|

Medina المدينة The Prophet’s City |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

| Al Madinat Al Munawwarah المدينة المنورة |

|

From top, left to right: |

|

|

Medina Location of Medina Medina Medina (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 24°28′12″N 39°36′36″E / 24.47000°N 39.61000°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Medina Province |

| First settled | 9th century BCE |

| Hijrah | 622 CE (1 AH) |

| Saudi conquest of Hejaz | 5 December 1925 |

| Named for | Muhammad |

| Districts |

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Madinah Regional Municipality |

| • Mayor | Fahad Al-Belaihshi[1] |

| • Provincial Governor | Prince Faisal bin Salman Al Saud |

| Area | |

| • City | 589 km2 (227 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 293 km2 (117 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 296 km2 (114 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 620 m (2,030 ft) |

| Highest elevation

(Mount Uhud) |

1,077 m (3,533 ft) |

| Population

(2010) |

|

| • City | 1,183,205 |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 2,009/km2 (5,212/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 785,204 |

| • Urban density | 2,680/km2 (6,949/sq mi) |

| • Rural | 398,001 |

| Demonym(s) | Madani مدني |

| Time zone | UTC+03:00 (SAST) |

| Website | amana-md.gov.sa/En/ |

Medina,[a] officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (Arabic: المدينة المنورة, romanized: al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah, lit. ‘The Enlightened City’, Hejazi pronunciation: [almadiːna almʊnawːara], and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (المدينة, al-Madina, Hejazi pronunciation: [almadiːna]), is the second-holiest city in Islam and the capital of Medina Province in Saudi Arabia. As of 2020, the estimated population of the city is 1,488,782,[2] making it the fourth-most populous city in the country.[3] Located at the core of the Medina Province in the western reaches of the country, the city is distributed over 589 km2 (227 sq mi), of which 293 km2 (113 sq mi) constitutes the city’s urban area, while the rest is occupied by the Hejaz Mountains, empty valleys, agricultural spaces and older dormant volcanoes.

Medina is generally considered to be the «cradle of Islamic culture and civilization».[4] The city is considered to be the second-holiest of three key cities in Islamic tradition, with Mecca and Jerusalem serving as the holiest and third-holiest cities respectively. Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (lit. ‘The Prophet’s Mosque’) is of exceptional importance in Islam and serves as burial site of the last Islamic prophet, Muhammad, by whom the mosque was built in 622 CE. Observant Muslims usually visit his tomb, or rawdhah, at least once in their lifetime during a pilgrimage known as Ziyarat, although this is not obligatory.[5] The original name of the city before the advent of Islam was Yathrib (Hebrew: יתריב; Arabic: يَثْرِب), and it is referred to by this name in Chapter 33 (Al-Aḥzāb, lit. ‘The Confederates’) of the Quran. It was renamed to Madīnat an-Nabī (lit. ‘City of the Prophet’ or ‘The Prophet’s City’) after Muhammad’s death and later to al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (lit. ‘The Enlightened City’) before being simplified and shortened to its modern name, Madinah (lit. ‘The City’), from which the English-language spelling of «Medina» is derived. Saudi road signage uses Madinah and al-Madinah al-Munawwarah interchangeably.[5]

The city existed for over 1,500 years before Muhammad’s migration from Mecca,[6] known as the Hijrah. Medina was the capital of a rapidly-increasing Muslim caliphate under Muhammad’s leadership, serving as its base of operations and as the cradle of Islam, where Muhammad’s Ummah (lit. ‘[Muslim] Community’)—composed of Medinan citizens (Ansar) as well as those who immigrated with Muhammad (Muhajirun), who were collectively known as the Sahabah—gained huge influence. Medina is home to three prominent mosques, namely al-Masjid an-Nabawi, Masjid Qubaʽa, and Masjid al-Qiblatayn, with the Masjid Quba’a being the oldest in Islam. A larger portion of the Qur’an was revealed in Medina in contrast to the earlier Meccan surahs.[7][8]

Much like most of the Hejaz, Medina has seen numerous exchanges of power within its comparatively short existence. The region has been controlled by Jewish-Arabian tribes (up until the 5th century CE), the ʽAws and Khazraj (up until Muhammad’s arrival), Muhammad and the Rashidun (622–660), the Umayyads (660–749), the Abbasids (749–1254), the Mamluks of Egypt (1254–1517), the Ottomans (1517–1805), the First Saudi State (1805–1811), Muhammad Ali Pasha (1811–1840), the Ottomans for a second time (1840–1918), the Sharifate of Mecca under the Hashemites (1918–1925) and finally is in the hands of the present-day Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (1925–present).[5]

In addition to visiting for Ziyarah, tourists come to visit the other prominent mosques and landmarks in the city that hold religious significance such as Mount Uhud, Al-Baqiʽ cemetery and the Seven Mosques among others. Recently, after the Saudi conquest of Hejaz.

History[edit]

Medina is home to several distinguished sites and landmarks, most of which are mosques and hold historic significance. These include the three aforementioned mosques, Masjid al-Fath (also known as Masjid al-Khandaq), the Seven Mosques, the Baqi’ Cemetery where the graves of many famous Islamic figures are presumed to be located; directly to the southeast of the Prophet’s Mosque, the Uhud mountain, site of the eponymous Battle of Uhud and the King Fahd Glorious Qur’an Printing Complex where most modern Qur’anic Mus’hafs are printed.

Etymology[edit]

Yathrib[edit]

Before the advent of Islam, the city was known as Yathrib (Arabic: يَثْرِب, romanized: Yaṯrib; pronounced [ˈjaθrɪb]), supposedly named after an Amalekite king, Yathrib Mahlaeil.[9][10] The word Yathrib appears in an inscription found in Harran, belonging to the Babylonian king Nabonidus (6th century BCE)[11] and is well asserted in several texts in the subsequent centuries.[12] The name has also been recorded in Āyah (verse) 13 of Surah (chapter) 33 of the Qur’an.[Quran 33:13] and is thus known to have been the name of the city up to the Battle of the Trench. According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad later forbade calling the city by this name.[13]

Taybah and Tabah[edit]

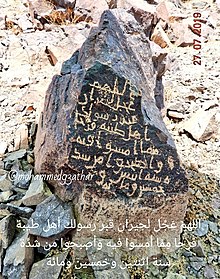

8th century rock inscription discovered in Madinah, refers to the city as ‘Taybah’

Sometime after the battle, Muhammad renamed the city Taybah (the Kind or the Good) ([ˈtˤajba]; طَيْبَة)[14] and Tabah (Arabic: طَابَة)[15] which is of similar meaning. This name is also used to refer to the city in the popular folk song, «Ya Taybah!» (O Taybah!). The two names are combined in another name the city is known by, Taybat at-Tabah (the Kindest of the Kind).

Madinah[edit]

The city has also simply been called Al-Madinah (i.e. ‘The City’) in some ahadith[15]. The names al-Madīnah an-Nabawiyyah (ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلنَّبَوِيَّة) and Madīnat un-Nabī (both meaning «City of the Prophet» or «The Prophet’s City») and al-Madīnat ul-Munawwarah («The Enlightened City») are all derivatives of this word. This is also the most commonly accepted modern name of the city, used in official documents and road signage, along with Madinah.

