Народный комиссариат внутренних дел — орган обеспечения революционного порядка Советской республики. Образован на II Всероссийском съезде Советов 8 ноября (21 октября) 1917 года. Позже созданы НКВД Украинской, Белорусской и Закавказской республик.

6 февраля 1922 года после упразднения ВЧК при НКВД РСФСР было создано Государственное политическое управление, которое 2 ноября 1923 года преобразовано в ОГПУ при СНК СССР. ГПУ выделяются из состава НКВД республик и подчиняются ОГПУ.

На НКВД РСФСР и НКВД других союзных республик возлагались следующие основные задачи:

руководство проведением в жизнь постановлений и распоряжений правительства по вопросам общего администрирования и обеспечения охраны революционного порядка и общественной безопасности;

руководство проведением в жизнь законов, регулирующих правовое положение иностранцев, проживающих в РСФСР, а также выдача гражданам РСФСР заграничных паспортов и наложение визы на выезд за пределы Союза ССР;

дача заключений по ходатайствам о приеме в гражданство РСФСР;

руководство проведением в жизнь законов, регулирующих организационную деятельность обществ и союзов, и наблюдение за законностью их деятельности;

руководство осуществлением законов по отделению церкви от государства в части административных мероприятий;

руководство деятельностью органов по регистрации актов гражданского состояния и учету населения;

надзор за правильностью и целесообразностью издания местными органами власти обязательных постановлений и правильным наложением административных взысканий за их нарушение;

вынесение через СНК и Президиум ВЦИК, в предусмотренных законом случаях, представлений о введении в отдельных местностях чрезвычайных мер охраны революционного порядка;

установление правил и наблюдение за проведением мероприятий по ликвидации стихийных бедствий;

организации мест заключения и управление ими;

надзор и контроль пожарным делом в РСФСР и ряд других задач.

15 декабря 1930 года НКВД и РСФСР и других союзных республик были упразднены, а их функции переданы различным ведомствам.

10 июля 1934 года был образован НКВД СССР с включением в его состав ОГПУ, переименованного в Главное управление государственной безопасности (ГУГБ). На НКВД СССР возлагались задачи по обеспечению государственной и общественной безопасности Советского Союза. Кроме ГУГБ, в НКВД входили: Управление делами, Административно-хозяйственное управление, Главное управление рабоче-крестьянской милиции, Главное управление ИТЛ и трудовых поселений, Главное управление пограничной и внутренней охраны, Главное управление пожарной охраны и отдел актов гражданского состояния.

В союзных республиках (за исключением РСФСР) были созваны НКВД республик. Обеспеченней государственной и общественной безопасности на территории РСФСР занимался непосредственно НКВД СССР.

3 февраля 1941 года НКВД СССР был разделен на НКВД СССР и НКГБ СССР. 20 июля 1941 года НКВД и НКГБ были объединены в единый НКВД СССР.

В апреле 1943 года из состава НКВД СССР вновь выделен НКГБ СССР. Тогда же из НКВД было выделено Управление особых отделов и на его базе созданы Главное управление контрразведки НКО СССР «Смерш» и Управление контрразведки НКВМФ СССР «Смерш».

В марте 1946 года НКВД СССР переименован о МВД СССР, а НКГБ СССР в МГБ СССР. В марте 1953 года органы МВД и МГБ были объединены в один орган — МВД СССР. В марте 1954 года органы государственной безопасности были переданы вновь созданному Комитету государственной безопасности при Совете Министров СССР.

13 января 1960 года Министерство внутренних дел СССР было упразднено, а в союзных республиках образованы министерства охраны общественного порядка (МООП).

26 июля 1966 года на базе МООП РСФСР создано союзно-республиканское Министерство охраны общественного порядка СССР, которое 25 ноября 1968 года вновь переименовано в Министерство внутренних дел СССР.

Контрразведывательный словарь. — Высшая краснознаменная школа Комитета Государственной Безопасности при Совете Министров СССР им. Ф. Э. Дзержинского.

1972.

| Народный комиссариат внутренних дел Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh dyél |

|

NKVD emblem |

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 10 July 1934; 88 years ago |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Dissolved | 15 March 1946; 76 years ago |

| Superseding agencies |

|

| Type |

• Law enforcement |

| Jurisdiction | Soviet Union |

| Headquarters | 11-13 ulitsa Bol. Lubyanka, Moscow, RSFSR, Soviet Union |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Council of the People’s Commissars |

| Child agencies |

|

The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, romanized: Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, pronounced [nɐˈrod.nɨj kə.mʲɪ.sə.rʲɪˈat ˈvnut.rʲɪ.nʲɪx̬ dʲel]), abbreviated NKVD (НКВД listen (help·info)), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

Established in 1917 as NKVD of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic,[1] the agency was originally tasked with conducting regular police work and overseeing the country’s prisons and labor camps.[2] It was disbanded in 1930, with its functions being dispersed among other agencies, only to be reinstated as an all-union commissariat in 1934.[3]

The functions of the OGPU (the secret police organization) were transferred to the NKVD around the year 1930, giving it a monopoly over law enforcement activities that lasted until the end of World War II.[2] During this period, the NKVD included both ordinary public order activities, and secret police activities.[4] The NKVD is known for its role in political repression and for carrying out the Great Purge under Joseph Stalin. It was led by Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov, and Lavrentiy Beria.[5][6][7]

The NKVD undertook mass extrajudicial executions of citizens, and conceived, populated and administered the Gulag system of forced labour camps. Their agents were responsible for the repression of the wealthier peasantry.[8][9] They oversaw the protection of Soviet borders and espionage (which included carrying out political assassinations), and enforced Soviet policy in communist movements and puppet governments in other countries,[10] most notably the repression and massacres in Poland in 1937 and 1938 to crush opposition and establish political control.[11]

In March 1946 all People’s Commissariats were renamed to Ministries. The NKVD became the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD).[12]

History and structure[edit]

After the Russian February Revolution of 1917, the Provisional Government dissolved the Tsarist police and set up the People’s Militsiya. The subsequent Russian October Revolution of 1917 saw a seizure of state power led by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who established a new Bolshevik regime, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). The Provisional Government’s Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), formerly under Georgy Lvov (from March 1917) and then under Nikolai Avksentiev (from 6 August [O.S. 24 July] 1917) and Alexei Nikitin (from 8 October [O.S. 25 September] 1917), turned into NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) under a People’s Commissar. However, the NKVD apparatus was overwhelmed by duties inherited from MVD, such as the supervision of the local governments and firefighting, and the Workers’ and Peasants’ Militsiya staffed by proletarians was largely inexperienced and unqualified. Realizing that it was left with no capable security force, the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR established (20 December [O.S. 7 December] 1917) a secret political police, the Cheka, led by Felix Dzerzhinsky. It gained the right to undertake quick non-judicial trials and executions, if that was deemed necessary in order to «protect the Russian Socialist-Communist revolution».

The Cheka was reorganized in 1922 as the State Political Directorate, or GPU, of the NKVD of the RSFSR.[13] In 1922 the USSR formed, with the RSFSR as its largest member. The GPU became the OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate), under the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR. The NKVD of the RSFSR retained control of the militsiya, and various other responsibilities.

In 1934 the NKVD of the RSFSR was transformed into an all-union security force, the NKVD (which the Communist Party of the Soviet Union leaders soon came to call «the leading detachment of our party»), and the OGPU was incorporated into the NKVD as the Main Directorate for State Security (GUGB); the separate NKVD of the RSFSR was not resurrected until 1946 (as the MVD of the RSFSR). As a result, the NKVD also took over control of all detention facilities (including the forced labor camps, known as the GULag) as well as the regular police. At various times, the NKVD had the following Chief Directorates, abbreviated as «ГУ»– Главное управление, Glavnoye upravleniye.

