Данное слово является существительным с предлогом или наречием, а употребляется в значении «на латинском языке». Со значением слова всё стало понятно. А возникнут ли вопросы при написании слова? Я думаю, что да. Поэтому, давайте разберёмся.

Как же правильно пишется: «по латыни» или «по-латыни»?

Согласно орфографической норме русского языка изучаемое слово пишется в обоих вариантах:

ПО ЛАТЫНИ

ПО-ЛАТЫНИ

Важно знать, что оба варианта правописания являются верными. Однако выбор в пользу первого или второго зависит от контекста предложения.

Почему напишем раздельно?

Напишем раздельно, если в предложении слово является существительным с предлогом и обозначает дисциплину «латинский язык».

Почему напишем через дефис?

Напишем раздельно, если слово является наречием в предложении и отвечает на вопрос «как?».

В данном случае действует правило русского языка: наречия, образованные от имён прилагательных при помощи приставки «по» и суффикса «и», пишутся через дефис.

Синонимы к слову:

- На латинском языке

- По-латински

- На древнем

Примеры предложений с данным словом:

- Мама, я получил по латыни твёрдую пятёрку.

- Незнакомцы разговаривали по-латыни, поэтому я ничего не понимал.

- Зачёт по латыни состоится через две недели.

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

Лили́т, нескл., ж. (мифол.)

Рядом по алфавиту:

ли́ктор , -а

ли́кторский

ликтро́с , -а

лику́юще , нареч.

лику́ющий

лиле́йник , -а

лиле́йный

лиле́я , -и (устар. поэт. к ли́лия)

лилиеви́дный , кр. ф. -ден, -дна

лилиеобра́зный , кр. ф. -зен, -зна

лилиецве́тные , -ых

лилипу́т , -а

лилипу́тка , -и, р. мн. -ток

лилипу́товый

лилипу́тский

Лили́т , нескл., ж. (мифол.)

ли́лия , -и

ли́лльский , (от Лилль)

лилова́тенький

лилова́то-кра́сный

лилова́тость , -и

лилова́тый

лило́венький

лилове́ть , -е́ет

лило́во-голубо́й

лило́во-ро́зовый

лило́во-си́ний

лило́во-чёрный

лило́вость , -и

лило́вый

лима́н , -а

Lingva latina — один из красивейших языков индоевропейской семьи, прародитель современного итальянского, один из самых древних письменных индоевропейских языков. Чтобы научиться писать на нем, надо освоить язык на трех уровнях: орфографии, грамматики и синтаксиса.

Фонетика и правописание — определиться с системой. Современные лингвисты редко пытаются воспроизвести звучание классического (а тем более архаического) латинского языка, хотя и берут за основу правописание и звучание образованных римлян 147-30 года до нашей эры. В настоящее время существует несколько систем латинского произношения. Каждая система зависит от страны, в которой преподается латынь. В русском языке принята «средневековая» немецкая традиция передачи латинских имен и названий. Чтобы избежать расхождений в орфографических правилах, лучше не мешать российские учебники с итальянскими и английскими пособиями.

Грамматика — выучить ее. Латынь с русским языком схожа тем, что имеет систему падежей, три рода, три наклонения, систему времен и залогов. Латинская грамматика легко дается тем, кто учит романские языки. Но в целом, русскоговорящие воспринимают ее как логичную и интуитивно понятную. В интернете достаточно самоучителей и форумов, где можно выложить свое упражнение, написанное на латинском языке, на проверку или попросить о помощи с переводом. http://www.lingualatina.ru/osnovnoi-uchebnik — один из доступных в сети учебников. На том же сайте существует довольно активное сообщество специалистов и энтузиастов латинского языка.

Синтаксис — уловить различия с русским языком. Латинские предложения, так же как и русские, состоят в большинстве случаев из подлежащего в именительном падеже и сказуемого. Порядок слов не так важен, хотя классическая латынь подразумевает существительное или местоимение в начале предложения, а глагол- перед точкой. Например, крылатая фраза «Бог есть в каждом из нас» переводится как «Deus in omni nostrum est». Прямое дополнение ставится перед сказуемым. Найти бесплатный учебник, где разъясняются основы латинского ситаксиса, можно, например, здесь: http://latinum.ru/load/2-1-0-31.

→

по-латыни — наречие, опред., спос.,

Часть речи: наречие — по-латыни

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Слова русского языка,

поиск и разбор слов онлайн

- Слова русского языка

- Л

- Лилит

Правильно слово пишется: Лили́т

Ударение падает на 2-й слог с буквой и.

Всего в слове 5 букв, 2 гласных, 3 согласных, 2 слога.

Гласные: и, и;

Согласные: л, л, т.

Номера букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «Лилит» в прямом и обратном порядке:

- 5

Л

1 - 4

и

2 - 3

л

3 - 2

и

4 - 1

т

5

- Слова русского языка

- Русский язык

- О сайте

- Подборки слов

- Поиск слов по маске

- Составление словосочетаний

- Словосочетаний из предложений

- Деление слов на слоги

- Словари

- Орфографический словарь

- Словарь устаревших слов

- Словарь новых слов

- Орфография

- Орфограммы

- Проверка ошибок в словах

- Исправление ошибок

- Лексика

- Омонимы

- Устаревшие слова

- Заимствованные слова

- Новые слова

- Диалекты

- Слова-паразиты

- Сленговые слова

- Профессиональные слова

- Интересные слова

This article is about the Jewish mythological figure Lilith. For other uses, see Lilith (disambiguation).

|

Lilith |

|

|---|---|

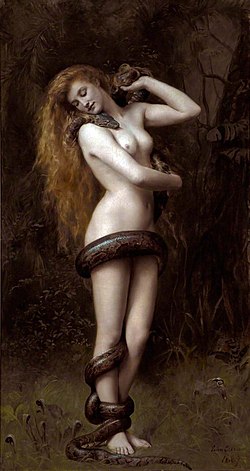

Lilith (1887) by John Collier in Atkinson Art Gallery, Merseyside, England |

|

| Born |

Garden of Eden |

«The only thing I can tell you about Lilith is that according to Jewish folklore, she left her husband, Adam, after she refused to become subservient to him. Although… Dr. Holly Brown writes: ‘The demonization of Lilith was designed to keep women alienated from their own power and spiritual authority.’ Now that’s what I call girl power.»

«She was a demon?»

«She’s Jewish?»

Lilith (/ˈlɪlɪθ/; Hebrew: <templatestyles src=»Script/styles_hebrew.css» />לִילִית Lîlîṯ) is a figure in Jewish mythology, developed earliest in the Babylonian Talmud (3rd to 5th century AD). From c. AD 700–1000 onwards Lilith appears as Adam’s first wife, created at the same time (Rosh Hashanah) and from the same clay as Adam—compare Genesis 1:27.[1] The figure of Lilith may relate in part to a historically earlier class of female demons (lilītu) in ancient Mesopotamian religion, found in cuneiform texts of Sumer, the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, and Babylonia.

Lilith continues to serve as source material in modern western culture, literature, occultism, fantasy, and horror.

History

In Jewish folklore, Alphabet of Sirach (c. AD 700–1000) onwards, Lilith appears as Adam’s first wife, who was created at the same time (Rosh Hashanah) and from the same clay as Adam—compare Genesis 1:27 (This contrasts with Eve, who was created from one of Adam’s ribs: Genesis 2:22.) The legend of Lilith developed extensively during the Middle Ages, in the tradition of Aggadah, the Zohar, and Jewish mysticism.[2] For example, in the 13th-century writings of Isaac ben Jacob ha-Cohen, Lilith left Adam after she refused to become subservient to him and then would not return to the Garden of Eden after she had coupled with the archangel Samael.[3]

Interpretations of Lilith found in later Jewish materials are plentiful, but little information has survived relating to the Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian view of this class of demons. While researchers almost universally agree that a connection exists, recent scholarship has disputed the relevance of two sources previously used to connect the Jewish lilith to an Akkadian lilītu—the Gilgamesh appendix and the Arslan Tash amulets.[4] (See below for discussion of these two problematic sources.) «Other scholars, such as Lowell K. Handy, agree that Lilith derives from Mesopotamian demons but argue against finding evidence of the Hebrew Lilith in many of the epigraphical and artifactual sources frequently cited as such (e.g., the Sumerian Gilgamesh fragment, the Sumerian incantation from Arshlan-Tash).»[3]:174

In Hebrew-language texts, the term lilith or lilit (translated as «night creatures», «night monster», «night hag», or «screech owl») first occurs in a list of animals in Isaiah 34:14, either in singular or plural form according to variations in the earliest manuscripts. Commentators and interpreters often envision the figure of Lilith as a dangerous demon of the night, who is sexually wanton, and who steals babies in the darkness. In the Dead Sea Scrolls 4Q510-511, the term first occurs in a list of monsters. Jewish magical inscriptions on bowls and amulets from the 6th century AD onwards identify Lilith as a female demon and provide the first visual depictions of her.

