Разбор слова «колорадо»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «колорадо» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «колорадо» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «колорадо».

Содержимое:

- 1 Как перенести слово «колорадо»

- 2 Синонимы слова «колорадо»

- 3 Значение слова «колорадо»

- 4 Склонение слова «колорадо» по подежам

- 5 Как правильно пишется слово «колорадо»

- 6 Ассоциации к слову «колорадо»

Как перенести слово «колорадо»

ко—лорадо

коло—радо

колора—до

Синонимы слова «колорадо»

Значение слова «колорадо»

1. восьмой по площади штат США, располагается на западе центральной части США, один из так называемых Горных штатов (Викисловарь)

Склонение слова «колорадо» по подежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Единственное числоЕд.ч. | Множественное числоМн.ч. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ИменительныйИм. | что? | Колорадо | Колорадо |

| РодительныйРод. | чего? | Колорадо | Колорадо |

| ДательныйДат. | чему? | Колорадо | Колорадо |

| ВинительныйВин. | что? | Колорадо | Колорадо |

| ТворительныйТв. | чем? | Колорадо | Колорадо |

| ПредложныйПред. | о чём? | Колорадо | Колорадо |

Как правильно пишется слово «колорадо»

Правописание слова «колорадо»

Орфография слова «колорадо»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «колорадо» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «колорадо»

-

Денвер

-

Ют

-

Штат

-

Калифорния

-

Техас

-

Калифорний

-

Каньон

-

Миссисипи

-

Аляска

-

Стэнли

-

Бакалавр

-

Огайо

-

Флорида

-

Плато

-

Торонто

-

Пенсильвания

-

Мэн

-

Мексика

-

Квебек

-

Ранчо

-

Монреаль

-

Прииск

-

Хоккеист

-

Уинстон

-

Колумбия

-

Курорт

-

Даллас

-

Лыжа

-

Филадельфия

-

Плотина

-

Вашингтон

-

Верховье

-

Юго-запад

-

Прерия

-

Джорджия

-

Вирджиния

-

Гора

-

Городок

-

Чикаго

-

Гранд

-

Раунд

-

Старатель

-

Отложение

-

Дамба

-

Шайба

-

Кортес

-

Предгорье

-

Приток

-

Городишко

-

Канада

-

Рудник

-

Джефферсон

-

Округа

-

Линкор

-

Бостон

-

Майами

-

Дельта

-

Долорес

-

Сити

-

Коэн

-

Нападающий

-

Университет

-

Альберта

-

Вратарь

-

Губернатор

-

Штаб-квартира

-

Эван

-

Моррисон

-

Река

-

Сиэтл

-

Поселенец

-

Колледж

-

Юго-восток

-

Переезд

-

Ареал

-

Запад

-

Сенатор

-

Остин

-

Северо-запад

-

Скалистый

-

Калифорнийский

-

Юго-западный

-

Хоккейный

-

Юго

-

Лыжный

-

Индейский

-

Флагманский

-

Мексиканский

-

Нью

-

Хилый

-

Военно-воздушный

-

Баскетбольный

-

Тихоокеанский

-

Юго-восточный

-

Обменять

-

Переехать

-

Покататься

-

Обыграть

-

Граничить

-

Округ

Правильное написание слова колорадо:

колорадо

Криптовалюта за ходьбу!

Количество букв в слове: 8

Слово состоит из букв:

К, О, Л, О, Р, А, Д, О

Правильный транслит слова: kolorado

Написание с не правильной раскладкой клавиатуры: rjkjhflj

Тест на правописание

§ 13. Географические названия

1. Географические названия пишутся с прописной буквы: Арктика, Европа, Финляндия, Кавказ, Крым, Байкал, Урал, Волга, Киев.

С прописной буквы пишутся также неофициальные названия территорий:

1) на -ье, образованные с помощью приставок за-, по-, под-, пред-, при-: Забайкалье, Заволжье; Поволжье, Пообье; Подмосковье; Предкавказье, Предуралье; Приамурье, Приморье;

2) на -ье, образованные без приставки: Оренбуржье, Ставрополье;

3) на -щин(а): Полтавщина, Смоленщина, Черниговщина.

2. В составных географических названиях все слова, кроме служебных и слов, обозначающих родовые понятия (гора, залив, море, озеро, океан, остров, пролив, река и т. п.), пишутся с прописной буквы: Северная Америка, Новый Свет, Старый Свет, Южная Африка, Азиатский материк, Северный Ледовитый океан, Кавказское побережье, Южный полюс, тропик Рака, Красное море, остров Новая Земля, острова Королевы Шарлотты, остров Земля Принца Карла, остров Святой Елены, Зондские острова, полуостров Таймыр, мыс Доброй Надежды, мыс Капитана Джеральда, Берингов пролив, залив Святого Лаврентия, Главный Кавказский хребет, гора Магнитная, Верхние Альпы (горы), Онежское озеро, город Красная Поляна, река Нижняя Тунгуска, Москва-река, вулкан Везувий.

В составных географических названиях существительные пишутся с прописной буквы, только если они утратили свое лексическое значение и называют объект условно: Белая Церковь (город), Красная Горка (город), Чешский Лес (горный хребет), Золотой Рог (бухта), Болванскай Нос (мыс). Ср.: залив Обская губа (губа — ‘залив’), отмель Куршская банка (банка — ‘мель’).

В составное название населенного пункта могут входить самые разные существительные и прилагательные. Например:

Белая Грива

Большой Исток

Борисоглебские Слободы

Верхний Уфалей

Высокая Гора

Горные Ключи

Гусиное Озеро

Дальнее Константиново

Железная Балка

Жёлтая Река

Зелёная Роща

Золотая Гора

Зубова Поляна

Каменный Яр

Камское Устье

Камышовая Бухта

Капустин Яр

Кичменгский Городок

Княжьи Горы

Конские Раздоры

Красная Равнина

Красный Базар

Липовая Долина

Липин Бор

Лисий Нос

Лиственный Мыс

Лукашкин Яр

Малая Пурга

Малиновое Озеро

Мокрая Ольховка

Мурованные Куриловцы

Мутный Материк

Нефтяные Камни

Нижние Ворцта

Новая Дача

Песчаный Брод

Петров Вал

Светлый Яр

Свинцовый Рудник

Свободный Порт

Сенная Губа

Серебряные Пруды

Старый Ряд

Турий Рог

Чёрный Отрог и т. п.

3. Части сложного географического названия пишутся с прописной буквы и соединяются дефисом, если название образовано:

1) сочетанием двух существительных (сочетание имеет значение единого объекта): Эльзас-Лотарингия, Шлезвиг-Гольштейн (но: Чехословакия, Индокитай), мыс Сердце-Камень;

2) сочетанием существительного с прилагательным: Новгород-Северский, Переславль-Залесский, Каменец-Подольский, Каменск-Уральский, Горно-Алтайск;

3) сложным прилагательным: Западно-Сибирская низменность, Южно-Австралийская котловина, Военно-Грузинская дорога, Волго-Донской канал;

4) сочетанием иноязычных элементов: Алма-Ата, Нью-Йорк.

4. Иноязычные родовые наименования, входящие в состав географических названий, но не употребляющиеся в русском языке в качестве нарицательных существительных, пишутся с прописной буквы: Йошкар-Ола (ола — ‘город’), Рио-Колорадо (рио — ‘река’), Сьерра-Невада (сьерра — ‘горная цепь’).

Однако иноязычные родовые наименования, вошедшие в русский язык в качестве нарицательных существительных, пишутся со строчной буквы: Варангер-фиорд, Беркли-сквер, Уолл-стрит, Мичиган-авеню.

5. Артикли, предлоги и частицы, находящиеся в начале иноязычных географических названий, пишутся с прописной буквы и присоединяются дефисом: Ле-Крезо, Лос-Эрманос, острова Де-Лонга. Так же: Сан-Франциско, Санта-Крус, Сен-Готард, Сент-Этьен.

6. Служебные слова, находящиеся в середине сложных географических названий (русских и иноязычных), пишутся со строчной буквы и присоединяются двумя дефисами: Комсомольск-на-Амуре, Ростов-на-Дону, Никольское-на-Черемшане, Франкфурт-на-Майне, Рио-де-Жанейро, Пинар-дель-Рио, Сан-Жозе-дус-Кампус, Сан-Жозе-де-Риу-Прету, Сан-Бендетто-дель-Тронто, Лидо-ди-Остия, Реджо-нель-Эмилия, Шуази-ле-Руа, Орадур-сюр-Глан, Абруццо-э-Молизе, Дар-эс-Салам.

7. Названия стран света пишутся со строчной буквы: восток, запад, север, юг; вест, норд, ост. Так же: северо-запад, юго-восток; норд-ост, зюйд-ост.

Однако названия стран света, когда они входят в состав названий территорий или употребляются вместо них, пишутся с прописной буквы: Дальний Восток, Крайний Север, народы Востока (т. е. восточных стран), страны Запада, регионы Северо-Запада.

