| Эта статья создана ботом Требуется выполнить первичную проверку статьи и проставить плашки необходимых работ |

Иероглифы для слова «манга», написанные Санто Кёдэном в издании «Сики но юкикай» 1798 года.

Ма́нга (漫画, マンガ) ж., скл. — японские комиксы, иногда называемые комикку (コミック). Манга, в той форме, в которой она существует в настоящее время, начала развиваться после окончания Второй мировой войны, испытав сильное влияние западной традиции, однако имеет глубокие корни в более раннем японском искусстве.

В Японии мангу читают люди всех возрастов, она уважаема и как форма изобразительного искусства, и как литературное явление, поэтому существует множество произведений самых разных жанров и на самые разнообразные темы: приключения, романтика, спорт, история, юмор, фантастика, ужасы, эротика, бизнес и другие. Она стала популярной и в остальном мире, особенно в США, где продажи по данным на 2006 год находились в районе 175—200 млн долларов. Почти вся манга рисуется и издаётся чёрно-белой, хотя существует и цветная, например, «Colorful», название которой переводится с английского как «красочный». По популярной манге, чаще всего длинным манга-сериалам (иногда неоконченным), снимается аниме. Сценарий экранизаций может претерпевать некоторые изменения: смягчаются, если есть, сцены схваток и боёв, убираются чересчур откровенные сцены. Художник, рисующий мангу, называется мангака, часто он же является и автором сценария. Если написание сценария берёт на себя отдельный человек, тогда такой сценарист называется гэнсакуся (или, точнее, манга-гэнсакуся). Бывает, что манга создаётся на основе уже существующего аниме или фильма, например, по «Звёздным войнам». Однако культура аниме и «отаку» не возникла бы без манги, потому что немногие продюсеры желают вкладывать время и деньги в проект, который не доказал свою популярность, окупаясь в виде комикса.

Этимология[]

Слово «манга» дословно означает «гротески», «странные (или весёлые) картинки». Этот термин возник в конце XVIII — начале XIX века с публикацией работ художников Канкэй Судзуки «Манкай дзуйхицу» (1771 г.), Санто Кёдэна «Сидзи-но юкикай» (1798 г.), Минва Аикава «Манга хякудзё» (1814), издавшего серию иллюстрированных альбомов «Хокусай манга» («Рисунки Хокусая») в 1814—1834 гг. Считается, что современное значение слова ввел мангака Ракутэн Китадзава. Идут споры о том, допустимо ли употреблять его по-русски во множественном числе. Изначально справочный портал Грамота.ру не советовал склонять слово «манга», однако в последнее время отметил, что «судя по практике его употребления, оно выступает как склоняемое существительное».

Понятие «манга» вне Японии изначально ассоциируют с комиксами, изданными в Японии. Так или иначе, манга и её производные, помимо оригинальных произведений, существуют в других частях света, в частности на Тайване, в Южной Корее, в Китае, особенно в Гонконге, и называются соответственно манхва и маньхуа. Названия сходны потому, что во всех трёх языках это слово записывается одними и теми же иероглифами. Во Франции, «la nouvelle manga» (новая манга) — форма комиксов, созданная под влиянием японской манги. Комиксы в стиле манга, нарисованные в США, называют «америманга» или OEL, от original English-language manga — «манга англоязычного происхождения».

История[]

Гравюры Хокусая.

Первые упоминания о создании в Японии историй в картинках относятся ещё к XII веку, когда буддийский монах Тоба (другое имя — Какую) Приёмы, которые он использовал в своих работах, заложили основы современной манги — как, например, изображение человеческих ног в состоянии бега.

Развиваясь, манга вобрала в себя традиции укиё-э и западные техники. После реставрации Мэйдзи, когда японский железный занавес пал и началась модернизация страны, художники также начали учиться у своих иностранных коллег особенностям композиции, пропорциям, цвету — вещам, которым в укиё-э не уделялось внимания, так как смысл и идея рисунка считались более важными, нежели форма. В период 1900—1940 г. манга не носила роль значимого социального явления, была скорее одним из модных увлечений молодежи. Манга в своём современном виде начала становление во время и особенно после Второй мировой войны. Большое влияние на развитие манги оказала европейская карикатура и американские комиксы, ставшие известными в Японии во второй половине XIX века.

Во время войны манга служила пропагандистским целям, печаталась на хорошей бумаге и в цвете. Её издание финансировалось государством (неофициально её называют «токийская манга»). После окончания войны, когда страна лежала в руинах, на смену ей пришла т. н. «осакская» манга, издававшаяся на самой дешёвой бумаге и продававшаяся за бесценок. Этой работой Тэдзука определил многие стилистические составляющие манги в её современном виде. За свою жизнь Тэдзука создал ещё множество работ, приобрёл учеников и последователей, развивших его идеи, и сделал мангу полноправным (если не основным) направлением массовой культуры.

В настоящее время в мир манги втянуто практически все население Японии. Тиражи популярных произведений — «One Piece» и «Наруто» — сравнимы с тиражами книг о Гарри Поттере, считает, что манга — один из способов вывода страны из экономического кризиса и улучшения ее имиджа на мировой арене. «Превращая популярность японской „мягкой силы“ в бизнес, мы можем к 2020 году создать колоссальную индустрию стоимостью в 20–30 триллионов иен и дать работу еще примерно 500 тысячам человек», — сказал Таро Асо в апреле 2009 года.

Публикация[]

Книжный магазин в Токио, заставленный томами («танкобонами») манги.

Манга составляет примерно четверть всей публикуемой в Японии печатной продукции, а популярные манга-сериалы позже переиздаются в виде отдельных томов, так называемых танкобонов.

Основной классификацией манги (в любом формате) является пол целевой аудитории, поэтому издания для молодых людей и для девушек обычно легко отличаются по обложке и располагаются на разных полках книжного магазина. На каждом томе имеются пометки: «для шестилетних», «для среднего школьного возраста», «для чтения в пути». Существуют также отделы «манга на раз»: покупаешь за полцены, по прочтении возвращаешь за четверть суммы.

Также в Японии распространены манга-кафе (漫画喫茶, マンガ喫茶 манга кисса), в которых можно выпить чаю или кофе и почитать мангу. Оплата обычно почасовая: час стоит в среднем 400 иен. В некоторых кафе люди за отдельную плату могут остаться на ночь.

Журналы[]

Журналов аниме, по сравнению с манга-периодикой, гораздо меньше. Первый журнал манги — Eshinbun Nipponchi — был создан в 1874 году. Большинство таких изданий, как «Shonen Sunday» или «Shonen Jump», выходит еженедельно, но есть и ежемесячные, например, «Zero Sum». В просторечии такие журналы именуются «телефонными книгами», так как очень их напоминают и по формату, и по качеству печати. В них одновременно публикуется сразу несколько (около десятка) манга-сериалов, по одной главе (около 30 страниц). А в 1995 году тираж «Shonen Jump» составил 6 млн экземпляров.

В журналах используется низкокачественная бумага, поэтому распространена практика закрашивания черно-белых страниц разными цветами — жёлтым, розовым. Посредством журналов создатели манги получили возможность демонстрировать свои работы. Без них мангак бы не существовало, считает критик Харуюки Накано.

Танкобоны[]

Шаблон:Main

Танкобон, как правило, насчитывает около 200 страниц, имеет размер с обыкновенную книгу карманного формата, мягкую обложку, более качественную, нежели в журналах, бумагу, а также комплектуется суперобложкой. Существует как манга, сразу вышедшая в виде танкобонов (например, хентайная), так и никогда в виде томов не выходящая — недостаточно успешная. Кроме того, существует понятие айдзобан (愛蔵版 айдзо:бан) — специальное издание для коллекционеров. Так печатается только наиболее успешная манга, например, «Dragon Ball» или «Fruits Basket». Айдзобаны издаются ограниченным тиражом, на высококачественной бумаге и снабжаются дополнительными бонусами: футляром, другой обложкой и т. п.

Многие мангаки любят порадовать своих читателей, поместив в конец тома манги различные занятные дополнения, по-японски омаке — это могут быть странички с дизайнами персонажей и местности, авторскими комментариями, просто зарисовками. Иногда всё это выпускается отдельными книгами.

Додзинси[]

Шаблон:Main

Кроме профессиональной манги, существует манга любительская, называемая додзинси и издающаяся маленькими тиражами на средства авторов. Многие нынешние профессиональные мангаки начинали как авторы додзинси, например, CLAMP, целиком посвящен додзинси. Кроме оригинальных историй, которые от начала и до конца придуманы авторами, встречаются пародии или работы, включающие существующих персонажей из известных аниме и манги. В 2007 году было продано додзинси на 245 млн долларов.

