Человечество знакомо с калием больше полутора веков. В лекции, прочитанной в Лондоне 20 ноября 1807 г. Хэмфри Дэви сообщил, что при электролизе едкого калия он получил «маленькие шарики с сильным металлическим блеском… Некоторые из них сейчас же после своего образования сгорали со взрывом». Это и был калий.

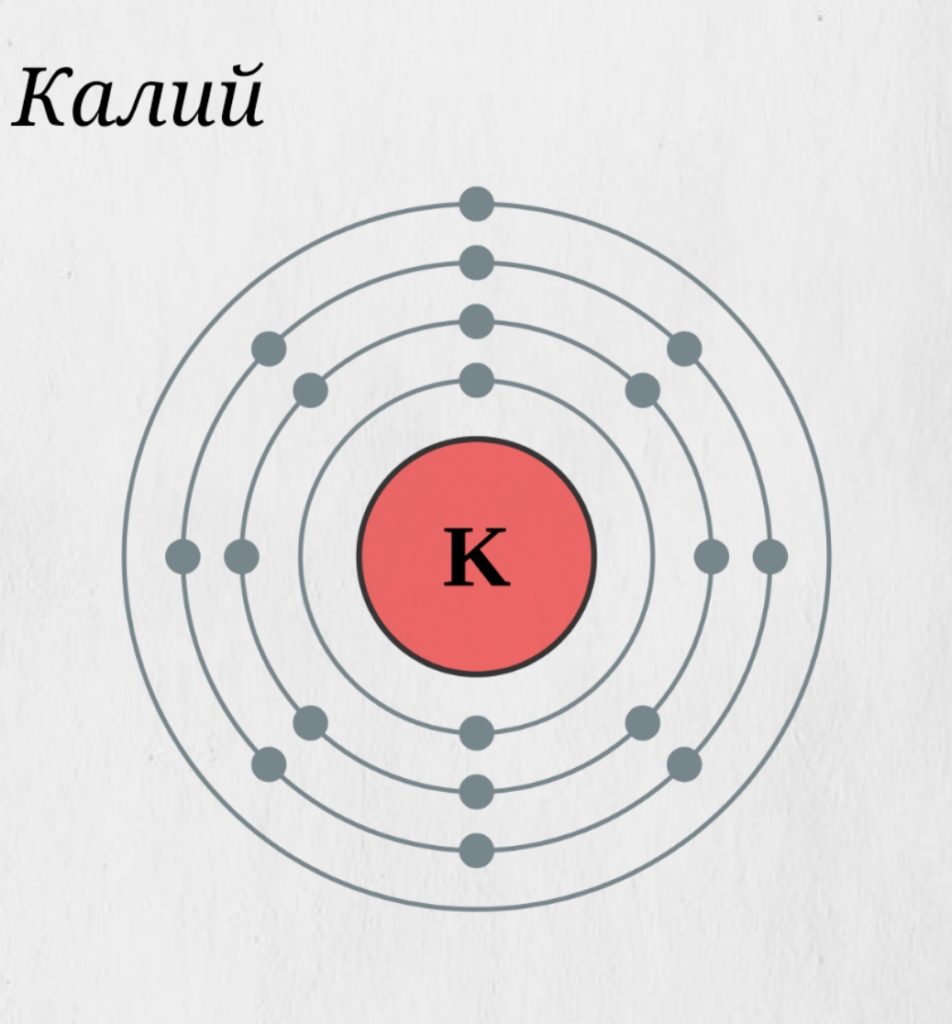

Обратите внимание: его атомный номер 19, атомная масса 39, во внешнем электронном слое — один электрон, валентность 1+. Как считают химики, именно этим объясняется исключительная подвижность калия в природе. Он входит в состав нескольких сотен минералов. Он находится в почве, в растениях, в организмах людей и животных. Он — как классический Фигаро: здесь — там — повсюду.

Калий и почва

Вряд ли можно объяснить случайностью или прихотью лингвистов тот факт, что в русском языке одним словом обозначаются и сама наша планета, и ее верхний слой — почва. «Земля-матушка», «земля-кормилица» — это, скорее, о почве, чем о планете в целом…

Но что такое почва? Самостоятельное и весьма своеобразное природное тело. Оно образуется из поверхностных слоев разнообразных горных пород под действием воздуха, воды, температурных перепадов, жизнедеятельности всевозможных обитателей Земли. Ниже, под почвой, скрыты так называемые материнские горные породы, сложенные из различных минералов. Они постепенно разрушаются и пополняют «запасы» почвы. А в почве, помимо чисто механического, постоянно происходит и другое разрушение. Его называют химическим выветриванием. Вода и углекислый газ (в меньшей мере другие вещества) постепенно разрушают минералы.

Почти 18% веса земной коры приходится на долю калийсодержащего минерала — ортоклаза. Это двойная соль кремневой кислоты K2Al2Si6O16 или K2O-Al2O3-BSiO2. Вот что происходит с ортоклазом в результате химического выветривания:

K2O*AI2O3*6SO2 + 2Н2О + CO2 → K2CO3+ Al2O3*2SO2*2H2O + + 4SiO2.

Ортоклаз превращается в каолин (разновидность глины), песок и поташ. Песок и глина идут на построение минерального костяка почвы, а K, перешедший из ортоклаза в поташ, «раскрепощается», становится доступным для растений. Но не весь сразу.

В почвенных водах молекулы K2CO3 диссоциируют: К2СO3 ↔ + К+ + КСO3— ↔ 2К+ + CO32-. Часть ионов калия остается в почвенном растворе, который для растений служит источником питания. Но большая часть ионов калия поглощается коллоидными частицами почвы, откуда корням растений извлечь их довольно трудно. Вот и получается, что, хотя калия в земле много, часто растениям его не хватает. Из-за того, что комочки почвы «запирают» большую часть калия, содержание этого элемента в морской воде почти в 50 раз меньше, чем натрия. Подсчитано, что из тысячи атомов калия, освобождающихся при химическом выветривании, только два достигают морских бассейнов, а 998 остаются в почве. «Почва поглощает калий, и в этом ее чудодейственная сила», — писал академик А. Е. Ферсман.

Калий и растения

Калий содержится во всех растениях. Отсутствие калия приводит растение к гибели. Почти весь калий находится в растениях в ионной форме — K+. Часть ионов находится в клеточном соке, другая часть поглощена структурными элементами клетки. Ионы калия участвуют во многих биохимических процессах, происходящих в растении. Установлено, что в клетках растений эти ионы находятся главным образом в протоплазме. В клеточном ядре они не обнаружены. Следовательно, в процессах размножения и в передаче наследственных признаков элемент № 19 не участвует. Но и без этого роль калия в жизни растения велика и многообразна.

Калий входит и в плоды, и в корни, и в стебли, и в листья, причем в вегетативных органах его, как правило, больше, чем в плодах. Еще одна характерная особенность: в молодых растениях больше калия, чем в старых. Замечено также, что по мере старения отдельных органов растений ионы калия перемещаются в точки наиболее интенсивного роста. При недостатке калия растения медленнее растут, их листья, особенно старые, желтеют и буреют по краям, стебель становится тонким и непрочным, а семена теряют всхожесть.

Установлено, что ионы калия активизируют синтез органических веществ в растительных клетках. Особенно сильно влияют они на процессы образования углеводов. Если калия не хватает, растение хуже усваивает углекислый газ, и для синтеза новых молекул углеводов ему недостает углеродного «сырья». Одновременно усиливаются процессы дыхания, и сахара, содержащиеся в клеточном соке, окисляются. Таким образом, запасы углеводов в растениях, оказавшихся на голодном пайке (по калию), не пополняются, а расходуются. Плоды такого растения — это особенно заметно на фруктах — будут менее сладкими, чем у растений, получивших нормальную дозу калия. Крахмал — тоже углевод, поэтому и на его содержание в плодах сильно влияет элемент № 19.

Но и это не все. Растения, получившие достаточно калия, легче переносят засуху и морозные зимы. Это объясняется тем, что элемент № 19 влияет на способность коллоидных веществ растительных клеток поглощать воду и набухать. Не хватает калия — клетки хуже усваивают и удерживают влагу, сжимаются, отмирают.

Ионы калия влияют и на азотный обмен веществ. При недостатке калия в клетках накапливается избыток аммиака. Это может привести к отравлению и гибели растения.

Уже упоминалось, что K влияет и на дыхание растений, а усиление дыхания сказывается не только на содержании углеводов. Чем интенсивнее дыхание, тем активнее идут все окислительные процессы, и многие органические вещества превращаются в органические кислоты. Избыток кислот может вызвать распад белков. Продукты этого распада — весьма благоприятная среда для грибков и бактерий. Вот почему при калийном голодании растения намного чаще поражаются болезнями и вредителями. Фрукты и овощи, содержащие продукты распада белков, плохо переносят транспортировку, их нельзя долго хранить.Одним словом, хочешь получать вкусные и хорошо сохраняющиеся плоды — корми растение калием вволю. А для зерновых калий важен еще по одной причине: он увеличивает прочность соломы и тем самым предупреждает полегание хлебов…

Интересное о калии

- ВСТРЕЧА С КАЛИЕМ? Если на складе или на товарной станции вы увидите стальные ящики с надписями: «Огнеопасно!», «От воды взрывается», то весьма вероятно, что вы встретились с калием.

Много предосторожностей предпринимают при перевозке этого металла. Поэтому, вскрыв стальной ящик, вы не увидите калия, а увидите тщательно запаянные стальные банки. В них — калий и инертный газ — единственная безопасная для калия среда. Большие партии калия перевозят в герметических контейнерах под давлением инертного газа, равным 1,5 атм.

- ЗАЧЕМ НУЖЕН МЕТАЛЛИЧЕСКИЙ КАЛИЙ? Металлический K используют как катализатор в производстве некоторых видов синтетического каучука, а также в лабораторной практике. В последнее время основным применением этого металла стало производство перекиси калия K2O2, используемой для регенерации кислорода. Сплав калия с натрием служит теплоносителем в атомных реакторах, а в производстве титана — восстановителем.

- ИЗ СОЛИ И ЩЕЛОЧИ. Получают элемент №19 чаще всего в обменной реакции расплавленных едкого калия и металлического натрия: KOH + Na → NaOH + K. Процесс идет в ректификационной колонне из никеля при температуре 380-440°С. Подобным образом получают элемент № 19 и из хлористого калия, только в этом случае температура процесса выше — 760-800°С. При такой температуре и натрий, и калий превращаются в пар, а хлористый калий (с добавками) плавится. Пары натрия пропускают через расплавленную соль и конденсируют полученные пары калия. Этим же способом получают и сплавы натрия с калием. Состав сплава в большой мере зависит от условий процесса.

