А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

скандина́вский

Рядом по алфавиту:

с кандибо́бером , (сниж.)

сканда́льно изве́стный

сканда́льность , -и

сканда́льный , кр. ф. -лен, -льна

сканда́льчик , -а

сканда́лящий(ся)

ска́ндиевый

ска́ндий , -я

скандинави́зм , -а

скандинави́ст , -а

скандинави́стика , -и

скандинави́стский

Скандина́вия , -и

скандина́вка , -и, р. мн. -вок

Скандина́вские стра́ны

скандина́вский

Скандина́вский полуо́стров

скандина́вы , -ов, ед. -на́в, -а

сканди́рование , -я

сканди́рованный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

сканди́ровать(ся) , -рую, -рует(ся)

скандиро́вка , -и

ска́нер , -а

ска́нерный

ска́нец , -нца, тв. -нцем, р. мн. -нцев

скани́рование , -я

скани́рованный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

скани́ровать(ся) , -рую, -рует(ся)

сканиро́вщик , -а

скани́рующий(ся)

сканогра́мма , -ы

Как написать слово «скандинавский» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «скандинавский»?

скандина́вский

Правильное написание — скандинавский, ударение падает на букву: а, безударными гласными являются: а, и, и.

Выделим согласные буквы — скандинавский, к согласным относятся: с, к, н, д, в, й, звонкие согласные: н, д, в, й, глухие согласные: с, к.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 13,

- слогов — 4,

- гласных — 4,

- согласных — 9.

Формы слова: скандина́вский.

- О́дин, -а (мифол.)

- оди́н, одно́, одного́, одна́, одно́й, вин. одну́, мн. одни́, одни́х

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова трансформер:

Ассоциации к слову «один»

Синонимы к слову «один»

Синонимы к слову «Один»

Предложения со словом «один»

- Но есть ещё одна сторона дела, которая, как может показаться с первого раза, указывает на существенную разницу между старым рефлексом и этим новым явлением, которое я сейчас также назвал рефлексом.

- Человеческий фактор имеет ещё одну сторону, почти не тронутую психологами, – духовную.

- У меня в списке первоочередников оставался ещё один человек, на которого, впрочем, никаких особых надежд я возлагать не осмеливался.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «один»

- Кисельников. Приятель, Погуляев? У меня один есть приятель, два есть приятеля.

- Шурочка посадила рядом с собой с одной стороны Тальмана, а с другой — Ромашова.

- В городе, в котором находился наш острог, жила одна дама, Настасья Ивановна, […одна дама, Настасья Ивановна…

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение слова «один»

-

ОДИ́Н, одного́, м.; одна́, одно́й, ж.; одно́, одного́, ср.; мн. одни́, —и́х; числ. колич. 1. Число 1. К одному прибавить три. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова ОДИН

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «один»

- Гений — это нация в одном лице.

- Желуди-то одинаковы, но когда вырастут из них молодые дубки — из одного дубка делают кафедру для ученого, другой идет на рамку для портрета любимой девушки, в из третьего дубка смастерят такую виселицу, что любо-дорого…

- Любовь-нежность (жалость) — все отдает, и нет ей предела. И никогда она на себя не оглядывается, потому что «не ищет своего». Только одна и не ищет.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Смотрите также

ОДИ́Н, одного́, м.; одна́, одно́й, ж.; одно́, одного́, ср.; мн. одни́, —и́х; числ. колич. 1. Число 1. К одному прибавить три.

Все значения слова «один»

-

Но есть ещё одна сторона дела, которая, как может показаться с первого раза, указывает на существенную разницу между старым рефлексом и этим новым явлением, которое я сейчас также назвал рефлексом.

-

Человеческий фактор имеет ещё одну сторону, почти не тронутую психологами, – духовную.

-

У меня в списке первоочередников оставался ещё один человек, на которого, впрочем, никаких особых надежд я возлагать не осмеливался.

- (все предложения)

- какой-то

- какой-нибудь

- некоторый

- единственный

- лишь

- (ещё синонимы…)

- божество

- бог

- Вотан

- (ещё синонимы…)

- одна

- цифра

- единство

- монография

- однообразный

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- богов

- управляющий

- одноглазый

- духов

- учёный

- (ещё…)

- Разбор по составу слова «один»

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — скандинавский

Ударение и произношение — скандин`авский

Значение слова -прил. 1) Относящийся к Скандинавии, скандинавам, связанный с ними. 2) Свойственный скандинавам, характерный для них и для Скандинавии. 3) Принадлежащий Скандинавии, скандинавам. 4) Созданный, выведенный и т.п. в Скандинавии или скандинавами.

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — ИЗДРЕВЛЕ?

Слово состоит из букв:

С,

К,

А,

Н,

Д,

И,

Н,

А,

В,

С,

К,

И,

Й,

Похожие слова:

скандий

скандинав

скандинавизм

Скандинавия

скандинавка

скандировавший

скандировавшийся

скандировал

скандирование

скандированн

Рифма к слову скандинавский

раевский, пржебышевский, измайловский, понятовский, козловский, корчевский, кутузовский, семеновский, георгиевский, московский, августовский, платовский, киевский, поэтический, купеческий, панический, эгоистический, виртембергский, голландский, педантический, княжеский, героический, комический, фурштадский, ольденбургский, павлоградский, ребяческий, дипломатический, персидский, дружеский, сангвинический, политический, кавалергардский, логический, стратегический, адский, человеческий, шведский, электрический, иронический, энергический, физический, чарторижский, господский, нелогический, трагический, католический, исторический, фантастический, петербургский, робкий, ловкий, дикий, низкий, узкий, негромкий, одинокий, бойкий, звонкий, тонкий, крепкий, глубокий, великий, гладкий, жаркий, сладкий, жалкий, легкий, скользкий, пылкий, неловкий, невысокий, резкий, высокий, жестокий, близкий, некий, далекий, редкий, яркий, неробкий, широкий, громкий, дерзкий, краснорожий, удовольствий, георгий, препятствий, рыжий, похожий, строгий, орудий, приветствий, жребий, отлогий, бедствий, свежий, действий, происшествий, условий, сергий, пологий, божий, проезжий, религий, сословий, хорунжий, самолюбий, непохожий, дивизий, кривоногий, толсторожий, муругий, последствий, приезжий

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

На нашем сайте в электронном виде представлен справочник по орфографии русского языка. Справочником можно пользоваться онлайн, а можно бесплатно скачать на свой компьютер.

Надеемся, онлайн-справочник поможет вам изучить правописание и синтаксис русского языка!

РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК

Отделение историко-филологических наук Институт русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова

ПРАВИЛА РУССКОЙ ОРФОГРАФИИ И ПУНКТУАЦИИ

ПОЛНЫЙ АКАДЕМИЧЕСКИЙ СПРАВОЧНИК

Авторы:

Н. С. Валгина, Н. А. Еськова, О. Е. Иванова, С. М. Кузьмина, В. В. Лопатин, Л. К. Чельцова

Ответственный редактор В. В. Лопатин

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. — М: АСТ, 2009. — 432 с.

ISBN 978-5-462-00930-3

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. — М: Эксмо, 2009. — 480 с.

ISBN 978-5-699-18553-5

Справочник представляет собой новую редакцию действующих «Правил русской орфографии и пунктуации», ориентирован на полноту правил, современность языкового материала, учитывает существующую практику письма.

Полный академический справочник предназначен для самого широкого круга читателей.

Предлагаемый справочник подготовлен Институтом русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН и Орфографической комиссией при Отделении историко-филологических наук Российской академии наук. Он является результатом многолетней работы Орфографической комиссии, в состав которой входят лингвисты, преподаватели вузов, методисты, учителя средней школы.

В работе комиссии, многократно обсуждавшей и одобрившей текст справочника, приняли участие: канд. филол. наук Б. 3. Бук-чина, канд. филол. наук, профессор Н. С. Валгина, учитель русского языка и литературы С. В. Волков, доктор филол. наук, профессор В. П. Григорьев, доктор пед. наук, профессор А. Д. Дейкина, канд. филол. наук, доцент Е. В. Джанджакова, канд. филол. наук Н. А. Еськова, академик РАН А. А. Зализняк, канд. филол. наук О. Е. Иванова, канд. филол. наук О. Е. Кармакова, доктор филол. наук, профессор Л. Л. Касаткин, академик РАО В. Г. Костомаров, академик МАНПО и РАЕН О. А. Крылова, доктор филол. наук, профессор Л. П. Крысин, доктор филол. наук С. М. Кузьмина, доктор филол. наук, профессор О. В. Кукушкина, доктор филол. наук, профессор В. В. Лопатин (председатель комиссии), учитель русского языка и литературы В. В. Луховицкий, зав. лабораторией русского языка и литературы Московского института повышения квалификации работников образования Н. А. Нефедова, канд. филол. наук И. К. Сазонова, доктор филол. наук А. В. Суперанская, канд. филол. наук Л. К. Чельцова, доктор филол. наук, профессор А. Д. Шмелев, доктор филол. наук, профессор М. В. Шульга. Активное участие в обсуждении и редактировании текста правил принимали недавно ушедшие из жизни члены комиссии: доктора филол. наук, профессора В. Ф. Иванова, Б. С. Шварцкопф, Е. Н. Ширяев, кандидат филол. наук Н. В. Соловьев.

Основной задачей этой работы была подготовка полного и отвечающего современному состоянию русского языка текста правил русского правописания. Действующие до сих пор «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации», официально утвержденные в 1956 г., были первым общеобязательным сводом правил, ликвидировавшим разнобой в правописании. Со времени их выхода прошло ровно полвека, на их основе были созданы многочисленные пособия и методические разработки. Естественно, что за это время в формулировках «Правил» обнаружился ряд существенных пропусков и неточностей.

Неполнота «Правил» 1956 г. в большой степени объясняется изменениями, произошедшими в самом языке: появилось много новых слов и типов слов, написание которых «Правилами» не регламентировано. Например, в современном языке активизировались единицы, стоящие на грани между словом и частью слова; среди них появились такие, как мини, макси, видео, аудио, медиа, ретро и др. В «Правилах» 1956 г. нельзя найти ответ на вопрос, писать ли такие единицы слитно со следующей частью слова или через дефис. Устарели многие рекомендации по употреблению прописных букв. Нуждаются в уточнениях и дополнениях правила пунктуации, отражающие стилистическое многообразие и динамичность современной речи, особенно в массовой печати.

Таким образом, подготовленный текст правил русского правописания не только отражает нормы, зафиксированные в «Правилах» 1956 г., но и во многих случаях дополняет и уточняет их с учетом современной практики письма.

