Philips — торговая марка потребительской электроники, бытовой техники для кухни и дома, а также товаров для красоты и здоровья.

Компания Koninklijke Philips N.V. (англ. Royal Philips) появилась в 1891 году как небольшая фабрика по производству электрических лам. Теперь это международный концерн, деятельность которого делится на три направления:

- здравоохранение

- световые решения

- потребительские товары

В 2012 году Philips и один из крупнейших мировых производителей компьютерных мониторов и ЖК-телевизоров TPV Technology (бренд AOC) создали совместное предприятие под названием TP Vision. Доли были распределены так: 70% новой компании получила гонконгская TPV Technology, а 30% — концерн Royal Philips. Именно TP Vision сегодня занимается производством телевизоров под брендом Philips.

Продукция

Производство

Страны-производители Philips

Страна сборки техники, поставляемой в Россию, зависит от типа продукции:

- Россия — телевизоры

- Китай — DVD-плееры, микрофоны, наушники и гарнитуры, блендеры, мясорубки, миксеры, мультиварки, тостеры, хлебопечки, кофеварки, соковыжималки, пароочистители, пылесосы, утюги, машинки для стрижки волос, фены, щипцы и плойки для укладки волос, бритвы

- Румыния — кофемашины

- Италия — кофемашины

- Чехия — миксеры

- Венгрия — миксеры, кухонные комбайны

- Сингапур — чайники

- Польша — чайники, пылесосы

- Южная Корея — воздухоочистители и увлажнители,

- Индонезия — утюги, машинки для стрижки волос

- Сингапур — утюги

- Нидерланды — утюги с парогенератором, бритвы

- Великобритания — молокоотсосы

Поставщики Philips

Современные телевизоры нуждаются в предварительной настройке: подключение к сети, поиск каналов. В целом, процедура интуитивно понятная: следует просто довериться подсказкам системы. Однако у некоторых пользователей все равно возникают трудности. Ниже мы приведем подробный мануал для телевизоров марки Philips.

Поддерживает ли телевизор цифровое ТВ

Если сохранилась коробка от аппарата, то на ней должна быть краткая спецификация с указанием поддержки формата DVB-T2. Аналогичную информацию можно найти в инструкции по эксплуатации. Если документация отсутствует, то стоит осмотреть тыловую панель телевизора. Интерфейс с маркировкой DigitalInput говорит о том, что модель поддерживает цифровое ТВ.

Важно! Устройства, выпущенные до 1998 года, не работают с форматом DVB-T2. Техника до 2004 года оснащалась цифровыми выходами лишь отчасти: это были дорогие телевизоры с диагональю больше 40 дюймов. Повсеместно формат начал внедряться после 2005 года.

Также можно посетить сайт бренда. После ввода в поисковой строке модели телевизора откроется страница с подробным описанием устройства, где указаны все характеристики, в том числе поддержка DVB-T2. В качестве альтернативы официальному ресурсу можно использовать тот же «Яндекс Маркет» или любые другие крупные торговые площадки. Если телевизор не поддерживает цифровое вещание, то придётся покупать специальную приставку.

Приставка для цифрового ТВ

Первичная настройка

В случае с новой техникой потребуется первичная настройка. Модели, купленные в отечественных магазинах, имеют русскоязычную локализацию, поэтому серьёзных проблем быть не должно. Первым делом необходимо выставить язык интерфейса. Переходим посредством настроек в языковую панель и выбираем «Русский».

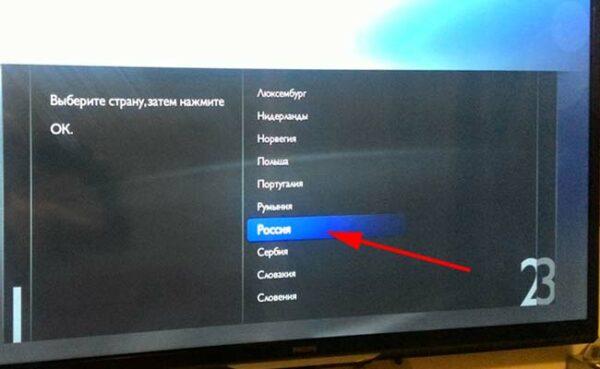

Таким же образом указываем страну – Россия. В противном случае часть функционала может работать некорректно. Нелишним будет указать часовой пояс и задать правильное время, если система не сделала это в автоматическом порядке: пригодится при активации таймера и других возможностей, привязанных к временным интервалам.

Указываем страну — Россия

Модели формата SmartTV при первом включении могут запросить информацию о месте установке телевизора – дома или в магазине. В последнем случае будут транслироваться демонстрационные ролики и только, тогда как вариант «Дом» открывает все возможности. Также мастер-помощник спросит о типе установки – подставка или настенное крепление, открыв тем самым специфические настройки для каждого варианта.

Подключение антенны

Подсоединять антенну необходимо при отключённом питании, иначе можно перегрузить блок управления. Важно не перепутать эфирный вход (RF-IN) со спутниковым (SatelliteIN). Последний идёт с резьбой, а внутренняя его часть заполнена пластиком с небольшим отверстием посередине.

Эфирный вход чуть больше в диаметре и полый внутри. Штекер должен вставляться с небольшим усилием и не ходить в разъёме. Плохой контакт – это шумы, артефакты и прочие проблемы с изображением. Иногда разъём маркируется как ANT.

Антенный вход на телевизоре

Автоматический поиск каналов

После подключения антенны нужно провести сканирование каналов. Часть моделей проводят эту процедуру в автоматическом порядке, тогда как другие требуют ручной настройки. Конкретные шаги зависят от года выпуска телевизора.

Техника до 2011 года выпуска:

- Заходим в настройки нажав на клавишу Home.

- Открываем раздел «Конфигурация».

- Переходим на вкладку «Установка» и соглашаемся с предупреждением ОС о последствиях вносимых изменений.

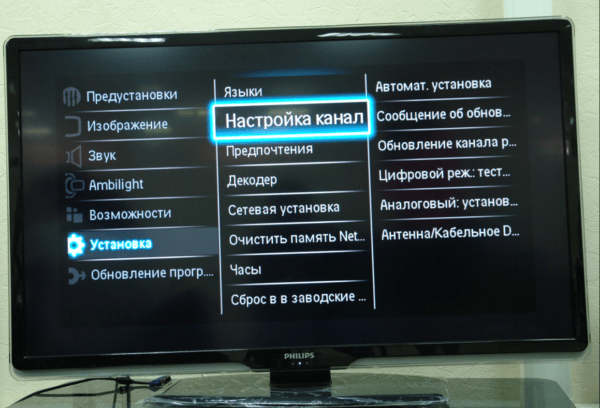

- Кликаем на «Настройка каналов» -> «Автоматическая» -> «Запуск».

- Некоторые прошивки предлагают выбрать страну. Если в перечне нет России, то останавливаемся на Швейцарии, Финляндии или Германии.

- Ставим галочку на пункте «Цифровой» в «Режиме настройки».

- В качестве источника сигнала выбираем «ТВ-антенна».

- Нажимаем «Автопоиск» и дожидаемся окончания процедуры.

- Сохраняем найденные каналы нажатием на «Готово».

Важно! На одном из этапов операционная система может потребовать ввести пароль. Если ранее он не менялся, то должны подойти варианты: 0000, 1234 или 1111.

Меню настройки каналов

Настройка каналов на современных ТВ:

- Заходим в основное меню нажатием на клавишу Home.

- Кликаем на разделе «Установка».

- Открываем подменю «Поиск каналов».

- В следующем окне выбираем «Переустановить каналы».

- В выпадающем списке стран кликаем на России (Германия, Финляндия, Швеция).

- Устанавливаем режим поиска – цифровой.

- Источник сигнала – антенна.

- Нажимаем на «Сканирование частоты» -> «Быстрое» -> «Запуск».

- Дожидаемся окончания процедуры и сохраняем изменения.

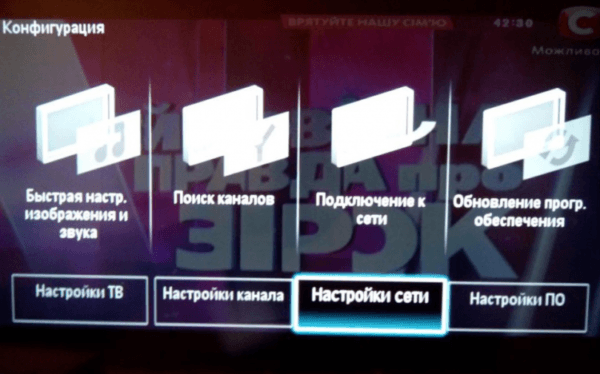

Сетевые настройки SmartTV

Для техники формата SmartTV может дополнительно потребоваться ручная подстройка сети. Это необходимо в первую очередь для получения обновлений прошивки, что позволит по максимуму использовать возможности телевизора.

Настройка сети на Филипс

Настройка сети на SmartTV:

- Подключаем кабель к ТВ или активируем беспроводной роутер.

- В настройках выбираем «Подключиться к сети».

- Кликаем на нужной строчке: кабель или Wi-Fi.

- В случае с роутером запускаем сканирование и при необходимости вводим пароль.

