic White residents increased from 8.4% to 13.3%. As the city has become more gentrified, some empty nesters and many young white people have moved into the city, increasing housing values and once again forcing African Americans to move.[197] Gentrification in Detroit has become a rather controversial issue as reinvestment will hopefully lead to economic growth and an increase in population; however, it has already forced many black families to relocate to the suburbs[citation needed]. Despite revitalization efforts, Detroit remains one of the most racially segregated cities in the United States.[188][198] One of the implications of racial segregation, which correlates with class segregation, may correlate to overall worse health for some populations.[198][199]

Asians and Asian Americans[edit]

As of 2002, of all of the municipalities in the Wayne County-Oakland County-Macomb County area, Detroit had the second-largest Asian population. As of that year, Detroit’s percentage of Asians was 1%, far lower than the 13.3% of Troy.[200] By 2000 Troy had the largest Asian American population in the tri-county area, surpassing Detroit.[201]