Функционирует при финансовой поддержке Министерства цифрового развития, связи и массовых коммуникаций Российской Федерации

- Словари

- Проверка слова

- Какие бывают словари

- Аудиословарь «Русский устный»

- Словари в Сети

- Библиотека

- Каталог

- Читальный зал

- Гостиная

- Справка

- Справочное бюро

- Задать вопрос

- Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации (1956)

- Письмовник

- Класс

- Азбучные истины

- Репетитор онлайн

- Учебники

- Олимпиады

- Видео

- Полезные ссылки

- Лента

- Новости

- О чём говорят и пишут

- Ближайшие конференции

- Грамотный календарь

- Игра

- Игра «Балда»

- Викторины

- Конкурсы

- Головоломки

- Застольные игры

- Загадки

- Медиатека

- Грамотные понедельники

- Забытые классики

- Что показывают

- Реклама словаря

- Поиск ответа

- Горячие вопросы

- Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации (1956)

- Письмовник

- Справочник по пунктуации

- Предисловие

- Структура словарной статьи

- Приложение 1. Непервообразные предлоги

- Приложение 2. Вводные слова и сочетания

- Приложение 3. Составные союзы

- Алфавитный список вводных слов и выражений

- Список учебной и справочной литературы

- Авторы

- Справочник по фразеологии

- Словарь трудностей

- Словарь улиц Москвы

- Непростые слова

- Официальные документы

- Книги о русском языке и лингвистике

- Книги о лингвистике, языке и письменности

- Лингвистические энциклопедии

- Научно-популярные, научно-публицистические, художественно-научные книги о русском языке

- Наша библиотека

- Словарь языка интернета

- Словарь трудностей русского языка для работников СМИ. Ударение, произношение, грамматические формы

- Словарь Россия. Для туристов и не только

- Словарь модных слов

- Лингвокультурологический словарь. Английские литературные имена

- Проект свода школьных орфографических правил

Поиск ответа

Всего найдено: 1

китайский новый год: какое слово пишется с большой буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: китайский Новый год.

Как правильно пишется словосочетание «китайский новый год»

- Как правильно пишется словосочетание «Новый год»

- Как правильно пишется слово «китайский»

- Как правильно пишется слово «новый»

- Как правильно пишется слово «год»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: секстет — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «на новый год»

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «новый год»

Ассоциации к слову «китайский»

Ассоциации к слову «новый»

Ассоциации к слову «год»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «китайский новый год»

Предложения со словосочетанием «китайский новый год»

- Изменения в своём доме желательно проводить до наступления китайского нового года, а именно до 4 февраля 2011 года.

- Дата китайского нового года поэтому плавающая и попадает в период от 21 января до 20 февраля.

- Если у нас – подождите кидать камни, православные – не прекращается эта война, и миллионы озлобленных женщин растят своих сирот, ожидая принцев в белых лимузинах, а миллионы деклассированных мужчин спиваются по съёмным углам, то у них – кто его знает, какой ценой, – но они вместе: что крестьянка, что профессор чинно вдвоём с мужем навещает свекровь и свёкра в первый день китайского нового года, и так всегда было, и так всегда будет.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «китайский новый год»

- Корею, в политическом отношении, можно было бы назвать самостоятельным государством; она управляется своим государем, имеет свои постановления, свой язык; но государи ее, достоинством равные степени королей, утверждаются на престоле китайским богдыханом. Этим утверждением только и выражается зависимость Кореи от Китая, да разве еще тем, что из Кореи ездят до двухсот человек ежегодно в Китай поздравить богдыхана с Новым годом. Это похоже на зависимость отделенного сына, живущего своим домом, от дома отца.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение словосочетания «новый год»

-

Новый год — праздник, наступающий в момент перехода с последнего дня года в первый день следующего года. Отмечается многими народами в соответствии с принятым календарём. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания НОВЫЙ ГОД

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

Новый год — праздник, наступающий в момент перехода с последнего дня года в первый день следующего года. Отмечается многими народами в соответствии с принятым календарём.

Все значения словосочетания «новый год»

1. буквальный перевод английской фразы Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Все значения словосочетания «Весёлого Рождества и счастливого Нового года»

1. религ. выражение тёплых пожеланий в связи с наступлением новогодних и рождественских праздников

Все значения словосочетания «Счастливого Рождества и весёлого Нового года»

Встреча нового года — празднование в канун нового года. См. также встреча.

Все значения словосочетания «встреча нового года»

«С новым годом!» (фр. La Bonne Année) — кинофильм. 2 приза МКФ.

Все значения словосочетания «с новым годом»

-

Изменения в своём доме желательно проводить до наступления китайского нового года, а именно до 4 февраля 2011 года.

-

Дата китайского нового года поэтому плавающая и попадает в период от 21 января до 20 февраля.

-

Если у нас – подождите кидать камни, православные – не прекращается эта война, и миллионы озлобленных женщин растят своих сирот, ожидая принцев в белых лимузинах, а миллионы деклассированных мужчин спиваются по съёмным углам, то у них – кто его знает, какой ценой, – но они вместе: что крестьянка, что профессор чинно вдвоём с мужем навещает свекровь и свёкра в первый день китайского нового года, и так всегда было, и так всегда будет.

- (все предложения)

- китайский календарь

- китайский народ

- китайская традиция

- китайские императоры

- китайское правительство

- (ещё синонимы…)

- подарки

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- ёлка

- подарок

- праздник

- подарки

- мороз

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- языки

- переводчица

- фонарик

- иероглиф

- даба

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- старый

- новичок

- новенький

- обновление

- ёлочка

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- месяц

- декада

- ёлочка

- полугодие

- второгодник

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- китайский язык

- американец китайского происхождения

- не знать китайского

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- новый год

- на новое место жительства

- начать новую жизнь

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- новый год

- в годы войны

- тысячи лет

- годы шли

- прожить год

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «китайский»

- Разбор по составу слова «новый»

- Разбор по составу слова «год»

- Как правильно пишется словосочетание «Новый год»

- Как правильно пишется слово «китайский»

- Как правильно пишется слово «новый»

- Как правильно пишется слово «год»

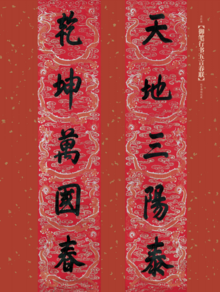

Когда и как празднуют китайский Новый год в 2022-ом? Согласно восточному календарю, 1 февраля 2022 года наступит год Черного Тигра. Этот праздник можно встретить дома, а можно заказать в новогоднюю ночь столик в китайском ресторане.

Встречать этот праздник нужно в одежде темно-синего или черного цвета, приветствуются также оттенки серого, голубого цвета. Не забудьте приготовить угощение для Тигра – например, мясные деликатесы в корзине или красивой коробке перевязанные белой или синей лентой.

Если вы решите встретить праздник дома, оформите помещение соответствующим образом. Используйте традиционный китайский элемент декора – красные фонарики, которые можно купить в магазине восточных сувениров, а можно изготовить самим из цветной бумаги.

На праздничном столе должны стоять свечи белого цвета и благовония, что даст возможность снискать расположение высших сил.

Чтобы праздник удался, нужно продумать не только праздничное меню (в него желательно включить традиционные китайские новогодние блюда – пельмени с креветками, различные виды лапши с соусами и др.), но и развлекательную программу для гостей.

Этот праздник в 2022 году будет отмечаться на протяжении 15 дней — с 1 по 15 февраля. У вас есть партнеры по бизнесу, коллеги по работе или друзья китайцы? Отправьте им поздравления с Новым годом на китайском языке.

Как поздравить китайца с Новым 2022 годом?

В этой стране традиционно говорят:

***

新年快乐! (Xīnnián kuàilè) Весёлого Нового года!

***

恭贺新禧! (Gōnghè xīnxǐ) Поздравляю с Новым годом!

***

全体大家新年快乐! 万事如意!身体健康!阖家幸福! (Quántǐ dàjiā xīnnián kuàilè! Wànshì rúyì! Shēntǐ jiànkāng! Hé jiā xìngfú!) Всем счастливого Нового года! Исполнения всех желаний! Крепкого здоровья! Счастья всей семье!

На нашем сайте вы найдете красивые поздравления с Новым годом по-китайски. Такие китайские пожелания на Новый год можно отправить по электронной почте или в виде смс.

***

祝你新年大吉大利! (Zhù nǐ xīnnián dàjí dàlì!) Желаю тебе в новом году необыкновенной удачи!

***

新春祝你事事好,生活妙,工资高! (Xīnchūn zhù nǐ shì shì hǎo, shēnghuó miào, gōngzī gāo!) В новом году желаю успехов в делах, замечательной жизни и высокой зарплаты!

Поздравления с Новым годом на китайском языке

Вашим партнерам по бизнесу и друзьям будет приятно получить от вас слова поздравления с этим праздником на китайском языке. Мы подскажем, как поздравить китайца с Новым годом.

