гештальтпсихология

- гештальтпсихология

-

гештальтпсихология

Слитно или раздельно? Орфографический словарь-справочник. — М.: Русский язык.

.

1998.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «гештальтпсихология» в других словарях:

-

гештальтпсихология — (от нем. Gestalt образ, форма) направление в западной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой трети ХХ в. и выдвинувшее программу изучения психики с точки зрения целостных структур (гештальтов), первичных по отношению к своим компонентам. Г.… … Большая психологическая энциклопедия

-

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ — (от немецкого Gestalt форма, образ, структура), одна из основных школ (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1 й половины 20 в. Подчеркивала целостный и структурный характер психических образований, опираясь на представление о гештальткачестве как … Современная энциклопедия

-

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ — (от нем. Gestalt структура, образ, форма, конфигурация) одно из влиятельных направлений в психологии пер. пол. 20 в. Сформировалось под непосредственным влиянием филос. феноменологии (Э. Гуссерль), утверждавшей, что восприятие мира носит… … Философская энциклопедия

-

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ — [нем. Geschtalt образ, форма + психология] психол. направление в западной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой трети XX в. и выдвинувшее программу изучения психики с точки зрения целостных структур (гештальтов), первичных по отношению к… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

Гештальтпсихология — (от немецкого Gestalt форма, образ, структура), одна из основных школ (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1 й половины 20 в. Подчеркивала целостный и структурный характер психических образований, опираясь на представление о “гештальткачестве”… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ — (нем. Gestalt форма образ, структура), одна из основных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1 й пол. 20 в. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологии выдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Гештальтпсихология — психологическое направление, возникшее в Германии в начале 10 х и просуществовавшее до середины 30 х гг. ХХ в. (до прихода к власти гитлеровцев, когда большинство ее представителей эмигрировали) и продолжив … Психологический словарь

-

гештальтпсихология — сущ., кол во синонимов: 1 • психология (21) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ — (от нем. Gestalt целостная форма, образ, структура, греч. psyche душа и logos слово, учение) англ. gestal tpsychology; нем. Gestaltpsychologie. Направление в психологии, исходящее из целостности человеческой психики, не сводимой к простейшим… … Энциклопедия социологии

-

Гештальтпсихология — (нем. Gestalt форма, образ, структура) одна из основных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1 й пол. 20 в. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологии выдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон… … Политология. Словарь.

Как правильно пишется слово «гештальтпсихология»

гештальтпсихоло́гия

гештальтпсихоло́гия, -и

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: ужение — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Синонимы к слову «гештальтпсихология»

Предложения со словом «гештальтпсихология»

- Принципы гештальтпсихологии появились как результат практических и теоретических научных исследований, что даёт нам основание признать их доказательный характер.

- Понимание основ гештальтпсихологии помогает нам понять процессы, происходящие в сознании зрителя при разглядывании картины.

- Заслуга гештальтпсихологии состоит в том, что ей были найдены современные подходы к изучению проблем психологии, однако проблемы, вызвавшие кризис, до конца так и не были разрешены.

- (все предложения)

Значение слова «гештальтпсихология»

-

Гештáльт-психолóгия (от нем. Gestalt — личность, образ, форма) — школа психологии начала XX века. Основана Максом Вертгеймером, Вольфгангом Кёлером и Куртом Коффкой в 1912 году. (Википедия)

Все значения слова ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Синонимы слова «ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ»:

ПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Смотреть что такое ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ в других словарях:

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

одна из крупнейших школ зарубежной психологии 1-й половины 20 в., выдвинувшая в качестве центрального тезис о необходимости проведения принципа… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

гештальтпсихология

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 1

• психология (21)

Словарь синонимов ASIS.В.Н. Тришин.2013.

.

Синонимы:

психология

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. Gestalt — структура, образ, форма, конфигурация) — одно из влиятельных направлений в психологии пер. пол. 20 в. Сформир… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

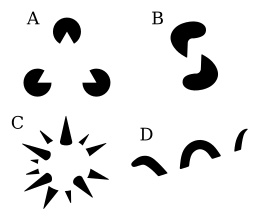

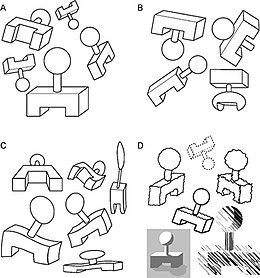

гештальтизм) — направление в западной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой трети XX в. Выдвинула программу изучения психики с точки зрения целостных структур — гештальтов, первичных по отношению к своим компонентам. Она выступила против выдвинутого психологией структурной принципа расчленения сознания на элементы и построения из них — по законам ассоциации или творческого синтеза — сложных психических феноменов. В противовес ассоцианистским представлениям о создании образа через синтез отдельных элементов была выдвинута идея целостности образа и несводимости его свойств к сумме свойств элементов; в связи с этим часто подчеркивается роль гештальт-психологии в становлении системного подхода — не только в психологии, но и науке в целом. По мнению ее теоретиков, предметы, составляющие наше окружение, воспринимаются чувствами не в виде отдельных объектов, кои должны интегрироваться либо сознанием, как полагают структуралисты, либо механизмами обусловливания, как утверждают бихевиористы. Мир состоит из организованных форм, и восприятие мира тоже организованно: воспринимается некое организованное целое, а не просто сумма его частей. Возможно, что механизмы такой организации восприятий существуют еще до рождения — это предположение подтверждается наблюдениями. Итак, восприятие не сводится к сумме ощущений, свойства фигуры не описываются через свойства частей. Изучение деятельности мозга головного и самонаблюдение феноменологическое, обращенное на различные содержания сознания, могут рассматриваться как взаимодополняющие методы, изучающие одно и то же, но использующие разные понятийные языки. Субъективные переживания представляют собой всего лишь феноменальное выражение различных электрических процессов в мозге головном. По аналогии с электромагнитными полями в физике, сознание в гештальт-психологии понимается как динамическое целое — поле, в коем каждая точка взаимодействует со всеми остальными. Для исследования экспериментального этого поля вводится единица анализа, в качестве коей выступает гештальт. Гештальты обнаруживаются при восприятии формы, кажущегося движения, оптико-геометрических иллюзий. В качестве основного закона группировки отдельных элементов постулируется закон прегнантности — как стремления психологического поля к образованию самой устойчивой, простой и экономной конфигурации. При этом выделяются факторы, способствующие группировке элементов в целостные гештальты, — такие как фактор близости, фактор сходства, фактор продолжения хорошего, фактор судьбы общей. Идея о том, что внутренняя, системная организаций целого определяет свойства и функции образующих его частей, применяется к экспериментальному изучению восприятия — преимущественно зрительного. Это позволило изучить ряд его важных особенностей: константность; структурность, зависимость образа предмета-фигуры — от его окружения — фона, и пр. Понятия фигуры и фона (-> фигура фон) — важнейшие в гештальт-психологии. Психологи пытались обнаружить законы, по коим фигура выделяется из фона — как структурированная целостность менее дифференцированного пространства, находящегося как бы позади фигуры. К этим законам относятся такие, как закон близости элементов, Симметричность, сходство, замкнутость и пр. Явления фигуры и фона отчетливо выступают в так называемых двойственных изображениях, где фигура и фон как бы произвольно меняются местами — происходит внезапное «реструктурирование». Понятия фигуры и фона и явление реструктурирования — внезапного усмотрения новых отношений между элементами — распространяется и за пределы психологии восприятия; они важны и при рассмотрении творческого мышления, внезапного обнаружения нового способа решения задачи. В гештальт-психологии это явление названо ага-решением, применяется также термин «озарение» («инсайт»). Оно обнаруживается не только у человека, но и у высших животных. Усмотрение новых, отношений — центральный момент мышления творческого. При этом появление некоего решения в продуктивном мышлении животных и человека трактуется как результат образования хороших гештальтов в психологическом поле. В области психологии мышления в гештальт-психологи применялся метод экспериментального исследования мышления — метод рассуждения вслух. При этом было внесено понятие ситуации проблемной (М. Вертхаймер, К. Дункер). При анализе интеллектуального поведения была прослежена роль сенсорного образа в организации реакций двигательных. Построение этого образа объяснялось особым психическим актом постижения, мгновенного схватывания отношений в воспринимаемом поле. Эти положения были противопоставлены бихевиоризму, объяснявшему поведение в ситуации проблемной перебором двигательных проб, случайно приводящих к удачному решению. При исследовании процессов мышления основной упор делался на преобразование структур познавательных, благодаря коему эти процессы становятся продуктивными, что отличает их от формально-логических операций, алгоритмов и пр. В 20-х гг. XX в. К. Левин расширил сферу применения гештальт-психологии путем введения личностного измерения. Хотя гештальт-психология как таковая уступила место другим направлениям, ее вкладом не стоит пренебрегать. Многие концепции, выдвинутые в ней, вошли в различные разделы психологии — от изучения восприятия до динамики групп. Она оказала существенное влияние на необихевиоризм, психологию когнитивную, школу «Нового Взгляда» (New Look). Ее идеи оказались весьма эвристичными — по сути, был открыт новый способ психологического мышления. Хотя в «чистом» виде это направление ныне практически не представлено, а ряд положений частично обесценился (например, было показано, что восприятие определяется не только формой объекта, но прежде всего значением в культуре и практике конкретного человека), многие идеи оказали глубокое влияние на появление и развитие ряда психологических направлений. Идея целостности широко проникла в психотерапевтическую практику, а исследования мышления в гештальт-психологии во многом определили идею обучения проблемного. Однако свойственная гештальт-психологии методология, восходящая к феноменологии, препятствовала детерминистскому анализу этих процессов психических. Психические гештальты и их преобразования трактовались как свойства индивидуального сознания, зависимость коего от предметного мира и деятельности системы нервной представлялась организованной по типу изоморфизма — структурного подобия, варианта параллелизма психофизического. Выделенные как законы гештальта положения отразили общую методологическую ориентацию, порой придавшую характер законов отдельным фактам, выявленным при изучении процесса восприятия, и склонную толковать само восприятие как чистый феномен сознания, а не как психический образ реальности. Наиболее известные гештальт-психологи, это М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка. Близкие гештальт-психологии общенаучные позиции занимали: 1) К. Левин и его школа, распространившие принцип системности и идею приоритета целого в динамике психических образований на мотивацию человеческого поведения; 2) К. Гольдштейн — сторонник холизма в патопсихологии; 3) Ф. Хайдер, введший понятие о гештальте в психологию социальную для объяснения восприятия межличностного. … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(нем. gestalt — образ, форма; gestalten — конфигурация). Данное направление психологической науки возникло в первой половине XX в. и получило развитие, прежде всего, в трудах М. Вертхаймера, В. Келера, К. Коффки, К. Левина и др. В его основу легли исследования зрительного восприятия, доказавшие, что люди склонны воспринимать окружающий мир в виде упорядоченных целостных конфигураций, а не отдельных фрагментов. Образно говоря, человек изначально воспринимает лес вообще и, лишь затем может выделить отдельные деревья как части целого. Такие конфигурации и получили название «гештальтов». На базе исследований восприятия были сформулированы два основополагающих принципа гештальтпсихологии.

