Иногда при произношении названия столицы Монголии возникает сомнение, куда ставится ударение. Попробуем разобраться, как правильно говорить «Улан-Батор».

Как поставить ударение в слове: «Улан-Батор»?

В соответствии с орфоэпическими требованиями единственным вариантом произношения, который считается правильным, считается «Ула́н-Ба́тор», где ставится ударение в каждой части слова.

Какое регулирует правило

Перед нами имя существительное, собственное. Оно обозначает название столицы Монголии. Это сложное слово, образованное путем слияния отдельных простых слов. Каждое из простых слов имеет свое ударение. В родном языке Ulaanbaatar произносится с двойным ударением. Согласно русской орфоэпии при заимствовании сохраняется произношение языка-оригинала.

Как запомнить ударение

Едет нова́тор

В Ула́н-Ба́тор.

Примеры предложений

В отпуск мы едем в Ула́н-Ба́тор к родственникам бабушки.

Ула́н-Ба́тор – красочный и зеленый город, столица Монголии.

Неправильное ударение

Неправильными вариантами произношения считаются «У́лан-Бато́р», «Ула́н-«Бато́р», где в первом слове ударение приходится на первый слог, а во втором – на второй слог.

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — Улан-Батор

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — СТЕПЕНЕЙ?

Слово состоит из букв:

У,

Л,

А,

Н,

-,

Б,

А,

Т,

О,

Р,

Похожие слова:

улан-баторский

Рифма к слову Улан-Батор

оратор, импэратор, оператор, император, губернатор, сенатор, администратор, ритор, простор, ефрейтор, аудитор, берейтор, доктор, архитектор, форейтор, договор, собор, подбор, говор, напор, купор, коридор, колидор, упор, перебор, заговор, сговор, азор, майор, раздор, укор, тенор, вздор, гор, позор, топор, вор, сбор, свор, набор, узор, профессор, пор, рессор, выговор, двор, спор, разговор, бугор, выбор, приговор, шпор, дюпор, федор, уговор, обзор, кор, отпор, капор, прибор, забор, хведор

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

|

Ulaanbaatar Улаанбаатар |

|

|---|---|

|

Municipality |

|

|

Clockwise from top: City center with Sükhbaatar Square in the background, Choijin Lama Temple, Ugsarmal panel buildings built in the socialist era, Naadam ceremony at the National Sports Stadium, National University of Mongolia, Ger districts, Gandantegchinlen Monastery |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Nickname(s):

УБ (UB), Нийслэл (capital), Хот (city) |

|

|

|

|

Ulaanbaatar Location of Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia Ulaanbaatar Ulaanbaatar (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 47°55′13″N 106°55′02″E / 47.92028°N 106.91722°ECoordinates: 47°55′13″N 106°55′02″E / 47.92028°N 106.91722°E | |

| Country | |

| Monastic center established | 1639 |

| Current location | 1778 |

| Named Ulaanbaatar | 1924 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager |

| • Body | Citizens’ Representatives Khural of the Capital City |

| • Governor of the Capital City and Mayor of Ulaanbaatar | Dolgorsürengiin Sumyaabazar (MPP)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,704.4 km2 (1,816.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,350 m (4,429 ft) |

| Population

(2021) |

|

| • Total | 1,612,005[1] |

| • Density | 311/km2 (807/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (H) |

| Postal code |

210 xxx |

| Area code | +976 (0)11 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.810[3] – very high · 1st |

| License plate | УБ, УН |

| ISO 3166-2 | MN-1 |

| Climate | BSk |

| Website | www.ulaanbaatar.mn |

Ulaanbaatar (; Mongolian: Улаанбаатар, pronounced [ʊˌɮaːm‿ˈpaːʰtə̆r] (listen), lit. «Red Hero»), previously anglicized as Ulan Bator, is the capital and most populous city of Mongolia. It is the coldest capital city in the world, on average.[4] The municipality is located in north central Mongolia at an elevation of about 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) in a valley on the Tuul River. The city was originally founded in 1639 as a nomadic Buddhist monastic center, changing location 28 times, and was permanently settled at its current location in 1778.

During its early years, as Örgöö (anglicized as Urga), it became Mongolia’s preeminent religious center and seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, the spiritual head of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. Following the regulation of Qing-Russian trade by the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727, a caravan route between Beijing and Kyakhta opened up, along which the city was eventually settled. With the collapse of the Qing Empire in 1911, the city was a focal point for independence efforts, leading to the proclamation of the Bogd Khanate in 1911 led by the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, or Bogd Khan, and again during the communist revolution of 1921. With the proclamation of the Mongolian People’s Republic in 1924, the city was officially renamed Ulaanbaatar and declared the country’s capital. Modern urban planning began in the 1950s, with most of the old Ger districts replaced by Soviet-style flats. In 1990, Ulaanbaatar was a major site of demonstrations that led to Mongolia’s transition to democracy and a market economy. Since 1990, an influx of migrants from the rest of the country has led to an explosive growth in its population, a major portion of whom live in Ger districts, which has led to harmful air pollution in winter.

Governed as an independent municipality, Ulaanbaatar is surrounded by Töv Province, whose capital Zuunmod lies 43 kilometres (27 mi) south of the city. With a population of just over 1.5 million as of December 2022, it contains almost half of the country’s total population.[5] As the country’s primate city, it serves as the cultural, industrial and financial heart as well as the center of Mongolia’s transport network, connected by rail to both the Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia and the Chinese railway system.[6]

Names and etymology[edit]

The city at its establishment in 1639 was referred to as Örgöö (Mongolian: ᠥᠷᠭᠦᠭᠡ; Өргөө, lit. ‘Palace’). This name was eventually adapted as Urga[7] in the West. By 1651, it began to be referred to as Nomiĭn Khüree (Mongolian: ᠨᠣᠮ ᠤᠨ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Номын хүрээ, lit. ‘Khüree of Wisdom’), and by 1706 it was referred to as Ikh Khüree (Mongolian: ᠶᠡᠬᠡ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Их хүрээ, lit. ‘Great Khüree’). The Chinese equivalent, Dà Kùlún (Chinese: 大庫倫, Mongolian: Да Хүрээ), was rendered into Western languages as Kulun or Kuren.

Other names include Bogdiin Khuree (Mongolian: ᠪᠣᠭᠳᠠ ᠶᠢᠨ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Богдын хүрээ, lit. ‘The Bogd’s Khüree’), or simply Khüree (Mongolian: ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Хүрээ, romanized: Küriye), itself a term originally referring to an enclosure or settlement.

Upon independence in 1911, with both the secular government and the Bogd Khan’s palace present, the city’s name was changed to Niĭslel Khüree (Mongolian: ᠨᠡᠶᠢᠰᠯᠡᠯ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Нийслэл Хүрээ, lit. ‘Capital Khüree’).

When the city became the capital of the new Mongolian People’s Republic in 1924, its name was changed to Ulaanbaatar (lit. ‘Red Hero’).

In the Western world, Ulaanbaatar continued to be generally known as Urga or Khuree until 1924, and afterward as Ulan Bator (a spelling derived from the Russian Улан-Батор). This form was defined two decades before the Mongolian name got its current Cyrillic spelling and transliteration (1941–1950); however, the name of the city was spelled Ulaanbaatar koto during the decade in which Mongolia used the Latin alphabet.

Today, the city is referred to simply as khot (Mongolian: хот, lit. ‘city’), as well as UB (you-be), from the English transliteration.

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

Human habitation at the site of Ulaanbaatar dates from the Lower Paleolithic, with a number of sites on the Bogd Khan, Buyant-Ukhaa and Songinokhairkhan mountains, revealing tools which date from 300,000 years ago to 40,000–12,000 years ago. These Upper Paleolithic people hunted mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, the bones of which are found abundantly around Ulaanbaatar.[citation needed]

Before 1639[edit]

Remains of Wang Khan’s 12th-century palace in Ulaanbaatar

A number of Xiongnu-era royal tombs have been discovered around Ulaanbaatar, including the tombs of Belkh Gorge near Dambadarjaalin monastery and tombs of Songinokhairkhan. Located on the banks of the Tuul River, Ulaanbaatar has been well within the sphere of Turco-Mongol nomadic empires throughout history.

Wang Khan, Toghrul of the Keraites, a Nestorian Christian monarch whom Marco Polo identified as the legendary Prester John, is said to have had his palace here (the Black Forest of the Tuul River) and forbade hunting in the holy mountain Bogd Uul. The palace is said to be where Genghis Khan stayed with Yesui Khatun before attacking the Tangut in 1226.[citation needed]

During the Mongol Empire (1206-1368) and Northern Yuan Dynasty (1368-1635) the main, natural route from the capital region of Karakorum to the birthplace and tomb of the Khans in the Khentii mountain region (Ikh Khorig) passed through the area of Ulaanbaatar. The Tuul River naturally leads to the north-side of Bogd Khan Mountain, which stands out as a large island of forest positioned conspicuously at the south-western edge of the Khentii mountains. As the main gate and stopover point on the route to and from the holy Khentii mountains, the Bogd Khan Mountain saw large amounts of traffic going past it and was protected from early times. Even after the Northern Yuan period it served as the location of the annual and triannual Assembly of Nobles (Khan Uuliin Chuulgan).

