- Русский алфавит

- Алфавиты и азбуки

- Латинский алфавит

Латинский алфавит

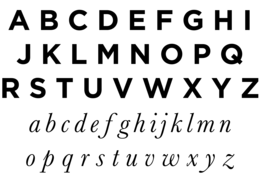

В «современном» латинском алфавите 26 букв. С таким количество букв он зафиксирован Международной организацией по стандартизации (ISO). Латинский алфавит по написанию совпадает с английским алфавитом.

100%

A aа B bбэ C cцэ D dдэ E eе/э F fэф G gгэ/жэ H hха/аш I iи J jйот/жи K kка L lэль M mэм N nэн O oо P pпэ Q qку R rэр S sэс T tтэ U uу V vвэ W wдубль-вэ X xикс Y yигрек/ипсилон Z zзед

Латинский алфавит с нумерацией: буквы в прямом и обратном порядке с указанием номера.

- Aa

1

26 - Bb

2

25 - Cc

3

24 - Dd

4

23 - Ee

5

22 - Ff

6

21 - Gg

7

20 - Hh

8

19 - Ii

9

18 - Jj

10

17 - Kk

11

16 - Ll

12

15 - Mm

13

14 - Nn

14

13 - Oo

15

12 - Pp

16

11 - Qq

17

10 - Rr

18

9 - Ss

19

8 - Tt

20

7 - Uu

21

6 - Vv

22

5 - Ww

23

4 - Xx

24

3 - Yy

25

2 - Zz

26

1

Впервые латинский язык начал использоваться в Римской Империи, откуда, ввиду масштабных завоеваний, распространился по всему миру. Латынь прочно закрепилась в первой мировой религии христианстве, что позволило ей дойти до наших дней. Именно на латыни принято было писать все священные тексты. Поскольку религия является родоначальником науки, медицины и искусства, то латынь стала основным языком в этих областях. От латинского алфавита произошли практически все известные сегодня языки: английский, французский, немецкий, русский и другие. На сегодняшний день латынь является мертвым языком и практически не используется.

| Латинский алфавит | |

|---|---|

| Тип: | консонантно-вокалическое |

| Языки: | Первоначально латинский, языки Западной и Центральной Европы, некоторые языки Азии, многие языки Африки, Америки, Австралии и Океании |

| Место возникновения: | Италия |

| Территория: | Первоначально Италия, затем вся Западная Европа, Америка, Австралия и Океания |

| Дата создания: | ~700 г. до н.э. |

| Период: | ~700 г. до н.э. по настоящее время |

| Направление письма: | слева направо |

| Знаков: | 26 |

| Происхождение: | Ханаанейское письмо

|

| Родственные: | Кириллица Коптский алфавит Армянский Руны |

|

|

| См. также: Проект:Лингвистика |

Современный латинский алфавит, являющийся основой письменности германских, романских и многих других языков, состоит из 26 букв. Буквы в разных языках называются по-разному. В таблице приведены русские и «русские математические» названия, которые следуют французской традиции.

| Латинская буква | Название буквы | Латинская буква | Название буквы | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | а | N n | эн | |

| B b | бэ | O o | о | |

| C c | це | P p | пэ | |

| D d | дэ | Q q | ку | |

| E e | е, э | R r | эр | |

| F f | эф | S s | эс | |

| G g | гэ, же | T t | тэ | |

| H h | ха, аш | U u | у | |

| I i | и | V v | вэ | |

| J j | йот, жи | W w | дубль-вэ | |

| K k | ка | X x | икс | |

| L l | эль | Y y | игрек, ипсилон | |

| M m | эм | Z z | зет, зета |

Письменность на основе латинского алфавита используют языки балтийской, германской, романской и кельтской групп, а также некоторые языки других групп: все западно- и часть южнославянских языков, некоторые финно-угорские и тюркские языки, а также албанский и вьетнамский языки.

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Модификации букв

- 3 Распространённость

- 4 Латинский алфавит как международный

- 5 См. также

- 6 Внешние ссылки

История

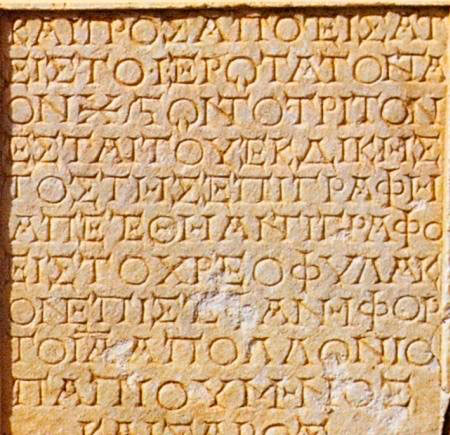

Латинский алфавит происходит от этрусского алфавита, основанного, в свою очередь, на одном из вариантов западного (южноиталийского) греческого алфавита. Латинский алфавит обособился примерно в VII веке до н.э. и первоначально включал только 21 букву:

A B C D E F Z H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X

Буква Z была исключена из алфавита в 312 г. до н. э. (позже её восстановили). Буква C использовалась для обозначения звуков [k] и [g]; в 234 г. до н. э. была создана отдельная буква G путем добавления к C поперечной черточки. В I веке до н. э. были добавлены буквы Y и Z для записи слов, заимствованных из греческого языка. В итоге получился классический латинский алфавит из 23 букв:

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z

Клавдиевы буквы

Император Клавдий безуспешно пытался добавить в латинский алфавит знаки для звуков oe (как в слове Phoebus), ps/bs (по аналогии с греческим), а также v — в отличие от u (в классическом латинском алфавите буква V использовалась для двух звуков, U и V). После смерти Клавдия «Клавдиевы буквы» были забыты.

Уже в новое время произошла дифференциация слоговых и неслоговых вариантов букв I и V (I/J и U/V), а также стал считаться отдельной буквой диграф VV, использующийся в письме германских языков. В итоге получился современный алфавит из 26 букв:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Однако, когда говорят об алфавите собственно латинского языка, то W чаще всего не включают в состав букв (тогда латинский алфавит состоит из 25 букв).

В средние века в скандинавских и английском алфавитах использовалась руническая буква þ (название: thorn) для звука th (как в современном английском the), однако позднее она вышла из употребления. В настоящее время thorn используется только в исландском алфавите.

Все прочие добавочные знаки современных латинских алфавитов происходят от указанных выше 26 букв с добавлением диакритических знаков или в виде лигатур (немецкая буква ß происходит из готической лигатуры букв S и Z).

Древние римляне использовали только заглавные формы букв; современные строчные буквы появились на рубеже античности и средних веков; в целом буквы в своем современном виде оформились около 800 года н. э. (так называемый каролингский минускул)

Модификации букв

Для большинства языков обычного латинского алфавита недостаточно, поэтому часто используются разные диакритические знаки, лигатуры и другие модификации букв. Примеры:

Ā Ă Â Ä Å Æ Ç Ð Ē Ğ Ģ Î Ķ Ł Ñ Ö Ø Œ ß Ş Ţ Ū Ŭ Þ Ž

Распространённость

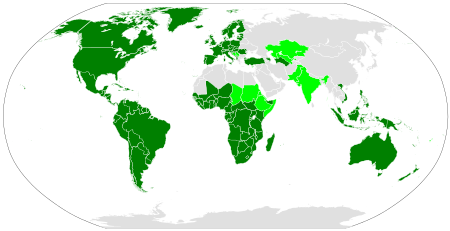

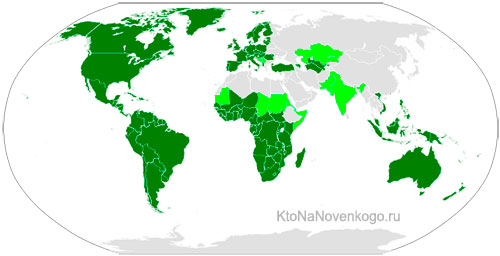

На схеме показана распространённость латинского алфавита в мире. Тёмно-зелёным цветом обозначены страны, в которых латинский алфавит является единственной письменностью; светло-зелёным — государства, в которых латинский алфавит используется наряду с другими письменностями.