Первый из них — принцип взаимодействия фигуры и фона — гласит, что каждый гештальт воспринимается как фигура, имеющая четкие очертания и выделяющаяся в данный момент из окружающего мира, представляющего собой по отношению к фигуре более размытый и недифференцированный фон. Формирование фигуры, с точки зрения гештальтпсихологии, означает проявление интереса к чему-либо и сосредоточение внимания на данном объекте с целью удовлетворения возникшего интереса.

Второй принцип, часто называемый законом прегнантности или равновесия, базируется на том, что человеческая психика, как и любая динамическая система, стремится к максимальному в наличных условиях состоянию стабильности. В контексте первого принципа это означает, что, выделяя фигуру из фона, люди обычно стремятся придать ей наиболее «удобоваримую», с точки зрения удовлетворения изначального интереса, форму. Форма такого рода характеризуется простотой, регулярностью, близостью и завершенностью. Фигуру, отвечающую данным критериям часто называют «хорошим гештальтом».

Впоследствии эти принципы были дополнены теорией научения К. Коффки, концепцией энергетического баланса и мотивации К. Левина и введенным последним принципом «здесь и сейчас», согласно которому первостепенным фактором, опосредствующим поведение и социальную функциональность личности, является не содержание прошлого опыта (в этом кардинальное отличие гештальтпсихологии от психоанализа), а качество осознавания актуальной ситуации. На этой методологической базе Ф. Перлзом, Е. Полстером и рядом других гештальтпсихологов была разработана теория цикла контакта, ставшая базовой моделью практически всех практикоориентированных подходов в гештальтпсихологии.

Согласно данной модели весь процесс взаимодействия индивида с фигурой — от момента возникновения спонтанного интереса до полного его удовлетворения включает в себя шесть стадий: ощущение, осознавание, энергию, действие, контакт и разрешение.

На первой стадии спонтанный интерес к объекту носит характер смутного, неопределенного ощущения, часто беспокойства, тем самым, вызывая начальное напряжение. Потребность понять и конкретизировать источник ощущения побуждает индивида к сосредоточению внимания на вызвавшем его объекте (переход на стадию осознавания). Целью осознавания является насыщение фигуры значимым содержанием, ее конкретизация и идентификация. По сути дела, процесс выделения фигуры из фона сводится к двум первым стадиям контакта.

Уже в процессе осознавания происходит мобилизация энергии, связанной с изначально возникшим напряжением и необходимой для сосредоточения и удержания внимания. Если выделенная в результате осознавания из фона фигура оказывается значимой для субъекта, то изначальный интерес стимулируется, а напряжение не только не снижается, а, напротив, возрастает, постепенно приобретая характер «заряженной энергией озабоченности». В результате наступает третья стадия цикла, на которой энергия системы достигает своего пика, а фигура в субъективном восприятии максимально «приближается» к индивиду. Тем самым создаются условия для перехода к стадии действия.

На этой стадии индивид переходит от собственно восприятия или перцептивного поведения к попыткам активно воздействовать на вызвавшую интерес фигуру, что должно привести к адаптации последней к физическому, либо психологическому «присвоению» или ассимиляции. Под ассимиляцией Ф. Перлз понимал избирательную интеграцию не целостного, сохраняющего изначальную структуру объекта, как это имеет место в классическом понятии интроекции, а тех его компонентов, которые реально отвечают потребностям индивида. Для этого необходимо расчленение фигуры на составляющие, образно говоря, ее «пережевывание», что и является квинтэссенцией действия в рассматриваемой схеме. Например, в контексте социальных отношений, вступая в контакт с определенным человеком, индивид должен не только осознать свои потребности, но и определить, какие из них данный партнер объективно может и субъективно готов удовлетворить.

В результате действия, направленного на вызвавшую интерес фигуру, возникает максимально насыщенное переживание, в рамках которого интегрируются впечатления, полученные от сенсорного осознавания и моторного акта. В логике данной модели контакт есть точка максимально возможного в наличествующих условиях удовлетворения исходного интереса или потребности.

Завершающая стадия разрешения (у некоторых авторов обозначается как завершение) предполагает рефлексию опыта, полученного на стадии контакта, и его интеграцию на внутриличностном уровне. Именно так в логике гештальтпсихологии происходит научение.

По завершении цикла контакта фигура перестает быть актуальной и привлекать к себе внимание — гештальт завершается, что то же самое, разрушается. В результате возникает возможность нового ощущения и возобновления цикла. С точки зрения гештальтпсихологии вся жизнь человека представляет собой непрерывную цепь таких циклов.

На основании представленной модели Ф. Перлзом и его последователями была разработана оригинальная система психотерапии, нашедшая широкое применение. В социальной психологии данная схема и психотехники, связанные с настоящим подходом применяются для исследования стилей коммуникации, групповых норм, межличностного и межгруппового взаимодействия. Они также нашли широкое применение в сфере организационного консультирования, коучинга и профессиональной подготовки практических социальных психологов…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТ-ПСИХОЛОГИЯ (англ. Gestalt psychology) — психологическое направление, существовавшее в Германии с нач. 1910-х до середины 1930-х гг. Основные представители Г.-п. (М. Вертгеймер, В. Кёлер, К. Коффка) работали, г. о., в Берлинском ун-те, поэтому Г.-п. иногда называют Берлинской школой. В Г-п. получила дальнейшую разработку проблема целостности, поставленная Австрийской школой, при решении которой Г.-п., вышла за пределы элементаристской методологии, подвергнув ее теоретической и экспериментальной критике, и создала целостный подход к изучению психики и сознания.<br><br>Философской основой Г.-п. является «критический реализм», основные положения которого родственны философским идеям Э. Геринга, Э. Махха, Э. Гуссерля и И. Мюллера. Согласно Г.-п., для человека существуют 2 отличных друг от друга «мира»: мир физический, лежащий «за» переживаниями, и мир наших переживаний (ощущений), который в Г.-п. называли в разных контекстах «объективным» или «субъективным». Последний Г.-п. рассматривала в 2 отношениях: как физиологическую реальность (процессы в мозге как отражения воздействий внешнего мира) и как психическую (феноменальную) реальность, которые связаны между собой отношениями изоморфизма (взаимно-однозначного соответствия).<br><br>Следовательно, психологические законы сводились в Г.-п. к законам физиологии мозга. Вместе с тем Г.-п. не отказывается и от изучения феноменов сознания методом феноменологического самонаблюдения. Само сознание понималось как некое динамическое целое, «поле», каждая точка которого взаимодействует со всеми остальными (по аналогии с электромагнитными полями в физике). Единицей анализа сознания выступает гештальт как целостная образная структура, не сводимая к сумме составляющих его ощущений.<br><br>Различные формы гештальтов изучались в Г.-п. на материале восприятия кажущегося движения, формы (в т. ч. отношений «фигуры-фона»), оптико-геометрических иллюзий. Были выделены т. н. факторы восприятия, которые способствуют группировке отдельных элементов физического мира в соответствующем ему «психологическом поле» в целостные гештальты: «фактор близости», «фактор сходства», «фактор хорошего продолжения» (объединяются в гештальт те элементы изображения, которые в совокупности образуют прегнантные, наиболее простые конфигурации), «фактор общей судьбы» (объединение в 1 гештальт, напр., 3 движущихся в одном направлении точек среди множества др., движущихся в разных направлениях) и т. д. В основе принципов группировки лежит более общий закон перцептивного поля — закон прегнантности, т. е. тенденция этого поля к образованию наиболее устойчивой, простой и «экономной» конфигурации. С т. зр. Г.-п., данные законы представляют собой феноменальное выражение различных электрических процессов в головном мозге (образование токов различной направленности, «насыщение» отдельных участков мозга электрическими зарядами и т. п.). В этом решении психофизиологической проблемы проявилась обоснованная в Г.-п. К. Гольдштейном т. зр. «антилокализационизма» (см. Локализация высших психических функций), впоследствии подвергнутая справедливой критике и отвергнутая большинством неврологов и нейропсихологов.<br><br>При разработке проблем мышления Г.-п. подвергла острой критике бихевиористские взгляды на мышление как образование «навыков» путем проб и ошибок и ввела в психологию такие понятия, как проблемная ситуация (см. Задача), инсайт, а также новый метод эмпирического исследования мышления — метод «рассуждения вслух», который уже выходил за рамки исходных феноменологических установок Г.-п. и предполагал подлинно объективное исследование процессов мышления (М. Вертгеймер, К. Дункер и др.). Однако при объяснении «продуктивного мышления» у животных и творческого мышления у человека Г.-п. неправомерно отрицала роль активности и прошлого опыта субъекта в процессе решения творческих задач, считая возникновение такого решения результатом все тех же процессов образования «хороших гештальтов» в «здесь и теперь» складывающемся «психологическом поле».<br><br>В 1920-е гг. К. Левин предпринял попытку дополнить и углубить модель психического мира человека, предложенную Г.-п., введя в нее «личностное измерение» (см. Временная перспектива, Топологическая и векторная психология).<br><br>После прихода к власти нацистов Г.-п. как школа распалась в результате эмиграции большинства ее членов. Идеи Г.-п. оказали значительное влияние на развитие необихевиоризма, психологии восприятия (школу «New Look»), когнитивной психологии, системного подхода в науке, отдельных направлений психологической практики (в частности, гештальт-терапии), некоторых концепций межличностного восприятия (Ф. Хайдер) и др. Вместе с тем критики Г.-п. (среди которых были Л. С. Выготский, Лейпцигская школа и др.) отмечали антиисторизм и антигенетизм Г.-п., фактическое отрицание прошлого опыта в процессе образования гештальтов, редукционистские установки в плане сведения психологических закономерностей к принципам физиологической работы мозга и др.<br><br>С конца 1970-х гг. в связи с развитием идей системного подхода в психологии наблюдается определенное возрождение интереса к Г.-п., что нашло свое отражение в образовании межд. «Общества гештальт-теории и ее приложений» и выпуске соответствующего журнала. (Е. Е. Соколова.)<br><br><br>… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

