- танграм,

Существительное

мн. танграмы

Склонение существительного танграмм.р.,

2-е склонение

Единственное число

Множественное число

Единственное число

Именительный падеж

(Кто? Что?)

танграм

танграмы

Родительный падеж

(Кого? Чего?)

танграма

танграмов

Дательный падеж

(Кому? Чему?)

танграму

танграмам

Винительный падеж

(Кого? Что?)

танграм

танграмы

Творительный падеж

(Кем? Чем?)

танграмом

танграмами

Предложный падеж

(О ком? О чем?)

танграме

танграмах

Множественное число

Сервис Спряжение и склонение позволяет вам спрягать глаголы и склонять существительные, прилагательные, местоимения и числительные. Здесь можно узнать род и склонение существительных, прилагательных и числительных, степени сравнения прилагательных, спряжение глаголов, посмотреть таблицы времен для английского, немецкого, русского, французского, итальянского, португальского и испанского. Спрягайте глаголы, изучайте правила спряжения и склонения, смотрите переводы в контекстных примерах и словаре.

- танграм,

Существительное

мн. танграмы

Склонение существительного танграмм.р.,

2-е склонение

Единственное число

Множественное число

Единственное число

Именительный падеж

(Кто? Что?)

танграм

танграмы

Родительный падеж

(Кого? Чего?)

танграма

танграмов

Дательный падеж

(Кому? Чему?)

танграму

танграмам

Винительный падеж

(Кого? Что?)

танграм

танграмы

Творительный падеж

(Кем? Чем?)

танграмом

танграмами

Предложный падеж

(О ком? О чем?)

танграме

танграмах

Множественное число

Сервис Спряжение и склонение позволяет вам спрягать глаголы и склонять существительные, прилагательные, местоимения и числительные. Здесь можно узнать род и склонение существительных, прилагательных и числительных, степени сравнения прилагательных, спряжение глаголов, посмотреть таблицы времен для английского, немецкого, русского, французского, итальянского, португальского и испанского. Спрягайте глаголы, изучайте правила спряжения и склонения, смотрите переводы в контекстных примерах и словаре.

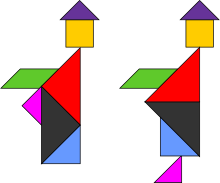

Like most modern sets, this wooden tangram is stored in the square configuration.

The tangram (Chinese: 七巧板; pinyin: qīqiǎobǎn; lit. ‘seven boards of skill’) is a dissection puzzle consisting of seven flat polygons, called tans, which are put together to form shapes. The objective is to replicate a pattern (given only an outline) generally found in a puzzle book using all seven pieces without overlap. Alternatively the tans can be used to create original minimalist designs that are either appreciated for their inherent aesthetic merits or as the basis for challenging others to replicate its outline. It is reputed to have been invented in China sometime around the late 18th century and then carried over to America and Europe by trading ships shortly after.[1] It became very popular in Europe for a time, and then again during World War I. It is one of the most widely recognized dissection puzzles in the world and has been used for various purposes including amusement, art, and education. [2][3][4]

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the word ‘tangram’ is unclear. One conjecture holds that it is a compound of the Greek element ‘-gram’ derived from γράμμα (‘written character, letter, that which is drawn’) with the ‘tan-‘ element being variously conjectured to be Chinese t’an ‘to extend’ or Cantonese t’ang ‘Chinese’.[5] Alternatively, the word may be derivative of the archaic English ‘tangram’ meaning «an odd, intricately contrived thing».[6]

In either case, the first known use of the word is believed to be found in the 1848 book Geometrical Puzzle for the Young by mathematician and future Harvard University president Thomas Hill who likely coined the term in the same work. Hill vigorously promoted the word in numerous articles advocating for the puzzle’s use in education and in 1864 it received official recognition in the English language when it was included in Noah Webster’s American Dictionary.[7]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Despite its relatively recent emergence in the West, there is a much older tradition of dissection amusements in China which likely played a role in its inspiration. In particular, the modular banquet tables of the Song dynasty bear an uncanny resemblance to the playing pieces of the Tangram and there were books dedicated to arranging them together to form pleasing patterns.[8]

Several Chinese sources broadly report a well-known Song dynasty polymath Huang Bosi 黄伯思 who developed a form of entertainment for his dinner guests based on creative arrangements of six small tables called 宴几 or 燕几(feast tables or swallow tables respectively). One diagram shows these as oblong rectangles, and other reports suggest a seventh table being added later, perhaps by a later inventor.[9][10]

According to Western sources, however, the tangram’s historical Chinese inventor is unknown except through the pen name Yang-cho-chu-shih (Dim-witted (?) recluse, recluse = 处士). It is believed that the puzzle was originally introduced in a book titled Ch’i chi’iao t’u which was already being reported as lost in 1815 by Shan-chiao in his book New Figures of the Tangram. Nevertheless, it is generally reputed that the puzzle’s origins would have been around 20 years earlier than this.[11]

The prominent third-century mathematician Liu Hui made use of construction proofs in his works and some bear a striking resemblance to the subsequently developed Banquet tables which in turn seem to anticipate the Tangram. While there is no reason to suspect that tangrams were used in the proof of the Pythagorean theorem, as is sometimes reported, it is likely that this style of geometric reasoning went on to exert an influence on Chinese cultural life that lead directly to the puzzle.[12]

The early years of attempting to date the Tangram were confused by the popular but fraudulently written history by famed puzzle maker Samuel Loyd in his 1908 The Eighth Book Of Tan. This work contains many whimsical features that aroused both interest and suspicion amongst contemporary scholars who attempted to verify the account. By 1910 it was clear that it was a hoax. A letter dated from this year from the Oxford Dictionary editor Sir James Murray on behalf of a number of Chinese scholars to the prominent puzzlist Henry Dudeney reads «The result has been to show that the man Tan, the god Tan, and the Book of Tan are entirely unknown to Chinese literature, history or tradition.»[6] Along with its many strange details The Eighth Book of Tan’s date of creation for the puzzle of 4000 years in antiquity had to be regarded as entirely baseless and false.

Reaching the Western world (1815–1820s)[edit]

A caricature published in France in 1818, when the tangram craze was at its peak. The caption reads: » ‘Take care of yourself, you’re not made of steel. The fire has almost gone out and it is winter.’ ‘It kept me busy all night. Excuse me, I will explain it to you. You play this game, which is said to hail from China. And I tell you that what Paris needs right now is to welcome that which comes from far away.’ «

The earliest extant tangram was given to the Philadelphia shipping magnate and congressman Francis Waln in 1802 but it was not until over a decade later that Western audiences, at large, would be exposed to the puzzle.[1][disputed – discuss] In 1815, American Captain M. Donnaldson was given a pair of author Sang-Hsia-koi’s books on the subject (one problem and one solution book) when his ship, Trader docked there. They were then brought with the ship to Philadelphia, in February 1816. The first tangram book to be published in America was based on the pair brought by Donnaldson.[13]

The puzzle eventually reached England, where it became very fashionable. The craze quickly spread to other European countries. This was mostly due to a pair of British tangram books, The Fashionable Chinese Puzzle, and the accompanying solution book, Key.[14] Soon, tangram sets were being exported in great number from China, made of various materials, from glass, to wood, to tortoise shell.[15]

Many of these unusual and exquisite tangram sets made their way to Denmark. Danish interest in tangrams skyrocketed around 1818, when two books on the puzzle were published, to much enthusiasm.[16] The first of these was Mandarinen (About the Chinese Game). This was written by a student at Copenhagen University, which was a non-fictional work about the history and popularity of tangrams. The second, Det nye chinesiske Gaadespil (The new Chinese Puzzle Game), consisted of 339 puzzles copied from The Eighth Book of Tan, as well as one original.[16]

One contributing factor in the popularity of the game in Europe was that although the Catholic Church forbade many forms of recreation on the sabbath, they made no objection to puzzle games such as the tangram.[17]

Second craze in Germany (1891–1920s)[edit]

Tangrams were first introduced to the German public by industrialist Friedrich Adolf Richter around 1891.[18] The sets were made out of stone or false earthenware,[19] and marketed under the name «The Anchor Puzzle».[18]

More internationally, the First World War saw a great resurgence of interest in tangrams, on the homefront and trenches of both sides. During this time, it occasionally went under the name of «The Sphinx» an alternative title for the «Anchor Puzzle» sets.[20][21]

Paradoxes[edit]

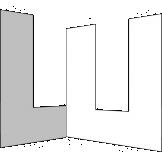

Explanation of the two-monks paradox:

In figure 1, side lengths are labelled assuming the square has unit sides.

In figure 2, overlaying the bodies shows that footless body is larger by the foot’s area. The change in area is often unnoticed as √2 is close to 1.5.

A tangram paradox is a dissection fallacy: Two figures composed with the same set of pieces, one of which seems to be a proper subset of the other.[22] One famous paradox is that of the two monks, attributed to Dudeney, which consists of two similar shapes, one with and the other missing a foot.[23] In reality, the area of the foot is compensated for in the second figure by a subtly larger body.

