Ye[a] ( YAY; born Kanye Omari West KAHN-yay; June 8, 1977) is an American rapper, singer, songwriter, record producer, and fashion designer.[1][2][3][4]

|

Kanye West |

|

|---|---|

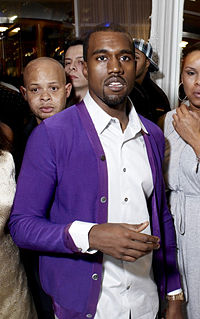

West in April 2009 |

|

| Born |

Kanye Omari West June 8, 1977 (age 45) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1996–present |

| Organizations |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Kim Kardashian (m. 2014; div. 2022) |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Genres |

|

| Labels |

|

| Member of |

|

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | kanyewest.com |

Born in Atlanta and raised in Chicago,[5][6] West gained recognition as a producer for Roc-A-Fella Records in the early 2000s, producing singles for several artists and developing the «chipmunk soul» sampling style. Intent on pursuing a solo career as a rapper, he released his debut studio album, The College Dropout (2004), to critical and commercial success. He founded the record label GOOD Music later that year. West explored diverse musical elements like orchestras, synthesizers, and autotune on the albums Late Registration (2005), Graduation (2007), and 808s & Heartbreak (2008). His fifth and sixth albums My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010) and Yeezus (2013) were also met with critical and commercial success. West further diversified his musical styles on The Life of Pablo (2016) and Ye (2018) and explored Christian and gospel music on Jesus Is King (2019). His tenth album Donda (2021) was released to continued commercial success but mixed critical reception. West’s discography also includes the two full-length collaborative albums Watch the Throne (2011) with Jay-Z and Kids See Ghosts (2018) with Kid Cudi.

One of the world’s best-selling music artists, with over 160 million records sold, West has won 22 Grammy Awards and 75 nominations, the joint tenth-most of all time, and the joint-most Grammy awards of any rapper along with Jay-Z.[7] Among his other awards are the Billboard Artist Achievement Award, a joint-record three Brit Awards for Best International Male Solo Artist and the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award.[8] Six of West’s albums were included on Rolling Stone‘s 2020 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list with the same publication naming him one of the 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time.[9] He holds the joint record (with Bob Dylan) for most albums (4) topping the annual Pazz & Jop critic poll, and has the 5th most appearances on the Billboard Hot 100 (133 entries). Time named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2005 and 2015.[10][11] As a fashion designer, he has collaborated with Nike, Louis Vuitton, Gap, and A.P.C. on clothing and footwear and led the Yeezy collaboration with Adidas. He is also the founder and head of the creative content company Donda.

West’s outspoken views have received significant media coverage; he has been a frequent source of controversy due to his conduct on social media[12] and at awards shows and public settings, as well as his comments on the music and fashion industries, U.S. politics, race, and slavery. His Christian faith, high-profile marriage to Kim Kardashian, and mental health have also been topics of media attention.[13][14] In 2020, West launched an unsuccessful independent presidential campaign that primarily advocated for a consistent life ethic. In 2022, he was widely condemned and lost many sponsors and partnerships—including his collaborations with Adidas, Gap, and Balenciaga—after making a series of antisemitic statements.[15][16] In November 2022, he announced his 2024 presidential campaign, appearing publicly with Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist. He later publicly praised Adolf Hitler, denied the Holocaust,[17][18] and identified as a Nazi.[19][20]

Early life

West was born on June 8, 1977, in Atlanta, Georgia.[b] After his parents divorced when he was three years old, he moved with his mother to Chicago, Illinois.[23][24] His father, Ray West, is a former Black Panther and was one of the first black photojournalists at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Ray later became a Christian counselor,[24] and in 2006, opened the Good Water Store and Café in Lexington Park, Maryland, with startup capital from his son.[25][26] West’s mother, Donda C. West (née Williams),[27] was a professor of English at Clark Atlanta University and the Chair of the English Department at Chicago State University before retiring to serve as his manager.

West was raised in a middle-class environment, attending Polaris School for Individual Education[5] in suburban Oak Lawn, Illinois, after living in Chicago.[6] At the age of 10, West moved with his mother to Nanjing, China, where she was teaching at Nanjing University as a Fulbright Scholar.[28] According to his mother, West was the only foreigner in his class, but settled in well and quickly picked up the language, although he has since forgotten most of it.[29] When asked about his grades in high school, West replied, «I got A’s and B’s.»[30]

West demonstrated an affinity for the arts at an early age; he began writing poetry when he was five years old.[31] West started rapping in the third grade and began making musical compositions in the seventh grade, eventually selling them to other artists.[32] West crossed paths with producer No I.D., who became West’s friend and mentor.[33]: 557 After graduating from high school, West received a scholarship to attend Chicago’s American Academy of Art in 1997 and began taking painting classes. Shortly after, he transferred to Chicago State University to study English. At age 20, he dropped out to pursue his musical career.[34] This greatly displeased his mother, who was also a professor at the university, athough she would later accept the decision.[33]: 558

Musical career

1996–2002: Early work and Roc-A-Fella

West began his early production career in the mid-1990s, creating beats primarily for burgeoning local artists around his area. His first official production credits came at nineteen when he produced eight tracks on Down to Earth, the 1996 debut album of a Chicago rapper, Grav.[35] In 1998, West was the first person signed to the management-production company Hip Hop Since 1978.[36] For a time, West acted as a ghost producer for Deric «D-Dot» Angelettie. Because of his association with D-Dot, West was not able to release a solo album, so he formed the Go-Getters, a rap group composed of him, GLC, Timmy G, Really Doe, and Arrowstar.[37][38] The Go-Getters released their first and only studio album World Record Holders in 1999.[37] West spent much of the late 1990s producing records for several well-known artists and music groups.[39] He produced the third track on Foxy Brown’s second studio album Chyna Doll, which became the first hip-hop album by a female rapper to debut at the top of the U.S. Billboard 200 chart.[39]

West received early acclaim for his production work on Jay-Z’s The Blueprint. The two are pictured here in 2011.

In 2000, West began producing for artists on Roc-A-Fella. West is often credited with revitalizing Jay-Z’s career with his contributions to Jay-Z’s 2001 album The Blueprint,[40] which Rolling Stone ranked among their list of greatest hip-hop albums.[41] Serving as an in-house producer for Roc-A-Fella, West produced music for other artists on the label, including Beanie Sigel, Freeway, and Cam’ron. He also crafted hit songs for Ludacris, Alicia Keys, and Janet Jackson.[40][42] Meanwhile, West struggled to attain a record deal as a rapper.[43] Multiple record companies, including Capitol Records,[32] denied or ignored him because he did not portray the gangsta image prominent in mainstream hip hop at the time.[33]: 556 Desperate to keep West from defecting to another label, then-label head Damon Dash reluctantly signed West to Roc-A-Fella.[33]: 556 [44]

A 2002 car accident, which shattered his jaw,[45][46] inspired West; two weeks after being admitted to the hospital, he recorded «Through the Wire» at the Record Plant Studios with his jaw still wired shut.[45] The song was first available on West’s «Get Well Soon …» mixtape, released in December 2002.[47] At the same time, West announced that he was working on an album called The College Dropout, whose overall theme was to «make your own decisions. Don’t let society tell you, ‘This is what you have to do.'»[48]

2003–2006: The College Dropout and Late Registration

West recorded the remainder of the album in Los Angeles while recovering from the car accident. It was leaked months before its release date,[43] and West used the opportunity to remix, remaster, and revise the album before its release;[49] West added new verses, string arrangements, gospel choirs, and improved drum programming.[43] The album was postponed three times from its initial date in August 2003,[50][51] and was eventually released in February 2004, reaching No. 2 on the Billboard 200 as his debut single, «Through the Wire» peaked at No. 15 while on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for five weeks.[52] «Slow Jamz», his second single, featuring Twista and Jamie Foxx, became the three musicians’ first No. 1 hit. The College Dropout received near-universal critical acclaim, was voted the top album of the year by two major music publications,[which?] and has consistently been ranked among the great hip-hop works and debut albums by artists.[53][54]

