| Constellation | |

List of stars in Ursa Minor |

|

| Abbreviation | UMi[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Ursae Minoris[1] |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Symbolism | the Little Bear[1] |

| Right ascension | 08h 41.4m to 22h 54.0m [1] |

| Declination | 65.40° to 90°[1] |

| Quadrant | NQ3 |

| Area | 256 sq. deg. (56th) |

| Main stars | 7 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars |

23 |

| Stars with planets | 4 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 3 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | Polaris[2] (1.97m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | Ursids |

| Bordering constellations |

|

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −10°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of June[2]. |

Ursa Minor (Latin: ‘Lesser Bear’, contrasting with Ursa Major), also known as the Little Bear, is a constellation located in the far northern sky. As with the Great Bear, the tail of the Little Bear may also be seen as the handle of a ladle, hence the North American name, Little Dipper: seven stars with four in its bowl like its partner the Big Dipper. Ursa Minor was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. Ursa Minor has traditionally been important for navigation, particularly by mariners, because of Polaris being the north pole star.

Polaris, the brightest star in the constellation, is a yellow-white supergiant and the brightest Cepheid variable star in the night sky, ranging in apparent magnitude from 1.97 to 2.00. Beta Ursae Minoris, also known as Kochab, is an aging star that has swollen and cooled to become an orange giant with an apparent magnitude of 2.08, only slightly fainter than Polaris. Kochab and 3rd-magnitude Gamma Ursae Minoris have been called the «guardians of the pole star» or «Guardians of The Pole».[3] Planets have been detected orbiting four of the stars, including Kochab. The constellation also contains an isolated neutron star—Calvera—and H1504+65, the hottest white dwarf yet discovered, with a surface temperature of 200,000 K.

History and mythology[edit]

Ursa Minor, with Draco looping around it, as depicted in Urania’s Mirror,[4] a set of constellation maps published in London c. 1825

In the Babylonian star catalogues, Ursa Minor was known as the «Wagon of Heaven» (MULMAR.GÍD.DA.AN.NA, also associated with the goddess Damkina). It is listed in the MUL.APIN catalogue, compiled around 1000 BC, among the «Stars of Enlil»—that is, the northern sky.[5]

According to Diogenes Laërtius, citing Callimachus, Thales of Miletus «measured the stars of the Wagon by which the Phoenicians sail». Diogenes identifies these as the constellation of Ursa Minor, which for its reported use by the Phoenicians for navigation at sea were also named Phoinikē.[6][7]

The tradition of naming the northern constellations «bears» appears to be genuinely Greek, although Homer refers to just a single «bear».[8]

The original «bear» is thus Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor was admitted as the second, or «Phoenician Bear» (Ursa Phoenicia, hence Φοινίκη, Phoenice)

only later, according to Strabo (I.1.6, C3) due to a suggestion by Thales, who suggested it as a navigation aid to the Greeks, who had been navigating by Ursa Major. In classical antiquity, the celestial pole was somewhat closer to Beta Ursae Minoris than to Alpha Ursae Minoris, and the entire constellation was taken to indicate the northern direction. Since the medieval period, it has become convenient to use Alpha Ursae Minoris (or «Polaris») as the North Star. (Even though, in the medieval period, Polaris was still several degrees away from the celestial pole.[9][a] ) Now, Polaris is within 1° of the north celestial pole and remains the current Pole star. Its New Latin name of stella polaris was coined only in the early modern period.[10]

The ancient name of the constellation is Cynosura (Greek Κυνοσούρα «dog’s tail»).

The origin of this name is unclear (Ursa Minor being a «dog’s tail» would imply that another constellation nearby is «the dog», but no such constellation is known).[11]

Instead, the mythographic tradition of Catasterismi makes Cynosura the name of an Oread nymph described as a nurse of Zeus, honoured by the god with a place in the sky.[12]

There are various proposed explanations for the name Cynosura. One suggestion connects it to the myth of Callisto, with her son Arcas replaced by her dog being placed in the sky by Zeus.[11]

Others have suggested that an archaic interpretation of Ursa Major was that of a cow, forming a group with Boötes as herdsman, and Ursa Minor as a dog.[13] George William Cox explained it as a variant of Λυκόσουρα, understood as «wolf’s tail» but by him etymologized as «trail, or train, of light» (i.e. λύκος «wolf» vs. λύκ- «light»). Allen points to the Old Irish name of the constellation, drag-blod «fire trail», for comparison.

Brown (1899) suggested a non-Greek origin of the name (a loan from an Assyrian An‑nas-sur‑ra «high-rising»).[14]

An alternative myth tells of two bears that saved Zeus from his murderous father Cronus by hiding him on Mount Ida. Later Zeus set them in the sky, but their tails grew long from their being swung up into the sky by the god.[15]

Because Ursa Minor consists of seven stars, the Latin word for «north» (i.e., where Polaris points) is septentrio, from septem (seven) and triones (oxen), from seven oxen driving a plough, which the seven stars also resemble. This name has also been attached to the main stars of Ursa Major.[16]

In Inuit astronomy, the three brightest stars—Polaris, Kochab and Pherkad—were known as Nuutuittut «never moving», though the term is more frequently used in the singular to refer to Polaris alone. The Pole Star is too high in the sky at far northern latitudes to be of use in navigation.[17] In Chinese astronomy, the main stars of Ursa Minor are divided between two asterisms:

勾陳 Gòuchén (Curved Array) (including α UMi, δ UMi, ε UMi, ζ UMi, η UMi, θ UMi, λ UMi) and

北極 Běijí (Northern Pole) (including β UMi and γ UMi).[18]

Characteristics[edit]

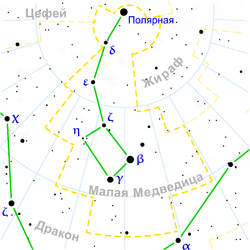

Ursa Minor is bordered by Camelopardalis to the west, Draco to the west, and Cepheus to the east. Covering 256 square degrees, it ranks 56th of the 88 constellations in size. Ursa Minor is colloquially known in the US as the Little Dipper because its seven brightest stars seem to form the shape of a dipper (ladle or scoop). The star at the end of the dipper handle is Polaris. Polaris can also be found by following a line through the two stars—Alpha and Beta Ursae Majoris, popularly called the Pointers—that form the end of the «bowl» of the Big Dipper, for 30 degrees (three upright fists at arms’ length) across the night sky.[19] The four stars constituting the bowl of the Little Dipper are of second, third, fourth, and fifth magnitudes, respectively, and provide an easy guide to determining what magnitude stars are visible, useful for city dwellers or testing one’s eyesight.[20]

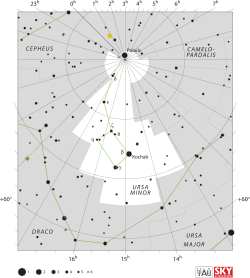

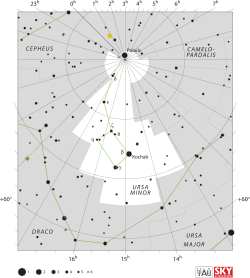

The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the IAU (International Astronomical Union) in 1922, is «UMi».[21] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 22 segments (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 08h 41.4m and 22h 54.0m , while the declination coordinates range from the north celestial pole to 65.40° in the south.[1] Its position in the far northern celestial hemisphere means that the whole constellation is visible only to observers in the northern hemisphere.[22][b]

Features[edit]

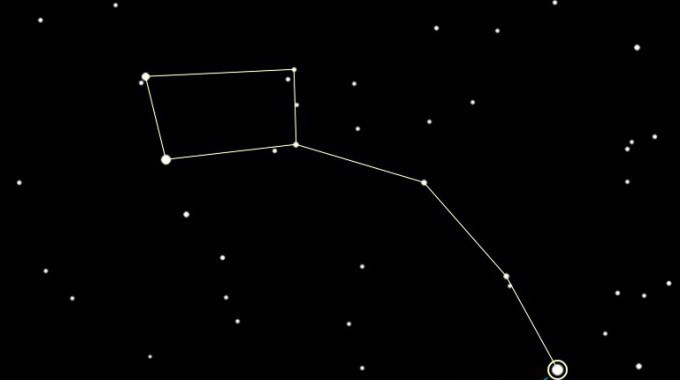

The constellation Ursa Minor as it can be seen by the naked eye (with connections and label added). Notice the seven stars of Ursa Major that form the Big Dipper and then make a line from the outermost Big Dipper stars (sometimes called the «pointers») to Polaris.

