Время прочтения:

2 минуты

Дата публикации:

20 июля 2022

Интересные подробности об имени самой могущественной женщины Османской империи

Сегодня имя Хюррем известно во всем мире и во многом, конечно, благодаря культовому сериалу «Великолепный век». Но мало кто знает два интересных факта о его происхождении и некоторых особенностях, которые точно заслуживают внимания зрителей культовой саги.

Итак, в картине мы видели, что Сулейман сам дал славянке Александре ее новое имя. И если верить версии, показанной в этом сериале, то и придумал он его специально для нее. Существует две истории, объясняющие его происхождение:

- Хюррем стало производным от персидского «khorram», что в переводе означает цветущая, приятная веселая.

- Но в переводе с тюркского «khorram» — это радость приносящая, смеющаяся. И именно второй перевод в сериале и использовал оманский падишах. Он неспроста назвал свою женщину именно так – это имя полностью описывало те эмоции, которые славянка ему дарила.

Но мало кто знает о том, что есть и еще одна версия, согласно которой именно Валиде дала Александре новое имя, как своей личной фаворитке в гареме. Более подробно об этом мы писали вот здесь. В любом случае до появления Александры в гареме никто во дворце не носил имя Хюррем – оно действительно было придумано специально для нее. Но вот кто из членов правящей династии так нарек любимицу Сулеймана, современники уже никогда не узнают.

Второй интересный факт гласит, что после того, как великая Хасеки-султан покинула этот мир, больше никто в Османской империи не называл этим именем своих дочерей. Правда, есть легенда, которая говорит о том, что внучка Сулеймана – единственная дочь его погибшего шехзаде Мехмета все же назвала именем Хюррем одну из своих дочерей. Но документального подтверждения этой версии нет.

Причина, по которой, единственной Роксоланой в истории была именно супруга султана Сулеймана Кануни проста – ни одна другая женщина в мире не могла сравниться с ней силой духа и могуществом. К тому же османы были суеверными людьми. Многие из них помнили о том, какая тяжелая судьба была у Хюррем-султан и поэтому опасались, что вместе с именем к их дочерям могут перейти и ее беды.

Кстати, современные потомки османов – жители Турции также избегают нарекать своих дочерей этим именем. Причина проста, турки довольно негативно относятся к супруге султана Сулеймана, они уверены, что именно эта женщина и стала причиной гибели великой империи.

В любом случае Хюррем – это имя, принадлежавшее поистине великой женщине, сравниться с которой не сможет уже никто и никогда.

Фотографии: стоп-кадры из сериала «Великолепный век»

Основные характеристики:

-

Происхождение

:

персидское -

Значение

:

радостная; весёлая, жизнерадостная, довольная; цветущая, свежая -

Унисекс (гендерно-нейтральное)

:

нет -

Женское / Мужское

:

женское -

Популярность

:

популярное -

Национальность и народность

:

турецкое -

Иностранное

:

да -

Языческое

:

нет -

Древнерусское

:

нет -

Старинное

:

да

Посмотреть все характеристики

Хюррем – персидское имя, наполненное радостью и весельем, самим жизнелюбием. Оно очень популярно в Турции, а после выхода сериала «Великолепный век» его распространенность стала еще большей.

История происхождения

Хюррем – это производное от персидского khorram, означает «цветущая, веселая». В переводе же с тюркского имя будет означать «смеющаяся, радость приносящая».

Сокращенные и уменьшительно-ласкательные формы

В семейном кругу или дружеской среде носительницу имени можно называть и по-другому: Хюрремка, Хюрри, Рема.

Характер в детстве и юности

Хюррем очень разная, в ней словно совмещаются два человека, но очень органично. Одновременно общительная и застенчивая, смелая и трогательно ласковая, решительная и скромная. Это очень осторожный человек: с самого детства девочка не любит необоснованного риска, бережет себя и старается окружить надежными людьми.

Она обидчива, нередко добивается чего-то своими капризами. Это качество в Хюррем сильно, но перебороть его можно, особенно если этому не будут потакать родители. От них и зависит, усугубится ли в девочке такая черта, или она с детства будет относиться к ней как к своей слабости.

Девочка растет впечатлительной и эмоциональной. Она обожает всякие концерты, шоу, выставки, музеи, экскурсии, и ее обязательно нужно этим наполнять. Восприимчивость к прекрасному – большой капитал для Хюррем, который может раскрыть ее личность, принести ей успех. А главное, что она с детства может понять, где ее вечное убежище красоты и высокого, где можно спрятаться от всех жизненных невзгод.

Но при этом Хюррем очень внушаема. Девочкой она готова буквально слиться с личностью человека, который оказывает на нее воздействие. И это опасно прежде всего тем, что этим могут воспользоваться не в лучших целях. В школе Хюррем будет тянуться к гуманитарным наукам, а с точными на протяжении всех учебных лет могут быть проблемы.

Она неровная, если можно так сказать о взрослеющей девочке: в ней преобладают то эмоции, то желание закрыться от всего мира. Она может подростком быть той еще тусовщицей, а потом резко стать чуть ли не затворницей, которая днями сидит в библиотеке и всему общению предпочитает аудиокниги в наушниках.

С ней бывает нелегко: она изменчива, импульсивна, может быть гневливой и несдержанной. В подростковом возрасте ее нередко захлестывают истерики, которые ей самой тяжело подавить. Тут нужен мудрый взрослый, что отличит мятежный дух от человеческой сути. В душе Хюррем добрая, нежная, отзывчивая, жаждущая любви. Ее она действительно ищет с детства как что-то абсолютно ценное, гарантирующее ей счастье.

Ей нравится быть красивой и чувственной, и в юности девушка уже осознает этому цену. Она учится быть женщиной, в ней это проступает довольно рано, и заглушить это не получается. Нужно просто давать ей много любви дома, быть понимающими родителями, не шантажировать ничем (благами, деньгами, принятием), потому что тогда Хюррем будет бежать из дома в поисках любви. И может наделать глупостей.

Характеристика во взрослой жизни

Взрослая Хюррем – это сначала женщина, а потом профессионал, мама, подруга, дочь, соратница. В ней очень сильно женское начало, и оно в ней довольно ломаное, сложное, противоречивое. Но она его взращивает в себе и может превратить во что-то тонкое, штучное, необъяснимо притягательное. Ее главное достоинство в этом смысле – она легкая. Заламывать руки и цепляться к словам Хюррем вряд ли будет. Ей нравится быть озорной, смешливой, игривой, кокетливой. И такая женщина очень нравится мужчинам: многие из них так устали от всего серьезного и сложного в жизни, что они буквально бегут к этой легкости и мягкости.

Но пока она вырастает в такую женщину, ей свойственны и ошибки, и переигрывания, и чрезмерные увлечения. В юности это могут быть романы просто до избытка чувств. Из-за любви Хюррем может отказываться от друзей, убегать из дома, бросать учебу, делать явные глупости. Особенно если предмет страсти ведет себя нелинейно: то приголубит, то отстранит.

Кажется, что на своих ошибках она не учится. И новый избранник снова сводит всю ее жизнь только к себе. Но это не будет длиться всегда. Она взрослеет, познает новые грани жизни, и ей интересно сложнее ее выстраивать. У Хюррем нет зацикленности на чем-то или на ком-то, взрослой женщине интересно развиваться, видеть какие-то перспективы.

Ее характер тоже меняется на протяжении жизни. Из несговорчивой и импульсивной, довольно обидчивой девушки Хюррем превращается в кроткую и мягкую (хоть часто это и обманчиво), гибкую и мудрую женщину. Ей нравится лелеять свой образ, дополнять его, становиться краше и загадочнее, быть более манкой и желанной.

Но все это не значит, что работа для Хюррем второстепенна. Просто не всегда она ее может оценить сразу. Профессию порой выбирает без особенных раздумий, учится без увлеченности, но в целом неплохо. Интерес к профессиональной реализации к Хюррем часто приходит после 30, особенно на фоне какого-то яркого успеха. Ее заводит идея новых достижений, и она начинает работать, еще чаще – вкалывать, проводя на работе куда больше времени, чем полагается. Нередко это происходит после декретного отпуска, в котором Хюррем часто откровенно скучает.

Какой будет женщина в работе, зависит от ее увлеченности этой сферой деятельности. В худшем случае – безынициативной, но исполнительной. В лучшем – самым эффективным сотрудником в команде. Важно, чтобы через работу могла реализоваться еще и ее женственность, тогда у Хюррем все шансы на успех. Нередко она обращается к условно мужским профессиям вроде политика или журналиста, чтобы создать интересный контраст. Ее даже манят мужские профессии.

В кругу друзей она то мягкий и скромный человек, то настоящий эпицентр самых активных действий. Опять же, все зависит от людей, что вокруг нее. Она как была внушаемой, так и остается, потому ближний круг будет очень на нее влиять. У Хюррем редко остаются друзья из детства: их обиды она может помнить очень долго, а потому взрослой словно отречется от этих детских травм.