| Chronology of Soviet security agencies |

|

|

|

|

| 1917–22 | Cheka under SNK of the RSFSR (All-Russian Extraordinary Commission) |

| 1922–23 | GPU under NKVD of the RSFSR (State Political Directorate) |

| 1920–91 | PGU KGB or INO under Cheka (later KGB) of the USSR (First Chief Directorate) |

| 1923–34 | OGPU under SNK of the USSR (Joint State Political Directorate) |

| 1934–46 | NKVD of the USSR (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) |

| 1934–41 | GUGB of the NKVD of the USSR (Main Directorate of State Security of People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) |

| 1941 | NKGB of the USSR (People’s Commissariat of State Security) |

| 1943–46 | NKGB of the USSR (People’s Commissariat for State Security) |

| 1946–53 | MGB of the USSR (Ministry of State Security) |

| 1946–54 | MVD of the USSR (Ministry of Internal Affairs) |

| 1947–51 |

KI MID of the USSR |

| 1954–78 | KGB under the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (Committee for State Security) |

| 1978–91 | KGB of the USSR (Committee for State Security) |

| 1991 | MSB of the USSR (Interrepublican Security Service) |

| 1991 | TsSB of the USSR (Central Intelligence Service) |

| 1991 | KOGG of the USSR (Committee for the Protection of the State Border) |

|

- ГУГБ – государственной безопасности, of State Security (GUGB, Glavnoye upravleniye gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti)

- ГУРКМ– рабоче-крестьянской милиции, of Workers and Peasants Militsiya (GURKM, Glavnoye upravleniye raboče-krest’yanskoi militsyi)

- ГУПВО– пограничной и внутренней охраны, of Border and Internal Guards (GUPVO, GU pograničnoi i vnytrennei okhrany)

- ГУПО– пожарной охраны, of Firefighting Services (GUPO, GU požarnoi okhrany)

- ГУШосДор– шоссейных дорог, of Highways (GUŠD, GU šosseynykh dorog)

- ГУЖД– железных дорог, of Railways (GUŽD, GU železnykh dorog)

- ГУЛаг– Главное управление исправительно-трудовых лагерей и колоний, (GULag, Glavnoye upravleniye ispravitelno-trudovykh lagerey i kolonii)

- ГЭУ – экономическое, of Economics (GEU, Glavnoye ekonomičeskoie upravleniye)

- ГТУ – транспортное, of Transport (GTU, Glavnoye transportnoie upravleniye)

- ГУВПИ – военнопленных и интернированных, of POWs and interned persons (GUVPI, Glavnoye upravleniye voyennoplennikh i internirovannikh)

Yezhov era[edit]

Until the reorganization begun by Nikolai Yezhov with a purge of the regional political police in the autumn of 1936 and formalized by a May 1939 directive of the All-Union NKVD by which all appointments to the local political police were controlled from the center, there was frequent tension between centralized control of local units and the collusion of those units with local and regional party elements, frequently resulting in the thwarting of Moscow’s plans.[14]

During Yezhov’s time in office, the Great Purge reached its height. In the years 1937 and 1938 alone, at least 1.3 million were arrested and 681,692 were executed for ‘crimes against the state’. The Gulag population swelled by 685,201 under Yezhov, nearly tripling in size in just two years, with at least 140,000 of these prisoners (and likely many more) dying of malnutrition, exhaustion and the elements in the camps (or during transport to them).[15]

On 3 February 1941, the 4th Department (Special Section, OO) of GUGB NKVD security service responsible for the Soviet Armed Forces military counter-intelligence,[16] consisting of 12 Sections and one Investigation Unit, was separated from GUGB NKVD USSR.

The official liquidation of OO GUGB within NKVD was announced on 12 February by a joint order No. 00151/003 of NKVD and NKGB USSR. The rest of GUGB was abolished and staff was moved to newly created People’s Commissariat for State Security (NKGB). Departments of former GUGB were renamed Directorates. For example, foreign intelligence unit known as Foreign Department (INO) became Foreign Directorate (INU); GUGB political police unit represented by Secret Political Department (SPO) became Secret Political Directorate (SPU), and so on. The former GUGB 4th Department (OO) was split into three sections. One section, which handled military counter-intelligence in NKVD troops (former 11th Section of GUGB 4th Department OO) become 3rd NKVD Department or OKR (Otdel KontrRazvedki), the chief of OKR NKVD was Aleksander Belyanov.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union (June 1941), the NKGB USSR was abolished and on July 20, 1941, the units that formed NKGB became part of the NKVD. The military CI was also upgraded from a department to a directorate and put in NKVD organization as the (Directorate of Special Departments or UOO NKVD USSR). The NKVMF, however, did not return to the NKVD until January 11, 1942. It returned to NKVD control on January 11, 1942, as UOO 9th Department controlled by P. Gladkov. In April 1943, Directorates of Special Departments was transformed into SMERSH and transferred to the People’s Defense and Commissariates. At the same time, the NKVD was reduced in size and duties again by converting the GUGB to an independent unit named the NKGB.

In 1946, all Soviet Commissariats were renamed «ministries». Accordingly, the Peoples Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) of the USSR became the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), while the NKGB was renamed as the Ministry of State Security (MGB).

In 1953, after the arrest of Lavrenty Beria, the MGB merged back into the MVD. The police and security services finally split in 1954 to become:

- The USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), responsible for the criminal militia and correctional facilities.

- The USSR Committee for State Security (KGB), responsible for the political police, intelligence, counter-intelligence, personal protection (of the leadership) and confidential communications.

Main Directorates (Departments)[edit]

- State Security

- Workers-Peasants Militsiya

- Border and Internal Security

- Firefighting security

- Correction and Labor camps

- Other smaller departments

- Department of Civil registration

- Financial (FINO)

- Administration

- Human resources

- Secretariat

- Special assignment

Ranking system (State Security)[edit]

In 1935–1945 Main Directorate of State Security of NKVD had its own ranking system before it was merged in the Soviet military standardized ranking system.

- Top-level commanding staff

- Commissioner General of State Security (later in 1935)

- Commissioner of State Security 1st Class

- Commissioner of State Security 2nd Class

- Commissioner of State Security 3rd Class

- Commissioner of State Security (Senior Major of State Security, before 1943)

- Senior commanding staff

- Colonel of State Security (Major of State Security, before 1943)

- Lieutenant Colonel of State Security (Captain of State Security, before 1943)

- Major of State Security (Senior Lieutenant of State Security, before 1943)

- Mid-level commanding staff

- Captain of State Security (Lieutenant of State Security, before 1943)

- Senior Lieutenant of State Security (Junior Lieutenant of State Security, before 1943)

- Lieutenant of State Security (Sergeant of State Security, before 1942)

- Junior Lieutenant of State Security (Sergeant of State Security, before 1942)

- Junior commanding staff

- Master Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

- Senior Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

- Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

- Junior Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

NKVD activities[edit]

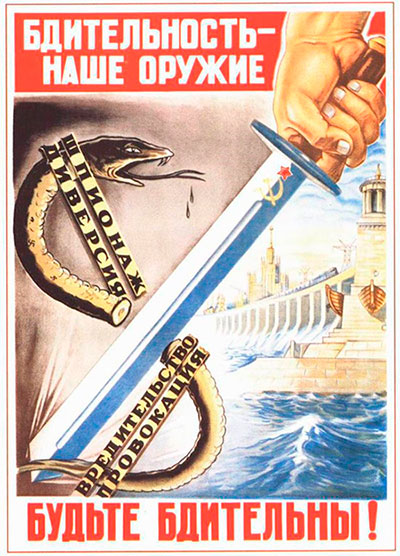

The main function of the NKVD was to protect the state security of the Soviet Union. This role was accomplished through massive political repression, including authorised murders of many thousands of politicians and citizens, as well as kidnappings, assassinations and mass deportations.

Domestic repressions[edit]

In implementing Soviet internal policy towards perceived enemies of the Soviet state («enemies of the people»), untold multitudes of people were sent to GULAG camps and hundreds of thousands were executed by the NKVD. Formally, most of these people were convicted by NKVD troikas («triplets»)– special courts martial. Evidential standards were very low: a tip-off by an anonymous informer was considered sufficient grounds for arrest. Use of «physical means of persuasion» (torture) was sanctioned by a special decree of the state, which opened the door to numerous abuses, documented in recollections of victims and members of the NKVD itself. Hundreds of mass graves resulting from such operations were later discovered throughout the country. Documented evidence exists that the NKVD committed mass extrajudicial executions, guided by secret «plans». Those plans established the number and proportion of victims (officially «public enemies») in a given region (e.g. the quotas for clergy, former nobles etc., regardless of identity). The families of the repressed, including children, were also automatically repressed according to NKVD Order no. 00486.

