|

stg[1] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| ISO 4217 | ||||

| Code | GBP (numeric: 826) | |||

| Subunit | 0.01 | |||

| Unit | ||||

| Unit | pound | |||

| Plural | pounds | |||

| Symbol | £ | |||

| Denominations | ||||

| Subunit | ||||

| 1⁄100 | penny | |||

| Plural | ||||

| penny | pence | |||

| Symbol | ||||

| penny | p | |||

| Banknotes | ||||

| Freq. used |

|

|||

| Rarely used |

|

|||

| Coins |

|

|||

| Rarely used | 25p[2][3] | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Date of introduction | c. 800; 1223 years ago | |||

| User(s) |

|

|||

| Issuance | ||||

| Central bank | Bank of England | |||

| Website | www.bankofengland.co.uk | |||

| Printer | De La Rue[4] | |||

| Mint | Royal Mint | |||

| Website | www.royalmint.com | |||

| Valuation | ||||

| Inflation | 8.2% or 9.4% | |||

| Source | Office for National Statistics, 20 July 2022[5] | |||

| Method | CPIH or CPI | |||

| Pegged by | see § Pegged currencies |

Sterling (abbreviation: stg;[1] ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories.[6] The pound (sign: £) is the main unit of sterling,[7] and the word «pound» is also used to refer to the British currency generally,[8] often qualified in international contexts as the British pound or the pound sterling.[7][8]

Sterling is the world’s oldest currency that is still in use and that has been in continuous use since its inception.[9] It is currently the fourth most-traded currency in the foreign exchange market, after the United States dollar, the euro, and the Japanese yen.[10] Together with those three currencies and Renminbi, it forms the basket of currencies which calculate the value of IMF special drawing rights. As of late 2022, sterling is also the fourth most-held reserve currency in global reserves.[11]

The Bank of England is the central bank for sterling, issuing its own banknotes, and regulating issuance of banknotes by private banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Sterling banknotes issued by other jurisdictions are not regulated by the Bank of England; their governments guarantee convertibility at par. Historically, sterling was also used to varying degrees by the colonies and territories of the British Empire.

Names[edit]

«Sterling» is the name of the currency as a whole while «pound» and «penny» are the units of account. This is analogous to the distinction between «renminbi» and «yuan» when discussing the official currency of the People’s Republic of China.

Sterling Pound 5, 10, 20, 50

Etymology[edit]

There are various theories regarding the origin of the word «sterling». The Oxford English Dictionary states that the «most plausible» etymology is a derivation from the Old English steorra for «star» with the added diminutive suffix «-ling», to yield «little star». The reference is to the silver penny used in Norman England in the twelfth century, which bore a small star.[12]

Another argument, according to which the Hanseatic League was the origin of both its definition and manufacture as well as its name is that the German name for the Baltic is «Ostsee», or «East Sea», and from this the Baltic merchants were called «Osterlings», or «Easterlings».[13] In 1260, Henry III granted them a charter of protection and land for their Kontor, the Steelyard of London, which by the 1340s was also called «Easterlings Hall», or Esterlingeshalle.[14] Because the League’s money was not frequently debased like that of England, English traders stipulated to be paid in pounds of the «Easterlings», which was contracted to «‘sterling».[15] The OED dismisses this theory as unlikely, since the stressed first syllable would not have been elided.[12]

Encyclopædia Britannica states the (pre-Norman) Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had silver coins called «sterlings» and that the compound noun «pound sterling» was derived from a pound (weight) of these sterlings.[16]

Symbol[edit]

The currency sign for the pound unit of sterling is £, which (depending on typeface) may be drawn with one or two bars:[17] the Bank of England has exclusively used the single bar variant since 1975.[18][19] Historically, a simple capital L (in the historic black-letter typeface,

Notable style guides recommend that the pound sign be used without any abbreviation or qualification to indicate sterling (e.g., £12,000).[25][26][27] Notations with a more explicit sterling abbreviation such as £ […] stg. (e.g., £12,000 stg.),[28] £stg. (e.g., £stg. 12,000),[29] stg or STG (e.g., Stg. 12,000 or STG 12,000),[1] or the ISO 4217 code GBP (e.g., 12,000 GBP) may be seen, but are not usually used unless disambiguation is absolutely necessary.

Currency code[edit]

The ISO 4217 currency code for sterling is «GBP», formed from the ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 code for the United Kingdom, «GB», and the first letter of «pound». Banking and finance often use the abbreviation stg or the pseudo-ISO code STG. The Crown Dependencies use their own abbreviations which are not ISO codes but may be used like them: GGP (Guernsey pound), JEP (Jersey pound) and IMP (Isle of Man pound). Stock prices are often quoted in pence, so traders may abbreviate the penny as GBX (sometimes GBp) when listing stock prices.

Cable[edit]

The exchange rate of sterling against the US dollar is referred to as «cable» in the wholesale foreign exchange markets.[30] The origins of this term are attributed to the fact that from the mid-19th century, the sterling/dollar exchange rate was transmitted via transatlantic cable.[31]

Slang terms [edit]

Historically almost every British coin had a widely recognised nickname, such as «tanner» for the sixpence and «bob» for the shilling.[32] Since decimalisation these have mostly fallen out of use except as parts of proverbs.

A common slang term for the pound unit is quid (singular and plural, except in the common phrase «quids in!»).[33] The term may have come via Italian immigrants from «scudo», the name for a number of currency units used in Italy until the 19th century; or from Latin ‘quid’ via the common phrase quid pro quo, literally, «what for what», or, figuratively, «An equal exchange or substitution».[34] The term «nicker» (also singular and plural) may also refer to the pound.

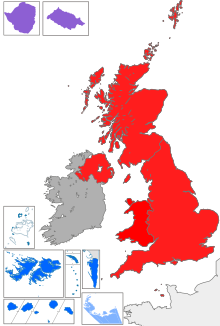

Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories[edit]

The currency of all the Crown Dependencies and most British Overseas Territories is either sterling or is pegged to sterling at par. These are Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, Saint Helena and the British Antarctic Territory,[35][36] and Tristan da Cunha.[37]

Some British Overseas Territories have a local currency that is pegged to the U.S. dollar or the New Zealand dollar. The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia (in Cyprus) use the euro.

Subdivisions and other units[edit]

Decimal coinage[edit]

Since decimalisation on Decimal Day in 1971, the pound has been divided into 100 pence (denoted on coinage, until 1981, as «new pence»). The symbol for the penny is «p»; hence an amount such as 50p (£0.50) properly pronounced «fifty pence» is often pronounced «fifty pee» /fɪfti piː/. The old sign d was not reused for the new penny in order to avoid confusion between the two units. A decimal halfpenny (1/2p, worth 1.2 old pennies) was issued until 1984 but was withdrawn due to inflation.[38]

Pre-decimal[edit]

|

||||

| Unit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plural | Pounds | |||

| Symbol | £ | |||

| Denominations | ||||

| Superunit | ||||

| 1 | Pound | |||

| Subunit | ||||

| 1⁄20 | Shilling | |||

| 1⁄240 | Penny | |||

| Plural | ||||

| Shilling | Shillings | |||

| Penny | Pence | |||

| Symbol | ||||

| Shilling | s or / | |||

| Penny | d | |||

| Banknotes | ||||

| Freq. used |

|

|||

| Rarely used |

|

|||

| Coins |

|

|||

| This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. |

Main article: £sd

The Hatter’s hat shows an example of the old pre-decimal notation: the hat costs 10/6 (ten shillings and sixpence, a half guinea).

Before decimalisation in 1971, the pound was divided into 20 shillings, and each shilling into 12 pence, making 240 pence to the pound. The symbol for the shilling was «s.» – not from the first letter of «shilling», but from the Latin solidus. The symbol for the penny was «d.», from the French denier, from the Latin denarius (the solidus and denarius were Roman coins). A mixed sum of shillings and pence, such as 3 shillings and 6 pence, was written as «3/6» or «3s. 6d.» and spoken as «three and six» or «three and sixpence» except for «1/1», «2/1» etc., which were spoken as «one and a penny», «two and a penny», etc. 5 shillings, for example, was written as «5s.» or, more commonly, «5/–» (five shillings, no pence).

Various coin denominations had, and in some cases continue to have, special names, such as florin (2/–), crown (5/–), half crown (2/6d), farthing (1⁄4d), sovereign (£1) and guinea (q.v.). See Coins of the pound sterling and List of British coins and banknotes for details.