А

Б

В

Г

Д

Е

Ж

З

И

Й

К

Л

М

Н

О

П

Р

р. (река) § 209

Ра § 180

рабски покорный § 131

раввин § 107

равеннцы § 109

равенство § 64 п. 2

равнение § 35 п. 1

равнина § 35 п. 1

равно § 35 п. 1

равновесие § 35 п. 1

равноденствие § 35 п. 1

равноправный § 35 п. 1

равносильный § 35 п. 1

равноценный § 35 п. 1

равный § 35 п. 1

равнять § 35 п. 1

равняться § 35 п. 1

равн — ровн § 35 п. 1

ради бога § 181 прим. 3

радий (о радии) § 71 п. 1

радикал-экстремизм § 121 п. 1

радио- § 117 п. 3

радиоактивный § 117 п. 3

радио-Буратино § 151

радио-мюзик-холл § 152

радиоприёмник § 117 п. 3

радиотелеуправление § 117 п. 3

радиофикация § 66

радостный § 83

рад-радёшенек § 118 п. 2

радуются не нарадуются § 155 а)

Раечка § 48

раёшник § 91

раёшный § 91

раз- (рас-)/роз- (рос-) § 40, § 82

разбирать § 36

раз-Брюллов § 151

развевать § 34

разведенец § 105

разведёнка § 105

разведчик § 86

разведывать § 61

разве не § 78 п. 4 а), § 147 п. 3

разверстый § 79 п. 2 б)

развёртывать § 61

разве что § 142 п. 2

развеянный § 60

развивать § 34

раздатчик § 87

раздать § 40

раздирать (раздеру) § 36

разжать § 89

разжечь § 40

разжигать § 36

раз за разом § 137 п. 4

раззвонить § 93

разлагать § 35 п. 1

разливанный (разливанное море) § 99 п. 3 а)

разливать § 40

разливной § 40

разлинованный § 98 п. 1

разлюли малина § 122 п. 3

размазывать § 61

размежёванный § 19 п. 2

размежёвка § 19 п. 3

размежёвывание § 19 п. 2

размежёвывать § 19 п. 2

размер/вес § 114

размешанный § 60

разминать § 36

размозжить § 106

размягчённый § 19 п. 5

размягчить § 79 п. 2 б) прим.

раз на раз § 137 п. 4

разниться § 35 п. 1

разница § 35 п. 1

разноголосица § 35 п. 1

разнородный § 35 п. 1

разносторонний § 35 п. 1

разносчик § 88

разнотипный § 128 п. 3 а)

разн — розн § 35 п. 1

разный § 35 п. 1

разобранный § 41

разобрать § 41

разовью § 41

разогнаться § 41

раз от разу § 137 п. 4

разредить § 34

разровнять § 35 п. 1

разрозненный § 35 п. 1

разрубить § 82

разрядить § 34

разъёмный § 27 п. 1 а)

разъехаться § 27 п. 1 а)

разыграть § 40

разыздеваться § 12 п. 2

разыскивать § 40

разыскной § 40

разэдакий § 6 п. 4 б)

Раичка § 48 прим.

райадминистрация § 26 п. 1

Райкин-младший § 159 прим.

район § 26 п. 2

районный совет народных депутатов § 193

райуполномоченный § 26 п. 1

ракетно-технический § 130 п. 3

рак-отшельник § 120 п. 1 б)

Рамазан (Рамадан) § 183

Рамбуйе § 26 п. 3

Рамсесы § 159

раненный § 98 п. 3

раненый § 60, § 98 п. 3

Раннее Возрождение § 179

ранний § 95

ранчо § 21

раным-рано § 118 п. 2

рапорт § 107

раса § 107

раскатисто-громкий § 129 п. 2

раскланяться § 35 п. 1

расковырянный § 60

раскорчёванный § 19 п. 2

распашонка § 18 п. 2

распаяться § 35 п. 1

распивочный § 43

распинать § 36

расписание § 40

расписка § 40

распустить § 40

распутанный § 98 п. 2 а)

рассказ «Дама с собачкой» § 195 а)

рассказчик § 88

рассориться § 96

расстелить § 36,

расстелет § 36 прим. 4

расстилать § 36, § 36 прим. 4

расстрелянный § 60

рассчитать § 36, § 93 прим.

рассчитывать § 93 прим.

рассыпать § 40, § 93

рассыпать § 40

рассыпной § 40

растение § 35 п. 1

растеньице § 52

растереть § 36

расти (расту) § 35 п. 1

растирание § 36 прим. 2

растирать § 36

растительность § 35 п. 1

растительноядный § 128 п. 3 а)

растить § 35 п. 1

растлевать § 62

растоптать § 82

растяпа растяпой § 122 п. 4 а)

расфасовать § 82

расхожий § 82

расценка § 82

расчёска § 19 п. 7, § 88

расчесть § 93 прим.

расчесться § 93 прим.

расчёсывать § 19 п. 7

расчёт § 18 п. 5, § 19 п. 7, § 93 прим.

расчётливый § 93 прим.

расчётный § 93 прим.

расчехлить § 88

расшевелить § 82

расшибить § 89

расщепление § 82

Рафаэлева Мадонна § 166

рахат-лукум § 121 п. 3

ращу § 35 п. 1

реакция § 79 п. 2 б)

ребятушки § 54

ревизия § 44

революция § 16

революция 1905 года § 179 прим. 5

ревю-оперетта § 120 п. 2

регби § 9

реестр § 7 п. 1

режьте § 32 в)

резус-фактор § 120 п. 4

резче § 88

резчик § 88

резюме § 9

рейтинг § 9

рейхсканцлер § 121 п. 2

рейхстаг § 191

река Волга § 122 п. 1 б)

реквием § 7 п. 1

реле-станция § 120 п. 2

религиоведение § 65

ре минор § 122 п. 6

ре-минорный § 129 п. 5

Ренессанс § 179

ренессанс § 194 прим. 5

ренклод § 198 прим.

рентген § 158, § 163

рентгеновы лучи § 166

реорганизованный § 98 п. 1

Рерих § 9

реснитчатый § 87

Республика Татарстан § 170

ретро- § 117 п. 3

ретромода § 117 п. 3

ретушёвка § 19 п. 3

ретушёр § 19 п. 4

Реформация § 179

речевой § 18 п. 3

речовка § 18 п. 3

решённый § 98 п. 2 б)

решённый-перерешённый § 99 п. 3

решёта (мн. ч.) § 19 п. 7

решетчатый § 19 п. 7

реэвакуация § 117 п. 1

реэкспорт § 6 п. 4 а)

Риего-и-Нуньес § 123 п. 5 прим. 1, § 160

риелтор § 7 п. 1

рижский § 90

риксдаг § 191

Римка § 109

римляне § 69

Римма § 107

Римский-Корсаков § 124 п. 1, § 159

Римско-католическая церковь § 184

Рио-де-Жанейро § 126 п. 6, § 169 прим. 2

рио-де-жанейрский § 129 п. 1

Рио-Колорадо § 169 прим. 3

Рио-Негро § 126 п. 5

р. и руб. (рубль) § 209

рислинг § 199 прим.

рисующий § 58

Ричард Львиное Сердце § 123 п. 2, § 159

р-н (район) § 210

Робеспьеры § 158

робин-гудовский § 129 п. 3

робинзон § 158

ровесник § 35 п. 1, § 83 прим.

ровненский § 55

ровный § 35 п. 1

ровнять § 35 п. 1

Рогожская Застава (площадь) § 169 прим. 1

Родина § 203

Родительская суббота § 183

рождаемость § 59

рождённый § 98 п. 2 б)

рождественский § 55

Рождество § 183

Роже Мартен дю Гар § 123 п. 3, § 123 п. 5, § 160

рожон § 18 п. 5

рожь § 32 а)

роз- (рос-)/раз- (рас-) § 40, § 82

роздал § 40

розданный § 40

розжиг § 36 прим. 3, § 40

розлив § 40

розмарин § 198 прим.

розниться § 35 п. 1

рознь § 35 п. 1

розыгрыш § 40

розыск § 12 п. 2, § 40, § 82

рок-ансамбль § 120 п. 4

рококо § 194 прим. 5

Рокфеллер-старший § 123 п. 2 прим., § 159 прим.

роман «Дворянское гнездо» § 195 а) «Роман без вранья» § 195 б)

Романовы § 159

ромбоэдр § 7 прим.

ромен-роллановский § 129 п. 3

ропот § 64 п. 3 а)

рос, росла, росли (прош. вр.) § 35 п. 1

рослый § 35 п. 1

роспись § 40, § 82

роспуск § 40

росс, (российский) § 209

Российская академия наук § 189

Российская Федерация § 170

российский § 106

Российский (в названиях) § 192 прим.

Российский научный центр «Курчатовский институт» § 192 прим.

Российское государство § 174

Россия § 106

Россияне § 106

Россыпь § 40

Рост § 35 п. 1

РОСТА (Российское телеграфное агентство) § 208 прим. 1

Ростов-на-Дону § 126 п. 6, § 157, § 169 прим. 2

ростовой § 35 п. 1

ростовщик § 35 п. 1

росток § 35 п. 1

рос(т) — рас(т) — ращ § 35 п. 1

росший § 89

рощ (род. п. мн. ч.) § 32

р/с и р/сч (расчётный счёт) § 210

рубашонка § 18 п. 2

Рудный Алтай (горная цепь) § 127

ружей (род. п. мн. ч.) § 64 п. 3

ружьецо § 52

рука об руку § 137 п. 4

руки-ноги § 118 п. 4

руководитель департамента § 196

рус. (русский) § 209

русалка § 162 прим. 2

русист § 106 прим.

русификация § 66, § 106 прим.

русифицированный § 106 прим. «Руслан» § 200

русофил § 106 прим.

русофоб § 106 прим.

Русская православная церковь § 184

русский § 95, § 106 прим.

Русский музей § 189

русскоговорящий § 106 прим.

русскоязычный § 106 прим., § 128 п. 3 б)

руставелиевский § 42 прим.

ручательство § 43

ручища § 70

ручонка § 18 п. 2

рушник § 91

рыба-попугай § 120 п. 1 б), § 122 п. 1 а) прим.

рыба треска § 122 п. 1 а)

рыбацкий § 85

рыжевато-коричневый § 129 п. 2

рыжеватый § 43

рыцарский § 30 п. 2 а) прим.