Etymology

In the Akkadian language of Assyria and Babylonia, the terms lili and līlītu mean spirits. Some uses of līlītu are listed in The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD, 1956, L.190), in Wolfram von Soden‘s Akkadisches Handwörterbuch (AHw, p. 553), and Reallexikon der Assyriologie (RLA, p. 47).[5]

The Sumerian female demons lili have no etymological relation to Akkadian lilu, «evening».[6]

Archibald Sayce (1882)[7] considered that Hebrew lilit (or lilith) לילית and the earlier Akkadian līlītu are from proto-Semitic. Charles Fossey (1902) has this literally translating to «female night being/demon», although cuneiform inscriptions from Mesopotamia exist where Līlīt and Līlītu refers to disease-bearing wind spirits.[8]

Mesopotamian mythology

Main article: Lilu (mythology)

The spirit in the tree in the Gilgamesh cycle

Samuel Noah Kramer (1932, published 1938)[9] translated ki-sikil-lil-la-ke as Lilith in «Tablet XII» of the Epic of Gilgamesh dated c. 600 BC. «Tablet XII» is not part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, but is a later Assyrian Akkadian translation of the latter part of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh.[10] The ki-sikil-lil-la-ke is associated with a serpent and a zu bird.[11] In Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, a huluppu tree grows in Inanna‘s garden in Uruk, whose wood she plans to use to build a new throne. After ten years of growth, she comes to harvest it and finds a serpent living at its base, a Zu bird raising young in its crown, and that a ki-sikil-lil-la-ke made a house in its trunk. Gilgamesh is said to have killed the snake, and then the zu bird flew away to the mountains with its young, while the ki-sikil-lil-la-ke fearfully destroys its house and runs for the forest.[12][13] Identification of ki-sikil-lil-la-ke as Lilith is stated in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (1999).[14] According to a new source from late antiquity, Lilith appears in a Mandaic magic story where she is considered to represent the branches of a tree with other demonic figures that form other parts of the tree, though this may also include multiple «Liliths».[15]

Suggested translations for the Tablet XII spirit in the tree include ki-sikil as «sacred place», lil as «spirit», and lil-la-ke as «water spirit».[16] but also simply «owl», given that the lil is building a home in the trunk of the tree.[17]

A connection between the Gilgamesh ki-sikil-lil-la-ke and the Jewish Lilith was rejected by Dietrich Opitz (1932)[18][not in citation given] and rejected on textual grounds by Sergio Ribichini (1978).[19]

The bird-footed woman in the Burney Relief

File:Burney Relief Babylon -1800-1750.JPG Burney Relief, Babylon (BC 1800–1750).

Main article: Burney Relief

Kramer’s translation of the Gilgamesh fragment was used by Henri Frankfort (1937)[20] and Emil Kraeling (1937)[21] to support identification of a woman with wings and bird-feet in the Burney Relief as related to Lilith. Frankfort and Kraeling incorrectly identified the figure in the relief with Lilith, based on a misreading of an outdated translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh.[22] Modern research has identified the figure as one of the main goddesses of the Mesopotamian pantheons, most probably Inanna or Ereshkigal.[23]

The Arslan Tash amulets

Main article: Arslan Tash amulets

The Arslan Tash amulets are limestone plaques discovered in 1933 at Arslan Tash, the authenticity of which is disputed. William F. Albright, Theodor H. Gaster,[24] and others, accepted the amulets as a pre-Jewish source which shows that the name Lilith already existed in the 7th century BC but Torczyner (1947) identified the amulets as a later Jewish source.[25]

In the Hebrew Bible

The word lilit (or lilith) only appears once in the Hebrew Bible, while the other seven terms in the list appear more than once and thus are better documented. The reading of scholars and translators is often guided by a decision about the complete list of eight creatures as a whole.[26][27][28] Quoting from Isaiah 34 (NAB):

(12) Her nobles shall be no more, nor shall kings be proclaimed there; all her princes are gone. (13) Her castles shall be overgrown with thorns, her fortresses with thistles and briers. She shall become an abode for jackals and a haunt for ostriches. (14) Wildcats shall meet with desert beasts, satyrs shall call to one another; There shall the Lilith repose, and find for herself a place to rest. (15) There the hoot owl shall nest and lay eggs, hatch them out and gather them in her shadow; There shall the kites assemble, none shall be missing its mate. (16) Look in the book of the LORD and read: No one of these shall be lacking, For the mouth of the LORD has ordered it, and His spirit shall gather them there. (17) It is He who casts the lot for them, and with His hands He marks off their shares of her; They shall possess her forever, and dwell there from generation to generation.

Hebrew text

In the Masoretic Text:

Hebrew: וּפָגְשׁוּ צִיִּים אֶת-אִיִּים, וְשָׂעִיר עַל-רֵעֵהוּ יִקְרָא; אַךְ-שָׁם הִרְגִּיעָה לִּילִית, וּמָצְאָה לָהּ מָנוֹח

Hebrew (ISO 259): u-pagšu ṣiyyim et-ʾiyyim w-saʿir ʿal-rēʿēhu yiqra; ʾak-šam hirgiʿa lilit u-maṣʾa lah manoaḥ

34:14 «And shall-meet wildcats[29] with jackals

the goat he-calls his- fellow

lilit (lilith) she-rests and she-finds rest[30]

34:15 there she-shall-nest the great-owl, and she-lays-(eggs), and she-hatches, and she-gathers under her-shadow:

hawks [kites, gledes] also they-gather, every one with its mate.

In the Dead Sea Scrolls, among the 19 fragments of Isaiah found at Qumran, the Great Isaiah Scroll (1Q1Isa) in 34:14 renders the creature as plural liliyyot (or liliyyoth).[31][32]

Eberhard Schrader (1875)[33] and Moritz Abraham Levy (1885)[34] suggest that Lilith was a goddess of the night, known also by the Jewish exiles in Babylon. Schrader’s and Levy’s view is therefore partly dependent on a later dating of Deutero-Isaiah to the 6th century BC, and the presence of Jews in Babylon which would coincide with the possible references to the Līlītu in Babylonian demonology. However, this view is challenged by some modern research such as by Judit M. Blair (2009) who considers that the context indicates unclean animals.[35]

Greek version

The Septuagint translates both the reference to lilith and the word for jackals or «wild beasts of the island» within the same verse into Greek as onokentauros, apparently assuming them as referring to the same creatures and gratuitously omitting «wildcats/wild beasts of the desert» (so, instead of the wildcats or desert beasts meeting with the jackals or island beasts, the goat or «satyr» crying «to his fellow» and lilith or «screech-owl» resting «there», it is the goat or «satyr», translated as daimonia «demons», and the jackals or island beasts «onocentaurs» meeting with each other and crying «one to the other» and the latter resting there in the translation).[36]

Latin Bible

The early 5th-century Vulgate translated the same word as lamia.[37][38]

et occurrent daemonia onocentauris et pilosus clamabit alter ad alterum ibi cubavit lamia et invenit sibi requiem

—Isaiah (Isaias Propheta) 34.14, Vulgate

The translation is, «And demons shall meet with monsters, and one hairy one shall cry out to another; there the lamia has lain down and found rest for herself».

English versions

Wycliffe’s Bible (1395) preserves the Latin rendering lamia:

Isa 34:15 Lamya schal ligge there, and foond rest there to hir silf.

The Bishops’ Bible of Matthew Parker (1568) from the Latin:

Isa 34:14 there shall the Lamia lye and haue her lodgyng.

Douay–Rheims Bible (1582/1610) also preserves the Latin rendering lamia:

Isa 34:14 And demons and monsters shall meet, and the hairy ones shall cry out one to another, there hath the lamia lain down, and found rest for herself.

The Geneva Bible of William Madison Whittington (1587) from the Hebrew:

Isa 34:14 and the screech owl shall rest there, and shall finde for her selfe a quiet dwelling.

Then the King James Version (1611):

Isa 34:14 The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest.

The «screech owl» translation of the King James Version is, together with the «owl» (yanšup, probably a water bird) in 34:11 and the «great owl» (qippoz, properly a snake) of 34:15, an attempt to render the passage by choosing suitable animals for difficult-to-translate Hebrew words.

Later translations include:

- night-owl (Young, 1898)

- night-spectre (Rotherham, Emphasized Bible, 1902)

- night monster (ASV, 1901; JPS 1917, Good News Translation, 1992; NASB, 1995)

- vampires (Moffatt Translation, 1922; Knox Bible, 1950)

- night hag (Revised Standard Version, 1947)

- Lilith (Jerusalem Bible, 1966)

- lilith (New American Bible, 1970)

- Lilith (New Revised Standard Version, 1989)

- Lilith (The Message (Bible), Peterson, 1993)

- night creature (New International Version, 1978; New King James Version, 1982; New Living Translation, 1996, Today’s New International Version)

- nightjar (New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, 1984)

- night bird (English Standard Version, 2001)

Jewish tradition

Major sources in Jewish tradition regarding Lilith in chronological order include:

- c. 40–10 BC Dead Sea Scrolls – Songs for a Sage (4Q510-511)

- c. 200 Mishnah – not mentioned

- c. 500 Gemara of the Talmud

- c. 800 The Alphabet of Ben-Sira

- c. 900 Midrash Abkir

- c. 1260 Treatise on the Left Emanation, Spain

- c. 1280 Zohar, Spain.