Латинский алфавит как международный

В настоящее время латинский алфавит знако́м почти всем людям Земли, поскольку изучается всеми школьниками либо на уроках математики, либо на уроках иностранного языка (не говоря уже о том, что для многих языков латинский алфавит является родным), поэтому он де-факто является «алфавитом международного общения».

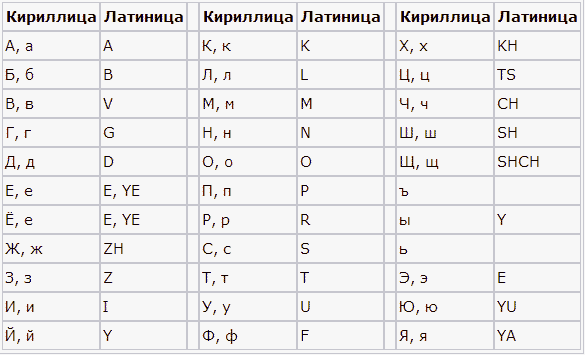

Для всех языков с нелатинской письменностью существуют также системы записи латиницей — даже если иностранец и не знает правильного чтения, ему гораздо легче иметь дело со знакомыми латинскими буквами, чем с «китайской грамотой». В ряде стран вспомогательное письмо латиницей стандартизировано и дети изучают его в школе (в Японии, Китае).

Запись латиницей в ряде случаев диктуется техническими трудностями: международные телеграммы всегда писались латиницей; в электронной почте и на веб-форумах также часто можно встретить запись русского языка латиницей из-за отсутствия поддержки кириллицы или из-за несовпадения кодировок (см. транслит; то же относится и к греческому языку).

С другой стороны, в текстах на нелатинском алфавите иностранные названия нередко оставляют латиницей из-за отсутствия общепринятого и легко узнаваемого написания в своей системе. Дело доходит до того, что в русском тексте и японские названия иногда пишут латиницей, хотя японский язык использует свою собственную систему письма, а вовсе не латиницу.

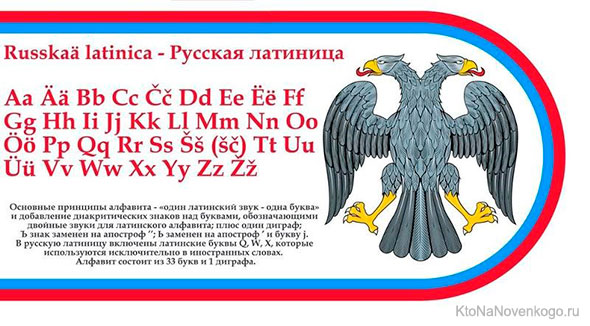

Неоднократно выдвигалась идея перевода всех языков на латинское письмо — например, в СССР в 1920-х годах (см. латинизация). Сторонником глобальной латинизации был также известный датский лингвист Отто Есперсен.

См. также

- Латинское произношение и орфография

- Алфавиты на основе латинского

- Латинский алфавит в Юникоде

- Латинизация — проект по переводу письменностей народов СССР на латиницу

- Авиационный алфавит

Внешние ссылки

- Лингвистический энциклопедический словарь (1990) / Латинское письмо

|

Письменности мира |

||

|---|---|---|

| Общие статьи | История письменности • Графема • Дешифровка • Палеография |  |

| Списки | Список письменностей • Список языков по системам письма • Список письменностей по количеству носителей • Список письменностей по времени создания • Список нерасшифрованных письменностей • Список создателей письменности | |

| Типы | ||

| Консонантные | Арамейское • Арабское • Джави • Древнеливийское • Еврейское • Набатейское • Пахлави • Самаритянское • Сирийское • Согдийское • Угаритское • Финикийское • Южноаравийское | |

| Абугиды |

Индийские письменности: Балийское • Батак • Бирманское • Брахми • Бухидское • Варанг-кшити • Восточное нагари • Грантха • Гуджарати • Гупта • Гурмукхи • Деванагари • Кадамба • Кайтхи • Калинга • Каннада • Кхмерское • Ланна • Лаосское • Лепча • Лимбу • Лонтара • Малаялам • Манипури • Митхилакшар • Моди • Мон • Монгольское квадратное письмо • Нагари • Непальское • Ория • Паллава • Ранджана • Реджанг • Саураштра • Сиддхаматрика • Сингальское • Соёмбо • Суданское • Тагальское • Тагбанва • Такри • Тамильское • Телугу • Тайское • Тибетское • Тохарское • Хануноо • Хуннское • Шарада • Яванское Другие: Скоропись Бойда • Канадское слоговое письмо • Кхароштхи • Мероитское • Скоропись Питмана • Письмо Полларда • Соранг Сомпенг • Тана • Скоропись Томаса • Эфиопское |

|

| Алфавиты |

Линейные: Авестийский • Агванский • Армянский • Басса • Глаголица • Готский • Скоропись Грегга • Греко-иберийский • Греческий • Грузинский • Древневенгерский • Древнепермский • Древнетюркский • Кириллица • Коптское • Латиница • Мандейский • Малоазийские алфавиты • Международный фонетический • Маньчжурский • Нко • Obɛri ɔkaimɛ • Огамический • Ол Чики • Рунический • Северноэтрусские алфавиты • Сомалийский • Старомонгольский • Тифинаг • Этрусский • Хангыль Нелинейные: Шрифт Брайля • Азбука Морзе • Шрифт Муна • Оптический телеграф • Русская семафорная азбука • Флаги международного свода сигналов |

|

| Идео- и Пиктограммы | Ацтекское • Донгба • Микмак • Миштекское письмо • Мезоамериканские системы письма • Нсибиди | |

| Логографические |

Китайское письмо: Традиционное • Упрощённое • Тьы-ном • Кандзи • Ханчча Лого-консонантное: Демотическое • Египетское иероглифическое • Иератическое |

|

| Слоговые | Афака • Ваи • Геба • Древнеперсидское • И (современное) • Катакана • Кикакуи • Кипрское • Кпелле • Линейное письмо Б • Манъёгана • Нюй-шу • Хирагана • Чероки • Югтун | |

| Переходные | Иберское • Кельтиберское • Чжуинь | |

| Недешифрованные | Библское • Иссыкское • Кипро-минойское • Критские «иероглифы» • Линейное письмо А (частично) • Миштекское письмо • Письменность Цзяху • Символы культуры полей погребальных урн • Синайское • Табличка из Диспилио • Тэртэрийские надписи • Фестский диск • Ханаанейское | |

| Вымышленные и мнимые | Славянские руны • Тенгвар | |

| Мнемонические приёмы | Кипу |

| Латинский алфавит |

|---|

| Aa Bb Cc Dd Ee Ff Gg Hh Ii Jj Kk Ll Mm Nn Oo Pp Qq Rr Ss Tt Uu Vv Ww Xx Yy Zz |

| Ää Öö Üü ß ſ Åå Ææ Œœ Øø Çç Ðð Þþ Ññ Ũũ Ó |

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

For the Latin script originally used by the ancient Romans to write Latin, see Latin alphabet.

| Latin

Roman |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c. 700 BC – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

Official script in: 132 sovereign states

Co-official script in: 15 sovereign states

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

|

Child systems |

|

|

Sister systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

See Latin characters in Unicode |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern Italy (Magna Grecia). It was adopted by the Etruscans and subsequently by the Romans. Several Latin-script alphabets exist, which differ in graphemes, collation and phonetic values from the classical Latin alphabet.

