From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Clownfish | |

|---|---|

|

|

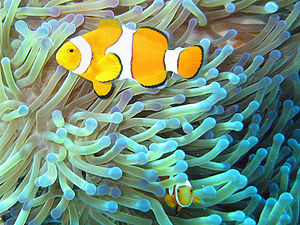

| Ocellaris clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Clade: | Percomorpha |

| (unranked): | Ovalentaria |

| Family: | Pomacentridae |

| Subfamily: | Amphiprioninae Allen, 1975 |

| Genera | |

|

Clownfish swimming movements

Clownfish or anemonefish are fishes from the subfamily Amphiprioninae in the family Pomacentridae. Thirty species of clownfish are recognized: one in the genus Premnas, while the remaining are in the genus Amphiprion. In the wild, they all form symbiotic mutualisms with sea anemones. Depending on the species, anemonefish are overall yellow, orange, or a reddish or blackish color, and many show white bars or patches. The largest can reach a length of 17 cm (6+1⁄2 in), while the smallest barely achieve 7–8 cm (2+3⁄4–3+1⁄4 in).

Distribution and habitat[edit]

Anemonefish are endemic to the warmer waters of the Indian Ocean, including the Red Sea, and Pacific Ocean, the Great Barrier Reef, Southeast Asia, Japan, and the Indo-Malaysian region. While most species have restricted distributions, others are widespread. Anemonefish typically live at the bottom of shallow seas in sheltered reefs or in shallow lagoons. No anemonefish are found in the Atlantic.[1]

Diet[edit]

Anemonefish are omnivorous and can feed on undigested food from their host anemones, and the fecal matter from the anemonefish provides nutrients to the sea anemone. Anemonefish primarily feed on small zooplankton from the water column, such as copepods and tunicate larvae, with a small portion of their diet coming from algae, with the exception of Amphiprion perideraion, which primarily feeds on algae.[2][3]

Symbiosis and mutualism[edit]

Anemonefish and sea anemones have a symbiotic, mutualistic relationship, each providing many benefits to the other. The individual species are generally highly host specific. The sea anemone protects the anemonefish from predators, as well as providing food through the scraps left from the anemone’s meals and occasional dead anemone tentacles, and functions as a safe nest site. In return, the anemonefish defends the anemone from its predators and parasites.[4][5] The anemone also picks up nutrients from the anemonefish’s excrement.[6] The nitrogen excreted from anemonefish increases the number of algae incorporated into the tissue of their hosts, which aids the anemone in tissue growth and regeneration.[3] The activity of the anemonefish results in greater water circulation around the sea anemone,[7] and it has been suggested that their bright coloring might lure small fish to the anemone, which then catches them.[8] Studies on anemonefish have found that they alter the flow of water around sea anemone tentacles by certain behaviors and movements such as «wedging» and «switching». Aeration of the host anemone tentacles allows for benefits to the metabolism of both partners, mainly by increasing anemone body size and both anemonefish and anemone respiration.[9]

Bleaching of the host anemone can occur when warm temperatures cause a reduction in algal symbionts within the anemone. Bleaching of the host can cause a short-term increase in the metabolic rate of resident anemonefish, probably as a result of acute stress.[10] Over time, however, there appears to be a down-regulation of metabolism and a reduced growth rate for fish associated with bleached anemones. These effects may stem from reduced food availability (e.g. anemone waste products, symbiotic algae) for the anemonefish.[11]

Several theories are given about how they can survive the sea anemone poison:

- The mucus coating of the fish may be based on sugars rather than proteins. This would mean that anemones fail to recognize the fish as a potential food source and do not fire their nematocysts, or sting organelles.

- The coevolution of certain species of anemonefish with specific anemone host species may have allowed the fish to evolve an immunity to the nematocysts and toxins of their hosts. Amphiprion percula may develop resistance to the toxin from Heteractis magnifica, but it is not totally protected since it was shown experimentally to die when its skin, devoid of mucus, was exposed to the nematocysts of its host.[12]

Anemonefish are the best known example of fish that are able to live among the venomous sea anemone tentacles, but several others occur, including juvenile threespot dascyllus, certain cardinalfish (such as Banggai cardinalfish), incognito (or anemone) goby, and juvenile painted greenling.[13][14][15]

Reproduction[edit]

In a group of anemonefish, a strict dominance hierarchy exists. The largest and most aggressive female is found at the top. Only two anemonefish, a male and a female, in a group reproduce – through external fertilization. Anemonefish are protandrous sequential hermaphrodites, meaning they develop into males first, and when they mature, they become females. If the female anemonefish is removed from the group, such as by death, one of the largest and most dominant males becomes a female. The remaining males move up a rank in the hierarchy. Clownfish live in a hierarchy, like Hyenas, except smaller and based on size not gender, and order of joining/birth. In a clownfish anemone only two clownfish get to mate, the male and the female. The other clownfish do not breed unless the female dies then one of them becomes the dominant male, while the old dominant male becomes the new breeding female.

Anemonefish lay eggs on any flat surface close to their host anemones. In the wild, anemonefish spawn around the time of the full moon. Depending on the species, they can lay hundreds or thousands of eggs. The male parent guards the eggs until they hatch about 6–10 days later, typically two hours after dusk.[16]

Parental investment[edit]

Anemonefish colonies usually consist of the reproductive male and female and a few male juveniles, which help tend the colony.[17] Although multiple males cohabit an environment with a single female, polygamy does not occur and only the adult pair exhibits reproductive behavior. However, if the female dies, the social hierarchy shifts with the breeding male exhibiting protandrous sex reversal to become the breeding female. The largest juvenile then becomes the new breeding male after a period of rapid growth.[18] The existence of protandry in anemonefish may rest on the case that nonbreeders modulate their phenotype in a way that causes breeders to tolerate them. This strategy prevents conflict by reducing competition between males for one female. For example, by purposefully modifying their growth rate to remain small and submissive, the juveniles in a colony present no threat to the fitness of the adult male, thereby protecting themselves from being evicted by the dominant fish.[19]

The reproductive cycle of anemonefish is often correlated with the lunar cycle. Rates of spawning for anemonefish peak around the first and third quarters of the moon. The timing of this spawn means that the eggs hatch around the full moon or new moon periods. One explanation for this lunar clock is that spring tides produce the highest tides during full or new moons. Nocturnal hatching during high tide may reduce predation by allowing for a greater capacity for escape. Namely, the stronger currents and greater water volume during high tide protect the hatchlings by effectively sweeping them to safety. Before spawning, anemonefish exhibit increased rates of anemone and substrate biting, which help prepare and clean the nest for the spawn.[18]

Before making the clutch, the parents often clear an oval-shaped clutch varying in diameter for the spawn. Fecundity, or reproductive rate, of the females, usually ranges from 600 to 1500 eggs depending on her size. In contrast to most animal species, the female only occasionally takes responsibility for the eggs, with males expending most of the time and effort. Male anemonefish care for their eggs by fanning and guarding them for 6 to 10 days until they hatch. In general, eggs develop more rapidly in a clutch when males fan properly, and fanning represents a crucial mechanism of successfully developing eggs. This suggests that males can control the success of hatching an egg clutch by investing different amounts of time and energy towards the eggs. For example, a male could choose to fan less in times of scarcity or fan more in times of abundance. Furthermore, males display increased alertness when guarding more valuable broods, or eggs in which paternity was guaranteed. Females, though, display generally less preference for parental behavior than males. All these suggest that males have increased parental investment towards the eggs compared to females.[20]

Taxonomy[edit]

Historically, anemonefish have been identified by morphological features and color pattern in the field, while in a laboratory, other features such as scalation of the head, tooth shape, and body proportions are used.[2] These features have been used to group species into six complexes: percula, tomato, skunk, clarkii, saddleback, and maroon.[21] As can be seen from the gallery, each of the fish in these complexes has a similar appearance. Genetic analysis has shown that these complexes are not monophyletic groups, particularly the 11 species in the A. clarkii group, where only A. clarkii and A. tricintus are in the same clade, with six species,A. allardi A. bicinctus, A. chagosensis, A. chrosgaster, A. fuscocaudatus, A. latifasciatus, and A. omanensis being in an Indian clade, A. chrysopterus having monospecific lineage, and A. akindynos in the Australian clade with A. mccullochi.[22] Other significant differences are that A. latezonatus also has monospecific lineage, and A. nigripes is in the Indian clade rather than with A. akallopisos, the skunk anemonefish.[23] A. latezonatus is more closely related to A. percula and Premnas biaculeatus than to the saddleback fish with which it was previously grouped.[24][23]