Стиль и характерные черты[]

Манга по графическому и литературному стилю заметно отличается от западных комиксов. Первым в такой стилистике стал рисовать уже упоминавшийся Осаму Тэдзука, чьи персонажи были созданы под влиянием героев американских мультфильмов, в частности, Бетти Буп (девушки с огромными глазами), а после большого успеха Осаму Тэдзуки другие авторы начали копировать его стиль.

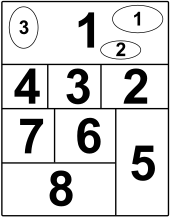

Традиционный порядок чтения в манге.

Читается манга справа налево, причиной чему японская письменность, в которой столбцы иероглифов пишутся именно так. Часто (но не всегда) при издании переводной манги за рубежом страницы зеркально переворачиваются, чтобы их можно было читать так, как привычно западному читателю — слева направо. Считается, что жители стран с письменностью слева направо естественным образом воспринимают композицию кадров в манге совсем не так, как это задумывал автор. Некоторые мангаки, в частности, Акира Торияма, выступают против такой практики и просят иностранные издательства публиковать их мангу в оригинальном виде. Поэтому, а также благодаря многочисленным просьбам отаку, сделала это своим главным козырем. Случается, что манга выходит сразу в обоих форматах (в обычном и незеркалированном), как было с «Евангелионом» от Viz Media.

Некоторые мангаки не считают необходимым определять сюжетную линию раз и навсегда и публикуют несколько работ, в которых одни и те же герои состоят то в одних взаимоотношениях, то в других, то знают друг друга, то нет. Ярким примером тому является сериал «Tenchi», в котором существует больше тридцати сюжетных линий, особенного отношения друг к другу не имеющих, но рассказывающих о парне Тэнти и его друзьях.

Манга в других странах[]

Влияние манги на международный рынок существенно возросло за последние несколько десятилетий. Наиболее широко за пределами Японии манга представлена в США и Канаде, Германии, Франции, Польше, где существует несколько издательств, занимающихся мангой, и сформирована достаточно обширная читательская база.

США[]

Америка была одной из первых стран, где начала выходить переведённая манга. В 1970-х и 1980-х годах она была практически недоступна для рядового читателя. Однако на сегодняшний день достаточно крупные издательства выпускают мангу на английском: Tokyopop, Viz Media, Del Rey, Dark Horse Comics. Одной из первых работ, переведенных на английский язык, стал «Босоногий Гэн», повествующий об атомной бомбардировке Хиросимы. В конце 1980-х годов были выпущены «Golgo 13» (1986 г.), «Lone Wolf and Cub» от First Comics (1987 г.), «Area 88» и «Mai the Psychic Girl» (1987 г.) от Viz Media и Eclipse Comics.

Мальчик в американском магазине читает «Black Cat».

В 1986 году предприниматель и переводчик Торен Смит (Toren Smith) основал издательство Studio Proteus, работавшее в сотрудничестве с Viz, Innovation Publishing, Eclipse Comics и Dark Horse Comics. На Studio Proteus было переведено большое количество манги, включая «Appleseed» и «Моя богиня!».

Структура рынка и предпочтения публики в США довольно сильно напоминают японские, хотя объёмы, конечно, всё равно несопоставимы. Появились свои манга-журналы: «Shojo Beat» с тиражом 38 тыс. экземпляров, «Shonen Jump USA». Статьи, посвященные данной индустрии, появляются в крупных печатных изданиях: «New York Times», «Wired».

Американские манга-издательства известны своим пуританством: издаваемые произведения регулярно подвергаются цензуре.

Европа[]

Манга пришла в Европу через Францию и Италию, где в 1970-х годах начали показывать аниме.

Во Франции рынок манги весьма развит и известен своей разносторонностью. В этой стране популярны в том числе работы в жанрах, не нашедших отклика у читателей других стран за пределами Японии, как, например, драматические произведения для взрослых, экспериментальные и авангардные работы. Не особенно известные на Западе авторы, как, например, Дзиро Танигути, во Франции обрели большой вес. Это отчасти объясняется тем, что во Франции сильны позиции своей культуры комиксов.

В Германии в 2001 году впервые за пределами Японии манга начала издаваться в формате «телефонных книг» на японский манер. До этого на Западе манга публиковалась в формате западных комиксов — ежемесячными выпусками по одной главе, переиздаваясь потом в виде отдельных томов. Первым таким журналом стал «Banzai», рассчитанный на юношескую аудиторию и просуществовавший до 2006 г. В начале 2003 года начал выходить сёдзё-журнал «Daisuki». Новый для западного читателя периодический формат стал успешным, и сейчас почти все зарубежные манга-издатели отказываются от отдельных выпусков, переходя на «телефонные книги».

Россия[]

Из всех развитых европейских стран хуже всего манга представлена в России. По мнению директора компании «Эгмонт-Россия» Льва Елина, в Японии любят комиксы с сексом и насилием, а «в России за эту нишу вряд ли кто возьмется». Как полагает рецензент журнала Деньги, перспективы «просто блестящие», «тем более что японские лицензии обходятся даже дешевле американских — $10-20 за страницу». Сергей Харламов из издательства «Сакура-пресс» считает эту нишу перспективной, но трудной в продвижении на рынок, так как «в России комиксы считаются детской литературой».

Что касается лицензий на переводы, то инициатива обычно исходит от русских издателей. В том же году Comix-ART, партнер издательского дома «Эксмо», приобрела права на «Тетрадь смерти», «Наруто» и «Блич», а также на некоторые другие работы, включая «Gravitation» и «Princess Ai».

Русские издатели, как правило, публикуют не только мангу, но и манхву, причем не делают между ними разделения, именуя мангой и то, и другое. В частности, Comix-ART из коммерческих соображений называет мангой америмангу «Бизенгаст» и «Ван-Вон Хантер», а на официальном сайте издательства «Истари комикс» в разделе «Манга» находится, к примеру, маньхуа «КЭТ» (Confidential Assassination Troop) тайваньского автора Фуна Йиньпана.

Так же, как и во всем мире, манга в России распространяется в виде любительских переводов — сканлейта.

Появились проекты, аналогичные журналам манги в Японии, — альманах русской манги «MNG» от издательства «Фабрика комиксов», которое собирается печатать мангу, нарисованную в России.

В июле 2008 года вышел первый крупный сборник любительской русской манги «Manga Cafe».

Премии[]

В японской манга-индустрии существует большое количество наград, которые спонсируют крупные издательства. Как пример, можно привести следующие: Dengeki Comic Grand Prix (короткая манга, «синглы»), Премия манги издательства Kodansha (несколько жанров), Seiun Award, Премия манги Shogakukan, Награда Тэдзуки, присуждаемая начинающим мангакам, Культурная премия Осаму Тэдзуки и другие. В России манга представлена на ежегодном московском фестивале рисованных историй «КомМиссия», где участвуют как профессионалы, так и художники-любители из России и других стран.

В 2007 году возникла международная премия International Manga Award («Международная премия манга»), за получение которой боролись художники Китая, Германии, Франции, Малайзии, Тайваня, России, Великобритании, Испании. По мнению премьер-министра Асо Таро, учреждение данной премии позволит зарубежным авторам углубить свое понимание культуры Японии. В 2008 году на «Международная премия манга» второе место заняла российская мангака Светлана Чежина с англоязычной версией работы «Портрет/ShoZo», выпущенной в России издательством «Маглатроникс». Ранее среди международных конкурсов наиболее почетным считался ежегодный международный фестиваль «de la Bande Dessinee» во Франции (участвует только манга, переведенная на французский).