Знакомства Хюррем заводит легко, она умеет вести легкие беседы, быть любезной, нравиться. Ей несложно налаживать отношения с малознакомыми людьми. Она коммуникабельна, и где-то это может обрести некрасивый оттенок – Хюррем склонна к разведению интриг. Это не значит, что всякая Хюррем – интриганка, но при определенных обстоятельствах такое может проявиться в женщине.

В любви она идет до конца, ей всегда хочется испить всю чашу. Она терзается, мечется, в ней много страсти и много нетерпеливости. Но с каждым новым романом будет выстраиваться новая Хюррем, более строгая к себе и более хитрая, внимательная, осторожная. Ее супругом, скорее всего, станет не самая большая любовь, а тот, кто примет ее со всеми недостатками. По-настоящему, взросло она полюбит человека, великодушного к ней. Он должен быть менее темпераментным и более земным, и тогда они совпадут.

Как мать Хюррем тоже может быть разной. Если ребенок появился рано и без особенных проблем, подлинное материнство в ней может включиться не сразу. Если ребенок выстраданный, это будет самая любящая в мире мать, готовая изменить всю свою жизнь ради счастья потомков. Но в целом она будет спокойной мамой, принимающей своих детей такими, какие они есть.

В отношениях с родственниками Хюррем становится более терпеливой и мудрой примерно после 30-35 лет. Какие-то детские обиды могут долго жить в ней, а человеческое общение не является особенной ценностью, пока гремят бури любви. Но потом Хюррем обязательно разглядит все грани жизненной мозаики, ей захочется прожить то, что она не успела в детстве – побыть очень любимой и заботливой дочерью, сестрой, например.

Рекомендации

У Хюррем в жизни будет много внутренних противоречий и даже конфликтов. И это словно задачка ей на все этапы взросления – совершенствовать себя, находить правильные решения, становиться мягче и умнее, формировать из себя цельную личность. Хороший совет для нее – увлечься психологией. С юности читать книги по психологии, выбирая действительно качественную публицистику. Это как психогигиена, как правильный подход к выстраиванию самой себя.

А также Хюррем стоит понимать, что нельзя чему-то одному в жизни уделять так много внимания, чтобы страдали другие важные сферы. Любовные чары ослабевают, ради них не стоит бросать учебу или рушить построенное. Где-то Хюррем не хватает внутренней дисциплины, но ведь над этим можно работать, и интуитивно она знает – как.

В ней много энергии, которую она часто тратит впустую. На любовные страдания или желание вылепить из себя кого-то идеального внешне (и все равно ей что-то будет не нравиться). Ей стоит научиться направлять эту энергию во что-то качественное. Например, в волонтерство – эта сфера может оказаться для нее очень интересной, стать новой точкой роста. А также Хюррем может стать каким-то общественным деятелем: она нравится людям, она умеет с ними коммуницировать, и ей интересны крупные цели. При должной дисциплине у нее в этом смысле получится не просто успех, она может построить головокружительную карьеру.

Интересные факты об имени

Есть мнение, что в Турции это имя не самое популярное, хоть его распространенность несколько и выросла снова. Дело в том, что та самая Хюррем, супруга султана Сулеймана, у многих вызывает исключительно негативные эмоции. Они считают ее едва ли не главной виновницей распада Османской империи. Но скорее избегали этого имени потомки Сулеймана, а не все подряд турки.

Кстати, имя своей знаменитой наложнице султан дал сам, так было принято тогда, ведь в имени отражалась личность избранницы. В данном случае Сулейман хотел подчеркнуть легкий и веселый нрав девушки.

Известные личности

Хюррем Хасеки-султан, Роксолана (наложница султана Сулеймана Великолепного, жена и мать его детей), Хюррем Муфтюгиль (турецкий политик), Хюррем Эрман (турецкий продюсер).

| Hürrem Sultan | ||

|---|---|---|

Portrait by Titian titled La Sultana Rossa, c. 1550 |

||

| Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Imperial Consort) |

||

| Tenure | c. 1533 – 15 April 1558 | |

| Successor | Nurbanu Sultan | |

| Born | Alexandra or Anastasia c. 1504 Rohatyn, Ruthenia, Kingdom of Poland (now Ukraine) |

|

| Died | 15 April 1558 (aged c. 53-54) Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire (now Turkey) |

|

| Burial |

Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul |

|

| Spouse |

Suleiman I (m. 1533) year disputed |

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| Father | Lisovsky, possibly a Ruthenian Orthodox Priest[1] | |

| Mother | Leksandra Lisowska[2] | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam, previously Eastern Orthodox Christian |

Roxelana (Ukrainian: Роксолана, romanized: Roksolana; lit. ‘the Ruthenian one’; c. 1504 – 15 April 1558), also known as Hurrem Sultan (Turkish pronunciation: [hyɾˈɾæm suɫˈtan]; Ottoman Turkish: خُرّم سلطان, romanized: Ḫurrem Sulṭān; Modern Turkish: Hürrem Sultan), was the chief consort and legal wife of the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She became one of the most powerful and influential women in Ottoman history as well as a prominent and controversial figure during the era known as the Sultanate of Women.

Born in Ruthenia (then an eastern region of the Kingdom of Poland, now Rohatyn, Ukraine) to a Ruthenian Orthodox priest, Roxelana was captured by Crimean Tatars during a slave raid and eventually taken to Istanbul, the Ottoman capital.[3] She entered the Imperial Harem where her name was changed to Hurrem, rose through the ranks and became the favourite of Sultan Suleiman. Breaking Ottoman tradition, he married Roxelana, making her his legal wife. Sultans had previously married only foreign free noble ladies. She was the first imperial consort to receive the title Haseki Sultan. Roxelana remained in the sultan’s court for the rest of her life, enjoying a close relationship with her husband, and having six children with him, including the future sultan, Selim II.

Roxelana eventually achieved power, influencing the politics of the Ottoman Empire. Through her husband, she played an active role in affairs of the state. She probably acted as the sultan’s advisor, wrote diplomatic letters to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland (r. 1548–1572) and patronized major public works (including the Haseki Sultan Complex and the Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse). She died in 1558, in Istanbul and was buried in a mausoleum within the Süleymaniye Mosque complex.

Names[edit]

Roxelana’s birth name is unknown. Leslie P. Peirce has written that it may have been either Anastasia, or Aleksandra Lisowska. Among the Ottomans, she was known mainly as Haseki Hurrem Sultan or Hurrem Haseki Sultan. Hurrem or Khorram (Persian: خرم) means «the joyful one» in Persian. The name Roxalane derives from Roksolanes, which was the generic term used by the Ottomans to describe girls from Podolia and Galicia who were taken in slave raids.

Origin[edit]

Sources indicate that Roxelana was originally from Ruthenia, which was then part of the Polish Crown.[4] She was born in the town of Rohatyn 68 km (42 mi) southeast of Lwów (Lviv), a major city of the Ruthenian Voivodeship of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland,[5] in what is now Ukraine. According to late 16th-century and early 17th-century sources, such as the Polish poet Samuel Twardowski (died 1661), who researched the subject in Turkey, Roxelana was seemingly born to a man surnamed Lisovski, who was an Orthodox priest of Ruthenian origin.[5][6][7] Her native language was Ruthenian, the precursor to modern Ukrainian.[8]

During the reign of Selim I,[9] which means some time between 1512 and 1520, Crimean Tatars kidnapped her during one of their Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe. The Tatars may have first taken her to the Crimean city of Kaffa, a major centre of the Ottoman slave trade, before she was taken to Istanbul.[5][6][7] In Istanbul, Valide Hafsa Sultan selected Roxelana as a gift for her son, Suleiman. Roxelana later managed to become the first Haseki Sultan or «favorite concubine» of the Ottoman imperial harem.[4] Michalo Lituanus wrote in the 16th century that «the most beloved wife of the present Turkish emperor – mother of his first [son] who will govern after him, was kidnapped from our land».[i][10]

Shaykh Qutb al-Din al-Nahrawali, a Meccan religious figure, who visited Istanbul in late 1557, noted in his memoirs that Hurrem Sultan was of Ruthenian origin. She had been a servant in the household of Hançerli Zeynep Fatma Sultan, daughter of Şehzade Mahmud, son of Sultan Bayezid II.[11]

European ambassadors of that period called her la Rossa, la Rosa, and Roxelana, meaning «the Russian woman»[12] or «the Ruthenian one» for her alleged Ruthenian origins.[13] She is the sultan’s consort with the most portraits in her name in the Ottoman Empire, though the portraits are imaginary depictions by painters.[14]

Relationship with Suleiman[edit]

Roxelana, called Hurrem Sultan by the Ottomans, probably entered the harem around seventeen years of age. The precise year that she entered the harem is unknown, but scholars believe that she became Suleiman’s concubine around the time he became sultan in 1520.[15]

Roxelana’s unprecedented rise from harem slave to Suleiman’s legal wife and Ottoman Empress attracted jealousy and disfavor not only from her rivals in the harem, but also from the general populace.[4] She soon became Suleiman’s most prominent consort beside Mahidevran (also known as Gülbahar), and their relationship was monogamous. While the exact dates for the births of her children are disputed, there is academic consensus that the births of her five children —Şehzade Mehmed, Mihrimah Sultan, Şehzade Abdullah, Sultan Selim II and Şehzade Bayezid — occurred quickly over the next four to five years.[15]: 130 Suleiman and Roxelana’s last child, Şehzade Cihangir was born with a hunchback, but by that time Roxelana had given birth to enough healthy sons to secure the future of the Ottoman dynasty.[15]: 131

Her joyful spirit and playful temperament earned her a new name, Hurrem, from Persian Khorram, «the cheerful one». In the Istanbul harem, Hurrem became a rival to Mahidevran and her influence over the sultan soon became legendary.

