|

H. P. Lovecraft |

|

|---|---|

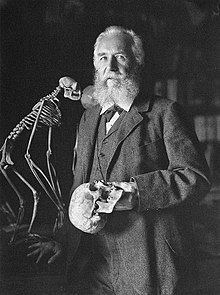

Lovecraft in 1934 |

|

| Born | Howard Phillips Lovecraft August 20, 1890 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | March 15, 1937 (aged 46) Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Resting place | Swan Point Cemetery, Providence 41°51′14″N 71°22′52″W / 41.854021°N 71.381068°W |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | Lovecraftian horror, weird fiction, horror fiction, science fiction, gothic fiction, fantasy |

| Literary movement |

|

| Years active | 1917–1937 |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Sonia Greene (m. ) |

| Signature | |

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (; August 20, 1890 – March 15, 1937) was an American writer of weird, science, fantasy, and horror fiction. He is best known for his creation of the Cthulhu Mythos.[a]

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Lovecraft spent most of his life in New England. After his father’s institutionalization in 1893, he lived affluently until his family’s wealth dissipated after the death of his grandfather. Lovecraft then lived with his mother, in reduced financial security, until her institutionalization in 1919. He began to write essays for the United Amateur Press Association, and in 1913 wrote a critical letter to a pulp magazine that ultimately led to his involvement in pulp fiction. He became active in the speculative fiction community and was published in several pulp magazines. Lovecraft moved to New York City, marrying Sonia Greene in 1924, and later became the center of a wider group of authors known as the «Lovecraft Circle». They introduced him to Weird Tales, which would become his most prominent publisher. Lovecraft’s time in New York took a toll on his mental state and financial conditions. He returned to Providence in 1926 and produced some of his most popular works, including The Call of Cthulhu, At the Mountains of Madness, The Shadow over Innsmouth, and The Shadow Out of Time. He would remain active as a writer for 11 years until his death from intestinal cancer at the age of 46.

Lovecraft’s literary corpus is based around the idea of cosmicism, which was simultaneously his personal philosophy and the main theme of his fiction. Cosmicism posits that humanity is an insignificant part of the cosmos, and could be swept away at any moment. He incorporated fantasy and science fiction elements into his stories, representing the perceived fragility of anthropocentrism. This was tied to his ambivalent views on knowledge. His works were largely set in a fictionalized version of New England. Civilizational decline also plays a major role in his works, as he believed that the West was in decline during his lifetime. Lovecraft’s early political opinions were conservative and traditionalist; additionally, he held a number of racist views for much of his adult life. Following the Great Depression, Lovecraft became a socialist, no longer believing a just aristocracy would make the world more fair.

Throughout his adult life, Lovecraft was never able to support himself from earnings as an author and editor. He was virtually unknown during his lifetime and was almost exclusively published in pulp magazines before his death. A scholarly revival of Lovecraft’s work began in the 1970s, and he is now regarded as one of the most significant 20th-century authors of supernatural horror fiction. Many direct adaptations and spiritual successors followed. Works inspired by Lovecraft, adaptations or original works, began to form the basis of the Cthulhu Mythos, which utilizes Lovecraft’s characters, setting, and themes.

Biography

Early life and family tragedies

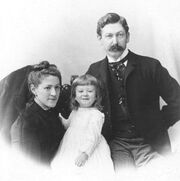

Sarah, Howard, and Winfield Lovecraft in 1892

Lovecraft was born in his family home on August 20, 1890, in Providence, Rhode Island. He was the only child of Winfield Scott Lovecraft and Sarah Susan (née Phillips) Lovecraft.[2] Susie’s family was of substantial means at the time of their marriage, as her father, Whipple Van Buren Phillips, was involved in business ventures.[3] In April 1893, after a psychotic episode in a Chicago hotel, Winfield was committed to Butler Hospital in Providence. His medical records state that he had been «doing and saying strange things at times» for a year before his commitment.[4] The person who reported these symptoms is unknown.[5] Winfield spent five years in Butler before dying in 1898. His death certificate listed the cause of death as general paresis, a term synonymous with late-stage syphilis.[6] Throughout his life, Lovecraft maintained that his father fell into a paralytic state, due to insomnia and overwork, and remained that way until his death. It is not known whether Lovecraft was simply kept ignorant of his father’s illness or whether his later statements were intentionally misleading.[7]

After his father’s institutionalization, Lovecraft resided in the family home with his mother, his maternal aunts Lillian and Annie, and his maternal grandparents Whipple and Robie.[8] According to family friends, his mother, known as Susie, doted on the young Lovecraft excessively, pampering him and never letting him out of her sight.[9] Lovecraft later recollected that his mother was «permanently stricken with grief» after his father’s illness. Whipple became a father figure to Lovecraft in this time, Lovecraft noting that his grandfather became the «centre of my entire universe». Whipple, who often traveled to manage his business, maintained correspondence by letter with the young Lovecraft who, by the age of three, was already proficient at reading and writing.[10]

Whipple encouraged the young Lovecraft to have an appreciation of literature, especially classical literature and English poetry. In his old age, he helped raise the young H. P. Lovecraft and educated him not only in the classics, but also in original weird tales of «winged horrors» and «deep, low, moaning sounds» which he created for his grandchild’s entertainment. The original sources of Phillips’ weird tales are unidentified. Lovecraft himself guessed that they originated from Gothic novelists like Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis, and Charles Maturin.[11] It was during this period that Lovecraft was introduced to some of his earliest literary influences, such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner illustrated by Gustave Doré, One Thousand and One Nights, Thomas Bulfinch’s Age of Fable, and Ovid’s Metamorphoses.[12]

While there is no indication that Lovecraft was particularly close to his grandmother Robie, her death in 1896 had a profound effect on him. By his own account, it sent his family into «a gloom from which it never fully recovered». His mother and aunts wore black mourning dresses that «terrified» him. This is also the time that Lovecraft, approximately five-and-a-half years old, started having nightmares that later would inform his fictional writings. Specifically, he began to have recurring nightmares of beings he referred to as «night-gaunts». He credited their appearance to the influence of Doré’s illustrations, which would «whirl me through space at a sickening rate of speed, the while fretting & impelling me with their detestable tridents.» Thirty years later, night-gaunts would appear in Lovecraft’s fiction.[13]

Lovecraft’s earliest known literary works were written at the age of seven, and were poems restyling the Odyssey and other Greco-Roman mythological stories.[14] Lovecraft would later write that during his childhood he was fixated on the Greco-Roman pantheon, and briefly accepted them as genuine expressions of divinity, foregoing his Christian upbringing.[15] He recalled, at five years old, being told Santa Claus did not exist and retorted by asking why «God is not equally a myth?»[16] At the age of eight, he took a keen interest in the sciences, particularly astronomy and chemistry. He also examined the anatomical books that were held in the family library, which taught him the specifics of human reproduction that were not yet explained to him. As a result, he found that it «virtually killed my interest in the subject.»[17]

In 1902, according to Lovecraft’s later correspondence, astronomy became a guiding influence on his worldview. He began publishing the periodical Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy, using the hectograph printing method.[18] Lovecraft went in and out of elementary school repeatedly, oftentimes with home tutors making up for the lost years, missing time due to health concerns that have not been determined. The written recollections of his peers described him as withdrawn but welcoming to those who shared his then-current fascination with astronomy, inviting them to look through his prized telescope.[19]

Education and financial decline

By 1900, Whipple’s various business concerns were suffering a downturn, which resulted in the slow erosion of his family’s wealth. He was forced to let his family’s hired servants go, leaving Lovecraft, Whipple, and Susie, being the only unmarried sister, alone in the family home.[20] In the spring of 1904, Whipple’s largest business venture suffered a catastrophic failure. Within months, he died at age 70 due to a stroke. After Whipple’s death, Susie was unable to financially support the upkeep of the expansive family home on what remained of the Phillips’ estate. Later that year, she was forced to move to a small duplex with her son.[21]