Stars[edit]

The German cartographer Johann Bayer used the Greek letters alpha to theta to label the most prominent stars in the constellation, while his countryman Johann Elert Bode subsequently added iota through phi. Only lambda and pi remain in use, likely because of their proximity to the north celestial pole.[16] Within the constellation’s borders, there are 39 stars brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[22][c]

Marking the Little Bear’s tail,[16] Polaris, or Alpha Ursae Minoris, is the brightest star in the constellation, varying between apparent magnitudes 1.97 and 2.00 over a period of 3.97 days.[24] Located around 432 light-years away from Earth,[25] it is a yellow-white supergiant that varies between spectral types F7Ib and F8Ib,[24] and has around 6 times the Sun’s mass, 2,500 times its luminosity, and 45 times its radius. Polaris is the brightest Cepheid variable star visible from Earth. It is a triple star system, the supergiant primary star having two yellow-white main-sequence star companions that are 17 and 2,400 astronomical units (AU) distant and take 29.6 and 42,000 years respectively to complete one orbit.[26]

Traditionally called Kochab, Beta Ursae Minoris, at apparent magnitude 2.08, is slightly less bright than Polaris.[27] Located around 131 light-years away from Earth,[28][d] it is an orange giant—an evolved star that has used up the hydrogen in its core and moved off the main sequence—of spectral type K4III.[27] Slightly variable over a period of 4.6 days, Kochab has had its mass estimated at 1.3 times that of the Sun via measurement of these oscillations.[29] Kochab is 450 times more luminous than the Sun and has 42 times its diameter, with a surface temperature of approximately 4,130 K.[30] Estimated to be around 2.95 billion years old, ±1 billion years, Kochab was announced to have a planetary companion around 6.1 times as massive as Jupiter with an orbit of 522 days.[31]

Ursa Minor and Ursa Major in relation to Polaris

Traditionally known as Pherkad, Gamma Ursae Minoris has an apparent magnitude that varies between 3.04 and 3.09 roughly every 3.4 hours.[32] It and Kochab have been termed the «guardians of the pole star».[3] A white bright giant of spectral type A3II-III,[32] with around 4.8 times the Sun’s mass, 1,050 times its luminosity and 15 times its radius,[33] it is 487±8 light-years distant from Earth.[28] Pherkad belongs to a class of stars known as Delta Scuti variables[32]—short period (six hours at most) pulsating stars that have been used as standard candles and as subjects to study asteroseismology.[34] Also possibly a member of this class is Zeta Ursae Minoris,[35] a white star of spectral type A3V,[36] which has begun cooling, expanding and brightening. It is likely to have been a B3 main-sequence star and is now slightly variable.[35] At magnitude 4.95 the dimmest of the seven stars of the Little Dipper is Eta Ursae Minoris.[37] A yellow-white main-sequence star of spectral type F5V, it is 97 light-years distant.[38] It is double the Sun’s diameter, 1.4 times as massive, and shines with 7.4 times its luminosity.[37] Nearby Zeta lies 5.00-magnitude Theta Ursae Minoris. Located 860 ± 80 light-years distant,[39] it is an orange giant of spectral type K5III that has expanded and cooled off the main sequence, and has an estimated diameter around 4.8 times that of the Sun.[40]

Making up the handle of the Little Dipper are Delta Ursae Minoris, or Yildun,[41] and Epsilon Ursae Minoris. Just over 3.5 degrees from the north celestial pole, Delta is a white main-sequence star of spectral type A1V with an apparent magnitude of 4.35,[42] located 172±1 light-years from Earth.[28] It has around 2.8 times the diameter and 47 times the luminosity of the Sun.[43] A triple star system,[44] Epsilon Ursae Minoris shines with a combined average light of magnitude 4.22.[45] A yellow giant of spectral type G5III,[45] the primary is a RS Canum Venaticorum variable star. It is a spectroscopic binary, with a companion 0.36 AU distant, and a third star—an orange main-sequence star of spectral type K0—8100 AU distant.[44]

Located close to Polaris is Lambda Ursae Minoris, a red giant of spectral type M1III. It is a semiregular variable varying between magnitudes 6.35 and 6.45.[46] The northerly nature of the constellation means that the variable stars can be observed all year: The red giant R Ursae Minoris is a semiregular variable varying from magnitude 8.5 to 11.5 over 328 days, while S Ursae Minoris is a long-period variable that ranges between magnitudes 8.0 and 11 over 331 days.[47] Located south of Kochab and Pherkad towards Draco is RR Ursae Minoris,[3] a red giant of spectral type M5III that is also a semiregular variable ranging from magnitude 4.44 to 4.85 over a period of 43.3 days.[48] T Ursae Minoris is another red-giant variable star that has undergone a dramatic change in status—from being a long-period (Mira) variable ranging from magnitude 7.8 to 15 over 310–315 days, to being a semiregular variable.[49] The star is thought to have undergone a shell helium flash—a point where the shell of helium around the star’s core reaches a critical mass and ignites—marked by its abrupt change in variability in 1979.[50] Z Ursae Minoris is a faint variable star that suddenly dropped 6 magnitudes in 1992 and was identified as one of a rare class of stars—R Coronae Borealis variables.[51]

Eclipsing variables are star systems that vary in brightness because of one star passing in front of the other rather than from any intrinsic change in luminosity. W Ursae Minoris is one such system, its magnitude ranging from 8.51 to 9.59 over 1.7 days.[52] The combined spectrum of the system is A2V, but the masses of the two component stars are unknown. A slight change in the orbital period in 1973 suggests there is a third component of the multiple star system—most likely a red dwarf—with an orbital period of 62.2±3.9 years.[53] RU Ursae Minoris is another example, ranging from 10 to 10.66 over 0.52 days.[54] It is a semidetached system, as the secondary star is filling its Roche lobe and transferring matter to the primary.[55]

RW Ursae Minoris is a cataclysmic variable star system that flared up as a nova in 1956, reaching magnitude 6. In 2003, it was still two magnitudes brighter than its baseline, and dimming at a rate of 0.02 magnitude a year. Its distance has been calculated as 5,000±800 parsecs (16,300 light-years), which puts its location in the galactic halo.[56]

Taken from the villain in The Magnificent Seven, Calvera is the nickname given to an X-ray source known as 1RXS J141256.0+792204 in the ROSAT All-Sky Survey Bright Source Catalog (RASS/BSC).[57] It has been identified as an isolated neutron star, one of the closest of its kind to Earth.[58] Ursa Minor has two enigmatic white dwarfs. Documented on January 27, 2011, H1504+65 is a faint (magnitude 15.9) star with the hottest surface temperature—200,000 K—yet discovered for a white dwarf. Its atmosphere, composed of roughly half carbon, half oxygen and 2% neon, is devoid of hydrogen and helium—its composition unexplainable by current models of stellar evolution.[59] WD 1337+705 is a cooler white dwarf that has magnesium and silicon in its spectrum, suggesting a companion or circumstellar disk, though no evidence for either has come to light.[60] WISE 1506+7027 is a brown dwarf of spectral type T6 that is a mere 11.1+2.3

−1.3 light-years away from Earth.[61] A faint object of magnitude 14, it was discovered by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) in 2011.[62]

Kochab aside, three more stellar systems have been discovered to contain planets. 11 Ursae Minoris is an orange giant of spectral type K4III around 1.8 times as massive as the Sun. Around 1.5 billion years old, it has cooled and expanded since it was an A-type main-sequence star. Around 390 light-years distant, it shines with an apparent magnitude of 5.04. A planet around 11 times the mass of Jupiter was discovered in 2009 orbiting the star with a period of 516 days.[63] HD 120084 is another evolved star, a yellow giant of spectral type G7III, around 2.4 times the mass of the Sun. It has a planet 4.5 times the mass of Jupiter, with one of the most eccentric planetary orbits (e = 0.66), discovered by precisely measuring the radial velocity of the star in 2013.[64] HD 150706 is a sunlike star of spectral type G0V some 89 light-years distant from the Solar System. It was thought to have a planet as massive as Jupiter at a distance of 0.6 AU, but this was discounted in 2007.[65] A further study published in 2012 showed that it has a companion around 2.7 times as massive as Jupiter that takes around 16 years to complete an orbit and is 6.8 AU distant from its star.[66]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

Ursa Minor is rather devoid of deep-sky objects. The Ursa Minor Dwarf, a dwarf spheroidal galaxy, was discovered by Albert George Wilson of the Lowell Observatory in the Palomar Sky Survey in 1955.[67] Its centre is around 225000 light-years distant from Earth.[68] In 1999, Kenneth Mighell and Christopher Burke used the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm that the galaxy had had a single burst of star formation that took place around 14 billion years ago and lasted around 2 billion years,[69] and that the galaxy was probably as old as the Milky Way itself.[70]

NGC 3172 (also known as Polarissima Borealis) is a faint, magnitude-14.9 galaxy that happens to be the closest NGC object to the north celestial pole.[71] It was discovered by John Herschel in 1831.[72]

NGC 6217 is a barred spiral galaxy located some 67 million light-years away,[73] which can be located with a 10 cm (4 in) or larger telescope as an 11th-magnitude object about 2.5° east-northeast of Zeta Ursae Minoris.[74] It has been characterized as a starburst galaxy, which means it is undergoing a high rate of star formation compared with a typical galaxy.[75]

NGC 6251 is an active supergiant elliptical radio galaxy more than 340 million light-years away from Earth. It has a Seyfert 2 active galactic nucleus, and is one of the most extreme examples of a Seyfert galaxy. This galaxy may be associated with gamma-ray source 3EG J1621+8203, which has high-energy gamma-ray emission.[76] It is also noted for its one-sided radio jet—one of the brightest known—discovered in 1977.[77]

Meteor showers[edit]

The Ursids, a prominent meteor shower that occurs in Ursa Minor, peaks between December 18 and 25. Its parent body is the comet 8P/Tuttle.[78]

See also[edit]

- Polaris Flare

- Ursa Minor Beta, fictional planet in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

- Ursa Minor (Chinese astronomy)

Notes[edit]

- ^ The position of the north celestial pole moves in accordance with the Earth’s axial precession such that in 12,000 years’ time, Vega will be the Pole Star.[9]

- ^ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between the equator and 24°S, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[22]

- ^ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[23]

- ^ Or more specifically 130.9±0.6 light-years by parallax measurement.[28]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f «Ursa Minor, Constellation Boundary». The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ a b Department of Astronomy (1995). «Ursa Minor». University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Arnold, H. J. P.; Doherty, Paul; Moore, Patrick (1999). The Photographic Atlas of the Stars. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-7503-0654-6.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «Urania’s Mirror c.1825 – Ian Ridpath’s Old Star Atlases». Self-published. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Rogers, John H. (1998). «Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108….9R.

