Всего найдено: 7

Здравствуйте!

В Интернете везде по-разному, а из примеров на вашем сайте не вполне понятно: склоняется ли название департамента Франции Кот-д‘Ор? Понятно, что со словом департамент не склоняется, а если отдельно? Из Кот-д‘Ор? или из Кот-д‘Ора? Заранее спасибо.

Евгения

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Это склоняемое слово, правильно: из Кот-д’Ора.

Доброе утро, уважаемая Грамота! Расскажите, пожалуйста, каковы функции апострофа в совр. рус. языке? (И в частности корректно ли, н-р, китайские и японские иероглифы в рус. транскрипции в косвенных падежах отделять апострофом? Н-р: Син’а.) (И еще: можно ли в слове «апостроф» делать ударение на втором слоге?)

С нетерпением жду ответ!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Апостроф (ударение в этом слове ставится на последнем слоге, вариант апостроф недопустим) в современном русском письме используется для передачи иностранных фамилий с начальными буквами Д и О; при этом воспроизводится написание языка-источника: д’Артаньян, Жанна д’Арк, О’Нил, О’Коннор; то же в географических наименованиях: Кот-д‘Ивуар.

Кроме этого, апострофом отделяются русские окончания и суффиксы от предшествующей части слова, передаваемой средствами иной графической системы (в частности, латиницей), например: c-moll’ная увертюра, пользоваться e-mail’ом. Если иноязычное слово передается кириллицей, апостроф не используется.

Следует также отметить, что после орфографической реформы 1917 – 1918 гг., упразднившей написание Ъ на конце слов, пишущие иногда избегали и употребления разделительного Ъ, хотя оно было регламентировано правилами правописания. В практике письма получило некоторое распространение употребление апострофа в функции Ъ: с’езд, об’ём, из’ятие и т. п. Однако такое употребление апострофа не соответствует современным нормам письма.

Здравствуйте. Скажите, пожалуйста, какого правильное написание названия страны Кот-д‘Ивуар (особо интересует правомерность использования апострофа) и города Шарм-эль-Шейх (появилось ли определённость или существует два равнозначных варианта). Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Кот-д’Ивуар, Шарм-эш-Шейх.

Общероссийский классификатор стран мира: Кот д’Ивуар.

Словарь имён собственных: Кот-д‘Ивуар.

Как правильно?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правилен второй вариант c дефисом.

Здравствуйте!

Склоняется ли Кот-д‘Ивуар по падежам? Можно ли сказать, например, «я была в Кот-д‘Ивуаре?

Заранее благодарю.

Ольга.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, это название склоняется, Вы написали верно.

Как правильно пишется название страны: Республика Кит Д’Ивуар?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Кот-д‘Ивуар_.

Есть такое государство — Тринидад и Тобаго.

Как называются жители этой страны?

Тринидадцы, тобажане, тринбагонианцы?

Или жители Кот Д’Ивуара?

Ивуарийцы, котдивуарийцы?

Есть ли какие-то правила при формировании таких слов?

Монегаски, манкунианцы, валлийцы, ливерпудлианцы — это корректные названия?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Жители Тринидада и Тобаго — _тринидадцы_. Жители Кот-д‘Ивуара — _ивуарийцы_ и _котдивуарцы_. _Монегаски, валлийцы_ — корректно, возможно также _монакцы_ и _уэльсцы_. О _манчестерцах_ и _манкунианцах_ см. подробно в http://spravka.gramota.ru/hardwords.html?no=109&_sf=80 [«Непростых словах»]. Аналогично: ливерпульцы — жители Ливерпуля, ливерпудлианцы — игроки футбольного клуба из этого города.

Русский язык не выработал единых и всеобъемлющих правил создания слов — названий жителей. Есть, конечно, некоторые общие закономерности, но многое определяется традицией, степенью распространенности самоназваний жителей, историческими особенностями и пр.

Coordinates: 8°N 5°W / 8°N 5°W

|

Republic of Côte d’Ivoire République de Côte d’Ivoire (French) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Motto: ‘Union – Discipline – Travail’ (French) ‘Unity – Discipline – Work’ |

|

| Anthem: L’Abidjanaise (English: «Song of Abidjan») |

|

|

|

| Capital | Yamoussoukro (political) Abidjan (economic) 6°51′N 5°18′W / 6.850°N 5.300°W |

| Largest city | Abidjan |

| Official languages | French |

| Vernacular languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2018) |

|

| Religion

(2021 census)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

|

• President |

Alassane Ouattara |

|

• Vice President |

Tiémoko Meyliet Koné |

|

• Prime Minister |

Patrick Achi |

| Legislature | Parliament of Ivory Coast |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

National Assembly |

| History | |

|

• Republic established |

4 December 1958 |

|

• Independence from France |

7 August 1960 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

322,463 km2 (124,504 sq mi) (68th) |

|

• Water (%) |

1.4[2] |

| Population | |

|

• 2021 census |

29,389,150[3] |

|

• Density |

91.1/km2 (235.9/sq mi) (139th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2015) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 159th |

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (GMT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +225 |

| ISO 3166 code | CI |

| Internet TLD | .ci |

|

|

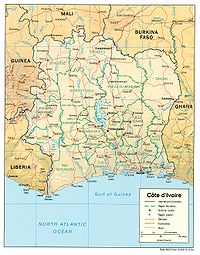

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d’Ivoire,[a] officially the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is the port city of Abidjan. It borders Guinea to the northwest, Liberia to the west, Mali to the northwest, Burkina Faso to the northeast, Ghana to the east, and the Gulf of Guinea (Atlantic Ocean) to the south. Its official language is French, and indigenous languages are also widely used, including Bété, Baoulé, Dioula, Dan, Anyin, and Cebaara Senufo. In total, there are around 78 different languages spoken in Ivory Coast. The country has a religiously diverse population, including numerous followers of Islam, Christianity, and indigenous faiths such as Animism.[1]

Before its colonization by Europeans, Ivory Coast was home to several states, including Gyaaman, the Kong Empire, and Baoulé. The area became a protectorate of France in 1843 and was consolidated as a French colony in 1893 amid the European Scramble for Africa. It achieved independence in 1960, led by Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who ruled the country until 1993. Relatively stable by regional standards, Ivory Coast established close political-economic ties with its West African neighbours while maintaining close relations with the West, especially France. Its stability was diminished by a coup d’état in 1999, then two civil wars—first between 2002 and 2007[8] and again during 2010–2011. It adopted a new constitution in 2016.[citation needed]

Ivory Coast is a republic with strong executive power vested in its president. Through the production of coffee and cocoa, it was an economic powerhouse in West Africa during the 1960s and 1970s, then experienced an economic crisis in the 1980s, contributing to a period of political and social turmoil that extended until 2011. Ivory Coast has experienced again high economic growth since the return of peace and political stability in 2011. From 2012 to 2021, the economy grew by an average of 7.4% per year in real terms, the second-fastest rate of economic growth in Africa and fourth-fastest rate in the world.[9] In 2020 Ivory Coast was the world’s largest exporter of cocoa beans and had high levels of income for its region.[10] In the 21st century, the economy still relies heavily on agriculture, with smallholder cash-crop production predominating.[2]

Etymology[edit]

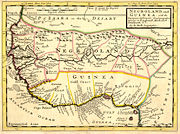

Originally, Portuguese and French merchant-explorers in the 15th and 16th centuries divided the west coast of Africa, very roughly, into four «coasts» reflecting resources available from each coast. The coast that the French named the Côte d’Ivoire and the Portuguese named the Costa do Marfim—both meaning «Coast of Ivory»—lay between what was known as the Guiné de Cabo Verde, so-called «Upper Guinea» at Cap-Vert, and Lower Guinea.[11][12] There was also a Pepper Coast, also known as the «Grain Coast» (present-day Liberia), a «Gold Coast» (Ghana), and a «Slave Coast» (Togo, Benin and Nigeria). Like those, the name «Ivory Coast» reflected the major trade that occurred on that particular stretch of the coast: the export of ivory.[13][11][14][12][15]

