Not to be confused with manganese (Mn).

«mg» redirects here. For the milligram (mg) or megagram (Mg), see kilogram § SI multiples. For other uses, see MG.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnesium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (mag-NEE-zee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | shiny grey solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Mg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnesium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 2 (alkaline earth metals) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 923 K (650 °C, 1202 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1363 K (1091 °C, 1994 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 1.738 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 1.584 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 8.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 128 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.869[2] J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 0,[3] +1,[4] +2 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 160 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 141±7 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 173 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of magnesium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4940 m/s (at r.t.) (annealed) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 24.8[5] µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 156[6] W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 43.9[7] nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +13.1×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 45 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 17 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 35.4[9] GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.290 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 1–2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 44–260 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-95-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Magnesia, Greece[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Joseph Black (1755[10]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Humphry Davy (1808[10]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of magnesium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic table) it occurs naturally only in combination with other elements and it almost always has an oxidation state of +2. It reacts readily with air to form a thin passivation coating of magnesium oxide that inhibits further corrosion of the metal. The free metal burns with a brilliant-white light. The metal is obtained mainly by electrolysis of magnesium salts obtained from brine. It is less dense than aluminium and is used primarily as a component in strong and lightweight alloys that contain aluminium.

In the cosmos, magnesium is produced in large, aging stars by the sequential addition of three helium nuclei to a carbon nucleus. When such stars explode as supernovas, much of the magnesium is expelled into the interstellar medium where it may recycle into new star systems. Magnesium is the eighth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust[11] and the fourth most common element in the Earth (after iron, oxygen and silicon), making up 13% of the planet’s mass and a large fraction of the planet’s mantle. It is the third most abundant element dissolved in seawater, after sodium and chlorine.[12]

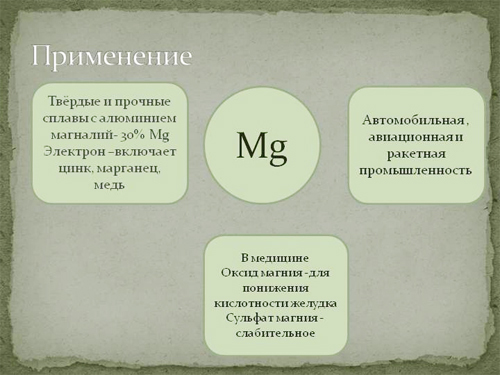

This element is the eleventh most abundant element by mass in the human body and is essential to all cells and some 300 enzymes.[13] Magnesium ions interact with polyphosphate compounds such as ATP, DNA, and RNA. Hundreds of enzymes require magnesium ions to function. Magnesium compounds are used medicinally as common laxatives and antacids (such as milk of magnesia), and to stabilize abnormal nerve excitation or blood vessel spasm in such conditions as eclampsia.[13]

Characteristics

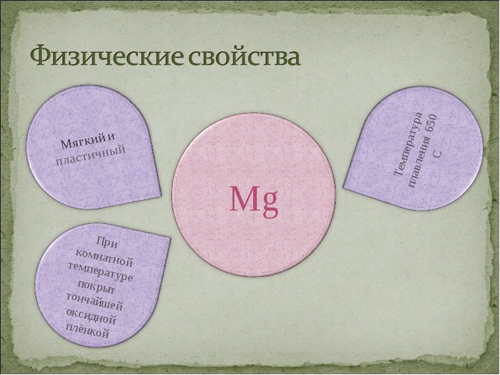

Physical properties

Elemental magnesium is a gray-white lightweight metal, two-thirds the density of aluminium. Magnesium has the lowest melting (923 K (650 °C)) and the lowest boiling point 1,363 K (1,090 °C) of all the alkaline earth metals.[14]

Pure polycrystalline magnesium is brittle and easily fractures along shear bands. It becomes much more malleable when alloyed with small amount of other metals, such as 1% aluminium.[15] The malleability of polycrystalline magnesium can also be significantly improved by reducing its grain size to ca. 1 micron or less.[16]

When finely powdered, magnesium can react with water to produce hydrogen gas:

- Mg(s) + 2H2O(g) → Mg(OH)2(aq) + H2(g) + 1203.6 kJ

However, this reaction is much less dramatic than the reactions of the alkali metals with water, because the magnesium hydroxide tends to build up on the surface of the pure magnesium metal and prevent the reaction from occurring.[17]

Chemical properties

General chemistry

It tarnishes slightly when exposed to air, although, unlike the heavier alkaline earth metals, an oxygen-free environment is unnecessary for storage because magnesium is protected by a thin layer of oxide that is fairly impermeable and difficult to remove.

Direct reaction of magnesium with air or oxygen at ambient pressure forms only the «normal» oxide MgO. However, this oxide may be combined with hydrogen peroxide to form Magnesium peroxide, MgO2, and at low temperature the peroxide may be further reacted with ozone to form magnesium superoxide Mg(O2)2.[18]

Magnesium reacts with water at room temperature, though it reacts much more slowly than calcium, a similar group 2 metal. When submerged in water, hydrogen bubbles form slowly on the surface of the metal – though, if powdered, it reacts much more rapidly. The reaction occurs faster with higher temperatures (see safety precautions). Magnesium’s reversible reaction with water can be harnessed to store energy and run a magnesium-based engine. Magnesium also reacts exothermically with most acids such as hydrochloric acid (HCl), producing the metal chloride and hydrogen gas, similar to the HCl reaction with aluminium, zinc, and many other metals.

Flammability

Magnesium is highly flammable, especially when powdered or shaved into thin strips, though it is difficult to ignite in mass or bulk. Flame temperatures of magnesium and magnesium alloys can reach 3,100 °C (5,610 °F),[19] although flame height above the burning metal is usually less than 300 mm (12 in).[20] Once ignited, such fires are difficult to extinguish, because combustion continues in nitrogen (forming magnesium nitride), carbon dioxide (forming magnesium oxide and carbon), and water (forming magnesium oxide and hydrogen, which also combusts due to heat in the presence of additional oxygen). This property was used in incendiary weapons during the firebombing of cities in World War II, where the only practical civil defense was to smother a burning flare under dry sand to exclude atmosphere from the combustion.

Magnesium may also be used as an igniter for thermite, a mixture of aluminium and iron oxide powder that ignites only at a very high temperature.

Organic chemistry

Organomagnesium compounds are widespread in organic chemistry. They are commonly found as Grignard reagents. Magnesium can react with haloalkanes to give Grignard reagents. Examples of Grignard reagents are phenylmagnesium bromide and ethylmagnesium bromide. The Grignard reagents function as a common nucleophile, attacking the electrophilic group such as the carbon atom that is present within the polar bond of a carbonyl group.

A prominent organomagnesium reagent beyond Grignard reagents is magnesium anthracene with magnesium forming a 1,4-bridge over the central ring. It is used as a source of highly active magnesium. The related butadiene-magnesium adduct serves as a source for the butadiene dianion.

