Как правильно пишется слово «Ренессанс»

Ренесса́нс

Ренесса́нс, -а (Возрождение) и ренесса́нс, -а (период расцвета чего-н.; архит. стиль)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: проковка — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «Ренессанс»

Синонимы к слову «Ренессанс»

Синонимы к слову «ренессанс»

Предложения со словом «ренессанс»

- Здания, построенные в царский период в конце XIX века, в стиле ренессанс перегружены украшениями.

- Древние греки и римляне, люди XV и XVI столетий, как бы придут нам на помощь, а может быть, и покажут дорогу к следующей эпохе ренессанса творческого духа.

- Той мировоззренческой истиной, без которой все попытки русского ренессанса будут бессмысленны, все предстоящие усилия и траты обернутся тщетой.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «Ренессанс»

- Я почувствовал в себе веяние духа, которое в начале XX века создало русский культурный ренессанс.

- Третье течение в русском ренессансе связано с расцветом русской поэзии.

- Такие великие явления мировой культуры, как греческая трагедия или культурный ренессанс, как германская культура XIX в. или русская литература XIX в., совсем не были порождениями изолированного индивидуума и самоуслаждением творцов, они были явлением свободного творческого духа.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Каким бывает «ренессанс»

Значение слова «ренессанс»

-

РЕНЕССА́НС, -а, м. 1. (с прописной буквы). То же, что Возрождение. Эпоха Ренессанса. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова РЕНЕССАНС

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

РЕНЕССА́НС, -а, м. 1. (с прописной буквы). То же, что Возрождение. Эпоха Ренессанса.

Все значения слова «ренессанс»

-

Здания, построенные в царский период в конце XIX века, в стиле ренессанс перегружены украшениями.

-

Древние греки и римляне, люди XV и XVI столетий, как бы придут нам на помощь, а может быть, и покажут дорогу к следующей эпохе ренессанса творческого духа.

-

Той мировоззренческой истиной, без которой все попытки русского ренессанса будут бессмысленны, все предстоящие усилия и траты обернутся тщетой.

- (все предложения)

- стиль

- Возрождение

- эпоха Возрождения

- эпоха Ренессанса

- позднее средневековье

- (ещё синонимы…)

- возрождение

- реставрация

- обновление

- воссоздание

- восстановление

- (ещё синонимы…)

- возрождение

- эпоха

- просвещение

- искусство

- культура

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- итальянский ренессанс

- русский ренессанс

- эпоха ренессанса

- в стиле ренессанса

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- итальянский

- ранний

- культурный

- религиозный

- европейский

- (ещё…)

- Разбор по составу слова «ренессанс»

На чтение 1 мин.

Значение слова «Ренессанс»

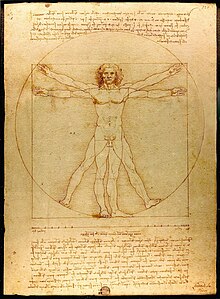

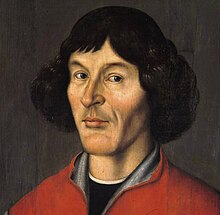

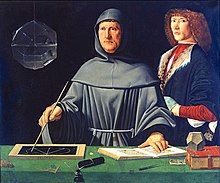

— период бурного расцвета науки и искусства в ряде стран Европы, наступивший после средневековья и породивший жизнеутверждающее, гуманистическое мировоззрение, создавший замечательные образцы реалистического искусства; Возрождение

— эпоха расцвета, подъема в развитии науки и искусства какой-либо страны (разговорное)

Содержание

- Транскрипция слова

- MFA Международная транскрипция

- Цветовая схема слова

Транскрипция слова

[р’ин’иса́нс]

MFA Международная транскрипция

[rʲɪnʲɪˈsans]

| р | [р’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий парный |

| е | [и] | гласный, безударный |

| н | [н’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий парный |

| е | [и] | гласный, безударный |

| с | [с] | согласный, глухой парный, твердый парный |

| с | [-] | |

| а | [́а] | гласный, ударный |

| н | [н] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), твердый парный |

| с | [с] | согласный, глухой парный, твердый парный |

Букв: 9 Звуков: 8

Цветовая схема слова

ренессанс

Как правильно пишется «Ренессанс»

Ренесса́нс

Ренесса́нс, -а (Возрождение) и ренесса́нс, -а (период расцвета чего-н.; архит. стиль)

Как правильно перенести «Ренессанс»

ре—нес—са́нс

Часть речи

Часть речи слова «Ренессанс» — Имя существительное

Морфологические признаки.

Ренессанс (именительный падеж, единственного числа)

Постоянные признаки:

- нарицательное

- неодушевлённое

- мужской

- 2-e склонение

Непостоянные признаки:

- именительный падеж

- единственного числа

Может относится к разным членам предложения.

Склонение слова «Ренессанс»

| Падеж | Единственное число | Множественное число |

|---|---|---|

| Именительный Кто? Что? |

ренесса́нс | ренесса́нсы |

| Родительный Кого? Чего? |

ренесса́нса | ренесса́нсов |

| Дательный Кому? Чему? |

ренесса́нсу | ренесса́нсам |

| Винительный (неод.) Кого? Что? |

ренесса́нс | ренесса́нсы |

| Творительный Кем? Чем? |

ренесса́нсом | ренесса́нсами |

| Предложный О ком? О чём? |

ренесса́нсе | ренесса́нсах |

Разбор по составу слова «Ренессанс»

Состав слова «ренессанс»:

корень — [ренессанс], нулевое окончание — [ ]

Проверьте свои знания русского языка

Категория: Русский язык

Каким бывает «ренессанс»;

Синонимы к слову «Ренессанс»

эпоха Возрождения

эпоха Ренессанса

позднее средневековье

Ассоциации к слову «Ренессанс»

Предложения со словом «ренессанс»

- Здания, построенные в царский период в конце XIX века, в стиле ренессанс перегружены украшениями.

Клеменс Подевильс, Бои на Дону и Волге. Офицер вермахта на Восточном фронте. 1942-1943

- Древние греки и римляне, люди XV и XVI столетий, как бы придут нам на помощь, а может быть, и покажут дорогу к следующей эпохе ренессанса творческого духа.

Марджори Квеннелл, Гомеровская Греция. Быт, религия, культура

- Той мировоззренческой истиной, без которой все попытки русского ренессанса будут бессмысленны, все предстоящие усилия и траты обернутся тщетой.

Александр Проханов, Технологии «Пятой Империи», 2007

Происхождение слова «Ренессанс»

Происходит от франц. renaissance «возрождение», далее из renaître «рождаться вновь, возрождаться» далее из renasci «возрождаться», далее из re- «обратно; опять, снова; против», далее из неустановленной формы + nasci «рождаться, происходить», далее из архаичн. gnasci; восходит к праиндоевр. *gen-/*gn- «порождать, производить».

ренессанс

- ренессанс

-

ренессанс. Произносится [рэнэссанс].

Словарь трудностей произношения и ударения в современном русском языке. — СПб.: «Норинт»..

.

2000.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «ренессанс» в других словарях:

-

ренессанс — а, м. renaissance возрождение. 1. Период бурного расцвета науки и искусства в ряде стран Европы, наступивший после средневековья и обусловленный развитием капиталистических отношений; то же, что Возрождение. БАС 1. Частные письма ни для кого не… … Исторический словарь галлицизмов русского языка

-

Ренессанс — (Renaissance, Rinascimento) Возрождение слово, в своем специальном смысле впервые пущенное в оборот Джорджо Вазари в «Жизнеописаниях художников» (1550). И у него же оно (rinascita) фигурирует уже в двух пониманиях. В одном случае Вазари говорит о … Литературная энциклопедия

-

Ренессанс — (фр. renaissance қайта өрлеу, қайта өркендеу) – XIV ғ. алдымен Италияда басталып, кейін Батыс Еуропа елдерінде өріс алған білім, ғылым, өнер, әдебиет, сәулет салаларындағы мәдени төңкеріс дәуірі, кезеңі. Ол антикалық идеалдар мен құндылықтарды… … Философиялық терминдердің сөздігі

-

Ренессанс — (Зеленоградск,Россия) Категория отеля: Адрес: Улица Гагарина 17 Б, Зеленоградск, Россия … Каталог отелей