Obligate mutualism was thought to be the key innovation that allowed anemonefish to radiate rapidly, with rapid and convergent morphological changes correlated with the ecological niches offered by the host anemones.[24] The complexity of mitochondrial DNA structure shown by genetic analysis of the Australian clade suggested evolutionary connectivity among samples of A. akindynos and A. mccullochi that the authors theorize was the result of historical hybridization and introgression in the evolutionary past. The two evolutionary groups had individuals of both species detected, thus the species lacked reciprocal monophyly. No shared haplotypes were found between species.[25]

Phylogenetic relationships[edit]

| Scientific name | Common name | Clade [22] | Complex | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus Amphiprion:[26] | ||||

| Amphiprion akallopisos | Skunk anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk |

|

| A. akindynos | Barrier reef anemonefish | Australian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. allardi | Allard’s anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. barberi | Barber’s anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. bicinctus | Two-band anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. chagosensis | Chagos anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. chrysogaster | Mauritian anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. chrysopterus | Orange-fin anemonefish | Monospecific lineage | A. clarkii |

|

| A. clarkii | Clark’s anemonefish | A. clarkii | A. clarkii |

|

| A. ephippium | Red saddleback anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. frenatus | Tomato anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. fuscocaudatus | Seychelles anemonefish | Indian [n 1] | Clarkii |

|

| A. latezonatus | Wide-band anemonefish | Monospecific lineage | Saddleback |

|

| A. latifasciatus | Madagascar anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. leucokranos | White-bonnet anemonefish | Likely hybrid | Skunk |

|

| A. mccullochi | Whitesnout anemonefish | Australian | A. ephippium |

|

| A. melanopus | Red and black anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. nigripes | Maldive anemonefish | Indian | Skunk |

|

| A. ocellaris | False clown anemonefish | Percula | Clownfish |

|

| A. omanensis | Oman anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. pacificus | Pacific anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk | |

| A. percula | Clown anemonefish | Percula | Clownfish |

|

| A. perideraion | Pink skunk anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk |

|

| A. polymnus | Saddleback anemonefish | A. polymnus | Saddleback |

|

| A. rubrocinctus | Australian anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. sandaracinos | Orange anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk |

|

| A. sebae | Sebae anemonefish | A. polymnus | Saddleback |

|

| A. thiellei | Thielle’s anemonefish | Likely hybrid | Skunk | |

| A. tricinctus | Three-band anemonefish | Clarkii | Clarkii |

|

| Genus Premnas:[27] | ||||

| Premnas biaculeatus | Maroon anemonefish | Percula | Maroon |

|

Morphological diversity by complex[edit]

In the aquarium[edit]

Anemonefish make up approximately 43% of the global marine ornamental trade, and approximately 25% of the global trade comes from fish bred in captivity, while the majority is captured from the wild,[28][29] accounting for decreased densities in exploited areas.[30] Public aquaria and captive-breeding programs are essential to sustain their trade as marine ornamentals, and has recently become economically feasible.[31][32] It is one of a handful of marine ornamentals whose complete lifecycle has been in closed captivity. Members of some anemonefish species, such as the maroon clownfish, become aggressive in captivity; others, like the false percula clownfish, can be kept successfully with other individuals of the same species.[33]

When a sea anemone is not available in an aquarium, the anemonefish may settle in some varieties of soft corals, or large polyp stony corals.[34] Once an anemone or coral has been adopted, the anemonefish will defend it. Anemonefish, however, are not obligately tied to hosts, and can survive alone in captivity.[35][36]

In popular culture[edit]

In Disney Pixar’s 2003 film Finding Nemo and its 2016 sequel Finding Dory main characters Nemo, his father Marlin, and his mother Coral are clownfish from the species A. ocellaris.[37] The popularity of anemonefish for aquaria increased following the film’s release; it is the first film associated with an increase in the numbers of those captured in the wild.[38]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Exemplars of A. fuscocaudatus have never been sequenced. The authors hypothetically placed this species in the Indian clade because it is the most parsimonious solution regarding the biogeography of anemonefish species.[22]

References[edit]

- ^ Society, National Geographic (10 May 2011). «Clown Anemonefish, Clown Anemonefish Pictures, Clown Anemonefish Facts – National Geographic».

- ^ a b Fautin, Daphne G.; Allen, Gerald R. (1997). Field Guide to Anemone Fishes and Their Host Sea Anemones. Western Australian Museum. ISBN 9780730983651. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015.

- ^ a b Porat, D.; Chadwick-Furman, N.E. (March 2005). «Effects of anemonefish on giant sea anemones: Ammonium uptake, zooxanthella content and tissue regeneration». Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology. 38 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1080/10236240500057929. S2CID 53051081.

- ^ «Clown Anemonefish». Nat Geo Wild: Animals. National Geographic Society. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ «Clownfish» at the Encyclopedia of Life Dead link

- ^ Holbrook, S. J. and Schmitt, R. J. Growth, reproduction and survival of a tropical sea anemone (Actiniaria): benefits of hosting anemonefish, 2005, cited in blogspot.com

- ^ Szczebak, J. T.; Henry, R. P.; Al-Horani, F. A.; Chadwick, N. E. (15 March 2013). «Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night». Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (6): 970–976. doi:10.1242/jeb.075648. PMID 23447664.

- ^ «Clown Anemonefishes, Amphiprion ocellaris«. Marinebio. The MarineBio Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Szczebak, J. T.; Henry, R. P.; Al-Horani, F. A.; Chadwick, N. E. (15 March 2013). «Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night». Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (6): 970–976. doi:10.1242/jeb.075648. PMID 23447664. S2CID 205352.

- ^ Norin, Tommy; Mills, Suzanne; Crespel, Amelie; Cortese, Daphne; Beldade, Ricardo; Killen, Shaun (2018). «Anemone bleaching increases the metabolic demands of symbiont anemonefish». Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 285 (1876). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0282. PMC 5904320. PMID 29643214.

- ^ Cortese, Daphne; Norin, Tommy; Beldade, Ricardo; Crespel, Amelie; Killen, Shaun; Mills, Suzanne (2021). «Physiological and behavioural effects of anemone bleaching on symbiont anemonefish in the wild». Functional Ecology. 35 (3): 663–674. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13729.

- ^ Mebs, D. (September 1994). «Anemonefish symbiosis: Vulnerability and resistance of fish to the toxin of the sea anemone». Toxicon. 32 (9): 1059–1068. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90390-5. PMID 7801342.

- ^ Lieske, E.; and R. Myers (1999). Coral Reef Fishes. ISBN 0-691-00481-1

- ^ Patzner, R.A. (5 July 2017). «Gobius incognitus». Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Fretwell, K.; and B. Starzomski (2014). Painted greenling. Biodiversity of the Central Coast. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ Clownfish Breeding for Beginners by Jeff Hesketh of Mad Hatter’s Reef

- ^ Stephanie Boyer. «Clown Anemofish». Florida Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 28 October 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ a b Ross, Robert M. (1978). «Reproductive Behavior of the Anemonefish Amphiprion melanopus on Guam». Copeia. 1978 (1): 103–107. doi:10.2307/1443829. JSTOR 1443829.

- ^ Buston, Peter (November 2004). «Does the presence of non-breeders enhance the fitness of breeders? An experimental analysis in the clown anemonefish Amphiprion percula». Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 57 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1007/s00265-004-0833-2. S2CID 24516887.

- ^ Ghosh, Swagat; Kumar, T. T. Ajith; Balasubramanian, T. (October 2012). «Determining the level of parental care relating fanning behavior of five species of clownfishes in captivity» (PDF). Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences. 41 (5): 430–441.

