This article is about the musician. For the associated band, see Marilyn Manson (band).

|

Marilyn Manson |

|

|---|---|

Manson performing in 2017 |

|

| Born |

Brian Hugh Warner January 5, 1969 (age 54) Canton, Ohio, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1989–present |

| Spouses |

Dita Von Teese (m. 2005; div. 2007) Lindsay Usich (m. 2020) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Labels |

|

| Member of |

|

| Website | marilynmanson.com |

| Signature | |

Brian Hugh Warner (born January 5, 1969), known professionally as Marilyn Manson, is an American rock musician. He came to prominence as the lead singer of the band that shares his name, of which he remains the only constant member since its formation in 1989. Known for his controversial stage personality and public image, his stage name (like the other founding members of the band) was formed by combining the names of two opposing American cultural icons: actress Marilyn Monroe and cult leader Charles Manson.

Manson is best known for music released in the 1990s, including the albums Portrait of an American Family (1994), Antichrist Superstar (1996) and Mechanical Animals (1998), which earned him a reputation in mainstream media as a controversial figure and negative influence on young people when combined with his public image.[1][2] In the U.S. alone, three of the band’s albums have been awarded platinum status and three more went gold, and the band has had eight releases debut in the top 10, including two No. 1 albums. Manson has been ranked at No. 44 on the list of the «Top 100 Heavy Metal Vocalists» by Hit Parader and, along with his band, has been nominated for four Grammy Awards–Manson himself earned an additional Grammy nomination for his work on Kanye West’s Donda. Manson made his film debut as an actor in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997), and has since appeared in a variety of minor roles and cameos. In 2002, his first art show, The Golden Age of Grotesque, was held at the Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions center.

He is widely considered one of the most controversial figures in heavy metal music, and has been involved in numerous controversies throughout his career. His lyrics were criticized by American politicians and were examined in congressional hearings. Several U.S. states enacted legislation specifically banning the group from performing in state-operated venues. In 1999, news media falsely blamed Manson for influencing the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre. His work has been cited in several other violent events; his paintings and films appeared as evidence in a murder trial, and he has been accused of inspiring several other murders and school shootings. In 2021, multiple women accused Manson of psychologically and sexually abusing them, allegations he denied.[3]

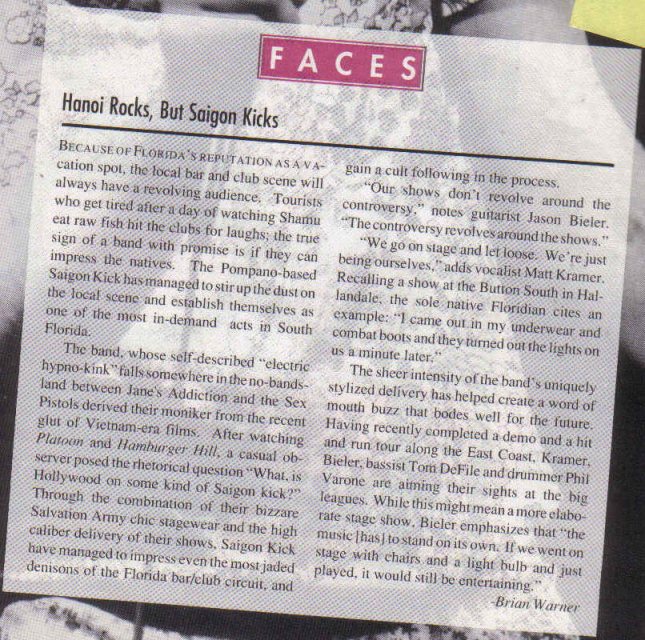

Early life

Brian Hugh Warner was born in Canton, Ohio, on January 5, 1969,[4] the son of Barbara Warner Wyer (died May 13, 2014)[5] and Hugh Angus Warner (died July 7, 2017).[6][7] He is of English, German, Irish, and Polish descent,[8][9] and has also claimed that his mother’s family (who hailed from the Appalachian Mountains in West Virginia) had Sioux heritage.[10] As a child, he attended his mother’s Episcopal church, though his father was a Roman Catholic.[11][12] He attended Heritage Christian School from first to tenth grade. In that school, his instructors tried to show children what music they were not supposed to listen to; Warner then fell in love with what he «wasn’t supposed to.»[13] Warner later transferred to GlenOak High School and graduated from there in 1987. After relocating with his parents, he became a student at Broward Community College in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in 1990. He was working towards a degree in journalism, gaining experience in the field by writing articles for the music magazine 25th Parallel.[14] He also interviewed musicians and soon met several of the musicians to whom his own work was later compared, including Groovie Mann from My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult and Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails, with the latter later becoming his mentor and producing his debut album.[15]

Career

Music

The band was formed in 1989 by Warner and guitarist Scott Putesky,[16][17] with Warner writing lyrics and Putesky composing the majority of music.[18] Warner adopted the stage name Marilyn Manson and, alongside a revolving lineup of musicians, recorded the band’s first demo tape as Marilyn Manson & the Spooky Kids in 1990.[19][20] The group quickly developed a loyal fanbase within the South Florida punk and hardcore music scene, primarily as a result of their intentionally shocking concerts; band members often performed in women’s clothing or bizarre costumes, and live shows routinely featured amateur pyrotechnics, naked women nailed to crucifixes, children locked in cages,[21][22] as well as experiments in reverse psychology and butchered animals remains.[N 1] Within six months of forming, they were playing sold-out shows in 300-capacity nightclubs throughout Florida.[24] They signed a record deal with Sony Music in early 1991, although this deal was rescinded before any material was recorded for the label. The band instead used the proceeds of this deal to fund the recording of subsequent demo tapes, which were released independently.[25]

Left to right: Twiggy, Gacy and Manson performing at the «A Night of Nothing» industry showcase, 1995

The name of the group was shortened to Marilyn Manson in 1992, and they continued to perform and release cassettes until the summer of 1993,[21] when Reznor signed the act to his vanity label Nothing Records.[26] Their debut studio album, Portrait of an American Family, was released in July 1994.[27] Manson later criticized Nothing Records and its parent label Interscope for a perceived lack of promotion.[N 2] While recording b-sides and remixes for the album’s proposed third single, «Dope Hat», the band decided to issue the resultant material as a standalone release titled Smells Like Children.[29] The record included their cover version of the Eurythmics’s «Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)», which established the band as a mainstream act.[26][30] The song’s music video was placed on heavy rotation on MTV,[31] and earned the band their first nomination for Best Rock Video at the 1996 MTV Video Music Awards.[32] Their second studio album, 1996’s Antichrist Superstar, sparked a fierce backlash among Christian fundamentalists.[33] The album was an immediate commercial success, debuting at number three on the Billboard 200 and selling almost 2 million copies in the United States alone,[34][35] and 7 million copies worldwide.[36][37] Lead single «The Beautiful People» received three nominations at the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards,[38] where the band also performed.[39]

For 1998’s Mechanical Animals, Manson said he took inspiration from 1970s glam rock, and adopted a wardrobe and hairstyle similar to David Bowie.[40] He said he did this to avoid being portrayed as a «bogeyman», a role which had been ascribed to him by mainstream media following the band’s commercial breakthrough.[33] Interscope’s promotion of the album was massive,[41] with the label erecting enormous billboards of Manson as an androgynous extraterrestrial in Times Square and the Sunset Strip.[40] Lead single «The Dope Show» was nominated for Best Hard Rock Performance at the 41st Annual Grammy Awards.[42] The album debuted at number one on the Billboard 200,[43] but was the lowest-selling number-one album of 1998 in the United States,[44] with sales of 1.4 million copies in the country as of 2017.[45] The album was not well received by longtime fans, who complained about its radio-friendly sound and accused the vocalist of «selling out»,[46] and Interscope were reportedly disappointed with its commercial performance.[N 3]

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) was a return to the band’s industrial metal roots after the glam-influenced Mechanical Animals,[48] and was the vocalist’s response to media coverage blaming him for influencing the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre. The album was a critical success, with numerous publications praising it as the band’s finest work.[49] Despite being certified gold in the United States for shipments in excess of half a million units,[50] mainstream media openly questioned the band’s commercial appeal, noting the dominance of nu metal and controversial hip hop artists such as Eminem.[51][52] A cover of «Tainted Love» was an international hit in 2002, peaking at number one in several territories.[53]

The Golden Age of Grotesque was released the following year, an album primarily inspired by the swing and burlesque movements of 1920s Berlin.[54] In an extended metaphor found throughout the record, Manson compared his own often-criticized work to the Entartete Kunst banned by the Nazi regime.[55] Like Mechanical Animals in 1998, The Golden Age of Grotesque debuted at number one on the Billboard 200,[34] but was the lowest-selling studio album to debut at number one that year, selling 527,000 copies in the United States as of 2008.[44] The album was more successful in Europe, where it sold over 400,000 on its first week of release to debut at number one on Billboard‘s European Top 100 Albums.[56] Manson began his collaboration with French fashion designer Jean-Paul Gaultier during this period, who designed much of the elaborate attire worn by the band on the supporting «Grotesk Burlesk Tour».[57] The greatest hits compilation Lest We Forget: The Best Of was released in 2004.[58]

«He’s very savvy in that he lets people think things about him or plays into things to see what will happen, almost like a performance artist. He’s a visionary in a way, because he identified a culture that was coming and now that culture is everywhere.»

