Kawaii (Japanese: かわいい or 可愛い, IPA: [kawaiꜜi]; ‘lovely’, ‘loveable’, ‘cute’, or ‘adorable’)[1] is the culture of cuteness in Japan.[2][3][4] It can refer to items, humans and non-humans that are charming, vulnerable, shy and childlike.[2] Examples include cute handwriting, certain genres of manga, anime, and characters including Hello Kitty and Pikachu from Pokémon.[5][6]

The cuteness culture, or kawaii aesthetic, has become a prominent aspect of Japanese popular culture, entertainment, clothing, food, toys, personal appearance, and mannerisms.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The word kawaii originally derives from the phrase 顔映し kao hayushi, which literally means «(one’s) face (is) aglow,» commonly used to refer to flushing or blushing of the face. The second morpheme is cognate with -bayu in mabayui (眩い, 目映い, or 目映ゆい) «dazzling, glaring, blinding, too bright; dazzlingly beautiful» (ma- is from 目 me «eye») and -hayu in omohayui (面映い or 面映ゆい) «embarrassed/embarrassing, awkward, feeling self-conscious/making one feel self-conscious» (omo- is from 面 omo, an archaic word for «face, looks, features; surface; image, semblance, vestige»). Over time, the meaning changed into the modern meaning of «cute» or «shine» , and the pronunciation changed to かわゆい kawayui and then to the modern かわいい kawaii.[8][9][10] It is commonly written in hiragana, かわいい, but the ateji, 可愛い, has also been used. The kanji in the ateji literally translates to «able to love/be loved, can/may love, lovable.»

History[edit]

Original definition[edit]

Kogal girl, identified by her shortened skirt. The soft bag and teddy bear that she carries are part of kawaii.

The original definition of kawaii came from Lady Murasaki’s 11th century novel The Tale of Genji, where it referred to pitiable qualities.[11] During the Shogunate period[when?] under the ideology of neo-Confucianism, women came to be included under the term kawaii as the perception of women being animalistic was replaced with the conception of women as docile.[11] However, the earlier meaning survives into the modern Standard Japanese adjectival noun かわいそう kawaisō (often written with ateji as 可哀相 or 可哀想) «piteous, pitiable, arousing compassion, poor, sad, sorry» (etymologically from 顔映様 «face / projecting, reflecting, or transmitting light, flushing, blushing / seeming, appearance»). Forms of kawaii and its derivatives kawaisō and kawairashii (with the suffix -rashii «-like, -ly») are used in modern dialects to mean «embarrassing/embarrassed, shameful/ashamed» or «good, nice, fine, excellent, superb, splendid, admirable» in addition to the standard meanings of «adorable» and «pitiable.»

Cute handwriting[edit]

In the 1970s, the popularity of the kawaii aesthetic inspired a style of writing.[12] Many teenage girls participated in this style; the handwriting was made by writing laterally, often while using mechanical pencils.[12] These pencils produced very fine lines, as opposed to traditional Japanese writing that varied in thickness and was vertical.[12] The girls would also write in big, round characters and they added little pictures to their writing, such as hearts, stars, emoticon faces, and letters of the Latin alphabet.[12]

These pictures made the writing very difficult to read.[12] As a result, this writing style caused a lot of controversy and was banned in many schools.[12] During the 1980s, however, this new «cute» writing was adopted by magazines and comics and was often put onto packaging and advertising[12] of products, especially toys for children or “cute accessories”.

From 1984 to 1986, Kazuma Yamane (山根一眞, Yamane Kazuma) studied the development of the cute handwriting (which he called Anomalous Female Teenage Handwriting) in depth.[12] This type of cute Japanese handwriting has also been called: marui ji (丸い字), meaning «round writing», koneko ji (小猫字), meaning «kitten writing», manga ji (漫画字), meaning «comic writing», and burikko ji (鰤子字), meaning «fake-child writing».[13] Although it was commonly thought that the writing style was something that teenagers had picked up from comics, Kazuma found that teenagers had come up with the style themselves, spontaneously, as an ‘underground trend’. His conclusion was based on an observation that cute handwriting predates the availability of technical means for producing rounded writing in comics.[12]

Cute merchandise[edit]

Baby-faced girl characters are rooted in Japanese society

Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, says cute fashion in Japan can be traced back to the Edo period with the popularity of netsuke.[14] Illustrator Rune Naito, who produced illustrations of «large-headed» (nitōshin) baby-faced girls and cartoon animals for Japanese girls’ magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s, is credited with pioneering what would become the culture and aesthetic of kawaii.[15]

Because of this growing trend, companies such as Sanrio came out with merchandise like Hello Kitty. Hello Kitty was an immediate success and the obsession with cute continued to progress in other areas as well. More recently, Sanrio has released kawaii characters with deeper personalities that appeal to an older audience, such as Gudetama and Aggretsuko. These characters have enjoyed strong popularity as fans are drawn to their unique quirks in addition to their cute aesthetics.[16] The 1980s also saw the rise of cute idols, such as Seiko Matsuda, who is largely credited with popularizing the trend. Women began to emulate Seiko Matsuda and her cute fashion style and mannerisms, which emphasized the helplessness and innocence of young girls.[17] The market for cute merchandise in Japan used to be driven by Japanese girls between 15 and 18 years old.[18]

Aesthetics[edit]

Soichi Masubuchi (増淵宗一, Masubuchi Sōichi), in his work Kawaii Syndrome, claims «cute» and «neat» have taken precedence over the former Japanese aesthetics of «beautiful» and «refined».[11] As a cultural phenomenon, cuteness is increasingly accepted in Japan as a part of Japanese culture and national identity. Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, believes that «cuteness» is rooted in Japan’s harmony-loving culture, and Nobuyoshi Kurita (栗田経惟, Kurita Nobuyoshi), a sociology professor at Musashi University in Tokyo, has stated that «cute» is a «magic term» that encompasses everything that is acceptable and desirable in Japan.[19]

Physical attractiveness[edit]

In Japan, being cute is acceptable for both men and women. A trend existed of men shaving their legs to mimic the neotenic look. Japanese women often try to act cute to attract men.[20] A study by Kanebo, a cosmetic company, found that Japanese women in their 20s and 30s favored the «cute look» with a «childish round face».[14] Women also employ a look of innocence in order to further play out this idea of cuteness. Having large eyes is one aspect that exemplifies innocence; therefore many Japanese women attempt to alter the size of their eyes. To create this illusion, women may wear large contact lenses, false eyelashes, dramatic eye makeup, and even have an East Asian blepharoplasty, commonly known as double eyelid surgery.[21]

Idols[edit]

Japanese idols (アイドル, aidoru) are media personalities in their teens and twenties who are considered particularly attractive or cute and who will, for a period ranging from several months to a few years, regularly appear in the mass media, e.g. as singers for pop groups, bit-part actors, TV personalities (tarento), models in photo spreads published in magazines, advertisements, etc. (But not every young celebrity is considered an idol. Young celebrities who wish to cultivate a rebellious image, such as many rock musicians, reject the «idol» label.) Speed, Morning Musume, AKB48, and Momoiro Clover Z are examples of popular idol groups in Japan during the 2000s & 2010s.[22]

Cute fashion[edit]

Lolita[edit]

Lolita fashion is a very well-known and recognizable style in Japan. Based on Victorian fashion and the Rococo period, girls mix in their own elements along with gothic style to achieve the porcelain-doll look.[23] The girls who dress in Lolita fashion try to look cute, innocent, and beautiful.[23] This look is achieved with lace, ribbons, bows, ruffles, bloomers, aprons, and ruffled petticoats. Parasols, chunky Mary Jane heels, and Bo Peep collars are also very popular.[24]

Sweet Lolita is a subset of Lolita fashion that includes even more ribbons, bows, and lace, and is often fabricated out of pastels and other light colors. Head-dresses such as giant bows or bonnets are also very common, while lighter make-up is sometimes used to achieve a more natural look. Curled hair extensions, sometimes accompanied by eyelash extensions, are also popular in helping with the baby doll look.[25] Another subset of Lolita fashion related to «sweet Lolita» is Fairy Kei.

Themes such as fruits, flowers and sweets are often used as patterns on the fabrics used for dresses. Purses often go with the themes and are shaped as hearts, strawberries, or stuffed animals. Baby, the Stars Shine Bright is one of the more popular clothing stores for this style and often carries themes. Mannerisms are also important to many Sweet Lolitas. Sweet Lolita is sometimes not only a fashion, but also a lifestyle.[25] This is evident in the 2004 film Kamikaze Girls where the main Lolita character, Momoko, drinks only tea and eats only sweets.[26]

Gothic Lolita, Kuro Lolita, Shiro Lolita, and Military Lolita are all subtypes, also, in the US Anime Convention scene Casual Lolita.