Other names for the area included the Côte de Dents,[b] literally «Coast of Teeth», again reflecting the ivory trade;[17][18][13][12][15][19] the Côte de Quaqua, after the people whom the Dutch named the Quaqua (alternatively Kwa Kwa);[18][11][16] the Coast of the Five and Six Stripes, after a type of cotton fabric also traded there;[18] and the Côte du Vent,[c] the Windward Coast, after perennial local off-shore weather conditions.[13][11] In the 19th century, usage switched to Côte d’Ivoire.[18]

The coastline of the modern state is not quite coterminous with what the 15th- and 16th-century merchants knew as the «Teeth» or «Ivory» coast, which was considered to stretch from Cape Palmas to Cape Three Points and which is thus now divided between the modern states of Ghana and Ivory Coast (with a minute portion of Liberia).[17][14][19][16] It retained the name through French rule and independence in 1960.[20] The name had long since been translated literally into other languages,[d] which the post-independence government considered increasingly troublesome whenever its international dealings extended beyond the Francophone sphere. Therefore, in April 1986, the government declared that Côte d’Ivoire (or, more fully, République de Côte d’Ivoire[22]) would be its formal name for the purposes of diplomatic protocol and has since officially refused to recognize any translations from French to other languages in its international dealings.[21][23][24] Despite the Ivorian government’s request, the English translation «Ivory Coast» (often «the Ivory Coast») is still frequently used in English by various media outlets and publications.[e][f]

History[edit]

Land migration[edit]

The first human presence in Ivory Coast has been difficult to determine because human remains have not been well preserved in the country’s humid climate. However, newly found weapon and tool fragments (specifically, polished axes cut through shale and remnants of cooking and fishing) have been interpreted as a possible indication of a large human presence during the Upper Paleolithic period (15,000 to 10,000 BC),[32] or at the minimum, the Neolithic period.[33]

The earliest known inhabitants of the Ivory Coast have left traces scattered throughout the territory. Historians believe that they were all either displaced or absorbed by the ancestors of the present indigenous inhabitants,[34] who migrated south into the area before the 16th century. Such groups included the Ehotilé (Aboisso), Kotrowou (Fresco), Zéhiri (Grand-Lahou), Ega and Diès (Divo).[35]

Pre-Islamic and Islamic periods[edit]

The first recorded history appears in the chronicles of North African (Berber) traders, who, from early Roman times, conducted a caravan trade across the Sahara in salt, slaves, gold, and other goods.[34] The southern terminuses of the trans-Saharan trade routes were located on the edge of the desert, and from there supplemental trade extended as far south as the edge of the rainforest.[34] The most important terminals—Djenné, Gao, and Timbuctu—grew into major commercial centres around which the great Sudanic empires developed.[34]

By controlling the trade routes with their powerful military forces, these empires were able to dominate neighbouring states.[34] The Sudanic empires also became centres of Islamic education.[34] Islam had been introduced in the western Sudan by Muslim Berbers; it spread rapidly after the conversion of many important rulers.[34] From the 11th century, by which time the rulers of the Sudanic empires had embraced Islam, it spread south into the northern areas of contemporary Ivory Coast.[34]

The Ghana Empire, the earliest of the Sudanic empires, flourished in the region encompassing present-day southeast Mauritania and southern Mali between the 4th and 13th centuries.[34] At the peak of its power in the 11th century, its realms extended from the Atlantic Ocean to Timbuktu.[34] After the decline of Ghana, the Mali Empire grew into a powerful Muslim state, which reached its apogee in the early part of the 14th century.[34] The territory of the Mali Empire in the Ivory Coast was limited to the northwest corner around Odienné.[34]

Its slow decline starting at the end of the 14th century followed internal discord and revolts by vassal states, one of which, Songhai, flourished as an empire between the 14th and 16th centuries.[34] Songhai was also weakened by internal discord, which led to factional warfare.[34] This discord spurred most of the migrations southward toward the forest belt.[34] The dense rainforest covering the southern half of the country created barriers to the large-scale political organizations that had arisen in the north.[34] Inhabitants lived in villages or clusters of villages; their contacts with the outside world were filtered through long-distance traders.[36] Villagers subsisted on agriculture and hunting.[36]

Pre-European modern period[edit]

Five important states flourished in Ivory Coast during the pre-European early modern period.[36] The Muslim Kong Empire was established by the Dyula in the early 18th century in the north-central region inhabited by the Sénoufo, who had fled Islamization under the Mali Empire.[36] Although Kong became a prosperous centre of agriculture, trade, and crafts, ethnic diversity and religious discord gradually weakened the kingdom.[37] In 1895 the city of Kong was sacked and conquered by Samori Ture of the Wassoulou Empire.[37]

The Abron kingdom of Gyaaman was established in the 17th century by an Akan group, the Abron, who had fled the developing Ashanti confederation of Asanteman in what is present-day Ghana.[37] From their settlement south of Bondoukou, the Abron gradually extended their hegemony over the Dyula people in Bondoukou, who were recent arrivals from the market city of Begho.[37] Bondoukou developed into a major centre of commerce and Islam.[37] The kingdom’s Quranic scholars attracted students from all parts of West Africa.[37] In the mid-17th century in east-central Ivory Coast, other Akan groups fleeing the Asante established a Baoulé kingdom at Sakasso and two Agni kingdoms, Indénié and Sanwi.[37]

The Baoulé, like the Ashanti, developed a highly centralized political and administrative structure under three successive rulers.[37] It finally split into smaller chiefdoms.[37] Despite the breakup of their kingdom, the Baoulé strongly resisted French subjugation.[37] The descendants of the rulers of the Agni kingdoms tried to retain their separate identity long after Ivory Coast’s independence; as late as 1969, the Sanwi attempted to break away from Ivory Coast and form an independent kingdom.[37]

Establishment of French rule[edit]

Compared to neighbouring Ghana, Ivory Coast, though practising slavery and slave raiding, suffered little from the slave trade.[38] European slave and merchant ships preferred other areas along the coast.[38] The earliest recorded European voyage to West Africa was made by the Portuguese in 1482.[citation needed] The first West African French settlement, Saint-Louis, was founded in the mid-17th century in Senegal, while at about the same time, the Dutch ceded to the French a settlement at Gorée Island, off Dakar.[39] A French mission was established in 1687 at Assinie near the border with the Gold Coast (now Ghana).[39] The Europeans suppressed the local practice of slavery at this time and forbade the trade to their merchants.[citation needed]

Assinie’s survival was precarious, however; the French were not firmly established in Ivory Coast until the mid-19th century.[39] In 1843–44, French Admiral Louis Edouard Bouët-Willaumez signed treaties with the kings of the Grand-Bassam and Assinie regions, making their territories a French protectorate.[40] French explorers, missionaries, trading companies, and soldiers gradually extended the area under French control inland from the lagoon region.[39][40] Pacification was not accomplished until 1915.[40]

Activity along the coast stimulated European interest in the interior, especially along the two great rivers, the Senegal and the Niger.[39] Concerted French exploration of West Africa began in the mid-19th century but moved slowly, based more on individual initiative than on government policy.[39] In the 1840s, the French concluded a series of treaties with local West African chiefs that enabled the French to build fortified posts along the Gulf of Guinea to serve as permanent trading centres.[39] The first posts in Ivory Coast included one at Assinie and another at Grand-Bassam, which became the colony’s first capital.[39] The treaties provided for French sovereignty within the posts and for trading privileges in exchange for fees or coutumes paid annually to the local chiefs for the use of the land.[39] The arrangement was not entirely satisfactory to the French, because trade was limited and misunderstandings over treaty obligations often arose.[39] Nevertheless, the French government maintained the treaties, hoping to expand trade.[39] France also wanted to maintain a presence in the region to stem the increasing influence of the British along the Gulf of Guinea coast.[39]

The defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and the subsequent annexation by Germany of the French province of Alsace–Lorraine caused the French government to abandon its colonial ambitions and withdraw its military garrisons from its West African trading posts, leaving them in the care of resident merchants.[39] The trading post at Grand-Bassam was left in the care of a shipper from Marseille, Arthur Verdier, who in 1878 was named Resident of the Establishment of Ivory Coast.[39]

In 1886, to support its claims of effective occupation, France again assumed direct control of its West African coastal trading posts and embarked on an accelerated program of exploration in the interior.[41] In 1887, Lieutenant Louis-Gustave Binger began a two-year journey that traversed parts of Ivory Coast’s interior. By the end of the journey, he had concluded four treaties establishing French protectorates in Ivory Coast.[42] Also in 1887, Verdier’s agent, Marcel Treich-Laplène, negotiated five additional agreements that extended French influence from the headwaters of the Niger River Basin through Ivory Coast.[42]

French colonial era[edit]

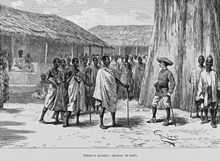

Arrival in Kong of new French West Africa governor Louis-Gustave Binger in 1892.

