|

|

| Type | Cooperative society[1] |

|---|---|

| Industry | Telecommunications |

| Founded | 3 May 1973; 49 years ago |

| Headquarters | La Hulpe, Belgium 50°44′04″N 4°28′43″E / 50.73444°N 4.47861°ECoordinates: 50°44′04″N 4°28′43″E / 50.73444°N 4.47861°E |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Financial telecommunication |

|

Number of employees |

>3,000 |

| Website | www.swift.com |

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), legally S.W.I.F.T. SC, is a Belgian cooperative society providing services related to the execution of financial transactions and payments between banks worldwide. Its principal function is to serve as the main messaging network through which international payments are initiated.[2] It also sells software and services to financial institutions, mostly for use on its proprietary «SWIFTNet», and assigns ISO 9362 Business Identifier Codes (BICs), popularly known as «SWIFT codes».

The SWIFT messaging network is a component of the global payments system.[3] SWIFT acts as a carrier of the «messages containing the payment instructions between financial institutions involved in a transaction».[4][5] However, the organization does not manage accounts on behalf of individuals or financial institutions, and it does not hold funds from third parties.[6] It also does not perform clearing or settlement functions.[7][5] After a payment has been initiated, it must be settled through a payment system, such as TARGET2 in Europe.[8] In the context of cross-border transactions, this step often takes place through correspondent banking accounts that financial institutions have with each other.[4]

As of 2018, around half of all high-value cross-border payments worldwide used the SWIFT network,[9] and in 2015, SWIFT linked more than 11,000 financial institutions in over 200 countries and territories, who were exchanging an average of over 32 million messages per day (compared to an average of 2.4 million daily messages in 1995).[10]

Though widely utilized, SWIFT has been criticized for its inefficiency. In 2018, the London-based Financial Times noted that transfers frequently «pass through multiple banks before reaching their final destination, making them time-consuming, costly and lacking transparency on how much money will arrive at the other end».[9] SWIFT has since introduced an improved service called «Global Payments Innovation» (GPI), claiming it was adopted by 165 banks and was completing half its payments within 30 minutes.[9]

As a cooperative society under Belgian law, SWIFT is owned by its member financial institutions. It is headquartered in La Hulpe, Belgium, near Brussels; its main building was designed by Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura and completed in 1989.[11] The chairman of SWIFT is Yawar Shah[12] of Pakistan,[13] and its CEO is Javier Pérez-Tasso of Spain.[14] SWIFT hosts an annual conference, called Sibos, specifically aimed at the financial services industry.[15]

History[edit]

SWIFT was founded in Brussels on 3 May 1973 under the leadership of its inaugural Swedish CEO, Carl Reuterskiöld (1973–1989), a former employee at Wallenberg-owned Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken, and was supported by 239 banks in 15 countries.[16] Before its establishment, international financial transactions were communicated over Telex, a public system involving manual writing and reading of messages.[17] It was set up out of fear of what might happen if a single private and fully American entity controlled global financial flows – which before was First National City Bank (FNCB) of New York – later Citibank. In response to FNCB’s protocol, FNCB’s competitors in the US and Europe pushed an alternative «messaging system that could replace the public providers and speed up the payment process».[18] SWIFT started to establish common standards for financial transactions and a shared data processing system and worldwide communications network designed by Logica and developed by the Burroughs Corporation.[19] Fundamental operating procedures and rules for liability were established in 1975, and the first message was sent in 1977. SWIFT’s first international (non-European) operations centre was inaugurated by Governor John N. Dalton of Virginia in 1979.[20]

Standards[edit]

SWIFT has become the industry standard for syntax in financial messages. Messages formatted to SWIFT standards can be read and processed by many well-known financial processing systems, whether or not the message travelled over the SWIFT network. SWIFT cooperates with international organizations for defining standards for message format and content. SWIFT is also Registration authority (RA) for the following ISO standards:

[21]

- ISO 9362: 1994 Banking – Banking telecommunication messages – Bank identifier codes

- ISO 10383: 2003 Securities and related financial instruments – Codes for exchanges and market identification (MIC)

- ISO 13616: 2003 IBAN Registry

- ISO 15022: 1999 Securities – Scheme for messages (Data Field Dictionary) (replaces ISO 7775)

- ISO 20022-1: 2004 and ISO 20022-2:2007 Financial services – Universal Financial Industry message scheme

In RFC 3615 urn:swift: was defined as Uniform Resource Names (URNs) for SWIFT FIN.[22]

Operations centres[edit]

The SWIFT secure messaging network is run from three data centres, located in the United States, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. These centres share information in near real-time. In case of a failure in one of the data centres, another is able to handle the traffic of the complete network. SWIFT uses submarine communications cables to transmit its data.[23]

Shortly after opening its third data centre in Switzerland in 2009,[24] SWIFT introduced new distributed architecture with two messaging zones, European and Trans-Atlantic, so data from European SWIFT members no longer mirrored the U.S. data centre.[25] European zone messages are stored in the Netherlands and in part of the Swiss operating centre; Trans-Atlantic zone messages are stored in the United States and in another part of the Swiss operating centre that is segregated from the European zone messages. Countries outside of Europe were by default allocated to the Trans-Atlantic zone, but could choose to have their messages stored in the European zone.

| SN | SWIFT data centres | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zoeterwoude, Netherlands | OPC (Operating Centre) |

| 2 | Culpeper, Virginia, United States | OPC (Operating Centre) |

| 3 | Diessenhofen, Switzerland[26] | OPC (Operating Centre) |

| 4 | Hong Kong | Command and control |

SWIFTNet network[edit]

SWIFT moved to its current IP network infrastructure, known as SWIFTNet, from 2001 to 2005,[27] providing a total replacement of the previous X.25 infrastructure. The process involved the development of new protocols that facilitate efficient messaging, using existing and new message standards. The adopted technology chosen to develop the protocols was XML, where it now provides a wrapper around all messages legacy or contemporary. The communication protocols can be broken down into:

|

InterAct

|

FileAct

|

Browse

|

Architecture[edit]

SWIFT provides a centralized store-and-forward mechanism, with some transaction management. For bank A to send a message to bank B with a copy or authorization involving institution C, it formats the message according to standards and securely sends it to SWIFT. SWIFT guarantees its secure and reliable delivery to B after the appropriate action by C. SWIFT guarantees are based primarily on high redundancy of hardware, software, and people.

SWIFTNet Phase 2[edit]

During 2007 and 2008, the entire SWIFT network migrated its infrastructure to a new protocol called SWIFTNet Phase 2. The main difference between Phase 2 and the former arrangement is that Phase 2 requires banks connecting to the network to use a Relationship Management Application (RMA) instead of the former bilateral key exchange (BKE) system. According to SWIFT’s public information database on the subject, RMA software should eventually prove more secure and easier to keep up-to-date; however, converting to the RMA system meant that thousands of banks around the world had to update their international payments systems to comply with the new standards. RMA completely replaced BKE on 1 January 2009.

Products and interfaces[edit]

SWIFT means several things in the financial world:

- a secure network for transmitting messages between financial institutions;

- a set of syntax standards for financial messages (for transmission over SWIFTNet or any other network)

- a set of connection software and services allowing financial institutions to transmit messages over SWIFT network.

Under 3 above, SWIFT provides turn-key solutions for members, consisting of linkage clients to facilitate connectivity to the SWIFT network and CBTs or «computer based terminals» which members use to manage the delivery and receipt of their messages. Some of the more well-known interfaces and CBTs provided to their members are:

- SWIFTNet Link (SNL) software which is installed on the SWIFT customer’s site and opens a connection to SWIFTNet. Other applications can only communicate with SWIFTNet through the SNL.

- Alliance Gateway (SAG) software with interfaces (e.g., RAHA = Remote Access Host Adapter), allowing other software products to use the SNL to connect to SWIFTNet

- Alliance WebStation (SAB) desktop interface for SWIFT Alliance Gateway with several usage options:

- administrative access to the SAG

- direct connection SWIFTNet by the SAG, to administrate SWIFT Certificates

- so-called Browse connection to SWIFTNet (also by SAG) to use additional services, for example Target2

- Alliance Access (SAA) and Alliance Messaging Hub (AMH) are the main messaging software applications by SWIFT, which allow message creation for FIN messages, routing and monitoring for FIN and MX messages. The main interfaces are FTA (files transfer automated, not FTP) and MQSA, a WebSphere MQ interface.

