Всего найдено: 4

Добрый день

Как правильно написать:

Пеппи Длинный Чулок или Пеппи ДлинныйчулокСпасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словарная рекомендация: Пеппи Длинныйчулок. См.: Лопатин В. В., Нечаева И. В., Чельцова Л. К. Прописная или строчная? Орфографический словарь. М., 2011.

Появился такой вопрос. Как правильно писать имя Пеппи Длинный Чулок. Посмотрел пару современных книг, там Длинныйчулок пишется одним словом. Хотя из детства помню, что в книгах писали двумя отдельными словами: Длинный Чулок (оба слова с большой буквы). Так как же правильно? Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Согласно рекомендациям словарей, правильно: Пеппи Длинныйчулок.

Подскажите, как правильно пишется: Пеппи Длинный Чулок или Пеппи Длинныйчулок?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Пеппи Длинныйчулок.

Пеппи Длинный Чулок. Как правильно?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

_Пеппи Длинныйчулок_ — перевод Л. Брауде, Е. Паклиной. _Пеппи длинныйчулок_ — перевод Л.Лунгиной.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Pippi Longstocking | |

|---|---|

Pippi Longstocking as illustrated by Ingrid Vang Nyman on the Swedish cover of Pippi Goes On Board |

|

| First appearance | Pippi Longstocking (1945) |

| Last appearance | Pippi in the South Seas (1948) |

| Created by | Astrid Lindgren |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | Pippi |

| Gender | Female |

| Nationality | Swedish |

Pippi Longstocking (Swedish: Pippi Långstrump) is the fictional main character in an eponymous series of children’s books by Swedish author Astrid Lindgren. Pippi was named by Lindgren’s daughter Karin, who asked her mother for a get-well story when she was off school.

Pippi is red-haired, freckled, unconventional and superhumanly strong – able to lift her horse one-handed. She is playful and unpredictable. She often makes fun of unreasonable adults, especially if they are pompous and condescending. Her anger comes out in extreme cases, such as when a man mistreats his horse. Pippi, like Peter Pan, does not want to grow up. She is the daughter of a buccaneer captain and has adventure stories to tell about that, too. Her four best friends are her horse and monkey, and the neighbours’ children, Tommy and Annika.

After being rejected by Bonnier Publishers in 1944, Lindgren’s first manuscript was accepted by Rabén and Sjögren. The three Pippi chapter books (Pippi Longstocking, Pippi Goes on Board, and Pippi in the South Seas) were published from 1945 to 1948, followed by three short stories and a number of picture book adaptations. They have been translated into 76 languages as of 2018[1] and made into several films and television series.

Character[edit]

Pippi Longstocking is a nine-year-old girl.[2] At the start of the first novel, she moves into Villa Villekulla: the house she shares with her monkey, named Mr. Nilsson, and her horse that is not named in the novels but called Lilla Gubben (Little Old Man) in the movies.[3] Pippi soon befriends the two children living next door, Tommy and Annika Settergren.[4][5] With her suitcase of gold coins, Pippi maintains an independent lifestyle without her parents: her mother died soon after her birth; her father, Captain Ephraim Longstocking, goes missing at sea, ultimately turning up as king of a South Sea island.[6][7] Despite periodic attempts by village authorities to make her conform to cultural expectations of what a child’s life should be, Pippi happily lives free from social conventions.[8][9] According to Eva-Maria Metcalf, Pippi «loves her freckles and her tattered clothes; she makes not the slightest attempt to suppress her wild imagination, or to adopt good manners.»[9] Pippi also has a penchant for storytelling, which often takes the form of tall tales.[10]

When discussing Pippi, Astrid Lindgren explained that «Pippi represents my own childish longing for a person who has power but does not abuse it.»[11] Although she is the self-proclaimed «strongest girl in the world», Pippi often uses nonviolence to solve conflicts or protect other children from bullying.[12][13] Pippi has been variously described by literary critics as «warm-hearted»,[8] compassionate,[14] kind,[15] clever,[7] generous,[8][16] playful,[17] and witty to the point of besting adult characters in conversation.[8] Laura Hoffeld wrote that while Pippi’s «naturalness entails selfishness, ignorance, and a marked propensity to lie», the character «is simultaneously generous, quick and wise, and true to herself and others.»[18]

Development[edit]

Biographer Jens Andersen locates a range of influences and inspiration for Pippi not only within educational theories of the 1930s, such as those of A. S. Neill and Bertrand Russell, but also contemporary films and comics that featured «preternaturally strong characters» (e.g. Superman and Tarzan).[19] Literary inspiration for the character can be found in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Strange Child, Anne of Green Gables, and Daddy Long Legs in addition to myths, fairytales, and legends.[19] Andersen argues that the «misanthropic, emotionally stunted age» of the Second World War, during which Lindgren was developing the character, provided the most influence: the original version of Pippi, according to Andersen, «was a cheerful pacifist whose answer to the brutality and evil of war was goodness, generosity, and good humor.»[20]

Pippi originates from bedside stories told for Lindgren’s daughter, Karin. In the winter of 1941, Karin had come down with an illness and was confined to her sickbed; inspired by Karin’s request to tell her stories about Pippi Longstocking—a name Karin had created on the spot[21]—Lindgren improvised stories about an «anything-but-pious» girl with «boundless energy.»[22] As a child, Karin related more to Annika and Tommy, rather than Pippi, who she felt was very different from her personality.[23] Pippi became a staple within the household, with Karin’s friends and cousins also enjoying her adventures.[22] In April 1944, while recovering from a twisted ankle, Lindgren wrote her stories about Pippi in shorthand, a method she used throughout her writing career; a copy of the clean manuscript was turned into a homemade book for Karin and given to her on May 21, while another was posted to publisher Bonnier Förlag, where it was rejected in September on the grounds of being «too advanced.»[24]

After her critical success with her debut children’s novel The Confidences of Britt-Mari (1944),[25] Lindgren sent the manuscript for Pippi Longstocking to her editor at Rabén and Sjögren, the children’s librarian and critic Elsa Olenius, in May 1945. Olenius advised her to revise some of the «graphic» elements, such as a full chamber pot being used as a fire extinguisher, and then to enter it into the upcoming competition at Rabén and Sjögren, which was for books targeted at children between the ages of six and ten.[26] Critic Ulla Lundqvist estimates that a third of the manuscript was altered, with some changes made to improve its prose and readability, and others done to the character of Pippi, who according to Lundqvist «acquire[d] a new modesty and tenderness, and also a slight touch of melancholy,» as well as «less intricate» dialogue.[4] Pippi Longstocking placed first and was subsequently published in November 1945 with illustrations by Ingrid Vang Nyman.[27] Two more books followed: Pippi Goes on Board (1946) and Pippi in the South Seas (1948).[28] Three picture books were also produced: Pippi’s After Christmas Party (1950), Pippi on the Run (1971), and Pippi Longstocking in the Park (2001).[29]

Name[edit]

Pippi in the original Swedish language books says her full name is Pippilotta Viktualia Rullgardina Krusmynta Efraimsdotter Långstrump. Although her surname Långstrump – literally long stocking – translates easily into other languages, her personal names include invented words that cannot translate directly,[30] and a patronymic (Efraimsdotter) which is unfamiliar to many cultures. English language books and films about Pippi have given her name in the following forms:

- Pippilotta Rollgardinia Victualia Peppermint Longstocking[31]

- Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraim’s Daughter Longstocking[32]

- Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraimsdotter Longstocking[33]

- Pippilotta Provisionia Gaberdina Dandeliona Ephraimsdaughter Longstocking[34]

In 2005, UNESCO published lists of the most widely translated books. In regard to children’s literature, Pippi Longstocking was listed as the fifth most widely translated work with versions in 70 different languages.[35][36] As of 2017, it was revealed that Lindgren’s works had been translated into 100 languages.[37] Here are the character’s names in some languages other than English.

- In Afrikaans Pippi Langkous

- In Albanian Pipi Çorapegjata

- In Arabic جنان ذات الجورب الطويل Jinān ḏāt al-Jawrab aṭ-Ṭawīl

- In Armenian Երկարագուլպա Պիպին Erkaragulpa Pipin

- In Azerbaijani Pippi Uzuncorablı

- In Basque Pippi Kaltzaluze

- In Belarusian Піпі Доўгаяпанчоха Pipi Doŭhajapanchokha

- In Bulgarian Пипи Дългото чорапче Pipi Dǎlgoto chorapche

- In Breton Pippi hir he loeroù

- In Catalan Pippi Calcesllargues

- In Chinese 长袜子皮皮 Chángwàzi Pípí

- In Czech Pipilota Citrónie Cimprlína Mucholapka Dlouhá punčocha

- In Danish Pippi Langstrømpe

- In Dutch Pippi Langkous

- In Esperanto Pipi Ŝtrumpolonga

- In Estonian Pipi Pikksukk

- In Faroese Pippi Langsokkur

- In Filipino Potpot Habangmedyas

- In Finnish Peppi Pitkätossu

- In French Fifi Brindacier (literally «Fifi Strand of Steel»)

- In Galician Pippi Mediaslongas

- In Georgian პეპი გრძელიწინდა Pepi Grdzelitsinda or პეპი მაღალიწინდა Pepi Magalitsinda

- In German Pippilotta Viktualia Rollgardina Pfefferminz (book) or Schokominza (film) Efraimstochter Langstrumpf

