| Hercule Poirot | |

|---|---|

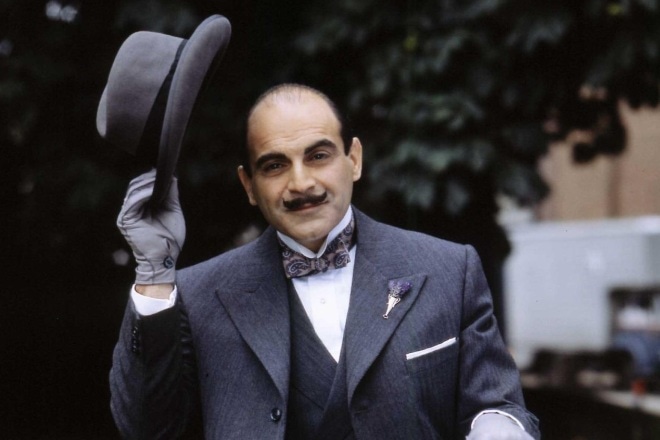

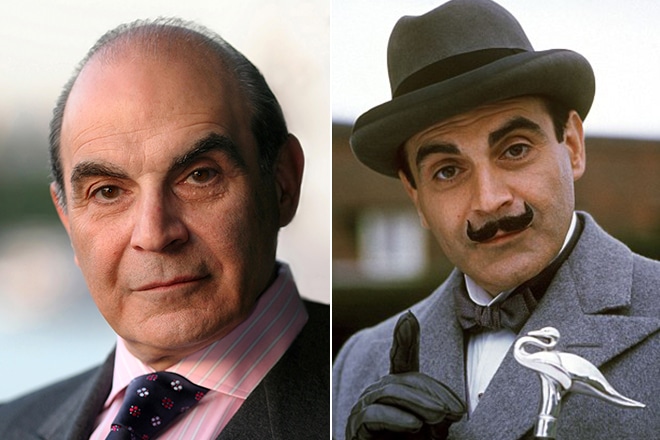

David Suchet as Hercule Poirot in Agatha Christie’s Poirot |

|

| First appearance | The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) |

| Last appearance | Curtain (1975) |

| Created by | Agatha Christie |

| Portrayed by | Charles Laughton Francis L. Sullivan Austin Trevor Orson Welles Harold Huber Richard Williams John Malkovich José Ferrer Martin Gabel Tony Randall Albert Finney Dudley Jones Peter Ustinov Ian Holm David Suchet John Moffatt Maurice Denham Peter Sallis Konstantin Raikin Alfred Molina Robert Powell Jason Durr Kenneth Branagh Anthony O’Donnell Shirō Itō (Takashi Akafuji) Mansai Nomura (Takeru Suguro) Tom Conti |

| Voiced by | Kōtarō Satomi |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Private investigator Police officer (former occupation) |

| Family | Jules-Louis Poirot (father) Godelieve Poirot (mother) |

| Religion | Catholic |

| Nationality | Belgian |

Hercule Poirot (, [1]) is a fictional Belgian detective created by British writer Agatha Christie. Poirot is one of Christie’s most famous and long-running characters, appearing in 33 novels, two plays (Black Coffee and Alibi), and 51 short stories published between 1920 and 1975.

Poirot has been portrayed on radio, in film and on television by various actors, including Austin Trevor, John Moffatt, Albert Finney, Peter Ustinov, Ian Holm, Tony Randall, Alfred Molina, Orson Welles, David Suchet, Kenneth Branagh, and John Malkovich.

Overview[edit]

Influences[edit]

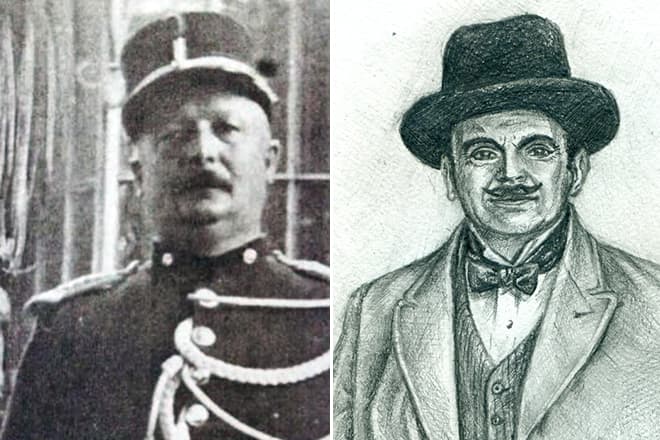

Poirot’s name was derived from two other fictional detectives of the time: Marie Belloc Lowndes’ Hercule Popeau and Frank Howel Evans’ Monsieur Poiret, a retired French police officer living in London.[2] Evans’ Jules Poiret «was small and rather heavyset, hardly more than five feet, but moved with his head held high. The most remarkable features of his head were the stiff military moustache. His apparel was neat to perfection, a little quaint and frankly dandified.» He was accompanied by Captain Harry Haven, who had returned to London from a Colombian business venture ended by a civil war. [3]

A more obvious influence on the early Poirot stories is that of Arthur Conan Doyle. In An Autobiography, Christie states, «I was still writing in the Sherlock Holmes tradition – eccentric detective, stooge assistant, with a Lestrade-type Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Japp».[4] For his part, Conan Doyle acknowledged basing his detective stories on the model of Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin and his anonymous narrator, and basing his character Sherlock Holmes on Joseph Bell, who in his use of «ratiocination» prefigured Poirot’s reliance on his «little grey cells».

Poirot also bears a striking resemblance to A. E. W. Mason’s fictional detective Inspector Hanaud of the French Sûreté, who first appeared in the 1910 novel At the Villa Rose and predates the first Poirot novel by 10 years.

Christie’s Poirot was clearly the result of her early development of the detective in her first book, written in 1916 and published in 1920. Belgium’s occupation by Germany during World War I provided a plausible explanation of why such a skilled detective would be available to solve mysteries at an English country house.[5] At the time of Christie’s writing, it was considered patriotic to express sympathy towards the Belgians,[6] since the invasion of their country had constituted Britain’s casus belli for entering World War I, and British wartime propaganda emphasised the «Rape of Belgium».

Popularity[edit]

Poirot first appeared in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (published in 1920) and exited in Curtain (published in 1975). Following the latter, Poirot was the only fictional character to receive an obituary on the front page of The New York Times.[7][8]

By 1930, Agatha Christie found Poirot «insufferable», and by 1960 she felt that he was a «detestable, bombastic, tiresome, ego-centric little creep». Despite this, Poirot remained an exceedingly popular character with the general public. Christie later stated that she refused to kill him off, claiming that it was her duty to produce what the public liked.[9]

Appearance and proclivities[edit]

Captain Arthur Hastings’s first description of Poirot:

He was hardly more than five feet four inches but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. Even if everything on his face was covered, the tips of moustache and the pink-tipped nose would be visible.

The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandified little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police.[5]

Agatha Christie’s initial description of Poirot in The Murder on the Orient Express:

By the step leading up into the sleeping-car stood a young French lieutenant, resplendent in uniform, conversing with a small man [Hercule Poirot] muffled up to the ears of whom nothing was visible but a pink-tipped nose and the two points of an upward-curled moustache. [10]

In the later books, his limp is not mentioned, suggesting it may have been a temporary wartime injury. (In Curtain, Poirot admits he was wounded when he first came to England.) Poirot has green eyes that are repeatedly described as shining «like a cat’s» when he is struck by a clever idea,[11] and dark hair, which he dyes later in life. In Curtain, he admits to Hastings that he wears a wig and a false moustache.[12] However, in many of his screen incarnations, he is bald or balding.

Frequent mention is made of his patent leather shoes, damage to which is frequently a source of misery for him, but comical for the reader.[13] Poirot’s appearance, regarded as fastidious during his early career, later falls hopelessly out of fashion.[14]

Among Poirot’s most significant personal attributes is the sensitivity of his stomach:

The plane dropped slightly. «Mon estomac,» thought Hercule Poirot, and closed his eyes determinedly.[15]

He suffers from sea sickness,[16] and, in Death in the Clouds, he states that his air sickness prevents him from being more alert at the time of the murder. Later in his life, we are told:

Always a man who had taken his stomach seriously, he was reaping his reward in old age. Eating was not only a physical pleasure, it was also an intellectual research.[15]

Poirot is extremely punctual and carries a pocket watch almost to the end of his career.[17] He is also particular about his personal finances, preferring to keep a bank balance of 444 pounds, 4 shillings, and 4 pence.[18] Actor David Suchet, who portrayed Poirot on television, said «there’s no question he’s obsessive-compulsive».[19] Film portrayer Kenneth Branagh said that he «enjoyed finding the sort of obsessive-compulsive» in Poirot.[20]

As mentioned in Curtain and The Clocks, he is fond of classical music, particularly Mozart and Bach.