By the 1950s, coins of Kings George III, George IV and William IV had disappeared from circulation, but coins (at least the penny) bearing the head of every British monarch from Queen Victoria onwards could be found in circulation. Silver coins were replaced by those in cupro-nickel in 1947, and by the 1960s the silver coins were rarely seen. Silver/cupro-nickel sixpences, shillings (from any period after 1816) and florins (2 shillings) remained legal tender after decimalisation (as 2½p, 5p and 10p respectively) until 1980, 1990 and 1993 respectively, but are now officially demonetised.[39][40]

History (600–1945)[edit]

The pound sterling emerged after the adoption of the Carolingian monetary system in England c. 800. Here is a summary of changes to its value in terms of silver or gold until 1914.[41][42]

| year | silver | gold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| grams | troy ounces | grams | troy ounces | |

| 800 | 349.9 g | 11.25 ozt | – | – |

| 1158 | 323.7 g | 10.41 ozt | – | – |

| 1351 | 258.9 g | 8.32 ozt | 23.21 g | 0.746 ozt |

| 1412 | 215.8 g | 6.94 ozt | 20.89 g | 0.672 ozt |

| 1464 | 172.6 g | 5.55 ozt | 15.47 g | 0.497 ozt |

| 1551 | 115.1 g | 3.70 ozt | 10.31 g | 0.331 ozt |

| 1601 | 111.4 g | 3.58 ozt | variable | |

| 1717 | 111.4 g | 3.58 ozt | 7.32238 g | 0.235420 ozt |

| 1816 | – | – | 7.32238 g | 0.235420 ozt |

Anglo-Saxon[edit]

The pound was a unit of account in Anglo-Saxon England. By the ninth century it was equal to 240 silver pence.[44]

The accounting system of dividing one pound into twenty shillings, a shilling into twelve pence, and a penny into four farthings was adopted[when?] from that introduced by Charlemagne to the Frankish Empire (see livre carolingienne).[citation needed] The penny was abbreviated to «d», from denarius, the Roman equivalent of the penny; the shilling to «s» from solidus (later evolving into a simple /); and the pound to «L» (subsequently £) from Libra or Livre.[when?]

The origins of sterling lie in the reign of King Offa of Mercia (757–796), who introduced a «sterling» coin made by physically dividing a Tower pound (5,400 grains, 349.9 grams) of silver into 240 parts.[45] In practice, the weights of the coins were not consistent, 240 of them seldom added up to a full pound; there were no shilling or pound coins and these units were used only as an accounting convenience.[46]

Halfpennies and farthings worth 1⁄2 and 1⁄4 penny respectively were also minted, but small change was more commonly produced by cutting up a whole penny.[47]

Medieval, 1158[edit]

Penny of Henry III, 13th century

The early pennies were struck from fine silver (as pure as was available). In 1158, a new coinage was introduced by King Henry II (known as the Tealby penny), with a Tower Pound (5,400 grains, 349.9 g) of 92.5% silver minted into 240 pennies, each penny containing 20.82 grains (1.349 g) of fine silver.[41] Called sterling silver, the alloy is harder than the 99.9% fine silver that was traditionally used, and sterling silver coins did not wear down as rapidly as fine silver ones.

The introduction of the larger French gros tournois coins in 1266, and their subsequent popularity, led to additional denominations in the form of groats worth four pence and half groats worth two pence.[48] A gold penny weighing twice the silver penny and valued at 20 silver pence was also issued in 1257 but was not successful.[49]

The English penny remained nearly unchanged from 800 and was a prominent exception in the progressive debasements of coinage which occurred in the rest of Europe. The Tower Pound, originally divided into 240 pence, devalued to 243 pence by 1279.[50]

Edward III, 1351[edit]

Edward III noble (80 pence), 1354–55

During the reign of King Edward III, the introduction of gold coins received from Flanders as payment for English wool provided substantial economic and trade opportunities but also unsettled the currency for the next 200 years.[41]: 41 The first monetary changes in 1344 consisted of

- English pennies reduced to 20+1⁄4 grains (1.312 g; 0.042 ozt) of sterling silver (or 20.25gr @ 0.925 fine = 18.73 gr pure silver) and

- Gold double florins weighing 108 gr (6.998 g; 0.225 ozt) and valued at 6 shillings (or 72 pence).[41] (or 108gr @ 0.9948 fine = 107.44 gr pure gold).

The resulting gold-silver ratio of 1:12.55 was much higher than the ratio of 1:11 prevailing in the Continent, draining England of its silver coinage and requiring a more permanent remedy in 1351 in the form of

- Pennies reduced further to 18 gr (1.2 g; 0.038 ozt) of sterling silver (or 18 @ 0.925 fine = 15.73 gr pure silver) and

- New gold nobles weighing 120 grains (7.776 grams; 0.250 troy ounces) of the finest gold possible at the time (191/192 or 99.48% fine),[51] (meaning 120gr @ 0.9948 fine = 119.38 gr pure gold) and valued at 6 shillings and 8 pence (80 pence, or 1⁄3rd of a pound). The pure gold-silver ratio was thus 1:(80 × 15.73 / 119.38) = 1:10.5.

These gold nobles, together with half-nobles (40 pence) and farthings or quarter-nobles (20 pence),[51] would become the first English gold coins produced in quantity.[52]

Henry IV, 1412[edit]

The exigencies of the Hundred Years’ War during the reign of King Henry IV resulted in further debasements toward the end of his reign, with the English penny reduced to 15 grains sterling silver (0.899 g fine silver)[clarification needed] and the half-noble reduced to 54 grains (3.481 g fine gold).[clarification needed][41] The gold-silver ratio went down to 40 × 0.899 / 3.481 = 10.3.

After the French monetary reform of 1425, the gold half-noble (1⁄6th pound, 40 pence) was worth close to one Livre Parisis (French pound) or 20 sols, while the silver half-groat (2 pence, fine silver 1.798 g) was worth close to 1 sol parisis (1.912 g).[53] Also, after the Flemish monetary reform of 1434, the new Dutch florin was valued close to 40 pence while the Dutch stuiver (shilling) of 1.63 g fine silver was valued close to 2 pence sterling at 1.8 g.[54] This approximate pairing of English half-nobles and half-groats to Continental livres and sols persisted up to the 1560s.

Great slump, 1464[edit]

The Great Bullion Famine and the Great Slump of the mid-15th century resulted in another reduction in the English penny to 12 grains sterling silver (0.719 g fine silver) and the introduction of a new half-angel gold coin of 40 grains (2.578 g), worth 1⁄6th pound or 40 pence.[41] The gold-silver ratio rose again to 40 × 0.719⁄2.578 = 11.2. The reduction in the English penny approximately matched those with the French sol Parisis and the Flemish stuiver; furthermore, from 1469 to 1475 an agreement between England and the Burgundian Netherlands made the English groat (4-pence) mutually exchangeable with the Burgundian double patard (or 2-stuiver) minted under Charles the Rash.[55][56]

40 pence or 1⁄6th pound sterling made one Troy Ounce (480 grains, 31.1035 g) of sterling silver. It was approximately on a par with France’s livre parisis of one French ounce (30.594 g), and in 1524 it would also be the model for a standardised German currency in the form of the Guldengroschen, which also weighed 1 German ounce of silver or 29.232 g (0.9398 ozt).[41]: 361

Tudor, 1551[edit]

Crown (5/–) of Edward VI, 1551

The last significant depreciation in sterling’s silver standard occurred amidst the 16th century influx of precious metals from the Americas arriving through the Habsburg Netherlands. Enforcement of monetary standards amongst its constituent provinces was loose, spending under King Henry VIII was extravagant, and England loosened the importation of cheaper continental coins for exchange into full-valued English coins.[55][57] All these contributed to The Great Debasement which resulted in a significant 1⁄3rd reduction in the bullion content of each pound sterling in 1551.[58][42]

The troy ounce of sterling silver was henceforth raised in price by 50% from 40 to 60 silver pennies (each penny weighing 8 grains sterling silver and containing 0.4795 g (0.01542 ozt) fine silver).[42] The gold half-angel of 40 grains (2.578 g (0.0829 ozt) fine gold) was raised in price from 40 pence to 60 pence (5 shillings or 1⁄4 pound) and was henceforth known as the Crown.

Prior to 1551, English coin denominations closely matched with corresponding sol (2d) and livre (40d) denominations in the Continent, namely:

- Silver; see farthing (1⁄4d), halfpenny (1⁄2d), penny (1d), half-groat (2d), and groat (4d)

- Gold; see 1351: 1⁄4 noble (20d), 1⁄2 noble (40d) and noble or angel (80d).

