Лошадь Пржевальского

- Лошадь Пржевальского

-

Жарг. мол. Шутл. 1. или Пренебр. То же, что ломовая лошадь. 2. О громко смеющемся человеке. 3. О чём-л. редком, вызывающем удивление. Максимов, 230.

Большой словарь русских поговорок. — М: Олма Медиа Групп.

.

2007.

Смотреть что такое «Лошадь Пржевальского» в других словарях:

-

Лошадь Пржевальского — в зооп … Википедия

-

Лошадь Пржевальского — Лошадь Пржевальского. ЛОШАДЬ ПРЖЕВАЛЬСКОГО, дикая лошадь. Длина тела около 2,3 м, высота в холке около 1,3 м. Открыта в 1878 в Центральной Азии Н.М. Пржевальским. Обитала в пустынях Джунгарии, там же в 1968 ее видели (в естественных условиях)… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

Лошадь Пржевальского — Equus przewalskli см. также 7.1.1. Род Лошади Equus Лошадь Пржевальского [160] Equus przewalskli Лошадь желтоватой масти, большеголовая, со стоячей гривой без челки, с темным ремнем вдоль спины. В прошлом обитала в степях юга Сибири. Она также… … Животные России. Справочник

-

лошадь Пржевальского — Лошадь Пржевальского. лошадь Пржевальского (Equus przewalskii), непарнокопытное животное рода лошадей. Единственный дикий вид настоящих лошадей, сохранившийся до наших дней. Открыта Н. М. Пржевальским (1878) в Центральной Азии. Л. П. мелкорослая… … Сельское хозяйство. Большой энциклопедический словарь

-

ЛОШАДЬ ПРЖЕВАЛЬСКОГО — непарнокопытное животное рода лошадей. Длина тела ок. 2,3 м, высота в холке ок. 1,3 м. Открыта в 1878 в Центр. Азии Н. М. Пржевальским. Была широко распространена, но к кон. 19 в. сохранилась лишь на юго западе Монголии, где в 1968 ее видели (в… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ЛОШАДЬ ПРЖЕВАЛЬСКОГО — (Е. caballus Przewalskii), дикая л., открытая в XIX в. во время экспедиции Н.М. Пржевальского в Монголию. В наст. время сохранилась, очевидно, только в неволе. Имеет большую голову, короткую толстую шею, слабо выраженную холку. Высота в холке ок … Справочник по коневодству

-

ЛОШАДЬ ПРЖЕВАЛЬСКОГО — (Equus przewalskii), вид лошадей; иногда считают подвидом тарпана. Длина тела до 230 см, выc. в холке до 130 см, масса до 300 кг; самки мельче. Окраска тела палевая или красновато жёлтая, вдоль хребта узкая тёмная полоса («ремень»), живот и конец … Биологический энциклопедический словарь

-

лошадь Пржевальского — непарнокопытное животное рода лошадей. Длина тела около 2,3 м, высота в холке около 1,3 м. Открыта в 1878 в Центральной Азии Н. М. Пржевальским. Была широко распространена, но к концу XIX в. сохранилась лишь на юго западе Монголии, где в 1968 её… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Лошадь Пржевальского — (Equus przewalskii) непарнокопытное животное рода лошадей (См. Лошади). Открыта Н. М. Пржевальским (См. Пржевальский) (1879) в Центральной Азии. От домашней лошади отличается короткой стоячей гривой, отсутствием чёлки, хвостом, основание… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

Лошадь Пржевальского — непарнокопытное животное рода лошадей; открыто в 1878 г. в Центральной Азии Н. М. Пржевальским. Лошадь была широко распространена, но к концу XIX в. сохранилась лишь на юго западе Монголии, где в 1968 г. ее видели (в естественных условиях) в… … Судьба эпонимов. Словарь-справочник

-

ЛОШАДЬ ПРЖЕВАЛЬСКОГО — (Equus przewalskii), непарнокопытное ж ное рода лошадей. Единств. дикий вид настоящих лошадей, сохранившийся до наших дней. Открыта Н. М. Пржевальским (1878) в Центр. Азии. Л. П. мелкорослая (дл. ок. 2,3 м, выс. в холке ок. 1,3 м, масса до 300… … Сельско-хозяйственный энциклопедический словарь

| Przewalski’s horse | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Przewalski’s horse | |

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

|

CITES Appendix I (CITES)[2] |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: |

E. ferus |

| Subspecies: |

E. f. przewalskii |

| Trinomial name | |

| Equus ferus przewalskii

(I. S. Polyakov, 1881) |

|

|

|

| Przewalski’s horse range (reintroduced; missing distribution in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine) |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Przewalski’s horse (,[3] ,[3][4] (Пржевальский Russian: [prʐɨˈvalʲskʲɪj]), Polish: [pʂɛˈvalskʲi]) (Equus ferus przewalskii or Equus przewalskii[5]), also called the takhi,[6] Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered horse originally native to the steppes of Central Asia. It is named after the Russian geographer and explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky. Once extinct in the wild, it has been reintroduced to its native habitat since the 1990s in Mongolia at the Khustain Nuruu National Park, Takhin Tal Nature Reserve, and Khomiin Tal, as well as several other locales in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.[1]

Several genetic characteristics of Przewalski’s horse differ from what is seen in modern domestic horses, indicating neither is an ancestor of the other. For example, the Przewalski has 33 chromosome pairs, compared to 32 for the domestic horse. Their ancestral lineages split from a common ancestor between 38,000 and 160,000 years ago, long before the domestication of the horse. Przewalski’s horse was long considered the only remaining truly wild horse, in contrast with the American Mustang or the Australian brumby, which are instead feral horses descended from domesticated animals. This assumption was challenged in 2018 when DNA analysis of horse remains associated with the 5,000-year-old Botai culture of Central Asia revealed the animals were of Przewalski lineage. However, the domestication status of these animals has been questioned. Its taxonomic position is still debated, with some taxonomists treating Przewalski’s horse as a species, E. przewalskii, others as a subspecies of wild horse (E. ferus przewalskii) or a variety of the domesticated horse (E. caballus).

The Przewalski’s horse is stockily built, smaller, and shorter than its domesticated relatives. Typical height is about 12–14 hands (48–56 inches, 122–142 cm), and the average weight is around 300 kilograms (660 lb). They have a dun coat with pangaré features and often have dark primitive markings.

Taxonomy[edit]

Przewalski’s horse was formally described as a novel species in 1881 by Ivan Semyonovich Polyakov. The taxonomic position of Przewalski’s horse remains controversial, and no consensus exists whether it is a full species (as Equus przewalskii); a subspecies of Equus ferus the wild horse, (as Equus ferus przewalskii in trinomial nomenclature, along with two other subspecies, the domestic horse E. f. caballus, and the extinct tarpan E. f. ferus), or even a subpopulation of the domestic horse.[7][8][9] The American Society of Mammalogists considers the Przewalski’s horse and the tarpan to both be subspecies of Equus ferus, and classifies the domestic horse as separate species, Equus caballus.[10]

Lineage[edit]

Early sequencing studies of DNA revealed several genetic characteristics of Przewalski’s horse that differ from what is seen in modern domestic horses, indicating neither is ancestor of the other, and supporting the status of Przewalski horses as a remnant wild population not derived from modern domestic horses.[11] The evolutionary divergence of the two populations was estimated to have occurred about 45,000 YBP,[12][13] while the archaeological record places the first horse domestication about 5,500 YBP by the ancient central-Asian Botai culture.[12][14] The two lineages thus split well before domestication, most likely due to climate, topography, or other environmental changes.[12]

Several subsequent DNA studies produced partially contradictory results. A 2009 molecular analysis using ancient DNA recovered from archaeological sites placed Przewalski’s horse in the middle of the domesticated horses.[9] However, a 2011 mitochondrial DNA analysis suggested that Przewalski’s and modern domestic horses diverged some 160,000 years ago.[15] An analysis based on whole genome sequencing and calibration with DNA from old horse bones gave a divergence date of 38,000–72,000 years ago.[16]

