| Mississippi River | |

|---|---|

The Mississippi in Iowa |

|

Mississippi River basin |

|

| Etymology | Ojibwe Misi-ziibi, meaning «Great River» |

| Nickname(s) | «Old Man River,» «Father of Waters»[1][2][3] |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana |

| Cities | Saint Cloud, MN, Minneapolis, MN, St. Paul, MN, La Crosse, WI, Quad Cities, IA/IL, St. Louis, MO, Memphis, TN, Greenville, MS, Vicksburg, MS, Baton Rouge, LA, New Orleans, LA |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Lake Itasca (traditional)[4] |

| • location | Itasca State Park, Clearwater County, MN |

| • coordinates | 47°14′23″N 95°12′27″W / 47.23972°N 95.20750°W |

| • elevation | 1,475 ft (450 m) |

| Mouth | Gulf of Mexico |

|

• location |

Pilottown, Plaquemines Parish, LA |

|

• coordinates |

29°09′04″N 89°15′12″W / 29.15111°N 89.25333°W |

|

• elevation |

0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 2,340 mi (3,770 km) |

| Basin size | 1,151,000 sq mi (2,980,000 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | None (Sumative representation of catchment: View source); max and min at Baton Rouge, LA[5] |

| • average | 593,000 cu ft/s (16,800 m3/s)[5] |

| • minimum | 159,000 cu ft/s (4,500 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 3,065,000 cu ft/s (86,800 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Vicksburg[6] |

| • average | 768,075 cu ft/s (21,749.5 m3/s) (2009–2020 water years) |

| • minimum | 144,000 cu ft/s (4,100 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 2,340,000 cu ft/s (66,000 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | St. Louis[7] |

| • average | 168,000 cu ft/s (4,800 m3/s)[7] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | St. Croix River, Wisconsin River, Rock River, Illinois River, Kaskaskia River, Ohio River, Yazoo River, Big Black River |

| • right | Minnesota River, Des Moines River, Missouri River, White River, Arkansas River, Ouachita River, Red River, Atchafalaya River |

The Mississippi River[a] is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system.[15][16] From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it flows generally south for 2,340 miles (3,770 km)[16] to the Mississippi River Delta in the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi’s watershed drains all or parts of 32 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces between the Rocky and Appalachian mountains.[17] The main stem is entirely within the United States; the total drainage basin is 1,151,000 sq mi (2,980,000 km2), of which only about one percent is in Canada. The Mississippi ranks as the thirteenth-largest river by discharge in the world. The river either borders or passes through the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana.[18][19]

Native Americans have lived along the Mississippi River and its tributaries for thousands of years. Most were hunter-gatherers, but some, such as the Mound Builders, formed prolific agricultural and urban civilizations. The arrival of Europeans in the 16th century changed the native way of life as first explorers, then settlers, ventured into the basin in increasing numbers.[20] The river served first as a barrier, forming borders for New Spain, New France, and the early United States, and then as a vital transportation artery and communications link. In the 19th century, during the height of the ideology of manifest destiny, the Mississippi and several western tributaries, most notably the Missouri, formed pathways for the western expansion of the United States.

Formed from thick layers of the river’s silt deposits, the Mississippi embayment is one of the most fertile regions of the United States; steamboats were widely used in the 19th and early 20th centuries to ship agricultural and industrial goods. During the American Civil War, the Mississippi’s capture by Union forces marked a turning point towards victory, due to the river’s strategic importance to the Confederate war effort. Because of the substantial growth of cities and the larger ships and barges that replaced steamboats, the first decades of the 20th century saw the construction of massive engineering works such as levees, locks and dams, often built in combination. A major focus of this work has been to prevent the lower Mississippi from shifting into the channel of the Atchafalaya River and bypassing New Orleans.

Since the 20th century, the Mississippi River has also experienced major pollution and environmental problems — most notably elevated nutrient and chemical levels from agricultural runoff, the primary contributor to the Gulf of Mexico dead zone.

Name and significance

The word Mississippi itself comes from Misi zipi, the French rendering of the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe or Algonquin) name for the river, Misi-ziibi (Great River).[21]

In the 18th century, the river was the primary western boundary of the young United States, and since the country’s expansion westward, the Mississippi River has been a convenient line dividing the Western United States from the Eastern, Southern, and Midwestern regions. This is symbolized by the Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the phrase «Trans-Mississippi» as used in the name of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

Regional landmarks are often classified in relation to the river, such as «the highest peak east of the Mississippi»[22] or «the oldest city west of the Mississippi».[23] The FCC also uses it as the dividing line for broadcast call-signs, which begin with W to the east and K to the west, overlapping in media markets along the river.

Divisions

The Mississippi River can be divided into three sections: the Upper Mississippi, the river from its headwaters to the confluence with the Missouri River; the Middle Mississippi, which is downriver from the Missouri to the Ohio River; and the Lower Mississippi, which flows from the Ohio to the Gulf of Mexico.

Upper Mississippi

The first bridge (and only log bridge) over the Mississippi, about 25 feet south of its source at Lake Itasca

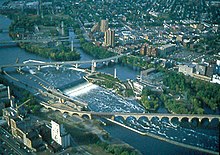

Former head of navigation, St. Anthony Falls, Minneapolis, Minnesota

The Upper Mississippi runs from its headwaters to its confluence with the Missouri River at St. Louis, Missouri. It is divided into two sections:

- The headwaters, 493 miles (793 km) from the source to Saint Anthony Falls in Minneapolis, Minnesota; and

- A navigable channel, formed by a series of man-made lakes between Minneapolis and St. Louis, Missouri, some 664 miles (1,069 km).

The source of the Upper Mississippi branch is traditionally accepted as Lake Itasca, 1,475 feet (450 m) above sea level in Itasca State Park in Clearwater County, Minnesota. The name Itasca was chosen to designate the «true head» of the Mississippi River as a combination of the last four letters of the Latin word for truth (veritas) and the first two letters of the Latin word for head (caput).[24] However, the lake is in turn fed by a number of smaller streams.

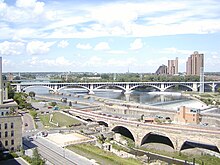

From its origin at Lake Itasca to St. Louis, Missouri, the waterway’s flow is moderated by 43 dams. Fourteen of these dams are located above Minneapolis in the headwaters region and serve multiple purposes, including power generation and recreation. The remaining 29 dams, beginning in downtown Minneapolis, all contain locks and were constructed to improve commercial navigation of the upper river. Taken as a whole, these 43 dams significantly shape the geography and influence the ecology of the upper river. Beginning just below Saint Paul, Minnesota, and continuing throughout the upper and lower river, the Mississippi is further controlled by thousands of wing dikes that moderate the river’s flow in order to maintain an open navigation channel and prevent the river from eroding its banks.

The head of navigation on the Mississippi is the St. Anthony Falls Lock.[25] Before the Coon Rapids Dam in Coon Rapids, Minnesota, was built in 1913, steamboats could occasionally go upstream as far as Saint Cloud, Minnesota, depending on river conditions.

The uppermost lock and dam on the Upper Mississippi River is the Upper St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam in Minneapolis. Above the dam, the river’s elevation is 799 feet (244 m). Below the dam, the river’s elevation is 750 feet (230 m). This 49-foot (15 m) drop is the largest of all the Mississippi River locks and dams. The origin of the dramatic drop is a waterfall preserved adjacent to the lock under an apron of concrete. Saint Anthony Falls is the only true waterfall on the entire Mississippi River. The water elevation continues to drop steeply as it passes through the gorge carved by the waterfall.

