Not to be confused with Liberia.

|

State of Libya

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: ليبيا ليبيا ليبيا «Libya, Libya, Libya» |

|

Location of Libya (dark green) in northern Africa |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Tripoli[1] 32°52′N 13°11′E / 32.867°N 13.183°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[b] |

| Local vernacular | Libyan Arabic |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion | 99.7% Islam (official) 0.3% Others |

| Demonym(s) | Libyan |

| Government | Unitary provisional unity government |

|

• Chairman of the Presidential Council |

Mohamed al-Menfi |

|

• Vice Chairman of the Presidential Council |

Musa Al-Koni |

|

• Prime Minister |

Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh (disputed)[n 1] |

|

• Speaker of the House of Representatives |

Aguila Saleh Issa |

| Legislature | House of Representatives |

| Independence

from Italy |

|

|

• Independence declared |

10 February 1947 |

|

• Kingdom established |

24 December 1951 |

|

• Coup d’état by Muammar Gaddafi |

1 September 1969 |

|

• Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya |

2 March 1977 |

|

• Revolution |

17 February 2011 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

1,759,541 km2 (679,363 sq mi) (16th) |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

7,054,493[4] (104th) |

|

• 2006 census |

5,670,688 |

|

• Density |

3.74/km2 (9.7/sq mi) (218th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| HDI (2021) | high · 104th |

| Currency | Libyan dinar (LYD) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +218 |

| ISO 3166 code | LY |

| Internet TLD | .ly ليبيا. |

|

Libya (; Arabic: ليبيا, romanized: Lībiyā, pronounced [liː.bi.jæː]), officially the State of Libya (Arabic: دولة ليبيا, romanized: Dawlat Lībiyā),[7][8][9][10] is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad to the south, Niger to the southwest, Algeria to the west, and Tunisia to the northwest. Libya is made of three historical regions: Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica. With an area of almost 1.8 million km2 (700,000 sq mi), it is the fourth-largest country in Africa and the Arab world, and the 16th-largest in the world.[11] Libya has the 10th-largest proven oil reserves in the world.[12] The largest city and capital, Tripoli, is located in western Libya and contains over three million of Libya’s seven million people.[13]

Libya has been inhabited by Berbers since the late Bronze Age as descendants from Iberomaurusian and Capsian cultures.[14] In classical antiquity, the Phoenicians established city-states and trading posts in western Libya, while several Greek cities were established in the East. Parts of Libya were variously ruled by Carthaginians, Persians, and Greeks before the entire region becoming a part of the Roman Empire. Libya was an early center of Christianity. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the area of Libya was mostly occupied by the Vandals until the 7th century when invasions brought Islam to the region. In the 16th century, the Spanish Empire and the Knights of St John occupied Tripoli until Ottoman rule began in 1551. Libya was involved in the Barbary Wars of the 18th and 19th centuries. Ottoman rule continued until the Italo-Turkish War, which resulted in the Italian occupation of Libya and the establishment of two colonies, Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica (1911–1934), later unified in the Italian Libya colony from 1934 to 1943.

During the Second World War, Libya was an area of warfare in the North African Campaign. The Italian population then went into decline. Libya became independent as a kingdom in 1951. A bloodless military coup in 1969, initiated by a coalition led by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, overthrew King Idris I and created a republic.[15] Gaddafi was often described by critics as a dictator, and was one of the world’s longest serving non-royal leaders, ruling for 42 years.[16] He ruled until being overthrown and killed in the 2011 Libyan Civil War during the wider Arab Spring, with authority transferred to the National Transitional Council then to the elected General National Congress. By 2014 two rival authorities claimed to govern Libya,[17][18][19] which led to a second civil war, with parts of Libya split between the Tobruk and Tripoli-based governments as well as various tribal and Islamist militias.[20] The two main warring sides signed a permanent ceasefire in 2020, and a unity government took authority to plan for democratic elections, however political rivalries continue to delay this.[21]

Libya is a member of the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement, the African Union, the Arab League, the OIC and OPEC. The country’s official religion is Islam, with 96.6% of the Libyan population being Sunni Muslims. The official language of Libya is Arabic. Vernacular Libyan Arabic is the most spoken, and the majority of Libya’s population is Arab.[22]

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the name «Libya» first appeared in an inscription of Ramesses II, written as rbw in hieroglyphic. The name derives from a generalized identity given to a large confederacy of ancient east «Libyan» berbers, African people(s) and tribes who lived around the lush regions of Cyrenaica and Marmarica. An army of 40,000 men[23] and a confederacy of tribes known as «Great Chiefs of the Libu» were led by King Meryey who fought a war against pharaoh Merneptah in year 5 (1208 BCE). This conflict was mentioned in the Great Karnak Inscription in the western delta during the 5th and 6th years of his reign and resulted in a defeat for Meryey. According to the Great Karnak Inscription, the military alliance comprised the Meshwesh, the Lukka, and the «Sea Peoples» known as the Ekwesh, Teresh, Shekelesh, and the Sherden.

The Great karnak inscription reads:

«… the third season, saying: ‘The wretched, fallen chief of Libya, Meryey, son of Ded, has fallen upon the country of Tehenu with his bowmen — Sherden, Shekelesh, Ekwesh, Lukka, Teresh. Taking the best of every warrior and every man of war of his country. He has brought his wife and his children — leaders of the camp, and he has reached the western boundary in the fields of Perire.»

The modern name of «Libya» is an evolution of the «Libu» or «Libúē» name (from Greek Λιβύη, Libyē), generally encompassing the people of Cyrenaica and Marmarica. The «Libúē» or «libu» name likely came to be used in the classical world as an identity for the natives of the North African region, and it possibly derives from Proto-Afroasiatic labiʔ- (lion), compare Somali libaax. The name was revived in 1934 for Italian Libya from the ancient Greek Λιβύη (Libúē).[24] It was intended to supplant terms applied to Ottoman Tripolitania, the coastal region of what is today Libya, having been ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1911 as the Eyalet of Tripolitania. The name «Libya» was brought back into use in 1903 by Italian geographer Federico Minutilli.[25]

Libya gained independence in 1951 as the United Libyan Kingdom (المملكة الليبية المتحدة al-Mamlakah al-Lībiyyah al-Muttaḥidah), changing its name to the Kingdom of Libya (المملكة الليبية al-Mamlakah al-Lībiyyah), literally «Libyan Kingdom», in 1963.[26] Following a coup d’état led by Muammar Gaddafi in 1969, the name of the state was changed to the Libyan Arab Republic (الجمهورية العربية الليبية al-Jumhūriyyah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah). The official name was «Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya» from 1977 to 1986 (الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية), and «Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya»[27] (الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية العظمى,[28] al-Jamāhīriyyah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah ash-Sha‘biyyah al-Ishtirākiyyah al-‘Udmá listen (help·info)) from 1986 to 2011.

The National Transitional Council, established in 2011, referred to the state as simply «Libya». The UN formally recognized the country as «Libya» in September 2011[29] based on a request from the Permanent Mission of Libya citing the Libyan interim Constitutional Declaration of 3 August 2011. In November 2011, the ISO 3166-1 was altered to reflect the new country name «Libya» in English, «Libye (la)» in French.[30]

In December 2017 the Permanent Mission of Libya to the United Nations informed the United Nations that the country’s official name was henceforth the «State of Libya»; «Libya» remained the official short form, and the country continued to be listed under «L» in alphabetical lists.[31]

History[edit]

Ancient Libya[edit]

The coastal plain of Libya was inhabited by Neolithic peoples from as early as 8000 BC. The Afroasiatic ancestors of the Berber people are assumed to have spread into the area by the Late Bronze Age. The earliest known name of such a tribe was the Garamantes, based in Germa. The Phoenicians were the first to establish trading posts in Libya.[32] By the 5th century BC, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, Carthage, had extended its hegemony across much of North Africa, where a distinctive civilization, known as Punic, came into being.