- КАК БЫТЬ, ЕСЛИ вы впервые имеете дело с металлическим калием. Необходимо помнить о высочайшей реакционной способности этого металла, о том, что калий воспламеняется от малейших следов воды. Работать с калием обязательно в резиновых перчатках и защитных очках, а лучше — в маске» закрывающей все лицо. С большими количествами калия работают в специальных камерах, заполненных азотом или аргоном. (Разумеется, в специальных скафандрах.) А если K все-таки воспламенился, его тушат не водой, а содой или поваренной солью.

- КАК БЫТЬ С ОТХОДАМИ. Правила безопасности категорически запрещают накапливать в лабораториях больше двух граммов остатков или отходов какого-либо щелочного металла, калия в том числе. Отходы подлежат уничтожению на месте. Классический способ — образование под действием этилового спирта этилата калия C2H5OK: просто льют в отходы спирт. Но есть и другой — безспиртовой способ. Отходы заливают керосином или бензином. Калий с ними не реагирует и, будучи легче воды, но тяжелее этих органических жидкостей, оседает на дно. И тогда в наклоненный сосуд начинают по каплям добавлять воду. Когда вода доберется до металла, произойдет реакция и K превратится в едкое кали. Слои щелочного раствора и керосина или бензина довольно легко разделяются на делительной воронке.

- ЕСТЬ ЛИ В РАСТВОРЕ ИОНЫ КАЛИЯ? Выяснить это несложно. Проволочное колечко опустите в раствор, а затем внесите в пламя газовой горелки. Если калий есть, пламя окрасится в фиолетовый цвет, правда, не в такой яркий, как желтый цвет, придаваемый пламени соединениями натрия. Сложнее определить, сколько калия в растворе. Нерастворимых в воде соединений у этого металла немного. Обычно калий осаждают в виде перхлората — соли очень сильной хлорной кислоты HClO4. Кстати, перхлорат калия — очень сильный окислитель и в этом качестве применяется в производстве некоторых взрывчатых веществ и ракетных топлив.

- ДЛЯ ЧЕГО НУЖЕН ЦИАНИСТЫЙ КАЛИЙ? Для извлечения золота и серебра из руд. Для гальванического золочения и серебрения неблагородных металлов. Для получения многих органических веществ. Для азотирования стали — это придает ее поверхности большую прочность. К сожалению, это очень нужное вещество чрезвычайно ядовито. А выглядит KCN вполне безобидно: мелкие кристаллы белого цвета с коричневатым или серым оттенком.

- ЧТО ТАКОЕ ХРОМПИК? Точнее — хромпик калиевый. Это оранжевые кристаллы состава K2Cr2O7. Хромпик используют в производстве красителей, а его растворы — для «хромового» дубления кож, а также в качестве протравы при окраске и печатании тканей. Раствор хромпика в серной кислоте — хромовая смесь, которую во всех лабораториях применяют для мытья стеклянной посуды.

- ЗАЧЕМ НУЖНО ЕДКОЕ КАЛИ? В самом деле, зачем? Ведь свойства этой щелочи и более дешевого едкого натра практически одинаковы. Разницу между этими веществами химики обнаружили лишь в XVIII в. Самое заметное различие между NaOH и KOH в том, что едкое кали в воде растворяется еще лучше, чем едкий натр. KOH получают электролизом растворов хлористого калия. Чтобы примесь хлоридов была минимальной, используют ртутные катоды. А нужно это вещество прежде всего как исходный продукт для получения различных солей калия. Кроме того, без едкого кали не обойтись в производстве жидких мыл, некоторых красителей и органических соединений. Раствор едкого кали используется в качестве электролита в щелочных аккумуляторах.

- СЕЛИТРА ИЛИ СЕЛИТРЫ? Правильнее — селитры. Это общее название азотнокислых солей щелочных и щелочноземельных металлов. Если же говорят просто «селитра» (не «натриевая» или «кальциевая» или «аммиачная», а просто — «селитра»), то имеют в виду нитрат калия. Этим веществом человечество пользуется уже больше тысячи лет — для получения черного пороха. Кроме того, селитра — первое двойное удобрение: из трех важнейших для растений элементов в ней есть два — азот и калий. Вот как описал селитру Д. И. Менделеев в «Основах химии»:

«Селитра представляет бесцветную соль, имеющую особый прохладительный вкус. Она легко кристаллизуется длинными, по бокам бороздчатыми, ромбическими, шестигранными призмами, оканчивающимися такими же пирамидами. Ее кристаллы (уд. вес 1,93) не содержат воды. При слабом накаливании (339°) селитра плавится в совершенно бесцветную жидкость. При обыкновенной температуре в твердом виде KNO3 малодеятельна и неизменна, но при возвышенной температуре она действует как весьма сильное окисляющее средство, потому что может отдать смешанным с нею веществам значительное количество кислорода. Брошенная на раскаленный уголь селитра производит быстрое его горение, а механическая смесь ее с измельченным углем загорается от прикосновения с накаленным телом и продолжает сама собою гореть. При этом выделяется азот, а кислород селитры идет на окисление угля, вследствие чего и получаются углекалиевая соль и углекислый газ…

В химической практике и технике селитра употребляется во многих случаях как окислительное сродство, действующее при высокой температуре. На этом же основано применение ее для обыкновенного пороха, который есть механическая смесь мелко измельченных: серы, селитры и угля».

- ГДЕ И ДЛЯ ЧЕГО ПРИМЕНЯЮТСЯ ПРОЧИЕ СОЛИ КАЛИЯ? Бромистый калий KBr — в фотографии, чтобы предохранить негатив или отпечаток от вуали.

- Йодистый калий KI — в медицине и как химический реактив.

- Фтористый калий KF — в составе металлургических флюсов и для введения фтора в органические соединения.

- Углекислый калий (поташ) K2CO3 — в стекольном и мыловаренном производствах, а также как удобрение.

- Фосфаты калия, в частности K4P2O7 и K5P3O10, — как компоненты моющих средств.

- Хлорат калия (бертолетова соль) KClO3 — в спичечном производстве и пиротехнике.

- Кремнефтористый калий K2SiF6 — как добавка к шихте при извлечении редкоземельных элементов из минералов.

- Железистосинеродистый калий (желтая кровяная соль) K4Fe(CN)6-SH2O — как протрава при крашении тканей и в фотографии.

- ПОЧЕМУ КАЛИЙ НАЗВАЛИ КАЛИЕМ? Слово это арабского происхождения. По-арабски, «аль-кали» — зола растений. Впервые калий получен из едкого кали, а едкое кали — из поташа, выделенного из золы растений… Впрочем, в английском и других европейских языках сохранилось название potassium, данное калию его первооткрывателем X. Дэви. В русскую химическую номенклатуру название «калий» введено в 1831 г. Г. И. Гессом.

- ОТНЮДЬ HE ТОЛЬКО В КУРАГЕ. Сердечникам, в первую очередь людям, перенесшим инфаркт, для восполнения потерь калия в организме настоятельно рекомендуют есть курагу. Или в крайнем случае изюм. В 100 граммах кураги до 2 г калия. Столько же ее в урюке (но для точности при расчете надо вычесть вес косточек). Изюм содержит калия примерно вдвое меньше. Но не надо думать, будто сухофрукты — единственный источник калия. Его довольно много почти в любой растительной пище. Например, сорок граммов жареного картофеля эквивалентны 10 граммам отборной кураги. Богаты калием бобовые, чай, порошок какао. Одним словом, суточную дозу калия (2,5-5 г) при нормальном питании получить нетрудно.

Калий встречается в природе в виде двух стабильных нуклидов: 39К (93, 10% по массе) и 41К (6, 88%), а также одного радиоактивного 40К (0, 02%). Период полураспада калия-40 Т1/2 примерно в 3 раза меньше, чем Т1/2 урана-238 и составляет 1, 28 миллиарда лет. При β-распаде калия-40 образуется стабильный кальций-40, а при распаде по типу электронного захвата образуется инертный газ аргон-40.

Калий принадлежит к числу щелочных металлов. В периодической системе Менделеева калий занимает место в четвертом периоде в подгруппе IА. Конфигурация внешнего электронного слоя 4s1, поэтому калий всегда проявляет степень окисления +1 (валентность I).

Атомный радиус калия 0, 227 нм, радиус иона K+ 0, 133 нм. Энергии последовательной ионизации атома калия 4, 34 и 31, 8 эВ. Электроотрицательность калия по Полингу 0, 82, что говорит о его ярко выраженных металлических свойствах.

В свободном виде — мягкий, легкий, серебристый металл.

Соединения калия, как и его ближайшего химического аналога — натрия, были известны с древности и находили применение в различных областях человеческой деятельности. Однако сами эти металлы были впервые выделены в свободном состоянии только в 1807 году в ходе экспериментов английского ученого Г. Дэви. Дэви, используя гальванические элементы как источник электрического тока, провел электролиз расплавов поташа и каустической соды и таким образом выделил металлические калий и натрий, которые назвал «потассием» (отсюда сохранившееся в англоязычных странах и Франции название калия — potassium) и «содием». В 1809 году английский химик Л. В. Гильберт предложил название «калий» (от арабского аль-кали — поташ).

Содержание калия в земной коре 2, 41% по массе, калий входит в первую десятку наиболее распространенных в земной коре элементов. Основные минералы, содержащие калий: сильвин KСl (52, 44% К), сильвинит (Na, K)Cl (этот минерал представляет собой плотно спрессованную механическую смесь кристалликов хлорида калия KCl и хлорида натрия NaCl), карналлит KCl·MgCl2·6H2O (35, 8% К), различные алюмосиликаты, содержащие калий, каинит KCl·MgSO4·3H2O, полигалит K2SO4·MgSO4·2CaSO4·2H2O, алунит KAl3(SO4)2(OH)6. В морской воде содержится около 0, 04% калия.

В настоящее время калий получают при взаимодействии с жидким натрием расплавленных KOH (при 380-450°C) или KCl (при 760-890°C):

Na + KOH = NaOH + K

Калий также получают электролизом расплава KCl в смеси с K2CO3 при температурах, близких к 700°C:

2KCl = 2K + Cl2

От примесей калий очищают вакуумной дистилляцией.

Металлический калий мягок, он легко режется ножом и поддается прессованию и прокатке. Обладает кубической объемно центрированной кубической решеткой, параметр а = 0, 5344 нм. Плотность калия меньше плотности воды и равна 0, 8629 г/см3. Как и все щелочные металлы, калий легко плавится (температура плавления 63, 51°C) и начинает испаряться уже при сравнительно невысоком нагревании (температура кипения калия 761°C).