- In Greek Πίπη η Φακιδομύτη Pípē ē Fakidomýtē (literally «Pippi the freckle-nosed girl»)

- In Hebrew בילבי בת-גרב Bilbi Bat-Gerev or גילגי Gilgi or the phonetic matching בילבי לא-כלום bílbi ló khlum, literally «Bilby Nothing»[38]: p.28 in old translations

- In Hungarian Harisnyás Pippi

- In Icelandic Lína Langsokkur

- In Indonesian Pippilotta Viktualia Gorden Tirai Permen Efraimputri Langstrump[39]

- In Irish Pippi Longstocking

- In Italian Pippi Calzelunghe

- In Japanese 長くつ下のピッピ Nagakutsushita no Pippi

- In Karelian Peppi Pitküsukku

- In Khmer ពីពីស្រោមជើងវែង

- In Korean 말괄량이 소녀 삐삐 Malgwallyang-i Sonyeo Ppippi

- In Kurdish Pippi-Ya Goredirey

- In Latvian Pepija Garzeķe

- In Lithuanian Pepė Ilgakojinė

- In Macedonian Пипи долгиот чорап Pipi dolgot chorap

- In Mongolian Урт Оймст Пиппи Urt Oimst Pippi

- In Norwegian Pippi Langstrømpe

- In Persian پیپی جوراببلنده Pipi Jôrâb-Bolandeh

- In Polish Pippi Pończoszanka or Fizia Pończoszanka

- In Portuguese Píppi Meialonga (Brazil), Pipi das Meias Altas (Portugal)

- In Romanian Pippi Șosețica (Romania), Pepi Ciorap-Lung (Moldova)

- In Russian Пеппи Длинный Чулок Peppi Dlinnyj Chulok or Пеппи Длинныйчулок Peppi Dlinnyjchulok

- In Scottish Gaelic Pippi Fhad-stocainneach[40]

- In Scots Pippi Langstoking

- In Serbian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Bosnian Pipi Duga Čarapa / Пипи Дуга Чарапа

- In Slovak Pipi Dlhá Pančucha

- In Slovene Pika Nogavička

- In Spanish Pipi Calzaslargas (Spain), Pippi Mediaslargas or Pippa Mediaslargas (Latin America)

- In Sinhala: දිගමේස්දානලාගේ පිප්පි Digamēsdānalāgē Pippi

- In Thai ปิ๊ปปี้ ถุงเท้ายาว Bpíp-bpîi Tǔng-Táo-Yaao

- In Turkish Pippi Uzunçorap

- In Ukrainian Пеппі Довгапанчоха Peppi Dovhapanchokha

- In Urdu Pippī Lambemoze

- In Vietnamese Pippi Tất Dài

- In Welsh Pippi Hosan-hir

- In Yiddish פּיפּפּי לאָנגסטאָקקינג Pippi Longstokking

Cultural impact[edit]

Pippi Longstocking quickly became popular in Sweden upon publication, and by the end of the 1940s, 300,000 copies had been sold, saving Rabén and Sjögren from impending financial ruin.[41] This was partially due to Olenius’s marketing: she ensured that the book was frequently read to a radio audience, as well as helping to put on a popular adaptation of the book at her children’s theatre at Medborgarhuset, Stockholm, in March 1946, for which only a library card was required for admission.[42] This performance also toured other Swedish cities, including Norrköping, Göteborg, and Eskilstuna.[42] Another factor in the book’s success was two positive reviews by the influential Swedish critics of children’s culture, Eva von Zweigbergk and Greta Bolin, writing for Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet, respectively; they praised the main character as «a liberatory force.»[43] Zweigbergk wrote that Pippi could provide an outlet for regular children who do not have the considerable freedom she possesses, with which Bolin agreed, remarking that Pippi’s humor and antics would also appeal to adults for the same reason.[44]

Subsequent reviews of Pippi Longstocking echoed the general opinions of von Zweigbergk and Bolin towards the book, until John Landquist’s criticism in an August 1946 piece published in Aftonbladet, titled «BAD AND PRIZEWINNING.»[45] Landquist, who worked as a professor at Lund University, argued that the book was badly done, harmful to children, and that Pippi herself was mentally disturbed.[45][46] Further criticism of Pippi’s supposedly «unnatural» and harmful behavior followed in an article in the teachers’ magazine Folkskollärarnas Tidning and in readers’ letters to magazines.[45][47] This debate over Pippi’s performance of childhood colored the reviews of the sequel Pippi Goes On Board (October 1946), some of which responded to Landquist’s argument within the review itself.[45][47] Regardless, Pippi continued to maintain her popularity and was featured in a range of merchandising, adaptations, and advertising.[48]

In 1950, Pippi Longstocking was translated into American English by Viking Books,[nb 1] featuring Louis Glanzman’s artwork.[49] It did not become a bestseller, although sales did eventually improve after the initial release; more than five million copies had been sold by 2000.[50] Pippi was positively received by American reviewers, who did not find her behavior «subversive» or problematic, but rather «harmless» and entertaining.[51] Eva-Maria Metcalf has argued that Pippi was subject to a «double distancing» as both a foreign character and one believed to be nonsensical, thus minimizing her potentially subversive actions that had stirred the minor controversy earlier in Sweden.[52] As a result of Pippi and Lindgren’s growing recognition in the United States, Pippi’s behavior in later books became more critically scrutinized by literary critics, some of whom were less sure of the «hilarious nonsensical behavior, the goodness of her heart, and the freedom of her spirit» that had been lauded in earlier reviews.[53] Reviewers of Pippi in the South Seas in The Horn Book Magazine and The Saturday Review found Pippi to be less charming than in earlier books, with The Saturday Review describing her as «noisy and rude and unfunny.»[54]

A screenshot of the 1969 television series, showing Inger Nilsson as Pippi Longstocking

An influential television adaptation of Pippi Longstocking debuted on 8 February 1969 in Sweden, and was broadcast for thirteen weeks, during which it acquired a considerable following.[55] It was directed by Olle Hellbom, who later directed other adaptations of Lindgren’s works.[56] Inger Nilsson starred as Pippi, and upon the broadcast of the television series, she became a celebrity along with her co-stars Pär Sundberg and Maria Persson, who played Tommy and Annika respectively.[55] In this adaptation Pippi’s horse that is unnamed in the novels was called Lilla Gubben (Little Old Man).[3] As a result of Lindgren’s considerable unhappiness with the lesser-known Swedish film adaptation of Pippi Longstocking (1949), she wrote the screenplay for the television adaptation, which stuck more closely to the narrative of the books than the film had.[57] Scholar Christine Anne Holmlund briefly discussed the difference she found between the two iterations of Pippi, namely that Viveca Serlachius’s portrayal of Pippi sometimes took on middle-class sensibilities in a way that other iterations of Pippi had not, for example, purchasing a piano in one scene only to show it off in Villa Villakula. In contrast, the Pippi of Hellbom’s television series and subsequent tie-in 1970 films, Pippi in the South Seas and Pippi on the Run,[58][59] is an «abnormal, even otherworldly,» periodically gender-defying bohemian reminiscent of Swedish hippies.[60] Holmlund argued that both Gunvall and Hellbom’s adaptations depict her as a «lovably eccentric girl.»[61]

An actress portrays Pippi in front of a scale model of Villa Villekulla at Astrid Lindgren’s World.

In the twenty-first century, Pippi has continued to maintain her popularity, often placing on lists of favorite characters from children’s literature or feminist characters.[62][63][64] She is regarded as the most well-known of Lindgren’s creations,[61] and appears as a character in Astrid Lindgren’s World, a theme park in Vimmerby, Sweden, dedicated to Lindgren’s works,[65] and on the obverse of the Swedish 20 kronor note, as issued by Riksbank.[66] Additionally, Pika’s Festival, a children’s festival in Slovenia, borrows its name from her.[67] Pippi has also inspired other literary creations: for his character Lisbeth Salander in the Millennium series, Stieg Larsson was inspired by his idea of what Pippi might have been like as an adult.[68] Pippi has continued to remain popular with critics, who often cite her freedom as part of her appeal. The Independent‘s Paul Binding described her as «not simply a girl boldly doing boys’ things,» but rather «[i]n her panache and inventiveness she appeals to the longings, the secret psychic demands of girls and boys, and indeed has happily united them in readership all over the world.»[69] Susanna Forest of The Telegraph called Pippi «still outrageous and contemporary» and «the ultimate imaginary friend to run along rooftops and beat up the bad guys.»[70] In 100 Best Books for Children, Anita Silvey praised the character as «the perfect fantasy heroine — one who lives without supervision but with endless money to execute her schemes.»[65]

Pippi has been subject to censorship in translations. A censored edition of Pippi Longstocking appeared in France, with changes made to her character to make her «a fine young lady» instead of «a strange, maladjusted child.»[71] Additionally, the publisher, Hachette, thought that Pippi’s ability to lift a horse would seem unrealistic to French child readers, and thus changed the horse to a pony.[72] In response to this change, Lindgren requested that the publisher give her a photo of a real French girl lifting a pony, as that child would have a «secure» weightlifting career.[73] Sara Van den Bossche has hypothesized that the lack of controversy as a result of the censorship might be why Pippi Longstocking went mainly unremarked upon in France, whereas in Germany and Sweden, the book quickly became accepted within the countries’ respective children’s literature canon, even as it stirred controversy over its «anti-authoritarian tendencies.»[71][clarification needed] In 1995, an uncensored version of Pippi Longstocking was released in France, which «shook» French readers, although the book did not reach the cultural status as it had in Germany and Sweden.[74][clarification needed]

