Слова русского языка,

поиск и разбор слов онлайн

Правильно слово пишется: маммогра́фия

Ударение падает на 3-й слог с буквой а.

Всего в слове 11 букв, 5 гласных, 6 согласных, 5 слогов.

Гласные: а, о, а, и, я;

Согласные: м, м, м, г, р, ф.

Номера букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «маммография» в прямом и обратном порядке:

- 11

м

1 - 10

а

2 - 9

м

3 - 8

м

4 - 7

о

5 - 6

г

6 - 5

р

7 - 4

а

8 - 3

ф

9 - 2

и

10 - 1

я

11

- Медицинская энциклопедия

I

Маммография (анат. mamma молочная железа + греч. graphō писать, изображать; синоним мастография)

рентгенография молочной железы. Выполняется при наличии в ней уплотнений неясной природы, для дифференцирования опухолей молочной железы и новообразований, исходящих из грудной стенки, уточнения формы мастопатии (Мастопатия) и наблюдения за ее течением, при раке молочной железы для установления стадии процесса. В связи с тем, что М. позволяет выявить скрыто протекающие патологические процессы в молочной железе, она имеет большое значение в профилактических обследованиях женщин старше 40 лет, особенно из групп риска. Показана также при гинекомастии.

Маммографию выполняют на 3—8-й день после окончания менструации. Женщинам, находящимся в менопаузе, М. проводят в любое время.

Исследование осуществляют на специальных рентгеновских установках — маммографах. В связи с тем, что молочная железа состоит из тканей, мало различающихся по способности поглощать рентгеновское излучение, М. выполняют при низком напряжении генерируемого излучения, для чего используют трубки с молибденовым анодом и выходным окном из бериллия. В ряде случаев М. проводят с помощью электрорентгенографа, однако при этом создается большая, чем при использовании маммографа, лучевая нагрузка. Снимки производят в прямой и боковой (или косой) проекциях. Для компрессии молочной железы применяют длинный тубус.

Дополнительно к обзорным маммограммам иногда бывают необходимы прицельные снимки отдельных участков молочной железы. В таких случаях исследуемый участок маркируют, помещая над ним (на кожу) свинцовые метки и применяют узкий тубус. Точное место пункции определяют с помощью специальной решетки с отверстиями, расположенными на равном расстоянии друг от друга. Женщинам, у которых имеются выделения из сосков, М. проводят после введения рентгеноконтрастных веществ в млечные протоки (дуктография).

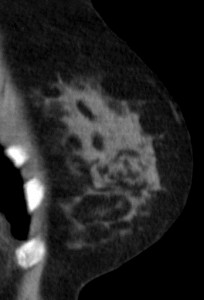

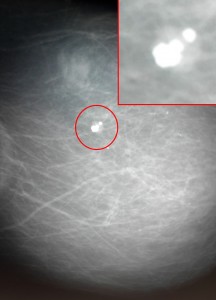

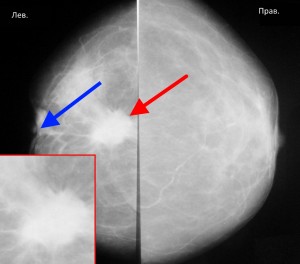

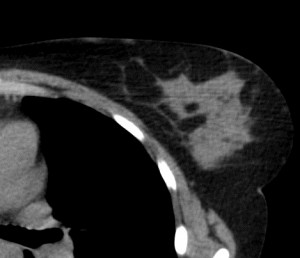

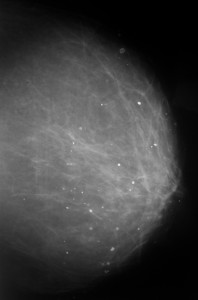

На маммограммах четко дифференцируются все структуры молочной железы: ее железистая и соединительная ткань, крупные сосуды и протоки. Обнаружив на маммограммах патологические очаги, устанавливают их число, расположение, величину, форму, очертания, структуру (рис.). При анализе маммограмм учитывают анамнестические и клинические данные.

В связи с малой лучевой нагрузкой при изготовлении двух маммограмм (при современной технологии 0,001—0,008 Гр) опасность индуцирования рака практически исключается.

Библиогр.: Аннотированный указатель отечественной и зарубежной литературы по маммографии за 1976—1981 гг., сост. Н.И. Рожкова и др., М., 1982: Линденбратен Л.Д. и Зальцман И.Н. Комплексная рентгенодиагностика заболеваний молочных желез, ч. 2—3, М., 1976; Рожкова Н.И. Диагностическое значение контрастного исследования протоков молочной железы (дуктографии), Вестн. рентгенол. и радиол., № 1, с. 65, 1979, библиогр.; Розин Д.Л. Опухоли молочных протоков, Баку, 1989.

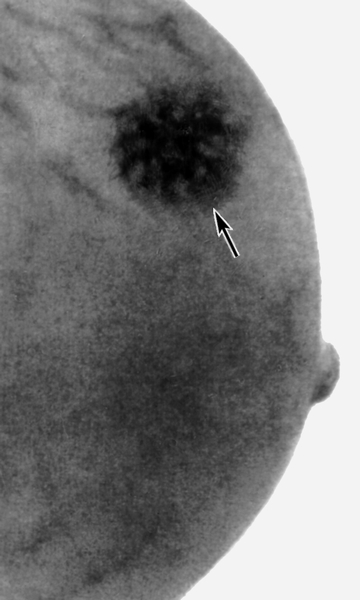

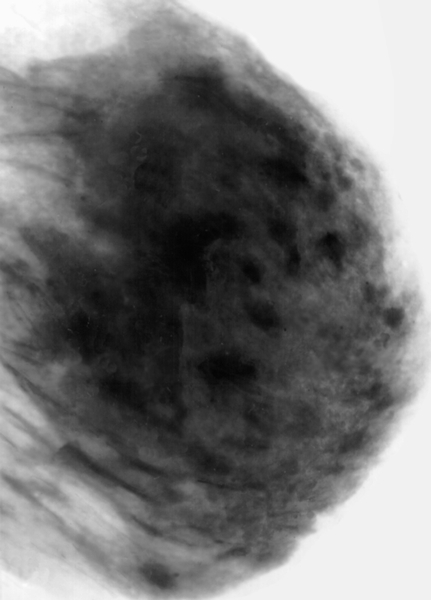

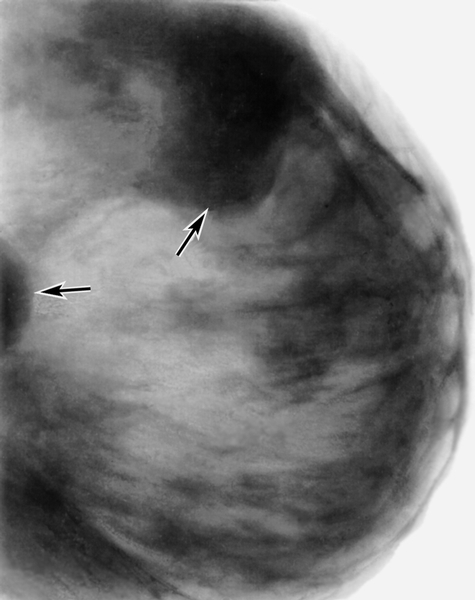

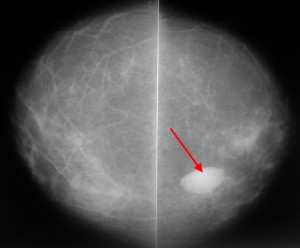

Рис. в). Маммограмма при раке молочной железы — определяется тень опухоли неправильной формы с неровными очертаниями (указана стрелкой).

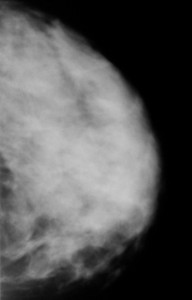

Рис. а). Маммограмма в норме.

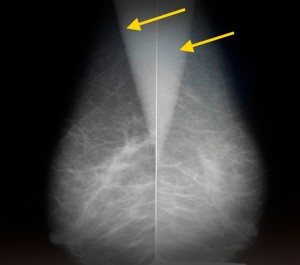

Рис. б). Маммограмма при мастопатии — определяются тени крупных кистовидных образований (указаны стрелками).

II

Маммография (mammographia; Маммо- +греч. grapho писать, изображать; син. мастография)

рентгенография молочной железы без применения контрастных веществ.

Источник:

Медицинская энциклопедия

на Gufo.me

Значения в других словарях

- маммография —

орф. маммография, -и

Орфографический словарь Лопатина - маммография —

МАММОГРАФИЯ -и; ж. [от греч. mamma — женская грудь и graphō — пишу] Метод диагностики с помощью маммографа. Специалист по маммографии.

Толковый словарь Кузнецова - МАММОГРАФИЯ —

МАММОГРАФИЯ (от лат. mamma — женская грудь и…графия) — рентгенологическое исследование молочных желез (обычно без применения контрастных веществ).