In 630 BC, the ancient Greeks colonized the area around Barca in Eastern Libya and founded the city of Cyrene.[33] Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area that became known as Cyrenaica.[34] The area was home to the renowned philosophy school of the Cyrenaics. In 525 BC the Persian army of Cambyses II overran Cyrenaica, which for the next two centuries remained under Persian or Egyptian rule. Alexander the Great ended Persian rule 331 BC and received tribute from Cyrenaica. Eastern Libya again fell under the control of the Greeks, this time as part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

After the fall of Carthage the Romans did not immediately occupy Tripolitania (the region around Tripoli), but left it instead under control of the kings of Numidia, until the coastal cities asked and obtained its protection.[35] Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome, which formally annexed the region in 74 BC and joined it to Crete as a Roman province. As part of the Africa Nova province, Tripolitania was prosperous,[35] and reached a golden age in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the city of Leptis Magna, home to the Severan dynasty, was at its height.[35]

On the Eastern side, Cyrenaica’s first Christian communities were established by the time of the Emperor Claudius.[36] It was heavily devastated during the Kitos War[37] and almost depopulated of Greeks and Jews alike.[38] Although repopulated by Trajan with military colonies,[37] from then started its decline.[36] Libya was early to convert to Nicene Christianity and was the home of Pope Victor I; however, Libya was also home to many non-Nicene varieties of early Christianity, such as Arianism and Donatism.

Islamic Libya[edit]

Under the command of Amr ibn al-As, the Rashidun army conquered Cyrenaica.[39] In 647 an army led by Abdullah ibn Saad took Tripoli from the Byzantines definitively.[39] The Fezzan was conquered by Uqba ibn Nafi in 663. The Berber tribes of the hinterland accepted Islam, however they resisted Arab political rule.[40]

For the next several decades, Libya was under the purview of the Umayyad Caliph of Damascus until the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and Libya came under the rule of Baghdad. When Caliph Harun al-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor of Ifriqiya in 800, Libya enjoyed considerable local autonomy under the Aghlabid dynasty. By the 10th century, the Shiite Fatimids controlled Western Libya, and ruled the entire region in 972 and appointed Bologhine ibn Ziri as governor.[35]

Ibn Ziri’s Berber Zirid dynasty ultimately broke away from the Shiite Fatimids, and recognised the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs. In retaliation, the Fatimids brought about the migration of thousands from mainly two Arab Qaisi tribes, the Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal to North Africa. This act drastically altered the fabric of the Libyan countryside, and cemented the cultural and linguistic Arabisation of the region.[35]

Zirid rule in Tripolitania was short-lived though, and already in 1001 the Berbers of the Banu Khazrun broke away. Tripolitania remained under their control until 1146, when the region was overtaken by the Normans of Sicily.[41] It was not until 1159 that the Almohad empire reconquered Tripoli from European rule. For the next 50 years, Tripolitania was the scene of numerous battles among Ayyubids, the Almohad rulers and insurgents of the Banu Ghaniya. Later, a general of the Almohads, Muhammad ibn Abu Hafs, ruled Libya from 1207 to 1221 before the later establishment of a Tunisian Hafsid dynasty[41] independent from the Almohads. The Hafsids ruled Tripolitania for nearly 300 years. By the 16th century the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire.

After weakening control of Abbasids, Cyrenaica was under Egypt based states such as Tulunids, Ikhshidids, Ayyubids and Mamluks before Ottoman conquest in 1517. Finally Fezzan acquired independence under Awlad Muhammad dynasty after Kanem rule. Ottomans finally conquered Fezzan between 1556 and 1577.

Ottoman Tripolitania[edit]

The siege of Tripoli in 1551 allowed the Ottomans to capture the city from the Knights of St. John.

After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510,[41] and its handover to the Knights of St. John, the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha took control of Libya in 1551.[41] His successor Turgut Reis was named the Bey of Tripoli and later Pasha of Tripoli in 1556. By 1565, administrative authority as regent in Tripoli was vested in a pasha appointed directly by the sultan in Constantinople/Istanbul. In the 1580s, the rulers of Fezzan gave their allegiance to the sultan, and although Ottoman authority was absent in Cyrenaica, a bey was stationed in Benghazi late in the next century to act as agent of the government in Tripoli.[36] European slaves and large numbers of enslaved Blacks transported from Sudan were also a feature of everyday life in Tripoli. In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved almost the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo, some 5,000 people, sending them to Libya.[42][43]

In time, real power came to rest with the pasha’s corps of janissaries.[41] In 1611 the deys staged a coup against the pasha, and Dey Sulayman Safar was appointed as head of government. For the next hundred years, a series of deys effectively ruled Tripolitania. The two most important Deys were Mehmed Saqizli (r. 1631–49) and Osman Saqizli (r. 1649–72), both also Pasha, who ruled effectively the region.[44] The latter conquered also Cyrenaica.[44]

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer Ahmed Karamanli.[44] The Karamanlis ruled from 1711 until 1835 mainly in Tripolitania, and had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well by the mid-18th century. Ahmed’s successors proved to be less capable than himself, however, the region’s delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli. The 1793–95 Tripolitanian civil war occurred in those years. In 1793, Turkish officer Ali Pasha deposed Hamet Karamanli and briefly restored Tripolitania to Ottoman rule. Hamet’s brother Yusuf (r. 1795–1832) re-established Tripolitania’s independence.

A US Navy expedition under Commodore Edward Preble engaging gunboats and fortifications in Tripoli, 1804

In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War. By 1819, the various treaties of the Napoleonic Wars had forced the Barbary states to give up piracy almost entirely, and Tripolitania’s economy began to crumble. As Yusuf weakened, factions sprung up around his three sons. Civil war soon resulted.[45]

Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II sent in troops ostensibly to restore order, marking the end of both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania.[45] Order was not recovered easily, and the revolt of the Libyan under Abd-El-Gelil and Gûma ben Khalifa lasted until the death of the latter in 1858.[45] The second period of direct Ottoman rule saw administrative changes, and greater order in the governance of the three provinces of Libya. Ottoman rule finally reasserted to Fezzan between 1850 and 1875 for earning income from Saharan commerce.

Italian colonization and Allied occupation[edit]

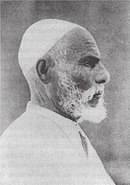

Omar Mukhtar was a prominent leader of Libyan resistance in Cyrenaica against Italian colonization.

After the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912), Italy simultaneously turned the three regions into colonies.[46] From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. Some 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly 20% of the total population.[47]

Omar Mukhtar rose to prominence as a resistance leader against Italian colonization and became a national hero despite his capture and execution on 16 September 1931.[48] His face is currently printed on the Libyan ten dinar note in memory and recognition of his patriotism. Another prominent resistance leader, Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), Emir of Cyrenaica, continued to lead the Libyan resistance until the outbreak of the Second World War.

The so-called «pacification of Libya» by the Italians resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in Cyrenaica, killing approximately one quarter of Cyrenaica’s population of 225,000.[49] Ilan Pappé estimates that between 1928 and 1932 the Italian military «killed half the Bedouin population (directly or through disease and starvation in Italian concentration camps in Libya).»[50]

In 1934, Italy combined Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan and adopted the name «Libya» (used by the Ancient Greeks for all of North Africa except Egypt) for the unified colony, with Tripoli as its capital.[51] The Italians emphasized infrastructure improvements and public works. In particular, they greatly expanded Libyan railway and road networks from 1934 to 1940, building hundreds of kilometers of new roads and railways and encouraging the establishment of new industries and dozens of new agricultural villages.

In June 1940, Italy entered World War II. Libya became the setting for the hard-fought North African Campaign that ultimately ended in defeat for Italy and its German ally in 1943.

From 1943 to 1951, Libya was under Allied occupation. The British military administered the two former Italian Libyan provinces of Tripolitana and Cyrenaïca, while the French administered the province of Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.[52]

Independence, Kingdom and Libya under Gaddafi[edit]

King Idris I of the Senussi order became the first head of state of Libya in 1951.

