Uruguay, Uruguayan

Смотрите также: уругвай

- Uruguay |ˈjʊrəɡwaɪ| — Уругвай

- Uruguayan |ˌjərəˈɡweɪən| — уругваец, уругвайка

Что нужно знать о Меле: 🌇 расположение на карте, сколько у них сейчас время и какой часовой пояс, население города, как пишется по-английски, а так же в какой стране находится

Местное время в Меле

12:5450

6 мая 2022

Разница с вами:

| Страна | 🇺🇾 Уругвай |

|---|---|

| Название города | Мел |

| По-английски | Melo |

| Столица региона | Мел является столицей региона |

| Население города | 51 023 чел. |

| Аэропорт | Мело MLZ (гражданских аэропортов нет) |

| Часовой пояс | America/Montevideo |

Где находится Мел на карте

Уругвай — 1) Восточная Республика Уругвай, гос во в Юж. Америке. В колониальное время территория совр. гос ва входила в состав исп. генерал губернаторства Ла Плата в качестве пров. Восточный Берег (с 1815г. Восточная пров.); название по расположению на… … Географическая энциклопедия

Уругвай — Уругвай. Выпас крупного рогатого скота в субтропической саванне. УРУГВАЙ (Восточная Республика Уругвай), государство на юго востоке Южной Америки, на юге омывается Атлантическим океаном. Площадь 178 тыс. км2. Население 3,15 млн. человек, главным… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

Уругвай — I (Uruguay), река в Южной Америке. 2200 км, площадь бассейна 307 тыс. км2. Впадает в залив Ла Плата. Средний расход воды 5500 м3/с. Судоходна для морских судов от города Пайсанду. II Восточная Республика Уругвай (Republica Oriental del Uruguay),… … Энциклопедический словарь

УРУГВАЙ — Восточная республика Уругвай, государство в Юж. Америке. Омывается водами Атлантического ок. 178 тыс. км². население 3,15 млн. человек (1993), главным образом уругвайцы. Городское население 85,5% (1990). Официальный язык испанский. Верующие в … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

УРУГВАЙ — (Uruguay), Восточная Республика Уругвай (Republica Oriental del Uruguay), государство на Ю. В. Юж. Америки. Пл. 176 т. км2. Население 2970 т. ч. (1983). Столица Монтевидео (1,3 млн. ж, 1980) У. индустр. агр страна с развитым животноводством До… … Демографический энциклопедический словарь

Уругвай — (Uruguay), Восточная Республика Уругвай, государство на юго востоке Южной Америки. Искусство Уругвая почти полностью сложилось в новое время. От культуры индейцев чарруа сохранились антропоморфные и зооморфные камни, колоколовидные… … Художественная энциклопедия

уругвай — американская швейцария Словарь русских синонимов. уругвай сущ., кол во синонимов: 3 • американская швейцария (1) • … Словарь синонимов

УРУГВАЙ — Территория 186,9 тыс.кв.км, население 3 млн.человек (1987). Уругвай аграрно дромышленная страна. Основа экономики производство продуктов животноводства. Развито мясо шерстное овцеводство. В 1990 году насчитывалось 16 млн.овец, произведено 98 тыс … Мировое овцеводство

Уругвай — (Uruguay), гос во в Юж. Америке. В колон, период назывался пров. Восточный берег и являлся частью исп. вице королевства Рио де ла Плата. В 1814г. лидеры Восточного берега, в частности Артигас, порвали с воен. хунтой в Аргентине и возглавили… … Всемирная история

Уругвай — I Уругвай (Uruguay) река в Южной Америке; верхнее течение в Бразилии, остальная часть служит границей между Аргентиной на З., Бразилией и Уругваем на В. Образуется слиянием рр. Пелотас и Каноас, берущих начало на зап. склонах хр. Серра ду … Большая советская энциклопедия

Уругвай — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Уругвай (значения). Восточная Республика Уругвай República Oriental del Uruguay … Википедия

Переводы

пересъёмка на английском языке — peresёmka, retake

урочный на английском языке — the appointed, certain, fixed, predestined, determined, precise, determinate, definite, …

уругваец на английском языке — uruguayan, the uruguayan

уругвайка на английском языке — uruguayan

уругвайский на английском языке — uruguayan, the uruguayan, the uruguay, uruguay, a uruguayan

Уругвай на английском языке — Словарь: русском » английский

Переводы: uruguay, Uruguay, to Uruguay, of Uruguay

Home>Слова, начинающиеся на букву У>Уругвай>Перевод на английский язык

Здесь Вы найдете слово Уругвай на английском языке. Надеемся, это поможет Вам улучшить свой английский язык.

Вот как будет Уругвай по-английски:

Uruguay

[править]

Уругвай на всех языках

Другие слова рядом со словом Уругвай

- урология

- урон

- уронить

- Уругвай

- урчать

- усадить

- усадьба

Цитирование

«Уругвай по-английски.» In Different Languages, https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/ru/%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BE/%D1%83%D1%80%D1%83%D0%B3%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%B9/%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8.

Копировать

Скопировано

Посмотрите другие переводы русских слов на английский язык:

- взятка

- время завтрака

- заместитель

- Какая музыка тебе нравится?

- национально-культурный

- подсистема

- правление

- смещение

- украинский

Слова по Алфавиту

Разбор слова «уругвай»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «уругвай» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «уругвай» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «уругвай».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «уругвай» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «уругвай»

- 3 Синонимы слова «уругвай»

- 4 Ударение в слове «уругвай»

- 5 Фонетическая транскрипция слова «уругвай»

- 6 Фонетический разбор слова «уругвай» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

- 7 Значение слова «уругвай»

- 8 Как правильно пишется слово «уругвай»

- 9 Ассоциации к слову «уругвай»

Слоги в слове «уругвай» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 3

По слогам: у-ру-гвай

По правилам школьной программы слово «Уругвай» можно поделить на слоги разными способами. Допускается вариативность, то есть все варианты правильные. Например, такой:

у-руг-вай

По программе института слоги выделяются на основе восходящей звучности:

у-ру-гвай

Ниже перечислены виды слогов и объяснено деление с учётом программы института и школ с углублённым изучением русского языка.

г примыкает к этому слогу, а не к предыдущему, так как не является сонорной (непарной звонкой согласной)

Как перенести слово «уругвай»

Уру—гвай

Уруг—вай

Синонимы слова «уругвай»

1. страна

2. река

3. американская швейцария

Ударение в слове «уругвай»

уругва́й — ударение падает на 3-й слог

Фонетическая транскрипция слова «уругвай»

[уругв`ай’]

Фонетический разбор слова «уругвай» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

| Буква | Звук | Характеристики звука | Цвет |

|---|---|---|---|

| У | [у] | гласный, безударный | У |

| р | [р] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), твёрдый | р |

| у | [у] | гласный, безударный | у |

| г | [г] | согласный, звонкий парный, твёрдый, шумный | г |

| в | [в] | согласный, звонкий парный, твёрдый, шумный | в |

| а | [`а] | гласный, ударный | а |

| й | [й’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий | й |

Число букв и звуков:

На основе сделанного разбора делаем вывод, что в слове 7 букв и 7 звуков.

Буквы: 3 гласных буквы, 4 согласных букв.

Звуки: 3 гласных звука, 4 согласных звука.

