|

Houston |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

| City of Houston | |

|

Downtown Houston Sam Houston Monument at Hermann Park Texas Medical Center Uptown Houston Johnson Space Center Museum of Fine Arts |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nickname(s):

Space City (official), more … |

|

Interactive map of Houston |

|

| Coordinates: 29°45′46″N 95°22′59″W / 29.76278°N 95.38306°WCoordinates: 29°45′46″N 95°22′59″W / 29.76278°N 95.38306°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Counties | Harris, Fort Bend, Montgomery |

| Incorporated | June 5, 1837 |

| Named for | Sam Houston |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong Mayor-Council |

| • Body | Houston City Council |

| • Mayor | Sylvester Turner (D) |

| Area

[1] |

|

| • City | 671.67 sq mi (1,739.62 km2) |

| • Land | 640.44 sq mi (1,658.73 km2) |

| • Water | 31.23 sq mi (80.89 km2) |

| Elevation | 80 ft (32 m) |

| Population

(2020)[2] |

|

| • City | 2,304,580 |

| • Estimate

(2021)[2] |

2,288,250 |

| • Rank | 4th in the United States 1st in Texas |

| • Density | 3,598.43/sq mi (1,389.36/km2) |

| • Urban

[3] |

5,853,575 (US: 5th) |

| • Urban density | 3,339.8/sq mi (1,289.5/km2) |

| • Metro

[4] |

7,122,240 (US: 5th) |

| Demonym | Houstonian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

770xx, 772xx (P.O. Boxes) |

| Area codes | 713, 281, 832, 346 |

| FIPS code | 48-35000[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1380948[6] |

| Website | www.houstontx.gov |

Houston (; HEW-stən) is the most populous city in Texas and in the Southern United States. It is the fourth most populous city in the United States after New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago, and the sixth most populous city in North America. With a population of 2,304,580 in 2020,[2] Houston is located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the seat and largest city of Harris County and the principal city of the Greater Houston metropolitan area, which is the fifth-most populous metropolitan statistical area in the United States and the second-most populous in Texas after Dallas–Fort Worth. Houston is the southeast anchor of the greater megaregion known as the Texas Triangle.[7]

Comprising a land area of 640.4 square miles (1,659 km2),[8] Houston is the ninth-most expansive city in the United States (including consolidated city-counties). It is the largest city in the United States by total area whose government is not consolidated with a county, parish, or borough. Though primarily in Harris County, small portions of the city extend into Fort Bend, and Montgomery counties, bordering other principal communities of Greater Houston such as Sugar Land and The Woodlands.

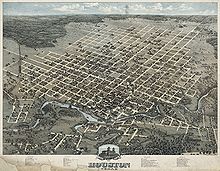

The city of Houston was founded by land investors on August 30, 1836,[9] at the confluence of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou (a point now known as Allen’s Landing) and incorporated as a city on June 5, 1837.[10][11] The city is named after former General Sam Houston, who was president of the Republic of Texas and had won Texas’s independence from Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto 25 miles (40 km) east of Allen’s Landing.[11] After briefly serving as the capital of the Texas Republic in the late 1830s, Houston grew steadily into a regional trading center for the remainder of the 19th century.[12]

The arrival of the 20th century brought a convergence of economic factors that fueled rapid growth in Houston, including a burgeoning port and railroad industry, the decline of Galveston as Texas’s primary port following a devastating 1900 hurricane, the subsequent construction of the Houston Ship Channel, and the Texas oil boom.[12] In the mid-20th century, Houston’s economy diversified, as it became home to the Texas Medical Center—the world’s largest concentration of healthcare and research institutions—and NASA’s Johnson Space Center, home to the Mission Control Center.

Since the late 19th century Houston’s economy has had a broad industrial base, in energy, manufacturing, aeronautics, and transportation. Leading in healthcare sectors and building oilfield equipment, Houston has the second-most Fortune 500 headquarters of any U.S. municipality within its city limits (after New York City).[13][14] The Port of Houston ranks first in the United States in international waterborne tonnage handled and second in total cargo tonnage handled.[15]

Nicknamed the «Bayou City», «Space City», «H-Town», and «the 713», Houston has become a global city, with strengths in culture, medicine, and research. The city has a population from various ethnic and religious backgrounds and a large and growing international community. Houston is the most diverse metropolitan area in Texas and has been described as the most racially and ethnically diverse major city in the U.S.[16] It is home to many cultural institutions and exhibits, which attract more than seven million visitors a year to the Museum District. The Museum District is home to nineteen museums, galleries, and community spaces. Houston has an active visual and performing arts scene in the Theater District, and offers year-round resident companies in all major performing arts.[17]

History[edit]

The Houston area occupying land that was home of the Karankawa (kə rang′kə wä′,-wô′,-wə) and the Atakapa (əˈtɑːkəpə) indigenous peoples for at least 2,000 years before the first known settlers arrived.[18][19][20] These tribes are almost nonexistent today; this was most likely caused by foreign disease, and competition with various settler groups in the 18th and 19th centuries.[21] However, the land then remained largely uninhabited from the late the 1700s until settlement in the 1830s.[22]

Early settlement to the 20th century[edit]

The Allen brothers—Augustus Chapman and John Kirby—explored town sites on Buffalo Bayou and Galveston Bay. According to historian David McComb, «[T]he brothers, on August 26, 1836, bought from Elizabeth E. Parrott, wife of T.F.L. Parrott and widow of John Austin, the south half of the lower league [2,214-acre (896 ha) tract] granted to her by her late husband. They paid $5,000 total, but only $1,000 of this in cash; notes made up the remainder.»[23]

The Allen brothers ran their first advertisement for Houston just four days later in the Telegraph and Texas Register, naming the notional town in honor of President Sam Houston.[11] They successfully lobbied the Republic of Texas Congress to designate Houston as the temporary capital, agreeing to provide the new government with a state capitol building.[24] About a dozen persons resided in the town at the beginning of 1837, but that number grew to about 1,500 by the time the Texas Congress convened in Houston for the first time that May.[11] The Republic of Texas granted Houston incorporation on June 5, 1837, as James S. Holman became its first mayor.[11] In the same year, Houston became the county seat of Harrisburg County (now Harris County).[25]

In 1839, the Republic of Texas relocated its capital to Austin. The town suffered another setback that year when a yellow fever epidemic claimed about one life for every eight residents, yet it persisted as a commercial center, forming a symbiosis with its Gulf Coast port, Galveston. Landlocked farmers brought their produce to Houston, using Buffalo Bayou to gain access to Galveston and the Gulf of Mexico. Houston merchants profited from selling staples to farmers and shipping the farmers’ produce to Galveston.[11]

The great majority of enslaved people in Texas came with their owners from the older slave states. Sizable numbers, however, came through the domestic slave trade. New Orleans was the center of this trade in the Deep South, but slave dealers were in Houston. Thousands of enslaved black people lived near the city before the American Civil War. Many of them near the city worked on sugar and cotton plantations,[26] while most of those in the city limits had domestic and artisan jobs.[27]

In 1840, the community established a chamber of commerce, in part to promote shipping and navigation at the newly created port on Buffalo Bayou.[28]

By 1860, Houston had emerged as a commercial and railroad hub for the export of cotton.[25] Railroad spurs from the Texas inland converged in Houston, where they met rail lines to the ports of Galveston and Beaumont. During the American Civil War, Houston served as a headquarters for Confederate Major General John B. Magruder, who used the city as an organization point for the Battle of Galveston.[29] After the Civil War, Houston businessmen initiated efforts to widen the city’s extensive system of bayous so the city could accept more commerce between Downtown and the nearby port of Galveston. By 1890, Houston was the railroad center of Texas.[30]

In 1900, after Galveston was struck by a devastating hurricane, efforts to make Houston into a viable deep-water port were accelerated.[31] The following year, the discovery of oil at the Spindletop oil field near Beaumont prompted the development of the Texas petroleum industry.[32] In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt approved a $1 million improvement project for the Houston Ship Channel. By 1910, the city’s population had reached 78,800, almost doubling from a decade before. African Americans formed a large part of the city’s population, numbering 23,929 people, which was nearly one-third of Houston’s residents.[33]

President Woodrow Wilson opened the deep-water Port of Houston in 1914, seven years after digging began. By 1930, Houston had become Texas’s most populous city and Harris County the most populous county.[34] In 1940, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Houston’s population as 77.5% White and 22.4% Black.[35]

