- С русского на:

- Итальянский

- С итальянского на:

- Русский

неаполь

-

1

Неаполь

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > Неаполь

-

2

Nàpoli

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > Nàpoli

-

3

Napoli

Итальяно-русский универсальный словарь > Napoli

-

4

passare per Napoli

гл.общ.заехать в Неаполь, проехать через Неаполь

Итальяно-русский универсальный словарь > passare per Napoli

-

5

sud

Il nuovo dizionario italiano-russo > sud

-

6

-N13

vedi Napoli, e (poi) mori!

prov.посмотри на Неаполь и можешь умирать! (все равно лучшего в жизни не увидишь):

«Vedi Napoli e poi muori» aveva detto due o tre volte un viaggiatore seduto di fronte a lui. «Muori tu, cornuto!» s’era ripetuto fra sé Salvatore. (P. A. Buttita, «Il volantino»)

— Посмотри на Неаполь и умри, — два или три раза повторил попутчик, сидевший напротив. — Умирай сам, болван, — повторял про себя Сальваторе.

Frasario italiano-russo > -N13

-

7

N

I , m; = n

II

1) Nord Север, Норд

2) scacchi Nero чёрные

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > N

-

8

napoletano

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > napoletano

-

9

Napoli

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > Napoli

-

10

passare

1. (e)

passa là!, passa via! — кыш (отсюда)!, пошёл вон!

è passata la voglia — прошла охота

è passato l’appetito — пропал аппетит

4) проходить, проникать

le cose sono passate così… — дело произошло так…

6) быть принятым; быть терпимым / приемлемым

per questa volta, passi / passa — на этот раз сойдёт

9) входить

2. vt

3) превосходить; превышать

…e passa — с лишним

9) разг. прощать

•

Syn:

Ant:

••

passi! — 1) войдите! 2) допустим!, пусть!

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > passare

-

11

scalo

m

2) мор.

4) ж.-д. грузовая станция; платформа разгрузки; товарная станция сортировочная станция

5) ав. (промежуточная) остановка

6) ав. кратковременная посадка

9) ав. аэропорт

10) ав. аэродром

•

Syn:

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > scalo

-

12

Napoli

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > Napoli

-

13

n

N, n f, m invar эннэ (12-я буква итальянского алфавита) N come Napoli — ╚энне╩ как в слове Наполи <Неаполь> (при произнесении слова по буквам в телефонном разговоре)

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > n

-

14

napoletano

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > napoletano

-

15

passare

passare 1. vi (e) 1) проходить; проезжать; пролетать; проплывать passare per Napoli — проехать через <заехать в> Неаполь passare per la farmacia — зайти в аптеку passare dal sarto — зайти к портному passa là!, passa via! — кыш (отсюда)!, пошел вон! 2) проходить; протекать( о времени) sono passati due mesi — прошло два месяца 3) проходить, миновать, прекращаться Х passata la pioggia — дождь прошел Х passata la voglia — прошла охота Х passato l’appetito — прошел аппетит 4) проходить, проникать (напр о свете, воде) 5) случаться, совершаться, происходить le cose sono passate così… — дело произошло так… 6) быть принятым; быть терпимым <приемлемым> la legge Х passata — закон одобрен <принят> il lavoro può passare — работа может быть принята per questa volta, passi

— на этот раз сойдет 7) переходить passare al nemico — перейти на сторону противника passare in seconda classe — перейти во второй класс passare all’esame — выдержать экзамен passare oltre — перейти к другой теме passare in cancrena — перейти в гангрену passare dalla gioia alla disperazione — перейти от радости к отчаянию passare capitano — получить чин капитана

(per) слыть, считаться; быть принятым passare per medico — сойти за врача questa (cosa) può passare — это подойдет <сойдет> 9) (in) входить passare in uso — войти в обычай 10) (sopra a) не обращать внимания (на что-л), не придавать значения (чемул) 2. vt 1) переходить; переезжать; переплывать passare la via — перейти улицу passare il confine — переехать границу passare il mare — переплыть море 2) проводить (время) passare l’estate in città — провести лето в городе passare la notte senza dormire — провести ночь без сна 3) превосходить; превышать passare i compagni a scuola — опередить товарищей в школе passare di peso il chilo — весить больше килограмма passare la misura — превзойти меру passare i limiti — выйти за пределы… e passa — с лишним un chilo e passa — килограмм с лишним diecimila e passa — больше десяти тысяч ce ne saranno mille e passa — их там с тысячу, а то и больше 4) пронизывать; прокалывать; продевать, просовывать passare da parte a parte — пронзить <пробить, проколоть> насквозь 5) cuc протирать; просеивать; процеживать; обваливать passare nel pangrattato — обвалять в сухарях 6) передавать passare la lettera — передать письмо 7) переносить, переживать, претерпевать passare un guaio — пережить горе passare un’ora di felicità — пережить счастливые минуты

повышать( по службе) passare qd da un grado all’altro — повысить в чине 9) fam прощать stavolta te la passo — на этот раз прощаю non gliela passo mai — ни за что ему этого не прощу passarsela — жить, поживать passarsela bene — наслаждаться жизнью passi! а) войдите! б) допустим!, пусть! passo! а) пас! (в карточной игре) б) radio прием!

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > passare

-

16

scalo

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > scalo

-

17

n

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > n

-

18

napoletano

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > napoletano

-

19

Napoli

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > Napoli

-

20

passare

passare

1. vi (e)

1) проходить; проезжать; пролетать; проплывать

passare per Napoli — проехать через <заехать в> Неаполь

passare per la farmacia — зайти в аптеку

passare dal sarto — зайти к портному

passa là!, passa via! — кыш (отсюда)!, пошёл вон!

2) проходить; протекать ( о времени)

sono passati due mesi — прошло два месяца

3) проходить, миновать, прекращаться

è passata la pioggia — дождь прошёл

è passata la voglia — прошла охота

è passato l’appetito — прошёл аппетит

4) проходить, проникать (напр о свете, воде)

5) случаться, совершаться, происходить

le cose sono passate così … — дело произошло так …

6) быть принятым; быть терпимым <приемлемым>

la legge è passata — закон одобрен <принят>

il lavoro può passare — работа может быть принята

per questa volta, passi — на этот раз сойдёт

7) переходить

passare al nemico — перейти на сторону противника

passare in seconda [in terza] classe — перейти во второй [в третий] класс

passare all’esame — выдержать экзамен

passare oltre — перейти к другой теме

passare in cancrena — перейти в гангрену

passare dalla gioia alla disperazione — перейти от радости к отчаянию

passare capitano — получить чин капитана

( per) слыть, считаться; быть принятым

passare per medico — сойти за врача

questa (cosa) può passare — это подойдёт <сойдёт>

9) (in) входить

passare in uso — войти в обычай

10) ( sopra a) не обращать внимания ( на что-л), не придавать значения ( чемул)

2. vt

1) переходить; переезжать; переплывать

passare la via — перейти улицу

passare il confine — переехать границу

passare il mare — переплыть море

2) проводить ( время)

passare l’estate in città — провести лето в городе

passare la notte senza dormire — провести ночь без сна

3) превосходить; превышать

passare i compagni a scuola — опередить товарищей в школе

passare di peso il chilo — весить больше килограмма

passare la misura — превзойти меру

passare i limiti — выйти за пределы

… e passa — с лишним

un chilo e passa — килограмм с лишним

diecimila e passa — больше десяти тысяч

ce ne saranno mille e passa — их там с тысячу, а то и больше

4) пронизывать; прокалывать; продевать, просовывать

passare da parte a parte — пронзить <пробить, проколоть> насквозь

5) cuc протирать; просеивать; процеживать; обваливать

passare nel pangrattato [nella farina] — обвалять в сухарях [в муке]

6) передавать

passare la lettera — передать письмо

7) переносить, переживать, претерпевать

passare un guaio — пережить горе

passare un’ora di felicità — пережить счастливые минуты

повышать ( по службе)

passare qd da un grado all’altro — повысить в чине

9) fam прощать

stavolta te la passo — на этот раз прощаю

non gliela passo mai — ни за что ему этого не прощу

Большой итальяно-русский словарь > passare

См. также в других словарях:

-

Неаполь — город в Юж. Италии, адм. ц. обл. Кампания. Первоначально др. греч. колония Партенопия, названная в честь богини Афины, которую называли также Афина Парфенос ( вечно девственная ). В IV в. до н. э. город разрушен италийцами, но вскоре рядом с ним… … Географическая энциклопедия