On 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya,[53] a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris, Libya’s only monarch. The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world’s poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government’s finances, resentment among some factions began to build over the increased concentration of the nation’s wealth in the hands of King Idris.[54]

Gaddafi (left) with Egyptian President Nasser in 1969[55]

On 1 September 1969, a group of rebel military officers led by Muammar Gaddafi launched a coup d’état against King Idris, which became known as the Al Fateh Revolution.[56] Gaddafi was referred to as the «Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution» in government statements and the official Libyan press.[57] Moving to reduce Italian influence, in October 1970 all Italian-owned assets were expropriated and the 12,000-strong Italian community was expelled from Libya alongside the smaller community of Libyan Jews. The day became a national holiday known as «Vengeance Day».[58] Libya’s increase in prosperity was accompanied by increased internal political repression, and political dissent was made illegal under Law 75 of 1973. Widespread surveillance of the population was carried out through Gaddafi’s Revolutionary Committees.[59][60][61]

Gaddafi also wanted to combat the strict social restrictions that had been imposed on women by the previous regime, establishing the Revolutionary Women’s Formation to encourage reform. In 1970, a law was introduced affirming equality of the sexes and insisting on wage parity. In 1971, Gaddafi sponsored the creation of a Libyan General Women’s Federation. In 1972, a law was passed criminalizing the marriage of any females under the age of sixteen and ensuring that a woman’s consent was a necessary prerequisite for a marriage.[62]

On 25 October 1975, a coup attempt was launched by some 20 military officers, mostly from the city of Misrata.[63] This resulted in the arrest and executions of the coup plotters.[64] On 2 March 1977, Libya officially became the «Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya». Gaddafi officially passed power to the General People’s Committees and henceforth claimed to be no more than a symbolic figurehead.[65] The new jamahiriya (Arab for «republic») governance structure he established was officially referred to as «direct democracy».[66]

Gaddafi, in his vision of democratic government and political philosophy, published The Green Book in 1975. His short book inscribed a representative mix of utopian socialism and Arab nationalism with a streak of Bedouin supremacy.

Versions of the Libyan flag in modern history

In February 1977, Libya started delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People’s Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan War began in earnest when Libya’s support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an invasion. Later that same year, Libya and Egypt fought a four-day border war that came to be known as the Egyptian–Libyan War. Both nations agreed to a ceasefire under the mediation of the Algerian president Houari Boumédiène.[67] Hundreds of Libyans lost their lives in the country’s support for Idi Amin’s Uganda in its war against Tanzania. Gaddafi financed various other groups from anti-nuclear movements to Australian trade unions.[68]

Libya adopted its plain green national flag on 19 November 1977. Before 2011, it became the only plain-coloured flag in the world.

From 1977 onward, per capita income in the country rose to more than US$11,000, the fifth-highest in Africa,[69] while the Human Development Index became the highest in Africa and greater than that of Saudi Arabia.[70] This was achieved without borrowing any foreign loans, keeping Libya debt-free.[71] The Great Manmade River was also built to allow free access to fresh water across large parts of the country.[70] In addition, financial support was provided for university scholarships and employment programs.[72]

Much of Libya’s income from oil, which soared in the 1970s, was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring dozens of paramilitaries and terrorist groups around the world.[73][74][75] An American airstrike intended to kill Gaddafi failed in 1986. Libya was finally put under sanctions by the United Nations after the bombing of a commercial flight at Lockerbie in 1988 killed 270 people.[76] In 2003, Gaddafi announced that all of his regime’s weapons of mass destruction were disassembled, and that Libya was transitioning toward nuclear power.

First Libyan Civil War[edit]

The first civil war came during the Arab Spring movements which overturned the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt. Libya first experienced protests against Gaddafi’s regime on 15 February 2011, with a full-scale revolt beginning on 17 February.[77] Libya’s authoritarian regime led by Muammar Gaddafi put up much more of a resistance compared to the regimes in Egypt and Tunisia. While overthrowing the regimes in Egypt and Tunisia was a relatively quick process, Gaddafi’s campaign posed significant stalls on the uprising in Libya.[78] The first announcement of a competing political authority appeared online and declared the Interim Transitional National Council as an alternative government. One of Gaddafi’s senior advisors responded by posting a tweet, wherein he resigned, defected, and advised Gaddafi to flee.[79] By 20 February, the unrest had spread to Tripoli. On 27 February 2011, the National Transitional Council was established to administer the areas of Libya under rebel control. On 10 March 2011, the United States and many other nations recognised the council headed by Mahmoud Jibril as acting prime minister and as the legitimate representative of the Libyan people and withdrawing the recognition of Gaddafi’s regime.[80][81]

Pro-Gaddafi forces were able to respond militarily to rebel pushes in Western Libya and launched a counterattack along the coast toward Benghazi, the de facto centre of the uprising.[82] The town of Zawiya, 48 kilometres (30 mi) from Tripoli, was bombarded by air force planes and army tanks and seized by Jamahiriya troops, «exercising a level of brutality not yet seen in the conflict.»[83]

Organizations of the United Nations, including United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon[84] and the United Nations Human Rights Council, condemned the crackdown as violating international law, with the latter body expelling Libya outright in an unprecedented action.[85][86]

On 17 March 2011 the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973,[87] with a 10–0 vote and five abstentions including Russia, China, India, Brazil and Germany. The resolution sanctioned the establishment of a no-fly zone and the use of «all means necessary» to protect civilians within Libya.[88] On 19 March, the first act of NATO allies to secure the no-fly zone began by destroying Libyan air defenses when French military jets entered Libyan airspace on a reconnaissance mission heralding attacks on enemy targets.[89]

In the weeks that followed, US American forces were in the forefront of NATO operations against Libya. More than 8,000 US personnel in warships and aircraft were deployed in the area. At least 3,000 targets were struck in 14,202 strike sorties, 716 of them in Tripoli and 492 in Brega.[90] The US air offensive included flights of B-2 Stealth bombers, each bomber armed with sixteen 2000-pound bombs, flying out of and returning to their base in Missouri in the continental United States.[91] The support provided by the NATO air forces contributed to the ultimate success of the revolution.[92]

By 22 August 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli and occupied Green Square,[93] which they renamed Martyrs’ Square in honour of those killed since 17 February 2011. On 20 October 2011, the last heavy fighting of the uprising came to an end in the city of Sirte. The Battle of Sirte was both the last decisive battle and the last one in general of the First Libyan Civil War where Gaddafi was captured and killed by NATO-backed forces on 20 October 2011. Sirte was the last Gaddafi loyalist stronghold and his place of birth. The defeat of loyalist forces was celebrated on 23 October 2011, three days after the fall of Sirte.

At least 30,000 Libyans died in the civil war.[94] In addition, the National Transitional Council estimated 50,000 wounded.[95]

Interwar period and the Second Libyan Civil War[edit]

Following the defeat of loyalist forces, Libya was torn among numerous rival, armed militias affiliated with distinct regions, cities and tribes, while the central government had been weak and unable to effectively exert its authority over the country. Competing militias pitted themselves against each other in a political struggle between Islamist politicians and their opponents.[96] On 7 July 2012, Libyans held their first parliamentary elections since the end of the former regime. On 8 August, the National Transitional Council officially handed power over to the wholly-elected General National Congress, which was then tasked with the formation of an interim government and the drafting of a new Libyan Constitution to be approved in a general referendum.[97]

On 25 August 2012, in what Reuters reported as «the most blatant sectarian attack» since the end of the civil war, unnamed organized assailants bulldozed a Sufi mosque with graves, in broad daylight in the center of the Libyan capital Tripoli. It was the second such razing of a Sufi site in two days.[98] Numerous acts of vandalism and destruction of heritage were carried out by suspected Islamist militias, including the removal of the Nude Gazelle Statue and the destruction and desecration of World War II-era British grave sites near Benghazi.[99][100] Many other cases of heritage vandalism were reported to be carried out by Islamist-related radical militias and mobs that either destroyed, robbed, or looted a number of historic sites.