World War II to the late 20th century[edit]

When World War II started, tonnage levels at the port decreased and shipping activities were suspended; however, the war did provide economic benefits for the city. Petrochemical refineries and manufacturing plants were constructed along the ship channel because of the demand for petroleum and synthetic rubber products by the defense industry during the war.[36] Ellington Field, initially built during World War I, was revitalized as an advanced training center for bombardiers and navigators.[37] The Brown Shipbuilding Company was founded in 1942 to build ships for the U.S. Navy during World War II. Due to the boom in defense jobs, thousands of new workers migrated to the city, both blacks, and whites competing for the higher-paying jobs. President Roosevelt had established a policy of nondiscrimination for defense contractors, and blacks gained some opportunities, especially in shipbuilding, although not without resistance from whites and increasing social tensions that erupted into occasional violence. Economic gains of blacks who entered defense industries continued in the postwar years.[38]

In 1945, the M.D. Anderson Foundation formed the Texas Medical Center. After the war, Houston’s economy reverted to being primarily port-driven. In 1948, the city annexed several unincorporated areas, more than doubling its size. Houston proper began to spread across the region.[11][39] In 1950, the availability of air conditioning provided impetus for many companies to relocate to Houston, where wages were lower than those in the North; this resulted in an economic boom and produced a key shift in the city’s economy toward the energy sector.[40][41]

The increased production of the expanded shipbuilding industry during World War II spurred Houston’s growth,[42] as did the establishment in 1961 of NASA’s «Manned Spacecraft Center» (renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in 1973). This was the stimulus for the development of the city’s aerospace industry. The Astrodome, nicknamed the «Eighth Wonder of the World»,[43] opened in 1965 as the world’s first indoor domed sports stadium.

During the late 1970s, Houston had a population boom as people from the Rust Belt states moved to Texas in large numbers.[44] The new residents came for numerous employment opportunities in the petroleum industry, created as a result of the Arab oil embargo. With the increase in professional jobs, Houston has become a destination for many college-educated persons, most recently including African Americans in a reverse Great Migration from northern areas.

In 1997, Houstonians elected Lee P. Brown as the city’s first African American mayor.[45]

Early 21st century[edit]

Tropical Storm Allison’s effects in Houston

Houston has continued to grow into the 21st century, with the population increasing 17% from 2000 to 2019.[46]

Oil & gas have continued to fuel Houston’s economic growth, with major oil companies including Phillips 66, ConocoPhillips, Occidental Petroleum, Halliburton, and ExxonMobil having their headquarters in the Houston area. In 2001, Enron Corporation, a Houston company with $100 billion in revenue, became engulfed in an accounting scandal which bankrupted the company in 2001.[47] Health care has emerged as a major industry in Houston. The Texas Medical Center is now the largest medical complex in the world and employs 106,000 people.

Three new sports stadiums opened downtown in the first decade of the 21st century. In 2000, the Houston Astros opened their new baseball stadium, Minute Maid Park, in downtown adjacent to the old Union Station. The Houston Texans were formed in 2002 as an NFL expansion team, replacing the Houston Oilers, which had left the city in 1996. NRG Stadium opened the same year. In 2003, the Toyota Center opened as the home for the Houston Rockets. In 2005, the Houston Dynamo soccer team was formed. In 2017, the Houston Astros won their first World Series.

Hurricane Harvey flooding

Flooding has been a recurring problem in the Houston area, exacerbated by a lack of zoning laws, which allowed unregulated building of residential homes and other structures in flood-prone areas.[48] In June 2001, Tropical Storm Allison dumped up to 40 inches (1,000 mm) of rain on parts of Houston, causing what was then the worst flooding in the city’s history and billions of dollars in damage, and killed 20 people in Texas.[49] In August 2005, Houston became a shelter to more than 150,000 people from New Orleans, who evacuated from Hurricane Katrina.[50] One month later, about 2.5 million Houston-area residents evacuated when Hurricane Rita approached the Gulf Coast, leaving little damage to the Houston area. This was the largest urban evacuation in the history of the United States.[51][52] In May 2015, seven people died after 12 inches of rain fell in 10 hours during what is known as the Memorial Day Flood. Eight people died in April 2016 during a storm that dropped 17 inches of rain.[53] The worst came in late August 2017, when Hurricane Harvey stalled over southeastern Texas, much like Tropical Storm Allison did sixteen years earlier, causing severe flooding in the Houston area, with some areas receiving over 50 inches (1,300 mm) of rain.[54] The rainfall exceeded 50 inches in several areas locally, breaking the national record for rainfall. The damage for the Houston area was estimated at up to $125 billion U.S. dollars,[55] and was considered to be one of the worst natural disasters in the history of the United States,[56] with the death toll exceeding 70 people.

Geography[edit]

Satellite image of Houston, 2020

Houston is 165 miles (266 km) east of Austin,[57] 88 miles (142 km) west of the Louisiana border,[58] and 250 miles (400 km) south of Dallas.[59] The city has a total area of 637.4 square miles (1,651 km2);[8] this comprises over 599.59 square miles (1,552.9 km2) of land and 22.3 square miles (58 km2) covered by water.[60] Most of Houston is on the gulf coastal plain, and its vegetation is classified as Western Gulf coastal grasslands while further north, it transitions into a subtropical jungle, the Big Thicket.

Much of the city was built on forested land, marshes, or swamps, and all are still visible in surrounding areas.[61] Flat terrain and extensive greenfield development have combined to worsen flooding.[62] Downtown stands about 50 feet (15 m) above sea level,[63] and the highest point in far northwest Houston is about 150 feet (46 m) in elevation.[64] The city once relied on groundwater for its needs, but land subsidence forced the city to turn to ground-level water sources such as Lake Houston, Lake Conroe, and Lake Livingston.[11][65] The city owns surface water rights for 1.20 billion US gallons (4.5 Gl) of water a day in addition to 150 million US gallons (570 Ml) a day of groundwater.[66]

Houston has four major bayous passing through the city that accept water from the extensive drainage system. Buffalo Bayou runs through Downtown and the Houston Ship Channel, and has three tributaries: White Oak Bayou, which runs through the Houston Heights community northwest of Downtown and then towards Downtown; Brays Bayou, which runs along the Texas Medical Center;[67] and Sims Bayou, which runs through the south of Houston and Downtown Houston. The ship channel continues past Galveston and then into the Gulf of Mexico.[36]

Geology[edit]

Aerial view of central Houston, showing Downtown and surrounding neighborhoods, March 2018

Houston is a flat, marshy area where an extensive drainage system has been built. The adjoining prairie land drains into the city, which is prone to flooding.[68] Underpinning Houston’s land surface are unconsolidated clays, clay shales, and poorly cemented sands up to several miles deep. The region’s geology developed from river deposits formed from the erosion of the Rocky Mountains. These sediments consist of a series of sands and clays deposited on decaying organic marine matter, that over time, transformed into oil and natural gas. Beneath the layers of sediment is a water-deposited layer of halite, a rock salt. The porous layers were compressed over time and forced upward. As it pushed upward, the salt dragged surrounding sediments into salt dome formations, often trapping oil and gas that seeped from the surrounding porous sands. The thick, rich, sometimes black, surface soil is suitable for rice farming in suburban outskirts where the city continues to grow.[69][70]

The Houston area has over 150 active faults (estimated to be 300 active faults) with an aggregate length of up to 310 miles (500 km),[71][72][73] including the Long Point–Eureka Heights fault system which runs through the center of the city. No significant historically recorded earthquakes have occurred in Houston, but researchers do not discount the possibility of such quakes having occurred in the deeper past, nor occurring in the future. Land in some areas southeast of Houston is sinking because water has been pumped out of the ground for many years. It may be associated with slip along the faults; however, the slippage is slow and not considered an earthquake, where stationary faults must slip suddenly enough to create seismic waves.[74] These faults also tend to move at a smooth rate in what is termed «fault creep»,[65] which further reduces the risk of an earthquake.

Cityscape[edit]

Houston’s superneighborhoods

The city of Houston was incorporated in 1837 and adopted a ward system of representation shortly afterward, in 1840.[75] The six original wards of Houston are the progenitors of the 11 modern-day geographically oriented Houston City Council districts, though the city abandoned the ward system in 1905 in favor of a commission government, and, later, the existing mayor–council government.