—Billy Corgan on Marilyn Manson, 2014[59]

After a three-year hiatus, in which the vocalist pursued other interests,[60] the band returned with 2007’s Eat Me, Drink Me. The album’s lyrical content largely related to the dissolution of Manson’s marriage to Dita Von Teese and his affair with 19-year-old actress Evan Rachel Wood.[61] Seventh studio album The High End of Low was released in 2009, and was their final album issued by Interscope. While promoting the record, Manson made a series of disparaging comments about the label and its artistic censorship, as well as its president Jimmy Iovine.[62] Manson signed a lucrative recording contract with British independent record label Cooking Vinyl in 2011, with the band and label sharing profits equally after the label recouped costs associated with marketing, promotion and distribution.[63] The first album released under the deal was 2012’s Born Villain.[64] Lead single «No Reflection» earned the band their fourth Grammy nomination.[42] Subsequent albums were released in the United States by Loma Vista Recordings, beginning with 2015’s The Pale Emperor, which was widely seen as a return to form[65][66] and was a commercial success upon release.[67][68]

Heaven Upside Down followed in 2017,[69] with its single «Kill4Me» becoming the band’s highest-peaking single ever on Billboard‘s Mainstream Rock.[70] While touring in support of the record, Manson was injured by two large falling stage props as he performed on stage at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York, breaking his fibula in two places, requiring a plate and ten screws to be inserted in the bone, as well as another screw in his ankle, which he had sprained during a show in Pittsburgh.[71][72] «God’s Gonna Cut You Down» was released as a non-album single in 2019,[73][74] and is the band’s highest-peaking single on Billboard‘s Hot Rock Songs and Rock Digital Songs.[75][76] Their most recent studio album, 2020’s We Are Chaos, was the band’s tenth top ten release on the Billboard 200.[77]

According to Nielsen SoundScan, the band sold 8.7 million albums alone in the United States as of 2011.[63] Three of their albums received platinum awards from the Recording Industry Association of America, and a further three received gold certifications.[78] Ten of their releases debuted in the top ten of the Billboard 200, including two number-one albums.[77] In the United Kingdom, the band are certified for sales of almost 1.75 million units.[79] Marilyn Manson has sold over 50 million records worldwide.[80][81][82][83]

Musical collaborations

In addition to his work with the band, Manson has collaborated extensively with other musicians.[84] Cello rock act Rasputina opened for the band throughout the «Dead to the World Tour», the controversial tour supporting Antichrist Superstar.[85] Lead vocalist Melora Creager performed cello and backing vocals for the band, most notably for renditions of «Apple of Sodom», a live version of which appeared as a b-side on Manson’s 1998 single «The Dope Show».[86] Manson also created three remixes of the song «Transylvanian Concubine», two of which appeared on their 1997 EP Transylvanian Regurgitations.[87] Manson befriended The Smashing Pumpkins vocalist Billy Corgan in 1997,[88] and performed renditions of «Eye» and «The Beautiful People» alongside that band at the 1997 edition of Bridge School Benefit concert.[89] Manson frequently consulted Corgan during the early stages of recording Mechanical Animals. Referring to its inclusion of glam rock influences, Corgan advised Manson that «This is definitely the right direction» but to «go all the way with it. Don’t just hint at it».[90] In 2015, Marilyn Manson and the Smashing Pumpkins embarked on a co-healining tour titled «The End Times Tour».[91]

To promote Mechanical Animals in 1998, the band embarked on their first co-headlining concert tour: the «Beautiful Monsters Tour» with Hole.[92] The tour was problematic,[93] with Manson and Hole vocalist Courtney Love frequently insulting one another both on-stage and during interviews.[94] Private disputes also arose over finances, as Hole were unwittingly financing most of Manson’s production costs, which were disproportionately high relative to Hole’s.[95] The tour was to consist of thirty-seven dates,[92] although Hole left after nine.[94] When Hole departed from the tour, it was renamed the «Rock Is Dead Tour», with Jack Off Jill announced as one of the support acts.[96] Manson had produced many of Jack Off Jill’s demo recordings in the early 90s, and later wrote the liner notes to their 2006 compilation Humid Teenage Mediocrity 1992–1996.[97][98]

Manson launched his own vanity label in 2000, Posthuman Records.[99] The label released two albums – the 2000 soundtrack to Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 and Godhead’s 2001 album 2000 Years of Human Error – before being dissolved in 2003.[100] The latter album sold over 100,000 copies in the United States,[101] and featured him performing vocals on the track «Break You Down».[102] He performed vocals on «Redeemer», a song written by Korn vocalist Jonathan Davis that featured on the 2002 album Queen of the Damned: Music from the Motion Picture.[103] Davis had been prevented from singing the song due to contractual issues with his record label.[104] Manson also contributed a remix of the Linkin Park song «By Myself» to that band’s remix album Reanimation,[105] and collaborated with Marco Beltrami to create the score for the 2002 film Resident Evil.[106]

He performed vocals on the Chew Fu GhettoHouse Fix remix of Lady Gaga’s «LoveGame», which was featured as a b-side on the song’s single in 2008.[107] He was a featured vocalist on «Can’t Haunt Me»,[108] a track recorded in 2011 for Skylar Grey’s unreleased album Invinsible.[109] He appeared on «Bad Girl», a song from Avril Lavigne’s 2013 self-titled album,[84] and featured on the song «Hypothetical» from Emigrate’s 2014 album Silent So Long.[110] New Orleans brass ensemble the Soul Rebels performed «The Beautiful People» alongside Manson at the 2015 edition of the Japanese Summer Sonic Festival.[111] Manson recorded vocals on a cover of Bowie’s «Cat People (Putting Out Fire)» for country musician Shooter Jennings’s 2016 album Countach (For Giorgio).[112][113] The two were introduced in 2013 by Manson’s then-bassist Twiggy Ramirez,[114] and the pair first collaborated that same year on a song for the soundtrack to television series Sons of Anarchy.[115] Their version of the song, «Join the Human Gang», remains unreleased, but the track was eventually rewritten and released by The White Buffalo as «Come Join the Murder».[114] Jennings later produced Manson’s 2020 album We Are Chaos.[114]

Manson has collaborated with numerous hip hop artists. In 1998, he featured on «The Omen (Damien II)», a track on DMX’s album Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood.[116][117] Following the Columbine High School massacre, Manson was mentioned in the lyrics to Eminem’s «The Way I Am» from The Marshall Mathers LP, in the lyric «When a dude’s getting bullied and he shoots up the school and they blame it on Marilyn». Manson appeared in the song’s music video, and a remix created by Danny Lohner and featuring Manson appeared on special editions of The Marshall Mathers LP. Manson also joined Eminem on-stage for several live performances of the track, one of which featured on Eminem’s 2002 video album All Access Europe.[118] He featured on «Pussy Wet», a song on Gucci Mane’s 2013 mixtape Diary of a Trap God,[119] and provided vocals on the song «Marilyn Manson» on the 2020 mixtape Floor Seats II by ASAP Ferg.[120][121]