-

РЕНЕССАНС — возрождение; эпоха Возрождения XV и XVI вв. характеризуется возрождением классического искусства и литературы, освобождением мысли и личности, подъемом научного творчества и возникновением нескольких новых вероисповеданий, последователи которых… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

ренессанс — эпоха (ренессанса, возрождения), возрождение Словарь русских синонимов. Ренессанс см. Возрождение 2 Словарь синонимов русского языка. Практический справочник. М.: Русский язык. З. Е. Александрова … Словарь синонимов

-

РЕНЕССАНС — (Ренессанс), (Р прописное), ренессанса, мн. нет, муж. (франц. renaissance). То же, что возрождение2. Толковый словарь Ушакова. Д.Н. Ушаков. 1935 1940 … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

РЕНЕССАНС — (от франц. Renaissance) Возрождение, а именно эпоха Возрождения классической древности, возникновение нового ощущения, чувства жизни, которое рассматривалось как родственное жизненному чувству античности и как противоположное средневековому… … Философская энциклопедия

-

РЕНЕССАНС — РЕНЕССАНС, смотри Возрождение … Современная энциклопедия

-

РЕНЕССАНС — (франц. Renaissance) см. Возрождение … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

РЕНЕССАНС — РЕНЕССАНС, а, муж. То же, что Возрождение (во 2 знач.). Искусство Ренессанса. | прил. ренессансный, ая, ое. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

Разбор слова «ренессанс»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «ренессанс» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «ренессанс» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «ренессанс».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «ренессанс» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «ренессанс»

- 3 Морфологический разбор слова «ренессанс»

- 4 Разбор слова «ренессанс» по составу

- 5 Сходные по морфемному строению слова «ренессанс»

- 6 Синонимы слова «ренессанс»

- 7 Ударение в слове «ренессанс»

- 8 Фонетическая транскрипция слова «ренессанс»

- 9 Фонетический разбор слова «ренессанс» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

- 10 Предложения со словом «ренессанс»

- 11 Сочетаемость слова «ренессанс»

- 12 Значение слова «ренессанс»

- 13 Как правильно пишется слово «ренессанс»

- 14 Ассоциации к слову «ренессанс»

Слоги в слове «ренессанс» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 3

По слогам: ре-не-ссанс

По правилам школьной программы слово «Ренессанс» можно поделить на слоги разными способами. Допускается вариативность, то есть все варианты правильные. Например, такой:

ре-нес-санс

По программе института слоги выделяются на основе восходящей звучности:

ре-не-ссанс

Ниже перечислены виды слогов и объяснено деление с учётом программы института и школ с углублённым изучением русского языка.

сдвоенные согласные сс не разбиваются при выделении слогов и парой отходят к следующему слогу

Как перенести слово «ренессанс»

ре—нессанс

ренес—санс

Морфологический разбор слова «ренессанс»

Часть речи:

Имя существительное

Грамматика:

часть речи: имя существительное;

одушевлённость: неодушевлённое;

род: мужской;

число: единственное;

падеж: именительный, винительный;

отвечает на вопрос: (есть) Что?, (вижу/виню) Что?

Начальная форма:

ренессанс

Разбор слова «ренессанс» по составу

| ренессанс | корень |

| ø | нулевое окончание |

ренессанс

Сходные по морфемному строению слова «ренессанс»

Сходные по морфемному строению слова

Синонимы слова «ренессанс»

1. стиль

2. возрождение

3. эпоха возрождения

4. эпоха ренессанса

Ударение в слове «ренессанс»

ренесса́нс — ударение падает на 3-й слог

Фонетическая транскрипция слова «ренессанс»

[р’ин’ис`ан’с]

Фонетический разбор слова «ренессанс» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

| Буква | Звук | Характеристики звука | Цвет |

|---|---|---|---|

| р | [р’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий | р |

| е | [и] | гласный, безударный | е |

| н | [н’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий | н |

| е | [и] | гласный, безударный | е |

| с | [с] | согласный, глухой парный, твёрдый, шумный | с |

| с | — | не образует звука | с |

| а | [`а] | гласный, ударный | а |

| н | [н’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий | н |

| с | [с] | согласный, глухой парный, твёрдый, шумный | с |

Число букв и звуков:

На основе сделанного разбора делаем вывод, что в слове 9 букв и 8 звуков.

Буквы: 3 гласных буквы, 6 согласных букв.

Звуки: 3 гласных звука, 5 согласных звуков.

Предложения со словом «ренессанс»

Я, вообще, вырос, как певец, в эпоху ренессанса.

Источник: Олеся Рябцева, Без дураков. Лучшие из людей. Эхо Москвы, 2015.

С этого места открывался прекрасный вид на сам дом — жемчужину итальянского ренессанса в оправе из парка с озером, беседками и ухоженным английским садом.

Источник: Ким Лоренс, Любовь и прочие неприятности, 2013.

При оформлении интерьера в стиле ренессанс в цветовой гамме должны сочетаться светлые, тёмные и яркие тона.

Источник: А. Е. Батурина, 3000 практических советов для дома, 2010.

Сочетаемость слова «ренессанс»

1. итальянский ренессанс

2. русский ренессанс

3. поздний ренессанс

4. эпоха ренессанса

5. в стиле ренессанса

6. искусство ренессанса

7. (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение слова «ренессанс»

РЕНЕССА́НС , -а, м. 1. (с прописной буквы). То же, что Возрождение. Эпоха Ренессанса. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Как правильно пишется слово «ренессанс»

Правописание слова «ренессанс»

Орфография слова «ренессанс»

Правильно слово пишется: Ренесса́нс

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «ренессанс» в прямом и обратном порядке:

- 9

Р

1 - 8

е

2 - 7

н

3 - 6

е

4 - 5

с

5 - 4

с

6 - 3

а

7 - 2

н

8 - 1

с

9

Ассоциации к слову «ренессанс»

-

Средневековье

-

Эпоха

-

Стиль

-

Возрождение

-

Архитектура

-

Ратуша

-

Микеланджело

-

Флоренция

-

Фреска

-

Леонардо

-

Живописец

-

Страхование

-

Капелла

-

Живопись

-

Расцвет

-

Фасад

-

Шедевр

-

Капитал

-

Архитектор

-

Скульптура

-

Просвещение

-

Смешение

-

Подражание

-

Скульптор

-

Интерьер

-

Мадонна

-

Франциск

-

Витраж

-

Зао

-

Наследие

-

Италия

-

Гобелен

-

Искусство

-

Византия

-

Классик

-

Альбрехт

-

Рафаэль

-

Мыслитель

-

Франческо

-

Драматург

-

Век

-

Отделка

-

Художник

-

Элемент

-

Творчество

-

Культура

-

Полотно

-

Период

-

Венеция

-

Поэтесса

-

Современность

-

Поэзия

-

Эля

-

Идеал

-

Ансамбль

-

Роспись

-

Убранство

-

Орнамент

-

Якоб

-

Упадок

-

Мотив

-

Готический

-

Итальянский

-

Архитектурный

-

Инвестиционный

-

Античный

-

Венецианский

-

Изобразительный

-

Средневековый

-

Нидерландский

-

Монументальный

-

Картинный

-

Переходный

-

Византийский

-

Культурный

-

Мусульманский

-

Скульптурный

-

Декоративный

-

Древнерусский

-

Переходной

-

Галантный

-

Европейский

-

Дворцовый

-

Хорватский

-

Македонский

-

Голландский

-

Страховой

-

Камерный

-

Классический

-

Древнегреческий

-

Кафедральный

-

Перестроить

-

Сочетать

-

Спроектировать

-

Охарактеризовать

-

Обставить

-

Сочетаться

-

Изображаться

-

Возвести

-

Построить

РЕНЕССАНС

Ренесс’анс, -а (Возрождение) и ренесс’анс, -а (период расцвета чего-н.; архит. стиль)

Синонимы:

возрождение, стиль, эпоха возрождения, эпоха ренессанса

РЕНЕССАНСНЫЙ →← РЕНЕГАТСТВОВАТЬ

Синонимы слова «РЕНЕССАНС»:

ВОЗРОЖДЕНИЕ, СТИЛЬ, ЭПОХА ВОЗРОЖДЕНИЯ, ЭПОХА РЕНЕССАНСА

Смотреть что такое РЕНЕССАНС в других словарях:

РЕНЕССАНС

(итал. Rinascimento, франц. Renaissance = Возрождение) — общепринятое название эпохи, следовавшей в истории западноевропейского искусства за готической… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

(франц. Renaissance — Возрождение, от renaitre — возрождаться) эпоха в развитии ряда стран Западной и Центральной Европы, переходная от средневе… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

РЕНЕССАНС, -а, м. То же, что Возрождение (во 2 знач.). ИскусствоРенессанса. II прил. ренессансный, -ая, oое.

