|

Galileo Galilei |

|

|---|---|

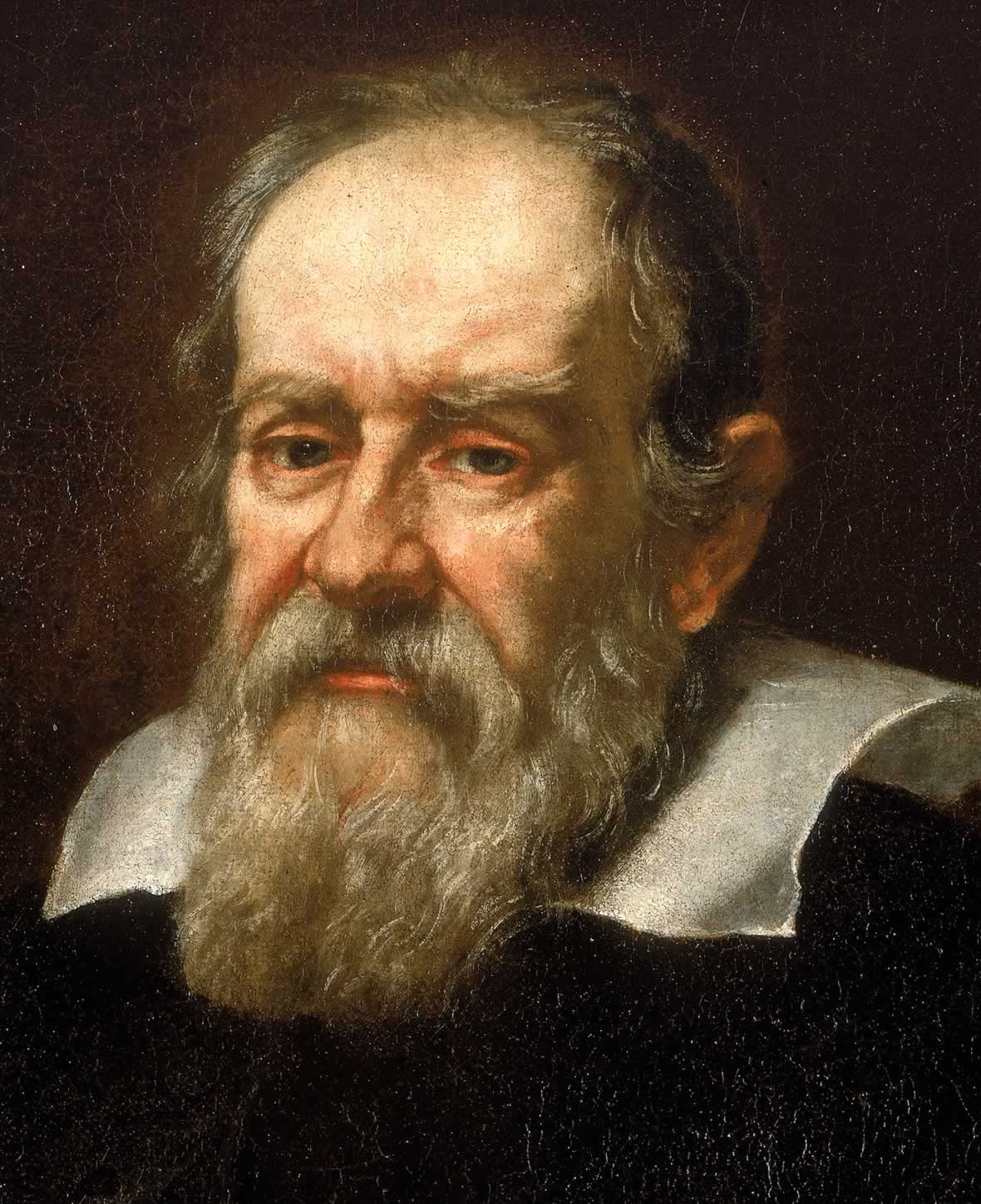

Portrait by Justus Sustermans, 1636 |

|

| Born |

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de’ Galilei[1] 15 February 1564[2] Pisa, Duchy of Florence |

| Died | 8 January 1642 (aged 77)

Arcetri, Grand Duchy of Tuscany |

| Education | University of Pisa |

| Known for |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Patrons |

|

| Academic advisors | Ostilio Ricci da Fermo |

| Notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Signature | |

|

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de’ Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (GAL-ih-LAY-oh GAL-ih-LAY-ee, Italian: [ɡaliˈlɛːo ɡaliˈlɛi]). He was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence.[4] Galileo has been called the «father» of observational astronomy,[5] modern-era classical physics,[6] the scientific method,[7] and modern science.[8]

Galileo studied speed and velocity, gravity and free fall, the principle of relativity, inertia, projectile motion and also worked in applied science and technology, describing the properties of pendulums and «hydrostatic balances». He invented the thermoscope and various military compasses, and used the telescope for scientific observations of celestial objects. His contributions to observational astronomy include telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus, observation of the four largest satellites of Jupiter, observation of Saturn’s rings, and analysis of lunar craters and sunspots.

Galileo’s championing of Copernican heliocentrism (Earth rotating daily and revolving around the Sun) was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church and from some astronomers. The matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, which concluded that heliocentrism was foolish, absurd, and heretical since it contradicted Holy Scripture.[9][10][11]

Galileo later defended his views in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which appeared to attack Pope Urban VIII and thus alienated both the Pope and the Jesuits, who had both supported Galileo up until this point.[9] He was tried by the Inquisition, found «vehemently suspect of heresy», and forced to recant. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.[12][13] During this time, he wrote Two New Sciences (1638), primarily concerning kinematics and the strength of materials, summarizing work he had done around forty years earlier.[14]

Early life and family

Galileo was born in Pisa (then part of the Duchy of Florence), Italy, on 15 February 1564,[15] the first of six children of Vincenzo Galilei, a lutenist, composer, and music theorist, and Giulia Ammannati, who had married in 1562. Galileo became an accomplished lutenist himself and would have learned early from his father a scepticism for established authority.[16]

Three of Galileo’s five siblings survived infancy. The youngest, Michelangelo (or Michelagnolo), also became a lutenist and composer who added to Galileo’s financial burdens for the rest of his life.[17] Michelangelo was unable to contribute his fair share of their father’s promised dowries to their brothers-in-law, who would later attempt to seek legal remedies for payments due. Michelangelo would also occasionally have to borrow funds from Galileo to support his musical endeavours and excursions. These financial burdens may have contributed to Galileo’s early desire to develop inventions that would bring him additional income.[18]

When Galileo Galilei was eight, his family moved to Florence, but he was left under the care of Muzio Tedaldi for two years. When Galileo was ten, he left Pisa to join his family in Florence and there he was under the tutelage of Jacopo Borghini.[15] He was educated, particularly in logic, from 1575 to 1578 in the Vallombrosa Abbey, about 30 km southeast of Florence.[19][20]

Name

Galileo tended to refer to himself only by his given name. At the time, surnames were optional in Italy, and his given name had the same origin as his sometimes-family name, Galilei. Both his given and family name ultimately derive from an ancestor, Galileo Bonaiuti, an important physician, professor, and politician in Florence in the 15th century.[21][22] Galileo Bonaiuti was buried in the same church, the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, where about 200 years later, Galileo Galilei was also buried.[23]

When he did refer to himself with more than one name, it was sometimes as Galileo Galilei Linceo, a reference to his being a member of the Accademia dei Lincei, an elite pro-science organization in Italy. It was common for mid-sixteenth-century Tuscan families to name the eldest son after the parents’ surname.[24] Hence, Galileo Galilei was not necessarily named after his ancestor Galileo Bonaiuti. The Italian male given name «Galileo» (and thence the surname «Galilei») derives from the Latin «Galilaeus», meaning «of Galilee», a biblically significant region in Northern Israel.[25][21] Because of that region, the adjective galilaios (Greek Γαλιλαῖος, Latin Galilaeus, Italian Galileo), which means «Galilean», was used in antiquity (particularly by emperor Julian) to refer to Christ and his followers.[26]

The biblical roots of Galileo’s name and surname were to become the subject of a famous pun.[27] In 1614, during the Galileo affair, one of Galileo’s opponents, the Dominican priest Tommaso Caccini, delivered against Galileo a controversial and influential sermon. In it he made a point of quoting Acts 1:11, «Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven?» (in the Latin version found in the Vulgate: Viri Galilaei, quid statis aspicientes in caelum?).[28]

Portrait believed to be of Galileo’s elder daughter Virginia, who was particularly devoted to her father