- Если версия прошивки не актуальна, то при установлении соединения ОС предложит её обновить.

После окончания процедуры можно приступать к сканированию каналов. На смарт-ТВ достаточно открыть пункт «Настройка каналов» и нажать на клавишу «Поиск». Всё остальное ОС сделает сама.

Ручная настройка каналов

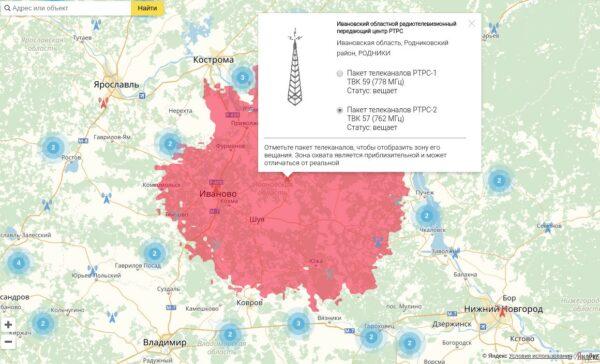

Если с автоматическим поиском возникают какие-то проблемы, то сканирование можно выполнить в ручном режиме. Узнать конкретные данные вещания цифрового ТВ можно с помощью онлайн-сервиса РТРС. Достаточно указать ближайшую вышку.

Параметры вышки для ручной настройки

Ручная настройка цифрового вещания:

- Открываем меню ТВ и переходим в настройки.

- Кликаем на разделе «Установка».

- Заходим в «Поиск каналов»

- Выбираем «Ручной режим».

- Вводим данные с сайта РТРС.

- Запускаем сканирование.

- По окончании сохраняем список каналов.

Поиск может заметно затянуться, если вышка находится на значительном расстоянии от антенны. Когда за окном сильный дождь, гроза и другая непогода, то сканирование лучше перенести на другой более погожий день.

Если все манипуляции были выполнены без ошибок, «умное» изделие начинает показывать все сохраненные цифровые каналы, которые доступны в вашем регионе. При возникновении проблем с показом, стоит узнать, почему телевизор не ловит каналы.

Вот и все сложности, как настроить цифровые каналы на телевизоре Филипс, когда у него имеются функции современного Смарт ТВ. Возможно, многим пользователем поможет при выполнении таких настроек следующее видео:

Очередная статья с секретными кодами… Будем идти по нарастающей. Рассматриваем для начала не очень популярные марки сотовых телефонов, чтобы потом перейти наконец к более распространённым. Да, такие марки как LG, Alcatel, Philips выбирает меньшее количество людей, но всё-таки кто-то их выбирает. Поэтому обойти вниманием эти телефоны никак не могу.

Сегодня — секретные коды для Philips.

*#4377*# — включение / отключение подзарядки аккумулятора, если телефон подключен к зарядному устройству

*#47*# — включение / выключение Half Rate — кодека, обеспечивающего баланс между загруженностью сети и качеством связи

*#337*# — вкл/выкл улучшенного кодирования речи. Влияет на качество звука и скорость разряда батареи.

Представленные секретные коды для Philips могут не работать на вашей модели. Если возникнут какие-то вопросы, пишите в ОБРАТНУЮ СВЯЗЬ. Спасибо!

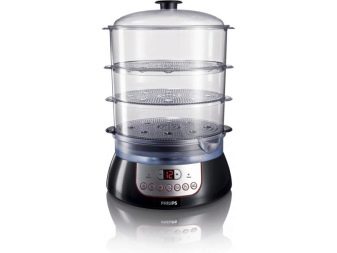

На современной кухне присутствует много полезных девайсов, среди которых особенно выделяется пароварка. Такие изделия помогают приготовить максимально полезные и вкусные блюда. В этой статье поговорим о пароварках от известного бренда Philips.

Комплектующие

Среди всех пароварок Philips наиболее популярные модели – это HD 9120 и HD 9140. У каждой – по три паровые корзины и одинаковые показатели мощности. А по цене они очень даже демократичны.

Данные модели являются аналогом большинства пароварок, которые можно увидеть в продаже. В нижней части изделия есть камера для разогрева воды, откуда и поступает пар. Над нею расположены отсеки для размещения пищи, которая готовится именно благодаря поступлению из нижнего отсека горячего пара.

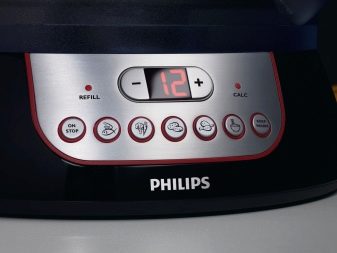

В управлении пароваркой Philips нет ничего сложного, нужно просто понимать, что обозначают знаки на кнопках её управляющей панели (включить-выключить, приготовление рыбы, овощей, курицы и так далее). Выбрав необходимый режим, вы просто устанавливаете время, необходимое на готовку блюда. Когда оно закончится, пароварка автоматически выключится.

Как правило, в пароварке имеется три корзины для размещения в них продуктов. В основании каждой из них находится отверстие, благодаря которому происходит распространение пара. Корзины бывают двух типов – одинаковые по размеру и разные, которые можно вставлять одна в одну.

В комплекте с пароваркой идёт чаша, расположенная в одной из корзин. В этой чаше можно отваривать рис. И ещё один атрибут пароварки – это держатели для шести яиц.

Процесс готовки риса обычным способом, в кастрюле, займёт минут 20, а в пароварке процесс будет более длительным, зато и результат впечатлит отличным вкусом и зёрнами, которые будут каждое отдельно, не слипшиеся.

У одинаковых по ёмкости корзин обычно имеются добавочные адаптеры — внешние датчики воды. Это очень удобно, ведь так удобно вести контроль за оставшимся количеством воды в ёмкости и не допустить процесса кипения всухую.

Ещё одна комплектующая – это «носик», через который заливают воду. Благодаря ему, делать это можно без снятия корзин, а значит ошпариваний, как и ожогов можно, таким образом, избежать.

В пароварке обязательно имеется метка, находящаяся в наружной части ёмкости под воду и показывающая максимально допустимый уровень воды, а также минимально допустимый. Если нарушить правило и налить воды выше, пароварка будет выплёскивать излишки воды, причём горячие.

Особенности

Если корзины в пароварке все одинакового размера, то есть возможность менять их местами, изменяя, таким образом, воздействие на них температуры. Это относится к плюсам, а минус в данном случае будет в том, что корзины не могут быть компактно сложены одна в одну.

Если же корзины разного размера, то в данном случае плюс будет в возможности их компактного хранения, а минус – в невозможности менять корзины местами, так что процесс готовки в этом случае должен быть обдуман заранее.

Довольно частое явление – съёмное основание у пароварки. Таким образом, процесс готовки становится более гибким – убрав основание, количество пара можно увеличить. Кроме того, при съёмном основании, облегчается ручная чистка пароварки, да и в посудомойку так её легче уложить.

Основные преимущества

На большинстве таких устройств находятся таймеры, с помощью которых можно установить время, которое понадобится на приготовление того или иного блюда. Когда время закончится, пароварка уведомит вас об этом коротким звоночком.

На некоторых моделях имеются удобные ручки, чтобы их переносить с места на место, например, в посудомоечную машину или на хранение в шкаф. Эти устройства хороши ещё и тем, что еда в них после приготовления будет оставаться горячей ещё в течение минимум часа, а то и двух.

Эта функция специально настраивается во время готовки, только не забудьте проверить, чтобы по завершению процесса готовки, вода в нижней ёмкости ещё бы оставалась. В противном случае, еда не сохранится горячей, потому что процесс не сможет функционировать.

Кроме того, в некоторых моделях Philips есть специальная ёмкость, в которую собирается сок. Она имеет вид дополнительной чаши непосредственно над водяной камерой. Полученный сок может быть основой соуса или супа.

Daily Collection

В этой модели дополнительно есть уникальный контейнер, в котором можно размещать травы и специи, что придаёт готовящемуся блюду уникальные вкусовые качества. Вы можете просто положить те приправы, которые любите больше всего, а пар выполнит остальную работу, насытив готовое блюдо непередаваемым ароматом тех специй, которые вы предпочитаете.

Какая модель лучше?

Для любой модели Philips, прежде всего, важны система её управления, а также рабочая мощность. На эти параметры в первую очередь обращают внимание, когда покупают пароварку.

Есть такое мнение, что лучшей моделью является та, мощность которой самая большая. Однако, с этим утверждением можно поспорить. Ведь на многих таких устройствах мощность регулируется и может быть выставлена, как 650 Вт, так и все 2000. Понятно, что при более высокой мощности процесс готовки будет идти быстрее, но скорость зависит и от количества пара, то есть – от величины самой корзины, в которой находится еда и от типа конструкции изделия.

Но какая же модель Philips самая хорошая? Если не самая мощная, тогда какая? Однозначно на такой вопрос не ответить, потому что при выборе пароварки, должно учитываться всё вместе, а не один какой-то параметр. Многое зависит, например, от системы управления, казалось бы – что там особенного, всё же предельно просто, но здесь существуют небольшие особенности. Все модели Philips подразделяются на два вида:

Электронная система управления

Это самые функциональные изделия. Здесь возможно отсрочить готовку или подогревать готовую еду заданное время. У этой системы управления обязательно имеется дисплей, показывающий все режимы, заданные устройству.

