Мало кто знает, почему на русском языке мы говорим «Стамбул», в то время как например на английском воспроизводится турецкий вариант: «Истамбул».

Дело в том, что полное название на греческом языке звучало как Константинополис.

То есть от латинского имени «Константин» и греческого «полис» (город)

. Кон+стан-та = «со+стоя-нная» в латинском языке означает по-стоянный, уверенный, надёжный, жёсткий и.т.п.

Однако поскольку для греческих антропонимов характерно двойственность то часто вместо полного имени греческие имена сокращаются оставля только одну половину.

Например Алекс+Андрей = АлекСАНдр, превращается просто в Саня, Саша.

Ев+Генадий (благо-родный) = ЕвГЕНий, превращается просто в Женя.

Тоже самое произошло и с именем Константин.

В разговорной речи длинные названия сокращаются.

Например говорится Петербург или даже Питер, а не СанктПетербург.

Или например Франковск (Хранковск) а не ИваноФранковск (бывш. Станислав)

Таком образом на разговорном греческом языке Стамполис означало тоже самое, что и официально Константинополис, только кратко.

«м» вместо «н» по понятным фонетическим причинам перехода носовой язычной, в носовую губную

перед аналогичной губной «п».

Когда турки взяли этот город, греки стали назвывать его «и спамполис» подчёркивая, что это уже

«НЕ стамполис (не константинополис).

В Российской Империи , где почти официально мечтали снова «водрузить крест над Константинополем», потому этот город продолжали называть без приставки отрицания.

Интересно, что Турция во некотором отношении похожа на Россию.

Только туркам повезло гораздо больше.

После того как Османская Империя «сотни народов» и «оплот мирового ислама» с треском рухнула по результатам мировой войны — нашёлся такой человек как Кемаль и Турция стала строить национальное тюрское государство из того что осталось. То есть на базе турецкого языка, который к тому же тщательно отчистили от в результате столетнего доминирования ислама арабизмов создали новую тюрскую нацию.

Собственно сами различия между «тюрский» и «турецкий» это опять таки изобретение российских и советских филологов. Также самом как изобретение «российский» в противоположность «русский».

В турецком (тюрском) языке нет ничего подобного и то и другое называется «тюркче».

Также само как идиотская идея «панславизма» всегда подкидывалась русскому народу представителями каких-то захолустных полудиких славяноязычных народнишек, которые всегда давным давно просвистев, либо никогда не имев и близко собственной национальной государственности будучи просто не способны к национальной самоорганизации мечтали при помоши «русской дубины» решать свои собственные проблемы.

Также само идея «пан-тюркизма» подкидывается Турции в основном со стороны разного рода «россиян» Характерно, что в современной Турции идея пантюркизма настолько же маргинальна как и например в Польше идея панславизма. Даже гораздо больше.

В то время как большинство идеологов «пантюркизма» вещают в интернете на русском языке и их сайты находятся на территории СНГ.

Сама идея, что что народы, говорящие по каким-то причинам на похожих языках являются частью «одного и того же народа» глубоко антинациональна ибо полностью отрицает и размывает сам факт самобытности национальной государственности. Не говоря уже о том что этнически это могут быть совершенно разные народы.

Парадокс заключается в том, что сам термин «панютркизм» куда более откровенно, чем «панславизм» пришивает все народы к одному — к туркам, возлагая на Турцию роль «паровоза», как раз только потому

что именно турки имеют своё собственное самостоятельное национальное государство.

Понимая, что это слишком противоречиво был введён термир «Туран». Хотя вряд ли есть действительно что-то общее между этнонимом «тюрк» в малой Азии с топонимом «туран» в раёне Алтая.

Сам термин «тюрки» употребляется исключительно в лингвистическом смысле. Когда мы говорим о «тюрских народах» мы имеем в виду лишь то, что их языки походи на язык Турции (Тюркии).

Также само как когда мы говорим о «германских» языках мы имеем в виду что их языки похожи

на язык Германии. Однако же никому и в голову не взбредёт придумать будто бы например какие-то

бывшие африканские колонии Англии населены «потомкамаи древних германцев» на том основании,

что негры говорят на английском языке, который условно считается германским. Даже ирландцев никто ведь этнически «англо-саксами» не считает.

В этническо-историческом смысле правильнее говорить «хунны» или в крайнем случае «тюрко-монголы». И тут как раз разношёрствоен население собствено Турции (Малой Азии), которое фактически является абсолютно тем же, что и во времена Восточной Римской Империи менее всего соответсвует этой категории. Фактически турки являются смесью греков (ромеев) и.т.п. с арабами, армянами, курдами и.т.п. И в гораздо меньшей степени с тюрко-монголами. Как собственно и сами греки, болгары, итальянцы и.т.д и.т.п. жители Средиземноморских стран.

Почему же в России между всеми славяноязычными или между тюркоязычными (турецкоязычными) народами всегда ставится жирный знак «равно»?

Что общего между турками и казахами или тем более якутами и башкирами?

Или между болгарами и поляками?

Откуда такое неуёмное желание — братания со всеми, кто говорит на похожем языке, даже

если говорить с ними в общем-то не о чем, ибо нет ничего общего.

Это всё такого сорта имперские идеи, которые противоположные национальному строительству. Они были актуальны тогда, когда странами и народами правили кланы и династии, которым было в общем-то абсолютно всё равно какого сорта их подданые, лишь бы их было побольше, чтобы собирать как можно больше дохода в столичную казну.

В России же после крушение монархии и Империи «ста народов» вместо строительства национального

русского государства было начато как раз изничтожение всего русского представителями как раз этих «ста народов» при чём от разного рода славянских «братушек» в вышиванках, Россия пострадала как раз больше всего.

То есть если турки в ходе крушения империи потеряли периферию, но сохранили национальное ядро, в результате чего Турция превратилась в развитое национальное государство, то в России как раз произошло всё наоборот. Инородцами была уничтожена и втоптана в грязь именно русская национальная

идентичность. Ядро России было уничтожено выходцами из периферии. В основном из Юго-Западных провинций бывшей РИ.

В России, в отличиен от Турции просто не нашлось в начале 20-го века людей, которые бы вместо давным давно маргинальных на то время идей торжества

всемирного ислама

всемирного православия загадившей умы национально-сознательной части русской элиты, выдвинули бы идеи построения светского русского национального государства. То есть национально-сознательная элита оказалась ещё большими маргиналами, чем даже большевики.

В результате разруха, гражданская война, истребление миллионов лучших людей в ходе коллективизации и репрессий, втягивание во вторую мировую войну с чудовищными миллиоными жертвами, превращение экономических отношений в сплошной концентрационный лагерь — тотальная ликвидация экономической свободы и превращение населения в полное бесправное неимущее большинство.

Всего этого избежала Турецкая республика.

В результате население с момента провозглашения турецкой республики увеличилось чуть ли не в 5 раз. В то время как население России не увеличилось не разу, а если считать именно молодёжь то даже намного уменьшилось.

Разумеется я далёк от мысли чтобы считать что увеличение количества населения есть всегда благо, либо что это всегда есть показатель благополучия. Однако же для России с её немеренными пространствами (в отличие от мелких стран Европы) резкое уменьшение роста численности населения и даже значительное его уменьшение является свидетельством совсем не «отсутсвия куда расти», но результатом чудовищных

условий жизни и просто физического истребления масс народа.

Характерно также, что хотя по «валовому» ВВП Турция почти в 2 раза отстаёт от Российской федерации, однако минимальная зарплата в Турции составляет 90 процентов от ВВП, в то время как в России всего 10.

Не говоря уже о структуре экономики. Львиная доля российского ВВП составляет нефть и газ, прочее сырьё а также продукты тяжёлой индустрии. В то время как в Турции почти половину занимает сфера услуг, лёгкая промышленность, а также строительная индустрия занимает не менее 5 процентов от ВВП.

Малый и средний бизнес в Турции составляет в отличие от России основную часть ВВП, что разумеется способствует равномерному распределению доходов. Ибо в России получается доходы Вексельберга

и Абрамовича складывают с доходами пенсионеров и делят на общее число, в результате конечно россияне получаются как бы «богатые».