Alongside DaBaby, Manson co-wrote and was a featured artist on «Jail pt 2», a song on Kanye West’s 2021 album Donda.[122] Manson and DaBaby appeared alongside West at several events promoting the album, including at a listening event held at Soldier Field in August, and at one of West’s Sunday Church Services in October.[123][124] The appearances attracted significant media attention and controversy.[125] West said the trio collaborated on a total of five songs.[122] The album was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album, which entitled Manson to a co-nomination credit for his work on the song.[126][127] Manson continued his collaboration with West for the follow-up album, Donda 2.[128] West collaborator Digital Nas said Manson was in the recording studio «every day» while the album was recorded, and explained that West «doesn’t want Marilyn to play rap beats. He wants Marilyn to play what he makes, and then Ye will take parts of that and sample parts of that and use parts of that, like he did [generally when making] Yeezus.»[129] Manson band-member Tim Skold has confirmed he was involved in the process.[130]

While with The Spooky Kids, Manson teamed with Jeordie White (also known as Twiggy Ramirez) and Stephen Gregory Bier Jr. (also known as Madonna Wayne Gacy) in two side-projects: Satan on Fire, a faux-Christian metal ensemble where he played bass guitar, and drums in Mrs. Scabtree, a collaborative band formed with White and then girlfriend Jessicka (vocalist with the band Jack Off Jill) as a way to combat contractual agreements that prohibited Marilyn Manson from playing in certain clubs.[citation needed]

Film and television

Manson made his film debut in 1997, as an actor in David Lynch’s Lost Highway. Since then he has appeared in many minor roles and cameos, including Party Monster; then-girlfriend Rose McGowan’s 1999 film Jawbreaker; Asia Argento’s 2004 film The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things; Rise; The Hire: Beat The Devil, the sixth installment in the BMW films series; and Showtime’s comedy-drama TV series Californication in 2013, in which Manson portrayed himself. He also appeared on HBO’s Eastbound & Down,[131] of which Manson is reportedly a longtime fan,[132] and had lobbied to appear on for years; and ABC’s Once Upon a Time, for which he provided the voice of the character «Shadow».[133]

He was interviewed in Michael Moore’s political documentary Bowling for Columbine (2002) discussing possible motivations for the Columbine massacre and allegations that his music was somehow a factor.[citation needed] He has appeared in animated form in Clone High and participated in several episodes of the MTV series Celebrity Deathmatch, becoming the show’s unofficial champion and mascot; he often performed the voice for his claymated puppet, and contributed the song «Astonishing Panorama of the Endtimes» to the soundtrack album.[citation needed] In July 2005, Manson told Rolling Stone that he was shifting his focus from music to filmmaking – «I just don’t think the world is worth putting music into right now. I no longer want to make art that other people – particularly record companies – are turning into a product. I just want to make art.»[citation needed] Johnny Depp reportedly used Manson as his inspiration for his performance as Willy Wonka in the film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.[134] Manson himself expressed interest in playing the role of Willy Wonka in the film.[135]

He had been working on his directorial debut, Phantasmagoria: The Visions of Lewis Carroll, a project that has been in development hell since 2004, with Manson also set to portray the role of Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Initially announced as a web-only release, it was later decided to give the estimated $4.2 million budget film a conventional cinema release, with a slated release date of mid-2007. The film was to have an original music soundtrack with previously unreleased songs.[136] Production of the film had been postponed indefinitely until after the Eat Me, Drink Me tour.[137] In 2010, studio bosses shut down production on the project, reportedly due to viewers’ responses to the violent content of clips released on the internet. The film was later officially put on «indefinite production hold».[138]

However, according to a 2010 interview with co-writer Anthony Silva about the hold, the film was still on and the talk of it being shut down was just a myth.[139]

In a June 2013 interview, Manson stated that he had «resurrected» the project, and that Roger Avary would direct it.[140] In a separate interview during the previous year, he said a small crew similar to what he used for his «Slo-Mo-Tion» music video would be used, and would rather film the movie on an iPhone than not film it at all. In a Reddit AMA with Billy Corgan on April 4, 2015, Manson commented that he had withdrawn from the project because the writing process for the film was «so… damaging to my psyche, I’ve decided I don’t want to have anything to do with it», and further commented that the only footage that had been created thus far had been content created for the trailer, which was made in order to promote the film.[141][142]

Manson appeared in the final season of the TV series Sons of Anarchy, portraying white supremacist Ron Tully.[143] In January 2016, it was announced that Manson would be joining the cast for season 3 of WGN’s Salem. He played Thomas Dinley, a barber and surgeon described as «the go-to man in Salem, from a shave and a haircut to being leeched, bled, sliced open or sewn up».[144] In 2020, Manson was a guest star on the HBO television series The New Pope, in which he has a personal audience with the series’ Pope and recommends that he visit the prior Pope that lies unconscious in a coma.[145]

Art

Manson as Mechanical Animals‘ antagonist/character «Omega»

Manson stated in a 2004 interview with i-D magazine to have begun his career as a watercolor painter in 1999 when he made five-minute concept pieces and sold them to drug dealers. On September 13–14, 2002, his first show, The Golden Age of Grotesque, was held at the Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions Centre. Art in America‘s Max Henry likened them to the works of a «psychiatric patient given materials to use as therapy» and said his work would never be taken seriously in a fine art context, writing that the value was «in their celebrity, not the work».[146] On September 14–15, 2004, Manson held a second exhibition on the first night in Paris and the second in Berlin. The show was named ‘Trismegistus’ which was also the title of the center piece of the exhibit – a large, three-headed Christ painted onto an antique wood panel from a portable embalmers table.

Manson named his self-proclaimed art movement Celebritarian Corporation. He has coined a slogan for the movement: «We will sell our shadow to those who stand within it.» In 2005 he said that the Celebritarian Corporation has been «incubating for seven years» which if correct would indicate that Celebritarian Corporation, in some form, started in 1998.[147] Celebritarian Corporation is also the namesake of an art gallery owned by Manson, called the Celebritarian Corporation Gallery of Fine Art in Los Angeles for which his third exhibition was the inaugural show. From April 2–17, 2007, his works were on show at the Space 39 Modern & Contemporary art gallery in Fort Myers, Florida. Forty pieces from this show traveled to Germany’s Gallery Brigitte Schenk in Cologne to be publicly exhibited from June 28 – July 28, 2007. Manson revealed a series of 20 paintings in 2010 entitled Genealogies of Pain, an exhibition showcased at Vienna’s Kunsthalle gallery which the artist collaborated on with David Lynch.[148]

Video games

Manson has made an appearance in the video game Area 51 as Edgar, a grey alien. His song «Cruci-Fiction in Space» is featured in a commercial for the video game, The Darkness. His likeness is also featured on the Celebrity Deathmatch video game for which he recorded a song for the soundtrack (2003). The song «Use Your Fist and Not Your Mouth» was the credits score of the game Cold Fear as well as Spawn: Armageddon. The song «Four Rusted Horses» had an alternate version used in trailers for the video game Fear 3. A remix of the song «Tainted Love» appears in the debut trailer for the 2010 video game, Need for Speed: Hot Pursuit and in the launch trailer of the 2012 video game Twisted Metal. Manson’s song «The Beautiful People» was featured in WWE SmackDown! Shut Your Mouth, KickBeat and Brütal Legend. The song «Arma-goddamn-motherfuckin-geddon» is also featured in Saints Row: The Third. His music video to the song «Personal Jesus» was used in some parts of the Buzz! game series.[citation needed]

Other ventures

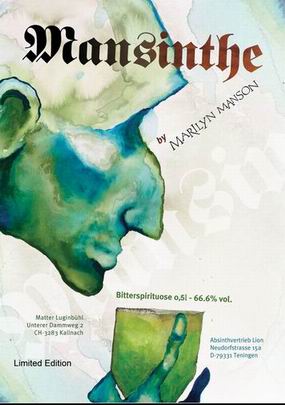

Manson launched «Mansinthe», his own brand of Swiss-made absinthe, which has received mixed reviews; some critics described the taste as being «just plain»,[150] but it came second to Versinthe in an Absinthe top five[151] and won a gold medal at the 2008 San Francisco World Spirits Competition.[152] Other reviewers, such as critics at The Wormwood Society, have given the absinthe moderately high praise.[153] In 2015, Manson stated he was no longer drinking absinthe.[154][155]

Vocal style

Manson predominantly delivers lyrics in a melodic fashion,[156] although he invariably enhances his vocal register by utilizing several extended vocal techniques, such as vocal fry,[157] screaming,[158] growling[159] and crooning.[160][161] In one interview he claimed his voice has five different tones,[162] which mixing engineer Robert Carranza discovered can form a pentagram when imported into a phrasal analyzer.[163][164] He possesses a baritone vocal type,[165] and has a vocal range which spans three octaves.[166] His lowest bass note of A1 can be heard in «Arma-goddamn-motherfuckin-geddon», while his highest note, an E6 — the first note of the whistle register — can be heard on the Born Villain song «Hey, Cruel World…».[167]

Name

Marilyn Monroe, 1954

Charles Manson, 1968

The name «Marilyn Manson» juxtaposes Marilyn Monroe and Charles Manson—a sex symbol and a mass murderer, respectively, both of whom became American cultural icons.