Intersection of Bagby and McGowen streets in western Midtown, 2016

Locations in Houston are generally classified as either being inside or outside the Interstate 610 loop. The «Inner Loop» encompasses a 97-square-mile (250 km2) area which includes Downtown, pre–World War II residential neighborhoods and streetcar suburbs, and newer high-density apartment and townhouse developments.[76] Outside the loop, the city’s typology is more suburban, though many major business districts—such as Uptown, Westchase, and the Energy Corridor—lie well outside the urban core. In addition to Interstate 610, two additional loop highways encircle the city: Beltway 8, with a radius of approximately 10 miles (16 km) from Downtown, and State Highway 99 (the Grand Parkway), with a radius of 25 miles (40 km). Approximately 470,000 people lived within the Interstate 610 loop, while 1.65 million lived between Interstate 610 and Beltway 8 and 2.25 million lived within Harris County outside Beltway 8 in 2015.[77]

Though Houston is the largest city in the United States without formal zoning regulations, it has developed similarly to other Sun Belt cities because the city’s land use regulations and legal covenants have played a similar role.[78][79] Regulations include mandatory lot size for single-family houses and requirements that parking be available to tenants and customers. Such restrictions have had mixed results. Though some have blamed the city’s low density, urban sprawl, and lack of pedestrian-friendliness on these policies, others have credited the city’s land use patterns with providing significant affordable housing, sparing Houston the worst effects of the 2008 real estate crisis. The city issued 42,697 building permits in 2008 and was ranked first in the list of healthiest housing markets for 2009.[80] In 2019, home sales reached a new record of $30 billion.[81]

In referendums in 1948, 1962, and 1993, voters rejected efforts to establish separate residential and commercial land-use districts. Consequently, rather than a single central business district as the center of the city’s employment, multiple districts and skylines have grown throughout the city in addition to Downtown, which include Uptown, the Texas Medical Center, Midtown, Greenway Plaza, Memorial City, the Energy Corridor, Westchase, and Greenspoint.[82]

Architecture[edit]

Houston had the fifth-tallest skyline in North America (after New York City, Chicago, Toronto and Miami) and 36th-tallest in the world in 2015.[83] A seven-mile (11 km) system of tunnels and skywalks links Downtown buildings containing shops and restaurants, enabling pedestrians to avoid summer heat and rain while walking between buildings. In the 1960s, Downtown Houston consisted of a collection of mid-rise office structures. Downtown was on the threshold of an energy industry–led boom in 1970. A succession of skyscrapers was built throughout the 1970s—many by real estate developer Gerald D. Hines—culminating with Houston’s tallest skyscraper, the 75-floor, 1,002-foot (305 m)-tall JPMorgan Chase Tower (formerly the Texas Commerce Tower), completed in 1982. It is the tallest structure in Texas, 19th tallest building in the United States, and was previously 85th-tallest skyscraper in the world, based on highest architectural feature. In 1983, the 71-floor, 992-foot (302 m)-tall Wells Fargo Plaza (formerly Allied Bank Plaza) was completed, becoming the second-tallest building in Houston and Texas. Based on highest architectural feature, it is the 21st-tallest in the United States. In 2007, Downtown had over 43 million square feet (4,000,000 m2) of office space.[84]

Centered on Post Oak Boulevard and Westheimer Road, the Uptown District boomed during the 1970s and early 1980s when a collection of midrise office buildings, hotels, and retail developments appeared along Interstate 610 West. Uptown became one of the most prominent instances of an edge city. The tallest building in Uptown is the 64-floor, 901-foot (275 m)-tall, Philip Johnson and John Burgee designed landmark Williams Tower (known as the Transco Tower until 1999). At the time of construction, it was believed to be the world’s tallest skyscraper outside a central business district. The new 20-story Skanska building[85] and BBVA Compass Plaza[86] are the newest office buildings built in Uptown after 30 years. The Uptown District is also home to buildings designed by noted architects I. M. Pei, César Pelli, and Philip Johnson. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a mini-boom of midrise and highrise residential tower construction occurred, with several over 30 stories tall.[87][88][89] Since 2000 over 30 skyscrapers have been developed in Houston; all told, 72 high-rises tower over the city, which adds up to about 8,300 units.[90] In 2002, Uptown had more than 23 million square feet (2,100,000 m2) of office space with 16 million square feet (1,500,000 m2) of class A office space.[91]

-

The Niels Esperson Building stood as the tallest building in Houston from 1927 to 1929.

-

The JPMorgan Chase Tower is the tallest building in Texas and the tallest 5-sided building in the world.

-

The Williams Tower is the tallest building in the US outside a central business district.

Climate[edit]

Houston’s climate is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification system), typical of the Southern United States. While not in Tornado Alley, like much of Northern Texas, spring supercell thunderstorms sometimes bring tornadoes to the area.[92] Prevailing winds are from the south and southeast during most of the year, which bring heat and moisture from the nearby Gulf of Mexico and Galveston Bay.[93]

During the summer, temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 106.5 days per year, including a majority of days from June to September. Additionally, an average of 4.6 days per year reach or exceed 100 °F (37.8 °C).[94] Houston’s characteristic subtropical humidity often results in a higher apparent temperature, and summer mornings average over 90% relative humidity.[95] Air conditioning is ubiquitous in Houston; in 1981, annual spending on electricity for interior cooling exceeded $600 million (equivalent to $1.79 billion in 2021), and by the late 1990s, approximately 90% of Houston homes featured air conditioning systems.[96][97] The record highest temperature recorded in Houston is 109 °F (43 °C) at Bush Intercontinental Airport, during September 4, 2000, and again on August 27, 2011.[94]

Houston has mild winters, with occasional cold spells. In January, the normal mean temperature at George Bush Intercontinental Airport is 53 °F (12 °C), with an average of 13 days per year with a low at or below 32 °F (0 °C), occurring on average between December 3 and February 20, allowing for a growing season of 286 days.[94] Twenty-first century snow events in Houston include a storm on December 24, 2004, which saw 1 inch (3 cm) of snow accumulate in parts of the metro area,[98] and an event on December 7, 2017, which precipitated 0.7 inches (2 cm) of snowfall.[99][100] Snowfalls of at least 1 inch (2.5 cm) on both December 10, 2008, and December 4, 2009, marked the first time measurable snowfall had occurred in two consecutive years in the city’s recorded history. Overall, Houston has seen measurable snowfall 38 times between 1895 and 2018. On February 14 and 15, 1895, Houston received 20 inches (51 cm) of snow, its largest snowfall from one storm on record.[101] The coldest temperature officially recorded in Houston was 5 °F (−15 °C) on January 18, 1930.[94] The last time Houston saw single digit temperatures was on December 23, 1989. The temperature dropped to 7 °F (−14 °C) at Bush Airport, marking the coldest temperature ever recorded there. 1.7 inches of snow fell at George Bush Intercontinental Airport the previous day.[102]

Houston generally receives ample rainfall, averaging about 49.8 in (1,260 mm) annually based on records between 1981 and 2010. Many parts of the city have a high risk of localized flooding due to flat topography,[103] ubiquitous low-permeability clay-silt prairie soils,[104] and inadequate infrastructure.[103] During the mid-2010s, Greater Houston experienced consecutive major flood events in 2015 («Memorial Day»),[105] 2016 («Tax Day»),[106] and 2017 (Hurricane Harvey).[107] Overall, there have been more casualties and property loss from floods in Houston than in any other locality in the United States.[108] The majority of rainfall occurs between April and October (the wet season of Southeast Texas), when the moisture from the Gulf of Mexico evaporates extensively over the city.[105][108]

Houston has excessive ozone levels and is routinely ranked among the most ozone-polluted cities in the United States.[109] Ground-level ozone, or smog, is Houston’s predominant air pollution problem, with the American Lung Association rating the metropolitan area’s ozone level twelfth on the «Most Polluted Cities by Ozone» in 2017, after major cities such as Los Angeles, Phoenix, New York City, and Denver.[110] The industries along the ship channel are a major cause of the city’s air pollution.[111] The rankings are in terms of peak-based standards, focusing strictly on the worst days of the year; the average ozone levels in Houston are lower than what is seen in most other areas of the country, as dominant winds ensure clean, marine air from the Gulf.[112] Excessive man-made emissions in the Houston area led to a persistent increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide over the city. Such an increase, often regarded as «CO2 urban dome», is driven by a combination of strong emissions and stagnant atmospheric conditions. Moreover, Houston is the only metropolitan area with less than ten million citizens where such a CO2 dome can be detected by satellites.[113]

| Climate data for Houston (Intercontinental Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1888–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