- ^ Goemans, B. «Anemonefishes». Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Litsios, Glenn; Salamin, Nicolas (December 2014). «Hybridisation and diversification in the adaptive radiation of clownfishes». BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 245. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0245-5. PMC 4264551. PMID 25433367.

- ^ a b DeAngelis, R. «What we really know about the diversity of Clownfish». Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ a b Litsios, Glenn; Sims, Carrie A; Wüest, Rafael O; Pearman, Peter B; Zimmermann, Niklaus E; Salamin, Nicolas (2012). «Mutualism with sea anemones triggered the adaptive radiation of clownfishes». BMC Evolutionary Biology. 12 (1): 212. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-212. PMC 3532366. PMID 23122007.

- ^ van der Meer, M. H.; Jones, G. P.; Hobbs, J.-P. A.; van Herwerden, L. (July 2012). «Historic hybridization and introgression between two iconic Australian anemonefish and contemporary patterns of population connectivity: Historic Hybridization between Anemonefish». Ecology and Evolution. 2 (7): 1592–1604. doi:10.1002/ece3.251. PMC 3434915. PMID 22957165.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). Species of Amphiprion in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). Species of Premnas in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- ^ Dhaneesh, K. V.; Vinoth, R.; Ghosh, Swagat; Gopi, M.; Kumar, T. T. Ajith; Balasubramanian, T. (2013). «Hatchery Production of Marine Ornamental Fishes: An Alternate Livelihood Option for the Island Community at Lakshadweep». Climate Change and Island and Coastal Vulnerability. pp. 253–265. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6016-5_17. ISBN 978-94-007-6015-8.

- ^ Taylor, M.; Razak, T. & Green, E. (2003). From ocean to aquarium: A global trade in marine ornamental species (PDF). UNEP world conservation and monitoring centre (WCMC). pp. 1–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Shuman, Craig S.; Hodgson, Gregor; Ambrose, Richard F. (December 2005). «Population impacts of collecting sea anemones and anemonefish for the marine aquarium trade in the Philippines». Coral Reefs. 24 (4): 564–573. Bibcode:2005CorRe..24..564S. doi:10.1007/s00338-005-0027-z. S2CID 25027153.

- ^ Watson, Craig A.; Hill, Jeffrey E. (May 2006). «Design criteria for recirculating, marine ornamental production systems». Aquacultural Engineering. 34 (3): 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.aquaeng.2005.07.002.

- ^ Hall, Heather; Douglas Warmolts (2003). «23». In James C. Cato; Christopher L. Brown (eds.). Marine Ornamental Species: Collection, Culture and Conservation. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 303–326. ISBN 978-0-8138-2987-6.

- ^ Tullock, John (1998). Clownfish and Sea Anemones (illustrated ed.). Barron’s Educational Series. pp. 11–22. ISBN 9780764105111. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Fatherree, James W. «Aquarium Fish: On the Clownfishes’ Range of Hosts». Advanced Aquarist. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Daphne Gail Fautin (1991). «The anemonefish symbiosis: what is known and what is not» (PDF). Symbiosis. 10: 23–46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2012.

- ^ Ronald L. Shimek (2004). Marine Invertebrates. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-890087-66-1.

- ^ «Finding Nemo (2003)». Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Calado, Ricardo; Olivotto, Ike; Oliver, Miquel Planas; Holt, G. Joan (6 March 2017). Marine Ornamental Species Aquaculture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 179. ISBN 9780470673904 – via Google Books.

Further reading[edit]

- Casas, Laura; Saborido-Rey, Fran; Ryu, Taewoo; Michell, Craig; Ravasi, Timothy; Irigoien, Xabier (17 October 2016). «Sex Change in Clownfish: Molecular Insights from Transcriptome Analysis». Scientific Reports. 6: 35461. doi:10.1038/srep35461. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5066260. PMID 27748421.

- Roux, Natacha; Lami, Raphaël; Salis, Pauline; Magré, Kévin; Romans, Pascal; Masanet, Patrick; Lecchini, David; Laudet, Vincent (December 2019). «Sea anemone and clownfish microbiota diversity and variation during the initial steps of symbiosis». Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 19491. Bibcode:2019NatSR…919491R. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55756-w. PMC 6925283. PMID 31862916.

- Vargas-Abúndez, Arturo Jorge; Randazzo, Basilio; Foddai, Marco; Sanchini, Lorenzo; Truzzi, Cristina; Giorgini, Elisabetta; Gasco, Laura; Olivotto, Ike (January 2019). «Insect meal based diets for clownfish: Biometric, histological, spectroscopic, biochemical and molecular implications». Aquaculture. 498: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.08.018. hdl:2318/1674109. S2CID 92357750.

External links[edit]

- (in German) Photo Gallery of Amphiprion ocellaris and their eggs

- Monterey Bay Aquarium: Video and information

- Clown Fish underwater photography gallery

- Aquaticcommunity.com

- Tolweb.org

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Clownfish | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Ocellaris clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Clade: | Percomorpha |

| (unranked): | Ovalentaria |

| Family: | Pomacentridae |

| Subfamily: | Amphiprioninae Allen, 1975 |

| Genera | |

|

Clownfish swimming movements

Clownfish or anemonefish are fishes from the subfamily Amphiprioninae in the family Pomacentridae. Thirty species of clownfish are recognized: one in the genus Premnas, while the remaining are in the genus Amphiprion. In the wild, they all form symbiotic mutualisms with sea anemones. Depending on the species, anemonefish are overall yellow, orange, or a reddish or blackish color, and many show white bars or patches. The largest can reach a length of 17 cm (6+1⁄2 in), while the smallest barely achieve 7–8 cm (2+3⁄4–3+1⁄4 in).

Distribution and habitat[edit]

Anemonefish are endemic to the warmer waters of the Indian Ocean, including the Red Sea, and Pacific Ocean, the Great Barrier Reef, Southeast Asia, Japan, and the Indo-Malaysian region. While most species have restricted distributions, others are widespread. Anemonefish typically live at the bottom of shallow seas in sheltered reefs or in shallow lagoons. No anemonefish are found in the Atlantic.[1]

Diet[edit]

Anemonefish are omnivorous and can feed on undigested food from their host anemones, and the fecal matter from the anemonefish provides nutrients to the sea anemone. Anemonefish primarily feed on small zooplankton from the water column, such as copepods and tunicate larvae, with a small portion of their diet coming from algae, with the exception of Amphiprion perideraion, which primarily feeds on algae.[2][3]

Symbiosis and mutualism[edit]

Anemonefish and sea anemones have a symbiotic, mutualistic relationship, each providing many benefits to the other. The individual species are generally highly host specific. The sea anemone protects the anemonefish from predators, as well as providing food through the scraps left from the anemone’s meals and occasional dead anemone tentacles, and functions as a safe nest site. In return, the anemonefish defends the anemone from its predators and parasites.[4][5] The anemone also picks up nutrients from the anemonefish’s excrement.[6] The nitrogen excreted from anemonefish increases the number of algae incorporated into the tissue of their hosts, which aids the anemone in tissue growth and regeneration.[3] The activity of the anemonefish results in greater water circulation around the sea anemone,[7] and it has been suggested that their bright coloring might lure small fish to the anemone, which then catches them.[8] Studies on anemonefish have found that they alter the flow of water around sea anemone tentacles by certain behaviors and movements such as «wedging» and «switching». Aeration of the host anemone tentacles allows for benefits to the metabolism of both partners, mainly by increasing anemone body size and both anemonefish and anemone respiration.[9]

Bleaching of the host anemone can occur when warm temperatures cause a reduction in algal symbionts within the anemone. Bleaching of the host can cause a short-term increase in the metabolic rate of resident anemonefish, probably as a result of acute stress.[10] Over time, however, there appears to be a down-regulation of metabolism and a reduced growth rate for fish associated with bleached anemones. These effects may stem from reduced food availability (e.g. anemone waste products, symbiotic algae) for the anemonefish.[11]

Several theories are given about how they can survive the sea anemone poison:

- The mucus coating of the fish may be based on sugars rather than proteins. This would mean that anemones fail to recognize the fish as a potential food source and do not fire their nematocysts, or sting organelles.