Регламентируя правописание, данный справочник, естественно, не может охватить и исчерпать все конкретные сложные случаи написания слов. В этих случаях необходимо обращаться к орфографическим словарям. Наиболее полным нормативным словарем является в настоящее время академический «Русский орфографический словарь» (изд. 2-е, М., 2005), содержащий 180 тысяч слов.

Данный справочник по русскому правописанию предназначается для преподавателей русского языка, редакционно-издательских работников, всех пишущих по-русски.

Для облегчения пользования справочником текст правил дополняется указателями слов и предметным указателем.

Составители приносят благодарность всем научным и образовательным учреждениям, принявшим участие в обсуждении концепции и текста правил русского правописания, составивших этот справочник.

Авторы

Ав. — Л.Авилова

Айт. — Ч. Айтматов

Акун. — Б. Акунин

Ам. — Н. Амосов

А. Меж. — А. Межиров

Ард. — В. Ардаматский

Ас. — Н. Асеев

Аст. — В. Астафьев

А. Т. — А. Н. Толстой

Ахм. — А. Ахматова

Ахмад. — Б. Ахмадулина

- Цвет. — А. И. Цветаева

Багр. — Э. Багрицкий

Бар. — Е. А. Баратынский

Бек. — М. Бекетова

Бел. — В. Белов

Белин. — В. Г. Белинский

Бергг. — О. Берггольц

Бит. — А. Битов

Бл. — А. А. Блок

Бонд. — Ю. Бондарев

Б. П. — Б. Полевой

Б. Паст. — Б. Пастернак

Булг. — М. А. Булгаков

Бун. — И.А.Бунин

- Бык. — В. Быков

Возн. — А. Вознесенский

Вороб. — К. Воробьев

Г. — Н. В. Гоголь

газ. — газета

Гарш. — В. М. Гаршин

Гейч. — С. Гейченко

Гил. — В. А. Гиляровский

Гонч. — И. А. Гончаров

Гр. — А. С. Грибоедов

Гран. — Д. Гранин

Грин — А. Грин

Дост. — Ф. М. Достоевский

Друн. — Ю. Друнина

Евт. — Е. Евтушенко

Е. П. — Е. Попов

Ес. — С. Есенин

журн. — журнал

Забол. — Н. Заболоцкий

Зал. — С. Залыгин

Зерн. — Р. Зернова

Зл. — С. Злобин

Инб. — В. Инбер

Ис — М. Исаковский

Кав. — В. Каверин

Каз. — Э. Казакевич

Кат. — В. Катаев

Кис. — Е. Киселева

Кор. — В. Г. Короленко

Крут. — С. Крутилин

Крыл. — И. А. Крылов

Купр. — А. И. Куприн

Л. — М. Ю. Лермонтов

Леон. — Л. Леонов

Лип. — В. Липатов

Лис. — К. Лисовский

Лих. — Д. С. Лихачев

Л. Кр. — Л. Крутикова

Л. Т. — Л. Н. Толстой

М. — В. Маяковский

Майк. — А. Майков

Мак. — В. Маканин

М. Г. — М. Горький

Мих. — С. Михалков

Наб. — В. В. Набоков

Нагиб. — Ю. Нагибин

Некр. — H.A. Некрасов

Н.Ил. — Н. Ильина

Н. Матв. — Н. Матвеева

Нов.-Пр. — А. Новиков-Прибой

Н. Остр. — H.A. Островский

Ок. — Б. Окуджава

Орл. — В. Орлов

П. — A.C. Пушкин

Пан. — В. Панова

Панф. — Ф. Панферов

Пауст. — К. Г. Паустовский

Пелев. — В. Пелевин

Пис. — А. Писемский

Плат. — А. П. Платонов

П. Нил. — П. Нилин

посл. — пословица

Пришв. — М. М. Пришвин

Расп. — В. Распутин

Рожд. — Р. Рождественский

Рыб. — А. Рыбаков

Сим. — К. Симонов

Сн. — И. Снегова

Сол. — В. Солоухин

Солж. — А. Солженицын

Ст. — К. Станюкович

Степ. — Т. Степанова

Сух. — В. Сухомлинский

Т. — И.С.Тургенев

Тв. — А. Твардовский

Тендр. — В. Тендряков

Ток. — В. Токарева

Триф. — Ю. Трифонов

Т. Толст. — Т. Толстая

Тын. — Ю. Н. Тынянов

Тютч. — Ф. И. Тютчев

Улиц. — Л. Улицкая

Уст. — Т. Устинова

Фад. — А. Фадеев

Фед. — К. Федин

Фурм. — Д. Фурманов

Цвет. — М. И. Цветаева

Ч.- А. П. Чехов

Чак. — А. Чаковский

Чив. — В. Чивилихин

Чуд. — М. Чудакова

Шол. — М. Шолохов

Шукш. — В. Шукшин

Щерб. — Г. Щербакова

Эр. — И.Эренбург

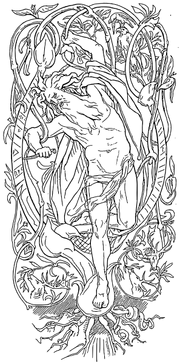

Один (/ˈouːðɪn/, /ˈoːðẽnː/, от древнескандинавского Óðinn, от протогерманского *Wōdanaz.) — в германо-скандинавской мифологии верховный ас, бог мудрости и военного дела. Внук первопредка Бури, сын Бора и Бестлы, Один имеет великанское происхождение.

Бог Один в скандинавской мифологии имеет особое значение. Это не просто верховное божество, и не просто “отец всех богов”. Это воин и сказитель, мудрец и шаман.

Характерной чертой Одина является готовность к самопожертвованию: с целью приобретения мудрости и тайных знаний, он принес себя в жертву самому себе. Это благородное, мужественное божество, которое фигурирует и во многих скандинавских мифах и легендах, и в средневековом фольклоре. Его альтер-эго, его “темной стороной” является коварный Локи.

Содержание

- Словарь

- Этимология

- Отец богов

- Кто такой Один

- Внешний облик и характеристика

- Рим и Британия

- Атрибуты Одина

- Происхождение среды

- Некоторые научные теории

- Современный фольклор

- Один в мифах и легендах

- Один в мире людей

- Еще одна песня

- Мед поэзии

- Миф о дикой охоте

Словарь

Один (Odinn) — в скандинавской мифологии верховный бог, соответствующий Водану (Вотану) у континентальных германцев. Этимология имени Одина (Водана) указывает на возбуждение и поэтическое вдохновение, на шаманский экстаз. Таков смысл др.-исл. odr (см. Од, ср. готское woths, «неистовствующий», и лат. vates, «поэт», «провидец»). Тацит (I в. н. э.) описывает Водана под римским именем Меркурия, тот же самый день недели (среда) связывается с его именем («Германия», IX). К VI–VIII вв. относятся надписи с именами Одина и Водана в разных местах. Во Втором мерзебургском заклинании (на исцеление захромавшего коня) (записано в X в.) Водан выступает как основная фигура, как носитель магической силы. Имеются свидетельства почитания Водана германскими племенами — франками, саксами, англами, вандалами, готами. В «Истории лангобардов» Павла Диакона (VIII в.) рассказывается о том, что перед битвой винилов с вандалами первые просили о победе у жены Водана Фрии (Фригг), а вторые у самого Водана. Водан предсказал победу тем, кого увидит первыми. Это были жены винилов, которые по совету его жены сделали из волос бороды (объяснение названия «лангобарды» — длиннобородые). О споре Одина и Фригг из-за своих любимцев рассказывается и во введении к «Речам Гримнира» («Старшая Эдда»). В позднейших немецких легендах он фигурирует как водитель «дикой охоты» — душ мертвых воинов (этот мотив, как убедительно показал О. Хефлер, восходит к тайным мужским союзам германцев).

По-видимому, Водан в генезисе — хтонический демон, покровитель воинских союзов и воинских инициаций и бог-колдун (шаман). В отличие от Тиу-Тюра и Донара-Тора, имеющих определенные соответствия в индоевропейской мифологической системе, Водан-Один первоначально не входил в небесный пантеон богов. Это, разумеется, не исключает правомерность его сравнения с индийским богом Варуной (как выражающим темную сторону небесного бога) или с Рудрой (по «характеру»), с кельтским Лугом и т. д. (Впрочем, не менее близкую параллель находим в финском Вяйнямёйнене.) В конечном счете (но далеко не с самого начала) Водан-Один стал представлять в том числе и духовную власть и мудрость как первую функцию богов в трехфункциональной системе (другие функции — военная сила и богатство-плодородие), которую Ж. Дюмезиль считает специфичной для индоевропейских мифологий.

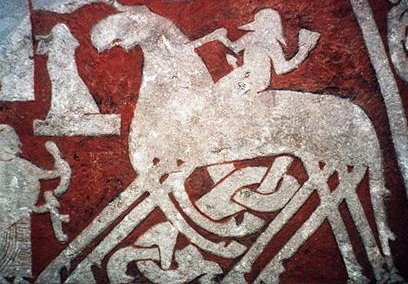

Превращение Водана-Одина в небесного и верховного бога связано не только с укреплением воинских союзов и повышением удельного веса бога — покровителя военных дружин (имелась даже упрощенная попытка представить Одина как «аристократического» бога — военного вождя — в противоположность «крестьянскому» богу Тору), но и с расщеплением первоначального представления о загробном мире и с перенесением на небо особого царства мертвых для избранных — смелых воинов, павших в бою. В качестве «хозяина» такого воинского «рая» (Вальхаллы) Один оказался важнейшим небесным божеством и сильно потеснил и Тюра, и Тора в функции богов и неба, и войны. Процесс превращения Одина в верховного небесного бога, по-видимому, завершился в Скандинавии. Здесь Один оставил заметные следы в топонимике (главным образом в названии водоемов, гор). Правда, если судить по современным толкованиям скандинавских наскальных изображений эпохи бронзы, в то время там еще не было отчетливого эквивалента Одина.

В дошедших до нас источниках по скандинавской мифологии Один — глава скандинавского пантеона, первый и главный ас (см. Асы), сын Бора (как и его братья Вили и Ве) и Бестлы, дочери великана Бёльторна, муж Фригг и отец других богов из рода асов. В частности, от Фригг у него сын Бальдр, а от любовных связей с Ринд и Грид сыновья Вали и Видар. Тор также считается сыном Одина.

Один выступает под многочисленными именами и прозвищами (см. список имён Одина), часто меняет обличья. Он живет в Асгарде в небесном жилище Гладсхейм, восседая там на престоле Хлидскьяльв. Также с Одином связывают крытый серебром Валаскьяльв.

