|

Ernest Hemingway |

|

|---|---|

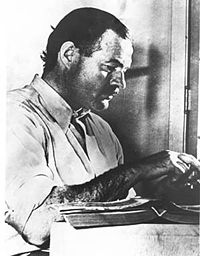

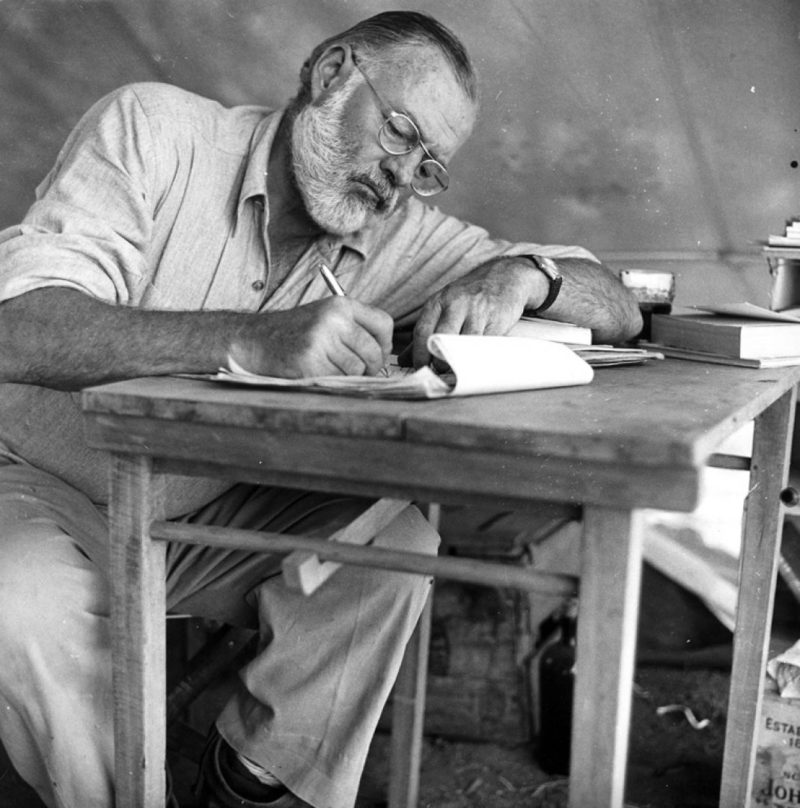

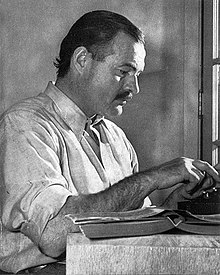

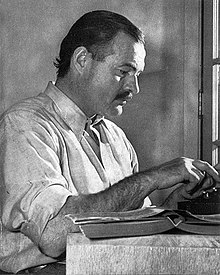

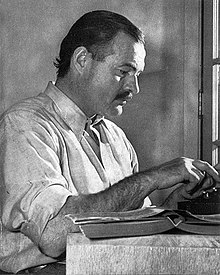

Hemingway working on his book For Whom the Bell Tolls at the Sun Valley Lodge, Idaho, in December 1939 |

|

| Born | July 21, 1899 Oak Park, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | July 2, 1961 (aged 61) Ketchum, Idaho, U.S. |

| Notable works | The Sun Also Rises A Farewell to Arms For Whom the Bell Tolls The Old Man and the Sea |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

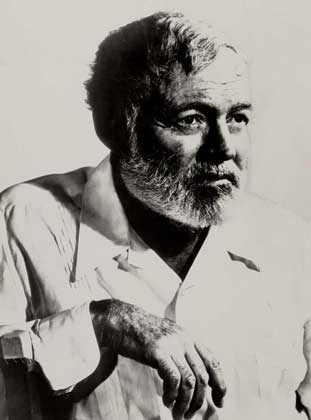

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which included his iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fiction, while his adventurous lifestyle and public image brought him admiration from later generations. Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, and he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. He published seven novels, six short-story collections, and two nonfiction works. Three of his novels, four short-story collections, and three nonfiction works were published posthumously. Many of his works are considered classics of American literature.

Hemingway was raised in Oak Park, Illinois. After high school, he was a reporter for a few months for The Kansas City Star before leaving for the Italian Front to enlist as an ambulance driver in World War I. In 1918, he was seriously wounded and returned home. His wartime experiences formed the basis for his novel A Farewell to Arms (1929).

In 1921, he married Hadley Richardson, the first of four wives. They moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star[1] and fell under the influence of the modernist writers and artists of the 1920s’ «Lost Generation» expatriate community. Hemingway’s debut novel The Sun Also Rises was published in 1926. He divorced Richardson in 1927, and married Pauline Pfeiffer. They divorced after he returned from the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), which he covered as a journalist and which was the basis for his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). Martha Gellhorn became his third wife in 1940. He and Gellhorn separated after he met Mary Welsh in London during World War II. Hemingway was present with Allied troops as a journalist at the Normandy landings and the liberation of Paris.

He maintained permanent residences in Key West, Florida (in the 1930s) and in Cuba (in the 1940s and 1950s). He almost died in 1954 after two plane crashes on successive days, with injuries leaving him in pain and ill health for much of the rest of his life. In 1959, he bought a house in Ketchum, Idaho, where, in mid-1961, he died by suicide.

Life

Early life

Hemingway was the second child and first son born to Clarence and Grace.

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, an affluent suburb just west of Chicago,[2] to Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a physician, and Grace Hall Hemingway, a musician. His parents were well-educated and well-respected in Oak Park,[3] a conservative community about which resident Frank Lloyd Wright said, «So many churches for so many good people to go to.»[4] When Clarence and Grace Hemingway married in 1896, they lived with Grace’s father, Ernest Miller Hall,[5] after whom they named their first son, the second of their six children.[3] His sister Marcelline preceded him in 1898, followed by Ursula in 1902, Madelaine in 1904, Carol in 1911, and Leicester in 1915.[3] Grace followed the Victorian convention of not differentiating children’s clothing by gender. With only a year separating the two, Ernest and Marcelline resembled one-another strongly. Grace wanted them to appear as twins, so in Ernest’s first three years she kept his hair long and dressed both children in similarly frilly feminine clothing.[6]

The Hemingway family in 1905 (from the left): Marcelline, Sunny, Clarence, Grace, Ursula, and Ernest

Hemingway’s mother, a well-known musician in the village,[7] taught her son to play the cello despite his refusal to learn; though later in life he admitted the music lessons contributed to his writing style, evidenced for example in the «contrapuntal structure» of For Whom the Bell Tolls.[8] As an adult Hemingway professed to hate his mother, although biographer Michael S. Reynolds points out that he shared similar energies and enthusiasms.[7]

Each summer the family traveled to Windemere on Walloon Lake, near Petoskey, Michigan. There young Ernest joined his father and learned to hunt, fish, and camp in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan, early experiences that instilled a life-long passion for outdoor adventure and living in remote or isolated areas.[9]

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School in Oak Park from 1913 until 1917. He was a good athlete, involved with a number of sports—boxing, track and field, water polo, and football; performed in the school orchestra for two years with his sister Marcelline; and received good grades in English classes.[7] During his last two years at high school he edited the Trapeze and Tabula (the school’s newspaper and yearbook), where he imitated the language of sportswriters and used the pen name Ring Lardner Jr.—a nod to Ring Lardner of the Chicago Tribune whose byline was «Line O’Type».[10] Like Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis, Hemingway was a journalist before becoming a novelist. After leaving high school he went to work for The Kansas City Star as a cub reporter.[10] Although he stayed there for only six months, he relied on the Star‘s style guide as a foundation for his writing: «Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative.»[11]

World War I

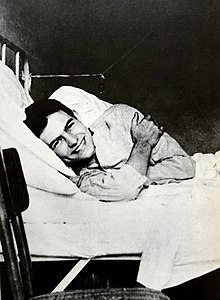

Hemingway in uniform in Milan, 1918. He drove ambulances for two months until he was wounded.