After the completion of the St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam in 1963, the river’s head of navigation moved upstream, to the Coon Rapids Dam. However, the Locks were closed in 2015 to control the spread of invasive Asian carp, making Minneapolis once again the site of the head of navigation of the river.[25]

The Upper Mississippi has a number of natural and artificial lakes, with its widest point being Lake Winnibigoshish, near Grand Rapids, Minnesota, over 11 miles (18 km) across. Lake Onalaska, created by Lock and Dam No. 7, near La Crosse, Wisconsin, is more than 4 miles (6.4 km) wide. Lake Pepin, a natural lake formed behind the delta of the Chippewa River of Wisconsin as it enters the Upper Mississippi, is more than 2 miles (3.2 km) wide.[26]

By the time the Upper Mississippi reaches Saint Paul, Minnesota, below Lock and Dam No. 1, it has dropped more than half its original elevation and is 687 feet (209 m) above sea level. From St. Paul to St. Louis, Missouri, the river elevation falls much more slowly and is controlled and managed as a series of pools created by 26 locks and dams.[27]

The Upper Mississippi River is joined by the Minnesota River at Fort Snelling in the Twin Cities; the St. Croix River near Prescott, Wisconsin; the Cannon River near Red Wing, Minnesota; the Zumbro River at Wabasha, Minnesota; the Black, La Crosse, and Root rivers in La Crosse, Wisconsin; the Wisconsin River at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; the Rock River at the Quad Cities; the Iowa River near Wapello, Iowa; the Skunk River south of Burlington, Iowa; and the Des Moines River at Keokuk, Iowa. Other major tributaries of the Upper Mississippi include the Crow River in Minnesota, the Chippewa River in Wisconsin, the Maquoketa River and the Wapsipinicon River in Iowa, and the Illinois River in Illinois.

The Upper Mississippi River at its confluence with the Missouri River north of St. Louis

The Upper Mississippi is largely a multi-thread stream with many bars and islands. From its confluence with the St. Croix River downstream to Dubuque, Iowa, the river is entrenched, with high bedrock bluffs lying on either side. The height of these bluffs decreases to the south of Dubuque, though they are still significant through Savanna, Illinois. This topography contrasts strongly with the Lower Mississippi, which is a meandering river in a broad, flat area, only rarely flowing alongside a bluff (as at Vicksburg, Mississippi).

The confluence of the Mississippi (left) and Ohio (right) rivers at Cairo, Illinois, the demarcation between the Middle and the Lower Mississippi River

Middle Mississippi

The Mississippi River is known as the Middle Mississippi from the Upper Mississippi River’s confluence with the Missouri River at St. Louis, Missouri, for 190 miles (310 km) to its confluence with the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois.[28][29]

The Middle Mississippi is relatively free-flowing. From St. Louis to the Ohio River confluence, the Middle Mississippi falls 220 feet (67 m) over 180 miles (290 km) for an average rate of 1.2 feet per mile (23 cm/km). At its confluence with the Ohio River, the Middle Mississippi is 315 feet (96 m) above sea level. Apart from the Missouri and Meramec rivers of Missouri and the Kaskaskia River of Illinois, no major tributaries enter the Middle Mississippi River.

Lower Mississippi

Lower Mississippi River at Algiers Point in New Orleans

The Mississippi River is called the Lower Mississippi River from its confluence with the Ohio River to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico, a distance of about 1,000 miles (1,600 km). At the confluence of the Ohio and the Middle Mississippi, the long-term mean discharge of the Ohio at Cairo, Illinois is 281,500 cubic feet per second (7,970 cubic meters per second),[30] while the long-term mean discharge of the Mississippi at Thebes, Illinois (just upriver from Cairo) is 208,200 cu ft/s (5,900 m3/s).[31] Thus, by volume, the main branch of the Mississippi River system at Cairo can be considered to be the Ohio River (and the Allegheny River further upstream), rather than the Middle Mississippi.

In addition to the Ohio River, the major tributaries of the Lower Mississippi River are the White River, flowing in at the White River National Wildlife Refuge in east-central Arkansas; the Arkansas River, joining the Mississippi at Arkansas Post; the Big Black River in Mississippi; and the Yazoo River, meeting the Mississippi at Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Deliberate water diversion at the Old River Control Structure in Louisiana allows the Atchafalaya River in Louisiana to be a major distributary of the Mississippi River, with 30% of the combined flow of the Mississippi and Red Rivers flowing to the Gulf of Mexico by this route, rather than continuing down the Mississippi’s current channel past Baton Rouge and New Orleans on a longer route to the Gulf.[32][33][34][35] Although the Red River was once an additional tributary, its water now flows separately into the Gulf of Mexico through the Atchafalaya River.[36]

Watershed

Map of the Mississippi River watershed

An animation of the flows along the rivers of the Mississippi watershed

The Mississippi River has the world’s fourth-largest drainage basin («watershed» or «catchment»). The basin covers more than 1,245,000 square miles (3,220,000 km2), including all or parts of 32 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. The drainage basin empties into the Gulf of Mexico, part of the Atlantic Ocean. The total catchment of the Mississippi River covers nearly 40% of the landmass of the continental United States. The highest point within the watershed is also the highest point of the Rocky Mountains, Mount Elbert at 14,440 feet (4,400 m).[37]

Sequence of NASA MODIS images showing the outflow of fresh water from the Mississippi (arrows) into the Gulf of Mexico (2004)

In the United States, the Mississippi River drains the majority of the area between the crest of the Rocky Mountains and the crest of the Appalachian Mountains, except for various regions drained to Hudson Bay by the Red River of the North; to the Atlantic Ocean by the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River; and to the Gulf of Mexico by the Rio Grande, the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers, the Chattahoochee and Appalachicola rivers, and various smaller coastal waterways along the Gulf.

The Mississippi River empties into the Gulf of Mexico about 100 miles (160 km) downstream from New Orleans. Measurements of the length of the Mississippi from Lake Itasca to the Gulf of Mexico vary somewhat, but the United States Geological Survey’s number is 2,340 miles (3,770 km). The retention time from Lake Itasca to the Gulf is typically about 90 days.[38]

The stream gradient of the entire river is 0.01%, a drop of 450 m over 3,766 km.

Outflow

The Mississippi River discharges at an annual average rate of between 200 and 700 thousand cubic feet per second (6,000 and 20,000 m3/s).[39] The Mississippi is the fourteenth largest river in the world by volume. On average, the Mississippi has 8% the flow of the Amazon River,[40]

which moves nearly 7 million cubic feet per second (200,000 m3/s) during wet seasons.

Before 1900, the Mississippi River transported an estimated 440 million short tons (400 million metric tons) of sediment per year from the interior of the United States to coastal Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico. During the last two decades, this number was only 160 million short tons (145 million metric tons) per year. The reduction in sediment transported down the Mississippi River is the result of engineering modification of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio rivers and their tributaries by dams, meander cutoffs, river-training structures, and bank revetments and soil erosion control programs in the areas drained by them.[41]

Mixing with salt water

Denser salt water from the Gulf of Mexico forms a salt wedge along the river bottom near the mouth of the river, while fresh water flows near the surface. In drought years, with less fresh water to push it out, salt water can travel many miles upstream—64 miles (103 km) in 2022—contaminating drinking water supplies and requiring the use of desalination. The United States Army Corps of Engineers constructed «saltwater sills» or «underwater levees» to contain this 1988, 1999, 2012, and 2022. This consists of a large mound of sand spanning the width of the river 55 feet below the surface, allowing fresh water and large cargo ships to pass over.[42]

Fresh river water flowing from the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico does not mix into the salt water immediately. The images from NASA’s MODIS show a large plume of fresh water, which appears as a dark ribbon against the lighter-blue surrounding waters. These images demonstrate that the plume did not mix with the surrounding sea water immediately. Instead, it stayed intact as it flowed through the Gulf of Mexico, into the Straits of Florida, and entered the Gulf Stream. The Mississippi River water rounded the tip of Florida and traveled up the southeast coast to the latitude of Georgia before finally mixing in so thoroughly with the ocean that it could no longer be detected by MODIS.

Course changes

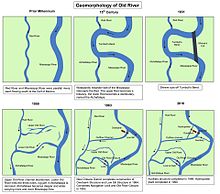

Over geologic time, the Mississippi River has experienced numerous large and small changes to its main course, as well as additions, deletions, and other changes among its numerous tributaries, and the lower Mississippi River has used different pathways as its main channel to the Gulf of Mexico across the delta region.

Through a natural process known as avulsion or delta switching, the lower Mississippi River has shifted its final course to the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico every thousand years or so. This occurs because the deposits of silt and sediment begin to clog its channel, raising the river’s level and causing it to eventually find a steeper, more direct route to the Gulf of Mexico. The abandoned distributaries diminish in volume and form what are known as bayous. This process has, over the past 5,000 years, caused the coastline of south Louisiana to advance toward the Gulf from 15 to 50 miles (24 to 80 km). The currently active delta lobe is called the Birdfoot Delta, after its shape, or the Balize Delta, after La Balize, Louisiana, the first French settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi.