-

НЕАПОЛЬ — НЕАПОЛЬ, город в Италии, у подножия Везувия. 1,2 млн. жителей. Порт в Неаполитанском заливе Тирренского моря (грузооборот около 15 млн. т в год); международный аэропорт. Нефтеперерабатывающая и нефтехимическая промышленность, машиностроение… … Современная энциклопедия

-

Неаполь — (Napoli), город на юге Италии, на берегу Неаполитанского залива Тирренского моря, у подножия вулкана Везувий; главный город исторической области Кампания. Расположенный амфитеатром на прибрежных холмах, Неаполь сохранил в центральной… … Художественная энциклопедия

-

НЕАПОЛЬ — скифский (3 в. до н. э. 3 в. н. э.) столица скифского государства в Крыму. Развалины около современного Симферополя: укрепления, жилые и хозяйственные постройки, мавзолей, каменные склепы с росписями и др … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Неаполь — ( новый город ), порт. город в 15 км от Филипп. Здесь начиналась знаменитая рим. Эгнатиева дорога, ведущая через Амфиполь и Фессалоники в Ахаию. Ап. Павел впервые вступил на европ. землю, когда прибыл в Н. (Деян 16:11). Ныне город, стоящий на… … Библейская энциклопедия Брокгауза

-

неаполь — сущ., кол во синонимов: 3 • город (2765) • парфенопа (3) • порт (361) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Триш … Словарь синонимов

-

Неаполь — Неаполь: 1) пров. итал. королевства, в юго вост. части Кампании; 1066кв. км, 1 115007 жит. Богатство моря рыбой, моллюсками, каракатицами,морскими звездами и т.п. обусловливает собой занятия большинстваприморского населения. Кроме продуктов… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

Неаполь — (Naples), город и порт на берегу Неаполитанского зал. в Юж. Италии. В древности был заселен греками из Халкиды и Афин, в 328 г. до н.э. покорен римлянами, с ослаблением Римской империи находился под властью готов. В 6 в. благодаря Византии Н.… … Всемирная история

-

Неаполь — НЕАПОЛЬ, первоклас. итал. воен. и коммерч. портъ въ глубинѣ одноимен. залива, закрытаго съ ю. о вами Капри, Исрія и Процида; бывш. столица корол ва обѣихъ Сицилій. Одинъ изъ лучш. рейдовъ въ мірѣ, станція почтов. пароходовъ, идущихъ на Востокъ,… … Военная энциклопедия

-

Неаполь — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Неаполь (значения). Город Неаполь Napoli … Википедия

-

Неаполь — I Неаполь (Napoli) город в Южной Италии, расположен на берегу Неаполитанского залива Тирренского моря, у подножия вулкана Везувий. Главный город области Кампания и провинции Неаполь. Важнейший экономический и культурный центр юга страны.… … Большая советская энциклопедия

|

Naples Napoli (Italian) |

|

|---|---|

|

Comune |

|

| Comune di Napoli | |

|

Clockwise from top: panorama view of Mergellina Port, Mergellina, Chiaia area, overview of Mount Vesuvius; Piazza del Plebiscito; Toledo metro station; Castel Nuovo; Museo di Capodimonte; and view of Royal Palace of Naples |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Nickname:

Partenope |

|

|

Location of Naples |

|

|

Naples Location of Naples in Campania Naples Naples (Campania) |

|

| Coordinates: 40°50′N 14°15′E / 40.833°N 14.250°ECoordinates: 40°50′N 14°15′E / 40.833°N 14.250°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Campania |

| Metropolitan city | Naples (NA) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gaetano Manfredi (Independent) |

| Area

[1] |

|

| • Total | 117.27 km2 (45.28 sq mi) |

| Elevation

[1] |

99.8 m (327.4 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 453 m (1,486 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population

(30 June 2022)[2] |

|

| • Total | 909,048 |

| • Density | 7,800/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Napoletano Partenopeo Napulitano (Neapolitan) Neapolitan (English) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code |

80100, 80121-80147 |

| Dialing code | 081 |

| ISTAT code | 063049 |

| Patron saint | Januarius |

| Saint day | 19 September |

| Website | comune.napoli.it |

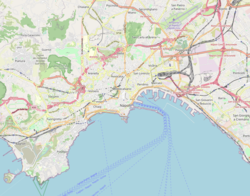

Naples ( NAY-pəlz; Italian: Napoli [ˈnaːpoli] (listen); Neapolitan: Napule [ˈnɑːpələ])[a] is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city’s administrative limits as of 2022.[3] Its province-level municipality is the third-most populous metropolitan city in Italy with a population of 3,115,320 residents,[4] and its metropolitan area stretches beyond the boundaries of the city wall for approximately 20 miles.

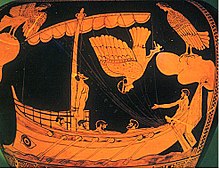

Founded by Greeks in the first millennium BC, Naples is one of the oldest continuously inhabited urban areas in the world. In the eighth century BC, a colony known as Parthenope (Ancient Greek: Παρθενόπη) was established on the Pizzofalcone hill. In the sixth century BC, it was refounded as Neápolis.[5] The city was an important part of Magna Graecia, played a major role in the merging of Greek and Roman society, and was a significant cultural centre under the Romans.[6]

Naples served as the capital of the Duchy of Naples (661–1139), subsequently as the capital of the Kingdom of Naples (1282–1816), and finally as the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies — until the unification of Italy in 1861. Naples is also considered a capital of the Baroque, beginning with the artist Caravaggio’s career in the 17th century and the artistic revolution he inspired.[7] It was also an important centre of humanism and Enlightenment.[8][9] The city has long been a global point of reference for classical music and opera through the Neapolitan School.[10] Between 1925 and 1936, Naples was expanded and upgraded by Benito Mussolini’s government. During the later years of World War II, it sustained severe damage from Allied bombing as they invaded the peninsula. The city received extensive post-1945 reconstruction work.[11]

Since the late 20th century, Naples has had significant economic growth, helped by the construction of the Centro Direzionale business district and an advanced transportation network, which includes the Alta Velocità high-speed rail link to Rome and Salerno and an expanded subway network. Naples is the third-largest urban economy in Italy by GDP, after Milan and Rome.[12] The Port of Naples is one of the most important in Europe. In addition to commercial activities, it is home to the Allied Joint Force Command Naples, the NATO body that oversees North Africa, the Sahel, and the Middle East.[13]

Naples’ historic city centre is the largest in Europe and has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A wide range of culturally and historically significant sites are nearby, including the Palace of Caserta and the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Naples is also known for its natural beauties, such as Posillipo, Phlegraean Fields, Nisida and Vesuvius.[14] Neapolitan cuisine is noted for its association with pizza, which originated in the city, as well as numerous other local dishes. Restaurants in the Naples’ area have earned the most stars from the Michelin Guide of any Italian province.[15] Naples’ Centro Direzionale was built in 1994 as the first grouping of skyscrapers in Italy, remaining the only such grouping in Italy until 2009. The most widely-known sports team in Naples is the Serie A football club S.S.C. Napoli, two-time Italian champions who play at the Stadio Diego Armando Maradona in the west of the city, in the Fuorigrotta quarter.

History[edit]

Greek birth and Roman acquisition[edit]

Mount Echia, the place where the polis of Parthenope arose

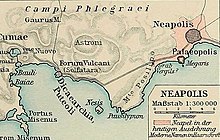

Map of pre-Roman Neapolis

Naples has been inhabited since the Neolithic period.[17] In the second millennium BC, a first Mycenaean settlement arose not far from the geographical position of the future city of Parthenope.[18]

Sailors from the Greek island of Rhodes established probably a small commercial port called Parthenope (Παρθενόπη, meaning «Pure Eyes», a Siren in Greek mythology) on the island of Megaride in the ninth century BC.[19] By the eighth century BC, the settlement was expanded by Cumans, as evidenced by the archaeological findings, to include Monte Echia.[20] In the sixth century BC the city was refounded as Neápolis (Νεάπολις), eventually becoming one of the foremost cities of Magna Graecia.[21]

The city grew rapidly due to the influence of the powerful Greek city-state of Syracuse,[22] and became an ally of the Roman Republic against Carthage. During the Samnite Wars, the city, now a bustling centre of trade, was captured by the Samnites;[23] however, the Romans soon captured the city from them and made it a Roman colony.[24] During the Punic Wars, the strong walls surrounding Neápolis repelled the invading forces of the Carthaginian general Hannibal.[24]

The Romans greatly respected Naples as a paragon of Hellenistic culture. During the Roman era, the people of Naples maintained their Greek language and customs. At the same time, the city was expanded with elegant Roman villas, aqueducts, and public baths. Landmarks such as the Temple of Dioscures were built, and many emperors chose to holiday in the city, including Claudius and Tiberius.[24] Virgil, the author of Rome’s national epic, the Aeneid, received part of his education in the city, and later resided in its environs.

