- О других людях с этой фамилией см. Ришельё

| Арма́н Жан дю Плесси́, герцог де Ришельё Armand-Jean du Plessis, duc de Richelieu |

|

|

|

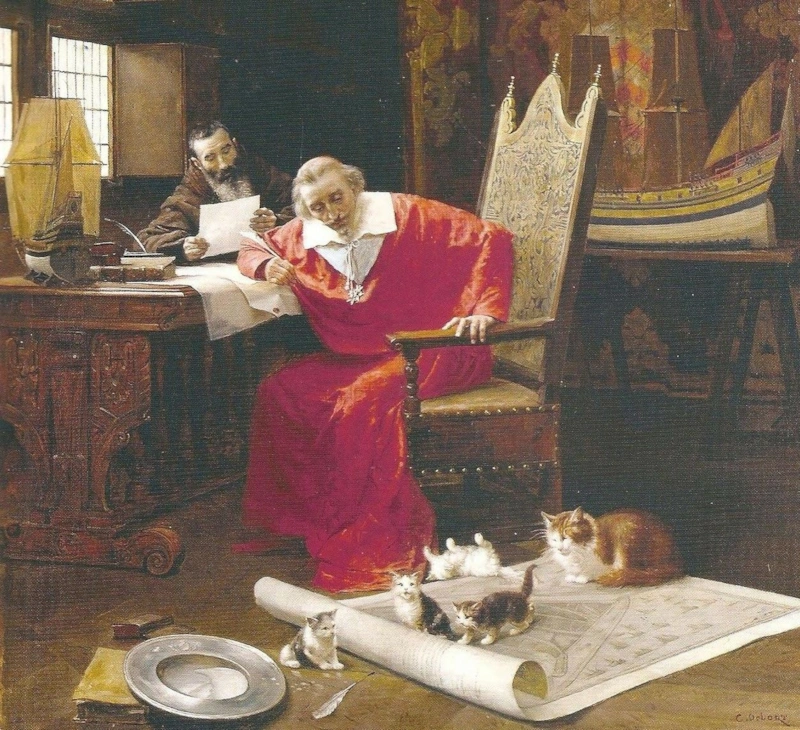

| Портрет работы Филиппа де Шампеня 1637 года | |

|

Первый Главный министр французского короля |

|

|---|---|

| 12 августа 1624 — 4 декабря 1642 | |

| Рождение: | 9 сентября 1585 Париж, Франция |

| Смерть: | 4 декабря 1642 Париж, Франция |

Герб кардинала Ришельё

Арма́н Жан дю Плесси́, герцог де Ришельё, Кардина́л Ришелье́, прозвище «Красный кардинал» (фр. Armand-Jean du Plessis, duc de Richelieu; 9 сентября 1585, Париж — 4 декабря 1642, Париж) — французский кардинал, аристократ и государственный деятель. Кардинал Ришелье был государственным секретарём с 1616 года и главой правительства («главным министром короля») с 1624 года до своей смерти.

Содержание

- 1 Биография

- 2 Факты и память

- 3 Сочинения и фразы Ришельё

- 4 Ришельё в искусстве

- 4.1 Художественная литература

- 4.2 Кинематограф

- 5 Литература

- 6 Примечания

- 7 Ссылки

Биография

Родился в Париже, в приходе Сент-Эсташ, на улице Булуа (или Булуар). Крещён был только 5 мая 1586 года, через полгода после рождения, — по причине «тщедушного, болезненного» здоровья. Семья дю Плесси де Ришелье принадлежала к родовитому дворянству Пуату. Отец — Франсуа дю Плесси де Ришелье — видный государственный деятель времен правления Генриха III, 31 декабря 1585 года ставший рыцарем ордена Святого Духа. Во Франции насчитывалось всего 140 рыцарей этого ордена, представлявших 90 фамилий. Мать — Сюзанна де Ла Порт. Крестными отцами Ришелье были два маршала Франции — Арман де Гонто-Бирон и Жан д’Омон, давшие ему свои имена. Крёстная мать — его бабка Франсуаза де Ришельё, урождённая Рошешуар.

Окончил Наваррский коллеж. Был посвящён в сан епископа Люсонского 17 апреля 1607 года. Защитил диссертацию в Сорбонне на степень доктора богословия 29 октября 1607 года. 21 декабря 1608 года вступил во владение Люсонским епископатом. Депутат Генеральных штатов 1614 года от духовенства. Выступал за укрепление королевской власти. Был замечен при дворе и в 1615 году, после женитьбы Людовика XIII на Анне Австрийской, назначен духовником молодой королевы. После проведения успешных переговоров с мятежным принцем Конде вошёл в узкий круг личных советников королевы-регентши Марии Медичи. В ноябре 1616 назначен на пост государственного секретаря. 19 мая 1617 года. Ришельё становится главой совета королевы-матери. 7 апреля 1618 года был сослан в Авиньон. Глава французского правительства при Людовике XIII (с 1624 до конца жизни). 29 декабря 1629 года кардинал, получив титул генерал-лейтенанта Его Величества, отправился командовать войском в Италию, где подтвердил свои военные таланты и познакомился с Джулио Мазарини. 5 декабря 1642 года король Людовик XIII назначил Джулио Мазарини главным министром. Об этом человеке, которого в интимном кругу называли «брат Палаш (Colmardo)»[1], сам Ришельё сказал так:

Я знаю лишь одного человека, способного стать моим преемником, хотя он иностранец.

Историк Франсуа Блюш констатирует:

Двумя самыми известными деяниями министра Ришельё являются взятие Ла-Рошели (1628) и «День одураченных» (1630).

Так, вслед за будущим академиком, острословом Гильомом Ботрю, графом де Серрана, стали называть понедельник 11 ноября 1630 года. В этот день Ришельё готовил свою отставку; королева-мать Мария Медичи и хранитель печати Луи де Марильяк были уверены в своей победе, но вечером в Версале кардинал узнал от короля, что в опале оказалась происпанская «партия святош».

В основу своей политики Ришелье положил выполнение программы Генриха IV: укрепление государства, его централизация, обеспечение главенства светской власти над церковью и центра над провинциями, ликвидация аристократической оппозиции, противодействие испано-австрийской гегемонии в Европе. Главный итог государственной деятельности Ришелье состоит в утверждении абсолютизма во Франции. Холодный, расчетливый, весьма часто суровый до жестокости, подчинявший чувство рассудку, кардинал Ришелье крепко держал в своих руках бразды правления и, с замечательной зоркостью и дальновидностью замечая грозящую опасность, предупреждал ее при самом появлении.

Факты и память

- Кардинал своей жалованной грамотой от 29 января 1635 года основал знаменитую Французскую Академию, существующую до сих пор и имеющую 40 членов — «бессмертных». Как указывалось в грамоте, Академия создана, «чтобы сделать французский язык не только элегантным, но и способным трактовать все искусства и науки».

- Кардинал Ришельё основал город имени самого себя. Ныне этот город так и называется — Ришельё (en:Richelieu, Indre-et-Loire). Город располагается в регионе Сантр (Centre), в департаменте Эндр и Луара.

- Во Франции существовал тип линкоров Ришельё, названный в честь кардинала.

- В 1987 году во Франции закончено строительство авианосца «Ришельё», который в 1988 году был переименован в «Шарль де Голль» и спущен на воду в 2001 году.

Сочинения и фразы Ришельё

- Le testament politique ou les maximes d’etat.

- Рус. пер.: Ришельё А.-Ж. дю Плесси. Политическое завещание. Принципы управления государством. — М.: Ладомир, 2008. — 500 с. — ISBN 978-5-86218-434-1.

- Memoires (изд. 1723).

- Рус. пер.: Ришелье. Мемуары.

- — М.: АСТ, Люкс, Наш дом — L’Age d’Homme, 2005. — 464 с. — Серия «Историческая библиотека». — ISBN 5-17-029090-Х, ISBN 5-9660-1434-5, ISBN 5-89136-004-7.

- — М.: АСТ, АСТ Москва, Наш дом — L’Age d’Homme, 2008. — 464 с. — Серия «Историческая библиотека». — ISBN 978-5-17-051468-7, ISBN 978-5-9713-8064-1, ISBN 978-5-89136-004-4.

Также Ришелье является автором фраз: «Моей первой целью было величие короля, моей второй целью было могущество государства» и «Кто владеет информацией, тот владеет миром»

Ришельё в искусстве

Художественная литература

Кардинал является одним из героев популярного романа Александра Дюма «Три мушкетёра».

Кинематограф

- Кардинал изображён в экранизациях романа «Три мушкетёра».

- Во Франции в 1977 году был снят биографический телевизионный шестисерийный фильм о кардинале.

Литература

- Блюш Ф. Ришелье / Серия «ЖЗЛ». — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2006. — ISBN 5-235-02904-6.