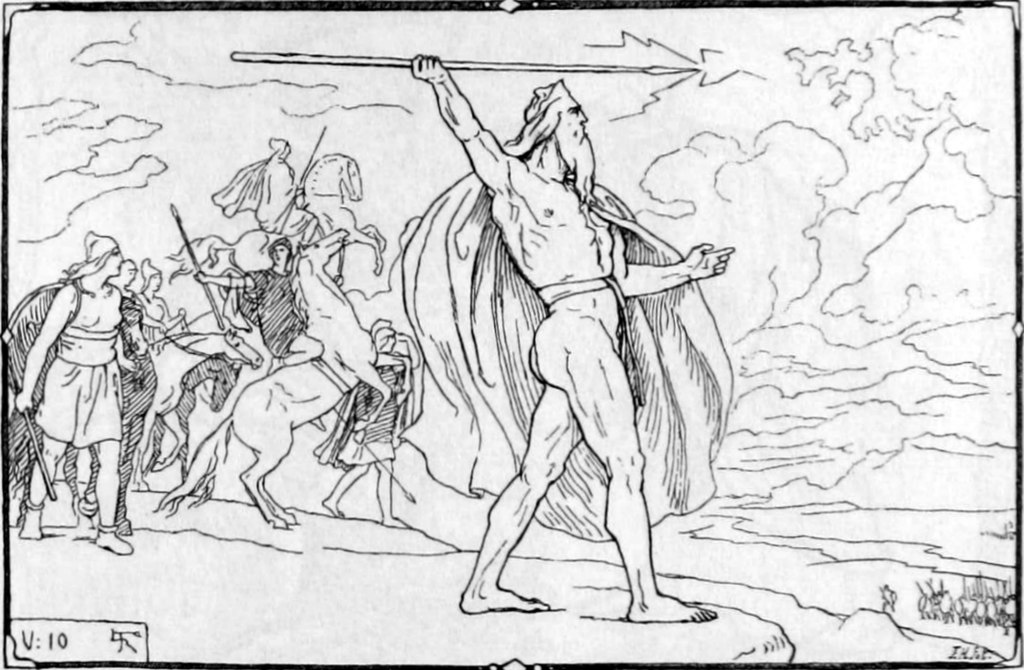

Один и на севере сохранил черты хтонического демона, ему служат хтонические звери — вороны и волки (известны, напр., имена его воронов — Хугин и Мунин, «думающий» и «помнящий»; волков — Гери и Фреки, «жадный» и «прожорливый»; Один кормит их мясом в Вальхалле); хтонические черты имеет и его восьминогий конь Слейпнир («скользящий»), на котором сын Одина — Хермод скачет в царство мёртвых Хель; он сам одноглаз (а судя по некоторым эпитетам, даже слеп), ходит в синем плаще и надвинутой на лоб широкополой шляпе. В небесном царстве мёртвых, где живет его дружина — павшие воины, ему подчинены воинственные валькирии, распределяющие по его приказу победы и поражения в битвах. Один — бог войны и военной дружины (в отличие от Тора, который, скорее, олицетворяет вооруженный народ), даритель победы и поражения (воинской судьбы), покровитель героев (в том числе Сигмунда и Сигурда), сеятель военных раздоров. Один, по-видимому, — инициатор первой войны (война между асами и ванами), он кидает копье в войско ванов. Копье (не дающий промаха Гунгнир) — символ военной власти и военной магии — постоянный атрибут Одина.

Как покровитель воинских инициации и жертвоприношений (особенно в форме пронзания копьем и повешения), Один, по-видимому, — скрытый виновник «ритуальной» смерти своего юного сына Бальдра (убийцу Бальдра — Хёда, возможно, следует толковать как ипостась самого Одина; «двойником» Одина отчасти является и подсунувший Хёду прут из омелы злокозненный Локи).

Один является инициатором распри конунгов Хёгни и Хедина из-за похищения Хедином дочери Хёгни по имени Хильд (см. Хедин и Хильд). Отец и муж Хильд во главе своих воинов сражаются, убивают друг друга, ночью Хильд их оживляет для новых битв. Эта битва т. н. хьяднингов напоминает эйнхериев, дружину Одина, которая также сражается, умирает и снова воскресает для новых битв.

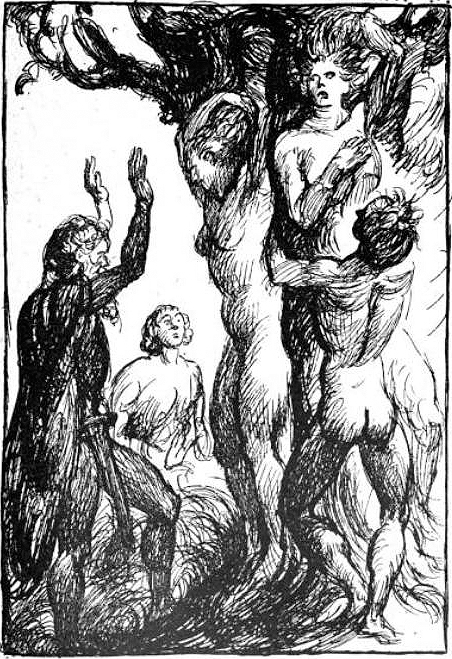

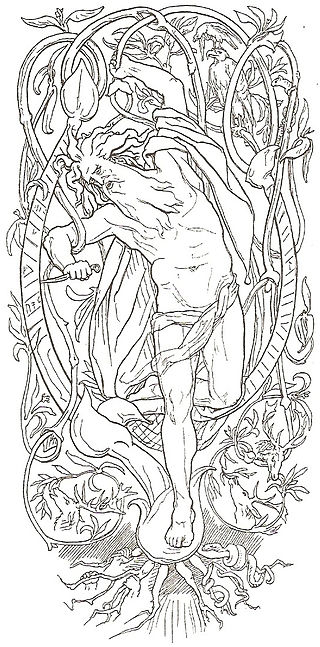

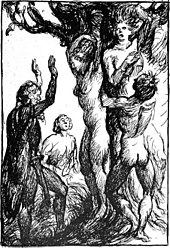

Один сам себя приносит в жертву, когда, пронзенный собственным копьем, девять дней висит на мировом древе Иггдрасиль, после чего утоляет жажду священным мёдом из рук дяди по матери, сына великана Бёльторна и получает от него руны — носители мудрости. Это «жертвоприношение» Одина, описанное в «Речах Высокого» в «Старшей Эдде», представляет, однако, не столько воинскую, сколько шаманскую инициацию. Это миф о посвящении первого шамана (ср. близкий сюжет в «Речах Гримнира»: Один под видом странника Гримнира, захваченный в плен конунгом Гейррёдом, восемь ночей мучается между двух костров, пока юный Агнар не дает ему напиться, после чего Один начинает вещать и заставляет Гейррёда упасть на свой меч). Шаманистский аспект Одина сильно разрастается на севере, может быть, отчасти под влиянием финско-саамского этнокультурного окружения. Шаманский характер имеет поездка Одина в Хель, где он пробуждает вёльву (пророчицу), спящую смертным сном, и выпытывает у нее судьбу богов [«Старшая Эдда», «Прорицание вёльвы» и «Песнь о Вегтаме» (или «Сны Бальдра»)]. Функция шаманского посредничества между богами и людьми сближает Одина с мировым древом, соединяющим различные миры. Последнее даже носит имя Иггдрасиль, что буквально означает «конь Игга» (т. е. конь Одина). Один — отец колдовства и колдовских заклинаний (гальдр), владелец магических рун, бог мудрости. Мудрость Одина отчасти обязана шаманскому экстазу и возбуждающему вдохновение шаманского мёду, который иногда прямо называется мёдом поэзии; его Один добыл у великанов. Соответственно Один мыслится и как бог поэзии, покровитель скальдов. В «Прорицании вёльвы» есть намек на то, что Один отдал свой глаз великану Мимиру за мудрость, содержащуюся в его медовом источнике. Правда, одновременно говорится и о Мимире, пьющим мёд из источника, в котором скрыт глаз Одина, так что можно понять, что сам глаз Одина, в свою очередь, — источник мудрости; Один советуется с мёртвой головой мудреца Мимира. Мудрость оказывается в чем-то сродни хтоническим силам, ибо ею обладают мертвый Мимир, пробужденная от смертного сна вёльва, сам Один после смертных мук на дереве или между костров. В мудрости Одина имеется, однако, не только экстатическое (шаманское), но и строго интеллектуальное начало. Один — божественный тул, т. е. знаток рун, преданий, мифических перечней, жрец. В «Речах Высокого» он вещает с «престола тула». Соревнуясь в мудрости, Один побеждает мудрейшего великана Вафтруднира. Гномика и дидактика (правила житейской мудрости, поучения) собраны в «Старшей Эдде» главным образом в виде изречений Одина («Речи Высокого», «Речи Гримнира») или диалогов Одина с Вафтрудниром, вёльвой.

Один — воплощение ума, не отделенного, впрочем, от шаманской «интуиции» и магического искусства, от хитрости и коварства. В «Песни о Харбарде» («Старшая Эдда») Один представлен умным и злым насмешником, который издевается над простодушным силачом Тором, стоящим на другом берегу реки и потому неопасным для Одина (последний под видом перевозчика Харбарда отказывается перевезти Тора через реку). Хитрость и коварство Одина резко отличают его от Тора и сближают его с Локи. Именно по инициативе Одина Локи похищает Брисингамен у Фрейи.

Один вместе с другими «сынами Бора» участвует в поднятии земли и устройстве Мидгарда, в составе троицы асов (вместе с Хёниром и Лодуром) находит и оживляет древесные прообразы первых людей (см. Аск и Эмбла). Кроме этого участия в космо- и антропогенезе, Один выступает также в качестве культурного героя, добывающего мёд поэзии. В «Младшей Эдде» также рассказывается о соревновании Одина в конной скачке с великаном Хрунгниром и об участии (совместно с Локи и Хёниром) в добывании клада карлика Андвари. В эсхатологической последней битве (Рагнарёк) Один сражается с волком Фенриром и побежден в этом поединке (волк проглатывает Одина); за него мстит сын Видар. С Одином в какой-то степени связаны и мотивы плодородия, о чем, возможно, свидетельствует такой его атрибут, как кольцо Драупнир («капающий»), порождающее себе подобных.