Hurrem was allowed to give birth to more than one son which was a stark violation of the old imperial harem principle, «one concubine mother — one son,» which was designed to prevent both the mother’s influence over the sultan and the feuds of the blood brothers for the throne.[10] She was to bear the majority of Suleiman’s children. Hurrem gave birth to her first son Mehmed in 1521 (who died in 1543) and then to four more sons, destroying Mahidevran’s status as the mother of the sultan’s only son.[16]

Suleiman’s mother, Hafsa Sultan, partially suppressed the rivalry between the two women.[17] According to Bernardo Navagero’s report, as a result of the bitter rivalry a fight between the two women broke out, with Mahidevran beating Hurrem, which angered Suleiman.[18] According to Necdet Sakaoğlu, a Turkish historian, these accusations were not truthful. After the death of Suleiman’s mother Hafsa Sultan in 1534, Hurrem’s influence in the palace increased, and she took over the ruling of the Harem.[19] Hurrem became the only partner of the ruler and received the title of Haseki, which means the favorite. When Suleiman freed and married her, she became the Haseki Sultan (adding the word sultan to a woman’s name or title indicated that she was a part of the dynasty).[20]

Around 1526/1534 (the exact date is unknown),[10] Suleiman married Hurrem in a magnificent formal ceremony. Never before had a former slave been elevated to the status of the sultan’s lawful spouse, a development which astonished observers in the palace and in the city.[21] It was only possible for Hurrem to marry Suleiman after the death of Hafsa Sultan. It was not because Hafsa Sultan was firmly against this unification, but because it was not allowed for a concubine to rise above the status of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother).[22]

Hurrem became the first consort to receive the title Haseki Sultan.[23] This title, used for a century, reflected the great power of imperial consorts (most of them were former slaves) in the Ottoman court, elevating their status higher than Ottoman princesses, and making them the equals of empresses consort in Europe. In this case, Suleiman not only broke the old custom, but began a new tradition for the future Ottoman sultans: To marry in a formal ceremony and to give their consorts significant influence on the court, especially in matters of succession. Hurrem’s salary was 2,000 aspers a day, making her one of the highest-paid Hasekis.[10] After the wedding, the idea circulated that the sultan had limited his autonomy and was dominated and controlled by his wife.[24] Also, in Ottoman society, mothers played more influential roles in their sons’ educations and in guiding their careers.[24]

After the death of Suleiman’s mother, Hafsa Sultan, in 1534, Hurrem became the most trusted news source of Suleiman. In one of her letters to Suleiman, she informs him about the situation of the plague in the capital. She wrote, «My dearest Sultan! If you ask about Istanbul, the city still suffers from the plague; however, it is not like the previous one. God willing, it will go away as soon as you return to the city. Our ancestors said that the plague goes away once the trees shed their leaves in autumn.»[25]

Later, Hurrem became the first woman to remain in the sultan’s court for the duration of her life. In the Ottoman imperial family tradition, a sultan’s consort was to remain in the harem only until her son came of age (around 16 or 17), after which he would be sent away from the capital to govern a faraway province, and his mother would follow him. This tradition was called Sancak Beyliği. The consorts were never to return to Istanbul unless their sons succeeded to the throne.[26] In defiance of this age-old custom, Hurrem stayed behind in the harem, even after her sons went to govern the empire’s remote provinces.

Moreover, remaining in Istanbul, she moved out of the harem located in the Old Palace (Eski Saray) and permanently moved into the Topkapı Palace after a fire destroyed the old harem. Some sources say she moved to Topkapı, not because of the fire, but as a result of her marriage to Suleiman. Either way, this was another significant break from established customs, as Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror had specifically issued a decree to the effect that no women would be allowed to reside in the same building where government affairs were conducted.[15]: 131 After Hurrem resided at Topkapı it became known as the New Palace (saray-ı jedid).[27]

She wrote many love letters to Suleiman when he was away for campaigns. In one of her letters, she wrote:

- «After I put my head on the ground and kiss the soil that your blessed feet step upon, my nation’s sun and wealth my sultan, if you ask about me, your servant who has caught fire from the zeal of missing you, I am like the one whose liver (in this case, meaning heart) has been broiled; whose chest has been ruined; whose eyes are filled with tears, who cannot distinguish anymore between night and day; who has fallen into the sea of yearning; desperate, mad with your love; in a worse situation than Ferhat and Majnun, this passionate love of yours, your slave, is burning because I have been separated from you. Like a nightingale, whose sighs and cries for help do not cease, I am in such a state due to being away from you. I would pray to Allah to not afflict this pain even upon your enemies. My dearest sultan! As it has been one-and-a-half months since I last heard from you, Allah knows that I have been crying night and day waiting for you to come back home. While I was crying without knowing what to do, the one and only Allah allowed me to receive good news from you. Once I heard the news, Allah knows, I came to life once more since I had died while waiting for you.[25]

Under his pen name, Muhibbi, Sultan Suleiman composed this poem for Hurrem Sultan:

«Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight.

My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence, my Sultan, my one and only love.

The most beautiful among the beautiful…

My springtime, my merry faced love, my daytime, my sweetheart, laughing leaf…

My plants, my sweet, my rose, the one only who does not distress me in this world…

My Istanbul, my Caraman, the earth of my Anatolia

My Badakhshan, my Baghdad and Khorasan

My woman of the beautiful hair, my love of the slanted brow, my love of eyes full of mischief…

I’ll sing your praises always

I, lover of the tormented heart, Muhibbi of the eyes full of tears, I am happy.»[28]

State affairs[edit]

Hurrem Sultan is known as the first woman in Ottoman history to concern herself with state affairs. Thanks to her intelligence, she acted as Suleiman’s chief adviser on matters of state, and seems to have had an influence upon foreign policy and international politics. She frequently accompanied him as a political adviser. She imprinted her seal and watched the council meetings through a wire mesh window. With many other revolutionary movements like these, she had started an era in Ottoman Empire called the Reign of Women.[29] Hurrem’s influence on Suleiman was so significant that rumors circulated around the Ottoman court that the sultan had been bewitched.[4]

Her influence with Suleiman made her one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history and in the world at that time. Even as a consort, her power was comparable with the most powerful woman of the Imperial Harem, who by tradition was the sultan’s mother or valide sultan. For this reason, she has become a controversial figure in Ottoman history — subject to allegations of plotting against and manipulating her political rivals.

Controversial figure[edit]

16th century Latin oil painting of Hurrem Sultan titled Rosa Solymanni Vxor (Rosa, Süleyman’s Wife)

Hurrem’s influence in state affairs not only made her one of the most influential women, but also a controversial figure in Ottoman history, especially in her rivalry with Mahidevran and her son Şehzade Mustafa, and the grand viziers Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha and Kara Ahmed Pasha.

