Муковисцидóз (кистозный фиброз) — системное наследственное заболевание, обусловленное мутацией гена трансмембранного регулятора муковисцидоза и характеризующееся поражением желёз внешней секреции, тяжёлыми нарушениями функций органов дыхания. Муковисцидоз представляет особый интерес не только из-за широкой распространённости, но и потому, что это одно из первых наследственных заболеваний, которое пытались лечить.

Все значения слова «муковисцидоз»

-

Мужчины и женщины с муковисцидозом доживают до зрелого возраста, о чём раньше не приходилось и мечтать; доноров почки ищут в Facebook; некоторые больные после проведения реанимационных мероприятий в отделении интенсивной терапии борются с посттравматическим стрессовым расстройством, другие оказываются до конца жизни прикованы к аппарату искусственной вентиляции лёгких в специализированных медицинских центрах.

-

Потому что защита больных муковисцидозом – это именно политика.

-

Европейское общество муковисцидоза уполномочило Carlo Castellani и Harry Heijerman собрать вместе коллектив высококвалифицированных специалистов в данной области для участия в этой монографии.

- (все предложения)

- лямблиоз

- аскаридоз

- кольпит

- гельминтоз

- лимфогранулематоз

- (ещё синонимы…)

| Cystic fibrosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mucoviscidosis |

|

|

| Specialty | Medical genetics, pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Difficulty breathing, coughing up mucus, poor growth, fatty stool[1] |

| Usual onset | Symptoms recognizable ~6 month[2] |

| Duration | Life long[3] |

| Causes | Genetic (autosomal recessive)[1] |

| Risk factors | Genetic |

| Diagnostic method | Sweat test, genetic testing[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, pancreatic enzyme replacement, lung transplantation[1] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy between 42 and 50 years (developed world)[4] |

| Frequency | 1 out of 3,000 (Northern European)[1] |

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare[5][6] genetic disorder that affects mostly the lungs, but also the pancreas, liver, kidneys, and intestine.[1][7] Long-term issues include difficulty breathing and coughing up mucus as a result of frequent lung infections.[1] Other signs and symptoms may include sinus infections, poor growth, fatty stool, clubbing of the fingers and toes, and infertility in most males.[1] Different people may have different degrees of symptoms.[1]

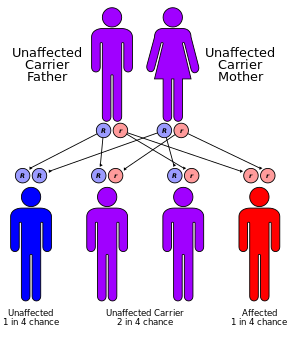

Cystic fibrosis is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.[1] It is caused by the presence of mutations in both copies of the gene for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein.[1] Those with a single working copy are carriers and otherwise mostly healthy.[3] CFTR is involved in the production of sweat, digestive fluids, and mucus.[8] When the CFTR is not functional, secretions which are usually thin instead become thick.[9] The condition is diagnosed by a sweat test and genetic testing.[1] Screening of infants at birth takes place in some areas of the world.[1]

There is no known cure for cystic fibrosis.[3] Lung infections are treated with antibiotics which may be given intravenously, inhaled, or by mouth.[1] Sometimes, the antibiotic azithromycin is used long term.[1] Inhaled hypertonic saline and salbutamol may also be useful.[1] Lung transplantation may be an option if lung function continues to worsen.[1] Pancreatic enzyme replacement and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation are important, especially in the young.[1] Airway clearance techniques such as chest physiotherapy have some short-term benefit, but long-term effects are unclear.[10] The average life expectancy is between 42 and 50 years in the developed world.[4][11] Lung problems are responsible for death in 80% of people with cystic fibrosis.[1]

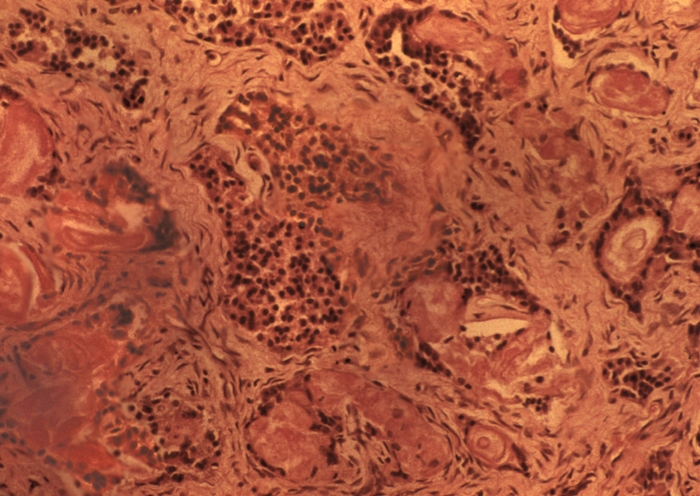

CF is most common among people of Northern European ancestry, for whom it affects about 1 out of 3,000 newborns,[1] and among which around 1 out of 25 people is a carrier.[3] It is least common in Africans and Asians, though it does occur in all races.[1] It was first recognized as a specific disease by Dorothy Andersen in 1938, with descriptions that fit the condition occurring at least as far back as 1595.[7] The name «cystic fibrosis» refers to the characteristic fibrosis and cysts that form within the pancreas.[7][12]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Health problems associated with cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis typically manifests early in life. Newborns and infants with cystic fibrosis tend to have frequent, large, greasy stools (a result of malabsorption) and are underweight for their age.[13] 15–20% of newborns have their small intestine blocked by meconium, often requiring surgery to correct.[13] Newborns occasionally have neonatal jaundice due to blockage of the bile ducts.[13] Children with cystic fibrosis lose excessive salt in their sweat, and parents often notice salt crystallizing on the skin, or a salty taste when they kiss their child.[13]

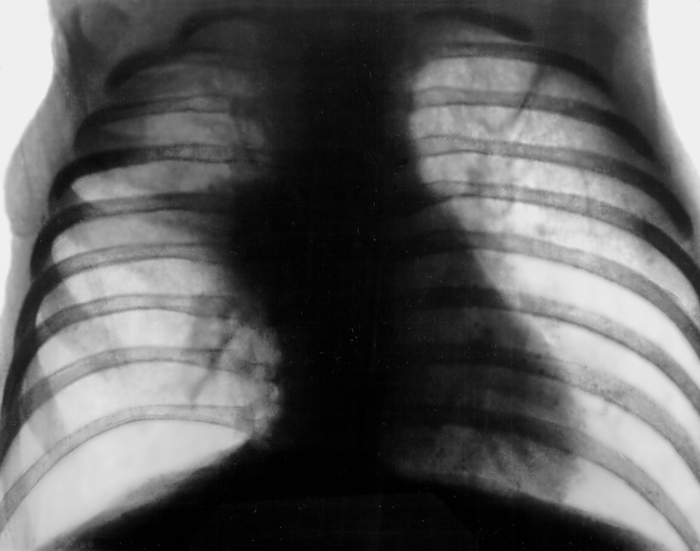

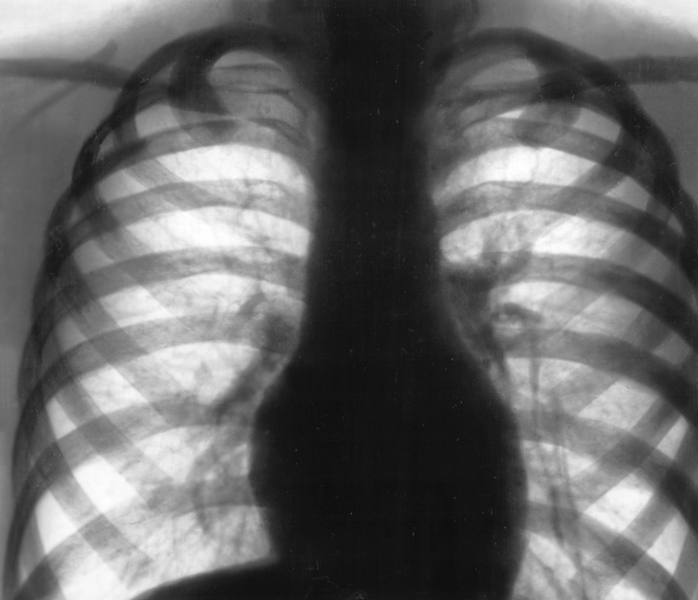

The primary cause of morbidity and death in people with cystic fibrosis is progressive lung disease, which eventually leads to respiratory failure.[14] This typically begins as a prolonged respiratory infection that continues until treated with antibiotics.[14] Chronic infection of the respiratory tract is nearly universal in people with cystic fibrosis, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, fungi, and mycobacteria all increasingly common over time.[15] Inflammation of the upper airway results in frequent runny nose and nasal obstruction. Nasal polyps are common, particularly in children and teenagers.[14] As the disease progresses, people tend to have shortness of breath, and a chronic cough that produces sputum.[14] Breathing problems make it increasingly challenging to exercise, and prolonged illness causes those affected to be underweight for their age.[14] In late adolescence or adulthood, people begin to develop severe signs of lung disease: wheezing, digital clubbing, cyanosis, coughing up blood, pulmonary heart disease, and collapsed lung (atelectasis or pneumothorax).[14]