On 11 September 2012, Islamist militants mounted an attack on the American diplomatic compound in Benghazi,[101] killing the U.S. ambassador to Libya, J. Christopher Stevens, and three others. The incident generated outrage in the United States and Libya.[102] On 7 October 2012, Libya’s Prime Minister-elect Mustafa A.G. Abushagur was ousted after failing a second time to win parliamentary approval for a new cabinet.[103][104][105] On 14 October 2012, the General National Congress elected former GNC member and human rights lawyer Ali Zeidan as prime minister-designate.[106] Zeidan was sworn in after his cabinet was approved by the GNC.[107][108] On 11 March 2014, after having been ousted by the GNC for his inability to halt a rogue oil shipment,[109] Prime Minister Zeidan stepped down, and was replaced by Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thani.[110]

The Second Civil War began in May 2014 following fighting between rival parliaments with tribal militias and jihadist groups soon taking advantage of the power vacuum. Most notably, radical Islamist fighters seized Derna in 2014 and Sirte in 2015 in the name of the Islamic State. In February 2015, neighbouring Egypt launched airstrikes against IS in support of the Tobruk government.[111][112][113]

In June 2014, elections were held to the House of Representatives, a new legislative body intended to take over from the General National Congress. The elections were marred by violence and low turnout, with voting stations closed in some areas.[114] Secularists and liberals did well in the elections, to the consternation of Islamist lawmakers in the GNC, who reconvened and declared a continuing mandate for the GNC, refusing to recognise the new House of Representatives.[115] Armed supporters of the General National Congress occupied Tripoli, forcing the newly elected parliament to flee to Tobruk.[116][117]

In January 2015, meetings were held with the aim to find a peaceful agreement between the rival parties in Libya. The so-called Geneva-Ghadames talks were supposed to bring the GNC and the Tobruk government together at one table to find a solution of the internal conflict. However, the GNC actually never participated, a sign that internal division not only affected the «Tobruk Camp», but also the «Tripoli Camp». Meanwhile, terrorism within Libya steadily increased, also affecting neighbouring countries. The terrorist attack against the Bardo Museum in Tunisia on 18 March 2015 was reportedly carried out by two Libyan-trained militants.[118]

During 2015 an extended series of diplomatic meetings and peace negotiations were supported by the United Nations, as conducted by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG), Spanish diplomat Bernardino León.[119][120] UN support for the SRSG-led process of dialogue carried on in addition to the usual work of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL).[121]

In July 2015 SRSG Leon reported to the UN Security Council on the progress of the negotiations, which at that point had just achieved a political agreement on 11 July setting out «a comprehensive framework… includ[ing] guiding principles… institutions and decision-making mechanisms to guide the transition until the adoption of a permanent constitution.» The stated purpose of that process was «…intended to culminate in the creation of a modern, democratic state based on the principle of inclusion, the rule of law, separation of powers and respect for human rights.» The SRSG praised the participants for achieving agreement, stating that «The Libyan people have unequivocally expressed themselves in favour of peace.» The SRSG then informed the Security Council that «Libya is at a critical stage» and urging «all parties in Libya to continue to engage constructively in the dialogue process», stating that «only through dialogue and political compromise, can a peaceful resolution of the conflict be achieved. A peaceful transition will only succeed in Libya through a significant and coordinated effort in supporting a future Government of National Accord…».

Talks, negotiations and dialogue continued on during mid-2015 at various international locations, culminating at Skhirat in Morocco in early September.[122][123]

Also in 2015, as part of the ongoing support from the international community, the UN Human Rights Council requested a report about the Libyan situation[124][125] and the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, established an investigative body (OIOL) to report on human rights and rebuilding the Libyan justice system.[126] Chaos-ridden Libya emerged as a major transit point for people trying to reach Europe. Between 2013 and 2018, nearly 700,000 migrants reached Italy by boat, many of them from Libya.[127][128]

In May 2018 Libya’s rival leaders agreed to hold parliamentary and presidential elections following a meeting in Paris.[129] In April 2019, Khalifa Haftar launched Operation Flood of Dignity, in an offensive by the Libyan National Army aimed to seize Western territories from the Government of National Accord (GNA).[130] In June 2019, forces allied to Libya’s UN-recognized Government of National Accord successfully captured Gharyan, a strategic town where military commander Khalifa Haftar and his fighters were based. According to a spokesman for GNA forces, Mustafa al-Mejii, dozens of LNA fighters under Haftar were killed, while at least 18 were taken prisoner.[131]

In March 2020, UN-backed government of Fayez Al-Sarraj commenced Operation Peace Storm. The government initiated the bid in response to the state of assaults carried by Haftar’s LNA. “We are a legitimate, civilian government that respects its obligations to the international community, but is committed primarily to its people and has an obligation to protect its citizens,” Sarraj said in line with his decision.[132] On 28 August 2020, the BBC Africa Eye and BBC Arabic Documentaries revealed that a drone operated by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) killed 26 young cadets at a military academy in Tripoli, on 4 January. Most of the cadets were teenagers and none of them were armed. The Chinese-made drone Wing Loong II fired Blue Arrow 7 missile, which was operated from UAE-run Al-Khadim Libyan air base. In February, these drones stationed in Libya were moved to an air base near Siwa in the western Egyptian desert.[133] The Guardian probed and discovered the blatant violation of UN arms embargo by the UAE and Turkey on 7 October 2020. As per the reporting, both the nations sent large-scale military cargo planes to Libya in support of their respective parties.[134]

On 23 October 2020, a permanent ceasefire was signed to end the war.[135]

Post-civil war years[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

In December 2021, the country’s first presidential election was scheduled, but was delayed to June 2022[136] and later postponed further.

Fathi Bashagha was appointed prime minister by the parliament in February 2022 to lead a transitional administration, but standing prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh refused to hand over power as of April 2022. In protest against the Dbeibah government, tribal leaders from the desert town of Ubari shut down the El Sharara oil field, Libya’s largest oil field, on 18 April 2022. The shut down threatened to cause oil shortages domestically in Libya, and preclude the state-run National Oil Corp. from exploiting the high oil prices on the international market resulting from the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[137] On 2 July, the House of Representatives was burned down by protesters.[138]

Geography[edit]

Libya map of Köppen climate classification

Libya extends over 1,759,540 square kilometres (679,362 sq mi), making it the 16th largest nation in the world by size. Libya is bound to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, the west by Tunisia and Algeria, the southwest by Niger, the south by Chad, the southeast by Sudan, and the east by Egypt. Libya lies between latitudes 19° and 34°N, and longitudes 9° and 26°E.

At 1,770 kilometres (1,100 mi), Libya’s coastline is the longest of any African country bordering the Mediterranean.[139][140] The portion of the Mediterranean Sea north of Libya is often called the Libyan Sea. The climate is mostly extremely dry and desertlike in nature. However, the northern regions enjoy a milder Mediterranean climate.[141]

Six ecoregions lie within Libya’s borders: Saharan halophytics, Mediterranean dry woodlands and steppe, Mediterranean woodlands and forests, North Saharan steppe and woodlands, Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands, and West Saharan montane xeric woodlands.[142]

Natural hazards come in the form of hot, dry, dust-laden sirocco (known in Libya as the gibli). This is a southern wind blowing from one to four days in spring and autumn. There are also dust storms and sandstorms. Oases can also be found scattered throughout Libya, the most important of which are Ghadames and Kufra.[143] Libya is one of the sunniest and driest countries in the world due to prevailing presence of desert environment.

Libya was a pioneer state in North Africa in species protection, with the creation in 1975 of the El Kouf protected area. The fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime favoured intense poaching: «Before the fall of Gaddafi even hunting rifles were forbidden. But since 2011, poaching has been carried out with weapons of war and sophisticated vehicles in which one can find up to 200 gazelle heads killed by militiamen who hunt to pass the time. We are also witnessing the emergence of hunters with no connection to the tribes that traditionally practice hunting. They shoot everything they find, even during the breeding season. More than 500,000 birds are killed in this way each year, when protected areas have been seized by tribal chiefs who have appropriated them. The animals that used to live there have all disappeared, hunted when they are edible or released when they are not,» explains zoologist Khaled Ettaieb.[144]

Libyan Desert[edit]

Libya is a predominantly desert country. Up to 90% of the land area is covered in desert.