The Latin script is the basis of the International Phonetic Alphabet, and the 26 most widespread letters are the letters contained in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

Latin script is the basis for the largest number of alphabets of any writing system[1] and is the

most widely adopted writing system in the world. Latin script is used as the standard method of writing for most western, central, and to a lesser extent some eastern European languages, as well as many languages in other parts of the world.

Name[edit]

The script is either called Latin script or Roman script, in reference to its origin in ancient Rome (though some of the capital letters are Greek in origin). In the context of transliteration, the term «romanization» (British English: «romanisation») is often found.[2][3] Unicode uses the term «Latin»[4] as does the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).[5]

The numeral system is called the Roman numeral system, and the collection of the elements is known as the Roman numerals. The numbers 1, 2, 3 … are Latin/Roman script numbers for the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.

History[edit]

Old Italic alphabet[edit]

| Letters | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Vv | Zz | Hh | Θθ | Ii | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Éé | Oo | Pp | Śś | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Xx | Φφ | Ψψ | Ff |

Archaic Latin alphabet[edit]

| As Old Italic | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Latin | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Zz | Hh | Ii | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Vv Uu | X |

The letter ⟨C⟩ was the western form of the Greek gamma, but it was used for the sounds /ɡ/ and /k/ alike, possibly under the influence of Etruscan, which might have lacked any voiced plosives. Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the letter ⟨Z⟩ – unneeded to write Latin properly – was replaced with the new letter ⟨G⟩, a ⟨C⟩ modified with a small horizontal stroke, which took its place in the alphabet. From then on, ⟨G⟩ represented the voiced plosive /ɡ/, while ⟨C⟩ was generally reserved for the voiceless plosive /k/. The letter ⟨K⟩ was used only rarely, in a small number of words such as Kalendae, often interchangeably with ⟨C⟩.

Classical Latin alphabet[edit]

After the Roman conquest of Greece in the 1st century BC, Latin adopted the Greek letters ⟨Y⟩ and ⟨Z⟩ (or readopted, in the latter case) to write Greek loanwords, placing them at the end of the alphabet. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters did not last. Thus it was during the classical Latin period that the Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:Italic text

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name (majus) | á | bé | cé | dé | é | ef | gé | há | ꟾ | ká | el | em | en | ó | pé | qv́ | er | es | té | v́ | ix | ꟾ graeca | zéta |

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ix | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation (IPA) | aː | beː | keː | deː | eː | ɛf | ɡeː | haː | iː | kaː | ɛl | ɛm | ɛn | oː | peː | kuː | ɛr | ɛs | teː | uː | iks | iː ˈɡraeka | ˈdzeːta |

Medieval and later developments[edit]

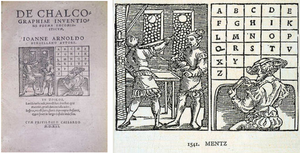

De chalcographiae inventione (1541, Mainz) with the 23 letters. J, U and W are missing.

It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter ⟨W⟩ (originally a ligature of two ⟨V⟩s) was added to the Latin alphabet, to represent sounds from the Germanic languages which did not exist in medieval Latin, and only after the Renaissance did the convention of treating ⟨I⟩ and ⟨U⟩ as vowels, and ⟨J⟩ and ⟨V⟩ as consonants, become established. Prior to that, the former had been merely allographs of the latter.[citation needed]

With the fragmentation of political power, the style of writing changed and varied greatly throughout the Middle Ages, even after the invention of the printing press. Early deviations from the classical forms were the uncial script, a development of the Old Roman cursive, and various so-called minuscule scripts that developed from New Roman cursive, of which the insular script developed by Irish literati & derivations of this, such as Carolingian minuscule were the most influential, introducing the lower case forms of the letters, as well as other writing conventions that have since become standard.

The languages that use the Latin script generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized, whereas Modern English writers and printers of the 17th and 18th century frequently capitalized most and sometimes all nouns[6] – e.g. in the preamble and all of the United States Constitution – a practice still systematically used in Modern German.

ISO basic Latin alphabet[edit]

| Uppercase Latin alphabet | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase Latin alphabet | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

The use of the letters I and V for both consonants and vowels proved inconvenient as the Latin alphabet was adapted to Germanic and Romance languages. W originated as a doubled V (VV) used to represent the Voiced labial–velar approximant /w/ found in Old English as early as the 7th century. It came into common use in the later 11th century, replacing the letter wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩, which had been used for the same sound. In the Romance languages, the minuscule form of V was a rounded u; from this was derived a rounded capital U for the vowel in the 16th century, while a new, pointed minuscule v was derived from V for the consonant. In the case of I, a word-final swash form, j, came to be used for the consonant, with the un-swashed form restricted to vowel use. Such conventions were erratic for centuries. J was introduced into English for the consonant in the 17th century (it had been rare as a vowel), but it was not universally considered a distinct letter in the alphabetic order until the 19th century.

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

Spread[edit]

The distribution of the Latin script. The dark green areas show the countries where the Latin script is the sole main script. Light green shows countries where Latin co-exists with other scripts. Latin-script alphabets are sometimes extensively used in areas coloured grey due to the use of unofficial second languages, such as French in Algeria and English in Egypt, and to Latin transliteration of the official script, such as pinyin in China.

The Latin alphabet spread, along with Latin, from the Italian Peninsula to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet.

Middle Ages[edit]

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted by the peoples of Northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets) or Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian.

The Latin script also came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism. The speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted Cyrillic along with Orthodox Christianity. The Serbian language uses both scripts, with Cyrillic predominating in official communication and Latin elsewhere, as determined by the Law on Official Use of the Language and Alphabet.[7]

Since the 16th century[edit]

As late as 1500, the Latin script was limited primarily to the languages spoken in Western, Northern, and Central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of Eastern and Southeastern Europe mostly used Cyrillic, and the Greek alphabet was in use by Greek speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic script was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Through European colonization the Latin script has spread to the Americas, Oceania, parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, in forms based on the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, German and Dutch alphabets.

It is used for many Austronesian languages, including the languages of the Philippines and the Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. Latin letters served as the basis for the forms of the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah; however, the sound values are completely different.[citation needed]

Under Portuguese missionary influence, a Latin alphabet was devised for the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters. The Latin-based alphabet replaced the Chinese characters in administration in the 19th century with French rule.

Since the 19th century[edit]

In the late 19th century, the Romanians switched to the Latin alphabet, which they had used until the Council of Florence in 1439,[8] primarily because Romanian is a Romance language. The Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and their Church, increasingly influenced by Russia after the fall of Byzantine Greek Constantinople in 1453 and capture of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, had begun promoting the Slavic Cyrillic.

Since 20th century[edit]

In 1928, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s reforms, the new Republic of Turkey adopted a Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing a modified Arabic alphabet. Most of the Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and others, had their writing systems replaced by the Latin-based Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s; but, in the 1940s, all were replaced by Cyrillic.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, three of the newly independent Turkic-speaking republics, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, as well as Romanian-speaking Moldova, officially adopted Latin alphabets for their languages. Kyrgyzstan, Iranian-speaking Tajikistan, and the breakaway region of Transnistria kept the Cyrillic alphabet, chiefly due to their close ties with Russia.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of Kurds replaced the Arabic script with two Latin alphabets. Although only the official Kurdish government uses an Arabic alphabet for public documents, the Latin Kurdish alphabet remains widely used throughout the region by the majority of Kurdish-speakers.

In 1957, the People’s Republic of China introduced a script reform to the Zhuang language, changing its orthography from Sawndip, a writing system based on Chinese, to a Latin script alphabet that used a mixture of Latin, Cyrillic, and IPA letters to represent both the phonemes and tones of the Zhuang language, without the use of diacritics. In 1982 this was further standardised to use only Latin script letters.