The character has also centered in debates about how to handle potentially offensive racial language in children’s literature. In 2014, the Swedish public broadcaster SVT edited the 1969 television adaptation of Pippi Longstocking with the approval of Astrid Lindgren’s heirs: the first edit removed Pippi’s reference to her father as «King of the Negroes,» a term now offensive in Sweden;[nb 2] and the second eliminated Pippi slanting her eyes, although it kept her pretending to sing in «Chinese».[76] These changes received a backlash: of the first 25,000 Swedish readers polled by the Aftonbladet on Facebook, eighty-one percent disagreed with the idea of removing outdated racial language and notions from Pippi Longstocking, and the columnist Erik Helmerson of Dagens Nyheter labelled the changes as censorship.[76] One of Lindgren’s grandchildren, Nils Nyman, defended the edits, arguing that to not do so might have diluted Pippi’s message of female empowerment.[76]

Pippi books in Swedish and English[edit]

The three main Pippi Longstocking books were published first in Swedish and later in English:

- Pippi Långstrump, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman (Stockholm, 1945),[77] first published in English as Pippi Longstocking, translated by Florence Lamborn, illustrated by Louis S. Glanzman (New York, 1950)[78]

- Pippi Långstrump går ombord, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman (Stockholm, 1946),[79] translated as Pippi Goes on Board, translated by Florence Laborn and illustrated by Louis S. Glanzman (New York, 1957)[80]

- Pippi Långstrump i Söderhavet (Stockholm, 1948), illustrated by Ingrid Nyman,[81] first published in English as Pippi in the South Seas (New York, 1959), translated by Gerry Bothmer and illustrated by Louis S. Glanzman[82]

There are also a number of additional Pippi stories, some just in Swedish, others in both Swedish and English:

- Pippi Långstrump har julgransplundring, a picture book first published in Swedish in the Christmas edition of Allers Magazine in 1948, later published in book form in 1979, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman.[83] It was first published in English in 1996 as Pippi Longstocking’s After-Christmas Party, translated by Stephen Keeler and illustrated by Michael Chesworth.[84]

- Pippi flyttar in, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman, was first published in Swedish as a picture book in 1969, and appeared as a comic book in 1992.[85][86] Translated by Tiina Nunnally, it was published in English as Pippi Moves In in 2012.[87]

- Pippi Långstrump i Humlegården, a picture book illustrated by Ingrid Nyman, published in Swedish in 2000.[88] It was published in English in April 2001 as Pippi Longstocking in the Park, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman.[89]

- Pippi ordnar allt (1969), translated as Pippi Fixes Everything (2010)[90]

Other books in Swedish include:[91]

- Känner du Pippi Långstrump? (1947)

- Sjung med Pippi Långstrump (1949)

- Pippi håller kalas (1970)

- Pippi är starkast i världen (1970)

- Pippi går till sjöss (1971)

- Pippi vill inte bli stor (1971)

- Pippi Långstrump på Kurrekurreduttön (2004)

- Pippi hittar en spunk (2008)

- Pippi går i affärer (2014)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Historically, translations of children’s literature have comprised a very small share of the market in the United States.[49]

- ^ Publisher Friedrich Oetinger had also revised the German translation of Pippi Longstocking in 2009, removing a reference to Pippi’s father as «Negro King» in favor of the «South Sea King.»[75] In Sweden, the term remained in the books, with a preface noting that the accepted language and terminology used to describe people of African ancestry had changed over the years.[76]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Astrid Lindgren official webpage». Astridlindgren.se. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 69.

- ^ a b «Pippi Långstrumps häst får vara versal». Språktidningen. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-13 – via PressReader.com.

- ^ a b Lundqvist 1989, p. 99.

- ^ Erol 1991, p. 118–119.

- ^ Erol 1991, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b Metcalf 1995, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Lundqvist 1989, p. 100.

- ^ a b Metcalf 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 70.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 71.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, p. 50.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 74.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, p. 51.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, p. 48.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 145.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 145–46.

- ^ Lundqvist 1989, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 144.

- ^ «The history». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 139–143, 156.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 157.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 162–63.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 164.

- ^ Lundqvist 1989, p. 97.

- ^ «Gale — Institution Finder».

- ^ Surmatz, Astrid (2005). Pippi Långstrump als Paradigma. Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie (in German). Vol. 34. A. Francke. pp. 150, 253–254. ISBN 978-3-7720-3097-0.

- ^ Pashko, Stan (June 1973). «Making the Scene». Boys’ Life. p. 6. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Pilon, A. Barbara (1978). Teaching language arts creatively in the elementary grades, John Wiley & Sons, page 215.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Pippi Longstocking, 2000

- ^ «5 of the most translated children’s books that are known and loved the world over!». AdHoc Translations. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ «Astrid worldwide». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Forslund, Anna (12 May 2017). «Astrid Lindgren now translated into 100 languages!». MyNewsDesk. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695 [1]

- ^ [2]Lindgren, Astrid (2001). Pippi Hendak Berlayar. Gramedia.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (2018). Pippi Fhad-stocainneach (in Scottish Gaelic). Akerbeltz. ISBN 9781907165313.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 168.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 170.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 169–70.

- ^ a b c d Lundqvist 1989, p. 102.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 173.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 174.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 185.

- ^ a b Metcalf 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 15–17.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 18–19.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 21.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 20–21.

- ^ a b «Pippi Longstocking (TV-series)». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, p. 7.

- ^ «Pippi in the South Seas». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ «Pippi on the Run». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ a b Holmlund 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kraft, Amy (20 September 2010). «20 Girl-Power Characters to Introduce to Your GeekGirl». Wired. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Doll, Jen (5 April 2012). «The Greatest Girl Characters of Young Adult Literature». The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Erbland, Kate (11 June 2014). «25 of Childhood Literature’s Most Beloved Female Characters, Ranked in Coolness». Bustle. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b Silvey 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Jacobsson, Leif (25 March 2013). «Copyright issues in the new banknote series» (pdf). Riksbank. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ «Pika’s Festival». Culture.si. Ljudmila Art and Science Laboratory. 25 November 2011.

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (5 January 2011). «The Mystery of the Dragon Tattoo: Stieg Larsson, the World’s Bestselling — and Most Enigmatic — Author». Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ Binding, Paul (26 August 2007). «Long live Pippi Longstocking: The girl with red plaits is back». The Independent. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Forest, Susanna (29 September 2007). «Pippi Longstocking: the Swedish superhero». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ a b Van den Bossche 2011, p. 58.

- ^ Lindgren 2017, pp. 192–93.

- ^ Lindgren 2017, p. 193.

- ^ Van den Bossche 2011, p. 59.

- ^ Wilder, Charly (16 January 2013). «Edit of Classic Children’s Book Hexes Publisher». Der Spiegel. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Donadio, Rachel (2 December 2014). «Sweden’s Storybook Heroine Ignites a Debate on Race». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1945). Pippi Långstrump. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 174.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1950). Pippi Longstocking. New York: Viking Press.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1946). Pippi Långstrump går ombord. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 192. ISBN 9789129621372.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1957). Pippi Goes on Board. New York: Viking Press.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1948). Pippi Långstrump i Söderhavet. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 166.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1959). Pippi in the South Seas. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9780670557110.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1979). Pippi har julgransplundring. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1996). Pippi Longstocking’s After-Christmas Party. Viking. ISBN 0-670-86790-X.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1969). «Pippi flyttar in». Rabén & Sjögren.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1992). Pippi flyttar in. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. ISBN 978-91-29-62055-9.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (October 2012). Pippi Moves In. Drawn & Quarterly Publications. ISBN 978-1-77046-099-7.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (2000). Pippi Langstrump I Humlegarden. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 24. ISBN 978-9129648782.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (2001). Pippi Longstocking in the Park. R / S Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-9129653076.

- ^ «Pippi Fixes Everything» (in Swedish). Astrid Lindgren Company. 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ «Astrid Lindgrens böcker» (in Swedish). Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

References[edit]

- Andersen, Jens (2018). Astrid Lindgren: The Woman Behind Pippi Longstocking. Translated by Caroline Waight. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Erol, Sibel (1991). «The Image of the Child in Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking«. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly. 1991: 112–119. doi:10.1353/chq.1991.0005.

- Hoffeld, Laura (1977). «Pippi Longstocking: The Comedy of the Natural Girl». The Lion and the Unicorn. 1 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0247. S2CID 144969573.

- Holmlund, Christine Anne (2003). «Pippi and Her Pals». Cinema Journal. 42 (2): 3–24. doi:10.1353/cj.2003.0005.

- Lindgren, Astrid (2017). Translated by Elizabeth Sofia Powell. «‘Why do we write children’s books?’ by Astrid Lindgren». Children’s Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press. 45: 188–195. doi:10.1353/chl.2017.0009.

- Lundqvist, Ulla (1989). «The Child of the Century». The Lion and the Unicorn. 13 (2): 97–102. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0168. S2CID 142926073.

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria (1995). Astrid Lindgren. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-4525-2.

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria (2011). «Pippi Longstocking in the United States». In Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina; Astrid Surmatz (eds.). Beyond Pippi Longstocking: Intermedial and International Aspects of Astrid Lindgren’s Works. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88353-5.