- Черкасов П. П. Кардинал Ришелье. Портрет государственного деятеля. — М.: Олма-пресс, 2002. — ISBN 5224003766.

- Черкасов П. П. Кардинал Ришелье. — М.: Международные отношения, 1990. — 384 с. — ISBN 5-7133-0206-7.

- Кнехт Р. Дж. Ришелье. — Ростов-на-Дону: Изд-во «Феникс», 1997. — 384 с. — ISBN 5-85880-456-Х.

Примечания

- ↑ Филипп Эрланже «Ришелье»

Ссылки

- Ришельё в БСЭ

- Ришелье Арман Жан в ЭСБЕ

- Ришельё в энциклопедии «Кругосвет»

- «Эхо Москвы», передача «Всё так»: Кардинал Ришелье

- Ришельё в БСЭ

- Кардинал Ришелье [Великие]

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

«The Red Eminence» redirects here. For the Soviet statesman also known by that epithet, see Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov.

|

His Grand Eminence The Cardinal Duke of Richelieu COHS |

|

|---|---|

Cardinal de Richelieu by Philippe de Champaigne, 1642 (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg) |

|

| First Minister of State | |

| In office 12 August 1624 – 4 December 1642 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | The Marquis of Ancre Vacant (1617–1624) |

| Succeeded by | Jules Mazarin |

| Governor of Brittany | |

| In office 17 April 1632 – 4 December 1642 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | The Marquis of Thémines [fr] |

| Succeeded by | Queen Anne |

| Grand Master of the Navigation | |

| In office 1626–1642 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | The Duke of Montmorency |

| Succeeded by | The Marquis of Brézé |

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 30 November 1616 – 24 April 1617 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | Claude Mangot [fr] |

| Succeeded by | The Marquis of Sillery |

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 25 November 1616 – 24 April 1617 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | Claude Mangot |

| Succeeded by | Nicolas Brulart de Sillery |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Armand Jean du Plessis 9 September 1585 |

| Died | 4 December 1642 (aged 57) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Sorbonne Chapel |

| Alma mater | College of Navarre |

| Profession | Clergyman, statesman |

| Cardinal, Bishop of Luçon | |

| Metropolis | Bordeaux |

| Diocese | Luçon |

| See | Luçon |

| Appointed | 18 December 1606 |

| Installed | 17 April 1607 |

| Term ended | Before 29 April 1624 |

| Predecessor | François Yver |

| Successor | Emery de Bragelongne |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 17 April 1607 by Anne d’Escars de Givry |

| Created cardinal | 5 September 1622 by Pope Gregory XV |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest |

| Personal details | |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms | |

| Styles of Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Grand Eminence |

| Spoken style | Your Grand Eminence |

| Informal style | Cardinal |

| See | Luçon |

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (French: [aʁmɑ̃ ʒɑ̃ dy plɛsi]; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu,[a] was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as l’Éminence rouge, or «the Red Eminence«, a term derived from the title «Eminence» applied to cardinals and the red robes that they customarily wear.

Consecrated a bishop in 1607, Richelieu was appointed Foreign Secretary in 1616. He continued to rise through the hierarchy of both the Catholic Church and the French government by becoming a cardinal in 1622 and chief minister to King Louis XIII of France in 1624. He retained that office until his death in 1642, when he was succeeded by Cardinal Mazarin, whose career he had fostered. He also became engaged in a bitter dispute with the king’s mother, Marie de Médicis, who had once been a close ally.

Richelieu sought to consolidate royal power and restrained the power of the nobility in order to transform France into a strong centralized state. In foreign policy, his primary objectives were to check the power of the Habsburg dynasty in Spain and Austria and to ensure French dominance in the Thirty Years’ War after the conflict engulfed Europe. Despite suppressing the Huguenot rebellions, he made alliances with Protestant states like the Kingdom of England and the Dutch Republic to help him achieve his goals. However, although he was a powerful political figure in his own right, events such as the Day of the Dupes, or Journée des Dupes, showed that Richelieu’s power was still dependent on the king’s confidence.

An alumnus of the University of Paris and headmaster of the College of Sorbonne, Richelieu renovated and extended the institution. He was famous for his patronage of the arts and founded the Académie Française, the learned society responsible for matters pertaining to the French language. As an advocate for Samuel de Champlain and New France, he founded the Compagnie des Cent-Associés; he also negotiated the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye under which Quebec City returned to French rule after its loss in 1629.

Richelieu is also known for being the inventor of the table knife. Annoyed by the bad manners that were commonly displayed at the dining table by users of sharp knives, who would often use them to pick their teeth,[6] in 1637 Richelieu ordered that all of the knives on his dining table have their blades dulled and their tips rounded. The design quickly became popular throughout France and later spread to other countries.[7]

Richelieu has frequently been depicted in popular fiction, principally as the lead villain in Alexandre Dumas’s 1844 novel The Three Musketeers and its numerous film adaptations.

Early life[edit]

Born in Paris on 9 September 1585, Armand du Plessis was the fourth of five children and the last of three sons: he was delicate from childhood, and suffered frequent bouts of ill-health throughout his life. His family belonged to the lesser nobility of Poitou:[8] his father, François du Plessis, seigneur de Richelieu, was a soldier and courtier who served as the Grand Provost of France,[9] and his mother, Susanne de La Porte, was the daughter of a famous jurist.[10]

When he was five years old, Richelieu’s father died of fever in the French Wars of Religion,[11] leaving the family in debt; with the aid of royal grants, however, the family was able to avoid financial difficulties. At the age of nine, young Richelieu was sent to the College of Navarre in Paris to study philosophy.[12] Thereafter, he began to train for a military career.[13] His private life seems to have been typical for a young officer of the era: in 1605, aged twenty, he was treated by Théodore de Mayerne for gonorrhea.[14]

Henry III had rewarded Richelieu’s father for his participation in the Wars of Religion by granting his family the Bishopric of Luçon.[15] The family appropriated most of the revenues of the bishopric for private use; they were, however, challenged by clergymen who desired the funds for ecclesiastical purposes. To protect the important source of revenue, Richelieu’s mother proposed to make her second son, Alphonse, the bishop of Luçon.[16] Alphonse, who had no desire to become a bishop, became instead a Carthusian monk.[17] Thus, it became necessary that the younger Richelieu join the clergy. He had strong academic interests and threw himself into studying for his new post.[18]

In 1606, Henry IV nominated Richelieu to become Bishop of Luçon.[16] As Richelieu had not yet reached the canonical minimum age, it was necessary that he journey to Rome for a special dispensation from Pope Paul V. This secured, Richelieu was consecrated bishop in April 1607. Soon after he returned to his diocese in 1608, Richelieu was heralded as a reformer.[19] He became the first bishop in France to implement the institutional reforms prescribed by the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563.[20]

At about this time, Richelieu became a friend of François Leclerc du Tremblay (better known as «Père Joseph« or «Father Joseph»), a Capuchin friar, who would later become a close confidant. Because of his closeness to Richelieu, and the grey colour of his robes, Father Joseph was also nicknamed L’éminence grise («the Grey Eminence»). Later, Richelieu often used him as an agent during diplomatic negotiations.[21]

Rise to power[edit]

In 1614, the clergymen of Poitou asked Richelieu to be one of their representatives to the Estates-General.[22] There, he was a vigorous advocate of the Church, arguing that it should be exempt from taxes and that bishops should have more political power. He was the most prominent clergyman to support the adoption of the decrees of the Council of Trent throughout France;[23] the Third Estate (commoners) was his chief opponent in this endeavour. At the end of the assembly, the First Estate (the clergy) chose him to deliver the address enumerating its petitions and decisions.[24] Soon after the dissolution of the Estates-General, Richelieu entered the service of King Louis XIII’s wife, Anne of Austria, as her almoner.[25]

Richelieu advanced politically by faithfully serving the Queen-Mother’s favourite, Concino Concini, the most powerful minister in the kingdom.[26] In 1616, Richelieu was made Secretary of State, and was given responsibility for foreign affairs.[24] Like Concini, the Bishop was one of the closest advisors of Louis XIII’s mother, Marie de Médicis. The Queen had become Regent of France when the nine-year-old Louis ascended the throne; although her son reached the legal age of majority in 1614, she remained the effective ruler of the realm.[27] However, her policies, and those of Concini, proved unpopular with many in France. As a result, both Marie and Concini became the targets of intrigues at court; their most powerful enemy was Charles de Luynes.[28] In April 1617, in a plot arranged by Luynes, Louis XIII ordered that Concini be arrested, and killed should he resist; Concini was consequently assassinated, and Marie de Médicis overthrown.[29] His patron having died, Richelieu also lost power; he was dismissed as Secretary of State, and was removed from the court.[29] In 1618, the King, still suspicious of the Bishop of Luçon, banished him to Avignon. There, Richelieu spent most of his time writing; he composed a catechism entitled L’Instruction du chrétien.[30]