Однако же это не учитывает тот факт, что большинство доходов получаемых российскими сверхбогатыми разумеется не могут быть ими освоенны с пользой для всего общества и страны а тратятся на безумные веши типа украшение брилиантами салонов автомобиля, покупки футбольных клубов и.т.п.

Более того львиная доля доходов российских частных лиц до 100 миллиардов долларов оседает в одном только Лондоне. А ведь есть ещё Испания, Швейцария и.т.д и.т.п.

Более того даже государственный доход Россия не в состоянии потратить на собственное развитие ибо

ничтожная российская экономика не может освоить такое количество денег. В результате миллиарды долларов полученных от продажи энергоресурсов складываются в американских банках развивая американскую экономику под ничтожный процент с большим риском вообще ничего не вернуть.

Относительно немногочисленный условный средний класс также основные свои доходы от высоких зарплат тратит на приобретение импортных вещей развивая экономики стран импортёров, при чём это касается не только товаров но и услуг. Например того же туризма в той же Турции.

В США живут миллионы итальянских мигрантов, которые по сей день уверены (им бабушки и дедушки рассказывали) что Италия это нищая грязная страна, где по 10 детей семьи, а большинство людей живут в сараях вместе с курами и козами, где сплошой криминал и.тд и.т.п..

Современная Италия конечно же хотя и далеко не самая богатая и чистая страна Европы, тем не менее живёт на уровне вполне приличном. Любой пенсионер имеет возможность снимать приличную 2 комнатную квартиру в Риме на свою пенсию даже живя в доме с детьми в провинции. Просто ради того чтобы «иногда» приехать «к себе», когда дети надоедят

То же самое касается современной Турции, которая в представлении многих является чем-то типа постсоветской Средней Азии или дикого постсоветского Кавказа и Закавказья.

А на самом деле это совсем не так.

Plan

- 1 Как правильно говорить Истанбул или Стамбул?

- 2 Почему Стамбул пишется Istanbul?

- 3 Чей раньше был Стамбул?

- 4 Какой страны столица Стамбул?

- 5 Как теперь называется город Константинополь?

- 6 Когда Константинополь стал столицей Римской империи?

- 7 Как Константинополь стал Стамбулом?

- 8 Что означает название города Стамбул?

- 9 Как делится Стамбул?

- 10 Почему Стамбул не столица?

- 11 Какой город расположен в двух частях света?

- 12 Где купаться в море в Стамбуле?

- 13 Какие города рядом со Стамбулом?

- 14 Где можно отдохнуть в Стамбуле?

- 15 Какой район лучше выбрать в Стамбуле?

- 16 Какой район Стамбула выбрать для жизни?

- 17 В каком районе Стамбула лучше остановиться для шопинга?

- 18 Где лучше выбрать отель в Стамбуле?

- 19 В каком районе лучше купить квартиру в Стамбуле?

- 20 Где лучше остановиться в Турции?

Как правильно говорить Истанбул или Стамбул?

Мало кто знает, почему на русском языке мы говорим «Стамбул», в то время как например на английском воспроизводится турецкий вариант: «Истамбул». Дело в том, что полное название на греческом языке звучало как Константинополис.

Почему Стамбул пишется Istanbul?

Происходит от нов. Στημπόλι [stimˈboli], от выражения εἰς την Πόλιν «в город» (под городом подразумевался Константинополь). Современное турецкое название города, İstanbul, отражает эгейский диалектный вариант произношения греческого выражения: εἰς τὰν Πόλιν» [istanˈbolin].

Когда горел Стамбул?

В сентябре 1509 года Стамбул сильно пострадал в результате мощного землетрясения.

Чей раньше был Стамбул?

Основание: город Византий Предшественником Стамбула является древнегреческий город Византий. Основали его дорийцы из древнегреческого города Мегары в 667 году до нашей эры.

Какой страны столица Стамбул?

Столицей Турции Стамбул не является. В 1923 году, после Войны за независимость Турции, Анкара стала новой турецкой столицей. Основан под названием Византион (Βυζάντιον) на мысе Сарайбурну около 660 г. до н. э. Город занимал стратегическое положение между Чёрным и Средиземным морем.

Чей раньше был Константинополь?

330 год – римский город Византий был назван Константинополем. Он стал столицей Восточной Римской империи, или Византии (которая образовалась после раздела Римской империи). 527-565 годы – масштабное народное восстание “Ника” против императора Юстиниана, который насильно переводил константинопольцев в христианскую веру.

Как теперь называется город Константинополь?

Город был официально переименован в Стамбул в 1930 году в ходе реформ Ататюрка.

Когда Константинополь стал столицей Римской империи?

История Константино́поля охватывает период от освящения в 330 году города, ставшего новой столицей Римской империи, до его захвата османами в 1453 году.

Как сейчас называется город Византий?

Константинополь

Как Константинополь стал Стамбулом?

по указу Мустафы Кемаля Ататюрка Константинополь был переименован в Стамбул. Смена вывески на вратах Царьграда стала одним из заключительных этапов реформ первого президента Турции и символизировала окончательный отказ страны от османского политического наследия и переход на светские рельсы.

Что означает название города Стамбул?

Современное турецкое название города — Истанбул (турец. İstanbul) — возникло еще в X в. Слово Истанбул произошло от греческой фразы «ис тим Поли» (греч. εἰς τὴν Πόλιν – в городе) и стало в турецкой разговорной речи обычным обозначением Константинополя еще до его завоевания.

Что означает название Стамбул?

„Стамполи“ наиболее близко к оригиналу». А Стамбул есть армянское произношение греческого слова, которое означает «городской», «из города». Вдохновленные армянским словом «Эсданбол» мы начали называть этот красивый город Стамбулом. И вообще, многие населенные пункты в Турции не имеют турецких названий.

Как делится Стамбул?

Стамбул делится на Европейскую и Азиатскую части и разделает их, собственно говоря, Босфор. Все основные достопримечательности и деловой центр города находятся на Европейской части.

Почему Стамбул не столица?

Когда то давно, когда еще существовала Византийская империя, столицей нынешней Турции был Константинополь, но во время падения этой империи, была основана новая Османская империя. Так Константинополь и был переименован в столицу Османской империи — Стамбул, один из самых крупных городов, имеющий свой порт.

На каком море находится Стамбул?

Ил Стамбул расположен одновременно в двух частях света — Европе и Азии, разделённых проливом Босфор. Площадь — 5170 км². С юга территория ила омывается водами Мраморного моря (включает Принцевы острова), с севера — Чёрного моря.

Какой город расположен в двух частях света?

Стамбул

Где купаться в море в Стамбуле?

Загородные пляжи Стамбула

- Как добраться до Кильос?

- High Beach Kilyos (Solar Beach)

- Пляж Тырмата (Tırmata Beach Kilyos)

- Пляж Байкуш (Baykuş Plajı Kilyos)

- Шиле (Şile)

- Принцевы острова (Adalar)

Какие курорты находятся рядом со Стамбулом?

Какие курорты Турции ближе к Стамбулу?

- Ялова. Самый близки курорт к Стамбулу – это Ялова.

- Коджаэли. Соседняя со Стамбулом провинция, которая также интересная курортным отдыхом.

- Бурса. В Муданье можно найти курортные отели с нормальными пляжами и завтраками.

- Чанаккале.

- Текирдаг.

- Сакарья.

Какие города рядом со Стамбулом?

результат

- местное время Bağcılar (Турция) расстояние : 8 Km.

- местное время Бурса (Турция) расстояние : 91 Km.

- местное время Измир (Турция) расстояние : 328 Km.

- местное время Анкара (Турция)

- местное время Çankaya (Турция)

- местное время Бухарест (Румыния)

- местное время Конья (Турция)

- местное время Анталия (Турция)

Где можно отдохнуть в Стамбуле?

Районы Стамбула: где лучше жить туристу

- Если вам плевать на толпы туристов, то селитесь в исторической квартале — Султанахмете.

- Альтернатива Султанахмету — район Бешикташ.

- Если вы хотите отдохнуть от шума и суеты города, то зачем вы вообще летите в Стамбул выбирайте Принцевы острова.

Что считается центром Стамбула?

Историческим центра города является Султанахмет (Sultanahmet), расположенный на берегу Босфора. Именно здесь находятся главные архитектурные достопримечательности Стамбула: Голубая мечеть, храм Святой Софии и др.

