Metascience (also known as meta-research) is the use of scientific methodology to study science itself. Metascience seeks to increase the quality of scientific research while reducing inefficiency. It is also known as «research on research» and «the science of science«, as it uses research methods to study how research is done and find where improvements can be made. Metascience concerns itself with all fields of research and has been described as «a bird’s eye view of science».[1] In the words of John Ioannidis, «Science is the best thing that has happened to human beings … but we can do it better.»[2]

In 1966, an early meta-research paper examined the statistical methods of 295 papers published in ten high-profile medical journals. It found that «in almost 73% of the reports read … conclusions were drawn when the justification for these conclusions was invalid.» Meta-research in the following decades found many methodological flaws, inefficiencies, and poor practices in research across numerous scientific fields. Many scientific studies could not be reproduced, particularly in medicine and the soft sciences. The term «replication crisis» was coined in the early 2010s as part of a growing awareness of the problem.[3]

Measures have been implemented to address the issues revealed by metascience. These measures include the pre-registration of scientific studies and clinical trials as well as the founding of organizations such as CONSORT and the EQUATOR Network that issue guidelines for methodology and reporting. There are continuing efforts to reduce the misuse of statistics, to eliminate perverse incentives from academia, to improve the peer review process, to systematically collect data about the scholarly publication system,[4] to combat bias in scientific literature, and to increase the overall quality and efficiency of the scientific process.

History[edit]

In 1966, an early meta-research paper examined the statistical methods of 295 papers published in ten high-profile medical journals. It found that, «in almost 73% of the reports read … conclusions were drawn when the justification for these conclusions was invalid.»[6] In 2005, John Ioannidis published a paper titled «Why Most Published Research Findings Are False», which argued that a majority of papers in the medical field produce conclusions that are wrong.[5] The paper went on to become the most downloaded paper in the Public Library of Science[7][8] and is considered foundational to the field of metascience.[9] In a related study with Jeremy Howick and Despina Koletsi, Ioannidis showed that only a minority of medical interventions are supported by ‘high quality’ evidence according to The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. [10] Later meta-research identified widespread difficulty in replicating results in many scientific fields, including psychology and medicine. This problem was termed «the replication crisis». Metascience has grown as a reaction to the replication crisis and to concerns about waste in research.[11]

Many prominent publishers are interested in meta-research and in improving the quality of their publications. Top journals such as Science, The Lancet, and Nature, provide ongoing coverage of meta-research and problems with reproducibility.[12] In 2012 PLOS ONE launched a Reproducibility Initiative. In 2015 Biomed Central introduced a minimum-standards-of-reporting checklist to four titles.

The first international conference in the broad area of meta-research was the Research Waste/EQUATOR conference held in Edinburgh in 2015; the first international conference on peer review was the Peer Review Congress held in 1989.[13] In 2016, Research Integrity and Peer Review was launched. The journal’s opening editorial called for «research that will increase our understanding and suggest potential solutions to issues related to peer review, study reporting, and research and publication ethics».[14]

Fields and topics of meta-research[edit]

An exemplary visualization of a conception of scientific knowledge generation structured by layers, with the «Institution of Science» being the subject of metascience.

Metascience can be categorized into five major areas of interest: Methods, Reporting, Reproducibility, Evaluation, and Incentives. These correspond, respectively, with how to perform, communicate, verify, evaluate, and reward research.[1]

Methods[edit]

Metascience seeks to identify poor research practices, including biases in research, poor study design, abuse of statistics, and to find methods to reduce these practices.[1] Meta-research has identified numerous biases in scientific literature.[15] Of particular note is the widespread misuse of p-values and abuse of statistical significance.[16]

Scientific data science[edit]

Scientific data science is the use of data science to analyse research papers. It encompasses both qualitative and quantitative methods. Research in scientific data science includes fraud detection[17] and citation network analysis.[18]

Journalology[edit]

Journalology, also known as publication science, is the scholarly study of all aspects of the academic publishing process.[19][20] The field seeks to improve the quality of scholarly research by implementing evidence-based practices in academic publishing.[21] The term «journalology» was coined by Stephen Lock, the former editor-in-chief of The BMJ. The first Peer Review Congress, held in 1989 in Chicago, Illinois, is considered a pivotal moment in the founding of journalology as a distinct field.[21] The field of journalology has been influential in pushing for study pre-registration in science, particularly in clinical trials. Clinical-trial registration is now expected in most countries.[21]

Reporting[edit]

Meta-research has identified poor practices in reporting, explaining, disseminating and popularizing research, particularly within the social and health sciences. Poor reporting makes it difficult to accurately interpret the results of scientific studies, to replicate studies, and to identify biases and conflicts of interest in the authors. Solutions include the implementation of reporting standards, and greater transparency in scientific studies (including better requirements for disclosure of conflicts of interest). There is an attempt to standardize reporting of data and methodology through the creation of guidelines by reporting agencies such as CONSORT and the larger EQUATOR Network.[1]

Reproducibility[edit]

The replication crisis is an ongoing methodological crisis in which it has been found that many scientific studies are difficult or impossible to replicate.[22][23] While the crisis has its roots in the meta-research of the mid- to late-1900s, the phrase «replication crisis» was not coined until the early 2010s[24] as part of a growing awareness of the problem.[1] The replication crisis particularly affects psychology (especially social psychology) and medicine,[25][26] including cancer research.[27][28] Replication is an essential part of the scientific process, and the widespread failure of replication puts into question the reliability of affected fields.[29]

Moreover, replication of research (or failure to replicate) is considered less influential than original research, and is less likely to be published in many fields. This discourages the reporting of, and even attempts to replicate, studies.[30][31]

Evaluation and incentives[edit]

Metascience seeks to create a scientific foundation for peer review. Meta-research evaluates peer review systems including pre-publication peer review, post-publication peer review, and open peer review. It also seeks to develop better research funding criteria.[1]

Metascience seeks to promote better research through better incentive systems. This includes studying the accuracy, effectiveness, costs, and benefits of different approaches to ranking and evaluating research and those who perform it.[1] Critics argue that perverse incentives have created a publish-or-perish environment in academia which promotes the production of junk science, low quality research, and false positives.[32][33] According to Brian Nosek, «The problem that we face is that the incentive system is focused almost entirely on getting research published, rather than on getting research right.»[34] Proponents of reform seek to structure the incentive system to favor higher-quality results.[35] For example, by quality being judged on the basis of narrative expert evaluations («rather than [only or mainly] indices»), institutional evaluation criteria, guaranteeing of transparency, and professional standards.[36]

- Contributorship

Studies proposed machine-readable standards and (a taxonomy of) badges for science publication management systems that hones in on contributorship – who has contributed what and how much of the research labor – rather that using traditional concept of plain authorship – who was involved in any way creation of a publication.[37][38][39][40] A study pointed out one of the problems associated with the ongoing neglect of contribution nuanciation – it found that «the number of publications has ceased to be a good metric as a result of longer author lists, shorter papers, and surging publication numbers».[41]

- Assessment factors

Factors other than a submission’s merits can substantially influence peer reviewers’ evaluations.[42] Such factors may however also be important such as the use of track-records about the veracity of a researchers’ prior publications and its alignment with public interests. Nevertheless, evaluation systems – include those of peer-review – may substantially lack mechanisms and criteria that are oriented or well-performingly oriented towards merit, real-world positive impact, progress and public usefulness rather than analytical indicators such as number of citations or altmetrics even when such can be used as partial indicators of such ends.[43][44] Rethinking of the academic reward structure «to offer more formal recognition for intermediate products, such as data» could have positive impacts and reduce data withholding.[45]

- Recognition of training

A commentary noted that academic rankings don’t consider where (country and institute) the respective researchers were trained.[46]

Scientometrics[edit]

Scientometrics concerns itself with measuring bibliographic data in scientific publications. Major research issues include the measurement of the impact of research papers and academic journals, the understanding of scientific citations, and the use of such measurements in policy and management contexts.[47] Studies suggest that «metrics used to measure academic success, such as the number of publications, citation number, and impact factor, have not changed for decades» and have to some degrees «ceased» to be good measures,[41] leading to issues such as «overproduction, unnecessary fragmentations, overselling, predatory journals (pay and publish), clever plagiarism, and deliberate obfuscation of scientific results so as to sell and oversell».[48]

Novel tools in this area include systems to quantify how much the cited-node informs the citing-node.[49] This can be used to convert unweighted citation networks to a weighted one and then for importance assessment, deriving «impact metrics for the various entities involved, like the publications, authors etc»[50] as well as, among other tools, for search engine- and recommendation systems.