Decora[edit]

Example of Decora fashion

Decora is a style that is characterized by wearing many «decorations» on oneself. It is considered to be self-decoration. The goal of this fashion is to become as vibrant and characterized as possible. People who take part in this fashion trend wear accessories such as multicolor hair pins, bracelets, rings, necklaces, etc. By adding on multiple layers of accessories on an outfit, the fashion trend tends to have a childlike appearance. It also includes toys and multicolor clothes. Decora and Fairy Kei have some crossover.

Kimo-kawaii

Kimo-kawaii means creepy-cute or gross-cute.[27] The style started around the 1990s when some people lost interest in cute and innocent characters and fashion. It is usually achieved by wearing creepy or gross clothes or accessories.

Kawaii men

Although typically a female-dominated fashion, some men partake in the kawaii trend. Men wearing masculine kawaii accessories is very uncommon, and typically the men cross-dress as kawaii women instead by wearing wigs, false eyelashes, applying makeup, and wearing kawaii female clothing.[28] This is seen predominately in male entertainers, such as Torideta-san, a DJ who transforms himself into a kawaii woman when working at his nightclub.[28]

Japanese pop stars and actors often have longer hair, such as Takuya Kimura of SMAP. Men are also noted as often aspiring to a neotenic look. While it doesn’t quite fit the exact specifications of what cuteness means for females, men are certainly influenced by the same societal mores — to be attractive in a specific sort of way that the society finds acceptable.[29] In this way both Japanese men and women conform to the expectations of Kawaii in some way or another.

Products[edit]

The concept of kawaii has had an influence on a variety of products, including candy, such as Hi-Chew, Koala’s March and Hello Panda. Cuteness can be added to products by adding cute features, such as hearts, flowers, stars and rainbows. Cute elements can be found almost everywhere in Japan, from big business to corner markets and national government, ward, and town offices.[20][30] Many companies, large and small, use cute mascots to present their wares and services to the public. For example:

- Pikachu, a character from Pokémon, adorns the side of ten ANA passenger jets, the Pokémon Jets.

- Asahi Bank used Miffy (Nijntje), a character from a Dutch series of children’s picture books, on some of its ATM and credit cards.

- The prefectures of Japan, as well as many cities and cultural institutions, have cute mascot characters known as yuru-chara to promote tourism. Kumamon, the Kumamoto Prefecture mascot, and Hikonyan, the city of Hikone mascot, are among the most popular.[31]

- The Japan Post «Yū-Pack» mascot is a stylized mailbox;[32] they also use other cute mascot characters to promote their various services (among them the Postal Savings Bank) and have used many such on postage stamps.

- Some police forces in Japan have their own moe mascots, which sometimes adorn the front of kōban (police boxes).

- NHK, the public broadcaster, has its own cute mascots. Domokun, the unique-looking and widely recognized NHK mascot, was introduced in 1998 and quickly took on a life of its own, appearing in Internet memes and fan art around the world.

- Sanrio, the company behind Hello Kitty and other similarly cute characters, runs the Sanrio Puroland theme park in Tokyo, and painted on some EVA Air Airbus A330 jets as well. Sanrio’s line of more than 50 characters takes in more than $1 billion a year and it remains the most successful company to capitalize on the cute trend.[30]

Cute can be also used to describe a specific fashion sense[33][34] of an individual, and generally includes clothing that appears to be made for young children, apart from the size, or clothing that accentuates the cuteness of the individual wearing the clothing. Ruffles and pastel colors are commonly (but not always) featured, and accessories often include toys or bags featuring anime characters.[30]

Non-kawaii imports[edit]

Kawaii goods outlet in 100 yen shop

There have been occasions on which popular Western products failed to meet the expectations of kawaii, and thus did not do well in the Japanese market. For example, Cabbage Patch Kids dolls did not sell well in Japan, because the Japanese considered their facial features to be «ugly» and «grotesque» compared to the flatter and almost featureless faces of characters such as Hello Kitty.[11] Also, the doll Barbie, portraying an adult woman, did not become successful in Japan compared to Takara’s Licca, a doll that was modeled after an 11-year-old girl.[11]

Industry[edit]

Kawaii has gradually gone from a small subculture in Japan to an important part of Japanese modern culture as a whole. An overwhelming number of modern items feature kawaii themes, not only in Japan but also worldwide.[35] And characters associated with kawaii are astoundingly popular. «Global cuteness» is reflected in such billion-dollar sellers as Pokémon and Hello Kitty.[36] «Fueled by Internet subcultures, Hello Kitty alone has hundreds of entries on eBay, and is selling in more than 30 countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, and Taiwan.»[36]

Japan has become a powerhouse in the kawaii industry and images of Doraemon, Hello Kitty, Pikachu, Sailor Moon and Hamtaro are popular in mobile phone accessories. However, Professor Tian Shenliang says that Japan’s future is dependent on how much of an impact kawaii brings to humanity.[37]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry has also recognized the power of cute merchandise and has sent three 18-year-old women overseas in the hopes of spreading Japanese culture around the world. The women dress in uniforms and maid costumes that are commonplace in Japan.[38]

Kawaii manga and magazines have brought tremendous profit to the Japanese press industry.[citation needed] Moreover, the worldwide revenue from the computer game and its merchandising peripherals are closing in on $5 billion, according to a Nintendo press release titled «It’s a Pokémon Planet».[36]

Influence upon other cultures[edit]

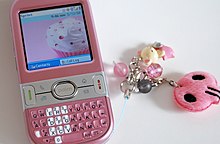

Kawaii keychain accessory attached to a pink Palm Centro smartphone

In recent years, Kawaii products have gained popularity beyond the borders of Japan in other East and Southeast Asian countries, and are additionally becoming more popular in the US among anime and manga fans as well as others influenced by Japanese culture. Cute merchandise and products are especially popular in other parts of East Asia, such as mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as Southeast Asian countries including the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.[30][39]

Sebastian Masuda, owner of 6%DOKIDOKI and a global advocate for kawaii influence, takes the quality from Harajuku to Western markets in his stores and artwork. The underlying belief of this Japanese designer is that «kawaii» actually saves the world.[40] The infusion of kawaii into other world markets and cultures is achieved by introducing kawaii via modern art; audio, visual, and written media; and the fashion trends of Japanese youth, especially in high school girls.[41]

Japanese kawaii seemingly operates as a center of global popularity due to its association with making cultural productions and consumer products «cute». This mindset pursues a global market,[42] giving rise to numerous applications and interpretations in other cultures.

The dissemination of Japanese youth fashion and «kawaii culture» is usually associated with the Western society and trends set by designers borrowed or taken from Japan.[41] With the emergence of China, South Korea and Singapore as global economic centers, the Kawaii merchandise and product popularity has shifted back to the East. In these East Asian and Southeast Asian markets, the kawaii concept takes on various forms and different types of presentation depending on the target audience.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia[edit]

Taiwanese culture, the government in particular, has embraced and elevated kawaii to a new level of social consciousness. The introduction of the A-Bian doll was seen as the development of a symbol to advance democracy and assist in constructing a collective imagination and national identity for Taiwanese people. The A-Bian dolls are kawaii likeness of sports figure, famous individuals, and now political figures that use kawaii images as a means of self-promotion and potential votes.[43] The creation of the A-Bian doll has allowed Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian staffers to create a new culture where the «kawaii» image of a politician can be used to mobilize support and gain election votes.[44]

Japanese popular «kawaii culture» has had an effect on Singaporean youth. The emergence of Japanese culture can be traced back to the mid-1980s when Japan became one of the economic powers in the world. Kawaii has developed from a few children’s television shows to an Internet sensation.[45] Japanese media is used so abundantly in Singapore that youths are more likely to imitate the fashion of their Japanese idols, learn the Japanese language, and continue purchasing Japanese oriented merchandise.[46]

The East Asian countries of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as the Southeast Asian country of Thailand either produce kawaii items for international consumption or have websites that cater for kawaii as part of the youth culture in their country. Kawaii has taken on a life of its own, spawning the formation of kawaii websites, kawaii home pages, kawaii browser themes and finally, kawaii social networking pages. While Japan is the origin and Mecca of all things kawaii, artists and businesses around the world are imitating the kawaii theme.[47]

Kawaii has truly become «greater» than itself. The interconnectedness of today’s world via the Internet has taken kawaii to new heights of exposure and acceptance, producing a kawaii «movement».[47]