Early history and Jewish control[edit]

Medina has been inhabited at least 1500 years before the Hijra, or approximately the 9th century BCE.[6] By the fourth century CE, Arab tribes began to encroach from Yemen, and there were three prominent Jewish tribes that inhabited the city around the time of Muhammad: the Banu Qaynuqa, the Banu Qurayza, and Banu Nadir.[16] Ibn Khordadbeh later reported that during the Persian Empire’s domination in Hejaz, the Banu Qurayza served as tax collectors for the Persian Shah.[17]

The situation changed after the arrival of two new Arab tribes, the ‘Aws or Banu ‘Aws and the Khazraj, also known as the Banu Khazraj. At first, these tribes were allied with the Jewish tribes who ruled the region, but later revolted and became independent.[18]

17th century bronze token depicting prophet’s Mosque, the inscription below reads ‘Madinah Shareef’ (Noble City)

Under the ‘Aws and Khazraj[edit]

Toward the end of the 5th century,[19] the Jewish rulers lost control of the city to the two Arab tribes. The Jewish Encyclopedia states that «by calling in outside assistance and treacherously massacring at a banquet the principal Jews», Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj finally gained the upper hand at Medina.[16]

Most modern historians accept the claim of the Muslim sources that after the revolt, the Jewish tribes became clients of the ‘Aws and the Khazraj.[20] However, according to Scottish scholar, William Montgomery Watt, the clientship of the Jewish tribes is not borne out by the historical accounts of the period prior to 627, and he maintained that the Jewish populace retained a measure of political independence.[18]

Early Muslim chronicler Ibn Ishaq tells of an ancient conflict between the last Yemenite king of the Himyarite Kingdom[21] and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two rabbis from the Banu Qurayza tribe, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place «to which a prophet of the Quraysh would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place.» The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in Mecca, they reportedly recognized the Ka’bah as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king «to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts.» On approaching Yemen, tells Ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.[22]

Eventually the Banu ‘Aws and the Banu Khazraj became hostile to each other and by the time of Muhammad’s Hijrah (emigration) to Medina in 622, they had been fighting for 120 years and were sworn enemies[23] The Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza were allied with the ‘Aws, while the Banu Qaynuqa sided with the Khazraj.[24] They fought a total of four wars.[18]

Their last and bloodiest known battle was the Battle of Bu’ath,[18] fought a few years prior to the arrival of Muhammad.[16] The outcome of the battle was inconclusive, and the feud continued. ‘Abd Allah ibn Ubayy, one Khazraj chief, had refused to take part in the battle, which earned him a reputation for equity and peacefulness. He was the most respected inhabitant of the city prior to Muhammad’s arrival. To solve the ongoing feud, concerned residents of Yathrib met secretly with Muhammad in ‘Aqaba, a place outside Mecca, inviting him and his small group of believers to come to the city, where Muhammad could serve a mediator between the factions and his community could practice its faith freely.

Under Muhammad and the Rashidun[edit]

In 622, Muhammad and an estimated 70 Meccan Muhajirun left Mecca over a period of a few months for sanctuary in Yathrib, an event that transformed the religious and political landscape of the city completely; the longstanding enmity between the Aus and Khazraj tribes was dampened as many of the two Arab tribes and some local Jews embraced the new religion of Islam. Muhammad, linked to the Khazraj through his great-grandmother, was agreed on as the leader of the city. The natives of Yathrib who had converted to Islam of any background—pagan Arab or Jewish—were called the Ansar («the Patrons» or «the Helpers»), while the Muslims would pay the Zakat tax.

According to Ibn Ishaq, all parties in the area agreed to the Constitution of Medina, which committed all parties to mutual cooperation under the leadership of Muhammad. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by Ibn Hisham is the subject of dispute among modern Western historians, many of whom maintain that this «treaty» is possibly a collage of different agreements, oral rather than written, of different dates, and that it is not clear exactly when they were made. Other scholars, however, both Western and Muslim, argue that the text of the agreement—whether a single document originally or several—is possibly one of the oldest Islamic texts we possess.[25] In Yemenite Jewish sources, another treaty was drafted between Muhammad and his Jewish subjects, known as Kitāb Dimmat al-Nabi, written in the 3rd year of the Hijra (625), and which gave express liberty to Jews living in Arabia to observe the Sabbath and to grow-out their side-locks. In return, they were to pay the jizya annually for protection by their patrons.[26][5]

Battle of Uhud[edit]

Mount Uhud, with the old Mosque of the Leader of Martyrs (جامع سيد الشهداء), named after Muhammad’s uncle, Hamza ibn Abdul Muttalib, in the foreground. The mosque was demolished in 2012 and a new, larger mosque with the same name was built in its place.[27]

In the year 625, Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, a senior chieftain of Mecca who later converted to Islam, led a Meccan force against Medina. Muhammad marched out to meet the Qurayshi army with an estimated 1,000 troops, but just as the army approached the battlefield, 300 men under ‘Abd Allah ibn Ubayy withdrew, dealing a severe blow to the Muslim army’s morale. Muhammad continued marching with his now 700-strong force and ordered a group of 50 archers to climb a small hill, now called Jabal ar-Rummaah (The Archers’ Hill) to keep an eye on the Meccan’s cavalry and to provide protection to the rear of the Muslim’s army. As the battle heated up, the Meccans were forced to retreat. The frontline was pushed further and further away from the archers and foreseeing the battle to be a victory for the Muslims, the archers decided to leave their posts to pursue the retreating Meccans. A small party, however, stayed behind; pleading the rest to not disobey Muhammad’s orders.

Seeing that the archers were starting to descend from the hill, Khalid ibn al-Walid commanded his unit to ambush the hill and his cavalry unit pursued the descending archers were systematically slain by being caught in the plain ahead of the hill and the frontline, watched upon by their desperate comrades who stayed behind up in the hill who were shooting arrows to thwart the raiders, but with little to no effect. However, the Meccans did not capitalize on their advantage by invading Medina and returned to Mecca. The Madanis (people of Medina) suffered heavy losses, and Muhammad was injured.[28]

Battle of the Trench[edit]

Three of the Seven Mosques at the site of the Battle of the Trench were combined into the modern Masjid al-Fath, here pictured with Jabal Sal’aa in the background and a shop selling local goods in the foreground.

In 627, Abu Sufyan led another force toward Medina. Knowing of his intentions, Muhammad asked for proposals for defending the northern flank of the city, as the east and west were protected by volcanic rocks and the south was covered with palm trees. Salman al-Farsi, a Persian Sahabi who was familiar with Sasanian war tactics recommended digging a trench to protect the city and Muhammad accepted it. The subsequent siege came to be known as the Battle of the Trench and the Battle of the Confederates. After a month-long siege and various skirmishes, the Meccans withdrew again due to the harsh winter.

During the siege, Abu Sufyan contacted the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza and formed an agreement with them, to attack the Muslim defenders and effectively encircle the defenders. It was however discovered by the Muslims and thwarted. This was in breach of the Constitution of Medina and after the Meccan withdrawal, Muhammad immediately marched against the Qurayza and laid siege to their strongholds. The Jewish forces eventually surrendered. Some members of the Aws negotiated on behalf of their old allies and Muhammad agreed to appoint one of their chiefs who had converted to Islam, Sa’d ibn Mu’adh, as judge. Sa’ad judged by Jewish law that all male members of the tribe should be killed and the women and children enslaved as was the law stated in the Old Testament for treason in the Book of Deutoronomy.[29] This action was conceived of as a defensive measure to ensure that the Muslim community could be confident of its continued survival in Medina. The French historian Robert Mantran proposes that from this point of view it was successful—from this point on, the Muslims were no longer primarily concerned with survival but with expansion and conquest.[29]

In the ten years following the hijra, Medina formed the base from which Muhammad and the Muslim army attacked and were attacked, and it was from here that he marched on Mecca, entering it without battle in 630. Despite Muhammad’s tribal connection to Mecca, the growing importance of Mecca in Islam, the significance of the Ka’bah as the center of the Islamic world, as the direction of prayer (Qibla), and in the Islamic pilgrimage (Hajj), Muhammad returned to Medina, which remained for some years the most important city of Islam and the base of operations of the early Rashidun Caliphate.[5]

The city is presumed to have been renamed Madinat al-Nabi («City of the Prophet» in Arabic) in honor of Muhammad’s prophethood and the city being the site of his burial. Alternatively, Lucien Gubbay suggests the name Medina could also have been a derivative from the Aramaic word Medinta, which the Jewish inhabitants could have used for the city.[30]

Under the first three caliphs Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman, Medina was the capital of a rapidly increasing Muslim Empire. During the reign of ‘Uthman ibn al-Affan, the third caliph, a party of Arabs from Egypt, disgruntled at some of his political decisions, attacked Medina in 656 and assassinated him in his own home. Ali, the fourth caliph, changed the capital of the caliphate from Medina to Kufa in Iraq for being in a more strategic location. Since then, Medina’s importance dwindled, becoming more a place of religious importance than of political power. Medina witnessed little to no economic growth during and after Ali’s reign.[5]

Under subsequent Islamic regimes[edit]

Umayyad Caliphate[edit]

After al-Hasan, the son of ‘Ali, ceded power to Mu’awiyah I, son of Abu Sufyan, Mu’awiyah marched into Kufa, Ali’s capital, and received the allegiance of the local ‘Iraqis. This is considered to be the beginning of the Umayyad caliphate. Mu’awiyah’s governors took special care of Medina and dug the ‘Ayn az-Zarqa’a («Blue Spring») spring along with a project that included the creation of underground ducts for the purposes of irrigation. Dams were built in some of the wadis and the subsequent agricultural boom led to the strengthening of the economy.