Methods[edit]

In The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Poirot operates as a fairly conventional, clue-based and logical detective; reflected in his vocabulary by two common phrases: his use of «the little grey cells» and «order and method». Hastings is irritated by the fact that Poirot sometimes conceals important details of his plans, as in The Big Four.[21] In this novel, Hastings is kept in the dark throughout the climax. This aspect of Poirot is less evident in the later novels, partly because there is rarely a narrator to mislead.

In Murder on the Links, still largely dependent on clues himself, Poirot mocks a rival «bloodhound» detective who focuses on the traditional trail of clues established in detective fiction (e.g., Sherlock Holmes depending on footprints, fingerprints, and cigar ash). From this point on, Poirot establishes his psychological bona fides. Rather than painstakingly examining crime scenes, he enquires into the nature of the victim or the psychology of the murderer. He predicates his actions in the later novels on his underlying assumption that particular crimes are committed by particular types of people.

Poirot focuses on getting people to talk. In the early novels, he casts himself in the role of «Papa Poirot», a benign confessor, especially to young women. In later works, Christie made a point of having Poirot supply false or misleading information about himself or his background to assist him in obtaining information.[22] In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Poirot speaks of a non-existent mentally disabled nephew[23] to uncover information about homes for the mentally unfit. In Dumb Witness, Poirot invents an elderly invalid mother as a pretence to investigate local nurses. In The Big Four, Poirot pretends to have (and poses as) an identical twin brother named Achille: however, this brother was mentioned again in The Labours of Hercules.[21]

«If I remember rightly – though my memory isn’t what it was – you also had a brother called Achille, did you not?” Poirot’s mind raced back over the details of Achille Poirot’s career. Had all that really happened? «Only for a short space of time,» he replied.[24]

Poirot is also willing to appear more foreign or vain in an effort to make people underestimate him. He admits as much:

It is true that I can speak the exact, the idiomatic English. But, my friend, to speak the broken English is an enormous asset. It leads people to despise you. They say – a foreigner – he can’t even speak English properly. … Also I boast! An Englishman he says often, «A fellow who thinks as much of himself as that cannot be worth much.» … And so, you see, I put people off their guard.[25]

He also has a tendency to refer to himself in the third person.[26][27]

In later novels, Christie often uses the word mountebank when characters describe Poirot, showing that he has successfully passed himself off as a charlatan or fraud.

Poirot’s investigating techniques assist him solving cases; «For in the long run, either through a lie, or through truth, people were bound to give themselves away…»[28] At the end, Poirot usually reveals his description of the sequence of events and his deductions to a room of suspects, often leading to the culprit’s apprehension.

Life[edit]

Origins[edit]

Christie was purposely vague about Poirot’s origins, as he is thought to be an elderly man even in the early novels. In An Autobiography, she admitted that she already imagined him to be an old man in 1920. At the time, however, she did not know that she would write works featuring him for decades to come.

A brief passage in The Big Four provides original information about Poirot’s birth or at least childhood in or near the town of Spa, Belgium: «But we did not go into Spa itself. We left the main road and wound into the leafy fastnesses of the hills, till we reached a little hamlet and an isolated white villa high on the hillside.»[29] Christie strongly implies that this «quiet retreat in the Ardennes»[30] near Spa is the location of the Poirot family home.

An alternative tradition holds that Poirot was born in the village of Ellezelles (province of Hainaut, Belgium).[31] A few memorials dedicated to Hercule Poirot can be seen in the centre of this village. There appears to be no reference to this in Christie’s writings, but the town of Ellezelles cherishes a copy of Poirot’s birth certificate in a local memorial ‘attesting’ Poirot’s birth, naming his father and mother as Jules-Louis Poirot and Godelieve Poirot.

Christie wrote that Poirot is a Catholic by birth,[32] but not much is described about his later religious convictions, except sporadic references to his «going to church».[33] Christie provides little information regarding Poirot’s childhood, only mentioning in Three Act Tragedy that he comes from a large family with little wealth, and has at least one younger sister. Apart from French and English, Poirot is also fluent in German.[34]

Policeman[edit]

Gustave … was not a policeman. I have dealt with policemen all my life and I know. He could pass as a detective to an outsider but not to a man who was a policeman himself.

- — Hercule Poirot Christie 1947c

Hercule Poirot was active in the Brussels police force by 1893.[35] Very little mention is made about this part of his life, but in «The Nemean Lion» (1939) Poirot refers to a Belgian case of his in which «a wealthy soap manufacturer … poisoned his wife in order to be free to marry his secretary». As Poirot was often misleading about his past to gain information, the truthfulness of that statement is unknown; it does, however, scare off a would-be wife-killer.

In the short story «The Chocolate Box» (1923), Poirot reveals to Captain Arthur Hastings an account of what he considers to be his only failure. Poirot admits that he has failed to solve a crime «innumerable» times:

I have been called in too late. Very often another, working towards the same goal, has arrived there first. Twice I have been struck down with illness just as I was on the point of success.

Nevertheless, he regards the 1893 case in «The Chocolate Box»,[36] as his only failure through his fault only. Again, Poirot is not reliable as a narrator of his personal history and there is no evidence that Christie sketched it out in any depth. During his police career, Poirot shot a man who was firing from a roof into the public below.[37] In Lord Edgware Dies, Poirot reveals that he learned to read writing upside down during his police career. Around that time he met Xavier Bouc, director of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits.

Inspector Japp offers some insight into Poirot’s career with the Belgian police when introducing him to a colleague:

You’ve heard me speak of Mr Poirot? It was in 1904 he and I worked together – the Abercrombie forgery case – you remember he was run down in Brussels. Ah, those were the days Moosier. Then, do you remember «Baron» Altara? There was a pretty rogue for you! He eluded the clutches of half the police in Europe. But we nailed him in Antwerp – thanks to Mr. Poirot here.[38]

In The Double Clue, Poirot mentions that he was Chief of Police of Brussels, until «the Great War» (World War I) forced him to leave for England.

Private detective[edit]

I had called in at my friend Poirot’s rooms to find him sadly overworked. So much had he become the rage that every rich woman who had mislaid a bracelet or lost a pet kitten rushed to secure the services of the great Hercule Poirot. [39]

During World War I, Poirot left Belgium for England as a refugee, although he returned a few times. On 16 July 1916 he again met his lifelong friend, Captain Arthur Hastings, and solved the first of his cases to be published, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. It is clear that Hastings and Poirot are already friends when they meet in Chapter 2 of the novel, as Hastings tells Cynthia that he has not seen him for «some years» (Agatha Christie’s Poirot has Hastings reveal that they met on a shooting case where Hastings was a suspect). Particulars such as the date of 1916 for the case and that Hastings had met Poirot in Belgium, are given in Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, Chapter 1. After that case, Poirot apparently came to the attention of the British secret service and undertook cases for the British government, including foiling the attempted abduction of the Prime Minister.[40] Readers were told that the British authorities had learned of Poirot’s keen investigative ability from certain members of Belgium’s royal family.

Florin Court became the fictional residence of Agatha Christie’s Poirot, known as «Whitehaven Mansions»

After the war, Poirot became a private detective and began undertaking civilian cases. He moved into what became both his home and work address, Flat 203 at 56B Whitehaven Mansions. Hastings first visits the flat when he returns to England in June 1935 from Argentina in The A.B.C. Murders, Chapter 1. The TV programmes place this in Florin Court, Charterhouse Square, in the wrong part of London. According to Hastings, it was chosen by Poirot «entirely on account of its strict geometrical appearance and proportion» and described as the «newest type of service flat». (The Florin Court building was actually built in 1936, decades after Poirot fictionally moved in.) His first case in this period was «The Affair at the Victory Ball», which allowed Poirot to enter high society and begin his career as a private detective.

Between the world wars, Poirot travelled all over Europe and the Middle East investigating crimes and solving murders. Most of his cases occurred during this time and he was at the height of his powers at this point in his life. In The Murder on the Links, the Belgian pits his grey cells against a French murderer. In the Middle East, he solved the cases Death on the Nile and Murder in Mesopotamia with ease and even survived An Appointment with Death. As he passed through Eastern Europe on his return trip, he solved The Murder on the Orient Express. However, he did not travel to Africa or Asia, probably to avoid seasickness.

