Всего найдено: 2

Я прочитала на вашем сайте, что следует писать «Лао-цзы«. А в электронной версии книги Розенталя «Справочник по правописанию и стилистике», изданной в 1997 г., я прочитала: «В к и т а й с к и х собственных именах лиц, состоящих из двух частей, обе части пишутся раздельно и с прописной буквы». А вот насчет японских имен там как раз написано: «Частица «сан» в японских именах пишется со строчной буквы и присоединяется дефисом: Тояма-сан». Может быть, «цзы» — это тоже не часть имени, как и «сан», и именно поэтому вы рекомендуете писать «Лао-цзы«? В общем, как мне лучше поступить?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мы рекомендуем написание через дефис согласно словарю Ф. Л. Агеенко «Собственные имена в русском языке».

Пожалуйста, ответьте, как правильно: Лао-цзы, Лао-Цзы, Лао Цзы? Спасибо!!!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Лао-цзы_.

Лао-цзы

- Лао-цзы

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Смотреть что такое «Лао-цзы» в других словарях:

-

Лао-цзы — 老子 … Википедия

-

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — («Старик младенец», «Старый философ») (6 5 вв. до н.э.) др. кит. легендарный основатель даосизма. Согласно «Ши цзи» («Историческим запискам») Сыма Цяня (145 87 до н.э.), Л. ц. уроженец селения Цюйжэнь, волости Ли, уезда Ку, царства Чу, имел имя… … Философская энциклопедия

-

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — легендарный древнекитайский мыслитель, основоположник религиозно философского направления даосизма, фигура загадочная во многих отношениях. под этим именем, которое, скорее всего, является прозвищем и означает буквально старый мудрец (и даже… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — («старый ребёнок»), легендарный основатель философского даосизма в Китае, живший будто бы в конце 7 в. до н. э., которому приписывается «Даодэцзин» («Книга о пути и добродетели»). Л. ц. был обожествлён в первых веках н. э., в период становления… … Энциклопедия мифологии

-

Лао-Цзы — (Ли Эр) (IV III вв. до н.э.) автор канонического сочинения даосизма «Дао Дэ Цзин» Голос истины неизящен, а изящная речь лжива. Нравственный человек не красноречив, а красноречивый лжец. Закон достойных творить добро и не ссориться. Великий… … Сводная энциклопедия афоризмов

-

Лао-цзы — имя китайского философа, жившего в VI в. до Р. Хр. Рождениеего приурочивается к 604 г. Фамилия его была Ли, детское имя Эр, взрелом возраст он назывался Бо янь, а посмертный титул его Дань;посему он в сочинениях встречается иногда с именем Ли эр… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

лао-цзы — Престарелый мудрец , Престарелый младенец Древнекит. философ, к рому приписывается авторство на классич. даос, филос. трактат Дао дэ цзин . Совр. наука подвергает сомнению историчность Л. ц., тем не менее в науч. лит ре он часто определяется как… … Китайская философия. Энциклопедический словарь.

-

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — (Ли Эр), автор древнекитайского трактата Лао цзы (древнее название Дао дэ цзин , 4 3 вв. до нашей эры), канонического сочинения даосизма. Основное понятие дао, которое метафорически уподобляется воде (податливость и неодолимость). Вытекающий из… … Современная энциклопедия

-

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — (Ли Эр) легендарный автор древнекитайского трактата Лао цзы (древнее название Дао дэ цзин , 4 3 вв. до н. э.), канонического сочинения даосизма. Основное понятие трактата дао, которое метафорически уподобляется воде (податливость и неодолимость) … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Лао-цзы — (Ли Эр) автор древнекитайского трактата Лао цзы (древнее название Дао дэ цзин, 4 3 вв. до н.э.), канонического сочинения даосизма. Основное понятие дао, которое метафорически уподобляется воде (податливость и неодолимость). Вытекающий из дао… … Исторический словарь

-

ЛАО ЦЗЫ — Основатель религии Китае, около 600 г. до Р. Х., учение которого называется Дао или религией правого пути, а последователи даосы. Объяснение 25000 иностранных слов, вошедших в употребление в русский язык, с означением их корней. Михельсон А.Д.,… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

|

Laozi |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Zhang Lu |

|

| Born | Trad. 6th century BC Sometimes 4th century BC Quren Village, Chu (present-day Luyi, Henan) |

| Died | Trad. 5th century BC

Didao, Qin (present-day Lintao, Gansu)[dubious – discuss] or immortal |

| Notable work | Tao Te Ching |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Taoism |

|

Notable ideas |

Tao Wu wei |

|

Influenced

|

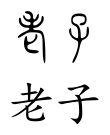

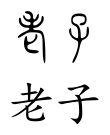

老子 in seal script (top) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Honorific Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 老子 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǎozǐ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | the Old Master the Old One |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 李耳 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǐ Ěr | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 李伯陽 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 李伯阳 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǐ Bóyáng | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posthumous Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 李聃 老聃 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǐ Dān Lǎo Dān |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Theonym | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 老君 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǎojūn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | the Old Lord | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For the book also known as Laozi, see Tao Te Ching.

Laozi (, Chinese: 老子), also known by numerous other names, was a semilegendary ancient Chinese Taoist philosopher. Laozi is a Chinese honorific, generally translated as «the Old Master». Traditional accounts say he was born as Li Er in the state of Chu in the 6th century BC during China’s Spring and Autumn Period, served as the royal archivist for the Zhou court at Wangcheng (modern Luoyang), met and impressed Confucius on one occasion, and composed the Tao Te Ching before retiring into the western wilderness. Chinese folk religion holds that he then became an immortal hermit or a god of the celestial bureaucracy under the name Laojun, one of the Three Pure Ones.

A central figure in Chinese culture, Laozi is generally considered the founder of philosophical and religious Taoism. He was claimed and revered as the ancestor of the 7th–10th century Tang dynasty and is similarly honored in modern China with the popular surname Li. His work had a profound influence on subsequent Chinese religious movements and on subsequent Chinese philosophers, who annotated, commended, and criticized his work extensively. Since the 20th century, however, archeological finds and textual criticism have caused some modern historians to question Laozi’s timing or even existence, believing that the received text of the Tao Te Ching was not composed until the 4th century BC Warring States Period.

Names[edit]

Laozi is the modern pinyin romanization of the Standard Mandarin pronunciation of the characters 老子. English approximates the Mandarin pronunciation as .[2][3] It is not a name but an honorific title, meaning «old» or «venerable master». The character 子 has several meanings, including «son», «person», «viscount», and «master», and some Taoists—particularly in English—have preferred to parse the title as meaning «Old Child» or «Old Boy», whether in reference to legends of Laozi being born already an old man[4][5][6] or to his playful philosophy.[7] However, the structure of the name exactly matches that of other ancient Chinese philosophers such as Kongzi, Mengzi, Zhuangzi, &c. and in context can only have the meaning of «master».[8] The title has been extremely variously romanized, including Lao Zi,[9] Lao Tzu[10] or Tzŭ,[4] Lao-tzu,[11] Lao Tse, Lao-tse,[12] Lao Tze, Lao-tze, Laotze,[13] Lao Tsu, and Lao-tsu but, compared with Confucius and Mencius, the latinized form Laocius has been relatively uncommon in English. «Lao-tse» was the most common romanization during the 19th century before being supplanted by Wade-Giles «Lao-tzu» and «Lao Tzu» around the 1920s; the pinyin form «Laozi» finally became more common in English during the 1990s.[citation needed] Historically, these varied romanizations have also led to a series of common spelling mispronunciations, including , ,[14][15] ,[16] &c., although the underlying Mandarin pronunciation has remained unchanged in the modern period.

Traditional accounts give Laozi the personal name Li Er (李耳, Lǐ Ěr), whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *C.rəʔ C.nəʔ.[1] Li is a common Chinese surname but literally means «plum tree»; because of legends tying Laozi’s birth to a plum, he has been venerated as the ancestor of all subsequent Lis, including the ruling family of the Tang dynasty. The character 耳 was the ancient Chinese word for «ear» or «ears». Laozi’s prominent posthumous name Dan (聃, Dān)[17][18][19] similarly means «Long-Ear» or «the Long-Earred One». These names have also been variously written as Li Erh, Li Dan, Lao Dan, Lao Tan, and Laodan.

Laozi is recorded bearing the courtesy name Boyang (伯陽, Bóyáng), whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *pˤrak laŋ.[1] The character 伯 was the title of a senior uncle of the father’s family, also used as a noble title equivalent to a count and as a general mark of respect, and the character 陽 is yang, the solar and masculine life force in Taoist belief. Lao Dan seems to have been used more generally, however, including by Sima Qian in his Records of the Grand Historian,[20] by Zhuangzi’s in his eponymous Taoist classic,[20] and by some modern scholars.[21]

Under the Tang, Laozi received a series of temple names of increasing grandeur. In the year 666, Emperor Gaozong named Laozi the «Supremely Mysterious and Primordial Emperor» (太上玄元皇帝, Tàishàng Xuán Yuán Huángdì).[22] In 743, Emperor Xuanzong declared him the «Sage Ancestor» (聖祖, Shèngzǔ) of the dynasty with the posthumous title of «Mysterious and Primordial Emperor» (玄元皇帝, Xuán Yuán Huángdì). Emperor Xuanzong also elevated Laozi’s parents to the ranks of «Innately Supreme Emperor» (先天太上皇, Xiāntiān Tàishàng Huáng) and «Innate Empress» (先天太后, Xiāntiān Tàihòu). In 749, Laozi was further honored as the «Sage Ancestor and Mysterious and Primordial Emperor of the Great Way» (聖祖大道玄元皇帝, Shèngzǔ Dàdào Xuán Yuán Huángdì) and then, in 754, as the «Great Sage Ancestor and Mysterious and Primordial Heavenly Emperor and Great Sovereign of the Golden Palace of the High and Supreme Great Way» (大聖祖高上大道金闕玄元天皇大帝, Dà Shèngzǔ Gāo Shǎng Dàdào Jīnquē Xuán Yuán Tiānhuáng Dàdì).

