Криптовалюта — цифровой актив, учёт которого децентрализован. Функционирование данных систем происходит при помощи распределённой компьютерной сети. При этом информация о транзакциях может не шифроваться и быть доступна в открытом виде. Для гарантирования неизменности цепочки блоков базы транзакций используется криптография. Термин закрепился вследствие статьи o Bitcoin «Crypto currency» (Криптографическая валюта), опубликованной в 2011 году в журнале Forbes. Сам же автор Bitcoin, как и многие другие, использовал термин «электронная наличность» (Electronic cash). Способ эмиссии криптовалют может представлять собой майнинг, форжинг или IPO.

Все значения слова «криптовалюта»

-

В конце 2016 года рынок криптовалют для многих людей выглядел крайне ненадёжным.

-

В то же время ряд проблем, равно как и повышенный интерес к самому биткоину, вызваны его растущей стоимостью и вниманием, проявляемым массовым инвестором к первой криптовалюте мира.

-

Рекордные активы альтернативной валюты делают рынок особенно интересным для спекуляций и создают стимулы для дальнейшего развития и выпуска новых криптовалют.

- (все предложения)

- вендор

- риск-менеджмент

- факторинг

- листинг

- леверидж

- (ещё синонимы…)

СЛИТНО ПИШУТСЯ:

1) аббревиатуры: МХАТ, замнач, физзарядка.

2. сложные существительные, первым элементом которых является иноязычный корень: авиа-, авто-, аэро-, фото-, электро-, гидро-, зоо-, теле-:

3) нарицательные, образованные сложением с соединительными гласными о и е:

4) при отсутствии соединительных гласных:

а) существительные, образованные от «дефисных» географических названий:

б) существительные с первой глагольной частью, оканчивающейся на и:

5) названия городов, второй частью которых является часть -град или -город:

6) сложные существительные и прилагательные, первая часть которых — числительное:

7) существительные с полу-:

ЧЕРЕЗ ДЕФИС ПИШУТСЯ:

1) слова, первым или последним элементом которых является числительное, написанное цифрами:

2) названия промежуточных направлений и стран света:

3) названия едениц измерения:

4) слова, в состав которых входит отдельная буква алфавита: y-лучи;

5) сложные существительные, части которых могут существовать самостоятельно:

6) составные русские и иноязычные фамилии: Сухово-Кобылин, Андерсен-Нексе;

7) составные географические названия: Орехово-Зуево, Комсомольск-на-Амуре, Ла-Плата;

Всего найдено: 13

Как правильно расставить знаки препинания? Все, что нужно знать о криптовалюте, – краткое руководство для новичков.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Лучше разбить предложение на два: Все, что нужно знать о криптовалюте. Краткое руководство для новичков.

Нужна ли запятая после слова «то» и почему? «Несмотря на то, что версия скриптов явно указана указана в файле version.conf конфигов дистрибутива, полезно иметь под рукой актуальные версии.»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятую можно оставить. См. «Справочник по пунктуации».

Добрый день! Как правильно: крипто-юань или криптоюань? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Следует писать слитно: криптоюань.

Здравствуйте. Правильно ли расставлены запятые в предложении «Размер «криптохвоста» сократили, однако, срок годности так и не попал в криптокод»? Если нет, то почему?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

После «однако» запятая не ставится (это союз, соединяющий части предложения).

Здравствуйте! Интересует ответ вот на какой вопрос. Организация получила лицензию «на осуществление разработки, производства, распространения шифровальных (криптографических) средств, информационных систем и телекоммуникационных систем, защищенных с использованием шифровальных (криптографических) средств, выполнения работ, оказания услуг в области шифрования информации, технического обслуживания шифровальных (криптографических) средств, информационных систем и телекоммуникационных систем, защищенных с использованием шифровальных (криптографических) средств (за исключением случая, если техническое обслуживание шифровальных (криптографических) средств, информационных систем и телекоммуникационных систем, защищенных с использованием шифровальных (криптографических) средств, осуществляется для обеспечения собственных нужд юридического лица или индивидуального предпринимателя).» Как правильно: лицензия на осуществление разработки, производства, распространения…, выполнения работ, оказания услуг …, технического обслуживания … ИЛИ лицензия на осуществление разработки, производство, распространение…, выполнение работ, оказание услуг …, техническое обслуживание … ?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Возможны оба варианта, а также вариант без слова «осуществление».

Укажите речевые ошибки, возникшие вследствие неоправданного употребления заимствованных слов (неясность высказывания, употребление слова без учета его семантики, нарушение лексической сочетаемости, речевая избыточность, смешение стилей и др.). Исправьте предложения. Образец: Двадцать лет своей автобиографии он посвятил выведению новых сортов земляники. Употребление слова без учета его семантики: автобиография – это последовательное описание человеком событий своей жизни. Двадцать лет своей жизни он посвятил выведению новых сортов земляники. 1. Мы выполнили работу по эксгумации народного фольклора. 2. Деятельность редакции по уточнению текстов лимитирована утратой части манускриптов. 3. Победителями тендера стал консорциум западных и российских банков, который возглавил CS First Boston. 4. Доверительные трастовые операции широко развиты за рубежом. Потребность в трастовых услугах, которые гарантируют целостность ваших сбережений, в России возникла в связи с накоплением отдельными гражданами и организациями значительных финансовых ресурсов и необходимостью умело распорядиться этими средствами. 5. Кафе, бистро, как и ателье разного профиля, должны функционировать по субботам. 6. Любые часы ценны только тогда, когда они фиксируют точное время.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

«Справочное бюро» не выполняет домашних заданий.

Добрый день! Сразу два вопроса:

1) Как правильно писать типы различные счетов? Крипто-счет, STP-счет и др. Нужен ли там дефис? Или следует писать криптосчет? А крипто-валюты или криптовалюты?

2) Грамотно ли так сказать? «Вам помогут ваши знания, аналитические способности и немного удачи»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Верно: криптовалюты, криптосчет, STP-счет.

2. Не вполне.

Здравствуйте!

Подскажите, правильно ли такое словосочетание: «надежная криптостойкость»?

Если можно, аргументируйте ответ.

Заранее спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Лексически правильно: высокая криптостойкость или высокая надежность криптографического алгоритма.

Как правильно написать слово «криптосервер» слитно/раздельно или через дефис?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно слитное написание.

можно ли сказать: «расшифровать криптограмму»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, можно.

Здравствуйте. Подскажите пожалуйста, как правильно будет писаться «не криптографическими», раздельно или слитно ? Спрашиваю потому, что в ряде случаев, видел написание данного слова, в различных технических документах, слитно.

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно раздельное написание. Слитное написание в подобных случаях уместно, если речь идет о терминах.

Скажите, пожалуйста, как пишется слово «криптозащищенность»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы написали корректно.

Уважаемые дамы и господа! Пощвольте поториться с вопросом. Очень надеюсь на Вашу помощь.

Перевожу список иллюстраций. Нужны ли в данном случае запятые. Текст книги и без того изобилует названиями дрвених манускриптов. Неужели и в списке иллюстраций и в тексте книги везде нужны кавычки? Разрешите, пожалуста, наш спор с редактором. Спасибо огромное!Стр. 33: Герцог Беррийский за столом. Из «Богатейшего часослова герцога Беррийского», Франция, 1411/16, Шантильи, музей Конде.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Рекомендуем «Справочник издателя и автора» А. Э. Мильчина и Л. К. Чельцовой.

«криптовалюта» — Фонетический и морфологический разбор слова, деление на слоги, подбор синонимов

Фонетический морфологический и лексический анализ слова «криптовалюта». Объяснение правил грамматики.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «криптовалюта» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «криптовалюта».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «криптовалюта» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «криптовалюта»

- 3 Предложения со словом «криптовалюта»

- 4 Значение слова «криптовалюта»

- 5 Как правильно пишется слово «криптовалюта»

Слоги в слове «криптовалюта» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 5

По слогам: кри-пто-ва-лю-та

По правилам школьной программы слово «криптовалюта» можно поделить на слоги разными способами. Допускается вариативность, то есть все варианты правильные. Например, такой:

крип-то-ва-лю-та

По программе института слоги выделяются на основе восходящей звучности:

кри-пто-ва-лю-та

Ниже перечислены виды слогов и объяснено деление с учётом программы института и школ с углублённым изучением русского языка.