In December 1917, after being rejected by the U.S. Army for poor eyesight,[12] Hemingway responded to a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on to be an ambulance driver in Italy,[13] In May 1918, he sailed from New York, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.[14] That June he arrived at the Italian Front. On his first day in Milan, he was sent to the scene of a munitions factory explosion to join rescuers retrieving the shredded remains of female workers. He described the incident in his 1932 non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon: «I remember that after we searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments.»[15] A few days later, he was stationed at Fossalta di Piave.[15]

Hemingway in American Red Cross Hospital, July 1918

On July 8, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, having just returned from the canteen bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line.[15] Despite his wounds, Hemingway assisted Italian soldiers to safety, for which he was decorated with the Italian War Merit Cross, the Croce al Merito di Guerra.[note 1][16] He was still only 18 at the time. Hemingway later said of the incident: «When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you … Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you.»[17] He sustained severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent an immediate operation at a distribution center, and spent five days at a field hospital before he was transferred for recuperation to the Red Cross hospital in Milan.[18] He spent six months at the hospital, where he met and formed a strong friendship with «Chink» Dorman-Smith that lasted for decades and shared a room with future American foreign service officer, ambassador, and author Henry Serrano Villard.[19]

While recuperating he fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a Red Cross nurse seven years his senior. When Hemingway returned to the United States in January 1919, he believed Agnes would join him within months and the two would marry. Instead, he received a letter in March with her announcement that she was engaged to an Italian officer. Biographer Jeffrey Meyers writes Agnes’s rejection devastated and scarred the young man; in future relationships, Hemingway followed a pattern of abandoning a wife before she abandoned him.[20]

Toronto and Chicago

Hemingway returned home early in 1919 to a time of readjustment. Before the age of 20, he had gained from the war a maturity that was at odds with living at home without a job and with the need for recuperation.[21] As Reynolds explains, «Hemingway could not really tell his parents what he thought when he saw his bloody knee.» He was not able to tell them how scared he had been «in another country with surgeons who could not tell him in English if his leg was coming off or not.»[22]

In September, he took a fishing and camping trip with high-school friends to the back-country of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.[17] The trip became the inspiration for his short story «Big Two-Hearted River», in which the semi-autobiographical character Nick Adams takes to the country to find solitude after returning from war.[23] A family friend offered him a job in Toronto, and with nothing else to do, he accepted. Late that year he began as a freelancer and staff writer for the Toronto Star Weekly. He returned to Michigan the following June[21] and then moved to Chicago in September 1920 to live with friends, while still filing stories for the Toronto Star.[24] In Chicago, he worked as an associate editor of the monthly journal Cooperative Commonwealth, where he met novelist Sherwood Anderson.[24]

When St. Louis native Hadley Richardson came to Chicago to visit the sister of Hemingway’s roommate, Hemingway became infatuated. He later claimed, «I knew she was the girl I was going to marry.»[25] Hadley, red-haired, with a «nurturing instinct», was eight years older than Hemingway.[25] Despite the age difference, Hadley, who had grown up with an overprotective mother, seemed less mature than usual for a young woman her age.[26] Bernice Kert, author of The Hemingway Women, claims Hadley was «evocative» of Agnes, but that Hadley had a childishness that Agnes lacked. The two corresponded for a few months and then decided to marry and travel to Europe.[25] They wanted to visit Rome, but Sherwood Anderson convinced them to visit Paris instead, writing letters of introduction for the young couple.[27] They were married on September 3, 1921; two months later Hemingway was hired as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, and the couple left for Paris. Of Hemingway’s marriage to Hadley, Meyers claims: «With Hadley, Hemingway achieved everything he had hoped for with Agnes: the love of a beautiful woman, a comfortable income, a life in Europe.»[28]

Paris

Hemingway’s 1923 passport photo. At this time, he lived in Paris with his wife Hadley, and worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star Weekly.

Carlos Baker, Hemingway’s first biographer, believes that while Anderson suggested Paris because «the monetary exchange rate» made it an inexpensive place to live, more importantly it was where «the most interesting people in the world» lived. In Paris, Hemingway met American writer and art collector Gertrude Stein, Irish novelist James Joyce, American poet Ezra Pound (who «could help a young writer up the rungs of a career»[27]) and other writers.

The Hemingway of the early Paris years was a «tall, handsome, muscular, broad-shouldered, brown-eyed, rosy-cheeked, square-jawed, soft-voiced young man.»[29] He and Hadley lived in a small walk-up at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the Latin Quarter, and he worked in a rented room in a nearby building.[27] Stein, who was the bastion of modernism in Paris,[30] became Hemingway’s mentor and godmother to his son Jack;[31] she introduced him to the expatriate artists and writers of the Montparnasse Quarter, whom she referred to as the «Lost Generation»—a term Hemingway popularized with the publication of The Sun Also Rises.[32] A regular at Stein’s salon, Hemingway met influential painters such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Juan Gris.[33] He eventually withdrew from Stein’s influence, and their relationship deteriorated into a literary quarrel that spanned decades.[34] While living in Paris in 1922, Hemingway befriended artist Henry Strater who painted two portraits of him.[35]

Ezra Pound met Hemingway by chance at Sylvia Beach’s bookshop Shakespeare and Company in 1922. The two toured Italy in 1923 and lived on the same street in 1924.[29] They forged a strong friendship, and in Hemingway, Pound recognized and fostered a young talent.[33] Pound introduced Hemingway to James Joyce, with whom Hemingway frequently embarked on «alcoholic sprees».[36]

During his first 20 months in Paris, Hemingway filed 88 stories for the Toronto Star newspaper.[37] He covered the Greco-Turkish War, where he witnessed the burning of Smyrna, and wrote travel pieces such as «Tuna Fishing in Spain» and «Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany».[38]

Hemingway was devastated on learning that Hadley had lost a suitcase filled with his manuscripts at the Gare de Lyon as she was traveling to Geneva to meet him in December 1922.[39] In the following September the couple returned to Toronto, where their son John Hadley Nicanor was born on October 10, 1923. During their absence, Hemingway’s first book, Three Stories and Ten Poems, was published. Two of the stories it contained were all that remained after the loss of the suitcase, and the third had been written early the previous year in Italy. Within months a second volume, in our time (without capitals), was published. The small volume included six vignettes and a dozen stories Hemingway had written the previous summer during his first visit to Spain, where he discovered the thrill of the corrida. He missed Paris, considered Toronto boring, and wanted to return to the life of a writer, rather than live the life of a journalist.[40]

Hemingway, Hadley and their son (nicknamed Bumby) returned to Paris in January 1924 and moved into a new apartment on the rue Notre-Dame des Champs.[40] Hemingway helped Ford Madox Ford edit The Transatlantic Review, which published works by Pound, John Dos Passos, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and Stein, as well as some of Hemingway’s own early stories such as «Indian Camp».[41] When In Our Time was published in 1925, the dust jacket bore comments from Ford.[42][43] «Indian Camp» received considerable praise; Ford saw it as an important early story by a young writer,[44] and critics in the United States praised Hemingway for reinvigorating the short story genre with his crisp style and use of declarative sentences.[45] Six months earlier, Hemingway had met F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the pair formed a friendship of «admiration and hostility».[46] Fitzgerald had published The Great Gatsby the same year: Hemingway read it, liked it, and decided his next work had to be a novel.[47]

Ernest, Hadley, and their son Jack («Bumby») in Schruns, Austria, 1926, just months before they separated

Ernest Hemingway with Lady Duff Twysden, Hadley, and friends, during the July 1925 trip to Spain that inspired The Sun Also Rises

With his wife Hadley, Hemingway first visited the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona, Spain, in 1923, where he became fascinated by bullfighting.[48] It is at this time that he began to be referred to as «Papa», even by much older friends. Hadley would much later recall that Hemingway had his own nicknames for everyone and that he often did things for his friends; she suggested that he liked to be looked up to. She did not remember precisely how the nickname came into being; however, it certainly stuck.[49][50][51][52] The Hemingways returned to Pamplona in 1924 and a third time in June 1925; that year they brought with them a group of American and British expatriates: Hemingway’s Michigan boyhood friend Bill Smith, Donald Ogden Stewart, Lady Duff Twysden (recently divorced), her lover Pat Guthrie, and Harold Loeb.[53] A few days after the fiesta ended, on his birthday (July 21), he began to write the draft of what would become The Sun Also Rises, finishing eight weeks later.[54] A few months later, in December 1925, the Hemingways left to spend the winter in Schruns, Austria, where Hemingway began revising the manuscript extensively. Pauline Pfeiffer joined them in January and against Hadley’s advice, urged Hemingway to sign a contract with Scribner’s. He left Austria for a quick trip to New York to meet with the publishers, and on his return, during a stop in Paris, began an affair with Pfeiffer, before returning to Schruns to finish the revisions in March.[55] The manuscript arrived in New York in April; he corrected the final proof in Paris in August 1926, and Scribner’s published the novel in October.[54][56][57]

The Sun Also Rises epitomized the post-war expatriate generation,[58] received good reviews and is «recognized as Hemingway’s greatest work».[59] Hemingway himself later wrote to his editor Max Perkins that the «point of the book» was not so much about a generation being lost, but that «the earth abideth forever»; he believed the characters in The Sun Also Rises may have been «battered» but were not lost.[60]

Hemingway’s marriage to Hadley deteriorated as he was working on The Sun Also Rises.[57] In early 1926, Hadley became aware of his affair with Pfeiffer, who came to Pamplona with them that July.[61][62] On their return to Paris, Hadley asked for a separation; in November she formally requested a divorce. They split their possessions while Hadley accepted Hemingway’s offer of the proceeds from The Sun Also Rises.[63] The couple were divorced in January 1927, and Hemingway married Pfeiffer in May.[64]