Hurrem and Mahidevran had given birth to Suleiman’s six şehzades (Ottoman princes), four of whom survived past the 1550s: Mehmed, Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir. Of these, Mahidevran’s son Mustafa was the eldest and preceded Hurrem’s children in the order of succession. Traditionally, when a new sultan rose to power, he would order all of his brothers killed in order to ensure there was no power struggle. This practice was called kardeş katliamı, literally «fraternal massacring».[30]

Mustafa was supported by Ibrahim Pasha, who became Suleiman’s grand vizier in 1523. Hurrem has usually been held at least partly responsible for the intrigues in nominating a successor.[15]: 132 Although she was Suleiman’s wife, she exercised no official public role. This did not, however, prevent Hurrem from wielding powerful political influence. Since the empire lacked, until the reign of Ahmed I (1603–1617), any formal means of nominating a successor, successions usually involved the death of competing princes in order to avert civil unrest and rebellions. In attempting to avoid the execution of her sons, Hurrem used her influence to eliminate those who supported Mustafa’s accession to the throne.[31]

A skilled commander of Suleiman’s army, Ibrahim eventually fell from grace after an imprudence committed during a campaign against the Persian Safavid empire during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), when he awarded himself a title including the word «Sultan». Another conflict occurred when Ibrahim and his former mentor, İskender Çelebi, repeatedly clashed over military leadership and positions during the Safavid war. These incidents launched a series of events which culminated in his execution in 1536 by Suleiman’s order. It is believed that Hurrem’s influence contributed to Suleiman’s decision.[32] After three other grand viziers in eight years, Suleiman selected Hurrem’s son-in-law, Damat Rüstem Pasha, husband of Mihrimah, to become the grand vizier. Scholars have wondered if Hurrem’s alliance with Mihrimah Sultan and Rüstem Pasha helped secure the throne for one of Hurrem’s sons.[15]: 132

Many years later, towards the end of Suleiman’s long reign, the rivalry between his sons became evident. Mustafa was later accused of causing unrest. During the campaign against Safavid Persia in 1553, because of fear of rebellion, Suleiman ordered the execution of Mustafa. According to a source he was executed that very year on charges of planning to dethrone his father; his guilt for the treason of which he was accused remains neither proven nor disproven.[33] It is also rumored that Hurrem Sultan conspired against Mustafa with the help of her daughter and son-in-law Rustem Pasha; they wanted to portray Mustafa as a traitor who secretly contacted the Shah of Iran. Acting on Hurrem Sultan’s orders, Rustem Pasha had engraved Mustafa’s seal and sent a letter seemingly written from his mouth to Shah Tahmasb I, and then sent Shah’s response to Suleiman.[19] After the death of Mustafa, Mahidevran lost her status in the palace as the mother of the heir apparent and moved to Bursa.[16] She did not spend her last years in poverty, as Hurrem’s son, Selim II, the new sultan after 1566, put her on a lavish salary.[33] Her rehabilitation had been possible after the death of Hurrem in 1558.[33] Cihangir, Hurrem’s youngest child, allegedly died of grief a few months after the news of his half-brother’s murder.[34]

Although the stories about Hurrem’s role in executions of Ibrahim, Mustafa, and Kara Ahmed are very popular, actually none of them are based on first-hand sources. All other depictions of Hurrem, starting with comments by sixteenth and seventeenth-century Ottoman historians as well as by European diplomats, observers, and travellers, are highly derivative and speculative in nature. Because none of these people – neither Ottomans nor foreign visitors – were permitted into the inner circle of the imperial harem, which was surrounded by multiple walls, they largely relied on the testimony of the servants or courtiers or on the popular gossip circulating around Istanbul.[10]

Even the reports of the Venetian ambassadors (baili) at Suleiman’s court, the most extensive and objective first-hand Western source on Hurrem to date, were often filled with the authors’ own interpretations of the harem rumours. Most other sixteenth-century Western sources on Hurrem, which are considered highly authoritative today — such as Turcicae epistolae (English: The Turkish Letters) of Ogier de Busbecq, the Emissary of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I at the Porte between 1554 and 1562; the account of the murder of Şehzade Mustafa by Nicholas de Moffan; the historical chronicles on Turkey by Paolo Giovio; and the travel narrative by Luidgi Bassano — derived from hearsay.[10]

Foreign policy[edit]

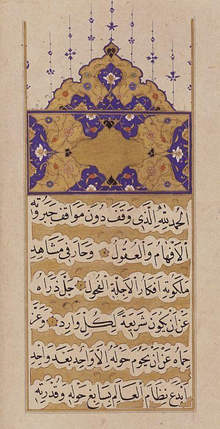

A letter of Hurrem Sultan to Sigismund II Augustus, congratulating him on his accession to the Polish throne in 1549.

Hurrem acted as Suleiman’s advisor on matters of state, and seems to have had an influence upon foreign policy and on international politics. Two of her letters to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland (reigned 1548–1572) have survived, and during her lifetime the Ottoman Empire generally had peaceful relations with the Polish state within a Polish–Ottoman alliance.

In her first short letter to Sigismund II, Hurrem expresses her highest joy and congratulations to the new king on the occasion of his ascension to the Polish throne after the death of his father Sigismund I the Old in 1548. There was a seal on the back of the letter. For the first and only time in the Ottoman Empire, a female sultan exchanged letters with a king. After that, although Hurrem’s successor Nurbanu Sultan and her successor Safiye Sultan exchanged letters with queens, there is no other example of a female sultan who personally contacted a king other than Hurrem Sultan.[19] She pleads with the King to trust her envoy Hassan Ağa who took another message from her by word of mouth.

In her second letter to Sigismund Augustus, written in response to his letter, Hurrem expresses in superlative terms her joy at hearing that the king is in good health and that he sends assurances of his sincere friendliness and attachment towards Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She quotes the sultan as saying, «with the old king we were like brothers, and if it pleases the All-Merciful God, with this king we will be as father and son.» With this letter, Hurrem sent Sigismund II the gift of two pairs of linen shirts and pants, some belts, six handkerchiefs, and a hand-towel, with a promise to send a special linen robe in the future.

There are reasons to believe that these two letters were more than just diplomatic gestures, and that Suleiman’s references to brotherly or fatherly feelings were not a mere tribute to political expediency. The letters also suggest Hurrem’s strong desire to establish personal contact with the king. In his 1551 letter to Sigismund II concerning the embassy of Piotr Opaliński, Suleiman wrote that the Ambassador had seen «Your sister and my wife.» Whether this phrase refers to a warm friendship between the Polish King and Ottoman Haseki, or whether it suggests a closer relation, the degree of their intimacy definitely points to a special link between the two states at the time.[10]

Charities[edit]

Aside from her political concerns, Hurrem engaged in several major works of public buildings, from Makkah to Jerusalem (Al-Quds), perhaps modelling her charitable foundations in part after the caliph Harun al-Rashid’s consort Zubaida. Among her first foundations were a mosque, two Quranic schools (madrassa), a fountain, and a women’s hospital near the women’s slave market (Avret Pazary) in Istanbul (Haseki Sultan Complex). It was the first complex constructed in Istanbul by Mimar Sinan in his new position as the chief imperial architect.[35]

She built mosque complexes in Adrianopole and Ankara. She commissioned a bath, the Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse, to serve the community of worshippers in the nearby Hagia Sophia.[36] In Jerusalem she established the Haseki Sultan Imaret in 1552, a public soup kitchen to feed the poor,[37] which was said to have fed at least 500 people twice a day.[38] She built a public soup kitchen in Makkah.[10]

She had a Kira who acted as her secretary and intermediary on several occasions, although the identity of the kira is uncertain (it may have been Strongilah[39] or Esther Handali[citation needed]).

Death[edit]

Hurrem died on 15 April 1558 due to an unknown illness and was buried in a domed mausoleum (türbe) decorated in exquisite Iznik tiles depicting the garden of paradise, perhaps in homage to her smiling and joyful nature.[40] Her mausoleum is adjacent to Suleiman’s, a separate and more somber domed structure, at the courtyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque.

Personality[edit]

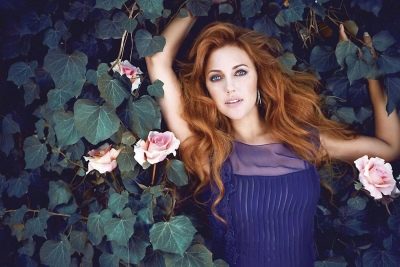

Roxelana’s contemporaries describe her as a woman who was strikingly good-looking, and different from everybody else because of her red hair.[41] Roxelana was also intelligent and had a pleasant personality. Her love of poetry is considered one of the reasons behind her being heavily favoured by Suleiman, who was a great admirer of poetry.[41]

Roxelana is known to have been very generous to the poor. She built numerous mosques, madrasahs, hammams, and resting places for pilgrims travelling to the Islamic holy city of Makkah. Her greatest philanthropical work was the Great Waqf of AlQuds, a large soup kitchen in Jerusalem that fed the poor.[42]

It is believed that Roxelana was a cunning, manipulative and stony-hearted woman who would execute anyone who stood in her way. However, her philanthropy is in contrast to this as she cared for the poor. Prominent Ukrainian writer Pavlo Zahrebelny describes Roxelana as «an intelligent, kind, understanding, openhearted, candid, talented, generous, emotional and grateful woman who cares about the soul rather than the body; who is not carried away with ordinary glimmers such as money, prone to science and art; in short, a perfect woman.»[43]

Legacy[edit]

Roxelana, or Hurrem Haseki Sultan, is well-known both in modern Turkey and in the West, and is the subject of many artistic works. In 1561, three years after her death, the French author Gabriel Bounin wrote a tragedy titled La Soltane.[44] This tragedy marks the first time the Ottomans were introduced on stage in France.[45] She has inspired paintings, musical works (including Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 63), an opera by Denys Sichynsky, a ballet, plays, and several novels written mainly in Russian and Ukrainian, but also in English, French, German and Polish.