«Jesus Walks», the album’s fourth single, reached the top 20 of the Billboard pop charts, despite industry executives’ predictions that a song containing such blatant declarations of faith would never make it to the radio.[53][54] The College Dropout was certified triple platinum in the US, and garnered West 10 Grammy nominations, including Album of the Year, and Best Rap Album (which it received).[55] During this period, West founded GOOD Music, a record label and management company that housed affiliate artists and producers, such as No I.D. and John Legend,[56] and produced singles for Brandy, Common, Legend, and Slum Village.[57]

West invested $2 million and took over a year to make his second album.[58] West was inspired by Roseland NYC Live, a 1998 live album by English trip hop group Portishead, produced with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra,[59] incorporating string arrangements into his hip-hop production. Though West had not been able to afford many live instruments around the time of his debut album, the money from his commercial success enabled him to hire a string orchestra for his second album Late Registration.[59] West collaborated with American film score composer Jon Brion, who served as the album’s co-executive producer for several tracks.[60][61] Late Registration sold over 2.3 million units in the United States alone by the end of 2005 and was considered by industry observers as the only successful major album release of the fall season, which had been plagued by steadily declining CD sales.[62]

When his song «Touch the Sky» failed to win Best Video at the 2006 MTV Europe Music Awards, West went onto the stage as the award was being presented to Justice and Simian for «We Are Your Friends» and argued that he should have won the award instead.[63][64] Hundreds of news outlets worldwide criticized the outburst. On November 7, 2006, West apologized for this outburst publicly during his performance as support act for U2 for their Vertigo concert in Brisbane.[65] He later spoofed the incident on the 33rd-season premiere of Saturday Night Live in September 2007.[66]

2007–2009: Graduation, 808s & Heartbreak, and VMAs incident

West’s third studio album, Graduation, garnered major publicity when its release date pitted West in a sales competition against rapper 50 Cent’s Curtis.[67] Upon their September 2007 releases, Graduation outsold Curtis by a large margin, debuting at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 chart and selling 957,000 copies in its first week.[68] Graduation continued the string of critical and commercial successes by West, and the album’s lead single, «Stronger», garnered his third number-one hit.[69] «Stronger», which samples French house duo Daft Punk, has been accredited to not only encouraging other hip-hop artists to incorporate house and electronica elements into their music, but also for playing a part in the revival of disco and electro-infused music in the late 2000s.[70] His mother’s death in November 2007[71] and the end of his engagement to Alexis Phifer[72] profoundly affected West, who set off for his 2008 Glow in the Dark Tour shortly thereafter.[73]

Recorded mostly in Honolulu, Hawaii in three weeks,[74] West announced his fourth album, 808s & Heartbreak, at the 2008 MTV Video Music Awards, where he performed its lead single, «Love Lockdown». Music audiences were taken aback by the uncharacteristic production style and the presence of Auto-Tune, which typified the pre-release response to the record.[75] 808s & Heartbreak was released by Island Def Jam in November 2008.[76][77] Upon its release, the lead single «Love Lockdown» debuted at number three on the Billboard Hot 100,[78] while follow-up single «Heartless» debuted at number four.[79] While it was criticized prior to release, 808s & Heartbreak is considered to have had a significant effect on hip-hop music, encouraging other rappers to take more creative risks with their productions.[80]

While Taylor Swift was accepting her award for Best Female Video at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards, West went on stage and grabbed the microphone from her to proclaim that Beyoncé deserved the award instead. He was subsequently removed from the remainder of the show for his actions.[81][82][83] West was criticized by various celebrities for the outburst,[81][84][85][86] and by President Barack Obama, who called West a «jackass».[87][88][89][90] The incident sparked a large influx of Internet photo memes.[91] West subsequently apologized,[85][92] including personally to Swift.[93][94][95] However, in a November 2010 interview, he seemed to recant his past apologies, describing the act at the 2009 awards show as «selfless».[96][97]

2010–2012: My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, Watch the Throne, and Cruel Summer

Following the highly publicized incident, West took a brief break from music and threw himself into fashion, only to hole up in Hawaii for the next few months writing and recording his next album.[98] Importing his favorite producers and artists to work on and inspire his recording, West kept engineers behind the boards 24 hours a day and slept only in increments. Noah Callahan-Bever, a writer for Complex, was present during the sessions and described the «communal» atmosphere as thus: «With the right songs and the right album, he can overcome any and all controversy, and we are here to contribute, challenge, and inspire.»[98] A variety of artists contributed to the project, including close friends Jay-Z, Kid Cudi and Pusha T, as well as off-the-wall collaborations, such as with Justin Vernon of Bon Iver.[99]

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, West’s fifth studio album, was released in November 2010 to widespread acclaim from critics, many of whom considered it his best work and said it solidified his comeback.[100] In stark contrast to his previous effort, which featured a minimalist sound, Dark Fantasy adopts a maximalist philosophy and deals with themes of celebrity and excess.[56] The record included the international hit «All of the Lights», and Billboard hits «Power», «Monster», and «Runaway»,[101] the latter of which accompanied a 35-minute film of the same name directed by and starring West.[102] During this time, West initiated the free music program GOOD Fridays through his website, offering a free download of previously unreleased songs each Friday, a portion of which were included on the album. This promotion ran from August to December 2010.[103] Dark Fantasy went on to go platinum in the United States,[104] but its omission as a contender for Album of the Year at the 54th Grammy Awards was viewed as a «snub» by several media outlets.[105]

2011 saw West embark on a festival tour to commemorate the release of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy performing and headlining numerous festivals including; SWU Music & Arts, Austin City Limits, Oya Festival, Flow Festival, Live Music Festival,

The Big Chill, Essence Music Festival, Lollapalooza and Coachella which was described by The Hollywood Reporter as «one of greatest hip-hop sets of all time»,[106] West released the collaborative album Watch the Throne with Jay-Z in August 2011. By employing a sales strategy that released the album digitally weeks before its physical counterpart, Watch the Throne became one of the few major label albums in the Internet age to avoid a leak.[107][108] «Niggas in Paris» became the record’s highest-charting single, peaking at number five on the Billboard Hot 100.[101] The co-headlining Watch the Throne Tour kicked off in October 2011 and concluded in June 2012.[109] In 2012, West released the compilation album Cruel Summer, a collection of tracks by artists from West’s record label GOOD Music.

2013–2015: Yeezus and the Yeezus Tour

Sessions for West’s sixth solo effort begin to take shape in early 2013 in his own personal loft’s living room at a Paris hotel.[110] Determined to «undermine the commercial»,[111] he once again brought together close collaborators and attempted to incorporate Chicago drill, dancehall, acid house, and industrial music.[112] Primarily inspired by architecture,[110] West’s perfectionist tendencies led him to contact producer Rick Rubin fifteen days shy of its due date to strip down the record’s sound in favor of a more minimalist approach.[113] Initial promotion of his sixth album included worldwide video projections of the album’s music and live television performances.[114][115] Yeezus, West’s sixth album, was released June 18, 2013, to rave reviews from critics.[116] It became his sixth consecutive number one debut, but also marked his lowest solo opening week sales.[117]

In September 2013, West announced he would be headlining his first solo tour in five years, to support Yeezus, with fellow American rapper Kendrick Lamar accompanying him as a supporting act.[118][119] The tour was met with rave reviews from critics.[120] Rolling Stone described it as «crazily entertaining, hugely ambitious, emotionally affecting (really!) and, most importantly, totally bonkers».[120] Writing for Forbes, Zack O’Malley Greenburg praised West for «taking risks that few pop stars, if any, are willing to take in today’s hyper-exposed world of pop», describing the show as «overwrought and uncomfortable at times, but [it] excels at challenging norms and provoking thought in a way that just isn’t common for mainstream musical acts of late».[121] West subsequently released a number of singles featuring Paul McCartney, including «Only One»[122] and «FourFiveSeconds», also featuring Rihanna.[123]

In November 2013, West stated that he was beginning work on his next studio album, hoping to release it by mid-2014,[124] with production by Rick Rubin and Q-Tip.[125] Having initially announced a new album entitled Yeezus II slated for a 2014 release, West announced in March 2015 that the album would instead be tentatively called So Help Me God.[126] In May 2015, West was awarded an honorary doctorate by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for his contributions to music, fashion, and popular culture.[127][128] The next month, West headlined at the Glastonbury Festival in the UK, despite a petition signed by almost 135,000 people against his appearance.[129] Another petition aimed to block West from headlining the 2015 Pan American Games, garnering 50,000 supporters.[130]