The Gold dinar of Umar II, also known as ‘Umar ibn Abdulaziz or the Fifth of the Rightly Guided Caliphs.

Following a period of unrest during the Second Fitna in 679, Husayn ibn ‘Ali was martyred at Karbala and Yazid assumed unchecked control for the next three years. In 682, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr declared himself Caliph of Mecca and the people of Medina swore allegiance to him. This led to an eight-year-long period of economic distress for the city. In 692, the Umayyads regained power and Medina experienced its second period of huge economic growth. Trade improved and more people moved into the city. The banks of Wadi al-‘Aqiq were now lush with greenery. This period of peace and prosperity coincided with the rule of ‘Umar ibn Abdulaziz, who many consider to be the fifth of the Rashidun.[5]

Abbasid Caliphate[edit]

Abdulbasit A. Badr, in his book, Madinah, The Enlightened City: History and Landmarks, divides this period into three distinct phases:[5]

Tomb of Salahuddin al-Ayyubi, who started a tradition of greatly funding Medina and protecting pilgrims visiting the holy city.

The Medina sanctuary and Green Dome, photographed in 1880 by Muhammad Sadiq. The dome was built during the Mamluk period, but given its signature color by the Ottomans nearly 600 years later.

Badr describes the period between 749 and 974 as a push-and-pull between peace and political turmoil, while Medina continued to pay allegiance to the Abbasids. From 974 to 1151, Medina was in a liaison with the Fatimids, even though the political stand between the two remained turbulent and did not exceed the normal allegiance. From 1151 onwards, Medina paid allegiance to the Zengids, and the Emir Nuruddin Zangi took care of the roads used by pilgrims and funded the fixing of the water sources and streets. When he visited Medina in 1162, he ordered the construction of a new wall that encompassed the new urban areas outside the old city wall. Zangi was succeeded by Salahuddin al-Ayyubi, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, who supported Qasim ibn Muhanna, the Governor of Medina, and greatly funded the growth of the city while slashing taxes paid by the pilgrims.[5] He also funded the Bedouins who lived on the routes used by pilgrims to protect them on their journeys. The later Abbasids also continued to fund the expenses of the city. While Medina was formally allied with the Abbasids during this period, they maintained closer relations with the Zengids and Ayyubids. The historic city formed an oval, surrounded by a strong wall, 30 to 40 ft (9.1 to 12.2 m) high, dating from this period, and was flanked with towers. Of its four gates, the Bab al-Salam («The Gate of Peace»), was remarked for its beauty. Beyond the walls of the city, the west and south were suburbs consisting of low houses, yards, gardens and plantations.[5]

Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo[edit]

After a brutal long conflict with the Abbasids, the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo took over the Egyptian governorate and effectively gained control of Medina.[5] In 1256, Medina was threatened by lava from the Harrat Rahat volcanic region but was narrowly saved from being burnt after the lava turned northward.[5][31][32] During Mamluk reign, the Masjid an-Nabawi caught fire twice. Once in 1256, when the storage caught fire, burning the entire mosque, and the other time in 1481, when the masjid was struck by lightning. This period also coincided with an increase in scholarly activity in Medina, with scholars such as Ibn Farhun, Al-Hafiz Zain al-Din al-‘Iraqi, Al Sakhawi and others settling in the city.[5] The striking iconic Green Dome also found its beginnings as a cupola built under Mamluk Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun as-Salihi in 1297.[5]

Ottoman rule[edit]

First Ottoman period[edit]

In 1517, the first Ottoman period began with Selim I’s conquest of Mamluk Egypt. This added Medina to their territory and they continued the tradition of showering Medina with money and aid. In 1532, Suleiman the Magnificent built a secure fortress around the city and constructed a strong castle armed by an Ottoman battalion to protect the city. This is also the period in which many of the Prophet’s Mosque’s modern features were built even though it wasn’t painted green yet.[33] These suburbs also had walls and gates. The Ottoman sultans took a keen interest in the Prophet’s Mosque and redesigned it over and over to suit their preferences.

First Saudi insurgency[edit]

As the Ottomans’ hold over their domains broke loose, the Madanis pledged alliance to Saud bin Abdulaziz, founder of the First Saudi state in 1805, who quickly took over the city. In 1811, Muhammad Ali Pasha, Ottoman commander and Wali of Egypt, commanded two armies under each of his two sons to seize Medina, the first one, under the elder Towson Pasha, failed to take Medina. But the second one, a larger army under the command of Ibrahim Pasha, succeeded after battling a fierce resistance movement.[5]

Muhammad Ali Pasha’s era[edit]

After defeating his Saudi foes, Muhammad Ali Pasha took over governance of Medina and although he did not formally declare independence, his governance took on more of a semi-autonomous style. Muhammad’s sons, Towson and Ibrahim, alternated in the governance of the city. Ibrahim renovated the city’s walls and the Prophet’s Mosque. He established a grand provision distribution center (taqiyya) to distribute food and alms to the needy and Medina lived a period of security and peace.[citation needed] In 1840, Muhammad moved his troops out of the city and officially handed the city to the central Ottoman command.[5]

Second Ottoman period[edit]

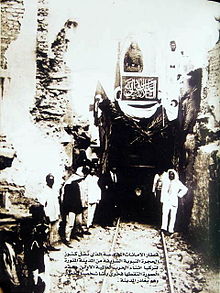

Four years in 1844, after Muhammad Ali Pasha’s departure, Davud Pasha was given the position of governor of Medina under the Ottoman sultan. Davud was responsible for renovating the Prophet’s Mosque on Sultan Abdulmejid I’s orders. When Abdul Hamid II assumed power, he made Medina stand out of the desert with a number of modern marvels, including a radio communication station, a power plant for the Prophet’s Mosque and its immediate vicinity, a telegraph line between Medina and Constantinople, and the Hejaz railway which ran from Damascus to Medina with a planned extension to Mecca. Within one decade, the population of the city multiplied by leaps and bounds and reached 80,000. Around this time, Medina started falling prey to a new threat, the Hashemite Sharifate of Mecca in the south. Medina witnessed the longest siege in its history during and after World War I.[5]

Modern history[edit]

Sharifate of Mecca and Saudi conquest[edit]

The Sharif of Mecca, Husayn ibn Ali, first attacked Medina on 6 June 1916, in the middle of World War I.[5] Four days later, Husayn held Medina in a bitter 3-year siege, during which the people faced food shortages, widespread disease and mass emigration.[5] Fakhri Pasha, governor of Medina, tenaciously held on during the Siege of Medina from 10 June 1916 and refused to surrender and held on another 72 days after the Armistice of Moudros, until he was arrested by his own men and the city was taken over by the Sharifate on 10 January 1919.[5][34] Husayn largely won the war due to his alliance with the British. In anticipation of the plunder and destruction to follow, Fakhri Pasha secretly dispatched the Sacred Relics of Muhammad to the Ottoman capital, Istanbul.[35] As of 1920, the British described Medina as «much more self-supporting than Mecca.»[36] After the Great War, the Sharif of Mecca, Sayyid Hussein bin Ali was proclaimed King of an independent Hejaz. Soon after, the people of Medina secretly entered an agreement with Ibn Saud in 1924, and his son, Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz conquered Medina as part of the Saudi conquest of Hejaz on 5 December 1925 which gave way to the whole of the Hejaz being incorporated into the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.[5]

Under the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia[edit]

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia focused more on the expansion of the city and the demolition of former sites that violated Islamic principles and Islamic law such as the tombs at al-Baqi. Nowadays, the city mostly only holds religious significance and as such, just like Mecca, has given rise to a number of hotels surrounding the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi, which unlike the Masjid Al-Ḥarām, is equipped with an underground parking. The old city’s walls have been destroyed and replaced with the three ring roads that encircle Medina today, named in order of length, King Faisal Road, King Abdullah Road and King Khalid Road. Medina’s ring roads generally see less traffic overall compared to the four ring roads of Mecca.