In 2018, a new analysis involved genomic sequencing of ancient DNA from horse remains associated with the mid-fourth-millennium BCE Botai culture and bearing marks considered characteristic of domestication, as well as domestic horses from more recent archaeological sites, for comparison with those of modern domestic and Przewalski’s horses. The study revealed that the Botai horses were members of the Przewalski’s horse lineage, rather than that of modern domestic horses as was previously believed. Further, all of the modern Przewalski’s horses analyzed were found to nest within the phylogenetic tree of the Botai horses, leading the authors to posit that modern Przewalski’s horses are feral descendants of the ancient Botai domesticated animals, rather than representing a surviving population of never-domesticated horses. The researchers suggested that because Botai horse domestication was relatively short-lived before they again became feral, the Przewalski’s horse retained more wild or primitive traits than did the domestic horse lineage.[17][18][19] However, a 2021 reevaluation of the Botai horses reached a conclusion in favor of the traditional view of Przewalski’s horses as a never-domesticated population.[20] These authors viewed the tooth wear previously attributed to bridle mouthpieces as more likely to have been caused by natural processes, while the age structure of the Botai horses seemed inconsistent with domesticated herding. Furthermore, some specimens were found associated with arrowheads, suggesting they had been hunted. They concluded that the horses associated with the Botai culture were wild instead of domesticated animals, and that the Przewalski’s horse lineage should indeed be viewed not as a feral lineage but as one that was always wild.[20]

In any case, the Botai horses were found to have negligible genetic contribution to any of the ancient or modern domestic horses studied, indicating that the domestication of the latter was independent, involving a different wild population, from any possible domestication of Przewalski’s horse by the Botai culture.[17][18][19]

Head shot, showing convex profile

Characteristics[edit]

Przewalski’s horse is stockily built in comparison to domesticated horses, with shorter legs, though being much smaller and shorter than its domesticated relatives. Typical height is about 12–14 hands (48–56 inches, 122–142 cm), and length is about 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in). It weighs around 300 kilograms (660 lb). The coat is generally dun in color with pangaré features, varying from dark brown around the mane, to pale brown on the flanks, and yellowish-white on the belly, as well as around the muzzle. The legs of Przewalski’s horse are often faintly striped, also typical of primitive markings.[21] The mane stands erect and does not extend as far forward,[22] while the tail is about 90 cm (35.43 in) long, with a longer dock and shorter hair than seen in domesticated horses. The hooves of Przewalski’s horse are longer in the front and have significantly thicker sole horns than feral horses, an adaptation that improves hoof performance on terrain.[23]

Genomics[edit]

The karyotype of Przewalski’s horse differs from that of the domestic horse, having 33 chromosome pairs versus 32, apparently due to a fission of a large chromosome ancestral to domestic horse chromosome 5 to produce Przewalski’s horse chromosomes 23 and 24,[24] though conversely, a Robertsonian translocation that fused two chromosomes ancestral to those seen in Przewalski’s horse to produce the single large domestic horse chromosome has also been proposed.[25]

Many smaller inversions, insertions and other rearrangements were observed between the chromosomes of domestic and Przewalski’s horses, while there was much lower heterozygosity in Przewalski’s horses, with extensive segments devoid of genetic diversity, a consequence of the recent severe bottleneck of the captive Przewalski’s horse population.[25] In comparison, the chromosomal differences between domestic horses and zebras include numerous large-scale translocations, fusions, inversions, and centromere repositioning.[24] Przewalski’s horse has the highest diploid chromosome number among all equine species. They can interbreed with the domestic horse and produce fertile offspring, with 65 chromosomes.[7]

Ecology and behavior[edit]

Przewalski reported the horses forming troops of between five and fifteen members, consisting of an old stallion, his mares and foals.[22] Modern reintroduced populations similarly form family groups of one adult stallion, one to three mares, and their common offspring that stay in the family group until they are no longer dependent, usually at two or three years old. Young females join other harems, while bachelor stallions as well as old stallions who have lost their harems join bachelor groups.[26] Family groups can join to form a herd that moves together.[citation needed]

The patterns of their daily lives exhibit horse behavior similar to that of feral horse herds. Stallions herd, drive, and defend all members of their family, while the mares often display leadership in the family. Stallions and mares stay with their preferred partners for years. While behavioral synchronization is high among mares, stallions other than the main harem stallion are generally less stable in this respect.[citation needed]

Home range in the wild is little studied, but estimated as 1.2–24 km2 (0.46–9.3 sq mi) in the Hustai National Park and 150–825 km2 (58–319 sq mi) in the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area.[27] The ranges of harems are separated, but slightly overlapping.[26] They have few modern predators, but one of the few is the Himalayan wolf.[28]

Horses maintain visual contact with their family and herd at all times, and have a host of ways to communicate with one another, including vocalizations, scent marking, and a wide range of visual and tactile signals. Each kick, groom, tilt of the ear, or other contact with another horse is a means of communicating. This constant communication leads to complex social behaviors among Przewalski’s horses.[29]

The historical population was said to have lived in the «wildest parts of the desert» with a preference for «especially saline districts».[22] They were observed mostly during spring and summer at natural wells, migrating to them by crossing valleys rather than by way of higher mountains.[30]

Diet[edit]

Przewalski horse’s diet consists mostly of vegetation. Many plant species are in a typical Przewalski’s horse environment, including: Elymus repens, Carex spp., Fabaceae, and Asteraceae.[31]

Looking at the species’ diet overall, Przewalski’s horses most often eat E. repens, Trifolium pratense, Vicia cracca, Poa trivialis, Dactylis glomerata, and Bromus inermis.[31]

While the horses eat a variety of different plant species, they tend to favor different species at different times of year. In the springtime, they favor Elymus repens, Corynephorus canescens, Festuca valesiaca, and Chenopodium album. In early summer, they favor Dactylis glomerata and Trifolium, and in late summer, they gravitate towards E. repens and Vicia cracca.[31]

In winter the horses eat Salix spp., Pyrus communis, Malus sylvatica, Pinus sylvestris, Rosa spp., and Alnus spp. Additionally, Przewalski’s horses may dig for Festuca spp., Bromus inermis, and E. repens that grow beneath the ice and snow. Their winter diet is very similar to the winter diet of domestic horses,[31] but differs from that revealed by isotope analysis of the historical (pre-captivity) population, which switched in winter to browsing shrubs, though the difference may be due to the extreme habitat pressure the historical population was under.[32] In the wintertime, they eat their food more slowly than they do during other times of the year. Przewalski’s horses seasonally display a set of changes collectively characteristic of physiologic adaptation to starvation, with their basal metabolic rate in winter being half what it is during springtime. This is not a direct consequence of decreased nutrient intake, but rather a programmed response to predictable seasonal dietary fluctuation.[33]

Reproduction[edit]

Mating occurs in late spring or early summer. Mating stallions do not start looking for mating partners until the age of five. Stallions assemble groups of mares or challenge the leader of another group for dominance. Females are able to give birth at the age of three and have a gestation period of 11–12 months. Foals are able to stand about an hour after birth.[34] The rate of infant mortality among foals is 25%, with 83.3% of these deaths resulting from leading stallion infanticide.[35] Foals begin grazing within a few weeks but are not weaned for 8–13 months after birth.[34] They reach sexual maturity at two years of age.[36]

Population[edit]

History[edit]

Przewalski’s-type wild horses appear in European cave art dating as far back as 20,000 years ago,[1] but genetic investigation of a 35,870-year-old specimen from one such cave instead showed affinity with extinct Iberian horse lineage and the modern domestic horse, suggesting that it was not Przewalski’s horse being depicted in this art.[37] Horse skeletons dating to the fifth to the third millennia BCE, found in Central Asia, with a range extending to the southern Urals and the Altai, belong to the genetic lineage of Przewalski’s horse.[38] Of particular note are the horses of this lineage found in the archaeological sites of the Chalcolithic Botai culture. Sites dating from the mid-fourth-millennium BCE show evidence of horse domestication,[39] though their status as domesticated horses has been recently challenged.[20] Analysis of ancient DNA from Botai horse specimens from about 3000 BCE reveal them to have DNA markers consistent with the lineage of modern Przewalski’s horses.[17]

There are sporadic reports of Przewalski’s horse in the historical record prior to its formal characterization. The Buddhist monk Bodowa wrote a description of what is thought to have been Przewalski’s horse about AD 900,[32] and an account from 1226 reports an incident involving wild horses during Genghis Khan’s campaign against the Tangut empire.[1] In the fifteenth century, Johann Schiltberger recorded one of the first European sightings of the horses in the journal recounting his trip to Mongolia as a prisoner of the Mongol Khan.[40] Another was recorded as a gift to the Manchurian emperor around 1630, its value as a gift suggesting a difficulty in obtaining them.[30] John Bell, a Scottish doctor in service to Peter the Great from 1719 to 1722, observed a horse in Russia’s Tomsk Oblast that was apparently this species,[32] and a few decades later in 1750, a large hunt with thousands of beaters organized by the Manchurian emperor killed between two and three hundred of these horses.[30]

Przewalski’s horse skull, Brno museum

The species is named after a Russian colonel of Polish descent, Nikolai Przhevalsky (1839–1888) (Nikołaj Przewalski in Polish). An explorer and naturalist, he obtained a skull and hide of an animal shot in 1878 in the Gobi near what is today’s China–Mongolia border, and he would make an expedition into the Dzungarian Basin to observe it in the wild.[32] In 1881, the horse received a formal scientific description and was named Equus przevalskii by Ivan Semyonovich Polyakov, based on Przewalski’s collection and description,[32][22] while in 1884, the sole exemplar of the horse in Europe was a preserved specimen in the Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.[22] This was supplemented in 1894 when the brothers Grum-Grzhimailo returned several hides and skulls to St. Petersburg and provided a description of the horse’s behavior in the wild.[30] A number of these horses were captured around 1900 by Carl Hagenbeck and placed in zoos, and these, along with one later captive, reproduced to give rise to today’s population.