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls contain one indisputable reference to Lilith in Songs of the Sage (4Q510–511)[39] fragment 1:

And I, the Instructor, proclaim His glorious splendour so as to frighten and to te[rrify] all the spirits of the destroying angels, spirits of the bastards, demons, Lilith, howlers, and [desert dwellers] … and those which fall upon men without warning to lead them astray from a spirit of understanding and to make their heart and their … desolate during the present dominion of wickedness and predetermined time of humiliations for the sons of lig[ht], by the guilt of the ages of [those] smitten by iniquity – not for eternal destruction, [bu]t for an era of humiliation for transgression.[40]

File:Great Isaiah Scroll.jpg Photographic reproduction of the Great Isaiah Scroll, which contains a reference to plural liliyyot

As with the Massoretic text of Isaiah 34:14, and therefore unlike the plural liliyyot (or liliyyoth) in the Isaiah scroll 34:14, lilit in 4Q510 is singular, this liturgical text both cautions against the presence of supernatural malevolence and assumes familiarity with Lilith; distinct from the biblical text, however, this passage does not function under any socio-political agenda, but instead serves in the same capacity as An Exorcism (4Q560) and Songs to Disperse Demons (11Q11).[41] The text is thus, to a community «deeply involved in the realm of demonology»,[42] an exorcism hymn.

Joseph M. Baumgarten (1991) identified the unnamed woman of The Seductress (4Q184) as related to female demon.[43] However, John J. Collins[44] regards this identification as «intriguing» but that it is «safe to say» that (4Q184) is based on the strange woman of Proverbs 2, 5, 7, 9:

Her house sinks down to death,

And her course leads to the shades.

All who go to her cannot return

And find again the paths of life.

Her gates are gates of death, and from the entrance of the house

She sets out towards Sheol.

None of those who enter there will ever return,

And all who possess her will descend to the Pit.

Early Rabbinic literature

Lilith does not occur in the Mishnah. There are five references to Lilith in the Babylonian Talmud in Gemara on three separate Tractates of the Mishnah:

- «Rab Judah citing Samuel ruled: If an abortion had the likeness of Lilith its mother is unclean by reason of the birth, for it is a child but it has wings.» (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Nidda 24b)[45]

- «[Expounding upon the curses of womanhood] In a Baraitha it was taught: She grows long hair like Lilith, sits when making water like a beast, and serves as a bolster for her husband.» (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Eruvin 100b)

- «For gira he should take an arrow of Lilith and place it point upwards and pour water on it and drink it. Alternatively he can take water of which a dog has drunk at night, but he must take care that it has not been exposed.» (Babylonian Talmud, tractate Gittin 69b). In this particular case, the «arrow of Lilith» is most probably a scrap of meteorite or a fulgurite, colloquially known as «petrified lightning» and treated as antipyretic medicine.[46]

- «Rabbah said: I saw how Hormin the son of Lilith was running on the parapet of the wall of Mahuza, and a rider, galloping below on horseback could not overtake him. Once they saddled for him two mules which stood on two bridges of the Rognag; and he jumped from one to the other, backward and forward, holding in his hands two cups of wine, pouring alternately from one to the other, and not a drop fell to the ground.» (Babylonian Talmud, tractate Bava Bathra 73a-b). Hormin who is mentioned here as the son of Lilith is most probably a result of a scribal error of the word «Hormiz» attested in some of the Talmudic manuscripts. The word itself in turn seems to a distortion of Ormuzd, the Zendavestan deity of light and goodness. If so, it is somewhat ironic that Ormuzd becomes here the son of a nocturnal demon.[46]

- «R. Hanina said: One may not sleep in a house alone [in a lonely house], and whoever sleeps in a house alone is seized by Lilith.» (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Shabbath 151b)

The above statement by Hanina may be related to the belief that nocturnal emissions engendered the birth of demons:

- «R. Jeremiah b. Eleazar further stated: In all those years [130 years after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden] during which Adam was under the ban he begot ghosts and male demons and female demons [or night demons], for it is said in Scripture: And Adam lived a hundred and thirty years and begot a son in own likeness, after his own image, from which it follows that until that time he did not beget after his own image … When he saw that through him death was ordained as punishment he spent a hundred and thirty years in fasting, severed connection with his wife for a hundred and thirty years, and wore clothes of fig on his body for a hundred and thirty years. – That statement [of R. Jeremiah] was made in reference to the semen which he emitted accidentally.» (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Eruvin 18b)

The Midrash Rabbah collection contains two references to Lilith. The first one is present in Genesis Rabbah 22:7 and 18:4: according to Rabbi Hiyya God proceeded to create a second Eve for Adam, after Lilith had to return to dust.[47] However, to be exact the said passages do not employ the Hebrew word lilith itself and instead speak of «the first Eve» (Heb. Chavvah ha-Rishonah, analogically to the phrase Adam ha-Rishon, i.e. the first Adam). Although in the medieval Hebrew literature and folklore, especially that reflected on the protective amulets of various kinds, Chavvah ha-Rishonah was identified with Lilith, one should remain careful in transposing this equation to the Late Antiquity.[46]

The second mention of Lilith, this time explicit, is present in Numbers Rabbah 16:25. The midrash develops the story of Moses’ plea after God expresses anger at the bad report of the spies. Moses responds to a threat by God that He will destroy the Israelite people. Moses pleads before God, that God should not be like Lilith who kills her own children.[46] Moses said:

[God,] do not do it [i.e. destroy the Israelite people], that the nations of the world may not regard you as a cruel Being and say: ‘The Generation of the Flood came and He destroyed them, the Generation of the Separation came and He destroyed them, the Sodomites and the Egyptians came and He destroyed them, and these also, whom he called My son, My firstborn (Ex. IV, 22), He is now destroying! As that Lilith who, when she finds nothing else, turns upon her own children, so Because the Lord was not able to bring this people into the land… He hath slain them’ (Num. XIV, 16)![48]

Incantation bowls

File:Incantation bowl demon Met L1999.83.3.jpg Incantation bowl with an Aramaic inscription around a demon, from Nippur, Mesopotamia, 6–7th century.

An individual Lilith, along with Bagdana «king of the lilits», is one of the demons to feature prominently in protective spells in the eighty surviving Jewish occult incantation bowls from Sassanid Empire Babylon (4th–6th century AD) with influence from Iranian culture.[47][49] These bowls were buried upside down below the structure of the house or on the land of the house, in order to trap the demon or demoness.[50] Almost every house was found to have such protective bowls against demons and demonesses.[50][51]

The centre of the inside of the bowl depicts Lilith, or the male form, Lilit. Surrounding the image is writing in spiral form; the writing often begins at the centre and works its way to the edge.[52] The writing is most commonly scripture or references to the Talmud. The incantation bowls which have been analysed, are inscribed in the following languages, Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, Syriac, Mandaic, Middle Persian, and Arabic. Some bowls are written in a false script which has no meaning.[49]

The correctly worded incantation bowl was capable of warding off Lilith or Lilit from the household. Lilith had the power to transform into a woman’s physical features, seduce her husband, and conceive a child. However, Lilith would become hateful towards the children born of the husband and wife and would seek to kill them. Similarly, Lilit would transform into the physical features of the husband, seduce the wife, she would give birth to a child. It would become evident that the child was not fathered by the husband, and the child would be looked down on. Lilit would seek revenge on the family by killing the children born to the husband and wife.[53]

Key features of the depiction of Lilith or Lilit include the following. The figure is often depicted with arms and legs chained, indicating the control of the family over the demon(ess). The demon(ess) is depicted in a frontal position with the whole face showing. The eyes are very large, as well as the hands (if depicted). The demon(ess) is entirely static.[49]

One bowl contains the following inscription commissioned from a Jewish occultist to protect a woman called Rashnoi and her husband from Lilith:

Thou liliths, male lili and female lilith, hag and ghool, I adjure you by the Strong One of Abraham, by the Rock of Isaac, by the Shaddai of Jacob, by Yah Ha-Shem by Yah his memorial, to turn away from this Rashnoi b. M. and from Geyonai b. M. her husband. [Here is] your divorce and writ and letter of separation, sent through holy angels. Amen, Amen, Selah, Halleluyah! (image)

—Excerpt from translation in Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur James Alan Montgomery 2011 p 156.[54]

Alphabet of Ben Sira

Main article: Alphabet of Ben Sira

File:Lilith (Carl Poellath).jpg Lilith, illustration by Carl Poellath from 1886 or earlier

The pseudepigraphical[55] 8th–10th centuries Alphabet of Ben Sira is considered to be the oldest form of the story of Lilith as Adam’s first wife. Whether this particular tradition is older is not known. Scholars tend to date the Alphabet between the 8th and 10th centuries AD. The work has been characterised as satirical.

In the text an amulet is inscribed with the names of three angels (Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof) and placed around the neck of newborn boys in order to protect them from the lilin until their circumcision.[56] The amulets used against Lilith that were thought to derive from this tradition are, in fact, dated as being much older.[57] The concept of Eve having a predecessor is not exclusive to the Alphabet, and is not a new concept, as it can be found in Genesis Rabbah. However, the idea that Lilith was the predecessor may be exclusive to the Alphabet.