The purges were organized in a number of waves according to the decisions of the Politburo of the Communist Party. Some examples are the campaigns among engineers (Shakhty Trial), party and military elite plots (Great Purge with Order 00447), and medical staff («Doctors’ Plot»). Gas vans were used in the Soviet Union during the Great Purge in the cities of Moscow, Ivanovo and Omsk[17][18][19][20]

A number of mass operations of the NKVD were related to the persecution of whole ethnic categories. For example, the Polish Operation of the NKVD in 1937–1938 resulted in the execution of 111,091 Poles.[21] Whole populations of certain ethnicities were forcibly resettled. Foreigners living in the Soviet Union were given particular attention. When disillusioned American citizens living in the Soviet Union thronged the gates of the U.S. embassy in Moscow to plead for new U.S. passports to leave the USSR (their original U.S. passports had been taken for ‘registration’ purposes years before), none were issued. Instead, the NKVD promptly arrested all the Americans, who were taken to Lubyanka Prison and later shot.[22] American factory workers at the Soviet Ford GAZ plant, suspected by Stalin of being ‘poisoned’ by Western influences, were dragged off with the others to Lubyanka by the NKVD in the very same Ford Model A cars they had helped build, where they were tortured; nearly all were executed or died in labor camps. Many of the slain Americans were dumped in the mass grave at Yuzhnoye Butovo District near Moscow.[23] Even so, the people of the Soviet Republics still formed the majority of NKVD victims.

The NKVD also served as arm of the Russian Soviet communist government for the lethal mass persecution and destruction of ethnic minorities and religious beliefs, such as the Russian Orthodox Church, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Greek Catholics, Islam, Judaism and other religious organizations, an operation headed by Yevgeny Tuchkov.

International operations[edit]

During the 1930s, the NKVD was responsible for political murders of those Stalin believed to oppose him. Espionage networks headed by experienced multilingual NKVD officers such as Pavel Sudoplatov and Iskhak Akhmerov were established in nearly every major Western country, including the United States. The NKVD recruited agents for its espionage efforts from all walks of life, from unemployed intellectuals such as Mark Zborowski to aristocrats such as Martha Dodd. Besides the gathering of intelligence, these networks provided organizational assistance for so-called wet business,[24] where enemies of the USSR either disappeared or were openly liquidated.[25]

The NKVD’s intelligence and special operations (Inostranny Otdel) unit organized overseas assassinations of political enemies of the USSR, such as leaders of nationalist movements, former Tsarist officials, and personal rivals of Joseph Stalin. Among the officially confirmed victims of such plots were:

- Leon Trotsky, a personal political enemy of Stalin and his most bitter international critic, killed in Mexico City in 1940;

- Yevhen Konovalets, prominent Ukrainian nationalist leader who was attempting to create a separatist movement in Soviet Ukraine; assassinated in Rotterdam, Netherlands

- Yevgeny Miller, former General of the Tsarist (Imperial Russian) Army; in the 1930s, he was responsible for funding anti-communist movements inside the USSR with the support of European governments. Kidnapped in Paris and brought to Moscow, where he was interrogated and executed

- Noe Ramishvili, Prime Minister of independent Georgia, fled to France after the Bolshevik takeover; responsible for funding and coordinating Georgian nationalist organizations and the August uprising, he was assassinated in Paris

- Boris Savinkov, Russian revolutionary and anti-Bolshevik terrorist (lured back into Russia and allegedly killed in 1924 by the Trust Operation of the GPU);

- Sidney Reilly, British agent of the MI6 who deliberately entered Russia in 1925 trying to expose the Trust Operation to avenge Savinkov’s death;

- Alexander Kutepov, former General of the Tsarist (Imperial Russian) Army, who was active in organizing anti-communist groups with the support of French and British governments

Prominent political dissidents were also found dead under highly suspicious circumstances, including Walter Krivitsky, Lev Sedov, Ignace Reiss and former German Communist Party (KPD) member Willi Münzenberg.[26][27][28][29][30]

The pro-Soviet leader Sheng Shicai in Xinjiang received NKVD assistance in conducting a purge to coincide with Stalin’s Great Purge in 1937. Sheng and the Soviets alleged a massive Trotskyist conspiracy and a «Fascist Trotskyite plot» to destroy the Soviet Union. The Soviet Consul General Garegin Apresoff, General Ma Hushan, Ma Shaowu, Mahmud Sijan, the official leader of the Xinjiang province Huang Han-chang and Hoja-Niyaz were among the 435 alleged conspirators in the plot. Xinjiang came under soviet influence.[31]

Spanish Civil War[edit]

During the Spanish Civil War, the NKVD ran Section X coordinating the Soviet intervention on behalf of the Spanish Republicans.[32] NKVD agents, acting in conjunction with the Communist Party of Spain, exercised substantial control over the Republican government, using Soviet military aid to help further Soviet influence.[33] The NKVD established numerous secret prisons around the capital Madrid, which were used to detain, torture, and kill hundreds of the NKVD’s enemies, at first focusing on Spanish Nationalists and Spanish Catholics, while from late 1938 increasingly anarchists and Trotskyists were the objects of persecution.[34] In 1937 Andrés Nin, the secretary of the Trotskyist POUM and his colleagues were tortured and killed in an NKVD prison in Alcalá de Henares.[35]

World War II operations[edit]

Prior to the German invasion, in order to accomplish its own goals, the NKVD was prepared to cooperate even with such organizations as the German Gestapo. In March 1940, representatives of the NKVD and the Gestapo met for one week in Zakopane, to coordinate the pacification of Poland; see Gestapo–NKVD conferences. For its part, the Soviet Union delivered hundreds of German and Austrian Communists to the Gestapo, as unwanted foreigners, together with their documents. However, many NKVD units were later to fight the Wehrmacht, for example the 10th NKVD Rifle Division, which fought at the Battle of Stalingrad.

After the German invasion, the NKVD evacuated and killed prisoners. During World War II, NKVD Internal Troops units were used for rear area security, including preventing the retreat of Soviet Union army divisions. Though mainly intended for internal security, NKVD divisions were sometimes used at the front to stem the occurrence of desertion through Stalin’s Order No. 270 and Order No. 227 decrees in 1941 and 1942, which aimed to raise troop morale via brutality and coercion. At the beginning of the war the NKVD formed 15 rifle divisions, which had expanded by 1945 to 53 divisions and 28 brigades.[36] A list of identified NKVD Internal Troops divisions can be seen at List of Soviet Union divisions 1917-1945. Though mainly intended for internal security, NKVD divisions were sometimes used in the front-lines, for example during the Battle of Stalingrad and the Crimean offensive.[36] Unlike the Waffen-SS, the NKVD did not field any armored or mechanized units.[36]

In the enemy-held territories, the NKVD carried out numerous missions of sabotage. After fall of Kyiv, NKVD agents set fire to the Nazi headquarters and various other targets, eventually burning down much of the city center.[37] Similar actions took place across the occupied Byelorussia and Ukraine.

The NKVD (later KGB) carried out mass arrests, deportations, and executions. The targets included both collaborators with Germany and non-Communist resistance movements such as the Polish Home Army and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army aiming to separate from the Soviet Union, among others. The NKVD also executed tens of thousands of Polish political prisoners in 1940–1941, including the Katyń massacre.[38][39] On 26 November 2010, the Russian State Duma issued a declaration acknowledging Stalin’s responsibility for the Katyn massacre, the execution of 22,000 Polish POW’s and intellectual leaders by Stalin’s NKVD. The declaration stated that archival material «not only unveils the scale of his horrific tragedy but also provides evidence that the Katyn crime was committed on direct orders from Stalin and other Soviet leaders.»[40]

NKVD units were also used to repress the prolonged partisan war in Ukraine and the Baltics, which lasted until the early 1950s. NKVD also faced strong opposition in Poland from the

Polish resistance known as the Armia Krajowa.

Postwar operations[edit]

After the death of Stalin in 1953, the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev halted the NKVD purges. From the 1950s to the 1980s, thousands of victims were legally «rehabilitated» (i.e., acquitted and had their rights restored). Many of the victims and their relatives refused to apply for rehabilitation out of fear or lack of documents. The rehabilitation was not complete: in most cases the formulation was «due to lack of evidence of the case of crime». Only a limited number of persons were rehabilitated with the formulation «cleared of all charges».

Very few NKVD agents were ever officially convicted of the particular violation of anyone’s rights. Legally, those agents executed in the 1930s were also «purged» without legitimate criminal investigations and court decisions. In the 1990s and 2000s (decade) a small number of ex-NKVD agents living in the Baltic states were convicted of crimes against the local population.

Intelligence activities[edit]

These included:

- Establishment of a widespread spy network through the Comintern.

- Operations of Richard Sorge, the «Red Orchestra», Willi Lehmann, and other agents who provided valuable intelligence during World War II.

- Recruitment of important UK officials as agents in the 1940s.