After 1903, there were no reports of the wild population until 1947, when several isolated groups were observed and a lone filly captured. Although local herdsmen reported seeing as many as 50 to 100 takhis grazing in small groups at that time, there were only sporadic sightings of single groups of two or three animals thereafter, mostly near natural wells.[30] Two scientific expeditions in 1955 and 1962 failed to find any, and after herders and naturalists reported single harem groups in 1966 and 1967, the last observation of the wild horse in its native habitat was of a single stallion in 1969.[30][41] Expeditions after this failed to locate any horses, and the species would be designated «extinct in the wild» for over 30 years.[30] Competition with livestock, hunting, capture of foals for zoological collections, military activities, and harsh winters recorded in 1945, 1948, and 1956 are considered to be main causes of the decline in Przewalski’s horse population.[15]

The wild population was already rare at the time of its first scientific characterization. Przewalski reported seeing them only from a distance and may actually have instead sighted herds of local onager, Mongolian wild asses, and he was only able to obtain the type specimen from Kirghiz hunters.[41] The range of Przewalski’s horse was limited to the arid Dzungarian Basin in the Gobi Desert.[22] It has been suggested that this was not their natural habitat, but, like the onager, they were a steppe animal driven to this inhospitable last refuge by the dual pressures of hunting and habitat loss to agricultural grazing.[32] There were two distinct populations recognized by local Mongolians, a lighter steppe variety and a darker mountain one, and this distinction is seen in early twentieth-century descriptions. Their mountainous habitat included the Takhiin Shar Nuruu (The Yellow Wild-Horse Mountain Range).[41] In their last decades in the wild, the remnant population was limited to the small region between the Takhiin Shar Nuruu and Bajtag-Bogdo mountain ridges.[30]

Vaska, a Przewalski’s horse trained to be ridden

Captivity[edit]

Attempts to obtain specimens for exhibit and captive breeding were largely unsuccessful until 1902, when 28 captured foals were brought to Europe. These, along with a small number of additional captives, would be distributed among zoos and breeding centers in Europe and the United States. Many facilities failed in their attempts at captive breeding, but a few programs were established. However, by the mid-1930s, inbreeding had caused reduced fertility and the captive population experienced a genetic bottleneck, with the surviving captive breeding stock descended from only 11 of the founder captives.[30] In addition, in at least one instance the progeny of interbreeding with a domestic horse was bred back into the captive Przewalski’s horse population, though recent studies have shown only minimal genetic contribution of this domestic horse to the captive population.[42]

The situation was improved when the exchange of breeding animals among facilities increased genetic diversity and there was a consequent improvement in fertility, but the population experienced another genetic bottleneck when many of the horses failed to survive World War II. The most valuable group, in Askania Nova, Ukraine, was shot by German soldiers during World War II occupation, and the group in the United States had died out.[15] Only two captive populations in zoos remained, in Munich and in Prague, and of the 31 remaining horses at war’s end, only 9 became ancestors of the subsequent captive population.[30] By the end of the 1950s, only 12 individual horses were left in the world’s zoos.[15]

In 1957, a wild-caught mare captured as a foal a decade earlier was introduced into the Ukrainian captive population. This would prove the last wild-caught horse, and with the presumed extinction of wild population, last sighted in Mongolia in the late 1960s, the captive population became the sole representatives of Przewalski’s horse.[30] Genetic diversity received a much needed boost from this new source, with the spread of her bloodline through the inbred captive groups leading to their increased reproductive success, and by 1965 there were more than 130 animals spread among thirty-two zoos and parks.

Conservation efforts[edit]

A Przewalski’s horse in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

In 1977, the Foundation for the Preservation and Protection of the Przewalski Horse was founded in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, by Jan and Inge Bouman. The foundation started a program of exchange between captive populations in zoos throughout the world to reduce inbreeding, and later began a breeding program of its own. As a result of such efforts, the extant herd has retained a far greater genetic diversity than its genetic bottleneck made likely.[15] By 1979, when this concerted program of population management to maximize genetic diversity was begun, there were almost four hundred horses in sixteen facilities,[30] a number that had grown by the early 1990s to over 1,500.[43]

While dozens of zoos worldwide have Przewalski’s horses in small numbers, specialized reserves are also dedicated primarily to the species. The world’s largest captive-breeding program for Przewalski’s horses is at the Askania Nova preserve in Ukraine. From 1998, thirty one horses were also released in the unenclosed Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine and Belarus, evacuated after the Chernobyl accident, which now serves as a deserted de facto nature reserve.[44] Though poaching took a toll on numbers,[45] as of 2019 the estimated population in the Chernobyl zone was over 100 individuals.[46][47][48][49][50]

Le Villaret, located in the Cevennes National Park in southern France and run by the Association Takh, is a breeding site for Przewalski’s horses that was created to allow the free expression of natural Przewalski’s horse behaviors. In 1993, eleven zoo-born horses were brought to Le Villaret. Horses born there are adapted to life in the wild, being free to choose their own mates and required to forage on their own. This was intended to produce individuals capable of being reintroduced into Mongolia. In 2012, 39 individuals were at Le Villaret.[51] An intensely researched population of free-ranging animals was also introduced to the Hortobágy National Park puszta in Hungary; data on social structure, behavior, and diseases gathered from these animals are used to improve the Mongolian conservation effort.[26] An additional breeding population of Przewalski’s horses roams the former Döberitzer Heide military proving ground, now a nature reserve in Dallgow-Döberitz, Germany. Established in 2008, this population comprised 24 horses in 2019.[52]

Przewalski’s horses at Döberitzer Heide nature reserve

Reintroduction[edit]

Reintroductions organized by Western European countries started in the 1990s. These were later stopped, mostly for financial reasons. In 2011, Prague Zoo started a new project, Return of the Wild Horses. With the support of public and many strategic partners, these yearly transports of captive-bred horses into the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area continue today.[53] Since 2004, there is also a program to reintroduce Przewalski’s horses that were bred in France into Mongolia.[54]

Several populations have now been released into the wild. A cooperative venture between the Zoological Society of London and Mongolian scientists has resulted in successful reintroduction of these horses from zoos into their natural habitat in Mongolia. In 1992, 16 horses were released into the wild in Mongolia, followed by additional animals later on. One of the areas to which they were reintroduced became Khustain Nuruu National Park in 1998. Another reintroduction site is Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area, located at the fringes of the Gobi desert. Lastly, in 2004 and 2005, 22 horses were released by the Association Takh to a third reintroduction site in the buffer zone of the Khar Us Nuur National Park, in the northern edge of the Gobi ecoregion. In the winter of 2009–2010, one of the worst dzud or snowy winter conditions ever hit Mongolia. The population of Przewalski’s horse in the Great Gobi B SPA was drastically affected, providing clear evidence of the risks associated with reintroducing small and sequestered species in unpredictable and unfamiliar environments.[citation needed] as of 2011, an estimated total of almost 400 horses existed in three free-ranging populations in the wild.[55] Since 2011, Prague Zoo has transported 35 horses to Mongolia in eight rounds, in cooperation with partners (Czech Air Force, European Breeding Programme for Przewalski’s Horses, Association pour le cheval de Przewalski: Takh, Czech Development Agency, Czech Embassy in Mongolia, and others) and it plans to continue to return horses to the wild in the future. In the framework of the project Return of the Wild Horses, it sustains its activities by supporting local inhabitants. The zoo has the longest uninterrupted history of breeding Przewalski’s horses in the world and keeps the studbook of this species.