***

2022 年新年快乐! 合家幸福! 在新的一年里好事多多! 笑容多多! 开心每一秒,快乐每一天,幸福每一年,健康到永远! (2022 nián xīnnián kuàilè! Héjiā xìngfú! Zài xīn de yī nián lǐ hǎoshì duōduō! Xiàoróng duōduō! Kāixīn měi yī miǎo, kuàilè měi yītiān, xìngfú yī nián, jiànkāng dào yǒngyuǎn!)

С новым 2022 годом! Счастья всей семье! Весь новый год много радостных событий! Много улыбок! Радость каждую секунду, веселья каждый день, счастья целый год, здоровья на века!

Выбирайте лучшие поздравления с Новым годом по-китайски и отправляйте своим бизнес-партнерам. Мы подобрали здесь китайские пожелания на Новый год, связанные с карьерой, бизнесом и богатством.

***

金生意兴隆 (shēng yì xīng lóng). Процветающего бизнеса.

***

万事如意 (wàn shì rú yì). Удачи во всех делах.

***

事业有成 (shì yè yǒu chéng). Успехов в карьере.

***

吉星高照 (jí xīng gāo zhào). Удачи (сияющей счастливой звезды).

***

吉祥如意 (jí xiáng rú yì). Удачи (желаю всего благоприятного).

***

恭喜發財 (gōng xǐ fā cái). Счастья и процветания (обычно говорят при получении подарков или счастливой новогодней монетки).

***

玉滿堂 (Jīnyùmǎntáng). Пусть богатство наполнит твой дом.

Как празднуют Новый год в Китае

Это самый главный и самый длинный праздник в китайском лунном календаре. В этой стране его отмечают уже два тысячелетия. Он приходится на новолуние по завершении полного лунного цикла между 21 января и 21 февраля (1 февраля в 2022 году). В переводе с китайского языка его название означает «Праздник весны».

В ночь накануне праздника, которую китайцы называют «ночью встречи после разлуки», семьи собираются дома за праздничным столом. По окончании ужина взрослые дарят детям деньги в красных конвертах. Считается, что такие подарки должны принести им счастье.

На улицах и площадях китайских городов и сел устраиваются шумные народные гулянья. Исполняются танцы драконов и львов, номера на ходулях, устраиваются фейерверки. Они должны отпугнуть злых духов, которые ищут себе пристанище в следующем году, и привлечь в семьи благополучие и счастье. Во время празднования Нового года китайцы делают подношения богам, которым приносят рис и бобы.

Согласно традиции, которая насчитывает тысячу лет, в качестве подарка друзьям и близким к празднику принято преподносить два мандарина (это словосочетание в китайском языке напоминает слово «золото»). Такой презент означает пожелание удачного года.

1 февраля 2022 года в Китае будет отмечаться яркий и веселый праздник – Новый год. Посвященные ему торжества продлятся две недели, до 26 февраля. Это самый главный и самый длинный праздник в китайском лунном календаре. В этой стране его отмечают уже два тысячелетия.

На улицах и площадях городов и сел проходят шумные народные гулянья. Исполняются танцы драконов и львов, номера на ходулях, устраиваются фейерверки. Они должны отпугнуть злых духов, которые, как считается, ищут себе пристанище в следующем году, и привлечь в семьи благополучие и счастье.

Согласно местному летоисчислению, в Китае наступит 4717 год. В соответствии с восточным календарем, его будет олицетворять одно из 12-ти животных. Символичен и его цвет, означающий одну из природных стихий: Огонь, Воду, Землю, Металл или Дерево.

Согласно гороскопу, в 2022 году вступит в свои права Черный Водяной Тигр, который символизирует трудолюбие и усердие, целеустремленность и упорство.

Если в вас есть партнеры по бизнесу, коллеги по работе или друзья китайцы, это стоит учитывать при составлении поздравления с 2022 Китайским Новым годом.

Как поздравить китайца с Китайским Новым годом?

В этой стране традиционно говорят:

新年快乐! (Xīnnián kuàilè) Веселого Нового года!

恭贺新禧! (Gōnghè xīnxǐ) Поздравляю с Новым годом!

恭贺新禧,万事如意С Новым годом, с новым счастьем! Желаю исполнения всех желаний!

全体大家新年快乐! 万事如意!身体健康!阖家幸福! (Quántǐ dàjiā xīnnián kuàilè! Wànshì rúyì! Shēntǐ jiànkāng! Hé jiā xìngfú!) Всем счастливого Нового года! Исполнения всех желаний! Крепкого здоровья! Счастья всей семье!

Новый год в Китае называют «Чуньцзе», что в переводе означает праздник весны, поэтому будет уместно и следующее пожелание: 新春快乐 Счастливой Новой весны!

Конечно, такое новогоднее поздравление на китайском языке с 2022 годом можно не только прочесть вслух за праздничным столом, но и отправить с помощью современных средств связи: по электронной почте или в виде смс, разместить на страничке в социальной сети.

Как у китайцев принято поздравить с Китайским Новым годом?

К этому празднику преподносят сувениры в восточном стиле, статуэтки, шкатулки для хранения украшений, фигурки фэн-шуй. Презентуют и подарки со смыслом – чашу богатства; счеты, приносящие успех в бизнесе; колокольчики, очищающие помещение от плохой энергии.

Можно обратить внимание на наборы парных предметов, символизирующих единство и семейную гармонию: это могут быть, например, две вазы, две кружки, подсвечник для двух свечей и т.п.

Один из самых популярных у китайцев презентов – деньги, которые кладут в красный конверт. Количество купюр должно быть четным – обычно их 8, ведь это число считается здесь счастливым.

Если вы идете в гости, не стоит выбирать слишком дорогие подарки: будет достаточно фруктов или хорошего алкоголя. Согласно традиции, которая насчитывает тысячу лет, в качестве подарка друзьям и близким принято преподносить два мандарина (это словосочетание в китайском языке напоминает слово «золото»). Такой презент означает пожелание удачного года.

Выбирая упаковку для подарков, учитывайте, что красный и золотой цвета считаются цветами удачи, а белый и черный использовать при этом не стоит.

Можно приложить к презенту открытку с поздравлением с 2022 Китайским Новым годом. Традиционно в эти дни люди желают друг друга здоровья, успеха в различных начинаниях и финансового благополучия.

Каким может быть поздравление с Китайским Новым годом 2022 по-китайски?

Это может быть следующее пожелание:

恭喜发财 Желаю вам успеха и процветания!

身体健康 (Shēntǐjiànkāng) Наслаждаться хорошим здоровьем.

福壽雙全 Счастья и долголетия.

福禄寿 Счастья, процветания и долголетия!

祝你新年大吉大利! (Zhù nǐ xīnnián dàjí dàlì!) Желаю тебе в новом году необыкновенной удачи!

恭祝健康、幸运,新年快乐 Желаю здоровья, удачи и счастья в Новом году!

恭贺新禧、万事如意С Новым годом, и чтобы все шло как задумано!

一帆风顺 (Yīfānfēngshùn) Пусть ваша жизнь проходит гладко.

吉星高照 (Jíxīnggāozhào) Фортуна улыбнется вам.

恭喜發財 (gōng xǐ fā cái). Счастья и процветания (обычно говорят при получении подарков или счастливой новогодней монетки).

玉滿堂 (Jīnyùmǎntáng) Пусть богатство наполнит твой дом.

阖家欢乐 Счастья для всей семьи.

心想事成 (xīnxiǎng shì chéng) Пусть сбудутся твои мечты.

祝你吉祥如意 Всего тебе хорошего, что пожелаешь.

Более многословное поздравление может выглядеть так:

2022 年新年快乐! 合家幸福! 在新的一年里好事多多! 笑容多多! 开心每一秒,快乐每一天,幸福每一年,健康到永远!

[2022 nián xīnnián kuàilè! Héjiā xìngfú! Zài xīn de yī nián lǐ hǎoshì duōduō! Xiàoróng duōduō! Kāixīn měi yī miǎo, kuàilè měi yītiān, xìngfú yī nián, jiànkāng dào yǒngyuǎn!]

С новым 2022 годом! Счастья всей семье! Весь новый год много радостных событий! Много улыбок! Радость каждую секунду, веселья каждый день, счастья целый год, здоровья на века!

Можно поздравить друзей в стихотворной форме:

新年到,短信早,祝福绕,人欢笑,生活好,步步高,重环保,健康牢,多关照,新目标,加力跑,乐淘淘! [Xīnnián dào, duănxìn zǎo, zhùfú rào, rén huānxiào, shēnghuó hǎo, bù bù gāo, chóng huánbào, jiànkāng láo, duō guānzhào, xīn mùbiāo, jiā lì pǎo, lè táo táo!]

Дословный перевод следующий: Новый год наступает, поздравительные смс-ки отправляем, счастья всем желаем. Люди весело смеются, все в жизни хорошо. Шагаем мы высоко, здоровья всем крепкого желаем, новых целей быстро достигаем и радость льется к нам рекой!