- ^ Hermann Hunger, David Edwin Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia (1999), p. 68.

- ^ Albright, William F. (1972). «Neglected Factors in the Greek Intellectual Revolution». Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 116 (3): 225–42. JSTOR 986117.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «Ursa Minor». Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

Blomberg, Peter E. (2007). «How Did the Constellation of the Bear Receive its Name?» (PDF). In Pásztor, Emília (ed.). Archaeoastronomy in Archaeology and Ethnography: Papers from the Annual Meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture), held in Kecskemét in Hungary in 2004. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress. pp. 129–32. ISBN 978-1-4073-0081-8. - ^ a b Kenneth R. Lang (2013). Essential Astrophysics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-3-642-35963-7.

- ^ «Ursa Minor – Polaris». Star Tales. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ a b Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. 447f.

«The origin of this word is uncertain, for the star group does not answer to its name unless the dog himself be attached; still some, recalling a variant legend of Kallisto and her Dog instead of Arcas, have thought that here lay the explanation. Others have drawn this title from that of the Attican promontory east of Marathon, because sailors, on their approach to it from the sea, saw these stars shining above it and beyond; but if there be any connection at all here, the reversed derivation is more probable; while Bournouf asserted that it is in no way associated with the Greek word for «dog.» - ^ Condos, T., The Katasterismoi (Part 1), 1967. Also mentioned by Servius On Virgilius’ Georgics 1. 246, c. AD 400; a mention of doubtful authenticity is Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.2.

- ^ 265f. Robert Brown, Researches into the origin of the primitive constellations of the Greeks, Phoenicians and Babylonians (1899),

«M. Syoronos (Types Mon. des anciens p. 116) is of opinion that in the case of some Kretan coin-types, Ursa Maj. is represented as a Cow, hence Boôtês as ‘the Herdsman’, and Ursa Min. as a Dog (‘Chienne’ cf. Kynosoura, Kynoupês), a Zeus-suckler.»

A supposed Latin tradition of naming Ursa Minor Catuli «whelps» or Canes Laconicae «Spartan dogs», recorded in Johann Heinrich Alsted (1649, 408), is probably an early modern innovation. - ^ «Very recently, however, Brown [Robert Brown, Researches into the origin of the primitive constellations of the Greeks, Phoenicians and Babylonians] has suggested that the word is not Hellenic in origin, but Euphratean; and, in confirmation of this, mentions a constellation title from that valley, transcribed by Sayce as An‑ta-sur‑ra, the Upper Sphere. Brown reads this An‑nas-sur‑ra, High in Rising, certainly very appropriate to Ursa Minor; and he compares it with Κ‑υν‑όσ‑ου‑ρα, or, the initial consonant being omitted, Unosoura.» (Allen, Richard Hinckley. «Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning.» New York, Dover Editions, 1963, p. 448.)

Brown points out that Aratus fittingly describes «Cynosura» as «high-running» («at the close of night Cynosura’s head runs very high», κεφαλὴ Κυνοσουρίδος ἀκρόθι νυκτὸς

ὕψι μάλα τροχάει v. 308f). - ^ Rogers, John H. (1998). «Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean traditions». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108…79R.

- ^ a b c Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 312, 518. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ^ MacDonald, John (1998). The Arctic Sky: Inuit Astronomy, Star Lore, and Legend. Toronto, Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum/Nunavut Research Institute. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-88854-427-8.

- ^ «Ursa Minor – Chinese associations». Star Tales. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ O’Meara, Stephen James (1998). The Messier Objects. Deep-sky Companions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-521-55332-2.

- ^ Olcott, William Tyler (2012) [1911]. Star Lore of All Ages: A Collection of Myths, Legends, and Facts Concerning the Constellations of the Northern Hemisphere. New York, New York: Courier Corporation. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-486-14080-3.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). «The New International Symbols for the Constellations». Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA…..30..469R.

- ^ a b c Ridpath, Ian. «Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula». Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). «The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale». Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b Otero, Sebastian Alberto (4 December 2007). «Alpha Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ «Alpha Ursae Minoris – Classical Cepheid (Delta Cep Type)». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. «Polaris». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ a b «Beta Ursae Minoris – Variable Star». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d van Leeuwen, F. (2007). «Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A…474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Tarrant, N.J.; Chaplin, W.J.; Elsworth, Y.; Spreckley, S.A.; Stevens, I.R. (June 2008). «Oscillations in ß Ursae Minoris. Observations with SMEI». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 483 (#3): L43–L46. arXiv:0804.3253. Bibcode:2008A&A…483L..43T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809738. S2CID 53546805.

- ^ Kaler, James B. «Kochab». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Lee, B.-C.; Han, I.; Park, M.-G.; Mkrtichian, D.E.; Hatzes, A.P.; Kim, K.-M. (2014). «Planetary Companions in K giants β Cancri, μ Leonis, and β Ursae Minoris». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 566: 7. arXiv:1405.2127. Bibcode:2014A&A…566A..67L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322608. S2CID 118631934. A67.

- ^ a b c Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «Gamma Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (20 December 2013). «Pherkad». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Templeton, Matthew (16 July 2010). «Delta Scuti and the Delta Scuti Variables». Variable Star of the Season. AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers). Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. «Alifa al Farkadain». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ «Zeta Ursae Minoris – Variable Star». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. «Anwar al Farkadain». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ «Eta Ursae Minoris». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ «Theta Ursae Minoris – Variable Star». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Pasinetti Fracassini, L. E.; Pastori, L.; Covino, S.; Pozzi, A. (February 2001). «Catalogue of Apparent Diameters and Absolute Radii of Stars (CADARS) – Third edition – Comments and statistics». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 367 (2): 521–24. arXiv:astro-ph/0012289. Bibcode:2001A&A…367..521P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000451. S2CID 425754.

- ^ «Naming Stars». IAU.org. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ «Delta Ursae Minoris». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. «Yildun». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. «Epsilon Ursae Minoris». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ a b «Epsilon Ursae Minoris – Variable of RS CVn type». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «Lambda Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Levy, David H. (1998). Observing Variable Stars: A Guide for the Beginner. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-521-62755-9.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (16 November 2009). «RR Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Uttenthaler, S.; van Stiphout, K.; Voet, K.; van Winckel, H.; van Eck, S.; Jorissen, A.; Kerschbaum, F.; Raskin, G.; Prins, S.; Pessemier, W.; Waelkens, C.; Frémat, Y.; Hensberge, H.; Dumortier, L.; Lehmann, H. (2011). «The Evolutionary State of Miras with Changing Pulsation Periods». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 531: A88. arXiv:1105.2198. Bibcode:2011A&A…531A..88U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116463. S2CID 56226953.

- ^ Mattei, Janet A.; Foster, Grant (1995). «Dramatic Period Decrease in T Ursae Minoris». The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. 23 (2): 106–16. Bibcode:1995JAVSO..23..106M.

- ^ Benson, Priscilla J.; Clayton, Geoffrey C.; Garnavich, Peter; Szkody, Paula (1994). «Z Ursa Minoris – a New R Coronae Borealis Variable». The Astronomical Journal. 108 (#1): 247–50. Bibcode:1994AJ….108..247B. doi:10.1086/117063.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «W Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Kreiner, J. M.; Pribulla, T.; Tremko, J.; Stachowski, G. S.; Zakrzewski, B. (2008). «Period Analysis of Three Close Binary Systems: TW And, TT Her and W UMi». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 383 (#4): 1506–12. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.383.1506K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12652.x.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «RU Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Manimanis, V. N.; Niarchos, P. G. (2001). «A Photometric Study of the Near-contact System RU Ursae Minoris». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 369 (3): 960–64. Bibcode:2001A&A…369..960M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010178.