- Penetration of British intelligence (MI6) and counter-intelligence (MI5) services.

- Collection of detailed nuclear weapons design information from the U.S. and Britain during the Manhattan Project.

- Disruption of several confirmed plots to assassinate Stalin.

- Establishment of the People’s Republic of Poland and earlier its communist party along with training activists, during World War II. The first President of Poland after the war was Bolesław Bierut, an NKVD agent.

Soviet economy[edit]

The extensive system of labor exploitation in the Gulag made a notable contribution to the Soviet economy and the development of remote areas. Colonization of Siberia, the North and Far East was among the explicitly stated goals in the very first laws concerning Soviet labor camps. Mining, construction works (roads, railways, canals, dams, and factories), logging, and other functions of the labor camps were part of the Soviet planned economy, and the NKVD had its own production plans.[citation needed]

The most unusual part of the NKVD’s achievements was its role in Soviet science and arms development. Many scientists and engineers arrested for political crimes were placed in special prisons, much more comfortable than the Gulag, colloquially known as sharashkas. These prisoners continued their work in these prisons, and later released, some of them became world leaders in science and technology. Among such sharashka members were Sergey Korolev, the head designer of the Soviet rocket program and first human space flight mission in 1961, and Andrei Tupolev, the famous airplane designer. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was also imprisoned in a sharashka, and based his novel The First Circle on his experiences there.

After World War II, the NKVD coordinated work on Soviet nuclear weaponry, under the direction of General Pavel Sudoplatov. The scientists were not prisoners, but the project was supervised by the NKVD because of its great importance and the corresponding requirement for absolute security and secrecy. Also, the project used information obtained by the NKVD from the United States.

People’s Commissars[edit]

The agency was headed by a people’s commissar (minister). His first deputy was the director of State Security Service (GUGB).

- 1934–1936 Genrikh Yagoda, both people’s commissar of Interior and director of State Security

- 1936–1938 Nikolai Yezhov, people’s commissar of Interior

- 1936–1937 Yakov Agranov, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1937–1938 Mikhail Frinovsky, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1938 Lavrentiy Beria, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1938–1945 Lavrentiy Beria, people’s commissar of Interior

- 1938–1941 Vsevolod Merkulov, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1941–1943 Vsevolod Merkulov, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1945–1946 Sergei Kruglov, people’s commissar of Interior

Note: In the first half of 1941 Vsevolod Merkulov transformed his agency into separate commissariat (ministry), but it was merged back to the people’s commissariat of Interior soon after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. In 1943 Merkulov once again split his agency this time for good.

Officers[edit]

Andrei Zhukov has singlehandedly identified every single NKVD officer involved in 1930s arrests and killings by researching a Moscow archive. There are just over 40,000 names on the list.[41]

See also[edit]

- Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Terror, famine and the Gulag

- Poison laboratory of the Soviet secret services

- 10th NKVD Rifle Division

- Hitler Youth conspiracy, an NKVD case pursued in 1938

- NKVD filtration camp

- NKVD special camps in Germany 1945–49, internment camps set up at the end of World War II in eastern Germany (often in former Nazi POW or concentration camps) and other areas under Soviet domination, to imprison those suspected of collaboration with the Nazis, or others deemed to be troublesome to Soviet ambitions.

References[edit]

- ^ Semukhina, Olga B.; Reynolds, Kenneth Michael (2013). Understanding the Modern Russian Police. CRC Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4822-1887-9.

- ^ a b Huskey, Eugene (2014). Russian Lawyers and the Soviet State: The Origins and Development of the Soviet Bar, 1917-1939. Princeton University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4008-5451-6.

- ^ Semukhina, Olga B.; Reynolds, Kenneth Michael (2013). Understanding the Modern Russian Police. CRC Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4398-0349-3.

- ^ Khlevniuk, Oleg V. (2015). Stalin: New Biography of a Dictator. Yale University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-300-16694-1.

- ^ Yevgenia Albats, KGB: The State Within a State. 1995, page 101

- ^ Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf, 2007 ISBN 978-1-4000-4005-6 p. 460

- ^ Catherine Merridale. Night of Stone: Death and Memory in Twentieth-Century Russia. Penguin Books, 2002 ISBN 978-0-14-200063-2 p. 200

- ^ Viola, Lynne (207). The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin’s Special Settlements. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2003). Gulag: A History. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ McDermott, Kevin (1995). «Stalinist Terror in the Comintern: New Perspectives». Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (1): 111–130. doi:10.1177/002200949503000105. JSTOR 260924. S2CID 161318303.

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956. New York: Random House.

- ^ Statiev, Alexander (2010). The Soviet Counterinsurgency in the Western Borderlands. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76833-7.

- ^ Blank Pages by G.C.Malcher ISBN 978-1-897984-00-0 Page 7

- ^

James Harris, «Dual subordination ? The political police and the party in the Urals region, 1918–1953», Cahiers du monde russe 22 (2001):423–446. - ^ Figes, Orlando (2007) The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin’s Russia ISBN 978-0-8050-7461-1, page 234.

- ^ GUGB NKVD. Archived 2020-10-08 at the Wayback Machine DocumentsTalk.com, 2008.

- ^ Человек в кожаном фартуке. Новая газета — Novayagazeta.ru (in Russian). 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- ^ Timothy J. Colton. Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis. Belknap Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-674-58749-6 p. 286

- ^ Газовые душегубки: сделано в СССР (Gas vans: made in the USSR) Archived August 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine by Dmitry Sokolov, Echo of Crimea, 09.10.2012

- ^ Григоренко П.Г. В подполье можно встретить только крыс… (Petro Grigorenko, «In the underground one can meet only rats») — Нью-Йорк, Издательство «Детинец», 1981, page 403, Full text of the book (Russian)

- ^ Goldman, Wendy Z. (2011). Inventing the Enemy: Denunciation and Terror in Stalin’s Russia. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19196-8. p. 217.

- ^ Tzouliadis, Tim, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia Penguin Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4: Many of the Americans desiring to return home were communists who had voluntarily moved to the Soviet Union, while others moved to Soviet Union as skilled auto workers to help produce cars at the recently constructed GAZ automobile factory built by the Ford Motor Company. All were U.S. citizens.

- ^ Tzouliadis, Tim, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia Penguin Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4

- ^ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G.P. Putnam (1945), p. 18: NKVD expression for a political murder

- ^ John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999)

- ^ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G.P. Putnam (1945), pp. 232–233

- ^ Orlov, Alexander, The March of Time, St. Ermin’s Press (2004), ISBN 978-1-903608-05-0

- ^ Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin, Vasili, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Basic Books (2000), ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9, ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9, p. 75

- ^ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G. P. Putnam (1945), pp. 17, 22

- ^ Sean McMeekin, The Red Millionaire: A Political Biography of Willi Münzenberg, Moscow’s Secret Propaganda Tsar in the West, 1917–1940, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press (2004), pp. 304–305

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ^ «4. The Spanish Civil War (1936– 1939)», Secret Wars, Princeton University Press, p. 115, 2018-12-31, doi:10.1515/9780691184241-005, ISBN 978-0-691-18424-1, S2CID 227568935, retrieved 2022-02-07

- ^ Robert W. Pringle (2015). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 288–89. ISBN 978-1-4422-5318-6.

- ^ Christopher Andrew (2000). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9.

- ^ David Clay Large (1991). Between Two Fires: Europe’s Path in the 1930s. W.W. Norton. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-393-30757-3.

- ^ a b c Zaloga, Steven J. The Red Army of the Great Patriotic War, 1941–45, Osprey Publishing, (1989), pp. 21–22

- ^ Birstein, Vadim (2013). Smersh: Stalin’s Secret Weapon. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84954-689-8. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Sanford, George (2007-05-07). Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice and Memory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-30299-4.

- ^ «Lviv museum recounts Soviet massacres | Центр досліджень визвольного руху». 2019-01-15. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Barry, Ellen (26 November 2010). «Russia: Stalin Called Responsible for Katyn Killings». The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (6 February 2017). «Stalin’s secret police finally named but killings still not seen as crimes». The Guardian.

Further reading[edit]

See also: Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Violence and terror and Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Terror, famine and the Gulag

- Hastings, Max (2015). The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939 -1945 (paperback). London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-750374-2.