А каким должно быть поздравление с 2022 Китайским Новым годом, адресованное китайским партнерам по бизнесу?

Вы можете пожелать им:

吉星高照 (jí xīng gāo zhào) Удачи (сияющей счастливой звезды).

吉祥如意 (jí xiáng rú yì) Удачи (желаю всего благоприятного).

万事如意 (wàn shì rú yì) Удачи во всех делах.

事业有成 (shì yè yǒu chéng) Успехов в карьере.

工作顺利 (gōng zuò shùn lì) Гладкой работы.

金生意兴隆 (shēng yì xīng lóng) Процветающего бизнеса.

祝您生意兴隆 Желаю вам прибыльного бизнеса.

大吉大利 (Dàjídàlì) Много удачи и прибыли.

一本萬利 (Yīběnwànlì) Малых затрат, большой прибыли.

事业成功,家庭美满Удачи в карьере и бизнесе, счастья и благополучия Вашей семье!

新春祝你事事好,生活妙,工资高!

[Xīnchūn zhù nǐ shì shì hǎo, shēnghuó miào, gōngzī gāo!]

В новом году желаю успехов в делах, замечательной жизни и высокой зарплаты!

Надеемся, что эта статья подскажет вам, какими словами лучше поздравить китайцев с 2022 Китайским Новым годом, и ваши теплые пожелания найдут отклик в сердцах тех, кому будут адресованы.

This article is about the festival observed on the traditional Chinese calendar. For the first day of the year observed on other lunar or lunisolar calendars, see Lunar New Year.

| Chinese New Year | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise from the top: Fireworks over Victoria Harbour in Hong Kong, lion dance in Boston Chinatown, red Lanterns on display, dragon dance in San Francisco, red envelopes, firecrackers exploding, spring couplet |

|

| Also called | Spring Festival, Lunar New Year |

| Observed by | Chinese people and Sinophone communities[1] |

| Type | Cultural Religious (Chinese folk religion, Buddhist, Confucian, Taoist, some Christian communities) |

| Celebrations | Lion dances, dragon dances, fireworks, family gathering, family meal, visiting friends and relatives, giving red envelopes, decorating with chunlian couplets |

| Date | First day of the first month of the Chinese calendar (between 21 January and 20 February) |

| 2022 date | 1 February |

| 2023 date | 22 January |

| 2024 date | 10 February[2] |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Lantern Festival, which concludes the celebration of the Chinese New Year. Mongolian New Year (Tsagaan Sar), Tibetan New Year (Losar), Japanese New Year (Shōgatsu), Korean New Year (Seollal), Vietnamese New Year (Tết), Indigenous Assamese New Year (Rongali Bihu) |

| Chinese New Year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Chinese New Year» in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 春節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 春节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Spring Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Agricultural Calendar New Year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 農曆新年 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 农历新年 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese New Year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國傳統新年 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国传统新年 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chinese New Year is the festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year on the traditional lunisolar Chinese calendar. In Chinese, the festival is commonly referred to as the Spring Festival (traditional Chinese: 春節; simplified Chinese: 春节; pinyin: Chūnjié)[3] as the spring season in the lunisolar calendar traditionally starts with lichun, the first of the twenty-four solar terms which the festival celebrates around the time of the Chinese New Year.[4] Marking the end of winter and the beginning of the spring season, observances traditionally take place from New Year’s Eve, the evening preceding the first day of the year to the Lantern Festival, held on the 15th day of the year. The first day of Chinese New Year begins on the new moon that appears between 21 January and 20 February.[note 1]

Chinese New Year is one of the most important holidays in Chinese culture, and has strongly influenced Lunar New Year celebrations of its 56 ethnic groups, such as the Losar of Tibet (Tibetan: ལོ་གསར་), and of China’s neighbours, including the Korean New Year (Korean: 설날; RR: Seollal), and the Tết of Vietnam,[6] as well as in Okinawa.[7] It is also celebrated worldwide in regions and countries that house significant Overseas Chinese or Sinophone populations, especially in Southeast Asia. These include Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar,[8] the Philippines,[9] Singapore,[10] Thailand, and Vietnam. It is also prominent beyond Asia, especially in Australia, Canada, Mauritius,[11] New Zealand, Peru,[12] South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States, as well as various European countries.[13][14][15]

The Chinese New Year is associated with several myths and customs. The festival was traditionally a time to honor deities as well as ancestors.[16] Within China, regional customs and traditions concerning the celebration of the New Year vary widely,[17] and the evening preceding the New Year’s Day is frequently regarded as an occasion for Chinese families to gather for the annual reunion dinner. It is also a tradition for every family to thoroughly clean their house, in order to sweep away any ill fortune and to make way for incoming good luck. Another custom is the decoration of windows and doors with red paper-cuts and couplets. Popular themes among these paper-cuts and couplets include good fortune or happiness, wealth, and longevity. Other activities include lighting firecrackers and giving money in red envelopes.

Dates in Chinese lunisolar calendar[edit]

Traditional paper cutting with the character for spring (春)

Chinese New Year eve in Meizhou on 8 February 2005.

The Chinese calendar defines the lunar month containing the winter solstice as the eleventh month, meaning that Chinese New Year usually falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice (rarely the third if an intercalary month intervenes).[18] In more than 96 percent of the years, Chinese New Year’s Day is the closest date to a new moon to lichun (Chinese: 立春; «start of spring«) on 4 or 5 February, and the first new moon after dahan (Chinese: 大寒; «major cold«). In the Gregorian calendar, the Chinese New Year begins at the new moon that falls between 21 January and 20 February.[19]

| Gregorian | Date | Animal | Day of the week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 22 Jan | Rabbit | Sunday | |

| 2024 | 10 Feb | Dragon | Saturday | |

| 2025 | 29 Jan | Snake | Wednesday | |

| 2026 | 17 Feb | Horse | Tuesday | |

| 2027 | 6 Feb | Goat | Saturday | |

| 2028 | 26 Jan | Monkey | Wednesday | |

| 2029 | 13 Feb | Rooster | Tuesday | |

| 2030 | 3 Feb | Dog | Sunday | |

| 2031 | 23 Jan | Pig | Thursday | |

| 2032 | 11 Feb | Rat | Wednesday | |

| 2033 | 31 Jan | Ox | Monday | |

| 2034 | 19 Feb | Tiger | Sunday |

Mythology[edit]

Hand-written Chinese New Year’s poetry pasted on the sides of doors leading to people’s homes, Lijiang, Yunnan

According to legend, Chinese New Year started with a mythical beast called the Nian (a beast that lives under the sea or in the mountains) during the annual Spring Festival. The Nian would eat villagers, especially children in the middle of the night.[20] One year, all the villagers decided to hide from the beast. An older man appeared before the villagers went into hiding and said that he would stay the night and would get revenge on the Nian. The old man put red papers up and set off firecrackers. The day after, the villagers came back to their town and saw that nothing had been destroyed. They assumed that the old man was a deity who came to save them. The villagers then understood that Yanhuang had discovered that the Nian was afraid of the color red and loud noises.[20] Then the tradition grew when New Year was approaching, and the villagers would wear red clothes, hang red lanterns, and red spring scrolls on windows and doors and used firecrackers and drums to frighten away the Nian. From then on, Nian never came to the village again. The Nian was eventually captured by Hongjun Laozu, an ancient Taoist monk.[21]

History[edit]

Before the new year celebration was established, ancient Chinese gathered and celebrated the end of harvest in autumn. However, this was not the Mid-Autumn Festival, during which Chinese gathered with family to worship the Moon. In the Classic of Poetry, a poem written during Western Zhou (1045 BC – 771 BC) by an anonymous farmer, described the traditions of celebrating the 10th month of the ancient solar calendar, which was in autumn.[22] According to the poem, during this time people clean millet-stack sites, toast guests with mijiu (rice wine), kill lambs and cook their meat, go to their masters’ home, toast the master, and cheer the prospect of living long together. The 10th-month celebration is believed to be one of the prototypes of Chinese New Year.[23]

The records of the first Chinese new year celebration can be traced to the Warring States period (475 BC – 221 AD). In the Lüshi Chunqiu, in Qin state an exorcism ritual to expel illness, called «Big Nuo» (大儺), was recorded as being carried out on the last day of the year.[24][25] Later, Qin unified China, and the Qin dynasty was founded; and the ritual spread. It evolved into the practice of cleaning one’s house thoroughly in the days preceding Chinese New Year.