The two-monks paradox – two similar shapes but one missing a foot:

The Magic Dice Cup tangram paradox – from Sam Loyd’s book The 8th Book of Tan (1903).[24] Each of these cups was composed using the same seven geometric shapes. But the first cup is whole, and the others contain vacancies of different sizes. (Notice that the one on the left is slightly shorter than the other two. The one in the middle is ever-so-slightly wider than the one on the right, and the one on the left is narrower still.)[25]

Clipped square tangram paradox – from Loyd’s book The Eighth Book of Tan (1903):[24]

The seventh and eighth figures represent the mysterious square, built with seven pieces: then with a corner clipped off, and still the same seven pieces employed.[26]

Number of configurations[edit]

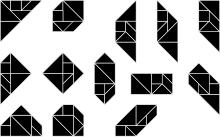

The 13 convex shapes matched with tangram set

Over 6500 different tangram problems have been created from 19th century texts alone, and the current number is ever-growing.[27] Fu Traing Wang and Chuan-Chin Hsiung proved in 1942 that there are only thirteen convex tangram configurations (config segment drawn between any two points on the configuration’s edge always pass through the configuration’s interior, i.e., configurations with no recesses in the outline).[28][29]

Pieces[edit]

Choosing a unit of measurement so that the seven pieces can be assembled to form a square of side one unit and having area one square unit, the seven pieces are:[30]

- 2 large right triangles (hypotenuse 1, sides √2/2, area 1/4)

- 1 medium right triangle (hypotenuse √2/2, sides 1/2, area 1/8)

- 2 small right triangles (hypotenuse 1/2, sides √2/4, area 1/16)

- 1 square (sides √2/4, area 1/8)

- 1 parallelogram (sides of 1/2 and √2/4, height of 1/4, area 1/8)

Of these seven pieces, the parallelogram is unique in that it has no reflection symmetry but only rotational symmetry, and so its mirror image can be obtained only by flipping it over. Thus, it is the only piece that may need to be flipped when forming certain shapes.

See also[edit]

- Egg of Columbus (tangram puzzle)

- Mathematical puzzle

- Ostomachion

- Tiling puzzle

References[edit]

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 21.

- ^ Campillo-Robles, Jose M.; Alonso, Ibon; Gondra, Ane; Gondra, Nerea (1 September 2022). «Calculation and measurement of center of mass: An all-in-one activity using Tangram puzzles». American Journal of Physics. 90 (9): 652. Bibcode:2022AmJPh..90..652C. doi:10.1119/5.0061884. ISSN 0002-9505. S2CID 251917733.

- ^ Slocum (2001), p. 9.

- ^ Forbrush, William Byron (1914). Manual of Play. Jacobs. p. 315. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1910, s.v.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 23.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 25.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 16.

- ^ Nie, Xuannan. «七巧板的前身(一)——燕几图 (The tangram’s origins, the Yanji Picture)». Zhihu. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ «七巧板是谁发明的? 七巧板是宋朝的黄伯思发明的 (Who invented the tangram? The tangram was invented by Huang Bosi)». Baidu Knowledge. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ Slocum (2003), pp. 16–19.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 30.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 31.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 49.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 51.

- ^ a b «Tangram the incredible timeless ‘Chinese’ puzzle». www.archimedes-lab.org.

- ^ Treasury Decisions Under customs and other laws, Volume 25. United States Department Of The Treasury. 1890–1926. p. 1421. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ^ Wyatt (26 April 2006). «Tangram – The Chinese Puzzle». h2g2. BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Braman, Arlette (2002). Kids Around The World Play!. John Wiley and Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-471-40984-7. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ Tangram Paradox, by Barile, Margherita, From MathWorld – A Wolfram Web Resource, created by Eric W. Weisstein.

- ^ Dudeney, H. (1958). Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications.

- ^ a b The 8th Book of Tan by Sam Loyd. 1903 – via Tangram Channel.

- ^ «The Magic Dice Cup». 2 April 2011.

- ^ Loyd, Sam (1968). The eighth book of Tan – 700 Tangrams by Sam Loyd with an introduction and solutions by Peter Van Note. New York: Dover Publications. p. 25.

- ^ Slocum 2001, p. 37.

- ^

Fu Traing Wang; Chuan-Chih Hsiung (November 1942). «A Theorem on the Tangram». The American Mathematical Monthly. 49 (9): 596–599. doi:10.2307/2303340. JSTOR 2303340. - ^ Read, Ronald C. (1965). Tangrams : 330 Puzzles. New York: Dover Publications. p. 53. ISBN 0-486-21483-4.

- ^ Brooks, David J. (1 December 2018). «How to Make a Classic Tangram Puzzle». Boys’ Life magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Sources

- Slocum, Jerry (2001). The Tao of Tangram. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-4351-0156-2.

- Slocum, Jerry (2003). The Tangram Book. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-0413-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Anno, Mitsumasa. Anno’s Math Games (three volumes). New York: Philomel Books, 1987. ISBN 0-399-21151-9 (v. 1), ISBN 0-698-11672-0 (v. 2), ISBN 0-399-22274-X (v. 3).

- Botermans, Jack, et al. The World of Games: Their Origins and History, How to Play Them, and How to Make Them (translation of Wereld vol spelletjes). New York: Facts on File, 1989. ISBN 0-8160-2184-8.

- Dudeney, H. E. Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications, 1958.

- Gardner, Martin. «Mathematical Games—on the Fanciful History and the Creative Challenges of the Puzzle Game of Tangrams», Scientific American Aug. 1974, p. 98–103.

- Gardner, Martin. «More on Tangrams», Scientific American Sep. 1974, p. 187–191.

- Gardner, Martin. The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961. ISBN 0-671-24559-7.

- Loyd, Sam. Sam Loyd’s Book of Tangram Puzzles (The 8th Book of Tan Part I). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1968.

- Slocum, Jerry, et al. Puzzles of Old and New: How to Make and Solve Them. De Meern, Netherlands: Plenary Publications International (Europe); Amsterdam, Netherlands: ADM International; Seattle: Distributed by University of Washington Press, 1986. ISBN 0-295-96350-6.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tangrams.

- Past & Future: The Roots of Tangram and Its Developments

- Turning Your Set of Tangram Into A Magic Math Puzzle by puzzle designer G. Sarcone

Like most modern sets, this wooden tangram is stored in the square configuration.

The tangram (Chinese: 七巧板; pinyin: qīqiǎobǎn; lit. ‘seven boards of skill’) is a dissection puzzle consisting of seven flat polygons, called tans, which are put together to form shapes. The objective is to replicate a pattern (given only an outline) generally found in a puzzle book using all seven pieces without overlap. Alternatively the tans can be used to create original minimalist designs that are either appreciated for their inherent aesthetic merits or as the basis for challenging others to replicate its outline. It is reputed to have been invented in China sometime around the late 18th century and then carried over to America and Europe by trading ships shortly after.[1] It became very popular in Europe for a time, and then again during World War I. It is one of the most widely recognized dissection puzzles in the world and has been used for various purposes including amusement, art, and education. [2][3][4]

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the word ‘tangram’ is unclear. One conjecture holds that it is a compound of the Greek element ‘-gram’ derived from γράμμα (‘written character, letter, that which is drawn’) with the ‘tan-‘ element being variously conjectured to be Chinese t’an ‘to extend’ or Cantonese t’ang ‘Chinese’.[5] Alternatively, the word may be derivative of the archaic English ‘tangram’ meaning «an odd, intricately contrived thing».[6]

In either case, the first known use of the word is believed to be found in the 1848 book Geometrical Puzzle for the Young by mathematician and future Harvard University president Thomas Hill who likely coined the term in the same work. Hill vigorously promoted the word in numerous articles advocating for the puzzle’s use in education and in 1864 it received official recognition in the English language when it was included in Noah Webster’s American Dictionary.[7]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Despite its relatively recent emergence in the West, there is a much older tradition of dissection amusements in China which likely played a role in its inspiration. In particular, the modular banquet tables of the Song dynasty bear an uncanny resemblance to the playing pieces of the Tangram and there were books dedicated to arranging them together to form pleasing patterns.[8]

Several Chinese sources broadly report a well-known Song dynasty polymath Huang Bosi 黄伯思 who developed a form of entertainment for his dinner guests based on creative arrangements of six small tables called 宴几 or 燕几(feast tables or swallow tables respectively). One diagram shows these as oblong rectangles, and other reports suggest a seventh table being added later, perhaps by a later inventor.[9][10]

According to Western sources, however, the tangram’s historical Chinese inventor is unknown except through the pen name Yang-cho-chu-shih (Dim-witted (?) recluse, recluse = 处士). It is believed that the puzzle was originally introduced in a book titled Ch’i chi’iao t’u which was already being reported as lost in 1815 by Shan-chiao in his book New Figures of the Tangram. Nevertheless, it is generally reputed that the puzzle’s origins would have been around 20 years earlier than this.[11]

The prominent third-century mathematician Liu Hui made use of construction proofs in his works and some bear a striking resemblance to the subsequently developed Banquet tables which in turn seem to anticipate the Tangram. While there is no reason to suspect that tangrams were used in the proof of the Pythagorean theorem, as is sometimes reported, it is likely that this style of geometric reasoning went on to exert an influence on Chinese cultural life that lead directly to the puzzle.[12]

The early years of attempting to date the Tangram were confused by the popular but fraudulently written history by famed puzzle maker Samuel Loyd in his 1908 The Eighth Book Of Tan. This work contains many whimsical features that aroused both interest and suspicion amongst contemporary scholars who attempted to verify the account. By 1910 it was clear that it was a hoax. A letter dated from this year from the Oxford Dictionary editor Sir James Murray on behalf of a number of Chinese scholars to the prominent puzzlist Henry Dudeney reads «The result has been to show that the man Tan, the god Tan, and the Book of Tan are entirely unknown to Chinese literature, history or tradition.»[6] Along with its many strange details The Eighth Book of Tan’s date of creation for the puzzle of 4000 years in antiquity had to be regarded as entirely baseless and false.