An international airport, named the Prince Mohammed Bin Abdulaziz International Airport, now serves the city and is located on Highway 340, known locally as the Old Qassim Road. The city now sits at the crossroads of two major Saudi Arabian highways, Highway 60, known as the Qassim–Medina Highway, and Highway 15 which connects the city to Mecca in the south and onward and Tabuk in the north and onward, known as the Al Hijrah Highway or Al Hijrah Road, after Muhammad’s journey.

The old Ottoman railway system was shutdown after their departure from the region and the old railway station has now been converted into a museum. The city has recently seen another connection and mode of transport between it and Mecca, the Haramain high-speed railway line connects the two cities via King Abdullah Economic City near Rabigh, King Abdulaziz International Airport and the city of Jeddah in under 3 hours.

Though the city’s sacred core of the old city is off limits to non-Muslims, the Haram area of Medina itself is much smaller than that of Mecca and Medina has recently seen an increase in the number of Muslim and Non-Muslim expatriate workers of other nationalities, most commonly South Asian peoples and people from other countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council. Almost all of the historic city has been demolished in the Saudi era. The rebuilt city is centered on the vastly expanded al-Masjid an-Nabawi.

Destruction of heritage in Medina[edit]

Saudi Arabia is hostile to any reverence given to historical or religious places of significance for fear that it may give rise to shirk (idolatry). As a consequence, under Saudi rule, Medina has suffered from considerable destruction of its physical heritage including the loss of many buildings over a thousand years old.[37] Critics have described this as «Saudi vandalism» and claim that 300 historic sites linked to Muhammad, his family or companions have been lost in Medina and Mecca over the last 50 years.[38] The most famous example of this is the demolition of al-Baqi.

Geography[edit]

Mount Uhud at night. The mountain is currently the highest peak in Medina and stands at 1,077 m (3,533 ft) of elevation.

Medina is located in the Hejaz region which is a 200 km (124 mi) wide strip between the Nafud desert and the Red Sea.[5] Located approximately 720 km (447 mi) northwest of Riyadh which is at the center of the Saudi desert, the city is 250 km (155 mi) away from the west coast of Saudi Arabia and at an elevation of approximately 620 m (2,030 ft) above sea level. It lies at 39º36′ longitude east and 24º28′ latitude north. It covers an area of about 589 km2 (227 sq mi). The city has been divided into twelve districts, 7 of which have been categorized as urban districts, while the other 5 have been categorized as suburban.

Elevation[edit]

Like most cities in the Hejaz region, Medina is situated at a very high elevation. Almost three times as high as Mecca, the city is situated at 620 m (2,030 ft) above sea level. Mount Uhud is the highest peak in Medina and is 1,077 meters (3,533 feet) tall.

Topography[edit]

Medina is a desert oasis surrounded by the Hejaz Mountains and volcanic hills. The soil surrounding Medina consists of mostly basalt, while the hills, especially noticeable to the south of the city, are volcanic ash which dates to the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era. It is surrounded by a number of famous mountains, most notably Jabal Al-Hujjaj (The Pilgrims’ Mountain) to the west, Sal’aa Mountain to the north-west, Jabal al-‘Ir or Caravan Mountain to the south and Mount Uhud to the north. The city is situated on a flat mountain plateau at the tripoint of the three valleys (wadis) of Wadi al ‘Aql, Wadi al ‘Aqiq, and Wadi al Himdh, for this reason, there are large green areas amidst a dry deserted mountainous region.[5]

Climate[edit]

Under the Köppen climate classification, Medina falls in a hot desert climate region (BWh). Summers are extremely hot and dry with daytime temperatures averaging about 43 °C (109 °F) with nights about 29 °C (84 °F). Temperatures above 45 °C (113 °F) are not unusual between June and September. Winters are milder, with temperatures from 12 °C (54 °F) at night to 25 °C (77 °F) in the day. There is very little rainfall, which falls almost entirely between November and May. In summer, the wind is north-western, while in the spring and winters, is south-western.

| Climate data for Medina (1985–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.2 (91.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

43.0 (109.4) |

46.0 (114.8) |

47.0 (116.6) |

49.0 (120.2) |

48.4 (119.1) |

46.4 (115.5) |

42.8 (109.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

49.0 (120.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.2 (75.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

39.6 (103.3) |

42.9 (109.2) |

42.9 (109.2) |

43.5 (110.3) |

42.3 (108.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

37.1 (98.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

28.4 (83.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.9 (85.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 6.3 (0.25) |

3.1 (0.12) |

9.8 (0.39) |

9.6 (0.38) |

5.1 (0.20) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.1 (0.04) |

4.0 (0.16) |

0.4 (0.02) |

2.5 (0.10) |

10.4 (0.41) |

7.8 (0.31) |

60.2 (2.37) |

| Average rainy days | 2.6 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 24.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 38 | 31 | 25 | 22 | 17 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 19 | 32 | 38 | 23 |

| Source: Jeddah Regional Climate Center[39] |

Significance in Islam[edit]

Medina’s importance as a religious site derives from the presence of two mosques, Masjid Quba’a and al-Masjid an-Nabawi. Both of these mosques were built by Muhammad himself. Islamic scriptures emphasize the sacredness of Medina. Medina is mentioned several times in the Quran, two examples are Surah At-Tawbah. verse 101 and Al-Hashr. verse 8. Medinan suras are typically longer than their Meccan counterparts and they are also larger in number. Muhammad al-Bukhari recorded in Sahih Bukhari that Anas ibn Malik quoted Muhammad as saying:

«Medina is a sanctuary from that place to that. Its trees should not be cut and no heresy should be innovated nor any sin should be committed in it, and whoever innovates in it an heresy or commits sins (bad deeds), then he will incur the curse of God, the angels, and all the people.»

The Prophet’s Mosque (al-Masjid an-Nabawi)[edit]

According to Islamic tradition, a prayer in The Prophet’s Mosque equates to 1,000 prayers in any other mosque except the Masjid al-Haram[40] where one prayer equates to 100,000 prayers in any other mosque.[40] The mosque was initially just an open space for prayer with a raised and covered minbar (pulpit) built within seven months and was located beside Muhammad’s rawdhah (residence, although the word literally means garden) to its side along with the houses of his wives. The mosque was expanded several times throughout history, with many of its internal features developed over time to suit contemporary standards.

The modern Prophet’s Mosque is famed for the Green Dome situated directly above Muhammad’s rawdhah, which currently serves as the burial site for Muhammad, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq and Umar ibn al-Khattab and is used in road signage along with its signature minaret as an icon for Medina itself. The entire piazza of the mosque is shaded from the sun by 250 membrane umbrellas.

Panoramic view of the Prophet’s Mosque, from the east at sunset.

Quba’a Mosque[edit]

It is Sunnah to perform prayer at the Quba’a Mosque. According to a hadith, Sahl ibn Hunayf reported that Muhammad said,

«Whoever purifies himself in his house, then comes to the mosque of Quba’ and prays in it, he will have a reward like the Umrah pilgrimage.»[13][40]

and in another narration,

«Whoever goes out until he comes to this mosque – meaning the Mosque of Quba’ – and prays there, that will be equivalent to ‘Umrah.»[13]

It has been recorded by al-Bukhari and Muslim that Muhammad used to go to Quba’a every Saturday to offer two rak’ahs of Sunnah prayer. The mosque at Quba’a was built by Muhammad himself upon his arrival to the old city of Medina. Quba’a and the mosque has been referred in the Qur’an indirectly in Surah At-Tawbah, verse 108.

Other sites[edit]

Masjid al-Qiblatayn[edit]

Masjid al-Qiblatayn is another mosque historically important to Muslims. Muslims believe that Muhammad was commanded to change his direction of prayer (qibla) from praying toward Jerusalem to praying toward the Ka’bah at Mecca, as he was commanded in Surah Al-Baqarah, verses 143 and 144.[41] The mosque is currently being expanded to be able to hold more than 4,000 worshippers.[42]

Masjid al-Fath and the Seven Mosques[edit]

Three of these historic six mosques were combined recently into the larger Masjid al-Fath with an open courtyard.[5] Sunni sources claim that there is no hadith or any other evidence to prove that Muhammad may have said something about the virtue of these mosques.