The Libyan Desert, which covers much of Libya, is one of the most arid and sun-baked places on earth.[56] In places, decades may pass without seeing any rainfall at all, and even in the highlands rainfall seldom happens, once every 5–10 years. At Uweinat, as of 2006 the last recorded rainfall was in September 1998.[145]

Likewise, the temperature in the Libyan Desert can be extreme; on 13 September 1922, the town of ‘Aziziya, which is located southwest of Tripoli, recorded an air temperature of 58 °C (136.4 °F), considered to be a world record.[146][147][148] In September 2012, however, the world record figure of 58 °C was determined to be invalid by the World Meteorological Organization.[147][148][149]

There are a few scattered uninhabited small oases, usually linked to the major depressions, where water can be found by digging to a few feet in depth. In the west there is a widely dispersed group of oases in unconnected shallow depressions, the Kufra group, consisting of Tazerbo, Rebianae and Kufra.[145] Aside from the scarps, the general flatness is only interrupted by a series of plateaus and massifs near the centre of the Libyan Desert, around the convergence of the Egyptian-Sudanese-Libyan borders.

Slightly further to the south are the massifs of Arkenu, Uweinat, and Kissu. These granite mountains are ancient, having formed long before the sandstones surrounding them. Arkenu and Western Uweinat are ring complexes very similar to those in the Aïr Mountains. Eastern Uweinat (the highest point in the Libyan Desert) is a raised sandstone plateau adjacent to the granite part further west.[145]

The plain to the north of Uweinat is dotted with eroded volcanic features. With the discovery of oil in the 1950s also came the discovery of a massive aquifer underneath much of Libya. The water in the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System pre-dates the last Ice ages and the Sahara Desert itself.[150] This area also contains the Arkenu structures, which were once thought to be two impact craters.[151]

Politics[edit]

The politics of Libya has been in a tumultuous state since the start of the Arab Spring and the NATO intervention related Libyan Crisis in 2011; the crisis resulted in the collapse of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and the killing of Muammar Gaddafi, amidst the First Civil War and the foreign military intervention.[152][153][154]

The crisis was deepened by the factional violence in the aftermath of the First Civil War, resulting in the outbreak of the Second Civil War in 2014.[155] The control over the country is currently split between the House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk and the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tripoli and their respective supporters, as well as various jihadist groups and tribal elements controlling parts of the country.[156][157]

The former legislature was the General National Congress, which had 200 seats.[158] The General National Congress (2014), a largely unrecognised rival parliament based in the de jure capital of Tripoli, claims to be a legal continuation of the GNC.[159][160]

On 7 July 2012, Libyans voted in parliamentary elections, the first free elections in almost 40 years.[161] Around thirty women were elected to become members of parliament.[161] Early results of the vote showed the National Forces Alliance, led by former interim Prime Minister Mahmoud Jibril, as front runner.[162] The Justice and Construction Party, affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood, has done less well than similar parties in Egypt and Tunisia.[163] It won 17 out of 80 seats that were contested by parties, but about 60 independents have since joined its caucus.[163]

As of January 2013, there was mounting public pressure on the National Congress to set up a drafting body to create a new constitution. Congress had not yet decided whether the members of the body would be elected or appointed.[164]

On 30 March 2014, the General National Congress voted to replace itself with a new House of Representatives. The new legislature allocates 30 seats for women, will have 200 seats overall (with individuals able to run as members of political parties) and allows Libyans of foreign nationalities to run for office.[165]

Following the 2012 elections, Freedom House improved Libya’s rating from Not Free to Partly Free, and now considers the country to be an electoral democracy.[166]

Gaddafi merged civil and sharia courts in 1973. Civil courts now employ sharia judges who sit in regular courts of appeal and specialise in sharia appellate cases.[167] Laws regarding personal status are derived from Islamic law.[168]

At a meeting of the European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs on 2 December 2014, UN Special Representative Bernardino León described Libya as a non-state.[169]

An agreement to form a national unity government was signed on 17 December 2015.[170] Under the terms of the agreement, a nine-member Presidency Council and a seventeen-member interim Government of National Accord would be formed, with a view to holding new elections within two years.[170] The House of Representatives would continue to exist as a legislature and an advisory body, to be known as the State Council, will be formed with members nominated by the General National Congress (2014).[171]

The formation of an interim unity government was announced on 5 February 2021, after its members were elected by the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF).[172] Seventy four members of the LPDF cast ballots for four-member slates which would fill positions including the Prime Minister and the head of the Presidential Council.[172] After no slates reached a 60% vote threshold, the two leading teams competed in a run-off election.[172] Mohamed al-Menfi, a former ambassador to Greece, became head of the Presidential Council.[173] Meanwhile, the LPDF confirmed that Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, a businessman, would be the transitional Prime Minister.[173] All of the candidates who ran in this election, including the members of the winning slate, promised to appoint women to 30% of all senior government positions.[173] The politicians elected to lead the interim government initially agreed not to stand in the national elections scheduled for 24 December 2021.[173] However, Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh announced his candidature for president despite the ban in November 2021.[174] The Appeals Court in Tripoli rejected appeals for his disqualification, and allowed Dbeibeh back on the candidates’ list, along with a number of other disqualified candidates, originally scheduled for December 24.[175] Even more controversially, the court also reinstated Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, a son of the former dictator, as a presidential candidate.[176][177] On 22 December 2021, Libya’s Election Commission called for the postponement of the election until 24 January 2022.[178] Earlier, a parliamentary commission said it would be «impossible» to hold the election on 24 December 2021.[179] The UN called on Libya’s interim leaders to «expeditiously address all legal and political obstacles to hold elections, including finalising the list of presidential candidates».[179] However, at the last minute, the election was postponed indefinitely and the international community agreed to continue its support and recognition of the interim government headed by Mr Dbeibeh.[180][181]

According to new election rules, a new prime minister has 21 days to form a cabinet that must be endorsed by the various governing bodies within Libya.[173] After this cabinet is agreed upon, the unity government will replace all «parallel authorities» within Libya, including the Government of National Accord in Tripoli and the administration led by General Haftar.[173]

Foreign relations[edit]

Libya’s foreign policies have fluctuated since 1951. As a Kingdom, Libya maintained a definitively pro-Western stance, and was recognized as belonging to the conservative traditionalist bloc in the League of Arab States (the present-day Arab League), of which it became a member in 1953.[182] The government was also friendly towards Western countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, France, Italy, Greece, and established full diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1955.[183]

Although the government supported Arab causes, including the Moroccan and Algerian independence movements, it took little active part in the Arab-Israeli dispute or the tumultuous inter-Arab politics of the 1950s and early 1960s. The Kingdom was noted for its close association with the West, while it steered a conservative course at home.[184]

Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken meets with Libyan interim Prime Minister Abdulhamid Dabaiba, in Berlin, Germany on June 24, 2021. [State Department photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain

After the 1969 coup, Muammar Gaddafi closed American and British bases and partly nationalized foreign oil and commercial interests in Libya.

Gaddafi was known for backing a number of leaders viewed as anathema to Westernization and political liberalism, including Ugandan President Idi Amin,[185] Central African Emperor Jean-Bédel Bokassa,[186][187] Ethiopian strongman Haile Mariam Mengistu,[187] Liberian President Charles Taylor,[188] and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević.[189]

Relations with the West were strained by a series of incidents for most of Gaddafi’s rule,[190][191][192] including the killing of London policewoman Yvonne Fletcher, the bombing of a West Berlin nightclub frequented by U.S. servicemen, and the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which led to UN sanctions in the 1990s, though by the late 2000s, the United States and other Western powers had normalised relations with Libya.[56]

Gaddafi’s decision to abandon the pursuit of weapons of mass destruction after the Iraq War saw Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein overthrown and put on trial led to Libya being hailed as a success for Western soft power initiatives in the War on Terror.[193][194][195] In October 2010, Gaddafi apologized to African leaders on behalf of Arab nations for their involvement in the trans-Saharan slave trade.[196]

Libya is included in the European Union’s European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer. Libyan authorities rejected European Union’s plans aimed at stopping migration from Libya.[197][198] In 2017, Libya signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[199]

Military[edit]

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (April 2016) |

Libya’s previous national army was defeated in the Libyan Civil War and disbanded. The Tobruk based House of Representatives who claim to be the legitimate government of Libya have attempted to reestablish a military known as the Libyan National Army. Led by Khalifa Haftar, they control much of eastern Libya.[200] In May 2012, an estimated 35,000 personnel had joined its ranks.[201] The internationally recognised Government of National Accord established in 2015 has its own army that replaced the LNA, but it consists largely of undisciplined and disorganised militia groups.