Children

Despite being a genuinely pious Roman Catholic,[29] Galileo fathered three children out of wedlock with Marina Gamba. They had two daughters, Virginia (born 1600) and Livia (born 1601), and a son, Vincenzo (born 1606).[30]

Due to their illegitimate birth, Galileo considered the girls unmarriageable, if not posing problems of prohibitively expensive support or dowries, which would have been similar to Galileo’s previous extensive financial problems with two of his sisters.[31] Their only worthy alternative was the religious life. Both girls were accepted by the convent of San Matteo in Arcetri and remained there for the rest of their lives.[32]

Virginia took the name Maria Celeste upon entering the convent. She died on 2 April 1634, and is buried with Galileo at the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence. Livia took the name Sister Arcangela and was ill for most of her life. Vincenzo was later legitimised as the legal heir of Galileo and married Sestilia Bocchineri.[33]

Career as a scientist

Although Galileo seriously considered the priesthood as a young man, at his father’s urging he instead enrolled in 1580 at the University of Pisa for a medical degree.[34] He was influenced by the lectures of Girolamo Borro and Francesco Buonamici of Florence.[20] In 1581, when he was studying medicine, he noticed a swinging chandelier, which air currents shifted about to swing in larger and smaller arcs. To him, it seemed, by comparison with his heartbeat, that the chandelier took the same amount of time to swing back and forth, no matter how far it was swinging. When he returned home, he set up two pendulums of equal length and swung one with a large sweep and the other with a small sweep and found that they kept time together. It was not until the work of Christiaan Huygens, almost one hundred years later, that the tautochrone nature of a swinging pendulum was used to create an accurate timepiece.[35] Up to this point, Galileo had deliberately been kept away from mathematics, since a physician earned a higher income than a mathematician. However, after accidentally attending a lecture on geometry, he talked his reluctant father into letting him study mathematics and natural philosophy instead of medicine.[35] He created a thermoscope, a forerunner of the thermometer, and, in 1586, published a small book on the design of a hydrostatic balance he had invented (which first brought him to the attention of the scholarly world). Galileo also studied disegno, a term encompassing fine art, and, in 1588, obtained the position of instructor in the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, teaching perspective and chiaroscuro. In the same year, upon invitation by the Florentine Academy, he presented two lectures, On the Shape, Location, and Size of Dante’s Inferno, in an attempt to propose a rigorous cosmological model of Dante’s hell.[36] Being inspired by the artistic tradition of the city and the works of the Renaissance artists, Galileo acquired an aesthetic mentality. While a young teacher at the Accademia, he began a lifelong friendship with the Florentine painter Cigoli.[37][38]

In 1589, he was appointed to the chair of mathematics in Pisa. In 1591, his father died, and he was entrusted with the care of his younger brother Michelagnolo. In 1592, he moved to the University of Padua where he taught geometry, mechanics, and astronomy until 1610.[39] During this period, Galileo made significant discoveries in both pure fundamental science (for example, kinematics of motion and astronomy) as well as practical applied science (for example, strength of materials and pioneering the telescope). His multiple interests included the study of astrology, which at the time was a discipline tied to the studies of mathematics and astronomy.[40][41]

Astronomy

Kepler’s supernova

Tycho Brahe and others had observed the supernova of 1572. Ottavio Brenzoni’s letter of 15 January 1605 to Galileo brought the 1572 supernova and the less bright nova of 1601 to Galileo’s notice. Galileo observed and discussed Kepler’s Supernova in 1604. Since these new stars displayed no detectable diurnal parallax, Galileo concluded that they were distant stars, and, therefore, disproved the Aristotelian belief in the immutability of the heavens.[42]

Refracting telescope

Based only on uncertain descriptions of the first practical telescope which Hans Lippershey tried to patent in the Netherlands in 1608,[43] Galileo, in the following year, made a telescope with about 3x magnification. He later made improved versions with up to about 30x magnification.[44] With a Galilean telescope, the observer could see magnified, upright images on the Earth—it was what is commonly known as a terrestrial telescope or a spyglass. He could also use it to observe the sky; for a time he was one of those who could construct telescopes good enough for that purpose. On 25 August 1609, he demonstrated one of his early telescopes, with a magnification of about 8 or 9, to Venetian lawmakers. His telescopes were also a profitable sideline for Galileo, who sold them to merchants who found them useful both at sea and as items of trade. He published his initial telescopic astronomical observations in March 1610 in a brief treatise entitled Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger).[45]

An illustration of the Moon from Sidereus Nuncius, published in Venice, 1610

Moon

On 30 November 1609, Galileo aimed his telescope at the Moon.[46] While not being the first person to observe the Moon through a telescope (English mathematician Thomas Harriot had done it four months before but only saw a «strange spottednesse»),[47] Galileo was the first to deduce the cause of the uneven waning as light occlusion from lunar mountains and craters. In his study, he also made topographical charts, estimating the heights of the mountains. The Moon was not what was long thought to have been a translucent and perfect sphere, as Aristotle claimed, and hardly the first «planet», an «eternal pearl to magnificently ascend into the heavenly empyrian», as put forth by Dante. Galileo is sometimes credited with the discovery of the lunar libration in latitude in 1632,[48] although Thomas Harriot or William Gilbert might have done it before.[49]

A friend of Galileo’s, the painter Cigoli, included a realistic depiction of the Moon in one of his paintings, though probably used his own telescope to make the observation.[37]

Jupiter’s moons

On 7 January 1610, Galileo observed with his telescope what he described at the time as «three fixed stars, totally invisible[a] by their smallness», all close to Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it.[50] Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these «stars» relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been inexplicable if they had really been fixed stars. On 10 January, Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days, he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter: he had discovered three of Jupiter’s four largest moons.[51] He discovered the fourth on 13 January. Galileo named the group of four the Medicean stars, in honour of his future patron, Cosimo II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Cosimo’s three brothers.[52] Later astronomers, however, renamed them Galilean satellites in honour of their discoverer. These satellites were independently discovered by Simon Marius on 8 January 1610 and are now called Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, the names given by Marius in his Mundus Iovialis published in 1614.[53]

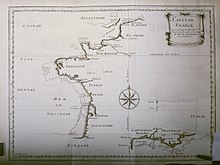

Map of France presented in 1684, showing the outline of an earlier map (light outline) compared to a new survey conducted using the moons of Jupiter as an accurate timing reference (heavier outline).

Galileo’s observations of the satellites of Jupiter caused a revolution in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth,[54][55] and many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing.[56][57] His observations were confirmed by the observatory of Christopher Clavius and he received a hero’s welcome when he visited Rome in 1611.[58] Galileo continued to observe the satellites over the next eighteen months, and by mid-1611, he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their periods—a feat which Johannes Kepler had believed impossible.[59][60]

Galileo saw a practical use for his discovery. Determining the east-west position of ships at sea required their clocks be synchronized with clocks at the prime meridian. Solving this longitude problem had great importance to safe navigation and large prizes were established by Spain and later Holland for its solution. Since eclipses of the moons he discovered were relatively frequent and their times could be predicted with great accuracy, they could be used to set shipboard clocks and Galileo applied for the prizes. Observing the moons from a ship proved too difficult, but the method was used for land surveys, including the remapping of France.[61]: 15–16 [62]

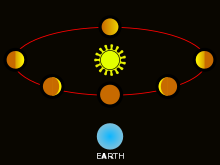

Phases of Venus

From September 1610, Galileo observed that Venus exhibits a full set of phases similar to that of the Moon. The heliocentric model of the Solar System developed by Nicolaus Copernicus predicted that all phases would be visible since the orbit of Venus around the Sun would cause its illuminated hemisphere to face the Earth when it was on the opposite side of the Sun and to face away from the Earth when it was on the Earth-side of the Sun. In Ptolemy’s geocentric model, it was impossible for any of the planets’ orbits to intersect the spherical shell carrying the Sun. Traditionally, the orbit of Venus was placed entirely on the near side of the Sun, where it could exhibit only crescent and new phases. It was also possible to place it entirely on the far side of the Sun, where it could exhibit only gibbous and full phases. After Galileo’s telescopic observations of the crescent, gibbous and full phases of Venus, the Ptolemaic model became untenable. In the early 17th century, as a result of his discovery, the great majority of astronomers converted to one of the various geo-heliocentric planetary models,[63][64] such as the Tychonic, Capellan and Extended Capellan models,[b] each either with or without a daily rotating Earth. These all explained the phases of Venus without the ‘refutation’ of full heliocentrism’s prediction of stellar parallax. Galileo’s discovery of the phases of Venus was thus his most empirically practically influential contribution to the two-stage transition from full geocentrism to full heliocentrism via geo-heliocentrism.[citation needed]