Калий, как и другие щелочные металлы, химически очень активен. Легко взаимодействует с кислородом воздуха с образованием смеси, преимущественно состоящей из пероксида К2О2 и супероксида KO2 (К2О4):

2K + O2 = K2O2, K + O2 = KO2.

При нагревании на воздухе калий сгорает фиолетово-красным пламенем. С водой и разбавленными кислотами калий взаимодействует со взрывом (воспламеняется образующийся водород):

2K + 2H2O = 2KOH + H2

Кислородсодержащие кислоты при таком взаимодействии могут восстанавливаться. Например, атом серы серной кислоты восстанавливается до S, SO2 или S2–:

8К + 4Н2SO4 = K2S + 3K2SO4 + 4H2O.

При нагревании до 200-300 °C калий реагирует с водородом с образованием солеподобного гидрида КН:

2K + H2 = 2KH

С галогенами калий взаимодействует со взрывом. Интересно отметить, что с азотом калий не взаимодействует.

Как и другие щелочные металлы, калий легко растворяется в жидком аммиаке с образованием голубых растворов. В таком состоянии калий используют для проведения некоторых реакций. При хранении калий медленно реагирует с аммиаком с образованием амида KNH2:

2K + 2NH3 жидк. = 2KNH2 + H2

Важнейшие соединения калия: оксид К2О, пероксид К2О2, супероксид К2О4, гидроксид КОН, иодид KI, карбонат K2CO3 и хлорид KCl.

Оксид калия К2О, как правило, получают косвенным путем за счет реакции пероксида и металлического калия:

2K + K2O2 = 2K2O

Этот оксид проявляет ярко выраженные основные свойства, легко реагирует с водой с образованием гидроксида калия КОН:

K2O + H2O = 2KOH

Гидроксид калия, или едкое кали, хорошо растворим в воде (до 49, 10% массе при 20°C). Образующийся раствор — очень сильное основание, относящееся к щелочам. КОН реагирует с кислотными и амфотерными оксидами:

SO2 + 2KOH = K2SO3 + H2O,

Al2O3 + 2KOH + 3H2O = 2K[Al(OH)4] (так реакция протекает в растворе) и

Al2O3 + 2KOH = 2KAlO2 + H2O (так реакция протекает при сплавлении реагентов).

В промышленности гидроксид калия KOH получают электролизом водных растворов KCl или K2CO3 c применением ионообменных мембран и диафрагм:

2KCl + 2H2O = 2KOH + Cl2+ H2,

или за счет обменных реакций растворов K2CO3 или K2SO4 с Ca(OH)2 или Ba(OH)2:

K2CO3 + Ba(OH)2 = 2KOH + BaCO3

Попадание твердого гидроксида калия или капель его растворов на кожу и в глаза вызывает тяжелые ожоги кожи и слизистых оболочек, поэтому работать с этими едкими веществами следует только в защитных очках и перчатках. Водные растворы гидроксида калия при хранении разрушают стекло, расплавы — фарфор.

Карбонат калия K2CO3 (обиходное название поташ) получают при нейтрализации раствора гидроксида калия углекислым газом:

2KOH + CO2 = K2CO3 + Н2О.

В значительных количествах поташ содержится в золе некоторых растений.

Металлический калий — материал для электродов в химических источниках тока. Сплав калия с другим щелочным металлом — натрием находит применение в качестве теплоносителя в ядерных реакторах.

В гораздо больших масштабах, чем металлический калий, находят применение его соединения. Калий — важный компонент минерального питания растений, он необходим им в значительных количествах для нормального развития, поэтому широкое применение находят калийные удобрения: хлорид калия КСl, нитрат калия, или калийная селитра, KNO3, поташ K2CO3 и другие соли калия. Поташ используют также при производстве специальных оптических стекол, как поглотитель сероводорода при очистке газов, как обезвоживающий агент и при дублении кож.

В качестве лекарственного средства находит применение иодид калия KI. Иодид калия используют также в фотографии и в качестве микроудобрения. Раствор перманганата калия КMnO4 («марганцовку») используют как антисептическое средство.

По содержанию в горных породах радиоактивного 40К определяют их возраст.

Калий — один из важнейших биогенных элементов, постоянно присутствующий во всех клетках всех организмов. Ионы калия К+ участвуют в работе ионных каналов и регуляции проницаемости биологических мембран, в генерации и проведении нервного импульса, в регуляции деятельности сердца и других мышц, в различных процессах обмена веществ. Содержание калия в тканях животных и человека регулируется стероидными гормонами надпочечников. В среднем организм человека (масса тела 70 кг) содержит около 140 г калия. Поэтому для нормальной жизнедеятельности с пищей в организм должно поступать 2-3 г калия в сутки. Богаты калием такие продукты, как изюм, курага, горох и другие.

Металлический калий может вызвать очень сильные ожоги кожи, при попадании мельчайших частичек калия в глаза возникают тяжелые поражения с потерей зрения, поэтому работать с металлическим калием можно только в защитных перчатках и очках. Загоревшийся калий заливают минеральным маслом или засыпают смесью талька и NaCl. Хранят калий в герметично закрытых железных контейнерах под слоем обезвоженного керосина или минерального масла.

- Коренман И. М. Аналитическая химия калия. М. 1964.

Калий — химический элемент, находящийся под номером 19 в периодической таблице Д.И.Менделеева. Как вещество, он представляет собой мягкий щёлочный металл с серебристо-белым цветом.

История открытия

О калии знали ещё с 11 века в Древней Греции и Риме, когда производили моющее средство под названием «поташа». Принцип его производства базировался на сжигании древесины или соломы. В получившуюся золу добавляли воду — образовывался щёлок. Консистенцию сперва фильтровали, а затем выпаривали. Остаток представлял собой соединения из карбоната калия, сульфата калия, соды и хлорида калия.

Как чистый металл, элемент начали выводить с 1807 года. Экспериментами занимались такие выдающиеся учёные, как английский химик Хэмфри Дэви, французские химики Гей-Люссак и Л. Тенар и немецкий физик Л.В. Гильберт. Обнаружить мягкий металл и отделить его от остальных веществ помог электролиз и прокаливание.

Название элемента переводится с арабского как «поташ» — смесь, получаемая после сжигания дерева. Иными словами — зола.

Где находится

Данный элемент, благодаря своей химической активности, встречается в природе исключительно в соединениях с другими веществами — с водой или минералами. Калий является 5-м металлом по распространённости в земной коре. Его добывают в России, Беларуси и Канаде.

В большом количестве металл находится в клетках человека. Он нормализует водный и кислотно-щёлочный баланс в организме, поддерживает общую концентрацию всех частиц в крови. Элемент необходим для нервной и сердечно-сосудистой системы. При его недостатке может развиться гипокалиемия.

Данная частица содержится в таких продуктах, как чечевица, шоколад, миндаль, арахис, какао, курага. Витамин В6 помогает усваиваться полезному компоненту в организме человека, а вот алкоголь наоборот, тормозит этот процесс.

Изотопы

Природный калий состоит из 3 изотопов. Два из них стабильны: 39K (изотопная распространённость 93,258 %) и 41K (6,730 %). Третий изотоп 40K (0,0117 %) является бета-активным.

Химические и физические свойства

Калий моментально вступает в реакцию практически со всеми веществами. На воздухе срез этого металла быстро тускнеет, образуя оксидно-карбонатную плёнку. Если контакт с воздухом будет продолжительным — он может полностью разрушиться. А в контакте с водой взрывается.

Для безопасного хранения металла следует исключить его взаимодействие с воздухом. Его поверхность необходимо покрыть слоем силиконового масла, бензина или керосина.

Калий образует интерметаллиды (химическое соединение двух или более металлов) со следующими элементами:

- натрий;

- таллий;

- олово;

- свинец;

- висмут.

Цвет мягкого металла — серебристый с характерным блеском. Но если данный элемент или соединения с ним внести в пламя горелки, то образуется фиолетовый цвет.

Как вещество, калий мало весит и легко плавится. Например, если его растворить в ртути, то образуются амальгамы — твёрдые или жидкие сплавы ртути с другими металлами.

Где применяется

В технической промышленности калий в соединении с натрием применяется в замкнутых системах для передачи тепловой энергии. Важную биологическую роль данный химический элемент играет в питании растений. От его недостатка листья культур желтеют. В агропромышленности этот металл, наряду с фосфором и азотом, используется как удобрение.

Соединения с данным элементом применяются в медицине для создания успокаивающих или антисептических средств. В составе пороха, спичек, осветительных зарядов и взрывчатых веществ также присутствует калий.

ка́лий

ка́лий, -я

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова веха (существительное):

Ассоциации к слову «калий»

Синонимы к слову «калий»

Предложения со словом «калий»

- Я возбуждённо шлёпнула по воде, приходя в восторг при мысли о том, что они здесь, что в этот самый миг вода уносит следы цианистого калия и стрихнина.

- Например, в кайсе, кураге и урюке содержание солей калия превышает 1,7 мг/100 г.

- При повышении содержания ионов калия также могут возникнуть нарушения ритма.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «калий»

- Институт наполнился запахом эфира и цианистого калия, которым чуть-чуть не отравился Панкрат, не вовремя снявший маску.

- Больше всего было пометок именно о вторичном люэсе. Реже попадался третичный. И тогда йодистый калий размашисто занимал графу «лечение».

- От сигары и двух глотков вина у него закружилась голова и началось сердцебиение, так что понадобилось принимать бромистый калий.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение слова «калий»

-

КА́ЛИЙ, -я, м. Химический элемент, металл серебристо-белого цвета, добываемый из углекалиевой соли (поташа). (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова КАЛИЙ

Смотрите также

КА́ЛИЙ, -я, м. Химический элемент, металл серебристо-белого цвета, добываемый из углекалиевой соли (поташа).

Все значения слова «калий»

-

Я возбуждённо шлёпнула по воде, приходя в восторг при мысли о том, что они здесь, что в этот самый миг вода уносит следы цианистого калия и стрихнина.

-

Например, в кайсе, кураге и урюке содержание солей калия превышает 1,7 мг/100 г.

-

При повышении содержания ионов калия также могут возникнуть нарушения ритма.