Whipple Van Buren Phillips

Lovecraft called this time one of the darkest of his life, remarking in a 1934 letter that he saw no point in living anymore; he considered the possibility of committing suicide. His scientific curiosity and desire to know more about the world prevented him from doing so.[22] In fall 1904, he entered high school. Much like his earlier school years, Lovecraft was periodically removed from school for long periods for what he termed «near breakdowns». He did say, though, that while having some conflicts with teachers, he enjoyed high school, becoming close with a small circle of friends. Lovecraft also performed well academically, excelling in particular at chemistry and physics.[23] Aside from a pause in 1904, he also resumed publishing the Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy as well as starting the Scientific Gazette, which dealt mostly with chemistry.[24] It was also during this period that Lovecraft produced the first of the fictional works that he would later be known for, namely «The Beast in the Cave» and «The Alchemist».[25]

It was in 1908, prior to what would have been his high school graduation, that Lovecraft suffered another unidentified health crisis, though this instance was more severe than his prior illnesses.[26] The exact circumstances and causes remain unknown. The only direct records are Lovecraft’s own correspondence wherein he retrospectively described it variously as a «nervous collapse» and «a sort of breakdown», in one letter blaming it on the stress of high school despite his enjoying it.[27] In another letter concerning the events of 1908, he notes, «I was and am prey to intense headaches, insomnia, and general nervous weakness which prevents my continuous application to any thing.»[26]

Though Lovecraft maintained that he was going to attend Brown University after high school, he never graduated and never attended school again. Whether Lovecraft suffered from a physical ailment, a mental one, or some combination thereof has never been determined. An account from a high school classmate described Lovecraft as exhibiting «terrible tics» and that at times «he’d be sitting in his seat and he’d suddenly up and jump». Harry Brobst, a psychology professor, examined the account and claimed that chorea minor was the probable cause of Lovecraft’s childhood symptoms, while noting that instances of chorea minor after adolescence are very rare.[27] In his letters, Lovecraft acknowledged that he suffered from bouts of chorea as a child.[28] Brobst further ventured that Lovecraft’s 1908 breakdown was attributed to a «hysteroid seizure», a term that has become synonymous with atypical depression.[29] In another letter concerning the events of 1908, Lovecraft stated that he «could hardly bear to see or speak to anyone, & liked to shut out the world by pulling down dark shades & using artificial light.»[30]

Earliest recognition

Few of Lovecraft and Susie’s activities between late 1908 and 1913 were recorded.[31] Lovecraft described the steady continuation of their financial decline highlighted by his uncle’s failed business that cost Susie a large portion of their already dwindling wealth.[32] One of Susie’s friends, Clara Hess, recalled a visit during which Susie spoke continuously about Lovecraft being «so hideous that he hid from everyone and did not like to walk upon the streets where people could gaze on him.» Despite Hess’ protests to the contrary, Susie maintained this stance.[33] For his part, Lovecraft said he found his mother to be «a positive marvel of consideration».[34] A next-door neighbor later pointed out that what others in the neighborhood often assumed were loud, nocturnal quarrels between mother and son, were actually recitations of Shakespeare, an activity that seemed to delight mother and son.[35]

During this period, Lovecraft revived his earlier scientific periodicals.[31] He endeavored to commit himself to the study of organic chemistry, Susie buying the expensive glass chemistry assemblage he wanted.[36] Lovecraft found his studies were stymied by the mathematics involved, which he found boring and would cause headaches that would incapacitate him for the remainder of the day.[37] Lovecraft’s first non-self-published poem appeared in a local newspaper in 1912. Called Providence in 2000 A.D., it envisioned a future where Americans of English descent were displaced by Irish, Italian, Portuguese, and Jewish immigrants.[38] In this period he also wrote racist poetry, including «New-England Fallen» and «On the Creation of Niggers», but there is no indication that either were published during his lifetime.[39]

In 1911, Lovecraft’s letters to editors began appearing in pulp and weird-fiction magazines, most notably Argosy.[40] A 1913 letter critical of Fred Jackson, one of Argosy’s more prominent writers, started Lovecraft down a path that would define the remainder of his career as a writer. In the following letters, Lovecraft described Jackson’s stories as being «trivial, effeminate, and, in places, coarse». Continuing, Lovecraft argued that Jackson’s characters exhibit the «delicate passions and emotions proper to negroes and anthropoid apes.»[41] This sparked a nearly year-long feud in the magazine’s letters section between the two writers and their respective supporters. Lovecraft’s most prominent opponent was John Russell, who often replied in verse, and to whom Lovecraft felt compelled to reply because he respected Russell’s writing skills.[42] The most immediate effect of this feud was the recognition garnered from Edward F. Daas, then head editor of the United Amateur Press Association (UAPA).[43] Daas invited Russell and Lovecraft to join the organization and both accepted, Lovecraft in April 1914.[44]

Rejuvenation and tragedy

With the advent of United I obtained a renewed will to live; a renewed sense of existence as other than a superfluous weight; and found a sphere in which I could feel that my efforts were not wholly futile. For the first time I could imagine that my clumsy gropings after art were a little more than faint cries lost in the unlistening void.

—Lovecraft in 1921.[45]

Lovecraft immersed himself in the world of amateur journalism for most of the following decade.[45] During this period, he advocated for amateurism’s superiority to commercialism.[46] Lovecraft defined commercialism as writing for what he considered low-brow publications for pay. This was contrasted with his view of «professional publication», which was what he called writing for what he considered respectable journals and publishers. He thought of amateur journalism as serving as practice for a professional career.[47]

Lovecraft was appointed chairman of the Department of Public Criticism of the UAPA in late 1914.[48] He used this position to advocate for what he saw as the superiority of archaic English language usage. Emblematic of the Anglophilic opinions he maintained throughout his life, he openly criticized other UAPA contributors for their «Americanisms» and «slang». Often, these criticisms were embedded in xenophobic and racist statements that the «national language» was being negatively changed by immigrants.[49] In mid-1915, Lovecraft was elected vice-president of the UAPA.[50] Two years later, he was elected president and appointed other board members who mostly shared his belief in the supremacy of British English over modern American English.[51] Another significant event of this time was the beginning of World War I. Lovecraft published multiple criticisms of the American government and public’s reluctance to join the war to protect England, which he viewed as America’s ancestral homeland.[52]

In 1916, Lovecraft published his first short story, «The Alchemist», in the main UAPA journal, which was a departure from his usual verse. Due to the encouragement of W. Paul Cook, another UAPA member and future lifelong friend, Lovecraft began writing and publishing more prose fiction.[53] Soon afterwards, he wrote «The Tomb» and «Dagon».[54] «The Tomb», by Lovecraft’s own admission, was greatly influenced by the style and structure of Edgar Allan Poe’s works.[55] Meanwhile, «Dagon» is considered Lovecraft’s first work that displays the concepts and themes that his writings would later become known for.[56] Lovecraft published another short story, «Beyond the Wall of Sleep» in 1919, which was his first science fiction story.[57]

Lovecraft’s term as president of the UAPA ended in 1918, and he returned to his former post as chairman of the Department of Public Criticism.[58] In 1917, as Lovecraft related to Kleiner, Lovecraft made an aborted attempt to enlist in the United States Army. Though he passed the physical exam,[59] he told Kleiner that his mother threatened to do anything, legal or otherwise, to prove that he was unfit for service.[60] After his failed attempt to serve in World War I, he attempted to enroll in the Rhode Island National Guard, but his mother used her family connections to prevent it.[61]

During the winter of 1918–1919, Susie, exhibiting the symptoms of a nervous breakdown, went to live with her elder sister, Lillian. The nature of Susie’s illness is unclear, as her medical papers were later destroyed in a fire at Butler Hospital.[62] Winfield Townley Scott, who was able to read the papers before the fire, described Susie as having suffered a psychological collapse.[62] Neighbour and friend Clara Hess, interviewed in 1948, recalled instances of Susie describing «weird and fantastic creatures that rushed out from behind buildings and from corners at dark.»[63] In the same account, Hess described a time when they crossed paths in downtown Providence and Susie was unaware of where she was.[63] In March 1919, she was committed to Butler Hospital, like her husband before her.[64] Lovecraft’s immediate reaction to Susie’s commitment was visceral, writing to Kleiner that «existence seems of little value», and that he wished «it might terminate».[65] During Susie’s time at Butler, Lovecraft periodically visited her and walked the large grounds with her.[66]