Magnesium in organic chemistry also appears as low valent magnesium compounds, primarily with the magnesium forming diatomic ions in the +1 oxidation state but more recently also with zero oxidation state or a mixture of +1 and zero states.[21] Such compounds find synthetic application as reducing agents and sources of nucleophilic metal atoms.

Source of light

When burning in air, magnesium produces a brilliant-white light that includes strong ultraviolet wavelengths. Magnesium powder (flash powder) was used for subject illumination in the early days of photography.[22][23] Later, magnesium filament was used in electrically ignited single-use photography flashbulbs. Magnesium powder is used in fireworks and marine flares where a brilliant white light is required. It was also used for various theatrical effects,[24] such as lightning,[25] pistol flashes,[26] and supernatural appearances.[27]

Detection in solution

The presence of magnesium ions can be detected by the addition of ammonium chloride, ammonium hydroxide and monosodium phosphate to an aqueous or dilute HCl solution of the salt. The formation of a white precipitate indicates the presence of magnesium ions.

Azo violet dye can also be used which turns deep blue in the presence of an alkaline solution of magnesium salt. The color is due to the adsorption of azo violet by Mg(OH)2.

Occurrence

Magnesium is the eighth-most-abundant element in the Earth’s crust by mass and tied in seventh place with iron in molarity.[11] It is found in large deposits of magnesite, dolomite, and other minerals, and in mineral waters, where magnesium ion is soluble.

Although magnesium is found in more than 60 minerals, only dolomite, magnesite, brucite, carnallite, talc, and olivine are of commercial importance.

The Mg2+

cation is the second-most-abundant cation in seawater (about 1⁄8 the mass of sodium ions in a given sample), which makes seawater and sea salt attractive commercial sources for Mg. To extract the magnesium, calcium hydroxide is added to seawater to form magnesium hydroxide precipitate.

- MgCl

2 + Ca(OH)

2 → Mg(OH)

2 + CaCl

2

Magnesium hydroxide (brucite) is insoluble in water and can be filtered out and reacted with hydrochloric acid to produced concentrated magnesium chloride.

- Mg(OH)

2 + 2 HCl → MgCl

2 + 2 H

2O

From magnesium chloride, electrolysis produces magnesium.

Forms

Alloys

Magnesium is brittle, and fractures along shear bands when its thickness is reduced by only 10% by cold rolling (top). However, after alloying Mg with 1% Al and 0.1% Ca, its thickness could be reduced by 54% using the same process (bottom).

As of 2013, magnesium alloys consumption was less than one million tonnes per year, compared with 50 million tonnes of aluminum alloys. Their use has been historically limited by the tendency of Mg alloys to corrode,[28] creep at high temperatures, and combust.[29]

Corrosion

The presence of iron, nickel, copper, and cobalt strongly activates corrosion. In more than trace amounts, these metals precipitate as intermetallic compounds, and the precipitate locales function as active cathodic sites that reduce water, causing the loss of magnesium.[29] Controlling the quantity of these metals improves corrosion resistance. Sufficient manganese overcomes the corrosive effects of iron. This requires precise control over composition, increasing costs.[29] Adding a cathodic poison captures atomic hydrogen within the structure of a metal. This prevents the formation of free hydrogen gas, an essential factor of corrosive chemical processes. The addition of about one in three hundred parts arsenic reduces its corrosion rate in a salt solution by a factor of nearly ten.[29][30]

High-temperature creep and flammability

Research showed that magnesium’s tendency to creep at high temperatures is eliminated by the addition of scandium and gadolinium. Flammability is greatly reduced by a small amount of calcium in the alloy.[29] By using rare-earth elements, it may be possible to manufacture magnesium alloys with an ignition temperature higher than magnesium’s liquidus and in some cases potentially pushing it close to magnesium’s boiling point.[31]

Compounds

Magnesium forms a variety of compounds important to industry and biology, including magnesium carbonate, magnesium chloride, magnesium citrate, magnesium hydroxide (milk of magnesia), magnesium oxide, magnesium sulfate, and magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (Epsom salts).

Isotopes

Magnesium has three stable isotopes: 24

Mg, 25

Mg and 26

Mg. All are present in significant amounts in nature (see table of isotopes above). About 79% of Mg is 24

Mg. The isotope 28

Mg is radioactive and in the 1950s to 1970s was produced by several nuclear power plants for use in scientific experiments. This isotope has a relatively short half-life (21 hours) and its use was limited by shipping times.

The nuclide 26

Mg has found application in isotopic geology, similar to that of aluminium. 26

Mg is a radiogenic daughter product of 26

Al, which has a half-life of 717,000 years. Excessive quantities of stable 26

Mg have been observed in the Ca-Al-rich inclusions of some carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. This anomalous abundance is attributed to the decay of its parent 26

Al in the inclusions, and researchers conclude that such meteorites were formed in the solar nebula before the 26

Al had decayed. These are among the oldest objects in the Solar System and contain preserved information about its early history.

It is conventional to plot 26

Mg/24

Mg against an Al/Mg ratio. In an isochron dating plot, the Al/Mg ratio plotted is27

Al/24

Mg. The slope of the isochron has no age significance, but indicates the initial 26

Al/27

Al ratio in the sample at the time when the systems were separated from a common reservoir.

Production

Magnesium sheets and ingots

World production was approximately 1,100 kt in 2017, with the bulk being produced in China (930 kt) and Russia (60 kt).[32] The United States was in the 20th century the major world supplier of this metal, supplying 45% of world production even as recently as 1995. Since the Chinese mastery of the Pidgeon process the US market share is at 7%, with a single US producer left: US Magnesium, a Renco Group company in Utah born from now-defunct Magcorp.[33]

In September 2021, China took steps to reduce production of magnesium as a result of a government initiative to reduce energy availability for manufacturing industries, leading to a significant price increase.[34]

- Pidgeon process

China is almost completely reliant on the silicothermic Pidgeon process (the reduction of the oxide at high temperatures with silicon, often provided by a ferrosilicon alloy in which the iron is but a spectator in the reactions) to obtain the metal.[35] The process can also be carried out with carbon at approx 2300 °C:

- 2MgO

(s) + Si

(s) + 2CaO

(s) → 2Mg

(g) + Ca

2SiO

4(s) - MgO

(s) + C

(s) → Mg

(g) + CO

(g)

- Dow process

In the United States, magnesium is obtained principally with the Dow process, by electrolysis of fused magnesium chloride from brine and sea water. A saline solution containing Mg2+

ions is first treated with lime (calcium oxide) and the precipitated magnesium hydroxide is collected:

- Mg2+

(aq) + CaO

(s) + H

2O → Ca2+

(aq) + Mg(OH)

2(s)

The hydroxide is then converted to a partial hydrate of magnesium chloride by treating the hydroxide with hydrochloric acid and heating of the product:

- Mg(OH)

2(s) + 2 HCl → MgCl

2(aq) + 2H

2O

(l)