Saturn and Neptune

In 1610, Galileo also observed the planet Saturn, and at first mistook its rings for planets,[65] thinking it was a three-bodied system. When he observed the planet later, Saturn’s rings were directly oriented at Earth, causing him to think that two of the bodies had disappeared. The rings reappeared when he observed the planet in 1616, further confusing him.[66]

Galileo observed the planet Neptune in 1612. It appears in his notebooks as one of many unremarkable dim stars. He did not realise that it was a planet, but he did note its motion relative to the stars before losing track of it.[67]

Sunspots

Galileo made naked-eye and telescopic studies of sunspots.[68] Their existence raised another difficulty with the unchanging perfection of the heavens as posited in orthodox Aristotelian celestial physics. An apparent annual variation in their trajectories, observed by Francesco Sizzi and others in 1612–1613,[69] also provided a powerful argument against both the Ptolemaic system and the geoheliocentric system of Tycho Brahe.[c] A dispute over claimed priority in the discovery of sunspots, and in their interpretation, led Galileo to a long and bitter feud with the Jesuit Christoph Scheiner. In the middle was Mark Welser, to whom Scheiner had announced his discovery, and who asked Galileo for his opinion. Both of them were unaware of Johannes Fabricius’ earlier observation and publication of sunspots.[73]

Milky Way and stars

Galileo observed the Milky Way, previously believed to be nebulous, and found it to be a multitude of stars packed so densely that they appeared from Earth to be clouds. He located many other stars too distant to be visible with the naked eye. He observed the double star Mizar in Ursa Major in 1617.[74]

In the Starry Messenger, Galileo reported that stars appeared as mere blazes of light, essentially unaltered in appearance by the telescope, and contrasted them to planets, which the telescope revealed to be discs. But shortly thereafter, in his Letters on Sunspots, he reported that the telescope revealed the shapes of both stars and planets to be «quite round». From that point forward, he continued to report that telescopes showed the roundness of stars, and that stars seen through the telescope measured a few seconds of arc in diameter.[75][76] He also devised a method for measuring the apparent size of a star without a telescope. As described in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, his method was to hang a thin rope in his line of sight to the star and measure the maximum distance from which it would wholly obscure the star. From his measurements of this distance and of the width of the rope, he could calculate the angle subtended by the star at his viewing point.[77][78][79]

In his Dialogue, he reported that he had found the apparent diameter of a star of first magnitude to be no more than 5 arcseconds, and that of one of sixth magnitude to be about 5/6 arcseconds. Like most astronomers of his day, Galileo did not recognise that the apparent sizes of stars that he measured were spurious, caused by diffraction and atmospheric distortion, and did not represent the true sizes of stars. However, Galileo’s values were much smaller than previous estimates of the apparent sizes of the brightest stars, such as those made by Brahe, and enabled Galileo to counter anti-Copernican arguments such as those made by Tycho that these stars would have to be absurdly large for their annual parallaxes to be undetectable.[80][81][82] Other astronomers such as Simon Marius, Giovanni Battista Riccioli, and Martinus Hortensius made similar measurements of stars, and Marius and Riccioli concluded the smaller sizes were not small enough to answer Tycho’s argument.[83][84]

Theory of tides

Cardinal Bellarmine had written in 1615 that the Copernican system could not be defended without «a true physical demonstration that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun».[85] Galileo considered his theory of the tides to provide such evidence.[86] This theory was so important to him that he originally intended to call his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems the Dialogue on the Ebb and Flow of the Sea.[87] The reference to tides was removed from the title by order of the Inquisition.[citation needed]

For Galileo, the tides were caused by the sloshing back and forth of water in the seas as a point on the Earth’s surface sped up and slowed down because of the Earth’s rotation on its axis and revolution around the Sun. He circulated his first account of the tides in 1616, addressed to Cardinal Orsini.[88] His theory gave the first insight into the importance of the shapes of ocean basins in the size and timing of tides; he correctly accounted, for instance, for the negligible tides halfway along the Adriatic Sea compared to those at the ends. As a general account of the cause of tides, however, his theory was a failure.[citation needed]

If this theory were correct, there would be only one high tide per day. Galileo and his contemporaries were aware of this inadequacy because there are two daily high tides at Venice instead of one, about 12 hours apart. Galileo dismissed this anomaly as the result of several secondary causes including the shape of the sea, its depth, and other factors.[89][90] Albert Einstein later expressed the opinion that Galileo developed his «fascinating arguments» and accepted them uncritically out of a desire for physical proof of the motion of the Earth.[91] Galileo also dismissed the idea, known from antiquity and by his contemporary Johannes Kepler, that the Moon[92] caused the tides—Galileo also took no interest in Kepler’s elliptical orbits of the planets.[93][94] Galileo continued to argue in favour of his theory of tides, considering it the ultimate proof of Earth’s motion.[95]

Controversy over comets and The Assayer

In 1619, Galileo became embroiled in a controversy with Father Orazio Grassi, professor of mathematics at the Jesuit Collegio Romano. It began as a dispute over the nature of comets, but by the time Galileo had published The Assayer (Il Saggiatore) in 1623, his last salvo in the dispute, it had become a much wider controversy over the very nature of science itself. The title page of the book describes Galileo as philosopher and «Matematico Primario» of the Grand Duke of Tuscany.[citation needed]

Because The Assayer contains such a wealth of Galileo’s ideas on how science should be practised, it has been referred to as his scientific manifesto.[96][97] Early in 1619, Father Grassi had anonymously published a pamphlet, An Astronomical Disputation on the Three Comets of the Year 1618,[98] which discussed the nature of a comet that had appeared late in November of the previous year. Grassi concluded that the comet was a fiery body that had moved along a segment of a great circle at a constant distance from the earth,[99][100] and since it moved in the sky more slowly than the Moon, it must be farther away than the Moon.[citation needed]

Grassi’s arguments and conclusions were criticised in a subsequent article, Discourse on Comets,[101] published under the name of one of Galileo’s disciples, a Florentine lawyer named Mario Guiducci, although it had been largely written by Galileo himself.[102] Galileo and Guiducci offered no definitive theory of their own on the nature of comets,[103][104] although they did present some tentative conjectures that are now known to be mistaken. (The correct approach to the study of comets had been proposed at the time by Tycho Brahe.) In its opening passage, Galileo and Guiducci’s Discourse gratuitously insulted the Jesuit Christoph Scheiner,[105][106][107] and various uncomplimentary remarks about the professors of the Collegio Romano were scattered throughout the work.[105] The Jesuits were offended,[105][104] and Grassi soon replied with a polemical tract of his own, The Astronomical and Philosophical Balance,[108] under the pseudonym Lothario Sarsio Sigensano,[109] purporting to be one of his own pupils.[citation needed]

The Assayer was Galileo’s devastating reply to the Astronomical Balance.[101] It has been widely recognized as a masterpiece of polemical literature,[110][111] in which «Sarsi’s» arguments are subjected to withering scorn.[112] It was greeted with wide acclaim, and particularly pleased the new pope, Urban VIII, to whom it had been dedicated.[113] In Rome, in the previous decade, Barberini, the future Urban VIII, had come down on the side of Galileo and the Lincean Academy.[114]

Galileo’s dispute with Grassi permanently alienated many Jesuits,[115] and Galileo and his friends were convinced that they were responsible for bringing about his later condemnation,[116] although supporting evidence for this is not conclusive.[117][118]

Controversy over heliocentrism

At the time of Galileo’s conflict with the Church, the majority of educated people subscribed to the Aristotelian geocentric view that the Earth is the center of the Universe and the orbit of all heavenly bodies, or Tycho Brahe’s new system blending geocentrism with heliocentrism.[119][120] Opposition to heliocentrism and Galileo’s writings on it combined religious and scientific objections. Religious opposition to heliocentrism arose from biblical passages implying the fixed nature of the Earth.[d] Scientific opposition came from Brahe, who argued that if heliocentrism were true, an annual stellar parallax should be observed, though none was at the time.[e] Aristarchus and Copernicus had correctly postulated that parallax was negligible because the stars were so distant. However, Tycho countered that since stars appear to have measurable angular size, if the stars were that distant and their apparent size is due to their physical size, they would be far larger than the Sun. In fact, it is not possible to observe the physical size of distant stars without modern telescopes.[123][f]