Late 1919 saw Lovecraft become more outgoing. After a period of isolation, he began joining friends in trips to writer gatherings; the first being a talk in Boston presented by Lord Dunsany, whom Lovecraft had recently discovered and idolized.[67] In early 1920, at an amateur writer convention, he met Frank Belknap Long, who would end up being Lovecraft’s most influential and closest confidant for the remainder of his life.[68] The influence of Dunsany is apparent in his 1919 output, which is part of what would be called Lovecraft’s Dream Cycle, including «The White Ship» and «The Doom That Came to Sarnath».[69] In early 1920, he wrote «The Cats of Ulthar» and «Celephaïs», which were also strongly influenced by Dunsany.[70]

It was later in 1920 that Lovecraft began publishing the earliest Cthulhu Mythos stories. The Cthulhu Mythos, a term coined by later authors, encompasses Lovecraft’s stories that share a commonality in the revelation of cosmic insignificance, initially realistic settings, and recurring entities and texts.[71] The prose poem «Nyarlathotep» and the short story «The Crawling Chaos», in collaboration with Winifred Virginia Jackson, were written in late 1920.[72] Following in early 1921 came «The Nameless City», the first story that falls definitively within the Cthulhu Mythos. In it is one of Lovecraft’s most enduring phrases, a couplet recited by Abdul Alhazred; «That is not dead which can eternal lie; And with strange aeons even death may die.»[73] In the same year, he also wrote «The Outsider», which has become one of Lovecraft’s most heavily analyzed, and differently interpreted, stories.[74] It has been variously interpreted as being autobiographical, an allegory of the psyche, a parody of the afterlife, a commentary on humanity’s place in the universe, and a critique of progress.[75]

On May 24, 1921, Susie died in Butler Hospital, due to complications from an operation on her gallbladder five days earlier.[76] Lovecraft’s initial reaction, expressed in a letter written nine days after Susie’s death, was a deep state of sadness that crippled him physically and emotionally. He again expressed a desire that his life might end.[77] Lovecraft’s later response was relief, as he had become able to live independently from his mother. His physical health also began to improve, although he was unaware of the exact cause.[78] Despite Lovecraft’s reaction, he continued to attend amateur journalist conventions. Lovecraft met his future wife, Sonia Greene, at one such convention in July.[79]

Marriage and New York

Lovecraft and Sonia Greene on July 5, 1921

Lovecraft’s aunts disapproved of his relationship with Sonia. Lovecraft and Greene married on March 3, 1924, and relocated to her Brooklyn apartment at 259 Parkside Avenue; she thought he needed to leave Providence to flourish and was willing to support him financially.[80] Greene, who had been married before, later said Lovecraft had performed satisfactorily as a lover, though she had to take the initiative in all aspects of the relationship. She attributed Lovecraft’s passive nature to a stultifying upbringing by his mother.[81] Lovecraft’s weight increased to 200 lb (91 kg) on his wife’s home cooking.[82]

He was enthralled by New York, and, in what was informally dubbed the Kalem Club, he acquired a group of encouraging intellectual and literary friends who urged him to submit stories to Weird Tales. Its editor, Edwin Baird, accepted many of Lovecraft’s stories for the ailing publication, including «Under the Pyramids», which was ghostwritten for Harry Houdini.[83] Established informally some years before Lovecraft arrived in New York, the core Kalem Club members were boys’ adventure novelist Henry Everett McNeil, the lawyer and anarchist writer James Ferdinand Morton Jr., and the poet Reinhardt Kleiner.[84]

On January 1, 1925, Sonia moved from Parkside to Cleveland in response to a job opportunity, and Lovecraft left for a small first-floor apartment on 169 Clinton Street «at the edge of Red Hook»—a location which came to discomfort him greatly.[85] Later that year, the Kalem Club’s four regular attendees were joined by Lovecraft along with his protégé Frank Belknap Long, bookseller George Willard Kirk, and Samuel Loveman.[86] Loveman was Jewish, but he and Lovecraft became close friends in spite of the latter’s antisemitic attitudes.[87] By the 1930s, writer and publisher Herman Charles Koenig would be one of the last to become involved with the Kalem Club.[88]

Not long after the marriage, Greene lost her business and her assets disappeared in a bank failure.[89] Lovecraft made efforts to support his wife through regular jobs, but his lack of previous work experience meant he lacked proven marketable skills.[90] The publisher of Weird Tales was attempting to make the loss-making magazine profitable and offered the job of editor to Lovecraft, who declined, citing his reluctance to relocate to Chicago on aesthetic grounds.[91] Baird was succeeded by Farnsworth Wright, whose writing Lovecraft had criticized. Lovecraft’s submissions were often rejected by Wright. This may have been partially due to censorship guidelines imposed in the aftermath of a Weird Tales story that hinted at necrophilia, although after Lovecraft’s death, Wright accepted many of the stories he had originally rejected.[92]

Sonia also became ill and immediately after recovering, relocated to Cincinnati, and then to Cleveland; her employment required constant travel.[93] Added to his feelings of failure in a city with a large immigrant population, Lovecraft’s single-room apartment was burgled, leaving him with only the clothes he was wearing.[94] In August 1925, he wrote «The Horror at Red Hook» and «He», in the latter of which the narrator says «My coming to New York had been a mistake; for whereas I had looked for poignant wonder and inspiration […] I had found instead only a sense of horror and oppression which threatened to master, paralyze, and annihilate me.»[95] This was an expression of his despair at being in New York.[96] It was at around this time he wrote the outline for «The Call of Cthulhu», with its theme of the insignificance of all humanity.[97] During this time, Lovecraft wrote «Supernatural Horror in Literature» on the eponymous subject. It later became one of the most influential essays on supernatural horror.[98] With a weekly allowance Greene sent, Lovecraft moved to a working-class area of Brooklyn Heights, where he resided in a tiny apartment. He had lost approximately 40 pounds (18 kg) of body weight by 1926, when he left for Providence.[99]

Return to Providence and death

Lovecraft’s final home, May 1933 until March 10, 1937

Back in Providence, Lovecraft lived with his aunts in a «spacious brown Victorian wooden house» at 10 Barnes Street until 1933.[100] He then moved to 66 Prospect Street, which would become his final home.[b][101] The period beginning after his return to Providence contains some of his most prominent works, including The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, «The Call of Cthulhu» and The Shadow over Innsmouth.[102] The former two stories are partially autobiographical, as scholars have argued that The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is about Lovecraft’s return to Providence and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward is, in part, about the city itself.[103] The former story also represents a partial repudiation of Dunsany’s influence, as Lovecraft had decided that his style did not come to him naturally.[104] At this time, he frequently revised work for other authors and did a large amount of ghostwriting, including The Mound, «Winged Death», and «The Diary of Alonzo Typer». Client Harry Houdini was laudatory, and attempted to help Lovecraft by introducing him to the head of a newspaper syndicate. Plans for a further project were ended by Houdini’s death in 1926.[105] After returning, he also began to engage in antiquarian travels across the eastern seaboard during the summer months.[106] During the spring–summer of 1930, Lovecraft visited, among other locations, New York City, Brattleboro, Vermont, Wilbraham, Massachusetts, Charleston, South Carolina, and Quebec City.[c][108]

Later, in August, Robert E. Howard wrote a letter to Weird Tales praising a then-recent reprint of H. P. Lovecraft’s «The Rats in the Walls» and discussing some of the Gaelic references used within.[109] Editor Farnsworth Wright forwarded the letter to Lovecraft, who responded positively to Howard, and soon the two writers were engaged in a vigorous correspondence that would last for the rest of Howard’s life.[110] Howard quickly became a member of the Lovecraft Circle, a group of writers and friends all linked through Lovecraft’s voluminous correspondence, as he introduced his many like-minded friends to one another and encouraged them to share their stories, utilize each other’s fictional creations, and help each other succeed in the field of pulp fiction.[111]