Какой район лучше выбрать в Стамбуле?

В рейтинге лучших районов Стамбула Султанахмет точно занял бы первое место. Как правило, именно с него начинается знакомство с городом. Султанахмет находится в старой части города, между Босфорским проливом, бухтой Золотой Рог и Мраморным морем.

Какой район Стамбула выбрать для жизни?

По данным компании İnanlar İnşaat, партнёра Tranio в Турции, самые престижные для проживания районы города — Бешикташ (Beşiktaş) и Сарыер (Sarıyer). Они находятся в европейской части Стамбула. «Для ведения бизнеса больше подходят многолюдные, оживлённые кварталы, в которых останавливается много туристов.

Где жить в Стамбуле?

Где остановиться в Стамбуле? Туристические и опасные районы

- Фатих (Fatih)

- Бейоглу (Beyoğlu) Таксим Галата Каракёй (Karaköy)

- Бешикташ (Beşıktaş)

- Принцевы острова (Адалар)

В каком районе Стамбула лучше остановиться для шопинга?

Для любителей шопинга лучше всего подходят районы: Кадыкёй, Лалели и Аксарай. Первый также хорош для любителей развлечений, поскольку имеет много ночных клубов и ресторанов. Самый большой выбор отелей Стамбула представлен на сайте booking.com.

Где лучше выбрать отель в Стамбуле?

Кварталов в Стамбуле очень много, но для выбора отеля вам достаточно знать основные (туристические) из них: Аксарай…С другой стороны бухты Золотой рог находятся:

- Дворец Долмабахче

- Галатская башня

- Улица Истикляль

- Площадь Таксим

- Один из самых крупных торговых центров в Европе

- Крепость Румели Хисары

Где лучше снимать квартиру в Стамбуле?

Районы Стамбула, где лучше остановиться туристу

- Султанахмет. Цены на жилье в историческом центре средние.

- Сиркеджи. Квартал рядом с одноименным вокзалом хорош для пеших прогулок в Султанахмет и к Египетскому базару.

- Бейоглу.

- Лалели.

- Бешикташ.

- Азиатская часть города.

В каком районе лучше купить квартиру в Стамбуле?

3 элитных района Стамбула, в которых стоит купить недвижимость

- В каком районе лучше купить квартиру в Стамбуле

- Бейоглу — район богемы и дипломатов

- Бешикташ: деловой центр в окружении дворцов

- Сарыер: респектабельность и релакс

Где лучше остановиться в Турции?

- Мармарис — курорт двух морей

- Кемер — молодёжный курорт

- Сиде — музей под открытым небом

- Алания — популярный курорт с демократичными ценами

- Белек — респектабельный отдых в Турции

- Бодрум — шумный курорт с яркой ночной жизнью

- Фетхие — спокойный и размеренный отдых

- Кушадасы — тихий курорт в окружении античности

Куда лучше поехать в Турцию в первый раз?

Куда поехать в первый раз в Турцию Например, Чиралы — сонный и маленький, Кемер — тихий, но развитый, а Анталья — большая и довольно шумная. Белек и Бодрум считаются престижными курортами, Аланья — самым недорогим. Мы жили в Кемере — там идеальное соотношение спокойствия, развитости курорта и красивой природы.

|

Istanbul İstanbul |

|

|---|---|

|

Metropolitan municipality |

|

|

Bosphorus Bridge Hagia Sophia Maiden’s Tower Ortaköy Mosque İstiklal Avenue Galata Tower Levent business district |

|

|

Flag |

|

|

OpenStreetMap |

|

|

Istanbul Location within Turkey Istanbul Location within Europe Istanbul Location within Asia |

|

| Coordinates: 41°00′49″N 28°57′18″E / 41.01361°N 28.95500°ECoordinates: 41°00′49″N 28°57′18″E / 41.01361°N 28.95500°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Marmara |

| Province | Istanbul |

| Provincial seat[a] | Cağaloğlu, Fatih |

| Districts | 39 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council government |

| • Body | Municipal Council of Istanbul |

| • Mayor | Ekrem İmamoğlu (CHP) |

| • Governor | Ali Yerlikaya |

| Area

[1][2] |

|

| • Urban | 2,576.85 km2 (994.93 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,343.22 km2 (2,063.03 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation

[3] |

537 m (1,762 ft) |

| Population

(31 December 2021)[4] |

|

| • Metropolitan municipality | 15,840,900 |

| • Rank | 1st in Turkey

1st in Europe |

| • Urban | 15,514,128 |

| • Urban density | 6,021/km2 (15,590/sq mi) |

| • Metro density | 2,965/km2 (7,680/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Istanbulite (Turkish: İstanbullu) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code |

34000 to 34990 |

| Area code(s) | +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side) |

| Vehicle registration | 34 |

| GDP (Nominal) | 2021[5] |

| — Total | US$ 248 billion |

| — Per capita | US$ 15,666 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.846[6] (very high) · 1st |

| GeoTLD | .ist, .istanbul |

| Website |

|

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

| Reference | 356bis |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

| Extensions | 2017 |

| Area | 765.5 ha (1,892 acres) |

Istanbul ( IST-an-BUUL,[7][8] IST-an-buul; Turkish: İstanbul [isˈtanbuɫ] (listen)), formerly known as Constantinople[b] (Greek: Κωνσταντινούπολις; Latin: Constantinopolis), is the largest city in Turkey, serving as the country’s economic, cultural and historic hub. The city straddles the Bosporus strait, lying in both Europe and Asia, and has a population of over 15 million residents, comprising 19% of the population of Turkey.[4] Istanbul is the most populous European city,[c] and the world’s 15th-largest city.

The city was founded as Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον, Byzantion) in the 7th century BCE by Greek settlers from Megara.[9] In 330 CE, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great made it his imperial capital, renaming it first as New Rome (Greek: Νέα Ῥώμη, Nea Rhomē; Latin: Nova Roma)[10] and then as Constantinople (Constantinopolis) after himself.[10][11] The city grew in size and influence, eventually becoming a beacon of the Silk Road and one of the most important cities in history.

The city served as an imperial capital for almost 1600 years: during the Roman/Byzantine (330–1204), Latin (1204–1261), late Byzantine (1261–1453), and Ottoman (1453–1922) empires.[12] The city played a key role in the advancement of Christianity during Roman/Byzantine times, hosting four (including Chalcedon (Kadıköy) on the Asian side) of the first seven ecumenical councils (all of which were in present-day Turkey) before its transformation to an Islamic stronghold following the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 CE—especially after becoming the seat of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1517.[13]

In 1923, after the Turkish War of Independence, Ankara replaced the city as the capital of the newly formed Republic of Turkey. In 1930, the city’s name was officially changed to Istanbul, the Turkish rendering of εἰς τὴν Πόλιν (romanized: eis tḕn Pólin; ‘to the City’), the appellation Greek speakers used since the 11th century to colloquially refer to the city.[10]

Over 13.4 million foreign visitors came to Istanbul in 2018, eight years after it was named a European Capital of Culture, making it the world’s eighth most visited city.[14] Istanbul is home to several UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and hosts the headquarters of numerous Turkish companies, accounting for more than thirty percent of the country’s economy.[15][16]

Toponymy

The first known name of the city is Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον, Byzántion), the name given to it at its foundation by Megarian colonists around 657 BCE.[10][18] Megarian colonists claimed a direct line back to the founders of the city, Byzas, the son of the god Poseidon and the nymph Ceroëssa.[18] Modern excavations have raised the possibility that the name Byzantium might reflect the sites of native Thracian settlements that preceded the fully-fledged town.[19] Constantinople comes from the Latin name Constantinus, after Constantine the Great, the Roman emperor who refounded the city in 324 CE.[18] Constantinople remained the most common name for the city in the West until the 1930s, when Turkish authorities began to press for the use of «Istanbul» in foreign languages. Ḳosṭanṭīnīye (Ottoman Turkish: قسطنطينيه) and İstanbul were the names used alternatively by the Ottomans during their rule.[20]