As of November 2012, it was deemed to be still in the embryonic stage of development.[202] President Mohammed el-Megarif promised that empowering the army and police force is the government’s biggest priority.[203] President el-Megarif also ordered that all of the country’s militias must come under government authority or disband.[204]

Militias have so far refused to be integrated into a central security force.[205] Many of these militias are disciplined, but the most powerful of them answer only to the executive councils of various Libyan cities.[205] These militias make up the so-called Libyan Shield, a parallel national force, which operates at the request, rather than at the order, of the defence ministry.[205]

Administrative divisions[edit]

Districts of Libya since 2007

Historically, the area of Libya was considered three provinces (or states), Tripolitania in the northwest, Barka (Cyrenaica) in the east, and Fezzan in the southwest. It was the conquest by Italy in the Italo-Turkish War that united them in a single political unit.

Since 2007, Libya has been divided into 22 districts (Shabiyat):

- Nuqat al Khams

- Zawiya

- Jafara

- Tripoli

- Murqub

- Misrata

- Sirte

- Benghazi

- Marj

- Jabal al Akhdar

- Derna

- Tobruk

- Nalut

- Jabal al Gharbi

- Wadi al Shatii

- Jufra

- Al Wahat

- Ghat

- Wadi al Hayaa

- Sabha

- Murzuq

- Kufra

In 2022, 18 provinces were declared by the Libyan Government of National Unity (Observer[permanent dead link]): the eastern coast, Jabal Al-Akhdar, Al-Hizam, Benghazi, Al-Wahat, Al-Kufra, Al-Khaleej, Al-Margab, Tripoli, Al-Jafara, Al-Zawiya, West Coast, Gheryan, Zintan, Nalut, Sabha, Al-Wadi, and Murzuq Basin.

Human rights[edit]

According to Human Rights Watch annual report 2016, journalists are still being targeted by the armed groups in Libya. The organization added that Libya ranked very low in the 2015 Press Freedom Index, 154th out of 180 countries.[206] For the 2021 Press Freedom Index its score dropped to 165th out of 180 countries.[207] Homosexuality is illegal in Libya.[208]

Economy[edit]

Change in per capita GDP of Libya, 1950–2018. Figures are inflation-adjusted to 2011 International dollars.

A proportional representation of Libya exports, 2019

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which account for over half of GDP and 97% of exports.[209] Libya holds the largest proven oil reserves in Africa and is an important contributor to the global supply of light, sweet crude.[210] During 2010, when oil averaged at $80 a barrel, oil production accounted for 54% of GDP.[211] Apart from petroleum, the other natural resources are natural gas and gypsum.[212] The International Monetary Fund estimated Libya’s real GDP growth at 122% in 2012 and 16.7% in 2013, after a 60% plunge in 2011.[209]

The World Bank defines Libya as an ‘Upper Middle Income Economy’, along with only seven other African countries.[213] Substantial revenues from the energy sector, coupled with a small population, give Libya one of the highest per capita GDPs in Africa.[212] This allowed the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya state to provide an extensive level of social security, particularly in the fields of housing and education.[214]

Libya faces many structural problems including a lack of institutions, weak governance, and chronic structural unemployment.[215] The economy displays a lack of economic diversification and significant reliance on immigrant labour.[216] Libya has traditionally relied on unsustainably high levels of public sector hiring to create employment.[217] In the mid-2000s, the government employed about 70% of all national employees.[216]

Unemployment rose from 8% in 2008 to 21% in 2009, according to the census figures.[218] According to an Arab League report, based on data from 2010, unemployment for women stands at 18% while for the figure for men is 21%, making Libya the only Arab country where there are more unemployed men than women.[219] Libya has high levels of social inequality, high rates of youth unemployment and regional economic disparities.[217] Water supply is also a problem, with some 28% of the population not having access to safe drinking water in 2000.[220]

Libya imports up to 90% of its cereal consumption requirements, and imports of wheat in 2012/13 was estimated at 1 million tonnes.[221] The 2012 wheat production was estimated at 200,000 tonnes.[221] The government hopes to increase food production to 800,000 tonnes of cereals by 2020.[221] However, natural and environmental conditions limit Libya’s agricultural production potential.[221] Before 1958, agriculture was the country’s main source of revenue, making up about 30% of GDP. With the discovery of oil in 1958, the size of the agriculture sector declined rapidly, comprising less than 5% GDP by 2005.[222]

The country joined OPEC in 1962.[212] Libya is not a WTO member, but negotiations for its accession started in 2004.[223]

In the early 1980s, Libya was one of the wealthiest countries in the world; its GDP per capita was higher than some developed countries.[224]

In the early 2000s officials of the Jamahiriya era carried out economic reforms to reintegrate Libya into the global economy.[226] UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction.[citation needed] Other steps have included applying for membership of the World Trade Organization, reducing subsidies, and announcing plans for privatization.[227]

Authorities privatized more than 100 government owned companies after 2003 in industries including oil refining, tourism and real estate, of which 29 were 100% foreign owned.[228] Many international oil companies returned to the country, including oil giants Shell and ExxonMobil.[229] After sanctions were lifted there was a gradual increase of air traffic, and by 2005 there were 1.5 million yearly air travellers.[230] Libya had long been a notoriously difficult country for Western tourists to visit due to stringent visa requirements.[231]

In 2007 Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the second-eldest son of Muammar Gaddafi, was involved in a green development project called the Green Mountain Sustainable Development Area, which sought to bring tourism to Cyrene and to preserve Greek ruins in the area.[232]

In August 2011 it was estimated that it would take at least 10 years to rebuild Libya’s infrastructure. Even before the 2011 war, Libya’s infrastructure was in a poor state due to «utter neglect» by Gaddafi’s administration, according to the NTC.[233] By October 2012, the economy had recovered from the 2011 conflict, with oil production returning to near normal levels.[209] Oil production was more than 1.6 million barrels per day before the war. By October 2012, the average oil production has surpassed 1.4 million bpd.[209] The resumption of production was made possible due to the quick return of major Western companies, like TotalEnergies, Eni, Repsol, Wintershall and Occidental.[209] In 2016, an announcement from the company said the company aims 900,000 barrel per day in the next year. Oil production has fallen from 1.6 million barrel per day to 900,000 in four years of war.[234]

The Great Man-Made River is the world’s largest irrigation project.[235] The project utilizes a pipeline system that pumps fossil water from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System from down south in Libya to cities in the populous Libyan northern Mediterranean coast including Tripoli and Benghazi. The water provides 70% of all freshwater used in Libya.[236] During the second Libyan civil war, lasting from 2014 to 2020, the water infrastructure suffered neglect and occasional breakdowns.[237]

By 2017, 60% of the Libyan population were malnourished. Since then, 1.3 million people are waiting for emergency humanitarian aid, out of a total population of 6.4 million.[238]

On 3 October 2022, Libya’s Tripoli government signed economic deals with Turkey. The memorandums of understanding were signed by both the countries in Tripoli, paving the way for further bilateral cooperation in the hydrocarbon and oil sectors.[239]

Demographics[edit]

Libya is a large country with a relatively small population, and the population is concentrated very narrowly along the coast.[240] Population density is about 50 inhabitants per square kilometre (130/sq mi) in the two northern regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, but falls to less than 1 inhabitant per square kilometre (2.6/sq mi) elsewhere. Ninety percent of the people live in less than 10% of the area, primarily along the coast.

