В данном слове ударение должно быть поставлено на слог с буквой И — тарантИт.

от слова тарантить

Задайте свой вопрос или пожалуйтесь на ошибку в комментариях.

На текущей странице указано на какой слог правильно ставить ударение в слове тарантит. В слове «тарантит» ударение падает на слог с буквой И — таранти́т.

Надеемся, что теперь у вас не возникнет вопросов, как пишется слово тарантит, куда ставить ударение, какое ударение, или где должно стоять ударение в слове тарантит, чтобы верно его произносить.

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

тасо́ванный, кр. ф. -ан, -ана

Рядом по алфавиту:

таска́ние , -я

та́сканный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана, прич.

та́сканый , прил.

таска́ть(ся) , -а́ю(сь), -а́ет(ся)

таскба́р , -а (инф.)

та́скивать , наст. вр. не употр.

таскме́неджер , -а (программ.)

та́ском , нареч.

таскотня́ , -и́

таску́н , -уна́

таску́нья , -и, р. мн. -ний

тасмани́йка , -и, р. мн. -и́ек

тасмани́йский , (от Тасма́ния)

тасмани́йцы , -ев, ед. -и́ец, -и́йца, тв. -и́йцем

тасова́ние , -я

тасо́ванный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

тасова́ть(ся) , тасу́ю, тасу́ет(ся)

тасо́вка , -и (к тасова́ть)

та́ссовец , -вца, тв. -вцем, р. мн. -вцев

тассо́вка , -и, р. мн. -вок (к ТАСС, сниж.)

та́ссовский , (от ТАСС)

тастату́ра , -ы

тастату́рный

тата́канье , -я

тата́кать , -аю, -ает

тата́ми , нескл., м. и с.

татарва́ , -ы́

тата́рка , -и, р. мн. -рок

тата́рник , -а

тата́ро-монго́лы , -ов

тата́ро-монго́льский

Определить верный вариант написания лексемы «потрачено» или «потраченно» непросто. Согласно норме русского языка следует писать в этом слове одну или две «н»? Поможет выбрать правильный вариант орфографическое правило. Приведём его ниже.

Как правильно пишется?

В суффиксе изучаемой лексемы следует писать одну «н» – «потрачено».

Какое правило применяется?

«Потрачено» (что сделано?) – это краткое страдательное причастие прошедшего времени и среднего рода (совершенный вид). Лексема образовалась от полного причастия «потраченный».

Известно, что в суффиксах кратких страдательных причастий прошедшего времени корректно писать одну согласную «н».

Значит, правильно – «потрачено», где:

- «по» – префикс;

- «трач» – корень;

- «ен» – суффикс;

- «о» – окончание.

Основа – «потрачен».

Примеры предложений

- На поиск подарка было потрачено много времени и сил.

- Зрители даже не догадывались, сколько времени было потрачено на отработку этого трюка.

- На новые проектные разработки было потрачено больше двух недель.

- За период строительства денег было потрачено меньше, чем предполагалось.

Как неправильно писать

Неверным считается написание краткого причастия с двумя «н» – «потраченно».

Правильное написание слова тарантасик:

тарантасик

Крутая NFT игра. Играй и зарабатывай!

Количество букв в слове: 10

Слово состоит из букв:

Т, А, Р, А, Н, Т, А, С, И, К

Правильный транслит слова: tarantasik

Написание с не правильной раскладкой клавиатуры: nfhfynfcbr

Тест на правописание

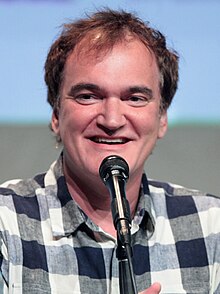

Что означает имя Тарантино? Что обозначает имя Тарантино? Что значит имя Тарантино для человека? Какое значение имени Тарантино, происхождение, судьба и характер носителя? Какой национальности имя Тарантино? Как переводится имя Тарантино? Как правильно пишется имя Тарантино? Совместимость c именем Тарантино — подходящий цвет, камни обереги, планета покровитель и знак зодиака. Полная характеристика имени Тарантино и его подробный анализ вы можете прочитать онлайн в этой статье совершенно бесплатно.

Анализ имени Тарантино

Имя Тарантино состоит из 9 букв. Имена из девяти букв – признак склонности к «экономии энергии» или, проще говоря – к лени. Таким людям больше всего подходит образ жизни кошки или кота. Чтобы «ни забот, ни хлопот», только возможность нежить свое тело, когда и сколько хочется, а так же наличие полной уверенности в том, что для удовлетворения насущных потребностей не придется делать «лишних движений». Проанализировав значение каждой буквы в имени Тарантино можно понять его тайный смысл и скрытое значение.

Значение имени Тарантино в нумерологии

Нумерология имени Тарантино может подсказать не только главные качества и характер человека. Но и определить его судьбу, показать успех в личной жизни, дать сведения о карьере, расшифровать судьбоносные знаки и даже предсказать будущее. Число имени Тарантино в нумерологии — 8. Девиз имени Тарантино и восьмерок по жизни: «Я лучше всех!»

- Планета-покровитель для имени Тарантино — Сатурн.

- Знак зодиака для имени Тарантино — Лев, Скорпион и Рыбы.

- Камни-талисманы для имени Тарантино — кальцит, киноварь, коралл, диоптаза, слоновая кость, черный лигнит, марказит, мика, опал, селенит, серпентин, дымчатый кварц.

«Восьмерка» в качестве одного из чисел нумерологического ядра – это показатель доминанантного начала, практицизма, материализма и неистребимой уверенности в собственных силах.

«Восьмерка» в числах имени Тарантино – Числе Выражения, Числе Души и Числе внешнего облика – это, прежде всего, способность уверенно обращаться с деньгами и обеспечивать себе стабильное материальное положение.

Лидеры по натуре, восьмерки невероятно трудолюбивы и выносливы. Природные организаторские способности, целеустремленность и незаурядный ум позволяют им достигать поставленных целей.

Человек Восьмерки напоминает сейф, так сложно его понять и расшифровать. Истинные мотивы и желания Восьмерки с именем Тарантино всегда скрыты от других, трудно найти точки соприкосновения и установить легкие отношения. Восьмерка хорошо разбирается в людях, чувствует характер, распознает слабости и сильные стороны окружающих. Любит контролировать и доминировать в общении, сама не признает своих ошибок. Очень часто жертвует своими интересами во имя семьи. Восьмерка азартна, любит нестандартные решения. В любой профессии добивается высокого уровня мастерства. Это хороший стратег, который не боится ответственности, но Восьмерке трудно быть на втором плане. Тарантино учится быстро, любит историю, искусство. Умеет хранить чужие секреты, по натуре прирожденный психолог. Порадовать Восьмерку можно лишь доверием и открытым общением.

- Влияние имени Тарантино на профессию и карьеру. Оптимальные варианты профессиональной самореализации «восьмерки – собственный бизнес, руководящая должность или политика. Окончательный выбор часто зависит от исходных предпосылок. Например, от того, кто папа – сенатор или владелец ателье мод — зависит, что значит число 8 в выборе конкретного занятия в жизни. Подходящие профессии: финансист, управленец, политик.

- Влияние имени Тарантино на личную жизнь. Число 8 в нумерологии отношений превращает совместную жизнь или брак в такое же коммерческое предприятие, как и любое другое. И речь в данном случае идет не о «браке по расчету» в общепринятом понимании этого выражения. Восьмерки обладают волевым характером, огромной энергией и авторитетом. Однажды разочаровавшись в человеке, они будут предъявлять огромные требования к следующим партнерам. Поэтому им важны те, кто просто придет им на помощь без лишних слов. Им подойдут единицы, двойки и восьмерки.

Планета покровитель имени Тарантино

Число 8 для имени Тарантино означает планету Сатурн. Люди этого типа одиноки, они часто сталкиваются с непониманием со стороны окружающих. Внешне обладатели имени Тарантино холодны, но это лишь маска, чтобы скрыть свою природную тягу к теплу и благополучию. Люди Сатурна не любят ничего поверхностного и не принимают опрометчивых решений. Они склонны к стабильности, к устойчивому материальному положению. Но всего этого им хоть и удается достичь, но только своим потом и кровью, ничего не дается им легко. Они постоянны во всем: в связях, в привычках, в работе. К старости носители имени Тарантино чаще всего материально обеспечены. Помимо всего прочего, упрямы, что способствует достижению каких-либо целей. Эти люди пунктуальны, расчетливы в хорошем смысле этого слова, осторожны, методичны, трудолюбивы. Как правило, люди Сатурна подчиняют себе, а не подчиняются сами. Они всегда верны и постоянны, на них можно положиться. Гармония достигается с людьми второго типа.