The name İstanbul (Turkish pronunciation: [isˈtanbuɫ] (listen), colloquially Turkish pronunciation: [ɯsˈtambuɫ]) is commonly held to derive from the Medieval Greek phrase «εἰς τὴν Πόλιν» (pronounced Greek pronunciation: [is tim ˈbolin]), which means «to the city»[21] and is how Constantinople was referred to by the local Greeks. This reflected its status as the only major city in the vicinity. The importance of Constantinople in the Ottoman world was also reflected by its nickname Der Saadet meaning the ‘Gate to Prosperity’ in Ottoman Turkish.[22] An alternative view is that the name evolved directly from the name Constantinople, with the first and third syllables dropped.[18] Some Ottoman sources of the 17th century, such as Evliya Çelebi, describe it as the common Turkish name of the time; between the late 17th and late 18th centuries, it was also in official use. The first use of the word Islambol (Ottoman Turkish: اسلامبول) on coinage was in 1730 during the reign of Sultan Mahmud I.[23] In modern Turkish, the name is written as İstanbul, with a dotted İ, as the Turkish alphabet distinguishes between a dotted and dotless I. In English the stress is on the first or last syllable, but in Turkish it is on the second syllable (-tan-).[24] A person from the city is an İstanbullu (plural: İstanbullular); Istanbulite is used in English.[25]

History

Neolithic artifacts, uncovered by archeologists at the beginning of the 21st century, indicate that Istanbul’s historic peninsula was settled as far back as the 6th millennium BCE.[26] That early settlement, important in the spread of the Neolithic Revolution from the Near East to Europe, lasted for almost a millennium before being inundated by rising water levels.[27][26][28][29] The first human settlement on the Asian side, the Fikirtepe mound, is from the Copper Age period, with artifacts dating from 5500 to 3500 BCE,[30] On the European side, near the point of the peninsula (Sarayburnu), there was a Thracian settlement during the early 1st millennium BCE. Modern authors have linked it to the Thracian toponym Lygos,[31] mentioned by Pliny the Elder as an earlier name for the site of Byzantium.[32]

The history of the city proper begins around 660 BCE,[10][33][d] when Greek settlers from Megara established Byzantium on the European side of the Bosporus. The settlers built an acropolis adjacent to the Golden Horn on the site of the early Thracian settlements, fueling the nascent city’s economy.[39] The city experienced a brief period of Persian rule at the turn of the 5th century BCE, but the Greeks recaptured it during the Greco-Persian Wars.[40] Byzantium then continued as part of the Athenian League and its successor, the Second Athenian League, before gaining independence in 355 BCE.[41] Long allied with the Romans, Byzantium officially became a part of the Roman Empire in 73 CE.[42] Byzantium’s decision to side with the Roman usurper Pescennius Niger against Emperor Septimius Severus cost it dearly; by the time it surrendered at the end of 195 CE, two years of siege had left the city devastated.[43] Five years later, Severus began to rebuild Byzantium, and the city regained—and, by some accounts, surpassed—its previous prosperity.[44]

Rise and fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire

Constantine the Great effectively became the emperor of the whole of the Roman Empire in September 324.[45] Two months later, he laid out the plans for a new, Christian city to replace Byzantium. As the eastern capital of the empire, the city was named Nova Roma; most called it Constantinople, a name that persisted into the 20th century.[46] On 11 May 330, Constantinople was proclaimed the capital of the Roman Empire, which was later permanently divided between the two sons of Theodosius I upon his death on 17 January 395, when the city became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.[47]

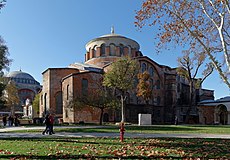

The establishment of Constantinople was one of Constantine’s most lasting accomplishments, shifting Roman power eastward as the city became a center of Greek culture and Christianity.[47][48] Numerous churches were built across the city, including Hagia Sophia which was built during the reign of Justinian the Great and remained the world’s largest cathedral for a thousand years.[49] Constantine also undertook a major renovation and expansion of the Hippodrome of Constantinople; accommodating tens of thousands of spectators, the hippodrome became central to civic life and, in the 5th and 6th centuries, the center of episodes of unrest, including the Nika riots.[50][51] Constantinople’s location also ensured its existence would stand the test of time; for many centuries, its walls and seafront protected Europe against invaders from the east and the advance of Islam.[48] During most of the Middle Ages, the latter part of the Byzantine era, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city on the European continent and at times the largest in the world.[52][53] Constantinople is generally considered to be the center and the «cradle of Orthodox Christian civilization».[54][55]

Constantinople began to decline continuously after the end of the reign of Basil II in 1025. The Fourth Crusade was diverted from its purpose in 1204, and the city was sacked and pillaged by the crusaders.[56] They established the Latin Empire in place of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.[57] Hagia Sophia was converted to a Catholic church in 1204. The Byzantine Empire was restored, albeit weakened, in 1261.[58] Constantinople’s churches, defenses, and basic services were in disrepair,[59] and its population had dwindled to a hundred thousand from half a million during the 8th century.[e] After the reconquest of 1261, however, some of the city’s monuments were restored, and some, like the two Deesis mosaics in Hagia Sophia and Kariye, were created.[60]

Various economic and military policies instituted by Andronikos II, such as the reduction of military forces, weakened the empire and left it vulnerable to attack.[61] In the mid-14th-century, the Ottoman Turks began a strategy of gradually taking smaller towns and cities, cutting off Constantinople’s supply routes and strangling it slowly.[62] On 29 May 1453, after an eight-week siege (during which the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI, was killed), Sultan Mehmed II «the Conqueror» captured Constantinople and declared it the new capital of the Ottoman Empire. Hours later, the sultan rode to the Hagia Sophia and summoned an imam to proclaim the Islamic creed, converting the grand cathedral into an imperial mosque due to the city’s refusal to surrender peacefully.[63] Mehmed declared himself as the new Kayser-i Rûm (the Ottoman Turkish equivalent of the Caesar of Rome) and the Ottoman state was reorganized into an empire.[64][65]

Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic eras

Map of Istanbul in the 16th century by the Ottoman polymath Matrakçı Nasuh

Following the conquest of Constantinople,[f] Mehmed II immediately set out to revitalize the city. Cognizant that revitalization would fail without the repopulation of the city, Mehmed II welcomed everyone–foreigners, criminals, and runaways– showing extraordinary openness and willingness to incorporate outsiders that came to define Ottoman political culture.[67] He also invited people from all over Europe to his capital, creating a cosmopolitan society that persisted through much of the Ottoman period.[68] Revitalizing Istanbul also required a massive program of restorations, of everything from roads to aqueducts.[69] Like many monarchs before and since, Mehmed II transformed Istanbul’s urban landscape with wholesale redevelopment of the city center.[70] There was a huge new palace to rival, if not overshadow, the old one, a new covered market (still standing as the Grand Bazaar), porticoes, pavilions, walkways, as well as more than a dozen new mosques.[69] Mehmed II turned the ramshackle old town into something that looked like an imperial capital.[70]

Social hierarchy was ignored by the rampant plague, which killed the rich and the poor alike in the 16th century.[71] Money could not protect the rich from all the discomforts and harsher sides of Istanbul.[71] Although the Sultan lived at a safe remove from the masses, and the wealthy and poor tended to live side by side, for the most part Istanbul was not zoned as modern cities are.[71] Opulent houses shared the same streets and districts with tiny hovels.[71] Those rich enough to have secluded country properties had a chance of escaping the periodic epidemics of sickness that blighted Istanbul.[71]

The Ottoman Dynasty claimed the status of caliphate in 1517, with Constantinople remaining the capital of this last caliphate for four centuries.[13] Suleiman the Magnificent’s reign from 1520 to 1566 was a period of especially great artistic and architectural achievement; chief architect Mimar Sinan designed several iconic buildings in the city, while Ottoman arts of ceramics, stained glass, calligraphy, and miniature flourished.[72] The population of Constantinople was 570,000 by the end of the 18th century.[73]

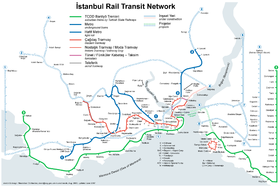

A period of rebellion at the start of the 19th century led to the rise of the progressive Sultan Mahmud II and eventually to the Tanzimat period, which produced political reforms and allowed new technology to be introduced to the city.[74] Bridges across the Golden Horn were constructed during this period,[75] and Constantinople was connected to the rest of the European railway network in the 1880s.[76] Modern facilities, such as a water supply network, electricity, telephones, and trams, were gradually introduced to Constantinople over the following decades, although later than to other European cities.[77] The modernization efforts were not enough to forestall the decline of the Ottoman Empire.[78]