The first mention of celebrating at the start of a new year was recorded during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD). In the book Simin Yueling (四民月令), written by the Eastern Han agronomist Cui Shi (崔寔), a celebration was described: «The starting day of the first month, is called Zheng Ri. I bring my wife and children, to worship ancestors and commemorate my father.» Later he wrote: «Children, wife, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren all serve pepper wine to their parents, make their toast, and wish their parents good health. It’s a thriving view.»[26] The practice of worshipping ancestors on New Year’s Eve is maintained by Chinese people to this day.[27]

Han Chinese also started the custom of visiting acquaintances’ homes and wishing each other a happy new year. In Book of the Later Han, volume 27, a county officer was recorded as going to his prefect’s house with a government secretary, toasting the prefect, and praising the prefect’s merit.[28][29]

During the Jin dynasty (266 – 420 AD), people started the New Year’s Eve tradition of all-night revelry called shousui (守歲). It was described in Western Jin general Zhou Chu’s article Fengtu Ji (風土記 “Notes on Local Conditions”): «At the ending of a year, people gift and wish each other, calling it Kuisui (饋歲 “gift time”); people invited others with drinks and food, calling it Biesui (別歲 “others time”); on New Year’s Eve, people stayed up all night until sunrise, calling it Shousui (守歲 “guard the year”).»[30] The article used the word chu xi (除夕) to indicate New Year’s Eve, and the name is still used until this day.

The Northern and Southern dynasties book Jingchu Suishiji described the practice of firing bamboo in the early morning of New Year’s Day,[31] which became a New Year tradition of the ancient Chinese. Poet and chancellor of the Tang dynasty Lai Gu also described this tradition in his poem Early Spring (早春): «新曆才将半纸开,小亭猶聚爆竿灰», meaning «Another new year just started as a half opening paper, and the family gathered around the dust of exploded bamboo pole».[32] The practice was used by ancient Chinese people to scare away evil spirits, since firing bamboo would noisily crack or explode the hard plant.

During the Tang dynasty, people established the custom of sending bai nian tie (拜年帖), which are New Year’s greeting cards. It is said that the custom was started by Emperor Taizong of Tang. The emperor wrote «普天同慶» (whole nation celebrate together) on gold leaves and sent them to his ministers. Word of the emperor’s gesture spread, and later it became the custom of people in general, who used Xuan paper instead of gold leaves.[33] Another theory is that bai nian tie was derived from the Han dynasty’s name tag, «門狀» (door opening). As imperial examinations became essential and reached their heyday under the Tang dynasty, candidates curried favour to become pupils of respected teachers, in order to get recommendation letters. After obtaining good examination marks, a pupil went to the teacher’s home with a men zhuang (门状) to convey their gratitude. Therefore, eventually men zhuang became a symbol of good luck, and people started sending them to friends on New Year’s Day, calling them by a new name, bai nian tie (拜年帖, New Year’s Greetings).[34]

The Chunlian (Spring Couplets) was written by Meng Chang, an emperor of the Later Shu (935 – 965 AD), during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period:»新年納餘慶,嘉節號長春» (Enjoying past legacies in the new year, the holiday foreseeing the long-lasting spring). As described by Song dynasty official Zhang Tangying in his book Shu Tao Wu, volume 2: on the day of New Year’s Eve, the emperor ordered the scholar Xin Yinxun to write the couplets on peach wood and hang them on the emperor’s bedroom door.[35][36] It is believed that placing the couplets on the door to the home in the days preceding the new year was widespread during the Song dynasty. The famous Northern Song politician, litterateur, philosopher, and poet Wang Anshi recorded the custom in his poem «元日» (New Year’s Day).[37]

|

爆竹聲中一歲除, |

Amid the sound of firecrackers a year has come to an end, |

| —王安石, 元日 | —Wang Anshi, New Year’s Day |

The poem Yuan Ri (元日) also includes the word «爆竹» (bao zhu, exploding bamboo), which is believed to be a reference to firecrackers, instead of the previous tradition of firing bamboo, both of which are called the same in the Chinese language. After gunpowder was invented in the Tang dynasty and widely used under the Song dynasty, people modified the tradition of firing bamboo by filling the bamboo pole with gunpowder, which made for louder explosions. Later under the Song, people discarded the bamboo and started to use paper to wrap the gunpowder in cylinders, in imitation of the bamboo. The firecracker was still called «爆竹», thus equating the new and old traditions. It is also recorded that people linked the firecrackers with hemp rope and created the «鞭炮» (bian pao, gunpowder whip) in the Song dynasty. Both «爆竹» and «鞭炮» are still used by present-day people to celebrate the Chinese New Year and other festive occasions.[38]

It was also during the Song dynasty that people started to give money to children in celebration of a new year. The money was called sui nian qian (随年钱), meaning «the money based on age». In the chapter «Ending of a year» (歲除) of Wulin jiushi (武林舊事), the writer recorded that concubines of the emperor prepared a hundred and twenty coins for princes and princesses, to wish them long lives.[39]

The new year celebration continued under the Yuan dynasty, when people also gave nian gao (年糕, year cakes) to relatives.[40]

The tradition of eating Chinese dumplings jiaozi (餃子) was established under the Ming dynasty at the latest. It is described in the book Youzhongzhi (酌中志): «People get up at 5 in the morning of new year’s day, burn incense and light firecrackers, throw door latch or wooden bars in the air three times, drink pepper and thuja wine, eat dumplings. Sometimes put one or two silver currency inside dumplings, and whoever gets the money will attain a year of fortune.»[41] Modern Chinese people also put other food that is auspicious into dumplings: such as dates, which prophesy a flourishing new year; candy, which predicts sweet days; and nian gao, which foretells a rich life.

In the Qing dynasty, the name ya sui qian (壓歲錢, New Year’s Money) was given to the lucky money given to children at the new year. The book Qing Jia Lu (清嘉錄) recorded: «elders give children coins threaded together by a red string, and the money is called Ya Sui Qian.»[42] The name is still used by modern Chinese people. The lucky money was presented in one of two forms: one was coins strung on red string; the other was a colorful purse filled with coins.[43]

In 1928, the ruling Kuomintang party decreed that the Chinese New Year would fall on 1 Jan of the Gregorian Calendar, but this was abandoned due to overwhelming popular opposition. In 1967, during the Cultural Revolution, official Chinese New Year celebrations were banned in China. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China announced that the public should «change customs»; have a «revolutionized and fighting Spring Festival»; and since people needed to work on Chinese New Year Eve, they did not need holidays during Spring Festival day. The old celebrations were reinstated in 1980.[44]

Naming[edit]

While «Chinese New Year» remains the official name for the festival in Taiwan, the name «Spring Festival» was adopted by the People’s Republic of China instead. On the other hand, some in the Chinese diaspora use the term «Lunar New Year», while «Chinese New Year» remains a popular and convenient translation for people of non-Chinese cultural backgrounds. Along with the Han Chinese in and outside Greater China, as many as 29 of the 55 ethnic minority groups in China also celebrate Chinese New Year. Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines celebrate it as an official festival.[45]

Public holiday[edit]

Chinese New Year is observed as a public holiday in some countries and territories where there is a sizable Chinese population. Since Chinese New Year falls on different dates on the Gregorian calendar every year on different days of the week, some of these governments opt to shift working days in order to accommodate a longer public holiday. In some countries, a statutory holiday is added on the following work day if the New Year (as a public holiday) falls on a weekend, as in the case of 2013, where the New Year’s Eve (9 February) falls on Saturday and the New Year’s Day (10 February) on Sunday. Depending on the country, the holiday may be termed differently; common names in English are «Chinese New Year», «Lunar New Year», «New Year Festival», and «Spring Festival».

For New Year celebrations that are lunar but are outside of China and Chinese diaspora (such as Korea’s Seollal and Vietnam’s Tết), see the article on Lunar New Year.

For other countries and regions where Chinese New Year is celebrated but not an official holiday, see the table below.

| Country and region | Official name | Description | Number of days |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaysia | Tahun Baru Cina | The first 2 days of Chinese New Year.[46] | 2[47][46] |

| Singapore | Chinese New Year | The first 2 days of Chinese New Year.[48] | 2 |

| Brunei | Tahun Baru Cina | Half-day on Chinese New Year’s Eve and the first day of Chinese New Year.[49] | 1 |

| Hong Kong | Lunar New Year | The first 3 days of Chinese New Year.[50] | 3 |

| Macau | Novo Ano Lunar | The first 3 days of Chinese New Year[51] | 3 |

| Indonesia | Tahun Baru Imlek (Sin Cia) | The first day of Chinese New Year.[52][53] | 1 |

| China | Spring Festival (Chūn Jié) | The first 3 days of Chinese New Year. Extra holiday days are de facto added adjusting the weekend days before and after the three days holiday, resulting in a full week of public holiday known as Golden Week.[54][55] During the Chunyun holiday travel season. | 3 (official holiday days) / 7 (de facto holiday days) |

| Philippines | Chinese New Year | Half-day on Chinese New Year’s Eve and the first day of Chinese New Year.[56] | 1 |

| South Korea | Korean New Year (Seollal) | The first 3 days of Chinese New Year. | 3 |

| Taiwan | Lunar New Year / Spring Festival | Chinese New Year’s Eve and the first 3 days of Chinese New Year; will be made up on subsequent working days if any of the 4 days fall on Saturday or Sunday. The day before Chinese New Year’s Eve is also designated as holiday, but as a bridge holiday, and will be made up on an earlier or later Saturday. Additional bridge holidays may apply, resulting in 9-day or 10-day weekends.[57][58][59] | 4 (legally), 9–10 (including Saturdays and Sundays)[60] |

| Thailand | Wan Trut Chin (Chinese New Year’s Day) | Observed by Thai Chinese and parts of the private sector. Usually celebrated for three days, starting on the day before the Chinese New Year’s Eve. Chinese New Year is observed as a public holiday in Narathiwat, Pattani, Yala, Satun[61] and Songkhla Provinces.[48] | 1 |

| Vietnam | Tết Nguyên Đán (Vietnamese New Year) | The first 3 days of Chinese New Year. | 3 |

| California, United States | Lunar New Year | The first day of Chinese New Year. | 1 |

| Suriname | Maan Nieuwjaar | The first day of Chinese New Year. | 1 |

Festivities[edit]

Red couplets and red lanterns are displayed on the door frames and light up the atmosphere. The air is filled with strong Chinese emotions. In stores in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and other cities, products of traditional Chinese style have started to lead fashion trend[s]. Buy yourself a Chinese-style coat, get your kids tiger-head hats and shoes, and decorate your home with some beautiful red Chinese knots, then you will have an authentic Chinese-style Spring Festival.