In 1619, Marie de Médicis escaped from her confinement in the Château de Blois, becoming the titular leader of an aristocratic rebellion. The King and the duc de Luynes recalled Richelieu, believing that he would be able to reason with the Queen. Richelieu was successful in this endeavour, mediating between her and her son.[31] Complex negotiations bore fruit when the Treaty of Angoulême was ratified; Marie de Médicis was given complete freedom, but would remain at peace with the King. The Queen-Mother was also restored to the royal council.[32]

After the death of the King’s favourite, the duc de Luynes, in 1621, Richelieu rose to power quickly. The year after, the King nominated Richelieu for a cardinalate, which Pope Gregory XV accordingly granted in September 1622.[33] Crises in France, including a rebellion of the Huguenots, rendered Richelieu a nearly indispensable advisor to the King. After he was appointed to the royal council of ministers on 29 April 1624,[34] he intrigued against the chief minister, Charles, duc de La Vieuville.[31] On 12 August of the same year, La Vieuville was arrested on charges of corruption, and Cardinal Richelieu took his place as the King’s principal minister the following day, although the Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld nominally remained president of the council (Richelieu was officially appointed president in November 1629).[35]

Chief minister[edit]

Jean Warin, Cardinal de Richelieu 1622 (obverse), 1631

Cardinal Richelieu’s policy involved two primary goals: centralization of power in France[36] and opposition to the Habsburg dynasty (which ruled in both Austria and Spain).[37] He saw the reestablishment of the Catholic orthodoxy as a political maneuver of the Habsburg and Austrian States which is detrimental to the French national interests.[38]

Shortly after he became Louis’ principal minister, he was faced with a crisis in Valtellina, a valley in Lombardy (northern Italy). To counter Spanish designs on the territory, Richelieu supported the Protestant Swiss canton of Grisons, which also claimed the strategically important valley. The Cardinal deployed troops to Valtellina, from which the Pope’s garrisons were driven out.[39] Richelieu’s early decision to support a Protestant canton against the Pope was a foretaste of the purely diplomatic power politics he would espouse in his foreign policy.

To further consolidate power in France, Richelieu sought to suppress the influence of the feudal nobility. In 1626, he abolished the position of Constable of France and ordered all fortified castles razed, with the exception only of those needed to defend against invaders.[40] Thus he stripped the princes, dukes, and lesser aristocrats of important defences that could have been used against the King’s armies during rebellions. As a result, Richelieu was hated by most of the nobility.

Another obstacle to the centralization of power was religious division in France. The Huguenots, one of the largest political and religious factions in the country, controlled a significant military force, and were in rebellion.[41] Moreover, the King of England, Charles I, declared war on France in an attempt to aid the Huguenot faction. In 1627, Richelieu ordered the army to besiege the Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle; the Cardinal personally commanded the besieging troops.[42] English troops under the Duke of Buckingham led an expedition to help the citizens of La Rochelle, but failed abysmally. The city, however, remained firm for over a year before capitulating in 1628.

Although the Huguenots suffered a major defeat at La Rochelle, they continued to fight, led by Henri, duc de Rohan. Protestant forces, however, were defeated in 1629; Rohan submitted to the terms of the Peace of Alais.[43] As a result, religious toleration for Protestants, which had first been granted by the Edict of Nantes in 1598, was permitted to continue, but the Cardinal abolished their political rights and protections.[43] Rohan was not executed (as were leaders of rebellions later in Richelieu’s tenure); in fact, he later became a commanding officer in the French army.

Habsburg Spain exploited the French conflict with the Huguenots to extend its influence in northern Italy. It funded the Huguenot rebels to keep the French army occupied, meanwhile expanding its Italian dominions. Richelieu, however, responded aggressively; after La Rochelle capitulated, he personally led the French army to northern Italy to restrain Spain. On 26 November 1629, he was created duc de Richelieu and a Peer of France.

In the next year, Richelieu’s position was seriously threatened by his former patron, Marie de Médicis. Marie believed that the Cardinal had robbed her of her political influence; thus, she demanded that her son dismiss the chief minister.[44] Louis XIII was not, at first, averse to such a course of action, as he personally disliked Richelieu.[24] Despite this, the persuasive statesman was able to secure the king as an ally against his own mother. On 11 November 1630, Marie de Médicis and the King’s brother, Gaston, duc d’Orléans, secured the King’s agreement for the dismissal. Richelieu, however, was aware of the plan, and quickly convinced the King to repent.[45] This day, known as the Day of the Dupes, was the only one on which Louis XIII took a step toward dismissing his minister. Thereafter, the King was unwavering in his political support for him.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, Marie de Médicis was exiled to Compiègne. Both Marie and the duc d’Orléans continued to conspire against Richelieu, but their schemes came to nothing. The nobility also remained powerless. The only important rising was that of Henri, duc de Montmorency in 1632; Richelieu, ruthless in suppressing opposition, ordered the duke’s execution. In 1634, the Cardinal had one of his outspoken critics, Urbain Grandier, burned at the stake in the Loudun affair. These and other harsh measures were orchestrated by Richelieu to intimidate his enemies. He also ensured his political security by establishing a large network of spies in France as well as in other European countries.[citation needed]

-

On the «Day of the Dupes» in 1630, it appeared that Marie de Médicis had secured Richelieu’s dismissal. Richelieu, however, survived the scheme, and Marie was exiled as a result.

Thirty Years’ War[edit]

Before Richelieu’s ascent to power, most of Europe had become enmeshed in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). France was not openly at war with the Habsburgs, who ruled Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, so subsidies and aid were provided secretly to their adversaries.[46] He considered the Dutch Republic as one of France’s most important allies, for it bordered directly with the Spanish Netherlands and was right in the middle of the Eighty Years’ War with Spain at that time. Luckily for him, Richelieu was a bon français, just like the king, who had already decided to subsidize the Dutch to fight against the Spanish via the Treaty of Compiègne in June 1624, prior to Richelieu’s appointment to First Minister in August.[47] That same year, a military expedition, secretly financed by France and commanded by Marquis de Coeuvres, started an action with the intention of liberating the Valtelline from Spanish occupation. In 1625, Richelieu also sent money to Ernst von Mansfeld, a famous mercenary general operating in Germany in English service. However, in May 1626, when war costs had almost ruined France, king and cardinal made peace with Spain via the Treaty of Monçon.[48] This peace quickly broke down after tensions due to the War of the Mantuan Succession.[49]

In 1629, Emperor Ferdinand II subjugated many of his Protestant opponents in Germany. Richelieu, alarmed by Ferdinand’s growing influence, incited Sweden to intervene, providing money.[50] In the meantime, France and Spain remained hostile due to Spain’s ambitions in northern Italy. At that time northern Italy was a major strategic region in Europe’s balance of power, serving as a link between the Habsburgs in the Empire and in Spain. Had the imperial armies dominated this region, France would have been threatened by Habsburg encirclement. Spain was meanwhile seeking papal approval for a universal monarchy. When in 1630 French diplomats in Regensburg agreed to make peace with Spain, Richelieu refused to support them. The agreement would have prohibited French interference in Germany. Therefore, Richelieu advised Louis XIII to refuse to ratify the treaty. In 1631, he allied France to Sweden, who had just invaded the empire, in the Treaty of Bärwalde.[50]

Military expenses placed a considerable strain on royal revenues. In response, Richelieu raised the gabelle (salt tax) and the taille (land tax).[51] The taille was enforced to provide funds to raise armies and wage war. The clergy, nobility, and high bourgeoisie either were exempt or could easily avoid payment, so the burden fell on the poorest segment of the nation. To collect taxes more efficiently, and to keep corruption to a minimum, Richelieu bypassed local tax officials, replacing them with intendants (officials in the direct service of the Crown).[52] Richelieu’s financial scheme, however, caused unrest among the peasants; there were several uprisings in 1636 to 1639.[53] Richelieu crushed the revolts violently, and dealt with the rebels harshly.[54]

Because he openly aligned France with Protestant powers, Richelieu was denounced by many as a traitor to the Roman Catholic Church. Military action, at first, was disastrous for the French, with many victories going to Spain and the Empire.[55] Neither side, however, could obtain a decisive advantage, and the conflict lingered on after Richelieu’s death. Richelieu was instrumental in redirecting the Thirty Years’ War from the conflict of Protestantism versus Catholicism to that of nationalism versus Habsburg hegemony.[56] In this conflict France effectively drained the already overstretched resources of the Habsburg empire and drove it inexorably towards bankruptcy.[57] The defeat of Habsburg forces at the Battle of Lens in 1648, coupled with their failure to prevent a French invasion of Catalonia, effectively spelled the end for Habsburg domination of the continent, and for the personal career of Spanish prime minister Olivares.[57] Indeed, in the subsequent years it would be France, under the leadership of Louis XIV, who would attempt to fill the vacuum left by the Habsburgs in the Spanish Netherlands and supplant Spain as the dominant European power.[citation needed]

