Как написать имя на японском легче понять, изучив основы японских азбук. Написать русское имя по-японски можно на хирагане, катакане и иероглифами.

Сегодня мы немного узнаем о системе японской письменности и научимся писать ваши имена по-японски. Русские и японские имена сильно отличаются друг от друга. На нашем сайте уже есть статья со списком японских имен (женских и мужских), объясняющая то, как они образуются. А чтобы понять, как можно написать русские имена на японском языке, сначала надо разобраться в японских системах письменности. Одной из особенностей этого языка является то, что в нем существуют целых три основных вида письма: две слоговые азбуки (кана) и иероглифы (кандзи).

Применение хираганы и катаканы

Зачем же японцам две азбуки? Исторически так сложилось, что азбука хирагана используется для записи грамматических частиц и изменяемых частей слов. Хираганой можно писать японские слова – например, если вы не знаете, как слово пишется иероглифом. Также в некоторых текстах она используется в качестве подсказок, записываемых мелким шрифтом рядом с кандзи, чтобы было легче определить, как он читается. Именно поэтому хирагана — это основная азбука в японском письме. С нее начинается знакомство с языком, закладывается база для чтения и понимания написанного.

Катакана в основном используется для записи иностранных имен и заимствованных слов: например, японские слова «пэн» (от английского «ручка») и «банана» (от английского «банан») будут записываться этой азбукой. Ваши имена также будут писаться катаканой.

Знаки катаканы проще по начертанию и более угловатые, раньше они использовались только мужчинами, хирагана же более округлая, линии плавные: она была придумана японскими придворными дамами. Как мы видим, характер написания черт отражает мужской (катакана) и женский (хирагана) характер.

Структура азбуки

Обе азбуки – хирагана и катакана – произошли от иероглифов. Они построены по слоговому принципу, то есть каждая буква означает слог, который состоит из глухой согласной и одной из пяти гласных: «а», «и», «у», «э», «о». Также существует несколько отдельных букв: три гласные — «я», «ю», «ё» — и одна согласная «н». Эти слоги являются основными, их в каждой азбуке 46.

Помимо основных, есть еще и дополнительные слоги. Они образуются из звонких согласных (например «га» и «да») или при слиянии слога, оканчивающегося на «и», с одной из трех отдельных гласных. Так, например, если соединить «ки» и «ё», получится новый слог «кё».

Азбука хирагана

Азбука катакана

Русские имена на катакане

Русские имена по-японски будут записываться слогами на катакане, схожими с оригинальным звучанием имени. Проблемы в написании имени могут возникать при столкновении со звуками, которые в японском языке отсутствуют.

В отличие от русского языка, в японском нет звука «л», поэтому все иностранные слова (и имена в том числе), которые содержат этот звук, будут писаться через «р». Например, «Лена» по-японски будет звучать и писаться как «Рэна», а «Алексей» – «Арэкусэи».

Также надо отметить букву «ву»(ヴ), которая была создана специально для того, чтобы обозначать в иностранных словах несуществующий в японском звук «в». В русском же он довольно распространен и множество русских имен пишется именно через букву «ву». Например, имя «Владимир» можно написать так: «Вурадимиру».

Однако из-за сложности произношения японцы предпочитают заменять звук «в» на «б». Таким образом, имя Валерия, например, можно написать двумя способами: «Вуарэрия» и «Барэрия».

Иногда в имени, написанном на японском, можно встретить знак 「―」. Он служит в качестве ударения, удлиняя гласный звук, стоящий впереди. Например, имя «Ирина» по-японски можно написать с этим знаком: «Ири:на», или 「イリーナ」.

В русском языке также распространены сокращенные имена. В большинстве случаев такие имена будут писаться с помощью дополнительных слогов. Например, при написании «Даша» или «Саша» используется составной слог «ща» (シャ). А чтобы написать «Катя» или «Настя» на японском языке, нужно будет использовать «тя»(チャ). Таким образом, эти имена будут звучать и записываться так:

- «Даща» (ダシャ);

- «Саща» (サーシャ) ;

- «Катя» (カチャ);

- «Настя» (ナスチャ).

Нужно учитывать, что нет единственно верного написания вашего имени на катакане. Оно может варьироваться, так как некоторые звуки можно записать разными слогами.

Применение иероглифов кандзи

В японском языке существует ещё одна система письменности, которая используется для записи основы слов: иероглифы, или кандзи. Они были заимствованы из Китая и немного изменены. Поэтому каждый иероглиф не только имеет собственное значение, как в китайском языке, но и несколько вариантов чтения: китайское (онъёми) и японское (кунъёми).

Имена и фамилии самих японцев записываются кандзи, но возможно ли записать русские имена японскими иероглифами? Есть несколько способов сделать это. Однако необходимо учитывать, что все они обычно служат для развлечения, например, чтобы создавать ники на японском языке.

Первый способ — это подобрать кандзи, похожие по фонетическому звучанию на русские имена. Так, например, имя «Анна» на японском языке можно написать иероглифом「穴」, который произносится как «ана», а имя «Юлия» — иероглифами「湯理夜」, которые звучат как «юрия». В этом случае кандзи подбираются по звучанию, а смыслу внимание не уделяется.

Есть и другой способ, который, наоборот, делает акцент на значении кандзи. Перевод имени на японский язык с русского невозможен, но, если обратиться к его первоначальному значению, пришедшему из греческого, латинского или какого-либо другого языка, то сделать это вполне реально. Например, имя «Александр», произошедшее с греческого, означает «защитник», что на японский язык можно перевести как «Мамору» (守る). По такому принципу можно перевести любое другое имя.

Ниже в таблице приведено несколько примеров того, как русские имена произносятся и пишутся на катакане и как их можно перевести на японский через первоначальное значение имени.

Мужские имена

| Имя на русском | Написание на катакане | Значение имени | Перевод на японский |

|---|---|---|---|

| Александр | アレクサンダ

Арэкусанда |

Защищающий | 守る

Мамору |

| Андрей | アンドレイ

Андорэи |

Храбрец | 勇気お

Юкио |

| Алексей | アレクセイ

Арэкусэи |

Помощник | 助け

Таскэ |

| Владимир | ヴラディミル

Вурадимиру |

Владеющий миром | 平和主

Хэвануши |

| Владислав | ヴラディスラフ

Вурадисурафу |

Владеющий славой | 評判主

Хёбанщю |

| Дмитрий | ドミトリ

Домитори |

Земледелец | 果実

Кадзицу |

| Денис | デニース

Дени:су |

Природные жизненные силы | 自然力

Шидзэнрёку |

| Кирилл | キリール

Кири:ру |

Солнце, господин | 太陽の領主

Таёнорёщю |

| Максим | マクシム

Макусиму |

Величайший | 全くし

Маттакуши |

| Никита | 二キータ

Ники:та |

Победитель | 勝利と

Щёрито |

| Сергей | セルギェイ

Сэругеи |

Высокочтимый | 敬した

Кешита |

Женские имена

| Имя на русском | Написание на катакане | Значение имени | Перевод на японский |

|---|---|---|---|

| Алина | アリナ

Арина |

Ангел | 天使

Тенши |

| Алёна | アリョナ

Арёна |

Солнечная, сияющая | 光り

Хикари |

| Анастасия | アナスタシーア

Анастаси:а |

Возвращение к жизни | 復活美

Фуккацуми |

| Анна | アンナ

Анна |

Благосклонность | 慈悲子

Джихико |

| Валерия | バレーリア

Барэ:риа |

Здоровая, крепкая | 達者

Тащща |

| Виктория | ヴィクトリア

Бикуториа |

Победа | 勝里

Щёри |

| Дарья | ダリア

Дариа |

Огонь великий | 大火子

Охико |

| Екатерина | エカテリナ

Экатэрина |

Вечно чистая, непорочная | 公平里

Кохэри |

| Ирина | イリーナ

Ири:на |

Мир | 世界

Сэкай |

| Кристина | クリスティナ

Куристина |

Христианка | 神の子

Каминоко |

| Наталья | ナタリヤ

Натария |

Благословенная, рождественская | 生ま里

Умари |

| Полина | ポリーナ

Пори:на |

Солнечная | 晴れた

Харета |

| Светлана | スベトラーナ

Субетора:на |

Светлая | 光る

Хикару |

| Юлия | ユーリヤ

Ю:рия |

Волнистая | 波状花

Хадзёка |

Сейчас можно выяснить, как пишется ваше имя на японском языке онлайн с помощью многих сайтов. Однако научиться писать его самостоятельно, обратившись к японской азбуке, совсем не сложно.

Сперва может показаться, что письмо на японском языке это сложно и непонятно. Несколько азбук могут вас напугать, но очень быстро вы поймете, что научиться писать на хирагане и катакане так же просто, как и на латинице. Но нужно с чего-то начать! И сделать это можно с написания своего имени.

Давайте теперь попробуем написать Ваше имя катаканой! Уверена, у Вас получится! Напишите результат в комментариях.

А чтобы вы могли быстрее научиться писать не только своё имя на японском, но и ваших близких, получите бесплатный мини-курс по изучению катаканы.

Считаете, что выучить японский нереально? А что вы подумаете, если мы вам скажем, что уже через год обучения японскому на курсах Дарьи Мойнич вы сможете свободно общаться с японцами на повседневные темы? Спорим, у вас получится? Тогда скорее записывайтесь в группу, ибо количество мест ограничено. Желающих учиться много! Узнать подробнее о годовой программе обучения и записаться на курсы вы можете по ссылке.

Японские имена

Привет! Добро пожаловать в это введение в японские имена. Я очень рад, что вам интересны японские имена. В этой статье я расскажу вам основы того, как они работают. Японские имена настолько уникальны и круты, и у них есть много особенностей. Надеюсь, вам понравится!

- Прежде всего, что идет первым, фамилия или имя?

- Символы, используемые в японских именах

- Фамилия

- Собственное имя

- Японские имена: список

- Японские имена: заключение

Прежде всего, что идет первым, фамилия или имя?