- The Alliance Workstation (SAW) is the desktop software for administration, monitoring and FIN message creation. Since Alliance Access is not yet capable of creating MX messages, Alliance Messenger (SAM) has to be used for this purpose.

- Alliance Web Platform (SWP) as new thin-client desktop interface provided as an alternative to existing Alliance WebStation, Alliance Workstation (soon)[when?] and Alliance Messenger.

- Alliance Integrator built on Oracle’s Java Caps which enables customer’s back office applications to connect to Alliance Access or Alliance Entry.

- Alliance Lite2 is a secure and reliable, cloud-based way to connect to the SWIFT network which is a light version of Alliance Access specifically targeting customers with low volume of traffic.

Services[edit]

There are four key areas that SWIFT services fall under in the financial marketplace: securities, treasury & derivatives, trade services. and payments-and-cash management.

|

Securities

|

Treasury and derivatives

|

Cash management

|

Trade services

|

SWIFTREF[edit]

Swift Ref, the global payment reference data utility, is SWIFT’s unique reference data service. Swift Ref sources data direct from data originators, including central banks, code issuers and banks making it easy for issuers and originators to maintain data regularly and thoroughly. SWIFTRef constantly validates and cross-checks data across the different data sets.[29]

SWIFTNet Mail[edit]

SWIFT offers a secure person-to-person messaging service, SWIFTNet Mail, which went live on 16 May 2007.[30] SWIFT clients can configure their existing email infrastructure to pass email messages through the highly secure and reliable SWIFTNet network instead of the open Internet. SWIFTNet Mail is intended for the secure transfer of sensitive business documents, such as invoices, contracts and signatories, and is designed to replace existing telex and courier services, as well as the transmission of security-sensitive data over the open Internet. Seven financial institutions, including HSBC, FirstRand Bank, Clearstream, DnB NOR, Nedbank, and Standard Bank of South Africa, as well as SWIFT piloted the service.[31]

U.S. government involvement[edit]

Terrorist Finance Tracking Program[edit]

A series of articles published on 23 June 2006 in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times revealed a program, named the Terrorist Finance Tracking Program, which the US Treasury Department, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and other United States governmental agencies initiated after the 11 September attacks to gain access to the SWIFT transaction database.[32]

After the publication of these articles, SWIFT quickly came under pressure for compromising the data privacy of its customers by allowing governments to gain access to sensitive personal information. In September 2006, the Belgian government declared that these SWIFT dealings with American governmental authorities were a breach of Belgian and European privacy laws.[citation needed]

In response, and to satisfy members’ concerns about privacy, SWIFT began a process of improving its architecture by implementing a distributed architecture with a two-zone model for storing messages (see Operations centres).

Concurrently, the European Union negotiated an agreement with the United States government to permit the transfer of intra-EU SWIFT transaction information to the United States under certain circumstances. Because of concerns about its potential contents, the European Parliament adopted a position statement in September 2009, demanding to see the full text of the agreement and asking that it be fully compliant with EU privacy legislation, with oversight mechanisms emplaced to ensure that all data requests were handled appropriately.[33] An interim agreement was signed without European Parliamentary approval by the European Council on 30 November 2009,[34] the day before the Lisbon Treaty—which would have prohibited such an agreement from being signed under the terms of the codecision procedure—formally came into effect. While the interim agreement was scheduled to come into effect on 1 January 2010, the text of the agreement was classified as «EU Restricted» until translations could be provided in all EU languages and published on 25 January 2010.

On 11 February 2010, the European Parliament decided to reject the interim agreement between the EU and the US by 378 to 196 votes.[35][36] One week earlier, the parliament’s civil liberties committee had already rejected the deal, citing legal reservations.[37]

In March 2011, it was reported that two mechanisms of data protection had failed: EUROPOL released a report complaining that requests for information from the US had been too vague (making it impossible to make judgments on validity)[38] and that the guaranteed right for European citizens to know whether their information had been accessed by US authorities had not been put into practice.[38]

Monitoring by the NSA[edit]

Der Spiegel reported in September 2013 that the National Security Agency (NSA) widely monitors banking transactions via SWIFT, as well as credit card transactions.[39] The NSA intercepted and retained data from the SWIFT network used by thousands of banks to securely send transaction information. SWIFT was named as a «target», according to documents leaked by Edward Snowden. The documents revealed that the NSA spied on SWIFT using a variety of methods, including reading «SWIFT printer traffic from numerous banks».[39] In April 2017, a group known as the Shadow Brokers released files allegedly from the NSA which indicate that the agency monitored financial transactions made through SWIFT.[40][41]

Use in sanctions[edit]

Belarus[edit]

The European Union issued the first set of sanctions against Belarus — the first was introduced on 27 February 2022, which banned certain categories of Belarusian items in the EU, including timber, steel, mineral fuels and tobacco.[42] After the Lithuanian prime minister proposed disconnecting Belarus from SWIFT,[43] the European Union, which does not recognise Lukashenko as the legitimate President of Belarus, started to plan an extension of the sanctions already issued against Russian entities and top officials to its ally.[44]

Iran[edit]

In January 2012, the advocacy group United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) implemented a campaign calling on SWIFT to end all relations with Iran’s banking system, including the Central Bank of Iran. UANI asserted that Iran’s membership in SWIFT violated US and EU financial sanctions against Iran as well as SWIFT’s own corporate rules.[45]

Consequently, in February 2012, the U.S. Senate Banking Committee unanimously approved sanctions against SWIFT aimed at pressuring it to terminate its ties with blacklisted Iranian banks. Expelling Iranian banks from SWIFT would potentially deny Iran access to billions of dollars in revenue using SWIFT but not from using IVTS. Mark Wallace, president of UANI, praised the Senate Banking Committee.[46]

Initially SWIFT denied that it was acting illegally,[46] but later[when?] said that «it is working with U.S. and European governments to address their concerns that its financial services are being used by Iran to avoid sanctions and conduct illicit business».[47] Targeted banks would be—amongst others—Saderat Bank of Iran, Bank Mellat, Post Bank of Iran and Sepah Bank.[48] On 17 March 2012, following agreement two days earlier between all 27 member states of the Council of the European Union and the Council’s subsequent ruling, SWIFT disconnected all Iranian banks that had been identified as institutions in breach of current EU sanctions from its international network and warned that even more Iranian financial institutions could be disconnected from the network.

In February 2016, most Iranian banks reconnected to the network following the lift of sanctions due to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.[49]

Russia[edit]

Similarly, in August 2014 the UK planned to press the EU to block Russian use of SWIFT as a sanction due to Russian military intervention in Ukraine.[50] However, SWIFT refused to do so.[51] SPFS, a Russia-based SWIFT equivalent, was created by the Central Bank of Russia as a backup measure.[52]

During the prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States developed preliminary possible sanctions against Russia, but excluded banning Russia from SWIFT.[53] Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the foreign ministers of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia called for Russia to be cut off from SWIFT. However, other EU member states were reluctant, both because European lenders held most of the nearly $30 billion in foreign banks’ exposure to Russia and because Russia had developed the SPFS alternative.[54] The European Union, United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States finally agreed to remove select Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine; the governments of France, Germany, Italy and Japan individually released statements alongside the EU.[55][5]

Israel[edit]

In 2014, SWIFT rejected calls from pro-Palestinian activists to revoke Israeli banks’ access to its network.[56]

Competitors[edit]

Alternatives to the SWIFT system include:

- CIPS: sponsored by China, for trade-related deals to internationalize Chinese currency RMB use. 1280 financial institutions in 103 countries and regions have connected to the system[57][58]

- SFMS: sponsored by India

- SPFS: sponsored by Russia, mostly composed of Russian banks[59]

- INSTEX: sponsored by the European Union, limited to non-USD transactions for trade with Iran, largely unused and ineffective[60][61]

Security[edit]