New World[edit]

When Richelieu came to power, New France, where the French had a foothold since Jacques Cartier, had no more than 100 permanent European inhabitants.[58] Richelieu encouraged Louis XIII to colonize the Americas by the foundation of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France in imitation of the Dutch West India Company. Unlike the other colonial powers, France encouraged a peaceful coexistence in New France between Natives and Colonists and sought the integration of Indians into colonial society.[59][failed verification][60] Samuel de Champlain, governor of New France at the time of Richelieu, saw intermarriage between French and Indians as a solution to increase population in its colony.[61] Under the guidance of Richelieu, Louis XIII issued the Ordonnance of 1627 by which the Indians, converted to Catholicism, were considered as «natural Frenchmen»:

The descendants of the French who are accustomed to this country [New France], together with all the Indians who will be brought to the knowledge of the faith and will profess it, shall be deemed and renowned natural Frenchmen, and as such may come to live in France when they want, and acquire, donate, and succeed and accept donations and legacies, just as true French subjects, without being required to take letters of declaration of naturalization.[62]

The 1666 census of New France, conducted some 20 years after the death of Cardinal Richelieu, showed a population of 3,215 habitants in New France, many more than there had been only a few decades earlier, but also a great difference in the number of men (2,034) and women (1,181).[63]

Final years[edit]

Towards the end of his life, Richelieu alienated many people, including Pope Urban VIII. Richelieu was displeased by the Pope’s refusal to name him the papal legate in France;[64] in turn, the Pope did not approve of the administration of the French church, or of French foreign policy. However, the conflict was largely resolved when the Pope granted a cardinalate to Jules Mazarin, one of Richelieu’s foremost political allies, in 1641. Despite troubled relations with the Roman Catholic Church, Richelieu did not support the complete repudiation of papal authority in France, as was advocated by the Gallicanists.[65]

As he neared death, Richelieu faced a plot that threatened to remove him from power. The cardinal had introduced a young man named Henri Coiffier de Ruzé, marquis de Cinq-Mars to Louis XIII’s court.[66] The Cardinal had been a friend of Cinq-Mars’s father.[66] More importantly, Richelieu hoped that Cinq-Mars would become Louis’s favourite, so that he could indirectly exercise greater influence over the monarch’s decisions. Cinq-Mars had become the royal favourite by 1639, but, contrary to Cardinal Richelieu’s belief, he was not easy to control. The young marquis realized that Richelieu would not permit him to gain political power.[67] In 1641, he participated in the comte de Soissons’s failed conspiracy against Richelieu, but was not discovered.[68] Then, the following year, he schemed with leading nobles (including the King’s brother, the duc d’Orléans) to raise a rebellion; he also signed a secret agreement with the King of Spain, who promised to aid the rebels.[69] Richelieu’s spy service, however, discovered the plot, and the Cardinal received a copy of the treaty.[70] Cinq-Mars was promptly arrested and executed; although Louis approved the use of capital punishment, he grew more distant from Richelieu as a result.[citation needed]

However, Richelieu was now dying. For many years he had suffered from recurrent fevers (possibly malaria), strangury, intestinal tuberculosis with fistula, and migraine. Now his right arm was suppurating with tubercular osteitis, and he coughed blood (after his death, his lungs were found to have extensive cavities and caseous necrosis). His doctors continued to bleed him frequently, further weakening him.[71] As he felt his death approaching, he named Mazarin, one of his most faithful followers, to succeed him as chief minister to the King.[72]

Richelieu died on 4 December 1642, aged 57. His body was embalmed and interred at the church of the Sorbonne. During the French Revolution, the corpse was removed from its tomb, and the mummified front of his head, having been removed and replaced during the original embalming process, was stolen. It ended up in the possession of Nicholas Armez of Brittany by 1796, and he occasionally exhibited the well-preserved face. His nephew, Louis-Philippe Armez, inherited it and also occasionally exhibited it and lent it out for study. In 1866, Napoleon III persuaded Armez to return the face to the government for re-interment with the rest of Richelieu’s body. An investigation of subsidence of the church floor enabled the head to be photographed in 1895.[73][74]

Arts and culture[edit]

Richelieu was a famous patron of the arts. An author of various religious and political works (most notably his Political Testament), he sent his agents abroad[75] in search of books and manuscripts for his unrivaled library, which he specified in his will – leaving it to Armand Jean de Vignerot du Plessis, his great-nephew, fully funded – should serve not merely his family but to be open at fixed hours to scholars. The manuscripts alone numbered some 900, bound as codices in red Morocco with the cardinal’s arms. The library was transferred to the Sorbonne in 1660.[76] He funded the literary careers of many writers. He was a lover of the theatre, which was not considered a respectable art form during that era; a private theatre, the Grande Salle, was a feature of his Paris residence, the Palais-Cardinal. Among the individuals he patronized was the famous playwright Pierre Corneille.[77] Richelieu was also the founder and patron of the Académie française, the pre-eminent French literary society.[78] The institution had previously been in informal existence; in 1635, however, Cardinal Richelieu obtained official letters patent for the body. The Académie française includes forty members, promotes French literature, and remains the official authority on the French language. Richelieu served as the Académie’s protector. Since 1672, that role has been fulfilled by the French head of state.[citation needed]

Bust of Cardinal Richelieu by Gianlorenzo Bernini

In 1622, Richelieu was elected the proviseur or principal of the Sorbonne.[79] He presided over the renovation of the college’s buildings and over the construction of its famous chapel, where he is now entombed. As he was Bishop of Luçon, his statue stands outside the Luçon cathedral.[citation needed]

Richelieu oversaw the construction of his own palace in Paris, the Palais-Cardinal.[80] The palace, renamed the Palais-Royal after Richelieu’s death, now houses the French Constitutional Council, the Ministry of Culture, and the Conseil d’État. The Galerie de l’avant-cour had ceiling paintings by the Cardinal’s chief portraitist, Philippe de Champaigne, celebrating the major events of the Cardinal’s career; the Galerie des hommes illustres had twenty-six historicizing portraits of great men, larger than life, from Abbot Suger to Louis XIII; some were by Simon Vouet, others were careful copies by Philippe de Champaigne from known portraits;[81] with them were busts of Roman emperors. Another series of portraits of authors complemented the library. The architect of the Palais-Cardinal, Jacques Lemercier, also received a commission to build a château and a surrounding town in Indre-et-Loire; the project culminated in the construction of the Château Richelieu and the town of Richelieu. To the château, he added one of the largest art collections in Europe and the largest collection of ancient Roman sculpture in France. The heavily resurfaced and restored Richelieu Bacchus continued to be admired by neoclassical artists.[82] Among his 300 paintings by moderns, most notably, he owned Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, The Family of the Virgin by Andrea del Sarto, the two famous Bacchanales of Nicolas Poussin, as well as paintings by Veronese and Titian, and Diana at the Bath by Rubens, for which he was so glad to pay the artist’s heirs 3,000 écus, that he made a gift to Rubens’ widow of a diamond-encrusted watch. His marble portrait bust by Bernini was not considered a good likeness and was banished to a passageway.[83]

The fittings of his chapel in the Palais-Cardinal, for which Simon Vouet executed the paintings, were of solid gold – crucifix, chalice, paten, ciborium, candlesticks – set with 180 rubies and 9,000 diamonds.[84] His taste also ran to massive silver, small bronzes and works of vertu, enamels and rock crystal mounted in gold, Chinese porcelains, tapestries and Persian carpets, cabinets from Italy, and Antwerp and the heart-shaped diamond bought from Alphonse Lopez that he willed to the king. When the Palais-Cardinal was complete, he donated it to the Crown, in 1636. With the Queen in residence, the paintings of the Grand Cabinet were transferred to Fontainebleau and replaced by copies, and the interiors were subjected to much rearrangement.[citation needed]

Michelangelo’s two Slaves were among the rich appointments of the château Richelieu, where there were the Nativity triptych by Dürer, and paintings by Mantegna, Lorenzo Costa and Perugino, lifted from the Gonzaga collection at Mantua by French military forces in 1630, as well as numerous antiquities.[citation needed]

Legacy[edit]

Richelieu’s tenure was a crucial period of reform for France. Earlier, the nation’s political structure was largely feudal, with powerful nobles and a wide variety of laws in different regions.[86] Parts of the nobility periodically conspired against the King, raised private armies, and allied themselves with foreign powers. This system gave way to centralized power under Richelieu.[87] Local and even religious interests were subordinated to those of the whole nation, and of the embodiment of the nation – the King. Equally critical for France was Richelieu’s foreign policy, which helped restrain Habsburg influence in Europe. Richelieu did not survive to the end of the Thirty Years’ War. However, the conflict ended in 1648, with France emerging in a far better position than any other power, and the Holy Roman Empire entering a period of decline.[citation needed]