By the end of the 1880s, France had established control over the coastal regions, and in 1889 Britain recognized French sovereignty in the area.[42] That same year, France named Treich-Laplène the titular governor of the territory.[42] In 1893, Ivory Coast became a French colony, with its capital in Grand-Bassam, and Captain Binger was appointed governor.[42] Agreements with Liberia in 1892 and with Britain in 1893 determined the eastern and western boundaries of the colony, but the northern boundary was not fixed until 1947 because of efforts by the French government to attach parts of Upper Volta (present-day Burkina Faso) and French Sudan (present-day Mali) to Ivory Coast for economic and administrative reasons.[42]

France’s main goal was to stimulate the production of exports. Coffee, cocoa, and palm oil crops were soon planted along the coast. Ivory Coast stood out as the only West African country with a sizeable population of European settlers; elsewhere in West and Central Africa, Europeans who emigrated to the colonies were largely bureaucrats. As a result, French citizens owned one-third of the cocoa, coffee, and banana plantations and adopted the local forced-labour system.[citation needed]

Throughout the early years of French rule, French military contingents were sent inland to establish new posts.[42] The African population resisted French penetration and settlement, even in areas where treaties of protection had been in force.[42] Among those offering the greatest resistance was Samori Ture, who in the 1880s and 1890s was establishing the Wassoulou Empire, which extended over large parts of present-day Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast.[42] Ture’s large, well-equipped army, which could manufacture and repair its own firearms, attracted strong support throughout the region.[42] The French responded to Ture’s expansion and conquest with military pressure.[42] French campaigns against Ture, which were met with fierce resistance, intensified in the mid-1890s until he was captured in 1898 and his empire dissolved.[42]

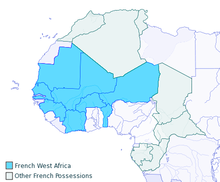

France’s imposition of a head tax in 1900 to support the colony’s public works program provoked protests.[43] Many Ivorians saw the tax as a violation of the protectorate treaties because they felt that France was demanding the equivalent of a coutume from the local kings, rather than the reverse.[43] Many, especially in the interior, also considered the tax a humiliating symbol of submission.[43] In 1905, the French officially abolished slavery in most of French West Africa.[44] From 1904 to 1958, Ivory Coast was part of the Federation of French West Africa.[40] It was a colony and an overseas territory under the Third Republic.[40] In World War I, France organized regiments from Ivory Coast to fight in France, and colony resources were rationed from 1917 to 1919.[citation needed] Until the period following World War II, governmental affairs in French West Africa were administered from Paris.[40] France’s policy in West Africa was reflected mainly in its philosophy of «association», meaning that all Africans in Ivory Coast were officially French «subjects» but without rights to representation in Africa or France.[40]

French colonial policy incorporated concepts of assimilation and association.[45] Based on the assumed superiority of French culture, in practice the assimilation policy meant the extension of the French language, institutions, laws, and customs to the colonies.[45] The policy of association also affirmed the superiority of the French in the colonies, but it entailed different institutions and systems of laws for the colonizer and the colonized.[45] Under this policy, the Africans in Ivory Coast were allowed to preserve their own customs insofar as they were compatible with French interests.[45]

An indigenous elite trained in French administrative practice formed an intermediary group between French and Africans.[45] After 1930, a small number of Westernized Ivorians were granted the right to apply for French citizenship.[45] Most Ivorians, however, were classified as French subjects and were governed under the principle of association.[45] As subjects of France, natives outside the civilized elite had no political rights.[46] They were drafted for work in mines, on plantations, as porters, and on public projects as part of their tax responsibility.[46] They were expected to serve in the military and were subject to the indigénat, a separate system of law.[46]

During World War II, the Vichy regime remained in control until 1943, when members of General Charles de Gaulle’s provisional government assumed control of all French West Africa.[40] The Brazzaville Conference of 1944, the first Constituent Assembly of the Fourth Republic in 1946, and France’s gratitude for African loyalty during World War II, led to far-reaching governmental reforms in 1946.[40] French citizenship was granted to all African «subjects», the right to organize politically was recognized, and various forms of forced labour were abolished.[40] Between 1944 and 1946, many national conferences and constituent assemblies took place between France’s government and provisional governments in Ivory Coast.[citation needed] Governmental reforms were established by late 1946, which granted French citizenship to all African «subjects» under the colonial control of the French.[citation needed]

Until 1958, governors appointed in Paris administered the colony of Ivory Coast, using a system of direct, centralized administration that left little room for Ivorian participation in policy-making.[45] The French colonial administration also adopted divide-and-rule policies, applying ideas of assimilation only to the educated elite.[45] The French were also interested in ensuring that the small but influential Ivorian elite was sufficiently satisfied with the status quo to refrain from developing anti-French sentiments and calls for independence.[45] Although strongly opposed to the practices of association, educated Ivorians believed that they would achieve equality in the French colonial system through assimilation rather than through complete independence from France.[45] After the assimilation doctrine was implemented through the postwar reforms, though, Ivorian leaders realized that even assimilation implied the superiority of the French over the Ivorians and that discrimination and inequality would end only with independence.[45]

Independence[edit]

Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the son of a Baoulé chief, became Ivory Coast’s father of independence. In 1944, he formed the country’s first agricultural trade union for African cocoa farmers like himself. Angered that colonial policy favoured French plantation owners, the union members united to recruit migrant workers for their own farms. Houphouët-Boigny soon rose to prominence and was elected to the French Parliament in Paris within a year. A year later, the French abolished forced labour. Houphouët-Boigny established a strong relationship with the French government, expressing a belief that Ivory Coast would benefit from the relationship, which it did for many years. France appointed him as a minister, the first African to become a minister in a European government.[47]

A turning point in relations with France was reached with the 1956 Overseas Reform Act (Loi Cadre), which transferred several powers from Paris to elected territorial governments in French West Africa and also removed the remaining voting inequities.[40] On 4 December 1958, Ivory Coast became an autonomous member of the French Community, which had replaced the French Union.[48]

By 1960, the country was easily French West Africa’s most prosperous, contributing over 40% of the region’s total exports. When Houphouët-Boigny became the first president, his government gave farmers good prices for their products to further stimulate production, which was further boosted by a significant immigration of workers from surrounding countries. Coffee production increased significantly, catapulting Ivory Coast into third place in world output, behind Brazil and Colombia. By 1979, the country was the world’s leading producer of cocoa. It also became Africa’s leading exporter of pineapples and palm oil. French technicians contributed to the «Ivorian miracle». In other African nations, the people drove out the Europeans following independence, but in Ivory Coast, they poured in. The French community grew from only 30,000 before independence to 60,000 in 1980, most of them teachers, managers, and advisors.[49] For 20 years, the economy maintained an annual growth rate of nearly 10%—the highest of Africa’s non-oil-exporting countries.

Houphouët-Boigny administration[edit]

Houphouët-Boigny’s one-party rule was not amenable to political competition. Laurent Gbagbo, who would become the president of Ivory Coast in 2000, had to flee the country in the 1980s after he incurred the ire of Houphouët-Boigny by founding the Front Populaire Ivoirien.[50] Houphouët-Boigny banked on his broad appeal to the population, who continued to elect him. He was criticized for his emphasis on developing large-scale projects.