In 2001, Przewalski’s horses were reintroduced into the Kalamaili Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China.[35] The Przewalski’s Horse Reintroduction Project of China was initiated in 1985 when 11 wild horses were imported from overseas. After more than two decades of effort, the Xinjiang Wild Horse Breeding Centre has bred a large number of the horses, 55 of which were released into the Kalamely Mountain area. The animals quickly adapted to their new environment. In 1988, six foals were born and survived, and by 2001, over 100 horses were at the centre. As of 2013, the center hosted 127 horses divided into 13 breeding herds and three bachelor herds.

The first reintroduction into the Orenburg region, on the Russian steppe, occurred in 2016.[56][57] Plans were also announced in 2014 to reintroduce them in central Kazakhstan.[58]

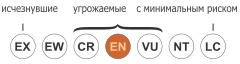

The reintroduced horses successfully reproduced, and the status of the animal was changed from «extinct in the wild» to «endangered» in 2005,[43] while on the IUCN Red List they were reclassified from «extinct in the wild» to «critically endangered» after a reassessment in 2008,[59] and from «critically endangered» to «endangered» after a 2011 reassessment.[55]

Assisted reproduction and cloning[edit]

In the earlier decades of captivity, the insular breeding by individual zoos led to inbreeding and reduced fertility. In 1979, several American zoos began a collaborative breeding-exchange program to maximize genetic diversity.[60] Recent advances in equine reproductive science have also been used to preserve and expand the gene pool. Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Zoo successfully reversed a vasectomy on a Przewalski’s horse in 2007—the first operation of its kind on this species, and possibly the first ever on any endangered species. While normally a vasectomy may be performed on an endangered animal under limited circumstances, particularly if an individual has already produced many offspring and its genes are overrepresented in the population, scientists realized the animal in question was one of the most genetically valuable Przewalski’s horses in the North American breeding program.[61] The first birth by artificial insemination occurred on 27 July 2013 at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.[62][63]

In 2020, the first cloned Przewalski’s horse was born, the result of a collaboration between San Diego Zoo Global, ViaGen Equine and Revive & Restore.[64] The cloning was carried out by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), whereby a viable embryo is created by transplanting the DNA-containing nucleus of a somatic cell into an immature egg cell (oocyte) that has had its own nucleus removed, producing offspring genetically identical to the somatic cell donor.[65] Since the oocyte used was from a domestic horse, this was an example of interspecies SCNT.[66]

The somatic cell donor was a Przewalski’s horse stallion named Kuporovic, born in the UK in 1975, and relocated three years later to the US, where he died in 1998. Due to concerns over the loss of genetic variation in the captive Przewalski’s horse population, and in anticipation of the development of new cloning techniques, tissue from the stallion was cryopreserved at the San Diego Zoo’s Frozen Zoo. Breeding of this individual in the 1980s had already substantially increased the genetic diversity of the captive population, after he was discovered to have more unique alleles than any other horse living at the time, including otherwise-lost genetic material from two of the original captive founders.[64] To produce the clone, frozen skin fibroblasts were thawed, and grown in cell culture.[67] An oocyte was collected from a domestic horse, and its nucleus replaced by a nucleus collected from a cultured Przewalski’s horse fibroblast. The resulting embryo was induced to begin division, and was cultured until it reached the blastocyst stage, then implanted into a domestic horse surrogate mare,[67] which carried the embryo to term and delivered a foal with the Przewalski’s horse DNA of the long-deceased stallion.

The cloned horse was named Kurt, after Dr. Kurt Benirschke, a geneticist who developed the idea of cryopreserving genetic material from species considered to be endangered. His ideas led to the creation of the Frozen Zoo as a genetic library.[68] Once the foal matures, he will be relocated to the breeding herd at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park,[69] so as to pass Kuporovic’s genes into the larger captive Przewalski’s horse population and thereby increase the genetic variation of the species.[64]

See also[edit]

- Mongolian horse (domestic)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Boyd, L.; King, S. R. B.; Zimmermann, W. & Kendall, B.E. (2015). «Equus ferus«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ «Appendices | CITES». cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b «Przewalski’s horse». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.[dead link]

- ^ «Przewalski’s horse». Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ «The Takhi». International Takhi-Group. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ «Takhi: Holy Animal of Mongolia». International Takhi Group. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ a b Lau, Allison; Lei Peng; Hiroki Goto; Leona Chemnick; Oliver A. Ryder; Kateryna D. Makova (2009). «Horse Domestication and Conservation Genetics of Przewalski’s Horse Inferred from Sex Chromosomal and Autosomal Sequences». Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 (1): 199–208. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn239. PMID 18931383.

- ^ Kavar, Tatjana; Peter Dovč (2008). «Domestication of the horse: Genetic relationships between domestic and wild horses». Livestock Science. 116 (1–3): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2008.03.002.

- ^ a b Cai, Dawei; Zhuowei Tang; Lu Han; Camilla F. Speller; Dongya Y. Yang; Xiaolin Ma; Jian’en Cao; Hong Zhu; Hui Zhou (2009). «Ancient DNA provides new insights into the origin of the Chinese domestic horse». Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (3): 835–842. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.11.006.

- ^ «Explore the Database». www.mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Goto, Hiroki; Ryder, Oliver A.; Fisher, Allison R.; Schultz, Bryant; Pond, Sergei L. Kosakovsky; Nekrutenko, Anton; Makova, Kateryna D. (1 January 2011). «A massively parallel sequencing approach uncovers ancient origins and high genetic variability of endangered Przewalski’s horses». Genome Biology and Evolution. 3: 1096–1106. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr067. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 3194890. PMID 21803766. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Machugh, David E.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2016). «Taming the past: Ancient DNA and the study of animal domestication». Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 329–351. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022747. PMID 27813680. S2CID 21991146.

- ^ der Sarkissian, C.; Ermini, L.; Schubert, M.; Yang, M.A.; Librado, P.; et al. (2015). «Evolutionary genomics and conservation of the endangered Przewalski’s horse». Curr. Biol. 25 (19): 2577–83. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.032. PMC 5104162. PMID 26412128.

- ^ Outram, A.K.; Stear, N.A.; Bendrey, R.; Olsen, S.; Kasparov, A.; et al. (2009). «The earliest horse harnessing and milking». Science. 323 (5919): 1332–1335. Bibcode:2009Sci…323.1332O. doi:10.1126/science.1168594. PMID 19265018. S2CID 5126719.

- ^ a b c d e Ryder, O A; Fisher, A R; Schultz, B; Kosakovsky Pond, S; Nekrutenko, A; Makova, K D (2011). «A massively parallel sequencing approach uncovers ancient origins and high genetic variability of endangered Przewalski’s horses». Genome Biology and Evolution. 3: 1096–1106. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr067. PMC 3194890. PMID 21803766.

- ^ Orlando, L.; Ginolhac, A.L.; Zhang, G.; Froese, D.; Albrechtsen, A.; Stiller, M.; et al. (2013). «Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse». Nature. 499 (7456): 74–78. Bibcode:2013Natur.499…74O. doi:10.1038/nature12323. PMID 23803765. S2CID 4318227.

- ^ a b c Pennisi, Elizabeth (22 February 2018). «Ancient DNA upends the horse family tree». sciencemag.org.

- ^ a b Orlando, Ludovic; Outram, Alan K.; Librado, Pablo; Willerslev, Eske; Zaibert, Viktor; Merz, Ilja; Merz, Victor; Wallner, Barbara; Ludwig, Arne (6 April 2018). «Ancient genomes revisit the ancestry of domestic and Przewalski’s horses». Science. 360 (6384): 111–114. Bibcode:2018Sci…360..111G. doi:10.1126/science.aao3297. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29472442.

- ^ a b «Ancient DNA rules out archeologists’ best bet for horse domestication». ArsTechnica. 25 February 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Taylor, William Timothy Treal; Barrón‑Ortiz, Christina Isabelle (2021). «Rethinking the evidence for early horse domestication at Botai». Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 7440. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.7440T. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86832-9. PMC 8018961. PMID 33811228.

- ^ «Przewalski’s horse». Smithsonian’s National Zoo. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f «Przevalsky’s Wild Horse», Nature, 30:391-392 (1884).

- ^ Patan-Zugaj, B., Hermann, C., & Budras, K.-D. (2013). History of the Przewalski horse (Equus Przewalskii) and morphological examination of seasonal changes of the hoof in Przewalski and feral horses. Retrieved from http://www.pferdeheilkunde.de/10.21836/PEM20130302.

- ^ a b Piras, F.M.; Nergadze, S.G.; Poletto, V.; Cerutti, F.; Ryder, O.A.; Leeb, T.; Raimondi, E.; Giulotto, E. (2009). «Phylogeny of Horse Chromosome 5q in the Genus Equus and Centromere Repositioning». Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 126 (1–2): 165–172. doi:10.1159/000245916. PMID 20016166. S2CID 24884868.