In 2016 an $81 million theft from the Bangladesh central bank via its account at the New York Federal Reserve Bank was traced to hacker penetration of SWIFT’s Alliance Access software, according to a New York Times report. It was not the first such attempt, the society acknowledged, and the security of the transfer system was undergoing new examination accordingly.[62] Soon after the reports of the theft from the Bangladesh central bank, a second, apparently related, attack was reported to have occurred on a commercial bank in Vietnam.[63]

Both attacks involved malware written to both issue unauthorized SWIFT messages and to conceal that the messages had been sent. After the malware sent the SWIFT messages that stole the funds, it deleted the database record of the transfers then took further steps to prevent confirmation messages from revealing the theft. In the Bangladeshi case, the confirmation messages would have appeared on a paper report; the malware altered the paper reports when they were sent to the printer. In the second case, the bank used a PDF report; the malware altered the PDF viewer to hide the transfers.[63]

In May 2016, Banco del Austro (BDA) in Ecuador sued Wells Fargo after Wells Fargo honoured $12 million in fund transfer requests that had been placed by thieves. In this case, the thieves sent SWIFT messages that resembled recently cancelled transfer requests from BDA, with slightly altered amounts; the reports do not detail how the thieves gained access to send the SWIFT messages. BDA asserts that Wells Fargo should have detected the suspicious SWIFT messages, which were placed outside of normal BDA working hours and were of an unusual size. Wells Fargo claims that BDA is responsible for the loss, as the thieves gained access to the legitimate SWIFT credentials of a BDA employee and sent fully authenticated SWIFT messages.

In the first half of 2016, an anonymous Ukrainian bank and others—even «dozens» that are not being made public—were variously reported to have been «compromised» through the SWIFT network and to have lost money.[65]

In March 2022, Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung reported about the increased security precautions by the State Police of Thurgau at the SWIFT data centre in Diessenhofen. After most of the Russian banks have been excluded from the private payment system, the risk of sabotage was considered higher. Inhabitants of the town described the large complex as a «fortress» or «prison» where frequent security check of the fenced property are conducted.[66]

See also[edit]

- ABA routing transit number

- Bilateral key exchange and the new Relationship Management Application (RMA)

- Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS)

- Cryptocurrency / Digital currency

- Digital renminbi

- Digital Rupee

- Electronic money

- Indian Financial System Code (IFSC)

- Structured Financial Messaging System (SFMS)

- Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX)

- International sanctions

- Internationalization of the renminbi

- ISO 9362, the SWIFT/BIC code standard

- ISO 15022

- ISO 20022

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- Routing number (Canada)

- Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA)

- Sibos conference

- SPFS

- Terrorist Finance Tracking Program

- TIPANET

- Value transfer system

References[edit]

- ^ «CBE Public Search». kbopub.economie.fgov.be. FPS Economy, SMEs, Self-Employed and Energy. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Scott, Susan V.; Zachariadis, Markos (2014). The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) : cooperative governance for network innovation, standards, and community. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 1, 35. doi:10.4324/9781315849324. ISBN 978-1-317-90952-1. OCLC 862930816.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 33.

- ^ a b Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Kowsmann, Patricia; Talley, Ian (26 February 2022). «What Is Swift and Why Is It Being Used to Sanction Russia?». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 1-2.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 1-2, 35.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Martin (6 June 2018). «Ripple and Swift slug it out over cross-border payments». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ «Swift Company Information». SWIFT. 9 March 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Serena Vergano, ed. (2009). Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura: Architecture in the era of local culture and international experience. RBTA. p. 130.

- ^ «Board members». SWIFT. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ «Yawar Shah – 1996 – 40 Under Forty – Crain’s New York Business». Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ «SWIFT Management». SWIFT. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ «Javier Pérez-Tasso». SWIFT. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Susan V. Scott; Markos Zachariadis (30 October 2013). The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT): Cooperative governance for network innovation, standards, and community. Routledge. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-317-90953-8.

- ^ Annex 1: The History and Detailed Functioning of SWIFT. ECahiers de l’Institut. Graduate Institute Publications. 6 September 2011. ISBN 9782940415731.

- ^ Farrell, Henry; Newman, Abraham L. (July 2019). «Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion». International Security. 44 (1): 42–79. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00351. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 198952367.

- ^ «Logica history».

- ^ «Carl Reuterskiöld». SWIFT. March 2006. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ «ISO — Maintenance agencies and registration authorities». ISO.

- ^ «RFC 3615 — A Uniform Resource Name (URN) Namespace for SWIFT Fin (RFC3615)». www.faqs.org.

- ^ Sechrist, Michael (23 March 2010). «Cyberspace in Deep Water: Protecting Undersea Communication Cables By Creating an International Public-Private Partnership» (PDF). Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2018.

For example, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), which describes itself as «the global provider of secure financial messaging services», uses undersea fiber-optic communications cables to transmit financial data between 208 countries

- ^ «SWIFT: SIBOS issues» (PDF). SWIFT. 16 September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2015. p.12

- ^ «Distributed architecture». SWIFT. 6 June 2008.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Ritter, Dieter. «Startschuss für Rechenzentrum». St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- «Das Daten-Fort-Knox am Rhein». Tages-Anzeiger (in German). ISSN 1422-9994. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Hettich, Barbara. «Swift: Der Rohbau steht». St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Ritter, Dieter. «Swift: Mit dem Bau begonnen». St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ «SWIFT History». SWIFT.

- ^ a b «Accord». 26 November 2015.

- ^ «Value-Added Alliances». Surecomp. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Mail: simple, secure and reliable email». SWIFT. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- ^ «SWIFTNet Mail pilot phase underway». Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ Brand, Constant (28 September 2005). «Belgian PM: Data Transfer Broke Rules». The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «European Parliament resolution of 17 September 2009 on the SWIFT Agreement». European Parliament. 17 September 2009.

- ^ «European Parliament to vote on interim agreement at February session». European Parliament. 21 January 2010.

- ^ Brand, Constant (11 February 2010). «Parliament rejects bank transfer data deal». European Voice.

- ^ «Euro MPs block bank data deal with US». BBC News. 11 February 2010.

- ^ «European parliament rejects SWIFT deal for sharing bank data with US». DW. Reuters. 11 February 2010.

- ^ a b Schult, Christoph (16 March 2011). «Brussels Eyes a Halt to SWIFT Data Agreement». Der Spiegel.

- ^ a b «‘Follow the Money’: NSA Spies on International Payments». Der Spiegel. 15 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Baldwin, Clare (15 April 2017). «Hackers release files indicating NSA monitored global bank transfers». Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Lawler, Richard. «Shadow Brokers release also suggests NSA spied on bank transactions». Engadget. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Martin, Jessica (27 February 2022). «EU extends Russia sanctions to airspace, media, Belarus». Euractiv. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ @nexta_tv (27 February 2022). «Lithuanian Prime Minister proposed to disconnect Belarus from SWIFT» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ «EU to impose new sanctions on Belarus this week -EU official». Reuters. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (31 January 2012). «Iran Praises Nuclear Talks with Team from U.N.» The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ a b Gladstone, Rick (3 February 2012). «Senate Panel Approves Potentially Toughest Penalty Yet Against Iran’s Wallet». The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Solomon, Jay; & Adam Entous (4 February 2012). «Banking Hub Adds to Pressure on Iran». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ «Banking’s SWIFT says ready to block Iran transactions». Reuters. 17 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Torchia, Andrew (17 February 2016). «Iranian banks reconnected to SWIFT network after four-year hiatus». Reuters. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Hutton, Robert; Ian Wishart (29 August 2014). «U.K. Wants EU to Block Russia From SWIFT Banking Network». Bloomberg News. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ «SWIFT Sanctions Statement». swift.com (Press release).

- ^ Turak, Natasha (23 May 2018). «Russia’s central bank governor touts Moscow alternative to SWIFT transfer system as protection from US sanctions». CNBC. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (11 February 2022). «SWIFT off Russia sanctions list, state banks likely target -U.S., EU officials». Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «EU unlikely to cut Russia off SWIFT for now, sources say». Reuters. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ «Joint Statement on further restrictive economic measures». ec.europa.eu. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ International banking giant refuses to cut off Israel, despite boycott calls. Haaretz. 7 October 2014.

- ^ «Exclusive — China’s payments system scaled back; trade deals only: sources». Reuters. 13 July 2015.