— Xinwen Lianbo, January 2001, quoted by Li Ren, Imagining China in the Era of Global Consumerism and Local Consciousness[62]

During the festival, people around China will prepare different gourmet dishes for their families and guests. Influenced by the flourished cultures, foods from different places look and taste totally different. Among them, the most well-known ones are dumplings from northern China and Tangyuan from southern China.[citation needed]

Preceding days[edit]

On the eighth day of the lunar month prior to Chinese New Year, the Laba holiday (腊八; 臘八; làbā), a traditional porridge, Laba porridge (腊八粥; 臘八粥; làbā zhōu), is served in remembrance of an ancient festival, called La, that occurred shortly after the winter solstice.[63] Pickles such as Laba garlic, which turns green from vinegar, are also made on this day. For those that practice Buddhism, the Laba holiday is also considered Bodhi Day. Layue (腊月; 臘月; Làyuè) is a term often associated with Chinese New Year as it refers to the sacrifices held in honor of the gods in the twelfth lunar month, hence the cured meats of Chinese New Year are known as larou (腊肉; 臘肉; làròu). The porridge was prepared by the women of the household at first light, with the first bowl offered to the family’s ancestors and the household deities. Every member of the family was then served a bowl, with leftovers distributed to relatives and friends.[64] It’s still served as a special breakfast on this day in some Chinese homes. The concept of the «La month» is similar to Advent in Christianity. Many families eat vegetarian on Chinese New Year eve, the garlic and preserved meat are eaten on Chinese New Year day.

Receive the Gods in Chinese New Year, (1900s)

On the days immediately before the New Year celebration, Chinese families give their homes a thorough cleaning. There is a Cantonese saying «Wash away the dirt on nin ya baat» (Chinese: 年廿八,洗邋遢; pinyin: nián niàn bā, xǐ lātà; Jyutping: nin4 jaa6 baat3, sai2 laap6 taap3 (laat6 taat3)), but the practice is not restricted to nin ya baat (the 28th day of month 12). It is believed the cleaning sweeps away the bad luck of the preceding year and makes their homes ready for good luck. Brooms and dust pans are put away on the first day so that the newly arrived good luck cannot be swept away. Some people give their homes, doors and window-frames a new coat of red paint; decorators and paper-hangers do a year-end rush of business prior to Chinese New Year.[65] Homes are often decorated with paper cutouts of Chinese auspicious phrases and couplets. Purchasing new clothing and shoes also symbolize a new start. Any hair cuts need to be completed before the New Year, as cutting hair on New Year is considered bad luck due to the homonymic nature of the word «hair» (fa) and the word for «prosperity». Businesses are expected to pay off all the debts outstanding for the year before the new year eve, extending to debts of gratitude. Thus it is a common practice to send gifts and rice to close business associates, and extended family members.

In many households where Buddhism or Taoism is observed, home altars and statues are cleaned thoroughly, and decorations used to adorn altars over the past year are taken down and burned a week before the new year starts on Little New Year, to be replaced with new decorations. Taoists (and Buddhists to a lesser extent) will also «send gods back to heaven» (Chinese: 送神; pinyin: sòngshén), an example would be burning a paper effigy of Zao Jun the Kitchen God, the recorder of family functions. This is done so that the Kitchen God can report to the Jade Emperor of the family household’s transgressions and good deeds. Families often offer sweet foods (such as candy) in order to «bribe» the deities into reporting good things about the family.

Prior to the Reunion Dinner, a prayer of thanksgiving is held to mark the safe passage of the previous year. Confucianists take the opportunity to remember their ancestors, and those who had lived before them are revered. Some people do not give a Buddhist prayer due to the influence of Christianity, with a Christian prayer offered instead.

Chinese New Year’s Eve[edit]

The day before the Chinese New Year (Chinese: 除夕) usually accompanied with a dinner feast, consisting of special meats are served at the tables, as a main course for the dinner and as an offering for the New Year. This meal is comparable to Thanksgiving dinner in the U.S. and remotely similar to Christmas dinner in other countries with a high percentage of Christians.

In northern China, it is customary to make jiaozi, or dumplings, after dinner to eat around midnight. Dumplings symbolize wealth because their shape resembles a Chinese sycee. In contrast, in the South, it is customary to make a glutinous new year cake (niangao) and send pieces of it as gifts to relatives and friends in the coming days. Niángāo [Pinyin] literally means «new year cake» with a homophonous meaning of «increasingly prosperous year in year out».[66]

After dinner, some families may visit local temples hours before midnight to pray for success by lighting the first incense of the year; however in modern practice, many households held parties to celebrate. Traditionally, firecrackers were lit to ward evil spirits when the household doors sealed, and are not to be reopened until dawn in a ritual called «opening the door of fortune» (开财门; 開財門; kāicáimén).[67] A tradition of staying up late on Chinese New Year’s Eve is known as shousui (Chinese: 守岁), which is still practised as it is thought to add on to one’s parents’ longevity.

First day[edit]

The first day, known as the «Spring Festival» (春節 / 春节) is for the welcoming of the deities of the heavens and Earth on midnight. It is a traditional practice to light fireworks, burn bamboo sticks and firecrackers, and lion dance troupes, were done commonly as a tradition to ward off evil spirits.

Typical actions such as lighting fires and using knives are considered taboo, thus all consumable food has to be cooked prior. Using the broom, swearing, and breaking any dinnerware without appeasing the deities are also considered taboo.[68]

Normal traditions occurring on the first day involve house gatherings to the families, specifically the elders and families to the oldest and most senior members of their extended families, usually their parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, and trading Mandarin oranges as a courtesy to symbolize wealth and good luck. Members of the family who are married also give red envelopes containing cash known as lai see (Cantonese: 利事) or angpow (Hokkien and Teochew), or hongbao (Mandarin: 红包), a form of a blessing and to suppress both the aging and challenges that were associated with the coming year, to junior members of the family, mostly children and teenagers. Business managers may also give bonuses in the form of red packets to employees.[69] The money can be of any form, specifically numbers ending with 8, which sounded as huat (Mandarin: 发), meaning prosperity, but packets with denominations of odd numbers or without money are usually not allowed due to bad luck, especially the number 4 which sounded as si (Mandarin: 死), which means death.[70][69]

While fireworks and firecrackers are traditionally very popular, some regions have banned them due to concerns over fire hazards. For this reason, various city governments (e.g., Kowloon, Beijing, Shanghai for a number of years) issued bans over fireworks and firecrackers in certain precincts of the city. As a substitute, large-scale fireworks display have been launched by governments in Hong Kong and Singapore.

Second day[edit]

Incense is burned at the graves of ancestors as part of the offering and prayer rituals.

The second day, entitled «a year’s beginning» (开年; 開年; kāinián),[71] oversees married daughters visiting their birth parents, relatives and close friends, often renew family ties and relationship. (Traditionally, married daughters didn’t have the opportunity to visit their birth families frequently.)

The second day also saw giving offering money and sacrifices to God of Wealth (Chinese: Chinese: 财神) to symbolize a rewarding time after hardship in the preceding year. During the days of imperial China, «beggars and other unemployed people circulate[d] from family to family, carrying a picture [of the God of Wealth] shouting, «Cai Shen dao!» [The God of Wealth has come!].»[72] Householders would respond with «lucky money» to reward the messengers. Business people of the Cantonese dialect group will hold a ‘Hoi Nin’ prayer to start their business on the second day of Chinese New Year, blessing business to strive in the coming year.

As this day is believed to be The Birthday of Che Kung, a deity worshipped in Hong Kong, worshippers go to Che Kung Temples to pray for his blessing. A representative from the government asks Che Kung about the city’s fortune through kau cim.