Galileo defended heliocentrism based on his astronomical observations of 1609. In December 1613, the Grand Duchess Christina of Florence confronted one of Galileo’s friends and followers, Benedetto Castelli, with biblical objections to the motion of the Earth.[g] Prompted by this incident, Galileo wrote a letter to Castelli in which he argued that heliocentrism was actually not contrary to biblical texts, and that the Bible was an authority on faith and morals, not science. This letter was not published, but circulated widely.[124] Two years later, Galileo wrote a letter to Christina that expanded his arguments previously made in eight pages to forty pages.[125]

By 1615, Galileo’s writings on heliocentrism had been submitted to the Roman Inquisition by Father Niccolò Lorini, who claimed that Galileo and his followers were attempting to reinterpret the Bible,[d] which was seen as a violation of the Council of Trent and looked dangerously like Protestantism.[126] Lorini specifically cited Galileo’s letter to Castelli.[127] Galileo went to Rome to defend himself and his ideas. At the start of 1616, Monsignor Francesco Ingoli initiated a debate with Galileo, sending him an essay disputing the Copernican system. Galileo later stated that he believed this essay to have been instrumental in the action against Copernicanism that followed.[128] Ingoli may have been commissioned by the Inquisition to write an expert opinion on the controversy, with the essay providing the basis for the Inquisition’s actions.[129] The essay focused on eighteen physical and mathematical arguments against heliocentrism. It borrowed primarily from Tycho Brahe’s arguments, notably that heliocentrism would require the stars as they appeared to be much larger than the Sun.[h] The essay also included four theological arguments, but Ingoli suggested Galileo focus on the physical and mathematical arguments, and he did not mention Galileo’s biblical ideas.[131]

In February 1616, an Inquisitorial commission declared heliocentrism to be «foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture». The Inquisition found that the idea of the Earth’s movement «receives the same judgement in philosophy and … in regard to theological truth it is at least erroneous in faith».[132] Pope Paul V instructed Cardinal Bellarmine to deliver this finding to Galileo, and to order him to abandon heliocentrism. On 26 February, Galileo was called to Bellarmine’s residence and ordered «to abandon completely … the opinion that the sun stands still at the center of the world and the Earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing.»[133] The decree of the Congregation of the Index banned Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus and other heliocentric works until correction.[133]

For the next decade, Galileo stayed well away from the controversy. He revived his project of writing a book on the subject, encouraged by the election of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini as Pope Urban VIII in 1623. Barberini was a friend and admirer of Galileo, and had opposed the admonition of Galileo in 1616. Galileo’s resulting book, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, was published in 1632, with formal authorization from the Inquisition and papal permission.[134]

Earlier, Pope Urban VIII had personally asked Galileo to give arguments for and against heliocentrism in the book, and to be careful not to advocate heliocentrism. Whether unknowingly or deliberately, Simplicio, the defender of the Aristotelian geocentric view in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, was often caught in his own errors and sometimes came across as a fool. Indeed, although Galileo states in the preface of his book that the character is named after a famous Aristotelian philosopher (Simplicius in Latin, «Simplicio» in Italian), the name «Simplicio» in Italian also has the connotation of «simpleton».[135][136] This portrayal of Simplicio made Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems appear as an advocacy book: an attack on Aristotelian geocentrism and defence of the Copernican theory.[citation needed]

Most historians agree Galileo did not act out of malice and felt blindsided by the reaction to his book.[i] However, the Pope did not take the suspected public ridicule lightly, nor the Copernican advocacy.[citation needed]

Galileo had alienated one of his biggest and most powerful supporters, the Pope, and was called to Rome to defend his writings[140] in September 1632. He finally arrived in February 1633 and was brought before inquisitor Vincenzo Maculani to be charged. Throughout his trial, Galileo steadfastly maintained that since 1616 he had faithfully kept his promise not to hold any of the condemned opinions, and initially he denied even defending them. However, he was eventually persuaded to admit that, contrary to his true intention, a reader of his Dialogue could well have obtained the impression that it was intended to be a defence of Copernicanism. In view of Galileo’s rather implausible denial that he had ever held Copernican ideas after 1616 or ever intended to defend them in the Dialogue, his final interrogation, in July 1633, concluded with his being threatened with torture if he did not tell the truth, but he maintained his denial despite the threat.[141][142][143]

The sentence of the Inquisition was delivered on 22 June. It was in three essential parts:

- Galileo was found «vehemently suspect of heresy» (though he was never formally charged with heresy, relieving him of facing corporal punishment),[144] namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to «abjure, curse and detest» those opinions.[145][146][147][148]

- He was sentenced to formal imprisonment at the pleasure of the Inquisition.[149] On the following day, this was commuted to house arrest, under which he remained for the rest of his life.[150]

- His offending Dialogue was banned; and in an action not announced at the trial, publication of any of his works was forbidden, including any he might write in the future.[151][152]

Portrait, originally attributed to Murillo, of Galileo gazing at the words «E pur si muove» (And yet it moves) (not legible in this image) scratched on the wall of his prison cell. The attribution and narrative surrounding the painting have since been contested.

According to popular legend, after recanting his theory that the Earth moved around the Sun, Galileo allegedly muttered the rebellious phrase «And yet it moves». There was a claim that a 1640s painting by the Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo or an artist of his school, in which the words were hidden until restoration work in 1911, depicts an imprisoned Galileo apparently gazing at the words «E pur si muove» written on the wall of his dungeon. The earliest known written account of the legend dates to a century after his death. Based on the painting, Stillman Drake wrote «there is no doubt now that the famous words were already attributed to Galileo before his death».[153] However, an intensive investigation by astrophysicist Mario Livio has revealed that said painting is most probably a copy of a 1837 painting by the Flemish painter Roman-Eugene Van Maldeghem.[154]

After a period with the friendly Ascanio Piccolomini (the Archbishop of Siena), Galileo was allowed to return to his villa at Arcetri near Florence in 1634, where he spent part of his life under house arrest. Galileo was ordered to read the Seven Penitential Psalms once a week for the next three years. However, his daughter Maria Celeste relieved him of the burden after securing ecclesiastical permission to take it upon herself.[155]

It was while Galileo was under house arrest that he dedicated his time to one of his finest works, Two New Sciences. Here he summarised work he had done some forty years earlier, on the two sciences now called kinematics and strength of materials, published in Holland to avoid the censor. This book was highly praised by Albert Einstein.[156] As a result of this work, Galileo is often called the «father of modern physics». He went completely blind in 1638 and had developed a painful hernia and insomnia, so he was permitted to travel to Florence for medical advice.[14]

Dava Sobel argues that prior to Galileo’s 1633 trial and judgement for heresy, Pope Urban VIII had become preoccupied with court intrigue and problems of state and began to fear persecution or threats to his own life. In this context, Sobel argues that the problem of Galileo was presented to the pope by court insiders and enemies of Galileo. Having been accused of weakness in defending the church, Urban reacted against Galileo out of anger and fear.[157] Mario Livio places Galileo and his discoveries in modern scientific and social contexts. In particular, he argues that the Galileo affair has its counterpart in science denial.[158]

Death

Galileo continued to receive visitors until 1642, when, after suffering fever and heart palpitations, he died on 8 January 1642, aged 77.[14][159] The Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando II, wished to bury him in the main body of the Basilica of Santa Croce, next to the tombs of his father and other ancestors, and to erect a marble mausoleum in his honour.[160][161]

Middle finger of Galileo’s right hand

These plans were dropped, however, after Pope Urban VIII and his nephew, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, protested,[160][161][162] because Galileo had been condemned by the Catholic Church for «vehement suspicion of heresy».[163] He was instead buried in a small room next to the novices’ chapel at the end of a corridor from the southern transept of the basilica to the sacristy.[160][164] He was reburied in the main body of the basilica in 1737 after a monument had been erected there in his honour;[165][166] during this move, three fingers and a tooth were removed from his remains.[167] These fingers are currently on exhibition at the Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy.[168]

Scientific contributions

Scientific methods

Galileo made original contributions to the science of motion through an innovative combination of experiment and mathematics.[169] More typical of science at the time were the qualitative studies of William Gilbert, on magnetism and electricity. Galileo’s father, Vincenzo Galilei, a lutenist and music theorist, had performed experiments establishing perhaps the oldest known non-linear relation in physics: for a stretched string, the pitch varies as the square root of the tension.[170] These observations lay within the framework of the Pythagorean tradition of music, well known to instrument makers, which included the fact that subdividing a string by a whole number produces a harmonious scale. Thus, a limited amount of mathematics had long related music and physical science, and young Galileo could see his own father’s observations expand on that tradition.[171]