In early modern Spain, she appears or is alluded to in works by Quevedo and other writers as well as in a number of plays by Lope de Vega. In a play entitled The Holy League, Titian appears on stage at the Venetian Senate, and stating that he has just come from visiting the Sultan, displays his painting of Sultana Rossa or Roxelana.[46]

In 2007, Muslims in Mariupol, a port city in Ukraine opened a mosque to honour Roxelana.[47]

In the 2003 TV miniseries, Hürrem Sultan, she was played by Turkish actress and singer Gülben Ergen. In the 2011–2014 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, Hurrem Sultan is portrayed by Turkish-German actress Meryem Uzerli from seasons one to three. For the series’ last season, she is portrayed by Turkish actress Vahide Perçin.

In 2019, mention of the Russian origin of Roxelana was removed from the visitor panel near her tomb at the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul at the request of the Ukrainian Embassy in Turkey.[48]

Visual tradition[edit]

Anon., published by Matteo Pagani, Portrait of Roxelana, 1540–50. The inscription describes her as «the most beautiful and favorite wife of the Grand Turk, called la Rossa.»

Despite the fact that male European artists were denied access to Roxelana in the Harem, there are many Renaissance paintings of the famous sultana. Scholars thus agree that European artists created a visual identity for Ottoman women that was largely imagined.[49] Artists Titian, Melchior Lorich, and Sebald Beham were all influential in creating a visual representation of Roxelana. Images of the chief consort emphasized her beauty and wealth, and she is almost always depicted with elaborate headwear.

The Venetian painter Titian is reputed to have painted Roxelana in 1550. Although he never visited Istanbul, he either imagined her appearance or had a sketch of her. In a letter to Philip II of Spain, the painter claims to have sent him a copy of this «Queen of Persia» in 1552. The Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida, purchased the original or a copy around 1930.[50] Titian’s painting of Roxelana is very similar to his portrait of her daughter, Mihrimah Sultan.[49]

Children[edit]

With Suleiman, she had five sons and one daughter.

- Şehzade Mehmed (1521, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul – 7 November 1543, Manisa Palace, Manisa, buried in Şehzade Mosque, Istanbul): Hurrem’s first son. Mehmed became the ruler of Manisa from 1541 until his death.

- Mihrimah Sultan (1522, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul – 25 January 1578, buried in Suleiman I Mausoleum, Süleymaniye Mosque): Hurrem’s only daughter. She was married to Rüstem Pasha, later Ottoman Grand Vizier, on 26 November 1539.

- Selim II (28 May 1524, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul – 15 December 1574, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque): He was governor of Manisa after Mehmed’s death and later governor of Konya. He ascended to the throne on 7 September 1566 as Selim II.

- Şehzade Abdullah (1525, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul – c. 1528, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, buried in Yavuz Selim Mosque)[51][52]

- Şehzade Bayezid (1527, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul – killed on 25 September 1561, Qazvin, Safavid Empire, buried in Melik-i Acem Türbe, Sivas): He was governor of Kütahya and later Amasya.[53]

- Şehzade Cihangir (9 December 1531, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul – 27 November 1553, Aleppo, buried in Şehzade Mosque, Istanbul)

Gallery[edit]

-

18th century portrait of Hurrem Sultan kept at Topkapı Palace.

-

A portrait of Roxelana in the British Royal Collection, c. 1600–70

-

A painting of Hurrem Sultan by a follower of Titian, 16th century

-

16th century oil on wood painting of Hurrem Sultan

-

Tribute to Roxelana on 1997 Ukrainian postage stamp

-

The Hagia Sophia Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse built in 1556

See also[edit]

- Ottoman dynasty

- Ottoman family tree

- List of mothers of the Ottoman sultans

- List of consorts of the Ottoman sultans

- Haseki Sultan Complex, Fatih, Istanbul

- Hagia Sophia Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse, Fatih, Istanbul

- Haseki Sultan Imaret, Jerusalem

- Suleiman the Magnificent

- Sultanate of Women

Notes[edit]

- ^ The title of his book is De moribus tartarorum, lituanorum et moscorum or On the customs of Tatars, Lithuanians and Moscovians.

References[edit]

- ^ Dr Galina I Yermolenko (2013). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culturea. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-409-47611-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017.

- ^ Dr Galina I Yermolenko (2013). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culturea. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-409-47611-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017.

- ^ «2 Reasons Why Hurrem Sultan and Empress Ki were similar». Hyped For History. 13 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Bonnie G. Smith, ed. (2008). «Hürrem, Sultan». The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195148909. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Abbott, Elizabeth (1 September 2011). Mistresses: A History of the Other Woman. Overlook. ISBN 978-1-59020-876-2.

- ^ a b «The Speech of Ibrahim at the Coronation of Maximilian II», Thomas Conley, Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Summer 2002), 266.

- ^ a b Kemal H. Karpat, Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History: Selected Articles and Essays, (Brill, 2002), 756.

- ^ Yermolenko, Galina I. (13 February 2010). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9781409403746 – via Google Books.

- ^ Baltacı, Cahit. «Hürrem Sultan». İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yermolenko, Galina (April 2005). «Roxolana: ‘The Greatest Empresse of the East’«. The Muslim World. 95 (2): 231–248. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2005.00088.x.

- ^ Nahrawālī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad; Blackburn, Richard (2005). Journey to the Sublime Porte: the Arabic memoir of a Sharifian agent’s diplomatic mission to the Ottoman Imperial Court in the era of Suleyman the Magnificent; the relevant text from Quṭb al-Dīn al-Nahrawālī’s al-Fawāʼid al-sanīyah fī al-riḥlah al-Madanīyah wa al-Rūmīyah. Orient-Institut. pp. 200, 201 and n. 546. ISBN 978-3-899-13441-4.

- ^ Charles Thornton Forster, Francis Henry Blackburne Daniell (1881). The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. London: Louisiana State University Press. note 1 pp. 111-112.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Robert Lewis (1999). «Roxelana». Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Faroqhi, Suraiya (2019). The Ottoman and Mughal Empires: Social History in the Early Modern World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 62-63. ISBN 9781788318723.

- ^ a b c d e f Levin, Carole (2011). Extraordinary women of the Medieval and Renaissance world: a biographical dictionary. Westport, Conn. [u.a.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30659-4.

- ^ a b «Ottoman Empire History Encyclopedia — Letter H — Ottoman Turkish history with pictures — Learn Turkish». www.practicalturkish.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Selçuk Aksin Somel: Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, Oxford, 2003, ISBN 0-8108-4332-3, p. 123

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 59-60.

- ^ a b c Content in this edit is translated from the existing Turkish Wikipedia article at tr :Hürrem Sultan; see its history for attribution.

- ^ Pierce, Leslie (2017). Hürrem Sultan. İstanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları. p. 5. ISBN 978-605-295-916-9.

- ^ Mansel, Philip (1998). Constantinople : City of the World’s Desire, 1453–1924. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-18708-8. p, 86.

- ^ Pierce, Leslie (2017). Hürrem Sultan. Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları. p. 13. ISBN 978-605-295-916-9.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 91.

- ^ a b Peirce 1993, p. 109.

- ^ a b «Hürrem Sultan: A beloved wife or master manipulator? | Ottoman History». ottoman.ahya.net. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650 : The Structure of Power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-61386-3. p, 90.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 119.

- ^ «A Message For The Sultan — Sample Activity (Women in World History Curriculum)». www.womeninworldhistory.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ Content in this edit is translated from the existing Turkish Wikipedia article at [[:tr :Hürrem Sultan]]; see its history for attribution.

- ^ Akman, Mehmet (1 January 1997). Osmanlı devletinde kardeş katli. Eren. ISBN 978-975-7622-65-9.

- ^ Mansel, Phillip (1998). Constantinople : City of the World’s Desire, 1453–1924. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-312-18708-8.

- ^ Mansel, 87.

- ^ a b c Peirce, 55.

- ^ Mansel, 89.

- ^ «Historical Architectural Texture». Ayasofya Hürrem Sultan Hamamı. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ «Historical Architectural Texture». Ayasofya Hürrem Sultan Hamamı. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Peri, Oded. Waqf and Ottoman Welfare Policy, The Poor Kitchen of Hasseki Sultan in Eighteenth-Century Jerusalem, pg 169

- ^ Singer, Amy. Serving Up Charity: The Ottoman Public Kitchen, pg 486

- ^ Minna Rozen: A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul, The Formative Years, 1453 – 1566 (2002).

- ^ Öztuna, Yılmaz (1978). Şehzade Mustafa. İstanbul: Ötüken Yayınevi. ISBN 9754371415.

- ^ a b Talhami, Ghada. Historical Dictionaries of Women in the World: Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Scarecrow Press, 2012. p. 271

- ^ Talhami, Ghada. Historical Dictionaries of Women in the World: Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Scarecrow Press, 2012. p. 272

- ^ Chitchi, S. «Orientalist view on the Ottoman in the novel Roxalana (Hurrem Sultan) by Ukrainian author Pavlo Arhipovich Zahrebelniy». The Journal of International Social Research Vol. 7, Issue 33, p. 64

- ^ The Literature of the French Renaissance by Arthur Augustus Tilley, p.87 Tilley, Arthur Augustus (December 2008). The Literature of the French Renaissance. ISBN 9780559890888. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge p.418 Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 1838. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Frederick A. de Armas «The Allure of the Oriental Other: Titian’s Rossa Sultana and Lope de Vega’s La santa Liga,» Brave New Words. Studies in Spanish Golden Age Literature, eds. Edward H. Friedman and Catherine Larson. New Orleans: UP of the South, 1996: 191-208.