The idea in the text that Adam had a wife prior to Eve may have developed from an interpretation of the Book of Genesis and its dual creation accounts; while Genesis 2:22 describes God’s creation of Eve from Adam’s rib, an earlier passage, 1:27, already indicates that a woman had been made: «So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.» The Alphabet text places Lilith’s creation after God’s words in Genesis 2:18 that «it is not good for man to be alone»; in this text God forms Lilith out of the clay from which he made Adam but she and Adam bicker. Lilith claims that since she and Adam were created in the same way they were equal and she refuses to submit to him:

After God created Adam, who was alone, He said, «It is not good for man to be alone.» He then created a woman for Adam, from the earth, as He had created Adam himself, and called her Lilith. Adam and Lilith immediately began to fight. She said, «I will not lie below,» and he said, «I will not lie beneath you, but only on top. For you are fit only to be in the bottom position, while I am to be the superior one.» Lilith responded, «We are equal to each other inasmuch as we were both created from the earth.» But they would not listen to one another. When Lilith saw this, she pronounced the Ineffable Name and flew away into the air.

Adam stood in prayer before his Creator: «Sovereign of the universe!» he said, «the woman you gave me has run away.» At once, the Holy One, blessed be He, sent these three angels Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof, to bring her back.

Said the Holy One to Adam, «If she agrees to come back, what is made is good. If not, she must permit one hundred of her children to die every day.» The angels left God and pursued Lilith, whom they overtook in the midst of the sea, in the mighty waters wherein the Egyptians were destined to drown. They told her God’s word, but she did not wish to return. The angels said, «We shall drown you in the sea.»

«Leave me!’ she said. «I was created only to cause sickness to infants. If the infant is male, I have dominion over him for eight days after his birth, and if female, for twenty days.»

When the angels heard Lilith’s words, they insisted she go back. But she swore to them by the name of the living and eternal God: «Whenever I see you or your names or your forms in an amulet, I will have no power over that infant.» She also agreed to have one hundred of her children die every day. Accordingly, every day one hundred demons perish, and for the same reason, we write the angels’ names on the amulets of young children. When Lilith sees their names, she remembers her oath, and the child recovers.

The background and purpose of The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is unclear. It is a collection of stories about heroes of the Bible and Talmud, it may have been a collection of folk-tales, a refutation of Christian, Karaite, or other separatist movements; its content seems so offensive to contemporary Jews that it was even suggested that it could be an anti-Jewish satire,[58] although, in any case, the text was accepted by the Jewish mystics of medieval Germany. In turn, other scholars argue that the target of the Alphabet’s satire is very difficult to establish exactly because of the variety of the figures and values ridiculed therein: criticism is actually directed against Adam, who turns out to be weak and ineffective in his relations with his wife. Apparently, the first man is not the only male figure who is mocked: even God cannot subjugate Lilith and needs to ask his messengers, who only manage to go as far as negotiating the conditions of the agreement.[46]

File:Filippino Lippi- Adam.JPG Adam clutches a child in the presence of the child-snatcher Lilith. Fresco by Filippino Lippi, basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence

The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is the earliest surviving source of the story, and the conception that Lilith was Adam’s first wife became only widely known with the 17th century Lexicon Talmudicum of German scholar Johannes Buxtorf.

In this folk tradition that arose in the early Middle Ages Lilith, a dominant female demon, became identified with Asmodeus, King of Demons, as his queen.[59] Asmodeus was already well known by this time because of the legends about him in the Talmud. Thus, the merging of Lilith and Asmodeus was inevitable.[60] The second myth of Lilith grew to include legends about another world and by some accounts this other world existed side by side with this one, Yenne Velt is Yiddish for this described «Other World». In this case Asmodeus and Lilith were believed to procreate demonic offspring endlessly and spread chaos at every turn.[61]

Two primary characteristics are seen in these legends about Lilith: Lilith as the incarnation of lust, causing men to be led astray, and Lilith as a child-killing witch, who strangles helpless neonates. These two aspects of the Lilith legend seemed to have evolved separately; there is hardly a tale where she encompasses both roles.[61] But the aspect of the witch-like role that Lilith plays broadens her archetype of the destructive side of witchcraft. Such stories are commonly found among Jewish folklore.[61]

The influence of the rabbinic traditions

Although the image of Lilith of the Alphabet of Ben Sira is unprecedented, some elements in her portrayal can be traced back to the talmudic and midrashic traditions that arose around Eve:

- First and foremost, the very introduction of Lilith to the creation story rests on the rabbinic myth, prompted by the two separate creation accounts in Genesis 1:1–2:25, that there were two original women. A way of resolving the apparent discrepancy between these two accounts was to assume that there must have been some other first woman, apart from the one later identified with Eve. The Rabbis, noting Adam’s exclamation, «this time (zot hapa‘am) [this is] bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh» (Genesis 2:23), took it as an intimation that there must already have been a «first time». According to Genesis rabah 18:4, Adam was disgusted upon seeing the first woman full of «discharge and blood», and God had to provide him with another one. The subsequent creation is performed with adequate precautions: Adam is made to sleep, so as not to witness the process itself ( Sanhedrin 39a), and Eve is adorned with fine jewellery (Genesis rabah 18:1) and brought to Adam by the angels Gabriel and Michael (ibid. 18:3). However, nowhere do the rabbis specify what happened to the first woman, leaving the matter open for further speculation. This is the gap into which the later tradition of Lilith could fit.

- Second, this new woman is still met with harsh rabbinic allegations. Again playing on the Hebrew phrase zot hapa‘am, Adam, according to the same midrash, declares: «it is she [zot] who is destined to strike the bell [zog] and to speak [in strife] against me, as you read, ‘a golden bell [pa‘amon] and a pomegranate’ [Exodus 28:34] … it is she who will trouble me [mefa‘amtani] all night» (Genesis Rabbah 18:4). The first woman also becomes the object of accusations ascribed to Rabbi Joshua of Siknin, according to whom Eve, despite the divine efforts, turned out to be «swelled-headed, coquette, eavesdropper, gossip, prone to jealousy, light-fingered and gadabout» (Genesis Rabbah 18:2). A similar set of charges appears in Genesis Rabbah 17:8, according to which Eve’s creation from Adam’s rib rather than from the earth makes her inferior to Adam and never satisfied with anything.

- Third, and despite the terseness of the biblical text in this regard, the erotic iniquities attributed to Eve constitute a separate category of her shortcomings. Told in Genesis 3:16 that «your desire shall be for your husband», she is accused by the Rabbis of having an overdeveloped sexual drive (Genesis Rabhah 20:7) and constantly enticing Adam (Genesis Rabbab 23:5). However, in terms of textual popularity and dissemination, the motif of Eve copulating with the primeval serpent takes priority over her other sexual transgressions. Despite the rather unsettling picturesqueness of this account, it is conveyed in numerous places: Genesis Rabbah 18:6, and BT Sotah 9b, Shabbat 145b–146a and 156a, Yevamot 103b and Avodah Zarah 22b.[46]

Kabbalah

Template:Kabbalah

Main article: Lilith (Lurianic Kabbalah)

Kabbalistic mysticism attempted to establish a more exact relationship between Lilith and God. With her major characteristics having been well developed by the end of the Talmudic period, after six centuries had elapsed between the Aramaic incantation texts that mention Lilith and the early Spanish Kabbalistic writings in the 13th century, she reappears, and her life history becomes known in greater mythological detail.[62] Her creation is described in many alternative versions.

One mentions her creation as being before Adam’s, on the fifth day, because the «living creatures» with whose swarms God filled the waters included Lilith. A similar version, related to the earlier Talmudic passages, recounts how Lilith was fashioned with the same substance as Adam was, shortly before. A third alternative version states that God originally created Adam and Lilith in a manner that the female creature was contained in the male. Lilith’s soul was lodged in the depths of the Great Abyss. When God called her, she joined Adam. After Adam’s body was created, a thousand souls from the Left (evil) side attempted to attach themselves to him. However, God drove them off. Adam was left lying as a body without a soul. Then a cloud descended and God commanded the earth to produce a living soul. This God breathed into Adam, who began to spring to life and his female was attached to his side. God separated the female from Adam’s side. The female side was Lilith, whereupon she flew to the Cities of the Sea and attacked humankind.