РЕНЕССАНС

Ренессанс м. 1) Период бурного расцвета науки и искусства в ряде стран Европы, наступивший после средневековья и породивший жизнеутверждающее, гуманистическое мировоззрение, создавший замечательные образцы реалистического искусства; Возрождение. 2) разг. Эпоха расцвета, подъема в развитии науки и искусства какой-л. страны.<br><br><br>… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

ренессанс м. Архитектурный стиль эпохи Возрождения, сменивший готический и воспринявший элементы греко-римской архитектуры.

РЕНЕССАНС

Ренессанс м.the Renaissance, Renascence

РЕНЕССАНС

ренессанс

эпоха (ренессанса, возрождения), возрождение

Словарь русских синонимов.

Ренессанс

см. Возрождение 2

Словарь синонимов русского языка. Практический справочник. — М.: Русский язык.З. Е. Александрова.2011.

Ренессанс

сущ.

• Возрождение

• эпоха Возрождения

• эпоха Ренессанса

Словарь русских синонимов. Контекст 5.0 — Информатик.2012.

ренессанс

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 4

• возрождение (23)

• стиль (95)

• эпоха возрождения (3)

• эпоха ренессанса (3)

Словарь синонимов ASIS.В.Н. Тришин.2013.

.

Синонимы:

возрождение, стиль, эпоха возрождения, эпоха ренессанса… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

РЕНЕССАНС (франц. Renaissance —

Возрождение, от renaitre — возрождаться), эпоха в развитии ряда стран Зап.

и Центр. Европы, переходная от ср.-век. ку… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

Ренессанс (итал. Rinascimento, франц. Renaissance = Возрождение) — общепринятое название эпохи, следовавшей в истории западноевропейского искусства за готической и продолжавшейся с середины XV до начала XVI столетия. Главное, чем характеризуется эта эпоха — возвращение в архитектуре к принципам и формам античного, преимущественно римского искусства, а в живописи и ваянии, кроме того — сближением художников с природой, ближайшим проникновением их в законы анатомии, перспективы, действия света и других естественных явлений. Движение в этом направлении возникло прежде всего в Италии, где первые его признаки были заметны еще в XIII и XIV вв. (в деятельности семейства Пизано, Джотто, Орканьи и др.), но где оно твердо установилось только с 20-х годов XV в. Во Франции, Германии и др. странах это движение началось значительно позже; несмотря на то, его свойства и ход развития, особенно в том, что касается до архитектуры, были везде почти одинаковы. Вообще эпоху Р. можно разделить на три периода. Первый из них, период так называемого «Раннего Возрождения», обнимает собой в Италии время с 1420 по 1500 гг. В течение этих восьмидесяти лет искусство еще не вполне отрешается от преданий недавнего прошлого, но пробует примешивать к ним элементы, заимствованные из классической древности, и старается примирить между собой те и другие. Лишь впоследствии, и только мало-помалу, под влиянием все сильнее и сильнее изменяющихся условий жизни и культуры, художники совершенно бросают средневековые основы и смело пользуются образцами античного искусства как в общей концепции своих произведений, так и в их деталях. Церковное зодчество остается еще верным типу базилик с плоским потолком или с крестовыми сводами, но в обработке частностей, в расстановке колонн и столбов, в их отделке, в распределении арок и архитравов, в обработке окон и порталов, подражает греко-римским памятникам, причем стремится — по крайней мере в Италии — к образованию обширных, свободных пространств внутри зданий. Особенно излюбленным становится коринфский орден, капители которого подвергаются разнообразным видоизменениям, подчас весьма остроумным и красивым. Еще больше, чем в храмоздательство, новизна проникает в гражданскую архитектуру, произведения которой, главным образом дворцы владетельных особ, городских властей и знатных людей, хотя и удерживают в себе нечто средневековое, но изменяют свой прежний крепостной, угрюмый характер на более приветливый и нарядный, становятся столь же непохожими на прежние замки, как новая, более безопасная жизнь не похожа на тревожное существование предшествовавшего времени. Важную роль в этих постройках играют просторные, красивые внутренние дворы, обнесенные в нижнем и в верхнем этажах крытыми галереями на арках, которые поддерживаются либо колоннами, либо пилястрами античной формы и с античными капителями. Повсюду в зданиях видно стремление их строителей соблюсти симметричность и гармонию пропорций; фасад обыкновенно расчленяется в горизонтальном направлении посредством изящных карнизов и увенчивается вверху особенно роскошным главным карнизом, образующим сильный выступ под крышей. Замечательнейшие из итальянских архитектурных памятников раннего Р. мы находим во Флоренции; это — купол тамошнего собора и палаццо Питти (создания Ф. Брунеллески), дворцы Риккарди (построенные Микелоццо-Микелоцци), Строци (Бенедетто да-Майяно и С. Кронака), Гонди (Джульяно да-Сан-Галло), Руччеллаи (Л.-Б. Альберти) и некоторые др.; кроме того, любопытны относящиеся к рассматриваемому периоду малый и большой венецианские дворцы в Риме (Бернардо ди-Лоренцо), Чертоза в Павии (Амбр. Боргоньоне), палаццо Вендрамин-Калерджи (П. Ломбардо), Корнер-Спинелли, Тревизан, Кантарини и, наконец, дворец дожей, в Венеции. Тогда как искусство в Италии уже решительно шло по пути подражания классической древности, в других странах оно долго держалось традиций готического стиля. К северу от Альп, а также в Испании, Возрождение наступает только в конце XV столетия, и его ранний период длится, приблизительно, до середины следующего столетия, не производя, впрочем, ничего особенно замечательного. Второй период Возрождения — время самого пышного развития его стиля — принято называть «Высоким Р.» (Hochrenaissance); он простирается в Италии приблизительно от 1500 по 1580 гг. В это время центр тяжести итальянского искусства, которое возделывалось дотоле, главным образом, во Флоренции, перемещается в Рим, благодаря вступлению на папский престол Юлия II, человека честолюбивого, смелого и предприимчивого, привлекшего к своему двору лучших артистов Италии, занимавшего их многочисленными и важными работами и дававшего собой другим пример любви к художествам. При этом папе и его ближайших преемниках, Рим становится как бы новыми Афинами времен Перикла: в нем созидается множество монументальных зданий, исполняются великолепные скульптурные произведения, пишутся фрески и картины, до сих пор считающиеся перлами живописи; при этом все три отрасли искусства стройно идут рука об руку, помогая одно другому и взаимно действуя друг на друга. Античное изучается теперь более основательно, воспроизводится с большей строгостью и последовательностью; спокойствие и достоинство водворяются вместо игривой красоты, которая составляла стремление предшествовавшего периода; припоминания средневекового совершенно