- The coevolution of certain species of anemonefish with specific anemone host species may have allowed the fish to evolve an immunity to the nematocysts and toxins of their hosts. Amphiprion percula may develop resistance to the toxin from Heteractis magnifica, but it is not totally protected since it was shown experimentally to die when its skin, devoid of mucus, was exposed to the nematocysts of its host.[12]

Anemonefish are the best known example of fish that are able to live among the venomous sea anemone tentacles, but several others occur, including juvenile threespot dascyllus, certain cardinalfish (such as Banggai cardinalfish), incognito (or anemone) goby, and juvenile painted greenling.[13][14][15]

Reproduction[edit]

In a group of anemonefish, a strict dominance hierarchy exists. The largest and most aggressive female is found at the top. Only two anemonefish, a male and a female, in a group reproduce – through external fertilization. Anemonefish are protandrous sequential hermaphrodites, meaning they develop into males first, and when they mature, they become females. If the female anemonefish is removed from the group, such as by death, one of the largest and most dominant males becomes a female. The remaining males move up a rank in the hierarchy. Clownfish live in a hierarchy, like Hyenas, except smaller and based on size not gender, and order of joining/birth. In a clownfish anemone only two clownfish get to mate, the male and the female. The other clownfish do not breed unless the female dies then one of them becomes the dominant male, while the old dominant male becomes the new breeding female.

Anemonefish lay eggs on any flat surface close to their host anemones. In the wild, anemonefish spawn around the time of the full moon. Depending on the species, they can lay hundreds or thousands of eggs. The male parent guards the eggs until they hatch about 6–10 days later, typically two hours after dusk.[16]

Parental investment[edit]

Anemonefish colonies usually consist of the reproductive male and female and a few male juveniles, which help tend the colony.[17] Although multiple males cohabit an environment with a single female, polygamy does not occur and only the adult pair exhibits reproductive behavior. However, if the female dies, the social hierarchy shifts with the breeding male exhibiting protandrous sex reversal to become the breeding female. The largest juvenile then becomes the new breeding male after a period of rapid growth.[18] The existence of protandry in anemonefish may rest on the case that nonbreeders modulate their phenotype in a way that causes breeders to tolerate them. This strategy prevents conflict by reducing competition between males for one female. For example, by purposefully modifying their growth rate to remain small and submissive, the juveniles in a colony present no threat to the fitness of the adult male, thereby protecting themselves from being evicted by the dominant fish.[19]

The reproductive cycle of anemonefish is often correlated with the lunar cycle. Rates of spawning for anemonefish peak around the first and third quarters of the moon. The timing of this spawn means that the eggs hatch around the full moon or new moon periods. One explanation for this lunar clock is that spring tides produce the highest tides during full or new moons. Nocturnal hatching during high tide may reduce predation by allowing for a greater capacity for escape. Namely, the stronger currents and greater water volume during high tide protect the hatchlings by effectively sweeping them to safety. Before spawning, anemonefish exhibit increased rates of anemone and substrate biting, which help prepare and clean the nest for the spawn.[18]

Before making the clutch, the parents often clear an oval-shaped clutch varying in diameter for the spawn. Fecundity, or reproductive rate, of the females, usually ranges from 600 to 1500 eggs depending on her size. In contrast to most animal species, the female only occasionally takes responsibility for the eggs, with males expending most of the time and effort. Male anemonefish care for their eggs by fanning and guarding them for 6 to 10 days until they hatch. In general, eggs develop more rapidly in a clutch when males fan properly, and fanning represents a crucial mechanism of successfully developing eggs. This suggests that males can control the success of hatching an egg clutch by investing different amounts of time and energy towards the eggs. For example, a male could choose to fan less in times of scarcity or fan more in times of abundance. Furthermore, males display increased alertness when guarding more valuable broods, or eggs in which paternity was guaranteed. Females, though, display generally less preference for parental behavior than males. All these suggest that males have increased parental investment towards the eggs compared to females.[20]

Taxonomy[edit]

Historically, anemonefish have been identified by morphological features and color pattern in the field, while in a laboratory, other features such as scalation of the head, tooth shape, and body proportions are used.[2] These features have been used to group species into six complexes: percula, tomato, skunk, clarkii, saddleback, and maroon.[21] As can be seen from the gallery, each of the fish in these complexes has a similar appearance. Genetic analysis has shown that these complexes are not monophyletic groups, particularly the 11 species in the A. clarkii group, where only A. clarkii and A. tricintus are in the same clade, with six species,A. allardi A. bicinctus, A. chagosensis, A. chrosgaster, A. fuscocaudatus, A. latifasciatus, and A. omanensis being in an Indian clade, A. chrysopterus having monospecific lineage, and A. akindynos in the Australian clade with A. mccullochi.[22] Other significant differences are that A. latezonatus also has monospecific lineage, and A. nigripes is in the Indian clade rather than with A. akallopisos, the skunk anemonefish.[23] A. latezonatus is more closely related to A. percula and Premnas biaculeatus than to the saddleback fish with which it was previously grouped.[24][23]

Obligate mutualism was thought to be the key innovation that allowed anemonefish to radiate rapidly, with rapid and convergent morphological changes correlated with the ecological niches offered by the host anemones.[24] The complexity of mitochondrial DNA structure shown by genetic analysis of the Australian clade suggested evolutionary connectivity among samples of A. akindynos and A. mccullochi that the authors theorize was the result of historical hybridization and introgression in the evolutionary past. The two evolutionary groups had individuals of both species detected, thus the species lacked reciprocal monophyly. No shared haplotypes were found between species.[25]

Phylogenetic relationships[edit]

| Scientific name | Common name | Clade [22] | Complex | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus Amphiprion:[26] | ||||

| Amphiprion akallopisos | Skunk anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk |

|

| A. akindynos | Barrier reef anemonefish | Australian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. allardi | Allard’s anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. barberi | Barber’s anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. bicinctus | Two-band anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. chagosensis | Chagos anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. chrysogaster | Mauritian anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. chrysopterus | Orange-fin anemonefish | Monospecific lineage | A. clarkii |

|

| A. clarkii | Clark’s anemonefish | A. clarkii | A. clarkii |

|

| A. ephippium | Red saddleback anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. frenatus | Tomato anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. fuscocaudatus | Seychelles anemonefish | Indian [n 1] | Clarkii |

|

| A. latezonatus | Wide-band anemonefish | Monospecific lineage | Saddleback |

|

| A. latifasciatus | Madagascar anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. leucokranos | White-bonnet anemonefish | Likely hybrid | Skunk |

|

| A. mccullochi | Whitesnout anemonefish | Australian | A. ephippium |

|

| A. melanopus | Red and black anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. nigripes | Maldive anemonefish | Indian | Skunk |

|

| A. ocellaris | False clown anemonefish | Percula | Clownfish |

|

| A. omanensis | Oman anemonefish | Indian | A. clarkii |

|

| A. pacificus | Pacific anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk | |

| A. percula | Clown anemonefish | Percula | Clownfish |

|

| A. perideraion | Pink skunk anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk |

|

| A. polymnus | Saddleback anemonefish | A. polymnus | Saddleback |

|

| A. rubrocinctus | Australian anemonefish | A. ephippium | A. ephippium |

|

| A. sandaracinos | Orange anemonefish | A. akallopisos | Skunk |

|

| A. sebae | Sebae anemonefish | A. polymnus | Saddleback |

|

| A. thiellei | Thielle’s anemonefish | Likely hybrid | Skunk | |

| A. tricinctus | Three-band anemonefish | Clarkii | Clarkii |

|

| Genus Premnas:[27] | ||||

| Premnas biaculeatus | Maroon anemonefish | Percula | Maroon |

|

Morphological diversity by complex[edit]

In the aquarium[edit]

Anemonefish make up approximately 43% of the global marine ornamental trade, and approximately 25% of the global trade comes from fish bred in captivity, while the majority is captured from the wild,[28][29] accounting for decreased densities in exploited areas.[30] Public aquaria and captive-breeding programs are essential to sustain their trade as marine ornamentals, and has recently become economically feasible.[31][32] It is one of a handful of marine ornamentals whose complete lifecycle has been in closed captivity. Members of some anemonefish species, such as the maroon clownfish, become aggressive in captivity; others, like the false percula clownfish, can be kept successfully with other individuals of the same species.[33]