The Kawaii concept has become something of a global phenomenon. The aesthetic cuteness of Japan is very appealing to people globally. The wide popularity of Japanese kawaii is often credited with it being «culturally odorless». The elimination of exoticism and national branding has helped kawaii to reach numerous target audiences and span every culture, class, and gender group.[48] The palatable characteristics of kawaii have made it a global hit, resulting in Japan’s global image shifting from being known for austere rock gardens to being known for «cute-worship».[14]

In 2014, the Collins English Dictionary in the United Kingdom entered «kawaii» into its then latest edition, defining it as a «Japanese artistic and cultural style that emphasizes the quality of cuteness, using bright colours and characters with a childlike appearance».[49]

Controversy[edit]

In his book The Power of Cute, Simon May talks about the 180 degree turn in Japan’s history, from the violence of war to kawaii starting around the 1970s, in the works of artists like Takashi Murakami, amongst others. By 1992, kawaii was seen as «the most widely used, widely loved, habitual word in modern living Japanese.»[50] Since then, there has been some controversy surrounding the term kawaii and the expectations of it in Japanese culture. Natalia Konstantinovskaia, in her article “Being Kawaii in Japan”, says that based on the increasing ratio of young Japanese girls that view themselves as kawaii, there is a possibility that “from early childhood, Japanese people are socialized into the expectation that women must be kawaii.”[51] The idea of kawaii can be tricky to balance — if a woman’s interpretation of kawaii seems to have gone too far, she is then labeled as buriko, “a woman who plays bogus innocence.”[51] In the article “Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop”, the authors make the argument that female J-pop singers are expected to be recognizable by their outfits, voice, and mannerisms as kawaii — young and cute. Any woman who becomes a J-pop icon must stay kawaii, or keep her girlishness, rather than being perceived as a woman, even if she is over 18.[52]

Superficial Charm[edit]

Japanese women who feign kawaii behaviors (e.g., high-pitched voice, squealing giggles[53]) that could be viewed as forced or inauthentic are called burikko and this is considered superficial charm.[54] The neologism developed in the 1980s, perhaps originated by comedian Kuniko Yamada (山田邦子, Yamada Kuniko).[54]

See also[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Kawaii.

- Aegyo

- Camp (style)

- Chibi (slang)

- Culture of Japan

- Ingénue

- Kawaii metal, Kawaii bass (Music genre)

- Moe

- Yuru-chara

References[edit]

- ^ The Japanese Self in Cultural Logic Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Takei Sugiyama Libre, c. 2004 University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2840-2, p. 86.

- ^ a b Kerr, Hui-Ying (23 November 2016). «What is kawaii – and why did the world fall for the ‘cult of cute’?» Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, The Conversation.

- ^ «kawaii Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine», Oxford Dictionaries Online.

- ^ Kim, T. Beautiful is an Adjective. Accessed May 7, 2011, from http://www.guidetojapanese.org/adjectives.html Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Okazaki, Manami and Johnson, Geoff (2013). Kawaii!: Japan’s Culture of Cute. Prestel, p. 8.

- ^ Marcus, Aaron, 1943 (2017-10-30). Cuteness engineering : designing adorable products and services. ISBN 9783319619613. OCLC 1008977081.

- ^ Diana Lee, «Inside Look at Japanese Cute Culture Archived 2005-10-25 at the Wayback Machine» (September 1, 2005).

- ^ かわいい. 語源由来辞典 (Dictionary of Etymology) (in Japanese). 5 September 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛い. デジタル大辞泉 (Digital Daijisen) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛いとは. 大辞林第3版(Daijirin 3rd Ed.) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Shiokawa. «Cute But Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics». Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad and Sexy. Ed. John A. Lent. Bowling Green, Kentucky: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999. 93–125. ISBN 0-87972-779-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kinsella, Sharon. 1995. «Cuties in Japan» [1] Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine accessed August 1, 2009.

- ^ Skov, L. (1995). Women, media, and consumption in Japan. Hawai’i Press, USA.

- ^ a b c TheAge.Com: «Japan smitten by love of cute» http://www.theage.com.au/news/people/cool-or-infantile/2006/06/18/1150569208424.html Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ogawa, Takashi (25 December 2019). «Aichi exhibition showcases Rune Naito, pioneer of ‘kawaii’ culture». Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 14 January 2020.[dead link]

- ^ «The New Breed of Kawaii – Characters Who Get Us». UmamiBrain. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ See «(Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness — Japan Forum». Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2009-02-12. URL accessed February 11, 2009.

- ^ Time Asia: Young Japan: She’s a material girl http://www.time.com/time/asia/asia/magazine/1999/990503/style1.html Archived 2001-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quotes and paraphrases from: Yuri Kageyama (June 14, 2006). «Cuteness a hot-selling commodity in Japan». Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Bloomberg Businessweek, «In Japan, Cute Conquers All» Archived 2017-04-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ RiRi, Madame. «Some Japanese customs that may confuse foreigners». Japan Today. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ «Momoiro Clover Z dazzles audiences with shiny messages of hope». The Asahi Shimbun. 2012-08-29. Archived from the original on 2013-10-24.

- ^ a b Fort, Emeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Holson, Laura M. (13 March 2005). «Gothic Lolitas: Demure vs. Dominatrix». The New York Times.

- ^ a b Fort, Emmeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Mitani, Koki (29 May 2004). «Kamikaze Girls». IMDB. Archived from the original on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ^ Michel, Patrick St (2014-04-14). «The Rise of Japan’s Creepy-Cute Craze». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ a b Suzuki, Kirin. «Makeup Changes Men». Tokyo Kawaii, Etc. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Bennette, Colette (18 November 2011). «It’s all Kawaii: Cuteness in Japanese Culture». CNN. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d «Cute Inc». WIRED. December 1999. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ «Top Ten Japanese Character Mascots». Finding Fukuoka. 2012-01-13. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- ^ Japan Post site showing mailbox mascot Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ Time Asia: «Arts: Kwest For Kawaii». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.time.com/time/asia/arts/magazine/0,9754,131022,00.html Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The New Yorker «FACT: SHOPPING REBELLION: What the kids want». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?020318fa_FACT Archived 2002-03-20 at archive.today.

- ^ (Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness Archived 2013-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Roach, Mary. «Cute Inc.» Wired Dec. 1999. 01 May 2005 https://www.wired.com/wired/archive/7.12/cute_pr.html Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 卡哇伊熱潮 扭轉日本文化 Archived 2013-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «日本的»卡哇伊文化»_中国台湾网». Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ «Cute Power!». Newsweek. 7 November 1999. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ (Kataoka, 2010)

- ^ a b Tadao, T. «Dissemination of Japanese Young Fashion and Culture to the World-Enjoyable Japanese Cute (Kawaii) Fashions Spreading to the World and its Meaning». Sen-I Gakkaishi. 66 (7): 223–226.

- ^ Brown, J. (2011). «Re-framing ‘Kawaii’: Interrogating Global Anxieties Surrounding the Aesthetic of ‘Cute’ in Japanese Art and Consumer Products». International Journal of the Image. 1 (2): 1–10. doi:10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v01i02/44194.

- ^ [1]A-Bian Family. http://www.akibo.com.tw/home/gallery/mark/03.htm Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chuang, Y. C. (2011, September). «Kawaii in Taiwan politics». International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, 7(3). 1–16. Retrieved from here Archived 2019-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2]All things Kawaii. http://www.allthingskawaii.net/links/ Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hao, X., Teh, L.L. (2004). «The impact of japanese popular culture on the Singaporean youth». Keio Communication Review, 24. 17–32. Retrieved from: http://www.mediacom.keio.ac.jp/publication/pdf2004/review26/3.pdf Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Rutledge, B. (2010, October). I love kawaii. Ibuki Magazine. 1–2. Retrieved from: http://ibukimagazine.com/lifestyle-/other-trends/212-i-love-kawaii Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shearin, M. (2011, October). Triumph of kawaii. William & Mary ideation. Retrieved from: http://www.wm.edu/research/ideation/ideation-stories-for-borrowing/2011/triumph-of-kawaii5221.php Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Kawaii culture in the UK: Japan’s trend for cute». BBC News. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ May, Simon (2019). The Power of Cute. Princeton University Press. pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b Konstantinovskaia, Natalia (21 July 2017). «Being Kawaii in Japan». UCLA Study for the Center of Women.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Keith, Sarah; Hughes, Diane (December 2016). «Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop: Hughes and Keith». Journal of Popular Music Studies. 28 (4): 474–487. doi:10.1111/jpms.12195.

- ^ Merry White (29 September 1994). The material child: coming of age in Japan and America. University of California Press. pp. 129. ISBN 978-0-520-08940-2. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b «You are doing urikko!: Censoring/scrutinizing artificers of cute femininity in Japanese,» Laura Miller in Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People, edited by Janet Shibamoto Smith and Shigeko Okamoto, Oxford University Press, 2004. In Japanese.