исчезают, и вполне классический отпечаток ложится на все создания искусства. Но подражание древним не заглушает в художниках их самостоятельности, и они, с большой находчивостью и живостью фантазии, свободно перерабатывают и применяют к делу то, что считают уместным заимствовать для него из греко-римского искусства. Лучшие памятники, оставленные нам итальянской архитектурой этой блестящей поры — опять-таки дворцы и вообще здания светского характера, большинство которых пленяет нас гармоничностью и величием своих пропорций, изяществом расчленений, благородством деталей, отделкой и орнаментацией карнизов, окон, дверей и пр., а также дворцами с легкими, по большей части двухъярусными галереями на колоннах и столбах. Церковное зодчество, со своей стороны, стремится к колоссальности и внушительной величественности; отказавшись от средневекового крестового свода, оно почти постоянно пользуется римским коробовым сводом и любит купола, подпираемые четырьмя массивными столбами. Главным двигателем архитектуры Высокого Р. был Донато Браманте, прославившийся сооружением колоссального «палаццо делла-Канчеллериа», менее значительного, но превосходного дворца Жиро, двора Сен-Дамазо в Ватиканском дворце и «Темпьетто» при церкви Сан-Пьетро-ин-Монторио, в Риме, а также составлением плана для нового Петровского собора, который и был начат постройкой под его руководством. Из последователей этого художника, наиболее выдаются Бальдассаре Перуцци, лучшие произведения которого — Фарнезинская вилла и палаццо-Массими, в Риме, великий Рафаэль Санти, построивший дворец Пандольфини, во Флоренции, Антонио да-Сангалло, строитель палаццо-Фарнезе, в Риме и Джулио Романо, выказавший себя талантливым зодчим в вилле-Мадама, в Риме, и в палаццо дель-Те, в Мантуе. Кроме римской архитектурной школы, в рассматриваемый период блистательно развилась венецианская, главным представителем которой явился Якопо Татти, прозванный Сансовино, оставивший нам доказательства своего таланта в сооруженных им библиотеке св. Марка и в роскошном палаццо-Корнер. Выступление на сцену Микеланджело Буонаротти, положившего надолго печать своего гения на все три образные искусства, обозначает в истории зодчества наступление самого полного расцвета стиля Р. Несравненные памятники его творчества в области архитектуры — усыпальница семейства Медичи при церкви Сан-Лоренцо, во Флоренции, произведенная по его проекту застройка в Риме Капитолийского холма, с его зданиями, верхней площадью и ведущей на нее лестницей, и такое чудо в своем роде, как громадный по размерам и до крайности смелый по конструкции купол Петровского собора. С 1550 г., в итальянском зодчестве заметна перемена, а именно более холодное, рассудочное отношение художников к их задачам, стремление еще более точно воспроизводить античные формы, систематическому применению которых посвящаются теперь целые трактаты; несмотря на то, возводимые сооружения продолжают отличаться высоким изяществом и ничем не нарушенным благородством. Главные представители этого направления, характеризующего вторую пору Высокого Р., суть Дж. Бароцци, прозванный Виньолой (церковь иезуитов, в Риме, и замок Капрарола, в Витербо), живописец и биограф художников Дж. Вазари (дворец Уффици, во Флоренции), Ант. Палладио (несколько дворцов, базилик и олимпийский театр в Виченце), генуэзец Галеаццо Алесси (церковь Мадонны да-Кариньяно и дворцы Спинола и Саули, в Генуе) и некоторые др. За пределами Италии, цветущая пора Р. наступила полувеком позже, чем в этой стране, и длилась до середины XVII столетия. Стиль, выработанный итальянцами, проник всюду и пользовался везде почетом, но при этом, приноравливаясь ко вкусам и условиям жизни других национальностей, утратил свою чистоту и до некоторой степени легкость и гармоничность; тем не менее он выразился во многих прекрасных сооружениях, каковы, например, во Франции западный фасад Луврского дворца в Париже (архитектор П. Леско), королевский замок в Фонтенбло, замок Ане и Тюильри (Филибер Делорм), Экуэнский замок, дворец в Блуа; в Испании — Эскорьяльский дворец (X. де-Толедо и X. де-Эррера), в Германии — Отто-Генриховская часть Гейдельбергского замка, Альтенбургская ратуша, сени Кельнской ратуши, Фюрстенгоф в Вильмаре и др. Третий период искусства Возрождения, так называемый период «позднего Р.», отличается каким-то страстным, беспокойным стремлением художников совсем произвольно, без разумной последовательности, разрабатывать и комбинировать античные мотивы, добиваться мнимой живописности утрировкой и вычурностью форм. Признаки этого стремления, породившего стиль барокко, а затем, в XVIII столетии, стиль рококо, выказывались еще в предшествовавшем периоде в значительной степени по невольной вине великого Микеланджело, своим гениальным, но слишком субъективным творчеством давшего опасный пример крайне свободного отношения к принципам и формам античного искусства; но теперь направление это делается всеобщим. Ровные фасады и ритмичная правильность их разделки перестают удовлетворять архитекторов; не ограничиваясь устройством выступов, балконов, порталов, боковых флигелей и других уместных с конструктивной или декоративной точки зрения частностей в зданиях, они капризно усложняют детали, скучивают колонны, полуколонны и пилястры без цели или даже наперекор ей, изгибают, ломают и прерывают архитектурные линии самым причудливым образом, пускаются в затейливую, преувеличенную орнаментацию. Главным представителем такого искаженного стиля, оставившего, однако, немало весьма любопытных, роскошных памятников по себе во всей Европе, был итальянец Л. Бернини, трудившийся также и по части скульптуры, в которую введены им подобная же утрированность, подобное жеманство (полуциркульные колоннады при Петровском соборе, сень над его главным престолом, дворцы Барберини и Браччьяно, скульптурная группа «Похищение Прозерпины» в вилле Лудовизи, колоссальная статуя императора Константина верхом на коне, в притворе Петровского собора, надгробные памятники пап Урбана VII и Александра VII, там же, и многие др. работы в Риме). Еще более изысканным является в своих произведениях соперник этого художника, Фр. Борромини (северный фасад церкви Санта-Сапиенца, церкви св. Агнесы на Навонской площади, часть коллегии Пропаганды, отделка возобновленной внутренности Латеранской базилики и др. римские постройки). Стиль барокко господствовал в Италии приблизительно до 1715 г., в прочих странах — до 1720 или 1740 гг. Ср. J. Burckhardt, «Die Kunst der Renaissance in Italien» (3 изд., 1877); его же, «Geschichte der R. in Italien» (1867); W. Lü bke, «Geschichte der R. in Frankreich» (1868); его же, «Geschichte der R. in Deutschland» (2 изд., 1881); Voigt, «Die Wiederbelebung des klassischen Altertums» (3 изд., 1893) и пр. <i> А. С—в. </i><br><br><br>… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