Historical views[edit]

In the mid-twentieth century, a consensus emerged among Western scholars that the historicity of the person known as Laozi is doubtful and that the Tao Te Ching was «a compilation of Taoist sayings by many hands».[23][24] Following new archaeological discoveries, many Chinese scholars have reverted to affirming the existence of a historical Laozi.[25]

The earliest certain reference to the present figure of Laozi is found in the 1st‑century BC Records of the Grand Historian collected by the historian Sima Qian from earlier accounts.[26] In one account, Laozi was said to be a contemporary of Confucius during the 6th or 5th century BC. His personal name was Er or Dan. He was an official in the imperial archives and wrote a book in two parts before departing to the west. In another, Laozi was a different contemporary of Confucius titled Lao Laizi (老莱子) and wrote a book in 15 parts. In a third, he was the court astrologer Lao Dan who lived during the 4th century BC reign of the Duke Xian of Qin.[27][28] The oldest text of the Tao Te Ching so far recovered was part of the Guodian Chu Slips. It was written on bamboo slips, and dates to the late 4th century BC.[29]

According to traditional accounts, Laozi was a scholar who worked as the Keeper of the Archives for the royal court of Zhou. This reportedly allowed him broad access to the works of the Yellow Emperor and other classics of the time. The stories assert that Laozi never opened a formal school but nonetheless attracted a large number of students and loyal disciples. There are many variations of a story retelling his encounter with Confucius, most famously in the Zhuangzi.[30][31]

Sima Qian reports that Laozi was born in the village of Quren (曲仁里, Qūrén lǐ) in the southern state of Chu,[32] within present-day Luyi in Henan..[33] He was said to be the son of the Censor-in-Chief of the Zhou dynasty and Lady Yishou (益壽氏, Yìshòu shì). In accounts where Laozi married, he was said to have had a son who became a celebrated soldier of Wei during the Warring States period.

The story tells of Zong the Warrior who defeats an enemy and triumphs, and then abandons the corpses of the enemy soldiers to be eaten by vultures. By coincidence Laozi, traveling and teaching the way of the Tao, comes on the scene and is revealed to be the father of Zong, from whom he was separated in childhood. Laozi tells his son that it is better to treat respectfully a beaten enemy, and that the disrespect to their dead would cause his foes to seek revenge. Convinced, Zong orders his soldiers to bury the enemy dead. Funeral mourning is held for the dead of both parties and a lasting peace is made.

Many clans of the Li family trace their descent to Laozi,[34] including the emperors of the Tang dynasty.[35][34][36] This family was known as the Longxi Li lineage (隴西李氏). According to the Simpkinses, while many (if not all) of these lineages are questionable, they provide a testament to Laozi’s impact on Chinese culture.[37]

The third story in Sima Qian states that Laozi grew weary of the moral decay of life in Chengzhou and noted the kingdom’s decline. He ventured west to live as a hermit in the unsettled frontier at the age of 80. At the western gate of the city (or kingdom), he was recognized by the guard Yinxi. The sentry asked the old master to record his wisdom for the good of the country before he would be permitted to pass. The text Laozi wrote was said to be the Tao Te Ching, although the present version of the text includes additions from later periods. In some versions of the tale, the sentry was so touched by the work that he became a disciple and left with Laozi, never to be seen again.[38] In others, the «Old Master» journeyed all the way to India and was the teacher of Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha. Others say he was the Buddha himself.[30][39]

A seventh-century work, the Sandong Zhunang («Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns»), embellished the relationship between Laozi and Yinxi. Laozi pretended to be a farmer when reaching the western gate, but was recognized by Yinxi, who asked to be taught by the great master. Laozi was not satisfied by simply being noticed by the guard and demanded an explanation. Yinxi expressed his deep desire to find the Tao and explained that his long study of astrology allowed him to recognize Laozi’s approach. Yinxi was accepted by Laozi as a disciple. This is considered an exemplary interaction between Taoist master and disciple, reflecting the testing a seeker must undergo before being accepted. A would-be adherent is expected to prove his determination and talent, clearly expressing his wishes and showing that he had made progress on his own towards realizing the Tao.[40]

The Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns continues the parallel of an adherent’s quest. Yinxi received his ordination when Laozi transmitted the Tao Te Ching, along with other texts and precepts, just as Taoist adherents receive a number of methods, teachings and scriptures at ordination. This is only an initial ordination and Yinxi still needed an additional period to perfect his virtue, thus Laozi gave him three years to perfect his Tao. Yinxi gave himself over to a full-time devotional life. After the appointed time, Yinxi again demonstrates determination and perfect trust, sending out a black sheep to market as the agreed sign. He eventually meets again with Laozi, who announces that Yinxi’s immortal name is listed in the heavens and calls down a heavenly procession to clothe Yinxi in the garb of immortals. The story continues that Laozi bestowed a number of titles upon Yinxi and took him on a journey throughout the universe, even into the nine heavens. After this fantastic journey, the two sages set out to western lands of the barbarians. The training period, reuniting and travels represent the attainment of the highest religious rank in medieval Taoism called «Preceptor of the Three Caverns». In this legend, Laozi is the perfect Taoist master and Yinxi is the ideal Taoist student. Laozi is presented as the Tao personified, giving his teaching to humanity for their salvation. Yinxi follows the formal sequence of preparation, testing, training and attainment.[41]

The story of Laozi has taken on strong religious overtones since the Han dynasty. As Taoism took root, Laozi was worshipped as a god. Belief in the revelation of the Tao from the divine Laozi resulted in the formation of the Way of the Celestial Masters, the first organized religious Taoist sect. In later mature Taoist tradition, Laozi came to be seen as a personification of the Tao. He is said to have undergone numerous «transformations» and taken on various guises in various incarnations throughout history to initiate the faithful in the Way. Religious Taoism often holds that the «Old Master» did not disappear after writing the Tao Te Ching but rather spent his life traveling and revealing the Tao.[42]

Taoist myths state that Laozi was a virgin birth, conceived when his mother gazed upon a falling star. He supposedly remained in her womb for 62 years before being born while his mother was leaning against a plum tree. (The Chinese surname Li literally means «plum tree».) Laozi was said to have emerged as a grown man with a full grey beard and long earlobes, both symbols of wisdom and long life.[43][44] Other myths state that he was reborn 13 times after his first life during the days of Fuxi. In his last incarnation as Laozi, he lived nine hundred and ninety years and spent his life traveling to reveal the Tao.[42]

Tao Te Ching[edit]

Laozi is traditionally regarded as the author of the Tao Te Ching, though the identity of its author(s) or compiler(s) has been debated throughout history.[45][46] It is one of the most significant treatises in Chinese cosmogony. As with most other ancient Chinese philosophers, Laozi often explains his ideas by way of paradox, analogy, appropriation of ancient sayings, repetition, symmetry, rhyme, and rhythm. In fact, the whole book can be read as an analogy – the ruler is the awareness, or self, in meditation and the myriad creatures or empire is the experience of the body, senses and desires.

The Tao Te Ching, often called simply Laozi after its reputed author, describes the Tao as the source and ideal of all existence: it is unseen, but not transcendent, immensely powerful yet supremely humble, being the root of all things. People have desires and free will (and thus are able to alter their own nature). Many act «unnaturally», upsetting the natural balance of the Tao. The Tao Te Ching intends to lead students to a «return» to their natural state, in harmony with Tao.[47] Language and conventional wisdom are critically assessed. Taoism views them as inherently biased and artificial, widely using paradoxes to sharpen the point.[48]

Livia Kohn provides an example of how Laozi encouraged a change in approach, or return to «nature», rather than action. Technology may bring about a false sense of progress. The answer provided by Laozi is not the rejection of technology, but instead seeking the calm state of wu wei, free from desires. This relates to many statements by Laozi encouraging rulers to keep their people in «ignorance», or «simple-minded». Some scholars insist this explanation ignores the religious context, and others question it as an apologetic of the philosophical coherence of the text. It would not be unusual political advice if Laozi literally intended to tell rulers to keep their people ignorant. However, some terms in the text, such as «valley spirit» (gushen) and «soul» (po), bear a metaphysical context and cannot be easily reconciled with a purely ethical reading of the work.[48]

Wu wei (無為), literally «non-action» or «not acting», is a central concept of the Tao Te Ching. The concept of wu wei is multifaceted, and reflected in the words’ multiple meanings, even in English translation; it can mean «not doing anything», «not forcing», «not acting» in the theatrical sense, «creating nothingness», «acting spontaneously», and «flowing with the moment».[49]

It is a concept used to explain ziran (自然), or harmony with the Tao. It includes the concepts that value distinctions are ideological and seeing ambition of all sorts as originating from the same source. Laozi used the term broadly with simplicity and humility as key virtues, often in contrast to selfish action. On a political level, it means avoiding such circumstances as war, harsh laws and heavy taxes. Some Taoists see a connection between wu wei and esoteric practices, such as zuowang «sitting in oblivion» (emptying the mind of bodily awareness and thought) found in the Zhuangzi.[48]

Influence[edit]

Potential officials throughout Chinese history drew on the authority of non-Confucian sages, especially Laozi and Zhuangzi, to deny serving any ruler at any time. Zhuangzi, Laozi’s most famous follower in traditional accounts, had a great deal of influence on Chinese literati and culture. Laozi influenced millions of Chinese people by his psychological understanding. He persuaded people by his inaction and non-speaking.[50]

Political theorists influenced by Laozi have advocated humility in leadership and a restrained approach to statecraft, either for ethical and pacifist reasons, or for tactical ends. In a different context, various antiauthoritarian movements have embraced Laozi’s teachings on the power of the weak.[51][12]

Laozi was a proponent of limited government.[52] Left-libertarians in particular have been influenced by Laozi – in his 1937 book Nationalism and Culture, the anarcho-syndicalist writer and activist Rudolf Rocker praised Laozi’s «gentle wisdom» and understanding of the opposition between political power and the cultural activities of the people and community.[53] In his 1910 article for the Encyclopædia Britannica, Peter Kropotkin also noted that Laozi was among the earliest proponents of essentially anarchist concepts.[54] More recently, anarchists such as John P. Clark and Ursula K. Le Guin have written about the conjunction between anarchism and Taoism in various ways, highlighting the teachings of Laozi in particular.[55] In her rendition of the Tao Te Ching, Le Guin writes that Laozi «does not see political power as magic. He sees rightful power as earned and wrongful power as usurped… He sees sacrifice of self or others as a corruption of power, and power as available to anyone who follows the Way. No wonder anarchists and Taoists make good friends.»[56]

The right-libertarian economist Murray Rothbard suggested that Laozi was the first libertarian,[57] likening Laozi’s ideas on government to Friedrich Hayek’s theory of spontaneous order.[58] James A. Dorn agreed, writing that Laozi, like many 18th-century liberals, «argued that minimizing the role of government and letting individuals develop spontaneously would best achieve social and economic harmony.»[59] Similarly, the Cato Institute’s David Boaz includes passages from the Tao Te Ching’ in his 1997 book The Libertarian Reader and noted in an article for the Encyclopædia Britannica that Laozi advocated for rulers to «do nothing» because «without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony.»[60][61] Philosopher Roderick Long argues that libertarian themes in Taoist thought are actually borrowed from earlier Confucian writers.[62]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d Baxter, William; Sagart, Laurent (20 September 2014). «Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction» (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ «Lao-tzu», Merriam-Webster, 2022.