Mobile monastery[edit]

Founded in 1639 as a yurt monastery, Ulaanbaatar, originally Örgöö (palace-yurt), was first located at Lake Shireet Tsagaan nuur (75 kilometres (47 miles) directly east of the imperial capital Karakorum) in what is now Burd sum, Övörkhangai, around 230 kilometres (143 miles) south-west from the present site of Ulaanbaatar, and was intended by the Mongol nobles to be the seat of Zanabazar, the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu. Zanabazar returned to Mongolia from Tibet in 1651, and founded seven aimags (monastic departments) in Urga, later establishing four more.[8]

As a mobile monastery-town, Örgöö was often moved to various places along the Selenge, Orkhon and Tuul rivers, as supply and other needs would demand. During the Dzungar wars of the late 17th century, it was even moved to Inner Mongolia.[9] As the city grew, it moved less and less.[10]

The movements of the city can be detailed as follows: Shireet Tsagaan Nuur (1639), Khoshoo Tsaidam (1640), Khentii Mountains (1654), Ogoomor (1688), Inner Mongolia (1690), Tsetserlegiin Erdene Tolgoi (1700), Daagandel (1719), Usan Seer (1720), Ikh Tamir (1722), Jargalant (1723), Eeven Gol (1724), Khujirtbulan (1729), Burgaltai (1730), Sognogor (1732), Terelj (1733), Uliastai River (1734), Khui Mandal (1736), Khuntsal (1740), Udleg (1742), Ogoomor (1743), Selbe (1747), Uliastai River (1756), Selbe (1762), Khui Mandal (1772) and Selbe (1778).[citation needed]

In 1778, the city moved from Khui Mandal and settled for good at its current location, near the confluence of the Selbe and Tuul rivers, and beneath Bogd Khan Uul, at that time also on the caravan route from Beijing to Kyakhta.[11]

One of the earliest Western mentions of Urga is the account of the Scottish traveller John Bell in 1721:

What they call the Urga is the court, or the place where the prince (Tusheet Khan) and high priest (Bogd Jebtsundamba Khutugtu) reside, who are always encamped at no great distance from one another. They have several thousand tents about them, which are removed from time to time. The Urga is much frequented by merchants from China and Russia, and other places.[12]

By Zanabazar’s death in 1723, Urga was Mongolia’s preeminent monastery in terms of religious authority. A council of seven of the highest-ranking lamas (Khamba Nomon Khan, Ded Khamba and five Tsorj) made most of the city’s religious decisions. It had also become Outer Mongolia’s commercial center. From 1733 to 1778, Urga moved around the vicinity of its present location. In 1754, the Erdene Shanzodba Yam ^ of Urga was given authority to supervise the administrative affairs of the Bogd’s subjects. It also served as the city’s chief judicial court. In 1758, the Qianlong Emperor appointed the Khalkha Vice General Sanzaidorj as the first Mongol amban of Urga, with full authority to «oversee the Khuree and administer well all the Khutugtu’s subjects».[13]

In 1761, a second amban was appointed for the same purpose, a Manchu one. A quarter-century later, in 1786, a decree issued in Peking gave right to the Urga ambans to decide the administrative affairs of Tusheet Khan and Setsen Khan territories. With this, Urga became the highest civil authority in the country. Based on Urga’s Mongol governor Sanzaidorj’s petition, the Qianlong Emperor officially recognized an annual ceremony on Bogd Khan Mountain in 1778 and provided the annual imperial donations. The city was the seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtus, two Qing ambans, and a Chinese trade town grew «four trees» 4.24 km (2.63 mi) east of the city center at the confluence of the Uliastai and Tuul rivers.[citation needed]

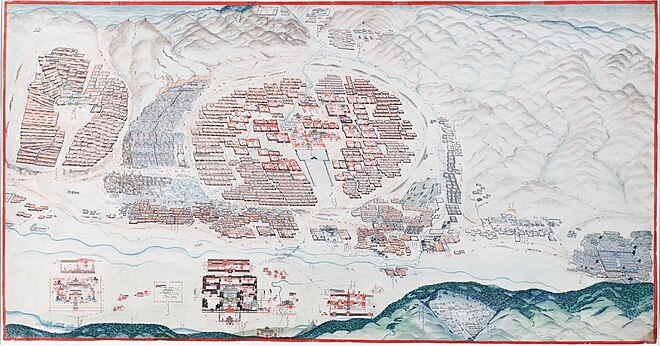

Detail of 19th-century painting of Urga (Ulaanbaatar): in the center the movable square temple of Bat Tsagaan, built in 1654, besides numerous other temples

By 1778, Urga may have had as many as ten thousand monks, who were regulated by a monastic rule, Internal Rule of the Grand Monastery or Yeke Kuriyen-u Doto’adu Durem. For example, in 1797 a decree of the 4th Jebtsundamba forbade «singing, playing with archery, myagman, chess, usury and smoking»). Executions were forbidden where the holy temples of the Bogd Jebtsundama could be seen, so capital punishment took place away from the city.[citation needed]

In 1839, the 5th Bogd Jebtsundamba moved his residence to Gandan Hill, an elevated position to the west of the Baruun Damnuurchin markets. Part of the city was moved to nearby Tolgoit. In 1855, the part of the camp that moved to Tolgoit was brought back to its 1778 location, and the 7th Bogd Jebtsundamba returned to the Zuun Khuree. The Gandan Monastery flourished as a center of philosophical studies.[citation needed]

The Russian Consulate of Urga (Ulaanbaatar) and the Holy Trinity Church, both built in 1863

Urga and the Kyakhta trade[edit]

Following the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727, Urga (Ulaanbaatar) was a major point of the Kyakhta trade between Russia and China – mostly Siberian furs for Chinese cloth and later tea. The route ran south to Urga, southeast across the Gobi Desert to Kalgan, and southeast over the mountains to Peking. Urga was also a collection point for goods coming from further west. These were either sent to China or shipped north to Russia via Kyakhta, because of legal restrictions and the lack of good trade routes to the west.[citation needed]

By 1908,[14] there was a Russian quarter with a few hundred merchants and a Russian club and informal Russian mayor. East of the main town was the Russian consulate, built in 1863, with an Orthodox church, a post office and 20 Cossack guards. It was fortified in 1900 and briefly occupied by troops during the Boxer Rebellion. There was a telegraph line north to Kyakhta and southeast to Kalgan and weekly postal service along these routes.[citation needed]

Beyond the Russian consulate was the Chinese trading post called Maimaicheng, and nearby the palace of the Manchu viceroy. With the growth of Western trade at the Chinese ports, the tea trade to Russia declined, some Chinese merchants left, and wool became the main export. Manufactured goods still came from Russia, but most were now brought from Kalgan by caravan. The annual trade was estimated at 25 million rubles, nine-tenths in Chinese hands and one-tenth in Russian.[citation needed]

Engraving of N.A.Charushin’s panorama photo of the old center of Urga from trip (1888) with Potanin

A 1913 panorama of Urga. The large circular compound in the middle is the Zuun Khuree temple-palace complex. The Gandan temple complex is to the left. The palaces of the Bogd are to the south of the river. To the far bottom right of the painting is the Maimaicheng district. To its left are the white buildings of the Russian consulate area. Manjusri Monastery can be seen on Mount Bogd Khan Uul at the bottom-right of the painting

The Moscow trade expedition of the 1910s estimated the population of Urga at 60,000, based on Nikolay Przhevalsky’s study in the 1870s.[15]

The city’s population swelled during the Naadam festival and major religious festivals to more than 100,000. In 1919, the number of monks had reached 20,000, up from 13,000 in 1810.[15]

Independence and Niislel Khüree[edit]

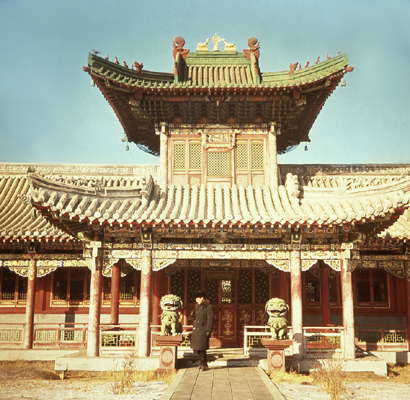

1913 color photo of Gandan Monastery

In 1910, the amban Sando went to quell a major fight between Gandan lamas and Chinese traders started by an incident at the Da Yi Yu shop in the Baruun Damnuurchin market district. He was unable to bring the lamas under control, and was forced to flee back to his quarters. In 1911, with the Qing Dynasty in China headed for total collapse, Mongolian leaders in Ikh Khüree for Naadam met in secret on Mount Bogd Khan Uul and resolved to end 220 years of Manchu control of their country.[citation needed]

On 29 December 1911, the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutughtu was declared ruler of an independent Mongolia and assumed the title Bogd Khan.[10] Khüree as the seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu was the logical choice for the capital of the new state. However, following the tripartite Kyakhta agreement of 1915, Mongolia’s status was effectively reduced to mere autonomy.