РЕНЕССАНС (Renaissance, Rinascimento) — Возрождение — слово, в своем специальном смысле впервые пущенное в оборот Джорджо Вазари в «Жизнеописани… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС

РЕНЕССАНС (Renaissance, Rinascimento) — Возрождение — слово, в своем специальном смысле впервые пущенное в оборот Джорджо Вазари в «Жизнеописаниях художников» (1550). И у него же оно (rinascita) фигурирует уже в двух пониманиях. В одном случае Вазари говорит о «возрождении» как об определенном моменте («от возрождения искусств до нашего времени»), в двух других — так, как слово понимается теперь: как об эпохе («ход возрождения» и «первый период возрождения»). У Вазари Р. рассматривался в применении исключительно к истории искусства. Позднее понятие расширилось и стало применяться к вопросам литературы, идеологии вообще, культуры в широком смысле этого слова (см.: A. Philippi, Der Begriff d. Renaissance, 1912). Теорией, суммировавшей господствующие взгляды на Р., еще и сейчас является теория Якоба Буркгардта, швейцарского историка и искусствоведа, к-рый воспользовался некоторыми формулами Мишле и дал стройную синтетическую схему Р. в своей книге «Культура Ренессанса в Италии» (Die Kultur d. Renaissance in Italien, 1860). Основная мысль Буркгардта, руководившегося гегельянскими общими понятиями, заключается в том, что Р. в Италии — это историческая грань между средними веками и новым временем, что Р. является разрывом со всем тем, что было темного и отсталого в средние века, и зарею нового времени, что он создал новую европейскую культуру, широкую, смелую, свободную. Италия выдвигалась в этой теории на первый план по понятным причинам: она сильно опередила в своем развитии другие европейские страны, и те процессы, которые совершались потом в остальной Европе, впервые прошли в Италии. Так как эта мысль была совершенно бесспорна, то после Буркгардта стало обычным во всех рассуждениях о Ренессансе главное место отводить Италии.<p class=»tab»>После империалистической войны, в связи с непрерывно усиливавшимися фашистскими настроениями в западном буржуазном обществе, схема Буркгардта подверглась ожесточенной критике. Главным объектом нападок послужила как раз та мысль Буркгардта, к-рая подчеркивала оригинальность созданного итальянцами в сфере идеологической, литературной и художественной. Эта критика (назовем две типичные в этом отношении работы самого последнего времени: голландского историка Huyzing’a «Das Problem der Renaissance» (1930) и шведского историка Nordstrom’a «Moyen age et la Renaissance» (1933)), наоборот, пытается доказать, что все существенное, что было сделано итальянцами во всех этих областях, было неоригинально и опиралось на средневековые образцы, что никакого разрыва между средними веками и новым временем не было, что Р. вовсе не был каким-либо рубежом. Реакционный характер этой критики бросается в глаза: источник ее — в стремлении доказать, что вся европейская культура создана в ту эпоху, когда царил феодальный порядок и безраздельно господствовала церковь, а вовсе не тогда, когда феодальный порядок стал рушиться и церковь потеряла власть над умами и совестью людей.</p><p class=»tab»>Теория Буркгардта нуждается в критике совсем другого рода. Основная ошибка Буркгардта заключается в том, что он всю итальянскую культуру XIII-XVI вв., от Данте до Джордано Бруно, во всех частях Италии рассматривает как нечто единообразное, лишенное движения и локальной специфики. Такое построение не только искажает всю картину, но мешает ему углубить те элементы социологического анализа, к-рые имеются в его книге. Культура Италии в эпоху Р. в разные моменты, а иногда в один и тот же момент, но в разных частях Италии представляла различные картины. И неправильно утверждать, что существовала однородная культура Ренессанса в Италии. Была культура Флоренции, Венеции, Феррары, Урбино и т. д. И была культура Флоренции XIII в., XIV в., XV в., XVI в. Иначе не могло быть, потому что экономические процессы, создавшие территорию, общественный строй и политич. порядок в каждой из итальянских коммун, т. е. свободных городских республик, были очень сложны и разнообразны.</p><p class=»tab»>Можно считать бесспорным, что культура Р. создана верхушкой буржуазии итальянских коммун. Это доказывается тем, что вся эта культура — идеология всех видов, наука, литература, искусство — получала при своем создании такую форму и такое содержание, которые отвечали интересам именно верхних слоев буржуазии и порою резко противоречили интересам других общественных слоев и классов коммуны. Следовательно можно говорить о единой культуре Р. в Италии только в одном смысле: постольку, поскольку в различные моменты этого времени и в различных частях Италии один и тот же класс, верхушка буржуазии, создавал одинаковые культурные ценности. Так как буржуазия в XIII-XVI вв. господствовала в наиболее богатых и славных коммунах и так как история именно этих коммун — прежде всего Флоренции — наиболее известна, то у исследователей, даже таких крупных, как Буркгардт, создавалось впечатление, что культура Р. везде в Италии была единообразна и что факты истории Флоренции эпохи ее наивысшего расцвета можно считать типичными для любой части Италии.</p><p class=»tab»>Зато само возникновение этой буржуазной культуры в Италии (раньше чем где бы то ни было в Европе) было, что бы ни говорили фашистские ученые, настоящим рубежом. Эту мысль Буркгардта принимают и такие буржуазные историки, не чуждающиеся социологического анализа, как Мартин в недавней своей книге «Soziologie der Renaissance» (1932). В историко-материалистическом понимании эта мысль дана Энгельсом, сказавшим, что Р. является настоящим «переворотом» в истории Европы. Этот культурный переворот сделался возможным лишь после того, как Италия, раньше других частей Европы, пережила — пережитый позднее и ими — хозяйственный переворот, лишивший феодальный способ производства руководящего значения в наиболее важных ее областях, со всеми последствиями этого факта в области, социальной, политической и культурной.</p><p class=»tab»>Начало новой экономической эры в передовых частях Италии и означало, что господство там переходит от феодальных классов к наиболее богатым группам буржуазии. И прежде всего это означало расцвет и усиление коммун, средоточий новой экономической жизни, резиденций того класса, к-рый взял в свои руки руководство хозяйством, власть политическую и культурное строительство. Но было бы большой ошибкой предполагать, что этот процесс совершился сразу на протяжении всей Италии. В наиболее отсталых частях феодальный способ производства и феодальные отношения в социальной области продолжали держаться, и феодальные пережитки в некоторых местах дожили до первых десятилетий XVI века. И не только дожили, но и помогали победе феодальной реакции, положившей конец торговому и промышленному расцвету Италии и сокрушившей политическую власть буржуазии.</p><p class=»tab»>По мере того как росли коммуны и накоплялись капиталы буржуазии, перед нею выдвигались все новые и новые задачи в области выработки нужного ей миропонимания и нужной культуры. Так как буржуазия создала свое благополучие в борьбе с силами феодального мира, идеология к-рого создавалась церковью, то естественно с самого начала новой культуре и новому миропониманию старались придать мирской характер. А так как вера не могла быть искоренена из человеческого сознания сразу, то пытались создать новую веру, не подчиненную церковному контролю; в истории она сохранила название, которым клеймила ее церковь, — ересь.</p><p class=»tab»>Еретическая культура представляет собою, для Италии во всяком случае, особый переходный этап. В ней сказываются еще пережитки феодальных отношений. Рыцарская идеология бросает еще яркий отсвет на зарождающуюся буржуазную. Еретическая культура определяет далеко не одну только область религии (учение Арнольда Брешианского (XII век), проповедовавшего полное отречение духовенства от светской власти и богатств, называвшего пап и кардиналов фарисеями и книжниками от христианства, а папскую курию разбойничьим притоном, прокламировавшего идеи личной связи верующего с божеством; движение, возглавленное «апостолом бедности» св. Франциском (XIII в.), в более умеренной форме продолжавшего идеи Арнольда; движение апостольских братьев и др.). Она оказывала влияние на самые различные сферы жизни. При дворе Фридриха II Гогенштауфена и сына его Ванфреда в Палермо она царила безраздельно. Во многих синьориях Северной Италии — в Вероне при Эццелино да Романо, в Ферраре при первых д’Эсте, в Луниджане при маркизах Маласпина, в Монферрате и во многих других центрах — она дала пышные ростки. Во Флоренции последних десятилетий XIII в. с нею была тесно связана не только вся культурная деятельность гибеллинов, но и такие факты, как распространение провансальской поэзии, господство первого, додантовского периода dolce stil nuovo, когда главою школы был Гвидо Кавальканти. С еретической культурой тесно связаны первые ростки пространственных искусств в Италии: деятельность Николо и Джованни Пизано, Чимабуэ, даже Джотто, поскольку последний вдохновлялся сюжетами из жизни св. Франциска, самого настоящего еретика, ставшего святым.