After 1551 new denominations were introduced,[59] weighing similarly to 1464-issued coins but increased in value 1+1⁄2 times, namely:

- In silver: the threepence (3d), replacing the half-groat; the sixpence (6d), replacing the groat; and a new shilling or testoon (1/–).

- In silver or gold: the half crown (2/6d or 30d), replacing the 1⁄4 angel of 20d; and the crown (5/- or 60d), replacing the 1⁄2 angel of 40d.

- And in gold: the new half sovereign (10/–) and sovereign (£1 or 20/–)

1601 to 1816[edit]

A golden guinea coin minted during the reign of King James II in 1686. The «Elephant and Castle» motif below his head is the symbol of the Royal African Company, Britain’s foremost slave trading company.[60] The RAC transported the gold used in the coin from West Africa to England after purchasing it from African merchants in the Guinea region, who in turn sourced it from the Ashanti Empire.[61]

The silver basis of sterling remained essentially unchanged until the 1816 introduction of the Gold Standard, save for the increase in the number of pennies in a troy ounce from 60 to 62 (hence, 0.464 g fine silver in a penny). Its gold basis remained unsettled, however, until the gold guinea was fixed at 21 shillings in 1717.

The guinea was introduced in 1663 with 44+1⁄2 guineas minted out of 12 troy ounces of 22-karat gold (hence, 7.6885 g fine gold) and initially worth £1 or 20 shillings. While its price in shillings was not legally fixed at first, its persistent trade value above 21 shillings reflected the poor state of clipped underweight silver coins tolerated for payment. Milled shillings of full weight were hoarded and exported to the Continent, while clipped, hand-hammered shillings stayed in circulation (as Gresham’s law describes).[62]

In the 17th century, English merchants tended to pay for imports in silver but were generally paid for exports in gold.[citation needed] This effect was notably driven by trade with the Far East, as the Chinese insisted on payments for their exports being settled in silver. From the mid-17th century, around 28,000 metric tons (27,600 long tons) of silver were received by China, principally from European powers, in exchange for Chinese tea and other goods. In order to be able to purchase Chinese exports in this period, England initially had to export to other European nations and request payment in silver,[citation needed] until the British East India Company was able to foster the indirect sale of opium to the Chinese.[63]

Domestic demand for silver bullion in Britain further reduced silver coinage in circulation, as the improving fortunes of the merchant class led to increased demand for tableware. Silversmiths had always regarded coinage as a source of raw material, already verified for fineness by the government. As a result, sterling silver coins were being melted and fashioned into «sterling silverware» at an accelerating rate. An Act of the Parliament of England in 1697 tried to stem this tide by raising the minimum acceptable fineness on wrought plate from sterling’s 92.5% to a new Britannia silver standard of 95.83%. Silverware made purely from melted coins would be found wanting when the silversmith took his wares to the assay office, thus discouraging the melting of coins.[citation needed]

During the time of Sir Isaac Newton, Master of the Mint, the gold guinea was fixed at 21 shillings (£1/1/-) in 1717. But without addressing the problem of underweight silver coins, and with the high resulting gold-silver ratio of 15.2, it gave sterling a firmer footing in gold guineas rather than silver shillings, resulting in a de facto gold standard. Silver and copper tokens issued by private entities partly relieved the problem of small change until the Great Recoinage of 1816.[64]

Establishment of modern currency[edit]

The Bank of England was founded in 1694, followed by the Bank of Scotland a year later. Both began to issue paper money.

Currency of Great Britain (1707) and the United Kingdom (1801)[edit]

In the 17th century Scots currency was pegged to sterling at a value of £12 Scots = £1 sterling.[65]

In 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland merged into the Kingdom of Great Britain. In accordance with the Treaty of Union, the currency of Great Britain was sterling, with the pound Scots soon being replaced by sterling at the pegged value.

In 1801, Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland were united to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. However, the Irish pound was not replaced by sterling until January 1826.[66] The conversion rate had long been £13 Irish to £12 sterling.[citation needed] In 1928, six years after the Anglo-Irish Treaty restored Irish autonomy within the British Empire, the Irish Free State established a new Irish pound, pegged at par to sterling.[67]

Use in the Empire[edit]

Sterling circulated in much of the British Empire. In some areas it was used alongside local currencies. For example, the gold sovereign was legal tender in Canada despite the use of the Canadian dollar. Several colonies and dominions adopted the pound as their own currency. These included Australia, Barbados,[68] British West Africa, Cyprus, Fiji, British India, the Irish Free State, Jamaica, New Zealand, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia. Some of these retained parity with sterling throughout their existence (e.g. the South African pound), while others deviated from parity after the end of the gold standard (e.g. the Australian pound). These currencies and others tied to sterling constituted the core of the sterling area.

The original English colonies on mainland North America were not party to the sterling area because the above-mentioned silver shortage in England coincided with these colonies’ formative years. As a result of equitable trade (and rather less equitable piracy), the Spanish milled dollar became the most common coin within the English colonies.

Gold standard[edit]

«Shield reverse» sovereign of Queen Victoria, 1842

During the American War of Independence and the Napoleonic wars, Bank of England notes were legal tender, and their value floated relative to gold. The Bank also issued silver tokens to alleviate the shortage of silver coins. In 1816, the gold standard was adopted officially,[citation needed] with silver coins minted at a rate of 66 shillings to a troy pound (weight) of sterling silver, thus rendering them as «token» issues (i.e. not containing their value in precious metal). In 1817, the sovereign was introduced, valued at 20/–. Struck in 22‑carat gold, it contained 113 grains or 7.32238 g (0.235420 ozt) of fine gold and replaced the guinea as the standard British gold coin without changing the gold standard.

By the 19th century, sterling notes were widely accepted outside Britain. The American journalist Nellie Bly carried Bank of England notes on her 1889–1890 trip around the world in 72 days.[69] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many other countries adopted the gold standard. As a consequence, conversion rates between different currencies could be determined simply from the respective gold standards. £1 sterling was equal to US$4.87 in the United States, Can$4.87 in Canada, ƒ12.11 in Dutch territories, F 25.22 in French territories (or equivalent currencies of the Latin Monetary Union), 20ℳ 43₰ in Germany, Rbls 9.46 in Russia or K 24.02 in Austria-Hungary.[citation needed] After the International Monetary Conference of 1867 in Paris, the possibility of the UK joining the Latin Monetary Union was discussed, and a Royal Commission on International Coinage examined the issues,[70] resulting in a decision against joining monetary union.

First world war: suspension of the gold standard[edit]

The gold standard was suspended at the outbreak of First World War in 1914, with Bank of England and Treasury notes becoming legal tender. Before that war, the United Kingdom had one of the world’s strongest economies, holding 40% of the world’s overseas investments. But after the end of the war, the country was highly indebted: Britain owed £850 million (about £44.1 billion today)[71] with interest costing the country some 40% of all government spending.[72] The British government under Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Chancellor of the Exchequer Austen Chamberlain tried to make up for the deficit with a deflationary policy, but this only led to the Depression of 1920–21.[73]

By 1917, production of gold sovereigns had almost halted (the remaining production was for collector’s sets and other very specific occasions), and by 1920, the silver coinage was debased from its original .925 fine to just .500 fine.[citation needed] That was due to a drastic increase in silver prices from an average 27/6d. [£1.375] per troy pound in the period between 1894 and 1913, to 89/6d. [£4.475] in August 1920.[74]

Interwar period: gold standard reinstated[edit]

To try to resume stability, a version of the gold standard was reintroduced in 1925, under which the currency was fixed to gold at its pre-war peg, but one could only exchange currency for gold bullion, not for coins. On 21 September 1931, this was abandoned during the Great Depression, and sterling suffered an initial devaluation of some 25%.[75]

Since the suspension of the gold standard in 1931, sterling has been a fiat currency, with its value determined by its continued acceptance in the national and international economy.

World War II[edit]

In 1940, an agreement with the US pegged sterling to the US dollar at a rate of £1 = US$4.03. (Only the year before, it had been US$4.86.)[76] This rate was maintained through the Second World War and became part of the Bretton Woods system which governed post-war exchange rates.

History (1946–present)[edit]

Bretton Woods[edit]

Under continuing economic pressure, and despite months of denials that it would do so, on 19 September 1949 the government devalued the pound by 30.5% to US$2.80.[77] The 1949 sterling devaluation prompted several other currencies to be devalued against the dollar.