Third day[edit]

The third day is known as «red mouth» (赤口; Chìkǒu). Chikou is also called «Chigou’s Day» (赤狗日; Chìgǒurì). Chigou, literally «red dog», is an epithet of «the God of Blazing Wrath» (Chinese: 熛怒之神; pinyin: Biāo nù zhī shén). Rural villagers continue the tradition of burning paper offerings over trash fires. It is considered an unlucky day to have guests or go visiting.[73] Hakka villagers in rural Hong Kong in the 1960s called it the Day of the Poor Devil and believed everyone should stay at home.[74] This is also considered a propitious day to visit the temple of the God of Wealth and have one’s future told.

Fourth day[edit]

In those communities that celebrate Chinese New Year for 15 days, the fourth day is when corporate «spring dinners» kick off and business returns to normal. Other areas that have a longer Chinese New Year holiday will celebrate and welcome the gods that were previously sent on this day.

Fifth day[edit]

This day is the god of Wealth’s birthday. In northern China, people eat jiaozi, or dumplings, on the morning of powu (Chinese: 破五; pinyin: pòwǔ). In Taiwan, businesses traditionally re-open on the next day (the sixth day), accompanied by firecrackers.

It is also common in China that on the 5th day people will shoot off firecrackers to get Guan Yu’s attention, thus ensuring his favor and good fortune for the new year.[75]

Sixth day[edit]

The sixth day is Horse’s Day, on which people drive away the Ghost of Poverty by throwing out the garbage stored up during the festival. The ways vary but basically have the same meaning—to drive away the Ghost of Poverty, which reflects the general desire of the Chinese people to ring out the old and ring in the new, to send away the previous poverty and hardship and to usher in the good life of the New Year.[76]

Seventh day[edit]

The seventh day, traditionally known as Renri (the common person’s birthday), is the day when everyone grows one year older. In some overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Singapore, it is also the day when tossed raw fish salad, yusheng, is eaten for continued wealth and prosperity.

For many Chinese Buddhists, this is another day to avoid meat, the seventh day commemorating the birth of Sakra, lord of the devas in Buddhist cosmology who is analogous to the Jade Emperor.

Eighth day[edit]

Another family dinner is held to celebrate the eve of the birth of the Jade Emperor, the ruler of heaven. People normally return to work by the eighth day, therefore the Store owners will host a lunch/dinner with their employees, thanking their employees for the work they have done for the whole year.

Ninth day[edit]

The ninth day is traditionally known as the birthday of the Jade Emperor of Heaven (Chinese: 玉皇; pinyin: Yù Huáng) and many people offered prayer in the Taoist Pantheon as thanks or gratitude.,[77] and it is commonly known as called Ti Kong Dan (Chinese: 天公誕; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Thiⁿ-kong Tan), Ti Kong Si (Chinese: 天公生; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Thiⁿ-kong Siⁿ/Thiⁿ-kong Seⁿ) or Pai Ti Kong (拜天公; Pài Thiⁿ-kong), which is especially important to Hokkiens other than the first day of the Chinese New Year.[78]

A prominent requisite offering is sugarcane.[78] Legends holds that the Hokkien were spared from a massacre by Japanese pirates by hiding in a sugarcane plantation between the eighth and ninth days of the Chinese New Year, coinciding with the Jade Emperor’s birthday.[78] «Sugarcane» (甘蔗; kam-chià) is a near homonym to «thank you» (感謝; kám-siā) in the Hokkien dialect.[78]

In the morning (traditionally anytime between midnight and 7 am), Taiwanese households set up an altar table with three layers: one top (containing offertories of six vegetables (Chinese: 六齋; pinyin: liù zhāi; those being noodles, fruits, cakes, tangyuan, vegetable bowls, and unripe betel), all decorated with paper lanterns) and two lower levels (five sacrifices and wines) to honor the deities below the Jade Emperor.[77] The household then kneels three times and kowtows nine times to pay obeisance and wish him a long life.[77]

Incense, tea, fruit, vegetarian food or roast pig, and gold paper, are served as a customary protocol for paying respect to an honored person.

Tenth day[edit]

The nation celebrates the Jade Emperor’s birthday on this day.

Fifteenth day[edit]

The fifteenth day of the new year is celebrated as the Lantern Festival, also known as the Yuanxiao Festival (元宵节; 元宵節; Yuán xiāo jié), the Shangyuan Festival (上元节; 上元節; Shàng yuán jié), and Chap Goh Meh (十五暝; Cha̍p-gō͘-mê; ‘the fifteen night’ in Hokkien). Rice dumplings, or tangyuan (汤圆; 湯圓; tang yuán), a sweet glutinous rice ball brewed in a soup, are eaten this day. Candles are lit outside houses as a way to guide wayward spirits home. Families may walk the streets carrying lanterns, which sometimes have riddles attached to or written on them as a tradition.[79]

In China and Malaysia, this day is celebrated by individuals seeking a romantic partner, akin to Valentine’s Day.[80] Nowadays, single women write their contact number on mandarin oranges and throw them in a river or a lake after which single men collect the oranges and eat them. The taste is an indication of their possible love: sweet represents a good fate while sour represents a bad fate.

This day often marks the end of the Chinese New Year festivities.

Traditional food[edit]

One version of niangao, New Year rice cake

A reunion dinner (nián yè fàn) is held on New Year’s Eve during which family members gather for a celebration.[81] The venue will usually be in or near the home of the most senior member of the family. The New Year’s Eve dinner is very large and sumptuous and traditionally includes dishes of meat (namely, pork and chicken) and fish. Most reunion dinners also feature a communal hot pot as it is believed to signify the coming together of the family members for the meal. Most reunion dinners (particularly in the Southern regions) also prominently feature specialty meats (e.g. wax-cured meats like duck and Chinese sausage) and seafood (e.g. lobster and abalone) that are usually reserved for this and other special occasions during the remainder of the year. In most areas, fish (鱼; 魚; yú) is included, but not eaten completely (and the remainder is stored overnight), as the Chinese phrase «may there be surpluses every year» (年年有余; 年年有餘; niánnián yǒu yú) sounds the same as «let there be fish every year.» Eight individual dishes are served to reflect the belief of good fortune associated with the number. If in the previous year a death was experienced in the family, seven dishes are served.

Other traditional foods consists of noodles, fruits, dumplings,[82] spring rolls,[83] and Tangyuan[81] which are also known as sweet rice balls. Each dish served during Chinese New Year represents something special. The noodles used to make longevity noodles are usually very thin, long wheat noodles. These noodles are longer than normal noodles that are usually fried and served on a plate, or boiled and served in a bowl with its broth. The noodles symbolize the wish for a long life. The fruits that are typically selected would be oranges, tangerines, and pomelos as they are round and «golden» color symbolizing fullness and wealth. Their lucky sound when spoken also brings good luck and fortune. The Chinese pronunciation for orange is 橙 (chéng), which sounds the same as the Chinese for ‘success’ (成). One of the ways to spell tangerine(桔 jú) contains the Chinese character for luck (吉 jí). Pomelos are believed to bring constant prosperity. Pomelo in Chinese (柚 yòu) sounds similar to ‘to have’ (有 yǒu), disregarding its tone, however it sounds exactly like ‘again’ (又 yòu). Dumplings and spring rolls symbolize wealth, whereas sweet rice balls symbolize family togetherness.

Red packets for the immediate family are sometimes distributed during the reunion dinner. These packets contain money in an amount that reflects good luck and honorability. Several foods are consumed to usher in wealth, happiness, and good fortune. Several of the Chinese food names are homophones for words that also mean good things.

Many families in China still follow the tradition of eating only vegetarian food on the first day of the New Year, as it is believed that doing so will bring good luck into their lives for the whole year.[84]

Like many other New Year dishes, certain ingredients also take special precedence over others as these ingredients also have similar-sounding names with prosperity, good luck, or even counting money.