Значение слова «уругвай»

1. государство в юго-восточной части Южной Америки, граничащее на севере с Бразилией, на западе — с Аргентиной, на востоке и юге омывается Атлантическим океаном (Викисловарь)

Как правильно пишется слово «уругвай»

Правописание слова «уругвай»

Орфография слова «уругвай»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «уругвай» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «уругвай»

-

Аргентина

-

Чили

-

Венесуэла

-

Бразилия

-

Перу

-

Колумбия

-

Сборная

-

Бомбардир

-

Панама

-

Футбол

-

Чемпионат

-

Мексика

-

Полузащитник

-

Куба

-

Матч

-

Чемпион

-

Хосе

-

Футболист

-

Зеландия

-

Турнир

-

Португалия

-

Родригес

-

Департамент

-

Дивизион

-

Полуфинал

-

Люксембург

-

Бельгия

-

Гол

-

Таиланд

-

Америка

-

Исландия

-

Нидерланды

-

Четвертьфинал

-

Ямайка

-

Нападающий

-

Корея

-

Марокко

-

Румыния

-

Пакистан

-

Заявка

-

Первенство

-

Канада

-

Австралия

-

Хорватия

-

Альберто

-

Сербия

-

Албания

-

Норвегия

-

Словакия

-

Вратарь

-

Югославия

-

Швеция

-

Тунис

-

Флорида

-

Ливерпуль

-

Олимпиада

-

Кубок

-

Даний

-

Рубен

-

Розыгрыш

-

Арбитр

-

Фрг

-

Таблица

-

Колорадо

-

Швейцария

-

Диего

-

Чехословакия

-

Финал

-

Турция

-

Чехия

-

Испания

-

Хуан

-

Венгрия

-

Франция

-

Аравия

-

Конго

-

Тайм

-

Греция

-

Аргентинский

-

Сборный

-

Товарищеский

-

Молодёжный

-

Отборочный

-

Бразильский

-

Групповой

-

Атлантический

-

Футбольный

-

Финальный

-

Саудовский

-

Любительский

-

Апостольский

-

Южный

-

Юго-западный

-

Тренерский

-

Олимпийский

-

Дебютировать

-

Обыграть

-

Сыграть

-

Забить

-

Вызываться

|

Oriental Republic of Uruguay República Oriental del Uruguay (Spanish) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Motto: Libertad o Muerte «Freedom or Death» |

|

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Uruguay «National Anthem of Uruguay» |

|

| Sol de Mayo[1][2] (Sun of May)  |

|

Location of Uruguay (dark green) in South America |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Montevideo 34°53′S 56°10′W / 34.883°S 56.167°W |

| Official language |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2011) |

|

| Religion

(2021)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Uruguayan |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

|

• President |

Luis Lacalle Pou |

|

• Vice President |

Beatriz Argimón |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

Chamber of Representatives |

| Independence

from Brazil |

|

|

• Declared |

25 August 1825 |

|

• Recognized |

27 August 1828 |

|

• Current constitution |

15 February 1967 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

181,034 km2 (69,898 sq mi) (89th) |

|

• Water (%) |

1.5 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

3,407,213[6] (132nd) |

|

• Density |

19.8/km2 (51.3/sq mi) (206th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2019) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 58th |

| Currency | Uruguayan peso (UYU) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (UYT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +598 |

| ISO 3166 code | UY |

| Internet TLD | .uy |

Uruguay (;[10] Spanish: [uɾuˈɣwai] (listen)), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay or the Eastern Republic of Uruguay (Spanish: República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast. It is part of the Southern Cone region of South America. Uruguay covers an area of approximately 181,034 square kilometers (69,898 sq mi) and has a population of an estimated 3.4 million, of whom around 2 million live in the metropolitan area of its capital and largest city, Montevideo.

The area that became Uruguay was first inhabited by groups of hunter–gatherers 13,000 years ago.[11] The predominant tribe at the moment of the arrival of Europeans was the Charrúa people, when the Portuguese first established Colónia do Sacramento in 1680; Uruguay was colonized by Europeans late relative to neighboring countries. The Spanish founded Montevideo as a military stronghold in the early 18th century because of the competing claims over the region. Uruguay won its independence between 1811 and 1828, following a four-way struggle between Portugal and Spain, and later Argentina and Brazil. It remained subject to foreign influence and intervention throughout the 19th century, with the military playing a recurring role in domestic politics. A series of economic crises and the political repression against left-wing guerrilla activity in the late 1960s and early 1970s put an end to a democratic period that had begun in the early 20th century,[clarification needed] culminating in the 1973 coup d’état, which established a civic-military dictatorship. The military government persecuted leftists, socialists, and political opponents, resulting in deaths and numerous instances of torture by the military; the military relinquished power to a civilian government in 1985. Uruguay is today a democratic constitutional republic, with a president who serves as both head of state and head of government.

Uruguay is ranked first in the Americas for democracy, and first in Latin America in peace, low perception of corruption,[12] and e-government.[13][14] It is the lowest ranking South American nation in the Global Terrorism Index, and ranks second in the continent on economic freedom, income equality, per-capita income, and inflows of FDI.[12] Uruguay is the third-best country on the continent in terms of Human Development Index, GDP growth,[15] innovation, and infrastructure.[12] Uruguay is regarded as one of the most socially progressive countries in Latin America.[16] It ranks high on global measures of personal rights, tolerance, and inclusion issues,[17] including its acceptance of the LGBT community.[18] The country has legalized cannabis, same-sex marriage, prostitution and abortion. Uruguay is a founding member of the United Nations, OAS, and Mercosur.

Etymology[edit]

The country name of Uruguay derives from the namesake Río Uruguay, from the Indigenous Guaraní language. There are several interpretations, including «bird-river» («the river of the uru, via Charruan, urú being a common noun of any wild fowl).[19][20] The name could also refer to a river snail called uruguá (Pomella megastoma) that was plentiful across its shores.[21]

One of the most popular interpretations of the name was proposed by the renowned Uruguayan poet Juan Zorrilla de San Martín, «the river of painted birds»;[22] this interpretation, although dubious, still holds an important cultural significance in the country.[23]

In Spanish colonial times, and for some time thereafter, Uruguay and some neighboring territories were called Banda Oriental [del Uruguay] («Eastern Bank [of the Uruguay River]»), then for a few years the «Eastern Province». Since its independence, the country has been known as «República Oriental del Uruguay«, which literally translates to «Republic East of the Uruguay [River]». However, it is officially translated either as the «Oriental Republic of Uruguay«[24][25] or the «Eastern Republic of Uruguay«.[26]

History[edit]

Monument to the last four Charrúa, the indigenous people of Uruguay

Pre-colonial[edit]

Uruguay was first inhabited around 13,000 years ago by hunter-gatherers.[11] It is estimated that at the time of the first contact with Europeans in the 16th century there were about 9,000 Charrúa and 6,000 Chaná and some Guaraní island-settlements.[27]

There is an extensive archeological collection of man-made tumuli known as «Cerritos de Indios» in the eastern part of the country, some of them dating back to 5,000 years ago. Very little is known about the people who built them as they left no written record, but evidence has been found in place of pre-columbian agriculture and of extinct pre-columbian dogs.[28]

In 1831 Fructuoso Rivera, Uruguay’s first president, organized the final strike of the Charrua genocide, eradicating the last remnants of the Uruguayan native population in the Salsipuedes Massacre.[29]

Early colonization[edit]

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to enter the region of present-day Uruguay in 1512.[30][31] The Spanish arrived in present-day Uruguay in 1516.[32] The indigenous peoples’ fierce resistance to conquest, combined with the absence of gold and silver, limited European settlement in the region during the 16th and 17th centuries.[32] Uruguay then became a zone of contention between the Spanish and Portuguese empires. In 1603, the Spanish began to introduce cattle, which became a source of wealth in the region. The first permanent Spanish settlement was founded in 1624 at Soriano on the Río Negro. In 1669–71, the Portuguese built a fort at Colonia del Sacramento (Colônia do Sacramento).

Montevideo was founded by the Spanish in the early 18th century as a military stronghold in the country. Its natural harbor soon developed into a commercial area competing with Río de la Plata’s capital, Buenos Aires.[32] Uruguay’s early 19th-century history was shaped by ongoing fights for dominance in the Platine region,[32] between British, Spanish, Portuguese and other colonial forces. In 1806 and 1807, the British army attempted to seize Buenos Aires and Montevideo as part of the Napoleonic Wars. Montevideo was occupied by a British force from February to September 1807.

Independence struggle[edit]

In 1811, José Gervasio Artigas, who became Uruguay’s national hero, launched a successful revolt against the Spanish authorities, defeating them on 18 May at the Battle of Las Piedras.[32]

In 1813, the new government in Buenos Aires convened a constituent assembly where Artigas emerged as a champion of federalism, demanding political and economic autonomy for each area, and for the Banda Oriental in particular.[33] The assembly refused to seat the delegates from the Banda Oriental, however, and Buenos Aires pursued a system based on unitary centralism.[33]

As a result, Artigas broke with Buenos Aires and besieged Montevideo, taking the city in early 1815.[33] Once the troops from Buenos Aires had withdrawn, the Banda Oriental appointed its first autonomous government.[33] Artigas organized the Federal League under his protection, consisting of six provinces, four of which later became part of Argentina.[33]

In 1816, a force of 10,000 Portuguese troops invaded the Banda Oriental from Brazil; they took Montevideo in January 1817.[33] After nearly four more years of struggle, the Portuguese Kingdom of Brazil annexed the Banda Oriental as a province under the name of «Cisplatina».[33] The Brazilian Empire became independent of Portugal in 1822. In response to the annexation, the Thirty-Three Orientals, led by Juan Antonio Lavalleja, declared independence on 25 August 1825 supported by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (present-day Argentina).[32] This led to the 500-day-long Cisplatine War. Neither side gained the upper hand and in 1828 the Treaty of Montevideo, fostered by the United Kingdom through the diplomatic efforts of Viscount John Ponsonby, gave birth to Uruguay as an independent state. 25 August is celebrated as Independence Day, a national holiday.[34] The nation’s first constitution was adopted on 18 July 1830.[32]

19th century[edit]

At the time of independence, Uruguay had an estimated population of just under 75,000.[35] The political scene in Uruguay became split between two parties: the conservative Blancos (Whites) headed by the second President Manuel Oribe, representing the agricultural interests of the countryside; and the liberal Colorados (Reds) led by the first President Fructuoso Rivera, representing the business interests of Montevideo. The Uruguayan parties received support from warring political factions in neighboring Argentina, which became involved in Uruguayan affairs.