- ^ «Factbox: What is China’s onshore yuan clearing and settlement system CIPS?». Reuters. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ «Перечень пользователей СПФС Банка России | Банк России». www.cbr.ru.

- ^ «Iran blames EU on INSTEX ineffectiveness». Tehran Times. 18 January 2021.

- ^ «No transaction has been done through INSTEX: Iranian diplomat». Tehran Times. 4 March 2020.

- ^ Corkery, Michael, «Hackers’ $81 Million Sneak Attack on World Banking», The New York Times, 30 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ a b Corkery, Michael (12 May 2016). «Once Again, Thieves Enter Swift Financial Network and Steal». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Metzger, Max (28 June 2016). «SWIFT robbers swoop on Ukrainian bank». SC Magazine UK. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Gyr, Marcel (1 March 2022). «Das Swift-Rechenzentrum in der Schweiz wird polizeilich geschützt – wegen der Gefahr von Sabotage» (in German) NZZ.com. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Farrell, Henry and Abraham Newman. 2019. Of Privacy and Power: The Transatlantic Struggle over Freedom and Security. Princeton University Press.

External links[edit]

- Official website

|

|

| Type | Cooperative society[1] |

|---|---|

| Industry | Telecommunications |

| Founded | 3 May 1973; 49 years ago |

| Headquarters | La Hulpe, Belgium 50°44′04″N 4°28′43″E / 50.73444°N 4.47861°ECoordinates: 50°44′04″N 4°28′43″E / 50.73444°N 4.47861°E |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Financial telecommunication |

|

Number of employees |

>3,000 |

| Website | www.swift.com |

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), legally S.W.I.F.T. SC, is a Belgian cooperative society providing services related to the execution of financial transactions and payments between banks worldwide. Its principal function is to serve as the main messaging network through which international payments are initiated.[2] It also sells software and services to financial institutions, mostly for use on its proprietary «SWIFTNet», and assigns ISO 9362 Business Identifier Codes (BICs), popularly known as «SWIFT codes».

The SWIFT messaging network is a component of the global payments system.[3] SWIFT acts as a carrier of the «messages containing the payment instructions between financial institutions involved in a transaction».[4][5] However, the organization does not manage accounts on behalf of individuals or financial institutions, and it does not hold funds from third parties.[6] It also does not perform clearing or settlement functions.[7][5] After a payment has been initiated, it must be settled through a payment system, such as TARGET2 in Europe.[8] In the context of cross-border transactions, this step often takes place through correspondent banking accounts that financial institutions have with each other.[4]

As of 2018, around half of all high-value cross-border payments worldwide used the SWIFT network,[9] and in 2015, SWIFT linked more than 11,000 financial institutions in over 200 countries and territories, who were exchanging an average of over 32 million messages per day (compared to an average of 2.4 million daily messages in 1995).[10]

Though widely utilized, SWIFT has been criticized for its inefficiency. In 2018, the London-based Financial Times noted that transfers frequently «pass through multiple banks before reaching their final destination, making them time-consuming, costly and lacking transparency on how much money will arrive at the other end».[9] SWIFT has since introduced an improved service called «Global Payments Innovation» (GPI), claiming it was adopted by 165 banks and was completing half its payments within 30 minutes.[9]

As a cooperative society under Belgian law, SWIFT is owned by its member financial institutions. It is headquartered in La Hulpe, Belgium, near Brussels; its main building was designed by Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura and completed in 1989.[11] The chairman of SWIFT is Yawar Shah[12] of Pakistan,[13] and its CEO is Javier Pérez-Tasso of Spain.[14] SWIFT hosts an annual conference, called Sibos, specifically aimed at the financial services industry.[15]

History[edit]

SWIFT was founded in Brussels on 3 May 1973 under the leadership of its inaugural Swedish CEO, Carl Reuterskiöld (1973–1989), a former employee at Wallenberg-owned Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken, and was supported by 239 banks in 15 countries.[16] Before its establishment, international financial transactions were communicated over Telex, a public system involving manual writing and reading of messages.[17] It was set up out of fear of what might happen if a single private and fully American entity controlled global financial flows – which before was First National City Bank (FNCB) of New York – later Citibank. In response to FNCB’s protocol, FNCB’s competitors in the US and Europe pushed an alternative «messaging system that could replace the public providers and speed up the payment process».[18] SWIFT started to establish common standards for financial transactions and a shared data processing system and worldwide communications network designed by Logica and developed by the Burroughs Corporation.[19] Fundamental operating procedures and rules for liability were established in 1975, and the first message was sent in 1977. SWIFT’s first international (non-European) operations centre was inaugurated by Governor John N. Dalton of Virginia in 1979.[20]

Standards[edit]

SWIFT has become the industry standard for syntax in financial messages. Messages formatted to SWIFT standards can be read and processed by many well-known financial processing systems, whether or not the message travelled over the SWIFT network. SWIFT cooperates with international organizations for defining standards for message format and content. SWIFT is also Registration authority (RA) for the following ISO standards:

[21]

- ISO 9362: 1994 Banking – Banking telecommunication messages – Bank identifier codes

- ISO 10383: 2003 Securities and related financial instruments – Codes for exchanges and market identification (MIC)

- ISO 13616: 2003 IBAN Registry

- ISO 15022: 1999 Securities – Scheme for messages (Data Field Dictionary) (replaces ISO 7775)

- ISO 20022-1: 2004 and ISO 20022-2:2007 Financial services – Universal Financial Industry message scheme

In RFC 3615 urn:swift: was defined as Uniform Resource Names (URNs) for SWIFT FIN.[22]

Operations centres[edit]

The SWIFT secure messaging network is run from three data centres, located in the United States, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. These centres share information in near real-time. In case of a failure in one of the data centres, another is able to handle the traffic of the complete network. SWIFT uses submarine communications cables to transmit its data.[23]

Shortly after opening its third data centre in Switzerland in 2009,[24] SWIFT introduced new distributed architecture with two messaging zones, European and Trans-Atlantic, so data from European SWIFT members no longer mirrored the U.S. data centre.[25] European zone messages are stored in the Netherlands and in part of the Swiss operating centre; Trans-Atlantic zone messages are stored in the United States and in another part of the Swiss operating centre that is segregated from the European zone messages. Countries outside of Europe were by default allocated to the Trans-Atlantic zone, but could choose to have their messages stored in the European zone.

| SN | SWIFT data centres | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zoeterwoude, Netherlands | OPC (Operating Centre) |

| 2 | Culpeper, Virginia, United States | OPC (Operating Centre) |

| 3 | Diessenhofen, Switzerland[26] | OPC (Operating Centre) |

| 4 | Hong Kong | Command and control |

SWIFTNet network[edit]

SWIFT moved to its current IP network infrastructure, known as SWIFTNet, from 2001 to 2005,[27] providing a total replacement of the previous X.25 infrastructure. The process involved the development of new protocols that facilitate efficient messaging, using existing and new message standards. The adopted technology chosen to develop the protocols was XML, where it now provides a wrapper around all messages legacy or contemporary. The communication protocols can be broken down into:

|

InterAct

|

FileAct

|

Browse

|

Architecture[edit]

SWIFT provides a centralized store-and-forward mechanism, with some transaction management. For bank A to send a message to bank B with a copy or authorization involving institution C, it formats the message according to standards and securely sends it to SWIFT. SWIFT guarantees its secure and reliable delivery to B after the appropriate action by C. SWIFT guarantees are based primarily on high redundancy of hardware, software, and people.

SWIFTNet Phase 2[edit]

During 2007 and 2008, the entire SWIFT network migrated its infrastructure to a new protocol called SWIFTNet Phase 2. The main difference between Phase 2 and the former arrangement is that Phase 2 requires banks connecting to the network to use a Relationship Management Application (RMA) instead of the former bilateral key exchange (BKE) system. According to SWIFT’s public information database on the subject, RMA software should eventually prove more secure and easier to keep up-to-date; however, converting to the RMA system meant that thousands of banks around the world had to update their international payments systems to comply with the new standards. RMA completely replaced BKE on 1 January 2009.