Prehistoric courses

The current form of the Mississippi River basin was largely shaped by the Laurentide Ice Sheet of the most recent Ice Age. The southernmost extent of this enormous glaciation extended well into the present-day United States and Mississippi basin. When the ice sheet began to recede, hundreds of feet of rich sediment were deposited, creating the flat and fertile landscape of the Mississippi Valley. During the melt, giant glacial rivers found drainage paths into the Mississippi watershed, creating such features as the Minnesota River, James River, and Milk River valleys. When the ice sheet completely retreated, many of these «temporary» rivers found paths to Hudson Bay or the Arctic Ocean, leaving the Mississippi Basin with many features «over-sized» for the existing rivers to have carved in the same time period.

Ice sheets during the Illinoian Stage, about 300,000 to 132,000 years before present, blocked the Mississippi near Rock Island, Illinois, diverting it to its present channel farther to the west, the current western border of Illinois. The Hennepin Canal roughly follows the ancient channel of the Mississippi downstream from Rock Island to Hennepin, Illinois. South of Hennepin, to Alton, Illinois, the current Illinois River follows the ancient channel used by the Mississippi River before the Illinoian Stage.[43][44]

Timeline of outflow course changes[45]

- c. 5000 BC: The last ice age ended; world sea level became what it is now.

- c. 2500 BC: Bayou Teche became the main course of the Mississippi.

- c. 800 BC: The Mississippi diverted further east.

- c. 200 AD: Bayou Lafourche became the main course of the Mississippi.

- c. 1000 AD: The Mississippi’s present course took over.

- Before c. 1400 AD: The Red River of the South flowed parallel to the lower Mississippi to the sea

- 15th century: Turnbull’s Bend in the lower Mississippi extended so far west that it captured the Red River of the South. The Red River below the captured section became the Atchafalaya River.

- 1831: Captain Henry M. Shreve dug a new short course for the Mississippi through the neck of Turnbull’s Bend.

- 1833 to November 1873: The Great Raft (a huge logjam in the Atchafalaya River) was cleared. The Atchafalaya started to capture the Mississippi and to become its new main lower course.

- 1963: The Old River Control Structure was completed, controlling how much Mississippi water entered the Atchafalaya.

Historic course changes

In March 1876, the Mississippi suddenly changed course near the settlement of Reverie, Tennessee, leaving a small part of Tipton County, Tennessee, attached to Arkansas and separated from the rest of Tennessee by the new river channel. Since this event was an avulsion, rather than the effect of incremental erosion and deposition, the state line still follows the old channel.[46]

The town of Kaskaskia, Illinois once stood on a peninsula at the confluence of the Mississippi and Kaskaskia (Okaw) Rivers. Founded as a French colonial community, it later became the capital of the Illinois Territory and was the first state capital of Illinois until 1819. Beginning in 1844, successive flooding caused the Mississippi River to slowly encroach east. A major flood in 1881 caused it to overtake the lower 10 miles (16 km) of the Kaskaskia River, forming a new Mississippi channel and cutting off the town from the rest of the state. Later flooding destroyed most of the remaining town, including the original State House. Today, the remaining 2,300 acres (930 ha) island and community of 14 residents is known as an enclave of Illinois and is accessible only from the Missouri side.[47]

New Madrid Seismic Zone

The New Madrid Seismic Zone, along the Mississippi River near New Madrid, Missouri, between Memphis and St. Louis, is related to an aulacogen (failed rift) that formed at the same time as the Gulf of Mexico. This area is still quite active seismically. Four great earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, estimated at 8 on the Richter magnitude scale, had tremendous local effects in the then sparsely settled area, and were felt in many other places in the Midwestern and eastern U.S. These earthquakes created Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee from the altered landscape near the river.

Length

When measured from its traditional source at Lake Itasca, the Mississippi has a length of 2,340 miles (3,770 km). When measured from its longest stream source (most distant source from the sea), Brower’s Spring in Montana, the source of the Missouri River, it has a length of 3,710 miles (5,970 km), making it the fourth longest river in the world after the Nile, Amazon, and Yangtze.[48] When measured by the largest stream source (by water volume), the Ohio River, by extension the Allegheny River, would be the source, and the Mississippi would begin in Pennsylvania.[citation needed]

Depth

At its source at Lake Itasca, the Mississippi River is about 3 feet (0.91 m) deep. The average depth of the Mississippi River between Saint Paul and Saint Louis is between 9 and 12 feet (2.7–3.7 m) deep, the deepest part being Lake Pepin, which averages 20–32 feet (6–10 m) deep and has a maximum depth of 60 feet (18 m). Between where the Missouri River joins the Mississippi at Saint Louis, Missouri, and Cairo, Illinois, the depth averages 30 feet (9 m). Below Cairo, where the Ohio River joins, the depth averages 50–100 feet (15–30 m) deep. The deepest part of the river is in New Orleans, where it reaches 200 feet (61 m) deep.[49][50]

Cultural geography

State boundaries

The Mississippi River runs through or along 10 states, from Minnesota to Louisiana, and is used to define portions of these states borders, with Wisconsin, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi along the east side of the river, and Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas along its west side. Substantial parts of both Minnesota and Louisiana are on either side of the river, although the Mississippi defines part of the boundary of each of these states.

In all of these cases, the middle of the riverbed at the time the borders were established was used as the line to define the borders between adjacent states.[51][52] In various areas, the river has since shifted, but the state borders have not changed, still following the former bed of the Mississippi River as of their establishment, leaving several small isolated areas of one state across the new river channel, contiguous with the adjacent state. Also, due to a meander in the river, a small part of western Kentucky is contiguous with Tennessee but isolated from the rest of its state.

Communities along the river

| Metro Area | Population |

|---|---|

| Minneapolis–Saint Paul | 3,946,533 |

| St. Louis | 2,916,447 |

| Memphis | 1,316,100 |

| New Orleans | 1,214,932 |

| Baton Rouge | 802,484 |

| Quad Cities, IA-IL | 387,630 |

| St. Cloud, MN | 189,148 |

| La Crosse, WI | 133,365 |

| Cape Girardeau–Jackson MO-IL | 96,275 |

| Dubuque, IA | 93,653 |

In Minnesota, the Mississippi River runs through the Twin Cities (2007)

Community of boathouses on the Mississippi River in Winona, MN (2006)

The Mississippi River at the Chain of Rocks just north of St. Louis (2005)

Many of the communities along the Mississippi River are listed below; most have either historic significance or cultural lore connecting them to the river. They are sequenced from the source of the river to its end.