- ^ Bianchini, A.; Tappert, C.; Canterna, R.; Tamburini, F.; Osborne, H.; Cantrell, K. (2003). «RW Ursae Minoris (1956): An Evolving Postnova System». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 115 (#809): 811–18. Bibcode:2003PASP..115..811B. doi:10.1086/376434.

- ^ «Rare Dead Star Found Near Earth». BBC News: Science/Nature. BBC. 20 August 2007. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ Rutledge, Robert; Fox, Derek; Shevchuk, Andrew (2008). «Discovery of an Isolated Compact Object at High Galactic Latitude». The Astrophysical Journal. 672 (#2): 1137–43. arXiv:0705.1011. Bibcode:2008ApJ…672.1137R. doi:10.1086/522667. S2CID 7915388.

- ^ Werner, K.; Rauch, T. (2011). «UV Spectroscopy of the Hot Bare Stellar Core H1504+65 with the HST Cosmic Origins Spectrograph». Astrophysics and Space Science. 335 (1): 121–24. Bibcode:2011Ap&SS.335..121W. doi:10.1007/s10509-011-0617-x. S2CID 116910726.

- ^ Dickinson, N. J.; Barstow, M. A.; Welsh, B. Y.; Burleigh, M.; Farihi, J.; Redfield, S.; Unglaub, K. (2012). «The Origin of Hot White Dwarf Circumstellar Features». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 423 (2): 1397–1410. arXiv:1203.5226. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.423.1397D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20964.x. S2CID 119212643.

- ^ Marsh, Kenneth A.; Wright, Edward L.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gelino, Christopher R.; Cushing, Michael C.; Griffith, Roger L.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Eisenhardt, Peter R. (2013). «Parallaxes and Proper Motions of Ultracool Brown Dwarfs of Spectral Types Y and Late T». The Astrophysical Journal. 762 (2): 119. arXiv:1211.6977. Bibcode:2013ApJ…762..119M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/762/2/119. S2CID 42923100.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Cushing, Michael C.; Gelino, Christopher R.; Griffith, Roger L.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Marsh, Kenneth A.; Wright, Edward L.; Mainzer, Amy K.; Eisenhardt, Peter R.; McLean, Ian S.; Thompson, Maggie A.; Bauer, James M.; Benford, Dominic J.; Bridge, Carrie R.; Lake, Sean E.; Petty, Sara M.; Stanford, Spencer Adam; Tsai, Chao-Wei; Bailey, Vanessa; Beichman, Charles A.; Bloom, Joshua S.; Bochanski, John J.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Capak, Peter L.; Cruz, Kelle L.; Hinz, Philip M.; Kartaltepe, Jeyhan S.; Knox, Russell P.; Manohar, Swarnima; Masters, Daniel; Morales-Calderon, Maria; Prato, Lisa A.; Rodigas, Timothy J.; Salvato, Mara; Schurr, Steven D.; Scoville, Nicholas Z.; Simcoe, Robert A.; Stapelfeldt, Karl R.; Stern, Daniel; Stock, Nathan D.; Vacca, William D. (2011). «The First Hundred Brown Dwarfs Discovered by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)». The Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 197 (2): 19. arXiv:1108.4677v1. Bibcode:2011ApJS..197…19K. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/197/2/19. S2CID 16850733.

- ^ Döllinger, M. P.; Hatzes, A.P.; Pasquini, L.; Guenther, E. W.; Hartmann, M. (2009). «Planetary Companions around the K Giant Stars 11 Ursae Minoris and HD 32518». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 505 (3): 1311–17. arXiv:0908.1753. Bibcode:2009A&A…505.1311D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911702. S2CID 9686080.

- ^ Sato, Bun’ei; Omiya, Masashi; Harakawa, Hiroki; Liu, Yu-Juan; Izumiura, Hideyuki; Kambe, Eiji; Takeda, Yoichi; Yoshida, Michitoshi; Itoh, Yoichi; Ando, Hiroyasu; Kokubo, Eiichiro; Ida, Shigeru (2013). «Planetary Companions to Three Evolved Intermediate-Mass Stars: HD 2952, HD 120084, and omega Serpentis». Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 65 (4): 1–15. arXiv:1304.4328. Bibcode:2013PASJ…65…85S. doi:10.1093/pasj/65.4.85. S2CID 119248666.

- ^ Wright, J.T.; Marcy, G.W.; Fischer, D. A.; Butler, R. P.; Vogt, S. S.; Tinney, C. G.; Jones, H. R. A.; Carter, B. D.; Johnson, J. A.; McCarthy, C.; Apps, K. (2007). «Four New Exoplanets and Hints of Additional Substellar Companions to Exoplanet Host Stars». The Astrophysical Journal. 657 (1): 533–45. arXiv:astro-ph/0611658. Bibcode:2007ApJ…657..533W. doi:10.1086/510553. S2CID 35682784.

- ^ Boisse, Isabelle; Pepe, Francesco; Perrier, Christian; Queloz, Didier; Bonfils, Xavier; Bouchy, François; Santos, Nuno C.; Arnold, Luc; Beuzit, Jean-Luc; Dìaz, Rodrigo F.; Delfosse, Xavier; Eggenberger, Anne; Ehrenreich, David; Forveille, Thierry; Hébrard, Guillaume; Lagrange, Anne-Marie; Lovis, Christophe; Mayor, Michel; Moutou, Claire; Naef, Dominique; Santerne, Alexandre; Ségransan, Damien; Sivan, Jean-Pierre; Udry, Stéphane (2012), «The SOPHIE search for northern extrasolar planets V. Follow-up of ELODIE candidates: Jupiter-analogs around Sun-like stars», Astronomy and Astrophysics, 545: A55, arXiv:1205.5835, Bibcode:2012A&A…545A..55B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118419, S2CID 119109836

- ^ Bergh, Sidney (2000). The Galaxies of the Local Group. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-139-42965-8.

- ^ Grebel, Eva K.; Gallagher, John S., III; Harbeck, Daniel (2003). «The Progenitors of Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies». The Astronomical Journal. 125 (4): 1926–39. arXiv:astro-ph/0301025. Bibcode:2003AJ….125.1926G. doi:10.1086/368363. S2CID 18496644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van den Bergh, Sidney (April 2000). «Updated Information on the Local Group». The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 112 (#770): 529–36. arXiv:astro-ph/0001040. Bibcode:2000PASP..112..529V. doi:10.1086/316548. S2CID 1805423.

- ^ Mighell, Kenneth J.; Burke, Christopher J. (1999). «WFPC2 Observations of the Ursa Minor Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy». The Astronomical Journal. 118 (366): 366–380. arXiv:astro-ph/9903065. Bibcode:1999AJ….118..366M. doi:10.1086/300923. S2CID 119085245.

- ^ «NGC 3172». sim-id. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ «New General Catalog Objects: NGC 3150 — 3199». cseligman.com. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ Gusev, A. S.; Pilyugin, L. S.; Sakhibov, F.; Dodonov, S. N.; Ezhkova, O. V.; Khramtsova, M. S.; Garzónhuhed, F. (2012). «Oxygen and Nitrogen Abundances of H II regions in Six Spiral Galaxies». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 424 (#3): 1930–40. arXiv:1205.3910. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.424.1930G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21322.x. S2CID 118437910.

- ^ O’Meara, Stephen James (2007). Steve O’Meara’s Herschel 400 Observing Guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-521-85893-9.

- ^ Calzetti, Daniela (1997). «Reddening and Star Formation in Starburst Galaxies». Astronomical Journal. 113: 162–84. arXiv:astro-ph/9610184. Bibcode:1997AJ….113..162C. doi:10.1086/118242. S2CID 16526015.

- ^ «NGC 6251 – Seyfert 2 Galaxy». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Perley, R. A.; Bridle, A. H.; Willis, A. G. (1984). «High-resolution VLA Observations of the Radio Jet in NGC 6251». Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 54: 291–334. Bibcode:1984ApJS…54..291P. doi:10.1086/190931.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (September 2012). «Mapping Meteoroid Orbits: New Meteor Showers Discovered». Sky & Telescope: 24.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ursa Minor.

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Ursa Minor

- The clickable Ursa Minor

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Ursa Minor)

| Constellation | |

List of stars in Ursa Minor |

|

| Abbreviation | UMi[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Ursae Minoris[1] |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Symbolism | the Little Bear[1] |

| Right ascension | 08h 41.4m to 22h 54.0m [1] |

| Declination | 65.40° to 90°[1] |

| Quadrant | NQ3 |

| Area | 256 sq. deg. (56th) |

| Main stars | 7 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars |

23 |

| Stars with planets | 4 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 3 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | Polaris[2] (1.97m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | Ursids |

| Bordering constellations |

|

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −10°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of June[2]. |

Ursa Minor (Latin: ‘Lesser Bear’, contrasting with Ursa Major), also known as the Little Bear, is a constellation located in the far northern sky. As with the Great Bear, the tail of the Little Bear may also be seen as the handle of a ladle, hence the North American name, Little Dipper: seven stars with four in its bowl like its partner the Big Dipper. Ursa Minor was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. Ursa Minor has traditionally been important for navigation, particularly by mariners, because of Polaris being the north pole star.