рэкет § 8 п. 1

рэкетир § 8 п. 1

Рэлей § 8 п. 2

рэлей § 8 п. 2

Рэмбо § 8 п. 2

рэп § 8 п. 1

рюкзак § 80

Рюриковичи § 159

Рязанщина § 30 п. 3 С

Т

У

Ф

Х

Ц

Ч

Ш

Щ

Ы

Э

Ю

Я

§ 169. В

географических и административно-территориальных названиях — названиях

материков, морей, озер, рек, возвышенностей, гор, стран, краев, областей,

населенных пунктов, улиц и т. п. — с прописной буквы пишутся все слова, кроме

родовых понятий (остров, море, гора, область, провинция, улица,

площадь и т. п.), служебных слов, а также слов года, лет,

напр.:

Альпы, Америка, Европа, Болгария, Новая

Зеландия, Северная Америка, Центральная Азия; Южный полюс, Северное полушарие;

Волга, Везувий, Большая Багамская банка,

водопад Кивач, долина Тамашлык, Голодная степь, залив Благополучия, котловина

Больших Озёр, ледник Северный Энгильчек, Днепровский лиман, мыс Доброй Надежды,

Абиссинское нагорье, Онежское озеро, Северный Ледовитый океан, Белое

море, плато Устюрт, Среднесибирское плоскогорье, полуостров Таймыр, Большая

Песчаная пустыня, Голубой Нил, Москва-река, Большой Барьерный риф, течение

Западных Ветров, тропик Рака, хребет Академии Наук, Главный Кавказский хребет;

Краснодарский край, Орловская область,

Щёлковский район, графство Суссекс, департамент Верхние Пиренеи, штат Южная

Каролина, округ Колумбия, область Тоскана, префектура Хоккайдо, провинция

Сычуань, Щецинское воеводство, Нижний Новгород, Киев, Париж, Новосибирск;

Тверская улица, улица Малая Грузинская, улица

26 Бакинских Комиссаров, Лаврушинский переулок, Арбатская площадь, Фрунзенская

набережная, проспект Мира, Цветной бульвар, Садовое кольцо, улица 1905 года,

площадь 50 лет Октября, Андреевский спуск, Большой Каменный мост.

В названиях, начинающихся на Северо- (и

Северно-), Юго- (и Южно-),

Восточно-, Западно-, Центрально-, с прописной буквы

пишутся (через дефис) оба компонента первого сложного слова, напр.: Северо-Байкальское нагорье, Восточно-Китайское море, Западно-Сибирская

низменность, Центрально-Чернозёмный регион, Юго-Западный территориальный округ.

Так же пишутся в составе географических названий компоненты других

пишущихся через дефис слов и их сочетаний, напр.: Индо-Гангская

равнина, Волго-Донской канал, Военно-Грузинская дорога, Алма-Атинский

заповедник, Сен-Готардский перевал (и туннель), земля Баден-Вюртемберг, мыс Сердце-Камень, Новгород-Северский,

Соль-Илецк, Усть-Илимск, Садовая-Сухаревская улица.

Примечание 1. Нарицательные существительные в

составных географических названиях пишутся с прописной буквы, если они

употреблены не в своем обычном значении, напр.: Новая Земля, Огненная Земля (архипелаги),

Золотой Рог (бухта),

Чешский Лес (горы),

Белая Церковь, Минеральные Воды,

Сосновый Бор, Вятские Поляны, Царское Село (города), Пушкинские Горы, Камское Устье

(поселки), Голодная Губа

(озеро), Большой Бассейн

(плоскогорье), Золотые Ворота

(пролив), Кузнецкий Мост, Охотный

Ряд, Земляной Вал (улицы), Никитские Ворота, Рогожская Застава (площади), Марьина Роща (район в

Москве), Елисейские Поля

(улица в Париже).

Примечание 2. Служебные слова (артикли,

предлоги, частицы), находящиеся в начале географических названий, пишутся с

прописной буквы, напр.: Под

Вязом, На Скалах (улицы), Лос-Анджелес, Ла-Манш, Лас-Вегас, Ле-Крезо, Де-Лонга. Также

пишутся начальные части Сан-,

Сен-, Сент-, Санкт-, Сайта-, напр.: Сан-Диего, Сен-Дени, Сент-Луис, Санта-Барбара,

Санкт-Мориц (города). Однако служебные слова, находящиеся в

середине географических названий, пишутся со строчной буквы, напр.: Ростов-на-Дону, Франкфурт-на-Майне,

Экс-ан-Прованс, Стратфорд-он-Эйвон, Рио-де-Жанейро, Шуази-ле-Руа,

Абруццо-э-Молизе, Дар-эс-Салам, Булонь-сюр-Мер.

Примечание 3. Некоторые иноязычные родовые

наименования, входящие в географическое название, но не употребляющиеся в

русском языке как нарицательные существительные, пишутся с прописной буквы,

напр.: Йошкар-Ола (ола — город), Рио-Колорадо (рио — река), Аракан-Йома (йома — хребет), Иссык-Куль (куль — озеро). Однако

иноязычные родовые наименования, которые могут употребляться в русском языке

как нарицательные существительные, пишутся со строчной буквы, напр.: Согне-фьорд, Уолл-стрит, Мичиган-авеню,

Пятая авеню, Беркли-сквер, Гайд-парк.

Примечание 4. Названия титулов, званий,

профессий, должностей и т. п. в составе географических названий пишутся с

прописной буквы, напр.: Земля

Королевы Шарлотты (острова), остров Принца Уэльского, мыс Капитана Джеральда, улица

Зодчего Росси, проспект Маршала Жукова. Аналогично пишутся

названия, в состав которых входит слово святой: остров Святой Елены, залив Святого Лаврентия.

Примечание 5. Слова, обозначающие участки

течения рек, пишутся со строчной буквы, если не входят в состав названий,

напр.: верхняя Припять, нижняя

Березина, но: Верхняя

Тура, Нижняя Тунгуска (названия рек).

| Штат США | ||

|

Колорадо |

||

|

||

|

Девиз штата |

«Ничто без Провидения» | |

|

Прозвище штата |

«Штат Столетия» | |

|

Столица |

Денвер | |

|

Крупнейший город |

Денвер | |

|

Крупные города |

Колорадо-Спрингс, Форт-Коллинс, Арвада, Пуэбло, Вестминстер, Боулдер | |

|

Население |

5 782 171[1] (2020 год) 21-е по США |

|

| плотность | 21,40 чел./км² 39-е по США |

|

|

Площадь |

8-е место | |

| всего | 269 837 км² | |

| водная поверхность | (0,36 %) | |

| широта | 37°0′ с. ш. по 41°0′ с. ш., 612 км | |

| долгота | 102°8′ з. д. по 109°0′ з. д., 451 км | |

|

Высота над уровнем моря |

||

| максимальная | 4399 м | |

| средняя | 2073 м | |

| минимальная | 1011 м | |

|

Принятие статуса штата |

1 августа 1876 38 по счёту |

|

| до принятия статуса | Территория Колорадо | |

|

Губернатор |

Джаред Полис | |

|

Вице-губернатор |

Д. Примавера | |

|

Законодательный орган |

Генеральная Ассамблея | |

| верхняя палата | Сенат | |

| нижняя палата | Палата представителей | |

|

Сенаторы |

Майкл Беннет, Джон Хикенлупер |

|

|

Часовой пояс |

Горное время: UTC-7/-6 | |

|

Сокращение |

CO | |

|

Официальный сайт |

www.colorado.gov | |

|

|

Колора́до[2][3] (англ. Colorado, американское произношение: [ˌkɒləˈrædoʊ] ( слушать) или [ˌkɒləˈrɑːdoʊ]) — штат[4] на западе центральной части США, один из так называемых Горных штатов. Колорадо граничит со штатами Вайоминг (на севере), Небраска (на северо-востоке), Канзас (на востоке), Оклахома (на юго-востоке), Нью-Мексико (на юге), Аризона (на юго-западе), Юта (на западе).

Колорадо — восьмой по площади штат США, его площадь 269 837 км². Население штата — 5 782 171 человек (21-е по США)[1]. Столица и крупнейший город — Денвер. Другие крупные города — Арвада, Боулдер, Уэстминстер, Колорадо-Спрингс, Лейквуд, Орора, Пуэбло, Сентенниал, Торнтон, Форт-Коллинс.

Колорадо — 38-й штат США, он был образован 1 августа 1876 года, когда страна отмечала своё столетие. Из-за этого официальное прозвище Колорадо — «Столетний штат» (англ. Centennial State).

История[править | править код]

В начале XVI в. территорию будущего штата обследовали испанцы. С 1706 года территория Колорадо была объявлена колонией Испании. Своё название земля получила от реки Колорадо, которая в свою очередь была названа из-за красно-коричневого ила, содержащегося в воде. Затем провинция перешла к Франции. США получили восточную часть Колорадо в результате Луизианской покупки 1803 года. Центральная часть Колорадо перешла к США в 1845 году, а западная часть — в 1848 году, в результате войны с Мексикой.

В 1850-х годах неподалёку от Денвера было найдено золото, и сюда хлынули толпы переселенцев. В 1861 году началась Гражданская война. Многие золотоискатели сочувствовали Конфедерации, но большинство золотоискателей были верны Союзу. В 1862 году армия Конфедерации под командованием бригадного генерала Генри Хопкинса Сибли вышла из Форт-Блисс в Техасе и направилась вдоль Рио-Гранде, вторглась в северную часть Территории Нью-Мексико. Целью кампании был контроль над Территорией Колорадо, в частности золотыми приисками, и Калифорнией. 1-й полк добровольцев Колорадо под командованием полковника Джона Слау совершил переход из Денвера через перевал Ратон и 26 марта вступил в решающее сражение у перевала Глориета в горах Сангре-де-Кристо в Скалистых горах.

С 1863 по 1865 годы на землях территории Колорадо происходило вооружённое противостояние между белыми американцами, с одной стороны, и индейскими племенами арапахо, шайенов, сиу, кайова и команчей, с другой. Результатом стало переселение остатков племён арапахо, шайенн, кайова и команчей с территории Колорадо в резервации в Оклахоме.

3 марта 1875 года Конгресс США принял закон, определяющий требования к территории Колорадо, которые необходимо выполнить, чтобы стать штатом. Наконец, 1 августа 1876 года, спустя 28 дней после празднования столетия Дня независимости, президент США подписал указ, допускающий 38-й штат США к Союзу.