См. также[]

- Аниме

- Маньхуа (китайские комиксы)

- Манхва (корейские комиксы)

- Оэкаки

- Омаке

- Лайт-новел

Шаблон:Wikipedia

This article is about the comics or graphic novels created in Japan. For other uses, see Manga (disambiguation).

| Manga | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Publishers |

|

| Publications |

|

| Creators |

|

| Series |

|

| Languages | Japanese |

| Related articles | |

|

Manga (Japanese: 漫画 [maŋga])[a] are comics or graphic novels originating from Japan. Most manga conform to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century,[1] and the form has a long history in earlier Japanese art.[2] The term manga is used in Japan to refer to both comics and cartooning. Outside of Japan, the word is typically used to refer to comics originally published in the country.[3]

In Japan, people of all ages and walks of life read manga. The medium includes works in a broad range of genres: action, adventure, business and commerce, comedy, detective, drama, historical, horror, mystery, romance, science fiction and fantasy, erotica (hentai and ecchi), sports and games, and suspense, among others.[4][5] Many manga are translated into other languages.[6]

Since the 1950s, manga has become an increasingly major part of the Japanese publishing industry.[7] By 1995, the manga market in Japan was valued at ¥586.4 billion ($6–7 billion),[8] with annual sales of 1.9 billion manga books and manga magazines in Japan (equivalent to 15 issues per person).[9] In 2020 Japan’s manga market value hit a new record of ¥612.6 billion due to the fast growth of digital manga sales as well as increase of print sales.[10][11] Manga have also gained a significant worldwide audience.[12][13][14] Beginning with the late 2010s manga started massively outselling American comics.[15] In 2020 the North American manga market was valued at almost $250 million.[16] According to NPD BookScan manga made up 76% of overall comics and graphic novel sales in the US in 2021.[17] The fast growth of the North American manga market has been attributed to manga’s wide availability on digital reading apps, book retailer chains such as Barnes & Noble and online retailers such as Amazon as well as the increased streaming of anime.[18][19] According to Jean-Marie Bouissou, manga represented 38% of the French comics market in 2005.[20] This is equivalent to approximately 3 times that of the United States and was valued at about €460 million ($640 million).[21] In Europe and the Middle East, the market was valued at $250 million in 2012.[22]

Manga stories are typically printed in black-and-white—due to time constraints, artistic reasons (as coloring could lessen the impact of the artwork)[23] and to keep printing costs low[24]—although some full-color manga exist (e.g., Colorful). In Japan, manga are usually serialized in large manga magazines, often containing many stories, each presented in a single episode to be continued in the next issue. Collected chapters are usually republished in tankōbon volumes, frequently but not exclusively paperback books.[25] A manga artist (mangaka in Japanese) typically works with a few assistants in a small studio and is associated with a creative editor from a commercial publishing company.[26] If a manga series is popular enough, it may be animated after or during its run.[27] Sometimes, manga are based on previous live-action or animated films.[28]

Manga-influenced comics, among original works, exist in other parts of the world, particularly in those places that speak Chinese («manhua»), Korean («manhwa»), English («OEL manga»), and French («manfra»), as well as in the nation of Algeria («DZ-manga»).[29][30]

Etymology

The kanji for «manga» from the preface to Shiji no yukikai (1798)

The word «manga» comes from the Japanese word 漫画[31] (katakana: マンガ; hiragana: まんが), composed of the two kanji 漫 (man) meaning «whimsical or impromptu» and 画 (ga) meaning «pictures».[32][33] The same term is the root of the Korean word for comics, «manhwa», and the Chinese word «manhua».[34]

The word first came into common usage in the late 18th century[35] with the publication of such works as Santō Kyōden’s picturebook Shiji no yukikai (1798),[36][32] and in the early 19th century with such works as Aikawa Minwa’s Manga hyakujo (1814) and the celebrated Hokusai Manga books (1814–1834)[37] containing assorted drawings from the sketchbooks of the famous ukiyo-e artist Hokusai.[38] Rakuten Kitazawa (1876–1955) first used the word «manga» in the modern sense.[39]

In Japanese, «manga» refers to all kinds of cartooning, comics, and animation. Among English speakers, «manga» has the stricter meaning of «Japanese comics», in parallel to the usage of «anime» in and outside Japan. The term «ani-manga» is used to describe comics produced from animation cels.[40]

History and characteristics

According to art resource Widewalls manga originated from emakimono (scrolls), Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, dating back to the 12th century. During the Edo period (1603–1867), a book of drawings titled Toba Ehon further developed what would later be called manga.[41][42] The word itself first came into common usage in 1798,[35] with the publication of works such as Santō Kyōden’s picturebook Shiji no yukikai (1798),[36][32] and in the early 19th century with such works as Aikawa Minwa’s Manga hyakujo (1814) and the Hokusai Manga books (1814–1834).[38][43] Adam L. Kern has suggested that kibyoshi, picture books from the late 18th century, may have been the world’s first comic books. These graphical narratives share with modern manga humorous, satirical, and romantic themes.[44] Some works were mass-produced as serials using woodblock printing.[9] however Eastern comics are generally held separate from the evolution of Western comics and Western comic art probably originated in 17th Italy,[45]

Writers on manga history have described two broad and complementary processes shaping modern manga. One view represented by other writers such as Frederik L. Schodt, Kinko Ito, and Adam L. Kern, stress continuity of Japanese cultural and aesthetic traditions, including pre-war, Meiji, and pre-Meiji culture and art.[46] The other view, emphasizes events occurring during and after the Allied occupation of Japan (1945–1952), and stresses U.S. cultural influences, including U.S. comics (brought to Japan by the GIs) and images and themes from U.S. television, film, and cartoons (especially Disney).[47]

Regardless of its source, an explosion of artistic creativity occurred in the post-war period,[48] involving manga artists such as Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy) and Machiko Hasegawa (Sazae-san). Astro Boy quickly became (and remains) immensely popular in Japan and elsewhere,[49] and the anime adaptation of Sazae-san drew more viewers than any other anime on Japanese television in 2011.[41] Tezuka and Hasegawa both made stylistic innovations. In Tezuka’s «cinematographic» technique, the panels are like a motion picture that reveals details of action bordering on slow motion as well as rapid zooms from distance to close-up shots. This kind of visual dynamism was widely adopted by later manga artists.[50] Hasegawa’s focus on daily life and on women’s experience also came to characterize later shōjo manga.[51] Between 1950 and 1969, an increasingly large readership for manga emerged in Japan with the solidification of its two main marketing genres, shōnen manga aimed at boys and shōjo manga aimed at girls.[52]

In 1969 a group of female manga artists (later called the Year 24 Group, also known as Magnificent 24s) made their shōjo manga debut («year 24» comes from the Japanese name for the year 1949, the birth-year of many of these artists).[53] The group included Moto Hagio, Riyoko Ikeda, Yumiko Ōshima, Keiko Takemiya, and Ryoko Yamagishi.[25] Thereafter, primarily female manga artists would draw shōjo for a readership of girls and young women.[54] In the following decades (1975–present), shōjo manga continued to develop stylistically while simultaneously evolving different but overlapping subgenres.[55] Major subgenres include romance, superheroines, and «Ladies Comics» (in Japanese, redisu レディース, redikomi レディコミ, and josei 女性).[56]

Modern shōjo manga romance features love as a major theme set into emotionally intense narratives of self-realization.[57] With the superheroines, shōjo manga saw releases such as Pink Hanamori’s Mermaid Melody Pichi Pichi Pitch, Reiko Yoshida’s Tokyo Mew Mew, and Naoko Takeuchi’s Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon, which became internationally popular in both manga and anime formats.[58] Groups (or sentais) of girls working together have also been popular within this genre. Like Lucia, Hanon, and Rina singing together, and Sailor Moon, Sailor Mercury, Sailor Mars, Sailor Jupiter, and Sailor Venus working together.[59]

Manga for male readers sub-divides according to the age of its intended readership: boys up to 18 years old (shōnen manga) and young men 18 to 30 years old (seinen manga);[60] as well as by content, including action-adventure often involving male heroes, slapstick humor, themes of honor, and sometimes explicit sex.[61] The Japanese use different kanji for two closely allied meanings of «seinen»—青年 for «youth, young man» and 成年 for «adult, majority»—the second referring to pornographic manga aimed at grown men and also called seijin («adult» 成人) manga.[62] Shōnen, seinen, and seijin manga share a number of features in common.

Boys and young men became some of the earliest readers of manga after World War II. From the 1950s on, shōnen manga focused on topics thought to interest the archetypal boy, including subjects like robots, space-travel, and heroic action-adventure.[63] Popular themes include science fiction, technology, sports, and supernatural settings. Manga with solitary costumed superheroes like Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man generally did not become as popular.[64]

The role of girls and women in manga produced for male readers has evolved considerably over time to include those featuring single pretty girls (bishōjo)[65] such as Belldandy from Oh My Goddess!, stories where such girls and women surround the hero, as in Negima and Hanaukyo Maid Team, or groups of heavily armed female warriors (sentō bishōjo)[66]

With the relaxation of censorship in Japan in the 1990s, an assortment of explicit sexual material appeared in manga intended for male readers, and correspondingly continued into the English translations.[67] In 2010, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government considered a bill to restrict minors’ access to such content.[68][needs update]

The gekiga style of storytelling—thematically somber, adult-oriented, and sometimes deeply violent—focuses on the day-in, day-out grim realities of life, often drawn in a gritty and unvarnished fashion.[69][70] Gekiga such as Sampei Shirato’s 1959–1962 Chronicles of a Ninja’s Military Accomplishments (Ninja Bugeichō) arose in the late 1950s and 1960s partly from left-wing student and working-class political activism,[71] and partly from the aesthetic dissatisfaction of young manga artists like Yoshihiro Tatsumi with existing manga.[72]

Publications and exhibition

Delegates of 3rd Asian Cartoon Exhibition, held at Tokyo (Annual Manga Exhibition) by The Japan Foundation[73]

In Japan, manga constituted an annual 40.6 billion yen (approximately US$395 million) publication-industry by 2007.[74] In 2006 sales of manga books made up for about 27% of total book-sales, and sale of manga magazines, for 20% of total magazine-sales.[75] The manga industry has expanded worldwide, where distribution companies license and reprint manga into their native languages.