Yet another version claims that Lilith emerged as a divine entity that was born spontaneously, either out of the Great Supernal Abyss or out of the power of an aspect of God (the Gevurah of Din). This aspect of God was negative and punitive, as well as one of his ten attributes (Sefirot), at its lowest manifestation has an affinity with the realm of evil and it is out of this that Lilith merged with Samael.[63]

An alternative story links Lilith with the creation of luminaries. The «first light», which is the light of Mercy (one of the Sefirot), appeared on the first day of creation when God said «Let there be light». This light became hidden and the Holiness became surrounded by a husk of evil. «A husk (klippa) was created around the brain» and this husk spread and brought out another husk, which was Lilith.[64]

Midrash ABKIR

The first medieval source to depict Adam and Lilith in full was the Midrash A.B.K.I.R. (c. 10th century), which was followed by the Zohar and other Kabbalistic writings. Adam is said to be perfect until he recognises either his sin or Cain’s fratricide that is the cause of bringing death into the world. He then separates from holy Eve, sleeps alone, and fasts for 130 years. During this time «Pizna», either an alternate name for Lilith or a daughter of hers, desires his beauty and seduces him against his will. She gives birth to multitudes of djinns and demons, the first of them being named Agrimas. However, they are defeated by Methuselah, who slays thousands of them with a holy sword and forces Agrimas to give him the names of the rest, after which he casts them away to the sea and the mountains.[65]

Treatise on the Left Emanation

Main article: Treatise on the Left Emanation

The mystical writing of two brothers Jacob and Isaac Hacohen, Treatise on the Left Emanation, which predates the Zohar by a few decades, states that Samael and Lilith are in the shape of an androgynous being, double-faced, born out of the emanation of the Throne of Glory and corresponding in the spiritual realm to Adam and Eve, who were likewise born as a hermaphrodite. The two twin androgynous couples resembled each other and both «were like the image of Above»; that is, that they are reproduced in a visible form of an androgynous deity.

19. In answer to your question concerning Lilith, I shall explain to you the essence of the matter. Concerning this point there is a received tradition from the ancient Sages who made use of the Secret Knowledge of the Lesser Palaces, which is the manipulation of demons and a ladder by which one ascends to the prophetic levels. In this tradition it is made clear that Samael and Lilith were born as one, similar to the form of Adam and Eve who were also born as one, reflecting what is above. This is the account of Lilith which was received by the Sages in the Secret Knowledge of the Palaces.[66]

Another version[67] that was also current among Kabbalistic circles in the Middle Ages establishes Lilith as the first of Samael’s four wives: Lilith, Naamah, Eisheth, and Agrat bat Mahlat. Each of them are mothers of demons and have their own hosts and unclean spirits in no number.[68] The marriage of archangel Samael and Lilith was arranged by «Blind Dragon», who is the counterpart of «the dragon that is in the sea». Blind Dragon acts as an intermediary between Lilith and Samael:

Blind Dragon rides Lilith the Sinful — may she be extirpated quickly in our days, Amen! — And this Blind Dragon brings about the union between Samael and Lilith. And just as the Dragon that is in the sea (Isa. 27:1) has no eyes, likewise Blind Dragon that is above, in the likeness of a spiritual form, is without eyes, that is to say, without colors…. (Patai 81:458) Samael is called the Slant Serpent, and Lilith is called the Tortuous Serpent.[69]

The marriage of Samael and Lilith is known as the «Angel Satan» or the «Other God», but it was not allowed to last. To prevent Lilith and Samael’s demonic children Lilin from filling the world, God castrated Samael. In many 17th century Kabbalistic books, this seems to be a reinterpretation of an old Talmudic myth where God castrated the male Leviathan and slew the female Leviathan in order to prevent them from mating and thereby destroying the Earth with their offspring.[70] With Lilith being unable to fornicate with Samael anymore, she sought to couple with men who experience nocturnal emissions. A 15th or 16th century Kabbalah text states that God has «cooled» the female Leviathan, meaning that he has made Lilith infertile and she is a mere fornication.

File:Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem — The Fall of Man — WGA05250.jpg The Fall of Man by Cornelis van Haarlem (1592), showing the serpent in the Garden of Eden as a woman.

The Treatise on the Left Emanation also says that there are two Liliths, the lesser being married to the great demon Asmodeus.

The Matron Lilith is the mate of Samael. Both of them were born at the same hour in the image of Adam and Eve, intertwined in each other. Asmodeus the great king of the demons has as a mate the Lesser (younger) Lilith, daughter of the king whose name is Qafsefoni. The name of his mate is Mehetabel daughter of Matred, and their daughter is Lilith.[71]

Another passage charges Lilith as being a tempting serpent of Eve.

And the Serpent, the Woman of Harlotry, incited and seduced Eve through the husks of Light which in itself is holiness. And the Serpent seduced Holy Eve, and enough said for him who understands. And all this ruination came about because Adam the first man coupled with Eve while she was in her menstrual impurity – this is the filth and the impure seed of the Serpent who mounted Eve before Adam mounted her. Behold, here it is before you: because of the sins of Adam the first man all the things mentioned came into being. For Evil Lilith, when she saw the greatness of his corruption, became strong in her husks, and came to Adam against his will, and became hot from him and bore him many demons and spirits and Lilin. (Patai81:455f)

Zohar

References to Lilith in the Zohar include the following:

She roams at night, and goes all about the world and makes sport with men and causes them to emit seed. In every place where a man sleeps alone in a house, she visits him and grabs him and attaches herself to him and has her desire from him, and bears from him. And she also afflicts him with sickness, and he knows it not, and all this takes place when the moon is on the wane.[72]

This passage may be related to the mention of Lilith in Talmud Shabbath 151b (see above), and also to Talmud Eruvin 18b where nocturnal emissions are connected with the begettal of demons.

According to Rapahel Patai, older sources state clearly that after Lilith’s Red Sea sojourn (mentioned also in Louis Ginzberg‘s Legends of the Jews), she returned to Adam and begat children from him by forcing herself upon him. Before doing so, she attaches herself to Cain and bears him numerous spirits and demons. In the Zohar, however, Lilith is said to have succeeded in begetting offspring from Adam even during their short-lived sexual experience. Lilith leaves Adam in Eden, as she is not a suitable helpmate for him.[73] Gershom Scholem proposes that the author of the Zohar, Rabbi Moses de Leon, was aware of both the folk tradition of Lilith and another conflicting version, possibly older.[74]

The Zohar adds further that two female spirits instead of one, Lilith and Naamah, desired Adam and seduced him. The issue of these unions were demons and spirits called «the plagues of humankind», and the usual added explanation was that it was through Adam’s own sin that Lilith overcame him against his will.[73]

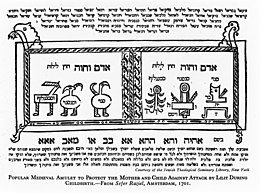

17th-century Hebrew magical amulets

File:Medieval amulet to protect mother and child. Wellcome M0008070.jpg Medieval Hebrew amulet intended to protect a mother and her child from Lilith

A copy of Jean de Pauly‘s translation of the Zohar in the Ritman Library contains an inserted late 17th century printed Hebrew sheet for use in magical amulets where the prophet Elijah confronts Lilith.[75]

The sheet contains two texts within borders, which are amulets, one for a male (‘lazakhar’), the other one for a female (‘lanekevah’). The invocations mention Adam, Eve and Lilith, ‘Chavah Rishonah’ (the first Eve, who is identical with Lilith), also devils or angels: Sanoy, Sansinoy, Smangeluf, Shmari’el (the guardian) and Hasdi’el (the merciful). A few lines in Yiddish are followed by the dialogue between the prophet Elijah and Lilith when he met her with her host of demons to kill the mother and take her new-born child (‘to drink her blood, suck her bones and eat her flesh’). She tells Elijah that she will lose her power if someone uses her secret names, which she reveals at the end: lilith, abitu, abizu, hakash, avers hikpodu, ayalu, matrota …[76]

In other amulets, probably informed by The Alphabet of Ben-Sira, she is Adam’s first wife. (Yalqut Reubeni, Zohar 1:34b, 3:19[77])

Greco-Roman mythology

Main article: Lamia (mythology)

File:Lamia and the Soldier.jpg Lamia (first version) by John William Waterhouse, 1905

In the Latin Vulgate Book of Isaiah 34:14, Lilith is translated lamia.

According to Augustine Calmet, Lilith has connections with early views on vampires and sorcery:

Some learned men have thought they discovered some vestiges of vampirism in the remotest antiquity; but all that they say of it does not come near what is related of the vampires. The lamiæ, the strigæ, the sorcerers whom they accused of sucking the blood of living persons, and of thus causing their death, the magicians who were said to cause the death of new-born children by charms and malignant spells, are nothing less than what we understand by the name of vampires; even were it to be owned that these lamiæ and strigæ have really existed, which we do not believe can ever be well proved.