- ^ a b Huang, Jinlong; Zhao, Yiping; Shiraigol, Wunierfu; Li, Bei; Bai, Dongyi; Ye, Weixing; et al. (2015). «Analysis of horse genomes provides insight into the diversification and adaptive evolution of karyotype». Scientific Reports. 4: 4958. doi:10.1038/srep04958. PMC 4021364. PMID 24828444.

- ^ a b c Kerekes, Viola; Sándor, István; Nagy, Dorina; Ozogány, Katalin; Göczi, Loránd; Ibler, Benjamin; Széles, Lajos; Barta, Zoltán (2021). «Trends in demography, genetics, and social structure of Przewalski’s horses in the Hortobagy National Park, Hungary over the last 22 years». Global Ecology and Conservation. 25: e01307. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01407.

- ^ «Przewalski’s Horse (Equus ferus) Fact Sheet: Behavior & Ecology». San Diego Zoo Global Library – via IELC.

- ^ Balajeid Lyngdoh, S.; Habib, B.; Shrotriya, S. (January 2020). «Dietary spectrum in Himalayan wolves: comparative analysis of prey choice in conspecifics across high‐elevation rangelands of Asia» (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 310 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1111/jzo.12724. S2CID 202010931. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Feh, C. (2005). «Relationships and communication in socially natural horse herds». In Mills, Daniel; McDonnell, Sue (eds.). The Domestic Horse: the evolution, development and management of its behaviour. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bouman, Inge; Bouman, Jan (1994). Boyd, Lee; Houpt, Katherine A. (eds.). The History of Przewalski’s Horse. Przewalski’s Horse. pp. 5–38. ISBN 9780791418895.

- ^ a b c d Kateryna Slivinska; Grzegorz Kopij (July 2011). «Diet of the Przewalski’s horse Equus przewalskii in the Chernobyl exclusion zone» (PDF). Polish Journal of Ecology. 59 (4): 841–847. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaczensky, Petra; Burnik Šturm, Martina; Sablin, Mikhail V.; Voigt, Christian C.; Smith, Steve; Ganbaatar, Oyunsaikhan; Balint, Boglarka; Walzer, Chris; Spasskaya, Natalia N. (2017). «Stable isotopes reveal diet shift from pre-extinction to reintroduced Przewalski’s horses». Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 5950. Bibcode:2017NatSR…7.5950K. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05329-6. PMC 5519547. PMID 28729625.

- ^ Arnold, Walter; Ruf, Thomas; Kuntz, Regina (2006). «Seasonal adjustment of energy budget in a large wild mammal, the Przewalski horse (Equus ferus przewalskii) II. Energy expenditure». The Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (22): 4566–4573. doi:10.1242/jeb.02536. PMID 17079726. S2CID 250512.

- ^ a b Luu, J. «Equus caballus przewalskii«. Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

- ^ a b Chen, Jinliang; Weng, Qiang; Chao, Jie; Hu, Defu; Taya, Kazuyoshi (2008). «Reproduction and Development of the Released Przewalski’s Horses (Equus przewalskii) in Xinjiang, China». Journal of Equine Science. 19 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1294/jes.19.1. PMC 4019202. PMID 24833949.

- ^ «Przewalski’s Horse». aboutanimals.

- ^ Fages, Antoine; Hanghøj, Kristian; Khan, Naveed; et al. (2019). «Tracking Five Millennia of Horse Management with Extensive Ancient Genome Time Series». Cell. 177 (6): 1419–1435. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.049. PMC 6547883. PMID 31056281.

- ^ Librado, Pablo; Khan, Naveed; kusliy, Mariya A.; et al. (2021). «The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes». Nature. 596 (7882): 634–640. Bibcode:2021Natur.598..634L. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04018-9. PMC 8550961. PMID 34671162. S2CID 239050837.

- ^ Outram, Alan K; Stear, Natalie A; Bendrey, Robin; Olsen, Sandra; Kasparov, Alexei; Zaibert, Victor; Thorpe, Nick; Evershed, Richard P (2009). «The Earliest Horse Harnessing and Milking». Science. 323 (5919): 1332–1335. Bibcode:2009Sci…323.1332O. doi:10.1126/science.1168594. PMID 19265018. S2CID 5126719.

- ^ «Przewalski Horse». Breeds of Livestock, Department of Animal Science. Breeds of Livestock. Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Fijn, Natasha (2015). «13. The domestic and the wild in the Mongolian horse and the takhi». In Behie, Alison M; Ozenham, Marc F (eds.). Taxonomic Tapestries: The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research. Canberra: ANU Press, The Australian National University. pp. 279–298. doi:10.22459/TT.05.2015.13.

- ^ Bowling, Ann T.; Ryder, Oliver A. (1987). «Genetic studies of blood markers in Przewalski’s horse» (PDF). The Journal of Heredity. 78 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110340. PMID 3584938.

- ^ a b «An extraordinary return from the brink of extinction for worlds last wild horse». ZSL Living Conservation. 19 December 2005. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- ^ Mulvey, Stephen (20 April 2006). «Wildlife defies Chernobyl radiation». BBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ Gill, Victoria (27 July 2011). «Chernobyl’s Przewalski’s horses are poached for meat». BBC Nature. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ «У Чорнобильській зоні прижилися коні Пржевальського». 26 October 2018.

- ^ «Чорнобильський заповідник спільно з Київським зоопарком вивчають диких коней Пржевальського у зоні відчуження». Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «У Чорнобилі знайшли обгоріле лоша. Тепер лікують у притулку». BBC News Україна.

- ^ «Завезені з Монголії коні Пржевальського прижилися у зоні відчуження ЧАЕС». zora-irpin.info (in Ukrainian). 19 February 2020.

- ^ Wendle, John (18 April 2016). «Animals Rule Chernobyl 30 Years After Nuclear Disaster». National Geographic. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Przewalski’s Horse — the last wild horse, Association Takh

- ^ «Die Przewalski-Pferde in der Döberitzer Heide» (in German). 25 March 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ «Return of the Przewalski’s Horse to Mongolia». Zoo Praha. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Strauss, Gary (17 November 2016). «A Wild Horse on the Comeback Trail». National Geographic. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b «Another leap towards the Barometer of Life». International Union for the Conservation of Nature. 10 November 2011. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011.

- ^ Blua, Antoine (13 March 2016). «Endangered Przewalski’s Horses Back On Russian Steppe». RadioFreeEurope. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Bakirova, Rafilia T; Sharkikh, Tatjana (2019). «Programme on establishing a semi-free population of Przewalski’s horse in Orenburg State Nature Reserve: the first successful project on the reintroduction of the species in Russia». Nature Conservation Research. 4 (Supplement 2): 57–64. doi:10.24189/ncr.2019.025.

- ^ Rutz, Julia (11 November 2014). «Effort Begins to Revive Endangered Przewalski Horse Population in Kazakhstan». Astana Times. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ «Equus ferus (Asian Wild Horse, Mongolian Wild Horse, Przewalski’s Horse)». IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ^ Ryder, Oliver A.; Wedemeyera, Elizabeth A. (April 1982). «Cooperative breeding programme for the Mongolian wild horse Equus przewalskii in the United States». Biological Conservation. 22 (4): 259–271. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(82)90021-0.

- ^ Zongker, Brett (17 June 2008). «Rare horse gets reverse vasectomy». Today.com / NBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ «Przewalski’s Horse Foal Born via Artificial Insemination». TheHorse.com. 2 August 2013.

- ^ Shenk, Emily (5 August 2013). «First Przewalski’s Horse Born Via Artificial Insemination». National Geographic. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ a b c «Przewalski’s Horse (Takhi) Project | Revive & Restore». Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Tian, X. Cindy; Kubota, Chikara; Enright, Brian; Yang, Xiangzhong (13 November 2003). «Cloning animals by somatic cell nuclear transfer – biological factors». Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 1 (1): 98. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-1-98. ISSN 1477-7827. PMC 521203. PMID 14614770.

- ^ Lagutina, Irina; Fulka, Helena; Lazzari, Giovanna; Galli, Cesare (October 2013). «Interspecies Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer: Advancements and Problems». Cellular Reprogramming. 15 (5): 374–384. doi:10.1089/cell.2013.0036. ISSN 2152-4971. PMC 3787369. PMID 24033141.

- ^ a b «About Cloning | Revive & Restore». Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ «Kurt Benirschke (1924-) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia». embryo.asu.edu. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Beale, Mel (10 June 2021). «Why a cloned foal born at a USA zoo is key to the survival of his endangered breed». Your Horse.