Большой энциклопедический словарь - МАММОГРАФИЯ —

МАММОГРАФИЯ, рентгеновская процедура для просвечивания тканей груди для обнаружения РАКА. Позволяет обнаружить злокачественную опухоль на ранних стадиях развития.

Научно-технический словарь

Как написать слово «маммография» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «маммография»?

маммогра́фия

Правильное написание — маммография, ударение падает на букву: а, безударными гласными являются: а, о, и, я.

Выделим согласные буквы — маммография, к согласным относятся: м, г, р, ф, звонкие согласные: м, г, р, глухие согласные: ф.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 11,

- слогов — 5,

- гласных — 5,

- согласных — 6.

Формы слова: маммогра́фия, -и.

Маммогра́фия — раздел медицинской диагностики, занимающийся неинвазивным исследованием молочной железы, преимущественно женской.

Все значения слова «маммография»

-

Хуже того, если мы возьмём в расчёт 10 тыс. женщин старше 50 лет, которые каждый год в течение 10 лет делали маммографию, то только пяти из них (0,05 %) удастся избежать смерти от рака молочной железы, в то время как 6 тыс. (60 %) получат хотя бы один ложноположительный результат.

-

Кабинет маммографии, расположенный неподалёку от приёмного покоя, оказался свободен, и я спросила сестричку – к счастью, знакомую, – можно ли нам на несколько минут воспользоваться помещением для осмотра пострадавшей беременной женщины.

-

Если вы по натуре оптимист, то можете утешать себя тем, что это вдвое эффективнее маммографии (0,5 на 1 тыс.)!

- (все предложения)

- химиотерапия

- рентгенология

- туберкулин

- витаминотерапия

- томография

- (ещё синонимы…)

маммогра́фия

Правильное ударение в этом слове падает на 3-й слог. На букву а

Посмотреть все слова на букву М

Смотреть что такое МАММОГРАФИЯ в других словарях:

МАММОГРАФИЯ

IМаммографи́я (анат. mamma молочная железа + греч. graphō писать, изображать; синоним мастография)рентгенография молочной железы. Выполняется при налич… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

1) Орфографическая запись слова: маммография2) Ударение в слове: маммогр`афия3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): маммография4) Фонетическая тран… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

маммография

и, мн. нет, ж. (нем. Mammographie < лат. mamma (женская) грудь + греч. graphō пишу).мед. Диагностический метод рентгенологического исслед… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

Фарм Фара Фаг Ром Рог Рия Рифя Рифма Риф Рио Римма Рим Рига Риа Рая Рафия Раф Рао Рами Рам Раия Рага Ория Орига Оргия Орг Омар Морф Морг Мор Момма Моир Могар Миф Миро Мир Миома Миограф Мио Мимо Мим Мигом Миг Мга Мая Мафория Мафия Марфа Мария Марго Мара Маори Мао Маммография Маммограф Мама Маго Магма Магия Маг Маар Ирма Ирга Имя Имам Имаго Игра Иго Гром Гриф Гримм Грим Графия Граф Грамм Гофр Гори Гор Гифа Гиф Гиря Гаф Фига Фигаро Гамма Фима Фира Фирма Гамия Фома Фора Форма Гам Фра Афар Афагия Фрг Фри Фря Яга Арфа Армия Арифм Аир Агро Агора Агор Агар Агамия Агам Ага Яро Аграф Ярмо Аграфия Амия Амми Амфора Арам Арго Ария Арма… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

«…Маммография — профилактическое или диагностическое рентгенологическое исследование молочной железы у женщин…» Источник: «ЗАЩИТА НАСЕЛЕНИЯ ПРИ НА… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

Ударение в слове: маммогр`афияУдарение падает на букву: аБезударные гласные в слове: маммогр`афия

МАММОГРАФИЯ

МАММОГРАФИЯ, рентгеновская процедура для просвечивания тканей груди для обнаружения РАКА. Позволяет обнаружить злокачественную опухоль на ранних стадия… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

(mammography) рентгенография молочной железы или получение ее изображения с помощью инфракрасных лучей. Применяется для раннего обнаружения опухолей молочной железы. См. также Рентгенография, Термография…. смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

— рентгенологическое исследование молочных желез. Применяется в диагностике рака молочной железы в совокупности с другими исследованиями.

Источник: «Медицинская Популярная Энциклопедия»… смотреть

МАММОГРАФИЯ

МАММОГРАФИЯ (от лат . mamma — женская грудь и …графия), рентгенологическое исследование молочных желез (обычно без применения контрастных веществ).

МАММОГРАФИЯ

МАММОГРАФИЯ (от лат. mamma — женская грудь и …графия) — рентгенологическое исследование молочных желез (обычно без применения контрастных веществ).

МАММОГРАФИЯ

(от лат. mamma — женская грудь и …графия), рентгенологич. исследование молочных желез (обычно без применения контрастных в-в).

МАММОГРАФИЯ

(mammographia; маммо- +греч. grapho писать, изображать; сип. мастография) рентгенография молочной железы без применения контрастных веществ.

МАММОГРАФИЯ

— (от лат. mamma — женская грудь и …графия) -рентгенологическое исследование молочных желез (обычно без примененияконтрастных веществ).

МАММОГРАФИЯ

ж. рентг. mammography, breast radiography— двусторонняя маммография

МАММОГРАФИЯ

Начальная форма — Маммография, единственное число, женский род, именительный падеж, неодушевленное

МАММОГРАФИЯ

f

Mammographie f, röntgenologische Brustdrüsendarstellung f

МАММОГРАФИЯ

ж. мед.

mammografia

Итальяно-русский словарь.2003.

МАММОГРАФИЯ (MAMMOGRAPHY)

рентгенография молочной железы или получение ее изображения с помощью инфракрасных лучей. Применяется для раннего обнаружения опухолей молочной железы. См. также Рентгенография, Термография.

Источник: «Медицинский словарь»… смотреть

| Mammography | |

|---|---|

Mammography |

|

| Other names | Mastography |

| ICD-10-PCS | BH0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 87.37 |

| MeSH | D008327 |

| OPS-301 code | 3–10 |

| MedlinePlus | 003380 |

|

[edit on Wikidata] |

Mammography (also called mastography) is the process of using low-energy X-rays (usually around 30 kVp) to examine the human breast for diagnosis and screening. The goal of mammography is the early detection of breast cancer, typically through detection of characteristic masses or microcalcifications.

As with all X-rays, mammograms use doses of ionizing radiation to create images. These images are then analyzed for abnormal findings. It is usual to employ lower-energy X-rays, typically Mo (K-shell X-ray energies of 17.5 and 19.6 keV) and Rh (20.2 and 22.7 keV) than those used for radiography of bones. Mammography may be 2D or 3D (tomosynthesis), depending on the available equipment and/or purpose of the examination. Ultrasound, ductography, positron emission mammography (PEM), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are adjuncts to mammography. Ultrasound is typically used for further evaluation of masses found on mammography or palpable masses that may or may not be seen on mammograms. Ductograms are still used in some institutions for evaluation of bloody nipple discharge when the mammogram is non-diagnostic. MRI can be useful for the screening of high risk patients, for further evaluation of questionable findings or symptoms, as well as for pre-surgical evaluation of patients with known breast cancer, in order to detect additional lesions that might change the surgical approach (for example, from breast-conserving lumpectomy to mastectomy).

For the average woman, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends (2016) mammography every two years between the ages of 50 and 74, concluding that «the benefit of screening mammography outweighs the harms by at least a moderate amount from age 50 to 74 years and is greatest for women in their 60s».[1] The American College of Radiology and American Cancer Society recommend yearly screening mammography starting at age 40.[2] The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (2012) and the European Cancer Observatory (2011) recommend mammography every 2 to 3 years between ages 50 and 69.[3][4] These task force reports point out that in addition to unnecessary surgery and anxiety, the risks of more frequent mammograms include a small but significant increase in breast cancer induced by radiation.[5][6] Additionally, mammograms should not be performed with increased frequency in patients undergoing breast surgery, including breast enlargement, mastopexy, and breast reduction.[7] The Cochrane Collaboration (2013) concluded after ten years that trials with adequate randomization did not find an effect of mammography screening on total cancer mortality, including breast cancer. The authors of this Cochrane review write: «If we assume that screening reduces breast cancer mortality by 15% and that overdiagnosis and over-treatment is at 30%, it means that for every 2,000 women invited for screening throughout 10 years, one will avoid dying of breast cancer and 10 healthy women, who would not have been diagnosed if there had not been screening, will be treated unnecessarily. Furthermore, more than 200 women will experience important psychological distress including anxiety and uncertainty for years because of false positive findings.» The authors conclude that the time has come to re-assess whether universal mammography screening should be recommended for any age group.[8] They state that universal screening may not be reasonable.[9] The Nordic Cochrane Collection updated research in 2012 and stated that advances in diagnosis and treatment make mammography screening less effective today, rendering it «no longer effective». They conclude that «it therefore no longer seems reasonable to attend» for breast cancer screening at any age, and warn of misleading information on the internet.[9] On the contrary, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine attributes the poor effectiveness of national mammography screening programs at reducing breast cancer mortality to radiation-induced cancers.[10]

Mammography has a false-negative (missed cancer) rate of at least ten percent. This is partly due to dense tissue obscuring the cancer and the appearance of cancer on mammograms having a large overlap with the appearance of normal tissue. A meta-analysis review of programs in countries with organized screening found a 52% over-diagnosis rate.[9]

History[edit]

As a medical procedure that induces ionizing radiation, the origin of mammography can be traced to the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895.