2016–2017: The Life of Pablo and tour cancellation

West announced in January 2016 that SWISH would be released on February 11, and later that month, released new songs «Real Friends» and a snippet of «No More Parties in LA» with Kendrick Lamar. On January 26, 2016, West revealed he had renamed the album from SWISH to Waves.[131] In the weeks leading up to the album’s release, West became embroiled in several Twitter controversies.[132] Several days ahead of its release, West again changed the title, this time to The Life of Pablo.[133][134] On February 11, West premiered the album at Madison Square Garden as part of the presentation of his Yeezy Season 3 clothing line.[135] Following the preview, West announced that he would be modifying the tracklist once more before its release to the public.[136] He released the album exclusively on Tidal on February 14, 2016, following a performance on SNL.[137][138] Following its release, West continued to tinker with mixes of several tracks, describing the work as «a living breathing changing creative expression»[139] and proclaiming the end of the album as a dominant release form.[140] Despite West’s earlier comments, in addition to Tidal, the album was released through several other competing services starting in April.[141]

In February 2016, West stated on Twitter that he was planning to release another album in the summer of 2016, tentatively called Turbo Grafx 16 in reference to the 1990s video game console of the same name.[142][143] In June 2016, West released the collaborative lead single «Champions» off the GOOD Music album Cruel Winter, which has yet to be released.[144][145] Later that month, West released a controversial video for «Famous», which depicted wax figures of several celebrities (including West, Kardashian, Taylor Swift, businessman and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, comedian Bill Cosby, and former president George W. Bush) sleeping nude in a shared bed.[146]

In August 2016, West embarked on the Saint Pablo Tour in support of The Life of Pablo.[147] The performances featured a mobile stage suspended from the ceiling.[147] West postponed several dates in October following the Paris robbery of several of his wife’s effects.[148] On November 21, 2016, West cancelled the remaining 21 dates on the Saint Pablo Tour, following a week of no-shows, curtailed concerts and rants about politics.[149] He was later admitted for psychiatric observation at UCLA Medical Center.[150][151] He stayed hospitalized over the Thanksgiving weekend because of a temporary psychosis stemming from sleep deprivation and extreme dehydration.[152] Following this episode West took an 11-month break from posting on Twitter and the public in general.[153]

2017–2019: Ye and the Wyoming Sessions

It was reported in May 2017 that West was recording new music in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, with a wide range of collaborators.[154][155][156] In April 2018, West announced plans to write a philosophy book entitled Break the Simulation,[157] later clarifying that he was sharing the book «in real time» on Twitter and began posting content that was likened to «life coaching».[158] Later that month, he also announced two new albums, a solo album and self-titled collaboration with Kid Cudi under the name Kids See Ghosts, both of which would be released in June.[159] Additionally, he revealed he would produce upcoming albums by GOOD Music label-mates Pusha T and Teyana Taylor, as well as Nas.[160] Shortly thereafter, West released the non-album singles «Lift Yourself», a «strange, gibberish track» featuring nonsensical lyrics, and «Ye vs. the People», in which he and T.I. discussed West’s controversial support of Donald Trump.[161]

Pusha T’s Daytona, «the first project out of Wyoming», was released in May to critical acclaim, although the album’s artwork—a photograph of deceased singer Whitney Houston’s bathroom that West paid $85,000 to license—attracted some controversy.[162][163] The following week, West released his eighth studio album, Ye. West has suggested that he scrapped the original recordings of the album and re-recorded it within a month.[164] The week after, West released a collaborative album with Kid Cudi, titled Kids See Ghosts, named after their group of the same name. West also completed production work on Nas’ Nasir[165] and Teyana Taylor’s K.T.S.E., which were released in June 2018.[166]

In September, West announced his ninth studio album Yandhi to be released by the end of the month and a collaborative album with fellow Chicagoan rapper Chance the Rapper titled Good Ass Job. That same month, West announced that he would be changing his stage name to «Ye».[167] Yandhi was originally set for release in September 2018 but was postponed multiple times.[168] In January 2019, West pulled out of headlining that year’s Coachella festival after negotiations broke down due to discord regarding stage design.[169] In July, it was reported that songs from West’s unreleased album Yandhi were leaked online.[170] The following month, Kim Kardashian announced that West’s next album would be titled Jesus Is King, effectively scrapping Yandhi.[171][172] By October, the entire unfinished album was available for a short time on streaming services Spotify and Tidal.[173]

2019–present: Jesus Is King, Donda, and Donda 2

On January 6, 2019, West started his weekly «Sunday Service» orchestration which includes soul variations of both West’s and others’ songs attended by multiple celebrities including the Kardashians, Charlie Wilson, and Kid Cudi.[174] West previewed a new song, «Water» at his «Sunday Service» orchestration performance at Coachella 2019,[175] which was later revealed to feature on his upcoming album Jesus Is King;[176] West released the album on October 25, 2019.[177] It became the first to ever top the Billboard 200, Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums, Top Rap Albums, Top Christian Albums and Top Gospel Albums at the same time.[178] On December 25, 2019, West and Sunday Service released Jesus Is Born, containing 19 songs including several re-workings of older West songs.[179]

West released a single titled «Wash Us in the Blood» on June 30, 2020, featuring fellow American rapper and singer Travis Scott, along with the music video, which was set to serve as the lead single from his tenth studio album Donda.[180] However, in September 2020, West stated that he would not be releasing any further music until he is «done with [his] contract with Sony and Universal».[181] On October 16, he released the single «Nah Nah Nah».[182] West held several listening parties at Mercedes-Benz Stadium for his upcoming album Donda in the summer of 2021, where he had taken up temporary residence in one of the stadium’s locker rooms, converting it into a recording studio to finish the recording.[183][184] After multiple delays, Donda was released on August 29, 2021.[185] West claimed the album was released early without his approval and alleged that Universal had altered the tracklist.[186] He released a delux edition of Donda, including five new songs, to streaming services on November 14, 2021.[187] On November 20, days after ending their long-running feud,[188] West and rapper Drake confirmed that they would stage the «Free Larry Hoover» benefit concert on December 9 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.[189]

On January 5, 2022, West was announced as one of the 2022 headliners of Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.[190] Later that month on January 15, West released the first single for his upcoming album Donda 2, «Eazy» featuring The Game,[191] to be executive produced by American rapper Future.[192] West hosted a listening event for the album at LoanDepot Park in Miami, Florida, on February 22.[193] In April, shortly before Coachella, West pulled out as headlining act,[194] then proceeded to pull out of headlining Rolling Loud.[195] West and The Game performed the single on July 22, marking West’s first performance in five months following the low profile he had been keeping since Donda 2 remained unfinished.[196] A day later, despite cancelling as headliner, he appeared at Rolling Loud during Lil Durk’s set.[197]

In December 2022, after weeks of controversial anti-Semitic statements, West released a new song «Someday We’ll All Be Free» on his Instagram.[198]

Musical style

West’s musical career is defined by frequent stylistic shifts and different musical approaches.[199] In the subsequent years since his debut, West has both musically and lyrically taken an increasingly experimental approach to crafting progressive hip hop music while maintaining accessible pop sensibilities.[200][201][202] Ed Ledsham of PopMatters said that «West’s melding of multiple genres into the hip-hop fold is a complex act that challenges the dominant white notions of what constitutes true ‘art’ music.»[203] West’s rhymes have been described as funny, provocative and articulate, capable of seamlessly segueing from shrewd commentary to comical braggadocio to introspective sensitivity.[204] West imparts that he strives to speak in an inclusive manner so groups from different racial and gender backgrounds can comprehend his lyrics, saying he desired to sound «just as ill as Jadakiss and just as understandable as Will Smith».[205] Early in his career, West pioneered a style of hip-hop production dubbed «chipmunk-soul»,[206][207] a sampling technique involving the manipulation of tempo in order to chop and stretch pitched-up samples from vintage soul songs.[208][1]