| Food item | Simplified Chinese | Traditional Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddha’s delight | 罗汉斋 | 羅漢齋 | Luóhàn zhāi | An elaborate vegetarian dish served by Chinese families on the eve and the first day of the New Year. A type of black hair-like algae, pronounced «fat choy» in Cantonese, is also featured in the dish for its name, which sounds like «prosperity». Hakkas usually serve kiu nyuk (扣肉; kòuròu) and ngiong teu fu. |

| Chicken | 鸡 | 雞 | Jī | Boiled chicken is served because it is figured that any family, no matter how humble their circumstances, can afford a chicken for Chinese New Year. |

| Apples | 苹果 | 蘋果 | Píngguǒ | Apples symbolize peace because the word for apple («ping») is a homonym of the word for peace. |

| Fish | 鱼 | 魚 | Yú | Is usually eaten or merely displayed on the eve of Chinese New Year. The pronunciation of fish makes it a homophone for «surpluses»(余; 餘; yú). |

| Garlic | 蒜 | Suàn | Is usually served in a dish with rondelles of Chinese sausage or Chinese cured meat during Chinese New Year. The pronunciation of Garlic makes it a homophone for «calculating (money)» (算; suàn). The Chinese cured meat is so chosen because it is traditionally the primary method for storing meat over the winter and the meat rondelles resemble coins. | |

| Jau gok | 油角 | Yóu jiǎo | The main Chinese new year dumpling for Cantonese families. It is believed to resemble a sycee or yuánbǎo, the old Chinese gold and silver ingots, and to represent prosperity for the coming year. | |

| Jiaozi | 饺子 | 餃子 | Jiǎozi | The common dumpling eaten in northern China, also believed to resemble sycee. In the reunion dinner, Chinese people add various food into Jiaozi fillings to represent good fortune: coin, Niangao, dried date, candy, etc. |

| Mandarin oranges | 桔子 | Júzi | Oranges, particularly mandarin oranges, are a common fruit during Chinese New Year. They are particularly associated with the festival in southern China, where its name is a homophone of the word for «luck» in dialects such as Teochew (in which 橘, jú, and 吉, jí, are both pronounced gik).[85] | |

| Melon seed/Guazi | 瓜子 | Guāzi | Other variations include sunflower, pumpkin and other seeds. It symbolizes fertility and having many children. | |

| Niangao | 年糕 | Niángāo | Most popular in eastern China (Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Shanghai) because its pronunciation is a homophone for «a more prosperous year (年高 lit. year high)». Niangao is also popular in the Philippines because of its large Chinese population and is known as tikoy (Chinese: 甜粿, from Min Nan) there. Known as Chinese New Year pudding, niangao is made up of glutinous rice flour, wheat starch, salt, water, and sugar. The color of the sugar used determines the color of the pudding (white or brown). | |

| Noodles | 面条 | 麵條 | Miàntiáo | Families may serve uncut noodles (making them as long as they can[86]), which represent longevity and long life, though this practice is not limited to the new year. |

| Sweets | 糖果 | Tángguǒ | Sweets and similar dried fruit goods are stored in a red or black Chinese candy box. | |

| Rougan (Yok Gon) | 肉干 | 肉乾 | Ròugān | Chinese salty-sweet dried meat, akin to jerky, which is trimmed of the fat, sliced, marinated and then smoked for later consumption or as a gift. |

| Taro cakes | 芋头糕 | 芋頭糕 | Yùtougāo | Made from the vegetable taro, the cakes are cut into squares and often fried. |

| Turnip cakes | 萝卜糕 | 蘿蔔糕 | Luóbogāo | A dish made of shredded radish and rice flour, usually fried and cut into small squares. |

| Yusheng or Yee sang | 鱼生 | 魚生 | Yúshēng | Raw fish salad. Eating this salad is said to bring good luck. This dish is usually eaten on the seventh day of the New Year, but may also be eaten throughout the period. |

| Five Xinpan | 五辛盘 | 五辛盤 | Wǔ xīnpán | Five Xin include onion, garlic, pepper, ginger, mustard. As an ancient traditional folk culture, it has been existing since the Jin Dynasty. It symbolizes health. In a well-economic development dynasty, like Song, The Five Xinpan not only have five spicy vegetables. Also, include Chinese bacon and other vegetables. Moreover, it offered to the family’s ancestors to express respect and seek a blessing.[87] |

| Laba porridge | 腊八粥 | 臘八粥 | Làbā zhōu | This dish is eaten on Laba Festival, the eighth day of the twelfth month of the Chinese lunar calendar. The congees are made of mixed walnut, pine nuts, mushrooms, persimmon. The congees are for commemorating the sacrifices of ancestors and celebrating the harvest.[88] |

Practices[edit]

Red envelopes[edit]

Shoppers at a New Year market in Chinatown, Singapore

Traditionally, red envelopes or red packets

(Mandarin: simplified Chinese: 红包; traditional Chinese: 紅包; pinyin: hóngbāo; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: âng-pau; Hakka: fung bao / Cantonese: Chinese: 利是, 利市 or 利事; pinyin: lìshì; Cantonese Yale: lai sze / lai see) are passed out during the Chinese New Year’s celebrations, from married couples or the elderly to unmarried juniors or children. During this period, red packets are also known as «yasuiqian» (压岁钱; 壓歲錢; yāsuìqián, which was evolved from 压祟钱; 壓祟錢; yāsuìqián, literally, «the money used to suppress or put down the evil spirit»).[89] According to legend, a demon named Sui patted a child on the head three times on New Year’s Eve, and the child would have a fever. The parents wrapped coins in red paper and placed them next to their children’s pillows. When Sui came, the flash of the coin scared him away. From then on, every New Year’s Eve, parents will wrap the coin in red paper to protect their children.[90]

Red packets almost always contain money, usually varying from a couple of dollars to several hundred. Chinese superstitions favour amounts that begin with even numbers, such as 8 (八, pinyin: bā) — a homophone for «wealth», and 6 (六, pinyin: liù) — a homophone for «smooth», except for the number 4 (四, pinyin: sì) — as it is a homophone of «death», and is, as such, considered unlucky in Asian culture. Odd numbers are also avoided, as they are associated with cash given during funerals (帛金, pinyin: báijīn).[91][92] It is also customary for bills placed inside a red envelope to be new.[93]

The act of asking for red packets is normally called (Mandarin): 討紅包 tǎo-hóngbāo, 要利是 or (Cantonese): 逗利是. A married person would not turn down such a request as it would mean that he or she would be «out of luck» in the new year. Red packets are generally given by married couples to the younger non-married members of the family.[83] It is custom and polite for children to wish elders a happy new year and a year of happiness, health and good fortune before accepting the red envelope.[83] Red envelopes are then kept under the pillow and slept on for seven nights after Chinese New Year before opening because that symbolizes good luck and fortune.

In Taiwan in the 2000s, some employers also gave red packets as a bonus to maids, nurses or domestic workers from Southeast Asian countries, although whether this is appropriate is controversial.[94][95]

In the mid-2010s, Chinese messaging apps such as WeChat popularized the distribution of red envelopes in a virtual format via mobile payments, usually within group chats.[96][97] In 2017, it was estimated that over 100 billion of these virtual red envelopes would be sent over the New Year holiday.[98][99]

Mythology[edit]

In ancient times, there is a monster named sui (祟) which comes out on New Year’s Eve and touches the heads of sleeping children. The child will be frightened by the touch and wake up and have a fever. The fever eventually will cause the child to have intellectual disabilities. Hence, families will light up their homes and stay awake, leading to a tradition of 守祟, to guide against sui from harming their children.

A folklore tale of sui is about an elderly couple with a precious son. On the night of New Year’s Eve, since they were afraid that sui would come, they took out eight pieces of copper coins to play with their son in order to keep him awake. Their son was very sleepy, however, so they let him go to sleep after placing a red paper bag containing the copper coins under the child’s pillow. The two older children also stayed with him for the whole night. Suddenly, the doors and windows were blown open by a strange wind, and even the candlelight was extinguished. It turned out to be a sui. When the sui was going to reach out and touch the child’s head, the pillow suddenly brightened with the golden light, and the sui was scared away, so the exorcism effect of «red paper wrapped copper money» spread in the past China[100] (see also Chinese numismatic charms). The money is then called «ya sui qian (壓歲錢)», the money to suppress sui.

Another tale is that a huge demon was terrorising a village and there was nobody in the village who was able to defeat the demon; many warriors and statesmen had tried with no luck. A young orphan stepped in, armed with a magical sword that was inherited from his ancestors, and battled the demon, eventually killing it. Peace was finally restored to the village, and the elders all presented the brave young man with a red envelope filled with money to repay the young orphan for his courage and for ridding the village of the demon.[101]

Gift exchange[edit]

In addition to red envelopes, which are usually given from older people to younger people, small gifts (usually food or sweets) are also exchanged between friends or relatives (of different households) during Chinese New Year. Gifts are usually brought when visiting friends or relatives at their homes. Common gifts include fruits (typically oranges, but never trade pears), cakes, biscuits, chocolates, and candies. Gifts are preferred to be wrapped with red or golden paper, which symbolises good luck.

Certain items should not be given, as they are considered taboo. Taboo gifts include:[102][103][104]

- items associated with funerals (i.e. handkerchiefs, towels, chrysanthemums, items colored white and black)

- items that show that time is running out (i.e. clocks and watches)

- sharp objects that symbolize cutting a tie (i.e. scissors and knives)

- items that symbolize that you want to walk away from a relationship (examples: shoes and sandals)

- mirrors

- homonyms for unpleasant topics (examples: «clock» sounds like «the funeral ritual» or «the end of life», green hats because «wear a green hat» sounds like «cuckold», «handkerchief» sounds like «goodbye», «pear» sounds like «separate», «umbrella» sounds like «disperse», and «shoe» sounds like a «rough» year).

Markets[edit]

Markets or village fairs are set up as the New Year is approaching. These usually open-air markets feature new year related products such as flowers, toys, clothing, and even fireworks and firecrackers. It is convenient for people to buy gifts for their new year visits as well as their home decorations. In some places, the practice of shopping for the perfect plum tree is not dissimilar to the Western tradition of buying a Christmas tree.

Fireworks[edit]

A Chinese man setting off fireworks during Chinese New Year in Shanghai.