When a sea anemone is not available in an aquarium, the anemonefish may settle in some varieties of soft corals, or large polyp stony corals.[34] Once an anemone or coral has been adopted, the anemonefish will defend it. Anemonefish, however, are not obligately tied to hosts, and can survive alone in captivity.[35][36]

In popular culture[edit]

In Disney Pixar’s 2003 film Finding Nemo and its 2016 sequel Finding Dory main characters Nemo, his father Marlin, and his mother Coral are clownfish from the species A. ocellaris.[37] The popularity of anemonefish for aquaria increased following the film’s release; it is the first film associated with an increase in the numbers of those captured in the wild.[38]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Exemplars of A. fuscocaudatus have never been sequenced. The authors hypothetically placed this species in the Indian clade because it is the most parsimonious solution regarding the biogeography of anemonefish species.[22]

References[edit]

- ^ Society, National Geographic (10 May 2011). «Clown Anemonefish, Clown Anemonefish Pictures, Clown Anemonefish Facts – National Geographic».

- ^ a b Fautin, Daphne G.; Allen, Gerald R. (1997). Field Guide to Anemone Fishes and Their Host Sea Anemones. Western Australian Museum. ISBN 9780730983651. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015.

- ^ a b Porat, D.; Chadwick-Furman, N.E. (March 2005). «Effects of anemonefish on giant sea anemones: Ammonium uptake, zooxanthella content and tissue regeneration». Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology. 38 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1080/10236240500057929. S2CID 53051081.

- ^ «Clown Anemonefish». Nat Geo Wild: Animals. National Geographic Society. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ «Clownfish» at the Encyclopedia of Life Dead link

- ^ Holbrook, S. J. and Schmitt, R. J. Growth, reproduction and survival of a tropical sea anemone (Actiniaria): benefits of hosting anemonefish, 2005, cited in blogspot.com

- ^ Szczebak, J. T.; Henry, R. P.; Al-Horani, F. A.; Chadwick, N. E. (15 March 2013). «Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night». Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (6): 970–976. doi:10.1242/jeb.075648. PMID 23447664.

- ^ «Clown Anemonefishes, Amphiprion ocellaris«. Marinebio. The MarineBio Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Szczebak, J. T.; Henry, R. P.; Al-Horani, F. A.; Chadwick, N. E. (15 March 2013). «Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night». Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (6): 970–976. doi:10.1242/jeb.075648. PMID 23447664. S2CID 205352.

- ^ Norin, Tommy; Mills, Suzanne; Crespel, Amelie; Cortese, Daphne; Beldade, Ricardo; Killen, Shaun (2018). «Anemone bleaching increases the metabolic demands of symbiont anemonefish». Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 285 (1876). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0282. PMC 5904320. PMID 29643214.

- ^ Cortese, Daphne; Norin, Tommy; Beldade, Ricardo; Crespel, Amelie; Killen, Shaun; Mills, Suzanne (2021). «Physiological and behavioural effects of anemone bleaching on symbiont anemonefish in the wild». Functional Ecology. 35 (3): 663–674. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13729.

- ^ Mebs, D. (September 1994). «Anemonefish symbiosis: Vulnerability and resistance of fish to the toxin of the sea anemone». Toxicon. 32 (9): 1059–1068. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90390-5. PMID 7801342.

- ^ Lieske, E.; and R. Myers (1999). Coral Reef Fishes. ISBN 0-691-00481-1

- ^ Patzner, R.A. (5 July 2017). «Gobius incognitus». Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Fretwell, K.; and B. Starzomski (2014). Painted greenling. Biodiversity of the Central Coast. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ Clownfish Breeding for Beginners by Jeff Hesketh of Mad Hatter’s Reef

- ^ Stephanie Boyer. «Clown Anemofish». Florida Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 28 October 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ a b Ross, Robert M. (1978). «Reproductive Behavior of the Anemonefish Amphiprion melanopus on Guam». Copeia. 1978 (1): 103–107. doi:10.2307/1443829. JSTOR 1443829.

- ^ Buston, Peter (November 2004). «Does the presence of non-breeders enhance the fitness of breeders? An experimental analysis in the clown anemonefish Amphiprion percula». Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 57 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1007/s00265-004-0833-2. S2CID 24516887.

- ^ Ghosh, Swagat; Kumar, T. T. Ajith; Balasubramanian, T. (October 2012). «Determining the level of parental care relating fanning behavior of five species of clownfishes in captivity» (PDF). Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences. 41 (5): 430–441.

- ^ Goemans, B. «Anemonefishes». Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Litsios, Glenn; Salamin, Nicolas (December 2014). «Hybridisation and diversification in the adaptive radiation of clownfishes». BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 245. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0245-5. PMC 4264551. PMID 25433367.

- ^ a b DeAngelis, R. «What we really know about the diversity of Clownfish». Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ a b Litsios, Glenn; Sims, Carrie A; Wüest, Rafael O; Pearman, Peter B; Zimmermann, Niklaus E; Salamin, Nicolas (2012). «Mutualism with sea anemones triggered the adaptive radiation of clownfishes». BMC Evolutionary Biology. 12 (1): 212. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-212. PMC 3532366. PMID 23122007.

- ^ van der Meer, M. H.; Jones, G. P.; Hobbs, J.-P. A.; van Herwerden, L. (July 2012). «Historic hybridization and introgression between two iconic Australian anemonefish and contemporary patterns of population connectivity: Historic Hybridization between Anemonefish». Ecology and Evolution. 2 (7): 1592–1604. doi:10.1002/ece3.251. PMC 3434915. PMID 22957165.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). Species of Amphiprion in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). Species of Premnas in FishBase. December 2011 version.

- ^ Dhaneesh, K. V.; Vinoth, R.; Ghosh, Swagat; Gopi, M.; Kumar, T. T. Ajith; Balasubramanian, T. (2013). «Hatchery Production of Marine Ornamental Fishes: An Alternate Livelihood Option for the Island Community at Lakshadweep». Climate Change and Island and Coastal Vulnerability. pp. 253–265. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6016-5_17. ISBN 978-94-007-6015-8.

- ^ Taylor, M.; Razak, T. & Green, E. (2003). From ocean to aquarium: A global trade in marine ornamental species (PDF). UNEP world conservation and monitoring centre (WCMC). pp. 1–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Shuman, Craig S.; Hodgson, Gregor; Ambrose, Richard F. (December 2005). «Population impacts of collecting sea anemones and anemonefish for the marine aquarium trade in the Philippines». Coral Reefs. 24 (4): 564–573. Bibcode:2005CorRe..24..564S. doi:10.1007/s00338-005-0027-z. S2CID 25027153.

- ^ Watson, Craig A.; Hill, Jeffrey E. (May 2006). «Design criteria for recirculating, marine ornamental production systems». Aquacultural Engineering. 34 (3): 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.aquaeng.2005.07.002.

- ^ Hall, Heather; Douglas Warmolts (2003). «23». In James C. Cato; Christopher L. Brown (eds.). Marine Ornamental Species: Collection, Culture and Conservation. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 303–326. ISBN 978-0-8138-2987-6.

- ^ Tullock, John (1998). Clownfish and Sea Anemones (illustrated ed.). Barron’s Educational Series. pp. 11–22. ISBN 9780764105111. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Fatherree, James W. «Aquarium Fish: On the Clownfishes’ Range of Hosts». Advanced Aquarist. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Daphne Gail Fautin (1991). «The anemonefish symbiosis: what is known and what is not» (PDF). Symbiosis. 10: 23–46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2012.

- ^ Ronald L. Shimek (2004). Marine Invertebrates. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-890087-66-1.

- ^ «Finding Nemo (2003)». Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Calado, Ricardo; Olivotto, Ike; Oliver, Miquel Planas; Holt, G. Joan (6 March 2017). Marine Ornamental Species Aquaculture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 179. ISBN 9780470673904 – via Google Books.