Polaris, the brightest star in the constellation, is a yellow-white supergiant and the brightest Cepheid variable star in the night sky, ranging in apparent magnitude from 1.97 to 2.00. Beta Ursae Minoris, also known as Kochab, is an aging star that has swollen and cooled to become an orange giant with an apparent magnitude of 2.08, only slightly fainter than Polaris. Kochab and 3rd-magnitude Gamma Ursae Minoris have been called the «guardians of the pole star» or «Guardians of The Pole».[3] Planets have been detected orbiting four of the stars, including Kochab. The constellation also contains an isolated neutron star—Calvera—and H1504+65, the hottest white dwarf yet discovered, with a surface temperature of 200,000 K.

History and mythology[edit]

Ursa Minor, with Draco looping around it, as depicted in Urania’s Mirror,[4] a set of constellation maps published in London c. 1825

In the Babylonian star catalogues, Ursa Minor was known as the «Wagon of Heaven» (MULMAR.GÍD.DA.AN.NA, also associated with the goddess Damkina). It is listed in the MUL.APIN catalogue, compiled around 1000 BC, among the «Stars of Enlil»—that is, the northern sky.[5]

According to Diogenes Laërtius, citing Callimachus, Thales of Miletus «measured the stars of the Wagon by which the Phoenicians sail». Diogenes identifies these as the constellation of Ursa Minor, which for its reported use by the Phoenicians for navigation at sea were also named Phoinikē.[6][7]

The tradition of naming the northern constellations «bears» appears to be genuinely Greek, although Homer refers to just a single «bear».[8]

The original «bear» is thus Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor was admitted as the second, or «Phoenician Bear» (Ursa Phoenicia, hence Φοινίκη, Phoenice)

only later, according to Strabo (I.1.6, C3) due to a suggestion by Thales, who suggested it as a navigation aid to the Greeks, who had been navigating by Ursa Major. In classical antiquity, the celestial pole was somewhat closer to Beta Ursae Minoris than to Alpha Ursae Minoris, and the entire constellation was taken to indicate the northern direction. Since the medieval period, it has become convenient to use Alpha Ursae Minoris (or «Polaris») as the North Star. (Even though, in the medieval period, Polaris was still several degrees away from the celestial pole.[9][a] ) Now, Polaris is within 1° of the north celestial pole and remains the current Pole star. Its New Latin name of stella polaris was coined only in the early modern period.[10]

The ancient name of the constellation is Cynosura (Greek Κυνοσούρα «dog’s tail»).

The origin of this name is unclear (Ursa Minor being a «dog’s tail» would imply that another constellation nearby is «the dog», but no such constellation is known).[11]

Instead, the mythographic tradition of Catasterismi makes Cynosura the name of an Oread nymph described as a nurse of Zeus, honoured by the god with a place in the sky.[12]

There are various proposed explanations for the name Cynosura. One suggestion connects it to the myth of Callisto, with her son Arcas replaced by her dog being placed in the sky by Zeus.[11]

Others have suggested that an archaic interpretation of Ursa Major was that of a cow, forming a group with Boötes as herdsman, and Ursa Minor as a dog.[13] George William Cox explained it as a variant of Λυκόσουρα, understood as «wolf’s tail» but by him etymologized as «trail, or train, of light» (i.e. λύκος «wolf» vs. λύκ- «light»). Allen points to the Old Irish name of the constellation, drag-blod «fire trail», for comparison.

Brown (1899) suggested a non-Greek origin of the name (a loan from an Assyrian An‑nas-sur‑ra «high-rising»).[14]

An alternative myth tells of two bears that saved Zeus from his murderous father Cronus by hiding him on Mount Ida. Later Zeus set them in the sky, but their tails grew long from their being swung up into the sky by the god.[15]

Because Ursa Minor consists of seven stars, the Latin word for «north» (i.e., where Polaris points) is septentrio, from septem (seven) and triones (oxen), from seven oxen driving a plough, which the seven stars also resemble. This name has also been attached to the main stars of Ursa Major.[16]

In Inuit astronomy, the three brightest stars—Polaris, Kochab and Pherkad—were known as Nuutuittut «never moving», though the term is more frequently used in the singular to refer to Polaris alone. The Pole Star is too high in the sky at far northern latitudes to be of use in navigation.[17] In Chinese astronomy, the main stars of Ursa Minor are divided between two asterisms:

勾陳 Gòuchén (Curved Array) (including α UMi, δ UMi, ε UMi, ζ UMi, η UMi, θ UMi, λ UMi) and

北極 Běijí (Northern Pole) (including β UMi and γ UMi).[18]

Characteristics[edit]

Ursa Minor is bordered by Camelopardalis to the west, Draco to the west, and Cepheus to the east. Covering 256 square degrees, it ranks 56th of the 88 constellations in size. Ursa Minor is colloquially known in the US as the Little Dipper because its seven brightest stars seem to form the shape of a dipper (ladle or scoop). The star at the end of the dipper handle is Polaris. Polaris can also be found by following a line through the two stars—Alpha and Beta Ursae Majoris, popularly called the Pointers—that form the end of the «bowl» of the Big Dipper, for 30 degrees (three upright fists at arms’ length) across the night sky.[19] The four stars constituting the bowl of the Little Dipper are of second, third, fourth, and fifth magnitudes, respectively, and provide an easy guide to determining what magnitude stars are visible, useful for city dwellers or testing one’s eyesight.[20]

The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the IAU (International Astronomical Union) in 1922, is «UMi».[21] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 22 segments (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 08h 41.4m and 22h 54.0m , while the declination coordinates range from the north celestial pole to 65.40° in the south.[1] Its position in the far northern celestial hemisphere means that the whole constellation is visible only to observers in the northern hemisphere.[22][b]

Features[edit]

The constellation Ursa Minor as it can be seen by the naked eye (with connections and label added). Notice the seven stars of Ursa Major that form the Big Dipper and then make a line from the outermost Big Dipper stars (sometimes called the «pointers») to Polaris.

Stars[edit]

The German cartographer Johann Bayer used the Greek letters alpha to theta to label the most prominent stars in the constellation, while his countryman Johann Elert Bode subsequently added iota through phi. Only lambda and pi remain in use, likely because of their proximity to the north celestial pole.[16] Within the constellation’s borders, there are 39 stars brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[22][c]

Marking the Little Bear’s tail,[16] Polaris, or Alpha Ursae Minoris, is the brightest star in the constellation, varying between apparent magnitudes 1.97 and 2.00 over a period of 3.97 days.[24] Located around 432 light-years away from Earth,[25] it is a yellow-white supergiant that varies between spectral types F7Ib and F8Ib,[24] and has around 6 times the Sun’s mass, 2,500 times its luminosity, and 45 times its radius. Polaris is the brightest Cepheid variable star visible from Earth. It is a triple star system, the supergiant primary star having two yellow-white main-sequence star companions that are 17 and 2,400 astronomical units (AU) distant and take 29.6 and 42,000 years respectively to complete one orbit.[26]

Traditionally called Kochab, Beta Ursae Minoris, at apparent magnitude 2.08, is slightly less bright than Polaris.[27] Located around 131 light-years away from Earth,[28][d] it is an orange giant—an evolved star that has used up the hydrogen in its core and moved off the main sequence—of spectral type K4III.[27] Slightly variable over a period of 4.6 days, Kochab has had its mass estimated at 1.3 times that of the Sun via measurement of these oscillations.[29] Kochab is 450 times more luminous than the Sun and has 42 times its diameter, with a surface temperature of approximately 4,130 K.[30] Estimated to be around 2.95 billion years old, ±1 billion years, Kochab was announced to have a planetary companion around 6.1 times as massive as Jupiter with an orbit of 522 days.[31]

Ursa Minor and Ursa Major in relation to Polaris

Traditionally known as Pherkad, Gamma Ursae Minoris has an apparent magnitude that varies between 3.04 and 3.09 roughly every 3.4 hours.[32] It and Kochab have been termed the «guardians of the pole star».[3] A white bright giant of spectral type A3II-III,[32] with around 4.8 times the Sun’s mass, 1,050 times its luminosity and 15 times its radius,[33] it is 487±8 light-years distant from Earth.[28] Pherkad belongs to a class of stars known as Delta Scuti variables[32]—short period (six hours at most) pulsating stars that have been used as standard candles and as subjects to study asteroseismology.[34] Also possibly a member of this class is Zeta Ursae Minoris,[35] a white star of spectral type A3V,[36] which has begun cooling, expanding and brightening. It is likely to have been a B3 main-sequence star and is now slightly variable.[35] At magnitude 4.95 the dimmest of the seven stars of the Little Dipper is Eta Ursae Minoris.[37] A yellow-white main-sequence star of spectral type F5V, it is 97 light-years distant.[38] It is double the Sun’s diameter, 1.4 times as massive, and shines with 7.4 times its luminosity.[37] Nearby Zeta lies 5.00-magnitude Theta Ursae Minoris. Located 860 ± 80 light-years distant,[39] it is an orange giant of spectral type K5III that has expanded and cooled off the main sequence, and has an estimated diameter around 4.8 times that of the Sun.[40]