It is this villainous sea that troubles me! The mal de mer – it is horrible suffering![41]

It was during this time he met the Countess Vera Rossakoff, a glamorous jewel thief. The history of the countess is, like Poirot’s, steeped in mystery. She claims to have been a member of the Russian aristocracy before the Russian Revolution and suffered greatly as a result, but how much of that story is true is an open question. Even Poirot acknowledges that Rossakoff offered wildly varying accounts of her early life. Poirot later became smitten with the woman and allowed her to escape justice.[42]

It is the misfortune of small, precise men always to hanker after large and flamboyant women. Poirot had never been able to rid himself of the fatal fascination that the countess held for him.[43]

Although letting the countess escape was morally questionable, it was not uncommon. In The Nemean Lion, Poirot sided with the criminal, Miss Amy Carnaby, allowing her to evade prosecution by blackmailing his client Sir Joseph Hoggins, who, Poirot discovered, had plans to commit murder. Poirot even sent Miss Carnaby two hundred pounds as a final payoff prior to the conclusion of her dog kidnapping campaign. In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Poirot allowed the murderer to escape justice through suicide and then withheld the truth to spare the feelings of the murderer’s relatives. In The Augean Stables, he helped the government to cover up vast corruption. In Murder on the Orient Express, Poirot allowed the murderers to go free after discovering that twelve different people participated in the murder, each one stabbing the victim in a darkened carriage after drugging him into unconsciousness so that there was no way for anyone to definitively determine which of them actually delivered the killing blow. The victim had committed a disgusting crime which led to the deaths of at least five people, and there was no question of his guilt, but he had been acquitted in America in a miscarriage of justice. Considering it poetic justice that twelve jurors had acquitted him and twelve people had stabbed him, Poirot produced an alternative sequence of events to explain the death involving an unknown additional passenger on the train, with the medical examiner agreeing to doctor his own report to support this theory.

After his cases in the Middle East, Poirot returned to Britain. Apart from some of the so-called Labours of Hercules (see next section) he very rarely went abroad during his later career. He moved into Styles Court towards the end of his life.

While Poirot was usually paid handsomely by clients, he was also known to take on cases that piqued his curiosity, although they did not pay well.

Poirot shows a love of steam trains, which Christie contrasts with Hastings’ love of autos: this is shown in The Plymouth Express, The Mystery of the Blue Train, Murder on the Orient Express, and The ABC Murders (in the TV series, steam trains are seen in nearly all of the episodes).

Retirement[edit]

That’s the way of it. Just a case or two, just one case more – the Prima Donna’s farewell performance won’t be in it with yours, Poirot.[44]

Confusion surrounds Poirot’s retirement. Most of the cases covered by Poirot’s private detective agency take place before his retirement to attempt to grow larger marrows, at which time he solves The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. It has been said that the twelve cases related in The Labours of Hercules (1947) must refer to a different retirement, but the fact that Poirot specifically says that he intends to grow marrows indicates that these stories also take place before Roger Ackroyd, and presumably Poirot closed his agency once he had completed them. There is specific mention in «The Capture of Cerberus» of the twenty-year gap between Poirot’s previous meeting with Countess Rossakoff and this one. If the Labours precede the events in Roger Ackroyd, then the Ackroyd case must have taken place around twenty years later than it was published, and so must any of the cases that refer to it. One alternative would be that having failed to grow marrows once, Poirot is determined to have another go, but this is specifically denied by Poirot himself.[45] Also, in «The Erymanthian Boar», a character is said to have been turned out of Austria by the Nazis, implying that the events of The Labours of Hercules took place after 1937. Another alternative would be to suggest that the Preface to the Labours takes place at one date but that the labours are completed over a matter of twenty years. None of the explanations is especially attractive.

In terms of a rudimentary chronology, Poirot speaks of retiring to grow marrows in Chapter 18 of The Big Four[46] (1927) which places that novel out of published order before Roger Ackroyd. He declines to solve a case for the Home Secretary because he is retired in Chapter One of Peril at End House (1932). He has certainly retired at the time of Three Act Tragedy (1935) but he does not enjoy his retirement and repeatedly takes cases thereafter when his curiosity is engaged. He continues to employ his secretary, Miss Lemon, at the time of the cases retold in Hickory Dickory Dock and Dead Man’s Folly, which take place in the mid-1950s. It is, therefore, better to assume that Christie provided no authoritative chronology for Poirot’s retirement but assumed that he could either be an active detective, a consulting detective, or a retired detective as the needs of the immediate case required.

One consistent element about Poirot’s retirement is that his fame declines during it so that in the later novels he is often disappointed when characters (especially younger characters) recognise neither him nor his name:

«I should, perhaps, Madame, tell you a little more about myself. I am Hercule Poirot.»

The revelation left Mrs Summerhayes unmoved.

«What a lovely name,» she said kindly. «Greek, isn’t it?»[47]

Post–World War II[edit]

He, I knew, was not likely to be far from his headquarters. The time when cases had drawn him from one end of England to the other was past.

Poirot is less active during the cases that take place at the end of his career. Beginning with Three Act Tragedy (1934), Christie had perfected during the inter-war years a subgenre of Poirot novel in which the detective himself spent much of the first third of the novel on the periphery of events. In novels such as Taken at the Flood, After the Funeral, and Hickory Dickory Dock, he is even less in evidence, frequently passing the duties of main interviewing detective to a subsidiary character. In Cat Among the Pigeons, Poirot’s entrance is so late as to be almost an afterthought. Whether this was a reflection of his age or of Christie’s distaste for him, is impossible to assess. Crooked House (1949) and Ordeal by Innocence (1957), which could easily have been Poirot novels, represent a logical endpoint of the general diminution of his presence in such works.

Towards the end of his career, it becomes clear that Poirot’s retirement is no longer a convenient fiction. He assumes a genuinely inactive lifestyle during which he concerns himself with studying famous unsolved cases of the past and reading detective novels. He even writes a book about mystery fiction in which he deals sternly with Edgar Allan Poe and Wilkie Collins.[49][page needed] In the absence of a more appropriate puzzle, he solves such inconsequential domestic riddles as the presence of three pieces of orange peel in his umbrella stand.[50][page needed]

Poirot (and, it is reasonable to suppose, his creator)[a] becomes increasingly bemused by the vulgarism of the up-and-coming generation’s young people. In Hickory Dickory Dock, he investigates the strange goings-on in a student hostel, while in Third Girl (1966) he is forced into contact with the smart set of Chelsea youths. In the growing drug and pop culture of the sixties, he proves himself once again but has become heavily reliant on other investigators (especially the private investigator, Mr. Goby) who provide him with the clues that he can no longer gather for himself.

You’re too old. Nobody told me you were so old. I really don’t want to be rude but – there it is. You’re too old. I’m really very sorry.

— Norma Restarick to Poirot in Third Girl, Chapter 1[49][page needed]

Notably, during this time his physical characteristics also change dramatically, and by the time Arthur Hastings meets Poirot again in Curtain, he looks very different from his previous appearances, having become thin with age and with obviously dyed hair.

Death[edit]

On the ITV television series, Poirot died in October 1949[53] from complications of a heart condition at the end of Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case. This took place at Styles Court, the scene of his first English case in 1916. In Christie’s novels, he lived into the early 1970s, perhaps even until 1975 when Curtain was published. In both the novel and the television adaptation, he had moved his amyl nitrite pills out of his own reach, possibly because of guilt. He thereby became the murderer in Curtain, although it was for the benefit of others. Poirot himself noted that he wanted to kill his victim shortly before his own death so that he could avoid succumbing to the arrogance of the murderer, concerned that he might come to view himself as entitled to kill those whom he deemed necessary to eliminate.

The «murderer» that he was hunting had never actually killed anyone, but he had manipulated others to kill for him, subtly and psychologically manipulating the moments where others desire to commit murder so that they carry out the crime when they might otherwise dismiss their thoughts as nothing more than a momentary passion. Poirot thus was forced to kill the man himself, as otherwise he would have continued his actions and never been officially convicted, as he did not legally do anything wrong. It is revealed at the end of Curtain that he fakes his need for a wheelchair to fool people into believing that he is suffering from arthritis, to give the impression that he is more infirm than he is. His last recorded words are «Cher ami!«, spoken to Hastings as the Captain left his room. (The TV adaptation adds that as Poirot is dying alone, he whispers out his final prayer to God in these words: «Forgive me… forgive…») Poirot was buried at Styles, and his funeral was arranged by his best friend Hastings and Hastings’ daughter Judith. Hastings reasoned, «Here was the spot where he had lived when he first came to this country. He was to lie here at the last.»

Poirot’s actual death and funeral occurred in Curtain, years after his retirement from the active investigation, but it was not the first time that Hastings attended the funeral of his best friend. In The Big Four (1927), Poirot feigned his death and subsequent funeral to launch a surprise attack on the Big Four.

Recurring characters[edit]

Captain Arthur Hastings[edit]

Hastings, a former British Army officer, meets Poirot during Poirot’s years as a police officer in Belgium and almost immediately after they both arrive in England. He becomes Poirot’s lifelong friend and appears in many cases. Poirot regards Hastings as a poor private detective, not particularly intelligent, yet helpful in his way of being fooled by the criminal or seeing things the way the average man would see them and for his tendency to unknowingly «stumble» onto the truth.[54] Hastings marries and has four children – two sons and two daughters. As a loyal, albeit somewhat naïve companion, Hastings is to Poirot what Watson is to Sherlock Holmes.