</p><p class=»tab»>Пора еретической культуры, которая кончается на рубеже XIV века, еще не Р., но в творчестве Данте Алигиери, «последнего поэта средних веков и первого поэта нового времени» (Энгельс), есть уже много черт, которые его предвещают. Данте сам в X песне «Ада» провел грань между собою и Гвидо Кавальканти. Гвидо «относился с пренебрежением» (ebbe in disdegno) к Вергилию.</p><p class=»tab»>Люди еретической культуры не любили латинского языка, ибо он был языком Рима, не древнего, а современного, папского, их злейшего врага. Данте, а следом за ним и другие еще до Петрарки освободились от этого предрассудка. Данте любил римских поэтов, а «Энеиду» знал наизусть.</p><p class=»tab»>Различие между еретической культурой и культурой Р. заключается в том, что в первой буржуазия еще подчиняет всю область культуры — поскольку ей придается жизненный смысл — религиозной идее, а Р. начинается тогда, когда понятие культуры берется независимо от религии, хотя бы и свободной, когда культура секуляризируется, когда мирская точка зрения побеждает окончательно. Буржуазия отвергает авторитет церкви в вопросах идеологических, она отказывается допускать религиозные критерии в чем бы то ни было и делает мерилом всего собственный рассчитывающий и размышляющий ум. Разрушая каноны средневекового мышления, она прокламирует права человеческой личности, веру в силу человеческого ума, «открытие человека». «Духовная диктатура церкви была сломлена». «Рамки старого orbis terrarum были разбиты; только теперь собственно была открыта земля и положены основы для позднейшей мировой торговли и для перехода ремесла в мануфактуру…» (Энгельс, старое введение к «Диалектике природы»). Молодая буржуазия стремительно раздвигала горизонты дотоле известного мира. Рост торговли и промышленности стимулировал успехи точных знаний. Наряду с интересом к человеку появился и быстро развивался интерес к природе и ее тайнам, совершалось величественное «открытие мира». И вот, отталкиваясь от средневековой идеологии, представители поднимавшейся буржуазии, в поисках новых идеологических формул, обратились в сторону античной культуры, выросшей на почве развитого товарно-денежного хозяйства и богатой готовыми формулами. В Италии обращение к древности напрашивалось особенно настоятельно. Страна была богата памятниками старины, преданиями о былом величии, о господстве над миром далеких предков. Ореол древнего Рима был живой легендой, и воскрешение античной культуры казалось не орудием социальной борьбы, чем оно было прежде всего, а восстановлением былой славы.</p><p class=»tab»>Изучение древности в соединении со всем тем, что должно делать человека «человечнее», т. е. лучше в моральном смысле и полноценнее в интеллектуальном, создало гуманизм (см. Гуманисты). В нем Р. получил мощное орудие, неисчерпаемый источник идейных лозунгов. Эти лозунги появлялись по мере того, как буржуазия, повиновавшаяся все усложнявшимся интересам, расширяла и углубляла свои запросы. И постепенно создалась группа людей, к-рые целиком посвятили себя этой идейной работе, первенцы европейской интеллигенции — гуманисты.</p><p class=»tab»>Их работа привела очень скоро к двум результатам. Во-первых, стремясь дать возможно более исчерпывающие ответы на запросы, предъявляемые развитием буржуазных отношений, гуманисты углубили изучение классического литературного наследства. Они расширили фонд античных рукописей путем планомерных поисков. Они привлекли к изучению кроме римских писателей, известных в значительной мере средневековым ученым, еще и греческих, к-рых последние знали лишь в переводе, ибо не были знакомы с греческим языком. Они собирали большой подсобный материал по эпиграфике и древностям всякого рода, словом, все, что обогащало их знание древности. Во-вторых, их изучение античности связано с эстетическими моментами, которые облегчали пропаганду и усвоение античных идей теми группами, интересам которых античные идеи служили. Что это были группы крупной буржуазии, подтверждается строго аристократическим характером гуманистической культуры, начиная от первых ее апостолов — Петрарки (см.), Бокаччо (см.) и их сверстников.</p><p class=»tab»>Этой особенности было почти совершенно лишено второе идейное орудие Р. в Италии — литература на итальянском языке. Гуманизм одно время был для нее большой помехой. После Данте, сознательно писавшего по-итальянски, чтобы быть понятым всеми, первые последовательные гуманисты (Салутати, Никколи, Бруни) стали отрицать за итальянской литературой серьезное значение и даже вести с нею борьбу. Это конечно ни к чему не приводило. Итальянская литература продолжала развиваться до середины XV в. в замедленном темпе, потом все быстрее. И она не была обусловлена исключительно идеологией одной только верхушки буржуазии, как гуманистическая литература, а отвечала запросам всех ее групп. Поэзия и проза при этом развертывались одинаково. Это — второе очень важное отличие от средних веков, к-рые, можно сказать, совершенно не знали прозаической литературы на национальных языках. Создание лит-ой прозы, так же как и приобщение греческого языка к научной работе, — целиком дело Р. Из видов прозаической литературы, созданных Р., наибольшее распространение получил тот жанр, который больше всего соответствовал буржуазным вкусам, — новелла (см.). В ней получила наиболее полное осуществление эстетика буржуазии. Деловому уму и настроению поднимавшейся буржуазии во все эпохи, когда она могла диктовать литературе свои вкусы, больше всего отвечал реализм. Литература, к-рая была лишена реалистических черт, не могла рассчитывать на успех у буржуазии. Поэтому черты реализма прививались ко всем литературным жанрам. Р. организовал эту тенденцию. По мере развития литературы на национальных языках реализм становился ее особенностью и в эпосе и в драме. Но реализм стал особенностью не только литературы. Он преобразовал и всю область искусства. Начиная от Брунелески, Донателло, Мазаччо, реализм все больше и больше становится господствующим стилем в искусстве. Как и в литературе, на первых порах это делалось стихийно, а потом постепенно превратилось в ясно осознанную тенденцию, под к-рую художники старались подвести научный фундамент. Мало-по-малу в своих теоретических сочинениях такие художники, как Л. Б. Альберти, Гиберти, Франческо ди Джорджо, Пьеро делла Франческа, стали пропагандировать мысль о том, что для наибольшего успеха своего искусства художник должен вооружить себя различными теоретическими знаниями, в конечном счете знанием математики. К математике вели запросы и архитектуры через механику, и скульптуры через учение о пропорциях человеческого тела, и живописи через учение о перспективе. В «Трактате о живописи» Леонардо да Винчи все эти мысли нашли чрезвычайно яркое выражение и оплодотворили не только профессиональные запросы художников, но и теоретические изыскания ученых. Великой исторической заслугой итальянского Р. навсегда останется то, что в его исканиях и достижениях гармонически сливались интересы науки, искусства, литературы. На первых порах реалистическая литература изощряла свой стиль гл. обр. в новелле. В произведениях своего гениального представителя Бокаччо новелла отвечала интересам и вкусам крупной буржуазии; недаром Бокаччо был видным гуманистом. Но уже в конце XIV в. в той же Флоренции, где был создан «Декамерон», появился сборник Франко Саккетти (см.), рассчитанный на вкусы мелкой буржуазии.</p><p class=»tab»>Это разнообразие новелла сохранила до конца не только в Италии, но и в других странах совершенно так же, как и поэзия на национальных языках.</p><p class=»tab»>С поэзией в Италии было несколько сложнее, чем с прозой. Над итальянской лирикой долго тяготело наследие эпохи еретической культуры: куртуазные условности, привитые провансальской поэзией и густо пропитанные рыцарскими, т. е. феодальными тенденциями. Лирика освободилась от них с трудом и не скоро. Не только на дантовой лирике, но и на стихах Петрарки, не имевшего прочных связей с бытом итальянской коммуны, эти условности еще заметны. От них была совершенно свободна лирика, отвечавшая вкусам низших групп буржуазии (Фольгоре да Сан Джиминиано и Чекко Анджолиери в Сиене, Гвидо Орланди во Флоренции); она была вполне реалистична. Эти неровности отмечают линию постепенного освобождения от вкусов феодальной эпохи.