In rare cases, cystic fibrosis can manifest itself as a coagulation disorder. Vitamin K is normally absorbed from breast milk, formula, and later, solid foods. This absorption is impaired in some CF patients. Young children are especially sensitive to vitamin K malabsorptive disorders because only a very small amount of vitamin K crosses the placenta, leaving the child with very low reserves and limited ability to absorb vitamin K from dietary sources after birth. Because clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X are vitamin K–dependent, low levels of vitamin K can result in coagulation problems. Consequently, when a child presents with unexplained bruising, a coagulation evaluation may be warranted to determine whether an underlying disease is present.[16]

Lungs and sinuses[edit]

Lung disease results from clogging of the airways due to mucus build-up, decreased mucociliary clearance, and resulting inflammation.[17][18] In later stages, changes in the architecture of the lung, such as pathology in the major airways (bronchiectasis), further exacerbate difficulties in breathing. Other signs include high blood pressure in the lung (pulmonary hypertension), heart failure, difficulties getting enough oxygen to the body (hypoxia), and respiratory failure requiring support with breathing masks, such as bilevel positive airway pressure machines or ventilators.[19] Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the three most common organisms causing lung infections in CF patients.[18]: 1254 In addition, opportunistic infection due to Burkholderia cepacia complex can occur, especially through transmission from patient to patient.[20]

In addition to typical bacterial infections, people with CF more commonly develop other types of lung diseases. Among these is allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, in which the body’s response to the common fungus Aspergillus fumigatus causes worsening of breathing problems. Another is infection with Mycobacterium avium complex, a group of bacteria related to tuberculosis, which can cause lung damage and do not respond to common antibiotics.[21]

Mucus in the paranasal sinuses is equally thick and may also cause blockage of the sinus passages, leading to infection. This may cause facial pain, fever, nasal drainage, and headaches. Individuals with CF may develop overgrowth of the nasal tissue (nasal polyps) due to inflammation from chronic sinus infections.[22] Recurrent sinonasal polyps can occur in 10% to 25% of CF patients.[18]: 1254 These polyps can block the nasal passages and increase breathing difficulties.[23][24]

Cardiorespiratory complications are the most common causes of death (about 80%) in patients at most CF centers in the United States.[18]: 1254

Gastrointestinal[edit]

In addition, protrusion of internal rectal membranes (rectal prolapse) is more common, occurring in as many as 10% of children with CF,[18] and it is caused by increased fecal volume, malnutrition, and increased intra–abdominal pressure due to coughing.[25]

The thick mucus seen in the lungs has a counterpart in thickened secretions from the pancreas, an organ responsible for providing digestive juices that help break down food. These secretions block the exocrine movement of the digestive enzymes into the duodenum and result in irreversible damage to the pancreas, often with painful inflammation (pancreatitis).[26] The pancreatic ducts are totally plugged in more advanced cases, usually seen in older children or adolescents.[18] This causes atrophy of the exocrine glands and progressive fibrosis.[18]

Individuals with CF also have difficulties absorbing the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.[27]

In addition to the pancreas problems, people with CF experience more heartburn,[27] intestinal blockage by intussusception, and constipation.[28] Older individuals with CF may develop distal intestinal obstruction syndrome, which occurs when feces becomes thick with mucus (inspissated) and can cause bloating, pain, and incomplete or complete bowel obstruction.[29][27]

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency occurs in the majority (85–90%) of patients with CF.[18]: 1253 It is mainly associated with «severe» CFTR mutations, where both alleles are completely nonfunctional (e.g. ΔF508/ΔF508).[18]: 1253 It occurs in 10–15% of patients with one «severe» and one «mild» CFTR mutation where little CFTR activity still occurs, or where two «mild» CFTR mutations exist.[18]: 1253 In these milder cases, sufficient pancreatic exocrine function is still present so that enzyme supplementation is not required.[18]: 1253 Usually, no other GI complications occur in pancreas-sufficient phenotypes, and in general, such individuals usually have excellent growth and development.[18]: 1254 Despite this, idiopathic chronic pancreatitis can occur in a subset of pancreas-sufficient individuals with CF, and is associated with recurrent abdominal pain and life-threatening complications.[18]

Thickened secretions also may cause liver problems in patients with CF. Bile secreted by the liver to aid in digestion may block the bile ducts, leading to liver damage. Impaired digestion or absorption of lipids can result in steatorrhea. Over time, this can lead to scarring and nodularity (cirrhosis). The liver fails to rid the blood of toxins and does not make important proteins, such as those responsible for blood clotting.[30][31] Liver disease is the third-most common cause of death associated with CF.[18]

Around 5–7% of people experience liver damage severe enough to cause symptoms: typically gallstones causing biliary colic.[32]

Endocrine[edit]

The pancreas contains the islets of Langerhans, which are responsible for making insulin, a hormone that helps regulate blood glucose. Damage to the pancreas can lead to loss of the islet cells, leading to a type of diabetes unique to those with the disease.[33] This cystic fibrosis-related diabetes shares characteristics of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and is one of the principal nonpulmonary complications of CF.[34]

Vitamin D is involved in calcium and phosphate regulation. Poor uptake of vitamin D from the diet because of malabsorption can lead to the bone disease osteoporosis in which weakened bones are more susceptible to fractures.[35]

Infertility[edit]

Infertility affects both men and women. At least 97% of men with cystic fibrosis are infertile, but not sterile, and can have children with assisted reproductive techniques.[36] The main cause of infertility in men with cystic fibrosis is congenital absence of the vas deferens (which normally connects the testes to the ejaculatory ducts of the penis), but potentially also by other mechanisms such as causing no sperm, abnormally shaped sperm, and few sperm with poor motility.[37] Many men found to have congenital absence of the vas deferens during evaluation for infertility have a mild, previously undiagnosed form of CF.[38] Around 20% of women with CF have fertility difficulties due to thickened cervical mucus or malnutrition. In severe cases, malnutrition disrupts ovulation and causes a lack of menstruation.[39]

Causes[edit]

Cystic fibrosis has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance.

CF is caused by a mutation in the gene cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). The most common mutation, ΔF508, is a deletion (Δ signifying deletion) of three nucleotides that results in a loss of the amino acid phenylalanine (F) at the 508th position on the protein.[40][41] This mutation accounts for two-thirds (66–70%[18]) of CF cases worldwide and 90% of cases in the United States; however, over 1500 other mutations can produce CF.[42] Although most people have two working copies (alleles) of the CFTR gene, only one is needed to prevent cystic fibrosis. CF develops when neither allele can produce a functional CFTR protein. Thus, CF is considered an autosomal recessive disease.[43]

The CFTR gene, found at the q31.2 locus of chromosome 7, is 230,000 base pairs long, and creates a protein that is 1,480 amino acids long. More specifically, the location is between base pair 117,120,016 and 117,308,718 on the long arm of chromosome 7, region 3, band 1, subband 2, represented as 7q31.2. Structurally, the CFTR is a type of gene known as an ABC gene. The product of this gene (the CFTR protein) is a chloride ion channel important in creating sweat, digestive juices, and mucus. This protein possesses two ATP-hydrolyzing domains, which allows the protein to use energy in the form of ATP. It also contains two domains comprising six alpha helices apiece, which allow the protein to cross the cell membrane. A regulatory binding site on the protein allows activation by phosphorylation, mainly by cAMP-dependent protein kinase.[19] The carboxyl terminal of the protein is anchored to the cytoskeleton by a PDZ domain interaction.[44] The majority of CFTR in the lung’s passages is produced by rare ion-transporting cells that regulate mucus properties.[45]

In addition, the evidence is increasing that genetic modifiers besides CFTR modulate the frequency and severity of the disease. One example is mannan-binding lectin, which is involved in innate immunity by facilitating phagocytosis of microorganisms. Polymorphisms in one or both mannan-binding lectin alleles that result in lower circulating levels of the protein are associated with a threefold higher risk of end-stage lung disease, as well as an increased burden of chronic bacterial infections.[18]

Carriers[edit]

Up to one in 25 individuals of Northern European ancestry is considered a genetic carrier. The disease appears only when two of these carriers have children, as each pregnancy between them has a 25% chance of producing a child with the disease. Although only about one of every 3,000 newborns of the affected ancestry has CF, more than 900 mutations of the gene that causes CF are known. Current tests look for the most common mutations.[46]

The mutations screened by the test vary according to a person’s ethnic group or by the occurrence of CF already in the family. More than 10 million Americans, including one in 25 white Americans, are carriers of one mutation of the CF gene. CF is present in other races, though not as frequently as in white individuals. About one in 46 Hispanic Americans, one in 65 African Americans, and one in 90 Asian Americans carry a mutation of the CF gene.[46]

Pathophysiology[edit]

The CFTR protein is a channel protein that controls the flow of H2O and Cl− ions in and out of cells inside the lungs. When the CFTR protein is working correctly, ions freely flow in and out of the cells. However, when the CFTR protein is malfunctioning, these ions cannot flow out of the cell due to a blocked channel. This causes cystic fibrosis, characterized by the buildup of thick mucus in the lungs.