Further reading[edit]

- Boyd, Lee; Houpt, Katherine A. (1994). Przewalski’s Horse: The history and biology of an endangered species. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1889-5. OCLC 28256312 – via Google Books.

- «FC Wales turns clock back thousands of years with ‘wild’ solution to looking after ancient forest site» (Media release). Forestry Commission, Wales, U.K. 16 September 2004. No: 7001. Archived from the original on 6 July 2006.

- «Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved». Bull. Zool. Nomencl. International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 60: 81–84. 2003. Opinion 2027 (Case 3010). Archived from the original on 24 February 2006.

- Ishida, Nobushige; et al. (1995). «Mitochondrial DNA sequences of various species of the genus Equus with special reference to the phylogenetic relationship between Przewalskii’s wild horse and domestic horse». Journal of Molecular Evolution. 41 (2): 180–188. Bibcode:1995JMolE..41..180I. doi:10.1007/BF00170671. PMID 7666447. S2CID 2884878.

- Jansen, Thomas; et al. (2002). «Mitochondrial DNA and the origins of the domestic horse». PNAS. 99 (16): 10905–10910. Bibcode:2002PNAS…9910905J. doi:10.1073/pnas.152330099. PMC 125071. PMID 12130666.

- King, S. R. B.; Gurnell, J. (2006). «Scent-marking behaviour by stallions: an assessment of function in a reintroduced population of Przewalski horses (Equus ferus przewalskii)». Journal of Zoology. 272 (1): 30–36. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00243.x.

- van Cleaf, K. (2006). Przewalski’s Horses (Print ed.). Edina, MN: ABDO Pub. Co.

- Wakefield, S.; Knowles, J.; Zimmermann, W.; Van Dierendonck, M. (2002). «Status and action plan for the Przewalski’s Horse (Equus ferus przewalski)» (PDF). In Moehlman, P.D. (ed.). Equids: Zebras, Asses and Horses. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. pp. 82–92.

- Wilford, John Noble (11 October 2005). «Foal by Foal, the Wildest of Horses Is Coming Back». New York Times.

- «Financial losses puts at risk Chinese program of reintroducing Przewalski’s horses». Welcome2Mongolia. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009.

- [no title given]. PBS (video).

- Chen, Xia; Huang, Shan (28 December 2007). «Returning Home — Przewalski’s horse reintroduction project». China.org.cn.

- Cao Jie. «Przewalski’s Horse Reintroduction Project of China».

- «Przewalski’s horse — Equus ferus przewalskii«. IUCN SSC Equid Specialist Group.

- Slivinska, Kateryna; Kopij, Grzegorz (2011). «Diet of the Przewalski’s Horse Equus Przewalskii in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone». Polish Journal of Ecology. 59: 841–47.

- Scheibe, KM; Eichhorn, K.; Kalz, B.; Streich, WJ; Scheibe, A. (1998). «Water consumption and watering behavior of Przewalski horses (Equus ferus przewalskii) in a semi-reserve». Zoo Biology. 17 (3): 181–192. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-2361(1998)17:3<181::aid-zoo3>3.3.co;2-m.

- Brinkmann, Lea; Gerken, Martina; Riek, Alexander (2012). «Adaptation Strategies to Seasonal Changes in Environmental Conditions of a Domesticated Horse Breed, the Shetland Pony (Equus ferus caballus)». Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (7): 1061–1068. doi:10.1242/jeb.064832. PMID 22399650.

- Ferreira, Luis Miguel M.; Celaya, Rafael; Benavides, Raquel; Jauregui, Berta M.; Garcia, Urcesino; Sofia Santos, Ana; Rosa Garcia, Rocio; Miguel; Rodrigues, Antonio M.; Osoro, Koldo (2013). «Foraging Behaviour of Domestic Herbivore Species Grazing on Heathlands Associated with Improved Pasture Areas». Livestock Science. 155 (2–3): 373–383. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2013.05.007.

- McCue, Molly E.; Bannasch, Danika L.; Petersen, Jessica L.; Gurr, Jessica; Bailey, Ernie; Binns, Matthew M.; Distl, Ottmar; Guérin, Gérard; Hasegawa, Telhisa; Hill, Emmeline W.; Leeb, Tosso; Lindgren, Gabriella; Penedo, M. Cecilia T.; Røed, Knut H.; Ryder, Oliver A.; Swinburne, June E.; Tozaki, Teruaki; Valberg, Stephanie J.; Vaudin, Mark; Lindblad-Toh, Kerstin; Wade, Claire M.; Mickelson, James R.; Georges, Michel (12 January 2012). «A High Density SNP Array for the Domestic Horse and Extant Perissodactyla: Utility for Association Mapping, Genetic Diversity, and Phylogeny Studies». PLOS Genetics. 8 (1): e1002451. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002451. PMC 3257288. PMID 22253606.

- Goto, Hiroki; Ryder, Oliver A.; Fisher, Allison R.; Schultz, Bryant; Pond, Sergei L. Kosakovsky; Nekrutenko, Anton; Makova, Kateryna D. (1 January 2011). «A massively parallel sequencing approach uncovers ancient origins and high genetic variability of endangered Przewalski’s horses». Genome Biology and Evolution. 3: 1096–1106. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr067. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 3194890. PMID 21803766. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015.

- Heptner, V.G.; Nasimovich, A.A.; Bannikov, A.G.; Hoffman, R.S. (1988). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. I. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Ridgeway, William (1908). «Environment and race». The Geographical Journal. Royal Geographical Society. 32 (4): 405–412, esp. 407. doi:10.2307/1776930. JSTOR 1776930.

External links[edit]

- «images and movies of the Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii)». ARKive. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006.

- «Details of the re-introduction program for Przewalski’s horse».

- «Umbrella organization of all institutions participating in the reintroduction of takhis in Mongolia». Archived from the original on 28 September 2006.

- «Przewalski horse conservation organization, reintroduced the species to Mongolia in 2004 and 2005 and continues research and conservation on the Mongolian steppe». Association Takh.

| Przewalski’s horse | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Przewalski’s horse | |

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

|

CITES Appendix I (CITES)[2] |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: |

E. ferus |

| Subspecies: |

E. f. przewalskii |

| Trinomial name | |

| Equus ferus przewalskii

(I. S. Polyakov, 1881) |

|

|

|

| Przewalski’s horse range (reintroduced; missing distribution in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine) |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Przewalski’s horse (,[3] ,[3][4] (Пржевальский Russian: [prʐɨˈvalʲskʲɪj]), Polish: [pʂɛˈvalskʲi]) (Equus ferus przewalskii or Equus przewalskii[5]), also called the takhi,[6] Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered horse originally native to the steppes of Central Asia. It is named after the Russian geographer and explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky. Once extinct in the wild, it has been reintroduced to its native habitat since the 1990s in Mongolia at the Khustain Nuruu National Park, Takhin Tal Nature Reserve, and Khomiin Tal, as well as several other locales in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.[1]

Several genetic characteristics of Przewalski’s horse differ from what is seen in modern domestic horses, indicating neither is an ancestor of the other. For example, the Przewalski has 33 chromosome pairs, compared to 32 for the domestic horse. Their ancestral lineages split from a common ancestor between 38,000 and 160,000 years ago, long before the domestication of the horse. Przewalski’s horse was long considered the only remaining truly wild horse, in contrast with the American Mustang or the Australian brumby, which are instead feral horses descended from domesticated animals. This assumption was challenged in 2018 when DNA analysis of horse remains associated with the 5,000-year-old Botai culture of Central Asia revealed the animals were of Przewalski lineage. However, the domestication status of these animals has been questioned. Its taxonomic position is still debated, with some taxonomists treating Przewalski’s horse as a species, E. przewalskii, others as a subspecies of wild horse (E. ferus przewalskii) or a variety of the domesticated horse (E. caballus).

The Przewalski’s horse is stockily built, smaller, and shorter than its domesticated relatives. Typical height is about 12–14 hands (48–56 inches, 122–142 cm), and the average weight is around 300 kilograms (660 lb). They have a dun coat with pangaré features and often have dark primitive markings.