Further reading[edit]

- Harris, Daniel (2001). Cute, quaint, hungry, and romantic: the aesthetics of consumerism. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo. ISBN 9780306810473.

- Brehm, Margrit, ed. (2002). The Japanese experience: inevitable. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany New York, New York: Hatje Cantz; Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 9783775712545.

- Cross, Gary (2004). The cute and the cool: wondrous innocence and modern American children’s culture. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195156669.

- Carpi, Giancarlo (2012). Gabriels and the Italian cute nymphet. Milan: Mazzotta. ISBN 9788820219932.

- Nittono, Hiroshi; Fukushima, Michiko; Yano, Akihiro; Moriya, Hiroki (September 2012). «The power of kawaii: viewing cute images promotes a careful behavior and narrows attentional focus». PLOS One. 7 (9): e46362. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…746362N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046362. PMC 3458879. PMID 23050022.

- Asano-Cavanagh, Yuko (October 2014). «Linguistic manifestation of gender reinforcement through the use of the Japanese term kawaii». Gender and Language. 8 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1558/genl.v8i3.341.

- Ohkura, Michiko (2019). Kawaii Engineering. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 9789811379642.

Kawaii (Japanese: かわいい or 可愛い, IPA: [kawaiꜜi]; ‘lovely’, ‘loveable’, ‘cute’, or ‘adorable’)[1] is the culture of cuteness in Japan.[2][3][4] It can refer to items, humans and non-humans that are charming, vulnerable, shy and childlike.[2] Examples include cute handwriting, certain genres of manga, anime, and characters including Hello Kitty and Pikachu from Pokémon.[5][6]

The cuteness culture, or kawaii aesthetic, has become a prominent aspect of Japanese popular culture, entertainment, clothing, food, toys, personal appearance, and mannerisms.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The word kawaii originally derives from the phrase 顔映し kao hayushi, which literally means «(one’s) face (is) aglow,» commonly used to refer to flushing or blushing of the face. The second morpheme is cognate with -bayu in mabayui (眩い, 目映い, or 目映ゆい) «dazzling, glaring, blinding, too bright; dazzlingly beautiful» (ma- is from 目 me «eye») and -hayu in omohayui (面映い or 面映ゆい) «embarrassed/embarrassing, awkward, feeling self-conscious/making one feel self-conscious» (omo- is from 面 omo, an archaic word for «face, looks, features; surface; image, semblance, vestige»). Over time, the meaning changed into the modern meaning of «cute» or «shine» , and the pronunciation changed to かわゆい kawayui and then to the modern かわいい kawaii.[8][9][10] It is commonly written in hiragana, かわいい, but the ateji, 可愛い, has also been used. The kanji in the ateji literally translates to «able to love/be loved, can/may love, lovable.»

History[edit]

Original definition[edit]

Kogal girl, identified by her shortened skirt. The soft bag and teddy bear that she carries are part of kawaii.

The original definition of kawaii came from Lady Murasaki’s 11th century novel The Tale of Genji, where it referred to pitiable qualities.[11] During the Shogunate period[when?] under the ideology of neo-Confucianism, women came to be included under the term kawaii as the perception of women being animalistic was replaced with the conception of women as docile.[11] However, the earlier meaning survives into the modern Standard Japanese adjectival noun かわいそう kawaisō (often written with ateji as 可哀相 or 可哀想) «piteous, pitiable, arousing compassion, poor, sad, sorry» (etymologically from 顔映様 «face / projecting, reflecting, or transmitting light, flushing, blushing / seeming, appearance»). Forms of kawaii and its derivatives kawaisō and kawairashii (with the suffix -rashii «-like, -ly») are used in modern dialects to mean «embarrassing/embarrassed, shameful/ashamed» or «good, nice, fine, excellent, superb, splendid, admirable» in addition to the standard meanings of «adorable» and «pitiable.»

Cute handwriting[edit]

In the 1970s, the popularity of the kawaii aesthetic inspired a style of writing.[12] Many teenage girls participated in this style; the handwriting was made by writing laterally, often while using mechanical pencils.[12] These pencils produced very fine lines, as opposed to traditional Japanese writing that varied in thickness and was vertical.[12] The girls would also write in big, round characters and they added little pictures to their writing, such as hearts, stars, emoticon faces, and letters of the Latin alphabet.[12]

These pictures made the writing very difficult to read.[12] As a result, this writing style caused a lot of controversy and was banned in many schools.[12] During the 1980s, however, this new «cute» writing was adopted by magazines and comics and was often put onto packaging and advertising[12] of products, especially toys for children or “cute accessories”.

From 1984 to 1986, Kazuma Yamane (山根一眞, Yamane Kazuma) studied the development of the cute handwriting (which he called Anomalous Female Teenage Handwriting) in depth.[12] This type of cute Japanese handwriting has also been called: marui ji (丸い字), meaning «round writing», koneko ji (小猫字), meaning «kitten writing», manga ji (漫画字), meaning «comic writing», and burikko ji (鰤子字), meaning «fake-child writing».[13] Although it was commonly thought that the writing style was something that teenagers had picked up from comics, Kazuma found that teenagers had come up with the style themselves, spontaneously, as an ‘underground trend’. His conclusion was based on an observation that cute handwriting predates the availability of technical means for producing rounded writing in comics.[12]

Cute merchandise[edit]

Baby-faced girl characters are rooted in Japanese society

Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, says cute fashion in Japan can be traced back to the Edo period with the popularity of netsuke.[14] Illustrator Rune Naito, who produced illustrations of «large-headed» (nitōshin) baby-faced girls and cartoon animals for Japanese girls’ magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s, is credited with pioneering what would become the culture and aesthetic of kawaii.[15]

Because of this growing trend, companies such as Sanrio came out with merchandise like Hello Kitty. Hello Kitty was an immediate success and the obsession with cute continued to progress in other areas as well. More recently, Sanrio has released kawaii characters with deeper personalities that appeal to an older audience, such as Gudetama and Aggretsuko. These characters have enjoyed strong popularity as fans are drawn to their unique quirks in addition to their cute aesthetics.[16] The 1980s also saw the rise of cute idols, such as Seiko Matsuda, who is largely credited with popularizing the trend. Women began to emulate Seiko Matsuda and her cute fashion style and mannerisms, which emphasized the helplessness and innocence of young girls.[17] The market for cute merchandise in Japan used to be driven by Japanese girls between 15 and 18 years old.[18]

Aesthetics[edit]

Soichi Masubuchi (増淵宗一, Masubuchi Sōichi), in his work Kawaii Syndrome, claims «cute» and «neat» have taken precedence over the former Japanese aesthetics of «beautiful» and «refined».[11] As a cultural phenomenon, cuteness is increasingly accepted in Japan as a part of Japanese culture and national identity. Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, believes that «cuteness» is rooted in Japan’s harmony-loving culture, and Nobuyoshi Kurita (栗田経惟, Kurita Nobuyoshi), a sociology professor at Musashi University in Tokyo, has stated that «cute» is a «magic term» that encompasses everything that is acceptable and desirable in Japan.[19]

Physical attractiveness[edit]

In Japan, being cute is acceptable for both men and women. A trend existed of men shaving their legs to mimic the neotenic look. Japanese women often try to act cute to attract men.[20] A study by Kanebo, a cosmetic company, found that Japanese women in their 20s and 30s favored the «cute look» with a «childish round face».[14] Women also employ a look of innocence in order to further play out this idea of cuteness. Having large eyes is one aspect that exemplifies innocence; therefore many Japanese women attempt to alter the size of their eyes. To create this illusion, women may wear large contact lenses, false eyelashes, dramatic eye makeup, and even have an East Asian blepharoplasty, commonly known as double eyelid surgery.[21]

Idols[edit]

Japanese idols (アイドル, aidoru) are media personalities in their teens and twenties who are considered particularly attractive or cute and who will, for a period ranging from several months to a few years, regularly appear in the mass media, e.g. as singers for pop groups, bit-part actors, TV personalities (tarento), models in photo spreads published in magazines, advertisements, etc. (But not every young celebrity is considered an idol. Young celebrities who wish to cultivate a rebellious image, such as many rock musicians, reject the «idol» label.) Speed, Morning Musume, AKB48, and Momoiro Clover Z are examples of popular idol groups in Japan during the 2000s & 2010s.[22]

Cute fashion[edit]

Lolita[edit]

Lolita fashion is a very well-known and recognizable style in Japan. Based on Victorian fashion and the Rococo period, girls mix in their own elements along with gothic style to achieve the porcelain-doll look.[23] The girls who dress in Lolita fashion try to look cute, innocent, and beautiful.[23] This look is achieved with lace, ribbons, bows, ruffles, bloomers, aprons, and ruffled petticoats. Parasols, chunky Mary Jane heels, and Bo Peep collars are also very popular.[24]

Sweet Lolita is a subset of Lolita fashion that includes even more ribbons, bows, and lace, and is often fabricated out of pastels and other light colors. Head-dresses such as giant bows or bonnets are also very common, while lighter make-up is sometimes used to achieve a more natural look. Curled hair extensions, sometimes accompanied by eyelash extensions, are also popular in helping with the baby doll look.[25] Another subset of Lolita fashion related to «sweet Lolita» is Fairy Kei.