По переписи населения в 1930 году численность жителей штата превысила миллион человек. Колорадо сильно пострадал от Великой депрессии, но его состояние было восстановлено после Второй мировой войны. Важнейшими отраслями экономики штата стали горнодобывающая промышленность, сельское хозяйство и туризм.

В 1999 году в городе Литтл-Джефферсон произошло массовое убийство в школе Колумбайн. В итоге погибло 15 человек (включая нападавших), и было ранено 23 человека.

В 2014 году Колорадо стал первым штатом Америки, легализовавшим марихуану[5].

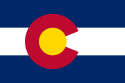

Герб и флаг[править | править код]

По закону 1911 года официальный флаг штата представляет собой прямоугольное полотнище. Красная буква «C» обозначает «Colorado» (штат назван по одноимённой реке), что в переводе с испанского языка значит «красный» (значение «цветной», «окрашенный», которое часто приводится в публикациях, является менее употребительным). Золотой шар внутри «C» говорит о наличии золотых приисков в штате. Голубые и белые полоски на флаге символизируют голубые небеса и белые снега Скалистых гор Колорадо. На гербе штата, который был официально принят в 1877 году, треугольная фигура символизирует всевидящий глаз Бога. На гербе изображены горы штата, земля и кирка, которые символизируют горнодобывающую промышленность Колорадо — основу экономики штата.

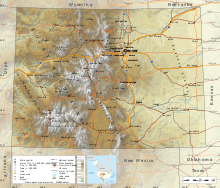

География[править | править код]

Великий континентальный раздел

Колорадо — один из трёх штатов (наряду с Вайомингом и Ютой), все границы которого представляют собой параллели и меридианы, и, как и Вайоминг, образует просто «прямоугольник» (точнее, сектор земной поверхности) между парой широт и парой долгот. Площадь занимаемой Колорадо территории — 269 837 км². 37 % территории Колорадо занимают национальные парки.

Рельеф[править | править код]

Рельеф Колорадо разнообразен. В центральной части территория штата пересекается с севера на юг хребтами Скалистых гор (высшая точка — гора Элберт, 4399 м). Они образуют так называемый Великий континентальный раздел: реки, протекающие западнее этих гор, относятся к бассейну Тихого океана, а те реки, которые находятся восточнее, относятся к бассейну Атлантического океана. Склоны гор большей частью покрыты хвойным лесом — лишь немногие вершины круглый год находятся под снегом. Бо́льшая часть населения штата проживает рядом с восточными склонами гор, так как это место защищено от штормовых ветров Тихого океана. В Колорадо находятся 55 из 104 горных вершин США, имеющих абсолютную высоту более 4000 метров и относительную — более 500 метров.

Восточнее Скалистые горы переходят в Великие равнины — плато с преобладающей степной растительностью. На Западе штата находится плато Колорадо — полупустынная зона с каньонами, останцами и другими характерными формами рельефа.

Горы[править | править код]

Вершина горы Элберт на высоте 14 440 футов (4401,2 м) в округе Лейк является самой высокой точкой в Колорадо и Скалистых горах Северной Америки[6]. Колорадо является единственным штатом США, который полностью лежит на высоте более 1000 метров. Место, где река Арикэри вытекает из округа Юма, штат Колорадо, и впадает в округ Шайенн, штат Канзас, является самой низкой точкой в штате Колорадо на высоте 3317 футов (1011 м). [7]

Климат[править | править код]

Климатическая картина Колорадо неоднородная: южная часть штата не всегда теплее северной, на климат сильно влияют Скалистые горы: с увеличением высоты температура понижается, а влажность повышается. По климатическим условиям штат делится на две части: восточные равнины и западные предгорья.

Река Арканзас в штате Колорадо

На востоке климат умеренно континентальный: низкая влажность, умеренные осадки (380—630 мм в год). Здесь отмечена одна из самых высоких среднесуточных температур в США. Летом температура возрастает до 35 °C (в среднем), а зимой может опуститься до −18 °C.

Климат западного Колорадо более однородный. Здесь присутствуют засушливые места, на возвышенностях горный климат. Самый жаркий месяц — июль (21 °C). Зима здесь очень влажная, что является противоположностью восточной части штата.

Гидрография[править | править код]

Река Колорадо — одна из крупных в штате. Здесь, на севере находится её исток. Она протекает в западной части Колорадо. На юге штата находится исток ещё одной крупной реки — Рио-Гранде. Она берёт своё начало в Скалистых горах и спускается к югу. Можно выделить и реку Арканзас, исток которой также находится в Колорадо. Она течёт на восток по Великим равнинам и затем впадает в реку Миссисипи. Ещё одна крупная река штата — Саут-Платт.

Крупнейшее по площади и по глубине в штате озеро — Гранд-Лейк, второе место занимает озеро Сан-Кристобал.

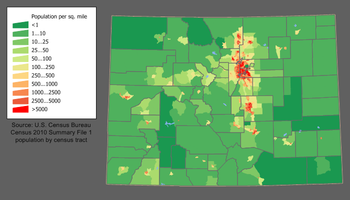

Население[править | править код]

По данным на июль 2013 года в Колорадо проживают 5 268 367 человек. Прирост населения велик за счёт высокой рождаемости и большого количества иммигрантов. Наибольший рост населения ожидается у восточного подножия Скалистых гор, особенно в Денвере.

Самый густонаселённый город штата и его столица — Денвер. В его агломерации Денвер-Орора-Боулдер проживает 2 927 900 человек, то есть приблизительно две трети всего населения штата.

В Колорадо проживает большое количество испанцев. Они проживают преимущественно в Денвере и на юге штата и являются потомками первых поселенцев этих земель. В результате переписи населения 2000 года выяснилось, что 10,5 % жителей штата говорят на испанском языке.

Также на территории штата проживают множество афроамериканцев, людей китайской, корейской и прочих национальностей. Преимущественно они проживают на востоке Денвера, в районе Орора. Многие из них являются потомками переселенцев, прибывших на территорию Колорадо во время золотой лихорадки.

Религиозный состав[править | править код]

Католическая церковь неподалёку от города Боулдер

Христианство — самая популярная религия штата — её исповедуют 65 % населения. Протестантизм — самая популярная ветвь христианства — её исповедуют 44 % жителей Колорадо. Католицизм исповедуют около 19 % населения штата.

Религиозный состав населения штата Колорадо:

- Христианство — 65 %

- Протестантизм — 44 %

- Католицизм — 19 %

- Мормоны — 2 %

- Православие — 1 %

- Иудаизм — 2 %

- Ислам — 1 %

- Другие религии — 5 %

- Атеизм — 25 %

В среднем в США 17 % атеистов, в Колорадо — 25 %.

Экономика[править | править код]

Кукурузная плантация в Колорадо

ВВП штата Колорадо в 2007 году был равен 236 миллиардов долларов. На душу населения доход составлял $ 41 192. По этому показателю штат занимает 11-е место в США. С середины XIX века основу экономики штата стали составлять горнодобывающая промышленность и сельское хозяйство. Во второй половине XX века возросла роль сферы услуг.

В Колорадо развита пищевая промышленность, машиностроение, химическая промышленность, металлургия. В штате имеются месторождения и добыча угля, нефти, природного газа, ванадия, урана, цинка, золота, серебра и молибдена. Штат является одним из лидеров в США по производству пива. Экономика штата отличается высокой технологичностью и хорошим качеством.

Денвер является важнейшим финансовым центром Колорадо. В нём расположены монетный двор, несколько крупных банков. Работают предприятия пищевой промышленности, машиностроения, лёгкой промышленности.

В Колорадо подоходный налог равен 4,63 % вне зависимости от размера дохода. В отличие от большинства штатов, где налог рассчитывается на основе «федерального скорректированного валового дохода», в штате Колорадо налоговой базой считается «налогооблагаемый доход» (доход после федеральных льгот и федеральных стандартных отчислений). В штате недвижимость и личные предприятия подлежат налогообложению, а государственное имущество было освобождено от этого в 2003 году. По состоянию на январь 2010 года уровень безработицы в Колорадо 7,4 %.

См. также[править | править код]

- Список городов Колорадо по численности населения

Примечания[править | править код]

Ссылки[править | править код]

- colorado.gov (англ.) — официальный сайт штата Колорадо

Внимание! Copyright

! Перепечатка возможна только с письменного разрешения автора. . Нарушители авторских прав будут преследоваться в соответствии с действующим законодательством.

Маша Денежкина, Таня Марчант

В оригинале:

Colorado

Столица:

Denver

)

Вошёл в состав США

: 1 августа 1876 года

Площадь:

269,7 тысяч кв.км

Население:

5,024 тыс. человек (2009 год)

Крупнейшие города:

Denver, Colorado Springs, Aurora Lakewood, Fort Collins, Arvada, Pueblo, Westminster, Boulder, Thornton

Колорадо – штат, знаменитый потрясающими природными ландшафтами пояса Скалистых гор (Rocky Mountain).

Впечатляющая уникальная красота заснеженных скал, покрытых хвойными лесами и мягкий климат штата, окруженного и защищенного от ветров поясом гор, сделали Колорадо центром летнего туризма США.

Зимой снежные склоны гор, сверкающие под теплыми лучами солнца, привлекают любителей горнолыжного спорта. Облюбовав знаменитые лыжные курорты штата, в Колорадо съезжаются многочисленные туристы не только из США, но и со всего мира. Ежегодно миллионы гостей штата прибывают в известные туристические горные районы Колорадо: Аспен (Aspen), Ист Парк (Estes Park) и Колорадо Спрингс (Colorado Springs).

Но не только горы Колорадо, привлекающие туристов, дают огромный доход в казну штата. Большинство граждан штата живет и работает в его восточной части — в сухой равнинной местности, которая занимает две пятых территории Колорадо.