Making up the handle of the Little Dipper are Delta Ursae Minoris, or Yildun,[41] and Epsilon Ursae Minoris. Just over 3.5 degrees from the north celestial pole, Delta is a white main-sequence star of spectral type A1V with an apparent magnitude of 4.35,[42] located 172±1 light-years from Earth.[28] It has around 2.8 times the diameter and 47 times the luminosity of the Sun.[43] A triple star system,[44] Epsilon Ursae Minoris shines with a combined average light of magnitude 4.22.[45] A yellow giant of spectral type G5III,[45] the primary is a RS Canum Venaticorum variable star. It is a spectroscopic binary, with a companion 0.36 AU distant, and a third star—an orange main-sequence star of spectral type K0—8100 AU distant.[44]

Located close to Polaris is Lambda Ursae Minoris, a red giant of spectral type M1III. It is a semiregular variable varying between magnitudes 6.35 and 6.45.[46] The northerly nature of the constellation means that the variable stars can be observed all year: The red giant R Ursae Minoris is a semiregular variable varying from magnitude 8.5 to 11.5 over 328 days, while S Ursae Minoris is a long-period variable that ranges between magnitudes 8.0 and 11 over 331 days.[47] Located south of Kochab and Pherkad towards Draco is RR Ursae Minoris,[3] a red giant of spectral type M5III that is also a semiregular variable ranging from magnitude 4.44 to 4.85 over a period of 43.3 days.[48] T Ursae Minoris is another red-giant variable star that has undergone a dramatic change in status—from being a long-period (Mira) variable ranging from magnitude 7.8 to 15 over 310–315 days, to being a semiregular variable.[49] The star is thought to have undergone a shell helium flash—a point where the shell of helium around the star’s core reaches a critical mass and ignites—marked by its abrupt change in variability in 1979.[50] Z Ursae Minoris is a faint variable star that suddenly dropped 6 magnitudes in 1992 and was identified as one of a rare class of stars—R Coronae Borealis variables.[51]

Eclipsing variables are star systems that vary in brightness because of one star passing in front of the other rather than from any intrinsic change in luminosity. W Ursae Minoris is one such system, its magnitude ranging from 8.51 to 9.59 over 1.7 days.[52] The combined spectrum of the system is A2V, but the masses of the two component stars are unknown. A slight change in the orbital period in 1973 suggests there is a third component of the multiple star system—most likely a red dwarf—with an orbital period of 62.2±3.9 years.[53] RU Ursae Minoris is another example, ranging from 10 to 10.66 over 0.52 days.[54] It is a semidetached system, as the secondary star is filling its Roche lobe and transferring matter to the primary.[55]

RW Ursae Minoris is a cataclysmic variable star system that flared up as a nova in 1956, reaching magnitude 6. In 2003, it was still two magnitudes brighter than its baseline, and dimming at a rate of 0.02 magnitude a year. Its distance has been calculated as 5,000±800 parsecs (16,300 light-years), which puts its location in the galactic halo.[56]

Taken from the villain in The Magnificent Seven, Calvera is the nickname given to an X-ray source known as 1RXS J141256.0+792204 in the ROSAT All-Sky Survey Bright Source Catalog (RASS/BSC).[57] It has been identified as an isolated neutron star, one of the closest of its kind to Earth.[58] Ursa Minor has two enigmatic white dwarfs. Documented on January 27, 2011, H1504+65 is a faint (magnitude 15.9) star with the hottest surface temperature—200,000 K—yet discovered for a white dwarf. Its atmosphere, composed of roughly half carbon, half oxygen and 2% neon, is devoid of hydrogen and helium—its composition unexplainable by current models of stellar evolution.[59] WD 1337+705 is a cooler white dwarf that has magnesium and silicon in its spectrum, suggesting a companion or circumstellar disk, though no evidence for either has come to light.[60] WISE 1506+7027 is a brown dwarf of spectral type T6 that is a mere 11.1+2.3

−1.3 light-years away from Earth.[61] A faint object of magnitude 14, it was discovered by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) in 2011.[62]

Kochab aside, three more stellar systems have been discovered to contain planets. 11 Ursae Minoris is an orange giant of spectral type K4III around 1.8 times as massive as the Sun. Around 1.5 billion years old, it has cooled and expanded since it was an A-type main-sequence star. Around 390 light-years distant, it shines with an apparent magnitude of 5.04. A planet around 11 times the mass of Jupiter was discovered in 2009 orbiting the star with a period of 516 days.[63] HD 120084 is another evolved star, a yellow giant of spectral type G7III, around 2.4 times the mass of the Sun. It has a planet 4.5 times the mass of Jupiter, with one of the most eccentric planetary orbits (e = 0.66), discovered by precisely measuring the radial velocity of the star in 2013.[64] HD 150706 is a sunlike star of spectral type G0V some 89 light-years distant from the Solar System. It was thought to have a planet as massive as Jupiter at a distance of 0.6 AU, but this was discounted in 2007.[65] A further study published in 2012 showed that it has a companion around 2.7 times as massive as Jupiter that takes around 16 years to complete an orbit and is 6.8 AU distant from its star.[66]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

Ursa Minor is rather devoid of deep-sky objects. The Ursa Minor Dwarf, a dwarf spheroidal galaxy, was discovered by Albert George Wilson of the Lowell Observatory in the Palomar Sky Survey in 1955.[67] Its centre is around 225000 light-years distant from Earth.[68] In 1999, Kenneth Mighell and Christopher Burke used the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm that the galaxy had had a single burst of star formation that took place around 14 billion years ago and lasted around 2 billion years,[69] and that the galaxy was probably as old as the Milky Way itself.[70]

NGC 3172 (also known as Polarissima Borealis) is a faint, magnitude-14.9 galaxy that happens to be the closest NGC object to the north celestial pole.[71] It was discovered by John Herschel in 1831.[72]

NGC 6217 is a barred spiral galaxy located some 67 million light-years away,[73] which can be located with a 10 cm (4 in) or larger telescope as an 11th-magnitude object about 2.5° east-northeast of Zeta Ursae Minoris.[74] It has been characterized as a starburst galaxy, which means it is undergoing a high rate of star formation compared with a typical galaxy.[75]

NGC 6251 is an active supergiant elliptical radio galaxy more than 340 million light-years away from Earth. It has a Seyfert 2 active galactic nucleus, and is one of the most extreme examples of a Seyfert galaxy. This galaxy may be associated with gamma-ray source 3EG J1621+8203, which has high-energy gamma-ray emission.[76] It is also noted for its one-sided radio jet—one of the brightest known—discovered in 1977.[77]

Meteor showers[edit]

The Ursids, a prominent meteor shower that occurs in Ursa Minor, peaks between December 18 and 25. Its parent body is the comet 8P/Tuttle.[78]

See also[edit]

- Polaris Flare

- Ursa Minor Beta, fictional planet in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

- Ursa Minor (Chinese astronomy)

Notes[edit]

- ^ The position of the north celestial pole moves in accordance with the Earth’s axial precession such that in 12,000 years’ time, Vega will be the Pole Star.[9]

- ^ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between the equator and 24°S, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[22]

- ^ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[23]

- ^ Or more specifically 130.9±0.6 light-years by parallax measurement.[28]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f «Ursa Minor, Constellation Boundary». The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ a b Department of Astronomy (1995). «Ursa Minor». University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Arnold, H. J. P.; Doherty, Paul; Moore, Patrick (1999). The Photographic Atlas of the Stars. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-7503-0654-6.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «Urania’s Mirror c.1825 – Ian Ridpath’s Old Star Atlases». Self-published. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Rogers, John H. (1998). «Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108….9R.

- ^ Hermann Hunger, David Edwin Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia (1999), p. 68.

- ^ Albright, William F. (1972). «Neglected Factors in the Greek Intellectual Revolution». Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 116 (3): 225–42. JSTOR 986117.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «Ursa Minor». Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

Blomberg, Peter E. (2007). «How Did the Constellation of the Bear Receive its Name?» (PDF). In Pásztor, Emília (ed.). Archaeoastronomy in Archaeology and Ethnography: Papers from the Annual Meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture), held in Kecskemét in Hungary in 2004. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress. pp. 129–32. ISBN 978-1-4073-0081-8. - ^ a b Kenneth R. Lang (2013). Essential Astrophysics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-3-642-35963-7.

- ^ «Ursa Minor – Polaris». Star Tales. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ a b Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. 447f.

«The origin of this word is uncertain, for the star group does not answer to its name unless the dog himself be attached; still some, recalling a variant legend of Kallisto and her Dog instead of Arcas, have thought that here lay the explanation. Others have drawn this title from that of the Attican promontory east of Marathon, because sailors, on their approach to it from the sea, saw these stars shining above it and beyond; but if there be any connection at all here, the reversed derivation is more probable; while Bournouf asserted that it is in no way associated with the Greek word for «dog.» - ^ Condos, T., The Katasterismoi (Part 1), 1967. Also mentioned by Servius On Virgilius’ Georgics 1. 246, c. AD 400; a mention of doubtful authenticity is Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.2.