- Bemidji, Minnesota

- Grand Rapids, Minnesota

- Jacobson, Minnesota

- Palisade, Minnesota

- Aitkin, Minnesota

- Riverton, Minnesota

- Brainerd, Minnesota

- Fort Ripley, Minnesota

- Little Falls, Minnesota

- Sartell, Minnesota

- St. Cloud, Minnesota

- Monticello, Minnesota

- Anoka, Minnesota

- Coon Rapids, Minnesota

- Brooklyn Park, Minnesota

- Brooklyn Center, Minnesota

- Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Nininger, Minnesota

- Hastings, Minnesota

- Prescott, Wisconsin

- Prairie Island, Minnesota

- Diamond Bluff, Wisconsin

- Red Wing, Minnesota

- Hager City, Wisconsin

- Maiden Rock, Wisconsin

- Stockholm, Wisconsin

- Lake City, Minnesota

- Maple Springs, Minnesota

- Camp Lacupolis, Minnesota

- Pepin, Wisconsin

- Reads Landing, Minnesota

- Wabasha, Minnesota

- Nelson, Wisconsin

- Alma, Wisconsin

- Buffalo City, Wisconsin

- Weaver, Minnesota

- Minneiska, Minnesota

- Fountain City, Wisconsin

- Winona, Minnesota

- Homer, Minnesota

- Trempealeau, Wisconsin

- Dakota, Minnesota

- Dresbach, Minnesota

- La Crescent, Minnesota

- La Crosse, Wisconsin

- Brownsville, Minnesota

- Stoddard, Wisconsin

- Genoa, Wisconsin

- Victory, Wisconsin

- Potosi, Wisconsin

- De Soto, Wisconsin

- Lansing, Iowa

- Ferryville, Wisconsin

- Lynxville, Wisconsin

- Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin

- Marquette, Iowa

- McGregor, Iowa

- Wyalusing, Wisconsin

- Guttenberg, Iowa

- Cassville, Wisconsin

- Dubuque, Iowa

- Galena, Illinois

- Bellevue, Iowa

- Savanna, Illinois

- Sabula, Iowa

- Fulton, Illinois

- Clinton, Iowa

- Cordova, Illinois

- Port Byron, Illinois

- LeClaire, Iowa

- Rapids City, Illinois

- Hampton, Illinois

- Bettendorf, Iowa

- East Moline, Illinois

- Moline, Illinois

- Davenport, Iowa

- Rock Island, Illinois

- Buffalo, Iowa

- Muscatine, Iowa

- New Boston, Illinois

- Keithsburg, Illinois

- Oquawka, Illinois

- Burlington, Iowa

- Dallas City, Illinois

- Fort Madison, Iowa

- Nauvoo, Illinois

- Keokuk, Iowa

- Warsaw, Illinois

- Quincy, Illinois

- Hannibal, Missouri

- Louisiana, Missouri

- Clarksville, Missouri

- Grafton, Illinois

- Portage Des Sioux, Missouri

- Alton, Illinois

- St. Louis, Missouri

- Ste. Genevieve, Missouri

- Kaskaskia, Illinois

- Chester, Illinois

- Grand Tower, Illinois

- Cape Girardeau, Missouri

- Thebes, Illinois

- Commerce, Missouri

- Cairo, Illinois

- Wickliffe, Kentucky

- Columbus, Kentucky

- Hickman, Kentucky

- New Madrid, Missouri

- Tiptonville, Tennessee

- Caruthersville, Missouri

- Osceola, Arkansas

- Reverie, Tennessee

- Memphis, Tennessee

- West Memphis, Arkansas

- Tunica, Mississippi

- Helena-West Helena, Arkansas

- Napoleon, Arkansas (historical)

- Arkansas City, Arkansas

- Greenville, Mississippi

- Mayersville, Mississippi

- Vicksburg, Mississippi

- Waterproof, Louisiana

- Natchez, Mississippi

- Morganza, Louisiana

- St. Francisville, Louisiana

- New Roads, Louisiana

- Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Donaldsonville, Louisiana

- Lutcher, Louisiana

- Destrehan, Louisiana

- New Orleans, Louisiana

- Pilottown, Louisiana

- La Balize, Louisiana (historical)

Bridge crossings

The road crossing highest on the Upper Mississippi is a simple steel culvert, through which the river (locally named «Nicolet Creek») flows north from Lake Nicolet under «Wilderness Road» to the West Arm of Lake Itasca, within Itasca State Park.[53]

The earliest bridge across the Mississippi River was built in 1855. It spanned the river in Minneapolis where the current Hennepin Avenue Bridge is located.[54] No highway or railroad tunnels cross under the Mississippi River.

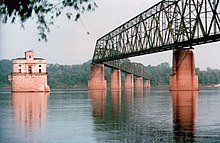

The first railroad bridge across the Mississippi was built in 1856. It spanned the river between the Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois and Davenport, Iowa. Steamboat captains of the day, fearful of competition from the railroads, considered the new bridge a hazard to navigation. Two weeks after the bridge opened, the steamboat Effie Afton rammed part of the bridge, setting it on fire. Legal proceedings ensued, with Abraham Lincoln defending the railroad. The lawsuit went to the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled in favor of the railroad.[55]

Below is a general overview of selected Mississippi bridges that have notable engineering or landmark significance, with their cities or locations. They are sequenced from the Upper Mississippi’s source to the Lower Mississippi’s mouth.

- Stone Arch Bridge – Former Great Northern Railway (now pedestrian) bridge at Saint Anthony Falls connecting downtown Minneapolis with the historic Marcy-Holmes neighborhood.

- I-35W Saint Anthony Falls Bridge – In Minneapolis, opened in September 2008, replacing the I-35W Mississippi River bridge which had collapsed catastrophically on August 1, 2007, killing 13 and injuring over 100.

- Eisenhower Bridge (Mississippi River) – In Red Wing, Minnesota, opened by Dwight D. Eisenhower in November 1960.

- I-90 Mississippi River Bridge – Connects La Crosse, Wisconsin, and Winona County, Minnesota, located just south of Lock and Dam No. 7.

- Black Hawk Bridge – Connects Lansing in Allamakee County, Iowa and rural Crawford County, Wisconsin; locally referred to as the Lansing Bridge and documented in the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Dubuque-Wisconsin Bridge – Connects Dubuque, Iowa, and Grant County, Wisconsin.

- Julien Dubuque Bridge – Joins the cities of Dubuque, Iowa, and East Dubuque, Illinois; listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

- Savanna-Sabula Bridge – A truss bridge and causeway connecting the city of Savanna, Illinois, and the island city of Sabula, Iowa. The bridge carries U.S. Highway 52 over the river, and is the terminus of both Iowa Highway 64 and Illinois Route 64. Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1999.

- Fred Schwengel Memorial Bridge – A 4-lane steel girder bridge that carries Interstate 80 and connects LeClaire, Iowa, and Rapids City, Illinois. Completed in 1966.

- Clinton Railroad Bridge – A swing bridge that connects Clinton, Iowa and Fulton (Albany), Illinois. Known as the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad Bridge.

- I-74 Bridge – Connects Bettendorf, Iowa, and Moline, Illinois; originally known as the Iowa-Illinois Memorial Bridge.

- Government Bridge – Connects Rock Island, Illinois and Davenport, Iowa, adjacent to Lock and Dam No. 15; the fourth crossing in this vicinity, built in 1896.

- Rock Island Centennial Bridge – Connects Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa; opened in 1940.

- Sergeant John F. Baker, Jr. Bridge – Connects Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa; opened in 1973.

Norbert F. Beckey bridge at Muscatine, Iowa, with LED lighting

- Norbert F. Beckey Bridge – Connects Muscatine, Iowa, and Rock Island County, Illinois; became first U.S. bridge to be illuminated with light-emitting diode (LED) lights decoratively illuminating the facade of the bridge.

- Great River Bridge – A cable-stayed bridge connecting Burlington, Iowa, to Gulf Port, Illinois.

- Fort Madison Toll Bridge – Connects Fort Madison, Iowa, and unincorporated Niota, Illinois; also known as the Santa Fe Swing Span Bridge; at the time of its construction the longest and heaviest electrified swing span on the Mississippi River. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places since 1999.

- Keokuk–Hamilton Bridge – Connects Keokuk, Iowa and Hamilton, Illinois; opened in 1985 replacing an older bridge which is still in use as a railroad bridge.

- Bayview Bridge – A cable-stayed bridge bringing westbound U.S. Highway 24 over the river, connecting the cities of West Quincy, Missouri, and Quincy, Illinois.

- Quincy Memorial Bridge – Connects the cities of West Quincy, Missouri, and Quincy, Illinois, carrying eastbound U.S. 24, the older of these two U.S. 24 bridges.

- Clark Bridge – A cable-stayed bridge connecting West Alton, Missouri, and Alton, Illinois, also known as the Super Bridge as the result of an appearance on the PBS program, Nova; built in 1994, carrying U.S. Route 67 across the river. This is the northernmost river crossing in the St. Louis metropolitan area, replacing the Old Clark Bridge, a truss bridge built in 1928, named after explorer William Clark.

- Chain of Rocks Bridge – Located on the northern edge of St. Louis, notable for a 22-degree bend occurring at the middle of the crossing, necessary for navigation on the river; formerly used by U.S. Route 66 to cross the Mississippi. Replaced for road traffic in 1966 by a nearby pair of new bridges; now a pedestrian bridge.

- Eads Bridge – A combined road and railway bridge, connecting St. Louis and East St. Louis, Illinois. When completed in 1874, it was the longest arch bridge in the world, with an overall length of 6,442 feet (1,964 m). The three ribbed steel arch spans were considered daring, as was the use of steel as a primary structural material; it was the first such use of true steel in a major bridge project.

- Chester Bridge – A truss bridge connecting Route 51 in Missouri with Illinois Route 150, between Perryville, Missouri, and Chester, Illinois. The bridge can be seen at the beginning of the 1967 film In the Heat of the Night. In the 1940s, the main span was destroyed by a tornado.

- Bill Emerson Memorial Bridge—Connecting Cape Girardeau, Missouri and East Cape Girardeau, Illinois, completed in 2003 and illuminated by 140 lights.

- Caruthersville Bridge – A single tower cantilever bridge carrying Interstate 155 and U.S. Route 412 across the Mississippi River between Caruthersville, Missouri and Dyersburg, Tennessee.

- Hernando de Soto Bridge – A through arch bridge carrying Interstate 40 across the Mississippi between West Memphis, Arkansas, and Memphis, Tennessee.