Two aerial photos showing the Golden Horn and the Bosporus, taken from a German zeppelin on 19 March 1918

Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the Ottoman Parliament, closed since 14 February 1878, was reopened 30 years later on 23 July 1908, which marked the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era.[79] A series of wars in the early 20th century, such as the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), plagued the ailing empire’s capital and resulted in the 1913 Ottoman coup d’état, which brought the regime of the Three Pashas.[80]

The Ottoman Empire joined World War I (1914–1918) on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The deportation of Armenian intellectuals on 24 April 1915 was among the major events which marked the start of the Armenian genocide during WWI.[82] Due to Ottoman and Turkish policies of Turkification and ethnic cleansing, the city’s Christian population declined from 450,000 to 240,000 between 1914 and 1927.[83] The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918 and the Allies occupied Constantinople on 13 November 1918. The Ottoman Parliament was dissolved by the Allies on 11 April 1920 and the Ottoman delegation led by Damat Ferid Pasha was forced to sign the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920.[citation needed]

Following the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, and the last Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed VI, was declared persona non grata. Leaving aboard the British warship HMS Malaya on 17 November 1922, he went into exile and died in Sanremo, Italy, on 16 May 1926. The Treaty of Lausanne was signed on 24 July 1923, and the occupation of Constantinople ended with the departure of the last forces of the Allies from the city on 4 October 1923.[84] Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the Liberation Day of Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul’un Kurtuluşu) and is commemorated every year on its anniversary.[84] On 29 October 1923 the Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Ankara as its capital. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the Republic’s first President.[85][86]

A 1942 wealth tax assessed mainly on non-Muslims led to the transfer or liquidation of many businesses owned by religious minorities.[87] From the late 1940s and early 1950s, Istanbul underwent great structural change, as new public squares, boulevards, and avenues were constructed throughout the city, sometimes at the expense of historical buildings.[88] The population of Istanbul began to rapidly increase in the 1970s, as people from Anatolia migrated to the city to find employment in the many new factories that were built on the outskirts of the sprawling metropolis. This sudden, sharp rise in the city’s population caused a large demand for housing, and many previously outlying villages and forests became engulfed into the metropolitan area of Istanbul.[89]

Geography

Istanbul is located in north-western Turkey and straddles the strait Bosporus, which provides the only passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean via the Sea of Marmara.[15] Historically, the city has been ideally situated for trade and defense: The confluence of the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Golden Horn provide both ideal defense against enemy attack and a natural toll-gate.[15] Several picturesque islands—Büyükada, Heybeliada, Burgazada, Kınalıada, and five smaller islands—are part of the city.[15] Istanbul’s shoreline has grown beyond its natural limits. Large sections of Caddebostan sit on areas of landfill, increasing the total area of the city to 5,343 square kilometers (2,063 sq mi).[15]

Despite the myth that seven hills make up the city, there are, in fact, more than 50 hills within the city limits. Istanbul’s tallest hill, Aydos, is 537 meters (1,762 ft) high.[15]

The nearby North Anatolian Fault is responsible for much earthquake activity, although it doesn’t physically pass through the city itself.[90] The fault caused the earthquakes in 1766 and 1894.[90] The threat of major earthquakes plays a large role in the city’s infrastructure development, with over 500,000[90] vulnerable buildings demolished and replaced since 2012.[91] The city has repeatedly upgraded its building codes, most recently in 2018,[91] requiring retrofits for older buildings and higher engineering standards for new construction.

Climate

Istanbul has a borderline Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa, Trewartha Cs), humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa, Trewartha Cf) and oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb, Trewartha Do) under both classifications. It experiences cool winters with frequent precipitation, and warm to hot (mean temperature peaking at 20 °C (68 °F) to 25 °C (77 °F) in August, depending on location), moderately dry summers.[92] Spring and fall are usually mild, with varying conditions dependent on wind direction.[93][94]

Istanbul’s weather is strongly influenced by the Sea of Marmara to the south, and the Black Sea to the north. This moderates temperature swings and produces a mild temperate climate with low diurnal temperature variation. Consequently, Istanbul’s temperatures almost always oscillate between −5 °C (23 °F) and 32 °C (90 °F),[95] and most of the city does not experience temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) for more than 14 days a year.[96] Another effect of Istanbul’s maritime position is its persistently high dew points, near-saturation morning humidity,[97] and frequent fog,[98][95] which also limits Istanbul’s sunshine hours to levels closer to Western Europe,[99] and gives the city its noticeable seasonal lag; Istanbul is one of the few cities in the temperate Northern Hemisphere where March is, on average, colder than December.

Because of its hilly topography and maritime influences, Istanbul exhibits a multitude of distinct microclimates.[100] Within the city, rainfall varies widely owing to the rain shadow of the hills in Istanbul, from around 600 millimeters (24 in) on the southern fringe at Florya to 1,200 millimeters (47 in) on the northern fringe at Bahçeköy.[101] Furthermore, while the city itself lies in USDA hardiness zones 9a to 9b, its inland suburbs lie in zone 8b with isolated pockets of zone 8a, restricting the cultivation of cold-hardy subtropical plants to the coasts.[96][102]

As Istanbul is only slightly rain shadowed from Mediterranean storms and is otherwise surrounded by water, it usually receives some amount of precipitation from both Western European and Mediterranean systems. This results in frequent precipitation: the average number of rainy days in the city is 131, and in some parts it may reach up to 152 days. Furthermore, during early and mid-winter, the city’s frequency of precipitation is virtually unparalleled in the Mediterranean basin; January averages 20 days of precipitation when counting trace accumulations,[103] 17 when using a 0.1 mm threshold, and 12 when using a 1.0 mm threshold.[104] Summer is considerably drier; unlike a true Mediterranean climate however, there is no true dry season as defined by Köppen.[105]

According to a study, an average of more than 60 centimeters (24 in) of snow falls every year on the area of the airport, making Istanbul the snowiest major city in the Mediterranean basin, despite not having the cold winters typical of snowy cities.[95][106] Snowfall varies widely between years and different areas of the city, with districts facing north more prone to receive snow than southerly ones. This is largely caused by lake-effect snow, which forms when cold air, originating from the North Pole or Siberia, develops into moist and unstable air that ascends to form snow squalls along the lee shores of the Black Sea, upon contact with the relatively warm water.[107] These snow squalls are heavy snow bands and occasionally thundersnows, with accumulation rates approaching 5–8 centimeters (2–3 in) per hour.[108]

The highest recorded temperature at the official downtown observation station in Sarıyer was 41.5 °C (107 °F) and on 13 July 2000.[107] The lowest recorded temperature was −16.1 °C (3 °F) on 9 February 1929.[107] The highest recorded snow cover in the city center was 80 centimeters (31 in) on 4 January 1942, and 104 centimeters (41 in) in the northern suburbs on 11 January 2017.[109][107][110]

| Climate data for Kireçburnu, Istanbul (normals 1981–2010, extremes 1929–2018, snowy days 1996-2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

29.3 (84.7) |

33.6 (92.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

40.2 (104.4) |

41.5 (106.7) |

40.5 (104.9) |

39.6 (103.3) |

34.2 (93.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

41.5 (106.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.9 (7.0) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 99.5 (3.92) |

82.1 (3.23) |

69.2 (2.72) |

43.1 (1.70) |

31.5 (1.24) |

40.6 (1.60) |

39.6 (1.56) |

41.9 (1.65) |

64.4 (2.54) |

102.3 (4.03) |

110.3 (4.34) |

125.1 (4.93) |

849.6 (33.45) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 16.9 | 15.2 | 13.2 | 10.0 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 12.3 | 13.9 | 17.5 | 131.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 cm) | 4.5 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.7 | 15.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 68.2 | 89.6 | 142.6 | 180.0 | 248.0 | 297.6 | 319.3 | 288.3 | 234.0 | 158.1 | 93.0 | 62.0 | 2,180.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.2 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 5.9 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 12 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22 | 29 | 38 | 46 | 57 | 64 | 69 | 66 | 65 | 46 | 31 | 22 | 46 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source: [107][111][112] |

| Climate data for Florya, Istanbul (normals 1991–2020, extremes 1937–present, sunshine 1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.5 (68.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.6 (101.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