Знаки зодиака имени Тарантино

Для имени Тарантино подходят следующие знаки зодиака:

Цвет имени Тарантино

Розовый цвет имени Тарантино. Люди с именем, носящие розовый цвет, — сдержанные и хорошие слушатели, они никогда не спорят. Хотя всегда имеют своё мнение, которому строго следуют. От носителей имени Тарантино невозможно услышать критики в адрес других. А вот себя они оценивают люди с именем Тарантино всегда критично, из-за чего бывают частые душевные стяжания и депрессивные состояния. Они прекрасные семьянины, ведь их невозможно не любить. Положительные черты характера имени Тарантино – человеколюбие и душевность. Отрицательные черты характера имени Тарантино – депрессивность и критичность.

Как правильно пишется имя Тарантино

В русском языке грамотным написанием этого имени является — Тарантино. В английском языке имя Тарантино может иметь следующий вариант написания — Tarantino.

Видео значение имени Тарантино

Вы согласны с описанием и значением имени Тарантино? Какую судьбу, характер и национальность имеют ваши знакомые с именем Тарантино? Каких известных и успешных людей с именем Тарантино вы еще знаете? Будем рады обсудить имя Тарантино более подробно с посетителями нашего сайта в комментариях ниже.

Если вы нашли ошибку в описании имени, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

| В Википедии есть статья «Тарантино». |

Содержание

- 1 Русский

- 1.1 Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

- 1.2 Произношение

- 1.3 Семантические свойства

- 1.3.1 Значение

- 1.3.2 Синонимы

- 1.3.3 Антонимы

- 1.3.4 Гиперонимы

- 1.3.5 Гипонимы

- 1.4 Родственные слова

- 1.5 Этимология

- 1.6 Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- 1.7 Перевод

- 1.8 Библиография

Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| м. | ж. | ||

| Им. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Р. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Д. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| В. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Тв. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Пр. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

Та—ран—ти́—но

Существительное, одушевлённое, несклоняемое. Имя собственное (фамилия).

Корень: -Тарантино-.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [tərɐnʲˈtʲinə]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- итальянская фамилия ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

- —

Антонимы[править]

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- фамилия

Гипонимы[править]

- —

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Разбор слова «тарантино»

Фонетический (звуко-буквенный), а также морфемный (по составу, по частям речи) разбор слова «тарантино». Транскрипция, слоги, цветовые схемы и другие справочные материалы.

Морфемный разбор слова «тарантино»

Слоги в слове «тарантино»

Синонимы, антонимы и гипонимы к слову «тарантино»

Гиперонимы к слову «тарантино»:

- фамилия

А вы знаете, что означает слово «тарантино»?

(Tarantino) Квентин (р.

1963), американский киноактер, сценарист, режиссер. В кино дебютировал, снявшись в англоязычном фильме Ж.-Л. Годара «Король Лир» (

1987). Одна из самых ярких и талантливых фигур мирового кино 1990-х гг., в большой степени повлиявшая на формирование кинопроцесса. После режиссерского дебюта («Бешеные псы»,

1992) приобрел репутацию «второго Мартина Скорсезе», т. е. режиссера, не боящегося показа откровенного насилия, но скрывающего под жанровой сюжетной оболочкой четкий моральный посыл. За второй фильм «Криминальное чтиво» в 1994 получил «Золотую пальмовую ветвь» Каннского кинофестиваля и «Оскар» за лучший сценарий (совместно с Р. Эйвари).

(Современный толковый словарь, БСЭ)

Что Такое Тарантино- Значение Слова Тарантино

Русский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| м. | ж. | ||

| Им. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Р. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Д. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| В. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Тв. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

| Пр. | Таранти́но | Таранти́но | Таранти́но |

Та—ран—ти́—но

Существительное, одушевлённое, несклоняемое. Имя собственное (фамилия).

Корень: -Тарантино-.

Произношение

- МФА: [tərɐnʲˈtʲinə]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- итальянская

- —

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

-

- —

Родственные слова

Ближайшее родство - существительные: тарантиноман

- прилагательные:

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

Список переводов Библиография

|

Quentin Tarantino |

|

|---|---|

Tarantino at the 2015 San Diego Comic-Con |

|

| Born |

Quentin Jerome Tarantino March 27, 1963 (age 59) Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S.[1] |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1987–present |

| Works | Filmography |

| Spouse |

Daniella Pick (m. ) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

|

Quentin Jerome Tarantino (; born March 27, 1963) is an American film director, writer, producer, and actor. His films are characterized by frequent references to popular culture and film genres, non-linear storylines, dark humor, stylized violence, extended dialogue, pervasive use of profanity, cameos and ensemble casts.

Tarantino began his career as an independent filmmaker with the release of the crime film Reservoir Dogs in 1992. His second film, Pulp Fiction (1994), a dark comedy crime thriller, was a major success with critics and audiences winning numerous awards, including the Palme d’Or and the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. In 1996, he appeared in From Dusk till Dawn, also writing the screenplay. Tarantino’s third film, Jackie Brown (1997), paid homage to blaxploitation films.

In 2003, Tarantino directed Kill Bill: Volume 1, inspired by the traditions of martial arts films; it was followed by Volume 2 in 2004. He then made the exploitation slasher Death Proof (2007), part of a double feature with Robert Rodriguez, released under the collective title Grindhouse. His next film Inglourious Basterds (2009) told an alternate history with the war film genre. He followed this with Django Unchained (2012), a slave revenge Spaghetti Western, which won him his second Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. Tarantino’s eighth film, The Hateful Eight (2015), was a revisionist Western thriller and opened to audiences with a roadshow release. His most recent film, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), is a comedy drama set in the late 1960s about the transition of Old Hollywood to New Hollywood. A novelization of the film was also published in 2021, becoming his debut novel.

Tarantino’s work has been subject to controversy, such as the depictions of violence, frequent inclusion of racial slurs and the alleged negligence of safety in his handling of stunt scenes on Kill Bill: Volume 2. During his career, Tarantino’s films have garnered a cult following, as well as critical and commercial success. He has been considered «the single most influential director of his generation», and listed as one of the most influential people in the world. Apart from receiving the Palme d’Or and two Academy Awards, his other major awards include two BAFTAs and four Golden Globes.

Early life

Tarantino was born on March 27, 1963, in Knoxville, Tennessee, the only child of Connie McHugh and aspiring actor Tony Tarantino, who left the family before his son’s birth.[1][2] He is of Irish ancestry through his mother, though he claims she is half-Cherokee; his father is of Italian descent.[3][2] He was named in part after Quint Asper, Burt Reynolds’s character in the TV series Gunsmoke.[4] Tarantino’s mother met his father during a trip to Los Angeles. After a brief marriage and divorce, Connie left Los Angeles and moved to Knoxville, where her parents lived. In 1966, Tarantino returned with his mother to Los Angeles.[5][6]

Tarantino’s mother married musician Curtis Zastoupil soon after arriving in Los Angeles, and the family moved to Torrance, a city in Los Angeles County’s South Bay area.[7][8] Zastoupil accompanied Tarantino to numerous film screenings while his mother allowed him to see more mature movies, such as Carnal Knowledge (1971) and Deliverance (1972). After his mother divorced Zastoupil in 1973, and received a misdiagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Tarantino was sent to live with his grandparents in Tennessee. He remained there less than a year before returning to California.[9][10]

At 14 years old, Tarantino wrote one of his earliest works, a screenplay called Captain Peachfuzz and the Anchovy Bandit, based on the 1977 film Smokey and the Bandit. Tarantino later revealed that his mother had ridiculed his writing skills when he was younger; as a result, he vowed that he would never share his wealth with her.[11] As a 15-year-old, Tarantino was grounded by his mother for shoplifting Elmore Leonard’s novel The Switch from Kmart. He was allowed to leave only to attend the Torrance Community Theater, where he participated in such plays as Two Plus Two Makes Sex and Romeo and Juliet.[9] The same year, he dropped out of Narbonne High School in Harbor City, Los Angeles.[12][13]