On his debut studio album, The College Dropout (2004), West formed the constitutive elements of his style, described as intricate hip-hop beats, topical subject matter, and clumsy rapping laced with inventive wordplay.[200][209] The record saw West diverge from the then-dominant gangster persona in hip hop in favor of more diverse, topical lyrical subjects,[210] including higher education, materialism, self-consciousness, minimum-wage labor, institutional prejudice, class struggle, family, sexuality, his struggles in the music industry, and middle-class upbringing.[211][212][201] Over time, West has explored a variety of music genres, encompassing and taking inspiration from chamber pop on his second studio album, Late Registration (2005),[60] arena rock and europop on his third album, Graduation (2007),[213][214] synth-driven electropop on his fourth album, 808s & Heartbreak (2008),[215][216] acid-house, drill, industrial rap and trap on Yeezus (2013),[112][217] gospel and Christian rap on The Life of Pablo (2016), Jesus is King (2019) and Donda (2021),[218][219][220][221] and psychedelic music on Kids See Ghosts (2018).[222]

Other ventures

Fashion

Early in his career, West made clear his interest in fashion and desire to work in the clothing design industry.[199][110] He launched his own clothing line in spring 2006,[223] and developed it over the following four years before the line was ultimately cancelled in 2009.[224][225] In January 2007, West’s first sneaker collaboration was released, a special-edition Bapesta from A Bathing Ape.[226][227] In 2009, West collaborated with Nike to release his own shoe, the Air Yeezys, becoming the first non-athlete to be given a shoe deal with the company.[228] In January 2009, he introduced his first shoe line designed for Louis Vuitton during Paris Fashion Week. The line was released in summer 2009.[229] West has additionally designed shoewear for Italian shoemaker Giuseppe Zanotti.[230]

In fall 2009, West moved to Rome, where he interned at Italian fashion brand Fendi, giving ideas for the men’s collection.[231] In March 2011, West collaborated with M/M Paris for a series of silk scarves featuring artwork from My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.[232] In October 2011, West premiered his women’s fashion label at Paris Fashion Week.[233] His debut fashion show received mixed-to-negative reviews.[234] In March 2012, West premiered a second fashion line at Paris Fashion Week.[235][236] Critics deemed the sophomore effort «much improved» compared to his first show.[237]

On December 3, 2013, Adidas officially confirmed a new shoe collaboration deal with West.[238] After months of anticipation and rumors, West confirmed the release of the Adidas Yeezy Boosts. In 2015, West unveiled a Yeezy clothing line, premiering in collaboration with Adidas early that year.[239] In June 2016, Adidas announced a new long-term contract with Kanye West that extended the Yeezy line to a number of stores, planning to sell sports performance products like basketball, football, and soccer,[240] although Adidas terminated the partnership with West in October 2022 due to his antisemitic remarks.[241] In May 2021, West signed a 10-year deal linking Yeezy with GAP, however, in September 2022, West announced that he was ending the deal.[242]

Business ventures

West founded the record label and production company GOOD Music in 2004, in conjunction with Sony BMG, shortly after releasing his debut album, The College Dropout. West, alongside then-unknown Ohio singer John Legend and fellow Chicago rapper Common were the label’s inaugural artists.[243] The label houses artists including West, Big Sean, Pusha T, Teyana Taylor, Yasiin Bey / Mos Def, D’banj and John Legend, and producers including Hudson Mohawke, Q-Tip, Travis Scott, No I.D., Jeff Bhasker, and S1. GOOD Music has released ten albums certified gold or higher by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). In November 2015, West appointed Pusha T the new president of GOOD Music.[244]

In August 2008, West revealed plans to open 10 Fatburger restaurants in the Chicago area; the first was set to open in September 2008 in Orland Park. The second followed in January 2009, while a third location is yet to be revealed, although the process is being finalized. His company, KW Foods LLC, bought the rights to the chain in Chicago.[245] Ultimately, in 2009, only two locations actually opened. In February 2011, West shut down the Fatburger located in Orland Park.[246] Later that year, the remaining Beverly location also was shuttered.[247]

In January 2012, West announced his establishment of the creative content company Donda, named after his late mother.[248] In his announcement, West proclaimed that the company would «pick up where Steve Jobs left off»; Donda would operate as a «design company» with a goal to «make products and experiences that people want and can afford».[249] In stating Donda’s creative philosophy, West articulated the need to «put creatives in a room together with like minds» in order to «simplify and aesthetically improve everything we see, taste, touch, and feel.»[249] West is notoriously secretive about the company’s operations, maintaining neither an official website nor a social media presence.[250][251] Contemporary critics have noted the consistent minimalistic aesthetic exhibited throughout Donda creative projects.[252][253][254]

West expressed interest in starting an architecture firm in May 2013, saying «I want to do product, I am a product person, not just clothing but water bottle design, architecture … I make music but I shouldn’t be limited to one place of creativity»[255][256] and then later in November 2013, delivering a manifesto on his architectural goals during a visit to Harvard Graduate School of Design.[257] In May 2018, West announced he was starting an architecture firm called Yeezy Home, which will act as an arm of his already successful Yeezy fashion label.[258] In June 2018, the first Yeezy Home collaboration was announced by designer Jalil Peraza, teasing an affordable concrete prefabricated home as part of a social housing project.[259][260]

In March 2015, it was announced that West is a co-owner, with various other music artists, in the music streaming service Tidal. The service specialises in lossless audio and high definition music videos. Jay-Z acquired the parent company of Tidal, Aspiro, in the first quarter of 2015.[261] Sixteen artist stakeholders including Jay-Z, Rihanna, Beyoncé, Madonna, Chris Martin, Nicki Minaj co-own Tidal, with the majority owning a 3% equity stake.[262] In October 2022, in direct response to bans he received on Twitter and Instagram stemming from his antisemitic comments,[263] West reached an agreement in principle to acquire the alt-tech social network Parler for an undisclosed amount.[264][265] Parler and West mutually agreed to terminate the proposed deal in mid-November.[266]

Philanthropy

West, alongside his mother, founded the Kanye West Foundation in Chicago in 2003, tasked with a mission to battle dropout and illiteracy rates, while partnering with community organizations to provide underprivileged youth access to music education.[267] In 2007, West and the Foundation partnered with Strong American Schools as part of their «Ed in ’08» campaign.[268][269] As spokesman for the campaign, West appeared in a series of PSAs for the organization, and hosted an inaugural benefit concert in August of that year.[270] In 2008, following the death of West’s mother, the foundation was rechristened The Dr. Donda West Foundation.[267][271] The foundation ceased operations in 2011.[272] In 2013, Kanye West and friend Rhymefest founded Donda’s House, Inc., a program aimed at helping at-risk Chicago youth.[273]

West has contributed to hurricane relief in 2005 by participating in a Hurricane Katrina benefit concert after the storm had ravaged black communities in New Orleans[274] and in 2012 when he performed at a Hurricane Sandy benefit concert.[275] In January 2019, West donated $10 million towards the completion of the Roden Crater by American artist James Turrell.[276] In June 2020, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the following protests, he donated $2 million between the family of Floyd and other victims of police brutality, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. The donation funded legal fees for Arbery and Taylor’s families, as well as establishing a 529 plan to fully cover college tuition for Floyd’s daughter.[277]

Acting and filmmaking

West made cameo appearances as himself in the films State Property 2 (2005) and The Love Guru (2008),[278][279] and in an episode of the television show Entourage in 2007.[280] West provided the voice for «Kenny West», a rapper, in the animated sitcom The Cleveland Show.[279] In 2009, he starred in the Spike Jonze-directed short film We Were Once a Fairytale (2009), playing himself acting belligerently while drunk in a nightclub.[281] West wrote, directed, and starred in the musical short film Runaway (2010), which heavily features music from My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.[102] The film depicts a relationship between a man, played by West, and a half-woman, half-phoenix creature.[282]

In 2012, West wrote and directed another short film, titled Cruel Summer, which premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival in a custom pyramid-shaped screening pavilion featuring seven screens constructed for the film. The film was inspired by the compilation album of the same name. West made a cameo appearance in the comedy Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues (2013) as a MTV News representative in the film’s fight scene.[283] In September 2018, West announced starting of film production company named Half Beast, LLC.[284] A documentary shot over 21 years featuring footage of West’s early days in Chicago through the death of his mother to his presidential run was announced to debut in 2021. Titled Jeen-Yuhs, it was acquired by Netflix for $30 million.[285]