- Harahan Bridge – A cantilevered through truss bridge, carrying two rail lines of the Union Pacific Railroad across the river between West Memphis, Arkansas, and Memphis, Tennessee.

- Frisco Bridge – A cantilevered through truss bridge, carrying a rail line across the river between West Memphis, Arkansas, and Memphis, Tennessee, previously known as the Memphis Bridge. When it opened on May 12, 1892, it was the first crossing of the Lower Mississippi and the longest span in the U.S. Listed as a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

- Memphis & Arkansas Bridge – A cantilevered through truss bridge, carrying Interstate 55 between Memphis and West Memphis; listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Helena Bridge

- Greenville Bridge

- Old Vicksburg Bridge

- Vicksburg Bridge

- Natchez-Vidalia Bridge

- John James Audubon Bridge – The second-longest cable-stayed bridge in the Western Hemisphere; connects Pointe Coupee and West Feliciana Parishes in Louisiana. It is the only crossing between Baton Rouge and Natchez. This bridge was opened a month ahead of schedule in May 2011, due to the 2011 floods.

- Huey P. Long Bridge – A truss cantilever bridge carrying US 190 (Airline Highway) and one rail line between East Baton Rouge and West Baton Rouge Parishes in Louisiana.

- Horace Wilkinson Bridge – A cantilevered through truss bridge, carrying six lanes of Interstate 10 between Baton Rouge and Port Allen in Louisiana. It is the highest bridge over the Mississippi River.

- Sunshine Bridge

- Gramercy Bridge

- Hale Boggs Memorial Bridge

- Huey P. Long Bridge – In Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, the first Mississippi River span built in Louisiana.

- Crescent City Connection – Connects the east and west banks of New Orleans, Louisiana; the fifth-longest cantilever bridge in the world.

Navigation and flood control

Mississippi River levels at Memphis, Tennessee

Major flood stage

Moderate flood stage

Flood stage

Action stage

River levels

Minimum operating limit (-12 feet)

Downbound barge rates

In late 2022 there was low river levels that caused two backups on the Lower Mississippi River that held up over 100 tow boats with 2,000 barge units and caused barge rates to soar[56][57]

Ships on the lower part of the Mississippi

A clear channel is needed for the barges and other vessels that make the main stem Mississippi one of the great commercial waterways of the world. The task of maintaining a navigation channel is the responsibility of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which was established in 1802.[58] Earlier projects began as early as 1829 to remove snags, close off secondary channels and excavate rocks and sandbars.

Oil tanker on the Lower Mississippi near the Port of New Orleans

Barge on the Lower Mississippi River

A series of 29 locks and dams on the upper Mississippi, most of which were built in the 1930s, is designed primarily to maintain a 9-foot-deep (2.7 m) channel for commercial barge traffic.[59][60] The lakes formed are also used for recreational boating and fishing. The dams make the river deeper and wider but do not stop it. No flood control is intended. During periods of high flow, the gates, some of which are submersible, are completely opened and the dams simply cease to function. Below St. Louis, the Mississippi is relatively free-flowing, although it is constrained by numerous levees and directed by numerous wing dams. The scope and scale of the levees, built along either side of the river to keep it on its course, has often been compared to the Great Wall of China.[32]

On the lower Mississippi, from Baton Rouge to the mouth of the Mississippi, the navigation depth is 45 feet (14 m), allowing container ships and cruise ships to dock at the Port of New Orleans and bulk cargo ships shorter than 150-foot (46 m) air draft that fit under the Huey P. Long Bridge to traverse the Mississippi to Baton Rouge.[61] There is a feasibility study to dredge this portion of the river to 50 feet (15 m) to allow New Panamax ship depths.[62]

19th century

In 1829, there were surveys of the two major obstacles on the upper Mississippi, the Des Moines Rapids and the Rock Island Rapids, where the river was shallow and the riverbed was rock. The Des Moines Rapids were about 11 miles (18 km) long and just above the mouth of the Des Moines River at Keokuk, Iowa. The Rock Island Rapids were between Rock Island and Moline, Illinois. Both rapids were considered virtually impassable.

In 1848, the Illinois and Michigan Canal was built to connect the Mississippi River to Lake Michigan via the Illinois River near Peru, Illinois. The canal allowed shipping between these important waterways. In 1900, the canal was replaced by the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. The second canal, in addition to shipping, also allowed Chicago to address specific health issues (typhoid fever, cholera and other waterborne diseases) by sending its waste down the Illinois and Mississippi river systems rather than polluting its water source of Lake Michigan.

The Corps of Engineers recommended the excavation of a 5-foot-deep (1.5 m) channel at the Des Moines Rapids, but work did not begin until after Lieutenant Robert E. Lee endorsed the project in 1837. The Corps later also began excavating the Rock Island Rapids. By 1866, it had become evident that excavation was impractical, and it was decided to build a canal around the Des Moines Rapids. The canal opened in 1877, but the Rock Island Rapids remained an obstacle. In 1878, Congress authorized the Corps to establish a 4.5-foot-deep (1.4 m) channel to be obtained by building wing dams that direct the river to a narrow channel causing it to cut a deeper channel, by closing secondary channels and by dredging. The channel project was complete when the Moline Lock, which bypassed the Rock Island Rapids, opened in 1907.

To improve navigation between St. Paul, Minnesota, and Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, the Corps constructed several dams on lakes in the headwaters area, including Lake Winnibigoshish and Lake Pokegama. The dams, which were built beginning in the 1880s, stored spring run-off which was released during low water to help maintain channel depth.

20th century

In 1907, Congress authorized a 6-foot-deep (1.8 m) channel project on the Mississippi River, which was not complete when it was abandoned in the late 1920s in favor of the 9-foot-deep (2.7 m) channel project.

In 1913, construction was complete on Lock and Dam No. 19 at Keokuk, Iowa, the first dam below St. Anthony Falls. Built by a private power company (Union Electric Company of St. Louis) to generate electricity (originally for streetcars in St. Louis), the Keokuk dam was one of the largest hydro-electric plants in the world at the time. The dam also eliminated the Des Moines Rapids. Lock and Dam No. 1 was completed in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1917. Lock and Dam No. 2, near Hastings, Minnesota, was completed in 1930.

Before the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the Corps’s primary strategy was to close off as many side channels as possible to increase the flow in the main river. It was thought that the river’s velocity would scour off bottom sediments, deepening the river and decreasing the possibility of flooding. The 1927 flood proved this to be so wrong that communities threatened by the flood began to create their own levee breaks to relieve the force of the rising river.

The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1930 authorized the 9-foot (2.7 m) channel project, which called for a navigation channel 9 feet (2.7 m) feet deep and 400 feet (120 m) wide to accommodate multiple-barge tows.[63][64] This was achieved by a series of locks and dams, and by dredging. Twenty-three new locks and dams were built on the upper Mississippi in the 1930s in addition to the three already in existence.

Formation of the Atchafalaya River and construction of the Old River Control Structure.

Until the 1950s, there was no dam below Lock and Dam 26 at Alton, Illinois. Chain of Rocks Lock (Lock and Dam No. 27), which consists of a low-water dam and an 8.4-mile-long (13.5 km) canal, was added in 1953, just below the confluence with the Missouri River, primarily to bypass a series of rock ledges at St. Louis. It also serves to protect the St. Louis city water intakes during times of low water.

U.S. government scientists determined in the 1950s that the Mississippi River was starting to switch to the Atchafalaya River channel because of its much steeper path to the Gulf of Mexico. Eventually, the Atchafalaya River would capture the Mississippi River and become its main channel to the Gulf of Mexico, leaving New Orleans on a side channel. As a result, the U.S. Congress authorized a project called the Old River Control Structure, which has prevented the Mississippi River from leaving its current channel that drains into the Gulf via New Orleans.[66]

Because the large scale of high-energy water flow threatened to damage the structure, an auxiliary flow control station was built adjacent to the standing control station. This $300 million project was completed in 1986 by the Corps of Engineers. Beginning in the 1970s, the Corps applied hydrological transport models to analyze flood flow and water quality of the Mississippi. Dam 26 at Alton, Illinois, which had structural problems, was replaced by the Mel Price Lock and Dam in 1990. The original Lock and Dam 26 was demolished.