- (все предложения)

- поташ

- потассий

- щёлочь

- витамин

- вещество

- (ещё синонимы…)

- натрий

- кальций

- соль

- марганцовка

- химия

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- цианистый

- хлористый

- углекислый

- едкий

- йодистый

- (ещё…)

- Склонение

существительного «калий» - Разбор по составу слова «калий»

×òî òàêîå «ÊÀËÈÉ»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

ÊÀËÈÉ (îò àðàá. àëü-êàëè — ïîòàø; ëàò. Kalium) Ê, õèì. ýëåìåíò I ãð. ïåðèîäè÷. ñèñòåìû; îòíîñèòñÿ ê ùåëî÷íûì ìåòàëëàì, àò. í. 19, àò. ì. 39,0983. Ñîñòîèò èç äâóõ ñòàáèëüíûõ èçîòîïîâ 39 Ê (93,259%) è 41 Ê (6,729%), à òàêæå ðàäèîàêòèâíîãî èçîòîïà 40 Ê (Ò 1/2 1,32.109 ëåò). Ïîïåðå÷íîå ñå÷åíèå çàõâàòà òåïëîâûõ íåéòðîíîâ äëÿ ïðèð. ñìåñè èçîòîïîâ 1,97.10-28 ì 2. Êîíôèãóðàöèÿ âíåø. ýëåêòðîííîé îáîëî÷êè 4s1; ñòåïåíü îêèñëåíèÿ +1; ýíåðãèÿ èîíèçàöèè Ê 0 : Ê + : Ê 2+ ñîîòâ. 4,34070 ý è 31,8196 ýÂ; ñðîäñòâî ê ýëåêòðîíó 0,47 ýÂ; ýëåêòðîîòðèöàòåëüíîñòü ïî Ïîëèíãó 0,8; àòîìíûé ðàäèóñ 0,2313 íì, èîííûé ðàäèóñ (â ñêîáêàõ óêàçàíî êîîðäèíàö. ÷èñëî) Ê + 0,151 íì (4), 0,152 íì (6), 0,160 íì (7), 0,165 íì (8), 0,178 íì (12). Ñîäåðæàíèå â çåìíîé êîðå 2,41% ïî ìàññå. Îñí. ìèíåðàëû: ñèëüâèí ÊÑl, êàðíàëëèò KCl.MgCl2.6H2O, êàëèåâûé ïîëåâîé øïàò (îðòîêëàç) K[AlSi3O8], ìóñêîâèò êàëèåâàÿ ñëþäà) KAl2[AlSi3O10](OH, F)2, êàèíèò ÊÑl.MgSO4.3H2O, ïîëèãàëèò K2SO4.MgSO4.2CaSO4.2Í 2 Î, àëóíèò KAl3(SO4)2(OH)6. Ñâîéñòâà. Ê. — ìÿãêèé ñåðåáðèñòî-áåëûé ìåòàëë ñ êóáè÷. ðåøåòêîé, à =0,5344 íì, z =2, ïðîñòðàíñòâ. ãðóïïà Im3m. Ò. ïë. 63,51 °Ñ, ò. êèï. 761 °Ñ; ïëîòí. 0,8629 ã/ñì 3; Ñ 0p 29,60 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); DH0 ïë 2,33 êÄæ/ìîëü, DH0 âîçã 89,0 êÄæ/ìîëü; S029864,68 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); óð-íèå òåìïåðàòóðíîé çàâèñèìîñòè äàâëåíèÿ ïàðà (â ìì ðò. ñò.): lgp =7,34 — 4507/T(373-474 Ê); r 6,23.10-8 Îì. ì (0°Ñ), 8,71.10-8 Îì. ì (25°C) è 13,38.10-8 Îì. ì (77°Ñ); g 0,114 Í/ì (334 Ê), h 5,096.10-4 Í. ñ/ì 2 (350 Ê); òåïëîïðîâîäíîñòü 99,3 Âò/(ì. Ê) ïðè 273 Ê è 44,9 Âò/(ì. Ê) ïðè 473 Ê; ïðè 273-323 Ê òåìïåðàòóðíûå êîýô. ëèíåéíîãî è îáúåìíîãî ðàñøèðåíèÿ ñîñòàâëÿþò ñîîòâ. 8,33.10-5 Ê -1 è 2,498.10-4 Ê -1. Ê. ìîæåò îáðàáàòûâàòüñÿ ïðåññîâàíèåì è ïðîêàòêîé. Ê. õèìè÷åñêè î÷åíü àêòèâåí. Ëåãêî âçàèìîä. ñ Î 2 âîçäóõà, îáðàçóÿ êàëèÿ îêñèä Ê 2 Î, ïåðîêñèä Ê 2 Î 2 è íàäïåðîêñèä ÊÎ 2; ïðè íàãð. íà âîçäóõå çàãîðàåòñÿ. Ñ âîäîé è ðàçá. ê-òàìè âçàèìîä. ñî âçðûâîì è âîñïëàìåíåíèåì, ïðè÷åì H2SO4 âîññòàíàâëèâàåòñÿ äî S2-, S0 è SO2, à ÍNÎ 3 — äî NO, N2O è N2. Ïðè íàãð. äî 200-350 °Ñ ðåàãèðóåò ñ Í 2 ñ îáðàçîâàíèåì ãèäðèäà ÊÍ. Âîñïëàìåíÿåòñÿ â àòìîñôåðå F2, ñëàáî âçàèìîä. ñ æèäêèì Ñl2, íî âçðûâàåòñÿ ïðè ñîïðèêîñíîâåíèè ñ Âr2 è ðàñòèðàíèè ñ I2; ïðè êîíòàêòå ñ ìåæãàëîãåííûìè ñîåä. âîñïëàìåíÿåòñÿ èëè âçðûâàåòñÿ. Ñ S, Se è Òå ïðè ñëàáîì íàãðåâàíèè îáðàçóåò ñîîòâ. K2S, K2Se è Ê 2 Òå, ïðè íàãð. ñ Ð â àòìîñôåðå àçîòà — Ê 3 Ð è Ê 2 Ð 5, ñ ãðàôèòîì ïðè 250-500 °Ñ — ñëîèñòûå ñîåä. ñîñòàâà Ñ 8 Ê-Ñ 60 Ê. Ñ ÑÎ 2 íå ðåàãèðóåò çàìåòíî ïðè 10-30°Ñ; ñòåêëî è ïëàòèíó ðàçðóøàåò âûøå 350-400 °Ñ. Ê. ðàñòâ. â æèäêîì NH3 (35,9 ã â 100 ìë ïðè — 70 °Ñ), àíèëèíå, ýòèëåíäèàìèíå, ÒÃÔ è äèãëèìå ñ îáðàçîâàíèåì ð-ðîâ ñ ìåòàëëè÷. ïðîâîäèìîñòüþ. Ð-ð â NH3 èìååò òåìíî-ñèíèé öâåò, â ïðèñóò. Pt è ñëåäîâ âîäû ðàçëàãàåòñÿ, äàâàÿ KNH2 è Í 2. Ñ àçîòîì Ê. íå âçàèìîä. äàæå ïîä äàâëåíèåì ïðè âûñîêèõ ò-ðàõ. Ïðè âçàèìîä. ñ NH4N3 â æèäêîì NH3 îáðàçóåòñÿ àçèä KN3. Ê. íå ðàñòâ. â æèäêèõ Li, Mg, Cd, Zn, Al è Ga è íå ðåàãèðóåò ñ íèìè. Ñ íàòðèåì îáðàçóåò èíòåðìåòàëëèä KNa2 (ïëàâèòñÿ èíêîíãðóýíòíî ïðè 7°Ñ), ñ ðóáèäèåì è öåçèåì -òâåðäûå ð-ðû, äëÿ ê-ðûõ ìèíèì. ò-ðû ïëàâëåíèÿ ñîñòàâëÿþò ñîîòâ. 32,8 °Ñ (81,4% ïî ìàññå Rb) è — 37,5 °Ñ (77,3% Cs). Ñ ðòóòüþ äàåò àìàëüãàìó, ñîäåðæàùóþ äâà ìåðêóðèäà -KHg2 è KHg (ò. ïë. ñîîòâ. 270 °Ñ è 180°Ñ). Ñ òàëëèåì îáðàçóåò ÊÒl (ò. ïë. 335 °Ñ), ñ îëîâîì — K2Sn, KSn, KSn2 è KSn4, ñî ñâèíöîì — ÊÐb (ò. ïë. 568 °Ñ) è ôàçû ñîñòàâà Ê 2 Ðb3, ÊÐb2 è ÊÐb4, ñ ñóðüìîé — Ê 3Sb è KSb (ò. ïë. ñîîòâ. 812 è 605 °Ñ), ñ âèñìóòîì — K3Bi, K3Bi2 è KBi2 (ò. ïë. ñîîòâ. 671, 420 è 553 °C). Ê. ýíåðãè÷íî âçàèìîä. ñ îêñèäàìè àçîòà, à ïðè âûñîêèõ ò-ðàõ — ñ ÑÎ è ÑÎ 2. Âîññòàíàâëèâàåò  2 Î 3 è SiO2 ñîîòâ. äî  è Si, îêñèäû Al, Hg, Ag, Ni è äð. — äî ñâîá. ìåòàëëîâ, ñóëüôàòû, ñóëüôèòû, íèòðàòû, íèòðèòû, êàðáîíàòû è ôîñôàòû ìåòàëëîâ — äî îêñèäîâ èëè ñâîá. ìåòàëëîâ. Ñî ñïèðòàìè Ê. îáðàçóåò àëêîãîëÿòû, ñ ãàëîãåíàëêèëàìè è ãàëîãåíàðèëàìè — ñîîòâ. êàëèéàëêèëû è êàëèéàðèëû. Âàæíåéøèì ñîåä. Ê. ïîñâÿùåíû îòä. ñòàòüè (ñì., íàïð., Êàëèÿ ãèäðîêñèä, Êàëèÿ èîäèä, Êàëèÿ êàðáîíàò, Êàëèÿ õëîðèä). Íèæå ïðèâîäÿòñÿ ñâåäåíèÿ î äð. âàæíûõ ñîåäèíåíèÿõ. Ïåðîêñèä Ê 2 Î 2 — áåñöâ. êðèñòàëëû ñ ðîìáè÷. ðåøåòêîé ( à =0,6736 íì, b= 0,7001 íì, ñ =0,6479 íì, z = 4, ïðîñòðàíñòâ. ãðóïïà Ðïïï); ò. ïë. 545 °Ñ; ïëîòí. 2,40 ã/ñì 3; C0p 90,8 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); DH0 ïë 20,5 êÄæ/ìîëü, DH0 îáð -443,0 êÄæ/ìîëü; S0298 117 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê). Íà âîçäóõå Ê 2 Î 2 ìãíîâåííî îêèñëÿåòñÿ äî ÊÎ 2; ýíåðãè÷íî âçàèìîä. ñ âîäîé ñ îáðàçîâàíèåì ÊÎÍ è Î 2, ñ ÑÎ 2 äàåò Ê 2 ÑÎ 3 è Î 2. Ïîëó÷àþò ïåðîêñèä ïðîïóñêàíèåì äîçèðîâàííîãî êîë-âà Î 2 ÷åðåç ð-ð Ê. â æèäêîì NH3, ðàçëîæåíèåì ÊÎ 2 â âàêóóìå ïðè 340-350 °Ñ. Íàäïåðîêñèä ÊÎ 2 — æåëòûå êðèñòàëëû ñ òåòðàãîí. ðåøåòêîé ( à ×0,5704 íì, ñ ×0,6699 íì, z = 4, ïðîñòðàíñòâ. ãðóïïà I4/mmm; ïëîòí. 