Marketeers primarily classify manga by the age and gender of the target readership.[76] In particular, books and magazines sold to boys (shōnen) and girls (shōjo) have distinctive cover-art, and most bookstores place them on different shelves. Due to cross-readership, consumer response is not limited by demographics. For example, male readers may subscribe to a series intended for female readers, and so on. Japan has manga cafés, or manga kissa (kissa is an abbreviation of kissaten). At a manga kissa, people drink coffee, read manga and sometimes stay overnight.

The Kyoto International Manga Museum maintains a very large website listing manga published in Japanese.[77]

Magazines

Eshinbun Nipponchi is credited as the first manga magazine ever made.

Manga magazines or anthologies (漫画雑誌, manga zasshi) usually have many series running concurrently with approximately 20–40 pages allocated to each series per issue. Other magazines such as the anime fandom magazine Newtype featured single chapters within their monthly periodicals. Other magazines like Nakayoshi feature many stories written by many different artists; these magazines, or «anthology magazines», as they are also known (colloquially «phone books»), are usually printed on low-quality newsprint and can be anywhere from 200 to more than 850 pages thick. Manga magazines also contain one-shot comics and various four-panel yonkoma (equivalent to comic strips). Manga series can run for many years if they are successful. Popular shonen magazines include Weekly Shōnen Jump, Weekly Shōnen Magazine and Weekly Shōnen Sunday — Popular shoujo manga include Ciao, Nakayoshi and Ribon. Manga artists sometimes start out with a few «one-shot» manga projects just to try to get their name out. If these are successful and receive good reviews, they are continued. Magazines often have a short life.[78]

Collected volumes

After a series has run for a while, publishers often collect the chapters and print them in dedicated book-sized volumes, called tankōbon. These can be hardcover, or more usually softcover books, and are the equivalent of U.S. trade paperbacks or graphic novels. These volumes often use higher-quality paper, and are useful to those who want to «catch up» with a series so they can follow it in the magazines or if they find the cost of the weeklies or monthlies to be prohibitive. «Deluxe» versions have also been printed as readers have gotten older and the need for something special grew. Old manga have also been reprinted using somewhat lesser quality paper and sold for 100 yen (about $1 U.S. dollar) each to compete with the used book market.

History

Kanagaki Robun and Kawanabe Kyōsai created the first manga magazine in 1874: Eshinbun Nipponchi. The magazine was heavily influenced by Japan Punch, founded in 1862 by Charles Wirgman, a British cartoonist. Eshinbun Nipponchi had a very simple style of drawings and did not become popular with many people. Eshinbun Nipponchi ended after three issues. The magazine Kisho Shimbun in 1875 was inspired by Eshinbun Nipponchi, which was followed by Marumaru Chinbun in 1877, and then Garakuta Chinpo in 1879.[79] Shōnen Sekai was the first shōnen magazine created in 1895 by Iwaya Sazanami, a famous writer of Japanese children’s literature back then. Shōnen Sekai had a strong focus on the First Sino-Japanese War.[80]

In 1905 the manga-magazine publishing boom started with the Russo-Japanese War,[81] Tokyo Pakku was created and became a huge hit.[82] After Tokyo Pakku in 1905, a female version of Shōnen Sekai was created and named Shōjo Sekai, considered the first shōjo magazine.[83] Shōnen Pakku was made and is considered the first children’s manga magazine. The children’s demographic was in an early stage of development in the Meiji period. Shōnen Pakku was influenced from foreign children’s magazines such as Puck which an employee of Jitsugyō no Nihon (publisher of the magazine) saw and decided to emulate. In 1924, Kodomo Pakku was launched as another children’s manga magazine after Shōnen Pakku.[82] During the boom, Poten (derived from the French «potin») was published in 1908. All the pages were in full color with influences from Tokyo Pakku and Osaka Puck. It is unknown if there were any more issues besides the first one.[81] Kodomo Pakku was launched May 1924 by Tokyosha and featured high-quality art by many members of the manga artistry like Takei Takeo, Takehisa Yumeji and Aso Yutaka. Some of the manga featured speech balloons, where other manga from the previous eras did not use speech balloons and were silent.[82]

Published from May 1935 to January 1941, Manga no Kuni coincided with the period of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Manga no Kuni featured information on becoming a mangaka and on other comics industries around the world. Manga no Kuni handed its title to Sashie Manga Kenkyū in August 1940.[84]

Dōjinshi

Dōjinshi, produced by small publishers outside of the mainstream commercial market, resemble in their publishing small-press independently published comic books in the United States. Comiket, the largest comic book convention in the world with around 500,000 visitors gathering over three days, is devoted to dōjinshi. While they most often contain original stories, many are parodies of or include characters from popular manga and anime series. Some dōjinshi continue with a series’ story or write an entirely new one using its characters, much like fan fiction. In 2007, dōjinshi sales amounted to 27.73 billion yen (US$245 million).[74] In 2006 they represented about a tenth of manga books and magazines sales.[75]

Digital manga

Thanks to the advent of the internet, there have been new ways for aspiring mangaka to upload and sell their manga online. Before, there were two main ways in which a mangaka’s work could be published: taking their manga drawn on paper to a publisher themselves, or submitting their work to competitions run by magazines.[85]

Web manga

In recent years, there has been a rise in manga released digitally. Web manga, as it is known in Japan, has seen an increase thanks in part to image hosting websites where anyone can upload pages from their works for free. Although released digitally, almost all web manga sticks to the conventional black-and-white format despite some never getting physical publication. Pixiv is the most popular site where amateur and professional work gets published on the site. It has grown to be the most visited site for artwork in Japan.[86] Twitter has also become a popular place for web manga with many artists releasing pages weekly on their accounts in the hope of their work getting picked up or published professionally. One of the best examples of an amateur work becoming professional is One-Punch Man which was released online and later received a professional remake released digitally and an anime adaptation soon thereafter.[87]

Many of the big print publishers have also released digital only magazines and websites where web manga get published alongside their serialized magazines. Shogakukan for instance has two websites, Sunday Webry and Ura Sunday, that release weekly chapters for web manga and even offer contests for mangaka to submit their work. Both Sunday Webry and Ura Sunday have become one of the top web manga sites in Japan.[88][89] Some have even released apps that teach how to draw professional manga and learn how to create them. Weekly Shōnen Jump released Jump Paint, an app that guides users on how to make their own manga from making storyboards to digitally inking lines. It also offers more than 120 types of pen tips and more than 1,000 screentones for artists to practice.[85] Kodansha has also used the popularity of web manga to launch more series and also offer better distribution of their officially translated works under Kodansha Comics thanks in part to the titles being released digitally first before being published physically.[90]

The rise web manga has also been credited to smartphones and computers as more and more readers read manga on their phones rather than from a print publication. While paper manga has seen a decrease over time, digital manga have been growing in sales each year. The Research Institute for Publications reports that sales of digital manga books excluding magazines jumped 27.1 percent to ¥146 billion in 2016 from the year before while sales of paper manga saw a record year-on-year decline of 7.4 percent to ¥194.7 billion. They have also said that if the digital and paper keep the same growth and drop rates, web manga would exceed their paper counterparts.[91] In 2020 manga sales topped the ¥600 billion mark for the first time in history, beating the 1995 peak due to a fast growth of the digital manga market which rose by ¥82.7 billion from a previous year, surpassing print manga sales which have also increased.[92][93]

Webtoons

While webtoons have caught on in popularity as a new medium for comics in Asia, Japan has been slow to adopt webtoons as the traditional format and print publication still dominate the way manga is created and consumed(although this is beginning to change). Despite this, one of the biggest webtoon publishers in the world, Comico, has had success in the traditional Japanese manga market. Comico was launched by NHN Japan, the Japanese subsidiary of Korean company, NHN Entertainment. As of now[when?], there are only two webtoon publishers that publish Japanese webtoons: Comico and Naver Webtoon (under the name XOY in Japan). Kakao has also had success by offering licensed manga and translated Korean webtoons with their service Piccoma. All three companies credit their success to the webtoon pay model where users can purchase each chapter individually instead of having to buy the whole book while also offering some chapters for free for a period of time allowing anyone to read a whole series for free if they wait long enough.[94] The added benefit of having all of their titles in color and some with special animations and effects have also helped them succeed. Some popular Japanese webtoons have also gotten anime adaptations and print releases, the most notable being ReLIFE and Recovery of an MMO Junkie.[95][96]

International markets

By 2007, the influence of manga on international comics had grown considerably over the past two decades.[97] «Influence» is used here to refer to effects on the comics markets outside Japan and to aesthetic effects on comics artists internationally.