Reaching the Western world (1815–1820s)[edit]

A caricature published in France in 1818, when the tangram craze was at its peak. The caption reads: » ‘Take care of yourself, you’re not made of steel. The fire has almost gone out and it is winter.’ ‘It kept me busy all night. Excuse me, I will explain it to you. You play this game, which is said to hail from China. And I tell you that what Paris needs right now is to welcome that which comes from far away.’ «

The earliest extant tangram was given to the Philadelphia shipping magnate and congressman Francis Waln in 1802 but it was not until over a decade later that Western audiences, at large, would be exposed to the puzzle.[1][disputed – discuss] In 1815, American Captain M. Donnaldson was given a pair of author Sang-Hsia-koi’s books on the subject (one problem and one solution book) when his ship, Trader docked there. They were then brought with the ship to Philadelphia, in February 1816. The first tangram book to be published in America was based on the pair brought by Donnaldson.[13]

The puzzle eventually reached England, where it became very fashionable. The craze quickly spread to other European countries. This was mostly due to a pair of British tangram books, The Fashionable Chinese Puzzle, and the accompanying solution book, Key.[14] Soon, tangram sets were being exported in great number from China, made of various materials, from glass, to wood, to tortoise shell.[15]

Many of these unusual and exquisite tangram sets made their way to Denmark. Danish interest in tangrams skyrocketed around 1818, when two books on the puzzle were published, to much enthusiasm.[16] The first of these was Mandarinen (About the Chinese Game). This was written by a student at Copenhagen University, which was a non-fictional work about the history and popularity of tangrams. The second, Det nye chinesiske Gaadespil (The new Chinese Puzzle Game), consisted of 339 puzzles copied from The Eighth Book of Tan, as well as one original.[16]

One contributing factor in the popularity of the game in Europe was that although the Catholic Church forbade many forms of recreation on the sabbath, they made no objection to puzzle games such as the tangram.[17]

Second craze in Germany (1891–1920s)[edit]

Tangrams were first introduced to the German public by industrialist Friedrich Adolf Richter around 1891.[18] The sets were made out of stone or false earthenware,[19] and marketed under the name «The Anchor Puzzle».[18]

More internationally, the First World War saw a great resurgence of interest in tangrams, on the homefront and trenches of both sides. During this time, it occasionally went under the name of «The Sphinx» an alternative title for the «Anchor Puzzle» sets.[20][21]

Paradoxes[edit]

Explanation of the two-monks paradox:

In figure 1, side lengths are labelled assuming the square has unit sides.

In figure 2, overlaying the bodies shows that footless body is larger by the foot’s area. The change in area is often unnoticed as √2 is close to 1.5.

A tangram paradox is a dissection fallacy: Two figures composed with the same set of pieces, one of which seems to be a proper subset of the other.[22] One famous paradox is that of the two monks, attributed to Dudeney, which consists of two similar shapes, one with and the other missing a foot.[23] In reality, the area of the foot is compensated for in the second figure by a subtly larger body.

The two-monks paradox – two similar shapes but one missing a foot:

The Magic Dice Cup tangram paradox – from Sam Loyd’s book The 8th Book of Tan (1903).[24] Each of these cups was composed using the same seven geometric shapes. But the first cup is whole, and the others contain vacancies of different sizes. (Notice that the one on the left is slightly shorter than the other two. The one in the middle is ever-so-slightly wider than the one on the right, and the one on the left is narrower still.)[25]

Clipped square tangram paradox – from Loyd’s book The Eighth Book of Tan (1903):[24]

The seventh and eighth figures represent the mysterious square, built with seven pieces: then with a corner clipped off, and still the same seven pieces employed.[26]

Number of configurations[edit]

The 13 convex shapes matched with tangram set

Over 6500 different tangram problems have been created from 19th century texts alone, and the current number is ever-growing.[27] Fu Traing Wang and Chuan-Chin Hsiung proved in 1942 that there are only thirteen convex tangram configurations (config segment drawn between any two points on the configuration’s edge always pass through the configuration’s interior, i.e., configurations with no recesses in the outline).[28][29]

Pieces[edit]

Choosing a unit of measurement so that the seven pieces can be assembled to form a square of side one unit and having area one square unit, the seven pieces are:[30]

- 2 large right triangles (hypotenuse 1, sides √2/2, area 1/4)

- 1 medium right triangle (hypotenuse √2/2, sides 1/2, area 1/8)

- 2 small right triangles (hypotenuse 1/2, sides √2/4, area 1/16)

- 1 square (sides √2/4, area 1/8)

- 1 parallelogram (sides of 1/2 and √2/4, height of 1/4, area 1/8)

Of these seven pieces, the parallelogram is unique in that it has no reflection symmetry but only rotational symmetry, and so its mirror image can be obtained only by flipping it over. Thus, it is the only piece that may need to be flipped when forming certain shapes.

See also[edit]

- Egg of Columbus (tangram puzzle)

- Mathematical puzzle

- Ostomachion

- Tiling puzzle

References[edit]

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 21.

- ^ Campillo-Robles, Jose M.; Alonso, Ibon; Gondra, Ane; Gondra, Nerea (1 September 2022). «Calculation and measurement of center of mass: An all-in-one activity using Tangram puzzles». American Journal of Physics. 90 (9): 652. Bibcode:2022AmJPh..90..652C. doi:10.1119/5.0061884. ISSN 0002-9505. S2CID 251917733.

- ^ Slocum (2001), p. 9.

- ^ Forbrush, William Byron (1914). Manual of Play. Jacobs. p. 315. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1910, s.v.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 23.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 25.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 16.

- ^ Nie, Xuannan. «七巧板的前身(一)——燕几图 (The tangram’s origins, the Yanji Picture)». Zhihu. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ «七巧板是谁发明的? 七巧板是宋朝的黄伯思发明的 (Who invented the tangram? The tangram was invented by Huang Bosi)». Baidu Knowledge. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ Slocum (2003), pp. 16–19.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 30.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 31.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 49.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 51.

- ^ a b «Tangram the incredible timeless ‘Chinese’ puzzle». www.archimedes-lab.org.

- ^ Treasury Decisions Under customs and other laws, Volume 25. United States Department Of The Treasury. 1890–1926. p. 1421. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ^ Wyatt (26 April 2006). «Tangram – The Chinese Puzzle». h2g2. BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Braman, Arlette (2002). Kids Around The World Play!. John Wiley and Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-471-40984-7. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ Tangram Paradox, by Barile, Margherita, From MathWorld – A Wolfram Web Resource, created by Eric W. Weisstein.

- ^ Dudeney, H. (1958). Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications.

- ^ a b The 8th Book of Tan by Sam Loyd. 1903 – via Tangram Channel.

- ^ «The Magic Dice Cup». 2 April 2011.

- ^ Loyd, Sam (1968). The eighth book of Tan – 700 Tangrams by Sam Loyd with an introduction and solutions by Peter Van Note. New York: Dover Publications. p. 25.

- ^ Slocum 2001, p. 37.

- ^

Fu Traing Wang; Chuan-Chih Hsiung (November 1942). «A Theorem on the Tangram». The American Mathematical Monthly. 49 (9): 596–599. doi:10.2307/2303340. JSTOR 2303340. - ^ Read, Ronald C. (1965). Tangrams : 330 Puzzles. New York: Dover Publications. p. 53. ISBN 0-486-21483-4.

- ^ Brooks, David J. (1 December 2018). «How to Make a Classic Tangram Puzzle». Boys’ Life magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Sources

- Slocum, Jerry (2001). The Tao of Tangram. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-4351-0156-2.

- Slocum, Jerry (2003). The Tangram Book. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-0413-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Anno, Mitsumasa. Anno’s Math Games (three volumes). New York: Philomel Books, 1987. ISBN 0-399-21151-9 (v. 1), ISBN 0-698-11672-0 (v. 2), ISBN 0-399-22274-X (v. 3).

- Botermans, Jack, et al. The World of Games: Their Origins and History, How to Play Them, and How to Make Them (translation of Wereld vol spelletjes). New York: Facts on File, 1989. ISBN 0-8160-2184-8.

- Dudeney, H. E. Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications, 1958.