- Silvey, Anita (2005). 100 Best Books for Children. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Van den Bossche, Sara (2011). «We Love What We know: The Canonicity of Pippi Longstocking in Different Media in Flanders». In Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina; Astrid Surmatz (eds.). Beyond Pippi Longstocking: Intermedial and International Aspects of Astrid Lindgren’s Works. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88353-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Frasher, Ramona S. (1977). «Boys, Girls and Pippi Longstocking». The Reading Teacher. 30 (8): 860–863. JSTOR 20194413.

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria (1990). «Tall Tale and Spectacle in Pippi Longstocking». Children’s Literature Association Quarterly. 15 (3): 130–135. doi:10.1353/chq.0.0791.

External links[edit]

Media related to Pippi Longstocking at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website

- The home of Pippi Longstocking

- Pippi Longstocking and Astrid Lindgren

- Japanese stage musical starring Tomoe Shinohara (in Japanese)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Pippi Longstocking | |

|---|---|

Pippi Longstocking as illustrated by Ingrid Vang Nyman on the Swedish cover of Pippi Goes On Board |

|

| First appearance | Pippi Longstocking (1945) |

| Last appearance | Pippi in the South Seas (1948) |

| Created by | Astrid Lindgren |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | Pippi |

| Gender | Female |

| Nationality | Swedish |

Pippi Longstocking (Swedish: Pippi Långstrump) is the fictional main character in an eponymous series of children’s books by Swedish author Astrid Lindgren. Pippi was named by Lindgren’s daughter Karin, who asked her mother for a get-well story when she was off school.

Pippi is red-haired, freckled, unconventional and superhumanly strong – able to lift her horse one-handed. She is playful and unpredictable. She often makes fun of unreasonable adults, especially if they are pompous and condescending. Her anger comes out in extreme cases, such as when a man mistreats his horse. Pippi, like Peter Pan, does not want to grow up. She is the daughter of a buccaneer captain and has adventure stories to tell about that, too. Her four best friends are her horse and monkey, and the neighbours’ children, Tommy and Annika.

After being rejected by Bonnier Publishers in 1944, Lindgren’s first manuscript was accepted by Rabén and Sjögren. The three Pippi chapter books (Pippi Longstocking, Pippi Goes on Board, and Pippi in the South Seas) were published from 1945 to 1948, followed by three short stories and a number of picture book adaptations. They have been translated into 76 languages as of 2018[1] and made into several films and television series.

Character[edit]

Pippi Longstocking is a nine-year-old girl.[2] At the start of the first novel, she moves into Villa Villekulla: the house she shares with her monkey, named Mr. Nilsson, and her horse that is not named in the novels but called Lilla Gubben (Little Old Man) in the movies.[3] Pippi soon befriends the two children living next door, Tommy and Annika Settergren.[4][5] With her suitcase of gold coins, Pippi maintains an independent lifestyle without her parents: her mother died soon after her birth; her father, Captain Ephraim Longstocking, goes missing at sea, ultimately turning up as king of a South Sea island.[6][7] Despite periodic attempts by village authorities to make her conform to cultural expectations of what a child’s life should be, Pippi happily lives free from social conventions.[8][9] According to Eva-Maria Metcalf, Pippi «loves her freckles and her tattered clothes; she makes not the slightest attempt to suppress her wild imagination, or to adopt good manners.»[9] Pippi also has a penchant for storytelling, which often takes the form of tall tales.[10]

When discussing Pippi, Astrid Lindgren explained that «Pippi represents my own childish longing for a person who has power but does not abuse it.»[11] Although she is the self-proclaimed «strongest girl in the world», Pippi often uses nonviolence to solve conflicts or protect other children from bullying.[12][13] Pippi has been variously described by literary critics as «warm-hearted»,[8] compassionate,[14] kind,[15] clever,[7] generous,[8][16] playful,[17] and witty to the point of besting adult characters in conversation.[8] Laura Hoffeld wrote that while Pippi’s «naturalness entails selfishness, ignorance, and a marked propensity to lie», the character «is simultaneously generous, quick and wise, and true to herself and others.»[18]

Development[edit]

Biographer Jens Andersen locates a range of influences and inspiration for Pippi not only within educational theories of the 1930s, such as those of A. S. Neill and Bertrand Russell, but also contemporary films and comics that featured «preternaturally strong characters» (e.g. Superman and Tarzan).[19] Literary inspiration for the character can be found in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Strange Child, Anne of Green Gables, and Daddy Long Legs in addition to myths, fairytales, and legends.[19] Andersen argues that the «misanthropic, emotionally stunted age» of the Second World War, during which Lindgren was developing the character, provided the most influence: the original version of Pippi, according to Andersen, «was a cheerful pacifist whose answer to the brutality and evil of war was goodness, generosity, and good humor.»[20]

Pippi originates from bedside stories told for Lindgren’s daughter, Karin. In the winter of 1941, Karin had come down with an illness and was confined to her sickbed; inspired by Karin’s request to tell her stories about Pippi Longstocking—a name Karin had created on the spot[21]—Lindgren improvised stories about an «anything-but-pious» girl with «boundless energy.»[22] As a child, Karin related more to Annika and Tommy, rather than Pippi, who she felt was very different from her personality.[23] Pippi became a staple within the household, with Karin’s friends and cousins also enjoying her adventures.[22] In April 1944, while recovering from a twisted ankle, Lindgren wrote her stories about Pippi in shorthand, a method she used throughout her writing career; a copy of the clean manuscript was turned into a homemade book for Karin and given to her on May 21, while another was posted to publisher Bonnier Förlag, where it was rejected in September on the grounds of being «too advanced.»[24]

After her critical success with her debut children’s novel The Confidences of Britt-Mari (1944),[25] Lindgren sent the manuscript for Pippi Longstocking to her editor at Rabén and Sjögren, the children’s librarian and critic Elsa Olenius, in May 1945. Olenius advised her to revise some of the «graphic» elements, such as a full chamber pot being used as a fire extinguisher, and then to enter it into the upcoming competition at Rabén and Sjögren, which was for books targeted at children between the ages of six and ten.[26] Critic Ulla Lundqvist estimates that a third of the manuscript was altered, with some changes made to improve its prose and readability, and others done to the character of Pippi, who according to Lundqvist «acquire[d] a new modesty and tenderness, and also a slight touch of melancholy,» as well as «less intricate» dialogue.[4] Pippi Longstocking placed first and was subsequently published in November 1945 with illustrations by Ingrid Vang Nyman.[27] Two more books followed: Pippi Goes on Board (1946) and Pippi in the South Seas (1948).[28] Three picture books were also produced: Pippi’s After Christmas Party (1950), Pippi on the Run (1971), and Pippi Longstocking in the Park (2001).[29]

Name[edit]

Pippi in the original Swedish language books says her full name is Pippilotta Viktualia Rullgardina Krusmynta Efraimsdotter Långstrump. Although her surname Långstrump – literally long stocking – translates easily into other languages, her personal names include invented words that cannot translate directly,[30] and a patronymic (Efraimsdotter) which is unfamiliar to many cultures. English language books and films about Pippi have given her name in the following forms:

- Pippilotta Rollgardinia Victualia Peppermint Longstocking[31]

- Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraim’s Daughter Longstocking[32]

- Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraimsdotter Longstocking[33]

- Pippilotta Provisionia Gaberdina Dandeliona Ephraimsdaughter Longstocking[34]

In 2005, UNESCO published lists of the most widely translated books. In regard to children’s literature, Pippi Longstocking was listed as the fifth most widely translated work with versions in 70 different languages.[35][36] As of 2017, it was revealed that Lindgren’s works had been translated into 100 languages.[37] Here are the character’s names in some languages other than English.

- In Afrikaans Pippi Langkous

- In Albanian Pipi Çorapegjata

- In Arabic جنان ذات الجورب الطويل Jinān ḏāt al-Jawrab aṭ-Ṭawīl

- In Armenian Երկարագուլպա Պիպին Erkaragulpa Pipin

- In Azerbaijani Pippi Uzuncorablı

- In Basque Pippi Kaltzaluze

- In Belarusian Піпі Доўгаяпанчоха Pipi Doŭhajapanchokha

- In Bulgarian Пипи Дългото чорапче Pipi Dǎlgoto chorapche

- In Breton Pippi hir he loeroù

- In Catalan Pippi Calcesllargues

- In Chinese 长袜子皮皮 Chángwàzi Pípí

- In Czech Pipilota Citrónie Cimprlína Mucholapka Dlouhá punčocha

- In Danish Pippi Langstrømpe

- In Dutch Pippi Langkous

- In Esperanto Pipi Ŝtrumpolonga

- In Estonian Pipi Pikksukk

- In Faroese Pippi Langsokkur

- In Filipino Potpot Habangmedyas

- In Finnish Peppi Pitkätossu

- In French Fifi Brindacier (literally «Fifi Strand of Steel»)

- In Galician Pippi Mediaslongas

- In Georgian პეპი გრძელიწინდა Pepi Grdzelitsinda or პეპი მაღალიწინდა Pepi Magalitsinda

- In German Pippilotta Viktualia Rollgardina Pfefferminz (book) or Schokominza (film) Efraimstochter Langstrumpf

- In Greek Πίπη η Φακιδομύτη Pípē ē Fakidomýtē (literally «Pippi the freckle-nosed girl»)