In 1919, Mongolian nobles, over the opposition of the Bogd Khan, agreed with the Chinese resident Chen Yi on a settlement of the «Mongolian question» along Qing-era lines, but before this settlement could be put into effect, Khüree was occupied by the troops of Chinese warlord Xu Shuzheng, who forced the Mongolian nobles and clergy to renounce autonomy completely.[citation needed]

The city changed hands twice in 1921. First, on 4 February, a mixed Russian/Mongolian force led by White Russian warlord Roman von Ungern-Sternberg captured the city, freeing the Bogd Khan from Chinese imprisonment and killing a part of the Chinese garrison. Baron Ungern’s capture of Urga was followed by the clearing out of Mongolia’s small gangs of demoralized Chinese soldiers and, at the same time, looting and murder of foreigners, including a vicious pogrom that killed off the Jewish community.[16][17][18]

On 22 February 1921, the Bogd Khan was once again elevated to Great Khan of Mongolia in Urga.[19] However, at the same time that Baron Ungern was taking control of Urga, a Soviet-supported Communist Mongolian force led by Damdin Sükhbaatar was forming in Russia, and in March they crossed the border. Ungern and his men rode out in May to meet Red Russian and Red Mongolian troops, but suffered a disastrous defeat in June.[20]

In July 1921, the Communist Soviet-Mongolian army became the second conquering force in six months to enter Urga, and Mongolia came under the control of Soviet Russia. On 29 October 1924, the town was renamed Ulaanbaatar. On the session of the 1st Great People’s Khuraldaan of Mongolia in 1924, a majority of delegates had expressed their wish to change the capital city’s name to Baatar Khot («Hero City»). However, under pressure from Turar Ryskulov, a Soviet activist of the Communist International, the city was named Ulaanbaatar Khot («City of Red Hero»).[21]

[edit]

Green areas were increased in the city center during the communist era.

Outdoor market near Gandan hill in 1972; State Department Store in the background

During the socialist period, especially following the Second World War, most of the old ger districts were replaced by Soviet-style blocks of flats, often financed by the Soviet Union. Urban planning began in the 1950s, and most of the city today is a result of construction between 1960 and 1985.[22]

The Trans-Mongolian Railway, connecting Ulaanbaatar with Moscow and Beijing, was completed in 1956, and cinemas, theaters, museums and other modern facilities were erected. Most of the temples and monasteries of pre-socialist Khüree were destroyed following the anti-religious purges of the late 1930s. The Gandan monastery was reopened in 1944 when the U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace asked to see a monastery during his visit to Mongolia.[citation needed]

Democratic protests of 1989–1990[edit]

Ulaanbaatar was a major site of demonstrations that led to Mongolia’s transition to democracy and market economy in 1990. On 10 December 1989, protesters outside the Youth Culture Center called for Mongolia to implement perestroika and glasnost in their full sense. Dissident leaders demanded free elections and economic reform. On 14 January 1990, the protesters, having grown from two hundred to over a thousand, met at the Lenin Museum in Ulaanbaatar. A demonstration in Sükhbaatar Square on 21 January followed. Afterwards, weekend demonstrations were held in January and February, accompanied by the forming of Mongolia’s first opposition parties.[citation needed]

On 7 March, ten dissidents assembled in Sükhbaatar Square and went on a hunger strike. Thousands of supporters joined them. More arrived the following day and the crowd grew more unruly. 71 people were injured, one fatally. On 9 March, the Communist Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP) government resigned. The provisional government announced Mongolia’s first free elections, which were held in July. The MPRP won the election and resumed power.[23]

Since 1990[edit]

Since Mongolia’s transition to a market economy in 1990, the city has experienced further growth—especially in the ger districts, as construction of new blocks of flats had basically slowed to a halt in the 1990s. The population has more than doubled to over one million inhabitants. The rapid growth has caused a number of social, environmental and transportation problems. In recent years, construction of new buildings has gained new momentum, especially in the city center, and apartment prices have skyrocketed.[citation needed]

In 2008, Ulaanbaatar was the scene of riots after the Mongolian Democratic, Civic Will Party and Republican parties disputed the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party’s victory in the parliamentary elections. A four-day state of emergency was declared, the capital was placed under a 22:00-to-08:00 curfew, and alcohol sales banned;[24] following these measures, rioting did not resume.[25] This was the first deadly riot in modern Ulaanbaatar’s history.

In April 2013, Ulaanbaatar hosted the 7th Ministerial Conference of the Community of Democracies, and has also lent its name to the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security.

Demolition of historic buildings[edit]

In October 2019, one of the oldest structures in Ulaanbaatar, the wooden building that housed the Victims of Political Persecution Memorial Museum, was demolished.[26] The 2019 Mongolian government budget furthermore included items for the demolition of a number of historic neoclassical buildings in the heart of Ulaanbaatar, including the Natural History Museum, Opera and Ballet House, Drama Theatre and Central Library.[27] The decision was met by a public outcry and criticism from the Union of Mongolian Architects, which demanded that the buildings be preserved and restored.[28] Despite daily sit-ins by protesters, the Natural History Museum was duly demolished. In January 2020, culture minister Yondonperenlein Baatarbileg denied that the government intended to demolish the other buildings and stated that the government planned to renovate them instead.[29]

Geography[edit]

The private sector with yurts against the backdrop of high-rise new buildings in Ulaanbaatar.

Ulaanbaatar is located at about 1,350 metres (4,430 ft) above mean sea level, slightly east of the center of Mongolia, on the Tuul River, a sub-tributary of the Selenge, in a valley at the foot of the mountain Bogd Khan Uul. Bogd Khan Uul is a broad, heavily forested mountain rising 2,250 metres (7,380 ft) to the south of Ulaanbaatar. It forms the boundary between the steppe zone to the south and the forest-steppe zone to the north.

The forests of the mountains surrounding Ulaanbaatar are composed of evergreen pines, deciduous larches and birches, while the riverine forest of the Tuul River is composed of broad-leaved, deciduous poplars, elms and willows. Ulaanbaatar lies at roughly the same latitude as Vienna, Munich, Orléans and Seattle. It lies at roughly the same longitude as Chongqing, Hanoi and Jakarta.[citation needed]

Climate[edit]

Owing to its high elevation, its relatively high latitude, its location hundreds of kilometres from any coast, and the effects of the Siberian anticyclone, Ulaanbaatar is the coldest national capital in the world,[30] with a monsoon-influenced, cold semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk, USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 3b[31]). Aside from precipitation and from a thermal standpoint, the city is on the boundary between humid continental (Dwb) and subarctic (Dwc). This is due to its 10 °C (50 °F) mean temperature for the month of May.

The city features brief, warm summers and long, bitterly cold and dry winters. The coldest January temperatures, usually at the time just before sunrise, are between −36 and −40 °C (−32.8 and −40.0 °F) with no wind, due to temperature inversion. Most of the annual precipitation of 267 millimetres (10.51 in) falls from May to September. The highest recorded annual precipitation in the city was 659 millimetres or 25.94 inches at the Khureltogoot Astronomical Observatory on Mount Bogd Khan Uul. Ulaanbaatar has an average annual temperature of −0.4 °C or 31.3 °F,[32] making it the coldest capital in the world (almost as cold as Nuuk, Greenland, but Greenland is not independent). Nuuk has a tundra climate with consistent cold temperatures throughout the year. Ulaanbaatar’s annual average is brought down by its cold winter temperatures even though it is significantly warm from late April to early October.