Саксон Грамматик в «Деяниях датчан» (нач. XIII в.) представляет Одина и других богов древнейшими королями. Он сообщает о том, что после измены Фригг Один ушел и место его временно занял Mythothyn. В другом месте «заместителем» Одина выступает бог Улль. В «Саге об Инглингах» Вили и Ве узурпируют власть в отсутствие Одина. Эти легенды о «заместителях» Одина конунга являются, по-видимому, реликтами культа царя-жреца и его ритуальной смены при одряхлении или племенном неблагополучии (неурожаи и т. п.). От Водана ведут свой род англосаксонские короли. Датский королевский род Скьёльдунгов (согласно англосаксонскому эпосу о Беовульфе) ведет свое происхождение от Скьёльда (др.-исл. Skjoldr, англосакс. Skyld) — сына Одина. Согласно «Саге о Вёльсунгах», Один стоит и у начала легендарного королевского рода Вёльсунгов, к которому принадлежит и Сигурд — знаменитый герой общегерманского эпоса (Нибелунги).

Этимология

От прото-норвежского ᚹᛟᛞᛁᚾᛦ (wodinz), от протогерманского *Wōdanaz, откуда также древнеанглийское Wōden, древнесаксонское Wōden, древневерхненемецкое Wuotan, Wodan. Относится к прилагательному óðr, буквально означающему «сумасшедший».

Отец богов

Бог Один (Вотан) — в германо-скандинавской мифологии верховное божество. Является отцом и предводителем асов.

Один — сын Бора и Бестлы, внук Бури. В некоторых источниках его называют “отцом колдовства”, мудрецом, шаманом, знатоком рун и сказов. Это одновременно жрец, воин и сказитель.

Вот что говорится в книге “Речи Гримнира”:

“Один ныне зовусь,

Игг звался прежде,

Тунд звался тоже,

Вак и Скильвинг,

Вавуд и Хрофтатюр,

Гаут и Яльк у богов,

Офнир и Свафнир,

но все имена

стали мной неизменно.”

Один — бог войны и победы. Он покровительствовал военной аристократии. Является хозяином Вальхаллы и повелителем валькирий.

В германо-скандинавских эсхатологических мифах говорится о том, что в день Рагнарёка Один погибнет в схватке с чудовищным волком Фенриром.

Кто такой Один

Один — верховный бог скандинавской мифологии. Скальды называли это божество Всеотцом — отцом всех богов и людей. На самом деле, Один не был отцом всем богам.

Вот, что написано в книге “Видение Гюльви”:

“Есть в Асгарде место Хлидскьяльв. Когда Один восседал там на престоле, видел он все миры и все дела людские, и была ему ведома суть всего видимого.”

По некоторым сведениям, Один и Тюр (древний небесный бог у скандинавов) дополняли друг друга. Они считались богами магической власти и права. Один в большей степени был, конечно, магом. Например, пока его тело лежало бездыханным, дух (хамингья) мог превратиться в зверя или в птицу. Это позволяло божеству проникать во все миры — всюду, куда только он пожелает.

Один охотно пользовался своей способностью к оборотничеству. Кроме того, Один мог легко потушить даже сильный огонь, усмирить море, повернуть ветер в нужную для него сторону.

Особенно охотно Один пользовался колдовством. С его помощью он вызывал из могилы мертвых и выведывал у них тайны мира. При необходимости он при помощи вредоносных мертвецов насылал на неугодных порчу. Еще Один мог легко отнимать силу у одних и передавать ее другим.

Это божество не брезговало даже ограблением древних курганов. При помощи специальных заклинаний он лишал мертвецов силы и отнимал их сокровища.

Мудрость и тайные знания дались Одину нелегко. Вот что говорится в книге “Речи Высокого”:

“Знаю, висел я

в ветвях на ветру

девять долгих ночей,

пронзенный копьем,

посвященный Одину,

в жертву себе же,

на дереве том,

чьи корни сокрыты

в недрах неведомых.

139 Никто не питал,

никто не поил меня,

взирал я на землю,

поднял я руны,

стеная их поднял —

и с древа рухнул.

140 Девять песен узнал я

от сына Бёльторна,

Бестли отца,

меду отведал

великолепного,

что в Одрёрир налит.

141 Стал созревать я

и знанья множить,

расти, процветая;

слово от слова

слово рождало,

дело от дела

дело рождало.

142 Руны найдешь

и постигнешь знаки,

сильнейшие знаки,

крепчайшие знаки,

Хрофт их окрасил,

а создали боги

и Один их вырезал”

В “Саге об Инглингах” Снорри Стурлусон писал, что колдовство — занятие недостойного благородного мужа и воина. Издревле колдовству обучались женщины-жрицы, но никак не мужчины. Колдовство, как и оборотничество, вообще не считалось занятием, достойным божества. Скорее, это был удел нечистой силы, или ведьм, которые превращались в тюленей, волков, или коней.

В эпоху постоянных кровопролитных битв, которая знаменовала Переселение народов, а также в век викингов, который завершил эти переселения, магия и воинская ярость оказались гораздо выше традиционного права. Таким образом Один оттеснил благородного Тюра и стал называться богом богов, или отцом всех богов.

Один и его братья создавали мир, и, по некоторым данным — были причастны к созданию людей.

Вот, что написано в книге “Видение Гюльви”:

“Шли сыновья Бора [Один, Хёнир и Лодур] берегом моря и увидали два дерева. Взяли они те деревья и сделали из них людей. Первый дал им жизнь и душу, второй — разум и движенье, третий — облик, речь, слух и зрение. Дали они им одежду и имена: мужчину нарекли Ясенем, а женщину Ивой. И от них-то пошел род людской, поселенный богами в стенах Мидгарда.”

А вот отрывок из Старшей Эдды. Книга называется “Прорицания Вельвы”:

“Они не дышали,

в них не было духа,

румянца на лицах,

тепла и голоса;

дал Один дыханье,

а Хёнир — дух,

а Лодур — тепло

и лицам румянец.”

Жену Одина в скандинавской мифологии зовут Фригг. Это богиня-провидица, и родоначальница рода асов.

Практически все дети Одина в скандинавской мифологии (кроме Тора, Видара и Бальдра) не были божествами, однако они присоединились к божественному миру. Другие дети Одина в скандинавской мифологии: Хёд, Хермод, Вали, Хеймдалль, и Браги. Считается также, что сыном Одина был родоначальник инглингов, Ингви.

Также Один именуется отцом павших (в мифологии часто говорится о сынах Одина — об эйнхериях). Это обусловлено тем, что воины, которые героически сражались на поле битвы, и погибли в бою, становились его приемными сыновьями.

Тор и Один в мифологии скандинавов имеют особое значение. Они — отец и сын, и оба будут принимать участие в последней битве богов, сражаясь на одной стороне.

Смерть Одина в мифологии достаточно драматична. Кто убил Одина в мифологии древних скандинавов? Согласно эсхатологическим легендам, в день Рагнарёк это сделал чудовищный волк Фенрир.

Внешний облик и характеристика

Отец Одина в скандинавской мифологии — Бор, сын Бури. История бога Одина в скандинавской мифологии начинается с того, что он вместе с братьями, Вили и Ве, убивают первовеликана Имира, из плоти которого произошел мир. Но он вовсе не был таким кровожадным. Это очень неоднозначное верховное божество.

У Одина много имен. Одно из них — Херьян (Воитель) свидетельствует о прочной связи этого божества с погибшими воинами. Другие имена Одина: Игг (Страшный), Хникар (Сеятель раздоров). Всех имен этого божества не знал никто.

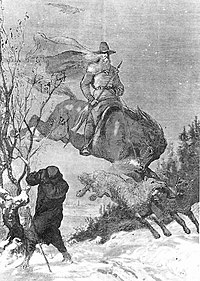

Один с легкостью изменял свой облик. Однако его обычно описывали как странника с посохом в руках. Он был одет в синий плащ, а на голове у него была широкополая шляпа, которую божество надвигало на лоб.

О том, почему у Одина один глаз, в скандинавской мифологии есть интересный сюжет. Верховное божество не всегда было таким мудрым, каким его знают. Однажды он услышал о существовании источника мудрости. Этот источник принадлежал злейшим врагам асов — великанам. Чтобы испить из него, Один и пожертвовал один глаз.

В скандинавской мифологии есть несколько версий того, как Один потерял свой глаз.

Согласно одной из версий, Один отправился в Йотунхейм, уже зная о жертве, которую ему предстоит сделать. По другой версии, он принял решение расстаться с глазом спонтанно. По третьей версии, он сделал это по требованию великанов.

Для павших героев Один построил в Асгарде два загробных чертога. Главным была великая Вальхалла (Вальгалла), которая также имела другое имя — Глядсхейм, зала мертвых. Другой чертог зался Вингольв, или “Обитель блаженства”, которая также должна была уцелеть после Рагнарёка. Интересно, что Вингольвом также именуется святилище богинь на небе. Вероятно, это не случайно. В древних источниках говорится, что одна из богинь поровну делила с Одином павших, и это была не Фригг, а Фрейя.

Древние скандинавы верили, что под видом бедного странника (в некоторых источниках — в образе уродливого карла) Один бродит по свету. Часто он, желая испытать того или иного человека, просится н ночлег, и горе тому, кто не пустит его на порог.

Также бытовали верования о том, что Один часто объезжает землю на своем коне, Слейпнире. В эпоху кровопролитных войн говорилось о том, что божество, оставаясь невидимым, принимало участие в сражениях, и помогало наиболее достойным воинам одержать победу.

Во многих историях скандинавской мифологии бог Один описан как существо, которое, в отличие от других божеств, не нуждается в пище. Живет он тем, что пьет мед, брагу, или вино.

Рим и Британия

В какой мифологии есть “аналог” бога Одина — Меркурий. По крайней мере, именно так его идентифицирует римский писатель и историк Тацит. Говоря о религии свевов (германцев), он писал, что “среди богов они в основном поклоняются Меркурию. Они считают своим религиозным долгом приносить ему в определенные дни человеческие, а также другие жертвы”. Тора Тацит именовал на римский манер — Геркулесом.

А вот, что пишет на эту тему Павел Диакон. История лангобардов. (Бенедиктинский монах, церковный писатель. 720 г. н.э.) (Источник: Текст -Кузнецова Т. И. Перевод — Тhietmar):

“И тем не менее верно то, что лангобарды, первоначально называвшиеся винилами, впоследствии получили свое название от длинных бород, не тронутых бритвой. Ведь на их языке слово «lang» означает «длинный», a «bart» – борода» . А Годан, которого они, прибавив одну букву, называли Гводаном, это тот самый, кто у римлян зовется Меркурием и кому поклонялись как богу все народы Германии, не наших, однако, времен, а гораздо более древних. И не Германии он собственно принадлежит, а Греции.”