In 1961, 1964, and 1966, sterling came under renewed pressure, as speculators were selling pounds for dollars. In summer 1966, with the value of the pound falling in the currency markets, exchange controls were tightened by the Wilson government. Among the measures, tourists were banned from taking more than £50 out of the country in travellers’ cheques and remittances, plus £15 in cash;[b] this restriction was not lifted until 1979. Sterling was devalued by 14.3% to £1 = US$2.40 on 18 November 1967.[77][78]

Decimalisation[edit]

Until decimalisation, amounts in sterling were expressed in pounds, shillings, and pence, with various widely understood notations. The same amount could be stated as 32s. 6d., 32/6, £1. 12s. 6d., or £1/12/6. It was customary to specify some prices (for example professional fees and auction prices for works of art) in guineas (abbr: gn. or gns.), although guinea coins were no longer in use.

Formal parliamentary proposals to decimalise sterling were first made in 1824 when Sir John Wrottesley, MP for Staffordshire, asked in the House of Commons whether consideration had been given to decimalising the currency.[79] Wrottesley raised the issue in the House of Commons again in 1833,[80] and it was again raised by John Bowring, MP for Kilmarnock Burghs, in 1847[81] whose efforts led to the introduction in 1848 of what was in effect the first decimal coin in the United Kingdom, the florin, valued at one-tenth of a pound. However, full decimalisation was resisted, although the florin coin, re-designated as ten new pence, survived the transfer to a full decimal system in 1971, with examples surviving in British coinage until 1993.

John Benjamin Smith, MP for Stirling Burghs, raised the issue of full decimalisation again in Parliament in 1853,[82] resulting in the Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Gladstone, announcing soon afterwards that «the great question of a decimal coinage» was «now under serious consideration».[83] A full proposal for the decimalisation of sterling was then tabled in the House of Commons in June 1855, by William Brown, MP for Lancashire Southern, with the suggestion that the pound sterling be divided into one thousand parts, each called a «mil», or alternatively a farthing, as the pound was then equivalent to 960 farthings which could easily be rounded up to one thousand farthings in the new system.[84] This did not result in the conversion of sterling into a decimal system, but it was agreed to establish a Royal Commission to look into the issue.[85] However, largely due to the hostility to decimalisation of two of the appointed commissioners, Lord Overstone (a banker) and John Hubbard (Governor of the Bank of England), decimalisation in Britain was effectively quashed for over a hundred years.[86]

However, sterling was decimalised in various British colonial territories before the United Kingdom (and in several cases in line with William Brown’s proposal that the pound be divided into 1,000 parts, called mils). These included Hong Kong from 1863 to 1866;[87] Cyprus from 1955 until 1960 (and continued on the island as the division of the Cypriot pound until 1983); and the Palestine Mandate from 1926 until 1948.[88]

Later, in 1966, the UK Government decided to include in the Queen’s Speech a plan to convert sterling into a decimal currency.[89] As a result of this, on 15 February 1971, the UK decimalised sterling, replacing the shilling and the penny with a single subdivision, the new penny, which was worth 2.4d. For example, a price tag of £1/12/6. became £1.62+1⁄2. The word «new» was omitted from coins minted after 1981.

Free-floating pound[edit]

With the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, sterling floated from August 1971 onwards. At first, it appreciated a little, rising to almost US$2.65 in March 1972 from US$2.42, the upper bound of the band in which it had been fixed. The sterling area effectively ended at this time, when the majority of its members also chose to float freely against sterling and the dollar.

1976 sterling crisis[edit]

UK bonds 1960–2022: the yield on UK Government benchmark ten-year bonds increased to over 15% in the 1970s and early 1980s.

James Callaghan became Prime Minister in 1976. He was immediately told the economy was facing huge problems, according to documents released in 2006 by the National Archives.[90] The effects of the failed Barber Boom and the 1973 oil crisis were still being felt,[91] with inflation rising to nearly 27% in 1975.[92] Financial markets were beginning to believe the pound was overvalued, and in April that year The Wall Street Journal advised the sale of sterling investments in the face of high taxes, in a story that ended with «goodbye, Great Britain. It was nice knowing you».[93] At the time the UK Government was running a budget deficit, and the Labour government at the time’s strategy emphasised high public spending.[77] Callaghan was told there were three possible outcomes: a disastrous free fall in sterling, an internationally unacceptable siege economy, or a deal with key allies to prop up the pound while painful economic reforms were put in place. The US Government feared the crisis could endanger NATO and the European Economic Community (EEC), and in light of this the US Treasury set out to force domestic policy changes. In November 1976, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced the conditions for a loan, including deep cuts in public expenditure.[94]

1979–1989[edit]

The Conservative Party was elected to office in 1979, on a programme of fiscal austerity. Initially, sterling rocketed, moving above £1 to US$2.40, as interest rates rose in response to the monetarist policy of targeting money supply. The high exchange rate was widely blamed for the deep recession of 1981. Sterling fell sharply after 1980; at its lowest, £1 stood at just US$1.03 in March 1985, before rising to US$1.70 in December 1989.[95]

Following the Deutsche Mark[edit]

In 1988, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson, decided that sterling should «shadow» the Deutsche Mark (DM), with the unintended result of a rapid rise in inflation as the economy boomed due to low interest rates.[96]

Following German reunification in 1990, the reverse held true, as high German borrowing costs to fund Eastern reconstruction, exacerbated by the political decision to convert the Ostmark to the D–Mark on a 1:1 basis, meant that interest rates in other countries shadowing the D–Mark, especially the UK, were far too high relative to domestic circumstances, leading to a housing decline and recession.

Following the European Currency Unit[edit]

On 8 October 1990 the Conservative government (Third Thatcher ministry) decided to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), with £1 set at DM 2.95. However, the country was forced to withdraw from the system on «Black Wednesday» (16 September 1992) as Britain’s economic performance made the exchange rate unsustainable. The event was also triggered by comments by Bundesbank president Helmut Schlesinger who suggested the pound would eventually have to be devalued.[97][98]

«Black Wednesday» saw interest rates jump from 10% to 15% in an unsuccessful attempt to stop the pound from falling below the ERM limits. The exchange rate fell to DM 2.20. Those who had argued[99] for a lower GBP/DM exchange rate were vindicated since the cheaper pound encouraged exports and contributed to the economic prosperity of the 1990s.[citation needed]

Following inflation targets[edit]

In 1997, the newly elected Labour government handed over day-to-day control of interest rates to the Bank of England (a policy that had originally been advocated by the Liberal Democrats).[100] The Bank is now responsible for setting its base rate of interest so as to keep inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI)) very close to 2% per annum. Should CPI inflation be more than one percentage point above or below the target, the Governor of the Bank of England is required to write an open letter to the Chancellor of the Exchequer explaining the reasons for this and the measures which will be taken to bring this measure of inflation back in line with the 2% target. On 17 April 2007, annual CPI inflation was reported at 3.1% (inflation of the Retail Prices Index was 4.8%). Accordingly, and for the first time, the Governor had to write publicly to the UK Government explaining why inflation was more than one percentage point higher than its target.[101]

Euro[edit]

In 2007, Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, ruled out membership in the eurozone for the foreseeable future, saying that the decision not to join had been right for Britain and for Europe.[102]

On 1 January 2008, with the Republic of Cyprus switching its currency from the Cypriot pound to the euro, the British sovereign bases on Cyprus (Akrotiri and Dhekelia) followed suit, making the Sovereign Base Areas the only territory under British sovereignty to officially use the euro.[103]

The government of former Prime Minister Tony Blair had pledged to hold a public referendum to decide on the adoption of the Euro should «five economic tests» be met, to increase the likelihood that any adoption of the euro would be in the national interest. In addition to these internal (national) criteria, the UK would have to meet the European Union’s economic convergence criteria (Maastricht criteria) before being allowed to adopt the euro. The Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government (2010–2015) ruled out joining the euro for that parliamentary term.

The idea of replacing sterling with the euro was always controversial with the British public, partly because of sterling’s identity as a symbol of British sovereignty and because it would, according to some critics, have led to suboptimal interest rates, harming the British economy.[104] In December 2008, the results of a BBC poll of 1,000 people suggested that 71% would vote no to the euro, 23% would vote yes, while 6% said they were unsure.[105] Sterling did not join the Second European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) after the euro was created. Denmark and the UK had opt-outs from entry to the euro. Theoretically, every EU nation but Denmark must eventually sign up.