Meanwhile, Lovecraft was increasingly producing work that brought him no remuneration.[112] Affecting a calm indifference to the reception of his works, Lovecraft was in reality extremely sensitive to criticism and easily precipitated into withdrawal. He was known to give up trying to sell a story after it had been once rejected.[113] Sometimes, as with The Shadow over Innsmouth, he wrote a story that might have been commercially viable but did not try to sell it. Lovecraft even ignored interested publishers. He failed to reply when one inquired about any novel Lovecraft might have ready: although he had completed such a work, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, it was never typed up.[114] A few years after Lovecraft had moved to Providence, he and his wife Sonia Greene, having lived separately for so long, agreed to an amicable divorce. Greene moved to California in 1933 and remarried in 1936, unaware that Lovecraft, despite his assurances to the contrary, had never officially signed the final decree.[115]

As a result of the Great Depression, he shifted towards socialism, decrying both his prior political beliefs and the rising tide of fascism.[116] He thought that socialism was a workable middle ground between what he saw as the destructive impulses of both the capitalists and the Marxists of his day. This was based in a general opposition to cultural upheaval, as well as support for an ordered society. Electorally, he supported Franklin D. Roosevelt, but he thought that the New Deal was not sufficiently leftist. Lovecraft’s support for it was based in his view that no other set of reforms were possible at that time.[117]

H. P. Lovecraft’s gravestone

In late 1936, he witnessed the publication of The Shadow over Innsmouth as a paperback book.[d] 400 copies were printed, and the work was advertised in Weird Tales and several fan magazines. However, Lovecraft was displeased, as this book was riddled with errors that required extensive editing. It sold slowly and only approximately 200 copies were bound. The remaining 200 copies were destroyed after the publisher went out of business for the next seven years. By this point, Lovecraft’s literary career was reaching its end. Shortly after having written his last original short story, «The Haunter of the Dark», he stated that the hostile reception of At the Mountains of Madness had done «more than anything to end my effective fictional career». His declining psychological and physical states made it impossible for him to continue writing fiction.[120]

On June 11, Robert E. Howard was informed that his chronically ill mother would not awaken from her coma. He walked out to his car and committed suicide with a pistol that he had stored there. His mother died shortly thereafter.[121] This deeply affected Lovecraft, who consoled Howard’s father through correspondence. Almost immediately after hearing about Howard’s death, Lovecraft wrote a brief memoir titled «In Memoriam: Robert Ervin Howard», which he distributed to his correspondents.[122] Meanwhile, Lovecraft’s physical health was deteriorating. He was suffering from an affliction that he referred to as «grippe».[e][124]

Due to his fear of doctors, Lovecraft was not examined until a month before his death. After seeing a doctor, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer of the small intestine.[125] He remained hospitalized until he died. He lived in constant pain until his death on March 15, 1937, in Providence. In accordance with his lifelong scientific curiosity, he kept a diary of his illness until he was physically incapable of holding a pen.[126] Lovecraft was listed along with his parents on the Phillips family monument.[127] In 1977, fans erected a headstone in Swan Point Cemetery on which they inscribed his name, the dates of his birth and death, and the phrase «I AM PROVIDENCE»—a line from one of his personal letters.[128]

Personal views

Politics

H. P. Lovecraft as an eighteenth-century gentleman by Virgil Finlay

Lovecraft began his life as a Tory,[129] which was likely the result of his conservative upbringing. His family supported the Republican Party for the entirety of his life. While it is unclear how consistently he voted, he voted for Herbert Hoover in the 1928 presidential election.[130] Rhode Island as a whole remained politically conservative and Republican into the 1930s.[131] Lovecraft himself was an Anglophile who supported the British monarchy. He opposed democracy and thought that the United States should be governed by an aristocracy. This viewpoint emerged during his youth and lasted until the end of the 1920s.[132] During World War I, his Anglophilia caused him to strongly support the entente against the Central Powers. Many of his earlier poems were devoted to then-current political subjects, and he published several political essays in his amateur journal, The Conservative.[133] He was a teetotaler who supported the implementation of Prohibition, which was one of the few reforms that he supported during the early part of his life.[134] While remaining a teetotaller, he later became convinced that Prohibition was ineffectual in the 1930s.[135] His personal justification for his early political viewpoints was primarily based on tradition and aesthetics.[136]

As a result of the Great Depression, Lovecraft reexamined his political views.[137] Initially, he thought that affluent people would take on the characteristics of his ideal aristocracy and solve America’s problems. When this did not occur, he became a socialist. This shift was caused by his observation that the Depression was harming American society. It was also influenced by the increase in socialism’s political capital during the 1930s. One of the main points of Lovecraft’s socialism was its opposition to Soviet Marxism, as he thought that a Marxist revolution would bring about the destruction of American civilization. Lovecraft thought that an intellectual aristocracy needed to be formed to preserve America.[138] His ideal political system is outlined in his 1933 essay «Some Repetitions on the Times». Lovecraft used this essay to echo the political proposals that had been made over the course of the last few decades. In this essay, he advocates governmental control of resource distribution, fewer working hours and a higher wage, and unemployment insurance and old age pensions. He also outlines the need for an oligarchy of intellectuals. In his view, power must be restricted to those who are sufficiently intelligent and educated.[139] He frequently used the term «fascism» to describe this form of government, but, according to S. T. Joshi, it bears little resemblance to that ideology.[140]

Lovecraft had varied views on the political figures of his day. He was an ardent supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt.[141] He saw that Roosevelt was trying to steer a middle course between the conservatives and the revolutionaries, which he approved of. While he thought that Roosevelt should have been enacting more progressive policies, he came to the conclusion that the New Deal was the only realistic option for reform. He thought that voting for his opponents on the political left would be a wasted effort.[142] Internationally, like many Americans, he initially expressed support for Adolf Hitler. More specifically, he thought that Hitler would preserve German culture. However, he thought that Hitler’s racial policies should be based on culture rather than descent. There is evidence that, at the end of his life, Lovecraft began to oppose Hitler. According to Harry K. Brobst, Lovecraft’s downstairs neighbor went to Germany and witnessed Jews being beaten. Lovecraft and his aunt were angered by this. His discussions of Hitler drop off after this point.[143]

Atheism

Lovecraft was an atheist. His viewpoints on religion are outlined in his 1922 essay «A Confession of Unfaith». In this essay, he describes his shift away from the Protestantism of his parents to the atheism of his adulthood. Lovecraft was raised by a conservative Protestant family. He was introduced to the Bible and the mythos of Saint Nicholas when he was two. He passively accepted both of them. Over the course of the next few years, he was introduced to Grimms’ Fairy Tales and One Thousand and One Nights, favoring the latter. In response, Lovecraft took on the identity of «Abdul Alhazred», a name he would later use for the author of the Necronomicon.[144] Lovecraft experienced a brief period as a Greco-Roman pagan shortly thereafter.[145] According to this account, his first moment of skepticism occurred before his fifth birthday, when he questioned if God is a myth after learning that Santa Claus is not real. In 1896, he was introduced to Greco-Roman myths and became «a genuine pagan».[15]

This came to an end in 1902, when Lovecraft was introduced to space. He later described this event as the most poignant in his life. In response to this discovery, Lovecraft took to studying astronomy and described his observations in the local newspaper.[146] Before his thirteenth birthday, he had become convinced of humanity’s impermanence. By the time he was seventeen, he had read detailed writings that agreed with his worldview. Lovecraft ceased writing positively about progress, instead developing his later cosmic philosophy. Despite his interests in science, he had an aversion to realistic literature, so he became interested in fantastical fiction. Lovecraft became pessimistic when he entered amateur journalism in 1914. The Great War seemed to confirm his viewpoints. He began to despise philosophical idealism. Lovecraft took to discussing and debating his pessimism with his peers, which allowed him to solidify his philosophy. His readings of Friedrich Nietzsche and H. L. Mencken, among other pessimistic writers, furthered this development. At the end of his essay, Lovecraft states that all he desired was oblivion. He was willing to cast aside any illusion that he may still have held.[147]

Race

Race is the most controversial aspect of Lovecraft’s legacy, expressed in many disparaging remarks against non-Anglo-Saxon races and cultures in his works. Scholars have argued that these racial attitudes were common in the American society of his day, particularly in New England.[148] As he grew older, his original racial worldview became a classism or elitism, which regarded the superior race to include all those self-ennobled through high culture. Lovecraft was a white supremacist.[149] Despite this, he did not hold all white people in uniform high regard, but rather esteemed English people and those of English descent.[150] In his early published essays, private letters, and personal utterances, he argued for a strong color line to preserve race and culture.[151] His arguments were supported using disparagements of various races in his journalism and letters, and allegorically in some of his fictional works that depict miscegenation between humans and non-human creatures.[152] This is evident in his portrayal of the Deep Ones in The Shadow over Innsmouth. Their interbreeding with humanity is framed as being a type of miscegenation that corrupts both the town of Innsmouth and the protagonist.[153]