- Gardner, Martin. «Mathematical Games—on the Fanciful History and the Creative Challenges of the Puzzle Game of Tangrams», Scientific American Aug. 1974, p. 98–103.

- Gardner, Martin. «More on Tangrams», Scientific American Sep. 1974, p. 187–191.

- Gardner, Martin. The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961. ISBN 0-671-24559-7.

- Loyd, Sam. Sam Loyd’s Book of Tangram Puzzles (The 8th Book of Tan Part I). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1968.

- Slocum, Jerry, et al. Puzzles of Old and New: How to Make and Solve Them. De Meern, Netherlands: Plenary Publications International (Europe); Amsterdam, Netherlands: ADM International; Seattle: Distributed by University of Washington Press, 1986. ISBN 0-295-96350-6.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tangrams.

- Past & Future: The Roots of Tangram and Its Developments

- Turning Your Set of Tangram Into A Magic Math Puzzle by puzzle designer G. Sarcone

Слово «танграм»

Слово состоит из 7 букв, начинается и заканчивается на согласную, первая буква — «т», вторая буква — «а», третья буква — «н», четвёртая буква — «г», пятая буква — «р», шестая буква — «а», последняя буква — «м».

- Синонимы к слову

- Написание слова наоборот

- Написание слова в транслите

- Написание слова шрифтом Брайля

- Передача слова на азбуке Морзе

- Произношение слова на дактильной азбуке

- Остальные слова из 7 букв

Танграм. Развивающие игры. Развивающие игры своими руками.

109. Детский психолог В. Паевская. Танграм, Тангос (от 1,5 до 7 лет)

Геометрическая головоломка №6 (ТАНГРАМ)

Танграм: Что это и как играть в танграм?

Танграм для детей. Делаем своими руками.

Синонимы к слову «танграм»

Какие близкие по смыслу слова и фразы, а также похожие выражения существуют. Как можно написать по-другому или сказать другими словами.

Фразы

- + взаимная рекурсия −

- + геометрические фигуры −

- + группа орнамента −

- + делящаяся плитка −

- + дерево квадрантов −

- + знак деления −

- + китайские иероглифы −

- + контактное число −

- + конфигурация вершины −

- + математические обозначения −

- + метод галеры −

- + механическая головоломка −

- + многоугольник видимости −

- + модульное оригами −

- + наборная доска −

- + отсечённый ромбоикосододекаэдр −

- + плосконосый многогранник −

- + прямолинейный скелет −

- + редактор формул −

- + спектральная кластеризация −

- + усечённая квадратная мозаика −

- + черепашья графика −

- + четыре символа −

- + шахматная диаграмма −

Ваш синоним добавлен!

Написание слова «танграм» наоборот

Как это слово пишется в обратной последовательности.

маргнат 😀

Написание слова «танграм» в транслите

Как это слово пишется в транслитерации.

в армянской🇦🇲 տանգրամ

в греческой🇬🇷 θαγγραμ

в грузинской🇬🇪 თანგრამ

в еврейской🇮🇱 טאנגראמ

в латинской🇬🇧 tangram

Как это слово пишется в пьюникоде — Punycode, ACE-последовательность IDN

xn--80aai1bctk

Как это слово пишется в английской Qwerty-раскладке клавиатуры.

nfyuhfv

Написание слова «танграм» шрифтом Брайля

Как это слово пишется рельефно-точечным тактильным шрифтом.

⠞⠁⠝⠛⠗⠁⠍

Передача слова «танграм» на азбуке Морзе

Как это слово передаётся на морзянке.

– ⋅ – – ⋅ – – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – – –

Произношение слова «танграм» на дактильной азбуке

Как это слово произносится на ручной азбуке глухонемых (но не на языке жестов).

Передача слова «танграм» семафорной азбукой

Как это слово передаётся флажковой сигнализацией.

Остальные слова из 7 букв

Какие ещё слова состоят из такого же количества букв.

- аа-лава

- ааленец

- ааронов

- аахенец

- аба-ван

- аба-вуа

- абадзех

- абазгия

- абазины

- абакост

- абакумы

- абандон

- абацист

- аббатов

- абгаллу

- абдалов

- абдерит

- абдомен

- абдулла

- абевега

- абелева

- абелево

- абессив

- абиетин

×

Здравствуйте!

У вас есть вопрос или вам нужна помощь?

Спасибо, ваш вопрос принят.

Ответ на него появится на сайте в ближайшее время.

Народный словарь великого и могучего живого великорусского языка.

Онлайн-словарь слов и выражений русского языка. Ассоциации к словам, синонимы слов, сочетаемость фраз. Морфологический разбор: склонение существительных и прилагательных, а также спряжение глаголов. Морфемный разбор по составу словоформ.

По всем вопросам просьба обращаться в письмошную.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Like most modern sets, this wooden tangram is stored in the square configuration.

The tangram (Chinese: 七巧板; pinyin: qīqiǎobǎn; lit. ‘seven boards of skill’) is a dissection puzzle consisting of seven flat polygons, called tans, which are put together to form shapes. The objective is to replicate a pattern (given only an outline) generally found in a puzzle book using all seven pieces without overlap. Alternatively the tans can be used to create original minimalist designs that are either appreciated for their inherent aesthetic merits or as the basis for challenging others to replicate its outline. It is reputed to have been invented in China sometime around the late 18th century and then carried over to America and Europe by trading ships shortly after.[1] It became very popular in Europe for a time, and then again during World War I. It is one of the most widely recognized dissection puzzles in the world and has been used for various purposes including amusement, art, and education. [2][3][4]

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the English word ‘tangram’ is unclear. One conjecture holds that it is a compound of the Greek element ‘-gram’ derived from γράμμα (‘written character, letter, that which is drawn’) with the ‘tan-‘ element being variously conjectured to be Chinese t’an ‘to extend’ or Cantonese t’ang ‘Chinese’.[5] Alternatively, the word may be derivative of the archaic English ‘tangram’ meaning «an odd, intricately contrived thing».[6]

In either case, the first known use of the word is believed to be found in the 1848 book Geometrical Puzzle for the Young by mathematician and future Harvard University president Thomas Hill.[7] Hill likely coined the term in the same work, and vigorously promoted the word in numerous articles advocating for the puzzle’s use in education, and in 1864 the word received official recognition in the English language when it was included in Noah Webster’s American Dictionary.[8]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Despite its relatively recent emergence in the West, there is a much older tradition of dissection amusements in China which likely played a role in its inspiration. In particular, the modular banquet tables of the Song dynasty bear an uncanny resemblance to the playing pieces of the Tangram and there were books dedicated to arranging them together to form pleasing patterns.[9]

Several Chinese sources broadly report a well-known Song dynasty polymath Huang Bosi 黄伯思 who developed a form of entertainment for his dinner guests based on creative arrangements of six small tables called 宴几 or 燕几(feast tables or swallow tables respectively). One diagram shows these as oblong rectangles, and other reports suggest a seventh table being added later, perhaps by a later inventor.[10][11]

According to Western sources, however, the tangram’s historical Chinese inventor is unknown except through the pen name Yang-cho-chu-shih (Dim-witted (?) recluse, recluse = 处士). It is believed that the puzzle was originally introduced in a book titled Ch’i chi’iao t’u which was already being reported as lost in 1815 by Shan-chiao in his book New Figures of the Tangram. Nevertheless, it is generally reputed that the puzzle’s origins would have been around 20 years earlier than this.[12]

The prominent third-century mathematician Liu Hui made use of construction proofs in his works and some bear a striking resemblance to the subsequently developed Banquet tables which in turn seem to anticipate the Tangram. While there is no reason to suspect that tangrams were used in the proof of the Pythagorean theorem, as is sometimes reported, it is likely that this style of geometric reasoning went on to exert an influence on Chinese cultural life that lead directly to the puzzle.[13]

The early years of attempting to date the Tangram were confused by the popular but fraudulently written history by famed puzzle maker Samuel Loyd in his 1908 The Eighth Book Of Tan. This work contains many whimsical features that aroused both interest and suspicion amongst contemporary scholars who attempted to verify the account. By 1910 it was clear that it was a hoax. A letter dated from this year from the Oxford Dictionary editor Sir James Murray on behalf of a number of Chinese scholars to the prominent puzzlist Henry Dudeney reads «The result has been to show that the man Tan, the god Tan, and the Book of Tan are entirely unknown to Chinese literature, history or tradition.»[6] Along with its many strange details The Eighth Book of Tan’s date of creation for the puzzle of 4000 years in antiquity had to be regarded as entirely baseless and false.