As a member of the European Union, the United Kingdom could have adopted the euro as its currency. However, the subject was always politically controversial, and the UK negotiated an opt-out on this issue. Following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, on 31 January 2020, the Bank of England ended its membership of the European System of Central Banks,[106] and shares in the European Central Bank were reallocated to other EU banks.[107]

Recent exchange rates[edit]

The cost of one Euro in sterling (from 1999)

Sterling and the euro fluctuate in value against one another, although there may be correlation between movements in their respective exchange rates with other currencies such as the US dollar. Inflation concerns in the UK led the Bank of England to raise interest rates in late 2006 and 2007. This caused sterling to appreciate against other major currencies and, with the US dollar depreciating at the same time, sterling hit a 15-year high against the US dollar on 18 April 2007, with £1 reaching US$2 the day before, for the first time since 1992. Sterling and many other currencies continued to appreciate against the dollar; sterling hit a 26-year high of £1 to US$2.1161 on 7 November 2007 as the dollar fell worldwide.[108] From mid-2003 to mid-2007, the pound/euro rate remained within a narrow range (€1.45 ± 5%).[109]

Following the global financial crisis in late 2008, sterling depreciated sharply, declining to £1 to US$1.38 on 23 January 2009[110] and falling below £1 to €1.25 against the euro in April 2008.[111] There was a further decline during the remainder of 2008, most dramatically on 29 December when its euro rate hit an all-time low at €1.0219, while its US dollar rate depreciated.[112][113] Sterling appreciated in early 2009, reaching a peak against the euro of £1 to €1.17 in mid-July. In the following months sterling remained broadly steady against the euro, with £1 valued on 27 May 2011 at €1.15 and US$1.65.

On 5 March 2009, the Bank of England announced that it would pump £75 billion of new capital into the British economy, through a process known as quantitative easing (QE). This was the first time in the United Kingdom’s history that this measure had been used, although the Bank’s Governor Mervyn King suggested it was not an experiment.[114]

The process saw the Bank of England creating new money for itself, which it then used to purchase assets such as government bonds, secured commercial paper, or corporate bonds.[115] The initial amount stated to be created through this method was £75 billion, although Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling had given permission for up to £150 billion to be created if necessary.[116] It was expected that the process would continue for three months, with results only likely in the long term.[114] By 5 November 2009, some £175 billion had been injected using QE, and the process remained less effective in the long term. In July 2012, the final increase in QE meant it had peaked at £375 billion, then holding solely UK Government bonds, representing one third of the UK national debt.[117]

The result of the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership caused a major decline in sterling against other world currencies as the future of international trade relationships and domestic political leadership became unclear.[118] The referendum result weakened sterling against the euro by 5% overnight. The night before the vote, sterling was trading at £1 to €1.30; the next day, this had fallen to £1 to €1.23. By October 2016, the exchange rate was £1 to €1.12, a fall of 14% since the referendum. By the end of August 2017 sterling was even lower, at £1 to €1.08.[119] Against the US dollar, meanwhile, sterling fell from £1 to $1.466 to £1 to $1.3694 when the referendum result was first revealed, and down to £1 to $1.2232 by October 2016, a fall of 16%.[120]

In September 2022, under the influence of inflation and tax cuts funded by borrowing,[121] sterling’s value reached an all-time low of just over $1.03.[122]

Annual inflation rate[edit]

UK inflation data

CPIH (CPI+OOH)

The Bank of England had stated in 2009 that the decision had been taken to prevent the rate of inflation falling below the 2% target rate.[115] Mervyn King, the Governor of the Bank of England, had also suggested there were no other monetary options left, as interest rates had already been cut to their lowest level ever (0.5%) and it was unlikely that they would be cut further.[116]

The inflation rate rose in following years, reaching 5.2% per year (based on the Consumer Price Index) in September 2011, then decreased to around 2.5% the following year.[123] After a number of years when inflation remained near or below the Bank’s 2% target, 2021 saw a significant and sustained increase on all indices: as of November 2021, RPI had reached 7.1%, CPI 5.1% and CPIH 4.6%.[124]

Coins[edit]

Pre-decimal coins[edit]

The silver penny (plural: pence; abbreviation: d) was the principal and often the only coin in circulation from the 8th century until the 13th century. Although some fractions of the penny were struck (see farthing and halfpenny), it was more common to find pennies cut into halves and quarters to provide smaller change. Very few gold coins were struck, with the gold penny (equal in value to 20 silver pennies) a rare example. However, in 1279, the groat, worth 4d, was introduced, with the half groat following in 1344. 1344 also saw the establishment of a gold coinage with the introduction (after the failed gold florin) of the noble worth six shillings and eight pence (6/8d) (i.e. 3 nobles to the pound), together with the half and quarter noble. Reforms in 1464 saw a reduction in value of the coinage in both silver and gold, with the noble renamed the ryal and worth 10/– (i.e. 2 to the pound) and the angel introduced at the noble’s old value of 6/8d.

The reign of Henry VII saw the introduction of two important coins: the shilling (abbr.: s; known as the testoon, equivalent to twelve pence) in 1487 and the pound (known as the sovereign, abbr.: £ before numerals or «l.» after them, equivalent to twenty shillings) in 1489. In 1526, several new denominations of gold coins were added, including the crown and half crown, worth five shillings (5/–) and two shillings and six pence (2/6, two and six) respectively. Henry VIII’s reign (1509–1547) saw a high level of debasement which continued into the reign of Edward VI (1547–1553). This debasement was halted in 1552, and new silver coinage was introduced, including coins for 1d, 2d, 3d, 4d and 6d, 1/–, 2/6d and 5/–. In the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603), silver 3⁄4d and 1+1⁄2d coins were added, but these denominations did not last. Gold coins included the half-crown, crown, angel, half-sovereign (10/–) and sovereign (£1). Elizabeth’s reign also saw the introduction of the horse-drawn screw press to produce the first «milled» coins.

Following the succession of the Scottish King James VI to the English throne, a new gold coinage was introduced, including the spur ryal (15/–), the unite (20/–) and the rose ryal (30/–). The laurel, worth 20/–, followed in 1619. The first base metal coins were also introduced: tin and copper farthings. Copper halfpenny coins followed in the reign of Charles I. During the English Civil War, a number of siege coinages were produced, often in unusual denominations.

Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the coinage was reformed, with the ending of production of hammered coins in 1662. The guinea was introduced in 1663, soon followed by the 1⁄2, 2 and 5 guinea coins. The silver coinage consisted of denominations of 1d, 2d, 3d, 4d and 6d, 1/–, 2/6d and 5/–. Due to the widespread export of silver in the 18th century, the production of silver coins gradually came to a halt, with the half crown and crown not issued after the 1750s, the 6d and 1/– stopping production in the 1780s. In response, copper 1d and 2d coins and a gold 1⁄3 guinea (7/–) were introduced in 1797. The copper penny was the only one of these coins to survive long.

To alleviate the shortage of silver coins, between 1797 and 1804, the Bank of England counterstamped Spanish dollars (8 reales) and other Spanish and Spanish colonial coins for circulation. A small counterstamp of the King’s head was used. Until 1800, these circulated at a rate of 4/9d for 8 reales. After 1800, a rate of 5/– for 8 reales was used. The Bank then issued silver tokens for 5/– (struck over Spanish dollars) in 1804, followed by tokens for 1/6d and 3/– between 1811 and 1816.

In 1816, a new silver coinage was introduced in denominations of 6d, 1/–, 2/6d (half-crown) and 5/– (crown). The crown was only issued intermittently until 1900. It was followed by a new gold coinage in 1817 consisting of 10/– and £1 coins, known as the half sovereign and sovereign. The silver 4d coin was reintroduced in 1836, followed by the 3d in 1838, with the 4d coin issued only for colonial use after 1855. In 1848, the 2/– florin was introduced, followed by the short-lived double florin in 1887. In 1860, copper was replaced by bronze in the farthing (quarter penny, 1⁄4d), halfpenny and penny.

During the First World War, production of the sovereign and half-sovereign was suspended, and although the gold standard was later restored, the coins saw little circulation thereafter. In 1920, the silver standard, maintained at .925 since 1552, was reduced to .500. In 1937, a nickel-brass 3d coin was introduced; the last silver 3d coins were issued seven years later. In 1947, the remaining silver coins were replaced with cupro-nickel, with the exception of Maundy coinage which was then restored to .925. Inflation caused the farthing to cease production in 1956 and be demonetised in 1960. In the run-up to decimalisation, the halfpenny and half-crown were demonetised in 1969.

Decimal coins[edit]

| £1 coin (new design, 2016) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Elizabeth II | English rose, Welsh leek, Scottish thistle, and Northern Irish shamrock |

British coinage timeline:

- 1968: The first decimal coins were introduced. These were cupro-nickel 5p and 10p coins which were the same size as, equivalent in value to, and circulated alongside, the one shilling coin and the florin (two shilling coin) respectively.