Hastings is capable of great bravery and courage, facing death unflinchingly when confronted by The Big Four and displaying unwavering loyalty towards Poirot. However, when forced to choose between Poirot and his wife in that novel, he initially chooses to betray Poirot to protect his wife. Later, though, he tells Poirot to draw back and escape the trap.

The two are an airtight team until Hastings meets and marries Dulcie Duveen, a beautiful music hall performer half his age, after investigating the Murder on the Links. They later emigrated to Argentina, leaving Poirot behind as a «very unhappy old man». However, Poirot and Hastings reunite during the novels The Big Four, Peril at End House, The ABC Murders, Lord Edgware Dies, and Dumb Witness, when Hastings arrives in England for business, with Poirot noting in ABC Murders that he enjoys having Hastings over because he feels that he always has his most interesting cases with Hastings. The two collaborate for the final time in Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case when the seemingly-crippled Poirot asks Hastings to assist him in his final case. When the killer they are tracking nearly manipulates Hastings into committing murder, Poirot describes this in his final farewell letter to Hastings as the catalyst that prompted him to eliminate the man himself, as Poirot knew that his friend was not a murderer and refused to let a man capable of manipulating Hastings in such a manner go on.

Mrs Ariadne Oliver[edit]

Detective novelist Ariadne Oliver is Agatha Christie’s humorous self-caricature. Like Christie, she is not overly fond of the detective whom she is most famous for creating–in Ariadne’s case, Finnish sleuth Sven Hjerson. We never learn anything about her husband, but we do know that she hates alcohol and public appearances and has a great fondness for apples until she is put off them by the events of Hallowe’en Party. She also has a habit of constantly changing her hairstyle, and in every appearance by her much is made of her clothes and hats. Her maid Maria prevents the public adoration from becoming too much of a burden on her employer but does nothing to prevent her from becoming too much of a burden on others.

She has authored more than 56 novels and greatly dislikes people modifying her characters. She is the only one in Poirot’s universe to have noted that «It’s not natural for five or six people to be on the spot when B is murdered and all have a motive for killing B.» She first met Poirot in the story Cards on the Table and has bothered him ever since.

Miss Felicity Lemon[edit]

Poirot’s secretary, Miss Felicity Lemon, has few human weaknesses. The only mistakes she makes within the series are a typing error during the events of Hickory Dickory Dock and the mis-mailing of an electricity bill, although she was worried about strange events surrounding her sister who worked at a student hostel at the time. Poirot described her as being «Unbelievably ugly and incredibly efficient. Anything that she mentioned as worth consideration usually was worth consideration.» She is an expert on nearly everything and plans to create the perfect filing system. She also worked for the government statistician-turned-philanthropist Parker Pyne. Whether this was during one of Poirot’s numerous retirements or before she entered his employment is unknown.[citation needed] In The Agatha Christie Hour, she was portrayed by Angela Easterling, while in Agatha Christie’s Poirot she was portrayed by Pauline Moran. On a number of occasions, she joins Poirot in his inquiries or seeks out answers alone at his request.

Chief Inspector James Harold Japp[edit]

Japp is a Scotland Yard Inspector and appears in many of the stories trying to solve cases that Poirot is working on. Japp is outgoing, loud, and sometimes inconsiderate by nature, and his relationship with the refined Belgian is one of the stranger aspects of Poirot’s world. He first met Poirot in Belgium in 1904, during the Abercrombie Forgery. Later that year they joined forces again to hunt down a criminal known as Baron Altara. They also meet in England where Poirot often helps Japp and lets him take credit in return for special favours. These favours usually entail Poirot being supplied with other interesting cases.[55] In Agatha Christie’s Poirot, Japp was portrayed by Philip Jackson. In the film, Thirteen at Dinner (1985), adapted from Lord Edgware Dies, the role of Japp was taken by the actor David Suchet, who would later star as Poirot in the ITV adaptations.

Major novels[edit]

The Poirot books take readers through the whole of his life in England, from the first book (The Mysterious Affair at Styles), where he is a refugee staying at Styles, to the last Poirot book (Curtain), where he visits Styles before his death. In between, Poirot solves cases outside England as well, including his most famous case, Murder on the Orient Express (1934).

Hercule Poirot became famous in 1926 with the publication of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, whose surprising solution proved controversial. The novel is still among the most famous of all detective novels: Edmund Wilson alludes to it in the title of his well-known attack on detective fiction, «Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?» Aside from Roger Ackroyd, the most critically acclaimed Poirot novels appeared from 1932 to 1942, including Murder on the Orient Express (1934); The ABC Murders (1935); Cards on the Table (1936); and Death on the Nile (1937), a tale of multiple murders upon a Nile steamer. Death on the Nile was judged by the famed detective novelist John Dickson Carr to be among the ten greatest mystery novels of all time.[56]

The 1942 novel Five Little Pigs (a.k.a. Murder in Retrospect), in which Poirot investigates a murder committed sixteen years before by analysing various accounts of the tragedy, has been called «the best Christie of all»[57] by critic and mystery novelist Robert Barnard.

In 2014, the Poirot canon was added to by Sophie Hannah, the first author to be commissioned by the Christie estate to write an original story. The novel was called The Monogram Murders, and was set in the late 1920s, placing it chronologically between The Mystery of the Blue Train and Peril at End House. A second Hannah-penned Poirot came out in 2016, called Closed Casket, and a third, The Mystery of Three Quarters, in 2018.[58]

Portrayals[edit]

Stage[edit]

The first actor to portray Poirot was Charles Laughton. He appeared on the West End in 1928 in the play Alibi which had been adapted by Michael Morton from the novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

In 1932, the play was performed as The Fatal Alibi on Broadway. Another Poirot play, Black Coffee opened in London at the Embassy Theatre on 8 December 1930 and starred Francis L. Sullivan as Poirot. Another production of Black Coffee ran in Dublin, Ireland from 23 to 28 June 1931, starring Robert Powell. American playwright Ken Ludwig adapted Murder on the Orient Express into a play, which premiered at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey on 14 March 2017. It starred Allan Corduner in the role of Hercule Poirot.

Film[edit]

Austin Trevor[edit]

Austin Trevor debuted the role of Poirot on screen in the 1931 British film Alibi. The film was based on the stage play. Trevor reprised the role of Poirot twice, in Black Coffee and Lord Edgware Dies. Trevor said once that he was probably cast as Poirot simply because he could do a French accent.[59] Notably, Trevor’s Poirot did not have a moustache. Leslie S. Hiscott directed the first two films, and Henry Edwards took over for the third.

Tony Randall[edit]

Tony Randall portrayed Poirot in The Alphabet Murders, a 1965 film also known as The ABC Murders. This was more a satire of Poirot than a straightforward adaptation and was greatly changed from the original. Much of the story, set in modern times, was played for comedy, with Poirot investigating the murders while evading the attempts by Hastings (Robert Morley) and the police to get him out of England and back to Belgium.

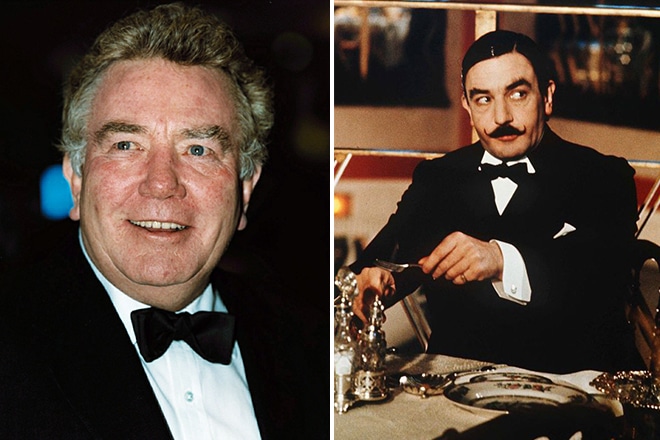

Albert Finney[edit]

Albert Finney played Poirot in 1974 in the cinematic version of Murder on the Orient Express. As of now, Finney is the only actor to receive an Academy Award nomination for playing Poirot, though he did not win.

Peter Ustinov[edit]

Peter Ustinov played Poirot six times, starting with Death on the Nile (1978). He reprised the role in Evil Under the Sun (1982) and Appointment with Death (1988).

Christie’s daughter Rosalind Hicks observed Ustinov during a rehearsal and said, «That’s not Poirot! He isn’t at all like that!» Ustinov overheard and remarked «He is now!«[60]

He appeared again as Poirot in three television films: Thirteen at Dinner (1985), Dead Man’s Folly (1986), and Murder in Three Acts (1986). Earlier adaptations were set during the time in which the novels were written, but these television films were set in the contemporary era. The first of these was based on Lord Edgware Dies and was made by Warner Bros. It also starred Faye Dunaway, with David Suchet as Inspector Japp, just before Suchet began to play Poirot. David Suchet considers his performance as Japp to be «possibly the worst performance of [his] career».[61]

Kenneth Branagh[edit]

Kenneth Branagh played Poirot in film adaptations of Murder on the Orient Express in 2017 and Death on the Nile in 2022, both of which he also directed. He is currently set to return for a third film.