The Colorados favored the exiled Argentine liberal Unitarios, many of whom had taken refuge in Montevideo while the Blanco president Manuel Oribe was a close friend of the Argentine ruler Manuel de Rosas. On 15 June 1838, an army led by the Colorado leader Rivera overthrew President Oribe, who fled to Argentina.[35] Rivera declared war on Rosas in 1839. The conflict would last 13 years and become known as the Guerra Grande (the Great War).[35]

In 1843, an Argentine army overran Uruguay on Oribe’s behalf but failed to take the capital. The siege of Montevideo, which began in February 1843, would last nine years.[36] The besieged Uruguayans called on resident foreigners for help, which led to a French and an Italian legion being formed, the latter led by the exiled Giuseppe Garibaldi.[36]

In 1845, Britain and France intervened against Rosas to restore commerce to normal levels in the region. Their efforts proved ineffective and, by 1849, tired of the war, both withdrew after signing a treaty favorable to Rosas.[36] It appeared that Montevideo would finally fall when an uprising against Rosas, led by Justo José de Urquiza, governor of Argentina’s Entre Ríos Province, began. The Brazilian intervention in May 1851 on behalf of the Colorados, combined with the uprising, changed the situation and Oribe was defeated. The siege of Montevideo was lifted and the Guerra Grande finally came to an end.[36] Montevideo rewarded Brazil’s support by signing treaties that confirmed Brazil’s right to intervene in Uruguay’s internal affairs.[36]

In accordance with the 1851 treaties, Brazil intervened militarily in Uruguay as often as it deemed necessary.[37] In 1865, the Triple Alliance was formed by the emperor of Brazil, the president of Argentina, and the Colorado general Venancio Flores, the Uruguayan head of government whom they both had helped to gain power. The Triple Alliance declared war on the Paraguayan leader Francisco Solano López[37] and the resulting Paraguayan War ended with the invasion of Paraguay and its defeat by the armies of the three countries. Montevideo, which was used as a supply station by the Brazilian navy, experienced a period of prosperity and relative calm during the war.[37]

The first railway line was assembled in Uruguay in 1867 with the opening of a branch consisting of a horse-drawn train. The present-day State Railways Administration of Uruguay maintains 2,900 kms of extendable railway network.[38]

The constitutional government of General Lorenzo Batlle y Grau (1868–72) suppressed the Revolution of the Lances by the Blancos.[39] After two years of struggle, a peace agreement was signed in 1872 that gave the Blancos a share in the emoluments and functions of government, through control of four of the departments of Uruguay.[39]

This establishment of the policy of co-participation represented the search for a new formula of compromise, based on the coexistence of the party in power and the party in opposition.[39]

Despite this agreement, Colorado rule was threatened by the failed Tricolor Revolution in 1875 and the Revolution of the Quebracho in 1886.

The Colorado effort to reduce Blancos to only three departments caused a Blanco uprising of 1897, which ended with the creation of 16 departments, of which the Blancos now had control over six. Blancos were given ⅓ of seats in Congress.[40] This division of power lasted until the President Jose Batlle y Ordonez instituted his political reforms which caused the last uprising by Blancos in 1904 that ended with the Battle of Masoller and the death of Blanco leader Aparicio Saravia.

Between 1875 and 1890, the military became the center of power.[41] During this authoritarian period, the government took steps toward the organization of the country as a modern state, encouraging its economic and social transformation. Pressure groups (consisting mainly of businessmen, hacendados, and industrialists) were organized and had a strong influence on government.[41] A transition period (1886–90) followed, during which politicians began recovering lost ground and some civilian participation in government occurred.[41]

After the Guerra Grande, there was a sharp rise in the number of immigrants, primarily from Italy and Spain. By 1879, the total population of the country was over 438,500.[42] The economy reflected a steep upswing (if demonstrated graphically, above all other related economic determinants), in livestock raising and exports.[42] Montevideo became a major economic center of the region and an entrepôt for goods from Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay.[42]

20th century[edit]

The Colorado leader José Batlle y Ordóñez was elected president in 1903.[43] The following year, the Blancos led a rural revolt and eight bloody months of fighting ensued before their leader, Aparicio Saravia, was killed in battle. Government forces emerged victorious, leading to the end of the co-participation politics that had begun in 1872.[43] Batlle had two terms (1903–07 and 1911–15) during which, taking advantage of the nation’s stability and growing economic prosperity, he instituted major reforms, such as a welfare program, government participation in many facets of the economy, and a plural executive.[32]

Gabriel Terra became president in March 1931. His inauguration coincided with the effects of the Great Depression,[44] and the social climate became tense as a result of the lack of jobs. There were confrontations in which police and leftists died.[44] In 1933, Terra organized a coup d’état, dissolving the General Assembly and governing by decree.[44] A new constitution was promulgated in 1934, transferring powers to the president.[44] In general, the Terra government weakened or neutralized economic nationalism and social reform.[44]

In 1938, general elections were held and Terra’s brother-in-law, General Alfredo Baldomir, was elected president. Under pressure from organized labor and the National Party, Baldomir advocated free elections, freedom of the press, and a new constitution.[45] Although Baldomir declared Uruguay neutral in 1939, British warships and the German ship Admiral Graf Spee fought a battle not far off Uruguay’s coast.[45] The Admiral Graf Spee took refuge in Montevideo, claiming sanctuary in a neutral port, but was later ordered out.[45]

In the late 1950s, partly because of a worldwide decrease in demand for Uruguyan agricultural products, Uruguayans suffered from a steep drop in their standard of living, which led to student militancy and labor unrest. An armed group, known as the Tupamaros emerged in the 1960s, engaging in activities such as bank robbery, kidnapping and assassination, in addition to attempting an overthrow of the government.

Civic-military and Dictatorship regime[edit]

President Jorge Pacheco declared a state of emergency in 1968, followed by a further suspension of civil liberties in 1972. In 1973, amid increasing economic and political turmoil, the armed forces, asked by the President Juan María Bordaberry, disbanded Parliament and established a civilian-military regime.[32] The CIA-backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence operations and assassination of opponents was called Operation Condor.[46] The media were censored or banned, the trade union movement was destroyed and tons of books were burned after the banning of some writers’ works. People on file as opponents of the regime were excluded from the civil service and from education. According to one source, around 180 Uruguayans are known to have been killed and disappeared, with thousands more illegally detained and tortured during the 12-year civil-military rule of 1973 to 1985.[47] Most were killed in Argentina and other neighboring countries, with 36 of them having been killed in Uruguay.[48] According to Edy Kaufman (cited by David Altman[49]), Uruguay at the time had the highest per capita number of political prisoners in the world. «Kaufman, who spoke at the U.S. Congressional Hearings of 1976 on behalf of Amnesty International, estimated that one in every five Uruguayans went into exile, one in fifty were detained, and one in five hundred went to prison (most of them tortured).» Minister of Economy and Finance Alejandro Végh Villegas seeks to promote the financial sector and foreign investment. Social spending was reduced and many state-owned companies were privatized. However, the economy did not improve and deteriorated after 1980, the GDP fell by 20% and unemployment rose to 17%. The state intervened by trying to bail out failing companies and banks.[50]

Return to democracy (1984–present)[edit]

A new constitution, drafted by the military, was rejected in a November 1980 referendum.[32] Following the referendum, the armed forces announced a plan for the return to civilian rule, and national elections were held in 1984.[32] Colorado Party leader Julio María Sanguinetti won the presidency and served from 1985 to 1990. The first Sanguinetti administration implemented economic reforms and consolidated democracy following the country’s years under military rule.[32]

The National Party’s Luis Alberto Lacalle won the 1989 presidential election and amnesty for human rights abusers was endorsed by referendum. Sanguinetti was then re-elected in 1994.[51] Both presidents continued the economic structural reforms initiated after the reinstatement of democracy and other important reforms were aimed at improving the electoral system, social security, education, and public safety.