Many felt the millions of dollars spent transforming his home village, Yamoussoukro, into the new political capital were wasted; others supported his vision to develop a centre for peace, education, and religion in the heart of the country. In the early 1980s, the world recession and a local drought sent shock waves through the Ivorian economy. The overcutting of timber and collapsing sugar prices caused the country’s external debt to increase three-fold. Crime rose dramatically in Abidjan as an influx of villagers exacerbated unemployment caused by the recession.[51] In 1990, hundreds of civil servants went on strike, joined by students protesting institutional corruption. The unrest forced the government to support multi-party democracy. Houphouët-Boigny became increasingly feeble and died in 1993. He favoured Henri Konan Bédié as his successor.

Bédié administration[edit]

In October 1995, Bédié overwhelmingly won re-election against a fragmented and disorganised opposition. He tightened his hold over political life, jailing several hundred opposition supporters. In contrast, the economic outlook improved, at least superficially, with decreasing inflation and an attempt to remove foreign debt. Unlike Houphouët-Boigny, who was very careful to avoid any ethnic conflict and left access to administrative positions open to immigrants from neighbouring countries, Bedié emphasized the concept of Ivoirité to exclude his rival Alassane Ouattara, who had two northern Ivorian parents, from running for the future presidential election. As people originating from foreign countries are a large part of the Ivorian population, this policy excluded many people of Ivorian nationality. The relationship between various ethnic groups became strained, resulting in two civil wars in the following decades.

Similarly, Bedié excluded many potential opponents from the army. In late 1999, a group of dissatisfied officers staged a military coup, putting General Robert Guéï in power. Bedié fled into exile in France. The new leadership reduced crime and corruption, and the generals pressed for austerity and campaigned in the streets for a less wasteful society.

First civil war[edit]

A presidential election was held in October 2000 in which Laurent Gbagbo vied with Guéï, but it was not peaceful. The lead-up to the election was marked by military and civil unrest. Following a public uprising that resulted in around 180 deaths, Guéï was swiftly replaced by Gbagbo. Ouattara was disqualified by the country’s Supreme Court because of his alleged Burkinabé nationality. The constitution did not allow noncitizens to run for the presidency. This sparked violent protests in which his supporters, mainly from the country’s north, battled riot police in the capital, Yamoussoukro.

In the early hours of 19 September 2002, while the Gbago was in Italy, an armed uprising occurred. Troops who were to be demobilised mutinied, launching attacks in several cities. The battle for the main gendarmerie barracks in Abidjan lasted until mid-morning, but by lunchtime, the government forces had secured Abidjan. They had lost control of the north of the country, and rebel forces made their stronghold in the northern city of Bouaké. The rebels threatened to move on to Abidjan again, and France deployed troops from its base in the country to stop their advance. The French said they were protecting their citizens from danger, but their deployment also helped government forces. That the French were helping either side was not established as a fact, but each side accused the French of supporting the opposite side. Whether French actions improved or worsened the situation in the long term is disputed. What exactly happened that night is also disputed.

The government claimed that former president Robert Guéï led a coup attempt, and state TV showed pictures of his dead body in the street; counter-claims stated that he and 15 others had been murdered at his home, and his body had been moved to the streets to incriminate him. Ouattara took refuge in the German embassy; his home had been burned down. President Gbagbo cut short his trip to Italy and on his return stated, in a television address, that some of the rebels were hiding in the shanty towns where foreign migrant workers lived. Gendarmes and vigilantes bulldozed and burned homes by the thousands, attacking residents. An early ceasefire with the rebels, which had the backing of much of the northern populace, proved short-lived and fighting over the prime cocoa-growing areas resumed. France sent in troops to maintain the cease-fire boundaries, and militias, including warlords and fighters from Liberia and Sierra Leone, took advantage of the crisis to seize parts of the west.

In January 2003, Gbagbo and rebel leaders signed accords creating a «government of national unity». Curfews were lifted, and French troops patrolled the country’s western border. The unity government was unstable, and central problems remained with neither side achieving its goals. In March 2004, 120 people were killed at an opposition rally, and subsequent mob violence led to the evacuation of foreign nationals. A report concluded the killings were planned. Though UN peacekeepers were deployed to maintain a «Zone of Confidence», relations between Gbagbo and the opposition continued to deteriorate.

Early in November 2004, after the peace agreement had effectively collapsed because the rebels refused to disarm, Gbagbo ordered airstrikes against the rebels. During one of these airstrikes in Bouaké, on 6 November 2004, French soldiers were hit, and nine were killed; the Ivorian government said it was a mistake, but the French claimed it was deliberate. They responded by destroying most Ivorian military aircraft (two Su-25 planes and five helicopters), and violent retaliatory riots against the French broke out in Abidjan.[52]

Gbagbo’s original term as president expired on 30 October 2005, but a peaceful election was deemed impossible, so his term in office was extended for a maximum of one year, according to a plan worked out by the African Union and endorsed by the United Nations Security Council.[53] With the late-October deadline approaching in 2006, the election was regarded as very unlikely to be held by that point, and the opposition and the rebels rejected the possibility of another term extension for Gbagbo.[54] The UN Security Council endorsed another one-year extension of Gbagbo’s term on 1 November 2006; however, the resolution provided for strengthening of Prime Minister Charles Konan Banny’s powers. Gbagbo said the next day that elements of the resolution deemed to be constitutional violations would not be applied.[55]

A peace accord between the government and the rebels, or New Forces, was signed on 4 March 2007, and subsequently Guillaume Soro, leader of the New Forces, became prime minister. These events were seen by some observers as substantially strengthening Gbagbo’s position.[56] According to UNICEF, at the end of the civil war, water and sanitation infrastructure had been greatly damaged. Communities across the country required repairs to their water supply.[57]

Second civil war[edit]

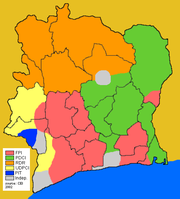

The presidential elections that should have been organized in 2005 were postponed until November 2010. The preliminary results showed a loss for Gbagbo in favour of former Prime Minister Ouattara.[58] The ruling FPI contested the results before the Constitutional Council, charging massive fraud in the northern departments controlled by the rebels of the New Forces. These charges were contradicted by United Nations observers (unlike African Union observers). The report of the results led to severe tension and violent incidents. The Constitutional Council, which consisted of Gbagbo supporters, declared the results of seven northern departments unlawful and that Gbagbo had won the elections with 51% of the vote – instead of Ouattara winning with 54%, as reported by the Electoral Commission.[58] After the inauguration of Gbagbo, Ouattara—who was recognized as the winner by most countries and the United Nations—organized an alternative inauguration. These events raised fears of a resurgence of the civil war; thousands of refugees fled the country.[58] The African Union sent Thabo Mbeki, former president of South Africa, to mediate the conflict. The United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution recognising Ouattara as the winner of the elections, based on the position of the Economic Community of West African States, which suspended Ivory Coast from all its decision-making bodies[59] while the African Union also suspended the country’s membership.[60]

In 2010, a colonel of Ivory Coast armed forces, Nguessan Yao, was arrested in New York in a year-long U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement operation charged with procuring and illegal export of weapons and munitions: 4,000 handguns, 200,000 rounds of ammunition, and 50,000 tear-gas grenades, in violation of a UN embargo.[61] Several other Ivory Coast officers were released because they had diplomatic passports. His accomplice, Michael Barry Shor, an international trader, was located in Virginia.[62][63]

A shelter for internally displaced persons during the 2011 civil war

The 2010 presidential election led to the 2010–2011 Ivorian crisis and the Second Ivorian Civil War. International organizations reported numerous human-rights violations by both sides. In Duékoué, hundreds of people were killed. In nearby Bloléquin, dozens were killed.[64] UN and French forces took military action against Gbagbo.[65] Gbagbo was taken into custody after a raid into his residence on 11 April 2011.[66] The country was severely damaged by the war, and it was observed that Ouattara had inherited a formidable challenge to rebuild the economy and reunite Ivorians.[67] Gbagbo was taken to the International Criminal Court in January 2016. He was declared acquitted by the court but given a conditional release[68] in January 2019.[69] Belgium has been designated as a host country.[70]

Ouattara administration[edit]

Ouattara has ruled the country since 2010. President Ouattara was re-elected in 2015 presidential election.[71] In November 2020, he won third term in office in elections boycotted by the opposition. His opponents argued it was illegal for Ouattara to run for a third term.[72] Ivory Coast’s Constitutional Council formally ratified President Ouattara’s re-election to a third term in November 2020.[73]

Government and politics[edit]

The government is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The Parliament of Ivory Coast, consists of the indirectly elected Senate and the National Assembly which has 255 members, elected for five-year terms.