The city lies in the zone of discontinuous permafrost, which means that building is difficult in sheltered locations that preclude thawing in the summer, but easier on more exposed ones where soils fully thaw. Suburban residents live in traditional yurts that do not protrude into the soil.[33] Extreme temperatures in the city range from −42.2 °C (−44.0 °F) in January and February 1957 to 39.0 °C (102.2 °F) in July 1988.[34]

| Climate data for Ulaanbaatar city weather station (WMO identifier: 44292) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

38.3 (100.9) |

39.0 (102.2) |

34.9 (94.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −21.6 (−6.9) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −25.9 (−14.6) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−15.7 (3.7) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −42.2 (−44.0) |

−42.2 (−44.0) |

−38.9 (−38.0) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−37.0 (−34.6) |

−37.8 (−36.0) |

−42.2 (−44.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 2 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

4 (0.2) |

10 (0.4) |

21 (0.8) |

46 (1.8) |

64 (2.5) |

70 (2.8) |

27 (1.1) |

10 (0.4) |

6 (0.2) |

4 (0.2) |

267 (10.5) |

| Average rainy days | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 2 | 7 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 63 |

| Average snowy days | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 59 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 73 | 61 | 48 | 46 | 54 | 60 | 63 | 59 | 60 | 71 | 78 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.1 | 204.8 | 265.2 | 262.5 | 299.3 | 269.0 | 249.3 | 258.3 | 245.7 | 227.5 | 177.4 | 156.4 | 2,794.5 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[34] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[35] |

| Climate data for Buyant-Ukhaa International Airport weather station (WMO identifier: 44291) (between 1985-2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −26 (−15) |

−22 (−8) |

−15 (5) |

−9 (16) |

−3 (27) |

5 (41) |

10 (50) |

8 (46) |

0 (32) |

−7 (19) |

−16 (3) |

−24 (−11) |

−8 (17) |

| Source: Time and Date[36] |

Administration and subdivisions[edit]

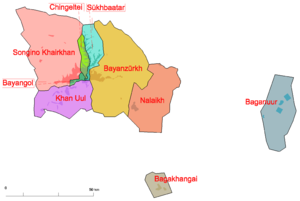

Map of the districts of Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar is divided into nine districts (Mongolian: дүүрэг, romanized: Düüreg): Baganuur, Bagakhangai, Bayangol, Bayanzürkh, Chingeltei, Khan Uul, Nalaikh, Songino Khairkhan and Sükhbaatar. Each district is subdivided into khoroos, of which there are 173. Each district also serves as a constituency that elects one or more representatives into the State Great Khural, the national parliament.

Although administratively part of Ulaanbaatar, Nalaikh and Baganuur are separate cities. Bagakhangai and Baganuur are noncontiguous exclaves, the former located within the Töv Province, the latter on the border between Töv and Khentii provinces.

The capital is governed by a Citizens’ Representatives Khural of the Capital city (city council) with 45 members, elected every four years. The Prime Minister of Mongolia appoints the Governor of the Capital city and Mayor of Ulaanbaatar with four-year terms upon the city council’s nomination. When his predecessor Sainbuyangiin Amarsaikhan became member of State Great Khural in July 2020, First Deputy Governor of the capital city Jantsangiin Batbayasgalan was elected as acting Governor of the Capital city and Mayor of Ulaanbaatar. Ulaanbaatar is governed as an independent first-level region, separate from the surrounding Töv Aimag.

Economy[edit]

The largest corporations and conglomerates of Mongolia are almost all headquartered in Ulaanbaatar. In 2017 Ulaanbaatar had five billionaires and 90 multimillionaires with net worth above 10 million dollars.[37][38] Major Mongolian companies include MCS Group, Gatsuurt LLC, Genco, MAK, Altai Trading, Tavan Bogd Group, Mobicom Corporation, Bodi, Shunkhlai, Monnis and Petrovis. While not on the level of multinational corporations, most of these companies are multi-sector conglomerates with far-reaching influence in the country.

Ulaanbaatar (Urga) has been a key location where the economic history and wealth creation of the nation has played out. Unlike the highly mobile dwellings of herders nomadizing between winter and summer pastures, Urga was set up to be a semi-permanent residence of the high lama Zanabazar.[citation needed] It stood in one location (Khoshoo Tsaidam) from 1640 to 1654, an unusually long period of 15 years, before Zanabazar moved it east to the foot of Mount Saridag in the Khentii Mountains. Here he set about building a permanent monastery town with stone buildings. Urga stayed at Mount Saridag for a full 35 years and was indeed assumed to be permanent there when Oirats suddenly invaded the region in 1688 and burnt down the city. With a major part of his life’s work destroyed, Zanabazar had to take the mobile portion of Urga and flee to Inner Mongolia.[citation needed]

More than half the wealth created in Urga in the period from 1639 to 1688 is thought to have been lost in 1688. Only in 1701 did Urga return to the region and start a second period of expansion, but it had to remain mobile until the end of the 70-year-long Dzungar-Qing Wars in 1757. After settling down in its current location in 1778, Urga saw sustained economic growth, but most of the wealth went to the Buddhist clergy, nobles as well as the temporary Shanxi merchants based in the eastern and western China-towns of Urga. There were numerous companies called puus (пүүс) and temple treasuries called jas (жас), which functioned as businesses, but none of these survived the Communist period. During the Mongolian People’s Republic, private property was only marginally tolerated, while most assets were state-owned. The oldest companies still operating in Ulaanbaatar date to the early MPR. Only the Gandantegchinlen Monastery has been operating non-stop for 205 years (with a 6-year gap during World War II), but whether it can be seen as a business is still debated.

As the main industrial center of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar produces a variety of consumer goods [39] and is responsible for about two-thirds of Mongolia’s total gross domestic product (GDP).[40]

The transition to a market economy in 1990 has so far correlated with an increase in GDP, leading to a shift towards service industries (which now make up up 43% of the city’s GDP) along with rapid urbanization and population growth.[41]

Mining is the second-largest contributor to Ulaanbaatar’s GDP, at 25%. North of the city are several gold mines, including the Boroo Gold Mine, and foreign investment in the sector has allowed for growth and development. However, in light of a noticeable drop in GDP during the financial crisis of 2008, as demand for mining exports dropped,[41] there has been movement towards diversifying the economy.[40]

Architecture and landmarks[edit]

The city consists of a central district built in Soviet 1940s- and 1950s-style architecture, surrounded by and mingled with residential concrete towerblocks and large ger districts. In recent years, many of the towerblocks’ ground floors have been modified and upgraded to small shops, and many new buildings have been erected—some illegally, as some private companies erect buildings without legal licenses/permits in forbidden places.

Ulaanbaatar’s main landmarks include the Gandantegchinlen Monastery[42] with the large Janraisig statue, the socialist monument complex at Zaisan Memorial with its great view over the city, the Winter Palace of the Bogd Khan, Sükhbaatar Square and the nearby Choijin Lama Temple.[43]

The city also houses numerous museums, two of the prominent ones being the National Museum of Mongolia and the Zanabazar Fine Arts Museum. Popular destinations for day trips are the Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, the Manzushir monastery ruins on the southern flank of Bogd Khan Uul and Genghis Khan Equestrian Statue.

Important shopping districts include the 3rd Microdistrict Boulevard (simply called Khoroolol or «the District»), Peace Avenue around the State Department Store (simply called Ikh Delguur or «Great Store») and the Narantuul «Black Market» area (simply called Zakh or «the Market»).

Ulaanbaatar presently has three large cinemas, one modern ski resort, two large indoor stadiums, several large department stores and one large amusement park. Food, entertainment and recreation venues are steadily increasing in variety. KFC, Round Table Pizza, Cinnabon, Louis Vuitton, Ramada and Kempinski have opened branches in key locations.

The skyline is dominated by the 105-metre-tall (344-foot) Blue Sky Tower. A 309-metre-tall (1,014-foot) tower called the Morin Khuur Tower (Horsehead Fiddle Tower) is planned to be built next to the Central Stadium.[44][45] The 41-floor Mak Tower is being built by Lotte Construction and Engineering, a South Korean firm.

-

-

International Food Festival, held annually in UB in September

-

-

One of many events in the city (shown here, Naadam)

-

-

Street art at UB’s Peace Avenue

-

The Beatles monument, a popular place for the youth of UB to gather around

-

Dambadarjaalin Monastery in UlaanBaatar

Monasteries[edit]

Among the notable older monasteries is the Choijin Lama Monastery, a Buddhist monastery that was completed in 1908. It escaped the destruction of Mongolian monasteries when it was turned into a museum in 1942.[46]

Another is the Gandan Monastery, which dates to the 19th century. Its most famous attraction is a 26.5-meter-high golden statue of Migjid Janraisig.[47] These monasteries are among the very few in Mongolia to escape the wholesale destruction of Mongolian monasteries under Khorloogiin Choibalsan.

Winter Palace[edit]

Peace Gate of the Winter Palace (Amgalan Enkhiin Khaalga in Mongolian, Andimen in Chinese), for which no nails were used

The old city of Ikh Khüree, once it was set up as a permanent capital, had a number of palaces and noble residences in an area called Öndgiin sürgiin nutag. The Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, who was later crowned Bogd Khan, had four main imperial residences, which were located between the Middle (Dund gol) and Tuul rivers. The summer palace was called Erdmiin dalai buyan chuulgan süm or Bogd khaanii serüün ord. Other palaces were the White Palace (Tsagaan süm, or Gьngaa dejidlin), and the Pandelin Palace (also called Naro Kha Chod süm), which was situated on the left bank of the Tuul River. Some of the palaces were also used for religious purposes.[48]

The only palace that remains is the winter palace; the Winter Palace of the Bogd Khan (Bogd khaanii nogoon süm or Bogd khaanii öwliin ordon) remains as a museum of the last monarch. The complex includes six temples, and many of the Bogd Khan’s and his wife’s possessions are on display in the main building.