Further reading[edit]

- Casas, Laura; Saborido-Rey, Fran; Ryu, Taewoo; Michell, Craig; Ravasi, Timothy; Irigoien, Xabier (17 October 2016). «Sex Change in Clownfish: Molecular Insights from Transcriptome Analysis». Scientific Reports. 6: 35461. doi:10.1038/srep35461. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5066260. PMID 27748421.

- Roux, Natacha; Lami, Raphaël; Salis, Pauline; Magré, Kévin; Romans, Pascal; Masanet, Patrick; Lecchini, David; Laudet, Vincent (December 2019). «Sea anemone and clownfish microbiota diversity and variation during the initial steps of symbiosis». Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 19491. Bibcode:2019NatSR…919491R. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55756-w. PMC 6925283. PMID 31862916.

- Vargas-Abúndez, Arturo Jorge; Randazzo, Basilio; Foddai, Marco; Sanchini, Lorenzo; Truzzi, Cristina; Giorgini, Elisabetta; Gasco, Laura; Olivotto, Ike (January 2019). «Insect meal based diets for clownfish: Biometric, histological, spectroscopic, biochemical and molecular implications». Aquaculture. 498: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.08.018. hdl:2318/1674109. S2CID 92357750.

External links[edit]

- (in German) Photo Gallery of Amphiprion ocellaris and their eggs

- Monterey Bay Aquarium: Video and information

- Clown Fish underwater photography gallery

- Aquaticcommunity.com

- Tolweb.org

Содержание

- 1 Русский

- 1.1 Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

- 1.2 Произношение

- 1.3 Семантические свойства

- 1.3.1 Значение

- 1.3.2 Синонимы

- 1.3.3 Антонимы

- 1.3.4 Гиперонимы

- 1.3.5 Гипонимы

- 1.4 Родственные слова

- 1.5 Этимология

- 1.6 Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- 1.7 Перевод

- 1.8 Библиография

Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

рыба-клоун

Существительное, одушевлённое, мужской род (тип склонения ?? по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

- ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

«рыба-клоун» по падежам

рыба-клоун — имя существительное, единственное число, мужской род, одушевленное.

| Падежи | Единственное числоЕд.ч. | Множественное числоМн.ч. |

|---|---|---|

| ИменительныйИм. | рыба-клоун | рыба-клоуны |

| РодительныйРод. | рыба-клоуна | рыба-клоунов |

| ДательныйДат. | рыба-клоуну | рыба-клоунам |

| ВинительныйВин. | рыба-клоуна | рыба-клоунов |

| ТворительныйТв. | рыба-клоуном | рыба-клоунами |

| ПредложныйПред. | рыба-клоуне | рыба-клоунах |

Рыба-клоун

- Рыба-клоун

-

Рыбы-клоуны (лат. Amphiprioninae) — подсемейство, включающие в себя нескольких видов рыб семейства помацентровые, под которым чаще всего подразумевается аквариумная рыбка Amphiprion percula. Небольшая рыба с ярко-оранжевой окраской с черным и белыми полосами. Для рыб данного вида характерен симбиоз с различными видами актиний.

Виды

- Род Amphiprion

- Скунсовый клоун (Amphiprion akallopisos)

- Чернохвостый клоун (Amphiprion akindynos)

- Клоун Алларда (Amphiprion allardi)

- Двухполосый клоун (Amphiprion bicinctus)

- Клоун Чагос (Amphiprion chagosensis)

- Оранжево-жёлтый клоун (Amphiprion chrysogaster)

- Оранжевоплавничный клоун (Amphiprion chrysopterus)

- Клоун Кларка (Amphiprion clarkii)

- Клоун седлоспинный (Amphiprion ephippium)

- Клоун томатный (Amphiprion frenatus)

- Сейшельский клоун (Amphiprion fuscocaudatus)

- Широкополостный клоун (Amphiprion latezonatus)

- Мадагаскарский клоун (Amphiprion latifasciatus)

- Бело-шапковый клоун (Amphiprion leucokranos)

- Белолицый клоун (Amphiprion mccullochi)

- Красно-чёрный клоун (Amphiprion melanopus)

- Мальдивский клоун (Amphiprion nigripes)

- Анемоновая рыба (Amphiprion ocellaris)

- Омановский клоун (Amphiprion omanensis)

- Настоящий клоун (Amphiprion percula)

- Клоун розовый (Amphiprion perideraion)

- Седлистый клоун (Amphiprion polymnus)

- Красный клоун (Amphiprion rubacinctus)

- Клоун оранжевый (Amphiprion sandaracinos)

- Клоун Себа (Amphiprion sebae)

- Клоун Тилли (Amphiprion thiellei)

- Трехполосый клоун (Amphiprion tricinctus)

- Род Premnas

- Мавританский клоун (Premnas biaculeatus)

Ссылки

Рыба-клоун

Изображения

Скунсовый клоун

Чернохвостый клоун

Клоун Алларда

Двухполосый клоун

Оранжево-жёлтый клоун

Оранжевоплавничный клоун

Клоун Кларка

Клоун седлоспинный

Клоун томатный

Сейшельский клоун

Широкополостный клоун

Красно-чёрный клоун

Мальдивский клоун

Анемоновая рыба

Настоящий клоун

Клоун розовый

Седлистый клоун

Клоун оранжевый

Клоун Себа

Мавританский клоун

- Род Amphiprion

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Синонимы:

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Рыба-клоун» в других словарях:

-

рыба-клоун — сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • анемоновая рыба (2) • рыба (773) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Таитийская бородавчатая рыба-клоун — ? Таитийская бородавчатая рыба клоун Научная класси … Википедия

-

гавайская бородавчатая рыба клоун — havajinė karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius analis angl. Waikiki anglerfish rus. гавайская бородавчатая рыба клоун ryšiai: platesnis terminas – karpotosios klounžuvės … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

калифорнийская бородавчатая рыба клоун — kaliforninė karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius avalonis angl. rough jawed frogfish rus. калифорнийская бородавчатая рыба клоун ryšiai: platesnis terminas – karpotosios… … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

алая бородавчатая рыба клоун — rausvoji karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius coccineus angl. freckled angler; Jordan’s frogfish rus. алая бородавчатая рыба клоун ryšiai: platesnis terminas – karpotosios… … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

бородавчатая рыба клоун Коммерсона — juodoji karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius commersoni angl. big angler; black angler; black fishing frog rus. бородавчатая рыба клоун Коммерсона ryšiai: platesnis terminas … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

новогвинейская бородавчатая рыба клоун — gvinėjinė karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius dorehensis angl. bandtail anglerfish; white spotted anglerfish rus. новогвинейская бородавчатая рыба клоун ryšiai: platesnis… … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

косматая бородавчатая рыба клоун — zebrinė karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius hispidus angl. shaggy angler; shaggy fishing frog; zebra anglerfish rus. косматая бородавчатая рыба клоун ryšiai: platesnis… … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

пятнистая бородавчатая рыба клоун — dėmėtoji karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius multiocellatus angl. Martin’s pescador; ocellated fishing frog rus. пятнистая бородавчатая рыба клоун ryšiai: platesnis… … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

-

красная бородавчатая рыба клоун — raudonoji karpotoji klounžuvė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Antennarius nummifer angl. coin bearing frogfish; ocellated anglerfish; ocellated fringed fishing frog; red toadfish; scarlet angler;… … Žuvų pavadinimų žodynas

Разбор частей речи

Далее давайте разберем морфологические признаки каждой из частей речи русского языка на примерах. Согласно лингвистике русского языка, выделяют три группы из 10 частей речи, по общим признакам:

1. Самостоятельные части речи:

- существительные (см. морфологические нормы сущ. );

- глаголы:

-

- причастия;

- деепричастия;

- прилагательные;

- числительные;

- местоимения;

- наречия;

2. Служебные части речи:

- предлоги;

- союзы;

- частицы;

3. Междометия.

Ни в одну из классификаций (по морфологической системе) русского языка не попадают:

- слова да и нет, в случае, если они выступают в роли самостоятельного предложения.