Механическое управление

Эти изделия марки Philips хороши по-своему. Прежде всего, не нужно разбираться с мудрёными режимами и кучей непонятных кнопок. Вы можете просто задать по таймеру время готовки и больше ни о чём не думать – в нужный момент пароварка вас уведомит, что еда готова.

Критерии выбора

Если все изделия хороши, то на каком же остановиться? Первым делом, осмотрите поддон. Его бортики не должны быть ниже, чем 2-2,5 сантиметра, иначе вы будете иметь с ними кучу проблем, то и дело, сливая конденсат, который в поддоне будет накапливаться. Это лишняя трата вашего времени, с таким устройством вам не удастся просто задать время и удалиться – придётся постоянно находиться рядом.

А не сливать лишнюю воду никак нельзя, потому что устройство может прийти в негодность из-за того, что в нагревательный элемент попадёт влага. Важно также, чтобы у поддона имелись ручки, ведь конденсат будет всегда горячим и без специальных ручек можно будет легко обжечь руки.

Другой критерий отбора пароварки Philips – количество поддонов. Несколько поддонов потребуется в том случае, если пропитка блюд, которые помещены в нижние корзины, верхними ароматами нежелательна. Но, возможно, вы считаете, что это даже хорошо, если овощи пропитались ароматом мяса – тогда выбирайте модель с одним поддоном.

Если же в комплект выбранной вами модели Philips входит чаша для риса, верхние продукты можно уложить в неё, и тогда сок сверху не будет протекать в нижние корзины.

Это все основные параметры, по которым обычно выбирают пароварки, и только вам решать, какую именно выберете вы.

Отзывы

Отзывы о пароварках фирмы Philips в подавляющем большинстве случаев положительные. Многие пишут о пользе пищи, приготовленной на пару, о том, что готовка не требует постоянного вашего присутствия – очень удобно пользоваться — включить и забыть о кухне, пока не услышите звонок.

Пользователи также отмечают возможность готовить одновременно несколько блюд (это зависит от количества ярусов), а также простоту ухода за изделием. Нравится и то, как легко управлять устройством – просто наливается в отсек вода и на нужное время включается таймер. Пароварку Philips с прозрачным корпусом расхваливают за то, что можно наблюдать за всем процессом приготовления пищи.

Недовольство вызывает ситуация, при которой после готовки в поддоне и в ёмкости для специй собирается столько воды, что донести до раковины, не разлив её – никак не получается. Но это происходит только при изначальном максимальном уровне воды – это во-первых, а во-вторых, можно ведь, прежде, чем в раковину нести, отчерпнуть немного воды в какую-нибудь ёмкость. Так что недостаток этот вовсе и не недостаток никакой.

Headquarters in Amsterdam, 2009 |

|

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Type | Public (N.V.) |

|

Traded as |

|

| Industry | Conglomerate |

| Founded | 15 May 1891; 131 years ago Eindhoven, Netherlands |

| Founders | Gerard and Anton Philips |

| Headquarters | Amsterdam, Netherlands |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

74,451 (2022) |

| Website | philips.com |

| Footnotes / references [1] |

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (lit. ‘Royal Philips’), commonly shortened to Philips, is a Dutch multinational conglomerate corporation that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, it has been mostly headquartered in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarters is still in Eindhoven. Philips was formerly one of the largest electronics companies in the world, but is currently focused on the area of health technology, having divested its other divisions.

The company was founded in 1891 by Gerard Philips and his father Frederik, with their first products being light bulbs. It currently employs around 80,000 people across 100 countries.[2] The company gained its royal honorary title (hence the Koninklijke) in 1998 and dropped the «Electronics» in its name in 2013,[3] due to its refocusing from consumer electronics to healthcare technology.

Philips is organized into three main divisions: Personal Health (formerly Philips Consumer Electronics and Philips Domestic Appliances and Personal Care), Connected Care, and Diagnosis & Treatment (formerly Philips Medical Systems).[4] The lighting division was spun off as a separate company, Signify N.V.

The company started making electric shavers in 1939 under the Philishave and Norelco brands, and post-war they developed the Compact Cassette format and co-developed the Compact Disc format with Sony, as well as numerous other technologies. As of 2012, Philips was the largest manufacturer of lighting in the world as measured by applicable revenues.

Philips has a primary listing on the Euronext Amsterdam stock exchange and is a component of the Euro Stoxx 50 stock market index.[5] It has a secondary listing on the New York Stock Exchange. Acquisitions include that of Signetics and Magnavox. It also founded a multidisciplinary sports club called PSV Eindhoven in 1913.

History[edit]

The Philips Company was founded in 1891, by Dutch entrepreneur Gerard Philips and his father Frederik Philips. Frederik, a banker based in Zaltbommel, financed the purchase and setup of an empty factory building in Eindhoven, where the company started the production of carbon-filament lamps and other electro-technical products in 1892. This first factory has since been adapted and is used as a museum.[6]

The very first Philips factory in Eindhoven, now a public museum

In 1895, after a difficult first few years and near-bankruptcy, the Philipses brought in Anton, Gerard’s younger brother by sixteen years. Though he had earned a degree in engineering, Anton started work as a sales representative; soon, however, he began to contribute many important business ideas. With Anton’s arrival, the family business began to expand rapidly, resulting in the founding of Philips Metaalgloeilampfabriek N.V. (Philips Metal Filament Lamp Factory Ltd.) in Eindhoven in 1908, followed in 1912, by the foundation of Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken N.V. (Philips Lightbulb Factories Ltd.). After Gerard and Anton Philips changed their family business by founding the Philips corporation, they laid the foundations for the later multinational.

In the 1920s, the company started to manufacture other products, such as vacuum tubes.

In 1924, Philips joined with German lamp trust Osram to form the Phoebus cartel.[7]

Radio[edit]

Share of the Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken, issued 14 December 1928

On 11 March 1927, Philips went on the air, inaugurating the shortwave radio station PCJJ (later PCJ) which was joined in 1929 by a sister station (Philips Omroep Holland-Indië, later PHI). PHOHI broadcast in Dutch to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and later PHI broadcast in English and other languages to the Eastern hemisphere, while PCJJ broadcast in English, Spanish and German to the rest of the world.[citation needed]

The international program Sundays commenced in 1928, with host Eddie Startz hosting the Happy Station show, which became the world’s longest-running shortwave program. Broadcasts from the Netherlands were interrupted by the German invasion in May 1940. The Germans commandeered the transmitters in Huizen to use for pro-Nazi broadcasts, some originating from Germany, others concerts from Dutch broadcasters under German control.

Philips ‘Chapel’ radio model 930A, 1931

In the early 1930s, Philips introduced the «Chapel», a radio with a built-in loudspeaker.

Philips Radio was absorbed shortly after liberation when its two shortwave stations were nationalised in 1947 and renamed Radio Netherlands Worldwide, the Dutch International Service. Some PCJ programs, such as Happy Station, continued on the new station.

Stirling engine[edit]

Philips was instrumental in the revival of the Stirling engine when, in the early 1930s, the management decided that offering a low-power portable generator would assist in expanding sales of its radios into parts of the world where mains electricity was unavailable and the supply of batteries uncertain. Engineers at the company’s research lab carried out a systematic comparison of various power sources and determined that the almost forgotten Stirling engine would be most suitable, citing its quiet operation (both audibly and in terms of radio interference) and ability to run on a variety of heat sources (common lamp oil – «cheap and available everywhere» – was favoured).[8] They were also aware that, unlike steam and internal combustion engines, virtually no serious development work had been carried out on the Stirling engine for many years and asserted that modern materials and know-how should enable great improvements.[9]

Encouraged by their first experimental engine, which produced 16 W of shaft power from a bore and stroke of 30 mm × 25 mm,[10] various development models were produced in a program which continued throughout World War II. By the late 1940s, the ‘Type 10’ was ready to be handed over to Philips’s subsidiary Johan de Witt in Dordrecht to be produced and incorporated into a generator set as originally planned. The result, rated at 180/200 W electrical output from a bore and stroke of 55 mm × 27 mm, was designated MP1002CA (known as the «Bungalow set»). Production of an initial batch of 250 began in 1951, but it became clear that they could not be made at a competitive price, besides the advent of transistor radios with their much lower power requirements meant that the original rationale for the set was disappearing. Approximately 150 of these sets were eventually produced.[11]

In parallel with the generator set, Philips developed experimental Stirling engines for a wide variety of applications and continued to work in the field until the late 1970s, though the only commercial success was the ‘reversed Stirling engine’ cryocooler. However, they filed a large number of patents and amassed a wealth of information, which they later licensed to other companies.[12]

Shavers[edit]

The first Philips shaver was introduced in 1939, and was simply called Philishave. In the US, it was called Norelco. The Philishave has remained part of the Philips product line-up until the present.