The name Marilyn Manson is formed by a juxtaposition of two opposing American pop cultural icons: Marilyn Monroe and Charles Manson.[168] Monroe, an actress, was one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and continues to be a major icon over 50 years after,[169] while Manson, a cult leader, was responsible for the murder of actress Sharon Tate, as well as several others; and served a life sentence on murder and conspiracy charges until his death in 2017.[170][171]

Manson was a culture war agitator for our side, someone willing to jar and frighten the fuck out of the power structures that seemed there to keep teenagers in their place … and his tactics made him a target, both of mass-culture disdain and of superior alt-culture snark. All that was by design. He put himself out there to take those attacks. And on some level, he’s a saint for that.

—Stereogum on Marilyn Manson.[172]

Manson has mentioned on at least two occasions that he trademarked the name Marilyn Manson. In an interview at the 2015 Cannes Lions Festival, he said: «I trademarked the name ‘Marilyn Manson’ the same way as Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse. It’s not a stage name. It’s not my legal name. … Marilyn Manson is owned by Brian Warner, my real name.»[173] He also mentioned this in a 2013 interview with Larry King.[174] The records of the United States Patent and Trademark Office show that he registered four trademarks of the name between 1994 and 1999, protecting entertainment services, merchandising and branding.[175][176][177][178]

Manson says he used those trademark registrations to issue cease and desist orders to media outlets who wrongly blamed him for the Columbine High School massacre. One journalist had erroneously reported the shooters were «wearing Marilyn Manson makeup and t-shirts», although the reports were soon proved incorrect.[173] However, Manson said, «Once the wheels started spinning, Fox News started going.»[173] As a result of these accusations, Manson’s career was seriously harmed: He was shunned by many venue owners and received numerous death threats.[179]

Manson generally uses the name in lieu of his birth name. Though his mother referred to him by his birth name of Brian, his father opted to refer to his son as simply «Manson» since about 1993, saying, «It’s called respect of the artist.»[180]

Lawsuits

In September 1996, former bassist Gidget Gein negotiated a settlement with Manson where he would receive US$17,500 and 20 percent of any royalties paid for recordings and for any songs he had a hand in writing and his share of any other royalties or fees the group earned while he was a member and he could market himself as a former member of Marilyn Manson. This settlement was not honored, however.[181]

Former guitarist and founding member Scott Putesky (a.k.a. Daisy Berkowitz) filed a $15 million lawsuit in a Fort Lauderdale court against the singer, the band and the band’s attorney (David Codikow) in January 1998 after his departure from the group in the spring of 1996. Berkowitz claimed «thousands of dollars in royalties, publishing rights, and performance fees» and filed an attorney malpractice suit against Codikow, alleging that «Codikow represented Warner’s interests more than the band’s and … gave Warner disproportionate control..»[182][183] By October of that year, the suit had been settled out of court for an undisclosed amount.[184]

On November 30, 1998, a few days after the band accumulated «[a] total [of] more than $25,000» in backstage and hotel room damages during the Poughkeepsie, New York, stop of their Mechanical Animals Tour,[185] SPIN editor Craig Marks filed a $24-million lawsuit against Manson and his bodyguards. On February 19, 1999, Manson counter-sued Marks for libel, slander and defamation, seeking US$40 million in reparation.[186] Marks later dropped the lawsuit.[187] Manson apologized for the Poughkeepsie incident and offered to make financial restitution.[188][189]

In a civil battery suit, David Diaz, a security officer from a concert in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on October 27, 2000, sued for US$75,000 in a Minneapolis federal court.[190] The federal court jury found in Manson’s favor.[191] In a civil suit presented by Oakland County, Michigan, Manson was charged with sexual misconduct against another security officer, Joshua Keasler, during a concert in Clarkston, Michigan, on July 30, 2001. Oakland County originally filed assault and battery and criminal sexual misconduct charges,[192] but the judge reduced the latter charge to misdemeanor disorderly conduct.[193] Manson pleaded no contest to the reduced charges, paid a US$4,000 fine,[194] and later settled the lawsuit under undisclosed terms.[195]

On April 3, 2002, Maria St. John filed a lawsuit in Los Angeles Superior Court accusing Manson of providing her adult daughter, Jennifer Syme, with cocaine and instructing her to drive while under the influence.[196] After attending a party at Manson’s house, Syme was given a lift home;[197] Manson claims she was taken home by a designated driver.[196] After she got home, she got behind the wheel of her own vehicle and was killed when she crashed it into three parked cars. Manson is reported to have said there were no alcohol or other drugs at the party; St. John’s lawyer disputed this claim.[196]

On August 2, 2007, former band member Stephen Bier filed a lawsuit against Manson for unpaid «partnership proceeds», seeking $20 million in back pay. Several details from the lawsuit leaked to the press.[198][199] In December 2007, Manson countersued, claiming that Bier failed to fulfill his duties as a band member to play for recordings and to promote the band.[200] On December 28, 2009, the suit was settled with an agreement which saw Bier’s attorneys being paid a total of $380,000.[201]

Philanthropy

Manson has supported various charitable causes throughout his career. In 2002, he worked with the Make-A-Wish Foundation to collaborate with a fan who had been diagnosed with a life-threatening illness. 16-year-old Andrew Baines from Tennessee was invited into the band’s recording studio to record backing vocals for their then-upcoming album, The Golden Age of Grotesque. Manson said on his website, «Yesterday, I spent the afternoon with Andrew, who reminded me the things I create are only made complete by those who enjoy them. I just want to simply say, thank you to Andrew for sharing such an important wish with me.»[202][203] He contributed to Oxfam’s 2013 «Rumble in the Jumble» event, which raised money to aid victims of domestic and sexual abuse in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[204] He has supported various organizations – such as Music for Life and Little Kids Rock — which enable access to musical instruments and education to children of low-income families. He has also worked with Project Nightlight, a group that encourages children and teenagers to speak out against physical and sexual abuse.[205] In 2019, he performed alongside Cyndi Lauper at her annual ‘Home for the Holidays’ benefit concert, with all proceeds donated to Lauper’s True Colors United, which «works to develop solutions to youth homelessness that focus on the unique experiences of LGBTQ young people».[206][207]

Personal life

Relationships

Manson is heterosexual.[208] He was engaged to actress Rose McGowan from February 1999 to January 2001. McGowan later ended their engagement, citing «lifestyle differences.»[209]

Manson and burlesque dancer, model, and costume designer Dita Von Teese became a couple in 2001. He proposed on March 22, 2004, and they were married in a private, non-denominational ceremony officiated by Chilean film director Alejandro Jodorowsky.[210] On December 30, 2006, Von Teese filed for divorce due to «irreconcilable differences».[211] Von Teese also eventually stated she did not agree with Manson’s «partying or his relationship with another girl».[212] Manson’s «heavy boozing» and distant behavior were also cited as cause for the split.[213] A judgment of divorce was entered in Los Angeles Superior Court on December 27, 2007.[214]

Manson’s relationship with actress, model, and musician Evan Rachel Wood was made public in 2007.[215] They reportedly maintained an on-again, off-again relationship for several years. He proposed to Wood during a Paris stage performance in January 2010, but the couple broke off the engagement later that year.[216]

In the March 2012 issue of Revolver magazine, American photographer Lindsay Usich was referred to as Manson’s girlfriend. The article referenced a new painting by him featuring her. Usich is credited as the photo source for the cover art of Manson’s 2012 album, Born Villain. It was later confirmed that the two were romantically involved.[217] In February 2015, Manson told Beat magazine that he is «newly single».[218]