About 88% of the population is urban, mostly concentrated in the three largest cities, Tripoli, Benghazi and Misrata. Libya has a population of about 6.7 million,[241][242] 27.7% of whom are under the age of 15.[226] In 1984 the population was 3.6 million, an increase from the 1.54 million reported in 1964.[243]

The majority of the Libyan population today identifies as Arab, that is, Arabic-speaking and Arab-cultured. Berber Libyans, those who retain Berber language and Berber culture, represent the second largest ethnic group and are found primarily in Nafusa Mountains and Zuwarah. Libya is the only Arab-Majority country in the Maghreb. Additionally, the South of Libya, primarily Sebha, Kufra, Ghat, Ghadamis and Murzuk, are also inhabited by two additional Libyan ethnicities: the Tuareg and Toubou. Libya is one of the world’s most tribal countries. There are about 140 tribes and clans in Libya.[244]

Family life is important for Libyan families, the majority of which live in apartment blocks and other independent housing units, with precise modes of housing depending on their income and wealth. Although the Arab Libyans traditionally lived nomadic lifestyles in tents, they have now settled in various towns and cities.[245]

Because of this, their old ways of life are gradually fading out. An unknown small number of Libyans still live in the desert as their families have done for centuries. Most of the population has occupations in industry and services, and a small percentage is in agriculture.

According to the UNHCR, there were around 8,000 registered refugees, 5,500 unregistered refugees, and 7,000 asylum seekers of various origins in Libya in January 2013. Additionally, 47,000 Libyan nationals were internally displaced and 46,570 were internally displaced returnees.[246]

Health[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2013) |

In 2010, spending on healthcare accounted for 3.88% of the country’s GDP. In 2009, there were 18.71 physicians and 66.95 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.[247] The life expectancy at birth was 74.95 years in 2011, or 72.44 years for males and 77.59 years for females.[248]

Education[edit]

|

|

Parts of this article (those related to post-23 October 2011 national tertiary level education in Libya) need to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. |

Al Manar Royal Palace in central Benghazi – the location of the University of Libya’s first campus, founded by royal decree in 1955

Libya’s population includes 1.7 million students, over 270,000 of whom study at the tertiary level.[249] Basic education in Libya is free for all citizens,[250] and is compulsory up to the secondary level. The adult literacy rate in 2010 was 89.2%.[251]

After Libya’s independence in 1951, its first university – the University of Libya – was established in Benghazi by royal decree.[252] In the 1975–76 academic year the number of university students was estimated to be 13,418. As of 2004, this number has increased to more than 200,000, with an extra 70,000 enrolled in the higher technical and vocational sector.[249] The rapid increase in the number of students in the higher education sector has been mirrored by an increase in the number of institutions of higher education.

Since 1975 the number of universities has grown from two to nine and after their introduction in 1980, the number of higher technical and vocational institutes currently stands at 84 (with 12 public universities).[? clarification needed][249] Since 2007 some new private universities such as the Libyan International Medical University have been established. Although before 2011 a small number of private institutions were given accreditation, the majority of Libya’s higher education has always been financed by the public budget. In 1998 the budget allocation for education represented 38.2% of Libya’s total national budget.[252]

Ethnicity[edit]

A map indicating the ethnic composition of Libya in 1974

The original inhabitants of Libya belonged predominantly to various Berber ethnic groups; however, the long series of foreign invasions and migrations – particularly by Arabs and Turks – have had a profound and lasting ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and identity influence on Libya’s demographics.

Today, the great majority of Libya’s inhabitants are Arab,[22] with many tracing their ancestry to Bedouin Arab tribes like Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal, beside Turkish and Berber minorities. The Turkish minority are often called «Kouloughlis» and are concentrated in and around villages and towns.[253] Additionally, there are some Libyan ethnic minorities, such as the Berber Tuareg and the Black African Tebou.[254]

Most Italian settlers, at their height numbering over half a million, left after Italian Libya’s independence in 1947. More repatriated in 1970 after the accession of Muammar Gaddafi, but a few hundred of them returned in the 2000s.[255]

Immigrant labour[edit]

As of 2013, the UN estimates that around 12% of Libya’s population (upwards of 740,000 people) was made up of foreign migrants.[13] Prior to the 2011 revolution official and unofficial figures of migrant labour range from 25% to 40% of the population (between 1.5 and 2.4 million people). Historically, Libya has been a host state for millions of low- and high-skilled Egyptian migrants, in particular.[256]

It is difficult to estimate the total number of immigrants in Libya as there are often differences between census figures, official counts and usually more accurate unofficial estimates. In the 2006 census, around 359,540 foreign nationals were resident in Libya out of a population of over 5.5 million (6.35% of the population). Almost half of these were Egyptians, followed by Sudanese and Palestinian immigrants.[257]

During the 2011 revolution, 768,362 immigrants fled Libya as calculated by the IOM, around 13% of the population at the time, although many more stayed on in the country.[257][258]

If consular records prior to the revolution are used to estimate the immigrant population, as many as 2 million Egyptian migrants were recorded by the Egyptian embassy in Tripoli in 2009, followed by 87,200 Tunisians, and 68,200 Moroccans by their respective embassies. Turkey recorded the evacuation of 25,000 workers during the 2011 uprising.[259] The number of Asian migrants before the revolution were just over 100,000 (60,000 Bangladeshis, 20,000 Filipinos, 18,000 Indians, 10,000 Pakistanis, as well as Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Thai and other workers).[260][261] This would put the immigrant population at almost 40% before the revolution and is a figure more consistent with government estimates in 2004 which put the regular and irregular migrant numbers at 1.35 to 1.8 million (25–33% of the population at the time).[257]

Libya’s native population of Arabs-Berbers as well as Arab migrants of various nationalities collectively make up 97% of the population as of 2014.

Languages[edit]

According to the CIA, the official language of Libya is Arabic.[262] The local Libyan Arabic variety is spoken alongside Modern Standard Arabic. Various Berber languages are also spoken, including Tamasheq, Ghadamis, Nafusi, Suknah and Awjilah.[262] The Libyan Amazigh High Council (LAHC) has declared the Amazigh (Berber or Tamazight) language as an official language in the cities and districts inhabited by the Berbers in Libya.[263]

In addition, English is widely understood in the major cities,[264] while the former colonial language of Italian is also used in commerce and by remaining Italian population.[262]

Religion[edit]

Mosque in Ghadames, close to the Tunisian and Algerian border.

About 97% of the population in Libya are Muslims, most of whom belong to the Sunni branch.[226][265] Small numbers of Ibadi Muslims live in the country.[266][267]

Before the 1930s, the Senussi Sunni Sufi movement was the primary Islamic movement in Libya. This was a religious revival adapted to desert life. Its zawaaya (lodges) were found in Tripolitania and Fezzan, but Senussi influence was strongest in Cyrenaica. Rescuing the region from unrest and anarchy, the Senussi movement gave the Cyrenaican tribal people a religious attachment and feelings of unity and purpose.[268] This Islamic movement was eventually destroyed by the Italian invasion. Gaddafi asserted that he was a devout Muslim, and his government was taking a role in supporting Islamic institutions and in worldwide proselytising on behalf of Islam.[269]

Since the fall of Gaddafi, ultra-conservative strains of Islam have reasserted themselves in places. Derna in eastern Libya, historically a hotbed of jihadist thought, came under the control of militants aligned with the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in 2014.[270] Jihadist elements have also spread to Sirte and Benghazi, among other areas, as a result of the Second Libyan Civil War.[271][272]

There are small foreign communities of Christians. Coptic Orthodox Christianity, which is the Christian Church of Egypt, is the largest and most historical Christian denomination in Libya. There are about 60,000 Egyptian Copts in Libya.[273] There are three Coptic Churches in Libya, one in Tripoli, one in Benghazi, and one in Misurata.