Several mutations in the CFTR gene can occur, and different mutations cause different defects in the CFTR protein, sometimes causing a milder or more severe disease. These protein defects are also targets for drugs which can sometimes restore their function. ΔF508-CFTR gene mutation, which occurs in >90% of patients in the U.S., creates a protein that does not fold normally and is not appropriately transported to the cell membrane, resulting in its degradation.[47]

Other mutations result in proteins that are too short (truncated) because production is ended prematurely. Other mutations produce proteins that do not use energy (in the form of ATP) normally, do not allow chloride, iodide, and thiocyanate to cross the membrane appropriately,[48] and degrade at a faster rate than normal. Mutations may also lead to fewer copies of the CFTR protein being produced.[19]

The protein created by this gene is anchored to the outer membrane of cells in the sweat glands, lungs, pancreas, and all other remaining exocrine glands in the body.

The protein spans this membrane and acts as a channel connecting the inner part of the cell (cytoplasm) to the surrounding fluid. This channel is primarily responsible for controlling the movement of halide anions from inside to outside of the cell; however, in the sweat ducts, it facilitates the movement of chloride from the sweat duct into the cytoplasm. When the CFTR protein does not resorb ions in sweat ducts, chloride and thiocyanate[49] released from sweat glands are trapped inside the ducts and pumped to the skin.

Additionally hypothiocyanite, OSCN, cannot be produced by the immune defense system.[50][51] Because chloride is negatively charged, this modifies the electrical potential inside and outside the cell that normally causes cations to cross into the cell. Sodium is the most common cation in the extracellular space. The excess chloride within sweat ducts prevents sodium resorption by epithelial sodium channels and the combination of sodium and chloride creates the salt, which is lost in high amounts in the sweat of individuals with CF. This lost salt forms the basis for the sweat test.[19]

Most of the damage in CF is due to blockage of the narrow passages of affected organs with thickened secretions. These blockages lead to remodeling and infection in the lung, damage by accumulated digestive enzymes in the pancreas, blockage of the intestines by thick feces, etc. Several theories have been posited on how the defects in the protein and cellular function cause the clinical effects. The most current theory suggests that defective ion transport leads to dehydration in the airway epithelia, thickening mucus.[52] In airway epithelial cells, the cilia exist in between the cell’s apical surface and mucus in a layer known as airway surface liquid (ASL). The flow of ions from the cell and into this layer is determined by ion channels such as CFTR. CFTR not only allows chloride ions to be drawn from the cell and into the ASL, but it also regulates another channel called ENac, which allows sodium ions to leave the ASL and enter the respiratory epithelium. CFTR normally inhibits this channel, but if the CFTR is defective, then sodium flows freely from the ASL and into the cell.[citation needed]

As water follows sodium, the depth of ASL will be depleted and the cilia will be left in the mucous layer.[53] As cilia cannot effectively move in a thick, viscous environment, mucociliary clearance is deficient and a buildup of mucus occurs, clogging small airways.[54] The accumulation of more viscous, nutrient-rich mucus in the lungs allows bacteria to hide from the body’s immune system, causing repeated respiratory infections. The presence of the same CFTR proteins in the pancreatic duct and sweat glands in the skin also cause symptoms in these systems.[citation needed]

Chronic infections[edit]

The lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis are colonized and infected by bacteria from an early age. These bacteria, which often spread among individuals with CF, thrive in the altered mucus, which collects in the small airways of the lungs. This mucus leads to the formation of bacterial microenvironments known as biofilms that are difficult for immune cells and antibiotics to penetrate. Viscous secretions and persistent respiratory infections repeatedly damage the lung by gradually remodeling the airways, which makes infection even more difficult to eradicate.[55] The natural history of CF lung infections and airway remodeling is poorly understood, largely due to the immense spatial and temporal heterogeneity both within and between the microbiomes of CF patients.[56]

Over time, both the types of bacteria and their individual characteristics change in individuals with CF. In the initial stage, common bacteria such as S. aureus and H. influenzae colonize and infect the lungs.[18] Eventually, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (and sometimes Burkholderia cepacia) dominates. By 18 years of age, 80% of patients with classic CF harbor P. aeruginosa, and 3.5% harbor B. cepacia.[18] Once within the lungs, these bacteria adapt to the environment and develop resistance to commonly used antibiotics. Pseudomonas can develop special characteristics that allow the formation of large colonies, known as «mucoid» Pseudomonas, which are rarely seen in people who do not have CF.[55] Scientific evidence suggests the interleukin 17 pathway plays a key role in resistance and modulation of the inflammatory response during P. aeruginosa infection in CF.[57] In particular, interleukin 17-mediated immunity plays a double-edged activity during chronic airways infection; on one side, it contributes to the control of P. aeruginosa burden, while on the other, it propagates exacerbated pulmonary neutrophilia and tissue remodeling.[57]

Infection can spread by passing between different individuals with CF.[58] In the past, people with CF often participated in summer «CF camps» and other recreational gatherings.[59][60] Hospitals grouped patients with CF into common areas and routine equipment (such as nebulizers)[61] was not sterilized between individual patients.[62] This led to transmission of more dangerous strains of bacteria among groups of patients. As a result, individuals with CF are now routinely isolated from one another in the healthcare setting, and healthcare providers are encouraged to wear gowns and gloves when examining patients with CF to limit the spread of virulent bacterial strains.[63]

CF patients may also have their airways chronically colonized by filamentous fungi (such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Scedosporium apiospermum, Aspergillus terreus) and/or yeasts (such as Candida albicans); other filamentous fungi less commonly isolated include Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus nidulans (occur transiently in CF respiratory secretions) and Exophiala dermatitidis and Scedosporium prolificans (chronic airway-colonizers); some filamentous fungi such as Penicillium emersonii and Acrophialophora fusispora are encountered in patients almost exclusively in the context of CF.[64] Defective mucociliary clearance characterizing CF is associated with local immunological disorders. In addition, the prolonged therapy with antibiotics and the use of corticosteroid treatments may also facilitate fungal growth. Although the clinical relevance of the fungal airway colonization is still a matter of debate, filamentous fungi may contribute to the local inflammatory response and therefore to the progressive deterioration of the lung function, as often happens with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis – the most common fungal disease in the context of CF, involving a Th2-driven immune response to Aspergillus species.[64][65]

Diagnosis[edit]

The location of the CFTR gene on chromosome 7

In many localities all newborns are screened for cystic fibrosis within the first few days of life, typically by blood test for high levels of immunoreactive trypsinogen.[66] Newborns with positive tests or those who are otherwise suspected of having cystic fibrosis based on symptoms or family history, then undergo a sweat test. An electric current is used to drive pilocarpine into the skin, stimulating sweating. The sweat is collected and analyzed for salt levels. Having unusually high levels of chloride in the sweat suggests CFTR is dysfunctional; the person is then diagnosed with cystic fibrosis.[67][note 1] Genetic testing is also available to identify the CFTR mutations typically associated with cystic fibrosis. Many laboratories can test for the 30–96 most common CFTR mutations, which can identify over 90% of people with cystic fibrosis.[67]

People with CF have less thiocyanate and hypothiocyanite in their saliva[69] and mucus (Banfi et al.). In the case of milder forms of CF, transepithelial potential difference measurements can be helpful. CF can also be diagnosed by identification of mutations in the CFTR gene.[70]

In many cases, a parent makes the diagnosis because the infant tastes salty.[18] Immunoreactive trypsinogen levels can be increased in individuals who have a single mutated copy of the CFTR gene (carriers) or, in rare instances, in individuals with two normal copies of the CFTR gene. Due to these false positives, CF screening in newborns can be controversial.[71][72]

By 2010 every US state had instituted newborn screening programs [73] and as of 2016, 21 European countries had programs in at least some regions.[74]

Prenatal[edit]

Women who are pregnant or couples planning a pregnancy can have themselves tested for the CFTR gene mutations to determine the risk that their child will be born with CF. Testing is typically performed first on one or both parents and, if the risk of CF is high, testing on the fetus is performed. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends all people thinking of becoming pregnant be tested to see if they are a carrier.[75]

Because development of CF in the fetus requires each parent to pass on a mutated copy of the CFTR gene and because CF testing is expensive, testing is often performed initially on one parent. If testing shows that parent is a CFTR gene mutation carrier, the other parent is tested to calculate the risk that their children will have CF. CF can result from more than a thousand different mutations.[43] As of 2016, typically only the most common mutations are tested for, such as ΔF508[43] Most commercially available tests look for 32 or fewer different mutations. If a family has a known uncommon mutation, specific screening for that mutation can be performed. Because not all known mutations are found on current tests, a negative screen does not guarantee that a child will not have CF.[76]