- 1969: The curved equilateral heptagonal cupro-nickel 50p coin replaced the ten shilling note (10/–).

- 1970: The half crown (2/6d, 12.5p) was demonetised.

- 1971: The decimal coinage was completed when decimalisation came into effect in 1971 with the introduction of the bronze half new penny (1⁄2p), new penny (1p), and two new pence (2p) coins and the withdrawal of the (old) penny (1d) and (old) threepence (3d) coins.

- 1980: Withdrawal of the sixpence (6d) coin, which had continued in circulation at a value of 2+1⁄2p.

- 1982: The word «new» was dropped from the coinage and a 20p coin was introduced.

- 1983: A (round, brass) £1 coin was introduced.

- 1983: The 1⁄2p coin was last produced.

- 1984: The 1⁄2p coin was withdrawn from circulation.

- 1990: The crown, historically valued at five shillings (25p), was re-tariffed for future issues as a commemorative coin at £5.

- 1990: A new 5p coin was introduced, replacing the original size that had been the same as the shilling coins of the same value that it had in turn replaced. These first generation 5p coins and any remaining old shilling coins were withdrawn from circulation in 1991.

- 1992: A new 10p coin was introduced, replacing the original size that had been the same as the florin or two shilling coins of the same value that it had in turn replaced. These first generation 10p coins and any remaining old florin coins were withdrawn from circulation over the following two years.

- 1992: 1p and 2p coins began to be minted in copper-plated steel (the original bronze coins continued in circulation).

- 1997: A new 50p coin was introduced, replacing the original size that had been in use since 1969, and the first generation 50p coins were withdrawn from circulation.

- 1998: The bi-metallic £2 coin was introduced.

- 2007: By now the value of copper in the pre-1992 1p and 2p coins (which are 97% copper) exceeded those coins’ face value to such an extent that melting down the coins by entrepreneurs was becoming worthwhile (with a premium of up to 11%, with smelting costs reducing this to around 4%)—although this is illegal, and the market value of copper has subsequently fallen dramatically from these earlier peaks.

- In April 2008, an extensive redesign of the coinage was unveiled. The 1p, 2p, 5p, 10p, 20p, and 50p coins feature parts of the Royal Shield on their reverse; and the reverse of the pound coin showed the whole shield. The coins were issued gradually into circulation, starting in mid-2008. They have the same sizes, shapes and weights as those with the old designs which, apart from the round pound coin which was withdrawn in 2017, continue to circulate.

- 2012: The 5p and 10p coins were changed from cupro-nickel to nickel-plated steel.

- 2017: A more secure twelve-sided bi-metallic £1 coin was introduced to reduce forgery. The old round £1 coin ceased to be legal tender on 15 October 2017.[125]

As of 2020, the oldest circulating coins in the UK are the 1p and 2p copper coins introduced in 1971. No other coins from before 1982 are in circulation. Prior to the withdrawal from circulation in 1992, the oldest circulating coins usually dated from 1947: although older coins were still legal tender, inflation meant that their silver content was worth more than their face value, so they tended to be removed from circulation and hoarded. Before decimalisation in 1971, a handful of change might have contained coins over 100 years old, bearing any of five monarchs’ heads, especially in the copper coins.

Banknotes[edit]

Selection of current sterling banknotes printed by all banks

The first sterling notes were issued by the Bank of England shortly after its foundation in 1694. Denominations were initially handwritten on the notes at the time of issue. From 1745, the notes were printed in denominations between £20 and £1,000, with any odd shillings added by hand. £10 notes were added in 1759, followed by £5 in 1793 and £1 and £2 in 1797. The lowest two denominations were withdrawn after the end of the Napoleonic wars. In 1855, the notes were converted to being entirely printed, with denominations of £5, £10, £20, £50, £100, £200, £300, £500 and £1,000 issued.

The Bank of Scotland began issuing notes in 1695. Although the pound Scots was still the currency of Scotland, these notes were denominated in sterling in values up to £100. From 1727, the Royal Bank of Scotland also issued notes. Both banks issued some notes denominated in guineas as well as pounds. In the 19th century, regulations limited the smallest note issued by Scottish banks to be the £1 denomination, a note not permitted in England.

With the extension of sterling to Ireland in 1825, the Bank of Ireland began issuing sterling notes, later followed by other Irish banks. These notes included the unusual denominations of 30/– and £3. The highest denomination issued by the Irish banks was £100.

In 1826, banks at least 65 miles (105 km) from London were given permission to issue their own paper money. From 1844, new banks were excluded from issuing notes in England and Wales but not in Scotland and Ireland. Consequently, the number of private banknotes dwindled in England and Wales but proliferated in Scotland and Ireland. The last English private banknotes were issued in 1921.

In 1914, the Treasury introduced notes for 10/– and £1 to replace gold coins. These circulated until 1928 when they were replaced by Bank of England notes. Irish independence reduced the number of Irish banks issuing sterling notes to five operating in Northern Ireland. The Second World War had a drastic effect on the note production of the Bank of England. Fearful of mass forgery by the Nazis (see Operation Bernhard), all notes for £10 and above ceased production, leaving the bank to issue only 10/–, £1 and £5 notes. Scottish and Northern Irish issues were unaffected, with issues in denominations of £1, £5, £10, £20, £50 and £100.

Due to repeated devaluations and spiralling inflation the Bank of England reintroduced £10 notes in 1964. In 1969, the 10/– note was replaced by the 50p coin, again due to inflation. £20 Bank of England notes were reintroduced in 1970, followed by £50 in 1981.[126] A £1 coin was introduced in 1983, and Bank of England £1 notes were withdrawn in 1988. Scottish and Northern Irish banks followed, with only the Royal Bank of Scotland continuing to issue this denomination.

UK notes include raised print (e.g. on the words «Bank of England»); watermarks; embedded metallic thread; holograms; and fluorescent ink visible only under UV lamps. Three printing techniques are involved: offset litho, intaglio and letterpress; and the notes incorporate a total of 85 specialized inks.[127]

The Bank of England produces notes named «giant» and «titan». A giant is a one million pound note, and a titan is a one hundred million pound bank note.[128] Giants and titans are used only within the banking system.[129]

Polymer banknotes[edit]

The Northern Bank £5 note, issued by Northern Ireland’s Northern Bank (now Danske Bank) in 2000, was the only polymer banknote in circulation until 2016. The Bank of England introduced £5 polymer banknotes in September 2016, and the paper £5 notes were withdrawn on 5 May 2017. A polymer £10 banknote was introduced on 14 September 2017, and the paper note was withdrawn on 1 March 2018. A polymer £20 banknote was introduced on 20 February 2020, followed by a polymer £50 in 2021.[130]

Monetary policy[edit]

As the central bank of the United Kingdom which has been delegated authority by the government, the Bank of England sets the monetary policy for the British pound by controlling the amount of money in circulation. It has a monopoly on the issuance of banknotes in England and Wales and regulates the amount of banknotes issued by seven authorized banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland.[131] HM Treasury has reserve powers to give orders to the committee «if they are required in the public interest and by extreme economic circumstances» but such orders must be endorsed by Parliament within 28 days.[132]

Unlike banknotes which have separate issuers in Scotland and Northern Ireland, all British coins are issued by the Royal Mint, an independent enterprise (wholly owned by the Treasury) which also mints coins for other countries.