от нем. Gestalt – образ, структура, целостная форма) – одно из направлений идеалистич. психологии, возникшее в Германии в 1-й четверти 20 в. и выдвинувшее в качестве осн. объясняющего принципа психологии целостное объединение элементов психич. жизни, несводимое к сумме составляющих, – «гештальт». Филос. основой Г. послужили феноменология Гуссерля, махизм, а также т.н. «философия формы», получившая свое развитие в конце 20-х гг. в работах Г. Фридмана о «морфологическом идеализме». Теория Г. тесно связана также с идеалистич. трактовкой эстетики изобразит. иск-ва (А. Гильдебранд). Подобно другим развившимся в то время направлениям психологии (вюрцбургской школе мышления, лейпцигской школе целостной психологии, бихевиоризму), возникновение Г. явилось реакцией на ассоцианизм (см. Ассоциативная психология) и в какой-то мере на «физиологическую» психологию и способствовало усилению наметившейся тогда дезинтеграции бурж. психологии (начало т.н. кризиса психологии). Приобретавшая все большее распространение идея целостности реализовалась в Г. как целостность динамич. ситуации и ее формальной структуры. Понятие «гештальт» было введено Эренфельсом в 1890 при исследовании им зрит. восприятий. Распространив его впоследствии на др. виды восприятий, Эренфельс вкладывал в него след. содержание: если дается нек-рая последовательность, допустим, слуховых раздражений (тонов), то они воспринимаются не просто как множественность не связанных друг с другом звуков, а как мелодия, представляющая собой определ. структуру, «гештальт» этих звуков. По мнению Эренфельса, специфичность гештальта выражается прежде всего тем, что ему присуще свойство переноса: мелодия остается при переводе из одной тональности в другую, гештальт квадрата сохраняется независимо от размера, положения и окраски последнего и т.д. Однако сам Эренфельс не развил теории Г.; начало ее обычно связывают с появлением работы Вертхеймера (1912), в к-рой уже прямо ставилось под сомнение наличие отд. элементов в акте восприятия. Непосредственно после этого и в особенности в 20-х гг. складывается т.н. берлинская школа Г., представители к-рой Келер, Вертхеймер, Коффка, Левин провели ряд плодотворных экспериментальных исследований восприятия. Г. оказала значительное влияние на др. науки, в частности на структурную лингвистику. Берлинская школа Г. просуществовала до 30-х гг., когда значит, часть ее представителей эмигрировала из Германии. Эволюция Г. пошла по пути расширения понятия «гештальт», его универсализации и выхода не только за пределы восприятия [в область мышления и памяти – Коффка, Келер, Вертхеймер, Дункер (т.н. «продуктивное мышление»)], чувств и потребностей (Левин), психологии развития (Коффка), психофизиология, проблемы (Келер), но и за пределы собственно психологии – в область теоретич. физики и физиологии (Келер) и даже экономич. отношений (Вертхеймер). Наряду с этим понятие «гештальт» под влиянием развития теории обучения претерпевает определ. изменения в плане слияния его с понятием динамизма, согласно к-рому течение психо-физич. процессов определяется внутренне замкнутыми отношениями (Келер, Левин). Как осн. положение об изначальности гештальта, так и др. теоретич. положения Г. были подвергнуты резкой критике мн. психологами и физиологами, напр. И. Павловым, Л. Выготским. В наст. время, несмотря на значит. снижение роли Г., ряд зарубежных психологов стремится использовать ее положение при установлении общих закономерностей восприятия и мышления. Так, напр., А. Мишотт установил, что понятие физич. причинности, по крайней мере в ее механич. форме, феноменалистически наличествует в самом акте восприятия и допускает истолкование в понятиях Г. Школа «генетической эпистемологии» (Ж. Пиаже) стремится использовать результаты работ Г. для обоснования «операциональных» и «формальных» структур мышления. При этом понятия Г. подвергаются существ. переработке. Лит.: Келер В., Исследование интеллекта человекоподобных обезьян, пер. с нем., М., 1930; Коффка К., Основы психологического развития, пер. с нем., М.–Л., 1934; Павловские среды. Протоколы и стенограммы физиологических бесед, [под ред. Л. А. Орбели], т. 2, М.–Л., 1949; Выготский Л. С., Избр. психологические исследования. Мышление и речь, М., 1956; Wertheimer M., Experimentelle Studien ?ber das Sehen von Bewegung, «Z. Psychol, und Physiol. Sinnesorgane», Lpz., Abtl. l, Bd 61, H. 3–4, 1910–11, S. 161–265; K?hler W., Die physischen Gestalten in Ruhe und im station?ren Zustand, Braunschweig, 1920; Ehrenfels Ch., ?ber «Gestaltqualit?ten», «Vierteljahrschr. wiss. Philos.», Lpz., 1890, Jg 14, H. 3, S. 249–92; M?ller G., Komplextheorie und Gestalttheorie, G?ttingen, 1923; Wertheimer M., ?ber Gestalttheorie. Erlangen, 1925; его же, Gestalt theory, «Social Res.», N. Y., 1944, v. 11, No 1, p. 78–99; его же. Productive thinking, N. Y.–L., 1945; Heidbreder E., Seven psychologies, L., 1933; Koffka K., Principles of gestalt psychology, N. Y., 1935; K?hler W., Gestalt psychology. An introduction to new concepts in modern psychology, N. Y., 1947. M. Роговин. Москва. … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТ-ПСИХОЛОГИЯ — одно из ведущих направлений в западной психологии. Появилось в конце 19 в. в Германии и Австрии. Для объяснения явлений психическ… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

— одно из ведущих направлений в западной психологии. Появилось в конце 19 в. в Германии и Австрии. Для объяснения явлений психической, жизни Г. взяла на вооружение принцип целостности, несводимости элементов психической жизни к простой сумме ее составляющих. Это ключевое положение было зафиксировано в активном использовании понятия «гештальт» (немец. Gestalt — образ, структура, целостная форма, которое также близко к понятиям «паттерн» и «конфигурация»). Впервые феномен «гештальта» был выявлен при исследовании стробоскопического движения в 1912 М.Вертхаймером совместно с В. Келером и К. Коффкой, ставшими позже также центральными фигурами в Г. Иллюзия движения двух последовательно вспыхивающих точек ими впервые была объяснена наличием целостного перцептивного поля. Воспринимаемое движение являлось функцией неизолированных стимулов и зависело от их взаимоотношения в рамках определенного гештальта. Первоначально наиболее активно исследования велись в области восприятия с целью выявления его целостного характера. Для объяснения ряда феноменов, выявленных в ходе этих работ, были введены в психологию такие понятия, как фигура и фон, прегнантность фигуры, законы прегнантности и др. В 20-40-х 20 в. Г. стала применяться для изучения интеллектуальной сферы животных (Ке-лер) и творческого мышления человека (Вертхаймер). Экспериментальные исследования гештальт-психологов (Келер, Вертхаймер, Дункер) выявили один из главных механизмов мышления — обнаружение новых сторон предметов путем мысленного их включения в новые связи и отношения путем их переструктурирования и придания им прегнантности. В 30-40-х при описании групповых процессов и объяснении закономерностей групповой динамики К. Левин исходил из законов «организм — среда» таким образом, чтобы его актуальные потребности удовлетворились. Ф. Перле создал модель психологического роста, в основу которой положено определение психологического здоровья как наличия у индивида способности и энергии для перехода от опоры на среду к опоре на себя и к саморегулированию. Психологический рост может проходить по-разному. Это прежде всего завершение (проживание «здесь и теперь») незавершенных ситуаций или гештальтов с помощью терапевта. Он совершается и при последовательном прохождении индивидом пяти невротических уровней; клише, игр, тупика, внутреннего взрыва, внешнего взрыва. В ходе взаимодействия с клиентом терапевт должен помочь ему восстановить границы контакта путем работы с невротическими механизмами, препятствующими росту: проекцией, интроекцией, ретрофлексией и конфлюенцией. Психологический рост непосредственно связан с расширением зон самосознавания, со способностью человека жить в этом потоке сознавания, находиться на континууме сознавания, т.е. осознавать собственный опыт, свои ощущения чувства, мысли, желания, каждое мгновение своей жизни, переходя от одного фрагмента «здесь и теперь» к следующему и т.д. В Г. считается, что сознавание уже само по себе обладает позитивной, оздоравливающей силой. Поэтому Перле и целый ряд его последователей (П. Гудмэн, Р. Хефферлин, К. Наранхо, Дж. Энрайт и др.) постоянно пы тались и пытаются расширить арсенал процедур и упражнений, направленных на активизацию сознавания, формируя на базе Г. методы гештальт-терапии (см. Гештальт-терапия). С.С. Харин… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

нем. gestalt — форма, образ, структура), одна из основных школ зарубежной психологии первой половины XX в., представители которой исходят из целостности человеческой психики, не сводимой к ее простейшим формам. Гештальтпсихология исследует психическую деятельность субъекта, строящуюся на основе восприятия окружающего мира в виде гештальтов. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологии выдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон Эренфельсом понятие гештальта) в качестве основы при исследовании сложных психических явлений. Исходила из учения Ф. Брентано и Э. Гуссерля об интенциональности (см. Интенция) сознания. Возникла в Германии в начале 10-х и просуществовала до середины 30-х гг. ХХ в. (до прихода к власти гитлеровцев, когда большинство ее представителей эмигрировали). Продолжила разработку проблемы целостности, поставленной Австрийской школой. К этому направлению принадлежат прежде всего М. Вертгеймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка. Методологической базой гештальтпсихологии послужили философские идеи «критического реализма» и положения, развивавшиеся Э. Герингом, Э. Махом, Э. Гуссерлем, И. Мюллером, согласно которым физиологическая реальность процессов в мозге и психическая, или феноменальная, связаны друг с другом отношениями изоморфизма.