- In Hebrew בילבי בת-גרב Bilbi Bat-Gerev or גילגי Gilgi or the phonetic matching בילבי לא-כלום bílbi ló khlum, literally «Bilby Nothing»[38]: p.28 in old translations

- In Hungarian Harisnyás Pippi

- In Icelandic Lína Langsokkur

- In Indonesian Pippilotta Viktualia Gorden Tirai Permen Efraimputri Langstrump[39]

- In Irish Pippi Longstocking

- In Italian Pippi Calzelunghe

- In Japanese 長くつ下のピッピ Nagakutsushita no Pippi

- In Karelian Peppi Pitküsukku

- In Khmer ពីពីស្រោមជើងវែង

- In Korean 말괄량이 소녀 삐삐 Malgwallyang-i Sonyeo Ppippi

- In Kurdish Pippi-Ya Goredirey

- In Latvian Pepija Garzeķe

- In Lithuanian Pepė Ilgakojinė

- In Macedonian Пипи долгиот чорап Pipi dolgot chorap

- In Mongolian Урт Оймст Пиппи Urt Oimst Pippi

- In Norwegian Pippi Langstrømpe

- In Persian پیپی جوراببلنده Pipi Jôrâb-Bolandeh

- In Polish Pippi Pończoszanka or Fizia Pończoszanka

- In Portuguese Píppi Meialonga (Brazil), Pipi das Meias Altas (Portugal)

- In Romanian Pippi Șosețica (Romania), Pepi Ciorap-Lung (Moldova)

- In Russian Пеппи Длинный Чулок Peppi Dlinnyj Chulok or Пеппи Длинныйчулок Peppi Dlinnyjchulok

- In Scottish Gaelic Pippi Fhad-stocainneach[40]

- In Scots Pippi Langstoking

- In Serbian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Bosnian Pipi Duga Čarapa / Пипи Дуга Чарапа

- In Slovak Pipi Dlhá Pančucha

- In Slovene Pika Nogavička

- In Spanish Pipi Calzaslargas (Spain), Pippi Mediaslargas or Pippa Mediaslargas (Latin America)

- In Sinhala: දිගමේස්දානලාගේ පිප්පි Digamēsdānalāgē Pippi

- In Thai ปิ๊ปปี้ ถุงเท้ายาว Bpíp-bpîi Tǔng-Táo-Yaao

- In Turkish Pippi Uzunçorap

- In Ukrainian Пеппі Довгапанчоха Peppi Dovhapanchokha

- In Urdu Pippī Lambemoze

- In Vietnamese Pippi Tất Dài

- In Welsh Pippi Hosan-hir

- In Yiddish פּיפּפּי לאָנגסטאָקקינג Pippi Longstokking

Cultural impact[edit]

Pippi Longstocking quickly became popular in Sweden upon publication, and by the end of the 1940s, 300,000 copies had been sold, saving Rabén and Sjögren from impending financial ruin.[41] This was partially due to Olenius’s marketing: she ensured that the book was frequently read to a radio audience, as well as helping to put on a popular adaptation of the book at her children’s theatre at Medborgarhuset, Stockholm, in March 1946, for which only a library card was required for admission.[42] This performance also toured other Swedish cities, including Norrköping, Göteborg, and Eskilstuna.[42] Another factor in the book’s success was two positive reviews by the influential Swedish critics of children’s culture, Eva von Zweigbergk and Greta Bolin, writing for Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet, respectively; they praised the main character as «a liberatory force.»[43] Zweigbergk wrote that Pippi could provide an outlet for regular children who do not have the considerable freedom she possesses, with which Bolin agreed, remarking that Pippi’s humor and antics would also appeal to adults for the same reason.[44]

Subsequent reviews of Pippi Longstocking echoed the general opinions of von Zweigbergk and Bolin towards the book, until John Landquist’s criticism in an August 1946 piece published in Aftonbladet, titled «BAD AND PRIZEWINNING.»[45] Landquist, who worked as a professor at Lund University, argued that the book was badly done, harmful to children, and that Pippi herself was mentally disturbed.[45][46] Further criticism of Pippi’s supposedly «unnatural» and harmful behavior followed in an article in the teachers’ magazine Folkskollärarnas Tidning and in readers’ letters to magazines.[45][47] This debate over Pippi’s performance of childhood colored the reviews of the sequel Pippi Goes On Board (October 1946), some of which responded to Landquist’s argument within the review itself.[45][47] Regardless, Pippi continued to maintain her popularity and was featured in a range of merchandising, adaptations, and advertising.[48]

In 1950, Pippi Longstocking was translated into American English by Viking Books,[nb 1] featuring Louis Glanzman’s artwork.[49] It did not become a bestseller, although sales did eventually improve after the initial release; more than five million copies had been sold by 2000.[50] Pippi was positively received by American reviewers, who did not find her behavior «subversive» or problematic, but rather «harmless» and entertaining.[51] Eva-Maria Metcalf has argued that Pippi was subject to a «double distancing» as both a foreign character and one believed to be nonsensical, thus minimizing her potentially subversive actions that had stirred the minor controversy earlier in Sweden.[52] As a result of Pippi and Lindgren’s growing recognition in the United States, Pippi’s behavior in later books became more critically scrutinized by literary critics, some of whom were less sure of the «hilarious nonsensical behavior, the goodness of her heart, and the freedom of her spirit» that had been lauded in earlier reviews.[53] Reviewers of Pippi in the South Seas in The Horn Book Magazine and The Saturday Review found Pippi to be less charming than in earlier books, with The Saturday Review describing her as «noisy and rude and unfunny.»[54]

A screenshot of the 1969 television series, showing Inger Nilsson as Pippi Longstocking

An influential television adaptation of Pippi Longstocking debuted on 8 February 1969 in Sweden, and was broadcast for thirteen weeks, during which it acquired a considerable following.[55] It was directed by Olle Hellbom, who later directed other adaptations of Lindgren’s works.[56] Inger Nilsson starred as Pippi, and upon the broadcast of the television series, she became a celebrity along with her co-stars Pär Sundberg and Maria Persson, who played Tommy and Annika respectively.[55] In this adaptation Pippi’s horse that is unnamed in the novels was called Lilla Gubben (Little Old Man).[3] As a result of Lindgren’s considerable unhappiness with the lesser-known Swedish film adaptation of Pippi Longstocking (1949), she wrote the screenplay for the television adaptation, which stuck more closely to the narrative of the books than the film had.[57] Scholar Christine Anne Holmlund briefly discussed the difference she found between the two iterations of Pippi, namely that Viveca Serlachius’s portrayal of Pippi sometimes took on middle-class sensibilities in a way that other iterations of Pippi had not, for example, purchasing a piano in one scene only to show it off in Villa Villakula. In contrast, the Pippi of Hellbom’s television series and subsequent tie-in 1970 films, Pippi in the South Seas and Pippi on the Run,[58][59] is an «abnormal, even otherworldly,» periodically gender-defying bohemian reminiscent of Swedish hippies.[60] Holmlund argued that both Gunvall and Hellbom’s adaptations depict her as a «lovably eccentric girl.»[61]

An actress portrays Pippi in front of a scale model of Villa Villekulla at Astrid Lindgren’s World.

In the twenty-first century, Pippi has continued to maintain her popularity, often placing on lists of favorite characters from children’s literature or feminist characters.[62][63][64] She is regarded as the most well-known of Lindgren’s creations,[61] and appears as a character in Astrid Lindgren’s World, a theme park in Vimmerby, Sweden, dedicated to Lindgren’s works,[65] and on the obverse of the Swedish 20 kronor note, as issued by Riksbank.[66] Additionally, Pika’s Festival, a children’s festival in Slovenia, borrows its name from her.[67] Pippi has also inspired other literary creations: for his character Lisbeth Salander in the Millennium series, Stieg Larsson was inspired by his idea of what Pippi might have been like as an adult.[68] Pippi has continued to remain popular with critics, who often cite her freedom as part of her appeal. The Independent‘s Paul Binding described her as «not simply a girl boldly doing boys’ things,» but rather «[i]n her panache and inventiveness she appeals to the longings, the secret psychic demands of girls and boys, and indeed has happily united them in readership all over the world.»[69] Susanna Forest of The Telegraph called Pippi «still outrageous and contemporary» and «the ultimate imaginary friend to run along rooftops and beat up the bad guys.»[70] In 100 Best Books for Children, Anita Silvey praised the character as «the perfect fantasy heroine — one who lives without supervision but with endless money to execute her schemes.»[65]

Pippi has been subject to censorship in translations. A censored edition of Pippi Longstocking appeared in France, with changes made to her character to make her «a fine young lady» instead of «a strange, maladjusted child.»[71] Additionally, the publisher, Hachette, thought that Pippi’s ability to lift a horse would seem unrealistic to French child readers, and thus changed the horse to a pony.[72] In response to this change, Lindgren requested that the publisher give her a photo of a real French girl lifting a pony, as that child would have a «secure» weightlifting career.[73] Sara Van den Bossche has hypothesized that the lack of controversy as a result of the censorship might be why Pippi Longstocking went mainly unremarked upon in France, whereas in Germany and Sweden, the book quickly became accepted within the countries’ respective children’s literature canon, even as it stirred controversy over its «anti-authoritarian tendencies.»[71][clarification needed] In 1995, an uncensored version of Pippi Longstocking was released in France, which «shook» French readers, although the book did not reach the cultural status as it had in Germany and Sweden.[74][clarification needed]

