|

Other native names

|

|

|---|---|

Satellite image, 2012, with Ireland to the west and France to the south-east |

|

|

|

| Geography | |

| Location | North-western Europe |

| Coordinates | 54°N 2°W / 54°N 2°WCoordinates: 54°N 2°W / 54°N 2°W |

| Archipelago | British Isles |

| Adjacent to | Atlantic Ocean |

| Area | 209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi)[1] |

| Area rank | 9th |

| Highest elevation | 1,345 m (4413 ft) |

| Highest point | Ben Nevis[2] |

| Administration | |

|

United Kingdom |

|

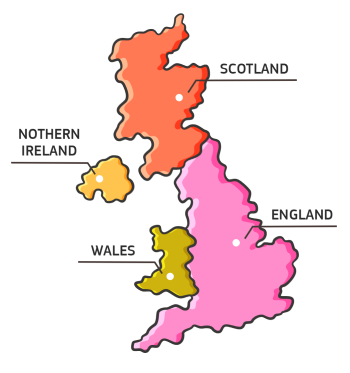

| Countries |

|

| Largest city | London (pop. 8,878,892) |

| Demographics | |

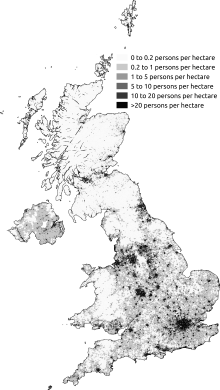

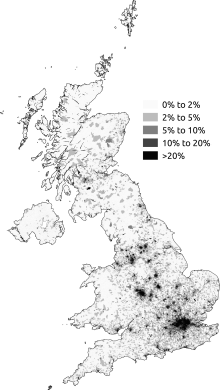

| Population | 60,800,000 (2011 census)[3] |

| Population rank | 3rd |

| Pop. density | 302/km2 (782/sq mi) |

| Languages |

|

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| • Summer (DST) |

|

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe. With an area of 209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi), it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world.[6][note 1] It is dominated by a maritime climate with narrow temperature differences between seasons. The 60% smaller island of Ireland is to the west—these islands, along with over 1,000 smaller surrounding islands and named substantial rocks, form the British Isles archipelago.[8]

Connected to mainland Europe until 9,000 years ago by a landbridge now known as Doggerland,[9] Great Britain has been inhabited by modern humans for around 30,000 years. In 2011, it had a population of about 61 million, making it the world’s third-most-populous island after Java in Indonesia and Honshu in Japan.[10][11]

The term «Great Britain» can also refer to the political territory of England, Scotland and Wales, which includes their offshore islands.[12] Great Britain and Northern Ireland constitute the United Kingdom.[13] The single Kingdom of Great Britain resulted from the 1707 Acts of Union between the kingdoms of England (which at the time incorporated Wales) and Scotland.

Terminology

Toponymy

The archipelago has been referred to by a single name for over 2000 years: the term ‘British Isles’ derives from terms used by classical geographers to describe this island group. By 50 BC Greek geographers were using equivalents of Prettanikē as a collective name for the British Isles.[14] However, with the Roman conquest of Britain the Latin term Britannia was used for the island of Great Britain, and later Roman-occupied Britain south of Caledonia.[15][16][17]

The earliest known name for Great Britain is Albion (Greek: Ἀλβιών) or insula Albionum, from either the Latin albus meaning «white» (possibly referring to the white cliffs of Dover, the first view of Britain from the continent) or the «island of the Albiones«.[18] The oldest mention of terms related to Great Britain was by Aristotle (384–322 BC), or possibly by Pseudo-Aristotle, in his text On the Universe, Vol. III. To quote his works, «There are two very large islands in it, called the British Isles, Albion and Ierne».[19]

The first known written use of the word Britain was an ancient Greek transliteration of the original P-Celtic term in a work on the travels and discoveries of Pytheas that has not survived. The earliest existing records of the word are quotations of the periplus by later authors, such as those within Strabo’s Geographica, Pliny’s Natural History and Diodorus of Sicily’s Bibliotheca historica.[20] Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) in his Natural History records of Great Britain: «Its former name was Albion; but at a later period, all the islands, of which we shall just now briefly make mention, were included under the name of ‘Britanniæ.'»[21]

The name Britain descends from the Latin name for Britain, Britannia or Brittānia, the land of the Britons. Old French Bretaigne (whence also Modern French Bretagne) and Middle English Bretayne, Breteyne. The French form replaced the Old English Breoton, Breoten, Bryten, Breten (also Breoton-lond, Breten-lond). Britannia was used by the Romans from the 1st century BC for the British Isles taken together. It is derived from the travel writings of Pytheas around 320 BC, which described various islands in the North Atlantic as far north as Thule (probably Norway).

The peoples of these islands of Prettanike were called the Πρεττανοί, Priteni or Pretani.[18]

Priteni is the source of the Welsh language term Prydain, Britain, which has the same source as the Goidelic term Cruithne used to refer to the early Brythonic-speaking inhabitants of Ireland.[22] The latter were later called Picts or Caledonians by the Romans. Greek historians Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo preserved variants of Prettanike from the work of Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia, who travelled from his home in Hellenistic southern Gaul to Britain in the 4th century BC. The term used by Pytheas may derive from a Celtic word meaning «the painted ones» or «the tattooed folk» in reference to body decorations.[23] According to Strabo, Pytheas referred to Britain as Bretannikē, which is treated a feminine noun.[24][25][26][27] Marcian of Heraclea, in his Periplus maris exteri, described the island group as αἱ Πρεττανικαὶ νῆσοι (the Prettanic Isles).[28]

Derivation of Great

A 1490 Italian reconstruction of the relevant map of Ptolemy who combined the lines of roads and of the coasting expeditions during the first century of Roman occupation. Two great faults, however, are an eastward-projecting Scotland and none of Ireland seen to be at the same latitude of Wales, which may have been if Ptolemy used Pytheas’ measurements of latitude.[29] Whether he did so is a much debated issue. This «copy» appears in blue below.

The Greco-Egyptian scientist Ptolemy referred to the larger island as great Britain (μεγάλη Βρεττανία megale Brettania) and to Ireland as little Britain (μικρὰ Βρεττανία mikra Brettania) in his work Almagest (147–148 AD).[30] In his later work, Geography (c. 150 AD), he gave the islands the names Alwion, Iwernia, and Mona (the Isle of Man),[31] suggesting these may have been the names of the individual islands not known to him at the time of writing Almagest.[32] The name Albion appears to have fallen out of use sometime after the Roman conquest of Britain, after which Britain became the more commonplace name for the island.[18]

After the Anglo-Saxon period, Britain was used as a historical term only. Geoffrey of Monmouth in his pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) refers to the

island of Great Britain as Britannia major («Greater Britain»), to distinguish it from Britannia minor («Lesser Britain»), the continental region which approximates to modern Brittany, which had been settled in the fifth and sixth centuries by Celtic Briton migrants from Great Britain.[citation needed]

The term Great Britain was first used officially in 1474, in the instrument drawing up the proposal for a marriage between Cecily, daughter of Edward IV of England, and James, son of James III of Scotland, which described it as «this Nobill Isle, callit Gret Britanee». While promoting a possible royal match in 1548, Lord Protector Somerset said that the English and Scots were, «like as twoo brethren of one Islande of great Britaynes again.» In 1604, James VI and I styled himself «King of Great Brittaine, France and Ireland».[33]

Modern use of the term Great Britain

Great Britain refers geographically to the island of Great Britain. Politically, it may refer to the whole of England, Scotland and Wales, including their smaller offshore islands.[34] It is not technically correct to use the term to refer to the whole of the United Kingdom which includes Northern Ireland, though the Oxford English Dictionary states «…the term is also used loosely to refer to the United Kingdom.»[35][36]

Similarly, Britain can refer to either all islands in Great Britain, the largest island, or the political grouping of countries.[37] There is no clear distinction, even in government documents: the UK government yearbooks have used both Britain[38] and United Kingdom.[39]

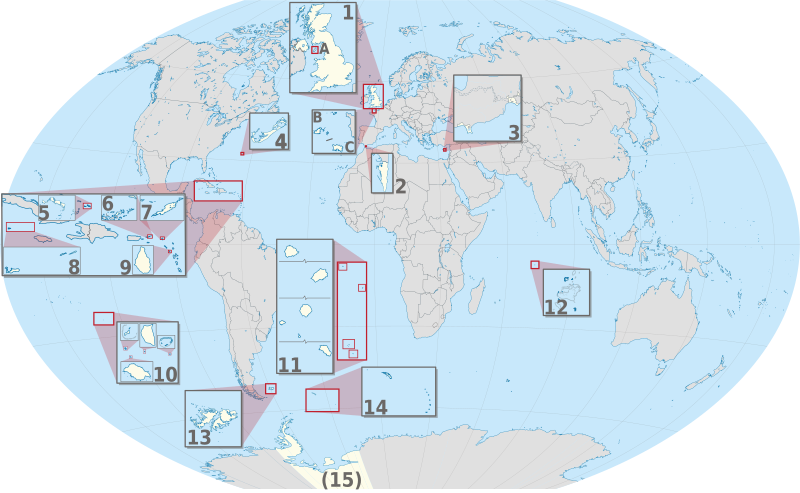

GB and GBR are used instead of UK in some international codes to refer to the United Kingdom, including the Universal Postal Union, international sports teams, NATO, and the International Organization for Standardization country codes ISO 3166-2 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-3, whilst the aircraft registration prefix is G.