External links[edit]

Media related to NKVD at Wikimedia Commons

- For evidence on Soviet espionage in the United States during the Cold War, see the full text of Alexander Vassiliev’s Notebooks from the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP)

- NKVD.org: information site about the NKVD

- (in Russian) MVD: 200-year history of the Ministry

- (in Russian) Memorial: history of the OGPU/NKVD/MGB/KGB Archived 2016-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

Coordinates: 55°45′38″N 37°37′41″E / 55.7606°N 37.6281°E

| Народный комиссариат внутренних дел Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh dyél |

|

NKVD emblem |

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 10 July 1934; 88 years ago |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Dissolved | 15 March 1946; 76 years ago |

| Superseding agencies |

|

| Type |

• Law enforcement |

| Jurisdiction | Soviet Union |

| Headquarters | 11-13 ulitsa Bol. Lubyanka, Moscow, RSFSR, Soviet Union |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Council of the People’s Commissars |

| Child agencies |

|

The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, romanized: Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, pronounced [nɐˈrod.nɨj kə.mʲɪ.sə.rʲɪˈat ˈvnut.rʲɪ.nʲɪx̬ dʲel]), abbreviated NKVD (НКВД listen (help·info)), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

Established in 1917 as NKVD of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic,[1] the agency was originally tasked with conducting regular police work and overseeing the country’s prisons and labor camps.[2] It was disbanded in 1930, with its functions being dispersed among other agencies, only to be reinstated as an all-union commissariat in 1934.[3]

The functions of the OGPU (the secret police organization) were transferred to the NKVD around the year 1930, giving it a monopoly over law enforcement activities that lasted until the end of World War II.[2] During this period, the NKVD included both ordinary public order activities, and secret police activities.[4] The NKVD is known for its role in political repression and for carrying out the Great Purge under Joseph Stalin. It was led by Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov, and Lavrentiy Beria.[5][6][7]

The NKVD undertook mass extrajudicial executions of citizens, and conceived, populated and administered the Gulag system of forced labour camps. Their agents were responsible for the repression of the wealthier peasantry.[8][9] They oversaw the protection of Soviet borders and espionage (which included carrying out political assassinations), and enforced Soviet policy in communist movements and puppet governments in other countries,[10] most notably the repression and massacres in Poland in 1937 and 1938 to crush opposition and establish political control.[11]

In March 1946 all People’s Commissariats were renamed to Ministries. The NKVD became the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD).[12]

History and structure[edit]

After the Russian February Revolution of 1917, the Provisional Government dissolved the Tsarist police and set up the People’s Militsiya. The subsequent Russian October Revolution of 1917 saw a seizure of state power led by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who established a new Bolshevik regime, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). The Provisional Government’s Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), formerly under Georgy Lvov (from March 1917) and then under Nikolai Avksentiev (from 6 August [O.S. 24 July] 1917) and Alexei Nikitin (from 8 October [O.S. 25 September] 1917), turned into NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) under a People’s Commissar. However, the NKVD apparatus was overwhelmed by duties inherited from MVD, such as the supervision of the local governments and firefighting, and the Workers’ and Peasants’ Militsiya staffed by proletarians was largely inexperienced and unqualified. Realizing that it was left with no capable security force, the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR established (20 December [O.S. 7 December] 1917) a secret political police, the Cheka, led by Felix Dzerzhinsky. It gained the right to undertake quick non-judicial trials and executions, if that was deemed necessary in order to «protect the Russian Socialist-Communist revolution».

The Cheka was reorganized in 1922 as the State Political Directorate, or GPU, of the NKVD of the RSFSR.[13] In 1922 the USSR formed, with the RSFSR as its largest member. The GPU became the OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate), under the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR. The NKVD of the RSFSR retained control of the militsiya, and various other responsibilities.

In 1934 the NKVD of the RSFSR was transformed into an all-union security force, the NKVD (which the Communist Party of the Soviet Union leaders soon came to call «the leading detachment of our party»), and the OGPU was incorporated into the NKVD as the Main Directorate for State Security (GUGB); the separate NKVD of the RSFSR was not resurrected until 1946 (as the MVD of the RSFSR). As a result, the NKVD also took over control of all detention facilities (including the forced labor camps, known as the GULag) as well as the regular police. At various times, the NKVD had the following Chief Directorates, abbreviated as «ГУ»– Главное управление, Glavnoye upravleniye.

| Chronology of Soviet security agencies |

|

|

|

|

| 1917–22 | Cheka under SNK of the RSFSR (All-Russian Extraordinary Commission) |

| 1922–23 | GPU under NKVD of the RSFSR (State Political Directorate) |

| 1920–91 | PGU KGB or INO under Cheka (later KGB) of the USSR (First Chief Directorate) |

| 1923–34 | OGPU under SNK of the USSR (Joint State Political Directorate) |

| 1934–46 | NKVD of the USSR (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) |

| 1934–41 | GUGB of the NKVD of the USSR (Main Directorate of State Security of People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) |

| 1941 | NKGB of the USSR (People’s Commissariat of State Security) |

| 1943–46 | NKGB of the USSR (People’s Commissariat for State Security) |

| 1946–53 | MGB of the USSR (Ministry of State Security) |

| 1946–54 | MVD of the USSR (Ministry of Internal Affairs) |

| 1947–51 |

KI MID of the USSR |

| 1954–78 | KGB under the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (Committee for State Security) |

| 1978–91 | KGB of the USSR (Committee for State Security) |

| 1991 | MSB of the USSR (Interrepublican Security Service) |

| 1991 | TsSB of the USSR (Central Intelligence Service) |

| 1991 | KOGG of the USSR (Committee for the Protection of the State Border) |

|

- ГУГБ – государственной безопасности, of State Security (GUGB, Glavnoye upravleniye gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti)

- ГУРКМ– рабоче-крестьянской милиции, of Workers and Peasants Militsiya (GURKM, Glavnoye upravleniye raboče-krest’yanskoi militsyi)

- ГУПВО– пограничной и внутренней охраны, of Border and Internal Guards (GUPVO, GU pograničnoi i vnytrennei okhrany)

- ГУПО– пожарной охраны, of Firefighting Services (GUPO, GU požarnoi okhrany)

- ГУШосДор– шоссейных дорог, of Highways (GUŠD, GU šosseynykh dorog)

- ГУЖД– железных дорог, of Railways (GUŽD, GU železnykh dorog)

- ГУЛаг– Главное управление исправительно-трудовых лагерей и колоний, (GULag, Glavnoye upravleniye ispravitelno-trudovykh lagerey i kolonii)

- ГЭУ – экономическое, of Economics (GEU, Glavnoye ekonomičeskoie upravleniye)

- ГТУ – транспортное, of Transport (GTU, Glavnoye transportnoie upravleniye)

- ГУВПИ – военнопленных и интернированных, of POWs and interned persons (GUVPI, Glavnoye upravleniye voyennoplennikh i internirovannikh)

Yezhov era[edit]

Until the reorganization begun by Nikolai Yezhov with a purge of the regional political police in the autumn of 1936 and formalized by a May 1939 directive of the All-Union NKVD by which all appointments to the local political police were controlled from the center, there was frequent tension between centralized control of local units and the collusion of those units with local and regional party elements, frequently resulting in the thwarting of Moscow’s plans.[14]

During Yezhov’s time in office, the Great Purge reached its height. In the years 1937 and 1938 alone, at least 1.3 million were arrested and 681,692 were executed for ‘crimes against the state’. The Gulag population swelled by 685,201 under Yezhov, nearly tripling in size in just two years, with at least 140,000 of these prisoners (and likely many more) dying of malnutrition, exhaustion and the elements in the camps (or during transport to them).[15]

On 3 February 1941, the 4th Department (Special Section, OO) of GUGB NKVD security service responsible for the Soviet Armed Forces military counter-intelligence,[16] consisting of 12 Sections and one Investigation Unit, was separated from GUGB NKVD USSR.

The official liquidation of OO GUGB within NKVD was announced on 12 February by a joint order No. 00151/003 of NKVD and NKGB USSR. The rest of GUGB was abolished and staff was moved to newly created People’s Commissariat for State Security (NKGB). Departments of former GUGB were renamed Directorates. For example, foreign intelligence unit known as Foreign Department (INO) became Foreign Directorate (INU); GUGB political police unit represented by Secret Political Department (SPO) became Secret Political Directorate (SPU), and so on. The former GUGB 4th Department (OO) was split into three sections. One section, which handled military counter-intelligence in NKVD troops (former 11th Section of GUGB 4th Department OO) become 3rd NKVD Department or OKR (Otdel KontrRazvedki), the chief of OKR NKVD was Aleksander Belyanov.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union (June 1941), the NKGB USSR was abolished and on July 20, 1941, the units that formed NKGB became part of the NKVD. The military CI was also upgraded from a department to a directorate and put in NKVD organization as the (Directorate of Special Departments or UOO NKVD USSR). The NKVMF, however, did not return to the NKVD until January 11, 1942. It returned to NKVD control on January 11, 1942, as UOO 9th Department controlled by P. Gladkov. In April 1943, Directorates of Special Departments was transformed into SMERSH and transferred to the People’s Defense and Commissariates. At the same time, the NKVD was reduced in size and duties again by converting the GUGB to an independent unit named the NKGB.