Richelieu’s successes were extremely important to Louis XIII’s successor, King Louis XIV. He continued Richelieu’s work of creating an absolute monarchy; in the same vein as the Cardinal, he enacted policies that further suppressed the once-mighty aristocracy, and utterly destroyed all remnants of Huguenot political power with the Edict of Fontainebleau. Moreover, Louis took advantage of his nation’s success during the Thirty Years’ War to establish French hegemony in continental Europe. Thus, Richelieu’s policies were the requisite prelude to Louis XIV becoming the most powerful monarch, and France the most powerful nation, in all of Europe during the late seventeenth century.[citation needed]

Richelieu is also notable for the authoritarian measures he employed to maintain power. He censored the press,[88] established a large network of internal spies, forbade the discussion of political matters in public assemblies such as the Parlement de Paris (a court of justice), and had those who dared to conspire against him prosecuted and executed. The Canadian historian and philosopher John Ralston Saul has referred to Richelieu as the «father of the modern nation-state, modern centralised power [and] the modern secret service.»[citation needed]

Richelieu’s motives are the focus of much debate among historians: some see him as a patriotic supporter of the monarchy, while others view him as a power-hungry cynic. The latter image gained further currency due to Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers, which depicts Richelieu as a self-serving and ruthless de facto ruler of France.[citation needed]

Despite such arguments, Richelieu remains an honoured personality in France. He has given his name to a battleship and a battleship class.

His legacy is also important for the world at large; his ideas of a strong nation-state and aggressive foreign policy helped create the modern system of international politics. The notions of national sovereignty and international law can be traced, at least in part, to Richelieu’s policies and theories, especially as enunciated in the Treaty of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years’ War.[citation needed]

His pioneering approach to French diplomatic relations using raison d’etat vis-a-vis the power relationship at play were first scorned upon but later emulated by other European nation-states to add to their diplomatic strategic arsenal.[89]

A less renowned aspect of his legacy is his involvement with Samuel de Champlain and the fledgling colony along the St. Lawrence River. The retention and promotion of Canada under Richelieu allowed it – and through the settlement’s strategic location, the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes gateway into the North American interior – to develop into a French empire in North America, parts of which eventually became modern Canada and Louisiana.[citation needed]

Portrayals in fiction[edit]

As of April 2013, the Internet Movie Database listed 94 films and television programs in which Cardinal Richelieu is a character. Richelieu is one of the clergymen most frequently portrayed in film, notably in the many versions of Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. He is usually portrayed as a sinister character, but the 1950 Cyrano de Bergerac shows Richelieu (played by Edgar Barrier in a scene not from Rostand’s original verse drama) as compassionate to Cyrano’s financial plight, and playfully having enjoyed the duel at the theatre. Actors who have portrayed Cardinal Richelieu on film and television include Nigel De Brulier, George Arliss, Miles Mander, Vincent Price, Charlton Heston, Aleksandr Trofimov, Tcheky Karyo, Stephen Rea, Tim Curry, Christoph Waltz and Peter Capaldi.

Richelieu is indirectly mentioned in a famous line of Alessandro Manzoni’s novel The Betrothed (1827–1840), set in 1628, as a Lombard peasant expresses his own conspiracy theories about the bread riots happening in Milan.

The 1839 play Richelieu; Or the Conspiracy, by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, portrayed Richelieu uttering the now famous line, «The pen is mightier than the sword.» The play was adapted into the 1935 film Cardinal Richelieu.[citation needed]

The Monty Python’s Flying Circus episode «How to Recognise Different Types of Trees from Quite a Long Way Away», first released in 1969, features the sketch «Court Scene with Cardinal Richelieu», in which Richelieu (played by Michael Palin) is seen to be doing wildly absurd acts.[90]

In the 1632/Ring of Fire series by Eric Flint, he is one of the primary antagonists to the nascent United States of Europe.

Richelieu and Louis XIII are depicted in Ken Russell’s 1971 film The Devils.

Literary works[edit]

- Political Testament[citation needed]

- The principal points of the faith of the Catholic Church defended (1635)[citation needed]

Honours[edit]

Many sites and landmarks were named to honor Cardinal Richelieu. They include:[32]

- Richelieu, Indre et Loire, a town founded by the Cardinal

- Avenue Richelieu, located in Shawinigan, Quebec, Canada

- The provincial electoral district of Richelieu, Quebec

- Richelieu River, in Montérégie, Quebec

- Richelieu Squadron, a squadron of Officer Cadets from the Royal Military College Saint-Jean.[91]

- A wing of the Louvre Museum, Paris, France

- Rue de Richelieu, a Parisian street named in the Cardinal’s honor, and places located in this street, as the Paris Métro station Richelieu-Drouot, or the historical site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France

- French ship Richelieu, four warships of the French Navy

There is also an ornate style of lace, Richelieu lace, named in honor of the cardinal.[92]

See also[edit]

Biography portal

- Nicolas Fouquet

Notes[edit]

- ^ ,[1][2][3] ;[3][4][5] French: Cardinal de Richelieu [kaʁdinal d(ə) ʁiʃ(ə)ljø] (

listen)

References[edit]

- ^ «Richelieu». Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ «Richelieu, Duc de». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022.

- ^ a b «Richelieu, Cardinal». Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ «Richelieu». The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ «Richelieu». Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Downie, David (2017). A Taste of Paris: A History of the Parisian Love Affair with Food. New York: St. Martin’s Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-25-008295-4.

- ^ Long, Tony. «May 13, 1637: Cardinal Richelieu Makes His Point». Wired. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Bergin, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Treasure, p. 3.

- ^ Bergin, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Bergin, p. 24.

- ^ Bergin, p. 55.

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 187.

- ^ Bergin, p. 58; Trevor-Roper, p. 66.

- ^ Bergin, p. 57.

- ^ a b Bergin, p. 61.

- ^ Bergin, p. 62.

- ^ Federn, Karl (1928). Richelieu. New York: Haskell House Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 1432516361.

- ^ Munck, p. 43.

- ^ Bergin, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 189.

- ^ Bergin, p. 130.

- ^ Bergin, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Treasure, p. 4.

- ^ Bergin, p. 135.

- ^ Pardoe, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Collins, p. 45.

- ^ Pardoe, p. 23.

- ^ a b Parker, 1984, p. 130.

- ^ Bergin, p. 99.

- ^ a b Parker, 1984, p. 199.

- ^ a b Carl J. Burckhardt, Richelieu and His Age (1967). Vol. 3, appendix.

- ^ R J Knecht (2014). Richelieu. Routledge. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-317-87455-3. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Lodge & Ketcham, 1903, p. 85.

- ^ Dyer, 1861, p. 525.

- ^ Zagorin, p. 9.

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 188.

- ^ Kissinger, p. 59

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 195.

- ^ Collins, p. 48.

- ^ Zagorin, p. 16.

- ^ Zagorin, p. 17.

- ^ a b Zagorin, p. 18.

- ^ Pardoe, p. 176.

- ^ Munck, p. 44.

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 270.

- ^ A. Lloyd Moote, Louis XIII, the Just, pp. 135–136, 178.[full citation needed]

- ^ Moote, pp. 179–183, esp. 182

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 247.

- ^ a b Parker, 1984, p. 219.

- ^ Collins, p. 62.

- ^ Collins, p. 53.

- ^ Munck, p. 48.

- ^ Zagorin, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 452.

- ^ Henry Bertram Hill, Political Testament of Cardinal Richelieu, p. vii, supports general thesis.

- ^ a b Wedgwood, p. 450.

- ^ «Cercle Richelieu Senghor de Paris – Tribune internationale de la francophonie». www.cercle-richelieu-senghor.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ «Le grand atout de la France est d’avoir mis en place des conditions favorisant les établissements stables, grâce aux alliances avec les peuples autochtones.» Cercle Richelieu [1] Archived 30 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kenneth M. Morrison, The Embattled Northeast: The Elusive Ideal of Alliance in Abenaki-Euramerican Relations, 1984, p. 94 [2]

- ^ Roger L. Nichols, Indians in the United States and Canada: A Comparative History, 1999, p. 32 [3] Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Acte pour l’établissement de la Compagnie des Cent Associés pour le commerce du Canada, contenant les articles accordés à la dite Compagnie par M. le Cardinal de Richelieu, le 29 avril 1627 [4] Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Statistics for the 1666 Census». Library and Archives Canada. 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Perkins, p. 273.

- ^ Phillips, p. 3.

- ^ a b Perkins, p. 195.

- ^ Perkins, p. 198.

- ^ Perkins, p. 191.

- ^ Perkins, p. 200.

- ^ Perkins, p. 204.

- ^ Cabanès, «Le Medecin de Richelieu», pp. 16–43, for a full account of his medical history.