Science governance[edit]

Science funding and science governance can also be explored and informed by metascience.[51]

Incentives[edit]

Various interventions such as prioritization can be important. For instance, the concept of differential technological development refers to deliberately developing technologies – e.g. control-, safety- and policy-technologies versus risky biotechnologies – at different precautionary paces to decrease risks, mainly global catastrophic risk, by influencing the sequence in which technologies are developed.[52][53] Relying only on the established form of legislation and incentives to ensure the right outcomes may not be adequate as these may often be too slow[54] or inappropriate.

Other incentives to govern science and related processes, including via metascience-based reforms, may include ensuring accountability to the public (in terms of e.g. accessibility of, especially publicly-funded, research or of it addressing various research topics of public interest in serious manners), increasing the qualified productive scientific workforce, improving the efficiency of science to improve problem-solving in general, and facilitating that unambiguous societal needs based on solid scientific evidence – such as about human physiology – are adequately prioritized and addressed. Such interventions, incentives and intervention-designs can be subjects of metascience.

Science funding and awards[edit]

Cluster network of scientific publications in relation to Nobel prizes.

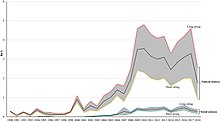

Funding for climate research in the natural and technical sciences versus the social sciences and humanities[55]

Scientific awards are one category of science incentives. Metascience can explore existing and hypothetical systems of science awards. For instance, it found that work honored by Nobel prizes clusters in only a few scientific fields with only 36/71 having received at least one Nobel prize of the 114/849 domains science could be divided into according to their DC2 and DC3 classification systems. Five of the 114 domains were shown to make up over half of the Nobel prizes awarded 1995–2017 (particle physics [14%], cell biology [12.1%], atomic physics [10.9%], neuroscience [10.1%], molecular chemistry [5.3%]).[56][57]

A study found that delegation of responsibility by policy-makers – a centralized authority-based top-down approach – for knowledge production and appropriate funding to science with science subsequently somehow delivering «reliable and useful knowledge to society» is too simple.[51]

Measurements show that allocation of bio-medical resources can be more strongly correlated to previous allocations and research than to burden of diseases.[58]

A study suggests that «[i]f peer review is maintained as the primary mechanism of arbitration in the competitive selection of research reports and funding, then the scientific community needs to make sure it is not arbitrary».[42]

Studies indicate there to is a need to «reconsider how we measure success» (see #Factors of success and progress).[41]

- Funding data

Funding information from grant databases and funding acknowledgment sections can be sources of data for scientometrics studies, e.g. for investigating or recognition of the impact of funding entities on the development of science and technology.[59]

Research questions and coordination[edit]

Scientists often communicate open research questions. Sometimes such questions are crowdsourced and/or aggregated, sometimes supplemented with priorities or other details. A common way open research questions are identified, communicated, established/confirmed and prioritized are their inclusion in scientific reviews of a sub-field or specific research question, including in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Other channels include reports by science journalists and dedicated (sub-)websites such as 80000hours.org’s «research questions by discipline»[60] or the Wikipedia articles of the lists of unsolved problems,[61][62][63] aggregative/integrative studies,[61] as well as unsolved online posts on Q&A websites and forums, sometimes categorized/marked as unsolved.[64] There have been online surveys used to generate priority research topics which were then classified into broader themes.[65] Such may improve research relevance and value[66] or strengthen rationale for societal dedication of limited resources or expansions of the limited resources or for funding a specific study.[citation needed]

Risk governance[edit]

See also: § Differential R&D

Biosecurity requires the cooperation of scientists, technicians, policy makers, security engineers, and law enforcement officials.[67][68]

Philosopher Toby Ord, in his 2020 book The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity, puts into question whether the current international conventions regarding biotechnology research and development regulation, and self-regulation by biotechnology companies and the scientific community are adequate.[69][70]

In a paywalled article, American scientists proposed various policy-based measures to reduce the large risks from life sciences research – such as pandemics through accident or misapplication. Risk management measures may include novel international guidelines, effective oversight, improvement of US policies to influence policies globally, and identification of gaps in biosecurity policies along with potential approaches to address them.[71][72]

Science communication and public use[edit]

It has been argued that «science has two fundamental attributes that underpin its value as a global public good: that knowledge claims and the evidence on which they are based are made openly available to scrutiny, and that the results of scientific research are communicated promptly and efficiently».[73] Metascientific research is exploring topics of science communication such as media coverage of science, science journalism and online communication of results by science educators and scientists.[74][75][76][77] A study found that the «main incentive academics are offered for using social media is amplification» and that it should be «moving towards an institutional culture that focuses more on how these [or such] platforms can facilitate real engagement with research».[78] Science communication may also involve the communication of societal needs, concerns and requests to scientists.

- Alternative metrics tools

Alternative metrics tools can be used not only for help in assessment (performance and impact)[58] and findability, but also aggregate many of the public discussions about a scientific paper in social media such as reddit, citations on Wikipedia, and reports about the study in the news media which can then in turn be analyzed in metascience or provided and used by related tools.[79] In terms of assessment and findability, altmetrics rate publications’ performance or impact by the interactions they receive through social media or other online platforms,[80] which can for example be used for sorting recent studies by measured impact, including before other studies are citing them. The specific procedures of established altmetrics are not transparent[80] and the used algorithms can not be customized or altered by the user as open source software can. A study has described various limitations of altmetrics and points «toward avenues for continued research and development».[81] They are also limited in their use as a primary tool for researchers to find received constructive feedback. (see above)

- Societal implications and applications

It has been suggested that it may benefit science if «intellectual exchange—particularly regarding the societal implications and applications of science and technology—are better appreciated and incentivized in the future».[58]

- Knowledge integration

Primary studies «without context, comparison or summary are ultimately of limited value» and various types[additional citation(s) needed] of research syntheses and summaries integrate primary studies.[82] Progress in key social-ecological challenges of the global environmental agenda is «hampered by a lack of integration and synthesis of existing scientific evidence», with a «fast-increasing volume of data», compartmentalized information and generally unmet evidence synthesis challenges.[83] According to Khalil, researchers are facing the problem of too many papers – e.g. in March 2014 more than 8,000 papers were submitted to arXiv – and to «keep up with the huge amount of literature, researchers use reference manager software, they make summaries and notes, and they rely on review papers to provide an overview of a particular topic». He notes that review papers are usually (only)» for topics in which many papers were written already, and they can get outdated quickly» and suggests «wiki-review papers» that get continuously updated with new studies on a topic and summarize many studies’ results and suggest future research.[84] A study suggests that if a scientific publication is being cited in a Wikipedia article this could potentially be considered as an indicator of some form of impact for this publication,[80] for example as this may, over time, indicate that the reference has contributed to a high-level of summary of the given topic.

Further information: § Knowledge integration and living documents

- Science journalism

Science journalists play an important role in the scientific ecosystem and in science communication to the public and need to «know how to use, relevant information when deciding whether to trust a research finding, and whether and how to report on it», vetting the findings that get transmitted to the public.[85]

Science education[edit]

Some studies investigate science education, e.g. the teaching about selected scientific controversies[86] and historical discovery process of major scientific conclusions,[87] and common scientific misconceptions.[88] Education can also be a topic more generally such as how to improve the quality of scientific outputs and reduce the time needed before scientific work or how to enlarge and retain various scientific workforces.