It was during this period that Christianity first arrived in Naples; the apostles Peter and Paul are said to have preached in the city. Januarius, who would become Naples’ patron saint, was martyred there in the fourth century AD.[25]

The last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, was exiled to Naples by the Germanic king Odoacer in the fifth century AD.

Duchy of Naples[edit]

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, Naples was captured by the Ostrogoths, a Germanic people, and incorporated into the Ostrogothic Kingdom.[26] However, Belisarius of the Byzantine Empire recaptured Naples in 536, after entering the city via an aqueduct.[27]

In 543, during the Gothic Wars, Totila briefly took the city for the Ostrogoths, but the Byzantines seized control of the area following the Battle of Mons Lactarius on the slopes of Vesuvius.[26] Naples was expected to keep in contact with the Exarchate of Ravenna, which was the centre of Byzantine power on the Italian Peninsula.[28]

After the exarchate fell, a Duchy of Naples was created. Although Naples’ Greco-Roman culture endured, it eventually switched allegiance from Constantinople to Rome under Duke Stephen II, putting it under papal suzerainty by 763.[28]

The years between 818 and 832 saw tumultuous relations with the Byzantine Emperor, with numerous local pretenders feuding for possession of the ducal throne.[29] Theoctistus was appointed without imperial approval; his appointment was later revoked and Theodore II took his place. However, the disgruntled general populace chased him from the city and elected Stephen III instead, a man who minted coins with his initials rather than those of the Byzantine Emperor. Naples gained complete independence by the early ninth century.[29] Naples allied with the Muslim Saracens in 836 and asked for their support to repel the siege of Lombard troops coming from the neighbouring Duchy of Benevento. However, during the 850s, Muhammad I Abu ‘l-Abbas led the Arab-Muslim to sack the city.[30][31]

The duchy was under the direct control of the Lombards for a brief period after the capture by Pandulf IV of the Principality of Capua, a long-term rival of Naples; however, this regime lasted only three years before the Greco-Roman-influenced dukes were reinstated.[29] By the 11th century, Naples had begun to employ Norman mercenaries to battle their rivals; Duke Sergius IV hired Rainulf Drengot to wage war on Capua for him.[32]

By 1137, the Normans had attained great influence in Italy, controlling previously independent principalities and duchies such as Capua, Benevento, Salerno, Amalfi, Sorrento and Gaeta; it was in this year that Naples, the last independent duchy in the southern part of the peninsula, came under Norman control. The last ruling duke of the duchy, Sergius VII, was forced to surrender to Roger II, who had been proclaimed King of Sicily by Antipope Anacletus II seven years earlier. Naples thus joined the Kingdom of Sicily, with Palermo as the capital.[33]

As part of the Kingdom of Sicily[edit]

After a period of Norman rule, in 1189 the Kingdom of Sicily was in a succession dispute between Tancred, King of Sicily of an illegitimate birth and the Hohenstaufens, a Germanic royal house,[34] as its Prince Henry had married Princess Constance the last legitimate heir to the Sicilian throne. In 1191 Henry invaded Sicily after being crowned as Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, and many cities surrendered. Still, Naples resisted him from May to August under the leadership of Richard, Count of Acerra, Nicholas of Ajello, Aligerno Cottone and Margaritus of Brindisi before the Germans suffered from disease and were forced to retreat. Conrad II, Duke of Bohemia and Philip I, Archbishop of Cologne died of disease during the siege. During his counterattack, Tancred captured Constance, now empress. He had the empress imprisoned at Castel dell’Ovo at Naples before her release on May 1192 under the pressure of Pope Celestine III. In 1194 Henry started his second campaign upon the death of Tancred, but this time Aligerno surrendered without resistance, and finally, Henry conquered Sicily, putting it under the rule of Hohenstaufens.

The University of Naples, the first university in Europe dedicated to training secular administrators,[35] was founded by Frederick II, making Naples the intellectual centre of the kingdom. Conflict between the Hohenstaufens and the Papacy led in 1266 to Pope Innocent IV crowning the Angevin duke Charles I King of Sicily:[36] Charles officially moved the capital from Palermo to Naples, where he resided at the Castel Nuovo.[37] Having a great interest in architecture, Charles I imported French architects and workmen and was personally involved in several building projects in the city.[38] Many examples of Gothic architecture sprang up around Naples, including the Naples Cathedral, which remains the city’s main church.[39]

Kingdom of Naples[edit]

The Castel Nuovo, a.k.a. Maschio Angioino, a seat of medieval kings of Naples, Aragon and Spain

In 1282, after the Sicilian Vespers, the Kingdom of Sicily was divided into two. The Angevin Kingdom of Naples included the southern part of the Italian peninsula, while the island of Sicily became the Aragonese Kingdom of Sicily.[36] Wars between the competing dynasties continued until the Peace of Caltabellotta in 1302, which saw Frederick III recognised as king of Sicily, while Charles II was recognised as king of Naples by Pope Boniface VIII.[36] Despite the split, Naples grew in importance, attracting Pisan and Genoese merchants,[40] Tuscan bankers, and some of the most prominent Renaissance artists of the time, such as Boccaccio, Petrarch and Giotto.[41] During the 14th century, the Hungarian Angevin king Louis the Great captured the city several times. In 1442, Alfonso I conquered Naples after his victory against the last Angevin king, René, and Naples was unified with Sicily again for a brief period.[42]

Aragonese and Spanish[edit]

Sicily and Naples were separated since 1282, but remained dependencies of Aragon under Ferdinand I.[43] The new dynasty enhanced Naples’ commercial standing by establishing relations with the Iberian Peninsula. Naples also became a centre of the Renaissance, with artists such as Laurana, da Messina, Sannazzaro and Poliziano arriving in the city.[44] In 1501, Naples came under direct rule from France under Louis XII, with the Neapolitan king Frederick being taken as a prisoner to France; however, this state of affairs did not last long, as Spain won Naples from the French at the Battle of Garigliano in 1503.[45]

Following the Spanish victory, Naples became part of the Spanish Empire, and remained so throughout the Spanish Habsburg period.[45] The Spanish sent viceroys to Naples to directly deal with local issues: the most important of these viceroys was Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, who was responsible for considerable social, economic and urban reforms in the city; he also tried to introduce the Inquisition.[46][better source needed] In 1544, around 7,000 people were taken as slaves by Barbary pirates and brought to the Barbary Coast of North Africa (see Sack of Naples).[47]

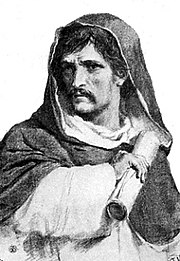

By the 17th century, Naples had become Europe’s second-largest city – second only to Paris – and the largest European Mediterranean city, with around 250,000 inhabitants.[48] The city was a major cultural centre during the Baroque era, being home to artists such as Caravaggio, Salvator Rosa and Bernini, philosophers such as Bernardino Telesio, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella and Giambattista Vico, and writers such as Giambattista Marino. A revolution led by the local fisherman Masaniello saw the creation of a brief independent Neapolitan Republic in 1647. However, this lasted only a few months before Spanish rule was reasserted.[45] In 1656, an outbreak of bubonic plague killed about half of Naples’ 300,000 inhabitants.[49]

In 1714, Spanish rule over Naples came to an end as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession; the Austrian Charles VI ruled the city from Vienna through viceroys of his own.[50] However, the War of the Polish Succession saw the Spanish regain Sicily and Naples as part of a personal union, with the 1738 Treaty of Vienna recognising the two polities as independent under a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons.[51]

In 1755, the Duke of Noja commissioned an accurate topographic map of Naples, later known as the Map of the Duke of Nojo, employing rigorous surveying accuracy and becoming an essential urban planning tool for Naples.