Politics

2020 presidential campaign

On July 4, 2020, West announced on Twitter that he would be running in the 2020 presidential election.[286][287] On July 7, West was interviewed by Forbes about his presidential run, where he announced that his running mate would be Wyoming preacher Michelle Tidball, and that he would run as an independent under the «Birthday Party», explaining his decision of why he chose the name, saying, «Because when we win, it’s everybody’s ‘birthday’.»[288] West also said he no longer supported Trump because he «hid in [a] bunker» during the COVID-19 pandemic.[289] Continuing, he said, «You know? Obama’s special. Trump’s special. We say Kanye West is special. America needs special people that lead. Bill Clinton? Special. Joe Biden’s not special.»[289]

Various political pundits speculated that West’s presidential run was a publicity stunt to promote his latest music releases.[290] On July 15, 2020, official paperwork was filed with the Federal Election Commission for West, under the «BDY» Party affiliation[291] amid claims that he was preparing to drop out.[292] West held his first rally that weekend, on July 19.[293] West aligned himself with the philosophy of a consistent life ethic, a tenet of Christian democracy.[294] His platform advocated for the creation of a culture of life, endorsing environmental stewardship, supporting the arts, buttressing faith-based organizations, restoring school prayer, providing for a strong national defense, and «America First» diplomacy.[295] In July 2020, West told Forbes that he is ignorant on issues such as taxes and foreign policy.[296]

West conceded on Twitter on November 4, 2020.[297][298] He received 66,365 votes in the 12 states he had ballot access in, receiving an average of 0.32%. Reported write-in votes gave West an additional 3,931 votes across 5 states. In addition, the Roque De La Fuente / Kanye West ticket won 60,160 votes in California (0.34%).[299] According to Reuters, on January 4, 2021, a Kanye West-linked publicist pressured a Georgia election worker to confess to bogus charges of election tampering to assist Trump’s claims of election interference.[300][301][302] In December 2021, The Daily Beast reported that West’s presidential campaign received millions of dollars in services from a secret network of Republican operatives, payments to which the committee did not report. According to campaign finance experts, this was done to conceal a connection.[303][304]

2024 presidential campaign

West has stated his intentions to run for president again in the 2024 presidential election. In November 2019, he said at an event, «When I run for president in 2024, we would’ve created so many jobs that I’m not going to run, I’m going to walk.» He was met with laughter from the audience.[305] On October 24, 2020, while running for president, West told Joe Rogan on his podcast that he would be open to running for Governor of California.[306] On May 19, 2021, Fox News reported that it had obtained a letter concerning an RFAI (Request for further information) from the Federal Election Commission regarding an exploratory presidential committee. West’s representatives stated, «Kanye West has not decided whether to become a candidate for president in the 2024 election, and the activity of the Kanye 2020 committee that prompted this RFAI is strictly exploratory.»[307] On subsequent interviews, merchandise, and in songs lyrics, West would repeatedly insinuate that he will indeed run.[308] On November 20, 2022, Kanye announced his intention to run in 2024.[309]

Controversial views

West has been an outspoken and controversial celebrity throughout his career, receiving criticism from the mainstream media, industry colleagues and entertainers, and three U.S. presidents.[199][110] West has voiced his opposition to abortion in 2013, citing his belief in the Sixth Commandment,[310] and in 2022 deemed abortion «genocide and population control» of black people.[311] He has stated that the 400-year enslavement of Africans «sounds like a choice»,[312] before elaborating that his comment was in reference to mental enslavement and argued for free thought.[313] He later apologized for the comment.[314]

In late 2022, West made a series of antisemitic statements,[315] resulting in the termination of his collaborations, sponsorships, and partnerships with Vogue, CAA, Balenciaga, Gap, and Adidas.[316] West was widely condemned after appearing at a dinner hosted by Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago beside Nick Fuentes, a white nationalist.[315] In a subsequent December appearance on Alex Jones’s InfoWars, West praised Adolf Hitler, denied the Holocaust,[317] and identified as a Nazi.[19][20] Following the interview, West’s Twitter account was terminated after he posted an image depicting a swastika entangled within a Star of David.[318][319] Subsequently, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago rescinded West’s honorary degree.[320]

Personal life

West’s net worth was as high as $1.8 billion in 2021.[321] In October 2022, Forbes estimated his net worth to have dropped to $400 million in large part due to Adidas’s termination of their partnership following a series of public antisemitic statements.[322] In August 2021, West applied to have his legal name changed from «Kanye Omari West» to «Ye,» with no middle or last name;[323] he cited «personal reasons» for the change.[324] The request was granted in October.[325] West had alluded to wishing to change his name since 2018 and had used Ye as a nickname for several years prior,[324] stating in a 2018 interview that «ye» () was the most commonly used word in the Bible:[c] «In the Bible it means ‘you’. So, I’m you. I’m us. It’s us. It went from being Kanye, which means the only one, to just Ye.»[325]

Relationships and family

Kim Kardashian

In April 2012, West began dating reality television star Kim Kardashian, with whom he had already been long-time friends.[327][328] West and Kardashian became engaged in October 2013,[329][330] and married at Fort di Belvedere in Florence in May 2014.[331] Their private ceremony was subject to widespread mainstream coverage, with which West took issue.[332] The couple’s high-profile status and respective careers have resulted in their relationship becoming subject to heavy media coverage; The New York Times referred to their marriage as «a historic blizzard of celebrity».[333]

West and Kardashian have four children: North West (born June 2013),[334][335] Saint West (born December 2015),[336] Chicago West (born via surrogate in January 2018),[337][338] and Psalm West (born via surrogate in May 2019).[339][340] In July 2020, during a presidential campaign rally of his, West revealed that he had previously considered abortion during Kardashian’s first pregnancy but has since taken anti-abortion views.[341] In April 2015, West and Kardashian traveled to Jerusalem to have North baptized in the Armenian Apostolic Church at the Cathedral of St. James.[342][343] Their other children were all baptized at Etchmiadzin Cathedral, the mother church of the Armenian Church, in October 2019.[344]

In September 2018, West announced that he would be permanently moving back to Chicago to establish his Yeezy company headquarters there.[345][346] This did not actually occur, and West instead went on to purchase two ranches near Cody, Wyoming, where he recorded his eighth solo studio album, Ye. Kardashian resides with their children in a home that the now-divorced couple owns in California,[347] whereas West moved into a home across the street to continue to be near their children.[348] In fall 2021, West began the process of selling his Wyoming ranch.[349]

In July 2020, West acknowledged the possibility of Kardashian ending their marriage due to his adoption of anti-abortion views. Later that month, West wrote on Twitter that he had been attempting to divorce Kardashian. He also wrote that the Kardashian family was attempting «to lock [him] up».[341] In January 2021, CNN reported that the couple were discussing divorce.[347] A month later, Kardashian filed for divorce,[350] with the couple citing «irreconcilable differences», agreeing to joint custody of their children, and declining spousal support from each other.[351] The divorce was finalized in November 2022, and West was ordered to pay $200,000 in monthly child support and be responsible for half of the children’s medical, educational, and security expenses.[352]

Other relationships

West began an on-and-off relationship with the designer Alexis Phifer in 2002, and they became engaged in August 2006. They ended their 18-month engagement in 2008.[353] Phifer stated that the pair had split amicably and remained friends.[354] West dated model Amber Rose from 2008 until mid-2010.[355] In an interview following their split, West stated that he had to take «30 showers» before committing to his next relationship with Kim Kardashian.[356] In response, Rose stated that she had been «bullied» and «slut-shamed» by West throughout their relationship.[357]

In January 2022, actress Julia Fox confirmed in an Interview essay that she was dating West.[358] West continued to say that he wanted his «family back» and publicly lashed out at Kardashian’s new boyfriend, comedian Pete Davidson.[359] His treatment of Davidson and Kardashian has been described by commentators as harassment and abusive; the 64th Annual Grammy Awards dropped him as a performer in response to his «concerning online behavior».[360][361][362] Less than two months after confirming their relationship, Fox said that she and West had split up but remained on good terms.[363] She later said that she dated West purely to «give people something to talk about» during the COVID-19 pandemic[364] and to «get him off Kim’s case».[365]