With the collapse of the Derg and subsequent end of decades of Amharic assimilation in 1991, various ethnic groups in Ethiopia dropped the Geʽez script, which was deemed unsuitable for languages outside of the Semitic branch.[9] In the following years the Kafa,[10] Oromo,[11] Sidama,[12] Somali,[12] and Wolaitta[12] languages switched to Latin while there is continued debate on whether to follow suit for the Hadiyya and Kambaata languages.[13]

21st century[edit]

On 15 September 1999 the authorities of Tatarstan, Russia, passed a law to make the Latin script a co-official writing system alongside Cyrillic for the Tatar language by 2011.[14] A year later, however, the Russian government overruled the law and banned Latinization on its territory.[15]

In 2015, the government of Kazakhstan announced that a Kazakh Latin alphabet would replace the Kazakh Cyrillic alphabet as the official writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.[16] There are also talks about switching from the Cyrillic script to Latin in Ukraine,[17] Kyrgyzstan,[18][19] and Mongolia.[20] Mongolia, however, has since opted to revive the Mongolian script instead of switching to Latin.[21]

In October 2019, the organization National Representational Organization for Inuit in Canada (ITK) announced that they will introduce a unified writing system for the Inuit languages in the country. The writing system is based on the Latin alphabet and is modeled after the one used in the Greenlandic language.[22]

On 12 February 2021 the government of Uzbekistan announced it will finalize the transition from Cyrillic to Latin for the Uzbek language by 2023. Plans to switch to Latin originally began in 1993 but subsequently stalled and Cyrillic remained in widespread use.[23][24]

At present the Crimean Tatar language uses both Cyrillic and Latin. The use of Latin was originally approved by Crimean Tatar representatives after the Soviet Union’s collapse[25] but was never implemented by the regional government. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 the Latin script was dropped entirely. Nevertheless Crimean Tatars outside of Crimea continue to use Latin and on 22 October 2021 the government of Ukraine approved a proposal endorsed by the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People to switch the Crimean Tatar language to Latin by 2025.[26]

In July 2020, 2.6 billion people (36% of the world population) use the Latin alphabet.[27]

International standards[edit]

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage.

As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

National standards[edit]

The DIN standard DIN 91379 specifies a subset of Unicode letters, special characters, and sequences of letters and diacritic signs to allow the correct representation of names and to simplify data exchange in Europe. This specification supports all official languages of European Union countries (thus also Greek and Cyrillic for Bulgarian) as well as the official languages of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, and also the German minority languages. To allow the transliteration of names in other writing systems to the Latin script according to the relevant ISO standards all necessary combinations of base letters and diacritic signs are provided.[28]

Efforts are being made to further develop it into a European CEN standard.[29]

As used by various languages[edit]

In the course of its use, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use in new languages, sometimes representing phonemes not found in languages that were already written with the Roman characters. To represent these new sounds, extensions were therefore created, be it by adding diacritics to existing letters, by joining multiple letters together to make ligatures, by creating completely new forms, or by assigning a special function to pairs or triplets of letters. These new forms are given a place in the alphabet by defining an alphabetical order or collation sequence, which can vary with the particular language.

Letters[edit]

Some examples of new letters to the standard Latin alphabet are the Runic letters wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨Þ þ⟩, and the letter eth ⟨Ð/ð⟩, which were added to the alphabet of Old English. Another Irish letter, the insular g, developed into yogh ⟨Ȝ ȝ⟩, used in Middle English. Wynn was later replaced with the new letter ⟨w⟩, eth and thorn with ⟨th⟩, and yogh with ⟨gh⟩. Although the four are no longer part of the English or Irish alphabets, eth and thorn are still used in the modern Icelandic alphabet, while eth is also used by the Faroese alphabet.

Some West, Central and Southern African languages use a few additional letters that have sound values similar to those of their equivalents in the IPA. For example, Adangme uses the letters ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩, and Ga uses ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩, ⟨Ŋ ŋ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩. Hausa uses ⟨Ɓ ɓ⟩ and ⟨Ɗ ɗ⟩ for implosives, and ⟨Ƙ ƙ⟩ for an ejective. Africanists have standardized these into the African reference alphabet.

Dotted and dotless I — ⟨İ i⟩ and ⟨I ı⟩ — are two forms of the letter I used by the Turkish, Azerbaijani, and Kazakh alphabets.[30] The Azerbaijani language also has ⟨Ə ə⟩, which represents the near-open front unrounded vowel.

Multigraphs[edit]

A digraph is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters in sequence. Examples are ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩, ⟨rh⟩, ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨th⟩ in English, and ⟨ij⟩, ⟨ee⟩, ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨ei⟩ in Dutch. In Dutch the ⟨ij⟩ is capitalized as ⟨IJ⟩ or the ligature ⟨IJ⟩, but never as ⟨Ij⟩, and it often takes the appearance of a ligature ⟨ij⟩ very similar to the letter ⟨ÿ⟩ in handwriting.

A trigraph is made up of three letters, like the German ⟨sch⟩, the Breton ⟨c’h⟩ or the Milanese ⟨oeu⟩. In the orthographies of some languages, digraphs and trigraphs are regarded as independent letters of the alphabet in their own right. The capitalization of digraphs and trigraphs is language-dependent, as only the first letter may be capitalized, or all component letters simultaneously (even for words written in title case, where letters after the digraph or trigraph are left in lowercase).

Ligatures[edit]

A ligature is a fusion of two or more ordinary letters into a new glyph or character. Examples are ⟨Æ æ⟩ (from ⟨AE⟩, called «ash»), ⟨Œ œ⟩ (from ⟨OE⟩, sometimes called «oethel»), the abbreviation ⟨&⟩ (from Latin: et, lit. ‘and’, called «ampersand»), and ⟨ẞ ß⟩ (from ⟨ſʒ⟩ or ⟨ſs⟩, the archaic medial form of ⟨s⟩, followed by an ⟨ʒ⟩ or ⟨s⟩, called «sharp S» or «eszett»).

Diacritics[edit]

A diacritic, in some cases also called an accent, is a small symbol that can appear above or below a letter, or in some other position, such as the umlaut sign used in the German characters ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ or the Romanian characters ă, â, î, ș, ț. Its main function is to change the phonetic value of the letter to which it is added, but it may also modify the pronunciation of a whole syllable or word, indicate the start of a new syllable, or distinguish between homographs such as the Dutch words een (pronounced [ən]) meaning «a» or «an», and één, (pronounced [e:n]) meaning «one». As with the pronunciation of letters, the effect of diacritics is language-dependent.

English is the only major modern European language that requires no diacritics for its native vocabulary[note 1]. Historically, in formal writing, a diaeresis was sometimes used to indicate the start of a new syllable within a sequence of letters that could otherwise be misinterpreted as being a single vowel (e.g., “coöperative”, “reëlect”), but modern writing styles either omit such marks or use a hyphen to indicate a syllable break (e.g. “cooperative”, “re-elect”). [note 2][31]

Collation[edit]

Some modified letters, such as the symbols ⟨å⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ö⟩, may be regarded as new individual letters in themselves, and assigned a specific place in the alphabet for collation purposes, separate from that of the letter on which they are based, as is done in Swedish. In other cases, such as with ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ in German, this is not done; letter-diacritic combinations being identified with their base letter. The same applies to digraphs and trigraphs. Different diacritics may be treated differently in collation within a single language. For example, in Spanish, the character ⟨ñ⟩ is considered a letter, and sorted between ⟨n⟩ and ⟨o⟩ in dictionaries, but the accented vowels ⟨á⟩, ⟨é⟩, ⟨í⟩, ⟨ó⟩, ⟨ú⟩, ⟨ü⟩ are not separated from the unaccented vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩.

Capitalization[edit]

The languages that use the Latin script today generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized; whereas Modern English of the 18th century had frequently all nouns capitalized, in the same way that Modern German is written today, e.g. German: Alle Schwestern der alten Stadt hatten die Vögel gesehen, lit. ‘All of the sisters of the old city had seen the birds’.