21st century

The Corps now actively creates and maintains spillways and floodways to divert periodic water surges into backwater channels and lakes, as well as route part of the Mississippi’s flow into the Atchafalaya Basin and from there to the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The main structures are the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway in Missouri; the Old River Control Structure and the Morganza Spillway in Louisiana, which direct excess water down the west and east sides (respectively) of the Atchafalaya River; and the Bonnet Carré Spillway, also in Louisiana, which directs floodwaters to Lake Pontchartrain (see diagram). Some experts blame urban sprawl for increases in both the risk and frequency of flooding on the Mississippi River.[67]

Some of the pre-1927 strategy remains in use today, with the Corps actively cutting the necks of horseshoe bends, allowing the water to move faster and reducing flood heights.[68]

History

Approximately 50,000 years ago, the Central United States was covered by an inland sea, which was drained by the Mississippi and its tributaries into the Gulf of Mexico—creating large floodplains and extending the continent further to the south in the process. The soil in areas such as Louisiana was thereafter found to be very rich.[69]

Native Americans

The area of the Mississippi River basin was first settled by hunting and gathering Native American peoples and is considered one of the few independent centers of plant domestication in human history.[70] Evidence of early cultivation of sunflower, a goosefoot, a marsh elder and an indigenous squash dates to the 4th millennium BC. The lifestyle gradually became more settled after around 1000 BC during what is now called the Woodland period, with increasing evidence of shelter construction, pottery, weaving and other practices.

A network of trade routes referred to as the Hopewell interaction sphere was active along the waterways between about 200 and 500 AD, spreading common cultural practices over the entire area between the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes. A period of more isolated communities followed, and agriculture introduced from Mesoamerica based on the Three Sisters (maize, beans and squash) gradually came to dominate. After around 800 AD there arose an advanced agricultural society today referred to as the Mississippian culture, with evidence of highly stratified complex chiefdoms and large population centers.

The most prominent of these, now called Cahokia, was occupied between about 600 and 1400 AD[71] and at its peak numbered between 8,000 and 40,000 inhabitants, larger than London, England of that time. At the time of first contact with Europeans, Cahokia and many other Mississippian cities had dispersed, and archaeological finds attest to increased social stress.[72][73][74]

Modern American Indian nations inhabiting the Mississippi basin include Cheyenne, Sioux, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Fox, Kickapoo, Tamaroa, Moingwena, Quapaw and Chickasaw.

The word Mississippi itself comes from Messipi, the French rendering of the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe or Algonquin) name for the river, Misi-ziibi (Great River).[75][76] The Ojibwe called Lake Itasca Omashkoozo-zaaga’igan (Elk Lake) and the river flowing out of it Omashkoozo-ziibi (Elk River). After flowing into Lake Bemidji, the Ojibwe called the river Bemijigamaag-ziibi (River from the Traversing Lake). After flowing into Cass Lake, the name of the river changes to Gaa-miskwaawaakokaag-ziibi (Red Cedar River) and then out of Lake Winnibigoshish as Wiinibiigoonzhish-ziibi (Miserable Wretched Dirty Water River), Gichi-ziibi (Big River) after the confluence with the Leech Lake River, then finally as Misi-ziibi (Great River) after the confluence with the Crow Wing River.[77] After the expeditions by Giacomo Beltrami and Henry Schoolcraft, the longest stream above the juncture of the Crow Wing River and Gichi-ziibi was named «Mississippi River». The Mississippi River Band of Chippewa Indians, known as the Gichi-ziibiwininiwag, are named after the stretch of the Mississippi River known as the Gichi-ziibi. The Cheyenne, one of the earliest inhabitants of the upper Mississippi River, called it the Máʼxe-éʼometaaʼe (Big Greasy River) in the Cheyenne language. The Arapaho name for the river is Beesniicíe.[78] The Pawnee name is Kickaátit.[79]

The Mississippi was spelled Mississipi or Missisipi during French Louisiana and was also known as the Rivière Saint-Louis.[80][81][82]

European exploration

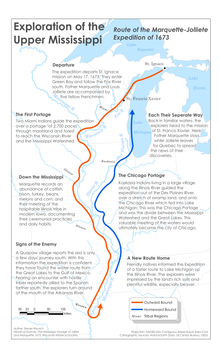

Route of the Marquette-Jolliete Expedition of 1673

In 1519 Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda became the first recorded European to reach the Mississippi River, followed by Hernando de Soto who reached the river on May 8, 1541, and called it Río del Espíritu Santo («River of the Holy Spirit»), in the area of what is now Mississippi.[83] In Spanish, the river is called Río Mississippi.[84]

French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette began exploring the Mississippi in the 17th century. Marquette traveled with a Sioux Indian who named it Ne Tongo («Big river» in Sioux language) in 1673. Marquette proposed calling it the River of the Immaculate Conception.

When Louis Jolliet explored the Mississippi Valley in the 17th century, natives guided him to a quicker way to return to French Canada via the Illinois River. When he found the Chicago Portage, he remarked that a canal of «only half a league» (less than 2 miles or 3 kilometers) would join the Mississippi and the Great Lakes.[85] In 1848, the continental divide separating the waters of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley was breached by the Illinois and Michigan canal via the Chicago River.[86] This both accelerated the development, and forever changed the ecology of the Mississippi Valley and the Great Lakes.

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Henri de Tonti claimed the entire Mississippi River valley for France, calling the river Colbert River after Jean-Baptiste Colbert and the region La Louisiane, for King Louis XIV. On March 2, 1699, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville rediscovered the mouth of the Mississippi, following the death of La Salle.[87] The French built the small fort of La Balise there to control passage.[88]

In 1718, about 100 miles (160 km) upriver, New Orleans was established along the river crescent by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, with construction patterned after the 1711 resettlement on Mobile Bay of Mobile, the capital of French Louisiana at the time.

In 1727, Étienne Perier begins work, using enslaved African laborers, on the first levees on the Mississippi River.

Colonization

Following Britain’s victory in the Seven Years War, the Mississippi became the border between the British and Spanish Empires. The Treaty of Paris (1763) gave Great Britain rights to all land east of the Mississippi and Spain rights to land west of the Mississippi. Spain also ceded Florida to Britain to regain Cuba, which the British occupied during the war. Britain then divided the territory into East and West Florida.

Article 8 of the Treaty of Paris (1783) states, «The navigation of the river Mississippi, from its source to the ocean, shall forever remain free and open to the subjects of Great Britain and the citizens of the United States». With this treaty, which ended the American Revolutionary War, Britain also ceded West Florida back to Spain to regain the Bahamas, which Spain had occupied during the war. Initial disputes around the ensuing claims of the U.S. and Spain were resolved when Spain was pressured into signing Pinckney’s Treaty in 1795. However, in 1800, under duress from Napoleon of France, Spain ceded an undefined portion of West Florida to France in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso. The United States then secured effective control of the river when it bought the Louisiana Territory from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This triggered a dispute between Spain and the U.S. on which parts of West Florida Spain had ceded to France in the first place, which would decide which parts of West Florida the U.S. had bought from France in the Louisiana Purchase, versus which were unceded Spanish property. Due to ongoing U.S. colonization creating facts on the ground, and U.S. military actions, Spain ceded both West and East Florida in their entirety to the United States in the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

The last serious European challenge to U.S. control of the river came at the conclusion of the War of 1812, when British forces mounted an attack on New Orleans just 15 days after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent. The attack was repulsed by an American army under the command of General Andrew Jackson.

In the Treaty of 1818, the U.S. and Great Britain agreed to fix the border running from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains along the 49th parallel north. In effect, the U.S. ceded the northwestern extremity of the Mississippi basin to the British in exchange for the southern portion of the Red River basin.

So many settlers traveled westward through the Mississippi river basin, as well as settled in it, that Zadok Cramer wrote a guidebook called The Navigator, detailing the features, dangers, and navigable waterways of the area. It was so popular that he updated and expanded it through 12 editions over 25 years.

Shifting sand bars made early navigation difficult.

The colonization of the area was barely slowed by the three earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, estimated at 8 on the Richter magnitude scale, that were centered near New Madrid, Missouri.

Steamboat era

Mark Twain’s book, Life on the Mississippi, covered the steamboat commerce, which took place from 1830 to 1870, before more modern ships replaced the steamer. Harper’s Weekly first published the book as a seven-part serial in 1875. James R. Osgood & Company published the full version, including a passage from the then unfinished Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and works from other authors, in 1885.