Themes such as fruits, flowers and sweets are often used as patterns on the fabrics used for dresses. Purses often go with the themes and are shaped as hearts, strawberries, or stuffed animals. Baby, the Stars Shine Bright is one of the more popular clothing stores for this style and often carries themes. Mannerisms are also important to many Sweet Lolitas. Sweet Lolita is sometimes not only a fashion, but also a lifestyle.[25] This is evident in the 2004 film Kamikaze Girls where the main Lolita character, Momoko, drinks only tea and eats only sweets.[26]

Gothic Lolita, Kuro Lolita, Shiro Lolita, and Military Lolita are all subtypes, also, in the US Anime Convention scene Casual Lolita.

Decora[edit]

Example of Decora fashion

Decora is a style that is characterized by wearing many «decorations» on oneself. It is considered to be self-decoration. The goal of this fashion is to become as vibrant and characterized as possible. People who take part in this fashion trend wear accessories such as multicolor hair pins, bracelets, rings, necklaces, etc. By adding on multiple layers of accessories on an outfit, the fashion trend tends to have a childlike appearance. It also includes toys and multicolor clothes. Decora and Fairy Kei have some crossover.

Kimo-kawaii

Kimo-kawaii means creepy-cute or gross-cute.[27] The style started around the 1990s when some people lost interest in cute and innocent characters and fashion. It is usually achieved by wearing creepy or gross clothes or accessories.

Kawaii men

Although typically a female-dominated fashion, some men partake in the kawaii trend. Men wearing masculine kawaii accessories is very uncommon, and typically the men cross-dress as kawaii women instead by wearing wigs, false eyelashes, applying makeup, and wearing kawaii female clothing.[28] This is seen predominately in male entertainers, such as Torideta-san, a DJ who transforms himself into a kawaii woman when working at his nightclub.[28]

Japanese pop stars and actors often have longer hair, such as Takuya Kimura of SMAP. Men are also noted as often aspiring to a neotenic look. While it doesn’t quite fit the exact specifications of what cuteness means for females, men are certainly influenced by the same societal mores — to be attractive in a specific sort of way that the society finds acceptable.[29] In this way both Japanese men and women conform to the expectations of Kawaii in some way or another.

Products[edit]

The concept of kawaii has had an influence on a variety of products, including candy, such as Hi-Chew, Koala’s March and Hello Panda. Cuteness can be added to products by adding cute features, such as hearts, flowers, stars and rainbows. Cute elements can be found almost everywhere in Japan, from big business to corner markets and national government, ward, and town offices.[20][30] Many companies, large and small, use cute mascots to present their wares and services to the public. For example:

- Pikachu, a character from Pokémon, adorns the side of ten ANA passenger jets, the Pokémon Jets.

- Asahi Bank used Miffy (Nijntje), a character from a Dutch series of children’s picture books, on some of its ATM and credit cards.

- The prefectures of Japan, as well as many cities and cultural institutions, have cute mascot characters known as yuru-chara to promote tourism. Kumamon, the Kumamoto Prefecture mascot, and Hikonyan, the city of Hikone mascot, are among the most popular.[31]

- The Japan Post «Yū-Pack» mascot is a stylized mailbox;[32] they also use other cute mascot characters to promote their various services (among them the Postal Savings Bank) and have used many such on postage stamps.

- Some police forces in Japan have their own moe mascots, which sometimes adorn the front of kōban (police boxes).

- NHK, the public broadcaster, has its own cute mascots. Domokun, the unique-looking and widely recognized NHK mascot, was introduced in 1998 and quickly took on a life of its own, appearing in Internet memes and fan art around the world.

- Sanrio, the company behind Hello Kitty and other similarly cute characters, runs the Sanrio Puroland theme park in Tokyo, and painted on some EVA Air Airbus A330 jets as well. Sanrio’s line of more than 50 characters takes in more than $1 billion a year and it remains the most successful company to capitalize on the cute trend.[30]

Cute can be also used to describe a specific fashion sense[33][34] of an individual, and generally includes clothing that appears to be made for young children, apart from the size, or clothing that accentuates the cuteness of the individual wearing the clothing. Ruffles and pastel colors are commonly (but not always) featured, and accessories often include toys or bags featuring anime characters.[30]

Non-kawaii imports[edit]

Kawaii goods outlet in 100 yen shop

There have been occasions on which popular Western products failed to meet the expectations of kawaii, and thus did not do well in the Japanese market. For example, Cabbage Patch Kids dolls did not sell well in Japan, because the Japanese considered their facial features to be «ugly» and «grotesque» compared to the flatter and almost featureless faces of characters such as Hello Kitty.[11] Also, the doll Barbie, portraying an adult woman, did not become successful in Japan compared to Takara’s Licca, a doll that was modeled after an 11-year-old girl.[11]

Industry[edit]

Kawaii has gradually gone from a small subculture in Japan to an important part of Japanese modern culture as a whole. An overwhelming number of modern items feature kawaii themes, not only in Japan but also worldwide.[35] And characters associated with kawaii are astoundingly popular. «Global cuteness» is reflected in such billion-dollar sellers as Pokémon and Hello Kitty.[36] «Fueled by Internet subcultures, Hello Kitty alone has hundreds of entries on eBay, and is selling in more than 30 countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, and Taiwan.»[36]

Japan has become a powerhouse in the kawaii industry and images of Doraemon, Hello Kitty, Pikachu, Sailor Moon and Hamtaro are popular in mobile phone accessories. However, Professor Tian Shenliang says that Japan’s future is dependent on how much of an impact kawaii brings to humanity.[37]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry has also recognized the power of cute merchandise and has sent three 18-year-old women overseas in the hopes of spreading Japanese culture around the world. The women dress in uniforms and maid costumes that are commonplace in Japan.[38]

Kawaii manga and magazines have brought tremendous profit to the Japanese press industry.[citation needed] Moreover, the worldwide revenue from the computer game and its merchandising peripherals are closing in on $5 billion, according to a Nintendo press release titled «It’s a Pokémon Planet».[36]

Influence upon other cultures[edit]

Kawaii keychain accessory attached to a pink Palm Centro smartphone

In recent years, Kawaii products have gained popularity beyond the borders of Japan in other East and Southeast Asian countries, and are additionally becoming more popular in the US among anime and manga fans as well as others influenced by Japanese culture. Cute merchandise and products are especially popular in other parts of East Asia, such as mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as Southeast Asian countries including the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.[30][39]

Sebastian Masuda, owner of 6%DOKIDOKI and a global advocate for kawaii influence, takes the quality from Harajuku to Western markets in his stores and artwork. The underlying belief of this Japanese designer is that «kawaii» actually saves the world.[40] The infusion of kawaii into other world markets and cultures is achieved by introducing kawaii via modern art; audio, visual, and written media; and the fashion trends of Japanese youth, especially in high school girls.[41]

Japanese kawaii seemingly operates as a center of global popularity due to its association with making cultural productions and consumer products «cute». This mindset pursues a global market,[42] giving rise to numerous applications and interpretations in other cultures.