On the Internet, .uk is the country code top-level domain for the United Kingdom. A .gb top-level domain was used to a limited extent, but is now deprecated; although existing registrations still exist (mainly by government organizations and email providers), the domain name registrar will not take new registrations.

In the Olympics, Team GB is used by the British Olympic Association to represent the British Olympic team. The Olympic Federation of Ireland represents the whole island of Ireland, and Northern Irish sportspeople may choose to compete for either team,[40] most choosing to represent Ireland.[41]

Political definition

Political definition of Great Britain (dark green)

– in Europe (green & dark grey)

Politically, Great Britain refers to the whole of England, Scotland and Wales in combination,[42] but not Northern Ireland; it includes islands, such as the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, the Isles of Scilly, the Hebrides and the island groups of Orkney and Shetland, that are part of England, Wales, or Scotland. It does not include the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.[42][43]

The political union that joined the kingdoms of England and Scotland happened in 1707 when the Acts of Union ratified the 1706 Treaty of Union and merged the parliaments of the two nations, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain, which covered the entire island. Before this, a personal union had existed between these two countries since the 1603 Union of the Crowns under James VI of Scotland and I of England.[citation needed]

History

Prehistoric period

Great Britain was probably first inhabited by those who crossed on the land bridge from the European mainland. Human footprints have been found from over 800,000 years ago in Norfolk[44] and traces of early humans have been found (at Boxgrove Quarry, Sussex) from some 500,000 years ago[45] and modern humans from about 30,000 years ago. Until about 16,000 years ago, it was connected to Ireland by only an ice bridge, prior to 9,000 years ago it retained a land connection to the continent, with an area of mostly low marshland joining it to what are now Denmark and the Netherlands.[46][47]

In Cheddar Gorge, near Bristol, the remains of animal species native to mainland Europe such as antelopes, brown bears, and wild horses have been found alongside a human skeleton, ‘Cheddar Man’, dated to about 7150 BC.[48] Great Britain became an island at the end of the last glacial period when sea levels rose due to the combination of melting glaciers and the subsequent isostatic rebound of the crust.

Great Britain’s Iron Age inhabitants are known as Britons; they spoke Celtic languages.

Roman and medieval period

Prima Europe tabula. A copy of Ptolemy’s 2nd-century map of Roman Britain. See notes to image above.

The Romans conquered most of the island (up to Hadrian’s Wall in northern England) and this became the Ancient Roman province of Britannia. In the course of the 500 years after the Roman Empire fell, the Britons of the south and east of the island were assimilated or displaced by invading Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, often referred to collectively as Anglo-Saxons). At about the same time, Gaelic tribes from Ireland invaded the north-west, absorbing both the Picts and Britons of northern Britain, eventually forming the Kingdom of Scotland in the 9th century. The south-east of Scotland was colonised by the Angles and formed, until 1018, a part of the Kingdom of Northumbria. Ultimately, the population of south-east Britain came to be referred to as the English people, so-named after the Angles.

Germanic speakers referred to Britons as Welsh. This term came to be applied exclusively to the inhabitants of what is now Wales, but it also survives in names such as Wallace and in the second syllable of Cornwall. Cymry, a name the Britons used to describe themselves, is similarly restricted in modern Welsh to people from Wales, but also survives in English in the place name of Cumbria. The Britons living in the areas now known as Wales, Cumbria and Cornwall were not assimilated by the Germanic tribes, a fact reflected in the survival of Celtic languages in these areas into more recent times.[49] At the time of the Germanic invasion of Southern Britain, many Britons emigrated to the area now known as Brittany, where Breton, a Celtic language closely related to Welsh and Cornish and descended from the language of the emigrants, is still spoken. In the 9th century, a series of Danish assaults on northern English kingdoms led to them coming under Danish control (an area known as the Danelaw). In the 10th century, however, all the English kingdoms were unified under one ruler as the kingdom of England when the last constituent kingdom, Northumbria, submitted to Edgar in 959. In 1066, England was conquered by the Normans, who introduced a Norman-speaking administration that was eventually assimilated. Wales came under Anglo-Norman control in 1282, and was officially annexed to England in the 16th century.

Early modern period

On 20 October 1604 King James, who had succeeded separately to the two thrones of England and Scotland, proclaimed himself «King of Great Brittaine, France, and Ireland».[50] When James died in 1625 and the Privy Council of England was drafting the proclamation of the new king, Charles I, a Scottish peer, Thomas Erskine, 1st Earl of Kellie, succeeded in insisting that it use the phrase «King of Great Britain», which James had preferred, rather than King of Scotland and England (or vice versa).[51] While that title was also used by some of James’s successors, England and Scotland each remained legally separate countries, each with its own parliament, until 1707, when each parliament passed an Act of Union to ratify the Treaty of Union that had been agreed the previous year. This created a single kingdom with one parliament with effect from 1 May 1707. The Treaty of Union specified the name of the new all-island state as «Great Britain», while describing it as «One Kingdom» and «the United Kingdom». To most historians, therefore, the all-island state that existed between 1707 and 1800 is either «Great Britain» or the «Kingdom of Great Britain».

Geography

View of Britain’s coast from Cap Gris-Nez in northern France

Great Britain lies on the European continental shelf, part of the Eurasian Plate and off the north-west coast of continental Europe, separated from this European mainland by the North Sea and by the English Channel, which narrows to 34 km (18 nmi; 21 mi) at the Straits of Dover.[52] It stretches over about ten degrees of latitude on its longer, north–south axis and covers 209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi), excluding the much smaller surrounding islands.[53] The North Channel, Irish Sea, St George’s Channel and Celtic Sea separate the island from the island of Ireland to its west.[54] The island is since 1993 joined, via one structure, with continental Europe: the Channel Tunnel, the longest undersea rail tunnel in the world. The island is marked by low, rolling countryside in the east and south, while hills and mountains predominate in the western and northern regions. It is surrounded by over 1,000 smaller islands and islets. The greatest distance between two points is 968.0 km (601+1⁄2 mi) (between Land’s End, Cornwall and John o’ Groats, Caithness), 838 miles (1,349 km) by road.

The English Channel is thought to have been created between 450,000 and 180,000 years ago by two catastrophic glacial lake outburst floods caused by the breaching of the Weald-Artois Anticline, a ridge that held back a large proglacial lake, now submerged under the North Sea.[55] Around 10,000 years ago, during the Devensian glaciation with its lower sea level, Great Britain was not an island, but an upland region of continental north-western Europe, lying partially underneath the Eurasian ice sheet. The sea level was about 120 metres (390 ft) lower than today, and the bed of the North Sea was dry and acted as a land bridge, now known as Doggerland, to the Continent. It is generally thought that as sea levels gradually rose after the end of the last glacial period of the current ice age, Doggerland reflooded cutting off what was the British peninsula from the European mainland by around 6500 BC.[56]

Geology

Great Britain has been subject to a variety of plate tectonic processes over a very extended period of time. Changing latitude and sea levels have been important factors in the nature of sedimentary sequences, whilst successive continental collisions have affected its geological structure with major faulting and folding being a legacy of each orogeny (mountain-building period), often associated with volcanic activity and the metamorphism of existing rock sequences. As a result of this eventful geological history, the island shows a rich variety of landscapes.