Al-Baqi’ Cemetery[edit]

Al-Baqi’ is a significant cemetery in Medina where several family members of Muhammad, caliphs and scholars are known to have been buried.[5]

In Islamic eschatology[edit]

End of civilization[edit]

Concerning the end of civilization in Medina, Abu Hurairah is recorded to have said that Muhammad said:[43]

«The people will leave Medina in spite of the best state it will have, and none except the wild birds and the beasts of prey will live in it, and the last persons who will die will be two shepherds from the tribe of Muzaina, who will be driving their sheep towards Medina, but will find nobody in it, and when they reach the valley of Thaniyat-al-Wada’h, they will fall down on their faces dead.»[43] (al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, Book 30, Hadith 98)

Sufyan ibn Abu Zuhair said Muhammad said:[43]

«Yemen will be conquered and some people will migrate (from Medina) and will urge their families, and those who will obey them to migrate (to Yemen) although Medina will be better for them; if they but knew. Sham will also be conquered and some people will migrate (from Medina) and will urge their families and those who will obey them, to migrate (to Sham) although Medina will be better for them; if they but knew. ‘Iraq will be conquered and some people will migrate (from Medina) and will urge their families and those who will obey them to migrate (to ‘Iraq) although Medina will be better for them; if they but knew.»[43] (al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, Book 30, Hadith 99)

Protection from plague and ad-Dajjal (the False Messiah)[edit]

With regards to Medina’s protection from plague and ad-Dajjal, the following ahadith were recorded:

by Abu Bakra:[43]

«The terror caused by Al-Masih Ad-Dajjal will not enter Medina and at that time Medina will have seven gates and there will be two angels at each gate guarding them.»[43] (al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, Book 30, Hadith 103)

by Abu Hurairah:

«There are angels guarding the entrances (or roads) of Medina, neither plague nor Ad-Dajjal will be able to enter it.»[43] (al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, Book 30, Hadith 104)

Demographics[edit]

Medina Sex Pyramid Chart as of 2018[44]

As of 2018, the recorded population was 2,188,138,[44] with a growth rate of 2.32%.[45] Being a destination of Muslims from around the world, Medina witnesses illegal immigration after performing Hajj or Umrah, despite the strict rules the government has enforced. However, the Central Hajj Commissioner Prince Khalid bin Faisal stated that the numbers of illegal staying visitors dropped by 29% in 2018.[46]

Religion[edit]

As with most cities in Saudi Arabia, Islam is the religion followed by the majority of the population of Medina.

Sunnis of different schools (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i and Hanbali) constitute the majority, while there is a significant Shia minority in and around Medina, such as the Nakhawila. Outside the haram, there are significant numbers of Non-Muslim migrant workers and expats.

Culture[edit]

Similar to that of Mecca, Medina exhibits a cross-cultural environment, a city where people of many nationalities and cultures live together and interact with each other on a daily basis. This only helps the King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran. Established in 1985, the biggest publisher of Quran in the world, it employs around 1100 people and publishes 361 different publications in many languages. It is reported that more than 400,000 people from around the world visit the complex every year.[47][48] Every visitor is gifted a free copy of the Qur’an at the end of a tour of the facility.[48]

Museums and arts[edit]

The Al Madinah Museum has several exhibits concerning the cultural and historical heritage of the city featuring different archeological collections, visual galleries and rare images of the old city.[49] It also includes the Hejaz Railway Museum. The Dar Al Madinah Museum opened in 2011 and it uncovers the history of Medina specializing in the architectural and urban heritage of the city.[50] There is no archeology or architecture from the time of Mohammed, except what remains of a few stone defensive towers[51] The Holy Qur’an Exhibition houses rare manuscripts of the Quran, along with other exhibitions that encircle the Masjid an-Nabawi.[52]

The Madinah Arts Center, founded in 2018 and operated by the MMDA’s Cultural Wing, focuses on modern and contemporary arts. The center aims to enhance arts and enrich the artistic and cultural movement of society, empowering artists of all groups and ages. As of February 2020, before the implementation of social distancing measures and curfews, it held more than 13 group and solo art galleries, along with weekly workshops and discussions. The center is located in King Fahd Park, close to Quba Mosque on an area of 8,200 square meters (88,264 square feet)[53]

In 2018, the MMDA launched Madinah Forum of Arabic Calligraphy, an annual forum to celebrate Arabic calligraphy and renowned Arabic calligraphers. The event includes discussions about Arabic Calligraphy, and a gallery to show the work of 50 Arabic calligraphers from 10 countries.[54] The Dar al-Qalam Center for Arabic Calligraphy is located to the northwest of the Masjid an-Nabawi, just across the Hejaz Railway Museum. In April 2020, it was announced that the center was renamed the Prince Mohammed bin Salman Center for Arabic Calligraphy, and upgraded to an international hub for Arabic Calligraphers, in conjunction with the «Year of Arabic Calligraphy» event organized by the Ministry of Culture during the years 2020 and 2021.[55]

Other projects launched by the MMDA Cultural Wing include the Madinah Forum of Live Sculpture held at Quba Square, with 16 sculptors from 11 countries. The forum aimed to celebrate sculpture as it is an ancient art, and to attract young artists to this form of art.[56]

Economy[edit]

Panel representing the Mosque of Medina. Found in İznik, Turkey, 18th century. Composite body, silicate coat, transparent glaze, underglaze painted.

Historically, Medina’s economy was dependent on the sale of dates and other agricultural activities. As of 1920, 139 varieties of dates were being grown in the area, along with other vegetables.[57] Religious tourism plays a major part in Medina’s economy, being the second holiest city in Islam, and holding many historical Islamic locations, it attracts more than 7 million annual visitors who come to perform Hajj during the Hajj season, and Umrah throughout the year.[58]

Medina has two industrial areas, the larger one was established in 2003 with a total area of 10,000,000 m2, and managed by the Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones (MODON). It is located 50 km from Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz International Airport, and 200 km from Yanbu Commercial Port, and has 236 factories, which produce petroleum products, building materials, food products, and many other products.[59] The Knowledge Economic City (KEC) is a Saudi Arabian joint stock company founded in 2010. It focuses on real estate development and knowledge-based industries.[60] The project is under development and is expected to highly increase the number of jobs in Medina by its completion.[61]

Human resources[edit]

Education and scholarly activity[edit]

Primary and secondary education[edit]

The Ministry of Education is the governing body of education in the al-Madinah Province and it operates 724 and 773 public schools for boys and girls respectively throughout the province.[62] Taibah High School is one of the most notable schools in Saudi Arabia. Established in 1942, it was the second-largest school in the country at that time. Saudi ministers and government officials have graduated from this high school.[63]

Higher education and research[edit]

Taibah University is a public university providing higher education for the residents of the province, it has 28 colleges, of which 16 are in Medina. It offers 89 academic programs and has a strength of 69210 students as of 2020.[64] The Islamic University, established in 1961, is the oldest higher education institution in the region, with around 22000 students enrolled. It offers majors in Sharia, Qur’an, Usul ad-Din, Hadith, and the Arabic language.[65] The university offers Bachelor of Arts degrees and also Master’s and Doctorate degrees.[66] The admission is open to Muslims based on scholarships programs that provide accommodation and living expenses. In 2012, the university expanded its programs by establishing the College of Science, which offers Engineering and Computer science majors.[67] Al Madinah College of Technology, which is governed by TVTC, offers a variety of degree programs including Electrical engineering, Mechanical engineering, Computer Sciences and Electronic Sciences.[circular reference] Private universities at Medina include University of Prince Muqrin, the Arab Open University, and Al Rayyan Colleges.

Transport[edit]

Air[edit]

Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz Airport

Medina is served by the Prince Mohammad bin Abdulaziz International Airport located off Highway 340. It handles domestic flights, while it has scheduled international services to regional destinations in the Middle East. It is the fourth-busiest airport in Saudi Arabia, handling 8,144,790 passengers in 2018.[68] The airport project was announced as the world’s best by Engineering News-Record’s 3rd Annual Global Best Projects Competition held on 10 September 2015.[69][70] The airport also received the first Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold certificate in the MENA region.[71] The airport receives higher numbers of passengers during the Hajj.