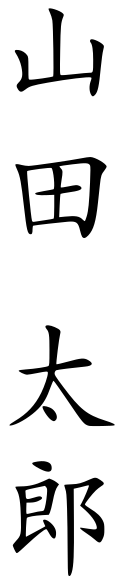

В японском языке фамилия стоит перед именем. Итак, великий режиссер анимации Хаяо Миядзаки упоминается в Японии как Миядзаки Хаяо. Миядзаки — его фамилия, а Хаяо — его имя. Многие японцы меняют порядок при общении с иностранцами, что затрудняет понимание того, какое имя какое. Большинство японцев имеют одну фамилию и одно имя и не имеют отчества. (У людей с иностранными родителями могут быть вторые имена.)

Символы, используемые в японских именах

Японские имена обычно пишутся кандзи (иероглифы), а некоторые имена пишутся хираганой или катаканой. Это три набора символов, используемых в японском языке.

Кандзи: иероглифы подобны идеографическим символам. Каждый кандзи символизирует собственное значение и имеет несколько разных произношений. Кандзи имеет китайское происхождение, но использование и произношение кандзи были изменены, чтобы соответствовать японскому языку. Поскольку у каждого кандзи есть несколько возможных вариантов произношения, когда вы видите только имя, написанное на кандзи, вы не знаете, как это имя произносится.

Хирагана: символы хираганы являются основным фонетическим письмом Японии. Они подобны алфавиту, поэтому каждая хирагана сама по себе не имеет значения. Существует около 50 основных символов хираганы.

Катакана: есть еще один набор фонетических шрифтов, который называется катакана. Символы катаканы в основном используются для слов, импортированных из иностранных языков. Как и в хирагане, существует около 50 основных символов. Хирагана и катакана представляют собой один и тот же набор звуков и представляют все звуки в японском языке.

Фамилия

Фамилия обычно передается по наследству от отца, и количество фамилий в Японии очень и очень велико. Большинство женщин берут фамилию мужа, и лишь немногие женщины сохраняют девичью фамилию после замужества. Удивительно то, что многие японские фамилии произошли от природы, что говорит о том, насколько японцы любили и уважали природу с древних времен. Вот несколько примеров.

Позвольте мне объяснить два кандзи, которые используются для обозначения «Миядзаки». Кандзи Мия означает «храм, дворец», а кандзи саки означает «мыс, полуостров». Куросава означает «черное болото». Кандзи Куро означает «черный, темный», а сава означает «болото, болото». А Сузуки означает «колокольня». Кандзи Сузу означает «колокольчик», а ки означает «дерево, дерево».

Как и в этих примерах, подавляющее большинство фамилий состоит из двух иероглифов. В большинстве фамилий используется от одного до трех иероглифов.

Собственное имя

Японские имена имеют крутую особенность. Дело в том, что их можно очень изобретательно выбирать или, точнее, создавать их. Несмотря на то, что символы кандзи, которые могут использоваться в именах, регулируются, есть много тысяч кандзи на выбор! Как и фамилии, многие японские имена состоят из двух иероглифов. Большинство имен состоит из одного-трех иероглифов.

Японские имена: список

Вам интересно, какие японские имена существуют или что они обозначают? Тогда вы находитесь на нужной вам странице. Мы подготовили для вас полный список имен для девочек и мальчиков! Японские имена также будет полезно знать тем, кто собирается работать или учиться в Японии. В список включены имя, значение и наиболее часто используемые кандзи (японские символы):

- AI означает «любовь» (愛 藍) — имя японской девушки.

- AIKA означает «песня о любви» (愛 佳) — японское женское имя.

- AIKO означает «дитя любви» (愛 子) — японское имя девушки.

- AIMI означает «любить красоту» (愛美) — японское имя девушки.

- AINA означает «любить овощи» (愛 菜) — японское женское имя.

- AIRI означает «любить жасмин» (愛莉) — имя японской девушки.

- AKANE означает «ярко-красный» (茜) — японское женское имя.

- AKEMI означает «яркая красивая» (明 美) — японское имя девушки.

- AKI означает «яркий / осенний» (明 / 秋) — японское унисекс-имя.

- AKIHIRO означает «великая яркость» (明 宏) — японское имя мальчика.

- AKIKO означает « умный ребенок» (明子) — японское имя девочки.

- AKIO означает « умный мужчина» (昭夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- AKIRA означает «яркий / чистый» (明 / 亮) — японское унисекс-имя.

- AMATERASU означает «сияющие небеса» (天 照) — японское женское имя.

- AMI означает «красивая азия» (亜 美) — имя японской девушки.

- AOI означает «синий» (碧) — японские имена, унисекс-имя.

- ARATA означает «новый, свежий» (新) — японское имя мальчика.

- ASAMI означает «утренняя красавица» (麻美) — японское имя девушки.

- АСУКА означает «аромат завтрашнего дня» (明日香) — имя японской девушки.

- АЦУКО означает «добрый ребенок» (篤 子) — японское имя девушки.

- АЦУШИ означает «трудолюбивый директор» (敦 司) — японское имя мальчика.

- AYA означает «цвет» (彩) — японское имя девушки.

- АЯКА означает «красочный цветок» (彩 花) — имя японской девушки.

- АЯКО означает «красочный ребенок» (彩 子) — японское имя девочки.

- AYAME означает «ирис» (菖蒲) — японское имя девушки.

- AYANE означает «красочный звук» (彩 音) — имя японской девушки.

- AYANO означает «мой цвет» (彩 乃) — имя японской девушки.

- AYUMU означает «прогулка, мечта, видение» (歩 夢) — японское имя мальчика.

- ЧИЕ означает «мудрость, интеллект» (恵) — имя японской девушки.

- ЧИЕКО означает «дитя ума, мудрости» (恵 子) — японское имя девушки.

- CHIHARU означает «тысяча весен» (千 春) — японское имя девушки.

- CHIKA означает «разбросанные цветы» (散花) — японское имя девушки.

- ЧИКАКО означает «дитя тысячи ароматов» (千 香 子) — японское имя девушки.

- ТИНАЦУ означает «тысяча лет» (千 夏) — японское женское имя.

- CHIYO означает «тысяча эпох» (千代) — японское женское имя.

- ЧИЁКО означает «ребенок тысячи эпох» (千代 子) — японское имя девушки.

- CHO означает «бабочка» (蝶) — японское имя девушки.

- CHOUKO означает «дитя-бабочка» (蝶 子) — японское имя девочки.

- DAI означает «великий, большой» (大) — японское имя мальчика.

- ДАИЧИ означает «великая земля» (大地) — японское имя мальчика.

- DAIKI означает «великая слава / великое благородство» (大 輝 / 大 貴) — японское имя мальчика.

- DAISUKE означает «великий помощник » (大 輔) — японское имя мальчика.

- EIJI означает «порядок вечности» (永 次) — японское имя мальчика.

- EIKO означает «дитя великолепия» (栄 子) — японское имя девушки.

- EMI означает «прекрасное благословение» (恵 美) — японское имя девушки.

- EMIKO означает «прекрасный благословенный ребенок» (恵 美 子) — японское имя девочки.

- ERI означает «благословенный приз» (絵 理) — японское имя девушки.

- ETSUKO означает «дитя радости» (悦子) — японское имя девушки.

- ФУМИКО означает «дитя безмерной красоты» (富 美 子) — японское имя девушки.

- FUMIO означает «литературный герой» (文 雄) — имя японского мальчика.

- GORO означает «пятый сын» (五郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- HACHIRO означает «восьмой сын» (八郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- HAJIME, что означает «начало» (肇) — японское имя мальчика.

- HANA означает «цветок» (花) — японское женское имя.

- HANAKO означает «дитя цветка» (花子) — японское имя девушки.

- HARU означает «весна» (春) — японские имена, унисекс-имя.

- HARUKA означает «весенний цветок» (春花) — японское имя девушки.

- HARUKI означает «сияющее солнце» (陽 輝) — японское имя мальчика.

- HARUKO означает «весенний ребенок» (春 子) — японское имя девочки.

- HARUMI означает «красивая весна» (春 美) — японское имя девушки.

- HARUNA, что означает «весенние овощи» (春 菜) — имя японской девушки.

- HARUO означает «человек весны» (春 男) — японское имя мальчика.

- HARUTO означает «летящее солнце» (陽 斗) — японское имя мальчика.

- HAYATE, что означает «гладкий» (颯) — японское имя мальчика.

- HAYATO означает «человек-сокол» (隼 人) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIBIKI означает «звук, эхо» (響) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIDEAKI, что означает «отличный, яркий, сияющий» (英明) — имя мальчика в Японии.

- HIDEKI означает «превосходные деревянные деревья» (英 樹) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIDEKO означает «дитя совершенства» (秀 子) — японское имя девушки.

- HIDEO означает «отличный муж» (英 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIDEYOSHI означает «превосходное качество» (秀 良) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIKARI означает «свет, сияние» (光) — имя японской девушки.

- HIKARU означает «свет, сияние» (光) — японские имена, унисекс-имя.

- HINA означает «солнечные овощи» (陽 菜) — имя японской девушки.

- HINATA означает «подсолнух / обращенный к солнцу» (向日葵 / 陽 向) — японское унисекс-имя.

- HIRAKU означает «открывать, расширять» (拓) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIRO означает «щедрый» (寛) — японские имена, унисекс-имя.

- HIROAKI означает «широкий, просторный свет» (広 明) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIROKI означает «огромные деревья» (弘 樹) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIROKO означает «щедрый ребенок» (寛 子) — японское имя девушки.

- HIROMI означает «щедрая красота» (寛 美) — японское имя девушки.

- HIRONORI означает « хроника командования, уважения» (博 紀) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIROSHI означает «щедрый» (寛) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIROTO означает «большой полет» (大 斗) — японское имя мальчика.

- HIROYUKI означает «великое путешествие» (宏 行) — японское имя мальчика.