The first steamboat to travel the full length of the Lower Mississippi from the Ohio River to New Orleans was the New Orleans in December 1811. Its maiden voyage occurred during the series of New Madrid earthquakes in 1811–12. The Upper Mississippi was treacherous, unpredictable and to make traveling worse, the area was not properly mapped out or surveyed. Until the 1840s, only two trips a year to the Twin Cities landings were made by steamboats, which suggests it was not very profitable.[89]

Steamboat transport remained a viable industry, both in terms of passengers and freight, until the end of the first decade of the 20th century. Among the several Mississippi River system steamboat companies was the noted Anchor Line, which, from 1859 to 1898, operated a luxurious fleet of steamers between St. Louis and New Orleans.

Italian explorer Giacomo Beltrami wrote about his journey on the Virginia, which was the first steamboat to make it to Fort St. Anthony in Minnesota. He referred to his voyage as a promenade that was once a journey on the Mississippi. The steamboat era changed the economic and political life of the Mississippi, as well as of travel itself. The Mississippi was completely changed by the steamboat era as it transformed into a flourishing tourist trade.[90]

Civil War

Mississippi River from Eunice, Arkansas, a settlement destroyed by gunboats during the Civil War.

Control of the river was a strategic objective of both sides in the American Civil War, forming a part of the U.S. Anaconda Plan. In 1862, Union forces coming down the river successfully cleared Confederate defenses at Island Number 10 and Memphis, Tennessee, while Naval forces coming upriver from the Gulf of Mexico captured New Orleans, Louisiana. One of the last major Confederate strongholds was on the heights overlooking the river at Vicksburg, Mississippi; the Union’s Vicksburg Campaign (December 1862–July 1863), and the fall of Port Hudson, completed control of the lower Mississippi River. The Union victory ended the Siege of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, and was pivotal to the Union’s final victory of the Civil War.

20th and 21st centuries

The «Big Freeze» of 1918–19 blocked river traffic north of Memphis, Tennessee, preventing transportation of coal from southern Illinois. This resulted in widespread shortages, high prices, and rationing of coal in January and February.[91]

In the spring of 1927, the river broke out of its banks in 145 places, during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and inundated 27,000 sq mi (70,000 km2) to a depth of up to 30 feet (9.1 m).

In 1930, Fred Newton was the first person to swim the length of the river, from Minneapolis to New Orleans. The journey took 176 days and covered 1,836 miles.[92][93]

In 1962 and 1963, industrial accidents spilled 3.5 million US gallons (13,000 m3) of soybean oil into the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. The oil covered the Mississippi River from St. Paul to Lake Pepin, creating an ecological disaster and a demand to control water pollution.[94]

On October 20, 1976, the automobile ferry, MV George Prince, was struck by a ship traveling upstream as the ferry attempted to cross from Destrehan, Louisiana, to Luling, Louisiana. Seventy-eight passengers and crew died; only eighteen survived the accident.

In 1988, the water level of the Mississippi fell to 10 feet (3.0 m) below zero on the Memphis gauge. The remains of wooden-hulled water craft were exposed in an area of 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) on the bottom of the Mississippi River at West Memphis, Arkansas. They dated to the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The State of Arkansas, the Arkansas Archeological Survey, and the Arkansas Archeological Society responded with a two-month data recovery effort. The fieldwork received national media attention as good news in the middle of a drought.[95]

The Great Flood of 1993 was another significant flood, primarily affecting the Mississippi above its confluence with the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois.

Two portions of the Mississippi were designated as American Heritage Rivers in 1997: the lower portion around Louisiana and Tennessee, and the upper portion around Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri and Wisconsin. The Nature Conservancy’s project called «America’s Rivershed Initiative» announced a ‘report card’ assessment of the entire basin in October 2015 and gave the grade of D+. The assessment noted the aging navigation and flood control infrastructure along with multiple environmental problems.[96]

Campsite at the river in Arkansas

In 2002, Slovenian long-distance swimmer Martin Strel swam the entire length of the river, from Minnesota to Louisiana, over the course of 68 days. In 2005, the Source to Sea Expedition[97] paddled the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers to benefit the Audubon Society’s Upper Mississippi River Campaign.[98][99]

Future

Geologists believe that the lower Mississippi could take a new course to the Gulf. Either of two new routes—through the Atchafalaya Basin or through Lake Pontchartrain—might become the Mississippi’s main channel if flood-control structures are overtopped or heavily damaged during a severe flood.[100][101][102][103][104]

Failure of the Old River Control Structure, the Morganza Spillway, or nearby levees would likely re-route the main channel of the Mississippi through Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Basin and down the Atchafalaya River to reach the Gulf of Mexico south of Morgan City in southern Louisiana. This route provides a more direct path to the Gulf of Mexico than the present Mississippi River channel through Baton Rouge and New Orleans.[102] While the risk of such a diversion is present during any major flood event, such a change has so far been prevented by active human intervention involving the construction, maintenance, and operation of various levees, spillways, and other control structures by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Old River Control Structure, between the present Mississippi River channel and the Atchafalaya Basin, sits at the normal water elevation and is ordinarily used to divert 30% of the Mississippi flow to the Atchafalaya River. There is a steep drop here away from the Mississippi’s main channel into the Atchafalaya Basin. If this facility were to fail during a major flood, there is a strong concern the water would scour and erode the river bottom enough to capture the Mississippi’s main channel. The structure was nearly lost during the 1973 flood, but repairs and improvements were made after engineers studied the forces at play. In particular, the Corps of Engineers made many improvements and constructed additional facilities for routing water through the vicinity. These additional facilities give the Corps much more flexibility and potential flow capacity than they had in 1973, which further reduces the risk of a catastrophic failure in this area during other major floods, such as that of 2011.

Because the Morganza Spillway is slightly higher and well back from the river, it is normally dry on both sides.[105] Even if it failed at the crest during a severe flood, the floodwaters would have to erode to normal water levels before the Mississippi could permanently jump channel at this location.[106][107] During the 2011 floods, the Corps of Engineers opened the Morganza Spillway to 1/4 of its capacity to allow 150,000 cubic feet per second (4,200 m3/s) of water to flood the Morganza and Atchafalaya floodways and continue directly to the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing Baton Rouge and New Orleans.[108] In addition to reducing the Mississippi River crest downstream, this diversion reduced the chances of a channel change by reducing stress on the other elements of the control system.[109]

Some geologists have noted that the possibility for course change into the Atchafalaya also exists in the area immediately north of the Old River Control Structure. Army Corps of Engineers geologist Fred Smith once stated, «The Mississippi wants to go west. 1973 was a forty-year flood. The big one lies out there somewhere—when the structures can’t release all the floodwaters and the levee is going to have to give way. That is when the river’s going to jump its banks and try to break through.»[110]

Another possible course change for the Mississippi River is a diversion into Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans. This route is controlled by the Bonnet Carré Spillway, built to reduce flooding in New Orleans. This spillway and an imperfect natural levee about 12–20 ft (3.7–6.1 m) high are all that prevents the Mississippi from taking a new, shorter course through Lake Pontchartrain to the Gulf of Mexico.[111] Diversion of the Mississippi’s main channel through Lake Pontchartrain would have consequences similar to an Atchafalaya diversion, but to a lesser extent, since the present river channel would remain in use past Baton Rouge and into the New Orleans area.