During the time of Ferdinand IV, the effects of the French Revolution were felt in Naples: Horatio Nelson, an ally of the Bourbons, arrived in the city in 1798 to warn against the French republicans. Ferdinand was forced to retreat and fled to Palermo, where he was protected by a British fleet.[52] However, Naples’ lower class lazzaroni were strongly pious and royalist, favouring the Bourbons; in the mêlée that followed, they fought the Neapolitan pro-Republican aristocracy, causing a civil war.[52]

Eventually, the Republicans conquered Castel Sant’Elmo and proclaimed a Parthenopaean Republic, secured by the French Army.[52] A counter-revolutionary religious army of lazzaroni known as the sanfedisti under Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo was raised; they met with great success, and the French were forced to surrender the Neapolitan castles, with their fleet sailing back to Toulon.[52]

Ferdinand IV was restored as king; however, after only seven years, Napoleon conquered the kingdom and installed Bonapartist kings, including his brother Joseph Bonaparte (King of Spain).[53] With the help of the Austrian Empire and its allies, the Bonapartists were defeated in the Neapolitan War. Ferdinand IV once again regained the throne and the kingdom.[53]

Independent Two Sicilies[edit]

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 saw the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily combine to form the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies,[53] with Naples as the capital city. In 1839, Naples became the first city on the Italian peninsula to have a railway, with the construction of the Naples–Portici railway.[54]

Italian unification to the present day[edit]

Entrance of Garibaldi into Naples on 7 September 1860

After the Expedition of the Thousand led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, which culminated in the controversial siege of Gaeta, Naples became part of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 as part of the Italian unification, ending the era of Bourbon rule. The economy of the area formerly known as the Two Sicilies declined, leading to an unprecedented wave of emigration,[55] with an estimated 4 million people emigrating from the Naples area between 1876 and 1913.[56] In the forty years following unification, the population of Naples grew by only 26%, vs. 63% for Turin and 103% for Milan; however, by 1884, Naples was still the largest city in Italy with 496,499 inhabitants, or roughly 64,000 per square kilometre (more than twice the population density of Paris).[57]: 11–14, 18

Public health conditions in certain areas of the city were poor, with twelve epidemics of cholera and typhoid fever claiming some 48,000 people between 1834 and 1884. A death rate 31.84 per thousand, high even for the time, insisted in the absence of epidemics between 1878 and 1883.[57] Then in 1884, Naples fell victim to a major cholera epidemic, caused largely by the city’s poor sewerage infrastructure. In response to these problems, in 1852, the government prompted a radical transformation of the city called risanamento to improve the sewerage infrastructure and replace the most clustered areas, considered the main cause of insalubrity, with large and airy avenues. The project proved difficult to accomplish politically and economically due to corruption, as shown in the Saredo Inquiry, land speculation and extremely long bureaucracy. This led to the project to massive delays with contrasting results. The most notable transformations made were the construction of Via Caracciolo in place of the beach along the promenade, the creation of Galleria Umberto I and Galleria Principe and the construction of Corso Umberto.[58][59]

Allied bombardment of Naples, 1943

Naples was the most-bombed Italian city during World War II.[11] Though Neapolitans did not rebel under Italian Fascism, Naples was the first Italian city to rise up against German military occupation; the city was completely freed by 1 October 1943, when British and American forces entered the city.[60] Departing Germans burned the library of the university, as well as the Italian Royal Society. They also destroyed the city archives. Time bombs planted throughout the city continued to explode into November.[61] The symbol of the rebirth of Naples was the rebuilding of the church of Santa Chiara, which had been destroyed in a United States Army Air Corps bombing raid.[11]

Special funding from the Italian government’s Fund for the South was provided from 1950 to 1984, helping the Neapolitan economy to improve somewhat, with city landmarks such as the Piazza del Plebiscito being renovated.[62] However, high unemployment continues to affect Naples.

Italian media attributed the past city’s waste disposal issues to the activity of the Camorra organised crime network.[63] Due to this event, environmental contamination and increased health risks are also prevalent.[64] In 2007, Silvio Berlusconi’s government held senior meetings in Naples to demonstrate their intention to solve these problems.[65] However, the late-2000s recession had a severe impact on the city, intensifying its waste-management and unemployment problems.[66] By August 2011, the number of unemployed in the Naples area had risen to 250,000, sparking public protests against the economic situation.[67] In June 2012, allegations of blackmail, extortion, and illicit contract tendering emerged concerning the city’s waste management issues.[68][69]

Naples hosted the sixth World Urban Forum in September 2012[70] and the 63rd International Astronautical Congress in October 2012.[71] In 2013, it was the host of the Universal Forum of Cultures and the host for the 2019 Summer Universiade.

Architecture[edit]

UNESCO World Heritage Site[edit]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 726 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

| Area | 1,021 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,350 ha |

Naples’ 2,800-year history has left it with a wealth of historical buildings and monuments, from medieval castles to classical ruins, and a wide range of culturally and historically significant sites nearby, including the Palace of Caserta and the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. In 2017 the BBC defined Naples as «the Italian city with too much history to handle».[72]

The most prominent forms of architecture visible in present-day Naples are the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque styles.[73] Naples has a total of 448 historical churches (1000 in total[74]), making it one of the most Catholic cities in the world in terms of the number of places of worship.[75] In 1995, the historic centre of Naples was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, a United Nations programme which aims to catalogue and conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of mankind.

Naples is one of the most ancient cities in Europe, whose contemporary urban fabric preserves the elements of its long and eventful history. The rectangular grid layout of the ancient Greek foundation of Neapolis is still discernible. It has indeed continued to provide the layout for the present-day Historic Centre of Naples, one of the major Mediterranean port cities. From the Middle Ages to the 18th century, Naples was a focal point in terms of art and architecture, expressed in its ancient forts, the royal ensembles such as the Royal Palace of 1600, and the palaces and churches sponsored by the noble families.

Piazzas, palaces and castles[edit]

The main city square or piazza of the city is the Piazza del Plebiscito. Its construction was begun by the Bonapartist king Joachim Murat and finished by the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV. The piazza is bounded on the east by the Royal Palace and on the west by the church of San Francesco di Paola, with the colonnades extending on both sides. Nearby is the Teatro di San Carlo, which is the oldest opera house in Italy. Directly across San Carlo is Galleria Umberto.

Naples is well known for its castles: The most ancient is Castel dell’Ovo («Egg Castle»), which was built on the tiny islet of Megarides, where the original Cumaean colonists had founded the city. In Roman times the islet became part of Lucullus’s villa, later hosting Romulus Augustulus, the exiled last western Roman emperor.[76] It had also been the prison for Empress Constance between 1191 and 1192 after her being captured by Sicilians, and Conradin and Giovanna I of Naples before their executions.

Castel Nuovo, also known as Maschio Angioino, is one of the city’s top landmarks; it was built during the time of Charles I, the first king of Naples. Castel Nuovo has seen many notable historical events: for example, in 1294, Pope Celestine V resigned as pope in a hall of the castle, and following this Pope Boniface VIII was elected pope by the cardinal collegium, before moving to Rome.[77]

Castel Capuano was built in the 12th century by William I, the son of Roger II of Sicily, the first monarch of the Kingdom of Naples. It was expanded by Frederick II and became one of his royal palaces. The castle was the residence of many kings and queens throughout its history. In the 16th century, it became the Hall of Justice.[78]

Another Neapolitan castle is Castel Sant’Elmo, which was completed in 1329 and is built in the shape of a star. Its strategic position overlooking the entire city made it a target of various invaders. During the uprising of Masaniello in 1647, the Spanish took refuge in Sant’Elmo to escape the revolutionaries.[79]

The Carmine Castle, built in 1392 and highly modified in the 16th century by the Spanish, was demolished in 1906 to make room for the Via Marina, although two of the castle’s towers remain as a monument. The Vigliena Fort, built in 1702, was destroyed in 1799 during the royalist war against the Parthenopean Republic and is now abandoned and in ruin.[80]

Museums[edit]

Naples is widely known for its wealth of historical museums. The Naples National Archaeological Museum is one of the city’s main museums, with one of the most extensive collections of artefacts of the Roman Empire in the world.[81] It also houses many of the antiques unearthed at Pompeii and Herculaneum, as well as some artefacts from the Greek and Renaissance periods.[81]

Previously a Bourbon palace, now a museum and art gallery, the Museo di Capodimonte is another museum of note. The gallery features paintings from the 13th to the 18th centuries, including major works by Simone Martini, Raphael, Titian, Caravaggio, El Greco, Jusepe de Ribera and Luca Giordano. The royal apartments are furnished with antique 18th-century furniture and a collection of porcelain and majolica from the various royal residences: the famous Capodimonte Porcelain Factory once stood just adjacent to the palace.