- HISAKO означает «дитя долгой жизни» (久 子) — японское имя девушки.

- HISAO означает «долгожитель» (寿 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- HISASHI означает «правитель» (久 司) — японское имя мальчика.

- HISOKA означает «осторожный, сдержанный» (密) — японское унисекс-имя.

- HITOMI означает «острый глаз» (瞳) — японское имя девушки.

- HITOSHI означает «мотивированный человек» (人 志) — японское имя мальчика.

- HONOKA означает «цветок гармонии» (和 花) — японское женское имя.

- HOSHI означает «звезда» (星) — японское имя девушки.

- HOSHIKO означает «звездный ребенок» (星子) — японское имя девушки.

- HOTAKA означает «высокое зерно» (穂 高) — японское имя мальчика.

- HOTARU означает «светлячок» (蛍) — японское имя девушки.

- ICHIRO означает «первый сын» (一郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- ISAMU означает «храбрый, отважный» (勇) — имя японского мальчика.

- ISAO означает «заслуга» (勲) — японское имя мальчика.

- ITSUKI означает «деревянные деревья» (樹) — японское имя мальчика.

🙋♂️Хочешь выучить японский язык❓

Забирай лучший вариант обучения по самой привлекательной цене в интернете. Расширяй границы собственных возможностей 🔍 и открывай для себя новые способы заработка 💰

И начни понимать, читать и говорить на японском языке 🗣👂✍️

- IZUMI означает «весна, фонтан» (泉) — имя японской девушки.

- JIRO означает «второй сын» (二郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- JUN означает «послушный» (順) — японские имена, унисекс-имя.

- JUNICHI означает «послушный первый (сын)» (順 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- JUNKO означает «чистый, настоящий ребенок» (純 子) — японское имя девочки.

- ДЖУРО означает «десятый сын» (十郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- KAEDE означает «клен» (楓) — японское унисекс-имя.

- KAITO означает «летящий по океану» (海 斗) — японское имя мальчика.

- КАМИКО означает «высший ребенок» (上 子) — японское имя девочки.

- КАНАКО означает «благоухающий ребенок Нара (город в Японии)» (香奈 子) — японское имя девушки.

- KANOKO означает «дитя цветочной мелодии» (花 音 子) — японское имя девушки.

- KANON означает «цветочный звук» (花 音) — имя японской девушки.

- KAORI означает «духи, аромат» (香) — имя японской девушки.

- KAORU означает «аромат» (薫) — японское унисекс-имя.

- КАСУМИ означает «туман» (霞) — японское имя девушки.

- KATASHI означает «фирма» (堅) — японское имя мальчика.

- KATSU означает «победа» (勝) — японское имя мальчика.

- KATSUMI означает «победоносная красота» (勝 美) — японское женское имя.

- KATSUO означает «победоносный, героический человек» (勝雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- KATSURO означает «сын-победитель» (勝 郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- KAZUE означает «первое благословение» (一 恵) — японское женское имя.

- KAZUHIKO означает «гармоничный мальчик» (和 彦) — японское имя мальчика.

- КАЗУХИРО означает «великая гармония» (和 宏) — японское имя мальчика.

- KAZUKI означает «надежда на гармонию» (和 希) — японское имя мальчика.

- КАЗУКО означает «дитя гармонии» (和 子) — японское женское имя.

- КАЗУМИ означает «гармоничная красота» (和美) — японское имя девушки.

- КАЗУО означает «человек гармонии» (和 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- KEI означает «уважительный» (敬) — японское женское имя.

- KEIKO означает «благословенное дитя / почтительное дитя» (恵 子 / 敬 子) — японское имя девочки.

- KEN означает «сильный, здоровый» (健) — японское имя мальчика.

- KENICHI означает «сильный, здоровый первый (сын)» (健 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- KENJI означает «сильный, здоровый второй (сын)» (健 二) — японское имя мальчика.

- KENSHIN означает «скромный правдивый» (謙信) — японское имя мальчика.

- KENTA означает «большой, сильный, здоровый» (健 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- КИЧИРО означает «счастливый сын» (吉 郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- KIKO означает «ребенокхроники» (紀 子) — японское имя девочки.

- KIKU означает «хризантема» (菊) — японское женское имя.

- KIMI означает «благородный» (君) — имя японской девушки.

- KIMIKO означает «дитя императрицы» (后 子) — японское имя девушки.

- KIN означает «золото» (金) — японское унисекс-имя.

- KIYOKO означает «чистый ребенок» (清 子) — японское имя девушки.

- KIYOMI означает «чистая красота» (清 美) — японское имя девушки.

- KIYOSHI означает «чистота» (淳) — японское имя мальчика.

- KOHAKU означает «янтарь» (琥珀) — японское унисекс-имя.

- КОКОРО означает «душа, сердце» (心) — имя японской девушки.

- KOTONE означает «звук кото (японской арфы)» (琴音) — имя японской девушки.

- KOUKI означает «светлая надежда» (光 希) — японское имя мальчика.

- KOUTA означает «великий мир» (康 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- KUMIKO означает «давний прекрасный ребенок» (久 美 子) — японское имя девушки.

- КУНИО означает «деревенский человек» (國 男) — имя японского мальчика.

- KURO означает «девятый сын» (九郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- KYO означает «сотрудничество» (協) — японское унисекс-имя.

- KYOKO означает «почтительный ребенок» (恭子) — японское имя девушки.

- MADOKA означает «круг, круглый» (円) — японское унисекс-имя.

- MAI означает «танец» (舞) — имя японской девушки.

- МАЙКО означает «дитя танца» (舞 子) — японское имя девушки.

- МАКИ означает «настоящая надежда» (真 希) — японское имя девушки.

- MAKOTO означает «искренний» (誠) — японское унисекс-имя.

- МАМИ означает «истинная красота» (真 美) — японское имя девушки.

- MAMORU означает «защитник, охранник» (守) — японское имя мальчика.

- MANA означает «любовь» (愛) — японское женское имя.

- MANABU означает «ученик» (学) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАНАМИ означает «любить красивую» (愛美) — имя японской девушки.

- MAO означает «танец цветущей сакуры» (舞 桜) — японское женское имя.

- МАРИКО означает «настоящий деревенский ребенок» (真 里 子) — японское имя девочки.

- MASA означает «правда» (正 / 真) — японское унисекс-имя.

- МАСААКИ, что означает «приятная яркость» (良 昭) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАХИКО означает «праведный мальчик» (正彦) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАХИРО означает «великое процветание» (昌宏) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАКИ означает «большое деревянное дерево» (昌 樹) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАМИ означает «стать красивой» (成 美) — японское имя девушки.

- МАСАНОРИ означает «образец праведности, справедливости» (正 則) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАО означает «праведник» (正 男) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАРУ означает «победа» (勝) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАСИ означает «праведное стремление» (正 志) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАТО означает «праведник» (正人) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСАЙОШИ означает «праведный, благородный» (正義) — имя японского мальчика.

- МАСАЮКИ означает «праведное благословение» (正 幸) — японское имя мальчика.

- МАСУМИ означает «истинная ясность» (真澄) — японское унисекс-имя.

- MASUYO означает «приносит пользу миру» (益 世) — японское женское имя.

- MAYU означает «истинная нежность» (真 優) — имя японской девушки.

- МАЮМИ означает «истинная нежная красота» (真 優美) — имя японской девушки.

- MEGUMI означает «благословение» (恵) — имя японской девушки.

- MEI означает «прорастающая жизнь» (芽 生) — японское женское имя.

- МИ означает «красивая» (美) — японское имя девушки.

- MICHI означает «путь» (道) — японское унисекс-имя.

- MICHIKO означает «красивый мудрый ребенок» (美智子) — японское имя девушки.

- MICHIO означает «мужчина в путешествии» (道夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- MIDORI означает «зеленый» (緑) — японское имя девушки.

- MIEKO означает «прекрасное благословенное дитя» (美 枝子) — японское имя девочки.

- MIHO означает «защищенная, гарантированная красота» (美 保) — японское имя девушки.

- MIKA означает «красивый аромат» (美 香) — японское женское имя.

- MIKI означает «прекрасная принцесса» (美 姫) — японское имя девушки.

- МИКИО означает «мужчина со стволом дерева» (幹 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- MIKU означает «красивое небо» (美 空) — японское имя девушки.

- MINAKO означает «красивый ребенок» (美奈子) — японское имя девушки.

- MINORI означает «правда» (実) — японское унисекс-имя.

- MINORU означает «правда» (実) — японское имя мальчика.

- MIO означает «красивый цвет сакуры» (美 桜) — японское женское имя.

- MISAKI означает «красивый цветок» (美 咲) — имя японской девушки.

- MITSUKO означает «дитя света» (光子) — японское имя девушки.

- MITSUO означает «сияющий герой» (光 雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- MITSURU означает «удовлетворить, полный» (満) — японское унисекс-имя.

- MIU означает «красивое перо» (美 羽) — японское имя девушки.

- MIWA означает «красивая гармония, мир» (美 和) — японское женское имя.

- MIYAKO означает «красивый ночной ребенок» (美 夜 子) — японское имя девушки.

- MIYOKO означает «прекрасный ребенок поколений» (美 代 子) — японское имя девушки.

- MIYU означает «красивая нежная» (美 優) — имя японской девушки.

- MIYUKI, что означает «прекрасное благословение» (美幸) — японское имя девушки.

- MIZUKI означает «красивая луна» (美 月) — японское имя девушки.

- MOE означает «прорастающий» (萌) — японское имя девушки.

- MOMOE означает «сто благословений» (百 恵) — японское женское имя.

- МОМОКА означает «цветок персикового дерева» (桃花) — имя японской девушки.

- MOMOKO означает «ребенок персикового дерева» (桃子) — японское имя девочки.

- MORIKO означает «дитя леса» (森 子) — японское имя девушки.

- NANA означает «семерка» (七) — японское женское имя.

- NANAMI означает «семь морей» (七 海) — японское имя девушки.