In January 2023, it was reported that West had informally «married» Australian architect Bianca Censori, who works for West’s Yeezy brand, in a private ceremony in Beverly Hills.[366][367] The ceremony had no legal standing; the couple did not file for a marriage license.[368] In response to West’s subsequent trips to Australia to visit Censori’s family, Australian Minister for Education Jason Clare commented that West may be denied a visa due to his recent antisemitic remarks. The Executive Council of Australian Jewry further argued against granting West entry.[369]

Legal problems

In December 2006, Robert «Evel» Knievel sued the rapper for trademark infringement of his name and likeness in West’s video for «Touch the Sky». Knievel took issue with the «vulgar and offensive» and «sexually charged video» in which West takes on the persona of «Evel Kanyevel» that Knievel claimed damaged his reputation. The suit sought monetary damages and an injunction to stop distribution of the video.[370] West’s attorneys argued that the music video amounted to satire and therefore was covered under the First Amendment. Days before his death in November 2007, Knievel amicably settled the suit after being paid a visit by West, saying, «I thought he was a wonderful guy and quite a gentleman.»[371]

In 2014, after an altercation with a paparazzo at the Los Angeles Airport, West was sentenced to serve two years’ probation for a misdemeanor battery conviction, and was required to attend 24 anger management sessions, perform 250 hours of community service, and pay restitution to the photographer.[372] A separate civil lawsuit brought by the paparazzo was settled in 2015, a week before it was due for trial.[373] According to TMZ, an appeal to have West’s conviction expunged from his criminal record was granted by a judge in 2016.[374][375]

Religious beliefs

After the success of his song «Jesus Walks» from the album The College Dropout, West was questioned on his beliefs and said, «I will say that I’m spiritual. I have accepted Jesus as my Savior. And I will say that I fall short every day.»[376] In a 2008 interview with The Fader, West stated that «I’m like a vessel, and God has chosen me to be the voice and the connector».[377] In a 2009 interview with online magazine Bossip, West stated that he believed in God, but at the time felt that he «would never go into a religion».[378] In 2014, West referred to himself as a Christian during one of his concerts.[379] Kim Kardashian stated in September 2019: «He has had an amazing evolution of being born again and being saved by Christ.»[380] In October 2019, West said with respect to his past, «When I was trying to serve multiple gods it drove me crazy» in reference to the «god of ego, god of money, god of pride, the god of fame»,[381] and that «I didn’t even know what it meant to be saved» and that now «I love Jesus Christ. I love Christianity.»[14]

Politics

In September 2012, West donated $1,000 to Barack Obama’s re-election campaign, and in August 2015 he donated $2,700 to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign. He also donated $15,000 to the Democratic National Committee in October 2014.[382][383][384] In December 2016, West met with President-elect Donald Trump to discuss bullying, supporting teachers, modernizing curriculums, and violence in Chicago.[385][386] West subsequently stated he would have voted for Trump had he voted.[387] In February 2017, however, West deleted all his tweets about Trump in purported dislike of the new president’s policies, particularly the travel ban.[388] West reiterated his support for Donald Trump in April 2018.[389] In October 2018, West donated to progressive Chicago mayoral candidate Amara Enyia.[390] That same month, he voiced support for the Blexit movement,[391] a campaign started by conservative commentator Candace Owens, whom he had previously associated with.[392]

Mental health

On November 19, 2016, West abruptly ended a concert[393] before being committed at the recommendation of authorities to the UCLA Medical Center with hallucinations and paranoia.[394] While the episode was first described as one of «temporary psychosis» caused by dehydration and sleep deprivation, West’s mental state was abnormal enough for his 21 cancelled concerts to be covered by his insurance policy.[395] He was reportedly paranoid and depressed throughout the hospitalization,[396] but remained formally undiagnosed.[397] Some have speculated that the Paris robbery of his wife may have triggered the paranoia.[398] On November 30, West was released from the hospital.[399]

In his song «FML» and his featured verse on Vic Mensa’s song «U Mad», he refers to using the antidepressant medication Lexapro, and in his unreleased song «I Feel Like That», he mentions feeling many common symptoms of depression and anxiety.[400] In a 2018 interview, West said that he had become addicted to opioids when they were prescribed to him after liposuction. The addiction may have contributed to his nervous breakdown in 2016.[401] West said that he often has suicidal ideation.[402] West was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2016,[403] though his diagnosis was not made public until his 2018 album Ye.[404] He told President Donald Trump that it was a misdiagnosis.[405] He had reportedly accepted the diagnosis again by 2019,[406][407] but again suggested that it had been a misdiagnosis in 2022.[408] In December 2022, he suggested that he may be autistic.[409]

Musical influence

West is among the most critically acclaimed popular music artists of the 21st century, earning praise from music critics, fans, industry peers, and wider cultural figures.[410][411] In 2014, NME named him the third most influential artist in music.[412] Billboard senior editor Alex Gale declared West «absolutely one of the best, and you could make the argument for the best artist of the 21st century.»[1] Sharing similar sentiments, Dave Bry of Complex Magazine called West the twenty-first century’s «most important artist of any art form, of any genre.»[413] The Atlantic writer David Samuels commented, «Kanye’s power resides in his wild creativity and expressiveness, his mastery of form, and his deep and uncompromising attachment to a self-made aesthetic that he expresses through means that are entirely of the moment: rap music, digital downloads, fashion, Twitter, blogs, live streaming video.»[414] Joe Muggs of The Guardian argued that «there is nobody else who can sell as many records as West does […] while remaining so resolutely experimental and capable of stirring things up culturally and politically.»[415]

Rolling Stone credited West with transforming hip-hop’s mainstream, «establishing a style of introspective yet glossy rap» while deeming him «a producer who created a signature sound and then abandoned it to his imitators, a flashy, free-spending sybarite with insightful things to say about college, culture, and economics, an egomaniac with more than enough artistic firepower to back it up.»[416] Writing for Highsnobiety, Shahzaib Hussain stated that West’s first three albums «cemented his role as a progressive rap progenitor».[417] AllMusic editor Jason Birchmeier described West as «[shattering] certain stereotypes about rappers, becoming a superstar on his own terms without adapting his appearance, his rhetoric, or his music to fit any one musical mold».[199] Lawrence Burney of Noisey has credited West with the commercial decline of the gangsta rap genre that once dominated mainstream hip-hop.[418] The release of his third studio album has been described as a turning point in the music industry,[419] and is considered to have helped pave the way for new rappers who did not follow the hardcore-gangster mold to find wider mainstream acceptance.[420][421][422]

Hip-hop artists like Drake,[423] Nicki Minaj,[424] Travis Scott,[425] Lil Uzi Vert,[426] and Chance the Rapper[427] have acknowledged being influenced by West. Several other artists and music groups of various genres have named West as an influence on their work.[d]

Awards and achievements

West is the fourth-highest certified artist in the US by digital singles (69 million).[445] He had the most RIAA digital song certifications by a male artist in the 2000s (19),[446] and was the fourth best-selling digital songs artist of the 2000s in the US.[447] In Spotify’s first ten years from 2008 to 2018, West was the sixth most streamed artist, and the fourth fastest artist to reach one billion streams.[448] West has the joint-most consecutive studio album to debut at number one on the Billboard 200 (9).[449] He ranked third on Billboard‘s 2000s decade-end list of top producers[450] and has topped the annual Pazz & Jop critics’ poll the joint-most times (four albums).[451]

West has won 22 Grammys, holding the record of the second-most wins and nominations (68) for a rapper in the history of the ceremony.[citation needed] He has been the most nominated act at five ceremonies,[452] and has received the fourth-most wins overall in the 2000s.[453] In 2008, West became the first solo artist to have his first three albums receive nominations for Album of the Year.[454] West has won a Webby Award for Artist of the Year,[455] an Accessories Council Excellence Award for being a stylemaker,[456] International Man of the Year at the GQ Awards,[457] a Clio Award for The Life of Pablo Album Experience,[458] and an honour by The Recording Academy.[459] West is one of eight acts to have won the Billboard Artist Achievement Award.[460] In 2011, he became the first artist to win Best Male Hip-Hop Artist at the BET Awards three times.[citation needed] He also holds the most wins of a male artist for Video of the Year at the ceremony,[citation needed] and is the only person to have been awarded the Visionary Award at The BET Honors.[461] In 2015, he became the third rap act to win the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award.[8]