Reaching the Western world (1815–1820s)[edit]

A caricature published in France in 1818, when the tangram craze was at its peak. The caption reads: » ‘Take care of yourself, you’re not made of steel. The fire has almost gone out and it is winter.’ ‘It kept me busy all night. Excuse me, I will explain it to you. You play this game, which is said to hail from China. And I tell you that what Paris needs right now is to welcome that which comes from far away.’ «

The earliest extant tangram was given to the Philadelphia shipping magnate and congressman Francis Waln in 1802 but it was not until over a decade later that Western audiences, at large, would be exposed to the puzzle.[1][disputed – discuss] In 1815, American Captain M. Donnaldson was given a pair of author Sang-Hsia-koi’s books on the subject (one problem and one solution book) when his ship, Trader docked there. They were then brought with the ship to Philadelphia, in February 1816. The first tangram book to be published in America was based on the pair brought by Donnaldson.[14]

The puzzle eventually reached England, where it became very fashionable. The craze quickly spread to other European countries. This was mostly due to a pair of British tangram books, The Fashionable Chinese Puzzle, and the accompanying solution book, Key.[15] Soon, tangram sets were being exported in great number from China, made of various materials, from glass, to wood, to tortoise shell.[16]

Many of these unusual and exquisite tangram sets made their way to Denmark. Danish interest in tangrams skyrocketed around 1818, when two books on the puzzle were published, to much enthusiasm.[17] The first of these was Mandarinen (About the Chinese Game). This was written by a student at Copenhagen University, which was a non-fictional work about the history and popularity of tangrams. The second, Det nye chinesiske Gaadespil (The new Chinese Puzzle Game), consisted of 339 puzzles copied from The Eighth Book of Tan, as well as one original.[17]

One contributing factor in the popularity of the game in Europe was that although the Catholic Church forbade many forms of recreation on the sabbath, they made no objection to puzzle games such as the tangram.[18]

Second craze in Germany (1891–1920s)[edit]

Tangrams were first introduced to the German public by industrialist Friedrich Adolf Richter around 1891.[19] The sets were made out of stone or false earthenware,[20] and marketed under the name «The Anchor Puzzle».[19]

More internationally, the First World War saw a great resurgence of interest in tangrams, on the homefront and trenches of both sides. During this time, it occasionally went under the name of «The Sphinx» an alternative title for the «Anchor Puzzle» sets.[21][22]

Paradoxes[edit]

Explanation of the two-monks paradox:

In figure 1, side lengths are labelled assuming the square has unit sides.

In figure 2, overlaying the bodies shows that footless body is larger by the foot’s area. The change in area is often unnoticed as √2 is close to 1.5.

A tangram paradox is a dissection fallacy: Two figures composed with the same set of pieces, one of which seems to be a proper subset of the other.[23] One famous paradox is that of the two monks, attributed to Dudeney, which consists of two similar shapes, one with and the other missing a foot.[24] In reality, the area of the foot is compensated for in the second figure by a subtly larger body.

The two-monks paradox – two similar shapes but one missing a foot:

The Magic Dice Cup tangram paradox – from Sam Loyd’s book The 8th Book of Tan (1903).[25] Each of these cups was composed using the same seven geometric shapes. But the first cup is whole, and the others contain vacancies of different sizes. (Notice that the one on the left is slightly shorter than the other two. The one in the middle is ever-so-slightly wider than the one on the right, and the one on the left is narrower still.)[26]

Clipped square tangram paradox – from Loyd’s book The Eighth Book of Tan (1903):[25]

The seventh and eighth figures represent the mysterious square, built with seven pieces: then with a corner clipped off, and still the same seven pieces employed.[27]

Number of configurations[edit]

The 13 convex shapes matched with tangram set

Over 6500 different tangram problems have been created from 19th century texts alone, and the current number is ever-growing.[28] Fu Traing Wang and Chuan-Chin Hsiung proved in 1942 that there are only thirteen convex tangram configurations (config segment drawn between any two points on the configuration’s edge always pass through the configuration’s interior, i.e., configurations with no recesses in the outline).[29][30]

Pieces[edit]

Choosing a unit of measurement so that the seven pieces can be assembled to form a square of side one unit and having area one square unit, the seven pieces are:[31]

- 2 large right triangles (hypotenuse 1, sides √2/2, area 1/4)

- 1 medium right triangle (hypotenuse √2/2, sides 1/2, area 1/8)

- 2 small right triangles (hypotenuse 1/2, sides √2/4, area 1/16)

- 1 square (sides √2/4, area 1/8)

- 1 parallelogram (sides of 1/2 and √2/4, height of 1/4, area 1/8)

Of these seven pieces, the parallelogram is unique in that it has no reflection symmetry but only rotational symmetry, and so its mirror image can be obtained only by flipping it over. Thus, it is the only piece that may need to be flipped when forming certain shapes.

See also[edit]

- Egg of Columbus (tangram puzzle)

- Mathematical puzzle

- Ostomachion

- Tiling puzzle

References[edit]

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 21.

- ^ Campillo-Robles, Jose M.; Alonso, Ibon; Gondra, Ane; Gondra, Nerea (1 September 2022). «Calculation and measurement of center of mass: An all-in-one activity using Tangram puzzles». American Journal of Physics. 90 (9): 652. Bibcode:2022AmJPh..90..652C. doi:10.1119/5.0061884. ISSN 0002-9505. S2CID 251917733.

- ^ Slocum (2001), p. 9.

- ^ Forbrush, William Byron (1914). Manual of Play. Jacobs. p. 315. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1910, s.v.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 23.

- ^ Hill, Thomas (1848). Puzzles to teach geometry : in seventeen cards numbered from the first to the seventeenth inclusive. Boston : Wm. Crosby & H.P. Nichols.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 25.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 16.

- ^ Nie, Xuannan. «七巧板的前身(一)——燕几图 (The tangram’s origins, the Yanji Picture)». Zhihu. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ «七巧板是谁发明的? 七巧板是宋朝的黄伯思发明的 (Who invented the tangram? The tangram was invented by Huang Bosi)». Baidu Knowledge. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ Slocum (2003), pp. 16–19.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 30.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 31.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 49.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 51.

- ^ a b «Tangram the incredible timeless ‘Chinese’ puzzle». www.archimedes-lab.org.

- ^ Treasury Decisions Under customs and other laws, Volume 25. United States Department Of The Treasury. 1890–1926. p. 1421. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ^ Wyatt (26 April 2006). «Tangram – The Chinese Puzzle». h2g2. BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Braman, Arlette (2002). Kids Around The World Play!. John Wiley and Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-471-40984-7. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ Tangram Paradox, by Barile, Margherita, From MathWorld – A Wolfram Web Resource, created by Eric W. Weisstein.

- ^ Dudeney, H. (1958). Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications.

- ^ a b The 8th Book of Tan by Sam Loyd. 1903 – via Tangram Channel.

- ^ «The Magic Dice Cup». 2 April 2011.

- ^ Loyd, Sam (1968). The eighth book of Tan – 700 Tangrams by Sam Loyd with an introduction and solutions by Peter Van Note. New York: Dover Publications. p. 25.

- ^ Slocum 2001, p. 37.

- ^

Fu Traing Wang; Chuan-Chih Hsiung (November 1942). «A Theorem on the Tangram». The American Mathematical Monthly. 49 (9): 596–599. doi:10.2307/2303340. JSTOR 2303340. - ^ Read, Ronald C. (1965). Tangrams : 330 Puzzles. New York: Dover Publications. p. 53. ISBN 0-486-21483-4.

- ^ Brooks, David J. (1 December 2018). «How to Make a Classic Tangram Puzzle». Boys’ Life magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Sources

- Slocum, Jerry (2001). The Tao of Tangram. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-4351-0156-2.

- Slocum, Jerry (2003). The Tangram Book. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-0413-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Anno, Mitsumasa. Anno’s Math Games (three volumes). New York: Philomel Books, 1987. ISBN 0-399-21151-9 (v. 1), ISBN 0-698-11672-0 (v. 2), ISBN 0-399-22274-X (v. 3).

- Botermans, Jack, et al. The World of Games: Their Origins and History, How to Play Them, and How to Make Them (translation of Wereld vol spelletjes). New York: Facts on File, 1989. ISBN 0-8160-2184-8.

- Dudeney, H. E. Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications, 1958.

- Gardner, Martin. «Mathematical Games—on the Fanciful History and the Creative Challenges of the Puzzle Game of Tangrams», Scientific American Aug. 1974, p. 98–103.

- Gardner, Martin. «More on Tangrams», Scientific American Sep. 1974, p. 187–191.

- Gardner, Martin. The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961. ISBN 0-671-24559-7.

- Loyd, Sam. Sam Loyd’s Book of Tangram Puzzles (The 8th Book of Tan Part I). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1968.

- Slocum, Jerry, et al. Puzzles of Old and New: How to Make and Solve Them. De Meern, Netherlands: Plenary Publications International (Europe); Amsterdam, Netherlands: ADM International; Seattle: Distributed by University of Washington Press, 1986. ISBN 0-295-96350-6.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tangrams.

- Past & Future: The Roots of Tangram and Its Developments

- Turning Your Set of Tangram Into A Magic Math Puzzle by puzzle designer G. Sarcone

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Like most modern sets, this wooden tangram is stored in the square configuration.