п примыкает к этому слогу, а не к предыдущему, так как не является сонорной (непарной звонкой согласной)

Как перенести слово «криптовалюта»

кри—птовалюта

крип—товалюта

крипто—валюта

криптова—люта

криптовалю—та

Предложения со словом «криптовалюта»

В конце 2016 года рынок криптовалют для многих людей выглядел крайне ненадёжным.

Дмитрий Карпиловский, Биткоин, блокчейн и как заработать на криптовалютах, 2018.

В то же время ряд проблем, равно как и повышенный интерес к самому биткоину, вызваны его растущей стоимостью и вниманием, проявляемым массовым инвестором к первой криптовалюте мира.

Майкл Кейси, Машина правды, 2018.

В конечном счёте мы оценили грандиозный потенциал биткоина, и эта книга в определённой мере отражает этапы наших собственных путешествий в мире криптовалют.

Майкл Кейси, Эпоха криптовалют, 2015.

Значение слова «криптовалюта»

Криптовалюта — цифровой актив, учёт которого децентрализован. Функционирование данных систем происходит при помощи распределённой компьютерной сети. При этом информация о транзакциях может не шифроваться и быть доступна в открытом виде. Для гарантирования неизменности цепочки блоков базы транзакций используется криптография. Термин закрепился вследствие статьи o Bitcoin «Crypto currency» (Криптографическая валюта), опубликованной в 2011 году в журнале Forbes. Сам же автор Bitcoin, как и многие другие, использовал термин «электронная наличность» (Electronic cash). Способ эмиссии криптовалют может представлять собой майнинг, форжинг или IPO. (Википедия)

Как правильно пишется слово «криптовалюта»

Правописание слова «криптовалюта»

Орфография слова «криптовалюта»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «криптовалюта» в прямом и обратном порядке:

A cryptocurrency, crypto-currency, or crypto is a digital currency designed to work as a medium of exchange through a computer network that is not reliant on any central authority, such as a government or bank, to uphold or maintain it.[2] It is a decentralized system for verifying that the parties to a transaction have the money they claim to have, eliminating the need for traditional intermediaries, such as banks, when funds are being transferred between two entities.[3]

Individual coin ownership records are stored in a digital ledger, which is a computerized database using strong cryptography to secure transaction records, control the creation of additional coins, and verify the transfer of coin ownership.[4][5][6] Despite their name, cryptocurrencies are not considered to be currencies in the traditional sense, and while varying treatments have been applied to them, including classification as commodities, securities, and currencies, cryptocurrencies are generally viewed as a distinct asset class in practice.[7][8][9] Some crypto schemes use validators to maintain the cryptocurrency. In a proof-of-stake model, owners put up their tokens as collateral. In return, they get authority over the token in proportion to the amount they stake. Generally, these token stakers get additional ownership in the token over time via network fees, newly minted tokens, or other such reward mechanisms.[10]

Cryptocurrency does not exist in physical form (like paper money) and is typically not issued by a central authority. Cryptocurrencies typically use decentralized control as opposed to a central bank digital currency (CBDC).[11] When a cryptocurrency is minted, or created prior to issuance, or issued by a single issuer, it is generally considered centralized. When implemented with decentralized control, each cryptocurrency works through distributed ledger technology, typically a blockchain, that serves as a public financial transaction database.[12] Traditional asset classes like currencies, commodities, and stocks, as well as macroeconomic factors, have modest exposures to cryptocurrency returns.[13]

The first decentralized cryptocurrency was Bitcoin, which was first released as open-source software in 2009. As of March 2022, there were more than 9,000 other cryptocurrencies in the marketplace, of which more than 70 had a market capitalization exceeding $1 billion.[14]

History

In 1983, American cryptographer David Chaum conceived of a type of cryptographic electronic money called ecash.[15][16] Later, in 1995, he implemented it through Digicash,[17] an early form of cryptographic electronic payments. Digicash required user software in order to withdraw notes from a bank and designate specific encrypted keys before it can be sent to a recipient. This allowed the digital currency to be untraceable by a third party.

In 1996, the National Security Agency published a paper entitled How to Make a Mint: the Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash, describing a cryptocurrency system. The paper was first published in an MIT mailing list[18] and later in 1997 in The American Law Review.[19]

In 1998, Wei Dai described «b-money», an anonymous, distributed electronic cash system.[20] Shortly thereafter, Nick Szabo described bit gold.[21] Like Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies that would follow it, bit gold (not to be confused with the later gold-based exchange BitGold) was described as an electronic currency system which required users to complete a proof of work function with solutions being cryptographically put together and published.

In January 2009, Bitcoin was created by pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto. It used SHA-256, a cryptographic hash function, in its proof-of-work scheme.[22][23] In April 2011, Namecoin was created as an attempt at forming a decentralized DNS. In October 2011, Litecoin was released which used scrypt as its hash function instead of SHA-256. Peercoin, created in August 2012, used a hybrid of proof-of-work and proof-of-stake.[24]

On 6 August 2014, the UK announced its Treasury had commissioned a study of cryptocurrencies, and what role, if any, they could play in the UK economy. The study was also to report on whether regulation should be considered.[25] Its final report was published in 2018,[26] and it issued a consultation on cryptoassets and stablecoins in January 2021.[27]

In June 2021, El Salvador became the first country to accept Bitcoin as legal tender, after the Legislative Assembly had voted 62–22 to pass a bill submitted by President Nayib Bukele classifying the cryptocurrency as such.[28]

In August 2021, Cuba followed with Resolution 215 to recognize and regulate cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.[29]

In September 2021, the government of China, the single largest market for cryptocurrency, declared all cryptocurrency transactions illegal. This completed a crackdown on cryptocurrency that had previously banned the operation of intermediaries and miners within China.[30]

On 15 September 2022, the world second largest cryptocurrency at that time, Ethereum transitioned its consensus mechanism from proof-of-work (PoW) to proof-of-stake (PoS) in an upgrade process known as «the Merge». According to the Ethereum Founder, the upgrade can cut Ethereum’s energy use by 99.9% and carbon-dioxide emissions by 99.9%.[31]

On 11 November 2022, FTX Trading Ltd., a cryptocurrency exchange, which also operated a crypto hedge fund, and had been valued at $18 billion,[32] filed for bankruptcy.[33] The financial impact of the collapse extended beyond the immediate FTX customer base, as reported,[34] while, at a Reuters conference, financial industry executives said that «regulators must step in to protect crypto investors.»[35] Technology analyst Avivah Litan commented on the cryptocurrency ecosystem that «everything…needs to improve dramatically in terms of user experience, controls, safety, customer service.»[36]

Formal definition

According to Jan Lansky, a cryptocurrency is a system that meets six conditions:[37]

- The system does not require a central authority; its state is maintained through distributed consensus.

- The system keeps an overview of cryptocurrency units and their ownership.

- The system defines whether new cryptocurrency units can be created. If new cryptocurrency units can be created, the system defines the circumstances of their origin and how to determine the ownership of these new units.

- Ownership of cryptocurrency units can be proved exclusively cryptographically.

- The system allows transactions to be performed in which ownership of the cryptographic units is changed. A transaction statement can only be issued by an entity proving the current ownership of these units.

- If two different instructions for changing the ownership of the same cryptographic units are simultaneously entered, the system performs at most one of them.

In March 2018, the word cryptocurrency was added to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.[38]

Altcoins

Tokens, cryptocurrencies, and other digital assets other than Bitcoin are collectively known as alternative cryptocurrencies,[39][40][41] typically shortened to «altcoins» or «alt coins»,[42][43] or disparagingly «shitcoins».[44] Paul Vigna of The Wall Street Journal also described altcoins as «alternative versions of Bitcoin»[45] given its role as the model protocol for altcoin designers.