The dissemination of Japanese youth fashion and «kawaii culture» is usually associated with the Western society and trends set by designers borrowed or taken from Japan.[41] With the emergence of China, South Korea and Singapore as global economic centers, the Kawaii merchandise and product popularity has shifted back to the East. In these East Asian and Southeast Asian markets, the kawaii concept takes on various forms and different types of presentation depending on the target audience.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia[edit]

Taiwanese culture, the government in particular, has embraced and elevated kawaii to a new level of social consciousness. The introduction of the A-Bian doll was seen as the development of a symbol to advance democracy and assist in constructing a collective imagination and national identity for Taiwanese people. The A-Bian dolls are kawaii likeness of sports figure, famous individuals, and now political figures that use kawaii images as a means of self-promotion and potential votes.[43] The creation of the A-Bian doll has allowed Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian staffers to create a new culture where the «kawaii» image of a politician can be used to mobilize support and gain election votes.[44]

Japanese popular «kawaii culture» has had an effect on Singaporean youth. The emergence of Japanese culture can be traced back to the mid-1980s when Japan became one of the economic powers in the world. Kawaii has developed from a few children’s television shows to an Internet sensation.[45] Japanese media is used so abundantly in Singapore that youths are more likely to imitate the fashion of their Japanese idols, learn the Japanese language, and continue purchasing Japanese oriented merchandise.[46]

The East Asian countries of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as the Southeast Asian country of Thailand either produce kawaii items for international consumption or have websites that cater for kawaii as part of the youth culture in their country. Kawaii has taken on a life of its own, spawning the formation of kawaii websites, kawaii home pages, kawaii browser themes and finally, kawaii social networking pages. While Japan is the origin and Mecca of all things kawaii, artists and businesses around the world are imitating the kawaii theme.[47]

Kawaii has truly become «greater» than itself. The interconnectedness of today’s world via the Internet has taken kawaii to new heights of exposure and acceptance, producing a kawaii «movement».[47]

The Kawaii concept has become something of a global phenomenon. The aesthetic cuteness of Japan is very appealing to people globally. The wide popularity of Japanese kawaii is often credited with it being «culturally odorless». The elimination of exoticism and national branding has helped kawaii to reach numerous target audiences and span every culture, class, and gender group.[48] The palatable characteristics of kawaii have made it a global hit, resulting in Japan’s global image shifting from being known for austere rock gardens to being known for «cute-worship».[14]

In 2014, the Collins English Dictionary in the United Kingdom entered «kawaii» into its then latest edition, defining it as a «Japanese artistic and cultural style that emphasizes the quality of cuteness, using bright colours and characters with a childlike appearance».[49]

Controversy[edit]

In his book The Power of Cute, Simon May talks about the 180 degree turn in Japan’s history, from the violence of war to kawaii starting around the 1970s, in the works of artists like Takashi Murakami, amongst others. By 1992, kawaii was seen as «the most widely used, widely loved, habitual word in modern living Japanese.»[50] Since then, there has been some controversy surrounding the term kawaii and the expectations of it in Japanese culture. Natalia Konstantinovskaia, in her article “Being Kawaii in Japan”, says that based on the increasing ratio of young Japanese girls that view themselves as kawaii, there is a possibility that “from early childhood, Japanese people are socialized into the expectation that women must be kawaii.”[51] The idea of kawaii can be tricky to balance — if a woman’s interpretation of kawaii seems to have gone too far, she is then labeled as buriko, “a woman who plays bogus innocence.”[51] In the article “Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop”, the authors make the argument that female J-pop singers are expected to be recognizable by their outfits, voice, and mannerisms as kawaii — young and cute. Any woman who becomes a J-pop icon must stay kawaii, or keep her girlishness, rather than being perceived as a woman, even if she is over 18.[52]

Superficial Charm[edit]

Japanese women who feign kawaii behaviors (e.g., high-pitched voice, squealing giggles[53]) that could be viewed as forced or inauthentic are called burikko and this is considered superficial charm.[54] The neologism developed in the 1980s, perhaps originated by comedian Kuniko Yamada (山田邦子, Yamada Kuniko).[54]

See also[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Kawaii.

- Aegyo

- Camp (style)

- Chibi (slang)

- Culture of Japan

- Ingénue

- Kawaii metal, Kawaii bass (Music genre)

- Moe

- Yuru-chara

References[edit]

- ^ The Japanese Self in Cultural Logic Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Takei Sugiyama Libre, c. 2004 University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2840-2, p. 86.

- ^ a b Kerr, Hui-Ying (23 November 2016). «What is kawaii – and why did the world fall for the ‘cult of cute’?» Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, The Conversation.

- ^ «kawaii Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine», Oxford Dictionaries Online.

- ^ Kim, T. Beautiful is an Adjective. Accessed May 7, 2011, from http://www.guidetojapanese.org/adjectives.html Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Okazaki, Manami and Johnson, Geoff (2013). Kawaii!: Japan’s Culture of Cute. Prestel, p. 8.

- ^ Marcus, Aaron, 1943 (2017-10-30). Cuteness engineering : designing adorable products and services. ISBN 9783319619613. OCLC 1008977081.

- ^ Diana Lee, «Inside Look at Japanese Cute Culture Archived 2005-10-25 at the Wayback Machine» (September 1, 2005).

- ^ かわいい. 語源由来辞典 (Dictionary of Etymology) (in Japanese). 5 September 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛い. デジタル大辞泉 (Digital Daijisen) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛いとは. 大辞林第3版(Daijirin 3rd Ed.) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Shiokawa. «Cute But Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics». Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad and Sexy. Ed. John A. Lent. Bowling Green, Kentucky: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999. 93–125. ISBN 0-87972-779-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kinsella, Sharon. 1995. «Cuties in Japan» [1] Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine accessed August 1, 2009.

- ^ Skov, L. (1995). Women, media, and consumption in Japan. Hawai’i Press, USA.

- ^ a b c TheAge.Com: «Japan smitten by love of cute» http://www.theage.com.au/news/people/cool-or-infantile/2006/06/18/1150569208424.html Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ogawa, Takashi (25 December 2019). «Aichi exhibition showcases Rune Naito, pioneer of ‘kawaii’ culture». Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 14 January 2020.[dead link]

- ^ «The New Breed of Kawaii – Characters Who Get Us». UmamiBrain. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ See «(Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness — Japan Forum». Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2009-02-12. URL accessed February 11, 2009.

- ^ Time Asia: Young Japan: She’s a material girl http://www.time.com/time/asia/asia/magazine/1999/990503/style1.html Archived 2001-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quotes and paraphrases from: Yuri Kageyama (June 14, 2006). «Cuteness a hot-selling commodity in Japan». Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Bloomberg Businessweek, «In Japan, Cute Conquers All» Archived 2017-04-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ RiRi, Madame. «Some Japanese customs that may confuse foreigners». Japan Today. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ «Momoiro Clover Z dazzles audiences with shiny messages of hope». The Asahi Shimbun. 2012-08-29. Archived from the original on 2013-10-24.

- ^ a b Fort, Emeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Holson, Laura M. (13 March 2005). «Gothic Lolitas: Demure vs. Dominatrix». The New York Times.

- ^ a b Fort, Emmeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Mitani, Koki (29 May 2004). «Kamikaze Girls». IMDB. Archived from the original on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ^ Michel, Patrick St (2014-04-14). «The Rise of Japan’s Creepy-Cute Craze». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ a b Suzuki, Kirin. «Makeup Changes Men». Tokyo Kawaii, Etc. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Bennette, Colette (18 November 2011). «It’s all Kawaii: Cuteness in Japanese Culture». CNN. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d «Cute Inc». WIRED. December 1999. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ «Top Ten Japanese Character Mascots». Finding Fukuoka. 2012-01-13. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- ^ Japan Post site showing mailbox mascot Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ Time Asia: «Arts: Kwest For Kawaii». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.time.com/time/asia/arts/magazine/0,9754,131022,00.html Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The New Yorker «FACT: SHOPPING REBELLION: What the kids want». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?020318fa_FACT Archived 2002-03-20 at archive.today.

- ^ (Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness Archived 2013-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Roach, Mary. «Cute Inc.» Wired Dec. 1999. 01 May 2005 https://www.wired.com/wired/archive/7.12/cute_pr.html Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 卡哇伊熱潮 扭轉日本文化 Archived 2013-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «日本的»卡哇伊文化»_中国台湾网». Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ «Cute Power!». Newsweek. 7 November 1999. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ (Kataoka, 2010)

- ^ a b Tadao, T. «Dissemination of Japanese Young Fashion and Culture to the World-Enjoyable Japanese Cute (Kawaii) Fashions Spreading to the World and its Meaning». Sen-I Gakkaishi. 66 (7): 223–226.

- ^ Brown, J. (2011). «Re-framing ‘Kawaii’: Interrogating Global Anxieties Surrounding the Aesthetic of ‘Cute’ in Japanese Art and Consumer Products». International Journal of the Image. 1 (2): 1–10. doi:10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v01i02/44194.