The salt is then electrolyzed in the molten state. At the cathode, the Mg2+

ion is reduced by two electrons to magnesium metal:

- Mg2+

+ 2

e−

→ Mg

At the anode, each pair of Cl−

ions is oxidized to chlorine gas, releasing two electrons to complete the circuit:

- 2 Cl−

→ Cl

2 (g) + 2

e−

- YSZ process

A new process, solid oxide membrane technology, involves the electrolytic reduction of MgO. At the cathode, Mg2+

ion is reduced by two electrons to magnesium metal. The electrolyte is yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ). The anode is a liquid metal. At the YSZ/liquid metal anode O2−

is oxidized. A layer of graphite borders the liquid metal anode, and at this interface carbon and oxygen react to form carbon monoxide. When silver is used as the liquid metal anode, there is no reductant carbon or hydrogen needed, and only oxygen gas is evolved at the anode.[36] It has been reported that this method provides a 40% reduction in cost per pound over the electrolytic reduction method.[37]

History

The name magnesium originates from the Greek word for locations related to the tribe of the Magnetes, either a district in Thessaly called Magnesia[38] or Magnesia ad Sipylum, now in Turkey.[39] It is related to magnetite and manganese, which also originated from this area, and required differentiation as separate substances. See manganese for this history.

In 1618, a farmer at Epsom in England attempted to give his cows water from a well there. The cows refused to drink because of the water’s bitter taste, but the farmer noticed that the water seemed to heal scratches and rashes. The substance became known as Epsom salts and its fame spread.[40] It was eventually recognized as hydrated magnesium sulfate, MgSO

4·7 H

2O.

The metal itself was first isolated by Sir Humphry Davy in England in 1808. He used electrolysis on a mixture of magnesia and mercuric oxide.[41] Antoine Bussy prepared it in coherent form in 1831. Davy’s first suggestion for a name was magnium,[41] but the name magnesium is now used in English and all major European languages but Russian.

Uses as a metal

Magnesium is the third-most-commonly-used structural metal, following iron and aluminium.[42] The main applications of magnesium are, in order: aluminium alloys, die-casting (alloyed with zinc),[43] removing sulfur in the production of iron and steel, and the production of titanium in the Kroll process.[44]

Magnesium is used in lightweight materials and alloys. For example, when infused with silicon carbide nanoparticles, it has extremely high specific strength.[45]

Historically, magnesium was one of the main aerospace construction metals and was used for German military aircraft as early as World War I and extensively for German aircraft in World War II. The Germans coined the name «Elektron» for magnesium alloy, a term which is still used today. In the commercial aerospace industry, magnesium was generally restricted to engine-related components, due to fire and corrosion hazards. Magnesium alloy use in aerospace is increasing in the 21st century, driven by the importance of fuel economy.[46] Recent developments in metallurgy and manufacturing have allowed for the potential for magnesium alloys to act as replacements for aluminium and steel alloys in certain applications.[47][48]

In the form of thin ribbons, magnesium is used to purify solvents; for example, preparing super-dry ethanol.[citation needed]

Aircraft

- Wright Aeronautical used a magnesium crankcase in the WWII-era Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone aviation engine. This presented a serious problem for the earliest models of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber when an in-flight engine fire ignited the engine crankcase. The resulting combustion was as hot as 5,600 °F (3,100 °C) and could sever the wing spar from the fuselage.[49][50][51]

Automotive

Mg alloy motorcycle engine blocks

- Mercedes-Benz used the alloy Elektron in the bodywork of an early model Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR; these cars competed in the 1955 World Sportscar Championship including a win at the Mille Miglia, and at Le Mans where one was involved in the 1955 Le Mans disaster when spectators were showered with burning fragments of elektron.[citation needed]

- Porsche used magnesium alloy frames in the 917/053 that won Le Mans in 1971, and continues to use magnesium alloys for its engine blocks due to the weight advantage.[citation needed]

- Volkswagen Group has used magnesium in its engine components for many years.[52]

- Mitsubishi Motors uses magnesium for its paddle shifters.[citation needed]

- BMW used magnesium alloy blocks in their N52 engine, including an aluminium alloy insert for the cylinder walls and cooling jackets surrounded by a high-temperature magnesium alloy AJ62A. The engine was used worldwide between 2005 and 2011 in various 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7 series models; as well as the Z4, X1, X3, and X5.[citation needed]

- Chevrolet used the magnesium alloy AE44 in the 2006 Corvette Z06.[citation needed]

Both AJ62A and AE44 are recent developments in high-temperature low-creep magnesium alloys. The general strategy for such alloys is to form intermetallic precipitates at the grain boundaries, for example by adding mischmetal or calcium.[53] New alloy development and lower costs that make magnesium competitive with aluminium will increase the number of automotive applications.[citation needed]

Electronics

Because of low density and good mechanical and electrical properties, magnesium is used for manufacturing of mobile phones, laptop and tablet computers, cameras, and other electronic components.[citation needed] It was used as a premium feature because of its light weight in some 2020 laptops.[54]

Products made of magnesium: firestarter and shavings, sharpener, magnesium ribbon

Other

Magnesium, being readily available and relatively nontoxic, has a variety of uses:

- Magnesium is flammable, burning at a temperature of approximately 3,100 °C (3,370 K; 5,610 °F),[19] and the autoignition temperature of magnesium ribbon is approximately 473 °C (746 K; 883 °F).[55] It produces intense, bright, white light when it burns. Magnesium’s high combustion temperature makes it a useful tool for starting emergency fires. Other uses include flash photography, flares, pyrotechnics, fireworks sparklers, and trick birthday candles. Magnesium is also often used to ignite thermite or other materials that require a high ignition temperature. Magnesium continues to be used as an incendiary element in warfare.[56]

Magnesium firestarter (in left hand), used with a pocket knife and flint to create sparks that ignite the shavings

- In the form of turnings or ribbons, to prepare Grignard reagents, which are useful in organic synthesis.[citation needed]

- As an additive agent in conventional propellants and the production of nodular graphite in cast iron.[citation needed]

- As a reducing agent to separate uranium and other metals from their salts.[citation needed]

- As a sacrificial (galvanic) anode to protect boats, underground tanks, pipelines, buried structures, and water heaters.[citation needed]

- Alloyed with zinc to produce the zinc sheet used in photoengraving plates in the printing industry, dry-cell battery walls, and roofing.[43]

- As a metal, this element’s principal use is as an alloying additive to aluminium with these aluminium-magnesium alloys being used mainly for beverage cans, sports equipment such as golf clubs, fishing reels, and archery bows and arrows.[citation needed]

- Specialty, high-grade car wheels of magnesium alloy are called «mag wheels», although the term is often misapplied to aluminium wheels. Many car and aircraft manufacturers have made engine and body parts from magnesium.[citation needed]

- Magnesium batteries have been commercialized as primary batteries, and are an active topic of research for rechargeable batteries.[citation needed]

Safety precautions

Magnesium block heated with blowtorch to self-combustion, emitting intense white light

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H228, H251, H261 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P210, P231, P235, P410, P422[57] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

https://cameochemicals.noaa.gov/chemical/6949 0 1 1 |

Magnesium metal and its alloys can be explosive hazards; they are highly flammable in their pure form when molten or in powder or ribbon form. Burning or molten magnesium reacts violently with water. When working with powdered magnesium, safety glasses with eye protection and UV filters (such as welders use) are employed because burning magnesium produces ultraviolet light that can permanently damage the retina of a human eye.[58]

Magnesium is capable of reducing water and releasing highly flammable hydrogen gas:[59]

- Mg (s) + 2 H

2O (l) → Mg(OH)

2 (s) + H

2 (g)

Therefore, water cannot extinguish magnesium fires. The hydrogen gas produced intensifies the fire. Dry sand is an effective smothering agent, but only on relatively level and flat surfaces.