The logo of Ethereum, the second largest cryptocurrency

Altcoins often have underlying differences when compared to Bitcoin. For example, Litecoin aims to process a block every 2.5 minutes, rather than Bitcoin’s 10 minutes, which allows Litecoin to confirm transactions faster than Bitcoin.[46] Another example is Ethereum, which has smart contract functionality that allows decentralized applications to be run on its blockchain.[47] Ethereum was the most used blockchain in 2020, according to Bloomberg News.[48] In 2016, it had the largest «following» of any altcoin, according to the New York Times.[49]

Significant rallies across altcoin markets are often referred to as an «altseason».[50][51]

Stablecoins

Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies designed to maintain a stable level of purchasing power.[52] Notably, these designs are not foolproof, as a number of stablecoins have crashed or lost their peg. For example, on 11 May 2022, Terra’s stablecoin UST fell from $1 to 26 cents.[53][54] The subsequent failure of Terraform Labs resulted in the loss of nearly $40B invested in the Terra and Luna coins.[55] In September 2022, South Korean prosecutors requested the issuance of an Interpol Red Notice against the company’s founder, Do Kwon.[56] In Hong Kong, the expected regulatory framework for stablecoins in 2023/24 is being shaped and includes a few considerations.[57]

Architecture

Cryptocurrency is produced by an entire cryptocurrency system collectively, at a rate which is defined when the system is created and which is publicly stated. In centralized banking and economic systems such as the US Federal Reserve System, corporate boards or governments control the supply of currency.[citation needed] In the case of cryptocurrency, companies or governments cannot produce new units, and have not so far provided backing for other firms, banks or corporate entities which hold asset value measured in it. The underlying technical system upon which cryptocurrencies are based was created by Satoshi Nakamoto.[58]

Within a proof-of-work system such as Bitcoin, the safety, integrity and balance of ledgers is maintained by a community of mutually distrustful parties referred to as miners. Miners use their computers to help validate and timestamp transactions, adding them to the ledger in accordance with a particular timestamping scheme.[22] In a proof-of-stake blockchain, transactions are validated by holders of the associated cryptocurrency, sometimes grouped together in stake pools.

Most cryptocurrencies are designed to gradually decrease the production of that currency, placing a cap on the total amount of that currency that will ever be in circulation.[59] Compared with ordinary currencies held by financial institutions or kept as cash on hand, cryptocurrencies can be more difficult for seizure by law enforcement.[4]

Blockchain

The validity of each cryptocurrency’s coins is provided by a blockchain. A blockchain is a continuously growing list of records, called blocks, which are linked and secured using cryptography.[58][60] Each block typically contains a hash pointer as a link to a previous block,[60] a timestamp and transaction data.[61] By design, blockchains are inherently resistant to modification of the data. It is «an open, distributed ledger that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way».[62] For use as a distributed ledger, a blockchain is typically managed by a peer-to-peer network collectively adhering to a protocol for validating new blocks. Once recorded, the data in any given block cannot be altered retroactively without the alteration of all subsequent blocks, which requires collusion of the network majority.

Blockchains are secure by design and are an example of a distributed computing system with high Byzantine fault tolerance. Decentralized consensus has therefore been achieved with a blockchain.[63]

Nodes

A node is a computer that connects to a cryptocurrency network. The node supports the cryptocurrency’s network through either relaying transactions, validation, or hosting a copy of the blockchain. In terms of relaying transactions, each network computer (node) has a copy of the blockchain of the cryptocurrency it supports. When a transaction is made, the node creating the transaction broadcasts details of the transaction using encryption to other nodes throughout the node network so that the transaction (and every other transaction) is known.

Node owners are either volunteers, those hosted by the organization or body responsible for developing the cryptocurrency blockchain network technology, or those who are enticed to host a node to receive rewards from hosting the node network.[64]

Timestamping

Cryptocurrencies use various timestamping schemes to «prove» the validity of transactions added to the blockchain ledger without the need for a trusted third party.

The first timestamping scheme invented was the proof-of-work scheme. The most widely used proof-of-work schemes are based on SHA-256 and scrypt.[24]

Some other hashing algorithms that are used for proof-of-work include CryptoNight, Blake, SHA-3, and X11.

Another method is called the proof-of-stake scheme. Proof-of-stake is a method of securing a cryptocurrency network and achieving distributed consensus through requesting users to show ownership of a certain amount of currency. It is different from proof-of-work systems that run difficult hashing algorithms to validate electronic transactions. The scheme is largely dependent on the coin, and there’s currently no standard form of it. Some cryptocurrencies use a combined proof-of-work and proof-of-stake scheme.[24]

Mining

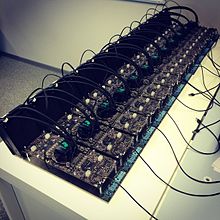

On a blockchain, mining is the validation of transactions. For this effort, successful miners obtain new cryptocurrency as a reward. The reward decreases transaction fees by creating a complementary incentive to contribute to the processing power of the network. The rate of generating hashes, which validate any transaction, has been increased by the use of specialized machines such as FPGAs and ASICs running complex hashing algorithms like SHA-256 and scrypt.[65] This arms race for cheaper-yet-efficient machines has existed since Bitcoin was introduced in 2009.[65] Mining is measured by hash rate typically in TH/s.[66]

With more people venturing into the world of virtual currency, generating hashes for validation has become more complex over time, forcing miners to invest increasingly large sums of money to improve computing performance. Consequently, the reward for finding a hash has diminished and often does not justify the investment in equipment and cooling facilities (to mitigate the heat the equipment produces), and the electricity required to run them.[67] Popular regions for mining include those with inexpensive electricity, a cold climate, and jurisdictions with clear and conducive regulations. By July 2019, Bitcoin’s electricity consumption was estimated to be approximately 7 gigawatts, around 0.2% of the global total, or equivalent to the energy consumed nationally by Switzerland.[68]

Some miners pool resources, sharing their processing power over a network to split the reward equally, according to the amount of work they contributed to the probability of finding a block. A «share» is awarded to members of the mining pool who present a valid partial proof-of-work.

As of February 2018, the Chinese Government has halted trading of virtual currency, banned initial coin offerings and shut down mining. Many Chinese miners have since relocated to Canada[69] and Texas.[70] One company is operating data centers for mining operations at Canadian oil and gas field sites, due to low gas prices.[71] In June 2018, Hydro Quebec proposed to the provincial government to allocate 500 megawatts of power to crypto companies for mining.[72] According to a February 2018 report from Fortune, Iceland has become a haven for cryptocurrency miners in part because of its cheap electricity.[73]

In March 2018, the city of Plattsburgh, New York put an 18-month moratorium on all cryptocurrency mining in an effort to preserve natural resources and the «character and direction» of the city.[74] In 2021, Kazakhstan became the second-biggest crypto-currency mining country, producing 18.1% of the global exahash rate. The country built a compound containing 50,000 computers near Ekibastuz.[75]

GPU price rise

An increase in cryptocurrency mining increased the demand for graphics cards (GPU) in 2017.[76] The computing power of GPUs makes them well-suited to generating hashes. Popular favorites of cryptocurrency miners such as Nvidia’s GTX 1060 and GTX 1070 graphics cards, as well as AMD’s RX 570 and RX 580 GPUs, doubled or tripled in price – or were out of stock.[77] A GTX 1070 Ti which was released at a price of $450 sold for as much as $1,100. Another popular card, the GTX 1060 (6 GB model) was released at an MSRP of $250, and sold for almost $500. RX 570 and RX 580 cards from AMD were out of stock for almost a year. Miners regularly buy up the entire stock of new GPU’s as soon as they are available.[78]

Nvidia has asked retailers to do what they can when it comes to selling GPUs to gamers instead of miners. Boris Böhles, PR manager for Nvidia in the German region, said: «Gamers come first for Nvidia.»[79]

Wallets

An example paper printable Bitcoin wallet consisting of one Bitcoin address for receiving and the corresponding private key for spending

A cryptocurrency wallet is a means of storing the public and private «keys» (address) or seed which can be used to receive or spend the cryptocurrency.[80] With the private key, it is possible to write in the public ledger, effectively spending the associated cryptocurrency. With the public key, it is possible for others to send currency to the wallet.