West’s first six solo studio albums were included on Rolling Stone‘s 2020 list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[462] Entertainment Weekly named The College Dropout the best album of the 2000s,[463] Complex named Graduation the best album released between 2002 and 2012,[464] 808s & Heartbreak was named by Rolling Stone as one of the 40 most groundbreaking albums of all time,[465] The A.V. Club named My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy the best album of the 2010s,[466] Yeezus was the most critically acclaimed album of 2013 according to Metacritic,[467] and The Life of Pablo was the first album to top the Billboard 200, go platinum in the US, and go gold in the UK, via streaming alone.[468][469]

Discography

Studio albums

- The College Dropout (2004)

- Late Registration (2005)

- Graduation (2007)

- 808s & Heartbreak (2008)

- My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010)

- Yeezus (2013)

- The Life of Pablo (2016)

- Ye (2018)

- Jesus Is King (2019)

- Donda (2021)

Collaborative albums

- Watch the Throne (2011) (with Jay-Z)

- Kids See Ghosts (2018) (with Kid Cudi, as Kids See Ghosts)

Compilation albums

- Cruel Summer (2012) (with GOOD Music)

Demo albums

- Donda 2 (2022)

Videography

- The College Dropout Video Anthology (2004)

- Late Orchestration (2006)

- VH1 Storytellers (2010)

- Runaway (2010)

- Jesus Is King (2019)

- Jeen-Yuhs (2022)

Tours

Headlining tours

- School Spirit Tour (2004)

- Touch the Sky Tour (2005–2006)

- Glow in the Dark Tour (2008)

- Watch the Throne Tour (with Jay-Z) (2011–2012)

- The Yeezus Tour (2013–2014)

- Saint Pablo Tour (2016)

Supporting tours

- Truth Tour (with Usher) (2004)

- Vertigo Tour (with U2) (2005–2006)

- A Bigger Bang (with The Rolling Stones) (2006)

Books

- Raising Kanye: Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar (2007)

- Thank You and You’re Welcome (2009)

- Through the Wire: Lyrics & Illuminations (2009)

- Glow in the Dark (2009)

See also

- Album era

- Black conservatism in the United States

- List of people with bipolar disorder

- List of Christian hip hop artists

- List of most-awarded music artists

Notes

- ^ a b Ye has been his legal name since late 2021 (see § Personal life).

- ^ Most biographies and reference works state that West was born in Atlanta, although some sources give his birthplace as Douglasville, a small city west of Atlanta.[21][22]

- ^ In the King James Bible, the most commonly used translation of the Christian Bible in the United States, the word that appears the most is not «ye», but rather «Lord» (not counting indefinite articles).[326]

- ^ Musical artists and groups naming West as an influence:

- Casey Veggies[428]

- Adele[429]

- Lily Allen[430]

- Daniel Caesar[431]

- Lorde[432]

- Rosalía[433]

- Halsey[434]

- Arctic Monkeys[435]

- Kasabian[436]

- MGMT[437]

- Yeah Yeah Yeahs[438]

- Fall Out Boy[439]

- James Blake[440]

- Daniel Lopatin[441]

- Tim Hecker[442]

- Rakim[443]

- John Legend[444]

References

- ^ a b c Ryan, Patrick (February 9, 2016). «Is Kanye West the greatest artist of the 21st century?». USA Today. Archived from the original on February 10, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ «New music review: Kanye West goes gospel with mixed results». Star Tribune. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ «The Year in Christian & Gospel Charts 2019: Kanye West Is Top Gospel Artist». Billboard. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ «Kanye West Biography (1977–)». Biography.com. 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Davis, Kimberly (June 2004). «The Many Faces of Kanye West». Ebony. p. 92. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ a b Tyrangiel, Josh (August 21, 2005). «Why You Can’t Ignore Kanye». Time. Archived from the original on April 1, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Ellie Abraham, Ellie (July 19, 2021). «Kanye West is rumoured to be dropping a new album this week – but not everyone’s convinced». The Independent. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Grein, Paul (August 12, 2018). «Missy Elliott to Become First Female Rapper to Receive MTV’s Video Vanguard Award». Billboard. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ «100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time». Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Tyrangiel, Josh (April 18, 2005). «The 2005 TIME 100 — Kanye West». Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Selby, Jenn (April 17, 2015). «Emma Watson and Kanye West named in TIME 100 most influential people of 2015». The Independent. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ «Instagram Restricts Kanye West’s Account and Deletes Content for Violating Policies». The Hollywood Reporter. October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Graham, Ruth (October 28, 2019). «Evangelicals Are Extremely Excited About Kanye’s Jesus Is King». Slate Magazine. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Schaffstall, Katherine (October 25, 2019). «Kanye West Unveils New ‘Jesus Is King’ Album; Talks «Cancel Culture» and «Christian Innovation»«. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ «Adidas cuts ties with rapper Kanye West over anti-Semitism». BBC News. October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ D’Zurilla, Christie (October 26, 2022). «Kanye West’s hits keep coming: Here are the companies that have cut ties with him». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ Limbong, Andrew (December 2, 2022). «Ye says ‘I see good things about Hitler’ on conspiracy theorist Alex Jones’ show». NPR. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Bort, Nikki McCann Ramirez,Ryan; Ramirez, Nikki McCann; Bort, Ryan (December 1, 2022). «Kanye to Alex Jones: ‘I Like Hitler’«. Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b «Kanye West praises Hitler, calls himself a Nazi in unhinged interview». The Times of Israel. December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Levin, Bess (December 1, 2022). «Kanye West, Donald Trump’s Dining Companion, Tells Alex Jones, «I’m a Nazi,» Lists Things He Loves About Hitler». Vanity Fair. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Borus, Audrey; Lynne, Douglas (2013). Kanye West: Grammy-Winning Hip-Hop Artist & Producer. ISBN 978-1-61783-623-7. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Revolt TV (June 8, 2018). «A timeline of Kanye West’s 41 years of excellence». Revolt. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Arney, Steve (March 8, 2006). «Kanye West Coming To Redbird». Pantagraph. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ a b Christian, Margena A. (May 14, 2007). «Dr. Donda West Tells How She Shaped Son To Be A Leader In Raising Kanye«. Jet. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ «About». Westar Waterworks, LLC t/a The Good Water Store and Café. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Tunison, Michael (December 7, 2006). «How’d You Like Your Water?». The Washington Post. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Borus, Audrey; Lynne, Douglas (2013). Kanye West: Grammy-Winning Hip-Hop Artist & Producer. ISBN 978-1-61783-623-7. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Dillon, Nancy (November 14, 2007). «Donda West gave her all to enrich son Kanye West’s life». New York Daily News. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ West, Donda (2007). Raising Kanye: Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar. New York City: Pocket Books. pp. 85–93. ISBN 978-1-4165-4470-8.

- ^ Mos, Corey (December 5, 2005). «College Dropout Kanye Tells High School Students Not To Follow in His Footsteps». MTV. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ^ «Kanye and His Mom Shared Special Bond». Chicago Tribune. November 13, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Calloway, Sway; Reid, Shaheem (February 20, 2004). «Kanye West: Kanplicated». MTV. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Dills, Todd (2007). Hess, Mickey (ed.). Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture. Vol. 2. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 555–578. ISBN 978-0-313-33904-2.

- ^ West, Donda, p. 106

- ^ «Photos: Kanye West’s Career Highs—and Lows 1 of 24». Rolling Stone. December 10, 2010. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ «Gee Starts Own Label». Hits Daily Double. December 21, 2012. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

«Gee, Is He Making Moves?». HitsDailyDouble. September 20, 2017. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020. - ^ a b Barber, Andrew (July 23, 2012). «93. Go-Getters «Let Em In» (2000)». Complex. Archived from the original on July 27, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem (September 30, 2005). «Music Geek Kanye’s Kast of Thousands». MTV. Archived from the original on April 15, 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2006.

- ^ a b Kanye West: Hip-Hop Biographies. Saddleback Education Publishing. 2013. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-62250-016-1.