During pregnancy, testing can be performed on the placenta (chorionic villus sampling) or the fluid around the fetus (amniocentesis). However, chorionic villus sampling has a risk of fetal death of one in 100 and amniocentesis of one in 200;[77] a recent study has indicated this may be much lower, about one in 1,600.[78]

Economically, for carrier couples of cystic fibrosis, when comparing preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) with natural conception (NC) followed by prenatal testing and abortion of affected pregnancies, PGD provides net economic benefits up to a maternal age around 40 years, after which NC, prenatal testing, and abortion have higher economic benefit.[79]

Management[edit]

While no cures for CF are known, several treatment methods are used. The management of CF has improved significantly over the past 70 years. While infants born with it 70 years ago would have been unlikely to live beyond their first year, infants today are likely to live well into adulthood. Recent advances in the treatment of cystic fibrosis have meant that individuals with cystic fibrosis can live a fuller life less encumbered by their condition. The cornerstones of management are the proactive treatment of airway infection, and encouragement of good nutrition and an active lifestyle. Pulmonary rehabilitation as a management of CF continues throughout a person’s life, and is aimed at maximizing organ function, and therefore the quality of life. Occupational therapists use energy conservation techniques (ECT) in the rehabilitation process for patients with Cystic Fibrosis.[80] Examples of energy conservation techniques are ergonomic principles, pursed lip breathing, and diaphragmatic breathing.[81] Patients with CF tend to have fatigue and dyspnoea due to chronic pulmonary infections, so reducing the amount of energy spent during activities can help patients feel better and gain more independence.[80] At best, current treatments delay the decline in organ function. Because of the wide variation in disease symptoms, treatment typically occurs at specialist multidisciplinary centers and is tailored to the individual. Targets for therapy are the lungs, gastrointestinal tract (including pancreatic enzyme supplements), the reproductive organs (including assisted reproductive technology), and psychological support.[82]

The most consistent aspect of therapy in CF is limiting and treating the lung damage caused by thick mucus and infection, with the goal of maintaining quality of life. Intravenous, inhaled, and oral antibiotics are used to treat chronic and acute infections. Mechanical devices and inhalation medications are used to alter and clear the thickened mucus. These therapies, while effective, can be extremely time-consuming. Oxygen therapy at home is recommended in those with significant low oxygen levels.[83] Many people with CF use probiotics, which are thought to be able to correct intestinal dysbiosis and inflammation, but the clinical trial evidence regarding the effectiveness of probiotics for reducing pulmonary exacerbations in people with CF is uncertain.[84]

Antibiotics[edit]

Many people with CF are on one or more antibiotics at all times, even when healthy, to prophylactically suppress infection. Antibiotics are absolutely necessary whenever pneumonia is suspected or a noticeable decline in lung function is seen, and are usually chosen based on the results of a sputum analysis and the person’s past response. This prolonged therapy often necessitates hospitalization and insertion of a more permanent IV such as a peripherally inserted central catheter or Port-a-Cath. Inhaled therapy with antibiotics such as tobramycin, colistin, and aztreonam is often given for months at a time to improve lung function by impeding the growth of colonized bacteria.[85][86][87] Inhaled antibiotic therapy helps lung function by fighting infection, but also has significant drawbacks such as development of antibiotic resistance, tinnitus, and changes in the voice.[88] Inhaled levofloxacin may be used to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis who are infected.[89] The early management of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection is easier and better, using nebulised antibiotics with or without oral antibiotics may sustain its eradication up to two years.[90] When choosing antibiotics to treat CF patients with lung infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis, it is still unclear whether the choice of antibiotics should be based on the results of testing antibiotics separately (one at a time) or in combination with each other.[91]

Antibiotics by mouth such as ciprofloxacin or azithromycin are given to help prevent infection or to control ongoing infection.[92] The aminoglycoside antibiotics (e.g. tobramycin) used can cause hearing loss, damage to the balance system in the inner ear or kidney failure with long-term use.[93] To prevent these side-effects, the amount of antibiotics in the blood is routinely measured and adjusted accordingly.[94]

All these factors related to the antibiotics use, the chronicity of the disease, and the emergence of resistant bacteria demand more exploration for different strategies such as antibiotic adjuvant therapy.[95] Currently, no reliable clinical trial evidence shows the effectiveness of antibiotics for pulmonary exacerbations in people with cystic fibrosis and Burkholderia cepacia complex[96] or for the use of antibiotics to treat nontuberculous mycobacteria in people with CF.[97]

Other medication[edit]

Aerosolized medications that help loosen secretions include dornase alfa and hypertonic saline.[98] Dornase is a recombinant human deoxyribonuclease, which breaks down DNA in the sputum, thus decreasing its viscosity.[99] Dornase alpha improves lung function and probably decreases the risk of exacerbations but there is insufficient evidence to know if it is more or less effective than other similar medications.[100] Dornase alpha may improve lung function, however there is no strong evidence that it is better than other hyperosmolar therapies.[100]

Denufosol, an investigational drug, opens an alternative chloride channel, helping to liquefy mucus.[101] Whether inhaled corticosteroids are useful is unclear, but stopping inhaled corticosteroid therapy is safe.[102] There is weak evidence that corticosteroid treatment may cause harm by interfering with growth.[102] Pneumococcal vaccination has not been studied as of 2014.[103] As of 2014, there is no clear evidence from randomized controlled trials that the influenza vaccine is beneficial for people with cystic fibrosis.[104]

Ivacaftor is a medication taken by mouth for the treatment of CF due to a number of specific mutations responsive to ivacaftor-induced CFTR protein enhancement.[105][106] It improves lung function by about 10%; however, as of 2014 it is expensive.[105] The first year it was on the market, the list price was over $300,000 per year in the United States.[105][needs update] In July 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved lumacaftor/ivacaftor.[107] In 2018, the FDA approved the combination ivacaftor/tezacaftor; the manufacturer announced a list price of $292,000 per year.[108] Tezacaftor helps move the CFTR protein to the correct position on the cell surface, and is designed to treat people with the F508del mutation.[109]

In 2019, the combination drug elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor marketed as Trikafta in the United States, was approved for CF patients over the age of 12.[110][111] In 2021, this was extended to include patients over the age of 6.[112] In Europe this drug was approved in 2020 and marketed as Kaftrio.[113] It is used in those that have a f508del mutation, which occurs in about 90% of patients with cystic fibrosis.[110][114] According to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, «this medicine represents the single greatest therapeutic advancement in the history of CF, offering a treatment for the underlying cause of the disease that could eventually bring modulator therapy to 90 percent of people with CF.»[115] In a clinical trial, participants who were administered the combination drug experienced a subsequent 63% decrease in pulmonary exacerbations and a 41.8 mmol/L decrease in sweat chloride concentration.[116] By mitigating a repertoire of symptoms associated with cystic fibrosis, the combination drug significantly improved quality-of-life metrics among patients with the disease as well.[116][115] The combination drug is also known to interact with CYP3A inducers, such as carbamazepine used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, causing elexafaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor to circulate in the body at decreased concentrations. As such, concomitant use is not recommended.[117] The list price in the US is going to be $311,000 per year;[118] however, insurance may cover much of the cost of the drug.[119]

Ursodeoxycholic acid, a bile salt, has been used, however there is insufficient data to show if it is effective.[120]

Nutrient supplementation[edit]

It is uncertain whether vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation have any effect on eye and skin problems caused by vitamin A deficiency.[121]

There is no strong evidence that people with cystic fibrosis can prevent osteoporosis by increasing their intake of vitamin D.[122]

For people with vitamin E deficiency and cystic fibrosis, there is evidence that vitamin E supplementation may improve vitamin E levels, although it is still uncertain what effect supplementation has on vitamin E‐specific deficiency disorders or on lung function.[123]

Robust evidence regarding the effects of vitamin K supplementation in people with cystic fibrosis is lacking as of 2020.[124]

Various studies have examined the effects of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for people with cystic fibrosis but the evidence is uncertain whether it has any benefits or adverse effects.[125]

Procedures[edit]

Several mechanical techniques are used to dislodge sputum and encourage its expectoration. One technique good for short-term airway clearance is chest physiotherapy where a respiratory therapist percusses an individual’s chest by hand several times a day, to loosen up secretions. This «percussive effect» can be administered also through specific devices that use chest wall oscillation or intrapulmonary percussive ventilator. Other methods such as biphasic cuirass ventilation, and associated clearance mode available in such devices, integrate a cough assistance phase, as well as a vibration phase for dislodging secretions. These are portable and adapted for home use.[10]

Another technique is positive expiratory pressure physiotherapy that consists of providing a back pressure to the airways during expiration. This effect is provided by devices that consists of a mask or a mouthpiece in which a resistance is applied only on the expiration phase.[126] Operating principles of this technique seems to be the increase of gas pressure behind mucus through collateral ventilation along with a temporary increase in functional residual capacity preventing the early collapse of small airways during exhalation.[127][128]