- ^ Treasure, p. 8.

- ^ Fontaine de Resbecq (pp. 11–18); Cabanès, «L’Odyssée d’un Crane»; Murphy, 1995.

- ^ Griffith, F (1906). «A Photograph of the Head of Cardinal Richelieu Taken Two Hundred and Fifty Years After Death». Medical Library and Historical Journal. 4 (2): 184–185. PMC 1692471. PMID 18340911.

- ^ Jacques Gaffrel in Italy and Jean Tileman Stella in Germany – Bonnaffé p. 13.

- ^ Bonnaffé, pp. 4, 12.

- ^ Auchincloss, p. 178.

- ^ Elliot, 1991, p. 30.

- ^ Pitte, p. 33.

- ^ Alexander, 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Bonnaffé :7ff (notes other portrait galleries assembled by Richelieu’s contemporaries), pp. 10ff.

- ^ The young Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres made a careful drawing of it.

- ^ «Le petit cabinet de passage pour aller à l’appartement vert» (Bonnaffé :10).

- ^ Bonnaffé :16

- ^ «Louvre Museum». Cartelen.louvre.fr. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ Collins, p. 1.

- ^ Collins, p. 1 – although Collin does note that this can be exaggerated.

- ^ Phillips, p. 266.

- ^ Kissinger, pp. 62-63

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Chadner (22 December 2006). «Monty Python – Court Scene» – via YouTube.

- ^ Departement of National Defence, Chief Military Personnel (27 May 2015). «Officer Cadet Division – Faculty and Staff – Royal Military College Saint-Jean». www.cmrsj-rmcsj.forces.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Willem. «Richelieu Work». www.trc-leiden.nl. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alexander, Edward Porter. Museums in Motion: an introduction to the history and functions of museums. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. (1996)

- Auchincloss, Louis. Richelieu. Viking Press. (1972)

- Bergin, Joseph. The Rise of Richelieu. Manchester: Manchester University Press. (1997)

- Blanchard, Jean-Vincent. Eminence: Cardinal Richelieu and the Rise of France (Walker & Company; 2011) 309 pages; a biography

- Bonnaffé, Edmond. Recherches sur les collections des Richelieu. Plon. (1883) (French)

- Cabanès, Augustin. «Le Médecin de Richelieu – La Maladie du Cardinal» and «L’Odyssée d’un Crane – La Tête du Cardinal», Le Cabinet Secret de l’Histoire, 4e serie. Paris: Dorbon Ainé. (1905) (French)

- Collins, James B. The State in Early Modern France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1995)

- Dyer, Thomas Henry. The history of modern Europe from the fall of Constantinople: in 1453, to the war in the Crimea, in 1857. J. Murray. (1861)

- Elliott, J. H. Richelieu and Olivares. Cambridge: Canto Press. (1991)

- Fontaine de Resbecq, Eugène de. Les Tombeaux des Richelieu à la Sorbonne, par un membre de la Société d’archéologie de Seine-et-Marne. Paris: Ernest Thorin. (1867) (French)

- Lodge, Sir Richard, and Ketcham, Henry. The life of Cardinal Richelieu Archived 31 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. A. L. Burt. (1903)

- Munck, Thomas. Seventeenth Century Europe, 1598–1700. London: Macmillan. (1990)

- Pardoe, Julia. The Life of Marie de Medici, volume 3. Colburn (1852); BiblioBazaar reprint (2006)

- Parker, Geoffrey. Europe in Crisis, 1598–1648. London: Fontana. (1984)

- Perkins, James Breck. Richelieu and the Growth of French Power. Ayer Publishing. (1971)

- Phillips, Henry. Church and Culture in Seventeenth Century France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1997)

- Pitte, Jean-Robert. La Sorbonne au service des humanités: 750 ans de création et de transmission du savoir, 1257–2007. Paris: Presses Paris Sorbonne. (2007) (French)

- Treasure, Geoffrey. Richelieu and Mazarin. London: Routledge. (1998)

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh Redwald. Europe’s physician: the various life of Sir Theodore de Mayerne. Yale: Yale University Press. (2006) ISBN 978-0-300-11263-4

- Wedgwood, C. V. The Thirty Years’ War. London: Methuen. (1981)

- Zagorin, Perez. Rebels and Rulers, 1500–1660. Volume II: Provincial rebellion: Revolutionary civil wars, 1560–1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1992)

Further reading[edit]

- Belloc, Hilaire (1929). Richelieu: A Study. London: J. B. Lippincott.

- Burckhardt, Carl J. (1967). Richelieu and His Age (3 volumes). trans. Bernard Hoy. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Church, William F. (1972). Richelieu and Reason of State. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691051994.

- Kissinger, Henry (1997). Diplomacy.

- Levi, Anthony (2000). Cardinal Richelieu and the Making of France. New York: Carroll and Graf.

- Lodge, Sir Richard (1896). Richelieu. London: Macmillan.

- Murphy, Edwin (1995). After the Funeral: The Posthumous Adventures of Famous Corpses. New York: Barnes and Noble Books.

- O’Connell, D.P. (1968). Richelieu. New York: The World Publishing Company.

- Rehman, Iskander. 2019. «Raison d’Etat: Richelieu’s Grand Strategy During the Thirty Years’ War.» Texas National Security Review.

- Richelieu, Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal et Duc de (1964). The Political Testament of Cardinal Richelieu. trans. Henry Bertram Hill. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

- Damayanov, Orlin. (1996). «The Political Career and Personal Qualities of Richelieu.»

- Goyau, Georges. (1912). «Armand-Jean du Plessis, Duke de Richelieu.» The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume XIII. New York: Robert Appleton Company

- Schiller, Friedrich von. (1793). The History of the Thirty Years’ War. Translated by A. J. W. Morrison.

Cardinal Richelieu public domain audiobook at LibriVox

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Jacques de Veny d’Arbouze |

Abbot of Cluny 1635–1642 |

Succeeded by

Armand de Bourbon |

| Political offices | ||

| Vacant

Title last held by Concino Concini |

Chief minister to the French monarch 1624–1642 |

Succeeded by

Cardinal Mazarin |

«The Red Eminence» redirects here. For the Soviet statesman also known by that epithet, see Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov.

|

His Grand Eminence The Cardinal Duke of Richelieu COHS |

|

|---|---|

Cardinal de Richelieu by Philippe de Champaigne, 1642 (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg) |

|

| First Minister of State | |

| In office 12 August 1624 – 4 December 1642 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | The Marquis of Ancre Vacant (1617–1624) |

| Succeeded by | Jules Mazarin |

| Governor of Brittany | |

| In office 17 April 1632 – 4 December 1642 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | The Marquis of Thémines [fr] |

| Succeeded by | Queen Anne |

| Grand Master of the Navigation | |

| In office 1626–1642 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | The Duke of Montmorency |

| Succeeded by | The Marquis of Brézé |

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 30 November 1616 – 24 April 1617 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | Claude Mangot [fr] |

| Succeeded by | The Marquis of Sillery |

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 25 November 1616 – 24 April 1617 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XIII |

| Preceded by | Claude Mangot |

| Succeeded by | Nicolas Brulart de Sillery |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Armand Jean du Plessis 9 September 1585 |

| Died | 4 December 1642 (aged 57) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Sorbonne Chapel |

| Alma mater | College of Navarre |

| Profession | Clergyman, statesman |

| Cardinal, Bishop of Luçon | |

| Metropolis | Bordeaux |

| Diocese | Luçon |

| See | Luçon |

| Appointed | 18 December 1606 |

| Installed | 17 April 1607 |

| Term ended | Before 29 April 1624 |

| Predecessor | François Yver |

| Successor | Emery de Bragelongne |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 17 April 1607 by Anne d’Escars de Givry |

| Created cardinal | 5 September 1622 by Pope Gregory XV |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest |

| Personal details | |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms | |

| Styles of Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Grand Eminence |

| Spoken style | Your Grand Eminence |

| Informal style | Cardinal |

| See | Luçon |

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (French: [aʁmɑ̃ ʒɑ̃ dy plɛsi]; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu,[a] was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as l’Éminence rouge, or «the Red Eminence«, a term derived from the title «Eminence» applied to cardinals and the red robes that they customarily wear.

Consecrated a bishop in 1607, Richelieu was appointed Foreign Secretary in 1616. He continued to rise through the hierarchy of both the Catholic Church and the French government by becoming a cardinal in 1622 and chief minister to King Louis XIII of France in 1624. He retained that office until his death in 1642, when he was succeeded by Cardinal Mazarin, whose career he had fostered. He also became engaged in a bitter dispute with the king’s mother, Marie de Médicis, who had once been a close ally.