109 (43) |

109 (43) |

99 (37) |

89 (32) |

85 (29) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.9 (26.1) |

81.2 (27.3) |

85.4 (29.7) |

88.6 (31.4) |

93.8 (34.3) |

97.8 (36.6) |

99.1 (37.3) |

101.2 (38.4) |

97.3 (36.3) |

92.2 (33.4) |

84.9 (29.4) |

80.7 (27.1) |

102.1 (38.9) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.8 (17.7) |

67.8 (19.9) |

74.0 (23.3) |

80.1 (26.7) |

86.9 (30.5) |

92.3 (33.5) |

94.5 (34.7) |

94.9 (34.9) |

90.4 (32.4) |

82.8 (28.2) |

72.6 (22.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

80.5 (26.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.8 (12.1) |

57.7 (14.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

70.0 (21.1) |

77.4 (25.2) |

83.0 (28.3) |

85.1 (29.5) |

85.2 (29.6) |

80.5 (26.9) |

71.8 (22.1) |

62.0 (16.7) |

55.4 (13.0) |

70.5 (21.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 43.7 (6.5) |

47.6 (8.7) |

53.6 (12.0) |

59.8 (15.4) |

67.8 (19.9) |

73.7 (23.2) |

75.7 (24.3) |

75.4 (24.1) |

70.6 (21.4) |

60.9 (16.1) |

51.5 (10.8) |

45.6 (7.6) |

60.5 (15.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 27.5 (−2.5) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

35.0 (1.7) |

43.4 (6.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

66.5 (19.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

70.0 (21.1) |

58.3 (14.6) |

44.1 (6.7) |

34.2 (1.2) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 5 (−15) |

6 (−14) |

21 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

42 (6) |

52 (11) |

62 (17) |

54 (12) |

45 (7) |

29 (−2) |

19 (−7) |

7 (−14) |

5 (−15) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.76 (96) |

2.97 (75) |

3.47 (88) |

3.95 (100) |

5.01 (127) |

6.00 (152) |

3.77 (96) |

4.84 (123) |

4.71 (120) |

5.46 (139) |

3.87 (98) |

4.03 (102) |

51.84 (1,317) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.1 (0.25) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.0 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 104.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.7 | 73.4 | 72.7 | 73.1 | 75.0 | 74.6 | 74.4 | 75.1 | 76.8 | 75.4 | 76.0 | 75.5 | 74.7 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 41.5 (5.3) |

44.2 (6.8) |

51.3 (10.7) |

57.7 (14.3) |

65.1 (18.4) |

70.3 (21.3) |

72.1 (22.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

68.5 (20.3) |

59.5 (15.3) |

51.4 (10.8) |

44.8 (7.1) |

58.2 (14.6) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143.4 | 155.0 | 192.5 | 209.8 | 249.2 | 281.3 | 293.9 | 270.5 | 236.5 | 228.8 | 168.3 | 148.7 | 2,577.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 50 | 52 | 54 | 59 | 67 | 68 | 66 | 64 | 64 | 53 | 47 | 58 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1969–1990, sun 1961–1990)[94][115][116] |

| Climate data for Houston (William P. Hobby Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1941–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

87 (31) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

96 (36) |

90 (32) |

84 (29) |

108 (42) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.8 (17.7) |

67.6 (19.8) |

73.4 (23.0) |

79.3 (26.3) |

85.9 (29.9) |

91.0 (32.8) |

92.9 (33.8) |

93.5 (34.2) |

89.3 (31.8) |

82.1 (27.8) |

72.6 (22.6) |

65.7 (18.7) |

79.8 (26.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 55.0 (12.8) |

58.9 (14.9) |

64.7 (18.2) |

70.6 (21.4) |

77.6 (25.3) |

83.0 (28.3) |

84.8 (29.3) |

85.1 (29.5) |

81.1 (27.3) |

73.0 (22.8) |

63.3 (17.4) |

56.9 (13.8) |

71.2 (21.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 46.1 (7.8) |

50.1 (10.1) |

55.9 (13.3) |

61.8 (16.6) |

69.3 (20.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

76.6 (24.8) |

76.7 (24.8) |

72.9 (22.7) |

63.9 (17.7) |

54.0 (12.2) |

48.0 (8.9) |

62.5 (16.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 10 (−12) |

14 (−10) |

22 (−6) |

36 (2) |

44 (7) |

56 (13) |

64 (18) |

66 (19) |

50 (10) |

33 (1) |

25 (−4) |

9 (−13) |

9 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.09 (104) |

2.85 (72) |

3.28 (83) |

4.08 (104) |

5.42 (138) |

6.09 (155) |

4.59 (117) |

5.44 (138) |

5.76 (146) |

5.78 (147) |

3.90 (99) |

4.34 (110) |

55.62 (1,413) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.2 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 7.3 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 103.7 |

| Source: NOAA[94] |

Flooded parking lot during Hurricane Harvey, August 2017

Because of Houston’s wet season and proximity to the Gulf Coast, the city is prone to flooding from heavy rains; the most notable flooding events include Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017, along with most recent Tropical Storm Imelda in 2019 and Tropical Storm Beta in 2020. In response to Hurricane Harvey, Mayor Sylvester Turner of Houston initiated plans to require developers to build homes that will be less susceptible to flooding by raising them two feet above the 500-year floodplain. Hurricane Harvey damaged hundreds of thousands of homes and dumped trillions of gallons of water into the city.[117] In places this led to feet of standing water that blocked streets and flooded homes. The Houston City Council passed this regulation in 2018 with a vote of 9–7. Had these floodplain development rules had been in place all along, it is estimated that 84% of homes in the 100-year and 500-year floodplains would have been spared damage.[dubious – discuss][117]

In a recent case testing these regulations, near the Brickhouse Gulley, an old golf course that long served as a floodplain and reservoir for floodwaters, announced a change of heart toward intensifying development.[118] A nationwide developer, Meritage Homes, bought the land and planned to develop the 500-year floodplain into 900 new residential homes. Their plan would bring in $360 million in revenue and boost city population and tax revenue. In order to meet the new floodplain regulations, the developers needed to elevate the lowest floors two feet above the 500-year floodplain, equivalent to five or six feet above the 100-year base flood elevation, and build a channel to direct stormwater runoff toward detention basins. Before Hurricane Harvey, the city had bought $10.7 million in houses in this area specifically to take them out of danger. In addition to developing new streets and single-family housing within a floodplain, a flowing flood-water stream termed a floodway runs through the development area, a most dangerous place to encounter during any future flooding event.[119] Under Texas law Harris County, like other more rural Texas counties, cannot direct developers where to build or not build via land use controls such as a zoning ordinance, and instead can only impose general floodplain regulations for enforcement during subdivision approvals and building permit approvals.[119]

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,396 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,845 | 102.2% | |

| 1870 | 9,382 | 93.6% | |

| 1880 | 16,513 | 76.0% | |

| 1890 | 27,557 | 66.9% | |

| 1900 | 44,633 | 62.0% | |

| 1910 | 78,800 | 76.6% | |

| 1920 | 138,276 | 75.5% | |

| 1930 | 292,352 | 111.4% | |

| 1940 | 384,514 | 31.5% | |

| 1950 | 596,163 | 55.0% | |

| 1960 | 938,219 | 57.4% | |

| 1970 | 1,232,802 | 31.4% | |

| 1980 | 1,595,138 | 29.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,630,553 | 2.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,953,631 | 19.8% | |

| 2010 | 2,099,451 | 7.5% | |

| 2020 | 2,304,580 | 9.8% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 2,288,250 | −0.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census 2010–2020[2] |

Map of ethnic distribution in Houston, 2010 U.S. census. Each dot is 25 people: ⬤ White

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Other

The 2020 U.S. census determined Houston had a population of 2,304,580.[2] In 2017, the census-estimated population was 2,312,717, and in 2018 it was 2,325,502.[2] An estimated 600,000 undocumented immigrants resided in the Houston area in 2017,[120] comprising nearly 9% of the city’s metropolitan population.[121] At the 2010 United States census, Houston had a population of 2,100,263 residents,[122] up from the city’s 2,396 at the 1850 census.