The character has also centered in debates about how to handle potentially offensive racial language in children’s literature. In 2014, the Swedish public broadcaster SVT edited the 1969 television adaptation of Pippi Longstocking with the approval of Astrid Lindgren’s heirs: the first edit removed Pippi’s reference to her father as «King of the Negroes,» a term now offensive in Sweden;[nb 2] and the second eliminated Pippi slanting her eyes, although it kept her pretending to sing in «Chinese».[76] These changes received a backlash: of the first 25,000 Swedish readers polled by the Aftonbladet on Facebook, eighty-one percent disagreed with the idea of removing outdated racial language and notions from Pippi Longstocking, and the columnist Erik Helmerson of Dagens Nyheter labelled the changes as censorship.[76] One of Lindgren’s grandchildren, Nils Nyman, defended the edits, arguing that to not do so might have diluted Pippi’s message of female empowerment.[76]

Pippi books in Swedish and English[edit]

The three main Pippi Longstocking books were published first in Swedish and later in English:

- Pippi Långstrump, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman (Stockholm, 1945),[77] first published in English as Pippi Longstocking, translated by Florence Lamborn, illustrated by Louis S. Glanzman (New York, 1950)[78]

- Pippi Långstrump går ombord, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman (Stockholm, 1946),[79] translated as Pippi Goes on Board, translated by Florence Laborn and illustrated by Louis S. Glanzman (New York, 1957)[80]

- Pippi Långstrump i Söderhavet (Stockholm, 1948), illustrated by Ingrid Nyman,[81] first published in English as Pippi in the South Seas (New York, 1959), translated by Gerry Bothmer and illustrated by Louis S. Glanzman[82]

There are also a number of additional Pippi stories, some just in Swedish, others in both Swedish and English:

- Pippi Långstrump har julgransplundring, a picture book first published in Swedish in the Christmas edition of Allers Magazine in 1948, later published in book form in 1979, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman.[83] It was first published in English in 1996 as Pippi Longstocking’s After-Christmas Party, translated by Stephen Keeler and illustrated by Michael Chesworth.[84]

- Pippi flyttar in, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman, was first published in Swedish as a picture book in 1969, and appeared as a comic book in 1992.[85][86] Translated by Tiina Nunnally, it was published in English as Pippi Moves In in 2012.[87]

- Pippi Långstrump i Humlegården, a picture book illustrated by Ingrid Nyman, published in Swedish in 2000.[88] It was published in English in April 2001 as Pippi Longstocking in the Park, illustrated by Ingrid Nyman.[89]

- Pippi ordnar allt (1969), translated as Pippi Fixes Everything (2010)[90]

Other books in Swedish include:[91]

- Känner du Pippi Långstrump? (1947)

- Sjung med Pippi Långstrump (1949)

- Pippi håller kalas (1970)

- Pippi är starkast i världen (1970)

- Pippi går till sjöss (1971)

- Pippi vill inte bli stor (1971)

- Pippi Långstrump på Kurrekurreduttön (2004)

- Pippi hittar en spunk (2008)

- Pippi går i affärer (2014)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Historically, translations of children’s literature have comprised a very small share of the market in the United States.[49]

- ^ Publisher Friedrich Oetinger had also revised the German translation of Pippi Longstocking in 2009, removing a reference to Pippi’s father as «Negro King» in favor of the «South Sea King.»[75] In Sweden, the term remained in the books, with a preface noting that the accepted language and terminology used to describe people of African ancestry had changed over the years.[76]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Astrid Lindgren official webpage». Astridlindgren.se. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 69.

- ^ a b «Pippi Långstrumps häst får vara versal». Språktidningen. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-13 – via PressReader.com.

- ^ a b Lundqvist 1989, p. 99.

- ^ Erol 1991, p. 118–119.

- ^ Erol 1991, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b Metcalf 1995, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Lundqvist 1989, p. 100.

- ^ a b Metcalf 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 70.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 71.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, p. 50.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 74.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, p. 51.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Hoffeld 1977, p. 48.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 145.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 145–46.

- ^ Lundqvist 1989, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 144.

- ^ «The history». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 139–143, 156.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 157.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 162–63.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 164.

- ^ Lundqvist 1989, p. 97.

- ^ «Gale — Institution Finder».

- ^ Surmatz, Astrid (2005). Pippi Långstrump als Paradigma. Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie (in German). Vol. 34. A. Francke. pp. 150, 253–254. ISBN 978-3-7720-3097-0.

- ^ Pashko, Stan (June 1973). «Making the Scene». Boys’ Life. p. 6. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Pilon, A. Barbara (1978). Teaching language arts creatively in the elementary grades, John Wiley & Sons, page 215.

- ^ Metcalf 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Pippi Longstocking, 2000

- ^ «5 of the most translated children’s books that are known and loved the world over!». AdHoc Translations. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ «Astrid worldwide». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Forslund, Anna (12 May 2017). «Astrid Lindgren now translated into 100 languages!». MyNewsDesk. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695 [1]

- ^ [2]Lindgren, Astrid (2001). Pippi Hendak Berlayar. Gramedia.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (2018). Pippi Fhad-stocainneach (in Scottish Gaelic). Akerbeltz. ISBN 9781907165313.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 168.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 170.

- ^ Andersen 2018, pp. 169–70.

- ^ a b c d Lundqvist 1989, p. 102.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 173.

- ^ a b Andersen 2018, p. 174.

- ^ Andersen 2018, p. 185.

- ^ a b Metcalf 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 15–17.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 18–19.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 21.

- ^ Metcalf 2011, p. 20–21.

- ^ a b «Pippi Longstocking (TV-series)». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, p. 7.

- ^ «Pippi in the South Seas». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ «Pippi on the Run». Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Holmlund 2003, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ a b Holmlund 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kraft, Amy (20 September 2010). «20 Girl-Power Characters to Introduce to Your GeekGirl». Wired. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Doll, Jen (5 April 2012). «The Greatest Girl Characters of Young Adult Literature». The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Erbland, Kate (11 June 2014). «25 of Childhood Literature’s Most Beloved Female Characters, Ranked in Coolness». Bustle. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b Silvey 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Jacobsson, Leif (25 March 2013). «Copyright issues in the new banknote series» (pdf). Riksbank. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ «Pika’s Festival». Culture.si. Ljudmila Art and Science Laboratory. 25 November 2011.

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (5 January 2011). «The Mystery of the Dragon Tattoo: Stieg Larsson, the World’s Bestselling — and Most Enigmatic — Author». Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ Binding, Paul (26 August 2007). «Long live Pippi Longstocking: The girl with red plaits is back». The Independent. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Forest, Susanna (29 September 2007). «Pippi Longstocking: the Swedish superhero». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ a b Van den Bossche 2011, p. 58.

- ^ Lindgren 2017, pp. 192–93.

- ^ Lindgren 2017, p. 193.

- ^ Van den Bossche 2011, p. 59.

- ^ Wilder, Charly (16 January 2013). «Edit of Classic Children’s Book Hexes Publisher». Der Spiegel. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Donadio, Rachel (2 December 2014). «Sweden’s Storybook Heroine Ignites a Debate on Race». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1945). Pippi Långstrump. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 174.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1950). Pippi Longstocking. New York: Viking Press.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1946). Pippi Långstrump går ombord. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 192. ISBN 9789129621372.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1957). Pippi Goes on Board. New York: Viking Press.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1948). Pippi Långstrump i Söderhavet. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 166.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1959). Pippi in the South Seas. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9780670557110.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1979). Pippi har julgransplundring. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1996). Pippi Longstocking’s After-Christmas Party. Viking. ISBN 0-670-86790-X.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1969). «Pippi flyttar in». Rabén & Sjögren.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (1992). Pippi flyttar in. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. ISBN 978-91-29-62055-9.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (October 2012). Pippi Moves In. Drawn & Quarterly Publications. ISBN 978-1-77046-099-7.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (2000). Pippi Langstrump I Humlegarden. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 24. ISBN 978-9129648782.

- ^ Lindgren, Astrid (2001). Pippi Longstocking in the Park. R / S Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-9129653076.

- ^ «Pippi Fixes Everything» (in Swedish). Astrid Lindgren Company. 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ «Astrid Lindgrens böcker» (in Swedish). Astrid Lindgren Company. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

References[edit]

- Andersen, Jens (2018). Astrid Lindgren: The Woman Behind Pippi Longstocking. Translated by Caroline Waight. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Erol, Sibel (1991). «The Image of the Child in Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking«. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly. 1991: 112–119. doi:10.1353/chq.1991.0005.

- Hoffeld, Laura (1977). «Pippi Longstocking: The Comedy of the Natural Girl». The Lion and the Unicorn. 1 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0247. S2CID 144969573.

- Holmlund, Christine Anne (2003). «Pippi and Her Pals». Cinema Journal. 42 (2): 3–24. doi:10.1353/cj.2003.0005.

- Lindgren, Astrid (2017). Translated by Elizabeth Sofia Powell. «‘Why do we write children’s books?’ by Astrid Lindgren». Children’s Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press. 45: 188–195. doi:10.1353/chl.2017.0009.

- Lundqvist, Ulla (1989). «The Child of the Century». The Lion and the Unicorn. 13 (2): 97–102. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0168. S2CID 142926073.

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria (1995). Astrid Lindgren. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-4525-2.