В силу этого изучение деятельности мозга и феноменологическое самонаблюдение, обращенное на различные содержания сознания, могут рассматриваться как взаимодополняющие методы, изучающие одно и то же, но использующие разные понятийные языки. Субъективные переживания представляют собой всего лишь феноменальное выражение различных электрических процессов в головном мозге. По аналогии с электромагнитными полями в физике, сознание в гештальтпсихологии понималось как динамическое целое, «поле», в котором каждая точка взаимодействует со всеми остальными.

Для экспериментального исследования этого поля была введена единица анализа, в качестве которой стал выступать гештальт. Гештальты были обнаружены при восприятии формы, кажущегося движения, оптико-геометрических иллюзий. В качестве основного закона группировки отдельных элементов был постулирован закон прегнантности как стремления психологического поля к образованию наиболее устойчивой, простой и «экономной» конфигурации. При этом были выделены факторы, способствующие группировке элементов в целостные гештальты, такие как «фактор близости», «фактор сходства», «фактор хорошего продолжения», «фактор общей судьбы».

В области психологии мышления гештальтпсихологи разработали метод экспериментального исследования мышления — метод «рассуждения вслух» и внесли такие понятия, как проблемная ситуация, инсайт (М. Вертгеймер, К. Дункер). При этом возникновение того или иного решения в «продуктивном мышлении» животных и человека трактовалось как результат образования «хороших гештальтов» в психологическом поле. В 20-х гг. ХХ в. К. Левин расширил сферу применения гештальтпсихологии путем введения «личностного измерения». Гештальтпсихология оказала существенное влияние на необихевиормзм, когнитивную психологию, школу «New Look». … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Психологическая школа, основанная в Германии в 1910-х гг. Первоначально, выступая против структурализма, гешталь-тисты утверждали, что психологические явления могут быть поняты только, если рассматривать их как организованное, структурное целое (или гешталь-ты). Структуралистской позиции, согласно которой эти явления могут быть интроспективно разложены на простейшие перцептивные элементы, была противопоставлена гештальтистская точка зрения, что такой анализ не учитывает понятие целого, единой «сущности» явлений (например, является ли яблоко действительно определенной комбинацией простейших элементов, таких как краснота, форма, очертания, твердость и т.д., или этот анализ пропускает некоторую основную «яблочность», которая поддается восприятию только, когда целое рассматривается в целом?).

Ранние гештальтисты были мастерами изящных контрпримеров и представляли достаточно убедительные аргументы, наносившие серьезный ущерб ортодоксальной точке зрения структуралистов. Например, определенная мелодия легко распознается даже тогда, когда ее составляющие части значительно изменены: она может быть спета (в любом голосовом диапазоне), проиграна (любой комбинацией музыкальных инструментов), представлена во множестве вариаций и т.д., но при этом не разрушается ее распознаваемый геш-тапьт. Более того, каждая из нот в любой конкретной мелодии имеет различное феноменологическое значение в зависимости от того, проиграна ли она отдельно или включена в новую мелодию. Во всех случаях, утверждали они, целое доминирует над ощущением, и оно воспринимается не так, как просто сумма отдельных частей.

Научение рассматривалось гештальтистами не как связь между стимулами и реакциями (как утверждали бихевиористы), но как перестройка или реорганизация всей ситуации, часто с участием инсайта как важнейшей характеристики. Физиология мозга рассматривалась ими в той же манере. Не соглашаясь с общепринятой в то время точкой зрения, что кора головного мозга является статической, хорошо дифференцированной системой, они приводили доводы в пользу координированной физиологии, в которой кора головного мозга понималась как место, где входящие стимулы взаимодействуют в силовых полях. См. здесь изоморфизм (2). В социальной психологии их работа привела к созданию теории поля, а в образовании основное внимание уделялось продуктивному мышлению и творчеству.

Вообще, гештальтпсихология является антитезой атомистической психологии во всех ее вариациях (см. атомизм, элементаризм), и в равной степени враждебно это направление выступало против бихевиоризма и структурализма. Хотя вряд ли можно сказать, что гештальтпсихология существует сегодня как отдельная теория, многие из ее открытий вошли в структуру современных знаний, особенно в области восприятия. Основные представители этой школы: Макс Вертгеймер, Курт Коффка, Вольфганг Келер, и приверженцем их философии был Курт Левин…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Словообразование. Происходит от нем. Gestalt — форма, структура + греч. psyche — душа + logos — учение.

Авторы. Была основана М.Вертгеймером, В.Келером, К.Коффкой.

Категория. Психологическое направление.

Специфика. Возникла в противоположность экспериментальной психологии начала XX века. Продолжила разработку проблемы целостности, поставленной Австрийской школой. Приход нацистов к власти в Германии вынудил большинство из ее представителей эмигрировать в США. Методологической базой гештальтпсихологии послужили философские идеи «критического реализма» и положения, развивавшиеся Э.Герингом, Э.Махом, Э.Гуссерлем, И.Мюллером, согласно которым физиологическая реальность процессов в мозге и психическая, или феноменальная реальность, связаны друг с другом отношениями изоморфизма. В силу этого изучение деятельности мозга и феноменологическое самонаблюдение могут рассматриваться как взаимодополняющие методы, изучающие одно и то же, но использующие разные понятийные языки. Субъективные переживания представляют собой феноменальное выражение различных электрических процессов в головном мозге. По аналогии с электромагнитными полями в физике, сознание в гештальтпсихологии понималось как динамическое целое, «поле», в котором каждая точка взаимодействует со всеми остальными.

Для экспериментального исследования этого поля была введена единица анализа, в качестве которой стал выступать гештальт. Основой этого понятия выступало положение, что при связывании психологических элементов возникает новое качество. Гештальты были обнаружены при восприятии формы, кажущегося движения, оптико-геометрических иллюзий. В качестве основного закона группировки отдельных элементов был постулирован закон прегнантности как стремления психологического поля к образованию наиболее устойчивой, простой и «экономной» конфигурации. При этом были выделены факторы, способствующие группировке элементов в целостные гештальты, такие как «фактор близости», «фактор сходства», «фактор хорошего продолжения», «фактор общей судьбы». В области психологии мышления гештальтпсихологи разработали метод экспериментального исследования мышления — метод «рассуждения вслух» — и такие понятия, как проблемная ситуация, инcaйт (М.Вертгеймер, К.Дункер). При этом возникновение того или иного решения в «продуктивном мышлении» животных и человека трактовалось как результат образования «хороших гештальтов» в психологическом поле. Сформулированные при исследовании процессов восприятия и мышления законы гештальта затем были перенесены на другие области. В 20-х гг. ХХ в. К.Левин расширил сферу применения гештальтпсихологии путем введения «личностного измерения». Гештальтпсихология оказала существенное влияние на необихевиоризм, когнитивную психологию, школу «New Look».

Синоним. Берлинская школа.

Литература. Koffka K. Principles of Gestalt Psychology. B.-N.Y., 1971 … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. Gestalt — образ, форма) — направление в западной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой трети ХХ в. и выдвинувшее программу изучения психики с точки зрения целостных структур (гештальтов), первичных по отношению к своим компонентам. Г. выступила против выдвинутого структурной психологией (В. Вундт, Э. Б. Титченер и др.) принципа расчленения сознания на элементы и построения из них по законам ассоциации или творческого синтеза сложных психических феноменов. Идея о том, что внутренняя системная организация целого определяет свойства и функции образующих его частей, была применена первоначально к экспериментальному изучению восприятия (преимущественно зрительного). Это позволило изучить ряд его важных особенностей: константность, структурность, зависимость образа предмета (••«фигуры» ) от его окружения («фона») и др. (см. фигура и фон). При анализе интеллектуального поведения была прослежена роль сенсорного образа в организации двигательных реакций.Построение этого образа объяснялось особым психическим актом постижения, мгновенного схватывания отношений в воспринимаемом поле (см. инсайт). Эти положения Г. противопоставила бихевиоризму, который объяснял поведение организма в проблемной ситуации перебором «слепых» двигательных проб, случайно приводящих к удачному решению. При исследовании процессов человеческого мышления основной упор был сделан на преобразование («реорганизацию», новую «центрировку») познавательных структур, благодаря к-рому эти процессы приобретают продуктивный характер, отличающий их от формально-логических операций, алгоритмов и т. п. Хотя идеи Г. и полученные ею факты способствовали развитию знания о психических процессах (прежде всего разработке категории психического образа, а также утверждению системного подхода), ее методологические установки, отразившие феноменологический подход к сознанию, препятствовали детерминистскому (см. детерминизм) анализу этих процессов. Психические «гештальты» и их преобразования трактовались как свойства индивидуального сознания, зависимость к-рого от предметного мира и деятельности нервной системы представлялась по типу изоморфизма (структурного подобия), являющегося вариантом психофизического параллелизма. Главные представители — немецкие психологи М. Вертгеймер, В. Кёлер, К. Коффка. Близкие к ней общенаучные позиции занимали К. Левин и его школа, распространившие принцип системности и идею приоритета целого в динамике психических образований на мотивацию человеческого поведения, К. Гольдштейн — сторонник «холизма» (целостности) в патопсихологии, Ф. Хайдер, введший понятие о гештальте в социальную психологию с целью объяснения межличностного восприятия, и др…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. Gestalt форма, образ, облик, конфигурация), одно из ведущих направлений в зап.-европ., особенно нем., психологии 1920-30-х гг., к-рое в противовес атомизму интроспективной психологии (В. Вундт, Э. Б. Титченер) подчёркивало целостный и структурный характер психич. образований. Осн. представители Г.: М. Вертхеймер, В. Кёлер, К. Коффка, а также во многом близкие к ним К. Левин, К. Гольдштейн, X. Груле, К. Дункер и др. Сложившись первоначально на основе исследования зрит, восприятия, Г. распространила затем свои идеи на изучение мышления, памяти, действия, личности и социальной группы.