Тоннели, прорубленные в горах, доставляют воду в сухие прерии, в большие города и фермерские районы штата. Земли Колорадо расположены на полпути между центральными городами Калифорнии и Средним Западом США. Поэтому штат служит главной транспортной артерией и грузосортировочным центром для всего района Скалистых гор.

Во многих отраслях промышленности компании Колорадо являются лидирующими. Важнейшими отраслями сельско-зозяйственной промышленности штата можно назвать мясомолочное животноводство и овцеводство. Мелиоративные проекты штата позволили фермерам Колорадо успешно заниматься выращиванием картофеля, зерна и сахарной свеклы. В районах бывших сухих пустынных прерий сейчас располагаются бескрайние поля кукурузы.

Одной из важнейших отраслей экономики штата является горнодобывающая промышленность. В 1850 году в Колорадо случился первый «горный бум».

Истории времён золотой и серебряной лихорадки в Колорадо, берущей начало с 1850 года, передаются как легенды. Такие известные мюзиклы, как комедия «Непотопляемая Молли Браун» (The Unsinkable Molly Brown) и опера «Баллада о малыше До» (The Ballad of Baby Doe) хорошо описывают события, происходившие в Колорадо во время «горного бума».

В шахтах Колорадо и сейчас добывают золото и серебро. Но теперь важнейшим объектом горнодобывающей промышленности штата является нефть, а также — производство бензина.

Колорадо – лидирующий штат США по добыче молибдена и производству стали. Один из «монетных дворов» Соединенных Штатов находится в столице Колорадо, городе Денвере.

Владельцем более чем третьей части земель Колорадо является государство. Правительство США контролирует использование этих территорий для пастбищ и разработки полезных ископаемых.

Правительство также является крупным заказчиком компаний Колорадо, занятых в индустрии приборостроения для космических исследований. Близ города Колорадо Спрингс располагается Академия ВВС, штаб-квартира которой находится у подножия горы Шаен, а центр финансирования – в столице штата, Денвере.

По-испански слово «colorado» означает «окрашенный в красный». Это имя изначально было дано реке Колорадо, которая протекала через каньон в скалах, камни которых имели красноватый оттенок. Штат был назван в честь реки. Иначе Колорадо еще называют «Штат Столетия» (Centennial State), поскольку Колорадо вошел в Союз США в 1876 году – в год столетия знаменитой Декларации Независимости. Самый крупный город штата — его столица город Денвер.

Флаг и герб штата Колорадо

В 1911 году штат Колорадо принял закон об официальном флаге. Красная буква «С» обозначает «Colorado», что в переводе с испанского языка, читается как «красный цвет» (colored red). Золотой шар внутри «С» говорит о наличии золотых приисков в штате. А голубые и белые полоски на флаге символизируют голубые небеса и белые снега Скалистых гор Колорадо.

На гербе штата, который был официально принят в 1877 году, треугольная фигура символизирует всевидящий глаз Бога. Также на гербе изображены горы штата, земля и кирка, которые символизируют горнодобывающую промышленность Колорадо — основу экономики штата.

Колорадо располагается в возвышенной зоне. Его земли лежат на высоте 2100 метров над уровнем моря, и это — самый «высотный» штат государства.

Первой благотворительной организацией в столице штата — Денвере, стал фонд помощи, созданный в 1887 году, учрежденный священником, рабби и двумя министрами. Фонд был назван «Общественная Благотворительная Служба» (Charity Organization Society).

Самый крупный серебряный самородок, который когда-либо находили в Северной Америке, был обнаружен в 1894 году в районе города Аспен. Самородок весил 835 кг и поныне именно он является самым крупным в мире серебряным слитком.

Было время, когда Колорадо в один день было три губернатора. В 1905 году губернатором штата был Альва Адамс (Alva Adams). Но после двух месяцев службы на этом посту он был вынужден уйти в отставку, ибо его уличили в мошенничестве на выборах. 17 марта 1905 года Адамс покинул губернаторское кресло, и

законодательное собрание штата призвало на пост губернатора Джеймс Пибоди (James H. Peabody). Тот отказался от предложенной должности, и в тот же день офис губернатора штата возглавил бывший вице-губернатор Джесси Макдональд.

Национальный парк «Великие Песчаные Дюны» (Great Sand Dunes National Monument) называют одним из удивительнейших чудес природы. Эти громадные массивы песка, лежащие у подножия гор Сангре Де Кристо (Sangre de Cristo Mountains) в центральном южном районе Колорадо, постоянно движутся и принимают причудливые формы. Иногда высота песочных дюн достигает 210 метров.

Центр деловой, финансовой и промышленной активности штата, Колорадо Спрингс (Colorado Springs) – крупнейший туристический центр штата, а также – военный центр, в районе которого расположено несколько военных баз, в том числе Академия ВВС. Крупнейшим городом на западе Колорадо является Гранд Джанкшон (Grand Junction).

Музеи, туризм

В Музее Искусства города Денвер (The Denver Art Museum) собрана большая коллекция изделий американских индейцев, а Музей Естественной Истории (г. Денвер) представляет большую экспозицию животных континента.

Прекрасный штат ежегодно привлекает миллионы туристов. Летом гости Колорадо заполняют высокогорные лыжные курорты. На склонах гор, в лесах, у берегов горных ручьев туристы располагают свои палаточные лагеря и кемпинги. Альпинисты пробуют свои силы в восхождении на многочисленные пики Скалистых гор.

Старые шахтерские городки и индейские деревни интересны для туристов – краеведов. Любители рыбалки ловят форель в чистых горных реках штата. Осенью охотники бродят в лесах штата в поисках многочисленных оленей.

Зимой вновь заполняются лыжные курорты Аспен (Aspen) Арапахо Бэзин (Arapahoe Basin), Стимбот Спрингс (Steamboat Springs), Вейл (Vail) и Винтер Парк (Winter Park). Лыжный сезон в Колорадо начинается в ноябре и заканчивается в апреле.

В городе Гранд Джанкшон (Grand Junction) находится Музей Долина Динозавров (The Dinosaur Valley Museum), который представляет коллекцию ископаемых животных доисторического периода.

Природа штата

Главные районы Колорадо — это Плато Колорадо; Межгорье; Скалистые горы; Великие прерии.

(The Colorado Plateau) лежит вдоль западной границы штата и занимает пятую часть его территории. Это район высоких холмов, плато и долин. На этих землях фермеры выращивают различные сорта злаковых культур. А в летние месяцы на лугах плато пасутся многочисленные стада коров и овец.

Межгорье

(Intermontane Basin) находится на севере плато и является самым маленьким районом штата. Это регион небольших холмистых возвышенностей, которые лежат между горами на северо-западе штата. Слово «intermontane» означает «между горами». Этот район холмистых возвышенностей покрывают леса и луга, которые являются прекрасными пастбищами для овец.

(The Rocky Mountains) лежат в средней части Колорадо и покрывают две пятых территории штата. Горы Колорадо называют Крышей Северной Америки.

Около 55 высочайших пиков, возвышающихся на 4 270 км над уровнем моря, расположены в этом районе. Эти высоты являются высочайшими вершинами цепи Скалистых гор, которая тянется от штата Аляска до Нью-Мексико.

Скалистые горы в свою очередь, тоже состоят из пяти горных цепей: Front Range, Park Range, Sawatch Range, San Juan Mountains, Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

Восточная группа Front Range включает такие высокие горы, как гора Ивэнс (Mount Evans), высота которой 4348 метров, Лонгз Пик (Longs Peak) высотой 4345 метров, Пайкс Пик (Pikes Peak) высотой 4301 метров и другие горы, высота которых растет к западу от Денвера и Колорадо Спрингз.

Цепь гор Sangre de Cristo (Кровь Христа) лежит на юге цепи Front Range. Вместе же горные цепи Front Range и Sangre de Cristo являются своеобразной стеной, которая ограждает район Великих Прерий, расположенных на востоке штата.

Великие Прерии

востока Колорадо покрывают примерно две пятых территории штата. Район великих прерий Колорадо — это часть обширной Северо-Американской Равнины, которая тянется от Канады до Мексики. Она плавно возвышается с востока на запад от подножия Скалистых гор. Когда-то фермеры считали эти территории непригодными для сельского хозяйства. Но современные ирригационные проекты в долинах сделали некогда сухие земли пригодными для обширных территорий агропромышленной деятельности.

Реки и озера

Важнейшие реки многих штатов берут свое начало из крупнейшей водной артерии – реки Колорадо.

Истоки трех крупных водных систем Миссисиппи-Миссури расположены на восточных склонах Скалистых гор. Это реки Арканзас (Arkansas), Сауз Платт (South Platte) и Репабликен (Republican).

На западе Скалистых гор, в озере Гранд (Grand Lake) берет свое начало река Колорадо (Colorado River). Она несет свои воды через регион Middle Park к юго-западу штата Юта и занимает двенадцатую часть территории США.

Несколько главных притоков реки Колорадо, включая Анкомпагре (Uncompahgre), Джаннисон (Gunnison), Сан Хуан (San Juan) и Долорес (Dolores) также являются водными ресурсами штата Колорадо.

В районе реки Сан Хуан берет свое начало и река Рио-Гранде (Rio Grande), которая течет на востоке и юге штата Колорадо и пересекает его границу со штатом Нью Мексико. А река Ноз Платт берет начало на землях North Park и несет свои воды в штат Вайоминг.

Растительность

В виду огромного различия в высоте и влажности, на землях Колорадо произрастает множество самых разнообразных вариантов растений.

Интересно видовое многообразие кактусов и других растений пустынь, которые во множестве можно встретить в засушливых районах штата. Наиболее распространена в них «бизонья трава» (buffalo grass). Весной расцветают песчаные лилии, лютики, тысячелистники. Летом – коломбины, сирень, Индейские кисточки, горные лилии, маргаритки, ирисы и розы.

Более трети территории штата покрыто лесами хвойных пород деревьев: разнообразные виды осин, елей и сосен, а также разные виды кленов.