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria (2011). «Pippi Longstocking in the United States». In Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina; Astrid Surmatz (eds.). Beyond Pippi Longstocking: Intermedial and International Aspects of Astrid Lindgren’s Works. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88353-5.

- Silvey, Anita (2005). 100 Best Books for Children. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Van den Bossche, Sara (2011). «We Love What We know: The Canonicity of Pippi Longstocking in Different Media in Flanders». In Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina; Astrid Surmatz (eds.). Beyond Pippi Longstocking: Intermedial and International Aspects of Astrid Lindgren’s Works. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88353-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Frasher, Ramona S. (1977). «Boys, Girls and Pippi Longstocking». The Reading Teacher. 30 (8): 860–863. JSTOR 20194413.

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria (1990). «Tall Tale and Spectacle in Pippi Longstocking». Children’s Literature Association Quarterly. 15 (3): 130–135. doi:10.1353/chq.0.0791.

External links[edit]

Media related to Pippi Longstocking at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website

- The home of Pippi Longstocking

- Pippi Longstocking and Astrid Lindgren

- Japanese stage musical starring Tomoe Shinohara (in Japanese)

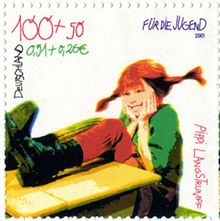

Пеппи Длинныйчулок на немецкой почтовой марке

Пеппилотта Виктуалия Рульгардина Крисминта Эфраимсдоттер Длинныйчулок (оригинальное имя: Pippilotta Viktualia Rullgardina Krusmynta Efraimsdotter Långstrump), более известная как Пеппи Длинныйчуло́к — центральный персонаж серии книг шведской писательницы Астрид Линдгрен.

Имя Pippi придумала дочь Астрид Линдгрен, Карин[1]. По-шведски она Пиппи Длинныйчулок. Переводчица Лилианна Лунгина решила в переводе изменить имя Пиппи на Пеппи из-за возможных неприятных смысловых коннотаций оригинального имени для носителя русского языка.

Персонаж

Вилла «Курица» — дом, участвовавший в съёмках шведского телесериала про Пеппи

Пеппи — маленькая рыжая веснушчатая девочка, которая живёт одна на вилле «Курица» в небольшом шведском городке вместе со своими животными: обезьянкой господином Нильсоном и лошадью. Пеппи — дочь капитана Эфраима Длинныйчулок, который впоследствии стал вождём чернокожего племени. От своего отца Пеппи унаследовала фантастическую физическую силу, а также чемодан с золотом, позволяющий ей безбедно существовать. Мама Пеппи умерла, когда та была ещё младенцем. Пеппи уверена, что она стала ангелом и смотрит на неё с неба («Моя мама — ангел, а папа — негритянский король. Не у всякого ребёнка такие знатные родители»).

Пеппи «перенимает», а скорее, придумывает разнообразные обычаи с разных стран и частей света: при ходьбе пятиться назад, ходить по улицам вниз головой, «потому что ногам жарко, когда ходишь по вулкану, а руки можно обуть в варежки».

Лучшие друзья Пеппи — Томми и Анника Сёттергрен, дети обычных шведских обывателей. В компании Пеппи они часто попадают в неприятности и смешные переделки, а иногда — настоящие приключения. Попытки друзей или взрослых повлиять на безалаберную Пеппи ни к чему не приводят: она не ходит в школу, неграмотна, фамильярна и всё время сочиняет небылицы. Тем не менее, у Пеппи доброе сердце и хорошее чувство юмора.

Пеппи Длинныйчулок — одна из самых фантастических героинь Астрид Линдгрен. Она независима и делает всё, что хочет. Например, спит с ногами на подушке и с головой под одеялом, носит разноцветные чулки, возвращаясь домой, пятится задом, потому что ей не хочется разворачиваться, раскатывает тесто прямо на полу и держит лошадь на веранде.

Она невероятно сильная и проворная, хотя ей всего девять лет. Она носит на руках собственную лошадь, побеждает знаменитого циркового силача, разбрасывает в стороны целую компанию хулиганов, обламывает рога свирепому быку, ловко выставляет из собственного дома двух полицейских, прибывших к ней, чтобы насильно забрать её в детский дом, и молниеносно забрасывает на шкаф двоих громил воров, которые решили её ограбить. Однако в расправах Пеппи нет жестокости. Она на редкость великодушна к своим поверженным врагам. Осрамившихся полицейских она угощает свежеиспеченными пряниками в форме сердечек. А сконфуженных воров, отработавших свое вторжение в чужой дом тем, что они всю ночь танцевали с Пеппи твист, она великодушно награждает золотыми монетами, на сей раз честно заработанными.

Пеппи не только на редкость сильна, она ещё и невероятно богата. Ей ничего не стоит купить для всех детей в городе «сто кило леденцов» и целый магазин игрушек, но сама она живёт в старом полуразвалившемся доме, носит единственное платье, сшитое из разноцветных лоскутов, и единственную пару туфель, купленных ей отцом «на вырост».

Но самое удивительное в Пеппи — это её яркая и буйная фантазия, которая проявляется и в играх, которые она придумывает, и в удивительных историях о разных странах, где она побывала вместе с папой-капитаном, и в бесконечных розыгрышах, жертвами которых становятся недотепы-взрослые. Любой свой рассказ Пеппи доводит до абсурда: вредная служанка кусает гостей за ноги, длинноухий китаец прячется под ушами во время дождя, а капризный ребёнок отказывается есть с мая по октябрь. Пеппи очень расстраивается, если кто-нибудь говорит, что она врет, ведь врать нехорошо, просто она иногда забывает об этом.

Пеппи — мечта ребёнка о силе и благородстве, богатстве и щедрости, свободе и самоотверженности. Но вот взрослые Пеппи почему-то не понимают. И аптекарь, и школьная учительница, и директор цирка, и даже мама Томми и Анники злятся на неё, поучают, воспитывают. Видимо поэтому больше всего на свете Пеппи не хочет взрослеть:

«Взрослым никогда не бывает весело. У них вечно уйма скучной работы, дурацкие платья и куминальные[2] налоги. И ещё они напичканы предрассудками и всякой ерундой. Они думают, что стрясётся ужасное несчастье, если сунуть в рот нож во время еды, и всё такое прочее».

Но «кто сказал, что нужно стать взрослым?» Никто не может заставить Пеппи делать то, чего она не хочет!

Книги о Пеппи Длинныйчулок исполненны оптимизма и неизменной веры в самое-самое хорошее.

Повести о Пeппи

- Пеппи поселяется на вилле «Курица» (1945)

- Пеппи собирается в путь (1946)

- Пеппи в стране Веселии (1948)

- Пеппи Длинныйчулок устраивает ёлку (1979)

Экранизации

- Пеппи Длинныйчулок (Pippi Långstrump — Швеция, 1969) — телесериал Олле Хелльбома. «Шведская» версия телесериала — в 13-ти сериях, версия ФРГ — 21 серия. В главной роли — Ингер Нильсон. Телесериал с 2004 года в «немецкой» версии показывается на канале «Культура». Киновариант — 4 фильма (выпуск 1969, 1970 гг.). Две кинокартины — «Пеппи Длинныйчулок» и «Пеппи в стране Така-Тука» демонстрировались в советском прокате.

- Пеппи Длинныйчулок (СССР, 1984) — телевизионный двухсерийный художественный фильм.

- Новые приключения Пеппи Длинныйчулок (The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking — США, Швеция, 1988)

- Пеппи Длинныйчулок (Pippi Longstocking — Швеция, Германия, Канада, 1997) — мультфильм

- Пеппи Длинныйчулок (Pippi Longstocking — Канада, 1997—1999) — мультсериал

- «Пеппи Длинныйчулок» — диафильм (СССР, 1971)

Примечания

- ↑ см. «К читателям» в книге: Астрид Линдгрен. Пиппи Длинныйчулок/ перевод Н. Беляковой, Л. Брауде и Е. Паклиной. — СПб: Азбука, 1997.

- ↑ Имеются в виду „коммунальные“.

Вымышленный персонаж

| Пеппи Длинныйчулок | |

|---|---|

Пеппи Длинныйчулок в исполнении Ингрид Ванг Найман на шведской обложке «Пеппи идет на борт» Пеппи Длинныйчулок в исполнении Ингрид Ванг Найман на шведской обложке «Пеппи идет на борт» |

|

| Первое появление | Пеппи Длинныйчулок (1945) |

| Последнее появление | Пеппи в Южных морях (1948) |

| Автор | Астрид Линдгрен |

| Ин- информация о вселенной | |

| Псевдоним | Пеппи |

| Пол | Женщина |

| Национальность | Швед |

Пеппи Длинныйчулок (Швед : Пиппи Långstrump) — вымышленный главный персонаж в одноименной серии детских книг шведского автора Астрид Линдгрен. Пеппи назвала дочь Линдгрен Карин, которая попросила ее мать рассказать историю выздоровления, когда она была вне школы.

Пеппи рыжеволосая, веснушчатая, необычная и сверхчеловеческая сила — способна поднять лошадь одной рукой. Она игрива и непредсказуема. Она часто высмеивает неразумных взрослых, особенно если они напыщенны и снисходительны. Ее гнев проявляется в крайних случаях, например, когда мужчина плохо обращается со своей лошадью. Пеппи, как и Питер Пэн, не хочет расти. Она дочь капитана пиратов, и у нее есть приключенческие истории, чтобы рассказать об этом. Четыре ее лучших друга — лошадь и обезьяна, а также дети соседей Томми и Анника.