In October 2020, Manson revealed in an interview with Nicolas Cage on ABC News Radio that he was married in a private ceremony during the COVID-19 pandemic.[219] The person he married was revealed to be Usich after she changed her social media name to «Lindsay Elizabeth Warner».[220]

Manson is the godfather of Lily-Rose Depp.[221]

Beliefs

Manson claims he was a friend of Anton LaVey,[222] and early on had also claimed LaVey inducted him as a minister in the Church of Satan. Later in his career, Manson downplayed this, saying he was «not necessarily» a minister: «that was something earlier… it was a friend of mine who’s now dead, who was a philosopher that I thought I learned a lot from. And that was a title I was given, so a lot of people made a lot out of it. But it’s not a real job, I didn’t get paid for it.»[223] The Church of Satan itself later confirmed Manson was never ordained as a minister in their church.[224]

Despite that, Manson has been described as «the highest profile Satanist ever» with strong anti-Christian views and social Darwinist leanings.[225] However, Manson denies this, and stated the following:

«I’m not a misanthrope. I’m not a nihilist. I’m not an atheist. I believe in spirituality, but it really has to come from somewhere else. I learned a long time ago, you can’t try to change the world, you can just try to make something in it. I think that’s my spirituality, it’s putting something into the world. If you take all the basic principles of any religion, it’s usually about creation. There’s also destruction, but creation essentially. I was raised Christian. I went to a Christian school, because my parents wanted me to get a better education. But when I got kicked out I was sent to public school, and got beat up more by the public school kids. But then I’d go to my friend’s Passover and have fun.»

— Marilyn Manson[226]

Manson is also familiar with the writings of Aleister Crowley and Friedrich Nietzsche. He quotes Crowley throughout his autobiography, including Thelema’s principal dictum, «Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.»[227] Crowley’s esoteric subject matter forms an important theme in much of Manson’s early work.[228]

Controversies

Marilyn Manson has been referred to as one of the most iconic and controversial figures in heavy metal music,[229][230][231][232][233] with some referring to him as a «pop culture icon».[234][235][236][237] Paste magazine said there were «few artists in the 90s as shocking as Marilyn Manson, the most famous of the shock-rockers».[238] In her book Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and Stories That Shaped Our Culture, author Jacqueline Edmondson writes that Manson creates music that «challenges people’s worldviews and provokes questions and further thinking».[239] Manson, his work, and the work of his eponymous band, have been involved in numerous controversies throughout their career.[240][241]

On May 30, 1996, the co-directors of political advocacy group Empower America organized a bipartisan press conference with Republican William Bennett and Democrats Joseph Lieberman and C. Delores Tucker, in which the record industry was admonished for selling «prepackaged, shrink-wrapped nihilism.» The three largely targeted rap music, but also referenced Manson; Tucker called Smells Like Children the «dirtiest, nastiest porno record directed at children that has ever hit the market» and said distributing record labels had «the blood of children on their hands», while Lieberman said the music «celebrates some of the most antisocial and immoral behaviors imaginable.» They also announced that Empower America would be launching a $25,000 radio advertising campaign to collect petitions from listeners who wanted record companies to «stop spreading this vicious, vulgar music.»[242]

The release of Antichrist Superstar in 1996 coincided with the band’s commercial breakthrough,[243] and much of the attention received by Manson from mainstream media was not positive.[244] Empower America organized another press conference in December 1996, where they criticized MCA—the owner of Interscope—president Edgar Bronfman Jr. for profiting from «profanity-laced» albums by Manson, Tupac Shakur and Snoop Doggy Dogg.[245][246] The band’s live performances also came under fire during this period; the «Dead to the World Tour» was followed by protesters at nearly every North American venue it visited.[247] Opponents of the band claimed the shows featured elements of Satanism, including a satanic altar, bestiality, rape, the distribution of free drugs,[243] homosexual acts, as well as animal and even human sacrifices.[248] Anonymous affidavits compiled by the Gulf Coast division of the American Family Association made various other claims about the live shows.[247] Students in Florida were threatened with expulsion for attending the band’s concerts.[243]

Several state legislatures, including the Utah State Legislature, South Carolina Legislature and the Virginia General Assembly, enacted legislation specifically targeting the group, banning them from performing at state-operated venues.[249][250][251] These laws would later be repealed, following separate lawsuits from fans and the American Civil Liberties Union.[249][251] Ozzy Osbourne sued the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority after they forced the cancelation of the New Jersey date of the 1997 Ozzfest at Giants Stadium; Manson’s appearance had been cited as the reason for the cancelation.[251][252] In November 1997, Manson’s lyrical content was examined during congressional hearings led by Lieberman and Sam Brownback, in an attempt to determine the effects—if any—of violent lyrics on young listeners.[253] The subcommittee heard testimony from Raymond Kuntz, who blamed his son’s suicide on Antichrist Superstar—specifically the song «The Reflecting God».[254] Lieberman went on to claim that the band’s music was driving young listeners to commit suicide,[255] and called the band the «sickest group ever promoted by a mainstream record company.»[256]

Columbine High School massacre

On April 20, 1999, Columbine High School students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed thirteen people and wounded twenty-one others before committing suicide.[257] At the time, it was the deadliest school shooting in US history.[258] In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, media reports surfaced that were heavily critical of Goth subculture,[259][260] alleging the perpetrators were wearing Marilyn Manson T-shirts during the massacre,[261] and that they were influenced by violence in entertainment, specifically movies, video games and music.[262] Five days after the incident, William Bennet and Joseph Lieberman – longtime critics of the vocalist – appeared on Meet the Press, where they cited his music as a contributing factor to the shooting.[263] Soon after, sensationalist headlines such as «Killers Worshipped Rock Freak Manson» and «Devil-Worshipping Maniac Told Kids To Kill» began appearing in media coverage of the tragedy.[264][265] Despite confirmation that the pair were fans of German industrial bands such as KMFDM and Rammstein,[266][267] and had «nothing but contempt» for Manson’s music,[268] mainstream media continued to direct the majority of blame for the shooting at Manson.[269][270]

The Mayor of Denver, Wellington Webb, successfully petitioned for the cancelation of KBPI-FM’s annual «Birthday Bash», at which Manson was scheduled to appear on April 30. Webb said the concert would be «inappropriate» because the two gunmen were thought to be fans of Manson.[271] Coloradoan politicians Bill Owens and Tom Tancredo accused Manson of promoting «hate, violence, death, suicide, drug use and the attitudes and actions of the Columbine High School killers.»[272] On April 29, ten US senators led by Brownback sent a letter to the head of Seagram, the conglomerate which owned Manson’s record label, requesting they stop distributing music to children that «glorifies violence». The letter named Manson, accusing him of producing songs that «eerily reflect» the actions of Harris and Klebold.[273]

Manson canceled the final four dates of the Rock Is Dead Tour out of respect for the victims while criticizing the media for their irresponsible coverage of the tragedy.[274][275] He elaborated on this point in an op-ed written for Rolling Stone titled «Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?». In the article, Manson castigated America’s gun culture and the political influence of the National Rifle Association, but was heavily critical of news media. He argued the media should be blamed for the next school shooting, as it was them who propagated the ensuing hysteria and «witch hunt», and said that instead of debating more relevant societal issues, the media instead facilitated the placing of blame on a scapegoat.[276][277]

On May 4, Brownback chaired a congressional hearing of the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation on the distribution and marketing of supposedly violent content to children by the film, music, television and video-game industries. The committee heard testimony from Bennett, the Archbishop of Denver Charles J. Chaput, as well as professors and mental health professionals; they criticized Manson, his label mates Nine Inch Nails, and the 1999 film The Matrix for their alleged contribution to a cultural environment enabling violence such as the Columbine shootings. Recording Industry Association of America executive Hilary Rosen said she refused to participate in the hearing as it was «staged as political theater. They just wanted to find a way to shame the industry, and I’m not ashamed.»[278] The committee eventually requested the Federal Trade Commission and the United States Department of Justice investigate the entertainment industry’s marketing practices to minors.[279] The lyrical content of the band’s 2000 album Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) was largely inspired by the massacre, with Manson saying it was a rebuttal to the accusations leveled against him by mainstream media.[280] He also discussed the massacre and its aftermath in Michael Moore’s 2002 documentary Bowling for Columbine.[281]