Science misconceptions and anti-science attitudes[edit]

Many students have misconceptions about what science is and how it works.[89] Anti-science attitudes and beliefs are also a subject of research.[90][91] Hotez suggests antiscience «has emerged as a dominant and highly lethal force, and one that threatens global security», and that there is a need for «new infrastructure» that mitigates it.[92]

Evolution of sciences[edit]

Scientific practice[edit]

Number of authors of research articles in six journals through time[36]

Trends of diversity of work cited, mean number of self-citations, and mean age of cited work may indicate papers are using «narrower portions of existing knowledge».[93]

Metascience can investigate how scientific processes evolve over time. A study found that teams are growing in size, «increasing by an average of 17% per decade».[58] (see labor advantage below)

ArXiv’s yearly submission rate growth over 30 years.[94]

It was found that prevalent forms of non-open access publication and prices charged for many conventional journals – even for publicly funded papers – are unwarranted, unnecessary – or suboptimal – and detrimental barriers to scientific progress.[73][95][96][97] Open access can save considerable amounts of financial resources, which could be used otherwise, and level the playing field for researchers in developing countries.[98] There are substantial expenses for subscriptions, gaining access to specific studies, and for article processing charges. Paywall: The Business of Scholarship is a documentary on such issues.[99]

Another topic are the established styles of scientific communication (e.g. long text-form studies and reviews) and the scientific publishing practices – there are concerns about a «glacial pace» of conventional publishing.[100] The use of preprint-servers to publish study-drafts early is increasing and open peer review,[101] new tools to screen studies,[102] and improved matching of submitted manuscripts to reviewers[103] are among the proposals to speed up publication.

Science overall and intrafield developments[edit]

A visualization of scientific outputs by field in OpenAlex.[104]

A study can be part of multiple fields[clarification needed] and lower numbers of papers is not necessarily detrimental[48] for fields.

Change of number of scientific papers by field according to OpenAlex[104]

Number of PubMed search results for «coronavirus» by year from 1949 to 2020.

Studies have various kinds of metadata which can be utilized, complemented and made accessible in useful ways. OpenAlex is a free online index of over 200 million scientific documents that integrates and provides metadata such as sources, citations, author information, scientific fields and research topics. Its API and open source website can be used for metascience, scientometrics and novel tools that query this semantic web of papers.[105][106][107] Another project under development, Scholia, uses metadata of scientific publications for various visualizations and aggregation features such as providing a simple user interface summarizing literature about a specific feature of the SARS-CoV-2 virus using Wikidata’s «main subject» property.[108]

- Subject-level resolutions

Beyond metadata explicitly assigned to studies by humans, natural language processing and AI can be used to assign research publications to topics – one study investigating the impact of science awards used such to associate a paper’s text (not just keywords) with the linguistic content of Wikipedia’s scientific topics pages («pages are created and updated by scientists and users through crowdsourcing»), creating meaningful and plausible classifications of high-fidelity scientific topics for further analysis or navigability.[109]

Further information: § Topic mapping

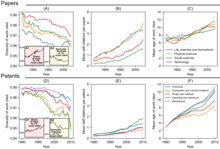

Growth or stagnation of science overall[edit]

Rough trend of scholarly publications about biomarkers according to Scholia; biomarker-related publications may not follow closely the number of viable biomarkers[110]

The CD index for papers published in Nature, PNAS, and Science and Nobel-Prize-winning papers[93]

The CD index may indicate a «decline of disruptive science and technology»[93]

Metascience research is investigating the growth of science overall, using e.g. data on the number of publications in bibliographic databases. A study found segments with different growth rates appear related to phases of «economic (e.g., industrialization)» – money is considered as necessary input to the science system – «and/or political developments (e.g., Second World War)». It also confirmed a recent exponential growth in the volume of scientific literature and calculated an average doubling period of 17.3 years.[111]

However, others have pointed out that is difficult to measure scientific progress in meaningful ways, partly because it’s hard to accurately evaluate how important any given scientific discovery is. A variety of perspectives of the trajectories of science overall (impact, number of major discoveries, etc) have been described in books and articles, including that science is becoming harder (per dollar or hour spent), that if science «slowing today, it is because science has remained too focused on established fields», that papers and patents are increasingly less likely to be «disruptive» in terms of breaking with the past as measured by the «CD index»,[93] and that there is a great stagnation – possibly as part of a larger trend[112] – whereby e.g. «things haven’t changed nearly as much since the 1970s» when excluding the computer and the Internet.

Better understanding of potential slowdowns according to some measures could be a major opportunity to improve humanity’s future.[113] For example, emphasis on citations in the measurement of scientific productivity, information overloads,[112] reliance on a narrower set of existing knowledge (which may include narrow specialization and related contemporary practices) ,[93] and risk-avoidant funding structures[114] may have «toward incremental science and away from exploratory projects that are more likely to fail».[115] The study that introduced the «CD index» suggests the overall number of papers has risen while the total of «highly disruptive» papers as measured by the index hasn’t (notably, the 1998 discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe has a CD index of 0). Their results also suggest scientists and inventors «may be struggling to keep up with the pace of knowledge expansion».[116][93]

Various ways of measuring «novelty» of studies, novelty metrics,[115] have been proposed to balance a potential anti-novelty bias – such as textual analysis[115] or measuring whether it makes first-time-ever combinations of referenced journals, taking into account the difficulty.[117] Other approaches include pro-actively funding risky projects.[58] (see above)

Topic mapping[edit]

Science maps could show main interrelated topics within a certain scientific domain, their change over time, and their key actors (researchers, institutions, journals). They may help find factors determine the emergence of new scientific fields and the development of interdisciplinary areas and could be relevant for science policy purposes.[118] (see above) Theories of scientific change could guide «the exploration and interpretation of visualized intellectual structures and dynamic patterns».[119] The maps can show the intellectual, social or conceptual structure of a research field.[120] Beyond visual maps, expert survey-based studies and similar approaches could identify understudied or neglected societally important areas, topic-level problems (such as stigma or dogma), or potential misprioritizations.[additional citation(s) needed] Examples of such are studies about policy in relation to public health[121] and the social science of climate change mitigation where it has been estimated that only 0.12% of all funding for climate-related research is spent on such despite the most urgent puzzle at the current juncture being working out how to mitigate climate change, whereas the natural science of climate change is already well established.

There are also studies that map a scientific field or a topic such as the study of the use of research evidence in policy and practice, partly using surveys.[123]

Controversies, current debates and disagreement[edit]

See also: § scite.ai, and § Topic mapping

Percent of all citances in each field that contain signals of disagreement[124]

Some research is investigating scientific controversy or controveries, and may identify currently ongoing major debates (e.g. open questions), and disagreement between scientists or studies.[additional citation(s) needed] One study suggests the level of disagreement was highest in the social sciences and humanities (0.61%), followed by biomedical and health sciences (0.41%), life and earth sciences (0.29%); physical sciences and engineering (0.15%), and mathematics and computer science (0.06%).[124] Such research may also show, where the disagreements are, especially if they cluster, including visually such as with cluster diagrams.

Challenges of interpretation of pooled results[edit]

Studies about a specific research question or research topic are often reviewed in the form of higher-level overviews in which results from various studies are integrated, compared, critically analyzed and interpreted. Examples of such works are scientific reviews and meta-analyses. These and related practices face various challenges and are a subject of metascience.