- ^ 265f. Robert Brown, Researches into the origin of the primitive constellations of the Greeks, Phoenicians and Babylonians (1899),

«M. Syoronos (Types Mon. des anciens p. 116) is of opinion that in the case of some Kretan coin-types, Ursa Maj. is represented as a Cow, hence Boôtês as ‘the Herdsman’, and Ursa Min. as a Dog (‘Chienne’ cf. Kynosoura, Kynoupês), a Zeus-suckler.»

A supposed Latin tradition of naming Ursa Minor Catuli «whelps» or Canes Laconicae «Spartan dogs», recorded in Johann Heinrich Alsted (1649, 408), is probably an early modern innovation. - ^ «Very recently, however, Brown [Robert Brown, Researches into the origin of the primitive constellations of the Greeks, Phoenicians and Babylonians] has suggested that the word is not Hellenic in origin, but Euphratean; and, in confirmation of this, mentions a constellation title from that valley, transcribed by Sayce as An‑ta-sur‑ra, the Upper Sphere. Brown reads this An‑nas-sur‑ra, High in Rising, certainly very appropriate to Ursa Minor; and he compares it with Κ‑υν‑όσ‑ου‑ρα, or, the initial consonant being omitted, Unosoura.» (Allen, Richard Hinckley. «Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning.» New York, Dover Editions, 1963, p. 448.)

Brown points out that Aratus fittingly describes «Cynosura» as «high-running» («at the close of night Cynosura’s head runs very high», κεφαλὴ Κυνοσουρίδος ἀκρόθι νυκτὸς

ὕψι μάλα τροχάει v. 308f). - ^ Rogers, John H. (1998). «Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean traditions». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108…79R.

- ^ a b c Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 312, 518. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ^ MacDonald, John (1998). The Arctic Sky: Inuit Astronomy, Star Lore, and Legend. Toronto, Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum/Nunavut Research Institute. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-88854-427-8.

- ^ «Ursa Minor – Chinese associations». Star Tales. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ O’Meara, Stephen James (1998). The Messier Objects. Deep-sky Companions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-521-55332-2.

- ^ Olcott, William Tyler (2012) [1911]. Star Lore of All Ages: A Collection of Myths, Legends, and Facts Concerning the Constellations of the Northern Hemisphere. New York, New York: Courier Corporation. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-486-14080-3.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). «The New International Symbols for the Constellations». Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA…..30..469R.

- ^ a b c Ridpath, Ian. «Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula». Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). «The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale». Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b Otero, Sebastian Alberto (4 December 2007). «Alpha Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ «Alpha Ursae Minoris – Classical Cepheid (Delta Cep Type)». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. «Polaris». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ a b «Beta Ursae Minoris – Variable Star». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d van Leeuwen, F. (2007). «Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A…474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Tarrant, N.J.; Chaplin, W.J.; Elsworth, Y.; Spreckley, S.A.; Stevens, I.R. (June 2008). «Oscillations in ß Ursae Minoris. Observations with SMEI». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 483 (#3): L43–L46. arXiv:0804.3253. Bibcode:2008A&A…483L..43T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809738. S2CID 53546805.

- ^ Kaler, James B. «Kochab». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Lee, B.-C.; Han, I.; Park, M.-G.; Mkrtichian, D.E.; Hatzes, A.P.; Kim, K.-M. (2014). «Planetary Companions in K giants β Cancri, μ Leonis, and β Ursae Minoris». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 566: 7. arXiv:1405.2127. Bibcode:2014A&A…566A..67L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322608. S2CID 118631934. A67.

- ^ a b c Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «Gamma Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (20 December 2013). «Pherkad». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Templeton, Matthew (16 July 2010). «Delta Scuti and the Delta Scuti Variables». Variable Star of the Season. AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers). Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. «Alifa al Farkadain». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ «Zeta Ursae Minoris – Variable Star». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. «Anwar al Farkadain». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ «Eta Ursae Minoris». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ «Theta Ursae Minoris – Variable Star». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Pasinetti Fracassini, L. E.; Pastori, L.; Covino, S.; Pozzi, A. (February 2001). «Catalogue of Apparent Diameters and Absolute Radii of Stars (CADARS) – Third edition – Comments and statistics». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 367 (2): 521–24. arXiv:astro-ph/0012289. Bibcode:2001A&A…367..521P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000451. S2CID 425754.

- ^ «Naming Stars». IAU.org. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ «Delta Ursae Minoris». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. «Yildun». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. «Epsilon Ursae Minoris». Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ a b «Epsilon Ursae Minoris – Variable of RS CVn type». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «Lambda Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Levy, David H. (1998). Observing Variable Stars: A Guide for the Beginner. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-521-62755-9.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (16 November 2009). «RR Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Uttenthaler, S.; van Stiphout, K.; Voet, K.; van Winckel, H.; van Eck, S.; Jorissen, A.; Kerschbaum, F.; Raskin, G.; Prins, S.; Pessemier, W.; Waelkens, C.; Frémat, Y.; Hensberge, H.; Dumortier, L.; Lehmann, H. (2011). «The Evolutionary State of Miras with Changing Pulsation Periods». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 531: A88. arXiv:1105.2198. Bibcode:2011A&A…531A..88U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116463. S2CID 56226953.

- ^ Mattei, Janet A.; Foster, Grant (1995). «Dramatic Period Decrease in T Ursae Minoris». The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. 23 (2): 106–16. Bibcode:1995JAVSO..23..106M.

- ^ Benson, Priscilla J.; Clayton, Geoffrey C.; Garnavich, Peter; Szkody, Paula (1994). «Z Ursa Minoris – a New R Coronae Borealis Variable». The Astronomical Journal. 108 (#1): 247–50. Bibcode:1994AJ….108..247B. doi:10.1086/117063.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «W Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Kreiner, J. M.; Pribulla, T.; Tremko, J.; Stachowski, G. S.; Zakrzewski, B. (2008). «Period Analysis of Three Close Binary Systems: TW And, TT Her and W UMi». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 383 (#4): 1506–12. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.383.1506K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12652.x.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). «RU Ursae Minoris». The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Manimanis, V. N.; Niarchos, P. G. (2001). «A Photometric Study of the Near-contact System RU Ursae Minoris». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 369 (3): 960–64. Bibcode:2001A&A…369..960M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010178.

- ^ Bianchini, A.; Tappert, C.; Canterna, R.; Tamburini, F.; Osborne, H.; Cantrell, K. (2003). «RW Ursae Minoris (1956): An Evolving Postnova System». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 115 (#809): 811–18. Bibcode:2003PASP..115..811B. doi:10.1086/376434.

- ^ «Rare Dead Star Found Near Earth». BBC News: Science/Nature. BBC. 20 August 2007. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ Rutledge, Robert; Fox, Derek; Shevchuk, Andrew (2008). «Discovery of an Isolated Compact Object at High Galactic Latitude». The Astrophysical Journal. 672 (#2): 1137–43. arXiv:0705.1011. Bibcode:2008ApJ…672.1137R. doi:10.1086/522667. S2CID 7915388.

- ^ Werner, K.; Rauch, T. (2011). «UV Spectroscopy of the Hot Bare Stellar Core H1504+65 with the HST Cosmic Origins Spectrograph». Astrophysics and Space Science. 335 (1): 121–24. Bibcode:2011Ap&SS.335..121W. doi:10.1007/s10509-011-0617-x. S2CID 116910726.

- ^ Dickinson, N. J.; Barstow, M. A.; Welsh, B. Y.; Burleigh, M.; Farihi, J.; Redfield, S.; Unglaub, K. (2012). «The Origin of Hot White Dwarf Circumstellar Features». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 423 (2): 1397–1410. arXiv:1203.5226. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.423.1397D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20964.x. S2CID 119212643.

- ^ Marsh, Kenneth A.; Wright, Edward L.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gelino, Christopher R.; Cushing, Michael C.; Griffith, Roger L.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Eisenhardt, Peter R. (2013). «Parallaxes and Proper Motions of Ultracool Brown Dwarfs of Spectral Types Y and Late T». The Astrophysical Journal. 762 (2): 119. arXiv:1211.6977. Bibcode:2013ApJ…762..119M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/762/2/119. S2CID 42923100.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Cushing, Michael C.; Gelino, Christopher R.; Griffith, Roger L.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Marsh, Kenneth A.; Wright, Edward L.; Mainzer, Amy K.; Eisenhardt, Peter R.; McLean, Ian S.; Thompson, Maggie A.; Bauer, James M.; Benford, Dominic J.; Bridge, Carrie R.; Lake, Sean E.; Petty, Sara M.; Stanford, Spencer Adam; Tsai, Chao-Wei; Bailey, Vanessa; Beichman, Charles A.; Bloom, Joshua S.; Bochanski, John J.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Capak, Peter L.; Cruz, Kelle L.; Hinz, Philip M.; Kartaltepe, Jeyhan S.; Knox, Russell P.; Manohar, Swarnima; Masters, Daniel; Morales-Calderon, Maria; Prato, Lisa A.; Rodigas, Timothy J.; Salvato, Mara; Schurr, Steven D.; Scoville, Nicholas Z.; Simcoe, Robert A.; Stapelfeldt, Karl R.; Stern, Daniel; Stock, Nathan D.; Vacca, William D. (2011). «The First Hundred Brown Dwarfs Discovered by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)». The Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 197 (2): 19. arXiv:1108.4677v1. Bibcode:2011ApJS..197…19K. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/197/2/19. S2CID 16850733.