- ^ «Religious Information Service of Ukraine». Archived from the original on 22 December 2012.

- ^ «Reference to Roxelana’s Russian origin removed from label near her tomb in Istanbul at Ukraine’s request». Interfax-Ukraine. 26 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ a b Madar, Heather (2011). «Before the Odalisque: Renaissance Representations of Elite Ottoman Women». Early Modern Women. 6: 11. doi:10.1086/EMW23617325. JSTOR 23617325. S2CID 164805076 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Harold Edwin Wethey The Paintings of Titian: The Portraits, Phaidon, 1971, p. 275.

- ^ Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı; Karal, Enver Ziya (1975). Osmanlı tarihi, Volume 2. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. p. 401.

- ^ Peirce, Leslie (2017). Empress of the East: How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books.

- ^ Peirce, Leslie (2017). Empress of the East: How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books.

Further reading[edit]

- Peirce, Leslie (1993). Empress of the East: How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire. New York Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03251-8..

- Peirce, Leslie P. The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire (Oxford University Press, 1993)

- There are many historical novels in English about Roxelana: P.J. Parker’s Roxelana and Suleyman[1] (2012; Revised 2016); Barbara Chase Riboud’s Valide (1986); Alum Bati’s Harem Secrets (2008); Colin Falconer, Aileen Crawley (1981–83), and Louis Gardel (2003); Pawn in Frankincense, the fourth book of the Lymond Chronicles by Dorothy Dunnett; and pulp fiction author Robert E. Howard in The Shadow of the Vulture imagined Roxelana to be sister to its fiery-tempered female protagonist, Red Sonya.

- David Chataignier, «Roxelane on the French Tragic Stage (1561-1681)» in Fortune and Fatality: Performing the Tragic in Early Modern France, ed. Desmond Hosford and Charles Wrightington (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), 95–117.

- Parker, P. J. Roxelana and Suleyman (Raider Publishing International, 2011).

- Thomas M. Prymak, «Roxolana: Wife of Suleiman the Magnificent,» Nashe zhyttia/Our Life, LII, 10 (New York, 1995), 15–20. An illustrated popular-style article in English with a bibliography.

- Galina Yermolenko, «Roxolana: The Greatest Empresse of the East,» The Muslim World, 95, 2 (2005), 231–48. Makes good use of European, especially Italian, sources and is familiar with the literature in Ukrainian and Polish.

- Galina Yermolenko (ed.), Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture (Farmham, UK: Ashgate, 2010). ISBN 9780754667612 318 pp. Illustrated. Contains important articles by Oleksander Halenko and others, as well as several translations of works about Roxelana from various European literatures, and an extensive bibliography.

- For Ukrainian language novels, see Osyp Nazaruk (1930) (English translation is available),[2] Mykola Lazorsky (1965), Serhii Plachynda (1968), and Pavlo Zahrebelnyi (1980).

- There have been novels written in other languages: in French, a fictionalized biography by Willy Sperco (1972); in German, a novel by Johannes Tralow (1944, reprinted many times); a very detailed novel in Serbo-Croatian by Radovan Samardzic (1987); one in Turkish by Ulku Cahit (2001).

References[edit]

- ^ «Roxelana and Suleyman». www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017.

- ^ Nazaruk, Osyp. Roxelana – via Amazon.

External links[edit]

- University of Calgary | Roxelana

- Hürrem Sultan’s tomb

| Ottoman royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title

position established |

Haseki Sultan 1533/1534 – 15 April 1558 |

Succeeded by

Nurbanu Sultan |

| Hürrem Sultan | ||

|---|---|---|

Portrait by Titian titled La Sultana Rossa, c. 1550 |

||

| Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Imperial Consort) |

||

| Tenure | c. 1533 – 15 April 1558 | |

| Successor | Nurbanu Sultan | |

| Born | Alexandra or Anastasia c. 1504 Rohatyn, Ruthenia, Kingdom of Poland (now Ukraine) |

|

| Died | 15 April 1558 (aged c. 53-54) Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire (now Turkey) |

|

| Burial |

Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul |

|

| Spouse |

Suleiman I (m. 1533) year disputed |

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| Father | Lisovsky, possibly a Ruthenian Orthodox Priest[1] | |

| Mother | Leksandra Lisowska[2] | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam, previously Eastern Orthodox Christian |

Roxelana (Ukrainian: Роксолана, romanized: Roksolana; lit. ‘the Ruthenian one’; c. 1504 – 15 April 1558), also known as Hurrem Sultan (Turkish pronunciation: [hyɾˈɾæm suɫˈtan]; Ottoman Turkish: خُرّم سلطان, romanized: Ḫurrem Sulṭān; Modern Turkish: Hürrem Sultan), was the chief consort and legal wife of the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She became one of the most powerful and influential women in Ottoman history as well as a prominent and controversial figure during the era known as the Sultanate of Women.

Born in Ruthenia (then an eastern region of the Kingdom of Poland, now Rohatyn, Ukraine) to a Ruthenian Orthodox priest, Roxelana was captured by Crimean Tatars during a slave raid and eventually taken to Istanbul, the Ottoman capital.[3] She entered the Imperial Harem where her name was changed to Hurrem, rose through the ranks and became the favourite of Sultan Suleiman. Breaking Ottoman tradition, he married Roxelana, making her his legal wife. Sultans had previously married only foreign free noble ladies. She was the first imperial consort to receive the title Haseki Sultan. Roxelana remained in the sultan’s court for the rest of her life, enjoying a close relationship with her husband, and having six children with him, including the future sultan, Selim II.

Roxelana eventually achieved power, influencing the politics of the Ottoman Empire. Through her husband, she played an active role in affairs of the state. She probably acted as the sultan’s advisor, wrote diplomatic letters to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland (r. 1548–1572) and patronized major public works (including the Haseki Sultan Complex and the Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse). She died in 1558, in Istanbul and was buried in a mausoleum within the Süleymaniye Mosque complex.

Names[edit]

Roxelana’s birth name is unknown. Leslie P. Peirce has written that it may have been either Anastasia, or Aleksandra Lisowska. Among the Ottomans, she was known mainly as Haseki Hurrem Sultan or Hurrem Haseki Sultan. Hurrem or Khorram (Persian: خرم) means «the joyful one» in Persian. The name Roxalane derives from Roksolanes, which was the generic term used by the Ottomans to describe girls from Podolia and Galicia who were taken in slave raids.

Origin[edit]

Sources indicate that Roxelana was originally from Ruthenia, which was then part of the Polish Crown.[4] She was born in the town of Rohatyn 68 km (42 mi) southeast of Lwów (Lviv), a major city of the Ruthenian Voivodeship of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland,[5] in what is now Ukraine. According to late 16th-century and early 17th-century sources, such as the Polish poet Samuel Twardowski (died 1661), who researched the subject in Turkey, Roxelana was seemingly born to a man surnamed Lisovski, who was an Orthodox priest of Ruthenian origin.[5][6][7] Her native language was Ruthenian, the precursor to modern Ukrainian.[8]

During the reign of Selim I,[9] which means some time between 1512 and 1520, Crimean Tatars kidnapped her during one of their Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe. The Tatars may have first taken her to the Crimean city of Kaffa, a major centre of the Ottoman slave trade, before she was taken to Istanbul.[5][6][7] In Istanbul, Valide Hafsa Sultan selected Roxelana as a gift for her son, Suleiman. Roxelana later managed to become the first Haseki Sultan or «favorite concubine» of the Ottoman imperial harem.[4] Michalo Lituanus wrote in the 16th century that «the most beloved wife of the present Turkish emperor – mother of his first [son] who will govern after him, was kidnapped from our land».[i][10]

Shaykh Qutb al-Din al-Nahrawali, a Meccan religious figure, who visited Istanbul in late 1557, noted in his memoirs that Hurrem Sultan was of Ruthenian origin. She had been a servant in the household of Hançerli Zeynep Fatma Sultan, daughter of Şehzade Mahmud, son of Sultan Bayezid II.[11]

European ambassadors of that period called her la Rossa, la Rosa, and Roxelana, meaning «the Russian woman»[12] or «the Ruthenian one» for her alleged Ruthenian origins.[13] She is the sultan’s consort with the most portraits in her name in the Ottoman Empire, though the portraits are imaginary depictions by painters.[14]

Relationship with Suleiman[edit]

Roxelana, called Hurrem Sultan by the Ottomans, probably entered the harem around seventeen years of age. The precise year that she entered the harem is unknown, but scholars believe that she became Suleiman’s concubine around the time he became sultan in 1520.[15]

Roxelana’s unprecedented rise from harem slave to Suleiman’s legal wife and Ottoman Empress attracted jealousy and disfavor not only from her rivals in the harem, but also from the general populace.[4] She soon became Suleiman’s most prominent consort beside Mahidevran (also known as Gülbahar), and their relationship was monogamous. While the exact dates for the births of her children are disputed, there is academic consensus that the births of her five children —Şehzade Mehmed, Mihrimah Sultan, Şehzade Abdullah, Sultan Selim II and Şehzade Bayezid — occurred quickly over the next four to five years.[15]: 130 Suleiman and Roxelana’s last child, Şehzade Cihangir was born with a hunchback, but by that time Roxelana had given birth to enough healthy sons to secure the future of the Ottoman dynasty.[15]: 131

Her joyful spirit and playful temperament earned her a new name, Hurrem, from Persian Khorram, «the cheerful one». In the Istanbul harem, Hurrem became a rival to Mahidevran and her influence over the sultan soon became legendary.