Richelieu sought to consolidate royal power and restrained the power of the nobility in order to transform France into a strong centralized state. In foreign policy, his primary objectives were to check the power of the Habsburg dynasty in Spain and Austria and to ensure French dominance in the Thirty Years’ War after the conflict engulfed Europe. Despite suppressing the Huguenot rebellions, he made alliances with Protestant states like the Kingdom of England and the Dutch Republic to help him achieve his goals. However, although he was a powerful political figure in his own right, events such as the Day of the Dupes, or Journée des Dupes, showed that Richelieu’s power was still dependent on the king’s confidence.

An alumnus of the University of Paris and headmaster of the College of Sorbonne, Richelieu renovated and extended the institution. He was famous for his patronage of the arts and founded the Académie Française, the learned society responsible for matters pertaining to the French language. As an advocate for Samuel de Champlain and New France, he founded the Compagnie des Cent-Associés; he also negotiated the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye under which Quebec City returned to French rule after its loss in 1629.

Richelieu is also known for being the inventor of the table knife. Annoyed by the bad manners that were commonly displayed at the dining table by users of sharp knives, who would often use them to pick their teeth,[6] in 1637 Richelieu ordered that all of the knives on his dining table have their blades dulled and their tips rounded. The design quickly became popular throughout France and later spread to other countries.[7]

Richelieu has frequently been depicted in popular fiction, principally as the lead villain in Alexandre Dumas’s 1844 novel The Three Musketeers and its numerous film adaptations.

Early life[edit]

Born in Paris on 9 September 1585, Armand du Plessis was the fourth of five children and the last of three sons: he was delicate from childhood, and suffered frequent bouts of ill-health throughout his life. His family belonged to the lesser nobility of Poitou:[8] his father, François du Plessis, seigneur de Richelieu, was a soldier and courtier who served as the Grand Provost of France,[9] and his mother, Susanne de La Porte, was the daughter of a famous jurist.[10]

When he was five years old, Richelieu’s father died of fever in the French Wars of Religion,[11] leaving the family in debt; with the aid of royal grants, however, the family was able to avoid financial difficulties. At the age of nine, young Richelieu was sent to the College of Navarre in Paris to study philosophy.[12] Thereafter, he began to train for a military career.[13] His private life seems to have been typical for a young officer of the era: in 1605, aged twenty, he was treated by Théodore de Mayerne for gonorrhea.[14]

Henry III had rewarded Richelieu’s father for his participation in the Wars of Religion by granting his family the Bishopric of Luçon.[15] The family appropriated most of the revenues of the bishopric for private use; they were, however, challenged by clergymen who desired the funds for ecclesiastical purposes. To protect the important source of revenue, Richelieu’s mother proposed to make her second son, Alphonse, the bishop of Luçon.[16] Alphonse, who had no desire to become a bishop, became instead a Carthusian monk.[17] Thus, it became necessary that the younger Richelieu join the clergy. He had strong academic interests and threw himself into studying for his new post.[18]

In 1606, Henry IV nominated Richelieu to become Bishop of Luçon.[16] As Richelieu had not yet reached the canonical minimum age, it was necessary that he journey to Rome for a special dispensation from Pope Paul V. This secured, Richelieu was consecrated bishop in April 1607. Soon after he returned to his diocese in 1608, Richelieu was heralded as a reformer.[19] He became the first bishop in France to implement the institutional reforms prescribed by the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563.[20]

At about this time, Richelieu became a friend of François Leclerc du Tremblay (better known as «Père Joseph« or «Father Joseph»), a Capuchin friar, who would later become a close confidant. Because of his closeness to Richelieu, and the grey colour of his robes, Father Joseph was also nicknamed L’éminence grise («the Grey Eminence»). Later, Richelieu often used him as an agent during diplomatic negotiations.[21]

Rise to power[edit]

In 1614, the clergymen of Poitou asked Richelieu to be one of their representatives to the Estates-General.[22] There, he was a vigorous advocate of the Church, arguing that it should be exempt from taxes and that bishops should have more political power. He was the most prominent clergyman to support the adoption of the decrees of the Council of Trent throughout France;[23] the Third Estate (commoners) was his chief opponent in this endeavour. At the end of the assembly, the First Estate (the clergy) chose him to deliver the address enumerating its petitions and decisions.[24] Soon after the dissolution of the Estates-General, Richelieu entered the service of King Louis XIII’s wife, Anne of Austria, as her almoner.[25]

Richelieu advanced politically by faithfully serving the Queen-Mother’s favourite, Concino Concini, the most powerful minister in the kingdom.[26] In 1616, Richelieu was made Secretary of State, and was given responsibility for foreign affairs.[24] Like Concini, the Bishop was one of the closest advisors of Louis XIII’s mother, Marie de Médicis. The Queen had become Regent of France when the nine-year-old Louis ascended the throne; although her son reached the legal age of majority in 1614, she remained the effective ruler of the realm.[27] However, her policies, and those of Concini, proved unpopular with many in France. As a result, both Marie and Concini became the targets of intrigues at court; their most powerful enemy was Charles de Luynes.[28] In April 1617, in a plot arranged by Luynes, Louis XIII ordered that Concini be arrested, and killed should he resist; Concini was consequently assassinated, and Marie de Médicis overthrown.[29] His patron having died, Richelieu also lost power; he was dismissed as Secretary of State, and was removed from the court.[29] In 1618, the King, still suspicious of the Bishop of Luçon, banished him to Avignon. There, Richelieu spent most of his time writing; he composed a catechism entitled L’Instruction du chrétien.[30]

In 1619, Marie de Médicis escaped from her confinement in the Château de Blois, becoming the titular leader of an aristocratic rebellion. The King and the duc de Luynes recalled Richelieu, believing that he would be able to reason with the Queen. Richelieu was successful in this endeavour, mediating between her and her son.[31] Complex negotiations bore fruit when the Treaty of Angoulême was ratified; Marie de Médicis was given complete freedom, but would remain at peace with the King. The Queen-Mother was also restored to the royal council.[32]

After the death of the King’s favourite, the duc de Luynes, in 1621, Richelieu rose to power quickly. The year after, the King nominated Richelieu for a cardinalate, which Pope Gregory XV accordingly granted in September 1622.[33] Crises in France, including a rebellion of the Huguenots, rendered Richelieu a nearly indispensable advisor to the King. After he was appointed to the royal council of ministers on 29 April 1624,[34] he intrigued against the chief minister, Charles, duc de La Vieuville.[31] On 12 August of the same year, La Vieuville was arrested on charges of corruption, and Cardinal Richelieu took his place as the King’s principal minister the following day, although the Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld nominally remained president of the council (Richelieu was officially appointed president in November 1629).[35]

Chief minister[edit]

Jean Warin, Cardinal de Richelieu 1622 (obverse), 1631

Cardinal Richelieu’s policy involved two primary goals: centralization of power in France[36] and opposition to the Habsburg dynasty (which ruled in both Austria and Spain).[37] He saw the reestablishment of the Catholic orthodoxy as a political maneuver of the Habsburg and Austrian States which is detrimental to the French national interests.[38]

Shortly after he became Louis’ principal minister, he was faced with a crisis in Valtellina, a valley in Lombardy (northern Italy). To counter Spanish designs on the territory, Richelieu supported the Protestant Swiss canton of Grisons, which also claimed the strategically important valley. The Cardinal deployed troops to Valtellina, from which the Pope’s garrisons were driven out.[39] Richelieu’s early decision to support a Protestant canton against the Pope was a foretaste of the purely diplomatic power politics he would espouse in his foreign policy.

To further consolidate power in France, Richelieu sought to suppress the influence of the feudal nobility. In 1626, he abolished the position of Constable of France and ordered all fortified castles razed, with the exception only of those needed to defend against invaders.[40] Thus he stripped the princes, dukes, and lesser aristocrats of important defences that could have been used against the King’s armies during rebellions. As a result, Richelieu was hated by most of the nobility.

Another obstacle to the centralization of power was religious division in France. The Huguenots, one of the largest political and religious factions in the country, controlled a significant military force, and were in rebellion.[41] Moreover, the King of England, Charles I, declared war on France in an attempt to aid the Huguenot faction. In 1627, Richelieu ordered the army to besiege the Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle; the Cardinal personally commanded the besieging troops.[42] English troops under the Duke of Buckingham led an expedition to help the citizens of La Rochelle, but failed abysmally. The city, however, remained firm for over a year before capitulating in 1628.

Although the Huguenots suffered a major defeat at La Rochelle, they continued to fight, led by Henri, duc de Rohan. Protestant forces, however, were defeated in 1629; Rohan submitted to the terms of the Peace of Alais.[43] As a result, religious toleration for Protestants, which had first been granted by the Edict of Nantes in 1598, was permitted to continue, but the Cardinal abolished their political rights and protections.[43] Rohan was not executed (as were leaders of rebellions later in Richelieu’s tenure); in fact, he later became a commanding officer in the French army.