- ^ LaFargue, Michael (2007), «Spelling and Pronouncing Chinese Words», Asian Religions, Boston: University of Massachusetts.

- ^ a b Watters (1870), p. 16.

- ^ Legge (1891), p. 313.

- ^ Welch (1957), p. 1.

- ^ Mair (1983), p. 93.

- ^ Lin, Derek (29 December 2016), «The «Ancient Child» Fallacy», Taoism.net.

- ^ Swofford, Mark (19 November 2011), «Laozi or Lao Zi?», Pinyin News, Banqiao.

- ^ Le Guin (2009).

- ^ «Lao-tzu – Founder of Taoism». en.hubei.gov.cn. Government of Hubei, China. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b «Lao-tse». ztopics.com.

- ^ «Laotze», Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ «Lao-tzu», Random House Unabridged Dictionary, New York: Random House, 2022.

- ^ «Lao Tzu», American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.), Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2016.

- ^ «Laotze». Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Luo (2004), p. 118.

- ^ Kramer (1986), p. 118.

- ^ Kohn (2000), p. 2.

- ^ a b Rainey, Lee Dian (2013), Decoding Dao: Reading the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching) and the Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu), John Wiley & Sons, p. 31, ISBN 978-1118465677.

- ^ Carr, Dr Brian; et al. (2002), Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, Routledge, p. 497, ISBN 978-1134960583.

- ^ 傅勤家 (1996). 道教史概論 (in Chinese). Taipei: 臺灣商務印書館. p. 82. ISBN 978-9570513240.

- ^ Watson (1968), p. 8.

- ^ Kohn (2000), p. 4

- ^ Liu, Xiaogan (2014). «Did Daoism Have a Founder? Textual Issues of the Laozi». Dao companion to Daoist philosophy. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 9789048129270.

- ^ «Sages and Saints Part XV: Lao Zi, the Dragon». Purple Cloud. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Fowler (2005), p. 96.

- ^ Robinet (1997), p. 26.

- ^ «Laozi». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. 2018.

The discovery of two Laozi silk manuscripts at Mawangdui, near Changsha, Hunan province in 1973 marks an important milestone in modern Laozi research. The manuscripts, identified simply as ‘A’ (jia) and ‘B’ (yi), were found in a tomb that was sealed in 168 BC. The texts themselves can be dated earlier, the ‘A’ manuscript being the older of the two, copied in all likelihood before 195 BC.

«Until recently, the Mawangdui manuscripts have held the pride of place as the oldest extant manuscripts of the Laozi. In late 1993, the excavation of a tomb (identified as M1) in Guodian, Jingmen city, Hubei, has yielded among other things some 800 bamboo slips, of which 730 are inscribed, containing over 13,000 Chinese characters. Some of these, amounting to about 2,000 characters, match the Laozi. The tomb…is dated around 300 BC. - ^ a b Simpkins & Simpkins (1999), pp. 12–13

- ^ Morgan (2001), pp. 223–224.

- ^ Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese).

- ^ Morgan (2001).

- ^ a b Woolf, Greg (2007). Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art. Barnes & Noble. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-1435101210.

- ^ Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1934), The Chinese: their history and culture, Volume 1 (2 ed.), Macmillan, p. 191, retrieved 8 February 2012,

T’ai Tsung’s family professed descent from Lao Tzu (for the latter’s reputed patronymic was likewise Li)

- ^ Hargett, James M. (2006). Stairway to Heaven: A Journey to the Summit of Mount Emei. SUNY Press. pp. 54 ff. ISBN 978-0791466827.

- ^ Simpkins & Simpkins (1999), p. 12.

- ^ Kohn (1998), pp. 14, 17, 54–55.

- ^ Morgan (2001), pp. 224–225.

- ^ Kohn (1998), p. 55.

- ^ Kohn (1998), pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Kohn (2000), pp. 3–4

- ^ Simpkins (1999), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Morgan (2001), p. 303.

- ^ Simpkins (1999), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Morgan (2001), p. 223.

- ^ Van Norden (2005), p. 162.

- ^ a b c Kohn (2000), p. 22

- ^ Watts (1975), pp. 78–86.

- ^ Reynolds, Beatrice K. (February 1969). «Lao Tzu: Persuasion through inaction and non-speaking». Today’s Speech. 17 (1): 23–25. doi:10.1080/01463376909368862. ISSN 0040-8573.

- ^ Roberts (2004), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Dorn (2008), pp. 282–283.

- ^ Rocker (1997), pp. 82 & 256.

- ^ «Britannica: Anarchism». Dwardmac.pitzer.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Clark, John P. «Master Lao and the Anarchist Prince». Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Le Guin (2009), p. 20.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (2005). Excerpt from «Concepts of the Role of Intellectuals in Social Change Toward Laissez Faire», The Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. IX, No. 2 (Fall 1990) at mises.org

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (2005). «The Ancient Chinese Libertarian Tradition», Mises Daily, (5 December 2005) (original source unknown) at mises.org

- ^ Dorn (2008).

- ^ Boaz, David (30 January 2009). «Libertarianism». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

An appreciation for spontaneous order can be found in the writings of the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu (6th century bce), who urged rulers to «do nothing» because «without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony.»

- ^ Boaz (1997).

- ^ Long (2003).

Sources[edit]

- Boaz, David (1997), The libertarian reader: classic and contemporary readings from Lao-tzu to Milton Friedman, New York: Free Press, ISBN 978-0684847672

- Dorn, James A. (2008). «Lao Tzu (c. 600 B.C.)». In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n169. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Fowler, Jeaneane (2005), An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845190859

- Welch, Holmes Hinkley Jr. (1957), Taoism: The Parting of the Way, Beacon Press, ISBN 9780807059739.

- Kohn, Livia (2000), Daoism Handbook (Handbook of Oriental Studies / Handbuch der Orientalisk – Part 4: China, 14), Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-9004112087

- Kohn, Livia; Lafargue, Michael, eds. (1998), Lao-Tzu and the Tao-Te-Ching, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791435991.

- Kramer, Kenneth (1986), World scriptures: an introduction to comparative religions, New York: Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0809127818.

- Legge, James (1891), «App. VII: The Stone Tablet to Lâo-ʒze», The Texts of Taoism, Part II, The Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XL, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780486209913.

- Long, Roderick T. (Summer 2003), «Austro-Libertarian Themes in Early Confucianism» (PDF), The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 3, 17: 35–62

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (2009), Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching: A Book about the Way and the Power of the Way (2nd ed.), Washington, DC: Shambhala Publications Inc., ISBN 978-1590307441

- Luo Jing (2004), Over a cup of tea: an introduction to Chinese life and culture, Washington, DC: University Press of America, ISBN 978-0761829379

- Mair, Victor Henry (1983), Experimental Essays on Chuang-Tzu, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press

- Maspero, Henri (1981), Taoism and Chinese religion, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, ISBN 978-0870233081

- Morgan, Diane (2001), The Best Guide to Eastern Philosophy and Religion, New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, ISBN 978-1580631976

- Renard, John (2002), 101 Questions and answers on Confucianism, Daoism, and Shinto, New York: Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0809140916

- Roberts, Moss (2004), Dao De Jing: The Book of the Way, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520242210

- Robinet, Isabelle (1997), Taoism: Growth of a Religion, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0804728393

- Simpkins, Annellen M.; Simpkins, C. Alexander (1999), Simple Taoism: a guide to living in balance (3rd Printing ed.), Boston: Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0804831734

- Van Norden, Bryan W.; Ivanhoe, Philip J. (2006), Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy (2nd ed.), Indianapolis, Ind: Hackett Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0872207806

- Watson, Burton (1968), Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, New York: Columbia Univ. Press (UNESCO Collection of Representative Works: Chinese Series), ISBN 978-0231031479

- Watters, Thomas (1870), Lao-Tzŭ: A Study in Chinese Philosophy, Hong Kong: China Mail.

- Watts, Alan; Huan, Al Chung-liang (1975), Tao: The Watercourse Way, New York, NY: Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0394733111

- Rocker, Rudolf (1997). Nationalism and Culture. Black Rose Books.

Further reading[edit]

- Kaltenmark, Max (1969), Lao Tzu and Taoism, translated by Greaves, Roger, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0804706896.

- Sterckx, Roel (2019), Ways of Heaven: An Introduction to Chinese Thought, New York: Basic Books.