По мнению исследователя скандинавских мифов, Э.Бирли, идентификация Одина с Меркурием связана с тем, что оба эти божества были странниками. Оба изображались одетыми в длинный плащ, оба, отправляясь в дальнее странствие, брали с собой посох.

При размышлениях о боге Одине, и о том, кто это в мифологии, нельзя не упомянуть о том, что в древнеанглийской литературе сохранились упоминания о нем, как об основателе древнеанглийской королевской семьи.

Прямо или косвенно Один несколько раз упоминается в сохранившихся древнеанглийских текстах — в частности в заклинании “Девять трав” и в древнеанглийской рунической поэме.

Предположительно, упоминания об этом божестве содержится в одной из загадок в древнеанглийской поэме “Соломон и Сатурн”. Также упоминания об Одине содержатся в древнеанглийской гномической поэме “Максимы I” в аллитерационной фразе «Woden worhte weos».

В “Заговоре девяти трав” Один представлен убийцей некоего страшного дракона. Стихотворение датируется 9 столетием, и считается одним из самых загадочных древнеанглийских текстов.

Вот, что говорится в строфе, в которой упоминается Один (Воден):

“Wyrm com snican, toslat he man;

ða genam Woden VIIII wuldortanas,

Sloh ða þa næddran, heo on VIIII tofleah.

Крадучись червь пришел, но не сгубил никого он,

Воден взял эти стебли, девять побегов славы,

И от удара аспид на девять [частей] распался.”

Дальше рассказывается о том, как были созданы две волшебные травы — фенхель и кервель. В стихотворении говорится, что их создал некий мудрец, когда висел в небесах.

Эти травы он подарил человечеству. Этот текст ассоциируется с Одином, потому что он пошел на самопожертвование (ритуальное самоповешение) во имя знаний.

В одной из древнеанглийских рунических поэм был описан рунический алфавит. С Одином была связана руна Ос:

“Os byþ ordfruma ælere spræce,

wisdomes wraþu ond witena frofur

and eorla gehwam eadnys ond tohiht.

Бог — источник всей речи,

мудрости столп и мудрым утеха,

дар и надежда герою.”

Первое слово в этой строфе является омофоном древнеанглийского слова os, что означало “языческий бог”.

Есть предположение. что поэма цензурировалась, и изначально речь в ней шла именно об Одине.

По словам Кэтлин Герберт, “Os родственно скандинавскому As, т.е. один из асов, верховного племени богов”.

В поэме “Соломон и Сатурн” говорится о Меркурии-Великане, который изобрел буквы. Вероятно, здесь также речь идет об Одине: именно Один в мифологии Скандинавии был первооткрывателем рунических алфавитов. Сама поэма была написана в стиле поздних скандинавских песней, участником которых было это божество — в частности, в стиле “Речей Вафтруднира”. Это произведение рассказывало о том, как однажды Один вступил в смертельный поединок с великаном Вафтрудниром, и победил его.

В письменном памятнике 9 столетия из Майнца (Германия), который известен как “Древнесаксонская крестильная клятва”, говорится о трех древних саксонских божествах, одним из которых был Один (Воден).

В Мерзебурге (Германия) была обнаружена рукопись, датируемая 10 столетием. В этой рукописи находилось так называемое Второе Мерзебургское заклинание. Там к Одина и некоторых других божеств из пантеона континентальных германских племен призывали, чтобы они помогли вылечить коня:

“Phol ende uuodan uuoran zi holza.

du uuart demo balderes uolon sin uuoz birenkit.

thu biguol en sinthgunt, sunna era suister,

thu biguol en friia, uolla era suister

thu biguol en uuodan, so he uuola conda:

sose benrenki, sose bluotrenki, sose lidirenki:

ben zi bena, bluot si bluoda,

lid zi geliden, sose gelimida sin!

Пфол и Водан выехали в рощу.

Тут Бальдеров жеребчик вывихнул бабку.

Заклинала Синтгунт с Сунною-сестрицей;

Заклинала Фрия с Фоллою-сестрицей;

Заклинал и Водан; заговор он ведал

От полома кости, от потока крови, от вывиха членов.

Склейся кость с костью, слейся кровь с кровью,

К суставу сустав, как слепленный, пристань[25].”

Культ божества был распространен даже в раннем средневековье.

Атрибуты Одина

В скандинавской мифологии у бога Одина есть следующие атрибуты:

- Скидбладнир. Это самый быстрый в мире корабль. В мифах говорится о том, что удивительное судно способно вместить любое количество воинов. Однако, при необходимости корабль можно сложить напополам и спрятать в кармане;

- Слейпнир. Это волшебный восьминогий конь божества, на котором оно путешествует между мирами. Это самый быстрый конь в мире, и его бег не может замедлить ни одна из стихий;

- Гунгнир. Легендарное копье Одина, способное поразить любую цель, пробить самый толстый щит и разбить на куски даже самый закаленный меч.

Один, едущий верхом на Слейпнире, стал особым образом.

Вот, что говорится в Саге о Хервёр и Хейдреке:

“Тогда сказал Гестумблинди:

Что это за двое,

у которых десять ног,

три глаза

и один хвост?

Конунг Хейдрек,

думай над загадкой.

— Это Один скачет на Слейпнире.”

Когда боги и герои собираются на пиршество в Вальхалле, у ног Одина ложатся два свирепых волка, которых зовут Гери и Фреки. А на плечах у божества сидят два ворона, Хугин и Мунин, которые рассказывают ему обо всем, что происходит во всех мирах.

Еще у Одина есть священный престол, который называется Хлидскьяльв. Этимология точно неизвестна: возможно, это название обозначает утес или отверзающуюся скалу. Самым главным является то, что с этой скалы божество может обозревать все миры. Это роднит престол Одина с мировым древом.

Кстати, гора Одина является распространенным названием урочищ у древних германцев: в очень давние времена там существовали его святилища.

Происхождение среды

Имя Одина (Вотана) восходит в древнегерманскому корню wut, что буквально обозначает “воинственный”, или “буйство”.

По мнению мифологов и культурологов, у древних германцев существовало единство религиозных представлений. Свидетельством этого стали названия дней недели. Семидневную неделю германцы переняли у римлян. Но названия дней они заменили именами своих богов.

Среда, которая досталась Одину (у римлян среда была днем Меркурия), дословно переводится с древнегерманского как “День Одина”. В связи с этим можно предположить, что не римляне отождествляли скандинавское божество с Меркурием, а наоборот — германцы отождествляли римского бога со своим Одином.

Некоторые научные теории

Бог Один в скандинавской мифологии часто является героем научных исследований. Например, ему посвятил свою докторскую диссертацию Генри Петерсен. Он предположил, что Один был более поздним божеством, покровительствовавшим вождям и поэтам.

По мнению других исследователем, Один в мифологию и историю скандинавов из легенд других народов. Считается, что родиной Одина является юго-восточная Европа, и что первые упоминания о нем встречаются в легендах железного века. По мнению других ученых, Один — персонаж, появившийся в результате галльского влияния.

В 16 столетии считалось, что Один был первым шведским королем. Такое мнение высказывалось и во времена правления Карла IX.

Исследуя функции Одина и его атрибутику, некоторые скандинавоведы интерпретировали его как божество ветра или смерти.

Есть легенда, что название племени лангобардов происходит “От Одина”. Вот, что говорит на эту тему Павел Диакон. История лангобардов. (Бенедиктинский монах, писатель. 720 г. н.э.) (Источник: Текст -Кузнецова Т. И. Перевод — Тhietmar):

“Старое предание рассказывает по этому поводу забавную сказку: будто бы вандалы обратились к Годану с просьбой даровать им победу над винилами и он ответил им, что даст победу тем, кого прежде увидит при восходе солнца. После этого, будто бы Гамбара обратилась к Фрее, супруге Годана, и умоляла ее о победе для винилов. И Фрея дала совет приказать винильским женщинам распустить волосы по лицу так, чтобы они казались бородой, затем, с утра пораньше, вместе со своими мужьями, выйти на поле сражения и стать там, где Годан мог бы их увидеть, когда он, по обыкновению, смотрит утром в окно. Все так и случилось. Лишь только Годан при восходе солнца увидел их, как спросил: «Кто эти длиннобородые?» Тогда Фрея и настояла на том, чтобы он даровал победу тем, кого сам наделил именем. И таким образом Годан даровал победу винилам”.

Адам Бременский:

“Теперь скажем несколько слов о верованиях свеонов. У этого племени есть знаменитое

святилище, которое называется Убсола и расположено недалеко от города Сиктоны. Храм сей

весь украшен золотом, а в нем находятся статуи трех почитаемых народом богов. Самый

могущественный из их богов-Top — восседает на престоле в середине парадного зала, с одной

стороны от него — Водан, с другой — Фриккон. Вот как распределяются их полномочия: «Тор,

— говорят свеоны, — царит в эфире, он управляет громами и реками, ветрами и дождями,

ясной погодой и урожаями. Водан, что означает «ярость», — бог войны, он возбуждает

мужество в воинах, сражающихся с неприятелем. Третий бог — Фриккон — дарует смертным мир

и наслаждения. Последнего они изображают с огромным фаллосом. Водана же свеоны

представляют вооруженным, как у нас обычно Марса. А Тор напоминает своим скипетром

Юпитера. Они также почитают обожествленных людей, даря им бессмертие за славные деяния.”

Современный фольклор

Легенды об Одине бытовали в Скандинавии даже в 19 столетии. Он, конечно, уже не был тем грозным божеством. Но истории о боге Одина в скандинавской мифологии “перекочевали” в фольклор.

Люди называли его “Одином Старым”. В Швеции у крестьян была традиция обязательно оставлять на поле большой сноп для лошадей Одина.

Также существуют примечательные сведения о некоем кургане, который был обнаружен в 18 столетии. Согласно местным поверьям, там лежало тело Одина. В быличках рассказывается и о том, что в момент, когда курган раскрыли, вспыхнул яркий огонь, подобный молнии.

Есть другая легенда, записанная Бенджамином Торпом. Одна из местных легенд гласила, что некий человек однажды посеял рожь на поле. Когда она взошла, с холма спустился Один. Он был настолько огромен, что возвышался над всеми постройками фермерского хозяйства. В течение нескольких ночей грозный призрак никому не позволял ни входить, ни выходить из жилищ. Так продолжалось до тех пор, пока всю рожь не собрали.

Также Торп пишет следующее: в Швеции, “когда ночью слышен шум, подобный шуму экипажей и лошадей, люди говорят: “Один проходит мимо”.

В позднесредневековых балладах рассказывается о том, как Один, бог скандинавской мифологии, а также Локи и Хенир помогли некоему мальчику, на которого напали ётуны.