- ^ [1]A-Bian Family. http://www.akibo.com.tw/home/gallery/mark/03.htm Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chuang, Y. C. (2011, September). «Kawaii in Taiwan politics». International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, 7(3). 1–16. Retrieved from here Archived 2019-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2]All things Kawaii. http://www.allthingskawaii.net/links/ Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hao, X., Teh, L.L. (2004). «The impact of japanese popular culture on the Singaporean youth». Keio Communication Review, 24. 17–32. Retrieved from: http://www.mediacom.keio.ac.jp/publication/pdf2004/review26/3.pdf Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Rutledge, B. (2010, October). I love kawaii. Ibuki Magazine. 1–2. Retrieved from: http://ibukimagazine.com/lifestyle-/other-trends/212-i-love-kawaii Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shearin, M. (2011, October). Triumph of kawaii. William & Mary ideation. Retrieved from: http://www.wm.edu/research/ideation/ideation-stories-for-borrowing/2011/triumph-of-kawaii5221.php Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Kawaii culture in the UK: Japan’s trend for cute». BBC News. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ May, Simon (2019). The Power of Cute. Princeton University Press. pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b Konstantinovskaia, Natalia (21 July 2017). «Being Kawaii in Japan». UCLA Study for the Center of Women.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Keith, Sarah; Hughes, Diane (December 2016). «Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop: Hughes and Keith». Journal of Popular Music Studies. 28 (4): 474–487. doi:10.1111/jpms.12195.

- ^ Merry White (29 September 1994). The material child: coming of age in Japan and America. University of California Press. pp. 129. ISBN 978-0-520-08940-2. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b «You are doing urikko!: Censoring/scrutinizing artificers of cute femininity in Japanese,» Laura Miller in Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People, edited by Janet Shibamoto Smith and Shigeko Okamoto, Oxford University Press, 2004. In Japanese.

Further reading[edit]

- Harris, Daniel (2001). Cute, quaint, hungry, and romantic: the aesthetics of consumerism. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo. ISBN 9780306810473.

- Brehm, Margrit, ed. (2002). The Japanese experience: inevitable. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany New York, New York: Hatje Cantz; Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 9783775712545.

- Cross, Gary (2004). The cute and the cool: wondrous innocence and modern American children’s culture. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195156669.

- Carpi, Giancarlo (2012). Gabriels and the Italian cute nymphet. Milan: Mazzotta. ISBN 9788820219932.

- Nittono, Hiroshi; Fukushima, Michiko; Yano, Akihiro; Moriya, Hiroki (September 2012). «The power of kawaii: viewing cute images promotes a careful behavior and narrows attentional focus». PLOS One. 7 (9): e46362. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…746362N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046362. PMC 3458879. PMID 23050022.

- Asano-Cavanagh, Yuko (October 2014). «Linguistic manifestation of gender reinforcement through the use of the Japanese term kawaii». Gender and Language. 8 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1558/genl.v8i3.341.

- Ohkura, Michiko (2019). Kawaii Engineering. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 9789811379642.

Каваий[1] (яп. 可愛い?) — японское слово, означающее «милый», «прелестный», «хорошенький»[1], «славный», «любезный». Это субъективное определение может описывать любой объект, который индивидуум сочтёт прелестным.

С 1970-х годов прелесть стала едва ли не повсеместно почитаемым аспектом японской культуры, развлечений, одежды, еды, игрушек, а также внешнего вида, стиля поведения и манер. В результате, слово «каваий» часто можно услышать в Японии, также оно встречается при обсуждении японских культурных явлений. Западные наблюдатели часто относятся к «каваий» с любопытством, так как японцы прибегают к такой эстетике, несмотря на пол, возраст и во множестве таких ситуаций, которые в западной культуре сочли бы неуместно инфантильными или легкомысленными (например, помимо прочего, в правительственных публикациях, коммунальных объявлениях и объявлениях о вербовке, в учреждениях, на пассажирских самолётах).

Содержание

- 1 Распространение

- 2 Восприятие в Японии

- 3 Проявления за пределами Японии

- 4 Особенности употребления

- 5 См. также

- 6 Примечания

- 7 Внешние ссылки

Распространение

Элементы «каваий» встречаются в Японии повсеместно, в крупных компаниях и в небольших магазинчиках, в правительстве страны и в муниципальных учреждениях. Множество компаний, больших и малых, используют прелестные талисманы (маскоты) для представления публике своих товаров и услуг. Например:

- Пикачу, персонаж «Покемонов», украшает борта трёх пассажирских самолётов авиакомпании All Nippon Airways;

- Банк Асахи изображает Миффи, персонажа голландской серии детских книжек, на некоторых пластиковых картах;

- Все 47 префектур имеют прелестных персонажей-талисманов;

- Японская почтовая служба использует талисман в виде стилизованного почтового ящика;

- Каждое подразделение японской полиции имеет свои забавные талисманы, многие из которых украшают кобаны (полицейские будки).

Прелестная сувенирная продукция чрезвычайно популярна в Японии. Два крупнейших производителя такой продукции — Sanrio (производитель «Hello Kitty») и San-X. Товары с этими персонажами имеют большой успех в Японии как среди детей, так и среди взрослых.

«Каваий» также может использоваться для описания восприятия моды индивидуумом, обычно подразумевая одежду, кажущуюся (если не обращать внимания на размер) сделанной для детей, или одежду, подчёркивающую «кавайность» носителя одежды. Обычно (но не всегда) используются гофры и пастельные тона, в качестве аксессуаров часто используются игрушки или сумки, изображающие персонажей мультфильмов.

Восприятие в Японии

«Каваий» как культурное явление всё в большей степени признаётся частью японской культуры и национального самосознания. Томоёки Сугияма, автор книги «Cool Japan», считает, что истоки «прелести» лежат в почитающей гармонию японской культуре, а Нобоёси Курита, профессор социологии токийского Университета Мусаси, утверждает, что «прелесть» — это «волшебное слово», охватывающее всё, что считают приятным и желанным.

С другой стороны, меньшая часть японцев скептически относится к «каваий», считая его признаком инфантильного склада ума. В частности, Хирото Мурасава, профессор красоты и культуры Женского университета Осака Сёин, утверждает, что «каваий» — это «образ мышления, порождающий нежелание отстаивать свою точку зрения <…> Индивидуум, решивший выделиться, терпит поражение».

Проявления за пределами Японии

Прелестная сувенирная продукция и другие «кавайные» товары популярны в других частях восточной Азии, включая Китай, Тайвань и Корею. Слово «каваий» хорошо известно и в последнее время часто используется поклонниками японской поп-культуры (включая любителей аниме и манги) в англоговорящих странах, в Европе и в России. Более того, слово «kawaii» начинает становиться частью массовой англоязычной поп-культуры, войдя, например, в видеоклип Гвен Стефани «Harajuku Girls» и в список неологизмов, составленный студентами и выпускниками Райсовского университета города Хьюстона (США).

Особенности употребления

В японском языке «каваий» также может относиться к чему-либо, что выглядит маленьким, иногда имея двойное значение «прелестный» и «маленький». Слово также может использоваться для описания взрослых, демонстрирующих ребяческое или наивное поведение.

При произношении и записи по-русски слово нередко используется в форме «кавай», более удобной для словоизменения (например, «о кавае», «кавайный»), но далёкой от общепринятой системы записи японских слов. В молодёжном сленге появилось слово «кавайность».

В программировании употребляется как префикс для названий классов ответственных за сабклассинг. Например CKawaiWindow

По аналогии со словом «каваий» и для создания комического эффекта часто употребляется слово «ковай» (яп. 怖い, «страшный») и образованные от него «ковайный», «ковайность».

См. также

- Бисёдзё

- Ваби-саби

- Готическая лолита

- Красота

- Моэ

- Прелесть

- Тиби

- Цундэрэ

-

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 Неверов С.В., Попов К.А., Сыромятников Н.А. и др. Большой японско-русский словарь. — М.: Советская энциклопедия, 1970. — Т. 1. — С. 299. — 808 с. — 26000 экз.

Внешние ссылки

- Crazy and Kawaii — подборка статей о Каваий

- Исихара Соитиро, Обата Кадзуюки, Канно Каёко Привлекательный мир «каваий» // Ниппония : журнал. — Токио: Heibonsha Ltd., 15 марта 2007 г.. — № 40.

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

О японском понятии kawaii, ставшим глобальным.