Career

1980s: Early jobs and screenplays

Through the 1980s, Tarantino had a number of jobs. After lying about his age, he worked as an usher at an adult movie theater in Torrance, called the Pussycat Theater. He spent time as a recruiter in the aerospace industry, and for five years he worked at Video Archives, a video store in Manhattan Beach, California.[14][15] He was well known in the local community for his film knowledge and video recommendations; Tarantino stated, «When people ask me if I went to film school, I tell them, ‘No, I went to films.»[16][a] In 1986, Tarantino was employed in his first Hollywood job, working with Video Archives colleague Roger Avary, as production assistants on Dolph Lundgren’s exercise video, Maximum Potential.[17]

Before working at Video Archives, Tarantino co-wrote Love Birds In Bondage with Scott Magill. Tarantino would go on to produce and direct the short film. Magill committed suicide in 1987, but not before destroying all footage that had been shot.[18] Later, Tarantino attended acting classes at the James Best Theatre Company, where he met several of his eventual collaborators for his next film.[19][20][b] In 1987, Tarantino co-wrote and directed My Best Friend’s Birthday (1987). It was left uncompleted, but some of its dialogue was included in True Romance.[23]

The following year, he played an Elvis impersonator in «Sophia’s Wedding: Part 1», an episode in the fourth season of The Golden Girls, which was broadcast on November 19, 1988.[24] Tarantino recalled that the pay he received for the part helped support him during the preproduction of Reservoir Dogs; he estimated he was initially paid about $650, however the episode was frequently rerun because it was on a «best of…» lineup, therefore received about $3,000 in residuals over three years.[25]

1990s: Breakthrough

After meeting Lawrence Bender at a friend’s barbecue, Tarantino discussed with him about an unwritten dialogue-driven heist film. Bender encouraged Tarantino to write the screenplay, which he wrote in three-and-a-half weeks and presented to Bender unformatted. Impressed with the script, Bender managed to forward it through contacts to director Monte Hellman.[9] Hellman cleaned up the screenplay and helped secure funding from Richard N. Gladstein at Live Entertainment (which later became Artisan, now known as Lionsgate).[26] Harvey Keitel read the script and also contributed to the budget, taking a role as co-producer and also playing a major part in the picture. In January 1992, it was released as Tarantino’s crime thriller Reservoir Dogs—which he wrote, directed, and acted in as Mr. Brown—and screened at the Sundance Film Festival. The film was an immediate hit, receiving a positive response from critics.[27][28]

Tarantino’s screenplay True Romance was optioned and the film was eventually released in 1993. The second script that Tarantino sold was for the film Natural Born Killers, which was revised by Dave Veloz, Richard Rutowski and director Oliver Stone. Tarantino was given story credit and stated in an interview that he wished the film well, but later disowned the final film.[29][30] Tarantino also did an uncredited rewrite on It’s Pat (1994).[31][32] Other films where he was an uncredited screenwriter include Crimson Tide (1995) and The Rock (1996).[33]

Following the success of Reservoir Dogs, Tarantino was approached by major film studios and offered projects that included Speed (1994) and Men in Black (1997), but he instead retreated to Amsterdam to work on his script for Pulp Fiction.[34][35]

Tarantino wrote, directed, and acted in the dark comedy crime film Pulp Fiction in 1994, maintaining the stylized violence from his earlier film and also non-linear storylines. Tarantino received the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, which he shared with Roger Avary, who contributed to the story. He also received a nomination in the Best Director category. The film received another five nominations, including for Best Picture. Tarantino also won the Palme d’Or for the film at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival. The film grossed over $200 million[36] and earned positive reviews.[37][38]

In 1995, Tarantino participated in the anthology film Four Rooms, a collaboration that also included directors Robert Rodriguez, Allison Anders and Alexandre Rockwell. Tarantino directed and acted in the fourth segment of «The Man from Hollywood», a tribute to the Alfred Hitchcock Presents episode «Man from the South».[39][40] He joined Rodriguez again later in the year with a supporting role in Desperado.[41][42] One of Tarantino’s first paid writing assignments was for From Dusk till Dawn, which Rodriguez directed later in 1996, re-teaming with Tarantino in another acting role, alongside Harvey Keitel, George Clooney and Juliette Lewis.[43][44][c]

His third feature film was Jackie Brown (1997), an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s novel Rum Punch. An homage to blaxploitation films, it starred Pam Grier, who starred in many of the films of that genre in the 1970s. It received positive reviews and was called a «comeback» for Grier and co-star Robert Forster.[47] Leonard considered Jackie Brown to be his favorite of the 26 different screen adaptations of his novels and short stories.[48]

In the 1990s, Tarantino had a number of other minor acting roles, including in Eddie Presley (1992),[49] The Coriolis Effect (1994),[50] Sleep With Me (1994),[51][52] Somebody to Love (1994),[53] All-American Girl (1995), Destiny Turns on the Radio (1995),[54] and Girl 6 (1996).[55] Also in 1996, he starred in Steven Spielberg’s Director’s Chair, a simulation video game that uses pre-generated film clips.[56] In 1998, Tarantino made his major Broadway stage debut as an amoral psycho killer in a revival of the 1966 play Wait Until Dark, which received unfavorable reviews for his performance from critics.[57][58]

2000s: Subsequent success

Tarantino went on to write and direct Kill Bill, a highly stylized «revenge flick» in the cinematic traditions of Chinese martial arts films, Japanese period dramas, Spaghetti Westerns, and Italian horror.[59] It was based on a character called The Bride and a plot that he and Kill Bill‘s lead actress Uma Thurman had developed during the making of Pulp Fiction.[60] It was originally set for a single theatrical release, but its four-hour running time prompted Tarantino to divide it into two movies.[61]: 1:02:10 Tarantino says he still considers it a single film in his overall filmography.[61]: 1:23:35 Volume 1 was released in 2003 and Volume 2 was released in 2004.[62][63]

From 2002 to 2004, Tarantino portrayed villain McKenas Cole in the ABC television series Alias.[64] In 2004, Tarantino attended the 2004 Cannes Film Festival, where he served as President of the Jury.[65] Also Volume 2 of Kill Bill had a screening, but was not in competition.[66]

Tarantino then contributed to Robert Rodriguez’s 2005 neo-noir film Sin City, and was credited as «Special Guest Director» for his work directing the car sequence featuring Clive Owen and Benicio del Toro.[67] In May 2005, Tarantino co-wrote and directed «Grave Danger», the fifth season finale of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. For this episode, Tarantino was nominated for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Drama Series at the 57th Primetime Emmy Awards.[68]

In 2007, Tarantino directed the exploitation slasher film Death Proof. Released as a take on 1970s double features, under the banner Grindhouse, it was co-directed with Rodriguez who did the other feature which was the body horror film Planet Terror.[69] Box-office sales were low but the film garnered mostly positive reviews.[70][71]

Tarantino’s film Inglourious Basterds, released in 2009, is the story of a group of Jewish-American guerrilla soldiers in Nazi-occupied France in an alternate history of World War II.[72] He had planned to start work on the film after Jackie Brown but postponed this to make Kill Bill after a meeting with Uma Thurman.[73] Filming began on «Inglorious Bastards«, as it was provisionally titled, in October 2008.[74] The film opened in August 2009 to positive reviews with the highest box office gross in the US and Canada for the weekend on release.[75] For the film, Tarantino received his second nomination for the Academy Award for Best Director and Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[76]

2010s and 2020s: Established auteur

Tarantino at the French premiere of Django Unchained in January 2013

In 2011, production began on Django Unchained, a film about the revenge of a former slave in the Southern United States in 1858. The film stemmed from Tarantino’s desire to produce a Spaghetti Western set in America’s Deep South during the Antebellum Period. Tarantino called the proposed style «a southern»,[77] stating that he wanted «to do movies that deal with America’s horrible past with slavery and stuff but do them like spaghetti westerns, not like big issue movies. I want to do them like they’re genre films, but they deal with everything that America has never dealt with because it’s ashamed of it, and other countries don’t really deal with because they don’t feel they have the right to».[77] It was released in December 2012 and became his highest grossing film to date.[78][79] He also received his second Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[80]