Hurrem was allowed to give birth to more than one son which was a stark violation of the old imperial harem principle, «one concubine mother — one son,» which was designed to prevent both the mother’s influence over the sultan and the feuds of the blood brothers for the throne.[10] She was to bear the majority of Suleiman’s children. Hurrem gave birth to her first son Mehmed in 1521 (who died in 1543) and then to four more sons, destroying Mahidevran’s status as the mother of the sultan’s only son.[16]

Suleiman’s mother, Hafsa Sultan, partially suppressed the rivalry between the two women.[17] According to Bernardo Navagero’s report, as a result of the bitter rivalry a fight between the two women broke out, with Mahidevran beating Hurrem, which angered Suleiman.[18] According to Necdet Sakaoğlu, a Turkish historian, these accusations were not truthful. After the death of Suleiman’s mother Hafsa Sultan in 1534, Hurrem’s influence in the palace increased, and she took over the ruling of the Harem.[19] Hurrem became the only partner of the ruler and received the title of Haseki, which means the favorite. When Suleiman freed and married her, she became the Haseki Sultan (adding the word sultan to a woman’s name or title indicated that she was a part of the dynasty).[20]

Around 1526/1534 (the exact date is unknown),[10] Suleiman married Hurrem in a magnificent formal ceremony. Never before had a former slave been elevated to the status of the sultan’s lawful spouse, a development which astonished observers in the palace and in the city.[21] It was only possible for Hurrem to marry Suleiman after the death of Hafsa Sultan. It was not because Hafsa Sultan was firmly against this unification, but because it was not allowed for a concubine to rise above the status of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother).[22]

Hurrem became the first consort to receive the title Haseki Sultan.[23] This title, used for a century, reflected the great power of imperial consorts (most of them were former slaves) in the Ottoman court, elevating their status higher than Ottoman princesses, and making them the equals of empresses consort in Europe. In this case, Suleiman not only broke the old custom, but began a new tradition for the future Ottoman sultans: To marry in a formal ceremony and to give their consorts significant influence on the court, especially in matters of succession. Hurrem’s salary was 2,000 aspers a day, making her one of the highest-paid Hasekis.[10] After the wedding, the idea circulated that the sultan had limited his autonomy and was dominated and controlled by his wife.[24] Also, in Ottoman society, mothers played more influential roles in their sons’ educations and in guiding their careers.[24]

After the death of Suleiman’s mother, Hafsa Sultan, in 1534, Hurrem became the most trusted news source of Suleiman. In one of her letters to Suleiman, she informs him about the situation of the plague in the capital. She wrote, «My dearest Sultan! If you ask about Istanbul, the city still suffers from the plague; however, it is not like the previous one. God willing, it will go away as soon as you return to the city. Our ancestors said that the plague goes away once the trees shed their leaves in autumn.»[25]

Later, Hurrem became the first woman to remain in the sultan’s court for the duration of her life. In the Ottoman imperial family tradition, a sultan’s consort was to remain in the harem only until her son came of age (around 16 or 17), after which he would be sent away from the capital to govern a faraway province, and his mother would follow him. This tradition was called Sancak Beyliği. The consorts were never to return to Istanbul unless their sons succeeded to the throne.[26] In defiance of this age-old custom, Hurrem stayed behind in the harem, even after her sons went to govern the empire’s remote provinces.

Moreover, remaining in Istanbul, she moved out of the harem located in the Old Palace (Eski Saray) and permanently moved into the Topkapı Palace after a fire destroyed the old harem. Some sources say she moved to Topkapı, not because of the fire, but as a result of her marriage to Suleiman. Either way, this was another significant break from established customs, as Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror had specifically issued a decree to the effect that no women would be allowed to reside in the same building where government affairs were conducted.[15]: 131 After Hurrem resided at Topkapı it became known as the New Palace (saray-ı jedid).[27]

She wrote many love letters to Suleiman when he was away for campaigns. In one of her letters, she wrote:

- «After I put my head on the ground and kiss the soil that your blessed feet step upon, my nation’s sun and wealth my sultan, if you ask about me, your servant who has caught fire from the zeal of missing you, I am like the one whose liver (in this case, meaning heart) has been broiled; whose chest has been ruined; whose eyes are filled with tears, who cannot distinguish anymore between night and day; who has fallen into the sea of yearning; desperate, mad with your love; in a worse situation than Ferhat and Majnun, this passionate love of yours, your slave, is burning because I have been separated from you. Like a nightingale, whose sighs and cries for help do not cease, I am in such a state due to being away from you. I would pray to Allah to not afflict this pain even upon your enemies. My dearest sultan! As it has been one-and-a-half months since I last heard from you, Allah knows that I have been crying night and day waiting for you to come back home. While I was crying without knowing what to do, the one and only Allah allowed me to receive good news from you. Once I heard the news, Allah knows, I came to life once more since I had died while waiting for you.[25]

Under his pen name, Muhibbi, Sultan Suleiman composed this poem for Hurrem Sultan:

«Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight.

My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence, my Sultan, my one and only love.

The most beautiful among the beautiful…

My springtime, my merry faced love, my daytime, my sweetheart, laughing leaf…

My plants, my sweet, my rose, the one only who does not distress me in this world…

My Istanbul, my Caraman, the earth of my Anatolia

My Badakhshan, my Baghdad and Khorasan

My woman of the beautiful hair, my love of the slanted brow, my love of eyes full of mischief…

I’ll sing your praises always

I, lover of the tormented heart, Muhibbi of the eyes full of tears, I am happy.»[28]

State affairs[edit]

Hurrem Sultan is known as the first woman in Ottoman history to concern herself with state affairs. Thanks to her intelligence, she acted as Suleiman’s chief adviser on matters of state, and seems to have had an influence upon foreign policy and international politics. She frequently accompanied him as a political adviser. She imprinted her seal and watched the council meetings through a wire mesh window. With many other revolutionary movements like these, she had started an era in Ottoman Empire called the Reign of Women.[29] Hurrem’s influence on Suleiman was so significant that rumors circulated around the Ottoman court that the sultan had been bewitched.[4]

Her influence with Suleiman made her one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history and in the world at that time. Even as a consort, her power was comparable with the most powerful woman of the Imperial Harem, who by tradition was the sultan’s mother or valide sultan. For this reason, she has become a controversial figure in Ottoman history — subject to allegations of plotting against and manipulating her political rivals.

Controversial figure[edit]

16th century Latin oil painting of Hurrem Sultan titled Rosa Solymanni Vxor (Rosa, Süleyman’s Wife)

Hurrem’s influence in state affairs not only made her one of the most influential women, but also a controversial figure in Ottoman history, especially in her rivalry with Mahidevran and her son Şehzade Mustafa, and the grand viziers Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha and Kara Ahmed Pasha.