In front of the Royal Palace of Naples stands the Galleria Umberto I, which contains the Coral Jewellery Museum. Occupying a 19th-century palazzo renovated by the Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina (MADRE) features an enfilade procession of permanent installations by artists such as Francesco Clemente, Richard Serra, and Rebecca Horn.[82] The 16th-century palace of Roccella hosts the Palazzo delle Arti Napoli, which contains the civic collections of art belonging to the City of Naples, and features temporary exhibits of art and culture. Palazzo Como, which dates from the 15th century, hosts the Museo Filangieri of plastic arts, created in 1883 by Gaetano Filangieri.

Churches and other religious structures[edit]

Naples is the seat of the Archdiocese of Naples; there are hundreds of churches in the city.[75] The Cathedral of Naples is the city’s premier place of worship; each year on 19 September, it hosts the longstanding Miracle of Saint Januarius, the city’s patron saint.[83] During the miracle, which thousands of Neapolitans flock to witness, the dried blood of Januarius is said to turn to liquid when brought close to holy relics said to be of his body.[83] Below is a selective list of Naples’ major churches, chapels, and monastery complexes:

- Certosa di San Martino

- Naples Cathedral

- San Francesco di Paola

- Gesù Nuovo

- Girolamini

- San Domenico Maggiore

- Santa Chiara

- San Paolo Maggiore

- Santa Maria della Sanità, Naples

- Santa Maria del Carmine

- Sant’Agostino alla Zecca

- Madre del Buon Consiglio

- Santa Maria Donna Regina Nuova

- San Lorenzo Maggiore

- Santa Maria Donna Regina Vecchia

- Santa Caterina a Formiello

- Santissima Annunziata Maggiore

- San Gregorio Armeno

- San Giovanni a Carbonara

- Santa Maria La Nova

- Sant’Anna dei Lombardi

- Sant’Eligio Maggiore

- Santa Restituta

- Sansevero Chapel

- San Pietro a Maiella

- San Gennaro extra Moenia

- San Ferdinando

- Pio Monte della Misericordia

- Santa Maria di Montesanto

- Sant’Antonio Abate

- Santa Caterina a Chiaia

- San Pietro Martire

- Hermitage of Camaldoli

- Archbishop’s Palace

Other features[edit]

Aside from the Piazza del Plebiscito, Naples has two other major public squares: the Piazza Dante and the Piazza dei Martiri. The latter originally had only a memorial to religious martyrs, but in 1866, after the Italian unification, four lions were added, representing the four rebellions against the Bourbons.[84]

The San Gennaro dei Poveri is a Renaissance-era hospital for the poor, erected by the Spanish in 1667. It was the forerunner of a much more ambitious project, the Bourbon Hospice for the Poor started by Charles III. This was for the destitute and ill of the city; it also provided a self-sufficient community where the poor would live and work. Though a notable landmark, it is no longer a functioning hospital.[85]

Subterranean Naples[edit]

Underneath Naples lies a series of caves and structures created by centuries of mining, and the city rests atop a major geothermal zone. There are also several ancient Greco-Roman reservoirs dug out from the soft tufo stone on which, and from which, much of the city is built. Approximately one kilometre (0.62 miles) of the many kilometres of tunnels under the city can be visited from the Napoli Sotteranea, situated in the historic centre of the city in Via dei Tribunali. This system of tunnels and cisterns underlies most of the city and lies approximately 30 metres (98 ft) below ground level. During World War II, these tunnels were used as air-raid shelters, and there are inscriptions on the walls depicting the suffering endured by the refugees of that era.

There are large catacombs in and around the city, and other landmarks such as the Piscina Mirabilis, the main cistern serving the Bay of Naples during Roman times.

Several archeological excavations are also present; they revealed in San Lorenzo Maggiore the macellum of Naples, and in Santa Chiara, the biggest thermal complex of the city in Roman times.

Parks, gardens, villas, fountains and stairways[edit]

Of the various public parks in Naples, the most prominent are the Villa Comunale, which was built by the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV in the 1780s;[86] the park was originally a «Royal Garden», reserved for members of the royal family, but open to the public on special holidays. The Bosco di Capodimonte, the city’s largest green space, served as a royal hunting reserve. The Park has 16 additional historical buildings, including residences, lodges, churches, fountains, statues, orchards and woods.[87]

Another important park is the Parco Virgiliano, which looks towards the tiny volcanic islet of Nisida; beyond Nisida lie Procida and Ischia.[88] Parco Virgiliano was named after Virgil, the classical Roman poet and Latin writer who is thought to be entombed nearby.[88] Naples is noted for its numerous stately villas, fountains and stairways, such as the Neoclassical Villa Floridiana, the Fountain of Neptune and the Pedamentina stairways.

Neo-Gothic, Liberty Napoletano and modern architecture[edit]

Aselmeyer Castle, built by Lamont Young in the Neo-Gothic style

One of the city’s various examples of Liberty Napoletano

Various buildings inspired by the Gothic Revival are extant in Naples, due to the influence that this movement had on the Scottish-Indian architect Lamont Young, one of the most active Neapolitan architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Young left a significant footprint in the cityscape and designed many urban projects, such as the city’s first subway.

In the first years of the 20th century, a local version of the Art Nouveau phenomenon, known as «Liberty Napoletano», developed in the city, creating many buildings which still stand today. In 1935, the Rationalist architect Luigi Cosenza designed a new fish market for the city. During the Benito Mussolini era, the first structures of the city’s «service center» were built, all in a Rationalist-Functionalist style, including the Palazzo delle Poste and the Pretura buildings. The Centro Direzionale di Napoli is the only adjacent cluster of skyscrapers in southern Europe.

Geography[edit]

The city is situated on the Gulf of Naples, on the western coast of southern Italy; it rises from sea level to an elevation of 450 metres (1,480 ft). The small rivers that formerly crossed the city’s centre have since been covered by construction. It lies between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei (English: Phlegraean Fields). Campi Flegrei is considered a supervolcano.[89] The islands of Procida, Capri and Ischia can all be reached from Naples by hydrofoils and ferries. Sorrento and the Amalfi Coast are situated south of the city. At the same time, the Roman ruins of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae, which were destroyed in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, are also visible nearby. The port towns of Pozzuoli and Baia, which were part of the Roman naval facility of Portus Julius, lie to the west of the city.

Quarters[edit]

The thirty quarters (quartieri) of Naples are listed below. For administrative purposes, these thirty districts are grouped together into ten governmental community boards.[90]

Climate[edit]

Naples has a Mediterranean climate (Csa) in the Köppen climate classification.[91][92] The climate and fertility of the Gulf of Naples made the region famous during Roman times, when emperors such as Claudius and Tiberius holidayed near the city.[24] The climate is a crossover between maritime and continental features, as typical of peninsular Italy. Maritime features mitigate the winters but occasionally cause heavy rainfall, particularly in the autumn and winter. Summers feature high temperatures and humidity. The continental influence still ensures summer highs averaging near 30 °C (86 °F), and Naples falls within the subtropical climate range with summer daily-mean above 22 °C (72 °F) with hot days, warm nights and occasional summer thunderstorms.[citation needed]

Winters are mild, and snow is rare in the city area but frequent on Mount Vesuvius.

November is the wettest month in Naples, while July is the driest.

| Climate data for Naples-Capodichino, district on the outskirts (altitude: 72 metres (236 feet) above sea level.[93]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.1 (70.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 92.1 (3.63) |

95.3 (3.75) |

77.9 (3.07) |

98.6 (3.88) |

59.0 (2.32) |

32.8 (1.29) |

28.5 (1.12) |

35.5 (1.40) |

88.9 (3.50) |

135.5 (5.33) |

152.1 (5.99) |

112.0 (4.41) |

1,008.2 (39.69) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 86.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 73 | 71 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 70 | 69 | 73 | 74 | 76 | 75 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.7 | 127.6 | 158.1 | 189.0 | 244.9 | 279.0 | 313.1 | 294.5 | 234.0 | 189.1 | 126.0 | 105.4 | 2,375.4 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico[94] and NOAA (1961-1990, humidity)[95] |

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.6 °C (58.3 °F) | 13.9 °C (57.0 °F) | 14.2 °C (57.6 °F) | 15.6 °C (60.1 °F) | 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) | 23.6 °C (74.5 °F) | 25.9 °C (78.6 °F) | 26.0 °C (78.8 °F) | 24.9 °C (76.8 °F) | 21.5 °C (70.7 °F) | 19.2 °C (66.6 °F) | 16.4 °C (61.5 °F) | 19.6 °C (67.3 °F) |