- NAO означает «честный» (直) — японское унисекс-имя.

- НАОКИ означает «честное деревянное дерево» (直樹) — японское имя мальчика.

- NAOKO означает «честный ребенок» (直 子) — японское имя девушки.

- НАОМИ означает «честная красивая» (直 美) — японское имя девушки.

- НАЦУКИ означает «летняя надежда» (夏希) — японское имя девушки.

- НАЦУКО означает «летний ребенок» (夏 子) — японское имя девочки.

- НАЦУМИ означает «прекрасное лето» (夏 美) — японское имя девушки.

- NOA означает «моя любовь» (乃 愛) — японское имя девушки.

- NOBORU означает «восходить, подниматься» (翔) — японское имя мальчика.

- NOBU означает «продлить» (延) — японское имя мальчика.

- NOBUKO означает «верный, заслуживающий доверия ребенок» (信 子) — японское имя девочки.

- NOBUO означает «верный, заслуживающий доверия мужчина» (信 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- NOBURU означает «расширять» (伸) — японское имя мальчика.

- NOBUYUKI означает « истинная радость» (信 幸) — японское имя мальчика.

- NORI означает «править» (儀) — японское имя мальчика.

- NORIKO означает «законный ребенок» (典 子) — японское имя девочки.

- NORIO означает «законный мужчина» (法 男) — японское имя мальчика.

- OSAMU означает «дисциплинированный, прилежный» (修) — японское имя мальчика.

- RAN означает «орхидея» (蘭) — имя японской девушки.

- REI означает «прекрасный» (麗) — имя японской девушки.

- REIKO означает «милый ребенок» (麗 子) — японское имя девочки.

- REN означает «лотос / любовь» (蓮 / 恋) — японское унисекс-имя.

- RIE означает «истинное благословение» (理 恵) — японское имя девушки.

- RIKA означает «настоящий аромат» (理 香) — имя японской девушки.

- RIKO означает «дитя истины» (理 子) — японское имя девушки.

- RIKU означает «земля» (陸) — японское имя мальчика.

- RIKUTO означает «человек земли» (陸 人) — японское имя мальчика.

- RIN означает «достойный» (凛) — имя японской девушки.

- RINA означает «жасмин» (莉奈) — японское женское имя.

- RIO означает «деревенская сакура» (里 桜) — японское женское имя.

- РОКУРО означает «шестой сын» (六郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- RYO означает «освежающий, крутой» (涼) — японское имя мальчика.

- RYOICHI означает «хороший первый (сын)» (良 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- RYOKO означает «освежающий ребенок» (涼子) — японское имя девочки.

- RYOTA означает «отличное освежение» (涼 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- RYUU означает «дракон, императорский» (龍) — японское имя мальчика.

- RYUUNOSUKE означает «предшественник дворянина» (隆 之 介) — японское имя мальчика.

- САБУРО означает «третий сын» (三郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- САЧИКО означает «радостный, счастливый ребенок» (幸 子) — японское имя девочки.

- САДАО означает «праведный герой» (貞 雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- САКИ означает «цветок надежды» (咲 希) — имя японской девушки.

- САКУРА означает «цветение сакуры» (桜 / さ く ら) — японское имя девушки.

- САКУРАКО, что означает «ребенок сакуры» (桜 子) — японское имя девушки.

- SATOKO означает «мудрое дитя» (聡 子) — японское имя девушки.

- SATOMI означает «красивая и мудрая» (聡 美) — японское женское имя.

- SATORU означает «мудрый, быстрый ученик» (聡) — японское имя мальчика.

- SATOSHI означает «мудрый, быстрый ученик» (聡) — японское имя мальчика.

- САЮРИ означает «маленькая лилия» (小百合) — японское женское имя.

- SEIICHI означает «изысканный, чистый первый (сын)» (精一) — японское имя мальчика.

- SEIJI означает «изысканный, чистый второй (сын)» (精 二) — японское имя мальчика.

- SETSUKO означает «мелодичный ребенок» (節 子) — японское имя девушки.

- ШИЧИРО означает «седьмой сын» (七郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHIGEKO означает «растущий ребенок» (成 子) — японское имя девочки.

- ШИГЕО означает «тяжелый мужчина» (重 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- ШИГЕРУ означает «пышный, хорошо выращенный» (茂) — японское имя мальчика.

- ШИКА означает «олень» (鹿) — японское имя девушки.

- SHIN означает «правда» (真) — японское имя мальчика.

- ШИНИЧИ означает «настоящий первый (сын)» (真 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- ШИНДЗИ означает «истинный второй (сын)» (真 二) — японское имя мальчика.

- ШИНДЗЮ означает «жемчужина» (真珠) — имя японской девушки.

- СИНОБУ означает «выносливость» (忍) — японское имя унисекс.

- SHIORI означает «стихотворение» (詩織) — имя японской девушки.

- ШИРО означает «четвертый сын» (四郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHIZUKA означает «тихое лето» (静 夏) — имя японской девушки.

- SHIZUKO означает «тихий ребенок» (静 子) — японское имя девушки.

- SHO означает «летать» (翔) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHOICHI означает «летающий сын (первый)» (翔 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHOJI означает «летающий сын (второй)» (翔 二) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHOUTA означает «большой летающий» (翔 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHUICHI означает «дисциплинированный, прилежный первый (сын)» (修 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- SHUJI означает «дисциплинированный, прилежный второй (сын)» (修 二) — японское имя мальчика.

- ИЗБЕГАЙТЕ, что означает «скорость, быстро» (駿) — имя японской девушки.

- SORA означает «небо» (昊 / 空) — японское унисекс-имя.

- SOUTA, что означает «внезапно большой» (颯 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- СУМИКО означает «дитя ясности» (澄 子) — японское женское имя.

- SUSUMU означает «продвигаться, действовать» (進) — имя японского мальчика.

- SUZU означает «колокольчик» (鈴) — имя японской девушки.

- СУЗУМЕ означает «воробей» (雀) — японское имя девушки.

- TADAO означает «верный мужчина» (忠 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- TADASHI означает «верный» (忠) — японское имя мальчика.

- TAICHI означает «большой первый (сын)» (太 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- TAIKI означает «великое сияние, сияние» (大 輝) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКАХИРО означает «великая ценность, благородство» (貴 大) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКАКО означает «благородное дитя» (貴子) — японское имя девушки.

- ТАКАО означает «дворянин» (貴 夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКАРА означает «сокровище» (宝) — японское имя девушки.

- ТАКАСИ означает «процветающий, благородный» (隆) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКАЮКИ означает «благородное путешествие» (隆 行) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКЕХИКО означает «бамбуковый принц» (竹 彦) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКЕО означает «воин-герой» (武雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКЕШИ означает «свирепый воин» (武) — японское имя мальчика.

- TAKUMA означает «открывающая истина» (拓 真) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАКУМИ означает «ремесленник» (匠) — японское имя мальчика.

- TAMIKO означает «дитя многих красавиц» (多 美 子) — японское имя девушки.

- ТАМОЦУ означает «защитник, хранитель» (保) — японское имя мальчика.

- ТАРО означает «большой сын» (太郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- TATSUO означает «дракон, имперский герой» (竜 雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- TATSUYA означает «быть императором, драконом» (竜 也) — японское имя мальчика.

- TERUKO означает «сияющий ребенок» (照 子) — японское имя девушки.

- TETSUYA означает «философия, ясность» (哲 也) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOMIKO означает «дитя богатства, удачи» (富 子) — японское имя девушки.

- TOMIO означает «богатство, удача» (富) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOMOHIRO означает «западная деревня» (西村) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOMOKO означает «дитя мудрости, интеллекта» (智子) — японское имя девушки.

- TOMOMI означает «прекрасный друг» (朋 美) — японское имя девушки.

- TORU означает «проникнуть, прояснить» (徹) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOSHI означает «мудрый» (慧) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOSHIAKI означает «выгодный свет» (利明) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOSHIKO означает «умный ребенок» (敏 子) — японское имя девочки.

- TOSHIO означает «гениальный лидер, герой» (俊雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- TOSHIYUKI означает «мудрость» (智 之) — японское имя мальчика.

- ЦУБАКИ означает «цветок камелии» (椿) — имя японской девушки.

- TSUBAME означает «ласточка (птица)» (燕) — имя японской девушки.

- TSUKIKO означает «лунный ребенок» (月 子) — японское имя девушки.

- TSUNEO означает «последовательный герой» (恒 雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- ЦУТОМУ означает «усердие» (勤) — японское имя мальчика.

- TSUYOSHI означает «сильный» (剛) — японское имя мальчика.

- UME означает «слива» (梅) — имя японской девушки.

- UMEKO означает «сливовое дитя» (梅子) — японское имя девушки.

- УСАГИ означает «кролик» (兎) — японское имя девушки.

- ВАКАНА означает «гармоничная музыка» (和 奏) — японское женское имя.

- Ямато означает «великая гармония» (大 和) — японское имя мальчика.

- YASU означает «мир» (康) — японское унисекс-имя.

- ЯСУКО означает «дитя мира» (康 子) — японское имя девушки.

- ЯСУО означает «человек мира» (康夫) — японское имя мальчика.

- ЯСУШИ означает «мирный» (靖) — имя японского мальчика.

- YOICHI означает «солнечный свет, первый положительный сын» (陽 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOKO означает «дитя солнечного света» (陽 子) — японское имя девушки.

- YORI означает «доверие» (頼) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHI означает «удачливый / праведный» (吉 / 義) — японское унисекс-имя.

- YOSHIAKI означает «сияющая праведность» (義 昭) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHIE означает «красивый ручей» (佳 江) — японское имя девушки.

- YOSHIKAZU означает «мир, Япония» (良 和) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHIKO означает «дитя доброты» (良 子) — японское имя девушки.