Romanization[edit]

Words from languages natively written with other scripts, such as Arabic or Chinese, are usually transliterated or transcribed when embedded in Latin-script text or in multilingual international communication, a process termed romanization.

Whilst the romanization of such languages is used mostly at unofficial levels, it has been especially prominent in computer messaging where only the limited seven-bit ASCII code is available on older systems. However, with the introduction of Unicode, romanization is now becoming less necessary. Note that keyboards used to enter such text may still restrict users to romanized text, as only ASCII or Latin-alphabet characters may be available.

See also[edit]

- List of languages by writing system#Latin script

- Western Latin character sets (computing)

- European Latin Unicode subset (DIN 91379)

- Latin letters used in mathematics

- Latin omega

Notes[edit]

- ^ In formal English writing, however, diacritics are often preserved on many loanwords, such as «café», «naïve», «façade», «jalapeño» or the German prefix «über-«.

- ^ As an example, an article containing a diaeresis in «coöperate» and a cedilla in «façade» as well as a circumflex in the word «crêpe»: Grafton, Anthony (23 October 2006). «Books: The Nutty Professors, The history of academic charisma». The New Yorker.

- ^ Alongside Chinese and Tamil

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Haarmann 2004, p. 96.

- ^ «Search results | BSI Group». Bsigroup.com. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «Romanisation_systems». Pcgn.org.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «ISO 15924 – Code List in English». Unicode.org. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ «Search – ISO». Iso.org. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521530330 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Zakon O Službenoj Upotrebi Jezika I Pisama» (PDF). Ombudsman.rs. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ «Descriptio_Moldaviae». La.wikisource.org. 1714. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Smith, Lahra (2013). «Review of Making Citizens in Africa: Ethnicity, Gender, and National Identity in Ethiopia«. African Studies. 125 (3): 542–544. doi:10.1080/00083968.2015.1067017. S2CID 148544393 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Pütz, Martin (1997). Language Choices: Conditions, constraints, and consequences. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 216. ISBN 9789027275844.

- ^ Gemeda, Guluma (18 June 2018). «The History and Politics of the Qubee Alphabet». Ayyaantuu. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Yohannes, Mekonnen (2021). «Language Policy in Ethiopia: The Interplay Between Policy and Practice in Tigray Regional State». Language Policy. 24: 33. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63904-4. ISBN 978-3-030-63903-7. S2CID 234114762 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Pasch, Helma (2008). «Competing scripts: The Introduction of the Roman Alphabet in Africa» (PDF). International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 191: 8 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Andrews, Ernest (2018). Language Planning in the Post-Communist Era: The Struggles for Language Control in the New Order in Eastern Europe, Eurasia and China. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-319-70926-0.

- ^ Faller, Helen (2011). Nation, Language, Islam: Tatarstan’s Sovereignty Movement. Central European University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-963-9776-84-5.

- ^ Kazakh language to be converted to Latin alphabet – MCS RK. Inform.kz (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ «Klimkin welcomes discussion on switching to Latin alphabet in Ukraine». UNIAN (27 March 2018).

- ^ «Moscow Bribes Bishkek to Stop Kyrgyzstan From Changing to Latin Alphabet». The Jamestown Organization (12 October 2017).

- ^ «Kyrgyzstan: Latin (alphabet) fever takes hold». Eurasianet (13 September 2019).

- ^ «Russian Influence in Mongolia is Declining». Global Security Review (2 March 2019). 2 March 2019.

- ^ Tang, Didi (20 March 2020). «Mongolia abandons Soviet past by restoring alphabet». The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ «Canadian Inuit Get Common Written Language». High North News (8 October 2019).

- ^ Sands, David (12 February 2021). «Latin lives! Uzbeks prepare latest switch to Western-based alphabet». The Washington Times. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ «Uzbekistan Aims For Full Transition To Latin-Based Alphabet By 2023». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (2007). Ukraine — Crimea — Russia: Triangle of Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-3-8382-5761-7.

- ^ «Cabinet approves Crimean Tatar alphabet based on Latin letters». Ukrinform. 22 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ «The world’s scripts and alphabets». WorldStandards. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ «DIN 91379:2022-08: Characters and defined character sequences in Unicode for the electronic processing of names and data exchange in Europe, with CD-ROM». Beuth Verlag. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^

Koordinierungsstelle für IT-Standards (KoSIT). «String.Latin+ 1.2: eine kommentierte und erweiterte Fassung der DIN SPEC 91379. Inklusive einer umfangreichen Liste häufig gestellter Fragen. Herausgegeben von der Fachgruppe String.Latin. (zip, 1.7 MB)» [String.Latin+ 1.2: Commented and extended version of DIN SPEC 91379.] (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2022. - ^ «Localize Your Font: Turkish i». Glyphs. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ «The New Yorker’s odd mark — the diaeresis». 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

Sources[edit]

- Haarmann, Harald (2004). Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

Further reading[edit]

- Boyle, Leonard E. 1976. «Optimist and recensionist: ‘Common errors’ or ‘common variations.'» In Latin script and letters A.D. 400–900: Festschrift presented to Ludwig Bieler on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Edited by John J. O’Meara and Bernd Naumann, 264–74. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Morison, Stanley. 1972. Politics and script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. Oxford: Clarendon.

External links[edit]

- Unicode collation chart—Latin letters sorted by shape

- Diacritics Project – All you need to design a font with correct accents

For the Latin script originally used by the ancient Romans to write Latin, see Latin alphabet.

| Latin

Roman |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c. 700 BC – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

Official script in: 132 sovereign states

Co-official script in: 15 sovereign states

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

|

Child systems |

|

|

Sister systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

See Latin characters in Unicode |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern Italy (Magna Grecia). It was adopted by the Etruscans and subsequently by the Romans. Several Latin-script alphabets exist, which differ in graphemes, collation and phonetic values from the classical Latin alphabet.

The Latin script is the basis of the International Phonetic Alphabet, and the 26 most widespread letters are the letters contained in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

Latin script is the basis for the largest number of alphabets of any writing system[1] and is the

most widely adopted writing system in the world. Latin script is used as the standard method of writing for most western, central, and to a lesser extent some eastern European languages, as well as many languages in other parts of the world.

Name[edit]

The script is either called Latin script or Roman script, in reference to its origin in ancient Rome (though some of the capital letters are Greek in origin). In the context of transliteration, the term «romanization» (British English: «romanisation») is often found.[2][3] Unicode uses the term «Latin»[4] as does the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).[5]

The numeral system is called the Roman numeral system, and the collection of the elements is known as the Roman numerals. The numbers 1, 2, 3 … are Latin/Roman script numbers for the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.

History[edit]

Old Italic alphabet[edit]

| Letters | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Vv | Zz | Hh | Θθ | Ii | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Éé | Oo | Pp | Śś | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Xx | Φφ | Ψψ | Ff |

Archaic Latin alphabet[edit]

| As Old Italic | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Latin | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Zz | Hh | Ii | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Vv Uu | X |

The letter ⟨C⟩ was the western form of the Greek gamma, but it was used for the sounds /ɡ/ and /k/ alike, possibly under the influence of Etruscan, which might have lacked any voiced plosives. Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the letter ⟨Z⟩ – unneeded to write Latin properly – was replaced with the new letter ⟨G⟩, a ⟨C⟩ modified with a small horizontal stroke, which took its place in the alphabet. From then on, ⟨G⟩ represented the voiced plosive /ɡ/, while ⟨C⟩ was generally reserved for the voiceless plosive /k/. The letter ⟨K⟩ was used only rarely, in a small number of words such as Kalendae, often interchangeably with ⟨C⟩.