2,158 ã/ñì 3); âûøå 149°Ñ ïåðåõîäèò â êóáè÷. ìîäèôèêàöèþ (à= 0,609 íì); ò. ïë. 535 °Ñ; Ñ 0p 77,5 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); DH0 îáð — 283,2 êÄæ/ìîëü, DH0 ïë 20,6 êÄæ/ìîëü; S0298 125,4 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); ïàðàìàãíåòèê. Ñèëüíûé îêèñëèòåëü. Âçàèìîä. ñ âîäîé ñ îáðàçîâàíèåì ÊÎÍ è Î 2. Äèññîöèèðóåò, íàïð., â áåíçîëå, äàâàÿ àíèîí-ðàäèêàë Î 2-. Ñåðà ïðè íàãð. ñ ÊÎ 2 âîñïëàìåíÿåòñÿ è äàåò K2SO4. Ñ âëàæíûìè ÑÎ 2 è ÑÎ íàäïåðîêñèä îáðàçóåò Ê 2 ÑÎ 3 è Î 2, ñ NO2 — KNO3 è Î 2, ñ SO2 — K2SO4 è Î 2. Ïðè äåéñòâèè êîíö. H2SO4 âûäåëÿåòñÿ Î 3, ïðè ð-öèè ñ NH3 îáðàçóþòñÿ N2, H2O è ÊÎÍ. Ñìåñü ÊÎ 2 ñ ãðàôèòîì âçðûâàåò. Ïîëó÷àþò íàäïåðîêñèä ñæèãàíèåì Ê. â âîçäóõå, îáîãàùåííîì âëàæíûì Î 2 è íàãðåòîì äî 75-80 °Ñ. Îçîíèä ÊÎ 3 — êðàñíûå êðèñòàëëû ñ òåòðàãîí. ðåøåòêîé ( à =0,8597 íì, ñ= 0,7080 íì, ïðîñòðàíñòâ. ãðóïïà I4/mcm); ïëîòí. 1,99 ã/ñì 3; óñòîé÷èâ òîëüêî ïðè õðàíåíèè â ãåðìåòè÷åñêè çàêðûòûõ ñîñóäàõ íèæå 0°Ñ, ïðè áîëåå âûñîêîé ò-ðå ðàñïàäàåòñÿ íà ÊÎ 2 è Î 2; Ñ 0p >75 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); S0298 105 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); ïàðàìàãíåòèê. Ð-ðèìîñòü â æèäêîì NH3 (ã â 100 ã); 14,82 (-35°Ñ), 12,00 (-63,5°Ñ), ýâòåêòèêà NH3 — KO3 (5 ã â 100 ã NH3) èìååò ò. ïë. — 80 °Ñ; ïðè äëèò. õðàíåíèè àììèà÷íûå ð-ðû ðàçëàãàþòñÿ íà NH4O3 è KNH2. Ðàñòâ. â ôðåîíàõ. ÊÎ 3 — ñèëüíûé îêèñëèòåëü; ìãíîâåííî ðåàãèðóåò ñ âîäîé óæå ïðè 0 °Ñ, äàâàÿ ÊÎÍ è Î 2; ñ âëàæíûì ÑÎ 2 îáðàçóåò Ê 2 ÑÎ 3 è ÊÍÑÎ 3. Ïîëó÷àþò: âçàèìîä. ñìåñè Î 3 è Î 2 ñ ÊÎÍ èëè ÊÎ 2 ïðè ò-ðå íèæå 0°Ñ ñ ïîñëåä. ýêñòðàêöèåé æèäêèì NH3; îçîíèðîâàíèåì ñóñïåíçèè ÊÎ 2 èëè ÊÎÍ âî ôðåîíå 12. Íàäïåðîêñèä, ïåðîêñèä è îçîíèä Ê. — êîìïîíåíòû ñîñòàâîâ äëÿ ðåãåíåðàöèè âîçäóõà â çàìêíóòûõ ñèñòåìàõ (øàõòû, ïîäâîäíûå ëîäêè, êîñìè÷. êîðàáëè). Ãèäðèä ÊÍ — áåñöâ. êðèñòàëëû ñ êóáè÷. ðåøåòêîé ( à =0,570 íì, z = 4, ïðîñòðàíñòâ. ãðóïïà Fm3m); ò. ïë. 619 °Ñ ïðè äàâëåíèè âîäîðîäà 6,86 ÌÏà; ïëîòí. 1,52 ã/ñì 3; Ñ 0p38,1 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); DH0 îáð -57,8 êÄæ/ìîëü, DH0 ïë 21,3 êÄæ/ìîëü; S0298 50,2 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê). Ðàçëàãàåòñÿ ïðè íàãð. íà Ê. è Í 2. Ñèëüíûé âîññòàíîâèòåëü. Âîñïëàìåíÿåòñÿ âî âëàæíîì âîçäóõå, â ñðåäå F2 è Ñl2. Ýíåðãè÷íî âçàèìîä. ñ âîäîé, äàâàÿ ÊÎÍ è Í 2. Ïðè íàãð. ñ N2 èëè NH3 îáðàçóåò KNH2, ñ H2S — K2S è Í 2, ñ ðàñïëàâë. ñåðîé — K2S è H2S, ñ âëàæíûì ÑO2 — ÍÑÎÎÊ, ñ ÑÎ — ÍÑÎÎÊ è Ñ. Ïîëó÷àþò ÊÍ âçàèìîä. Ê. ñ èçáûòêîì Í 2 ïðè 300-400 °Ñ. Ãèäðèä âîññòàíîâèòåëü â íåîðã. è îðã. ñèíòåçàõ. Àçèä ÊN3 — áåñöâ. êðèñòàëëû ñ òåòðàãîí. ðåøåòêîé (à= 0,6094 íì, ñ= 0,7056 íì, z = 4, ïðîñòðàíñòâ. ãðóïïà I4/mcm); Ñ 0 ð >76,9 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); DH0 îáð -1,7 êÄæ/ìîëü; S0298 104,0 Äæ/(ìîëü. Ê); ò. ïë. 354 °Ñ, âûøå ðàçëàãàåòñÿ íà Ê. è àçîò; ïëîòí. 2,056 ã/ñì 3. Ð-ðèìîñòü (ã â 100 ã ð-ðèòåëÿ): âîäà -41,4 (0°Ñ), 105,7 (100°Ñ), ýòàíîë — 0,137 (16°Ñ).  ýôèðå è áåíçîëå ðàñòâ. ïëîõî. Âîäîé ãèäðîëèçóåòñÿ; ýâòåêòèêà Í 2 Î -KN3 (35,5 ã â 100 ã) èìååò ò. ïë. — 12°Ñ. Ïîëó÷àþò: âçàèìîä. N2O ñ ðàñïëàâë. KNH2 ïðè 280 °Ñ; äåéñòâèåì ÊÎÍ íà ð-ð HN3. Ïîëó÷åíèå. Ê. ïðîèçâîäÿò âçàèìîä. Na ñ ÊÎÍ ïðè 380-450 °Ñ èëè ÊÑl ïðè 760-890 °Ñ. Ð-öèè ïðîâîäÿò â àòìîñôåðå N2. Âçàèìîä. ÊÎÍ ñ æèäêèì Na îñóùåñòâëÿþò ïðîòèâîòîêîì â òàðåëü÷àòîé êîëîííå èç Ni. Ïðè ð-öèè ñ ÊÑl ïàðû Na ïðîïóñêàþò ÷åðåç ðàñïëàâ ÊÑl. Ïðîäóêò ð-öèé -ñïëàâ Ê — Na. Åãî ïîäâåðãàþò ðåêòèôèêàöèè è ïîëó÷àþò Ê. ñ ñîäåðæàíèåì ïðèìåñåé (â % ïî ìàññå): 1.10-3 Na è 1.10-4 Ñ1. Êðîìå òîãî, Ê. ïîëó÷àþò: âàêóóì-òåðìè÷. âîññòàíîâëåíèåì ÊÑl êàðáèäîì ÑàÑ 2, ñïëàâàìè Si-Fe èëè Si-Al ïðè 850-950 °Ñ è îñòàòî÷íîì äàâëåíèè 1,33 13,3 Ïà; íàãðåâàíèåì Ê 2 Ñr2 Î 7 ñ Zr ïðè 400 °Ñ; ýëåêòðîëèçîì ÊÎÍ ñ æåëåçíûì êàòîäîì; ýëåêòðîëèçîì ÊÑl (èëè åãî ñìåñè Ê 2 ÑÎ 3) ñ æèäêèì ñâèíöîâûì êàòîäîì ïðè 680-720 °Ñ ñ ïîñëåä. ðàçäåëåíèåì Ê è Ðb âàêóóìíîé äèñòèëëÿöèåé; ýëåêòðîëèçîì 50%-íîãî ð-ðà KNH2 â æèäêîì NH3 ïðè 25 °Ñ è äàâëåíèè 0,75 ÌÏà ñ àìàëüãàìîé Ê. â êà÷åñòâå àíîäà è êàòîäîì èç íåðæàâåþùåé ñòàëè, ïðè ýòîì îáðàçóåòñÿ 30%-íûé ð-ð Ê. â æèäêîì NH3, ê-ðûé âûâîäèòñÿ èç àïïàðàòà äëÿ îòäåëåíèÿ Ê. Îïðåäåëåíèå. Êà÷åñòâåííî Ê. îáíàðóæèâàþò ïî ðîçîâî-ôèîëåòîâîìó îêðàøèâàíèþ ïëàìåíè è ïî õàðàêòåðíûì ëèèíèÿì ñïåêòðà: 404,41, 404,72, 766,49, 769,90 íì. Íàèá. ðàñïðîñòðàíåííûå êîëè÷åñòâ. ìåòîäû, îñîáåííî â ïðèñóò. äð. ùåëî÷íûõ ìåòàëëîâ, — ýìèññèîííàÿ ïëàìåííàÿ ôîòîìåòðèÿ (÷óâñòâèòåëüíîñòü 1.10-4 ìêã/ìë) è àòîìíî-àáñîðáö. ñïåêòðîìåòðèÿ (÷óâñòâèòåëüíîñòü 0,01 ìêã/ìë).  ìåíüøåé ñòåïåíè èñïîëüçóþòñÿ õèìèêî-ñïåêòðàëüíûé è ñïåêòðîôîòîìåòðè÷. ìåòîäû ñ ïðèìåíåíèåì äèïèêðèëàìèíà (÷óâñòâèòåëüíîñòü 0,2-1,0 ìêã/ìë). Ïðè áîëüøîì ñîäåðæàíèè Ê. â ïðîáå ïðèìåíÿþò ãðàâèìåòðè÷. ìåòîä ñ îñàæäåíèåì Ê. â âèäå òåòðàôåíèëáîðàòà, K2[PtCl6] èëè ÊÑlO4 â ñðåäå áóòàíîëà. Ïðèìåíåíèå. Ê. — ìàòåðèàë ýëåêòðîäîâ â õèì. èñòî÷íèêàõ òîêà; êîìïîíåíò êàòîäîâ-ýìèòòåðîâ ôîòîýëåìåíòîâ è òåðìîýìèññèîííûõ ïðåîáðàçîâàòåëåé, à òàêæå ôîòîýëåêòðîííûõ óìíîæèòåëåé; ãåòòåð â âàêóóìíûõ ðàäèîëàìïàõ; àêòèâàòîð êàòîäîâ ãàçîðàçðÿäíûõ óñòðîéñòâ. Ñïëàâ Ê. ñ Na -òåïëîíîñèòåëü â ÿäåðíûõ ðåàêòîðàõ. Ðàäèîàêòèâíûé èçîòîï 40 Ê ñëóæèò äëÿ îïðåäåëåíèÿ âîçðàñòà ãîðíûõ ïîðîä (êàëèéàðãîíîâûé ìåòîä). Èñêóññòâ. èçîòîï 42 Ê (T1/2 12,52 ãîäà) -ðàäèîàêòèâíûé èíäèêàòîð â ìåäèöèíå è áèîëîãèè. Ê. — âàæíåéøèé ýëåìåíò (â âèäå ñîåä.) äëÿ ïèòàíèÿ ðàñòåíèé (ñì. Êàëèéíûå óäîáðåíèÿ). Ê. âûçûâàåò ñèëüíûå îæîãè êîæè, ïðè ïîïàäàíèè ìåëü÷àéøèõ åãî êðîøåê â ãëàçà òÿæåëî èõ ïîðàæàåò, âîçìîæíà ïîòåðÿ çðåíèÿ. Çàãîðåâøèéñÿ Ê. çàëèâàþò ìèíåð. ìàñëîì èëè çàñûïàþò ñìåñüþ òàëüêà è NaCl. Õðàíÿò Ê. â ãåðìåòè÷åñêè çàêðûòûõ æåëåçíûõ êîðîáêàõ ïîä ñëîåì îáåçâîæåííîãî êåðîñèíà èëè ìèíåð. ìàñëà. Îòõîäû Ê. óòèëèçèðóþò îáðàáîòêîé èõ ñóõèì ýòàíîëîì èëè ïðîïàíîëîì ñ ïîñëåä. ðàçëîæåíèåì îáðàçîâàâøèõñÿ àëêîãîëÿòîâ âîäîé. Ê. îòêðûë Ã. Äýâè â 1807. Ëèò.: Íàòðèé è êàëèé, Ë., 1959; Êîðåíìàí È. Ì., Àíàëèòè÷åñêàÿ õèìèÿ êàëèÿ, Ì., 1964; Òåïëîôèçè÷åñêèe ñâîéñòâà ùåëî÷íûõ ìåòàëëîâ, Ì., 1970, (Òð. ÌÝÈ, â. 75); Âîëüíîâ È. È., Ïåðåêèñíûå ñîåäèíåíèÿ ùåëî÷íûõ ìåòàëëîâ, Ì., 1980. Á. Ä. Ñòåïèí.