In November 2013, Tarantino said he was working on a new film and that it would be another Western, though not a sequel to Django Unchained.[81] On January 11, 2014, it was revealed that the film would be titled The Hateful Eight.[82] The script was then leaked in January 2014.[83] Aggrieved by the breach of confidence, Tarantino considered abandoning the production which was due to start the next winter and publish it as a novel instead.[84] He stated that he had given the script to a few trusted colleagues, including Bruce Dern, Tim Roth and Michael Madsen.[85][86]

On April 19, 2014, Tarantino directed a live reading of the leaked script at the United Artists Theater in the Ace Hotel Los Angeles for the Live Read series.[87] Tarantino explained that they would read the first draft of the script, and added that he was writing two new drafts with a different ending.[88] Filming went ahead as planned with the new draft in January 2015.[89] The Hateful Eight was released on December 25, 2015, as a roadshow presentation in 70 mm film-format theaters, before being released in digital theaters on December 30, 2015.[90] The film received mostly positive reviews from critics.[91]

In July 2017, it was reported that Tarantino’s next project would be a film about the Manson Family murders.[92] In February 2018, it was announced that the film’s title would be Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, and that Leonardo DiCaprio would play Rick Dalton, a fictional star of television Westerns, with Brad Pitt as Dalton’s longtime stunt double Cliff Booth; Margot Robbie would be playing real life actress Sharon Tate, portrayed as Dalton’s next-door neighbor.[93] Filming took place in the summer of 2018.[94] In wake of the Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse allegations, Tarantino severed ties to The Weinstein Company and Miramax and sought a new distributor after working with Weinstein for his entire career.[95] The film officially premiered at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, where it was in competition for the Palme d’Or.[96] Sony Pictures eventually distributed the film, which was theatrically released in July 2019.[97]

In November 2022, Tarantino revealed plans to shoot an eight-episode television series in 2023. No further details were provided.[98]

As a producer

Tarantino has used his Hollywood power to give smaller and foreign films more attention. These films are often labeled «Presented by Quentin Tarantino» or «Quentin Tarantino Presents». In 1995, Tarantino formed Rolling Thunder Pictures with Miramax to release or re-release several independent and foreign features. By 1997, Miramax had shut down the company due to poor sales.[99] The following films were released by Rolling Thunder Pictures: Chungking Express (1994, dir. Wong Kar-wai), Switchblade Sisters (1975, dir. Jack Hill), Sonatine (1993, dir. Takeshi Kitano), Hard Core Logo (1996, dir. Bruce McDonald), The Mighty Peking Man (1977, dir. Ho Meng Hua), Detroit 9000 (1973, dir. Arthur Marks), The Beyond (1981, dir. Lucio Fulci), and Curdled (1996, dir. Reb Braddock).[100]

In 2001, he produced the US release of the Hong Kong martial arts film Iron Monkey, which made over $14 million worldwide.[101][102] In 2004, he brought the Chinese martial arts film Hero to the US. It opened at number-one at the box office and eventually earning $53.5 million.[103]

While Tarantino was in negotiations with Lucy Liu for Kill Bill, the two helped produce the Hungarian sports documentary Freedom’s Fury, which was released in 2006.[104] When he was approached about a documentary about the Blood in the Water match, Tarantino said «This is the best story I’ve ever been told. I’d love to be involved».[104]

In 2006, another «Quentin Tarantino presents» production, Hostel, opened at number-one at the box office with a $20.1 million opening weekend.[105] He presented 2006’s The Protector, and is a producer of the 2007 film Hostel: Part II.[106][107] In 2008, he produced the Larry Bishop-helmed Hell Ride, a revenge biker film.[108]

As a film exhibitor

In February 2010, Tarantino bought the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles. Tarantino allowed the previous owners to continue operating the theater, but stated he would make occasional programming suggestions. He was quoted as saying: «As long as I’m alive, and as long as I’m rich, the New Beverly will be there, showing films shot on 35 mm.»[109] Starting in 2014, Tarantino took a more active role in programming film screenings at the New Beverly, showing his own films as well as prints from his personal collection.[110] In 2021, Tarantino announced that he had also purchased the Vista Theatre in Los Angeles, stating that he intends to keep it a first-run theatre, and that like The New Beverly it will only show movies on film.[111]

Film criticism

In June 2020 Tarantino became an officially recognized critic on the review aggregation website, Rotten Tomatoes. His reviews are part of the «Tomatometer» rating.[112][113]

Tarantino reappraises films that go against the views of mainstream film criticism, for example, he considers the 1983 film Psycho II to be superior to the original 1960 film Psycho.[114][115] He is also among a few notable directors, including Martin Scorsese and Edgar Wright, who appreciate Elaine May’s 1987 film Ishtar, despite its reputation as being a notorious box-office flop and one of the worst films ever made.[116][117]

Tarantino praised Mel Gibson’s 2006 film Apocalypto, saying, «I think it’s a masterpiece. It was perhaps the best film of that year.»[118] In 2009, he named Kinji Fukasaku’s violent action film Battle Royale as his favorite film released since he became a director in 1992.[119] In 2020, Tarantino named David Fincher’s film The Social Network his favorite movie of the 2010s.[120]

In August 2022, Tarantino stated that Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is «the greatest movie of all time. Maybe not the best film, but the best movie ever made». The director continued his praise for Spielberg, «I think my favourite Spielberg-directed movie, again with Jaws carved out on its own Mount Rushmore, is Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom«, because “He [Spielberg] pushes the envelope, he creates PG-13; a movie so fucking badass it created a new level in the MPAA.”[121][122] He also views favorably the fourth film in the Indiana Jones franchise, asserting that he found Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull more enjoyable when compared to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.[123][124]

Books

In 2020, Tarantino signed a two-book deal with HarperCollins.[125] He published his first novel in June 2021, a novelization of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. It received positive reviews from The New York Times[126] and The Guardian.[127] The second book he published under the deal titled Cinema Speculation, about films of the New Hollywood era, was inspired by film critic Pauline Kael and published on November 1, 2022.[125][128]

Podcast

In June 2021, Tarantino announced plans to start a podcast with Roger Avary. The podcast is named after Video Archives, a video rental store that both directors had worked at prior to their film careers, and will feature the directors, and a guest, examining a film which could have been offered for rental at the store.[129] The podcast premiered on July 18, 2022.[130]

Unproduced films

A number of film projects have been considered by Tarantino throughout his career. They have included comic book adaptations (Green Lantern, Iron Man, Luke Cage, Silver Surfer),[131][132][133][134] sequels (Kill Bill:Volume 3),[135] spin-offs of previous works (The Vega Brothers),[136] crossovers of his own work with other genres (Django/Zorro),[137] literary adaptations of well-known authors (Len Deighton, Bret Easton Ellis),[138][139] and campaigning to direct in major film franchises (James Bond and Star Trek).[140][141] Most of the projects he has discussed have been speculative, but none of them have been accomplished. In November 2014, Tarantino said he would retire from films after directing his tenth film.[142]

Final tenth film

In 2009, Tarantino said that he plans to retire from filmmaking when he is 60, in order to focus on writing novels and film literature. He is skeptical of the film industry going digital, saying, «If it actually gets to the place where you can’t show 35 mm film in theaters anymore and everything is digital projection, I won’t even make it to 60.»[143][144] He has also stated that he has a plan, although «not etched in stone», to retire after making his tenth movie: «If I get to the 10th, do a good job and don’t screw it up, well that sounds like a good way to end the old career.»[142]

Influences and style of filmmaking

Early influences

In the 2012 Sight & Sound directors’ poll, Tarantino listed his top 12 films: Apocalypse Now, The Bad News Bears, Carrie, Dazed and Confused, The Great Escape, His Girl Friday, Jaws, Pretty Maids All in a Row, Rolling Thunder, Sorcerer, Taxi Driver and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.[145]

Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Western films were a profound influence including Once Upon a Time in the West.[146] He is an admirer of the 1981 film Blow Out, directed by Brian De Palma, which led to his casting of John Travolta in Pulp Fiction.[147] Similarly, Tarantino was captivated with Jim McBride’s 1983 remake of Breathless and with Richard Gere’s unlikable but charismatic protagonist.[148][149] The film’s popular culture references, in particular the comic book Silver Surfer, inspired him to have the character’s poster on Mr. Orange’s apartment wall in Reservoir Dogs.[150] Tarantino has also labeled Rio Bravo as one of his influences.[151] He listed the Australian suspense film Roadgames (1981) as another favorite film.[152]