Per the 2019 American Community Survey, Houston’s age distribution was 482,402 under 15; 144,196 aged 15 to 19; 594,477 aged 20 to 34; 591,561 aged 35 to 54; 402,804 aged 55 to 74; and 101,357 aged 75 and older. The median age of the city was 33.4.[123] At the 2014-2018 census estimates, Houston’s age distribution was 486,083 under 15; 147,710 aged 15 to 19; 603,586 aged 20 to 34; 726,877 aged 35 to 59; and 357,834 aged 60 and older.[124] The median age was 33.1, up from 32.9 in 2017 and down from 33.5 in 2014; the city’s youthfulness has been attributed to an influx of an African American New Great Migration, Hispanic and Latino American, and Asian immigrants into Texas.[125][126][127] For every 100 females, there were 98.5 males.[124]

There were 987,158 housing units in 2019 and 876,504 households.[123][128] An estimated 42.3% of Houstonians owned housing units, with an average of 2.65 people per household.[129] The median monthly owner costs with a mortgage were $1,646, and $536 without a mortgage. Houston’s median gross rent from 2015 to 2019 was $1,041. The median household income in 2019 was $52,338 and 20.1% of Houstonians lived at or below the poverty line.

Race and ethnicity[edit]

| Racial and ethnic composition | 2020[130] | 2010[131] | 2000[132] | 1990[35] | 1970[35] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 44.0% | 43.8% | 37.4% | 27.6% | 11.3%[133] |

| Whites (Non-Hispanic) | 23.7% | 25.6%[134] | 30.8%[135] | 40.6% | 62.4%[133] |

| Black or African American | 22.1% | 23.7% | 25.3% | 28.1% | 25.7% |

| Asian | 7.1% | 6.0% | 5.3% | 4.1% | 0.4% |

Houston is a majority-minority city. The Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research, a think tank, has described Greater Houston as «one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse metropolitan areas in the country».[136] Houston’s diversity, historically fueled by large waves of Hispanic and Latino American, and Asian immigrants, has been attributed to its relatively low cost of living, strong job market, and role as a hub for refugee resettlement.[137][138]

Houston has long been known as a popular destination for African Americans due to the city’s well-established and influential African American community. Houston has become known as a Black Mecca akin to Atlanta because it is a popular living destination for Black professionals and entrepreneurs.[139] The Houston area is home to the largest African American community west of the Mississippi River.[140][141][142] A 2012 Kinder Institute report found that, based on the evenness of population distribution between the four major racial groups in the United States (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian), Greater Houston was the most ethnically diverse metropolitan area in the United States, ahead of New York City.[143]

In 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, non-Hispanic whites made up 23.3% of the population of Houston proper, Hispanics and Latino Americans 45.8%, Blacks or African Americans 22.4%, and Asian Americans 6.5%.[123] In 2018, non-Hispanic whites made up 20.7% of the population, Hispanics or Latino Americans 44.9%, Blacks or African Americans 30.3%, and Asian Americans 8.2%.[124] The largest Hispanic or Latino American ethnic groups in the city were Mexican Americans (31.6%), Puerto Ricans (0.8%), and Cuban Americans (0.8%) in 2018.[124]

As documented, Houston has a higher proportion of minorities than non-Hispanic whites; in 2010, whites (including Hispanic whites) made up 57.6% of the city of Houston’s population; 24.6% of the total population was non-Hispanic white.[144] Blacks or African Americans made up 22.5% of Houston’s population, American Indians made up 0.3% of the population, Asians made up 6.9% (1.7% Vietnamese, 1.3% Chinese, 1.3% Indian, 0.9% Pakistani, 0.4% Filipino, 0.3% Korean, 0.1% Japanese) and Pacific Islanders made up 0.1%. Individuals from some other race made up 15.69% of the city’s population.[131] Individuals from two or more races made up 2.1% of the city.[144]

At the 2000 U.S. census, the racial makeup of the city in was 49.3% White, 25.3% Black or African American, 5.3% Asian, 0.7% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 16.5% from some other race, and 3.1% from two or more races. In addition, Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 37.4% of Houston’s population in 2000, while non-Hispanic whites made up 30.8%.[145] The proportion of non-Hispanic whites in Houston has decreased significantly since 1970, when it was 62.4%.[35]

Sexual orientation and gender identity[edit]

Houston is home to one of the largest LGBT communities and pride parades in the United States.[146][147][148] In 2018, the city scored a 70 out of 100 for LGBT friendliness.[149] Jordan Blum of the Houston Chronicle stated levels of LGBT acceptance and discrimination varied in 2016 due to some of the region’s traditionally conservative culture.[150]

Before the 1970s, the city’s gay bars were spread around Downtown Houston and what is now midtown Houston. LGBT Houstonians needed to have a place to socialize after the closing of the gay bars. They began going to Art Wren, a 24-hour restaurant in Montrose. LGBT community members were attracted to Montrose as a neighborhood after encountering it while patronizing Art Wren, and they began to gentrify the neighborhood and assist its native inhabitants with property maintenance. Within Montrose, new gay bars began to open.[151] By 1985, the flavor and politics of the neighborhood were heavily influenced by the LGBT community, and in 1990, according to Hill, 19% of Montrose residents identified as LGBT. Paul Broussard was murdered in Montrose in 1991.[152]

Before the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States the Marriage of Billie Ert and Antonio Molina, considered the first same-sex marriage in Texas history, took place on October 5, 1972.[153] Houston elected the first openly lesbian mayor of a major city in 2009, and she served until 2016.[153][154] During her tenure she authorized the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance which was intended to improve anti-discrimination coverage based on sexual orientation and gender identity in the city, specifically in areas such as housing and occupation where no anti-discrimination policy existed.[155]

Religion[edit]

Houston and its metropolitan area are the third-most religious and Christian area by percentage of population in the United States, and second in Texas behind the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex.[156][157] Historically, Houston has been a center of Protestant Christianity, being part of the Bible Belt.[158] Other Christian groups including Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christianity, and non-Christian religions did not grow for much of the city’s history because immigration was predominantly from Western Europe (which at the time was dominated by Western Christianity and favored by the quotas in federal immigration law). The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 removed the quotas, allowing for the growth of other religions.[159]

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, 73% of the population of the Houston area identified themselves as Christians, about 50% of whom claimed Protestant affiliations and about 19% claimed Roman Catholic affiliations. Nationwide, about 71% of respondents identified as Christians. About 20% of Houston-area residents claimed no religious affiliation, compared to about 23% nationwide.[160] The same study says area residents who identify with other religions (including Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, and Hinduism) collectively made up about 7% of the area population.[160]

In 2020, the Public Religion Research Institute estimated 40% were Protestant and 29% Catholic; overall, Christianity represented 72% of the population.[161] In 2020, the Association of Religion Data Archives determined the Catholic Church numbered 1,299,901 for the metropolitan area; the second-largest single Christian denomination (Southern Baptists) numbered 800,688; following, non-denominational Protestant churches represented the third-largest Christian cohort at 666,548.[162] Altogether, however, Baptists of the Southern Baptist Convention, the American Baptist Association, American Baptist Churches USA, Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship, National Baptist Convention USA and National Baptist Convention of America, and the National Missionary Baptist Convention numbered 926,554. Non-denominational Protestants, the Disciples of Christ, Christian Churches and Churches of Christ, and the Churches of Christ numbered 723,603 altogether according to this study.