Legal tender and national issues[edit]

The British Islands (red) and overseas territories (blue) using sterling or their local issue

Legal tender in the United Kingdom is defined such that «a debtor cannot successfully be sued for non-payment if he pays into court in legal tender.» Parties can alternatively settle a debt by other means with mutual consent. Strictly speaking, it is necessary for the debtor to offer the exact amount due as there is no obligation for the other party to provide change.[133]

Throughout the UK, £1 and £2 coins are legal tender for any amount, with the other coins being legal tender only for limited amounts. Bank of England notes are legal tender for any amount in England and Wales, but not in Scotland or Northern Ireland.[133] (Bank of England 10/– and £1 notes were legal tender, as were Scottish banknotes, during World War II under the Currency (Defence) Act 1939, which was repealed on 1 January 1946.) Channel Islands and Manx banknotes are legal tender only in their respective jurisdictions.[134]

Bank of England, Scottish, Northern Irish, Channel Islands, Isle of Man, Gibraltar, and Falkland banknotes may be offered anywhere in the UK, although there is no obligation to accept them as a means of payment, and acceptance varies. For example, merchants in England generally accept Scottish and Northern Irish notes, but some unfamiliar with them may reject them.[135] However, Scottish and Northern Irish notes both tend to be accepted in Scotland and Northern Ireland, respectively. Merchants in England generally do not accept Jersey, Guernsey, Manx, Gibraltarian, and Falkland notes but Manx notes are generally accepted in Northern Ireland.[136] Bank of England notes are generally accepted in the Falklands and Gibraltar, but for example, Scottish and Northern Irish notes are not.[137] Since all of the notes are denominated in sterling, banks will exchange them for locally issued notes at face value,[138][failed verification] though some in the UK have had trouble exchanging Falkland Islands notes.[139]

Commemorative £5 and 25p (crown) coins, and decimal sixpences (6p, not the pre-decimalisation 6d, equivalent to 2+1⁄2p) made for traditional wedding ceremonies and Christmas gifts, although rarely if ever seen in circulation, are formally legal tender,[140] as are the bullion coins issued by the Mint.

| Coin | Maximum usable as legal tender[141] |

|---|---|

| £100 (produced from 2015)[133] | unlimited |

| £20 (produced from 2013) | unlimited |

| £5 (post-1990 crown) | unlimited |

| £2 | unlimited |

| £1 | unlimited |

| 50p | £10 |

| 25p (pre-1990 crown) | £10 |

| 20p | £10 |

| 10p | £5 |

| 5p | £5 |

| 2p | 20p |

| 1p | 20p |

Pegged currencies[edit]

In Britain’s Crown Dependencies, the Manx pound, Jersey pound, and Guernsey pound are unregulated by the Bank of England and are issued independently.[142] However, they are maintained at a fixed exchange rate by their respective governments, and Bank of England notes have been made legal tender on the islands, forming a sort of one-way de facto currency union. Internationally they are considered local issues of sterling so do not have ISO 4217 codes. «GBP» is usually used to represent all of them; informal abbreviations resembling ISO codes are used where the distinction is important.

British Overseas Territories are responsible for the monetary policy of their own currencies (where they exist),[143] and have their own ISO 4217 codes. The Falkland Islands pound, Gibraltar pound, and Saint Helena pound are set at a fixed 1:1 exchange rate with the British pound by local governments.

Value[edit]

In 2006, the House of Commons Library published a research paper which included an index of prices for each year between 1750 and 2005, where 1974 was indexed at 100.[144]

Regarding the period 1750–1914 the document states: «Although there was considerable year on year fluctuation in price levels prior to 1914 (reflecting the quality of the harvest, wars, etc.) there was not the long-term steady increase in prices associated with the period since 1945». It goes on to say that «Since 1945 prices have risen in every year with an aggregate rise of over 27 times».

The value of the index in 1751 was 5.1, increasing to a peak of 16.3 in 1813 before declining very soon after the end of the Napoleonic Wars to around 10.0 and remaining in the range 8.5–10.0 at the end of the 19th century. The index was 9.8 in 1914 and peaked at 25.3 in 1920, before declining to 15.8 in 1933 and 1934—prices were only about three times as high as they had been 180 years earlier.[145]

Inflation has had a dramatic effect during and after World War II: the index was 20.2 in 1940, 33.0 in 1950, 49.1 in 1960, 73.1 in 1970, 263.7 in 1980, 497.5 in 1990, 671.8 in 2000 and 757.3 in 2005.

The following table shows the equivalent amount of goods and services that, in a particular year, could be purchased with £1.[146]

The table shows that from 1971 to 2018 £1 sterling. lost 92.74% of its buying power.

| Year | Equivalent buying power | Year | Equivalent buying power | Year | Equivalent buying power | Year | Equivalent buying power | Year | Equivalent buying power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | £1.00 | 1981 | £0.271 | 1991 | £0.152 | 2001 | £0.117 | 2011 | £0.0900 |

| 1972 | £0.935 | 1982 | £0.250 | 1992 | £0.146 | 2002 | £0.115 | 2012 | £0.0850 |

| 1973 | £0.855 | 1983 | £0.239 | 1993 | £0.144 | 2003 | £0.112 | 2013 | £0.0826 |

| 1974 | £0.735 | 1984 | £0.227 | 1994 | £0.141 | 2004 | £0.109 | 2014 | £0.0800 |

| 1975 | £0.592 | 1985 | £0.214 | 1995 | £0.136 | 2005 | £0.106 | 2015 | £0.0780 |

| 1976 | £0.510 | 1986 | £0.207 | 1996 | £0.133 | 2006 | £0.102 | 2016 | £0.0777 |

| 1977 | £0.439 | 1987 | £0.199 | 1997 | £0.123 | 2007 | £0.0980 | 2017 | £0.0744 |

| 1978 | £0.407 | 1988 | £0.190 | 1998 | £0.125 | 2008 | £0.0943 | 2018 | £0.0726 |

| 1979 | £0.358 | 1989 | £0.176 | 1999 | £0.123 | 2009 | £0.0952 | ||

| 1980 | £0.303 | 1990 | £0.161 | 2000 | £0.119 | 2010 | £0.0910 |

The smallest coin in 1971 was the 1⁄2p, worth about 6.4p in 2015 prices.

Exchange rate[edit]

Sterling is freely bought and sold on the foreign exchange markets around the world, and its value relative to other currencies therefore fluctuates.[c]

| Current GBP exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR HKD JPY USD |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR HKD JPY USD |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR HKD JPY USD |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR HKD JPY USD |

Reserve[edit]

Sterling is used as a reserve currency around the world. As of 2020, it is ranked fourth in value held as reserves.

|

2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1995 | 1990 | 1985 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1965 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US dollar | 58.81% | 58.92% | 60.75% | 61.76% | 62.73% | 65.36% | 65.73% | 65.14% | 61.24% | 61.47% | 62.59% | 62.14% | 62.05% | 63.77% | 63.87% | 65.04% | 66.51% | 65.51% | 65.45% | 66.50% | 71.51% | 71.13% | 58.96% | 47.14% | 56.66% | 57.88% | 84.61% | 84.85% | 72.93% |

| Euro (until 1999 — ECU) | 20.64% | 21.29% | 20.59% | 20.67% | 20.17% | 19.14% | 19.14% | 21.20% | 24.20% | 24.05% | 24.40% | 25.71% | 27.66% | 26.21% | 26.14% | 24.99% | 23.89% | 24.68% | 25.03% | 23.65% | 19.18% | 18.29% | 8.53% | 11.64% | 14.00% | 17.46% | |||

| Japanese yen | 5.57% | 6.03% | 5.87% | 5.19% | 4.90% | 3.95% | 3.75% | 3.54% | 3.82% | 4.09% | 3.61% | 3.66% | 2.90% | 3.47% | 3.18% | 3.46% | 3.96% | 4.28% | 4.42% | 4.94% | 5.04% | 6.06% | 6.77% | 9.40% | 8.69% | 3.93% | 0.61% | ||

| Pound sterling | 4.78% | 4.73% | 4.64% | 4.43% | 4.54% | 4.35% | 4.71% | 3.70% | 3.98% | 4.04% | 3.83% | 3.94% | 4.25% | 4.22% | 4.82% | 4.52% | 3.75% | 3.49% | 2.86% | 2.92% | 2.70% | 2.75% | 2.11% | 2.39% | 2.03% | 2.40% | 3.42% | 11.36% | 25.76% |

| Chinese renminbi | 2.79% | 2.29% | 1.94% | 1.89% | 1.23% | 1.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canadian dollar | 2.38% | 2.08% | 1.86% | 1.84% | 2.03% | 1.94% | 1.77% | 1.75% | 1.83% | 1.42% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Australian dollar | 1.81% | 1.83% | 1.70% | 1.63% | 1.80% | 1.69% | 1.77% | 1.59% | 1.82% | 1.46% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Swiss franc | 0.20% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.14% | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.27% | 0.24% | 0.27% | 0.21% | 0.08% | 0.13% | 0.12% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.17% | 0.23% | 0.41% | 0.25% | 0.27% | 0.33% | 0.84% | 1.40% | 2.25% | 1.34% | 0.61% | |

| Deutsche Mark | 15.75% | 19.83% | 13.74% | 12.92% | 6.62% | 1.94% | 0.17% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| French franc | 2.35% | 2.71% | 0.58% | 0.97% | 1.16% | 0.73% | 1.11% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dutch guilder | 0.32% | 1.15% | 0.78% | 0.89% | 0.66% | 0.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other currencies | 3.01% | 2.65% | 2.51% | 2.45% | 2.43% | 2.33% | 2.86% | 2.83% | 2.84% | 3.26% | 5.49% | 4.43% | 3.04% | 2.20% | 1.83% | 1.81% | 1.74% | 1.87% | 2.01% | 1.58% | 1.31% | 1.49% | 4.87% | 4.89% | 2.13% | 1.29% | 1.58% | 0.43% | 0.03% |

| Source: World Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves International Monetary Fund |

See also[edit]

- Commonwealth banknote-issuing institutions

- List of British currencies

- List of currencies in Europe

- List of the largest trading partners of United Kingdom

- Pound (currency) – other currencies with a «pound» unit of account.