Magnesium reacts with carbon dioxide exothermically to form magnesium oxide and carbon:[60]

- 2 Mg + CO

2 → 2 MgO + C (s)

Hence, carbon dioxide fuels rather than extinguishes magnesium fires.

Burning magnesium can be quenched by using a Class D dry chemical fire extinguisher, or by covering the fire with sand or magnesium foundry flux to remove its air source.[61]

Useful compounds

Magnesium compounds, primarily magnesium oxide (MgO), are used as a refractory material in furnace linings for producing iron, steel, nonferrous metals, glass, and cement. Magnesium oxide and other magnesium compounds are also used in the agricultural, chemical, and construction industries. Magnesium oxide from calcination is used as an electrical insulator in fire-resistant cables.[62]

Magnesium hydride is under investigation as a way to store hydrogen.

Magnesium reacted with an alkyl halide gives a Grignard reagent, which is a very useful tool for preparing alcohols.

Magnesium salts are included in various foods, fertilizers (magnesium is a component of chlorophyll), and microbe culture media.

Magnesium sulfite is used in the manufacture of paper (sulfite process).

Magnesium phosphate is used to fireproof wood used in construction.

Magnesium hexafluorosilicate is used for moth-proofing textiles.

Biological roles

Mechanism of action

The important interaction between phosphate and magnesium ions makes magnesium essential to the basic nucleic acid chemistry of all cells of all known living organisms. More than 300 enzymes require magnesium ions for their catalytic action, including all enzymes using or synthesizing ATP and those that use other nucleotides to synthesize DNA and RNA. The ATP molecule is normally found in a chelate with a magnesium ion.[63]

Nutrition

Diet

Examples of food sources of magnesium (clockwise from top left): bran muffins, pumpkin seeds, barley, buckwheat flour, low-fat vanilla yogurt, trail mix, halibut steaks, garbanzo beans, lima beans, soybeans, and spinach

Spices, nuts, cereals, cocoa and vegetables are rich sources of magnesium.[13] Green leafy vegetables such as spinach are also rich in magnesium.[64]

Beverages rich in magnesium are coffee, tea, and cocoa.[65]

Dietary recommendations

In the UK, the recommended daily values for magnesium are 300 mg for men and 270 mg for women.[66] In the U.S. the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) are 400 mg for men ages 19–30 and 420 mg for older; for women 310 mg for ages 19–30 and 320 mg for older.[67]

Supplementation

Numerous pharmaceutical preparations of magnesium and dietary supplements are available. In two human trials magnesium oxide, one of the most common forms in magnesium dietary supplements because of its high magnesium content per weight, was less bioavailable than magnesium citrate, chloride, lactate or aspartate.[68][69]

Metabolism

An adult body has 22–26 grams of magnesium,[13][70] with 60% in the skeleton, 39% intracellular (20% in skeletal muscle), and 1% extracellular.[13] Serum levels are typically 0.7–1.0 mmol/L or 1.8–2.4 mEq/L. Serum magnesium levels may be normal even when intracellular magnesium is deficient. The mechanisms for maintaining the magnesium level in the serum are varying gastrointestinal absorption and renal excretion. Intracellular magnesium is correlated with intracellular potassium. Increased magnesium lowers calcium[71] and can either prevent hypercalcemia or cause hypocalcemia depending on the initial level.[71] Both low and high protein intake conditions inhibit magnesium absorption, as does the amount of phosphate, phytate, and fat in the gut. Unabsorbed dietary magnesium is excreted in feces; absorbed magnesium is excreted in urine and sweat.[72]

Detection in serum and plasma

Magnesium status may be assessed by measuring serum and erythrocyte magnesium concentrations coupled with urinary and fecal magnesium content, but intravenous magnesium loading tests are more accurate and practical.[73] A retention of 20% or more of the injected amount indicates deficiency.[74] As of 2004, no biomarker has been established for magnesium.[75]

Magnesium concentrations in plasma or serum may be monitored for efficacy and safety in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims, or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdose. The newborn children of mothers who received parenteral magnesium sulfate during labor may exhibit toxicity with normal serum magnesium levels.[76]

Deficiency

Low plasma magnesium (hypomagnesemia) is common: it is found in 2.5–15% of the general population.[77] From 2005 to 2006, 48 percent of the United States population consumed less magnesium than recommended in the Dietary Reference Intake.[78] Other causes are increased renal or gastrointestinal loss, an increased intracellular shift, and proton-pump inhibitor antacid therapy. Most are asymptomatic, but symptoms referable to neuromuscular, cardiovascular, and metabolic dysfunction may occur.[77] Alcoholism is often associated with magnesium deficiency. Chronically low serum magnesium levels are associated with metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus type 2, fasciculation, and hypertension.[79]

Therapy

- Intravenous magnesium is recommended by the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death for patients with ventricular arrhythmia associated with torsades de pointes who present with long QT syndrome; and for the treatment of patients with digoxin induced arrhythmias.[80]

- Magnesium sulfate – intravenous – is used for the management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.[81][82]

- Hypomagnesemia, including that caused by alcoholism, is reversible by oral or parenteral magnesium administration depending on the degree of deficiency.[83]

- There is limited evidence that magnesium supplementation may play a role in the prevention and treatment of migraine.[84]

Sorted by type of magnesium salt, other therapeutic applications include:

- Magnesium sulfate, as the heptahydrate called Epsom salts, is used as bath salts, a laxative, and a highly soluble fertilizer.[85]

- Magnesium hydroxide, suspended in water, is used in milk of magnesia antacids and laxatives.

- Magnesium chloride, oxide, gluconate, malate, orotate, glycinate, ascorbate and citrate are all used as oral magnesium supplements.

- Magnesium borate, magnesium salicylate, and magnesium sulfate are used as antiseptics.

- Magnesium bromide is used as a mild sedative (this action is due to the bromide, not the magnesium).

- Magnesium stearate is a slightly flammable white powder with lubricating properties. In pharmaceutical technology, it is used in pharmacological manufacture to prevent tablets from sticking to the equipment while compressing the ingredients into tablet form.