Products and interfaces[edit]

SWIFT means several things in the financial world:

- a secure network for transmitting messages between financial institutions;

- a set of syntax standards for financial messages (for transmission over SWIFTNet or any other network)

- a set of connection software and services allowing financial institutions to transmit messages over SWIFT network.

Under 3 above, SWIFT provides turn-key solutions for members, consisting of linkage clients to facilitate connectivity to the SWIFT network and CBTs or «computer based terminals» which members use to manage the delivery and receipt of their messages. Some of the more well-known interfaces and CBTs provided to their members are:

- SWIFTNet Link (SNL) software which is installed on the SWIFT customer’s site and opens a connection to SWIFTNet. Other applications can only communicate with SWIFTNet through the SNL.

- Alliance Gateway (SAG) software with interfaces (e.g., RAHA = Remote Access Host Adapter), allowing other software products to use the SNL to connect to SWIFTNet

- Alliance WebStation (SAB) desktop interface for SWIFT Alliance Gateway with several usage options:

- administrative access to the SAG

- direct connection SWIFTNet by the SAG, to administrate SWIFT Certificates

- so-called Browse connection to SWIFTNet (also by SAG) to use additional services, for example Target2

- Alliance Access (SAA) and Alliance Messaging Hub (AMH) are the main messaging software applications by SWIFT, which allow message creation for FIN messages, routing and monitoring for FIN and MX messages. The main interfaces are FTA (files transfer automated, not FTP) and MQSA, a WebSphere MQ interface.

- The Alliance Workstation (SAW) is the desktop software for administration, monitoring and FIN message creation. Since Alliance Access is not yet capable of creating MX messages, Alliance Messenger (SAM) has to be used for this purpose.

- Alliance Web Platform (SWP) as new thin-client desktop interface provided as an alternative to existing Alliance WebStation, Alliance Workstation (soon)[when?] and Alliance Messenger.

- Alliance Integrator built on Oracle’s Java Caps which enables customer’s back office applications to connect to Alliance Access or Alliance Entry.

- Alliance Lite2 is a secure and reliable, cloud-based way to connect to the SWIFT network which is a light version of Alliance Access specifically targeting customers with low volume of traffic.

Services[edit]

There are four key areas that SWIFT services fall under in the financial marketplace: securities, treasury & derivatives, trade services. and payments-and-cash management.

|

Securities

|

Treasury and derivatives

|

Cash management

|

Trade services

|

SWIFTREF[edit]

Swift Ref, the global payment reference data utility, is SWIFT’s unique reference data service. Swift Ref sources data direct from data originators, including central banks, code issuers and banks making it easy for issuers and originators to maintain data regularly and thoroughly. SWIFTRef constantly validates and cross-checks data across the different data sets.[29]

SWIFTNet Mail[edit]

SWIFT offers a secure person-to-person messaging service, SWIFTNet Mail, which went live on 16 May 2007.[30] SWIFT clients can configure their existing email infrastructure to pass email messages through the highly secure and reliable SWIFTNet network instead of the open Internet. SWIFTNet Mail is intended for the secure transfer of sensitive business documents, such as invoices, contracts and signatories, and is designed to replace existing telex and courier services, as well as the transmission of security-sensitive data over the open Internet. Seven financial institutions, including HSBC, FirstRand Bank, Clearstream, DnB NOR, Nedbank, and Standard Bank of South Africa, as well as SWIFT piloted the service.[31]

U.S. government involvement[edit]

Terrorist Finance Tracking Program[edit]

A series of articles published on 23 June 2006 in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times revealed a program, named the Terrorist Finance Tracking Program, which the US Treasury Department, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and other United States governmental agencies initiated after the 11 September attacks to gain access to the SWIFT transaction database.[32]

After the publication of these articles, SWIFT quickly came under pressure for compromising the data privacy of its customers by allowing governments to gain access to sensitive personal information. In September 2006, the Belgian government declared that these SWIFT dealings with American governmental authorities were a breach of Belgian and European privacy laws.[citation needed]

In response, and to satisfy members’ concerns about privacy, SWIFT began a process of improving its architecture by implementing a distributed architecture with a two-zone model for storing messages (see Operations centres).

Concurrently, the European Union negotiated an agreement with the United States government to permit the transfer of intra-EU SWIFT transaction information to the United States under certain circumstances. Because of concerns about its potential contents, the European Parliament adopted a position statement in September 2009, demanding to see the full text of the agreement and asking that it be fully compliant with EU privacy legislation, with oversight mechanisms emplaced to ensure that all data requests were handled appropriately.[33] An interim agreement was signed without European Parliamentary approval by the European Council on 30 November 2009,[34] the day before the Lisbon Treaty—which would have prohibited such an agreement from being signed under the terms of the codecision procedure—formally came into effect. While the interim agreement was scheduled to come into effect on 1 January 2010, the text of the agreement was classified as «EU Restricted» until translations could be provided in all EU languages and published on 25 January 2010.

On 11 February 2010, the European Parliament decided to reject the interim agreement between the EU and the US by 378 to 196 votes.[35][36] One week earlier, the parliament’s civil liberties committee had already rejected the deal, citing legal reservations.[37]

In March 2011, it was reported that two mechanisms of data protection had failed: EUROPOL released a report complaining that requests for information from the US had been too vague (making it impossible to make judgments on validity)[38] and that the guaranteed right for European citizens to know whether their information had been accessed by US authorities had not been put into practice.[38]

Monitoring by the NSA[edit]

Der Spiegel reported in September 2013 that the National Security Agency (NSA) widely monitors banking transactions via SWIFT, as well as credit card transactions.[39] The NSA intercepted and retained data from the SWIFT network used by thousands of banks to securely send transaction information. SWIFT was named as a «target», according to documents leaked by Edward Snowden. The documents revealed that the NSA spied on SWIFT using a variety of methods, including reading «SWIFT printer traffic from numerous banks».[39] In April 2017, a group known as the Shadow Brokers released files allegedly from the NSA which indicate that the agency monitored financial transactions made through SWIFT.[40][41]

Use in sanctions[edit]

Belarus[edit]

The European Union issued the first set of sanctions against Belarus — the first was introduced on 27 February 2022, which banned certain categories of Belarusian items in the EU, including timber, steel, mineral fuels and tobacco.[42] After the Lithuanian prime minister proposed disconnecting Belarus from SWIFT,[43] the European Union, which does not recognise Lukashenko as the legitimate President of Belarus, started to plan an extension of the sanctions already issued against Russian entities and top officials to its ally.[44]

Iran[edit]

In January 2012, the advocacy group United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) implemented a campaign calling on SWIFT to end all relations with Iran’s banking system, including the Central Bank of Iran. UANI asserted that Iran’s membership in SWIFT violated US and EU financial sanctions against Iran as well as SWIFT’s own corporate rules.[45]

Consequently, in February 2012, the U.S. Senate Banking Committee unanimously approved sanctions against SWIFT aimed at pressuring it to terminate its ties with blacklisted Iranian banks. Expelling Iranian banks from SWIFT would potentially deny Iran access to billions of dollars in revenue using SWIFT but not from using IVTS. Mark Wallace, president of UANI, praised the Senate Banking Committee.[46]

Initially SWIFT denied that it was acting illegally,[46] but later[when?] said that «it is working with U.S. and European governments to address their concerns that its financial services are being used by Iran to avoid sanctions and conduct illicit business».[47] Targeted banks would be—amongst others—Saderat Bank of Iran, Bank Mellat, Post Bank of Iran and Sepah Bank.[48] On 17 March 2012, following agreement two days earlier between all 27 member states of the Council of the European Union and the Council’s subsequent ruling, SWIFT disconnected all Iranian banks that had been identified as institutions in breach of current EU sanctions from its international network and warned that even more Iranian financial institutions could be disconnected from the network.