The oldest rocks in Great Britain are the Lewisian gneisses, metamorphic rocks found in the far north west of the island and in the Hebrides (with a few small outcrops elsewhere), which date from at least 2,700 My ago. South of the gneisses are a complex mixture of rocks forming the North West Highlands and Grampian Highlands in Scotland. These are essentially the remains of folded sedimentary rocks that were deposited between 1,000 My and 670 My ago over the gneiss on what was then the floor of the Iapetus Ocean.

In the current era the north of the island is rising as a result of the weight of Devensian ice being lifted. Counterbalanced, the south and east is sinking, generally estimated at 1 mm (1⁄25 inch) per year, with the London area sinking at double this partly due to the continuing compaction of the recent clay deposits.

Fauna

The robin is popularly known as «Britain’s favourite bird».[57]

Animal diversity is modest, as a result of factors including the island’s small land area, the relatively recent age of the habitats developed since the last glacial period and the island’s physical separation from continental Europe, and the effects of seasonal variability.[58] Great Britain also experienced early industrialisation and is subject to continuing urbanisation, which have contributed towards the overall loss of species.[59] A DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) study from 2006 suggested that 100 species have become extinct in the UK during the 20th century, about 100 times the background extinction rate. However, some species, such as the brown rat, red fox, and introduced grey squirrel, are well adapted to urban areas.

Rodents make up 40% of the mammal species.[citation needed] These include squirrels, mice, voles, rats and the recently reintroduced European beaver.[59] There is also an abundance of European rabbit, European hare, shrews, European mole and several species of bat.[59] Carnivorous mammals include the red fox, Eurasian badger, Eurasian otter, weasel, stoat and elusive Scottish wildcat.[60] Various species of seal, whale and dolphin are found on or around British shores and coastlines. The largest land-based wild animals today are deer. The red deer is the largest species, with roe deer and fallow deer also prominent; the latter was introduced by the Normans.[60][61] Sika deer and two more species of smaller deer, muntjac and Chinese water deer, have been introduced, muntjac becoming widespread in England and parts of Wales while Chinese water deer are restricted mainly to East Anglia. Habitat loss has affected many species. Extinct large mammals include the brown bear, grey wolf and wild boar; the latter has had a limited reintroduction in recent times.[59]

There is a wealth of birdlife, with 628 species recorded,[62] of which 258 breed on the island or remain during winter.[63] Because of its mild winters for its latitude, Great Britain hosts important numbers of many wintering species, particularly waders, ducks, geese and swans.[64] Other well known bird species include the golden eagle, grey heron, common kingfisher, common wood pigeon, house sparrow, European robin, grey partridge, and various species of crow, finch, gull, auk, grouse, owl and falcon.[65] There are six species of reptile on the island; three snakes and three lizards including the legless slowworm. One snake, the adder, is venomous but rarely deadly.[66] Amphibians present are frogs, toads and newts.[59] There are also several introduced species of reptile and amphibian.[67]

Flora

In a similar sense to fauna, and for similar reasons, the flora consists of fewer species compared to much larger continental Europe.[68] The flora comprises 3,354 vascular plant species, of which 2,297 are native and 1,057 have been introduced.[69] The island has a wide variety of trees, including native species of birch, beech, ash, hawthorn, elm, oak, yew, pine, cherry and apple.[70] Other trees have been naturalised, introduced especially from other parts of Europe (particularly Norway) and North America. Introduced trees include several varieties of pine, chestnut, maple, spruce, sycamore and fir, as well as cherry plum and pear trees.[70] The tallest species are the Douglas firs; two specimens have been recorded measuring 65 metres or 212 feet.[71] The Fortingall Yew in Perthshire is the oldest tree in Europe.[72]

There are at least 1,500 different species of wildflower.[73] Some 107 species are particularly rare or vulnerable and are protected by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. It is illegal to uproot any wildflowers without the landowner’s permission.[73][74]

A vote in 2002 nominated various wildflowers to represent specific counties.[75] These include red poppies, bluebells, daisies, daffodils, rosemary, gorse, iris, ivy, mint, orchids, brambles, thistles, buttercups, primrose, thyme, tulips, violets, cowslip, heather and many more.[76][77][78][79]

There is also more than 1000 species of bryophyte including algae and mosses across the island. The currently known species include 767 mosses, 298 liverworts and 4 hornworts.[80]

Fungi

There are many species of fungi including lichen-forming species, and the mycobiota is less poorly known than in many other parts of the world. The most recent checklist of Basidiomycota (bracket fungi, jelly fungi, mushrooms and toadstools, puffballs, rusts and smuts), published in 2005, accepts over 3600 species.[81] The most recent checklist of Ascomycota (cup fungi and their allies, including most lichen-forming fungi), published in 1985, accepts another 5100 species.[82] These two lists did not include conidial fungi (fungi mostly with affinities in the Ascomycota but known only in their asexual state) or any of the other main fungal groups (Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota and Zygomycota). The number of fungal species known very probably exceeds 10,000. There is widespread agreement among mycologists that many others are yet to be discovered.

Demographics

Settlements

London is the capital of England and the whole of the United Kingdom, and is the seat of the United Kingdom’s government. Edinburgh and Cardiff are the capitals of Scotland and Wales, respectively, and house their devolved governments.

- Largest urban areas

| Rank | City-region | Built-up area[83] | Population (2011 Census) |

Area (km2) |

Density (people/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | London | Greater London | 9,787,426 | 1,737.9 | 5,630 |

| 2 | Manchester–Salford | Greater Manchester | 2,553,379 | 630.3 | 4,051 |

| 3 | Birmingham–Wolverhampton | West Midlands | 2,440,986 | 598.9 | 4,076 |

| 4 | Leeds–Bradford | West Yorkshire | 1,777,934 | 487.8 | 3,645 |

| 5 | Glasgow | Greater Glasgow | 1,209,143 | 368.5 | 3,390 |

| 6 | Liverpool | Liverpool | 864,122 | 199.6 | 4,329 |

| 7 | Southampton–Portsmouth | South Hampshire | 855,569 | 192.0 | 4,455 |

| 8 | Newcastle upon Tyne–Sunderland | Tyneside | 774,891 | 180.5 | 4,292 |

| 9 | Nottingham | Nottingham | 729,977 | 176.4 | 4,139 |

| 10 | Sheffield | Sheffield | 685,368 | 167.5 | 4,092 |

Language

In the Late Bronze Age, Britain was part of a culture called the Atlantic Bronze Age, held together by maritime trading, which also included Ireland, France, Spain and Portugal. In contrast to the generally accepted view[84] that Celtic originated in the context of the Hallstatt culture, since 2009, John T. Koch and others have proposed that the origins of the Celtic languages are to be sought in Bronze Age Western Europe, especially the Iberian Peninsula.[85][86][87][88] Koch et al.’s proposal has failed to find wide acceptance among experts on the Celtic languages.[84]

All the modern Brythonic languages (Breton, Cornish, Welsh) are generally considered to derive from a common ancestral language termed Brittonic, British, Common Brythonic, Old Brythonic or Proto-Brythonic, which is thought to have developed from Proto-Celtic or early Insular Celtic by the 6th century AD.[89] Brythonic languages were probably spoken before the Roman invasion at least in the majority of Great Britain south of the rivers Forth and Clyde, though the Isle of Man later had a Goidelic language, Manx. Northern Scotland mainly spoke Pritennic, which became Pictish, which may have been a Brythonic language. During the period of the Roman occupation of Southern Britain (AD 43 to c. 410), Common Brythonic borrowed a large stock of Latin words. Approximately 800 of these Latin loan-words have survived in the three modern Brythonic languages. Romano-British is the name for the Latinised form of the language used by Roman authors.

British English is spoken in the present day across the island, and developed from the Old English brought to the island by Anglo-Saxon settlers from the mid 5th century. Some 1.5 million people speak Scots—which was indigenous language of Scotland and has become closer to English over centuries.[90][91] An estimated 700,000 people speak Welsh,[92] an official language in Wales.[93] In parts of north west Scotland, Scottish Gaelic remains widely spoken. There are various regional dialects of English, and numerous languages spoken by some immigrant populations.