There exist multiple methods of storing keys or seed in a wallet. These methods range from using paper wallets (which are public, private or seed keys written on paper), to using hardware wallets (which are hardware to store your wallet information), to a digital wallet (which is a computer with a software hosting your wallet information), to hosting your wallet using an exchange where cryptocurrency is traded, or by storing your wallet information on a digital medium such as plaintext.[81]

Anonymity

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, rather than anonymous; the cryptocurrency in a wallet is not tied to a person, but rather to one or more specific keys (or «addresses»).[82] Thereby, Bitcoin owners are not immediately identifiable, but all transactions are publicly available in the blockchain.[83] Still, cryptocurrency exchanges are often required by law to collect the personal information of their users.[84]

Some cryptocurrencies, such as Monero, Zerocoin, Zerocash, and CryptoNote, implement additional measures to increase privacy, such as by using zero-knowledge proofs.[85][86]

Economics

Cryptocurrencies are used primarily outside banking and governmental institutions and are exchanged over the Internet.

Block rewards

Proof-of-work cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, offer block rewards incentives for miners. There has been an implicit belief that whether miners are paid by block rewards or transaction fees does not affect the security of the blockchain, but a study suggests that this may not be the case under certain circumstances.[87]

The rewards paid to miners increase the supply of the cryptocurrency. By making sure that verifying transactions is a costly business, the integrity of the network can be preserved as long as benevolent nodes control a majority of computing power. The verification algorithm requires a lot of processing power, and thus electricity in order to make verification costly enough to accurately validate public blockchain. Not only do miners have to factor in the costs associated with expensive equipment necessary to stand a chance of solving a hash problem, they further must consider the significant amount of electrical power in search of the solution. Generally, the block rewards outweigh electricity and equipment costs, but this may not always be the case.[88]

The current value, not the long-term value, of the cryptocurrency supports the reward scheme to incentivize miners to engage in costly mining activities.[89] Some sources[weasel words] claim that the current Bitcoin design is very inefficient, generating a welfare loss of 1.4% relative to an efficient cash system. The main source for this inefficiency is the large mining cost, which is estimated to be US$360 million per year. This translates into users being willing to accept a cash system with an inflation rate of 230% before being better off using Bitcoin as a means of payment. However, the efficiency of the Bitcoin system can be significantly improved by optimizing the rate of coin creation and minimizing transaction fees. Another potential improvement is to eliminate inefficient mining activities by changing the consensus protocol altogether.[90]

Transaction fees

Transaction fees for cryptocurrency depend mainly on the supply of network capacity at the time, versus the demand from the currency holder for a faster transaction.[citation needed] The currency holder can choose a specific transaction fee, while network entities process transactions in order of highest offered fee to lowest.[citation needed] Cryptocurrency exchanges can simplify the process for currency holders by offering priority alternatives and thereby determine which fee will likely cause the transaction to be processed in the requested time.[citation needed]

For Ethereum, transaction fees differ by computational complexity, bandwidth use, and storage needs, while Bitcoin transaction fees differ by transaction size and whether the transaction uses SegWit. In September 2018[needs update], the median transaction fee for Ether corresponded to $0.017,[91] while for Bitcoin it corresponded to $0.55.[92]

Some cryptocurrencies have no transaction fees, and instead rely on client-side proof-of-work as the transaction prioritization and anti-spam mechanism.[93][94][95]

Exchanges

Cryptocurrency exchanges allow customers to trade cryptocurrencies[96] for other assets, such as conventional fiat money, or to trade between different digital currencies.

Crypto marketplaces do not guarantee that an investor is completing a purchase or trade at the optimal price. As a result, as of 2020 it was possible to arbitrage to find the difference in price across several markets.[97]

Atomic swaps

Atomic swaps are a mechanism where one cryptocurrency can be exchanged directly for another cryptocurrency, without the need for a trusted third party such as an exchange.[98]

ATMs

Jordan Kelley, founder of Robocoin, launched the first Bitcoin ATM in the United States on 20 February 2014. The kiosk installed in Austin, Texas, is similar to bank ATMs but has scanners to read government-issued identification such as a driver’s license or a passport to confirm users’ identities.[99]

Initial coin offerings

An initial coin offering (ICO) is a controversial means of raising funds for a new cryptocurrency venture. An ICO may be used by startups with the intention of avoiding regulation. However, securities regulators in many jurisdictions, including in the U.S., and Canada, have indicated that if a coin or token is an «investment contract» (e.g., under the Howey test, i.e., an investment of money with a reasonable expectation of profit based significantly on the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others), it is a security and is subject to securities regulation. In an ICO campaign, a percentage of the cryptocurrency (usually in the form of «tokens») is sold to early backers of the project in exchange for legal tender or other cryptocurrencies, often Bitcoin or Ether.[100][101][102]

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, four of the 10 biggest proposed initial coin offerings have used Switzerland as a base, where they are frequently registered as non-profit foundations. The Swiss regulatory agency FINMA stated that it would take a «balanced approach» to ICO projects and would allow «legitimate innovators to navigate the regulatory landscape and so launch their projects in a way consistent with national laws protecting investors and the integrity of the financial system.» In response to numerous requests by industry representatives, a legislative ICO working group began to issue legal guidelines in 2018, which are intended to remove uncertainty from cryptocurrency offerings and to establish sustainable business practices.[103]

Price trends

The market capitalization of a cryptocurrency is calculated by multiplying the price by the number of coins in circulation. The total cryptocurrency market cap has historically been dominated by Bitcoin accounting for at least 50% of the market cap value where altcoins have increased and decreased in market cap value in relation to Bitcoin. Bitcoin’s value is largely determined by speculation among other technological limiting factors known as blockchain rewards coded into the architecture technology of Bitcoin itself. The cryptocurrency market cap follows a trend known as the «halving», which is when the block rewards received from Bitcoin are halved due to technological mandated limited factors instilled into Bitcoin which in turn limits the supply of Bitcoin. As the date reaches near of a halving (twice thus far historically) the cryptocurrency market cap increases, followed by a downtrend.[104]

By June 2021, cryptocurrency had begun to be offered by some wealth managers in the US for 401(k)s.[105][106][107]

Volatility

Cryptocurrency prices are much more volatile than established financial assets such as stocks. For example, over one week in May 2022, Bitcoin lost 20% of its value and Ethereum lost 26%, while Solana and Cardano lost 41% and 35% respectively. The falls were attributed to warnings about inflation. By comparison, in the same week, the Nasdaq tech stock index fell 7.6 per cent and the FTSE 100 was 3.6 per cent down.[108]

In the longer term, of the 10 leading cryptocurrencies identified by the total value of coins in circulation in January 2018, only four (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Cardano and Ripple (XRP)) were still in that position in early 2022.[109] The total value of all cryptocurrencies was $2 trillion at the end of 2021, but had halved nine months later.[110][111] The Wall Street Journal has commented that the crypto sector has become “intertwined” with the rest of the capital markets and “sensitive to the same forces that drive tech stocks and other risk assets”, such as inflation forecasts.[112]

Databases

There are also centralized databases, outside of blockchains, that store crypto market data. Compared to the blockchain, databases perform fast as there is no verification process. Four of the most popular cryptocurrency market databases are CoinMarketCap, CoinGecko, BraveNewCoin, and Cryptocompare.[113]

Social and political aspects

According to Alan Feuer of The New York Times, libertarians and anarcho-capitalists were attracted to the philosophical idea behind Bitcoin. Early Bitcoin supporter Roger Ver said: «At first, almost everyone who got involved did so for philosophical reasons. We saw Bitcoin as a great idea, as a way to separate money from the state.»[114] Economist Paul Krugman argues that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are «something of a cult» based in «paranoid fantasies» of government power.[115]