Demographics[edit]

Urban density in central Naples

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 800 | 50,000 | — |

| 1000 | 30,000 | −0.26% |

| 1300 | 60,000 | +0.23% |

| 1500 | 150,000 | +0.46% |

| 1600 | 275,000 | +0.61% |

| 1700 | 207,000 | −0.28% |

| 1861 | 484,026 | +0.53% |

| 1871 | 489,008 | +0.10% |

| 1881 | 535,206 | +0.91% |

| 1901 | 621,213 | +0.75% |

| 1911 | 751,290 | +1.92% |

| 1921 | 859,629 | +1.36% |

| 1931 | 831,781 | −0.33% |

| 1936 | 865,913 | +0.81% |

| 1951 | 1,010,550 | +1.04% |

| 1961 | 1,182,815 | +1.59% |

| 1971 | 1,226,594 | +0.36% |

| 1981 | 1,212,387 | −0.12% |

| 1991 | 1,067,365 | −1.27% |

| 2001 | 1,004,500 | −0.61% |

| 2011 | 957,811 | −0.47% |

| 2017 | 970,185 | +0.21% |

| Sources: ISTAT (2001), City of Naples (2011)[97][98][99][100] |

As of 2022, the population of the comune di Napoli totals around 910,000. Naples’ wider metropolitan area, sometimes known as Greater Naples, has a population of approximately 4.4 million.[101] The demographic profile for the Neapolitan province in general is relatively young: 19% are under the age of 14, while 13% are over 65, compared to the national average of 14% and 19%, respectively.[101] Naples has a higher percentage of females (52.5%) than males (47.5%).[97] Naples currently has a higher birth rate than other parts of Italy, with 10.46 births per 1,000 inhabitants, compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.[102]

Naples’s population rose from 621,000 in 1901 to 1,226,000 in 1971, declining to 910,000 in 2022 as city dwellers moved to the suburbs. According to different sources, Naples’ metropolitan area is either the second-most-populated metropolitan area in Italy after Milan (with 4,434,136 inhabitants according to Svimez Data)[103] or the third (with 3.5 million inhabitants according to the OECD).[104] In addition, Naples is Italy’s most densely populated major city, with approximately 8,182 people per square kilometre;[97] however, it has seen a notable decline in population density since 2003, when the figure was over 9,000 people per square kilometre.[105]

| 2017 largest resident foreign-born groups[106] | |

|---|---|

| Country of birth | Population |

| 15,195 | |

| 8,590 | |

| 5,411 | |

| 2,703 | |

| 2,529 | |

| 1,961 | |

| 1,745 | |

| 1,346 | |

| 1,248 | |

| 1,184 | |

| 1,091 |

In contrast to many northern Italian cities, there are relatively few foreign immigrants in Naples; 94.3% of the city’s inhabitants are Italian nationals. In 2017, there were a total of 58,203 foreigners in the city of Naples; the majority of these are mostly from Sri Lanka, China, Ukraine, Pakistan and Romania.[106] Statistics show that, in the past, the vast majority of immigrants in Naples were female; this happened because male immigrants in Italy tended to head to the wealthier north.[101][107]

Education[edit]

Naples is noted for its numerous higher education institutes and research centres. Naples hosts what is thought to be the oldest state university in the world, in the form of the University of Naples Federico II, which was founded by Frederick II in 1224. The university is among the most prominent in Italy, with around 100,000 students and over 3,000 professors in 2007.[108] It is host to the Botanical Garden of Naples, which was opened in 1807 by Joseph Bonaparte, using plans drawn up under the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV. The garden’s 15 hectares feature around 25,000 samples of over 10,000 species.[109]

Naples is also served by the «Second University» (today named University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli), a modern university which opened in 1989, and which has strong links to the nearby province of Caserta.[110] Another notable centre of education is the Istituto Universitario Orientale, which specialises in Eastern culture, and was founded by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ripa in 1732, after he returned from the court of Kangxi, the Emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty of China.[111]

Other prominent universities in Naples include the Parthenope University of Naples, the private Istituto Universitario Suor Orsola Benincasa, and the Jesuit Theological Seminary of Southern Italy.[112][113] The San Pietro a Maiella music conservatory is the city’s foremost institution of musical education; the earliest Neapolitan music conservatories were founded in the 16th century under the Spanish.[114] The Academy of Fine Arts located on the Via Santa Maria di Costantinopoli is the city’s foremost art school and one of the oldest in Italy.[115]

Naples hosts also the Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte, established in 1812 by the king Joachim Murat and the astronomer Federigo Zuccari,[116] the oldest marine zoological study station in the world, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, created in 1872 by German scientist Anton Dohrn, and the world’s oldest permanent volcano observatory, the Vesuvius Observatory, founded in 1841. The Observatory lies on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, near the city of Ercolano, and is now a permanent specialised institute of the Italian National Institute of Geophysics.

Politics[edit]

Palazzo delle Poste in Naples, Gino Franzi, 1936. The masterpiece of modernism, marble and diorite.

Governance[edit]

Each of the 7,904 comune in Italy is today represented locally by a city council headed by an elected mayor, known as a sindaco and informally called the first citizen (primo cittadino). This system, or one very similar to it, has been in place since the invasion of Italy by Napoleonic forces in 1808. When the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was restored, the system was kept in place with members of the nobility filling mayoral roles. By the end of the 19th century, party politics had begun to emerge; during the fascist era, each commune was represented by a podestà. Since World War II, the political landscape of Naples has been neither strongly right-wing nor left-wing – both Christian democrats and democratic socialists have governed the city at different times, with roughly equal frequency. Currently, the mayor of Naples is Gaetano Manfredi, an independent politician, former minister of university and research in the second Conte government, and former rector of the University of Naples Federico II.

Administrative subdivisions[edit]

| 1st municipality | – Chiaia, Posillipo, San Ferdinando |

| 2nd municipality | – Avvocata, Mercato, Montecalvario, Pendino, Porto, San Giuseppe |

| 3rd municipality | – San Carlo all’Arena, Stella |

| 4th municipality | – Poggioreale, San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Zona Industriale |

| 5th municipality | – Arenella, Vomero |

| 6th municipality | – Barra, Ponticelli, San Giovanni a Teduccio |

| 7th municipality | – Miano, San Pietro a Patierno, Secondigliano |

| 8th municipality | – Chiaiano, Marianella, Piscinola, Scampia |

| 9th municipality | – Pianura, Soccavo |

| 10th municipality | – Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta |

Economy[edit]

Naples, within its administrative limits, is Italy’s fourth-largest economy after Milan, Rome and Turin, and is the world’s 103rd-largest urban economy by purchasing power, with an estimated 2011 GDP of US$83.6 billion, equivalent to $28,749 per capita.

[117][118]

Naples is a major cargo terminal, and the port of Naples is one of the Mediterranean’s largest and busiest. The city has experienced significant economic growth since World War II, but joblessness remains a major problem,[119][120][121] and the city is characterised by high levels of political corruption and organised crime, as well as in other cities of the country.[68][69][failed verification]

Naples is a major national, and international tourist destination, one of Italy’s and Europe’s top tourist cities.[122] Tourists began visiting Naples in the 18th century during the Grand Tour.

In the last decades, there has been a move away from a traditional agriculture-based economy in the province of Naples to one based on service industries. The service sector employs the majority of Neapolitans, although more than half of these are small enterprises with fewer than 20 workers; about 70 companies are said to be medium-sized with more than 200 workers, and about 15 have more than 500 workers.

Tourism[edit]

Naples is, with Florence, Rome, Venice and Milan, one of the main Italian tourist destinations. With 3,700,000 visitors in 2018,[123] the city has completely emerged from the strong tourist depression of past decades (due primarily to the unilateral destination of an industrial city but also to the damage to image caused by the Italian media,[124][125] from the 1980 Irpinia earthquake and the waste crisis, in favor of the coastal centers of its metropolitan area).[126] To adequately assess the phenomenon, however, it must be considered that a large slice of tourists visit Naples per year, staying in the numerous localities in its surroundings,[127] connected to the city with both private and public direct lines.[128][129] Daily visits to Naples are carried out by various Roman tour operators and by all the main tourist resorts of Campania: as of 2019, Naples is the tenth most visited municipality in Italy and the first in the South.[130]

The sector is constantly growing[131][132] and the prospect of reaching the art cities of its level is once again expected in a relatively short time;[133] tourism is increasingly assuming a decisive weight for the city’s economy, which is why, exactly as happened for example in the case of Venice or Florence, the risk of gentrification of the historic center is now high.[134]

Transport[edit]

Naples is served by several major motorways (it: autostrade). The Autostrada A1, the longest motorway in Italy, links Naples to Milan.[137] The A3 runs southwards from Naples to Salerno, where the motorway to Reggio Calabria begins, while the A16 runs east to Canosa.[138] The A16 is nicknamed the autostrada dei Due Mari («Motorway of the Two Seas») because it connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea.[139]

Suburban rail services are provided by Trenitalia, Circumvesuviana, Ferrovia Cumana and Metronapoli.