Климат

Преимущественно климат Колорадо сухой и солнечный. Но поскольку на территории штата между его различными районами существует разница в высоте, температура воздуха также варьируется в зависимости от расположения региона. В горах всегда холоднее, чем в долинах и на плато.

В городе Барлингтоне (Burlington), расположенном на равнинных землях, средняя температура января равняется –2°C. А в городе Лидвилле (Leadville), который находится в горах, в январе –8°C. Разница в летних температурах этих же городов составляет +23°C в Барлингтоне и +13°C в Лидвилле.

Самая высокая температура воздуха была зарегистрирована в Колорадо в июле 1888г в городе Беннетт (Bennett). Она равнялась +48 °C. А самая низкая температура была 1 февраля 1985г в городе Мейбелл (Maybell), когда градусник показал –52 °C!

Производство

Производственный товарооборот штата Колорадо ежегодно составляет 19 миллиардов долларов. В основном на производства штата поступают полуфабрикаты, которые заводы и фабрики Колорадо доводят до конечной кондиции готовых товаров.

В сфере промышленного производства Колорадо лидирующими отраслями являются компьютерная и электронная техника. Около 60% экспортного производства штата составляет электроника, так называемый «хай тек сектор». Компьютерная техника и электронное производство – преобладающая отрасль экономики штата. Компании, производящие электронную технику и компьютерное оборудование располагаются в городах Болдер, Колорадо Спрингз, Денвер и Форт Коллинз.

Другими не менее важными отраслями промышленности Колорадо следует назвать производство медицинской техники и детали для различных электрических приборов.

Вторым ведущим направлением промышленности Колорадо считается изготовление специальных машин и агрегатов для пищевого производства. Аппараты для пивоварения, конвейеры для разлива напитков по бутылкам, линии для упаковки мясных продуктов – вот основные механизированные линии для пищевой индустрии, производимые в Колорадо.

Третья по величине пивоваренная компания США «Coors Brewing Company» имеет свой «головной офис» в Колорадском городе Голден (Golden). Кроме этого, несколько других крупных американских пивоваренных компаний размещают свои производства в городе Форт Коллинз.

Другими лидирующими отраслями промышленности штата можно назвать оборудование для транспорта, химических производств и металлургию. Части автомобильных двигателей и аэрокосмического оборудования являются важнейшими объектами производства штата. Колорадо на государственном уровне лидирует по производству фармацевтических препаратов, а также чистящих и лакокрасочных материалов.

Горнорудная промышленность

Нефть, уголь и природный газ — важнейшие продукты горнодобывающей промышленности Колорадо. Округ Рио Бланко (Rio Blanco County), расположенный на северо-западе штата добывает наибольшее количество нефти Колорадо. Нефтяные залежи этих земель содержат половину подземных нефтяных запасов штата. Кроме того, на востоке Денвера так же обнаружены обширные залежи нефти.

Сельское хозяйство

Около 60% земель Колорадо занимают сельскохозяйственные угодья. В штате насчитывается около 29 тысяч различных ферм. От огромных ранчо до маленьких «truck» — овощных огородов.

Животноводческие хозяйства и продукция животноводства дает две трети прибыли от сельскохозяйственного производства штата. Производство говядины – основная отрасль фермерской продукции Колорадо, штат является одним из главных поставщиков говядины на государственном рынке.

Много лет работа на пастбищах и ранчо была важнейшей сферой деятельности жителей штата. Фермеры Колорадо и сейчас занимаются откармливанием скота. Но уже – применяя современные технологии сельского хозяйства. Операторы «кормовых пультов раздачи» закупают телят, откармливая их на ранчо до необходимой кондиции.

Разумеется, такой научно разработанный, «пищевой конвейер», обогащенный необходимыми для роста минеральными солями и витаминами, гораздо быстрее увеличивает массу животного, нежели натуральные пастбища. А более тяжелые по весу животные ценятся на рынке гораздо выше. Регион Грили (Greeley) является важнейшим районом откормки животных.

Молочное производство штата – самая главная отрасль сельского хозяйства Колорадо. Кроме того, Колорадо – лидер шерстяного и мясного овцеводства. Также в штате выращивают свиней и домашнюю птицу.

Перепечатка, публикация статьи на сайтах, форумах, в блогах, группах в контакте и рассылках допускается только при наличии активной ссылки

на сайт .

С XV в. до н. э. примерно до XII в. н. э. на нынешней территории Колорадо жили индейские племена, называвшие себя «анасази», представители развитой сельскохозяйственной цивилизации. Их возможные потомки — племена юта и шайен знакомы нам по американским вестернам.

В XVII в. на территорию будущего Колорадо приходят испанцы, которые дают региону нынешнее название. Вслед за ними прибывают французы из уже освоенной колонии Луизианы. Начинается длительная борьба за контроль над этой территорией.

В начале XIX в. Соединенные Штаты Америки оккупируют Колорадо, и в 1876 г. он становится тридцать восьмым штатом.

В течение 1913 г., благодаря одному норвежцу, среди местных жителей появилось пристрастие к лыжному спорту. Так Колорадо становится одним из главных центров «белого безумия» горнолыжного спорта. Еще раньше, в семидесятые годы XIX в., с появлением в регионе железной дороги сюда хлынули толпы золотоискателей. Но «золотая лихорадка» в Колорадо была недолгой.

На первый взгляд штат Колорадо представляет собой только скалы и горы, но на самом деле он изобилует достопримечательностями.

Большая часть штата Колорадо расположена на территории горного массива , по которому проходит климатическая граница между западными штатами (Калифорния, Юта и Невада), центральной и восточной частями США. Савотч — один из двух горных хребтов, который пересекает штат с севера на юг и служит гидрографической границей между бассейнами Тихого и Атлантического океанов.

Самая высокая вершина Колорадо — Элберт (4398 м).

Восточная часть Колорадо представляет собой равнинную область. Здесь занимаются животноводством и добывают в значительных объемах нефть, газ, олово, молибден, цинк, уголь и серебро.

Возле Колорадо-Спрингс располагаются офисы компаний, занимающихся электроникой и информационными технологиями.

В Колорадо туризм играет очень большую роль. Аспен, расположенный на 354 км юго-западнее Денвера, известен любителям зимнего спорта всего мира. Влиятельные и богатые персоны, ищущие ярких впечатлений, ежегодно приезжают сюда, чтобы насладиться захватывающими спусками.

Близ Колорадо-Спрингс расположен Сад Богов — скалы из красного и белого песчаника и других осадочных пород в окружении вечнозеленых кипарисов. Это удивительный пейзаж, особенно во время восхода солнца.

Непременно следует посетить Колорадо-Спрингс. Здесь находится восстановленное старинное ранчо, которое как будто пришло к нам из вестернов. Стоит прогуляться и по Национальному парку , который объявлен культурным наследием ЮНЕСКО. Здесь можно встретить следы пребывания первых жителей этого штата, относящиеся к культуре племен анасази.

Общая информация

Тридцать восьмой штат США (с 1876 г.).

Общие границы со штатами:

Вайоминг, Небраска, Канзас, Оклахома, Нью-Мексико, Аризона, Юта.

Столица:

Денвер 598 707 чел., в агломерации — 2 506 626 чел. (2008 г.).

Язык:

английский.

Валюта:

доллар США.

Религия:

христианство.

Самые значительные города:

Колорадо-Спрингс, Лейквуд, Боулдер, Пуэбло, Арвада.

Реки:

Колорадо. Арканзас, Саут-Платт, Рио-Гранде.

Горы:

хребет Медисин-Боу, хребет Савотч, Сан-Хуан.

Цифры

Площадь:

269 837 км 2 .

Население:

4 301 261 чел. (2000 г.).

Плотность населения:

15,9 чел./км 2 .

Средняя высота над уровнем моря:

2100 м.

Высочайшая точка:

Элберт (4398 м).

Экономика

Полезные ископаемые:

металлические руды, уголь, природный газ, уран.

Сельское хозяйство:

выращивание картофеля, сахарной свеклы, животноводство.

Любопытные факты

■ Колорадо по-испански означает — «окрашенный в красные тона». Видимо, все дело в том, что река Колорадо течет между скал красного оттенка.

■ С 1858 по 1860 г. Денвер, главный город Колорадо, назывался Аурариа.

■ Близ Колорадо-Спрингс находится одно из самых значительных учебных заведений США — Академия ВВС Соединенных Штатов Америки.

■ Около 1850 г. свыше 10 000 человек, охваченных «золотой лихорадкой», в погоне за удачей устремились в Колорадо-Спрингс.

Не смотря на обильно падающий снег, нам удалось улететь из мокрого и грязного Нью-Йорка

И хотя в новостях пишут что через полчаса после нашего отлета из аэропорта LaGuardia

там выкатился за пределы ВПП самолет а/к Delta

, наш United

обильно политый красноватой незамерзайкой и заведенный с толкача, проваливаясь в воздушные ямы так что народ охал и ахал… все же прорвался из циклонического плена где-то над Иллинойсом (штат США)

В Колорадо

(штат США) солнечно и безветренно

Совершенно другая Америка — улыбающаяся и дружелюбная

И хотя дороги сухие — нам сказали, что мы можем творить с арендованной машиной все что хотим — она полностью застрахована

Выбор автомобиля для аренды в США

До места домчались за час…

Путешествие по США началось!

Первая остановка: недалеко от города Colorado Springs

парк Garden of the Gods

(Сад Богов)

Приложения

:

Нью-Йорк:

Рекомендую остановиться в уютных домиках рядом с парком Garden of the Gods

: Sunflower Lodge

Чем дальше в глубь «одноэтажной Америки» — тем дешевле цены в магазинах и мотелях.

Попадаются бородатые и лохматые деды в засаленных комбинезонах. Они ездят на доисторических джипах типа Шевроле и не могут скрыть удивления увидев нас.