As lung disease worsens, mechanical breathing support may become necessary. Individuals with CF may need to wear special masks at night to help push air into their lungs. These machines, known as bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) ventilators, help prevent low blood oxygen levels during sleep. Non-invasive ventilators may be used during physical therapy to improve sputum clearance.[129] It is not known if this type of therapy has an impact on pulmonary exacerbations or disease progression.[129] It is not known what role non-invasive ventilation therapy has for improving exercise capacity in people with cystic fibrosis.[129] However, the authors noted that «non‐invasive ventilation may be a useful adjunct to other airway clearance techniques, particularly in people with cystic fibrosis who have difficulty expectorating sputum.»[130] During severe illness, a tube may be placed in the throat (a procedure known as a tracheostomy) to enable breathing supported by a ventilator.[131][132]

For children, preliminary studies show massage therapy may help people and their families’ quality of life.[133]

Some lung infections require surgical removal of the infected part of the lung. If this is necessary many times, lung function is severely reduced.[134] The most effective treatment options for people with CF who have spontaneous or recurrent pneumothoraces is not clear.[135]

Transplantation[edit]

Lung transplantation may become necessary for individuals with CF as lung function and exercise tolerance decline. Although single lung transplantation is possible in other diseases, individuals with CF must have both lungs replaced because the remaining lung might contain bacteria that could infect the transplanted lung. A pancreatic or liver transplant may be performed at the same time to alleviate liver disease and/or diabetes.[136] Lung transplantation is considered when lung function declines to the point where assistance from mechanical devices is required or someone’s survival is threatened.[137] According to Merck Manual, «bilateral lung transplantation for severe lung disease is becoming more routine and more successful with experience and improved techniques. Among adults with CF, median survival posttransplant is about 9 years.»[138]

Other aspects[edit]

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection can be used to provide fertility for men with cystic fibrosis.

Newborns with intestinal obstruction typically require surgery, whereas adults with distal intestinal obstruction syndrome typically do not. Treatment of pancreatic insufficiency by replacement of missing digestive enzymes allows the duodenum to properly absorb nutrients and vitamins that would otherwise be lost in the feces. However, the best dosage and form of pancreatic enzyme replacement is unclear, as are the risks and long-term effectiveness of this treatment.[139]

So far, no large-scale research involving the incidence of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease in adults with cystic fibrosis has been conducted. This is likely because the vast majority of people with cystic fibrosis do not live long enough to develop clinically significant atherosclerosis or coronary heart disease.[140]

Diabetes is the most common nonpulmonary complication of CF. It mixes features of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and is recognized as a distinct entity, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes.[34][141] While oral antidiabetic drugs are sometimes used, the recommended treatment is the use of insulin injections or an insulin pump,[142] and, unlike in type 1 and 2 diabetes, dietary restrictions are not recommended.[34] While Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is relatively common in people with cystic fibrosis, the evidence about the effectiveness of antibiotics for S. maltophilia is uncertain.[143]

Bisphosphonates taken by mouth or intravenously can be used to improve the bone mineral density in people with cystic fibrosis.[144][needs update] When taking bisphosphates intravenously, adverse effects such as pain and flu-like symptoms can be an issue.[144] The adverse effects of bisphosphates taken by mouth on the gastrointestinal tract are not known.[144]

Poor growth may be avoided by insertion of a feeding tube for increasing food energy through supplemental feeds or by administration of injected growth hormone.[145]

Sinus infections are treated by prolonged courses of antibiotics. The development of nasal polyps or other chronic changes within the nasal passages may severely limit airflow through the nose, and over time reduce the person’s sense of smell. Sinus surgery is often used to alleviate nasal obstruction and to limit further infections. Nasal steroids such as fluticasone propionate are used to decrease nasal inflammation.[146]

Female infertility may be overcome by assisted reproduction technology, particularly embryo transfer techniques. Male infertility caused by absence of the vas deferens may be overcome with testicular sperm extraction, collecting sperm cells directly from the testicles. If the collected sample contains too few sperm cells to likely have a spontaneous fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection can be performed.[147] Third party reproduction is also a possibility for women with CF. Whether taking antioxidants affects outcomes is unclear.[148]

Physical exercise is usually part of outpatient care for people with cystic fibrosis.[149] Aerobic exercise seems to be beneficial for aerobic exercise capacity, lung function and health-related quality of life; however, the quality of the evidence was poor.[149]

Due to the use of aminoglycoside antibiotics, ototoxicity is common. Symptoms may include «tinnitus, hearing loss, hyperacusis, aural fullness, dizziness, and vertigo».[150]

Gastrointestinal[edit]

Problems with the gastrointestinal system including constipation and obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract including distal intestinal obstruction syndrome are frequent complications for people with cystic fibrosis.[29] Treatment of gastrointestinal problems is required in order to prevent a complete obstruction, reduce other CF symptoms, and improve the quality of life.[29] While stool softeners, laxatives, and prokinetics (GI-focused treatments) are often suggested, there is no clear consensus from experts at to which approach is the best and comes with the least risks.[29] Mucolytics or systemic treatments aimed at dysfunctional CFTR are also sometimes suggested to improve symptoms.[151]

Prognosis[edit]

The prognosis for cystic fibrosis has improved due to earlier diagnosis through screening and better treatment and access to health care. In 1959, the median age of survival of children with CF in the United States was six months.[152]

In 2010, survival is estimated to be 37 years for women and 40 for men.[153] In Canada, median survival increased from 24 years in 1982 to 47.7 in 2007.[154] In the United States those born with CF in 2016 have an predicted life expectancy of 47.7 when cared for in specialty clinics.[155]

In the US, of those with CF who are more than 18 years old as of 2009, 92% had graduated from high school, 67% had at least some college education, 15% were disabled, 9% were unemployed, 56% were single, and 39% were married or living with a partner.[156]

Quality of life[edit]

Chronic illnesses can be difficult to manage. CF is a chronic illness that affects the «digestive and respiratory tracts resulting in generalized malnutrition and chronic respiratory infections».[157] The thick secretions clog the airways in the lungs, which often cause inflammation and severe lung infections.[158][159] If it is compromised, it affects the quality of life of someone with CF and their ability to complete such tasks as everyday chores.[citation needed]

According to Schmitz and Goldbeck (2006), CF significantly increases emotional stress on both the individual and the family, «and the necessary time-consuming daily treatment routine may have further negative effects on quality of life».[160] However, Havermans and colleagues (2006) have established that young outpatients with CF who have participated in the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised «rated some quality of life domains higher than did their parents».[161] Consequently, outpatients with CF have a more positive outlook for themselves. As Merck Manual notes, «with appropriate support, most patients can make an age-appropriate adjustment at home and school. Despite myriad problems, the educational, occupational, and marital successes of patients are impressive.»[138]

Furthermore, there are many ways to enhance the quality of life in CF patients. Exercise is promoted to increase lung function. Integrating an exercise regimen into the CF patient’s daily routine can significantly improve quality of life.[162] No definitive cure for CF is known, but diverse medications are used, such as mucolytics, bronchodilators, steroids, and antibiotics, that have the purpose of loosening mucus, expanding airways, decreasing inflammation, and fighting lung infections, respectively.[163]

Epidemiology[edit]

| Mutation | Frequency worldwide[164] |

|---|---|

| ΔF508 | 66–70%[18] |

| G542X | 2.4% |

| G551D | 1.6% |

| N1303K | 1.3% |

| W1282X | 1.2% |

| All others | 27.5% |

Cystic fibrosis is the most common life-limiting autosomal recessive disease among people of European heritage.[165] In the United States, about 30,000 individuals have CF; most are diagnosed by six months of age. In Canada, about 4,000 people have CF.[166] Around 1 in 25 people of European descent, and one in 30 of white Americans,[167] is a carrier of a CF mutation. Although CF is less common in these groups, roughly one in 46 Hispanics, one in 65 Africans, and one in 90 Asians carry at least one abnormal CFTR gene.[168][169] Ireland has the world’s highest prevalence of CF, at one in 1353.[170]

Although technically a rare disease, CF is ranked as one of the most widespread life-shortening genetic diseases. It is most common among nations in the Western world. An exception is Finland, where only one in 80 people carries a CF mutation.[171] The World Health Organization states, «In the European Union, one in 2000–3000 newborns is found to be affected by CF».[172] In the United States, one in 3,500 children is born with CF.[173] In 1997, about one in 3,300 white children in the United States was born with CF. In contrast, only one in 15,000 African American children have it, and in Asian Americans, the rate was even lower at one in 32,000.[174]

Cystic fibrosis is diagnosed equally in males and females. For reasons that remain unclear, data have shown that males tend to have a longer life expectancy than females,[175][176] though recent studies suggest this gender gap may no longer exist, perhaps due to improvements in health care facilities.[177][178] A recent study from Ireland identified a link between the female hormone estrogen and worse outcomes in CF.[179]

The distribution of CF alleles varies among populations. The frequency of ΔF508 carriers has been estimated at one in 200 in northern Sweden, one in 143 in Lithuanians, and one in 38 in Denmark. No ΔF508 carriers were found among 171 Finns and 151 Saami people.[180] ΔF508 does occur in Finland, but it is a minority allele there. CF is known to occur in only 20 families (pedigrees) in Finland.[181]

Evolution[edit]

The ΔF508 mutation is estimated to be up to 52,000 years old.[182] Numerous hypotheses have been advanced as to why such a lethal mutation has persisted and spread in the human population. Other common autosomal recessive diseases such as sickle-cell anemia have been found to protect carriers from other diseases, an evolutionary trade-off known as heterozygote advantage. Resistance to the following have all been proposed as possible sources of heterozygote advantage:

- Cholera: With the discovery that cholera toxin requires normal host CFTR proteins to function properly, it was hypothesized that carriers of mutant CFTR genes benefited from resistance to cholera and other causes of diarrhea.[183][184] Further studies have not confirmed this hypothesis.[185][186]

- Typhoid: Normal CFTR proteins are also essential for the entry of Salmonella Typhi into cells,[187] suggesting that carriers of mutant CFTR genes might be resistant to typhoid fever. No in vivo study has yet confirmed this. In both cases, the low level of cystic fibrosis outside of Europe, in places where both cholera and typhoid fever are endemic, is not immediately explicable.