Other films he cited as formative influences include Hong Kong martial arts films (such as Five Fingers of Death and Enter the Dragon), John Woo action films (A Better Tomorrow II and The Killer), John Carpenter films (Assault on Precinct 13 and The Thing), blaxploitation films (including The Mack and Foxy Brown), Jean-Luc Godard films (Bande à Part and the 1960 version of Breathless), and Sonny Chiba’s work (The Street Fighter and Shadow Warriors).[150]

In August 2007, while teaching in a four-hour film course during the 9th Cinemanila International Film Festival in Manila, Tarantino cited Filipino directors Cirio H. Santiago, Eddie Romero and Gerardo de León as personal icons from the 1970s.[153] He referred to De Leon’s «soul-shattering, life-extinguishing» movies on vampires and female bondage, citing in particular Women in Cages; «It is just harsh, harsh, harsh», he said, and described the final shot as one of «devastating despair».[153] Upon his arrival in the Philippines, Tarantino was quoted in the local newspaper as saying, «I’m a big fan of RP [Republic of the Philippines] cinema.»[154]

Style

Tarantino’s films often feature graphic violence, a tendency which has sometimes been criticized.[155][156][157] Reservoir Dogs was initially denied United Kingdom certification because of his use of torture as entertainment.[158] Tarantino has frequently defended his use of violence, saying that «violence is so good. It affects audiences in a big way».[159] The number of expletives and deaths in Tarantino’s films were measured by analytics website FiveThirtyEight. In the examples given by the site, «Reservoir Dogs features ‘just’ 10 on-screen deaths, but 421 profanities. Django Unchained, on the other hand, has ‘just’ 262 profanities but 47 deaths.»[160] He often blends aesthetic elements, in tribute to his favorite films and filmmakers. In Kill Bill, he melds comic strip formulas and visuals within a live action film sequence, in some cases by the literal use of cartoon or anime images.[161][162]

Tarantino has also occasionally used a non-linear story structure in his films, most notably with Pulp Fiction. He has also used the style in Reservoir Dogs, Kill Bill, and The Hateful Eight.[163][164] Tarantino’s script for True Romance was originally told in a non-linear style, before director Tony Scott decided to use a more linear approach.[165][166] Critics have since referred to the use of this shifting timeline in films as the «Tarantino Effect».[167] Actor Steve Buscemi has described Tarantino’s novel style of filmmaking as «bursting with energy» and «focused».[168] According to Tarantino, a hallmark of all his movies is that there is a different sense of humor in each one, which prompts the viewer to laugh at scenes that are not funny.[169] However, he insists that his films are dramas, not comedies.[170]

Tarantino’s use of dialogue is noted for its mundane conversations with popular culture references. For example, when Jules and Vincent in Pulp Fiction are driving to a hit, they talk about Vincent’s trip to Europe, discussing the differences in countries such as a McDonald’s «Quarter Pounder with Cheese» being called a «Royale with Cheese» in France because of the metric system. In the opening scene to Reservoir Dogs, Mr. Brown (played by Tarantino) interprets the meaning of Madonna’s song «Like a Virgin». In Jackie Brown, Jackie and Max chat over a cup of coffee while listening to a vinyl record by the Delfonics’ «Didn’t I (Blow Your Mind This Time)».[171][172]

He also creates his own products and brands that he uses in his films to varying degrees.[173] His own fictional brands, including «Acuña Boys Tex-Mex Food», «Big Kahuna Burger», «G.O. Juice», «Jack Rabbit Slim’s», «K-Billy», «Red Apple cigarettes», «Tenku Brand Beer» and «Teriyaki Donut», replace the use of product placement, sometimes to a humorous extent.[174][162] Tarantino is also known for his choice of music in his films,[175] including soundtracks that often use songs from the 1960s and 70s.[176][177][178] In 2011, he was recognized at the 16th Critics’ Choice Awards with the inaugural Music+Film Award.[179][180]

A recurring image in his films are scenes where women’s bare feet feature prominently. When asked about foot fetishism, Tarantino responded, «I don’t take it seriously. There’s a lot of feet in a lot of good directors’ movies. That’s just good direction. Like, before me, the person foot fetishism was defined by was Luis Buñuel, another film director. And [Alfred] Hitchcock was accused of it and Sofia Coppola has been accused of it.»[181][182]

Tarantino has stated in many interviews that his writing process is like writing a novel before formatting it into a script, saying that this creates the blueprint of the film and makes the film feel like literature. About his writing process he told website The Talks, «[My] head is a sponge. I listen to what everyone says, I watch little idiosyncratic behavior, people tell me a joke and I remember it. People tell me an interesting story in their life and I remember it. … when I go and write my new characters, my pen is like an antenna, it gets that information, and all of a sudden these characters come out more or less fully formed. I don’t write their dialogue, I get them talking to each other.»[183]

Appraisals

During his career, Tarantino’s films have garnered a cult following, as well as critical and commercial success.[1][184] In 2005, he was included on the annual Time 100 list of the most influential people in the world.[185] Filmmaker and historian Peter Bogdanovich has called him «the single most influential director of his generation».[186] Tarantino has received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his contributions to the film industry.[187]

In 2013, a survey of seven academics was carried out to discover which filmmakers had been referenced the most in essays and dissertations on film that had been marked in the previous five years. It revealed that Tarantino was the most-studied director in the United Kingdom, ahead of Alfred Hitchcock, Christopher Nolan, Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.[188]

Controversies

Gun violence

Tarantino has said he does not believe that violence in film inspires real acts of violence.[189] In an interview with Terry Gross, Tarantino expressed «annoyance» at the suggestion that there is a link between the two, saying, «I think it’s disrespectful to [the] memory of those who died to talk about movies … Obviously the issue is gun control and mental health.»[190] Soon after, in response to a Hollywood PSA video titled «Demand a Plan», which featured celebrities rallying for gun control legislation,[191] a pro-gun group used scenes from Tarantino’s film Django Unchained to label celebrities as «hypocrites» for appearing in violent movies.[192]

Racial slurs in films

In 1997, Spike Lee questioned Tarantino’s use of racial slurs in his films, especially the word «nigger», particularly in Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown.[193] In a Variety interview discussing Jackie Brown, Lee said, «I’m not against the word … And some people speak that way, but Quentin is infatuated with that word… I want Quentin to know that all African Americans do not think that word is trendy or slick.»[194] Tarantino responded on The Charlie Rose Show:

As a writer, I demand the right to write any character in the world that I want to write. I demand the right to be them, I demand the right to think them and I demand the right to tell the truth as I see they are, all right? And to say that I can’t do that because I’m white, but the Hughes brothers can do that because they’re black, that is racist. That is the heart of racism, all right. And I do not accept that … That is how a segment of the black community that lives in Compton, lives in Inglewood, where Jackie Brown takes place, that lives in Carson, that is how they talk. I’m telling the truth. It would not be questioned if I was black, and I resent the question because I’m white. I have the right to tell the truth. I do not have the right to lie.[195]

Tarantino said on The Howard Stern Show that Lee would have to «stand on a chair to kiss [his] ass».[196] Samuel L. Jackson, who has appeared in both directors’ films, defended Tarantino. At the Berlin Film Festival, where Jackie Brown was screened, Jackson said: «I don’t think the word is offensive in the context of this film … Black artists think they are the only ones allowed to use the word. Well, that’s bull. Jackie Brown is a wonderful homage to black exploitation films. This is a good film, and Spike hasn’t made one of those in a few years.»[197] Tarantino argued that black audiences appreciated his blaxploitation-influenced films more than some of his critics, and that Jackie Brown was primarily made for black audiences.[198]

Django Unchained was the subject of controversy because of its use of racial slurs and depiction of slavery. Reviewers defended the use of the language by pointing out the historic context of race and slavery in America.[199][200] Lee, in an interview with Vibe, said that he would not see the film: «All I’m going to say is that it’s disrespectful to my ancestors. That’s just me … I’m not speaking on behalf of anybody else.»[201] Lee later tweeted: «American slavery was not a Sergio Leone spaghetti western. It was a holocaust. My ancestors are slaves. Stolen from Africa. I will honor them.»[202]