- YOSHINORI означает «отличная модель» (佳 範) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHIO означает «радостная жизнь» (吉 生) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHIRO означает «праведный сын» (義 郎) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHITO означает «церемониальный, правильный человек» (儀 人) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOSHIYUKI означает «праведный путь» (義 行) — японское имя мальчика.

- YOUTA означает «великий солнечный свет» (陽 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUA означает «связывающая любовь» (結 愛) — японское имя девушки.

- YUI означает «связать одежду» (結 衣) — имя японской девушки.

- ЮИЧИ означает «героический первый (сын)» (雄 一) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUINA означает « соединить вместе» (結 奈) — японское имя девушки.

- YUJI означает «героический второй (сын)» (雄 二) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUKA, что означает «нежный цветок» (優 花) — японское женское имя.

- ЮКАРИ означает «красивое грушевое дерево» (佳 梨) — японское имя девушки.

- YUKI означает «счастье / снег» (幸 / 雪) — японское унисекс-имя.

- ЮКИКО означает «ребенок снега / ребенок счастья» (幸 子 / 雪 子) — японское имя девушки.

- ЮКИО означает «благословенный герой» (幸雄) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUKO означает «нежный ребенок» (優 子) — японское имя девушки.

- YUMI, означающее « разумная красота» (由 美) — японское имя девушки.

- ЮМИКО, что означает «разум прекрасного ребенка» (由美子) — японское имя девушки.

- ЮРИ означает «лилия» (百合) — имя японской девушки.

- ЮРИКО означает «дитя лилии» (百合 子) — японское имя девушки.

- ЮТАКА означает « изобильный , богатый» (豊) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUU означает «нежный» (優) — японское унисекс-имя.

- ЮУДАИ означает «великий герой» (雄 大) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUUKI означает «нежная, высшая надежда» (優 希) — японское имя унисекс.

- ЮУМА означает «нежная, высшая правда» (優 真) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUUNA означает «нежный» (優 奈) — имя японской девушки.

- ЮУТА означает «великая храбрость» (勇 太) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUUTO означает «нежный человек» (悠 人) — японское имя мальчика.

- YUZUKI означает «нежная луна» (優 月) — японское женское имя.

🙋♂️Хочешь выучить японский язык❓

Забирай лучший вариант обучения по самой привлекательной цене в интернете. Расширяй границы собственных возможностей 🔍 и открывай для себя новые способы заработка 💰

И начни понимать, читать и говорить на японском языке 🗣👂✍️

Японские имена: заключение

Поздравляем! Вот мы и узнали все самые популярные японские имена. А еще мы подготовили для вас список самых популярных японских фамилий со значениями.

Узнайте больше о культуре и традициях Японии.

Для работы проектов iXBT.com нужны файлы cookie и сервисы аналитики.

Продолжая посещать сайты проектов вы соглашаетесь с нашей

Политикой в отношении файлов cookie

Японские имена

имеют богатую и красивую историю, начиная от их значений и заканчивая иероглифами, используемыми для их написания. Понимание японских имен поможет вам понять происхождение и историю японских семей, а также при создании собственной с одним из представителей страны восходящего солнца подобрать имя собственному ребенку. В статье для лучшего понимания правильного произношения, где необходимо, будет использоваться латинский алфавит при написании имен и окончаний к ним.

Содержание

- История японских

имен - Условные

обозначения для японских имен - Японское

почтение - Символы,

используемые в японских именах - Фамилия

- Имена мальчиков

- Имена девочек

- Сэймэй Ханьдань

- Неяпонские имени

- Японский язык письменности

- Идеографическое письмо: японский кандзи

- Современные японские имена

- Итог

Писатель Мами

Судзуки объясняет, что уже в 300 г. до н.э. японские семьи объединялись в

кланы. Имена кланов использовались как фамилии, называемые удзи (氏). Эти имена часто основывались на

географических особенностях или занятиях членов клана.

Со временем

возникли могущественные кланы, одним из самых сильных из которых был Ямато. В

конце концов другие кланы объединились под властью Ямато. В дополнение к

названию клана им давали кабанэ (姓), разновидность аристократического титула. В результате сочетание удзи и кабанэ стало

способом обозначения различных клановых групп в королевстве Ямато. Японские

фамилии выросли из системы удзи-кабане.

Порядок

имен в японском языке соответствует восточноазиатскому стилю: фамилия ставится

на первое место, а имя — на второе. Например, в имени Судзуки Хироши «Судзуки»

— фамилия, а «Хироши» — имя.

Напротив,

многие западные страны, особенно те, которые используют латинский алфавит,

используют сначала имена, а затем фамилии. Люди из Японии, проживающие в

западных странах, могут следовать западной традиции ставить фамилию на второе

место, особенно когда их имена написаны латинскими

буквами. Какое-то время даже те, кто жил в Японии, иногда ставили свои фамилии

на второе место, когда их имена писались латинскими буквами.

Однако не

все согласились с этой адаптацией, и 1 января 2020 года правительство Японии постановило, что в официальных документах должен использоваться традиционный

порядок имен, даже если эти имена написаны латинским алфавитом.

Традиционно

японские имена не включают отчества. Но японские пары, которые живут в западной

культуре или имеют смешанную этническую принадлежность, могут перенять эту

практику для своих детей.

В японской

культуре очень важно правильное использование почетных знаков или титулов. На

самом деле, неиспользование подходящего титула считается нарушением этикета.

Официальные

титулы добавляются к фамилии человека и включают следующее:

Сан —

универсальный вежливый титул. Он добавляется к фамилии и может использоваться

как для мужчин, так и для женщин, например, Судзуки-сан. Это очень похоже на

значение мистера, миссис или мисс.

Сама —

более формальная версия слова сан. Он используется для обращения к кому-то

более высокого ранга, он также используется для обозначения клиентов в заведении, например,

Окада-сама.

Сэнсэй —

это титул, используемый для врачей, учителей и других лиц с похожими

профессиями, например, Такахаши-сэнсэй.

Менее

формальные титулы используются для членов семьи и друзей или теми, кто имеет

более высокий ранг, по отношению к тем, кто имеет более низкий ранг или статус.

Эти титулы обычно используются с именем человека, а не с фамилией.

Вот наиболее

распространенные неофициальные титулы:

Кун обычно

используется при обращении к юноше или мальчику по имени, например, Хироши-кун.

Это похоже на присвоение человеку по имени «Джон» прозвища «Джонни».

Тян чаще

всего используется для молодых девушек, хотя его также можно использовать как

нежное обращение к другому взрослому, например, Хару-тян. Это похоже на то,

как дать кому-то по имени «Сьюзен» прозвище «Сьюзи».

Кун и тян

также могут быть добавлены к сокращенной версии имени человека, например,

Ма-кун для Масато или Я-тян для Ясуё. Добавление кун или тян к сокращенной

версии имени считается более привычным, чем добавление их к полному имени.

Японские

имена могут быть написаны тремя способами. Наиболее распространенный способ — использовать кандзи, которые представляют собой логографические символы

китайского происхождения с японским произношением. Имена,

написанные кандзи, обычно состоят из двух символов. Эти имена регулируются

правилами Министерства юстиции Японии об использовании кандзи в именах.

Японские

кандзи

Поскольку

кандзи, используемые в именах, могут иметь несколько значений и вариантов

произношения, фуригана может оказаться полезной. Фуригана — это маленькие

символы кана, написанные рядом с кандзи или над ними и служащие руководством по

произношению. Фуриганы чаще всего используются в детских

книгах, но они также могут использоваться в книгах для взрослых, когда имя

человека может быть трудночитаемым или двусмысленным.

Японские имена для мужчин состоят из символов кандзи, тогда как женские имена обычно пишутся хираганой или катаканой. Хирагана, японская слоговая азбука — система письма, в которой каждый символ обозначает слог, а не звук или целое слово. Другое японское слоговое письмо, катакана, может использоваться для иностранных имен.

Японские имена трудно читать и произносить, поэтому при заполнении форм есть фонетическое руководство, которое человек должен упомянуть, а именно фуригана. Имена японских политиков часто пишутся хираганой или катаканой, потому что их легче читать, чем кандзи.

Имя человека

часто содержит два кандзи. Оба значения символов имеют положительные

коннотации, такие как красота, любовь, свет, названия цветов, природные явления

и т. д.

Многие имена

написаны кандзи одинаково, но произношение может отличаться. Пол человека часто можно угадать

по окончаниям его имен.

Пример: -ro,

-shi, -ya или -o обычно являются окончаниями мужских имен, тогда как -ko, -mi,

-e и -yo обычно являются окончаниями женских имен.

Японские фамилии

обычно используются для обращения друг к другу. Большинство

японских фамилий легко читаются, но есть и трудные исключения.

Иногда иероглифы,

которые вы читаете, могут не совпадать с иероглифами, которые вы произносите,

например: 八月一日 читается как «хатигацу цуитачи», но произносится как Ходзуми.

Фамилии

обычно происходят от географических особенностей или мест, например: яма

(гора), ки (дерево), сима (остров), мура (деревня) и т. д.

Некоторые кандзи, используемые в

распространенных японских фамилиях:

| Использованный кандзи | Значение | Пример фамилии |

|---|---|---|

| Yama | Гора | Yamamoto |

| Shima | Остров | Matsushima |

| Ki | Дерево | Haruki |

| Moto | Рядом | Morimoto |

| Oka | Холм | Okada |

| Ta/da | Рисовое поле | Honda |

Такие имена, как

Дзюнпей, Коросуке, Сарута-хико, все японские. Так как же японские имена составляют для мальчиков? Японские имена для мальчиков часто заканчиваются на

-hiko, -hei, -suke. Они также иногда заканчиваются на -o, например: Akio,

Suniyo, Teruo и т. д.