The reading direction in a traditional manga

Traditionally, manga stories flow from top to bottom and from right to left. Some publishers of translated manga keep to this original format. Other publishers mirror the pages horizontally before printing the translation, changing the reading direction to a more «Western» left to right, so as not to confuse foreign readers or traditional comics-consumers. This practice is known as «flipping».[98] For the most part, criticism suggests that flipping goes against the original intentions of the creator (for example, if a person wears a shirt that reads «MAY» on it, and gets flipped, then the word is altered to «YAM»), who may be ignorant of how awkward it is to read comics when the eyes must flow through the pages and text in opposite directions, resulting in an experience that’s quite distinct from reading something that flows homogeneously. If the translation is not adapted to the flipped artwork carefully enough it is also possible for the text to go against the picture, such as a person referring to something on their left in the text while pointing to their right in the graphic. Characters shown writing with their right hands, the majority of them, would become left-handed when a series is flipped. Flipping may also cause oddities with familiar asymmetrical objects or layouts, such as a car being depicted with the gas pedal on the left and the brake on the right, or a shirt with the buttons on the wrong side, however these issues are minor when compared to the unnatural reading flow, and some of them could be solved with an adaptation work that goes beyond just translation and blind flipping.[99]

Asia

Manga has highly influenced the art styles of manhwa and manhua.[100] Manga in Indonesia is published by Elex Media Komputindo, Level Comic, M&C and Gramedia. Manga has influenced Indonesia’s original comic industry. Manga in the Philippines were imported from the US and were sold only in specialty stores and in limited copies. The first manga in Filipino language is Doraemon which was published by J-Line Comics and was then followed by Case Closed.[citation needed] In 2015, Boy’s Love manga became popular through the introduction of BL manga by printing company BLACKink. Among the first BL titles to be printed were Poster Boy, Tagila, and Sprinters, all were written in Filipino. BL manga have become bestsellers in the top three bookstore companies in the Philippines since their introduction in 2015. During the same year, Boy’s Love manga have become a popular mainstream with Thai consumers, leading to television series adapted from BL manga stories since 2016.[citation needed]

Europe

The comic book and manga store Sakura Eldorado in Hamburg.

Manga has influenced European cartooning in a way that is somewhat different from in the U.S. Broadcast anime in France and Italy opened the European market to manga during the 1970s.[101] French art has borrowed from Japan since the 19th century (Japonism)[102] and has its own highly developed tradition of bande dessinée cartooning.[103] In France, beginning in the mid-1990s,[104] manga has proven very popular to a wide readership, accounting for about one-third of comics sales in France since 2004.[105] By mid-2021, 75 percent of the €300 value of Culture Pass [fr] accounts given to French 18 year-olds was spent on manga.[106] According to the Japan External Trade Organization, sales of manga reached $212.6 million within France and Germany alone in 2006.[101] France represents about 50% of the European market and is the second worldwide market, behind Japan.[22] In 2013, there were 41 publishers of manga in France and, together with other Asian comics, manga represented around 40% of new comics releases in the country,[107] surpassing Franco-Belgian comics for the first time.[108] European publishers marketing manga translated into French include Asuka, Casterman, Glénat, Kana, and Pika Édition, among others.[citation needed] European publishers also translate manga into Dutch, German, Italian, and other languages. In 2007, about 70% of all comics sold in Germany were manga.[109]

Manga publishers based in the United Kingdom include Gollancz and Titan Books.[citation needed] Manga publishers from the United States have a strong marketing presence in the United Kingdom: for example, the Tanoshimi line from Random House.[citation needed] In 2019 The British Museum held a mass exhibition dedicated to manga.[110][111][112]

United States

Manga made their way only gradually into U.S. markets, first in association with anime and then independently.[113] Some U.S. fans became aware of manga in the 1970s and early 1980s.[114] However, anime was initially more accessible than manga to U.S. fans,[115] many of whom were college-age young people who found it easier to obtain, subtitle, and exhibit video tapes of anime than translate, reproduce, and distribute tankōbon-style manga books.[116] One of the first manga translated into English and marketed in the U.S. was Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, an autobiographical story of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima issued by Leonard Rifas and Educomics (1980–1982).[117] More manga were translated between the mid-1980s and 1990s, including Golgo 13 in 1986, Lone Wolf and Cub from First Comics in 1987, and Kamui, Area 88, and Mai the Psychic Girl, also in 1987 and all from Viz Media-Eclipse Comics.[118] Others soon followed, including Akira from Marvel Comics’ Epic Comics imprint, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind from Viz Media, and Appleseed from Eclipse Comics in 1988, and later Iczer-1 (Antarctic Press, 1994) and Ippongi Bang’s F-111 Bandit (Antarctic Press, 1995).

In the 1980s to the mid-1990s, Japanese animation, like Akira, Dragon Ball, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Pokémon, made a bigger impact on the fan experience and in the market than manga.[119] Matters changed when translator-entrepreneur Toren Smith founded Studio Proteus in 1986. Smith and Studio Proteus acted as an agent and translator of many Japanese manga, including Masamune Shirow’s Appleseed and Kōsuke Fujishima’s Oh My Goddess!, for Dark Horse and Eros Comix, eliminating the need for these publishers to seek their own contacts in Japan.[120]

Simultaneously, the Japanese publisher Shogakukan opened a U.S. market initiative with their U.S. subsidiary Viz, enabling Viz to draw directly on Shogakukan’s catalogue and translation skills.[98]

Japanese publishers began pursuing a U.S. market in the mid-1990s due to a stagnation in the domestic market for manga.[121] The U.S. manga market took an upturn with mid-1990s anime and manga versions of Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell (translated by Frederik L. Schodt and Toren Smith) becoming very popular among fans.[122] An extremely successful manga and anime translated and dubbed in English in the mid-1990s was Sailor Moon.[123] By 1995–1998, the Sailor Moon manga had been exported to over 23 countries, including China, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, North America and most of Europe.[124] In 1997, Mixx Entertainment began publishing Sailor Moon, along with CLAMP’s Magic Knight Rayearth, Hitoshi Iwaaki’s Parasyte and Tsutomu Takahashi’s Ice Blade in the monthly manga magazine MixxZine. Mixx Entertainment, later renamed Tokyopop, also published manga in trade paperbacks and, like Viz, began aggressive marketing of manga to both young male and young female demographics.[125]

During this period, Dark Horse Manga was a major publisher of translated manga. In addition to Oh My Goddess!, the company published Akira, Astro Boy, Berserk, Blade of the Immortal, Ghost in the Shell, Lone Wolf and Cub, Yasuhiro Nightow’s Trigun and Blood Blockade Battlefront, Gantz, Kouta Hirano’s Hellsing and Drifters, Blood+, Multiple Personality Detective Psycho, FLCL, Mob Psycho 100, and Oreimo. The company received 13 Eisner Award nominations for its manga titles, and three of the four manga creators admitted to The Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame — Osamu Tezuka, Kazuo Koike, and Goseki Kojima — were published in Dark Horse translations.[126]

In the following years, manga became increasingly popular, and new publishers entered the field while the established publishers greatly expanded their catalogues.[127] The Pokémon manga Electric Tale of Pikachu issue #1 sold over 1 million copies in the United States, making it the best-selling single comic book in the United States since 1993.[128] By 2008, the U.S. and Canadian manga market generated $175 million in annual sales.[129] Simultaneously, mainstream U.S. media began to discuss manga, with articles in The New York Times, Time magazine, The Wall Street Journal, and Wired magazine.[130] As of 2017, manga distributor Viz Media is the largest publisher of graphic novels and comic books in the United States, with a 23% share of the market.[131] BookScan sales show that manga is one of the fastest-growing areas of the comic book and narrative fiction markets. From January 2019 to May 2019, the manga market grew 16%, compared to the overall comic book market’s 5% growth. The NPD Group noted that, compared to other comic book readers, manga readers are younger (76% under 30) and more diverse, including a higher female readership (16% higher than other comic books).[132]

As of January 2020 manga is the second largest category in the US comic book and graphic novel market, accounting for 27% of the entire market share.[133] During the COVID-19 pandemic some stores of the American bookseller Barnes & Noble saw up to a 500% increase in sales from graphic novel and manga sales due to the younger generations showing a high interest in the medium.[134] Sales of print manga titles in the U.S. increased by 3.6 million units in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the same period in 2020.[135] In 2021 24.4 million units of manga were sold in the United States. This is an increase of about 15 million(160%) more sales than in 2020.[136][137]

Localized manga

A number of artists in the United States have drawn comics and cartoons influenced by manga. As an early example, Vernon Grant drew manga-influenced comics while living in Japan in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[138] Others include Frank Miller’s mid-1980s Ronin, Adam Warren and Toren Smith’s 1988 The Dirty Pair,[139] Ben Dunn’s 1987 Ninja High School and Manga Shi 2000 from Crusade Comics (1997).