World War II[edit]

On 9 May 1940, the Philips directors learned that the German invasion of the Netherlands was to take place the following day. Having prepared for this, Anton Philips and his son-in-law Frans Otten, as well as other Philips family members, fled to the United States, taking a large amount of the company capital with them. Operating from the US as the North American Philips Company, they managed to run the company throughout the war. At the same time, the company was moved (on paper) to the Netherlands Antilles to keep it out of German hands.[13]

On 6 December 1942, the British No. 2 Group RAF undertook Operation Oyster, which heavily damaged the Philips Radio factory in Eindhoven with few casualties among the Dutch workers and civilians.[14] The Philips works in Eindhoven was bombed again by the RAF on 30 March 1943.[15][16]

Frits Philips, the son of Anton, was the only Philips family member to stay in the Netherlands. He saved the lives of 382 Jews by convincing the Nazis that they were indispensable for the production process at Philips.[17] In 1943, he was held at the internment camp for political prisoners at Vught for several months because a strike at his factory reduced production. For his actions in saving the hundreds of Jews, he was recognized by Yad Vashem in 1995 as a «Righteous Among the Nations».[18]

1945–1999[edit]

After the war, the company was moved back to the Netherlands, with their headquarters in Eindhoven.

The Philips Light Tower in Eindhoven, originally a light bulb factory and later the company headquarters[19]

The Evoluon in Eindhoven, opened in 1966

In 1949, the company began selling television sets.[20] In 1950, it formed Philips Records, which eventually formed part of PolyGram in 1962.

Philips introduced the Compact Cassette audio tape format in 1963, and it was wildly successful. Cassettes were initially used for dictation machines for office typing stenographers and professional journalists. As their sound quality improved, cassettes would also be used to record sound and became the second mass media alongside vinyl records used to sell recorded music.

An early portable Compact Cassette recorder by Philips (model D6350)

Philips introduced the first combination portable radio and cassette recorder, which was marketed as the «radio recorder», and is now better known as the boom box. Later, the cassette was used in telephone answering machines, including a special form of cassette where the tape was wound on an endless loop. The C-cassette was used as the first mass storage device for early personal computers in the 1970s and 1980s. Philips reduced the cassette size for professional needs with the Mini-Cassette, although it would not be as successful as the Olympus Microcassette. This became the predominant dictation medium up to the advent of fully digital dictation machines.[citation needed] Philips continued with computers through the early 1990s (see separate article: Philips Computers).

In 1972, Philips launched the world’s first home video cassette recorder, in the UK, the N1500. Its relatively bulky video cassettes could record 30 minutes or 45 minutes. Later one-hour tapes were also offered. As the competition came from Sony’s Betamax and the VHS group of manufacturers, Philips introduced the N1700 system which allowed double-length recording. For the first time, a 2-hour movie could fit onto one video cassette. In 1977, the company unveiled a special promotional film for this system in the UK, featuring comedy writer and presenter Denis Norden.[21] The concept was quickly copied by the Japanese makers, whose tapes were significantly cheaper. Philips made one last attempt at a new standard for video recorders with the Video 2000 system, with tapes that could be used on both sides and had 8 hours of total recording time. As Philips only sold its systems on the PAL standard and in Europe, and the Japanese makers sold globally, the scale advantages of the Japanese proved insurmountable and Philips withdrew the V2000 system and joined the VHS Coalition.[citation needed]

Philips CD-100, the second ever commercially released CD player (after partner Sony’s CDP-101)

Philips had developed a LaserDisc early on for selling movies, but delayed its commercial launch for fear of cannibalizing its video recorder sales. Later Philips joined with MCA to launch the first commercial LaserDisc standard and players. In 1982, Philips teamed with Sony to launch the Compact Disc; this format evolved into the CD-R, CD-RW, DVD and later Blu-ray, which Philips launched with Sony in 1997[22] and 2006 respectively.

In 1984, the Dutch Philips Group bought out nearly a one-third share and took over the management of the German company Grundig.

In 1984, Philips split off its activities on the field of photolithographic integrated circuit production equipment, the so-called wafer steppers, into a joint venture with ASM International, located in Veldhoven under the name ASML. Over the years, this new company has evolved into the world’s leading manufacturer of chip production machines at the expense of competitors like Nikon and Canon.

Philips partnered with Sony again later to develop a new «interactive» disc format called CD-i, described by them as a «new way of interacting with a television set».[23] Philips created the majority of CD-i compatible players. After low sales, Philips repositioned the format as a video game console, but it was soon discontinued after being heavily criticized amongst the gaming community.[24][25]

In the 1980s, Philips’s profit margin dropped below 1 percent, and in 1990 the company lost more than US$2 billion (biggest corporate loss in Dutch history). Troubles for the company continued into the 1990s as its status as a leading electronics company was swiftly lost.[26]

In 1985, Philips was the largest founding investor in TSMC[27] which was established as a joint venture between Philips, the Taiwan government and other private investors.

In 1991, the company’s name was changed from N.V. Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken to Philips Electronics N.V.[28] At the same time, North American Philips was formally dissolved, and a new corporate division was formed in the US with the name Philips Electronics North America Corp.[citation needed]

In 1997, the company officers decided to move the headquarters from Eindhoven to Amsterdam along with the corporate name change to Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V., the latter of which was finalized on 16 March 1998.[29]

In 1998, looking to spur innovation, Philips created an Emerging Businesses group for its Semiconductors unit, based in Silicon Valley. The group was designed to be an incubator where promising technologies and products could be developed.[30][31]

2000s[edit]

The move of the headquarters to Amsterdam was completed in 2001. Initially, the company was housed in the Rembrandt Tower. In 2002, it moved again, this time to the Breitner Tower. Philips Lighting, Philips Research, Philips Semiconductors (spun off as NXP in September 2006), and Philips Design, are still based in Eindhoven. Philips Healthcare is headquartered in both Best, Netherlands (near Eindhoven) and Andover, Massachusetts, United States (near Boston).

In 2000, Philips bought Optiva Corporation, the maker of Sonicare electric toothbrushes. The company was renamed Philips Oral Healthcare and made a subsidiary of Philips DAP. In 2001, Philips acquired Agilent Technologies’ Healthcare Solutions Group (HSG) for EUR 2 billion.[32] Philips created a computer monitors joint venture with LG called LG.Philips Displays in 2001.

In 2001, after growing the unit’s Emerging Businesses group to nearly $1 billion in revenue, Scott A. McGregor was named the new president and CEO of Philips Semiconductors. McGregor’s appointment completed the company’s shift to having dedicated CEOs for all five of the company’s product divisions, which would in turn leave the Board of Management to concentrate on issues confronting the Philips Group as a whole.[30]

In February 2001 Philips sold its remaining interest in battery manufacturing to its then partner Matsushita (which itself became Panasonic in 2008).[33][34]

In 2004, Philips abandoned the slogan «Let’s make things better» in favour of a new one: «Sense and Simplicity».[35]

In December 2005, Philips announced its intention to sell or demerge its semiconductor division. On 1 September 2006, it was announced in Berlin that the name of the new company formed by the division would be NXP Semiconductors. On 2 August 2006, Philips completed an agreement to sell a controlling 80.1% stake in NXP Semiconductors to a consortium of private equity investors consisting of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR), Silver Lake Partners and AlpInvest Partners. On 21 August 2006, Bain Capital and Apax Partners announced that they had signed definitive commitments to join the acquiring consortium, a process which was completed on 1 October 2006.[citation needed]

In 2006, Philips bought out the company Lifeline Systems headquartered in Framingham, Massachusetts, in a deal valued at $750 million, its biggest move yet to expand its consumer-health business (M).[36] In August 2007, Philips acquired the company Ximis, Inc. headquartered in El Paso, Texas, for their Medical Informatics Division.[37] In October 2007, it purchased a Moore Microprocessor Patent (MPP) Portfolio license from The TPL Group.

On 21 December 2007, Philips and Respironics, Inc. announced a definitive agreement pursuant to which Philips acquired all of the outstanding shares of Respironics for US$66 per share, or a total purchase price of approximately €3.6 billion (US$5.1 billion) in cash.[38]

On 21 February 2008, Philips completed the acquisition of VISICU in Baltimore, Maryland, through the merger of its indirect wholly-owned subsidiary into VISICU. As a result of that merger, VISICU has become an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Philips. VISICU was the creator of the eICU concept of the use of Telemedicine from a centralized facility to monitor and care for ICU patients.[39]

The Philips physics laboratory was scaled down in the early 21st century, as the company ceased trying to be innovative in consumer electronics through fundamental research.[40]

2010s[edit]

Philips made several acquisitions during 2011, announcing on 5 January 2011 that it had acquired Optimum Lighting,[41] a manufacturer of LED based luminaires. In January 2011, Philips agreed to acquire the assets of Preethi, a leading India-based kitchen appliances company.[42] On 27 June 2011, Philips acquired Sectra Mamea AB, the mammography division of Sectra AB.[43]

Because net profit slumped 85 percent in Q3 2011, Philips announced a cut of 4,500 jobs to match part of an €800 million ($1.1 billion) cost-cutting scheme to boost profits and meet its financial target.[44] In 2011, the company posted a loss of €1.3 billion, but earned a net profit in Q1 and Q2 2012, however the management wanted €1.1 billion cost-cutting which was an increase from €800 million and may cut another 2,200 jobs until end of 2014.[45]

In March 2012, Philips announced its intention to sell, or demerge its television manufacturing operations to TPV Technology.[46]