32.3 (90.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

19.2 (66.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

11.7 (53.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.6 (9.3) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 72.0 (2.83) |

78.8 (3.10) |

61.0 (2.40) |

51.5 (2.03) |

30.2 (1.19) |

31.5 (1.24) |

19.8 (0.78) |

26.1 (1.03) |

44.7 (1.76) |

80.4 (3.17) |

69.3 (2.73) |

87.3 (3.44) |

648.0 (25.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 18.3 | 16.8 | 15.5 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 6.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 11.8 | 13.5 | 17.2 | 132.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 cm) | 2.7 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 8.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.3 | 103.4 | 154.8 | 198.2 | 279.0 | 286.2 | 310.7 | 284.2 | 201.7 | 152.1 | 112.0 | 83.3 | 2,254.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.9 | 6.6 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 4.9 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 6.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 28 | 32 | 40 | 50 | 64 | 63 | 66 | 65 | 55 | 44 | 37 | 28 | 48 |

| Source: [113][114][115][116] |

| Climate data for Bahçeköy, Istanbul (normals and extremes 1981–2010, snowy days 1990-1999) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.3 (77.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

38.7 (101.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

38.2 (100.8) |

35.7 (96.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

38.7 (101.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

17.3 (63.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.9 (47.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.0 (3.2) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 163.7 (6.44) |

112.5 (4.43) |

101.3 (3.99) |

68.3 (2.69) |

55.8 (2.20) |

47.4 (1.87) |

45.3 (1.78) |

71.9 (2.83) |

79.6 (3.13) |

119.0 (4.69) |

164.3 (6.47) |

188.3 (7.41) |

1,217.4 (47.93) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.8 | 14.2 | 12.9 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 7.4 | 12.6 | 15.4 | 19.8 | 135.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 cm) | 4.6 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 16.2 |

| Source: [117][118] |

| Climate data for Istanbul | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.5 (60.0) |

| Source: Weather Atlas [112] |

Climate change

As with virtually every part of the world, climate change is causing more heatwaves,[119] droughts,[120] storms,[121] and flooding[122][123] in Istanbul. Furthermore, as Istanbul is a large and rapidly expanding city, its urban heat island has been intensifying the effects of climate change.[95] Considering past data,[124] it is very likely that these two factors are responsible for urban Istanbul’s shift, from a warm-summer climate to a hot-summer one in the Köppen climate classification, and from the cool temperate zone to the warm temperate/subtropical zone in the Trewartha climate classification.[125][126][127] If trends continue, sea level rise is likely to affect city infrastructure, for example Kadıkoy metro station is threatened with flooding.[128]

Xeriscaping of green spaces has been suggested,[129] and Istanbul has a climate-change action plan.[130]

Cityscape

Districts and neighborhoods

European side

The Fatih district, which was named after Sultan Mehmed II (Turkish: Fatih Sultan Mehmed), corresponds to what was, until the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the whole of the city of Constantinople (today is the capital district and called the historic peninsula of Istanbul) on the southern shore of the Golden Horn, across the medieval Genoese citadel of Galata on the northern shore. The Genoese fortifications in Galata were largely demolished in the 19th century, leaving only the Galata Tower, to make way for the northward expansion of the city.[131] Galata (Karaköy) is today a quarter within the Beyoğlu (Pera) district, which forms Istanbul’s commercial and entertainment center and includes İstiklal Avenue and Taksim Square.[132]

Dolmabahçe Palace, the seat of government during the late Ottoman period, is in the Beşiktaş district on the European shore of the Bosporus strait, to the north of Beyoğlu. The former village of Ortaköy is within Beşiktaş and gives its name to the Ortaköy Mosque on the Bosporus, near the Bosporus Bridge. Lining both the European and Asian shores of the Bosporus are the historic yalıs, luxurious chalet mansions built by Ottoman aristocrats and elites as summer homes.[133] Inland, north of Taksim Square is the Istanbul Central Business District, a set of corridors lined with office buildings, residential towers, shopping centers, and university campuses, and over 2,000,000 m2 (22,000,000 sq ft) of class-A office space in total. Maslak, Levent, and Bomonti are important nodes within the CBD.[134][135]

The Atatürk Airport corridor is another such edge city-style business, residential and shopping corridor with over 900,000 m2 (9,700,000 sq ft) of class-A office space.[135]

Originally outside the city, yalı residences along the Bosporus are now homes in some of Istanbul’s elite neighborhoods.

Asian side

During the Ottoman period, Üsküdar (then Scutari) and Kadıköy were outside the scope of the urban area, serving as tranquil outposts with seaside yalıs and gardens. But in the second half of the 20th century, the Asian side experienced major urban growth; the late development of this part of the city led to better infrastructure and tidier urban planning when compared with most other residential areas in the city.[136] Much of the Asian side of the Bosporus functions as a suburb of the economic and commercial centers in European Istanbul, accounting for a third of the city’s population but only a quarter of its employment.[136] However, Kozyatağı–Ataşehir, Altunizade, Kavacik and Umraniye, all together having around 1.4 million sqm of class-A office space) are now important «edge cities», i.e. corridors and nodes of business and shopping centers and of tall residential buildings.[135]

Expansion

As a result of Istanbul’s exponential growth in the 20th century, a significant portion of the city is composed of gecekondus (literally «built overnight»), referring to illegally constructed squatter buildings.[137] At present, some gecekondu areas are being gradually demolished and replaced by modern mass-housing compounds.[138] Moreover, large scale gentrification and urban renewal projects have been taking place,[139] such as the one in Tarlabaşı;[140] some of these projects, like the one in Sulukule, have faced criticism.[141] The Turkish government also has ambitious plans for an expansion of the city west and northwards on the European side in conjunction with the new Istanbul Airport, opened in 2019; the new parts of the city will include four different settlements with specified urban functions, housing 1.5 million people.[142]

Parks

Istanbul does not have a primary urban park, but it has several green areas. Gülhane Park and Yıldız Park were originally included within the grounds of two of Istanbul’s palaces — Topkapı Palace and Yıldız Palace—but they were repurposed as public parks in the early decades of the Turkish Republic.[143] Another park, Fethi Paşa Korusu, is on a hillside adjacent to the Bosphorus Bridge in Anatolia, opposite Yıldız Palace in Europe. Along the European side, and close to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, is Emirgan Park, which was known as the Kyparades (Cypress Forest) during the Byzantine period. In the Ottoman period, it was first granted to Nişancı Feridun Ahmed Bey in the 16th century, before being granted by Sultan Murad IV to the Safavid Emir Gûne Han in the 17th century, hence the name Emirgan. The 47-hectare (120-acre) park was later owned by Khedive Ismail Pasha of Ottoman Egypt and Sudan in the 19th century. Emirgan Park is known for its diversity of plants and an annual tulip festival is held there since 2005.[144] The AKP government’s decision to replace Taksim Gezi Park with a replica of the Ottoman era Taksim Military Barracks (which was transformed into the Taksim Stadium in 1921, before being demolished in 1940 for building Gezi Park) sparked a series of nationwide protests in 2013 covering a wide range of issues. Popular during the summer among Istanbulites is Belgrad Forest, spreading across 5,500 hectares (14,000 acres) at the northern edge of the city. The forest originally supplied water to the city and remnants of reservoirs used during Byzantine and Ottoman times survive.[145][146]

Architecture

Istanbul is primarily known for its Byzantine and Ottoman architecture. Despite its development as a Turkish city since 1453, it contains many ancient, Roman, Byzantine, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish monuments.

The Neolithic settlement in the Yenikapı quarter on the European side, which dates back to c. 6500 BCE and predates the formation of the Bosporus strait by approximately a millennium (when the Sea of Marmara was still a lake)[147] was discovered during the construction of the Marmaray railway tunnel.[26] It is the oldest known human settlement on the European side of the city.[26] The oldest known human settlement on the Asian side is the Fikirtepe Mound near Kadıköy, with relics dating to c. 5500-3500 BCE (Chalcolithic period).