- ^ Döllinger, M. P.; Hatzes, A.P.; Pasquini, L.; Guenther, E. W.; Hartmann, M. (2009). «Planetary Companions around the K Giant Stars 11 Ursae Minoris and HD 32518». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 505 (3): 1311–17. arXiv:0908.1753. Bibcode:2009A&A…505.1311D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911702. S2CID 9686080.

- ^ Sato, Bun’ei; Omiya, Masashi; Harakawa, Hiroki; Liu, Yu-Juan; Izumiura, Hideyuki; Kambe, Eiji; Takeda, Yoichi; Yoshida, Michitoshi; Itoh, Yoichi; Ando, Hiroyasu; Kokubo, Eiichiro; Ida, Shigeru (2013). «Planetary Companions to Three Evolved Intermediate-Mass Stars: HD 2952, HD 120084, and omega Serpentis». Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 65 (4): 1–15. arXiv:1304.4328. Bibcode:2013PASJ…65…85S. doi:10.1093/pasj/65.4.85. S2CID 119248666.

- ^ Wright, J.T.; Marcy, G.W.; Fischer, D. A.; Butler, R. P.; Vogt, S. S.; Tinney, C. G.; Jones, H. R. A.; Carter, B. D.; Johnson, J. A.; McCarthy, C.; Apps, K. (2007). «Four New Exoplanets and Hints of Additional Substellar Companions to Exoplanet Host Stars». The Astrophysical Journal. 657 (1): 533–45. arXiv:astro-ph/0611658. Bibcode:2007ApJ…657..533W. doi:10.1086/510553. S2CID 35682784.

- ^ Boisse, Isabelle; Pepe, Francesco; Perrier, Christian; Queloz, Didier; Bonfils, Xavier; Bouchy, François; Santos, Nuno C.; Arnold, Luc; Beuzit, Jean-Luc; Dìaz, Rodrigo F.; Delfosse, Xavier; Eggenberger, Anne; Ehrenreich, David; Forveille, Thierry; Hébrard, Guillaume; Lagrange, Anne-Marie; Lovis, Christophe; Mayor, Michel; Moutou, Claire; Naef, Dominique; Santerne, Alexandre; Ségransan, Damien; Sivan, Jean-Pierre; Udry, Stéphane (2012), «The SOPHIE search for northern extrasolar planets V. Follow-up of ELODIE candidates: Jupiter-analogs around Sun-like stars», Astronomy and Astrophysics, 545: A55, arXiv:1205.5835, Bibcode:2012A&A…545A..55B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118419, S2CID 119109836

- ^ Bergh, Sidney (2000). The Galaxies of the Local Group. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-139-42965-8.

- ^ Grebel, Eva K.; Gallagher, John S., III; Harbeck, Daniel (2003). «The Progenitors of Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies». The Astronomical Journal. 125 (4): 1926–39. arXiv:astro-ph/0301025. Bibcode:2003AJ….125.1926G. doi:10.1086/368363. S2CID 18496644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van den Bergh, Sidney (April 2000). «Updated Information on the Local Group». The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 112 (#770): 529–36. arXiv:astro-ph/0001040. Bibcode:2000PASP..112..529V. doi:10.1086/316548. S2CID 1805423.

- ^ Mighell, Kenneth J.; Burke, Christopher J. (1999). «WFPC2 Observations of the Ursa Minor Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy». The Astronomical Journal. 118 (366): 366–380. arXiv:astro-ph/9903065. Bibcode:1999AJ….118..366M. doi:10.1086/300923. S2CID 119085245.

- ^ «NGC 3172». sim-id. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ «New General Catalog Objects: NGC 3150 — 3199». cseligman.com. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ Gusev, A. S.; Pilyugin, L. S.; Sakhibov, F.; Dodonov, S. N.; Ezhkova, O. V.; Khramtsova, M. S.; Garzónhuhed, F. (2012). «Oxygen and Nitrogen Abundances of H II regions in Six Spiral Galaxies». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 424 (#3): 1930–40. arXiv:1205.3910. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.424.1930G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21322.x. S2CID 118437910.

- ^ O’Meara, Stephen James (2007). Steve O’Meara’s Herschel 400 Observing Guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-521-85893-9.

- ^ Calzetti, Daniela (1997). «Reddening and Star Formation in Starburst Galaxies». Astronomical Journal. 113: 162–84. arXiv:astro-ph/9610184. Bibcode:1997AJ….113..162C. doi:10.1086/118242. S2CID 16526015.

- ^ «NGC 6251 – Seyfert 2 Galaxy». SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Perley, R. A.; Bridle, A. H.; Willis, A. G. (1984). «High-resolution VLA Observations of the Radio Jet in NGC 6251». Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 54: 291–334. Bibcode:1984ApJS…54..291P. doi:10.1086/190931.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (September 2012). «Mapping Meteoroid Orbits: New Meteor Showers Discovered». Sky & Telescope: 24.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ursa Minor.

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Ursa Minor

- The clickable Ursa Minor

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Ursa Minor)

§ 15. Астрономические названия

1. Астрономические названия пишутся с прописной буквы: Марс, Сатурн, Галактика (в которую входит наша Солнечная система; но: отдалённые галактики), Персеиды.

2. В составных астрономических наименованиях все слова, кроме родовых названий и порядковых обозначений светил (обычно названий букв греческого алфавита), пишутся с прописной буквы: Большая Медведица, Южный Крест, Млечный Путь, Гончие Псы, туманность Андромеды, звезда Эрцгерцога Карла, созвездие Большого Пса, альфа Малой Медведицы, бета Весов; но на Луне: Море Дождей, Океан Бурь.

3. Слова Солнце, Земля, Луна пишутся с прописной буквы, когда служат названиями небесных тел: протуберанцы на Солнце; различные теории происхождения Земли; фотоснимки обратной стороны Луны; но: взошло солнце, распаханная земля, свет луны.

Одним из самых известных созвездий является Малая Медведица. Оно небольшого размера, в нем нет ярких звезд. А где находится Малая Медведица и важно ли оно? Это скопление звезд расположено недалеко от северного полюса. На протяжении долгих столетий оно играло важную роль в астрономии, мореплавании и не только.

Происхождение созвездия

Созвездие относится к числу самых древних скоплений звезд, из-за чего определить точное происхождение весьма сложно. В древних писаниях есть упоминания Гомером Большой Медведицы, а вот информация о Малой зарегистрирована позже, примерно в седьмом веке до нашей эры. В своих писаниях Страбон писал, что в эпоху Гомера, вероятнее всего, не было Малой Медведицы, так как эту группу звезд еще не знали до тех пор, пока финикийцы не стали использовать их для мореплавания.

Астрономы предполагают, что раньше люди не знали, где находится Малая Медведица, и не имели понятия о ее существовании. В отдельное созвездие ее вывели только из-за близкого расположения к северному полюсу. По Малой Медведице проще всего ориентироваться. В астрономию это созвездие было введено примерно в шестисотом году до нашей эры Ф. Милетским.

Мифы и легенды

О созвездии сложены легенды и мифы. Первый миф говорит, что родная мать Рея спрятала малыша от отца Кроноса, который из-за пророчества убивал всех своих детей. Когда Зевс родился, мать подложила вместо него камень, таким образом обманув Кроноса. Она спрятала младенца в пещере, где его выкармливали две медведицы – Гелис и Мелисса, позже они были вознесены на небо. А когда Зевс вырос, он сверг отца и освободил своих братьев, сестер. Все они стали олимпийскими богами.

В другой легенде говорится о Каллисто, дочери Ликаона, правителя Аркади. В легенде сказано, что у царицы была необычная красота, восхищавшая Зевса. Он принял обличие богини-охотницы Артемиды, которой служила Каллисто. Зевс проник к девушке, и у нее родился сын Аркан. Об этом узнала жена Зевса Гера и превратила Каллисто в медведицу. Спустя годы, Аркан вырос. Однажды, отправившись на охоту, он увидел след медведя и пошел по нему, ничего не подозревая. Хотел убить зверя. Но Зевс не позволил это сделать и превратил сына тоже в медведя: он перенес Каллисто и Аркана на небо. Этот поступок разозлил Геру. Она встретилась с Посейдоном и попросила не пускать любовницу мужа и ее дитя в свое царство. Из-за этого Малая и Большая Медведицы никогда не заходят за горизонт.

Расположение созвездия