In 1913, German surgeon Albert Salomon performed a mammography study on 3,000 mastectomies, comparing X-rays of the breasts to the actual removed tissue, observing specifically microcalcifications.[11][12] By doing so, he was able to establish the difference as seen on an X-ray image between cancerous and non-cancerous tumors in the breast.[12] Salomon’s mammographs provided substantial information about the spread of tumors and their borders.[13]

In 1930, American physician and radiologist Stafford L. Warren published «A Roentgenologic Study of the Breast»,[14] a study where he produced stereoscopic X-rays images to track changes in breast tissue as a result of pregnancy and mastitis.[15][16] In 119 women who subsequently underwent surgery, he correctly found breast cancer in 54 out of 58 cases.[15]

As early as 1937, Jacob Gershon-Cohen developed a form a mammography for a diagnostic of breast cancer at earlier stages to improve survival rates.[17] In the early 1950s, Uruguayan radiologist Raul Leborgne developed the breast compression technique to produce better quality images, and described the differences between benign and malign microcalcifications.[18] In 1956, Gershon-Cohen conducted clinical trails on over 1,000 asymptomatic women at the Albert Einstein Medical Center on his screening technique,[17] and the same year, Robert Egan at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center combined a technique of low kVp with high mA and single emulsion films to devise a method of screening mammography. He published these results in 1959 in a paper, subsequently vulgarized in a 1964 book called Mammography.[19] The «Egan technique», as it became known, enabled physicians to detect calcification in breast tissue;[20] of the 245 breast cancers that were confirmed by biopsy among 1,000 patients, Egan and his colleagues at M.D. Anderson were able to identify 238 cases by using his method, 19 of which were in patients whose physical examinations had revealed no breast pathology.

Use of mammography as a screening technique spread clinically after a 1966 study demonstrating the impact of mammograms on mortality and treatment led by Philip Strax. This study, based in New York, was the first large-scale randomized controlled trial of mammography screening.[21][22]

Procedure[edit]

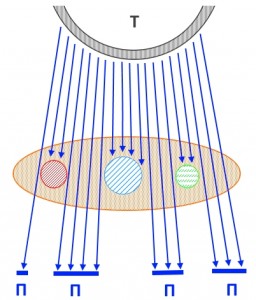

Illustration of a mammogram

A mobile mammography unit in New Zealand

During the procedure, the breast is compressed using a dedicated mammography unit. Parallel-plate compression evens out the thickness of breast tissue to increase image quality by reducing the thickness of tissue that X-rays must penetrate, decreasing the amount of scattered radiation (scatter degrades image quality), reducing the required radiation dose, and holding the breast still (preventing motion blur). In screening mammography, both head-to-foot (craniocaudal, CC) view and angled side-view (mediolateral oblique, MLO) images of the breast are taken. Diagnostic mammography may include these and other views, including geometrically magnified and spot-compressed views of the particular area of concern.[citation needed] Deodorant[citation needed], talcum powder[23] or lotion may show up on the X-ray as calcium spots, so women are discouraged from applying them on the day of their exam. There are two types of mammogram studies: screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms. Screening mammograms, consisting of four standard X-ray images, are performed yearly on patients who present with no symptoms. Diagnostic mammograms are reserved for patients with breast symptoms (such as palpable lumps, breast pain, skin changes, nipple changes, or nipple discharge), as follow-up for probably benign findings (coded BI-RADS 3), or for further evaluation of abnormal findings seen on their screening mammograms. Diagnostic mammograms may also performed on patients with personal and/or family histories of breast cancer. Patients with breast implants and other stable benign surgical histories generally do not require diagnostic mammograms.

Until some years ago, mammography was typically performed with screen-film cassettes. Today, mammography is undergoing transition to digital detectors, known as digital mammography or Full Field Digital Mammography (FFDM). The first FFDM system was approved by the FDA in the U.S. in 2000. This progress is occurring some years later than in general radiology. This is due to several factors:

- The higher spatial resolution demands of mammography

- Significantly increased expense of the equipment

- Concern by the FDA that digital mammography equipment demonstrate that it is at least as good as screen-film mammography at detecting breast cancers without increasing dose or the number of women recalled for further evaluation.

As of March 1, 2010, 62% of facilities in the United States and its territories have at least one FFDM unit.[24] (The FDA includes computed radiography units in this figure.[25])

Tomosynthesis, otherwise known as 3D mammography, was first introduced in clinical trials in 2008 and has been Medicare-approved in the United States since 2015. As of 2023, 3D mammography has become widely available in the US and has been shown to have improved sensitivity and specificity over 2D mammography.

Mammograms are either looked at by one (single reading) or two (double reading) trained professionals:[26] these film readers are generally radiologists, but may also be radiographers, radiotherapists, or breast clinicians (non-radiologist physicians specializing in breast disease).[27] Double reading, which is standard practice in the UK, but less common in the US, significantly improves the sensitivity and specificity of the procedure.[26] Clinical decision support systems may be used with digital mammography (or digitized images from analogue mammography[28]), but studies suggest these approaches do not significantly improve performance or provide only a small improvement.[26][29]

Digital[edit]

Digital mammography is a specialized form of mammography that uses digital receptors and computers instead of X-ray film to help examine breast tissue for breast cancer.[30] The electrical signals can be read on computer screens, permitting more manipulation of images to allow radiologists to view the results more clearly .[30][31] Digital mammography may be «spot view», for breast biopsy,[32] or «full field» (FFDM) for screening.[30]

Digital mammography is also utilized in stereotactic biopsy. Breast biopsy may also be performed using a different modality, such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

While radiologists[33] had hoped for more marked improvement, the effectiveness of digital mammography was found comparable to traditional X-ray methods in 2004, though there may be reduced radiation with the technique and it may lead to fewer retests.[30] Specifically, it performs no better than film for post-menopausal women, who represent more than three-quarters of women with breast cancer.[34] The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against digital mammography.[35]

Digital mammography is a NASA spin-off, utilizing technology developed for the Hubble Space Telescope.[36] As of 2007, about 8% of American screening centers used digital mammography. Around the globe, systems by Fujifilm Corporation are the most widely used.[citation needed] In the United States, GE’s digital imaging units typically cost US$300,000 to $500,000, far more than film-based imaging systems.[34] Costs may decline as GE begins to compete with the less expensive Fuji systems.[34]

3D mammography[edit]

Three-dimensional mammography, also known as digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), tomosynthesis, and 3D breast imaging, is a mammogram technology that creates a 3D image of the breast using X-rays. When used in addition to usual mammography, it results in more positive tests.[37] Cost effectiveness is unclear as of 2016.[38] Another concern is that it more than doubles the radiation exposure.[39]

Photon counting[edit]

Photon-counting mammography was introduced commercially in 2003 and was shown to reduce the X-ray dose to the patient by approximately 40% compared to conventional methods while maintaining image quality at an equal or higher level.[40] The technology was subsequently developed to enable spectral imaging with the possibility to further improve image quality, to distinguish between different tissue types,[41] and to measure breast density.[42][43]

Galactography[edit]

A galactography (or breast ductography) is a now infrequently used type of mammography used to visualize the milk ducts. Prior to the mammography itself, a radiopaque substance is injected into the duct system. This test is indicated when nipple discharge exists.