Galileo was one of the first modern thinkers to clearly state that the laws of nature are mathematical. In The Assayer, he wrote «Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe … It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures;….»[172] His mathematical analyses are a further development of a tradition employed by late scholastic natural philosophers, which Galileo learned when he studied philosophy.[173] His work marked another step towards the eventual separation of science from both philosophy and religion; a major development in human thought. He was often willing to change his views in accordance with observation. In order to perform his experiments, Galileo had to set up standards of length and time, so that measurements made on different days and in different laboratories could be compared in a reproducible fashion. This provided a reliable foundation on which to confirm mathematical laws using inductive reasoning.[citation needed]

Galileo showed a modern appreciation for the proper relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics, and experimental physics. He understood the parabola, both in terms of conic sections and in terms of the ordinate (y) varying as the square of the abscissa (x). Galileo further asserted that the parabola was the theoretically ideal trajectory of a uniformly accelerated projectile in the absence of air resistance or other disturbances. He conceded that there are limits to the validity of this theory, noting on theoretical grounds that a projectile trajectory of a size comparable to that of the Earth could not possibly be a parabola,[174][175][176] but he nevertheless maintained that for distances up to the range of the artillery of his day, the deviation of a projectile’s trajectory from a parabola would be only very slight.[174][177][178]

Astronomy

A replica of the earliest surviving telescope attributed to Galileo Galilei, on display at the Griffith Observatory

Using his refracting telescope, Galileo observed in late 1609 that the surface of the Moon is not smooth.[37] Early the next year, he observed the four largest moons of Jupiter.[52] Later in 1610, he observed the phases of Venus—a proof of heliocentrism—as well as Saturn, though he thought the planet’s rings were two other planets.[65] In 1612, he observed Neptune and noted its motion, but did not identify it as a planet.[67]

Galileo made studies of sunspots,[68] the Milky Way, and made various observations about stars, including how to measure their apparent size without a telescope.[77][78][79]

Engineering

Galileo made a number of contributions to what is now known as engineering, as distinct from pure physics. Between 1595 and 1598, Galileo devised and improved a geometric and military compass suitable for use by gunners and surveyors. This expanded on earlier instruments designed by Niccolò Tartaglia and Guidobaldo del Monte. For gunners, it offered, in addition to a new and safer way of elevating cannons accurately, a way of quickly computing the charge of gunpowder for cannonballs of different sizes and materials. As a geometric instrument, it enabled the construction of any regular polygon, computation of the area of any polygon or circular sector, and a variety of other calculations. Under Galileo’s direction, instrument maker Marc’Antonio Mazzoleni produced more than 100 of these compasses, which Galileo sold (along with an instruction manual he wrote) for 50 lire and offered a course of instruction in the use of the compasses for 120 lire.[179]

In 1593, Galileo constructed a thermometer, using the expansion and contraction of air in a bulb to move water in an attached tube.[citation needed]

In 1609, Galileo was, along with Englishman Thomas Harriot and others, among the first to use a refracting telescope as an instrument to observe stars, planets or moons. The name «telescope» was coined for Galileo’s instrument by a Greek mathematician, Giovanni Demisiani,[180][181] at a banquet held in 1611 by Prince Federico Cesi to make Galileo a member of his Accademia dei Lincei.[182] In 1610, he used a telescope at close range to magnify the parts of insects.[183][184] By 1624, Galileo had used a compound microscope. He gave one of these instruments to Cardinal Zollern in May of that year for presentation to the Duke of Bavaria,[185] and in September, he sent another to Prince Cesi.[186] The Linceans played a role again in naming the «microscope» a year later when fellow academy member Giovanni Faber coined the word for Galileo’s invention from the Greek words μικρόν (micron) meaning «small», and σκοπεῖν (skopein) meaning «to look at». The word was meant to be analogous with «telescope».[187][188] Illustrations of insects made using one of Galileo’s microscopes and published in 1625, appear to have been the first clear documentation of the use of a compound microscope.[186]

The earliest known pendulum clock design. Conceived by Galileo Galilei

In 1612, having determined the orbital periods of Jupiter’s satellites, Galileo proposed that with sufficiently accurate knowledge of their orbits, one could use their positions as a universal clock, and this would make possible the determination of longitude. He worked on this problem from time to time during the remainder of his life, but the practical problems were severe. The method was first successfully applied by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1681 and was later used extensively for large land surveys; this method, for example, was used to survey France, and later by Zebulon Pike of the midwestern United States in 1806. For sea navigation, where delicate telescopic observations were more difficult, the longitude problem eventually required the development of a practical portable marine chronometer, such as that of John Harrison.[189] Late in his life, when totally blind, Galileo designed an escapement mechanism for a pendulum clock (called Galileo’s escapement), although no clock using this was built until after the first fully operational pendulum clock was made by Christiaan Huygens in the 1650s.[citation needed]

Galileo was invited on several occasions to advise on engineering schemes to alleviate river flooding. In 1630 Mario Guiducci was probably instrumental in ensuring that he was consulted on a scheme by Bartolotti to cut a new channel for the Bisenzio River near Florence.[190]

Physics

Galileo’s theoretical and experimental work on the motions of bodies, along with the largely independent work of Kepler and René Descartes, was a precursor of the classical mechanics developed by Sir Isaac Newton. Galileo conducted several experiments with pendulums. It is popularly believed (thanks to the biography by Vincenzo Viviani) that these began by watching the swings of the bronze chandelier in the cathedral of Pisa, using his pulse as a timer. Later experiments are described in his Two New Sciences. Galileo claimed that a simple pendulum is isochronous, i.e. that its swings always take the same amount of time, independently of the amplitude. In fact, this is only approximately true,[191] as was discovered by Christiaan Huygens. Galileo also found that the square of the period varies directly with the length of the pendulum. Galileo’s son, Vincenzo, sketched a clock based on his father’s theories in 1642. The clock was never built and, because of the large swings required by its verge escapement, would have been a poor timekeeper.[citation needed]

Galileo is lesser known for, yet still credited with, being one of the first to understand sound frequency. By scraping a chisel at different speeds, he linked the pitch of the sound produced to the spacing of the chisel’s skips, a measure of frequency. In 1638, Galileo described an experimental method to measure the speed of light by arranging that two observers, each having lanterns equipped with shutters, observe each other’s lanterns at some distance. The first observer opens the shutter of his lamp, and, the second, upon seeing the light, immediately opens the shutter of his own lantern. The time between the first observer’s opening his shutter and seeing the light from the second observer’s lamp indicates the time it takes light to travel back and forth between the two observers. Galileo reported that when he tried this at a distance of less than a mile, he was unable to determine whether or not the light appeared instantaneously.[192] Sometime between Galileo’s death and 1667, the members of the Florentine Accademia del Cimento repeated the experiment over a distance of about a mile and obtained a similarly inconclusive result.[193] The speed of light has since been determined to be far too fast to be measured by such methods.

Galileo put forward the basic principle of relativity, that the laws of physics are the same in any system that is moving at a constant speed in a straight line, regardless of its particular speed or direction. Hence, there is no absolute motion or absolute rest. This principle provided the basic framework for Newton’s laws of motion and is central to Einstein’s special theory of relativity.

Falling bodies

A biography by Galileo’s pupil Vincenzo Viviani stated that Galileo had dropped balls of the same material, but different masses, from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to demonstrate that their time of descent was independent of their mass.[194] This was contrary to what Aristotle had taught: that heavy objects fall faster than lighter ones, in direct proportion to weight.[195][196] While this story has been retold in popular accounts, there is no account by Galileo himself of such an experiment, and it is generally accepted by historians that it was at most a thought experiment which did not actually take place.[197] An exception is Stillman Drake,[198] who argues that the experiment did take place, more or less as Viviani described it. The experiment described was actually performed by Simon Stevin (commonly known as Stevinus) and Jan Cornets de Groot,[35] although the building used was actually the church tower in Delft in 1586. However, most of his experiments with falling bodies were carried out using inclined planes where both the issues of timing and air resistance were much reduced.[199] In any case, observations that similarly sized objects of different weights fell at the same speed is documented in works as early as those of John Philoponus in the sixth century and which Galileo was aware of.[200][201]

During the Apollo 15 mission in 1971, astronaut David Scott showed that Galileo was right: acceleration is the same for all bodies subject to gravity on the Moon, even for a hammer and a feather.