The city’s main railway station is Napoli Centrale, which is located in Piazza Garibaldi; other significant stations include the Napoli Campi Flegrei[140] and Napoli Mergellina. Napoli Afragola serves high-speed trains that do not start or finish at Napoli Centrale. Naples’ streets are famously narrow (it was the first city in the world to set up a pedestrian one-way street),[141] so the general public commonly use compact hatchback cars and scooters for personal transit.[142] Since 2007 trains running at 300 km/h (186 mph) have connected Naples with Rome with a journey time of under an hour,[143] and direct high speed services also operate to Florence, Bologna, Milan, Turin and Salerno. Direct sleeper ‘boat train’ services operate nightly to cities in Sicily.

The port of Naples runs several ferry, hydrofoil, and SWATH catamaran lines to Capri, Ischia and Sorrento, Salerno, Positano and Amalfi.[144] Services are also available to Sicily, Sardinia, Ponza and the Aeolian Islands.[144] The port serves over 6 million local passengers annually,[145] plus a further 1 million international cruise ship passengers.[146] A regional hydrofoil transport service, the «Metropolitana del Mare», runs annually from July to September, maintained by a consortium of shipowners and local administrations.[147]

The Naples International Airport is located in the suburb of San Pietro a Patierno. It is the largest airport in southern Italy, with around 250 national and international flights arriving or departing daily.[148]

The average commute with public transit in Naples on a weekday is 77 minutes. Nineteen per cent of public transit commuters ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 27 minutes, while 56% of riders wait for over 20 minutes. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 7.1 km (4.4 mi), while 11% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[149]

Urban public transport[edit]

Naples has an extensive public transport network, including trams, buses and trolleybuses,[150] most of which are operated by the municipally owned company Azienda Napoletana Mobilità (ANM).

The city furthermore operates the Metropolitana di Napoli, the Naples Metro, an underground rapid transit railway system which integrates both surface railway lines and the city’s metro stations, many of which are noted for their decorative architecture and public art. In fact, the station of Via Toledo is often in the top spots of the rankings of the most beautiful metro stations in the world.[150]

There are also four funiculars in the city (operated by ANM): Centrale, Chiaia, Montesanto and Mergellina.[151] Four public elevators are in operation in the city: within the bridge of Chiaia, in via Acton, near the Sanità Bridge,[152] and in the Ventaglieri Park, accompanied by two public escalators.[153]

Culture[edit]

Art[edit]

A Romantic painting by Salvatore Fergola showing the 1839 inauguration of the Naples-Portici railway line

Naples has long been a centre of art and architecture, dotted with Medieval-, Baroque- and Renaissance-era churches, castles and palaces. A critical factor in the development of the Neapolitan school of painting was Caravaggio’s arrival in Naples in 1606. In the 18th century, Naples went through a period of neoclassicism, following the discovery of the remarkably intact Roman ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii.

The Neapolitan Academy of Fine Arts, founded by Charles III of Bourbon in 1752 as the Real Accademia di Disegno (en: Royal Academy of Design), was the centre of the artistic School of Posillipo in the 19th century. Artists such as Domenico Morelli, Giacomo Di Chirico, Francesco Saverio Altamura and Gioacchino Toma worked in Naples during this period, and many of their works are now exhibited in the academy’s art collection. The modern Academy offers courses in painting, decorating, sculpture, design, restoration, and urban planning. Naples is also known for its theatres, which are among the oldest in Europe: the Teatro di San Carlo opera house dates back to the 18th century.

Naples is also the home of the artistic tradition of Capodimonte porcelain. In 1743, Charles of Bourbon founded the Royal Factory of Capodimonte, many of whose artworks are now on display in the Museum of Capodimonte. Several of Naples’ mid-19th-century porcelain factories remain active today.

Cuisine[edit]

Naples is internationally famous for its cuisine and wine; it draws culinary influences from the numerous cultures which have inhabited it throughout its history, including the Greeks, Spanish and French. Neapolitan cuisine emerged as a distinct form in the 18th century. The ingredients are typically rich in taste while remaining affordable to the general populace.[154]

Naples is traditionally credited as the home of pizza.[155] This originated as a meal of the poor, but under Ferdinand IV it became popular among the upper classes: famously, the Margherita pizza was named after Queen Margherita of Savoy after her visit to the city.[155] Cooked traditionally in a wood-burning oven, the ingredients of Neapolitan pizza have been strictly regulated by law since 2004, and must include wheat flour type «00» with the addition of flour type «0» yeast, natural mineral water, peeled tomatoes or fresh cherry tomatoes, mozzarella, sea salt and extra virgin olive oil.[156]

Spaghetti is also associated with the city and is commonly eaten with clams vongole or lupini di mare: a popular Neapolitan folkloric symbol is the comic figure Pulcinella eating a plate of spaghetti.[157] Other dishes popular in Naples include Parmigiana di melanzane, spaghetti alle vongole and casatiello.[158] As a coastal city, Naples is furthermore known for numerous seafood dishes, including impepata di cozze (peppered mussels), purpetiello affogato (octopus poached in broth), alici marinate (marinated anchovies), baccalà alla napoletana (salt cod) and baccalà fritto (fried cod), a dish commonly eaten during the Christmas period.

Naples is well known for its sweet dishes, including colourful gelato, which is similar to ice cream, though more fruit-based. Popular Neapolitan pastry dishes include zeppole, babà, sfogliatelle and pastiera, the latter of which is prepared specially for Easter celebrations.[159] Another seasonal sweet is struffoli, a sweet-tasting honey dough decorated and eaten around Christmas.[160] Neapolitan coffee is also widely acclaimed. The traditional Neapolitan flip coffee pot, known as the cuccuma or cuccumella, was the basis for the invention of the espresso machine, and also inspired the Moka pot.

Wineries in the Vesuvius area produce wines such as the Lacryma Christi («tears of Christ») and Terzigno. Naples is also the home of limoncello, a popular lemon liqueur.[161][162]

Festivals[edit]

The cultural significance of Naples is often represented through a series of festivals held in the city. The following is a list of several festivals that take place in Naples (note: some festivals are not held on an annual basis).

An 1813 depiction of the Piedigrotta festival

- Festa di Piedigrotta («Piedigrotta Festival») – A musical event typically held in September in memory of the famous Madonna of Piedigrotta. Throughout the month, a series of musical workshops, concerts, religious events and children’s events are held to entertain the citizens of Naples and surrounding areas.[163]

- Pizzafest – As Naples is famous for being home to pizza, the city hosts an eleven-day festival dedicated to this iconic dish. This is a key event for Neapolitans and tourists alike, as various stations are open for tasting a wide range of true Neapolitan pizza. In addition to pizza tasting, a variety of entertainment shows are displayed.[164]

- Maggio dei Monumenti («May of Monuments») – A cultural event where the city hosts a variety of special events dedicated to the birth of King Charles of Bourbon. It festival features art and music of the 18th century, and many buildings which may normally be closed throughout the year are opened for visitors to view.[165]

- Il Ritorno della festa di San Gennaro («The Return of the Feast of San Gennaro») – An annual celebration and feast of faith held over three days, commemorating Saint Gennaro. Throughout the festival, parades, religious processions and musical entertainment are featured. An annual celebration is also held in «Little Italy» in Manhattan.[166][167]

Language[edit]

The Naples language, considered to be a distinct language and mainly spoken in the city, is also found in the region of Campania and has been diffused into other areas of Southern Italy by Neapolitan migrants, and in many different places in the world.