Тезис о принципиальной несводимости целого к сумме составляющих его частей был выдвинут в кон. 19 в. австр. искусствоведом X. Эренфельсом в противовес господствовавшим в то время представлениям ассоцианизма. Специфич. характеристика целого была названа Эренфельсом «геттальткачеством» переживания; она может сохраняться при изменении всех отд. частей (напр., одна и та же мелодия может быть проиграна в разных тональностях или на разной «высоте» и т. п.) и, наоборот, теряться при их сохранении (напр., мелодия, проигранная «с конца») т. н. критерии гешталь-та, по Эренфельсу. Следующий шаг в развитии Г. (Вертхеймер, 1912) состоял в демонстрации того, что целое вообще нечто другое, нежели сумма «частей», к-рые выделяются из него посредством «изоляции» (обособления). Далее в работах Кёлера и Вертхеймера было показано, что части целого в собственном смысле суть «функции» или «роли» в нём, т. е. целое имеет функциональную структуру. Структура эта обладает динамич. характером, всякий гештальт под действием внутр. сил (к-рые порождают, поддерживают и восстанавливают определ. тип его организации, а также производят

его реорганизацию) стремится перейти в состояние максимально возможного при данных условиях равновесия. Это состояние характеризуется предельно достижимой црегнантностью (от нем. pragnant чёткий, выразительный) организации гештальта, т. е. её простотой, правильностью, завершённостью, выразительностью и осмысленностью. В качестве языка для описания гештальтов был использован заимствованный из физики аппарат теории поля (Кёлер, 1920), а затем теории «открытых систем» (Кёлер, 1958).

Выдвинутый Г. принцип целостности при анализе психич. явлений был воспринят в последующем развитии психологии; при этом были подвергнуты критике известный физикализм общей концепции Г., игнорирование ею культурно-историч. характера человеч. психики…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ[нем. Geschtalt — образ, форма + психология] — психол. направление в западной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой трети XX в. и… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Палеология Палеолит Ошалелость Охотиться Охота Охлопье Охи Охать Оха Отшить Оттоль Оттоле Отто Отсель Отпить Отпеть Отпаять Отопитель Отолит Отлиться Отлить Отлитие Отлет Отит Отель Отелло Отел Ося Ось Ость Остол Остит Остеит Остгот Осташ Остап Ост Оспа Осот Осло Ослиха Осип Осетия Осгит Оса Опять Оптоль Опт Опоясать Ополье Оплот Оплатить Опиться Опитость Опись Описатель Опиат Опель Опасть Опал Опа Оолит Оля Ольха Ольга Олигохета Олесь Олег Олеат Оао Лях Ляпис Ляп Льяло Лье Льгота Лох Лотто Лотос Лото Лот Лось Лосиха Лопасть Лолита Логотипия Логотип Логос Логопатия Логопат Логия Логист Лог Лишать Лихость Лихо Литься Литье Лить Литота Литология Литолог Лита Листие Листатель Лист Лисель Лис Липа Лиля Лилия Лилит Лиепая Лиеп Лиго Лига Леша Лех Летяга Летопись Лето Леталь Леся Лесть Лесото Леса Лепта Лепота Лепить Леля Легость Легист Легаш Легато Легат Лгать Ласт Ласло Лапоть Лаос Лал Лагос Лаг Ишиас Ихтиостега Ихтиолог Ихтиол Итого Итог Итл Итиль Италия Испить Исеть Иса Ипс Ипат Иох Иолит Иол Илья Илот Илл Иго Игла Игил Ехать Есь Есть Ель Египтология Египтолог Гто Гоша Готья Гот Гостья Гость Гостия Гост Госпиталь Гос Гоплит Гольтепа Голье Голь Голос Голо Голль Голлиста Гол Гоист Гогот Гоголь Гоголиха Гога Гляс Глот Глог Глия Глист Глипт Глиепс Глет Гласить Глас Глаголь Глагол Гит Гистология Гистолог Гисто Гипсолит Гипс Гипостиль Гиль Гилея Гига Гиалит Гея Гештальтпсихология Гештальт Геть Гетто Гетит Гет Гестапо Гест Гепатолог Гепатит Геолотия Геология Геолог Гель Гелия Гелитология Гелиостат Гелиос Гелио Гашпиль Гать Гаситель Гас Гаплостель Гаплология Гап Галя Галтелья Галтель Галс Галоп Гало Галлия Галле Галл Галит Галисия Галиот Галиля Галег Гаити Аят Ахолия Ахиллес Ахилия Ахи Атто Аттил Атолл Палех Палея Атлет Атипия Атеист Ася Апсель Апостол Апостиль Апология Апологист Палия Палоло Паль Пальто Пастель Пасти Пасть Пат Апологет Патио Аполог Апог Патло Апис Аоот Аля Альгология Алость Аллея Алле Алл Алеш Аистих Аил Агиология Аггел Патология Агит Аист Алгол Алголь Алех Альголог Альп Альт Альтист Патолог… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. Gestalt — образ, структура, форма) — направление в европейской (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й половины 20 в., выдвинувшее принцип… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

шк. совр. психологии, в к-рой первичным и осн. элементом психики считаются психич. структуры, целостные образования (гештальты). Осн. представители: Х.Эренфельс, В.Келер, К.Коффка, М.Вертхаймер, В.Бенусси, А.Мейнонг. Для Г.-П. характерно преувеличение роли формы в псих. деятельности, неистор. понимание психики. Согл. Г.-П. предметы воспринимаются чувствами не в виде отд. объектов, к-рые должны интегрироваться либо сознанием, как полагают структуралисты, либо механизмами обусловливания, как утверждают бихевиористы. Мир состоит из организованных форм, и восприятие мира тоже организовано: воспринимается некое организованное целое, а не просто сумма его частей. Возможно, что механизмы такой организации восприятий существуют еще до рождения — это предположение подтверждается нек-рыми наблюдениями. Идеи Г.-П. оказались весьма эвристичными — по сути, был открыт новый способ психол. мышления. Хотя в «чистом» виде это направление ныне практически не представлено, а ряд положений обесценился (напр., было показано, что восприятие определяется не только формой объекта, но прежде всего его значением в культуре и практике конкретного человека), мн. идеи оказали глубокое влияние на развитие и возникновение ряда психол. направлений. Идея целостности проникла в психотерапевтическую практику, а исследования мышления в Г.-П. во мн. определили идею проблемного обучения. Н.Д.Наумов … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Гештальтпсихология

(нем. Gestalt форма, образ, структура)

одна из основных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й пол. 20 в. В усл… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

1) Орфографическая запись слова: гештальтпсихология2) Ударение в слове: гештальтпсихол`огия3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): гештальтпсихологи… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

( нем. Gestalt – образ, целостная форма, греч. psyche – душа, logos – учение, наука). Идеалистическое направление в зарубежной психологии конца XIX – первой трети XX вв. (v. Ehrenfels Ch., 1890; Wertheimer E., 1912). Термин был предложен Ch.v. Ehrenfels. Г. изучала психику с точки зрения целостных структур (гештальтов). В отличие от структурной психологии, выделявшей в психике, сознании отдельные элементы и синтезировавшей из них более сложные психические феномены, Г. выдвигала принцип внутренней системной организации психики, определявшей и особенности ее составных частей. Гештальт не является простой суммой, составленной из отдельных элементов, это целостное переживание, данное первично, изначально присущая душе человека психическая форма, структура (Koffka К.). Гештальт не является ощущением, чувственным образом отдельных свойств предметов и явлений. Развитие Г. способствовало обогащению знаний о психических процессах, хотя ее методология препятствовала каузальному их анализу. Тем не менее Г. была шагом вперед по сравнению с механистической структурной психологией, она внесла новое в изучение восприятия и мышления в эксперименте и теории, стимулировала развитие социальной психологии, патопсихологии…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(нем. Gestalt – образ, целостная форма, греч. psyche – душа, logos – учение, наука). Идеалистическое направление в зарубежной психологии конца XIX – первой трети XX вв. (v. Ehrenfels Ch., 1890; Wertheimer E., 1912). Термин был предложен Ch.v. Ehrenfels. Г. изучала психику с точки зрения целостных структур (гештальтов). В отличие от структурной психологии, выделявшей в психике, сознании отдельные элементы и синтезировавшей из них более сложные психические феномены, Г. выдвигала принцип внутренней системной организации психики, определявшей и особенности ее составных частей. Гештальт не является простой суммой, составленной из отдельных элементов, это целостное переживание, данное первично, изначально присущая душе человека психическая форма, структура (Koffka К.). Гештальт не является ощущением, чувственным образом отдельных свойств предметов и явлений. Развитие Г. способствовало обогащению знаний о психических процессах, хотя ее методология препятствовала каузальному их анализу. Тем не менее Г. была шагом вперед по сравнению с механистической структурной психологией, она внесла новое в изучение восприятия и мышления в эксперименте и теории, стимулировала развитие социальной психологии, патопсихологии…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