- Magnesium carbonate powder is used by athletes such as gymnasts, weightlifters, and climbers to eliminate palm sweat, prevent sticking, and improve the grip on gymnastic apparatus, lifting bars, and climbing rocks.

Overdose

Overdose from dietary sources alone is unlikely because excess magnesium in the blood is promptly filtered by the kidneys,[77] and overdose is more likely in the presence of impaired renal function. In spite of this, megadose therapy has caused death in a young child,[86] and severe hypermagnesemia in a woman[87] and a young girl[88] who had healthy kidneys.

The most common symptoms of overdose are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; other symptoms include hypotension, confusion, slowed heart and respiratory rates, deficiencies of other minerals, coma, cardiac arrhythmia, and death from cardiac arrest.[71]

Function in plants

Plants require magnesium to synthesize chlorophyll, essential for photosynthesis. Magnesium in the center of the porphyrin ring in chlorophyll functions in a manner similar to the iron in the center of the porphyrin ring in heme. Magnesium deficiency in plants causes late-season yellowing between leaf veins, especially in older leaves, and can be corrected by either applying epsom salts (which is rapidly leached), or crushed dolomitic limestone, to the soil.

See also

- List of countries by magnesium production

- Magnesium oil

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Magnesium». CIAAW. 2011.

- ^ Rumble, p. 4.61

- ^ Mg(0) has been synthesized in a compound containing a Na2Mg22+ cluster coordinated to a bulky organic ligand; see Rösch, B.; Gentner, T. X.; Eyselein, J.; Langer, J.; Elsen, H.; Li, W.; Harder, S. (2021). «Strongly reducing magnesium(0) complexes». Nature. 592 (7856): 717–721. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..717R. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03401-w. PMID 33911274. S2CID 233447380

- ^ Bernath, P. F.; Black, J. H. & Brault, J. W. (1985). «The spectrum of magnesium hydride» (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 298: 375. Bibcode:1985ApJ…298..375B. doi:10.1086/163620.. See also Low valent magnesium compounds.

- ^ Rumble, p. 12.135

- ^ Rumble, p. 12.137

- ^ Rumble, p. 12.28

- ^ Rumble, p. 4.70

- ^ Gschneider, K. A. (1964). Physical Properties and Interrelationships of Metallic and Semimetallic Elements. Solid State Physics. Vol. 16. p. 308. doi:10.1016/S0081-1947(08)60518-4. ISBN 9780126077162.

- ^ a b c Rumble, p. 4.19

- ^ a b Railsback, L. Bruce. «Abundance and form of the most abundant elements in Earth’s continental crust» (PDF). Some Fundamentals of Mineralogy and Geochemistry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ Anthoni, J Floor (2006). «The chemical composition of seawater». seafriends.org.nz.

- ^ a b c d e «Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Magnesium». Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 11 February 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ «alkaline-earth metal — Physical and chemical behaviour | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Sandlöbes, S.; Friák, M.; Korte-Kerzel, S.; Pei, Z.; Neugebauer, J.; Raabe, D. (2017). «A rare-earth free magnesium alloy with improved intrinsic ductility». Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 10458. Bibcode:2017NatSR…710458S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10384-0. PMC 5585333. PMID 28874798.

- ^ Zeng, Zhuoran; Nie, Jian-Feng; Xu, Shi-Wei; h. j. Davies, Chris; Birbilis, Nick (2017). «Super-formable pure magnesium at room temperature». Nature Communications. 8 (1): 972. Bibcode:2017NatCo…8..972Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01330-9. PMC 5715137. PMID 29042555.

- ^ «Reactions of Group 2 Elements with Water». Chemistry LibreTexts. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Vol’nov, I.I., Tokareva, S.A., Belevskii, V.N. et al. «The formation of magnesium perperoxide Mg(O2)2 in the reaction of magnesium peroxide with ozone» _Russ Chem Bull_ **19**, 468–471 (1970). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00848959

- ^ a b Dreizin, Edward L.; Berman, Charles H. & Vicenzi, Edward P. (2000). «Condensed-phase modifications in magnesium particle combustion in air». Scripta Materialia. 122 (1–2): 30–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.488.2456. doi:10.1016/S0010-2180(00)00101-2.

- ^ DOE Handbook – Primer on Spontaneous Heating and Pyrophoricity. U.S. Department of Energy. December 1994. p. 20. DOE-HDBK-1081-94. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ B. Rösch, T. X. Gentner, J. Eyselein, J. Langer, H. Elsen & S. Harder, «Strongly reducing magnesium(0) complexes», _Nature_ **592**, 717–721 (2021). [doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03401-w](https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03401-w)

- ^ Hannavy, John (2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-1135873271.

- ^ Scientific American: Supplement. Vol. 48. Munn and Company. 1899. p. 20035.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 1974. p. 20.

- ^ Altman, Rick (2007). Silent Film Sound. Columbia University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0231116633.

- ^ Lindsay, David (2005). Madness in the Making: The Triumphant Rise & Untimely Fall of America’s Show Inventors. iUniverse. p. 210. ISBN 978-0595347667.

- ^ McCormick, John; Pratasik, Bennie (2005). Popular Puppet Theatre in Europe, 1800–1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0521616157.

- ^ Makar, G. L.; Kruger, J. (1993). «Corrosion of magnesium». International Materials Reviews. 38 (3): 138–153. Bibcode:1993IMRv…38..138M. doi:10.1179/imr.1993.38.3.138.

- ^ a b c d e Dodson, Brian (29 August 2013). «Stainless magnesium breakthrough bodes well for manufacturing industries». Gizmag.com. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Birbilis, N.; Williams, G.; Gusieva, K.; Samaniego, A.; Gibson, M. A.; McMurray, H. N. (2013). «Poisoning the corrosion of magnesium». Electrochemistry Communications. 34: 295–298. doi:10.1016/j.elecom.2013.07.021.

- ^ Czerwinski, Frank. «Controlling the ignition and flammability of magnesium for aerospace applications.» Corrosion Science 86 (2014): 1-16.

- ^ Bray, E. Lee (February 2019) Magnesium Metal. Mineral Commodity Summaries, U.S. Geological Survey

- ^ Vardi, Nathan. «Man With Many Enemies». Forbes. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ What to do about the magnesium shortage, Supply Management, published 17 February 2022, accessed 12 June 2022

- ^ «Magnesium Overview». China magnesium Corporation. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ Pal, Uday B.; Powell, Adam C. (2007). «The Use of Solid-Oxide-Membrane Technology for Electrometallurgy». JOM. 59 (5): 44–49. Bibcode:2007JOM….59e..44P. doi:10.1007/s11837-007-0064-x. S2CID 97971162.

- ^ Derezinski, Steve (12 May 2011). «Solid Oxide Membrane (SOM) Electrolysis of Magnesium: Scale-Up Research and Engineering for Light-Weight Vehicles» (PDF). MOxST. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ «Magnesium: historical information». webelements.com. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ languagehat (28 May 2005). «MAGNET». languagehat.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Ainsworth, Steve (1 June 2013). «Epsom’s deep bath». Nurse Prescribing. 11 (6): 269. doi:10.12968/npre.2013.11.6.269.