A meta-analysis of several small studies does not always predict the results of a single large study.[125] Some have argued that a weakness of the method is that sources of bias are not controlled by the method: a good meta-analysis cannot correct for poor design or bias in the original studies.[126] This would mean that only methodologically sound studies should be included in a meta-analysis, a practice called ‘best evidence synthesis’.[126] Other meta-analysts would include weaker studies, and add a study-level predictor variable that reflects the methodological quality of the studies to examine the effect of study quality on the effect size.[127] However, others have argued that a better approach is to preserve information about the variance in the study sample, casting as wide a net as possible, and that methodological selection criteria introduce unwanted subjectivity, defeating the purpose of the approach.[128]

Various issues with included or available studies such as, for example, heterogeneity of methods used may lead to faulty conclusions of the meta-analysis.[129]

Knowledge integration and living documents[edit]

Various problems require swift integration of new and existing science-based knowledge. Especially setting where there are a large number of loosely related projects and initiatives benefit from a common ground or «commons».[108]

Evidence synthesis can be applied to important and, notably, both relatively urgent and certain global challenges: «climate change, energy transitions, biodiversity loss, antimicrobial resistance, poverty eradication and so on». It was suggested that a better system would keep summaries of research evidence up to date via living systematic reviews – e.g. as living documents. While the number of scientific papers and data (or information and online knowledge) has risen substantially,[additional citation(s) needed] the number of published academic systematic reviews has risen from «around 6,000 in 2011 to more than 45,000 in 2021».[130] An evidence-based approach is important for progress in science, policy, medical and other practices. For example, meta-analyses can quantify what is known and identify what is not yet known[82] and place «truly innovative and highly interdisciplinary ideas» into the context of established knowledge which may enhance their impact.[58] (see above)

Factors of success and progress[edit]

See also: § Growth or stagnation of science overall

It has been hypothesized that a deeper understanding of factors behind successful science could «enhance prospects of science as a whole to more effectively address societal problems».[58]

- Novel ideas and disruptive scholarship

Two metascientists reported that «structures fostering disruptive scholarship and focusing attention on novel ideas» could be important as in a growing scientific field citation flows disproportionately consolidate to already well-cited papers, possibly slowing and inhibiting canonical progress.[131][132] A study concluded that to enhance impact of truly innovative and highly interdisciplinary novel ideas, they should be placed in the context of established knowledge.[58]

- Mentorship, partnerships and social factors

Other researchers reported that the most successful – in terms of «likelihood of prizewinning, National Academy of Science (NAS) induction, or superstardom» – protégés studied under mentors who published research for which they were conferred a prize after the protégés’ mentorship. Studying original topics rather than these mentors’ research-topics was also positively associated with success.[133][134] Highly productive partnerships are also a topic of research – e.g. «super-ties» of frequent co-authorship of two individuals who can complement skills, likely also the result of other factors such as mutual trust, conviction, commitment and fun.[135][58]

- Study of successful scientists and processes, general skills and activities

The emergence or origin of ideas by successful scientists is also a topic of research, for example reviewing existing ideas on how Mendel made his discoveries,[136] – or more generally, the process of discovery by scientists. Science is a «multifaceted process of appropriation, copying, extending, or combining ideas and inventions» [and other types of knowledge or information], and not an isolated process.[58] There are also few studies investigating scientists’ habits, common modes of thinking, reading habits, use of information sources, digital literacy skills, and workflows.[137][138][139][140][141]

- Labor advantage

A study theorized that in many disciplines, larger scientific productivity or success by elite universities can be explained by their larger pool of available funded laborers.[142][143][further explanation needed]

- Ultimate impacts

Success (in science) is often measured in terms of metrics like citations, not in terms of the eventual or potential impact on lives and society, which awards (see above) sometimes do.[additional citation(s) needed] Problems with such metrics are roughly outlined elsewhere in this article and include that reviews replace citations to primary studies.[82] There are also proposals for changes to the academic incentives systems that increase the recognition of societal impact in the research process.[144]

- Progress studies

A proposed field of «Progress Studies» could investigate how scientists (or funders or evaluators of scientists) should be acting, «figuring out interventions» and study progress itself.[145] The field was explicitly proposed in a 2019 essay and described as an applied science that prescribes action.[146]

- As and for acceleration of progress

A study suggests that improving the way science is done could accelerate the rate of scientific discovery and its applications which could be useful for finding urgent solutions to humanity’s problems, improve humanity’s conditions, and enhance understanding of nature. Metascientific studies can seek to identify aspects of science that need improvement, and develop ways to improve them.[84] If science is accepted as the fundamental engine of economic growth and social progress, this could raise «the question of what we – as a society – can do to accelerate science, and to direct science toward solving society’s most important problems.»[147] However, one of the authors clarified that a one-size-fits-all approach is not thought to be right answer – for example, in funding, DARPA models, curiosity-driven methods, allowing «a single reviewer to champion a project even if his or her peers do not agree», and various other approaches all have their uses. Nevertheless, evaluation of them can help build knowledge of what works or works best.[114]

Reforms[edit]

Meta-research identifying flaws in scientific practice has inspired reforms in science. These reforms seek to address and fix problems in scientific practice which lead to low-quality or inefficient research.

A 2015 study lists «fragmented» efforts in meta-research.[1]

Pre-registration[edit]

The practice of registering a scientific study before it is conducted is called pre-registration. It arose as a means to address the replication crisis. Pregistration requires the submission of a registered report, which is then accepted for publication or rejected by a journal based on theoretical justification, experimental design, and the proposed statistical analysis. Pre-registration of studies serves to prevent publication bias (e.g. not publishing negative results), reduce data dredging, and increase replicability.[148][149]

Reporting standards[edit]

Studies showing poor consistency and quality of reporting have demonstrated the need for reporting standards and guidelines in science, which has led to the rise of organisations that produce such standards, such as CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) and the EQUATOR Network.

The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research)[150] Network is an international initiative aimed at promoting transparent and accurate reporting of health research studies to enhance the value and reliability of medical research literature.[151] The EQUATOR Network was established with the goals of raising awareness of the importance of good reporting of research, assisting in the development, dissemination and implementation of reporting guidelines for different types of study designs, monitoring the status of the quality of reporting of research studies in the health sciences literature, and conducting research relating to issues that impact the quality of reporting of health research studies.[152] The Network acts as an «umbrella» organisation, bringing together developers of reporting guidelines, medical journal editors and peer reviewers, research funding bodies, and other key stakeholders with a mutual interest in improving the quality of research publications and research itself.

Applications[edit]

The areas of application of metascience include ICTs, medicine, psychology and physics.

ICTs[edit]

Metascience is used in the creation and improvement of technical systems (ICTs) and standards of science evaluation, incentivation, communication, commissioning, funding, regulation, production, management, use and publication. Such can be called «applied metascience»[153][better source needed] and may seek to explore ways to increase quantity, quality and positive impact of research. One example for such is the development of alternative metrics.[58]

- Study screening and feedback

Various websites or tools also identify inappropriate studies and/or enable feedback such as PubPeer, Cochrane’s Risk of Bias Tool[154] and RetractionWatch. Medical and academic disputes are as ancient as antiquity and a study calls for research into «constructive and obsessive criticism» and into policies to «help strengthen social media into a vibrant forum for discussion, and not merely an arena for gladiator matches».[155] Feedback to studies can be found via altmetrics which is often integrated at the website of the study – most often as an embedded Altmetrics badge – but may often be incomplete, such as only showing social media discussions that link to the study directly but not those that link to news reports about the study. (see above)

- Tools used, modified, extended or investigated

Tools may get developed with metaresearch or can be used or investigated by such. Notable examples may include:

- The tool scite.ai aims to track and link citations of papers as ‘Supporting’, ‘Mentioning’ or ‘Contrasting’ the study.[156][157][158]

- The Scite Reference Check bot is an extension of scite.ai that scans new article PDFs «for references to retracted papers, and posts both the citing and retracted papers on Twitter» and also «flags when new studies cite older ones that have issued corrections, errata, withdrawals, or expressions of concern».[158] Studies have suggested as few as 4% of citations to retracted papers clearly recognize the retraction.[158]

- Search engines like Google Scholar are used to find studies and the notification service Google Alerts enables notifications for new studies matching specified search terms. Scholarly communication infrastructure includes search databases.[159]

- Shadow library Sci-hub is a topic of metascience[160]

- Personal knowledge management systems for research-, knowledge- and task management, such as saving information in organized ways[161] with multi-document text editors for future use[162][163] Such systems could be described as part of, along with e.g. Web browser (tabs-addons[164] etc) and search software,[additional citation(s) needed] «mind-machine partnerships» that could be investigated by metascience for how they could improve science.[58]

- Scholia – efforts to open scholarly publication metadata and use it via Wikidata.[165] (see above)

- Various software enables common metascientific practices such as bibliometric analysis.[166]

- Development

According to a study «a simple way to check how often studies have been repeated, and whether or not the original findings are confirmed» is needed due to reproducibility issues in science.[167][168] A study suggests a tool for screening studies for early warning signs for research fraud.[169]

Medicine[edit]