Other alleged incidents

In 2000, an elderly nun was murdered by three schoolgirls in Italy, with their diaries reportedly containing numerous references to and pictures of Manson.[282] Soon after, he was arrested following a concert in Rome for allegedly «tearing off his genitals».[282] Manson said the arrest was politically motivated following his implication in the murder by Italian tabloids.[283] In 2003, French media[which?] blamed Manson when several teenagers vandalized the graves of British war heroes in Arras, France.[282]

On June 30, 2003, 14-year old schoolgirl Jodi Jones was brutally murdered in Scotland.[284] Her mutilated body was discovered in woodland near her home, with her injuries said to closely resemble those of Elizabeth Short, commonly referred to by media as the Black Dahlia.[285][286] Ten months later, Jones’s boyfriend Luke Mitchell, then-fifteen years old, was arrested on suspicion of her murder.[287] Police confiscated a copy of The Golden Age of Grotesque containing the short film Doppelherz during a search of Mitchell’s family home,[288] which had been purchased by Mitchell two days after Jones’s death.[289] A ten-minute excerpt from the film, as well as several paintings created by Manson depicting the Black Dahlia’s mutilated body, were presented as evidence during the trial.[288][290][291] Mitchell was found guilty of her murder and was sentenced to a minimum of twenty years in prison.[292] In his closing summation, Lord Nimmo Smith said he believed Mitchell «carried an image of [Manson’s] paintings in your memory when you killed Jodi.»[293] Mitchell continues to profess his innocence.[294]

The controversy connecting Manson to school shootings continued on October 10, 2007, when fourteen-year old Asa Coon shot four people at SuccessTech Academy in Cleveland, Ohio, before committing suicide.[295] While exiting a bathroom, Coon was punched in the face by another student, and responded by shooting his attacker in the abdomen.[296] Coon then walked down the hallway and shot in to two occupied classrooms – wounding two teachers and a student – before entering a bathroom and committing suicide.[297] Coon was wearing a Marilyn Manson T-shirt during the shooting.[298][299] A photograph of Coon’s dead body was circulated online by Cleveland police officer Walter Emerick.[300] On May 18, 2009, Justin Doucet, a fifteen-year-old student at Larose-Cut Off Middle School in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, entered the school with a semi-automatic pistol.[301] After a teacher refused to comply with Doucet’s demand to say «Hail Marilyn Manson», he fired two shots that narrowly missed the teacher’s head, before shooting himself.[302][303] Doucet died from his injuries a week later.[304]

Abuse allegations

Several of Manson’s former acquaintances began communicating with one another in September 2020.[305][306] In a letter dated January 21, 2021, California State Senator Susan Rubio wrote to the director of the FBI and the U.S. Attorney General, asking them to investigate allegations several women had made against Manson.[307] On February 1, former fiancée Evan Rachel Wood wrote on Instagram and in a statement to Vanity Fair, accusing Manson of being abusive during their relationship a decade earlier.[308] Four other women simultaneously issued statements also accusing Manson of abuse.[309] Wood continued to make allegations against Manson and his wife Lindsay Usich on Instagram, claiming that his alleged abuse included antisemitism,[310] and said she filed a report with the Los Angeles Police Department against Usich for threatening to leak photographs of Wood dressed in a Nazi uniform while wearing an Adolf Hitler-style toothbrush moustache.[311] A total of sixteen people have made various allegations against Manson,[3][312] including five accusations of sexual assault.[313]

Manson was immediately dropped by distributing record label Loma Vista Recordings,[314] his talent agency Creative Artists,[315] and his long-time manager Tony Ciulla.[316] He was also removed from future episodes of TV series American Gods and Creepshow, in which he was scheduled to appear.[3][317] On February 2, Manson issued a statement via Instagram, saying, «Obviously, my art and my life have long been magnets for controversy, but these recent claims about me are horrible distortions of reality. My intimate relationships have always been entirely consensual with like-minded partners», and claimed the accusers were «misrepresenting the past».[318] His former wife Dita Von Teese stated that «the details made public do not match my personal experience during our 7 years together as a couple.»[319] Former girlfriend Rose McGowan said that Manson was not abusive during their relationship but that her experience had «no bearing on whether he was like that with others before or after».[320] On February 3, the LAPD performed a «welfare check» at Manson’s home after receiving a call from a purported friend who was concerned for his wellbeing.[321][322] The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department confirmed on February 19 that they were investigating Manson due to allegations of domestic violence.[323]

Four women filed civil lawsuits against Manson in the months that followed Wood’s allegations:[324] Esmé Bianco,[325] Ashley Morgan Smithline,[326] Ashley Walters,[327] and an anonymous woman.[328] Manson’s legal team issued statements denying the allegations.[329][330] They filed a motion to dismiss these lawsuits, calling the claims «untrue, meritless» and alleging that several of the accusers «spent months plotting, workshopping, and fine-tuning their stories to turn what were consensual friendships and relationships with Warner from more than a decade ago, into twisted tales that bear no resemblance to reality».[331] The lawsuit filed by the anonymous woman was initially dismissed because it exceeded the statute of limitations,[332][333] although an amended complaint was refiled soon after.[334][335] Manson’s legal team also sought to have Bianco’s lawsuit dismissed because it exceeded the statute of limitations, although a federal judge denied that motion.[336][337] Walters’s lawsuit was dismissed with prejudice in May.[338][339] Morgan Smithline’s lawsuit was also dismissed by a federal judge, after her lawyer withdrew from her case and she did not meet a court-ordered deadline regarding her representation in the case.[340] Bianco and Manson reached an out-of-court settlement in January 2023 with undisclosed terms of agreement.[341]

Manson filed a lawsuit against Wood and Ashley «Illma» Gore for defamation, intentional infliction of emotional distress, violations of the California Comprehensive Computer Data Access and Fraud Act, as well as the impersonation of an FBI agent and falsifying federal documents.[342] In the suit, it is alleged that Wood and Gore spent three years contacting his former girlfriends and provided «checklists and scripts» to prospective accusers in order to corroborate Wood’s claims,[343][344] and that the pair impersonated and falsified documents from an FBI agent.[345] The suit additionally claims Gore hacked into Manson’s computers and social media, and created fake email accounts to manufacture evidence he had been distributing «illicit pornography».[346] It is also alleged that Gore swatted Manson by calling the FBI claiming to be a friend concerned about an «emergency» at his home. As a result of the call, several police officers were dispatched to his property, where «there was no emergency».[347] He is seeking a jury trial.[348][349]

The LACSD presented the findings of their 19-month investigation of the sexual assault allegations made against Manson to California district attorney George Gascón in September 2022.[350] Gascón called the file «partial» and said more evidence was needed in order to file charges.[351][352] Smithline, who previously attempted to sue Manson, recanted her allegations in legal documents in February 2023, claiming she was «manipulated» and «pressured» by Wood and her associates to make allegations against Manson that were «not true».[313][353][354]

Discography

Studio albums

- Portrait of an American Family (1994)

- Antichrist Superstar (1996)

- Mechanical Animals (1998)

- Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) (2000)

- The Golden Age of Grotesque (2003)

- Eat Me, Drink Me (2007)

- The High End of Low (2009)

- Born Villain (2012)

- The Pale Emperor (2015)

- Heaven Upside Down (2017)

- We Are Chaos (2020)

Guest appearances in music videos

- 1992: Nine Inch Nails – «Gave Up»

- 2000: Nine Inch Nails – «Starfuckers, Inc.»