- ^ a b Davy, H. (1808). «Electro-chemical researches on the decomposition of the earths; with observations on the metals obtained from the alkaline earths, and on the amalgam procured from ammonia». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 98: 333–370. Bibcode:1808RSPT…98..333D. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0023. JSTOR 107302.

- ^ Segal, David (2017). Materials for the 21st Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192526090.

- ^ a b Baker, Hugh D. R.; Avedesian, Michael (1999). Magnesium and magnesium alloys. Materials Park, OH: Materials Information Society. p. 4. ISBN 978-0871706577.

- ^ Ketil Amundsen; Terje Kr. Aune; Per Bakke; Hans R. Eklund; Johanna Ö. Haagensen; Carlos Nicolas; et al. (2002). «Magnesium». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_559. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Chin, Matthew (23 December 2015). «UCLA researchers create super-strong magnesium metal». ucla.edu.

- ^ Aghion, E.; Bronfin, B. (2000). «Magnesium Alloys Development towards the 21st Century». Materials Science Forum. 350–351: 19–30. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.350-351.19. S2CID 138429749.

- ^ Shu, Dong Wei, and Iram Raza Ahmad. «Magnesium Alloys: An Alternative for Aluminium in Structural Applications.» In Advanced Materials Research, vol. 168, pp. 1631-1635. Trans Tech Publications Ltd, 2011.

- ^ Magnesium alloy as a lighter alternative to aluminum alloy, Phys.org, November 29th 2017

- ^ Dreizin, Edward L.; Berman, Charles H.; Vicenzi, Edward P. (2000). «Condensed-phase modifications in magnesium particle combustion in air». Scripta Materialia. 122 (1–2): 30–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.488.2456. doi:10.1016/S0010-2180(00)00101-2.

- ^ Dorr, Robert F. (15 September 2012). Mission to Tokyo: The American Airmen Who Took the War to the Heart of Japan. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1610586634.

- ^ AAHS Journal. Vol. 44–45. American Aviation Historical Society. 1999.

- ^ «1950: The metal is magnesium, the car is the Beetle». www.hydro.com. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Luo, Alan A. & Powell, Bob R. (2001). Tensile and Compressive Creep of Magnesium-Aluminum-Calcium Based Alloys (PDF) (Report). Materials & Processes Laboratory, General Motors Research & Development Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ Dignan, Larry (2 January 2020). «Blue magnesium alloy laptops: Premium price, plastic feel, but lightweight». ZDNet, A RED VENTURES COMPANY.

- ^ «Magnesium (Powder)». International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). IPCS INCHEM. April 2000. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ «9N510 (ML-5) Submunition». Collective Awareness to UXO. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Magnesium. Sigma Aldrich

- ^ «Science Safety: Chapter 8». Government of Manitoba. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ «Chemistry : Periodic Table : magnesium : chemical reaction data». webelements.com. Retrieved 26 June 2006.

- ^ «The Reaction Between Magnesium and CO2«. Purdue University. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Cote, Arthur E. (2003). Operation of Fire Protection Systems. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 667. ISBN 978-0877655848.

- ^ Linsley, Trevor (2011). «Properties of conductors and insulators». Basic Electrical Installation Work. p. 362. ISBN 978-0080966281.

- ^

Romani, Andrea, M.P. (2013). «Chapter 3. Magnesium in Health and Disease». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 49–79. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_3. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470089. - ^ «Magnesium in diet». MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Gropper, Sareen S.; Smith, Jack L.; Carr, Timothy P. (5 October 2016). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-337-51421-7.

- ^ «Vitamins and minerals – Others – NHS Choices». Nhs.uk. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ «Magnesium», pp. 190–249 in «Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride». National Academy Press. 1997.

- ^ Firoz M; Graber M (2001). «Bioavailability of US commercial magnesium preparations». Magnes Res. 14 (4): 257–262. PMID 11794633.

- ^ Lindberg JS; Zobitz MM; Poindexter JR; Pak CY (1990). «Magnesium bioavailability from magnesium citrate and magnesium oxide». J Am Coll Nutr. 9 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1080/07315724.1990.10720349. PMID 2407766.

- ^ Saris NE, Mervaala E, Karppanen H, Khawaja JA, Lewenstam A (April 2000). «Magnesium. An update on physiological, clinical and analytical aspects». Clin Chim Acta. 294 (1–2): 1–26. doi:10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00258-2. PMID 10727669.

- ^ a b c «Magnesium». Umm.edu. University of Maryland Medical Center. 7 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Wester PO (1987). «Magnesium». Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 45 (5 Suppl): 1305–1312. doi:10.1093/ajcn/45.5.1305. PMID 3578120.

- ^ Arnaud MJ (2008). «Update on the assessment of magnesium status». Br. J. Nutr. 99 Suppl 3: S24–S36. doi:10.1017/S000711450800682X. PMID 18598586.

- ^ Rob PM; Dick K; Bley N; Seyfert T; Brinckmann C; Höllriegel V; et al. (1999). «Can one really measure magnesium deficiency using the short-term magnesium loading test?». J. Intern. Med. 246 (4): 373–378. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00580.x. PMID 10583708. S2CID 6734801.

- ^ Franz KB (2004). «A functional biological marker is needed for diagnosing magnesium deficiency». J Am Coll Nutr. 23 (6): 738S–741S. doi:10.1080/07315724.2004.10719418. PMID 15637224. S2CID 37427458.

- ^ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Biomedical Publications. pp. 875–877. ISBN 978-0962652370.

- ^ a b c Ayuk J.; Gittoes N.J. (March 2014). «Contemporary view of the clinical relevance of magnesium homeostasis». Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 51 (2): 179–188. doi:10.1177/0004563213517628. PMID 24402002. S2CID 21441840.

- ^ Rosanoff, Andrea; Weaver, Connie M; Rude, Robert K (March 2012). «Suboptimal magnesium status in the United States: are the health consequences underestimated?» (PDF). Nutrition Reviews. 70 (3): 153–164. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00465.x. PMID 22364157.

- ^ Geiger H; Wanner C (2012). «Magnesium in disease». Clin Kidney J. 5 (Suppl 1): i25–i38. doi:10.1093/ndtplus/sfr165. PMC 4455821. PMID 26069818.

- ^ Zipes DP; Camm AJ; Borggrefe M; et al. (2012). «ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society». Circulation. 114 (10): e385–e484. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178233. PMID 16935995.

- ^ James MF (2010). «Magnesium in obstetrics». Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 24 (3): 327–337. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.11.004. PMID 20005782.

- ^ Euser, A. G.; Cipolla, M. J. (2009). «Magnesium Sulfate for the Treatment of Eclampsia: A Brief Review». Stroke. 40 (4): 1169–1175. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.527788. PMC 2663594. PMID 19211496.