There are numerous ancient monuments in the city.[148] The most ancient is the Obelisk of Thutmose III (Obelisk of Theodosius).[148] Built of red granite, 31 m (100 ft) high, it came from the Temple of Karnak in Luxor, and was erected there by Pharaoh Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BCE) to the south of the seventh pylon.[148] The Roman emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361 CE) had it and another obelisk transported along the River Nile to Alexandria for commemorating his ventennalia or 20 years on the throne in 357. The other obelisk was erected on the spina of the Circus Maximus in Rome in the autumn of that year, and is now known as the Lateran Obelisk. The obelisk that would become the Obelisk of Theodosius remained in Alexandria until 390 CE, when Theodosius I (r. 379–395 CE) had it transported to Constantinople and put up on the spina of the Hippodrome there.[149] When re-erected at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, the obelisk was mounted on a decorative base, with reliefs that depict Theodosius I and his courtiers.[148] The lower part of the obelisk was damaged in antiquity, probably during its transport to Alexandria in 357 CE or during its re-erection at the Hippodrome of Constantinople in 390 CE. As a result, the current height of the obelisk is only 18.54 meters, or 25.6 meters if the base is included. Between the four corners of the obelisk and the pedestal are four bronze cubes, used in its transportation and re-erection.[150]

Next in age is the Serpent Column, from 479 BCE.[148] It was brought from Delphi in 324 CE, during the reign of Constantine the Great, and also erected at the spina of the Hippodrome.[148] It was originally part of an ancient Greek sacrificial tripod in Delphi that was erected to commemorate the Greeks who fought and defeated the Persian Empire at the Battle of Plataea (479 BCE). The three serpent heads of the 8-meter (26 ft) high column remained intact until the end of the 17th century (one is on display at the nearby Istanbul Archaeology Museums).[151]

Built in porphyry and erected at the center of the Forum of Constantine in 330 CE to mark the founding of the new Roman capital, the Column of Constantine was originally adorned with a sculpture of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great depicted as the solar god Apollo on its top, which fell in 1106 and was later replaced by a cross during the reign of Byzantine emperor Manuel Komnenos (r. 1143–1180).[17][148]

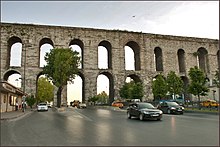

There are traces of the Byzantine era throughout the city, from ancient churches that were built over early Christian meeting places like the Hagia Irene, the Chora Church, the Monastery of Stoudios, the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, the Church of Theotokos Pammakaristos, the Monastery of the Pantocrator, the Monastery of Christ Pantepoptes, the Hagia Theodosia, the Church of Theotokos Kyriotissa, the Monastery of Constantine Lips, the Church of Myrelaion, the Hagios Theodoros, etc.; to palaces like the Great Palace of Constantinople and its Mosaic Museum, the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, Boukoleon Palace and Palace of Blachernae; and other public places and buildings like the Hippodrome, the Augustaion, the Basilica Cistern, Theodosius Cistern, Cistern of Philoxenos and Cistern of the Hebdomon, the Aqueduct of Valens, the Prison of Anemas, the Walls of Constantinople and the Porta Aurea (Golden Gate), among numerous others. The 4th century Harbor of Theodosius in Yenikapı, once the busiest port in Constantinople, was among the numerous archeological discoveries that took place during the excavations of the Marmaray tunnel.[26]

However, it is the Hagia Sophia that fully conveys the period of Constantinople as a city without parallel in Christendom. The Hagia Sophia, topped by a dome 31 meters (102 ft) in diameter over a square space defined by four arches, is the pinnacle of Byzantine architecture.[153] The Hagia Sophia stood as the world’s largest cathedral in the world until it was converted into a mosque in the 15th century.[153] The minarets date from that period.[153] Because of its historical significance, it was reopened as a museum in 1935. However, it was re-converted into a mosque in July 2020.

Over the next four centuries, the Ottomans transformed Istanbul’s urban landscape with a vast building scheme that included the construction of towering mosques and ornate palaces. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque), another landmark of the city, faces the Hagia Sophia at Sultanahmet Square (Hippodrome of Constantinople). The Süleymaniye Mosque, built by Suleiman the Magnificent, was designed by his chief architect Mimar Sinan, the most illustrious of all Ottoman architects, who designed many of the city’s renowned mosques and other types of public buildings and monuments.[155]

Among the oldest surviving examples of Ottoman architecture in Istanbul are the Anadoluhisarı and Rumelihisarı fortresses, which assisted the Ottomans during their siege of the city.[156] Over the next four centuries, the Ottomans made an indelible impression on the skyline of Istanbul, building towering mosques and ornate palaces.

Topkapı Palace, dating back to 1465, is the oldest seat of government surviving in Istanbul. Mehmed II built the original palace as his main residence and the seat of government.[157] The present palace grew over the centuries as a series of additions enfolding four courtyards and blending neoclassical, rococo, and baroque architectural forms.[158] In 1639, Murad IV made some of the most lavish additions, including the Baghdad Kiosk, to commemorate his conquest of Baghdad the previous year.[159] Government meetings took place here until 1786, when the seat of government was moved to the Sublime Porte.[157] After several hundred years of royal residence, it was abandoned in 1853 in favor of the baroque Dolmabahçe Palace.[158] Topkapı Palace became public property following the abolition of monarchy in 1922.[158] After extensive renovation, it became one of Turkey’s first national museums in 1924.[157]

The imperial mosques include Fatih Mosque, Bayezid Mosque, Yavuz Selim Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, Sultan Ahmed Mosque (the Blue Mosque), and Yeni Mosque, all of which were built at the peak of the Ottoman Empire, in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the following centuries, and especially after the Tanzimat reforms, Ottoman architecture was supplanted by European styles.[160] An example of which is the imperial Nuruosmaniye Mosque. Areas around İstiklal Avenue were filled with grand European embassies and rows of buildings in Neoclassical, Renaissance Revival and Art Nouveau styles, which went on to influence the architecture of a variety of structures in Beyoğlu—including churches, stores, and theaters—and official buildings such as Dolmabahçe Palace.[161]

Administration

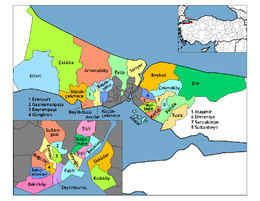

Istanbul’s districts extend far from the city center, along the full length of the Bosporus (with the Black Sea at the top and the Sea of Marmara at the bottom of the map).

Since 2004, the municipal boundaries of Istanbul have been coincident with the boundaries of its province.[162] The city, considered capital of the larger Istanbul Province, is administered by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (MMI), which oversees the 39 districts of the city-province.

The current city structure can be traced back to the Tanzimat period of reform in the 19th century, before which Islamic judges and imams led the city under the auspices of the Grand Vizier. Following the model of French cities, this religious system was replaced by a mayor and a citywide council composed of representatives of the confessional groups (millet) across the city. Pera (now Beyoğlu) was the first area of the city to have its own director and council, with members instead being longtime residents of the neighborhood.[163] Laws enacted after the Ottoman constitution of 1876 aimed to expand this structure across the city, imitating the twenty arrondissements of Paris, but they were not fully implemented until 1908 when the city was declared a province with nine constituent districts.[164][165] This system continued beyond the founding of the Turkish Republic, with the province renamed a belediye (municipality), but the municipality was disbanded in 1957.[166]

Small settlements adjacent to major population centers in Turkey, including Istanbul, were merged into their respective primary cities during the early 1980s, resulting in metropolitan municipalities.[167][168] The main decision-making body of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality is the Municipal Council, with members drawn from district councils.