Classical Latin alphabet[edit]

After the Roman conquest of Greece in the 1st century BC, Latin adopted the Greek letters ⟨Y⟩ and ⟨Z⟩ (or readopted, in the latter case) to write Greek loanwords, placing them at the end of the alphabet. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters did not last. Thus it was during the classical Latin period that the Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:Italic text

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name (majus) | á | bé | cé | dé | é | ef | gé | há | ꟾ | ká | el | em | en | ó | pé | qv́ | er | es | té | v́ | ix | ꟾ graeca | zéta |

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ix | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation (IPA) | aː | beː | keː | deː | eː | ɛf | ɡeː | haː | iː | kaː | ɛl | ɛm | ɛn | oː | peː | kuː | ɛr | ɛs | teː | uː | iks | iː ˈɡraeka | ˈdzeːta |

Medieval and later developments[edit]

De chalcographiae inventione (1541, Mainz) with the 23 letters. J, U and W are missing.

It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter ⟨W⟩ (originally a ligature of two ⟨V⟩s) was added to the Latin alphabet, to represent sounds from the Germanic languages which did not exist in medieval Latin, and only after the Renaissance did the convention of treating ⟨I⟩ and ⟨U⟩ as vowels, and ⟨J⟩ and ⟨V⟩ as consonants, become established. Prior to that, the former had been merely allographs of the latter.[citation needed]

With the fragmentation of political power, the style of writing changed and varied greatly throughout the Middle Ages, even after the invention of the printing press. Early deviations from the classical forms were the uncial script, a development of the Old Roman cursive, and various so-called minuscule scripts that developed from New Roman cursive, of which the insular script developed by Irish literati & derivations of this, such as Carolingian minuscule were the most influential, introducing the lower case forms of the letters, as well as other writing conventions that have since become standard.

The languages that use the Latin script generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized, whereas Modern English writers and printers of the 17th and 18th century frequently capitalized most and sometimes all nouns[6] – e.g. in the preamble and all of the United States Constitution – a practice still systematically used in Modern German.

ISO basic Latin alphabet[edit]

| Uppercase Latin alphabet | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase Latin alphabet | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

The use of the letters I and V for both consonants and vowels proved inconvenient as the Latin alphabet was adapted to Germanic and Romance languages. W originated as a doubled V (VV) used to represent the Voiced labial–velar approximant /w/ found in Old English as early as the 7th century. It came into common use in the later 11th century, replacing the letter wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩, which had been used for the same sound. In the Romance languages, the minuscule form of V was a rounded u; from this was derived a rounded capital U for the vowel in the 16th century, while a new, pointed minuscule v was derived from V for the consonant. In the case of I, a word-final swash form, j, came to be used for the consonant, with the un-swashed form restricted to vowel use. Such conventions were erratic for centuries. J was introduced into English for the consonant in the 17th century (it had been rare as a vowel), but it was not universally considered a distinct letter in the alphabetic order until the 19th century.

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

Spread[edit]

The distribution of the Latin script. The dark green areas show the countries where the Latin script is the sole main script. Light green shows countries where Latin co-exists with other scripts. Latin-script alphabets are sometimes extensively used in areas coloured grey due to the use of unofficial second languages, such as French in Algeria and English in Egypt, and to Latin transliteration of the official script, such as pinyin in China.

The Latin alphabet spread, along with Latin, from the Italian Peninsula to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet.

Middle Ages[edit]

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted by the peoples of Northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets) or Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian.

The Latin script also came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism. The speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted Cyrillic along with Orthodox Christianity. The Serbian language uses both scripts, with Cyrillic predominating in official communication and Latin elsewhere, as determined by the Law on Official Use of the Language and Alphabet.[7]

Since the 16th century[edit]

As late as 1500, the Latin script was limited primarily to the languages spoken in Western, Northern, and Central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of Eastern and Southeastern Europe mostly used Cyrillic, and the Greek alphabet was in use by Greek speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic script was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Through European colonization the Latin script has spread to the Americas, Oceania, parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, in forms based on the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, German and Dutch alphabets.

It is used for many Austronesian languages, including the languages of the Philippines and the Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. Latin letters served as the basis for the forms of the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah; however, the sound values are completely different.[citation needed]

Under Portuguese missionary influence, a Latin alphabet was devised for the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters. The Latin-based alphabet replaced the Chinese characters in administration in the 19th century with French rule.

Since the 19th century[edit]

In the late 19th century, the Romanians switched to the Latin alphabet, which they had used until the Council of Florence in 1439,[8] primarily because Romanian is a Romance language. The Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and their Church, increasingly influenced by Russia after the fall of Byzantine Greek Constantinople in 1453 and capture of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, had begun promoting the Slavic Cyrillic.

Since 20th century[edit]

In 1928, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s reforms, the new Republic of Turkey adopted a Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing a modified Arabic alphabet. Most of the Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and others, had their writing systems replaced by the Latin-based Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s; but, in the 1940s, all were replaced by Cyrillic.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, three of the newly independent Turkic-speaking republics, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, as well as Romanian-speaking Moldova, officially adopted Latin alphabets for their languages. Kyrgyzstan, Iranian-speaking Tajikistan, and the breakaway region of Transnistria kept the Cyrillic alphabet, chiefly due to their close ties with Russia.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of Kurds replaced the Arabic script with two Latin alphabets. Although only the official Kurdish government uses an Arabic alphabet for public documents, the Latin Kurdish alphabet remains widely used throughout the region by the majority of Kurdish-speakers.

In 1957, the People’s Republic of China introduced a script reform to the Zhuang language, changing its orthography from Sawndip, a writing system based on Chinese, to a Latin script alphabet that used a mixture of Latin, Cyrillic, and IPA letters to represent both the phonemes and tones of the Zhuang language, without the use of diacritics. In 1982 this was further standardised to use only Latin script letters.

With the collapse of the Derg and subsequent end of decades of Amharic assimilation in 1991, various ethnic groups in Ethiopia dropped the Geʽez script, which was deemed unsuitable for languages outside of the Semitic branch.[9] In the following years the Kafa,[10] Oromo,[11] Sidama,[12] Somali,[12] and Wolaitta[12] languages switched to Latin while there is continued debate on whether to follow suit for the Hadiyya and Kambaata languages.[13]

21st century[edit]

On 15 September 1999 the authorities of Tatarstan, Russia, passed a law to make the Latin script a co-official writing system alongside Cyrillic for the Tatar language by 2011.[14] A year later, however, the Russian government overruled the law and banned Latinization on its territory.[15]

In 2015, the government of Kazakhstan announced that a Kazakh Latin alphabet would replace the Kazakh Cyrillic alphabet as the official writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.[16] There are also talks about switching from the Cyrillic script to Latin in Ukraine,[17] Kyrgyzstan,[18][19] and Mongolia.[20] Mongolia, however, has since opted to revive the Mongolian script instead of switching to Latin.[21]

In October 2019, the organization National Representational Organization for Inuit in Canada (ITK) announced that they will introduce a unified writing system for the Inuit languages in the country. The writing system is based on the Latin alphabet and is modeled after the one used in the Greenlandic language.[22]

On 12 February 2021 the government of Uzbekistan announced it will finalize the transition from Cyrillic to Latin for the Uzbek language by 2023. Plans to switch to Latin originally began in 1993 but subsequently stalled and Cyrillic remained in widespread use.[23][24]

At present the Crimean Tatar language uses both Cyrillic and Latin. The use of Latin was originally approved by Crimean Tatar representatives after the Soviet Union’s collapse[25] but was never implemented by the regional government. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 the Latin script was dropped entirely. Nevertheless Crimean Tatars outside of Crimea continue to use Latin and on 22 October 2021 the government of Ukraine approved a proposal endorsed by the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People to switch the Crimean Tatar language to Latin by 2025.[26]

In July 2020, 2.6 billion people (36% of the world population) use the Latin alphabet.[27]

International standards[edit]

By the 1960s, it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their (ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage.