Religion

Christianity has been the largest religion by number of adherents since the Early Middle Ages: it was introduced under the ancient Romans, developing as Celtic Christianity. According to tradition, Christianity arrived in the 1st or 2nd century. The most popular form is Anglicanism (known as Episcopalism in Scotland). Dating from the 16th-century Reformation, it regards itself as both Catholic and Reformed. The Head of the Church is the monarch of the United Kingdom, as the Supreme Governor. It has the status of established church in England. There are just over 26 million adherents to Anglicanism in Britain today,[94] although only around one million regularly attend services. The second largest Christian practice is the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, which traces its history to the 6th century with Augustine’s mission and was the main religion for around a thousand years. There are over 5 million adherents today, 4.5 million in England and Wales[95] and 750,000 in Scotland,[96] although fewer than a million Catholics regularly attend mass.[97]

The Church of Scotland, a form of Protestantism with a Presbyterian system of ecclesiastical polity, is the third most numerous on the island with around 2.1 million members.[98] Introduced in Scotland by clergyman John Knox, it has the status of national church in Scotland. The monarch of the United Kingdom is represented by a Lord High Commissioner. Methodism is the fourth largest and grew out of Anglicanism through John Wesley.[99] It gained popularity in the old mill towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire, also amongst tin miners in Cornwall.[100] The Presbyterian Church of Wales, which follows Calvinistic Methodism, is the largest denomination in Wales. There are other non-conformist minorities, such as Baptists, Quakers, the United Reformed Church (a union of Congregationalists and English Presbyterians), Unitarians.[101] The first patron saint of Great Britain was Saint Alban.[102] He was the first Christian martyr dating from the Romano-British period, condemned to death for his faith and sacrificed to the pagan gods.[103] In more recent times, some have suggested the adoption of St Aidan as another patron saint of Britain.[104] From Ireland, he worked at Iona amongst the Dál Riata and then Lindisfarne where he restored Christianity to Northumbria.[104]

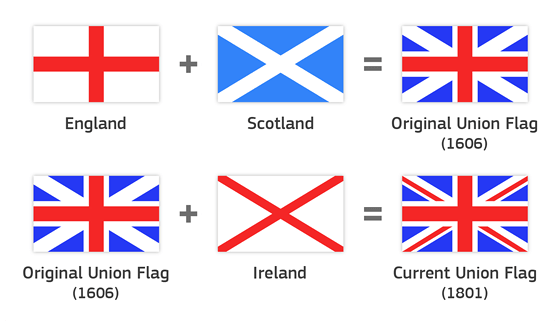

The three constituent countries of the United Kingdom have patron saints: Saint George and Saint Andrew are represented in the flags of England and Scotland respectively.[105] These two flags combined to form the basis of the Great Britain royal flag of 1604.[105] Saint David is the patron saint of Wales.[106] There are many other British saints. Some of the best known are Cuthbert, Columba, Patrick, Margaret, Edward the Confessor, Mungo, Thomas More, Petroc, Bede, and Thomas Becket.[106]

Numerous other religions are practised.[107] The 2011 census recorded that Islam had around 2.7 million adherents (excluding Scotland with about 76,000).[108] More than 1.4 million people (excluding Scotland’s about 38,000) believe in Hinduism, Sikhism, or Buddhism—religions that developed in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.[108] Judaism figured slightly more than Buddhism at the 2011 census, having 263,000 adherents (excluding Scotland’s about 6000).[108] Jews have inhabited Britain since 1070. However those resident and open about their religion were expelled from England in 1290, replicated in some other Catholic countries of the era. Jews were permitted to re-establish settlement as of 1656, in the interregnum which was a peak of anti-Catholicism.[109] Most Jews in Great Britain have ancestors who fled for their lives, particularly from 19th century Lithuania and the territories occupied by Nazi Germany.[110]

See also

- List of islands of England

- List of islands of Scotland

- List of islands of Wales

Notes

- ^ The political definition of Great Britain – that is, England, Scotland, and Wales combined – includes a number of offshore islands such as the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, and Shetland, which are not part of the geographical island of Great Britain. Those three countries combined have a total area of 234,402 km2 (90,503 sq mi).[7]

References

- ^ ISLAND DIRECTORY, United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ «Great Britain’s tallest mountain is taller». Ordnance Survey Blog. 18 March 2016.

- ^ 2011 Census: Population Estimates for the United Kingdom. In the 2011 census, the population of England, Wales and Scotland was estimated to be approximately 61,370,000; comprising 60,800,000 on Great Britain, and 570,000 on other islands. Retrieved 23 January 2014

- ^ «Ethnic Group by Age in England and Wales». www.nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «Ethnic groups, Scotland, 2001 and 2011» (PDF). www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «Islands by land area, United Nations Environment Programme». Islands.unep.ch. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ «The Countries of the UK». Office of National Statistics. 6 April 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ «says 803 islands which have a distinguishable coastline on an Ordnance Survey map, and several thousand more exist which are too small to be shown as anything but a dot». Mapzone.ordnancesurvey.co.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Nora McGreevy. «Study Rewrites History of Ancient Land Bridge Between Britain and Europe». smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ «Population Estimates» (PDF). National Statistics Online. Newport, Wales: Office for National Statistics. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ See Geohive.com Country data Archived 21 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine; Japan Census of 2000; United Kingdom Census of 2001. The editors of List of islands by population appear to have used similar data from the relevant statistics bureaux and totalled up the various administrative districts that make up each island, and then done the same for less populous islands. An editor of this article has not repeated that work. Therefore this plausible and eminently reasonable ranking is posted as unsourced common knowledge.

- ^ «Who, What, Why: Why is it Team GB, not Team UK?». BBC News. 14 August 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Oliver, Clare (2003). Great Britain. Black Rabbit Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-58340-204-7.

- ^ O’Rahilly 1946

- ^ 4.20 provides a translation describing Caesar’s first invasion, using terms which from IV.XX appear in Latin as arriving in «Britannia», the inhabitants being «Britanni», and on p30 «principes Britanniae» (i.e., «chiefs of Britannia») is translated as «chiefs of Britain».

- ^ Cunliffe 2002, pp. 94–95

- ^ «Anglo-Saxons». BBC News. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ a b c Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-631-22260-6.

- ^ «… ἐν τούτῳ γε μὴν νῆσοι μέγιστοι τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι δύο, Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Ἀλβίων καὶ Ἰέρνη, …», transliteration «… en toutôi ge mên nêsoi megistoi tynchanousin ousai dyo, Brettanikai legomenai, Albiôn kai Iernê, …», Aristotle: On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos., 393b, pages 360–361, Loeb Classical Library No. 400, London William Heinemann LTD, Cambridge, Massachusetts University Press MCMLV

- ^ Book I.4.2–4, Book II.3.5, Book III.2.11 and 4.4, Book IV.2.1, Book IV.4.1, Book IV.5.5, Book VII.3.1

- ^ Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia Book IV. Chapter XLI Latin text and

English translation, numbered Book 4, Chapter 30,

at the Perseus Project. - ^ O Corrain, Donnchadh, Professor of Irish History at University College Cork (1 November 2001). «Chapter 1: Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland«. In Foster, R F (ed.). The Oxford History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280202-6.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 4, ISBN 978-0-19-967945-4.

- ^ Βρεττανική. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book I. Chapter IV. Section 2 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book IV. Chapter II. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book IV. Chapter IV. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Marcianus Heracleensis; Müller, Karl Otfried; et al. (1855). «Periplus Maris Exteri, Liber Prior, Prooemium». In Firmin Didot, Ambrosio (ed.). Geographi Graeci Minores. Vol. 1. Paris: editore Firmin Didot. pp. 516–517. Greek text and Latin Translation thereof archived at the Internet Archive.

- ^ Tierney, James J. (1959). «Ptolemy’s Map of Scotland». The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 79: 132–148. doi:10.2307/627926. JSTOR 627926. S2CID 163631018.

- ^ Ptolemy, Claudius (1898). «Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ’, κε’» (PDF). In Heiberg, J.L. (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia. Vol. 1 Syntaxis Mathematica. Leipzig: in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Ptolemy, Claudius (1843). «Book II, Prooemium and chapter β’, paragraph 12» (PDF). In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia. Vol. 1. Leipzig: sumptibus et typis Caroli Tauchnitii. pp. 59, 67.

- ^ Freeman, Philip (2001). Ireland and the classical world. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-292-72518-8.

- ^ Nicholls, Andrew D., The Jacobean Union: A Reconsideration of British Civil Policies Under the Early Stuarts, 1999. p. 5.