David Golumbia says that the ideas influencing Bitcoin advocates emerge from right-wing extremist movements such as the Liberty Lobby and the John Birch Society and their anti-Central Bank rhetoric, or, more recently, Ron Paul and Tea Party-style libertarianism.[116] Steve Bannon, who owns a «good stake» in Bitcoin, sees cryptocurrency as a form of disruptive populism, taking control back from central authorities.[117]

Bitcoin’s founder, Satoshi Nakamoto has supported the idea that cryptocurrencies go well with libertarianism: «It’s very attractive to the libertarian viewpoint if we can explain it properly.» Nakamoto said in 2008.[118]

According to the European Central Bank, the decentralization of money offered by Bitcoin has its theoretical roots in the Austrian school of economics, especially with Friedrich von Hayek in his book Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined,[119] in which Hayek advocates a complete free market in the production, distribution and management of money to end the monopoly of central banks.[120]

Increasing regulation

The rise in the popularity of cryptocurrencies and their adoption by financial institutions has led some governments to assess whether regulation is needed to protect users. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has defined cryptocurrency-related services as «virtual asset service providers» (VASPs) and recommended that they be regulated with the same money laundering (AML) and know your customer (KYC) requirements as financial institutions.[121]

In May 2020, the Joint Working Group on interVASP Messaging Standards published «IVMS 101», a universal common language for communication of required originator and beneficiary information between VASPs. The FATF and financial regulators were informed as the data model was developed.[122]

In June 2020, FATF updated its guidance to include the «Travel Rule» for cryptocurrencies, a measure which mandates that VASPs obtain, hold, and exchange information about the originators and beneficiaries of virtual asset transfers.[123] Subsequent standardized protocol specifications recommended using JSON for relaying data between VASPs and identity services. As of December 2020, the IVMS 101 data model has yet to be finalized and ratified by the three global standard setting bodies that created it.[124]

The European Commission published a digital finance strategy in September 2020. This included a draft regulation on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA), which aimed to provide a comprehensive regulatory framework for digital assets in the EU.[125][126]

On 10 June 2021, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision proposed that banks that held cryptocurrency assets must set aside capital to cover all potential losses. For instance, if a bank were to hold Bitcoin worth $2 billion, it would be required to set aside enough capital to cover the entire $2 billion. This is a more extreme standard than banks are usually held to when it comes to other assets. However, this is a proposal and not a regulation.

The IMF is seeking a coordinated, consistent and comprehensive approach to supervising cryptocurrencies. Tobias Adrian, the IMF’s financial counsellor and head of its monetary and capital markets department said in a January 2022 interview that «Agreeing global regulations is never quick. But if we start now, we can achieve the goal of maintaining financial stability while also enjoying the benefits which the underlying technological innovations bring,»[127]

United States

In 2021, 17 states passed laws and resolutions concerning cryptocurrency regulation.[128] The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is considering what steps to take. On 8 July 2021, Senator Elizabeth Warren, part of the Senate Banking Committee, wrote to the chairman of the SEC and demanded that it provide answers on cryptocurrency regulation by 28 July 2021,[129][needs update] due to the increase in cryptocurrency exchange use and the danger this poses to consumers. On 17 February 2022, the Justice department named Eun Young Choi as the first director of a National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team to aid in identification of and dealing with misuse of cryptocurrencies and other digital assets.[130]

In February 2023, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ruled that cryptocurrency exchange Kraken’s estimated $42 billion in staked assets globally operated as an illegal securities seller. The company agreed to a $30 million settlement with the SEC and to cease selling its staking service in the U.S. The case would impact other major crypto exchanges operating staking programs.[131]

China

In September 2017, China banned ICOs to cause abnormal return from cryptocurrency decreasing during announcement window. The liquidity changes by banning ICOs in China was temporarily negative while the liquidity effect became positive after news.[132]

On 18 May 2021, China banned financial institutions and payment companies from being able to provide cryptocurrency transaction related services.[133] This led to a sharp fall in the price of the biggest proof of work cryptocurrencies. For instance, Bitcoin fell 31%, Ethereum fell 44%, Binance Coin fell 32% and Dogecoin fell 30%.[134] Proof of work mining was the next focus, with regulators in popular mining regions citing the use of electricity generated from highly polluting sources such as coal to create Bitcoin and Ethereum.[135]

In September 2021, the Chinese government declared all cryptocurrency transactions of any kind illegal, completing its crackdown on cryptocurrency.[30]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, as of 10 January 2021, all cryptocurrency firms, such as exchanges, advisors and professionals that have either a presence, market product or provide services within the UK market must register with the Financial Conduct Authority. Additionally, on 27 June 2021, the financial watchdog demanded that Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange,[136] cease all regulated activities in the UK.[137]

South Africa

South Africa, which has seen a large number of scams related to cryptocurrency, is said to be putting a regulatory timeline in place that will produce a regulatory framework.[138] The largest scam occurred in April 2021, where the two founders of an African-based cryptocurrency exchange called Africrypt, Raees Cajee and Ameer Cajee, disappeared with $3.8 billion worth of Bitcoin.[139] Additionally, Mirror Trading International disappeared with $170 million worth of cryptocurrency in January 2021.[139]

South Korea

In March 2021, South Korea implemented new legislation to strengthen their oversight of digital assets. This legislation requires all digital asset managers, providers and exchanges to be registered with the Korea Financial Intelligence Unit in order to operate in South Korea.[140] Registering with this unit requires that all exchanges are certified by the Information Security Management System and that they ensure all customers have real name bank accounts. It also requires that the CEO and board members of the exchanges have not been convicted of any crimes and that the exchange holds sufficient levels of deposit insurance to cover losses arising from hacks.[140]

Turkey

On 30 April 2021, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey banned the use of cryptocurrencies and cryptoassets for making purchases on the grounds that the use of cryptocurrencies for such payments poses significant transaction risks.[141]

El Salvador

On 9 June 2021, El Salvador announced that it will adopt Bitcoin as legal tender, the first country to do so.[142]

India

At present, India neither prohibits nor allows investment in the cryptocurrency market. In 2020, the Supreme Court of India had lifted the ban on cryptocurrency, which was imposed by the Reserve Bank of India.[143][144][145][146] Since then, an investment in cryptocurrency is considered legitimate, though there is still ambiguity about the issues regarding the extent and payment of tax on the income accrued thereupon and also its regulatory regime. But it is being contemplated that the Indian Parliament will soon pass a specific law to either ban or regulate the cryptocurrency market in India.[147] Expressing his public policy opinion on the Indian cryptocurrency market to a well-known online publication, a leading public policy lawyer and Vice President of SAARCLAW (South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation in Law) Hemant Batra has said that the «cryptocurrency market has now become very big with involvement of billions of dollars in the market hence, it is now unattainable and irreconcilable for the government to completely ban all sorts of cryptocurrency and its trading and investment».[148] He mooted regulating the cryptocurrency market rather than completely banning it. He favoured following IMF and FATF guidelines in this regard.

Switzerland

Switzerland was one of the first countries to implement the FATF’s Travel Rule. FINMA, the Swiss regulator, issued its own guidance to VASPs in 2019. The guidance followed the FATF’s Recommendation 16, however with stricter requirements. According to FINMA’s[149] requirements, VASPs need to verify the identity of the beneficiary of the transfer.

Legality

The legal status of cryptocurrencies varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. At least one study has shown that broad generalizations about the use of Bitcoin in illicit finance are significantly overstated and that blockchain analysis is an effective crime fighting and intelligence gathering tool.[150] While some countries have explicitly allowed their use and trade,[151] others have banned or restricted it. According to the Library of Congress in 2018, an «absolute ban» on trading or using cryptocurrencies applies in eight countries: Algeria, Bolivia, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. An «implicit ban» applies in another 15 countries, which include Bahrain, Bangladesh, China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Georgia, Indonesia, Iran, Kuwait, Lesotho, Lithuania, Macau, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Taiwan.[152] In the United States and Canada, state and provincial securities regulators, coordinated through the North American Securities Administrators Association, are investigating «Bitcoin scams» and ICOs in 40 jurisdictions.[153]

Various government agencies, departments, and courts have classified Bitcoin differently. China Central Bank banned the handling of Bitcoins by financial institutions in China in early 2014.