The Coptic Church has grown in recent years in Libya, due to the growing immigration of Egyptian Copts to Libya. There are an estimated 40,000 Roman Catholics in Libya who are served by two Bishops, one in Tripoli (serving the Italian community) and one in Benghazi (serving the Maltese community). There is also a small Anglican community, made up mostly of African immigrant workers in Tripoli; it is part of the Anglican Diocese of Egypt. People have been arrested on suspicion of being Christian missionaries, as proselytising is illegal.[274] Christians have also faced the threat of violence from radical Islamists in some parts of the country, with a well-publicised video released by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in February 2015 depicting the mass beheading of Christian Copts.[275][276] Libya is number four on Open Doors’ 2022 World Watch List, an annual ranking of the 50 countries where Christians face the most extreme persecution.[277]

Libya was once the home of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to at least 300 BC.[278] In 1942, the Italian Fascist authorities set up forced labor camps south of Tripoli for the Jews, including Giado (about 3,000 Jews), Gharyan, Jeren, and Tigrinna. In Giado some 500 Jews died of weakness, hunger, and disease. In 1942, Jews who were not in the concentration camps were heavily restricted in their economic activity and all men between 18 and 45 years were drafted for forced labor. In August 1942, Jews from Tripolitania were interned in a concentration camp at Sidi Azaz. In the three years after November 1945, more than 140 Jews were murdered, and hundreds more wounded, in a series of pogroms.[279] By 1948, about 38,000 Jews remained in the country. Upon Libya’s independence in 1951, most of the Jewish community emigrated.

Largest cities[edit]

Largest cities or towns in Libya [1][2][3] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

Tripoli  Benghazi |

1 | Tripoli | Tripoli | 1,250,000 |  Misrata  Beida |

| 2 | Benghazi | Benghazi | 700,000 | ||

| 3 | Misrata | Misurata | 350,000 | ||

| 4 | Beida | Jebel el-Akhdar | 250,000 | ||

| 5 | Khoms | Murqub | 201,000 | ||

| 6 | Zawiya | Zawiya | 200,000 | ||

| 7 | Ajdabiya | Al Wahat | 134,000 | ||

| 8 | Sebha | Sebha | 130,000 | ||

| 9 | Sirte | Sirte | 128,000 | ||

| 10 | Tobruk | Butnan | 120,000 |

Culture[edit]

Many Arabic speaking Libyans consider themselves as part of a wider Arab community. This was strengthened by the spread of Pan-Arabism in the mid-20th century, and their reach to power in Libya where they instituted Arabic as the only official language of the state. Under Gaddafi’s rule, the teaching and even use of indigenous Berber language was strictly forbidden.[280] In addition to banning foreign languages previously taught in academic institutions, leaving entire generations of Libyans with limitations in their comprehension of the English language. Both the spoken Arabic dialects and Berber, still retain words from Italian, that were acquired before and during the Libia Italiana period.

Libyans have a heritage in the traditions of the previously nomadic Bedouin Arabic speakers and sedentary Berber tribes. Most Libyans associate themselves with a particular family name originating from tribal or conquest based heritage.

Reflecting the «nature of giving» (Arabic: الاحسان Ihsan, Berber languages: ⴰⵏⴰⴽⴽⴰⴼ Anakkaf ), amongst the Libyan people as well as the sense of hospitality, recently the state of Libya made it to the top 20 on the world giving index in 2013.[281] According to CAF, in a typical month, almost three-quarters (72%) of all Libyans helped somebody they did not know – the third highest level across all 135 countries surveyed.

There are few theaters or art galleries due to the decades of cultural repression under the Qaddafi regime and lack of infrastructure development under the regime of dictatorship.[282] For many years there have been no public theaters, and only very few cinemas showing foreign films. The tradition of folk culture is still alive and well, with troupes performing music and dance at frequent festivals, both in Libya and abroad.[283]

A large number of Libyan television stations are devoted to political review, Islamic topics and cultural phenomena. A number of TV stations air various styles of traditional Libyan music.[? clarification needed] Tuareg music and dance are popular in Ghadames and the south. Libyan television broadcasts air programs mostly in Arabic though usually have time slots for English and French programs.[? clarification needed] A 1996 analysis by the Committee to Protect Journalists found Libya’s media was the most tightly controlled in the Arab world during the country’s dictatorship.[284] As of 2012 hundreds of TV stations have begun to air due to the collapse of censorship from the old regime and the initiation of «free media».

Many Libyans frequent the country’s beach and they also visit Libya’s archaeological sites—especially Leptis Magna, which is widely considered to be one of the best preserved Roman archaeological sites in the world.[285] The most common form of public transport between cities is the bus, though many people travel by automobile. There are no railway services in Libya, but these are planned for construction in the near future (see rail transport in Libya).[286]

Libya’s capital, Tripoli, has many museums and archives. These include the Government Library, the Ethnographic Museum, the Archaeological Museum, the National Archives, the Epigraphy Museum and the Islamic Museum. The Red Castle Museum located in the capital near the coast and right in the city center, built in consultation with UNESCO, may be the country’s most famous.[287]

Cuisine[edit]

Libyan cuisine is a mixture of the different Italian, Bedouin and traditional Arab culinary influences.[288] Pasta is the staple food in the Western side of Libya, whereas rice is generally the staple food in the east.

Common Libyan foods include several variations of red (tomato) sauce based pasta dishes (similar to the Italian Sugo all’arrabbiata dish); rice, usually served with lamb or chicken (typically stewed, fried, grilled, or boiled in-sauce); and couscous, which is steam cooked whilst held over boiling red (tomato) sauce and meat (sometimes also containing courgettes/zucchini and chickpeas), which is typically served along with cucumber slices, lettuce and olives.

Bazeen, a dish made from barley flour and served with red tomato sauce, is customarily eaten communally, with several people sharing the same dish, usually by hand. This dish is commonly served at traditional weddings or festivities. Asida is a sweet version of Bazeen, made from white flour and served with a mix of honey, ghee or butter. Another favorite way to serve Asida is with rub (fresh date syrup) and olive oil. Usban is animal tripe stitched and stuffed with rice and vegetables cooked in tomato based soup or steamed. Shurba is a red tomato sauce-based soup, usually served with small grains of pasta.[289]

A very common snack eaten by Libyans is known as khubs bi’ tun, literally meaning «bread with tuna fish», usually served as a baked baguette or pita bread stuffed with tuna fish that has been mixed with harissa (chili sauce) and olive oil. Many snack vendors prepare these sandwiches and they can be found all over Libya. Libyan restaurants may serve international cuisine, or may serve simpler fare such as lamb, chicken, vegetable stew, potatoes and macaroni.[citation needed] Due to severe lack of infrastructure, many under-developed areas and small towns do not have restaurants and instead food stores may be the only source to obtain food products. Alcohol consumption is illegal in the entire country.[citation needed]

There are four main ingredients of traditional Libyan food: olives (and olive oil), dates, grains and milk.[290] Grains are roasted, ground, sieved and used for making bread, cakes, soups and bazeen. Dates are harvested, dried and can be eaten as they are, made into syrup or slightly fried and eaten with bsisa and milk. After eating, Libyans often drink black tea. This is normally repeated a second time (for the second glass of tea), and in the third round of tea, it is served with roasted peanuts or roasted almonds known as shay bi’l-luz (mixed with the tea in the same glass).[290]

Sport[edit]

Football is the most popular sport in Libya. The country hosted the 1982 African Cup of Nations and almost qualified for the 1986 FIFA World Cup. The national team almost won the 1982 AFCON; they lost to Ghana on penalties 7–6. In 2014, Libya won the African Nations Championship after beating Ghana in the finals. Although the national team has never won a major competition or qualified for a World Cup, there is still lots of passion for the sport and the quality of football is improving.[291]

Horse racing is also a popular sport in Libya. It is a tradition of many special occasions and holidays.[292]

See also[edit]

- Outline of Libya

- Index of Libya-related articles

Notes[edit]

- ^ Disputed by Fathi Bashagha of the Government of National Stability

References[edit]

- ^ «The World Factbook Africa: Libya». The World Factbook. CIA. 18 May 2015. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/libya/#people-and-society

- ^ https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/1/6/libyas-berbers-fear-ethnic-conflict