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b Scotland and Northern Ireland only

- ^ £50 in 1966 is about £991 today.

- ^ For historic exchange rates with the pound, see OandA.com Currency Converter

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Leach, Robert (2021). «Section 2: Abbreviations». Leach’s Tax Dictionary. London: Spiramus Press Ltd. p. 838. ISBN 9781913507190. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022. Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen.

- ^ http://www.royalmint.com/help/help/how-can-i-dispose-of-commemorative-crowns[bare URL]

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20130517124642/http://www.royalmint.com/discover/uk-coins/circulation-coin-mintage-figures[bare URL]

- ^ «Our banknotes». Bank of England. 31 October 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ «Inflation and price indices». Office for National Statistics. 20 July 2022. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Hashimzade, Nigar; Myles, Gareth; Black, John (2017). A Dictionary of Economics (5 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198759430.

Sterling: The UK currency. The name originated from the pound Easterling, formerly used in trade with the Baltic.

- ^ a b Barber, Katherine, ed. (2004). «Pound». Canadian Oxford Dictionary (2 ed.). ISBN 9780195418163.

Pound:2. (in full pound sterling) (pl. same or pounds) the chief monetary unit of the UK and several other countries.

- ^ a b Moles, Peter; Terry, Nicholas (1999). The Handbook of International Financial Terms. ISBN 9780198294818.

Sterling (UK).: The name given to the currency of the United Kingdom (cf. cable). Also called pound sterling or pounds.

- ^ Rendall, Alasdair (12 November 2007). «Economic terms explained». BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ Jeff Desjardins (29 December 2016). «Here are the most traded currencies in 2016». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ «Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves». International Monetary Fund. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ a b «Entry 189985». OED Online. Oxford University Press. December 2011. Archived from the original on 25 June 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

sterling, n.1 and adj.

- ^ «Easterling theory». Sterling Judaica. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Huffman, Joseph P. (13 November 2003). Family, Commerce, and Religion in London and Cologne. p. 33. ISBN 9780521521932. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ The Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, Volumes 19–20. 1903. p. 129. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b «Pound sterling (money)». Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

Silver coins known as ‘sterlings’ were issued in the Saxon kingdoms, 240 of them being minted from a pound of silver… Hence, large payments came to be reckoned in ‘pounds of sterlings’, a phrase later shortened…

- ^ «History of the use of the single crossbar pound sign on Bank of England’s banknotes». Bank of England. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ a b «Withdrawn banknotes». Bank of England. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019. («£1 1st Series Treasury Issue» to «£5 Series B»)

- ^ «Current banknotes». Bank of England. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ For example,Samuel Pepys (2 January 1660). «Diary of Samuel Pepys/1660/January». Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

Then I went to Mr. Crew’s and borrowed L10 of Mr. Andrewes for my own use, and so went to my office, where there was nothing to do

- ^ His Majesty’s Stationery Office (10 July 1939). «Royal Mint Annual Report 1938 Volume No.69». Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

Some 58,000,000l of silver coin of the old fineness, comprising over a thousand million pieces, have already been withdrawn from circulation.

- ^ see for example Barnum and Bailey share certificate (early 20th century)

- ^ Thomas Snelling (1762). A View of the Silver Coin and Coinage of England from the Norman Conquest to the Present Time. T. Snelling. p. ii. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ «A brief history of the pound». The Dozenal Society of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ «ILO House style manual» (PDF). International Labour Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ «WHO style guide» (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ «Style guide for authors and editors» (PDF). Bloomsbury Academic. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ «Editorial style guide» (PDF). World Bank. p. 139. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ «Overseas trade in June 1934, and the year 1933–1934». Journal of the Board of Trade. 133 (1978): 654. 1 November 1934 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Barrett, Claer; Aglionby, John (12 November 2014). «Traders’ forex chatroom banter exposed». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

A trader from HSBC visits multiple chatrooms in an attempt to manipulate the 4pm WMR fix, declaring he is a net seller in «cable» (a slang term for GBP/USD currency pairing)

- ^ «STERLING CABLE RATES $3.19 TO $7 SINCE 1914; Top Reached When War Started and Bottom on Feb. 3, 1920, as Support Stopped». New York Times. 22 September 1931. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ «University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections ‘Research Guidance’ Weights and Measures § Money». Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ «Quid | Definition of Quid by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Quid». Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin. 20 August 1993.

- ^ «British Antarctic Territory Currency Ordinance 1990». Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ «Foreign and Commonwealth Office country profiles: British Antarctic Territory». British Foreign & Commonwealth Office. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ «Foreign and Commonwealth Office country profiles: Tristan da Cunha». British Foreign & Commonwealth Office. 12 February 2010. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ «1984: Halfpenny coin to meet its maker». BBC News. 2008. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ «Shilling». The Royal Mint Museum. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ «Florin». The Royal Mint Museum. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shaw, William Arthur (13 May 1896). «The History of Currency, 1252–1894: Being an Account of the Gold and Silver Moneys and Monetary Standards of Europe and America, Together with an Examination of the Effects of Currency and Exchange Phenomena on Commercial and National Progress and Well-being». Putnam. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Shaw, William Arthur (13 May 1896). «The History of Currency, 1252–1894: Being an Account of the Gold and Silver Moneys and Monetary Standards of Europe and America, Together with an Examination of the Effects of Currency and Exchange Phenomena on Commercial and National Progress and Well-being». Putnam. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Coin». British Museum. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Naismith, Rory (2014b). «Coinage». In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- ^ «Pound sterling». Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

Silver coins known as «sterlings» were issued in the Saxon kingdoms, 240 of them being minted from a pound of silver… Hence, large payments came to be reckoned in «pounds of sterlings,» a phrase later shortened…

- ^ Lowther, Ed (14 February 2014). «A short history of the pound». BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

Anglo-Saxon King Offa is credited with introducing the system of money to central and southern England in the latter half of the eighth century, overseeing the minting of the earliest English silver pennies – emblazoned with his name. In practice they varied considerably in weight and 240 of them seldom added up to a pound. There were at that time no larger denomination coins – pounds and shillings were merely useful units of account.

- ^ «Halfpenny and Farthing». www.royalmintmuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ «Coins of the Kings and Queens of England and Great Britain». Treasure Realm. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

2d, 4d issued since 1347

- ^ Snelling, Thomas (1763). A View Of The Gold Coin And Coinage Of England: From Henry The Third To the Present Time. Consider’d with Regard to Type, Legend, Sorts, Rarity, Weight, Fineness, Value and Proportion. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

The manuscript chronicle of the city of London says this king Henry III in 1258 coined a penny of fine gold of the weight of two sterlings and commanded it should go for 20 shillings if this be true these were the first pieces of gold coined in England NB The date should be 1257 and the value pence

- ^ Munro, John. «MONEY AND COINAGE IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN EUROPE» (PDF). Department of Economics, University of Toronto. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

240–243 pennies minted from a Tower Pound.

- ^ a b «Content and Fineness of the Gold Coins of England and Great Britain: Henry III – Richard III (1257–1485)». treasurerealm.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

Fineness 23.875 karats = 191/192, coins in Nobles, Halves, Quarters

- ^ «Noble (1361–1369) ENGLAND, KINGDOM – EDWARD III, 1327–1377 – n.d., Calais Wonderful coin with fine details. Very impressive». MA-Shops. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Shaw, William Arthur (1896). The History of Currency, 1252–1894: Being an Account of the Gold and Silver Moneys and Monetary Standards of Europe and America, Together with an Examination of the Effects of Currency and Exchange Phenomena on Commercial and National Progress and Well-being. p. 33. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

In 1427 a Mark (244.752 g) of silver was worth 8 livre tournois or 6.4 livre parisis

Hence one livre weighed 38.24 g and one sol at 1.912 g. Compare with 40d sterling at 36 g, 2d at 1.8 g. - ^ «The Vierlander, a precursor of the Euro. A first step towards monetary unification». Museum of the National Bank of Belgium. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.