После отклонения Bonnier Publishers в 1944 году первая рукопись Линдгрена была принята Рабеном и Сьёгреном. Три книги Пеппи глав (Пеппи Длинныйчулок, Пеппи идет на борт и Пеппи в Южных морях) были изданы с 1945 по 1948 год, за ними последовали три рассказа и несколько адаптированных картинок. По состоянию на 2018 год они были переведены на 76 языков и сняты в несколько фильмов и телесериалов.

Содержание

- 1 Персонаж

- 2 Развитие

- 3 Имя

- 4 Культурное влияние

- 5 Книги Пеппи на шведском и английском языках

- 6 Примечания

- 7 Цитаты

- 8 Ссылки

- 9 Дополнительная литература

- 10 Внешние ссылки

Персонаж

Пеппи Длинныйчулок — девятилетняя девочка. В начале первого романа она переезжает в виллу Виллекулла, дом, который она делит со своей обезьяной по имени мистер Нильссон и ее неназванной лошадью, и быстро подружится с двумя детьми, живущими по соседству, Томми и Анникой Сеттергрен.. С чемоданом золотых монет она ведет независимый образ жизни без родителей: ее мать умерла вскоре после ее рождения, а ее отец, капитан Эфраим Длинныйчулок, сначала пропал без вести в море, а затем стал королем Южного моря остров. Несмотря на периодические попытки деревенских властей заставить ее соответствовать культурным представлениям о том, какой должна быть жизнь ребенка, Пеппи счастливо живет свободной от социальных условностей. По словам Евы-Марии Меткалф, Пеппи «любит свои веснушки и свою рваную одежду и не делает ни малейших попыток подавить свое дикое воображение или научиться хорошим манерам». У нее есть склонность к рассказыванию историй, которое часто принимает форму небылиц.

Обсуждая Пеппи, Астрид Линдгрен объяснила, что «Пеппи представляет мое собственное детское стремление к человеку, который имеет власть, но не злоупотребляет ею». Хотя она самопровозглашенная «самая сильная девушка в мире», Пеппи часто использует ненасилие для разрешения конфликтов или защиты других детей от издевательств. Литературные критики по-разному описывали Пеппи как «сердечного, сострадательного, доброго, умного, щедрого, игривого и остроумного до такой степени, что в разговоре она превосходила взрослых персонажей. Лаура Хоффельд писала, что хотя «естественность Пеппи влечет за собой эгоизм, невежество и явную склонность ко лжи», характер «одновременно великодушен, быстр, мудр и верен себе и другим».

Развитие

Биограф Йенс Андерсен обнаруживает ряд влияний и источников вдохновения для Пеппи не только в образовательных теориях 1930-х годов, таких как теории А. С. Нил и Бертран Рассел, а также современные фильмы и комиксы, в которых представлены «сверхъестественно сильные персонажи» (например, Супермен и Тарзан ). Литературное вдохновение для персонажа можно найти в «Приключениях Алисы в стране чудес», E. «Странное дитя» Т. А. Хоффмана, Энн из Зеленых крыш и Длинноногий папа в дополнение к мифам, сказкам и легендам. Андерсен утверждает, что наибольшее влияние оказал «человеконенавистнический, эмоционально чахлый век» Второй мировой войны, в течение которого Линдгрен развивала характер: первоначальная версия Пеппи, по словам Андерсена, «была жизнерадостным пацифистом, ответившим на жестокость. а зло войны было добротой, щедростью и добрым юмором ».

Пеппи происходит от прикроватных историй, рассказанных дочери Линдгрен, Карин. Зимой 1941 года Карин заболела и была прикована к постели; Вдохновленная просьбой Карин рассказать свои истории о Пеппи Длинныйчулок — имя, которое Карин придумала на месте, — Линдгрен импровизировала истории о девушке, «совсем не набожной», с «безграничной энергией». В детстве Карин больше относилась к Аннике и Томми, чем к Пеппи, которая, по ее мнению, сильно отличалась от ее личности. Пеппи стала основным продуктом в доме, друзья и кузены Карин также наслаждались ее приключениями. В апреле 1944 года, оправляясь от вывиха лодыжки, Линдгрен написала свои рассказы о Пеппи в стенографии, метод, который она использовала на протяжении всей писательской карьеры; один экземпляр чистой рукописи был превращен в самодельную книгу для Карин и подарен ей 21 мая, а другой был отправлен в издательство Bonnier Förlag, где в сентябре он был отклонен на том основании, что «тоже» продвинутый. «

После ее критического успеха дебютного детского романа» Доверие Бритт-Мари «(1944) Линдгрен отправила рукопись Пеппи Длинныйчулок своему редактору в Rabén and Sjögren, детскому библиотекарю и критику Эльзе Олениус, в мае 1945 года. Олениус посоветовал ей пересмотреть некоторые «графические» элементы, такие как полный ночной горшок, используемый в качестве огнетушителя, а затем принять его участие в предстоящем соревновании в Рабене и Сьегрене., который был предназначен для книг для детей в возрасте от шести до десяти лет. Критик Улла Лундквист считает, что треть рукописи была изменена, с некоторыми изменениями, сделанными для улучшения ее прозы и читабельности, а другие — с персонажем Пеппи, которая, по словам Лундквиста, «приобрела новую скромность и нежность, а также легкая меланхолия », а также« менее замысловатые »диалоги. Пеппи Длинныйчулок заняла первое место и впоследствии была опубликована в ноябре 1945 года с иллюстрациями Ингрид Ванг Найман. Последовали еще две книги: Пеппи идет на борт (1946) и Пеппи в Южных морях (1948). Были также выпущены три иллюстрированные книги : «После Рождества» Пеппи (1950), «Пеппи в бегах» (1971) и Пеппи Длинныйчулок в парке (2001).

Имя

В оригинальных шведских книгах полное имя Пеппи указано как Пиппилотта Виктуалия Руллгардина Крусминта Эфраимсдоттер Лонгстрамп. Хотя ее фамилия Långstrump — буквально длинный чулок — легко переводится на другие языки, ее личные имена включают в себя придуманные слова, которые нельзя перевести напрямую, и отчество (Efraimsdotter), которое незнакомо многим культурам. Английский язык книги и фильмы о Пеппи дали ей имя в следующих формах:

- Пиппилотта Роллгардиния Victualia Мятный Длинныйчулок

- Пиппилотта Деликатесса Windowshade Mackrelmint Дочь Эфраима Длинныйчулок

- Pippilotta Provisionia Gaberdina Dandeliona Ephraimsdaughter Longstocking

<10a9>Пиппилотта Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraimsdotter Longstocking

В 2005 году ЮНЕСКО опубликовала списки наиболее переводимых книг. Что касается детской литературы, Пеппи Длинныйчулок заняла пятое место среди наиболее переводимых произведений с версиями на 70 различных языках. По состоянию на 2017 год выяснилось, что произведения Линдгрен переведены на 100 языков. Вот имена персонажей на некоторых языках, кроме английского.

- на африкаанс Пеппи Лангкоус

- на албанском Пипи Çorapegjata

- на Арабский جنان ذات الجورب الطويل Jinān ḏāt al-Jawrab aṭ-awīl

- In армянский Երկարագուլպա Պիպին Erkaragulpa Pipin <139137109>азербайджанский>Пиппи Узункораблы

- В Баскский Пеппи Кальтзалузе

- В Белорусский Піпі Доўгаяпанчоха Пипи Догаджапанчоха

- В Болгарский Пипи Дългото чорапче Pipi Dǎlgoto chorapche

- In Breton Pippi hir he loeroù

- In Каталонский Pippi Calcesllargues

- In Китайский 长袜子皮皮 Chángwàzi Pípí

- In Чешский Pipilota Citrónie Cimprlína Mucholapka Dlouhá punčocha

- In датский Pippi Langstrømpe

- На голландском Пиппи Лангкоус

- На эсперанто Пипи Ŝтрумполонга

- на эстонском Пипи Пикксукк

- В Фарерском Пеппи Лангсоккур

- В Филиппинец Potpot Habangmedyas

- На финском Пеппи Питкэтоссу

- На французском Фифи Бриндасье (буквально «Фифи Стальная нить»)

- В Галицкий Пеппи Медиаслонгас

- В Грузинский პეპი Пепи Магалицинда или პეპი გრძელიწინდა Пепи Грдзелицинда

- На Немецкий Pippilotta Viktualia Rollgardina Pfefferminz (книга) или Schokominza (фильм) Efraimstochter Langstrumpf

- На греческом πη η Φακιδομύτη Pípē ē Fakidom

- На иврите בילבי בת-גרב Bilbi Bat-Gerev или גילגי Gilgi или фонетическое сопоставление בילבי לא-כלום bílbi ló khlum, буквально «Bilby Nothing» в старых переводах

- В венгерский Харисняс Пиппи

- В исландский Линна Лангсоккур

- В индонезийский Пиппилотта Виктуалия Горден Тираи Пермен Эфраимпутри Лангстрамп

- В ирландском Пеппи Длинныйчулок

- В итальянском Пеппи Кальцелунге

- In японский 長靴 下 の ピ ッ ピ Nagakutsushita no Pippi