Lakewood Church in Houston, led by Pastor Joel Osteen, is the largest church in the United States. A megachurch, it had 44,800 weekly attendees in 2010, up from 11,000 weekly in 2000.[163] Since 2005, it has occupied the former Compaq Center sports stadium. In September 2010, Outreach magazine published a list of the 100 largest Christian churches in the United States, and on the list were the following Houston-area churches: Lakewood, Second Baptist Church Houston, Woodlands Church, Church Without Walls, and First Baptist Church.[163] According to the list, Houston and Dallas were tied as the second-most popular city for megachurches.[163]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, the largest Catholic jurisdiction in Texas and fifth-largest in the United States, was established in 1847.[164] The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston claimed approximately 1.7 million Catholics within its boundaries as of 2019.[164] Its co-cathedral is located within the Houston city limits, while the diocesan see is in Galveston. Other prominent Catholic jurisdictions include the Eastern Catholic Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church and Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church as well as the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter, whose cathedral is also in Houston.[165]

Debre Selam Medhanealem Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church

A variety of Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches can be found in Houston. Immigrants from Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Ethiopia, India, and other areas have added to Houston’s Eastern and Oriental Orthodox population. As of 2011 in the entire state, 32,000 people actively attended Orthodox churches.[166] In 2013 Father John Whiteford, the pastor of St. Jonah Orthodox Church near Spring, stated there were about 6,000-9,000 Eastern Orthodox Christians in Houston.[167] The Association of Religion Data Archives numbered 16,526 Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Houstonians in 2020.[162] The most prominent Eastern and Oriental Orthodox jurisdictions are the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America,[168] the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America,[169] the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria,[170] and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[171]

Houston’s Jewish community, estimated at 47,000 in 2001, has been present in the city since the 1800s. Houstonian Jews have origins from throughout the United States, Israel, Mexico, Russia, and other places. As of 2016, over 40 synagogues were in Greater Houston.[159] The largest synagogues are Congregation Beth Yeshurun, a Conservative Jewish temple, and the Reform Jewish congregations Beth Israel and Emanu-El. According to a study in 2016 by Berman Jewish DataBank, 51,000 Jews lived in the area, an increase of 4,000 since 2001.[172]

Houston has a large and diverse Muslim community; it is the largest in Texas and the Southern United States, as of 2012.[173] It is estimated that Muslims made up 1.2% of Houston’s population.[173] As of 2016, Muslims in the Houston area included South Asians, Middle Easterners, Africans, Turks, and Indonesians, as well as a growing population of Latino Muslim converts. In 2000 there were over 41 mosques and storefront religious centers, with the largest being the Al-Noor Mosque (Mosque of Light) of the Islamic Society of Greater Houston.[174]

The Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist communities form a growing sector of the religious demographic after Judaism and Islam. Large Hindu temples in the metropolitan area include the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Houston, affiliated with the Swaminarayan Sampradaya denomination in Fort Bend County, near the suburb of Stafford as well as the South Indian-style Sri Meenakshi Temple in suburban Pearland, in Brazoria County, which is the oldest Hindu temple in Texas and third-oldest Hindu temple in the United States.[175][176][177]

Of the irreligious community 16% practiced nothing in particular, 3% were agnostic, and 2% were atheist in 2014.[156]

Economy[edit]

| Fortune 500 companies based in Houston[178] | |

| Rank | Company |

|---|---|

| 27 | Phillips 66 |

| 56 | Sysco |

| 93 | ConocoPhillips |

| 98 | Plains GP Holdings |

| 101 | Enterprise Products Partners |

| 129 | Baker Hughes |

| 142 | Halliburton |

| 148 | Occidental Petroleum |

| 186 | EOG Resources |

| 207 | Waste Management |

| 242 | Kinder Morgan |

| 260 | CenterPoint Energy |

| 261 | Quanta Services |

| 264 | Group 1 Automotive |

| 319 | Calpine |

| 329 | Cheniere Energy |

| 365 | Targa Resources |

| 374 | NOV Inc. |

| 391 | Westlake Chemical |

| 465 | APA Corporation |

| 496 | Crown Castle |

| 501 | KBR |

| Companies in the petroleum industry |

Houston is recognized worldwide for its energy industry—particularly for oil and natural gas—as well as for biomedical research and aeronautics. Renewable energy sources—wind and solar—are also growing economic bases in the city,[179][180] and the City Government purchases 90% of its annual 1 TWh power mostly from wind, and some from solar.[181][182] The city has also been a growing hub for technology startup firms.[183] Major technology and software companies within Greater Houston include Crown Castle, KBR, Cybersoft, Houston Wire & Cable, and HostGator. On April 4, 2022, Hewlett Packard Enterprise relocated its global headquarters from California to the Greater Houston area.[184] The Houston Ship Channel is also a large part of Houston’s economic base.

Because of these strengths, Houston is designated as a global city by the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network and global management consulting firm A.T. Kearney.[14] The Houston area is the top U.S. market for exports, surpassing New York City in 2013, according to data released by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration. In 2012, the Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land area recorded $110.3 billion in merchandise exports.[185] Petroleum products, chemicals, and oil and gas extraction equipment accounted for roughly two-thirds of the metropolitan area’s exports last year. The top three destinations for exports were Mexico, Canada, and Brazil.[186]

The Houston area is a leading center for building oilfield equipment.[187] Much of its success as a petrochemical complex is due to its busy ship channel, the Port of Houston.[188] In the United States, the port ranks first in international commerce and 16th among the largest ports in the world.[189] Unlike most places, high oil and gasoline prices are beneficial for Houston’s economy, as many of its residents are employed in the energy industry.[190] Houston is the beginning or end point of numerous oil, gas, and products pipelines.[191]

The Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land metro area’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016 was $478 billion, making it the sixth-largest of any metropolitan area in the United States and larger than Iran’s, Colombia’s, or the United Arab Emirates’ GDP.[192] Only 27 countries other than the United States have a gross domestic product exceeding Houston’s regional gross area product (GAP).[193] In 2010, mining (which consists almost entirely of exploration and production of oil and gas in Houston) accounted for 26.3% of Houston’s GAP up sharply in response to high energy prices and a decreased worldwide surplus of oil production capacity, followed by engineering services, health services, and manufacturing.[194]

The University of Houston System’s annual impact on the Houston area’s economy equates to that of a major corporation: $1.1 billion in new funds attracted annually to the Houston area, $3.13 billion in total economic benefit, and 24,000 local jobs generated.[195][196] This is in addition to the 12,500 new graduates the U.H. System produces every year who enter the workforce in Houston and throughout Texas. These degree-holders tend to stay in Houston. After five years, 80.5% of graduates are still living and working in the region.[196]

In 2006, the Houston metropolitan area ranked first in Texas and third in the U.S. within the category of «Best Places for Business and Careers» by Forbes magazine.[197] Ninety-one foreign governments have established consular offices in Houston’s metropolitan area, the third-highest in the nation.[198] Forty foreign governments maintain trade and commercial offices here with 23 active foreign chambers of commerce and trade associations.[199] Twenty-five foreign banks representing 13 nations operate in Houston, providing financial assistance to the international community.[200]

In 2008, Houston received top ranking on Kiplinger’s Personal Finance «Best Cities of 2008» list, which ranks cities on their local economy, employment opportunities, reasonable living costs, and quality of life.[201] The city ranked fourth for highest increase in the local technological innovation over the preceding 15 years, according to Forbes magazine.[202] In the same year, the city ranked second on the annual Fortune 500 list of company headquarters,[203] first for Forbes magazine’s «Best Cities for College Graduates»,[204] and first on their list of «Best Cities to Buy a Home».[205] In 2010, the city was rated the best city for shopping, according to Forbes.[206]

In 2012, the city was ranked number one for paycheck worth by Forbes and in late May 2013, Houston was identified as America’s top city for employment creation.[207][208]

In 2013, Houston was identified as the number one U.S. city for job creation by the U.S. Bureau of Statistics after it was not only the first major city to regain all the jobs lost in the preceding economic downturn, but also after the crash, more than two jobs were added for every one lost. Economist and vice president of research at the Greater Houston Partnership Patrick Jankowski attributed Houston’s success to the ability of the region’s real estate and energy industries to learn from historical mistakes. Furthermore, Jankowski stated that «more than 100 foreign-owned companies relocated, expanded or started new businesses in Houston» between 2008 and 2010, and this openness to external business boosted job creation during a period when domestic demand was problematically low.[208] Also in 2013, Houston again appeared on Forbes‘ list of «Best Places for Business and Careers».[209]

Culture[edit]

Located in the American South, Houston is a diverse city with a large and growing international community.[210] The Greater Houston metropolitan area is home to an estimated 1.1 million (21.4 percent) residents who were born outside the United States, with nearly two-thirds of the area’s foreign-born population from south of the United States–Mexico border since 2009.[211] Additionally, more than one in five foreign-born residents are from Asia.[211] The city is home to the nation’s third-largest concentration of consular offices, representing 92 countries.[212]

Many annual events celebrate the diverse cultures of Houston. The largest and longest-running is the annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, held over 20 days from early to late March, and is the largest annual livestock show and rodeo in the world.[213] Another large celebration is the annual night-time Houston Gay Pride Parade, held at the end of June.[214] Other notable annual events include the Houston Greek Festival,[215] Art Car Parade, the Houston Auto Show, the Houston International Festival,[216] and the Bayou City Art Festival, which is considered to be one of the top five art festivals in the United States.[217][218]