A government-run bus in Medina at Salam Rd. Station

Roads[edit]

In 2015, the MMDA announced Darb as-Sunnah (Sunnah Path) Project, which aims to develop and transform the 3 km (2 mi) Quba’a Road connecting the Quba’a Mosque to the al-Masjid an-Nabawi to an avenue, paving the whole road for pedestrians and providing service facilities to the visitors. The project also aims to revive the Sunnah where Muhammed used to walk from his house (al-Masjid an-Nabawi) to Quba’a every Saturday afternoon.[72]

The city of Medina lies at the junction of two of the most important Saudi highways, Highway 60 and Highway 15. Highway 15 connects Medina to Mecca in the south and onward and Tabuk and Jordan in the north. Highway 60 connects the city with Yanbu, a port city on the Red Sea in the west and Al Qassim in the east. The city is served by three ring roads: King Faisal Road, a 5 km ring road that surrounds Al-Masjid an-Nabawi and the downtown area, King Abdullah Road, a 27 km road that surrounds most of urban Medina and King Khalid Road is the biggest ring road that surrounds the whole city and some rural areas with 60 km of roads.

Bus and rapid transit[edit]

The bus transport system in Medina was established in 2012 by the MMDA and is operated by SAPTCO. The newly established bus system includes 10 lines connecting different regions of the city to Masjid an-Nabawi and the downtown area, and serves around 20,000 passengers on a daily basis.[73][74] In 2017, the MMDA launched the Madinah Sightseeing Bus service. Open top buses take passengers on sightseeing trips throughout the day with two lines and 11 destinations, including Masjid an-Nabawi, Quba’a Mosque and Masjid al-Qiblatayn and offers audio tour guidance with 8 different languages.[75] By the end of 2019, the MMDA announced its plan to expand the bus network with 15 BRT lines. The project was set to be done in 2023.[76] In 2015, the MMDA announced a three-line metro project in extension to the public transportation master plan in Medina.[77]

Rail[edit]

The historic Ottoman railways were shut down and the railway stations, including the one in Medina, were converted into museums by the Saudi government. The Haramain High Speed Railway (HHR) came into operation in 2018, linking Medina and Mecca, and passes through three stations: Jeddah, King Abdul Aziz International Airport, and King Abdullah Economic City.[78] It runs along 444 kilometers (276 miles) with a speed of 300 km/h, and has an annual capacity of 60 million passengers.[79]

Further reading[edit]

- Mubarakpuri, Safiur Rahman (2011). The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet ﷺ. Riyadh: Darussalam Publishers. ISBN 978-603-50011-0-6

- Mubarakpuri, Safiur Rahman (2004). The History of Madinah Munawwarah. Riyadh: Darussalam Publishers. ISBN 978-996-08921-1-5

- Badr, Abdulbasit A. (2013). Madinah, The Enlightened City: History and Landmarks. Medina: Al-Madinah Al Munawwarah Research & Studies Center. ISBN 978-603-90414-7-4

See also[edit]

- Bibliography of the history of Medina

- Funky Cold Medina

References[edit]

- ^ ; Arabic: ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلْمُنَوَّرَة, al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah, «the radiant city»; or ٱلْمَدِيْنَة, al-Madīnah, (Hejazi pronunciation: [almaˈdiːna]), «the city»

- ^ «Fahad Al-Belaihshi Appointed Mayor of Madinah by a Royal Decree (Arabic)». Sabq Online Newspaper. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ «Medina Population (2020)». worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ «Population of Cities in Saudi Arabia (2020)». worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Lammens, H. (2013). Islam: Beliefs and Institutions. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 9781136994302.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Badr, Abdulbasit A. (2015). Madinah, The Enlightened City: History and Landmarks. Madinah. ISBN 9786039041474.

- ^ a b «Archived copy». www.al-madinah.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Historical value of the Qur’ân and the Ḥadith Archived 7 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine A.M. Khan

- ^ What Everyone Should Know About the Qur’an Archived 6 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Ahmed Al-Laithy

- ^ «Tarikh Ibn Khaldun«. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ «Al-Madeenah Al-Munawwarah». Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ C. J. Gadd (1958). «The Harran Inscriptions of Nabonidus». Anatolian Studies. 8: 59. doi:10.2307/3642415. JSTOR 3642415. S2CID 162791503. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ «A Pre-Islamic Nabataean Inscription Mentioning The Place Yathrib». Islamic Awareness. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ a b c <>. Ibn Ḥanbal, ʻAbd Allāh ibn Aḥmad, 828–903. ‘Amman: Bayt al-Afkar al-Dawliyah. 2003. ISBN 9957-21-049-1. OCLC 957317429. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj al-Qushayrī, approximately 821–875. (26 November 2019). Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim : with the full commentary by Imam al-Nawawi. Nawawī, ‡d 1233–1277., Salahi, Adil. London. ISBN 978-0-86037-786-3. OCLC 1134530211. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ a b Ibn Ḥajar al-ʻAsqalānī, Aḥmad ibn ʻAlī, 1372-1449.; ابن حجر العسقلاني، أحمد بن علي،, 1372–1449. (2017). Fatḥ al-Bārī : victory of the Creator. Williams, Khalid, Waley, M. I. [U.K.] ISBN 978-1-909460-11-9. OCLC 981125883. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Jewish Encyclopedia Medina Archived 18 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peters 193

- ^ a b c d «Al-Medina.» Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ for date see «J. Q. R.» vii. 175, note

- ^ See e.g., Peters 193; «Qurayza», Encyclopaedia Judaica

- ^ Muslim sources usually referred to Himyar kings by the dynastic title of «Tubba'».

- ^ Guillaume 7–9, Peters 49–50

- ^ Subhani, The Message: The Events of the First Year of Migration Archived 24 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For alliances, see Guillaume 253

- ^ Firestone 118. For opinions disputing the early date of the Constitution of Medina, see e.g., Peters 116; «Muhammad», «Encyclopaedia of Islam»; «Kurayza, Banu», «Encyclopaedia of Islam».

- ^ Shelomo Dov Goitein, The Yemenites – History, Communal Organization, Spiritual Life (Selected Studies), editor: Menahem Ben-Sasson, Jerusalem 1983, pp. 288–299. ISBN 965-235-011-7

- ^ «Jameh Syed al-Shohada Mosque». Madain Project. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Esposito, John L. «Islam.» Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, edited by Thomas Riggs, vol. 1: Religions and Denominations, Gale, 2006, pp. 349–379.

- ^ a b Robert Mantran, L’expansion musulmane Presses Universitaires de France 1995, p. 86.

- ^ «The Jews of Arabia». dangoor.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- ^ «Harrat Rahat». Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Bosworth,C. Edmund: Historic Cities of the Islamic World, p. 385 – «Half-a-century later, in 654/1256, Medina was threatened by a volcanic eruption. After a series of earthquakes, a stream of lava appeared, but fortunately flowed to the east of the town and then northwards.»

- ^ Somel, Selcuk Aksin (13 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810866065. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Peters, Francis (1994). Mecca: A Literary History of the Muslim Holy Land. PP376-377. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03267-X

- ^ Mohmed Reda Bhacker (1992). Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar: Roots of British Domination. Routledge Chapman & Hall. P63: Following the plunder of Medina in 1810 ‘when the Prophet’s tomb was opened and its jewels and relics sold and distributed among the Wahhabi soldiery’. P122: the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II was at last moved to act against such outrage.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 103. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Howden, Daniel (6 August 2005). «The destruction of Mecca: Saudi hardliners are wiping out their own heritage». The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Islamic heritage lost as Makkah modernises Archived 22 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Islamic Pluralism

- ^

«Climate Data for Saudi Arabia». Jeddah Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2015. - ^ a b c Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj al-Qushayrī, approximately 821–875 (8 October 2019). Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim : with the full commentary by Imam al-Nawawi, Volume two. Nawawī, 1233–1277, Salahi, M. A. London. ISBN 978-0-86037-767-2. OCLC 1151770048. Archived from the original on 28 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ «Place Pilgrims Visit During or After Performing Hajj / Umrah». Dawntravels.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ «10 Places To Visit in Madinah». muslim.sg. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bukhārī, Muḥammad ibn Ismāʻīl, 810–870.; بخاري، محمد بن اسماعيل،, 810–870. (1987) [1984]. Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī=The translation of the meanings of Ṣaḥīḥ AL-Buk̲h̲ārī : Arabic-English. Khan, Muhammad Muhsin. (Rev. ed.). New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan. ISBN 81-7151-013-2. OCLC 55626415. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b «Population in Madinah Region According to Gender and Age groups». Saudi Census. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ «Saudi Census Releases». Saudi Census. 17 December 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ «Al-Faisal : The Number of Illegal Staying Visitors have Dropped by 29%(Arabic)». Sabq Newspaper. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ «Publications of King Fahd Complex (Arabic)». King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ a b «About King Fahd Complex». King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ «Al Madinah Museum». sauditourism.sa. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Alhamdan, Shahd (23 January 2016). «Museum offers insight into history of Madinah». Saudigazette. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Robert Schick, Archaeology and the Quran, Encyclopaedia of the Qur’an