External links[edit]

- Works by Laozi in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Laozi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Laozi at Internet Archive

- Works by Laozi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Laozi

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Laozi

|

Laozi |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Zhang Lu |

|

| Born | Trad. 6th century BC Sometimes 4th century BC Quren Village, Chu (present-day Luyi, Henan) |

| Died | Trad. 5th century BC

Didao, Qin (present-day Lintao, Gansu)[dubious – discuss] or immortal |

| Notable work | Tao Te Ching |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Taoism |

|

Notable ideas |

Tao Wu wei |

|

Influenced

|

老子 in seal script (top) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Honorific Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 老子 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǎozǐ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | the Old Master the Old One |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 李耳 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǐ Ěr | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 李伯陽 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 李伯阳 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǐ Bóyáng | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Posthumous Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 李聃 老聃 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǐ Dān Lǎo Dān |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Theonym | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 老君 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǎojūn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | the Old Lord | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For the book also known as Laozi, see Tao Te Ching.

Laozi (, Chinese: 老子), also known by numerous other names, was a semilegendary ancient Chinese Taoist philosopher. Laozi is a Chinese honorific, generally translated as «the Old Master». Traditional accounts say he was born as Li Er in the state of Chu in the 6th century BC during China’s Spring and Autumn Period, served as the royal archivist for the Zhou court at Wangcheng (modern Luoyang), met and impressed Confucius on one occasion, and composed the Tao Te Ching before retiring into the western wilderness. Chinese folk religion holds that he then became an immortal hermit or a god of the celestial bureaucracy under the name Laojun, one of the Three Pure Ones.

A central figure in Chinese culture, Laozi is generally considered the founder of philosophical and religious Taoism. He was claimed and revered as the ancestor of the 7th–10th century Tang dynasty and is similarly honored in modern China with the popular surname Li. His work had a profound influence on subsequent Chinese religious movements and on subsequent Chinese philosophers, who annotated, commended, and criticized his work extensively. Since the 20th century, however, archeological finds and textual criticism have caused some modern historians to question Laozi’s timing or even existence, believing that the received text of the Tao Te Ching was not composed until the 4th century BC Warring States Period.

Names[edit]

Laozi is the modern pinyin romanization of the Standard Mandarin pronunciation of the characters 老子. English approximates the Mandarin pronunciation as .[2][3] It is not a name but an honorific title, meaning «old» or «venerable master». The character 子 has several meanings, including «son», «person», «viscount», and «master», and some Taoists—particularly in English—have preferred to parse the title as meaning «Old Child» or «Old Boy», whether in reference to legends of Laozi being born already an old man[4][5][6] or to his playful philosophy.[7] However, the structure of the name exactly matches that of other ancient Chinese philosophers such as Kongzi, Mengzi, Zhuangzi, &c. and in context can only have the meaning of «master».[8] The title has been extremely variously romanized, including Lao Zi,[9] Lao Tzu[10] or Tzŭ,[4] Lao-tzu,[11] Lao Tse, Lao-tse,[12] Lao Tze, Lao-tze, Laotze,[13] Lao Tsu, and Lao-tsu but, compared with Confucius and Mencius, the latinized form Laocius has been relatively uncommon in English. «Lao-tse» was the most common romanization during the 19th century before being supplanted by Wade-Giles «Lao-tzu» and «Lao Tzu» around the 1920s; the pinyin form «Laozi» finally became more common in English during the 1990s.[citation needed] Historically, these varied romanizations have also led to a series of common spelling mispronunciations, including , ,[14][15] ,[16] &c., although the underlying Mandarin pronunciation has remained unchanged in the modern period.

Traditional accounts give Laozi the personal name Li Er (李耳, Lǐ Ěr), whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *C.rəʔ C.nəʔ.[1] Li is a common Chinese surname but literally means «plum tree»; because of legends tying Laozi’s birth to a plum, he has been venerated as the ancestor of all subsequent Lis, including the ruling family of the Tang dynasty. The character 耳 was the ancient Chinese word for «ear» or «ears». Laozi’s prominent posthumous name Dan (聃, Dān)[17][18][19] similarly means «Long-Ear» or «the Long-Earred One». These names have also been variously written as Li Erh, Li Dan, Lao Dan, Lao Tan, and Laodan.

Laozi is recorded bearing the courtesy name Boyang (伯陽, Bóyáng), whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *pˤrak laŋ.[1] The character 伯 was the title of a senior uncle of the father’s family, also used as a noble title equivalent to a count and as a general mark of respect, and the character 陽 is yang, the solar and masculine life force in Taoist belief. Lao Dan seems to have been used more generally, however, including by Sima Qian in his Records of the Grand Historian,[20] by Zhuangzi’s in his eponymous Taoist classic,[20] and by some modern scholars.[21]

Under the Tang, Laozi received a series of temple names of increasing grandeur. In the year 666, Emperor Gaozong named Laozi the «Supremely Mysterious and Primordial Emperor» (太上玄元皇帝, Tàishàng Xuán Yuán Huángdì).[22] In 743, Emperor Xuanzong declared him the «Sage Ancestor» (聖祖, Shèngzǔ) of the dynasty with the posthumous title of «Mysterious and Primordial Emperor» (玄元皇帝, Xuán Yuán Huángdì). Emperor Xuanzong also elevated Laozi’s parents to the ranks of «Innately Supreme Emperor» (先天太上皇, Xiāntiān Tàishàng Huáng) and «Innate Empress» (先天太后, Xiāntiān Tàihòu). In 749, Laozi was further honored as the «Sage Ancestor and Mysterious and Primordial Emperor of the Great Way» (聖祖大道玄元皇帝, Shèngzǔ Dàdào Xuán Yuán Huángdì) and then, in 754, as the «Great Sage Ancestor and Mysterious and Primordial Heavenly Emperor and Great Sovereign of the Golden Palace of the High and Supreme Great Way» (大聖祖高上大道金闕玄元天皇大帝, Dà Shèngzǔ Gāo Shǎng Dàdào Jīnquē Xuán Yuán Tiānhuáng Dàdì).

Historical views[edit]

In the mid-twentieth century, a consensus emerged among Western scholars that the historicity of the person known as Laozi is doubtful and that the Tao Te Ching was «a compilation of Taoist sayings by many hands».[23][24] Following new archaeological discoveries, many Chinese scholars have reverted to affirming the existence of a historical Laozi.[25]

The earliest certain reference to the present figure of Laozi is found in the 1st‑century BC Records of the Grand Historian collected by the historian Sima Qian from earlier accounts.[26] In one account, Laozi was said to be a contemporary of Confucius during the 6th or 5th century BC. His personal name was Er or Dan. He was an official in the imperial archives and wrote a book in two parts before departing to the west. In another, Laozi was a different contemporary of Confucius titled Lao Laizi (老莱子) and wrote a book in 15 parts. In a third, he was the court astrologer Lao Dan who lived during the 4th century BC reign of the Duke Xian of Qin.[27][28] The oldest text of the Tao Te Ching so far recovered was part of the Guodian Chu Slips. It was written on bamboo slips, and dates to the late 4th century BC.[29]

According to traditional accounts, Laozi was a scholar who worked as the Keeper of the Archives for the royal court of Zhou. This reportedly allowed him broad access to the works of the Yellow Emperor and other classics of the time. The stories assert that Laozi never opened a formal school but nonetheless attracted a large number of students and loyal disciples. There are many variations of a story retelling his encounter with Confucius, most famously in the Zhuangzi.[30][31]

Sima Qian reports that Laozi was born in the village of Quren (曲仁里, Qūrén lǐ) in the southern state of Chu,[32] within present-day Luyi in Henan..[33] He was said to be the son of the Censor-in-Chief of the Zhou dynasty and Lady Yishou (益壽氏, Yìshòu shì). In accounts where Laozi married, he was said to have had a son who became a celebrated soldier of Wei during the Warring States period.

The story tells of Zong the Warrior who defeats an enemy and triumphs, and then abandons the corpses of the enemy soldiers to be eaten by vultures. By coincidence Laozi, traveling and teaching the way of the Tao, comes on the scene and is revealed to be the father of Zong, from whom he was separated in childhood. Laozi tells his son that it is better to treat respectfully a beaten enemy, and that the disrespect to their dead would cause his foes to seek revenge. Convinced, Zong orders his soldiers to bury the enemy dead. Funeral mourning is held for the dead of both parties and a lasting peace is made.

Many clans of the Li family trace their descent to Laozi,[34] including the emperors of the Tang dynasty.[35][34][36] This family was known as the Longxi Li lineage (隴西李氏). According to the Simpkinses, while many (if not all) of these lineages are questionable, they provide a testament to Laozi’s impact on Chinese culture.[37]

The third story in Sima Qian states that Laozi grew weary of the moral decay of life in Chengzhou and noted the kingdom’s decline. He ventured west to live as a hermit in the unsettled frontier at the age of 80. At the western gate of the city (or kingdom), he was recognized by the guard Yinxi. The sentry asked the old master to record his wisdom for the good of the country before he would be permitted to pass. The text Laozi wrote was said to be the Tao Te Ching, although the present version of the text includes additions from later periods. In some versions of the tale, the sentry was so touched by the work that he became a disciple and left with Laozi, never to be seen again.[38] In others, the «Old Master» journeyed all the way to India and was the teacher of Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha. Others say he was the Buddha himself.[30][39]

A seventh-century work, the Sandong Zhunang («Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns»), embellished the relationship between Laozi and Yinxi. Laozi pretended to be a farmer when reaching the western gate, but was recognized by Yinxi, who asked to be taught by the great master. Laozi was not satisfied by simply being noticed by the guard and demanded an explanation. Yinxi expressed his deep desire to find the Tao and explained that his long study of astrology allowed him to recognize Laozi’s approach. Yinxi was accepted by Laozi as a disciple. This is considered an exemplary interaction between Taoist master and disciple, reflecting the testing a seeker must undergo before being accepted. A would-be adherent is expected to prove his determination and talent, clearly expressing his wishes and showing that he had made progress on his own towards realizing the Tao.[40]

The Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns continues the parallel of an adherent’s quest. Yinxi received his ordination when Laozi transmitted the Tao Te Ching, along with other texts and precepts, just as Taoist adherents receive a number of methods, teachings and scriptures at ordination. This is only an initial ordination and Yinxi still needed an additional period to perfect his virtue, thus Laozi gave him three years to perfect his Tao. Yinxi gave himself over to a full-time devotional life. After the appointed time, Yinxi again demonstrates determination and perfect trust, sending out a black sheep to market as the agreed sign. He eventually meets again with Laozi, who announces that Yinxi’s immortal name is listed in the heavens and calls down a heavenly procession to clothe Yinxi in the garb of immortals. The story continues that Laozi bestowed a number of titles upon Yinxi and took him on a journey throughout the universe, even into the nine heavens. After this fantastic journey, the two sages set out to western lands of the barbarians. The training period, reuniting and travels represent the attainment of the highest religious rank in medieval Taoism called «Preceptor of the Three Caverns». In this legend, Laozi is the perfect Taoist master and Yinxi is the ideal Taoist student. Laozi is presented as the Tao personified, giving his teaching to humanity for their salvation. Yinxi follows the formal sequence of preparation, testing, training and attainment.[41]

The story of Laozi has taken on strong religious overtones since the Han dynasty. As Taoism took root, Laozi was worshipped as a god. Belief in the revelation of the Tao from the divine Laozi resulted in the formation of the Way of the Celestial Masters, the first organized religious Taoist sect. In later mature Taoist tradition, Laozi came to be seen as a personification of the Tao. He is said to have undergone numerous «transformations» and taken on various guises in various incarnations throughout history to initiate the faithful in the Way. Religious Taoism often holds that the «Old Master» did not disappear after writing the Tao Te Ching but rather spent his life traveling and revealing the Tao.[42]

Taoist myths state that Laozi was a virgin birth, conceived when his mother gazed upon a falling star. He supposedly remained in her womb for 62 years before being born while his mother was leaning against a plum tree. (The Chinese surname Li literally means «plum tree».) Laozi was said to have emerged as a grown man with a full grey beard and long earlobes, both symbols of wisdom and long life.[43][44] Other myths state that he was reborn 13 times after his first life during the days of Fuxi. In his last incarnation as Laozi, he lived nine hundred and ninety years and spent his life traveling to reveal the Tao.[42]

Tao Te Ching[edit]

Laozi is traditionally regarded as the author of the Tao Te Ching, though the identity of its author(s) or compiler(s) has been debated throughout history.[45][46] It is one of the most significant treatises in Chinese cosmogony. As with most other ancient Chinese philosophers, Laozi often explains his ideas by way of paradox, analogy, appropriation of ancient sayings, repetition, symmetry, rhyme, and rhythm. In fact, the whole book can be read as an analogy – the ruler is the awareness, or self, in meditation and the myriad creatures or empire is the experience of the body, senses and desires.

The Tao Te Ching, often called simply Laozi after its reputed author, describes the Tao as the source and ideal of all existence: it is unseen, but not transcendent, immensely powerful yet supremely humble, being the root of all things. People have desires and free will (and thus are able to alter their own nature). Many act «unnaturally», upsetting the natural balance of the Tao. The Tao Te Ching intends to lead students to a «return» to their natural state, in harmony with Tao.[47] Language and conventional wisdom are critically assessed. Taoism views them as inherently biased and artificial, widely using paradoxes to sharpen the point.[48]

Livia Kohn provides an example of how Laozi encouraged a change in approach, or return to «nature», rather than action. Technology may bring about a false sense of progress. The answer provided by Laozi is not the rejection of technology, but instead seeking the calm state of wu wei, free from desires. This relates to many statements by Laozi encouraging rulers to keep their people in «ignorance», or «simple-minded». Some scholars insist this explanation ignores the religious context, and others question it as an apologetic of the philosophical coherence of the text. It would not be unusual political advice if Laozi literally intended to tell rulers to keep their people ignorant. However, some terms in the text, such as «valley spirit» (gushen) and «soul» (po), bear a metaphysical context and cannot be easily reconciled with a purely ethical reading of the work.[48]

Wu wei (無為), literally «non-action» or «not acting», is a central concept of the Tao Te Ching. The concept of wu wei is multifaceted, and reflected in the words’ multiple meanings, even in English translation; it can mean «not doing anything», «not forcing», «not acting» in the theatrical sense, «creating nothingness», «acting spontaneously», and «flowing with the moment».[49]

It is a concept used to explain ziran (自然), or harmony with the Tao. It includes the concepts that value distinctions are ideological and seeing ambition of all sorts as originating from the same source. Laozi used the term broadly with simplicity and humility as key virtues, often in contrast to selfish action. On a political level, it means avoiding such circumstances as war, harsh laws and heavy taxes. Some Taoists see a connection between wu wei and esoteric practices, such as zuowang «sitting in oblivion» (emptying the mind of bodily awareness and thought) found in the Zhuangzi.[48]

Influence[edit]

Potential officials throughout Chinese history drew on the authority of non-Confucian sages, especially Laozi and Zhuangzi, to deny serving any ruler at any time. Zhuangzi, Laozi’s most famous follower in traditional accounts, had a great deal of influence on Chinese literati and culture. Laozi influenced millions of Chinese people by his psychological understanding. He persuaded people by his inaction and non-speaking.[50]

Political theorists influenced by Laozi have advocated humility in leadership and a restrained approach to statecraft, either for ethical and pacifist reasons, or for tactical ends. In a different context, various antiauthoritarian movements have embraced Laozi’s teachings on the power of the weak.[51][12]

Laozi was a proponent of limited government.[52] Left-libertarians in particular have been influenced by Laozi – in his 1937 book Nationalism and Culture, the anarcho-syndicalist writer and activist Rudolf Rocker praised Laozi’s «gentle wisdom» and understanding of the opposition between political power and the cultural activities of the people and community.[53] In his 1910 article for the Encyclopædia Britannica, Peter Kropotkin also noted that Laozi was among the earliest proponents of essentially anarchist concepts.[54] More recently, anarchists such as John P. Clark and Ursula K. Le Guin have written about the conjunction between anarchism and Taoism in various ways, highlighting the teachings of Laozi in particular.[55] In her rendition of the Tao Te Ching, Le Guin writes that Laozi «does not see political power as magic. He sees rightful power as earned and wrongful power as usurped… He sees sacrifice of self or others as a corruption of power, and power as available to anyone who follows the Way. No wonder anarchists and Taoists make good friends.»[56]

The right-libertarian economist Murray Rothbard suggested that Laozi was the first libertarian,[57] likening Laozi’s ideas on government to Friedrich Hayek’s theory of spontaneous order.[58] James A. Dorn agreed, writing that Laozi, like many 18th-century liberals, «argued that minimizing the role of government and letting individuals develop spontaneously would best achieve social and economic harmony.»[59] Similarly, the Cato Institute’s David Boaz includes passages from the Tao Te Ching’ in his 1997 book The Libertarian Reader and noted in an article for the Encyclopædia Britannica that Laozi advocated for rulers to «do nothing» because «without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony.»[60][61] Philosopher Roderick Long argues that libertarian themes in Taoist thought are actually borrowed from earlier Confucian writers.[62]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d Baxter, William; Sagart, Laurent (20 September 2014). «Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction» (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ «Lao-tzu», Merriam-Webster, 2022.

- ^ LaFargue, Michael (2007), «Spelling and Pronouncing Chinese Words», Asian Religions, Boston: University of Massachusetts.

- ^ a b Watters (1870), p. 16.

- ^ Legge (1891), p. 313.

- ^ Welch (1957), p. 1.

- ^ Mair (1983), p. 93.

- ^ Lin, Derek (29 December 2016), «The «Ancient Child» Fallacy», Taoism.net.

- ^ Swofford, Mark (19 November 2011), «Laozi or Lao Zi?», Pinyin News, Banqiao.

- ^ Le Guin (2009).

- ^ «Lao-tzu – Founder of Taoism». en.hubei.gov.cn. Government of Hubei, China. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b «Lao-tse». ztopics.com.

- ^ «Laotze», Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ «Lao-tzu», Random House Unabridged Dictionary, New York: Random House, 2022.

- ^ «Lao Tzu», American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.), Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2016.

- ^ «Laotze». Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Luo (2004), p. 118.

- ^ Kramer (1986), p. 118.

- ^ Kohn (2000), p. 2.

- ^ a b Rainey, Lee Dian (2013), Decoding Dao: Reading the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching) and the Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu), John Wiley & Sons, p. 31, ISBN 978-1118465677.

- ^ Carr, Dr Brian; et al. (2002), Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, Routledge, p. 497, ISBN 978-1134960583.

- ^ 傅勤家 (1996). 道教史概論 (in Chinese). Taipei: 臺灣商務印書館. p. 82. ISBN 978-9570513240.

- ^ Watson (1968), p. 8.

- ^ Kohn (2000), p. 4

- ^ Liu, Xiaogan (2014). «Did Daoism Have a Founder? Textual Issues of the Laozi». Dao companion to Daoist philosophy. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 9789048129270.

- ^ «Sages and Saints Part XV: Lao Zi, the Dragon». Purple Cloud. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Fowler (2005), p. 96.

- ^ Robinet (1997), p. 26.

- ^ «Laozi». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. 2018.

The discovery of two Laozi silk manuscripts at Mawangdui, near Changsha, Hunan province in 1973 marks an important milestone in modern Laozi research. The manuscripts, identified simply as ‘A’ (jia) and ‘B’ (yi), were found in a tomb that was sealed in 168 BC. The texts themselves can be dated earlier, the ‘A’ manuscript being the older of the two, copied in all likelihood before 195 BC.

«Until recently, the Mawangdui manuscripts have held the pride of place as the oldest extant manuscripts of the Laozi. In late 1993, the excavation of a tomb (identified as M1) in Guodian, Jingmen city, Hubei, has yielded among other things some 800 bamboo slips, of which 730 are inscribed, containing over 13,000 Chinese characters. Some of these, amounting to about 2,000 characters, match the Laozi. The tomb…is dated around 300 BC. - ^ a b Simpkins & Simpkins (1999), pp. 12–13

- ^ Morgan (2001), pp. 223–224.

- ^ Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese).

- ^ Morgan (2001).

- ^ a b Woolf, Greg (2007). Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art. Barnes & Noble. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-1435101210.