In his 1638 Discorsi, Galileo’s character Salviati, widely regarded as Galileo’s spokesman, held that all unequal weights would fall with the same finite speed in a vacuum. But this had previously been proposed by Lucretius[202] and Simon Stevin.[203] Cristiano Banti’s Salviati also held it could be experimentally demonstrated by the comparison of pendulum motions in air with bobs of lead and of cork which had different weight but which were otherwise similar.[citation needed]

Galileo proposed that a falling body would fall with a uniform acceleration, as long as the resistance of the medium through which it was falling remained negligible, or in the limiting case of its falling through a vacuum.[204][205] He also derived the correct kinematical law for the distance traveled during a uniform acceleration starting from rest—namely, that it is proportional to the square of the elapsed time (d∝t2).[206][207] Prior to Galileo, Nicole Oresme, in the 14th century, had derived the times-squared law for uniformly accelerated change,[208][209] and Domingo de Soto had suggested in the 16th century that bodies falling through a homogeneous medium would be uniformly accelerated.[206] Soto, however, did not anticipate many of the qualifications and refinements contained in Galileo’s theory of falling bodies. He did not, for instance, recognise, as Galileo did, that a body would fall with a strictly uniform acceleration only in a vacuum, and that it would otherwise eventually reach a uniform terminal velocity. Galileo expressed the time-squared law using geometrical constructions and mathematically precise words, adhering to the standards of the day. (It remained for others to re-express the law in algebraic terms.)[citation needed]

He also concluded that objects retain their velocity in the absence of any impediments to their motion,[210] thereby contradicting the generally accepted Aristotelian hypothesis that a body could only remain in so-called «violent», «unnatural», or «forced» motion so long as an agent of change (the «mover») continued to act on it.[211] Philosophical ideas relating to inertia had been proposed by John Philoponus and Jean Buridan. Galileo stated: «Imagine any particle projected along a horizontal plane without friction; then we know, from what has been more fully explained in the preceding pages, that this particle will move along this same plane with a motion which is uniform and perpetual, provided the plane has no limits».[212] But the surface of the earth would be an instance of such a plane if all its unevenness could be removed.[213] This was incorporated into Newton’s laws of motion (first law), except for the direction of the motion: Newton’s is straight, Galileo’s is circular (for example, the planets’ motion around the Sun, which according to him, and unlike Newton, takes place in absence of gravity). According to Dijksterhuis Galileo’s conception of inertia as a tendency to persevere in circular motion is closely related to his Copernican conviction.[214]

Mathematics

While Galileo’s application of mathematics to experimental physics was innovative, his mathematical methods were the standard ones of the day, including dozens of examples of an inverse proportion square root method passed down from Fibonacci and Archimedes. The analysis and proofs relied heavily on the Eudoxian theory of proportion, as set forth in the fifth book of Euclid’s Elements. This theory had become available only a century before, thanks to accurate translations by Tartaglia and others; but by the end of Galileo’s life, it was being superseded by the algebraic methods of Descartes. The concept now named Galileo’s paradox was not original with him. His proposed solution, that infinite numbers cannot be compared, is no longer considered useful.[215]

Legacy

Later Church reassessments

The Galileo affair was largely forgotten after Galileo’s death, and the controversy subsided. The Inquisition’s ban on reprinting Galileo’s works was lifted in 1718 when permission was granted to publish an edition of his works (excluding the condemned Dialogue) in Florence.[216] In 1741, Pope Benedict XIV authorised the publication of an edition of Galileo’s complete scientific works[217] which included a mildly censored version of the Dialogue.[218][217] In 1758, the general prohibition against works advocating heliocentrism was removed from the Index of prohibited books, although the specific ban on uncensored versions of the Dialogue and Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus remained.[219][217] All traces of official opposition to heliocentrism by the church disappeared in 1835 when these works were finally dropped from the Index.[220][221]

Interest in the Galileo affair was revived in the early 19th century, when Protestant polemicists used it (and other events such as the Spanish Inquisition and the myth of the flat Earth) to attack Roman Catholicism.[9] Interest in it has waxed and waned ever since. In 1939, Pope Pius XII, in his first speech to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, within a few months of his election to the papacy, described Galileo as being among the «most audacious heroes of research… not afraid of the stumbling blocks and the risks on the way, nor fearful of the funereal monuments».[222] His close advisor of 40 years, Professor Robert Leiber, wrote: «Pius XII was very careful not to close any doors (to science) prematurely. He was energetic on this point and regretted that in the case of Galileo.»[223]

On 15 February 1990, in a speech delivered at the Sapienza University of Rome,[224][225] Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) cited some current views on the Galileo affair as forming what he called «a symptomatic case that permits us to see how deep the self-doubt of the modern age, of science and technology goes today».[226] Some of the views he cited were those of the philosopher Paul Feyerabend, whom he quoted as saying: «The Church at the time of Galileo kept much more closely to reason than did Galileo himself, and she took into consideration the ethical and social consequences of Galileo’s teaching too. Her verdict against Galileo was rational and just and the revision of this verdict can be justified only on the grounds of what is politically opportune.»[226] The Cardinal did not clearly indicate whether he agreed or disagreed with Feyerabend’s assertions. He did, however, say: «It would be foolish to construct an impulsive apologetic on the basis of such views.»[226]

On 31 October 1992, Pope John Paul II acknowledged that the Church had erred in condemning Galileo for asserting that the Earth revolves around the Sun. «John Paul said the theologians who condemned Galileo did not recognize the formal distinction between the Bible and its interpretation.»[227]

In March 2008, the head of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Nicola Cabibbo, announced a plan to honour Galileo by erecting a statue of him inside the Vatican walls.[228] In December of the same year, during events to mark the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s earliest telescopic observations, Pope Benedict XVI praised his contributions to astronomy.[229] A month later, however, the head of the Pontifical Council for Culture, Gianfranco Ravasi, revealed that the plan to erect a statue of Galileo on the grounds of the Vatican had been suspended.[230]

Impact on modern science

According to Stephen Hawking, Galileo probably bears more of the responsibility for the birth of modern science than anybody else,[231] and Albert Einstein called him the father of modern science.[232][233]

Galileo’s astronomical discoveries and investigations into the Copernican theory have led to a lasting legacy which includes the categorisation of the four large moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo (Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto) as the Galilean moons. Other scientific endeavours and principles are named after Galileo including the Galileo spacecraft,[234] the first spacecraft to enter orbit around Jupiter, the proposed Galileo global satellite navigation system, the transformation between inertial systems in classical mechanics denoted Galilean transformation and the Gal (unit), sometimes known as the Galileo, which is a non-SI unit of acceleration.[citation needed]

Partly because the year 2009 was the fourth centenary of Galileo’s first recorded astronomical observations with the telescope, the United Nations scheduled it to be the International Year of Astronomy.[235] A global scheme was laid out by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), also endorsed by UNESCO—the UN body responsible for educational, scientific and cultural matters. The International Year of Astronomy 2009 was intended to be a global celebration of astronomy and its contributions to society and culture, stimulating worldwide interest not only in astronomy but science in general, with a particular slant towards young people.[citation needed]

Planet Galileo and asteroid 697 Galilea are named in his honour.[citation needed]

In artistic and popular media

Galileo is mentioned several times in the «opera» section of the Queen song, «Bohemian Rhapsody».[236] He features prominently in the song «Galileo» performed by the Indigo Girls and Amy Grant’s «Galileo» on her Heart in Motion album.[237]

Twentieth-century plays have been written on Galileo’s life, including Life of Galileo (1943) by the German playwright Bertolt Brecht, with a film adaptation (1975) of it, and Lamp at Midnight (1947) by Barrie Stavis,[238] as well as the 2008 play «Galileo Galilei».[239]

Kim Stanley Robinson wrote a science fiction novel entitled Galileo’s Dream (2009), in which Galileo is brought into the future to help resolve a crisis of scientific philosophy; the story moves back and forth between Galileo’s own time and a hypothetical distant future and contains a great deal of biographical information.[240]

Galileo Galilei was recently selected as a main motif for a high-value collectors’ coin: the €25 International Year of Astronomy commemorative coin, minted in 2009. This coin also commemorates the 400th anniversary of the invention of Galileo’s telescope. The obverse shows a portion of his portrait and his telescope. The background shows one of his first drawings of the surface of the moon. In the silver ring, other telescopes are depicted: the Isaac Newton Telescope, the observatory in Kremsmünster Abbey, a modern telescope, a radio telescope and a space telescope. In 2009, the Galileoscope was also released. This is a mass-produced, low-cost educational 2-inch (51 mm) telescope with relatively high quality.[citation needed]

Writings

Galileo’s early works describing scientific instruments include the 1586 tract entitled The Little Balance (La Billancetta) describing an accurate balance to weigh objects in air or water[241] and the 1606 printed manual Le Operazioni del Compasso Geometrico et Militare on the operation of a geometrical and military compass.[242]