In February 2016, most Iranian banks reconnected to the network following the lift of sanctions due to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.[49]

Russia[edit]

Similarly, in August 2014 the UK planned to press the EU to block Russian use of SWIFT as a sanction due to Russian military intervention in Ukraine.[50] However, SWIFT refused to do so.[51] SPFS, a Russia-based SWIFT equivalent, was created by the Central Bank of Russia as a backup measure.[52]

During the prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States developed preliminary possible sanctions against Russia, but excluded banning Russia from SWIFT.[53] Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the foreign ministers of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia called for Russia to be cut off from SWIFT. However, other EU member states were reluctant, both because European lenders held most of the nearly $30 billion in foreign banks’ exposure to Russia and because Russia had developed the SPFS alternative.[54] The European Union, United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States finally agreed to remove select Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine; the governments of France, Germany, Italy and Japan individually released statements alongside the EU.[55][5]

Israel[edit]

In 2014, SWIFT rejected calls from pro-Palestinian activists to revoke Israeli banks’ access to its network.[56]

Competitors[edit]

Alternatives to the SWIFT system include:

- CIPS: sponsored by China, for trade-related deals to internationalize Chinese currency RMB use. 1280 financial institutions in 103 countries and regions have connected to the system[57][58]

- SFMS: sponsored by India

- SPFS: sponsored by Russia, mostly composed of Russian banks[59]

- INSTEX: sponsored by the European Union, limited to non-USD transactions for trade with Iran, largely unused and ineffective[60][61]

Security[edit]

In 2016 an $81 million theft from the Bangladesh central bank via its account at the New York Federal Reserve Bank was traced to hacker penetration of SWIFT’s Alliance Access software, according to a New York Times report. It was not the first such attempt, the society acknowledged, and the security of the transfer system was undergoing new examination accordingly.[62] Soon after the reports of the theft from the Bangladesh central bank, a second, apparently related, attack was reported to have occurred on a commercial bank in Vietnam.[63]

Both attacks involved malware written to both issue unauthorized SWIFT messages and to conceal that the messages had been sent. After the malware sent the SWIFT messages that stole the funds, it deleted the database record of the transfers then took further steps to prevent confirmation messages from revealing the theft. In the Bangladeshi case, the confirmation messages would have appeared on a paper report; the malware altered the paper reports when they were sent to the printer. In the second case, the bank used a PDF report; the malware altered the PDF viewer to hide the transfers.[63]

In May 2016, Banco del Austro (BDA) in Ecuador sued Wells Fargo after Wells Fargo honoured $12 million in fund transfer requests that had been placed by thieves. In this case, the thieves sent SWIFT messages that resembled recently cancelled transfer requests from BDA, with slightly altered amounts; the reports do not detail how the thieves gained access to send the SWIFT messages. BDA asserts that Wells Fargo should have detected the suspicious SWIFT messages, which were placed outside of normal BDA working hours and were of an unusual size. Wells Fargo claims that BDA is responsible for the loss, as the thieves gained access to the legitimate SWIFT credentials of a BDA employee and sent fully authenticated SWIFT messages.

In the first half of 2016, an anonymous Ukrainian bank and others—even «dozens» that are not being made public—were variously reported to have been «compromised» through the SWIFT network and to have lost money.[65]

In March 2022, Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung reported about the increased security precautions by the State Police of Thurgau at the SWIFT data centre in Diessenhofen. After most of the Russian banks have been excluded from the private payment system, the risk of sabotage was considered higher. Inhabitants of the town described the large complex as a «fortress» or «prison» where frequent security check of the fenced property are conducted.[66]

See also[edit]

- ABA routing transit number

- Bilateral key exchange and the new Relationship Management Application (RMA)

- Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS)

- Cryptocurrency / Digital currency

- Digital renminbi

- Digital Rupee

- Electronic money

- Indian Financial System Code (IFSC)

- Structured Financial Messaging System (SFMS)

- Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX)

- International sanctions

- Internationalization of the renminbi

- ISO 9362, the SWIFT/BIC code standard

- ISO 15022

- ISO 20022

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- Routing number (Canada)

- Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA)

- Sibos conference

- SPFS

- Terrorist Finance Tracking Program

- TIPANET

- Value transfer system

References[edit]

- ^ «CBE Public Search». kbopub.economie.fgov.be. FPS Economy, SMEs, Self-Employed and Energy. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Scott, Susan V.; Zachariadis, Markos (2014). The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) : cooperative governance for network innovation, standards, and community. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 1, 35. doi:10.4324/9781315849324. ISBN 978-1-317-90952-1. OCLC 862930816.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 33.

- ^ a b Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Kowsmann, Patricia; Talley, Ian (26 February 2022). «What Is Swift and Why Is It Being Used to Sanction Russia?». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 1-2.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 1-2, 35.

- ^ Scott & Zachariadis 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Martin (6 June 2018). «Ripple and Swift slug it out over cross-border payments». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ «Swift Company Information». SWIFT. 9 March 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Serena Vergano, ed. (2009). Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura: Architecture in the era of local culture and international experience. RBTA. p. 130.

- ^ «Board members». SWIFT. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ «Yawar Shah – 1996 – 40 Under Forty – Crain’s New York Business». Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ «SWIFT Management». SWIFT. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ «Javier Pérez-Tasso». SWIFT. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Susan V. Scott; Markos Zachariadis (30 October 2013). The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT): Cooperative governance for network innovation, standards, and community. Routledge. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-317-90953-8.

- ^ Annex 1: The History and Detailed Functioning of SWIFT. ECahiers de l’Institut. Graduate Institute Publications. 6 September 2011. ISBN 9782940415731.

- ^ Farrell, Henry; Newman, Abraham L. (July 2019). «Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion». International Security. 44 (1): 42–79. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00351. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 198952367.

- ^ «Logica history».

- ^ «Carl Reuterskiöld». SWIFT. March 2006. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ «ISO — Maintenance agencies and registration authorities». ISO.

- ^ «RFC 3615 — A Uniform Resource Name (URN) Namespace for SWIFT Fin (RFC3615)». www.faqs.org.

- ^ Sechrist, Michael (23 March 2010). «Cyberspace in Deep Water: Protecting Undersea Communication Cables By Creating an International Public-Private Partnership» (PDF). Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2018.

For example, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), which describes itself as «the global provider of secure financial messaging services», uses undersea fiber-optic communications cables to transmit financial data between 208 countries

- ^ «SWIFT: SIBOS issues» (PDF). SWIFT. 16 September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2015. p.12

- ^ «Distributed architecture». SWIFT. 6 June 2008.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Ritter, Dieter. «Startschuss für Rechenzentrum». St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- «Das Daten-Fort-Knox am Rhein». Tages-Anzeiger (in German). ISSN 1422-9994. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Hettich, Barbara. «Swift: Der Rohbau steht». St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Ritter, Dieter. «Swift: Mit dem Bau begonnen». St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ «SWIFT History». SWIFT.

- ^ a b «Accord». 26 November 2015.

- ^ «Value-Added Alliances». Surecomp. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Mail: simple, secure and reliable email». SWIFT. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- ^ «SWIFTNet Mail pilot phase underway». Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ Brand, Constant (28 September 2005). «Belgian PM: Data Transfer Broke Rules». The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «European Parliament resolution of 17 September 2009 on the SWIFT Agreement». European Parliament. 17 September 2009.

- ^ «European Parliament to vote on interim agreement at February session». European Parliament. 21 January 2010.

- ^ Brand, Constant (11 February 2010). «Parliament rejects bank transfer data deal». European Voice.

- ^ «Euro MPs block bank data deal with US». BBC News. 11 February 2010.

- ^ «European parliament rejects SWIFT deal for sharing bank data with US». DW. Reuters. 11 February 2010.

- ^ a b Schult, Christoph (16 March 2011). «Brussels Eyes a Halt to SWIFT Data Agreement». Der Spiegel.

- ^ a b «‘Follow the Money’: NSA Spies on International Payments». Der Spiegel. 15 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Baldwin, Clare (15 April 2017). «Hackers release files indicating NSA monitored global bank transfers». Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Lawler, Richard. «Shadow Brokers release also suggests NSA spied on bank transactions». Engadget. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Martin, Jessica (27 February 2022). «EU extends Russia sanctions to airspace, media, Belarus». Euractiv. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ @nexta_tv (27 February 2022). «Lithuanian Prime Minister proposed to disconnect Belarus from SWIFT» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ «EU to impose new sanctions on Belarus this week -EU official». Reuters. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (31 January 2012). «Iran Praises Nuclear Talks with Team from U.N.» The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ a b Gladstone, Rick (3 February 2012). «Senate Panel Approves Potentially Toughest Penalty Yet Against Iran’s Wallet». The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Solomon, Jay; & Adam Entous (4 February 2012). «Banking Hub Adds to Pressure on Iran». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ «Banking’s SWIFT says ready to block Iran transactions». Reuters. 17 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Torchia, Andrew (17 February 2016). «Iranian banks reconnected to SWIFT network after four-year hiatus». Reuters. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Hutton, Robert; Ian Wishart (29 August 2014). «U.K. Wants EU to Block Russia From SWIFT Banking Network». Bloomberg News. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ «SWIFT Sanctions Statement». swift.com (Press release).