Initially, Lovecraft showed sympathy to minorities who adopted Western culture, even to the extent of marrying a Jewish woman he viewed as being «well assimilated».[154] By the 1930s, Lovecraft’s views on ethnicity and race had moderated.[155] He supported ethnicities’ preserving their native cultures; for example, he thought that «a real friend of civilisation wishes merely to make the Germans more German, the French more French, the Spaniards more Spanish, & so on.»[156] This represented a shift from his previous support for cultural assimilation. His shift was partially the result of his exposure to different cultures through his travels and circle. The former resulted in him writing positively about Québécois and First Nations cultural traditions in his travelogue of Quebec.[157] However, this did not represent a complete elimination of his racial prejudices.[158]

Influences

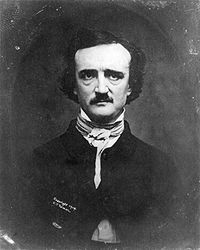

Lovecraft was influenced by Edgar Allan Poe and Lord Dunsany.

His interest in weird fiction began in his childhood when his grandfather, who preferred Gothic stories, would tell him stories of his own design.[12] Lovecraft’s childhood home on Angell Street had a large library that contained classical literature, scientific works, and early weird fiction. At the age of five, Lovecraft enjoyed reading One Thousand and One Nights, and was reading Nathaniel Hawthorne a year later.[159] He was also influenced by the travel literature of John Mandeville and Marco Polo.[160] This led to his discovery of gaps in then-contemporary science, which prevented Lovecraft from committing suicide in response to the death of his grandfather and his family’s declining financial situation during his adolescence.[160] These travelogues may have also had an influence on how Lovecraft’s later works describe their characters and locations. For example, there is a resemblance between the powers of the Tibetan enchanters in The Travels of Marco Polo and the powers unleashed on Sentinel Hill in «The Dunwich Horror».[160]

One of Lovecraft’s most significant literary influences was Edgar Allan Poe, whom he described as his «God of Fiction».[161] Poe’s fiction was introduced to Lovecraft when the latter was eight years old. His earlier works were significantly influenced by Poe’s prose and writing style.[162] He also made extensive use of Poe’s unity of effect in his fiction.[163] Furthermore, At the Mountains of Madness directly quotes Poe and was influenced by The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.[164] One of the main themes of the two stories is to discuss the unreliable nature of language as a method of expressing meaning.[165] In 1919, Lovecraft’s discovery of the stories of Lord Dunsany moved his writing in a new direction, resulting in a series of fantasies. Throughout his life, Lovecraft referred to Dunsany as the author who had the greatest impact on his literary career. The initial result of this influence was the Dream Cycle, a series of fantasies that originally take place in prehistory, but later shift to a dreamworld setting.[166] By 1930, Lovecraft decided that he would no longer write Dunsanian fantasies, arguing that the style did not come naturally to him.[167] Additionally, he also read and cited Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood as influences in the 1920s.[168]

Aside from horror authors, Lovecraft was significantly influenced by the Decadents, the Puritans, and the Aesthetic movement.[169] In «H. P. Lovecraft: New England Decadent», Barton Levi St. Armand, a professor emeritus of English and American studies at Brown University, has argued that these three influences combined to define Lovecraft as a writer.[170] He traces this influence to both Lovecraft’s stories and letters, noting that he actively cultivated the image of a New England gentleman in his letters.[169] Meanwhile, his influence from the Decadents and the Aesthetic Movement stems from his readings of Edgar Allan Poe. Lovecraft’s aesthetic worldview and fixation on decline stems from these readings. The idea of cosmic decline is described as having been Lovecraft’s response to both the Aesthetic Movement and the 19th century Decadents.[171] St. Armand describes it as being a combination of non-theological Puritan thought and the Decadent worldview.[172] This is used as a division in his stories, particularly in «The Horror at Red Hook», «Pickman’s Model», and «The Music of Erich Zann». The division between Puritanism and Decadence, St. Armand argues, represents a polarization between an artificial paradise and oneiriscopic visions of different worlds.[173]

A non-literary inspiration came from then-contemporary scientific advances in biology, astronomy, geology, and physics.[174] Lovecraft’s study of science contributed to his view of the human race as insignificant, powerless, and doomed in a materialistic and mechanistic universe.[175] Lovecraft was a keen amateur astronomer from his youth, often visiting the Ladd Observatory in Providence, and penning numerous astronomical articles for his personal journal and local newspapers.[176] Lovecraft’s materialist views led him to espouse his philosophical views through his fiction; these philosophical views came to be called cosmicism. Cosmicism took on a more pessimistic tone with his creation of what is now known as the Cthulhu Mythos, a fictional universe that contains alien deities and horrors. The term «Cthulhu Mythos» was likely coined by later writers after Lovecraft’s death.[1] In his letters, Lovecraft jokingly called his fictional mythology «Yog-Sothothery».[177]

Dreams had a major role in Lovecraft’s literary career.[178] In 1991, as a result of his rising place in American literature, it was popularly thought that Lovecraft extensively transcribed his dreams when writing fiction. However, the majority of his stories are not transcribed dreams. Instead, many of them are directly influenced by dreams and dreamlike phenomena. In his letters, Lovecraft frequently compared his characters to dreamers. They are described as being as helpless as a real dreamer who is experiencing a nightmare. His stories also have dreamlike qualities. The Randolph Carter stories deconstruct the division between dreams and reality. The dreamlands in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath are a shared dreamworld that can be accessed by a sensitive dreamer. Meanwhile, in «The Silver Key», Lovecraft mentions the concept of «inward dreams», which implies the existence of outward dreams. Burleson compares this deconstruction to Carl Jung’s argument that dreams are the source of archetypal myths. Lovecraft’s way of writing fiction required both a level of realism and dreamlike elements. Citing Jung, Burleson argues that a writer may create realism by being inspired by dreams.[179]

Themes

Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large. To me there is nothing but puerility in a tale in which the human form—and the local human passions and conditions and standards—are depicted as native to other worlds or other universes. To achieve the essence of real externality, whether of time or space or dimension, one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all. Only the human scenes and characters must have human qualities. These must be handled with unsparing realism, (not catch-penny romanticism) but when we cross the line to the boundless and hideous unknown—the shadow-haunted Outside—we must remember to leave our humanity and terrestrialism at the threshold.

— H. P. Lovecraft, in note to the editor of Weird Tales, on resubmission of «The Call of Cthulhu»[180]

Cosmicism

The central theme of Lovecraft’s corpus is cosmicism. Cosmicism is a literary philosophy that argues that humanity is an insignificant force in the universe. Despite appearing pessimistic, Lovecraft thought of himself being as being a cosmic indifferentist, which is expressed in his fiction. In it, human beings are often subject to powerful beings and other cosmic forces, but these forces are not so much malevolent as they are indifferent toward humanity. He believed in a meaningless, mechanical, and uncaring universe that human beings could never fully understand. There is no allowance for beliefs that could not be supported scientifically.[181] Lovecraft first articulated this philosophy in 1921, but he did not fully incorporate it into his fiction until five years later. «Dagon», «Beyond the Wall of Sleep», and «The Temple» contain early depictions of this concept, but the majority of his early tales do not analyze the concept. «Nyarlathotep» interprets the collapse of human civilization as being a corollary to the collapse of the universe. «The Call of Cthulhu» represents an intensification of this theme. In it, Lovecraft introduces the idea of alien influences on humanity, which would come to dominate all subsequent works.[182] In these works, Lovecraft expresses cosmicism through the usage of confirmation rather than revelation. Lovecraftian protagonists do not learn that they are insignificant. Instead, they already know it and have it confirmed to them through an event.[183]