ÊÀËÈÉ — ÊÀËÈÉ ì. ïîòàñèé, ìåòàëë, ñîñòàâëÿþùèé îñíîâàíüå êàëè, âåñüìà ñõîäíûé ñ íàòðèåì (ñîäèåì). Êàëè ñð. í… Òîëêîâûé ñëîâàðü Äàëÿ

ÊÀËÈÉ — ÊÀËÈÉ, Öÿ, ì. Õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò, ìÿãêèé ìåòàëë ñåðåáðèñòî-áåëîãî öâåòà…. Òîëêîâûé ñëîâàðü Îæåãîâà

ÊÀËÈÉ —

(Kalium)

Ê, õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò 1 ãðóïïû ïåðèîäè÷åñêîé ñèñòåìû Ìåíäåëååâà; àòîìíûé íîìåð 19,… Áîëüøàÿ Ñîâåòñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÊÀËÈÉ — ÊÀËÈÉ, êàëèÿ, ìí. íåò, ì., è êàëè, íåñêë., ñð. (àðàá. — ïîòàø) (õèì.). Õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò — ùåëî÷íûé… Òîëêîâûé ñëîâàðü Óøàêîâà

ÊÀËÈÉ — ì. 1. Õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò, ñåðåáðèñòî-áåëûé, ìÿãêèé, ëåãêîïëàâêèé ìåòàëë, ïðèìåíÿþùèéñÿ (â ñîåäèíåíè… Òîëêîâûé ñëîâàðü Åôðåìîâîé

ÊÀËÈÉ — ÊÀËÈÉ (Kalium), K, õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò I ãðóïïû ïåðèîäè÷åñêîé ñèñòåìû, àòîìíûé íîìåð 19, àòîìíàÿ ìàññ… Ñîâðåìåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÊÀËÈÉ — ÊÀËÈÉ (ëàò. Kalium) — Ê, õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò I ãðóïïû ïåðèîäè÷åñêîé ñèñòåìû, àòîìíûé íîìåð 19, àòîìíà… Áîëüøîé ýíöèêëîïåäè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

ÊÀËÈÉ —

I

(Kalium, Ê)

õèìè÷åñêèé ýëåìåíò ãëàâíîé ïîäãðóïïû I ãðóïïû ïåðèîäè÷åñêîé ñèñòåìû ýëåìåíòîâ Ä.È. Ìå… Ìåäèöèíñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÊÀËÈÉ —

K (îò àðàá, àëü-êàëè — ïîòàø * a. Potassium, potash; í. Kalium; ô. potassium; è. potasio), … Ãåîëîãè÷åñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

Potassium pearls (in paraffin oil, ~5 mm each) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potassium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (pə-TASS-ee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white, faint bluish-purple hue when exposed to air | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potassium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1: hydrogen and alkali metals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 8, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 336.7 K (63.5 °C, 146.3 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1030.793 K (757.643 °C, 1395.757 °F)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 0.89 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 0.82948 g/cm3[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 2223 K, 16 MPa[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.33 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 76.9 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 29.6 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, +1 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.82 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 227 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 203±12 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 275 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of potassium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 2000 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 83.3 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 102.5 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 72 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +20.8×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 3.53 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 1.3 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 3.1 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 0.363 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-09-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Humphry Davy (1807) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «K»: from New Latin kalium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of potassium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin kalium) and atomic number 19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife.[6] Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to form flaky white potassium peroxide in only seconds of exposure. It was first isolated from potash, the ashes of plants, from which its name derives. In the periodic table, potassium is one of the alkali metals, all of which have a single valence electron in the outer electron shell, which is easily removed to create an ion with a positive charge (which combines with anions to form salts). In nature, potassium occurs only in ionic salts. Elemental potassium reacts vigorously with water, generating sufficient heat to ignite hydrogen emitted in the reaction, and burning with a lilac-colored flame. It is found dissolved in seawater (which is 0.04% potassium by weight),[7][8] and occurs in many minerals such as orthoclase, a common constituent of granites and other igneous rocks.[9]

Potassium is chemically very similar to sodium, the previous element in group 1 of the periodic table. They have a similar first ionization energy, which allows for each atom to give up its sole outer electron. It was suspected in 1702 that they were distinct elements that combine with the same anions to make similar salts,[10] and this was proven in 1807 through using electrolysis. Naturally occurring potassium is composed of three isotopes, of which 40

K is radioactive. Traces of 40

K are found in all potassium, and it is the most common radioisotope in the human body.

Potassium ions are vital for the functioning of all living cells. The transfer of potassium ions across nerve cell membranes is necessary for normal nerve transmission; potassium deficiency and excess can each result in numerous signs and symptoms, including an abnormal heart rhythm and various electrocardiographic abnormalities. Fresh fruits and vegetables are good dietary sources of potassium. The body responds to the influx of dietary potassium, which raises serum potassium levels, by shifting potassium from outside to inside cells and increasing potassium excretion by the kidneys.

Most industrial applications of potassium exploit the high solubility of its compounds in water, such as saltwater soap. Heavy crop production rapidly depletes the soil of potassium, and this can be remedied with agricultural fertilizers containing potassium, accounting for 95% of global potassium chemical production.[11]

Etymology

The English name for the element potassium comes from the word potash,[12] which refers to an early method of extracting various potassium salts: placing in a pot the ash of burnt wood or tree leaves, adding water, heating, and evaporating the solution. When Humphry Davy first isolated the pure element using electrolysis in 1807, he named it potassium, which he derived from the word potash.

The symbol K stems from kali, itself from the root word alkali, which in turn comes from Arabic: القَلْيَه al-qalyah ‘plant ashes’. In 1797, the German chemist Martin Klaproth discovered «potash» in the minerals leucite and lepidolite, and realized that «potash» was not a product of plant growth but actually contained a new element, which he proposed calling kali.[13] In 1807, Humphry Davy produced the element via electrolysis: in 1809, Ludwig Wilhelm Gilbert proposed the name Kalium for Davy’s «potassium».[14] In 1814, the Swedish chemist Berzelius advocated the name kalium for potassium, with the chemical symbol K.[15]

The English and French-speaking countries adopted Davy and Gay-Lussac/Thénard’s name Potassium, whereas the Germanic countries adopted Gilbert/Klaproth’s name Kalium.[16] The «Gold Book» of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry has designated the official chemical symbol as K.[17]

Properties

Physical

Potassium is the second least dense metal after lithium. It is a soft solid with a low melting point, and can be easily cut with a knife. Freshly cut potassium is silvery in appearance, but it begins to tarnish toward gray immediately on exposure to air.[18] In a flame test, potassium and its compounds emit a lilac color with a peak emission wavelength of 766.5 nanometers.[19]

Neutral potassium atoms have 19 electrons, one more than the configuration of the noble gas argon. Because of its low first ionization energy of 418.8 kJ/mol, the potassium atom is much more likely to lose the last electron and acquire a positive charge, although negatively charged alkalide K− ions are not impossible.[20] In contrast, the second ionization energy is very high (3052 kJ/mol).