Following two decades in decline, Philips went through a major restructuring, shifting its focus from electronics to healthcare. Particularly from 2011 when a new CEO was appointed, Frans van Houten. The new health and medical strategy have helped Philips to thrive again in the 2010s.[26]

On 5 December 2012, the antitrust regulators of the European Union fined Philips and several other major companies for fixing prices of TV cathode-ray tubes in two cartels lasting nearly a decade.[47]

On 29 January 2013, it was announced that Philips had agreed to sell its audio and video operations to the Japan-based Funai Electric for €150 million, with the audio business planned to transfer to Funai in the latter half of 2013, and the video business in 2017.[48][49][50] As part of the transaction, Funai was to pay a regular licensing fee to Philips for the use of the Philips brand.[49] The purchase agreement was terminated by Philips in October because of breach of contract[51] and the consumer electronics operations remain under Philips. Philips said it would seek damages for breach of contract in the US$200-million sale.[52] In April 2016, the International Court of Arbitration ruled in favour of Philips, awarding compensation of €135 million in the process.[53]

In April 2013, Philips announced a collaboration with Paradox Engineering for the realization and implementation of a «pilot project» on network-connected street-lighting management solutions. This project was endorsed by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC).[54]

In 2013, Philips removed the word «Electronics» from its name – becoming Royal Philips N.V.[55] On 13 November 2013, Philips unveiled its new brand line «Innovation and You» and a new design of its shield mark. The new brand positioning is cited by Philips to signify company’s evolution and emphasize that innovation is only meaningful if it is based on an understanding of people’s needs and desires.[56]

On 28 April 2014, Philips agreed to sell their Woox Innovations subsidiary (consumer electronics) to Gibson Brands for $US135 million. On 23 September 2014, Philips announced a plan to split the company into two, separating the lighting business from the healthcare and consumer lifestyle divisions.[57] It moved to complete this in March 2015 to an investment group for $3.3 billion.[58]

In February 2015, Philips acquired Volcano Corporation to strengthen its position in non-invasive surgery and imaging.[59] In June 2016, Philips spun off its lighting division to focus on the healthcare division.[60] In June 2017, Philips announced it would acquire US-based Spectranetics Corp, a manufacturer of devices to treat heart disease, for €1.9 billion (£1.68 billion) expanding its current image-guided therapy business.

In May 2016, Philips’ lighting division Philips Lighting went through a spin-off process, and became an independent public company named Philips Lighting N.V.[61]

In 2017, Philips launched Philips Ventures, with a health technology venture fund as its main focus. Philips Ventures invested in companies including Mytonomy (2017) and DEARhealth (2019).[62][63]

On July 18th, 2017, Philips announced it’s acquisition of TomTec Imaging Systems GmbH.[64][65]

In 2018, the independent Philips Lighting N.V. was renamed Signify N.V. However, it continues to produce and market Philips-branded products such as Philips Hue color-changing LED light bulbs.[66]

2020s[edit]

In 2022, Philips announced that Frans Van Houten, who had served as CEO for 12 years will be stepping down and is to be replaced by Philips’s EVP and Chief Business Leader of Connected Care, Roy Jakobs, effective October 15, 2022.[67][68]

In 2023, the company announced that it would be cutting 6,000 jobs from the company worldwide over the next two years after reporting 1.6 billion euros in losses during the 2022 financial year. The cuts came in addition to a 4,000 staff reduction being announced in October 2022.[69]

Corporate affairs[edit]

CEOs[edit]

Past and present CEOs:

- 1891–1922: Gerard Philips

- 1922–1939: Anton Philips

- 1939–1961: Frans Otten

- 1961–1971: Frits Philips

- 1971–1977: Henk van Riemsdijk [nl]

- 1977–1981: Nico Rodenburg

- 1981–1982: Cor Dillen

- 1982–1986: Wisse Dekker

- 1986–1990: Cor van der Klugt

- 1990–1996: Jan Timmer

- 1996–2001: Cor Boonstra

- 2001–2011: Gerard Kleisterlee

- 2011–2022: Frans van Houten

- 2022–present: Roy Jakobs

CEOs lighting:

- 2003–2008: Theo van Deursen

- 2012–present: Eric Rondolat

CFOs[edit]

Past and present CFOs (chief financial officer)

- 1960–1968: Cor Dillen

- –1997: Dudley Eustace

- 1997–2005: Jan Hommen[citation needed]

- 2015–present: Abhijit Bhattacharya

Current Executive Committee[edit]

[70]

- CEO: Roy Jakobs

- CFO: Abhijit Bhattacharya

- COO: Willem Appelo

- Chief ESG & Legal Officer: Marnix van Ginneken

- Chief Patient Safety and Quality Officer: Steve C da Baca

- Chief Business Leader (Connected Care): Roy Jakobs

- Chief Business Leader (Personal Health): Deeptha Khanna

- Chief Business Leader (Image Guided Therapy): Bert van Meurs

- Chief Business Leader (Precision Diagnosis): Bert van Meurs (ad interim)

- CEO Philips Domestic Appliances: Henk Siebren de Jong

- Chief of International Markets: Edwin Paalvast

- Chief Medical, Innovation & Strategy Officer: Shez Partovi

- Chief Market Leader (Greater China): Andy Ho

- Chief Market Leader (North America): Jeff DiLullo

- Chief Human Resources Officer: Daniela Seabrook

Acquisitions[edit]

Companies acquired by Philips through the years include ADAC Laboratories, Agilent Healthcare Solutions Group, Amperex, ATL Ultrasound, EKCO, Lifeline Systems, Magnavox, Marconi Medical Systems, Philips Medical purchased Intermagnetics based out of Latham, New York for 1.3 billion in 2006, Optiva, Preethi, Pye, Respironics, Inc., Sectra Mamea AB, Signetics, VISICU, Volcano, VLSI, Ximis, portions of Westinghouse and the consumer electronics operations of Philco and Sylvania. Philips abandoned the Sylvania trademark which is now owned by Havells Sylvania except in Australia, Canada, Mexico, New Zealand, Puerto Rico and the US where it is owned by Osram. Formed in November 1999 as an equal joint venture between Philips and Agilent Technologies, the light-emitting diode manufacturer Lumileds became a subsidiary of Philips Lighting in August 2005 and a fully owned subsidiary in December 2006.[71][72] An 80.1 percent stake in Lumileds was sold to Apollo Global Management in 2017.[73]

On 18 July 2017, Philips announced it’s acquisition of TomTec Imaging Systems GmbH[64][65]

On 19 September 2018, Philips reported that it had acquired US-based Blue Willow Systems, a developer of a cloud-based senior living community resident safety platform.

On 7 March 2019, Philips announced that was acquiring the Healthcare Information Systems business of Carestream Health Inc., a US-based provider of medical imaging and healthcare IT solutions for hospitals, imaging centers, and specialty medical clinics.[74]

On 18 July 2019, Philips announced that it has expanded its patient management solutions in the US with the acquisition of Boston-based start-up company Medumo.[75]

On 27 August 2020, Philips announced the acquisition of Intact Vascular, Inc., a U.S.-based developer of medical devices for minimally invasive peripheral vascular procedures.[76]

On 18 December 2020, Philips and BioTelemetry, Inc., a leading U.S.-based provider of remote cardiac diagnostics and monitoring, announced that they had entered into a definitive merger agreement.[77]

On 19 January 2021, Philips announced the acquisition of Capsule Technologies, Inc., a provider of medical device integration and data technologies for hospitals and healthcare organizations.[78]

On 9 November 2021, Philips announced the acquisition of Cardiologs, an AI-powered cardiac diagnostic technology developer, to expand its cardiac diagnostics and monitoring portfolio.[79]

Operations[edit]

Philips is registered in the Netherlands as a naamloze vennootschap (public corporation) and has its global headquarters in Amsterdam.[80] At the end of 2013, Philips had 111 manufacturing facilities, 59 R&D facilities across 26 countries and sales and service operations in around 100 countries.[81]

Philips is organized into three main divisions: Philips Consumer Lifestyle (formerly Philips Consumer Electronics and Philips Domestic Appliances and Personal Care), Philips Healthcare (formerly Philips Medical Systems), and Philips Lighting (Former).[80] Philips achieved total revenues of €22.579 billion in 2011, of which €8.852 billion were generated by Philips Healthcare, €7.638 billion by Philips Lighting, €5.823 billion by Philips Consumer Lifestyle and €266 million from group activities.[80] At the end of 2011, Philips had a total of 121,888 employees, of whom around 44% were employed in Philips Lighting, 31% in Philips Healthcare and 15% in Philips Consumer Lifestyle.[80] The lighting division was spun out as a new company called Signify, which uses the Philips brand under license.