The 1999 national elections were held under a new electoral system established by a 1996 constitutional amendment. Colorado Party candidate Jorge Batlle, aided by the support of the National Party, defeated Broad Front candidate Tabaré Vázquez. The formal coalition ended in November 2002, when the Blancos withdrew their ministers from the cabinet,[32] although the Blancos continued to support the Colorados on most issues. On the economic front, the Batlle government (2000–2005) began negotiations with the United States to create the «Free Trade Area of the Americas» (FTAA). The period marked the culmination of a process aimed at a neoliberal reorientation of the country’s economy: deindustrialization, pressure on wages, growth of informal work, etc.[52] Low commodity prices and economic difficulties in Uruguay’s main export markets (starting in Brazil with the devaluation of the real, then in Argentina in 2002), caused a severe recession; the economy contracted by 11%, unemployment climbed to 21%, and the percentage of Uruguayans in poverty rose to over 30%.[53]

In 2004, Uruguayans elected Tabaré Vázquez as president, while giving the Broad Front a majority in both houses of Parliament.[54] Vázquez stuck to economic orthodoxy. As commodity prices soared and the economy recovered from the recession, he tripled foreign investment, cut poverty and unemployment, cut public debt from 79% of GDP to 60%, and kept inflation steady.[55]

In 2009, José Mujica, a former left-wing guerrilla leader (Tupamaros) who spent almost 15 years in prison during the country’s military rule, emerged as the new president as the Broad Front won the election for a second time.[56][57] Abortion was legalized in 2012,[58] followed by same-sex marriage[59] and cannabis in the following year.[60]

In 2014, Tabaré Vázquez was elected to a non-consecutive second presidential term, which began on 1 March 2015.[61] In 2020, he was succeeded by Luis Alberto Lacalle Pou, member of the conservative National Party, after 15 years of left-wing rule, as the 42nd President of Uruguay.[62]

Geography[edit]

Topographical map of Uruguay

With 176,214 km2 (68,037 sq mi) of continental land and 142,199 km2 (54,903 sq mi) of jurisdictional water and small river islands,[63] Uruguay is the second smallest sovereign nation in South America (after Suriname) and the third smallest territory (French Guiana is the smallest).[24] The landscape features mostly rolling plains and low hill ranges (cuchillas) with a fertile coastal lowland.[24] Uruguay has 660 km (410 mi) of coastline.[24]

A dense fluvial network covers the country, consisting of four river basins, or deltas: the Río de la Plata Basin, the Uruguay River, the Laguna Merín and the Río Negro. The major internal river is the Río Negro (‘Black River’). Several lagoons are found along the Atlantic coast.

The highest point in the country is the Cerro Catedral, whose peak reaches 514 metres (1,686 ft) AMSL in the Sierra Carapé hill range. To the southwest is the Río de la Plata, the estuary of the Uruguay River (which river forms the country’s western border).

Montevideo is the southernmost capital city in the Americas, and the third most southerly in the world (only Canberra and Wellington are further south). Uruguay is the only country in South America situated entirely south of the Tropic of Capricorn.

There are ten national parks in Uruguay: Five in the wetland areas of the east, three in the central hill country, and one in the west along the Rio Uruguay.

Uruguay is home to the Uruguayan savanna terrestrial ecoregion.[64] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.61/10, ranking it 147th globally out of 172 countries.[65]

Climate[edit]

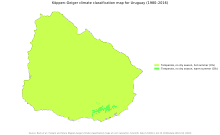

Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Uruguay

Located entirely within the southern temperate zone, Uruguay has a climate that is relatively mild and fairly uniform nationwide.[66] According to the Köppen Climate Classification, most of the country has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). Only in some spots of the Atlantic Coast and at the summit of the highest hills of the Cuchilla Grande the climate is oceanic (Cfb). The country experiences the four seasons, with summer being from December to March and winter from June to September. Seasonal variations are pronounced, but extremes in temperature are rare.[66] Summers are tempered by winds off the Atlantic, and severe cold in winter is unknown.[66][67] Although it never gets too cold, frosts occur every year during the winter months, and precipitation such as sleet and hail occur almost every winter, but snow is very rare; it does occur every couple of years at higher elevations, but almost always without accumulation. As would be expected with its abundance of water, high humidity and fog are common.[66] The absence of mountains, which act as weather barriers, makes all locations vulnerable to high winds and rapid changes in weather as fronts or storms sweep across the country.[66] These storms can be strong; they can bring squalls, hail, and sometimes even tornadoes.[68] The country experiences extratropical cyclones but no tropical cyclones, due to the fact that the South Atlantic Ocean is rarely warm enough for their development. Both summer and winter weather may vary from day to day with the passing of storm fronts, where a hot northerly wind may occasionally be followed by a cold wind (pampero) from the Argentine Pampas.[25]

Even though both temperature and precipitation are quite uniform nationwide, there are considerable differences across the territory. The average annual temperature of the country is 17.5 °C (63.5 °F), ranging from 16 °C (61 °F) in the southeast to 19 °C (66 °F) in the northwest.[69] Winter temperatures range from a daily average of 11 °C (52 °F) in the south to 14 °C (57 °F) in the north, while summer average daily temperatures range from 21 °C (70 °F) in the southeast to 25 °C (77 °F) in the northwest.[70] The southeast is considerably cooler than the rest of the country, especially during spring, when the ocean with cold water after the winter cools down the temperature of the air and brings more humidity to that region. However, the south of the country receives less precipitation than the north. For example, Montevideo receives approximately 1,100 millimetres (43 in) of precipitation per year, while the city of Rivera in the northeast receives 1,600 millimetres (63 in).[69] The heaviest precipitation occurs during the autumn months, although more frequent rainy spells occur in winter.[25] But still the difference is not big enough to consider a dry or wet season, periods of drought or excessive rain can occur anytime during the year.

National extreme temperatures at sea level are, 44 °C (111 °F) in Paysandú city (20 January 1943) and Florida city (January 14, 2022),[71] and −11.0 °C (12.2 °F) in Melo city (14 June 1967).[72]

Government and politics[edit]

Uruguay is a representative democratic republic with a presidential system.[73] The members of government are elected for a five-year term by a universal suffrage system.[73] Uruguay is a unitary state: justice, education, health, security, foreign policy and defense are all administered nationwide.[73] The Executive Power is exercised by the president and a cabinet of 13 ministers.[73]

The legislative power is constituted by the General Assembly, composed of two chambers: the Chamber of Representatives, consisting of 99 members representing the 19 departments, elected for a five-year term based on proportional representation; and the Chamber of Senators, consisting of 31 members, 30 of whom are elected for a five-year term by proportional representation and the vice-president, who presides over the chamber.[73]

The judicial arm is exercised by the Supreme Court, the Bench and Judges nationwide. The members of the Supreme Court are elected by the General Assembly; the members of the Bench are selected by the Supreme Court with the consent of the Senate, and the Judges are directly assigned by the Supreme Court.[73]

Uruguay adopted its current constitution in 1967.[74][75] Many of its provisions were suspended in 1973, but re-established in 1985. Drawing on Switzerland and its use of the initiative, the Uruguayan Constitution also allows citizens to repeal laws or to change the constitution by popular initiative, which culminates in a nationwide referendum. This method has been used several times over the past 15 years: to confirm a law renouncing prosecution of members of the military who violated human rights during the military regime (1973–1985); to stop privatization of public utilities companies; to defend pensioners’ incomes; and to protect water resources.[76]

For most of Uruguay’s history, the Partido Colorado has been in government.[77][78] However, in the 2004 Uruguayan general election, the Broad Front won an absolute majority in Parliamentary elections, and in 2009, José Mujica of the Broad Front defeated Luis Alberto Lacalle of the Blancos to win the presidency. In March 2020, Uruguay got a conservative government, meaning the end of 15 years of left-wing leadership under the Broad Front coalition. At the same time centre-right National Party’s Luis Lacalle Pou was sworn as the new President of Uruguay.[79]

A 2010 Latinobarómetro poll found that, within Latin America, Uruguayans are among the most supportive of democracy and by far the most satisfied with the way democracy works in their country.[80] Uruguay ranked 27th in the Freedom House «Freedom in the World» index. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2012, Uruguay scored an 8.17 in the Democracy Index and ranked equal 18th amongst the 25 countries considered to be full democracies in the world.[81] Uruguay ranks 21st as least corrupt in the World Corruption Perceptions Index composed by Transparency International.