Houston is highly regarded for its diverse food and restaurant culture. Several major publications have consistently named Houston one of «America’s Best Food Cities».[219][220][221][222][223] Houston received the official nickname of «Space City» in 1967 because it is the location of NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Other nicknames often used by locals include «Bayou City», «Clutch City», «Crush City», «Magnolia City», «H-Town», and «Culinary Capital of the South».[224][225][226]

Arts and theater[edit]

The Houston Theater District, in Downtown, is home to nine major performing arts organizations and six performance halls. It is the second-largest concentration of theater seats in a Downtown area in the United States.[227][228][229]

Houston is one of few United States cities with permanent, professional, resident companies in all major performing arts disciplines: opera (Houston Grand Opera), ballet (Houston Ballet), music (Houston Symphony Orchestra), and theater (The Alley Theatre, Theatre Under the Stars).[17][230] Houston is also home to folk artists, art groups and various small progressive arts organizations.[231]

Houston attracts many touring Broadway acts, concerts, shows, and exhibitions for a variety of interests.[232] Facilities in the Theater District include the Jones Hall—home of the Houston Symphony Orchestra and Society for the Performing Arts—and the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts.

The Museum District’s cultural institutions and exhibits attract more than 7 million visitors a year.[233][234] Notable facilities include The Museum of Fine Arts, the Houston Museum of Natural Science, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the Station Museum of Contemporary Art, the Holocaust Museum Houston, the Children’s Museum of Houston, and the Houston Zoo.[235][236][237]

Located near the Museum District are The Menil Collection, Rothko Chapel, the Moody Center for the Arts and the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum.

Bayou Bend is a 14-acre (5.7 ha) facility of the Museum of Fine Arts that houses one of America’s most prominent collections of decorative art, paintings, and furniture. Bayou Bend is the former home of Houston philanthropist Ima Hogg.[238]

The National Museum of Funeral History is in Houston near the George Bush Intercontinental Airport. The museum houses the original Popemobile used by Pope John Paul II in the 1980s along with numerous hearses, embalming displays, and information on famous funerals.

Venues across Houston regularly host local and touring rock, blues, country, dubstep, and Tejano musical acts. While Houston has never been widely known for its music scene,[239] Houston hip-hop has become a significant, independent music scene that is influential nationwide. Houston is the birthplace of the chopped and screwed remixing-technique in Hip-hop which was pioneered by DJ Screw from the city. Some other notable Hip-hop artists from the area include Destiny’s Child, Slim Thug, Paul Wall, Mike Jones, Bun B, Geto Boys, Trae tha Truth, Kirko Bangz, Z-Ro, South Park Mexican, Travis Scott and Megan Thee Stallion.[240]

Beyoncé Knowles also originated in Houston.

Tourism and recreation[edit]

The Theater District is a 17-block area in the center of Downtown Houston that is home to the Bayou Place entertainment complex, restaurants, movies, plazas, and parks. Bayou Place is a large multilevel building containing full-service restaurants, bars, live music, billiards, and Sundance Cinema. The Bayou Music Center stages live concerts, stage plays, and stand-up comedy.

Space Center Houston is the official visitors’ center of NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. The Space Center has many interactive exhibits including moon rocks, a shuttle simulator, and presentations about the history of NASA’s manned space flight program. Other tourist attractions include the Galleria (Texas’s largest shopping mall, in the Uptown District), Old Market Square, the Downtown Aquarium, and Sam Houston Race Park.

Houston’s current Chinatown and the Mahatma Gandhi District are two major ethnic enclaves, reflecting Houston’s multicultural makeup. Restaurants, bakeries, traditional-clothing boutiques, and specialty shops can be found in both areas.

Houston is home to 337 parks, including Hermann Park, Terry Hershey Park, Lake Houston Park, Memorial Park, Tranquility Park, Sesquicentennial Park, Discovery Green, Buffalo Bayou Park and Sam Houston Park. Within Hermann Park are the Houston Zoo and the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Sam Houston Park contains restored and reconstructed homes which were originally built between 1823 and 1905.[241] A proposal has been made to open the city’s first botanic garden at Herman Brown Park.[242]

Of the 10 most populous U.S. cities, Houston has the most total area of parks and green space, 56,405 acres (228 km2).[243] The city also has over 200 additional green spaces—totaling over 19,600 acres (79 km2) that are managed by the city—including the Houston Arboretum and Nature Center. The Lee and Joe Jamail Skatepark is a public skatepark owned and operated by the city of Houston, and is one of the largest skateparks in Texas consisting of a 30,000-ft2 (2,800 m2)in-ground facility.

The Gerald D. Hines Waterwall Park—in the Uptown District of the city—serves as a popular tourist attraction and for weddings and various celebrations. A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Houston the 23rd most walkable of the 50 largest cities in the United States.[244]

Sports[edit]

Houston has sports teams for every major professional league except the National Hockey League. The Houston Astros are a Major League Baseball expansion team formed in 1962 (known as the «Colt .45s» until 1965) that have won the World Series in 2017 and 2022 and appeared in it in 2005, 2019, and 2021. It is the only MLB team to have won pennants in both modern leagues.[245] The Houston Rockets are a National Basketball Association franchise based in the city since 1971. They have won two NBA Championships, one in 1994 and another in 1995, under star players Hakeem Olajuwon, Otis Thorpe, Clyde Drexler, Vernon Maxwell, and Kenny Smith.[246] The Houston Texans are a National Football League expansion team formed in 2002. The Houston Dynamo is a Major League Soccer franchise that has been based in Houston since 2006, winning two MLS Cup titles in 2006 and 2007. The Houston Dash team plays in the National Women’s Soccer League.[247] The Houston SaberCats are a rugby team that plays in Major League Rugby.[248]

Minute Maid Park (home of the Astros) and Toyota Center (home of the Rockets), are in Downtown Houston. Houston has the NFL’s first retractable-roof stadium with natural grass, NRG Stadium (home of the Texans).[249] Minute Maid Park is also a retractable-roof stadium. Toyota Center also has the largest screen for an indoor arena in the United States built to coincide with the arena’s hosting of the 2013 NBA All-Star Game.[250] PNC Stadium is a soccer-specific stadium for the Houston Dynamo, the Texas Southern Tigers football team, and Houston Dash, in East Downtown. Aveva Stadium (home of the SaberCats) is in south Houston. In addition, NRG Astrodome was the first indoor stadium in the world, built in 1965.[251] Other sports facilities include Hofheinz Pavilion (Houston Cougars basketball), Rice Stadium (Rice Owls football), and NRG Arena. TDECU Stadium is where the University of Houston’s Cougars football team plays.[252]

Houston has hosted several major sports events: the 1968, 1986 and 2004 Major League Baseball All-Star Games; the 1989, 2006 and 2013 NBA All-Star Games; Super Bowl VIII, Super Bowl XXXVIII, and Super Bowl LI, as well as hosting the 1981, 1986, 1994 and 1995 NBA Finals, winning the latter two, and hosting the 2005 World Series, 2017 World Series, 2019 World Series, 2021 World Series and 2022 World Series. The city won its first baseball championship during the 2017 event and won again 5 years later. NRG Stadium hosted Super Bowl LI on February 5, 2017.[253] Houston will host multiple matches during the 2026 FIFA World Cup.

The city has hosted several major professional and college sporting events, including the annual Houston Open golf tournament. Houston hosts the annual Houston College Classic baseball tournament every February, and the Texas Kickoff and Bowl in September and December, respectively.[254]

The Grand Prix of Houston, an annual auto race on the IndyCar Series circuit was held on a 1.7-mile temporary street circuit in NRG Park. The October 2013 event was held using a tweaked version of the 2006–2007 course.[255] The event had a 5-year race contract through 2017 with IndyCar.[256] In motorcycling, the Astrodome hosted an AMA Supercross Championship round from 1974 to 2003 and the NRG Stadium since 2003.

Houston is also one of the first cities in the world to have a major esports team represent it, in the form of the Houston Outlaws. The Outlaws play in the Overwatch League and are one of two Texan teams, the other being the Dallas Fuel. Houston is also one of eight cities to have an XFL team, the Houston Roughnecks.