Since 1983, Ivory Coast’s capital has been Yamoussoukro, while Abidjan was the administrative center. Most countries maintain their embassies in Abidjan. The Ivorian population has suffered because of the ongoing civil war as of September 2021. International human-rights organizations have noted problems with the treatment of captive non-combatants by both sides and the re-emergence of child slavery in cocoa production.

Although most of the fighting ended by late 2004, the country remained split in two, with the north controlled by the New Forces. A new presidential election was expected to be held in October 2005, and the rival parties agreed in March 2007 to proceed with this, but it continued to be postponed until November 2010 due to delays in its preparation.

Elections were finally held in 2010. The first round of elections was held peacefully and widely hailed as free and fair. Runoffs were held on 28 November 2010, after being delayed one week from the original date of 21 November. Laurent Gbagbo as president ran against former Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara.[74] On 2 December, the Electoral Commission declared that Ouattara had won the election by a margin of 54% to 46%. In response, the Gbagbo-aligned Constitutional Council rejected the declaration, and the government announced that country’s borders had been sealed. An Ivorian military spokesman said, «The air, land, and sea border of the country are closed to all movement of people and goods.»[75]

President Alassane Ouattara has led the country since 2010 and he was re-elected to a third term in November 2020 elections boycotted by two leading opposition figures former President Henri Konan Bedie and ex-Prime Minister Pascal Affi N’Guessan.[76] The Achi II government has ruled the country since April 2022.[77]

Foreign relations[edit]

In Africa, Ivorian diplomacy favors step-by-step economic and political cooperation. In 1959, Ivory Coast formed the Council of the Entente with Dahomey (Benin), Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Niger, and Togo; in 1965, the African and Malagasy Common Organization (OCAM); in 1972, the Economic Community of West Africa (CEAO). The latter organization changed to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 1975. A founding member of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 and then of the African Union in 2000, Ivory Coast defends respect for state sovereignty and peaceful cooperation between African countries.

Worldwide, Ivorian diplomacy is committed to fair economic and trade relations, including the fair trade of agricultural products and the promotion of peaceful relations with all countries. Ivory Coast thus maintains diplomatic relations with international organizations and countries all around the world. In particular, it has signed United Nations treaties such as the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Convention Governing Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. Ivory Coast is a member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, African Union, La Francophonie, Latin Union, Economic Community of West African States, and South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone.

Ivory Coast has partnered with nations of the Sub-Saharan region to strengthen water and sanitation infrastructure. This has been done mainly with the help of organizations such as UNICEF and corporations like Nestle.[57]

In 2015, the United Nations engineered the Sustainable Development Goals (replacing the Millennium Development Goals). They focus on health, education, poverty, hunger, climate change, water sanitation, and hygiene. A major focus was clean water and salinization. Experts working in these fields have designed the WASH concept. WASH focuses on safe drinkable water, hygiene, and proper sanitation. The group has had a major impact on the sub-Saharan region of Africa, particularly the Ivory Coast. By 2030, they plan to have universal and equal access to safe and affordable drinking water.[79]

Military[edit]

As of 2012, major equipment items reported by the Ivory Coast Army included 10 T-55 tanks (marked as potentially unserviceable), five AMX-13 light tanks, 34 reconnaissance vehicles, 10 BMP-1/2 armoured infantry fighting vehicles, 41 wheeled APCs, and 36+ artillery pieces.[80]

In 2012, the Ivory Coast Air Force consisted of one Mil Mi-24 attack helicopter and three SA330L Puma transports (marked as potentially unserviceable).[81]

In 2017, Ivory Coast signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[82]

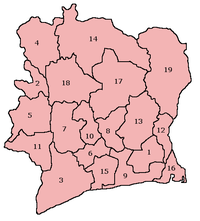

Administrative divisions[edit]

Since 2011, Ivory Coast has been administratively organised into 12 districts plus two district-level autonomous cities. The districts are sub-divided into 31 regions; the regions are divided into 108 departments; and the departments are divided into 510 sub-prefectures.[83] In some instances, multiple villages are organised into communes. The autonomous districts are not divided into regions, but they do contain departments, sub-prefectures, and communes. Since 2011, governors for the 12 non-autonomous districts have not been appointed. As a result, these districts have not yet begun to function as governmental entities.

The following is the list of districts, district capitals and each district’s regions:

Largest cities[edit]

Largest cities or towns in Ivory Coast According to the 2014 Census in Ivory Coast |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | |

Abidjan |

1 | Abidjan | Abidjan | 4,395,243 |

| 2 | Bouaké | Vallée du Bandama | 536,719 | |

| 3 | Daloa | Sassandra-Marahoué | 245,360 | |

| 4 | Korhogo | Savanes | 243,048 | |

| 5 | Yamoussoukro | Yamoussoukro | 212,670 | |

| 6 | San-Pédro | Bas-Sassandra | 164,944 | |

| 7 | Gagnoa | Gôh-Djiboua | 160,465 | |

| 8 | Man | Montagnes | 149,041 | |

| 9 | Divo | Gôh-Djiboua | 105,397 | |

| 10 | Anyama | Abidjan | 103,297 |

Geography[edit]

Köppen climate classification map of Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast is a country in western sub-Saharan Africa. It borders Liberia and Guinea in the west, Mali and Burkina Faso in the north, Ghana in the east, and the Gulf of Guinea (Atlantic Ocean) in the south. The country lies between latitudes 4° and 11°N, and longitudes 2° and 9°W. Around 64.8% of the land is agricultural land; arable land amounted to 9.1%, permanent pasture 41.5%, and permanent crops 14.2%. Water pollution is one of the biggest issues that the country is currently facing.[2]

Biodiversity[edit]

There are over 1,200 animal species including 223 mammals, 702 birds, 125 reptiles, 38 amphibians, and 111 species of fish, alongside 4,700 plant species. It is the most biodiverse country in West Africa, with the majority of its wildlife population living in the nation’s rugged interior.[86] The nation has nine national parks, the largest of which is Assgny National Park which occupies an area of around 17,000 hectares or 42,000 acres.[87]

The country contains six terrestrial ecoregions: Eastern Guinean forests, Guinean montane forests, Western Guinean lowland forests, Guinean forest–savanna mosaic, West Sudanian savanna, and Guinean mangroves.[88] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.64/10, ranking it 143rd globally out of 172 countries.[89]

Economy[edit]

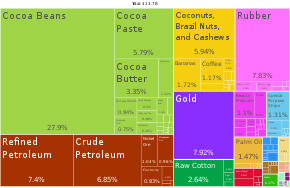

A proportional representation of Ivory Coast, 2019

GDP per capita development

Ivory Coast has, for the region, a relatively high income per capita (US$1,662 in 2017) and plays a key role in transit trade for neighbouring landlocked countries. The country is the largest economy in the West African Economic and Monetary Union, constituting 40% of the monetary union’s total GDP. Ivory Coast is the fourth-largest exporter of general goods in sub-Saharan Africa (following South Africa, Nigeria, and Angola).[90]

The country is the world’s largest exporter of cocoa beans. In 2009, cocoa-bean farmers earned $2.53 billion for cocoa exports and were projected to produce 630,000 metric tons in 2013.[91][92] Ivory Coast also has 100,000 rubber farmers who earned a total of $105 million in 2012.[93][94]