Hurrem and Mahidevran had given birth to Suleiman’s six şehzades (Ottoman princes), four of whom survived past the 1550s: Mehmed, Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir. Of these, Mahidevran’s son Mustafa was the eldest and preceded Hurrem’s children in the order of succession. Traditionally, when a new sultan rose to power, he would order all of his brothers killed in order to ensure there was no power struggle. This practice was called kardeş katliamı, literally «fraternal massacring».[30]

Mustafa was supported by Ibrahim Pasha, who became Suleiman’s grand vizier in 1523. Hurrem has usually been held at least partly responsible for the intrigues in nominating a successor.[15]: 132 Although she was Suleiman’s wife, she exercised no official public role. This did not, however, prevent Hurrem from wielding powerful political influence. Since the empire lacked, until the reign of Ahmed I (1603–1617), any formal means of nominating a successor, successions usually involved the death of competing princes in order to avert civil unrest and rebellions. In attempting to avoid the execution of her sons, Hurrem used her influence to eliminate those who supported Mustafa’s accession to the throne.[31]

A skilled commander of Suleiman’s army, Ibrahim eventually fell from grace after an imprudence committed during a campaign against the Persian Safavid empire during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), when he awarded himself a title including the word «Sultan». Another conflict occurred when Ibrahim and his former mentor, İskender Çelebi, repeatedly clashed over military leadership and positions during the Safavid war. These incidents launched a series of events which culminated in his execution in 1536 by Suleiman’s order. It is believed that Hurrem’s influence contributed to Suleiman’s decision.[32] After three other grand viziers in eight years, Suleiman selected Hurrem’s son-in-law, Damat Rüstem Pasha, husband of Mihrimah, to become the grand vizier. Scholars have wondered if Hurrem’s alliance with Mihrimah Sultan and Rüstem Pasha helped secure the throne for one of Hurrem’s sons.[15]: 132

Many years later, towards the end of Suleiman’s long reign, the rivalry between his sons became evident. Mustafa was later accused of causing unrest. During the campaign against Safavid Persia in 1553, because of fear of rebellion, Suleiman ordered the execution of Mustafa. According to a source he was executed that very year on charges of planning to dethrone his father; his guilt for the treason of which he was accused remains neither proven nor disproven.[33] It is also rumored that Hurrem Sultan conspired against Mustafa with the help of her daughter and son-in-law Rustem Pasha; they wanted to portray Mustafa as a traitor who secretly contacted the Shah of Iran. Acting on Hurrem Sultan’s orders, Rustem Pasha had engraved Mustafa’s seal and sent a letter seemingly written from his mouth to Shah Tahmasb I, and then sent Shah’s response to Suleiman.[19] After the death of Mustafa, Mahidevran lost her status in the palace as the mother of the heir apparent and moved to Bursa.[16] She did not spend her last years in poverty, as Hurrem’s son, Selim II, the new sultan after 1566, put her on a lavish salary.[33] Her rehabilitation had been possible after the death of Hurrem in 1558.[33] Cihangir, Hurrem’s youngest child, allegedly died of grief a few months after the news of his half-brother’s murder.[34]

Although the stories about Hurrem’s role in executions of Ibrahim, Mustafa, and Kara Ahmed are very popular, actually none of them are based on first-hand sources. All other depictions of Hurrem, starting with comments by sixteenth and seventeenth-century Ottoman historians as well as by European diplomats, observers, and travellers, are highly derivative and speculative in nature. Because none of these people – neither Ottomans nor foreign visitors – were permitted into the inner circle of the imperial harem, which was surrounded by multiple walls, they largely relied on the testimony of the servants or courtiers or on the popular gossip circulating around Istanbul.[10]

Even the reports of the Venetian ambassadors (baili) at Suleiman’s court, the most extensive and objective first-hand Western source on Hurrem to date, were often filled with the authors’ own interpretations of the harem rumours. Most other sixteenth-century Western sources on Hurrem, which are considered highly authoritative today — such as Turcicae epistolae (English: The Turkish Letters) of Ogier de Busbecq, the Emissary of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I at the Porte between 1554 and 1562; the account of the murder of Şehzade Mustafa by Nicholas de Moffan; the historical chronicles on Turkey by Paolo Giovio; and the travel narrative by Luidgi Bassano — derived from hearsay.[10]

Foreign policy[edit]

A letter of Hurrem Sultan to Sigismund II Augustus, congratulating him on his accession to the Polish throne in 1549.

Hurrem acted as Suleiman’s advisor on matters of state, and seems to have had an influence upon foreign policy and on international politics. Two of her letters to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland (reigned 1548–1572) have survived, and during her lifetime the Ottoman Empire generally had peaceful relations with the Polish state within a Polish–Ottoman alliance.

In her first short letter to Sigismund II, Hurrem expresses her highest joy and congratulations to the new king on the occasion of his ascension to the Polish throne after the death of his father Sigismund I the Old in 1548. There was a seal on the back of the letter. For the first and only time in the Ottoman Empire, a female sultan exchanged letters with a king. After that, although Hurrem’s successor Nurbanu Sultan and her successor Safiye Sultan exchanged letters with queens, there is no other example of a female sultan who personally contacted a king other than Hurrem Sultan.[19] She pleads with the King to trust her envoy Hassan Ağa who took another message from her by word of mouth.

In her second letter to Sigismund Augustus, written in response to his letter, Hurrem expresses in superlative terms her joy at hearing that the king is in good health and that he sends assurances of his sincere friendliness and attachment towards Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. She quotes the sultan as saying, «with the old king we were like brothers, and if it pleases the All-Merciful God, with this king we will be as father and son.» With this letter, Hurrem sent Sigismund II the gift of two pairs of linen shirts and pants, some belts, six handkerchiefs, and a hand-towel, with a promise to send a special linen robe in the future.

There are reasons to believe that these two letters were more than just diplomatic gestures, and that Suleiman’s references to brotherly or fatherly feelings were not a mere tribute to political expediency. The letters also suggest Hurrem’s strong desire to establish personal contact with the king. In his 1551 letter to Sigismund II concerning the embassy of Piotr Opaliński, Suleiman wrote that the Ambassador had seen «Your sister and my wife.» Whether this phrase refers to a warm friendship between the Polish King and Ottoman Haseki, or whether it suggests a closer relation, the degree of their intimacy definitely points to a special link between the two states at the time.[10]

Charities[edit]

Aside from her political concerns, Hurrem engaged in several major works of public buildings, from Makkah to Jerusalem (Al-Quds), perhaps modelling her charitable foundations in part after the caliph Harun al-Rashid’s consort Zubaida. Among her first foundations were a mosque, two Quranic schools (madrassa), a fountain, and a women’s hospital near the women’s slave market (Avret Pazary) in Istanbul (Haseki Sultan Complex). It was the first complex constructed in Istanbul by Mimar Sinan in his new position as the chief imperial architect.[35]

She built mosque complexes in Adrianopole and Ankara. She commissioned a bath, the Hurrem Sultan Bathhouse, to serve the community of worshippers in the nearby Hagia Sophia.[36] In Jerusalem she established the Haseki Sultan Imaret in 1552, a public soup kitchen to feed the poor,[37] which was said to have fed at least 500 people twice a day.[38] She built a public soup kitchen in Makkah.[10]

She had a Kira who acted as her secretary and intermediary on several occasions, although the identity of the kira is uncertain (it may have been Strongilah[39] or Esther Handali[citation needed]).

Death[edit]

Hurrem died on 15 April 1558 due to an unknown illness and was buried in a domed mausoleum (türbe) decorated in exquisite Iznik tiles depicting the garden of paradise, perhaps in homage to her smiling and joyful nature.[40] Her mausoleum is adjacent to Suleiman’s, a separate and more somber domed structure, at the courtyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque.

Personality[edit]

Roxelana’s contemporaries describe her as a woman who was strikingly good-looking, and different from everybody else because of her red hair.[41] Roxelana was also intelligent and had a pleasant personality. Her love of poetry is considered one of the reasons behind her being heavily favoured by Suleiman, who was a great admirer of poetry.[41]

Roxelana is known to have been very generous to the poor. She built numerous mosques, madrasahs, hammams, and resting places for pilgrims travelling to the Islamic holy city of Makkah. Her greatest philanthropical work was the Great Waqf of AlQuds, a large soup kitchen in Jerusalem that fed the poor.[42]

It is believed that Roxelana was a cunning, manipulative and stony-hearted woman who would execute anyone who stood in her way. However, her philanthropy is in contrast to this as she cared for the poor. Prominent Ukrainian writer Pavlo Zahrebelny describes Roxelana as «an intelligent, kind, understanding, openhearted, candid, talented, generous, emotional and grateful woman who cares about the soul rather than the body; who is not carried away with ordinary glimmers such as money, prone to science and art; in short, a perfect woman.»[43]

Legacy[edit]

Roxelana, or Hurrem Haseki Sultan, is well-known both in modern Turkey and in the West, and is the subject of many artistic works. In 1561, three years after her death, the French author Gabriel Bounin wrote a tragedy titled La Soltane.[44] This tragedy marks the first time the Ottomans were introduced on stage in France.[45] She has inspired paintings, musical works (including Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 63), an opera by Denys Sichynsky, a ballet, plays, and several novels written mainly in Russian and Ukrainian, but also in English, French, German and Polish.

In early modern Spain, she appears or is alluded to in works by Quevedo and other writers as well as in a number of plays by Lope de Vega. In a play entitled The Holy League, Titian appears on stage at the Venetian Senate, and stating that he has just come from visiting the Sultan, displays his painting of Sultana Rossa or Roxelana.[46]

In 2007, Muslims in Mariupol, a port city in Ukraine opened a mosque to honour Roxelana.[47]

In the 2003 TV miniseries, Hürrem Sultan, she was played by Turkish actress and singer Gülben Ergen. In the 2011–2014 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, Hurrem Sultan is portrayed by Turkish-German actress Meryem Uzerli from seasons one to three. For the series’ last season, she is portrayed by Turkish actress Vahide Perçin.