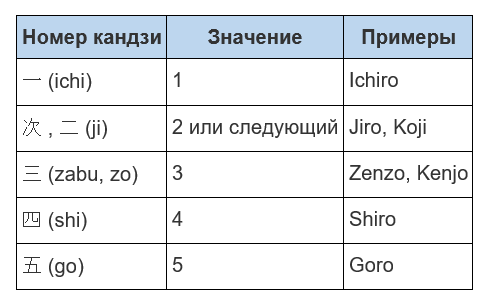

Также могут использоваться другие окончания вроде -shi, например, Watashi, Takashi, Atsushi и т. д. В именах

мальчиков часто есть символы кандзи, которые означают храбрость, правильность,

удачу и прочее. Раньше японских мальчиков называли по системе нумерации. Это потому, что у японских семей было несколько детей. Так что, если бы ребенок был первенцем, его назвали бы

Ичиро.

Ро означает «сын»

на японском языке, к которому добавлялся суффикс числа. Вторым сыном будет Дзиро и так далее.

Некоторые

распространенные японские имена для мальчиков: Акикадзу, Томокадзу, Коичи,

Сигеказу, Хидэкадзу, Кёити, Эйчи, Шуичи, Масакадзу от -ichi и -kazu.

Узнав, как

японские имена составляются для мальчиков, осталось узнать какие японские

имена подходят для девочек. Японские имена для девочек заканчиваются на -e, -yo, -mi и -ko,

написанные как 美 и 子

соответственно.

Некоторые

имена для вышеуказанных окончаний — Дораэми, Томоэ, Миёко и т. д. Другими наиболее

распространенными окончаниями, обозначающими японские имена для женщин, являются

-ka и -na, например: Мадока и Харуна соответственно.

Многие

женские имена имеют окончание -ko, что означает «ребенок». Это окончание обычно

предпочитают современные женщины типичным старым окончаниям.

Некоторые распространенные японские имена с -ko: Юко, Ацуко, Кейко, Йошико,

Тамико, Сейко, Рейко, Фудзико, Наёко и т. д.

Сэймэй Ханьдань —

один из способов гадания, связанного с именами. Он был предложен после эпохи

Мэйдзи и пришел из Китая. Гадание основано на количестве штрихов кандзи,

которые должны предсказать судьбу или личность человека.

Итак, как же работают японские имена в Сэймэй Ханьдань? Считается, что количество

штрихов кандзи указывает на удачу.

Вот список вещей,

которые вы можете узнать из японского имени для числа Сэймэй Ханьдань:

- Какие болезни вы можете получить в своей жизни;

- Род занятий, который подойдет для вашей жизни;

- Удача в браке и семье;

- Романтические отношения и тип вашего партнера;

- Будущая жизнь.

Многие люди

обращаются к Сэймэй Ханьдань, чтобы сохранить свои профессиональные имена или

имена своих детей. Существуют различные методы гадания с японскими именами с

Сэймэй Ханьдань, и результаты в каждом методе разные.

Имена, которые принадлежат

западу, обычно пишутся катаканой и зависят от того, как они звучат, а не от их

написания. Существуют

различные правила написания английских имен в катакане, например, множественное

число становится единственным, используемые гласные взяты из британского

произношения, а не из американского и т. д.

Однако для людей

с китайскими и корейскими именами в кандзи используется только японское

произношение.

Японские имена для людей занимают необычную нишу: если вы видите написанное

имя, это не значит, что вы знаете, как его произносить. Кроме того, то, что вы

слышите имя, не означает, что вы будете знать, как его написать, даже если вы

являетесь носителем японского языка.

В японском для

письма используются три вида письменности: идеограммы и два слоговых алфавита

(где каждый символ представляет собой слог).

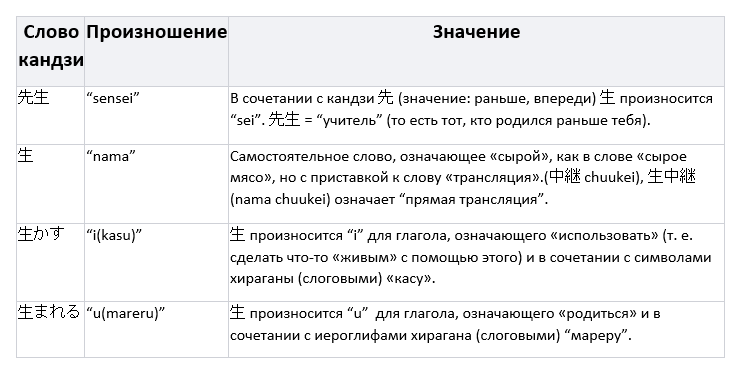

Кандзи — это

заимствованные китайские иероглифы, которые обозначают идею, но произношение

которых меняется в зависимости от контекста слова. Вот (неполная) выборка

различных произношений одного иероглифа кандзи.

Символ 生 имеет основное значение «жизнь». Он имеет особенно плодовитый набор произношений.

Фонетические сценарии: хирагана и катакана

Два слоговых алфавита, хирагана и катакана, в японском

языке представляют одни и те же 46 слогов, не придавая значения ни одному

символу. Как правило, хирагана, более пышная на вид, используется для японских

слов, а катакана — для заимствованных слов из других языков

HIRAGANA: あ, き, こ

KATAKANA: ア, キ, コ

ПРОИЗНОШЕНИЕ (СООТВЕТСВЕННО): a, ki, ko

Увидеть полную таблицу символов хираганы и катаканы можно здесь.

Как и в других культурах, имена и тенденции

именования проходят циклы популярности. В 2000-х годах многие родители выбирали чтение имени, а затем

творчески подбирали к нему символы кандзи. При этом они иногда полностью

игнорировали стандартные способы прочтения, связанные с этими иероглифами. Например, 一二三 (иероглифы кандзи для

чисел «1, 2, 3» читаются как «ити, ни, сан») можно сопоставить с чтением «до ре

ми» (да, как в музыкальных нотах.) Имена такого типа называются キラキラネーム («имя кира-кира»,

где «кира-кира» означает «блестящий/блестящий») или, более уничижительно, DQNネーム (произносится как «имя дон кён»).

Чтобы

обуздать заблудших родителей, которые могут назвать своего ребенка «демоном»

или чем-то еще, что может подвергнуть его насмешкам, Министерство юстиции

Японии ведет список разрешенных кандзи для использования в японских именах.

Процесс присвоения японскому ребенку имени довольно хлопотное и трудоемкое дело, так как нужно много чего учесть. Иногда в Японии просто следуют современным трендам на имена и сильно себя не утруждают в придумывании своего. Однако при его создании стоит учитывать легкость в прочтении, адекватное значение имени и его допустимость Министерством юстиции Японии. Если же японский ребенок будет проживать на западе, то можно использовать и местные имена или даже присвоить отчество.

Многие из нас знакомы с японскими именами по сюжетам из аниме, по литературным и художественным персонажам, по известным японским актерам и певцам. Но что же означают эти иногда красивые и милые, а иногда совсем неблагозвучные для нашего уха японские имена и фамилии? Какое японское имя самое популярное? Как можно перевести русские имена на японский язык? Какое значение имеют иероглифы японского имени? Какие японские имена встречаются редко? Об этом и многом другом я постараюсь рассказать, исходя из личного опыта проживания в Стране восходящего солнца. Так как тема эта весьма обширная, то я её разделю на три части: в первой речь пойдет о японских именах и фамилиях в целом, вторая будет посвящена мужским именам и фамилиям, а последняя – красивым женским именам и их значениям.

Японское имя состоит из фамилии и имени. Между ними иногда вставляют ник нэйм, например Накамура Нуэ Сатоси (здесь Нуэ – это ник), но его, естественно, нет в паспорте. Причём при перекличке и в списке авторов документов порядок будет именно такой: сначала фамилия, потом имя. Например, Хонда Йоске, а не Йоске Хонда.

В России, как правило, наоборот. Сравните сами, что привычнее Анастасия Сидорова или Сидорова Анастасия? Русские имена и фамилии в целом отличаются от японских тем, что у нас много людей с одинаковыми именами. В зависимости от поколения, в то или иное время среди наших одноклассников или одногрупников бывало по три Наташи, по четыре Александра или сплошные Ирины. У японцев, напротив, преобладают одинаковые фамилии.

По версии сайта myoji-yurai японские «Иванов, Петров, Сидоров» — это:

- Сатō (佐藤 – помощник + глициния, 1 млн. 877 тыс. человек),

- Судзуки (鈴木 — колокольчик + дерево, 1 млн. 806 тыс. человек) и

- Такахаси (高橋 – высокий мост, 1 млн. 421 тыс. человек).

Одинаковые же имена (не только по звучанию, но и с одинаковыми иероглифами) – это большая редкость.

Как же японские родители придумывают имена своим детям? Наиболее достоверный ответ можно получить рассматривая один из типичных японских сайтов – агрегаторов имен (да-да, такие существуют!) би-нейм.

- Сначала задаются фамилия родителей (женщины не всегда меняют фамилию при замужестве, но у детей – фамилия отца), например, Накамура 中村, затем их имена (например Масао и Митийо — 雅夫 и 美千代) и пол ребёнка (мальчик). Фамилия задается для того, чтобы подобрать сочетающиеся с ней имена. Это ничуть не отличается от России. Имена родителей нужны для того, чтобы задействовать один из иероглифов из имени отца (в случае мальчика) или из иероглифов матери (в случае девочки) в имени ребёнка. Так соблюдается преемственность.

- Далее выбирается количество иероглифов в имени. Чаще всего два: 奈菜 – Нана, реже один: 忍 – Синобу или три: 亜由美 — Аюми, и уж в исключительном случае четыре: 秋左衛門 — Акисаэмон.

- Следующий параметр – это тип знаков, из которых должно состоять желаемое имя: будут это только иероглифы: 和香 — Вака, либо же хирагана для тех, кто хочет быстрого написания имени: さくら — Сакура, или катакана, используемая для написания иностранных слов: サヨリ — Сайори. Также в имени могут использоваться смесь иероглифов и катаканы, иероглифов и хираганы.

При подборе иероглифов учитывается из скольких черт он состоит: различают благоприятное и неблагоприятное количество.Существует сформированная группа иероглифов, которые подходят для составления имен.