Close ties to France since independence in 1960, diversification of agricultural exports, and encouragement of foreign investment have been factors in economic growth. In recent years, Ivory Coast has been subject to greater competition and falling prices in the global marketplace for its primary crops of coffee and cocoa. That, compounded with high internal corruption, makes life difficult for the grower, those exporting into foreign markets, and the labour force; instances of indentured labour have been reported in the country’s cocoa and coffee production in every edition of the U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor since 2009.[95]

Ivory Coast’s economy has grown faster than that of most other African countries since independence. One possible reason for this might be taxes on exported agriculture. Ivory Coast, Nigeria, and Kenya were exceptions as their rulers were themselves large cash-crop producers, and the newly independent countries desisted from imposing penal rates of taxation on exported agriculture. As such, their economies did well.[96]

Around 7.5 million people made up the workforce in 2009. The workforce took a hit, especially in the private sector, during the early 2000s with numerous economic crises since 1999. Furthermore, these crises caused companies to close and move locations, especially in the tourism industry, and transit and banking companies. Decreasing job markets posed a huge issue as unemployment rates grew. Unemployment rates raised to 9.4% in 2012.[97] Solutions proposed to decrease unemployment included diversifying jobs in small trade. This division of work encouraged farmers and the agricultural sector. Self-employment policy, established by the Ivorian government, allowed for very strong growth in the field with an increase of 142% in seven years from 1995.[98]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 3,709,000 | — |

| 1975 | 6,709,600 | +4.08% |

| 1988 | 10,815,694 | +3.78% |

| 1998 | 15,366,672 | +3.32% |

| 2014 | 22,671,331 | +2.56% |

| 2021 | 29,389,150 | +3.48% |

| Source: 1960 UN estimate,[99] 1975-1998 censuses,[100] 2014 census,[101] 2021 census.[3] |

Congestion at a market in Abidjan

According to the December 14, 2021 census, the population was 29,389,150,[3] up from 22,671,331 at the 2014 census.[101] The first national census in 1975 counted 6.7 million inhabitants.[102] According to a Demographic and Health Surveys nationwide survey, the total fertility rate stood at 4.3 children per woman in 2021 (with 3.6 in urban areas and 5.3 in rural areas), down from 5.0 children per woman in 2012.[103]

Languages[edit]

It is estimated that 78 languages are spoken in Ivory Coast.[104] French, the official language, is taught in schools and serves as a lingua franca. A semi-creolized form of French, known as Nouchi, has emerged in Abidjan in recent years and spread among the younger generation.[105] One of the most common indigenous languages is Dyula, which acts as a trade language in much of the country, particularly in the north, and is mutually intelligible with other Manding languages widely spoken in neighboring countries.[106]

Ethnic groups[edit]

Macroethnic groupings in the country include Akan (42.1%), Voltaiques or Gur (17.6%), Northern Mandés (16.5%), Kru-speaking peoples (11%), Southern Mandés (10%), and others (2.8%, including 100,000 Lebanese[107] and 45,000 French; 2004). Each of these categories is subdivided into different ethnicities. For example, the Akan grouping includes the Baoulé, the Voltaique category includes the Senufo, the Northern Mande category includes the Dioula and the Maninka, the Kru category includes the Bété and the Kru, and the Southern Mande category includes the Yacouba.

About 77% of the population is considered Ivorian. Since Ivory Coast has established itself as one of the most successful West African nations, about 20% of the population (about 3.4 million) consists of workers from neighbouring Liberia, Burkina Faso, and Guinea. About 4% of the population is of non-African ancestry. Many are French,[49] Lebanese,[108][109] Vietnamese and Spanish citizens, as well as evangelical missionaries from the United States and Canada. In November 2004, around 10,000 French and other foreign nationals evacuated Ivory Coast due to attacks from pro-government youth militias.[110] Aside from French nationals, native-born descendants of French settlers who arrived during the country’s colonial period are present.

Religion[edit]

Ivory Coast is religiously diverse. According to the latest 2021 census data, adherents of Islam (mainly Sunni) represented 42.5% of the total population, while followers of Christianity (mainly Catholic and Evangelical) comprised 39.8% of the population. An additional 12.6% of the population identified as Irreligious, while 2.2% reported following Animism (traditional African religions).[1]

A 2020 estimate by the Pew Research Center, projected that Christians would represent 44% of the total population, while Muslims would represent 37.2% of the population. In addition, it estimated that 8.1% would be religiously unaffiliated, and 10.5% as followers of traditional African religions (animism).[111][2] In 2009, according to U.S. Department of State estimates, Christians and Muslims each made up 35% to 40% of the population, while an estimated 25% of the population practised traditional (animist) religions.[112]

Yamoussoukro is home to the largest church building in the world, the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace.[113]

Health[edit]

Life expectancy at birth was 42 for males in 2004; for females it was 47.[114] Infant mortality was 118 of 1000 live births.[114] Twelve physicians are available per 100,000 people.[114] About a quarter of the population lives below the international poverty line of US$1.25 a day.[115] About 36% of women have undergone female genital mutilation.[116] According to 2010 estimates, Ivory Coast has the 27th-highest maternal mortality rate in the world.[117] The HIV/AIDS rate was 19th-highest in the world, estimated in 2012 at 3.20% among adults aged 15–49 years.[118]

Education[edit]

Among sub-Saharan African countries, Ivory Coast has one of the highest literacy rates.[2] According to The World Factbook as of 2019, 89.9% of the population aged 15 and over can read and write.[119] A large part of the adult population, in particular women, is illiterate. Many children between 6 and 10 years old are not enrolled in school.[120] The majority of students in secondary education are male. At the end of secondary education, students can sit for the baccalauréat examination. Universities include Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny in Abidjan and the Université Alassane Ouattara in Bouaké.

Science and technology[edit]

According to the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Ivory Coast devotes about 0.13% of GDP to GERD. Apart from low investment, other challenges include inadequate scientific equipment, the fragmentation of research organizations and a failure to exploit and protect research results.[121] Ivory Coast was ranked 114st in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 103rd in 2019.[122][123][124][125] The share of the National Development Plan for 2012–2015 that is devoted to scientific research remains modest. Within the section on greater wealth creation and social equity (63.8% of the total budget for the Plan), just 1.2% is allocated to scientific research. Twenty-four national research programmes group public and private research and training institutions around a common research theme. These programmes correspond to eight priority sectors for 2012–2015, namely: health, raw materials, agriculture, culture, environment, governance, mining and energy; and technology.[121]

Culture[edit]

Each of the ethnic groups in the Ivory Coast has its own music genres, most showing strong vocal polyphony. Talking drums are common, especially among the Appolo, and polyrhythms, another African characteristic, are found throughout Ivory Coast and are especially common in the southwest. Popular music genres from Ivory Coast include zoblazo, zouglou, and Coupé-Décalé. A few Ivorian artists who have known international success are Magic Système, Alpha Blondy, Meiway, Dobet Gnahoré, Tiken Jah Fakoly, DJ Arafat, AfroB, Serge Beynaud and Christina Goh, of Ivorian descent.

Sport[edit]

The most popular sport is association football. The men’s national football team has played in the World Cup three times, in Germany 2006, in South Africa 2010, and Brazil in 2014. Côte d’Ivoire has produced many well-known footballers like Didier Drogba and Yaya Touré. The women’s football team played in the 2015 Women’s World Cup in Canada. The country has been the host of several major African sporting events, with the most recent being the 2013 African Basketball Championship. In the past, the country hosted the 1984 African Cup of Nations, in which the Ivory Coast football team finished fifth, and the 1985 African Basketball Championship, where the national basketball team won the gold medal.

400m metre runner Gabriel Tiacoh won the silver medal in the men’s 400 metres at the 1984 Olympics. The country hosted the 8th edition of Jeux de la Francophonie in 2017. In the sport of athletics, well known participants include Marie-Josée Ta Lou and Murielle Ahouré.