Clinical research in medicine is often of low quality, and many studies cannot be replicated.[170][171] An estimated 85% of research funding is wasted.[172] Additionally, the presence of bias affects research quality.[173] The pharmaceutical industry exerts substantial influence on the design and execution of medical research. Conflicts of interest are common among authors of medical literature[174] and among editors of medical journals. While almost all medical journals require their authors to disclose conflicts of interest, editors are not required to do so.[175] Financial conflicts of interest have been linked to higher rates of positive study results. In antidepressant trials, pharmaceutical sponsorship is the best predictor of trial outcome.[176]

Blinding is another focus of meta-research, as error caused by poor blinding is a source of experimental bias. Blinding is not well reported in medical literature, and widespread misunderstanding of the subject has resulted in poor implementation of blinding in clinical trials.[177] Furthermore, failure of blinding is rarely measured or reported.[178] Research showing the failure of blinding in antidepressant trials has led some scientists to argue that antidepressants are no better than placebo.[179][180] In light of meta-research showing failures of blinding, CONSORT standards recommend that all clinical trials assess and report the quality of blinding.[181]

Studies have shown that systematic reviews of existing research evidence are sub-optimally used in planning a new research or summarizing the results.[182] Cumulative meta-analyses of studies evaluating the effectiveness of medical interventions have shown that many clinical trials could have been avoided if a systematic review of existing evidence was done prior to conducting a new trial.[183][184][185] For example, Lau et al.[183] analyzed 33 clinical trials (involving 36974 patients) evaluating the effectiveness of intravenous streptokinase for acute myocardial infarction. Their cumulative meta-analysis demonstrated that 25 of 33 trials could have been avoided if a systematic review was conducted prior to conducting a new trial. In other words, randomizing 34542 patients was potentially unnecessary. One study[186] analyzed 1523 clinical trials included in 227 meta-analyses and concluded that «less than one quarter of relevant prior studies» were cited. They also confirmed earlier findings that most clinical trial reports do not present systematic review to justify the research or summarize the results.[186]

Many treatments used in modern medicine have been proven to be ineffective, or even harmful. A 2007 study by John Ioannidis found that it took an average of ten years for the medical community to stop referencing popular practices after their efficacy was unequivocally disproven.[187][188]

Psychology[edit]

Metascience has revealed significant problems in psychological research. The field suffers from high bias, low reproducibility, and widespread misuse of statistics.[189][190][191] The replication crisis affects psychology more strongly than any other field; as many as two-thirds of highly publicized findings may be impossible to replicate.[192] Meta-research finds that 80-95% of psychological studies support their initial hypotheses, which strongly implies the existence of publication bias.[193]

The replication crisis has led to renewed efforts to re-test important findings.[194][195] In response to concerns about publication bias and p-hacking, more than 140 psychology journals have adopted result-blind peer review, in which studies are pre-registered and published without regard for their outcome.[196] An analysis of these reforms estimated that 61 percent of result-blind studies produce null results, in contrast with 5 to 20 percent in earlier research. This analysis shows that result-blind peer review substantially reduces publication bias.[193]

Psychologists routinely confuse statistical significance with practical importance, enthusiastically reporting great certainty in unimportant facts.[197] Some psychologists have responded with an increased use of effect size statistics, rather than sole reliance on the p values.[citation needed]

Physics[edit]

Richard Feynman noted that estimates of physical constants were closer to published values than would be expected by chance. This was believed to be the result of confirmation bias: results that agreed with existing literature were more likely to be believed, and therefore published. Physicists now implement blinding to prevent this kind of bias.[198]

Organizations and institutes[edit]

There are several organizations and universities across the globe which work on meta-research – these include the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Berlin,[199] the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford,[200][201] the Meta-Research Center at Tilburg University, the Meta-research & Evidence Synthesis Unit, The George Institute for Global Health at India and Center for Open Science. Organizations that develop tools for metascience include Our Research, Center for Scientific Integrity and altmetrics companies. There is an annual Metascience Conference.[202]

See also[edit]

- Accelerating change

- Citation analysis

- Epistemology

- Evidence-based practices

- Evidence-based medicine

- Evidence-based policy

- Further research is needed

- HARKing

- Logology (science)

- Metadata#In science

- Metatheory

- Open science

- Philosophy of science

- Sociology of scientific knowledge

- Self-Organized Funding Allocation

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ioannidis, John P. A.; Fanelli, Daniele; Dunne, Debbie Drake; Goodman, Steven N. (2 October 2015). «Meta-research: Evaluation and Improvement of Research Methods and Practices». PLOS Biology. 13 (10): e1002264. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002264. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 4592065. PMID 26431313.

- ^ Bach, Becky (8 December 2015). «On communicating science and uncertainty: A podcast with John Ioannidis». Scope. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Pashler, Harold; Harris, Christine R. (2012). «Is the Replicability Crisis Overblown? Three Arguments Examined». Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (6): 531–536. doi:10.1177/1745691612463401. ISSN 1745-6916. PMID 26168109. S2CID 1342421.

- ^ Nishikawa-Pacher, Andreas; Heck, Tamara; Schoch, Kerstin (4 October 2022). «Open Editors: A dataset of scholarly journals’ editorial board positions». Research Evaluation. doi:10.1093/reseval/rvac037. eISSN 1471-5449. ISSN 0958-2029.

- ^ a b Ioannidis, JP (August 2005). «Why most published research findings are false». PLOS Medicine. 2 (8): e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. PMC 1182327. PMID 16060722.

- ^ Schor, Stanley (1966). «Statistical Evaluation of Medical Journal Manuscripts». JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 195 (13): 1123–1128. doi:10.1001/jama.1966.03100130097026. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 5952081.

- ^ «Highly Cited Researchers». Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ Medicine — Stanford Prevention Research Center. John P.A. Ioannidis

- ^ Robert Lee Hotz (September 14, 2007). «Most Science Studies Appear to Be Tainted By Sloppy Analysis». Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ Howick J, Koletsi D, Pandis N, Fleming PS, Loef M, Walach H, Schmidt S, Ioannidis JA. The quality of evidence for medical interventions does not improve or worsen: a metaepidemiological study of Cochrane reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2020;126:154-159 [1]

- ^ «Researching the researchers». Nature Genetics. 46 (5): 417. 2014. doi:10.1038/ng.2972. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 24769715.

- ^ Enserink, Martin (2018). «Research on research». Science. 361 (6408): 1178–1179. Bibcode:2018Sci…361.1178E. doi:10.1126/science.361.6408.1178. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30237336. S2CID 206626417.

- ^ Rennie, Drummond (1990). «Editorial Peer Review in Biomedical Publication». JAMA. 263 (10): 1317–1441. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03440100011001. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 2304208.

- ^ Harriman, Stephanie L.; Kowalczuk, Maria K.; Simera, Iveta; Wager, Elizabeth (2016). «A new forum for research on research integrity and peer review». Research Integrity and Peer Review. 1 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s41073-016-0010-y. ISSN 2058-8615. PMC 5794038. PMID 29451544.

- ^ Fanelli, Daniele; Costas, Rodrigo; Ioannidis, John P. A. (2017). «Meta-assessment of bias in science». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (14): 3714–3719. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.3714F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618569114. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5389310. PMID 28320937.

- ^ Check Hayden, Erika (2013). «Weak statistical standards implicated in scientific irreproducibility». Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14131. S2CID 211729036. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Markowitz, David M.; Hancock, Jeffrey T. (2016). «Linguistic obfuscation in fraudulent science». Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 35 (4): 435–445. doi:10.1177/0261927X15614605. S2CID 146174471.

- ^ Ding, Y. (2010). «Applying weighted PageRank to author citation networks». Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 62 (2): 236–245. arXiv:1102.1760. doi:10.1002/asi.21452. S2CID 3752804.

- ^ Galipeau, James; Moher, David; Campbell, Craig; Hendry, Paul; Cameron, D. William; Palepu, Anita; Hébert, Paul C. (March 2015). «A systematic review highlights a knowledge gap regarding the effectiveness of health-related training programs in journalology». Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 68 (3): 257–265. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.024. PMID 25510373.

- ^ Wilson, Mitch; Moher, David (March 2019). «The Changing Landscape of Journalology in Medicine». Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 49 (2): 105–114. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2018.11.009. hdl:10393/38493. PMID 30819390. S2CID 73471103.