- ^ Turak, Natasha (23 May 2018). «Russia’s central bank governor touts Moscow alternative to SWIFT transfer system as protection from US sanctions». CNBC. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (11 February 2022). «SWIFT off Russia sanctions list, state banks likely target -U.S., EU officials». Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «EU unlikely to cut Russia off SWIFT for now, sources say». Reuters. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ «Joint Statement on further restrictive economic measures». ec.europa.eu. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ International banking giant refuses to cut off Israel, despite boycott calls. Haaretz. 7 October 2014.

- ^ «Exclusive — China’s payments system scaled back; trade deals only: sources». Reuters. 13 July 2015.

- ^ «Factbox: What is China’s onshore yuan clearing and settlement system CIPS?». Reuters. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ «Перечень пользователей СПФС Банка России | Банк России». www.cbr.ru.

- ^ «Iran blames EU on INSTEX ineffectiveness». Tehran Times. 18 January 2021.

- ^ «No transaction has been done through INSTEX: Iranian diplomat». Tehran Times. 4 March 2020.

- ^ Corkery, Michael, «Hackers’ $81 Million Sneak Attack on World Banking», The New York Times, 30 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ a b Corkery, Michael (12 May 2016). «Once Again, Thieves Enter Swift Financial Network and Steal». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Metzger, Max (28 June 2016). «SWIFT robbers swoop on Ukrainian bank». SC Magazine UK. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Gyr, Marcel (1 March 2022). «Das Swift-Rechenzentrum in der Schweiz wird polizeilich geschützt – wegen der Gefahr von Sabotage» (in German) NZZ.com. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Farrell, Henry and Abraham Newman. 2019. Of Privacy and Power: The Transatlantic Struggle over Freedom and Security. Princeton University Press.

External links[edit]

- Official website

СВИФТ

- СВИФТ

- (англ. Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, SWIFT) – Сообщество всемирных межбанковских финансовых телекоммуникаций. Создано банками 15 стран в виде акц. специализир. общества в 1973 с целью организации эффективного выполнения банковских операций, передачи информации, ее сортировки и архивирования. Офиц. функционирует с 1977. Имеет центральный офис в Бельгии (Брюссель), региональные центры в США, Гонконге (спец. адм. р-н Сянган, КНР) и Нидерландах, к-рыми руководит Совет директоров. Деятельность СВИФТ контролирует Аудиторский совет и группа внешних аудиторов. Ведется постоянная работа по повышению культуры обслуживания, защите информации от несанкционированного доступа, совершенствуется уровень информац. технологий, система управления рисками. Внедрение системы связи СВИФТ позволило наладить круглосуточный информац. обмен между банками, стандартизировать и автоматизировать банковские операции на междунар. уровне, а именно: осуществлять безбумажные платежные операции с миним. привлечением труда людей и сокращением операц. расходов; ускорить обмен информацией между банками с помощью телекоммуникац. линий связи; минимизировать типичные виды банковского риска (потери документов, ошибочную адресацию, фальсификацию платежных документов и др.). На 2001 более 7000 финансовых институтов из 193 стран являлись пользователями системы, к-рая круглосуточно обрабатывает около 5 млн сообщений валютно-финансового, кредитного и информационного характера. В 1987 к системе СВИФТ присоединились небанковские финансовые институты. Россия стала членом системы в 1989. К июлю 2000 около 300 российских банков из 36 городов являлись ее участниками. Банковская Ассоциация стран Центральной и Восточной Европы использует систему СВИФТ при проведении расчетов с 1994. С 1995 через систему осуществляются биржевые, клиринговые операции (все расчеты по ЭКЮ совершались через телекоммуникационную систему с 1996, с янв. 1999 – в евро). В 1997 осуществлен запуск мировой автоматизир. системы контроля и стандартизации, в 1998 – системы управления рисками. Система коммерческих расчетов Bolеronet (Болеро-нет) присоединилась к СВИФТ в сент. 1999. На базе сети СВИФТ построены 29 платежных систем, к-рые обрабатывают 60% мирового объема клиринговых расчетов. СВИФТ позволяет банкам получить преимущества при проведении междунар. платежей и расчетов: предоставляет возможность передачи значит. объемов банковской информации на большие расстояния для обслуживания пользователей системы; значительно упрощает расчеты, т.к. предлагает пользователям бездокументарную пересылку данных; обеспечивает большую оперативность передачи банковской информации. Система надежна с т.з. обеспечения безопасности банковских операций, т.к. включает множеств. систему комбинаций физич., технич., а также процедурных средств безопасности. Система СВИФТ обеспечивает передачу банковской информации: название банкаотправителя сообщения СВИФТ; категория информации (платежное поручение банка, платежное поручение клиента, валютная, кредитная операция и т.д.). Банковские операции унифицированы – применяются 240 платежно-расчетных стандартов в зависимости от особенности поручения (созданные и используемые СВИФТ стандарты банковской документации признаны Международной организацией по стандартизации – ISO). Каждое поручение – информац. модель, к-рая содержит данные: банк-получатель; номер платежного поручения; дату валютирования; сумму валюты; название банка, по поручению к-рого производится платеж; название банка, производящего рамбурс (перевод средств); номер счета в банке; наименование получателя; детали платежа; ключ (реквизиты, «удостоверяющие» подлинность совершаемой операции) и т.д. Российская национальная ассоциация SWIFT (РОССВИФТ) разработала правила использования стандартов СВИФТ для передачи финанс. сообщений в валюте РФ (SWIFT – RUR5). Все сообщения автоматически шифруются с введением в информац. сеть; для обозначения вида сообщения и валют применяется цифровое и буквенное кодирование. Идентификация финансовых, коммерч. и др. институтов осуществляется посредством идентификационных кодов (Стандарт ISO 9362 «Банковские идентификационные коды»). Система СВИФТ совершенствуется: разработаны и действуют с 1993 SWIFT-II (Международная межбанковская организация по валютным и финансовым расчетам по телексу) и новая система START (автоматизир. система контроля за правильным осуществлением проводок по счетам).

Финансово-кредитный энциклопедический словарь. — М.: Финансы и статистика.

.

2002.

Синонимы:

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «СВИФТ» в других словарях:

-

Свифт — (точнее Суифт) Джонатан (Jonathan Swift, 1667 1745) знаменитый английский писатель. Происходил из провинциальной дворянской семьи, разоренной во время революции. Учился в Дублинском университете, готовясь к духовному званию. Когда после «славной… … Литературная энциклопедия

-

Свифт — (англ. Swift) английская фамилия. Известные носители Свифт, Джонатан (1667 1745) английский писатель. Свифт, Кей (1897 1993) американский композитор. Свифт, Льюис американский астроном, один из открывателей кометы Свифта Туттля.… … Википедия

-

Свифт — Свифт, Джонатан (1667 1745) английский писатель сатирик, автор блестящих политических памфлетов и знаменитого романа Путешествие Гулливера . Этот роман представляет собой одновременно политическую и бытовую сатиру и социальную утопию. Герой… … 1000 биографий

-

СВИФТ — Сообщество всемирных интербанковских финансовых телекоммуникаций: организация, созданная банками в форме кооператива и принадлежащая им, которая является оператором сети, оказывающей услуги по обмену платежными и другими финансовыми сообщениями… … Справочник технического переводчика

-

Свифт — Society of Worldwide Interbank Finfncial Telecommunications SWIFT автоматизированная система осуществления международных денежных расчетов и платежей путем передачи авизо и перевода самих финансовых средств. Словарь бизнес терминов. Академик.ру.… … Словарь бизнес-терминов