Taxonomy[edit]

Przewalski’s horse was formally described as a novel species in 1881 by Ivan Semyonovich Polyakov. The taxonomic position of Przewalski’s horse remains controversial, and no consensus exists whether it is a full species (as Equus przewalskii); a subspecies of Equus ferus the wild horse, (as Equus ferus przewalskii in trinomial nomenclature, along with two other subspecies, the domestic horse E. f. caballus, and the extinct tarpan E. f. ferus), or even a subpopulation of the domestic horse.[7][8][9] The American Society of Mammalogists considers the Przewalski’s horse and the tarpan to both be subspecies of Equus ferus, and classifies the domestic horse as separate species, Equus caballus.[10]

Lineage[edit]

Early sequencing studies of DNA revealed several genetic characteristics of Przewalski’s horse that differ from what is seen in modern domestic horses, indicating neither is ancestor of the other, and supporting the status of Przewalski horses as a remnant wild population not derived from modern domestic horses.[11] The evolutionary divergence of the two populations was estimated to have occurred about 45,000 YBP,[12][13] while the archaeological record places the first horse domestication about 5,500 YBP by the ancient central-Asian Botai culture.[12][14] The two lineages thus split well before domestication, most likely due to climate, topography, or other environmental changes.[12]

Several subsequent DNA studies produced partially contradictory results. A 2009 molecular analysis using ancient DNA recovered from archaeological sites placed Przewalski’s horse in the middle of the domesticated horses.[9] However, a 2011 mitochondrial DNA analysis suggested that Przewalski’s and modern domestic horses diverged some 160,000 years ago.[15] An analysis based on whole genome sequencing and calibration with DNA from old horse bones gave a divergence date of 38,000–72,000 years ago.[16]

In 2018, a new analysis involved genomic sequencing of ancient DNA from horse remains associated with the mid-fourth-millennium BCE Botai culture and bearing marks considered characteristic of domestication, as well as domestic horses from more recent archaeological sites, for comparison with those of modern domestic and Przewalski’s horses. The study revealed that the Botai horses were members of the Przewalski’s horse lineage, rather than that of modern domestic horses as was previously believed. Further, all of the modern Przewalski’s horses analyzed were found to nest within the phylogenetic tree of the Botai horses, leading the authors to posit that modern Przewalski’s horses are feral descendants of the ancient Botai domesticated animals, rather than representing a surviving population of never-domesticated horses. The researchers suggested that because Botai horse domestication was relatively short-lived before they again became feral, the Przewalski’s horse retained more wild or primitive traits than did the domestic horse lineage.[17][18][19] However, a 2021 reevaluation of the Botai horses reached a conclusion in favor of the traditional view of Przewalski’s horses as a never-domesticated population.[20] These authors viewed the tooth wear previously attributed to bridle mouthpieces as more likely to have been caused by natural processes, while the age structure of the Botai horses seemed inconsistent with domesticated herding. Furthermore, some specimens were found associated with arrowheads, suggesting they had been hunted. They concluded that the horses associated with the Botai culture were wild instead of domesticated animals, and that the Przewalski’s horse lineage should indeed be viewed not as a feral lineage but as one that was always wild.[20]

In any case, the Botai horses were found to have negligible genetic contribution to any of the ancient or modern domestic horses studied, indicating that the domestication of the latter was independent, involving a different wild population, from any possible domestication of Przewalski’s horse by the Botai culture.[17][18][19]

Head shot, showing convex profile

Characteristics[edit]

Przewalski’s horse is stockily built in comparison to domesticated horses, with shorter legs, though being much smaller and shorter than its domesticated relatives. Typical height is about 12–14 hands (48–56 inches, 122–142 cm), and length is about 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in). It weighs around 300 kilograms (660 lb). The coat is generally dun in color with pangaré features, varying from dark brown around the mane, to pale brown on the flanks, and yellowish-white on the belly, as well as around the muzzle. The legs of Przewalski’s horse are often faintly striped, also typical of primitive markings.[21] The mane stands erect and does not extend as far forward,[22] while the tail is about 90 cm (35.43 in) long, with a longer dock and shorter hair than seen in domesticated horses. The hooves of Przewalski’s horse are longer in the front and have significantly thicker sole horns than feral horses, an adaptation that improves hoof performance on terrain.[23]

Genomics[edit]

The karyotype of Przewalski’s horse differs from that of the domestic horse, having 33 chromosome pairs versus 32, apparently due to a fission of a large chromosome ancestral to domestic horse chromosome 5 to produce Przewalski’s horse chromosomes 23 and 24,[24] though conversely, a Robertsonian translocation that fused two chromosomes ancestral to those seen in Przewalski’s horse to produce the single large domestic horse chromosome has also been proposed.[25]

Many smaller inversions, insertions and other rearrangements were observed between the chromosomes of domestic and Przewalski’s horses, while there was much lower heterozygosity in Przewalski’s horses, with extensive segments devoid of genetic diversity, a consequence of the recent severe bottleneck of the captive Przewalski’s horse population.[25] In comparison, the chromosomal differences between domestic horses and zebras include numerous large-scale translocations, fusions, inversions, and centromere repositioning.[24] Przewalski’s horse has the highest diploid chromosome number among all equine species. They can interbreed with the domestic horse and produce fertile offspring, with 65 chromosomes.[7]

Ecology and behavior[edit]

Przewalski reported the horses forming troops of between five and fifteen members, consisting of an old stallion, his mares and foals.[22] Modern reintroduced populations similarly form family groups of one adult stallion, one to three mares, and their common offspring that stay in the family group until they are no longer dependent, usually at two or three years old. Young females join other harems, while bachelor stallions as well as old stallions who have lost their harems join bachelor groups.[26] Family groups can join to form a herd that moves together.[citation needed]

The patterns of their daily lives exhibit horse behavior similar to that of feral horse herds. Stallions herd, drive, and defend all members of their family, while the mares often display leadership in the family. Stallions and mares stay with their preferred partners for years. While behavioral synchronization is high among mares, stallions other than the main harem stallion are generally less stable in this respect.[citation needed]

Home range in the wild is little studied, but estimated as 1.2–24 km2 (0.46–9.3 sq mi) in the Hustai National Park and 150–825 km2 (58–319 sq mi) in the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area.[27] The ranges of harems are separated, but slightly overlapping.[26] They have few modern predators, but one of the few is the Himalayan wolf.[28]

Horses maintain visual contact with their family and herd at all times, and have a host of ways to communicate with one another, including vocalizations, scent marking, and a wide range of visual and tactile signals. Each kick, groom, tilt of the ear, or other contact with another horse is a means of communicating. This constant communication leads to complex social behaviors among Przewalski’s horses.[29]

The historical population was said to have lived in the «wildest parts of the desert» with a preference for «especially saline districts».[22] They were observed mostly during spring and summer at natural wells, migrating to them by crossing valleys rather than by way of higher mountains.[30]

Diet[edit]

Przewalski horse’s diet consists mostly of vegetation. Many plant species are in a typical Przewalski’s horse environment, including: Elymus repens, Carex spp., Fabaceae, and Asteraceae.[31]

Looking at the species’ diet overall, Przewalski’s horses most often eat E. repens, Trifolium pratense, Vicia cracca, Poa trivialis, Dactylis glomerata, and Bromus inermis.[31]

While the horses eat a variety of different plant species, they tend to favor different species at different times of year. In the springtime, they favor Elymus repens, Corynephorus canescens, Festuca valesiaca, and Chenopodium album. In early summer, they favor Dactylis glomerata and Trifolium, and in late summer, they gravitate towards E. repens and Vicia cracca.[31]

In winter the horses eat Salix spp., Pyrus communis, Malus sylvatica, Pinus sylvestris, Rosa spp., and Alnus spp. Additionally, Przewalski’s horses may dig for Festuca spp., Bromus inermis, and E. repens that grow beneath the ice and snow. Their winter diet is very similar to the winter diet of domestic horses,[31] but differs from that revealed by isotope analysis of the historical (pre-captivity) population, which switched in winter to browsing shrubs, though the difference may be due to the extreme habitat pressure the historical population was under.[32] In the wintertime, they eat their food more slowly than they do during other times of the year. Przewalski’s horses seasonally display a set of changes collectively characteristic of physiologic adaptation to starvation, with their basal metabolic rate in winter being half what it is during springtime. This is not a direct consequence of decreased nutrient intake, but rather a programmed response to predictable seasonal dietary fluctuation.[33]

Reproduction[edit]

Mating occurs in late spring or early summer. Mating stallions do not start looking for mating partners until the age of five. Stallions assemble groups of mares or challenge the leader of another group for dominance. Females are able to give birth at the age of three and have a gestation period of 11–12 months. Foals are able to stand about an hour after birth.[34] The rate of infant mortality among foals is 25%, with 83.3% of these deaths resulting from leading stallion infanticide.[35] Foals begin grazing within a few weeks but are not weaned for 8–13 months after birth.[34] They reach sexual maturity at two years of age.[36]

Population[edit]

History[edit]