In Russia, though owning cryptocurrency is legal, its residents are only allowed to purchase goods from other residents using the Russian ruble while nonresidents are allowed to use foreign currency.[154] Regulations and bans that apply to Bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.[155]

In August 2018, the Bank of Thailand announced its plans to create its own cryptocurrency, the Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).[156]

Advertising bans

Cryptocurrency advertisements have been banned on the following platforms:

- Google[157]

- Twitter[157]

- Facebook[157]

- Bing[158]

- Snapchat

- LinkedIn[159]

- MailChimp[160]

- Baidu

- Tencent

- Line

- Yandex[159]

U.S. tax status

On 25 March 2014, the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruled that Bitcoin will be treated as property for tax purposes. Therefore, virtual currencies are considered commodities subject to capital gains tax.[161]

Legal concerns relating to an unregulated global economy

As the popularity and demand for online currencies has increased since the inception of Bitcoin in 2009,[162] so have concerns that such an unregulated person to person global economy that cryptocurrencies offer may become a threat to society. Concerns abound that altcoins may become tools for anonymous web criminals.[163]

Cryptocurrency networks display a lack of regulation that has been criticized as enabling criminals who seek to evade taxes and launder money. Money laundering issues are also present in regular bank transfers, however with bank-to-bank wire transfers for instance, the account holder must at least provide a proven identity.

Transactions that occur through the use and exchange of these altcoins are independent from formal banking systems, and therefore can make tax evasion simpler for individuals. Since charting taxable income is based upon what a recipient reports to the revenue service, it becomes extremely difficult to account for transactions made using existing cryptocurrencies, a mode of exchange that is complex and difficult to track.[163]

Systems of anonymity that most cryptocurrencies offer can also serve as a simpler means to launder money. Rather than laundering money through an intricate net of financial actors and offshore bank accounts, laundering money through altcoins can be achieved through anonymous transactions.[163]

Cryptocurrency makes legal enforcement against extremist groups more complicated, which consequently strengthens them.[164] White supremacist Richard Spencer went as far as to declare Bitcoin the “currency of the alt-right.”[165]

Loss, theft, and fraud

In February 2014, the world’s largest Bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, declared bankruptcy. Likely due to theft, the company claimed that it had lost nearly 750,000 Bitcoins belonging to their clients. This added up to approximately 7% of all Bitcoins in existence, worth a total of $473 million. Mt. Gox blamed hackers, who had exploited the transaction malleability problems in the network. The price of a Bitcoin fell from a high of about $1,160 in December to under $400 in February.[166]

On 21 November 2017, Tether announced that it had been hacked, losing $31 million in USDT from its core treasury wallet.[167]

On 7 December 2017, Slovenian cryptocurrency exchange Nicehash reported that hackers had stolen over $70M using a hijacked company computer.[168]

On 19 December 2017, Yapian, the owner of South Korean exchange Youbit, filed for bankruptcy after suffering two hacks that year.[169][170] Customers were still granted access to 75% of their assets.

In May 2018, Bitcoin Gold had its transactions hijacked and abused by unknown hackers.[171] Exchanges lost an estimated $18m and Bitcoin Gold was delisted from Bittrex after it refused to pay its share of the damages.

On 13 September 2018, Homero Josh Garza was sentenced to 21 months of imprisonment, followed by three years of supervised release.[172] Garza had founded the cryptocurrency startups GAW Miners and ZenMiner in 2014, acknowledged in a plea agreement that the companies were part of a pyramid scheme, and pleaded guilty to wire fraud in 2015. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission separately brought a civil enforcement action against Garza, who was eventually ordered to pay a judgment of $9.1 million plus $700,000 in interest. The SEC’s complaint stated that Garza, through his companies, had fraudulently sold «investment contracts representing shares in the profits they claimed would be generated» from mining.[173]

In January 2018, Japanese exchange Coincheck reported that hackers had stolen $530M worth of cryptocurrencies.[174]

In June 2018, South Korean exchange Coinrail was hacked, losing over $37M worth of cryptos.[175] The hack worsened an already ongoing cryptocurrency selloff by an additional $42 billion.[176]

On 9 July 2018, the exchange Bancor, whose code and fundraising had been subjects of controversy, had $23.5 million in cryptocurrency stolen.[177]

A 2020 EU report found that users had lost crypto-assets worth hundreds of millions of US dollars in security breaches at exchanges and storage providers. Between 2011 and 2019, reported breaches ranged from four to twelve a year. In 2019, more than a billion dollars worth of cryptoassets was reported stolen. Stolen assets «typically find their way to illegal markets and are used to fund further criminal activity».[178]

According to a 2020 report produced by the United States Attorney General’s Cyber-Digital Task Force, the following three categories make up the majority of illicit cryptocurrency uses: «(1) financial transactions associated with the commission of crimes; (2) money laundering and the shielding of legitimate activity from tax, reporting, or other legal requirements; or (3) crimes, such as theft, directly implicating the cryptocurrency marketplace itself.» The report concludes that «for cryptocurrency to realize its truly transformative potential, it is imperative that these risks be addressed» and that «the government has legal and regulatory tools available at its disposal to confront the threats posed by cryptocurrency’s illicit uses».[179][180]

According to the UK 2020 national risk assessment—a comprehensive assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing risk in the UK—the risk of using cryptoassets such as Bitcoin for money laundering and terrorism financing is assessed as «medium» (from «low» in the previous 2017 report).[181] Legal scholars suggested that the money laundering opportunities may be more perceived than real.[182] Blockchain analysis company Chainalysis concluded that illicit activities like cybercrime, money laundering and terrorism financing made up only 0.15% of all crypto transactions conducted in 2021, representing a total of $14 billion.[183][184][185]

In December 2021, Monkey Kingdom — a NFT project based in Hong Kong lost US$1.3 million worth of cryptocurrencies via a phishing link used by the hacker.[186]

Money laundering

According to blockchain data company Chainalysis, criminals laundered US$8,600,000,000 worth of cryptocurrency in 2021, up by 30% from the previous year.[187] The data suggests that rather than managing numerous illicit havens, cybercriminals make use of a small group of purpose built centralized exchanges for sending and receiving illicit cryptocurrency. In 2021, those exchanges received 47% of funds sent by crime linked addresses.[188] Almost $2.2bn worth of cryptocurrencies was embezzled from DeFi protocols in 2021, which represents 72% of all cryptocurrency theft in 2021.

According to Bloomberg and the New York Times, Federation Tower, a two skyscraper complex in the heart of Moscow City, is home to many cryptocurrency businesses under suspicion of facilitating extensive money laundering, including accepting illicit cryptocurrency funds obtained through scams, darknet markets, and ransomware.[189] Notable businesses include Garantex, Eggchange, Cashbank, Buy-Bitcoin, Tetchange, Bitzlato, and Suex, which was sanctioned by the U.S. in 2021. Bitzlato founder and owner Anatoly Legkodymov was arrested following money-laundering charges by the United States Department of Justice.[190]

Dark money has also been flowing into Russia through a dark web marketplace called Hydra, which is powered by cryptocurrency, and enjoyed more than $1 billion in sales in 2020, according to Chainalysis.[191] The platform demands that sellers liquidate cryptocurrency only through certain regional exchanges, which has made it difficult for investigators to trace the money.

Almost 74% of ransomware revenue in 2021 — over $400 million worth of cryptocurrency — went to software strains likely affiliated with Russia, where oversight is notoriously limited.[189] However, Russians are also leaders in the benign adoption of cryptocurrencies, as the ruble is unreliable, and President Putin favours the idea of «overcoming the excessive domination of the limited number of reserve currencies.»[192]

Darknet markets

Properties of cryptocurrencies gave them popularity in applications such as a safe haven in banking crises and means of payment, which also led to the cryptocurrency use in controversial settings in the form of online black markets, such as Silk Road.[163] The original Silk Road was shut down in October 2013 and there have been two more versions in use since then. In the year following the initial shutdown of Silk Road, the number of prominent dark markets increased from four to twelve, while the amount of drug listings increased from 18,000 to 32,000.[163]

Darknet markets present challenges in regard to legality. Cryptocurrency used in dark markets are not clearly or legally classified in almost all parts of the world. In the U.S., Bitcoins are labelled as «virtual assets».[citation needed] This type of ambiguous classification puts pressure on law enforcement agencies around the world to adapt to the shifting drug trade of dark markets.[193][unreliable source?]