нем. Gestalt — форма, целостность) — идеалистическое сенсуалистическое направление совр. зарубежной психологии, возникшее в Германии в 1912 г. Предшественником Г. является X. фон Эренфельс (1859—1932). Гл. представители: М. Вертхеймер (1880—1944), В. Келер (1887—1967) и К. Коффка (1886—1941). Философская основа — гуссерлианство и махизм. В противоположность ассоциативной психологии Г. первичными и осн. элементами психики считает не ощущения, а некие психические структуры, целостные образования, или “гештальты”. Их формирование, согласно Г., подчиняется якобы внутренне присущей психике способности образовывать простые, симметричные, замкнутые фигуры. Теория Т. покоится на отрыве индивида от внешней среды и его практической деятельности. Целостность психических образований гештальтисты в конечном счете объясняют имманентными субъективными “законами”, что приводит их к идеализму. Позднее идеи Г. (особенно понятие “гештальт”) были распространены на область физических, физиологических и даже экономических явлений. Теоретическая несостоятельность Г. была показана психологами-материалистами (Л. С. Выготским и др.). … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Gestalt psychology, нем. Gestalt — форма, образ), одна из осн. школ психологии первой половины 20 в. Гештальтпсихологи уделяли значит, внимание проблемам восприятия и когнитивизма. Гл. представители Г.: Макс Вертхеймер (1880—1943), Курт Коффка (1886—1941) и Вольфганг Келер (1887—1967), эмигрировавшие из Европы в США. Их осн. тезис сводился к тому, что структурные законы целого определяют его части, но не наоборот. В кач-ве иллюстрации приводились, напр., прямоугольники и мелодии, в к-рых мы способны распознать тот же самый образ независимо от различия его отд. составляющих (размеров или тональности). Экспериментальные исследования зрительных образов и способов решения конкретных задач показали, что разум, интерпретируя окружающие явления, постоянно стремится к упрощению — вывод прямо противоположный предлагаемым бихевиоризмом и редукционизмом. Представители Г. предвосхитили совр. когнитивную психологию и оказали решающее влияние на развитие социальной психологии после 2-й мировой войны. … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ (нем . Gestalt — форма, образ, структура), одна из основных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й пол. 20 в. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологии выдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон Эренфельсом понятие гештальта) в качестве основы при исследовании сложных психических явлений. Исходила из учения Ф. Брентано и Э. Гуссерля об интенциональности (см. Интенция) сознания. Главные представители — М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка провели исследования в области восприятия, принципы которых были перенесены на изучение мышления, а также личности (К. Левин). Центральный орган — журнал «Психологические исследования» (основан в 1921). Школа распалась в кон. 1930-х гг.<br><br><br>… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ (нем. Gestalt — форма — образ, структура), одна из основных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й пол. 20 в. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологии выдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон Эренфельсом понятие гештальта) в качестве основы при исследовании сложных психических явлений. Исходила из учения Ф. Брентано и Э. Гуссерля об интенциональности (см. Интенция) сознания. Главные представители — М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка провели исследования в области восприятия, принципы которых были перенесены на изучение мышления, а также личности (К. Левин). Центральный орган — журнал «Психологические исследования» (основан в 1921). Школа распалась в кон. 1930-х гг.<br>… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

нем. Gestalt форма, образ, структура)

одна из основных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й пол. 20 в. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологии выдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон Эренфельсом понятие гештальта) в качестве основы при исследовании сложных психических явлений. Исходила из учения Ф. Брентано и Э. Гуссерля об интенциональности (см. Интенция) сознания. Главные представители — М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка провели исследования в области восприятия, принципы которых были перенесены на изучение мышления, а также личности (К. Левин). Центральный орган — журнал «Психологические исследования» (основан в 1921). Школа распалась в кон. 1930-х гг…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

— (нем. Gestalt — форма — образ, структура), одна изосновных школ зарубежной (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й пол. 20в. В условиях кризиса механистических концепций и ассоциативной психологиивыдвинула принцип целостности (введенное Г. фон Эренфельсом понятиегештальта) в качестве основы при исследовании сложных психических явлений.Исходила из учения Ф. Брентано и Э. Гуссерля об интенциональности (см.Интенция) сознания. Главные представители — М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К.Коффка провели исследования в области восприятия, принципы которых былиперенесены на изучение мышления, а также личности (К. Левин). Центральныйорган — журнал «»Психологические исследования»» (основан в 1921). Школараспалась в кон. 1930-х гг…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем.-форма, организация, образ, структура): представители данного направления в современной психологии ученые, в отличие от бихевиористов, главное внимание обращают на внутреннюю психическую деятельность человека. Они обосновывают целостный характер психологического восприятия человеком явлений действительности. Как утверждают представители гештальтпсихологии, любой образ человек видит как целостную фигуру. Если в данной фигуре он не видит каких-то частей, то достраивает их в своем воображении. Учение о целостном и организованном характере человеческого мышления весьма важно для его понимания и уяснения роли в практической деятельности людей, в том числе в деловом общении…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ (от немецкого Gestalt — форма, образ, структура), одна из основных школ (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й половины 20 в. Подчеркивала целостный и структурный характер психических образований, опираясь на представление о «гештальткачестве» как свойстве целого, которое сохраняется и при изменении отдельных его частей (например, мелодия, проигрываемая в разных тональностях, и т.п.). Основные представители: немецкие психологи М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка. Сложившись первоначально на основе исследования зрительного восприятия, гештальтпсихология распространила свои принципы на изучение мышления, памяти, личности и социальной группы. <br>… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от немецкого Gestalt — форма, образ, структура), одна из основных школ (преимущественно немецкой) психологии 1-й половины 20 в. Подчеркивала целостный и структурный характер психических образований, опираясь на представление о «гештальткачестве» как свойстве целого, которое сохраняется и при изменении отдельных его частей (например, мелодия, проигрываемая в разных тональностях, и т.п.). Основные представители: немецкие психологи М. Вертхаймер, В. Келер, К. Коффка. Сложившись первоначально на основе исследования зрительного восприятия, гештальтпсихология распространила свои принципы на изучение мышления, памяти, личности и социальной группы…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от гештальт и психология) — одно из ведущих направлений в современной психологии, основывающееся на тезисе о принципиальной несводимости целого (характеристика которого была названа «геш-тальткачеством») к сумме составляющих его частей. В учении утверждается, что целое вообще нечто другое, нежели сумма его частей, выделяемых из него посредством обособления, и что первичным и основным элементом психики являются психические структуры, целостные образования (гештальты).

Начала современного естествознания. Тезаурус. — Ростов-на-Дону.В.Н. Савченко, В.П. Смагин.2006.

Синонимы:

психология… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. gestalt – целостная форма, образ, структура) – одно из крупнейших направлений в зарубежной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой половины ХХ века и выдвинувшее в качестве центрального тезис о необходимости целостного подхода к анализу сложных психических явлений. Основное внимание г. уделила исследованию высших психических функций человека (восприятия, мышления, поведения и пр.) как целостных структур, первичных по отношению к своим компонентам (см.: инсайт). Главные представители этого направления – немецкие психологи М. Вертхеймер, В. Келнер, К. Коффка…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(нем. Gestalt, образ, целостная форма + Психология)одно из основных направлений в зарубежной психологии первой половины XX в., рассматривавшее психику … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

гештальтпсихология (нем. Gestalt, образ, целостная форма + психология) — одно из основных направлений в зарубежной психологии первой половины 20 в., ра… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. Gestalt — целостная форма, образ, структура, греч. psyche — душа и logos — слово, учение) — англ. gestal-tpsychology; нем. Gestaltpsychologie. Направление в психологии, исходящее из целостности человеческой психики, не сводимой к простейшим формам; исследует псих, деятельность субъекта, строящуюся на основе восприятия окружающего мира в виде гештальтов.

Antinazi.Энциклопедия социологии,2009

Синонимы:

психология… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Ударение в слове: гештальтпсихол`огияУдарение падает на букву: оБезударные гласные в слове: гештальтпсихол`огия

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(нем. Gestalt, образ, целостная форма + психология) одно из основных направлений в зарубежной психологии первой половины 20 в., рассматривавшее психику человека как совокупность целостных психических структур («гештальтов»), формирующихся независимо от объективной реальности; несмотря на ограниченность Г., ее конкретные достижения и антимеханистическая направленность были восприняты в последующем развитии психологии…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(Gestalt psychology). Направление психологии, оформившейся в 1910 году, направленное на изучение целостных феноменов, *гештальтов*. Основатели: М. Вертгеймер, К. Коффка и В. Келер. Впоследствии гештальт-психологом себя считал и Курт Левин. Гештальт-психологи считали, что образы не являются суммой отдельных ощущений, а представляют собой целостные феномены, формирующиеся сразу же и несводимые к отдельным элементам…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

— (от нем. Gestalt — целостная форма , образ , структура , греч. psyche — душа и logos — слово, учение ) — англ. gestal-tpsychology; нем. Gestaltpsychologie. Направление в психологии, исходящее из целостности человеческой психики, не сводимой к простейшим формам; исследует псих, деятельность субъекта, строящуюся на основе восприятия окружающего мира в виде гештальтов…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Течение в общей психологии, зародившееся под влиянием феноменологии в 1912 году (Эренфельс, Вертхаймер, Коффка, Келлер). Одним из основных положений гештальт-психологии является следующее: «целое отлично от суммы его частей», — и появляется в результате их многочисленных взаимодействий. Гештальт-психология особо подчеркивает значение субъективного восприятия…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Возникшее в Германии направление в психологической науке, основой которого является представление об организованной природе восприятия, развитое Вертхаймером, Кёхлером и Коффкой. В переводе с немецкого слово Gestalt означает «форма» или «конфигурация»…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Гештальтпсихология — психологическое направление, возникшее в Германии в начале 10 — х и просуществовавшее до середины 30 — х гг. ХХ в. (до прихода к власти гитлеровцев, когда большинство ее представителей эмигрировали) и продолжив… смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

направление в западной психологии, возникшее в Германии в первой трети ХХ в. и выдвинувшее программу изучения психики с точки зрения целостных структур — гештальтов, первичных по отношению к своим компонентам…. смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

(от нем. Gestalt — образ, форма) — направление в западной психологии, выдвинувшее программу изучения психики с точки зрения целостных структур (гештальтов), первичных по отношению к своим компонентам. … смотреть

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

немецкая школа психологии, возникшая в 20х годах XX века, подчеркивающая целостную природу сознательного восприятия.

ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

Начальная форма — Гештальтпсихология, единственное число, женский род, именительный падеж, неодушевленное

Как написать слово «гештальтпсихология» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «гештальтпсихология»?

гештальтпсихоло́гия

Правильное написание — гештальтпсихология, ударение падает на букву: о, безударными гласными являются: е, а, и, о, и, я.

Выделим согласные буквы — гештальтпсихология, к согласным относятся: г, ш, т, л, п, с, х, звонкие согласные: г, л, глухие согласные: ш, т, п, с, х.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 18,

- слогов — 7,

- гласных — 7,

- согласных — 10.

Формы слова: гештальтпсихоло́гия, -и.

×òî òàêîå «ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß

(îò íåì. Gestalt ñòðóêòóðà, îáðàç, ôîðìà, êîíôèãóðàöèÿ) îäíî èç âëèÿòåëüíûõ íàïðàâëåíèé â ïñèõîëîãèè ïåð. ïîë. 20 â. Ñôîðìèðîâàëîñü ïîä íåïîñðåäñòâåííûì âëèÿíèåì ôèëîñ. ôåíîìåíîëîãèè (Ý. Ãóññåðëü), óòâåðæäàâøåé, ÷òî âîñïðèÿòèå ìèðà íîñèò öåëîñòíûé, íåïîñðåäñòâåííûé õàðàêòåð, à â åãî îñíîâå ëåæàò èíòåíöèè ñóáúåêòà. Äð. èñòî÷íèêîì èäåé Ã. ÿâëÿþòñÿ èññëåäîâàíèÿ àâñòð. ïñèõîëîãà X. ôîí Ýðåíôåëüñà, ó÷åíèêà Ô. Áðåíòàíî, êîòîðîìó óäàëîñü îòêðûòü íå ñâîäèìûå ê ñóììå ýëåìåíòîâ ãåøòàëüò-êà÷åñòâà. Âïåðâûå ïðèíöèïû Ã. áûëè ñôîðìóëèðîâàíû Ì. Âåðòõàéìåðîì â ñòàòüå «Ýêñïåðèìåíòàëüíîå èññëåäîâàíèå äâèæåíèÿ» (1912) êàê àëüòåðíàòèâà ñòðóêòóðàëèçìó è áèõåâèîðèçìó. Ïðåäñòàâèòåëè ýòîãî íàïðàâëåíèÿ Âåðòõàéìåð, Â. ʸëåð, Ê. Êîôôêà, Ê. Ëåâèí è äð. èñõîäèëè èç ïðåäïîëîæåíèÿ, ÷òî ñëîæíûå ïñèõîëîãè÷åñêèå ôåíîìåíû íåëüçÿ ðàçëîæèòü íà ïðîñòûå ìåíòàëüíûå êîìïîíåíòû (ñòðóêòóðàëèçì) èëè öåïè ñòèìóë ðåàêöèÿ (áèõåâèîðèçì). Îíè äîêàçûâàëè, ÷òî àäåêâàòíîå îáúÿñíåíèå èíòåëëåêòóàëüíîãî ïîâåäåíèÿ òðåáóåò ññûëêè íà âíóòðåííèå ñîñòîÿíèÿ ïñèõèêè è âðîæäåííûå ñëîæíîîðãàíèçîâàííûå êîãíèòèâíûå ñòðóêòóðû, êîòîðûå ôîðìèðóþò íàø ïåðöåïòèâíûé îïûò è çíàíèå î ìèðå. Ñâîè ãèïîòåçû ãåøòàëüòèñòû ñòðåìèëèñü ïîäêðåïèòü ìíîãî÷èñëåííûìè ýêñïåðèìåíòàëüíûìè äàííûìè (ôåíîìåí ñòðîáîñêîïè÷åñêîãî äâèæåíèÿ è äð.). Ñîãëàñíî èõ âçãëÿäàì, íàøå ïåðöåïòèâíîå âîñïðèÿòèå ÿâëÿåòñÿ öåëîñòíûì, àêòèâíûì è êîíñòðóêòèâíûì ïðîöåññîì, ñòðîÿùèìñÿ íà äèíàìè÷åñêîì îòíîøåíèè ìåæäó äâóìÿ ýëåìåíòàìè âîñïðèíèìàåìîé ôîðìîé (ñòðóêòóðîé, ãåøòàëüòîì) è ôîíîì (ïîëåì âîñïðèÿòèÿ). Ôîðìà âñåãäà äîìèíèðóåò, îñòàâàÿñü ïðè ýòîì íåðàçðûâíî ñâÿçàííîé ñ ìåíåå ÷åòêî âîñïðèíèìàåìûì ôîíîì, íà êîòîðîì îíà âûäåëÿåòñÿ. Èíòåíöèÿ íàáëþäàòåëÿ ñïîíòàííî ñâÿçûâàåò ôîðìó è ôîí. Ãåøòàëüòèñòû îòêðûëè ëåæàùèé â îñíîâå âîñïðèÿòèÿ çàêîí «õîðîøåé ôîðìû», íàçâàííûé Âåðòõàéìåðîì «çàêîíîì ïðåãíàíòíîñòè», êîòîðûé ïðåäðàñïîëàãàåò ê âûáîðó íàèáîëåå ïðîñòûõ, ÷åòêèõ, óïîðÿäî÷åííûõ è îñìûñëåííûõ ôîðì.

Ìûøëåíèå Ã. òàêæå ðàññìàòðèâàëè êàê àêòèâíûé êîíñòðóêòèâíûé ïðîöåññ. Âåðòõàéìåð ðàçëè÷àë ïðîäóêòèâíîå è ðåïðîäóêòèâíîå ìûøëåíèå. Ïðîäóêòèâíîå ìûøëåíèå ïðåäïîëàãàåò ïîíèìàíèå ñòðóêòóðíûõ îòíîøåíèé, ïðèñóùèõ ïðîáëåìå èëè ñèòóàöèè, ñîïðîâîæäàþùååñÿ èíòåãðàöèåé ñîîòâåòñòâóþùèõ ÷àñòåé â äèíàìè÷åñêîå öåëîå. Íàïðîòèâ, ðåïðîäóêòèâíîå ìûøëåíèå ñâîäèòñÿ ëèøü ê ñëåïîìó ïîâòîðåíèþ óñâîåííûõ ðåàêöèé ïðèìåíèòåëüíî ê îòäåëüíûì ÷àñòÿì öåëîãî. Ýòîò òèï ìûøëåíèÿ íå ïîðîæäàåò èíñàéòà (Insight ïîíèìàíèå), îïðåäåëåííîãî ʸëåðîì êàê çàêðûòèå ïñèõîëîãè÷åñêîãî ïîëÿ, ãäå âñå ýëåìåíòû èíòåãðèðóþòñÿ â öåëîñòíóþ ñòðóêòóðó. Íàèáîëåå ñèñòåìàòè÷åñêèé è ïðàãìàòè÷åñêèé ïîäõîä ê ìûøëåíèþ êàê ðåøåíèþ çàäà÷ ñ ïîçèöèè Ã. áûë ðàçðàáîòàí Ê. Äóíêåðîì, êîòîðûé òðåáîâàë îò èñïûòóåìûõ «Äóìàòü âñëóõ», íàñòàèâàÿ íà íåîáõîäèìîñòè âåðáàëèçàöèè ëþáîé ìûñëè. Íà îñíîâå ïîëó÷åííûõ óñòíûõ è ïèñüìåííûõ ïðîòîêîëîâ Äóíêåð ïðèøåë ê âûâîäó, ÷òî ïðîöåäóðû ðåøåíèÿ çàäà÷ ìîãóò áûòü ôîðìàëèçîâàíû êàê ïîèñê ñðåäñòâ ðåøåíèÿ êîíôëèêòîâ ìåæäó òåêóùèìè ñèòóàöèÿìè è ñèòóàöèÿìè, îòâå÷àþùèìè æåëàåìûì öåëÿì. Ðåçóëüòàòû ìûñëèòåëüíûõ îïåðàöèé îí ðàññìàòðèâàë êàê ñîâîêóïíîñòü òåñíî èíòåãðèðîâàííûõ âíóòðåííèõ ðåïðåçåíòàöèé, êîòîðûå äåòàëèçèðóþò íàõîäÿùèåñÿ â ïðîòèâîðå÷èè ýëåìåíòû ïðîáëåìíîé ñèòóàöèè. Ñîîòâåòñòâåííî, ïîíèìàíèå è èíñàéò îïðåäåëÿëèñü èì êàê âíóòðåííèå êîãíèòèâíûå ñîñòîÿíèÿ ñóáúåêòà, çàâèñÿùèå îò êà÷åñòâà ðåïðåçåíòàöèé. Èññëåäîâàíèÿ Äóíêåðà ÿñíî ïîêàçàëè, ÷òî ïðè ðåøåíèè ïðîáëåì ñóáúåêòû ôîðìèðîâàëè ïëàíû, ãåíåðèðîâàëè öåëè è ðàçðàáàòûâàëè ñòðàòåãèè, îñíîâàííûå íà ïðèîáðåòåííîì çíàíèè. Îí òàêæå âûäâèíóë êîíöåïöèþ «ôóíêöèîíàëüíîé çàêðåïëåííîñòè», êîòîðàÿ óòâåðæäàëà, ÷òî îáúåêòû è èäåè âìåñòå ñ çàêðåïëåííûìè çà íèìè ôóíêöèÿìè ñòàíîâÿòñÿ ÷àñòüþ ñèòóàöèè ïî ðåøåíèþ çàäà÷è, è ýòà óñòàíîâêà ïðåïÿòñòâóåò èõ íîâîìó ïðèìåíåíèþ.