- вводные слова: итак, кстати, итого, в качестве отдельного предложения, а так же ряд других слов.

Морфологический разбор существительного

План морфологического разбора существительного

Пример:

«Малыш пьет молоко.»

Малыш (отвечает на вопрос кто?) – имя существительное;

- начальная форма – малыш;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: одушевленное, нарицательное, конкретное, мужского рода, I -го склонения;

- непостоянные морфологические признаки: именительный падеж, единственное число;

- при синтаксическом разборе предложения выполняет роль подлежащего.

Морфологический разбор слова «молоко» (отвечает на вопрос кого? Что?).

- начальная форма – молоко;

- постоянная морфологическая характеристика слова: среднего рода, неодушевленное, вещественное, нарицательное, II -е склонение;

- изменяемые признаки морфологические: винительный падеж, единственное число;

- в предложении прямое дополнение.

Приводим ещё один образец, как сделать морфологический разбор существительного, на основе литературного источника:

«Две дамы подбежали к Лужину и помогли ему встать. Он ладонью стал сбивать пыль с пальто. (пример из: «Защита Лужина», Владимир Набоков).»

Дамы (кто?) — имя существительное;

- начальная форма — дама;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: нарицательное, одушевленное, конкретное, женского рода, I склонения;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика существительного: единственное число, родительный падеж;

- синтаксическая роль: часть подлежащего.

Лужину (кому?) — имя существительное;

- начальная форма — Лужин;

- верная морфологическая характеристика слова: имя собственное, одушевленное, конкретное, мужского рода, смешанного склонения;

- непостоянные морфологические признаки существительного: единственное число, дательного падежа;

- синтаксическая роль: дополнение.

Ладонью (чем?) — имя существительное;

- начальная форма — ладонь;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: женского рода, неодушевлённое, нарицательное, конкретное, I склонения;

- непостоянные морфо. признаки: единственного числа, творительного падежа;

- синтаксическая роль в контексте: дополнение.

Пыль (что?) — имя существительное;

- начальная форма — пыль;

- основные морфологические признаки: нарицательное, вещественное, женского рода, единственного числа, одушевленное не охарактеризовано, III склонения (существительное с нулевым окончанием);

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика слова: винительный падеж;

- синтаксическая роль: дополнение.

(с) Пальто (С чего?) — существительное;

- начальная форма — пальто;

- постоянная правильная морфологическая характеристика слова: неодушевленное, нарицательное, конкретное, среднего рода, несклоняемое;

- морфологические признаки непостоянные: число по контексту невозможно определить, родительного падежа;

- синтаксическая роль как члена предложения: дополнение.

Морфологический разбор прилагательного

Имя прилагательное — это знаменательная часть речи. Отвечает на вопросы Какой? Какое? Какая? Какие? и характеризует признаки или качества предмета. Таблица морфологических признаков имени прилагательного:

- начальная форма в именительном падеже, единственного числа, мужского рода;

- постоянные морфологические признаки прилагательных:

-

- разряд, согласно значению:

-

- — качественное (теплый, молчаливый);

- — относительное (вчерашний, читальный);

- — притяжательное (заячий, мамин);

- степень сравнения (для качественных, у которых этот признак постоянный);

- полная / краткая форма (для качественных, у которых этот признак постоянный);

- непостоянные морфологические признаки прилагательного:

-

- качественные прилагательные изменяются по степени сравнения (в сравнительных степенях простая форма, в превосходных — сложная): красивый-красивее-самый красивый;

- полная или краткая форма (только качественные прилагательные);

- признак рода (только в единственном числе);

- число (согласуется с существительным);

- падеж (согласуется с существительным);

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: имя прилагательное бывает определением или частью составного именного сказуемого.

План морфологического разбора прилагательного

Пример предложения:

Полная луна взошла над городом.

Полная (какая?) – имя прилагательное;

- начальная форма – полный;

- постоянные морфологические признаки имени прилагательного: качественное, полная форма;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика: в положительной (нулевой) степени сравнения, женский род (согласуется с существительным), именительный падеж;

- по синтаксическому анализу — второстепенный член предложения, выполняет роль определения.

Вот еще целый литературный отрывок и морфологический разбор имени прилагательного, на примерах:

Девушка была прекрасна: стройная, тоненькая, глаза голубые, как два изумительных сапфира, так и заглядывали к вам в душу.

Прекрасна (какова?) — имя прилагательное;

- начальная форма — прекрасен (в данном значении);

- постоянные морфологические нормы: качественное, краткое;

- непостоянные признаки: положительная степень сравнения, единственного числа, женского рода;

- синтаксическая роль: часть сказуемого.

Стройная (какая?) — имя прилагательное;

- начальная форма — стройный;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: качественное, полное;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика слова: полное, положительная степень сравнения, единственное число, женский род, именительный падеж;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: часть сказуемого.

Тоненькая (какая?) — имя прилагательное;

- начальная форма — тоненький;

- морфологические постоянные признаки: качественное, полное;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика прилагательного: положительная степень сравнения, единственное число, женского рода, именительного падежа;

- синтаксическая роль: часть сказуемого.

Голубые (какие?) — имя прилагательное;

- начальная форма — голубой;

- таблица постоянных морфологических признаков имени прилагательного: качественное;

- непостоянные морфологические характеристики: полное, положительная степень сравнения, множественное число, именительного падежа;

- синтаксическая роль: определение.

Изумительных (каких?) — имя прилагательное;

- начальная форма — изумительный;

- постоянные признаки по морфологии: относительное, выразительное;

- непостоянные морфологические признаки: множественное число, родительного падежа;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: часть обстоятельства.

Морфологические признаки глагола

Согласно морфологии русского языка, глагол — это самостоятельная часть речи. Он может обозначать действие (гулять), свойство (хромать), отношение (равняться), состояние (радоваться), признак (белеться, красоваться) предмета. Глаголы отвечают на вопрос что делать? что сделать? что делает? что делал? или что будет делать? Разным группам глагольных словоформ присущи неоднородные морфологические характеристики и грамматические признаки.

Морфологические формы глаголов:

- начальная форма глагола — инфинитив. Ее так же называют неопределенная или неизменяемая форма глагола. Непостоянные морфологические признаки отсутствуют;

- спрягаемые (личные и безличные) формы;

- неспрягаемые формы: причастные и деепричастные.

Морфологический разбор глагола

- начальная форма — инфинитив;

- постоянные морфологические признаки глагола:

-

- переходность:

-

- переходный (употребляется с существительными винительного падежа без предлога);

- непереходный (не употребляется с существительным в винительном падеже без предлога);

- возвратность:

-

- возвратные (есть -ся, -сь);

- невозвратные (нет -ся, -сь);

- вид:

-

- несовершенный (что делать?);

- совершенный (что сделать?);

- спряжение:

-

- I спряжение (дела-ешь, дела-ет, дела-ем, дела-ете, дела-ют/ут);

- II спряжение (сто-ишь, сто-ит, сто-им, сто-ите, сто-ят/ат);

- разноспрягаемые глаголы (хотеть, бежать);

- непостоянные морфологические признаки глагола:

-

- наклонение:

-

- изъявительное: что делал? что сделал? что делает? что сделает?;

- условное: что делал бы? что сделал бы?;

- повелительное: делай!;

- время (в изъявительном наклонении: прошедшее/настоящее/будущее);

- лицо (в настоящем/будущем времени, изъявительного и повелительного наклонения: 1 лицо: я/мы, 2 лицо: ты/вы, 3 лицо: он/они);

- род (в прошедшем времени, единственного числа, изъявительного и условного наклонения);

- число;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении. Инфинитив может быть любым членом предложения:

-

- сказуемым: Быть сегодня празднику;

- подлежащим :Учиться всегда пригодится;

- дополнением: Все гости просили ее станцевать;

- определением: У него возникло непреодолимое желание поесть;

- обстоятельством: Я вышел пройтись.

Морфологический разбор глагола пример

Чтобы понять схему, проведем письменный разбор морфологии глагола на примере предложения:

Вороне как-то Бог послал кусочек сыру… (басня, И. Крылов)

Послал (что сделал?) — часть речи глагол;

- начальная форма — послать;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: совершенный вид, переходный, 1-е спряжение;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика глагола: изъявительное наклонение, прошедшего времени, мужского рода, единственного числа;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: сказуемое.