Wash trades

Various studies have found that crypto-trading is rife with wash trading. Wash trading is a process, illegal in some jurisdictions, involving buyers and sellers being the same person or group, and may be used to manipulate the price of a cryptocurrency or inflate volume artificially. Exchanges with higher volumes can demand higher premiums from token issuers.[194] A study from 2019 concluded that up to 80% of trades on unregulated cryptocurrency exchanges could be wash trades.[194] A 2019 report by Bitwise Asset Management claimed that 95% of all Bitcoin trading volume reported on major website CoinMarketCap had been artificially generated, and of 81 exchanges studied, only 10 provided legitimate volume figures.[195]

As a tool to evade sanctions

In 2022, cryptocurrencies attracted attention when Western nations imposed severe economic sanctions on Russia in the aftermath of its invasion of Ukraine in February. However, American sources warned in March that some crypto-transactions could potentially be used to evade economic sanctions against Russia and Belarus.[196]

In April 2022, the computer programmer Virgil Griffith received a five-year prison sentence in the US for attending a Pyongyang cryptocurrency conference, where he gave a presentation on blockchains which might be used for sanctions evasion.[197]

Impacts and analysis

| External video |

|---|

The Bank for International Settlements summarized several criticisms of cryptocurrencies in Chapter V of their 2018 annual report. The criticisms include the lack of stability in their price, the high energy consumption, high and variable transactions costs, the poor security and fraud at cryptocurrency exchanges, vulnerability to debasement (from forking), and the influence of miners.[198][199][200]

Speculation, fraud, and adoption

Cryptocurrencies have been compared to Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes[201] and economic bubbles,[202] such as housing market bubbles.[203] Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital Management stated in 2017 that digital currencies were «nothing but an unfounded fad (or perhaps even a pyramid scheme), based on a willingness to ascribe value to something that has little or none beyond what people will pay for it», and compared them to the tulip mania (1637), South Sea Bubble (1720), and dot-com bubble (1999), which all experienced profound price booms and busts.[204]

Regulators in several countries have warned against cryptocurrency and some have taken measures to dissuade users.[205] However, research in 2021 by the UK’s financial regulator suggests such warnings either went unheard, or were ignored. Fewer than one in 10 potential cryptocurrency buyers were aware of consumer warnings on the FCA website, and 12% of crypto users were not aware that their holdings were not protected by statutory compensation.[206][207] Of 1,000 respondents between the ages of eighteen and forty, almost 70% falsely assumed cryptocurrencies were regulated, 75% of younger crypto investors claimed to be driven by competition with friends and family, 58% said that social media enticed them to make high risk investments.[208] The FCA recommends making use of its warning list, which flags unauthorized financial firms.[209]

Many banks do not offer virtual currency services themselves and can refuse to do business with virtual currency companies.[210] In 2014, Gareth Murphy, a senior banking officer, suggested that the widespread adoption of cryptocurrencies may lead to too much money being obfuscated, blinding economists who would use such information to better steer the economy.[211] While traditional financial products have strong consumer protections in place, there is no intermediary with the power to limit consumer losses if Bitcoins are lost or stolen. One of the features cryptocurrency lacks in comparison to credit cards, for example, is consumer protection against fraud, such as chargebacks.

The French regulator Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) lists 16 websites of companies that solicit investment in cryptocurrency without being authorized to do so in France.[212]

An October 2021 paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that Bitcoin suffers from systemic risk as the top 10,000 addresses control about one-third of all Bitcoin in circulation.[213] It’s even worse for Bitcoin miners, with 0.01% controlling 50% of the capacity. According to researcher Flipside Crypto, less than 2% of anonymous accounts control 95% of all available Bitcoin supply.[214] This is considered risky as a great deal of the market is in the hands of a few entities.

A paper by John Griffin, a finance professor at the University of Texas, and Amin Shams, a graduate student found that in 2017 the price of Bitcoin had been substantially inflated using another cryptocurrency, Tether.[215]

Roger Lowenstein, author of «Bank of America: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve,» says in a New York Times story that FTX will face over $8 billion in claims.[216]

Non-fungible tokens

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are digital assets that represent art, collectibles, gaming, etc. Like crypto, their data is stored on the blockchain. NFTs are bought and traded using cryptocurrency. The Ethereum blockchain was the first place where NFTs were implemented, but now many other blockchains have created their own versions of NFTs. The popularity of NFTs has increased since 2021.[217]

Banks

As the first big Wall Street bank to embrace cryptocurrencies, Morgan Stanley announced on 17 March 2021 that they will be offering access to Bitcoin funds for their wealthy clients through three funds which enable Bitcoin ownership for investors with an aggressive risk tolerance.[218] BNY Mellon on 11 February 2021 announced that it would begin offering cryptocurrency services to its clients.[219]

On 20 April 2021,[220] Venmo added support to its platform to enable customers to buy, hold and sell cryptocurrencies.[221]

In October 2021, financial services company Mastercard announced it is working with digital asset manager Bakkt on a platform that would allow any bank or merchant on the Mastercard network to offer cryptocurrency services.[222]

Environmental impact

Mining for proof-of-work cryptocurrencies requires enormous amounts of electricity and consequently comes with a large carbon footprint due to causing greenhouse gas emissions.[223] Proof-of-work blockchains such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and Monero were estimated to have added between 3 million and 15 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere in the period from 1 January 2016 to 30 June 2017.[224] By November 2018, Bitcoin was estimated to have an annual energy consumption of 45.8TWh, generating 22.0 to 22.9 million tons of CO2, rivalling nations like Jordan and Sri Lanka.[225] By the end of 2021, Bitcoin was estimated to produce 65.4 million tons of CO2, as much as Greece,[226] and consume between 91 and 177 terawatt-hours annually.[227][228]

Critics have also identified a large electronic waste problem in disposing of mining rigs.[229] Mining hardware is improving at a fast rate, quickly resulting in older generations of hardware.[230]

Bitcoin is the least energy-efficient cryptocurrency, using 707.6 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction.[231]

The world’s second-largest cryptocurrency, Ethereum, uses 62.56 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction.[232] XRP is the world’s most energy efficient cryptocurrency, using 0.0079 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction.[233]

Although the biggest PoW blockchains consume energy on the scale of medium-sized countries, the annual power demand from proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchains is on a scale equivalent to a housing estate. The Times identified six «environmentally friendly» cryptocurrencies: Chia, IOTA, Cardano, Nano, Solarcoin and Bitgreen.[234] Academics and researchers have used various methods for estimating the energy use and energy efficiency of blockchains. A study of the six largest proof-of-stake networks in May 2021 concluded:

- Cardano has the lowest electricity use per node;

- Polkadot has the lowest electricity use overall; and

- Solana has the lowest electricity use per transaction.