Kill Bill car crash

Uma Thurman was in a serious car crash on the set of Kill Bill because Tarantino had insisted she perform her own driving stunts.[203] Tarantino said he did not force her to do the stunt.[204][205] Although Thurman said the incident was «negligent to the point of criminality», she believed Tarantino had no malicious intent.[206]

Roman Polanski

In a 2003 Howard Stern interview, Tarantino defended the director Roman Polanski against charges that Polanski had raped then-13-year-old Samantha Geimer in 1977. He said that Polanski’s actions were «not rape» and Geimer «…wanted to have it».[207] The interview resurfaced in 2018 and drew criticism, including from Geimer, who stated in an interview, «He was wrong. I bet he knows it… I hope he doesn’t make an ass of himself and keep talking that way.»[208] Within days of the interview resurfacing, Tarantino issued an apology, stating «Fifteen years later, I realize how wrong I was… I incorrectly played devil’s advocate in the debate for the sake of being provocative.»[209]

Anti-police brutality rally

In October 2015, Tarantino attended a rally held in New York protesting police brutality. The event aimed to call attention to «police brutality and its victims». At the event Tarantino made a speech, «I’m a human being with a conscience … And when I see murder I cannot stand by. And I have to call the murdered the murdered and I have to call the murderers the murderers.»[210]

As a response to Tarantino’s comments police unions across the United States called for a boycott of his upcoming film at the time, The Hateful Eight. Patrick J. Lynch, union president of the Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York, said, «It’s no surprise that someone who makes a living glorifying crime and violence is a cop-hater, too. The police officers that Quentin Tarantino calls ‘murderers’ aren’t living in one of his depraved big screen fantasies — they’re risking and sometimes sacrificing their lives to protect communities from real crime and mayhem.»[210] The Los Angeles Police Department Chief Charlie Beck said Tarantino «doesn’t understand the nature of the violence. Mr. Tarantino lives in a fantasy world. That’s how he makes his living. His movies are extremely violent, but he doesn’t understand violence. … Unfortunately, he mistakes lawful use of force for murder, and it’s not.»[211]

Tarantino’s response to the controversy was, «All cops are not murderers … I never said that. I never even implied that.»[210] In an MSNBC interview with Chris Hayes, he said, «Just because I was at an anti-police brutality protest doesn’t mean I’m anti-police.»[212] He clarified his protest comments, «We were at a rally where unarmed people – mostly black and brown – who have been shot and killed or beaten or strangled by the police, and I was obviously referring to the people in those types of situations. I was referring to Eric Garner, I was referring to Sam DuBose, I was referring to Antonio Guzman Lopez, I was referring to Tamir Rice … In those cases in particular that we’re talking about, I actually do believe that they were murder.»[213]

Harvey Weinstein

On October 18, 2017, Tarantino gave an interview discussing sexual harassment and assault allegations against producer Harvey Weinstein. Tarantino said his then-girlfriend Mira Sorvino told him in the mid-1990s about her experience with Weinstein. Tarantino confronted Weinstein at the time and received an apology.[214] Tarantino said: «What I did was marginalize the incidents. I knew enough to do more than I did.»[214]

On February 3, 2018, in an interview with The New York Times, the Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill actress Uma Thurman said Weinstein had sexually assaulted her, and that she had reported this to Tarantino. Tarantino said he confronted Weinstein, as he had previously when Weinstein made advances on his former partner, demanding he apologize. He banned him from contact with Thurman for the rest of the production.[204] In a June 2021 interview on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast, Tarantino said he regretted not pressing Weinstein further, saying he did not know the extent of his misconduct before the 2017 scandal. He remarked on his «sad» view of his past relationship with Weinstein, saying he once looked up to him for fostering his career and describing him as «a fucked up father figure».[215]

Bruce Lee

In 2019, Shannon Lee, daughter of Bruce Lee, called his depiction in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood disheartening and inaccurate.[216] Tarantino said: «Bruce Lee was kind of an arrogant guy. The way he was talking, I didn’t just make a lot of that up.»[217] During that time, China put the release of the movie on halt, with sources claiming that Shannon Lee filed a complaint to China’s National Film Administration.[218] Tarantino refused to recut the movie for the Chinese release.[219]

History of altercations

Tarantino has a history of clashing with people in the entertainment industry and being difficult with journalists.

In 1993, Tarantino sold his script for Natural Born Killers which was rewritten, giving him only a story credit. He later disowned the film which caused enmity; and the publication of a «tell-all» book titled Killer Instinct by Jane Hamsher—who with Don Murphy, had an original option on the screenplay and produced the film—calling Tarantino a «one-trick pony» and becoming «famous for being famous» led him to physically assault Murphy in the AGO restaurant in West Hollywood, California in October 1997.[220] Murphy subsequently filed a $5 million lawsuit against Tarantino; the case ended with the judge ordering Tarantino to pay Murphy $450.[221][222]

In 1994, Tarantino had an on-set feud with Denzel Washington during the filming of Crimson Tide over what was called «Tarantino’s racist dialogue added to the script». A few years later Washington apologized to Tarantino saying he «buried that hatchet».[223]

In 1997, during the Oscars, Tarantino was accompanying Mira Sorvino who had stopped to speak to MTV News host at the time Chris Connelly when he called her from the media scrum. Before she could talk to him Tarantino grabbed Sorvino telling her, «He’s the editor of Premiere and he did a story on my Dad,» and pulled her away. Connelly, a former Premiere magazine editor-in-chief said, «No, I didn’t.» As they walked off, Tarantino gave the journalist the finger saying «Fuck you!» and spat at him.[224][225] The article that angered Tarantino included a 1995 interview from a biography by Jami Bernard with his biological father Tony Tarantino, someone he had never met, which he considered «pretty tasteless».[226]

In 2009, Tarantino was set to appear on the talk show Late Show with David Letterman to promote Inglourious Basterds. A few years prior to this event, David Letterman had interviewed a former «unnamed» girlfriend of Tarantino on his show. Letterman joked about the relationship questioning why a «glorious movie star» would date a «little squirrelly guy». A couple of days later, Tarantino phoned Letterman screaming angrily, «I’m going to beat you to death! I’m going to kill you! I’m coming to New York, and I’m gonna beat the crap out of you! How can you say that about me?!»[227] Letterman offered to pay for Tarantino’s flight and let him choose the method of fighting, which Tarantino determined would be «bats». However, Letterman never heard from Tarantino again, until years later, when he came on the show to promote the new film. The host approached Tarantino in the make-up room, just before the show went live, and demanded an apology. Tarantino was not forthcoming, but at his publicist’s urging, he begrudgingly conceded.[228]

In 2013, during an interview with Krishnan Guru-Murthy on Channel 4 News while promoting Django Unchained in the UK, Tarantino reacted angrily when he was questioned about whether there was a link between movie violence and real-life violence. He informed Guru-Murthy that he was «shutting [his] butt down».[229] Tarantino further defied the journalist, saying: «I refuse your question. I’m not your slave and you’re not my master. You can’t make me dance to your tune. I’m not a monkey.»[230]

In 2019, during the Cannes Film Festival, at the Once Upon a Time in Hollywood press conference, a journalist asked why Margot Robbie had so few lines in the film. Tarantino snapped back, «Well, I just reject your hypothesis,» giving no further comment.[231]

Personal life

Relationships and marriage

In the early 1990s Tarantino dated comedians Margaret Cho and Kathy Griffin. From 1995 to 1998 he dated actress Mira Sorvino. He was her date at the 68th Oscars ceremony where she had won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. In March 1998 they separated with Sorvino releasing a statement that «[They] still love each other very much» but had reached a «mutual» decision to go their separate ways.»[232] From 2003 to 2005, Tarantino was in a romantic relationship with filmmaker Sofia Coppola. The two have remained friends since their breakup.[233]

On June 30, 2017, Tarantino became engaged to Israeli singer Daniella Pick, daughter of musician Zvika Pick. They met in 2009 when Tarantino was in Israel to promote Inglourious Basterds.[234] They married on November 28, 2018, in a Reform Jewish ceremony in their Beverly Hills Home.[235][236] As of January 2020, they were splitting their time between the Ramat Aviv Gimel neighborhood of Tel Aviv, Israel and Los Angeles.[237] On February 22, 2020, their son[238][239] was born in Israel.[240] Their second child, a girl, was born in July 2022.[241][242]