Scoring[edit]

Mammogram results are often expressed in terms of the BI-RADS Assessment Category, often called a «BI-RADS score». The categories range from 0 (Incomplete) to 6 (Known biopsy – proven malignancy). In the UK mammograms are scored on a scale from 1–5 (1 = normal, 2 = benign, 3 = indeterminate, 4 = suspicious of malignancy, 5 = malignant). Evidence suggests that accounting for genetic risk, factors improve breast cancer risk prediction.[44]

«Work-up» process[edit]

In the past several years, the «work-up» process has become highly formalized. It generally consists of screening mammography, diagnostic mammography, and biopsy when necessary, often performed via stereotactic core biopsy or ultrasound-guided core biopsy. After a screening mammogram, some women may have areas of concern which cannot be resolved with only the information available from the screening mammogram. They would then be called back for a «diagnostic mammogram». This phrase essentially means a problem-solving mammogram. During this session, the radiologist will be monitoring each of the additional films as they are taken by a radiographer. Depending on the nature of the finding, ultrasound may often be used as well.[45]

Generally, the cause of the unusual appearance is found to be benign. If the cause cannot be determined to be benign with sufficient certainty, a biopsy may be recommended. The biopsy procedure will be used to obtain actual tissue from the site for the pathologist to examine microscopically to determine the precise cause of the abnormality. In the past, biopsies were most frequently done in surgery, under local or general anesthesia. The majority are now done with needles in conjunction with either ultrasound or mammographic guidance to be sure that the area of concern is the area that is biopsied. These core biopsies require only local anesthesia, similar to what would be given during a minor dental procedure.[46]

Benefits[edit]

Mammography can detect cancer early when it’s most treatable and can be treated less invasively (thereby helping to preserve quality of life).

According to National Cancer Institute data, since mammography screening became widespread in the mid-1980s, the U.S. breast cancer death rate, unchanged for the previous 50 years, has dropped well over 30 percent.[47] In European countries like Denmark and Sweden, where mammography screening programs are more organized, the breast cancer death rate has been cut almost in half over the last 20 years.[as of?]

A study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention shows mammography screening cuts the risk of dying from breast cancer nearly in half.[48] A recent study published in Cancer showed that more than 70 percent of the women who died from breast cancer in their 40s at major Harvard teaching hospitals were among the 20 percent of women who were not being screened.[49] Some scientific studies[citation needed] have shown that the most lives are saved by screening beginning at age 40.

A recent study in the British Medical Journal shows that early detection of breast cancer – as with mammography – significantly improves breast cancer survival.[50]

The benefits of mammography screening at decreasing breast cancer mortality in randomized trials are not found in observational studies performed long after implementation of breast cancer screening programs (for instance, Bleyer et al.[51]) These discrepancies can be explained by cancers caused by mammograms.[10]

When to start screening[edit]

In 2014, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Institutes of Health reported the occurrence rates of breast cancer based on 1000 women in different age groups.[52] In the 40–44 age group, the incidence was 1.5 and in the 45–49 age group, the incidence was 2.3.[52] In the older age groups, the incidence was 2.7 in the 50–54 age group and 3.2 in the 55–59 age group.[52] While screening between ages 40 and 50 is somewhat controversial, the preponderance of the evidence indicates that there is a benefit in terms of early detection. Currently, the American Cancer Society, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American College of Radiology, and the Society of Breast Imaging encourage annual mammograms beginning at age 40.[53][54][55]

The National Cancer Institute encourages mammograms every one to two years for women ages 40 to 49.[56] In contrast, the American College of Physicians, a large internal medicine group, has recently encouraged individualized screening plans as opposed to wholesale biannual screening of women aged 40 to 49.[57] In 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that screening of women ages 40 to 49 be based on individual risk factors, and that screening should not be routine in this age group.[35] Their report says that the benefits of screenings before the age of 50 do not outweigh the risks.[58]

Starting screening at age 40[edit]

One in six breast cancers occur in women in their 40s. The ten year risk for breast cancer in a 40-year-old woman is 1 in 69 and only increases with age; 40 percent of all the years of life saved by mammography are for women in their 40s.

Screening mammography shows greatest benefit—a 39.6 percent mortality reduction—from annual screening of women 40–84 years old. This screening regimen saves 71 percent more lives than (the USPSTF-recommended regimen of) biennial screening of women 50–74 years old, which had a 23.2 percent mortality reduction.[59] By not getting a yearly mammogram after age 40, women increase their odds of dying from breast cancer and that treatment for any advanced cancers ultimately found will be more extensive and more expensive.

Note that women at elevated risk for breast cancer due to family history or other factors should speak with their doctor about starting screening earlier than age 40.

Arguments against the USPTF recommendations[edit]

Approximately 75 percent of women diagnosed with breast cancer have no family history of breast cancer or other factors that put them at high risk for developing the disease (so screening only high-risk women misses majority of cancers). An analysis by Hendrick and Helvie,[60] published in the American Journal of Roentgenology, showed that if USPSTF breast cancer screening guidelines were followed, approximately 6,500 additional women each year in the U.S. would die from breast cancer.

The largest (Hellquist et al)[61] and longest running (Tabar et al)[62] breast cancer screening studies in history, re-confirmed that regular mammography screening cut breast cancer deaths by roughly a third in all women ages 40 and over (including women ages 40–49). This renders the USPSTF calculations off by half. They used a 15% mortality reduction to calculate how many women needed to be invited to be screened to save a life. With the now re-confirmed 29% (or up) figure, the number to be screened using the USPSTF formula is half of their estimate and well within what they considered acceptable by their formula.

According to the USPSTF report, even for women 50+, skipping a mammogram every other year would miss up to 30 percent of cancers. A recent study published in Cancer[63] showed that more than 70 percent of the women who died from breast cancer in their 40s at major Harvard teaching hospitals were among the 20 percent of women who were not being screened.

There is a concern about bias and lack of experience regarding the panel that made the recommendations. The USPSTF did not contain or involve a single breast cancer expert (oncologist, radiologist, breast surgeon or radiation oncologist), but did have current or former members of the insurance industry (which some would argue has a vested interest in not paying for mammograms).[citation needed]

Arguments against mammography[edit]

Normal (left) versus cancerous (right) mammography image

The use of mammography as a screening tool for the detection of early breast cancer in otherwise healthy women without symptoms is seen by some as controversial.[64][65][66]

Keen and Keen indicated that repeated mammography starting at age fifty saves about 1.8 lives over 15 years for every 1,000 women screened.[67] This result has to be seen against the adverse effects of errors in diagnosis, over-treatment, and radiation exposure.

The Cochrane analysis of screening indicates that it is «not clear whether screening does more good than harm». According to their analysis, 1 in 2,000 women will have her life prolonged by 10 years of screening, while 10 healthy women will undergo unnecessary breast cancer treatment. Additionally, 200 women will experience significant psychological stress due to false positive results.[8]

Newman posits that screening mammography does not reduce death overall, but causes significant harm by inflicting cancer scare and unnecessary surgical interventions.[68] The Nordic Cochrane Collection notes that advances in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer may make breast cancer screening no longer effective in decreasing death from breast cancer, and therefore no longer recommend routine screening for healthy women as the risks might outweigh the benefits.[9]

Of every 1,000 U.S. women who are screened, about 7% will be called back for a diagnostic session (although some studies estimate the number to be closer to 10% to 15%).[69] About 10% of those who are called back will be referred for a biopsy. Of the 10% referred for biopsy, about 3.5% will have cancer and 6.5% will not. Of the 3.5% who have cancer, about 2 will have an early stage cancer that will be cured after treatment.

Mammography may also produce false negatives. Estimates of the numbers of cancers missed by mammography are usually around 20%.[70] Reasons for not seeing the cancer include observer error, but more frequently it is because the cancer is hidden by other dense tissue in the breast, and even after retrospective review of the mammogram the cancer cannot be seen. Furthermore, one form of breast cancer, lobular cancer, has a growth pattern that produces shadows on the mammogram that are indistinguishable from normal breast tissue.

Mortality[edit]

The Cochrane Collaboration states that the best quality evidence does not demonstrate a reduction in mortality or a reduction in mortality from all types of cancer from screening mammography.[8]

The Canadian Task Force found that for women ages 50 to 69, screening 720 women once every 2 to 3 years for 11 years would prevent one death from breast cancer. For women ages 40 to 49, 2,100 women would need to be screened at the same frequency and period to prevent a single death from breast cancer.[3]

Women whose breast cancer was detected by screening mammography before the appearance of a lump or other symptoms commonly assume that the mammogram «saved their lives».[71] In practice, the vast majority of these women received no practical benefit from the mammogram. There are four categories of cancers found by mammography:

- Cancers that are so easily treated that a later detection would have produced the same rate of cure (women would have lived even without mammography).

- Cancers so aggressive that even early detection is too late to benefit the patient (women who die despite detection by mammography).

- Cancers that would have receded on their own or are so slow-growing that the woman would die of other causes before the cancer produced symptoms (mammography results in over-diagnosis and over-treatment of this class).

- A small number of breast cancers that are detected by screening mammography and whose treatment outcome improves as a result of earlier detection.