Administrative divisions[edit]

A map of the departments of Uruguay

Uruguay is divided into 19 departments whose local administrations replicate the division of the executive and legislative powers.[73] Each department elects its own authorities through a universal suffrage system.[73] The departmental executive authority resides in a superintendent and the legislative authority in a departmental board.[73]

| Department | Capital | Area | Population (2011 census)[82] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | |||

| Artigas | Artigas | 11,928 | 4,605 | 73,378 |

| Canelones | Canelones | 4,536 | 1,751 | 520,187 |

| Cerro Largo | Melo | 13,648 | 5,270 | 84,698 |

| Colonia | Colonia del Sacramento | 6,106 | 2,358 | 123,203 |

| Durazno | Durazno | 11,643 | 4,495 | 57,088 |

| Flores | Trinidad | 5,144 | 1,986 | 25,050 |

| Florida | Florida | 10,417 | 4,022 | 67,048 |

| Lavalleja | Minas | 10,016 | 3,867 | 58,815 |

| Maldonado | Maldonado | 4,793 | 1,851 | 164,300 |

| Montevideo | Montevideo | 530 | 200 | 1,319,108 |

| Paysandú | Paysandú | 13,922 | 5,375 | 113,124 |

| Río Negro | Fray Bentos | 9,282 | 3,584 | 54,765 |

| Rivera | Rivera | 9,370 | 3,620 | 103,493 |

| Rocha | Rocha | 10,551 | 4,074 | 68,088 |

| Salto | Salto | 14,163 | 5,468 | 124,878 |

| San José | San José de Mayo | 4,992 | 1,927 | 108,309 |

| Soriano | Mercedes | 9,008 | 3,478 | 82,595 |

| Tacuarembó | Tacuarembó | 15,438 | 5,961 | 90,053 |

| Treinta y Tres | Treinta y Tres | 9,529 | 3,679 | 48,134 |

| Total[note 2] | — | 175,016 | 67,574 | 3,286,314 |

Foreign relations[edit]

Current Uruguay’s president Luis Lacalle Pou at a press conference, Apr. 22, 2022.

Argentina and Brazil are Uruguay’s most important trading partners: Argentina accounted for 20% of total imports in 2009.[24] Since bilateral relations with Argentina are considered a priority, Uruguay denies clearance to British naval vessels bound for the Falkland Islands, and prevents them from calling in at Uruguayan territories and ports for supplies and fuel.[83] A rivalry between the port of Montevideo and the port of Buenos Aires, dating back to the times of the Spanish Empire, has been described as a «port war». Officials of both countries emphasized the need to end this rivalry in the name of regional integration in 2010.[84]

Construction of a controversial pulp paper mill in 2007, on the Uruguayan side of the Uruguay River, caused protests in Argentina over fears that it would pollute the environment and lead to diplomatic tensions between the two countries.[85] The ensuing dispute remained a subject of controversy into 2010, particularly after ongoing reports of increased water contamination in the area were later proven to be from sewage discharge from the town of Gualeguaychú in Argentina.[86][87] In November 2010, Uruguay and Argentina announced they had reached a final agreement for joint environmental monitoring of the pulp mill.[88]

Brazil and Uruguay have signed cooperation agreements on defence, science, technology, energy, river transportation and fishing, with the hope of accelerating political and economic integration between these two neighbouring countries.[89] Uruguay has two uncontested boundary disputes with Brazil, over Isla Brasilera and the 235 km2 (91 sq mi) Invernada River region near Masoller. The two countries disagree on which tributary represents the legitimate source of the Quaraí/Cuareim River, which would define the border in the latter disputed section, according to the 1851 border treaty between the two countries.[24] However, these border disputes have not prevented both countries from having friendly diplomatic relations and strong economic ties. So far, the disputed areas remain de facto under Brazilian control, with little to no actual effort by Uruguay to assert its claims.

Uruguay has enjoyed friendly relations with the United States since its transition back to democracy.[53] Commercial ties between the two countries have expanded substantially in recent years, with the signing of a bilateral investment treaty in 2004 and a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement in January 2007.[53] The United States and Uruguay have also cooperated on military matters, with both countries playing significant roles in the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti.[53]

President Mujica backed Venezuela’s bid to join Mercosur. Venezuela had a deal to sell Uruguay up to 40,000 barrels of oil a day under preferential terms.[90]

On 15 March 2011, Uruguay became the seventh South American nation to officially recognize a Palestinian state,[91] although there was no specification for the Palestinian state’s borders as part of the recognition. In statements, the Uruguayan government indicated its firm commitment to the Middle East peace process, but refused to specify borders «to avoid interfering in an issue that would require a bilateral agreement».[91]

In 2017, Uruguay signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[92]

In March 2020, Uruguay rejoined the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (TIAR or «Rio Pact»). In September 2019, the previous left-wing government of Uruguay had withdrawn from TIAR as a response to the very critical view of Venezuela the other members of the regional defense agreement had.[93]

Military[edit]

The Uruguayan armed forces are constitutionally subordinate to the president, through the minister of defense.[32] Armed forces personnel number about 14,000 for the Army, 6,000 for the Navy, and 3,000 for the Air Force.[32] Enlistment is voluntary in peacetime, but the government has the authority to conscript in emergencies.[24]

Since May 2009, homosexuals have been allowed to serve in the military after the defense minister signed a decree stating that military recruitment policy would no longer discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation.[94] In the fiscal year 2010, the United States provided Uruguay with $1.7 million in military assistance, including $1 million in Foreign Military Financing and $480,000 in International Military Education and Training.[53]

Uruguay ranks first in the world on a per capita basis for its contributions to the United Nations peacekeeping forces, with 2,513 soldiers and officers in 10 UN peacekeeping missions.[32] As of February 2010, Uruguay had 1,136 military personnel deployed to Haiti in support of MINUSTAH and 1,360 deployed in support of MONUC in the Congo.[32] In December 2010, Uruguayan Major General Gloodtdofsky, was appointed Chief Military Observer and head of the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan.[95]

Economy[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2020) |

GDP per capita development since 1900

A proportional representation of Uruguay exports, 2019

In 1991, the country experienced an increase in strikes to obtain wage compensation to offset inflation and to oppose the privatizations desired by the government of Luis Alberto Lacalle. A general strike was called in 1992, and the privatization policy was widely rejected by referendum (71.6% against the privatization of telecommunications). In 1994 and 1995, Uruguay faced economic difficulties caused by the liberalization of foreign trade, which increased the trade deficit. The Montevideo Gas Company and the Pluma airline were turned over to the private sector, but the pace of privatization slowed down in 1996. Uruguay experienced a major economic and financial crisis between 1999 and 2002, principally a spillover effect from the economic problems of Argentina.[53] The economy contracted by 11%, and unemployment climbed to 21%.[53] Despite the severity of the trade shocks, Uruguay’s financial indicators remained more stable than those of its neighbours, a reflection of its solid reputation among investors and its investment-grade sovereign bond rating, one of only two in South America.[96][needs update]

In 2004, the Batlle government signed a three-year $1.1 billion stand-by arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), committing the country to a substantial primary fiscal surplus, low inflation, considerable reductions in external debt, and several structural reforms designed to improve competitiveness and attract foreign investment.[53] Uruguay terminated the agreement in 2006 following the early repayment of its debt but maintained a number of the policy commitments.[53]

Vázquez, who assumed the government in March 2005, created the Ministry of Social Development and sought to reduce the country’s poverty rate with a $240 million National Plan to Address the Social Emergency (PANES), which provided a monthly conditional cash transfer of approximately $75 to over 100,000 households in extreme poverty. In exchange, those receiving the benefits were required to participate in community work, ensure that their children attended school daily, and had regular health check-ups.[53]