I own that these terms [lamiæ and strigæ] are found in the versions of Holy Scripture. For instance, Isaiah, describing the condition to which Babylon was to be reduced after her ruin, says that she shall become the abode of satyrs, lamiæ, and strigæ (in Hebrew, lilith). This last term, according to the Hebrews, signifies the same thing, as the Greeks express by strix and lamiæ, which are sorceresses or magicians, who seek to put to death new-born children. Whence it comes that the Jews are accustomed to write in the four corners of the chamber of a woman just delivered, «Adam, Eve, be gone from hence lilith.» … The ancient Greeks knew these dangerous sorceresses by the name of lamiæ, and they believed that they devoured children, or sucked away all their blood till they died.[78]

According to Siegmund Hurwitz the Talmudic Lilith is connected with the Greek Lamia, who, according to Hurwitz, likewise governed a class of child stealing lamia-demons. Lamia bore the title «child killer» and was feared for her malevolence, like Lilith. She has different conflicting origins and is described as having a human upper body from the waist up and a serpentine body from the waist down.[79] One source states simply that she is a daughter of the goddess Hecate, another, that Lamia was subsequently cursed by the goddess Hera to have stillborn children because of her association with Zeus; alternatively, Hera slew all of Lamia’s children (except Scylla) in anger that Lamia slept with her husband, Zeus. The grief caused Lamia to turn into a monster that took revenge on mothers by stealing their children and devouring them.[79] Lamia had a vicious sexual appetite that matched her cannibalistic appetite for children. She was notorious for being a vampiric spirit and loved sucking men’s blood.[80] Her gift was the «mark of a Sibyl», a gift of second sight. Zeus was said to have given her the gift of sight. However, she was «cursed» to never be able to shut her eyes so that she would forever obsess over her dead children. Taking pity on Lamia, Zeus gave her the ability to remove and replace her eyes from their sockets.[79]

Arabic literature

Lilith is not found in the Quran or Hadith. The Sufi occult writer Ahmad al-Buni (d. 1225), in his Sun of the Great Knowledge (Arabic: شمس المعارف الكبرى), mentions a demon called «the mother of children» (ام الصبيان), a term also used «in one place».[81]

In Western literature

Further information: Lilith in popular culture

In German literature

File:Richard Westall — Faust and Lilith.jpg Faust and Lilith by Richard Westall (1831)

Lilith’s earliest appearance in the literature of the Romantic period (1789–1832) was in Goethe‘s 1808 work Faust: The First Part of the Tragedy.

Faust:

Who’s that there?

Mephistopheles:

Take a good look.

Lilith.

Faust:

Lilith? Who is that?

Mephistopheles:

Adam’s wife, his first. Beware of her.

Her beauty’s one boast is her dangerous hair.

When Lilith winds it tight around young men

She doesn’t soon let go of them again.

After Mephistopheles offers this warning to Faust, he then, quite ironically, encourages Faust to dance with «the Pretty Witch». Lilith and Faust engage in a short dialogue, where Lilith recounts the days spent in Eden.

Faust: [dancing with the young witch]

A lovely dream I dreamt one day

I saw a green-leaved apple tree,

Two apples swayed upon a stem,

So tempting! I climbed up for them.

The Pretty Witch:

Ever since the days of Eden

Apples have been man’s desire.

How overjoyed I am to think, sir,

Apples grow, too, in my garden.

In English literature

File:Lady-Lilith.jpg Lady Lilith by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1866–1868, 1872–1873)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which developed around 1848,[82] were greatly influenced by Goethe’s work on the theme of Lilith. In 1863, Dante Gabriel Rossetti of the Brotherhood began painting what would later be his first rendition of Lady Lilith, a painting he expected to be his «best picture hitherto».[82] Symbols appearing in the painting allude to the «femme fatale» reputation of the Romantic Lilith: poppies (death and cold) and white roses (sterile passion). Accompanying his Lady Lilith painting from 1866, Rossetti wrote a sonnet entitled Lilith, which was first published in Swinburne’s pamphlet-review (1868), Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition.

Of Adam’s first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

That, ere the snake’s, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative,

Draws men to watch the bright web she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

The rose and poppy are her flower; for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

Lo! As that youth’s eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

The poem and the picture appeared together alongside Rossetti’s painting Sibylla Palmifera and the sonnet Soul’s Beauty. In 1881, the Lilith sonnet was renamed «Body’s Beauty» in order to contrast it and Soul’s Beauty. The two were placed sequentially in The House of Life collection (sonnets number 77 and 78).[82]

Rossetti wrote in 1870:

Lady [Lilith] … represents a Modern Lilith combing out her abundant golden hair and gazing on herself in the glass with that self-absorption by whose strange fascination such natures draw others within their own circle.

—Rossetti, W. M. ii.850, D. G. Rossetti’s emphasis[82]

This is in accordance with Jewish folk tradition, which associates Lilith both with long hair (a symbol of dangerous feminine seductive power in Jewish culture), and with possessing women by entering them through mirrors.[83]

The Victorian poet Robert Browning re-envisioned Lilith in his poem «Adam, Lilith, and Eve». First published in 1883, the poem uses the traditional myths surrounding the triad of Adam, Eve, and Lilith. Browning depicts Lilith and Eve as being friendly and complicitous with each other, as they sit together on either side of Adam. Under the threat of death, Eve admits that she never loved Adam, while Lilith confesses that she always loved him:

As the worst of the venom left my lips,

I thought, ‘If, despite this lie, he strips

The mask from my soul with a kiss — I crawl

His slave, — soul, body, and all!

Browning focused on Lilith’s emotional attributes, rather than that of her ancient demon predecessors.[84]

Scottish author George MacDonald also wrote a fantasy novel entitled Lilith, first published in 1895. MacDonald employed the character of Lilith in service to a spiritual drama about sin and redemption, in which Lilith finds a hard-won salvation. Many of the traditional characteristics of Lilith mythology are present in the author’s depiction: Long dark hair, pale skin, a hatred and fear of children and babies, and an obsession with gazing at herself in a mirror. MacDonald’s Lilith also has vampiric qualities: she bites people and sucks their blood for sustenance.

Australian poet and scholar Christopher John Brennan (1870–1932), included a section titled «Lilith» in his major work «Poems: 1913» (Sydney : G. B. Philip and Son, 1914). The «Lilith» section contains thirteen poems exploring the Lilith myth and is central to the meaning of the collection as a whole.

C. L. Moore‘s 1940 story Fruit of Knowledge is written from Lilith’s point of view. It is a re-telling of the Fall of Man as a love triangle between Lilith, Adam and Eve – with Eve’s eating the forbidden fruit being in this version the result of misguided manipulations by the jealous Lilith, who had hoped to get her rival discredited and destroyed by God and thus regain Adam’s love.

British poet John Siddique‘s 2011 collection Full Blood has a suite of 11 poems called The Tree of Life, which features Lilith as the divine feminine aspect of God. A number of the poems feature Lilith directly, including the piece Unwritten which deals with the spiritual problem of the feminine being removed by the scribes from The Bible.

Lilith is also mentioned in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C.S.Lewis. The character Mr. Beaver ascribes the ancestry of the main antagonist, Jadis the White Witch, to Lilith.[85]

As the origin of the term «lullaby»

It has been claimed by some etymologists that the term «lullaby» derives from «Lilith-Abi» (Hebrew for «Lilith, begone»).[86][87][88][89] To guard against Lilith, Jewish mothers would hang four amulets on nursery walls with the inscription «Lilith – abei» [«Lilith – begone»].[90][91]

In modern occultism

See also: Black Moon Lilith

The depiction of Lilith in Romanticism continues to be popular among Wiccans and in other modern Occultism.[82] A few magical orders dedicated to the undercurrent of Lilith, featuring initiations specifically related to the arcana of the «first mother», exist. Two organisations that use initiations and magic associated with Lilith are the Ordo Antichristianus Illuminati and the Order of Phosphorus. Lilith appears as a succubus in Aleister Crowley‘s De Arte Magica. Lilith was also one of the middle names of Crowley’s first child, Nuit Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith Crowley (1904–1906), and Lilith is sometimes identified with Babalon in Thelemic writings. Many early occult writers that contributed to modern day Wicca expressed special reverence for Lilith. Charles Leland associated Aradia with Lilith: Aradia, says Leland, is Herodias, who was regarded in stregheria folklore as being associated with Diana as chief of the witches. Leland further notes that Herodias is a name that comes from west Asia, where it denoted an early form of Lilith.[92][93]

Gerald Gardner asserted that there was continuous historical worship of Lilith to present day, and that her name is sometimes given to the goddess being personified in the coven by the priestess. This idea was further attested by Doreen Valiente, who cited her as a presiding goddess of the Craft: «the personification of erotic dreams, the suppressed desire for delights».[94] In some contemporary concepts, Lilith is viewed as the embodiment of the Goddess, a designation that is thought to be shared with what these faiths believe to be her counterparts: Inanna, Ishtar, Asherah, Anath and Isis.[95] According to one view, Lilith was originally a Sumerian, Babylonian, or Hebrew mother goddess of childbirth, children, women, and sexuality.[96][97]

Raymond Buckland holds that Lilith is a dark moon goddess on par with the Hindu Kali.[98]

Many modern theistic Satanists consider Lilith as a goddess. She is considered a goddess of independence by those Satanists and is often worshipped by women, but women are not the only people who worship her. Lilith is popular among theistic Satanists because of her association with Satan. Some Satanists believe that she is the wife of Satan and thus think of her as a mother figure. Others base their reverence towards her based on her history as a succubus and praise her as a sex goddess.[99] A different approach to a Satanic Lilith holds that she was once a fertility and agricultural goddess.[100]

Modern Kabbalah and Western mystery tradition

The western mystery tradition associates Lilith with the Qliphoth of kabbalah. Samael Aun Weor in The Pistis Sophia Unveiled writes that homosexuals are the «henchmen of Lilith». Likewise, women who undergo wilful abortion, and those who support this practice are «seen in the sphere of Lilith».[101] Dion Fortune writes, «The Virgin Mary is reflected in Lilith»,[102] and that Lilith is the source of «lustful dreams».[102]

Popular culture

Main article: Lilith in popular culture

See also

- Eve

- Mesopotamian Religion

- Lilu, Akkadian demons

- Lilin, Hebrew term of demons in Targum Sheni Esther 1:3 and Apocalypse of Baruch

- Lilith (Lurianic Kabbalah)

- Lilith Fair

- Abyzou

- Daemon (classical mythology)

- Ishtar

- Inanna

- Norea

- Serpent seed

- Siren

- Spirit spouse

- Succubus

Notes

- ↑ Hammer, Jill. «Lilith, Lady Flying in Darkness». My Jewish Learning. http://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/lilith-lady-flying-in-darkness/. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Schwartz, Howard (2006). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-532713-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=5psRDAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kvam, Kristen E.; Schearing, Linda S.; Ziegler, Valarie H. (1999). Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Readings on Genesis and Gender. Indiana University Press. pp. 220–1. ISBN 978-0-253-21271-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ux3bSDa2rHkC&pg=PA220.