Only 3% to 13% of breast cancers detected by screening mammography will fall into this last category. Clinical trial data suggests that 1 woman per 1,000 healthy women screened over 10 years falls into this category.[71] Screening mammography produces no benefit to any of the remaining 87% to 97% of women.[71] The probability of a woman falling into any of the above four categories varies with age.[72][73]

A 2016 review for the United States Preventive Services Task Force found that mammography was associated with an 8%-33% decrease in breast cancer mortality in different age groups, but that this decrease was not statistically significant at the age groups of 39–49 and 70–74. The same review found that mammography significantly decreased the risk of advanced cancer among women aged 50 and older by 38%, but among those aged 39 to 49 the risk reduction was a non-significant 2%.[74] The USPSTF made their review based on data from randomized controlled trials (RCT) studying breast cancer in women between the ages of 40-49.[52]

The lack of effectiveness of mammography screening in reducing mortality may be explained by cancers caused by mammograms.[10]

False positives[edit]

The goal of any screening procedure is to examine a large population of patients and find the small number most likely to have a serious condition. These patients are then referred for further, usually more invasive, testing. Thus a screening exam is not intended to be definitive; rather it is intended to have sufficient sensitivity to detect a useful proportion of cancers. The cost of higher sensitivity is a larger number of results that would be regarded as suspicious in patients without disease. This is true of mammography. The patients without disease who are called back for further testing from a screening session (about 7%) are sometimes referred to as «false positives». There is a trade-off between the number of patients with disease found and the much larger number of patients without disease that must be re-screened.[citation needed]

Research shows[75] that false-positive mammograms may affect women’s well-being and behavior. Some women who receive false-positive results may be more likely to return for routine screening or perform breast self-examinations more frequently. However, some women who receive false-positive results become anxious, worried, and distressed about the possibility of having breast cancer, feelings that can last for many years.[citation needed]

False positives also mean greater expense, both for the individual and for the screening program. Since follow-up screening is typically much more expensive than initial screening, more false positives (that must receive follow-up) means that fewer women may be screened for a given amount of money. Thus as sensitivity increases, a screening program will cost more or be confined to screening a smaller number of women.[citation needed]

Overdiagnosis[edit]

The central harm of mammographic breast cancer screening is overdiagnosis: the detection of abnormalities that meet the pathologic definition of cancer but will never progress to cause symptoms or death. Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, a researcher at Dartmouth College, states that «screen-detected breast and prostate cancer survivors are more likely to have been over-diagnosed than actually helped by the test.»[71] Estimates of overdiagnosis associated with mammography have ranged from 1% to 54%.[76] In 2009, Peter C. Gotzsche and Karsten Juhl Jørgensen reviewed the literature and found that 1 in 3 cases of breast cancer detected in a population offered mammographic screening is over-diagnosed.[77] In contrast, a 2012 panel convened by the national cancer director for England and Cancer Research UK concluded that 1 in 5 cases of breast cancer diagnosed among women who have undergone breast cancer screening are over-diagnosed. This means an over-diagnosis rate of 129 women per 10,000 invited to screening.[78]

False negatives[edit]

Mammograms also have a rate of missed tumors, or «false negatives». Accurate data regarding the number of false negatives are very difficult to obtain because mastectomies cannot be performed on every woman who has had a mammogram to determine the false negative rate. Estimates of the false negative rate depend on close follow-up of a large number of patients for many years. This is difficult in practice because many women do not return for regular mammography making it impossible to know if they ever developed a cancer. In his book The Politics of Cancer, Dr. Samuel S. Epstein claims that in women ages 40 to 49, one in four cancers are missed at each mammography. Researchers have found that breast tissue is denser among younger women, making it difficult to detect tumors. For this reason, false negatives are twice as likely to occur in pre-menopausal mammograms (Prate). This is why the screening program in the UK does not start calling women for screening mammograms until age 50.[citation needed]

The importance of these missed cancers is not clear, particularly if the woman is getting yearly mammograms. Research on a closely related situation has shown that small cancers that are not acted upon immediately, but are observed over periods of several years, will have good outcomes. A group of 3,184 women had mammograms that were formally classified as «probably benign». This classification is for patients who are not clearly normal but have some area of minor concern. This results not in the patient being biopsied, but rather in having early follow up mammography every six months for three years to determine whether there has been any change in status. Of these 3,184 women, 17 (0.5%) did have cancers. Most importantly, when the diagnosis was finally made, they were all still stage 0 or 1, the earliest stages. Five years after treatment, none of these 17 women had evidence of re-occurrence. Thus, small early cancers, even though not acted on immediately, were still reliably curable.[79]

Radiation[edit]

The radiation exposure associated with mammography is a potential risk of screening, which appears to be greater in younger women. In scans where women receive 0.25–20 Gray (Gy) of radiation, they have more of an elevated risk of developing breast cancer.[80] A study of radiation risk from mammography concluded that for women 40 years of age and older, the risk of radiation-induced breast cancer was minuscule, particularly compared with the potential benefit of mammographic screening, with a benefit-to-risk ratio of 48.5 lives saved for each life lost due to radiation exposure.[81] This also correlates to a decrease in breast cancer mortality rates by 24%.[80] However, this estimate is based on modelling, not observations. In contrast epidemiologic studies show a high incidence of breast cancer following mammography screening.[10] Organizations such as the National Cancer Institute and United States Preventive Task Force do not take such risks into account when formulating screening guidelines.[5]

Other risks[edit]

The majority of health experts agree that the risk of breast cancer for asymptomatic women under 35 is not high enough to warrant the risk of radiation exposure. For this reason, and because the radiation sensitivity of the breast in women under 35 is possibly greater than in older women, most radiologists do not recommend screening mammography on women under 40. However, if there is a significant risk of cancer in a particular patient (due to genetic tests, positive family history, etc), mammography prior to age may still be important. Often, the radiologist will try to avoid mammography by using ultrasound or MRI imaging.

Pain[edit]

The mammography procedure can be painful. Reported pain rates range from 6–76%, with 23–95% experiencing pain or discomfort.[82] Experiencing pain is a significant predictor in women not re-attending screening.[83] There are few proven interventions to reduce pain in mammography, but evidence suggests that giving women information about the mammography procedure prior to it taking place may reduce the pain and discomfort experienced.[84] Furthermore, research has found that standardised compression levels can help to reduce patients’ pain while still allowing for optimal diagnostic images to be produced.[85]

Attendance[edit]

Many factors affect how many people attend breast cancer screenings. For example, people from minority ethnic communities are also less likely to attend cancer screening. In the UK, women of South Asian heritage are the least likely to attend breast cancer screening. Research is still needed to identify specific barriers for the different South Asian communities. For example, a study showed that British-Pakistani women faced cultural and language barriers and were not aware that breast screening takes place in a female-only environment.[86][87][88]

People with mental illnesses are also less likely to attend cancer screening appointments.[89][90] In Northern Ireland women with mental health problems were shown to be less likely to attend screening for breast cancer, than women without. The lower attendance numbers remained the same even when marital status and social deprivation were taken into account.[91][92]

Regulation[edit]

Mammography discover facilities in the United States and its territories (including military bases) are subject to the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA). The act requires annual inspections and accreditation every three years through an FDA-approved body. Facilities found deficient during the inspection or accreditation process can be barred from performing mammograms until corrective action has been verified or, in extreme cases, can be required to notify past patients that their exams were sub-standard and should not be relied upon.[93]

At this time, MQSA applies only to traditional mammography and not to related scans, such as breast ultrasound, stereotactic breast biopsy, or breast MRI.

Many states in the US require a notification to be given to women with dense breasts to inform them that mammography is less accurate if breast tissue density is high. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration proposed a rule that would require doctors inform these women that they may need other imaging tests in addition to mammograms.[94]

Alternative examination methods[edit]

For patients who do not want to undergo mammography, MRI and also breast computed tomography (also called breast CT) offer a painless alternative. Whether the respective method is suitable depends on the clinical picture and it is decided by the physician.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Computed tomography laser mammography

- Molecular breast imaging

- Xeromammography

References[edit]

- ^ «Breast Cancer: Screening». United States Preventive Services Task Force. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15.

- ^ «Breast Cancer Early Detection». cancer.org. 2013-09-17. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ a b Tonelli M, Connor Gorber S, Joffres M, Dickinson J, Singh H, Lewin G, et al. (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care) (November 2011). «Recommendations on screening for breast cancer in average-risk women aged 40–74 years». CMAJ. 183 (17): 1991–2001. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110334. PMC 3225421. PMID 22106103.

- ^ «Cancer screening: Breast». European Cancer Observatory. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11.

- ^ a b «Final Recommendation Statement: Breast Cancer: Screening». US Preventive Services Task Force. January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Friedenson B (March 2000). «Is mammography indicated for women with defective BRCA genes? Implications of recent scientific advances for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hereditary breast cancer». MedGenMed. 2 (1): E9. PMID 11104455. Archived from the original on 2001-11-21.

- ^ American Society of Plastic Surgeons (24 April 2014), «Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question», Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, archived from the original on 19 July 2014, retrieved 25 July 2014

- ^ a b c Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ (June 2013). «Screening for breast cancer with mammography». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. PMC 6464778. PMID 23737396.

- ^ a b c d «Mammography-leaflet; Screening for breast cancer with mammography» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- ^ a b c d Corcos D, Bleyer A (January 2020). «Epidemiologic Signatures in Cancer». The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (1): 96. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1914747. PMID 31875513. S2CID 209481963.