Следующий онлайн образец морфологического разбора глагола в предложении:

Какая тишина, прислушайтесь.

Прислушайтесь (что сделайте?) — глагол;

- начальная форма — прислушаться;

- морфологические постоянные признаки: совершенный вид, непереходный, возвратный, 1-го спряжения;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика слова: повелительное наклонение, множественное число, 2-е лицо;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: сказуемое.

План морфологического разбора глагола онлайн бесплатно, на основе примера из целого абзаца:

— Его нужно предостеречь.

— Не надо, пусть знает в другой раз, как нарушать правила.

— Что за правила?

— Подождите, потом скажу. Вошел! («Золотой телёнок», И. Ильф)

Предостеречь (что сделать?) — глагол;

- начальная форма — предостеречь;

- морфологические признаки глагола постоянные: совершенный вид, переходный, невозвратный, 1-го спряжения;

- непостоянная морфология части речи: инфинитив;

- синтаксическая функция в предложении: составная часть сказуемого.

Пусть знает (что делает?) — часть речи глагол;

- начальная форма — знать;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: несовершенный вид, невозвратный, переходный, 1-го спряжения;

- непостоянная морфология глагола: повелительное наклонение, единственного числа, 3-е лицо;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: сказуемое.

Нарушать (что делать?) — слово глагол;

- начальная форма — нарушать;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: несовершенный вид, невозвратный, переходный, 1-го спряжения;

- непостоянные признаки глагола: инфинитив (начальная форма);

- синтаксическая роль в контексте: часть сказуемого.

Подождите (что сделайте?) — часть речи глагол;

- начальная форма — подождать;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: совершенный вид, невозвратный, переходный, 1-го спряжения;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика глагола: повелительное наклонение, множественного числа, 2-го лица;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: сказуемое.

Вошел (что сделал?) — глагол;

- начальная форма — войти;

- постоянные морфологические признаки: совершенный вид, невозвратный, непереходный, 1-го спряжения;

- непостоянная морфологическая характеристика глагола: прошедшее время, изъявительное наклонение, единственного числа, мужского рода;

- синтаксическая роль в предложении: сказуемое.

Рыбы-клоуны, или амфиприоны[1] (лат. Amphiprion), — род морских лучепёрых рыб из семейства помацентровых. Чаще всего под этим названием фигурирует аквариумная рыбка оранжевый амфиприон (Amphiprion percula).

Для рыб-клоунов характерен симбиоз с различными видами актиний. Вначале рыба слегка касается актинии, позволяя ей ужалить себя и выясняя точный состав слизи, которым покрыта актиния, — эта слизь нужна актинии, чтобы она не жалила сама себя. Затем рыба-клоун воспроизводит этот состав и после этого может прятаться от врагов среди щупалец актинии. Рыба-клоун заботится об актинии — вентилирует воду и уносит непереваренные остатки пищи. Рыбки никогда не удаляются далеко от «своей» актинии. Самцы прогоняют от неё самцов, самки — самок. Территориальное поведение, видимо, стало причиной контрастной окраски. Протандрические гермафродиты: все молодые особи — самцы, однако в течение жизни рыба меняет пол. Стимул, запускающий смену пола, — гибель самки.

Окраска рыб варьирует от насыщенно пурпурного до огненно-оранжевого, красного и жёлтого.

28 видов обитают в рифах Индийского и Тихого океанов — от Восточной Африки до Французской Полинезии и от Японии до Восточной Австралии[2].

Виды

- Amphiprion akallopisos Bleeker, 1853 — Пестроносый амфиприон

- Amphiprion akindynos Allen, 1972

- Amphiprion allardi Klausewitz, 1970 (=Amphiprion xanthurus Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830)

- Amphiprion bicinctus Rüppell, 1830

- Amphiprion biaculeatus (=Premnas biaculeatus (Bloch, 1790))

- Amphiprion chagosensis Allen, 1972

- Amphiprion chrysogaster Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830 (=Amphiprion fusciventer Bennett, 1832, Amphiprion mauritiensis — Schultz, 1953)

- Amphiprion chrysopterus Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830

- Amphiprion clarkii (Bennett, 1830) (=Amphiprion boholensis Cartier, 1874, Amphiprion chrysargyrus Richardson, 1846, Anthias clarkii Bennett, 1830, Amphiprion japonicus Temminck et Schlegel, 1843, Amphiprion melanostolus Richardson, 1842, Sparus milii Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1831, Amphiprion papuensis Macleay, 1883, Amphiprion snyderi Ishikawa, 1904)

- Amphiprion ephippium (Bloch, 1790) (=Amphiprion calliops Schultz, 1966, Lutjanus ephippium Bloch, 1790)

- Amphiprion frenatus Brevoort, 1856 (=Prochilus polylepis Bleeker, 1877)

- Amphiprion fuscocaudatus Allen, 1972

- Amphiprion latezonatus Waite, 1900

- Amphiprion latifasciatus Allen, 1972

- Amphiprion leucokranos Allen, 1973 (=Amphiprion leucocranos Allen, 1973)

- Amphiprion mccullochi Whitley, 1929

- Amphiprion melanopus Bleeker, 1852 (=Amphiprion arion De Vis, 1884, Prochilus macrostoma Bleeker, 1877, Amphiprion monofasciatus Thiollière in Montrouzier, 1857, Amphiprion verweyi Whitley, 1933)

- Amphiprion nigripes Regan, 1908

- Amphiprion ocellaris Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830 (=Amphiprion bicolor Castelnau, 1873, Amphiprion melanurus Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830)

- Amphiprion omanensis Allen et Mee in Allen, 1991

- Amphiprion percula (Lacépède, 1802) — Оранжевый амфиприон (=Lutjanus percula Lacépède, 1802)

- Amphiprion perideraion Bleeker, 1855 (=Amphiprion amamiensis Mori, 1966, Amphiprion rosenbergii Richardson, 1859-60)

- Amphiprion polymnus (Linnaeus, 1758) (=Anthias bifasciatus Bloch, 1792, Paramphiprion hainanensis Wang, 1941, Amphiprion intermedius Schlegel et Müller, 1839, Lutjanus jourdin Lacépède, 1802, Amphiprion laticlavius Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830, Perca polymna Linnaeus, 1758, Amphiprion trifasciatus Cuvier in Cuvier et Valenciennes, 1830, Coracinus vittatus Gronow in Gray, 1854, Amphiprion bifasciatus annamensis Chevey, 1932)

- Amphiprion rubacinctus Richardson, 1842 (=Amphiprion tricolor Günther, 1861)

- Amphiprion sandaracinos Allen, 1972

- Amphiprion sebae Bleeker, 1853

- Amphiprion thiellei Burgess, 1981

- Amphiprion tricinctus Schultz et Welander in Schultz, 1953

Галерея

-

Amphiprion sandaracinos

-

Amphiprion akindynos

-

Amphiprion allardi

-

-

Amphiprion chrysogaster

-

Amphiprion chrysopterus

-

-

Клоун седлоспинный

-

-

Широкополостный клоун

-

Красно-чёрный клоун

-

-

-

-

-

-

Клоун оранжевый

-

Клоун Себа

-

Примечания

- ↑ Решетников Ю. С., Котляр А. Н., Расс Т. С., Шатуновский М. И. Пятиязычный словарь названий животных. Рыбы. Латинский, русский, английский, немецкий, французский. / . — М.: Рус. яз., 1989. — С. 305. — 12 500 экз. — ISBN 5-200-00237-0.

- ↑ Джеймс Просек (англ. James Prosek). Выгодное соседство // National Geographic Россия : Журнал / А. В. Дубровский. — ООО «Юнайтед Пресс», 2010. — Вып. январь 2010, № 1. — С. 126—137.

Эта страница в последний раз была отредактирована 18 октября 2022 в 10:11.

Как только страница обновилась в Википедии она обновляется в Вики 2.

Обычно почти сразу, изредка в течении часа.