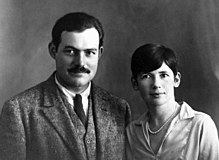

Ernest and Pauline Hemingway in Paris, 1927

Pfeiffer, who was from a wealthy Catholic Arkansas family, had moved to Paris to work for Vogue magazine. Before their marriage, Hemingway converted to Catholicism.[65] They honeymooned in Le Grau-du-Roi, where he contracted anthrax, and he planned his next collection of short stories,[66] Men Without Women, which was published in October 1927,[67] and included his boxing story «Fifty Grand». Cosmopolitan magazine editor-in-chief Ray Long praised «Fifty Grand», calling it, «one of the best short stories that ever came to my hands … the best prize-fight story I ever read … a remarkable piece of realism.»[68]

By the end of the year Pauline, who was pregnant, wanted to move back to America. John Dos Passos recommended Key West, and they left Paris in March 1928. Hemingway suffered a severe injury in their Paris bathroom when he pulled a skylight down on his head thinking he was pulling on a toilet chain. This left him with a prominent forehead scar, which he carried for the rest of his life. When Hemingway was asked about the scar, he was reluctant to answer.[69] After his departure from Paris, Hemingway «never again lived in a big city».[70]

Key West and the Caribbean

Hemingway and Pauline traveled to Kansas City, where their son Patrick was born on June 28, 1928. Pauline had a difficult delivery; Hemingway fictionalized a version of the event as a part of A Farewell to Arms. After Patrick’s birth, Pauline and Hemingway traveled to Wyoming, Massachusetts, and New York.[71] In the winter, he was in New York with Bumby, about to board a train to Florida, when he received a cable telling him that his father had killed himself.[note 2][72] Hemingway was devastated, having earlier written to his father telling him not to worry about financial difficulties; the letter arrived minutes after the suicide. He realized how Hadley must have felt after her own father’s suicide in 1903, and he commented, «I’ll probably go the same way.»[73]

Upon his return to Key West in December, Hemingway worked on the draft of A Farewell to Arms before leaving for France in January. He had finished it in August but delayed the revision. The serialization in Scribner’s Magazine was scheduled to begin in May, but as late as April, Hemingway was still working on the ending, which he may have rewritten as many as seventeen times. The completed novel was published on September 27.[74] Biographer James Mellow believes A Farewell to Arms established Hemingway’s stature as a major American writer and displayed a level of complexity not apparent in The Sun Also Rises.(The story was turned into a play by war veteran Laurence Stallings that was the basis for the film starring Gary Cooper.)[75] In Spain in mid-1929, Hemingway researched his next work, Death in the Afternoon. He wanted to write a comprehensive treatise on bullfighting, explaining the toreros and corridas complete with glossaries and appendices, because he believed bullfighting was «of great tragic interest, being literally of life and death.»[76]

During the early 1930s, Hemingway spent his winters in Key West and summers in Wyoming, where he found «the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West» and hunted deer, elk, and grizzly bear.[77] He was joined there by Dos Passos, and in November 1930, after bringing Dos Passos to the train station in Billings, Montana, Hemingway broke his arm in a car accident. The surgeon tended the compound spiral fracture and bound the bone with kangaroo tendon. Hemingway was hospitalized for seven weeks, with Pauline tending to him; the nerves in his writing hand took as long as a year to heal, during which time he suffered intense pain.[78]

Ernest, Pauline, Bumby, Patrick, and Gloria Hemingway pose with marlins after a fishing trip to Bimini in 1935

His third child, Gloria Hemingway, was born a year later on November 12, 1931, in Kansas City as «Gregory Hancock Hemingway».[79][80] Pauline’s uncle bought the couple a house in Key West with a carriage house, the second floor of which was converted into a writing studio.[81] While in Key West, Hemingway frequented the local bar Sloppy Joe’s.[82] He invited friends—including Waldo Peirce, Dos Passos, and Max Perkins[83]—to join him on fishing trips and on an all-male expedition to the Dry Tortugas. Meanwhile, he continued to travel to Europe and to Cuba, and—although in 1933 he wrote of Key West, «We have a fine house here, and kids are all well»—Mellow believes he «was plainly restless».[84]

In 1933, Hemingway and Pauline went on safari to Kenya. The 10-week trip provided material for Green Hills of Africa, as well as for the short stories «The Snows of Kilimanjaro» and «The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber».[85] The couple visited Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya; then moved on to Tanganyika Territory, where they hunted in the Serengeti, around Lake Manyara, and west and southeast of present-day Tarangire National Park. Their guide was the noted «white hunter» Philip Percival who had guided Theodore Roosevelt on his 1909 safari. During these travels, Hemingway contracted amoebic dysentery that caused a prolapsed intestine, and he was evacuated by plane to Nairobi, an experience reflected in «The Snows of Kilimanjaro». On Hemingway’s return to Key West in early 1934, he began work on Green Hills of Africa, which he published in 1935 to mixed reviews.[86]

Hemingway bought a boat in 1934, named it the Pilar, and began sailing the Caribbean.[87] In 1935 he first arrived at Bimini, where he spent a considerable amount of time.[85] During this period he also worked on To Have and Have Not, published in 1937 while he was in Spain, the only novel he wrote during the 1930s.[88]

Spanish Civil War

Hemingway (center) with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens and German writer Ludwig Renn (serving as an International Brigades officer) in Spain during Spanish Civil War, 1937

In 1937, Hemingway left for Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA), despite Pauline’s reluctance to have him working in a war zone.[89] He and Dos Passos both signed on to work with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens as screenwriters for The Spanish Earth.[90] Dos Passos left the project after the execution of José Robles, his friend and Spanish translator,[91] which caused a rift between the two writers.[92]

Hemingway was joined in Spain by journalist and writer Martha Gellhorn, whom he had met in Key West a year earlier. Like Hadley, Martha was a St. Louis native, and like Pauline, she had worked for Vogue in Paris. Of Martha, Kert explains, «she never catered to him the way other women did».[93] In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers’ Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war, held in Valencia, Barcelona and Madrid and attended by many writers including André Malraux, Stephen Spender and Pablo Neruda.[94] Late in 1937, while in Madrid with Martha, Hemingway wrote his only play, The Fifth Column, as the city was being bombarded by Francoist forces.[95] He returned to Key West for a few months, then back to Spain twice in 1938, where he was present at the Battle of the Ebro, the last republican stand, and he was among the British and American journalists who were some of the last to leave the battle as they crossed the river.[96][97]

Cuba

In early 1939, Hemingway crossed to Cuba in his boat to live in the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Havana. This was the separation phase of a slow and painful split from Pauline, which began when Hemingway met Martha Gellhorn.[98] Martha soon joined him in Cuba, and they rented «Finca Vigía» («Lookout Farm»), a 15-acre (61,000 m2) property 15 miles (24 km) from Havana. Pauline and the children left Hemingway that summer, after the family was reunited during a visit to Wyoming; when his divorce from Pauline was finalized, he and Martha were married on November 20, 1940, in Cheyenne, Wyoming.[99]

Hemingway moved his primary summer residence to Ketchum, Idaho, just outside the newly built resort of Sun Valley, and moved his winter residence to Cuba.[100] He had been disgusted when a Parisian friend allowed his cats to eat from the table, but he became enamored of cats in Cuba and kept dozens of them on the property.[101] Descendants of his cats live at his Key West home.

Gellhorn inspired him to write his most famous novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he began in March 1939 and finished in July 1940. It was published in October 1940.[102] His pattern was to move around while working on a manuscript, and he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Cuba, Wyoming, and Sun Valley.[98] It became a Book-of-the-Month Club choice, sold half a million copies within months, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and, in the words of Meyers, «triumphantly re-established Hemingway’s literary reputation».[103]

In January 1941, Martha was sent to China on assignment for Collier’s magazine.[104] Hemingway went with her, sending in dispatches for the newspaper PM, but in general he disliked China.[104] A 2009 book suggests during that period he may have been recruited to work for Soviet intelligence agents under the name «Agent Argo».[105] They returned to Cuba before the declaration of war by the United States that December, when he convinced the Cuban government to help him refit the Pilar, which he intended to use to ambush German submarines off the coast of Cuba.[17]

World War II

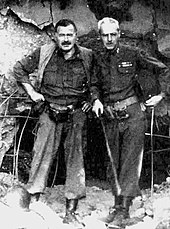

Hemingway with Col. Charles «Buck» Lanham in Germany, 1944, during the fighting in Hürtgenwald, after which he became ill with pneumonia.