Faith and religious views

As a youth, Tarantino attended an Evangelical church, describing himself as «baptized, born again and everything in between». Tarantino said this was an act of rebellion against his Catholic mother as she had encouraged what might usually be considered more conventional forms of rebellion, such as his interests in comic books and horror films. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Tarantino was evasive about his religious beliefs but said he believed in God, whom he credited with giving him his writing ability.[243]

In the 2010s, Tarantino continued ascribing his talents to gifts from God but expressed uncertainty regarding God’s existence. «I think I was born Catholic, but I was never practiced,» said Tarantino. «As time has gone on, as I’ve become a man and made my way further as an adult, I’m not sure how much any of that I believe in. I don’t really know if I believe in God, especially not in this Santa Claus character that people seemed to have conjured up.»[244][245] In June 2021, Tarantino said he was an atheist.[246]

Filmography

Tarantino has stated that he plans to make a total of just ten films before retiring as a director, as a means of ensuring an overall high quality within his filmography. He believes «most directors have horrible last movies,» that ending on a «decent movie is rare,» and that ending on a «good movie is kind of phenomenal.»[247] Tarantino considers Kill Bill 1 and 2 to be a single movie.[248]

Bibliography

- Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: A Novel (2021)

- Cinema Speculation (2022)

Collaborators

Tarantino has built up an informal «repertory company» of actors who have appeared in many roles in his films.[249][250] Most notable of these is Samuel L. Jackson, who has appeared in four films directed by Tarantino and a fifth written by him, True Romance.[251][252] Other frequent collaborators include Uma Thurman, who has been featured in three films and whom Tarantino has described as his «muse»; Zoë Bell, who has acted or performed stunts in seven Tarantino films; Michael Madsen, James Parks and Tim Roth, who respectively appear in five, four and three films. In addition, Roth appeared in Four Rooms, an anthology film where Tarantino directed the final segment, and filmed a scene for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood before it was cut for time.[252][253][254]

Other actors who have appeared in several films by Tarantino include Michael Bacall, Michael Bowen, Bruce Dern, Harvey Keitel, Michael Parks, Kurt Russell, and Craig Stark, who have appeared in three films each.

Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt have each appeared in two Tarantino films, the second of which, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, they appear in together.[255][256] Like Jackson, Pitt also appeared in the Tarantino-penned True Romance. Christoph Waltz appeared in two Tarantino films, Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, winning a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for each role. Waltz had been working as an actor since the 1970s in numerous German movies and TV shows but was a relative unknown in America when he was cast as Hans Landa in his first film for Tarantino.[257][258]

Editor Sally Menke, who worked on all Tarantino films until her death in 2010, was described by Tarantino in 2007 as «hands down my number one collaborator».[259][260]

|

Work Actor |

1992 | 1994 | 1997 | 2003 | 2004 | 2007 | 2009 | 2012 | 2015 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reservoir Dogs |

Pulp Fiction |

Jackie Brown |

Kill Bill: Volume 1 |

Kill Bill: Volume 2 |

Death Proof |

Inglourious Basterds |

Django Unchained |

The Hateful Eight |

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood |

|

| Michael Bacall | ||||||||||

| Zoë Bell | ||||||||||

| Michael Bowen | ||||||||||

| Bruce Dern | ||||||||||

| Leonardo DiCaprio | ||||||||||

| Omar Doom | ||||||||||

| Walton Goggins | ||||||||||

| Samuel L. Jackson | ||||||||||

| Harvey Keitel | ||||||||||

| Michael Madsen | ||||||||||

| James Parks | ||||||||||

| Michael Parks | ||||||||||

| Brad Pitt | ||||||||||

| Tim Roth | ||||||||||

| Kurt Russell | ||||||||||

| Uma Thurman | ||||||||||

| Christoph Waltz |

Awards and honors

Throughout his career, Tarantino and his films have frequently received nominations for major awards, including for Academy Awards, BAFTA Awards, Golden Globe Awards, Directors Guild of America Awards, and Saturn Awards. He has won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay twice, for Pulp Fiction and Django Unchained. He has four times been nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, winning once for Pulp Fiction in 1994. In addition to his recognition for writing and directing films, Tarantino has received five Grammy Award nominations and a Primetime Emmy Award nomination.

In 2005, Tarantino was awarded the honorary Icon of the Decade at the 10th Empire Awards.[261] He has earned lifetime achievement awards from two organizations in 2007, from Cinemanila,[262] and from the Rome Film Festival in 2012.[263] In 2011, Tarantino was awarded the Honorary César by the Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma.[264]

For his work of Pulp Fiction, Tarantino became the first director to ever sweep «The Big Four» critics awards (LA, NBR, NY, NSFC) and the first of the five directors (Curtis Hanson, Steven Soderbergh, David Fincher, and Barry Jenkins) to do so.

| Year | Film | Academy Awards | Palme d’Or | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | Saturn Awards | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | Wins | Nom. | Wins | Nom. | Wins | Nom. | Wins | Nom. | Wins | ||

| 1994 | Pulp Fiction | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1997 | Jackie Brown | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 2003 | Kill Bill: Volume 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 2 | ||||||

| 2004 | Kill Bill: Volume 2 | 2 | 7 | 3 | |||||||

| 2007 | Death Proof | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2009 | Inglourious Basterds | 8 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 | |

| 2012 | Django Unchained | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 2015 | The Hateful Eight | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | |||

| 2019 | Once Upon a Time in Hollywood | 10 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | |

| Total | 34 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 40 | 7 | 28 | 8 | 42 | 11 |

See also

- Quentin Tarantino Film Festival, a film festival in Austin, Texas, United States, hosted by Tarantino

- QT8: The First Eight, a 2019 documentary about Tarantino

References

Footnotes

- ^ Actor Danny Strong describes Tarantino as «such a movie buff. He had so much knowledge of films that he would try to get people to watch really cool movies.»[15]

- ^ While at James Best, Tarantino also met Craig Hamann, with whom he would collaborate to produce his second film in 1987.[21][22]

- ^ Robert Kurtzman hired Tarantino to write the script for From Dusk till Dawn in exchange for the make-up effects on Reservoir Dogs.[45][46]

Citations

- ^ a b c «Quentin Tarantino Biography». Biography.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ a b «Quentin Tarantino – The ‘Inglourious Basterds’ Interview». African American Literature Book Club. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (September 1, 2009). «Hollywood’s Jewish Avenger». The Atlantic. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (December 31, 2015). «Quentin Tarantino: The Hateful Eight interview». Entertainment Weekly. Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

His mother named him, in part, after Quint Asper, Burt Reynolds’s character in Gunsmoke…

- ^ Allan, Samuel (July 26, 2019). «how tarantino’s love of l.a. led to ‘once upon a time in hollywood’«. i-D. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

Quentin Tarantino moved to Los Angeles at the age of three.

- ^ Lee, Michael (July 24, 2019). «Inspiring Writing Lessons from the Greats: Quentin Tarantino». The Script Lab. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Holm, D.K. (2004). Quentin Tarantino: The Pocket Essential Guide. Summersdale Publishers. pp. 24–5. ISBN 978-1-84839-866-5.

- ^ Walker, Andrew (May 14, 2004). «Faces of the week – Quentin Tarantino». BBC News. Archived from the original on September 18, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c Holm, D.K. (2004). Quentin Tarantino: The Pocket Essential Guide. Summersdale Publishers. pp. 26–7. ISBN 978-1-84839-866-5.

- ^ Campbell, Chuck (March 27, 2017). «Knoxville-native director Tarantino works hometown into films». Knoxville News Sentinel. Gannett. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

…Tarantino returned to Knoxville for a brief while, attending fifth grade in South Clinton.

- ^ Hibberd, James (August 9, 2021). «Quentin Tarantino Vowed to Never Give His Mom ‘a Penny’ Due to Childhood Insult: ‘No House for You!’«. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ «Quentin Tarantino: ‘Inglourious’ Child Of Cinema». NPR.org. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Giang, Vivian (May 20, 2013). «10 Wildly Successful People Who Dropped Out Of High School». Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Holm, D.K. (2004). Quentin Tarantino: The Pocket Essential Guide. Summersdale Publishers. pp. 27–8. ISBN 978-1-84839-866-5.