Following the 2001 Argentine credit default, prices in the Uruguayan economy made a variety of services, including information technology and architectural expertise, once too expensive in many foreign markets, exportable.[97] The Frente Amplio government, while continuing payments on Uruguay’s external debt,[98] also undertook an emergency plan to attack the widespread problems of poverty and unemployment.[99] The economy grew at an annual rate of 6.7% during the 2004–2008 period.[100] Uruguay’s exports markets have been diversified to reduce dependency on Argentina and Brazil.[100] Poverty was reduced from 33% in 2002 to 21.7% in July 2008, while extreme poverty dropped from 3.3% to 1.7%.[100]

Between the years 2007 and 2009, Uruguay was the only country in the Americas that did not technically experience a recession (two consecutive downward quarters).[101] Unemployment reached a record low of 5.4% in December 2010 before rising to 6.1% in January 2011.[102] While unemployment is still at a low level, the IMF observed a rise in inflationary pressures,[103] and Uruguay’s GDP expanded by 10.4% for the first half of 2010.[104]

According to IMF estimates, Uruguay was likely to achieve growth in real GDP of between 8% and 8.5% in 2010, followed by 5% growth in 2011 and 4% in subsequent years.[103] Gross public sector debt contracted in the second quarter of 2010, after five consecutive periods of sustained increase, reaching $21.885 billion US dollars, equivalent to 59.5% of the GDP.[105] Uruguay was ranked 65th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 62nd in 2019.[106][107][108][109]

The growth, use, and sale of cannabis was legalized on 11 December 2013,[110] making Uruguay the first country in the world to fully legalize marijuana. The law was voted at the Uruguayan Senate on the same date with 16 votes to approve it and 13 against.

The number of union members has quadrupled since 2003, rising from 110,000 to more than 400,000 in 2015 for a working population of 1.5 million.According to the International Trade Union Confederation, Uruguay has become the most advanced country in the Americas in terms of respect for «fundamental labour rights, in particular the freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining and the right to strike. One of the effects of this high level of unionization was to reduce socio-economic inequalities.[52]

Agriculture[edit]

In 2010, Uruguay’s export-oriented agricultural sector contributed to 9.3% of the GDP and employed 13% of the workforce.[24] Official statistics from Uruguay’s Agriculture and Livestock Ministry indicate that meat and sheep farming in Uruguay occupies 59.6% of the land. The percentage further increases to 82.4% when cattle breeding is linked to other farm activities such as dairy, forage, and rotation with crops such as rice.[111]

According to FAOSTAT, Uruguay is one of the world’s largest producers of soybeans (9th), wool (12th), horse meat (14th), beeswax (14th), and quinces (17th). Most farms (25,500 out of 39,120) are family-managed; beef and wool represent the main activities and main source of income for 65% of them, followed by vegetable farming at 12%, dairy farming at 11%, hogs at 2%, and poultry also at 2%.[111] Beef is the main export commodity of the country, totaling over US$1 billion in 2006.[111]

In 2007, Uruguay had cattle herds totalling 12 million head, making it the country with the highest number of cattle per capita at 3.8.[111] However, 54% is in the hands of 11% of farmers, who have a minimum of 500 head. At the other extreme, 38% of farmers exploit small lots and have herds averaging below one hundred head.[111]

Tourism[edit]

The tourism industry in Uruguay is an important part of its economy. In 2012 the sector was estimated to account for 97,000 jobs and (directly and indirectly) 9% of GDP.[112]

In 2013, 2.8 million tourists entered Uruguay, of whom 59% came from Argentina and 14% from Brazil, with Chileans, Paraguayans, North Americans and Europeans accounting for most of the remainder.[112]

Cultural experiences in Uruguay include exploring the country’s colonial heritage, as found in Colonia del Sacramento. Montevideo, the country’s capital, houses the most diverse selection of cultural activities. Historical monuments such as Torres García Museum as well as Estadio Centenario, which housed the first world cup in history, are examples. However, simply walking the streets allows tourists to experience the city’s colorful culture.

One of the main natural attractions in Uruguay is Punta del Este. Punta del Este is situated on a small peninsula off the southeast coast of Uruguay. Its beaches are divided into Mansa, or tame (river) side and Brava, or rugged (ocean) side. The Mansa is more suited for sunbathing, snorkeling, & other low-key recreational opportunities, while the Brava is more suited for adventurous sports, such as surfing. Punta del Este adjoins the city of Maldonado, while to its northeast along the coast are found the smaller resorts of La Barra and José Ignacio.[113]

Uruguay is the Latin American country that receives the most tourists in relation to its population. For Uruguay, Argentine tourism is key, since it represents 56% of the external tourism they receive each year and 70% during the summer months. Although Argentine holidaymakers are an important target market for tourism in Uruguay, in recent years the country has managed to position itself as an important tourist destination to other markets, receiving a high flow of visitors from countries such as Brazil, Paraguay and the United States, among others.[114]

Transportation[edit]

The Port of Montevideo, handling over 1.1 million containers annually, is the most advanced container terminal in South America.[115] Its quay can handle 14-metre draught (46 ft) vessels. Nine straddle cranes allow for 80 to 100 movements per hour.[115] The port of Nueva Palmira is a major regional merchandise transfer point and houses both private and government-run terminals.[116]

Carrasco International Airport was initially inaugurated in 1947 and in 2009, Puerta del Sur, the airport owner and operator, with an investment of $165 million, commissioned Rafael Viñoly Architects to expand and modernize the existing facilities with a spacious new passenger terminal to increase capacity and spur commercial growth and tourism in the region.[117][118] The London-based magazine Frontier chose the Carrasco International Airport, serving Montevideo, as one of the best four airports in the world in its 27th edition. The airport can handle up to 4.5 million users per year.[117] PLUNA was the flag carrier of Uruguay, and was headquartered in Carrasco.[119][120]

The Punta del Este International Airport, located 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from Punta del Este in the Maldonado Department, is the second busiest air terminal in Uruguay, built by the Uruguayan architect Carlos Ott it was inaugurated in 1997.[116]

The Administración de Ferrocarriles del Estado is the autonomous agency in charge of rail transport and the maintenance of the railroad network. Uruguay has about 1,200 km (750 mi) of operational railroad track.[24] Until 1947, about 90% of the railroad system was British-owned.[121] In 1949, the government nationalized the railways, along with the electric trams and the Montevideo Waterworks Company.[121] However, in 1985 the «National Transport Plan» suggested passenger trains were too costly to repair and maintain.[121] Cargo trains would continue for loads more than 120 tons, but bus transportation became the «economic» alternative for travellers.[121] Passenger service was then discontinued in 1988.[121] However, rail passenger commuter service into Montevideo was restarted in 1993, and now comprises three suburban lines.

Surfaced roads connect Montevideo to the other urban centers in the country, the main highways leading to the border and neighboring cities. Numerous unpaved roads connect farms and small towns. Overland trade has increased markedly since Mercosur (Southern Common Market) was formed in the 1990s and again in the later 2000s.[122] Most of the country’s domestic freight and passenger service is by road rather than rail.

The country has several international bus services[123] connecting the capital and frontier localities to neighboring countries.[124] Namely, 17 destinations in Argentina,[note 3] 12 destinations in Brazil[note 5] and the capital cities of Chile and Paraguay.[125]

Telecommunications[edit]

The Telecommunications industry is more developed than in most other Latin American countries, being the first country in the Americas to achieve complete digital telephone coverage in 1997. The telephone system is completely digitized and has very good coverage over all the country. The system is government owned, and there have been controversial proposals to partially privatize since the 1990s.[126]

The mobile phone market is shared by the state-owned ANTEL and two private companies, Movistar and Claro.