- ^ Nass SJ, Henderson IC, et al. (Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Technologies for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer) (2001). Mammography and beyond: developing technologies for the early detection of breast cancer. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-07283-0.

- ^ a b Ingram A. «Breast Cancer Pioneer — Was the First Person to Use X-rays to Study Breast Cancer». Science Heroes. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Thomas A (2005). Classic papers in modern diagnostic radiology. Berlin: Springer. p. 540. ISBN 3-540-21927-7.

- ^ Warren SL (1930). «A Roentgenologic Study of the Breast». The American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy. 24: 113–124.

- ^ a b Gold 2005, p. 3

- ^ «History of Cancer Detection 1851–1995». Emory University. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Gardner, Kirsten E. Early Detection: Women, Cancer, and Awareness Campaigns in the Twentieth-Century United States. U of North Carolina P, 2006. p.179

- ^ Gold RH, Bassett LW, Widoff BE (November 1990). «Highlights from the history of mammography». Radiographics. 10 (6): 1111–1131. doi:10.1148/radiographics.10.6.2259767. PMID 2259767.

- ^ Medich DC, Martel C. Medical Health Physics. Health Physics Society 2006 Summer School. Medical Physics Publishing. ISBN 1930524315 pp.25

- ^ Skloot R (April 2001). «Taboo Organ» (PDF). University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. 3 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ^ Lerner BH (2003). ««To see today with the eyes of tomorrow»: A history of screening mammography». Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 20 (2): 299–321. doi:10.3138/cbmh.20.2.299. PMID 14723235. S2CID 2080082.

- ^ Shapiro S, Strax P, Venet L (February 1966). «Evaluation of periodic breast cancer screening with mammography. Methodology and early observations». JAMA. 195 (9): 731–738. doi:10.1001/jama.1966.03100090065016. PMID 5951878.

- ^ «Clinical Artefacts» (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ «Mammography Quality Scorecard». U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ «Mammography Frequently Asked Questions». American College of Radiology. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c Taylor P, Potts HW (April 2008). «Computer aids and human second reading as interventions in screening mammography: two systematic reviews to compare effects on cancer detection and recall rate» (PDF). European Journal of Cancer. 44 (6): 798–807. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.016. PMID 18353630.

- ^ Taylor P, Champness J, Given-Wilson R, Johnston K, Potts H (February 2005). «Impact of computer-aided detection prompts on the sensitivity and specificity of screening mammography». Health Technology Assessment. 9 (6): iii, 1-iii, 58. doi:10.3310/hta9060. PMID 15717938.

- ^ Taylor CG, Champness J, Reddy M, Taylor P, Potts HW, Given-Wilson R (September 2003). «Reproducibility of prompts in computer-aided detection (CAD) of breast cancer». Clinical Radiology. 58 (9): 733–738. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(03)00231-9. PMID 12943648.

- ^ Gilbert FJ, Astley SM, Gillan MG, Agbaje OF, Wallis MG, James J, et al. (October 2008). «Single reading with computer-aided detection for screening mammography». The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (16): 1675–1684. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0803545. PMID 18832239.

- ^ a b c d «Digital Mammography – Mammography – Imaginis – The Women’s Health & Wellness Resource Network». www.imaginis.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ (ACR), Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) and American College of Radiology. «Mammography (Mammogram)». radiologyinfo.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ «How To Perform An Ultrasound-Guided Breast Biopsy». www.theradiologyblog.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ «Radiology – Weill Cornell Medicine». weillcornell.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Sulik G (2010). Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women’s Health. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 193–195. ISBN 978-0-19-974045-1. OCLC 535493589.

- ^ a b «USPSTF recommendations on Screening for Breast Cancer». Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ^ «NASA Spinoffs» (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-11-25. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ^ Hodgson R, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Harvey SC, Edwards M, Shaikh J, Arber M, Glanville J (June 2016). «Systematic review of 3D mammography for breast cancer screening». Breast. 27: 52–61. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2016.01.002. PMID 27212700.

- ^ Gilbert FJ, Tucker L, Young KC (February 2016). «Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT): a review of the evidence for use as a screening tool». Clinical Radiology. 71 (2): 141–150. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2015.11.008. PMID 26707815.

- ^ Melnikow J, Fenton JJ, Whitlock EP, Miglioretti DL, Weyrich MS, Thompson JH, Shah K (February 2016). «Supplemental Screening for Breast Cancer in Women With Dense Breasts: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force». Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (4): 268–278. doi:10.7326/M15-1789. PMC 5100826. PMID 26757021.

- ^ Weigel S, Berkemeyer S, Girnus R, Sommer A, Lenzen H, Heindel W (May 2014). «Digital mammography screening with photon-counting technique: can a high diagnostic performance be realized at low mean glandular dose?». Radiology. 271 (2): 345–355. doi:10.1148/radiol.13131181. PMID 24495234.

- ^ Fredenberg E, Willsher P, Moa E, Dance DR, Young KC, Wallis MG (November 2018). «Measurement of breast-tissue x-ray attenuation by spectral imaging: fresh and fixed normal and malignant tissue». Physics in Medicine and Biology. 63 (23): 235003. arXiv:2101.02755. Bibcode:2018PMB….63w5003F. doi:10.1088/1361-6560/aaea83. PMID 30465547. S2CID 53717425.

- ^ Johansson H, von Tiedemann M, Erhard K, Heese H, Ding H, Molloi S, Fredenberg E (July 2017). «Breast-density measurement using photon-counting spectral mammography». Medical Physics. 44 (7): 3579–3593. Bibcode:2017MedPh..44.3579J. doi:10.1002/mp.12279. PMC 9560776. PMID 28421611.

- ^ Ding H, Molloi S (August 2012). «Quantification of breast density with spectral mammography based on a scanned multi-slit photon-counting detector: a feasibility study». Physics in Medicine and Biology. 57 (15): 4719–4738. Bibcode:2012PMB….57.4719D. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/57/15/4719. PMC 3478949. PMID 22771941.

- ^ Liu J, Page D, Nassif H, Shavlik J, Peissig P, McCarty C, et al. (2013). «Genetic variants improve breast cancer risk prediction on mammograms». AMIA … Annual Symposium Proceedings. AMIA Symposium. 2013: 876–885. PMC 3900221. PMID 24551380.

- ^ Lord SJ, Lei W, Craft P, Cawson JN, Morris I, Walleser S, et al. (September 2007). «A systematic review of the effectiveness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as an addition to mammography and ultrasound in screening young women at high risk of breast cancer». European Journal of Cancer. 43 (13): 1905–1917. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.007. PMID 17681781.

- ^ Dahlstrom JE, Jain S, Sutton T, Sutton S (May 1996). «Diagnostic accuracy of stereotactic core biopsy in a mammographic breast cancer screening programme». Histopathology. 28 (5): 421–427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.332376.x. PMID 8735717. S2CID 7707679.

- ^ «Cancer of the Breast (Female) — Cancer Stat Facts». National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

- ^ (Otto et al)

- ^ Webb, Matthew L.; Cady, Blake; Michaelson, James S.; Bush, Devon M.; Calvillo, Katherina Zabicki; Kopans, Daniel B.; Smith, Barbara L. (2014). «A failure analysis of invasive breast cancer: Most deaths from disease occur in women not regularly screened». Cancer. 120 (18): 2839–2846. doi:10.1002/cncr.28199. PMID 24018987. S2CID 19236625.

- ^ Saadatmand, S.; Bretveld, R.; Siesling, S.; Tilanus-Linthorst, M. M. (2015). «Influence of tumour stage at breast cancer detection on survival in modern times: Population based study in 173,797 patients». BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 351: h4901. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4901. PMC 4595560. PMID 26442924.

- ^ Bleyer A, Baines C, Miller AB (April 2016). «Impact of screening mammography on breast cancer mortality». Int J Cancer. 138 (8): 2003–2012. doi:10.1002/ijc.29925. PMID 26562826. S2CID 9538123.

- ^ a b c d Ray, Kimberly M.; Joe, Bonnie N.; Freimanis, Rita I.; Sickles, Edward A.; Hendrick, R. Edward (2018). «Screening Mammography in Women 40–49 Years Old: Current Evidence». American Journal of Roentgenology. 210 (2): 264–270. doi:10.2214/AJR.17.18707. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 29064760.

- ^ «American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer». Archived from the original on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ Lee CH, Dershaw DD, Kopans D, Evans P, Monsees B, Monticciolo D, et al. (January 2010). «Breast cancer screening with imaging: recommendations from the Society of Breast Imaging and the ACR on the use of mammography, breast MRI, breast ultrasound, and other technologies for the detection of clinically occult breast cancer». Journal of the American College of Radiology. 7 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2009.09.022. PMID 20129267. S2CID 31652981.