As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s, the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 (uppercase and lowercase) letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

National standards[edit]

The DIN standard DIN 91379 specifies a subset of Unicode letters, special characters, and sequences of letters and diacritic signs to allow the correct representation of names and to simplify data exchange in Europe. This specification supports all official languages of European Union countries (thus also Greek and Cyrillic for Bulgarian) as well as the official languages of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, and also the German minority languages. To allow the transliteration of names in other writing systems to the Latin script according to the relevant ISO standards all necessary combinations of base letters and diacritic signs are provided.[28]

Efforts are being made to further develop it into a European CEN standard.[29]

As used by various languages[edit]

In the course of its use, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use in new languages, sometimes representing phonemes not found in languages that were already written with the Roman characters. To represent these new sounds, extensions were therefore created, be it by adding diacritics to existing letters, by joining multiple letters together to make ligatures, by creating completely new forms, or by assigning a special function to pairs or triplets of letters. These new forms are given a place in the alphabet by defining an alphabetical order or collation sequence, which can vary with the particular language.

Letters[edit]

Some examples of new letters to the standard Latin alphabet are the Runic letters wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨Þ þ⟩, and the letter eth ⟨Ð/ð⟩, which were added to the alphabet of Old English. Another Irish letter, the insular g, developed into yogh ⟨Ȝ ȝ⟩, used in Middle English. Wynn was later replaced with the new letter ⟨w⟩, eth and thorn with ⟨th⟩, and yogh with ⟨gh⟩. Although the four are no longer part of the English or Irish alphabets, eth and thorn are still used in the modern Icelandic alphabet, while eth is also used by the Faroese alphabet.

Some West, Central and Southern African languages use a few additional letters that have sound values similar to those of their equivalents in the IPA. For example, Adangme uses the letters ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩, and Ga uses ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩, ⟨Ŋ ŋ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩. Hausa uses ⟨Ɓ ɓ⟩ and ⟨Ɗ ɗ⟩ for implosives, and ⟨Ƙ ƙ⟩ for an ejective. Africanists have standardized these into the African reference alphabet.

Dotted and dotless I — ⟨İ i⟩ and ⟨I ı⟩ — are two forms of the letter I used by the Turkish, Azerbaijani, and Kazakh alphabets.[30] The Azerbaijani language also has ⟨Ə ə⟩, which represents the near-open front unrounded vowel.

Multigraphs[edit]

A digraph is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters in sequence. Examples are ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩, ⟨rh⟩, ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨th⟩ in English, and ⟨ij⟩, ⟨ee⟩, ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨ei⟩ in Dutch. In Dutch the ⟨ij⟩ is capitalized as ⟨IJ⟩ or the ligature ⟨IJ⟩, but never as ⟨Ij⟩, and it often takes the appearance of a ligature ⟨ij⟩ very similar to the letter ⟨ÿ⟩ in handwriting.

A trigraph is made up of three letters, like the German ⟨sch⟩, the Breton ⟨c’h⟩ or the Milanese ⟨oeu⟩. In the orthographies of some languages, digraphs and trigraphs are regarded as independent letters of the alphabet in their own right. The capitalization of digraphs and trigraphs is language-dependent, as only the first letter may be capitalized, or all component letters simultaneously (even for words written in title case, where letters after the digraph or trigraph are left in lowercase).

Ligatures[edit]

A ligature is a fusion of two or more ordinary letters into a new glyph or character. Examples are ⟨Æ æ⟩ (from ⟨AE⟩, called «ash»), ⟨Œ œ⟩ (from ⟨OE⟩, sometimes called «oethel»), the abbreviation ⟨&⟩ (from Latin: et, lit. ‘and’, called «ampersand»), and ⟨ẞ ß⟩ (from ⟨ſʒ⟩ or ⟨ſs⟩, the archaic medial form of ⟨s⟩, followed by an ⟨ʒ⟩ or ⟨s⟩, called «sharp S» or «eszett»).

Diacritics[edit]

A diacritic, in some cases also called an accent, is a small symbol that can appear above or below a letter, or in some other position, such as the umlaut sign used in the German characters ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ or the Romanian characters ă, â, î, ș, ț. Its main function is to change the phonetic value of the letter to which it is added, but it may also modify the pronunciation of a whole syllable or word, indicate the start of a new syllable, or distinguish between homographs such as the Dutch words een (pronounced [ən]) meaning «a» or «an», and één, (pronounced [e:n]) meaning «one». As with the pronunciation of letters, the effect of diacritics is language-dependent.

English is the only major modern European language that requires no diacritics for its native vocabulary[note 1]. Historically, in formal writing, a diaeresis was sometimes used to indicate the start of a new syllable within a sequence of letters that could otherwise be misinterpreted as being a single vowel (e.g., “coöperative”, “reëlect”), but modern writing styles either omit such marks or use a hyphen to indicate a syllable break (e.g. “cooperative”, “re-elect”). [note 2][31]

Collation[edit]

Some modified letters, such as the symbols ⟨å⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ö⟩, may be regarded as new individual letters in themselves, and assigned a specific place in the alphabet for collation purposes, separate from that of the letter on which they are based, as is done in Swedish. In other cases, such as with ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨ü⟩ in German, this is not done; letter-diacritic combinations being identified with their base letter. The same applies to digraphs and trigraphs. Different diacritics may be treated differently in collation within a single language. For example, in Spanish, the character ⟨ñ⟩ is considered a letter, and sorted between ⟨n⟩ and ⟨o⟩ in dictionaries, but the accented vowels ⟨á⟩, ⟨é⟩, ⟨í⟩, ⟨ó⟩, ⟨ú⟩, ⟨ü⟩ are not separated from the unaccented vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩.

Capitalization[edit]

The languages that use the Latin script today generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized; whereas Modern English of the 18th century had frequently all nouns capitalized, in the same way that Modern German is written today, e.g. German: Alle Schwestern der alten Stadt hatten die Vögel gesehen, lit. ‘All of the sisters of the old city had seen the birds’.

Romanization[edit]

Words from languages natively written with other scripts, such as Arabic or Chinese, are usually transliterated or transcribed when embedded in Latin-script text or in multilingual international communication, a process termed romanization.

Whilst the romanization of such languages is used mostly at unofficial levels, it has been especially prominent in computer messaging where only the limited seven-bit ASCII code is available on older systems. However, with the introduction of Unicode, romanization is now becoming less necessary. Note that keyboards used to enter such text may still restrict users to romanized text, as only ASCII or Latin-alphabet characters may be available.

See also[edit]

- List of languages by writing system#Latin script

- Western Latin character sets (computing)

- European Latin Unicode subset (DIN 91379)

- Latin letters used in mathematics

- Latin omega

Notes[edit]

- ^ In formal English writing, however, diacritics are often preserved on many loanwords, such as «café», «naïve», «façade», «jalapeño» or the German prefix «über-«.

- ^ As an example, an article containing a diaeresis in «coöperate» and a cedilla in «façade» as well as a circumflex in the word «crêpe»: Grafton, Anthony (23 October 2006). «Books: The Nutty Professors, The history of academic charisma». The New Yorker.

- ^ Alongside Chinese and Tamil

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Haarmann 2004, p. 96.

- ^ «Search results | BSI Group». Bsigroup.com. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «Romanisation_systems». Pcgn.org.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ «ISO 15924 – Code List in English». Unicode.org. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ «Search – ISO». Iso.org. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521530330 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Zakon O Službenoj Upotrebi Jezika I Pisama» (PDF). Ombudsman.rs. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ «Descriptio_Moldaviae». La.wikisource.org. 1714. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Smith, Lahra (2013). «Review of Making Citizens in Africa: Ethnicity, Gender, and National Identity in Ethiopia«. African Studies. 125 (3): 542–544. doi:10.1080/00083968.2015.1067017. S2CID 148544393 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Pütz, Martin (1997). Language Choices: Conditions, constraints, and consequences. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 216. ISBN 9789027275844.