Energy[edit]

More than 97%[127] of Uruguay’s electricity comes from renewable energy. The dramatic shift, taking less than ten years and without government funding, lowered electricity costs and slashed the country’s carbon footprint.[128][129] Most of the electricity comes from hydroelectric facilities and wind parks. Uruguay no longer imports electricity.[130]

In 2021, Uruguay had, in terms of installed renewable electricity, 1,538 MW in hydropower, 1,514 MW in wind power (35th largest in the world), 258 MW in solar power (66nd largest in the world), and 423 MW in biomass.[131]

Demographics[edit]

Population pyramid in 2020

Uruguayans are of predominantly European origin, with over 87.7% of the population claiming European descent in the 2011 census.[132]

Most Uruguayans of European ancestry are descendants of 19th and 20th century immigrants from Spain and Italy,[32] and to a lesser degree Germany, France and Britain.[25] Earlier settlers had migrated from Argentina.[25] People of African descent make up around five percent of the total.[25] There are also important communities of Japanese.[133] Overall, the ethnic composition is similar to neighboring Argentine provinces as well as Southern Brazil.[134]

From 1963 to 1985, an estimated 320,000 Uruguayans emigrated.[135] The most popular destinations for Uruguayan emigrants are Argentina, followed by the United States, Australia, Canada, Spain, Italy and France.[135] In 2009, for the first time in 44 years, the country saw an overall positive influx when comparing immigration to emigration. 3,825 residence permits were awarded in 2009, compared with 1,216 in 2005.[136] 50% of new legal residents come from Argentina and Brazil. A migration law passed in 2008 gives immigrants the same rights and opportunities that nationals have, with the requisite of proving a monthly income of $650.[136]

Uruguay’s rate of population growth is much lower than in other Latin American countries.[25] Its median age is 35.3 years, is higher than the global average[32] due to its low birth rate, high life expectancy, and relatively high rate of emigration among younger people. A quarter of the population is less than 15 years old and about a sixth are aged 60 and older.[25] In 2017 the average total fertility rate (TFR) across Uruguay was 1.70 children born per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 5.76 children born per woman in 1882.[137]

Metropolitan Montevideo is the only large city, with around 1.9 million inhabitants, or more than half the country’s total population. The rest of the urban population lives in about 30 towns.[32]

A 2017 IADB report on labor conditions for Latin American nations, ranked Uruguay as the region’s leader overall and in all but one subindexes, including gender, age, income, formality and labor participation.[138]

Largest cities[edit]

|

Largest cities or towns in Uruguay «Uruguay». citypopulation.de. Retrieved 17 August 2021. |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||

Montevideo  Salto |

1 | Montevideo | Montevideo | 1,304,687 | 11 | Artigas | Artigas | 40,657 |  Ciudad de la Costa  Paysandú |

| 2 | Salto | Salto | 104,011 | 12 | Minas | Lavalleja | 38,446 | ||

| 3 | Ciudad de la Costa | Canelones | 95,176 | 13 | San José de Mayo | San José | 36,743 | ||

| 4 | Paysandú | Paysandú | 76,412 | 14 | Durazno | Durazno | 34,368 | ||

| 5 | Las Piedras | Canelones | 71,258 | 15 | Florida | Florida | 33,639 | ||

| 6 | Rivera | Rivera | 64,465 | 16 | Barros Blancos | Canelones | 31,650 | ||

| 7 | Maldonado | Maldonado | 62,590 | 17 | Ciudad del Plata | San José | 31,145 | ||

| 8 | Tacuarembó | Tacuarembó | 54,755 | 18 | San Carlos | Maldonado | 27,471 | ||

| 9 | Melo | Cerro Largo | 51,830 | 19 | Colonia del Sacramento | Colonia | 26,231 | ||

| 10 | Mercedes | Soriano | 41,974 | 20 | Pando | Canelones | 25,947 |

Health[edit]

Religion[edit]

Uruguay has no official religion; church and state are officially separated,[32] and religious freedom is guaranteed. A 2008 survey by the INE of Uruguay showed Catholic Christianity as the main religion, with 45.7% – 81.4%[141] of the population; 9.0% are non-Catholic Christians, 0.6% are Animists or Umbandists (an Afro-Brazilian religion), and 0.4% Jewish. 30.1% reported believing in a god, but not belonging to any religion, while 14% were atheist or agnostic.[142] Among the sizeable Armenian community in Montevideo, the dominant religion is Christianity, specifically Armenian Apostolic.[143]

Political observers consider Uruguay the most secular country in the Americas.[144] Uruguay’s secularization began with the relatively minor role of the church in the colonial era, compared with other parts of the Spanish Empire. The small numbers of Uruguay’s indigenous peoples and their fierce resistance to proselytism reduced the influence of the ecclesiastical authorities.[145]

After independence, anti-clerical ideas spread to Uruguay, particularly from France, further eroding the influence of the church.[146] In 1837 civil marriage was recognized, and in 1861 the state took over the running of public cemeteries. In 1907 divorce was legalized and, in 1909 all religious instruction was banned from state schools.[145] Under the influence of the Colorado politician José Batlle y Ordóñez (1903–1911), complete separation of church and state was introduced with the new constitution of 1917.[145]

Uruguay’s capital has 12 synagogues, and a community of 20,000 Jews by 2011. With a peak of 50,000 during the mid-1960s, Uruguay has the world’s highest rate of aliyah as a percentage of the Jewish population.[147]

Language[edit]

Uruguayan Spanish, as is the case with neighboring Argentina, employs both voseo and yeísmo (with [ʃ] or [ʒ]). English is common in the business world and its study has risen significantly in recent years, especially among the young. Uruguayan Portuguese is spoken as a native language by between 3% and 15%[dubious – discuss] of the Uruguayan population, in northern regions near the Brazilian border,[148][dubious – discuss][better source needed] making it the second most spoken language of the country. As few native people exist in the population, no indigenous languages are thought to remain in Uruguay.[149]

Another spoken dialect was the Patois, which is an Occitan dialect. The dialect was spoken mainly in the Colonia Department, where the first pilgrims settled, in the city called La Paz. Today it is considered a dead tongue, although some elders at the aforementioned location still practice it. There are still written tracts of the language in the Waldensians Library (Biblioteca Valdense) in the town of Colonia Valdense, Colonia Department.

Patois speakers arrived to Uruguay from the Piedmont. Originally they were Vaudois, who become Waldensians, giving their name to the city Colonia Valdense, which translated from the Spanish means «Waldensian Colony».[150]

In 2001, Uruguayan Sign Language (LSU) was recognized as an official language of Uruguay under Law 17.378.[4]

Education[edit]

Education in Uruguay is secular, free,[151] and compulsory for 14 years, starting at the age of 4.[152] The system is divided into six levels of education: early childhood (3–5 years); primary (6–11 years); basic secondary (12–14 years); upper secondary (15–17 years); higher education (18 and up); and post-graduate education.[152]

Public education is the primary responsibility of three institutions: the Ministry of Education and Culture, which coordinates education policies, the National Public Education Administration, which formulates and implements policies on early to secondary education, and the University of the Republic, responsible for higher education.[152] In 2009, the government planned to invest 4.5% of GDP in education.[151]

Uruguay ranks high on standardised tests such as PISA at a regional level, but compares unfavourably to the OECD average, and is also below some countries with similar levels of income.[151] In the 2006 PISA test, Uruguay had one of the greatest standard deviations among schools, suggesting significant variability by socio-economic level.[151]

Uruguay is part of the One Laptop per Child project, and in 2009 became the first country in the world to provide a laptop for every primary school student,[153] as part of the Plan Ceibal.[154] Over the 2007–2009 period, 362,000 pupils and 18,000 teachers were involved in the scheme; around 70% of the laptops were given to children who did not have computers at home.[154] The OLPC programme represents less than 5% of the country’s education budget.[154]

Culture[edit]

Uruguayan culture is strongly European and its influences from southern Europe are particularly important.[25] The tradition of the gaucho has been an important element in the art and folklore of both Uruguay and Argentina.[25]

Visual arts[edit]

Abstract painter and sculptor Carlos Páez Vilaró was a prominent Uruguayan artist. He drew from both Timbuktu and Mykonos to create his best-known work: his home, hotel and atelier Casapueblo near Punta del Este. Casapueblo is a «livable sculpture» and draws thousands of visitors from around the world. The 19th-century painter Juan Manuel Blanes, whose works depict historical events, was the first Uruguayan artist to gain widespread recognition.[25] The Post-Impressionist painter Pedro Figari achieved international renown for his pastel studies of subjects in Montevideo and the countryside. Blending elements of art and nature the work of the landscape architect Leandro Silva Delgado [es] has also earned international prominence.[25]

Uruguay has a small but growing film industry, and movies such as Whisky by Juan Pablo Rebella and Pablo Stoll (2004), Marcelo Bertalmío’s Los días con Ana (2000; «Days with Ana») and Ana Díez’s Paisito (2008), about the 1973 military coup, have earned international honours.[25]

Music[edit]

Tango dancers in Montevideo

It is among the most famous and recognizable tangos of all time.

Murga singers at carnival

The folk and popular music of Uruguay shares not only its gaucho roots with Argentina, but also those of the tango.[25] One of the most famous tangos, «La cumparsita» (1917), was written by the Uruguayan composer Gerardo Matos Rodríguez.[25] The candombe is a folk dance performed at Carnival, especially Uruguayan Carnival, mainly by Uruguayans of African ancestry.[25] The guitar is the preferred musical instrument, and in a popular traditional contest called the payada two singers, each with a guitar, take turns improvising verses to the same tune.[25]

Folk music is called canto popular and includes some guitar players and singers such as Alfredo Zitarrosa, José Carbajal «El Sabalero», Daniel Viglietti, Los Olimareños, and Numa Moraes.