The tangram (Chinese: 七巧板; pinyin: qīqiǎobǎn; lit. ‘seven boards of skill’) is a dissection puzzle consisting of seven flat polygons, called tans, which are put together to form shapes. The objective is to replicate a pattern (given only an outline) generally found in a puzzle book using all seven pieces without overlap. Alternatively the tans can be used to create original minimalist designs that are either appreciated for their inherent aesthetic merits or as the basis for challenging others to replicate its outline. It is reputed to have been invented in China sometime around the late 18th century and then carried over to America and Europe by trading ships shortly after.[1] It became very popular in Europe for a time, and then again during World War I. It is one of the most widely recognized dissection puzzles in the world and has been used for various purposes including amusement, art, and education. [2][3][4]

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the English word ‘tangram’ is unclear. One conjecture holds that it is a compound of the Greek element ‘-gram’ derived from γράμμα (‘written character, letter, that which is drawn’) with the ‘tan-‘ element being variously conjectured to be Chinese t’an ‘to extend’ or Cantonese t’ang ‘Chinese’.[5] Alternatively, the word may be derivative of the archaic English ‘tangram’ meaning «an odd, intricately contrived thing».[6]

In either case, the first known use of the word is believed to be found in the 1848 book Geometrical Puzzle for the Young by mathematician and future Harvard University president Thomas Hill.[7] Hill likely coined the term in the same work, and vigorously promoted the word in numerous articles advocating for the puzzle’s use in education, and in 1864 the word received official recognition in the English language when it was included in Noah Webster’s American Dictionary.[8]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Despite its relatively recent emergence in the West, there is a much older tradition of dissection amusements in China which likely played a role in its inspiration. In particular, the modular banquet tables of the Song dynasty bear an uncanny resemblance to the playing pieces of the Tangram and there were books dedicated to arranging them together to form pleasing patterns.[9]

Several Chinese sources broadly report a well-known Song dynasty polymath Huang Bosi 黄伯思 who developed a form of entertainment for his dinner guests based on creative arrangements of six small tables called 宴几 or 燕几(feast tables or swallow tables respectively). One diagram shows these as oblong rectangles, and other reports suggest a seventh table being added later, perhaps by a later inventor.[10][11]

According to Western sources, however, the tangram’s historical Chinese inventor is unknown except through the pen name Yang-cho-chu-shih (Dim-witted (?) recluse, recluse = 处士). It is believed that the puzzle was originally introduced in a book titled Ch’i chi’iao t’u which was already being reported as lost in 1815 by Shan-chiao in his book New Figures of the Tangram. Nevertheless, it is generally reputed that the puzzle’s origins would have been around 20 years earlier than this.[12]

The prominent third-century mathematician Liu Hui made use of construction proofs in his works and some bear a striking resemblance to the subsequently developed Banquet tables which in turn seem to anticipate the Tangram. While there is no reason to suspect that tangrams were used in the proof of the Pythagorean theorem, as is sometimes reported, it is likely that this style of geometric reasoning went on to exert an influence on Chinese cultural life that lead directly to the puzzle.[13]

The early years of attempting to date the Tangram were confused by the popular but fraudulently written history by famed puzzle maker Samuel Loyd in his 1908 The Eighth Book Of Tan. This work contains many whimsical features that aroused both interest and suspicion amongst contemporary scholars who attempted to verify the account. By 1910 it was clear that it was a hoax. A letter dated from this year from the Oxford Dictionary editor Sir James Murray on behalf of a number of Chinese scholars to the prominent puzzlist Henry Dudeney reads «The result has been to show that the man Tan, the god Tan, and the Book of Tan are entirely unknown to Chinese literature, history or tradition.»[6] Along with its many strange details The Eighth Book of Tan’s date of creation for the puzzle of 4000 years in antiquity had to be regarded as entirely baseless and false.

Reaching the Western world (1815–1820s)[edit]

A caricature published in France in 1818, when the tangram craze was at its peak. The caption reads: » ‘Take care of yourself, you’re not made of steel. The fire has almost gone out and it is winter.’ ‘It kept me busy all night. Excuse me, I will explain it to you. You play this game, which is said to hail from China. And I tell you that what Paris needs right now is to welcome that which comes from far away.’ «

The earliest extant tangram was given to the Philadelphia shipping magnate and congressman Francis Waln in 1802 but it was not until over a decade later that Western audiences, at large, would be exposed to the puzzle.[1][disputed – discuss] In 1815, American Captain M. Donnaldson was given a pair of author Sang-Hsia-koi’s books on the subject (one problem and one solution book) when his ship, Trader docked there. They were then brought with the ship to Philadelphia, in February 1816. The first tangram book to be published in America was based on the pair brought by Donnaldson.[14]

The puzzle eventually reached England, where it became very fashionable. The craze quickly spread to other European countries. This was mostly due to a pair of British tangram books, The Fashionable Chinese Puzzle, and the accompanying solution book, Key.[15] Soon, tangram sets were being exported in great number from China, made of various materials, from glass, to wood, to tortoise shell.[16]

Many of these unusual and exquisite tangram sets made their way to Denmark. Danish interest in tangrams skyrocketed around 1818, when two books on the puzzle were published, to much enthusiasm.[17] The first of these was Mandarinen (About the Chinese Game). This was written by a student at Copenhagen University, which was a non-fictional work about the history and popularity of tangrams. The second, Det nye chinesiske Gaadespil (The new Chinese Puzzle Game), consisted of 339 puzzles copied from The Eighth Book of Tan, as well as one original.[17]

One contributing factor in the popularity of the game in Europe was that although the Catholic Church forbade many forms of recreation on the sabbath, they made no objection to puzzle games such as the tangram.[18]

Second craze in Germany (1891–1920s)[edit]

Tangrams were first introduced to the German public by industrialist Friedrich Adolf Richter around 1891.[19] The sets were made out of stone or false earthenware,[20] and marketed under the name «The Anchor Puzzle».[19]

More internationally, the First World War saw a great resurgence of interest in tangrams, on the homefront and trenches of both sides. During this time, it occasionally went under the name of «The Sphinx» an alternative title for the «Anchor Puzzle» sets.[21][22]

Paradoxes[edit]

Explanation of the two-monks paradox:

In figure 1, side lengths are labelled assuming the square has unit sides.

In figure 2, overlaying the bodies shows that footless body is larger by the foot’s area. The change in area is often unnoticed as √2 is close to 1.5.

A tangram paradox is a dissection fallacy: Two figures composed with the same set of pieces, one of which seems to be a proper subset of the other.[23] One famous paradox is that of the two monks, attributed to Dudeney, which consists of two similar shapes, one with and the other missing a foot.[24] In reality, the area of the foot is compensated for in the second figure by a subtly larger body.

The two-monks paradox – two similar shapes but one missing a foot:

The Magic Dice Cup tangram paradox – from Sam Loyd’s book The 8th Book of Tan (1903).[25] Each of these cups was composed using the same seven geometric shapes. But the first cup is whole, and the others contain vacancies of different sizes. (Notice that the one on the left is slightly shorter than the other two. The one in the middle is ever-so-slightly wider than the one on the right, and the one on the left is narrower still.)[26]

Clipped square tangram paradox – from Loyd’s book The Eighth Book of Tan (1903):[25]

The seventh and eighth figures represent the mysterious square, built with seven pieces: then with a corner clipped off, and still the same seven pieces employed.[27]

Number of configurations[edit]

The 13 convex shapes matched with tangram set

Over 6500 different tangram problems have been created from 19th century texts alone, and the current number is ever-growing.[28] Fu Traing Wang and Chuan-Chin Hsiung proved in 1942 that there are only thirteen convex tangram configurations (config segment drawn between any two points on the configuration’s edge always pass through the configuration’s interior, i.e., configurations with no recesses in the outline).[29][30]

Pieces[edit]

Choosing a unit of measurement so that the seven pieces can be assembled to form a square of side one unit and having area one square unit, the seven pieces are:[31]

- 2 large right triangles (hypotenuse 1, sides √2/2, area 1/4)

- 1 medium right triangle (hypotenuse √2/2, sides 1/2, area 1/8)

- 2 small right triangles (hypotenuse 1/2, sides √2/4, area 1/16)

- 1 square (sides √2/4, area 1/8)

- 1 parallelogram (sides of 1/2 and √2/4, height of 1/4, area 1/8)

Of these seven pieces, the parallelogram is unique in that it has no reflection symmetry but only rotational symmetry, and so its mirror image can be obtained only by flipping it over. Thus, it is the only piece that may need to be flipped when forming certain shapes.

See also[edit]

- Egg of Columbus (tangram puzzle)

- Mathematical puzzle

- Ostomachion

- Tiling puzzle

References[edit]

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 21.

- ^ Campillo-Robles, Jose M.; Alonso, Ibon; Gondra, Ane; Gondra, Nerea (1 September 2022). «Calculation and measurement of center of mass: An all-in-one activity using Tangram puzzles». American Journal of Physics. 90 (9): 652. Bibcode:2022AmJPh..90..652C. doi:10.1119/5.0061884. ISSN 0002-9505. S2CID 251917733.

- ^ Slocum (2001), p. 9.

- ^ Forbrush, William Byron (1914). Manual of Play. Jacobs. p. 315. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1910, s.v.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), p. 23.

- ^ Hill, Thomas (1848). Puzzles to teach geometry : in seventeen cards numbered from the first to the seventeenth inclusive. Boston : Wm. Crosby & H.P. Nichols.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 25.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 16.