By the 21st century several U.S. manga publishers had begun to produce work by U.S. artists under the broad marketing-label of manga.[140] In 2002 I.C. Entertainment, formerly Studio Ironcat and now out of business, launched a series of manga by U.S. artists called Amerimanga.[141] In 2004 eigoMANGA launched the Rumble Pak and Sakura Pakk anthology series. Seven Seas Entertainment followed suit with World Manga.[142] Simultaneously, TokyoPop introduced original English-language manga (OEL manga) later renamed Global Manga.[143]

Francophone artists have also developed their own versions of manga (manfra), like Frédéric Boilet’s la nouvelle manga. Boilet has worked in France and in Japan, sometimes collaborating with Japanese artists.[144]

Awards

The Japanese manga industry grants a large number of awards, mostly sponsored by publishers, with the winning prize usually including publication of the winning stories in magazines released by the sponsoring publisher. Examples of these awards include:

- The Akatsuka Award for humorous manga

- The Dengeki Comic Grand Prix for one-shot manga

- The Japan Cartoonists Association Award various categories

- The Kodansha Manga Award (multiple genre awards)

- The Seiun Award for best science fiction comic of the year

- The Shogakukan Manga Award (multiple genres)

- The Tezuka Award for best new serial manga

- The Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize (multiple genres)

The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has awarded the International Manga Award annually since May 2007.[145]

University education

Kyoto Seika University in Japan has offered a highly competitive course in manga since 2000.[146][147] Then, several established universities and vocational schools (専門学校: Semmon gakkou) established a training curriculum.

Shuho Sato, who wrote Umizaru and Say Hello to Black Jack, has created some controversy on Twitter. Sato says, «Manga school is meaningless because those schools have very low success rates. Then, I could teach novices required skills on the job in three months. Meanwhile, those school students spend several million yen, and four years, yet they are good for nothing.» and that, «For instance, Keiko Takemiya, the then professor of Seika Univ., remarked in the Government Council that ‘A complete novice will be able to understand where is «Tachikiri» (i.e., margin section) during four years.’ On the other hand, I would imagine that, It takes about thirty minutes to completely understand that at work.»[148]

See also

- ACG (subculture)

- Alternative manga

- Anime

- Anime and manga fandom

- Cinema of Japan

- Cool Japan

- Culture of Japan

- Emakimono

- E-toki (horizontal, illustrated narrative form)

- Japanese language

- Japanese popular culture

- Kamishibai

- Lianhuanhua (small Chinese picture book)

- Light novel

- List of best-selling manga

- List of films based on manga

- List of licensed manga in English

- List of manga distributors

- List of manga magazines

- List of Japanese manga magazines by circulation

- Manga iconography

- Manga outside Japan

- Truyện tranh

- Manhua

- Manhwa

- Q-version (cartoonification)

- Ukiyo-e

- Visual novel

- Webtoon

- Weekly Shōnen Jump

Notes

- ^ ;

References

Inline citations

- ^ Lent 2001, pp. 3–4, Gravett 2004, p. 8

- ^ Kern 2006, Ito 2005, Schodt 1986

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2009

- ^ «Manga/Anime topics». mit.edu. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Brenner 2007.

- ^ Gravett 2004, p. 8

- ^ Kinsella 2000, Schodt 1996

- ^ Schodt 1996, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Mullen, Ruth (2 August 1997). «Manga, anime rooted in Japanese history». The Indianapolis Star. p. 44. Archived from the original on 30 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Manga Market in Japan Hits Record 612.6 Billion Yen in 2020». Anime News Network. 26 February 2021.

- ^ «Manga industry in Japan — statistics and facts». Statista. 11 March 2021.

- ^ Wong 2006, Patten 2004

- ^ «Paperback manga has taken over the world». Polygon. 13 May 2021.

- ^ «Did manga shape how the world sees Japan?». BBC. 12 June 2019.

- ^ «Why are manga outselling superhero comics?». Rutgers Today. 5 December 2019.

- ^ «Manga sales hit an all time high in North America». Icv2. 2 July 2021.

- ^ Grunenwald, Joe; MacDonald, Heidi (4 February 2022). «Report: Graphic novel sales were up 65% in 2021». The Beat. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ «Today’s North American manga market: The wins, the losses, and everything else». Book Riot. 13 August 2021.

- ^ «Manga’s Growth In Popularity Is Here To Stay, Industry Leaders Predict». Anime News Network. 13 May 2022.

- ^ Bouissou, Jean-Marie (2006). «JAPAN’S GROWING CULTURAL POWER: THE EXAMPLE OF MANGA IN FRANCE».

- ^ «The Manga Market: Eurasiam – Japanese art & communication School». Eurasiam. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b Danica Davidson (26 January 2012). «Manga grows in the heart of Europe». Geek Out! CNN. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ «Why Are U.S. Comics Colored and Japanese Mangas Not?». Slate. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Katzenstein & Shiraishi 1997

- ^ a b Gravett 2004, p. 8, Schodt 1986

- ^ Kinsella 2000

- ^ Kittelson 1998

- ^ Johnston-O’Neill 2007

- ^ Webb 2006

- ^ Wong 2002

- ^ Rousmaniere 2001, p. 54, Thompson 2007, p. xiii, Prohl & Nelson 2012, p. 596,Fukushima 2013, p. 19

- ^ a b c «Shiji no yukikai(Japanese National Diet Library)».

- ^ Webb 2006,Thompson 2007, p. xvi,Onoda 2009, p. 10,Petersen 2011, p. 120

- ^ Thompson 2007, p. xiii, Onoda 2009, p. 10, Prohl & Nelson 2012, p. 596, Fukushima 2013, p. 19

- ^ a b Prohl & Nelson 2012, p. 596,McCarthy 2014, p. 6

- ^ a b «Santō Kyōden’s picturebooks». Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ «Hokusai Manga (15 Vols complete)».

- ^ a b Bouquillard & Marquet 2007

- ^ Shimizu 1985, pp. 53–54, 102–103

- ^ «Inu Yasha Ani-MangaGraphic Novels». Animecornerstore.com. 1 November 1999. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ a b Kageyama, Y. (24 September 2016). «A Short History of Japanese Manga». Widewalls.ch. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ «MedievalManga in Midtown: The Choju-Giga at the Suntory Museum». Dai Nippom Printng Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Kern (2006), pp. 139–144, Fig. 3.3

- ^ Kern 2006

- ^ Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels by Julia Round page 24 and 25

- ^ Schodt 1986, Ito 2004, Kern 2006, Kern 2007

- ^ Kinsella 2000, Schodt 1986

- ^ Schodt 1986, Schodt 1996, Schodt 2007, Gravett 2004

- ^ Kodansha 1999, pp. 692–715, Schodt 2007

- ^ Schodt 1986

- ^ Gravett 2004, p. 8, Lee 2000, Sanchez 1997–2003

- ^ Schodt 1986, Toku 2006

- ^ Gravett 2004, pp. 78–80, Lent 2001, pp. 9–10

- ^ Schodt 1986, Toku 2006, Thorn 2001

- ^ Ōgi 2004

- ^ Gravett 2004, p. 8, Schodt 1996

- ^ Drazen 2003

- ^ Allison 2000, pp. 259–278, Schodt 1996, p. 92

- ^ Poitras 2001

- ^ Thompson 2007, pp. xxiii–xxiv

- ^ Brenner 2007, pp. 31–34

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 95, Perper & Cornog 2002

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–87, Gravett 2004, pp. 52–73

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–87

- ^ Perper & Cornog 2002, pp. 60–63

- ^ Gardner 2003

- ^ Perper & Cornog 2002

- ^ «Tokyo Moves a Step Closer to Manga Porn Crackdown». The Yomiuri Shimbun. 14 December 2010. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Roman (2011). «Gekiga as a site of Intercultural Exchange» (PDF). Kyoto Seika University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2016.

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–73, Gravett 2006

- ^ Schodt 1986, pp. 68–73, Gravett 2004, pp. 38–42, Isao 2001

- ^ Isao 2001, pp. 147–149, Nunez 2006

- ^ Manga Hai Kya, Comics : Shekhar Gurera The Pioneer, New Delhi

- ^ a b Cube 2007

- ^ a b «Manga Industry in Japan» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2012.