- Diarrhea: The prevalence of CF in Europe might be connected with the development of cattle domestication. In this hypothesis, carriers of a single mutant CFTR had some protection from diarrhea caused by lactose intolerance, before the mutations that created lactose tolerance appeared.[188]

- Tuberculosis: Another possible explanation is that carriers of the gene could have some resistance to tuberculosis.[189][190] This hypothesis is based on the thesis that CFTR gene mutation carriers have insufficient action in one of their enzymes – arylsulphatase — which is necessary for Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. As M. tuberculosis would use its host’s sources to affect the individual, and due to the lack of enzyme it could not presents its virulence, being a carrier of CFTR mutation could provide resistance against tuberculosis.[191]

History[edit]

CF is supposed to have appeared about 3,000 BC because of migration of peoples, gene mutations, and new conditions in nourishment.[192] Although the entire clinical spectrum of CF was not recognized until the 1930s, certain aspects of CF were identified much earlier. Indeed, literature from Germany and Switzerland in the 18th century warned «Wehe dem Kind, das beim Kuß auf die Stirn salzig schmeckt, es ist verhext und muss bald sterben» («Woe to the child who tastes salty from a kiss on the brow, for he is cursed and soon must die»), recognizing the association between the salt loss in CF and illness.[192]

In the 19th century, Carl von Rokitansky described a case of fetal death with meconium peritonitis, a complication of meconium ileus associated with CF. Meconium ileus was first described in 1905 by Karl Landsteiner.[192] In 1936, Guido Fanconi described a connection between celiac disease, cystic fibrosis of the pancreas, and bronchiectasis.[193]

In 1938, Dorothy Hansine Andersen published an article, «Cystic Fibrosis of the Pancreas and Its Relation to Celiac Disease: a Clinical and Pathological Study», in the American Journal of Diseases of Children. She was the first to describe the characteristic cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and to correlate it with the lung and intestinal disease prominent in CF.[12] She also first hypothesized that CF was a recessive disease and first used pancreatic enzyme replacement to treat affected children. In 1952, Paul di Sant’Agnese discovered abnormalities in sweat electrolytes; a sweat test was developed and improved over the next decade.[194]

The first linkage between CF and another marker (paraoxonase) was found in 1985 by Hans Eiberg, indicating that only one locus exists for CF. In 1988, the first mutation for CF, ΔF508, was discovered by Francis Collins, Lap-Chee Tsui, and John R. Riordan on the seventh chromosome. Subsequent research has found over 1,000 different mutations that cause CF.[citation needed]

Because mutations in the CFTR gene are typically small, classical genetics techniques had been unable to accurately pinpoint the mutated gene.[195] Using protein markers, gene-linkage studies were able to map the mutation to chromosome 7. Chromosome walking and chromosome jumping techniques were then used to identify and sequence the gene.[196] In 1989, Lap-Chee Tsui led a team of researchers at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto that discovered the gene responsible for CF. CF represents a classic example of how a human genetic disorder was elucidated strictly by the process of forward genetics.[citation needed]

Research[edit]

People with CF may be listed in a disease registry that allows researchers and doctors to track health results and identify candidates for clinical trials.[197]

Gene therapy[edit]

Gene therapy has been explored as a potential cure for CF. Results from clinical trials have shown limited success as of 2016, and using gene therapy as routine therapy is not suggested.[198] A small study published in 2015 found a small benefit.[199]

The focus of much CF gene therapy research is aimed at trying to place a normal copy of the CFTR gene into affected cells. Transferring the normal CFTR gene into the affected epithelium cells would result in the production of functional CFTR protein in all target cells, without adverse reactions or an inflammation response. To prevent the lung manifestations of CF, only 5–10% the normal amount of CFTR gene expression is needed.[200] Multiple approaches have been tested for gene transfer, such as liposomes and viral vectors in animal models and clinical trials. However, both methods were found to be relatively inefficient treatment options,[201] mainly because very few cells take up the vector and express the gene, so the treatment has little effect. Additionally, problems have been noted in cDNA recombination, such that the gene introduced by the treatment is rendered unusable.[202] There has been a functional repair in culture of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients.[203]

Phage therapy[edit]

Phage therapy is being studied for multidrug resistant bacteria in people with CF.[204][205]

Gene modulators[edit]

A number of small molecules that aim at compensating various mutations of the CFTR gene are under development. CFTR modulator therapies have been used in place of other types of genetic therapies. These therapies focus on the expression of a genetic mutation instead of the mutated gene itself. Modulators are split into two classes: potentiators and correctors. Potentiators act on the CFTR ion channels that are embedded in the cell membrane, and these types of drugs help open up the channel to allow transmembrane flow. Correctors are meant to assist in the transportation of nascent proteins, a protein that is formed by ribosomes before it is morphed into a specific shape, to the cell surface to be implemented into the cell membrane.[206]

Most target the transcription stage of genetic expression. One approach has been to try and develop medication that get the ribosome to overcome the stop codon and produce a full-length CFTR protein. About 10% of CF results from a premature stop codon in the DNA, leading to early termination of protein synthesis and truncated proteins. These drugs target nonsense mutations such as G542X, which consists of the amino acid glycine in position 542 being replaced by a stop codon. Aminoglycoside antibiotics interfere with protein synthesis and error-correction. In some cases, they can cause the cell to overcome a premature stop codon by inserting a random amino acid, thereby allowing expression of a full-length protein. Future research for these modulators is focused on the cellular targets that can be effected by a change in a gene’s expression. Otherwise, genetic therapy will be used as a treatment when modulator therapies do not work given that 10% of people with cystic fibrosis are not affected by these drugs.[207]

Elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor was approved in the United States in 2019 for cystic fibrosis.[208] This combination of previously developed medicines is able to treat up to 90% of people with cystic fibrosis.[206][208] This medications restores some effectiveness of the CFTR protein so that it can work as an ion channel on the cell’s surface.[209]

Ecological therapy[edit]

It has previously been shown that inter-species interactions are an important contributor to the pathology of CF lung infections. Examples include the production of antibiotic degrading enzymes such as β-lactamases and the production of metabolic by-products such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by anaerobic species, which can enhance the pathogenicity of traditional pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[210] Due to this, it has been suggested that the direct alteration of CF microbial community composition and metabolic function would provide an alternative to traditional antibiotic therapies.[56]

Society and culture[edit]

- Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life a posthumous memoir by Mallory Smith, a Californian with CF

- Sick: The Life and Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist, a 1997 documentary film

- 65 Redroses, a 2009 documentary film

- Breathing for a Living, a memoir by Laura Rothenberg

- Every Breath I Take, Surviving and Thriving With Cystic Fibrosis, book by Claire Wineland

- Five Feet Apart, a 2019 romantic drama film starring Cole Sprouse and Haley Lu Richardson

- Orla Tinsley: Warrior, a 2018 documentary film about CF campaigner Orla Tinsley

- The performance art of Martin O’Brien

- Continent Chasers, a traveller and CF patient documenting travel and CF blogs, continentchasers.com

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation recommends a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis for anyone suspected of cystic fibrosis (positive newborn screen, symptoms of cystic fibrosis, or a family history of cystic fibrosis) with sweat chloride above 60 millimoles/liter. Those with less than 30 millimoles/liter sweat chloride are unlikely to develop cystic fibrosis. For people with intermediate sweat chloride between 30 and 59 millimoles/liter, they recommend additional genetic testing.[68]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD (May 2009). «Cystic fibrosis». Lancet. 373 (9678): 1891–904. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60327-5. PMID 19403164. S2CID 46011502.

- ^ Allen JL, Panitch HB, Rubenstein RC (2016). Cystic Fibrosis. CRC Press. p. 92. ISBN 9781439801826. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Massie J, Delatycki MB (December 2013). «Cystic fibrosis carrier screening». Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 14 (4): 270–5. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2012.12.002. PMID 23466339.