Так, первый результат моего гипотетического запроса – Накамура Аики 中村 合希 (значение иероглифов — реализующий мечты). Это лишь один среди сотен вариантов.

Иероглифы можно выбирать еще и по звучанию. Отсюда возникает основная сложность в сопоставлении русских и японских имён. Как быть, если у имён сходное звучание, но разное значение? Решается этот вопрос по-разному. Например, моих сыновей зовут Рюга и Тайга, но русские бабушки с дедушками называют их Юрик и Толян, а мне удобнее звать их Рюгаша и Тайгуша.

Китайцы, которые пользуются исключительно иероглифами, просто записывают русские имена в соответствии с их звучанием, подбирая иероглифы с более-менее хорошим значением. На мой взгляд, наиболее последовательный перевод русских имён на японский язык должен исходить из их значений. Самый популярный пример реализации этого принципа – это имя Александр, то есть защитник, что на японском звучит как Мамору, означает то же самое и пишется одним иероглифом 守.

Теперь касательно использования имён в повседневной жизни. В Японии, точно так же как и в Америке, при формальном общении используют фамилии: господин Танака 田中さん, госпожа Ямада 山田さん. По имени + суффикс -сан называют друг друга женщины-подружки: Кейко-сан, Масако-сан.

В семьях при обращении членов семьи друг к другу используется их семейный статус, а не имя. Например, муж и жена не зовут друг друга по имени, они обращаются на «супуруг» и «супруга»: данна-сан 旦那さん и оку-сан 奥さん.

То же самое с бабушками, дедушками, братьями и сёстрами. Эмоциональную окраску и тот или иной статус домочадца подчеркивается небезызвестными суффиксами –кун, -тян, -сама. Например, «бабулечка» — это баа-тян ばあちゃん, прекрасная как принцесса жена – «оку-сама» 奥様. Тот редкий случай, когда мужчина может назвать подругу или жену по имени – в порыве страсти, когда он уже не может себя контролировать. Женщинам же допустимо обращаться на «анта» — あなた или «дорогой».

По именам называют только детей, при том не только своих. Также применяются суффиксы, старшая дочь, например, – Мана-сан, младший сын – Са-тян. При этом реальное имя «Саики» урезано до «Са». Это мило с японской точки зрения. Мальчиков, вышедших из младенческого возраста и вплоть до взрослого состояния называют на –кун, например: Наото-кун.

В Японии, также как и в России, существуют странные и даже вульгарные имена. Зачастую такие имена дают недальновидные родители, которые хотят как-то выделить своего ребенка из общей массы. Имена такие называются по-японски «кира-кира-нэму» キラキラネーム (от яп. «кира-кира» — звук, передающий блеск и от англ. name), то есть «блестящее имя». Они пользуются некоторой популярностью, но как и все спорные вещи, существуют удачные и неудачные примеры использования таких имен.

Скандальный случай, широко обсуждавшийся в японской прессе, — это когда сыну дали имя, буквально значащее «демон» — яп. Акума 悪魔. Имя это как и использование подобных иероглифов в имени после данного происшествия запретили. Еще один пример – Пикачу (это не шутка!!!) яп. ピカチュウ по имени героя анимэ.

Говоря об удачных «кира-кира-нэму», то нельзя не упомянуть женское имя Роза, которое пишется иероглифом «роза» — 薔薇 яп. «бара», но произносится на европейский манер. Также у меня есть одна из японских племянниц (потому что у меня их целых 7!!!) с блестящим именем. Её имя произносится как Дзюне. Если написать латиницей, то June, то есть «июнь». Она родилась в июне. А пишется имя 樹音 – дословно «звук дерева».

Подводя итог рассказу о таких разных и необычных японских именах, приведу таблицы популярных японских имён для девочек и мальчиков за 2017 год. Таблицы такие составляются каждый год на основе статистики. Зачастую именно данные таблицы становятся последним аргументом для японских родителей, выбирающих имя своему ребёнку. Наверное, японцы действительно любят быть как все. В этих таблицах отображен рейтинг имён по иероглифам. Также существуют похожий рейтинг по звучанию имени. Он менее популярен, потому что выбор иероглифов – это всегда очень трудная для японского родителя задача.

Рейтинг мужских имен в Японии по статистике за 2017 г.

| Место в рейтинге 2017 г. | Иероглифы | Произношение | Значение | Частота появления в 2017 г. |

| 1 | 蓮 | Рэн | Лотос | 261 |

| 2 | 悠真 | Юма / Yūma | Спокойный и правдивый | 204 |

| 3 | 湊 | Минато | Безопасная гавань | 198 |

| 4 | 大翔 | Хирото | Большие расправленные крылья | 193 |

| 5 | 優人 | Юто /Yūto | Нежный человек | 182 |

| 6 | 陽翔 | Харуто | Солнечный и свободный | 177 |

| 7 | 陽太 | Йōта | Солнечный и мужественный | 168 |

| 8 | 樹 | Ицки | Статный как дерево | 156 |

| 9 | 奏太 | Сōта | Гармоничный и мужественный | 153 |

| 10 | 悠斗 | Юто / Yūto | Спокойный и вечный как звёздное небо | 135 |

| 11 | 大和 | Ямато | Великий и примиряющий, древнее название Японии | 133 |

| 12 | 朝陽 | Асахи | Утреннее солнце | 131 |

| 13 | 蒼 | Сō | Зелёный луг | 128 |

| 14 | 悠 | Ю / Yū | Спокойный | 124 |

| 15 | 悠翔 | Юто / Yūto | Спокойный и свободный | 121 |

| 16 | 結翔 | Юто/ Yūto | Объединяющий и свободный | 121 |

| 17 | 颯真 | Сōма | Свежий ветер, правдивый | 119 |

| 18 | 陽向 | Хината | Солнечный и целеустремлённый | 114 |

| 19 | 新 | Арата | Обновлённый | 112 |

| 20 | 陽斗 | Харуто | Вечный как солнце и звёзды | 112 |

Рейтинг женских имен в Японии по статистике за 2017 г.

| Место в рейтинге 2017 г. | Иероглифы | Произношение | Значение | Частота появления в 2017 г. |

| 1 | 結衣 | Юи / Yūi | Согревающая своими объятьями | 240 |

| 2 | 陽葵 | Химари | Цветок, обращенный к солнцу | 234 |

| 3 | 凜 | Рин | Закаленная, яркая | 229 |

| 4 | 咲良 | Сакура | Очаровательная улыбка | 217 |

| 5 | 結菜 | Юна / Yūna | Пленительная как весенний цветок | 215 |

| 6 | 葵 | Аои | Нежная и элегантная, трилистник с герба семьи Токугава | 214 |

| 7 | 陽菜 | Хина | Солнечная, весенняя | 192 |

| 8 | 莉子 | Рико | Умиротворяющая, словно аромат жасмина | 181 |

| 9 | 芽依 | Мэи | Независимая, с большим жизненным потенциалом | 180 |

| 10 | 結愛 | Юа / Yūa | Объединяющая людей, пробуждающая любовь | 180 |

| 11 | 凛 | Рин | Величавая | 170 |

| 12 | さくら | Сакура | Сакура | 170 |

| 13 | 結月 | Юдзуки | Обладающая шармом | 151 |

| 14 | あかり | Акари | Светлая | 145 |

| 15 | 楓 | Каэдэ | Яркая, как осенний клён | 140 |

| 16 | 紬 | Цумуги | Крепкая и прочная, как полотно | 139 |

| 17 | 美月 | Мицки | Прекрасная, как луна | 133 |

| 18 | 杏 | Ан | Абрикос, плодородная | 130 |

| 19 | 澪 | Мио | Водный путь, дарящая спокойствие | 119 |

| 20 | 心春 | Михару | Согревающая сердца людей | 116 |

А вам какие японские имена понравились?

Japanese names (日本人の氏名、日本人の姓名、日本人の名前, Nihonjin no Shimei, Nihonjin no Seimei, Nihonjin no Namae) in modern times consist of a family name (surname) followed by a given name, in that order. Nevertheless, when a Japanese name is written in the Roman alphabet, ever since the Meiji era, the official policy has been to cater to Western expectations and reverse the order. As of 2019, the government has stated its intention to change this policy.[2] Japanese names are usually written in kanji, which are characters mostly Chinese in origin but Japanese in pronunciation. The pronunciation of Japanese kanji in names follows a special set of rules, though parents are able to choose pronunciations; many foreigners find it difficult to read kanji names because of parents being able to choose which pronunciations they want for certain kanji, though most pronunciations chosen are common when used in names. Some kanji are banned for use in names,[citation needed] such as the kanji for «weak» and «failure», amongst others.

Parents also have the option of using hiragana or katakana when giving a name to their newborn child. Names written in hiragana or katakana are phonetic renderings, and so lack the visual meaning of names expressed in the logographic kanji.

According to estimates, there are over 300,000 different surnames in use today in Japan.[3] The three most common family names in Japan are Satō (佐藤), Suzuki (鈴木), and Takahashi (高橋).[4] People in Japan began using surnames during the Muromachi period.[5] Japanese peasants had surnames in the Edo period; however, they could not use them in public.[6]

While family names follow relatively consistent rules, given names are much more diverse in pronunciation and characters. While many common names can easily be spelled or pronounced, many parents choose names with unusual characters or pronunciations, and such names cannot in general be spelled or pronounced unless both the spelling and pronunciation are given. Unusual pronunciations have especially become common, with this trend having increased significantly since the 1990s.[7][8] For example, the popular masculine name 大翔 is traditionally pronounced «Hiroto», but in recent years alternative pronunciations «Haruto», «Yamato», «Taiga», «Sora», «Taito», «Daito», and «Masato» have all entered use.[7]

Male names often end in -rō (郎, «son»), but also «clear, bright» (朗) (e.g. «Ichirō»); -ta (太, «great, thick» or «first [son]») (e.g. «Kenta») or -o (男/雄/夫, «man») (e.g. «Teruo» or «Akio»),[9] or contain ichi (一, «first [son]») (e.g. «Ken’ichi»), kazu (一, «first [son]») (also written with 一, along with several other possible characters; e.g. «Kazuhiro»), ji (二/次, «second [son]» or «next») (e.g. «Jirō»), or dai (大, «great, large») (e.g. «Daichi»).