Оказывается Бивис и Бадхед — не вымышленные персонажи: их срисовали с молодых людей «одноэтажной Америки» — могу засвидетельствовать.

С погодно-климатическими поясами что-то неладное творится: выехали январской стужей, а после обеда вокруг была уже середина мая.

Яркое солнце на синем небе, а внизу снега с утыканными как у ежика спина иголками — соснами и ёлками

Путешествие по Колорадо продолжится завтра в Colorado National Monument

Выезд в национальный парк Colorado National Monument

находится в 6 км от городка Grand Junction

И хотя парк открывается в 9 часов, мы въехали туда в 8

Могли бы раньше — с первыми лучами Солнца

Выезд в парк стоит 10 долларов и мы заплатили эту таксу при выезде

В 8 часов в будке служащего парка никого не было

Всего в парке пробыли 3 часа, но есть энтузиасты, которые ходят здесь пешком и тратят несколько дней на изучение этого места

Ну, а мы движемся теперь на восток — горнолыжные курорты у нас в завтрашней программе

Прикол:

Сейчас остановились в Крейге (на 40 дороге по направлению к горнолыжному курорту Стимбот). Ну знаете… этот Крейг — 2 улицы 3 дома. На горизонте дымят две трубы какой-то обогатительной фабрики или ГРЭС… Остановились в отеле этого городка. Там еще перед входом объявление висит: «Вытирайте грязные ноги перед входом». Но сам отель очень неплохой: люкс 100 баксов с налогами

Так вот — разговорилась Икринка с девушкой с ресепшена (девушка — типичная жительница Крейга: толстая, с черно-красными волосами и обильным пирсингом)

Та как узнала что мы из России — говорит:

— Я в Россию очень хочу поехать….

— ?

— Вообще-то мне в Крейге нравится.

— ?

— В этом году будет мое первое путешествие — на Филиппины. Но мои друзья, с которыми я еду на Филиппины говорят, что нужно ехать в Россию

— Слушай, это плохая идея — тебе ехать в Россию

— ?

— Ты начнешь там у всех спрашивать «Как дела?»? а в России это не любят и за это можно в глаз получить

— Все равно я хочу в Россию поехать

Не перестаю радоваться дорогам в Колорадо: кругом снег, на улице минус, а асфальт чистый и сухой

Сегодня проехали по 40 дороге мимо горнолыжного курорта Стимбот

.

Что сказать: я предпочту ездить кататься в Италию и Австрию: компактно, уютно… а тут целый город.

Думаю, что остальные крупные горнолыжные курорты в США такого же плана.

Галочку поставил

Парк Скалистые горы или Rocky Mountain National Park

совершенно не впечатлил: группы туристов фотографирующих полудохлого оленя и создавших пробку, игры фризби на Bear Lake

. Всё как-то высосано из пальца

Нет, возможно вся красота она там …. за горизонтом и чтобы ее увидеть надо одеть снегоступы и пилить туда пару суток — но это не наш метод

Тем не менее могу порекомендовать остановиться в отдельном коттедже от Wildwood Inn

— очень мило, просторно, с видом на речку, в 3 км от въезда в парк. Да и еще рядом ресторан Headtrail

— довольно неплохие бургеры из лося

Только написал это сообщение — мне Икринка в окно с улицы стучит: Бери фотоаппарат — у нас на парковке лось!

Это не лось оказался, а олень

Сегодня решили протупить и более по Колорадо не ездить: продлили наше пребывание в Estes Park

забронировав дополнительную ночь в коттедже Wildwood Inn

и завтра после обеда улетаем в штат Юта — Солт Лейк Сити

и это будет вторая часть путешествия по США (всего их 4 — по США)

Сегодня вчерашний лось решил действовать решительно и продемонстрировал Икринке что он не лось, а олень

Проехались по 7 дороге вниз — все заезды в парк закрыты. Вообщем вывод такой: в национальном парке Rocky Mountain

делать зимой совершенно нечего. Лучше всего сюда приезжать осенью, когда желтеют-краснеют листья. Тогда здесь красиво и колорно, как впрочем и называется этот штат США

Штат Колорадо — это один из самых крупных регионов США. Ежегодно сюда приезжает множество туристов, чтобы посетить широко известные Скалистые горы и насладиться всеми преимущества пребывания среди впечатляющих ландшафтов.

Общая информация

Площадь этого региона равна 269,7 тысяч кв. км, а его население насчитывает немного более 5 тысяч человек. Столица штата Колорадо — Денвер — является также и самым большим городом на этой территории. Район известен своими прекрасными природными ландшафтами, включающими пояса Скалистых гор.

Большинство туристов приезжает сюда именно для того, чтобы полюбоваться величием заснеженных скал, красотой хвойных лесов и насладиться мягким климатом. Регион является центром летнего и зимнего

Самые крупные города штата Колорадо — это Лейквуд, Аврора, Пуэбло и другие.

Туризм и промышленность

Тысячи поклонников горнолыжного спорта ежегодно приезжают в Колорадо зимой, чтобы провести время на снежных склонах, сверкающих под яркими солнечными лучами. К слову, здесь собираются не только жители США, а и туристы со всего мира. Самые известные горные туристические районы Колорадо: Аспен, Ист Парк, Колорадо Спрингс.

Серьезный доход в казну правительства приносит не только туризм: Колорадо также является важным промышленным центом. Большинство жителей этого округа живут и работают в его восточной части, которая занимает две пятых всей территории Колорадо. Штат также известен тоннелями, прорубленными в горах для того, чтобы обеспечивать водой сухие прерии фермерских районов, которые являются важным источником дохода на этой территории. Поскольку земли Колорадо расположены между основными городами Калифорнии и Средним Западом, здесь проходят важные транспортные артерии, обеспечивающие грузосортировку в районе Скалистых гор.

Сельскохозяйственная промышленность

Что касается сельскохозяйственных отраслей промышленности и агрокультуры Америки, то и здесь лидирующие позиции занимает штат Колорадо. США очень зависит от продукции, произведенной в этом районе. Наиболее примечательными и доходными являются овцеводство и мясомолочное животноводство. Это обусловлено большим количеством земель, идеально подходящих для разведения скота.

Разнообразные улучшения, проводимые правительством, помогают фермерам приняться за успешное выращивание таких культур, как картофель, зерно и сахарная свекла. На сегодняшний день территории, ранее занимаемые пустынными прериями, представляют собой бескрайние

Горнодобывающая промышленность

Важной составляющей экономики США выступает горнодобывающая промышленность Колорадо. Штат обрел известность (благодаря богатым запасам ценных металлов) уже в 1850 годах. В этот период здесь появились первые искатели приключений, ставшие жертвами серебряной и золотой лихорадок. Кстати, эта область до сих пор изобилует ценными металлами, хотя самым важным пунктом горнодобывающей промышленности Колорадо теперь является нефть и, следовательно, производство бензина.

Кроме того, штат занимает лидирующие позиции по добыче молибдена и изготовлению стали. В Денвере, столице Колорадо, даже располагается монетный двор США.

Флаг и герб

Главный символ Колорадо — флаг — был официально принят в 1911 году. Буква «С» красного цвета, изображенная на полотне, обозначает «Colorado», что в переводе с испанского означает «красный цвет». Золотой шар внутри буквы говорит о существовании золотых приисков. Голубые и белые полоски знамени символизируют природные красоты этой земли, голубое небо и белые снега в Скалистых горах.

Герб штата был принят в 1877 году. Изображенный на нем треугольник обозначает всевидящее божье око. Здесь также присутствуют символы горнодобывающей промышленности штата, которая приносит основной доход в казну. Это горы, земля и кирка.

Штат находится по большей части на возвышенных территориях. Его земли расположены на высоте 2100 над уровнем моря, что делает Колорадо самым «высотным» штатом в США.

Первая благотворительная организация была создана в Денвере. Это был фонд помощи, учрежденный священником, двумя министрами и рабби в 1882 году. Он носил название Общественная Благотворительная Служба.

Самый большой серебряный слиток в мире был найден на территории именно этого штата. Это произошло в городе Аспен, в 1894 году. Вес необработанного самородка достигал 835 килограмм, что позволяет ему до сих пор оставаться самым крупным слитком в мире.

Однажды на политической арене штата за один день сменилось три разных губернатора. В 1905 им стал Альва Адамс, который после двух месяцев работы был снят с должности: его уличили в жульничестве во время выборов. Инцидент произошел 17 марта, в этот же день законодательное собрание штата приняло решение поручить этот пост Джеймсу Пибоди, но он отказался. Немного позже, но в тот же день, пост губернатора занял Джесси Макдональд, бывший вице-губернатор.

Скалистые горы

Эта горная система находится в средней линии Колорадо. Штат на две пятых покрыт внушительным массивом. Скалистые горы называют Крышей Северной Америки. Здесь находятся 55 самых высоких пиков, некоторые из них достигают 4270 км над уровнем моря. Горная система тянется от Аляски вплоть до Нью-Мексико, но на территорию Колорадо приходятся самые высокие участки. В свою очередь, скалистые горы подразделяются на пять цепей.

Достопримечательности

Природные живописные ландшафты — это основные достопримечательности, с которыми можно ознакомиться, посетив штат Колорадо. На карте национальных парков в первую очередь рекомендуется ознакомиться с такими местами, как Старый форт Бент, Черный Каньон и заповедник динозавров.

Подводя итог, надо отметить, что Колорадо — это отличное место для семейного отдыха на природе или для того, чтобы провести отпуск, покоряя заснеженные вершины. Для США этот штат является не только важным туристическим центром, но и отличным источником полезных ископаемых и сельскохозяйственной продукции.

На вершине скалистых гор берет свое начало великая река Колорадо. Она не самая длинная в стране и не может похвастаться протяженностью. Но все же общепризнанно в мире ее считают Великой. Дело в том, что в течении сотен тысяч лет ее неспешные воды формировали удивительный природный ландшафт, все глубже вгрызаясь в землю и скалы. Результатом ее работы стал Большой Каньон, глубина которого превышает 2000 метров.