- ^ a b Mitchum, Rob. Review: The College Dropout. Pitchfork. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^ «500 Greatest Albums of All Time: #464 (The Blueprint)». Rolling Stone. November 18, 2003. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Serpick, Evan. Kanye West. Rolling Stone Jann Wenner. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Reid, Shaheem (February 9, 2005). «Road to the Grammys: The Making Of Kanye West’s College Dropout». MTV. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^ Williams, Jean A (October 1, 2007). «Kanye West: The Man, the Music, and the Message. (Biography)». The Black Collegian. Archived from the original on January 25, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ a b Kearney, Kevin (September 30, 2005). Rapper Kanye West on the cover of Time: Will rap music shed its «gangster» disguise?. World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ «How Kanye West’s 2002 Car Crash Shaped His Entire Career». Yahoo-Finance. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ Kamer, Foster (March 11, 2013). «9. Kanye West, Get Well Soon … (2003)—The 50 Best Rapper Mixtapes». Complex. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem (December 10, 2002). «Kanye West Raps Through His Broken Jaw, Lays Beats For Scarface, Ludacris». MTV. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ Patel, Joseph (June 5, 2003). «Producer Kanye West’s Debut LP Features Jay-Z, ODB, Mos Def». MTV. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ Goldstein, Hartley (December 5, 2003). «Kanye West: Get Well Soon / I’m Good». PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ Ahmed, Insanul (September 21, 2011). «Kanye West × The Heavy Hitters, Get Well Soon (2003)—Clinton Sparks’ 30 Favorite Mixtapes». Complex. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ Kanye West—Through the Wire—Music Charts. aCharts.us. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Jones, Steve (February 10, 2005). «Kanye West runs away with ‘Jesus Walks’«. USA Today. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ a b Leland, John (August 13, 2004). «Rappers Are Raising Their Churches’ Roofs». The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ Montgomery, James (December 7, 2004). «Kanye Scores 10 Grammy Nominations; Usher And Alicia Keys Land Eight». MTV. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob (November 22, 2010). Review: My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy Archived December 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ «2004–2005 production credits». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ Brown, p. 120

- ^ a b Scaggs, Austin (September 20, 2007). «Kanye West: A Genius In Praise of Himself». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Perez, Rodrigo (August 12, 2005). «Kanye’s Co-Pilot, Jon Brion, Talks About The Making Of Late Registration». MTV. Viacom. Retrieved March 2, 2006.

- ^ Brown, p. 124

- ^ Knopper, Steve (November 15, 2005). «Kanye Couldn’t Save Fall». Rolling Stone. RealNetworks, Inc. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved November 27, 2005.

- ^ «Kanye West Unleashes Tirade After Losing at MTV Europe Music Awards». Fox News. November 3, 2006. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ «EMAs Shocker: Kanye Stage Invasion!». MTV. Archived from the original on June 3, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Olsen, Jan M. (November 3, 2006). «Kanye West Upset at MTV Video Award Loss». Fox News. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ Navaroli, Joel (September 29, 2007). «SNL Archives | Episodes | September 29, 2007 #13». SNL Archives. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem. 50 Cent Or Kanye West, Who Will Win? Nas, Timbaland, More Share Their Predictions. MTV. Viacom. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ Mayfield, Geoff (September 12, 2007). «Kanye Well Ahead of 50 Cent in First-Day Sales Race». Billboard. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan (September 20, 2007). «Kanye Caps Banner Week With Hot 100 Chart-Topper». Billboard. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Sasha (March 30, 2009). «Dance Revolution». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ «Entertainment | Kanye’s mother dies after surgery». BBC News. November 12, 2007. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ McGee, Tiffany. «Kanye West’s Fiancée ‘Sad’ Over Breakup». People. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ Thorogood, Tom. «Kanye West Opens Up His Heart». MTV UK. Viacom International Media Networks. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ Macia, Peter. «FADER 58: Kanye West Cover Story and Interview». The Fader. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ «Urban Review: Kanye West, 808s and Heartbreak«. The Observer. London. November 9, 2008. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem. «Kanye West Inspires The Question: Should Rappers Sing?». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ Montgomery, James (November 10, 2008). «New Albums From Kanye West, Ludacris, Killers To Get Rare Monday Release on November 24». MTV. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ «T.I. Back Atop Hot 100, Kanye Debuts High». Billboard. July 2, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ Heartless: Hot 100 Charts Archived May 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Billboard. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ Carmichael, Emma (September 21, 2011). «Kanye’s ‘808s’: How A Machine Brought Heartbreak To Hip Hop». The Awl. Archived from the original on December 29, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Respers, Lisa (September 14, 2009). «Anger over West’s disruption at MTV awards». CNN. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ «Kanye West Storms the VMAs Stage During Taylor Swift’s Speech». Rolling Stone. September 13, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ Vozick, Simon (September 13, 2009). «Kanye West interrupts Taylor Swift’s VMAs moment: What was he thinking? by Simon Vozick-Levinson». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 18, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ^ «2009 MTV Video Music Awards—Best Female Video». MTV. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Martens, Todd; Villarreal, Yvonne (September 15, 2009). «Kanye West expresses Swift regret on blog and ‘The Jay Leno Show’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ «Adam Lambert, Donald Trump, Joe Jackson Slam Kanye West’s VMA Stunt». MTV. September 13, 2009. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ «Obama calls Kanye West a jackass». BBC News. September 16, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Gavin, Patrick (September 15, 2009). «Obama calls Kanye ‘jackass’«. The Politico. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ «Audio: President Obama Calls Kanye West a ‘Jackass’«. People. September 15, 2009. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ «Obama Calls Kanye West a ‘Jackass’«. Fox News Channel. September 15, 2009. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (September 16, 2009). «Kanye West’s VMA Interruption Gives Birth To Internet Photo Meme». MTV. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ^ Booth, Jenny (September 14, 2009). «Kanye West spoils the show at MTV awards». The Times. London. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (September 15, 2009). «Taylor Swift Tells ‘The View’ Kanye West Hasn’t Contacted Her. The country star discusses her reaction to the VMA incident». MTV. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ «Taylor Swift visits ‘The View,’ accepts Kanye apology». New York Post. May 15, 2009. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ «Kanye calls Taylor Swift after ‘View’ appearance». Today. September 15, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ «VIDEO: Kanye West Backtracks On Taylor Swift Apology | Radar Online». November 8, 2010.

- ^ «Kanye West Backtracks on Taylor Swift Apology». Archived from the original on August 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Callahan-Bever, Noah (November 2010). Kanye West: Project Runaway. Complex. Retrieved November 30, 2010. Archived December 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hermes, Will (October 25, 2010). Lost in the World by Kanye West feat. Bon Iver and Gil Scott-Heron | Rolling Stone Music. Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Fastenberg, Dan (December 9, 2010). «Kanye’s Beautiful, Dark Twittered Fantasy—The Top 10 Everything of 2010». Time. New York. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Kanye West Album & Song Chart History—Hot 100. Billboard. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Concepcion, Mariel (October 7, 2010). «Kanye West Premieres 35-Minute-Long ‘Runaway’ Video in London». Billboard, Inc. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Reiff, Corbin (November 22, 2015). «Cataloging G.O.O.D. Fridays: Kanye West’s beautiful dark twisted promotional campaign». The A.V. Club. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ «Searchable Database». Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Search: Kanye West. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Abebe, Nitsuh (December 1, 2011). «Explaining the Kanye Snub, and Other Thoughts on the Grammy Nominations». New York. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jeff (April 18, 2011). «Kanye West Delivers One of Greatest Hip-Hop Sets of All Time at Coachella». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ Gissen, Jesse (August 8, 2011). «Jay-Z & Kanye West Miraculously Manage to Keep Watch the Throne Leak-Free». XXL. Harris Publications. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ^ Perpetua, Matthew (August 8, 2011). «Jay-Z and Kanye West Avoid ‘Watch the Throne’ Leak». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ^ Doherty, Maggie (October 28, 2011). «Jay-Z & Kanye West Tease ‘Watch The Throne’ Tour Set List: Watch». Billboard. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Caramanica, Jon (June 11, 2013). «Behind Kanye’s Mask». The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Dombal, Ryan (June 24, 2013). «The Yeezus Sessions». Pitchfork. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (June 16, 2013). «Kanye West’s ‘Yeezus’ an uneasy listen». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 17, 2013.