Rugby union is popular, and the national rugby union team qualified to play at the Rugby World Cup in South Africa in 1995. Ivory Coast has won two Africa Cups: one in 1992 and the other in 2015. Ivory Coast is known for Taekwondo with well-known competitors such as Cheick Cissé, Ruth Gbagbi, and Firmin Zokou.

Cuisine[edit]

Yassa is a popular dish throughout West Africa prepared with chicken or fish. Chicken yassa is pictured.

Traditional cuisine is very similar to that of neighbouring countries in West Africa in its reliance on grains and tubers. Cassava and plantains are significant parts of Ivorian cuisine. A type of corn paste called aitiu is used to prepare corn balls, and peanuts are widely used in many dishes. Attiéké is a popular side dish made with grated cassava, a vegetable-based couscous. Common street food is alloco, plantain fried in palm oil, spiced with steamed onions and chili, and eaten along with grilled fish or boiled eggs. Chicken is commonly consumed and has a unique flavor because of its lean, low-fat mass in this region. Seafood includes tuna, sardines, shrimp, and bonito, which is similar to tuna. Mafé is a common dish consisting of meat in peanut sauce.[126]

Slow-simmered stews with various ingredients are another common food staple.[126] Kedjenou is a dish consisting of chicken and vegetables slow-cooked in a sealed pot with little or no added liquid, which concentrates the flavors of the chicken and vegetables and tenderizes the chicken.[126] It is usually cooked in a pottery jar called a canary, over a slow fire, or cooked in an oven.[126] Bangui is a local palm wine.

Ivorians have a particular kind of small, open-air restaurant called a maquis, which is unique to the region. A maquis normally features braised chicken, and fish covered in onions and tomatoes served with attiéké or kedjenou.

See also[edit]

- Index of Ivory Coast–related articles

- Outline of Ivory Coast

Notes[edit]

- ^ The latter being pronounced KOHT dee-VWAR in English and [kot divwaʁ] (

listen) in French.[7]

- ^ Joseph Vaissète, in his 1755 Géographie historique, ecclésiastique et civile, lists the name as La Côte des Dents («The Coast of the Teeth»), but notes that Côte de Dents is the more correct form.[16]

- ^ Côte du Vent sometimes denoted the combined «Ivory» and «Grain» coasts, or sometimes just the «Grain» coast.[13][11]

- ^ Literal translations include Elfenbeinküste (German), Costa d’Avorio (Italian), Norsunluurannikko (Finnish), Бе́рег Слоно́вой Ко́сти (Russian), and Ivory Coast.[21]

- ^ Many governments use «Côte d’Ivoire» for diplomatic reasons, as do their outlets, such as the Chinese CCTV News. Other organizations that use «Côte d’Ivoire» include the Central Intelligence Agency in its World Factbook[2] and the international sport organizations FIFA[25] and the IOC[26] (referring to their national football and Olympic teams in international games and in official broadcasts), news magazine The Economist,[27] the Encyclopædia Britannica[28] and the National Geographic Society.[29]

- ^ The BBC usually uses «Ivory Coast» both in news reports and on its page about the country.[30] The Guardian newspaper’s style guide says: «Ivory Coast, not ‘The Ivory Coast’ or ‘Côte d’Ivoire’; its nationals are Ivorians.»[31]

ABC News, Fox News, The Times, The New York Times, the South African Broadcasting Corporation, and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation all use «Ivory Coast» either exclusively or predominantly.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «OVERALL DEFINITIVE RESULTS OF THE RGPH 2021: THE POPULATION USUALLY LIVING ON IVORIAN TERRITORY IS 29,389,150 INHABITANTS». PORTAIL OFFICIEL DU GOUVERNEMENT DE COTE D’IVOIRE (in French). 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f «Côte d’Ivoire». The World Factbook. CIA Directorate of Intelligence. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Institut National de la Statistique de Côte d’Ivoire. «RGPH 2021 Résultats globaux» (PDF). Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d «World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022». IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ «Gini Index». World Bank. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Human Development Report 2021/2022» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ «Cote d’Ivoire definition». Dictionary.com. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Loi n° 2000-513 du 1er août 2000 portant Constitution de la République de Côte d’Ivoire» (PDF). Journal Officiel de la République de Côte d’Ivoire (in French). 42 (30): 529–538. 3 August 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009.,

- ^ IMF. «World Economic Outlook database: April 2022». Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ «Ivory Coast country profile». BBC News. 18 November 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Thornton 1996, p. 53–56.

- ^ a b c Lipski 2005, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d Duckett 1853, p. 594.

- ^ a b Homans 1858, p. 14.

- ^ a b Plée 1868, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Vaissète 1755, p. 185–186.

- ^ a b Blanchard 1818, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911, p. 100.

- ^ a b Walckenaer 1827, p. 35.

- ^ «The Ivory Coast». World Digital Library. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b David 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Auzias & Labourdette 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Lea & Rowe 2001, p. 127.

- ^ Jessup 1998, p. 351.

- ^ «CAF Member Associations». CAF Online. CAF-Confederation of African Football. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Côte d’Ivoire». International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Research Tools». The Economist. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ «Cote d’Ivoire». Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Places Directory». nationalgeographic.com. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Country profile: Ivory Coast». BBC News. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Guardian Style Guide: I». The Guardian. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Guédé, François Yiodé (1995). «Contribution à l’étude du paléolithique de la Côte d’Ivoire : État des connaissances». Journal des Africanistes. 65 (2): 79–91. doi:10.3406/jafr.1995.2432.

- ^ Rougerie 1978, p. 246

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Warner 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Kipré 1992, pp. 15–16

- ^ a b c d Warner 1988, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Warner 1988, p. 7.

- ^ a b Warner 1988, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Warner 1988, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k «Background Note: Cote d’Ivoire». U.S. Department of State. October 2003. Archived from the original on 29 February 2004.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Warner 1988, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Warner 1988, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Warner 1988, p. 11.

- ^ «Slave Emancipation and the Expansion of Islam, 1905–1914» (PDF). 2 May 2013. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Warner 1988, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Warner 1988, p. 14.

- ^ Mortimer 1969.

- ^ «French Ivory Coast (1946-1960)». University of Central Arkansas. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ a b «Ivory Coast – The Economy». countrystudies.us. Library of Congress.

- ^ McGovern 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 330.

- ^ Fenton, Tim (15 November 2004). «France’s ‘Little Iraq’«. CBS News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.[unreliable source?]

- ^ «UN endorses plan to leave president in office beyond mandate». IRIN. 14 October 2005.

- ^ Bavier, Joe (18 August 2006). «Ivory Coast Opposition, Rebels Say No to Term Extension for President». VOA News. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- ^ «Partial rejection of UN peace plan». IRIN. 2 November 2006.

- ^ «New Ivory Coast govt ‘a boost for Gbagbo’«. Independent Online. Agence France-Presse. 12 April 2007. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007.

- ^ a b «Water And Sanitation». UNICEF. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^ a b c «Thousands flee Ivory Coast for Liberia amid poll crisis». BBC News. 26 December 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Final Communique on the Extraordinary Session of the Authority of Heads of State and Government on Cote D’Ivoire». Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). 7 December 2010. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011.

- ^ «Communique of the 252nd Meeting of the Peace and Security Council» (PDF). African Union. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2011.

- ^ «ICE deports Ivory Coast army colonel convicted of arms trafficking». Immigration and Customs Enforcement . 30 November 2012. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018.

- ^ «FBI nabbed colonel on official business». United Press International. 21 September 2010.

- ^ United States v. Shor, Order on appeal from summary judgment, 9th Cir. Case No. 5:10-cr-00434-RMW-1, (December 18, 2015).