Один в мифах и легендах

Один и другие божества — главные герои скандинавских мифов. Одна из известных легенд гласит, как Один побывал у вёльвы.

Вот что пишется об этом в книге “Прорицание вёльвы”:

“Внимайте мне все

священные роды,

великие с малыми

Хеймдалля дети!

О́дин, ты хочешь,

чтоб я рассказала

о прошлом всех сущих,

о древнем, что помню.”

Прорицание вёльвы:

“Она колдовала

тайно однажды,

когда князь асов

в глаза посмотрел ей:

«Что меня вопрошать?

Зачем испытывать?

Знаю я, Один,

где глаз твой спрятан:

скрыт он в источнике

славном Мимира!»

Каждое утро

Мимир пьет мед

с залога Владыки —

довольно ли вам этого?”

Состязание в мудрости с существами из других миров не было для богов праздным развлечением. Победитель в таком состязании признавался повелителем мироздания, которому угрожали чудовища и великаны.

Поездка к великанам с целью состязания в мудрости была трудной задачей дажа для Одина, и поэтому он посоветовался с Фригг о том, стоит ли ему ехать к самому мудрому ётуну — Вафтрудниру.

Фригг, как могла, предостерегала мужа от этой поездки. Стоит сказать, она тревожилась не напрасно. Само слово “ётуна” означает “сильный в обмане”.

Когда Один приезжает на место и сообщает великану о том, что хотел бы состязаться с ним и постичь все его познания, тот разгневался. Он сообщил Одину, что вступит с ним в поединок, и горе ему, если он его не выиграет: живым ему в этом случае не уйти.

Один прекрасно знал, что в чужом, враждебном мире он не должен называться собственным именем. Поэтому он представился именем Ганград, что означает “Правящий победой”. Проявив смирение, “как бедный в доме богатого”, Один ответил сердитому великану, что готов ответить на все его вопросы.

Ётун тут же начал задавать Одину вопросы о мироздании. Тот прекрасно знал ответы, потому что сам принимал участие в создании мира. Великан вынужденно признал, что его гость обладает серьезными познаниями, и предложил ему сесть. Но к мирной беседе это не привело: великан предложил поспорить, кто мудрее, а на кон поставить свои головы.

Один согласился, и сам начал спрашивать обо всем ётуна. Тот легко отвечал на вопросы о том, каким образом был сотворен мир из тела Имира — ведь он сам был первобытным великаном.

Один в свою очередь признал, что его противник очень мудр, и поинтересовался, откуда он вообще имеет все эти сведения. Выяснилось, что ётун, также, как и Один, смог проникнуть во все миры, и даже спускался в Нифльхель.

И вот, Один принялся выспрашивать у великана о грядущих временах. Вероятно, именно это и было истинной целью его путешествия. Великан рассказал ему о том, что произойдет после того, как мир погибнет. Рассказал он и о том, какие потомки асов уцелеют, и кто отомстит за смерть самого Одина.

Один отчаянно нуждался в этих ответах, потому что Рагнарёк приближался, и Бальдр уже пил свой мед в Хельхейме…В конце-концов, Один достает свой козырь, и спрашивает у великана, что он шепнул Бальдру, когда тот лежал на погребальном костре. В этот момент ётун узнал Одина, и признал свое поражение.

Смысл этого мифа заключается не в том, что божество победило великана, а в том, как он это сделал, и что в итоге получил. Этот сюжет является одной из песней Старшей Эдды. Считается, что песнь исполнялась людьми, которые также жаждали постичь высшую мудрость.

Вероятно, она представляла собой живой диалог, который состоял из вопросов и ответов. Также считается, что в языческие времена, когда “Эдда” еще не была собранием увлекательных мифов, этот диалог имел ритуальный характер.

Он исполнялся в храме двумя жрецами, и происходило все это во время языческих празднеств — вероятнее всего, во время главного годового праздника, в канун Нового года: считалось, что именно в это время все судьбы открыты для будущего.

Сокровенные знания, которые добыл Один, достались людям. Он вообще достаточно охотно помогал смертным и покровительствовал им: лучшие из них становились героями и пополняли его дружину, во главе которой он должен был выйти на свою последнюю битву. Но эти знания часто были очень тяжкими — как и встречи с божеством.

Кстати, Один еще не раз бился на свою голову. В “Младшей Эдде” рассказывается, как он соревновался с Хрунгниром в конской скачке. Один посетил в Ётунхейме Хрунгнира и побился с ним об заклад на свою голову, что ни один конь великанов не сможет сравниться в беге со Слейпниром. Великан, как и следовало ожидать, тут же разъярился. И началась бешеная скачка.

Один прискакал в Асгард первым, но Хрунгнир каким-то образом тоже проскользнул в ворота…

Один в мире людей

В “Старшей Эдде” находится целый моральный кодекс викингов, создание которого древние скандинавы приписывали Одину, или Высокому, как иногда называл он себя.

В “Речах Высокого” содержится вся мудрость раннего средневековья. там находятся советы, как осматривать входы в своем жилище (а вдруг там затаился враг?), а также — полезные нравоучения.

В “Речах Высокого” Один постепенно раскрывает свою сущность. Он произносит краткую проповедь о пользе воздержания, но тут же дает советы мужчинам о том, как им следует вести себя с хитрыми девицами. В одном из мифов Один и сам попался на обман. В древней легенде рассказывается о том, как Один назначил красивой девушке любовную встречу. Та пообещала прийти, но не пришла. Придя на свидание, огорченный Один обнаружил только собаку, которая, поскуливая, лежала возле лежбища.

Исследуя “Речи Высокого”, можно найти интересные сведения о “взаимоотношениях” людей и богов. Закон язычества гласил, что эти отношения основывались на обмене. Причем, Один делал все, чтобы этот обмен не был равноценным.

Вот что говорится о коварстве божества в книге “Речи Высокого”:

“Клятву Один

дал на кольце;

не коварна ли клятва?

Напиток достал он

обманом у Суттунга

Гуннлёд на горе.

Пора мне с престола

тула поведать

у источника Урд.”

Завершаются “Речи Высокого” перечислением заклинаний, которые были известны только одному Одину. Особенно интересными кажутся два заклинания. Одно из них было направлено на того, кто собирался навести порчу при помощи кореньев: заклинание приводило к его смерти. Второе не позволяло ведьмам-оборотням вернуть себе человеческий облик.

Интересным и страшным кажется двенадцатое заклинание: оно сопровождается вырезанием рун под деревом, на котором висит повешенный. Один говорил, что после этого заклинания мертвец оживет и расскажет все тайны иного мира. Он знал, о чем говорил: недаром его также называли богом повешенных.

Пятнадцатое заклинание Один получил от некоего карлика. К сожалению, миф об этом странном событии потерялся. Интересным представляется то, что карлик является ночным хтоническим существом. Рискуя жизнью, он должен был сообщить Одину сокровенные знания: Один считался родителем Дня, а днем, под воздействием солнечных лучей, карлики в скандинавской мифологии превращались в камни. Только эта угроза могла заставить волшебное существо, враждебное богам, поделиться с ними тайным знанием.

Всего заклинаний восемнадцать. Это число считается священным (2 раза по 9). Сам поэтический перечень должен был способствовать запоминанию этой мифопоэтической системы заклятий. Все-таки, недаром Один называл себя тулом — жрецом-прорицателем.

Еще одна песня

В одной из песен рассказывается, как Один, оказавшись в мире людей, поначалу представился беспомощным стариком. В этой истории он попал в ловушку и не могу не только освободиться от пут, но и защититься от пыток. Разумеется, это была только игра: бог ждал от своих почитателей той самой мудрости, которой обучал их.

В “Старшей Эдде” рассказывается о том, как двух детей некоего конунга, которых звали Гейррёд и Ангар, унесло в лодке в открытое море. Лодка разбилась, и обоих детей приютили старик со старухой. Одного мальчика опекал старик, а второго — старуха. Когда наступила весна, старик что-то шепнул Гейррёду. Братья сели в лодку, и когда она достигла берега, Гейррёд вышел из лодки и проклял брата, сказав ему: “Плыви туда, где возьмут тебя тролли!”. После этого он вернулся в землю своего отца-конунга, которого уже не было в живых, и сам стал конунгом.

Это была предыстория. Через какое-то время Один и Фригг сидели в Асгарде осматривали все миры. В этот момент Один спросил Фригг, знает ли она, что произошло с ее воспитанником, Ангаром. Когда Фригг ответила отрицательно, Один злорадно ответил, что тот женился на великанше, в то время, как его воспитанник стал конунгом.

Один и Фригг часто соперничали. Ангар был потомком конунга и воспитанником самой Фригг (теми стариком и старухой были они с Одином), и связь с дикой великаншей была для него оскорбительной…

Но Фригг в долгу не осталась и парировала тем, что воспитанник ее супруга настолько скуп. что морит голодом гостей. Один поддался на провокацию и, приняв облик старика, отправился в мир людей — навестить Гейррёда.

Тем временем Фригг отправила в мир людей свою служанку Фуллу, которая должна была предупредить Гейррёда о том, что к нему явится злой колдун. Узнать этого колдуна можно было по тому, что на него не нападают собаки.

Конунг захватил гостя, который назвался Гримниром (Скрывающийся под маской) в плен и подверг его пытке огнем и голодом. Плен длился восемь лет.

У Гейррёда был сын, которого он, согласно древнему обычаю, назвал в честь брата, которого считал умершим (все, кого отправляли к троллям, считались умершими). Юный Ангар пожалел старика и дал ему напиться, за что тот предрек тому долгую и счастливую жизнь.

А далее божество сделало то, чего никогда не делало в мире великанов — оно открыло свое настоящее имя.

В итоге Гейррёд встретил свою смерть: услышав имя Одина, он вскочил. В его руке был полуобнаженный меч, который выскользнул из ножен, и конунг споткнулся. Он упал на меч и умер, а его сын Ангар стал конунгом.

Несмотря на весь свой гнев, Один проявил великодушие по отношению к бывшему воспитаннику. Смерть конунга все-таки была смертью от оружия, хотя и напоминала гибель от проклятия, которое накладывалось на клятвопреступников. Но одновременно это была жертвенная смерть — посвящение Одину.

Мед поэзии

Однажды Один решил раздобыть мед поэзии. С этой целью он отправился в Ётунхейм и увидел, как на лугу трудятся девять косарей. Достав точило, он наточил им косы, да так хорошо, что они принялись упрашивать его отдать чудесное точило им.

Один начал торговаться, но договориться им не удавалось. Тогда он бросил точило в воздух, и косари бросились за ним. Коварный трюк удался: все работники перерезали себе горла косами и погибли.