In 1946, all Soviet Commissariats were renamed «ministries». Accordingly, the Peoples Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) of the USSR became the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), while the NKGB was renamed as the Ministry of State Security (MGB).

In 1953, after the arrest of Lavrenty Beria, the MGB merged back into the MVD. The police and security services finally split in 1954 to become:

- The USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), responsible for the criminal militia and correctional facilities.

- The USSR Committee for State Security (KGB), responsible for the political police, intelligence, counter-intelligence, personal protection (of the leadership) and confidential communications.

Main Directorates (Departments)[edit]

- State Security

- Workers-Peasants Militsiya

- Border and Internal Security

- Firefighting security

- Correction and Labor camps

- Other smaller departments

- Department of Civil registration

- Financial (FINO)

- Administration

- Human resources

- Secretariat

- Special assignment

Ranking system (State Security)[edit]

In 1935–1945 Main Directorate of State Security of NKVD had its own ranking system before it was merged in the Soviet military standardized ranking system.

- Top-level commanding staff

- Commissioner General of State Security (later in 1935)

- Commissioner of State Security 1st Class

- Commissioner of State Security 2nd Class

- Commissioner of State Security 3rd Class

- Commissioner of State Security (Senior Major of State Security, before 1943)

- Senior commanding staff

- Colonel of State Security (Major of State Security, before 1943)

- Lieutenant Colonel of State Security (Captain of State Security, before 1943)

- Major of State Security (Senior Lieutenant of State Security, before 1943)

- Mid-level commanding staff

- Captain of State Security (Lieutenant of State Security, before 1943)

- Senior Lieutenant of State Security (Junior Lieutenant of State Security, before 1943)

- Lieutenant of State Security (Sergeant of State Security, before 1942)

- Junior Lieutenant of State Security (Sergeant of State Security, before 1942)

- Junior commanding staff

- Master Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

- Senior Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

- Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

- Junior Sergeant of Special Service (from 1943)

NKVD activities[edit]

The main function of the NKVD was to protect the state security of the Soviet Union. This role was accomplished through massive political repression, including authorised murders of many thousands of politicians and citizens, as well as kidnappings, assassinations and mass deportations.

Domestic repressions[edit]

In implementing Soviet internal policy towards perceived enemies of the Soviet state («enemies of the people»), untold multitudes of people were sent to GULAG camps and hundreds of thousands were executed by the NKVD. Formally, most of these people were convicted by NKVD troikas («triplets»)– special courts martial. Evidential standards were very low: a tip-off by an anonymous informer was considered sufficient grounds for arrest. Use of «physical means of persuasion» (torture) was sanctioned by a special decree of the state, which opened the door to numerous abuses, documented in recollections of victims and members of the NKVD itself. Hundreds of mass graves resulting from such operations were later discovered throughout the country. Documented evidence exists that the NKVD committed mass extrajudicial executions, guided by secret «plans». Those plans established the number and proportion of victims (officially «public enemies») in a given region (e.g. the quotas for clergy, former nobles etc., regardless of identity). The families of the repressed, including children, were also automatically repressed according to NKVD Order no. 00486.

The purges were organized in a number of waves according to the decisions of the Politburo of the Communist Party. Some examples are the campaigns among engineers (Shakhty Trial), party and military elite plots (Great Purge with Order 00447), and medical staff («Doctors’ Plot»). Gas vans were used in the Soviet Union during the Great Purge in the cities of Moscow, Ivanovo and Omsk[17][18][19][20]

A number of mass operations of the NKVD were related to the persecution of whole ethnic categories. For example, the Polish Operation of the NKVD in 1937–1938 resulted in the execution of 111,091 Poles.[21] Whole populations of certain ethnicities were forcibly resettled. Foreigners living in the Soviet Union were given particular attention. When disillusioned American citizens living in the Soviet Union thronged the gates of the U.S. embassy in Moscow to plead for new U.S. passports to leave the USSR (their original U.S. passports had been taken for ‘registration’ purposes years before), none were issued. Instead, the NKVD promptly arrested all the Americans, who were taken to Lubyanka Prison and later shot.[22] American factory workers at the Soviet Ford GAZ plant, suspected by Stalin of being ‘poisoned’ by Western influences, were dragged off with the others to Lubyanka by the NKVD in the very same Ford Model A cars they had helped build, where they were tortured; nearly all were executed or died in labor camps. Many of the slain Americans were dumped in the mass grave at Yuzhnoye Butovo District near Moscow.[23] Even so, the people of the Soviet Republics still formed the majority of NKVD victims.

The NKVD also served as arm of the Russian Soviet communist government for the lethal mass persecution and destruction of ethnic minorities and religious beliefs, such as the Russian Orthodox Church, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Greek Catholics, Islam, Judaism and other religious organizations, an operation headed by Yevgeny Tuchkov.

International operations[edit]

During the 1930s, the NKVD was responsible for political murders of those Stalin believed to oppose him. Espionage networks headed by experienced multilingual NKVD officers such as Pavel Sudoplatov and Iskhak Akhmerov were established in nearly every major Western country, including the United States. The NKVD recruited agents for its espionage efforts from all walks of life, from unemployed intellectuals such as Mark Zborowski to aristocrats such as Martha Dodd. Besides the gathering of intelligence, these networks provided organizational assistance for so-called wet business,[24] where enemies of the USSR either disappeared or were openly liquidated.[25]

The NKVD’s intelligence and special operations (Inostranny Otdel) unit organized overseas assassinations of political enemies of the USSR, such as leaders of nationalist movements, former Tsarist officials, and personal rivals of Joseph Stalin. Among the officially confirmed victims of such plots were:

- Leon Trotsky, a personal political enemy of Stalin and his most bitter international critic, killed in Mexico City in 1940;

- Yevhen Konovalets, prominent Ukrainian nationalist leader who was attempting to create a separatist movement in Soviet Ukraine; assassinated in Rotterdam, Netherlands

- Yevgeny Miller, former General of the Tsarist (Imperial Russian) Army; in the 1930s, he was responsible for funding anti-communist movements inside the USSR with the support of European governments. Kidnapped in Paris and brought to Moscow, where he was interrogated and executed

- Noe Ramishvili, Prime Minister of independent Georgia, fled to France after the Bolshevik takeover; responsible for funding and coordinating Georgian nationalist organizations and the August uprising, he was assassinated in Paris

- Boris Savinkov, Russian revolutionary and anti-Bolshevik terrorist (lured back into Russia and allegedly killed in 1924 by the Trust Operation of the GPU);

- Sidney Reilly, British agent of the MI6 who deliberately entered Russia in 1925 trying to expose the Trust Operation to avenge Savinkov’s death;

- Alexander Kutepov, former General of the Tsarist (Imperial Russian) Army, who was active in organizing anti-communist groups with the support of French and British governments

Prominent political dissidents were also found dead under highly suspicious circumstances, including Walter Krivitsky, Lev Sedov, Ignace Reiss and former German Communist Party (KPD) member Willi Münzenberg.[26][27][28][29][30]

The pro-Soviet leader Sheng Shicai in Xinjiang received NKVD assistance in conducting a purge to coincide with Stalin’s Great Purge in 1937. Sheng and the Soviets alleged a massive Trotskyist conspiracy and a «Fascist Trotskyite plot» to destroy the Soviet Union. The Soviet Consul General Garegin Apresoff, General Ma Hushan, Ma Shaowu, Mahmud Sijan, the official leader of the Xinjiang province Huang Han-chang and Hoja-Niyaz were among the 435 alleged conspirators in the plot. Xinjiang came under soviet influence.[31]

Spanish Civil War[edit]

During the Spanish Civil War, the NKVD ran Section X coordinating the Soviet intervention on behalf of the Spanish Republicans.[32] NKVD agents, acting in conjunction with the Communist Party of Spain, exercised substantial control over the Republican government, using Soviet military aid to help further Soviet influence.[33] The NKVD established numerous secret prisons around the capital Madrid, which were used to detain, torture, and kill hundreds of the NKVD’s enemies, at first focusing on Spanish Nationalists and Spanish Catholics, while from late 1938 increasingly anarchists and Trotskyists were the objects of persecution.[34] In 1937 Andrés Nin, the secretary of the Trotskyist POUM and his colleagues were tortured and killed in an NKVD prison in Alcalá de Henares.[35]

World War II operations[edit]

Prior to the German invasion, in order to accomplish its own goals, the NKVD was prepared to cooperate even with such organizations as the German Gestapo. In March 1940, representatives of the NKVD and the Gestapo met for one week in Zakopane, to coordinate the pacification of Poland; see Gestapo–NKVD conferences. For its part, the Soviet Union delivered hundreds of German and Austrian Communists to the Gestapo, as unwanted foreigners, together with their documents. However, many NKVD units were later to fight the Wehrmacht, for example the 10th NKVD Rifle Division, which fought at the Battle of Stalingrad.