</p><p class=»tab»>Гуманизм сохранял свое значение главного культурного и идеологического орудия крупной буржуазии до тех пор, пока держалось ее господство. В разных коммунах Италии это время не совпадало. Если взять Флоренцию, то в ней пора высшей мощи буржуазии будет довольно точно охватывать столетие между восстанием чомпи (1378), т. е. «оборванцев», — этим ярким проявлением классовой борьбы внутри итальянских коммун, где уже в эпоху Данте наметилось столкновение «тощего народа» (populo minuto — плебс, ремесленное мещанство) с «жирным народом» (populo grasso — верхушечные слои буржуазии), — и заговором Пацци (1478). Господство крупной буржуазии держалось все это время на крепком фундаменте хороших дел. Торговля, промышленность, банковое дело, одолев кризисы средних десятилетий XIV века, процветали как никогда. То была кульминационная пора Р., что и породило в науке неправильное представление, что гуманизм и Р. одно и то же или даже что Р. («возрождение классической древности») является первым веком гуманизма. Однако Р. не только начался раньше, чем появились первые гуманистические формулировки, он продолжался, когда гуманизм пришел в полное разложение. Гуманизм — не более как одно из течений Р.</p><p class=»tab»>Гуманизм стал терять свое первенствующее положение, как только появились первые признаки кризиса, сокрушившего политическое господство буржуазии. А эти признаки начали давать знать о себе как раз в 70-х гг. XV в. Ведь с 1453 в Дарданеллах и сирийских портах сидели турки, контрагент гораздо более суровый и тугой, чем дряблая Византия. В Европе зарождалось уже что-то вроде конкуренции, и некоторые государства, бывшие предметом итальянской эксплоатации в течение трех веков, стали собирать свои силы, создавать национальное единство и не только оказывали более энергичное сопротивление эксплоатации, но уже щетинились оружием против Италии: прежде всего Франция и Испания. Италии грозила утрата ее монополий, т. е. экономическая катастрофа. Деловые люди принимали меры: переводили капиталы из торговли и промышленности в землю. В культуре Р. в связи с этим наметился определенный поворот. Надо было бросать обычные темы гуманистических рассуждений: о благородстве, о добродетели, об изменчивости судьбы; они годились для спокойных безоблачных времен. Теперь надо было писать о вещах практически нужных: о том, как усовершенствовать прядильные и ткацкие приборы, как поднимать урожай, как вести хозяйство в обширных загородных имениях, чтобы оно давало больше дохода; нужно было больше интересоваться географией, чтобы ориентироваться в вопросе, где искать новых рынков сырья и сбыта; надо было изучать естествознание, чтобы господствовать над природой и лучше ее эксплоатировать; надо было наконец изучать математику как основу всех точных наук. Все это было разрывом с гуманизмом. Но это был Ренессанс, только на новом повороте. Паоло Тосканелли, Лука Пачоли, Леонардо да Винчи (см.), Тарталья, Кардано — такие же типы Р., как корифеи гуманизма: Поджо (см.), Валла, Полициано (см.).</p><p class=»tab»>Но и этого было мало. По мере того как угроза феодальной реакции усиливалась вместе с иноземными нашествиями, война раздирала итальянскую землю и опасность нависала над самим политическим бытием Италии, — выдвигались вопросы политического искусства и политической науки, а за ними их основание — социология. В них искали громоотвода против бури, бушевавшей в Италии. Никколо Макьявелли (см.), великий мыслитель, типичнейший выразитель интересов буржуазии, с колоссальным напряжением гения положил основание социологии и политике как самостоятельным дисциплинам. Это тоже было разрывом с гуманизмом, но это тоже был Ренессанс на более позднем этапе, когда опасность феодальной реакции стала уже совсем очевидной.</p><p class=»tab»>Художественная литература отражала эти экономические, социальные и политические процессы так же, как и наука, так же, как и искусство. Необыкновенное богатство литературных жанров и стилей в последние десятилетия XV в. и в первые десятилетия XVI объясняется именно тем, что разные культурные центры Италии переживали разные моменты социального и политического развития. Это сказывалось одинаково ярко и в лирике, и в эпосе, и в драме. Лирика, которая во Флоренции непрерывно и далеко не совсем мирно эволюционировала от демократического, иной раз бунтарского реализма (Буркиелло) к элегантным стихам Полициано и самого Лоренцо Медичи (см.), в центрах более выраженной дворянской культуры (Неаполь, Феррара, Урбино) принимала характер манерного петраркизма и давала ультравычурные вирши Каритео и Тебальдео. Драма совершала размах от яркой беспощадной реалистической сатиры Макьявелли во Флоренции до безобидных подражаний древним у Ариосто в дворянской Ферраре и от элегантной трагедии Триссино в Ломбардии до бесцеремонных комедий Аретино (см.) в Венеции. В эпосе была предпринята художественная переработка сюжетов каролингского цикла использованием приемов и тематики бретонских поэм Круглого Стола. Но во Флоренции это превратилось в осмеяние рыцарства и феодального быта у Пульчи (см.), а в Ферраре — в апологию рыцарства и феодального быта у Боярдо (см.) и Ариосто (см.). А когда феодальная реакция сочеталась с католической, Феррара же дала третью поэму с апологией и рыцарства и церкви — «Освобожденный Иерусалим» Тассо (см.). Новелла, жанр наиболее гибкий и подвижный, отразила эти перемены, в ней аристократические ноты звучали все сильнее. За исключением быть может одного Фортини, сиенца, все новеллисты XVI в. отдают дань этой тенденции, даже Ласка (см.) и Фиренцуола (см.), флорентинцы, но писавшие уже после 1530, т. е. во времена герцогства. Нечего говорить, что ломбардцы — Джиральди Чинтио и лучший из новеллистов Чинквеченто Банделло (см.) — отражают дух феодальной реакции все ярче. А в Урбино граф Балтасар Кастильоне (см.) написал книгу, которая сделалась катехизисом феодального придворного обычая во всей Европе, хотя ее замысел и ее идейное содержание гораздо шире.</p><p class=»tab»>Одна только Венеция, единственное крупное итальянское государство, сохранившее после 1530 республиканский режим, сопротивлялась этой тенденции и пыталась противопоставить ей публицистические выступления в ярко буржуазном духе (письма, «предсказания») самого буйного и самого смелого из итальянских писателей Р. после Лоренцо Валлы, Пьетро Аретино (см.), к-рый стал «бичом монархов» и играл эту роль весело и беззаботно с немалой выгодой для себя.</p><p class=»tab»>Культура Ренессанса в Италии как создание буржуазии пережила падение социального и политического господства буржуазии не надолго. Но когда наступил момент ее разрушения, дело ее было сделано: она успела оплодотворить европейскую культуру творениями итальянского гения во всех областях мысли и творчества.</p><p class=»tab»>Много было споров о том, насколько велики размеры влияния Италии на остальные европейские страны в эту эпоху. Марксистский анализ помогает установить эти размеры без большого труда. Процессы, которые вели к созданию культуры Р. в Италии и вне Италии, были одни и те же. В других странах они только запоздали по естественным причинам. Торговля и промышленность стояли там не на столь высоком уровне, а феодальные элементы были гораздо более устойчивы и мощны, чем в Италии. Но когда экономический процесс и классовая борьба в разных государствах привели к таким же социальным результатам, к каким раньше пришла Италия, влияние Италии стало сейчас же сказываться на темпах культурного роста. Заимствования, как всегда в социальных процессах, определяли больше детали, чем главное, ибо главное было обусловлено местными отношениями. Мирской дух, отрицание авторитета церкви, культ личности, индивидуалистические моменты вообще были даны социальными процессами и классовой борьбой внутри каждой страны. Буржуазия, как только оказывалась в силах, сейчас же провозглашала эти элементы нового миропонимания как некий догмат, и напр. такие произведения, как «Роман о розе» во Франции, особенно его вторая часть (середина XIV в.), или «Кентерберийские рассказы» Чосера (см.) в Англии (конец XIV в.), подводят итог местным процессам и отмечают те этапы, к-рые определяются первыми решительными победами буржуазии. Но на произведении Чосера лежит печать более близкого знакомства с Италией, чем на поэме Жана де Мена (Jean de Meung). Ибо Англия находилась в более тесных деловых сношениях с Италией, чем разоренная войной Франция, и Чосер в течение 70-х гг. XIV в. дважды побывал в Италии. Обе вещи пропитаны идеями Р., но их не причисляют к ренессансной литературе только потому, что после Мена и Чосера, современников Петрарки и Бокаччо, на родине каждого был перерыв в развитии культуры: в Англии — из-за войны Роз, во Франции — из-за разорения, вызванного Столетней войной. Германия не поспевала за культурным ростом Италии вследствие своей раздробленности, а Испания — вследствие трудных условий реконкисты, войны с маврами. Но поскольку внутренние процессы разложения феодального уклада совершались в большей или меньшей мере в каждой из этих стран и буржуазия отвоевывала себе право на культурную автономию, миропонимание Р. прокладывало себе пути и там, хотя медленно, но неуклонно.