- ^ a b Ong T, Ramsey BW (September 2015). «Update in Cystic Fibrosis 2014». American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 192 (6): 669–75. doi:10.1164/rccm.201504-0656UP. PMID 26371812.

- ^ Sencen L. «Cystic Fibrosis». NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ «Orphanet: Cystic fibrosis». www.orpha.net. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Hodson M, Geddes D, Bush A, eds. (2012). Cystic Fibrosis (3rd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4441-1369-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Buckingham L (2012). Molecular Diagnostics: Fundamentals, Methods and Clinical Applications (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8036-2975-2. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, Simon RH, Rodman D (January 2004). «Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report». Chest. 125 (1 Suppl): 1S–39S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.562.1904. doi:10.1378/chest.125.1_suppl.1S. PMID 14734689.

- ^ a b Warnock L, Gates A (December 2015). «Chest physiotherapy compared to no chest physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (12): CD001401. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001401.pub3. PMC 6768986. PMID 26688006.

- ^ Nazareth D, Walshaw M (October 2013). «Coming of age in cystic fibrosis — transition from paediatric to adult care». Clinical Medicine. 13 (5): 482–6. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.13-5-482. PMC 4953800. PMID 24115706.

- ^ a b Andersen DH (1938). «Cystic fibrosis of the pancreas and its relation to celiac disease: a clinical and pathological study». Am. J. Dis. Child. 56 (2): 344–99. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1938.01980140114013.

- ^ a b c d Egan, Schechter & Voynow 2020, «Clinical Manifestations».

- ^ a b c d e f Egan, Schechter & Voynow 2020, «Respiratory Tract».

- ^ Shteinberg M, Haq IJ, Polineni D, Davies JC (June 2021). «Cystic fibrosis». Lancet. 397 (10290): 2195–2211. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32542-3. PMID 34090606. S2CID 235327978.

- ^ Reaves J, Wallace G (2010). «Unexplained bruising: weighing the pros and cons of possible causes». Consultant for Pediatricians. 9: 201–2. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ, Robinson KA, Rosenblatt RL, Quittell L, Marshall BC (August 2010). «Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: pulmonary complications: hemoptysis and pneumothorax». American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 182 (3): 298–306. doi:10.1164/rccm.201002-0157OC. PMID 20675678.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Robbins SL, et al. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1253, 1254. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ a b c d Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ (May 2005). «Cystic fibrosis». The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (19): 1992–2001. doi:10.1056/NEJMra043184. PMID 15888700.

- ^ Saiman L, Siegel J (January 2004). «Infection control in cystic fibrosis». Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 17 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.1.57-71.2004. PMC 321464. PMID 14726455.

- ^ Girón RM, Domingo D, Buendía B, Antón E, Ruiz-Velasco LM, Ancochea J (October 2005). «[Nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis]». Archivos de Bronconeumologia (in Spanish). 41 (10): 560–5. doi:10.1016/S1579-2129(06)60283-8. PMID 16266669.

- ^ Franco LP, Camargos PA, Becker HM, Guimarães RE (2009). «Nasal endoscopic evaluation of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis». Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 75 (6): 806–13. doi:10.1590/S1808-86942009000600006. PMC 9446041. PMID 20209279.

- ^ Maldonado M, Martínez A, Alobid I, Mullol J (December 2004). «The antrochoanal polyp». Rhinology. 42 (4): 178–82. PMID 15626248.

- ^ Ramsey B, Richardson MA (September 1992). «Impact of sinusitis in cystic fibrosis». The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 90 (3 Pt 2): 547–52. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(92)90183-3. PMID 1527348.

- ^ Kulczycki LL, Shwachman H (August 1958). «Studies in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas; occurrence of rectal prolapse». The New England Journal of Medicine. 259 (9): 409–12. doi:10.1056/NEJM195808282590901. PMID 13578072.

- ^ Cohn JA, Friedman KJ, Noone PG, Knowles MR, Silverman LM, Jowell PS (September 1998). «Relation between mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene and idiopathic pancreatitis». The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (10): 653–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199809033391002. PMID 9725922.

- ^ a b c Assis DN, Freedman SD (March 2016). «Gastrointestinal Disorders in Cystic Fibrosis». Clinics in Chest Medicine (Review). 37 (1): 109–118. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.11.004. PMID 26857772.

- ^ Malfroot A, Dab I (November 1991). «New insights on gastro-oesophageal reflux in cystic fibrosis by longitudinal follow up». Archives of Disease in Childhood. 66 (11): 1339–1345. doi:10.1136/adc.66.11.1339. PMC 1793275. PMID 1755649.

- ^ a b c d Carroll W, Green J, Gilchrist FJ (December 2021). «Interventions for preventing distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS) in cystic fibrosis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (12): CD012619. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012619.pub3. PMC 8693853. PMID 34936085.

- ^ Williams SG, Westaby D, Tanner MS, Mowat AP (October 1992). «Liver and biliary problems in cystic fibrosis». British Medical Bulletin. 48 (4): 877–92. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072583. PMID 1458306.

- ^ Colombo C, Russo MC, Zazzeron L, Romano G (July 2006). «Liver disease in cystic fibrosis». Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 43 (Suppl 1): S49-55. doi:10.1097/01.mpg.0000226390.02355.52. PMID 16819402. S2CID 27836468.

- ^ Egan, Schechter & Voynow 2020, «Biliary Tract».

- ^ Moran A, Pyzdrowski KL, Weinreb J, Kahn BB, Smith SA, Adams KS, Seaquist ER (August 1994). «Insulin sensitivity in cystic fibrosis». Diabetes. 43 (8): 1020–6. doi:10.2337/diabetes.43.8.1020. PMID 8039595.

- ^ a b c de Aragão Dantas Alves C, Aguiar RA, Alves AC, Santana MA (2007). «Diabetes mellitus in patients with cystic fibrosis». Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 33 (2): 213–21. doi:10.1590/S1806-37132007000200017. PMID 17724542.

- ^ Haworth CS, Selby PL, Webb AK, Dodd ME, Musson H, McL Niven R, et al. (November 1999). «Low bone mineral density in adults with cystic fibrosis». Thorax. 54 (11): 961–7. doi:10.1136/thx.54.11.961. PMC 1745400. PMID 10525552.

- ^ McCallum TJ, Milunsky JM, Cunningham DL, Harris DH, Maher TA, Oates RD (October 2000). «Fertility in men with cystic fibrosis: an update on current surgical practices and outcomes». Chest. 118 (4): 1059–62. doi:10.1378/chest.118.4.1059. PMID 11035677.

- ^ Chen H, Ruan YC, Xu WM, Chen J, Chan HC (2012). «Regulation of male fertility by CFTR and implications in male infertility». Human Reproduction Update. 18 (6): 703–13. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms027. PMID 22709980.

- ^ Augarten A, Yahav Y, Kerem BS, Halle D, Laufer J, Szeinberg A, et al. (November 1994). «Congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens in the absence of cystic fibrosis». Lancet. 344 (8935): 1473–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90292-5. PMID 7968122. S2CID 28860665.

- ^ Gilljam M, Antoniou M, Shin J, Dupuis A, Corey M, Tullis DE (July 2000). «Pregnancy in cystic fibrosis. Fetal and maternal outcome». Chest. 118 (1): 85–91. doi:10.1378/chest.118.1.85. PMID 10893364. S2CID 32289370.

- ^ Guimbellot J, Sharma J, Rowe SM (November 2017). «Toward inclusive therapy with CFTR modulators: Progress and challenges». Pediatric Pulmonology. 52 (S48): S4–S14. doi:10.1002/ppul.23773. PMC 6208153. PMID 28881097.

- ^ Sharma J, Keeling KM, Rowe SM (August 2020). «Pharmacological approaches for targeting cystic fibrosis nonsense mutations». European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 200: 112436. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112436. PMC 7384597. PMID 32512483.

- ^ Bobadilla JL, Macek M, Fine JP, Farrell PM (June 2002). «Cystic fibrosis: a worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations—correlation with incidence data and application to screening». Human Mutation. 19 (6): 575–606. doi:10.1002/humu.10041. PMID 12007216. S2CID 35428054.

- ^ a b c Elborn JS (November 2016). «Cystic fibrosis». Lancet. 388 (10059): 2519–2531. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00576-6. PMID 27140670. S2CID 20948144.

- ^ Short DB, Trotter KW, Reczek D, Kreda SM, Bretscher A, Boucher RC, et al. (July 1998). «An apical PDZ protein anchors the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to the cytoskeleton». The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (31): 19797–801. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.31.19797. PMID 9677412.

- ^ Travaglini KJ, Krasnow MA (August 2018). «Profile of an unknown airway cell». Nature. 560 (7718): 313–314. Bibcode:2018Natur.560..313T. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05813-7. PMID 30097657.

- ^ a b Edwards QT, Seibert D, Macri C, Covington C, Tilghman J (November 2004). «Assessing ethnicity in preconception counseling: genetics—what nurse practitioners need to know». Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 16 (11): 472–80. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2004.tb00426.x. PMID 15617360. S2CID 7644129.