- ^ a b c Couzin-Frankel, Jennifer (18 September 2018). «‘Journalologists’ use scientific methods to study academic publishing. Is their work improving science?». Science. doi:10.1126/science.aav4758. S2CID 115360831.

- ^ Schooler, J. W. (2014). «Metascience could rescue the ‘replication crisis’«. Nature. 515 (7525): 9. Bibcode:2014Natur.515….9S. doi:10.1038/515009a. PMID 25373639.

- ^ Smith, Noah (2 November 2017). «Why ‘Statistical Significance’ Is Often Insignificant». Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Pashler, Harold; Wagenmakers, Eric Jan (2012). «Editors’ Introduction to the Special Section on Replicability in Psychological Science: A Crisis of Confidence?». Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (6): 528–530. doi:10.1177/1745691612465253. PMID 26168108. S2CID 26361121.

- ^ Gary Marcus (May 1, 2013). «The Crisis in Social Psychology That Isn’t». The New Yorker.

- ^ Jonah Lehrer (December 13, 2010). «The Truth Wears Off». The New Yorker.

- ^ «Dozens of major cancer studies can’t be replicated». Science News. 7 December 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ «Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology». www.cos.io. Center for Open Science. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Staddon, John (2017) Scientific Method: How science works, fails to work or pretends to work. Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Yeung, Andy W. K. (2017). «Do Neuroscience Journals Accept Replications? A Survey of Literature». Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 11: 468. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00468. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 5611708. PMID 28979201.

- ^ Martin, G. N.; Clarke, Richard M. (2017). «Are Psychology Journals Anti-replication? A Snapshot of Editorial Practices». Frontiers in Psychology. 8: 523. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00523. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 5387793. PMID 28443044.

- ^ Binswanger, Mathias (2015). «How Nonsense Became Excellence: Forcing Professors to Publish». In Welpe, Isabell M.; Wollersheim, Jutta; Ringelhan, Stefanie; Osterloh, Margit (eds.). Incentives and Performance. Incentives and Performance: Governance of Research Organizations. Springer International Publishing. pp. 19–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-09785-5_2. ISBN 978-3319097855. S2CID 110698382.

- ^ Edwards, Marc A.; Roy, Siddhartha (2016-09-22). «Academic Research in the 21st Century: Maintaining Scientific Integrity in a Climate of Perverse Incentives and Hypercompetition». Environmental Engineering Science. 34 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1089/ees.2016.0223. PMC 5206685. PMID 28115824.

- ^ Brookshire, Bethany (21 October 2016). «Blame bad incentives for bad science». Science News. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Smaldino, Paul E.; McElreath, Richard (2016). «The natural selection of bad science». Royal Society Open Science. 3 (9): 160384. arXiv:1605.09511. Bibcode:2016RSOS….360384S. doi:10.1098/rsos.160384. PMC 5043322. PMID 27703703.

- ^ a b Chapman, Colin A.; Bicca-Marques, Júlio César; Calvignac-Spencer, Sébastien; Fan, Pengfei; Fashing, Peter J.; Gogarten, Jan; Guo, Songtao; Hemingway, Claire A.; Leendertz, Fabian; Li, Baoguo; Matsuda, Ikki; Hou, Rong; Serio-Silva, Juan Carlos; Chr. Stenseth, Nils (4 December 2019). «Games academics play and their consequences: how authorship, h -index and journal impact factors are shaping the future of academia». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1916): 20192047. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2047. ISSN 0962-8452.

- ^ Holcombe, Alex O. (September 2019). «Contributorship, Not Authorship: Use CRediT to Indicate Who Did What». Publications. 7 (3): 48. doi:10.3390/publications7030048.

- ^ McNutt, Marcia K.; Bradford, Monica; Drazen, Jeffrey M.; Hanson, Brooks; Howard, Bob; Jamieson, Kathleen Hall; Kiermer, Véronique; Marcus, Emilie; Pope, Barbara Kline; Schekman, Randy; Swaminathan, Sowmya; Stang, Peter J.; Verma, Inder M. (13 March 2018). «Transparency in authors’ contributions and responsibilities to promote integrity in scientific publication». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (11): 2557–2560. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.2557M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1715374115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5856527. PMID 29487213.

- ^ Brand, Amy; Allen, Liz; Altman, Micah; Hlava, Marjorie; Scott, Jo (1 April 2015). «Beyond authorship: attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit». Learned Publishing. 28 (2): 151–155. doi:10.1087/20150211. S2CID 45167271.

- ^ Singh Chawla, Dalmeet (October 2015). «Digital badges aim to clear up politics of authorship». Nature. 526 (7571): 145–146. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..145S. doi:10.1038/526145a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 26432249. S2CID 256770827.

- ^ a b c Fire, Michael; Guestrin, Carlos (1 June 2019). «Over-optimization of academic publishing metrics: observing Goodhart’s Law in action». GigaScience. 8 (6): giz053. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giz053. PMC 6541803. PMID 31144712.

- ^ a b Elson, Malte; Huff, Markus; Utz, Sonja (1 March 2020). «Metascience on Peer Review: Testing the Effects of a Study’s Originality and Statistical Significance in a Field Experiment». Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. 3 (1): 53–65. doi:10.1177/2515245919895419. ISSN 2515-2459. S2CID 212778011.

- ^ McLean, Robert K D; Sen, Kunal (1 April 2019). «Making a difference in the real world? A meta-analysis of the quality of use-oriented research using the Research Quality Plus approach». Research Evaluation. 28 (2): 123–135. doi:10.1093/reseval/rvy026.

- ^ «Bringing Rigor to Relevant Questions: How Social Science Research Can Improve Youth Outcomes in the Real World» (PDF). Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Fecher, Benedikt; Friesike, Sascha; Hebing, Marcel; Linek, Stephanie (20 June 2017). «A reputation economy: how individual reward considerations trump systemic arguments for open access to data». Palgrave Communications. 3 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.51. ISSN 2055-1045.

- ^ La Porta, Caterina AM; Zapperi, Stefano (1 December 2022). «America’s top universities reap the benefit of Italian-trained scientists». Nature Italy. doi:10.1038/d43978-022-00163-5. S2CID 254331807. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Leydesdorff, L. and Milojevic, S., «Scientometrics» arXiv:1208.4566 (2013), forthcoming in: Lynch, M. (editor), International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences subsection 85030. (2015)

- ^ a b Singh, Navinder (8 October 2021). «Plea to publish less». arXiv:2201.07985 [physics.soc-ph].

- ^ Manchanda, Saurav; Karypis, George (November 2021). «Evaluating Scholarly Impact: Towards Content-Aware Bibliometrics». Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics: 6041–6053. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.488. S2CID 243865632.

- ^ Manchanda, Saurav; Karypis, George. «Importance Assessment in Scholarly Networks» (PDF).

- ^ a b Nielsen, Kristian H. (1 March 2021). «Science and public policy». Metascience. 30 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1007/s11016-020-00581-5. ISSN 1467-9981. PMC 7605730. S2CID 226237994.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 229–237. ISBN 978-0199678112.

- ^ Ord, Toby (2020). The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 978-1526600219.

- ^ «Technology is changing faster than regulators can keep up — here’s how to close the gap». World Economic Forum. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Overland, Indra; Sovacool, Benjamin K. (1 April 2020). «The misallocation of climate research funding». Energy Research & Social Science. 62: 101349. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101349. ISSN 2214-6296. S2CID 212789228.

- ^ «Nobel prize-winning work is concentrated in minority of scientific fields». phys.org. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Ioannidis, John P. A.; Cristea, Ioana-Alina; Boyack, Kevin W. (29 July 2020). «Work honored by Nobel prizes clusters heavily in a few scientific fields». PLOS ONE. 15 (7): e0234612. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1534612I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234612. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7390258. PMID 32726312.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fortunato, Santo; Bergstrom, Carl T.; Börner, Katy; Evans, James A.; Helbing, Dirk; Milojević, Staša; Petersen, Alexander M.; Radicchi, Filippo; Sinatra, Roberta; Uzzi, Brian; Vespignani, Alessandro; Waltman, Ludo; Wang, Dashun; Barabási, Albert-László (2 March 2018). «Science of science». Science. 359 (6379): eaao0185. doi:10.1126/science.aao0185. PMC 5949209. PMID 29496846. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Fajardo-Ortiz, David; Hornbostel, Stefan; Montenegro de Wit, Maywa; Shattuck, Annie (22 June 2022). «Funding CRISPR: Understanding the role of government and philanthropic institutions in supporting academic research within the CRISPR innovation system». Quantitative Science Studies. 3 (2): 443–456. doi:10.1162/qss_a_00187. S2CID 235266330.