- ^ Giannini, A. J. (1997). Drugs of Abuse (Second ed.). Los Angeles: Physicians Management Information Co. ISBN 978-0874894998.

- ^ Teigen L, Boes CJ (2014). «An evidence-based review of oral magnesium supplementation in the preventive treatment of migraine». Cephalalgia (Review). 35 (10): 912–922. doi:10.1177/0333102414564891. PMID 25533715. S2CID 25398410.

There is a strong body of evidence demonstrating a relationship between magnesium status and migraine. Magnesium likely plays a role in migraine development at a biochemical level, but the role of oral magnesium supplementation in migraine prophylaxis and treatment remains to be fully elucidated. The strength of evidence supporting oral magnesium supplementation is limited at this time.

- ^ Gowariker, Vasant; Krishnamurthy, V. P.; Gowariker, Sudha; Dhanorkar, Manik; Paranjape, Kalyani (8 April 2009). The Fertilizer Encyclopedia. p. 224. ISBN 978-0470431764.

- ^ McGuire, John; Kulkarni, Mona Shah; Baden, Harris (February 2000). «Fatal Hypermagnesemia in a Child Treated With Megavitamin/Megamineral Therapy». Pediatrics. 105 (2): E18. doi:10.1542/peds.105.2.e18. PMID 10654978. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Kontani M; Hara A; Ohta S; Ikeda T (2005). «Hypermagnesemia induced by massive cathartic ingestion in an elderly woman without pre-existing renal dysfunction». Intern. Med. 44 (5): 448–452. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.44.448. PMID 15942092.

- ^ Kutsal, Ebru; Aydemir, Cumhur; Eldes, Nilufer; Demirel, Fatma; Polat, Recep; Taspınar, Ozan; Kulah, Eyup (February 2000). «Severe Hypermagnesemia as a Result of Excessive Cathartic Ingestion in a Child Without Renal Failure». Pediatrics. 205 (2): 570–572. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31812eef1c. PMID 17726419.

Cited sources

- Rumble, John R., ed. (2018). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (99th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-1385-6163-2.

External links

- Magnesium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Chemistry in its element podcast (MP3) from the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Chemistry World: Magnesium

- «Magnesium – a versatile and often overlooked element: new perspectives with a focus on chronic kidney disease». Clin Kidney J. 5 (Suppl 1). February 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013.

Not to be confused with manganese (Mn).

«mg» redirects here. For the milligram (mg) or megagram (Mg), see kilogram § SI multiples. For other uses, see MG.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnesium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (mag-NEE-zee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | shiny grey solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Mg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnesium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 2 (alkaline earth metals) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 923 K (650 °C, 1202 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1363 K (1091 °C, 1994 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 1.738 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 1.584 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 8.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 128 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.869[2] J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 0,[3] +1,[4] +2 (a strongly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 160 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 141±7 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 173 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of magnesium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4940 m/s (at r.t.) (annealed) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 24.8[5] µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 156[6] W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 43.9[7] nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +13.1×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 45 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 17 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 35.4[9] GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.290 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 1–2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 44–260 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-95-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Magnesia, Greece[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Joseph Black (1755[10]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Humphry Davy (1808[10]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of magnesium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic table) it occurs naturally only in combination with other elements and it almost always has an oxidation state of +2. It reacts readily with air to form a thin passivation coating of magnesium oxide that inhibits further corrosion of the metal. The free metal burns with a brilliant-white light. The metal is obtained mainly by electrolysis of magnesium salts obtained from brine. It is less dense than aluminium and is used primarily as a component in strong and lightweight alloys that contain aluminium.

In the cosmos, magnesium is produced in large, aging stars by the sequential addition of three helium nuclei to a carbon nucleus. When such stars explode as supernovas, much of the magnesium is expelled into the interstellar medium where it may recycle into new star systems. Magnesium is the eighth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust[11] and the fourth most common element in the Earth (after iron, oxygen and silicon), making up 13% of the planet’s mass and a large fraction of the planet’s mantle. It is the third most abundant element dissolved in seawater, after sodium and chlorine.[12]

This element is the eleventh most abundant element by mass in the human body and is essential to all cells and some 300 enzymes.[13] Magnesium ions interact with polyphosphate compounds such as ATP, DNA, and RNA. Hundreds of enzymes require magnesium ions to function. Magnesium compounds are used medicinally as common laxatives and antacids (such as milk of magnesia), and to stabilize abnormal nerve excitation or blood vessel spasm in such conditions as eclampsia.[13]

Characteristics

Physical properties

Elemental magnesium is a gray-white lightweight metal, two-thirds the density of aluminium. Magnesium has the lowest melting (923 K (650 °C)) and the lowest boiling point 1,363 K (1,090 °C) of all the alkaline earth metals.[14]

Pure polycrystalline magnesium is brittle and easily fractures along shear bands. It becomes much more malleable when alloyed with small amount of other metals, such as 1% aluminium.[15] The malleability of polycrystalline magnesium can also be significantly improved by reducing its grain size to ca. 1 micron or less.[16]

When finely powdered, magnesium can react with water to produce hydrogen gas:

- Mg(s) + 2H2O(g) → Mg(OH)2(aq) + H2(g) + 1203.6 kJ

However, this reaction is much less dramatic than the reactions of the alkali metals with water, because the magnesium hydroxide tends to build up on the surface of the pure magnesium metal and prevent the reaction from occurring.[17]

Chemical properties

General chemistry

It tarnishes slightly when exposed to air, although, unlike the heavier alkaline earth metals, an oxygen-free environment is unnecessary for storage because magnesium is protected by a thin layer of oxide that is fairly impermeable and difficult to remove.

Direct reaction of magnesium with air or oxygen at ambient pressure forms only the «normal» oxide MgO. However, this oxide may be combined with hydrogen peroxide to form Magnesium peroxide, MgO2, and at low temperature the peroxide may be further reacted with ozone to form magnesium superoxide Mg(O2)2.[18]

Magnesium reacts with water at room temperature, though it reacts much more slowly than calcium, a similar group 2 metal. When submerged in water, hydrogen bubbles form slowly on the surface of the metal – though, if powdered, it reacts much more rapidly. The reaction occurs faster with higher temperatures (see safety precautions). Magnesium’s reversible reaction with water can be harnessed to store energy and run a magnesium-based engine. Magnesium also reacts exothermically with most acids such as hydrochloric acid (HCl), producing the metal chloride and hydrogen gas, similar to the HCl reaction with aluminium, zinc, and many other metals.

Flammability

Magnesium is highly flammable, especially when powdered or shaved into thin strips, though it is difficult to ignite in mass or bulk. Flame temperatures of magnesium and magnesium alloys can reach 3,100 °C (5,610 °F),[19] although flame height above the burning metal is usually less than 300 mm (12 in).[20] Once ignited, such fires are difficult to extinguish, because combustion continues in nitrogen (forming magnesium nitride), carbon dioxide (forming magnesium oxide and carbon), and water (forming magnesium oxide and hydrogen, which also combusts due to heat in the presence of additional oxygen). This property was used in incendiary weapons during the firebombing of cities in World War II, where the only practical civil defense was to smother a burning flare under dry sand to exclude atmosphere from the combustion.