Knowledge

Lovecraft’s fiction reflects his own ambivalent views regarding the nature of knowledge.[184] This expresses itself in the concept of forbidden knowledge. In Lovecraft’s stories, happiness is only achievable through blissful ignorance. Trying to know things that are not meant to be known leads to harm and psychological danger. This concept intersects with several other ideas. This includes the idea that the visible reality is an illusion masking the horrific true reality. Similarly, there are also intersections with the concepts of ancient civilizations that exert a malign influence on humanity and the general philosophy of cosmicism.[185] According to Lovecraft, self-knowledge can bring ruin to those who seek it. Those seekers would become aware of their own insignificance in the wider cosmos and would be unable to bear the weight of this knowledge. Lovecraftian horror is not achieved through external phenomenon. Instead, it is reached through the internalized psychological impact that knowledge has on its protagonists. «The Call of Cthulhu», The Shadow over Innsmouth, and The Shadow Out of Time feature protagonists who experience both external and internal horror through the acquisition of self-knowledge.[186] The Case of Charles Dexter Ward also reflects this. One of its central themes is the danger of knowing too much about one’s family history. Charles Dexter Ward, the protagonist, engages in historical and genealogical research that ultimately leads to both madness and his own self-destruction.[187]

Decline of civilization

For much of his life, Lovecraft was fixated on the concepts of decline and decadence. More specifically, he thought that the West was in a state of terminal decline.[188] Starting in the 1920s, Lovecraft became familiar with the work of the German conservative-revolutionary theorist Oswald Spengler, whose pessimistic thesis of the decadence of the modern West formed a crucial element in Lovecraft’s overall anti-modern worldview.[189] Spenglerian imagery of cyclical decay is a central theme in At the Mountains of Madness. S. T. Joshi, in H. P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West, places Spengler at the center of his discussion of Lovecraft’s political and philosophical ideas. According to him, the idea of decline is the single idea that permeates and connects his personal philosophy. The main Spenglerian influence on Lovecraft would be his view that politics, economics, science, and art are all interdependent aspects of civilization. This realization led him to shed his personal ignorance of then-current political and economic developments after 1927.[190] Lovecraft had developed his idea of Western decline independently, but Spengler gave it a clear framework.[191]

Science

Lovecraft shifted supernatural horror away from its previous focus on human issues to a focus on cosmic ones. In this way, he merged the elements of supernatural fiction that he deemed to be scientifically viable with science fiction. This merge required an understanding of both supernatural horror and then-contemporary science.[192] Lovecraft used this combined knowledge to create stories that extensively reference trends in scientific development. Beginning with «The Shunned House», Lovecraft increasingly incorporated elements of both Einsteinian science and his own personal materialism into his stories. This intensified with the writing of «The Call of Cthulhu», where he depicted alien influences on humanity. This trend would continue throughout the remainder of his literary career. «The Colour Out of Space» represents what scholars have called the peak of this trend. It portrays an alien lifeform whose otherness prevents it from being defined by then-contemporary science.[193]

Another part of this effort was the repeated usage of mathematics in an effort to make his creatures and settings appear more alien. Tom Hull, a mathematician, regards this as enhancing his ability to invoke a sense of otherness and fear. He attributes this use of mathematics to Lovecraft’s childhood interest in astronomy and his adulthood awareness of non-Euclidean geometry.[194] Another reason for his use of mathematics was his reaction to the scientific developments of his day. These developments convinced him that humanity’s primary means of understanding the world was no longer trustable. Lovecraft’s usage of mathematics in his fiction serves to convert otherwise supernatural elements into things that have in-universe scientific explanations. «The Dreams in the Witch House» and The Shadow Out of Time both have elements of this. The former uses a witch and her familiar, while the latter uses the idea of mind transference. These elements are explained using scientific theories that were prevalent during Lovecraft’s lifetime.[195]

Lovecraft Country

Setting plays a major role in Lovecraft’s fiction. Lovecraft Country, a fictionalized version of New England, serves as the central hub for his mythos. It represents the history, culture, and folklore of the region, as interpreted by Lovecraft. These attributes are exaggerated and altered to provide a suitable setting for his stories. The names of the locations in the region were directly influenced by the names of real locations in the region, which was done to increase their realism.[196] Lovecraft’s stories use their connections with New England to imbue themselves with the ability to instill fear.[197] Lovecraft was primarily inspired by the cities and towns in Massachusetts. However, the specific location of Lovecraft Country is variable, as it moved according to Lovecraft’s literary needs. Starting with areas that he thought were evocative, Lovecraft redefined and exaggerated them under fictional names. For example, Lovecraft based Arkham on the town of Oakham and expanded it to include a nearby landmark.[198] Its location was moved, as Lovecraft decided that it would have been destroyed by the recently-built Quabbin Reservoir. This is alluded to in «The Colour Out of Space», as the «blasted heath» is submerged by the creation of a fictionalized version of the reservoir.[199] Similarly, Lovecraft’s other towns were based on other locations in Massachusetts. Innsmouth was based on Newburyport, and Dunwich was based on Greenwich. The vague locations of these towns also played into Lovecraft’s desire to create a mood in his stories. In his view, a mood can only be evoked through reading.[200]

Critical reception

Literary

Early efforts to revise an established literary view of Lovecraft as an author of ‘pulp’ were resisted by some eminent critics; in 1945, Edmund Wilson sneered: «the only real horror in most of these fictions is the horror of bad taste and bad art.» However, Wilson praised Lovecraft’s ability to write about his chosen field; he described him as having written about it «with much intelligence».[201] According to L. Sprague de Camp, Wilson later improved his opinion of Lovecraft, citing a report of David Chavchavadze that Wilson had included a Lovecraftian reference in Little Blue Light: A Play in Three Acts. After Chavchavadze met with him to discuss this, Wilson revealed that he had been reading a copy of Lovecraft’s correspondence.[f][203] Two years before Wilson’s critique, Lovecraft’s works were reviewed by Winfield Townley Scott, the literary editor of The Providence Journal. He argued that Lovecraft was one of the most significant Rhode Island authors and that it was regrettable that he had received little attention from mainstream critics at the time.[204] Mystery and Adventure columnist Will Cuppy of the New York Herald Tribune recommended to readers a volume of Lovecraft’s stories in 1944, asserting that «the literature of horror and macabre fantasy belongs with mystery in its broader sense.»[205]

By 1957, Floyd C. Gale of Galaxy Science Fiction said that Lovecraft was comparable to Robert E. Howard, stating that «they appear more prolific than ever,» noting L. Sprague de Camp, Björn Nyberg, and August Derleth’s usage of their creations.[206] Gale also said that «Lovecraft at his best could build a mood of horror unsurpassed; at his worst, he was laughable.»[206] In 1962, Colin Wilson, in his survey of anti-realist trends in fiction The Strength to Dream, cited Lovecraft as one of the pioneers of the «assault on rationality» and included him with M. R. James, H. G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, J. R. R. Tolkien and others as one of the builders of mythicised realities contending against what he considered the failing project of literary realism.[207] Subsequently, Lovecraft began to acquire the status of a cult writer in the counterculture of the 1960s, and reprints of his work proliferated.[208]

Michael Dirda, a reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement, has described Lovecraft as being a «visionary» who is «rightly regarded as second only to Edgar Allan Poe in the annals of American supernatural literature.» According to him, Lovecraft’s works prove that mankind cannot bear the weight of reality, as the true nature of reality cannot be understood by either science or history. In addition, Dirda praises Lovecraft’s ability to create an uncanny atmosphere. This atmosphere is created through the feeling of wrongness that pervades the objects, places, and people in Lovecraft’s works. He also comments favorably on Lovecraft’s correspondence, and compares him to Horace Walpole. Particular attention is given to his correspondence with August Derleth and Robert E. Howard. The Derleth letters are called «delightful», while the Howard letters are described as being an ideological debate. Overall, Dirda believes that Lovecraft’s letters are equal to, or better than, his fictional output.[209]

Los Angeles Review of Books reviewer Nick Mamatas has stated that Lovecraft was a particularly difficult author, rather than a bad one. He described Lovecraft as being «perfectly capable» in the fields of story logic, pacing, innovation, and generating quotable phrases. However, Lovecraft’s difficulty made him ill-suited to the pulps; he was unable to compete with the popular recurring protagonists and damsel-in-distress stories. Furthermore, he compared a paragraph from The Shadow Out of Time to a paragraph from the introduction to The Economic Consequences of the Peace. In Mamatas’ view, Lovecraft’s quality is obscured by his difficulty, and his skill is what has allowed his following to outlive the followings of other then-prominent authors, such as Seabury Quinn and Kenneth Patchen.[210]