</p><p class=»tab»>Культурная жизнь вне Италии восстанавливается в последней трети XV в. Местные процессы к этому времени завершаются соответственно результатам классовой борьбы в каждой стране. Буржуазия становится на ноги, и тут открывается широкий путь для заимствований из Италии. Классическое наследие, усваиваемое уже в результатах работ итальянских гуманистов, естественно было лишено тех эстетико-патриотических украшений, в к-рых оно воспринималось в Италии, но оно сейчас же сделалось предметом самостоятельного изучения (Агрикола и Вимпфелинг в Германии, Гагэн (Gaguin) и Фише во Франции, Гроссаин (W. Grocyn) в Англии), к-рое пошло настолько успешно, что ученики обогнали учителей: таких филологов, как Рейхлин и Эразм (см.) в Германии, Колет (J. Colet) в Англии, Бюде во Франции, Италия соответствующего периода не имела.</p><p class=»tab»>Во всех этих трех странах гуманистическая наука скоро приняла ярко-боевой характер, которого в Италии она была лишена. Она сделалась опорою протестов против Рима местной буржуазии, кое-где сумевшей притянуть к себе в союзники и другие общественные группы. Гуманизм стал опорою реформационного движения. Такие вожди Реформации, как Лефевр д’Этапль во Франции, Меланхтон в Германии, Цвингли в Швейцарии, вышли из гуманистических рядов, не говоря уже о том, что за Реформацию ратовали наиболее пылкие передовые бойцы гуманизма: в Германии Гуттен (см.) и эрфуртская фаланга, общими силами сочинявшие «Письма темных людей» (см.), во Франции Этьен Доле, погибший на костре. Однако Реформация же развела повсюду по разным дорогам гуманистов. Наиболее авторитетные из немецких гуманистов, Рейхлин и Эразм, после некоторых колебаний остались в католическом лагере, за что им пришлось выслушивать яростные упреки Гуттена. Наиболее радикальные представители французского гуманизма, Деперье и Рабле, отвергли одинаково и католицизм и протестантизм. А наиболее живой и искренний из английских гуманистов Томас Мор (см.) сложил голову на плахе, не желая поддерживать реформационную политику Генриха VIII. Реформация, предъявлявшая большие требования к богословскому экзегетическому анализу, сделала гуманизм в этих странах более живучим, чем в Италии, где общественный смысл его существования утратился раньше, где гуманистов уже в 30-х гг. XVI века стали именовать педантами и где главный герольд буржуазного мировоззрения — Аретино — нещадно над ними издевался.</p><p class=»tab»>В области художественной литературы в различных странах отталкивание от средневековых принципов, так же как и в Италии, сказалось главным образом в том, что сразу же наметился переход от особенностей средневекового литературного стиля, типичного для феодально-церковной культуры, с его аллегоризмом, символизмом, отвлеченностью, к стилю, отвечающему вкусам и настроениям молодой буржуазии, — к реализму.</p><p class=»tab»>Как и в Италии, реализм, реалистическое восприятие жизни начали прокладывать себе дорогу очень рано и независимо от каких бы то ни было влияний. Художественный реализм как стиль сделался орудием социальной борьбы в области идеологии в руках молодой европейской буржуазии. Еще до того момента, когда в той или иной стране полностью утвердилась настоящая ренессансная идеология, реализм в области художественного стиля создал свои специальные жанры: фаблио (см.), шванки (см. Шванк), рассказы о животных и пр. Ренессанс укрепил и облагородил эту тенденцию тем, что внес, опять так же как и в Италии, реалистическое направление большое мастерство, изощренное на изучении античных образцов.</p><p class=»tab»>Литература на местных языках носила на себе печать подражания итальянскому в том, что было наименее оригинально, например в новелле во Франции. «Сто новых новелл», сборник, вышедший при Людовике XI, и «Гептамерон» (1559) Маргариты Ангулемской, вышедший при Франциске I, являются прямым подражанием итальянцам, как и некоторые писания Мурнера (см. «Немецкая литература», раздел «От Реформации до 30-летней войны») в Германии. Но те произведения, к-рые сделали эпоху в литературе каждой страны и проникнуты целиком духом Возрождения, т. е. тенденциями реализма и свободной мысли, глубоко оригинальны. И то обстоятельство, что они оригинальны, что они отвечают интересам и вкусам передового класса в каждой стране, сопричислило эти произведения к достоянию мировой литературы. Таков во Франции роман Рабле (см.), художественная энциклопедия, ироническая, стоящая у конечной грани Р., подобно тому как у его исходной грани стояла художественная энциклопедия патетическая — «Божественная комедия» Данте Алигиери. Таков в Испании роман Сервантеса (см.) и драма в первый период ее расцвета, к к-рому принадлежат не только Лопе де Руэда и интермедии Сервантеса, но в значительной мере и Лопе де Вега (см.) и Тирсо де Молина (см.). И такова драма в Англии у предшественников Шекспира и у самого Шекспира (см.). В Испании феодальная реакция, вызванная отливом золота из страны и банкротством торгового капитала, оказала свое действие на творчество Лопе де Веги и Тирсо и целиком определила творчество Кальдерона (см.), который выходит за пределы Р., а в Англии феодальная реакция, сказывавшаяся в политическом быту усилением шотландских влияний при Иакове I, наложила свой отпечаток на последние вещи Шекспира и на всю драматургию его последователей. Как и в Италии, влияние социальной реакции, вызванное конечно местными процессами, в литературе сказалось в том, что тускнел реализм, усиливалась тяга к фантастике и мистике и все большее место захватывала идеология дворянская.</p><p class=»tab»>В области общественной мысли Р. ярким предвестником далекого еще коммунизма выделяется проникнутая протестом против социальной несправедливости, разоблачающая «заговор богатых» «Утопия» Томаса Мора, вполне реалистическая в своей критической части, полная фантазии в части обрисовки идеального строя будущего. Но фантастика Мора не реакционная, как у Кальдерона, а новая, революционная, перехлестнувшая наивысший подъем идеологии Р.</p><p class=»tab»></p><p class=»tab»><span><b>Библиография:</b></span></p><p class=»tab»>Кроме указ. в тексте: Voigt G., Die Wiederbelebung des klassischen Altertums, oder das erste Jahrhundert des Humanismus, 3 Aufl., 1893; Geiger L., Renaissance u. Humanismus in Italien u. Deutschland, Berlin, 1882; Spingarn J. E., A History of literary criticism in the Renaissance, 2 ed., 1908; Burdach K., Sinn u. Ursprung der Worte Renaissance u. Reformation (Sitzungsberichte der kgl. Preuss. Akademie der Wissenschaften), 1910; Его же, Reformation, Renaissance u. Humanismus, Berlin, 1918, 2 Aufl., Berlin, 1926; Morf H., Geschichte der franzosischen Literatur im Zeitalter der Renaissance, 2 Aufl., Berlin, 1914; Arnold R., Die Kultur der Renaissance, 3 Aufl., Berlin, 1920; Hasse R. P., Die deutsche Renaissance, 2 Bde, Meerane, 1920-1925; Его же, Die italienische Renaissance, 2 Aufl., Lpz., 1925; Walser E., Studien zur Weltanschauung der Renaissance, Basel, 1920; Его же, Gesammelte Studien zur Geistesgeschichte der Renaissance, Basel, 1932; Monnier P., Le Quattrocento, 2-me ed., P., 1920; Engel-Janosi F., Soziale Probleme der Renaissance, Stuttgart, 1924; Hatzfeld H., Die franzosische Renaissancelyrik, Munchen, 1924; Schirmer W. F., Antike Renaissance u. Puritanismus, Munchen, 1924, 2 Aufl., 1933; Plattard J., La Renaissance des lettres en France de Louis XII a Henri IV, P., 1925; Riekel A., Die Philosophie der Renaissance, Munchen, 1925; Haupt A., Geschichte der Renaissance in Spanien u. Portugal, Stuttgart, 1927; Sainean L., Problemes litteraires du 16-e siecle, P., 1927; Aronstein P., Das englische Renaissancedrama, Lpz., 1929; Фойгт Г., Возрождение классической древности, или первый век гуманизма, тт. I-II, М., 1884-1885; Гейгер Л., История немецкого гуманизма, СПБ, 1899; Монье П., Кватроченто, Опыт литературной истории Италии XV в., СПБ, 1904; Буркгардт Я., Культура Италии в эпоху Возрождения, тт. I-II, СПБ, 1905-1906; Зайчик С., Люди и искусство итальянского Возрождения, СПБ, 1906; Веселовский А., Вилла Альберти. Новые материалы для характеристики литературного и общественного перелома в итальянской жизни XIV-XV вв., М., 1870 (или в «Собр. сочин.», изд. Академии наук, т. III, СПБ, 1901); Его же, Противоречия итальянского Возрождения, «ЖМНП», 1887, № 12; Корелин М., Очерки итальянского Возрождения, М., 1910; Его же, Ранний итальянский гуманизм и его историография, изд. 2, тт. I-IV, СПБ, 1914; Де ла Барт Ф., Беседы по истории всеобщей литературы, ч. 1. Средние века и Возрождение, М., 1914; Вульфиус А., Проблемы духовного развития гуманизма. Реформация и католическая реформа, П., 1922 (библиография); Дживелегов А., Начало итальянского Возрождения, изд. 2, Москва, 1925; Его же, Очерки итальянского Возрождения, Москва, 1929. См. также библиографию к писателям, называемым в тексте, а также к отдельным национальным литературам.</p>… смотреть

РЕНЕССАНС