- ^ «Research questions that could have a big social impact, organised by discipline». 80,000 Hours. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ a b Coley, Alan A (30 August 2017). «Open problems in mathematical physics». Physica Scripta. 92 (9): 093003. arXiv:1710.02105. Bibcode:2017PhyS…92i3003C. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/aa83c1. ISSN 0031-8949. S2CID 3892374.

- ^ Adolphs, Ralph (1 April 2015). «The unsolved problems of neuroscience». Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 19 (4): 173–175. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.01.007. ISSN 1364-6613. PMC 4574630. PMID 25703689.

As for Hilbert’s problems, there is a Wikipedia entry for ‘unsolved problems in neuroscience’; there are more popular writings; and there are books. In trying to brainstorm a list of my own, I read the above sources and asked around. This yields a predictable list ranging from ‘how can we cure psychiatric illness?’ to ‘what is consciousness?’ (Box 1). Asking Caltech faculty added entries about how networks function and what neural computation is. Caltech students had things figured out and got straight to the point (‘how can I sleep less?’, ‘how can we save our species?’, ‘can we become immortal?’).

- ^ Dev, Sukhendu B. (1 March 2015). «Unsolved problems in biology—The state of current thinking». Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 117 (2): 232–239. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.02.001. ISSN 0079-6107. PMID 25687284.

Among many of the responses I received, a large majority mentioned several aspects of neuroscience. This is not surprising since the brain remains the most uncharted area in humans. A list of unsolved problems in neuroscience can be found in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_unsolved_problems_in_neuroscience (Accessed January 12, 2015).

- ^ Cartaxo, Bruno; Pinto, Gustavo; Ribeiro, Danilo; Kamei, Fernando; Santos, Ronnie E.S.; da Silva, Fábio Q.B.; Soares, Sérgio (May 2017). «Using Q&A Websites as a Method for Assessing Systematic Reviews». 2017 IEEE/ACM 14th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR): 238–242. doi:10.1109/MSR.2017.5. ISBN 978-1-5386-1544-7. S2CID 5853766.

- ^ Synnot, Anneliese; Bragge, Peter; Lowe, Dianne; Nunn, Jack S; O’Sullivan, Molly; Horvat, Lidia; Tong, Allison; Kay, Debra; Ghersi, Davina; McDonald, Steve; Poole, Naomi; Bourke, Noni; Lannin, Natasha; Vadasz, Danny; Oliver, Sandy; Carey, Karen; Hill, Sophie J (May 2018). «Research priorities in health communication and participation: international survey of consumers and other stakeholders». BMJ Open. 8 (5): e019481. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019481. PMC 5942413. PMID 29739780.

- ^ Synnot, Anneliese J.; Tong, Allison; Bragge, Peter; Lowe, Dianne; Nunn, Jack S.; O’Sullivan, Molly; Horvat, Lidia; Kay, Debra; Ghersi, Davina; McDonald, Steve; Poole, Naomi; Bourke, Noni; Lannin, Natasha A.; Vadasz, Danny; Oliver, Sandy; Carey, Karen; Hill, Sophie J. (29 April 2019). «Selecting, refining and identifying priority Cochrane Reviews in health communication and participation in partnership with consumers and other stakeholders». Health Research Policy and Systems. 17 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s12961-019-0444-z. PMC 6489310. PMID 31036016.

- ^ Salerno, Reynolds M.; Gaudioso, Jennifer; Brodsky, Benjamin H. (2007). «Preface». Laboratory Biosecurity Handbook (Illustrated ed.). CRC Press. p. xi. ISBN 9781420006209. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Piper, Kelsey (2022-04-05). «Why experts are terrified of a human-made pandemic — and what we can do to stop it». Vox. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ^ Ord, Toby (2020-03-06). «Why we need worst-case thinking to prevent pandemics». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

This is an edited extract from The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity

- ^ Ord, Toby (2021-03-23). «Covid-19 has shown humanity how close we are to the edge». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Forschung an Krankheitserregern soll sicherer werden». www.sciencemediacenter.de. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ Pannu, Jaspreet; Palmer, Megan J.; Cicero, Anita; Relman, David A.; Lipsitch, Marc; Inglesby, Tom (16 December 2022). «Strengthen oversight of risky research on pathogens». Science. 378 (6625): 1170–1172. Bibcode:2022Sci…378.1170P. doi:10.1126/science.adf6020. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36480598. S2CID 254998228.

- University press release: «Stanford Researchers Recommend Stronger Oversight of Risky Research on Pathogens». Stanford University. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ a b «Science as a Global Public Good». International Science Council. 8 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Jamieson, Kathleen Hall; Kahan, Dan; Scheufele, Dietram A. (17 May 2017). The Oxford Handbook of the Science of Science Communication. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190497637.

- ^ Grochala, Rafał (16 December 2019). «Science communication in online media: influence of press releases on coverage of genetics and CRISPR». doi:10.1101/2019.12.13.875278. S2CID 213125031.

- ^ «FRAMING ANALYSIS OF NEWS COVERAGE ON RENEWABLE ENERGYIN THE STAR ONLINE NEWS PORTAL» (PDF). Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ MacLaughlin, Ansel; Wihbey, John; Smith, David (15 June 2018). «Predicting News Coverage of Scientific Articles». Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. 12 (1). doi:10.1609/icwsm.v12i1.14999. ISSN 2334-0770. S2CID 49412893.

- ^ Carrigan, Mark; Jordan, Katy (4 November 2021). «Platforms and Institutions in the Post-Pandemic University: a Case Study of Social Media and the Impact Agenda». Postdigital Science and Education. 4 (2): 354–372. doi:10.1007/s42438-021-00269-x. ISSN 2524-4868. S2CID 243760357.

- ^ Baykoucheva, Svetla (2015). «Measuring attention». Managing Scientific Information and Research Data: 127–136. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100195-0.00014-7. ISBN 978-0081001950.

- ^ a b c Zagorova, Olga; Ulloa, Roberto; Weller, Katrin; Flöck, Fabian (12 April 2022). ««I updated the <ref>»: The evolution of references in the English Wikipedia and the implications for altmetrics». Quantitative Science Studies. 3 (1): 147–173. doi:10.1162/qss_a_00171. S2CID 222177064.

- ^ Williams, Ann E. (12 June 2017). «Altmetrics: an overview and evaluation». Online Information Review. 41 (3): 311–317. doi:10.1108/OIR-10-2016-0294.

- ^ a b c Gurevitch, Jessica; Koricheva, Julia; Nakagawa, Shinichi; Stewart, Gavin (March 2018). «Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis». Nature. 555 (7695): 175–182. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..175G. doi:10.1038/nature25753. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 29517004. S2CID 3761687.

- ^ Balbi, Stefano; Bagstad, Kenneth J.; Magrach, Ainhoa; Sanz, Maria Jose; Aguilar-Amuchastegui, Naikoa; Giupponi, Carlo; Villa, Ferdinando (17 February 2022). «The global environmental agenda urgently needs a semantic web of knowledge». Environmental Evidence. 11 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s13750-022-00258-y. ISSN 2047-2382. S2CID 246872765.

- ^ a b Khalil, Mohammed M. (2016). «Improving Science for a Better Future». How Should Humanity Steer the Future?. The Frontiers Collection. Springer International Publishing: 113–126. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20717-9_11. ISBN 978-3-319-20716-2.

- ^ «How Do Science Journalists Evaluate Psychology Research?». psyarxiv.com.

- ^ Dunlop, Lynda; Veneu, Fernanda (1 September 2019). «Controversies in Science». Science & Education. 28 (6): 689–710. doi:10.1007/s11191-019-00048-y. ISSN 1573-1901. S2CID 255016078.