After the German invasion, the NKVD evacuated and killed prisoners. During World War II, NKVD Internal Troops units were used for rear area security, including preventing the retreat of Soviet Union army divisions. Though mainly intended for internal security, NKVD divisions were sometimes used at the front to stem the occurrence of desertion through Stalin’s Order No. 270 and Order No. 227 decrees in 1941 and 1942, which aimed to raise troop morale via brutality and coercion. At the beginning of the war the NKVD formed 15 rifle divisions, which had expanded by 1945 to 53 divisions and 28 brigades.[36] A list of identified NKVD Internal Troops divisions can be seen at List of Soviet Union divisions 1917-1945. Though mainly intended for internal security, NKVD divisions were sometimes used in the front-lines, for example during the Battle of Stalingrad and the Crimean offensive.[36] Unlike the Waffen-SS, the NKVD did not field any armored or mechanized units.[36]

In the enemy-held territories, the NKVD carried out numerous missions of sabotage. After fall of Kyiv, NKVD agents set fire to the Nazi headquarters and various other targets, eventually burning down much of the city center.[37] Similar actions took place across the occupied Byelorussia and Ukraine.

The NKVD (later KGB) carried out mass arrests, deportations, and executions. The targets included both collaborators with Germany and non-Communist resistance movements such as the Polish Home Army and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army aiming to separate from the Soviet Union, among others. The NKVD also executed tens of thousands of Polish political prisoners in 1940–1941, including the Katyń massacre.[38][39] On 26 November 2010, the Russian State Duma issued a declaration acknowledging Stalin’s responsibility for the Katyn massacre, the execution of 22,000 Polish POW’s and intellectual leaders by Stalin’s NKVD. The declaration stated that archival material «not only unveils the scale of his horrific tragedy but also provides evidence that the Katyn crime was committed on direct orders from Stalin and other Soviet leaders.»[40]

NKVD units were also used to repress the prolonged partisan war in Ukraine and the Baltics, which lasted until the early 1950s. NKVD also faced strong opposition in Poland from the

Polish resistance known as the Armia Krajowa.

Postwar operations[edit]

After the death of Stalin in 1953, the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev halted the NKVD purges. From the 1950s to the 1980s, thousands of victims were legally «rehabilitated» (i.e., acquitted and had their rights restored). Many of the victims and their relatives refused to apply for rehabilitation out of fear or lack of documents. The rehabilitation was not complete: in most cases the formulation was «due to lack of evidence of the case of crime». Only a limited number of persons were rehabilitated with the formulation «cleared of all charges».

Very few NKVD agents were ever officially convicted of the particular violation of anyone’s rights. Legally, those agents executed in the 1930s were also «purged» without legitimate criminal investigations and court decisions. In the 1990s and 2000s (decade) a small number of ex-NKVD agents living in the Baltic states were convicted of crimes against the local population.

Intelligence activities[edit]

These included:

- Establishment of a widespread spy network through the Comintern.

- Operations of Richard Sorge, the «Red Orchestra», Willi Lehmann, and other agents who provided valuable intelligence during World War II.

- Recruitment of important UK officials as agents in the 1940s.

- Penetration of British intelligence (MI6) and counter-intelligence (MI5) services.

- Collection of detailed nuclear weapons design information from the U.S. and Britain during the Manhattan Project.

- Disruption of several confirmed plots to assassinate Stalin.

- Establishment of the People’s Republic of Poland and earlier its communist party along with training activists, during World War II. The first President of Poland after the war was Bolesław Bierut, an NKVD agent.

Soviet economy[edit]

The extensive system of labor exploitation in the Gulag made a notable contribution to the Soviet economy and the development of remote areas. Colonization of Siberia, the North and Far East was among the explicitly stated goals in the very first laws concerning Soviet labor camps. Mining, construction works (roads, railways, canals, dams, and factories), logging, and other functions of the labor camps were part of the Soviet planned economy, and the NKVD had its own production plans.[citation needed]

The most unusual part of the NKVD’s achievements was its role in Soviet science and arms development. Many scientists and engineers arrested for political crimes were placed in special prisons, much more comfortable than the Gulag, colloquially known as sharashkas. These prisoners continued their work in these prisons, and later released, some of them became world leaders in science and technology. Among such sharashka members were Sergey Korolev, the head designer of the Soviet rocket program and first human space flight mission in 1961, and Andrei Tupolev, the famous airplane designer. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was also imprisoned in a sharashka, and based his novel The First Circle on his experiences there.

After World War II, the NKVD coordinated work on Soviet nuclear weaponry, under the direction of General Pavel Sudoplatov. The scientists were not prisoners, but the project was supervised by the NKVD because of its great importance and the corresponding requirement for absolute security and secrecy. Also, the project used information obtained by the NKVD from the United States.

People’s Commissars[edit]

The agency was headed by a people’s commissar (minister). His first deputy was the director of State Security Service (GUGB).

- 1934–1936 Genrikh Yagoda, both people’s commissar of Interior and director of State Security

- 1936–1938 Nikolai Yezhov, people’s commissar of Interior

- 1936–1937 Yakov Agranov, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1937–1938 Mikhail Frinovsky, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1938 Lavrentiy Beria, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1938–1945 Lavrentiy Beria, people’s commissar of Interior

- 1938–1941 Vsevolod Merkulov, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1941–1943 Vsevolod Merkulov, director of State Security (as the first deputy)

- 1945–1946 Sergei Kruglov, people’s commissar of Interior

Note: In the first half of 1941 Vsevolod Merkulov transformed his agency into separate commissariat (ministry), but it was merged back to the people’s commissariat of Interior soon after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. In 1943 Merkulov once again split his agency this time for good.

Officers[edit]

Andrei Zhukov has singlehandedly identified every single NKVD officer involved in 1930s arrests and killings by researching a Moscow archive. There are just over 40,000 names on the list.[41]

See also[edit]

- Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Terror, famine and the Gulag

- Poison laboratory of the Soviet secret services

- 10th NKVD Rifle Division

- Hitler Youth conspiracy, an NKVD case pursued in 1938

- NKVD filtration camp

- NKVD special camps in Germany 1945–49, internment camps set up at the end of World War II in eastern Germany (often in former Nazi POW or concentration camps) and other areas under Soviet domination, to imprison those suspected of collaboration with the Nazis, or others deemed to be troublesome to Soviet ambitions.

References[edit]

- ^ Semukhina, Olga B.; Reynolds, Kenneth Michael (2013). Understanding the Modern Russian Police. CRC Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4822-1887-9.

- ^ a b Huskey, Eugene (2014). Russian Lawyers and the Soviet State: The Origins and Development of the Soviet Bar, 1917-1939. Princeton University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4008-5451-6.

- ^ Semukhina, Olga B.; Reynolds, Kenneth Michael (2013). Understanding the Modern Russian Police. CRC Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4398-0349-3.

- ^ Khlevniuk, Oleg V. (2015). Stalin: New Biography of a Dictator. Yale University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-300-16694-1.

- ^ Yevgenia Albats, KGB: The State Within a State. 1995, page 101

- ^ Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf, 2007 ISBN 978-1-4000-4005-6 p. 460

- ^ Catherine Merridale. Night of Stone: Death and Memory in Twentieth-Century Russia. Penguin Books, 2002 ISBN 978-0-14-200063-2 p. 200

- ^ Viola, Lynne (207). The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin’s Special Settlements. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2003). Gulag: A History. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ McDermott, Kevin (1995). «Stalinist Terror in the Comintern: New Perspectives». Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (1): 111–130. doi:10.1177/002200949503000105. JSTOR 260924. S2CID 161318303.