Museums[edit]

Ulaanbaatar has several museums dedicated to Mongolian history and culture. The Natural History Museum features many dinosaur fossils and meteorites found in Mongolia.[49][50]

The National Museum of Mongolia includes exhibits from prehistoric times through the Mongol Empire to the present.[51][52] The Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts has a large collection of Mongolian art, including works of the 17th-century sculptor/artist Zanabazar, as well as Mongolia’s most famous painting, One Day In Mongolia by Baldugiin «Marzan» Sharav.[53][54]

The Mongolian Theatre Museum presents the history of the performing arts in Mongolia. The city’s former Lenin Museum announced plans in January 2013 to convert to a museum showcasing dinosaur and other prehistoric fossils.[55]

Pre-1778 artifacts that have never left the city since its founding include the Vajradhara statue made by Zanabazar himself in 1683 (the city’s main deity, kept at the Vajradhara temple); an ornate throne presented to Zanabazar by the Kangxi Emperor (before 1723); a sandalwood hat presented to Zanabazar by the Dalai Lama (c. 1663); Zanabazar’s large fur coat, also presented by the Kangxi Emperor; and a great number of original statues made by Zanabazar (e.g., the Green Tara).

The Military Museum of Mongolia features two permanent exhibition halls, commemorating the war history of the country from prehistoric times to the modern era. In the first hall, one can see various tools and weapons from the Paleolithic age to the times of the Manchu empire. The second hall showcases the modern history of the Mongolian military, from the Bogd Khan period (1911–24) up until Mongolia’s recent military involvement in peacekeeping operations.

The city’s museum offers a view of Ulaanbaatar’s history through old maps and photos. Among the permanent items is a huge painting of the capital as it looked in 1912, showing major landmarks such as Gandan Monastery and the Winter Palace of the Bogd Khan. Part of the museum is dedicated to special photo exhibits that change frequently. The Mongolian Railway History Museum is an open-air museum that displays six types of locomotives used during a 65-year period of Mongolian rail history.

The Puzzle Toys Museum displays a comprehensive collection of complex wooden toys that visitors can assemble.

The Victims of Political Persecution Memorial Museum – dedicated to those fallen under the Communist purge that took the lives of over 32,000 statesmen, herders, scholars, politicians and lamas in the 1930s – told about one of the most tragic periods in Mongolia’s 20th-century history.[56] The small building had fallen into serious disrepair and was demolished on 7 October 2019, despite public outcry in favor of renovation.[26]

-

A building of the Dambadarjaalin Monastery (1765) in Sukhbaatar District

-

Vajradhara Temple (1841) in the center, Zuu Temple (1869) on the left, connected by a passage built in 1945–1946

-

Zanabazar’s Fine Arts Museum, built in 1905 by Russian merchant Gudvintsal as a trading shop

-

Ulaanbaatar History Museum, built in 1904 by a Buryat-Mongol merchant

-

West Geser Temple, built in 1919–1920 by Guve Ovogt Zakhar

-

Residence of Prince Chin Wang Khanddorj (Minister of Foreign Affairs), built in 1913.

Sükhbaatar Square[edit]

Sükhbaatar Square, in the government district, is the center of Ulaanbaatar. The square is 31,068 square metres (334,413 square feet) in area.[57] In the middle of the square is a statue of Damdin Sükhbaatar on horseback; the spot was chosen because that was where Sükhbaatar’s horse had urinated (considered a good omen) on 8 July 1921 during a gathering of the Red Army. On the north side of Sükhbaatar Square is the Mongolian Parliament building, featuring a large statue of Chinggis Khan at the top of the front steps. Peace Avenue (Enkh Taivny Urgon Chuloo), the main thoroughfare through town, runs along the south side of the square.[58]

Zaisan Memorial[edit]

The Zaisan Memorial, dedicated to Soviet and Mongolian soldiers killed in World War II, sits on a hill south of the city. The Zaisan Memorial includes a Soviet tank paid for by the Mongolian people and a circular memorial painting which in the socialist realism style depicts scenes of friendship between the peoples of the Soviet Union and Mongolia. Visitors who make the long climb to the top are rewarded with a panoramic view of the whole city down in the valley.

National Sports Stadium[edit]

National Sports Stadium is the main sporting venue. The Naadam festival is held here every July.

Arts and culture[edit]

Ulaanbaatar features a mix of traditional and western-style theatres, offering world-class performances. Many of the traditional folklore bands play regularly around the world, including in New York, London and Tokyo. The Ulaanbaatar Opera House, situated in the center of the city, hosts concerts and musical performances as well as opera and ballet performances, some in collaboration with world ballet houses such as the Boston Theatre.

Mongolian National Song and Dance Academic Ensemble

The Mongolian State Grand National Orchestra was originally established during the reign of Kublai Khan, and reestablished in 1945. It has the largest orchestra of traditional instruments in the country, with a repertoire going beyond national music, encompassing dozens of international musical pieces.[59]

The Tumen Ekh Ensemble comprises artists who perform all types of Mongolian song, music and dance. They play traditional instruments, including the morin khuur (horsehead fiddle), and perform Mongolian long song, epic and eulogy songs, a shaman ritual dance, an ancient palace dance and a Tsam mask dance.[60]

The Morin Khuur Ensemble of Mongolia is part of the Mongolian State Philharmonic, based at Sükhbaatar Square. It is a popular ensemble featuring the national string instrument, the morin khuur, and performs various domestic and international works.

Parks[edit]

A number of nationally known parks and protected areas belong officially to the city. Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, a nature preserve with many tourist facilities, is approximately 70 km (43 mi) from Ulaanbaatar. It is accessible via paved road. The 40-metre-high (130-foot) Genghis Khan Equestrian Statue is 54 km (34 mi) east of the city.

Bogd Khan mountain is a strictly protected area with a length of 31 kilometres (19 miles) and width of 3 kilometres (1.9 miles), covering an area of 67,300 hectares (166,302 acres). Nature conservation dates back to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries when the Tooril Khan of the Mongolian Ancient Keraite Aimag – who prohibited logging and hunting activities – claimed the Bogd Khan as a holy mountain.

[61]

The National Amusement Park (Mongolian: Үндэсний соёл амралтын хүрээлэн, romanized: Ündesnii soyol amraltiin khüreelen) is an amusement park located in the downtown section, south of Shangri-La Hotel.[62] It is also a popular place for young people to hang out. This small amusement park features rides, games and paddle boats. Its original Artificial Lake Castle was built in 1969.

The National Park of Mongolia (Mongolian: Үндэсний Цэцэрлэгт Хүрээлэн, romanized: Ündesnii tsetserlegt khüreelen), in the southeastern outskirts of the city,[63] opened in 2009 and has become a popular summer destination for UB residents. It has a total area of 55 hectares, with over 100,000 trees planted. The park is geared towards becoming an educational center for healthy, responsible living as well as environmental education.

Religion[edit]

Ulaanbaatar has a long tradition of Buddhism, having been initially founded and settled as a monastic center. Prominent places of worship in the city include the Gandantegchinlen Monastery and Choijin Lama Temple. In modern times, it has become a multifaith center, having added multiple Christian churches (such as the Orthodox Holy Trinity Church, as well as Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, the official episcopal see of the Catholic Apostolic Prefecture of Ulaanbaatar).

According to the 2020 national census, 46.3% of the population over 15 years of age identified as being irreligious, while 53.7% identified as being religious, a decrease of 7.7 percentage points in religiosity since the 2010 census.[64]

Of the people identifying as religious, responses included Buddhism (89.1%), Shamanism (5.4%), Christianity (3.3%), and Islam (0.9%).[64]

Municipal symbols[edit]

The official symbol of Ulaanbaatar is the garuḍa, a mythical bird in both Buddhist and Hindu scriptures called Khan Garuda or Khangar’d (Mongolian: Хангарьд) by Mongols.

City emblem and flag[edit]

The garuḍa appears on Ulaanbaatar’s emblem. In its right hand is a key, a symbol of prosperity and openness, and in its left is a lotus flower, a symbol of peace, equality and purity. In its talons it is holding a snake, a symbol of evil of which it is intolerant. On the garuḍa‘s forehead is the soyombo symbol, which is featured on the flag of Mongolia. The city’s flag is sky blue with the garuḍa arms in the center.

Education[edit]

Ulaanbaatar is home to most of Mongolia’s major universities, among them the National University of Mongolia, Mongolian University of Science and Technology, Mongolian State University of Agriculture, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Mongolian State University of Education, and the Mongolian University of Art and Culture, and the University of Finance and Economics.