- ^ UK 2005: The Official Yearbook of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. London: Office for National Statistics. 29 November 2004. pp. vii. ISBN 978-0-11-621738-7. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press, archived from the original on 4 October 2013,

Great Britain: England, Wales, and Scotland considered as a unit. The name is also often used loosely to refer to the United Kingdom.

Great Britain is the name of the island that comprises England, Scotland, and Wales, although the term is also used loosely to refer to the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom is a political unit that includes these countries and Northern Ireland. The British Isles is a geographical term that refers to the United Kingdom, Ireland, and surrounding smaller islands such as the Hebrides and the Channel Islands. - ^ Brock, Colin (2018), Geography of Education: Scale, Space and Location in the Study of Education, London: Bloomsbury,

The political territory of Northern Ireland is not part of Britain, but is part of the nation ‘The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’ (UK). Great Britain comprises England, Scotland and Wales.

- ^ Britain, Oxford English Dictionary, archived from the original on 22 July 2011,

Britain:/ˈbrɪt(ə)n/ the island containing England, Wales, and Scotland. The name is broadly synonymous with Great Britain, but the longer form is more usual for the political unit.

- ^ Britain 2001:The Official Yearbook of the United Kingdom, 2001 (PDF). London: Office for National Statistics. August 2000. pp. vii. ISBN 978-0-11-621278-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2011.

- ^ UK 2002: The Official Yearbook of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (PDF). London: Office for National Statistics. August 2001. pp. vi. ISBN 978-0-11-621738-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2007.

- ^ HL Deb 21 October 2004 vol 665 c99WA Hansard

- ^ «Who’s who? Meet Northern Ireland’s Olympic hopefuls in Team GB and Team IRE». www.BBC.co.uk. BBC News. 28 July 2012.

- ^ a b «Key facts about the United Kingdom». Direct.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 November 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Ademuni-Odeke (1998). Bareboat Charter (ship) Registration. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 367. ISBN 978-90-411-0513-4.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (7 February 2014). «Earliest footprints outside Africa discovered in Norfolk». BBC News. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Gräslund, Bo (2005). «Traces of the early humans». Early humans and their world. London: Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-415-35344-1.

- ^ Edwards, Robin & al. «The Island of Ireland: Drowning the Myth of an Irish Land-bridge?» Accessed 15 February 2013.

- ^ Nora McGreevy. «Study Rewrites History of Ancient Land Bridge Between Britain and Europe». smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Lacey, Robert. Great Tales from English History. New York: Little, Brown & Co, 2004. ISBN 0-316-10910-X.

- ^ Ellis, Peter Berresford (1974). The Cornish language and its literature. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7100-7928-2.

- ^ «England/Great Britain: Royal Styles: 1604-1707». Archontology.org. 13 March 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ HMC 60, Manuscripts of the Earl of Mar and Kellie, vol.2 (1930), p. 226

- ^ «accessed 14 November 2009». Eosnap.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Island Directory Tables «Islands By Land Area». Retrieved from http://islands.unep.ch/Tiarea.htm on 13 August 2009

- ^ «Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition + corrections» (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1971. p. 42 [corrections to page 13]. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Gupta, Sanjeev; Collier, Jenny S.; Palmer-Felgate, Andy; Potter, Graeme (2007). «Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel». Nature. 448 (7151): 342–5. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..342G. doi:10.1038/nature06018. PMID 17637667. S2CID 4408290.

- Dave Mosher (18 July 2007). «Why the rift between Britain and France?». NBC News.

- ^ «Vincent Gaffney, «Global Warming and the Lost European Country»» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ «The Robin – Britain’s Favourite Bird». BritishBirdLovers.co.uk. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ «Decaying Wood: An Overview of Its Status and Ecology in the United Kingdom and Europe» (PDF). FS.fed.us. Retrieved 15 August 2011. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e «A Short History of the British Mammal Fauna». ABDN.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ a b Else, Great Britain, 85.

- ^ «The Fallow Deer Project, University of Nottingham». Nottingham.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ McInerny, Christopher (2022). «The British List: A Checklist of Birds of Britain (10th edition)». Ibis. British Ornithologist’s Union. 164 (3): 860–910. doi:10.1111/ibi.13065.

- ^ «Birds of Britain». BTO.org. 16 July 2010. Retrieved on 16 February 2009.

- ^ Balmer, Dawn (2013). Bird Atlas 2007-2011: The Breeding and Wintering Birds of Britain and Ireland. Thetford: BTO Books.

- ^ «Birds». NatureGrid.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved on 16 February 2009.

- ^ «The Adder’s Byte». CountySideInfo.co.uk. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «Species Identification». Reptiles & Amphibians of the UK.

- ^ «Plants of the Pacific Northwest in Western Europe». Botanical Electric News. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ Frodin, Guide to Standard Floras of the World, 599.

- ^ a b «Checklist of British Plants». Natural History Museum. Retrieved on 2 March 2009.

- ^ «Facts About Britain’s Trees». WildAboutBritain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved on 2 March 2009.

- ^ «The Fortingall Yew». PerthshireBigTreeCountry.co.uk. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ a b «Facts and Figures about Wildflowers». WildAboutFlowers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «Endangered British Wild Flowers». CountryLovers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2009. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «County Flowers of Great Britain». WildAboutFlowers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «People and Plants: Mapping the UK’s wild flora» (PDF). PlantLife.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2007. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «British Wildflower Images». Map-Reading.co.uk. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «List of British Wildlfowers by Common Name». WildAboutBritain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «British Plants and algae». Arkive.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2009. Retrieved on 23 February 2009.

- ^ «New atlas reveals spread of British bryophytes in response to cleaner air». UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ Legon & Henrici, Checklist of the British & Irish Basidiomycota

- ^ Cannon, Hawksworth & Sherwood-Pike, The British Ascomycotina. An Annotated Checklist

- ^ «2011 Census — Built-up areas». ONS. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b Eska, Joseph F. (December 2013). «Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2013.12.35». Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Aberystwyth University — News. Aber.ac.uk. Retrieved on 17 July 2013.

- ^ «Appendix» (PDF). O’Donnell Lecture. 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Koch, John (2009). «Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9» (PDF). Palaeohispánica: Revista Sobre Lenguas y Culturas de la Hispania Antigua. Palaeohispanica: 339–51. ISSN 1578-5386. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ Koch, John. «New research suggests Welsh Celtic roots lie in Spain and Portugal». Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2007). An Atlas for Celtic Studies. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-309-1.

- ^ Scotland’s Census 2011 – Language, All people aged 3 and over. Out of the 60,815,385 residents of the UK over the age of three, 1,541,693 (2.5%) can speak Scots.

- ^ A.J. Aitken in The Oxford Companion to the English Language, Oxford University Press 1992. p.894

- ^ Bwrdd yr Iaith Gymraeg, A statistical overview of the Welsh language, by Hywel M Jones, page 115, 13.5.1.6, England. Published February 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ «Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011». legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ «Global Anglicanism at a Crossroads». PewResearch.org. 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «People here ‘must obey the laws of the land’«. The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 February 2008. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2010. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «Cardinal not much altered by his new job». Living Scotsman. Retrieved 15 August 2011. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «How many Catholics are there in Britain?». BBC. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ^ «Analysis of Religion in the 2001 Census – Current Religion in Scotland». Scotland.gov.uk. 28 February 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2011. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «The Methodist Church». BBC.co.uk. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «Methodism in Britain». GoffsOakMethodistChurch.co.uk. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «Cambridge History of Christianity». Hugh McLeod. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ Dawkins, The Shakespeare Enigma, 343.

- ^ Butler, Butler’s Lives of the Saints, 141.

- ^ a b «Cry God for Harry, Britain and… St Aidan». The Independent. London. 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ a b «United Kingdom – History of the Flag». FlagSpot.net. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ a b «Saints». Brits at their Best. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «Guide to religions in the UK». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved on 16 August 2011

- ^ a b c «Religion in England and Wales 2011 — Office for National Statistics».

- ^ «From Expulsion (1290) to Readmission (1656): Jews and England» (PDF). Goldsmiths.ac.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2008. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

- ^ «Jews in Scotland». British-Jewry.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 May 2005. Retrieved on 1 February 2009.

Bibliography

- Pliny the Elder (translated by Rackham, Harris) (1938). Natural History. Harvard University Press.