Хозяин луга, Брауги, увидев своих косарей мертвыми, принялся сетовать и жаловаться. В этот момент к нему явился Один, и назвался вполне достойным его именем — Бёльверк, что в переводе означает “Злодей”. Он предложил себя в качестве работника, причем сказал, что будет работать за девятерых. Платой же должен был стать один глоток меда поэзии. Брауги согласился: волшебный мед хранился у его брата, и он обещал помочь достать его.

Один работал все лето, но Суттунг (хранитель меда) ни в какую не соглашался поделиться им. Тогда Один пошел на очередную хитрость. Он затеял очередное состязание, и едва не погиб, но ему помогло его умение менять обличия. Улучив момент, он превратился в змею, и проник туда, где сидела девушка, которая сторожила мед поэзии. Тут Один принял облик привлекательного молодого человека, и соблазнил ее. Он провел с ней три ночи, и, весьма довольная, великанская дева угостила возлюбленного вожделенным медом. Один выпил три глотка, причем, осушил несколько сосудов. После этого он превратился в орла и полетел в Асгард.

Узнав об обмане, Суттунг тоже превратился в орла и принялся преследовать Одина. Увидев, что он уже подлетает, асы подставили сосуд, в который верховный бог выплюнул мед. В этот миг Суттунг уже почти настиг его, и Один выпустил часть меда через задний проход. Этот — несобранный — мед достался рифмоплетам. А мед подлинной поэзии достался асам и скальдам.

В мифе не рассказывается о том, что произошло с Суттунгом. Вероятно, ему пришлось какое-то время простоять у ворот Асгарда. Возможно, потом асам надоело слушать его гневные вопли и брань, и они пригрозили ему, что сейчас придет Тор. Это подействовало: своя голова была дороже, чем мед поэзии. Суттунг от всей души пожелал асам подавиться и улетел к себе в Ётунхейм.

Миф о дикой охоте

Один — не только мифологический образ и верховное божество. Это еще и культурный герой: именно он дал людям руны и добыл мед поэзии.

В “Младшей Эдде” рассказывается о том, что Один, оседлав своего коня, вместе со свитой часто носится по миру. Происходит это, разумеется, темными зимними вечерами. Зачем он это делает — загадка. В поздних легендах говорится, что он собирает души людей.

С течением времени образ пугающей Дикой охоты трансформировался в культуре многих народов — в том числе и в культуре западных славян. В некоторых регионах Дикую охоту возглавлял не Один, а Фригг.

Odin (;[1] from Old Norse: Óðinn) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was also known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Uuôden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, in Old Frisian as Wêda, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōðanaz, meaning ‘lord of frenzy’, or ‘leader of the possessed’.

Odin appears as a prominent god throughout the recorded history of Northern Europe, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania (from c. 2 BCE) through movement of peoples during the Migration Period (4th to 6th centuries CE) and the Viking Age (8th to 11th centuries CE). In the modern period, the rural folklore of Germanic Europe continued to acknowledge Odin. References to him appear in place names throughout regions historically inhabited by the ancient Germanic peoples, and the day of the week Wednesday bears his name in many Germanic languages, including in English.

In Old English texts, Odin holds a particular place as a euhemerized ancestral figure among royalty, and he is frequently referred to as a founding figure among various other Germanic peoples, such as the Langobards, while some Old Norse sources depict him as an enthroned ruler of the gods. Forms of his name appear frequently throughout the Germanic record, though narratives regarding Odin are mainly found in Old Norse works recorded in Iceland, primarily around the 13th century. These texts make up the bulk of modern understanding of Norse mythology.

Old Norse texts portray Odin as the son of Bestla and Borr along with two brothers, Vili and Vé, and he fathered many sons, most famously the gods Thor (with Jörð) and Baldr (with Frigg). He is known by hundreds of names. Odin is frequently portrayed as one-eyed and long-bearded, wielding a spear named Gungnir or appearing in disguise wearing a cloak and a broad hat. He is often accompanied by his animal familiars—the wolves Geri and Freki and the ravens Huginn and Muninn, who bring him information from all over Midgard—and he rides the flying, eight-legged steed Sleipnir across the sky and into the underworld. In these texts he frequently seeks greater knowledge, most famously by obtaining the Mead of Poetry, and makes wagers with his wife Frigg over his endeavors. He takes part both in the creation of the world by slaying the primordial being Ymir and in giving life to the first two humans Ask and Embla. He also provides mankind knowledge of runic writing and poetry, showing aspects of a culture hero. He has a particular association with the Yule holiday.

Odin is also associated with the divine battlefield maidens, the valkyries, and he oversees Valhalla, where he receives half of those who die in battle, the einherjar, sending the other half to the goddess Freyja‘s Fólkvangr. Odin consults the disembodied, herb-embalmed head of the wise Mímir, who foretells the doom of Ragnarök and urges Odin to lead the einherjar into battle before being consumed by the monstrous wolf Fenrir. In later folklore, Odin sometimes appears as a leader of the Wild Hunt, a ghostly procession of the dead through the winter sky. He is associated with charms and other forms of magic, particularly in Old English and Old Norse texts.

The figure of Odin is a frequent subject of interest in Germanic studies, and scholars have advanced numerous theories regarding his development. Some of these focus on Odin’s particular relation to other figures; for example, Freyja‘s husband Óðr appears to be something of an etymological doublet of the god, while Odin’s wife Frigg is in many ways similar to Freyja, and Odin has a particular relation to Loki. Other approaches focus on Odin’s place in the historical record, exploring whether Odin derives from Proto-Indo-European mythology or developed later in Germanic society. In the modern period, Odin has inspired numerous works of poetry, music, and other cultural expressions. He is venerated with other Germanic gods in most forms of the new religious movement Heathenry; some branches focus particularly on him.

Name[edit]

Etymological origin[edit]

The Old Norse theonym Óðinn (runic ᚢᚦᛁᚾ on the Ribe skull fragment)[2] is a cognate of other medieval Germanic names, including Old English Wōden, Old Saxon Wōdan, Old Dutch Wuodan, and Old High German Wuotan (Old Bavarian Wûtan).[3][4][5] They all derive from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic masculine theonym *Wōðanaz (or *Wōdunaz).[3][6] Translated as ‘lord of frenzy’,[7] or as ‘leader of the possessed’,[8] *Wōðanaz stems from the Proto-Germanic adjective *wōðaz (‘possessed, inspired, delirious, raging’) attached to the suffix *-naz (‘master of’).[7]

Woðinz (read from right to left), a probably authentic attestation of a pre-Viking Age form of Odin, on the Strängnäs stone.

Internal and comparative evidence all point to the ideas of a divine possession or inspiration, and an ecstatic divination.[9][10] In his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (1075–1080 AD), Adam of Bremen explicitly associates Wotan with the Latin term furor, which can be translated as ‘rage’, ‘fury’, ‘madness’, or ‘frenzy’ (Wotan id est furor : «Odin, that is, furor«).[11] As of 2011, an attestation of Proto-Norse Woðinz, on the Strängnäs stone, has been accepted as probably authentic, but the name may be used as a related adjective instead meaning «with a gift for (divine) possession» (ON: øðinn).[12]

Other Germanic cognates derived from *wōðaz include Gothic woþs (‘possessed’), Old Norse óðr (‘mad, frantic, furious’), Old English wōd (‘insane, frenzied’) and Dutch woed (‘frantic, wild, crazy’), along with the substantivized forms Old Norse óðr (‘mind, wit, sense; song, poetry’), Old English wōþ (‘sound, noise; voice, song’), Old High German wuot (‘thrill, violent agitation’) and Middle Dutch woet (‘rage, frenzy’), from the same root as the original adjective. The Proto-Germanic terms *wōðīn (‘madness, fury’) and *wōðjanan (‘to rage’) can also be reconstructed.[3] Early epigraphic attestations of the adjective include un-wōdz (‘calm one’, i.e. ‘not-furious’; 200 CE) and wōdu-rīde (‘furious rider’; 400 CE).[10]

Philologist Jan de Vries has argued that the Old Norse deities Óðinn and Óðr were probably originally connected (as in the doublet Ullr–Ullinn), with Óðr (*wōðaz) being the elder form and the ultimate source of the name Óðinn (*wōða-naz). He further suggested that the god of rage Óðr–Óðinn stood in opposition to the god of glorious majesty Ullr–Ullinn in a similar manner to the Vedic contrast between Varuna and Mitra.[13]

The adjective *wōðaz ultimately stems from a Pre-Germanic form *uoh₂-tós, which is related to the Proto-Celtic terms *wātis, meaning ‘seer, sooth-sayer’ (cf. Gaulish wāteis, Old Irish fáith ‘prophet’) and *wātus, meaning ‘prophesy, poetic inspiration’ (cf. Old Irish fáth ‘prophetic wisdom, maxims’, Old Welsh guaut ‘prophetic verse, panegyric’).[9][10][14] According to some scholars, the Latin term vātēs (‘prophet, seer’) is probably a Celtic loanword from the Gaulish language, making *uoh₂-tós ~ *ueh₂-tus (‘god-inspired’) a shared religious term common to Germanic and Celtic rather than an inherited word of earlier Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origin.[9][10] In the case a borrowing scenario is excluded, a PIE etymon *(H)ueh₂-tis (‘prophet, seer’) can also be posited as the common ancestor of the attested Germanic, Celtic and Latin forms.[6]

Other names[edit]

More than 170 names are recorded for Odin; the names are variously descriptive of attributes of the god, refer to myths involving him, or refer to religious practices associated with him. This multitude makes Odin the god with the most known names among the Germanic peoples.[15] Professor Steve Martin has pointed out that the name Odinsberg (Ounesberry, Ounsberry, Othenburgh)[16] in Cleveland Yorkshire, now corrupted to Roseberry (Topping), may derive from the time of the Anglian settlements, with nearby Newton under Roseberry and Great Ayton[17] having Anglo Saxon suffixes. The very dramatic rocky peak was an obvious place for divine association, and may have replaced Bronze Age/Iron Age beliefs of divinity there, given that a hoard of bronze votive axes and other objects was buried by the summit.[18][19] It could be a rare example, then, of Nordic-Germanic theology displacing earlier Celtic mythology in an imposing place of tribal prominence.