- ^ Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1934), The Chinese: their history and culture, Volume 1 (2 ed.), Macmillan, p. 191, retrieved 8 February 2012,

T’ai Tsung’s family professed descent from Lao Tzu (for the latter’s reputed patronymic was likewise Li)

- ^ Hargett, James M. (2006). Stairway to Heaven: A Journey to the Summit of Mount Emei. SUNY Press. pp. 54 ff. ISBN 978-0791466827.

- ^ Simpkins & Simpkins (1999), p. 12.

- ^ Kohn (1998), pp. 14, 17, 54–55.

- ^ Morgan (2001), pp. 224–225.

- ^ Kohn (1998), p. 55.

- ^ Kohn (1998), pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Kohn (2000), pp. 3–4

- ^ Simpkins (1999), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Morgan (2001), p. 303.

- ^ Simpkins (1999), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Morgan (2001), p. 223.

- ^ Van Norden (2005), p. 162.

- ^ a b c Kohn (2000), p. 22

- ^ Watts (1975), pp. 78–86.

- ^ Reynolds, Beatrice K. (February 1969). «Lao Tzu: Persuasion through inaction and non-speaking». Today’s Speech. 17 (1): 23–25. doi:10.1080/01463376909368862. ISSN 0040-8573.

- ^ Roberts (2004), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Dorn (2008), pp. 282–283.

- ^ Rocker (1997), pp. 82 & 256.

- ^ «Britannica: Anarchism». Dwardmac.pitzer.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Clark, John P. «Master Lao and the Anarchist Prince». Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Le Guin (2009), p. 20.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (2005). Excerpt from «Concepts of the Role of Intellectuals in Social Change Toward Laissez Faire», The Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. IX, No. 2 (Fall 1990) at mises.org

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (2005). «The Ancient Chinese Libertarian Tradition», Mises Daily, (5 December 2005) (original source unknown) at mises.org

- ^ Dorn (2008).

- ^ Boaz, David (30 January 2009). «Libertarianism». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

An appreciation for spontaneous order can be found in the writings of the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu (6th century bce), who urged rulers to «do nothing» because «without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony.»

- ^ Boaz (1997).

- ^ Long (2003).

Sources[edit]

- Boaz, David (1997), The libertarian reader: classic and contemporary readings from Lao-tzu to Milton Friedman, New York: Free Press, ISBN 978-0684847672

- Dorn, James A. (2008). «Lao Tzu (c. 600 B.C.)». In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n169. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Fowler, Jeaneane (2005), An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845190859

- Welch, Holmes Hinkley Jr. (1957), Taoism: The Parting of the Way, Beacon Press, ISBN 9780807059739.

- Kohn, Livia (2000), Daoism Handbook (Handbook of Oriental Studies / Handbuch der Orientalisk – Part 4: China, 14), Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-9004112087

- Kohn, Livia; Lafargue, Michael, eds. (1998), Lao-Tzu and the Tao-Te-Ching, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791435991.

- Kramer, Kenneth (1986), World scriptures: an introduction to comparative religions, New York: Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0809127818.

- Legge, James (1891), «App. VII: The Stone Tablet to Lâo-ʒze», The Texts of Taoism, Part II, The Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XL, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780486209913.

- Long, Roderick T. (Summer 2003), «Austro-Libertarian Themes in Early Confucianism» (PDF), The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 3, 17: 35–62

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (2009), Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching: A Book about the Way and the Power of the Way (2nd ed.), Washington, DC: Shambhala Publications Inc., ISBN 978-1590307441

- Luo Jing (2004), Over a cup of tea: an introduction to Chinese life and culture, Washington, DC: University Press of America, ISBN 978-0761829379

- Mair, Victor Henry (1983), Experimental Essays on Chuang-Tzu, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press

- Maspero, Henri (1981), Taoism and Chinese religion, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, ISBN 978-0870233081

- Morgan, Diane (2001), The Best Guide to Eastern Philosophy and Religion, New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, ISBN 978-1580631976

- Renard, John (2002), 101 Questions and answers on Confucianism, Daoism, and Shinto, New York: Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0809140916

- Roberts, Moss (2004), Dao De Jing: The Book of the Way, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520242210

- Robinet, Isabelle (1997), Taoism: Growth of a Religion, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0804728393

- Simpkins, Annellen M.; Simpkins, C. Alexander (1999), Simple Taoism: a guide to living in balance (3rd Printing ed.), Boston: Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0804831734

- Van Norden, Bryan W.; Ivanhoe, Philip J. (2006), Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy (2nd ed.), Indianapolis, Ind: Hackett Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0872207806

- Watson, Burton (1968), Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, New York: Columbia Univ. Press (UNESCO Collection of Representative Works: Chinese Series), ISBN 978-0231031479

- Watters, Thomas (1870), Lao-Tzŭ: A Study in Chinese Philosophy, Hong Kong: China Mail.

- Watts, Alan; Huan, Al Chung-liang (1975), Tao: The Watercourse Way, New York, NY: Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0394733111

- Rocker, Rudolf (1997). Nationalism and Culture. Black Rose Books.

Further reading[edit]

- Kaltenmark, Max (1969), Lao Tzu and Taoism, translated by Greaves, Roger, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0804706896.

- Sterckx, Roel (2019), Ways of Heaven: An Introduction to Chinese Thought, New York: Basic Books.

External links[edit]

- Works by Laozi in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Laozi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Laozi at Internet Archive

- Works by Laozi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Laozi

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Laozi

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

Ла́о-цзы́, нескл., м.

Рядом по алфавиту:

ла-па́сский , (от Ла-Па́с)

ланце́тник , -а

ланце́тный

ланцетови́дный , кр. ф. -ден, -дна

ланцетоно́с , -а

ланч , -а, тв. -ем

ланъя́рд , -а

лань , -и

ла́о , нескл., мн., ед. м. и ж. (лаосцы)

Ла́о-цзы́ , нескл., м.

Лаокоо́н , -а

лао́ска , -и, р. мн. -сок

лао́сский , (от Лао́с)

лао́сцы , -ев, ед. -сец, -cца, тв. -сцем

лаотя́не , -я́н, ед. -я́нин, -а (от Лао́с)

лаотя́нка , -и, р. мн. -нок

лаотя́нский

ла́па , -ы

ла́па-отва́льчик , ла́пы-отва́льчика, ж.

ла́панный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана, прич. (сниж.)

ла́паный , прил. (сниж.)

ла́панье , -я (сниж.)

лапароско́п , -а

лапароскопи́ческий

лапароскопи́я , -и

лапаротоми́я , -и

ла́пать(ся) , -аю(сь), -ает(ся) (сниж.)

лапида́рий , -я

лапида́рность , -и

лапида́рный , кр. ф. -рен, -рна

лапи́лли , нескл., мн.; ед. с. (в вулканологии)

Рады помочь вам узнать, как пишется слово «Лао-цзы».

Пишите и говорите правильно.

×òî òàêîå «Ëàî-Öçû»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

Ëàî-Öçû Ëàî-Öçû

(Ëè Ýð) (IV-III ââ. äî í.ý.) àâòîð êàíîíè÷åñêîãî ñî÷èíåíèÿ äàîñèçìà «Äàî Äý Öçèí»

Ãîëîñ èñòèíû íåèçÿùåí, à èçÿùíàÿ ðå÷ü ëæèâà. Íðàâñòâåííûé ÷åëîâåê íå êðàñíîðå÷èâ, à êðàñíîðå÷èâûé ëæåö.

Çàêîí äîñòîéíûõ òâîðèòü äîáðî è íå ññîðèòüñÿ.

Âåëèêèé ÷åëîâåê äåðæèòñÿ ñóùåñòâåííîãî è îñòàâëÿåò íè÷òîæíîå. Îí âñå äåëàåò ïî ïðàâäå, íî íèêîãäà íå áóäåò îïèðàòüñÿ íà çàêîíû.

Ëåãêî äîñòèãíóòîå ñîãëàñèå íå çàñëóæèâàåò äîâåðèÿ.

Ãîëîñ èñòèíû ïðîòèâåí ñëóõó.

Êòî, ïðåäïðèíèìàÿ äåëî, ñïåøèò íàñêîðî äîñòè÷ü ðåçóëüòàòà, òîò íè÷åãî íå ñäåëàåò. Êòî îñòîðîæíî îêàí÷èâàåò ñâîå äåëî, êàê íà÷àë, òîò íå ïîòåðïèò íåóäà÷è.

Õîòÿ â ìèðå íåò ïðåäìåòà, êîòîðûé áûë áû ñëàáåå è íåæíåå âîäû, íî îíà ìîæåò ðàçðóøèòü ñàìûé òâåðäûé ïðåäìåò.

Êòî äåëàåò âèä, ÷òî ìíîãî çíàåò è êî âñåìó ñïîñîáåí, òîò íè÷åãî íå çíàåò è íè ê ÷åìó íå ñïîñîáåí.

Êòî äóìàåò, ÷òî ïîñòèã âñ¸, òîò íè÷åãî íå çíàåò.

Çíàþùèé ëþäåé ðàçóìåí, à çíàþùèé ñåáÿ ñàìîãî ïðîçîðëèâ.

Çíàþùèé ìíîãî ìîë÷àëèâ, à ãîâîðÿùèé ìíîãî íå çíàåò íè÷åãî.

Èñòèííî ïðîñâåùåííûé ÷åëîâåê íèêîãäà íå âîþåò.

Êòî, çíàÿ ìíîãî, äåðæèò ñåáÿ, êàê íå çíàþùèé íè÷åãî, òîò íðàâñòâåííûé ìóæ.

Óìíûå íå áûâàþò ó÷åíû; ó÷åíûå íå áûâàþò óìíû.

Äîñòîéíûé ìóæ âñåãäà ñòàðàåòñÿ áûòü áåñïðèñòðàñòíûì, íå ïðèäàâàòü öåííîñòè òðóäíîäîáûâàåìûì âåùàì è íå ñëóøàòü áåñïëîäíîãî ó÷åíèÿ.

Äîñòîéíûé ìóæ äåëàåò ìíîãî, íî íå õâàëèòñÿ ñäåëàííûì; ñîâåðøàåò çàñëóãè, íî íå ïðèçíàåò èõ, ïîòîìó ÷òî îí íå æåëàåò îáíàðóæèòü ñâîþ ìóäðîñòü.