- ^ Gemeda, Guluma (18 June 2018). «The History and Politics of the Qubee Alphabet». Ayyaantuu. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Yohannes, Mekonnen (2021). «Language Policy in Ethiopia: The Interplay Between Policy and Practice in Tigray Regional State». Language Policy. 24: 33. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63904-4. ISBN 978-3-030-63903-7. S2CID 234114762 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Pasch, Helma (2008). «Competing scripts: The Introduction of the Roman Alphabet in Africa» (PDF). International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 191: 8 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Andrews, Ernest (2018). Language Planning in the Post-Communist Era: The Struggles for Language Control in the New Order in Eastern Europe, Eurasia and China. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-319-70926-0.

- ^ Faller, Helen (2011). Nation, Language, Islam: Tatarstan’s Sovereignty Movement. Central European University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-963-9776-84-5.

- ^ Kazakh language to be converted to Latin alphabet – MCS RK. Inform.kz (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ «Klimkin welcomes discussion on switching to Latin alphabet in Ukraine». UNIAN (27 March 2018).

- ^ «Moscow Bribes Bishkek to Stop Kyrgyzstan From Changing to Latin Alphabet». The Jamestown Organization (12 October 2017).

- ^ «Kyrgyzstan: Latin (alphabet) fever takes hold». Eurasianet (13 September 2019).

- ^ «Russian Influence in Mongolia is Declining». Global Security Review (2 March 2019). 2 March 2019.

- ^ Tang, Didi (20 March 2020). «Mongolia abandons Soviet past by restoring alphabet». The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ «Canadian Inuit Get Common Written Language». High North News (8 October 2019).

- ^ Sands, David (12 February 2021). «Latin lives! Uzbeks prepare latest switch to Western-based alphabet». The Washington Times. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ «Uzbekistan Aims For Full Transition To Latin-Based Alphabet By 2023». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (2007). Ukraine — Crimea — Russia: Triangle of Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-3-8382-5761-7.

- ^ «Cabinet approves Crimean Tatar alphabet based on Latin letters». Ukrinform. 22 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ «The world’s scripts and alphabets». WorldStandards. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ «DIN 91379:2022-08: Characters and defined character sequences in Unicode for the electronic processing of names and data exchange in Europe, with CD-ROM». Beuth Verlag. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^

Koordinierungsstelle für IT-Standards (KoSIT). «String.Latin+ 1.2: eine kommentierte und erweiterte Fassung der DIN SPEC 91379. Inklusive einer umfangreichen Liste häufig gestellter Fragen. Herausgegeben von der Fachgruppe String.Latin. (zip, 1.7 MB)» [String.Latin+ 1.2: Commented and extended version of DIN SPEC 91379.] (in German). Retrieved 19 March 2022. - ^ «Localize Your Font: Turkish i». Glyphs. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ «The New Yorker’s odd mark — the diaeresis». 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

Sources[edit]

- Haarmann, Harald (2004). Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

Further reading[edit]

- Boyle, Leonard E. 1976. «Optimist and recensionist: ‘Common errors’ or ‘common variations.'» In Latin script and letters A.D. 400–900: Festschrift presented to Ludwig Bieler on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Edited by John J. O’Meara and Bernd Naumann, 264–74. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Morison, Stanley. 1972. Politics and script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. Oxford: Clarendon.

External links[edit]

- Unicode collation chart—Latin letters sorted by shape

- Diacritics Project – All you need to design a font with correct accents

Латинский алфавит, Латинский алфавит в строчку, Латинский алфавит через запятую, в обратную строну, прописные латинского алфавита, строчные. Все виды латинского алфавита!

Латинский алфавит

Пронумерованный латинский алфавит(буквы «прописная — строчная») с переводом на русский язык.

| № | Латинская буква.(Прописная — строчная) | Русское произношение |

| 1 | A — a | а |

| 2 | B — b | бэ |

| 3 | C — c | цэ |

| 4 | D — d | дэ |

| 5 | E — e | э |

| 6 | F — f | эф |

| 7 | G — g | гэ |

| 8 | H — h | ха/аш |

| 9 | I — i | и |

| 10 | J — j | йот/жи |

| 11 | K — k | ка |

| 12 | L — l | эль |

| 13 | M — m | эм |

| 14 | N — n | эн |

| 15 | O — o | о |

| 16 | P — p | пэ |

| 17 | Q — q | ку |

| 18 | R — r | эр |

| 19 | S — s | эс |

| 20 | T — t | тэ |

| 21 | U — u | у |

| 22 | V — v | вэ |

| 23 | W — w | дубль-вэ |

| 24 | X — x | икс |

| 25 | Y — y | игрек/ипсилон |

| 26 | Z — z | зед |

Классический латинский алфавит Римской империи состоял из 23 букв: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X, Y, Z.

Буквы J, U, W появился гораздо позднее.

Дополнительные буквы латинского алфавита:

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы без пробела

прописные латинские буквы без пробела в одну строку.

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

строчные латинские буквы без пробела в одну строку.

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

Латинский алфавит в обратную сторону:

Прописные латинские буквы без пробела в одну строку, в обратную сторону .

ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Строчные латинские буквы без пробела в одну строку, в обратную сторону .

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcba

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы с пробелом

Прописные латинские буквы с пробелом в одну строку .

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Строчные латинские буквы с пробелом в одну строку .

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Прописные латинские буквы с пробелом в одну строку, в обратную сторону .

Z Y X W V U T S R Q P O N M L K J I H G F E D C B A

Строчные латинские буквы с пробелом в одну строку, в обратную сторону .

z y x w v u t s r q p o n m l k j i h g f e d c b a

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы через запятую

Прописные латинские буквы через запятую в одну строку .

A , B , C , D , E , F , G , H , I , J , K , L , M , N , O , P , Q , R , S , T , U , V , W , X , Y , Z

Строчные латинские буквы через запятую в одну строку .

a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z,

И строчные, и прописные латинские буквы через запятую в одну строку .

A a, B b, C c, D d, E e, F f, G g, H h, I i, J j, K k, L l, M m, N n, O o, P p, Q q, R r, S s, T t, U u, V v, W w, X x, Y y, Z z

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы в столбик

Прописные латинские буквы в столбик.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

Строчные латинские буквы в столбик.

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o

p

q

r

s

t

u

v

w

x

y

z

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы в столбик.

A a

B b

C c

D d

E e

F f

G g

H h

I i

J j

K k

L l

M m

N n

O o

P p

Q q

R r

S s

T t

U u

V v

W w

X x

Y y

Z z

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы в столбик с запятой.

A a,

B b,

C c,

D d,

E e,

F f,

G g,

H h,

I i,

J j,

K k,

L l,

M m,

N n,

O o,

P p,

Q q,

R r,

S s,

T t,

U u,

V v,

W w,

X x,

Y y,

Z z,

Латинский алфавит в обратную сторону.

Прописные латинские буквы с пробелом в одну строку в обратную сторону.

Z Y X W V U T S R Q P O N M L K J I H G F E D C B A

Строчные латинские буквы с пробелом в одну строку в обратную сторону.

z y x w v u t s r q p o n m l k j i h g f e d c b a

Прописные латинские буквы через запятую в одну строку, в обратную сторону .

Z, Y, X, W, V, U, T, S, R, Q, P, O, N, M, L, K, J, I, H, G, F, E, D, C, B, A,

Строчные латинские буквы через запятую в одну строку, в обратную сторону .

z, y, x, w, v, u, t, s, r, q, p, o, n, m, l, k, j, i, h, g, f, e, d, c, b, a,

Прописные латинские буквы в столбик в обратную сторону.

Z

Y

X

W

V

U

T

S

R

Q

P

O

N

M

L

K

J

I

H

G

F

E

D

C

B

A

Строчные латинские буквы в столбик в обратную сторону.

z

y

x

w

v

u

t

s

r

q

p

o

n

m

l

k

j

i

h

g

f

e

d

c

b

a

Прописные и строчные латинские буквы в столбик в обратную сторону.

Z z