Government[edit]

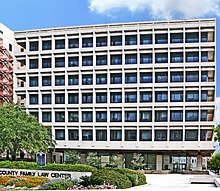

Harris County Family Law Center

The city of Houston has a strong mayoral form of municipal government.[257] Houston is a home rule city and all municipal elections in Texas are nonpartisan.[257][258] The city’s elected officials are the mayor, city controller and 16 members of the Houston City Council.[259] The current mayor of Houston is Sylvester Turner, a Democrat elected on a nonpartisan ballot. Houston’s mayor serves as the city’s chief administrator, executive officer, and official representative, and is responsible for the general management of the city and for seeing all laws and ordinances are enforced.[260]

The original city council line-up of 14 members (nine district-based and five at-large positions) was based on a U.S. Justice Department mandate which took effect in 1979.[261] At-large council members represent the entire city.[259] Under the city charter, once the population in the city limits exceeded 2.1 million residents, two additional districts were to be added.[262] The city of Houston’s official 2010 census count was 600 shy of the required number; however, as the city was expected to grow beyond 2.1 million shortly thereafter, the two additional districts were added for, and the positions filled during, the August 2011 elections.

The city controller is elected independently of the mayor and council. The controller’s duties are to certify available funds prior to committing such funds and processing disbursements. The city’s fiscal year begins on July 1 and ends on June 30. Chris Brown is the city controller, serving his first term as of January 2016.

As the result of a 2015 referendum in Houston, a mayor is elected for a four-year term and can be elected to as many as two consecutive terms.[263] The term limits were spearheaded in 1991 by conservative political activist Clymer Wright.[264] During 1991–2015, the city controller and city council members were subjected to a two-year, three-term limitation–the 2015 referendum amended term limits to two four-year terms. As of 2017 some councilmembers who served two terms and won a final term will have served eight years in office, whereas a freshman councilmember who won a position in 2013 can serve up to two additional terms under the previous term limit law–a select few will have at least 10 years of incumbency once their term expires.

Houston is considered to be a politically divided city whose balance of power often sways between Republicans and Democrats. According to the 2005 Houston Area Survey, 68 percent of non-Hispanic whites in Harris County are declared or favor Republicans while 89 percent of non-Hispanic blacks in the area are declared or favor Democrats. About 62 percent of Hispanics (of any nationality) in the area are declared or favor Democrats.[265] The city has often been known to be the most politically diverse city in Texas, a state known for being generally conservative.[265] As a result, the city is often a contested area in statewide elections.[265] In 2009, Houston became the first U.S. city with a population over 1 million citizens to elect a gay mayor, by electing Annise Parker.[266]

Texas has banned sanctuary cities,[267] but Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner said Houston will not assist ICE agents with immigration raids.[268]

Crime[edit]

Houston Police Department headquarters

Houston had 303 homicides in 2015 and 302 homicides in 2016. Officials predicted there would be 323 homicides in 2016. Instead, there was no increase in Houston’s homicide rate between 2015 and 2016.[269][discuss]

Houston’s murder rate ranked 46th of U.S. cities with a population over 250,000 in 2005 (per capita rate of 16.3 murders per 100,000 population).[270] In 2010, the city’s murder rate (per capita rate of 11.8 murders per 100,000 population) was ranked sixth among U.S. cities with a population of over 750,000 (behind New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Dallas, and Philadelphia) according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[271]

Murders fell by 37 percent from January to June 2011, compared with the same period in 2010. Houston’s total crime rate including violent and nonviolent crimes decreased by 11 percent.[272] The FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR) indicates a downward trend of violent crime in Houston over the ten- and twenty-year periods ending in 2016, which is consistent with national trends. This trend toward lower rates of violent crime in Houston includes the murder rate, though it had seen a four-year uptick that lasted through 2015. Houston’s violent crime rate was 8.6% percent higher in 2016 than the previous year. However, from 2006 to 2016, violent crime was still down 12 percent in Houston.[273]

Houston is a significant hub for trafficking of cocaine, cannabis, heroin, MDMA, and methamphetamine due to its size and proximity to major illegal drug exporting nations.[274]

In the early 1970s, Houston, Pasadena and several coastal towns were the site of the Houston mass murders, which at the time were the deadliest case of serial killing in American history.[275][276]

In 1853, the first execution in Houston took place in public at Founder’s Cemetery in the Fourth Ward; initially, the cemetery was the execution site, but post-1868 executions took place in the jail facilities.[277]

Education[edit]

The first Hattie Mae White Administration Building; it has been sold and demolished

Nineteen school districts exist within the city of Houston. The Houston Independent School District (HISD) is the seventh-largest school district in the United States and the largest in Texas.[278] HISD has over 100 campuses that serve as magnet or vanguard schools—specializing in such disciplines as health professions, visual and performing arts, and the sciences. There are also many charter schools that are run separately from school districts. In addition, some public school districts also have their own charter schools.

The Houston area encompasses more than 300 private schools,[279][280][281] many of which are accredited by Texas Private School Accreditation Commission recognized agencies. The Greater Houston metropolitan area’s independent schools offer education from a variety of different religious as well as secular viewpoints.[282] The Greater Houston area’s Catholic schools are operated by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston.

Colleges and universities[edit]

Houston has four state universities. The University of Houston (UH) is a research university and the flagship institution of the University of Houston System.[283][284][285] The third-largest university in Texas, the University of Houston has nearly 44,000 students on its 667-acre (270-hectare) campus in the Third Ward.[286] The University of Houston–Clear Lake and the University of Houston–Downtown are stand-alone universities within the University of Houston System; they are not branch campuses of the University of Houston. Slightly west of the University of Houston is Texas Southern University (TSU), one of the largest historically black universities in the United States with approximately 10,000 students. Texas Southern University is the first state university in Houston, founded in 1927.[287]

Several private institutions of higher learning are within the city. Rice University, the most selective university in Texas and one of the most selective in the United States,[288] is a private, secular institution with a high level of research activity.[289] Founded in 1912, Rice’s historic, heavily wooded 300-acre (120-hectare) campus, adjacent to Hermann Park and the Texas Medical Center, hosts approximately 4,000 undergraduate and 3,000 post-graduate students. To the north in Neartown, the University of St. Thomas, founded in 1947, is Houston’s only Catholic university. St. Thomas provides a liberal arts curriculum for roughly 3,000 students at its historic 19-block campus along Montrose Boulevard. In southwest Houston, Houston Christian University (formerly Houston Baptist University), founded in 1960, offers bachelor’s and graduate degrees at its Sharpstown campus. The school is affiliated with the Baptist General Convention of Texas and has a student population of approximately 3,000.

Three community college districts have campuses in and around Houston. The Houston Community College System (HCC) serves most of Houston proper; its main campus and headquarters are in Midtown. Suburban northern and western parts of the metropolitan area are served by various campuses of the Lone Star College System, while the southeastern portion of Houston is served by San Jacinto College, and a northeastern portion is served by Lee College.[290] The Houston Community College and Lone Star College systems are among the 10 largest institutions of higher learning in the United States.

Houston also hosts a number of graduate schools in law and healthcare. The University of Houston Law Center and Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University are public, ABA-accredited law schools, while the South Texas College of Law, in Downtown, serves as a private, independent alternative. The Texas Medical Center is home to a high density of health professions schools, including two medical schools: McGovern Medical School, part of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and Baylor College of Medicine, a highly selective private institution. Prairie View A&M University’s nursing school is in the Texas Medical Center. Additionally, both Texas Southern University and the University of Houston have pharmacy schools, and the University of Houston hosts a medical school and a college of optometry.

-

The University of Houston, in the Third Ward, is a public research university and the third-largest institution of higher education in Texas.[294]

Media[edit]

The current Houston Chronicle headquarters, formerly the Houston Post headquarters

The primary network-affiliated television stations are KPRC-TV channel 2 (NBC), KHOU channel 11 (CBS), KTRK-TV channel 13 (ABC), KTXH channel 20 (MyNetworkTV), KRIV channel 26 (Fox), KIAH channel 39 (The CW), KXLN-DT channel 45 (Univision), KTMD-TV channel 47 (Telemundo), KPXB-TV channel 49 (Ion Television), KYAZ channel 51 (MeTV) and KFTH-DT channel 67 (UniMás). KTRK-TV, KTXH, KRIV, KTXH, KIAH, KXLN-DT, KTMD-TV, KPXB-TV, KYAZ and KFTH-DT operate as owned-and-operated stations of their networks.[296]