Numerous radio stations and musical events reflect the popularity of rock music and the Caribbean genres, known as música tropical («tropical music»).[25] Early classical music in Uruguay showed heavy Spanish and Italian influence, but since the 20th century a number of composers of classical music, including Eduardo Fabini, Vicente Ascone [es], and Héctor Tosar, have made use of Latin American musical idioms.[25]

Tango has also affected Uruguayan culture, especially during the 20th century, particularly the ’30s and ’40s with Uruguayan singers such as Julio Sosa from Las Piedras.[155] When the famous tango singer Carlos Gardel was 29 years old he changed his nationality to be Uruguayan, saying he was born in Tacuarembó, but this subterfuge was probably done to keep French authorities from arresting him for failing to register in the French Army for World War I. Gardel was born in France and was raised in Buenos Aires. He never lived in Uruguay.[156] Nevertheless, a Carlos Gardel museum was established in 1999 in Valle Edén, near Tacuarembó.[157]

Rock and roll first broke into Uruguayan audiences with the arrival of the Beatles and other British bands in the early 1960s. A wave of bands appeared in Montevideo, including Los Shakers, Los Mockers, Los Iracundos, Los Moonlights, and Los Malditos, who became major figures in the so-called Uruguayan Invasion of Argentina.[158] Popular bands of the Uruguayan Invasion sang in English.

Popular Uruguayan rock bands include La Vela Puerca, No Te Va Gustar, El Cuarteto de Nos, Once Tiros, La Trampa, Chalamadre, Snake, Buitres, and Cursi. In 2004, the Uruguayan musician and actor Jorge Drexler won an Academy Award for composing the song «Al otro lado del río» from the movie The Motorcycle Diaries, which narrated the life of Che Guevara. Other Uruguayan famous songwriters are Jaime Roos, Eduardo Mateo, Rubén Rada, Pablo Sciuto, Daniel Viglietti, among others.

By mid-2015, the Uruguayan bands Rombai and Márama of the emerging subgenres «cumbia cheta» and «cumbia pop [es]» enjoyed great success all over Latin America even before publishing their first albums; particularly in their home country and in Argentina, where in a given moment they had together nine songs at the Spotify Top Ten ranking.[159] Other Uruguayan bands of success are: Toco Para Vos, Vi-Em [es], Toco Para Bailar and Golden Rocket.

Food[edit]

Uruguayan food culture comes mostly from the European cuisine culture. Most of the Uruguayan dishes are from Spain, France, Italy and Brazil, the result of immigration caused by past wars in Europe.

Daily meals vary between meats, pasta of all types, rice, sweet desserts and others. Meat being the principal dish, due to Uruguay being one of the world’s largest producers of quality meat.

Typical dishes include: «Asado uruguayo» (big grill or barbecue of all types of meat), roasted lamb, Chivito (sandwich containing thin grilled beef, lettuce, tomatoes, fried egg, ham, olives and others, and served with French fries), Milanesa (a kind of fried breaded beef), tortellini, spaghetti, gnocchi, ravioli, rice and vegetables.

One of the most consumed spreadables in Uruguay is Dulce de leche (a caramel confection from Latin America prepared by slowly heating sugar and milk). And the most typical sweet is Alfajor, which is a small cake, filled with Dulce de leche and covered with chocolate or meringue, it comes in various types, fillings, sizes and brands.

Other typical desserts include the Pastafrola (a type of cake filled with quince jelly), Chajá (meringue, sponge cake, whipped cream and fruits, typically peaches and strawberries are added).

Mate (drink) is the most typical beverage in Uruguay, being a portable beverage that Uruguayans take to all manner of places.

Literature[edit]

José Enrique Rodó (1871–1917), a modernist, is considered Uruguay’s most significant literary figure.[25] His book Ariel (1900) deals with the need to maintain spiritual values while pursuing material and technical progress.[25] Besides stressing the importance of upholding spiritual over materialistic values, it also stresses resisting cultural dominance by Europe and the United States.[25] The book continues to influence young writers.[25] Notable amongst Latin American playwrights is Florencio Sánchez (1875–1910), who wrote plays about contemporary social problems that are still performed today.[25]

From about the same period came the romantic poetry of Juan Zorrilla de San Martín (1855–1931), who wrote epic poems about Uruguayan history. Also notable are Juana de Ibarbourou (1895–1979), Delmira Agustini (1866–1914), Idea Vilariño (1920–2009), and the short stories of Horacio Quiroga and Juan José Morosoli (1899–1959).[25] The psychological stories of Juan Carlos Onetti (such as «No Man’s Land» and «The Shipyard») have earned widespread critical praise, as have the writings of Mario Benedetti.[25]

Uruguay’s best-known contemporary writer is Eduardo Galeano, author of Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971; «Open Veins of Latin America») and the trilogy Memoria del fuego (1982–87; «Memory of Fire»).[25] Other modern Uruguayan writers include Mario Levrero, Sylvia Lago, Jorge Majfud, and Jesús Moraes.[25] Uruguayans of many classes and backgrounds enjoy reading historietas, comic books that often blend humour and fantasy with thinly veiled social criticism.[25]

Media[edit]

The Reporters Without Borders worldwide press freedom index has ranked Uruguay as 19th of 180 reported countries in 2019.[160] Freedom of speech and media are guaranteed by the constitution, with qualifications for inciting violence or «insulting the nation».[99] Uruguayans have access to more than 100 private daily and weekly newspapers, more than 100 radio stations, and some 20 terrestrial television channels, and cable TV is widely available.[99]

Uruguay’s long tradition of freedom of the press was severely curtailed during the years of military dictatorship. On his first day in office in March 1985, Sanguinetti re-established complete freedom of the press.[161] Consequently, Montevideo’s newspapers, which account for all of Uruguay’s principal daily newspapers, greatly expanded their circulations.[161]

State-run radio and TV are operated by the official broadcasting service SODRE.[99] Some newspapers are owned by, or linked to, the main political parties.[99] El Día was the nation’s most prestigious paper until its demise in the early 1990s, founded in 1886 by the Colorado party leader and (later) president José Batlle y Ordóñez. El País, the paper of the rival Blanco Party, has the largest circulation.[25] Búsqueda is Uruguay’s most important weekly news magazine and serves as an important forum for political and economic analysis.[161] Although it sells only about 16,000 copies a week, its estimated readership exceeds 50,000.[161] MercoPress is an independent news agency focusing on news related to Mercosur and is based in Montevideo.[162]

Sport[edit]

Football is the most popular sport in Uruguay. The first international match outside the British Isles was played between Uruguay and Argentina in Montevideo in July 1902.[163] Uruguay won gold at the 1924 Paris Olympic Games[164] and again in 1928 in Amsterdam.[165]

The Uruguay national football team has won the FIFA World Cup on two occasions. Uruguay won the inaugural tournament on home soil in 1930 and again in 1950, famously defeating home favourites Brazil in the final match.[166] Uruguay has won the Copa América (an international tournament for South American nations and guests) 15 times, such as Argentina, the last one in 2011. Uruguay has by far the smallest population of any country that has won a World Cup.[166] Despite their early success, they missed three World Cups in four attempts from 1994 to 2006.[166] Uruguay performed very creditably in the 2010 FIFA World Cup, having reached the semi-final for the first time in 40 years. Diego Forlán was presented with the Golden Ball award as the best player of the 2010 tournament.[167] In the rankings for June 2012, Uruguay were ranked the second best team in the world, according to the FIFA world rankings, their highest ever point in football history, falling short of the first spot to the Spain national football team.[168]

Uruguay exported 1,414 football players during the 2000s, almost as many players as Brazil and Argentina.[169] In 2010, the Uruguayan government enacted measures intended to retain players in the country.[169]

Football was taken to Uruguay by English sailors and labourers in the late 19th century. Less successfully, they introduced rugby and cricket. There are two Montevideo-based football clubs, Nacional and Peñarol, who are successful in domestic and South American tournaments and have won three Intercontinental Cups each. When the two clubs play each other, it is known as Uruguayan Clásico and is the most important rivalry in Uruguay and one of the biggest in the American continent.[170]