Recreation

The sport of water skiing was invented on the river in a wide region between Minnesota and Wisconsin known as Lake Pepin.[112] Ralph Samuelson of Lake City, Minnesota, created and refined his skiing technique in late June and early July 1922. He later performed the first water ski jump in 1925 and was pulled along at 80 mph (130 km/h) by a Curtiss flying boat later that year.[112]

There are seven National Park Service sites along the Mississippi River. The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is the National Park Service site dedicated to protecting and interpreting the Mississippi River itself. The other six National Park Service sites along the river are (listed from north to south):

- Effigy Mounds National Monument

- Gateway Arch National Park (includes Gateway Arch)

- Vicksburg National Military Park

- Natchez National Historical Park

- New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park

- Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

Ecology

The Mississippi basin is home to a highly diverse aquatic fauna and has been called the «mother fauna» of North American freshwater.[113]

Fish

About 375 fish species are known from the Mississippi basin, far exceeding other North Hemisphere river basins exclusively within temperate/subtropical regions,[113] except the Yangtze.[114] Within the Mississippi basin, streams that have their source in the Appalachian and Ozark highlands contain especially many species. Among the fish species in the basin are numerous endemics, as well as relicts such as paddlefish, sturgeon, gar and bowfin.[113]

Because of its size and high species diversity, the Mississippi basin is often divided into subregions. The Upper Mississippi River alone is home to about 120 fish species, including walleye, sauger, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, white bass, northern pike, bluegill, crappie, channel catfish, flathead catfish, common shiner, freshwater drum, and shovelnose sturgeon.[115][116]

Other fauna

A large number of reptiles are native to the river channels and basin, including American alligators, several species of turtle, aquatic amphibians,[117] and cambaridae crayfish, are native to the Mississippi basin.[118]

In addition, approximately 40% of the migratory birds in the US use the Mississippi River corridor during Spring and Fall migrations; 60% of all migratory birds in North America (326 species) use the river basin as their flyway.[119]

Introduced species

Numerous introduced species are found in the Mississippi and some of these are invasive. Among the introductions are fish such as Asian carp, including the silver carp that have become infamous for out-competing native fish and their potentially dangerous jumping behavior. They have spread throughout much of the basin, even approaching (but not yet invading) the Great Lakes.[120] The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has designated much of the Mississippi River in the state as infested waters by the exotic species zebra mussels and Eurasian watermilfoil.[121]

See also

- Atchafalaya Basin

- Capes on the Mississippi River

- Chemetco

- Great River Road

- List of crossings of the Lower Mississippi River

- List of crossings of the Upper Mississippi River

- List of locks and dams of the Upper Mississippi River

- List of tributaries of the Mississippi River

- List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem)

- Mississippi embayment

- Mississippi River floods

- Mississippi River System

- The Waterways Journal Weekly

- Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge

Notes

- ^ Ojibwe: Misi-ziibi,[8] Dakota: Mníšošethąka,[9] Myaamia: Mihsi-siipiiwi,[10] Cheyenne: Ma’xeé’ometāā’e,[11] Kiowa: Xósáu,[12] Arapaho: Beesniicie,[13] Pawnee: Kickaátit[14]

References

- ^ James L. Shaffer and John T. Tigges. The Mississippi River: Father of Waters. Chicago, Ill.: Arcadia Pub., 2000.

- ^ The Upper Mississippi River Basin: A Portrait of the Father of Waters As Seen by the Upper Mississippi River Comprehensive Basin Study. Chicago, Ill.: Army Corps of Engineers, North Central Division, 1972.

- ^ Heilbron, Bertha L. «Father of Waters: Four Centuries of the Mississippi». American Heritage, vol. 2, no. 1 (Autumn 1950): 40–43.

- ^ The United States Geological Survey recognizes two contrasting definitions of a river’s source.USGS.gov Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine By the stricter definition, the Mississippi would share its source with its longest tributary, the Missouri, at Brower’s Spring in Montana. The other definition acknowledges «somewhat arbitrary decisions» and places the Mississippi’s source at Lake Itasca, which is publicly accepted as the source,USGS.gov and which had been identified as such by Brower himself.MT.gov Archived January 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine However, the river continues for several miles upstream from Lake Itasca to Nicolet Lake and its feeder stream.

- ^ a b Kammerer, J.C. (May 1990). «Largest Rivers in the United States». U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ «USGS 07289000 Mississippi River at Vicksburg, MS». United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Median of the 14,610 daily streamflows recorded by the USGS for the period 1967–2006.

- ^ Hirschfelder, Arlene B. (2012). The Extraordinary Book of Native American Lists. Paulette Fairbanks Molin. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8108-7710-8. OCLC 794706782.

- ^ «AISRI Dictionary Database Search». Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ «Myaamia Dictionary Search». Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ «English – Cheyenne». Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ «English – Kiowa». Archived from the original on July 13, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ «XML File of Arapaho Place Names». Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ «Southband Pawnee Dictionary». Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ United States Geological Survey Hydrological Unit Code: 08-09-01-00- Lower Mississippi-New Orleans Watershed

- ^ a b «Lengths of the major rivers». United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ «Mississippi River Facts – Mississippi National River and Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service)». www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ^ «United States Geography: Rivers». www.ducksters.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ «The 10 States That Border the Mississippi». ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ «Mississippi (river US) facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Mississippi (river US)». www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ «mississippi | Origin and meaning of the name mississippi by Online Etymology Dictionary». www.etymonline.com. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ Ethan Shaw. «The 10 Tallest Mountains East of the Mississippi». Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ «New Madrid – 220+ Years Old and Counting». Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ Upham, Warren. «Minnesota Place Names: A Geographical Encyclopedia». Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 8, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ a b «Upper St. Anthony Falls Lock Closure». US Army Corps of Engineers. 2015. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015.

- ^ «Mississippi River Facts». Nps.gov. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ 2001 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Upper Mississippi River Navigation Chart

- ^ Middle Mississippi River Regional Corridor: Collaborative Planning Study (July 2007 update). St. Louis, MO: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis District. 2007. p. 28.

- ^ «MMRP: Middle Mississippi River Partnership». Middle Mississippi River Partnership. Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Frits van der Leeden, Fred L. Troise, David Keith Todd: The Water Encyclopedia, 2nd edition, p. 126, Chelsea, Mich. (Lewis Publishers), 1990, ISBN 0-87371-120-3

- ^ USGS stream gage 07022000 Mississippi River at Thebes, IL Archived November 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b McPhee, John (February 23, 1987). «The Control of Nature: Atchafalaya». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011. Republished in McPhee, John (1989). The Control of Nature. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 272. ISBN 0-374-12890-1.

- ^ Angert, Joe and Isaac. «Old River Control». The Mighty Mississippi River. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2011. Includes map and pictures.

- ^ Kemp, Katherine (January 6, 2000). «The Mississippi Levee System and the Old River Control Structure». Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ «USACE Brochure: Old River Control, Jan 2009» (PDF). US Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans District. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ «Louisiana Old River Control Structure and Mississippi river flood protection». America’s Wetland Resource Center. Loyola University’s Center for Environmental Communication. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ «Mount Elbert, Colorado». Peakbagger. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ «General Information about the Mississippi River». Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. National Park Service. 2004. Archived from the original on June 13, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ «Americas Wetland: Resource Center». Americaswetlandresources.com. November 4, 1939. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ «Hydrologie du bassin de l’Amazone» (PDF). Grands Bassins Fluviaux, Paris (in French). November 22–24, 1993. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ Meade, R. H., and J. A. Moody, 1984, Causes for the decline of suspended-sediment discharge in the Mississippi River system, 1940–2007 Hydrology Processes vol. 24, pp. 35–49.

- ^ Saltwater is moving up the Mississippi River. Here’s what’s being done to stop it

- ^ McKay, E.D., 2007, Six Rivers, Five Glaciers, and an Outburst Flood: the Considerable Legacy of the Illinois River. Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (PDF) Proceedings of the 2007 Governor’s Conference on the Management of the Illinois River System: Our continuing Commitment, 11th Biennial Conference, Oct. 2–4, 2007, 11 p.

- ^ McKay, E.D., and R.C. Berg, 2008, Optical ages spanning two glacial-interglacial cycles from deposits of the ancient Mississippi River, north-central Illinois. Archived October 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Vol. 40, No. 5, p. 78 with Powerpoint presentation Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The New Yorker: Atchalafaya Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, File:Geomorphology of Old River.jpg, «Historical». Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ «Arkansas v. Tennessee, 246 U.S. 158 :: Volume 246 :: 1918». Supreme.justia.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Knopp, Lisa (2012). What the River carries: Encounters with the Mississippi, Missouri, and Platte. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8262-1974-9.

- ^ Bowden, Rob (January 27, 2005). Settlements of the Mississippi River. Heinemann-Raintree Library. ISBN 9781403457196. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Geology of the Mississippi River». Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ «Lake Pepin». Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ «encyclopediaofarkansas.net». encyclopediaofarkansas.net. April 28, 2010. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ Yale.edu «Treaty of Friendship, Limits, and Navigation«, Avalon project at the Yale Law School

- ^ Google Streetview image Archived August 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at 47.1938103 N, 95.2306761 W

- ^ Costello, Mary Charlotte (2002). Climbing the Mississippi River Bridge by Bridge. Vol. Two: Minnesota. Cambridge, Minnesota: Adventure Publications. ISBN 0-9644518-2-4.

- ^ Michael A. Ross (Summer 2009). «Hell Gate of the Mississippi: The Effie Afton Trial and Abraham Lincoln’s Role in It». The Annals of Iowa. 68 (3): 312–314. doi:10.17077/0003-4827.1361.