The American School of Ulaanbaatar and the International School of Ulaanbaatar are examples of Western-style K-12 education in English for Mongolian nationals and foreign residents.

Libraries[edit]

National Library[edit]

The National Library of Mongolia is located in Ulaanbaatar and includes an extensive historical collection, items in non-Mongolian languages and a special children’s collection.[65]

Public libraries[edit]

The Metropolitan Central Library of Ulaanbaatar, sometimes also referred to as the Ulaanbaatar Public Library, is a public library with a collection of about 500,000 items. It has 232,097 annual users and a total of 497,298 loans per year. It does charge users a registration fee of 3800 to 4250 tugrik, or about US$3.29 to 3.68. The fees may be the result of operating on a budget under $176,000 per year. They also host websites on classical and modern Mongolian literature and food, in addition to providing free internet access.[65]

In 1986, the Ulaanbaatar government created a centralized system for all public libraries in the city, known as the Metropolitan Library System of Ulaanbaatar (MLSU). This system coordinates management, acquisitions, finances and policy among public libraries in the capital, in addition to providing support to school and children’s libraries.[66] Other than the Metropolitan Central Library, the MLSU has four branch libraries. They are in the Chingeltei District (established in 1946), in the Han-Uul District (established in 1948), in the Bayanzurkh District (established in 1968) and in the Songino-Hairkhan District (established in 1991). There is also a Children’s Central Library, which was established in 1979.[67]

University libraries[edit]

- Library of Mongolian State University of Education[68]

- Library of the Academy of Management[69]

- Library of the National University of Mongolia[70]

- Institutes of the Academy of Sciences (3 department libraries)[71]

- Library of the Institute of Language and Literature[72]

- Library of the Institute of History[72]

- Library of the Institute of Finance and Economics[73]

- Library of the National University of Mongolia[74]

- Library of the Agriculture University

Digital libraries[edit]

The International Children’s Digital Library (ICDL) is an organization that publishes numerous children’s books in different languages on the web in child-friendly formats. In 2006 they began service in Mongolia and have made efforts to provide access to the library in rural areas. The ICDL effort in Mongolia is part of a larger project funded by the World Bank and administered by the Mongolian Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, called the Rural Education And Development Project (READ).[75]

Since Mongolia lacks a publishing industry, and few children’s books, the idea has been to «spur the publishing industry to create 200 new children’s books for classroom libraries in grades 1–5.» After these books were published and distributed to teachers they were also published online with the rest of the ICDL collection. While a significant portion of this project is supported by outside sources, an important component is to include training of Mongolian staff to make it continue in an effective way.[76][77]

The Press Institute in Ulaanbaatar oversees the Digital Archive of Mongolian Newspapers. It is a collection of 45 newspaper titles with a particular focus on the years after the fall of communism in Mongolia.[78] The project was supported by the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme. The Metropolitan Central Library in Ulaanbaatar maintains a digital monthly news archive.[79]

Special libraries[edit]

An important resource for academics is the American Center for Mongolian Studies (ACMS),[80] also based in Ulaanbaatar. Its goal is to facilitate research between Mongolia and the rest of the world and to foster academic partnerships. To help achieve this end, it operates a research library with a reading room and computers for Internet access. ACMS has 1,500 volumes related to Mongolia in numerous languages that may be borrowed with a deposit. It also hosts an online library that includes special reference resources and access to digital databases,[81] including a digital book collection.[82][83]

There is a Speaking Library at School #116 for the visually impaired, funded by the Zorig Foundation, and the collection is largely based on materials donated by Mongolian National Radio. «A sizable collection of literature, know-how topics, training materials, music, plays, science broadcasts are now available to the visually impaired at the school.»[84]

The Mongolia-Japan Center for Human Resources Development[85] maintains a library in Ulaanbaatar consisting of about 7,800 items. The materials in the collection have a strong focus on both aiding Mongolians studying Japanese and books in Japanese about Mongolia. It includes a number of periodicals, textbooks, dictionaries and audio-visual materials. Access to the collection does require payment of a 500 Tugrug fee, though materials are available for loan. They also provide audio-visual equipment for collection use and internet access for an hourly fee. There is an information retrieval reference service for questions that cannot be answered by their collection.[86]

Archives[edit]

There is a manuscript collection at the Danzan Ravjaa Museum of theological, poetic, medicinal, astrological and theatrical works. It consists of literature written and collected by the monk Danzan Ravjaa, who is famous for his poetry.

The British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme funded a project to take digital images of unique literature in the collection; however, it is not clear where the images are stored today.[87]

Sports[edit]

Biking event at Peace avenue. Turkish Embassy in the background

Ulaanbaatar hosted the official 2019 FIBA 3×3 Under-18 World Cup where Mongolia’s national Under-18 3×3 team finished sixth out of 20.[88]

Ulaanbaatar City FC is a professional football club based in the city and currently competes in Mongolian National Premier League.

Transport[edit]

Ulaanbaatar is served by the Chinggis Khaan International Airport, located 52 km (32 mi) south of the city which functions as the country’s main air hub. It replaced the former Buyant-Ukhaa International Airport in 2021.

Flights to Ulaanbaatar are available from Moscow, Paris, Frankfurt, Berlin, Tokyo, Seoul, Ulan-Ude, Irkutsk, Hong Kong, Beijing, Bishkek and Istanbul.[89]

There are rail connections to the Trans-Siberian railway via Naushki and to the Chinese railway system via Jining. Ulaanbaatar is connected by road to most of the major towns in Mongolia, but most roads in Mongolia are unpaved and unmarked, and road travel can be difficult. Even within the city, not all roads are paved and some of the ones that are paved are not in good condition.[90]

Existing plans to improve transportation include a subway system, several major road projects such as a 1,000-kilometre-long (620-mile) highway to link Ulaanbaatar to the regions of Altanbulag and Zamyn Uud,[91] plans to upgrade existing regional airports and roadways, and Mongolian Railway projects that will connect cities and mines.[92]

The national and municipal governments regulate a system of private transit providers which operate bus lines around the city. There is the Ulaanbaatar Railbus, and also the Ulaanbaatar trolleybus system. A secondary transit system of privately owned microbuses (passenger vans) operates alongside these bus lines. Additionally, Ulaanbaatar has over 4000 taxis. The capital has 418.2 km (259.9 mi) of road, of which 76.5 are paved.[93]

Air pollution[edit]

Ger district in Ulaanbaatar with the Temple of Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara at Gandantegchinlen Monastery in the background.

Air pollution is a serious problem in Ulaanbaatar, especially in winter. Concentrations of certain types of particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) regularly exceed WHO recommended maximum levels by more than a dozen times. They also exceed the concentrations measured in northern Chinese industrial cities. During the winter months, smoke regularly obscures vision and can even lead to problems with air traffic at the local airport.[94]

Sources of the pollution are mainly the simple stoves used for heating and cooking in the city’s ger districts, but also the local coal-fueled power plants. The problem is compounded by Ulaanbaatar’s location in a valley between relatively high mountains, which shield the city from the winter winds and thus obstruct air circulation.[95][96]

International relations[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Ulaanbaatar is twinned with:[97][98]

- Ankara, Turkey[99]

- Astana, Kazakhstan

- Bangkok, Thailand

- Beijing, China

- Bonn, Germany[100]

- Denver, United States[101]

- Elista, Russia

- Gaziantep, Turkey[102]

- Haikou, China[103]

- Hohhot, China[104]

- Incheon, South Korea

- Irkutsk, Russia

- Kazan, Russia

- Krasnoyarsk, Russia[105]

- Maardu, Estonia[106]

- Moscow, Russia

- Novosibirsk, Russia

- Pyongyang, North Korea

- Seoul, South Korea

- Strelcha, Bulgaria[107]

- Taipei, Taiwan[108]

- Tianjin, China

- Ulan-Ude, Russia

- Yinchuan, China[109]

Proximity to nearby urban centers abroad[edit]

Ulaanbaatar has close ties to cities like Seoul (1,995 kilometres or 1,240 miles from UB), Hong Kong (2,900 kilometres or 1,800 miles from UB), Tokyo (3,010 kilometres or 1,870 miles from UB) and Moscow (4,650 kilometres or 2,890 miles from UB). The Zamyn Uud-Erenhot and Altanbulag-Kyakhta borders are the only places where sustained interaction occurs between Mongolia and its neighbors. Other ports are much smaller. For now Ulaanbaatar remains the main, and almost only, point of contact between Mongolia and its neighbors. Beijing remains the closest global city to Ulaanbaatar (1,167 kilometres or 725 miles). The UB-Peking corridor is served by busy air, rail and road links.

Appearances in fiction[edit]

In the 1959 novel Alas, Babylon by Pat Frank, the pen name of Harry Hart Frank, the city was a relocation site for the Soviet leadership. In the novel it had a medium-wave station for communications.[110]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Transcribed as Ulaɣanbaɣatur.