Ãåøòàëüòïñèõîëîãè âíåñëè áîëüøîé âêëàä â ðàçâèòèå ïñèõîëîãèè ïðåæäå âñåãî ñâîèìè ýêñïåðèìåíòàëüíûìè èññëåäîâàíèÿìè îñîáåííîñòåé ñòðàòåãèè ïðîñòðàíñòâåííî-îáðàçíîãî, ïðàâîïîëóøàðíîãî ìûøëåíèÿ è äð. ÿâëåíèé, êîòîðûå íåëüçÿ áûëî îáúÿñíèòü ñ ïîìîùüþ ñòðóêòóðàëèñòñêèõ è áèõåâèîðèñòñêèõ ìîäåëåé. Îäíàêî èì íå óäàëîñü ñîçäàòü êàêîé-òî óíèâåðñàëüíîé, ïîñëåäîâàòåëüíîé è ïðîâåðÿåìîé òåîðèè. Èíñòðóìåíòàëüíûå ñðåäñòâà è ìåòîäû, íåîáõîäèìûå äëÿ àäåêâàòíîãî èññëåäîâàíèÿ ñëîæíûõ êîãíèòèâíûõ ôóíêöèé âîñïðèÿòèÿ, ìûøëåíèÿ, ðåøåíèÿ çàäà÷ è ò.ä. áûëè ðàçðàáîòàíû ïîçäíåå â êèáåðíåòèêå, òåîðèè èíôîðìàöèè è êîìïüþòåðíîé íàóêå (èíôîðìàòèêå). Âûäåëèâ äàëüíåéøåå ïîëå èññëåäîâàíèé, Ã. â êàêîì-òî ñìûñëå ïðåäâîñõèòèëà ðåâîëþöèþ â êîãíèòèâíîé íàóêå. Êîíöåïöèè ãåøòàëüòïñèõîëîãîâ ïîëó÷èëè øèðîêîå ïðèìåíåíèå â ðàçëè÷íûõ îáëàñòÿõ ôèëîñîôèè è ïðåæäå âñåãî â ýïèñòåìîëîãèè è ôèëîñîôèè íàóêè äëÿ îáúÿñíåíèÿ ñïåöèôèêè íåÿâíîãî, ëè÷íîñòíîãî çíàíèÿ, ìåõàíèçìîâ ðîñòà íàó÷íûõ çíàíèé è íàó÷íûõ ðåâîëþöèé (Ì. Ïîëàíè, Ò. Êóí, Ï. Ôåéåðàáåíä, Í. Õýíñîí è äð.).

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß —

îäíà èç êðóïíåéøèõ øêîë çàðóáåæíîé ïñèõîëîãèè 1-é ïîëîâèíû 20 â., âûäâèíóâøàÿ â êà÷åñòâå öå… Áîëüøàÿ Ñîâåòñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß — ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß (îò íåìåöêîãî Gestalt — ôîðìà, îáðàç, ñòðóêòóðà), îäíà èç îñíîâíûõ øêîë (ïðåèìóùå… Ñîâðåìåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß — ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß (íåì. Gestalt — ôîðìà — îáðàç, ñòðóêòóðà), îäíà èç îñíîâíûõ øêîë çàðóáåæíîé (ïðåè… Áîëüøîé ýíöèêëîïåäè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß — Ãåøòàëüòïñèõîëîãèÿ — ïñèõîëîãè÷åñêîå íàïðàâëåíèå, âîçíèêøåå â Ãåðìàíèè â íà÷àëå 10 — õ è ïðîñóùåñò… Ïñèõîëîãè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß — (íåì. Gestalt îáðàç, öåëîñòíàÿ ôîðìà, ãðå÷. psyche äóøà, logos ó÷åíèå, íàóêà). Èäåàëèñòè÷åñêîå… Òîëêîâûé ñëîâàðü ïñèõèàòðè÷åñêèõ òåðìèíîâ

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß — (îò íåì. Gestalt — îáðàç, ñòðóêòóðà, ôîðìà)

íàïðàâëåíèå â åâðîïåéñêîé (ïðåèìóùåñòâåííî íåìåöêîé… Ïåäàãîãè÷åñêèé òåðìèíîëîãè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

ÃÅØÒÀËÜÒÏÑÈÕÎËÎÃÈß —

Ãåøòàëüòïñèõîëîãèÿ

(íåì. Gestalt ôîðìà, îáðàç, ñòðóêòóðà)

îäíà èç îñíîâíûõ øêîë çàðóáåæíîé (ïðåèì… Ïîëèòîëîãèÿ. Ñëîâàðü.

гештальтпсихоло́гия

гештальтпсихоло́гия, -и

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова друид (существительное):

Синонимы к слову «гештальтпсихология»

Предложения со словом «гештальтпсихология»

- Принципы гештальтпсихологии появились как результат практических и теоретических научных исследований, что даёт нам основание признать их доказательный характер.

- Понимание основ гештальтпсихологии помогает нам понять процессы, происходящие в сознании зрителя при разглядывании картины.

- Заслуга гештальтпсихологии состоит в том, что ей были найдены современные подходы к изучению проблем психологии, однако проблемы, вызвавшие кризис, до конца так и не были разрешены.

- (все предложения)

Значение слова «гештальтпсихология»

-

Гештáльт-психолóгия (от нем. Gestalt — личность, образ, форма) — школа психологии начала XX века. Основана Максом Вертгеймером, Вольфгангом Кёлером и Куртом Коффкой в 1912 году. (Википедия)

Все значения слова ГЕШТАЛЬТПСИХОЛОГИЯ

→

гештальтпсихологии — существительное, родительный п., жен. p., ед. ч.

↳

гештальтпсихологии — существительное, дательный п., жен. p., ед. ч.

↳

гештальтпсихологии — существительное, предложный п., жен. p., ед. ч.

Часть речи: существительное

| Единственное число | Множественное число | |

|---|---|---|

| Им. |

гештальтпсихология |

|

| Рд. |

гештальтпсихологии |

|

| Дт. |

гештальтпсихологии |

|

| Вн. |

гештальтпсихологию |

|

| Тв. |

гештальтпсихологией |

|

| Пр. |

гештальтпсихологии |

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Not to be confused with the psychotherapy of Fritz Perls, Gestalt therapy.

Gestalt psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology that emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a theory of perception that was a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt’s and Edward Titchener’s elementalist and structuralist psychology.[1][2][3]

As used in Gestalt psychology, the German word Gestalt ( gə-SHTA(H)LT, -STAHLT, -S(H)TAWLT,[4][5] German: [ɡəˈʃtalt] (listen); meaning «form»[6]) is interpreted as «pattern» or «configuration».[7] Gestalt psychologists emphasize that organisms perceive entire patterns or configurations, not merely individual components.[7] The view is sometimes summarized using the adage, «the whole is more than the sum of its parts.»[8]: 13

Gestalt psychology was founded on works by Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhler, and Kurt Koffka.[7]

Origin and history[edit]

Max Wertheimer (1880–1943), Kurt Koffka (1886–1941), and Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967) founded Gestalt psychology in the early 20th century.[8]: 113–116 The dominant view in psychology at the time was structuralism, exemplified by the work of Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894), Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920), and Edward B. Titchener (1867–1927).[9][10]: 3 Structuralism was rooted firmly in British empiricism[9][10]: 3 and was based on three closely interrelated theories:

- «atomism,» also known as «elementalism,»[10]: 3 the view that all knowledge, even complex abstract ideas, is built from simple, elementary constituents

- «sensationalism,» the view that the simplest constituents—the atoms of thought—are elementary sense impressions

- «associationism,» the view that more complex ideas arise from the association of simpler ideas.[10]: 3 [11]

Together, these three theories give rise to the view that the mind constructs all perceptions and even abstract thoughts strictly from lower-level sensations that are related solely by being associated closely in space and time.[9] The Gestaltists took issue with this widespread «atomistic» view that the aim of psychology should be to break consciousness down into putative basic elements.[6]

In contrast, the Gestalt psychologists believed that breaking psychological phenomena down into smaller parts would not lead to understanding psychology.[8]: 13 The Gestalt psychologists believed, instead, that the most fruitful way to view psychological phenomena is as organized, structured wholes.[8]: 13 They argued that the psychological «whole» has priority and that the «parts» are defined by the structure of the whole, rather than vice versa. One could say that the approach was based on a macroscopic view of psychology rather than a microscopic approach.[12] Gestalt theories of perception are based on human nature being inclined to understand objects as an entire structure rather than the sum of its parts.[13]

Wertheimer had been a student of Austrian philosopher, Christian von Ehrenfels (1859–1932), a member of the School of Brentano. Von Ehrenfels introduced the concept of Gestalt to philosophy and psychology in 1890, before the advent of Gestalt psychology as such.[14][9] Von Ehrenfels observed that a perceptual experience, such as perceiving a melody or a shape, is more than the sum of its sensory components.[9] He claimed that, in addition to the sensory elements of the perception, there is something extra. Although in some sense derived from the organization of the component sensory elements, this further quality is an element in its own right. He called it Gestalt-qualität or «form-quality.»

For instance, when one hears a melody, one hears the notes plus something in addition to them that binds them together into a tune – the Gestalt-qualität. It is this Gestalt-qualität that, according to von Ehrenfels, allows a tune to be transposed to a new key, using completely different notes, while still retaining its identity. The idea of a Gestalt-qualität has roots in theories by David Hume, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Immanuel Kant, David Hartley, and Ernst Mach. Both von Ehrenfels and Edmund Husserl seem to have been inspired by Mach’s work Beiträge zur Analyse der Empfindungen (Contributions to the Analysis of Sensations, 1886), in formulating their very similar concepts of gestalt and figural moment, respectively.[14]