In his opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, Richard Wagner refers to the god as Wotan, a spelling of his own invention which combines the Old High German Wuotan with the Low German Wodan.[20]

Origin of Wednesday[edit]

The modern English weekday name Wednesday derives from Old English Wōdnesdæg, meaning ‘day of Wōden’. Cognate terms are found in other Germanic languages, such as Middle Low German and Middle Dutch Wōdensdach (modern Dutch woensdag), Old Frisian Wērnisdei (≈ Wērendei) and Old Norse Óðinsdagr (cf. Danish, Norwegian, Swedish onsdag). All of these terms derive from Late Proto-Germanic *Wodanesdag (‘Day of Wōðanaz’), a calque of Latin Mercurii dies (‘Day of Mercury’; cf. modern Italian mercoledì, French mercredi, Spanish miércoles).[21][22]

Attestations[edit]

Roman era to Migration Period[edit]

One of the Torslunda plates. The figure to the left was cast with both eyes, but afterwards the right eye was removed.[23]

The earliest records of the Germanic peoples were recorded by the Romans, and in these works Odin is frequently referred to—via a process known as interpretatio romana (where characteristics perceived to be similar by Romans result in identification of a non-Roman god as a Roman deity)—as the Roman god Mercury. The first clear example of this occurs in the Roman historian Tacitus’s late 1st-century work Germania, where, writing about the religion of the Suebi (a confederation of Germanic peoples), he comments that «among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship. They regard it as a religious duty to offer to him, on fixed days, human as well as other sacrificial victims. Hercules and Mars they appease by animal offerings of the permitted kind» and adds that a portion of the Suebi also venerate «Isis». In this instance, Tacitus refers to the god Odin as «Mercury», Thor as «Hercules», and Týr as «Mars». The «Isis» of the Suebi has been debated and may represent «Freyja».[24]

Anthony Birley noted that Odin’s apparent identification with Mercury has little to do with Mercury’s classical role of being messenger of the gods, but appears to be due to Mercury’s role of psychopomp.[24] Other contemporary evidence may also have led to the equation of Odin with Mercury; Odin, like Mercury, may have at this time already been pictured with a staff and hat, may have been considered a trader god, and the two may have been seen as parallel in their roles as wandering deities. But their rankings in their respective religious spheres may have been very different.[25] Also, Tacitus’s «among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship» is an exact quote from Julius Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico (1st century BCE) in which Caesar is referring to the Gauls and not the Germanic peoples. Regarding the Germanic peoples, Caesar states: «[T]hey consider the gods only the ones that they can see, the Sun, Fire and the Moon», which scholars reject as clearly mistaken, regardless of what may have led to the statement.[24]

There is no direct, undisputed evidence for the worship of Odin/Mercury among the Goths, and the existence of a cult of Odin among them is debated.[26] Richard North and Herwig Wolfram have both argued that the Goths did not worship Odin, Wolfram contending that the use of Greek names of the week in Gothic provides evidence of that.[27] One possible reading of the Gothic Ring of Pietroassa is that the inscription «gutaniowi hailag» means «sacred to Wodan-Jove», but this is highly disputed.[26]

Although the English kingdoms were converted to Christianity by the 7th century, Odin is frequently listed as a founding figure among the Old English royalty.[28]

Odin is also either directly or indirectly mentioned a few times in the surviving Old English poetic corpus, including the Nine Herbs Charm and likely also the Old English rune poem. Odin may also be referenced in the riddle Solomon and Saturn. In the Nine Herbs Charm, Odin is said to have slain a wyrm (serpent, European dragon) by way of nine «glory twigs». Preserved from an 11th-century manuscript, the poem is, according to Bill Griffiths, «one of the most enigmatic of Old English texts». The section that mentions Odin is as follows:

|

+ wyrm com snican, toslat he nan, |

A serpent came crawling (but) it destroyed no one |

The emendation of nan to ‘man’ has been proposed. The next stanza comments on the creation of the herbs chervil and fennel while hanging in heaven by the ‘wise lord’ (witig drihten) and before sending them down among mankind. Regarding this, Griffith comments that «In a Christian context ‘hanging in heaven’ would refer to the crucifixion; but (remembering that Woden was mentioned a few lines previously) there is also a parallel, perhaps a better one, with Odin, as his crucifixion was associated with learning.»[29] The Old English gnomic poem Maxims I also mentions Odin by name in the (alliterative) phrase Woden worhte weos, (‘Woden made idols’), in which he is contrasted with and denounced against the Christian God.[30]

The Old English rune ós, which is described in the Old English rune poem

The Old English rune poem recounts the Old English runic alphabet, the futhorc. The stanza for the rune ós reads as follows:

|

ōs byþ ordfruma ǣlcre sprǣce |

god is the origin of all language |

The first word of this stanza, ōs (Latin ‘mouth’) is a homophone for Old English os, a particularly heathen word for ‘god’. Due to this and the content of the stanzas, several scholars have posited that this poem is censored, having originally referred to Odin.[32] Kathleen Herbert comments that «Os was cognate with As in Norse, where it meant one of the Æsir, the chief family of gods. In Old English, it could be used as an element in first names: Osric, Oswald, Osmund, etc. but it was not used as a word to refer to the God of Christians. Woden was equated with Mercury, the god of eloquence (among other things). The tales about the Norse god Odin tell how he gave one of his eyes in return for wisdom; he also won the mead of poetic inspiration. Luckily for Christian rune-masters, the Latin word os could be substituted without ruining the sense, to keep the outward form of the rune name without obviously referring to Woden.»[33]

In the prose narrative of Solomon and Saturn, «Mercurius the Giant» (Mercurius se gygand) is referred to as an inventor of letters. This may also be a reference to Odin, who is in Norse mythology the founder of the runic alphabets, and the gloss a continuation of the practice of equating Odin with Mercury found as early as Tacitus.[34] One of the Solomon and Saturn poems is additionally in the style of later Old Norse material featuring Odin, such as the Old Norse poem Vafþrúðnismál, featuring Odin and the jötunn Vafþrúðnir engaging in a deadly game of wits.[35]

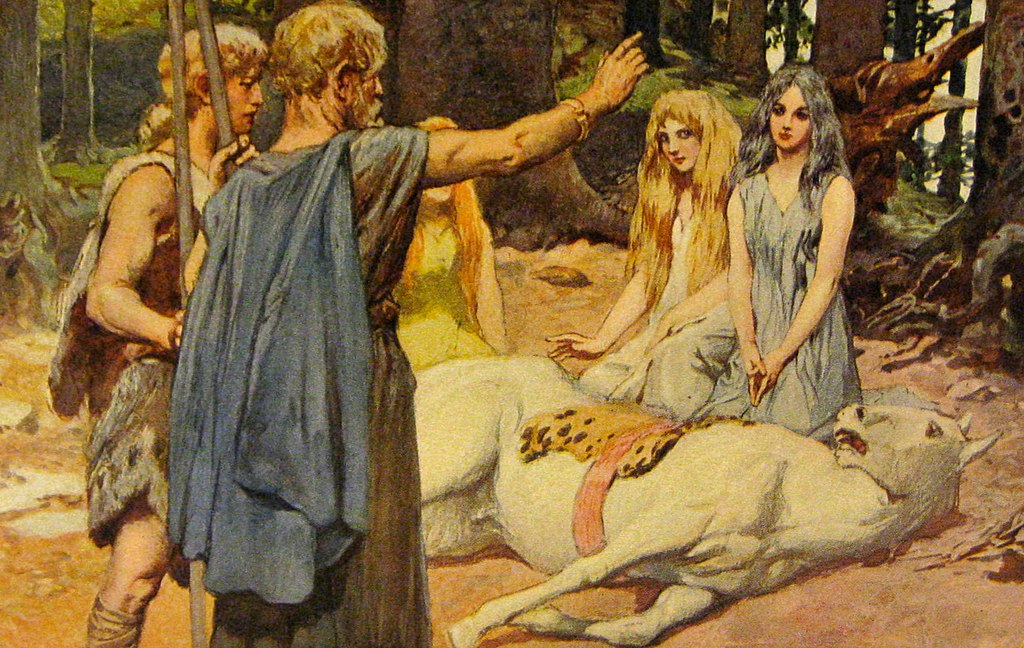

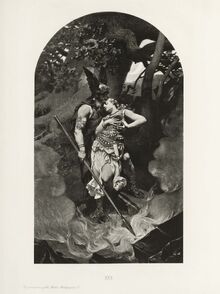

Odin and Frea look down from their window in the heavens to the Winnili women in an illustration by Emil Doepler, 1905

Winnili women with their hair tied as beards look up at Godan and Frea in an illustration by Emil Doepler, 1905

The 7th-century Origo Gentis Langobardorum, and Paul the Deacon’s 8th-century Historia Langobardorum derived from it, recount a founding myth of the Langobards (Lombards), a Germanic people who ruled a region of the Italian Peninsula. According to this legend, a «small people» known as the Winnili were ruled by a woman named Gambara who had two sons, Ybor and Aio. The Vandals, ruled by Ambri and Assi, came to the Winnili with their army and demanded that they pay them tribute or prepare for war. Ybor, Aio, and their mother Gambara rejected their demands for tribute. Ambri and Assi then asked the god Godan for victory over the Winnili, to which Godan responded (in the longer version in the Origo): «Whom I shall first see when at sunrise, to them will I give the victory.»[36]

Meanwhile, Ybor and Aio called upon Frea, Godan’s wife. Frea counselled them that «at sunrise the Winnil[i] should come, and that their women, with their hair let down around the face in the likeness of a beard should also come with their husbands». At sunrise, Frea turned Godan’s bed around to face east and woke him. Godan saw the Winnili and their whiskered women and asked, «who are those Long-beards?» Frea responded to Godan, «As you have given them a name, give them also the victory». Godan did so, «so that they should defend themselves according to his counsel and obtain the victory». Thenceforth the Winnili were known as the Langobards (‘long-beards’).[37]

Writing in the mid-7th century, Jonas of Bobbio wrote that earlier that century the Irish missionary Columbanus disrupted an offering of beer to Odin (vodano) «(whom others called Mercury)» in Swabia.[38] A few centuries later, 9th-century document from what is now Mainz, Germany, known as the Old Saxon Baptismal Vow records the names of three Old Saxon gods, UUôden (‘Woden’), Saxnôte, and Thunaer (‘Thor’), whom pagan converts were to renounce as demons.[39]

Odin Heals Balder’s Horse by Emil Doepler, 1905

A 10th-century manuscript found in Merseburg, Germany, features a heathen invocation known as the Second Merseburg Incantation, which calls upon Odin and other gods and goddesses from the continental Germanic pantheon to assist in healing a horse:

|

Phol ende uuodan uuoran zi holza. |

Phol and Woden travelled to the forest. |

Viking Age to post-Viking Age[edit]

A 16th-century depiction of Norse gods by Olaus Magnus: from left to right, Frigg, Odin, and Thor