Other[edit]

- Anatoly Ravikovich, Zagadka Endkhauza (End House Mystery) (1989; based on «Peril at End House»)

Television[edit]

David Suchet[edit]

David Suchet starred as Poirot in the ITV series Agatha Christie’s Poirot from 1989 until June 2013, when he announced that he was bidding farewell to the role. «No one could’ve guessed then that the series would span a quarter-century or that the classically trained Suchet would complete the entire catalogue of whodunits featuring the eccentric Belgian investigator, including 33 novels and dozens of short stories.»[62] His final appearance in the show was in an adaptation of Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, aired on 13 November 2013.

The writers of the «Binge!» article of Entertainment Weekly Issue #1343–44 (26 December 2014 – 3 January 2015) picked Suchet as «Best Poirot» in the «Hercule Poirot & Miss Marple» timeline.[63]

The episodes were shot in various locations in the UK and abroad (for example Triangle at Rhodes and Problem at Sea[64]), whilst other scenes were shot at Twickenham Studios.[65]

Other[edit]

- Heini Göbel, (1955; an adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express for the West German television series Die Galerie der großen Detektive)

- José Ferrer, Hercule Poirot (1961; Unaired TV Pilot, MGM; adaptation of «The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim»)

- Martin Gabel, General Electric Theater (4/1/1962; adaptation of «The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim»)

- Horst Bollmann, Black Coffee 1973

- Ian Holm, Murder by the Book, 1986

- Arnolds Liniņš, Slepkavība Stailzā (The Mysterious Affair at Styles), 1990

- Hugh Laurie, Spice World, 1997

- Alfred Molina, Murder on the Orient Express, 2001

- Konstantin Raikin, Neudacha Puaro (Poirot’s Failure) (2002; based on «The Murder of Roger Ackroyd»)

- Anthony O’Donnell, Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures, 2004

- Shirō Itō (Takashi Akafuji), Meitantei Akafuji Takashi (The Detective Takashi Akafuji), 2005

- Mansai Nomura (Takeru Suguro), Orient Kyūkō Satsujin Jiken (Murder on the Orient Express), 2015; Kuroido Goroshi (The Murder of Kuroido), 2018 (based on «The Murder of Roger Ackroyd»); Shi to no Yakusoku, 2021 (based on Appointment with Death)

- John Malkovich was Poirot in the 2018 BBC adaptation of The ABC Murders.[66]

Anime[edit]

In 2004, NHK (Japanese public TV network) produced a 39 episode anime series titled Agatha Christie’s Great Detectives Poirot and Marple, as well as a manga series under the same title released in 2005. The series, adapting several of the best-known Poirot and Marple stories, ran from 4 July 2004 through 15 May 2005, and in repeated reruns on NHK and other networks in Japan. Poirot was voiced by Kōtarō Satomi and Miss Marple was voiced by Kaoru Yachigusa.

Radio[edit]

From 1985 to 2007, BBC Radio 4 produced a series of twenty-seven adaptations of Poirot novels and short stories, adapted by Michael Bakewell and directed by Enyd Williams.[67] Twenty five starred John Moffatt as Poirot; Maurice Denham and Peter Sallis played Poirot on BBC Radio 4 in the first two adaptations, The Mystery of the Blue Train and in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas respectively.

In 1939, Orson Welles and the Mercury Players dramatised Roger Ackroyd on CBS’s Campbell Playhouse.[68][69]

On 6 October 1942, the Mutual radio series Murder Clinic broadcast «The Tragedy at Marsden Manor» starring Maurice Tarplin as Poirot.[70]

A 1945 radio series of at least 13 original half-hour episodes (none of which apparently adapt any Christie stories) transferred Poirot from London to New York and starred character actor Harold Huber,[71] perhaps better known for his appearances as a police officer in various Charlie Chan films. On 22 February 1945, «speaking from London, Agatha Christie introduced the initial broadcast of the Poirot series via shortwave».[68]

An adaptation of Murder in the Mews was broadcast on the BBC Light Programme in March 1955 starring Richard Williams as Poirot; this program was thought lost, but was discovered in the BBC archives in 2015.[72]

Other audio[edit]

In 2017, Audible released an original audio adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express starring Tom Conti as Poirot.[73] The cast included Jane Asher as Mrs. Hubbard, Jay Benedict as Monsieur Bouc, Ruta Gedmintas as Countess Andrenyi, Sophie Okonedo as Mary Debenham, Eddie Marsan as Ratchett, Walles Hamonde as Hector MacQueen, Paterson Joseph as Colonel Arbuthnot, Rula Lenska as Princess Dragimiroff and Art Malik as the Narrator. According to the Publisher’s Summary on Audible.com, «sound effects [were] recorded on the Orient Express itself.»

In 2021, L.A. Theatre Works produced an adaptation of The Murder on the Links, dramatised by Kate McAll. Alfred Molina starred as Poirot, with Simon Helberg as Hastings.[74]

Video games[edit]

The video game Agatha Christie — Hercule Poirot: The First Cases has Poirot voice acted by Will De Renzy-Martin.[citation needed]

Parodies and references[edit]

Parodies of Hercule Poirot have appeared in a number of movies, including Revenge of the Pink Panther, where Poirot makes a cameo appearance in a mental asylum, portrayed by Andrew Sachs and claiming to be «the greatest detective in all of France, the greatest in all the world»; Neil Simon’s Murder by Death, where «Milo Perrier» is played by American actor James Coco; the 1977 film The Strange Case of the End of Civilization as We Know It (1977); the film Spice World, where Hugh Laurie plays Poirot; and in Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened, Poirot appears as a young boy on the train transporting Holmes and Watson. Holmes helps the boy in opening a puzzle-box, with Watson giving the boy advice about using his «little grey cells».

In the book series Geronimo Stilton, the character Hercule Poirat is inspired by Hercule Poirot.

The Belgian brewery Brasserie Ellezelloise makes a stout called Hercule with a moustachioed caricature of Hercule Poirot on the label.[75]

In season 2, episode 4 of TVFPlay’s Indian web series Permanent Roommates, one of the characters refers to Hercule Poirot as her inspiration while she attempts to solve the mystery of the cheating spouse. Throughout the episode, she is mocked as Hercule Poirot and Agatha Christie by the suspects.[76] TVFPlay also telecasted a spoof of Indian TV suspense drama CID as «Qissa Missing Dimaag Ka: C.I.D Qtiyapa«. In the first episode, when Ujjwal is shown to browse for the best detectives of the world, David Suchet appears as Poirot in his search.[77]

See also[edit]

- Poirot Investigates

- Tropes in Agatha Christie’s novels

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ In The Pale Horse, Chapter 1, the novel’s narrator, Mark Easterbrook, disapprovingly describes a typical «Chelsea girl»[51][page needed] in much the same terms that Poirot uses in Chapter 1 of Third Girl, suggesting that the condemnation of fashion is authorial.[52][page needed]

References[edit]

- ^ «Definition». Oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Willis, Chris. «Agatha Christie (1890–1976)». London Metropolitan University. Retrieved 6 September 2006.

- ^ Frank Howell Evans. The Murder of Lady Malvern.

- ^ Reproduced as the «Introduction» to Christie 2013

- ^ a b Christie 1939.

- ^ Horace Cornelius Peterson (1968). Propaganda for War. The Campaign Against American Neutrality, 1914–1917. Kennikat. ISBN 9780804603652.

- ^ «Poirot». Official Agatha Christie website. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Lask, Thomas (6 August 1975). «Hercule Poirot is Dead; Famed Belgian Detective; Hercule Poirot, the Detective, Dies». The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Willis, Chris (16 July 2001). «Agatha Christie (1890–1976)». The Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company. ISSN 1747-678X. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Christie 2011.

- ^ E.g. «For about ten minutes [Poirot] sat in dead silence… and all the time his eyes grew steadily greener» Christie 1939, Chapter 5

- ^ as Hastings discovers in Christie 1991, Chapter 1

- ^ E.g. «Hercule Poirot looked down at the tips of his patent-leather shoes and sighed.» Christie 1947a

- ^ E.g. «And now here was the man himself. Really a most impossible person – the wrong clothes – button boots! an incredible moustache! Not his – Meredith Blake’s kind of fellow at all.» Christie 2011, Chapter 7

- ^ a b Christie 2010, Chapter 1.

- ^ «My stomach, it is not happy on the sea»Christie 1980, Chapter 8, iv

- ^ «he walked up the steps to the front door and pressed the bell, glancing as he did so at the neat wrist-watch which had at last replaced an old favourite – the large turnip-faced watch of early days. Yes, it was exactly nine-thirty. As ever, Hercule Poirot was exact to the minute.» Christie 2011b

- ^ Christie 2013a.