Philips invested a total of €1.61 billion in research and development in 2011, equivalent to 7.10% of sales.[80] Philips Intellectual Property and Standards is the group-wide division responsible for licensing, trademark protection and patenting.[82] Philips currently holds around 54,000 patent rights, 39,000 trademarks, 70,000 design rights and 4,400 domain name registrations.[80] In the 2021 review of WIPO’s annual World Intellectual Property Indicators Philips ranked 5th in the world for its 95 industrial design registrations being published under the Hague System during 2020.[83] This position is down on their previous 4th-place ranking for 85 industrial design registrations being published in 2019.[84][third-party source needed]

Asia[edit]

Thailand[edit]

Philips Thailand was established in 1952. It is a subsidiary that produces healthcare, lifestyle, and lighting products. Philips started manufacturing in Thailand in 1960 with an incandescent lamp factory. Philips has diversified its production facilities to include a fluorescent lamp factory and a luminaries factory, serving Thai and worldwide markets.[85]

Hong Kong[edit]

Philips Hong Kong began operations in 1948. Philips Hong Kong houses the global headquarters of Philips’ Audio Business Unit. It also house Philips’ Asia Pacific regional office and headquarters for its Design Division, Domestic Appliances & Personal Care Products Division, Lighting Products Division and Medical System Products Division.[86]

In 1974, Philips opened a lamp factory in Hong Kong. This has a capacity of 200 million pieces a year and is certified with ISO 9001:2000 and ISO 14001. Its product portfolio includes prefocus, lensend and E10 miniature light bulbs.[86]

China[edit]

Philips established its first Chinese factory in Zhuhai, Guangdong, in 1990. The site mainly manufactures Philishaves and healthcare products.[87] In early 2008, Philips Lighting, a division of Royal Philips Electronics, opened a small engineering center in Shanghai to adapt the company’s products to vehicles in Asia.[88] Today Philips has 27 WOFE/JVs in China, employing >17,500 people. China is its second largest market.[89]

India[edit]

Philips began operations in India in 1930, with the establishment of Philips Electrical Co. (India) Pvt Ltd in Kolkata as a sales outlet for imported Philips lamps. In 1938, Philips established its first Indian lamp manufacturing factory in Kolkata. In 1948, Philips started manufacturing radios in Kolkata. In 1959, a second radio factory was established near Pune. This was closed and sold around 2006. In 1957, the company converted into a public limited company, renamed «Philips India Ltd». In 1970, a new consumer electronics factory began operations in Pimpri near Pune. This is now called the ‘Philips Healthcare Innovation Centre’. Also, a manufacturing facility ‘Philips Centre for Manufacturing Excellence’ was set up in Chakan, Pune in 2012. In 1996, the Philips Software Centre was established in Bangalore, later renamed the Philips Innovation Campus.[90] In 2008, Philips India entered the water purifier market. In 2014, Philips was ranked 12th among India’s most trusted brands according to the Brand Trust Report, a study conducted by Trust Research Advisory.[91]

Now Philips India is one of the most diversified health care company & broadly focusing on Imaging, Utlrasound, MA & TC products & Sleep & respiratory care products. Philips is aspiring to touch life of 40 Million patients in India by next 2 years. In 2020, Philips introduced mobile ICUs in order to support clinicians to meet the rising demand of ICU beds due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Israel[edit]

Philips has been active in Israel since 1948 and in 1998, set up a wholly owned subsidiary, Philips Electronics (Israel) Ltd. The company has over 700 employees in Israel and generated sales of over $300 million in 2007.[92]

Philips Medical Systems Technologies Ltd. (Haifa) is a developer and manufacturer of Computerized Tomography (CT), diagnostic and Medical Imaging systems. The company was founded in 1969 as Elscint by Elron Electronic Industries and was acquired by Marconi Medical Systems in 1998, which was itself acquired by Philips in 2001.

Philips Semiconductors formerly had major operations in Israel; these now form part of NXP Semiconductors.

On 1 August 2019, Philips acquired Carestream HCIS division from Onex Corporation. As part of the acquisition, Algotec Systems LTD (Carestream HCIS R&D) located in Raanana Israel changed ownership in a share deal. In addition to that, Algotec changed its name to Philips Algotec and is part of Philips HCIS. Philips HCIS is a provider of medical imaging systems.[citation needed]

Pakistan[edit]

Philips has been active in Pakistan since 1948 and has a wholly owned subsidiary, Philips Pakistan Limited (Formerly Philips Electrical Industries of Pakistan Limited).[93]

The head office is in Karachi with regional sales offices in Lahore and Rawalpindi.

Singapore[edit]

A part of the former Philips Singapore HQ complex at Toa Payoh in September 2006. The new Philips APAC HQ was opened on the site of this particular building in June 2016

Philips began operations in Singapore in 1951, initially as a local distributor of imported Philips products.[94] Philips later established manufacturing sites at Boon Keng Road and Jurong Industrial Estate in 1968 and 1970 respectively.[95] Since 1972, its regional headquarters has been based in the central HDB town of Toa Payoh, which from the 1990s until the early 2010s consisted of four interconnected buildings housing offices and factory spaces. In 2016, a new Philips APAC HQ building was opened on the site of one of the former 1972 buildings.[96][97]

Europe[edit]

Denmark[edit]

Philips Denmark was founded in Copenhagen in 1927, and is now headquartered in Frederiksberg.[98]

In 1963, Philips established the Philips TV & Test Equipment laboratory in Brøndby Municipality which was where engineers Erik Helmer Nielsen and Finn Hendil (da; 1939–2011) created and developed some of Philips’ most iconic television test cards, such as the monochrome PM5540 and the colour PM5544 and TVE test cards.[99][100][101][102] Between 2000 and 2012, Philips TV & Test Equipment gradually became independent from Philips and renamed itself as ProTelevision Technologies,[103] now under the umbrella of the Italian company Elenos Group.

France[edit]

The headquarters of Philips France in Suresnes

Philips France has its headquarters in Suresnes. The company employs over 3600 people nationwide.

Philips Lighting has manufacturing facilities in Chalon-sur-Saône (fluorescent lamps), Chartres (automotive lighting), Lamotte-Beuvron (architectural lighting by LEDs and professional indoor lighting), Longvic (lamps), Miribel (outdoor lighting), Nevers (professional indoor lighting).

Germany[edit]

Philips Germany was founded in 1926 in Berlin. Now its headquarters is located in Hamburg. Over 4900 people are employed in Germany.[104]

- Hamburg

- Distribution center of the divisions Healthcare, Consumer Lifestyle, and Lighting.

- Philips Medical Systems DMC.

- Philips Innovative Technologies, Research Laboratories.

- Aachen

- Philips Innovative Technologies.

- Philips Innovation Services.

- Böblingen

- Philips Medical Systems, patient monitoring systems.

- Herrsching

- Philips Respironics.

- Ulm

- Philips Photonics, development and manufacture of vertical laser diodes (VCSELs) and photodiodes for sensing and data communication.

Greece[edit]

Philips’ Greece is headquartered in Halandri, Attica. As of 2012, Philips has no manufacturing plants in Greece, although previously there have been audio, lighting and telecommunications factories.

Italy[edit]

Philips founded its Italian headquarters in 1918, basing it in Monza (Milan) where it still operates, for commercial activities only.

Hungary[edit]

Philips founded PACH (Philips Assembly Centre Hungary) in 1992, producing televisions and consumer electronics in Székesfehérvár. After TPV entering the Philips TV business, the factory was moved under TP Vision, the new joint-venture company in 2011. Products have been transferred to Poland and China and factory was closed in 2013.

By Philips acquiring PLI in 2007 another Hungarian Philips factory emerged in Tamási, producing lamps under the name of Philips IPSC Tamási, later Philips Lighting. The factory was renamed to Signify in 2017, still producing Philips lighting products.

Poland[edit]

Philips’ operations in Poland include: a European financial and accounting centre in Łódź; Philips Lighting facilities in Bielsko-Biała, Piła, and Kętrzyn; and a Philips Domestic Appliances facility in Białystok.

Portugal[edit]

Philips started business in Portugal in 1927, as «Philips Portuguesa S.A.R.L.».[105] Currently, Philips Portuguesa S.A. is headquartered in Oeiras near Lisbon.[106] There were three Philips factories in Portugal: the FAPAE lamp factory in Lisbon;[105][107][108] the Carnaxide magnetic-core memory factory near Lisbon, where the Philips Service organization was also based; and the Ovar factory in northern Portugal making camera components and remote control devices.[107] The company still operates in Portugal with divisions for commercial lighting, medical systems and domestic appliances.[109]

Sweden[edit]

Philips Sweden has two main sites, Kista, Stockholm County, with regional sales, marketing and a customer support organization and Solna, Stockholm County, with the main office of the mammography division.

United Kingdom[edit]

Philips UK has its headquarters[110] in Guildford. The company employs over 2,500 people nationwide.

- Philips Healthcare Informatics, Belfast develops healthcare software products.

- Philips Consumer Products, Guildford provides sales and marketing for televisions, including High Definition televisions, DVD recorders, hi-fi and portable audio, CD recorders, PC peripherals, cordless telephones, home and kitchen appliances, personal care (shavers, hair dryers, body beauty and oral hygiene ).

- Philips Dictation Systems, Colchester.

- Philips Lighting: sales from Guildford and manufacture in Hamilton.

- Philips Healthcare, Guildford. Sales and technical support for X-ray, ultrasound, nuclear medicine, patient monitoring, magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and resuscitation products.

- Philips Research Laboratories, Cambridge (Until 2008 based in Redhill, Surrey. Originally these were the Mullard Research Laboratories.)