His early works on dynamics, the science of motion and mechanics were his circa 1590 Pisan De Motu (On Motion) and his circa 1600 Paduan Le Meccaniche (Mechanics). The former was based on Aristotelian–Archimedean fluid dynamics and held that the speed of gravitational fall in a fluid medium was proportional to the excess of a body’s specific weight over that of the medium, whereby in a vacuum, bodies would fall with speeds in proportion to their specific weights. It also subscribed to the Philoponan impetus dynamics in which impetus is self-dissipating and free-fall in a vacuum would have an essential terminal speed according to specific weight after an initial period of acceleration.[citation needed]

Galileo’s 1610 The Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius) was the first scientific treatise to be published based on observations made through a telescope. It reported his discoveries of:

- the Galilean moons

- the roughness of the Moon’s surface

- the existence of a large number of stars invisible to the naked eye, particularly those responsible for the appearance of the Milky Way

- differences between the appearances of the planets and those of the fixed stars—the former appearing as small discs, while the latter appeared as unmagnified points of light

Galileo published a description of sunspots in 1613 entitled Letters on Sunspots suggesting the Sun and heavens are corruptible.[243] The Letters on Sunspots also reported his 1610 telescopic observations of the full set of phases of Venus, and his discovery of the puzzling «appendages» of Saturn and their even more puzzling subsequent disappearance. In 1615, Galileo prepared a manuscript known as the «Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina» which was not published in printed form until 1636. This letter was a revised version of the Letter to Castelli, which was denounced by the Inquisition as an incursion upon theology by advocating Copernicanism both as physically true and as consistent with Scripture.[244] In 1616, after the order by the Inquisition for Galileo not to hold or defend the Copernican position, Galileo wrote the «Discourse on the Tides» (Discorso sul flusso e il reflusso del mare) based on the Copernican earth, in the form of a private letter to Cardinal Orsini.[245] In 1619, Mario Guiducci, a pupil of Galileo’s, published a lecture written largely by Galileo under the title Discourse on the Comets (Discorso Delle Comete), arguing against the Jesuit interpretation of comets.[246]

In 1623, Galileo published The Assayer—Il Saggiatore, which attacked theories based on Aristotle’s authority and promoted experimentation and the mathematical formulation of scientific ideas. The book was highly successful and even found support among the higher echelons of the Christian church.[247] Following the success of The Assayer, Galileo published the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo) in 1632. Despite taking care to adhere to the Inquisition’s 1616 instructions, the claims in the book favouring Copernican theory and a non-geocentric model of the solar system led to Galileo being tried and banned on publication. Despite the publication ban, Galileo published his Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences (Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche, intorno a due nuove scienze) in 1638 in Holland, outside the jurisdiction of the Inquisition.[citation needed]

Published written works

Galileo’s main written works are as follows:[248]

- The Little Balance (1586; in Italian: La Bilancetta)

- On Motion (c. 1590; in Latin: De Motu Antiquiora)[249]

- Mechanics (c. 1600; in Italian: Le Meccaniche)

- The Operations of Geometrical and Military Compass (1606; in Italian: Le operazioni del compasso geometrico et militare)

- The Starry Messenger (1610; in Latin: Sidereus Nuncius)

- Discourse on Floating Bodies (1612; in Italian: Discorso intorno alle cose che stanno in su l’acqua, o che in quella si muovono, «Discourse on Bodies that Stay Atop Water, or Move in It»)

- History and Demonstration Concerning Sunspots (1613; in Italian: Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari; work based on the Three Letters on Sunspots, Tre lettere sulle macchie solari, 1612)

- «Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina» (1615; published in 1636)

- «Discourse on the Tides» (1616; in Italian: Discorso del flusso e reflusso del mare)

- Discourse on the Comets (1619; in Italian: Discorso delle Comete)

- The Assayer (1623; in Italian: Il Saggiatore)

- Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632; in Italian: Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo)

- Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences (1638; in Italian: Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche, intorno a due nuove scienze)

Personal library

In the last years of his life, Galileo Galilei kept a library of at least 598 volumes (560 of which have been identified) at Villa Il Gioiello, on the outskirts of Florence.[250] Under the restrictions of house arrest, he was forbidden to write or publish his ideas. However, he continued to receive visitors right up to his death and it was through them that he remained supplied with the latest scientific texts from Northern Europe.[251]

With his past experience, Galileo may have feared that his collection of books and manuscripts would be seized by the authorities and burned, as no reference to such items was made in his last will and testament. An itemized inventory was only later produced after Galileo’s death, when the majority of his possessions including his library passed to his son, Vincenzo Galilei, Jr. On his death in 1649, the collection was inherited by his wife Sestilia Bocchineri.[251]

Galileo’s books, personal papers and unedited manuscripts were then collected by Vincenzo Viviani, his former assistant and student, with the intent of preserving his old teacher’s works in published form. Unfortunately, it was a project that never materialised and in his final will, Viviani bequeathed a significant portion of the collection to the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, where there already existed an extensive library. The value of Galileo’s possessions were not realised, and duplicate copies were dispersed to other libraries, such as the Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati, the public library in Sienna. In a later attempt to specialise the library’s holdings, volumes unrelated to medicine were transferred to the Biblioteca Magliabechiana, an early foundation for what was to become the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, the National Central Library in Florence.[251]

A small portion of Viviani’s collection, including the manuscripts of Galileo and those of his peers Evangelista Torricelli and Benedetto Castelli, were left to his nephew, Abbot Jacopo Panzanini. This minor collection was preserved until Panzanini’s death when it passed to his great-nephews, Carlo and Angelo Panzanini. The books from both Galileo and Viviani’s collection began to disperse as the heirs failed to protect their inheritance. Their servants sold several of the volumes for waste paper. Around 1750 the Florentine senator Giovanni Battista Clemente de’Nelli heard of this and purchased the books and manuscripts from the shopkeepers, and the remainder of Viviani’s collection from the Panzanini brothers. As recounted in Nelli’s memoirs: «My great fortune in obtaining such a wonderful treasure so cheaply came about through the ignorance of the people selling it, who were not aware of the value of those manuscripts…»

The library remained in Nelli’s care until his death in 1793. Knowing the value of their father’s collected manuscripts, Nelli’s sons attempted to sell what was left to them to the French government. Grand Duke Ferdinand III of Tuscany intervened in the sale and purchased the entire collection. The archive of manuscripts, printed books and personal papers were deposited with the Biblioteca Palatina in Florence, merging the collection with the Biblioteca Magliabechiana in 1861.[252]

See also

- Catholic Church and science

- Seconds pendulum

- Tribune of Galileo

- Villa Il Gioiello

Notes

- ^ i.e., invisible to the naked eye.

- ^ In the Capellan model only Mercury and Venus orbit the Sun, whilst in its extended version such as expounded by Riccioli, Mars also orbits the Sun, but the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn are centred on the Earth

- ^ In geostatic systems the apparent annual variation in the motion of sunspots could only be explained as the result of an implausibly complicated precession of the Sun’s axis of rotation[70][71][72] This did not apply, however, to the modified version of Tycho’s system introduced by his protégé, Longomontanus, in which the Earth was assumed to rotate. Longomontanus’s system could account for the apparent motions of sunspots just as well as the Copernican.

- ^ a b Such passages include Psalm 93:1, 96:10, and 1 Chronicles 16:30 which include text stating, «The world also is established. It can not be moved.» In the same manner, Psalm 104:5 says, «He (the Lord) laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be moved forever.» Further, Ecclesiastes 1:5 states, «The sun also rises, and the sun goes down, and hurries to its place where it rises», and Joshua 10:14 states, «Sun, stand still on Gibeon…».[121]

- ^ The discovery of the aberration of light by James Bradley in January 1729 was the first conclusive evidence for the movement of the Earth, and hence for Aristarchus, Copernicus and Kepler’s theories; it was announced in January 1729.[122] The second evidence was produced by Friedrich Bessel in 1838.

- ^ In Tycho’s system, the stars were a little more distant than Saturn, and the Sun and stars were comparable in size.[123]

- ^ According to Maurice Finocchiaro, this was done in a friendly and gracious manner, out of curiosity.[124]

- ^ Ingoli wrote that the great distance to the stars in the heliocentric theory «clearly proves … the fixed stars to be of such size, as they may surpass or equal the size of the orbit circle of the Earth itself».[130]

- ^ Drake asserts that Simplicio’s character is modelled on the Aristotelian philosophers Lodovico delle Colombe and Cesare Cremonini, rather than Urban.[137] He also considers that the demand for Galileo to include the Pope’s argument in the Dialogue left him with no option but to put it in the mouth of Simplicio.[138] Even Arthur Koestler, who is generally quite harsh on Galileo in The Sleepwalkers, after noting that Urban suspected Galileo of having intended Simplicio to be a caricature of him, says «this of course is untrue».[139]

References

Citations

- ^ Science: The Definitive Visual Guide. United Kingdom: DK Publishing. 2009. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7566-6490-9.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 1.