-

СВИФТ — (Swift) Джонатан (1667 1745), английский писатель, политический деятель. В памфлете Сказка бочки (1704) борьба католической, англиканской и пуританской церквей изображена в духе пародийного жития . Памфлеты Письма суконщика (1723 24) и Скромное… … Современная энциклопедия

-

СВИФТ — [англ. swift скорый, быстрый] фин. автоматизированная система осуществления международных платежей через сеть компьютеров (КОМПЬЮТЕР); создана в 1973 г. в Брюсселе. Словарь иностранных слов. Комлев Н.Г., 2006 … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

свифт — сущ., кол во синонимов: 1 • система (86) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Свифт — (Джонатан Swift) английский писатель, один из величайшихсатириков, род. 30 ноября 1667 г. в Дублине. Его врожденные свойства мрачное, даже злобное отношение к людям, беспредельный эгоизм, столь жебеспредельное честолюбие, в соединении, однако, с… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

СВИФТ — (англ. SWIFT, Society of Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) автоматизированная система осуществления международных денежных расчетов и платежей с использованием компьютеров и межбанковских телекоммуникаций. Создана в 1973 г. в… … Экономический словарь

-

СВИФТ — Международная электронная система межбанковских финансовых расчётов англ.: SWIFT, Society for worldwide interbank financial telecommunications англ., техн., фин … Словарь сокращений и аббревиатур

This content is not available in the selected language

Our foundations. Your future.

Together, we’re shaping the future of finance.

Here’s how

The Swift Tech Scholarship

We think the future of finance is for everyone. That’s why we’re offering 140 tech scholarships to people looking to retrain, re-enter the job market or return to civilian life.

Apply today

ISO 20022 for payments: Make sure you’re ready for March 2023

Read more

ISO 20022 for payments

Learn more

Get the latest information

Swift is working closely with its global community on the ISO 20022 migration for cross-border payments, with all necessary capabilities already in place for institutions to exchange rich data messages on an opt-in basis. Find out how we are responding to the needs of our community in the latest update on start of the migration.

Our solutions

Discover

Banking

Our messaging, standards and services connect you to your counterparties worldwide, so you can transact securely and reliably.

Read more

Discover

Capital Markets

Swift is advancing its solutions to address capital market challenges. Reduce costs and risks with securities transaction and FX market solutions.

Read more

Discover

Corporates

As a multinational, you want industry-standard ways to work with multiple banking partners for cash, trade and corporate treasury.

Read more

Discover

Market Infrastructures

Resilience, security and responsiveness are your core operational requirements. Our solutions help you deliver for your community.

Read more

Are you a customer?

MySWIFT is your one-stop shop to help you manage your Swift products and services, keep track of your orders and invoices, and access online support.

Cyber Security

Customer Security Programme (CSP)

Reinforcing the security of the global banking system

Press

Resilience, security and responsiveness are your core operational requirements. Our solutions help you deliver for your…

Business Identifier Code (BIC) Directory

Latest news & events

8 December 2022 | 4 min read

Why Payment Controls won Best Solution in Payments Fraud Prevention at the Regulation Asia awards

For the second year at the Regulation Asia awards, Payment Controls has been awarded Best Solution…

15 November 2022 | 7 min read

Top 10 takeaways from Swift at Sibos 2022

The future of cross-border transactions took centre stage on the Swift programme at Sibos 2022. Here…

5 October 2022 | 4 min read

Connecting digital islands: Paving the way for global use of CBDCs and tokenised assets

Our ground-breaking new innovation lays a path for digital currencies and tokenised assets to integrate seamlessly…

Как перевести деньги за рубеж? Как получить средства из другой страны? Один из способов – воспользоваться системой SWIFT-кодов, присваиваемых финансовым институтам по всему миру. Зная это сочетание букв и цифр, можно перечислить сумму из-за границы в любой российский банк и наоборот.

Из этой статьи вы узнаете:

- SWIFT-код банка

- Для чего нужен SWIFT-код

- Узнать SWIFT-код банка

- Сделать SWIFT-перевод

- Получить SWIFT-перевод

Что такое SWIFT-код банка

SWIFT-код (СВИФТ-код) – это уникальное сочетание латинских букв и цифр, которое присваивается каждому банку в системе международных расчетов. Он выдается финансовому институту после вступления в Общество всемирных межбанковских финансовых каналов связи.

%colored_text_box=3%

Суть системы SWIFT-кодов заключается в том, что в мировом пространстве финансовый институт можно идентифицировать не по названию, а по его уникальному коду. Так, если перевести деньги из банка Зимбабве в Альфа-Банк – по кодам финансовых институтов будет понятно направление и конечную точку перевода.

Официальное видео: «Что такое СВИФТ код и как узнать код своего банка?»

Из чего состоит СВИФТ-код?

Стандартно в него входит 11 символов в 4 группах:

WWWW XX YY ZZZ

Рассмотрим значение каждой из групп уникального кода.

- WWWW. Первые четыре символа – буквенное обозначение финансового института. Чаще всего это сокращенное название банка или корпорации на латинице.

Первые четыре цифры SWIFT: примеры

|

WWWW |

Страна |

Банк |

|

TICS |

Россия |

Тинькофф |

|

SABR |

Россия |

Сбербанк России |

|

VTBR |

Россия |

ВТБ Банк |

|

PRMS |

Россия |

Промсвязьбанк |

|

BANO |

Дания |

Nordic Bank |

|

AMPB |

Австралия |

AMP Bank |

|

ABOC |

Китая |

Сельскохозяйственный Банк Китая |

- ХХ. Вторые два символа – буквенное обозначение государства по стандарту ISO 3166. Эта часть позволяет понять в какую страну направляются средства. Например, для России – это RU, для Казахстана – KZ, для Германии – DE, для США – US и т.д.

- YY. Третьи два символа – буквенно-цифровое обозначение региона для упрощения поиска отделения банка по территории страны. Например, в России действуют такие коды, как ММ – Москва, 3Т – Тольятти, 8Х – Благовещенск.

%colored_text_box=1%

- ZZZ. Последние три символа – буквенно-цифровое обозначение филиала банка. Оно используется только в отношении крупных банков и корпораций с разветвленной сетью отделений.

%colored_text_box=2%

В полном виде SWIFT-код может выглядеть так:

- ALFARUMM – головной офис Альфа-Банка в Москве;

- SABRRUMMSE1 – отделение Сбербанка России в Центральном административном округе.

Для чего нужен SWIFT-код

Если необходимо перевести средства из одной страны в банк другой страны – необходимо знать СВИФТ-код этого финансового института. Уникальное сочетание букв и цифр необходимо отправителю. Получателю он не нужен – он просто снимает средства со своего счета.

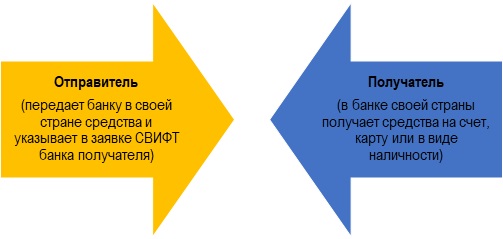

Рисунок 1. Как работает система СВИФТ

Переводы в международной системе SWIFT аналогичны стандартным денежным переводам. Если знать уникальный код банка получателя, то можно списывать средства даже с банковской карты.

%colored_text_box=4%

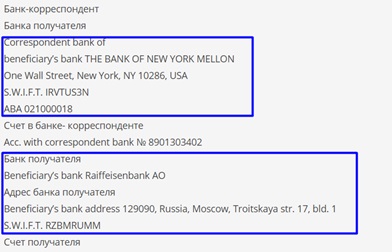

Рисунок 2. Примеры реквизитов для перевода средств

%colored_text_box=5%

Переводы средств могут осуществлять граждане, организации, предприниматели. Средства обычно поступают на счет получателя в течение 1-7 суток. По степени надежности и безопасности у системы СВИФТ в мире пока нет аналогов.

Как узнать SWIFT-код своего банка

Чтобы совершить международный денежный перевод, отправителю нужно взять у получателя уникальный СВИФТ-код его финансового института. Где его можно выяснить?

- На сайте любого российского банка его можно отыскать в разделе «Реквизиты».