The Municipal Council is responsible for citywide issues, including managing the budget, maintaining civic infrastructure, and overseeing museums and major cultural centers.[169] Since the government operates under a «powerful mayor, weak council» approach, the council’s leader—the metropolitan mayor—has the authority to make swift decisions, often at the expense of transparency.[170] The Municipal Council is advised by the Metropolitan Executive Committee, although the committee also has limited power to make decisions of its own.[171] All representatives on the committee are appointed by the metropolitan mayor and the council, with the mayor—or someone of his or her choosing—serving as head.[171][172]

District councils are chiefly responsible for waste management and construction projects within their respective districts. They each maintain their own budgets, although the metropolitan mayor reserves the right to review district decisions. One-fifth of all district council members, including the district mayors, also represent their districts in the Municipal Council.[169] All members of the district councils and the Municipal Council, including the metropolitan mayor, are elected to five-year terms.[173] Representing the Republican People’s Party, Ekrem İmamoğlu has been the Mayor of Istanbul since 27 June 2019.[174]

With the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and Istanbul Province having equivalent jurisdictions, few responsibilities remain for the provincial government. Like the MMI, the Istanbul Special Provincial Administration has a governor, a democratically elected decision-making body—the Provincial Parliament—and an appointed Executive Committee. Mirroring the executive committee at the municipal level, the Provincial Executive Committee includes a secretary-general and leaders of departments that advise the Provincial Parliament.[172][175] The Provincial Administration’s duties are largely limited to the building and maintenance of schools, residences, government buildings, and roads, and the promotion of arts, culture, and nature conservation.[176] Ali Yerlikaya has been the Governor of Istanbul Province since 26 October 2018.[177]

Demographics

Historical populations

Pre-Republic

|

Republic

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Jan Lahmeyer 2004,Chandler 1987, Morris 2010,Turan 2010[178] Pre-Republic figures estimated[e] |

Throughout most of its history, Istanbul has ranked among the largest cities in the world. By 500 CE, Constantinople had somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 people, edging out its predecessor, Rome, for the world’s largest city.[180] Constantinople jostled with other major historical cities, such as Baghdad, Chang’an, Kaifeng and Merv for the position of the world’s largest city until the 12th century. It never returned to being the world’s largest, but remained the largest city in Europe from 1500 to 1750, when it was surpassed by London.[181]

The Turkish Statistical Institute estimates that the population of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality was 15,519,267 at the end of 2019, hosting 19 percent of the country’s population.[182] 64.4% of the residents live on the European side and 35.6% on the Asian side.[182]

Istanbul ranks as the seventh-largest city proper in the world, and the second-largest urban agglomeration in Europe, after Moscow.[183][184] The city’s annual population growth of 1.5 percent ranks as one of the highest among the seventy-eight largest metropolises in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The high population growth mirrors an urbanization trend across the country, as the second and third fastest-growing OECD metropolises are the Turkish cities of Izmir and Ankara.[16]

Istanbul experienced especially rapid growth during the second half of the 20th century, with its population increasing tenfold between 1950 and 2000.[185] This growth was fueled by internal and international migration. Istanbul’s foreign population with a residence permit increased dramatically, from 43,000 in 2007[186] to 856,377 in 2019.[187][188]

According to 2020 TÜİK data around 2.1 million people in a population of over 15.4 million have been registered[g] in Istanbul, meanwhile the vast majority of the residents ultimately originate from Anatolian provinces, especially those in the Black Sea, Central and Eastern Anatolia regions due to internal migration since the 1950s.[189] People registered in Kastamonu, Ordu, Giresun, Erzurum, Samsun, Malatya, Trabzon, Sinop and Rize provinces represent the biggest population groups in Istanbul, meanwhile people registered in Sivas has the highest percentage with more than 760 thousand residents in the city.[190] A 2019 survey found that only 36% of the Istanbul’s population was born in the province.[191]

Ethnic and religious groups

| Ethnic groups among Turkish citizens in Istanbul (2019 KONDA survey) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Turks | 78% | |

| Kurds | 17% | |

| Zazas | 1% | |

| Arabs | 1% | |

| Others | 3% |

Istanbul has been a cosmopolitan city throughout much of its history, but it has become more homogenized since the end of the Ottoman era. The dominant ethnic group in the city is Turkish people, which also forms the majority group in Turkey. According to survey data 78% of the voting-age Turkish citizens in Istanbul state «Turkish» as their ethnic identity.[191]

With estimates ranging from 2 to 4 million, Kurds form one of the largest ethnic minorities in Istanbul and are the biggest group after Turks among Turkish citizens.[192][193] According to a 2019 KONDA study, Kurds constituted around 17% of Istanbul’s adult total population who were Turkish citizens.[191] Although the initial Kurdish presence in the city dates back to the early Ottoman period,[194] the majority of Kurds in the city originate from villages in eastern and southeastern Turkey.[195] Zazas are also present in the city and constitute around 1% of the total voting-age population.[191]

Arabs form the city’s other largest ethnic minority, with an estimated population of more than 2 million.[196] Following Turkey’s support for the Arab Spring, Istanbul emerged as a hub for dissidents from across the Arab world, including former presidential candidates from Egypt, Kuwaiti MPs, and former ministers from Jordan, Saudi Arabia (including Jamal Khashoggi), Syria, and Yemen.[197][198][199] The number of refugees of the Syrian Civil War in Turkey residing in Istanbul is estimated to be around 1 million.[200] Native Arab population in Turkey who are Turkish citizens are found to be making up less than 1% of city’s total adult population.[191]

2019 survey study by KONDA that examined the religiosity of the voting-age adults in Istanbul showed that 57% of the surveyed had a religion and were trying to practise its requirements. This was followed by nonobservant people with 26% who identified with a religion but generally did not practise its requirements. 11% stated they were fully devoted to their religion, meanwhile 6% were non-believers who did not believe the rules and requirements of a religion. 24% of the surveyed also identified themselves as «religious conservatives». Around 90% of Istanbul’s population are Sunni Muslims and Alevism forms the second biggest religious group.[191][201]

Into the 19th century, the Christians of Istanbul tended to be either Greek Orthodox, members of the Armenian Apostolic Church or Catholic Levantines.[202] Greeks and Armenians form the largest Christian population in the city. While Istanbul’s Greek population was exempted from the 1923 population exchange with Greece, changes in tax status and the 1955 anti-Greek pogrom prompted thousands to leave.[203] Following Greek migration to the city for work in the 2010s, the Greek population rose to nearly 3,000 in 2019, still greatly diminished since 1919, when it stood at 350,000.[203] There are today 50,000 to 70,000 Armenians in Istanbul[204] down from a peak of 164,000 in 1913.[205] As of 2019, an estimated 18,000 of the country’s 25,000 Christian Assyrians live in Istanbul.[206]

The majority of the Catholic Levantines (Turkish: Levanten) in Istanbul and Izmir are the descendants of traders/colonists from the Italian maritime republics of the Mediterranean (especially Genoa and Venice) and France, who obtained special rights and privileges called the Capitulations from the Ottoman sultans in the 16th century.[208] The community had more than 15,000 members during Atatürk’s presidency in the 1920s and 1930s, but today is reduced to only a few hundreds, according to Italo-Levantine writer Giovanni Scognamillo.[209] They continue to live in Istanbul (mostly in Karaköy, Beyoğlu and Nişantaşı), and Izmir (mostly in Karşıyaka, Bornova and Buca).

Istanbul became one of the world’s most important Jewish centers in the 16th and 17th century.[210] Romaniote and Ashkenazi communities existed in Istanbul before the conquest of Istanbul, but it was the arrival of Sephardic Jews that ushered a period of cultural flourishing. Sephardic Jews settled in the city after their expulsion from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497.[210] Sympathetic to the plight of Sephardic Jews, Bayezid II sent out the Ottoman Navy under the command of admiral Kemal Reis to Spain in 1492 in order to evacuate them safely to Ottoman lands.[210] In marked contrast to Jews in Europe, Ottoman Jews were allowed to work in any profession.[211] Ottoman Jews in Istanbul excelled in commerce and came to particularly dominate the medical profession.[211] By 1711, using the printing press, books came to be published in Spanish and Ladino, Yiddish, and Hebrew.[212] In large part due to emigration to Israel, the Jewish population in the city dropped from 100,000 in 1950[213] to 15,000 in 2021.[214][215][216]

Politics

Politically, Istanbul is seen as the most important administrative region in Turkey. In the run-up to local elections in 2019, Erdoğan claimed ‘if we fail in Istanbul, we will fail in Turkey’.[217] The contest in Istanbul carried deep political, economic and symbolic significance for Erdoğan, whose election of mayor of Istanbul in 1994 had served as his launchpad.[218] For Ekrem İmamoğlu, winning the mayorlty of Istanbul was a huge moral victory, but for Erdoğan it had practical ramifications: His party, AKP, lost control of the $4.8 billion municipal budget, which had sustained patronage at the point of delivery of many public services for 25 years.[219]