Удивительно, но на карты Гранд Каньон был нанесен чуть больше ста лет назад, когда геолог Джон Пауелл с небольшой командой совершил сплав вдоль всего русла реки. Каким же было его удивление, когда он впервые увидел Большой Каньон и понял, что причиной его образования стала река Колорадо, которая терпеливо продолжает прорубать себе дорогу в в горных породах. В древние времена эти места всегда принадлежали индейцам и впоследствии эти земли, особенно район Монументов, стал главной сценической площадкой для съемок вестернов. Индейцы племени Навахо до сих пор обитают в этих местах в резервациях.

Сегодня река Колорадо является единственным источником воды на многие сотни километров вокруг, что постепенно приводит к обмелению реки. Больше двадцати тысяч туристов стремятся сплавиться от верховья реки до Калифорнийского залива. Но очереди из желающих так огромны, что приходится резервировать заявку за два года вперед. Альтернативным вариантом полюбоваться рекой Колорадо и Большим Каньоном является путешествие вдоль его русла пешком или на джипах.

Координаты

: 31.81543800,-114.80403900

Бассейн с мышьяком в Гранд Каньоне

Гранд Каньон сам по себе удивительное творение природы. Миллионы лет река Колорадо прокладывала себе путь к заливу через горы, гранитные скалы и пустынные равнины. Результатом ее труда стал Большой каньон, который таит в себе множество удивительных памятников природы. Сплавляясь по реке через его ущелье можно встретить самые необычные явления. Например Тыквенный ручей.

В глубине каньона 342 километре можно увидеть необычный природный резервуар на левом берегу реки. Его округлые пузатые стенки и правда напоминают тыкву оранжевого цвета. Если подплыть поближе и встать в лодке, можно увидеть, что внутри она полая и наполнена странной зеленовато-желтой водой. Мы не рекомендуем к ней даже прикасаться, не то что пить. Дело в том, что тыква это формирование известковых отложений на углекислых источниках. Тысячу лет воды наращивала вокруг себе стенки, которые со временем превратились в тыкву, наполненную водой источника.

Но самое необычное заключается не в форме, а в содержимом. Теплая вода в бассейне просто переполнена минералами — цинком, медью и свинцом. И мышьяком. Обычная норма содержания этого яда в воде составляет около 50 мг на 1 литр, но здесь на литр приходится 1100 мг мышьяка. Даже крошечный глоток из этой тыковки может привести к смерти. Фотографируясь рядом с бассейном или искупавшись в нем, тщательно сполосните тело проточной водой.

Координаты

: 35.91553200,-113.33420800

А какие достопримечательности Колорадо вам понравились? Рядом с фотограйией есть иконки, кликнув по которым вы можете оценить то или иное место.

Скалистые горы

Вряд ли где найдется место в Соединенных Штатах, подходящее для альпинизма и скалолазания, больше чем территория национального парка «Скалистые горы». Он находится по обе стороны Водораздельного хребта и включает в себя чуть ли не треть всего штата. Отличительная особенность этих скал — необычный уклон поверхности и множество разнообразных трещин и уступов, позволяющих без труда преодолевать большие расстояния. Единственную трудность составляет выбор комфортного сезона для восхождения.

В начале лета скалы покрыты снегом и льдом, отчего привычные маршруты принимают совершенно немыслимую траекторию подъема, что привлекает особую категорию альпинистов.

Координаты

: 42.38333300,-115.93333300

Национальный парк Меса-Верде раскинулся в юго-западной части штата Колорадо, в местечке Монтесума-Кантри. Общая площадь парка насчитывает около двухсот квадратных километров, а перепад высот колеблется между 1900 и 2600 метрами над уровнем моря. Главная достопримечательность парка многочисленные руины каменных жилищ, созданных в выветрившихся каньонах из песчаника древним народом, более известным как индейское племя анасази. Эти строения были возведены в XIII столетии и являются первым в истории американской архитектуры образцом «многоквартирного дома». Количество жилых посещений в таких домах составляло до ста отдельных помещений.

Название парку был дано в честь одноименного плато, возвышающегося на 600 метров над окружающей местностью, склоны которого покрыты хвойным лесом. В переводе с испанского языка «Меса-Верде» означает «Зеленый стол». Популярность этих мест стала повышаться во второй половине XIX века, когда испанские исследователи начали понимать всю ценность древних скал для жизни индейцев. Первым исследователем Меса-Верде стал Ричарду Уэзерил историк-любитель, занимавшийся изучением истории пуэбло, кроме того, большое значение имели археологические работы шведского геолога Густава Норденшельда.

В 1906 году, в целях защиты древностей от возможного вандализма, Меса-Верде получил официальный статус национального парка, а спустя 60 лет вошел в Национальный реестр исторических мест США. С сентября 1978 года парк входит в список Всемирного культурного и природного наследия ЮНЕСКО.

Координаты

: 37.18769000,-108.49226800

Часовня кадетов Академии ВВС США

Часовня кадетов Академии ВВС США расположена в штате Колорадо, на территории военного городка и тренировочной базы филиала академии летчиков военно-воздушных сил США. Часовня была построена в 1962 году в стиле модернизма, спроектировал ее архитектор Уолтер Нетч.

Величественный вид часовне придают семнадцать рядов стальных рам, заканчивающихся пиками на высоте в 50 метров. Строение состоит из трех уровней, в которых проходят службы для представителей католической, протестантской и иудейской конфессий.

Часовня является популярным туристическим объектом, ежегодно на нее приезжают посмотреть около 500000 человек. В 1996 году часовня была удостоена премии Американского института архитектуры, в 2004 году как часть кадетского корпуса она была признана Национальным историческим памятником США.

Координаты

: 38.96400800,-104.81479000

Клуб Beta

Денверский клуб Beta отличается своей экологической позицией. Его лаундж комнаты — зеленые и выполнены с помощью устойчивых экологических продуктов, которые были повторно переработаны и использованы для строительства клуба. Его обязательным правилом является переработка использованных материалов в центрах переработки, которые располагаются на основных точках движения в клубе. Такими материалами являются пластик, стекло, алюминий, бумага и другие. Девиз ночного клуба: «Мы зеленые», что полностью подтверждает их позицию.

Клуб оснащен мощной системой аудио и видео, освещения и спецэффектов. Все эти удобства влияют на качество музыки и, следовательно, на посетителей. Целью Beta является развитие клубной культуры, и он постоянно двигается в этом направлении. Заведение никогда не стоит на месте, оно движется, ищет способы своего расширения и усовершенствования. Его креативные идеи каждый раз радуют постоянных посетителей.

Координаты

: 39.75365300,-104.99535600

Самые популярные достопримечательности в Колорадо с описанием и фотографиями на любой вкус. Выбирайте лучшие места для посещения известных мест Колорадо на нашем сайте.

|

Colorado |

|

|---|---|

|

State |

|

| State of Colorado | |

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nicknames:

The Centennial State |

|

| Motto(s):

Nil sine numine |

|

| Anthem: «Where the Columbines Grow» and «Rocky Mountain High»[1] |

|

Map of the United States with Colorado highlighted |

|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Colorado Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | August 1, 1876[2] (38th) |

| Capital (and largest city) |

Denver |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Denver |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Jared Polis (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Dianne Primavera (D) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Colorado Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators | Michael Bennet (D) John Hickenlooper (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 5 Democrats 3 Republicans (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 104,094 sq mi (269,837 km2) |

| • Land | 103,718 sq mi (268,875 km2) |

| • Water | 376 sq mi (962 km2) 0.36% |

| • Rank | 8th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 380 mi (610 km) |

| • Width | 280 mi (450 km) |

| Elevation | 6,800 ft (2,070 m) |

| Highest elevation

(Mount Elbert[3][4][a]) |

14,440 ft (4,401.2 m) |

| Lowest elevation

(Arikaree River[4][a]) |

3,317 ft (1,011 m) |

| Population

(2020) |

|

| • Total | 5,773,714 |

| • Rank | 21st |

| • Density | 55.47/sq mi (21.40/km2) |

| • Rank | 37th |

| • Median household income | $75,200[5] |

| • Income rank | 9th |

| Demonym | Coloradan |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| USPS abbreviation |

CO |

| ISO 3166 code | US-CO |

| Latitude | 37°N to 41°N |

| Longitude | 102°02′48″W to 109°02′48″W |

| Website | www.colorado.gov |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

Flag of Colorado |

|

Seal of Colorado |

|

| Slogan | Colorful Colorado |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Western tiger salamander Ambystoma mavortium |

| Bird | Lark bunting Calamospiza melanocoryus |

| Cactus | Claret cup cactus Echinocereus triglochidiatus |

| Fish | Greenback cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus clarki somias |

| Flower | Rocky Mountain columbine Aquilegia coerulea |

| Grass | Blue grama grass Bouteloua gracilis |

| Insect | Colorado Hairstreak Hypaurotis crysalus |

| Mammal | Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis |

| Pet | Colorado shelter pets Canis lupus familiaris and Felis catus |

| Reptile | Western painted turtle Chrysemys picta bellii |

| Tree | Colorado blue spruce Picea pungens |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Color(s) | Blue, red, yellow, white |

| Dinosaur | Stegosaurus |

| Folk dance | Square dance Chorea quadra |

| Fossil | Stegosaurus Stegosaurus armatus |

| Gemstone | Aquamarine |

| Mineral | Rhodochrosite |

| Rock | Yule Marble |

| Ship | USS Colorado (SSN-788) |

| Soil | Seitz |

| Sport | Pack burro racing |

| Tartan | Colorado state tartan |

| State route marker | |

|

|

| Lists of United States state symbols |

Colorado (,[6][7] other variants[8]) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the Great Plains. Colorado is the eighth most extensive and 21st most populous U.S. state. The 2020 United States census enumerated the population of Colorado at 5,773,714, an increase of 14.80% since the 2010 United States census.[9]