Hemingway was in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945. When he arrived in London, he met Time magazine correspondent Mary Welsh, with whom he became infatuated. Martha had been forced to cross the Atlantic in a ship filled with explosives because Hemingway refused to help her get a press pass on a plane, and she arrived in London to find him hospitalized with a concussion from a car accident. She was unsympathetic to his plight; she accused him of being a bully and told him that she was «through, absolutely finished».[106] The last time that Hemingway saw Martha was in March 1945 as he was preparing to return to Cuba,[107] and their divorce was finalized later that year.[106] Meanwhile, he had asked Mary Welsh to marry him on their third meeting.[106]

Hemingway accompanied the troops to the Normandy Landings wearing a large head bandage, according to Meyers, but he was considered «precious cargo» and not allowed ashore.[108] The landing craft came within sight of Omaha Beach before coming under enemy fire and turning back. Hemingway later wrote in Collier’s that he could see «the first, second, third, fourth and fifth waves of [landing troops] lay where they had fallen, looking like so many heavily laden bundles on the flat pebbly stretch between the sea and first cover».[109] Mellow explains that, on that first day, none of the correspondents were allowed to land and Hemingway was returned to the Dorothea Dix.[110]

Late in July, he attached himself to «the 22nd Infantry Regiment commanded by Col. Charles «Buck» Lanham, as it drove toward Paris», and Hemingway became de facto leader to a small band of village militia in Rambouillet outside of Paris.[111] Paul Fussell remarks: «Hemingway got into considerable trouble playing infantry captain to a group of Resistance people that he gathered because a correspondent is not supposed to lead troops, even if he does it well.»[17] This was in fact in contravention of the Geneva Convention, and Hemingway was brought up on formal charges; he said that he «beat the rap» by claiming that he only offered advice.[112]

On August 25, he was present at the liberation of Paris as a journalist; contrary to the Hemingway legend, he was not the first into the city, nor did he liberate the Ritz.[113] In Paris, he visited Sylvia Beach and Pablo Picasso with Mary Welsh, who joined him there; in a spirit of happiness, he forgave Gertrude Stein.[114] Later that year, he observed heavy fighting in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest.[113] On December 17, 1944, he had himself driven to Luxembourg in spite of illness to cover The Battle of the Bulge. As soon as he arrived, however, Lanham handed him to the doctors, who hospitalized him with pneumonia; he recovered a week later, but most of the fighting was over.[112]

In 1947, Hemingway was awarded a Bronze Star for his bravery during World War II. He was recognized for having been «under fire in combat areas in order to obtain an accurate picture of conditions», with the commendation that «through his talent of expression, Mr. Hemingway enabled readers to obtain a vivid picture of the difficulties and triumphs of the front-line soldier and his organization in combat».[17]

Cuba and the Nobel Prize

Hemingway said he «was out of business as a writer» from 1942 to 1945 during his residence in Cuba.[115] In 1946 he married Mary, who had an ectopic pregnancy five months later. The Hemingway family suffered a series of accidents and health problems in the years following the war: in a 1945 car accident, he «smashed his knee» and sustained another «deep wound on his forehead»; Mary broke first her right ankle and then her left in successive skiing accidents. A 1947 car accident left Patrick with a head wound and severely ill.[116] Hemingway sank into depression as his literary friends began to die: in 1939 William Butler Yeats and Ford Madox Ford; in 1940 F. Scott Fitzgerald; in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce; in 1946 Gertrude Stein; and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins, Hemingway’s long-time Scribner’s editor, and friend.[117] During this period, he suffered from severe headaches, high blood pressure, weight problems, and eventually diabetes—much of which was the result of previous accidents and many years of heavy drinking.[118] Nonetheless, in January 1946, he began work on The Garden of Eden, finishing 800 pages by June.[119][note 3] During the post-war years, he also began work on a trilogy tentatively titled «The Land», «The Sea» and «The Air», which he wanted to combine in one novel titled The Sea Book. However, both projects stalled, and Mellow says that Hemingway’s inability to continue was «a symptom of his troubles» during these years.[120][note 4]

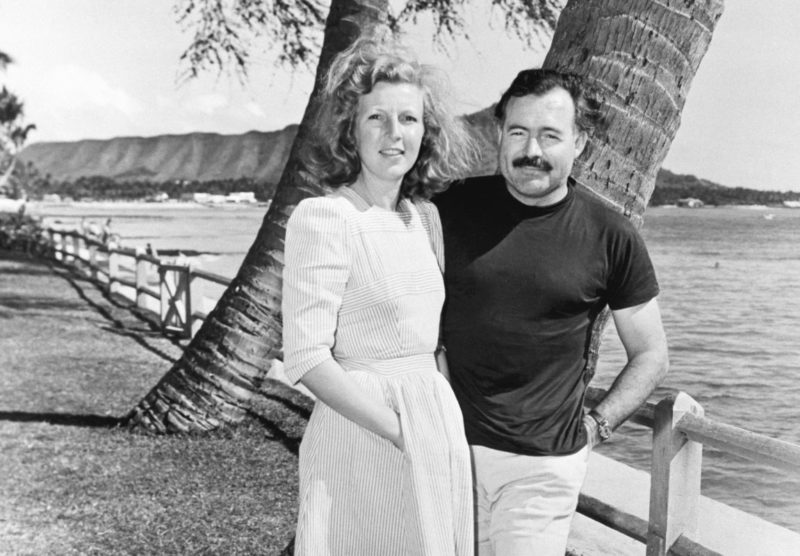

Hemingway and Mary in Africa before the two plane accidents

In 1948, Hemingway and Mary traveled to Europe, staying in Venice for several months. While there, Hemingway fell in love with the then 19-year-old Adriana Ivancich. The platonic love affair inspired the novel Across the River and into the Trees, written in Cuba during a time of strife with Mary, and published in 1950 to negative reviews.[121] The following year, furious at the critical reception of Across the River and Into the Trees, he wrote the draft of The Old Man and the Sea in eight weeks, saying that it was «the best I can write ever for all of my life».[118] The Old Man and the Sea became a book-of-the-month selection, made Hemingway an international celebrity, and won the Pulitzer Prize in May 1953, a month before he left for his second trip to Africa.[122][123]

In January 1954, while in Africa, Hemingway was almost fatally injured in two successive plane crashes. He chartered a sightseeing flight over the Belgian Congo as a Christmas present to Mary. On their way to photograph Murchison Falls from the air, the plane struck an abandoned utility pole and «crash landed in heavy brush». Hemingway’s injuries included a head wound, while Mary broke two ribs.[124] The next day, attempting to reach medical care in Entebbe, they boarded a second plane that exploded at take-off, with Hemingway suffering burns and another concussion, this one serious enough to cause leaking of cerebral fluid.[125] They eventually arrived in Entebbe to find reporters covering the story of Hemingway’s death. He briefed the reporters and spent the next few weeks recuperating and reading his erroneous obituaries.[126] Despite his injuries, Hemingway accompanied Patrick and his wife on a planned fishing expedition in February, but pain caused him to be irascible and difficult to get along with.[127] When a bushfire broke out, he was again injured, sustaining second-degree burns on his legs, front torso, lips, left hand and right forearm.[128] Months later in Venice, Mary reported to friends the full extent of Hemingway’s injuries: two cracked discs, a kidney and liver rupture, a dislocated shoulder and a broken skull.[127] The accidents may have precipitated the physical deterioration that was to follow. After the plane crashes, Hemingway, who had been «a thinly controlled alcoholic throughout much of his life, drank more heavily than usual to combat the pain of his injuries.»[129]

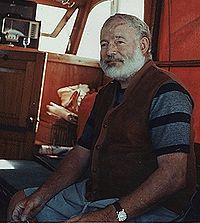

Hemingway in the cabin of his boat Pilar, off the coast of Cuba, c. 1950

In October 1954, Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature. He modestly told the press that Carl Sandburg, Isak Dinesen and Bernard Berenson deserved the prize,[130] but he gladly accepted the prize money.[131] Mellow says Hemingway «had coveted the Nobel Prize», but when he won it, months after his plane accidents and the ensuing worldwide press coverage, «there must have been a lingering suspicion in Hemingway’s mind that his obituary notices had played a part in the academy’s decision.»[132] Because he was suffering pain from the African accidents, he decided against traveling to Stockholm.[133] Instead he sent a speech to be read, defining the writer’s life:

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.[134][135]

From the end of the year in 1955 to early 1956, Hemingway was bedridden.[136] He was told to stop drinking to mitigate liver damage, advice he initially followed but then disregarded.[137] In October 1956, he returned to Europe and met Basque writer Pio Baroja, who was seriously ill and died weeks later. During the trip, Hemingway became sick again and was treated for «high blood pressure, liver disease, and arteriosclerosis».[136]

Opening statement of Nobel Prize acceptance speech, 1954 [recorded privately by Hemingway after the fact].