Ìóäðûé ÷åëîâåê íå âûñòàâëÿåò ñåáÿ íà ñâåò, ïîýòîìó áëåñòèò; îí íå ãîâîðèò î ñåáå, ïîýòîìó îí ñëàâåí; îí íå ïðîñëàâëÿåò ñåáÿ, ïîýòîìó îí çàñëóæåí; îí íå âîçâûøàåò ñåáÿ, ïîýòîìó îí ÿâëÿåòñÿ ñòàðøèì ñðåäè äðóãèõ.

Ìóäðåö èçáåãàåò âñÿêîé êðàéíîñòè.

Êòî ìíîãî ãîâîðèò, òîò ÷àñòî òåðïèò íåóäà÷ó.

Õîòÿ âîéíà ñòàâèò, áûòü ìîæåò, öåëüþ ñïîêîéñòâèå, íî îíà íåñîìíåííîå çëî.

Ïðè÷èíà òîãî, ÷òî òðóäíî óïðàâëÿòü íàðîäîì, çàêëþ÷àåòñÿ â òîì, ÷òî íàðîä ïðîñâåùàåòñÿ è â íåì ìíîãî óìíûõ.

Êîãäà ìíîæàòñÿ çàêîíû è ïðèêàçû, ðàñòåò ÷èñëî âîðîâ è ðàçáîéíèêîâ.

Ëþäè âûñøåé íðàâñòâåííîñòè íå ñ÷èòàþò ñåáÿ íðàâñòâåííûìè; ïîýòîìó îíè èìåþò âûñøóþ íðàâñòâåííîñòü.

Êîãäà âû áëàãîïîëó÷íû, òî ïîäóìàéòå, ÷òî íóæíî ïðåäïðèíÿòü âî âðåìÿ áåäû, òàê êàê âåëèêàÿ áåäà íà÷èíàåòñÿ ñ íåçíà÷èòåëüíîé.

Áåäà âñåãî ìèðà ïðîèñõîäèò èç ìåëî÷è, êàê âåëèêîå äåëî èç ìàëûõ.

Äîñòîéíûé ìóæ íàäåâàåò íà ñåáÿ õóäóþ îäåæäó, íî â ñåáå èìååò äðàãîöåííûé êàìåíü.

Òîëüêî ÷òî ðàñïóñòèâøååñÿ ðàñòåíèå íåæíî è ñëàáî. Çàñîõøåå ðàñòåíèå òâåðäî è íå ãèáêî. Îòñþäà ÿñíî, ÷òî íåæíîå è ñëàáîå æèâåò.

Ïîáåæäàþùèé äðóãèõ ñèëåí, à ïîáåæäàþùèé ñàìîãî ñåáÿ ìîãóùåñòâåí.

Ïðåâîñõîäíûé âîèí íèêîãäà íå ðàçãíåâàåòñÿ.

Íå ññîðÿùèéñÿ íå îñóæäàåòñÿ.

Êòî, çíàÿ ãðàíèöû ñâîåé äåÿòåëüíîñòè, íå ïðèáëèçèòñÿ ê îïàñíîñòÿì, òîò áóäåò æèòü äîëãî.

Íåò ãðåõà òÿæåëåå ñòðàñòåé.

Íåò áåäû òÿæåëåå íåçíàíèÿ óäîâëåòâîðåíèÿ.

Çíàþùèé ìåðó äîâîëåí ñâîèì ïîëîæåíèåì.

Âîçäåðæàíèå ýòî ïåðâàÿ ñòóïåíü äîáðîäåòåëè, êîòîðàÿ è åñòü íà÷àëî íðàâñòâåííîãî ñîâåðøåíñòâà.

Êòî âåäåò âîéíó ðàäè ÷åëîâåêîëþáèÿ, òîò ïîáåäèò âðàãîâ.

Êòî õðàáð, íå çíàÿ ÷åëîâåêîëþáèÿ, êòî ùåäð, íå çíàÿ áåðåæëèâîñòè, êòî èäåò âïåðåä, íå çíàÿ ñìèðåíèÿ, òîò ïîãèáíåò.

Íåò áåäû òÿæåëåå, ÷åì ïðåçèðàòü âðàãîâ.

Êòî, íå çíàÿ íè÷åãî, äåðæèò ñåáÿ êàê çíàþùèé ìíîãî, òîò áîëåí.

Ïî÷åñòü è ïîçîð îò ñèëüíûõ ìèðà (äëÿ ìóäðåöà) îäèíàêîâî ñòðàííû.

Äîâîëüñòâóþùèéñÿ ñàìèì ñîáîé áîãà÷.

Ïîòåðÿ åñòü íà÷àëî ðàçìíîæåíèÿ, ìíîæåñòâî íà÷àëî ïîòåðè.

Åñëè âåùü íå ãîäíà äëÿ îäíîé öåëè, åå ìîæíî óïîòðåáèòü äëÿ äðóãîé.

Êîãäà íåò âðàãîâ, òî íå áûâàåò âîéíû.

Áóäüòå âíèìàòåëüíû ê ñâîèì ìûñëÿì îíè íà÷àëî ïîñòóïêîâ.(Èñòî÷íèê: «Àôîðèçìû. Çîëîòîé ôîíä ìóäðîñòè.» Åðåìèøèí Î. — Ì.: Ïðîñâåùåíèå; 2006.)Ëàî-Öçû

Ëàî-Öçû (Lao Tseu) (íàñò. èìÿ — Ëè-Ýð) (êîíåö VI — íà÷àëî V â. äî í.ý.)

Êèòàéñêèé ôèëîñîô. Ëàî-öçû â ïåðâîäå — «ñòàðûé ðåáåíîê». Îñíîâàòåëü ôèëîñîôñêîé øêîëû äàîñèçìà, ñ÷èòàåòñÿ àâòîðîì òðàêòàòà «Ëàî-öçû» («Äàî äý öçèí»), õîòÿ íåêîòîðûìè èññëåäîâàòåëÿìè àâòîðñòâî òðàêòàòà ïðèïèñûâàåòñÿ åãî ó÷åíèêàì.

Àôîðèçìû, öèòàòû —

Ñàìûå ëó÷øèå âîæäè òå, ñóùåñòâîâàíèå êîòîðûõ íàðîä íå çàìå÷àåò.

Êîãäà âîæäü, çàñëóæèâàþùèé íàçâàíèå ñàìîãî ëó÷øåãî, çàâåðøàåò ñâîþ ðàáîòó, ëþäè ãîâîðÿò: «Ìû âñå ñäåëàëè ñàìè».

×òîáû âåñòè ëþäåé çà ñîáîé, èäè çà íèìè.

Êîãäà ìíîæàòñÿ çàêîíû è ïðèêàçû, ðàñòåò ÷èñëî âîðîâ è ðàçáîéíèêîâ.

Êòî õî÷åò áûòü âî âñåì ïðàâûì, òîãî íå ñëóøàþò.

Òàì, ãäå âåëèêèå ìóäðåöû èìåþò âëàñòü, ïîääàííûå íå çàìå÷àþò èõ ñóùåñòâîâàíèÿ. Òàì, ãäå âëàñòâóþò íåâåëèêèå ìóäðåöû, íàðîä áûâàåò ïðèâÿçàí ê íèì è õâàëèò èõ. Òàì, ãäå âëàñòâóþò åùå ìåíüøèå ìóäðåöû, íàðîä áîèòñÿ èõ, à òàì, ãäå åùå ìåíüøèå, íàðîä èõ ïðåçèðàåò.

Óìíûå íå áûâàþò ó÷åíû; ó÷åíûå íå áûâàþò óìíû.

Áóäüòå âíèìàòåëüíû ê ñâîèì ìûñëÿì, — îíè íà÷àëî ïîñòóïêîâ.

Ãîëîñ èñòèíû ïðîòèâåí ñëóõó.

Áåäà âñåãî ìèðà ïðîèñõîäèò èç ìåëî÷è, êàê âåëèêîå äåëî — èç ìàëûõ.

Çíàòü ìíîãî è íå âûñòàâëÿòü ñåáÿ çíàþùèì åñòü íðàâñòâåííàÿ âûñîòà. Çíàòü ìàëî è âûñòàâëÿòü ñåáÿ çíàþùèì åñòü áîëåçíü. Òîëüêî ïîíèìàÿ ýòó áîëåçíü, ìû ìîæåì èçáàâèòüñÿ îò íåå.

Ïðè÷èíà, ïî êîòîðîé ðåêè è ìîðÿ ïîëó÷àþò äàíü îò ñîòíè ãîðíûõ ïîòîêîâ, çàêëþ÷àåòñÿ â òîì, ÷òî îíè íàõîäÿòñÿ íèæå ïîñëåäíèõ. Áëàãîäàðÿ ýòîìó îíè â ñîñòîÿíèè ãîñïîäñòâîâàòü íàä âñåìè ãîðíûìè ïîòîêàìè. Òî÷íî òàê æå è ìóäðåö, æåëàþùèé áûòü âûøå ëþäåé, ñòàâèò ñåáÿ íèæå èõ.

Ïîáåæäàþùèé äðóãèõ ñèëåí, à ïîáåæäàþùèé ñàìîãî ñåáÿ ìîãóùåñòâåí.

Êòî äåëàåò âèä, ÷òî ìíîãî çíàåò è êî âñåìó ñïîñîáåí, òîò íè÷åãî íå çíàåò è íè ê ÷åìó íå ñïîñîáåí.

Ëåãêî äîñòèãíóòîå ñîãëàñèå íå çàñëóæèâàåò äîâåðèÿ.

Î íåñ÷àñòüå! Îíî ÿâëÿåòñÿ îïîðîé ñ÷àñòüÿ. Î ñ÷àñòüå!  íåì çàêëþ÷åíî íåñ÷àñòüå. Êòî çíàåò èõ ãðàíèöû? Îíè íå èìåþò ïîñòîÿíñòâà.

Çíàþùèé ëþäåé ðàçóìåí, à çíàþùèé ñåáÿ ñàìîãî ïðîçîðëèâ.