- ^ Barton, Laura (18 May 2009). «Poirot and me». The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ «Kenneth Branagh on His Meticulous Master Detective Role In ‘Murder on the Orient Express’«. NPR. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ a b Christie 2004b.

- ^ «It has been said of Hercule Poirot by some of his friends and associates, at moments when he has maddened them most, that he prefers lies to truth and will go out of his way to gain his ends by elaborate false statements, rather than trust to the simple truth.» Christie 2011a, Book One, Chapter 9

- ^ E.g. «After a careful study of the goods displayed in the window, Poirot entered and represented himself as desirous of purchasing a rucksack for a hypothetical nephew.» Hickory Dickory Dock, Chapter 13

- ^ Christie 1947.

- ^ Christie 2006b, final chapter.

- ^ Saner, Emine (28 July 2011). «Your next box set: Agatha Christie’s Poirot». The Guardian.

- ^ Pettie, Andrew (6 November 2013). «Poirot: The Labours of Hercules, ITV, review». The Telegraph.

- ^ Christie 2005, Chapter 18.

- ^ Christie 2004b, Chapter 16.

- ^ Christie 2004b, Chapter 17.

- ^ «In the province of Hainaut, the village of Ellezelles adopts detective Hercule Poirot». Belles Demeures. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ «Hercule Poirot was a Catholic by birth.» Christie 1947a

- ^ In Taken at the Flood, Book II, Chapter 6 Poirot goes into the church to pray and happens across a suspect with whom he briefly discusses ideas of sin and confession. Christie 1948

- ^ Christie 2011, Chapter 12

- ^ Christie 2009b, Chapter 15.

- ^ The date is given in Christie 2009b, Chapter 15

- ^ Christie 1975, Postscript.

- ^ Christie 1939, Chapter 7.

- ^ Christie 2013b.

- ^ Recounted in Christie 2012

- ^ Poirot, in Christie 2012

- ^ Cassatis, John (1979). The Diaries of A. Christie. London.

- ^ «The Capture of Cerebus» (1947). The first sentence quoted is also a close paraphrase of something said to Poirot by Hastings in Chapter 18 of The Big FourChristie 2004b

- ^ Christie 2006a Dr. Burton in the Preface

- ^ Christie 2004a, Chapter 13 in response to the suggestion that he might take up gardening in his retirement, Poirot answers «Once the vegetable marrows, yes – but never again».

- ^ Christie 2004b, Chapter 18.

- ^ Christie 1952, Chapter 4.

- ^ Christie 2004b, Chapter 1.

- ^ a b Christie 2011c, Chapter 1.

- ^ Christie 2006a, Chapter 14.

- ^ Christie 1961.

- ^ Christie 2011c.

- ^ The extensive letter addressed to Hastings where he explains how he solved the case is dated from October 1949 («Curtain», 2013)

- ^ Matthew, Bunson (2000). «Hastings, Captain Arthur, O.B.E.». The Complete Christie: An Agatha Christie Encyclopedia. New York: Pocket Books.

- ^ Captain Arthur Hastings Christie 2004b, Chapter 9

- ^ Veith, Gene Edward; Wilson, Douglas; Fischer, G. Tyler (2009). Omnibus IV: The Ancient World. Veritas Press. p. 460. ISBN 9781932168860.

- ^ Barnard (1980), p. 85

- ^ «Hannah, Sophie. Closed Casket: The New Hercule Poirot Mystery». link.galegroup.com. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ At the Hercule Poirot Central website Archived 30 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hercule Poirot, Map dig, archived from the original on 17 May 2014

- ^ Suchet, David, «Interview», Strand mag, archived from the original on 30 May 2015, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ^ Henry Chu (19 July 2013). «David Suchet bids farewell to Agatha Christie’s Poirot – Los Angeles Times». Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ «Binge! Agatha Christie: Hercule Poirot & Miss Marple». Entertainment Weekly. No. 1343–44. 26 December 2014. pp. 32–33.

- ^ Suchet, David (2013). Poirot and Me. London: Headline. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780755364190.

- ^ «Homes Used in Poirot Episodes». www.chimni.com. Chimni – the architectural wiki. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ «Casting announced for The ABC Murders BBC adaptation». Agatha Christie. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ «BBC Radio 4 Extra – Poirot – Episode guide». BBC.

- ^ a b Cox, Jim (2002). Radio Crime Fighters. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7864-1390-4.

- ^ «The Murder of Roger Ackroyd». Orson Welles on the Air, 1938–1946. Indiana University Bloomington. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ «Tragedy at Marsden Manor». Murder Clinic. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ «A list of episodes of the half-hour 1945 radio program». Otrsite.com. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ «Murder in the Mews, Poirot – BBC Radio 4 Extra». BBC.

- ^ «Audible Original dramatisation of Christie’s classic story». Agatha Christie. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ «The Murder on the Links». latw.org. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ «The Brasserie Ellezelloise’s Hercule». Brasserie-ellezelloise.be. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ «Watch TVF’s Permanent Roommates S02E04 – The Dinner on TVF Play». TVFPlay.

- ^ «Qissa Missing Dimaag Ka (Part 1/2)». TVFPlay.

Literature[edit]

Works[edit]

- Christie, Agatha (1939). The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-61298-214-4.

- Christie, Agatha (1947). Prologue. Collins.

- Christie, Agatha (1947a). The Apples of the Hesperides. Collins.

- Christie, Agatha (1947b). The Stymphalean Birds. Collins.

- Christie, Agatha (1947c). The Erymanthian Boar. Collins.

- Christie, Agatha (1948). Taken at the Flood.

- Christie, Agatha (1952). Mrs. McGinty’s Dead.

- Christie, Agatha (1961). The Pale Horse by A.Christie. Collins.

- Christie, Agatha (1975). Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-712112-0.

- Christie, Agatha (1980). Evil Under the Sun: Death Comes as the End; The Sittaford Mystery. Lansdowne Press. ISBN 978-0-7018-1458-8.

- Christie, Agatha (1991). The A.B.C. murders: [a Hercule Poirot mystery]. Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-425-13024-7.

- Christie, Agatha (28 September 2004a). The Clocks. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-174050-3.

- Christie, Agatha (6 January 2004b). The Big Four. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-173909-5.

- Christie, Agatha (25 January 2005). After the Funeral: Hercule Poirot Investigates. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-173991-0.

- Christie, Agatha (3 October 2006a). The Labours of Hercules: Hercule Poirot Investigates. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-174638-3.

- Christie, Agatha (3 October 2006b). Three Act Tragedy. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-175403-6.

- Christie, Agatha (17 March 2009). The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-176340-3.

- Christie, Agatha (17 March 2009b). Peril at End House. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-174927-8.

- Christie, Agatha (10 February 2010). Death in the Clouds. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-174311-5.

- Christie, Agatha (1 February 2011a). Five Little Pigs: A Hercule Poirot Mystery. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-207357-0.

- Christie, Agatha (29 March 2011). Murder on the Orient Express: A Hercule Poirot Mystery. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-207350-1.

- Christie, Agatha (1 September 2011b). The Dream: A Hercule Poirot Short Story. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-745198-2.

- Christie, Agatha (14 June 2011c). Third Girl: A Hercule Poirot Mystery. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-207376-1.

- Christie, Agatha (12 April 2012). The Kidnapped Prime Minister: A Hercule Poirot Short Story. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-00-748658-8.

- Christie, Agatha (2013). Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories: A Hercule Poirot Collection with Foreword by Charles Todd. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-225165-7.

- Christie, Agatha (9 July 2013a). The Lost Mine: A Hercule Poirot Story. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-229818-8.

- Christie, Agatha (23 July 2013b). Double Sin: A Hercule Poirot Story. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-229845-4.

Reviews[edit]

- Barnard, Robert (1980), A Talent to Deceive, London: Fontana/Collins

- Goddard, John (2018), Agatha Christie’s Golden Age: An Analysis of Poirot’s Golden Age Puzzles, Stylish Eye Press, ISBN 978-1-999-61200-9

- Hart, Anne (2004), Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Life and Times of Hercule Poirot, London: Harper and Collins

- Kretzschmar, Judith; Stoppe, Sebastian; Vollberg, Susanne, eds. (2016), Hercule Poirot trifft Miss Marple. Agatha Christie intermedial, Darmstadt: Büchner, ISBN 978-3-941310-48-3.