- ^ Wang XR, Li C (May 2014). «Decoding F508del misfolding in cystic fibrosis». Biomolecules. 4 (2): 498–509. doi:10.3390/biom4020498. PMC 4101494. PMID 24970227.

- ^ Childers M, Eckel G, Himmel A, Caldwell J (2007). «A new model of cystic fibrosis pathology: lack of transport of glutathione and its thiocyanate conjugates». Medical Hypotheses. 68 (1): 101–12. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.06.020. PMID 16934416.

- ^ Xu Y, Szép S, Lu Z (December 2009). «The antioxidant role of thiocyanate in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis and other inflammation-related diseases». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (48): 20515–9. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620515X. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911412106. PMC 2777967. PMID 19918082.

- ^ Moskwa P, Lorentzen D, Excoffon KJ, Zabner J, McCray PB, Nauseef WM, et al. (January 2007). «A novel host defense system of airways is defective in cystic fibrosis». American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 175 (2): 174–83. doi:10.1164/rccm.200607-1029OC. PMC 2720149. PMID 17082494.

- ^ Conner GE, Wijkstrom-Frei C, Randell SH, Fernandez VE, Salathe M (January 2007). «The lactoperoxidase system links anion transport to host defense in cystic fibrosis». FEBS Letters. 581 (2): 271–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.025. PMC 1851694. PMID 17204267.

- ^ Haq IJ, Gray MA, Garnett JP, Ward C, Brodlie M (March 2016). «Airway surface liquid homeostasis in cystic fibrosis: pathophysiology and therapeutic targets». Thorax. 71 (3): 284–287. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207588. PMID 26719229.

- ^ Verkman AS, Song Y, Thiagarajah JR (January 2003). «Role of airway surface liquid and submucosal glands in cystic fibrosis lung disease». American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 284 (1): C2-15. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00417.2002. PMID 12475759. S2CID 11790119.

- ^ Marieb EN, Hoehn K, Hutchinson M (2014). «22: The Respiratory System». Human Anatomy and Physiology. Pearson Education. p. 906. ISBN 978-0805361179.

- ^ a b Saiman L (2004). «Microbiology of early CF lung disease». Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 5 (Suppl A): S367-9. doi:10.1016/S1526-0542(04)90065-6. PMID 14980298.

- ^ a b Khanolkar RA, Clark ST, Wang PW, et al. (2020). «Ecological Succession of Polymicrobial Communities in the Cystic Fibrosis Airways». mSystems. 5 (6): e00809-20. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00809-20. PMC 7716390. PMID 33262240.

- ^ a b Lorè NI, Cigana C, Riva C, De Fino I, Nonis A, Spagnuolo L, et al. (May 2016). «IL-17A impairs host tolerance during airway chronic infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa». Scientific Reports. 6: 25937. Bibcode:2016NatSR…625937L. doi:10.1038/srep25937. PMC 4870500. PMID 27189736.

- ^ Tümmler B, Koopmann U, Grothues D, Weissbrodt H, Steinkamp G, von der Hardt H (June 1991). «Nosocomial acquisition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by cystic fibrosis patients». Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 29 (6): 1265–7. Bibcode:1991JPoSA..29.1265A. doi:10.1002/pola.1991.080290905. PMC 271975. PMID 1907611.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (June 1993). «Pseudomonas cepacia at summer camps for persons with cystic fibrosis». MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 42 (23): 456–9. PMID 7684813.

- ^ Pegues DA, Carson LA, Tablan OC, FitzSimmons SC, Roman SB, Miller JM, Jarvis WR (May 1994). «Acquisition of Pseudomonas cepacia at summer camps for patients with cystic fibrosis. Summer Camp Study Group». The Journal of Pediatrics. 124 (5 Pt 1): 694–702. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81357-5. PMID 7513755.

- ^ Pankhurst CL, Philpott-Howard J (April 1996). «The environmental risk factors associated with medical and dental equipment in the transmission of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia in cystic fibrosis patients». The Journal of Hospital Infection. 32 (4): 249–55. doi:10.1016/S0195-6701(96)90035-3. PMID 8744509.

- ^ Jones AM, Govan JR, Doherty CJ, Dodd ME, Isalska BJ, Stanbridge TN, Webb AK (June 2003). «Identification of airborne dissemination of epidemic multiresistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa at a CF centre during a cross infection outbreak». Thorax. 58 (6): 525–7. doi:10.1136/thorax.58.6.525. PMC 1746694. PMID 12775867.

- ^ Høiby N (June 1995). «Isolation and treatment of cystic fibrosis patients with lung infections caused by Pseudomonas (Burkholderia) cepacia and multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa». The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 46 (6): 280–7. doi:10.1016/0300-2977(95)00020-N. PMID 7643943.

- ^ a b Pihet M, Carrere J, Cimon B, Chabasse D, Delhaes L, Symoens F, Bouchara JP (June 2009). «Occurrence and relevance of filamentous fungi in respiratory secretions of patients with cystic fibrosis—a review». Medical Mycology. 47 (4): 387–97. doi:10.1080/13693780802609604. PMID 19107638.

- ^ Rapaka RR, Kolls JK (2009). «Pathogenesis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis: current understanding and future directions». Medical Mycology. 47 (Suppl 1): S331-7. doi:10.1080/13693780802266777. PMID 18668399.

- ^ «Newborn Screening for CF». Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ a b Egan, Schechter & Voynow 2020, «Diagnosis and Assessment».

- ^ Farrell PM, White TB, Ren CL, Hempstead SE, Accurso F, Derichs N, Howenstine M, McColley SA, Rock M, Rosenfeld M, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Southern KW, Marshall BC, Sosnay PR (February 2017). «Diagnosis of Cystic Fibrosis: Consensus Guidelines from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation». J Pediatr. 181S: S4–S15.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.064. PMID 28129811. S2CID 206410545.

- ^ Minarowski Ł, Sands D, Minarowska A, Karwowska A, Sulewska A, Gacko M, Chyczewska E (2008). «Thiocyanate concentration in saliva of cystic fibrosis patients». Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica. 46 (2): 245–6. doi:10.2478/v10042-008-0037-0. PMID 18519245.

- ^ Stern RC (February 1997). «The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis». The New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (7): 487–91. doi:10.1056/NEJM199702133360707. PMID 9017943.

- ^ Ross LF (September 2008). «Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: a lesson in public health disparities». The Journal of Pediatrics. 153 (3): 308–13. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.061. PMC 2569148. PMID 18718257.

- ^ Assael BM, Castellani C, Ocampo MB, Iansa P, Callegaro A, Valsecchi MG (September 2002). «Epidemiology and survival analysis of cystic fibrosis in an area of intense neonatal screening over 30 years». American Journal of Epidemiology. 156 (5): 397–401. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf064. PMID 12196308.

- ^ Hoch H, Sontag MK, Scarbro S, Juarez-Colunga E, McLean C, Kempe A, Sagel SD (November 2018). «Clinical outcomes in U.S. infants with cystic fibrosis from 2001 to 2012». Pediatric Pulmonology. 53 (11): 1492–1497. doi:10.1002/ppul.24165. PMID 30259702. S2CID 52845580.

- ^ Barben, Jürg, et al. (2017). «The expansion and performance of national newborn screening programmes for cystic fibrosis in Europe». Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 16 (2): 207–13. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2016.12.012. PMID 28043799.

- ^ «Carrier Screening in the Age of Genomic Medicine». American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2017. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Elias S, Annas GJ, Simpson JL (April 1991). «Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: implications for obstetric and gynecologic practice». American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 164 (4): 1077–83. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(91)90589-j. PMID 2014829.

- ^ Tabor A, Philip J, Madsen M, Bang J, Obel EB, Nørgaard-Pedersen B (June 1986). «Randomised controlled trial of genetic amniocentesis in 4606 low-risk women». Lancet. 1 (8493): 1287–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91218-3. PMID 2423826. S2CID 31237495.

- ^ Eddleman KA, Malone FD, Sullivan L, Dukes K, Berkowitz RL, Kharbutli Y, et al. (November 2006). «Pregnancy loss rates after midtrimester amniocentesis». Obstetrics and Gynecology. 108 (5): 1067–72. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000240135.13594.07. PMID 17077226. S2CID 19081825.

- ^ Davis LB, Champion SJ, Fair SO, Baker VL, Garber AM (April 2010). «A cost-benefit analysis of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for carrier couples of cystic fibrosis». Fertility and Sterility. 93 (6): 1793–804. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.053. PMID 19439290.

- ^ a b «Abstracts from the 25th Italian Congress of Cystic Fibrosis and the 15th National Congress of Cystic Fibrosis Italian Society : Assago, Milan. 10 — 12 October 2019». Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 46 (Suppl 1): 32. April 2020. doi:10.1186/s13052-020-0790-z. PMC 7110616. PMID 32234058.

- ^

- ^ Davies JC, Alton EW, Bush A (December 2007). «Cystic fibrosis». BMJ. 335 (7632): 1255–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39391.713229.AD. PMC 2137053. PMID 18079549.