Óìåëûé ïîëêîâîäåö íå äðà÷ëèâ. Òîò, êòî óìååò ñðàæàòüñÿ, íå äàåò âîëþ ÿðîñòè. Òîò, êòî óìååò ïîáåæäàòü âðàãà, íå âñòóïàåò ñ íèì â ñõâàòêó. Òîò, êòî óìååò èñïîëüçîâàòü äðóãèõ, ñòàâèò ñåáÿ íèæå èõ.

Êîãäà íåò âðàãîâ, òî íå áûâàåò âîéíû.

Õîòÿ â ìèðå íåò ïðåäìåòà, êîòîðûé áûë áû ñëàáåå è íåæíåå âîäû, íî îíà ìîæåò ðàçðóøèòü ñàìûé òâåðäûé ïðåäìåò.

(Èñòî÷íèê: «Àôîðèçìû ñî âñåãî ìèðà. Ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ ìóäðîñòè.» www.foxdesign.ru)

Ëàî-Öçû —

Ëè Ýð, àâòîð äðåâíåêèòàéñêîãî êëàññè÷åñêîãî äàîññêîãî òðàêòàòà «Ëàî-öçû» (äð. íàçâàíèå «Äàî… Áîëüøàÿ Ñîâåòñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

Ëàî-Öçû — ËÀÎ-ÖÇÛ (Ëè Ýð), àâòîð äðåâíåêèòàéñêîãî òðàêòàòà «Ëàî-öçû» (äðåâíåå íàçâàíèå — «Äàî äý öçèí», 4 — 3 … Ñîâðåìåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

Ëàî-Öçû — ËÀÎ-ÖÇÛ — ëåãåíäàðíûé äðåâíåêèòàéñêèé ìûñëèòåëü, îñíîâîïîëîæíèê ðåëèãèîçíî-ôèëîñîôñêîãî íàïðàâëåíèÿ … Áîëüøîé ýíöèêëîïåäè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

Ëàî-Öçû — 1-é èñòî÷íèê:

ËÀÎ-ÖÇÛ (êèò., áóêâ. ñòàðûé ó÷èòåëü) (ðîä. 604 äî Ð. X. â öàðñòâå ×ó, ïðîâèíöèÿ Õýíà… Ôèëîñîôñêèé ýíöèêëîïåäè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

Ëàî-Öçû —

ËÀÎ-ÖÇÛ (6-5 ââ. äî í.ý.) — ïîëóëåãåíäàðíûé îñíîâàòåëü äàîñèçìà, îäíîãî èç íàèáîëåå çíà÷èòåëüíûõ òå… Íîâåéøèé ôèëîñîôñêèé ñëîâàðü

Ëàî-Öçû —

ËÀÎ-ÖÇÛ

(65 ââ. äî í.ý.) ïîëóëåãåíäàðíûé îñíîâàòåëü äàîñèçìà, îäíîãî èç íàèáîëåå çíà÷èòåëüíûõ òå… Èñòîðèÿ ôèëîñîôèè

Толковый словарь русского языка. Поиск по слову, типу, синониму, антониму и описанию. Словарь ударений.

лао-цзы

ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

Ла́о-Цзы — настоящее имя Ли Эр, автор древнекитайского трактата «Лао-цзы» (древнее название — «Дао дэ цзин», IV-III вв. до н. э.), каноническое сочинение даосизма. Основное понятие — дао, которое метафорически уподобляется воде (податливость и неодолимость). Вытекающий из дао образ действий — недеяние (у вэй): уступчивость, покорность, отказ от желаний и борьбы. Правитель-мудрец должен, отвергнув роскошь и войну, возвратить народ к примитивной простоте, чистоте и неведению, существовавшим до возникновения культуры и морали.

* * *

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — ЛА́О-ЦЗЫ (Ли Эр), легендарный автор древнекитайского трактата «Лао-цзы» (древнее название — «Дао дэ цзин», 4-3 вв. до н. э.), канонического сочинения даосизма (см. ДАОСИЗМ). Основное понятие трактата — дао (см. ДАО), которое метафорически уподобляется воде (податливость и неодолимость). Вытекающий из дао образ действий — недеяние (у вэй): уступчивость, покорность, отказ от желаний и борьбы. Правитель-мудрец должен, отвергнув роскошь и войну, возвратить народ к примитивной простоте, чистоте и неведению, существовавшим до возникновения культуры и морали.

* * *

ЛА́О-ЦЗЫ, легендарный древнекитайский мыслитель, основоположник религиозно-философского направления даосизма (см. ДАОСИЗМ), фигура загадочная во многих отношениях. Под этим именем, которое, скорее всего, является прозвищем и означает буквально «старый мудрец» (и даже «старый младенец»), в традиции фигурируют по крайней мере три разных персонажа.

1) Ли Эр (Лао Дань, Ли Боян, Лао Лай-цзы), уроженец деревни Цюйжэнь волости Ли уезда Ку царства Чу, родившийся в 604 до н. э. По этой версии, восходящей к главе «Жизнеописание Лао-цзы Хань Фэй-цзы» в «Исторических записках» (Ши цзи) великого историка Сыма Цяня (ок. 145-86 до н. э.), Лао-цзы служил архивистом в чжоуском книгохранилище. Встречался с Конфуцием (см. КОНФУЦИЙ), который был на 55 лет моложе его, причем эта встреча произвела на молодого Конфуция неизгладимое впечатление. К концу своей карьеры разочаровался в современной ему действительности и отправился на запад с целью навсегда покинуть Китай. В пограничной области Ханьгу (территория современной провинции Хэнань) он был остановлен неким «стражем заставы» Инь Си (Гуань Инь-цзы), по просьбе которого написал или надиктовал пять тысяч слов; так возник главный текст даосизма — книга «Дао дэ цзин» («Книга о дао и дэ»). Затем он продолжил путь в Индию, где его проповедь привела к возникновению буддизма (см. БУДДИЗМ) (Лао-цзы представляли чуть ли не отцом самого основателя буддизма — Сиддхартхи (см. СИДДХАРТХА) Гаутамы).

2) Лао-цзы был известен под именем Лао-цзюнь как высшее божество даосского пантеона и воплощение дао (см. ДАО). В одном из позднейших сказаний говорится, что он родился в 1358 до н. э. от божественной «Нефритовой девы» (Юйнюй). В честь Лао-цзы был установлен официальный культ: первые жертвы ему были принесены по приказу императора на его родине в 156 до н. э. Позднее в так называемой «народной религии» Лао-цзы (Лао-цзюнь) стал одним из трех высших божеств в пантеоне, составив, наряду с «Нефритовым Императором» (Юйхуань шанди) и «Великим Первоначальным» (Тай ши), популярную фигуру так называемых «Трех Чистых» (Сань цин), которым часто поклонялись как одному божеству.

3) Наконец, именем Лао-цзы должен быть назван и реальный автор (или авторы) философских афоризмов, собранных в книгу «Дао дэ цзин».

Пафос философствования в стиле Лао-цзы — в обличении извращений человеческой природы, вызванных навязываемой индивиду репрессивной культурой, под которой подразумевается прежде всего конфуцианская мораль, и в призывах возвратиться к неким простым и естественным отношениям в условной деревенской идиллии.

БОЛЬШОЙ ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ (Ли Эр) — легендарный автор древнекитайского трактата «Лао-цзы» (древнее название — «Дао дэ цзин», 4-3 вв. до н. э.), канонического сочинения даосизма. Основное понятие трактата — дао, которое метафорически уподобляется воде (податливость и неодолимость). Вытекающий из дао образ действий — недеяние (у вэй): уступчивость, покорность, отказ от желаний и борьбы. Правитель-мудрец должен, отвергнув роскошь и войну, возвратить народ к примитивной простоте, чистоте и неведению, существовавшим до возникновения культуры и морали.

————————————

ЛАО-ЦЗЫ — легендарный древнекитайский мыслитель, основоположник религиозно-философского направления даосизма, фигура загадочная во многих отношениях. под этим именем, которое, скорее всего, является прозвищем и означает буквально «старый мудрец» (и даже «старый младенец»), в традиции фигурируют по крайней мере три разных персонажа. 1) Ли Эр (Лао Дань, Ли Боян, Лао Лай-цзы), уроженец деревни Цюйжэнь волости Ли уезда Ку царства Чу, родившийся в 604 до н. э. По этой версии, восходящей к главе «Жизнеописание Лао-цзы Хань Фэй-цзы» в «Исторических записках» (Ши цзи) великого историка Сыма Цяня (ок. 145-86 до н.

э.), Лао-цзы служил архивистом в чжоуском книгохранилище. Встречался с Конфуцием, который был на 55 лет моложе его, причем эта встреча произвела на молодого Конфуция неизгладимое впечатление. К концу своей карьеры разочаровался в современной ему действительности и отправился на запад с целью навсегда покинуть Китай. В пограничной области Ханьгу (территория современной провинции Хэнань) он был остановлен неким «стражем заставы» Инь Си (Гуань Инь-цзы), по просьбе которого написал или надиктовал пять тысяч слов; так возник главный текст даосизма — книга «Дао дэ цзин» («Книга о дао и дэ»). Затем он продолжил путь в Индию, где его проповедь привела к возникновению буддизма (Лао-цзы представляли чуть ли не отцом самого основателя буддизма — Сиддхартхи Гаутамы).

2) Лао-цзы был известен под именем Лао-цзюнь как высшее божество даосского пантеона и воплощение дао. В одном из позднейших сказаний говорится, что он родился в 1358 до н. э. от божественной «Нефритовой девы» (Юйнюй). В честь Лао-цзы был установлен официальный культ: первые жертвы ему были принесены по приказу императора на его родине в 156 до н. э. Позднее в так называемой «народной религии» Лао-цзы (Лао-цзюнь) стал одним из трех высших божеств в пантеоне, составив, наряду с «Нефритовым Императором» (Юйхуань шанди) и «Великим Первоначальным» (Тай ши), популярную фигуру так называемых «Трех Чистых» (Сань цин), которым часто поклонялись как одному божеству.