- ^ «Annual Mammograms Now Recommended for Women Beginning at Age 40». American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Archived from the original on 2013-09-04. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ «Screening Mammograms: Questions and Answers». National Cancer Institute. May 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-04-15. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ^ Qaseem A, Snow V, Sherif K, Aronson M, Weiss KB, Owens DK (April 2007). «Screening mammography for women 40 to 49 years of age: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians». Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (7): 511–515. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00007. PMID 17404353.

- ^ Sammons MB (November 2009). «New Mammogram Guidelines Spark Controversy». AOL Health. Archived from the original on 2009-11-22. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Hendrick, R. Edward; Helvie, Mark A. (2011-02-01). «United States Preventive Services Task Force Screening Mammography Recommendations: Science Ignored». American Journal of Roentgenology. 196 (2): W112–W116. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5609. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 21257850.

- ^ Hendrick, R. Edward; Helvie, Mark A. (2011-02-01). «United States Preventive Services Task Force Screening Mammography Recommendations: Science Ignored». American Journal of Roentgenology. 196 (2): W112–W116. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5609. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 21257850.

- ^ Hellquist, B. N.; Duffy, S. W.; Abdsaleh, S.; Björneld, L.; Bordás, P.; Tabár, L.; Viták, B.; Zackrisson, S.; Nyström, L.; Jonsson, H. (2011). «Hellquist et al». Cancer. 117 (4): 714–722. doi:10.1002/cncr.25650. PMID 20882563. S2CID 42253031.

- ^ «Tabar et al». Radiology.

- ^ Webb, Matthew L.; Cady, Blake; Michaelson, James S.; Bush, Devon M.; Calvillo, Katherina Zabicki; Kopans, Daniel B.; Smith, Barbara L. (2014). «A failure analysis of invasive breast cancer: Most deaths from disease occur in women not regularly screened». Cancer. 120 (18): 2839–2846. doi:10.1002/cncr.28199. PMID 24018987. S2CID 19236625.

- ^ Biller-Andorno N, Jüni P (May 2014). «Abolishing mammography screening programs? A view from the Swiss Medical Board» (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (21): 1965–1967. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1401875. PMID 24738641.

- ^ Kolata G (11 February 2014). «Vast Study Casts Doubts on Value of Mammograms». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Pace LE, Keating NL (April 2014). «A systematic assessment of benefits and risks to guide breast cancer screening decisions». JAMA. 311 (13): 1327–1335. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1398. PMID 24691608.

- ^ Mulcahy N (April 2, 2009). «Screening Mammography Benefits and Harms in Spotlight Again». Medscape. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015.

- ^ Newman DH (2008). Hippocrates’ Shadow. Scibner. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4165-5153-9.

- ^ Herdman R, Norton L, et al. (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on New Approaches to Early Detection and Diagnosis of Breast Cancer) (4 May 2018). «Wrap-Up Session». National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018 – via www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ «Mammograms». National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 2014-12-17.

- ^ a b c d Welch HG, Frankel BA (December 12, 2011). «Likelihood that a woman with screen-detected breast cancer has had her «life saved» by that screening». Archives of Internal Medicine. 171 (22): 2043–2046. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.476. PMID 22025097.

• Lay summary: Parker-Pope, Tara (October 24, 2011). «Mammogram’s Role as Savior Is Tested». The New York Times (blog). Archived from the original on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2011-10-28. - ^ Nassif H, Page D, Ayvaci M, Shavlik J, Burnside ES (2010). «Uncovering age-specific invasive and DCIS breast cancer rules using inductive logic programming». Proceedings of the ACM international conference on Health informatics — IHI ’10. pp. 76–82. doi:10.1145/1882992.1883005. ISBN 978-1-4503-0030-8. S2CID 2112731.

- ^ Ayvaci MU, Alagoz O, Chhatwal J, Munoz del Rio A, Sickles EA, Nassif H, et al. (August 2014). «Predicting invasive breast cancer versus DCIS in different age groups». BMC Cancer. 14 (1): 584. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-584. PMC 4138370. PMID 25112586.

- ^ Nelson HD, Fu R, Cantor A, Pappas M, Daeges M, Humphrey L (February 2016). «Effectiveness of Breast Cancer Screening: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation». Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (4): 244–255. doi:10.7326/M15-0969. PMID 26756588.

- ^ Brewer NT, Salz T, Lillie SE (April 2007). «Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms». Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (7): 502–510. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00006. PMID 17404352. S2CID 22260624.

- ^ de Gelder R, Heijnsdijk EA, van Ravesteyn NT, Fracheboud J, Draisma G, de Koning HJ (27 June 2011). «Interpreting overdiagnosis estimates in population-based mammography screening». Epidemiologic Reviews. 33 (1): 111–121. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr009. PMC 3132806. PMID 21709144.

- ^ Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC (July 2009). «Overdiagnosis in publicly organised mammography screening programmes: systematic review of incidence trends». BMJ. 339: b2587. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2587. PMC 2714679. PMID 19589821.

- ^ Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening (November 2012). «The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review». Lancet. 380 (9855): 1778–1786. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61611-0. PMID 23117178. S2CID 6857671.

- ^ Sickles EA (May 1991). «Periodic mammographic follow-up of probably benign lesions: results in 3,184 consecutive cases». Radiology. 179 (2): 463–468. doi:10.1148/radiology.179.2.2014293. PMID 2014293.

- ^ a b Feig, Stephen A.; Hendrick, R. Edward (1997–2001). «Radiation Risk From Screening Mammography of Women Aged 40-49 Years». JNCI Monographs. 1997 (22): 119–124. doi:10.1093/jncimono/1997.22.119. ISSN 1745-6614. PMID 9709287.

- ^ Feig SA, Hendrick RE (1997). «Radiation risk from screening mammography of women aged 40–49 years». Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 1997 (22): 119–124. doi:10.1093/jncimono/1997.22.119. PMID 9709287.

- ^ Armstrong K, Moye E, Williams S, Berlin JA, Reynolds EE (April 2007). «Screening mammography in women 40 to 49 years of age: a systematic review for the American College of Physicians». Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (7): 516–526. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00008. PMID 17404354.

- ^ Whelehan P, Evans A, Wells M, Macgillivray S (August 2013). «The effect of mammography pain on repeat participation in breast cancer screening: a systematic review». Breast. 22 (4): 389–394. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2013.03.003. PMID 23541681.

- ^ Miller D, Livingstone V, Herbison P (January 2008). «Interventions for relieving the pain and discomfort of screening mammography». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (1): CD002942. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002942.pub2. PMC 8989268. PMID 18254010.

- ^ Serwan E, Matthews D, Davies J, Chau M (September 2020). «Mammographic compression practices of force- and pressure-standardisation protocol: A scoping review». Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences. 67 (3): 233–242. doi:10.1002/jmrs.400. PMC 7476195. PMID 32420700.

- ^ «Cultural and language barriers need to be addressed for British-Pakistani women to benefit fully from breast screening». NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2020-09-15. doi:10.3310/alert_41135. S2CID 241324844.

- ^ Woof, Victoria G; Ruane, Helen; Ulph, Fiona; French, David P; Qureshi, Nadeem; Khan, Nasaim; Evans, D Gareth; Donnelly, Louise S (2019-12-02). «Engagement barriers and service inequities in the NHS Breast Screening Programme: Views from British-Pakistani women». Journal of Medical Screening. 27 (3): 130–137. doi:10.1177/0969141319887405. ISSN 0969-1413. PMC 7645618. PMID 31791172.

- ^ Woof, Victoria G.; Ruane, Helen; French, David P.; Ulph, Fiona; Qureshi, Nadeem; Khan, Nasaim; Evans, D. Gareth; Donnelly, Louise S. (2020-05-20). «The introduction of risk stratified screening into the NHS breast screening Programme: views from British-Pakistani women». BMC Cancer. 20 (1): 452. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-06959-2. ISSN 1471-2407. PMC 7240981. PMID 32434564.

- ^ «Cancer screening across the world is failing people with mental illness». NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2020-05-19. doi:10.3310/alert_40317. S2CID 243581455.

- ^ Solmi, Marco; Firth, Joseph; Miola, Alessandro; Fornaro, Michele; Frison, Elisabetta; Fusar-Poli, Paolo; Dragioti, Elena; Shin, Jae Il; Carvalho, Andrè F; Stubbs, Brendon; Koyanagi, Ai (28 November 2019). «Disparities in cancer screening in people with mental illness across the world versus the general population: prevalence and comparative meta-analysis including 4 717 839 people». The Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (1): 52–63. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30414-6. PMID 31787585. S2CID 208535709.

- ^ «Breast cancer screening: women with poor mental health are less likely to attend appointments». NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2021-06-21. doi:10.3310/alert_46400. S2CID 241919707.

- ^ Ross, Emma; Maguire, Aideen; Donnelly, Michael; Mairs, Adrian; Hall, Clare; O’Reilly, Dermot (2020-06-01). «Does poor mental health explain socio-demographic gradients in breast cancer screening uptake? A population-based study». European Journal of Public Health. 30 (3): 538–543. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckz220. ISSN 1101-1262. PMID 31834366.