- ^ Willam A. Wallace, Prelude to Galileo: Essays on Medieval and Sixteenth Century Sources of Galileo’s Thought (Dordrecht, 1981), pp. 136, 196–97.

- ^ Modinos, A. (2013). From Aristotle to Schrödinger: The Curiosity of Physics, Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-319-00750-2.

- ^ Singer, C. (1941). «A Short History of Science to the Nineteenth Century». Clarendon Press: 217.

- ^ Whitehouse, D. (2009). Renaissance Genius: Galileo Galilei & His Legacy to Modern Science. Sterling Publishing. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4027-6977-1.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes: Critical Assessments, Volume 1. Preston King. 1993. p. 59

- ^ Disraeli, I. (1835). Curiosities of Literature. W. Pearson & Company. p. 371.

- ^ a b c Hannam 2009, pp. 329–344.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 127–131.

- ^ Finocchiaro 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Finocchiaro 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Hilliam 2005, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Carney, J. E. (2000). Renaissance and Reformation, 1500–1620: a. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 978-0-313-30574-0.

- ^ a b O’Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E .F. «Galileo Galilei». The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Gribbin 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Gribbin 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Gribbin 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Gribbin, J. (2009). Science. A History. 1543–2001. London: Penguin. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-14-104222-0.

- ^ a b Gilbert, N. W. (1963). «Galileo and the School of Padua». Journal of the History of Philosophy. 1 (2): 223–231. doi:10.1353/hph.2008.1474. S2CID 144276512.

- ^ a b Sobel 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Williams, Matt (5 November 2015). «Who Was Galileo Galilei?».

- ^ Robin Santos Doak, Galileo: Astronomer and Physicist, Capstone, 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Sobel 2000, p. 13.

- ^ «Galilean». The Century Dictionary and Encyclopedia. Vol. III. New York: The Century Co. 1903 [1889]. p. 2436.

- ^ Against the Galilaeans

- ^ Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 300, 330.

- ^ Naess, A. (2004). Galileo Galilei: When the World Stood Still. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-3-540-27054-6.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 17, 213.

- ^ Rosen, J.; Gothard, L. Q. (2009). Encyclopedia of Physical Science. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8160-7011-4.

- ^ Gribbin 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Sobel 2000, p. 5.

- ^ Pedersen, O. (1985). «Galileo’s Religion». In Coyne, G.; Heller, M.; Życiński, J. (eds.). The Galileo Affair: A Meeting of Faith and Science. Vatican City: Specola Vaticana. pp. 75–102. Bibcode:1985gamf.conf…75P. OCLC 16831024.

- ^ Reston 2000, pp. 3–14.

- ^ a b c Asimov, Isaac (1964). Asimov’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. ISBN 978-0-385-17771-9

- ^ Len Fisher (16 February 2016). «Galileo, Dante Alighieri, and how to calculate the dimensions of hell». Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Ostrow, Steven F. (June 1996). «Cigoli’s Immacolata and Galileo’s Moon: Astronomy and the Virgin in early seicento Rome». MutualArt. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Panofsky, Erwin (1956). «Galileo as a Critic of the Arts: Aesthetic Attitude and Scientific Thought». Isis. 47 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1086/348450. JSTOR 227542. S2CID 145451645.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 45–66.

- ^ Rutkin, H. D. «Galileo, Astrology, and the Scientific Revolution: Another Look». Program in History & Philosophy of Science & Technology, Stanford University. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ Battistini, Andrea (2018). «Galileo as Practising Astrologer». Journal for the History of Astronomy. Journal of the History Of Astronomy, Sage. 49 (3): 388–391. Bibcode:2018JHA….49..345.. doi:10.1177/0021828618793218. S2CID 220119861. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Kollerstrom, N. (October 2004). «Galileo and the new star» (PDF). Astronomy Now. 18 (10): 58–59. Bibcode:2004AsNow..18j..58K. ISSN 0951-9726. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ King 2003, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Drake 1990, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Edgerton 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Edgerton 2009, p. 155.

- ^ Jacqueline Bergeron, ed. (2013). Highlights of Astronomy: As Presented at the XXIst General Assembly of the IAU, 1991. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 521. ISBN 978-94-011-2828-5.

- ^ Stephen Pumfrey (15 April 2009). «Harriot’s maps of the Moon: new interpretations». Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 63 (2): 163–168. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2008.0062.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 146.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 152.

- ^ a b Sharratt 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Pasachoff, J. M. (May 2015). «Simon Marius’s Mundus Iovialis: 400th Anniversary in Galileo’s Shadow». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 46 (2): 218–234. Bibcode:2015JHA….46..218P. doi:10.1177/0021828615585493. S2CID 120470649.

- ^ Linton 2004, pp. 98, 205.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 157.

- ^ Drake 1978, pp. 158–168.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Hannam 2009, p. 313.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 168.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, p. 93.

- ^ Edwin Danson (2006). Weighing the World. Qxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518169-7.

- ^ «Solving Longitude: Jupiter’s Moons». Royal Museums Greenwich. 16 October 2014.

- ^ Thoren 1989, p. 8.

- ^ Hoskin 1999, p. 117.

- ^ a b Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008). «History of Saturn». Universe Today. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Baalke, Ron. Historical Background of Saturn’s Rings. Archived 21 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, NASA. Retrieved on 11 March 2007

- ^ a b Drake & Kowal 1980.

- ^ a b Vaquero, J. M.; Vázquez, M. (2010). The Sun Recorded Through History. Springer. Chapter 2, p. 77: «Drawing of the large sunspot seen by naked-eye by Galileo, and shown in the same way to everybody during the days 19, 20, and 21 August 1612»

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 209.

- ^ Linton 2004, p. 212.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, p. 166.

- ^ Drake 1970, pp. 191–196.

- ^ Gribbin 2008, p. 40.

- ^ Ondra 2004, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Graney 2010, p. 455.

- ^ Graney & Grayson 2011, p. 353.

- ^ a b Van Helden 1985, p. 75.

- ^ a b Chalmers 1999, p. 25.

- ^ a b Galilei 1953, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 167–176.

- ^ Galilei 1953, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Ondra 2004, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Graney 2010, pp. 454–462.

- ^ Graney & Grayson 2011, pp. 352–355.

- ^ Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Naylor, R. (2007). «Galileo’s Tidal Theory». Isis. 98 (1): 1–22. Bibcode:2007Isis…98….1N. doi:10.1086/512829. PMID 17539198. S2CID 46174715.

- ^ Finocchiaro 1989, p. 354.

- ^ Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 119–133.

- ^ Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 127–131.

- ^ Galilei 1953, pp. 432–436.

- ^ Einstein 1953, p. xvii.

- ^ Galilei 1953, p. 462.

- ^ James Robert Voelkel. The Composition of Kepler’s Astronomia Nova. Princeton University Press, 2001. p. 74

- ^ Stillman Drake. Essays on Galileo and the History and Philosophy of Science, Volume 1. University of Toronto Press, 1999. p. 343

- ^ Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, fourth giornata

- ^ Drake 1960, pp. vii, xxiii–xxiv.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Grassi 1960a.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 268.

- ^ Grassi 1960a, p. 16).

- ^ a b Galilei & Guiducci 1960.

- ^ Drake 1960, p. xvi.

- ^ Drake 1957, p. 222.

- ^ a b Drake 1960, p. xvii.

- ^ a b c Sharratt 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Drake 1960, p. xii.

- ^ Galilei & Guiducci 1960, p. 24.

- ^ Grassi 1960b.

- ^ Drake 1978, p. 494.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, p. 137.

- ^ Drake 1957, p. 227.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 138–142.

- ^ Drake 1960, p. xix.

- ^ Alexander, A. (2014). Infinitesimal: How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World. Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-374-17681-5.

- ^ Drake 1960, p. vii.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, p. 175.

- ^ Sharratt 1994, pp. 175–178.

- ^ Blackwell 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Hannam 2009, pp. 303–316.

- ^ Blackwell, R. (1991). Galileo, Bellarmine, and the Bible. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-268-01024-9.

- ^ Brodrick 1965, p. 95.