References[edit]

- ^ «Хүн ам, орон сууцны 2020 оны улсын ээлжит тооллого — Нийслэлийн нэгсэн дүн». 1212.mn. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ Sh, Chimeg (2020-10-26). «Шинэ хотын даргад боломж, хариуцлагыг нь үүрүүл!». News.mn.

- ^ Sub-national HDI. «Area Database – Global Data Lab». hdi.globaldatalab.org.

- ^ Sen Nag, Oishimaya (2021-01-21). «The Coldest Capital Cities In The World». WorldAtlas. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ «Нийслэлийн статистикийн газар – Статистик үзүүлэлт – 01. Хүн амын тоо, хүйсээр, оны эхэнд, мянган хүн» (in Mongolian). Statis.ub.gov.mn. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ^ «Төрийн үйлчилгээний портал» (in Mongolian). Ulaanbaatar.mn. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Urga» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 795.

- ^ Улаанбаатар хотын хөгжлийн түүхэн замнал, хэтийн төлөв. УБ: УХГ. 1974.

- ^ Улаанбаатар, Ulaanbaatar 2001, pg. 9f

- ^ a b «Brief history of Ulaanbaatar». Ulaanbaatar.mn. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Kohn, Michael Lonely Planet Mongolia (4th edition, 2005); ISBN 1-74059-359-6, pg. 52.

- ^ John Bell, Travels from St. Petersburgh in Russia, to various parts of Asia (Volume 1), 1763, London, pg. 344

- ^ Majer, Zsuzsa & Krisztina Teleki, Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khuree, Ikh Khuree or Urga, the Old Capital City of Mongolia in the First Part of the Twentieth Century Archived 27 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lindon Wallace Bates, The Russian Road to China, 1910

- ^ a b «From Khutagtiin Khuree to Niislel Khuree Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Presentation of the Director of the General Archives Authority D. Ulziibaatar», archives.gov.mn; accessed 26 March 2018.

- ^ Othen, Christopher. «Urga, February 1921». Archived from the original on 2019-11-21. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- ^ Palmer, James (2009). The Bloody White Baron. Perseus Books. ISBN 9780465014484.

- ^ Bisher, Jamie. White Terror: Cossack Warlords Of The Trans-Siberian. p. 276.

- ^ Kuzmin, S.L. History of Baron Ungern: an Experience of Reconstruction. Moscow: KMK, 2011, pp. 165–200

- ^ Kuzmin, pp. 250–300

- ^ Протоколы 1-го Великого Хуралдана Монгольской Народной Республики. Улан-Батор-Хото, 1925.(in Russian)

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006; ISBN 99929-0-627-8, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Rossabi, Morris Modern Mongolia: From Khans to Commissars to Capitalists, University of California Press (2005), pp. 1–28; ISBN 0-520-24419-2

- ^ «Fatal clashes in Mongolia capital». BBC News. 2 July 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ «Streets calm in riot-hit Mongolia». BBC News. 3 July 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b Menarndt, Aubrey (17 October 2019). «‘A crime against culture’: Mongolian capital Ulan Bator set to demolish Soviet-era buildings – activists fight to save them and scent corruption». South China Morning Post. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

On October 7, Mongolia’s Victims of Political Persecution Memorial Museum was demolished. The museum was housed in one of Ulan Bator’s oldest buildings, a small, brown wooden house in the center of the city, which stood in contrast to the high-rises surrounding it.

- ^ Ankhtuyaa, B. (18 October 2019). «A crime against culture’: Ulaanbaatar set to demolish majestic Soviet-era buildings». News.mn. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

As the parliament began its autumn legislative agenda, the government budget for the year revealed several line items financing the demolition of the city’s Natural History Museum, Opera and Ballet House, Drama Theatre, and Central Library.

- ^ Baljmaa.T (13 January 2020). «Culture Minister: Three historical buildings to be renovated with MNT 6 billion». Montsame. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

This has garnered public criticism, including the Union of Mongolian Architects, who claimed that those buildings hold cultural heritage and architectural values, and demanding preservation and restoration of the buildings instead of demolition.

- ^ Baljmaa.T (13 January 2020). «Culture Minister: Three historical buildings to be renovated with MNT 6 billion». Montsame. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

Concerning the prolonged public outcry, Minister of Education, Culture Science and Sports Yo.Baatarbileg today clarified during his meeting with reporters that «Buildings of National Academic Drama Theater, National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet of Mongolia and Central Library of Mongolia are planned to go under renovation this year with funding of MNT 2 billion from state budget for each. The official position and decision of the Ministry of Culture not to demolish them remain the same as before».

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, ISBN 99929-0-627-8, pg. 35

- ^ «Hardiness Zones – WORLD MAP». Plantsdb.gr. 15 August 1965. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ «Climatological Normals of Ulan Bator». Hong Kong Observatory. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ Matt Rosenberg. «Coldest Capital Cities». About.com Education. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ^ a b

КЛИМАТ УЛАН-БАТОРА (in Russian). Pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved 4 January 2015. - ^ «Ulaanbaatar Climate Normals 1961–1990». National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ «Climate & Weather Averages at Ulan-Bator weather station». Time and Date. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ «Foreigners have determined the 10 richest people in Mongolia». Caak.mn. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ «The list of 100 richest Mongolians is causing a stir on a Russian website». Ugluu.mn. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ «Ulaanbaatar». encyclopedia.com. The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Edition. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b Economic Development in Mongolia. The Asia Foundation. Available here[permanent dead link]; accessed 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b Fan, Peilei; Chen, Jiquan; John, Ranjeet (2016-01-01). «Urbanization and environmental change during the economic transition on the Mongolian Plateau: Hohhot and Ulaanbaatar». Environmental Research. The Provision of Ecosystem Services in Response to Global Change. 144, Part B (Pt B): 96–112. Bibcode:2016ER….144…96F. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2015.09.020. PMID 26456409.

- ^ «Documentation of Mongolian Monasteries» http://mongoliantemples.org/index.php/en/

- ^ «Mongolia: Museum Highlights», San Francisco, 2005, pg. 89

- ^ ctbuh. «CTBUH Joins Launch of Mongolian Tower». www.ctbuh.org. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ «Татах хүч ХХК | Gravity LLC». Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- ^ [1] Archived 31 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kohn, pp. 63–4

- ^ Majer, Zsuzsa; Teleki, Krisztina. «Monasteries and Temples of Bogdiin Khьree, Ikh Khьree or Urga, the Old Capital City of Mongolia in the First Part of the Twentieth Century» (PDF). Budapest: Documentation of Mongolian Monasteries. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ^ [2] Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kohn, pg. 60

- ^ Kohn, pp. 61, 66

- ^ «National Museum». Nationalmuseum.mn. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Kohn, pg. 61

- ^ «Zanazabar Museum of Fine Arts». Zanabazarmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2011-09-24. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Branigan, Tania. «It’s goodbye Lenin, hello dinosaur as fossils head to Mongolia museum». The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ «Victims of Political Persecution Memorial Museum», Attractions, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, Asia. Lonely Planet. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia, 2006; ISBN 99929-0-627-8, pg. 34

- ^ Kohn, pg. 52

- ^ «Official Website». Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ «Official Website».

- ^ «Biosphere Reserve Information: BOGD KHAN UUL». Archived from the original on 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ^ Ulaanbaatar, Google Maps. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Ulaanbaatar, Google Maps. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ a b «Хүн ам, орон сууцны 2020 оны улсын ээлжит тооллого — Улаанбаатар нэгдсэн дүн». 1212.mn. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ a b «Metropolitan Central Library of Ulaanbaatar». Nla.gov.au. 1 March 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ [3] Archived 29 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [4] Archived 23 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Library of Mongolian State University of Education». Archived from the original on 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- ^ «lib.mn». www.aom.lib.mn. Archived from the original on 2004-10-14. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- ^ «Монгол Улсын Их Сургууль». www.num.edu.mn.

- ^ Institutes of the Academy of Sciences (3 department libraries) Archived 2010-11-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b «Шинжлэх ухааны академи». Archived from the original on 2011-08-24. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ^ «Library of the Institute of Finance and Economics». Archived from the original on 2011-08-29. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ^ «Номын сан». library.num.edu.mn. Archived from the original on 2011-08-26. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ^ ««Rural Education and Development (READ) Project (formerly Rural Education Support Project)» World Bank». Web.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ «No Hotel, Tent: The International Children’s Digital Library Goes to Mongolia». Childrenslibrary.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ «No Road, Drive: The ICDL Goes to the Mongolian Countryside». Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ «Digital Librarian Lends Expertise to Mongolian Project». Uwm.edu. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ [5] Archived 16 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «American Center of Mongolian Studies – ACMS». mongoliacenter.org.

- ^ «American Center of Mongolian Studies – Library». www.mongoliacenter.org.