In November 1956, while staying in Paris, he was reminded of trunks he had stored in the Ritz Hotel in 1928 and never retrieved. Upon re-claiming and opening the trunks, Hemingway discovered they were filled with notebooks and writing from his Paris years. Excited about the discovery, when he returned to Cuba in early 1957, he began to shape the recovered work into his memoir A Moveable Feast.[138] By 1959 he ended a period of intense activity: he finished A Moveable Feast (scheduled to be released the following year); brought True at First Light to 200,000 words; added chapters to The Garden of Eden; and worked on Islands in the Stream. The last three were stored in a safe deposit box in Havana, as he focused on the finishing touches for A Moveable Feast. Author Michael Reynolds claims it was during this period that Hemingway slid into depression, from which he was unable to recover.[139]

The Finca Vigía became crowded with guests and tourists, as Hemingway, beginning to become unhappy with life there, considered a permanent move to Idaho. In 1959 he bought a home overlooking the Big Wood River, outside Ketchum, and left Cuba—although he apparently remained on easy terms with the Castro government, telling The New York Times he was «delighted» with Castro’s overthrow of Batista.[140][141] He was in Cuba in November 1959, between returning from Pamplona and traveling west to Idaho, and the following year for his 61st birthday; however, that year he and Mary decided to leave after hearing the news that Castro wanted to nationalize property owned by Americans and other foreign nationals.[142] On July 25, 1960, the Hemingways left Cuba for the last time, leaving art and manuscripts in a bank vault in Havana. After the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Finca Vigía was expropriated by the Cuban government, complete with Hemingway’s collection of «four to six thousand books».[143] President Kennedy arranged for Mary Hemingway to travel to Cuba where she met Fidel Castro and obtained her husband’s papers and painting in return for donating Finca Vigía to Cuba.[144]

Idaho and suicide

Hemingway continued to rework the material that was published as A Moveable Feast through the 1950s.[138] In mid-1959, he visited Spain to research a series of bullfighting articles commissioned by Life magazine.[145] Life wanted only 10,000 words, but the manuscript grew out of control.[146] He was unable to organize his writing for the first time in his life, so he asked A. E. Hotchner to travel to Cuba to help him. Hotchner helped him trim the Life piece down to 40,000 words, and Scribner’s agreed to a full-length book version (The Dangerous Summer) of almost 130,000 words.[147] Hotchner found Hemingway to be «unusually hesitant, disorganized, and confused»,[148] and suffering badly from failing eyesight.[149]

Hemingway and Mary left Cuba for the last time on July 25, 1960. He set up a small office in his New York City apartment and attempted to work, but he left soon after. He then traveled alone to Spain to be photographed for the front cover of Life magazine. A few days later, the news reported that he was seriously ill and on the verge of dying, which panicked Mary until she received a cable from him telling her, «Reports false. Enroute Madrid. Love Papa.»[150] He was, in fact, seriously ill, and believed himself to be on the verge of a breakdown.[147] Feeling lonely, he took to his bed for days, retreating into silence, despite having the first installments of The Dangerous Summer published in Life in September 1960 to good reviews.[151] In October, he left Spain for New York, where he refused to leave Mary’s apartment, presuming that he was being watched. She quickly took him to Idaho, where physician George Saviers met them at the train.[147]

Hemingway was constantly worried about money and his safety.[149] He worried about his taxes and that he would never return to Cuba to retrieve the manuscripts that he had left in a bank vault. He became paranoid, thinking that the FBI was actively monitoring his movements in Ketchum.[152][153] The FBI had opened a file on him during World War II, when he used the Pilar to patrol the waters off Cuba, and J. Edgar Hoover had an agent in Havana watch him during the 1950s.[154] Unable to care for her husband, Mary had Saviers fly Hemingway to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota at the end of November for hypertension treatments, as he told his patient.[152] The FBI knew that Hemingway was at the Mayo Clinic, as an agent later documented in a letter written in January 1961.[155]

Hemingway was checked in under Saviers’s name to maintain anonymity.[151] Meyers writes that «an aura of secrecy surrounds Hemingway’s treatment at the Mayo» but confirms that he was treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as many as 15 times in December 1960 and was «released in ruins» in January 1961.[156] Reynolds gained access to Hemingway’s records at the Mayo, which document ten ECT sessions. The doctors in Rochester told Hemingway the depressive state for which he was being treated may have been caused by his long-term use of Reserpine and Ritalin.[157] Of the ECT therapy, Hemingway told Hotchner, “What is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business? It was a brilliant cure, but we lost the patient.”[158]

Hemingway was back in Ketchum in April 1961, three months after being released from the Mayo Clinic, when Mary «found Hemingway holding a shotgun» in the kitchen one morning. She called Saviers, who sedated him and admitted him to the Sun Valley Hospital and once the weather cleared Saviers flew again to Rochester with his patient.[159] Hemingway underwent three electroshock treatments during that visit.[160] He was released at the end of June and was home in Ketchum on June 30. Two days later he «quite deliberately» shot himself with his favorite shotgun in the early morning hours of July 2, 1961.[161] He had unlocked the basement storeroom where his guns were kept, gone upstairs to the front entrance foyer, and shot himself with the «double-barreled shotgun that he had used so often it might have been a friend», which was purchased from Abercrombie & Fitch.[162]

Mary was sedated and taken to the hospital, returning home the next day where she cleaned the house and saw to the funeral and travel arrangements. Bernice Kert writes that it «did not seem to her a conscious lie» when she told the press that his death had been accidental.[163] In a press interview five years later, Mary confirmed that he had shot himself.[164]

Family and friends flew to Ketchum for the funeral, officiated by the local Catholic priest, who believed that the death had been accidental.[163] An altar boy fainted at the head of the casket during the funeral, and Hemingway’s brother Leicester wrote: «It seemed to me Ernest would have approved of it all.»[165] He is buried in the Ketchum cemetery.[166]

Hemingway’s behavior during his final years had been similar to that of his father before he killed himself;[167] his father may have had hereditary hemochromatosis, whereby the excessive accumulation of iron in tissues culminates in mental and physical deterioration.[168] Medical records made available in 1991 confirmed that Hemingway had been diagnosed with hemochromatosis in early 1961.[169] His sister Ursula and his brother Leicester also killed themselves.[170] Hemingway’s health was further complicated by heavy drinking throughout most of his life.[118]

A memorial to Hemingway just north of Sun Valley is inscribed on the base with a eulogy Hemingway had written for a friend several decades earlier:[171]

- Best of all he loved the fall

- the leaves yellow on cottonwoods

- leaves floating on trout streams

- and above the hills

- the high blue windless skies

- …Now he will be a part of them forever.

Writing style

The New York Times wrote in 1926 of Hemingway’s first novel, «No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame.»[172] The Sun Also Rises is written in the spare, tight prose that made Hemingway famous, and, according to James Nagel, «changed the nature of American writing».[173] In 1954, when Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, it was for «his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style.»[174]

If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.

—Ernest Hemingway in Death in the Afternoon[175]

Henry Louis Gates believes Hemingway’s style was fundamentally shaped «in reaction to [his] experience of world war». After World War I, he and other modernists «lost faith in the central institutions of Western civilization» by reacting against the elaborate style of 19th-century writers and by creating a style «in which meaning is established through dialogue, through action, and silences—a fiction in which nothing crucial—or at least very little—is stated explicitly.»[17]

Because he began as a writer of short stories, Baker believes Hemingway learned to «get the most from the least, how to prune language, how to multiply intensities and how to tell nothing but the truth in a way that allowed for telling more than the truth.»[176] Hemingway called his style the iceberg theory: the facts float above water; the supporting structure and symbolism operate out of sight.[176] The concept of the iceberg theory is sometimes referred to as the «theory of omission». Hemingway believed the writer could describe one thing (such as Nick Adams fishing in «Big Two-Hearted River») though an entirely different thing occurs below the surface (Nick Adams concentrating on fishing to the extent that he does not have to think about anything else).[177] Paul Smith writes that Hemingway’s first stories, collected as In Our Time, showed he was still experimenting with his writing style,[178] and when he wrote about Spain or other countries he incorporated foreign words into the text, which sometimes appears directly in the other language (in italics, as occurs in The Old Man and the Sea) or in English as literal translations. He also often used bilingual puns and crosslingual wordplay as stylistic devices.[179] In general, he avoided complicated syntax. About 70 percent of the sentences are simple sentences without subordination—a simple childlike grammar structure.[180]

Jackson Benson believes Hemingway used autobiographical details as framing devices about life in general—not only about his life. For example, Benson postulates that Hemingway used his experiences and drew them out with «what if» scenarios: «what if I were wounded in such a way that I could not sleep at night? What if I were wounded and made crazy, what would happen if I were sent back to the front?»[181] Writing in «The Art of the Short Story», Hemingway explains: «A few things I have found to be true. If you leave out important things or events that you know about, the story is strengthened. If you leave or skip something because you do not know it, the story will be worthless. The test of any story is how very good the stuff that you, not your editors, omit.»[182]

The simplicity of the prose is deceptive. Zoe Trodd believes Hemingway crafted skeletal sentences in response to Henry James’s observation that World War I had «used up words». Hemingway offers a «multi-focal» photographic reality. His iceberg theory of omission is the foundation on which he builds. The syntax, which lacks subordinating conjunctions, creates static sentences. The photographic «snapshot» style creates a collage of images. Many types of internal punctuation (colons, semicolons, dashes, parentheses) are omitted in favor of short declarative sentences. The sentences build on each other, as events build to create a sense of the whole. Multiple strands exist in one story; an «embedded text» bridges to a different angle. He also uses other cinematic techniques of «cutting» quickly from one scene to the next; or of «splicing» a scene into another. Intentional omissions allow the reader to fill the gap, as though responding to instructions from the author and create three-dimensional prose.[183]

In the late summer that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the trees.