Chemical

Potassium reacts with oxygen, water, and carbon dioxide components in air. With oxygen it forms potassium peroxide. With water potassium forms potassium hydroxide (KOH). The reaction of potassium with water can be violently exothermic, especially since the coproduced hydrogen gas can ignite. Because of this, potassium and the liquid sodium-potassium (NaK) alloy are potent desiccants, although they are no longer used as such.[21]

Compounds

Structure of solid potassium superoxide (

KO2).

Four oxides of potassium are well studied: potassium oxide (K2O), potassium peroxide (K2O2), potassium superoxide (KO2)[22] and potassium ozonide (KO3). The binary potassium-oxygen compounds react with water forming KOH.

KOH is a strong base. Illustrating its hydrophilic character, as much as 1.21 kg of KOH can dissolve in a single liter of water.[23][24] Anhydrous KOH is rarely encountered. KOH reacts readily with carbon dioxide (CO2) to produce potassium carbonate (K2CO3), and in principle could be used to remove traces of the gas from air. Like the closely related sodium hydroxide, KOH reacts with fats to produce soaps.

In general, potassium compounds are ionic and, owing to the high hydration energy of the K+ ion, have excellent water solubility. The main species in water solution are the aquo complexes [K(H2O)n]+ where n = 6 and 7.[25]

Potassium heptafluorotantalate (K2[TaF7]) is an intermediate in the purification of tantalum from the otherwise persistent contaminant of niobium.[26]

Organopotassium compounds illustrate nonionic compounds of potassium. They feature highly polar covalent K–C bonds. Examples include benzyl potassium KCH2C6H5. Potassium intercalates into graphite to give a variety of graphite intercalation compounds, including KC8.

Isotopes

There are 25 known isotopes of potassium, three of which occur naturally: 39

K (93.3%), 40

K (0.0117%), and 41

K (6.7%) (by mole fraction). Naturally occurring 40

K has a half-life of 1.250×109 years. It decays to stable 40

Ar by electron capture or positron emission (11.2%) or to stable 40

Ca by beta decay (88.8%).[27] The decay of 40

K to 40

Ar is the basis of a common method for dating rocks. The conventional K-Ar dating method depends on the assumption that the rocks contained no argon at the time of formation and that all the subsequent radiogenic argon (40

Ar) was quantitatively retained. Minerals are dated by measurement of the concentration of potassium and the amount of radiogenic 40

Ar that has accumulated. The minerals best suited for dating include biotite, muscovite, metamorphic hornblende, and volcanic feldspar; whole rock samples from volcanic flows and shallow instrusives can also be dated if they are unaltered.[27][28] Apart from dating, potassium isotopes have been used as tracers in studies of weathering and for nutrient cycling studies because potassium is a macronutrient required for life[29] on Earth.

40

K occurs in natural potassium (and thus in some commercial salt substitutes) in sufficient quantity that large bags of those substitutes can be used as a radioactive source for classroom demonstrations. 40

K is the radioisotope with the largest abundance in the human body. In healthy animals and people, 40

K represents the largest source of radioactivity, greater even than 14

C. In a human body of 70 kg, about 4,400 nuclei of 40

K decay per second.[30] The activity of natural potassium is 31 Bq/g.[31]

Cosmic formation and distribution

Potassium is formed in supernovae by nucleosynthesis from lighter atoms. Potassium is principally created in Type II supernovae via an explosive oxygen-burning process.[32] (These are fusion reactions; do not confuse with chemical burning between potassium and oxygen.) 40

K is also formed in s-process nucleosynthesis and the neon burning process.[33]

Potassium is the 20th most abundant element in the solar system and the 17th most abundant element by weight in the Earth. It makes up about 2.6% of the weight of the Earth’s crust and is the seventh most abundant element in the crust.[34] The potassium concentration in seawater is 0.39 g/L[7] (0.039 wt/v%), about one twenty-seventh the concentration of sodium.[35][36]

Potash

Potash is primarily a mixture of potassium salts because plants have little or no sodium content, and the rest of a plant’s major mineral content consists of calcium salts of relatively low solubility in water. While potash has been used since ancient times, its composition was not understood. Georg Ernst Stahl obtained experimental evidence that led him to suggest the fundamental difference of sodium and potassium salts in 1702,[10] and Henri Louis Duhamel du Monceau was able to prove this difference in 1736.[37] The exact chemical composition of potassium and sodium compounds, and the status as chemical element of potassium and sodium, was not known then, and thus Antoine Lavoisier did not include the alkali in his list of chemical elements in 1789.[38][39] For a long time the only significant applications for potash were the production of glass, bleach, soap and gunpowder as potassium nitrate.[40] Potassium soaps from animal fats and vegetable oils were especially prized because they tend to be more water-soluble and of softer texture, and are therefore known as soft soaps.[11] The discovery by Justus Liebig in 1840 that potassium is a necessary element for plants and that most types of soil lack potassium[41] caused a steep rise in demand for potassium salts. Wood-ash from fir trees was initially used as a potassium salt source for fertilizer, but, with the discovery in 1868 of mineral deposits containing potassium chloride near Staßfurt, Germany, the production of potassium-containing fertilizers began at an industrial scale.[42][43][44] Other potash deposits were discovered, and by the 1960s Canada became the dominant producer.[45][46]

Metal

Pieces of potassium metal

Potassium metal was first isolated in 1807 by Humphry Davy, who derived it by electrolysis of molten KOH with the newly discovered voltaic pile. Potassium was the first metal that was isolated by electrolysis.[47] Later in the same year, Davy reported extraction of the metal sodium from a mineral derivative (caustic soda, NaOH, or lye) rather than a plant salt, by a similar technique, demonstrating that the elements, and thus the salts, are different.[38][39][48][49] Although the production of potassium and sodium metal should have shown that both are elements, it took some time before this view was universally accepted.[39]

Because of the sensitivity of potassium to water and air, air-free techniques are normally employed for handling the element. It is unreactive toward nitrogen and saturated hydrocarbons such as mineral oil or kerosene.[50] It readily dissolves in liquid ammonia, up to 480 g per 1000 g of ammonia at 0 °C. Depending on the concentration, the ammonia solutions are blue to yellow, and their electrical conductivity is similar to that of liquid metals. Potassium slowly reacts with ammonia to form KNH

2, but this reaction is accelerated by minute amounts of transition metal salts.[51] Because it can reduce the salts to the metal, potassium is often used as the reductant in the preparation of finely divided metals from their salts by the Rieke method.[52] Illustrative is the preparation of magnesium:

- MgCl2 + 2 K → Mg + 2 KCl

Geology

Elemental potassium does not occur in nature because of its high reactivity. It reacts violently with water (see section Precautions below)[50] and also reacts with oxygen. Orthoclase (potassium feldspar) is a common rock-forming mineral. Granite for example contains 5% potassium, which is well above the average in the Earth’s crust. Sylvite (KCl), carnallite (KCl·MgCl2·6H2O), kainite (MgSO4·KCl·3H2O) and langbeinite (MgSO4·K2SO4) are the minerals found in large evaporite deposits worldwide. The deposits often show layers starting with the least soluble at the bottom and the most soluble on top.[36] Deposits of niter (potassium nitrate) are formed by decomposition of organic material in contact with atmosphere, mostly in caves; because of the good water solubility of niter the formation of larger deposits requires special environmental conditions.[53]

Biological role

Potassium is the eighth or ninth most common element by mass (0.2%) in the human body, so that a 60 kg adult contains a total of about 120 g of potassium.[54] The body has about as much potassium as sulfur and chlorine, and only calcium and phosphorus are more abundant (with the exception of the ubiquitous CHON elements).[55] Potassium ions are present in a wide variety of proteins and enzymes.[56]

Biochemical function

Potassium levels influence multiple physiological processes, including[57][58][59]

- resting cellular-membrane potential and the propagation of action potentials in neuronal, muscular, and cardiac tissue. Due to the electrostatic and chemical properties, K+ ions are larger than Na+ ions, and ion channels and pumps in cell membranes can differentiate between the two ions, actively pumping or passively passing one of the two ions while blocking the other.[60]

- hormone secretion and action

- vascular tone

- systemic blood pressure control

- gastrointestinal motility

- acid–base homeostasis

- glucose and insulin metabolism

- mineralocorticoid action

- renal concentrating ability

- fluid and electrolyte balance

Homeostasis

Potassium homeostasis denotes the maintenance of the total body potassium content, plasma potassium level, and the ratio of the intracellular to extracellular potassium concentrations within narrow limits, in the face of pulsatile intake (meals), obligatory renal excretion, and shifts between intracellular and extracellular compartments.

Plasma levels

Plasma potassium is normally kept at 3.5 to 5.5 millimoles (mmol) [or milliequivalents (mEq)] per liter by multiple mechanisms.[61] Levels outside this range are associated with an increasing rate of death from multiple causes,[62] and some cardiac, kidney,[63] and lung diseases progress more rapidly if serum potassium levels are not maintained within the normal range.

An average meal of 40–50 mmol presents the body with more potassium than is present in all plasma (20–25 mmol). This surge causes the plasma potassium to rise up to 10% before clearance by renal and extrarenal mechanisms.[64]

Hypokalemia, a deficiency of potassium in the plasma, can be fatal if severe. Common causes are increased gastrointestinal loss (vomiting, diarrhea), and increased renal loss (diuresis).[65] Deficiency symptoms include muscle weakness, paralytic ileus, ECG abnormalities, decreased reflex response; and in severe cases, respiratory paralysis, alkalosis, and cardiac arrhythmia.[66]

Control mechanisms

Potassium content in the plasma is tightly controlled by four basic mechanisms, which have various names and classifications. The four are 1) a reactive negative-feedback system, 2) a reactive feed-forward system, 3) a predictive or circadian system, and 4) an internal or cell membrane transport system. Collectively, the first three are sometimes termed the «external potassium homeostasis system»;[67] and the first two, the «reactive potassium homeostasis system».

- The reactive negative-feedback system refers to the system that induces renal secretion of potassium in response to a rise in the plasma potassium (potassium ingestion, shift out of cells, or intravenous infusion.)