- ^ «ACMS Digital Books Collection». Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ «American Center for Mongolian Studies Library Homepage. American Center for Mongolian Studies, Ulaanbaatar». Mongoliacenter.org. 7 May 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ «Speaking Library at School No. 116». Ubpost.mongolnews.mn. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Mongolia-Japan Center for Human Resources Development Archived 2010-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [6] Archived 22 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [7] Archived 5 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «FIBA 3×3 U18 World Cup: seventh edition all set to tip off in Mongolia on June 3». Sportskeeda. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ «MIAT Route Map». Miat.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ «Transport in Mongolia». Web.worldbank.org. 20 July 2006. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ «Roads Week on WCN: Some of the key global road projects – World Construction Network». www.worldconstructionnetwork.com. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ <http://www.hydrant.co.uk>, Site designed and built by Hydrant (19 May 2015). «Major rail projects in Mongolia showing significant progress». Oxford Business Group. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Montsame News Agency. Mongolia. 2006, Foreign Service Office of Montsame News Agency; ISBN 99929-0-627-8, pp. 36, 90.

- ^ «Air Pollution Puts Lives At Risk Mongolia». BORGEN. 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ Hasenkopf, Christa. «Clearing the Air». World Policy Journal (Spring 2012). Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ The World Bank (December 2009). «Mongolia: Air Pollution in Ulaanbaatar – Initial Assessment of Current Situation and Effects of Abatement Measures» (PDF). Sustainable Development Series: Discussion Paper. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ ««Улаанбаатар олон улсын өдөрлөг-2019″ арга хэмжээ эхэллээ». ulaanbaatar.mn (in Mongolian). Ulaanbaatar. 2019-10-21. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Хотын дарга С.Батболд Токио хотын засаг дарга Юрико Койкэтэй уулзлаа». ulaanbaatar.mn (in Mongolian). Ulaanbaatar. 2017-04-20. Archived from the original on 2020-10-22. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Sister Cities of Ankara». ankara.bel.tr. Ankara. Archived from the original on 2013-04-28. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Partners across the world». bonn.de. Bonn. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Our Sister Cities». denversistercities.org. Denver Sister Cities. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «30 Kardeşli Gaziantep». gazianteppusula.com (in Turkish). Gaziantep Pusula. 2015-12-02. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ «友好城市». haikou.gov.cn (in Chinese). Haikou. Archived from the original on 2021-09-22. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Улаанбаатар хоттой ах, дүү хотууд». barilga.mn (in Mongolian). Barilga. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Города-побратимы». krskstate.ru (in Russian). Krasnoyarsk Krai. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Maardu partner cooperations». maardu.kovtp.ee. Maardu linn. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «Международно сътрудничество». strelcha.bg (in Bulgarian). Strelcha. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «International Sister Cities». tcc.gov.tw. Taipei City Council. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ «银川市友好城市及交流合作情况». yinchuan.gov.cn (in Chinese). Yinchuan. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ Frank, Pat (1959). Alas, Babylon. New York: Perennial 2005 (Lippincott 1959). ISBN 978-0-06-074187-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Lattimore, Owen. «Communism, Mongolian Brand», The Atlantic, September 1962. A unique, detailed historical snapshot of life in Mongolia at the height of the Cold War. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

External links[edit]

- Ulaanbaatar City Hall Archived 2012-08-06 at the Wayback Machine(Mongolia)

- Ulaanbaatar Travel Guide

- General information about Ulaanbaatar, up-to-date

- «Urga or Da Khuree» from A. M. Pozdneyev’s Mongolia and the Mongols

|

Ulaanbaatar Улаанбаатар |

|

|---|---|

|

Municipality |

|

|

Clockwise from top: City center with Sükhbaatar Square in the background, Choijin Lama Temple, Ugsarmal panel buildings built in the socialist era, Naadam ceremony at the National Sports Stadium, National University of Mongolia, Ger districts, Gandantegchinlen Monastery |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Nickname(s):

УБ (UB), Нийслэл (capital), Хот (city) |

|

|

|

|

Ulaanbaatar Location of Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia Ulaanbaatar Ulaanbaatar (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 47°55′13″N 106°55′02″E / 47.92028°N 106.91722°ECoordinates: 47°55′13″N 106°55′02″E / 47.92028°N 106.91722°E | |

| Country | |

| Monastic center established | 1639 |

| Current location | 1778 |

| Named Ulaanbaatar | 1924 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager |

| • Body | Citizens’ Representatives Khural of the Capital City |

| • Governor of the Capital City and Mayor of Ulaanbaatar | Dolgorsürengiin Sumyaabazar (MPP)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,704.4 km2 (1,816.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,350 m (4,429 ft) |

| Population

(2021) |

|

| • Total | 1,612,005[1] |

| • Density | 311/km2 (807/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (H) |

| Postal code |

210 xxx |

| Area code | +976 (0)11 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.810[3] – very high · 1st |

| License plate | УБ, УН |

| ISO 3166-2 | MN-1 |

| Climate | BSk |

| Website | www.ulaanbaatar.mn |

Ulaanbaatar (; Mongolian: Улаанбаатар, pronounced [ʊˌɮaːm‿ˈpaːʰtə̆r] (listen), lit. «Red Hero»), previously anglicized as Ulan Bator, is the capital and most populous city of Mongolia. It is the coldest capital city in the world, on average.[4] The municipality is located in north central Mongolia at an elevation of about 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) in a valley on the Tuul River. The city was originally founded in 1639 as a nomadic Buddhist monastic center, changing location 28 times, and was permanently settled at its current location in 1778.

During its early years, as Örgöö (anglicized as Urga), it became Mongolia’s preeminent religious center and seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, the spiritual head of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. Following the regulation of Qing-Russian trade by the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727, a caravan route between Beijing and Kyakhta opened up, along which the city was eventually settled. With the collapse of the Qing Empire in 1911, the city was a focal point for independence efforts, leading to the proclamation of the Bogd Khanate in 1911 led by the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, or Bogd Khan, and again during the communist revolution of 1921. With the proclamation of the Mongolian People’s Republic in 1924, the city was officially renamed Ulaanbaatar and declared the country’s capital. Modern urban planning began in the 1950s, with most of the old Ger districts replaced by Soviet-style flats. In 1990, Ulaanbaatar was a major site of demonstrations that led to Mongolia’s transition to democracy and a market economy. Since 1990, an influx of migrants from the rest of the country has led to an explosive growth in its population, a major portion of whom live in Ger districts, which has led to harmful air pollution in winter.

Governed as an independent municipality, Ulaanbaatar is surrounded by Töv Province, whose capital Zuunmod lies 43 kilometres (27 mi) south of the city. With a population of just over 1.5 million as of December 2022, it contains almost half of the country’s total population.[5] As the country’s primate city, it serves as the cultural, industrial and financial heart as well as the center of Mongolia’s transport network, connected by rail to both the Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia and the Chinese railway system.[6]

Names and etymology[edit]

The city at its establishment in 1639 was referred to as Örgöö (Mongolian: ᠥᠷᠭᠦᠭᠡ; Өргөө, lit. ‘Palace’). This name was eventually adapted as Urga[7] in the West. By 1651, it began to be referred to as Nomiĭn Khüree (Mongolian: ᠨᠣᠮ ᠤᠨ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Номын хүрээ, lit. ‘Khüree of Wisdom’), and by 1706 it was referred to as Ikh Khüree (Mongolian: ᠶᠡᠬᠡ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Их хүрээ, lit. ‘Great Khüree’). The Chinese equivalent, Dà Kùlún (Chinese: 大庫倫, Mongolian: Да Хүрээ), was rendered into Western languages as Kulun or Kuren.

Other names include Bogdiin Khuree (Mongolian: ᠪᠣᠭᠳᠠ ᠶᠢᠨ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Богдын хүрээ, lit. ‘The Bogd’s Khüree’), or simply Khüree (Mongolian: ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Хүрээ, romanized: Küriye), itself a term originally referring to an enclosure or settlement.

Upon independence in 1911, with both the secular government and the Bogd Khan’s palace present, the city’s name was changed to Niĭslel Khüree (Mongolian: ᠨᠡᠶᠢᠰᠯᠡᠯ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Нийслэл Хүрээ, lit. ‘Capital Khüree’).

When the city became the capital of the new Mongolian People’s Republic in 1924, its name was changed to Ulaanbaatar (lit. ‘Red Hero’).

In the Western world, Ulaanbaatar continued to be generally known as Urga or Khuree until 1924, and afterward as Ulan Bator (a spelling derived from the Russian Улан-Батор). This form was defined two decades before the Mongolian name got its current Cyrillic spelling and transliteration (1941–1950); however, the name of the city was spelled Ulaanbaatar koto during the decade in which Mongolia used the Latin alphabet.

Today, the city is referred to simply as khot (Mongolian: хот, lit. ‘city’), as well as UB (you-be), from the English transliteration.

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]