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956. New York: Random House.

- ^ Statiev, Alexander (2010). The Soviet Counterinsurgency in the Western Borderlands. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76833-7.

- ^ Blank Pages by G.C.Malcher ISBN 978-1-897984-00-0 Page 7

- ^

James Harris, «Dual subordination ? The political police and the party in the Urals region, 1918–1953», Cahiers du monde russe 22 (2001):423–446. - ^ Figes, Orlando (2007) The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin’s Russia ISBN 978-0-8050-7461-1, page 234.

- ^ GUGB NKVD. Archived 2020-10-08 at the Wayback Machine DocumentsTalk.com, 2008.

- ^ Человек в кожаном фартуке. Новая газета — Novayagazeta.ru (in Russian). 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- ^ Timothy J. Colton. Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis. Belknap Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-674-58749-6 p. 286

- ^ Газовые душегубки: сделано в СССР (Gas vans: made in the USSR) Archived August 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine by Dmitry Sokolov, Echo of Crimea, 09.10.2012

- ^ Григоренко П.Г. В подполье можно встретить только крыс… (Petro Grigorenko, «In the underground one can meet only rats») — Нью-Йорк, Издательство «Детинец», 1981, page 403, Full text of the book (Russian)

- ^ Goldman, Wendy Z. (2011). Inventing the Enemy: Denunciation and Terror in Stalin’s Russia. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19196-8. p. 217.

- ^ Tzouliadis, Tim, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia Penguin Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4: Many of the Americans desiring to return home were communists who had voluntarily moved to the Soviet Union, while others moved to Soviet Union as skilled auto workers to help produce cars at the recently constructed GAZ automobile factory built by the Ford Motor Company. All were U.S. citizens.

- ^ Tzouliadis, Tim, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia Penguin Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4

- ^ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G.P. Putnam (1945), p. 18: NKVD expression for a political murder

- ^ John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999)

- ^ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G.P. Putnam (1945), pp. 232–233

- ^ Orlov, Alexander, The March of Time, St. Ermin’s Press (2004), ISBN 978-1-903608-05-0

- ^ Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin, Vasili, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Basic Books (2000), ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9, ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9, p. 75

- ^ Barmine, Alexander, One Who Survived, New York: G. P. Putnam (1945), pp. 17, 22

- ^ Sean McMeekin, The Red Millionaire: A Political Biography of Willi Münzenberg, Moscow’s Secret Propaganda Tsar in the West, 1917–1940, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press (2004), pp. 304–305

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ^ «4. The Spanish Civil War (1936– 1939)», Secret Wars, Princeton University Press, p. 115, 2018-12-31, doi:10.1515/9780691184241-005, ISBN 978-0-691-18424-1, S2CID 227568935, retrieved 2022-02-07

- ^ Robert W. Pringle (2015). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 288–89. ISBN 978-1-4422-5318-6.

- ^ Christopher Andrew (2000). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9.

- ^ David Clay Large (1991). Between Two Fires: Europe’s Path in the 1930s. W.W. Norton. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-393-30757-3.

- ^ a b c Zaloga, Steven J. The Red Army of the Great Patriotic War, 1941–45, Osprey Publishing, (1989), pp. 21–22

- ^ Birstein, Vadim (2013). Smersh: Stalin’s Secret Weapon. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84954-689-8. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Sanford, George (2007-05-07). Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice and Memory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-30299-4.

- ^ «Lviv museum recounts Soviet massacres | Центр досліджень визвольного руху». 2019-01-15. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Barry, Ellen (26 November 2010). «Russia: Stalin Called Responsible for Katyn Killings». The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (6 February 2017). «Stalin’s secret police finally named but killings still not seen as crimes». The Guardian.

Further reading[edit]

See also: Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Violence and terror and Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union § Terror, famine and the Gulag

- Hastings, Max (2015). The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939 -1945 (paperback). London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-750374-2.

External links[edit]

Media related to NKVD at Wikimedia Commons

- For evidence on Soviet espionage in the United States during the Cold War, see the full text of Alexander Vassiliev’s Notebooks from the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP)

- NKVD.org: information site about the NKVD

- (in Russian) MVD: 200-year history of the Ministry

- (in Russian) Memorial: history of the OGPU/NKVD/MGB/KGB Archived 2016-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

Coordinates: 55°45′38″N 37°37′41″E / 55.7606°N 37.6281°E

НКВД: расшифровка, история создания, назначение

Здравствуйте, уважаемые читатели блога KtoNaNovenkogo.ru. Длинные названия каких-либо организаций принято сокращать до аббревиатуры, т.е. до первых букв слов, содержащихся в названии.

Например, МФЦ – многофункциональный центр, МЧС – министерство чрезвычайных ситуаций и т. д.

Но есть такие аббревиатуры, которые сами по себе стали именами нарицательными, а их расшифровки знают только специалисты. К таковым относится и НКВД.

Большинство из читающих эту статью, никогда не сталкивались с этой организацией. Но при ее упоминании холодок пробегает по спине, так прочно ее название ассоциируется с ужасами сталинских репрессий.

Что же такое НКВД, как расшифровывается, когда и с какой целью был создан – проанализируем в этой статье.

НКВД – это …

Для начала расшифруем аббревиатуру: НКВД – это народный комиссариат внутренних дел.

Теперь по порядку разберем, что обозначает каждое слово:

- «народный» — так назывались многие структуры в СССР в связи с тем, что социалистический строй подразумевает, что политическая власть принадлежит народу;

- «комиссариат» — с латинского переводится как «поручать», следовательно, это организация, выполняющая определенные (порученные) функции. С 1917 и по 1947 годы в СССР так назывались структуры, управляющие работой какой-либо отрасли государства или народного хозяйства. В наше время эти структуры называют министерствами;

- сфера «внутренних дел» — это деятельность, направленная на обеспечение безопасности и порядка в обществе в рамках государственной политики.

Таким образом, НКВД – это организация, реализующая меры по поддержанию общественного порядка, в том числе – по борьбе с преступностью. В некоторые периоды своего функционирования наркомат также выполнял задачи по обеспечению государственной безопасности.

Примечание: госбезопасность (ГБ) – это защищенность конкретного общественного и политического строя от внутренних и внешних угроз. Защита ГБ – это комплекс мер, направленных на сохранение территориальной целостности государства, на недопущение подрывной активности со стороны других стран и внутренних противников.

Создание и сфера деятельности

НКВД был образован в 1934 году. Сфера деятельности данного комиссариата была довольно обширна. В его компетенцию входило:

- управление строительством, ЖКХ и др.отраслями в формате курирования;

- регистрация записей актов гражданского состояния (ЗАГС);

- выявление политических преступников. Примечание: наркомату было дано право обвинять и приводить наказание в исполнение без суда и следствия;

- обеспечение общественного порядка и пожарной безопасности;

- охрана государственной и личной (не путаем с частной) собственности;

- руководство системой наказаний (тюрьмами, колониями, лагерями);

- осуществление внешней разведки (сбор информации о потенциальных внешних врагах);

- защита границы государства (пограничные войска);

- контрразведка (пресечение шпионской активности).

Очевидно, что одна госструктура не смогла бы справиться с таким огромным количеством делегируемых функций. Поэтому в рамках НКВД было создано множество организаций, каждая из которых занималась выполнением определенных задач:

- главное управление (ГУ) госбезопасности;

- ГУ милиции;

- ГУ пограничной и внутренней охраны;

- ГУ пожарной охраны;

- ГУ исправительных лагерей (ГУЛАГ);

- ЗАГС;

- структуры, обеспечивающие хозяйственную и финансовую основу деятельности перечисленных ведомств.

Руководители НКВД в разные периоды:

- 1934—1936 – Г.Ягода;

- 1936—1938 – Н.Ежов;

- 938-1945 – Л.Берия;

- 1945—1946 – С.Круглов.

Примечание: участь перечисленных комиссаров (кроме Круглова) довольно печальна. Все они были расстреляны.

В 1946 году комиссариат был преобразован и переименован в МВД (министерство внутренних дел). Функции по охране государственной безопасности, начиная с 1941 г., несколько раз передавались отдельному ведомству и возвращались обратно.

И только в 1954 году эти обязанности окончательно были делегированы специальной госструктуре – Комитету госбезопасности (КГБ).

Более подробно о датах и вехах можно прочитать в Википедии по этой ссылке.

Роль НКВД в укреплении советской власти и в политических репрессиях