- Ball, Martin John (1994). The Celtic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-01035-1.

- Butler, Alban (1997). Butler’s Lives of the Saints. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-86012-255-5.

- Frodin, D. G. (2001). Guide to Standard Floras of the World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79077-2.

- Spencer, Colin (2003). British Food: An Extraordinary Thousand Years of History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13110-0.

- Andrews, Robert (2004). The Rough Guide to Britain. Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84353-301-6.

- Dawkins, Peter (2004). The Shakespeare Enigma. Polair Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9545389-4-1.

- Major, John (2004). History in Quotations. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35387-3.

- Else, David (2005). Great Britain. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-921-4.

- Kaufman, Will; Slettedahl, Heidi Macpherson (2005). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). Origins of the British. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1890-0.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Massey, Gerald (2007). A Book of the Beginnings, Vol. 1. Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-60206-829-2.

- Taylor, Isaac (2008). Names and Their Histories: A Handbook of Historical Geography and Topographical Nomenclature. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-0-559-29667-3.

- Legon, N.W.; Henrici, A. (2005). Checklist of the British & Irish Basidiomycota. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1-84246-121-1.

- Cannon, P.F.; Hawksworth, D.L.; M.A., Sherwood-Pike (1985). The British Ascomycotina. An Annotated Checklist. Commonwealth Mycological Institute & British Mycological Society. ISBN 978-0-85198-546-6.

External links

- Coast – the BBC explores the coast of Great Britain

- The British Isles

- 200 Major Towns and Cities in the British Isles

- CIA Factbook United Kingdom

Video links

- Pathe travelogue, 1960, Journey through Britain Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Pathe newsreel, 1960, Know the British Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Pathe newsreel, 1950, Festival of Britain Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

|

Other native names

|

|

|---|---|

Satellite image, 2012, with Ireland to the west and France to the south-east |

|

|

|

| Geography | |

| Location | North-western Europe |

| Coordinates | 54°N 2°W / 54°N 2°WCoordinates: 54°N 2°W / 54°N 2°W |

| Archipelago | British Isles |

| Adjacent to | Atlantic Ocean |

| Area | 209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi)[1] |

| Area rank | 9th |

| Highest elevation | 1,345 m (4413 ft) |

| Highest point | Ben Nevis[2] |

| Administration | |

|

United Kingdom |

|

| Countries |

|

| Largest city | London (pop. 8,878,892) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 60,800,000 (2011 census)[3] |

| Population rank | 3rd |

| Pop. density | 302/km2 (782/sq mi) |

| Languages |

|

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| • Summer (DST) |

|

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe. With an area of 209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi), it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world.[6][note 1] It is dominated by a maritime climate with narrow temperature differences between seasons. The 60% smaller island of Ireland is to the west—these islands, along with over 1,000 smaller surrounding islands and named substantial rocks, form the British Isles archipelago.[8]

Connected to mainland Europe until 9,000 years ago by a landbridge now known as Doggerland,[9] Great Britain has been inhabited by modern humans for around 30,000 years. In 2011, it had a population of about 61 million, making it the world’s third-most-populous island after Java in Indonesia and Honshu in Japan.[10][11]

The term «Great Britain» can also refer to the political territory of England, Scotland and Wales, which includes their offshore islands.[12] Great Britain and Northern Ireland constitute the United Kingdom.[13] The single Kingdom of Great Britain resulted from the 1707 Acts of Union between the kingdoms of England (which at the time incorporated Wales) and Scotland.

Terminology

Toponymy

The archipelago has been referred to by a single name for over 2000 years: the term ‘British Isles’ derives from terms used by classical geographers to describe this island group. By 50 BC Greek geographers were using equivalents of Prettanikē as a collective name for the British Isles.[14] However, with the Roman conquest of Britain the Latin term Britannia was used for the island of Great Britain, and later Roman-occupied Britain south of Caledonia.[15][16][17]

The earliest known name for Great Britain is Albion (Greek: Ἀλβιών) or insula Albionum, from either the Latin albus meaning «white» (possibly referring to the white cliffs of Dover, the first view of Britain from the continent) or the «island of the Albiones«.[18] The oldest mention of terms related to Great Britain was by Aristotle (384–322 BC), or possibly by Pseudo-Aristotle, in his text On the Universe, Vol. III. To quote his works, «There are two very large islands in it, called the British Isles, Albion and Ierne».[19]

The first known written use of the word Britain was an ancient Greek transliteration of the original P-Celtic term in a work on the travels and discoveries of Pytheas that has not survived. The earliest existing records of the word are quotations of the periplus by later authors, such as those within Strabo’s Geographica, Pliny’s Natural History and Diodorus of Sicily’s Bibliotheca historica.[20] Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) in his Natural History records of Great Britain: «Its former name was Albion; but at a later period, all the islands, of which we shall just now briefly make mention, were included under the name of ‘Britanniæ.'»[21]

The name Britain descends from the Latin name for Britain, Britannia or Brittānia, the land of the Britons. Old French Bretaigne (whence also Modern French Bretagne) and Middle English Bretayne, Breteyne. The French form replaced the Old English Breoton, Breoten, Bryten, Breten (also Breoton-lond, Breten-lond). Britannia was used by the Romans from the 1st century BC for the British Isles taken together. It is derived from the travel writings of Pytheas around 320 BC, which described various islands in the North Atlantic as far north as Thule (probably Norway).

The peoples of these islands of Prettanike were called the Πρεττανοί, Priteni or Pretani.[18]

Priteni is the source of the Welsh language term Prydain, Britain, which has the same source as the Goidelic term Cruithne used to refer to the early Brythonic-speaking inhabitants of Ireland.[22] The latter were later called Picts or Caledonians by the Romans. Greek historians Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo preserved variants of Prettanike from the work of Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia, who travelled from his home in Hellenistic southern Gaul to Britain in the 4th century BC. The term used by Pytheas may derive from a Celtic word meaning «the painted ones» or «the tattooed folk» in reference to body decorations.[23] According to Strabo, Pytheas referred to Britain as Bretannikē, which is treated a feminine noun.[24][25][26][27] Marcian of Heraclea, in his Periplus maris exteri, described the island group as αἱ Πρεττανικαὶ νῆσοι (the Prettanic Isles).[28]

Derivation of Great

A 1490 Italian reconstruction of the relevant map of Ptolemy who combined the lines of roads and of the coasting expeditions during the first century of Roman occupation. Two great faults, however, are an eastward-projecting Scotland and none of Ireland seen to be at the same latitude of Wales, which may have been if Ptolemy used Pytheas’ measurements of latitude.[29] Whether he did so is a much debated issue. This «copy» appears in blue below.

The Greco-Egyptian scientist Ptolemy referred to the larger island as great Britain (μεγάλη Βρεττανία megale Brettania) and to Ireland as little Britain (μικρὰ Βρεττανία mikra Brettania) in his work Almagest (147–148 AD).[30] In his later work, Geography (c. 150 AD), he gave the islands the names Alwion, Iwernia, and Mona (the Isle of Man),[31] suggesting these may have been the names of the individual islands not known to him at the time of writing Almagest.[32] The name Albion appears to have fallen out of use sometime after the Roman conquest of Britain, after which Britain became the more commonplace name for the island.[18]

After the Anglo-Saxon period, Britain was used as a historical term only. Geoffrey of Monmouth in his pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) refers to the

island of Great Britain as Britannia major («Greater Britain»), to distinguish it from Britannia minor («Lesser Britain»), the continental region which approximates to modern Brittany, which had been settled in the fifth and sixth centuries by Celtic Briton migrants from Great Britain.[citation needed]

The term Great Britain was first used officially in 1474, in the instrument drawing up the proposal for a marriage between Cecily, daughter of Edward IV of England, and James, son of James III of Scotland, which described it as «this Nobill Isle, callit Gret Britanee». While promoting a possible royal match in 1548, Lord Protector Somerset said that the English and Scots were, «like as twoo brethren of one Islande of great Britaynes again.» In 1604, James VI and I styled himself «King of Great Brittaine, France and Ireland».[33]

Modern use of the term Great Britain

Great Britain refers geographically to the island of Great Britain. Politically, it may refer to the whole of England, Scotland and Wales, including their smaller offshore islands.[34] It is not technically correct to use the term to refer to the whole of the United Kingdom which includes Northern Ireland, though the Oxford English Dictionary states «…the term is also used loosely to refer to the United Kingdom.»[35][36]

Similarly, Britain can refer to either all islands in Great Britain, the largest island, or the political grouping of countries.[37] There is no clear distinction, even in government documents: the UK government yearbooks have used both Britain[38] and United Kingdom.[39]

GB and GBR are used instead of UK in some international codes to refer to the United Kingdom, including the Universal Postal Union, international sports teams, NATO, and the International Organization for Standardization country codes ISO 3166-2 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-3, whilst the aircraft registration prefix is G.