- ↑ Freedman, David Noel (ed.) (1997, 1992). Anchor Bible Dictionary. New York: Doubleday. «Very little information has been found relating to the Akkadian and Babylonian view of these figures. Two sources of information previously used to define Lilith are both suspect.»

- ↑ Erich Ebeling, Bruno Meissner, Dietz Otto Edzard Reallexikon der Assyriologie Volume 9 p 47, 50.

- ↑ Michael C. Astour Hellenosemitica: an ethnic and cultural study in west Semitic impact on Mycenaean. Greece 1965 Brill p 138.

- ↑ Sayce (1887)

- ↑ Fossey (1902)

- ↑ Kramer, S. N. Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree: A Reconstructed Sumerian Text. Assyriological Studies 10. Chicago. 1938.

- ↑ George, A. The epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian epic poem and other texts in Akkadian 2003 p 100 Tablet XII. Appendix The last Tablet in the ‘Series of Gilgamesh’ .

- ↑ Kramer translates the zu as «owl», but most often it is translated as «eagle«, «vulture«, or «bird of prey«.

- ↑ Chicago Assyrian Dictionary. Chicago: University of Chicago. 1956.<templatestyles src=»Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css»></templatestyles>

- ↑ Hurwitz (1980) p. 49

- ↑ Manfred Hutter article in Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst – 1999 pp. 520–521, article cites Hutter’s own 1988 work Behexung, Entsühnung und Heilung Eisenbrauns 1988. pp. 224–228.

- ↑ Müller-Kessler, C. (2002) «A Charm against Demons of Time», in C. Wunsch (ed.), Mining the Archives. Festschrift Christopher Walker on the Occasion of his 60th Birthday (Dresden), p. 185.

- ↑ Roberta Sterman Sabbath Sacred tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qur’an as literature and culture 2009.

- ↑ Sex and gender in the ancient Near East: proceedings of the 47th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Helsinki, July 2–6, 2001, Part 2 p. 481.

- ↑ Opitz, D. Ausgrabungen und Forschungsreisen Ur. AfO 8: 328.

- ↑ Ribichini, S. Lilith nell-albero Huluppu Pp. 25 in Atti del 1° Convegno Italiano sul Vicino Oriente Antico, Rome, 1976.

- ↑ Frankfort, H. The Burney Relief AfO 12: 128, 1937.

- ↑ Kraeling, E. G. A Unique Babylonian Relief BASOR 67: 168. 1937.

- ↑ Kraeling, Emil (1937). «A Unique Babylonian Relief». Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (67): 16–18. JSTOR 3218905.

- ↑ Albenda, Pauline (2005). «The «Queen of the Night» Plaque: A Revisit». Journal of the American Oriental Society 125 (2): 171–190. JSTOR 20064325.

- ↑ Gaster, T. H. 1942. A Canaanite Magical Text. Or 11:

- ↑ Torczyner, H. 1947. «A Hebrew Incantation against Night-Demons from Biblical Times». JNES 6: 18–29.

- ↑ de Waard, Jan (1997). A handbook on Isaiah. Winona Lake, IN. ISBN 1-57506-023-X. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ioLT-x9KtCoC.

- ↑ Delitzsch Isaiah.

- ↑ See The animals mentioned in the Bible Henry Chichester Hart 1888, and more modern sources; also entries Brown Driver Briggs Hebrew Lexicon for tsiyyim… ‘iyyim… sayir… liylith… qippowz… dayah.

- ↑ «Isaiah 34:14 (JPS 1917)». http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt1034.htm#14. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ↑ (מנוח manoaḥ, used for birds as Noah’s dove, Gen.8:9 and also humans as Israel, Deut.28:65; Naomi, Ruth 3:1).

- ↑ Blair J. «De-demonising the Old Testament» p.27.

- ↑ Christopher R. A. Morray-Jones A transparent illusion: the dangerous vision of water in Hekhalot Vol. 59 p 258 2002 «Early evidence of the belief in a plurality of liliths is provided by the Isaiah scroll from Qumran, which gives the name as liliyyot, and by the targum to Isaiah, which, in both cases, reads» (Targum reads: «when Lilith the Queen of [Sheba] and of Margod fell upon them.»)

- ↑ Jahrbuch für Protestantische Theologie 1, 1875. p 128.

- ↑ Levy, [Moritz] A.[braham] (1817–1872)]. Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft. ZDMG 9. 1885. pp. 470, 484.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)<templatestyles src=»Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css»></templatestyles>

- ↑ Judit M. Blair (2009). De-Demonising the Old Testament – An Investigation of Azazel, Lilit (Lilith), Deber (Dever), Qeteb (Qetev) and Reshep (Resheph) in the Hebrew Bible. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2 Reihe. Tübingen. ISBN 3-16-150131-4. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9wSlat5Tjc4C.

- ↑ 34:14 καὶ συναντήσουσιν δαιμόνια ὀνοκενταύροις καὶ βοήσουσιν ἕτερος πρὸς τὸν ἕτερον ἐκεῖ ἀναπαύσονται ὀνοκένταυροι εὗρον γὰρ αὑτοῖς ἀνάπαυσιν

Translation: And daemons shall meet with onocentaurs, and they shall cry one to the other: there shall the onocentaurs rest, having found for themselves [a place of] rest. - ↑ «The Old Testament (Vulgate)/Isaias propheta». Wikisource (Latin). http://la.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Old_Testament_(Vulgate)/Isaias_propheta. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ↑ «Parallel Latin Vulgate Bible and Douay-Rheims Bible and King James Bible; The Complete Sayings of Jesus Christ». Latin Vulgate. http://www.latinvulgate.com/verse.aspx?t=0&b=27&c=34. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ↑ Michael T. Davis, Brent A. Strawn Qumran studies: new approaches, new questions 2007 p 47: «two manuscripts that date to the Herodian period, with 4Q510 slightly earlier».

- ↑ Bruce Chilton, Darrell Bock, Daniel M. Gurtner A Comparative Handbook to the Gospel of Mark p 84.

- ↑ «Lilith» (in en). 2019-10-31. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/people-cultures-in-the-bible/people-in-the-bible/lilith/. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ↑ Revue de Qumrân 1991 p 133.

- ↑ Baumgarten, J. M. «On the Nature of the Seductress in 4Q184», Revue de Qumran 15 (1991–2), 133–143; «The seductress of Qumran», Bible Review 17 no 5 (2001), 21–23; 42.

- ↑ Collins, Jewish wisdom in the Hellenistic age.

- ↑ Tractate Niddah in the Mishnah is the only tractate from the Order of Tohorot which has Talmud on it. The Jerusalem Talmud is incomplete here, but the Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Niddah (2a–76b) is complete.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 Kosior, Wojciech (2018). «A Tale of Two Sisters: The Image of Eve in Early Rabbinic Literature and Its Influence on the Portrayal of Lilith in the Alphabet of Ben Sira». Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues (32): 112–130. doi:10.2979/nashim.32.1.10. https://www.academia.edu/36771379.

- ↑ Aish. «Lillith». http://www.aish.com/atr/Lillith.html. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah, in: Judaic Classics Library, Davka Corporation, 1999. (CD-ROM).

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Shaked, Shaul (2013). Aramaic bowl spells : Jewish Babylonian Aramaic bowls. Volume one. Ford, James Nathan; Bhayro, Siam; Morgenstern, Matthew; Vilozny, Naama. Leiden. ISBN 9789004229372. OCLC 854568886. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6yKp94t5J34C.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Lesses, Rebecca (2001). «Exe(o)rcising Power: Women as Sorceresses, Exorcists, and Demonesses in Babylonian Jewish Society of Late Antiquity». Journal of the American Academy of Religion 69 (2): 343–375. doi:10.1093/jaarel/69.2.343. ISSN 0002-7189. JSTOR 1465786.

- ↑ Descenders to the chariot: the people behind the Hekhalot literature, p. 277 James R. Davila – 2001: «that they be used by anyone and everyone. The whole community could become the equals of the sages. Perhaps this is why nearly every house excavated in the Jewish settlement in Nippur had one or more incantation bowl buried in it.»