- ^ «Holy Quran Exhibition | Medina, Saudi Arabia Attractions». Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ «MMDA Opens Medina Arts Center (Arabic)». Al-Yaum Newspaper. 17 July 2018. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ «Madinah Forum of Arabic Calligraphy (Arabic)». Al-Madina Newspaper. May 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ «Prince Mohammed bin Salman Center of Arabic Calligraphy (Arabic)». Saudi Press Agency. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ «16 Sculptors Participate in Madinah Forum of Live Sculpture (Arabic)». Saudi Press Agency. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Prothero, G. W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 83. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ «منصة البيانات المفتوحة». Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ «المدينة الصناعية بالمدينة المنورة». Modon.gov.sa. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ «Background». Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Economic cities a rise Archived 24 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Number of Schools in Medina (Arabic)». Madinah General Administration of Education. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ «History of Taibah High School (Arabic)». Al-Madina Newspaper. 4 June 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ «About Taibah University». Taibah University. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ University of Madinah Archived 13 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine Saudi Info.

- ^ «University of Madinah». Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ «The Islamic University Starts the Admission for Science Programs for the First Time (Arabic)». Al-Riyadh Newspaper. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ «TAV Traffic Results 2018» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ «Arabian Aerospace – TAV have constructed the world’s best airport». Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ «ENR Announces Winners of 3rd Annual Global Best Projects Competition». Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ «PressReleaseDetail». Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ «Darb Al-Sunnah Project (Arabic)». Al-Madinah Newspaper. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ «Madina Buses Official (Arabic)». Madina Buses Official Website. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ «Medina Buses Serves 20k Passengers Daily (Arabic)». Makkah Newspaper. 19 May 2019. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ «City Sightseeing Medina». City Sightseeing Medina Official Website. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ «36 Months to Create 15 Bus Lines in Medina (Arabic)». Al-Watan Newspaper. 31 December 2019. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ «MMDA Announces a 3-line Metro Project in Medina(Arabic)». Asharq Al-Awsat Newspaper. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ «Pictures: Saudi Arabia opens high-speed railway to public». gulfnews.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ «About Haramain High Speed Rail». Official Haramain High Speed Rail Website. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

External links[edit]

|

Medina المدينة The Prophet’s City |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

| Al Madinat Al Munawwarah المدينة المنورة |

|

From top, left to right: |

|

|

Medina Location of Medina Medina Medina (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 24°28′12″N 39°36′36″E / 24.47000°N 39.61000°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Medina Province |

| First settled | 9th century BCE |

| Hijrah | 622 CE (1 AH) |

| Saudi conquest of Hejaz | 5 December 1925 |

| Named for | Muhammad |

| Districts |

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Madinah Regional Municipality |

| • Mayor | Fahad Al-Belaihshi[1] |

| • Provincial Governor | Prince Faisal bin Salman Al Saud |

| Area | |

| • City | 589 km2 (227 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 293 km2 (117 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 296 km2 (114 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 620 m (2,030 ft) |

| Highest elevation

(Mount Uhud) |

1,077 m (3,533 ft) |

| Population

(2010) |

|

| • City | 1,183,205 |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 2,009/km2 (5,212/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 785,204 |

| • Urban density | 2,680/km2 (6,949/sq mi) |

| • Rural | 398,001 |

| Demonym(s) | Madani مدني |

| Time zone | UTC+03:00 (SAST) |

| Website | amana-md.gov.sa/En/ |

Medina,[a] officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (Arabic: المدينة المنورة, romanized: al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah, lit. ‘The Enlightened City’, Hejazi pronunciation: [almadiːna almʊnawːara], and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (المدينة, al-Madina, Hejazi pronunciation: [almadiːna]), is the second-holiest city in Islam and the capital of Medina Province in Saudi Arabia. As of 2020, the estimated population of the city is 1,488,782,[2] making it the fourth-most populous city in the country.[3] Located at the core of the Medina Province in the western reaches of the country, the city is distributed over 589 km2 (227 sq mi), of which 293 km2 (113 sq mi) constitutes the city’s urban area, while the rest is occupied by the Hejaz Mountains, empty valleys, agricultural spaces and older dormant volcanoes.

Medina is generally considered to be the «cradle of Islamic culture and civilization».[4] The city is considered to be the second-holiest of three key cities in Islamic tradition, with Mecca and Jerusalem serving as the holiest and third-holiest cities respectively. Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (lit. ‘The Prophet’s Mosque’) is of exceptional importance in Islam and serves as burial site of the last Islamic prophet, Muhammad, by whom the mosque was built in 622 CE. Observant Muslims usually visit his tomb, or rawdhah, at least once in their lifetime during a pilgrimage known as Ziyarat, although this is not obligatory.[5] The original name of the city before the advent of Islam was Yathrib (Hebrew: יתריב; Arabic: يَثْرِب), and it is referred to by this name in Chapter 33 (Al-Aḥzāb, lit. ‘The Confederates’) of the Quran. It was renamed to Madīnat an-Nabī (lit. ‘City of the Prophet’ or ‘The Prophet’s City’) after Muhammad’s death and later to al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (lit. ‘The Enlightened City’) before being simplified and shortened to its modern name, Madinah (lit. ‘The City’), from which the English-language spelling of «Medina» is derived. Saudi road signage uses Madinah and al-Madinah al-Munawwarah interchangeably.[5]

The city existed for over 1,500 years before Muhammad’s migration from Mecca,[6] known as the Hijrah. Medina was the capital of a rapidly-increasing Muslim caliphate under Muhammad’s leadership, serving as its base of operations and as the cradle of Islam, where Muhammad’s Ummah (lit. ‘[Muslim] Community’)—composed of Medinan citizens (Ansar) as well as those who immigrated with Muhammad (Muhajirun), who were collectively known as the Sahabah—gained huge influence. Medina is home to three prominent mosques, namely al-Masjid an-Nabawi, Masjid Qubaʽa, and Masjid al-Qiblatayn, with the Masjid Quba’a being the oldest in Islam. A larger portion of the Qur’an was revealed in Medina in contrast to the earlier Meccan surahs.[7][8]

Much like most of the Hejaz, Medina has seen numerous exchanges of power within its comparatively short existence. The region has been controlled by Jewish-Arabian tribes (up until the 5th century CE), the ʽAws and Khazraj (up until Muhammad’s arrival), Muhammad and the Rashidun (622–660), the Umayyads (660–749), the Abbasids (749–1254), the Mamluks of Egypt (1254–1517), the Ottomans (1517–1805), the First Saudi State (1805–1811), Muhammad Ali Pasha (1811–1840), the Ottomans for a second time (1840–1918), the Sharifate of Mecca under the Hashemites (1918–1925) and finally is in the hands of the present-day Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (1925–present).[5]

In addition to visiting for Ziyarah, tourists come to visit the other prominent mosques and landmarks in the city that hold religious significance such as Mount Uhud, Al-Baqiʽ cemetery and the Seven Mosques among others. Recently, after the Saudi conquest of Hejaz.

History[edit]

Medina is home to several distinguished sites and landmarks, most of which are mosques and hold historic significance. These include the three aforementioned mosques, Masjid al-Fath (also known as Masjid al-Khandaq), the Seven Mosques, the Baqi’ Cemetery where the graves of many famous Islamic figures are presumed to be located; directly to the southeast of the Prophet’s Mosque, the Uhud mountain, site of the eponymous Battle of Uhud and the King Fahd Glorious Qur’an Printing Complex where most modern Qur’anic Mus’hafs are printed.