Przewalski’s-type wild horses appear in European cave art dating as far back as 20,000 years ago,[1] but genetic investigation of a 35,870-year-old specimen from one such cave instead showed affinity with extinct Iberian horse lineage and the modern domestic horse, suggesting that it was not Przewalski’s horse being depicted in this art.[37] Horse skeletons dating to the fifth to the third millennia BCE, found in Central Asia, with a range extending to the southern Urals and the Altai, belong to the genetic lineage of Przewalski’s horse.[38] Of particular note are the horses of this lineage found in the archaeological sites of the Chalcolithic Botai culture. Sites dating from the mid-fourth-millennium BCE show evidence of horse domestication,[39] though their status as domesticated horses has been recently challenged.[20] Analysis of ancient DNA from Botai horse specimens from about 3000 BCE reveal them to have DNA markers consistent with the lineage of modern Przewalski’s horses.[17]

There are sporadic reports of Przewalski’s horse in the historical record prior to its formal characterization. The Buddhist monk Bodowa wrote a description of what is thought to have been Przewalski’s horse about AD 900,[32] and an account from 1226 reports an incident involving wild horses during Genghis Khan’s campaign against the Tangut empire.[1] In the fifteenth century, Johann Schiltberger recorded one of the first European sightings of the horses in the journal recounting his trip to Mongolia as a prisoner of the Mongol Khan.[40] Another was recorded as a gift to the Manchurian emperor around 1630, its value as a gift suggesting a difficulty in obtaining them.[30] John Bell, a Scottish doctor in service to Peter the Great from 1719 to 1722, observed a horse in Russia’s Tomsk Oblast that was apparently this species,[32] and a few decades later in 1750, a large hunt with thousands of beaters organized by the Manchurian emperor killed between two and three hundred of these horses.[30]

Przewalski’s horse skull, Brno museum

The species is named after a Russian colonel of Polish descent, Nikolai Przhevalsky (1839–1888) (Nikołaj Przewalski in Polish). An explorer and naturalist, he obtained a skull and hide of an animal shot in 1878 in the Gobi near what is today’s China–Mongolia border, and he would make an expedition into the Dzungarian Basin to observe it in the wild.[32] In 1881, the horse received a formal scientific description and was named Equus przevalskii by Ivan Semyonovich Polyakov, based on Przewalski’s collection and description,[32][22] while in 1884, the sole exemplar of the horse in Europe was a preserved specimen in the Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.[22] This was supplemented in 1894 when the brothers Grum-Grzhimailo returned several hides and skulls to St. Petersburg and provided a description of the horse’s behavior in the wild.[30] A number of these horses were captured around 1900 by Carl Hagenbeck and placed in zoos, and these, along with one later captive, reproduced to give rise to today’s population.

After 1903, there were no reports of the wild population until 1947, when several isolated groups were observed and a lone filly captured. Although local herdsmen reported seeing as many as 50 to 100 takhis grazing in small groups at that time, there were only sporadic sightings of single groups of two or three animals thereafter, mostly near natural wells.[30] Two scientific expeditions in 1955 and 1962 failed to find any, and after herders and naturalists reported single harem groups in 1966 and 1967, the last observation of the wild horse in its native habitat was of a single stallion in 1969.[30][41] Expeditions after this failed to locate any horses, and the species would be designated «extinct in the wild» for over 30 years.[30] Competition with livestock, hunting, capture of foals for zoological collections, military activities, and harsh winters recorded in 1945, 1948, and 1956 are considered to be main causes of the decline in Przewalski’s horse population.[15]

The wild population was already rare at the time of its first scientific characterization. Przewalski reported seeing them only from a distance and may actually have instead sighted herds of local onager, Mongolian wild asses, and he was only able to obtain the type specimen from Kirghiz hunters.[41] The range of Przewalski’s horse was limited to the arid Dzungarian Basin in the Gobi Desert.[22] It has been suggested that this was not their natural habitat, but, like the onager, they were a steppe animal driven to this inhospitable last refuge by the dual pressures of hunting and habitat loss to agricultural grazing.[32] There were two distinct populations recognized by local Mongolians, a lighter steppe variety and a darker mountain one, and this distinction is seen in early twentieth-century descriptions. Their mountainous habitat included the Takhiin Shar Nuruu (The Yellow Wild-Horse Mountain Range).[41] In their last decades in the wild, the remnant population was limited to the small region between the Takhiin Shar Nuruu and Bajtag-Bogdo mountain ridges.[30]

Vaska, a Przewalski’s horse trained to be ridden

Captivity[edit]

Attempts to obtain specimens for exhibit and captive breeding were largely unsuccessful until 1902, when 28 captured foals were brought to Europe. These, along with a small number of additional captives, would be distributed among zoos and breeding centers in Europe and the United States. Many facilities failed in their attempts at captive breeding, but a few programs were established. However, by the mid-1930s, inbreeding had caused reduced fertility and the captive population experienced a genetic bottleneck, with the surviving captive breeding stock descended from only 11 of the founder captives.[30] In addition, in at least one instance the progeny of interbreeding with a domestic horse was bred back into the captive Przewalski’s horse population, though recent studies have shown only minimal genetic contribution of this domestic horse to the captive population.[42]

The situation was improved when the exchange of breeding animals among facilities increased genetic diversity and there was a consequent improvement in fertility, but the population experienced another genetic bottleneck when many of the horses failed to survive World War II. The most valuable group, in Askania Nova, Ukraine, was shot by German soldiers during World War II occupation, and the group in the United States had died out.[15] Only two captive populations in zoos remained, in Munich and in Prague, and of the 31 remaining horses at war’s end, only 9 became ancestors of the subsequent captive population.[30] By the end of the 1950s, only 12 individual horses were left in the world’s zoos.[15]

In 1957, a wild-caught mare captured as a foal a decade earlier was introduced into the Ukrainian captive population. This would prove the last wild-caught horse, and with the presumed extinction of wild population, last sighted in Mongolia in the late 1960s, the captive population became the sole representatives of Przewalski’s horse.[30] Genetic diversity received a much needed boost from this new source, with the spread of her bloodline through the inbred captive groups leading to their increased reproductive success, and by 1965 there were more than 130 animals spread among thirty-two zoos and parks.

Conservation efforts[edit]

A Przewalski’s horse in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

In 1977, the Foundation for the Preservation and Protection of the Przewalski Horse was founded in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, by Jan and Inge Bouman. The foundation started a program of exchange between captive populations in zoos throughout the world to reduce inbreeding, and later began a breeding program of its own. As a result of such efforts, the extant herd has retained a far greater genetic diversity than its genetic bottleneck made likely.[15] By 1979, when this concerted program of population management to maximize genetic diversity was begun, there were almost four hundred horses in sixteen facilities,[30] a number that had grown by the early 1990s to over 1,500.[43]

While dozens of zoos worldwide have Przewalski’s horses in small numbers, specialized reserves are also dedicated primarily to the species. The world’s largest captive-breeding program for Przewalski’s horses is at the Askania Nova preserve in Ukraine. From 1998, thirty one horses were also released in the unenclosed Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine and Belarus, evacuated after the Chernobyl accident, which now serves as a deserted de facto nature reserve.[44] Though poaching took a toll on numbers,[45] as of 2019 the estimated population in the Chernobyl zone was over 100 individuals.[46][47][48][49][50]

Le Villaret, located in the Cevennes National Park in southern France and run by the Association Takh, is a breeding site for Przewalski’s horses that was created to allow the free expression of natural Przewalski’s horse behaviors. In 1993, eleven zoo-born horses were brought to Le Villaret. Horses born there are adapted to life in the wild, being free to choose their own mates and required to forage on their own. This was intended to produce individuals capable of being reintroduced into Mongolia. In 2012, 39 individuals were at Le Villaret.[51] An intensely researched population of free-ranging animals was also introduced to the Hortobágy National Park puszta in Hungary; data on social structure, behavior, and diseases gathered from these animals are used to improve the Mongolian conservation effort.[26] An additional breeding population of Przewalski’s horses roams the former Döberitzer Heide military proving ground, now a nature reserve in Dallgow-Döberitz, Germany. Established in 2008, this population comprised 24 horses in 2019.[52]

Przewalski’s horses at Döberitzer Heide nature reserve

Reintroduction[edit]

Reintroductions organized by Western European countries started in the 1990s. These were later stopped, mostly for financial reasons. In 2011, Prague Zoo started a new project, Return of the Wild Horses. With the support of public and many strategic partners, these yearly transports of captive-bred horses into the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area continue today.[53] Since 2004, there is also a program to reintroduce Przewalski’s horses that were bred in France into Mongolia.[54]