- ^ Nie, Xuannan. «七巧板的前身(一)——燕几图 (The tangram’s origins, the Yanji Picture)». Zhihu. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ «七巧板是谁发明的? 七巧板是宋朝的黄伯思发明的 (Who invented the tangram? The tangram was invented by Huang Bosi)». Baidu Knowledge. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ Slocum (2003), pp. 16–19.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 30.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 31.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 49.

- ^ a b Slocum (2003), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Slocum (2003), p. 51.

- ^ a b «Tangram the incredible timeless ‘Chinese’ puzzle». www.archimedes-lab.org.

- ^ Treasury Decisions Under customs and other laws, Volume 25. United States Department Of The Treasury. 1890–1926. p. 1421. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ^ Wyatt (26 April 2006). «Tangram – The Chinese Puzzle». h2g2. BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Braman, Arlette (2002). Kids Around The World Play!. John Wiley and Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-471-40984-7. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ Tangram Paradox, by Barile, Margherita, From MathWorld – A Wolfram Web Resource, created by Eric W. Weisstein.

- ^ Dudeney, H. (1958). Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications.

- ^ a b The 8th Book of Tan by Sam Loyd. 1903 – via Tangram Channel.

- ^ «The Magic Dice Cup». 2 April 2011.

- ^ Loyd, Sam (1968). The eighth book of Tan – 700 Tangrams by Sam Loyd with an introduction and solutions by Peter Van Note. New York: Dover Publications. p. 25.

- ^ Slocum 2001, p. 37.

- ^

Fu Traing Wang; Chuan-Chih Hsiung (November 1942). «A Theorem on the Tangram». The American Mathematical Monthly. 49 (9): 596–599. doi:10.2307/2303340. JSTOR 2303340. - ^ Read, Ronald C. (1965). Tangrams : 330 Puzzles. New York: Dover Publications. p. 53. ISBN 0-486-21483-4.

- ^ Brooks, David J. (1 December 2018). «How to Make a Classic Tangram Puzzle». Boys’ Life magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Sources

- Slocum, Jerry (2001). The Tao of Tangram. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-4351-0156-2.

- Slocum, Jerry (2003). The Tangram Book. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-0413-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Anno, Mitsumasa. Anno’s Math Games (three volumes). New York: Philomel Books, 1987. ISBN 0-399-21151-9 (v. 1), ISBN 0-698-11672-0 (v. 2), ISBN 0-399-22274-X (v. 3).

- Botermans, Jack, et al. The World of Games: Their Origins and History, How to Play Them, and How to Make Them (translation of Wereld vol spelletjes). New York: Facts on File, 1989. ISBN 0-8160-2184-8.

- Dudeney, H. E. Amusements in Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications, 1958.

- Gardner, Martin. «Mathematical Games—on the Fanciful History and the Creative Challenges of the Puzzle Game of Tangrams», Scientific American Aug. 1974, p. 98–103.

- Gardner, Martin. «More on Tangrams», Scientific American Sep. 1974, p. 187–191.

- Gardner, Martin. The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961. ISBN 0-671-24559-7.

- Loyd, Sam. Sam Loyd’s Book of Tangram Puzzles (The 8th Book of Tan Part I). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1968.

- Slocum, Jerry, et al. Puzzles of Old and New: How to Make and Solve Them. De Meern, Netherlands: Plenary Publications International (Europe); Amsterdam, Netherlands: ADM International; Seattle: Distributed by University of Washington Press, 1986. ISBN 0-295-96350-6.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tangrams.

- Past & Future: The Roots of Tangram and Its Developments

- Turning Your Set of Tangram Into A Magic Math Puzzle by puzzle designer G. Sarcone

«танграм» — Фонетический и морфологический разбор слова, деление на слоги, подбор синонимов

Фонетический морфологический и лексический анализ слова «танграм». Объяснение правил грамматики.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «танграм» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «танграм».

Содержимое:

- 1 Как перенести слово «танграм»

- 2 Предложения со словом «танграм»

- 3 Как правильно пишется слово «танграм»

Как перенести слово «танграм»

та—нграм

тан—грам

танг—рам

Предложения со словом «танграм»

То это были бирюльки, «флирт цветов», то шахматы, шашки, танграм.

Светлана Еремеева, Дверь в будущее, 2020.

Как правильно пишется слово «танграм»

Правописание слова «танграм»

Орфография слова «танграм»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «танграм» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Звуко буквенный разбор слова: чем отличаются звуки и буквы?

Прежде чем перейти к выполнению фонетического разбора с примерами обращаем ваше внимание, что буквы и звуки в словах — это не всегда одно и тоже.

Буквы — это письмена, графические символы, с помощью которых передается содержание текста или конспектируется разговор. Буквы используются для визуальной передачи смысла, мы воспримем их глазами. Буквы можно прочесть. Когда вы читаете буквы вслух, то образуете звуки — слоги — слова.

Список всех букв — это просто алфавит

Почти каждый школьник знает сколько букв в русском алфавите. Правильно, всего их 33. Русскую азбуку называют кириллицей. Буквы алфавита располагаются в определенной последовательности:

Алфавит русского языка:

| Аа | «а» | Бб | «бэ» | Вв | «вэ» | Гг | «гэ» |

| Дд | «дэ» | Ее | «е» | Ёё | «йо» | Жж | «жэ» |

| Зз | «зэ» | Ии | «и» | Йй | «й» | Кк | «ка» |

| Лл | «эл» | Мм | «эм» | Нн | «эн» | Оо | «о» |

| Пп | «пэ» | Рр | «эр» | Сс | «эс» | Тт | «тэ» |

| Уу | «у» | Фф | «эф» | Хх | «ха» | Цц | «цэ» |

| Чч | «чэ» | Шш | «ша» | Щщ | «ща» | ъ | «т.з.» |

| Ыы | «ы» | ь | «м.з.» | Ээ | «э» | Юю | «йу» |

| Яя | «йа» |

Всего в русском алфавите используется:

- 21 буква для обозначения согласных;

- 10 букв — гласных;

- и две: ь (мягкий знак) и ъ (твёрдый знак), которые указывают на свойства, но сами по себе не определяют какие-либо звуковые единицы.

Звуки — это фрагменты голосовой речи. Вы можете их услышать и произнести. Между собой они разделяются на гласные и согласные. При фонетическом разборе слова вы анализируете именно их.

Звуки в фразах вы зачастую проговариваете не так, как записываете на письме. Кроме того, в слове может использоваться больше букв, чем звуков. К примеру, «детский» — буквы «Т» и «С» сливаются в одну фонему [ц]. И наоборот, количество звуков в слове «чернеют» большее, так как буква «Ю» в данном случае произносится как [йу].

Что такое фонетический разбор?

Звучащую речь мы воспринимаем на слух. Под фонетическим разбором слова имеется ввиду характеристика звукового состава. В школьной программе такой разбор чаще называют «звуко буквенный» анализ. Итак, при фонетическом разборе вы просто описываете свойства звуков, их характеристики в зависимости от окружения и слоговую структуру фразы, объединенной общим словесным ударением.

Фонетическая транскрипция

Для звуко-буквенного разбора применяют специальную транскрипцию в квадратных скобках. К примеру, правильно пишется:

- чёрный -> [ч’о́рный’]

- яблоко -> [йа́блака]

- якорь -> [йа́кар’]

- ёлка -> [йо́лка]

- солнце -> [со́нцэ]

В схеме фонетического разбора используются особые символы. Благодаря этому можно корректно обозначить и отличить буквенную запись (орфографию) и звуковое определение букв (фонемы).

- фонетически разбираемое слово заключается квадратные скобки – [ ];

- мягкий согласный обозначается знаком транскрипции [’] — апострофом;

- ударный [´] — ударением;

- в сложных словоформах из нескольких корней применяется знак второстепенного ударения [`] — гравис (в школьной программе не практикуется);

- буквы алфавита Ю, Я, Е, Ё, Ь и Ъ в транскрипции НИКОГДА не используются (в учебной программе);

- для удвоенных согласных применяется [:] — знак долготы произнесения звука.

Ниже приводятся подробные правила для орфоэпического, буквенного и фонетического и разбора слов с примерами онлайн, в соответствии с общешкольными нормами современного русского языка. У профессиональных лингвистов транскрипция фонетических характеристик отличается акцентами и другими символами с дополнительными акустическими признаками гласных и согласных фонем.

Как сделать фонетический разбор слова?

Провести буквенный анализ вам поможет следующая схема:

- Выпишите необходимое слово и произнесите его несколько раз вслух.

- Посчитайте сколько в нем гласных и согласных букв.

- Обозначьте ударный слог. (Ударение при помощи интенсивности (энергии) выделяет в речи определенную фонему из ряда однородных звуковых единиц.)

- Разделите фонетическое слово по слогам и укажите их общее количество. Помните, что слогораздел в отличается от правил переноса. Общее число слогов всегда совпадает с количеством гласных букв.

- В транскрипции разберите слово по звукам.

- Напишите буквы из фразы в столбик.