- ^ Norsen, Travis (2016). «Back to the Future: Crowdsourcing Innovation by Refocusing Science Education». How Should Humanity Steer the Future?. The Frontiers Collection: 85–95. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20717-9_9. ISBN 978-3-319-20716-2.

- ^ Bschir, Karim (July 2021). «How to make sense of science: Mano Singham: The great paradox of science: why its conclusions can be relied upon even though they cannot be proven. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019, 332 pp, £ 22.99 HB». Metascience. 30 (2): 327–330. doi:10.1007/s11016-021-00654-z. S2CID 254792908.

- ^ «Correcting misconceptions — Understanding Science». 21 April 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Philipp-Muller, Aviva; Lee, Spike W. S.; Petty, Richard E. (26 July 2022). «Why are people antiscience, and what can we do about it?». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (30): e2120755119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11920755P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2120755119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9335320. PMID 35858405.

- ^ «The 4 bases of anti-science beliefs – and what to do about them». SCIENMAG: Latest Science and Health News. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Hotez, Peter J. «The Antiscience Movement Is Escalating, Going Global and Killing Thousands». Scientific American. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Park, Michael; Leahey, Erin; Funk, Russell J. (January 2023). «Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time». Nature. 613 (7942): 138–144. Bibcode:2023Natur.613..138P. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 36600070. S2CID 255466666.

- ^ Ginsparg, Paul (September 2021). «Lessons from arXiv’s 30 years of information sharing». Nature Reviews Physics. 3 (9): 602–603. doi:10.1038/s42254-021-00360-z. PMC 8335983. PMID 34377944.

- ^ «Nature Journals To Charge Authors Hefty Fee To Make Scientific Papers Open Access». IFLScience. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ «Harvard University says it can’t afford journal publishers’ prices». The Guardian. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Van Noorden, Richard (1 March 2013). «Open access: The true cost of science publishing». Nature. 495 (7442): 426–429. Bibcode:2013Natur.495..426V. doi:10.1038/495426a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 23538808. S2CID 27021567.

- ^ Tennant, Jonathan P.; Waldner, François; Jacques, Damien C.; Masuzzo, Paola; Collister, Lauren B.; Hartgerink, Chris. H. J. (21 September 2016). «The academic, economic and societal impacts of Open Access: an evidence-based review». F1000Research. 5: 632. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8460.3. PMC 4837983. PMID 27158456.

- ^ «Paywall: The business of scholarship review – analysis of a scandal». New Scientist. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Powell, Kendall (1 February 2016). «Does it take too long to publish research?». Nature. 530 (7589): 148–151. doi:10.1038/530148a. PMID 26863966. S2CID 1013588. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ «Open peer review: bringing transparency, accountability, and inclusivity to the peer review process». Impact of Social Sciences. 13 September 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Dattani, Saloni. «The Pandemic Uncovered Ways to Speed Up Science». Wired. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ «Speeding up the publication process at PLOS ONE». EveryONE. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ a b «Open Alex Data Evolution». observablehq.com. 8 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Singh Chawla, Dalmeet (24 January 2022). «Massive open index of scholarly papers launches». Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00138-y. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «OpenAlex: The Promising Alternative to Microsoft Academic Graph». Singapore Management University (SMU). Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «OpenAlex Documentation». Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ a b Waagmeester, Andra; Willighagen, Egon L.; Su, Andrew I.; Kutmon, Martina; Gayo, Jose Emilio Labra; Fernández-Álvarez, Daniel; Groom, Quentin; Schaap, Peter J.; Verhagen, Lisa M.; Koehorst, Jasper J. (22 January 2021). «A protocol for adding knowledge to Wikidata: aligning resources on human coronaviruses». BMC Biology. 19 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s12915-020-00940-y. ISSN 1741-7007. PMC 7820539. PMID 33482803.

- ^ Jin, Ching; Ma, Yifang; Uzzi, Brian (5 October 2021). «Scientific prizes and the extraordinary growth of scientific topics». Nature Communications. 12 (1): 5619. arXiv:2012.09269. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.5619J. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25712-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8492701. PMID 34611161.

- ^ «Scholia – biomarker». Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Bornmann, Lutz; Haunschild, Robin; Mutz, Rüdiger (7 October 2021). «Growth rates of modern science: a latent piecewise growth curve approach to model publication numbers from established and new literature databases». Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 8 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00903-w. ISSN 2662-9992. S2CID 229156128.

- ^ a b Thompson, Derek (1 December 2021). «America Is Running on Fumes». The Atlantic. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ Collison, Patrick; Nielsen, Michael (16 November 2018). «Science Is Getting Less Bang for Its Buck». The Atlantic. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b «How to escape scientific stagnation». The Economist. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Bhattacharya, Jay; Packalen, Mikko (February 2020). «Stagnation and Scientific Incentives» (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ^ Tejada, Patricia Contreras (13 January 2023). «With fewer disruptive studies, is science becoming an echo chamber?». Advanced Science News. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^

- ^ Petrovich, Eugenio (2020). «Science mapping». www.isko.org. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ Chen, Chaomei (21 March 2017). «Science Mapping: A Systematic Review of the Literature». Journal of Data and Information Science. 2 (2): 1–40. doi:10.1515/jdis-2017-0006. S2CID 57737772.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M.; Martínez, M. Ángeles; Moral-Munoz, J. A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Cobo, M. J. (1 May 2018). «Some bibliometric procedures for analyzing and evaluating research fields». Applied Intelligence. 48 (5): 1275–1287. doi:10.1007/s10489-017-1105-y. ISSN 1573-7497. S2CID 254227914.

- ^ Navarro, V. (31 March 2008). «Politics and health: a neglected area of research». The European Journal of Public Health. 18 (4): 354–355. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckn040. PMID 18524802.

- ^ Farley-Ripple, Elizabeth N.; Oliver, Kathryn; Boaz, Annette (7 September 2020). «Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice». Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 7 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-00571-2. ISSN 2662-9992.

- ^ a b Lamers, Wout S; Boyack, Kevin; Larivière, Vincent; Sugimoto, Cassidy R; van Eck, Nees Jan; Waltman, Ludo; Murray, Dakota (24 December 2021). «Investigating disagreement in the scientific literature». eLife. 10: e72737. doi:10.7554/eLife.72737. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 8709576. PMID 34951588.

- ^ LeLorier J, Grégoire G, Benhaddad A, Lapierre J, Derderian F (August 1997). «Discrepancies between meta-analyses and subsequent large randomized, controlled trials». The New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (8): 536–542. doi:10.1056/NEJM199708213370806. PMID 9262498.

- ^ a b Slavin RE (1986). «Best-Evidence Synthesis: An Alternative to Meta-Analytic and Traditional Reviews». Educational Researcher. 15 (9): 5–9. doi:10.3102/0013189X015009005. S2CID 146457142.

- ^ Hunter JE, Schmidt FL, Jackson GB, et al. (American Psychological Association. Division of Industrial-Organizational Psychology) (1982). Meta-analysis: cumulating research findings across studies. Beverly Hills, California: Sage. ISBN 978-0-8039-1864-1.

- ^ Glass GV, McGaw B, Smith ML (1981). Meta-analysis in social research. Beverly Hills, California: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0-8039-1633-3.

- ^ Stone, Dianna L.; Rosopa, Patrick J. (1 March 2017). «The Advantages and Limitations of Using Meta-analysis in Human Resource Management Research». Human Resource Management Review. 27 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.09.001. ISSN 1053-4822.

- ^ Elliott, Julian; Lawrence, Rebecca; Minx, Jan C.; Oladapo, Olufemi T.; Ravaud, Philippe; Tendal Jeppesen, Britta; Thomas, James; Turner, Tari; Vandvik, Per Olav; Grimshaw, Jeremy M. (December 2021). «Decision makers need constantly updated evidence synthesis». Nature. 600 (7889): 383–385. Bibcode:2021Natur.600..383E. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-03690-1. PMID 34912079. S2CID 245220047.

- ^ Snyder, Alison (14 October 2021). «New ideas are struggling to emerge from the sea of science». Axios. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Chu, Johan S. G.; Evans, James A. (12 October 2021). «Slowed canonical progress in large fields of science». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (41): e2021636118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11821636C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2021636118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8522281. PMID 34607941.