In 2005, the Library of America published a volume of Lovecraft’s works. This volume was reviewed by many publications, including The New York Times Book Review and The Wall Street Journal, and sold 25,000 copies within a month of release. The overall critical reception of the volume was mixed.[211] Several scholars, including S. T. Joshi and Alison Sperling, have said that this confirms H. P. Lovecraft’s place in the western canon.[212] The editors of The Age of Lovecraft, Carl H. Sederholm and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, attributed the rise of mainstream popular and academic interest in Lovecraft to this volume, along with the Penguin Classics volumes and the Modern Library edition of At the Mountains of Madness. These volumes led to a proliferation of other volumes containing Lovecraft’s works. According to the two authors, these volumes are part of a trend in Lovecraft’s popular and academic reception: increased attention by one audience causes the other to also become more interested. Lovecraft’s success is, in part, the result of his success.[213]

Lovecraft’s style has often been subject to criticism,[214] but scholars such as S. T. Joshi have argued that Lovecraft consciously utilized a variety of literary devices to form a unique style of his own—these include prose-poetic rhythm, stream of consciousness, alliteration, and conscious archaism.[215] According to Joyce Carol Oates, Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe have exerted a significant influence on later writers in the horror genre.[216] Horror author Stephen King called Lovecraft «the twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.»[217] King stated in his semi-autobiographical non-fiction book Danse Macabre that Lovecraft was responsible for his own fascination with horror and the macabre and was the largest influence on his writing.[218]

Philosophical

H. P. Lovecraft’s writings have influenced the speculative realist philosophical movement during the early twentieth-first century. The four founders of the movement, Ray Brassier, Iain Hamilton Grant, Graham Harman, and Quentin Meillassoux, have cited Lovecraft as an inspiration for their worldviews.[219] Graham Harman wrote a monograph, Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy, about Lovecraft and philosophy. In it, he argues that Lovecraft was a «productionist» author. He describes Lovecraft as having been an author who was uniquely obsessed with gaps in human knowledge.[220] He goes further and asserts Lovecraft’s personal philosophy as being in opposition to both idealism and David Hume. In his view, Lovecraft resembles Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Edmund Husserl in his division of objects into different parts that do not exhaust the potential meanings of the whole. The anti-idealism of Lovecraft is represented through his commentary on the inability of language to describe his horrors.[221] Harman also credits Lovecraft with inspiring parts of his own articulation of object-oriented ontology.[222] According to Lovecraft scholar Alison Sperling, this philosophical interpretation of Lovecraft’s fiction has caused other philosophers in Harmon’s tradition to write about Lovecraft. These philosophers seek to remove human perception and human life from the foundations of ethics. These scholars have used Lovecraft’s works as the central example of their worldview. They base this usage in Lovecraft’s arguments against anthropocentrism and the ability of the human mind to truly understand the universe. They have also played a role in Lovecraft’s improving literary reputation by focusing on his interpretation of ontology, which gives him a central position in Anthropocene studies.[223]

Legacy

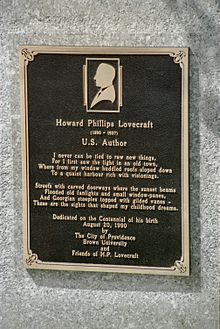

H. P. Lovecraft memorial plaque at 22 Prospect Street in Providence. Portrait by silhouettist E. J. Perry.

Lovecraft was relatively unknown during his lifetime. While his stories appeared in prominent pulp magazines such as Weird Tales, not many people knew his name.[224] He did, however, correspond regularly with other contemporary writers such as Clark Ashton Smith and August Derleth,[225] who became his friends, even though he never met them in person. This group became known as the «Lovecraft Circle», since their writings freely borrowed Lovecraft’s motifs, with his encouragement. He borrowed from them as well. For example, he made use of Clark Ashton Smith’s Tsathoggua in The Mound.[226]

After Lovecraft’s death, the Lovecraft Circle carried on. August Derleth founded Arkham House with Donald Wandrei to preserve Lovecraft’s works and keep them in print.[227] He added to and expanded on Lovecraft’s vision, not without controversy.[228] While Lovecraft considered his pantheon of alien gods a mere plot device, Derleth created an entire cosmology, complete with a war between the good Elder Gods and the evil Outer Gods, such as Cthulhu and his ilk. The forces of good were supposed to have won, locking Cthulhu and others beneath the earth, the ocean, and elsewhere. Derleth’s Cthulhu Mythos stories went on to associate different gods with the traditional four elements of fire, air, earth, and water, which did not line up with Lovecraft’s original vision of his mythos. However, Derleth’s ownership of Arkham House gave him a position of authority in Lovecraftiana that would not dissipate until his death, and through the efforts of Lovecraft scholars in the 1970s.[229]

Lovecraft’s works have influenced many writers and other creators. Stephen King has cited Lovecraft as a major influence on his works. As a child in the 1960s, he came across a volume of Lovecraft’s works which inspired him to write his fiction. He goes on to argue that all works in the horror genre that were written after Lovecraft were influenced by him.[217] In the field of comics, Alan Moore has described Lovecraft as having been a formative influence on his graphic novels.[230] Film director John Carpenter’s films include direct references and quotations of Lovecraft’s fiction, in addition to their use of a Lovecraftian aesthetic and themes. Guillermo del Toro has been similarly influenced by Lovecraft’s corpus.[231]

The first World Fantasy Awards were held in Providence in 1975. The theme was «The Lovecraft Circle». Until 2015, winners were presented with an elongated bust of Lovecraft that was designed by cartoonist Gahan Wilson, nicknamed the «Howard».[232] In November 2015 it was announced that the World Fantasy Award trophy would no longer be modeled on H. P. Lovecraft in response to the author’s views on race.[233] After the World Fantasy Award dropped their connection to Lovecraft, The Atlantic commented that «In the end, Lovecraft still wins—people who’ve never read a page of his work will still know who Cthulhu is for years to come, and his legacy lives on in the work of Stephen King, Guillermo del Toro, and Neil Gaiman.»[232]

In 2016, Lovecraft was inducted into the Museum of Pop Culture’s Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.[234] Three years later, Lovecraft and the other mythos authors were posthumously awarded the 1945 Retro-Hugo Award for Best Series for their contributions to the Cthulhu Mythos.[235]

Lovecraft studies

Starting in the early 1970s, a body of scholarly work began to emerge around Lovecraft’s life and works. Referred to as Lovecraft studies, its proponents sought to establish Lovecraft as a significant author in the American literary canon. This can be traced to Derleth’s preservation and dissemination of Lovecraft’s fiction, non-fiction, and letters through Arkham House. Joshi credits the development of the field to this process. However, it was marred by low quality editions and misinterpretations of Lovecraft’s worldview. After Derleth’s death in 1971, the scholarship entered a new phase. There was a push to create a book-length biography of Lovecraft. L. Sprague de Camp, a science fiction scholar, wrote the first major one in 1975. This biography was criticized by early Lovecraft scholars for its lack of scholarly merit and its lack of sympathy for its subject. Despite this, it played a significant role in Lovecraft’s literary rise. It exposed Lovecraft to the mainstream of American literary criticism. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a division in the field between the «Derlethian traditionalists» who wished to interpret Lovecraft through the lens of fantasy literature and the newer scholars who wished to place greater attention on the entirety of his corpus.[236]

The 1980s and 1990s saw a further proliferation of the field. The 1990 H. P. Lovecraft Centennial Conference and the republishing of older essays in An Epicure in the Terrible represented the publishing of many basic studies that would be used as a base for then-future studies. The 1990 centennial also saw the installation of the «H. P. Lovecraft Memorial Plaque» in a garden adjoining John Hay Library, that features a portrait by silhouettist E. J. Perry.[237] Following this, in 1996, S. T. Joshi wrote his own biography of Lovecraft. This biography was met with positive reviews and became the main biography in the field. It has since been superseded by his expanded edition of the book, I am Providence in 2010.[238]