- 2000: Eminem – «The Way I Am»

- 2002: Murderdolls – «Dead in Hollywood»

- 2010: Rammstein – «Haifisch»

- 2011: D’hask – «Tempat Ku»

- 2014: Die Antwoord – «Ugly Boy»

- 2017: Elton John – «Tiny Dancer»[355]

- 2020: Corey Taylor – «CMFT Must Be Stopped»

Tours

Awards and nominations

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | «The Dope Show» | Best Hard Rock Performance | Nominated |

| 2001 | «Astonishing Panorama of the Endtimes» | Best Metal Performance | Nominated |

| 2004 | «mOBSCENE» | Nominated | |

| 2013 | «No Reflection» | Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance | Nominated |

| 2022 | Donda (as featured artist) | Album of the Year | Nominated |

| Year | Winner | Category |

| 1997 | «Long Hard Road Out of Hell» | Best Song From a Movie Soundtrack[359] |

| 1999 | Marilyn Manson | Live Performer of the Year |

| 1998 | God Is in the TV | Home Video of the Year[360] |

| 2000 | Marilyn Manson | Male Performer of the Year[361] |

Filmography and TV roles

- Lost Highway (1997)

- Howard Stern (1997–2004)

- Celebrity Deathmatch (1998)

- Jawbreaker (1999)

- Clone High (2002)

- Bowling for Columbine (2002)

- Beat the Devil (2002)

- Party Monster (2003)

- The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things (2004)

- Born Villain (2011)

- Wrong Cops (2013)

- Californication (2013)

- Celebrity Ghost Stories[362]

- Once Upon a Time (2013) Voice of Peter Pan’s shadow

- Phantasmagoria: The Visions of Lewis Carroll (cancelled)

- Sons of Anarchy (2014) (Ron Tully)

- Let Me Make You a Martyr (2016) (Pope)[10]

- Salem (2016–2017) (Thomas Dinley)

- The New Pope (2020)[363]

- The New Mutants (2020) Voice of the Smile Man

- American Gods (2021) Johan Wengren

Books

- The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. New York: HarperCollins division ReganBooks, 1998 ISBN 0-06-039258-4.

- Holy Wood. New York: HarperCollins division ReganBooks, Unreleased.

- Genealogies of Pain. Nuremberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2011 ISBN 978-3-86984-129-8.

- Campaign. Calabasas: Grassy Slope Incorporated, 2011 ASIN B005J24ZHS.

References

Notes

- ^ «In an attempt to reiterate the lesson of Willy Wonka in my own style during shows, I hung a donkey piñata over the crowd and put a stick on the edge of the stage. Then I would warn, ‘Please, don’t break that open. I beg you not to.’ Human psychology being what it is, kids in the crowd would invariably grab the stick and smash the piñata apart, forcing everyone to suffer the consequence, which would be a shower of cow brains, chicken livers and pig intestines from [the] disemboweled donkey.»[23]

- ^ «Well, there was always a real chip on our shoulder that [Portrait of an American Family] never really got the push from the record label that we thought it deserved. It was all about us touring our fucking asses off. We toured for two years solid, opening up for Nine Inch Nails for a year and then doing our own club tours. It was all just about perseverance.»[28]

- ^ Michael Beinhorn, the co-producer of Mechanical Animals, said: «When Mechanical Animals came out, the projected sales figure for the first week was 300,000 copies. [The label was] excited, saying, ‘We’re going to hit No.1 and sell 300k!’. It sold 230,000 and got to No.1, but it wasn’t enough. The label lost interest, they took down the huge billboard they had in Times Square for the album, the president of the label called Manson up, screaming at him for having tits on the cover. I think that, and what happened at Columbine, which really affected him emotionally, meant that he never made an album up to the standard of Mechanical Animals or Antichrist Superstar again. He just didn’t get the support.»[47]

Bibliography

- Manson, Marilyn; Strauss, Neil (February 14, 1998). The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. New York: HarperCollins division ReganBooks. ISBN 0-06-039258-4.

References

- ^ Greg, Glasgow (April 23, 1999). «Marilyn Manson Concert Canceled». The Daily Camera. MediaNews Group. Archived from the original (Broadsheet) on May 24, 2006. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ Cullen, Dave. Inside the Columbine High investigation Archived January 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Salon News, September 23, 1999.

- ^ a b c «A Timeline of Abuse Allegations Against Marilyn Manson». Billboard. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ «UPI Almanac for Saturday, Jan. 5, 2019». United Press International. January 5, 2019. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson’s Mother Dies After Battle With Dementia». Blabbermouth.net. May 18, 2014. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ «Brian Hugh Warner (b. 1969)». MooseRoots.com. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson shares heartfelt words after father’s death». Alternative Press. July 8, 2017. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ «Ancestry of Marilyn Manson». Wargs.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ Manson, Marilyn (1998). The Long Hard Road out of Hell. HarperCollins. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-06-098746-6.

An imposing-looking family tree tracing the Warners back to Poland and Germany, where they were called the Wanamakers, was plastered on the wall nearby.

- ^ a b Grow, Kory (August 12, 2015). «See Marilyn Manson Play Native American Hit Man in Movie Trailer». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony. «Marilyn Manson: The Beliefnet Interview». Beliefnet.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson». Montreal Mirror. July 24, 1997. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ «4. Christian School». April 4, 2011. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015.

- ^ «25th Parallel». Spookykids.net. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Harper, Janet (June 4, 2014). «THRILL KILL’S MUSIC TO DANCE, SLAY BY – Meet the guy who freaked out Marilyn Manson». Folio Weekly. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Hamersly, Michael (February 4, 2008). «Interview with your vampire: Marilyn Manson». PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Tron, Gina (April 10, 2014). «Daisy Berkowitz: Portrait of an American Ex-Marilyn Manson Member». Vice. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 84, 90.

- ^ Kissell, Ted B. «Manson: The Florida Years». Cleveland Scene. Euclid Media Group. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Baker, Greg (July 20, 1994). «Manson Family Values». Miami New Times. Voice Media Group. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Diamond, Ollie H. (May 11, 2014). «Sunday Old School: Marilyn Manson». Metal Underground. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ , Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Stratton, Jeff (April 15, 2004). «Manson Family Feud». New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Voice Media Group. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Putesky, Scott (August 9, 2009). «When Marilyn Manson Left His Kids Behind». Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. «Marilyn Manson – Biography & History». AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon. «26 Years Ago: Marilyn Manson Issues ‘Portrait of an American Family’«. Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Manson & Strauss 1998, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (January 23, 1997). «Marilyn Manson: Sympathy for the Devil». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson Biography». Biography.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Considine, J.D. (September 4, 1996). «Video Music Awards offer stars and unpredictability». The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Boehm, Mike (March 12, 1999). «‘Mechanical’ Reaction». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Dansby, Andrew (March 21, 2003). «Manson Golden at Number One». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Paine, Andre (November 8, 2010). «Marilyn Manson Plots 2011 Comeback with Indie Label». Billboard. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ San Roman, Gabriel (October 7, 2011). «Marilyn Manson’s ‘Antichrist Superstar’ Turns 15 as ‘Born Villain’ Readies for Release». OC Weekly. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (March 8, 2016). «Record Store Day 2016: The full list of 557 exclusive music releases revealed». Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Jolson-Colburn, Jeffrey (July 23, 1997). «Jamiroquai Tops MTV Video Music Nom List». E! Online. E!. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Sori, Alexandra (June 3, 2017). «A Brief History of Marilyn Manson Pissing Off Jesus Christ». Noisey. Vice Media. Archived from the original on January 27, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Hochman, Steve (August 16, 1998). «Marilyn Manson Aims to Change Tide of the Mainstream». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Vanhorn, Teri (September 15, 1998). «Marilyn Manson Fans Queue Up For Mechanical Animals». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b McKinstry, Lee (February 6, 2015). «20 artists you may not have known were nominated for (and won) Grammy Awards». Alternative Press. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Boehlert, Eric (September 24, 1998). «Marilyn Manson Shows He’s Dope». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Grein, Paul (November 21, 2008). «Chart Watch Extra: What A Turkey! The 25 Worst-Selling #1 Albums». Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on September 26, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (September 22, 2017). «Marilyn Manson: Columbine Blame ‘Destroyed My Career’«. Loudwire. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Burk, Greg (January 10, 2001). «Marilyn: A Re-Examination». LA Weekly. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Hill, Stephen (August 2, 2019). «Marilyn Manson vs Courtney Love: The true story of 1999’s Beautiful Monsters Tour». Metal Hammer. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ «See Marilyn Manson Play ‘Disposable Teens’ on MTV New Years Eve Bash in 2000». Revolver. November 14, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Brannigan, Paul (April 20, 2020). «Columbine: How Marilyn Manson Became Mainstream Media’s Scapegoat». Kerrang!. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Childers, Chad (November 14, 2019). «20 Years Ago: Marilyn Manson Releases ‘Holy Wood’ Album». Loudwire. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson May Be in for a Shock». Los Angeles Times. November 20, 2000. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Udo, Tommy (July 28, 2016). «Marilyn Manson: The Story Of Holy Wood (In The Shadow Of The Valley Of Death)». Metal Hammer. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Promis, Jose (September 27, 2003). «Missing Tracks Mean Fewer U.S. Album Sales». Billboard. Vol. 115, no. 39. p. 14. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Saul, Heather (March 24, 2016). «Dita Von Teese on remaining friends with Marilyn Manson: ‘He encouraged all of my eccentricities’«. The Independent. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson über Stimmung in USA und ‘Entartete Kunst’» [«Marilyn Manson on the mood in the US and ‘Degenerate Art'»]. Der Standard (in German). May 5, 2003. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Sexton, Paul (May 26, 2003). «Kelly, Timberlake Continue U.K. Chart Reign». Billboard. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ MTV News Staff (April 28, 2003). «For The Record: Quick News on Marilyn Manson and Jean Paul Gaultier». MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ «Manson To Tour ‘Against All Gods’«. Billboard. October 5, 2004. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Ewens, Hannah (July 29, 2016). «The evolution of Marilyn Manson: from Columbine scapegoat to Belieber». The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Bychawski, Adam (July 18, 2005). «Marilyn Manson Unleashes ‘Horrorpilation’«. NME. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Ames, Jonathan (May 2007). «Marilyn Manson: Return of the Living Dead». Spin. SpinMedia. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (April 17, 2012). «Marilyn Manson: I’m Not Trying To Be Reborn, I’m Trying to Transform». Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Paine, Andre (November 8, 2010). «Marilyn Manson: Antichrist indie star». Billboard. Reuters. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Sherman, Maria (March 20, 2012). «Marilyn Manson & Johnny Depp Cover ‘You’re So Vain’«. Billboard. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (January 15, 2015). «A Dark Prince Steps Into the Light». The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Brophy, Aaron (January 20, 2015). «Why Marilyn Manson’s ‘The Pale Emperor’ Is A ‘F*ck You’ To The Devil». The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Lynch, Joe (January 28, 2015). «Who Says Rock Is Dead? Marilyn Manson, Fall Out Boy & More Notch Big Debuts». Billboard. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Sosa, Chris (February 2, 2015). «Marilyn Manson Just Made an Unexpected Comeback». The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Gaca, Anna (September 11, 2017). «Marilyn Manson Releases Single ‘We Know Where You Fucking Live’, Announces New Album Heaven Upside Down». Spin. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson – Mainstream Rock Airplay». Billboard. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson crushed by prop on stage». BBC News. October 1, 2017. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson addresses scary stage accident: ‘The pain was excruciating’«. Yahoo.com. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017 – via Yahoo.