Magnesium may also be used as an igniter for thermite, a mixture of aluminium and iron oxide powder that ignites only at a very high temperature.

Organic chemistry

Organomagnesium compounds are widespread in organic chemistry. They are commonly found as Grignard reagents. Magnesium can react with haloalkanes to give Grignard reagents. Examples of Grignard reagents are phenylmagnesium bromide and ethylmagnesium bromide. The Grignard reagents function as a common nucleophile, attacking the electrophilic group such as the carbon atom that is present within the polar bond of a carbonyl group.

A prominent organomagnesium reagent beyond Grignard reagents is magnesium anthracene with magnesium forming a 1,4-bridge over the central ring. It is used as a source of highly active magnesium. The related butadiene-magnesium adduct serves as a source for the butadiene dianion.

Magnesium in organic chemistry also appears as low valent magnesium compounds, primarily with the magnesium forming diatomic ions in the +1 oxidation state but more recently also with zero oxidation state or a mixture of +1 and zero states.[21] Such compounds find synthetic application as reducing agents and sources of nucleophilic metal atoms.

Source of light

When burning in air, magnesium produces a brilliant-white light that includes strong ultraviolet wavelengths. Magnesium powder (flash powder) was used for subject illumination in the early days of photography.[22][23] Later, magnesium filament was used in electrically ignited single-use photography flashbulbs. Magnesium powder is used in fireworks and marine flares where a brilliant white light is required. It was also used for various theatrical effects,[24] such as lightning,[25] pistol flashes,[26] and supernatural appearances.[27]

Detection in solution

The presence of magnesium ions can be detected by the addition of ammonium chloride, ammonium hydroxide and monosodium phosphate to an aqueous or dilute HCl solution of the salt. The formation of a white precipitate indicates the presence of magnesium ions.

Azo violet dye can also be used which turns deep blue in the presence of an alkaline solution of magnesium salt. The color is due to the adsorption of azo violet by Mg(OH)2.

Occurrence

Magnesium is the eighth-most-abundant element in the Earth’s crust by mass and tied in seventh place with iron in molarity.[11] It is found in large deposits of magnesite, dolomite, and other minerals, and in mineral waters, where magnesium ion is soluble.

Although magnesium is found in more than 60 minerals, only dolomite, magnesite, brucite, carnallite, talc, and olivine are of commercial importance.

The Mg2+

cation is the second-most-abundant cation in seawater (about 1⁄8 the mass of sodium ions in a given sample), which makes seawater and sea salt attractive commercial sources for Mg. To extract the magnesium, calcium hydroxide is added to seawater to form magnesium hydroxide precipitate.

- MgCl

2 + Ca(OH)

2 → Mg(OH)

2 + CaCl

2

Magnesium hydroxide (brucite) is insoluble in water and can be filtered out and reacted with hydrochloric acid to produced concentrated magnesium chloride.

- Mg(OH)

2 + 2 HCl → MgCl

2 + 2 H

2O

From magnesium chloride, electrolysis produces magnesium.

Forms

Alloys

Magnesium is brittle, and fractures along shear bands when its thickness is reduced by only 10% by cold rolling (top). However, after alloying Mg with 1% Al and 0.1% Ca, its thickness could be reduced by 54% using the same process (bottom).

As of 2013, magnesium alloys consumption was less than one million tonnes per year, compared with 50 million tonnes of aluminum alloys. Their use has been historically limited by the tendency of Mg alloys to corrode,[28] creep at high temperatures, and combust.[29]

Corrosion

The presence of iron, nickel, copper, and cobalt strongly activates corrosion. In more than trace amounts, these metals precipitate as intermetallic compounds, and the precipitate locales function as active cathodic sites that reduce water, causing the loss of magnesium.[29] Controlling the quantity of these metals improves corrosion resistance. Sufficient manganese overcomes the corrosive effects of iron. This requires precise control over composition, increasing costs.[29] Adding a cathodic poison captures atomic hydrogen within the structure of a metal. This prevents the formation of free hydrogen gas, an essential factor of corrosive chemical processes. The addition of about one in three hundred parts arsenic reduces its corrosion rate in a salt solution by a factor of nearly ten.[29][30]

High-temperature creep and flammability

Research showed that magnesium’s tendency to creep at high temperatures is eliminated by the addition of scandium and gadolinium. Flammability is greatly reduced by a small amount of calcium in the alloy.[29] By using rare-earth elements, it may be possible to manufacture magnesium alloys with an ignition temperature higher than magnesium’s liquidus and in some cases potentially pushing it close to magnesium’s boiling point.[31]

Compounds

Magnesium forms a variety of compounds important to industry and biology, including magnesium carbonate, magnesium chloride, magnesium citrate, magnesium hydroxide (milk of magnesia), magnesium oxide, magnesium sulfate, and magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (Epsom salts).

Isotopes

Magnesium has three stable isotopes: 24

Mg, 25

Mg and 26

Mg. All are present in significant amounts in nature (see table of isotopes above). About 79% of Mg is 24

Mg. The isotope 28

Mg is radioactive and in the 1950s to 1970s was produced by several nuclear power plants for use in scientific experiments. This isotope has a relatively short half-life (21 hours) and its use was limited by shipping times.

The nuclide 26

Mg has found application in isotopic geology, similar to that of aluminium. 26

Mg is a radiogenic daughter product of 26

Al, which has a half-life of 717,000 years. Excessive quantities of stable 26

Mg have been observed in the Ca-Al-rich inclusions of some carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. This anomalous abundance is attributed to the decay of its parent 26

Al in the inclusions, and researchers conclude that such meteorites were formed in the solar nebula before the 26

Al had decayed. These are among the oldest objects in the Solar System and contain preserved information about its early history.

It is conventional to plot 26

Mg/24

Mg against an Al/Mg ratio. In an isochron dating plot, the Al/Mg ratio plotted is27

Al/24

Mg. The slope of the isochron has no age significance, but indicates the initial 26

Al/27

Al ratio in the sample at the time when the systems were separated from a common reservoir.

Production

Magnesium sheets and ingots

World production was approximately 1,100 kt in 2017, with the bulk being produced in China (930 kt) and Russia (60 kt).[32] The United States was in the 20th century the major world supplier of this metal, supplying 45% of world production even as recently as 1995. Since the Chinese mastery of the Pidgeon process the US market share is at 7%, with a single US producer left: US Magnesium, a Renco Group company in Utah born from now-defunct Magcorp.[33]

In September 2021, China took steps to reduce production of magnesium as a result of a government initiative to reduce energy availability for manufacturing industries, leading to a significant price increase.[34]

- Pidgeon process