- Osborne, Charles (1982), The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie, London: Collins

External links[edit]

- Official Agatha Christie website

- A collection of public domain Poirot works as eBooks at Standard Ebooks

- Hercule Poirot on IMDb

- The Mysterious Affair at Styles at Project Gutenberg

- Listen to Orson Welles in «The Murder of Roger Ackroyd»

- Listen to the 1945 Hercule Poirot radio program

- Wiktionary definition of Edgar Allan Poe’s «ratiocination»

| Hercule Poirot | |

|---|---|

David Suchet as Hercule Poirot in Agatha Christie’s Poirot |

|

| First appearance | The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) |

| Last appearance | Curtain (1975) |

| Created by | Agatha Christie |

| Portrayed by | Charles Laughton Francis L. Sullivan Austin Trevor Orson Welles Harold Huber Richard Williams John Malkovich José Ferrer Martin Gabel Tony Randall Albert Finney Dudley Jones Peter Ustinov Ian Holm David Suchet John Moffatt Maurice Denham Peter Sallis Konstantin Raikin Alfred Molina Robert Powell Jason Durr Kenneth Branagh Anthony O’Donnell Shirō Itō (Takashi Akafuji) Mansai Nomura (Takeru Suguro) Tom Conti |

| Voiced by | Kōtarō Satomi |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Private investigator Police officer (former occupation) |

| Family | Jules-Louis Poirot (father) Godelieve Poirot (mother) |

| Religion | Catholic |

| Nationality | Belgian |

Hercule Poirot (, [1]) is a fictional Belgian detective created by British writer Agatha Christie. Poirot is one of Christie’s most famous and long-running characters, appearing in 33 novels, two plays (Black Coffee and Alibi), and 51 short stories published between 1920 and 1975.

Poirot has been portrayed on radio, in film and on television by various actors, including Austin Trevor, John Moffatt, Albert Finney, Peter Ustinov, Ian Holm, Tony Randall, Alfred Molina, Orson Welles, David Suchet, Kenneth Branagh, and John Malkovich.

Overview[edit]

Influences[edit]

Poirot’s name was derived from two other fictional detectives of the time: Marie Belloc Lowndes’ Hercule Popeau and Frank Howel Evans’ Monsieur Poiret, a retired French police officer living in London.[2] Evans’ Jules Poiret «was small and rather heavyset, hardly more than five feet, but moved with his head held high. The most remarkable features of his head were the stiff military moustache. His apparel was neat to perfection, a little quaint and frankly dandified.» He was accompanied by Captain Harry Haven, who had returned to London from a Colombian business venture ended by a civil war. [3]

A more obvious influence on the early Poirot stories is that of Arthur Conan Doyle. In An Autobiography, Christie states, «I was still writing in the Sherlock Holmes tradition – eccentric detective, stooge assistant, with a Lestrade-type Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Japp».[4] For his part, Conan Doyle acknowledged basing his detective stories on the model of Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin and his anonymous narrator, and basing his character Sherlock Holmes on Joseph Bell, who in his use of «ratiocination» prefigured Poirot’s reliance on his «little grey cells».

Poirot also bears a striking resemblance to A. E. W. Mason’s fictional detective Inspector Hanaud of the French Sûreté, who first appeared in the 1910 novel At the Villa Rose and predates the first Poirot novel by 10 years.

Christie’s Poirot was clearly the result of her early development of the detective in her first book, written in 1916 and published in 1920. Belgium’s occupation by Germany during World War I provided a plausible explanation of why such a skilled detective would be available to solve mysteries at an English country house.[5] At the time of Christie’s writing, it was considered patriotic to express sympathy towards the Belgians,[6] since the invasion of their country had constituted Britain’s casus belli for entering World War I, and British wartime propaganda emphasised the «Rape of Belgium».

Popularity[edit]

Poirot first appeared in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (published in 1920) and exited in Curtain (published in 1975). Following the latter, Poirot was the only fictional character to receive an obituary on the front page of The New York Times.[7][8]

By 1930, Agatha Christie found Poirot «insufferable», and by 1960 she felt that he was a «detestable, bombastic, tiresome, ego-centric little creep». Despite this, Poirot remained an exceedingly popular character with the general public. Christie later stated that she refused to kill him off, claiming that it was her duty to produce what the public liked.[9]

Appearance and proclivities[edit]

Captain Arthur Hastings’s first description of Poirot:

He was hardly more than five feet four inches but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. Even if everything on his face was covered, the tips of moustache and the pink-tipped nose would be visible.

The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandified little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police.[5]

Agatha Christie’s initial description of Poirot in The Murder on the Orient Express:

By the step leading up into the sleeping-car stood a young French lieutenant, resplendent in uniform, conversing with a small man [Hercule Poirot] muffled up to the ears of whom nothing was visible but a pink-tipped nose and the two points of an upward-curled moustache. [10]

In the later books, his limp is not mentioned, suggesting it may have been a temporary wartime injury. (In Curtain, Poirot admits he was wounded when he first came to England.) Poirot has green eyes that are repeatedly described as shining «like a cat’s» when he is struck by a clever idea,[11] and dark hair, which he dyes later in life. In Curtain, he admits to Hastings that he wears a wig and a false moustache.[12] However, in many of his screen incarnations, he is bald or balding.

Frequent mention is made of his patent leather shoes, damage to which is frequently a source of misery for him, but comical for the reader.[13] Poirot’s appearance, regarded as fastidious during his early career, later falls hopelessly out of fashion.[14]

Among Poirot’s most significant personal attributes is the sensitivity of his stomach:

The plane dropped slightly. «Mon estomac,» thought Hercule Poirot, and closed his eyes determinedly.[15]

He suffers from sea sickness,[16] and, in Death in the Clouds, he states that his air sickness prevents him from being more alert at the time of the murder. Later in his life, we are told:

Always a man who had taken his stomach seriously, he was reaping his reward in old age. Eating was not only a physical pleasure, it was also an intellectual research.[15]

Poirot is extremely punctual and carries a pocket watch almost to the end of his career.[17] He is also particular about his personal finances, preferring to keep a bank balance of 444 pounds, 4 shillings, and 4 pence.[18] Actor David Suchet, who portrayed Poirot on television, said «there’s no question he’s obsessive-compulsive».[19] Film portrayer Kenneth Branagh said that he «enjoyed finding the sort of obsessive-compulsive» in Poirot.[20]

As mentioned in Curtain and The Clocks, he is fond of classical music, particularly Mozart and Bach.

Methods[edit]

In The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Poirot operates as a fairly conventional, clue-based and logical detective; reflected in his vocabulary by two common phrases: his use of «the little grey cells» and «order and method». Hastings is irritated by the fact that Poirot sometimes conceals important details of his plans, as in The Big Four.[21] In this novel, Hastings is kept in the dark throughout the climax. This aspect of Poirot is less evident in the later novels, partly because there is rarely a narrator to mislead.

In Murder on the Links, still largely dependent on clues himself, Poirot mocks a rival «bloodhound» detective who focuses on the traditional trail of clues established in detective fiction (e.g., Sherlock Holmes depending on footprints, fingerprints, and cigar ash). From this point on, Poirot establishes his psychological bona fides. Rather than painstakingly examining crime scenes, he enquires into the nature of the victim or the psychology of the murderer. He predicates his actions in the later novels on his underlying assumption that particular crimes are committed by particular types of people.

Poirot focuses on getting people to talk. In the early novels, he casts himself in the role of «Papa Poirot», a benign confessor, especially to young women. In later works, Christie made a point of having Poirot supply false or misleading information about himself or his background to assist him in obtaining information.[22] In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Poirot speaks of a non-existent mentally disabled nephew[23] to uncover information about homes for the mentally unfit. In Dumb Witness, Poirot invents an elderly invalid mother as a pretence to investigate local nurses. In The Big Four, Poirot pretends to have (and poses as) an identical twin brother named Achille: however, this brother was mentioned again in The Labours of Hercules.[21]

«If I remember rightly – though my memory isn’t what it was – you also had a brother called Achille, did you not?” Poirot’s mind raced back over the details of Achille Poirot’s career. Had all that really happened? «Only for a short space of time,» he replied.[24]

Poirot is also willing to appear more foreign or vain in an effort to make people underestimate him. He admits as much:

It is true that I can speak the exact, the idiomatic English. But, my friend, to speak the broken English is an enormous asset. It leads people to despise you. They say – a foreigner – he can’t even speak English properly. … Also I boast! An Englishman he says often, «A fellow who thinks as much of himself as that cannot be worth much.» … And so, you see, I put people off their guard.[25]

He also has a tendency to refer to himself in the third person.[26][27]

In later novels, Christie often uses the word mountebank when characters describe Poirot, showing that he has successfully passed himself off as a charlatan or fraud.

Poirot’s investigating techniques assist him solving cases; «For in the long run, either through a lie, or through truth, people were bound to give themselves away…»[28] At the end, Poirot usually reveals his description of the sequence of events and his deductions to a room of suspects, often leading to the culprit’s apprehension.

Life[edit]

Origins[edit]

Christie was purposely vague about Poirot’s origins, as he is thought to be an elderly man even in the early novels. In An Autobiography, she admitted that she already imagined him to be an old man in 1920. At the time, however, she did not know that she would write works featuring him for decades to come.