- ^ Center for Devices and Radiological Health. «Facility Certification and Inspection (MQSA) – Mammography Safety Notifications». www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ LaVito A (2019-03-27). «FDA proposes rule to notify women with dense breasts about increased cancer risk and imprecise mammograms». CNBC. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

Further reading[edit]

- Reynolds H (2012). The Big Squeeze: A Social and Political History of the Controversial Mammogram. Ithaca: ILR Press/Cornell University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8014-5093-8.

External links[edit]

- Mammographic Image Analysis Homepage

- Screening Mammograms: Questions and Answers, from the National Cancer Institute

- American Cancer Society: Mammograms and Other Breast Imaging Procedures

- U.S. Preventive Task Force recommendations on screening mammography

| Mammography | |

|---|---|

Mammography |

|

| Other names | Mastography |

| ICD-10-PCS | BH0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 87.37 |

| MeSH | D008327 |

| OPS-301 code | 3–10 |

| MedlinePlus | 003380 |

|

[edit on Wikidata] |

Mammography (also called mastography) is the process of using low-energy X-rays (usually around 30 kVp) to examine the human breast for diagnosis and screening. The goal of mammography is the early detection of breast cancer, typically through detection of characteristic masses or microcalcifications.

As with all X-rays, mammograms use doses of ionizing radiation to create images. These images are then analyzed for abnormal findings. It is usual to employ lower-energy X-rays, typically Mo (K-shell X-ray energies of 17.5 and 19.6 keV) and Rh (20.2 and 22.7 keV) than those used for radiography of bones. Mammography may be 2D or 3D (tomosynthesis), depending on the available equipment and/or purpose of the examination. Ultrasound, ductography, positron emission mammography (PEM), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are adjuncts to mammography. Ultrasound is typically used for further evaluation of masses found on mammography or palpable masses that may or may not be seen on mammograms. Ductograms are still used in some institutions for evaluation of bloody nipple discharge when the mammogram is non-diagnostic. MRI can be useful for the screening of high risk patients, for further evaluation of questionable findings or symptoms, as well as for pre-surgical evaluation of patients with known breast cancer, in order to detect additional lesions that might change the surgical approach (for example, from breast-conserving lumpectomy to mastectomy).

For the average woman, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends (2016) mammography every two years between the ages of 50 and 74, concluding that «the benefit of screening mammography outweighs the harms by at least a moderate amount from age 50 to 74 years and is greatest for women in their 60s».[1] The American College of Radiology and American Cancer Society recommend yearly screening mammography starting at age 40.[2] The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (2012) and the European Cancer Observatory (2011) recommend mammography every 2 to 3 years between ages 50 and 69.[3][4] These task force reports point out that in addition to unnecessary surgery and anxiety, the risks of more frequent mammograms include a small but significant increase in breast cancer induced by radiation.[5][6] Additionally, mammograms should not be performed with increased frequency in patients undergoing breast surgery, including breast enlargement, mastopexy, and breast reduction.[7] The Cochrane Collaboration (2013) concluded after ten years that trials with adequate randomization did not find an effect of mammography screening on total cancer mortality, including breast cancer. The authors of this Cochrane review write: «If we assume that screening reduces breast cancer mortality by 15% and that overdiagnosis and over-treatment is at 30%, it means that for every 2,000 women invited for screening throughout 10 years, one will avoid dying of breast cancer and 10 healthy women, who would not have been diagnosed if there had not been screening, will be treated unnecessarily. Furthermore, more than 200 women will experience important psychological distress including anxiety and uncertainty for years because of false positive findings.» The authors conclude that the time has come to re-assess whether universal mammography screening should be recommended for any age group.[8] They state that universal screening may not be reasonable.[9] The Nordic Cochrane Collection updated research in 2012 and stated that advances in diagnosis and treatment make mammography screening less effective today, rendering it «no longer effective». They conclude that «it therefore no longer seems reasonable to attend» for breast cancer screening at any age, and warn of misleading information on the internet.[9] On the contrary, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine attributes the poor effectiveness of national mammography screening programs at reducing breast cancer mortality to radiation-induced cancers.[10]

Mammography has a false-negative (missed cancer) rate of at least ten percent. This is partly due to dense tissue obscuring the cancer and the appearance of cancer on mammograms having a large overlap with the appearance of normal tissue. A meta-analysis review of programs in countries with organized screening found a 52% over-diagnosis rate.[9]

History[edit]

As a medical procedure that induces ionizing radiation, the origin of mammography can be traced to the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895.

In 1913, German surgeon Albert Salomon performed a mammography study on 3,000 mastectomies, comparing X-rays of the breasts to the actual removed tissue, observing specifically microcalcifications.[11][12] By doing so, he was able to establish the difference as seen on an X-ray image between cancerous and non-cancerous tumors in the breast.[12] Salomon’s mammographs provided substantial information about the spread of tumors and their borders.[13]

In 1930, American physician and radiologist Stafford L. Warren published «A Roentgenologic Study of the Breast»,[14] a study where he produced stereoscopic X-rays images to track changes in breast tissue as a result of pregnancy and mastitis.[15][16] In 119 women who subsequently underwent surgery, he correctly found breast cancer in 54 out of 58 cases.[15]

As early as 1937, Jacob Gershon-Cohen developed a form a mammography for a diagnostic of breast cancer at earlier stages to improve survival rates.[17] In the early 1950s, Uruguayan radiologist Raul Leborgne developed the breast compression technique to produce better quality images, and described the differences between benign and malign microcalcifications.[18] In 1956, Gershon-Cohen conducted clinical trails on over 1,000 asymptomatic women at the Albert Einstein Medical Center on his screening technique,[17] and the same year, Robert Egan at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center combined a technique of low kVp with high mA and single emulsion films to devise a method of screening mammography. He published these results in 1959 in a paper, subsequently vulgarized in a 1964 book called Mammography.[19] The «Egan technique», as it became known, enabled physicians to detect calcification in breast tissue;[20] of the 245 breast cancers that were confirmed by biopsy among 1,000 patients, Egan and his colleagues at M.D. Anderson were able to identify 238 cases by using his method, 19 of which were in patients whose physical examinations had revealed no breast pathology.

Use of mammography as a screening technique spread clinically after a 1966 study demonstrating the impact of mammograms on mortality and treatment led by Philip Strax. This study, based in New York, was the first large-scale randomized controlled trial of mammography screening.[21][22]

Procedure[edit]

Illustration of a mammogram

A mobile mammography unit in New Zealand

During the procedure, the breast is compressed using a dedicated mammography unit. Parallel-plate compression evens out the thickness of breast tissue to increase image quality by reducing the thickness of tissue that X-rays must penetrate, decreasing the amount of scattered radiation (scatter degrades image quality), reducing the required radiation dose, and holding the breast still (preventing motion blur). In screening mammography, both head-to-foot (craniocaudal, CC) view and angled side-view (mediolateral oblique, MLO) images of the breast are taken. Diagnostic mammography may include these and other views, including geometrically magnified and spot-compressed views of the particular area of concern.[citation needed] Deodorant[citation needed], talcum powder[23] or lotion may show up on the X-ray as calcium spots, so women are discouraged from applying them on the day of their exam. There are two types of mammogram studies: screening mammograms and diagnostic mammograms. Screening mammograms, consisting of four standard X-ray images, are performed yearly on patients who present with no symptoms. Diagnostic mammograms are reserved for patients with breast symptoms (such as palpable lumps, breast pain, skin changes, nipple changes, or nipple discharge), as follow-up for probably benign findings (coded BI-RADS 3), or for further evaluation of abnormal findings seen on their screening mammograms. Diagnostic mammograms may also performed on patients with personal and/or family histories of breast cancer. Patients with breast implants and other stable benign surgical histories generally do not require diagnostic mammograms.

Until some years ago, mammography was typically performed with screen-film cassettes. Today, mammography is undergoing transition to digital detectors, known as digital mammography or Full Field Digital Mammography (FFDM). The first FFDM system was approved by the FDA in the U.S. in 2000. This progress is occurring some years later than in general radiology. This is due to several factors:

- The higher spatial resolution demands of mammography

- Significantly increased expense of the equipment

- Concern by the FDA that digital mammography equipment demonstrate that it is at least as good as screen-film mammography at detecting breast cancers without increasing dose or the number of women recalled for further evaluation.

As of March 1, 2010, 62% of facilities in the United States and its territories have at least one FFDM unit.[24] (The FDA includes computed radiography units in this figure.[25])

Tomosynthesis, otherwise known as 3D mammography, was first introduced in clinical trials in 2008 and has been Medicare-approved in the United States since 2015. As of 2023, 3D mammography has become widely available in the US and has been shown to have improved sensitivity and specificity over 2D mammography.