- ^ Bacior, Robin (October 18, 2019). «Stream Marilyn Manson — ‘God’s Gonna Cut You Down’«. Consequence of Sound. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Gwee, Karen (October 18, 2019). «Marilyn Manson releases ominous video for new single ‘God’s Gonna Cut You Down’«. NME. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson – Hot Rock Songs». Billboard. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson – Rock Digital Songs». Billboard. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Caulfield, Keith (September 20, 2020). «YoungBoy Never Broke Again Achieves Third No. 1 Album in Less Than a Year on the Billboard 200 Chart With ‘Top’«. Billboard. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ «American certifications – Marilyn Manson». Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ «British certifications – Marilyn Manson». British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved February 12, 2022. Type Marilyn Manson in the «Search BPI Awards» field and then press Enter.

- ^ Hedegaard, Erik (January 6, 2015). «Marilyn Manson: The Vampire of the Hollywood Hills». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Cadwalladr, Carole (January 18, 2015). «Marilyn Manson: ‘I created a fake world because I didn’t like the one I was living in’«. The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Stern, Marlow (January 21, 2015). «Marilyn Manson on Charlie Hebdo and Why You Should Avoid Foursomes». The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ Al-Sharif, Rabab (May 13, 2016). «Marilyn Manson to receive APMAs 2016 Icon Award — News». Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Gavin (January 14, 2015). «The A–Z Of Marilyn Manson». Metal Hammer. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ MTV News Staff (April 16, 1997). «Marilyn Manson May Be Shut Out Of Richmond, Virginia». MTV. Viacom Media Networks. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ The Dope Show (liner notes). Marilyn Manson. Interscope Records. 1998. INTDS–95599.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ MTV News Staff (May 29, 1997). «Marilyn Manson-Rasputina Remix To Creep Into Stores». MTV. Viacom Media Networks. Archived from the original on January 18, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ «Manson Teams With Corgan, Sparks Concert Rating Talk». MTV. March 6, 1997. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Manno, Lizzie (October 18, 2018). «Watch The Smashing Pumpkins Rock San Francisco on This Day in 1997». Paste. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Ali, Lorraine (September 2, 1998). «Marilyn Manson’s New (Happy) Face». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ Stapleton, Susan (April 6, 2015). «It’s the end times for The Smashing Pumpkins and Marilyn Manson in Las Vegas». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Gil (January 27, 1999). «Marilyn Manson, Hole Schedule ‘Beautiful Monsters’ Tour». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 27, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (March 10, 1999). «Best Of ’99: Boston Promoter Says Hole Dropping Off Manson Tour». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ a b MTV News Staff (March 15, 1999). «Hole Walks Out On Tour, Manson Injury Postpones Several Dates». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (March 11, 1999). «Hole Threaten To Drop Off Marilyn Manson Joint Tour». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ MTV News Staff (March 22, 1999). «Manson Resumes Tour Without Hole, Taps Nashville Pussy And Jack Off Jill For Upcoming Dates». MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Collar, Camilla. «Human Teenage Mediocrity: 1992-1995 – Jack Off Jill». AllMusic. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ «Booklet». Humid Teenage Mediocrity 1992–1996 (liner notes). Marilyn Manson. Los Angeles, United States: Sympathy for the Record Industry. 2020. SFTRI- 772.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ «Manson Launches New Posthuman Label». NME. April 12, 2000. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Manson’s 50 Greatest Achievements». Kerrang!. January 5, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ «Godhead Signs With Driven Music Group». Blabbermouth.net. June 6, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Sean (February 2001). CMJ New Music Monthly | Reviews | Godhead. CMJ New Music. p. 67. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. «Queen of the Damned [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]». AllMusic. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Moss, Corey (November 29, 2001). «Korn’s Davis Uses Stunt Double For Vampire Movie Soundtrack». MTV News. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ «Linkin Park’s ‘Hybrid Theory’ Certified 12 Times Platinum In U.S.» Blabbermouth.net. September 22, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Barker, Andrew (December 16, 2016). «The Music of ‘Resident Evil’: From Moody to Heavy Metal». Variety. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Childers, Chad. «Marilyn Manson Not a Big Fan of Lady Gaga». Loudwire.

- ^ Sciarretto, Amy. «Skylar Grey Recalls Approaching Marilyn Manson for ‘Can’t Haunt Me’«. PopCrush.

- ^ «Skylar Grey: ‘Eminem is scared to leave the house’«. NME. August 23, 2011.

- ^ Kaufman, Spencer. «Emigrate Discuss Collaborations With Lemmy + Marilyn Manson». Loudwire.

- ^ Fensterstock, Alison. «In Japan, the Soul Rebels perform with Marilyn Manson, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis: Watch». Nola.com.

- ^ Leahey, Andrew (January 4, 2016). «Shooter Jennings Enlists Marilyn Manson, Brandi Carlile for ‘Countach’«. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Kaye, Ben (February 18, 2016). «Marilyn Manson covers the hell out of David Bowie’s ‘Cat People’ — listen». Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on June 28, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c Horsley, Jonathan (September 23, 2020). «Shooter Jennings: ‘Marilyn Manson’s miraculous poetic ability doesn’t grow cold, like a lot of people’s songwriting’«. Guitar World. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Sara (September 1, 2020). «Marilyn Manson on ‘CHAOS,’ Collaboration, How Elton John Made Him Cry». Revolver. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ «10 Rock Collaborations You Won’t Believe Happened». Kerrang!.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R. (April 9, 2021). «DMX: Hear 10 Essential Songs». The New York Times.

- ^ «Watch Marilyn Manson Join Eminem for Unhinged «The Way I Am» Performance in 2001″. Revolver. August 31, 2018.

- ^ «Hear Gucci Mane and Marilyn Manson’s Collaboration, «Pussy Wet»«. The FADER.

- ^ «Best New Music This Week: ASAP Ferg, Polo G, Lil Wayne, and More». Complex.

- ^ Mamo, Heran (September 17, 2020). «A$AP Ferg Sits Down With Dennis Rodman to Announce ‘Floor Seats II’ Album». Billboard.