Lovecraft’s improving literary reputation has caused his works to receive increased attention by both classics publishers and scholarly fans.[239] His works have been published by several different series of literary classics. Penguin Classics published three volumes of Lovecraft’s works between 1999 and 2004. These volumes were edited by S. T. Joshi.[239] Barnes & Noble would publish their own volume of Lovecraft’s complete fiction in 2008. The Library of America published a volume of Lovecraft’s works in 2005. The publishing of these volumes represented a reversal of the traditional judgment that Lovecraft was not part of the Western canon.[240] Meanwhile, the biannual NecronomiCon Providence convention was first held in 2013. Its purpose is to serve as a fan and scholarly convention that discusses both Lovecraft and the wider field of weird fiction. It is organized by the Lovecraft Arts and Sciences organization and is held on the weekend of Lovecraft’s birth.[241] That July, the Providence City Council designated the «H. P. Lovecraft Memorial Square» and installed a commemorative sign at the intersection of Angell and Prospect streets, near the author’s former residences.[242]

Music

Lovecraft’s fictional Mythos has influenced a number of musicians, particularly in rock and heavy metal music.[243] This began in the 1960s with the formation of the psychedelic rock band H. P. Lovecraft, who released the albums H. P. Lovecraft and H. P. Lovecraft II in 1967 and 1968 respectively.[244] They broke up afterwards, but later songs were released. This included «The White Ship» and «At the Mountains of Madness», both titled after Lovecraft stories.[245] Extreme metal has also been influenced by Lovecraft.[246] This has expressed itself in both the names of bands and the contents of their albums. This began in 1970 with the release of Black Sabbath’s first album, Black Sabbath, which contained a song titled Behind the Wall of Sleep, deriving its name from the 1919 story «Beyond the Wall of Sleep.»[246] Heavy metal band Metallica was also inspired by Lovecraft. They recorded a song inspired by «The Call of Cthulhu», «The Call of Ktulu», and a song based on The Shadow over Innsmouth titled «The Thing That Should Not Be».[247] These songs contain direct quotations of Lovecraft’s works.[248] Joseph Norman, a speculative scholar, has argued that there are similarities between the music described in Lovecraft’s fiction and the aesthetics and atmosphere of black metal. He argues that this is evident through the «animalistic» qualities of black metal vocals. The usage of occult elements is also cited as a thematic commonality. In terms of atmosphere, he asserts that both Lovecraft’s works and extreme metal place heavy focus on creating a strong negative mood.[249]

Games

Lovecraft has also influenced gaming, despite having personally disliked games during his lifetime.[250] Chaosium’s tabletop role-playing game Call of Cthulhu, released in 1981 and currently in its seventh major edition, was one of the first games to draw heavily from Lovecraft.[251] It includes a Lovecraft-inspired insanity mechanic, which allowed for player characters to go insane from contact with cosmic horrors. This mechanic would go on to make appearance in subsequent tabletop and video games.[252] 1987 saw the release of another Lovecraftian board game, Arkham Horror, which was published by Fantasy Flight Games.[253] Though few subsequent Lovecraftian board games were released annually from 1987 to 2014, the years after 2014 saw a rapid increase in the number of Lovecraftian board games. According to Christina Silva, this revival may have been influenced by the entry of Lovecraft’s work into the public domain and a revival of interest in board games.[254] Few video games are direct adaptations of Lovecraft’s works, but many video games have been inspired or heavily influenced by Lovecraft.[252] Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth, a Lovecraftian first-person video game, was released in 2005.[252] It is a loose adaptation of The Shadow over Innsmouth, The Shadow Out of Time, and «The Thing on the Doorstep» that uses noir themes.[255] These adaptations focus more on Lovecraft’s monsters and gamification than they do on his themes, which represents a break from Lovecraft’s core theme of human insignificance.[256]

Religion and occultism

Several contemporary religions have been influenced by Lovecraft’s works. Kenneth Grant, the founder of the Typhonian Order, incorporated Lovecraft’s Mythos into his ritual and occult system. Grant combined his interest in Lovecraft’s fiction with his adherence to Aleister Crowley’s Thelema. The Typhonian Order considers Lovecraftian entities to be symbols through which people may interact with something inhuman.[257] Grant also argued that Crowley himself was influenced by Lovecraft’s writings, particularly in the naming of characters in The Book of the Law.[258] Similarly, The Satanic Rituals, co-written by Anton LaVey and Michael A. Aquino, includes the «Ceremony of the Nine Angles», which is a ritual that was influenced by the descriptions in «The Dreams in the Witch House». It contains invocations of several of Lovecraft’s fictional gods.[259]

There have been several books that have claimed to be an authentic edition of Lovecraft’s Necronomicon.[260] The Simon Necronomicon is one such example. It was written by an unknown figure who identified themselves as «Simon». Peter Levenda, an occult author who has written about the Necronomicon, claims that he and «Simon» came across a hidden Greek translation of the grimoire while looking through a collection of antiquities at a New York bookstore during the 1960s or 1970s.[261] This book was claimed to have borne the seal of the Necronomicon. Levenda went on to claim that Lovecraft had access to this purported scroll.[262] A textual analysis has determined that the contents of this book were derived from multiple documents that discuss Mesopotamian myth and magic. The finding of a magical text by monks is also a common theme in the history of grimoires.[263] It has been suggested that Levenda is the true author of the Simon Necronomicon.[264]

Correspondence

Although Lovecraft is known mostly for his works of weird fiction, the bulk of his writing consists of voluminous letters about a variety of topics, from weird fiction and art criticism to politics and history.[265] Lovecraft biographers L. Sprague de Camp and S. T. Joshi have estimated that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters in his lifetime, a fifth of which are believed to survive.[266] These letters were directed at fellow writers and members of the amateur press. His involvement in the latter was what caused him to begin writing them.[267] He included comedic elements in these letters. This included posing as an eighteenth-century gentleman and signing them with pseudonyms, most commonly «Grandpa Theobald» and «E’ch-Pi-El.»[g][269] According to Joshi, the most important sets of letters were those written to Frank Belknap Long, Clark Ashton Smith, and James F. Morton. He attributes this importance to the contents of these letters. With Long, Lovecraft argued in support and in opposition to many of Long’s viewpoints. The letters to Clark Ashton Smith are characterized by their focus on weird fiction. Lovecraft and Morton debated many scholarly subjects in their letters, resulting in what Joshi has called the «single greatest correspondence Lovecraft ever wrote.»[270]

Copyright and other legal issues

Despite several claims to the contrary, there is currently no evidence that any company or individual owns the copyright to any of Lovecraft’s works, and it is generally accepted that it has passed into the public domain.[271] Lovecraft had specified that R. H. Barlow would serve as the executor of his literary estate,[272] but these instructions were not incorporated into his will. Nevertheless, his surviving aunt carried out his expressed wishes, and Barlow was given control of Lovecraft’s literary estate upon his death. Barlow deposited the bulk of the papers, including the voluminous correspondence, in the John Hay Library, and attempted to organize and maintain Lovecraft’s other writings.[273] Lovecraft protégé August Derleth, an older and more established writer than Barlow, vied for control of the literary estate. He and Donald Wandrei, a fellow protégé and co-owner of Arkham House, falsely claimed that Derleth was the true literary executor.[274] Barlow capitulated, and later committed suicide in 1951.[275] This gave Derleth and Wandrei complete control over Lovecraft’s corpus.[276]

On October 9, 1947, Derleth purchased all rights to the stories that were published in Weird Tales. However, since April 1926 at the latest, Lovecraft had reserved all second printing rights to stories published in Weird Tales. Therefore, Weird Tales only owned the rights to at most six of Lovecraft’s tales. If Derleth had legally obtained the copyrights to these tales, there is no evidence that they were renewed before the rights expired.[277] Following Derleth’s death in 1971, Donald Wandrei sued his estate to challenge Derleth’s will, which stated that he only held the copyrights and royalties to Lovecraft’s works that were published under both his and Derleth’s names. Arkham House’s lawyer, Forrest D. Hartmann, argued that the rights to Lovecraft’s works were never renewed. Wandrei won the case, but Arkham House’s actions regarding copyright have damaged their ability to claim ownership of them.[278]