- ^ Schodt 1996

- ^ Manga Museum 2009

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 101

- ^ Eshinbun Nipponchi

- ^ Griffiths 2007

- ^ a b Poten

- ^ a b c Shonen Pakku

- ^ Lone 2007, p. 75

- ^ Manga no Kuni

- ^ a b Post, Washington (11 November 2017). «How new technology could alter manga publishing». Daily Herald.

- ^ «How Pixiv Built Japan’s 12th Largest Site With Manga-Girl Drawings (Redesign Sneak Peek And Invites)». 14 December 2011.

- ^ Chapman, Paul. ««One-Punch Man» Anime Greenlit». Crunchyroll.

- ^ Komatsu, Mikikazu. «Watch «Hayate the Combat Butler» Manga Author’s Drawing Video of Nagi». Crunchyroll.

- ^ Chapman, Paul. «Brawny Battling Manga «Kengan Ashura» Makes the Leap to Anime». Crunchyroll.

- ^ «Kodansha Comics May Digital-First Debuts». Anime News Network.

- ^ Nagata, Kazuaki (2 August 2017). «As manga goes digital via smartphone apps, do paper comics still have a place?». Japan Times Online.

- ^ «Manga sales top 600 billion yen in 2020 for first time on record». The Asahi Shimbun. 1 April 2021.

- ^ «Japan’s Manga and Comic Industry Hits Record Profits in 2020». Comicbook.com. 15 March 2021.

- ^ «Kakao mulls listing Japan unit». koreatimes. 5 September 2017.

- ^ «ReLIFE Anime Promotes July Premiere With Animated Promo». Anime News Network.

- ^ «Crunchyroll to Stream Recovery of an MMO Junkie Anime». Anime News Network.

- ^ Pink 2007, Wong 2007

- ^ a b Farago 2007

- ^ Randal, Bill (2005). «English, For Better or Worse». The Comics Journal (Special ed.). Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

- ^ Sugiyama, Rika. Comic Artists—Asia: Manga, Manhwa, Manhua. New York: Harper, 2004. Introduces the work of comics artists in Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong through artist profiles and interviews that provide insight into their processes.

- ^ a b Fishbein 2007

- ^ Berger 1992

- ^ Vollmar 2007

- ^ Mahousu 2005

- ^ Mahousu 2005, ANN 2004, Riciputi 2007

- ^ Breeden, Aurelien (31 July 2021). «France Gave Teenagers $350 for Culture. They’re Buying Comic Books». The New York Times. Vol. 170, no. 59136. p. C1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Brigid Alverson (12 February 2014). «Strong French Manga Market Begins to Dip». publishersweekly.com. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Rich Johnston (1 January 2014). «French Comics In 2013 – It’s Not All Asterix. But Quite A Bit Is». bleedingcool.com. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Jennifer Fishbein (27 December 2007). «Europe’s Manga Mania». Spiegel Online International. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ «The Citi exhibition Manga マンガ». The British Museum. 23 May 2019.

- ^ «Manga in the frame: images from the British Museum exhibition». The Guardian. 23 May 2019.

- ^ «Manga belongs in the British Museum as much as the Elgin marbles». The Guardian. 23 May 2019.

- ^ Patten 2004

- ^ In 1987, «…Japanese comics were more legendary than accessible to American readers», Patten 2004, p. 259

- ^ Napier 2000, pp. 239–256, Clements & McCarthy 2006, pp. 475–476

- ^ Patten 2004, Schodt 1996, pp. 305–340, Leonard 2004

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 309, Rifas 2004, Rifas adds that the original EduComics titles were Gen of Hiroshima and I SAW IT [sic].

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 37, 259–260, Thompson 2007, p. xv

- ^ Leonard 2004, Patten 2004, pp. 52–73, Farago 2007

- ^ Schodt 1996, pp. 318–321, Dark Horse Comics 2004

- ^ Brienza, Casey E. (2009). «Books, Not Comics: Publishing Fields, Globalization, and Japanese Manga in the United States». Publishing Research Quarterly. 25 (2): 101–117. doi:10.1007/s12109-009-9114-2. S2CID 143718638.

- ^ Kwok Wah Lau, Jenny (2003). «4». Multiple modernities: cinemas and popular media in transcultural East Asia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 78.

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 50, 110, 124, 128, 135, Arnold 2000

- ^ Schodt 1996, p. 95

- ^ Arnold 2000, Farago 2007, Bacon 2005

- ^ Horn, Carl Gustav. «Horsepower,» (Dark Horse Comics, March 2007).

- ^ Schodt 1996, pp. 308–319

- ^ «The last million-selling comic book in North America? It’s Batman vs. Pokémon for the title». Comichron. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Reid 2009

- ^ Glazer 2005, Masters 2006, Bosker 2007, Pink 2007

- ^ Magulick, Aaron (8 October 2017). «Viz Manga Sales are Destroying DC, Marvel in Comic Market». GoBoiano. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018.

- ^ «Sales of Manga Books are on the Rise in the United States, The NPD Group Says: A big wave of imported Japanese culture is finding a hungry and growing reading audience». The NPD Group. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ «Japan’s Image morphed from a fierce military empire to eccentric pop culture superpower». Quartz. 21 May 2020.

- ^ «The pandemic has sparked a book craze – and Barnes & Noble is cashing in». Fox Business. 19 September 2021.

- ^ «Streaming Anime Lifts Manga Sales». Publishers Weekly. 7 May 2021.

- ^ «Manga Sales Managed to Double in 2021, Says New Report». comicbook.com. 1 March 2022.

- ^ «Manga sales growth in the United States from 2019 to 2021». Statista. February 2022.

- ^ Stewart 1984

- ^ Crandol 2002

- ^ Tai 2007

- ^

ANN 2002 - ^ ANN 10 May 2006

- ^ ANN 5 May 2006

- ^

Boilet 2001, Boilet & Takahama 2004 - ^ ANN 2007, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2007

- ^ Obunsha Co., Ltd. (18 July 2014). 京都精華大学、入試結果 (倍率)、マンガ学科。 (in Japanese). Obunsha Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Kyoto Seika University. «Kyoto Seika University, Faculty of Manga». Kyoto Seika University. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Shuho Sato; et al. (26 July 2012). 漫画を学校で学ぶ意義とは (in Japanese). togetter. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

Works cited

- Allison, Anne (2000). «Sailor Moon: Japanese superheroes for global girls». In Craig, Timothy J. (ed.). Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0561-0.

- Arnold, Adam (2000). «Full Circle: The Unofficial History of MixxZine». Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Bacon, Michelle (14 April 2005). «Tangerine Dreams: Guide to Shoujo Manga and Anime». Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Berger, Klaus (1992). Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37321-0.

- Boilet, Frédéric (2001). Yukiko’s Spinach. Castalla-Alicante, Spain: Ponent Mon. ISBN 978-84-933093-4-3.

- Boilet, Frédéric; Takahama, Kan (2004). Mariko Parade. Castalla-Alicante, Spain: Ponent Mon. ISBN 978-84-933409-1-9.

- Bosker, Bianca (31 August 2007). «Manga Mania». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Bouquillard, Jocelyn; Marquet, Christophe (1 June 2007). Hokusai: First Manga Master. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-9341-9.

- Brenner, Robin E. (2007). Understanding Manga and Anime. Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited/Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-59158-332-5.

- Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (2006). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917, Revised and Expanded Edition. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-10-5.

- Crandol, Mike (14 January 2002). «The Dirty Pair: Run from the Future». Anime News Network. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Cube (18 December 2007). 2007年のオタク市場規模は1866億円―メディアクリエイトが白書 (in Japanese). Inside for All Games. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- «Dark Horse buys Studio Proteus» (Press release). Dark Horse Comics. 6 February 2004.

- Drazen, Patrick (2003). Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge. ISBN 978-1-880656-72-3.

- Farago, Andrew (30 September 2007). «Interview: Jason Thompson». The Comics Journal. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Fishbein, Jennifer (26 December 2007). «Europe’s Manga Mania». Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- Fukushima, Yoshiko (2013). Manga Discourse in Japan Theatre. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-136-77273-3.

- Gardner, William O. (November 2003). «Attack of the Phallic Girls». Science Fiction Studies (88). Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Glazer, Sarah (18 September 2005). «Manga for Girls». The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Gravett, Paul (2004). Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Harper Design. ISBN 978-1-85669-391-2.