- The reactive feed-forward system refers to an incompletely understood system that induces renal potassium secretion in response to potassium ingestion prior to any rise in the plasma potassium. This is probably initiated by gut cell potassium receptors that detect ingested potassium and trigger vagal afferent signals to the pituitary gland.

- The predictive or circadian system increases renal secretion of potassium during mealtime hours (e.g. daytime for humans, nighttime for rodents) independent of the presence, amount, or absence of potassium ingestion. It is mediated by a circadian oscillator in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the brain (central clock), which causes the kidney (peripheral clock) to secrete potassium in this rhythmic circadian fashion.

The action of the sodium-potassium pump is an example of primary active transport. The two carrier proteins embedded in the cell membrane on the left are using ATP to move sodium out of the cell against the concentration gradient; The two proteins on the right are using secondary active transport to move potassium into the cell. This process results in reconstitution of ATP.

- The ion transport system moves potassium across the cell membrane using two mechanisms. One is active and pumps sodium out of, and potassium into, the cell. The other is passive and allows potassium to leak out of the cell. Potassium and sodium cations influence fluid distribution between intracellular and extracellular compartments by osmotic forces. The movement of potassium and sodium through the cell membrane is mediated by the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase pump.[68] This ion pump uses ATP to pump three sodium ions out of the cell and two potassium ions into the cell, creating an electrochemical gradient and electromotive force across the cell membrane. The highly selective potassium ion channels (which are tetramers) are crucial for hyperpolarization inside neurons after an action potential is triggered, to cite one example. The most recently discovered potassium ion channel is KirBac3.1, which makes a total of five potassium ion channels (KcsA, KirBac1.1, KirBac3.1, KvAP, and MthK) with a determined structure. All five are from prokaryotic species.[69]

Renal filtration, reabsorption, and excretion

Renal handling of potassium is closely connected to sodium handling. Potassium is the major cation (positive ion) inside animal cells [150 mmol/L, (4.8 g)], while sodium is the major cation of extracellular fluid [150 mmol/L, (3.345 g)]. In the kidneys, about 180 liters of plasma is filtered through the glomeruli and into the renal tubules per day.[70] This filtering involves about 600 g of sodium and 33 g of potassium. Since only 1–10 g of sodium and 1–4 g of potassium are likely to be replaced by diet, renal filtering must efficiently reabsorb the remainder from the plasma.

Sodium is reabsorbed to maintain extracellular volume, osmotic pressure, and serum sodium concentration within narrow limits. Potassium is reabsorbed to maintain serum potassium concentration within narrow limits.[71] Sodium pumps in the renal tubules operate to reabsorb sodium. Potassium must be conserved, but because the amount of potassium in the blood plasma is very small and the pool of potassium in the cells is about 30 times as large, the situation is not so critical for potassium. Since potassium is moved passively[72][73] in counter flow to sodium in response to an apparent (but not actual) Donnan equilibrium,[74] the urine can never sink below the concentration of potassium in serum except sometimes by actively excreting water at the end of the processing. Potassium is excreted twice and reabsorbed three times before the urine reaches the collecting tubules.[75] At that point, urine usually has about the same potassium concentration as plasma. At the end of the processing, potassium is secreted one more time if the serum levels are too high.[citation needed]

With no potassium intake, it is excreted at about 200 mg per day until, in about a week, potassium in the serum declines to a mildly deficient level of 3.0–3.5 mmol/L.[76] If potassium is still withheld, the concentration continues to fall until a severe deficiency causes eventual death.[77]

The potassium moves passively through pores in the cell membrane. When ions move through Ion transporters (pumps) there is a gate in the pumps on both sides of the cell membrane and only one gate can be open at once. As a result, approximately 100 ions are forced through per second. Ion channel have only one gate, and there only one kind of ion can stream through, at 10 million to 100 million ions per second.[78] Calcium is required to open the pores,[79] although calcium may work in reverse by blocking at least one of the pores.[80] Carbonyl groups inside the pore on the amino acids mimic the water hydration that takes place in water solution[81] by the nature of the electrostatic charges on four carbonyl groups inside the pore.[82]

Nutrition

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. National Academy of Medicine (NAM), on behalf of both the U.S. and Canada, sets Dietary Reference Intakes, including Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs), or Adequate Intakes (AIs) for when there is not sufficient information to set EARs and RDAs.

For both males and females under 9 years of age, the AIs for potassium are: 400 mg of potassium for 0-6-month-old infants, 860 mg of potassium for 7-12-month-old infants, 2,000 mg of potassium for 1-3-year-old children, and 2,300 mg of potassium for 4-8-year-old children.

For males 9 years of age and older, the AIs for potassium are: 2,500 mg of potassium for 9-13-year-old males, 3,000 mg of potassium for 14-18-year-old males, and 3,400 mg for males that are 19 years of age and older.

For females 9 years of age and older, the AIs for potassium are: 2,300 mg of potassium for 9-18-year-old females, and 2,600 mg of potassium for females that are 19 years of age and older.

For pregnant and lactating females, the AIs for potassium are: 2,600 mg of potassium for 14-18-year-old pregnant females, 2,900 mg for pregnant females that are 19 years of age and older; furthermore, 2,500 mg of potassium for 14-18-year-old lactating females, and 2,800 mg for lactating females that are 19 years of age and older. As for safety, the NAM also sets tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals, but for potassium the evidence was insufficient, so no UL was established.[83][84]

As of 2004, most Americans adults consume less than 3,000 mg.[85]

Likewise, in the European Union, in particular in Germany, and Italy, insufficient potassium intake is somewhat common.[86] The British National Health Service recommends a similar intake, saying that adults need 3,500 mg per day and that excess amounts may cause health problems such as stomach pain and diarrhea.[87]

In 2019, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine revised the Adequate Intake for potassium to 2,600 mg/day for females 19 years of age and older who are not pregnant or lactating, and 3,400 mg/day for males 19 years of age and older.[88][89]

Food sources

Potassium is present in all fruits, vegetables, meat and fish. Foods with high potassium concentrations include yam, parsley, dried apricots, milk, chocolate, all nuts (especially almonds and pistachios), potatoes, bamboo shoots, bananas, avocados, coconut water, soybeans, and bran.[90]

The United States Department of Agriculture lists tomato paste, orange juice, beet greens, white beans, potatoes, plantains, bananas, apricots, and many other dietary sources of potassium, ranked in descending order according to potassium content. A day’s worth of potassium is in 5 plantains or 11 bananas.[91]

Deficient intake

Diets low in potassium can lead to hypertension[92] and hypokalemia.

Supplementation

Supplements of potassium are most widely used in conjunction with diuretics that block reabsorption of sodium and water upstream from the distal tubule (thiazides and loop diuretics), because this promotes increased distal tubular potassium secretion, with resultant increased potassium excretion.[medical citation needed] A variety of prescription and over-the counter supplements are available.[citation needed] Potassium chloride may be dissolved in water, but the salty/bitter taste makes liquid supplements unpalatable.[93] Typical doses range from 10 mmol (400 mg), to 20 mmol (800 mg).[medical citation needed] Potassium is also available in tablets or capsules, which are formulated to allow potassium to leach slowly out of a matrix, since very high concentrations of potassium ion that occur adjacent to a solid tablet can injure the gastric or intestinal mucosa.[medical citation needed] For this reason, non-prescription potassium pills are limited by law in the US to a maximum of 99 mg of potassium.[citation needed]

A meta-analysis concluded that a 1640 mg increase in the daily intake of potassium was associated with a 21% lower risk of stroke.[94] Potassium chloride and potassium bicarbonate may be useful to control mild hypertension.[95] In 2020, potassium was the 33rd most commonly prescribed medication in the U.S., with more than 17 million prescriptions.[96][97]

Detection by taste buds

Potassium can be detected by taste because it triggers three of the five types of taste sensations, according to concentration. Dilute solutions of potassium ions taste sweet, allowing moderate concentrations in milk and juices, while higher concentrations become increasingly bitter/alkaline, and finally also salty to the taste. The combined bitterness and saltiness of high-potassium solutions makes high-dose potassium supplementation by liquid drinks a palatability challenge.[93][98]

Commercial production

Mining

Potassium salts such as carnallite, langbeinite, polyhalite, and sylvite form extensive evaporite deposits in ancient lake bottoms and seabeds,[35] making extraction of potassium salts in these environments commercially viable. The principal source of potassium – potash – is mined in Canada, Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Germany, Israel, the U.S., Jordan, and other places around the world.[99][100][101] The first mined deposits were located near Staßfurt, Germany, but the deposits span from Great Britain over Germany into Poland. They are located in the Zechstein and were deposited in the Middle to Late Permian. The largest deposits ever found lie 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) below the surface of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The deposits are located in the Elk Point Group produced in the Middle Devonian. Saskatchewan, where several large mines have operated since the 1960s pioneered the technique of freezing of wet sands (the Blairmore formation) to drive mine shafts through them. The main potash mining company in Saskatchewan until its merge was the Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan, now Nutrien.[102] The water of the Dead Sea is used by Israel and Jordan as a source of potash, while the concentration in normal oceans is too low for commercial production at current prices.[100][101]

Several methods are used to separate potassium salts from sodium and magnesium compounds. The most-used method is fractional precipitation using the solubility differences of the salts. Electrostatic separation of the ground salt mixture is also used in some mines. The resulting sodium and magnesium waste is either stored underground or piled up in slag heaps. Most of the mined potassium mineral ends up as potassium chloride after processing. The mineral industry refers to potassium chloride either as potash, muriate of potash, or simply MOP.[36]

Pure potassium metal can be isolated by electrolysis of its hydroxide in a process that has changed little since it was first used by Humphry Davy in 1807. Although the electrolysis process was developed and used in industrial scale in the 1920s, the thermal method by reacting sodium with potassium chloride in a chemical equilibrium reaction became the dominant method in the 1950s.

- Na + KCl → NaCl + K

The production of sodium potassium alloys is accomplished by changing the reaction time and the amount of sodium used in the reaction. The Griesheimer process employing the reaction of potassium fluoride with calcium carbide was also used to produce potassium.[36][103]

- 2 KF + CaC2 → 2 K + CaF2 + 2 C

Reagent-grade potassium metal costs about $10.00/pound ($22/kg) in 2010 when purchased by the tonne. Lower purity metal is considerably cheaper. The market is volatile because long-term storage of the metal is difficult. It must be stored in a dry inert gas atmosphere or anhydrous mineral oil to prevent the formation of a surface layer of potassium superoxide, a pressure-sensitive explosive that detonates when scratched. The resulting explosion often starts a fire difficult to extinguish.[104][105]

Cation identification

Potassium is now quantified by ionization techniques, but at one time it was quantitated by gravimetric analysis.