- ^ a b P., Ken (May 19, 2003). «An Interview with Danny Strong». IGN. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Webb, Daisy (December 26, 2019). «Iconic directors who avoided the classroom». Film Daily News. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ «Maximum Potential». DOLPH :: the ultimate guide for. Jérémie D. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Rife, Katherine (October 1, 2012). If You Like Quentin Tarantino…: Here Are Over 200 Films, TV Shows, and Other Oddities That You Will Love. Limelight Editions. p. 14. ISBN 9780879103996. Archived from the original on March 12, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ «The Man, the Myth, the Legend: Quentin Tarantino». Living Magazine. July 15, 2019. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Walsh, John (January 11, 2013). «Quentin Tarantino: after Sandy Hook, has America lost its appetite for blood and guts?». The Independent. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ «Craig Hamann [Interview]». Trainwreck’d Society. February 3, 2020. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Ferrari, Alex (November 5, 2016). «Quentin Tarantino’s Unreleased Feature Film: My Best Friend’s Birthday». Indie Film Hustle. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Brevet, Brad (January 1, 2014). «Read Quentin Tarantino’s First Produced Screenplay for ‘My Best Friend’s Birthday’«. ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Neilan, Dan. «Hey, let’s remember the time Quentin Tarantino was on Golden Girls». News. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Quentin Tarantino Reveals How The Golden Girls Helped Get Reservoir Dogs Made. The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon (YouTube). January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021. Alt URL

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (September 22, 1994). «A Film Maker and the Art of the Deal». The New York Times.

- ^ Keitel heard of the script through his wife, who had attended a class with Lawrence Bender (see Reservoir Dogs special edition DVD commentary).

- ^ Mark, Seal (February 13, 2013). «The Making of Pulp Fiction: Quentin Tarantino’s and the Cast’s Retelling». Vanity Fair.

- ^ Fuller, Graham (1998). «Graham Fuller/1993». In Peary, Gerald (ed.). Quentin Tarantino: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-1-57806-051-1.

- ^ AFP, Telegraph Reporters and (October 11, 2013). «Quentin Tarantino: planet Earth couldn’t handle my serial killer movie». Archived from the original on January 10, 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (April 10, 2014). «Weird Trivia: Quentin Tarantino Did An Uncredited Rewrite On ‘It’s Pat’«. IndieWire.

- ^ Rochlin, Margy (November 1994). «Playboy November ’94: 20 Questions». thenewbev.com.

- ^ Peary, Gerald (August 1998). «Chronology». Quentin Tarantino Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. University Press of Mississippi. p. xviii. ISBN 978-1-57806-050-4. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Rindskopf, Jeff (February 21, 2018). «Quentin Tarantino and John Landis Turned Down The Chance To Direct Men In Black». Screen Rant. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ «Quentin Tarantino Biography». Yahoo Movies. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ «Pulp Fiction (1994)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ «Pulp Fiction (1994)». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 5, 2009. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ «Pulp Fiction Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 17, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ James Berardinelli (December 25, 1995). «Four Rooms review». ReelViews. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ «Four Rooms movie review & film summary (1995) | Roger Ebert». Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Howe, Desson (August 25, 1995). «Desperado». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 25, 1995). «Desperado». The Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 19, 1996). «From Dusk Till Dawn«. Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- ^ «AFI|Catalog — From Dusk till Dawn». AFI. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ «» ROBERT KURTZMAN INTERVIEW». backwoodshorror.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ «20 Things You Didn’t Know About From Dusk Till Dawn». Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ «Jackie Brown Movie Reviews, Pictures». Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Hudson, Jeff (July 30, 2004). «Detroit spinner». The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (August 22, 2017). «Quentin Tarantino’s 9 Strangest and Most Surprising Movie Projects». IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ «Coriolis Effect, The (1994) – Overview – TCM.com». Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Simpson, Mark (May 12, 2016). «How did Top Gun become so gay?». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ «Festival de Cannes: Sleep with Me». festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ Derek Elley (September 12, 1994). «Review: ‘Somebody to Love’«. Variety. Archived from the original on October 25, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 28, 1995). «Film Review; Hipness to the Nth Degree In a Candy-Colored World». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ Obenson, Tambay A. (November 23, 2015). «Tarantino Says He’ll Never Work w/ Spike Lee, Calls Him Contemptible + Says He Has 2 More Films Before Retirement». IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ «Remembering When Steven Spielberg Wanted To Create A Universal Film School With Quentin Tarantino – IFC». Ifc.com. June 6, 2011. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Lefkowitz, David (April 5, 1998). «Tarantino-Tomei Wait Until Dark Opens on B’way Apr. 5». Playbill.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (October 14, 2003). «The Return of Quentin Tarantino». Vanity Fair.

- ^ «Quentin Tarantino: Definitive Guide To Homages, Influences And References». WhatCulture.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ «How did Tarantino and Uma Thurman Conceive ‘The Bride’«. No Film School. July 8, 2020. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ a b «#1675 Quentin Tarantino». Joe Rogan Experience. June 29, 2021. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ «Kill Bill: Vol. 1». Box Office Mojo.

- ^ «Kill Bill: Vol. 2». Box Office Mojo.

- ^ «A Guide To Quentin Tarantino’s Best And Worst Acting Roles». IFC (U.S. TV network). August 18, 2015. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ^ «Tarantino to head Cannes jury». The Guardian. February 16, 2004. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Pulver, Andrew (May 12, 2004). «The Tarantino effect at Cannes 2004». the Guardian.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 31, 2015). «Original sin wets streets of ‘Sin City’«. RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ 57TH ANNUAL PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS Awards Broadcast Live From Los Angeles’ Shrine Auditorium on September 18 on the CBS Television Network Archived September 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Emmys.com (August 22, 2005). Retrieved on July 2, 2015.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (March 27, 2007). «Hungry zombies! A psychopath in a killer car! It’s Grindhouse!». Entertainment Weekly. Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Brandon (April 9, 2007). «‘Grindhouse’ Dilapidated Over Easter Weekend». Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ «Grindhouse». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 19, 2009). «Inglourious Basterds movie review (2009)». rogerebert.com.

- ^ Lyman, Rick (September 5, 2002). «Tarantino Behind the Camera in Beijing». The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Stephenson, Hunter (July 9, 2008). «Script Reviews for Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Bastards Hit Web! «Masterpiece» is the Buzz Word». SlashFilm. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ «Inglourious Basterds (2009)». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Child, Ben (December 15, 2009). «Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds dominates Critics’ Choice awards». The Guardian.

- ^ a b Hiscock, John (April 27, 2007). «Quentin Tarantino: I’m proud of my flop». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ «Django Unchained». Box Office Mojo.

- ^ McGinley, Rhys (December 14, 2019). «Quentin Tarantino’s Movies Ranked By Gross (According To Box Office Mojo)». ScreenRant.

- ^ O’Connell, Sean (January 13, 2020). «How Quentin Tarantino Can Make History On Oscar Night». CInemaBlend.

- ^ «Tarantino Reveals Plans For Next Movie». Yahoo: Nighttime in No Time. Archived from the original on November 30, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ Kit, Borys (January 11, 2014). «Quentin Tarantino’s New Movie Sets Title, Begins Casting». The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ «Quentin Tarantino Plans to drop ‘Hateful Eight’ after the Script Leaked». Movies that Matter. January 22, 2014. Archived from the original on January 30, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 21, 2014). «Quentin Tarantino Shelves ‘The Hateful Eight’ After Betrayal Results In Script Leak». Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ «Quentin Tarantino sues Gawker over Hateful Eight script leak». CBC News. January 21, 2014. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Gettell, Oliver (January 22, 2014). «Quentin Tarantino mothballs ‘Hateful Eight’ after script leak». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ «World Premiere of a Staged Reading by Quentin Tarantino: The Hateful Eight». April 19, 2014. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Anderton, Ethan (April 21, 2014). «Tarantino’s ‘Hateful Eight’ Live-Read Reveals Script Still Developing». FirstShowing.net. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Andy (January 7, 2016). «Making of ‘Hateful Eight’: How Tarantino Braved Sub-Zero Weather and a Stolen Screener». The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ «‘The Hateful Eight’s’ Nationwide Release Date Changes Again». The Hollywood Reporter. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ «The Hateful Eight reviews». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Dessem, Matthew (July 11, 2017). «Quentin Tarantino’s Next Movie Will Be About the Manson Family». Slate. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (February 28, 2018). «Quentin Tarantino Taps Brad Pitt To Join Leonardo DiCaprio In ‘Once Upon A Time In Hollywood’«. Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.