On the Internet, .uk is the country code top-level domain for the United Kingdom. A .gb top-level domain was used to a limited extent, but is now deprecated; although existing registrations still exist (mainly by government organizations and email providers), the domain name registrar will not take new registrations.

In the Olympics, Team GB is used by the British Olympic Association to represent the British Olympic team. The Olympic Federation of Ireland represents the whole island of Ireland, and Northern Irish sportspeople may choose to compete for either team,[40] most choosing to represent Ireland.[41]

Political definition

Political definition of Great Britain (dark green)

– in Europe (green & dark grey)

Politically, Great Britain refers to the whole of England, Scotland and Wales in combination,[42] but not Northern Ireland; it includes islands, such as the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, the Isles of Scilly, the Hebrides and the island groups of Orkney and Shetland, that are part of England, Wales, or Scotland. It does not include the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.[42][43]

The political union that joined the kingdoms of England and Scotland happened in 1707 when the Acts of Union ratified the 1706 Treaty of Union and merged the parliaments of the two nations, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain, which covered the entire island. Before this, a personal union had existed between these two countries since the 1603 Union of the Crowns under James VI of Scotland and I of England.[citation needed]

History

Prehistoric period

Great Britain was probably first inhabited by those who crossed on the land bridge from the European mainland. Human footprints have been found from over 800,000 years ago in Norfolk[44] and traces of early humans have been found (at Boxgrove Quarry, Sussex) from some 500,000 years ago[45] and modern humans from about 30,000 years ago. Until about 16,000 years ago, it was connected to Ireland by only an ice bridge, prior to 9,000 years ago it retained a land connection to the continent, with an area of mostly low marshland joining it to what are now Denmark and the Netherlands.[46][47]

In Cheddar Gorge, near Bristol, the remains of animal species native to mainland Europe such as antelopes, brown bears, and wild horses have been found alongside a human skeleton, ‘Cheddar Man’, dated to about 7150 BC.[48] Great Britain became an island at the end of the last glacial period when sea levels rose due to the combination of melting glaciers and the subsequent isostatic rebound of the crust.

Great Britain’s Iron Age inhabitants are known as Britons; they spoke Celtic languages.

Roman and medieval period

Prima Europe tabula. A copy of Ptolemy’s 2nd-century map of Roman Britain. See notes to image above.

The Romans conquered most of the island (up to Hadrian’s Wall in northern England) and this became the Ancient Roman province of Britannia. In the course of the 500 years after the Roman Empire fell, the Britons of the south and east of the island were assimilated or displaced by invading Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, often referred to collectively as Anglo-Saxons). At about the same time, Gaelic tribes from Ireland invaded the north-west, absorbing both the Picts and Britons of northern Britain, eventually forming the Kingdom of Scotland in the 9th century. The south-east of Scotland was colonised by the Angles and formed, until 1018, a part of the Kingdom of Northumbria. Ultimately, the population of south-east Britain came to be referred to as the English people, so-named after the Angles.

Germanic speakers referred to Britons as Welsh. This term came to be applied exclusively to the inhabitants of what is now Wales, but it also survives in names such as Wallace and in the second syllable of Cornwall. Cymry, a name the Britons used to describe themselves, is similarly restricted in modern Welsh to people from Wales, but also survives in English in the place name of Cumbria. The Britons living in the areas now known as Wales, Cumbria and Cornwall were not assimilated by the Germanic tribes, a fact reflected in the survival of Celtic languages in these areas into more recent times.[49] At the time of the Germanic invasion of Southern Britain, many Britons emigrated to the area now known as Brittany, where Breton, a Celtic language closely related to Welsh and Cornish and descended from the language of the emigrants, is still spoken. In the 9th century, a series of Danish assaults on northern English kingdoms led to them coming under Danish control (an area known as the Danelaw). In the 10th century, however, all the English kingdoms were unified under one ruler as the kingdom of England when the last constituent kingdom, Northumbria, submitted to Edgar in 959. In 1066, England was conquered by the Normans, who introduced a Norman-speaking administration that was eventually assimilated. Wales came under Anglo-Norman control in 1282, and was officially annexed to England in the 16th century.

Early modern period

On 20 October 1604 King James, who had succeeded separately to the two thrones of England and Scotland, proclaimed himself «King of Great Brittaine, France, and Ireland».[50] When James died in 1625 and the Privy Council of England was drafting the proclamation of the new king, Charles I, a Scottish peer, Thomas Erskine, 1st Earl of Kellie, succeeded in insisting that it use the phrase «King of Great Britain», which James had preferred, rather than King of Scotland and England (or vice versa).[51] While that title was also used by some of James’s successors, England and Scotland each remained legally separate countries, each with its own parliament, until 1707, when each parliament passed an Act of Union to ratify the Treaty of Union that had been agreed the previous year. This created a single kingdom with one parliament with effect from 1 May 1707. The Treaty of Union specified the name of the new all-island state as «Great Britain», while describing it as «One Kingdom» and «the United Kingdom». To most historians, therefore, the all-island state that existed between 1707 and 1800 is either «Great Britain» or the «Kingdom of Great Britain».

Geography

View of Britain’s coast from Cap Gris-Nez in northern France

Great Britain lies on the European continental shelf, part of the Eurasian Plate and off the north-west coast of continental Europe, separated from this European mainland by the North Sea and by the English Channel, which narrows to 34 km (18 nmi; 21 mi) at the Straits of Dover.[52] It stretches over about ten degrees of latitude on its longer, north–south axis and covers 209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi), excluding the much smaller surrounding islands.[53] The North Channel, Irish Sea, St George’s Channel and Celtic Sea separate the island from the island of Ireland to its west.[54] The island is since 1993 joined, via one structure, with continental Europe: the Channel Tunnel, the longest undersea rail tunnel in the world. The island is marked by low, rolling countryside in the east and south, while hills and mountains predominate in the western and northern regions. It is surrounded by over 1,000 smaller islands and islets. The greatest distance between two points is 968.0 km (601+1⁄2 mi) (between Land’s End, Cornwall and John o’ Groats, Caithness), 838 miles (1,349 km) by road.

The English Channel is thought to have been created between 450,000 and 180,000 years ago by two catastrophic glacial lake outburst floods caused by the breaching of the Weald-Artois Anticline, a ridge that held back a large proglacial lake, now submerged under the North Sea.[55] Around 10,000 years ago, during the Devensian glaciation with its lower sea level, Great Britain was not an island, but an upland region of continental north-western Europe, lying partially underneath the Eurasian ice sheet. The sea level was about 120 metres (390 ft) lower than today, and the bed of the North Sea was dry and acted as a land bridge, now known as Doggerland, to the Continent. It is generally thought that as sea levels gradually rose after the end of the last glacial period of the current ice age, Doggerland reflooded cutting off what was the British peninsula from the European mainland by around 6500 BC.[56]

Geology

Great Britain has been subject to a variety of plate tectonic processes over a very extended period of time. Changing latitude and sea levels have been important factors in the nature of sedimentary sequences, whilst successive continental collisions have affected its geological structure with major faulting and folding being a legacy of each orogeny (mountain-building period), often associated with volcanic activity and the metamorphism of existing rock sequences. As a result of this eventful geological history, the island shows a rich variety of landscapes.

The oldest rocks in Great Britain are the Lewisian gneisses, metamorphic rocks found in the far north west of the island and in the Hebrides (with a few small outcrops elsewhere), which date from at least 2,700 My ago. South of the gneisses are a complex mixture of rocks forming the North West Highlands and Grampian Highlands in Scotland. These are essentially the remains of folded sedimentary rocks that were deposited between 1,000 My and 670 My ago over the gneiss on what was then the floor of the Iapetus Ocean.

In the current era the north of the island is rising as a result of the weight of Devensian ice being lifted. Counterbalanced, the south and east is sinking, generally estimated at 1 mm (1⁄25 inch) per year, with the London area sinking at double this partly due to the continuing compaction of the recent clay deposits.