—Opening passage of A Farewell to Arms showing Hemingway’s use of the word and[184]

Hemingway habitually used the word «and» in place of commas. This use of polysyndeton may serve to convey immediacy. Hemingway’s polysyndetonic sentence—or in later works his use of subordinate clauses—uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images. Benson compares them to haikus.[185][186] Many of Hemingway’s followers misinterpreted his lead and frowned upon all expression of emotion; Saul Bellow satirized this style as «Do you have emotions? Strangle them.»[187] However, Hemingway’s intent was not to eliminate emotion, but to portray it more scientifically. Hemingway thought it would be easy, and pointless, to describe emotions; he sculpted collages of images in order to grasp «the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always».[188] This use of an image as an objective correlative is characteristic of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Marcel Proust.[189] Hemingway’s letters refer to Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past several times over the years, and indicate he read the book at least twice.[190]

Themes

Hemingway’s writing includes themes of love, war, travel, wilderness, and loss.[191] Critic Leslie Fiedler sees the theme he defines as «The Sacred Land»—the American West—extended in Hemingway’s work to include mountains in Spain, Switzerland and Africa, and to the streams of Michigan. The American West is given a symbolic nod with the naming of the «Hotel Montana» in The Sun Also Rises and For Whom the Bell Tolls.[192] According to Stoltzfus and Fiedler, in Hemingway’s work, nature is a place for rebirth and rest; and it is where the hunter or fisherman might experience a moment of transcendence at the moment they kill their prey.[193] Nature is where men exist without women: men fish; men hunt; men find redemption in nature.[192] Although Hemingway does write about sports, such as fishing, Carlos Baker notes the emphasis is more on the athlete than the sport.[194] At its core, much of Hemingway’s work can be viewed in the light of American naturalism, evident in detailed descriptions such as those in «Big Two-Hearted River».[9]

Hemingway often wrote about Americans abroad. In Hemingway’s Expatriate Nationalism, Jeffrey Herlihy describes “Hemingway’s Transnational Archetype” as one that involves characters who are «multilingual and bicultural, and have integrated new cultural norms from the host community into their daily lives by the time plots begin.”[195] In this way, «foreign scenarios, far from being mere exotic backdrops or cosmopolitan milieus, are motivating factors in-character action.»[196] Donald Monk comments that Hemingway’s use of “expatriation comes to be not so much a psychological as a metaphysical reality. It guarantees his world-view of his heroes, based on a type of rootless outsider.[197]

Fiedler believes Hemingway inverts the American literary theme of the evil «Dark Woman» versus the good «Light Woman». The dark woman—Brett Ashley of The Sun Also Rises—is a goddess; the light woman—Margot Macomber of «The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber»—is a murderess.[192] Robert Scholes says early Hemingway stories, such as «A Very Short Story», present «a male character favorably and a female unfavorably».[198] According to Rena Sanderson, early Hemingway critics lauded his male-centric world of masculine pursuits, and the fiction divided women into «castrators or love-slaves». Feminist critics attacked Hemingway as «public enemy number one», although more recent re-evaluations of his work «have given new visibility to Hemingway’s female characters (and their strengths) and have revealed his own sensitivity to gender issues, thus casting doubts on the old assumption that his writings were one-sidedly masculine.»[199] Nina Baym believes that Brett Ashley and Margot Macomber «are the two outstanding examples of Hemingway’s ‘bitch women.‘«[200]

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

—Ernest Hemingway in A Farewell to Arms[201]

The theme of women and death is evident in stories as early as «Indian Camp». The theme of death permeates Hemingway’s work. Young believes the emphasis in «Indian Camp» was not so much on the woman who gives birth or the father who kills himself, but on Nick Adams who witnesses these events as a child, and becomes a «badly scarred and nervous young man». Hemingway sets the events in «Indian Camp» that shape the Adams persona. Young believes «Indian Camp» holds the «master key» to «what its author was up to for some thirty-five years of his writing career».[202] Stoltzfus considers Hemingway’s work to be more complex with a representation of the truth inherent in existentialism: if «nothingness» is embraced, then redemption is achieved at the moment of death. Those who face death with dignity and courage live an authentic life. Francis Macomber dies happy because the last hours of his life are authentic; the bullfighter in the corrida represents the pinnacle of a life lived with authenticity.[193] In his paper The Uses of Authenticity: Hemingway and the Literary Field, Timo Müller writes that Hemingway’s fiction is successful because the characters live an «authentic life», and the «soldiers, fishers, boxers and backwoodsmen are among the archetypes of authenticity in modern literature».[203]

The theme of emasculation is prevalent in Hemingway’s work, notably in God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen and The Sun Also Rises. Emasculation, according to Fiedler, is a result of a generation of wounded soldiers; and of a generation in which women such as Brett gained emancipation. This also applies to the minor character, Frances Clyne, Cohn’s girlfriend in the beginning of The Sun Also Rises. Her character supports the theme not only because the idea was presented early on in the novel but also the impact she had on Cohn in the start of the book while only appearing a small number of times.[192] In God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen, the emasculation is literal, and related to religious guilt. Baker believes Hemingway’s work emphasizes the «natural» versus the «unnatural». In «An Alpine Idyll» the «unnaturalness» of skiing in the high country late spring snow is juxtaposed against the «unnaturalness» of the peasant who allowed his wife’s dead body to linger too long in the shed during the winter. The skiers and peasant retreat to the valley to the «natural» spring for redemption.[194]

Descriptions of food and drink feature prominently in many of Hemingway’s works. In the short story «Big Two-Hearted River» Hemingway describes a hungry Nick Adams cooking a can of pork and beans and a can of spaghetti over a fire in a heavy cast iron pot. The primitive act of preparing the meal in solitude is a restorative act and one of Hemingway’s narratives of post-war integration.[204]

Susan Beegel reports that Charles Stetler and Gerald Locklin read Hemingway’s The Mother of a Queen as both misogynistic and homophobic,[205] and Ernest Fontana thought that a «horror of homosexuality» drove the short story «A Pursuit Race».[206][207] Beegel found that «despite the academy’s growing interest in multiculturalism … during the 1980s … critics interested in multiculturalism tended to ignore the author as ‘politically incorrect.'», listing just two «apologetic articles on [his] handling of race».[207] Barry Gross, comparing Jewish characters in literature of the period, commented that «Hemingway never lets the reader forget that Cohn is a Jew, not an unattractive character who happens to be a Jew but a character who is unattractive because he is a Jew.»[208]

Influence and legacy

Hemingway’s legacy to American literature is his style: writers who came after him either emulated or avoided it.[209] After his reputation was established with the publication of The Sun Also Rises, he became the spokesperson for the post-World War I generation, having established a style to follow.[173] His books were burned in Berlin in 1933, «as being a monument of modern decadence», and disavowed by his parents as «filth».[210] Reynolds asserts the legacy is that «[Hemingway] left stories and novels so starkly moving that some have become part of our cultural heritage.»[211]

Benson believes the details of Hemingway’s life have become a «prime vehicle for exploitation», resulting in a Hemingway industry.[212] Hemingway scholar Hallengren believes the «hard-boiled style» and the machismo must be separated from the author himself.[210] Benson agrees, describing him as introverted and private as J. D. Salinger, although Hemingway masked his nature with braggadocio.[213] During World War II, Salinger met and corresponded with Hemingway, whom he acknowledged as an influence. In a letter to Hemingway, Salinger claimed their talks «had given him his only hopeful minutes of the entire war» and jokingly «named himself national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Clubs».[214]