- Напротив каждой буквы квадратных скобках [ ] укажите ее звуковое определение (как она слышатся). Помните, что звуки в словах не всегда тождественны буквам. Буквы «ь» и «ъ» не представляют никаких звуков. Буквы «е», «ё», «ю», «я», «и» могут обозначать сразу 2 звука.

- Проанализируйте каждую фонему по отдельности и обозначьте ее свойства через запятую:

- для гласного указываем в характеристике: звук гласный; ударный или безударный;

- в характеристиках согласных указываем: звук согласный; твёрдый или мягкий, звонкий или глухой, сонорный, парный/непарный по твердости-мягкости и звонкости-глухости.

- В конце фонетического разбора слова подведите черту и посчитайте общее количество букв и звуков.

Данная схема практикуется в школьной программе.

Пример фонетического разбора слова

Вот образец фонетического разбора по составу для слова «явление» → [йивл’э′н’ийэ]. В данном примере 4 гласных буквы и 3 согласных. Здесь всего 4 слога: я-вле′-ни-е. Ударение падает на второй.

Звуковая характеристика букв:

я [й] — согл., непарный мягкий, непарный звонкий, сонорный [и] — гласн., безударныйв [в] — согл., парный твердый, парный зв.л [л’] — согл., парный мягк., непарн. зв., сонорныйе [э′] — гласн., ударныйн [н’] — согласн., парный мягк., непарн. зв., сонорный и [и] — гласн., безударный [й] — согл., непарн. мягк., непарн. зв., сонорный [э] — гласн., безударный________________________Всего в слове явление – 7 букв, 9 звуков. Первая буква «Я» и последняя «Е» обозначают по два звука.

Теперь вы знаете как сделать звуко-буквенный анализ самостоятельно. Далее даётся классификация звуковых единиц русского языка, их взаимосвязи и правила транскрипции при звукобуквенном разборе.

Фонетика и звуки в русском языке

Какие бывают звуки?

Все звуковые единицы делятся на гласные и согласные. Гласные звуки, в свою очередь, бывают ударными и безударными. Согласный звук в русских словах бывает: твердым — мягким, звонким — глухим, шипящим, сонорным.

— Сколько в русской живой речи звуков?

Правильный ответ 42.

Делая фонетический разбор онлайн, вы обнаружите, что в словообразовании участвуют 36 согласных звуков и 6 гласных. У многих возникает резонный вопрос, почему существует такая странная несогласованность? Почему разнится общее число звуков и букв как по гласным, так и по согласным?

Всё это легко объяснимо. Ряд букв при участии в словообразовании могут обозначать сразу 2 звука. Например, пары по мягкости-твердости:

- [б] — бодрый и [б’] — белка;

- или [д]-[д’]: домашний — делать.

А некоторые не обладают парой, к примеру [ч’] всегда будет мягким. Сомневаетесь, попытайтесь сказать его твёрдо и убедитесь в невозможности этого: ручей, пачка, ложечка, чёрным, Чегевара, мальчик, крольчонок, черемуха, пчёлы. Благодаря такому практичному решению наш алфавит не достиг безразмерных масштабов, а звуко-единицы оптимально дополняются, сливаясь друг с другом.

Гласные звуки в словах русского языка

Гласные звуки в отличии от согласных мелодичные, они свободно как бы нараспев вытекают из гортани, без преград и напряжения связок. Чем громче вы пытаетесь произнести гласный, тем шире вам придется раскрыть рот. И наоборот, чем громче вы стремитесь выговорить согласный, тем энергичнее будете смыкать ротовую полость. Это самое яркое артикуляционное различие между этими классами фонем.

Ударение в любых словоформах может падать только на гласный звук, но также существуют и безударные гласные.

— Сколько гласных звуков в русской фонетике?

В русской речи используется меньше гласных фонем, чем букв. Ударных звуков всего шесть: [а], [и], [о], [э], [у], [ы]. А букв, напомним, десять: а, е, ё, и, о, у, ы, э, я, ю. Гласные буквы Е, Ё, Ю, Я не являются «чистыми» звуками и в транскрипции не используются. Нередко при буквенном разборе слов на перечисленные буквы падает ударение.

Фонетика: характеристика ударных гласных

Главная фонематическая особенность русской речи — четкое произнесение гласных фонем в ударных слогах. Ударные слоги в русской фонетике отличаются силой выдоха, увеличенной продолжительностью звучания и произносятся неискаженно. Поскольку они произносятся отчетливо и выразительно, звуковой анализ слогов с ударными гласными фонемами проводить значительно проще. Положение, в котором звук не подвергается изменениям и сохранят основной вид, называется сильной позицией. Такую позицию может занимать только ударный звук и слог. Безударные же фонемы и слоги пребывают в слабой позиции.

- Гласный в ударном слоге всегда находится в сильной позиции, то есть произносится более отчётливо, с наибольшей силой и продолжительностью.

- Гласный в безударном положении находится в слабой позиции, то есть произносится с меньшей силой и не столь отчётливо.

В русском языке неизменяемые фонетические свойства сохраняет лишь одна фонема «У»: кукуруза, дощечку, учусь, улов, — во всех положениях она произносятся отчётливо как [у]. Это означает, что гласная «У» не подвергается качественной редукции. Внимание: на письме фонема [у] может обозначатся и другой буквой «Ю»: мюсли [м’у´сл’и], ключ [кл’у´ч’] и тд.

Разбор по звукам ударных гласных

Гласная фонема [о] встречается только в сильной позиции (под ударением). В таких случаях «О» не подвергается редукции: котик [ко´т’ик], колокольчик [калако´л’ч’ык], молоко [малако´], восемь [во´с’им’], поисковая [паиско´вайа], говор [го´вар], осень [о´с’ин’].

Исключение из правила сильной позиции для «О», когда безударная [о] произносится тоже отчётливо, представляют лишь некоторые иноязычные слова: какао [кака’о], патио [па’тио], радио [ра’дио], боа [боа’] и ряд служебных единиц, к примеру, союз но.

Звук [о] в письменности можно отразить другой буквой«ё» – [о]: тёрн [т’о´рн], костёр [кас’т’о´р]. Выполнить разбор по звукам оставшихся четырёх гласных в позиции под ударением так же не представит сложностей.

Безударные гласные буквы и звуки в словах русского языка

Сделать правильный звуко разбор и точно определить характеристику гласного можно лишь после постановки ударения в слове. Не забывайте так же о существовании в нашем языке омонимии: за’мок — замо’к и об изменении фонетических качеств в зависимости от контекста (падеж, число):

- Я дома [йа до‘ма].

- Новые дома [но’выэ дама’].

В безударном положении гласный видоизменяется, то есть, произносится иначе, чем записывается:

- горы — гора = [го‘ры] — [гара’];

- он — онлайн = [о‘н] — [анла’йн]

- свидетельница = [св’ид’э‘т’ил’н’ица].

Подобные изменения гласных в безударных слогах называются редукцией. Количественной, когда изменяется длительность звучания. И качественной редукцией, когда меняется характеристика изначального звука.

Одна и та же безударная гласная буква может менять фонетическую характеристику в зависимости от положения:

- в первую очередь относительно ударного слога;

- в абсолютном начале или конце слова;

- в неприкрытых слогах (состоят только из одного гласного);

- од влиянием соседних знаков (ь, ъ) и согласного.

Так, различается 1-ая степень редукции. Ей подвергаются:

- гласные в первом предударном слоге;

- неприкрытый слог в самом начале;

- повторяющиеся гласные.

Примечание: Чтобы сделать звукобуквенный анализ первый предударный слог определяют исходя не с «головы» фонетического слова, а по отношению к ударному слогу: первый слева от него. Он в принципе может быть единственным предударным: не-зде-шний [н’из’д’э´шн’ий].

(неприкрытый слог)+(2-3 предударный слог)+ 1-й предударный слог ← Ударный слог → заударный слог (+2/3 заударный слог)

- впе-ре-ди [фп’ир’ид’и´];

- е-сте-стве-нно [йис’т’э´с’т’в’ин:а];

Любые другие предударные слоги и все заударные слоги при звуко разборе относятся к редукции 2-й степени. Ее так же называют «слабая позиция второй степени».

- поцеловать [па-цы-ла-ва´т’];

- моделировать [ма-ды-л’и´-ра-ват’];

- ласточка [ла´-ста-ч’ка];

- керосиновый [к’и-ра-с’и´-на-вый].

Редукция гласных в слабой позиции так же различается по ступеням: вторая, третья (после твердых и мягких соглас., — это за пределами учебной программы): учиться [уч’и´ц:а], оцепенеть [ацып’ин’э´т’], надежда [над’э´жда]. При буквенном анализе совсем незначительно проявятся редукция у гласного в слабой позиции в конечном открытом слоге (= в абсолютном конце слова):

- чашечка;

- богиня;

- с песнями;

- перемена.

Звуко буквенный разбор: йотированные звуки

Фонетически буквы Е — [йэ], Ё — [йо], Ю — [йу], Я — [йа] зачастую обозначают сразу два звука. Вы заметили, что во всех обозначенных случаях дополнительной фонемой выступает «Й»? Именно поэтому данные гласные называют йотированными. Значение букв Е, Ё, Ю, Я определяется их позиционным положением.