A brief passage in The Big Four provides original information about Poirot’s birth or at least childhood in or near the town of Spa, Belgium: «But we did not go into Spa itself. We left the main road and wound into the leafy fastnesses of the hills, till we reached a little hamlet and an isolated white villa high on the hillside.»[29] Christie strongly implies that this «quiet retreat in the Ardennes»[30] near Spa is the location of the Poirot family home.

An alternative tradition holds that Poirot was born in the village of Ellezelles (province of Hainaut, Belgium).[31] A few memorials dedicated to Hercule Poirot can be seen in the centre of this village. There appears to be no reference to this in Christie’s writings, but the town of Ellezelles cherishes a copy of Poirot’s birth certificate in a local memorial ‘attesting’ Poirot’s birth, naming his father and mother as Jules-Louis Poirot and Godelieve Poirot.

Christie wrote that Poirot is a Catholic by birth,[32] but not much is described about his later religious convictions, except sporadic references to his «going to church».[33] Christie provides little information regarding Poirot’s childhood, only mentioning in Three Act Tragedy that he comes from a large family with little wealth, and has at least one younger sister. Apart from French and English, Poirot is also fluent in German.[34]

Policeman[edit]

Gustave … was not a policeman. I have dealt with policemen all my life and I know. He could pass as a detective to an outsider but not to a man who was a policeman himself.

- — Hercule Poirot Christie 1947c

Hercule Poirot was active in the Brussels police force by 1893.[35] Very little mention is made about this part of his life, but in «The Nemean Lion» (1939) Poirot refers to a Belgian case of his in which «a wealthy soap manufacturer … poisoned his wife in order to be free to marry his secretary». As Poirot was often misleading about his past to gain information, the truthfulness of that statement is unknown; it does, however, scare off a would-be wife-killer.

In the short story «The Chocolate Box» (1923), Poirot reveals to Captain Arthur Hastings an account of what he considers to be his only failure. Poirot admits that he has failed to solve a crime «innumerable» times:

I have been called in too late. Very often another, working towards the same goal, has arrived there first. Twice I have been struck down with illness just as I was on the point of success.

Nevertheless, he regards the 1893 case in «The Chocolate Box»,[36] as his only failure through his fault only. Again, Poirot is not reliable as a narrator of his personal history and there is no evidence that Christie sketched it out in any depth. During his police career, Poirot shot a man who was firing from a roof into the public below.[37] In Lord Edgware Dies, Poirot reveals that he learned to read writing upside down during his police career. Around that time he met Xavier Bouc, director of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits.

Inspector Japp offers some insight into Poirot’s career with the Belgian police when introducing him to a colleague:

You’ve heard me speak of Mr Poirot? It was in 1904 he and I worked together – the Abercrombie forgery case – you remember he was run down in Brussels. Ah, those were the days Moosier. Then, do you remember «Baron» Altara? There was a pretty rogue for you! He eluded the clutches of half the police in Europe. But we nailed him in Antwerp – thanks to Mr. Poirot here.[38]

In The Double Clue, Poirot mentions that he was Chief of Police of Brussels, until «the Great War» (World War I) forced him to leave for England.

Private detective[edit]

I had called in at my friend Poirot’s rooms to find him sadly overworked. So much had he become the rage that every rich woman who had mislaid a bracelet or lost a pet kitten rushed to secure the services of the great Hercule Poirot. [39]

During World War I, Poirot left Belgium for England as a refugee, although he returned a few times. On 16 July 1916 he again met his lifelong friend, Captain Arthur Hastings, and solved the first of his cases to be published, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. It is clear that Hastings and Poirot are already friends when they meet in Chapter 2 of the novel, as Hastings tells Cynthia that he has not seen him for «some years» (Agatha Christie’s Poirot has Hastings reveal that they met on a shooting case where Hastings was a suspect). Particulars such as the date of 1916 for the case and that Hastings had met Poirot in Belgium, are given in Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, Chapter 1. After that case, Poirot apparently came to the attention of the British secret service and undertook cases for the British government, including foiling the attempted abduction of the Prime Minister.[40] Readers were told that the British authorities had learned of Poirot’s keen investigative ability from certain members of Belgium’s royal family.

Florin Court became the fictional residence of Agatha Christie’s Poirot, known as «Whitehaven Mansions»

After the war, Poirot became a private detective and began undertaking civilian cases. He moved into what became both his home and work address, Flat 203 at 56B Whitehaven Mansions. Hastings first visits the flat when he returns to England in June 1935 from Argentina in The A.B.C. Murders, Chapter 1. The TV programmes place this in Florin Court, Charterhouse Square, in the wrong part of London. According to Hastings, it was chosen by Poirot «entirely on account of its strict geometrical appearance and proportion» and described as the «newest type of service flat». (The Florin Court building was actually built in 1936, decades after Poirot fictionally moved in.) His first case in this period was «The Affair at the Victory Ball», which allowed Poirot to enter high society and begin his career as a private detective.

Between the world wars, Poirot travelled all over Europe and the Middle East investigating crimes and solving murders. Most of his cases occurred during this time and he was at the height of his powers at this point in his life. In The Murder on the Links, the Belgian pits his grey cells against a French murderer. In the Middle East, he solved the cases Death on the Nile and Murder in Mesopotamia with ease and even survived An Appointment with Death. As he passed through Eastern Europe on his return trip, he solved The Murder on the Orient Express. However, he did not travel to Africa or Asia, probably to avoid seasickness.

It is this villainous sea that troubles me! The mal de mer – it is horrible suffering![41]

It was during this time he met the Countess Vera Rossakoff, a glamorous jewel thief. The history of the countess is, like Poirot’s, steeped in mystery. She claims to have been a member of the Russian aristocracy before the Russian Revolution and suffered greatly as a result, but how much of that story is true is an open question. Even Poirot acknowledges that Rossakoff offered wildly varying accounts of her early life. Poirot later became smitten with the woman and allowed her to escape justice.[42]

It is the misfortune of small, precise men always to hanker after large and flamboyant women. Poirot had never been able to rid himself of the fatal fascination that the countess held for him.[43]

Although letting the countess escape was morally questionable, it was not uncommon. In The Nemean Lion, Poirot sided with the criminal, Miss Amy Carnaby, allowing her to evade prosecution by blackmailing his client Sir Joseph Hoggins, who, Poirot discovered, had plans to commit murder. Poirot even sent Miss Carnaby two hundred pounds as a final payoff prior to the conclusion of her dog kidnapping campaign. In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Poirot allowed the murderer to escape justice through suicide and then withheld the truth to spare the feelings of the murderer’s relatives. In The Augean Stables, he helped the government to cover up vast corruption. In Murder on the Orient Express, Poirot allowed the murderers to go free after discovering that twelve different people participated in the murder, each one stabbing the victim in a darkened carriage after drugging him into unconsciousness so that there was no way for anyone to definitively determine which of them actually delivered the killing blow. The victim had committed a disgusting crime which led to the deaths of at least five people, and there was no question of his guilt, but he had been acquitted in America in a miscarriage of justice. Considering it poetic justice that twelve jurors had acquitted him and twelve people had stabbed him, Poirot produced an alternative sequence of events to explain the death involving an unknown additional passenger on the train, with the medical examiner agreeing to doctor his own report to support this theory.

After his cases in the Middle East, Poirot returned to Britain. Apart from some of the so-called Labours of Hercules (see next section) he very rarely went abroad during his later career. He moved into Styles Court towards the end of his life.

While Poirot was usually paid handsomely by clients, he was also known to take on cases that piqued his curiosity, although they did not pay well.

Poirot shows a love of steam trains, which Christie contrasts with Hastings’ love of autos: this is shown in The Plymouth Express, The Mystery of the Blue Train, Murder on the Orient Express, and The ABC Murders (in the TV series, steam trains are seen in nearly all of the episodes).

Retirement[edit]

That’s the way of it. Just a case or two, just one case more – the Prima Donna’s farewell performance won’t be in it with yours, Poirot.[44]

Confusion surrounds Poirot’s retirement. Most of the cases covered by Poirot’s private detective agency take place before his retirement to attempt to grow larger marrows, at which time he solves The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. It has been said that the twelve cases related in The Labours of Hercules (1947) must refer to a different retirement, but the fact that Poirot specifically says that he intends to grow marrows indicates that these stories also take place before Roger Ackroyd, and presumably Poirot closed his agency once he had completed them. There is specific mention in «The Capture of Cerberus» of the twenty-year gap between Poirot’s previous meeting with Countess Rossakoff and this one. If the Labours precede the events in Roger Ackroyd, then the Ackroyd case must have taken place around twenty years later than it was published, and so must any of the cases that refer to it. One alternative would be that having failed to grow marrows once, Poirot is determined to have another go, but this is specifically denied by Poirot himself.[45] Also, in «The Erymanthian Boar», a character is said to have been turned out of Austria by the Nazis, implying that the events of The Labours of Hercules took place after 1937. Another alternative would be to suggest that the Preface to the Labours takes place at one date but that the labours are completed over a matter of twenty years. None of the explanations is especially attractive.