- ↑ Yamauchi, Edwin M. (October–December 1965). «Aramaic Magic Bowls». Journal of the American Oriental Society 85 (4): 511–523. doi:10.2307/596720. JSTOR 596720.

- ↑ Isbell, Charles D. (March 1978). «The Story of the Aramaic Magical Incantation Bowls» (in en). The Biblical Archaeologist 41 (1): 5–16. doi:10.2307/3209471. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209471.

- ↑ Full text in p 156 Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur James Alan Montgomery – 2011.

- ↑ The attribution to the sage Ben Sira is considered false, with the true author unknown.

- ↑ Alphabet of Ben Sirah, Question #5 (23a–b).

- ↑ Humm, Alan. Lilith in the Alphabet of Ben Sira

- ↑ Segal, Eliezer. Looking for Lilith

- ↑ Schwartz p. 7.

- ↑ Schwartz p 8.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Schwartz p. 8.

- ↑ Patai pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Patai p. 230.

- ↑ Patai p. 231.

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Dennis, The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition.

- ↑ Patai p.231.

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia demonology

- ↑ Patai p. 244.

- ↑ Humm, Alan. Lilith, Samael, & Blind Dragon

- ↑ Patai p. 246.

- ↑ R. Isaac b. Jacob Ha-Kohen. Lilith in Jewish Mysticism: Treatise on the Left Emanation

- ↑ Patai p. 233.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Patai p 232 «But Lilith, whose name is Pizna, — or according to the Zohar, two female spirits, Lilith and Naamah — found him, desired his beauty which was like that of the sun disk, and lay with him. The issue of these unions were demons and spirits»

- ↑ Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, p. 174.

- ↑ «Printed sheet, late 17th century or early 18th century, 185×130 mm.

- ↑ «Lilith Amulet-J.R. Ritman Library». Archived from the original on 2010-02-12. https://web.archive.org/web/20100212053545/http://www.ritmanlibrary.nl/c/p/exh/kabb/kab_pheb_25.html.

- ↑ Humm, Alan. Kabbalah: Lilith’s origins

- ↑ Calmet, Augustine (1751). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Hurwitz p. 43.

- ↑ Hurwitz p. 78.

- ↑ «an eine Stelle» Hurwitz S. Die erste Eva: Eine historische und psychologische Studie 2004 Page 160 «8) Lilith in der arabischen Literatur: Die Karina Auch in der arabischen Literatur hat der Lilith-Mythos seinen Niederschlag gefunden.»

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 Amy Scerba. «Changing Literary Representations of Lilith and the Evolution of a Mythical Heroine». http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- ↑ Howard Schwartz (1988). Lilith’s Cave: Jewish tales of the supernatural. San Francisco: Harper & Row. https://archive.org/details/lilithscavejewis00schw.

- ↑ Seidel, Kathryn Lee. The Lilith Figure in Toni Morrison’s Sula and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple

- ↑ The Lion, the Witch, and Wardrobe, Collier Books (paperback, Macmillan subsidiary), 1970, pg. 77.

- ↑ Faust, translated into English prose, by A. Hayward. Second edition, E. Moxon, 1834, page 285.

- ↑ Hines, Kathleen. «The Art of the Musical Zz: Cultural Implications of Lullabies around the World.» Miwah Li, John Moeller, and Charles Smith Wofford College (2013): 74.

- ↑ Pathak, Vrushali, and Shefali Mishra. «Psychological effect of lullabies in child development.» Indian Journal of Positive Psychology 8.4 (2017): 677–680.

- ↑ Levin, S. «The evil eye and the afflictions of children.» South African Medical Journal 32.6 (1958).

- ↑ The Human Interest Library: Wonder world, Midland Press, 1921, page 87.

- ↑ Hoy, Emme. «How do shifting depictions of Lilith,’The First Eve’, trace the contexts and hegemonic values of their times?» Teaching History 46.3 (2012): 54.

- ↑ Grimassi, Raven.Stregheria: La Vecchia Religione

- ↑ Leland, Charles.Aradia, Gospel of the Witches-Appendix

- ↑ «Lilith-The First Eve». Imbolc. 2002. http://www.whitedragon.org.uk/articles/lillith.htm.

- ↑ Grenn, Deborah J.History of Lilith Institute

- ↑ Hurwitz, Siegmund. «Excerpts from Lilith-The first Eve». http://www.daimon.ch/385630522X_2E.htm.

- ↑ «Lilith». Goddess. http://www.goddess.com.au/goddesses/Lilith.htm. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ↑ Raymond Buckland, The Witch Book, Visible Ink Press, November 1, 2001.

- ↑ Margi Bailobiginki. «Lilith and the modern Western world». http://theisticsatanism.com/rituals/standard/Lilith.html. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ↑ Charles Moffat. «The Sumerian legend of Lilith». http://www.poetry.charlesmoffat.com/#SumerianLilith. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ↑ Aun Weor, Samael (June 2005). Pistis Sophia Unveiled. p. 339. ISBN 9780974591681. https://books.google.com/?id=Rypqlr2O_sAC&dq=pistis+sophia+unveiled&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=homosexuals&f=false.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Fortune, Dion (1963). Psychic Self-Defence. pp. 126–128. ISBN 9781609254643. https://books.google.com/?id=EucEChcyoq4C&pg=PA126&lpg=PA126&dq=dion+fortune+virgin+mary+lilith#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

References

- Talmudic References: b. Erubin 18b; b. Erubin 100b; b. Nidda 24b; b. Shab. 151b; b. Baba Bathra 73a–b

- Kabbalist References: Zohar 3:76b–77a; Zohar Sitrei Torah 1:147b–148b; Zohar 2:267b; Bacharach,’Emeq haMelekh, 19c; Zohar 3:19a; Bacharach,’Emeq haMelekh, 102d–103a; Zohar 1:54b–55a

- Dead Sea Scroll References: 4QSongs of the Sage/4QShir; 4Q510 frag.11.4–6a//frag.10.1f; 11QPsAp

- Lilith Bibliography, Jewish and Christian Literature, Alan Humm ed., 5 March 2023.

- Charles Fossey, La Magie Assyrienne, Paris: 1902.

- Siegmund Hurwitz, Lilith, die erste Eva: eine Studie über dunkle Aspekte des Weiblichen. Zürich: Daimon Verlag, 1980, 1993. English tr. Lilith, the First Eve: Historical and Psychological Aspects of the Dark Feminine, translated by Gela Jacobson. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 1992 ISBN 3-85630-545-9.

- Siegmund Hurwitz, Lilith Switzerland: Daminon Press, 1992. Jerusalem Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1966.

- Samuel Noah Kramer, Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree: A reconstructed Sumerian Text. (Kramer’s Translation of the Gilgamesh Prologue), Assyriological Studies of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 10, Chicago: 1938.

- Raphael Patai, Adam ve-Adama, tr. as Man and Earth; Jerusalem: The Hebrew Press Association, 1941–1942.

- Raphael Patai, The Hebrew Goddess, 3rd enlarged edition New York: Discus Books, 1978.

- Archibald Sayce, Hibbert Lectures on Babylonian Religion 1887.

- Schwartz, Howard, Lilith’s Cave: Jewish tales of the supernatural, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988.

- R. Campbell Thompson, Semitic Magic, its Origin and Development, London: 1908.

- Isaiah, chapter 34. New American Bible

- Augustin Calmet, (1751) Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0

- Jeffers, Jen (2017) «Finding Lilith: The Most Powerful Hag In History». The Raven Report. https://theravenreport.com/2017/12/21/finding-lilith-the-most-powerful-hag-in-history/.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lilith |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Lilith

- Collection of Lilith information and links by Alan Humm

- International standard Bible Encyclopedia: Night-Monster

Template:Adam and Eve

This article is about the Jewish mythological figure Lilith. For other uses, see Lilith (disambiguation).

|

Lilith |

|

|---|---|

Lilith (1887) by John Collier in Atkinson Art Gallery, Merseyside, England |

|

| Born |

Garden of Eden |

«The only thing I can tell you about Lilith is that according to Jewish folklore, she left her husband, Adam, after she refused to become subservient to him. Although… Dr. Holly Brown writes: ‘The demonization of Lilith was designed to keep women alienated from their own power and spiritual authority.’ Now that’s what I call girl power.»

«She was a demon?»

«She’s Jewish?»

Lilith (/ˈlɪlɪθ/; Hebrew: <templatestyles src=»Script/styles_hebrew.css» />לִילִית Lîlîṯ) is a figure in Jewish mythology, developed earliest in the Babylonian Talmud (3rd to 5th century AD). From c. AD 700–1000 onwards Lilith appears as Adam’s first wife, created at the same time (Rosh Hashanah) and from the same clay as Adam—compare Genesis 1:27.[1] The figure of Lilith may relate in part to a historically earlier class of female demons (lilītu) in ancient Mesopotamian religion, found in cuneiform texts of Sumer, the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, and Babylonia.

Lilith continues to serve as source material in modern western culture, literature, occultism, fantasy, and horror.

History