In terms of annual consumption (kWh/yr), the figures were: Polkadot (70,237), Tezos (113,249), Avalanche (489,311), Algorand (512,671), Cardano (598,755) and Solana (1,967,930). This equates to Polkadot consuming 7 times the electricity of an average U.S. home, Cardano 57 homes and Solana 200 times as much. The research concluded that PoS networks consumed 0.001% the electricity of the Bitcoin network.[235] University College London researchers reached a similar conclusion.[236]

Variable renewable energy power stations could invest in Bitcoin mining to reduce curtailment, hedge electricity price risk, stabilize the grid, increase the profitability of renewable energy power stations and therefore accelerate transition to sustainable energy.[237][238][239][240][241]

Technological limitations

There are also purely technical elements to consider. For example, technological advancement in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin result in high up-front costs to miners in the form of specialized hardware and software.[242] Cryptocurrency transactions are normally irreversible after a number of blocks confirm the transaction. Additionally, cryptocurrency private keys can be permanently lost from local storage due to malware, data loss or the destruction of the physical media. This precludes the cryptocurrency from being spent, resulting in its effective removal from the markets.[243]

Academic studies

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It covers studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh.[244]

The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the Bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal Bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.[245][246]

Aid agencies

A number of aid agencies have started accepting donations in cryptocurrencies, including UNICEF.[247] Christopher Fabian, principal adviser at UNICEF Innovation, said the children’s fund would uphold donor protocols, meaning that people making donations online would have to pass checks before they were allowed to deposit funds.[248][249]

However, in 2021, there was a backlash against donations in Bitcoin because of the environmental emissions it caused. Some agencies stopped accepting Bitcoin and others turned to «greener» cryptocurrencies.[250] The U.S. arm of Greenpeace stopped accepting bitcoin donations after seven years. It said: «As the amount of energy needed to run Bitcoin became clearer, this policy became no longer tenable.»[251]

In 2022, the Ukrainian government raised over US$10,000,000 worth of aid through cryptocurrency following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[252]

Criticism

Bitcoin has been characterized as a speculative bubble by eight winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences: Paul Krugman,[253] Robert J. Shiller,[254] Joseph Stiglitz,[255] Richard Thaler,[256] James Heckman,[257] Thomas Sargent,[257] Angus Deaton,[257] and Oliver Hart;[257] and by central bank officials including Alan Greenspan,[258] Agustín Carstens,[259] Vítor Constâncio,[260] and Nout Wellink.[261]

The investors Warren Buffett and George Soros have respectively characterized it as a «mirage»[262] and a «bubble»;[263] while the business executives Jack Ma and J.P. Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon have called it a «bubble»[264] and a «fraud»,[265] respectively, although Jamie Dimon later said he regretted dubbing Bitcoin a fraud.[266] BlackRock CEO Laurence D. Fink called Bitcoin an «index of money laundering».[267]

In June 2022, Bill Gates said that cryptocurrencies are «100% based on greater fool theory».[268]

Legal scholars criticize the lack of regulation, which hinders conflict resolution when crypto assets are at the center of a legal dispute, for example a divorce or an inheritance. In Switzerland, jurists generally deny that cryptocurrencies are objects that fall under property law, as cryptocurrencies do not belong to any class of legally defined objects (Typenzwang, the legal numerus clausus). Therefore, it is debated whether anybody could even be sued for embezzlement of cryptocurrency if he/she had access to someone’s wallet. However, in the law of obligations and contract law, any kind of object would be legally valid, but the object would have to be tied to an identified counterparty. However, as the more popular cryptocurrencies can be freely and quickly exchanged into legal tender, they are financial assets and have to be taxed and accounted for as such.[269]

In 2018, an increase in crypto-related suicides was noticed after the cryptocurrency market crashed in August. The situation was particularly critical in Korea as crypto traders were on «suicide watch». A cryptocurrency forum on Reddit even started providing suicide prevention support to affected investors.[270][271][272]

The May 2022 collapse of the Luna currency operated by Terra also led to reports of suicidal investors in crypto-related subreddits.[273]

See also

- 2018 crypto crash

- Blockchain-based remittances company

- Cryptocurrency bubble

- Cryptocurrency exchange

- Cryptographic protocol

- List of cryptocurrencies

- Virtual currency law in the United States

References

- ^ Pagliery, Jose (2014). Bitcoin: And the Future of Money. Triumph Books. ISBN 978-1629370361. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Milutinović, Monia (2018). «Cryptocurrency». Ekonomika. 64 (1): 105–122. doi:10.5937/ekonomika1801105M. ISSN 0350-137X.

- ^ Yaffe-Bellany, David (15 September 2022). «Crypto’s Long-Awaited ‘Merge’ Reaches the Finish Line». The New York Times. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ a b Andy Greenberg (20 April 2011). «Crypto Currency». Forbes. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Polansek, Tom (2 May 2016). «CME, ICE prepare pricing data that could boost bitcoin». Reuters. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Pernice, Ingolf G. A.; Scott, Brett (20 May 2021). «Cryptocurrency». Internet Policy Review. 10 (2). doi:10.14763/2021.2.1561. ISSN 2197-6775.

- ^ «Bitcoin not a currency says Japan government». BBC News. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ «Is it a currency? A commodity? Bitcoin has an identity crisis». Reuters. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Brown, Aaron (7 November 2017). «Are Cryptocurrencies an Asset Class? Yes and No». www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Bezek, Ian (14 July 2021). «What Is Proof-of-Stake, and Why Is Ethereum Adopting It?».

- ^ Allison, Ian (8 September 2015). «If Banks Want Benefits of Blockchains, They Must Go Permissionless». International Business Times. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ Matteo D’Agnolo. «All you need to know about Bitcoin». timesofindia-economictimes. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015.

- ^ Liu, Jinan; Rahman, Sajjadur; Serletis, Apostolos (2020). «Cryptocurrency Shocks». SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3744260. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 233751995.

- ^ «Cryptocurrencies: What Are They?». Schwab Brokerage.

- ^ Chaum, David. «Blind Signatures for Untraceable Payments» (PDF). www.hit.bme.hu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ Chaum, David. «Untraceable Electronic Cash» (PDF). blog.koehntopp.de. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Pitta, Julie. «Requiem for a Bright Idea». Forbes. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ «How To Make A Mint: The Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash». groups.csail.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Law, Laurie; Sabett, Susan; Solinas, Jerry (11 January 1997). «How to Make a Mint: The Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash». American University Law Review. 46 (4). Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Wei Dai (1998). «B-Money». www.weidai.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011.

- ^ Peck, Morgen E. (30 May 2012). «Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists’ Answer to Cash». IEEE Spectrum.

Around the same time, Nick Szabo, a computer scientist who now blogs about law and the history of money, was one of the first to imagine a new digital currency from the ground up. Although many consider his scheme, which he calls «bit gold», to be a precursor to Bitcoin

- ^ a b Jerry Brito and Andrea Castillo (2013). «Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers» (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Niccolai, James (19 May 2013). «Bitcoin developer chats about regulation, open source, and the elusive Satoshi Nakamoto». PCWorld. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Steadman, Ian (11 May 2013). «Wary of Bitcoin? A guide to some other cryptocurrencies». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ «UK launches initiative to explore potential of virtual currencies». The UK News. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ «Cryptoassets Taskforce: final report» (PDF). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. HM Treasury. October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ «UK regulatory approach to cryptoassets and stablecoins: Consultation and call for evidence» (PDF). HM Treasury. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ «Bitcoin legal tender in El Salvador, first country ever». Mercopress. 10 June 2021.

- ^ Sigalos, MacKenzie (27 August 2021). «Cuba’s central bank now recognizes cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin». CNBC.

- ^ a b «China declares all crypto-currency transactions illegal». BBC News. 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ «Ethereum Finishes Long-Awaited Energy-Saving ‘Merge’ Upgrade». Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. 15 September 2022.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (20 July 2017). «Crypto Exchange FTX Valued at $18 Billion in Funding Round». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Hill, Jeremy (11 November 2022). «FTX Goes Bankrupt in Stunning Reversal for Crypto Exchange». Bloomberg News. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Khalili, Joel (11 November 2022). «The Fallout of the FTX Collapse». Wired. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Chatterjee, Sumeet; Davies, Megan; Aftab, Ahmed; McCrank, John; Nguyen, Lananh; Howcroft, Elizabeth; Azhar, Saeed; Sinclair Foley, John (2 December 2022). «After FTX collapse, pressure builds for tougher crypto rules». Reuters. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Wile, Rob (28 December 2022). «After FTX’s spectacular collapse, where does crypto go from here?». NBC News. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Lansky, Jan (January 2018). «Possible State Approaches to Cryptocurrencies». Journal of Systems Integration. 9/1: 19–31. doi:10.20470/jsi.v9i1.335. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ «The Dictionary Just Got a Whole Lot Bigger». Merriam-Webster. March 2018. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.