Bamboo stems filled with gunpowder that was burnt to create small explosions were once used in ancient China to drive away evil spirits. In modern times, this method has eventually evolved into the use of firecrackers during the festive season. Firecrackers are usually strung on a long fused string so it can be hung down. Each firecracker is rolled up in red papers, as red is auspicious, with gunpowder in its core. Once ignited, the firecracker lets out a loud popping noise and, as they are usually strung together by the hundreds, the firecrackers are known for their deafening explosions that are thought to scare away evil spirits. The burning of firecrackers also signifies a joyful time of year and has become an integral aspect of Chinese New Year celebrations.[105] Since the 2000s, firecrackers have been banned in various countries and towns.

Music[edit]

«Happy New Year!» (Chinese: 新年好呀; pinyin: Xīn Nián Hǎo Ya) is a popular children’s song for the New Year holiday.[106] The melody is similar to the American folk song, Oh My Darling, Clementine. Another popular Chinese New Year song is Gong Xi Gong Xi(Chinese: 恭喜恭喜!; pinyin: Gongxi Gongxi!)

.

Movies[edit]

Watching Chinese New Year films is an expression of Chinese cultural identity. During the New Year holidays, the stage boss gathers the most popular actors whom from various troupes let them perform repertories from Qing dynasty. Nowadays many people celebrate the new year by watching these movies.[107]

Hong Kong filmmakers also release Chinese New Year films, mostly comedies, at this time of year.

Clothing[edit]

Girls dressed in red (Hong Kong).

The color red is commonly worn throughout Chinese New Year; traditional beliefs held that red could scare away evil spirits.[83] The wearing of new clothes is another clothing custom during the festival;[108] the new clothes symbolize a new beginning in the year.[83]

Family portrait[edit]

In some places, the taking of a family portrait is an important ceremony after the relatives are gathered.[109] The photo is taken at the hall of the house or taken in front of the house. The most senior male head of the family sits in the center.

Symbolism[edit]

An inverted character fu is a sign of arriving blessings.

As with all cultures, Chinese New Year traditions incorporate elements that are symbolic of deeper meaning. One common example of Chinese New Year symbolism is the red diamond-shaped fu characters (Chinese: 福; pinyin: fú; Cantonese Yale: fuk1; lit. ‘blessings, happiness’), which are displayed on the entrances of Chinese homes. This sign is usually seen hanging upside down, since the Chinese word dao (Chinese: 倒; pinyin: dào; lit. ‘upside down’), is homophonous or nearly homophonous with (Chinese: 到; pinyin: dào; lit. ‘arrive’) in all varieties of Chinese. Therefore, it symbolizes the arrival of luck, happiness, and prosperity.

For the Cantonese-speaking people, if the fu sign is hung upside down, the implied dao (upside down) sounds like the Cantonese word for «pour», producing «pour the luck [away]», which would usually symbolize bad luck; this is why the fu character is not usually hung upside-down in Cantonese communities.

Red is the predominant color used in New Year celebrations. Red is the emblem of joy, and this color also symbolizes virtue, truth and sincerity. On the Chinese opera stage, a painted red face usually denotes a sacred or loyal personage and sometimes a great emperor. Candies, cakes, decorations and many things associated with the New Year and its ceremonies are colored red. The sound of the Chinese word for «red» (simplified Chinese: 红; traditional Chinese: 紅; pinyin: hóng; Cantonese Yale: hung4) is in Mandarin homophonous with the word for «prosperous.» Therefore, red is an auspicious color and has an auspicious sound.

According to Chinese tradition, the year of the pig is a generally unlucky year for the public, which is why you need to reevaluate most of your decisions before you reach a conclusion. However, this only helps you get even more control over your life as you learn to stay ahead of everything by being cautious.[110]

Nianhua[edit]

Nianhua can be a form of Chinese colored woodblock printing, for decoration during Chinese New Year.[111] Nianhua uses a range of subjects to express and invite positive prospects as the new year begins. The most popular representatives of these prospects take inspiration from nature, religion, folklore, etc., and are portrayed in flashy and lively ways.[112]

Flowers[edit]

The following are popular floral decorations for the New Year and are available at new year markets.

-

Floral Decor Meaning Plum Blossom symbolizes luckiness Kumquat symbolizes prosperity Calamondin Symbolizes luck Narcissus symbolizes prosperity Bamboo a plant used for any time of year, its sturdiness represents strength Sunflower means to have a good year Eggplant a plant to heal all of your sicknesses Chom Mon Plant a plant which gives you tranquility Orchid represents fertility and abundance, as well as good taste, beauty, luxury and innocence

Each flower has a symbolic meaning, and many Chinese people believe that it may usher in the values that it represents.[113] In general, except those in lucky colour like red and yellow, chrysanthemum should not be put at home during the new year, because it is normally used for ancestral veneration.[114]

Icons and ornaments[edit]

-

Icons Meaning Illustrations Lanterns These lanterns that differ from those of Mid-Autumn Festival in general. They will be red in color and tend to be oval in shape. These are the traditional Chinese paper lanterns. Those lanterns, used on the fifteenth day of the Chinese New Year for the Lantern Festival, are bright, colorful, and in many different sizes and shapes. Decoration Decorations generally convey a New Year greeting. They are not advertisements. Faichun, also known as Huichun—Chinese calligraphy of auspicious Chinese idioms on typically red posters—are hung on doorways and walls. Other decorations include a New year picture, Chinese knots, and papercutting and couplets. Dragon dance and Lion dance Dragon and lion dances are common during Chinese New Year. It is believed that the loud beats of the drum and the deafening sounds of the cymbals together with the face of the Dragon or lion dancing aggressively can evict bad or evil spirits. Lion dances are also popular for opening of businesses in Hong Kong and Macau. Fu Lu Shou Nianhua of the Fu Lu Shou Red envelope Typically given to children, elderly and Dragon/Lion Dance performers while saying t 恭喜發財 j gung1 hei2 faat3 coi4, s 恭喜发财 p gōng xǐ fā cái

Spring travel[edit]

Traditionally, families gather together during the Chinese New Year. In modern China, migrant workers in China travel home to have reunion dinners with their families on Chinese New Year’s Eve. Owing to a large number of interprovincial travelers, special arrangements were made by railways, buses and airlines starting from 15 days before the New Year’s Day. This 40-day period is called chunyun, and is known as the world’s largest annual migration.[115] More interurban trips are taken in China in this period than the total population of China.

In Taiwan, spring travel is also a major event. The majority of transportation in western Taiwan is in a north–south direction: long-distance travel between urbanized north and hometowns in the rural south. Transportation in eastern Taiwan and that between Taiwan and its islands is less convenient. Cross-strait flights between Taiwan and China began in 2003 as part of Three Links, mostly for «Taiwanese businessmen» to return to Taiwan for the new year.[116]

Festivities outside China[edit]

Decorations on the occasion of Chinese New Year – River Hongbao 2016, Singapore

Chinese New Year is also celebrated annually in many countries which houses significant Chinese populations. These include countries throughout Asia, Oceania, and North America. Sydney,[117] London,[118] and San Francisco[119] claim to host the largest New Year celebration outside of Asia and South America.

Southeast Asia[edit]

Chinese New Year is a national public holiday in many Southeast Asian countries and considered to be one of the most important holidays of the year.

Malaysia[edit]

Southeast Asia’s largest temple – Kek Lok Si near George Town in Penang, Malaysia – illuminated in preparation for the Chinese New Year.

Chinese New Year’s Eve is typically a half-day holiday in Malaysia, while Chinese New Year is a two-day public holiday. The biggest celebrations take place in Malaysia (notably in Kuala Lumpur, George Town, Johor Bahru and Ipoh.[120]

Singapore[edit]

In Singapore, Chinese New Year is officially a two-day public holiday. Chinese New Year is accompanied by various festive activities. One of the main highlights is the Chinatown celebrations. In 2010, this included a Festive Street Bazaar, nightly staged shows at Kreta Ayer Square and a lion dance competition.[121] The Chingay Parade also features prominently in the celebrations. It is an annual street parade in Singapore, well known for its colorful floats and wide variety of cultural performances.[122] The highlights of the Parade for 2011 include a Fire Party, multi-ethnic performances and an unprecedented travelling dance competition.[123]

Philippines[edit]

In the Philippines, Chinese New Year (Philippine Hokkien Chinese: 咱人年兜; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lán-nâng Nî-tau) is considered as one of the important festivals for Chinese Filipinos, and its celebration has also extended to the majority non-Chinese Filipinos, especially since in 2012, Chinese New Year was included as a public regular non-working holiday in the Philippines. During this time of year, the selling or giving of Tikoy, especially by Chinese Filipinos, is widely known and practiced in the country. Celebrations are centered primarily in Binondo in Manila, the oldest ever Chinatown in the world, with other celebrations in key cities.

Indonesia[edit]

Lanterns hung around Senapelan street, the Pekanbaru Chinatown in Riau, Indonesia