- ^ DiCampo, Peter (27 April 2011). «An Uncertain Future». Ivory Coast: Elections Turn to War. Pulitzer Center. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Lynch, Colum; Branigin, William (11 April 2011). «Ivory Coast strongman arrested after French forces intervene». Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ «Ivory Coast’s Laurent Gbagbo arrested – four months on». The Guardian. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Griffiths, Thalia (11 April 2011). «The war is over — but Ouattara’s struggle has barely begun». The Guardian. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «ICC orders conditional release of ex-Ivory Coast leader Gbagbo». France 24. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Former Ivory Coast President Laurent Gbagbo freed by International Criminal Court». CNN. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Ivory Coast’s ex-president Laurent Gbagbo released to Belgium». Al Jazeera. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Ivory Coast’s Ouattara re-elected by a landslide». Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ «Ivory Coast election: Alassane Ouattara wins amid boycott». BBC News. 3 November 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ «Ivory Coast Constitutional Council confirms Ouattara re-election». Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Agnero, Eric (10 November 2010). «Ivory Coast postpones presidential runoff vote». CNN. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Ivory Coast election: Army says it has sealed borders». BBC News. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Ivory Coast election: Ouattara wins the third term, opposition cries foul». Deutsche Welle. 3 November 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ «Côte d’Ivoire : un nouveau gouvernement, mais peu de changements – Jeune Afrique». JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ «Ivory Coast’s former president Laurent Gbagbo oversaw ‘unspeakable crimes’, says ICC». The Daily Telegraph. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ «Sustainable Development Goals». sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ IISS 2012, p. 429.

- ^ IISS 2012, p. 430.

- ^ «Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons». United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- ^ Geopolitical Entities, Names, and Codes (GENC) second edition

- ^ «Districts of Côte d’Ivoire». Statoids. Institut National de la Statistique, Côte d’Ivoire.

- ^ While Yamoussoukro is the seat of Bélier region, the city itself is not part of the region.

- ^ «COTE D’ IVOIRE (IVORY COAST)». Monga Bay.

- ^ «Parc national d’Azagny». United Nations Environment Programme. 1983. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; et al. (2017). «An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm». BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; et al. (2020). «Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity — Supplementary Material». Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ «Côte d’Ivoire: Financial Sector Profile». MFW4A.org. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ «Ivory Coast Makes 1st Cocoa Export Since January». Associated Press via NPR. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Monnier, Olivier (27 March 2013). «Ivory Coast San Pedro Port Sees Cocoa Exports Stagnating». Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ «Ivory Coast reaps more rubber as farmers shift from cocoa». Reuters. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ «Cote d’Ivoire | Office of the United States Trade Representative». Ustr.gov. 29 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ «2013 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor in Côte d’Ivoire». United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.

- ^ Baten 2016, p. 335.

- ^ «Ivory Coast Unemployment Rate | 1998–2017 | Data | Chart | Calendar». www.tradingeconomics.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Ministry of Economy 2007, pp. 176–180.

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. «World Population Prospects 2022». Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Institut National de la Statistique de Côte d’Ivoire. «Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat 2014 — Rapport d’exécution et Présentation des principaux résultats» (PDF). p. 3. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ a b Institut National de la Statistique de Côte d’Ivoire. «RGPH 2014 Résultats globaux» (PDF). Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ «Ivory Coast – Population». countrystudies.us. Library of Congress.

- ^ Institut National de la Statistique de Côte d’Ivoire and ICF International. «Enquête Démographique et de Santé — Côte d’Ivoire — 2021» (PDF). p. 10 (21). Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. (Page on «Languages of Côte d’Ivoire.» This page indicates that one of the 79 no longer has any speakers.)

- ^ Boutin, Akissi Béatrice (2021), Hurst-Harosh, Ellen; Brookes, Heather; Mesthrie, Rajend (eds.), «Exploring Hybridity in Ivorian French and Nouchi», Youth Language Practices and Urban Language Contact in Africa, Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 159–181, ISBN 978-1-107-17120-6, retrieved 9 October 2022

- ^ «Manding (Dioula)». Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ «Des investisseurs libanais à Abidjan pour investir en Afrique». VOA Afrique. 1 February 2018.

- ^ «From Lebanon to Africa». Al Jazeera. 28 October 2015.

- ^ «Ivory Coast – The Levantine Community». Countrystudies.us. Library of Congress. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Gregson, Brent (30 November 2004). «Rwanda Syndrome on the Ivory Coast». World Press Review.

- ^ «Ivory Coast». Global Religious Futures. Pew Research Center. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Côte d’Ivoire . State.gov. Retrieved on 17 August 2012.

- ^ Mark, Monica (15 May 2015). «Yamoussoukro’s Notre-Dame de la Paix, the world’s largest basilica — a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 37». the Guardian. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ a b c «WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region». World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ «Human Development Indices» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. January 2008. p. 35. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

Table 3: Human and income poverty

- ^ «Female genital mutilation and other harmful practices». World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ «Country Comparison :: Maternal Mortality Rate». The World Factbook. CIA.gov. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015.

- ^ «Country Comparison :: HIV/AIDS – Adult Prevalence Rate». The World Factbook. CIA.gov. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ^ «Literacy — The World Factbook». www.cia.gov.

- ^ «Population, Health, and Human Well-Being— Côte d’Ivoire» (PDF). EarthTrends. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ a b Essegbey, Diaby & Konté 2015, pp. 498–533, «West Africa».

- ^ «Global Innovation Index 2021». World Intellectual Property Organization. United Nations. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ «Global Innovation Index 2019». WIPO. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ «RTD — Item». ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ «Global Innovation Index». INSEAD Knowledge. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d «Ivory Coast, Côte d’Ivoire: Recipes and Cuisine». Whats4eats.com. 3 April 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2011.[unreliable source?]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Bibliography[edit]

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195337709 – via Google Books.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107507180.

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2008). Côte d’Ivoire. Petit futé Country Guides (in French). Petit Futé. ISBN 9782746924086.

- Blanchard, Pierre (1818). Le Voyageur de la jeunesse dans les quatre parties du monde (in French) (5th ed.). Paris: Le Prieur.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Ivory Coast». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.).

- David, Philippe (2000). La Côte d’Ivoire (in French) (KARTHALA Editions, 2009 ed.). Paris: Méridiens. ISBN 9782811101961.

- Duckett, William (1853). «Côte Des Dents». Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture inventaire raisonné des notions générales les plus indispensables à tous (in French). Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Paris: Michel Lévy frères.

- Essegbey, George; Diaby, Nouhou; Konté, Almamy (2015). «West Africa». UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Homans, Isaac Smith (1858). «Africa». A cyclopedia of commerce and commercial navigation. Vol. 1. New York: Harper & brothers.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (2012). Military Balance 2012. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-33356-9. OCLC 1147908458.

- Jessup, John E. (1998), An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945–1996, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-28112-9, OCLC 37742322

- Kipré, Pierre (1992), Histoire de la Côte d’Ivoire (in French), Abidjan: Editions AMI, OCLC 33233462

- Lea, David; Rowe, Annamarie (2001). «Côte d’Ivoire». A Political Chronology of Africa. Political Chronologies of the World. Vol. 4. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781857431162.

- Lipski, John M. (2005). A History of Afro-Hispanic Language: Five Centuries, Five Continents. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521822657.

- McGovern, Mike (2011). Making War in Côte d’Ivoire. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226514604.

- Ministry of Economy and Finances of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire (2007), La Côte d’Ivoire en chiffres (in French), Abidjan: Dialogue Production, OCLC 173763995

- Mortimer, Edward (1969). France and the Africans 1944–1960 – A Political History. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-08251-3. OCLC 31730.

- Plée, Victorine François (1868). «Côte des Dents où d’Ivoire». Peinture géographique du monde moderne: suivant l’ordre dans lequel il a été reconnu et decouvert (in French). Paris: Pigoreau.

- Rougerie, Gabriel (1978), L’Encyclopédie générale de la Côte d’Ivoire (in French), Abidjan: Nouvelles publishers africaines, ISBN 978-2-7236-0542-7, OCLC 5727980

- Thornton, John K. (1996). «The African background to American colonization». In Engerman, Stanley L.; Gallman, Robert E. (eds.). The Cambridge Economic History of the United States. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521394420.

- Vaissète, Jean Joseph (1755). Géographie historique, ecclesiastique et civile (in French). Vol. 11. Paris: chez Desaint & Saillant, J.-T. Herissant, J. Barois.