- Gravett, Paul (15 October 2006). «Gekiga: The Flipside of Manga». Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Griffiths, Owen (22 September 2007). «Militarizing Japan: Patriotism, Profit, and Children’s Print Media, 1894–1925». Japan Focus. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Isao, Shimizu (2001). «Red Comic Books: The Origins of Modern Japanese Manga». In Lent, John A. (ed.). Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2471-6.

- Ito, Kinko (2004). «Growing up Japanese reading manga». International Journal of Comic Art (6): 392–401.

- Ito, Kinko (2005). «A history of manga in the context of Japanese culture and society». The Journal of Popular Culture. 38 (3): 456–475. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.2005.00123.x.

- Johnston-O’Neill, Tom (3 August 2007). «Finding the International in Comic Con International». The San Diego Participant Observer. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Katzenstein, Peter J.; Shiraishi, Takashi (1997). Network Power: Japan in Asia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8373-8.

- Kern, Adam (2006). Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02266-9.

- Kern, Adam (2007). «Symposium: Kibyoshi: The World’s First Comicbook?». International Journal of Comic Art (9): 1–486.

- Kinsella, Sharon (2000). Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2318-4.

- Kittelson, Mary Lynn (1998). The Soul of Popular Culture: Looking at Contemporary Heroes, Myths, and Monsters. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9363-8.

- Lee, William (2000). «From Sazae-san to Crayon Shin-Chan». In Craig, Timothy J. (ed.). Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0561-0.

- Lent, John A. (2001). Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2471-6.

- Leonard, Sean (12 September 2004). «Progress Against the Law: Fan Distribution, Copyright, and the Explosive Growth of Japanese Animation» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33684-3.

- Mahousu (January 2005). «Les editeurs des mangas». self-published. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2007.[unreliable source?]

- Masters, Coco (10 August 2006). «America is Drawn to Manga». Time.

- «First International MANGA Award» (Press release). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 29 June 2007.

- McCarthy, Helen (2014). A Brief History of Manga: The Essential Pocket Guide to the Japanese Pop Culture Phenomenon. Hachette UK. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-78157-130-9.

- Napier, Susan J. (2000). Anime: From Akira to Princess Mononoke. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-23863-6.

- Nunez, Irma (24 September 2006). «Alternative Comics Heroes: Tracing the Genealogy of Gekiga». The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Ōgi, Fusami (2004). «Female subjectivity and shōjo (girls) manga (Japanese comics): shōjo in Ladies’ Comics and Young Ladies’ Comics». The Journal of Popular Culture. 36 (4): 780–803. doi:10.1111/1540-5931.00045.

- Onoda, Natsu (2009). God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga. University Press of Mississippi. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-60473-478-2.

- Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-92-1.

- Perper, Timothy; Cornog, Martha (2002). «Eroticism for the masses: Japanese manga comics and their assimilation into the U.S.». Sexuality & Culture. 6 (1): 3–126. doi:10.1007/s12119-002-1000-4. S2CID 143692243.

- Perper, Timothy; Cornog, Martha (2003). «Sex, love, and women in Japanese comics». In Francoeur, Robert T.; Noonan, Raymond J. (eds.). The Comprehensive International Encyclopedia of Sexuality. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1488-5.

- Petersen, Robert S. (2011). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36330-6.

- Prohl, Inken; Nelson, John K (2012). Handbook of Contemporary Japanese Religions. BRILL. p. 596. ISBN 978-90-04-23435-2.

- Pink, Daniel H. (22 October 2007). «Japan, Ink: Inside the Manga Industrial Complex». Wired. Vol. 15, no. 11. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Poitras, Gilles (2001). Anime Essentials: Every Thing a Fan Needs to Know. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge. ISBN 978-1-880656-53-2.

- Reid, Calvin (28 March 2006). «HarperCollins, Tokyopop Ink Manga Deal». Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- Reid, Calvin (6 February 2009). «2008 Graphic Novel Sales Up 5%; Manga Off 17%». Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- Riciputi, Marco (25 October 2007). «Komikazen: European comics go independent». Cafebabel.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.[unreliable source?]

- Rifas, Leonard (2004). «Globalizing Comic Books from Below: How Manga Came to America». International Journal of Comic Art. 6 (2): 138–171.

- Rousmaniere, Nicole (2001). Births and Rebirths in Japanese Art : Essays Celebrating the Inauguration of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures. Hotei Publishing. ISBN 978-90-74822-44-2.

- Sanchez, Frank (1997–2003). «Hist 102: History of Manga». AnimeInfo. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (1986). Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 978-0-87011-752-7.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (2007). The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-54-9.

- Shimizu, Isao (June 1985). 日本漫画の事典 : 全国のマンガファンに贈る (Nihon Manga no Jiten – Dictionary of Japanese Manga) (in Japanese). Sun lexica. ISBN 978-4-385-15586-9.

- Stewart, Bhob (October 1984). «Screaming Metal». The Comics Journal (94).

- Tai, Elizabeth (23 September 2007). «Manga outside Japan». Star Online. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Tchiei, Go (1998). «Characteristics of Japanese Manga». Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Thompson, Jason (2007). Manga: The Complete Guide. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-48590-8.

- Thorn, Matt (July–September 2001). «Shôjo Manga—Something for the Girls». The Japan Quarterly. 48 (3). Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Toku, Masami (Spring 2006). «Shojo Manga: Girl Power!». Chico Statements. California State University, Chico. ISBN 978-1-886226-10-4. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Vollmar, Rob (1 March 2007). «Frederic Boilet and the Nouvelle Manga revolution». World Literature Today. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- Webb, Martin (28 May 2006). «Manga by any other name is…» The Japan Times. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Wong, Wendy Siuyi (2002). Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-269-4.

- Wong, Wendy Siuyi (2006). «Globalizing manga: From Japan to Hong Kong and beyond». Mechademia: an Annual Forum for Anime, Manga, and the Fan Arts. pp. 23–45.

- Wong, Wendy (September 2007). «The Presence of Manga in Europe and North America». Media Digest. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- «About Manga Museum: Current situation of manga culture». Kyoto Manga Museum. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- «Correction: World Manga». Anime News Network. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- «I.C. promotes AmeriManga». Anime News Network. 11 November 2002. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- «Interview with Tokyopop’s Mike Kiley». ICv2. 7 September 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Japan: Profile of a Nation, Revised Edition. Tokyo: Kodansha International. 1999. ISBN 978-4-7700-2384-1.

- «Japan’s Foreign Minister Creates Foreign Manga Award». Anime News Network. 22 May 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- «manga». Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- «Manga-mania in France». Anime News Network. 4 February 2004. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- «‘Manga no Kuni’: A manga magazine from the Second Sino-Japanese War period». Kyoto International Manga Museum. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- «‘Poten’: a manga magazine from Kyoto». Kyoto International Manga Museum. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- «‘Shonen Pakku’; Japan’s first children’s manga magazine». Kyoto International Manga Museum. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- «The first Japanese manga magazine: Eshinbun Nipponchi». Kyoto International Manga Museum. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- «Tokyopop To Move Away from OEL and World Manga Labels». Anime News Network. 5 May 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

Further reading

- «Un poil de culture – Une introduction à l’animation japonaise» (in French). 11 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- Hattie Jones, «Manga girls: Sex, love, comedy and crime in recent boy’s manga and anime,» in Brigitte Steger and Angelika Koch (2013 eds): Manga Girl Seeks Herbivore Boy. Studying Japanese Gender at Cambridge. Lit Publisher, pp. 24–81.

- (in Italian) Marcella Zaccagnino and Sebastiano Contrari. «Manga: il Giappone alla conquista del mondo» (Archive) Limes, rivista italiana di geopolitica. 31 October 2007.

- Unser-Schutz, Giancarla (2015). «Influential or influenced? The relationship between genre, gender and language in manga». Gender and Language. 9 (2): 223–254. doi:10.1558/genl.v9i2.17331.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manga.

- Manga at Curlie

Anime and manga in Japan travel guide from Wikivoyage

This article is about the comics or graphic novels created in Japan. For other uses, see Manga (disambiguation).

| Manga | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Publishers |

|

| Publications |

|

| Creators |

|

| Series |

|

| Languages | Japanese |

| Related articles | |

|

Manga (Japanese: 漫画 [maŋga])[a] are comics or graphic novels originating from Japan. Most manga conform to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century,[1] and the form has a long history in earlier Japanese art.[2] The term manga is used in Japan to refer to both comics and cartooning. Outside of Japan, the word is typically used to refer to comics originally published in the country.[3]

In Japan, people of all ages and walks of life read manga. The medium includes works in a broad range of genres: action, adventure, business and commerce, comedy, detective, drama, historical, horror, mystery, romance, science fiction and fantasy, erotica (hentai and ecchi), sports and games, and suspense, among others.[4][5] Many manga are translated into other languages.[6]