Fauna

The robin is popularly known as «Britain’s favourite bird».[57]

Animal diversity is modest, as a result of factors including the island’s small land area, the relatively recent age of the habitats developed since the last glacial period and the island’s physical separation from continental Europe, and the effects of seasonal variability.[58] Great Britain also experienced early industrialisation and is subject to continuing urbanisation, which have contributed towards the overall loss of species.[59] A DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) study from 2006 suggested that 100 species have become extinct in the UK during the 20th century, about 100 times the background extinction rate. However, some species, such as the brown rat, red fox, and introduced grey squirrel, are well adapted to urban areas.

Rodents make up 40% of the mammal species.[citation needed] These include squirrels, mice, voles, rats and the recently reintroduced European beaver.[59] There is also an abundance of European rabbit, European hare, shrews, European mole and several species of bat.[59] Carnivorous mammals include the red fox, Eurasian badger, Eurasian otter, weasel, stoat and elusive Scottish wildcat.[60] Various species of seal, whale and dolphin are found on or around British shores and coastlines. The largest land-based wild animals today are deer. The red deer is the largest species, with roe deer and fallow deer also prominent; the latter was introduced by the Normans.[60][61] Sika deer and two more species of smaller deer, muntjac and Chinese water deer, have been introduced, muntjac becoming widespread in England and parts of Wales while Chinese water deer are restricted mainly to East Anglia. Habitat loss has affected many species. Extinct large mammals include the brown bear, grey wolf and wild boar; the latter has had a limited reintroduction in recent times.[59]

There is a wealth of birdlife, with 628 species recorded,[62] of which 258 breed on the island or remain during winter.[63] Because of its mild winters for its latitude, Great Britain hosts important numbers of many wintering species, particularly waders, ducks, geese and swans.[64] Other well known bird species include the golden eagle, grey heron, common kingfisher, common wood pigeon, house sparrow, European robin, grey partridge, and various species of crow, finch, gull, auk, grouse, owl and falcon.[65] There are six species of reptile on the island; three snakes and three lizards including the legless slowworm. One snake, the adder, is venomous but rarely deadly.[66] Amphibians present are frogs, toads and newts.[59] There are also several introduced species of reptile and amphibian.[67]

Flora

In a similar sense to fauna, and for similar reasons, the flora consists of fewer species compared to much larger continental Europe.[68] The flora comprises 3,354 vascular plant species, of which 2,297 are native and 1,057 have been introduced.[69] The island has a wide variety of trees, including native species of birch, beech, ash, hawthorn, elm, oak, yew, pine, cherry and apple.[70] Other trees have been naturalised, introduced especially from other parts of Europe (particularly Norway) and North America. Introduced trees include several varieties of pine, chestnut, maple, spruce, sycamore and fir, as well as cherry plum and pear trees.[70] The tallest species are the Douglas firs; two specimens have been recorded measuring 65 metres or 212 feet.[71] The Fortingall Yew in Perthshire is the oldest tree in Europe.[72]

There are at least 1,500 different species of wildflower.[73] Some 107 species are particularly rare or vulnerable and are protected by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. It is illegal to uproot any wildflowers without the landowner’s permission.[73][74]

A vote in 2002 nominated various wildflowers to represent specific counties.[75] These include red poppies, bluebells, daisies, daffodils, rosemary, gorse, iris, ivy, mint, orchids, brambles, thistles, buttercups, primrose, thyme, tulips, violets, cowslip, heather and many more.[76][77][78][79]

There is also more than 1000 species of bryophyte including algae and mosses across the island. The currently known species include 767 mosses, 298 liverworts and 4 hornworts.[80]

Fungi

There are many species of fungi including lichen-forming species, and the mycobiota is less poorly known than in many other parts of the world. The most recent checklist of Basidiomycota (bracket fungi, jelly fungi, mushrooms and toadstools, puffballs, rusts and smuts), published in 2005, accepts over 3600 species.[81] The most recent checklist of Ascomycota (cup fungi and their allies, including most lichen-forming fungi), published in 1985, accepts another 5100 species.[82] These two lists did not include conidial fungi (fungi mostly with affinities in the Ascomycota but known only in their asexual state) or any of the other main fungal groups (Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota and Zygomycota). The number of fungal species known very probably exceeds 10,000. There is widespread agreement among mycologists that many others are yet to be discovered.

Demographics

Settlements

London is the capital of England and the whole of the United Kingdom, and is the seat of the United Kingdom’s government. Edinburgh and Cardiff are the capitals of Scotland and Wales, respectively, and house their devolved governments.

- Largest urban areas

| Rank | City-region | Built-up area[83] | Population (2011 Census) |

Area (km2) |

Density (people/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | London | Greater London | 9,787,426 | 1,737.9 | 5,630 |

| 2 | Manchester–Salford | Greater Manchester | 2,553,379 | 630.3 | 4,051 |

| 3 | Birmingham–Wolverhampton | West Midlands | 2,440,986 | 598.9 | 4,076 |

| 4 | Leeds–Bradford | West Yorkshire | 1,777,934 | 487.8 | 3,645 |

| 5 | Glasgow | Greater Glasgow | 1,209,143 | 368.5 | 3,390 |

| 6 | Liverpool | Liverpool | 864,122 | 199.6 | 4,329 |

| 7 | Southampton–Portsmouth | South Hampshire | 855,569 | 192.0 | 4,455 |

| 8 | Newcastle upon Tyne–Sunderland | Tyneside | 774,891 | 180.5 | 4,292 |

| 9 | Nottingham | Nottingham | 729,977 | 176.4 | 4,139 |

| 10 | Sheffield | Sheffield | 685,368 | 167.5 | 4,092 |

Language

In the Late Bronze Age, Britain was part of a culture called the Atlantic Bronze Age, held together by maritime trading, which also included Ireland, France, Spain and Portugal. In contrast to the generally accepted view[84] that Celtic originated in the context of the Hallstatt culture, since 2009, John T. Koch and others have proposed that the origins of the Celtic languages are to be sought in Bronze Age Western Europe, especially the Iberian Peninsula.[85][86][87][88] Koch et al.’s proposal has failed to find wide acceptance among experts on the Celtic languages.[84]

All the modern Brythonic languages (Breton, Cornish, Welsh) are generally considered to derive from a common ancestral language termed Brittonic, British, Common Brythonic, Old Brythonic or Proto-Brythonic, which is thought to have developed from Proto-Celtic or early Insular Celtic by the 6th century AD.[89] Brythonic languages were probably spoken before the Roman invasion at least in the majority of Great Britain south of the rivers Forth and Clyde, though the Isle of Man later had a Goidelic language, Manx. Northern Scotland mainly spoke Pritennic, which became Pictish, which may have been a Brythonic language. During the period of the Roman occupation of Southern Britain (AD 43 to c. 410), Common Brythonic borrowed a large stock of Latin words. Approximately 800 of these Latin loan-words have survived in the three modern Brythonic languages. Romano-British is the name for the Latinised form of the language used by Roman authors.

British English is spoken in the present day across the island, and developed from the Old English brought to the island by Anglo-Saxon settlers from the mid 5th century. Some 1.5 million people speak Scots—which was indigenous language of Scotland and has become closer to English over centuries.[90][91] An estimated 700,000 people speak Welsh,[92] an official language in Wales.[93] In parts of north west Scotland, Scottish Gaelic remains widely spoken. There are various regional dialects of English, and numerous languages spoken by some immigrant populations.

Religion

Christianity has been the largest religion by number of adherents since the Early Middle Ages: it was introduced under the ancient Romans, developing as Celtic Christianity. According to tradition, Christianity arrived in the 1st or 2nd century. The most popular form is Anglicanism (known as Episcopalism in Scotland). Dating from the 16th-century Reformation, it regards itself as both Catholic and Reformed. The Head of the Church is the monarch of the United Kingdom, as the Supreme Governor. It has the status of established church in England. There are just over 26 million adherents to Anglicanism in Britain today,[94] although only around one million regularly attend services. The second largest Christian practice is the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, which traces its history to the 6th century with Augustine’s mission and was the main religion for around a thousand years. There are over 5 million adherents today, 4.5 million in England and Wales[95] and 750,000 in Scotland,[96] although fewer than a million Catholics regularly attend mass.[97]