Бутик Moussy, расположен на пятом этаже здания номер 109 округа Шибуя в Токио. Это мрачное, тесное и захламлённое помещение. Подобная атмосфера предполагает антимоду; в этой нарочитой небрежности нет ничего прикольного. Так почему же толпы ультра-модных девчонок выстраиваются в очередь перед вельветовой веревкой, сгорая от желания войти в магазин, где повсеместно лежат неаккуратные кучи маек и по углам рассованы рваные джинсы? Все это скорее напоминает гаражную распродажу. Но секрет вот в чем: если прислушаться, то среди всеобщего шума, наполняющего магазин, можно услышать одно слово, повторяющееся снова и снова: Каваи..каваи

Каваи, kawaii — прилагательное, которое обычно ошибочно переводится как «милый», стало чем-то большим, нежели просто словом. Это образ мысли для японских подростков. Для марки одежды, пытающейся пробиться в процветающую индустрию подростковой моды в Азии, бизнес сводится к спросу на каваи. Азиатские подростки стремятся носить то, что японские тинейджеры носили несколько минут назад . В отличие от модной индустрии на западе, где топ-дизайнеры и редакторы журналов диктуют что модно, а что нет, японская индустрия молодёжной моды вертится вокруг того, что токийские девочки считают каваи. Каждый месяц столичный студент тратит около 275 долларов на аксессуары и одежду — это в три раза больше, чем тратит средний японский студент (в общей сложности этот рынок составляет 2.5 миллиарда долларов ежегодно). Большая часть этих денег уходят бренду с самым новым, «прикольным» на данный момент стилем. А для тех брендов, которым удалось ухватить суть каваи, потенциальный рынок простирается от Токио до Ташкента. «Япония — это единственная страна, которая на данный момент является истинной движущей силой моолодежной моды,» — объясняет Joanne Ooi, CEO торговой компании StyleTrek. «сказать покупателю, что вещь популярна в Японии – это очень мощный аргумент в пользу продажи»

То что токийские девочки определят как каваи сегодня может быть розовая маечка с рюшечками, а завтра – грубая как винил миниюбка. Год назад самыми популярными в Шибуя моделями были светло-коричневые сапоги до колен на платформе и черная краска на лице. Этот стиль называется “Gal”.Сейчас в моде перешитая одежда, потёртые джинсы и обувь на низком каблуке. Зачем всё менять? «Я одевалась в стиле “Gal” потому что это было модно. Но всем это просто надоело, и, кстати, этот новый стиль гораздо более каваи,» — говорит продавщица Чи Сакакибара,22 года. Хироаки Морита, глава Teen’s Network Ship – консалтинговой фирмы для компаний, чьей целевой аудиторией являются подростки, утверждает, что перемена вкусов может быть результатом затяжного экономического спада в Японии. Девочки всё ещё хотят развлекаться, но не хотят тратить на это много денег. Чтобы оставаться в теме каваи, японские фирмы нанимают студентов на должности продавцов, стилистов и маркетологов. Это необходимо для бизнеса, в котором не существует сезонов, а только цунамиподобные модные направления, которые проходят через недели, месяцы или около того… И когда требуется узнать какой именно оттенок бежевого токийские законодатели моды хотят носить и насколько низко должны быть спущены джинсы, все молодёжные лейблы усиленно нанимают karisuma tenin (харизматичные девочки-продавщицы) из того самого 109 здания в Шибуя. «Они стали брать нас на работу, потому что мы носим необычную, интересную одежду, а журналы использовали наши фотографии. Через некоторое время все знали кто я такая», — говорит 23-летняя Мана Такаи, которая теперь работает дизайнером Jassie – ещё одного популярного лейбла. И все лейблы, желающие оставаться на плаву в унисон просили своих karisuma tenin пожалуйста-пожалуйста смоделировать одежду и для них . Несмотря на то, что большинство из них не умеют шить и рисовать и никогда не ходили в школу дизайна, лейблы понимают, что эти девушки тонко различают что является кавай, а что нет.Однако, стиль каваи безумно непостоянен. Несмотря на наём молодых дизайнеров, выслушивание покупателей и развитие сотрудничества с журналами, ни одна компания не может наверняка предсказать, когда вкусы молодёжи могут измениться. Иногда девочки хотят СЕЙЧАС! То, что надето на известном исполнителе в новом клипе. Но токийские модницы устают от того, что их сельские единомышленницы копируют их, и они начинают искать что-то новое. Это создаёт такую бурлящую среду, в которой бренд может пройти путь от неизвестности до полного расцвета всего за месяц. На данный момент стиль, который сейчас популярен в Японии лучше всего охарактеризовать как Otona (взрослый, самодостаточный). Это стиль, которому следует девушка, желающая вызвать к себе уважение. Это обратная реакция на высокие платформы, белые волосы и воинственный стиль прошлых лет. Девушки Шибуя говорят, что это и есть «kawaii» сейчас.

Триумфальное шествие Kawaii по Японии.

Aвтор Brian Bremner, журнал BusinessWeek.

Почему в современной культуре молодые люди подсажены на наркотик «милых» образов и кавайных вещей. Ответ не так прост, как кажется. Кажется, что в мире есть 2 типа людей: те, кто обожают марку Hello Kitty и те, кто искренне не понимает, почему этот идол эстетики kawaii, пушистый персонаж без рта, настолько популярен в мире и генерирует невероятную прибыль своим хозяевам. Hello Kitty — образ милой девочки-котенка, невинная, сентиментальная, которой нравится дружить и пить чай с друзьями. Как такая банальная пошлость может быть интересна людям старше 10 лет?! Но все сложнее, если вспомнить о том, что франшиза Hello Kitty приносит компании Sanrio более 1 миллиарда долларов каждый год. Sanrio -самая крупная японская компания, чей бизнес это производство кавайных персонажей. Нет ни одной товарной категории, которая не была бы представлена франшизой Hello Kitty — это молодежные и детские сумки, ручки, пеналы, зубные щетки, кружки и тарелки, мебель и игрушки…

Не поймите меня неправильно — я не собираюсь критиковать феномен каваи и Нello Kitty. Меня поражает увлеченность японцев культом kawaii, культом милого и прелестного. Обычный городской пейзаж Токио — реклама в метро и на домах, вывески магазинов и сетей быстрого питания, рекламные мониторы, многочисленные манга (вид японских комиксов) и модные журналы — все заполнено милыми персонажами, везде kawaii, kawaii, kawaii...

Все японские коммерческие бренды прибегают к помощи милых-kawaii персонажей для промо и собственной рекламы. Эта мания не обходит стороной даже банковский бизнес и авиакомпании. Кстати, многие из кавайных персонажей импортированы из Западного мира, такие как Снуппи, Винни-Пух и другие. Проведите 5 минут в торговом центре в районах Shibuya and Shinjuku — вы почувствуете себя как в мультфильме. Однако прелестные и милые персонажи (что и есть kawaii буквально) это не только маркетинговая уловка бизнесменов. Этот культурный феномен глубоко прописан в японском культурном коде и проявляется в социальных и половых ролях японской молодежи. Признаки стиля kawaii -розовая помада, накладные ресницы, мягкие пастельные цвета и многое другое — это не только мода, но и модель поведения.

Вечно молодые?

Феномен каваи появился 20 лет назад и похоже что становится все популярнее и популярнее. Это давно заинтересовало социальных психологов и японских интеллектуалов. Японские феминистки считают, что популярность kawaii — это следствие культурной эксплуатации женщин в Японии, их приниженного в обществе положения. С их точки зрения стиль Kawaii заставляет 20-30 летних женщин вести себя и выглядеть как девочки — невинными и безответственными, что не соответствует их возрасту и реалиям жизни. В японской порнографии один из самых распространенных образов -кукольно красивая женщина-девочка. Этот тренд распространяется и на мальчиков — в летом 2008 года стало модно брить ноги перед началом пляжного сезона. Не уверен, что консерваторы и феминистки правы, когда считают Hello Kitty опасным для общества явлением. Однако факт, что одержимость японцев милым, кавайным, то есть детским, имеет глубокую связь с японской эстетикой и уникальной культурой этой страны. В США, например, модель другая — детей стимулируют раньше взрослеть.

Я решил посетить самый центр kawaii — редакцию журнала Cawaii magazine (название обыгрывает правильное написание kawaii). Этот журнал выходит тиражом 300 000 копий и рассчитан на аудиторию с 15 до 20 лет. Это некое смешение концерта Britney Spears и детского магазина. В журнале интервью знаменитостей и советы, как добиться детско-кукольной красоты. Я встретился с Kazuhiko Sato, главным редактором журнала Cawaii. Ему 40 лет, и я не могу не спросить, как средних лет мужчина способен быть в модной и быстро-меняющейся теме каваи. Он мне ответил, что сам и не старается следить за модой — для этого он нанимает молодых работниц, которые глубоко разбираются в самых последних тенденциях.

Каваи -всегда над модой.

Редактор мне рассказал о том, что за последние 10 лет в Японии сменилось много модных трендов — было модно одеваться реппером, быть в американских джинсах, красить волосы в белый цвет, одеваться по моде 70х, перекрашивать волосы в черный цвет…Однако стиль каваи всегда как бы над текущей модой — в любом из перечисленных молодежных нарядов можно было найти что-то милое и кавайное, будь то аксессуар или какая-то деталь.

По мнению Sato, мода на каваи в Японии надолго, однако он не видит ничего опасного в этом. Он считает, что в движении kawaii нет никаго принижения личности женщины — просто таким способом девочки и привлекают к себе мальчиков.