In the past, Philips UK also included:

- Consumer product manufacturing in Croydon

- Television Tube Manufacturing Mullard Simonstone

- Philips Business Communications, Cambridge: offered voice and data communications products, specialising in Customer Relationship Management (CRM) applications, IP Telephony, data networking, voice processing, command and control systems and cordless and mobile telephony. In 2006 the business was placed into a 60/40 joint venture with NEC. NEC later acquired 100 per cent ownership and the business was renamed NEC Unified Solutions.

- Philips Electronics Blackburn; vacuum tubes, capacitors, delay-lines, Laserdiscs, CDs.

- Philips Domestic Appliances Hastings: Design and Production of Electric kettles, Fan Heaters plus former EKCO brand «Thermotube» Tubular Heaters and «Hostess» Domestic Food Warming Trolleys.

- Mullard Southampton and Hazel Grove, Stockport. Originally brought together as a joint venture between Mullard and GEC as Associated Semiconductor Manufacturers. They developed and manufactured rectifiers, diodes, transistors, integrated circuits and electro-optical devices. These became Philips Semiconductors before becoming part of NXP.

- London Carriers, logistics and transport division.

- Mullard Equipment Limited (MEL) which produced products for the military

- Ada (Halifax) Ltd, maker of washing machines and spin driers, refrigerators

- Pye TVT Ltd of Cambridge

- Pye Telecommunications Ltd of Cambridge

- TMC Limited of Malmesbury

North America[edit]

Canada[edit]

Philips headquarters in Markham

Philips Canada was founded in 1941 when it acquired Small Electric Motors Limited. It is well known in medical systems for diagnosis and therapy, lighting technologies, shavers, and consumer electronics.

The Canadian headquarters are located in Markham, Ontario.

For several years, Philips manufactured lighting products in two Canadian factories. The London, Ontario, plant opened in 1971. It produced A19 lamps (including the «Royale» long life bulbs), PAR38 lamps and T19 lamps (originally a Westinghouse lamp shape). Philips closed the factory in May 2003. The Trois-Rivières, Quebec plant was a Westinghouse facility which Philips continued to run it after buying Westinghouse’s lamp division in 1983. Philips closed this factory a few years later, in the late 1980s.

Mexico[edit]

Philips Mexico Commercial SA de CV is headquartered in Mexico City. This entity was incorporated in FY2016 to sales consumer lifestyle and healthcare portfolios in the market.

United States[edit]

Philips’ Electronics North American headquarters is in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[111] Philips Lighting has its corporate office in Somerset, New Jersey; with manufacturing plants in Danville, Kentucky; Salina, Kansas; Dallas and Paris, Texas and distribution centers in Mountain Top, Pennsylvania; El Paso, Texas; Ontario, California; and Memphis, Tennessee. Philips Healthcare is headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and operates a health-tech hub in Nashville, Tennessee, with over 1,000 jobs. The North American sales organization is based in Bothell, Washington. There are also manufacturing facilities in Bothell, Washington; Baltimore, Maryland; Cleveland, Ohio; Foster City, California; Gainesville, Florida; Milpitas, California; and Reedsville, Pennsylvania. Philips Healthcare also formerly had a factory in Knoxville, Tennessee. Philips Consumer Lifestyle has its corporate office in Stamford, Connecticut. Philips Lighting has a Color Kinetics office in Burlington, Massachusetts. Philips Research North American headquarters is in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 2007, Philips entered into a definitive merger agreement with North American luminaires company Genlyte Group Incorporated, which provides the company with a leading position in the North American luminaires (also known as «lighting fixtures»), controls and related products for a wide variety of applications, including solid state lighting. The company also acquired Respironics, which was a significant gain for its healthcare sector. On 21 February 2008, Philips completed the acquisition of Baltimore, Maryland-based VISICU. VISICU was the creator of the eICU concept of the use of Telemedicine from a centralized facility to monitor and care for ICU patients.

In April 2020, the United States Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) entered into a contract with Philips Respironics for 43,000 bundled Trilogy Evo Universal ventilator (EV300) hospital ventilators.[112] This included the production and delivery of ventilators to the Strategic National Stockpile—about 156,000 by the end of August 2020 and 187,000 more by the end of 2020.[113] During the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in March 2020, in response to an international demand, Philips increased production of the ventilators fourfold within five months. Production lines were added in the United States with employees working around the clock in factories producing ventilators, in Western Pennsylvania and California, for example.[113]

In March 2020, ProPublica published a series of articles on the Philips ventilator contract as negotiated by trade adviser Peter Navarro. In response to the ProPublica series, in August, the United States House of Representatives undertook a «congressional investigation» into the acquisition of the Philips ventilators. The lawmakers investigation found «evidence of fraud, waste and abuse».[114]—the deal negotiated by Navarro had resulted in an over-payment to Philips by the US government of «hundreds of millions».[114]

Oceania[edit]

Australia and New Zealand[edit]

Philips Australia was founded in 1927 and is headquartered in North Ryde, New South Wales, and also manages the New Zealand operation from there. The company currently employs around 800 people. Regional sales and support offices are located in Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth and Auckland.

Current activities include: Philips Healthcare (also responsible for New Zealand operations); Philips Lighting (also responsible for New Zealand operations); Philips Oral Healthcare, Philips Professional Dictation Solutions, Philips Professional Display Solutions, Philips AVENT Professional, Philips Consumer Lifestyle (also responsible for New Zealand operations); Philips Sleep & Respiratory Care (formerly Respironics), with its ever-increasing national network of Sleepeasy Centres; Philips Dynalite (Lighting Control systems, acquired in 2009, global design and manufacturing centre) and Philips Selecon NZ (Lighting Entertainment product design and manufacture).

South America[edit]

Brazil[edit]

Philips do Brasil was founded in 1924 in Rio de Janeiro.[115] In 1929, Philips started to sell radio receivers. In the 1930s, Philips was making its light bulbs and radio receivers in Brazil. From 1939 to 1945, World War II forced Brazilian branch of Philips to sell bicycles, refrigerators and insecticides. After the war, Philips had a great industrial expansion in Brazil, and was among the first groups to establish in Manaus Free Zone. In the 1970s, Philips Records was a major player in Brazil recording industry. Nowadays, Philips do Brasil is one of the largest foreign-owned companies in Brazil. Philips uses the brand Walita for domestic appliances in Brazil.

Colour television[edit]

Colour television was introduced in South America by then CEO, Cor Dillen.[citation needed]

Former operations[edit]

Philips subsidiary Philips-Duphar [nl] manufactured pharmaceuticals for human and veterinary use and products for crop protection. Duphar was sold to Solvay in 1990. In subsequent years, Solvay sold off all divisions to other companies (crop protection to UniRoyal, now Chemtura, the veterinary division to Fort Dodge, a division of Wyeth, and the pharmaceutical division to Abbott Laboratories).

PolyGram, Philips’ music television and movies division, was sold to Seagram in 1998; merged into Universal Music Group. Philips Records continues to operate as record label of UMG, its name licensed from its former parent.

In 1980, Philips acquired Marantz, a company renowned for high-end audio and video products, based at Kanagawa, Japan. In 2002, Marantz Japan merged with Denon to form D&M Holdings and Philips sold its remaining stake in D&M Holdings in 2008.

Origin, now part of Atos Origin, is a former division of Philips.

ASM Lithography is a spin-off from a division of Philips.

Hollandse Signaalapparaten was a manufacturer of military electronics. The business was sold to Thomson-CSF in 1990 and is now Thales Nederland.

NXP Semiconductors, formerly known as Philips Semiconductors, was sold a consortium of private equity investors in 2006. On 6 August 2010, NXP completed its IPO, with shares trading on NASDAQ.

Ignis,[citation needed] of Comerio, in the province of Varese, Italy, produced washing machines, dishwashers and microwave ovens, was one of the leading companies in the domestic appliance market, holding a 38% share in 1960. In 1970, 50% of the company’s capital was taken over by Philips, which acquired full control in 1972. Ignis was in those years, after Zanussi, the second largest domestic appliance manufacturer, and in 1973 its factories numbered over 10,000 employees only in Italy. With the transfer of ownership to the Dutch multinational, the corporate name of the company was changed, which became «IRE SpA» (Industrie Riunite Eurodomestici). Thereafter Philips used to sell major household appliances (whitegoods) under the name Philips. After selling the Major Domestic Appliances division to Whirlpool Corporation it changed from Philips Whirlpool to Whirlpool Philips and finally to just Whirlpool. Whirlpool bought a 53% stake in Philips’ major appliance operations to form Whirlpool International. Whirlpool bought Philips’ remaining interest in Whirlpool International in 1991.

Philips Cryogenics was split off in 1990 to form the Stirling Cryogenics BV, Netherlands. This company is still active in the development and manufacturing of Stirling cryocoolers and cryogenic cooling systems.

North American Philips distributed AKG Acoustics products under the AKG of America, Philips Audio/Video, Norelco and AKG Acoustics Inc. branding until AKG set up its North American division in San Leandro, California, in 1985. (AKG’s North American division has since moved to Northridge, California.)