On 14 October 2008, a regional law was enacted by Campania which has the effect that the use of the Neapolitan language is protected.[168]

The term «Neapolitan language» is often used to describe the language of all of Campania (except Cilento), and is sometimes applied to the entire South Italian language; Ethnologue refers to the latter as Napoletano-Calabrese.[169] This linguistic group is spoken throughout most of southern continental Italy, including the Gaeta and Sora district of southern Lazio, the southern part of Marche and Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, northern Calabria, and northern and central Apulia. In 1976, there were an estimated 7,047,399 native speakers of this group of dialects.[169]

Literature and philosophy[edit]

Naples is one of the leading centres of Italian literature. The history of the Neapolitan language was deeply entwined with that of the Tuscan dialect, which then became the current Italian language. The first written testimonies of the Italian language are the Placiti Cassinensi legal documents, dated 960 A.D., preserved in the Monte Cassino Abbey, which are, in fact, evidence of a language spoken in a southern dialect. The Tuscan poet Boccaccio lived for many years at the court of King Robert the Wise and his successor Joanna of Naples, using Naples as a setting for The Decameron and a number of his later novels. His works contain some words that are taken from Neapolitan instead of the corresponding Italian, e.g. «testo» (neap.: «testa»), which in Naples indicates a large terracotta jar used to cultivate shrubs and little trees. King Alfonso V of Aragon stated in 1442 that the Neapolitan language was to be used instead of Latin in official documents.

Later Neapolitan was replaced by Italian in the first half of the 16th century,[170][171] during Spanish domination. In 1458 the Accademia Pontaniana, one of the first academies in Italy, was established in Naples as a free initiative by men of letters, science and literature. In 1480 the writer and poet Jacopo Sannazzaro wrote the first pastoral romance, Arcadia, which influenced Italian literature. In 1634 Giambattista Basile collected Lo Cunto de li Cunti five books of ancient tales written in the Neapolitan dialect rather than Italian. Philosopher Giordano Bruno, who theorised the existence of infinite solar systems and the infinity of the entire universe, completed his studies at the University of Naples. Due to philosophers such as Giambattista Vico, Naples became one of the centres of the Italian peninsula for historical and philosophy of history studies.

Jurisprudence studies were enhanced in Naples thanks to eminent personalities of jurists like Bernardo Tanucci, Gaetano Filangieri and Antonio Genovesi. In the 18th century Naples, together with Milan, became one of the most important sites from which the Enlightenment penetrated Italy. Poet and philosopher Giacomo Leopardi visited the city in 1837 and died there. His works influenced Francesco de Sanctis, who studied in Naples and eventually became Minister of Instruction during the Italian kingdom. De Sanctis was one of the first literary critics to discover, study and diffuse the poems and literary works of the great poet from Recanati.

Writer and journalist Matilde Serao co-founded the newspaper Il Mattino with her husband Edoardo Scarfoglio in 1892. Serao was an acclaimed novelist and writer during her day. Poet Salvatore Di Giacomo was one of the most famous writers in the Neapolitan dialect, and many of his poems were adapted to music, becoming famous Neapolitan songs. In the 20th century, philosophers like Benedetto Croce pursued the long tradition of philosophy studies in Naples, and personalities like jurists and lawyer Enrico De Nicola pursued legal and constitutional studies. De Nicola later helped to draft the modern Constitution of the Italian Republic and was eventually elected to the office of President of the Italian Republic. Other noted Neapolitan writers and journalists include Antonio De Curtis, Curzio Malaparte, Giancarlo Siani, Roberto Saviano and Elena Ferrante.[172]

Theatre[edit]

Naples was one of the centres of the peninsula from which originated the modern theatre genre as nowadays intended, evolving from 16th century «comedy of art».

The masked character of Pulcinella is a worldwide famous figure either as a theatrical character or puppetry character.

The music Opera genre of opera buffa was created in Naples in the 18th century and then spread to Rome and northern Italy. In the period of Belle Époque, Naples rivalled Paris for its Café-chantants, and many famous Neapolitan songs were originally created to entertain the public in the cafès of Naples. Perhaps the most well-known song is «Ninì Tirabusciò». The history of how this song was born was dramatised in the eponymous comedy movie «Ninì Tirabusciò: la donna che inventò la mossa» starring Monica Vitti.

The Neapolitan popular genre of «Sceneggiata» is an important genre of modern folk theatre worldwide, dramatising common canon themes of thwarted love stories, comedies, tearjerker stories, commonly about honest people becoming camorra outlaws due to unfortunate events. The Sceneggiata became very popular amongst Neapolitans and eventually one of the best-known genres of Italian cinematography thanks to actors and singers like Mario Merola and Nino D’Angelo. Many writers and playwrights, such as Raffaele Viviani, wrote comedies and dramas for this genre. Actors and comedians like Eduardo Scarpetta and then his sons Eduardo De Filippo, Peppino De Filippo and Titina De Filippo contributed to making the Neapolitan theatre. Its comedies and tragedies, such as «Filumena Marturano» and «Napoli Milionaria», are well-known.

Music[edit]

Naples has played an important role in the history of Western European art music for more than four centuries.[173] The first music conservatories were established in the city under Spanish rule in the 16th century. The San Pietro a Majella music conservatory, founded in 1826 by Francesco I of Bourbon, continues to operate today as both a prestigious centre of musical education and a musical museum.

During the late Baroque period, Alessandro Scarlatti, the father of Domenico Scarlatti, established the Neapolitan school of opera; this was in the form of opera seria, which was a new development for its time.[174] Another form of opera originating in Naples is opera buffa, a style of comic opera strongly linked to Battista Pergolesi and Piccinni; later contributors to the genre included Rossini and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[175] The Teatro di San Carlo, built in 1737, is the oldest working theatre in Europe, and remains the operatic centre of Naples.[176]

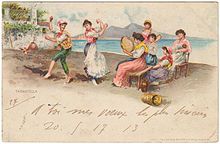

Tarantella in Napoli, a 1903 postcard

The earliest six-string guitar was created by the Neapolitan Gaetano Vinaccia in 1779; the instrument is now referred to as the romantic guitar. The Vinaccia family also developed the mandolin.[177][178] Influenced by the Spanish, Neapolitans became pioneers of classical guitar music, with Ferdinando Carulli and Mauro Giuliani being prominent exponents.[179] Giuliani, who was actually from Apulia but lived and worked in Naples, is widely considered to be one of the greatest guitar players and composers of the 19th century, along with his Catalan contemporary Fernando Sor.[180][181] Another Neapolitan musician of note was opera singer Enrico Caruso, one of the most prominent opera tenors of all time:[182] he was considered a man of the people in Naples, hailing from a working-class background.[183]

A popular traditional dance in Southern Italy and Naples is the Tarantella, which originated in Apulia and spread throughout the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Neapolitan tarantella is a courtship dance performed by couples whose «rhythms, melodies, gestures, and accompanying songs are quite distinct», featuring faster, more cheerful music.

A notable element of popular Neapolitan music is the Canzone Napoletana style, essentially the traditional music of the city, with a repertoire of hundreds of folk songs, some of which can be traced back to the 13th century.[184] The genre became a formal institution in 1835, after the introduction of the annual Festival of Piedigrotta songwriting competition.[184] Some of the best-known recording artists in this field include Roberto Murolo, Sergio Bruni and Renato Carosone.[185] There are furthermore various forms of music popular in Naples but not well known outside it, such as cantautore («singer-songwriter») and sceneggiata, which has been described as a musical soap opera; the most well-known exponent of this style is Mario Merola.[186]

Cinema and television[edit]

Totò, a famous Neapolitan actor

Naples has had a significant influence on Italian cinema. Because of the city’s relevance, many films and television shows are set (entirely or partially) in Naples. In addition to serving as the backdrop for several movies and shows, many talented celebrities (actors, actresses, directors, and producers) are originally from Naples.

Naples was the location for several early Italian cinema masterpieces. Assunta Spina (1915) was a silent film adapted from a theatrical drama by Neapolitan writer Salvatore Di Giacomo. The film was directed by Neapolitan Gustavo Serena. Serena also starred in the 1912 film Romeo and Juliet.[187][188][189]

A list of some well-known films that take place (fully or partially) in Naples includes:[190]

- Shoeshine (1946), directed by Neapolitan, Vittorio De Sica

- Hands over the City (1963), directed by Neapolitan, Francesco Rosi

- Journey to Italy (1954), directed by Roberto Rossellini

- Marriage Italian Style (1964), directed by Neapolitan, Vittorio De Sica

- It Started in Naples (1960), Directed by Melville Shavelson

- The Hand of God (film) (2021), Directed by Paolo Sorrentino

Naples is home to one of the first Italian colour films, Toto in Color (1952), starring Totò (Antonio de Curtis), a famous comedic actor born in Naples.[191]