Habsburg Spain exploited the French conflict with the Huguenots to extend its influence in northern Italy. It funded the Huguenot rebels to keep the French army occupied, meanwhile expanding its Italian dominions. Richelieu, however, responded aggressively; after La Rochelle capitulated, he personally led the French army to northern Italy to restrain Spain. On 26 November 1629, he was created duc de Richelieu and a Peer of France.

In the next year, Richelieu’s position was seriously threatened by his former patron, Marie de Médicis. Marie believed that the Cardinal had robbed her of her political influence; thus, she demanded that her son dismiss the chief minister.[44] Louis XIII was not, at first, averse to such a course of action, as he personally disliked Richelieu.[24] Despite this, the persuasive statesman was able to secure the king as an ally against his own mother. On 11 November 1630, Marie de Médicis and the King’s brother, Gaston, duc d’Orléans, secured the King’s agreement for the dismissal. Richelieu, however, was aware of the plan, and quickly convinced the King to repent.[45] This day, known as the Day of the Dupes, was the only one on which Louis XIII took a step toward dismissing his minister. Thereafter, the King was unwavering in his political support for him.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, Marie de Médicis was exiled to Compiègne. Both Marie and the duc d’Orléans continued to conspire against Richelieu, but their schemes came to nothing. The nobility also remained powerless. The only important rising was that of Henri, duc de Montmorency in 1632; Richelieu, ruthless in suppressing opposition, ordered the duke’s execution. In 1634, the Cardinal had one of his outspoken critics, Urbain Grandier, burned at the stake in the Loudun affair. These and other harsh measures were orchestrated by Richelieu to intimidate his enemies. He also ensured his political security by establishing a large network of spies in France as well as in other European countries.[citation needed]

-

On the «Day of the Dupes» in 1630, it appeared that Marie de Médicis had secured Richelieu’s dismissal. Richelieu, however, survived the scheme, and Marie was exiled as a result.

Thirty Years’ War[edit]

Before Richelieu’s ascent to power, most of Europe had become enmeshed in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). France was not openly at war with the Habsburgs, who ruled Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, so subsidies and aid were provided secretly to their adversaries.[46] He considered the Dutch Republic as one of France’s most important allies, for it bordered directly with the Spanish Netherlands and was right in the middle of the Eighty Years’ War with Spain at that time. Luckily for him, Richelieu was a bon français, just like the king, who had already decided to subsidize the Dutch to fight against the Spanish via the Treaty of Compiègne in June 1624, prior to Richelieu’s appointment to First Minister in August.[47] That same year, a military expedition, secretly financed by France and commanded by Marquis de Coeuvres, started an action with the intention of liberating the Valtelline from Spanish occupation. In 1625, Richelieu also sent money to Ernst von Mansfeld, a famous mercenary general operating in Germany in English service. However, in May 1626, when war costs had almost ruined France, king and cardinal made peace with Spain via the Treaty of Monçon.[48] This peace quickly broke down after tensions due to the War of the Mantuan Succession.[49]

In 1629, Emperor Ferdinand II subjugated many of his Protestant opponents in Germany. Richelieu, alarmed by Ferdinand’s growing influence, incited Sweden to intervene, providing money.[50] In the meantime, France and Spain remained hostile due to Spain’s ambitions in northern Italy. At that time northern Italy was a major strategic region in Europe’s balance of power, serving as a link between the Habsburgs in the Empire and in Spain. Had the imperial armies dominated this region, France would have been threatened by Habsburg encirclement. Spain was meanwhile seeking papal approval for a universal monarchy. When in 1630 French diplomats in Regensburg agreed to make peace with Spain, Richelieu refused to support them. The agreement would have prohibited French interference in Germany. Therefore, Richelieu advised Louis XIII to refuse to ratify the treaty. In 1631, he allied France to Sweden, who had just invaded the empire, in the Treaty of Bärwalde.[50]

Military expenses placed a considerable strain on royal revenues. In response, Richelieu raised the gabelle (salt tax) and the taille (land tax).[51] The taille was enforced to provide funds to raise armies and wage war. The clergy, nobility, and high bourgeoisie either were exempt or could easily avoid payment, so the burden fell on the poorest segment of the nation. To collect taxes more efficiently, and to keep corruption to a minimum, Richelieu bypassed local tax officials, replacing them with intendants (officials in the direct service of the Crown).[52] Richelieu’s financial scheme, however, caused unrest among the peasants; there were several uprisings in 1636 to 1639.[53] Richelieu crushed the revolts violently, and dealt with the rebels harshly.[54]

Because he openly aligned France with Protestant powers, Richelieu was denounced by many as a traitor to the Roman Catholic Church. Military action, at first, was disastrous for the French, with many victories going to Spain and the Empire.[55] Neither side, however, could obtain a decisive advantage, and the conflict lingered on after Richelieu’s death. Richelieu was instrumental in redirecting the Thirty Years’ War from the conflict of Protestantism versus Catholicism to that of nationalism versus Habsburg hegemony.[56] In this conflict France effectively drained the already overstretched resources of the Habsburg empire and drove it inexorably towards bankruptcy.[57] The defeat of Habsburg forces at the Battle of Lens in 1648, coupled with their failure to prevent a French invasion of Catalonia, effectively spelled the end for Habsburg domination of the continent, and for the personal career of Spanish prime minister Olivares.[57] Indeed, in the subsequent years it would be France, under the leadership of Louis XIV, who would attempt to fill the vacuum left by the Habsburgs in the Spanish Netherlands and supplant Spain as the dominant European power.[citation needed]

New World[edit]

When Richelieu came to power, New France, where the French had a foothold since Jacques Cartier, had no more than 100 permanent European inhabitants.[58] Richelieu encouraged Louis XIII to colonize the Americas by the foundation of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France in imitation of the Dutch West India Company. Unlike the other colonial powers, France encouraged a peaceful coexistence in New France between Natives and Colonists and sought the integration of Indians into colonial society.[59][failed verification][60] Samuel de Champlain, governor of New France at the time of Richelieu, saw intermarriage between French and Indians as a solution to increase population in its colony.[61] Under the guidance of Richelieu, Louis XIII issued the Ordonnance of 1627 by which the Indians, converted to Catholicism, were considered as «natural Frenchmen»:

The descendants of the French who are accustomed to this country [New France], together with all the Indians who will be brought to the knowledge of the faith and will profess it, shall be deemed and renowned natural Frenchmen, and as such may come to live in France when they want, and acquire, donate, and succeed and accept donations and legacies, just as true French subjects, without being required to take letters of declaration of naturalization.[62]

The 1666 census of New France, conducted some 20 years after the death of Cardinal Richelieu, showed a population of 3,215 habitants in New France, many more than there had been only a few decades earlier, but also a great difference in the number of men (2,034) and women (1,181).[63]

Final years[edit]

Towards the end of his life, Richelieu alienated many people, including Pope Urban VIII. Richelieu was displeased by the Pope’s refusal to name him the papal legate in France;[64] in turn, the Pope did not approve of the administration of the French church, or of French foreign policy. However, the conflict was largely resolved when the Pope granted a cardinalate to Jules Mazarin, one of Richelieu’s foremost political allies, in 1641. Despite troubled relations with the Roman Catholic Church, Richelieu did not support the complete repudiation of papal authority in France, as was advocated by the Gallicanists.[65]

As he neared death, Richelieu faced a plot that threatened to remove him from power. The cardinal had introduced a young man named Henri Coiffier de Ruzé, marquis de Cinq-Mars to Louis XIII’s court.[66] The Cardinal had been a friend of Cinq-Mars’s father.[66] More importantly, Richelieu hoped that Cinq-Mars would become Louis’s favourite, so that he could indirectly exercise greater influence over the monarch’s decisions. Cinq-Mars had become the royal favourite by 1639, but, contrary to Cardinal Richelieu’s belief, he was not easy to control. The young marquis realized that Richelieu would not permit him to gain political power.[67] In 1641, he participated in the comte de Soissons’s failed conspiracy against Richelieu, but was not discovered.[68] Then, the following year, he schemed with leading nobles (including the King’s brother, the duc d’Orléans) to raise a rebellion; he also signed a secret agreement with the King of Spain, who promised to aid the rebels.[69] Richelieu’s spy service, however, discovered the plot, and the Cardinal received a copy of the treaty.[70] Cinq-Mars was promptly arrested and executed; although Louis approved the use of capital punishment, he grew more distant from Richelieu as a result.[citation needed]

However, Richelieu was now dying. For many years he had suffered from recurrent fevers (possibly malaria), strangury, intestinal tuberculosis with fistula, and migraine. Now his right arm was suppurating with tubercular osteitis, and he coughed blood (after his death, his lungs were found to have extensive cavities and caseous necrosis). His doctors continued to bleed him frequently, further weakening him.[71] As he felt his death approaching, he named Mazarin, one of his most faithful followers, to succeed him as chief minister to the King.[72]