Polymer Vision was a Philips spin-off that manufactured a flexible e-ink display screen. The company was acquired by Taiwanese contract electronics manufacturer Wistron in 2009 and it was shut down in 2012, after repeated failed attempts to find a potential buyer.[116][117][118]

Products[edit]

Philips’ core products are consumer electronics and electrical products (including small domestic appliances, shavers, beauty appliances, mother and childcare appliances, electric toothbrushes and coffee makers (products like Smart Phones, audio equipment, Blu-ray players, computer accessories and televisions are sold under license); and healthcare products (including CT scanners, ECG equipment, mammography equipment, monitoring equipment, MRI scanners, radiography equipment, resuscitation equipment, ultrasound equipment and X-ray equipment);[119]

In January 2020 Philips announced that it is looking to sell its domestic appliances division, which includes products like coffee machines, air purifiers and airfryers.[120]

Lighting products[edit]

LED bulbs made by Philips.[121]

- Professional indoor luminaires[122]

- Professional outdoor luminaires[123]

- Professional lamps[124]

- Lighting controls and control systems[125]

- Digital projection lights[126]

- Horticulture lighting[127]

- Solar LED lights[128]

- Smart office lighting systems[129]

- Smart retail lighting systems[130]

- Smart city lighting systems[131]

- Home lamps[132]

- Home fixtures[133]

- Home systems (branded as Philips Hue)[134]

- Automotive Lighting[135]

Audio products[edit]

The Philips A5-PRO headphones

- Hi-fi systems

- Wireless speakers

- Radio systems

- Docking stations

- Headphones

- DJ mixers

- Alarm clocks

Healthcare products[edit]

Sonicare electric toothbrush

Philips healthcare products include:

Clinical informatics[edit]

- Cardiology informatics (IntelliSpace Cardiovascular, Xcelera)

- Enterprise Imaging Informatics (IntelliSpace PACS, XIRIS)

- IntelliSpace family of solutions

Imaging systems[edit]

- Cardio/Vascular X-Ray Wires and Catheters (Verrata)

- Computed tomography (CT)

- Fluoroscopy

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Mammography

- Mobile C-Arms

- Nuclear medicine

- PET (Positron emission tomography)

- PET/CT

- Radiography

- Radiation oncology Systemsroots

- Ultrasound

Diagnostic monitoring[edit]

- Diagnostic ECG

Defibrillators[edit]

- Accessories

- Equipment

- Software

Consumer[edit]

- Philips AVENTil

Patient care and clinical informatics[edit]

64-slice CT scanner originally developed by Elscint, now a Philips product[136]

- Anesthetic gas monitoring

- Blood pressure

- Capnography

- D.M.E.

- Diagnostic sleep testing

- ECG

- Enterprise patient informatics solutions

- OB TraceVue

- Compurecord

- ICIP

- eICU program

- Emergin

- Hemodynamic

- IntelliSpace Cardiovascular

- IntelliSpace PACS

- IntelliSpace portal

- Multi-measurement servers

- Neurophedeoiles

- Pulse oximetry

- Tasy[137]

- Temperature

- Transcutaneous gases

- Ventilation

- ViewForum

- Xcelera

- XIRIS

- Xper Information Management

Logo evolution[edit]

The famous Philips logo with the stars and waves was designed by Dutch architect Louis Kalff (1897–1976), who stated that the emblem had been created as a coincidence so he did not know how a radio system worked.[138]

-

1938–68

-

1968–2008[139]

-

2008–13

-

2013–present

-

Wordmark (1968–2008)

-

Wordmark (2008–present)

Slogans[edit]

- Trust In Philips Is Worldwide (1960-1974)

- Simply Years Ahead (1974-1981)

- We Want You To Have The Best (1981-1985)

- Take a Closer Look (1985-1995)

- Let’s Make Things Better (1995–2004)

- Sense & Simplicity (2004–2013)

- Innovation & You (2013–present)

[edit]

In 1913, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands, Philips founded Philips Sports Vereniging (Philips Sports Club, now commonly known as PSV). The club is active in numerous sports but is now best known for its football team, PSV Eindhoven, and swimming team. Philips owns the naming rights to Philips Stadium in Eindhoven, which is the home ground of PSV Eindhoven.

Outside of the Netherlands, Philips sponsors and has sponsored numerous sports clubs, sports facilities and events. In November 2008, Philips renewed and extended its F1 partnership with AT&T Williams. Philips owns the naming rights to the Philips Championship, the premier basketball league in Australia, traditionally known as the National Basketball League. From 1988 to 1993, Philips was the principal sponsor of the Australian rugby league team The Balmain Tigers and Indonesian football club side Persiba Balikpapan. From 1998 to 2000, Philips sponsored the Winston Cup No. 7 entry for Geoff Bodine Racing, later Ultra Motorsports, for drivers Geoff Bodine and Michael Waltrip. From 1999 to 2018, Philips held the naming rights to Philips Arena in Atlanta, home of the Atlanta Hawks of the National Basketball Association and former home of the defunct Atlanta Thrashers of the National Hockey League.

Outside of sports, Philips sponsors the international Philips Monsters of Rock festival.

Environmental record[edit]

Circular economy[edit]

Philips and its CEO, Frans van Houten, hold several global leadership positions in advancing the circular economy, including as a founding member and co-chair of the board of directors for the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE),[140] applying circular approaches in its capital equipment business,[141] and as a global partner of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.[142]

Planned obsolescence[edit]

Philips was a member of the Phoebus cartel along with Osram, Tungsram, Associated Electrical Industries, ELIN [de], Compagnie des Lampes, International General Electric, and the GE Overseas Group,[143] holding shares in the Swiss corporation proportional to their lamp sales. The cartel lowered operational costs and worked to standardize the life expectancy of light bulbs at 1,000 hours[144] (down from 2,500 hours),[144] and raised prices without fear of competition. The cartel tested their bulbs and fined manufacturers for bulbs that lasted more than 1,000 hours.

Green initiatives[edit]

Philips also runs the EcoVision initiative, which commits to a number of environmentally positive improvements, focusing on energy efficiency.[145]

Also, Philips marks its «green» products with the Philips Green Logo, identifying them as products that have a significantly better environmental performance than their competitors or predecessors.[146]

L-Prize competition[edit]

In 2011, Philips won a $10 million cash prize from the US Department of Energy for winning its L-Prize competition, to produce a high-efficiency, long operating life replacement for a standard 60-W incandescent lightbulb.[147] The winning LED lightbulb, which was made available to consumers in April 2012, produces slightly more than 900 lumens at an input power of 10 W.[148]

Greenpeace ranking[edit]

In Greenpeace’s 2012 Guide to Greener Electronics that ranks electronics manufacturers on sustainability, climate and energy and how green their products are, Philips ranks 10th place with a score of 3.8/10.[149] The company was the top scorer in the Energy section due to its energy advocacy work calling upon the EU to adopt a 30% reduction for greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. It is also praised for its new products which are free from PVC plastic and BFRs. However, the guide criticizes Philips’ sourcing of fibres for paper, arguing it must develop a paper procurement policy which excludes suppliers involved in deforestation and illegal logging.[150]

Philips have made some considerable progress since 2007 (when it was first ranked in this guide), in particular by supporting the Individual Producer Responsibility principle, which means that the company is accepting the responsibility for the toxic impacts of its products on e-waste dumps around the world.[151]

Publications[edit]

- A. Heerding: The origin of the Dutch incandescent lamp industry. (Vol. 1 of The history of N.V. Philips gloeilampenfabriek). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-521-32169-7

- A. Heerding: A company of many parts. (Vol. 2 of The history of N.V. Philips’ gloeilampenfabrieken). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-521-32170-0

- I.J. Blanken: The development of N.V. Philips’ Gloeilampenfabrieken into a major electrical group. Zaltbommel, European Library, 1999. (Vol. 3 of The history of Philips Electronics N.V.). ISBN 90-288-1439-6

- I.J. Blanken: Under German rule. Zaltbommel, European Library, 1999. (Vol. 4 of The history of Philips Electronics N.V). ISBN 90-288-1440-X

References[edit]

- ^ «Philips Annual Report 2022 (Form 20-F)». U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 21 February 2023.

- ^ «Philips Annual Report 2019» (PDF). Philips Results. 27 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ «Philips Drops ‘Electronics’ Name, in Strategy Switch | IndustryWeek». Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ «Philips Q1 2020 Quarterly Results». Philips Results. 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ «Börse Frankfurt (Frankfurt Stock Exchange): Stock market quotes, charts and news». Boerse-frankfurt.de. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ «Philips Museum». Philips-museum.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ «Corporations: A Very Tough Baby». Time Magazine. 23 July 1945. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ C.M. Hargreaves (1991). The Philips Stirling Engine. Elsevier Science. ISBN 0-444-88463-7. pp.28–30

- ^ Philips Technical Review Vol.9 No.4, page 97 (1947)

- ^ C.M. Hargreaves (1991), Fig. 3

- ^ C.M. Hargreaves (1991), p.61

- ^ C.M. Hargreaves (1991), p.77

- ^ «Philips Electronics NV | Dutch manufacturer». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ «BBC – WW2 People’s War – Operation Oyster, Part 1». Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Everitt, Chris; Middlebrook, Martin (2 April 2014). The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473834880. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bruce, Mr A I. «30th March 1943 WWII Timeline». Wehrmacht-history.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2016.