Etymology[edit]

Yathrib[edit]

Before the advent of Islam, the city was known as Yathrib (Arabic: يَثْرِب, romanized: Yaṯrib; pronounced [ˈjaθrɪb]), supposedly named after an Amalekite king, Yathrib Mahlaeil.[9][10] The word Yathrib appears in an inscription found in Harran, belonging to the Babylonian king Nabonidus (6th century BCE)[11] and is well asserted in several texts in the subsequent centuries.[12] The name has also been recorded in Āyah (verse) 13 of Surah (chapter) 33 of the Qur’an.[Quran 33:13] and is thus known to have been the name of the city up to the Battle of the Trench. According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad later forbade calling the city by this name.[13]

Taybah and Tabah[edit]

8th century rock inscription discovered in Madinah, refers to the city as ‘Taybah’

Sometime after the battle, Muhammad renamed the city Taybah (the Kind or the Good) ([ˈtˤajba]; طَيْبَة)[14] and Tabah (Arabic: طَابَة)[15] which is of similar meaning. This name is also used to refer to the city in the popular folk song, «Ya Taybah!» (O Taybah!). The two names are combined in another name the city is known by, Taybat at-Tabah (the Kindest of the Kind).

Madinah[edit]

The city has also simply been called Al-Madinah (i.e. ‘The City’) in some ahadith[15]. The names al-Madīnah an-Nabawiyyah (ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلنَّبَوِيَّة) and Madīnat un-Nabī (both meaning «City of the Prophet» or «The Prophet’s City») and al-Madīnat ul-Munawwarah («The Enlightened City») are all derivatives of this word. This is also the most commonly accepted modern name of the city, used in official documents and road signage, along with Madinah.

Early history and Jewish control[edit]

Medina has been inhabited at least 1500 years before the Hijra, or approximately the 9th century BCE.[6] By the fourth century CE, Arab tribes began to encroach from Yemen, and there were three prominent Jewish tribes that inhabited the city around the time of Muhammad: the Banu Qaynuqa, the Banu Qurayza, and Banu Nadir.[16] Ibn Khordadbeh later reported that during the Persian Empire’s domination in Hejaz, the Banu Qurayza served as tax collectors for the Persian Shah.[17]

The situation changed after the arrival of two new Arab tribes, the ‘Aws or Banu ‘Aws and the Khazraj, also known as the Banu Khazraj. At first, these tribes were allied with the Jewish tribes who ruled the region, but later revolted and became independent.[18]

17th century bronze token depicting prophet’s Mosque, the inscription below reads ‘Madinah Shareef’ (Noble City)

Under the ‘Aws and Khazraj[edit]

Toward the end of the 5th century,[19] the Jewish rulers lost control of the city to the two Arab tribes. The Jewish Encyclopedia states that «by calling in outside assistance and treacherously massacring at a banquet the principal Jews», Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj finally gained the upper hand at Medina.[16]

Most modern historians accept the claim of the Muslim sources that after the revolt, the Jewish tribes became clients of the ‘Aws and the Khazraj.[20] However, according to Scottish scholar, William Montgomery Watt, the clientship of the Jewish tribes is not borne out by the historical accounts of the period prior to 627, and he maintained that the Jewish populace retained a measure of political independence.[18]

Early Muslim chronicler Ibn Ishaq tells of an ancient conflict between the last Yemenite king of the Himyarite Kingdom[21] and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two rabbis from the Banu Qurayza tribe, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place «to which a prophet of the Quraysh would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place.» The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in Mecca, they reportedly recognized the Ka’bah as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king «to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts.» On approaching Yemen, tells Ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.[22]

Eventually the Banu ‘Aws and the Banu Khazraj became hostile to each other and by the time of Muhammad’s Hijrah (emigration) to Medina in 622, they had been fighting for 120 years and were sworn enemies[23] The Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza were allied with the ‘Aws, while the Banu Qaynuqa sided with the Khazraj.[24] They fought a total of four wars.[18]

Their last and bloodiest known battle was the Battle of Bu’ath,[18] fought a few years prior to the arrival of Muhammad.[16] The outcome of the battle was inconclusive, and the feud continued. ‘Abd Allah ibn Ubayy, one Khazraj chief, had refused to take part in the battle, which earned him a reputation for equity and peacefulness. He was the most respected inhabitant of the city prior to Muhammad’s arrival. To solve the ongoing feud, concerned residents of Yathrib met secretly with Muhammad in ‘Aqaba, a place outside Mecca, inviting him and his small group of believers to come to the city, where Muhammad could serve a mediator between the factions and his community could practice its faith freely.

Under Muhammad and the Rashidun[edit]

In 622, Muhammad and an estimated 70 Meccan Muhajirun left Mecca over a period of a few months for sanctuary in Yathrib, an event that transformed the religious and political landscape of the city completely; the longstanding enmity between the Aus and Khazraj tribes was dampened as many of the two Arab tribes and some local Jews embraced the new religion of Islam. Muhammad, linked to the Khazraj through his great-grandmother, was agreed on as the leader of the city. The natives of Yathrib who had converted to Islam of any background—pagan Arab or Jewish—were called the Ansar («the Patrons» or «the Helpers»), while the Muslims would pay the Zakat tax.

According to Ibn Ishaq, all parties in the area agreed to the Constitution of Medina, which committed all parties to mutual cooperation under the leadership of Muhammad. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by Ibn Hisham is the subject of dispute among modern Western historians, many of whom maintain that this «treaty» is possibly a collage of different agreements, oral rather than written, of different dates, and that it is not clear exactly when they were made. Other scholars, however, both Western and Muslim, argue that the text of the agreement—whether a single document originally or several—is possibly one of the oldest Islamic texts we possess.[25] In Yemenite Jewish sources, another treaty was drafted between Muhammad and his Jewish subjects, known as Kitāb Dimmat al-Nabi, written in the 3rd year of the Hijra (625), and which gave express liberty to Jews living in Arabia to observe the Sabbath and to grow-out their side-locks. In return, they were to pay the jizya annually for protection by their patrons.[26][5]

Battle of Uhud[edit]

Mount Uhud, with the old Mosque of the Leader of Martyrs (جامع سيد الشهداء), named after Muhammad’s uncle, Hamza ibn Abdul Muttalib, in the foreground. The mosque was demolished in 2012 and a new, larger mosque with the same name was built in its place.[27]

In the year 625, Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, a senior chieftain of Mecca who later converted to Islam, led a Meccan force against Medina. Muhammad marched out to meet the Qurayshi army with an estimated 1,000 troops, but just as the army approached the battlefield, 300 men under ‘Abd Allah ibn Ubayy withdrew, dealing a severe blow to the Muslim army’s morale. Muhammad continued marching with his now 700-strong force and ordered a group of 50 archers to climb a small hill, now called Jabal ar-Rummaah (The Archers’ Hill) to keep an eye on the Meccan’s cavalry and to provide protection to the rear of the Muslim’s army. As the battle heated up, the Meccans were forced to retreat. The frontline was pushed further and further away from the archers and foreseeing the battle to be a victory for the Muslims, the archers decided to leave their posts to pursue the retreating Meccans. A small party, however, stayed behind; pleading the rest to not disobey Muhammad’s orders.

Seeing that the archers were starting to descend from the hill, Khalid ibn al-Walid commanded his unit to ambush the hill and his cavalry unit pursued the descending archers were systematically slain by being caught in the plain ahead of the hill and the frontline, watched upon by their desperate comrades who stayed behind up in the hill who were shooting arrows to thwart the raiders, but with little to no effect. However, the Meccans did not capitalize on their advantage by invading Medina and returned to Mecca. The Madanis (people of Medina) suffered heavy losses, and Muhammad was injured.[28]

Battle of the Trench[edit]

Three of the Seven Mosques at the site of the Battle of the Trench were combined into the modern Masjid al-Fath, here pictured with Jabal Sal’aa in the background and a shop selling local goods in the foreground.

In 627, Abu Sufyan led another force toward Medina. Knowing of his intentions, Muhammad asked for proposals for defending the northern flank of the city, as the east and west were protected by volcanic rocks and the south was covered with palm trees. Salman al-Farsi, a Persian Sahabi who was familiar with Sasanian war tactics recommended digging a trench to protect the city and Muhammad accepted it. The subsequent siege came to be known as the Battle of the Trench and the Battle of the Confederates. After a month-long siege and various skirmishes, the Meccans withdrew again due to the harsh winter.