The extent of his influence is seen from the enduring and varied tributes to Hemingway and his works. 3656 Hemingway, a minor planet discovered in 1978 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Chernykh, was named for Hemingway,[215] and in 2009, a crater on Mercury was also named in his honor.[216] The Kilimanjaro Device by Ray Bradbury featured Hemingway being transported to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro,[79] while the 1993 motion picture Wrestling Ernest Hemingway explored the friendship of two retired men, played by Robert Duvall and Richard Harris, in a seaside Florida town.[217] His influence is further evident from the many restaurants bearing his name and the proliferation of bars called «Harry’s», a nod to the bar in Across the River and Into the Trees.[218] Hemingway’s son Jack (Bumby) promoted a line of furniture honoring his father,[219] Montblanc created a Hemingway fountain pen,[220] and multiple lines of clothing inspired by Hemingway have been produced.[221] In 1977, the International Imitation Hemingway Competition was created to acknowledge his distinct style and the comical efforts of amateur authors to imitate him; entrants are encouraged to submit one «really good page of really bad Hemingway» and the winners are flown to Harry’s Bar in Italy.[222]

Mary Hemingway established the Hemingway Foundation in 1965, and in the 1970s she donated her husband’s papers to the John F. Kennedy Library. In 1980, a group of Hemingway scholars gathered to assess the donated papers, subsequently forming the Hemingway Society, «committed to supporting and fostering Hemingway scholarship», publishing The Hemingway Review.[223][224][225][226] Numerous awards have been established in Hemingway’s honor to recognize significant achievement in the arts and culture, including the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award and the Hemingway Award.[227][228]

In 2012, he was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[229]

Almost exactly 35 years after Hemingway’s death, on July 1, 1996, his granddaughter Margaux Hemingway died in Santa Monica, California.[230] Margaux was a supermodel and actress, co-starring with her younger sister Mariel in the 1976 movie Lipstick.[231] Her death was later ruled a death by suicide.[232]

Three houses associated with Hemingway are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places: the Ernest Hemingway Cottage on Walloon Lake, Michigan, designated in 1968; the Ernest Hemingway House in Key West, designated in 1968; and the Ernest and Mary Hemingway House in Ketchum, designated in 2015. Hemingway’s childhood home in Oak Park and his Havana residence were also converted into museums.[233][234]

On April 5, 2021, Hemingway, a three-episode, six-hour documentary, a recapitulation of Hemingway’s life, labors, and loves, debuted on the Public Broadcasting System. It was co-produced and directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.[235]

Selected works

- (1925) In Our Time

- (1926) The Sun Also Rises

- (1929) A Farewell to Arms

- (1937) To Have and Have Not

- (1940) For Whom the Bell Tolls

- (1952) The Old Man and the Sea

See also

- Family tree showing Ernest Hemingway’s parents, siblings, wives, children and grandchildren

Notes

- ^ On awarding the medal, the Italians wrote of Hemingway: «Gravely wounded by numerous pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated.» See Mellow (1992), p. 61

- ^ Clarence Hemingway used his father’s Civil War pistol to shoot himself. See Meyers (1985), 2

- ^ The Garden of Eden was published posthumously in 1986. See Meyers (1985), 436

- ^ The manuscript for The Sea Book was published posthumously as Islands in the Stream in 1970. See Mellow (1992), 552

References

Citations

- ^ https://ehto.thestar.com/marks/how-hemingway-came-of-age-at-the-toronto-star

- ^ Oliver (1999), 140

- ^ a b c Reynolds (2000), 17–18

- ^ Meyers (1985), 4

- ^ Oliver (1999), 134

- ^ Meyers (1985), 9

- ^ a b c Reynolds (2000), 19

- ^ Meyers (1985), 3

- ^ a b Beegel (2000), 63–71

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 19–23

- ^ «KansasCity.com : Kansas City breaking local news, sports, entertainment, business». web.archive.org. April 8, 2014. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Meyers (1985), 26

- ^ Mellow (1992), 48–49

- ^ Meyers (1985), 27–31

- ^ a b c Mellow (1992), 57–60

- ^ Meyers (1985), 31

- ^ a b c d e f «Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath». archives.gov. August 15, 2016. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Desnoyers, 3

- ^ Meyers (1985), 34, 37–42

- ^ Meyers (1985), 37–42

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 45–53

- ^ Reynolds (1998), 21

- ^ Mellow (1992), 101

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 56–58

- ^ a b c Kert (1983), 83–90

- ^ Oliver (1999), 139

- ^ a b c Baker (1972), 7

- ^ Meyers (1985), 60–62

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 70–74

- ^ Mellow (1991), 8

- ^ Meyers (1985), 77

- ^ Mellow (1992), 308

- ^ a b Reynolds (2000), 28

- ^ Meyers (1985), 77–81

- ^ Voss, Frederick; Reynolds, Michael; Reynolds, Michael S.; Institution), National Portrait Gallery (Smithsonian; D.C.), National portrait gallery (Washington (January 1, 1999). Picturing Hemingway: A Writer in His Time. Yale University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-300-07926-5.

- ^ Meyers (1985), 82

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 24

- ^ Desnoyers, 5

- ^ Meyers (1985), 69–70

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 15–18

- ^ Meyers (1985), 126

- ^ Baker (1972), 34

- ^ Meyers (1985), 127

- ^ Mellow (1992), 236

- ^ Mellow (1992), 314

- ^ Meyers (1985), 159–160

- ^ Baker (1972), 30–34

- ^ Meyers (1985), 117–119

- ^ Harrington, Mary (December 28, 1946). «They Call Him Papa». New York Post Week-End Magazine. p. 3.

- ^ Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph, ed. (1986). Conversations with Ernest Hemingway. Literary conversations series. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-0-87805-273-8. ISSN 1555-7065. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ Richardson, Hadley (n.d.). «How Hemingway became Papa» (MP3) (Audio segment (4 m 37s) from interview). Interviewed by Alice Hunt Sokoloff. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016.

- ^ Baker, Allie (June 28, 2010). «How did Hemingway become Papa?». The Hemingway Project. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

In this clip, Alice Sokoloff asks Hadley if she remembers how the name ‘Papa’ began, which was sometime during their years in Paris.

- ^ Nagel (1996), 89

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 189

- ^ Reynolds (1989), vi–vii

- ^ Mellow (1992), 328

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 44

- ^ Mellow (1992), 302

- ^ Meyers (1985), 192

- ^ Baker (1972), 82

- ^ Baker (1972), 43

- ^ Mellow (1992), 333

- ^ Mellow (1992), 338–340

- ^ Meyers (1985), 172

- ^ Meyers (1985), 173, 184

- ^ Mellow (1992), 348–353

- ^ Meyers (1985), 195

- ^ Long (1932), 2–3

- ^ Robinson (2005)

- ^ Meyers (1985), 204

- ^ Meyers (1985), 208

- ^ Mellow (1992), 367

- ^ qtd. in Meyers (1985), 210

- ^ Meyers (1985), 215

- ^ Mellow (1992), 378

- ^ Baker (1972), 144–145

- ^ Meyers (1985), 222

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 31

- ^ a b Oliver (1999), 144

- ^ «Hemingway legacy feud ‘resolved’«. October 3, 2003. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Meyers (1985), 222–227

- ^ Mellow (1992), 402

- ^ Mellow (1992), 376–377

- ^ Mellow (1992), 424

- ^ a b Desnoyers, 9

- ^ Mellow (1992), 337–340

- ^ Meyers (1985), 280

- ^ Meyers (1985), 292

- ^ Mellow (1992), 488

- ^ Meyers (1985), 311

- ^ Meyers (1985), 308–311

- ^ Koch (2005), 164

- ^ Kert (1983), 287–295

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2012). The Spanish Civil War (50th Anniversary ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-141-01161-5.

- ^ Koch (2005), 134

- ^ Meyers (1985), 321

- ^ Thomas (2001), 833

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 326

- ^ Lynn (1987), 479

- ^ Meyers (1985), 342

- ^ Meyers (1985), 353

- ^ Meyers (1985), 334

- ^ Meyers (1985), 334–338

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 356–361

- ^ Dugdale, John (July 9, 2009). «Hemingway revealed as failed KGB spy». The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c Kert (1983), 393–398

- ^ Meyers (1985), 416

- ^ Meyers (1985), 400

- ^ Reynolds (1999), 96–98

- ^ Mellow (1992), 533

- ^ Meyers (1985), 398–405

- ^ a b Lynn (1987), 518–519

- ^ a b Meyers (1985) 408–411

- ^ Mellow (1992), 535–540

- ^ qtd. in Mellow (1992), 552

- ^ Meyers (1985), 420–421

- ^ Mellow (1992) 548–550

- ^ a b c Desnoyers, 12

- ^ Meyers (1985), 436

- ^ Mellow (1992), 552

- ^ Meyers (1985), 440–452

- ^ Desnoyers, 13

- ^ Meyers (1985), 489

- ^ Baker (1972), 331–333

- ^ Mellow (1992), 586

- ^ Mellow (1992), 587

- ^ a b Mellow (1992), 588

- ^ Meyers (1985), 505–507

- ^ Beegel (1996), 273

- ^ Lynn (1987), 574

- ^ Baker (1972), 38

- ^ Mellow (1992), 588–589

- ^ Meyers (1985), 509

- ^ «Ernest Hemingway The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Banquet Speech». The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ «The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954». NobelPrize.org. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 512

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 291–293

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 533

- ^ Reynolds (1999), 321

- ^ Mellow (1992), 494–495

- ^ Meyers (1985), 516–519

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 332, 344

- ^ Mellow (1992), 599

- ^ Eschner, Kat (August 25, 2017). «How Mary Hemingway and JFK Got Ernest Hemingway’s Legacy Out of Cuba». Smithsonian magazine. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Meyers (1985), 520

- ^ Baker (1969), 553

- ^ a b c Reynolds (1999), 544–547

- ^ qtd. in Mellow (1992), 598–600

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 542–544

- ^ qtd. in Reynolds (1999), 546

- ^ a b Mellow (1992), 598–601

- ^ a b Reynolds (1999), 548

- ^ Meyers (1985), 543

- ^ Mellow (1992), 597–598

- ^ Meyers (1985), 543–544

- ^ Meyers (1985), 547–550

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 350

- ^ Hotchner, A. E. (1983). Papa Hemingway: A personal Memoir. New York: Morrow. p. 280. ISBN 9781504051156.