Female names often end in -ko (子, «child») (e.g. «Keiko») or -mi (美, «beauty») (e.g. «Yumi»). Other popular endings for female names include -ka (香, «scent, perfume») or «flower» (花) (e.g. «Reika») and -na (奈/菜, «greens» or «apple tree») (e.g. «Haruna»).

Structure[edit]

The majority of Japanese people have one surname and one given name, except for the Japanese imperial family, whose members have no surname. The family name – myōji (苗字、名字), uji (氏) or sei (姓) – precedes the given name, called the «name» (名, mei) or «lower name» (下の名前, shita no namae). The given name may be referred to as the «lower name» because, in vertically written Japanese, the given name appears under the family name.[10] People with mixed Japanese and foreign parentage may have middle names.[11]

Historically, myōji, uji and sei had different meanings. Sei was originally the patrilineal surname which was granted by the emperor as a title of male rank. There were relatively few sei, and most of the medieval noble clans trace their lineage either directly to these sei or to the courtiers of these sei. Uji was another name used to designate patrilineal descent, but later merged with myōji around the same time. Myōji was, simply, what a family chooses to call itself, as opposed to the sei granted by the emperor. While it was passed on patrilineally in male ancestors including in male ancestors called haku (uncles), one had a certain degree of freedom in changing one’s myōji. See also kabane.

A single name-forming element, such as hiro («expansiveness») can be written by more than one kanji (博, 弘, or 浩). Conversely, a particular kanji can have multiple meanings and pronunciations. In some names, Japanese characters phonetically «spell» a name and have no intended meaning behind them. Many Japanese personal names use puns.[12]

Very few names can be surnames and given names (for example Mayumi (真弓), Kaneko (金子), Masuko (益子), or Arata (新). Therefore, to those familiar with Japanese names, which name is the surname and which is the given name is usually apparent, no matter which order the names are presented in. This thus makes it unlikely that the two names will be confused, for example, when writing in English while using the family name-given name naming order. However, due to the variety of pronunciations and differences in languages, some common surnames and given names may coincide when Romanized: e.g., Maki (真紀、麻紀、真樹) (given name) and Maki (槇、牧、薪) (surname).

Although usually written in kanji, Japanese names have distinct differences from Chinese names through the selection of characters in a name and the pronunciation of them. A Japanese person can distinguish a Japanese name from a Chinese name. Akie Tomozawa said that this was equivalent to how «Europeans can easily tell that the name ‘Smith’ is English and ‘Schmidt’ is German or ‘Victor’ is English or French and ‘Vittorio’ is Italian».[13]

Characters[edit]

Japanese names are usually written in kanji (Chinese characters), although some names use hiragana or even katakana, or a mixture of kanji and kana. While most «traditional» names use kun’yomi (native Japanese) kanji readings, a large number of given names and surnames use on’yomi (Chinese-based) kanji readings as well. Many others use readings which are only used in names (nanori), such as the female name Nozomi (希). The majority of surnames comprise one, two or three kanji characters. There are also a small number of four or five kanji surnames, such as Teshigawara (勅使河原), Kutaragi (久多良木) and Kadenokōji (勘解由小路), but these are extremely rare.[citation needed] The sound no, indicating possession (like the Saxon genitive in English), and corresponding to the character の, is often included in names but not written as a separate character, as in the common name i-no-ue (井上, well-(possessive)-top/above, top of the well), or historical figures such as Sen no Rikyū.[14]

Most personal names use one, two, or three kanji.[12] Four-syllable given names are common, especially in eldest sons.[15]

As mentioned above, female given names often end in the syllable -ko, written with the kanji meaning «child» (子), or -mi, written with the kanji meaning «beautiful» (美).[16]

The usage of -ko (子) has changed significantly over the years: prior to the Meiji Restoration (1868), it was reserved for members of the imperial family. Following the restoration, it became popular and was overwhelmingly common in the Taishō and early Shōwa era.[7] The suffix -ko increased in popularity after the mid-20th century. Around the year 2006, due to the citizenry mimicking naming habits of popular entertainers, the suffix -ko was declining in popularity. At the same time, names of western origin, written in kana, were becoming increasingly popular for naming of girls.[12] By 2004 there was a trend of using hiragana instead of kanji in naming girls. Molly Hakes said that this may have to do with using hiragana out of cultural pride, since hiragana is Japan’s indigenous writing form, or out of not assigning a meaning to a girl’s name so that others do not have a particular expectation of her.[16]

Names ending with -ko dropped significantly in popularity in the mid-1980s, but are still given, though much less than in the past. Male names occasionally end with the syllable -ko as in Mako, but very rarely using the kanji 子 (most often, if a male name ends in -ko, it ends in -hiko, using the kanji 彦 meaning «boy»). Common male name endings are -shi and -o; names ending with -shi are often adjectives, e.g., Atsushi, which might mean, for example, «(to be) faithful.» In the past (before World War II), names written with katakana were common for women, but this trend seems to have lost favour. Hiragana names for women are not unusual. Kana names for boys, particularly those written in hiragana, have historically been very rare. This may be in part because the hiragana script is seen as feminine; in medieval Japan, women generally were not taught kanji and wrote exclusively in hiragana.[citation needed]

In Japanese, words, and thus names, do not begin with the Syllabic consonant n (ん); this is in common with other proper Japanese words, though colloquial words may begin with ん, as in nmai (んまい) (variant of umai (うまい, «delicious»). Some names end in -n: the male names Ken, Shin, and Jun are examples. The syllable n should not be confused with the consonant n, which names can begin with; for example, the female name Naoko (尚子) or the male Naoya (直哉). (The consonant n needs to be paired with a vowel to form a syllable).

One large category of family names can be categorized as -tō names. The kanji 藤, meaning wisteria, has the on’yomi tō (or, with rendaku, dō). Many Japanese people have surnames that include this kanji as the second character. This is because the Fujiwara clan (藤原家) gave their samurai surnames (myōji) ending with the first character of their name, to denote their status in an era when commoners were not allowed surnames. Examples include Atō, Andō, Itō (although a different final kanji is also common), Udō, Etō, Endō, Gotō, Jitō, Katō, Kitō, Kudō, Kondō, Saitō, Satō, Shindō, Sudō, Naitō, Bitō, and Mutō. As already noted, some of the most common family names are in this list.

Japanese family names usually include characters referring to places and geographic features.[17]

Difficulty of reading names[edit]

A name written in kanji may have more than one common pronunciation, only one of which is correct for a given individual. For example, the surname written in kanji as 東海林 may be read either Tōkairin or Shōji. Conversely, any one name may have several possible written forms, and again, only one will be correct for a given individual. The character 一 when used as a male given name may be used as the written form for «Hajime,» «Hitoshi,» «Ichi-/-ichi» «Kazu-/-kazu,» and many others. The name Hajime may be written with any of the following: 始, 治, 初, 一, 元, 肇, 創, 甫, 基, 哉, 啓, 本, 源, 東, 大, 孟, or 祝. This many-to-many correspondence between names and the ways they are written is much more common with male given names than with surnames or female given names but can be observed in all these categories. The permutations of potential characters and sounds can become enormous, as some very overloaded sounds may be produced by over 500 distinct kanji and some kanji characters can stand for several dozen sounds. This can and does make the collation, pronunciation, and romanization of a Japanese name a very difficult problem. For this reason, business cards often include the pronunciation of the name as furigana, and forms and documents often include spaces to write the reading of the name in kana (usually katakana).

A few Japanese names, particularly family names, include archaic versions of characters. For example, the very common character shima, «island», may be written as 嶋 or 嶌 instead of the usual 島. Some names also feature very uncommon kanji, or even kanji which no longer exist in modern Japanese. Japanese people who have such names are likely to compromise by substituting similar or simplified characters. This may be difficult for input of kanji in computers, as many kanji databases on computers only include common and regularly used kanji, and many archaic or mostly unused characters are not included.

An example of such a name is Saitō: there are two common kanji for sai here. The two sai characters have different meanings: 斉 means «together» or «parallel», but 斎 means «to purify». These names can also exist written in archaic forms, as 齊藤 and 齋藤 respectively.

A problem occurs when an elderly person forgets how to write their name in old kanji that is no longer used.

Family names are sometimes written with periphrastic readings, called jukujikun, in which the written characters relate indirectly to the name as spoken. For example, 四月一日 would normally be read as shigatsu tsuitachi («April 1st»), but as a family name it is read watanuki («unpadded clothes»), because April 1 is the traditional date to switch from winter to summer clothes. In the same way 小鳥遊 would normally be read as kotori asobi («little birds play») or shōchōyū, but is read Takanashi, because little birds (kotori) play (asobi) where there are no (nashi) hawks (taka).

Most Japanese people and agencies have adopted customs to deal with these issues. Address books, for instance, often contain furigana or ruby characters to clarify the pronunciation of the name. Japanese nationals are also required to give a romanized name for their passport. The recent use of katakana in Japanese media when referring to Japanese celebrities who have gained international fame has started a fad among young socialites who attempt to invoke a cosmopolitan flair using katakana names as a badge of honor.[citation needed] All of these complications are also found in Japanese place names.

Not all names are complicated. Some common names are summarized by the phrase tanakamura («the village in the middle of the rice fields»): the three kanji (ta (田, «rice field»), naka (中, «middle») and mura (村, «village»)), together in any pair, form a simple, reasonably common surname: Tanaka, Nakamura, Murata, Nakata (Nakada), Muranaka, Tamura.

Despite these difficulties, there are enough patterns and recurring names that most native Japanese will be able to read virtually all family names they encounter and the majority of personal names.

Regulations[edit]