- ^ Meyers (1985), 551

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 355

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 16

- ^ Mellow (1992), 604

- ^ a b Kert (1983), 504

- ^ Gilroy, Harry (August 23, 1966). «Widow Believes Hemingway Committed Suicide; She Tells of His Depression and His ‘Breakdown’ Assails Hotchner Book». The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Hemingway (1996), 14–18

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 20869). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Burwell (1996), 234

- ^ Burwell (1996), 14

- ^ Burwell (1996), 189

- ^ Oliver (1999), 139–149

- ^ Carlton, Michael (July 12, 1987). «Idaho Remembers the Times of Papa Hemingway : Idaho: Hemingway Is Well Remembered». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ «Marital Tragedy». archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Nagel (1996), 87

- ^ «The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954». The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ qtd. in Oliver (1999), 322

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 117

- ^ Oliver (1999), 321–322

- ^ Smith (1996), 45

- ^ Gladstein (2006), 82–84

- ^ Wells (1975), 130–133

- ^ Benson (1989), 351

- ^ Hemingway (1975), 3

- ^ Trodd (2007), 8

- ^ qtd. in Mellow (1992), 379

- ^ McCormick, 49

- ^ Benson (1989), 309

- ^ qtd. in Hoberek (2005), 309

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon. New York: Simon and Schuster

- ^ McCormick, 47

- ^ Burwell (1996), 187

- ^ Svoboda (2000), 155

- ^ a b c d Fiedler (1975), 345–365

- ^ a b Stoltzfus (2005), 215–218

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 120–121

- ^ Herlihy, Jeffrey (2011). In Paris or Paname: Hemingway’s Expatriate Nationalism. New York: Rodopi. p. 49. ISBN 9042034092.

- ^ Herlihy, Jeffrey (2011). In Paris or Paname: Hemingway’s Expatriate Nationalism. New York: Rodopi. p. 3. ISBN 9042034092.

- ^ Monk, Donald (1978). «Hemingway’s Territirual Imperative». The Yearbook of English Studies. 8: 125-140 https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3506769.pdf.

- ^ Scholes (1990), 42

- ^ Sanderson (1996), 171

- ^ Baym (1990), 112

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest. (1929) A Farewell to Arms. New York: Scribner’s

- ^ Young (1964), 6

- ^ Müller (2010), 31

- ^ Justice, Hilary Kovar. (2012). «The Consolation of Critique: Food, Culture, and Civilization in Ernest Hemingway». The Hemingway review, Volume 32, issue 1. 16–28

- ^ Stetler, Charles; Locklin, Gerald (1982). «Beneath the Tip of the Iceberg in Hemingway’s ‘The Mother of a Queen’«. The Hemingway Review. 2.1 (Fall 1982): 68–69.

- ^ Fontana, Ernest (1984). «Hemingway’s ‘A Pursuit Race’«. Explicator. 42.4 (Summer 1984) (4): 43–45. doi:10.1080/00144940.1984.11483804.

- ^ a b Beegel (1996), 288

- ^ Gross, Barry (December 1985). «Yours Sincerely, Sinclair Levy». Commentary, The monthly magazine of opinion. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Oliver (1999), 140–141

- ^ a b «The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954». NobelPrize.org. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 15

- ^ Benson (1989), 347

- ^ Benson (1989), 349

- ^ Baker (1969), 420

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003) Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. New York: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3, 307

- ^ «Planetary Names: Crater, craters: Hemingway on Mercury». planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Oliver (1999), 360

- ^ Oliver (1999), 142

- ^ «A Line of Hemingway Furniture, With a Veneer of Taste». The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ «Hemingway». montblanc.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ «Willis&Geiger The Legend Collection». willis-and-geiger.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Jack (March 15, 1993). «Wanted: One Really Good Page of Really Bad Hemingway». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ «Leadership». The Hemingway Society. The Hemingway Society. April 18, 2021. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

Carl Eby Professor of English Appalachian State University, President (2020–2022); Gail Sinclair Rollins College, Vice President and Society Treasurer (2020–2022); Verna Kale The Pennsylvania State University, Ernest Hemingway Foundation Treasurer (2018–2020);

- ^ «Past Presidents of the Society». The Hemingway Society. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

H.R. Stoneback (Stoney) (SUNY, New Paltz) — 2014–2017; Joseph M. Flora (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) — 2018–2020;

- ^ «The Hemingway Review». The Hemingway Society. The Hemingway Society. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

The Hemingway Review —in its current form—was founded by Charles M. «Tod» Oliver in 1981 to serve as the publication for the newly founded Hemingway Society (1980). However, the Review began initially as Oliver’s attempt to revive Hemingway notes which was published by Ken Rosen at Dickinson College and Taylor Alderman at Youngstown State University from 1971 to 1974. Oliver published his version of Hemingway notes from 1979 until the first issue of The Hemingway Review in 1981.

- ^ Miller (2006), 78–80

- ^ «2012 Hemingway Foundation PEN Award Winner Announced | JFK Library». www.jfklibrary.org. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ «Premio Hemingway | 36^ Edizione del Premio Hemingway 19 / 23 GIUGNO 2019 – LIGNANO». www.premiohemingway.it. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ «Ernest Hemingway». Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2012. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Rainey, James (August 21, 1996). «Margaux Hemingway’s Death Ruled a Suicide». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Holloway, Lynette (July 3, 1996). «Margaux Hemingway Is Dead; Model and Actress Was 41». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ «Coroner Says Death of Actress Was Suicide». The New York Times. Associated Press. August 21, 1996. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ «Finca Vigía Foundation | Preserving Ernest Hemingway’s Legacy in Cuba». Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ «Hemingway Foundation». Hemingway Foundation. Archived from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Cain, Brooke (April 5, 2021). «What to Watch on Monday: The start of Ken Burns’ ‘Hemingway’ documentary». The News & Observer. Archived from the original on April 5, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

Bibliography

- Baker, Carlos. (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. ISBN 978-0-02-001690-8

- Baker, Carlos. (1972). Hemingway: The Writer as Artist. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01305-3

- Baker, Carlos. (1981). «Introduction» in Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917–1961. New York: Scribner’s. ISBN 978-0-684-16765-7

- Banks, Russell. (2004). «PEN/Hemingway Prize Speech». The Hemingway Review. Volume 24, issue 1. 53–60

- Baym, Nina. (1990). «Actually I Felt Sorry for the Lion», in Benson, Jackson J. (ed.), New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1067-9

- Beegel, Susan. (1996). «Conclusion: The Critical Reputation», in Donaldson, Scott (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45574-9

- Beegel, Susan (2000). «Eye and Heart: Hemingway’s Education as a Naturalist», in Wagner-Martin, Linda (ed.), A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512152-0

- Benson, Jackson. (1989). «Ernest Hemingway: The Life as Fiction and the Fiction as Life». American Literature. Volume 61, issue 3. 354–358

- Benson, Jackson. (1975). The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: Critical Essays. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0320-6

- Burwell, Rose Marie. (1996). Hemingway: the Postwar Years and the Posthumous Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48199-1

- Desnoyers, Megan Floyd. «Ernest Hemingway: A Storyteller’s Legacy» Archived August 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Online Resources. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- Fiedler, Leslie. (1975). Love and Death in the American Novel. New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-1799-7

- Gladstein, Mimi. (2006). «Bilingual Wordplay: Variations on a Theme by Hemingway and Steinbeck» The Hemingway Review Volume 26, issue 1. 81–95.

- Griffin, Peter. (1985). Along with Youth: Hemingway, the Early Years. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503680-0

- Hemingway, Ernest. (1929). A Farewell to Arms. New York: Scribner’s. ISBN 978-1-4767-6452-8